Federal Court of Australia

Firstmac Limited v Zip Co Limited [2023] FCA 540

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ZIPMONEY PAYMENTS PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and within seven days of the making of these Orders provide to the Associate to Markovic J proposed orders giving effect to these reasons.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the proposed orders referred to in Order 1 above, including the appropriate order as to costs, the areas of disagreement should be set out in mark up in the draft to be provided.

3. In the event that the parties are unable to agree on the proposed orders the proceeding be listed for case management hearing on 6 June 2023 at 9.30 am AEST for argument on the form of orders.

4. The text of the reasons for judgment published today is to be published and disclosed only to the parties and their legal advisors.

5. By midday AEST on 31 May 2023 the parties are to inform the Associate to Markovic J whether:

(a) the proposed redactions (shown in yellow highlight) at [344] of and Annexure B to the reasons published in accordance with Order 4 above are to be maintained having regard to the Orders of the Court made on 9 March 2022 (s 37AF Orders); and

(b) they propose any further redactions as a result of the s 37AF Orders.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

6. The reasons for judgment will be published on 1 June 2023 at 9.00 am AEST and any redactions made in the reasons are made in accordance with the s 37AF Orders which remain in place for 14 days from the date of publication of these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

[7] | |

[7] | |

[9] | |

[14] | |

[19] | |

[33] | |

[37] | |

[53] | |

[58] | |

[61] | |

[63] | |

[80] | |

[95] | |

[98] | |

[106] | |

[116] | |

[129] | |

[140] | |

[145] | |

[148] | |

[153] | |

[158] | |

[163] | |

[165] | |

[170] | |

[172] | |

[176] | |

[178] | |

[182] | |

[188] | |

[194] | |

[198] | |

[208] | |

[225] | |

[226] | |

[229] | |

[237] | |

Section 122(1)(a) of the TM Act: use of own name in good faith | [272] |

[285] | |

[300] | |

[304] | |

[307] | |

[312] | |

[353] | |

[365] | |

[366] | |

[367] | |

Is use of the Applicant’s Mark likely to deceive or cause confusion? | [371] |

Should the Register be rectified by cancellation of the Applicant’s Mark? | [379] |

[396] | |

[401] | |

[405] | |

[413] | |

[414] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MARKOVIC J:

1 Firstmac Limited, the applicant, is part of the Firstmac group of companies (Firstmac Group). The Firstmac Group is Australia’s largest non-bank lender and provides a number of financial products and services including home loans, car loans and investment funds.

2 Firstmac is and has been the registered owner of trade mark no. 1021128 (Applicant’s Mark) for the word ZIP in respect of “financial affairs (loans)” in class 36 (Services) since 20 September 2004.

3 Zip Co Limited and Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd, the first and second respondents respectively (who I will refer to collectively as the Zip Companies), operate a predominantly closed loop retail platform which is a point-of-sale unsecured line of credit product for retail consumers and a service provider, including a provider of digital payment services, to retail businesses. The platform is predominantly closed loop because it can only be used by consumers with a Zip account (Customers) to pay for goods and services from a merchant who has been accredited by, and has a contractual relationship with, Zipmoney Payments (Merchant).

4 As described below the Zip Companies promote their services under the trade mark ZIP or variants of it such as ZIP MONEY and ZIP PAY, including stylised versions of that branding. It is that fact which has led to this proceeding.

5 In summary:

(1) Firstmac alleges that by the Zip Companies’ use of ZIP and other variants of it as a trade mark they have infringed the Applicant’s Mark contrary to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act). The Zip Companies admit that the name and trade mark ZIP is substantially identical to the Applicant’s Mark and admit infringement by use of that mark subject to their defences, their cross-claim and their application for non-use. They otherwise deny that they have infringed the Applicant’s Mark by reason of their use of the ZIP mark in its stylised forms or the variants thereof either in plain or stylised form;

(2) in their defence, the Zip Companies plead positive defences under s 122 of the TM Act. They contend that they have not infringed the Applicant’s Mark because they used in good faith their own name (s 122(1)(a) of the TM Act) and/or they would obtain registration of the mark if one or other of them was to apply for it either on the basis of honest concurrent use or because of other circumstances it would be proper to do so (ss 122(1)(f) and (fa) of the TM Act). The Zip Companies also contend that Firstmac is precluded from obtaining relief because of estoppel, acquiescence, delay and/or laches;

(3) by their cross-claim the Zip Companies seek rectification of the Register of Trade Marks by cancellation of the Applicant’s Mark pursuant to s 88(2)(c) of the TM Act because as at 15 August 2019, the date on which the cross-claim was filed, Firstmac’s use of the Applicant’s Mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion as a result of the Zip Companies’ reputation and goodwill at that time; and

(4) a (second) non-use application filed by the Zip Companies with the Registrar has been referred to the Court for determination. In that application the Zip Companies contend that Firstmac did not at any time from 22 February 2016 to 22 February 2019 (second non-use period) use the Applicant’s Mark in Australia in relation to the Services or use it in good faith.

6 On 15 July 2019 I ordered that all issues of quantum and of any pecuniary relief are to be heard and determined separately from and after all issues of liability.

7 Firstmac led evidence from the following witnesses:

(1) David Gration who is the general manager, sales and operations of Firstmac. Mr Gration joined Firstmac in December 2011 by which time he had over 20 years’ experience in retail banking including in senior management roles at the National Australia Bank and Suncorp. Prior to his current role Mr Gration held the following roles at Firstmac: from about 2 December 2019 to 9 November 2013, head of legal, risk and compliance; from about 19 November 2013 to 23 November 2015, general manager sales and marketing; and from about 23 November 2015 to 19 July 2017, general manager sales and marketing. Mr Gration also acted in the position of managing director of Loans.com.au Pty Ltd, a member of the Firstmac Group, when the person who held that role was on maternity leave. Mr Gration was cross-examined;

(2) Tiska Sudarmana who is the product manager of Firstmac. Ms Sudarmana commenced her employment with Firstmac in February 2012 in the role of customer services officer. Insofar as that role was customer-facing, she was responsible for providing support or explanation to borrowers who contacted Firstmac with inquiries in relation to, for example, changes in interest rates, different repayment types and queries about refinancing existing loans to a different lender. Since February 2016 she has had the role of product manager. In that role she oversees a small team responsible for preparing and distributing product specifications which set out details of Firstmac’s new financial products and services and updates for existing products. She is also responsible for reviewing and approving any requests from originators, brokers, aggregators or managers for product variations. Ms Sudarmana was cross-examined;

(3) Samantha Elizabeth Pendrey who since 4 March 2019 has held the role of retail sales team leader with Loans.com.au. In that role Ms Pendrey assists in the day to day management of her team of about 23 sales staff in the promotion of the financial products and services offered by Loans.com.au. Prior to taking on her current role Ms Pendrey held the following roles: from about 27 February 2017 to 2 August 2018 she was a lending manager, which required her to speak to customers, i.e. potential or existing borrowers, to promote the financial products and services offered by Loans.com.au; and from 2 August 2018 to 4 March 2019 she was a senior lending manager, a role in which she had the same responsibilities as her previous role but with additional responsibilities. Ms Pendrey was not cross-examined; and

(4) Jacqueline Jessica Chelabian, a solicitor in the employ of Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd, Firstmac’s solicitors, who gave evidence about trade mark searches she undertook of the databases maintained by the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office and the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand and in relation to printouts obtained from the Wayback Machine of IP Australia’s website. Ms Chelabian was not cross-examined.

8 The Zip Companies led evidence from the following witnesses:

(1) Peter Gray who is chief operations officer, co-founder and a director of Zip Co and a director of Zipmoney Payments. Together with Larry Diamond, Mr Gray has been and is responsible for the commercial functions and operations of Zipmoney Payments. He also oversees the day to day operational and administrative functions of the business operated by Zip Co. For much of his career, commencing in 1990, Mr Gray worked in the finance industry. Most recently and prior to founding Zipmoney Payments he worked at Australia Finance Direct for about 12 years including as general manager for four years. Mr Gray was cross-examined; and

(2) Mr Diamond who is managing director, chief executive officer and co-founder of Zip Co and Zipmoney Payments and a director of Zipmoney Payments. Prior to founding the Zip Companies Mr Diamond worked for about 12 years in retail, information technology (IT), corporate finance and investment banking including in that period for Pacific Brands, Macquarie Capital and Deutsche Bank. Mr Diamond was cross-examined.

9 As set out above, Firstmac is part of the Firstmac Group. That group comprises several companies and trusts including Firstmac Origination Pty Ltd, Loans.com.au and www.Loans.com.au Pty Ltd. Firstmac’s financial products and services, broadly described at [1] above, are promoted, offered and provided to customers through two distribution channels. First, by Firstmac accredited mortgage brokers who promote and offer for sale its financial products under Firstmac’s corporate branding; and secondly, by mortgage originators, such as Loans.com.au, and mortgage managers who provide a direct retail channel and promote Firstmac’s financial products under the corporate branding of the particular originator or mortgage manager.

10 Each of the mortgage brokers, mortgage managers and mortgage originators within the distribution channels work with members of Mr Gration’s team at Firstmac who, in turn, report to him. That enables Mr Gration to monitor and evaluate the success of the distribution channel in promoting and offering Firstmac’s products and to make executive decisions such as determining which of Firstmac’s products are to be offered, or are to continue to be offered, to certain distribution channels and the specifications of the products.

11 Over the last 40 years Firstmac has provided over 100,000 home loans. It currently manages $12 billion in mortgages and $250 million in cash investments. Firstmac self-funds its operations through the release of highly rated residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS) and has issued more than $20 billion in RMBS bonds since 2003. The Firstmac Group has also received international ratings agency Standard & Poor’s highest possible ranking for loan serviceability.

12 Firstmac has offices in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, with its head office located in Brisbane. There are approximately 200 staff members located at Firstmac’s head office of whom around 140 are employees of Firstmac and around 60 are employees of Loans.com.au. Relevant managers at Firstmac and Loans.com.au, including those working with mortgage brokers, mortgage managers and mortgage originators ultimately report to Mr Gration in relation to the products that are promoted and marketed by Firstmac and, on its behalf, by Loans.com.au. The nature of the reports Mr Gration receives include:

(1) the number of home loans “sold”, which is the number of home loan applications filed;

(2) the value of those applications;

(3) the number of applications that proceed to approval;

(4) the quality of the applications received; and

(5) the performance of loans, prior to and after settlement. This identifies the number of loan applications which have been correctly or falsely completed and whether there are, and if so, the details of, any default in the repayment of a loan by a borrower.

These reports allow Mr Gration to monitor and evaluate the success of Firstmac’s products.

13 In his current role as general manager of sales and operations, Mr Gration oversees the sales and operations of Firstmac’s products and services and the retail and third-party sales of those products and services through the different distribution channels. In particular:

(1) for matters pre-settlement he provides sales and support, focusing on the processing of Firstmac’s products and services through to settlement or the establishment of new services. He also approves the structure and requirements of Firstmac’s products and the final form of any documents, such as rate sheets, sent within the Firstmac Group and to third parties and oversees and monitors all matters from the point-of-sale to approval of an application;

(2) for matters post-settlement, he provides contact centre support which focuses on queries about Firstmac’s products and services, queries about accounts and repayments and queries about the variations to terms of Firstmac’s products and oversees loan administration and the collection teams and business functions, including monitoring and reviewing the progress of home loans and any defaults in payments; and

(3) he oversees the IT team, which builds the systems and supports the underlying infrastructure for Firstmac to offer and provide its products and services, and the legal team.

Firstmac’s products and services

14 Firstmac’s financial products and services are promoted, funded, serviced and managed by Firstmac and, in part, depending on the distribution channel, through its originators, such as mortgage brokers, mortgage managers and mortgage originators, under origination and management agreements with Firstmac.

15 Mr Gration describes the various originators referred to in the preceding paragraph as follows:

(1) mortgage brokers are an intermediary who broker mortgage loans on behalf of Firstmac and its competitors. The broker prepares the loan application and submits it to Firstmac for its approval. Once the loan is approved and settled the borrower’s ongoing servicing relationship for the term of the loan is directly with Firstmac;

(2) mortgage managers promote and offer Firstmac products under their own corporate branding, process loan applications through to approval and settlement by Firstmac and then service the loan until such time as it is repaid in full. The mortgage manager remains the intermediary between the borrower and Firstmac during the term of the loan; and

(3) mortgage originators are similar to mortgage managers in that they promote and offer Firstmac products under their own corporate branding and process loan applications through to approval and settlement by Firstmac. However, Firstmac then services the loan. It does so under the corporate branding of the mortgage originator, until such time as the loan is repaid in full. The mortgage originator relies on Firstmac to take on all aspects of the home loan process from the date of settlement. This requires a backend IT banking system which allows Firstmac to provide the funding, ongoing servicing and management of the home loans, including generating statements, and meeting compliance and reporting requirements. Borrowers are provided with various telephone numbers, depending on the nature of their query, some of which are dealt with by Firstmac employees who respond to incoming inquiries as representatives of the mortgage originator.

16 Firstmac Origination operates Firstmac’s mortgage origination program under the control and direction of Firstmac. All mortgage originators and mortgage managers enter into an origination and management agreement with Firstmac Origination.

17 Firstmac also conducts all collection activities for its mortgage managers and mortgage originators and takes on the primary role of communicating and dealing with a borrower when the borrower has defaulted on a repayment.

18 Firstmac creates, structures and funds its products. This includes setting the requirements for each product and outlining any policies to ensure that any loan application complies with those requirements and Firstmac can ensure that any credit arranged by it through its mortgage managers and mortgage originators is not unsuitable for the borrower. Mr Gration explained that credit will usually be considered unsuitable where the borrower cannot pay or can only pay the credit with substantial hardship or the credit will not meet the borrower’s requirements and objectives. Firstmac is required to approve any changes to its products and to approve any loan application filed on behalf of a borrower.

Firstmac’s ZIP home loan – 2005 to 2014

19 Mr Gration understands that Firstmac first promoted and offered home loan products and services, such as term loans and lines of credit, under and by reference to the Applicant’s Mark in early 2005 (I will refer to this product as the original ZIP home loan).

20 The original ZIP home loan comprised a suite of home loan products including ZIP Fulldoc LOC, ZIP Fulldoc Term Loan, ZIP LoDoc LOC, ZIP LoDoc Term Loan, ZIP NoDoc LOC and ZIP NoDoc Term Loan. The terms “Fulldoc”, “LoDoc”, “NoDoc”, “LOC” and “Term Loan” are descriptive of the type of loan product being offered and are, as explained by Mr Gration, common terms in the trade. Fulldoc, LoDoc and NoDoc mean “full documentation”, “low documentation” and “no documentation” loans respectively and LOC and Term Loan mean “line of credit” or standard time based “term” loans respectively.

21 The original ZIP home loans require ongoing management and servicing, including the maintenance and operation of borrowers’ accounts for the loan and the direct debit card loan. The original ZIP home loans have a maximum term of 30 years and, for the line of credit options, a ZIP Visa account (with a ZIP Visa debit card) which can be used by the borrower, for example, to pay off regular bills and living expenses, and a redraw option, which means that the borrower has the option to pay off the loan more quickly, plus redraw up to the loan balance limit for the term of the loan. These features require an ongoing commercial relationship between Firstmac, the mortgage manager/mortgage originator and the borrower, where the originator is a mortgage manager or mortgage originator, and an ongoing relationship between Firstmac and the borrower directly, where the originator is a mortgage broker.

22 The pricing and terms of ZIP home loans are reviewed by Firstmac to remain competitive for potential new borrowers, for current borrowers to avoid them seeking to refinance the loans with another institution and for originators to encourage them to take on and market the ZIP home loans.

23 The original ZIP home loans were promoted up until early 2014 to originators such as Certified Mortgage Services Pty Ltd and Allied Mortgage Corporation by means of product rate sheets, product brochures and product training PowerPoint presentations.

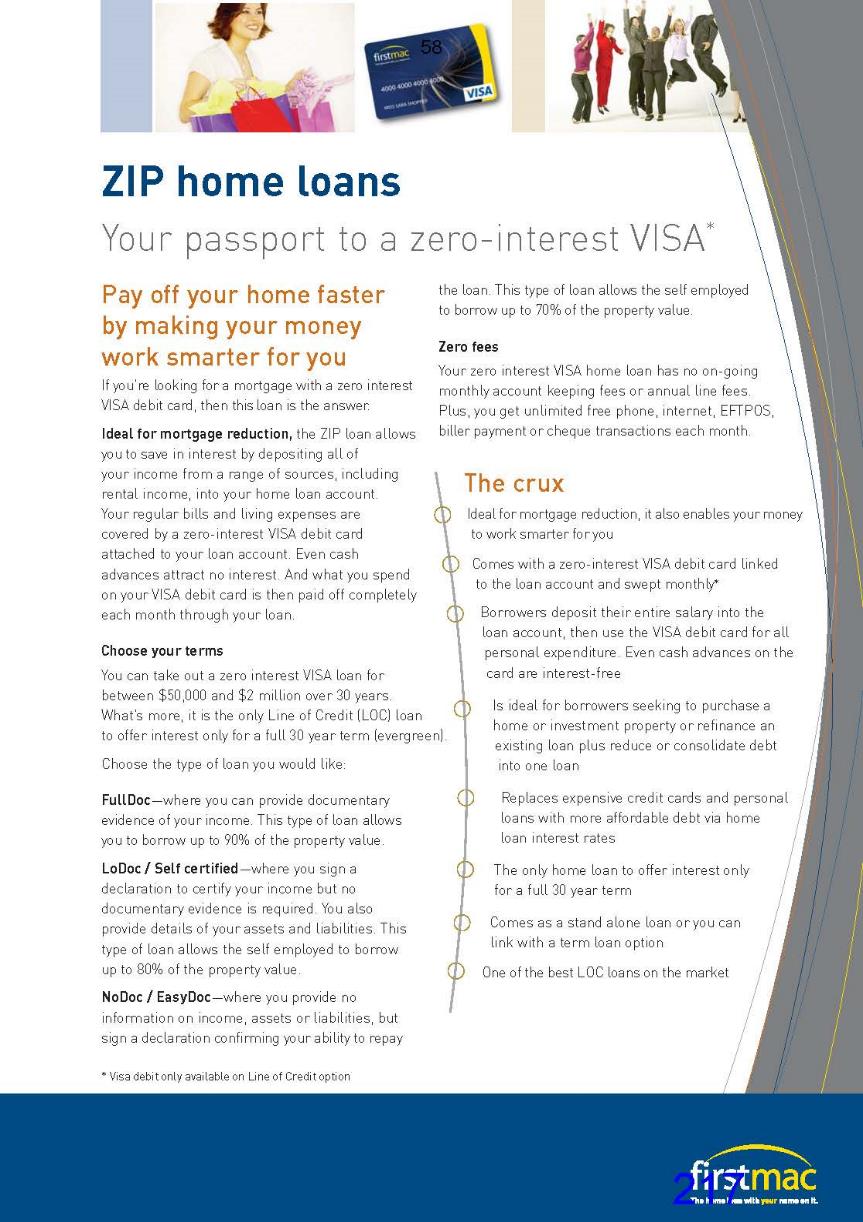

24 An example of an original ZIP home loan product sheet distributed to mortgage brokers and mortgage managers appears as follows:

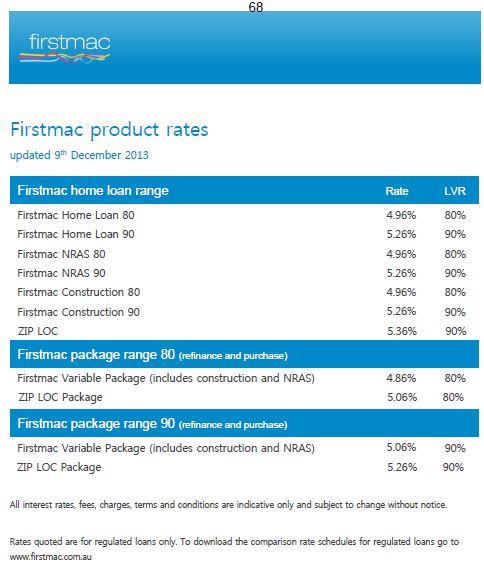

25 An example of a rate sheet dated 9 December 2013 distributed to originators to inform them of applicable interest rates and loan to value ratios for products is as follows:

The rate sheets were not provided to consumers.

26 In accordance with the practice described at [21] above, ZIP home loans settled by Firstmac through its mortgage brokers are managed and serviced by Firstmac. During the term of the loan Firstmac issues statements, correspondence and other information to each borrower which, according to Mr Gration, bear the Applicant’s Mark. Examples of these documents, some of which appear below, were in evidence before me.

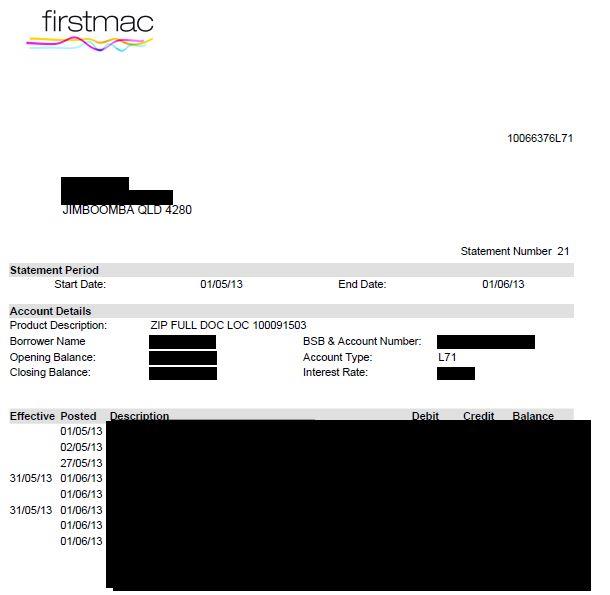

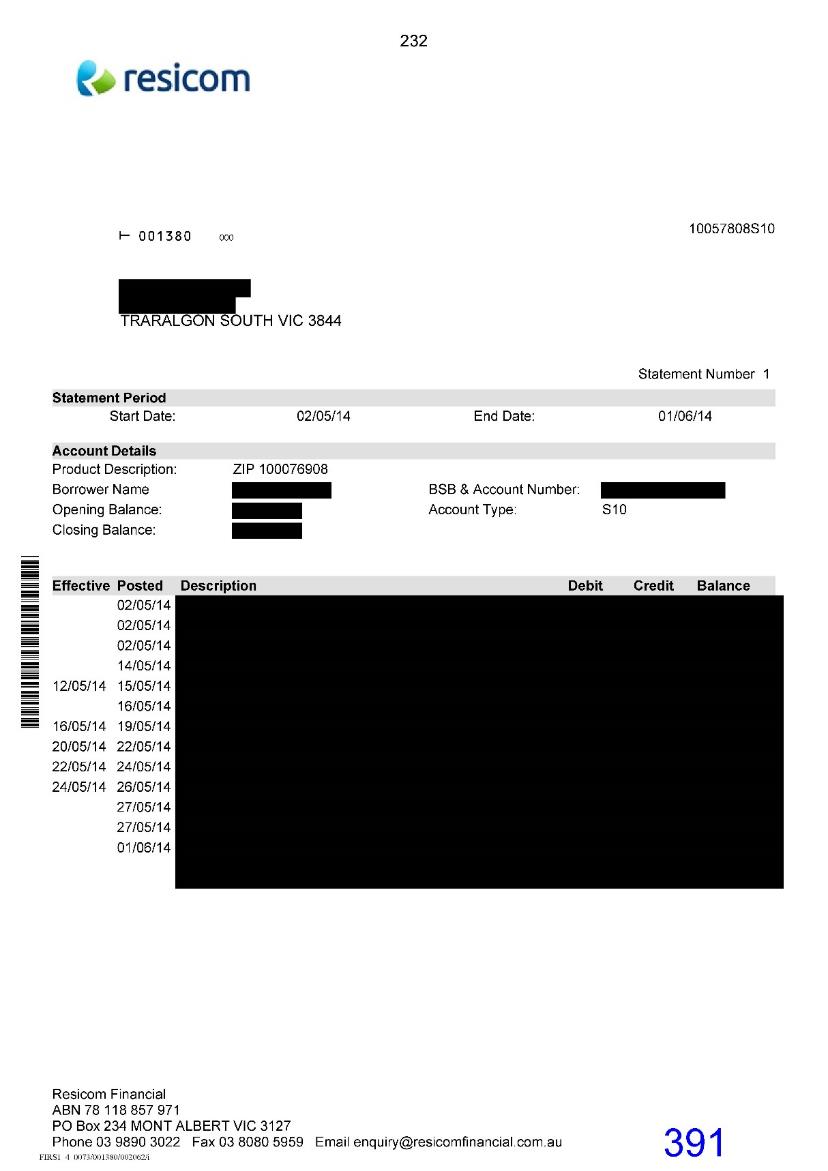

27 Statements for interest only loans are issued by Firstmac monthly and statements for principal and interest loans are issued by Firstmac every six months. Customers with ZIP home loans, including the original ZIP home loans, receive two statements, one for the debit card loan split (for the ZIP Visa) and one for the main loan split. Depending on when the loan was written, and the particular features of the loan, the loan splits are referred to differently in the statements. An example of a statement for the “ZIP FULL DOC LOC” appears as follows (with all identifying information redacted):

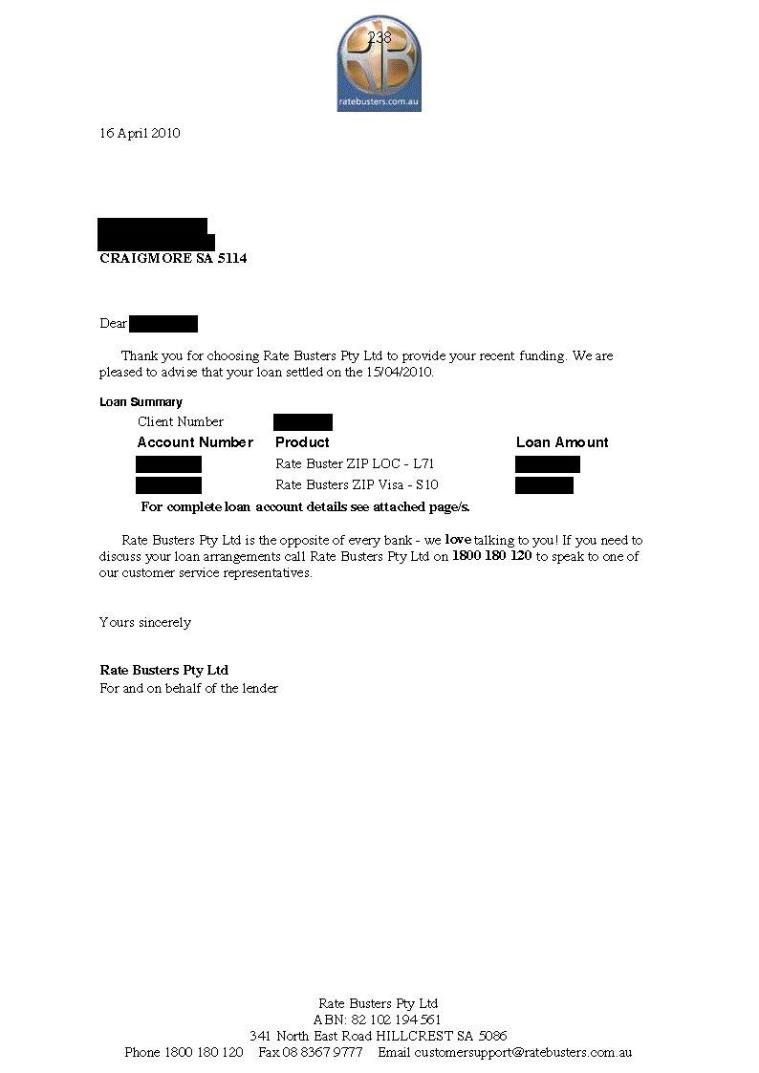

28 The correspondence issued by Firstmac for original ZIP home loans settled by mortgage brokers included letters to customers confirming preliminary approval of the loan, final approval, a welcome letter and a loan document pack enclosing a copy of the loan agreement. An example of that correspondence appears as follows (with all identifying information redacted):

29 For original ZIP home loans settled by Firstmac through its mortgage managers and mortgage originators, statements, correspondence and other information was issued to each borrower. Again, Mr Gration understands that those documents bear the Applicant’s Mark. Examples of those documents, some of which appear below, were also in evidence before me.

30 Statements issued for loans originating from a mortgage manager or mortgage originator, including for the original ZIP home loans, appear on the mortgage manager’s or mortgage originator’s letterhead but are generated and sent by Firstmac. That is to ensure that the statements are issued in a consistent format and in accordance with the frequency, depending on the type of repayment, of the terms of the original ZIP home loans set by Firstmac. An example of a statement issued by Resicom to a borrower (with identifying information redacted) is as follows:

31 Loans introduced by mortgage managers (unlike mortgage brokers) have post-settlement documents, including statements and correspondence, issued on the letterhead of the mortgage manager. An example of that correspondence (with identifying information redacted) for an original ZIP home loan is as follows:

32 In early 2014 Firstmac sought to streamline its product offerings and stopped offering, through its originators, the original ZIP home loans for further promotion to new customers in that form. However, Firstmac and its originators continued to manage and service original ZIP home loans held by existing customers. As part of its management and servicing Firstmac continued to issue statements for each original ZIP home loan created through a mortgage broker for the term of the loan and continued to issue statements on behalf of mortgage managers/originators for original ZIP home loans created through them. Throughout, Firstmac remained the contact for its mortgage originators and in some instances borrowers for original ZIP home loans that were created before 2014.

The September 2014 Origination Agreement

33 In September 2014 Loans.com.au entered into a mortgage origination and management agreement with Firstmac Origination (September 2014 Origination Agreement). Loans.com.au does not have its own home loan portfolio. Loans.com.au is an online lender which promotes Firstmac’s financial products and services.

34 Under the September 2014 Origination Agreement, Loans.com.au acts as a mortgage originator exclusively for Firstmac’s products and services and is responsible for the promotion of those products and services. Loans.com.au has a dedicated sales team which promotes Firstmac’s financial products and services (including ZIP home loans) to customers who have made an inquiry, takes customers through the loan application process and obtains the information required to enter into a loan agreement with Firstmac, after which Firstmac takes over the arrangements in the manner set out at [15(3)] above. The changeover between Loans.com.au and Firstmac occurs closer to settlement of the property the subject of the home loan once Firstmac approves the home loan application and arranges for it to be settled. Loans.com.au is involved in this process to the extent that it sends correspondence to the borrower to keep the borrower informed of the status of the progress of the borrower’s home loan application. The arrangement between Firstmac and Loans.com.au is reflected in credit guides issued by Loans.com.au to consumers.

35 Since September 2014 and under the September 2014 Origination Agreement Firstmac regularly issued product rate sheets to Loans.com.au which set out new products and services on offer by Firstmac and any changes (such as changes to interest rates) to any existing products and services. Mr Gration is responsible for approving the requirements of these products and services, and also approving the rate sheets which are prepared by the Firstmac product manager and circulated to Loans.com.au. Loans.com.au then, at its own cost, introduces the new products and services by updating its website located at www.loans.com.au, updating comparative websites, generating relevant posts on its social media pages and creating relevant material such as credit guides.

36 The marketing team, which is staffed by Firstmac employees, creates promotional material, such as brochures, for Loans.com.au for publication on its website and social media pages and designs and updates Loans.com.au’s website and social media pages. The costs of those marketing activities is reimbursed by Loans.com.au. Mr Gration approves the changes to be made to the Loans.com.au website in relation to the requirements of Firstmac’s products and services, which are then reported to Loans.com.au via email from the product manager at Firstmac. The in-house legal team and Marie Mortimer, the managing director of Loans.com.au are also involved in the approval process.

Re-introduction of the ZIP home loan in 2018

37 On 15 June 2018 Mr Gration sent an email to, among others, Ms Sudarmana, Celia Powell and Duncan MacFarlane, also of Firstmac, in which he wrote:

Tiska and Celia

Would you please consider the product and legal requirements to launch a new product, working title zip home loan, with the following spec

- home loan = redraw loan + visa debit account for up to $7500

- redraw loan at rate 3.72%

- visa debit account at rate 0%

- min loan amount and balance $190k

- standard valuation, credit, LVR, etc conditions apply to the total loan amount

- standard upfront fees val + settlement + government

- no ongoing fees

Target launch date in say 3 weeks on Monday 9 July.

Duncan...to celebrate reaching the massive $10 billion, being the largest non bank in Australia, plus being the fastest, smartest and more.... LCA is now providing a Visa card for up to $7,500 at 0% interest “forever” as part of its new zip home loan. That’s zip, zero, zilch forever! T&Cs apply

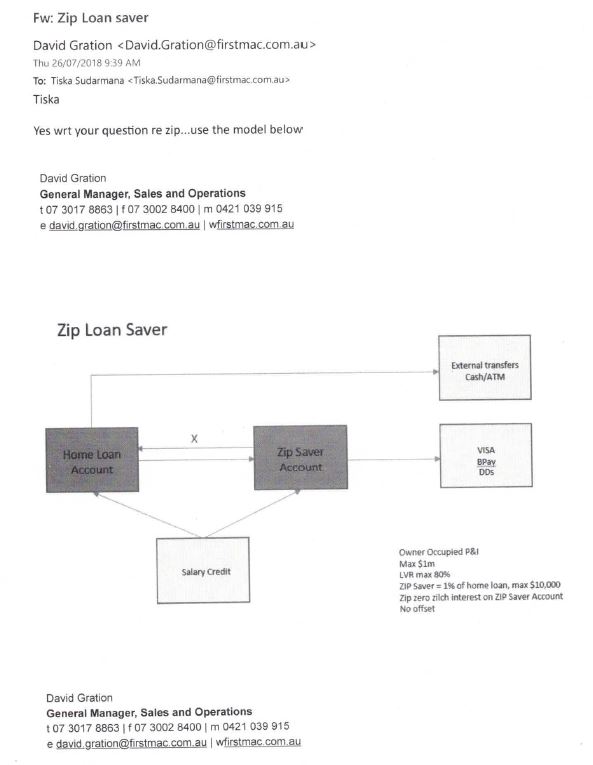

38 Ms Sudarmana recalls having conversations with Mr Gration in early to mid 2018 about campaigns (i.e. products and services) to be launched in around Spring that year which included a new home loan under the name ZIP. On 26 July 2018 Mr Gration sent a further email to Ms Sudarmana which she described as setting out at a high-level the requirements of the ZIP home loan (26 July Email). The email provided:

39 Mr Gration was cross-examined about the 26 July Email. Relevantly, senior counsel for the Zip Companies, Mr Bannon SC, had the following exchange with Mr Gration:

Mr Bannon: And then under that you say, “Zip, zero, zilch interest on ZIP Saver Account,” do you see that?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: And that was your description of the reference to the fact that there would be no interest payable on the ZIP Saver Account?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: And you’re using expressions well known to you of “zip, zero, zilch” to indicate nothing?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: And that was your explanation, may we take it, to Tiska of how – or part of your explanation as to how this loan operated, correct?

Mr Gration: Yes. At the time, yes.

Mr Bannon: When you say “at the time” the fundamental structure of this didn’t change, did it, when it was launched?

Mr Gration: There were elements that changed.

Br Bannon: The fact that “zip, zero, zilch interest” on the ZIP Saver Account never changed, did it?

Mr Gration: No, that didn’t change.

Mr Bannon: And the amount – the percentage amount accessible on the ZIP Saver Account, did that change?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: All right. But not by a significant order of magnitude, I take it?

Mr Gration: No, it was set at $5000.

Mr Bannon: All right. Instead of a percentage of the home loan?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: Yes. And then there’s a reference under there to “no offset.” Is that a shorthand for saying there – in this particular loan there wouldn’t be an account into which the borrower could deposit funds thereby from time to time reducing the amount of the principal and thereby from time to time reducing the amount of interest payable on the loan?

Mr Gration: Reducing the ..... of interest, yes.

Mr Bannon: Yes. And the way it reduced interest was on a from time to time basis if moneys were put into an offset account – I will start again. In terms of an explanation of an offset account generally, not speaking about this one, it’s an account which permits a borrower to put moneys in and take them out again from time to time?---

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: And usually the monthly balance of that amount will be offset against the principal?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: And resulting in a reduction in the amount of the interest payable?

Mr Gration: Yes.

…

Mr Bannon: And may we take it that it was important for you to explain to Ms Sudarmana the features of the loan having regard to her role as a product manager?

Mr Gration: Yes.

Mr Bannon: So that she could explain it in similar terms to anybody she dealt with?

Mr Gration: Yes.

40 In response to the 26 July Email, as product manager, Ms Sudarmana:

(1) prepared a product specification in the form of a rate card for the ZIP loans. The rate card was generated based on a template setting out the form rate cards are typically issued to Loans.com.au for Firstmac’s portfolio of products, with the logo of Loans.com.au on the front. The use of the logo in this way also assists Ms Sudarmana in identifying the channels (i.e. the originators, brokers, aggregators or managers and/or the specific person in that organisation) to which the rate card has been sent. On 25 September 2018 Ms Sudarmana sent the rate card by email to a number of people at Firstmac and Loans.com.au. Ms Sudarmana was also responsible for preparing and circulating subsequent rate cards with any varying interest rates for the ZIP loans. The rate cards were marked for “internal use only” and were to be used internally within Firstmac and Loans.com.au;

(2) co-ordinated the preparation of product brochures for the ZIP loans using personnel in the marketing department at Firstmac, which prepares marketing material for Loans.com.au. They were then made available for download from the website of Loans.com.au; and

(3) prepared and gave a PowerPoint presentation which set out the features of the ZIP loans to:

(a) personnel at Firstmac as the “Delegate Lending Authority”, which means that it is and continues to be responsible for the final assessment of ZIP loans, making the ultimate decision as to which borrowers Firstmac would lend to under the ZIP loans; and

(b) the team leaders at Loans.com.au to educate them about the nature of the ZIP home loan, its specification, its requirements, and how to prepare and submit loan applications using Firstmac’s Loan Application Wizard (a software application for mortgage groups to submit home loan applications). The team leaders were then expected, in turn, to educate the members of their respective teams to ensure they are trained to handle inquiries.

A copy of the PowerPoint presentation which was presented by Mr Sudarmana was in evidence before me. The Applicant’s Mark is used a number of times in it.

41 Ms Sudarmana described that ZIP loan conceived at this time as having two main parts: the ZIP home loan; and the ZIP Visa debit card (I will refer to this product as the 2018 ZIP home loan).

42 By September 2018, the 2018 ZIP home loan was ready to be offered as part of the portfolio of products offered by Firstmac through Loans.com.au. It was re-introduced as a term loan (rather than a line of credit) with a $5,000 interest free Visa debit card (rather than as initially envisaged the limit of the credit card being at 1% of the loan amount capped at $10,000) to provide transactional capability. According to Mr Gration this was a unique product offering in the industry. At the time there was fierce competition for home loans on internet comparison sites and Loans.com.au wanted a home loan product with a point of difference not likely or easily to be matched by the banks. The original ZIP home loan provided a platform and brand for this new product offering through Loans.com.au.

43 In cross-examination Mr Gration agreed that the key distinguishing feature of the 2018 ZIP home loan was the attached zero interest Visa debit card and that another feature of the product was the ability to eliminate debt “as quickly as possible”.

44 According to Mr Gration since September 2018 Loans.com.au has used the Applicant’s Mark to promote the 2018 ZIP home loan on behalf of Firstmac pursuant to the September 2014 Origination Agreement as follows:

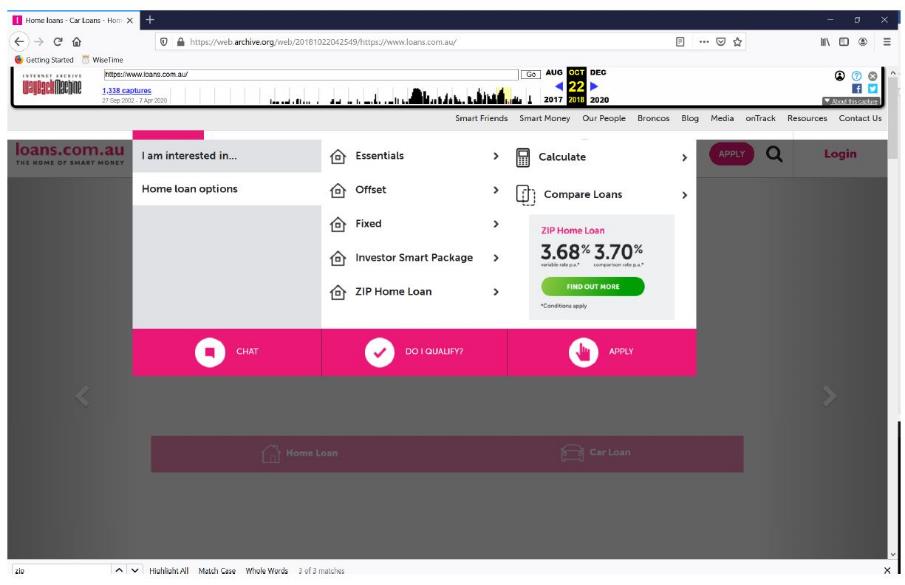

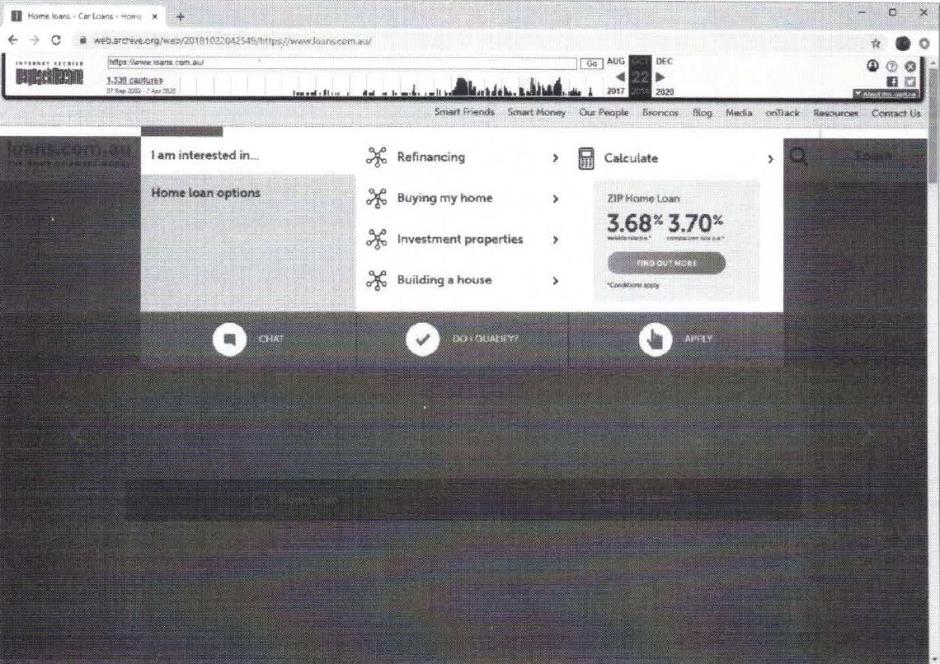

(1) on its website. In September 2018, Mr Gration, who is responsible for approving changes to the Loans.com.au website where they concern the requirements of Firstmac’s products and services, reviewed proposed changes to the website identifying the 2018 ZIP home loans before they went live. Mr Gration is familiar with the Loans.com.au website and refers to it regularly for a range of reasons, including to ensure that he continues to be comfortable with the content published on it. The 2018 ZIP home loans have been promoted on the Loans.com.au website since September 2018 and continue to be promoted. Screenshots of the website, as at the time Mr Gration swore his affidavit, May 2020, and dating back to October 2018 were in evidence before me. Mr Gration gave evidence that those screenshots were consistent with his recollection of the Loans.com.au website on and around the dates shown in them. By way of example a screenshot of the site as at October 2018 is as follows:

Loans.com.au is responsible for updating the features of the 2018 ZIP home loan on the online platforms it controls and operates (including its website) according to the product rate sheets;

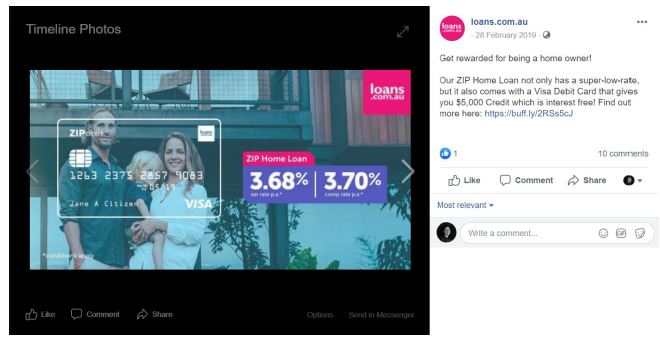

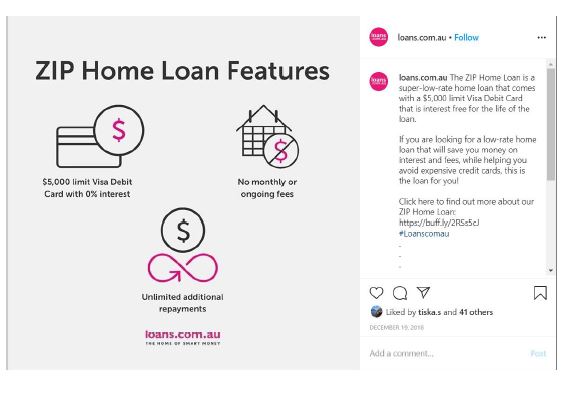

(2) on its social media pages. Loans.com.au has Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts. A selection of posts on those pages was in evidence before me and include:

(a) a Facebook post as at 28 February 2019:

(b) a Twitter post as at 28 February 2019:

(c) an Instagram post as at 19 December 2018:

(3) in its promotional material. The marketing team at Firstmac creates promotional material for the 2018 ZIP home loan which is used by Loans.com.au on its website, as a brochure which can be downloaded by customers, and on its social media pages;

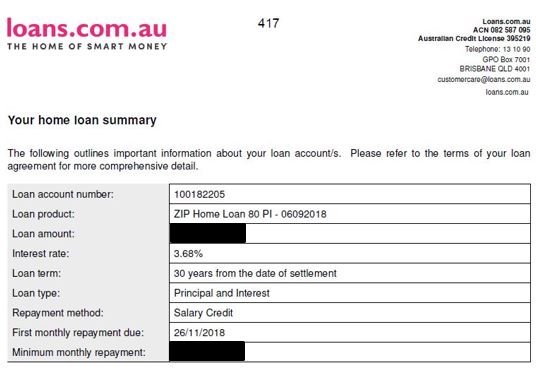

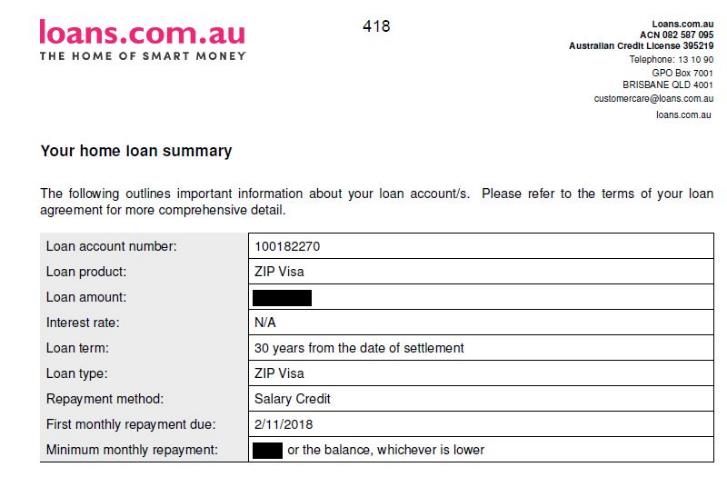

(4) in its correspondence. For a single loan there are a number of documents sent by Loans.com.au to the borrower which have been approved in content and layout by Mr Gration and his team. They include a preliminary approval, a final approval, a loan document pack, a mortgage document pack, a “home loan pack” and a welcome letter. A set of these documents sent by Loans.com.au to a particular borrower in October 2018 was in evidence before me. The welcome letter did not itself use the Applicant’s Mark but it enclosed a loan summary which provided (with identifying information redacted):

(5) on its statements. Once a new ZIP home loan has been approved and settlement is complete, Firstmac co-ordinates the issue of regular statements to each borrower, which are branded Loans.com.au, for the life of the loan. As is the case with the original ZIP home loan, for principal and interest loans, statements are issued every six months and for interest only loans, statements are issued every month. Firstmac also issues statements, again branded as Loans.com.au statements, for the debit card loan split i.e. the ZIP Visa. A bundle of statements was in evidence before me each of which bore the Applicant’s Mark as part of the “product description”.

45 The number of 2018 ZIP home loans settled by Loans.com.au and their total approximate value for the period September 2018 to April 2020 was in evidence before me. Given the confidential nature of the evidence I do not intend to reproduce it here.

46 The 2018 ZIP home loan has also appeared in third-party publications and on comparative websites, which permit borrowers to compare home loans being offered against a comparison rate by various institutions. The latter included websites operated by Mozo, Canstar and RateCity.

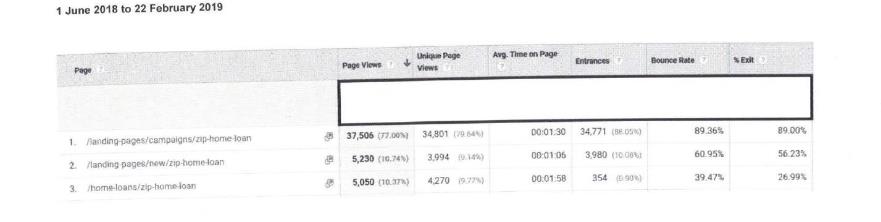

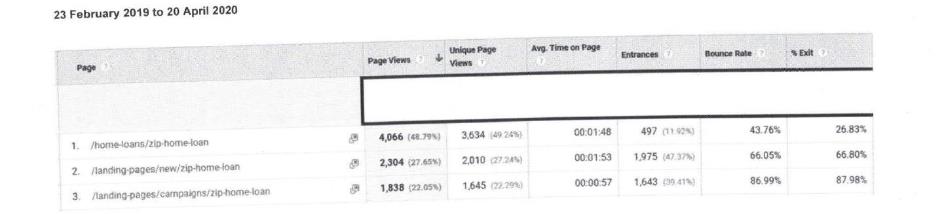

47 From time to time Ms Sudarmana obtains Google Analytics data for the product pages of the Loans.com.au website. She explains that as Loans.com.au is an online retailer Google Analytics is a useful resource to identify the traffic onto those product pages as an indicator of the level of interest in the relevant product. Ms Sudarmana obtained the Google Analytics results for three webpages for the 2018 ZIP home loans on the Loans.com.au site for the periods 1 June 2018 to 22 February 2019 and 23 February 2019 to 20 April 2020. The information for each period is divided into two tables: the first provides a general summary of the number of views to the three webpages and the second provides a breakdown according to the source of the traffic to the webpages e.g. from Facebook ads, the Google search engine, aggregator comparison websites such as Mozo, Canstar and Finder. The first general summary table for each period is as follows:

48 Since 22 February 2019, Loans.com.au has continued to act as mortgage originator and to promote and settle the 2018 ZIP home loans on behalf of Firstmac. As at May 2020 there was no intention on the part of Firstmac Origination to terminate the September 2014 Origination Agreement or on the part of Firstmac to remove the 2018 ZIP home loan as a product and service offering to Loans.com.au.

49 Towards the end of 2019 Firstmac decided to launch the ZIP home loan to third-party broker channels in addition to Loans.com.au. The reopening of the third-party broker channels does not impact, and has not impacted, Firstmac’s offering of the 2018 ZIP home loans to Loans.com.au, and the continued promotion of that product by Loans.com.au. The form of the ZIP home loans offered to these mortgage brokers is fundamentally the same as that offered to and by Loans.com.au.

50 Since February 2020 Firstmac has launched the 2018 ZIP home loans to over 8,000 of its accredited mortgage brokers across Australia. In Mr Gration’s view, the 2018 ZIP home loan would be more effectively sold by an intermediary broker presenting the full value and benefits of its unique proposition to the customer. In doing so, Firstmac reverted to the initial arrangement of promoting, offering and settling the 2018 ZIP home loans to borrowers through a broader range of originators. The mortgage brokers include aggregator mortgage broker groups including Fast, Choice, PLAN, Loan Market and Connective who can select to promote, through their respective different channels, third-party financial products and services, including the 2018 ZIP home loan, on behalf of Firstmac. The 2018 ZIP home loans need to be competitive so that they are taken up as a product and promoted by these aggregator broker groups.

51 Firstmac also continues to manage and service the original ZIP home loans arranged before and up to 2014 by Firstmac through its originators. As at 3 February 2020, there were 127 existing original ZIP home loans which continued to receive monthly statements. Firstmac estimates that the monthly statements for these existing loans will continue (assuming the loans are not terminated or discharged earlier) until 2044.

52 Mr Gration explained that at the time of launching the 2018 ZIP home loans in 2018, Firstmac’s objective was to create a home loan with distinctly unique features and name. It is Mr Gration’s understanding that the uniqueness of the home loan product is reinforced and enhanced by the use of a unique name. Mr Gration explained that the competition for home loans is crowded and fierce. Loans.com.au has a home loan product named “Essentials”. Five other lenders have a similar product with the same name. According to Mr Gration, to create a home loan with distinctly unique features and name is of tremendous value when brokers are searching in aggregator software with 30 plus lenders and hundreds of home loans. It is the platform for building a significant and sustained new business flow of home loans from brokers.

Loans.com.au and the 2018 ZIP home loan

53 As set out at [33]-[34] above, Loans.com.au is an online lender which promotes Firstmac’s financial products and services, acts as a mortgage originator exclusively for Firstmac’s products and services and promotes Firstmac’s financial products, including a range of ZIP home loans, and services.

54 Ms Pendrey recalls that she first became aware of the 2018 ZIP home loans in late 2018 when she was either in the role of lending manager or senior lending manager. While she had the roles of senior lending manager and then retail sales team leader, the 2018 ZIP home loan was one of the products that she and her team promoted and continue to promote, including by reference to the information and material set out on the “how it works” page on the Loans.com.au website. Both as a senior lending manager and retail sales team leader Ms Pendrey has relied on the Loans.com.au website to relay information to customers over the telephone.

55 Ms Pendrey estimates that in her role as lending manager and, to some extent, as senior lending manager, she referred customers to the Loans.com.au website on a daily basis and, in some instances, walked them through the website while on the telephone with them. She also refers to the website if she needs to confirm or check a detail about a product offered by Loans.com.au. Based on her observations of her team members and the way in which they interact with customers over the telephone, Ms Pendrey is aware that they have used, and continue to use, the Loans.com.au website in the same way as she does.

56 Ms Pendrey obtained screenshots of the Loans.com.au website, including from the Wayback Machine. According to Ms Pendrey those screenshots are consistent with her recollection of how the website has appeared since the time she held her role as senior lending manager and on around the dates of each screenshot. She has observed minor changes to the website over time such as the change in the length of time that Firstmac has been operating. By way of example the screenshot obtained as at 22 October 2018 which refers to the 2018 ZIP home loan is as follows:

57 Since September 2018 ZIP home loans have been continuously promoted, and continue to be promoted and offered, by Loans.com.au with generally the same specification and terms but with varying interest rates.

Mr Gration becomes aware of the Zip Companies

58 Mr Gration became aware of Zipmoney Payments in about late August or September 2016 after an application for removal of the Applicant’s Mark on the grounds of non-use (see [172]-[175] below). Firstmac opposed that application. At the time, Mr Gration considered that:

(1) by responding to and opposing the first non-use application, it was clear that Firstmac wanted to retain registration of the Applicant’s Mark and the associated exclusive rights given to Firstmac under the legislation;

(2) given the significant costs of litigation, it was prudent and desirable to defend the Applicant’s Mark before taking enforcement steps, although he did not then realise the length of time that would take; and

(3) while he had a general appreciation that “Zipmoney” had entered the market, he did not monitor what “Zipmoney” was doing and he had no insight or foresight into its commercial operations and plans.

59 Mr Gration expected that, if Firstmac was successful in defending its registration of the Applicant’s Mark, “Zipmoney” would stop using ZIP and it would have a contingency plan in place to cover such a situation.

60 Firstmac has not authorised or granted any licence or permission to the Zip Companies to use the Applicant’s Mark or any version of a trade mark including the word ZIP, nor have those companies asked Firstmac for permission to use the Applicant’s Mark or any version of a trade mark including ZIP, or for Firstmac’s consent or permission to register any trade marks for or including ZIP.

61 On 24 June 2013, when first incorporated, Zipmoney Payments had the name Zipmoney Pty Ltd. On 14 June 2015, it changed its name to its current corporate name, Zipmoney Payments.

62 The Zip Companies have a related company, Zipmoney Holdings Pty Ltd, which was also incorporated on 24 June 2013. Zipmoney Payments is a subsidiary of Zipmoney Holdings and Zip Co is the ultimate holding company of both Zipmoney Payments and Zipmoney Holdings.

The development of the ZIP business

63 In about mid-2012 Mr Diamond began to think about establishing a business based on digital/online short term lending to consumers. He was interested in creating a business that would disrupt traditional lenders and the credit card market and which used the point-of-sale experience as the point of origination of new customer credit accounts. He considered that an important feature of such a business would be the ability for retail customers to obtain credit quickly (in real time) and without a lengthy application process. At the time, Mr Diamond did not believe there to be a product offering of that type in Australia. For example, GE Money products were promoted on the retail sales floor, but still involved a traditional finance application.

64 Throughout the second half of 2012, Mr Diamond researched businesses operating as short term lenders, particularly in the United Kingdom (UK). He recalls that two of the businesses he looked at as part of his research were VirginMoney and GE Money (which was subsequently taken over by Latitude Financial). He also looked at the Swedish business Klarna and the UK business Wonga. He undertook this research around his other commitments. At the time Mr Diamond was providing consulting services to other businesses such as Prospa Advance, which focussed on digital lending to small businesses, Money in Advance, a digital short term lender in the UK, and Live TaxiEpay, which provided a payment platform for taxis. Through the combination of his research and consulting work, Mr Diamond began to develop an understanding of how he might be able to make his digital/online short term lending business work.

65 During the second half of 2012, although he does not now recall exactly when, it also occurred to Mr Diamond that the names ZIP or ZAP might be good brands for a digital short term consumer lending business. He liked those names because he thought they were short and catchy. The name ZIP seemed to evoke fast movement successfully, which was consistent with Mr Diamond’s idea of providing finance in “real time”. He was also aware at the time that, from a marketing perspective, a domain name with three letters was desirable. Three letter words are easily remembered and there is limited scope for misremembering short names. Mr Diamond considered that the names ZIP and ZAP also met this criterion, but he preferred the name ZIP because of the way it brought to mind fast movement.

66 When Mr Diamond started thinking about using the brand ZIP for the business, he also decided that it would be a good idea to also use the word “money” i.e. ZIP MONEY. This was because other finance businesses (such as VirginMoney and GE Money) used the word “money” in their names and because the word “money” indicates very clearly what the business is about. Mr Diamond considered that incorporating the word “money” into the brand helped to place the product into its category. His plan was to develop ZIP as a brand, but to use additional words like “money” to help position the brand in the financial sector, placing it alongside Visa, MasterCard and the like.

67 Mr Diamond liked the brand ZIP a lot, but it was not the only potential brand that he considered. As set out above, he also considered the name ZAP as well as some other options, although he could no longer recall what they were.

68 In about November 2012 Messrs Gray and Diamond met to discuss potential business opportunities, including Mr Diamond’s idea of a short term digital lending business. Mr Diamond recalls that at about this time he told Mr Gray that he had the brand ZIP or ZIP MONEY in mind for the business. Mr Diamond explained that when he referred to the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY as brands he meant that those names were to function not merely as a name but also as an identifier of the business and its products. To like effect Mr Gray recalls that in one of these early discussions Mr Diamond mentioned that he had the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY in mind for a proposed online retail consumer lending business, which was one of the business opportunities they discussed.

69 At about the time of his meeting described in the preceding paragraph, Mr Diamond decided that he should try to register a suitable domain name based on the brand ZIP. He looked at a number of domain names by typing the unique uniform resource locator (URL) into a web browser, although he does not now recall all of those he considered at the time. He does however recall that in the course of undertaking this process he discovered that the domain name www.zip.com was owned by Bank of America but, when he visited that domain name, it was not an active website. At the time, Mr Diamond was aware that Bank of America did not have any operations in Australia.

70 The upshot of this process was that Mr Diamond registered the domain name www.zipmoney.com.au. He considered that domain name to be suitable because it was consistent with his idea to use the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY for a business in Australia.

71 Following their initial discussions, Messrs Gray and Diamond decided to work on the digital short term lending business together.

72 Mr Gray recalls that in early 2013 shortly after his initial discussions with Mr Diamond described at [68] above, he undertook some internet searches in relation to the name ZIP. He undertook these searches reasonably frequently during this period because online research was part of the process of scoping out and identifying the opportunity for the online retail consumer lending business. Mr Gray does not recall all of the search results but does recall that some of them related to zip taps, which he has seen in use in offices, and that none of the searches generated any reference to Firstmac or any products provided by it.

73 During the first half of 2013 Messrs Diamond and Gray worked on developing the preliminary business model for the business, including developing the product they intended to offer and the technology required to support that product. Mr Diamond explained that this required a great deal of work by both of them. Between them they focussed on pitching the potential business to retailers (such as Kogan and Zuji), working out how to build a real time credit platform, seeking out seed capital and loan book funding, developing the economic model for the business and identifying key staff for recruitment.

74 Mr Gray also recalls that up until June 2013 he and Mr Diamond had been using the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY for the business and that while they had discussed some other names he regarded ZIP and ZIP MONEY as the preferred option.

75 By about June 2013, Messrs Diamond and Gray decided that they definitely wanted to use the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY for the business. Mr Diamond thought that they had progressed far enough with planning for the business to create a corporate structure. For that purpose, on 24 June 2013, he arranged, through his accountant, Quantum Partners, for the incorporation of Zipmoney Pty Ltd, now Zipmoney Payments, and Zipmoney Holdings. Mr Diamond said that the use of the words ZIP and MONEY as a part of these corporate names followed on from his and Mr Gray’s plan to use the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY for the business.

76 At about the time of the incorporation of the companies referred to in the preceding paragraph Mr Gray undertook some further internet searches in relation to the name ZIP. While he could not recall all of the results that came up in these searches, and did not keep records of them, he does recall that he did not see any reference to Firstmac or any products provided by it at the time.

77 In the preliminary phase of building and establishing the ZIP business, Mr Gray also applied to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission on behalf of Zipmoney Pty Ltd for an Australian Credit Licence to permit Zipmoney Pty Ltd to engage in credit activities. On 3 September 2013 Zipmoney Pty Ltd obtained credit licence no. 441878.

78 In late November 2013 Zipmoney Pty Ltd partnered with its first Merchant, Chappelli Cycles, and sometime after that it began offering credit and payment services to customers of Chappelli Cycles in Australia.

79 A screenshot of part of the www.zipmoney.com.au website as at 25 January 2014 obtained from the Wayback Machine appeared as follows:

Mr Gray accepted that, while he would need to check the Zip Companies’ records, it was likely that the five Merchants shown there were those who had signed up as at late January 2014.

80 Once Messrs Gray and Diamond had decided to use the names ZIP and ZIP MONEY, they commissioned the design of logos that could be used for the business. Mr Diamond commissioned a designer in Sri Lanka (whose name he cannot now recall) to design them. They also used a business called 99 Designs for alternative ideas. Ultimately Messrs Gray and Diamond settled on the logo designs presented by the Sri Lankan designer which were as follows:

The branding of the ZIP business has evolved over time and these logos are no longer used.

81 On 19 and 20 August 2013 Zipmoney Pty Ltd filed trade mark applications no. 1575528 and no. 1575717 for the logos set out above (2013 trade mark applications). Prior to filing the applications Mr Diamond did not do a search of the trade mark register and Zipmoney Pty Ltd did not seek any legal advice about registering these logos as trade marks. At the time, Mr Diamond thought it would be a straight forward process to register a trade mark. He was also very conscious about how they spent money as they had limited funding to get the business off the ground and he was keen to avoid any unnecessary outgoings. Legal advice about trade marks fell into that category at the time.

82 Mr Diamond does not recall what prompted Zipmoney Pty Ltd to file the 2013 trade mark applications but does recall he filed the applications himself. But in cross-examination he accepted that the 2013 trade mark applications were made to protect their rights, i.e. use of the trade marks, for when the business which they were focussed on building, was operational.

83 In cross-examination Mr Diamond also accepted that between June and mid-August 2013 he took some steps to inform himself about trade marks and their registration and he made the applications because he understood that trade marks could be registered. Relevantly, senior counsel for Firstmac, Mr Webb SC, had the following exchange with Mr Diamond:

Mr Webb: You agree, don’t you, with this proposition: knowing that trade marks were capable of registration, or that there was a registration system for them, and that registration gave protection in respect of them, at that time you understood it would be prudent business practice to seek registration of a trade mark you intended in future to use in a business?

Mr Diamond: Yes.

84 At some time later in 2013, Zipmoney Pty Ltd received adverse examination reports from IP Australia in relation to the 2013 trade mark applications (2013 Adverse Reports). Those reports were sent to the address PO Box 1501, Bondi Junction, NSW, 1355, which was a post office box that Messrs Gray and Diamond used for the business at the time. Mr Gray was responsible for clearing the PO Box. He recalls collecting the 2013 Adverse Reports from the PO Box. While he has no recollection of reading them in detail, he does recall understanding from them that the 2013 trade mark applications had not been accepted for registration. He understood that this was a potentially important matter for the business, and that the reason why the application had been unsuccessful was because there was another trade mark that was close to the one applied for, although he does not recall taking in that the 2013 Adverse Reports referred to Nationale Limited, which he now knows to be a former name of Firstmac, or the Applicant’s Mark.

85 As Mr Gray was not the person responsible for the 2013 trade mark applications, he provided the 2013 Adverse Reports to Mr Diamond.

86 The 2013 Adverse Reports were dated 1 and 16 October 2013 respectively and included:

(1) in relation to application no. 1575528 for ZIP MONEY logo under the heading “What are the problems with your trade mark?”:

Your trade mark is identical to or closely resembles trade mark number 1021128. This trade mark has an earlier priority date and is for the same or similar goods or services.

• Your trade mark closely resembles the earlier trade mark because the prominent and memorable feature of your trade mark is the word ZIP and the earlier trade mark is for the word ZIP.

AND

• The services are similar because you have claimed a variety of services in Class 36 relating to advice in relation to credit and the provision of credit and the earlier mark has claimed financial affairs (loans) in Class 36.

I have enclosed details of this trade mark.

The enclosed details were for trade mark registered no. 1021128 for the word mark ZIP owned by Nationale (now Firstmac) i.e. the Applicant’s Mark; and

(2) in relation to application no. 1575717 for the ZIP logo under the heading “What are the problems with your trade mark?”:

Your trade mark is identical to or closely resembles the following trade marks. These trade marks have earlier priority dates and are for the same or similar goods or services:

879664, 1021128

Trade mark number: 879664

• Your trade mark /closely resembles the earlier trade mark because the prominent and memorable element of both trade marks is the word ZIP.

AND

• The services are similar because you have claimed various general financial and financial advisory services in Class 36 and the earlier mark claims “advertising; business management; business administration; office functions; the activities may be carried out on-line via the Internet” in Class 35. General financial and financial advisory services are often provided incidentally with the types of business administration and management services claimed by the earlier trade mark.

Trade mark number: 1021128

• Your trade mark closely resembles the earlier trade mark because the prominent and memorable feature of your trade mark is the word ZIP and the earlier trade mark is for the word ZIP.

AND

• The services are similar because you have claimed a variety of services in Class 36 relating to advice in relation to credit and the provision of credit and the earlier mark has claimed financial affairs (loans) in Class 36.

I have enclosed details of these trade marks.

The enclosed details were for the Applicant’s Mark and for trade mark registered no. 879664 for the word mark ZIPFUND owned by Creative On-Line Technologies Ltd.

87 Mr Diamond recalls being aware in about late 2013 that Zipmoney Pty Ltd had received the 2013 Adverse Reports but at the time he gave them only cursory attention. He did not focus his attention on understanding or addressing the issues raised in them and he does not recall reading them in any detail. At the time:

(1) his time was dominated by a number of commercial issues;

(2) the second half, and particularly the last quarter, of 2013 was a hectic time for him and Mr Gray;

(3) they were in the middle of launching the ZIP business, which involved a number of urgent commercial challenges; and

(4) Mr Diamond was heavily focussed on building and testing the Zip Money product; developing relationships with potential retailer Customers; and securing funding for the loan book that would underpin the business. The latter was a particularly critical issue at the time as some of the early shareholders who had committed to provide funding had pulled out and there was an urgent need to find alternate funding.

88 Following receipt of the 2013 Adverse Reports, Zipmoney Pty Ltd did not seek any legal advice in relation to the 2013 trade mark applications. It did not occur to Mr Diamond to do so.

89 Similarly, throughout 2013 and 2014 Mr Gray was occupied with launching the ZIP business and with issues that were urgent and commercially critical including for example:

(1) creating a business plan;

(2) developing the suite of business policies and procedures that would underpin the ZIP business;

(3) developing the credit decision technology which is the “engine” that sits behind the Zip platform;

(4) developing the interface between the ZIP business and online retail platforms;

(5) securing seed capital and loan book funding;

(6) strategic hiring of key personnel;

(7) building awareness of the ZIP business and building the Merchant base; and

(8) managing regulatory filings (most notably the credit licence, which was a substantial undertaking), registration and reporting.

90 At the time, given his focus on commercial issues, Mr Gray did not treat the 2013 Adverse Reports as an important commercial issue and did not take any steps to respond to them. During 2014 and early 2015 he focussed his energy on building the ZIP business which was beginning to make progress in the market. The issue of obtaining trade mark registrations did not seem commercially significant or pressing to him at the time.

91 In cross-examination Mr Diamond gave the following evidence about the 2013 Adverse Reports and the steps taken after their receipt:

Mr Webb: Yes. And you knew that what it was saying was there was an obstacle to the registration on your application and it was the trademark that’s referred to at page 2980?---

Mr Diamond: We knew that there was a, you know, potential issue, but, again, we felt that we had done extensive research and felt that we had sort of satisfied that, and we were very focused on the business at the time.

Mr Webb: And by that do you mean to say that you received the report, understood it was adverse, and were happy to go ahead and adopt or start using Zip Money in the business once established, in any event?

Mr Diamond: No, I would frame it more we had done an extensive online research to – to – to satisfy ourselves that – that – that no one else was using this particular name, and we were very focused on trying to get a business off the ground, given our limited funding, and – and that was really concerning most of my time, to ensure that we could, I guess, continue the viability of the business. So, you know, that – that really was the – the primary focus.

Mr Webb: So because of the demands on your time, I take it from what you’ve just said, you decided not to bother with pursuit of the application for registration of Zip Money. Is that correct?

Mr Diamond: The – the commercial needs of the business were more focused on trying to stand up a business, more so than focusing on trademarks at that point in time.

92 Throughout 2014 and early 2015, Mr Diamond was focussed on establishing and building the ZIP business. It was an exciting and challenging period for him. New commercial opportunities and challenges were arising frequently and he was fully occupied addressing them. Mr Diamond explained that funding the business remained a critical and time-consuming issue. In 2014, the business had more or less run out of money and a number of people in the business were working for free. The majority of Mr Diamond’s time was consumed by trying to raise funding to keep the business afloat. In those circumstances, Mr Diamond did not regard obtaining trade mark registrations as a commercial priority.

93 Despite this, Mr Diamond noted that he has been subsequently informed by the Zip Companies’ then lawyers, Corrs Chambers Westgarth, that on 8 December 2014 Zipmoney Pty Ltd applied for an extension of time to respond to the 2013 Adverse Reports, an application for extension of time was made and an extension of one month was granted by IP Australia in respect of each trade mark application. The applications for extension of time were made in Mr Diamond’s name but he has no recollection of seeking the extension or why he did so. In cross-examination Mr Diamond explained that it was a very tense time and he was focussed on difficult commercial and viability matters with the business needing funding. As a result the 2013 trade mark applications did not get a lot of his attention.

94 Ultimately, Zipmoney Pty Ltd did not respond to the 2013 Adverse Reports and on 1 and 16 February 2015 respectively the 2013 trade mark applications lapsed.

95 In the course of planning and developing the ZIP business, Mr Diamond searched the internet on a number of occasions in relation to the name ZIP, although he cannot now recall the dates he undertook those searches and he did not keep a record of them. Mr Diamond recalls that his searches often turned up references to zip hot water and filtered taps.

96 Once the ZIP business had been launched, Mr Diamond regularly did searches for the name ZIP to see how the ZIP business was being referred to on the internet, which he considered to be an important way of tracking the progress of the business. While Mr Diamond cannot say precisely when he did those searches, his evidence was that they were a common part of his working week in the early days of the ZIP business. In undertaking those searches he does not recall ever seeing a reference to Firstmac or any use by it of the name ZIP.

97 From at least 2013 and throughout 2014 and 2015 Mr Gray also regularly undertook internet searches for ZIP and ZIP MONEY to see whether the ZIP business was being mentioned on internet pages. This was a day to day activity for Mr Gray and one of the ways he tracked the progress of the business. In the course of undertaking those searches and looking at the results Mr Gray did not recall seeing any search results which referred to Firstmac or any products provided by it.

Rubianna Resources Limited and the reverse takeover

98 On 8 April 2015 Rubianna Resources Limited, a mining and resources company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX), announced an option agreement to acquire Zipmoney Pty Ltd via the acquisition of all the issued shares in its parent company, Zipmoney Holdings.

99 On 4 June 2015 Rubianna Resources announced to the ASX that it had exercised its option to acquire 100% of the issued shares in Zipmoney Holdings and its subsidiaries.

100 The following exchange took place between Mr Webb SC and Mr Gray during cross-examination in relation to the rationale behind the transaction with Rubianna Resources:

Mr Webb: Yes. So that in June 2015 there was an agreement between Rubianna and the second respondent and companies associated with it for the acquisition of the business?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And what I want to suggest to you – that the existing facility as at that date, that is, the making of that agreement by exercise of the option in June 2015 was $5 million. The existing facility was $5 million?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: You agree with that?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Thank you. And, so, it was as part of the steps taken towards the reverse listing that the total facility was increased to 20 million?

Mr Gray: Yes.

…

Mr Webb: All right. I mean what the listing agreement involved was a movement from that current facility to an institutional funding agreement or facility with Columbus. You remember that?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. Which was properly described a warehouse facility?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. So there was a step taken – I’m sorry, I withdraw that. So what was happening in this process was you were severe – the Zip Money companies were severely constrained by their ability to grow the business through to June 2015 because they only had $5,000,000 of funding for their loan book?

Mr Gray: No, we weren’t severely constrained; it was a function of our size at the time. We’ve always had the ability … the increase our facilities as and when it has been required.

Mr Webb: And you wanted to grow the business and you needed more funding to do that?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: For your loan book?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. So what you did was pursue this backdoor listing to achieve an ability to grow?

Mr Gray: Generally, yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And it was a staged process where you used the fact of the agreement for the backdoor listing to top up the five to 20,000,000 and built into the listing agreement an arrangement to shift to a warehouse facility of an equivalent amount?

Mr Gray: Yes.

101 From mid-June 2015 drafts of the prospectus were circulated.

102 On 28 July 2015 Mr Gray was appointed chief operating officer and a director of Rubianna Resources.

103 On 11 August 2015 Rubianna Resources issued the prospectus for a public offering of 20 million shares at an issue price of $0.20 per share to raise a minimum of $4 million, with the ability to raise a further $1 million up to a maximum of $5 million.

104 On 19 August 2015 Zipmoney Holdings and Zipmoney Payments raised $5 million in capital as part of the reverse takeover of Rubianna Resources.

105 On 7 September 2015 Rubianna Resources was renamed Zipmoney Limited, on 21 September 2015 Zipmoney Limited reverse listed on the ASX and on 7 December 2017 Zipmoney Limited was renamed to Zip Co.

106 On 24 June 2015 John Winters, a private wealth advisor with Shaw & Partners, advisor to Rubianna Resources in relation to the transaction, sent an email to James Omond of Omond & Co, trade mark attorney, with subject “In confidence – zipMoney IP report/audit” and three attachments described as “DRAFT IP Report.pdf”, “20150526 Letter to Rubianna Resources.pdf” and “20150526 IP Audit Report zipMoney.pdf”.

107 On 25 June 2015 Omond & Co filed four trade mark applications on behalf of Zipmoney Payments (2015 trade mark applications) for registration of the following marks in class 36 for “Electronic payment services; Financial payment services; Payment administration services; Payment transaction card services; Loan services; Provision of loans; Advice regarding credit; Consumer credit services; Credit (financing); Financial credit services; Provision of credit; Provision of credit information; Provision of trade credit”:

(1) application no. 1703059 for:

(2) application no. 1703060 for:

(3) application no. 1703102 for the word ZIP; and

(4) application no. 1703103 for the word ZIPMONEY.

108 On 21 July 2015 the Trade Marks Office issued adverse examination reports for applications no. 1703059, no. 1703060 and no. 1703102 and on 22 July 2015 the Trade Marks Office issued an adverse examination report for application no. 1703103. In each case the Trade Marks Office reported that the application did not meet the requirements of the TM Act because it was similar to other trade marks, citing s 44 of the TM Act. The other trade marks were, in the case of applications no. 1702059 and no. 1703103, registered trade mark no. 1021128 owned by Nationale (i.e. the Applicant’s Mark) for the word ZIP and, in the case of applications no. 1703060 and no. 1703102, registered trade mark no. 1021128 owned by Nationale (i.e. the Applicant’s Mark) for the word ZIP and registered trade mark no. 879664 owned by Creative On-Line for the word ZIPFUND.

109 Part 1.3 of the prospectus, titled “Key Risks”, included in relation to “Registering trademarks”:

zipMoney has applied to IP Australia for the registration of its trademarks and awaits confirmation. The Proposed Directors note there are a number of prior trademarks with regard to similar trademarks. There is a risk that the owners of these trademarks may assert rights against zipMoney in relation to the use of the zipMoney trademarks and/or oppose the trademark applications made by zipMoney

This was further explained in part 8 of the prospectus titled “Risk Factors” as follows:

(i) Registering trademarks

zipMoney does not currently own its trademarks and has applied for registration of these with IP Australia. The Proposed Directors note there are a number of prior marks with regard to similar trademarks. There is a risk that the owners of these trademarks may assert rights against zipMoney in relation to the use of the zipMoney trademarks and/or oppose the trade mark applications made by zipMoney.

110 Mr Gray and Mr Diamond were each cross-examined about this disclosure in the prospectus:

(1) Mr Gray gave the following evidence:

Mr Webb: Yes. I want to suggest to you that you applied for trademarks at that time so that you could say that you had made an application as part of designing this statement for inclusion in the prospectus. Do you accept that?

Mr Gray: I didn’t make the applications, I couldn’t accept that.

Mr Webb: Is it the case that questions of trademark were outside your responsibility as at August 2015?

Mr Gray: My direct area of focus would have been on other things, yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. But you were in fact a director of Zip Money at all times up to August 2015, weren’t you?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And by July 2015 you had also been made a director of the resources company, hadn’t you? And that was part of the process of?

Mr Gray: Correct.

Mr Webb: listing?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: And you were one of the directors making the statement in this section of the risk in relation to registration trademarks?

Mr Gray: I was a director at the time, yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And the answer to my question is what?

Mr Gray: Sorry, what’s the question?

Mr Webb: You were one of the directors making this statement to the market about risk in August 2015, weren’t you?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And you informed yourself as to the appropriateness of that statement for the purpose of agreeing to the issue of the prospectus, didn’t you?

Mr Gray: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And what did you do to satisfy yourself as to that matter?

Mr Gray: I don’t recall.

Mr Webb: You don’t recall what you did?

Mr Gray: As I’ve indicated, it’s one of numerous risks here and my direct area of focus was on some significant other risks that are outlined here as well.

Mr Webb: It was an important matter, wasn’t it?

Mr Gray: One of many important matters.

…

Mr Webb: It was a very important matter, wasn’t it?

Mr Gray: It was one of the many risks called out in the prospectus.

Mr Webb: Are you unwilling to agree with the proposition that the securing of registered trademarks was a very important matter for both the second respondent and the first respondent at this time?

Mr Gray: Important matter, and it’s called out in the risks.

(2) Mr Diamond gave the following evidence:

Mr Webb: You’re aware of the note in the prospectus as to risk?

Mr Diamond: Yes.

Mr Webb: In respect of that matter, without seeing it now. I’m just asking whether you feel comfortable with agreeing with me without looking at the prospectus to confirm it?

Mr Diamond: I – I recall that that was a risk in the prospectus.

Mr Webb: Yes. And you know, don’t you – or you knew by at least June 2015 that that risk arose because of the two registered trademarks which were cited in the adverse reports we looked at a little while ago?

Mr Diamond: Yes.

Mr Webb: Yes. And although your initial applications for Zip Fund had lapsed in, I think, February 2015 fresh applications for those same marks were applied for in June 2015. You agree with that?

Mr Diamond: Do I agree that trademarks were made in – fresh trademarks were made in 2015?

Mr Webb: Yes, in June 2015?

Mr Diamond: Yes. We were – we were – we had – by 2015, if I recall, we had also appointed a legal advisor, James Omond, who was looking after these matters.

Mr Webb: Right. But all I’m asking you is whether you agree, firstly, that the risk identified was the risk posed to you obtaining registration by the two registered trademarks which were referred to in the adverse reports. Do you agree with that?

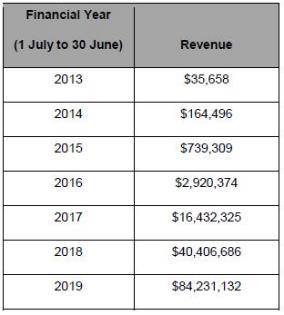

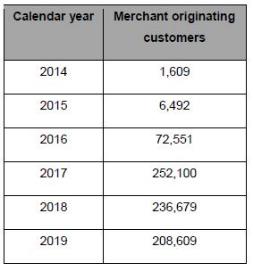

Mr Diamond: Yes.