Federal Court of Australia

Directed Electronics OE Pty Ltd v OE Solutions Pty Ltd (No 9) [2023] FCA 462

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 1pm on 19 May 2023 the parties are to file and serve minutes of proposed orders to accord with these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 These reasons address two issues that have arisen out of my decision published on 24 November 2022 (Directed Electronics OE Pty Ltd v OE Solutions Pty Ltd (No 8) [2022] FCA 1404). Unless otherwise indicated, I will adopt the defined terms and concepts that I used in my principal reasons.

2 The first issue concerns the appropriate quantification of the secret commission payments and the identity of the particular Hanhwa parties that are liable in respect of the associated claims.

3 The second issue concerns both the Hanhwa parties and Mr Meneses and relates to the appropriate award of interest on the quantified secret commission payments. Should this be simple interest or compound interest? And if the latter, should the periodic rests triggering compounding be monthly or yearly?

Quantum of secret commissions liability

4 Now flowing from my principal reasons, the amount Mr Meneses is to pay concerning the secret commission payments is not in dispute. This sum is $1,319,352. Further, the amount Mr Ryan Lee is to pay concerning the secret commission payments is also not in dispute. That sum is $976,697.

5 Only the amounts said to be payable by Hanhwa Korea, Leemen Korea and Hanhwa Aus are in dispute.

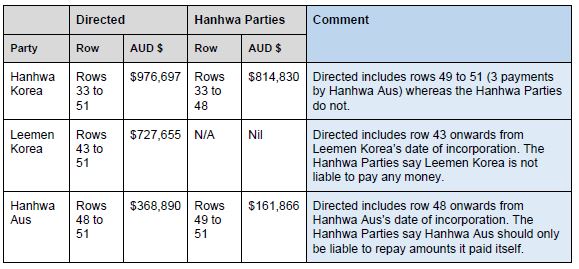

6 Now the Hanhwa parties argue that the relevant particular entity should only pay for the actual amounts which that entity paid to Mr Meneses and/or OE Solutions as set out in annexure D to my principal reasons. It is said that this conclusion is based on my having made no findings as against any of the other Hanhwa parties, including Leemen Korea.

7 But Directed submits that it is misconceived for the Hanhwa parties to adopt such a literal approach to my findings, and that it is incorrect to suggest that there were no findings against Leemen Korea.

8 It is said that my knowing assistance findings made in the specific context of the secret commissions conduct encompass conduct beyond actual payments made, and expressly refer to Leemen Korea (at [1476]):

Hanhwa Korea, Leemen Korea, Hanhwa Aus and Lee were knowing assisters in Meneses’ breach of his fiduciary obligations.

9 It is said that it was also found that Mr Lee’s knowledge and state of mind were to be attributed to those entities.

10 Directed says that accordingly the quantum of secret commission payments should reflect the relevant parties’ participation in the relevant wrongful conduct from the date of incorporation of each relevant Hanhwa entity, in addition to any payments they personally paid.

11 Directed submits that Hanhwa Korea should also be liable to pay the additional sum of $161,866, being three payments made to Mr Meneses by Hanhwa Aus, on the grounds of Hanhwa Korea’s participatory conduct.

12 Further, Directed says that whilst Leemen Korea made no payment itself, it was found to have participated in the relevant wrongful conduct as a knowing assister. It also pointed out that Leemen Korea was incorporated on 9 April 2014 and should therefore be liable for all payments of secret commissions following that date.

13 Further, it is said that Hanhwa Aus was found to have made three payments in its own right and was also found to have participated in the relevant wrongful conduct. And it is said that given that Hanhwa Aus was incorporated on 21 September 2016, it should therefore be liable for all payments of secret commissions following that date.

14 Directed has provided the following table setting out the competing position of the parties with respect to these amounts, by reference to annexure D of my principal reasons:

15 Now I prefer the Hanhwa parties’ position to Directed’s position.

16 In my view the appropriate final orders as to secret commissions should reflect the amounts paid by the individual entities, that is, each entity ought to be liable to pay the amount it paid to Mr Meneses and/or OE Solutions by way of secret commission payments.

17 Now although Directed suggests that each of Hanhwa Korea, Leemen Korea and Hanhwa Aus ought to be liable for all payments made after their respective incorporations, regardless of the relevant payer, and that the quantum of payments should reflect the relevant participation in the wrongful conduct from the date of incorporation, no principle of equity inevitably justifies such treatment.

18 Moreover, Directed identifies no direct participation on the part of any of the relevant Hanhwa entities in the payments made by any of the other Hanhwa entities. For example, the payments in rows 49 to 51 of annexure D to my principal reasons were made by Hanhwa Aus and the relevant wrongful conduct was, obviously, the payment of those secret commissions, but Directed has not identified how Hanhwa Korea or Leemen Korea participated in the conduct comprising those particular payments.

19 In my view the appropriate orders should reflect my rejection of in essence Directed’s claim of global cross-liability in respect of each of the Hanhwa parties for all of the payments made by way of secret commissions, subject to the date(s) of incorporation qualification. The appropriate orders should reflect my findings of liability of the corporate entities Hanhwa Korea and Hanhwa Aus based upon Mr Lee’s knowledge and involvement in the payments made by each of them individually.

20 Now adopting such an approach, Mr Lee is liable for all amounts paid by both Hanhwa Korea and Hanhwa Aus, totalling $976,697. Hanhwa Korea is liable for all amounts it paid, with Mr Lee’s knowledge and involvement, totalling $814,830. And Hanhwa Aus is liable for all amounts it paid, with Mr Lee’s knowledge and involvement, totalling $161,866.

21 Finally, in relation to Directed’s reference to [1476] of my principal reasons that was said to advance its position in respect of Leemen Korea, at that paragraph I made the finding that each of the corporate entities listed was, separately, a knowing assister in Mr Meneses’ breaches of fiduciary duties, but neither the language used nor the context in which the paragraph appears suggests that I was intending to make any finding of or foreshadowing the grant of relief tailored to achieving the cross-collateralisation of liability against each of the separate Hanhwa entities for the liability of the others in respect of the secret commissions payments liability.

22 On the contrary, the orders that I propose to make reflect my more precise observation (at [1456]) that:

the agent and the maker of the payment are jointly and severally liable to the principal to account for the amount of the bribe as money had and received and damages for any actual loss.

23 In summary, the appropriate orders concerning the quantification of the secret commissions payments liability should largely accord with the Hanhwa parties’ position.

24 For completeness I also note that the Hanhwa parties appear to accept that the amount held in a joint bank account opened during the proceeding should be paid towards the satisfaction of the amount due to be paid by any one of them.

The methodology for interest – simple or compounding?

25 Directed seeks an order that Mr Meneses and the Hanhwa parties pay compound interest on the secret commission amounts for which each is liable from the date when each payment was made and at the rate equal to the RBA cash rate at the date of payment plus 4% as envisaged in this Court’s practice note on the subject. Further, the compounding is sought with monthly rests.

26 I should say here that the context for considering compound interest concerns equitable compensation rather than a plain vanilla common law claim of the type dealt with in Hungerfords v Walker (1989) 171 CLR 125. I am only dealing with the prophylactic jurisdiction of equity and her protection of innocent parties affected by the wrongful conduct of fiduciaries and knowing assisters. And no one should doubt the malleability of her remedies.

27 Now an award of compound interest may be made in equity against a trustee or other fiduciary for breach of an equitable obligation. But it is not limited to the situation where funds have been withheld or misappropriated by a trustee or other fiduciary or where a trustee is under a duty or direction to accumulate income. The over-arching consideration is what justice demands in the particular circumstances. In other words, what is equitable?

28 Now it must be borne in mind that such an award is compensatory in nature. It is not designed to be punitive in purpose or effect. Such an award is designed to make good what the innocent party may have lost by reason of the breach of the equitable obligation.

29 It is not necessary to demonstrate fraud, dishonesty or other serious misconduct to justify an award of compound interest, although such a finding is not unhelpful as it may justify a more robust approach to drawing inferences in favour of the innocent party and against the miscreant fiduciary concerning use by the latter or loss by the former.

30 Further, for such an award, it is not strictly necessary to demonstrate that the recalcitrant or defaulting fiduciary has made a gain whether by the use of the innocent party’s money or in some other way, but of course if that is the case or it can reasonably be inferred, then any claim for compound interest would be fortified.

31 Further, in a modern mercantile setting, an award of compound interest is more likely to be consistent with commercial reality. Simple interest usually under-compensates, and the longer the period of the calculation, the greater the magnitude and magnification of such under-compensation. Is there any such thing as a lender or borrower who does not expect to receive or be charged respectively interest utilising periodic rests and thereby permitting or envisaging some level of compounding? I doubt it. Of course, setting a higher rate with simple interest may give you nearly arithmetic equivalence with otherwise setting a lower rate with compound interest. But assuming that the setting of the rate has not been massaged to achieve that end or to implicitly so reflect such an allowance, one would expect that some level of compounding should be the norm.

32 Now Directed says that the present case falls within the class of cases where the application of compound interest is appropriate to approximate the profit made from the use of the proceeds; see Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (No 2) (2012) 200 FCR 296 at [547] to [552] per Finn, Stone and Perram JJ.

33 And of course one of the circumstances in which compound interest is awarded with periodic rests, for example, weekly, monthly, quarterly or yearly, is where trust money is misused by a trustee or fiduciary in his or her own trade or business. And the informing principles may reflect those employed in accounting for profits, including presuming that the party against whom relief is sought has made that amount of profit which persons ordinarily would in analogous circumstances make in trade.

34 In such a class of case, the object of a compound interest award and the use of periodic rests is to reflect in the award a crude approximation of the profit likely to have been made by the fiduciary or trustee from the money misused where that profit could reasonably be supposed to exceed in value a simple interest award.

35 Now Directed submits that in order to arrive at a crude approximation of the profits considered likely to have been earned from the money misused, monthly rests are appropriate.

36 I note that on the question of periodic rests, in Grimaldi the Full Court ordered monthly rests. They overturned the decision of the trial judge who had ordered yearly rests, although it was unclear whether the trial judge may have intended to refer to monthly rests. The Full Court determined that monthly rests were appropriate on the basis that (at [753]):

The issue of incidence of rests is not one of comity. The question is what by the use of compound interest and rests is likely to prove a crude approximation of the profits considered likely to have been earned from the money misused. His Honour’s own appreciation, having had the advantage both of hearing the matter and of long reflection on it, was that monthly rests were appropriate. We consider this likely to be far closer to the mark than annual rests.

37 Now the Hanhwa parties at trial challenged any impropriety in making the secret commission payments, but I found that the secrecy was manifest and that the conduct was a corrupting influence on what otherwise should have been a mutually beneficial relationship of supplier and customer. I found that Mr Meneses’ conduct was fraudulent and dishonest and well known to be so by Mr YS Lee and the Hanhwa parties. The Hanhwa parties also failed to disclose the commission payments to Mr Tselepis and Mr Siolis.

38 And on the question of quantum, as was observed by me, the principle seems to be that it will be assumed that the true price of any goods bought by the principal was increased by at least the amount of the bribe paid to the agent.

39 Now in relation to the Hanhwa parties, the object of the secret commissions arrangements was to incentivise Mr Meneses to increase the Hanhwa parties’ business from which they would, and did, make profits. From Mr Meneses’ perspective, the arrangements provided him with payments to which he was never entitled and for which he is liable to account. The secret commissions arrangements between Mr Meneses and the relevant Hanhwa parties including their predecessors were on foot for some time. Mr Meneses commenced receiving secret commissions in 2009. The Hanhwa parties, subject to various differences between entities, paid secret commissions dating back some years.

40 Accordingly, the benefits obtained by the parties by reason of the bribes/secret commissions are difficult to calculate. And in circumstances where the relevant respondents’ profits by reason of the bribes can only be approximated, Directed submits that applying the relevant principles, this is an appropriate occasion for interest to be awarded on a compounding rather than simple basis, with the compounding to be based on monthly rests.

41 Let me then deal with the position of Mr Meneses first and the Hanhwa parties second.

42 Mr Meneses submits that the appropriate basis on which interest should be ordered is on a simple basis. Alternatively, he says that if I am minded to award compound interest, I should do so on yearly rests rather than monthly rests.

43 First, Mr Meneses says that there is no safe basis to presume that some “trading-type” profit was made by Mr Meneses which warrants an award of compound interest. There is no evidence that Mr Meneses invested the money in any business of his own or into that of any of the Hanhwa parties.

44 He referred to Burdick v Garrick (1870) LR 5 Ch App 233 at 242 where Lord Hatherley LC said:

… There is nothing like compound interest obtained upon the money employed by a solicitor ... no case arises here in which you could say that a profit has been made, or necessarily is to be inferred, and consequently that there was an error committed in directing compound interest.

45 As a result, Mr Meneses says that an award of compound interest risks the possibility of straying into punishment of Mr Meneses by way of interest. That risk is exacerbated by the fact that the relevant interest rate is 4% above the RBA cash rate. If compound interest were to be awarded, Mr Meneses says that it carries the implicit presumption that Mr Meneses achieved a nominal “profit” of significantly above the prevailing cash rate, and did so on a continual and compounding fashion. But that implicit presumption is not justified.

46 Second, if compound interest were to be awarded, Mr Meneses says that monthly rests are inappropriate. Now although monthly rests were adopted in Grimaldi, there is no universal rule requiring such a rest to be employed. I note that yearly rests were awarded in Hagan v Waterhouse (1991) 34 NSWLR 308 at 393 per Kearney J, Bullhead Pty Ltd v Brickmakers Place Pty Ltd (in liq) [No 2] (2019) 58 VR 129 at [53(5)] per Kyrou, McLeish and Hargrave JJA, Thomas v SMP (International) Pty Ltd (No 6) [2010] NSWSC 1311 at [24] per Pembroke J and Fang v Sun (No 2) [2014] NSWSC 1194 at [14] per Slattery J.

47 Accordingly, if compound interest were awarded, Mr Meneses says that the use of yearly rests is a more appropriate measure on which the calculation should be made.

48 But ultimately, Mr Meneses submits that an award of simple interest appropriately balances the need to ensure that a defaulting fiduciary does not receive a profit against the need to ensure that an award of interest does not act as a punishment.

49 Now I will make an order for compound interest against Mr Meneses. His breach of fiduciary duty was fraudulent and dishonest. But in my view, a better approximation in the present circumstances is to use yearly rests rather than monthly rests. I am not here dealing with a clear case of wrongfully retained property or direct loss of profits. And I do not have direct evidence of any loss of use claim justifying monthly rests. So, the parties will need to calculate the correct figures using yearly rests.

50 Let me now say something about the position concerning the Hanhwa parties.

51 The Hanhwa parties say that interest ought to be payable as simple interest and not compounding interest.

52 They say that any suggestion that my findings as to the making out of the claim for secret commissions were findings as to further aggravating factors is not correct. They say that the relevant passages referred to by Directed were findings setting out the foundation for the establishment of the more basal fact of liability.

53 Further, they say that Directed’s reference to the relevant arrangements being in place for a very long period of time with respect to the Hanhwa parties’ predecessors is also misguided given that I accepted that liability could not be sheeted home to any of the Hanhwa parties in respect of payments made by Nan-Skin Min and/or Hanhwa Enterprise. I agree, and have put this to one side as any justification for an award of compound interest.

54 Further, they say that Grimaldi can be distinguished as against the Hanhwa parties, since none of them were themselves fiduciaries of Directed or the alter ego/nominee of a fiduciary. The relevant passages cited by Directed only concerned the applicable interest to be applied when making an award against a fiduciary. Now that may be correct, but in my view it is not a sufficient answer to justify not awarding compound interest.

55 It is also pointed out that the Full Court in Grimaldi (at [550]) quoted Lord Hatherley LC’s observations in Burdick at 241 and 242 regarding the appropriateness or otherwise of compound interest for money paid into the common account of a firm of solicitors, but in the case before me I distinguished between the presumptive rule applicable to fiduciaries on the one hand, and knowing assistants on the other hand. Now that is true, but again it is not a complete answer.

56 Further, it is pointed out that ultimately, citing Grimaldi, I was not persuaded that Directed had established the necessary causal connection against the Hanhwa parties as knowing participants/assistants to satisfy the relevant evidentiary threshold burden (at [1513] to [1516]). But all of that was dealing with a slightly different point. I am not here dealing directly with the ascertained disgorging of profits as a relevant basis.

57 And related to this last point, it is said that Directed’s basing of its submission as to compound interest by reference to and reliance upon the Hanhwa parties’ profits, including as to periodic rests, appears to be an attempt to revisit its rejected trial submissions to the effect that Hanhwa Korea ought to be liable to disgorge all of its profits of supply to Directed between 2012 and 2018. I agree and have put this to one side as a relevant basis.

58 Moreover, Directed’s reference to [1454] to [1456] of my principal reasons is also misconceived. I went on to reject the argument as to the disgorgement of all of Hanhwa Korea’s profits between 2012 and 2018.

59 Now accepting that there is merit in some of the Hanhwa parties’ points, they are not sufficient to convince me that I should not make an award of compound interest. Given their knowledge and participation in Mr Meneses’ breaches of fiduciary duty, it is appropriate that they also pay compound interest with yearly rests. They facilitated indeed made the secret commission payments. They incentivised Mr Meneses to engage in the relevant wrongful conduct. I will so order the compounding of interest payable by the Hanhwa parties.

Conclusion

60 The parties should bring in minutes of orders to accord with these reasons.

I certify that the preceding sixty (60) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate:

VID 1157 of 2017 | |

LEEMAN AUS PTY LTD ACN 621 821 190 | |

Fifth Respondent: | HANHWA HIGHTECH CO., LTD |

Sixth Respondent: | JOHNNY MENESES |

Seventh Respondent: | CRAIG MILLS |

Eighth Respondent: | KICHANG (RYAN) LEE |

Ninth Respondent: | NATHAN MENESES |

Tenth Respondent: | GRIDTRAQ AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 154 515 394 |

Eleventh Respondent: | WEBHOUSE SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS PTY LTD ACN 152 567 416 |

Twelfth Respondent: | LEEMAN CO. LTD |

Thirteenth Respondent: | QUANTAM TELEMATICS PTY LTD ACN 159 485 051 |