Federal Court of Australia

BVT18 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs [2023] FCA 472

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION, CITIZENSHIP AND MULTICULTURAL AFFAIRS First Respondent ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the first respondent’s costs as agreed or taxed under r 40.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RAPER J:

Introduction

1 This is an appeal from a decision of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (FCCA), as it was then known, made on 3 February 2020: BVT18 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs & Anor [2020] FCCA 187 (J). In that decision, the primary judge dismissed an application for judicial review of a decision of the second respondent (Tribunal) made on 15 March 2018 (TD). The Tribunal had affirmed a decision of a delegate of the first respondent (Minister), made on 4 November 2015, refusing to grant the appellant a protection visa (Class XA) (Subclass 866) pursuant to s 65 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth).

2 This appeal concerned whether the Tribunal had erred in failing to allow the appellant to show the Tribunal documents on his mobile phone or in failing to invite him to submit the documents after the hearing.

3 I note that this Court’s jurisdiction is very confined and is unable to assess the merits of the appellant’s protection visa claims. The Court has jurisdiction to hear this appeal under s 24(1)(d) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). This Court cannot impugn a decision of a lower court on the basis that the decision is purportedly unfair or unjust, unless the decision is affected by jurisdictional error: see Attorney-General (NSW) v Quin [1990] HCA 21; 170 CLR 1 at 37. This means that the Court cannot substitute its own view as to the merits of the appellant’s claims for that of the Tribunal. It is not for this Court to determine whether the appellant’s claims as to why he fears harm if he were returned to China are true or correct.

4 For the following reasons the appeal must be dismissed. In essence I accept the Minister’s submission that whilst the Tribunal did not allow the appellant to show the Tribunal what was on his mobile phone, the Tribunal allowed the appellant to give evidence as to the substance of what was on his phone and took that into account in its reasons. Whilst the appellant believes that the Tribunal should have given more consideration to the “source” of the interest in him, namely the National Security Bureau, such that it could be inferred that the National Security Bureau’s interest was politically motivated, the appellant had, in effect, made that submission to the Tribunal and the Tribunal ultimately did not accept it. This disagreement with the Tribunal’s reasoning does not amount to an error of jurisdiction about which this Court can intervene.

Background

5 The appellant is a citizen of China, who arrived in Australia on 18 September 2014 on a Tourist Visa (subclass 600).

6 On 10 December 2014, the appellant applied for a protection visa, claiming he feared harm in his home country on account of his Christian faith and due to his attendance at “family gatherings” where fellow Christians went to “worship God” and engage in Bible study.

7 The appellant had operated a car rental and taxi business in China since 1988.

8 The appellant in his protection visa application claimed that the police had taken him from one of the Christian gatherings and beaten and tortured him and that he had been detained for one week until he paid a fine. He then claimed that his business deteriorated as a result of the police coming to check if he was organising these gatherings at his business. The appellant further claimed that as a result he moved cities where he was again arrested upon attendance at a gathering and was detained in a labour camp for a month (again being released after payment of a fine and forced to sign a guarantee that he would not attend the Christian gatherings again). The appellant claimed that as a result of the police continuing to attend his home and company he “thought there was no way for [him] in China and [he] would be arrested at any time” and so then decided to leave China. The appellant claimed he decided to go abroad and in July 2014 and August 2014 he travelled to Thailand and Malaysia, but he had no chance to stay there and returned to China before coming to Australia.

9 At his protection visa interview the appellant conceded that these claims were not entirely correct. Rather he told the delegate that he had never been arrested or held in a labour camp, had only ever been held for questioning for one day by police and on another occasion had been pushed violently to the floor by police. At the interview when asked what would happen to him if he returned to China he responded that officials would try to force him out of the market. The appellant had also repeated several times at the interview that he would have applied to migrate to Australia through his company but he could not do so as his business had been taken over and he was forced out of his business.

The delegate’s decision

10 The delegate accepted, inter alia, that the appellant owned and managed four businesses related to the car rental and taxi industry and experienced problems with officials and private competition in relation to three of his businesses. She also accepted that the appellant was unhappy with the way his businesses were controlled in China and that he may have encountered problems with local officials with respect to his businesses.

11 The delegate had put to the appellant, at the protection visa interview, that a court decision had been made, on 23 September 2014, that the appellant’s company should pay a penalty of 30,500 RMB to the plaintiff, but by that time the appellant had already travelled to Australia. The appellant responded that he had paid the penalty fee a long time ago. While the delegate accepted this, she took into consideration that he may have still been required to pay this latest penalty since his departure from China.

12 Ultimately, the delegate did not accept the appellant’s claimed reasons for departing China or his claim that he would be of adverse interest to the Chinese authorities, if he were to return to China. She considered that his claim, which related to “business/legal issues” did not fall within any of the grounds under the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, opened for signature 28 July 1951, 189 UNTS 150 (entered into force 22 April 1954) and that the appellant had in fact stated that he had applied for protection on religious grounds instead of applying to migrate for business reasons because he was having problems with his businesses.

13 In assessing the appellant’s claims, the delegate accepted that the appellant is interested in religion and may have attended some “Christian home gatherings” while in China, however, did not consider the appellant to be a dedicated Christian such that he would be at risk of serious harm or persecution from the Chinese authorities. In making this finding, the delegate considered the appellant’s evidence of his interest in different religions and country information regarding religious practices in China.

14 The delegate gave reasons for this finding, focusing on the discrepancies between the claims in the appellant’s protection visa application and his testimony at the protection visa interview (the latter of which was preferred by the delegate).

15 The delegate also took into account that the appellant was able to depart and return to China on several occasions between 2012 and 2014 without any difficulties when “he wanted to go for a break and relax as he could not decide what he wanted to do” and that he did not apply for refugee status in Malaysia because of his opinion that there was inequality and discrimination in Malaysia.

16 The delegate concluded as follows:

In considering his claims, circumstances, and the evidence of his case cumulatively, I am not satisfied that the applicant faces a real chance of serious harm for a Convention reason if he were to return to China. I do not accept that there is a real chance of persecution if the applicant were to return to China now or in the reasonably foreseeable future that he will be harmed for reasons of his religion or for any other Convention reason. I therefore find that his fear of persecution, as defined under the Refugees Convention, is not well founded.

17 As a result, the delegate found that the appellant did not meet the criteria under s 36(2)(a) of the Act and subcl 866.221(2) of Sch 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth).

18 The delegate then considered whether the appellant would satisfy the complementary protection criterion under s 36(2)(aa) of the Act. She was satisfied that the harm claimed by the appellant was significant harm for the purposes of s 36(2A) of the Act, however, was not satisfied that there was a real risk the appellant would suffer significant harm should he be returned to China, relying on the same information in making her findings on the refugee assessment.

The Tribunal’s decision

19 The Tribunal affirmed the delegate’s decision not to grant the appellant a protection visa on 15 March 2018.

20 This appeal concerns the appellant’s attempt at the Tribunal hearing to rely on evidence on his mobile phone. Therefore, it is worthwhile understanding what the potential mobile phone evidence went to within the context of the Tribunal’s reasoning overall.

21 The Tribunal noted that the appellant’s claims initially comprised that fact that he is a Christian who has suffered past harm in China due to his religious belief but at the Tribunal hearing the appellant raised that his political opinion also makes him at risk of persecution if he were to return to China: at TD[11]–[12].

22 The Tribunal gave reasons for its findings with respect to the appellant’s claims that he would suffer persecution on account of his Christian faith, and then with respect to the appellant’s claim he would suffer persecution on account of his political opinion.

23 Regarding the appellant’s claim on the basis of his Christianity, the Tribunal noted several inconsistencies between the appellant’s written application, what he had told the delegate in his protection visa interview and the evidence he gave before the Tribunal.

24 The Tribunal ultimately did not accept that the appellant was a Christian at all, that he had attended any Christian gatherings in China, had ever been detained or assaulted by the Chinese authorities, had ever been required to pay a fine to Chinese authorities on account of involvement at the Christian gatherings or that the authorities had ever attended his place of business out of concern as to his religious activities: at TD[36].

25 Next, at TD[37]–[41], the Tribunal considered the appellant’s claims that he feared harm on account of his political opinion. It is in this context that the request to rely on mobile phone evidence arose. Paragraphs [37]–[41] are extracted as follows:

Political Opinion

37. As noted previously, at the delegate interview on 3 November 2015 the applicant stated that he had trouble with the Chinese authorities regarding his business activities. This was the first time that these claims were raised with the delegate (apart from the applicant stating in his written application that police came to his company to check on him due to a suspicion that he may be holding religious gatherings at his work). At the time of the delegate interview, the applicant stated that he owned four car companies and that officials were trying to force him out of the car market.

38. At the Tribunal hearing, the applicant was at pains to demonstrate to the Tribunal that he had been wrongly treated by the Chinese authorities in his business activities. He told the Tribunal that in 2016, his taxi businesses were taken over ‘illegally’ by the local authorities and that the local authorities gave his business to other companies to operate. He said that his house was auctioned off by the authorities and that he now had no businesses in China.

39. As a result of his business experiences in China, he said that he became very hateful of the political system in China and had sent emails through his company work email and his WeChat messaging account suggesting that China should be more like Taiwan and China should allow multiple political parties and an independent judiciary. The applicant stated that these emails and messages could be considered a crime of wanting to overthrow the government in China. He said that these messages had been viewed by an employee who the applicant subsequently fired because of embezzlement of company funds. The applicant stated that he was fearful that the fired employee would have reported those messages to the authorities back in China in retaliation for being fired. He also said that his assistant in China had been taken in for questioning in either 2015 or 2016 as the authorities wanted to know where the applicant was. When pressed by the Tribunal as to why the authorities would be looking for him, the applicant stated that it was because the authorities suspected him of taking money out of the country.

40. It was clear from the way the applicant presented his evidence to the Tribunal that he was very frustrated by the fact that he was previously a successful businessman in China and now no longer has his businesses. He spoke to the Tribunal at length of wishing to affect change in China and that he wanted to participate in a revolution to overthrow the leadership. He told the Tribunal that he was depressed, turned to alcohol and gambling in Australia as a result of losing his businesses. He said that Australia was generous to immigrants from the Middle East but not so to Chinese immigrants. He told the Tribunal that he was a good person, who gave regularly to the homeless, was an environmentalist, was setting up an environmental taxi company in Australia, and did not take advantage of Medicare or other welfare services in Australia. He was at pains to demonstrate to the Tribunal that he had a lot to offer Australia if he was allowed to remain here.

41. The Tribunal is satisfied that the applicant had previous businesses in China and that he has encountered problems with local officials in regard to his businesses and the Tribunal is satisfied that the applicant has expressed dissatisfaction to colleagues and former colleagues about the Chinese political system. However, the Tribunal is not satisfied that the authorities in China are aware [sic] any of these communications. The applicant’s evidence to the Tribunal was that the authorities had asked his assistant the location of the applicant and this was in connection with an allegation that the applicant had ‘taken money out of the country’. There is no evidence before the Tribunal that the applicant is being sought for questioning because of his political opinion or his expression of dissatisfaction with the Chinese political system.

26 The Tribunal then concluded, first with respect to the refugee criterion (s 36(2)(a)) and then with respect to the complementary protection criterion (s 36(2)(aa)) as follows:

Refugee Criteria

42. Based on all the evidence before the Tribunal and having considered the claims singularly and on a cumulative basis, the Tribunal does not accept that there is a real chance that the applicant will face harm for the reasons of his religion or political opinion if he was to return to China now or in the foreseeable future.

43. As discussed above, the Tribunal does not accept that the applicant is a Christian, or has attended any gatherings in China, or participated in any Church activity either in China. While the Tribunal accepts that the applicant has experienced some difficulties with his business dealings in China and that he has voiced his dissatisfaction about the political system with his assistant and former employee, the Tribunal is not satisfied that the applicant has a well-founded fear of persecution for any convention related reason.

Complimentary Protection Criteria

44. Tribunal [sic] has considered whether on the evidence before the Tribunal there is a real risk that the applicant will suffer significant harm as a necessary and foreseeable consequence if he were to return to China.

45. The Tribunal does not accept that the applicant is a Christian, or has attended any church gatherings in China, or participated in any Church activity either in China. The Tribunal accepts that the applicant has experienced difficulties with his business dealings in China and that he has voiced his dissatisfaction [sic] the political system with his assistant and former employee, but the Tribunal does not accept that the applicant would face the death penalty, arbitrary deprivation of life or torture if he were to return to China.

46. Having considered the applicant’s circumstances on a cumulative basis and for all the reasons set out above, the Tribunal is not satisfied that there are substantial grounds for believing that as a necessary and foreseeable consequence of the applicant being removed from Australia and returned to China there is a real risk that he will face significant harm.

The primary judge’s decision

27 The appellant applied for judicial review of the Tribunal’s decision in the FCCA on 12 April 2018.

28 The appellant was unrepresented before the FCCA and had the assistance of a Mandarin interpreter. On 3 May 2018, at a directions hearing before a Registrar of the FCCA, the appellant was given leave to file and serve an amended application, together with any further evidence and submissions. However, at the time of the commencement of the hearing (on 4 November 2019) he had not filed any materials in support of his application: at J[21]–[24].

29 The appellant advanced the following four grounds of review, as extracted at J[25]:

“1. In the Immigration Bureau interview, I think that officials have intimidated me and said that they would leak my information to other countries. I have experienced it twice. This has caused serious damage to my spirit and psychology for three years. It caused me to drink alcohol every day, causing serious damage to my body. Due to drinking, I have a problem with my right knee now. I have seen Chinese medicine doctor. The diagnosis of traditional Chinese medicine doctor said it was caused by drinking. This incident also caused great harm to my spirit. I was seeking protection from the Australian government. However, I was not protected. It also caused greater mental stress and injuries. I can’t go back to China, but the Immigration Bureau made me feel threatened and falsely protected. You can cancel the protection visa for the Chinese and close this door. There is no need to give me second injury. In this way, I can fly to other countries before the travel sign expires, there is no need to endure the second injury in Australia. I reserve the right to sue the immigration authorities for compensation in the next step. While I was in Australia, the company was snatched by corrupt officials and the loss was as high as 30 million RMB. In addition, my house was also illegally auctioned, worth 6 million yuan. My body has problems with my legs now. Since you do not have the ability and patience to provide protection for the Chinese, you should not open this door. Do not only be a gentleman, but also be a hypocrite.

2. AAT interview officials are very good, very gentlemen, a typical representative of British culture, he is very patient. I began to describe what happened in China and what happened in Australia from 9:00 onwards, including the illegal acquisition of the company by corrupt officials (because of my beliefs), and my current political beliefs (I am against a party Dictatorship, I expressed appreciation and study of Taiwan’s political party system, and I expressed this point of view in the company. This document is now filed with the Public Security Bureau, the National Security Agency and the National Security Center (this is a special agency). My assistant was taken to the National Security Center (but I drink alcohol and melancholia every day. I don’t know whether it’s the National Security Center or the National Security Bureau. I have some cards and you can also get evidence).

3. AAT’s translator is a very good translator, and I think he has 99% accuracy in the translation of what I want to say. But during 11:30 – 11:49 he expressed that he had something to leave because of the timeout [sic] three times. At the [sic] 12 o’clock, the official asked me about my last question about faith. In fact, I have a lot to say about this issue, but in the end it did not give me time and opportunity to express my point of view. The translator repeatedly expressed his psychological pressure because of the time he had left and left me unable to speak. It is unfair, irrational, inhuman and cruel to reject me in this way. Because I left Australia, I cannot return to China. Where am I going? Go to the sea?

4. I am a person who can create wealth, not a person who consumes wealth. I create wealth and pay taxes and state expenses far more than any country has brought me. I did not work in Australia for a day. I did not come to Australia to work and earn money. I was here to pursue freedom and appreciate political freedom in a multi-party system. And I have the ability to continue to create wealth, of course, in a multi-party system and legal supremacy country.”

(Emphasis in original.)

30 As will be seen below, none of the bases are repeated or form part of the grounds on appeal save with respect to ground 2, in which the “document” appears to be the document(s) on the appellant’s mobile phone which he wished to show the Tribunal (as articulated in ground 2 before this Court).

31 The primary judge noted in her Honour’s reasons that at the first hearing on 4 November 2019 the appellant made oral submissions that he had wanted to show the Tribunal member this document on his phone, had not been allowed to, and had asked why the Tribunal had not asked him to provide the documents in writing: at J[28]. The primary judge did not consider the appellant’s grounds identified with particularity such a complaint and for which it “plainly require[d] evidence”. At hearing, her Honour then granted leave to the appellant to file and serve an amended application, any additional evidence and submissions and stood the matter over: at J[29].

32 Both the appellant and the Minister filed affidavits, each annexing an excerpt from the transcript of the Tribunal hearing. While the appellant provided an “extracted translation” of the transcript, the Minister provided the official Auscript transcript, which to the extent of any difference her Honour preferred the latter as accurately reflecting the transcript of the Tribunal hearing: at J[30], [33].

33 The appellant further raised in his affidavit his complaints about not being able to show the Tribunal member documents on his mobile phone and that the Tribunal did not give him an opportunity to provide further material post-hearing. The appellant deposed that the documents on his mobile phone served as evidence of his political views against one-party autocracies and corruption: at J[31]. However, the appellant did not annex to his affidavit any evidence of the documents on his mobile phone. The appellant also claimed that the Tribunal had failed to verify or investigate his claims (in breach of its duty), that his evidence was not given sufficient weight, carefully questioned or seriously considered and that the Tribunal did not pay sufficient attention to the appellant’s depression and his general physical and mental state: at J[30].

34 At the second FCCA hearing on 3 February 2020, the appellant confined his complaints to the Tribunal’s failure to allow him to show documents on his mobile phone and to invite him to provide the documents in writing. The appellant did not make any submissions in support of the other complaints identified in his initiating application and his affidavit.

35 In relation to what the transcript revealed about the appellant’s claim that the Tribunal erred by not allowing him to show the documents on his mobile phone, the primary judge found as follows:

37. These findings by the Tribunal, which were open to it on the evidence and material before it and for the reasons it gave, make clear that the Tribunal accepted what the applicant told the Tribunal was the substance of the information on his mobile phone and that the Tribunal had accepted that evidence and given it proper consideration.

38. In the circumstances, there is no jurisdictional error on the part of the Tribunal in failing to look at the material on the applicant’s mobile phone. Nor, in the circumstances, was it necessary for the Tribunal to invite the applicant to send copies of the information on the applicant’s mobile phone post hearing.

The present appeal

36 By the appellant’s notice of appeal filed 19 February 2020, the appellant advances the following grounds of appeal (extracted in full):

1. APPLICATION FOR FEDERAL CIRCUIT COURT HAS BEEN DISMISSED AND I DO NOT AGREE WITH ITS DECISION. FCC FAILED TO TREAT ME FAIRLY AND JUSTICALLY [sic].

2. AAT IGNORED MY IMPORTANT EVIDENCE PROVIDED AT THE HEARING AND REGARDLESS MY REQUEST TO FURTHER EXPLAINATION UPON IT. NEIRTHER [sic] GRANT CONSIDERATION NOR CONDUCT FOR INVESTIGATION

3. I AM THE VICTIM OF THE TRAGETY [sic] DIRECTLY COSTED BY MY PREVIOUSE [sic] “GOOD LUCK”, THE MIGRATION AGENT. SHE DELIBERATELY REVISED MY CALIM [sic] AND I STRONGLY INSIST THAT THE COURT CAN INVESTIGATE THIS CRITICAL EVENT FOR MY INTREST [sic].

4. BOTH AAT AND FCC CONCLUDE MY EVIDENCE PROVIDED AS UNPROBATIVE WHICH IS NOT ACCEPTABEL [sic] FOR ME.

5. I WISH TO DO FURTHER REVIEW WITH YOUR COURT AND GET A MORE FAIR DECISION

37 The appellant sought that the decision of the Tribunal and the judgment and orders of the primary judge be set aside and the matter be remitted to the Tribunal for reconsideration according to law.

38 This matter remained in abeyance due to the difficulties of holding in-person hearings during the COVID-19 pandemic. The matter was assigned to my docket in 2022 and on 8 June 2022 I ordered that the appellant be referred for pro bono legal assistance under r 4.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). In July 2022, counsel for the appellant accepted the referral. However, on 14 April 2023, the appellant’s counsel informed the Court that he could no longer represent the appellant. The appellant remained unrepresented at hearing and the filed notice of appeal remained extant.

Consideration

New evidence

39 At hearing, the appellant sought leave, pursuant to s 27 of the FCA Act, to rely on fresh evidence, namely:

(a) a document which the appellant submitted was the screenshot of the email on his mobile phone which he had wanted to show the Tribunal but was prevented from doing so;

(b) a document entitled “Report on Vehicle Update” and two documents entitled “Reporting on the Situation of Sha Long Company”; and

(c) portions of the Tribunal audio recording (from the hearing) at 4 minutes to 4 minutes and 55 seconds and 2 hours and 36 minutes to 2 hours and 37 minutes.

40 The application was not opposed with respect to the email screenshot and the portions of the Tribunal audio recording. As stated by the Full Court in Toki v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs [2022] FCAFC 164 at [66], the Court has the power to admit such evidence to ensure proceedings do not miscarry. No formal application as required in compliance with r 36.57 of the Federal Court Rules was made. As observed in BVZ21 v Commonwealth of Australia [2022] FCAFC 122 at [12]:

…In exercising the discretion, the Court will normally need to be satisfied that the further evidence, had it been adduced at trial, would very probably have meant that the result would have been different, and further that the party seeking to adduce the evidence was, at trial, unaware of the evidence and could not have been, with reasonable diligence, made aware of the evidence: Northern Land Council v Quall (No 3) [2021] FCAFC 2 at [15]-[16] (Griffiths, Mortimer and White JJ).

41 I note that the Minister did not oppose leave being granted to rely on the email screenshot nor the portions of the audio recording: A prudent and appropriate response to this aspect of the application. Leave is granted to rely on them both. I accept that, whilst not necessary, a party who claims to have been deprived of the opportunity to put evidence before the Tribunal, may seek to adduce the evidence which they were denied the opportunity to rely on. Regarding the audio recording, it was not apparent at hearing what the relevance of the first portion of the Tribunal audio recording was. However, I accept that the second portion of the audio recording (for which I also have a transcript of) is relevant on appeal, being the point in the transcript where the Tribunal refused to allow the appellant to show him the screenshot on his mobile phone.

42 However, I do not grant leave to the appellant to rely on the three documents identified at [39(b)] above. At hearing, the appellant submitted that he should be able to rely on the documents because they evince his version of the Chinese authorities taking his business from him. I am not satisfied that these documents go to the real issues such that, if they had been adduced, they would very probably have meant the result would have been different.

Ground of appeal

43 Whilst there are ostensibly five grounds of appeal, the only discernible ground is ground 2 in which the appellant claims that the Tribunal “ignored” important evidence. Ground 1 merely comprised a statement of general disagreement for which no basis or bases are identified and must fail. Ground 3 appears to relate to a dispute with a migration agent about which no comprehensible claim of error arising from the primary judge’s decision arises and must fail. Ground 4 is a generalised ground concerning the probative nature of the appellant’s evidence which appears to be either a submission in support of ground 2 or a general complaint about the Tribunal’s and FCCA’s treatment of the appellant’s evidence. As to the latter, no submissions were made by the appellant in support of this as a discrete ground and it must fail. Ground 5 comprises an aspiration for review and nothing more.

44 Ground 2 is premised on the purported denial of procedural fairness by the Tribunal refusing the appellant’s ability to rely on evidence he claimed to have on his mobile phone or to thereafter invite him to put on a further evidence or written submissions.

45 The appellant’s attempt to rely on this evidence occurred during that part of the Tribunal hearing where the Tribunal member sought clarification from the appellant regarding the basis for his fears of being persecuted. The appellant referred to the fact of his “objections” (namely opposition to the Chinese government, “through my emails”). The Tribunal sought to understand how the Chinese authorities knew the appellant had objected:

THE INTERPRETER: The more serious issue is that your objection – like, I mean, are you – I have already expressed my objections through my emails, my ..... so this is very bad and quite serious. They’ve known that I will object it.

MR GOETZ: And how do they know that you’ve objected?

THE INTERPRETER: Because I’ve written down it – I’ve written it down on my – through my email in rogue report.

MR GOETZ: .....

THE INTERPRETER: To my company, to my assistants in the company objecting - - -

MR GOETZ: Is this your company in China?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes. In Mayjo.

MR GOETZ: Right.

THE INTERPRETER: If I WeChat – if I WeChat – that I register through my – sorry, the Australian mobile phone. So the Chinese colleagues could have – could see my WeChat account. I mean if you need it, I could have plenty of information of me publishing the support for independent justice and multi parties.

MR GOETZ: When you say ..... some of your Chinese colleagues can look at your WeChat account which colleagues are you talking about?

THE INTERPRETER: This person was from Ganjo of Jiangxi province but I invited him to deal with my Mayjo company after he was robbed.

MR GOETZ: The what, sorry? The Mayjo - - -

THE INTERPRETER: Mayjo – Mayjo company – Mayjo company.

MR GOETZ: What’s a Mayjo company?

THE INTERPRETER: Mayjo is the place.

MR GOETZ: Yes. Okay. And what makes you think that that person that you were dealing with has passed that information on to the authorities?

THE INTERPRETER: The reason was because when he was dealing with my company affairs he was corrupted and he embezzled – he took over some of my assets – companies, I mean. So I fired him. And he hated me ..... my WeChat was open to public and this day that a person from Jiangxi province wanted to join me as a friend, and it was him. But I didn’t accept his offer. Sorry, your Honour, I like to raise your attention to the time as I really need to go.

MR GOETZ: I’m sorry. Can we just be four more minutes. Is that all right?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes, that’s fine.

MR GOETZ: Okay. I just want to check one more thing. So you said earlier in your evidence that you had – I think either you directly or your assistant had been contacted by a member of the security services.

THE INTERPRETER: My assistant was actually taken away by the national security bureau to investigate about me.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: I don’t remember whether it’s earlier this year or later last year but I got a screenshot of that email. I can show it to you.

MR GOETZ: Earlier this year or late last year.

THE INTERPRETER: They are the agents. They are not the police. I mean, they’re worse than the police.

MR GOETZ: ..... public security. All right. And how do you know that they’re looking for you?

THE INTERPRETER: They took my assistant over and ask about me and my company. Of course they’re going after me. They asked everything about my company and everything about me.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: If I could turn on the mobile phone I could show it to you.

MR GOETZ: No, you can just tell me and ..... so how did they contact you; was it an email or did your assistant pass on the message?

THE INTERPRETER: I communicated with my assistant through the emails.

MR GOETZ: Did your assistant pass on the message that the security services are looking for you?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: Assistant is a different person than the person from Jiangxi. One is a girl, one is a male.

MR GOETZ: Yes. I understand that.

THE INTERPRETER: She has been my assistant for over 10 years. She is now a civil agent of a small county government.

MR GOETZ: I’m surprised that you’re still having contact with anyone back in China if you’re that fearful of the Chinese government.

THE INTERPRETER: Emails – contacts from emails. I still got my company over there. How come I not have contacts.

MR GOETZ: And they haven’t shut down your company?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes, they did. They robbed my company. They robbed my market. They robbed my – over 10 years achievement. Like the 200-odd drivers that I trained.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: ..... they’ve taken away the nine million Chinese renminbi revenue and they’ve terminated my company’s name. And they’ve accused – mis-accused me of escaping with money. This is just on the part of the police. It’s not on the national security is a bureau site.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: They – after they’ve taken away my company, they’ve taken away my assets. When I send my solicitor over to – in – to – to inquire, in order to cover their face, in order to cover their – the wrong things they did, they said that I escape with money.

MR GOETZ: Okay.

THE INTERPRETER: Like, after I left – I mean, the driver – the drivers had some deported so I gave him the copy of my ..... the title deeds.

MR GOETZ: All right. That’s fine. I think I’ve got it all – enough but I will read the interview again with the department and then I will make a decision shortly.

(Emphasis added.)

46 Accordingly, a review of the transcript reveals that the appellant’s claims were as follows:

(a) that the Chinese authorities were aware of his “objections through [his] emails”;

(b) that the emails were to his company assistants in China;

(c) his Chinese colleagues could look at his WeChat account where he was “publishing the support for independent justice and multi-parties”;

(d) that his Chinese colleague passed on this information to the authorities after the appellant fired him because “he was corrupted [sic] and he embezzled [the appellant’s funds]”;

(e) that his assistant was taken away by the National Security Bureau “to investigate” him; and

(f) it is in this context of the latter claim that the appellant wanted to show the Tribunal a “screenshot of that email” and where the assistant had “pass[ed] on the message that the security services” were looking for him.

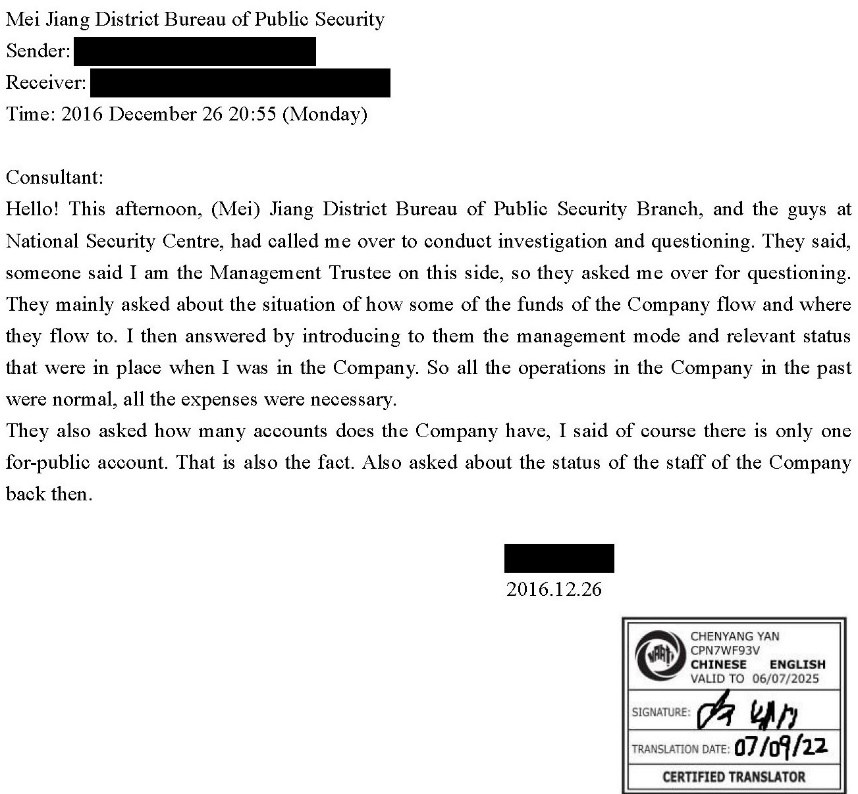

47 On appeal, the appellant relied on evidence of what he says he would have shown the Tribunal if he had been given the opportunity, which is extracted below:

48 The appellant submitted, and the Minister did not dispute the same, that it is an email he received from his assistant in China, who had been his personal assistant more than 10 years ago in the company.

49 Notably, the Tribunal accepted at TD[41] that the appellant had “expressed dissatisfaction to colleagues and former colleagues about the Chinese political system”. To the extent that the Tribunal did not accept the appellant’s claims, they were two-fold: (a) that the Chinese authorities were aware of any of these communications; and (b) that the Chinese authorities had sought out the appellant for questioning because of his political opinion or his expression of dissatisfaction with the Chinese political system.

50 This email does not contain any evidence on its face of either of these two matters. However, as will be dealt with further in these reasons, the appellant submits that the crucial aspect of this evidence is it purportedly corroborates the source of the interest in him, being the “Public Security Branch” from which the appellant says it can be inferred that they were interested in him for political as opposed to business reasons.

51 With respect to this aspect of the appellant’s claim before the primary judge, her Honour found at J[34]–[35]:

34. The transcript makes clear that the Tribunal member was exploring whether the applicant or his assistant had been contacted by a member of the security services. The applicant had stated that his assistant had been taken by the National Security Bureau to investigate the applicant, however he could not remember when. It was a screenshot of that email from his assistant to that effect that the applicant wished to show the Tribunal. While the Tribunal refused the applicant’s request to turn on his mobile phone, the Tribunal member invited the applicant to say how he was contacted by security and whether it was in an email, or had his assistant passed on the message. The applicant responded that he had communicated with his assistant by email. The Tribunal member then asked the applicant, did his assistant pass on a message that the security services were looking for the applicant. The applicant answered, Yes.

35. In its decision record, the Tribunal noted that the applicant had sent emails critical of China and which the applicant had stated could be considered a crime of wanting to overthrow the government in China. The Tribunal noted that the applicant said that the messages had been viewed by an employee who the applicant subsequently fired because of embezzlement of company funds, and the applicant feared that employee may report those messages to authorities in China. The Tribunal also noted that the applicant had stated that his assistant in China had been taking [sic] for questioning either in 2015 or 2016 as the authorities wanted to know where the applicant was, because the authorities suspected the applicant of taking money out of the country.

52 As the Minister contends, it is uncontentious that a decision-maker may fall into error if she or he fails to consider or assess relevant evidence or claims made by an applicant. However, the Minister submits that is not what happened here. On the Minister’s submission, although the form of the information was not before the Tribunal, the substance of the information was conveyed by the appellant’s own (oral) evidence in response to the questions of the Tribunal. The relevant exchange is extracted at [45] above.

53 The appellant submitted at hearing that the importance of this document was its identification of the source of interest, namely the National Security Bureau (as he had called it). The appellant submitted:

… so till now I still haven’t figured out what kind of organisation is that. So till last night I finally figured out this actually came from Public Security Bureau, the National Security Centre. It was an internal organisation. The purpose of this organisation is designed to suppress citizens in China. Six years ago when I saw this document and I saw the words National Security Centre, I told myself, “I’m screwed”. National Security Centre, that means I am trying to undermine the society…

54 The appellant submitted on appeal, that despite the email appearing to relate to concerns the Chinese authorities had about his company’s flow of funds, the Public Security Bureau had “no power, no authorisation to make inquiries about [his capital] status”. Once “they appeared, that means [he] was on the list of antisocial activists”. It is true that the appellant did not make this submission before the Tribunal explicitly but it is the case that the appellant did make clear to the Tribunal, during the exchange, that it could be inferred that the national security “agents” were “after” him.

55 The beginning of the exchange reveals that the Tribunal was aware of the source of the interest, being a “member of the security services”. It is the Tribunal that asks the appellant to clarify his earlier evidence about, paraphrasing the appellant’s evidence and stating, “either you directly or your assistant had been contacted by a member of the security services” and in response the appellant says that his assistant “was actually taken away by the national security bureau to investigate about [the appellant]”. Further the appellant goes on to say “[t]hey are the agents. They are not the police. I mean, they’re worse than the police” and by reason of this “[t]hey took my assistant over and ask about me and my company. Of course they’re going after me. They asked everything about my company and everything about me” (emphasis added). To which the Tribunal then asked “how” they (being the security services) contacted him, to which he replied through his assistant through emails.

56 The Tribunal’s reasons then reflect this exchange and refer to the appellant being “fearful that the fired employee would have reported [his emails and messages critical of China] to the authorities back in China… He also said that his assistant in China had been taken in for questioning in either 2015 or 2016 as the authorities wanted to know where the applicant was” (emphasis added): at TD[39]. The Tribunal accepted the appellant’s evidence that he had encountered problems with local officials in regard to his businesses and that he had expressed dissatisfaction to colleagues and former colleagues about the Chinese political system: at TD[41]. The Tribunal then found that the authorities had asked his assistant for his location and that this was in connection with an allegation that he had “taken money out of the country”. This was by reason of what is contained in a latter portion of the transcript.

57 By reason of the exchange and the Tribunal’s reasons, I accept the submission of the Minister that the substance of the material contained in the email was accepted. Ultimately, it was the characterisation of the evidence that was rejected. The Tribunal did not accept that the Chinese authorities were interested in the appellant because of his political opinion rather than by reason of his commercial activities.

58 It was open to the Tribunal to reject the appellant’s claim on that basis and, for the same reasons, the primary judge did not fall into error. As the primary judge found at J[40], the Tribunal is not required to accept uncritically the appellant’s claims (Randhawa v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1994) 52 FCR 437 at 451 per Beaumont J; Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Guo & Anor [1997] HCA 22; 191 CLR 559 at 596 per Kirby J; Prasad v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1985) 6 FCR 155 at 169–70 per Wilcox J) nor require rebutting evidence before holding that a particular assertion is not made out: Selvadurai v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs [1994] FCA 1105; 34 ALD 347 at 348 per Heerey J.

59 To the extent that the appellant contended that the Tribunal had an obligation to investigate his claims or invite him to make further submissions or provide further evidence after hearing, I accept, as the primary judge found (at J[39]–[40]), that there is no general obligation on a Tribunal to investigate an applicant’s claims (Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v SGLB [2004] HCA 32; 207 ALR 12 at [43] per Gummow and Hayne JJ (Gleeson CJ agreeing); Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v VSAF of 2003 [2005] FCAFC 73 at [20] per Black CJ, Sundberg and Bennett JJ) and that the duty imposed on the Tribunal is to review not to enquire: Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZIAI [2009] HCA 39; 259 ALR 429 at [25] per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ.

60 Even if I am wrong in this regard, I am of the view that any error was not material. I accept, as submitted by the Minister, that where the error arises from procedural unfairness, there is a low threshold to overcome in order for that error to be material. As the plurality of the High Court opined in Nathanson v Minister for Home Affairs [2022] HCA 26; 403 ALR 398, at [33], there will “generally” be a realistic possibility that the process could have resulted in a different outcome if a party was denied an opportunity to present evidence or make submissions on an issue that required consideration. However, a close reading of the email reveals that its production could not realistically have resulted in the making of a different decision: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZMTA [2019] HCA 3; 264 CLR 421 at [45]; MZAPC v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2021] HCA 17; 390 ALR 590 at [2]–[4]. As reasoned above, the Tribunal had accepted (and thus not denied the appellant an opportunity) the appellant’s evidence as to the substance of what was contained in the email on his phone. What the Tribunal did not accept was that the Chinese authorities’ interest in the appellant was for political and not business reasons. There is nothing in the email that goes to that issue. The email refers to the Bureau of Public Security Branch and the National Security Centre seeking information regarding the flow of the company’s funds. What the appellant indicated in the exchange was the substance of the email and goes no further with respect to the appellant’s submission as to the criticality of and inference to be derived from the source.

61 For these reasons, the Court is not persuaded, if error were established, that it was material.

Conclusion

62 For these reasons, I dismiss the appeal.

I certify that the preceding sixty-two (62) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Raper. |