FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Limited [2023] FCA 539

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | MLC LIMITED (ABN 90 000 000 402) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

In these declarations and orders, terms have the following meaning:

(a) AFSL means Australian Financial Services Licence.

(b) ASIC Act means the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) as in force during the relevant period.

(c) Corporations Act means the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) as in force during the relevant period.

(d) Insurance Contracts Act means the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) as in force during the relevant period.

(e) MLCL means the defendant, MLC Limited (ACN 000 000 402).

(f) SRA means severe rheumatoid arthritis.

(g) MS Breach means the Mail Suppression breach.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. a. In the period up to 31 October 2018:

(i) MLCL provided income protection cover to customers under policies of insurance (RBB Policies) which contained a term (RBB Term) by which MLCL promised to pay a sum of money to the customer described as a “Rehabilitation Bonus Benefit” (RBB) if the customer was eligible;

(ii) 119 customers made a claim to MLCL for indemnity under their respective RBB Policy and were in receipt of income protection benefits (each a RBB Impacted Customer);

(iii) each RBB Impacted Customer participated in an approved rehabilitation program, by reason of which each RBB Impacted Customer was eligible for the RBB;

(iv) between 18 November 2015 and 31 October 2018 each RBB Impacted Customer (or their agent or doctor) provided information to MLCL by which it knew or should have known that each RBB Impacted Customer was eligible for the RBB; and

(v) MLCL did not pay the RBB to each RBB Impacted Customer within a reasonable period of time after proof of satisfactory participation by the RBB Impacted Customer in an approved rehabilitation program.

b. By the above conduct in paragraphs 1(a)(i) - (v), MLCL represented to each of the 119 RBB Impacted Customers that the RBB Impacted Customers were not eligible for RBB (the Representation).

c. The Representation was made in trade or commerce and constituted:

(i) a false or misleading representation, that services were of a particular standard, had benefits, or contained conditions or rights, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, in contravention of ss 12DB(1)(a), (e) and (i) of the ASIC Act; and

(ii) misleading or deceptive conduct, or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive, in relation to financial services, in contravention of s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act.

2. MLCL breached the requirements of s 13 of the Insurance Contracts Act in relation to the 119 RBB Impacted Customers in the period 18 November 2015 to 31 October 2018 in that it failed to act towards each RBB Impacted Customer, in respect of each matter arising under or in relation to that customer’s RBB Policy, with the utmost good faith, by reason of engaging in the conduct the subject of declaration 1 above.

3. By reason of:

a. MLCL engaging in the conduct the subject of declaration 1 above; and

b. MLCL not having appropriate processes and procedures to ensure that it would pay the RBB to the 119 RBB Impacted Customers in the period 18 November 2015 to 31 October 2018,

MLCL thereby failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

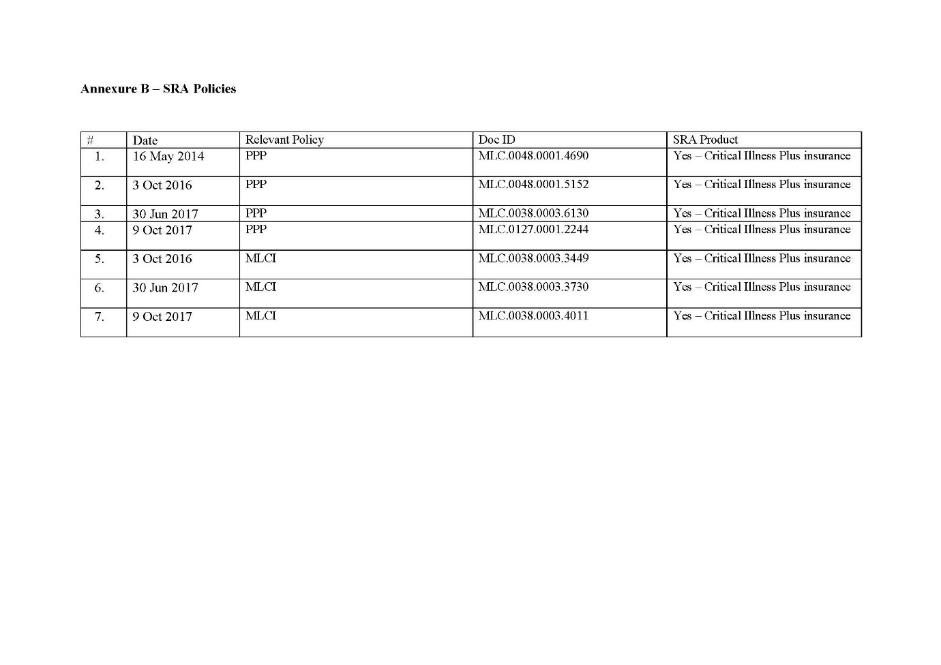

4. a. On 30 June 2017, MLCL updated its definition of SRA in MLCL Insurance and Personal Protection Portfolio policies for SRA (SRA Policies) diagnosed after 30 June 2017.

b. In the period 27 February 2015 to 30 June 2017, MLCL did not have adequate processes to review and if appropriate promptly update, medical definitions for critical illnesses in SRA Policies, in circumstances where it had received expert medical evidence or opinion concerning the currency of medical definitions which ought to have prompted it to review the relevant medical definitions.

c. By reason of the foregoing, between 27 February 2015 to 30 June 2017, MLCL failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

5. a. Between 18 November 2015 to March 2018:

(i) MLCL had a policy administration system called Eclipse which provided for, amongst other things, communications to insureds under MS Policies;

(ii) Eclipse was configured to enable MLCL to suppress the automated communications to insureds by manually applying the “mail suppression flag” (Flag) to the insured in Eclipse;

(iii) however, MLCL did not:

A. adequately train relevant MLCL staff to remove the Flag after the reasons for the suppression ended; nor

B. appropriately monitor relevant MLCL staff’s use of the Flag.

b. Accordingly, in the period 18 November 2015 to March 2018 and in relation to 282 life insureds (374 policies), MLCL failed to remove the Flag within a reasonable time after the reason for the mail suppression ended.

c. By reason of the matters in paragraph 5 (a)(iii) above, MLCL failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

6. Pursuant to s 12GBA(1) of the ASIC Act, within 30 days of the date of this order, MLCL pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $10 million in respect of MLCL’s conduct in paragraph 1 of the declarations declared to be contraventions of ss 12DB(1)(a), (e) and (i) of the ASIC Act.

7. MLCL pay the plaintiff’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding as agreed, and if not, taxed.

8. Pursuant to s 12GLB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, within 30 days of the order, MLCL publish, at its own expense, a written adverse publicity notice in the terms set out in Annexure A to these orders (Written Notice), by, for a period of no less than 90 days, maintaining a copy of the Written Notice, in font no less than 10 point, in an immediately visible area of the following web address: https://www.mlcinsurance.com.au (the webpage).

9. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding concerns three distinct categories of conduct relating to the provision of financial services by MLC Limited (MLCL) during the period 1999 to 9 November 2020.

2 The three categories of conduct can be summarised as follows:

(a) the non-provision of a rehabilitation bonus benefit (RBB) on top of monthly income protection benefits (which MLCL was providing) to 119 customers;

(b) MLCL’s lack of adequate processes for reviewing and, if appropriate, updating medical definitions for critical illness, including, in particular, severe rheumatoid arthritis (SRA); and

(c) MLCL’s failure to adequately train staff as regards the removal of a mail suppression (MS) ‘flag’ (Mail Suppression Flag) and appropriately monitor staff use of the flag, resulting in some customers not receiving communications from MLCL regarding their policies.

3 The plaintiff (ASIC) commenced this proceeding on 18 November 2021. By its originating process, ASIC sought declarations of contravention of provisions of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act), the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth), pecuniary penalty orders, adverse publicity orders and costs. ASIC’s case was set out in a concise statement.

4 Subsequently, MLCL filed a concise response in which it made substantial admissions.

5 Following a mediation, the parties reached an agreed position in relation to proposed declarations and proposed orders.

6 The parties have prepared a statement of agreement facts and admissions. An amended version of this document was subsequently prepared (SOAF). This document was filed with the Court on 16 May 2023. A copy of that document is annexed to these reasons.

7 By the SOAF, MLCL admits that its conduct in the three categories outlined above contravened the ASIC Act, the Corporations Act and the Insurance Contracts Act. The SOAF describes the three categories of conduct referred to above as the “RBB Breach”, the “SRA Breach” and the “MS Breach”. I will adopt those expressions in these reasons.

8 MLCL admits that:

(a) the RBB Breach contravened: ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(a), (e) and (i) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act; s 13 of the Insurance Contracts Act; and s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act;

(b) the SRA Breach contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act; and

(c) the MS Breach contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

9 The parties propose that the Court make declarations to reflect these admitted contraventions.

10 The conduct constituting the RBB Breach ceased by no later than on or around 31 October 2018. In the relevant period for that conduct, s 12DB of the ASIC Act was a provision in respect of which a pecuniary penalty could be imposed. The parties jointly propose that a pecuniary penalty of $10 million be imposed on MLCL in respect of its contraventions of s 12DB of the ASIC Act by the conduct described as the RBB Breach.

11 The parties also propose an order requiring MLCL to publish an adverse publicity notice in an agreed form. It is also proposed that there be an order that MLCL pay ASIC’s costs of the proceeding.

12 The material before the Court is as follows. In addition to the SOAF, there is a tender bundle of documents referred to in the SOAF, and an affidavit of Kent Bernard Griffin, the Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director of MLCL. The parties have provided joint submissions in support of the proposed declarations and orders (the Joint Submissions). MLCL has also filed submissions that supplement the Joint Submissions (MLCL’s Submissions). The parties appeared today and made oral submissions in support of the proposed declarations and orders.

13 In my view, for the reasons that follow, there is a proper basis and it is appropriate to make the declarations proposed by the parties. These will record, in a formal and public way, that MLCL contravened the law on multiple occasions in its dealings with its customers and in the conduct of its insurance business.

14 Further, in my view, the pecuniary penalty proposed by the parties appropriately reflects the seriousness of MLCL’s contraventions of s 12DB of the ASIC Act, and should serve the purposes of specific and general deterrence. I therefore consider it appropriate to impose a penalty of $10 million in respect of the relevant conduct.

15 I also consider the adverse publicity order and the order as to costs to be appropriate.

16 In preparing these reasons, I have drawn substantially on the Joint Submissions and MLCL’s Submissions.

Overview of the contravening conduct

General

17 MLCL at all material times held an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL).

18 MLCL is, and was at all relevant times, a major provider or issuer, in Australia, of life insurance products to consumers which it offers under its AFSL. Throughout the period 18 November 2015 (6 years before the proceeding was issued) to 18 November 2021 (the date of commencement of the proceeding) (this being the relevant period for penalty purposes), MLCL had net assets ranging from $1 billion to $2.8 billion.

19 In the period from 1999, National Australia Financial Management Limited (NAFM) and Norwich Union Life Australia Limited (Norwich) sold similar products. On 1 October 2006 and 2 October 2010, the life insurance businesses of each of NAFM and Norwich respectively were amalgamated with the life insurance business of MLCL. MLCL thereby assumed all contractual liabilities of NAFM and Norwich under the policies issued by those entities, and assessed claims under them.

RBB Breach

20 During the relevant period, MLCL, NAFM and Norwich issued income protection insurance policies which provided for the payment of an additional benefit (the RBB) to a customer if the customer was participating in an approved vocational rehabilitation program, subject to the terms and conditions of the relevant policy.

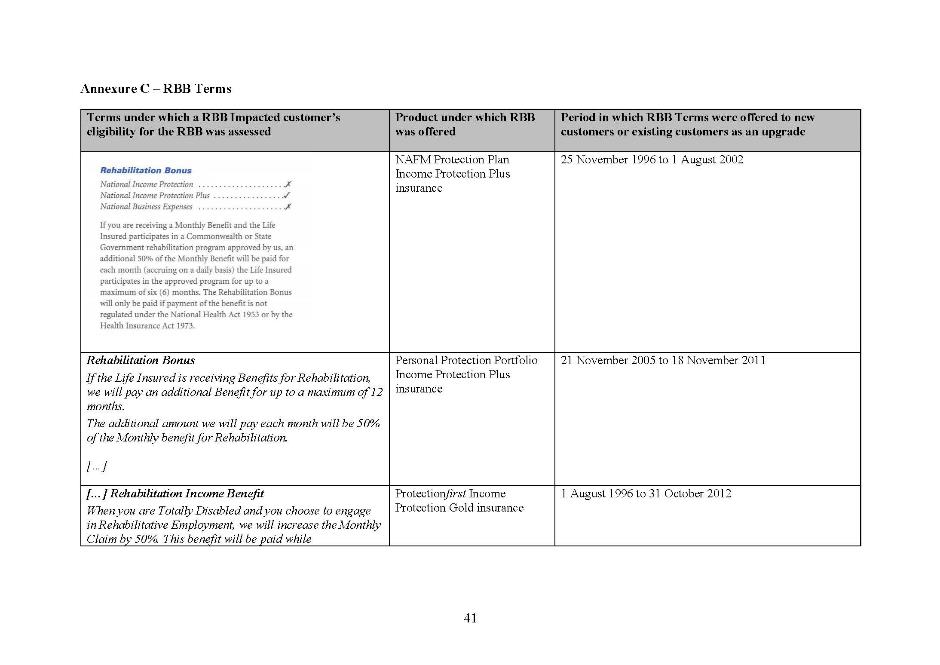

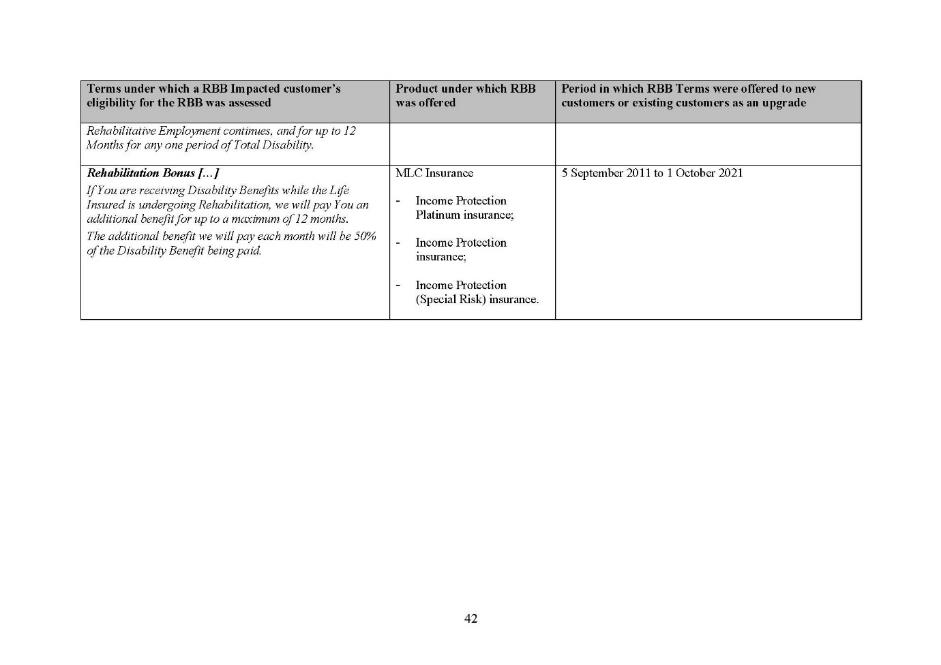

21 The RBB terms vary in detail, but broadly provided that if a customer was receiving a monthly income protection benefit and participated in a rehabilitation program approved by MLCL, an additional 50% of the monthly benefit would be paid to the customer each month for a period up to a maximum of either 6 or 12 months.

22 The typical stages of a claim by a customer under their policy during the relevant period are summarised at paragraph 26 of the SOAF.

23 In the period up to 31 October 2018, MLCL failed to pay the RBB to 119 customers (the RBB Impacted Customers) in receipt of income protection benefits, within a reasonable period of time after proof of satisfactory participation by the RBB Customer in an approved rehabilitation program, despite the RBB Impacted Customer (or their agent or doctor) providing information to MLCL such that it knew or should have known that the customer was eligible for the RBB.

24 In respect of the RBB Impacted Customers, MLCL has admitted that:

(a) in the period up to 31 October 2018:

(i) each of the relevant policies held by the RBB Impacted Customers contained a term by which MLCL promised to pay the RBB to the customer if the customer was eligible, subject to the terms and conditions of the policy;

(ii) the RBB Impacted Customers made a claim for indemnity (income protection) under their respective policies and were in receipt of income protection benefits;

(iii) each RBB Impacted Customer participated in an approved rehabilitation program, by reason of which each customer was eligible for the RBB;

(b) between 18 November 2015 and 31 October 2018:

(i) each RBB Impacted Customer (or their agent or doctor) provided information to MLCL by which MLCL knew or should have known that each RBB Impacted Customer was eligible for the RBB;

(ii) MLCL did not pay the RBB Impacted Customers the RBB within a reasonable period of time after proof of satisfactory participation by the RBB Impacted Customer in an approved rehabilitation program; and

(c) by reason of the conduct in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b), MLCL represented to each RBB Impacted Customer that they were not eligible for the RBB (the Representation); and

(d) the Representation was made in trade or commerce and, by reason of the MLCL’s conduct in relation to the RBB Impacted Customers set out in paragraphs 29 and 30 of the SOAF, constituted a false or misleading representation to each, and misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to each, RBB Impacted Customer (the RBB MD Conduct).

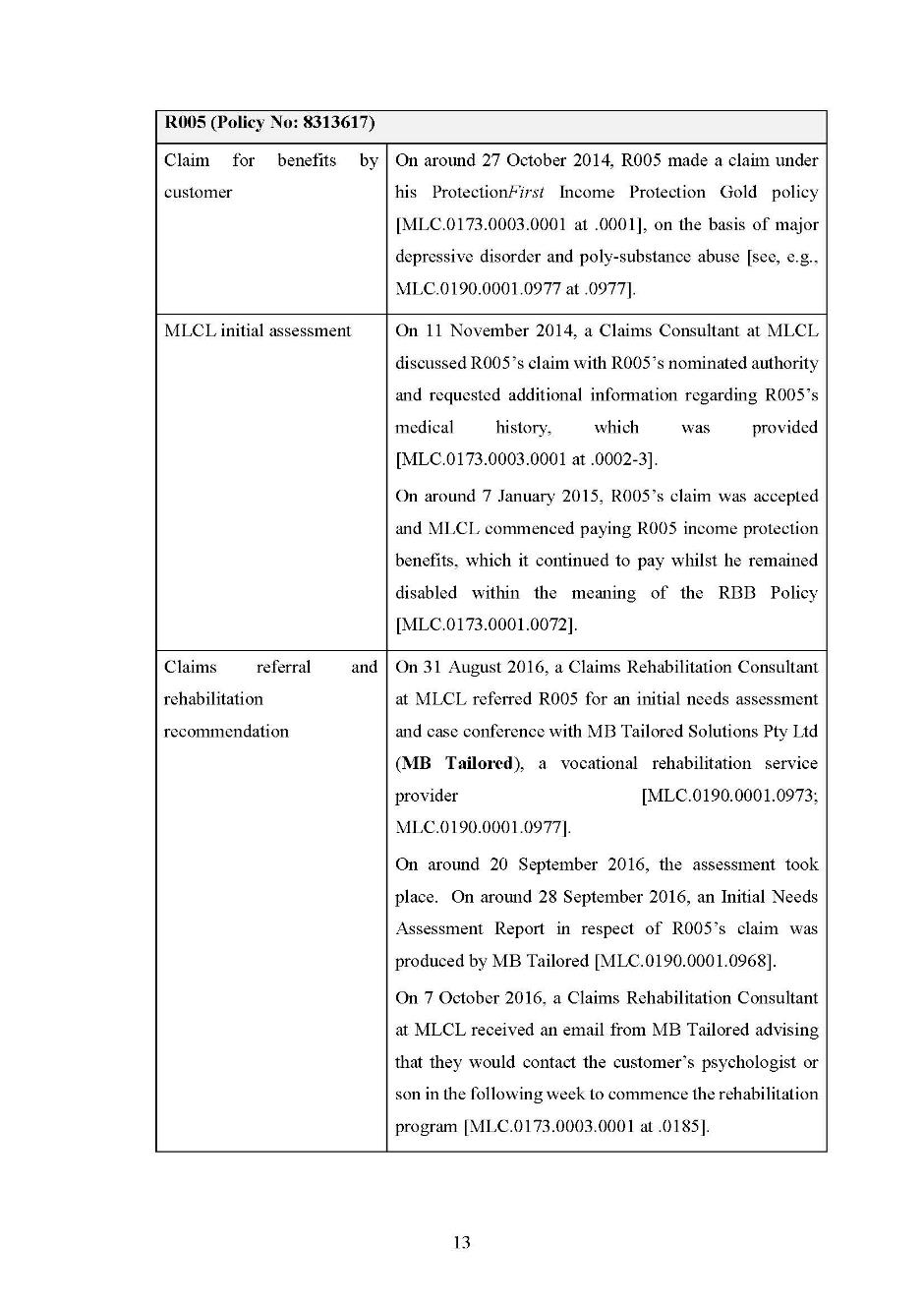

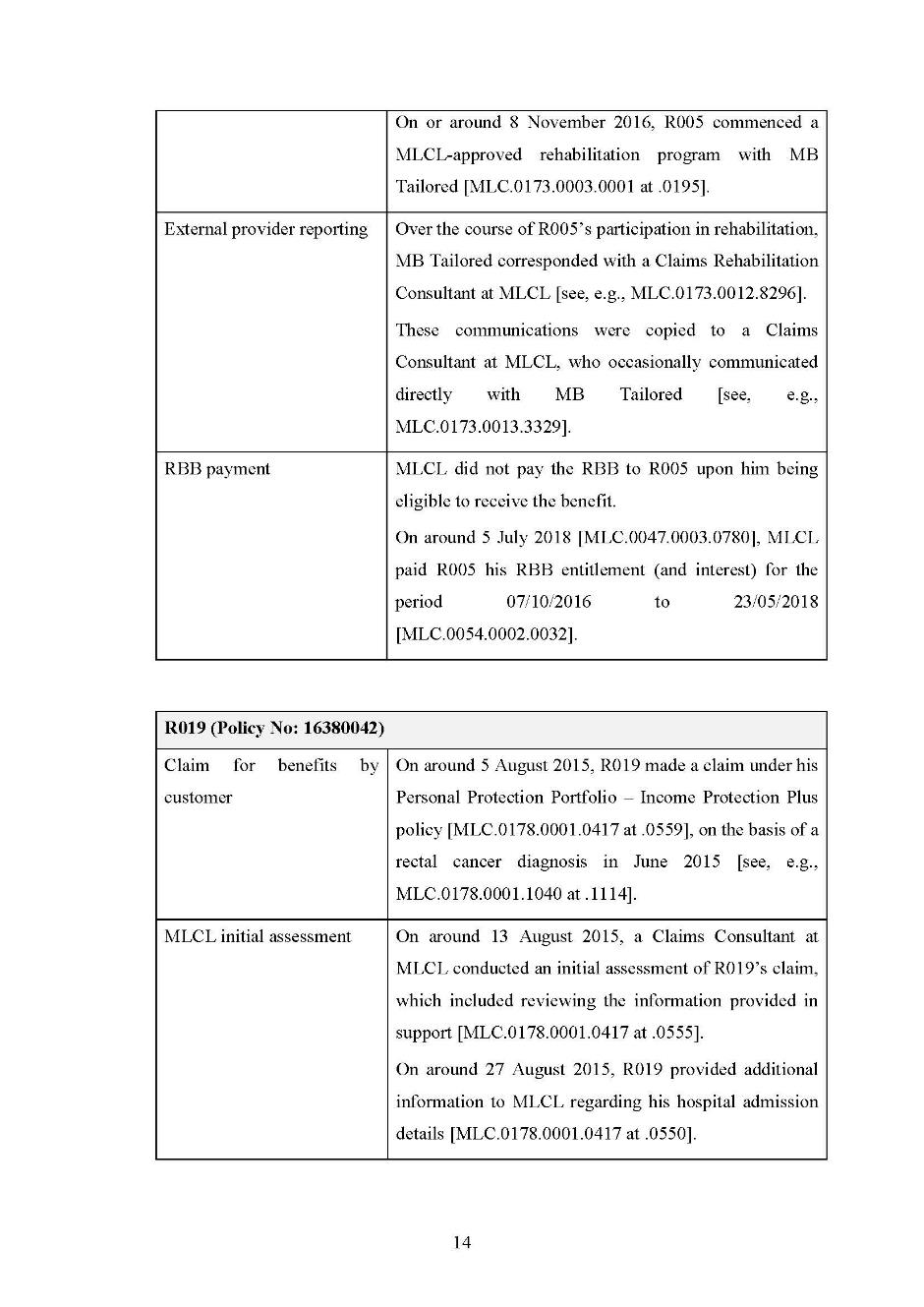

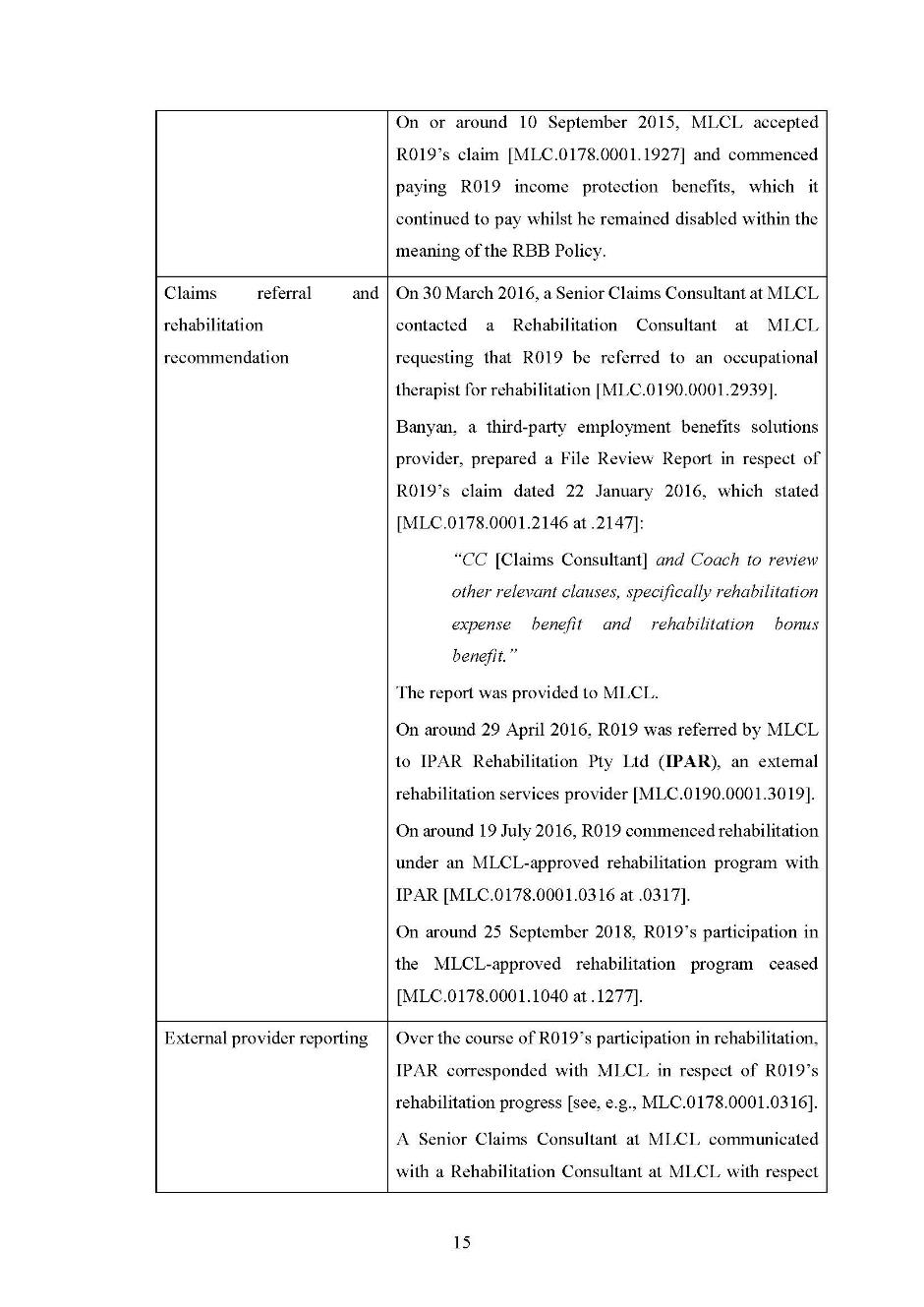

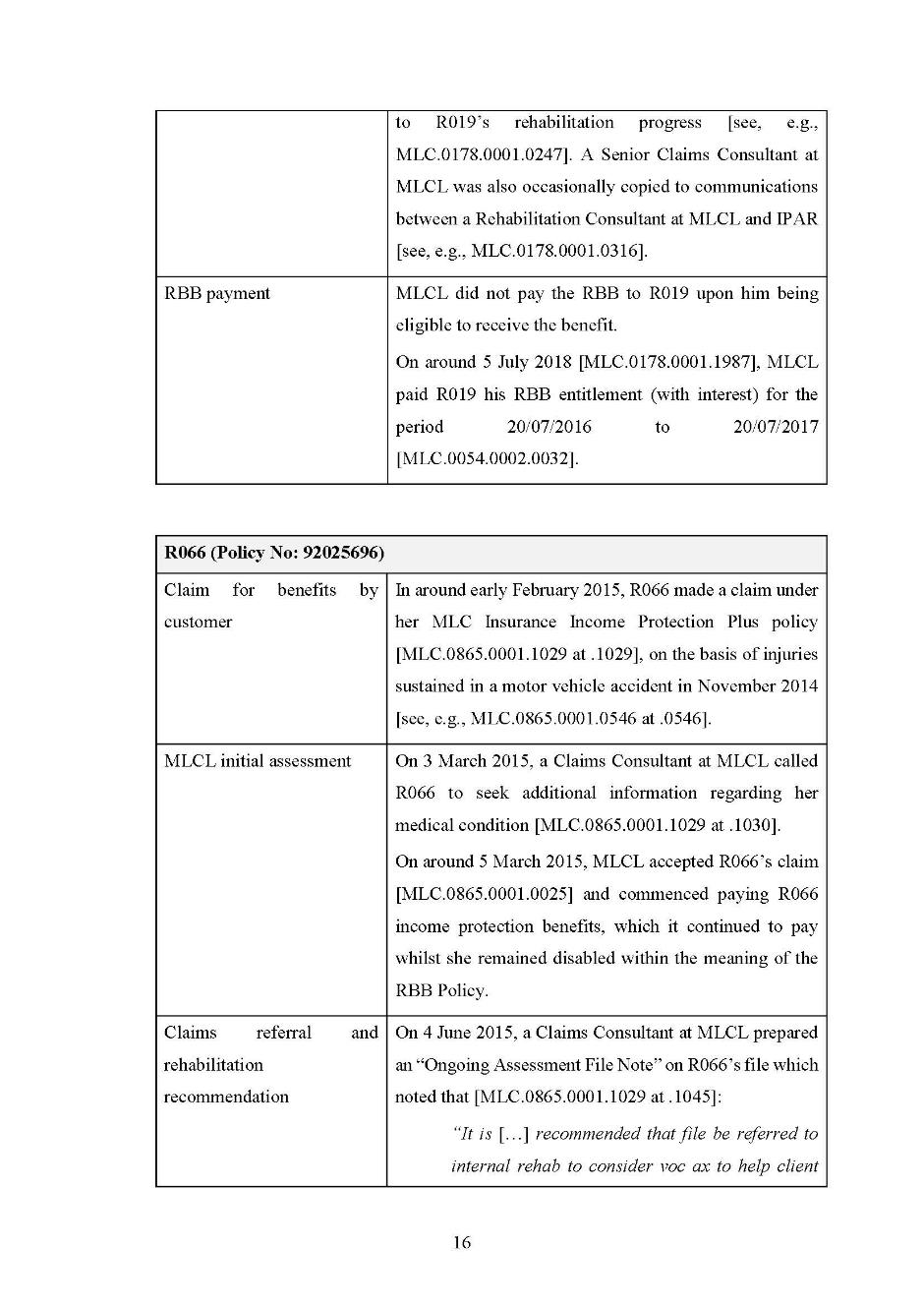

25 The SOAF contains examples of the process of claims assessment for three RBB Impacted Customers.

26 The RBB MD Conduct arose as a result of MLCL not having appropriate processes and procedures in place to ensure that it would pay the RBB to the RBB Impacted Customers.

27 As set out above, MLCL admits that the making of the Representation resulted in contraventions of the prohibitions against false or misleading representations and misleading or deceptive conduct in the ASIC Act and Corporations Act. By engaging in the RBB MD Conduct MLCL admits that it breached the duty of utmost good faith implied into insurance contracts by s 13 of the Insurance Contracts Act. MLCL also admits that it contravened the obligation on financial services licensees in s 912A of the Corporations Act to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its licence are provided efficiently, honestly and fairly by engaging in the RBB MD Conduct and by not having appropriate processes and procedures in place to ensure it would pay the RBB to the RBB Impacted Customers.

28 As explained in the Joint Submissions, ASIC and MLCL submit that each element of the relevant provisions is satisfied by the RBB Breach as admitted in the SOAF.

29 The relevant provisions relating to misleading or deceptive conduct, and false or misleading representations, are as follows. At the relevant times for the RBB Breach, ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(a), (e) and (i) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act provided:

12DA Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

12DB False or misleading representations

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

…

(e) make a false or misleading representation that services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, uses or benefits; or

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including an implied warranty under section 12ED); or

…

1041H Misleading or deceptive conduct (civil liability only)

(1) A person must not, in this jurisdiction, engage in conduct, in relation to a financial product or a financial service, that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

30 The phrase “misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive” has received extensive judicial consideration, and it is not necessary to discuss those cases for present purposes.

31 The RBB MD Conduct was directed to the RBB Impacted Customers, not to the public at large. Accordingly, “attention must be directed to the relationship between the two persons, the context in which the statement is made, the reasonably known characteristics of the recipient of the statement, and the effect on a reasonable person in the position of the recipient of the statement”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation (No 3) [2016] FCA 196; 337 ALR 647 at [219] per Edelman J.

32 The gravamen of the RBB MD Conduct is:

(a) a positive statement in the documented policy terms by MLCL to each of the RBB Impacted Customers that it would pay the RBB if certain conditions were met;

(b) MLCL being typically involved in the arrangement and/or monitoring of progress of the RBB Impacted Customers undertaking an MLCL approved rehabilitation program;

(c) MLCL receiving information by which it knew or should have known the RBB Impacted Customers were eligible for RBB; however,

(d) MLCL not paying the RBB Impacted Customers the RBB within a reasonable period of time after proof of satisfactory participation by the RBB Impacted Customers in an approved rehabilitation program.

33 That conduct, viewed as a whole, had the tendency to lead each of the RBB Impacted Customers into the false assumption that they were receiving their full entitlements under their policy, and therefore, represented they were not eligible for the RBB. An implicit nature of representations does not diminish their misleading character. As Lee J held in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Mazda Australia Pty Limited [2023] FCAFC 45 at [639]:

In my respectful view, the fact the contravening conduct was based on implied rather than express representations is not to the point. Speaking generally, and depending upon the context, conduct in the nature of silence or implied representations can often be as seriously misleading as express representations (and, in some circumstances, may be more serious because the misleading nature of the conduct may be more difficult to appreciate).

34 Section 12DB of the ASIC Act requires the Representation to concern specific matters. For ss 12DB(1)(a), (e) and (i) there must be a false or misleading representation that the financial services in question were (relevantly):

(a) of a particular standard;

(b) had benefits; or

(c) contained conditions or rights.

35 The RBB MD Conduct falls within each of those heads. Eligibility for the RBB upon participating in an approved rehabilitation program was a benefit, condition or right of the relevant policies held by the RBB Impacted Customers, and a feature or quality which gave those policies a particular standard. MLCL made a false or misleading representation that the RBB Impacted Customers were not eligible for the RBB, which thereby was directed to a benefit, standard, condition or right under the relevant policies.

36 The final requirement is that the misleading or deceptive conduct have the required connection to the financial product or services. This requirement is satisfied for the reasons set out in the Joint Submissions.

37 I am therefore satisfied that the agreed contraventions of ss 12DA and 12DB of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act are established.

38 The requirements of utmost good faith are implied into insurance contracts by reason of s 13(1) of the Insurance Contracts Act. That provision provides:

13 The duty of the utmost good faith

(1) A contract of insurance is a contract based on the utmost good faith and there is implied in such a contract a provision requiring each party to it to act towards the other party, in respect of any matter arising under or in relation to it, with the utmost good faith.

39 A breach of the implied requirement of utmost good faith under the Insurance Contracts Act is actionable by ASIC (see, for example, Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Youi Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1701) in the sense that ASIC has standing to seek declarations that the provision has been breached: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v TAL Life Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 193; 389 ALR 128 at [217] per Allsop CJ.

40 There has been significant judicial consideration of the bounds of the requirement to act with the utmost good faith. This includes the recent judgment of the High Court in Allianz Australia Insurance Limited v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2022] HCA 38; 406 ALR 632.

41 MLCL admits that the RBB MD Conduct amounts to a failure by it to act towards each of the RBB Impacted Customers with utmost good faith in respect of their eligibility to be paid benefits arising under or in relation to that customer’s relevant policy. MLCL’s conduct was not dishonest. However, it was inconsistent with commercial standards of decency and fairness for MLCL to fail to pay the benefit to customers in circumstances where it had information revealing their entitlement to it, particularly given the context in which the conduct occurred – namely, MLCL knew or should have known those customers were eligible to be paid the RBB, and there was a lack of appropriate processes and procedures on MLCL’s part to ensure payment of the RBB to the RBB Impacted Customers.

42 Section 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act requires a financial services licensee to:

do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by [its] licence are provided efficiently, honestly and fairly

43 Section 912A of the Corporations Act, and in particular s 912A(1)(a), has been considered extensively and it is not necessary for present purposes to refer to those cases.

44 In the present circumstances, MLCL was required to do all things necessary to ensure that its dealings in relation to the relevant policies were efficient, honest and fair. This required, among other things, that MLCL have appropriate processes and procedures in place to ensure that the benefits provided for in the relevant policies were paid to the RBB Impacted Customers within a reasonable period of time after them being eligible.

45 MLCL has admitted that its conduct contravened s 912A(1)(a) in two respects:

(a) by engaging in the RBB MD Conduct; and

(b) by not having appropriate processes and procedures to ensure that it would pay the RBB to the RBB Impacted Customers in the period 18 November 2015 to 31 October 2018.

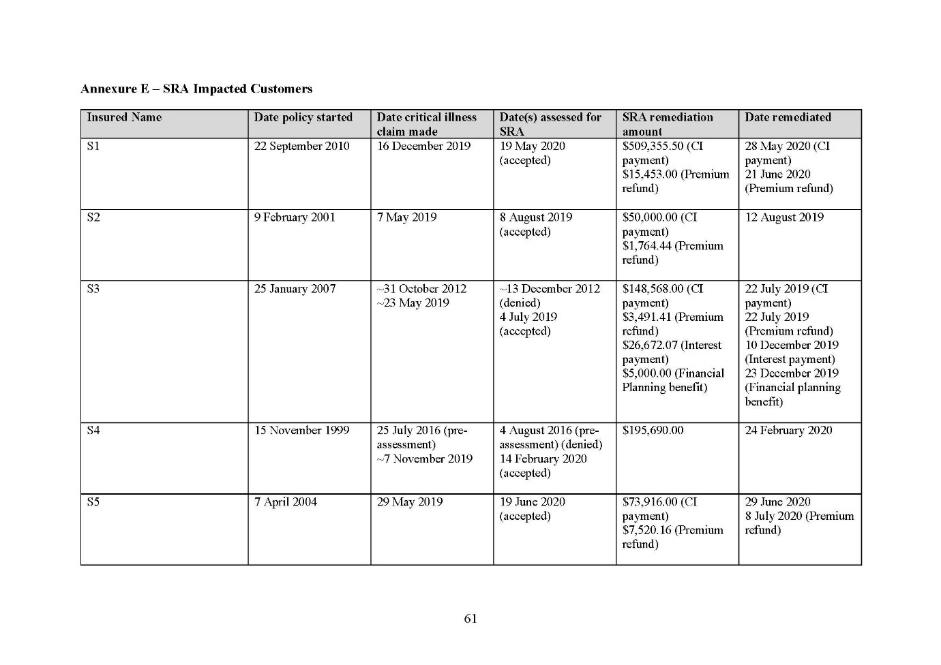

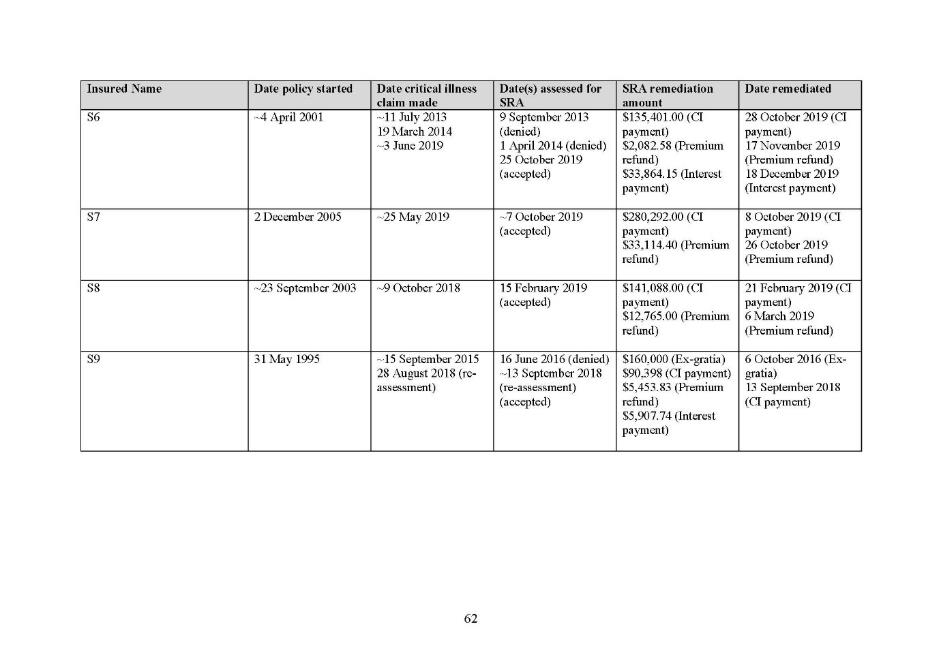

SRA Breach

46 MLCL provided insurance coverage for customers who suffered “critical illness” under certain policies (together, the SRA Policies).

47 SRA was included as a “critical condition” capable of constituting a “critical illness” under the SRA Policies. This means that where a customer with an SRA Policy was assessed as having SRA, as defined all else equal, they would receive a benefit for SRA under their SRA Policy.

48 The SRA Policies contained a definition of SRA by reference to medical diagnosis supported by evidence of specified criteria. In 2011 MLCL adopted the definition set out at paragraph 49 of the SOAF for the SRA Policies.

49 Over 2013 and 2014, the claims team responsible for assessing critical illness claims (the Claims Team) started to see an increase in the number of SRA claims being denied. In March 2014, a customer asked MLCL to review a claim decision relating to SRA. These events appear to have prompted MLCL to question whether the SRA Definitions set too high a bar for the diagnosis of SRA, having regard to then current medical diagnostic standards and treatments for rheumatoid arthritis. That occurred in around July 2014, when the matter was brought to MLCL’s Product Manager for “MLC Insurance” policies.

50 In October 2014, the Product Manager escalated the issue of whether the SRA Definitions were no longer current to MLCL’s General Manager – Claims.

51 In January 2015, MLCL engaged Professor Lesley Barnsley, Head of the Department of Rheumatology at Concord Hospital, to review the currency of the SRA Definition in one SRA Policy – a MLC Insurance policy – and a proposed upgraded definition of SRA (First Proposed Definition).

52 On 27 February 2015, Professor Barnsley provided his report to MLCL. Professor Barnsley advised to the effect that the First Proposed Definition was considerably in excess of current accepted definitions of rheumatoid arthritis which had become more liberal over time in that fewer joints and fewer other criteria were required to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis. A more detailed description of Professor Barnsley’s opinion is provided in the SOAF.

53 From around March 2015 until April 2016, the definition of SRA in the SRA Policies was not updated. In 2015 MLCL checked the SRA definitions of competitors, only to find that none had a more contemporaneous definition to use as a benchmark. As part of its consideration of updating the SRA definition, MLCL had to agree criteria for a new SRA definition that was fair to customers who may suffer SRA, and could be passed on to existing and prospective customers, but was premium neutral. This neutral pricing meant MLCL had to consider whether claims arising under a new SRA definition would exceed projected claims for SRA and, therefore, whether it would impact the pricing for existing and new customers.

54 In April 2016, MLCL’s Product Manager for MLC Insurance policies consulted with MLCL’s Chief Medical Officer about an update to the SRA Definitions. MLCL’s Chief Medical Officer advised that the existing definitions were not “serviceable in the Western World”. On 15 June 2016, MLCL’s Chief Medical Officer proposed new wording to replace the SRA Definitions.

55 In May 2016, MLCL instigated an informal process for assessing potential declinatures of claims for SRA. The process involved consultation with medical staff and claims were assessed against criteria that were less onerous than those in the SRA Definitions. This informal process was documented by MLCL in August 2016 but without specifying alternative criteria for meeting SRA.

56 In September 2016, MLCL engaged Dr Loretta Reiter to provide a further opinion concerning the adequacy of the SRA Definitions in personal protection portfolio policies. Dr Reiter produced a report dated 12 September 2016, which identified a guideline for determining whether a patient suffered from SRA that was employed by the American College of Rheumatology. MLCL continued to consider its SRA Definitions from late 2016 (including at the time of its separation from NAB in October 2016) to mid-2017.

57 In early 2017, MLCL undertook work to update its critical illness medical definitions, including SRA. On 30 June 2017, MLCL determined the wording it would adopt for the definition of SRA in the SRA Policies (Upgraded Definition). It is set out at paragraph 67 of the SOAF.

58 On 30 June 2017, the Upgraded Definition was introduced into the SRA Policies by product disclosure statements.

59 MLCL admits that in the period 27 February 2015 to 30 June 2017, it did not have adequate processes to review and, if appropriate, promptly update, medical definitions for critical illnesses in SRA Policies, in circumstances where it had received expert medical evidence or opinion concerning the currency of medical definitions which ought to have prompted it to review the relevant medical definitions.

60 MLCL admits that, by failing as such, it contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

MS Breach

61 During the relevant period, MLCL and Norwich used an information technology platform called “Eclipse” to store customer and policy data to assist with the administration of insurance policies. Norwich used Eclipse to administer its retail life insurance policies from 16 February 2002 until October 2010, at which time Norwich was amalgamated into MLCL. From October 2010, MLCL continued to use Eclipse to administer retail policies previously issued by Norwich, as well as new policies issued by MLCL (within the MLC Insurance range) from that date. Eclipse was decommissioned on 26 April 2020.

62 Among other things, Eclipse:

(a) stored customer and policy information (including customers’ personal information and contact details; the product type, policy commencement date, cover type, and sum insured for any policies held by the customer; and the premiums paid and payable by the customer); and

(b) generated written communications to customers, which related to the administration of their policy (for example, policy schedules and premium notices).

63 Norwich and MLCL were under a legal obligation to provide to customers certain communications. As explained in the SOAF, Eclipse was used to generate these (and other) communications by batch, in bulk.

64 From 2002, Eclipse included a function – the Mail Suppression Flag – which could be applied by Norwich or MLCL to a given customer’s profile to stop batch-triggered policy communications for that customer. The Mail Suppression Flag was primarily used by the “Customer Maintenance Insurance Team” (CMI Team), though there was no restriction on access for users of Eclipse. Relevantly, anyone with access to Eclipse could apply the Mail Suppression Flag at the customer level.

65 From time to time, MLCL or Norwich (as the case may be) applied the Mail Suppression Flag at a customer level, to customer profiles. This was done when a particular course of action had been agreed with a customer, which would be contradicted by the sending of system-generated correspondence that was automatically issued. The Mail Suppression Flag was applied primarily by the CMI Team when a customer activated the “economiser option”, or, where a policy anniversary needed to be “undone”.

66 In the period until April 2017, the Mail Suppression Flag had to be manually switched off by MLCL staff when the reason for suppression of communications ended. Otherwise, the customer would not receive batch-triggered communications suppressed by the Mail Suppression Flag relating to their policy.

67 Prior to identification of the MS Breach, training for the Mail Suppression Flag was only provided to members of the CMI Team, and not all staff who had access to Eclipse and who may therefore have used the Mail Suppression Flag.

68 Between 18 November 2015 (6 years before commencement of the proceeding) and March 2018, MLCL failed to adequately train relevant staff to remove the Mail Suppression Flag after the reasons for the suppression of communications ended. MLCL also failed to appropriately monitor the use of the Mail Suppression Flag. Prior to the identification of the MS Breach:

(a) there were no documented processes for how to apply and remove the Mail Suppression Flag appropriately;

(b) there was no monitoring in place to ensure that the Mail Suppression Flag was being applied and removed appropriately; and

(c) there were no limitations within Eclipse for how long the Mail Suppression Flag could be applied.

69 As a result of the limitations in training and monitoring identified above, between 18 November 2015 and March 2018 MLCL failed to remove the Mail Suppression Flag within a reasonable time after the reason for the mail suppression ended from the profiles of 282 customers, affecting 374 policies (MS Impacted Customers).

70 As a consequence, the MS Impacted Customers did not receive communications from MLCL that MLCL was under a legal obligation to provide. Those communications, one or more of which was not received by each MS Impacted Customer, included:

(a) First Notice of Premium Due – which provided notice of the premiums due by the customer, including an increase or variation in premium;

(b) Overdue Notices and Dishonour Notices – both of which contained notice of a proposed cancellation of the policy;

(c) Confirmation of Cancellation letters – which were issued where policies were cancelled for non-payment of premiums, at the request of a customer, or at the natural expiry of the policy;

(d) Annual Renewal Notices; and

(e) Exit Statements – provided on termination or expiry of a policy held within a superannuation fund.

71 Section 912A(1)(a) required MLCL to do all things necessary to ensure that services that it provided in relation to the administration of the relevant policies were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, which encompasses providing correspondence of the nature the subject of the MS Breach (e.g. annual renewal notices, exit notices and confirmations of cancellation) under those policies.

72 MLCL admits that during the period between 18 November 2015 and March 2018 it failed to:

(a) adequately train relevant MLCL staff to remove the Mail Suppression Flag after the reasons for the suppression ended; nor

(b) appropriately monitor relevant MLCL’s staff's use of the Mail Suppression Flag.

73 MLCL also admits that as a result of these failures, for the MS Impacted Customers, it failed to remove the Mail Suppression Flag within a reasonable time after the reason for the suppression ended, and that MS Impacted Customers therefore did not receive communications from MLCL that MLCL was under a legal obligation to provide.

74 This is plainly a failure by MLCL to do all things necessary to ensure the efficient, honest and fair provision of financial services (in relation to policy administration on Eclipse).

Applicable principles

75 I discussed the applicable principles in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1115 and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus [2022] FCA 1397. This section of these reasons is substantially based on those judgments.

Declaratory relief

76 This Court has the power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

77 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68, the Full Court stated (at [90]):

The fact that the parties have agreed that a declaration of contravention should be made does not relieve the Court of the obligation to satisfy itself that the making of the declaration is appropriate. … It is not the role of the Court to merely rubber stamp orders that are agreed as between a regulator and a person who has admitted contravening a public statute.

(Citations omitted.)

78 The Full Court continued (at [93]):

Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court's disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator's claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions …

(Citations omitted.)

79 In Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421, Gibbs J stated (at 437-438) that before making declarations three requirements should be satisfied:

(a) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor.

Civil penalties

80 At the relevant times for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty for the contraventions of s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act by the conduct described as the RBB Breach (i.e. from 18 November 2015 to 31 October 2018), s 12GBA of the ASIC Act provided in part:

12GBA Pecuniary penalties

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened a provision of Subdivision C, D or GC (other than section 12DA); or

…

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

(2) In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Subdivision to have engaged in any similar conduct.

…

81 At the relevant times, the maximum penalty for a contravention of s 12DB(1) by a body corporate was 10,000 penalty units. The value of a penalty unit was set by s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). During the relevant period, the value of a penalty unit was:

(a) $180 between 31 July 2015 and 30 June 2017;

(b) $210 between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2020; and

(c) $222 between 1 July 2020 and 31 December 2022.

82 The maximum penalty for the 119 contraventions of s 12DB(1) by the conduct described as the RBB Breach is therefore over $100 million.

83 In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 (the Agreed Penalties Case), the High Court emphasised that the primary purpose of civil penalties is to secure deterrence. In contrast to criminal sentences, they are not concerned with retribution and rehabilitation but are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: Agreed Penalties Case at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ; see also at [110] per Keane J. This point was also emphasised by the High Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 399 ALR 599 (Pattinson) at [15]-[16], [43], [45], [55] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ.

84 The plurality in Pattinson affirmed (at [18]) the well-known statements of French J, as his Honour then was, in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR ¶41-076. In that case, his Honour listed several factors that informed the assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). His Honour stated:

The assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors which have been canvassed in the cases. These include the following:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

85 After setting out the above passage, the plurality in Pattinson stated at [19]:

It may readily be seen that this list of factors includes matters pertaining both to the character of the contravening conduct (such as factors 1 to 3) and to the character of the contravenor (such as factors 4, 5, 8 and 9). It is important, however, not to regard the list of possible relevant considerations as a “rigid catalogue of matters for attention” as if it were a legal checklist. The court’s task remains to determine what is an “appropriate” penalty in the circumstances of the particular case.

(Footnotes omitted.)

86 The plurality in Pattinson considered the role of the prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick in a civil penalty context, affirming (at [53]) the explanation provided by the Full Court of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [155]-[156]. See also Pattinson at [54]-[55].

87 In determining the appropriate penalty, it is relevant to consider steps taken to ameliorate loss or damage (such as payment of compensation) as potentially mitigatory considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44; [2016] ATPR ¶42-251 at [166]-[167] per Edelman J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 399; 146 ALD 385 at [38] per White J.

88 Co-operation with authorities in the course of investigations and subsequent proceedings can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. The reduction reflects the fact that such co-operation: increases the likelihood of co-operation in future cases in a way that furthers the object of the legislation; frees up the regulator’s resources, thereby increasing the likelihood that other contravenors will be detected and brought to justice; and facilitates the course of justice: see, eg, Agreed Penalties Case at [46]; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293-294 (NW Frozen Foods).

89 In the Agreed Penalties Case, the High Court held that, in the context of civil penalty provisions, it was open to the Court to receive submissions, including joint submissions, as to an appropriate penalty. French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ (with whom Keane J agreed) stated at [46] that there is “an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings” and that “the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers”. Their Honours stated that, as was recognised in Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd (No 5) (1981) 60 FLR 38; 37 ALR 256 and determined in NW Frozen Foods, “such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention”.

90 Their Honours stated, at [57], that in civil proceedings there is generally very considerable scope for the parties to agree on the facts and their consequences, and that there “is also very considerable scope for them to agree upon the appropriate remedy and for the court to be persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy” (emphasis in original). In relation to civil penalty proceedings, their Honours stated at [58]:

Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and, for the reasons identified in Allied Mills, highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(Footnote omitted.)

91 Their Honours in the Agreed Penalties Case also made observations, at [60]-[61], regarding submissions by a regulator in such a context.

Application of principles to this case

Declarations

92 The parties have proposed declarations that reflect the agreed contraventions as summarised above. I am satisfied that the contraventions that are the subject of the proposed declarations are established by the facts and admissions set out in the SOAF. I consider it appropriate to make declarations as proposed by the parties. The preconditions for the making of declarations, set out above, are satisfied.

Civil penalties

93 The parties propose that a penalty of $10 million be imposed for MLCL’s contraventions of s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act by the conduct described as the RBB Breach. There were 119 contraventions of that provision. The maximum penalty has been set out above.

94 For the reasons set out below, which include consideration of the mandatory considerations in s 12GBA(2) and other considerations referred to in the authorities, I am satisfied that the proposed penalty is appropriate.

95 The contraventions involved MLCL having received information that 119 customers were entitled to the RBB benefit, but over an extended period not paying that benefit to those customers. The RBB Breach therefore represents a serious failure by MLCL which ought to be denounced by a serious penalty.

96 The RBB Breach extended from at least 18 November 2015 (the beginning of the relevant period for penalty purposes). MLCL did not have appropriate processes and procedures in place to prevent the breach. Facts prior to the penalty period may be taken into account in determining the penalty in the instinctive synthesis performed by the Court. An example is in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790, where Beach J held (at [9]) that although the pleaded contravening conduct occurred over a period of less than two years, “the seriousness of those contraventions is to be viewed in the context of CBA’s failings for a broader period of over 10 years”.

97 Here, similarly, although the RBB Impacted Customers are limited to those 119 people who were left unpaid during the penalty period, MLCL’s failure to have appropriate processes and procedures in place commenced well before that date.

98 It can be inferred that for the period in which the RBB Impacted Customers were not paid, MLCL retained the benefit of being able to apply those monies to other uses.

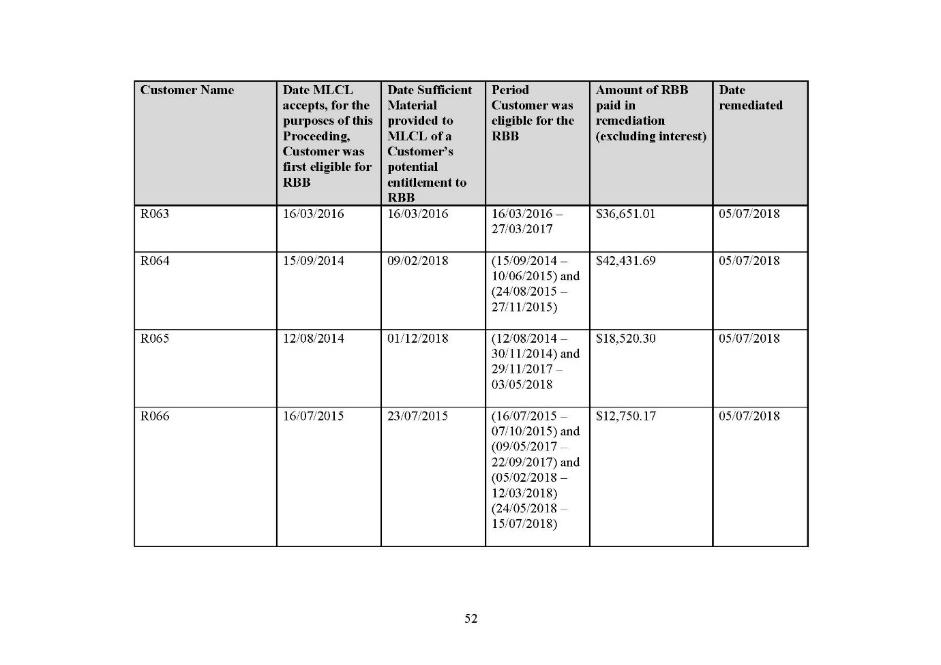

99 As the example of R066 (described in the SOAF) illustrates, some of the RBB Impacted Customers remained unpaid for significant periods of time, sometimes years. This underpayment was at a time when those people were undertaking rehabilitation for the purpose of recovering from their disabling conditions and, it can be inferred, were either not otherwise working or were working in a limited capacity (as they were in receipt of income protection benefits at the time).

100 MLCL is a major provider or issuer, in Australia, of life insurance products to consumers. The SOAF discloses that it had very significant assets during the period that is relevant for penalty purposes. A large penalty is required to provide for appropriate specific deterrence for a company of such substance.

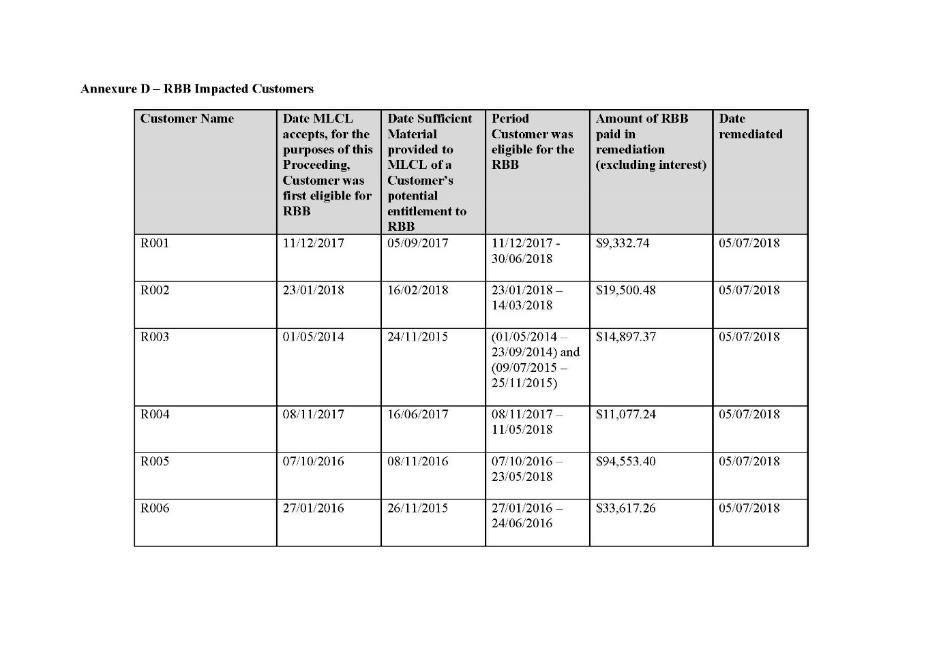

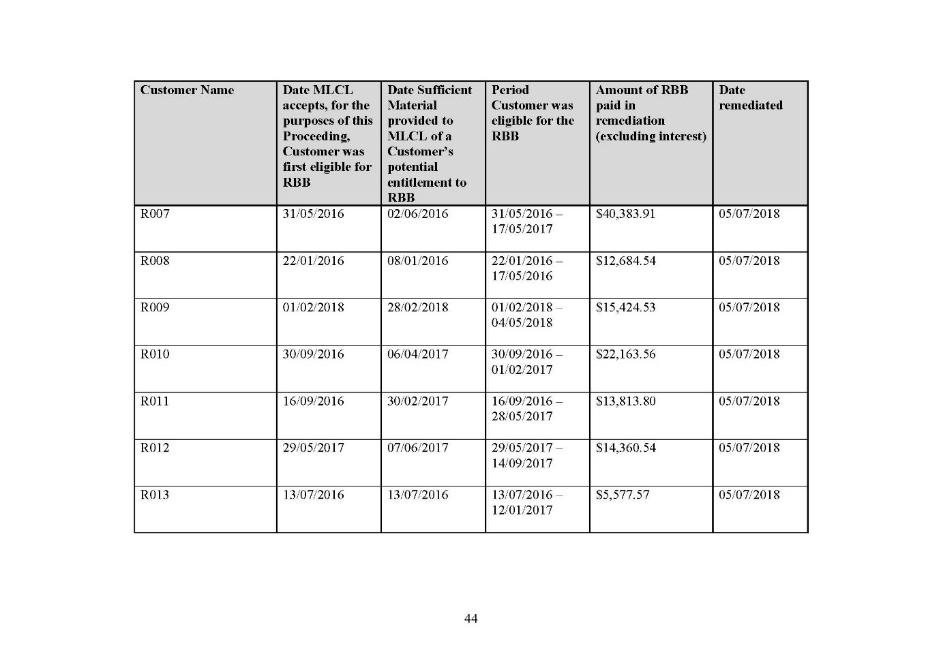

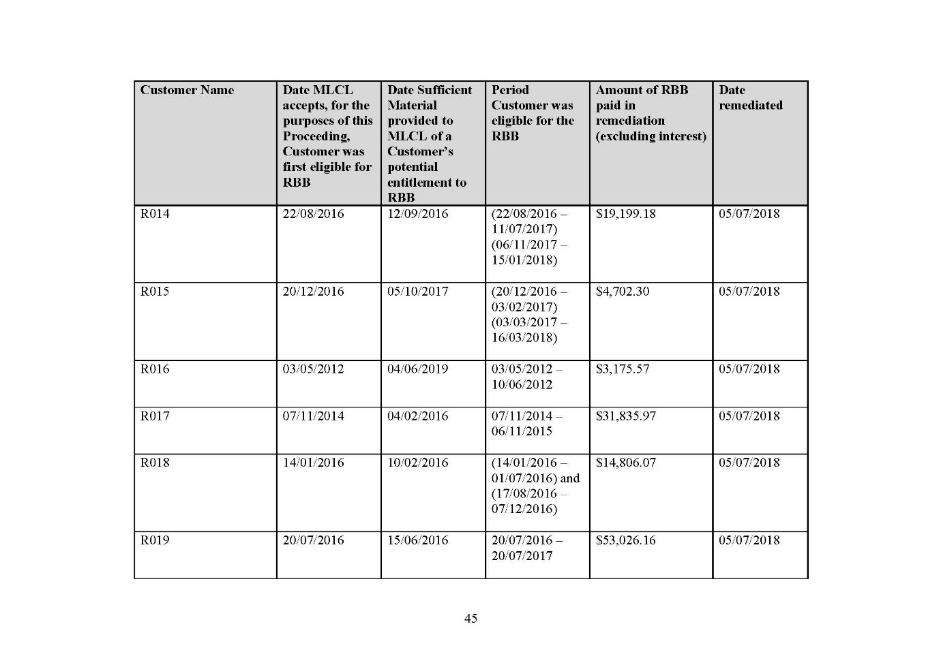

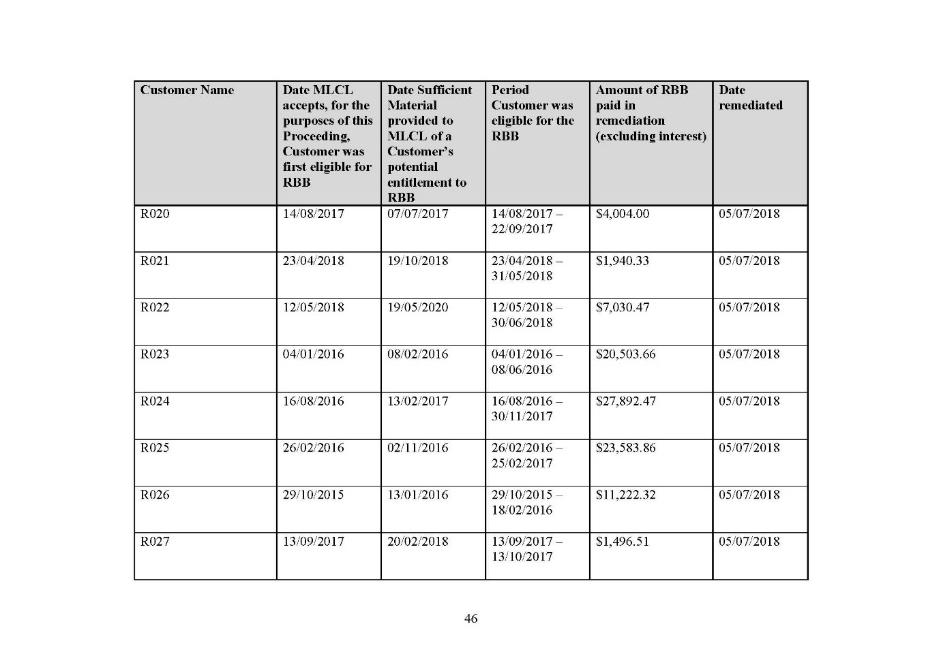

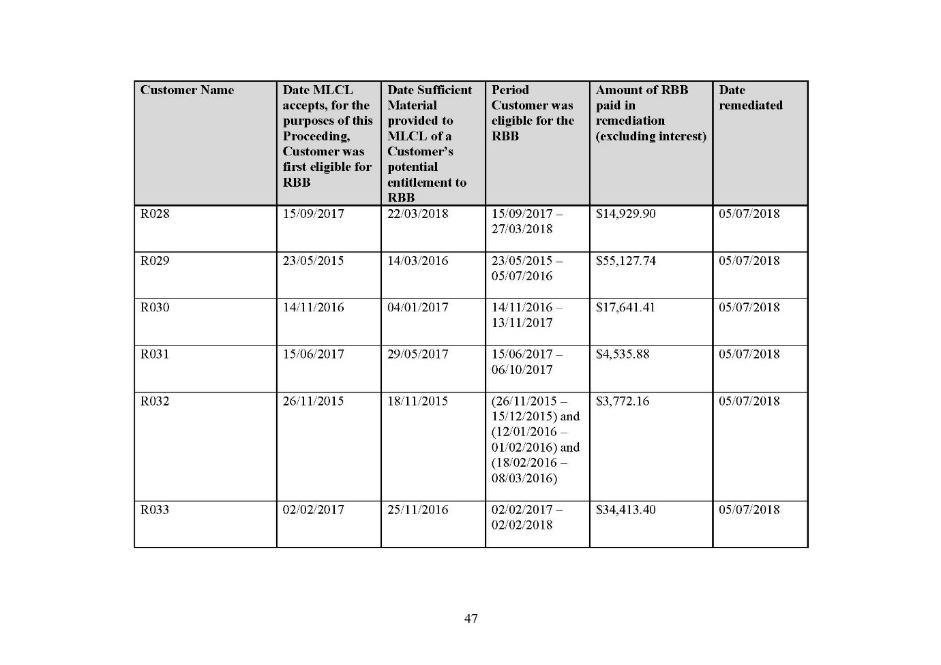

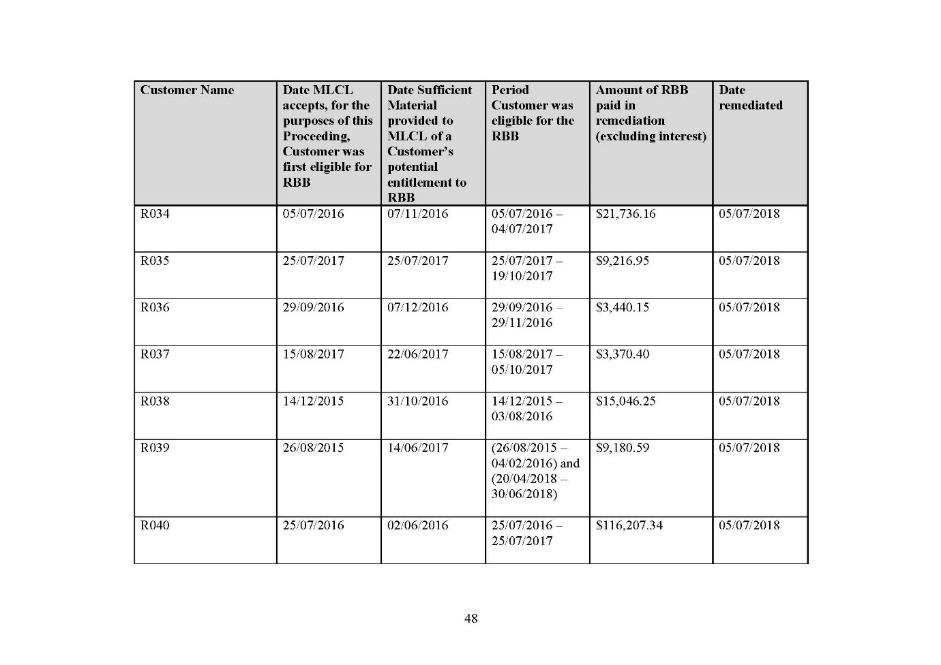

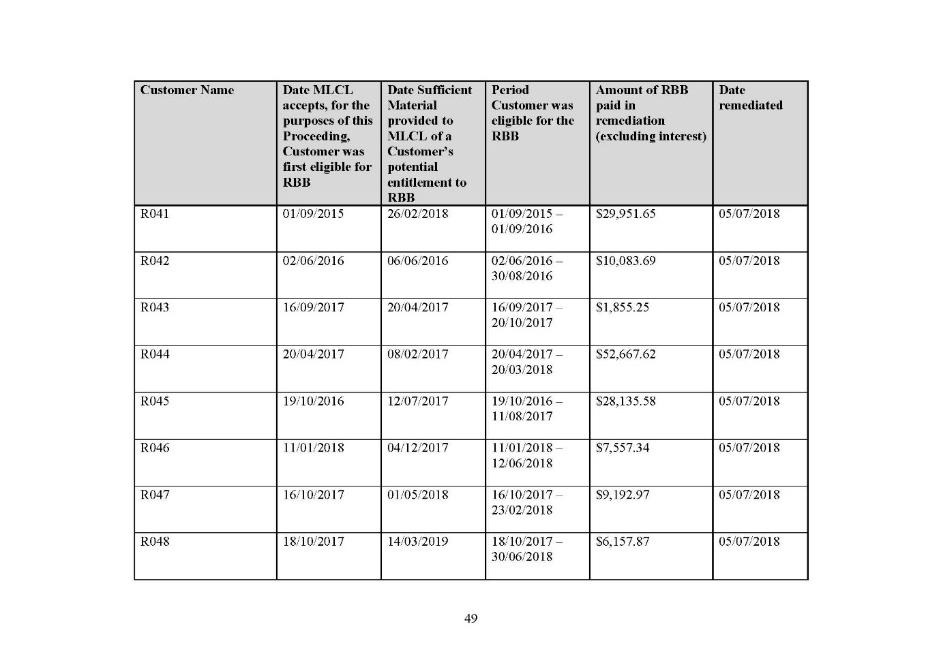

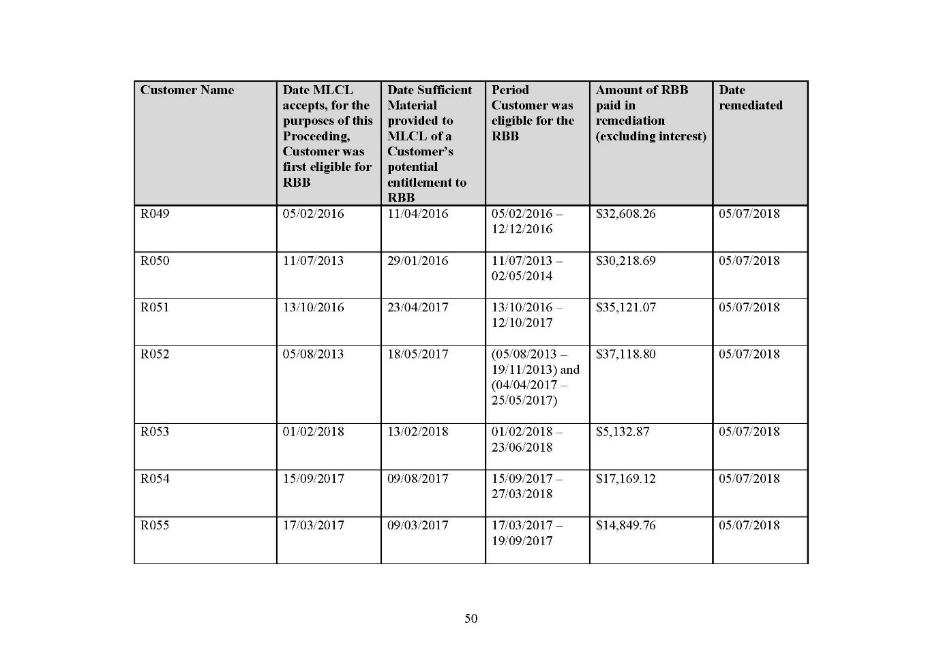

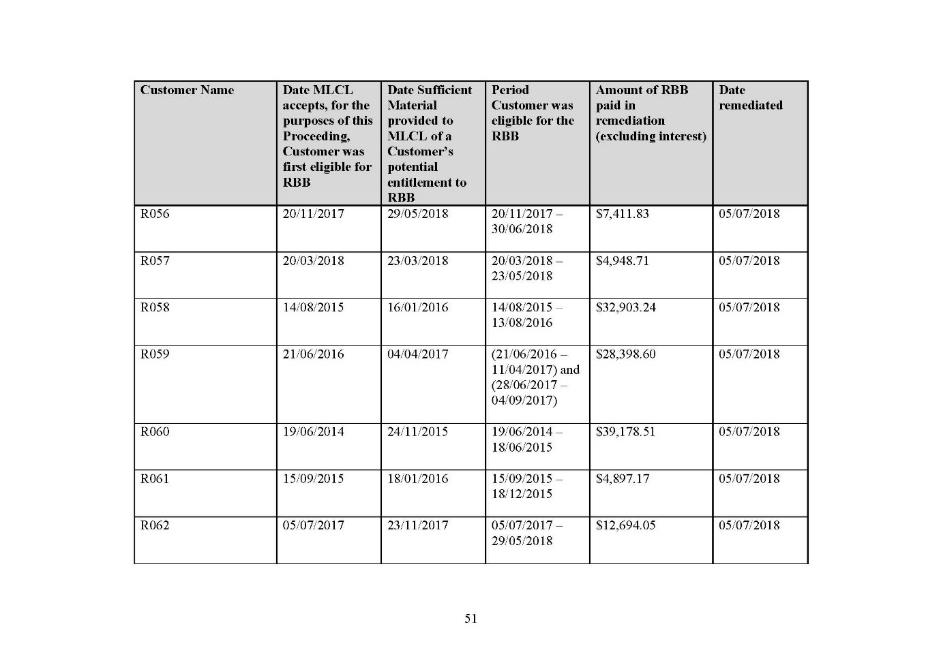

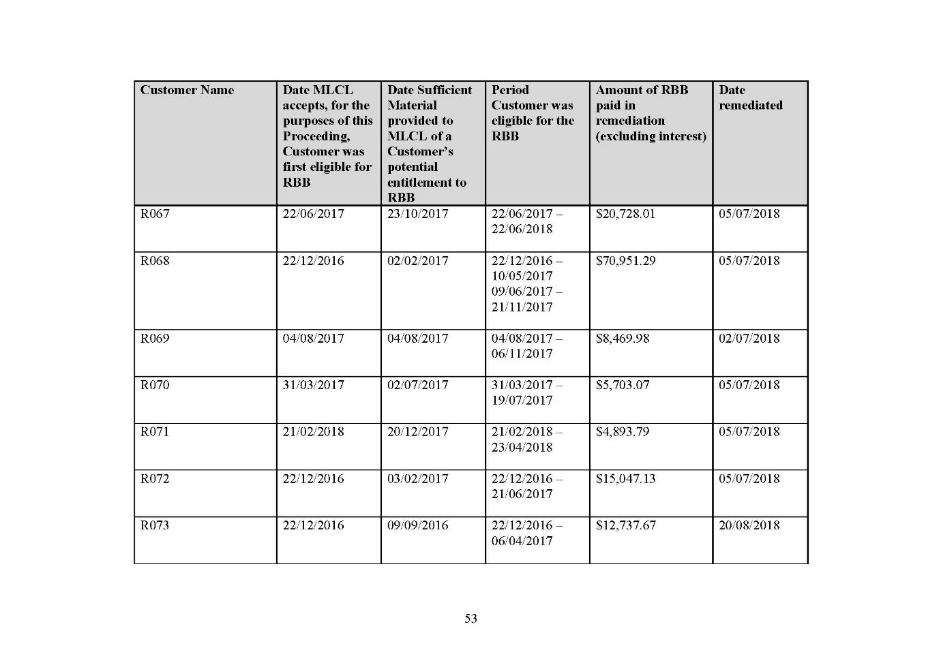

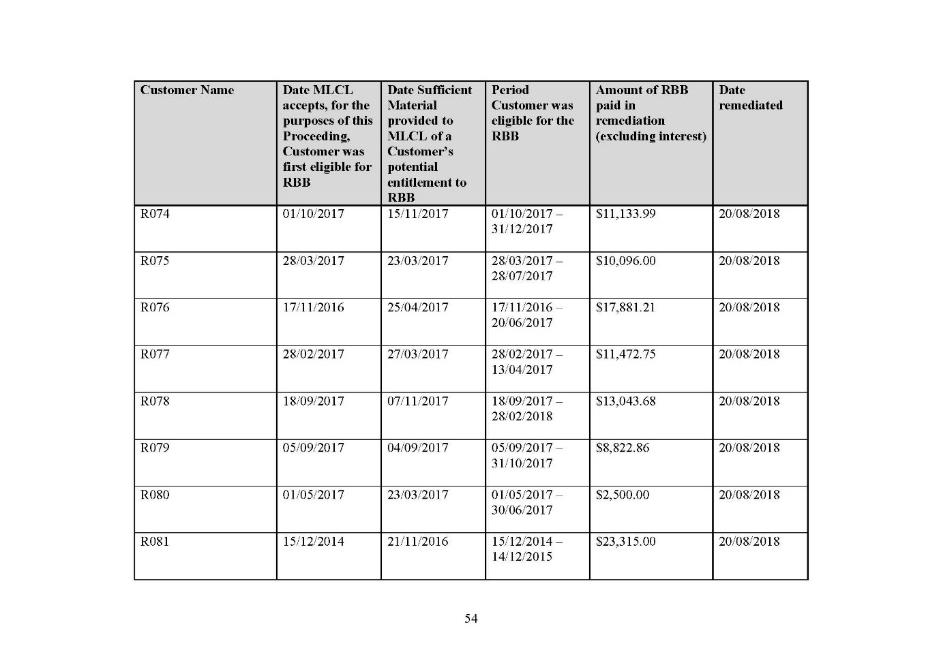

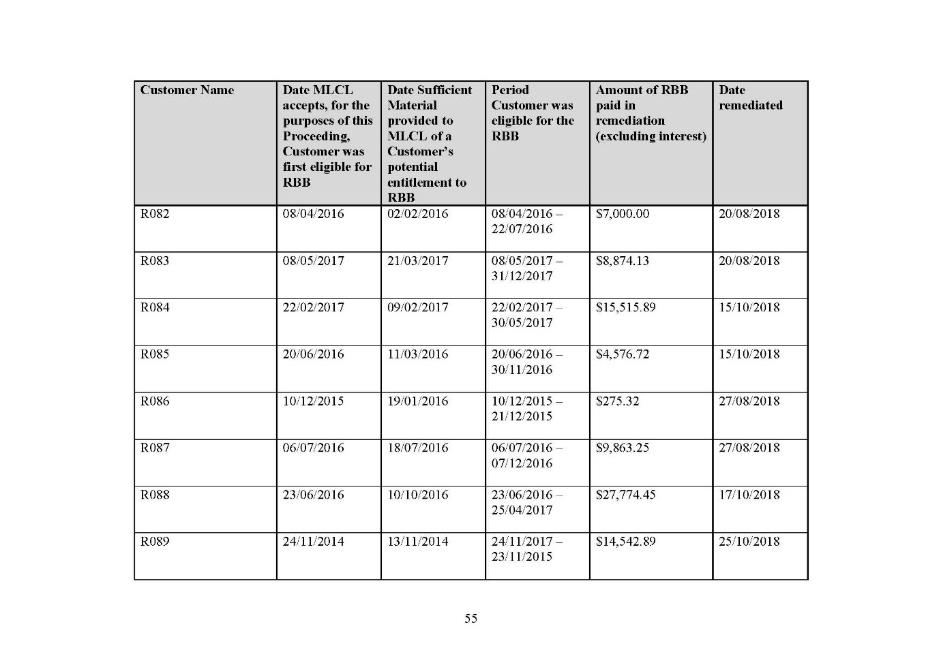

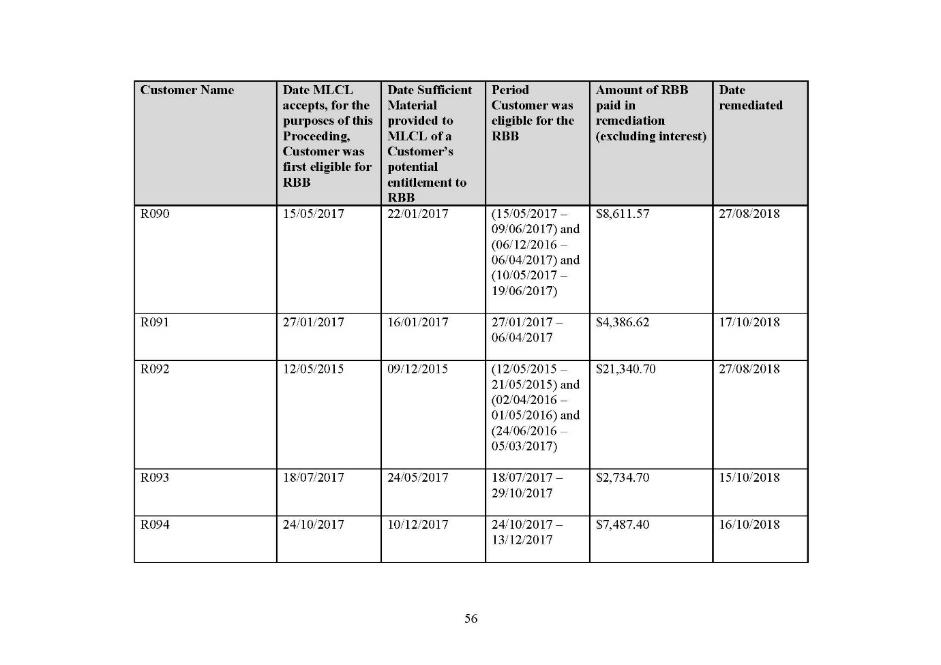

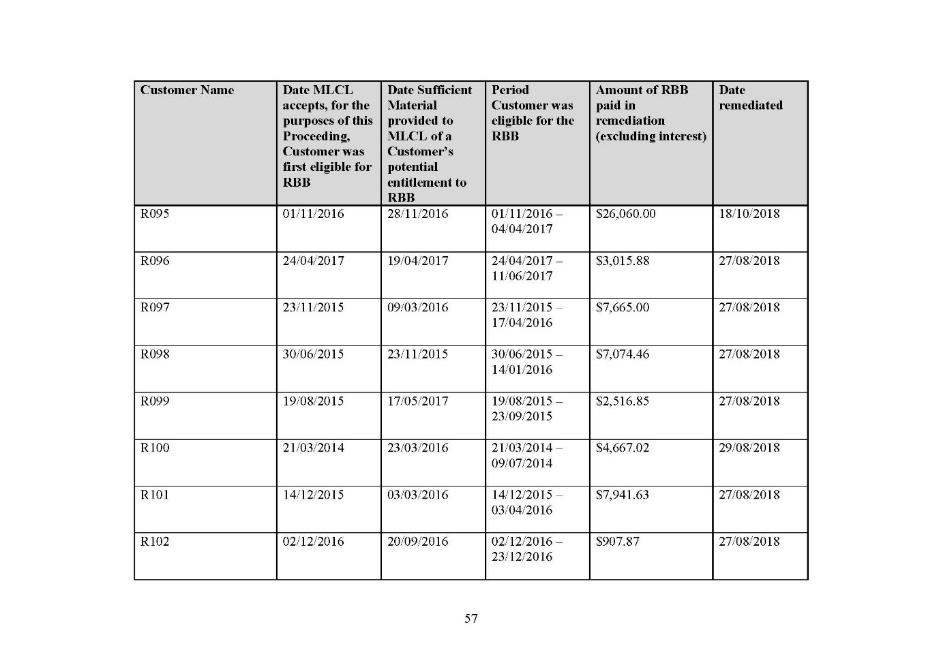

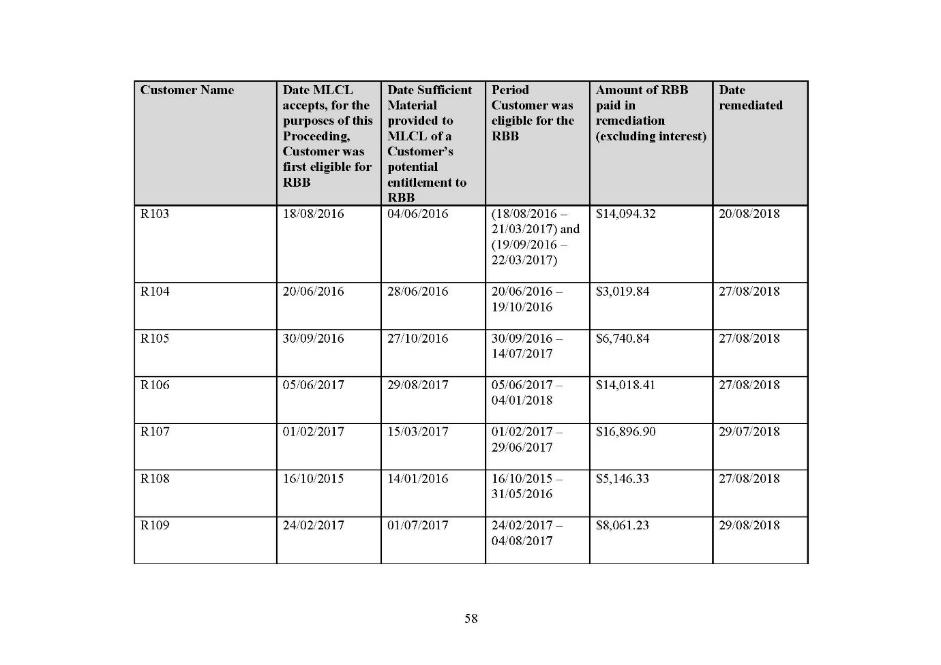

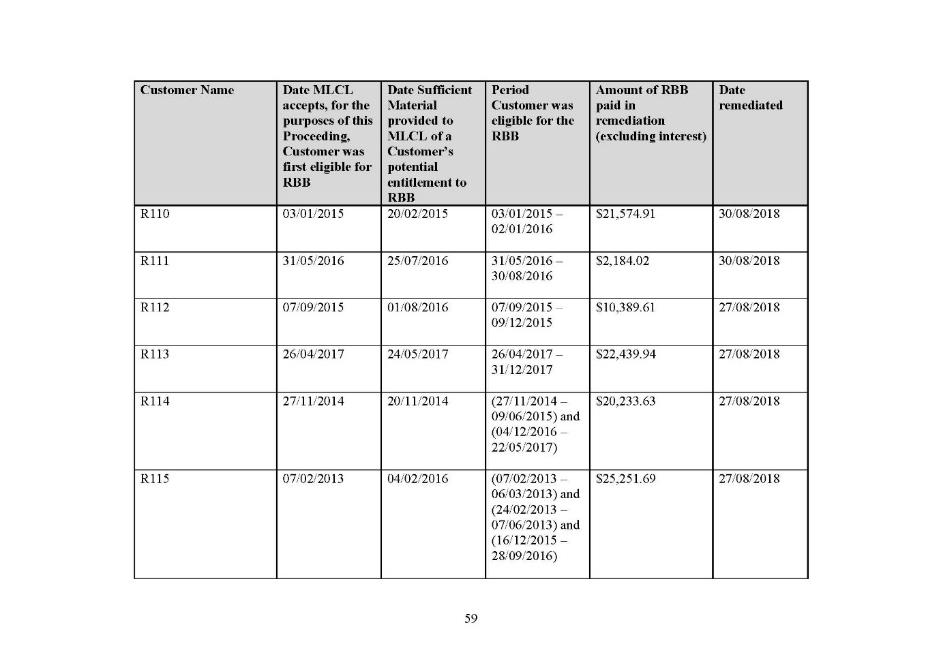

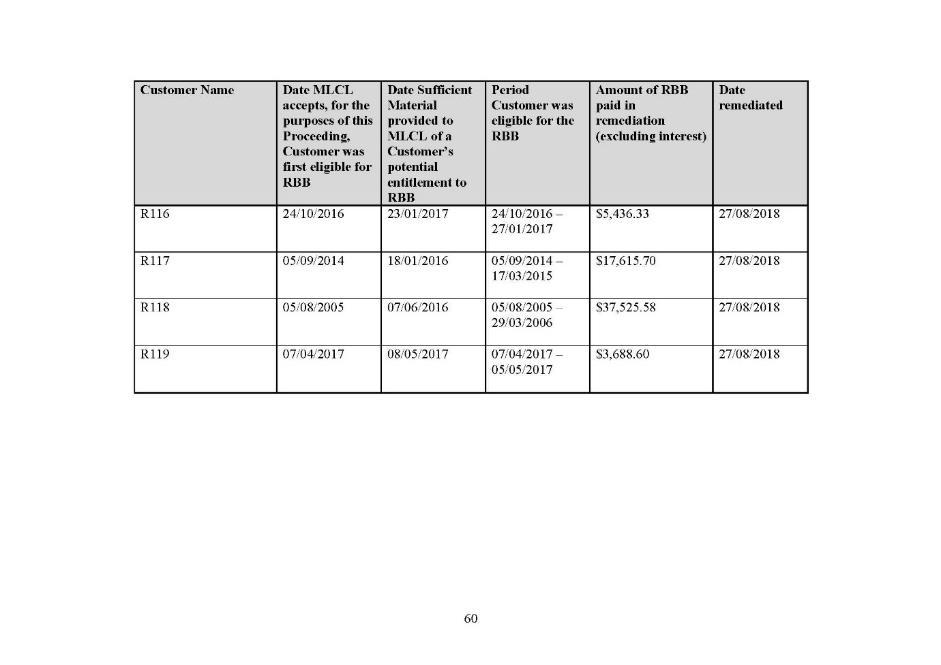

101 Another relevant consideration is MLCL’s conduct in remediating the RBB Impacted Customers. Part C-3 of the SOAF sets out the actions taken by MLCL to investigate the RBB Breach and to report the conduct to ASIC. Annexure C to the SOAF sets out each of the RBB Impacted Customers individually and lists the amount of the RBB (and interest) they were paid in remediation, and the period during which the customer was first eligible to receive the RBB but was nevertheless not paid the benefit.

102 Despite being rectified, Annexure C discloses that many of the RBB Impacted Customers were not remediated for months or years after first becoming eligible to receive the RBB, with some individuals not having received a benefit of tens of thousands of dollars. Further, the RBB Breach was first brought to MLCL’s attention by reason of the escalation of a customer complaint in 2016, then taking two years for the matter to be fully investigated and remediation to be completed.

103 In the SOAF, MLCL makes admissions of liability in respect of each category of conduct pressed by ASIC in the proceeding, including the RBB MD Conduct. MLCL’s admissions and its remediation of impacted customers provide evidence of contrition on the part of MLCL.

104 The contrition of MLCL is further emphasised by direct affidavit evidence from its Chief Executive Officer. In his affidavit, Mr Griffin conveys his deep regret that the breaches occurred and apologises to the Court, MLCL’s customers and all persons affected by the contraventions for their occurrence. Mr Griffin has given his apology on an informed basis and after a review of materials that include the SOAF. The provision of an apology through direct evidence is a matter that the Court is entitled to take into account in being satisfied that a proposed penalty meets the requirements of general and specific deterrence. MLCL has also expressed its contrition through apologies conveyed to customers at the time they were remediated.

105 MLCL has cooperated with ASIC in respect of its investigation into the RBB Breach. MLCL’s cooperation included voluntarily disclosing documents to ASIC. MLCL also reported the breaches to ASIC.

106 MLCL made an early admission in its concise response and sought an early order for mediation. An agreed resolution was reached prior to the filing of evidence, thereby saving ASIC costs that would otherwise have been expended in the preparation and presentation of the case.

107 ASIC has not alleged in this proceeding that the conduct described as the RBB Breach was committed knowingly or deliberately. Nor is it suggested that MLCL engaged in dishonesty or sought to conceal the contraventions.

108 Relevantly for the purposes of penalty, the RBB MD Conduct instead arose as a result of MLCL not having appropriate processes and procedures in place to ensure it would pay the RBB to the RBB Impacted Customers. While the contraventions remain serious, the absence of deliberate, intentional and dishonest misconduct is a relevant matter in assessing the appropriateness of the penalty.

109 The agreed facts do not suggest that senior officers of MLCL were involved in the RBB MD Conduct or directed, facilitated or condoned the conduct.

110 It is not suggested that MLCL has previously been found to have contravened the ASIC Act or the Corporations Act.

111 It is agreed that the deficiencies in the procedures and processes relevant to the RBB Breaches ceased by no later than 31 October 2018. The rectification work undertaken by MLCL is summarised in the affidavit of Mr Griffin, and was directed at seeking to correct the deficiencies that had been identified. The rectification work included an enhanced Quality Assurance Framework for claim consultants and the development of a Quality Assurance Framework for rehabilitation specialists to assess the application of the RBB during the performance review process. MLCL has sought to address the key problems that led to the RBB MD Conduct.

112 Mr Griffin also gives direct evidence concerning the company’s wider culture of compliance. As part of its commitment to striving for high standards of customer service, compliance and risk management, MLCL has invested over $640 million in further uplifting systems and controls across the business. While this investment cannot detract from the seriousness of the RBB MD Conduct, it is relevant that MLCL has taken significant steps to improve its processes and controls and remedy deficiencies as they arise.

113 Having regard to the above, I am satisfied that the proposed penalty of $10 million is appropriate in the circumstances. In particular, I am satisfied that it is sufficient to achieve the objects of specific and general deterrence.

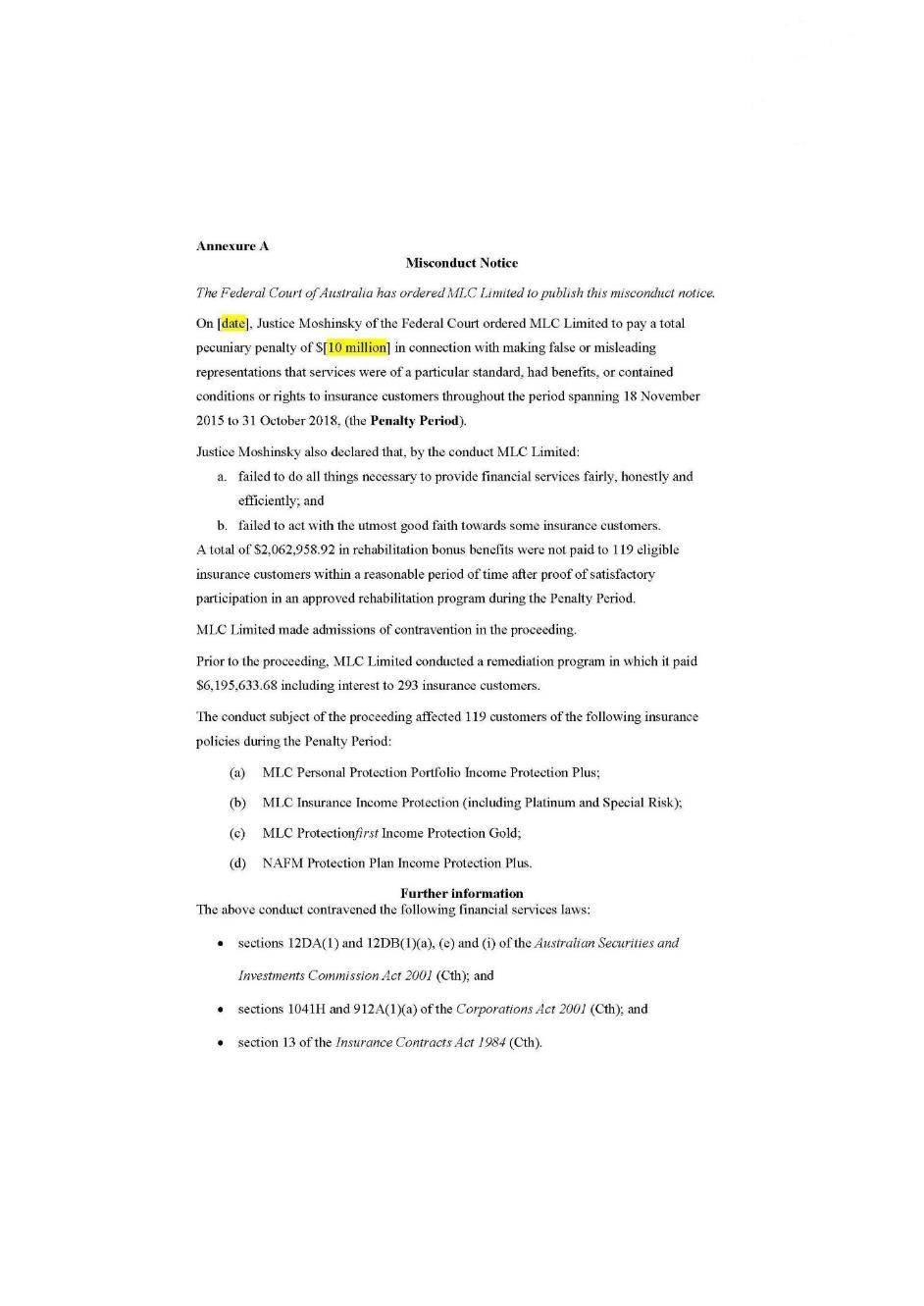

Adverse publicity order and costs

114 I am satisfied that the Court has power to impose, and that it is appropriate to impose, the adverse publicity order, for the reasons set out in the Joint Submissions. The costs order proposed by the parties is also appropriate.

Conclusion

115 I will therefore make declarations and orders substantially in the terms proposed by the parties.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and fifteen (115) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Moshinsky. |

Associate: