Federal Court of Australia

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney (Relief) [2023] FCA 537

ORDERS

NATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION INDUSTRY UNION First Applicant TIM ANDERSON Second Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent STEPHEN GARTON Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 May 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to agreeing by 4:00pm on 2 June 2023 orders to give effect to these reasons, including as to the appropriate terms of a stay.

2. The proceedings be listed at 10:00am on 5 June 2023 for resolution of any dispute as to appropriate orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The background to these proceedings may be found in:

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709 (Primary Judgment);

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2021] FCAFC 159; (2021) 392 ALR 252 (Appeal Judgment);

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 184 (Remittal Judgment); and

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2022] FCA 1265 (Contravention Judgment).

2 A short summary, adopting the abbreviations used in those judgments, is as follows. Dr Tim Anderson’s employment with the University of Sydney was terminated on 11 February 2019. Two of the relevant background events giving rise to his termination involved Dr Anderson’s use of an image of the Israeli flag with a swastika.

3 After his termination, the National Tertiary Education Industry Union (NTEU) and Dr Anderson brought proceedings in this Court alleging that the University, Professor Stephen Garton and Professor Annamarie Jagose had engaged in 21 contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). The 21 alleged contraventions gave rise to two principal sets of issues:

(1) The first set of issues related to alleged contraventions of s 50 of the FW Act and the question whether Dr Anderson had an enforceable right to “intellectual freedom” which he had been exercising.

(2) The second set of issues related to alleged contraventions of s 340 of the FW Act. This part of the proceedings gave rise to the questions whether:

(a) Dr Anderson exercised a workplace right by making “complaints” within the meaning of s 341(1)(c)(ii) of the FW Act; and

(b) the University had established that it did not impose certain warnings to terminate Dr Anderson’s employment because Dr Anderson exercised any one or more of the workplace rights.

4 The NTEU and Dr Anderson also contended that Professors Garton and Jagose breached s 550 of the FW Act by being involved in the alleged contraventions of ss 50 and 340. The accessorial liability claim against Professor Jagose was abandoned after she gave evidence in the primary proceeding.

5 In the Primary Judgment, I concluded that the case brought by the NTEU and Dr Anderson should be dismissed and that Dr Anderson’s employment had been lawfully terminated. My judgment was overturned on appeal in relation to the first set of issues. There was no challenge to the dismissing of the applicants’ case in respect of the second set of issues.

6 One of the questions in the first set of issues was whether Dr Anderson’s publishing of an “infographic” (the Gaza Graphic) constituted the exercise of intellectual freedom. The Gaza Graphic was first used in PowerPoint slides used by Dr Anderson as teaching materials in 2015. The Gaza Graphic was next used in a PowerPoint presentation at a seminar which took place on 21 April 2018. The Gaza Graphic was published with comments on Facebook on 23 April 2018 (the Third Comments) and was also published with comments on Twitter and Facebook on 19 or 20 October 2018 (the Fifth Comments).

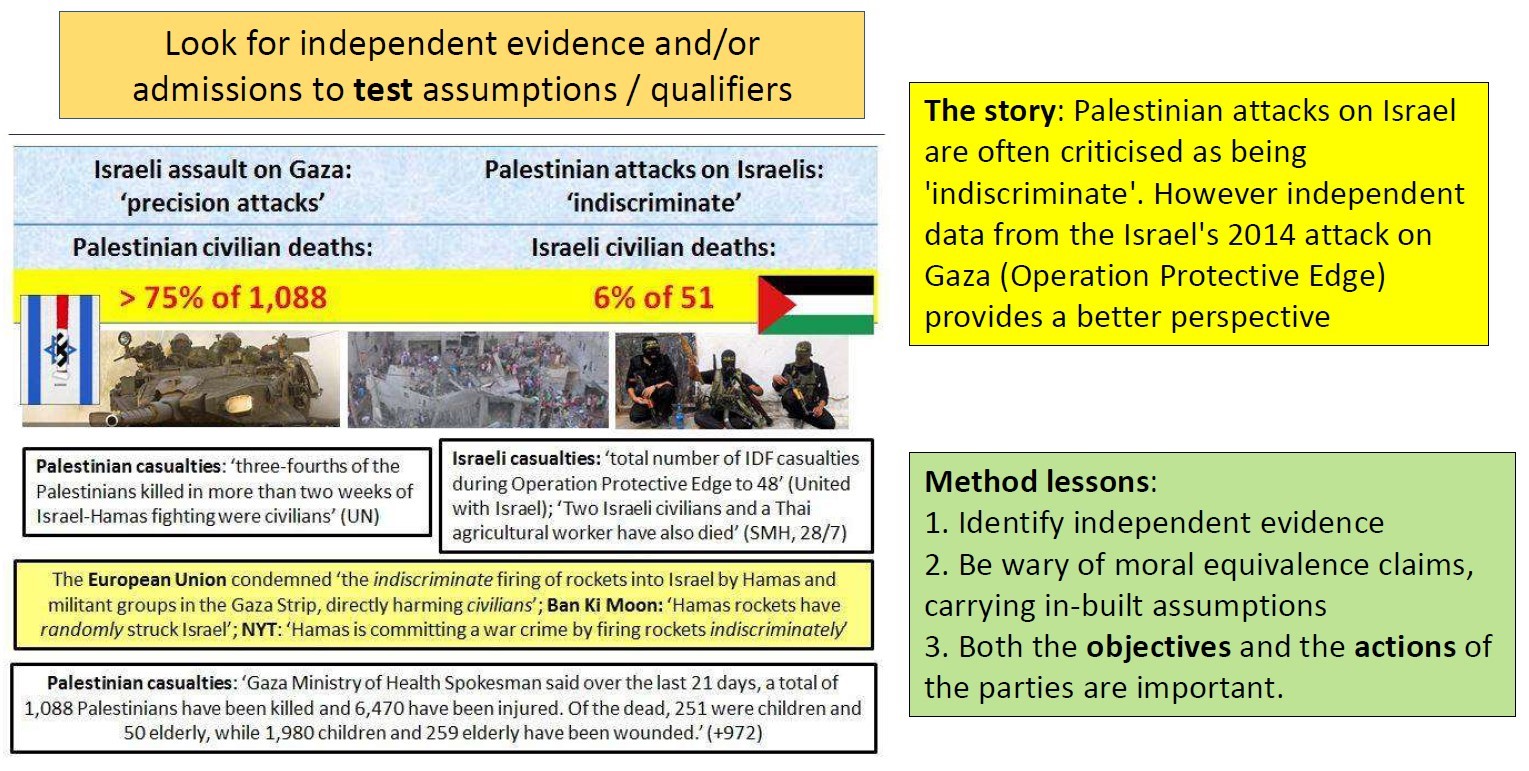

7 The Gaza Graphic as it appeared in the PowerPoint slides presented on 21 April 2018 and as published on Facebook on 23 April 2018 was as follows:

8 As can be seen, the slide contains an image of the Israeli flag with a swastika. It is difficult to see because the image is small, but if it is expanded it becomes clear that the image depicts the Israeli flag with a tear in the middle of it from the top of the flag to a little over half way down, revealing the flag of Nazi Germany underneath.

9 In the Primary Judgment, I held that there was an enforceable right to intellectual freedom, it being assumed in (but not created by) cl 315 and that cl 317 also recognised the right to intellectual freedom, being the right defined in cl 315, and that cl 317 was enforceable as to its rights and obligations according to its terms: [132], [135] and [140]. The Full Court held that cl 315 created the enforceable right to intellectual freedom and that cl 317 also created rights and obligations. In other words, there was no difference of opinion that there was an enforceable right to exercise intellectual freedom within the parameters of cll 315 and 317.

10 Whilst I held that Dr Anderson had a right to intellectual freedom, I held that the Fifth Comments were not a genuine exercise of that right: at [256]. I considered that the question of whether the Fifth Comments were an exercise of intellectual freedom was not necessarily determined by looking at whether the creation and use of the Gaza Graphic for use as part of teaching materials was an exercise in intellectual freedom: at [254].

11 My decision was held by the Full Court in the Appeal Judgment to be erroneous and the matter was remitted for determination according to law. In relation to what I had said at [254] to [256], the plurality stated at [266] of the Appeal Judgment:

[I]f: (a) an exercise of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317 cannot be misconduct at all (which is the case), and (b) posting the PowerPoint presentation initially was an exercise of that right in accordance with cll 315 and 317 (an issue of fact the Court must determine for itself on the remittal), then:

(1) Dr Anderson would be acting lawfully in wanting to “express his view that he had a right to post material of that kind if he wished” and would be right to insist he had the right to do so “without censure”. His self-described “assertion of my intellectual freedom” would be lawful. Contrary to J [256], these factors would not indicate that the conduct was not an exercise of the right of intellectual freedom;

(2) also contrary to J [256], it was not necessary for Dr Anderson to prove or explain what course he was teaching at the time that made it relevant to re-post the PowerPoint presentation. The right of intellectual freedom is not confined to public comments about the content of courses being taught or taught at the time of the public comment; and

(3) if Dr Anderson intended the re-posting of the PowerPoint presentation to be “an assertion of an unfettered right to exercise what he considered to be intellectual freedom” and was being “deliberately provocative” in conveying that Dr Anderson “could post such material if he wanted and the University had no right or entitlement to prevent him from doing so”, he would have been correct and entitled to make that point to the University by the re-posting of the material.

12 It followed from the terms of what the Full Court stated that, if the publishing of the Gaza Graphic on the first occasion (the Third Comments) was an exercise of intellectual freedom, it necessarily followed that the Fifth Comments were an exercise of intellectual freedom. As noted that is not the conclusion I reached in the Primary Judgment. It not the conclusion I would have reached in the Contravention Judgment on the particular facts of this case absent being required to apply the Full Court’s reasoning. It was not suggested by the respondents on the remittal hearing that the Full Court’s decision was incorrect as a result of anything said by the High Court in Ridd v James Cook University [2021] HCA 32; 394 ALR 12. The respondents elected not to seek special leave to appeal from the orders made by the Full Court in the Appeal Judgment.

13 In relation to the Third Comments, the plurality of the Full Court observed at [267] that it is the Israeli flag superimposed with the swastika which is the issue. I have noted earlier that this is not an accurate description of what is depicted, but nothing turns on that. The Full Court observed that “[e]verything else in the PowerPoint presentation involves the expression of a legitimate view, open to debate, about the relative morality of the actions of Israel and Palestinian people”. The plurality said:

[267] Consider the PowerPoint presentation in more detail. It is the Israeli flag superimposed with the swastika which is the issue. Everything else in the PowerPoint presentation involves the expression of a legitimate view, open to debate, about the relative morality of the actions of Israel and Palestinian people. Dr Anderson is making a public comment asserting that the concept of moral equivalence between Israel and Palestinian people who attack Israel is false, in part, because of an asserted higher number of deaths of civilian Palestinians in Gaza from purportedly “precision attacks” by Israel compared to an asserted far lower number of deaths of people in Israel from purportedly “indiscriminate” attacks by Palestinians. He is including Israel within a long history of colonial exploitation by one political entity over another weaker entity or people. It does not matter whether this comparison may be considered by some or many people to be offensive or insensitive or wrong. As discussed, offence and insensitivity cannot be relevant criteria for deciding if conduct does or does not constitute the exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317.

[268] What then of the swastika superimposed over the Israeli flag? That is deeply offensive and insensitive to Jewish people and to Israel. It may involve an assertion of the very kind of false moral equivalence (comparing Israel to Nazi Germany) against which Dr Anderson is advocating in the PowerPoint presentation. Again, however, the relevant issue cannot be the level of offence which the conduct generates or the insensitivity which it involves. The issue is only whether the conduct involves the exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317. Whether this part of the PowerPoint presentation operates to take the otherwise legitimate expressions of intellectual freedom elsewhere in the PowerPoint presentation outside of the scope of cll 315 and 317 is a question of fact which must be determined on the whole of the evidence. For example, did the evidence support an inference that the superimposition of the swastika over the flag of Israel was a form of racial vilification intended to incite hatred of Jewish people? That is a matter which may only be determined on the whole of the evidence as part of the remittal of the matter.

[269] Accordingly, the primary judge was required to decide, as a matter of objective fact by reference to the evidence of all the relevant circumstances, whether each or any of the instances of Dr Anderson’s impugned conduct (excluding the lunch photo) constituted an exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315-317 of the 2018 agreement (or, if applicable, the equivalent provisions of the 2013 agreement). This included consideration of whether the conduct did or did not involve harassment, vilification or intimidation or the upholding of the principle and practice of intellectual freedom in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

14 In the Contravention Judgment, after setting out Dr Anderson’s evidence, I concluded (having regard to what the Full Court stated at [267] to [269]) that Dr Anderson created the Gaza Graphic for an academic purpose and that the use and publication of the PowerPoint presentation comprising the Third Comments was an exercise of intellectual freedom at the time, taking into account the context in which it was published, and without paying regard to later events: at [39] to [50].

15 According to the reasoning of the Full Court at [266], it necessarily followed from this conclusion that Dr Anderson was acting lawfully when he re-posted the Gaza Graphic (the Fifth Comments).

16 In Orders made on 22 November 2022, giving effect to the Contravention Judgment, the Court made declarations that the University failed to comply with:

cl 254 of the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2013-2017 (2013 Agreement) in respect of the First Warning imposed on Dr Anderson on 2 August 2017 (Declaration 1);

cl 315 the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2018-2021 (2018 Agreement) in respect of the Final Warning imposed on Dr Anderson on 19 October 2018 (Declaration 3); and

cl 315 of the 2018 Agreement in respect of the Termination of Employment of Dr Anderson on 11 February 2019 (Declaration 5);

cl 384 of the 2018 Agreement in respect of the Termination of Employment of Dr Anderson on 11 February 2019 (Declaration 7).

17 The Court also concluded that Professor Garton was involved, within the meaning of s 550 of the FW Act, in contraventions of s 50 by the University (Declarations 2, 4, 6 and 8).

18 These reasons address relief consequent upon those contraventions.

19 The applicants sought the following:

(a) Pecuniary penalties, pursuant to s 546 of the FW Act on the University and on Professor Garton for each contravention of s 50 of the FW Act, together with an order that those penalties be paid to the NTEU.

(b) Reinstatement pursuant to s 545 of the FW Act:

• an order reinstating Dr Anderson to his employment with the University on the same terms and conditions as those he would have enjoyed had his employment not been terminated (including any pay increases to which he would have been entitled under the relevant enterprise agreement);

• an order that the University treat Dr Anderson’s employment as continuous for all purposes;

(c) Compensation pursuant to s 545 of the FW Act:

• an order that the University compensate Dr Anderson for the wages he would have earned but for the termination of his employment, including interest, along with a contribution to his nominated superannuation fund; and

• an order that the University and Professor Garton pay Dr Anderson $50,000 as general damages for the hurt, humiliation and distress suffered by reason of the imposition of the First Warning and the Final Warning and for the termination of his employment.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

20 Section 546 of the FW Act empowers the Court to impose penalties for contraventions of civil penalty provisions of the FW Act and, if satisfied it is appropriate, to order any such penalty to be paid to a specified person. Section 546 includes:

546 Pecuniary Penalty Orders

(1) The Federal Court, the Federal Circuit Court or an eligible State or Territory court may, on application, order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate if the court is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil remedy provision.

...

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(2) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is an individual — the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2); or

(b) if the person is a body corporate — 5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2).

Payment of penalty

(3) The court may order that the pecuniary penalty, or a part of the penalty, be paid to:

(a) the Commonwealth; or

(b) a particular organisation; or

(c) a particular person.

21 It follows from the terms of s 546(1) that the imposition of penalties is discretionary and that penalties are imposed where “appropriate”. The discretion must be exercised judicially having regard to the statutory context, that is the subject-matter, scope and purpose of the legislation.

22 The purpose of imposing a penalty is protective in promoting the public interest in compliance with the legislation: The Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ (Keane J agreeing) (the Agreed Penalties Case). The object is deterrence, both specific and general: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157 at [87] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 399 ALR 599 at [10], [15], [25] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ).

23 It was submitted by the University that the reference to “the particular case” at [46] in Pattinson “strongly suggests” that what the High Court stated in the Agreed Penalties Case at [55] has been overtaken by Pattinson to the extent it refers to general deterrence. The relevant passage in Pattinson at [46] is as follows:

Deterrence is the primary, if not sole, purpose of s 546 [of the FW Act]. There is no requirement that the penalty be “proportionate” to the contravention. The Court’s task is to determine what is an “appropriate” penalty in the circumstances of the particular case. An appropriate penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case.

24 I reject that submission. In Pattinson at [15], the High Court expressly endorsed what the High Court had stated in the Agreed Penalties Case at [55], saying:

Most importantly, it has long been recognised that, unlike criminal sentences, civil penalties are imposed primarily, if not solely, for the purpose of deterrence. The plurality in the Agreed Penalties Case said:

“[W]hereas criminal penalties import notions of retribution and rehabilitation, the purpose of a civil penalty, as French J explained in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [(1991) ATPR 41-076 at 52,152], is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance:

‘Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Trade Practices Act] … The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.’”

25 The reference to “the particular case” in Pattinson at [46] does not come close to implying that general deterrence is no longer a purpose of civil penalties.

26 The objective is to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high as to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene: Pattinson at [15]. The penalty should be fixed at a level sufficient to deter both the contravener and others with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business: Pattinson at [17]. The Court should have regard to all matters relevant to deterring contraventions of the relevant kind. In Pattinson at [18], the High Court stated:

In CSR, French J listed several factors which informed the assessment under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value:

“The assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors which have been canvassed in the cases. These include the following:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.”

27 Concepts such as totality, parity and course of conduct may assist in the assessment of what may be considered reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions of the FW Act: Pattinson at [45]. In this context, it should be noted that s 557(1) of the FW Act provides:

557 Course of conduct

(1) For the purposes of this Part, 2 or more contraventions of a civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (2) are, subject to subsection (3), taken to constitute a single contravention if:

(a) the contraventions are committed by the same person; and

(b) the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct by the person.

28 The “maximum penalty” is not reserved exclusively for the worst category of contravening conduct: Pattinson at [49]. The maximum penalty does not constrain the exercise of the discretion under s 546 of the FW Act beyond requiring “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”: Pattinson at [55]. This relationship of “reasonableness” may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravenor as well as by the circumstances of the conduct involved in the contravention: Pattinson at [55].

29 The maximum penalty for a contravention of the FW Act in the case of a corporation, including the University, is 300 penalty units: s 546(2)(b), read with column 4 of item 4 of s 539(2) of the FW Act. A “penalty unit” is defined in s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). At the time the contravening conduct occurred, the value of a penalty unit was $210. Accordingly, the maximum penalty that might be imposed for each contravention of s 50 of the FW Act by the University is $63,000.

30 The maximum penalty that might be imposed for each contravention of s 50 of the FW Act by Professor Garton is $12,600: s 546(2)(a), read with column 4 of item 4 of s 539(2) of the FW Act.

The applicants’ submissions

31 The applicants’ submissions were in summary:

(a) The contraventions were deliberate and the conduct giving rise to the contraventions occurred over some twenty months, involving multiple contraventions of the same kind.

(b) These contraventions were serious and occurred because of the University and Professor Garton’s failure to understand and apply the rights and protections that Dr Anderson enjoyed.

(c) The rights conferred by the relevant agreements were substantive and meaningful rights that were of real industrial and vocational importance, particularly to academic employees at the University.

(d) The purpose of the clauses was to protect and preserve a fundamental right. The conduct of the University and Professor Garton struck at the heart of the rights and protections to which Dr Anderson was entitled.

(e) The contraventions occurred in circumstances where the University was on notice that it was failing to comply with its obligations under the enterprise agreements. At each step in the process, Dr Anderson (and the NTEU) resisted the University’s unlawful conduct and asserted his rights. Despite that, the University and Professor Garton persisted in their unlawful conduct.

(f) When these proceedings commenced, the University and Professor Garton did not restrict their defence to the question of whether Dr Anderson had exercised his right to intellectual freedom in accordance with cl 317 of the 2018 Agreement (and its cognate in the earlier agreement) but defended the matter on the basis that the relevant agreements conferred no right to intellectual freedom at all.

(g) The contraventions were serious. They led to the most serious sanction available to the University, being the termination of employment. Termination of employment has a particular sting for academics, for whom there are limited job opportunities in a small sector where there is significant competition for available positions. Dr Anderson faced the additional complication that he was 67 years of age when dismissed.

(h) The University’s conduct was arrogant and highhanded. The contraventions were objectively serious, and that should be reflected in the penalty applied.

(i) Dr Anderson suffered sustained inconvenience, stress and anxiety arising from the period over which the contraventions occurred and the processes surrounding them, which were time-consuming and, at times, forcefully prosecuted by the University.

(j) The contraventions arose out of the conduct of senior management at the highest levels of the University. The University is a large statutory body corporate with access to specialist industrial relations and legal advice, and ample funds to obtain external advice. There is no evidence that the University or Professor Garton obtained any external advice, despite being on notice that the NTEU and Dr Anderson considered that they were failing to comply with the relevant enterprise agreements.

(k) Intellectual freedom, and particularly academic freedom, is at the heart of the University. There is no more fundamental right among the academy than the right to think, research and teach free from unlawful intervention and interference.

(l) The University is a public institution, with an important public purpose. There is an inherent importance in public institutions complying with the law.

(m) The University and Professor Garton have shown no contrition or remorse. They have not apologised to Dr Anderson, or otherwise expressed any regret for the consequences of their actions. They have not published any statement to employees and students about the Liability Judgment or its meaning and effect.

(n) There is no evidence that the University or Professor Garton have taken any corrective or remedial action.

(o) General deterrence is of particular significance. Rights of intellectual freedom are commonplace in enterprise agreements in the higher education sector. The penalty should be sufficiently high to deter other employees from similar contravening conduct.

32 The applicants submitted that, having regard to the public interest in employers complying with industrial bargains, the lack of contrition or remorse and the absence of any evidence that the University or Professor Garton have taken steps to ensure that they will not engage in further contraventions of the FW Act, the appropriate penalty for each contravention is:

(a) in the case of the University:

• a mid-range penalty of between 40% and 60% of the maximum for the contraventions constituted by the issuing of the First Warning and the Final Warning; and

• a high-range penalty of between 80% and 100% of the maximum for the contravention constituted by the dismissal of Dr Anderson from his employment;

(b) in the case of Professor Garton and allowing for the reduced likelihood that he will engage in similar conduct:

• a low-range penalty of between 20% and 35% of the maximum for the contraventions constituted by the issuing of the First Warning and the Final Warning; and

• a mid-range penalty of between 40% and 60% of the maximum for the contravention constituted by the dismissal of Dr Anderson from his employment.

The University’s submissions

33 The University submitted that no penalties should be ordered against it, or in the alternative, any penalties ordered should be minimal.

34 The University noted that each of the contraventions by the University arose out of actions taken by Professor Garton pursuant to his delegations to act on behalf of the University in his role as the Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor. Professor Garton has now retired from executive roles at the University. The University emphasised that, in the Contravention Judgment at [71], the Court found that: “Professor Garton did not act otherwise than honestly and in accordance with his genuinely held view as to the meaning and operation of the 2013 and 2018 Agreements”.

35 The University submitted that the proper meaning and operation of the intellectual freedom provisions in the enterprise agreements was determined in the Appeal Judgment and that, to the extent general deterrence might be relevant, it is achieved by the publication of the Appeal Judgment and Contravention Judgment. The University noted that, after the Appeal Judgment, the High Court delivered judgment in Ridd, providing further guidance about the content and purpose of academic intellectual freedom, at [29]-[33]. The Ridd litigation and the present proceeding and appeal were the first occasions substantive academic intellectual freedom issues have been determined by Australian courts.

36 As to specific deterrence, the University submitted that nothing is necessary by way of penalty. The University stated that it respects the Full Court’s determination. Referring to an affidavit affirmed on 20 December 2022 by Professor Jagose, the University submitted that Professor Jagose, as the current Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor, has affirmed the University’s commitment to ensuring compliance with the intellectual freedom provisions of the enterprise agreement. The University has no previous contraventions and has a system of review in place which provide “checks and balances” over the University’s decision making. The University has a resolution of complaints policy, applicable to academic staff, which enables them to raise any complaints about their employment. Professor Jagose has regularly had issues relating to academic conduct and misconduct raised with her in her current role and when she was Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. She was not aware of any circumstance in which the University had been found to have acted contrary to the intellectual freedom provisions of the enterprise agreement.

37 The University submitted that the contraventions were not deliberate, in the sense of knowing the conduct amounted to a contravention, nor in bad faith. The University submitted that its previous interpretation and application of the intellectual freedom provisions in the enterprise agreement has been found by the Full Court to be incorrect, but that its position was reasonably open.

38 The University submitted that its commitment to academic intellectual freedom was objectively proved by evidence of the University having defended Dr Anderson during his academic employment when it had received various complaints about Dr Anderson’s public comments. This was shown, for example, in the evidence given by Professor Garton to the Review Committee, which included:

44. The University supports and is committed to upholding the principles of academic freedom and the right of academic staff to discuss and express opinions on controversial or unpopular topics. However, any expression of academic freedom must be in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards. This is consistent with the object and values of the University and is reflected in the Enterprise Agreement, Code of Conduct and Public Comment Policy. At no point has the University required Dr Anderson to refrain from political commentary or to change his views but it has asked him on repeated occasions to frame his commentary in terms consistent with the requirements of the Code of Conduct and the Public Comment Policy.

45. Dr Anderson has had a lengthy career at the University and during much of his employment he has been a controversial figure who has contributed actively to public debate on a range of political and social issues. The University has supported Dr Anderson's right to do so on many occasions. Over Dr Anderson's period of employment, the University has received numerous complaints, both internal and external, about some of the views publicly expressed by Dr Anderson. Each complaint has been considered on its merits by the University and on most occasions, it has defended Dr Anderson's conduct.

46. By way of example: In January 2014, the University received a complaint signed by 13 federal Members of Parliament about Dr Anderson's recent visit to Syria and views he had expressed in favour of the Assad Syrian regime. The complainants requested that the University Immediately require Dr Anderson to desist from these activities.

47. I was acting Vice-Chancellor at the time and in that capacity I responded to the complaint in terms that included the following:

"The most important University value in this context is academic freedom and it is this value that the University must defend if Australia is to sustain an international reputation as a robust and open democracy.

The University's Code of Conduct and policy on public comment uphold the right of academics to make public comment regardless of popular or political opinion so long as the comment is not illegal. In this context we do not believe that Dr Anderson has infringed any policy despite the widespread view that his opinions are wrongheaded, ill-judged or based on a flawed interpretation of the evidence."

48. No action was taken by the University against Dr Anderson in relation to that complaint as the University was satisfied that there had been no breach of the Code of Conduct. I believe the University has acted consistently to uphold the right of its academic staff to express controversial or unpopular views and to encourage robust academic debate on all issues provided that this is done in accordance with the standards of conduct required by the University as set out in its policies.

39 The University also referred to an email from Professor Jagose to a complainant in which she stated that the University did not endorse the views expressed by Dr Anderson on his social media account, but that the University “will always defend the rights of our academics to contribute to public comment in their area of expertise” and noting that the University’s commitment meant that “we must tolerate a wide range of views, even when those views are unpopular or controversial”.

40 The University submitted that the contraventions in respect of the First Warning, the Final Warning and the Termination of Employment were founded on the same factual and legal circumstances and constituted a single course of conduct.

41 The University submitted in the alternative that the contraventions of cll 315 and 384 in respect of the Termination of Employment (orders 5 and 7) were founded on the same factual and legal circumstances, and constituted a single course of conduct. The University relied upon s 557(1) of the FW Act as well as the common law course of conduct principle in submitted that any penalty for those contraventions should be only for a single penalty.

42 The University also relied on the totality principle in submitting that any separate penalties for the contraventions in respect of each of the First Warning, the Final Warning and the Termination of Employment should be added together and the total amount of the penalties reduced in circumstances where the contraventions arose from the same misinterpretation and application of the intellectual freedom provisions in the two enterprise agreements.

43 The University accepted that the Court has a discretion to order that any pecuniary penalty be paid to the NTEU: s 546(3) of the FW Act. It submitted, however, that: (1) no evidence has been brought that the NTEU has “funded and borne the burden of the litigation” as had been submitted; (2) it would be a miscarriage of discretion for the power to be used so to allow the NTEU to recover its costs; (3) the NTEU had made excessive and unbalanced submissions in relation to the quantum of penalties; and (4) such orders should not be commonplace as it creates an intolerable conflict on the prosecutor, because the NTEU’s interests lie in maximising the penalty.

Professor Garton’s submissions

44 Professor Garton submitted that the Court should not exercise its discretion to impose pecuniary penalties on him. It was submitted that Professor Garton had made an honest mistake as to a debatable question of law. This was submitted to be relevant to: (a) whether to impose a penalty; and (b) if so, the level of penalty necessary to deter future contraventions of the FW Act. Professor Garton referred to Pattinson at [46]:

… It is important to recall that an “appropriate” penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case. A contravention may be a “one-off” result of inadvertence by the contravenor rather than the latest instance of the contravenor's pursuit of a strategy of deliberate recalcitrance in order to have its way. There may also be cases, for example, where a contravention has occurred through ignorance of the law on the part of a union official … a modest penalty, if any, may reasonably be thought to be sufficient to provide effective deterrence against further contraventions.

45 If penalties were appropriate, Professor Garton submitted that there was a strong interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of each of the four contraventions declared against him. Firstly, it was submitted that each contravention occurred as part of a related series of conduct and events, and in the common legal element of Professor Garton’s erroneous construction that the intellectual freedom clauses at clause 254 of the 2013 Agreement and clause 315 of the 2018 Agreement respectively did not apply to the comments made by Dr Anderson on social media. Each contravention involved the taking of disciplinary action against Dr Anderson on the basis of the same honest understanding as to the actions or steps that the University was entitled to take in circumstances where, it was understood, the intellectual freedom clauses were not engaged by Dr Anderson's comments.

46 Secondly, it was submitted that each of the contraventions were factually interrelated in that the disciplinary action taken against Dr Anderson was in response to similar conduct which culminated in his termination. The first contravention was the giving of the First Warning to Dr Anderson on 2 August 2017. The second contravention concerned the giving of the Final Warning to Dr Anderson on 19 October 2018. The Full Court has found that the Final Warning proceeded from the First Warning and was issued in response to Dr Anderson continuing to engage in similar conduct following the issuing of the First Warning. The third and fourth contraventions concerned the dismissal of Dr Anderson on 11 February 2019. The Court has found that in considering the disciplinary action to take, the University took into account the First Warning and the Final Warning.

47 Professor Garton submitted that, given the significant legal and factual interrelationship between the contraventions, s 557 requires that the four contraventions are taken to constitute a single contravention.

Consideration

48 It is convenient to address Professor Garton’s position first. As I stated in the Contravention Judgment at [71], Professor Garton did not act otherwise than honestly and in accordance with his genuinely held view as to the meaning and operation of the 2013 and 2018 Agreements.

49 Professor Garton acted at all times with balance, integrity and decency. He did not wilfully disregard any term of the enterprise agreements or any relevant policy. There was no element of blameworthy conduct of any description in connection with the contraventions. Professor Garton had defended Dr Anderson in the past and, as his evidence at trial made clear, plainly had the intellectual freedom of the University’s academics at the forefront of his concerns. It is true that, applying the reasoning of the Full Court in the Appeal Judgment, his actions were held in the Contravention Judgment to involve contraventions of the FW Act. The reasoning of the Full Court was not the only analysis reasonably open. The unlawful conduct arose out of an arguable but erroneous understanding of the rights and obligations under the relevant agreements and there was no flagrant or wilful disregard for the agreements – see: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1607; 168 IR 368 (Gordon J); Australian & International Pilots Association v Qantas Airways Ltd [2009] FCA 500 at [9], [10] (Gray J); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2021] FCA 1128 at [79] (Rangiah J). There is no sound basis for the imposition of a penalty on Professor Garton for reasons of specific deterrence.

50 Nor would the imposition of a financial penalty on Professor Garton further general deterrence. People in roles analogous to that which Professor Garton performed in this case, who conduct themselves reasonably, honestly and with integrity and who take proper account of the enterprise agreement but are reasonably mistaken about its operation, do not need deterrence.

51 The University is in no different position. The majority of the relevant conduct was the conduct of Professor Garton. The University also conducted a review in relation to termination. On the evidence before the Court, the University upholds and supports its academics in expressing views in their areas of expertise, including unpopular views, views which are likely to offend and views expressed in inflammatory terms. The evidence indicates that the University upholds and supports the exercise of intellectual freedom, thereby presumably enhancing its reputation as an institution of academic excellence.

52 The only hesitation I have arises by reason of the manner in which the University conducted the litigation at trial (and on appeal). It argued that there was no enforceable right to intellectual freedom. As I have said, that issue was resolved against the University both at trial and on appeal.

53 The conduct of the University in the litigation might be seen to be inconsistent with its actual conduct which was demonstrably to protect the intellectual freedom of its academics, even though it has now been held to have made a mistake in this particular case, giving rise to contraventions. However, this inconsistency is more apparent than real. It seems to have arisen out of forensic decisions by the legal representatives acting for the University at trial (and on appeal) not to concede the existence of an enforceable right to intellectual freedom, despite the University in fact acting on the basis that there was such a right whether or not enforceable. In any event, the way the litigation was conducted by the University at trial (and on appeal) was not ideal, but – assuming it is appropriate to take such considerations into account – I am not satisfied that it informs considerations of deterrence sufficiently to warrant the imposition of a penalty.

54 The evidence indicated that the University respects intellectual freedom, including by defending its academics. Outside of these proceedings, the University has not been found to have fallen short in this respect in the past.

55 I reject the submission advanced by the NTEU and Dr Anderson that the University’s conduct was “deliberate, arrogant and high handed”. The contravening conduct arose out of views which have been held to be erroneous, but honestly and reasonably so. That does not represent a departure from respect for and commitment to intellectual freedom. There is no likely risk of reoffending and there is no need for specific deterrence. Considerations of general deterrence do not lead to any different result.

56 It is not appropriate to order penalties against either Professor Garton or the University.

REINSTATEMENT

57 Reinstatement is an appropriate order where employment has been terminated for a prohibited reason and there is no particular reason why such an order should not be made: Independent Education Union v Geelong Grammar School [2000] FCA 557 at [34] per Finkelstein J; Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 1218; 228 IR 195 at [125] per Jessup J.

58 Dr Anderson wishes to be reinstated. Dr Anderson intended to continue working at the University as a Senior Lecturer on the same basis as he had been working, namely as a permanent employee in part-time employment at a 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE).

59 Dr Anderson’s evidence was that, at the time of hearing in December 2022, he intended to continue working for between five and ten years. Dr Anderson stated that his position at the University was central to his career. He has remained actively engaged in his areas of research, including by continuing to write and publish, and by speaking at international conferences and events relevant to his areas of expertise. He can immediately resume his employment at the University. Dr Anderson gave unchallenged evidence that he has maintained good relations with his colleagues and continued to contribute to the academic life of the University during the period of his dismissal. He gave unchallenged evidence that he is on friendly and collegiate terms with the Head of Department (who would be his immediate supervisor) and the Head of School of Social and Political Science. Many of the personnel involved in the events leading to Dr Anderson’s unlawful dismissal have moved on and, to the extent that the relevant personnel continue to be employed at the University, Dr Anderson would have limited interactions with them.

60 Dr Anderson submitted that the University is a prestigious institution and employment at the University carries with it significant reputational advantages. There are also practical benefits by way of access to databases, facilities, seminars, support for research, links to colleagues and a platform to present academic thought in research at national and international levels.

61 It was submitted that Dr Anderson would find it difficult to secure an equivalent position at another academic institution of comparable standing. This submission was supported by unchallenged evidence from Mr Cahill, the General Secretary of the NTEU and an Associate Professor of Political Economy at the University. I accept this submission. There are any number of reasons why Dr Anderson would find it difficult to secure an equivalent position at another institution, including the specialised area of Dr Anderson’s interests and the limited number of institutions of equivalent standing which would have a position for Dr Anderson.

62 The University advanced a case that there were structural difficulties which would be faced. In her affidavit of 20 December 2022, Professor Jagose stated:

Curriculum Sustainability Project

12 In 2018, under my leadership as the then-Dean, the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences initiated a Curriculum Sustainability Project. To ensure the ongoing sustainability of the Faculty and its comprehensive suite of disciplines, this project involved closely reviewing each unit of study offered by the Faculty against curriculum sustainability principles. Those principles were:

(a) Curricula will be collectively owned by all colleagues in a discipline;

(b) Student perspectives will inform curriculum design;

(c) Schools will be run so that a greater percentage of units of study return a surplus;

(d) There will be a clear pedagogic rationale for units of study that return a deficit;

(e) Units of study no longer on offer will be formally retired in system;

(f) The Faculty will have a clear sense of units that are co-taught, shell units or offered on rotation;

(g) Schools can ensure they have enough staff to teach the units of study on offer; and

(h) Schools can ensure that units of study can be offered regardless of individual staffing changes.

13 This project is ongoing in the Faculty with updated Curricula Reform Guidelines published in November 2021.

14 Moreover, the Faculty’s leadership in curriculum sustainability has been taken up at a whole-of-institution scale in the Sydney in 2032 strategic plan, which was launched in August 2022. Annexed and marked "AJ-4" is a copy of the University's strategy.

15 Under this Strategy, funding has been allocated to initiate a Curriculum Sustainability Project consistently across the University from 2023, co-sponsored by myself and the Deputy Vice Chancellor—Education, to ensure continuous curricular improvement at scale.

Introduction of the Sydney in 2032 Strategy

16 In 2022, the University introduced its Sydney in 2032 strategy.

17 Two core aspects of this Strategy are:

(a) Educational and Research Excellence - This will involve defining performance expectations specific to particular activities for academics at each level from A to E through an Academic Excellence Framework; and

(b) High Trust and High Accountability - The Strategy emphasises leading with high trust and high accountability to deliver high performance.

18 These aspects of the Strategy mean there will be much closer attention paid to the work of each academic, to ensure that this work is aligned with the Strategy and contributing to the University's defined aspirations. The Strategy and related initiatives identified in the first 2023-2025 strategic roadmap will develop detailed performance and evidence standards for teaching, research and governance, leadership, and engagement, which will, for example, require academics with teaching allocations to design hybrid (face-to-face and online) learning environments consistent with principles of effective learning evidenced in contemporary teaching and learning scholarship and academics with research allocations to apply for external research funding and target top quartile journals.

19 This drive for enhanced performance (for example, improved student satisfaction metrics; increased external research funding) supports the University’s ambition to increase its reputation and global rankings. There will therefore be an increased focus on supporting academic professional development and standardising academic performance appraisals (Academic Planning & Development) as part of this Strategy to ensure enhanced academic performance.

Changes to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

20 A Change Plan for FASS was implemented in 2022. This Plan resulted in the Faculty moving from a departmental to a disciplinary structure, and a reorientation of the disciplines internal to the Faculty’s schools.

63 Dr Anderson submitted that:

these are ordinary processes of restructure and change that are typical of large institutions;

there is no evidence that Dr Anderson’s employment would have been terminated as a result of these changes;

the changes are nothing more than a description of the changed environment in which Dr Anderson’s reinstatement will occur;

there is no evidence that any of these changes would impair Dr Anderson’s ability to return to the workplace quickly and effectively.

64 I accept these submissions.

65 Professor Jagose stated that she has a concern about whether Dr Anderson is willing to abide by lawful and reasonable directions. This concern was said to arise at least in part out of comments made during the course of proceedings. The fact is that, before the events the subject of these proceedings, Dr Anderson has not been shown not to have abided by lawful and reasonable directions. I place little weight on comments made by Dr Anderson during the litigation, particularly when it was so aggressively conducted by those representing the University at trial. It was unsurprising that he would be provoked at trial, just as the University may have been provoked by some of Dr Anderson’s conduct.

66 The University referred to Slonim v Fellows [1984] HCA 51; 154 CLR 505 at 515 in which Wilson J (with whom Mason and Deane JJ agreed) said that:

… the power to direct that A employ B is a very drastic one. It is not lightly to be inferred in the absence of compelling language … [I]t will always be a power to be exercised with caution having regard to the circumstances of the case. There will be many cases where the working relationship of employer and employee is so close that to impose such a relationship by an award would be quite destructive of industrial harmony.

67 The present circumstances do not fall within the sort of close employment relationship which must have been in contemplation when making those observations. There will be many cases where the size of the employer, the number of employees and the nature of the working environment are such that an order for reinstatement is unlikely to have serious effect on industrial harmony and where such an order would be appropriate. Given Dr Anderson’s unchallenged evidence about his relationships with those with whom he would be required to work, this is such a case.

68 Dr Anderson should be reinstated to his employment on the same terms and conditions as those to which he would have been entitled but for his dismissal, with full continuity of service for all purposes. The parties agreed that any such order should be stayed pending determination of an appeal currently pending from the orders made giving effect to the Contravention Judgment.

COMPENSATION

69 The Court’s power to order compensation under s 545(1) of the FW Act is discretionary and any order must be considered by the Court to be “appropriate”. Section 545(2)(b) relevantly provides that, without limitation to s 545(1), orders the Court may make include “an order awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention”.

70 Dr Anderson sought two forms of monetary compensation:

71 First, he sought to be compensated for the income he would have earned if he had not been dismissed from his employment. Dr Anderson has not held paid employment since his dismissal. He drew down from his self-funded pension and earned a small writing income to support himself. Dr Anderson has, consequently, sustained loss equal to the income he would have earned at the University.

72 Secondly, Dr Anderson sought compensation for hurt, humiliation and distress in the sum of $50,000. It was submitted that Dr Anderson has “suffered considerably by reason of the University’s unlawful conduct”. It was submitted that he “was unlawfully subjected to ongoing, sustained, disciplinary procedures as a result of the lawful exercise of rights under the applicable enterprise agreement”; that he “suffered embarrassment and distress at the imposition of the First Warning and Final Warning, each of which imperilled his ongoing employment and subjected him to a real and meaningful psychological burden”; and that the imposition of disciplinary outcomes, including the termination of his employment imposed a meaningful psychological burden on him.

73 I will address compensation for lost earnings first. Until the Termination of Employment on 11 February 2019, Dr Anderson was a member of the University’s academic staff employed in the position of Senior Lecturer on an ongoing part-time basis, at 0.5 FTE. Dr Anderson’s classification under the 2018 Agreement was Senior Lecturer (Level C), step 6, and as at 11 February 2019, Dr Anderson’s annual salary was $73,557.50 (calculated as 0.5 x $147,115 FTE). Dr Anderson was also entitled to employer superannuation contributions of 17% of salary.

74 The period for past economic loss commences five weeks after the Termination of Employment on 11 February 2019, given Dr Anderson was paid five weeks salary in lieu of notice.

75 The University accepted that amounts drawn down from Dr Anderson’s pension should be disregarded as should his modest writing income.

76 As to interest for past economic loss, Dr Anderson should be awarded interest at half the relevant rate to reflect the fact that the losses are spread over the whole period since his termination.

77 As to compensation for hurt and humiliation suffered because of a contravention of a civil remedy provision, the parties were agreed that compensation may be awarded under s 545: Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association v International Aviation Service Assistance Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 333; 193 FCR 526 at [441] to [444] (Barker J).

78 Whether or not an order for compensation should be made must be assessed having regard to the statutory context and the relevant circumstances.

79 Dr Anderson suffered the usual amount of distress which accompanies disciplinary actions commonly encountered in large organisations such as the University. He was afforded procedural fairness and an opportunity to respond in writing at all times in relation to the disciplinary warnings and the termination of employment. He was treated with respect. There was little if any objective evidence which established or supported any significant distress or hurt feelings. There was no medical evidence on the topic. It is clear enough from Dr Anderson’s posts the subject of these proceedings, that he is content to engage in provocative and vigorous debate, including of a personal nature and by expressing views known to be highly offensive to many people. None of Dr Anderson’s posts were of a kind which demonstrated an individual whose feelings might easily be hurt. I am not persuaded as a matter of fact that Dr Anderson has suffered hurt feelings, humiliation or “psychological burden” (to adopt his language) of a kind which would warrant an order for compensation in the circumstances.

80 Dr Anderson posted a picture of the Israeli flag with a swastika knowing that it would be deeply offensive and hurtful to many people. He published other material, including material of a provocative nature, knowing it was offensive to many people. My earlier conclusion that Dr Anderson has not suffered hurt or humiliation of a kind warranting compensation is reinforced by the fact that Dr Anderson did not present as a person who would be both insensitive to the hurt he was causing others and personally wounded by the reactions of others to his conduct.

81 I am not satisfied that it is appropriate to order compensation for hurt feelings and humiliation.

CONCLUSION

82 The parties should confer with a view to agreeing orders giving effect to these reasons, including as to the appropriate terms of a stay.

I certify that the preceding eighty-two (82) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Thawley. |

Associate:

Dated: 29 May 2023