Federal Court of Australia

CIP Group Pty Ltd v So (No 3) [2023] FCA 518

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 May 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Upon the usual undertaking as to damages given by Mr Marc Andrew Clancy:

1. The first and fourteenth to eighteenth respondents:

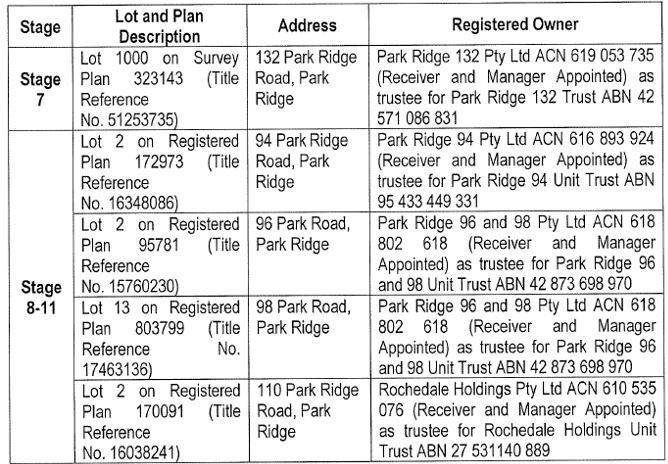

(a) notify the applicants in writing no later than 7 business days prior to the proposed settlement of any sale of any real property in Stages 7 to 11 of the development (such properties being identified in Annexure A);

(b) not assign or otherwise deal with any rights, entitlements or interests to any or all proceeds from the sale of any real property in Stages 7 to 11 (Stage 7 to 11 proceeds) under any instrument;

(c) hold in a trust account maintained by their solicitors, any or all of the Stage 7 to 11 proceeds purportedly payable to the seventeenth or eighteenth respondents pursuant to any asserted right, entitlement, or interest under any instrument;

(d) save for making any payment into a solicitors’ trust account in order to comply with Order 1(c) above, not dispose of or otherwise deal with or diminish the value of the Stage 7 to 11 proceeds.

2. Order 1 above is to apply until further order of the Court, or unless the applicants expressly provide prior written consent in respect of any proposed non-compliance orders, a request for such consent to be received no later than seven business days prior to the proposed non-compliance.

3. Orders 1 and 2 above will cease to have effect if, within 21 days from the date of these orders, the applicants and/or the second to thirteenth respondents have not made an application to join SEL Property Investments Pty Ltd, Ms Lai Wah Wong and Ms Suk Kuen Leung to these proceedings.

4. The costs of this application are the parties’ costs in the proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE A

DERRINGTON J:

Introduction

1 The circumstances in which the present parties find themselves in dispute are set out in the earlier decision of CIP Group Pty Ltd v So [2022] FCA 1490 (CIP Group Pty Ltd v So). In very general terms, Mr Clancy and certain companies controlled by him (the Clancy interests) and Mr So and certain companies controlled by him (the So interests) were engaged in a land development business, in the course of which they incorporated a number of additional companies as vehicles to undertake a specific development called Carver’s Reach Estate. Those entities include the second to thirteenth respondents in these proceedings, which have been referred to in connection with this application as the “Carver’s entities”. It is convenient to adopt that nomenclature, notwithstanding the fact that it has otherwise been used in these proceedings to refer to the second to twelfth respondents only, and those respondents are not all in a strictly identical position for the purposes of this application. Relevantly, both Mr Clancy and Mr So were directors of each of the Carver’s entities at the material times.

2 For the reasons set out in CIP Group Pty Ltd v So, the Clancy interests were granted leave pursuant to ss 236 and 237 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) to bring derivative proceedings in the name of the Carver’s entities against Mr So and the seventeenth respondent, Ultimate Investment Portfolio Pty Ltd (Ultimate), a company of which Mr So is the sole director and secretary. By an order of 10 March 2023, the grant of leave to bring derivative proceedings was extended so as to apply against the eighteenth respondent, UIP 1 Pty Ltd (UIP). Mr So was previously the sole director and secretary of UIP, but those positions have, since 1 July 2022, been held by his wife, Ms Tsang. The applicants and the Carver’s entities allege that UIP is a “related entity” of Ultimate. UIP does not admit that allegation, but recognises that it has been described as such in affidavit evidence filed in other proceedings in this Court involving certain of the present parties. The first and fourteenth to seventeenth respondents, representing the So interests, contend that the company is controlled by Ms Tsang and not Mr So.

3 The derivative proceedings have been commenced by the filing of a Statement of Claim. In general terms, and amongst other things, it is alleged that a loan and associated mortgages and securities entered into by the Carver’s entities with Ultimate are each liable to be set aside and that declarations should be made to the effect that Ultimate holds its interests in those agreements and instruments, as well as any proceeds it receives or has received from the sale of the land owned by the Carver’s entities (the Carver’s Estate land) by reason of those agreements and instruments, on constructive trust for the Carver’s entities. It is also alleged that UIP has acquired a loan payable by the Carver’s entities, together with supporting mortgages and securities, by the use of certain funds in which the Carver’s entities had a proprietary interest, such that the Carver’s entities are entitled to trace into those rights. On any view, there is an element of complexity in these proceedings, arising in large part from the nebulous corporate structures used by Mr Clancy and Mr So in their business, and from the intricate web of financial dealings between the various entities involved.

4 By an interlocutory application filed on 10 March 2023, the applicants and the Carver’s entities have sought injunctive relief to prevent the dissipation by Ultimate of the proceeds of any further sale of the Carver’s Estate land, which Ultimate is able to realise pursuant to the mortgages it holds over that land. Similar relief is sought against UIP in respect of the loan, mortgages and securities that it received by way of assignment from another company, IJ Financial Services Ltd (IJ Financial). The focus of that part of the application concerned the circumstances by which UIP became the holder of that loan, and the associated mortgages and securities. Although the opposition to the injunctions sought against Ultimate was not abandoned, it was the issues relating to the first-ranking securities held by UIP that assumed the most prominence.

5 The underlying foundation of the claim for relief against Ultimate is that the loan, mortgages and securities over the Carver’s Estate land were obtained by it with knowledge of their connection to certain breaches of the fiduciary duties owed by Mr So (the controlling mind of Ultimate) to the Carver’s entities, or were otherwise the result of its participation in, or being party to, those breaches. The basis of the substantive relief against UIP is more complex and, indeed, is partly founded upon the claims made against Ultimate. As articulated in the applicants’ and Carver’s entities’ written submissions on this application, it is that UIP “received proceeds from sales which occurred as a result of Ultimate having realised some of the Carver’s [Estate] land pursuant to, and in partial discharge of, Ultimate’s loan, mortgages and securities, which proceeds UIP has then used to pay out a secured debt owed to IJ Financial by the Carver’s entities and has received an assignment of IJ Financial’s mortgages and securities over the remaining Carver’s [Estate] land.” (AS [4]). In essence, this is a tracing claim, to the effect that Ultimate’s sale of some of the Carver’s Estate land, referred to as “Stage 6”, was associated with Mr So’s alleged breaches of duty, giving rise to a claim that Ultimate held the proceeds of the sale on constructive trust for the Carver’s entities, and that the Carver’s entities are now entitled to trace those proceeds into the loan, mortgages and securities that UIP subsequently acquired.

Background

6 Leaving aside the background facts referred to in CIP Group Pty Ltd v So, of particular importance to the present application is the conduct of Mr So in 2021 and 2022 in incorporating UIP and using it to acquire the first-ranking securities over the Carver’s Estate land, previously held by IJ Financial. The evidence as to these matters was substantial and was further supplemented by cross-examination of both the solicitor for UIP and Mr So himself.

7 UIP was incorporated on 24 November 2021 with Mr So as its sole director. Its sole shareholder was Hamilton 1 Pty Ltd, of which Mr So was also a director. Under cross-examination, Mr So claimed that he did not incorporate UIP for any particular purpose, but merely used the company for trading or conducting business.

8 On 16 December 2021, Mr So caused Ultimate to appoint Mr Marcus Watters of Hall Chadwick as receiver of the assets of the Carver’s entities, including those entities that were possessed of the Carver’s Estate land.

9 Shortly thereafter, Mr Watters refinanced the Carver’s entities’ first-ranking secured debt, then owed to Makro Finance Pty Ltd (Makro), in favour of IJ Financial Pty Ltd. This was done at the recommendation of Mr So and his lawyer at that time, Mr Wong of Thynne + Macartney. Mr So allegedly told Mr Watters that Ultimate was not prepared to pay out the Makro loan itself, with the consequence that refinancing had to occur through a third entity.

10 The IJ Financial loan facility was for a period of 12 months, expiring on 21 December 2022.

11 In or around July 2022, Ms Tsang became the sole director, secretary and shareholder of UIP.

12 It appears to be common ground that, between late 2021 and late 2022, the receiver of the Carver’s entities marketed and sold some of the properties owned by those entities (or in which those entities held an interest). The sale proceeds, totalling approximately $880,000, were paid to Ultimate, at least to some extent as an apparent repayment of its loan, and pursuant to its mortgages and securities.

13 By about late 2022, the receiver was preparing to sell an additional part of the Carver’s Estate land, known as “Stage 6”. On 8 November 2022, he accepted an offer to purchase Stage 6 for $8.25 million. The sale was thereafter completed by Ultimate in exercise of its power of sale under its mortgages.

14 It is apparent that, in accordance with the priority positions between the financiers involved in the development at that time, the indebtedness to IJ Financial ought to have been paid from the proceeds of the sale of Stage 6 before any money was paid to Ultimate, as the second-ranking security holder. However, the evidence revealed that a more complex arrangement was implemented immediately prior to the sale of Stage 6. The receiver, Mr Watters, described that arrangement at paragraph 199 of an affidavit dated 13 December 2022, filed in separate proceedings in this Court involving certain of the present parties. That affidavit became part of the evidence in the present proceedings as an annexure to the affidavit of Mr Benjamin Cohen dated 15 February 2023.

15 Specifically, Mr Watters explained that he needed to procure a release of mortgages with IJ Financial in order to sell Stage 6. To ensure that the Carver’s entities did not default under the IJ Financial loan, and to position himself to sell other stages of the Carver’s Estate land, he sought to find an outcome by which IJ Financial was paid before the expiry of its loan on 21 December 2022 and another “cooperative” mortgagee was in place for further sales. The arrangement ultimately settled on to achieve this outcome was described by Mr Watters as having the following effect:

(a) IJ Financial would release its mortgages upon the sale of Stage 6 (by Ultimate as mortgagee in possession) on 2 December 2022;

(b) IJ Financial would allow the net proceeds of the sale (being approximately $7.4 million), to which it would ordinarily have been entitled as first-ranking mortgagee, to be directed instead to Ultimate; and

(c) as consideration for forgoing that payment, IJ Finance’s debt would be discharged via an assignment of its debt and security to UIP, a “related entity of Ultimate” and a “cooperative first registered mortgagee”.

16 As appears subsequently in these reasons, there is a lack of clarity as to what precisely occurred upon the settlement of the sale of Stage 6 and, in particular, the identity of the entity that received the proceeds of sale.

17 It is said by Ultimate and UIP that, upon settlement on 2 December 2022, Ultimate received approximately $7.4 million in place of IJ Financial.

18 It is further said that, on the same date, UIP paid out IJ Financial’s loan of approximately $8.2 million, and took an assignment of its debt, securities and mortgages over the Carver’s Estate land in exchange.

19 The result of this transaction was, so it is said, that UIP became the holder of the first-ranking securities over the land, as well as the debt of the Carver’s entities, in the amount of $8.2 million. The securities are said to remain over land that was to be the site for Stages 7 to 11 of the development.

20 It was submitted by Mr Hodge KC, for the applicants and the Carver’s entities, that the So interests and the receiver were dilatory in providing them with information concerning the foregoing transactions and the financial arrangements put in place. It is apparent that, on 21 November 2022, the applicants sought information from the receiver as to, amongst other things, the amount currently owed by the Carver’s entities to Ultimate. In response, on 12 December 2022, the receiver, by his solicitors Thynne + Macartney, advised that he “ha[d] requested a current statement of account for Ultimate’s debt … from [Ultimate’s solicitors], but d[id] not have it to hand”, and added that “it is open to your client to request an account statement direct from Ultimate”.

21 The 12 December 2022 letter also identified that IJ Financial’s debt of approximately $8.2 million and security had been assigned to UIP. The facts and circumstances of the alleged assignment and the manner in which it occurred were initially unknown to the applicants or their solicitors. However, they were slowly revealed in the course of the correspondence leading up to the listing of this application for hearing.

22 On 13 January 2023, the applicants again requested from Thynne + Macartney, as solicitors for the receiver, information as to the Carver’s entities indebtedness to Ultimate, as well as a copy of the documentation evidencing the assignment to UIP of the debt previously owed to IJ Financial. Thynne + Macartney advised in correspondence on 30 January 2023 that it would seek a loan statement from the solicitors representing Ultimate, Colin Biggers & Paisley. It was also revealed in that correspondence that UIP was, at that time, the first-ranking mortgagee of the land on which Stages 7 to 11 of the development were to occur.

23 On 1 February 2023, the applicants requested directly from Colin Biggers & Paisley a statement confirming the remaining debt said to be owed to Ultimate, as well as copies of the documents recording the terms of the assignment of the IJ Financial loan to UIP. Much the same requests were made again to Thynne + Macartney on the same date, in response to which an unsigned copy of a “Deed of Assignment” between IJ Financial, UIP and Ultimate was provided. No response was received in relation to the request regarding the debt owed to Ultimate.

24 It would seem that, on 15 February 2023, Ultimate retired the appointment of the receiver with respect to the Carver’s Estate land that was still at that time owned by the Carver’s entities (being the land on which Stages 7 to 11 were to occur).

25 On 1 March 2023, the applicants wrote to Ultimate and UIP, seeking undertakings in relation to the sale of that remaining Carver’s Estate land, as well as any potential dealings with the proceeds of such a sale. Both Ultimate and UIP declined to provide the undertakings, citing potential adverse consequences that might follow under a loan deed and general security agreement dated 25 November 2022 between Ultimate, Mr So’s mother, Ms Wong, and Mr So’s wife’s aunt, Ms Leung. Nevertheless, a narrower undertaking was given pending the hearing of the current application for an injunction.

26 The relevance of Ms Wong and Ms Leung becomes clearer later in these reasons.

Principles in relation to the granting of injunctions.

27 The principles concerning the granting of injunctions by this Court, in circumstances where a party seeks to preserve the potential fruits of its litigation, are not in doubt. They were set out in the applicants’ and Carver’s entities’ written submissions and not contested by the So interests, or by UIP.

28 This Court has inherent jurisdiction, confirmed in rule 14.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), to grant an injunction where to do so would work to preserve the subject matter of, and relief sought in, a proceeding. The rationale for the existence of such a power was explained by Lindgren J in Williams v Minister for Environment and Heritage (2003) 74 ALD 111, where his Honour observed that (at 115 [16] – [17]):

A ‘superior court of record and … a court of law and equity’, such as [the Federal Court] (s 5(2) of the FCA Act), has inherent or implied power to make an interlocutory order which is necessary to enable it to perform its function as such a court. An example of that power is the power to make an order directed to preserving the subject matter of litigation or to preventing its processes from being frustrated and an available form of proceeding from being rendered nugatory.

29 Similarly, in A v C [1981] QB 956, Robert Goff J (as his Lordship then was) at 959 quoted the earlier unreported judgment of Templeman LJ in Mediterranea Raffineria Siciliana Petroli SpA v Mabanaft GmbH (unreported, Court of Appeal, 1 December 1978), where it was said that:

A court of equity has never hesitated to use the strongest powers to protect and preserve a trust fund in interlocutory proceedings on the basis that, if the trust fund disappears by the time the action comes to trial, equity will have been invoked in vain. That is why orders of this sort were made long before the recent orders for discovery, and they are at the heart of the Chancery Division's concern, and it is the concern of any court of equity, to see that the stable door is locked before the horse has gone.

30 It is not necessary, in order for the Court’s power to be enlivened, for it to be apprehended that the whole subject matter of the proceeding will be rendered nugatory if the injunction is not granted. It suffices that aspects of the relief sought will be “extremely difficult”: Slea Pty Ltd v Connective Services Pty Ltd [2019] VSC 201 (Slea), [199] – [206]; since “the overriding power is to make an order which is necessary to enable the Court to perform its functions as a Court”.

31 The usual issues that arise in relation to this form of injunctive relief are: (a) is there a serious question to be tried; (b) will the applicant suffer irreparable injury, for which damages will not be adequate compensation, unless the injunction is granted; and (c) does the balance of convenience favours granting the injunction: Slea at [195].

32 Injunctive relief is also available under ss 241(1)(a) and 1324(4) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and s 12GD(3) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), to support the grant of final relief in proceedings brought under that legislation: see, for example, Slea at [196]. Again, the purpose of the granting of an injunction is to “maintain the status quo pending the determination of the parties’ rights at trial”: Slea at [197], referring to Bradto Pty Ltd v State of Victoria (2006) 15 VR 65, where Maxwell P and Charles JA said that (at 73 [35]):

… the flexibility and adaptability of the remedy of an injunction as an instrument of justice will be best served by the adoption of the [Lord] Hoffman approach. That is, whether the relief sought is prohibitory or mandatory, the court should take whichever course appears to carry the lower risk of injustice if it should turn out to have been “wrong”, in the sense of granting an injunction to a party who fails to establish his rights at the trial, or in failing to grant an injunction to a party who succeeds at trial.

Are the requirements for the granting of an injunction satisfied?

33 The substantive point advanced by the respondents representing the So interests (including Ultimate) and UIP, was that no serious question to be tried arose in the circumstances of this case. They submitted that, in order to establish a serious question, the applicants and the Carver’s entities must make out “a prima facie case, in the sense that if the evidence remains as it is there is a probability that at the trial of the action [they] will be entitled to relief”: Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618, 622 – 623 per Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ; Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57, 68 – 69 [19] per Gleeson CJ and Crennan J, 81 – 84 [65] – [71] per Gummow and Hayne JJ. Here, it was submitted that the relief sought by the applicants and Carver’s entities would not be granted because not all necessary parties had been joined to the proceedings. So the submissions went, the absence of all necessary parties meant the application must fail in limine.

Nature of the claims against Ultimate and UIP

34 It is necessary to elaborate briefly upon the claims that are made against Ultimate and UIP in the current version of the Statement of Claim. At a very high level, they stem from Mr So’s statutory and fiduciary obligations as director of the Carver’s entities, and the activities in which he engaged whilst in that position in 2019, 2021 and 2022.

35 As to the 2019 conduct, it is alleged that, in effect and amongst other things, he found himself in a position of conflict when he caused Ultimate to enter into a written loan agreement with the Carver’s entities (in particular with GGPG Pty Ltd, the second respondent), supported by mortgages, a guarantee and indemnity and a general security deed, to finance the Carver’s Estate development. It is said that, by setting up that arrangement, he acted to protect his and Ultimate’s interests to the detriment of the Carver’s entities, such that he breached his statutory and fiduciary duties as a director of those entities. It is alleged that Ultimate, through Mr So, participated in the relevant conduct and was knowingly concerned in the resulting breaches of his statutory duties. It is also alleged that Ultimate, as Mr So’s alter ego, participated in, or alternatively was party to, the breaches of both his statutory and fiduciary duties.

36 As to the 2021 conduct, the essence of the allegation is that Mr So breached his statutory and fiduciary obligations by allowing the loan to Ultimate to go unpaid, by failing to refinance it prior to the date on which it was payable, and by causing Ultimate thereafter to enforce its rights under the mortgages, guarantee and indemnity, and general security deed. Ultimate is again alleged, variously, to have participated in, been knowingly concerned in, or been party to these breaches. It is also alleged to have knowingly assisted in a dishonest and fraudulent design attributable to Mr So.

37 The following matters are pleaded, broadly, in connection with the 2022 conduct:

(a) in December 2021, IJ Financial paid out the prior senior financier, Makro, and took fresh mortgages over the Carver’s Estate land, as well as entering into a loan agreement and associated security documents with the Carver’s entities;

(b) between June 2022 and September 2022, the receiver sold portions of the Carver’s Estate land and paid Ultimate at least $881,389.19;

(c) on 2 December 2022 the receiver sold Stage 6 for a purchase price of $8,250,000, albeit that the sale was completed by Ultimate exercising its power of sale under its mortgages, in the course of which it received proceeds of $163,212.01;

(d) IJ Financial, pursuant to an agreement with Ultimate and UIP, directed the payment it was to receive from the sale of Stage 6 (being $7.4 million) to Ultimate and, in return, received from UIP the full amount owed to it by the Carver’s entities in exchange for its loan and mortgages; and

(e) as a result of these events, by 2 December 2022, Ultimate had received $8,456,961.20 from the sale of the Carver’s Estate land in accordance with its mortgages and securities, and in purported repayment of its loan.

38 It is alleged that the amount received by Ultimate represented the traceable proceeds of the property of the Carver’s entities, and that those proceeds were in turn used by UIP to acquire the IJ Financial loan and mortgages. The result of this is said to be that UIP now holds the loan and mortgages subject to the Carver’s entities’ interests. Thus, it is submitted, the property of the Carver’s entities can be traced into the loan and mortgages held by UIP, which it received with knowledge of certain of Mr So’s alleged breaches of duty, such that it holds them on constructive trust.

The existence of additional persons interested in the loans and securities

39 As mentioned already, in the course of the applicants’ solicitors’ attempts to ascertain the level of the Carver’s entities’ indebtedness to Ultimate, the receiver sent to them a number of unexecuted documents including one headed “Deed of Assignment”, which was between IJ Financial, UIP and Ultimate. That document relevantly provided that:

(a) the expression “Debt” was defined as meaning “the sum of $8,160,000 and all other moneys secured by the Mortgages”;

(b) the “Mortgages” were listed in Schedule 1 to the Deed, and including those mortgages over the Carver’s Estate land granted by the Carver’s entities in favour of IJ Financial, as well as a “General Security Deed” granted by the Carver’s entities and other ancillary documents;

(c) the expression “Completion” was defined to mean “completion of the assignment in clause 3.1”;

(d) pursuant to clause 3.1(a), the Assignee (UIP) would pay the Debt to the Assignor (IJ Financial) on or before the Completion Date (being 2 December 2022) “in the manner agreed between the Assignor and Assignee’s solicitors”;

(e) pursuant to clause 3.1(b), contemporaneously with the payment of the Debt, the Assignor would assign to the Assignee absolutely all of its right, title and interest in the Mortgages, together with all obligations owed or to become owing to the Assignor and secured by those Mortgages;

(f) notices of the assignment would be signed in anticipation of Completion, and the original Mortgages and executed Transfer of Mortgage forms would be delivered to the Assignee after Completion.

40 An executed version of the Deed of Assignment was in evidence on this application. It was dated 1 December 2022, and also bore a duty stamp dated 2 December 2022. Its signing page contained signatures for UIP (by Ms Tsang) and Ultimate (by Mr So) both dated 19 November 2022, and a signature for IJ Financial dated 1 December 2022. There was otherwise no direct evidence as to when the Deed of Assignment was entered into.

41 On 3 March 2023, the solicitors for the So interests (including Ultimate), Colin Biggers & Paisley, wrote to the applicants’ solicitors and advised that their clients would not be providing undertakings not to deal with any proceeds of the sale of the land the subject of Stages 7 to 11. They made reference to the fact that Ultimate had entered into a loan deed and a general security deed with Ms Wong and Ms Leung in May 2020 and that it would be a “Material Adverse Event”, as defined in the former of those documents, if Ultimate was to limit its ability to repay its debt to those persons. It was said that the outstanding balance of the loan due from Ultimate to Ms Wong and Ms Leung was in the order of $8 million, and that interest was being incurred on that sum, pursuant to the loan deed, at a rate of 20% per annum (being $1.6 million per year).

42 On 8 March 2023, the then solicitors for UIP, RE Legal, wrote to the applicants’ solicitors, advising that UIP was indebted to Ms Wong and Ms Leung in the amount of $8.16 million, and that the giving of any undertaking could amount to a “Material Adverse Effect”, as defined in a general security deed dated 25 November 2022 between UIP, Ms Wong and Ms Leung. The letter enclosed a copy of that general security deed, pursuant to which UIP had granted a security interest over its property in favour of Ms Wong and Ms Leung in respect of the loan that they had made to it. Also included was a copy of the loan deed of the same date, pursuant to which Ms Wong and Ms Leung had purportedly agreed to lend to UIP the sum of $8.16 million for the purposes of paying consideration to IJ Financial in accordance with the terms of the Deed of Assignment.

43 Again, whilst these documents were dated 25 November 2022, no person deposed to the actual date of execution.

44 For the purposes of the present application, it was submitted by the So interests and UIP that Ms Wong and Ms Leung were persons who were interested in these proceedings and would be directly affected by the granting of an injunction. As they were not parties to the proceedings, final relief could not be granted in the action, making it inappropriate for any interlocutory injunction to be granted.

The further affidavit evidence

45 The manner in which Ultimate and UIP had dealt with the proceeds from the receiver’s sale of Stage 6 of the Carver’s Estate land was addressed in certain affidavits filed and relied upon by the So interests and UIP. The first was an affidavit of Mr Michael Gill, a solicitor of RE Legal, acting for UIP. He gave evidence on information and belief from Ms Tsang, Mr So’s wife and the sole director of UIP, as to the entering into of the loan deed and general security deed dated 25 November 2022 with Ms Wong and Ms Leung. Similar evidence was given in relation to the execution by UIP, Ms Wong, Ms Leung and Ultimate of another agreement of the same date, which was referred to as a “Payment by Direction Deed”. A copy of that final document was annexed to Mr Gill’s affidavit. Relevantly, it provided that the parties agreed that:

(a) upon the settlement of the sale of Stage 6, Ultimate, as mortgagee, would receive most of the sale proceeds and would use them (in the amount of $7.4 million) to make a repayment towards its debt owing to Ms Wong and Ms Leung under the loan deed dated 8 May 2020;

(b) once Ms Wong and Ms Leung received those funds, they would advance them under a new loan deed (which became the loan deed dated 25 November 2022) to UIP;

(c) UIP would receive those funds and use them for the sole purpose of paying part of the consideration due to IJ Financial under the terms of the Deed of Assignment, pursuant to which UIP would take a transfer of the Mortgages (that term taking the same meaning as it bore in the Deed of Assignment); and

(d) UIP would become possessed of a bank cheque in favour of IJ Financial, and would deliver it to IJ Financial or its solicitors by way of payment under the Deed of Assignment.

46 Unusually, IJ Financial was not a party to the Payment by Direction Deed. Yet, pursuant to its provisions, Ultimate was required to cause a bank cheque for $7.4 million in favour of IJ Financial to be delivered to UIP. It was not explained how, or by what authority, Ultimate might cause the bank cheque to be so delivered.

47 Importantly, Mr Gill also gave evidence at paragraph 2(e) of his affidavit that he had been informed by Ms Tsang and believed that, at the completion of the sale of the Stage 6 land:

(i) Ultimate received $7.4 million, which Ultimate paid to Ms Leung and Ms Wong in partial discharge of its debt to them;

(ii) Ms Leung and Ms Wong then lent $8.16 million to UIP, comprised of the $7.4 million which had been paid to them by Ultimate, plus a further $760,000; and

(iii) UIP used the $8.16 million lent to it by Ms Leung and Ms Wong to purchase from IJ Financial Services Limited as trustee for the IJ Lending Fund No. 1 (IJ Financial) a debt of $8.16 million and the securities held by IJ Financial for repayment of that debt.

48 He also gave evidence to the effect that, if and when UIP exercises its power of sale under the mortgages that were transferred to it by IJ Financial, it intends to use the funds that it receives to pay the debt owing to Ms Wong and Ms Leung. It is said that UIP will suffer loss and damage if restrained from doing so by the grant of an injunction, as it will be obliged to pay interest under the loan deed at a rate of 14% per annum.

49 It was further asserted that UIP was owed approximately $8.56 million in principal, interest and enforcement costs by the eleventh respondent (one of the Carver’s entities) under the loan agreement that UIP purchased from IJ Financial, and that UIP presently owed Ms Wong and Ms Leung approximately $8.44 million under the loan deed dated 25 November 2022.

Controversy about the proceeds from the sale of Stage 6

50 Mr Gill was cross-examined on the content of paragraph 2(e) of his affidavit and, in particular, as to the manner in which the sale proceeds of $7.4 million were dealt with. This issue was obviously important to the applicants’ and Carver’s entities’ tracing claims. The defence to that claim included the assertion that the proceeds of the sale of Stage 6 were received by Ultimate, which used them to repay its loan to Ms Wong and Ms Leung, who in turn lent a slightly larger sum to UIP, which used part of those funds to take a transfer of the first-ranking mortgages and associated instruments from IJ Financial. In support of this, a submission was made in UIP’s written outline on this application that:

… upon completion of the sale:

(a) the $7.4 million, which the seventeenth respondent (Ultimate) received at the direction of IJ Financial Services Ltd (IJ Financial), was repaid by Ultimate to its creditors, Ms Leung and Ms Wong, in accordance with clause 2(a) of the Payment by Direction Deed dated 25 November 2022.

51 There was no clear reference to the factual basis for the submission that Ultimate received the money “at the direction of IJ Financial Services Ltd”. Indeed, as the discussion below reveals, apart from the assertions by Mr Gill as to what he was allegedly told by Ms Tsang, there was no evidence that Ultimate received any money at all.

52 It appears that Mr Gill claimed that he believed the statements in paragraph 2(e) of his affidavit because he had seen the Payment by Direction Deed, and Ms Tsang had told him that the money had been dealt with in the manner that he ultimately identified. Despite what he might be taken to have said in his affidavit, however, he acknowledged in cross-examination that he had not seen anything that would suggest that there had been a physical movement of funds between the parties in the manner indicated in paragraph 2(e). H acknowledged, in particular, that he did not believe that there was any intention that money was to be passed from Ultimate to UIP.

53 Mr Gill was referred to a document, described as a “settlement adjustment sheet”, which related to the sale of Stage 6 of the Carver’s Estate land and the settlement occurring on 2 December 2022. The seller was identified in that document as Ultimate, as mortgagee exercising power of sale, and the purchaser as SKF Development Landholding No.3 Pty Ltd. The document set out payment directions, indicating the manner in which payments would be made by the purchaser upon settlement. Most significantly for the present purposes, the payment directions included one particular direction for $7.4 million to be paid to IJ Financial.

54 Mr Gill claimed that the first time that he saw this settlement statement was when he received the affidavit of Mr Benjamin Cohen of 15 February 2023, by which the document was introduced into evidence in these proceedings. As such, it can be presumed that he was aware of it at the time he swore his affidavit on 24 March 2023, where he said that he believed that the payments in relation to the settlement for Stage 6 occurred in the manner described by Ms Tsang.

55 He further said, under cross-examination, that he was not aware of the existence of any “direction” having been given by IJ Financial for Ultimate to receive the $7.4 million amount. In fact, he said that he did not believe that there was one. This, of course, is directly contrary to UIP’s written submissions as set out above, to the effect that Ultimate received those funds “at the direction of” IJ Financial. Mr Gill explained, instead, that the arrangement was more properly to be described as IJ Financial “stepping aside” to allow Ultimate, as second-ranking mortgagee, to receive the proceeds of sale. However, he immediately conceded that he had seen no document evidencing IJ Financial’s stepping aside for that purpose.

56 Mr So was also cross-examined, with the aid of an interpreter. In the course of his cross-examination he seemed to accept that the $7.4 million was never received by Ultimate by being banked into its account, or in any other fashion. He accepted that those funds were never received by Ms Wong and Ms Leung either. Mr So acknowledged that, from the sale proceeds, a bank cheque for $7.4 million was drawn in favour of IJ Financial, and was given to it. In cross-examination, the following exchange took place:

MR HODGE: Whatever your intention was, there was never any money that flowed from the sale of stage 6 through an Ultimate bank account through to your mother and your aunt, correct?

THE INTERPRETER: That’s correct, but we have got the Payment by Direction Deed, so it’s still, like, legally binding.

Conclusions in relation to the proceeds of sale

57 It is not necessary on this application to reach any final conclusion as to the events that occurred upon the sale of Stage 6. It must be stressed that it is apparent that all of the evidence in relation to that transaction may not be before the Court and that subsequent evidence may alter the complexion of the facts that arise.

58 Nevertheless, it is sufficient to observe that there is a serious question as to the manner in which UIP allegedly received funds as a result of the sale of the Carver’s Estate land. On the assumption that the Deed of Assignment, the loans between Ms Wong and Ms Leung and UIP, and the associated securities were actual transactions (the issue of “sham transactions” not having been raised), a question self-evidently arises as to the level of the indebtedness of the Carver’s entities pursuant to the loan made by IJ Financial. The evidence suggests that all that occurred in relation to the proceeds of the sale of Stage 6 was that a bank cheque in the amount of $7.4 million was made out by either the purchaser or the receiver to IJ Financial, and then received by that entity at or around the time of settlement. There is no evidence that the proceeds were dealt with otherwise, and it might even be inferred that the cheque was banked by IJ Financial. Whilst IJ Financial might conceivably have directed the cheque to Ultimate, as the So interests and UIP submitted, that would not impact the contractual relationship between it and the Carver’s entities. If, as the So interests and UIP necessarily accept, IJ Financial had the power to direct that the cheque be paid to Ultimate, it must have been the holder of that cheque as a consequence of the cheque having been delivered to it. That being so, the cheque would seem to have been received as payment or, at least, part payment of the indebtedness owed to it by the Carver’s entities, and it apparently accepted that cheque in reduction of that indebtedness. If so, the debt owed by the Carver’s entities to IJ Financial must thereby have been reduced by $7.4 million upon its receipt.

59 Whilst, as previously detailed, several transactions were apparently entered into, by which those funds were allegedly used to acquire IJ Financial’s mortgages and debt, in the circumstances revealed by the evidence at present, there is a real possibility that the debt secured by the mortgages was reduced in value by $7.4 million prior to any such assignment taking place. If so, it would not matter what arrangements were put in place as between IJ Financial, Ultimate, UIP and Ms Wong and Ms Leung. They could contractually agree to deal with their rights inter se in accordance with whatever arrangements they wish to create, but this would not affect the contractual rights and obligations as between IJ Financial and the Carver’s entities.

60 None of this is to suggest that the transactions entered into between Ultimate, UIP, Ms Wong and Ms Leung were shams. It may well be that they intended the agreements into which they entered to be efficacious and to operate according to their terms. Indeed, the agreements may have had that effect and impacted the parties’ respective rights regardless of whether the funds in question were transferred in the agreed manner: cf Equuscorp Pty Ltd v Glengallan Investments Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 471, 486 – 487 [46]. However, it does not follow that they did operate according to their terms if the parties were mistaken about that which was originally acquired. Here, there is a reasonable argument, based on the material presently before the Court, that IJ Financial’s debt was reduced by the amount of $7.4 million prior to the transfer of the debt and mortgages to UIP.

61 It should be recognised that this issue as to whether the payment of the bank cheque of $7.4 million to IJ Financial reduced the Carver’s entities’ debt to it by that amount was not directly raised by the applicants and the Carver’s entities. It was, however, evident on the analysis of the transactions that were the subject of scrutiny on the application. Since the present question involves, at least in part, the identification of the rights of the So interests and UIP vis-à-vis the Carver’s entities, the apparent discharge of the relevant debt to IJ Financial by that amount cannot be overlooked.

62 Although not uncommon on applications of this type, the investigation of the manner in which the proceeds of sale of Stage 6 were dealt with raises more questions than it answers. Specifically, in this case, the issue may be rendered more complex by the timing of events; in particular, the question of the dates on which the Payment by Direction Deed and Deed of Assignment were entered into. There was no direct evidence that they were actually entered into on 25 November 2022 and 1 December 2022, respectively. If they were, it is unclear why the $7.4 million bank cheque was made payable to IJ Financial. These issues may become clearer in the fullness of time, as the evidence emerges at, or in anticipation of, a final hearing.

63 There is potentially, but not necessarily, some tension between the above conclusions about the flow of funds on the sale of Stage 6 and the allegations made in the Statement of Claim as to the transactions involving IJ Financial. It is fair to say that those parties with the better knowledge of the circumstances of the sale of Stage 6, and the dealings with the proceeds of the sale, did not adduce very clear evidence as to what took place. The revelations as to those circumstances and dealings occurred too close to the hearing of this application for a fulsome analysis to be undertaken.

64 On the assumption that the purported transactions did occur and were efficacious, there is also a serious question as to the relevant parties’ rights to the proceeds of any future sale of the land intended to be the subject of the further stages of the Carver’s Estate development. It may be that some indebtedness remains in relation to the IJ Financial loan which has been assigned to UIP; although, perhaps, that amount is now only around $750,000. Ultimate seemingly has second-ranking mortgages over the land, but the debt and associated securities are said to have been obtained as a result of a breach of fiduciary duty on the part of Mr So. It was not seriously contested on this application that there was a serious question to be tried as to whether Mr So had breached his statutory and fiduciary duties to the Carver’s entities by arranging the loans with Ultimate, enforcing them, and otherwise dealing with them. If that claim is made out, it may well be that Ultimate holds the loan, mortgages and securities on constructive trust for the Carver’s entities, consequent upon its involvement in Mr So’s alleged breaches of duty.

65 A curiosity which might arise consequent upon the arrangements that were allegedly entered into is that Ultimate’s debt to Ms Wong and Ms Leung may have been discharged to the extent of $7.4 million, even though Ultimate never received the benefit of the bank cheque in that amount. If so, that may substantially reduce any interest that they may have in the proceeds of sale that Ultimate may eventually receive. On the other hand, the precise extent of the indebtedness between the entities is far from clear, such that those lenders to Ultimate may still have a valid security interest in its assets.

66 In relation to UIP, it is claimed that the Carver’s entities may trace into the loan and mortgages that it holds as a result of the transfer from IJ Financial. On the presently pleaded case, that relief does not depend on IJ Financial’s conduct in making the loan to the Carver’s entities and taking the securities as it did. Rather, it is said to arise from the fact that the funds that were made available to UIP to acquire the loan and mortgages held by IJ Financial were derived from Ultimate’s acquisition of certain mortgages of its own (including, most relevantly, over the Stage 6 land), and proceeds from its exercise of power of sale pursuant to the same, by reason of Mr So’s breaches of duty, and that UIP received those funds with knowledge of the breaches, such that it became chargeable with the property of the Carver’s entities (SC [148]). It would appear that the inference embedded in this claim is that UIP did not acquire the funds used to purchase the loan and mortgages from IJ Financial as a bona fide purchaser for value without notice. It is likely that, if UIP wishes to claim that it was a bona fide purchaser, then this is a matter that it would be required to plead and establish. Nevertheless, in general terms, a serious question was made out on the evidence as to whether the proceeds used by UIP to acquire the IJ Financial loan and mortgages were derived consequent upon Ultimate’s and/or Mr So’s breaches. Indeed, to the extent that the path of funds is relevant, that was more or less indicated by the evidence adduced by UIP.

67 Leaving aside for one moment the rights and interests of Ms Wong and Ms Leung, as a result of the evidence adduced on this application, the applicants and the Carver’s entities have established the existence of a serious question to be tried as to the latter’s entitlement to the proceeds of any future sale of the Carver’s Estate land.

Alleged defects in the interests claimed by the Carver’s entities

68 The main submission advanced by the So interests and UIP on this application was that no serious question had been raised because the applicants had failed to join to the proceedings all of the parties whose presence was necessary for the granting of the relief claimed. The second ground, advanced only by UIP, was that there could be no tracing of the funds in question because no attempt had been made to set aside the transactions through which the funds were sought to be traced. Finally, it was further submitted by UIP that it would be able to defeat any claim against it in relation to the mortgages assigned to it because those mortgages had been registered in its name, with the result that it was able to claim the benefits of indefeasibility.

The failure to join all necessary parties

69 It was submitted by UIP that the relief sought against it would fail because Ms Wong and Ms Leung, whose rights would be affected by the relief sought in the proceedings were not parties to these proceedings. More specifically, it was submitted that the effect of the relief sought (or at least certain aspects of it) would be to destroy, or impose a constructive trust over, the property that was “attached by security held by Ms Leung and Mr Wong”. Accordingly, Ms Leung and Ms Wong would be detrimentally affected by the making of the orders and should be parties to the proceedings. UIP submitted that the detriment would arise, more specifically, because Ms Wong and Ms Leung have security over UIP’s registered mortgages, which is “either a security interest in personal property for the purposes of Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) (PPSA), s.12, or an equitable charge attached to a registered mortgagee’s interest in land.” It is unnecessary to determine, for the present purposes, whether the security, which was registered on the Personal Property Securities Register on 7 December 2022, is strictly a PPSA security over the mortgages or an equitable charge. In either case, it is probable that Ms Wong’s and Ms Leung’s interests would be affected by the relief sought by the applicants and the Carver’s entities. It was not disputed that, to the extent that those parties successfully obtained the relief sought against UIP, the interests of Ms Wong and Ms Leung would be correspondingly diminished.

70 Mr Wilkins KC for UIP relied, specifically, at the hearing of this application, on the observations of the Queensland Court of Appeal in China First Pty Ltd v Mount Isa Mines Ltd [2019] 3 Qd R 173 (China First), where Gotterson JA (with whom Fraser and McMurdo JJA agreed) discussed the nature of the “direct effect” test to ascertain whether a third party should be joined to existing proceedings. His Honour quoted the judgment of Lord Diplock in Pegang Mining Co Ltd v Choong Sam [1969] 2 MLJ 52, 55 – 56, where it was explained that the purpose of the rule was to “enable the court to prevent injustice being done to a person whose rights will be affected by its judgment by proceeding to adjudicate upon the matter in dispute in the action without his being given an opportunity of being heard”. That concern necessitated a broad and flexible test, which was formulated as being: “will [the third party’s] rights against or liabilities to any party to the action in respect of the subject matter of the action be directly affected by any order which may be made in the action?”. The corollary of this is that “[a]n order which directly affects a third person’s rights against or liabilities to a party should not be made unless the person is also joined as a party”: News Ltd v Australian Rugby Football League Ltd (1996) 64 FCR 410 (News Ltd), 524 per Lockhart, Von Doussa and Sackville JJ. In that latter case, it was noted (at 524 – 525) that, “[w]here the orders sought [in a proceeding] establish or recognise a proprietary or security interest in land, chattels or a monetary fund, all persons who have or claim an interest in the subject matter are necessary parties”. As Gotterson JA further observed in China First, these observations in News Ltd were cited with approval by the High Court in John Alexander’s Clubs Pty Ltd v White City Tennis Club Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 1, 46 [131].

71 These submissions were essentially echoed by the respondents representing the So interests, who identified that Ultimate’s security was charged to Ms Wong and Ms Leung pursuant to a security registered on the Personal Property Securities Register. Ms Wong and Ms Leung were therefore said to be necessary parties to the proceedings against Ultimate, along with Ultimate’s other secured creditor, SEL Property Investments Pty Ltd (SEL).

72 Mr Hodge KC for the applicants and the Carver’s entities did not contest the proposition that, in light of the facts of the transactions that had (somewhat belatedly) been revealed, Ms Wong and Ms Leung and SEL were proper parties to the proceedings. He indicated to the Court that his clients were prepared to join them as parties as a condition of the granting of the injunction sought by way of this application. That was appropriate, and given the nature of the relief sought in the action, it is proper that SEL, Ms Wong and Ms Leung now be joined. That conclusion renders it unnecessary to consider the several authorities concerning the difference between persons who might be directly affected by an order and those who might be indirectly affected: see, generally, News Ltd at 525. It also relieves the Court from having to determine whether the interests of SEL and Ms Wong and Ms Leung are sufficiently protected by Ultimate and UIP being parties to the proceedings: see BPESAM IV M Ltd v DRA Global Ltd (2020) 381 ALR 252, 325 [273] per McKerracher J.

73 It is appropriate that some weeks’ grace be given to allow for the making of an application to join SEL and Ms Wong and Ms Leung. In that regard, given that the So interests and UIP have strongly submitted that the joinder of those third parties is necessary in order that their interests be protected, it is unlikely that the application will be opposed.

The failure to require that the transactions though which proceeds passed be avoided

74 Mr Wilkins KC further relied upon the principle that tracing was not available to the applicants and the Carver’s entities in this case because no attempt had been made by them to set aside certain transactions. He relied on the observations of the Full Court in Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (No 2) (2012) 200 FCR 296 (Grimaldi), 359 – 360 [254], to the effect that, where, by a transaction entered into as a result of a breach of a fiduciary duty owed by a director to a company, the company’s property is disposed of, “the company will not ordinarily be able to bring a proprietary claim against the recipient [of that property] as distinct from a personal one, unless and until the transaction itself has been avoided”. It should be noted that the Court in that case subsequently questioned the correctness of that principle. However, for present purposes, it might be accepted as stating the existing law.

75 The point sought to be made was that, in order to trace into proceeds or to seek the imposition of a constructive trust, which are ancillary forms of relief and not alternatives, it is necessary that there be rescission or avoidance of transactions that have been entered into in relation to the property in question. This, so it is said, is intended to take into account the interests of third parties: Grimaldi at 364 – 365 [277], referring, with approval, to Robins v Incentive Dynamics Pty Ltd (in liq) (2003) 175 FLR 286, 301 [73] – [74] per Mason P (with whom Stein JA agreed) and 302 – 303 [82] per Giles JA.

76 However, these propositions are not entirely absolute in the context of equitable tracing. The power to trace is dependent upon the ability to identify the proprietary interest that continues to exist through the relevant transactions. It does not require the person seeking to trace to exercise a power to unravel all intermediate agreements: El Ajou v Dollar Land Holdings plc [1993] 3 All ER 717, 737 per Millett J. Rather, in relation to intermediate transactions, the contrary may be true. In order to trace proceeds into the hands of the ultimate recipient, it may theoretically be necessary to ratify any earlier transaction that has included the misapplied property interest.

77 In the present case, the tracing claim is pleaded by alleging that the loan and the mortgages previously held by IJ Financial, now in the hands of UIP, “are the traceable proceeds of property of the Carver’s Entities”. UIP submitted that this is insufficient for the purposes of claiming a right to trace, because there must be established a continuing equitable interest in the property or a “proprietary base”. Here, it is said that the Carver’s entities can have no proprietary claim in respect of the loan or mortgages because there has been no attempt to seek the rescission of:

(a) the repayment by Ultimate of $7.4 million to Ms Leung and Ms Wong in partial discharge of Ultimate’s debt to them; and

(b) the loan by Ms Leung and Ms Wong to UIP of $8.16 million.

78 With respect, that submission is not correct.

79 In the first instance, for the purposes of this application, it is reasonably arguable that, in order to establish or enforce the traceable property interest, only the initial transaction by which the Carver’s entities’ rights were divested needs to be set aside: Grimaldi at 359 – 360 [254]; and there is no need to set aside the subsequent transactions. In the present case, the orders sought in paragraphs 4 and 5 of the prayer for relief in the Statement of Claim would seem to satisfy that requirement. Those orders have the effect that, insofar as Ultimate is concerned, the transactions are set at nought. There is, at least, a serious question to be tried on this matter and that is sufficient. If it is the case that ancillary relief in the nature of orders setting aside intermediate transactions is required, an appropriate amendment to the prayer for relief can be made.

80 Secondly, if the transactions occurred in the manner alleged by the applicants and Carver’s entities, their allegation that the loans and mortgages in the hands of Ultimate or UIP are “chargeable” or “traceable” tends to carry with it the acknowledgment that consideration provided by Ultimate or UIP might have to be made good at some stage. The claim is that the Carver’s entities have a proprietary interest in those loans and mortgages. In the case of UIP, that is allegedly because they had a relevant property interest in the funds used to acquire the loan and mortgages from IJ Financial. In the case of Ultimate, it is allegedly because the loan and mortgages were the product of its participating in or being concerned in Mr So’s breaches of fiduciary duty. In relation to each, the relevant relief sought may require the rescission of the last-occurring transaction or, at least, the Carver’s entities doing equity in relation to third parties whose interests are affected. UIP submits, effectively, that the applicants and the Carver’s entities have overlooked these critical steps for relief. However, in the context of the Statement of Claim, it may be possible to make some assumptions about the steps required to be taken in order for the relief sought to be obtained. In this case, those steps seem to be fairly clear. Although, if that is not so, perhaps it should be made clear by an amendment. The availability of that avenue may ensure that the claims are reasonably arguable.

81 Thirdly, it is to be recalled that the alleged transactions between Ultimate, UIP and Ms Wong and Ms Leung are not necessarily accepted by the applicants and the Carver’s entities as having occurred. Indeed, by reason of the first point above, it may well be that the transactions did not occur in the manner that the parties intended. The information about the occurrence of certain transactions involving Ms Wong and Ms Leung appeared only relatively recently, and it may well be that, in time, the applicants and the Carver’s entities will have to deal with them more directly and fulsomely. Although the evidence before the Court on this hearing was to the effect that the transactions did occur, it is possible that they did not occur in the manner, or to the extent, claimed by the So interests and UIP. As indicated above, Ms Wong and Ms Leung are contemplated to be joined as parties, and they will then be able to assert their rights pursuant to, or in respect of, the transactions through which they claim their security interests. If and when they do, the opposing parties can join issue as to the veracity of the transactions and, if those transactions are not demonstrated to be voidable or shams, it will be necessary to explore their efficacy in dealing with the proceeds derived from the sale of Stage 6.

82 UIP seemed to further submit that the transactions in question concern bona fide purchasers for value without notice, whose involvement has defeated the tracing claims. Certainly, if that allegation is made out, the tracing claims will not succeed. It is also beyond doubt that repayment of a debt can amount to sufficient consideration for those purposes: Taylor v Blakelock (1886) 32 Ch D 560, 568 per Cotton LJ and 570 per Bowen LJ; Re Stanford International Bank Limited (in liq) [2020] 1 BCLC 446, 472 [69] per Lord Briggs (with whom Lord Wilson and Sir Andrew Longmore agreed). At present, UIP has contended in its Defence that the Carver’s entities do not have any continuing proprietary interest in the loan and mortgages that it holds because (inter alia) “Ms Leung and Ms Wong were bona fide purchasers for value without notice of Mr So’s alleged breaches of duties”, both in receipt of repayment of the debt owing to them by Ultimate and in their lending to UIP. However, the circumstances in which Ms Wong and Ms Leung came to be involved in the transactions ought to be fully ventilated and tested by cross-examination. Whilst there is no need to make any further findings in relation to the issue at present, the existence of the familial relationships between Mr So, Ms Tsang, Ms Wong and Ms Leung, the fact that Ms Wong and Ms Leung seemed, at least in some respects, to rely upon Mr So in relation to the transactions, and the fact that no money was actually transferred between the parties, might give rise to some questions with which the Court will be required to deal. Whilst it should be accepted that the existence of a bona fide purchaser for value without notice in this case will likely impose an insurmountable hurdle to Carver’s entities’ success on the tracing claims, it is not possible at this point in time to make any solid finding that such a defence is available to the So interests and UIP.

83 Given the nature of the case advanced by the applicants and the Carver’s entities, and the flow and effect of the evidence to date, any incidental pleading inadequacy should not prevent it from being found that there is a serious question to be tried. Whilst some amendment might put the issue of the rescission of intermediate transactions to one side, it is far from clear, on the authorities, that any such amendment is required.

Indefeasibility

84 It was further submitted by UIP, in relation to the claims made against it, that, as it has become registered as the mortgagee of the Carver’s Estate land, its interest is indefeasible and is unaffected by any equitable claims that might be made by the Carver’s entities. That, so it was submitted, will be the case even if it had actual or constructive notice of those unregistered interests: Land Title Act 1994 (Qld) s 184. Quite simply, it was contended that registration of an instrument confers indefeasibility on the interest in land created or transferred by the instrument. In its written submissions on this application, the position was advanced by UIP in the following terms:

If a third party (i.e., a person other than the defaulting fiduciary) receives a mortgage of a company’s land with knowledge that the mortgage has been given by the company as a result of a breach of a fiduciary duty owed to the company by its director, and that mortgage is registered, the third party’s registered interest in the land as mortgagee is indefeasible; the in personam exception to indefeasibility in LTA, s.185(1)(a) does not apply: Super 1000 Pty Ltd v Pacific General Securities Ltd (2008) 221 FLR 427 at [211]–[234] per White J; Turner v O’Bryan-Turner at [101] per White JA, with whom Meagher and McCallum JJA agreed. Consequently, the “mortgage is not liable to be rescinded and is not held on trust for [the company]”: Super 1000 Pty Ltd v Pacific General Securities Ltd at [234].

85 Ultimately, the submissions made to the Court were insufficient to allow any substantive conclusions to be drawn in relation to this issue. However, the claim against UIP is not one or, at least, it does not necessarily appear to be one, that relies on the existence of some prior equity or equitable interest in the mortgages obtained by UIP in order to support the present claim of an interest in them. Such circumstances were the concern of the discussion of White J in Super 1000 Pty Ltd v Pacific General Securities Ltd (2008) 221 FLR 427 (Super 1000). There, his Honour sought to wrestle with the difficult question addressed in Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89 (Farah Constructions) as to whether a registered interest in real property could be affected by the fact that it had been the product of “knowing receipt”, under the first limb of the rule in Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244, in that its recipient had taken it with knowledge of a prior interest or breach of fiduciary duty or the like. In Super 1000, the particular point in contention was the creation of a registered mortgage over an interest in land, which was given by way of a breach of fiduciary duty in which the recipient of the mortgage knowingly participated. In broad terms, White J adopted the position, relying on the prior appellate authorities discussed in Farah Constructions, that, absent fraudulent conduct, the registered mortgage was indefeasible and no proprietary remedy was available against the recipient.

86 In its written submissions, UIP also relied upon the observation of White JA (with whom Meagher and McCallum JJA agreed) in Turner v O’Bryan-Turner (2022) 107 NSWLR 171, 193 [101], again considering the appellate authorities discussed in Farah Constructions, to the following effect:

Whatever might be one’s views about that reasoning (for example, Super 1000 Pty Ltd v Pacific General Securities Ltd (2008) 221 FLR 427; [2008] NSWSC 1222 at [213]–[217]; M Harding, “Barnes v Addy claims and the indefeasibility of Torrens Title” (2007) 31 Melbourne University Law Review 343 at 357ff; Chambers, “Knowing receipt: Frozen in Australia” (2007) 2 Journal of Equity 40 at 51–52), the High Court’s decision in Farah establishes for courts below the High Court that the in personam exceptions to indefeasibility do not extend to proprietary claims arising under the first limb of Barnes v Addy.

87 However, the circumstances dealt with in the above cases are quite different to those on which the Carver’s entities rely for the purpose of claiming an interest in the registered mortgages now held by UIP. Those cases were concerned with attempts to assert proprietary claims for knowing receipt in circumstances where the thing transferred and/or received (without fraud) was a registered interest in land.

88 Here, it is not alleged that the Carver’s entities had any interest in the loan or the mortgages held by IJ Financial before they were acquired by UIP. Nor is alleged that any such interest survived the registration of the mortgages. Rather, it is the case that the funds that were used by UIP to purchase the loan and mortgages from IJ Financial were monies that could be traced into UIP’s hands by the Carver’s entities because they had been derived from Ultimate’s involvement in Mr So’s breaches of fiduciary duty. In effect, UIP came to hold the $7.4 million initially received by Ultimate from the sale of Stage 6 on a constructive trust for the Carver’s entities and used it to purchase the loan and mortgages from IJ Financial, which were similarly held on trust.

89 It was submitted on behalf of UIP that there was no difference between this scenario and the scenario in the cases previously addressed, but no authority was cited for that proposition. Moreover, if it were correct, it would seemingly undermine substantial amounts of trust law, including, in particular, that concerning the “purchase money resulting trust”. Maintaining a distinction between these scenarios, contrary to UIP’s submission, is consistent with what was said by Leeming JA (with whom Bathurst CJ and Sackville AJA agreed) in Fistar v Riverwood Legion and Community Club Ltd (2016) 91 NSWLR 732, 749 [82], as follows:

Ms Fistar conceded that if the claim were viewed as a personal claim at law for the recovery of money, then indefeasibility of title did not apply. That concession was rightly made. It makes no difference whether a third party recipient of trust property (say, money) buys shares or Torrens title land or a motor vehicle: his or her personal liability is unaffected. To be clear, I do not understand the passage in Farah Constructions at [190]–[198] about the inapplicability of principles governing the receipt of trust property to title derived from registration under Torrens legislation to qualify the principles governing tracing in equity, or the personal liability of a volunteer to account for the value of the traceable proceeds of trust property retained by him or her. The Club made no submission that it did.

90 His Honour’s observation should be accepted, even though the potential for debate as to the scope of the decision in Farah Constructions was appropriately recognised.

91 The difficulty is that it is not possible, on the submissions made, to reach any final conclusion on this issue. To reach any satisfactory resolution would require more fulsome submissions and a more thorough analysis of the existing authorities. The issue is undoubtedly a difficult one, as the persistent flow of authorities on it seems to demonstrate. For the present purposes, it is sufficient to accept that there is, at least, an arguable case that, when UIP received the $7.4 million (in the form, by that time, of the loan from Ms Wong and Ms Leung) for the purposes of purchasing the loan and mortgages from IJ Financial, those funds were the traceable proceeds flowing from Mr So’s alleged breaches of fiduciary duty. Whilst there remain some questions as to whether the transactions through which the Carver’s entities seek to trace need to be avoided or rescinded, and whether they can be, there is some sufficient basis at present to accept that the claim might successfully be made. In reaching this conclusion, it is appropriate to take into account the observations made by Brereton JA in Twigg v Twigg (2022) 402 ALR 119, 200 [224] to the effect that the substance of the transactions must be considered when ascertaining whether the tracing links support a valid proprietary claim. There, his Honour said:

However, the fact that BBH was Max’s alter ego has a radical effect on this. In Federal Republic of Brazil v Durant International Corp (Jersey), the Privy Council said that in the tracing process, the court must focus on the substance of the transaction and not form, and that it is “particularly important that a court should not allow a camouflage of interconnected transactions to obscure its vision of their true overall purpose and effect”. As has been noted, the primary judge held that the Max entities — of which BBH was one — were Max’s alter egos. His Honour said (emphasis added):

“There can be no doubt that, to the extent that the proceeds of sale are traceable to property currently held by Max or one of the entities that he controls, those proceeds are properly described as trust property or the proceeds thereof which were converted to Max’s use. It does not matter that those proceeds were not held by Max himself. They are held by entities that are properly regarded as his alter egos; and the claim to recover those proceeds is in substance a claim to recover them from Max.”

92 The extent to which that liberal approach can be justified when the underlying rationale of tracing is recognised: see RnD Funding Pty Ltd v Roncane Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 28; might be the subject of debate. However, the important point is that a complex of transactions ought not to conceal what is, in reality, a fairly simple case of the acquisition of an asset with the use of traceable proceeds. As has been discussed, the precise nature of the transactions in the present case is uncertain, even though formal agreements were executed. It is reasonably arguable that, on one view of the facts, the funds used by UIP to acquire the loans and mortgages from IJ Financial were the traceable proceeds of Mr So’s breaches of fiduciary duty.

Conclusion as to a serious question to be tried

93 It follows that the So interests’ and UIP’s submissions that no serious question arises in this case should be rejected. That is so notwithstanding that some difficult questions of law and fact need to be considered and dealt with. It might also be observed that the essence of the claim originates from what is said to be Mr So’s breaches of statutory and fiduciary duty towards the Carver’s entities and, whist it must be acknowledged that each party’s evidence surrounding that issue is yet to be adduced and tested, that which is available at present permits more than a prima facie case to be discerned.

Balance of convenience

94 The balance of convenience favours the granting of the injunctive relief. That is not a difficult conclusion to draw in circumstances where, if the applicants and Carver’s entities are successful in these proceedings, the latter may be entitled to receive the proceeds from the sale of the remaining Carver’s Estate land in priority to any security interest in favour of Ultimate and UIP. Such funds would be payable to the Carver’s entities and used to meet the claims of all creditors, without Ultimate or UIP being able to assert priority. If the injunction is not granted, that relief is liable to be frustrated. It is likely that, by the time of final judgment, the Carver’s Estate land will have been sold and the proceeds distributed. Ultimate and UIP have indicated that the proceeds of any realisation will be paid, pursuant to the various agreements and securities in place, to Ms Wong and Ms Leung, the latter of whom lives in Hong Kong, as well as SEL (in the case of Ultimate specifically). Accordingly, if the applicants and Carver’s entities were successful, the judgment in their favour would potentially be rendered nugatory.

95 It is also apparent from the correspondence passing between the parties that Ultimate has no assets of its own from which it might meet any judgment. Little is known about UIP, save that it was incorporated in November 2021 with paid up capital of $100 held by Mr So’s wife. There is nothing to suggest that it has acquired any assets of substance. This may be sufficient to demonstrate, in the absence of any clear submissions to the contrary, that damages would be inadequate as a substitute for the proprietary relief sought in these proceedings, which may be frustrated if an injunction is not granted.

96 The concerns as to the potential outcome of the proceedings if the injunctive relief is not granted are exacerbated by the reluctance of the So interests to disclose the nature and extent of the Carver’s entities’ indebtedness to Ultimate. The applicants’ solicitors sought that information over an extended period, but no details were provided. The facts, as they are presently known, suggest that the liabilities may be as low as $2.6 million, but Mr So himself has estimated that they may be as high as $10.5 million. For the present purposes, it need only be observed that the extent of the indebtedness is unclear and, whilst the So interests were in a position to shed light on that issue, they failed to do so. In fact, their correspondence has tended to obscure the true state of affairs even further.

97 On the other hand, if the injunction is granted but the action fails, the outstanding indebtedness to UIP and Ultimate will not be repaid until after the hearing. However, it is not clear that the total amount to be repaid, including any interest, will not be available to UIP and Ultimate from the proceeds of the sale of the remaining Carver’s Estate land. Even if the land was not sufficient to repay that indebtedness, the detriment to UIP and Ultimate would not be as great as the detriment that the applicants and the Carver’s entities would suffer if they were unable to recover any part of a judgment in their favour.

98 In light of the above, it is appropriate to adopt the course that appears, on the current evidence, to carry the lower risk of injustice, taking into account the consequences if it turns out that the injunction should not have been granted.

99 As to the balance of convenience, UIP submitted that the grant of the injunction would result in detriment to third parties to the proceedings, namely Ms Wong and Ms Leung: see Patrick Stevedores Operations No 2 Pty Ltd v Maritime Union of Australia (1988) 195 CLR 1, 41 – 42 [65] per Brennan CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ. Specifically, it was contended that Ms Wong and Ms Leung presently stand to be injured as a result of the injunction operating to prevent UIP from repaying the more than $8 million that it owes to them, in circumstances where they have been given no notice of the application and afforded no opportunity to be heard on the matter. Whilst the absence of Ms Wong and Ms Leung on this application is perhaps regrettable, and some prejudice can be perceived in their being kept out of the money that they have loaned, it is not clear that this prejudice is overly significant in circumstances where interest will continue accruing on that loan amount while it remains outstanding. There is also, conceivably, some room for the potential prejudice to be ameliorated as a result of the applicants’ expressed willingness to join Ms Wong and Ms Leung (along with SEL) to the proceedings within a short time from the grant of the injunctive relief, were that to occur.