Federal Court of Australia

Girchow Enterprises Pty Ltd v Ultimate Franchising Group Pty Ltd (Final Hearing) [2023] FCA 420

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to agreeing by 4.00pm on 11 May 2023 orders:

(a) giving effect to these reasons; and

(b) with respect to costs.

2. The proceedings be listed at 9.00am on 12 May 2023 for resolution of any dispute as to appropriate orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

INTRODUCTION

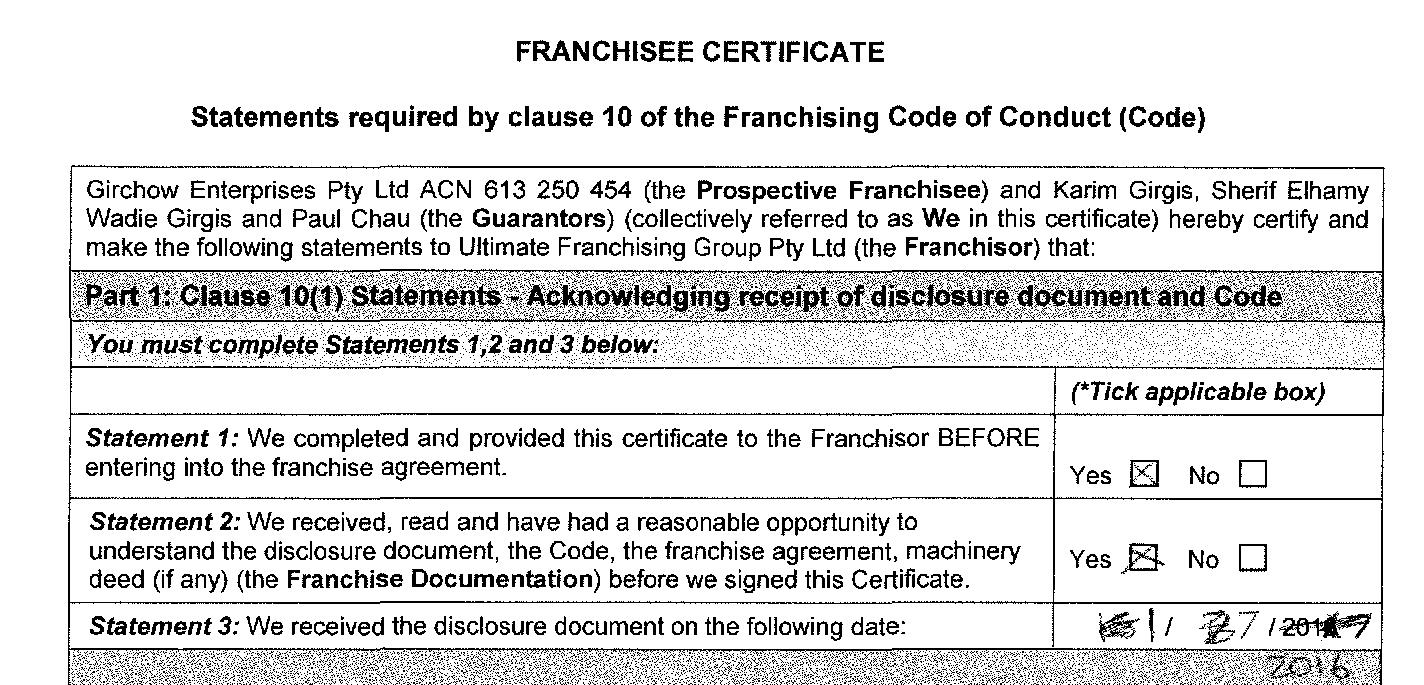

1 This proceeding concerns three Ultimate Fighting Championship Gym franchises, owned and operated by three unrelated companies. The franchises are referred to as the “Balcatta Franchise”, the “Blacktown Franchise” and the “Castle Hill Franchise”.

2 The first respondent, Ultimate Franchising Group Pty Ltd (UFG), is the Australian franchisor of the UFC Gym franchise, operating under a “Master Territory Agreement” with the Master Franchisor in the United States of America (USA), UG Franchise Operations LLC.

3 The franchisees and the relevant individuals behind them are as follows:

Balcatta Franchise: Girchow Enterprises Pty Ltd, the first applicant. Its director is the second applicant, Mr Karim Girgis. Interests in Girchow are also held by Mr Sherif Girgis and Mr Paul Chau, the third and fourth applicants. Mr K Girgis and Mr S Girgis are brothers. Each of the three individuals gave a guarantee to UFG guaranteeing the obligations of the Balcatta Franchisee under the Balcatta franchising agreement.

Blacktown Franchise: Activ Health Clubs Pty Ltd, the fifth applicant. Its director is the sixth applicant, Mr Richard Kim. The shareholders in Activ were Mr Kim and Mr Thi Ahn Tuyet Le, the sixth and seventh applicants. Mr Kim and Mr Le each gave a guarantee to UFG guaranteeing the obligations of the Blacktown Franchisee. Mr Le was removed as a party to the proceeding by a consent order made on 11 March 2021.

Castle Hill Franchise: Advanced Club Management Pty Ltd (ACM), the eighth applicant. Its sole director and shareholder is the ninth applicant, Mr Laziz Mirdjonov. Mr Mirdjonov gave a guarantee to UFG guaranteeing the obligations of the Castle Hill Franchisee under the Castle Hill franchising agreement.

4 The second and third respondents are Mr Mazen (Maz) Hagemrad and Mr Samer (Sam) Husseini, the directors of UFG at all relevant times.

5 The applicants claim that they were induced to enter into the franchise agreements and guarantees by conduct which was misleading or deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). The majority of the conduct complained of is constituted by representations alleged to have been made by UFG through Mr Hagemrad.

6 After opening the respective franchises, the franchisees discussed with each other their respective experiences. These proceedings were commenced after the applicants raised their concerns with UFG, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini. Although there is only one set of proceedings, as a matter of substance there are three distinct cases.

7 The parties agreed that the pleadings gave rise to 20 issues, covering four topics:

(a) Liability: Issues 1 to 7;

(b) Loss, damage and relief: Issues 8 to 13;

(c) MSA fees: Issues 14 to 17;

(d) Cross-Claim: Issues 18 to 20.

8 The applicants’ claim relating to MSA fees was abandoned in closing submissions. The cross-claim issues only arise if the applicants are unsuccessful in having the franchise agreements set aside.

9 For the reasons which follow, each of the franchise agreements and guarantees should be set aside and each corporate applicant is entitled to damages under s 236 of the ACL for losses sustained because of the respondents’ contravention of s 18 of the ACL. Issues 14 to 20 therefore do not arise. The structure of these reasons is:

first, to set out briefly the central legal principles relevant to liability;

secondly, to say something about the central witnesses;

thirdly, to make some brief comments about the affidavit evidence;

fourthly, to address liability in relation to each franchise, namely Issues 1 to 7;

finally, to address loss, damage and relief, namely Issues 8 to 13.

RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

10 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

11 Section 236(1) of the ACL provides:

(1) If:

(a) a person (the claimant) suffers loss or damage because of the conduct of another person; and

(b) the conduct contravened a provision of Chapter 2 or 3;

the claimant may recover the amount of the loss or damage by action against that other person, or against any person involved in the contravention.

12 In order to determine whether s 18 has been contravened it is necessary first to identify what constitutes the alleged infringing conduct: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [32]. Section 18 focusses on “conduct” not representations as such. The two are not co-extensive: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; 218 CLR 592 at [102]-[103]; Campbell at [102]. Where the contravening conduct involves representations, it is necessary to determine whether the representations were conveyed by the conduct as a whole, assessed in context. It is not sufficient to focus solely on particular conversations or parts of conversations, or particular documents or parts of documents, or particular written communications in a series of communications. A line in a document, or a statement during a conversation, must be assessed in the context of the whole document or conversation, and in the context of all of the events, including what was done and not done and what was said or not said: Butcher at [39], [109].

13 In a case like the present, where the applicants claim that they entered into agreements and gave guarantees because they were misled by various misrepresentations, it is necessary to examine everything that the respondents did and did not do up to the point in time that the franchise agreements and guarantees were entered into. As McHugh J stated in Butcher at [109], “[t]he effect of any relevant statements or actions or any silence or inaction occurring in the context of a single course of conduct must be deduced from the whole of course of conduct”. Something which was misleading when stated early during the relevant events might be corrected by later conduct or cease to have any causative effect.

14 The main representations relied upon as constituting conduct which contravened s 18 were representations with respect to future matters. In this regard, s 4 of the ACL provides:

4 Misleading representations with respect to future matters

(1) If:

(a) a person makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act); and

(b) the person does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation;

the representation is taken, for the purposes of this Schedule, to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made with respect to a future matter by:

(a) a party to the proceeding; or

(b) any other person;

the party or other person is taken not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation, unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the person who made the representation is taken to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the person who made the representation had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

(4) Subsection (1) does not limit by implication the meaning of a reference in this Schedule to:

(a) a misleading representation; or

(b) a representation that is misleading in a material particular; or

(c) conduct that is misleading or is likely or liable to mislead;

and, in particular, does not imply that a representation that a person makes with respect to any future matter is not misleading merely because the person has reasonable grounds for making the representation.

15 The critical elements of the operation of s 4 to the present case may be stated as follows:

a representation about a future matter will be deemed to be misleading or deceptive unless the respondent had reasonable grounds to make the representation;

the respondent will be deemed not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation unless the respondent adduces “evidence to the contrary”;

if the respondent does adduce “evidence to the contrary”, then the applicant bears the legal onus of establishing that the respondent did not have reasonable grounds for making the representation.

16 Section 4 of the ACL focusses attention on whether a person in fact had reasonable grounds for making a representation with respect to a future matter, not simply on whether there were reasonable grounds for making a representation. One way of articulating one of the intended effects of s 4 is to say that it “require[s] the representor to identify the facts or circumstances (if any) actually relied upon before turning it over to the trier of fact to decide whether they were objectively reasonable and whether they support the representation made” – see: Bathurst Regional Council v Local Government Financial Services Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 1200 at [2827(c)] (Jagot J), adopting the language of Mason P in City of Botany Bay Council v Jazabas Pty Ltd [2001] NSWCA 94; ATPR 46-210 at [85] (albeit concerning different statutory provisions); see also: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Ltd [2019] FCA 1039 at [117] – [131] (Mortimer J) (not relevantly affected on appeal).

17 The applicants referred to Sykes v Reserve Bank of Australia (1998) 88 FCR 511 at 513, also referred to by Mason P in Jazabas, and Mortimer J in Woolworths, in which Heerey J stated:

If there was a representation as to a future matter, s 51A [of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)] requires the representor to show:

• some facts or circumstances

• existing at the time of the representation

• on which the representor in fact relied

• which are objectively reasonable and

• which support the representation made.

18 The deeming in s 4(2) is only avoided by adducing “evidence to the contrary”; the evidentiary burden created by s 4(2) is not discharged simply by putting forward some evidence relevant to the topic: McGrath v Australian Naturalcare Products Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 2; 165 FCR 230 at [191] (Allsop J). The deeming in s 4(2) cannot be avoided, for example, merely by adducing some evidence which is relevant to the objective existence of reasonable grounds.

19 It is for the Court to evaluate whether the evidence adduced is sufficient to constitute “evidence to the contrary”: McGrath at [192]. Whether evidence adduced on the topic is sufficient to constitute “evidence to the contrary” should be evaluated having regard to the evident statutory object of requiring the party or person making the representation to adduce evidence of the actual grounds that the person had for making the representation.

20 Section 139B of the CCA provides for the attribution to the company of states of mind and conduct of directors, employees or agents of the company.

THE WITNESSES

The UFG witnesses

Mr Hagemrad

21 Mr Hagemrad was a director of UFG from 22 June 2016 until 10 December 2018. He has a Masters of Business Administration (Exec) from the University of New South Wales, a Bachelor of Applied Science (Physiotherapy) from the University of Sydney and a Masters of Science (Sports Physiotherapy) from the University of Sydney.

22 Mr Hagemrad approached the UFC Gym Master Franchisor in 2013 enquiring about the UFC Gym brand’s future international expansion. Over the next two and a half years he negotiated for the right to use the UFC Gym brand in Australia. During that time, he approached Mr Husseini whom he had known for over 20 years and Mr Jim Dimas whom he had known professionally for almost 15 years.

23 In about July 2015, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini travelled to the US for the final stages of the negotiations with the UFC Gym Master Franchisor. On 21 July 2015, UFG was registered and in September 2015 the Master Territory Agreement was signed.

24 I did not find Mr Hagemrad to be a reliable or credible witness. He could not recall a number of events which occurred. Where he could recall events, his recollection was often poor. His evidence was often in the form of argument. His evidence and credibility is discussed further below.

Mr Samer Husseini

25 Mr Husseini was not as deeply involved in the relevant events as Mr Hagemrad. He readily conceded that his recollection of events in which he was involved was not good. Mr Husseini was cross-examined only briefly.

Mr Jason Laurence

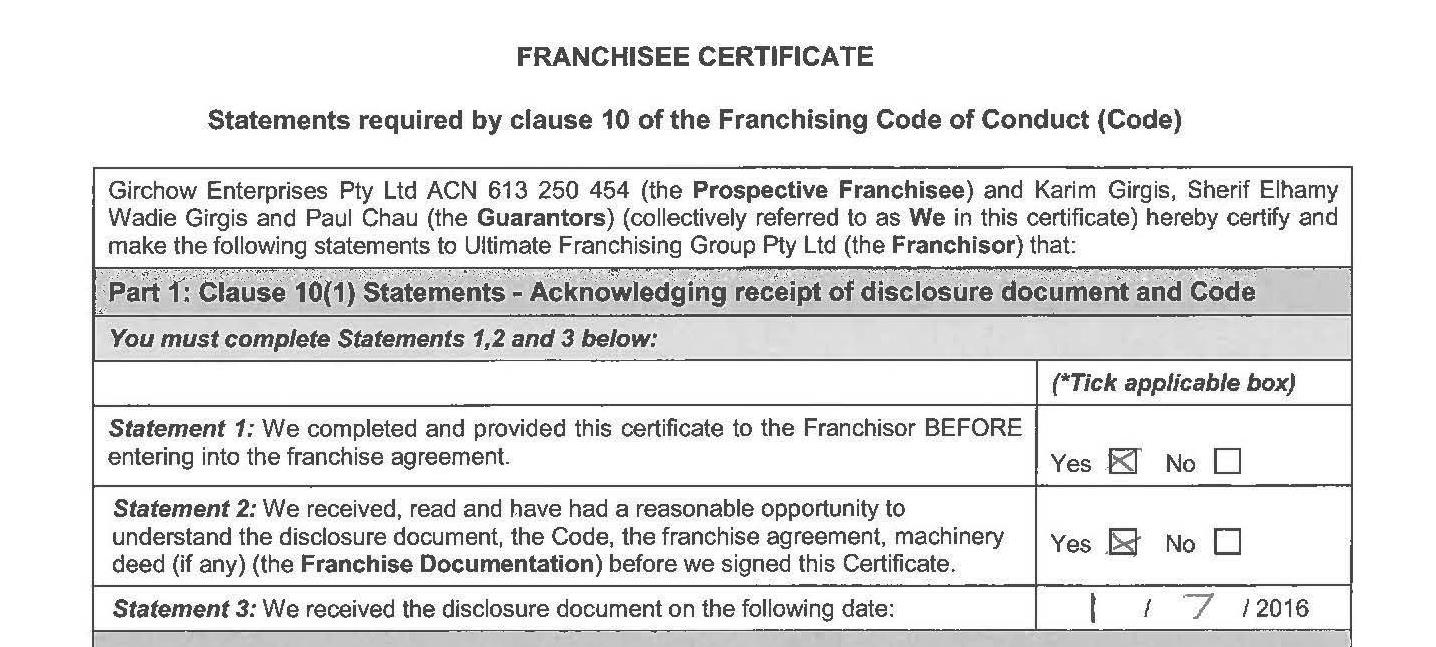

26 Through his business, 2020 Business Consultancy, Mr Laurence was an independent contractor working for UFG as franchise operations manager until August 2020. He appears to have first met Mr Hagemrad in person on 22 February 2016: Exhibit 20. Mr Hagemrad signed a consultancy agreement between UFG and 2020 Business Consultancy on 20 May 2016. It is not clear when Mr Laurence executed the agreement. The consultancy agreement stated that it was to commence on 1 July 2016 or a later date to be agreed between the parties. Mr Laurence’s evidence was that he commenced in October 2016.

27 Mr Laurence gave oral evidence in chief about his 20 year career in the fitness industry. T438: Mr Laurence was employed in various roles by Healthland Fitness International, Fitness First Australia and Goodlife Health Clubs Australia between 1999 and 2006. He was employed by Healthland as a sales consultant, then a sales manager at the Bondi Junction club and then as a cluster manager where he oversaw the operations of 3 clubs in Queensland. The Healthland clubs ranged from 2000 to 4000 square metres in size. He was employed by Fitness First as regional manager overseeing the operations of 11 gyms in Queensland which ranged from 1400 to 3500 square metres in size. Mr Laurence was employed by Goodlife as its national sales and marketing manager. He was involved in the operations of 37 gyms which ranged from 1000 to 10,000 square metres in size. He was involved in acquiring equipment and establishing clubs, including during a “pre-sale” phase before opening.

28 In 2006 Mr Laurence founded his own consultancy practice “2020 Business Consultancy”, which became his full time focus in 2008. Mr Laurence’s consultancy involved working with health club owners and national fitness chain clients. Mr Laurence has been engaged by nine “full-time” clients with over 20 gym facilities ranging from 500 to 6000 square metres and up to 6000 members.

29 Mr Laurence gave his evidence in a straightforward way without any obvious exaggeration.

Balcatta Franchise

Mr Karim Girgis

30 By the time of the relevant events in 2016, Mr K Girgis had experience in sales, exercise rehabilitation, property investment, share trading and businesses which included gym businesses . In 2012, Mr K Girgis opened a Jetts 24 Hour Fitness franchise with Mr S Girgis in Cannington, a suburb in Perth. The relevant franchise agreement was signed in 2011. A fit-out of premises was required but this was arranged by the franchisor, albeit Mr K Girgis had some limited involvement. Mr K Girgis resigned as a director in February 2014. Mr S Girgis continued as a director and the Jetts business was shut down in 2020.

31 Later, Mr K Girgis opened three F45 Functional Training studios, initially under licence, but later converted to franchises: T86.28. These were in the Perth suburbs of Claremont, Duncraig and Applecross. The Claremont studio opened in October 2014 and was owned by Mr K Girgis alone. It needed minor fit-out work and the purchase of some equipment. The studio in Duncraig was previously a gym and did not require much fit-out: T63.25. This was owned with Mr Chau and opened in October 2015, as was the studio in Applecross, which also required minor fit-out: T64.4.

32 Mr K Girgis agreed that each of these businesses grew and that he could see what kind of factors influenced growth, including management of the business, competition within the vicinity of the business and marketing or promotional activities: T64. His evidence explained some of the differences between the F45 gym concept and the Jetts gym concept.

33 I found Mr K Girgis to be a credible witness. He gave concessions readily when appropriate. He was careful to give accurate evidence. His evidence was given in a straightforward manner, without exaggeration.

Mr Sherif Girgis

34 Mr S Girgis obtained a Bachelor of Commerce from Curtin University. He was a trainee valuer with CBRE from February 2005 until December 2007. He was a pub owner from March 2008 to August 2012. He was a café owner and operator from December 2010 to December 2014.

35 As mentioned, Mr S Girgis held an interest with his brother, Mr K Girgis in the Jetts 24 Hour Fitness franchise in Cannington from about 2011. Mr S Girgis was not initially involved in the operations of the Jetts gym, although he signed a franchise agreement. Mr S Girgis was not involved much in the fit-out of the premises. Mr S Girgis became involved in the operation of the Jetts business when Mr K Girgis moved on to be involved in other businesses. The Jetts business was shut down “during Covid”.

36 I found Mr S Girgis to be generally credible.

Mr Paul Chau

37 Mr Chau described his background in a letter attached to an email sent on 9 June 2016. The letter included:

… I have completed a Bachelor of Economics degree, majoring in finance banking, and international business at the University of Western Australia ... Apart from banking specific training I have taken my education further and completed my MBA with the Graduate School of Management at the University of WA.

I was previously employed with the National Australia Bank for the past six years and from these roles, and my education, I have gained valuable experience in the corporate and business banking sectors. Duties that I have undertaken include sales and cross selling, building customer relationships, financial and credit analysis, and understanding all aspects of a business banking team.

Since 2009 I decided to utilise the skills that I have acquired through my education and employment in the finance sector and move into business for myself in a field which I am passionate about. It was at that time that I saw a unique opportunity with the Jetts Fitness Franchise which offers a 24hr, no contracts gym facility and recognised that it was the next big thing in the fitness industry. I opened my first Jetts in 2010 and to date have opened 5 more all of which have been highly profitable. More recently I recognised the market was again shifting to functional training and decided to move into that niche by joining the F45 Training franchise. In 2015 I opened two F 45 studios with my business partner and they are performing as forecasted. I believe that building successful and highly profitable business’s has been due to my ability to identify niches in the industry before the high growth phase before profits are normalised through entry by competition and from there strategically growing the business to ensure the brand is well established as the number one player in the market before our competitors do. I also pride myself on running a business and making sure we are the best at what we do …

38 Also attached to the 9 June 2016 email was a curriculum vitae which showed that Mr Chau completed a Bachelor of Economics, majoring in finance, banking and international business in 2002. He completed a Masters of Business Administration in 2008. His experience included working as a gym assistant from March 2008 to June 2010, where his responsibilities included day to day operations, managing memberships and marketing and accounting.

39 Mr Chau worked for the National Australia Bank Ltd (NAB) from 2001 to 2008. He started as a Customer Service Officer and later held positions as a Business Banking Assistant and an Analyst. His position as an Analyst involved analysing financial information and credit submissions, devising strategies on high risk lends and building relationships with clients. From April 2006 to February 2008, Mr Chau held the position of Senior Business Banker & Relieving Manager. His responsibilities included analysing financial information, preparing credit submissions and managing portfolios up to $60 million, that is, lending to clients amounts of up to $60 million each: T237. He agreed that he was accustomed to dealing with loan agreements, mortgage and other security documents and guarantees: T237.

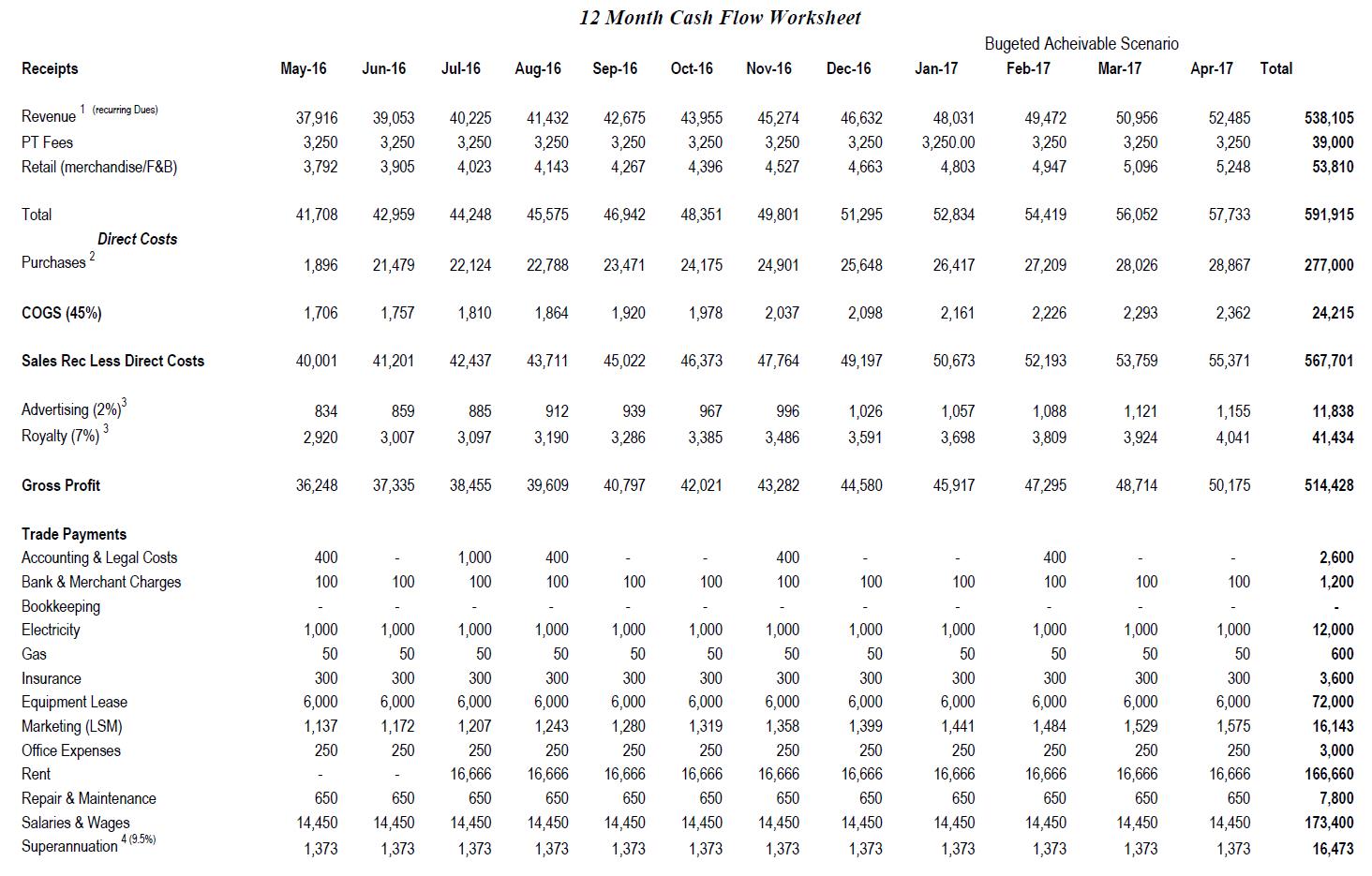

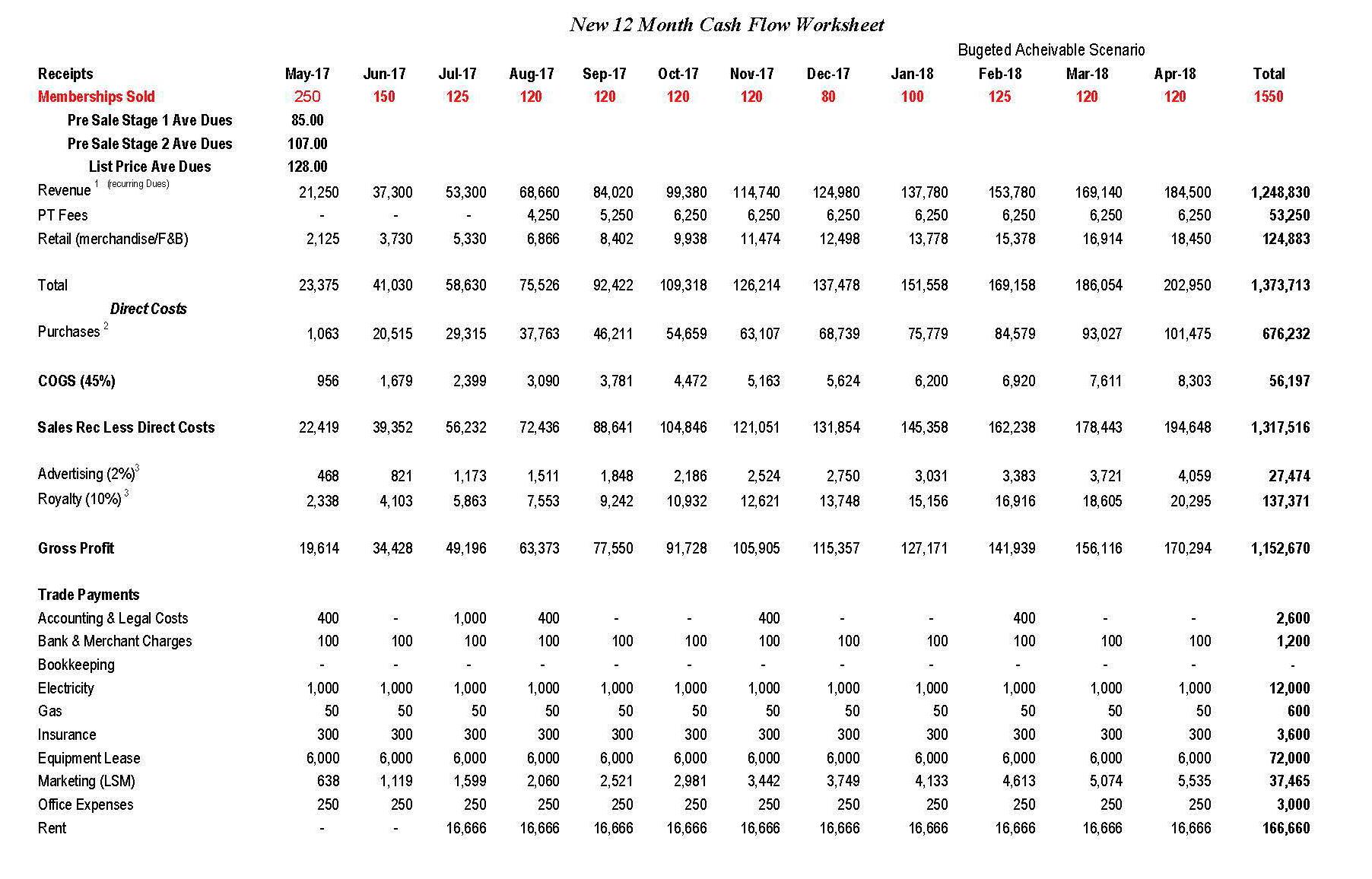

40 Mr Chau gave evidence in cross-examination that he signed a franchise agreement in relation to the Jetts gym he opened in 2010: T238. He was the sole owner of the business. He was involved in the operation of the business at times: T238.37.

41 He then opened another five Jetts 24 Hour Fitness franchises: T239. At the time of the relevant events in 2016, Mr Chau had opened six Jetts businesses in the Perth suburbs of Forrestfield, Morley, Innaloo, Dianella, Yokine and Bassendean. Each facility ranged from 300 to 400 square metres in size: T244. Each of them had a membership in excess of 1000 at some point in time between when the relevant business opened and 2016: T244. Mr Chau signed franchise agreements in relation to each of those businesses. Each of the businesses except Bassendean was run by a corporate entity of which Mr Chau was a director: T243. He signed the financial statements for at least some of the businesses. These financial statements indicated the expenses incurred in the start-up phases of the businesses: T244.

42 Mr Chau thought he had ceased his involvement with each of them, with the possible exception of Innaloo, by mid 2016, but could not be sure: T245. He ceased his involvement by selling his shares to his business partners or back to the franchisor: T240.

43 Consistently with Mr K Girgis’s evidence, Mr Chau stated that he opened two F45 studios in 2015 with Mr K Girgis: T246. They were in Applecross and Duncraig, in Perth. Both were about 150 square metres in size. Both were operated through a corporate vehicle of which Mr Chau was a director. Mr Chau signed the financial statements. The membership of each was possibly around 200 to 300. Mr Chau continued to hold an interest in these gyms in 2016: T247.

44 In 2016, Mr Chau, Mr S Girgis and Mr K Girgis sent a Draft Business Plan to UFG. Mr Chau was cross-examined in relation to the comment made in it that he had “vast” experience in the fitness industry. He gave the following evidence at T248:

From your involvement with those gyms, you were able to observe what factors could affect the size of a membership at the start of the business; correct?---Correct.

I should also ask this, Mr Chau: in addition to being a director of the companies which ran these gyms, you were also a shareholder; correct?---Yes, correct.

You were able to observe how the size of the membership of the gym grew over the first 12 months of operation; correct?---Correct.

You were able to observe how things such as marketing or promotional activities could affect the growth of the membership; correct?---Correct.

You were able to observe any patterns with the cancellation of membership over time?---Correct.

45 I considered Mr Chau to be credible and his evidence to be generally reliable.

Blacktown Franchise

Mr Richard Kim

46 Mr Kim is a physiotherapist by profession. From about 2012, Mr Kim owned and operated “a multi-location allied health company”, which operated from 8 locations, employed 20 staff and generated between $1.5 and $2 million per year. The business was run through a corporate entity of which he was a director and a shareholder.

47 Mr Kim was an impressive witness. He answered each question directly and honestly without any tendency to distort an answer in his own interest. I accept his evidence without reservation.

Castle Hill Franchise

Mr Laziz Mirjdonov

48 Mr Mirdjonov has two bachelor degrees. One was described as “Management in Information Technologies” obtained in Australia in 2006. The other is a degree in law, obtained in Russia in 1999. He practised criminal law in Uzbekistan for about a year after he completed his degree: T312, 356.

49 Mr Mirdjonov was the sole owner of a gym business founded in 2015, Spectrum Fitness Australia. The business was held by a corporate entity of which Mr Mirdjonov was the director and sole shareholder. It was not a franchise. The premises needed to be fitted-out which involved building work being carried out and equipment being acquired. It was about 350 square metres in size with a membership of around 300.

50 The reliability of Mr Mirdjonov’s evidence varied, although I generally preferred his recollection of events over Mr Hagemrad’s recollection.

THE EVIDENCE

51 The witness evidence was largely given by affidavit. There are two aspect of the affidavit evidence which warrant mention.

52 First, the affidavits contained numerous accounts of conversations, often in direct speech. It is fair to say that attention was not given to the sorts of considerations recently emphasised by Jackman J in Kane’s Hire Pty Ltd v Anderson Aviation Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 381 at [123] to [129]. Further, some of the accounts of conversations contained in the affidavits may have been affected by the matter referred to next.

53 The applicants’ affidavit evidence on reliance was criticised by the respondents as being “rudimentary, formulaic and given by each of them in identical, or almost identical, terms”. It is the reliance on affidavit evidence in identical or almost identical terms which is the second matter which warrants mention.

54 Mr K Girgis’s first affidavit dated 29 September 2020 contained the following (text in strikethrough was not read):

22 … I read the disclosure document in particular, and I noted:

(a) the knowledge and experience of Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini regarding the UFC Gym franchise operations at item 3.1; and

(b) the establishment costs at Table 1 of Schedule 5.

…

32 In deciding to enter into the Balcatta franchise agreement and agreeing to be a guarantor, I relied on:

(a) the cashflow forecasts regarding the future income of the franchise; and

(b) the forecast start-up and fit-out costs provided by Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini, as set out above in this affidavit.

33 Had I known the actual startup costs would be much larger that the forecasts (as they were in fact), or the income project[ion]s would not be realised, I would not have agreed to the Balcatta Franchisee becoming a franchisee, and I would not have agreed to be a guarantor of the franchise business.

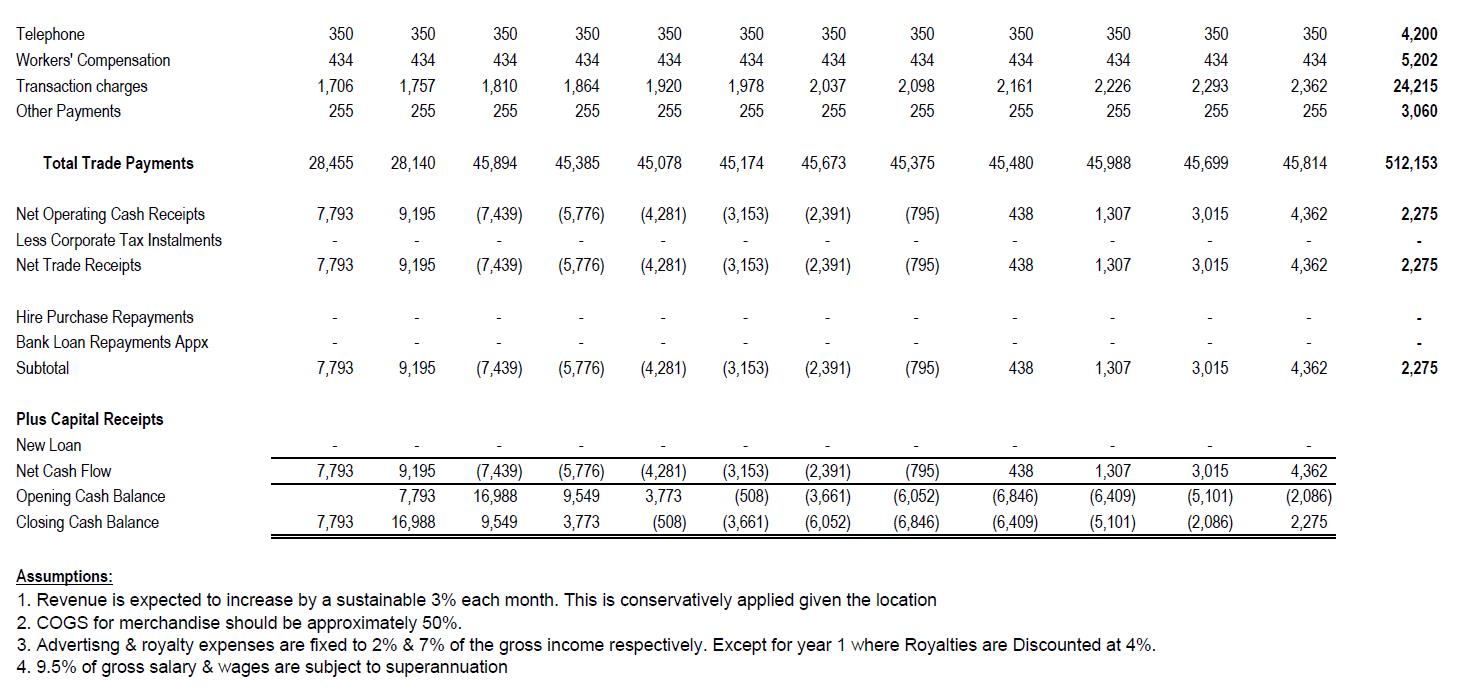

55 Mr S Girgis’s first affidavit dated 29 September 2020 contained the following:

12 At the time I read this disclosure document in particular, and I read about:

(a) the knowledge and experience of Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini regarding the UFC Gym franchise operations at item 3 .1; and

(b) the establishment costs at Table 1 of Schedule 5.

…

21 In deciding to enter into the Balcatta franchise agreement and agreeing to be a guarantor, I relied on:

(a) the cashflow forecasts regarding the future income of the franchise ; and

(b) the forecast start-up and fit-out costs provided by Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini, as set out above in this affidavit.

22 Had I known that the actual income would not grow as projected, or had I known the actual startup costs would be much larger than the forecasts (as they were in fact), or that the income project[ion]s were unreliable, I would not have agreed to the Balcatta Franchisee becoming a franchisee, and I would not have agreed to be a guarantor of the franchise business.

56 Mr Chau’s first affidavit dated 29 September 2020 contained the following:

28 At the time I read the disclosure document in particular, and in particular I read about:

(a) the knowledge and experience of Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini regarding the UFC Gym franchise operations at item 3.1; and

(b) the establishment costs for the gym (Table 1 of Schedule 5).

…

36 In deciding to enter into the Balcatta franchise agreement and agreeing to be a guarantor of that franchise, I relied on:

(a) the cashflow forecasts regarding the future income of the franchise; and

(b) the forecast start-up and fit-out costs provided by Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini, as set out above in this affidavit.

37 Had I known the actual startup costs would be much larger than the forecasts (as they were in fact), or that the income would not be as represented, I would not have agreed to the Balcatta Franchisee becoming a franchisee, and I would not have agreed to be a guarantor of the franchise business.

57 Mr K Girgis – who was the first witness to give evidence – was cross-examined extensively on the similarities between the affidavit.

58 The thrust of the cross-examination was that Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau had discussed their evidence and affidavits and the similarities were not purely coincidental. Mr K Girgis was challenged on other similarities in the affidavit evidence, including similarities in some accounts of conversations. Again, the thrust of the cross-examination was that he had discussed his evidence with Mr Chau and Mr S Girgis.

59 It was not put to Mr K Girgis that he discussed his evidence with Mr Kim or Mr Mirdjonov. Mr Kim’s affidavit contained the following:

22 I read the disclosure document and in particular I relied on:

(a) the knowledge and experience of Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini regarding the UFC Gym franchise operations at item 3.1; and

(b) the establishment costs at Table 1 of Schedule 5.

…

25 In deciding to enter into the Blacktown franchise agreement and agreeing to be a guarantor, I relied on:

(a) the cashflow forecasts regarding the future income of the franchise; and

(b) the forecast start-up and fit-out costs provided by Maz Hagemrad and the disclosure document, as set out above.

26 Had I known the actual startup costs would be much larger than the forecasts (as they were in fact), or the income project[ion]s would not be realised, I would not have agreed to the Blacktown Franchisee becoming a franchisee, and I would not have agreed to be a guarantor of the franchise business.

60 Mr Mirdjonov’s affidavit contained the following:

17 I read the disclosure document in particular, and from that document, what important to me was:

(a) the knowledge and experience of Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini regarding the UFC Gym franchise operations at item 3.1; and

(b) the startup costs at Table 1 of Schedule 5.

…

21 In deciding to enter into the Castle Hill franchise agreement and agreeing to be a guarantor, I relied on:

(a) the cashflow forecasts regarding the future income of the franchise; and

(b) the forecast start-up and fit-out costs as set out above in this affidavit.

22 Had I known the actual startup costs would be much larger that the forecasts or that the income project[ion]s would not be realised, I would not have agreed to the Castle Hill Franchisee becoming a franchisee, and I would not have agreed to be a guarantor of the franchise business. …

61 The reason the affidavits are all similar in the respects identified is because of the way in which the affidavits were prepared. I infer that the passages extracted above were “cut” and “pasted” between affidavits, before being altered in minor ways. The inference is compelling for many reasons, including the misspelling of the word “projects” rather than “projections”. These were not the only passages which appear to have been prepared in that way.

62 The consequence of what has occurred is that the affidavit evidence about reliance is called into question. It seems unlikely, for example, that each of the witnesses independently instructed that they read the relevant disclosure document and, when reading it, they each particularly noted: (a) the explanations of the experience of Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini in cl 3.1; and (b) Table 1 of Schedule 5, but apparently not Tables 2 and 3.

63 A further consequence of what has occurred is that witnesses were exposed to an attack on credibility which might have found favour if what had occurred was not so obvious, particularly once regard was had to the affidavits in the Blacktown and Castle Hill cases.

64 The drafting of affidavits in this way has a number of other negative consequences, including making it more difficult, and sometimes impossible, to give serious weight to the evidence. When the evidence is on a topic which must necessarily be established, such as reliance, the consequences could be fatal to the case being advanced.

65 Further, an affidavit must reflect a witness’s evidence, not the evidence which the legal practitioner would prefer to see in light of the case which the legal practitioner has pleaded or wishes to run. A legal practitioner must not suggest to a witness what the witness’s evidence should be. The placing of material in an affidavit which is not based on what the witness has instructed and is taken from a different witness’s affidavit – such as an account of events or a statement about what a person relied upon – amounts, in substance, to a suggestion about what the witness should say.

66 Where it appears that parts of affidavits have been copied from other affidavits, doubt is cast on the integrity of the whole process by which the affidavits have been prepared. This inevitably affects the assessment of the reliability of the whole affidavit. The problem is particularly acute where evidence of conversations appears to have been drafted in this way. It suggests a lack of attention on the part of the drafter of the affidavit to accurately recording the deponent’s actual recollection of what was said, or the gist of what was said, and risks causing a deponent to swear or affirm the truth of something outside his or her knowledge.

67 Similar issues were raised by Derrington J in Tour Squad Pty Ltd v Fifth Amendment Entertainment Inc (No 2) [2021] FCA 546; 151 ACSR 607 at [127]. The issue is important. The preparation of unambiguous, accurate and truthful affidavits is central to the fact finding process. The drafting of affidavits by a process of copying other witnesses’ affidavits might save time for the drafter of the affidavit at the time, but it results in increased risk to the witness and client, increased cost and delay overall and, potentially, professional conduct issues. It certainly impedes the efficient and effective determination of disputes by the Court.

68 It is in part to take proper account of the two matters raised in this section of these reasons that I have set out below lengthy extracts from the affidavits, together with the contemporaneous documents.

LIABILITY: BALCATTA FRANCHISE

Factual Background

69 After the Master Territory Agreement was signed, UFG set up a website and invited anyone who might be interested in learning about becoming a franchise owner of a UFC Gym in Australia to register.

70 On 7 January 2016, Mr Hagemrad arranged for invitations for a presentation to be held at Hyatt Regency Hotel in Perth on 19 January 2016 to be sent by email to all those who had registered on the website.

19 January 2016: Hyatt presentation

71 The Hyatt presentation proceeded on 19 January 2016. Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau attended. Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini were present. At the time, no UFC Gyms were operating in Australia. The formal part of the presentation was given by Mr Hagemrad by reference to PowerPoint slides which he prepared from slides given to him by the UFC Gym Master Franchisor. He edited some of the slides to reflect the Australian market as he knew it at that time.

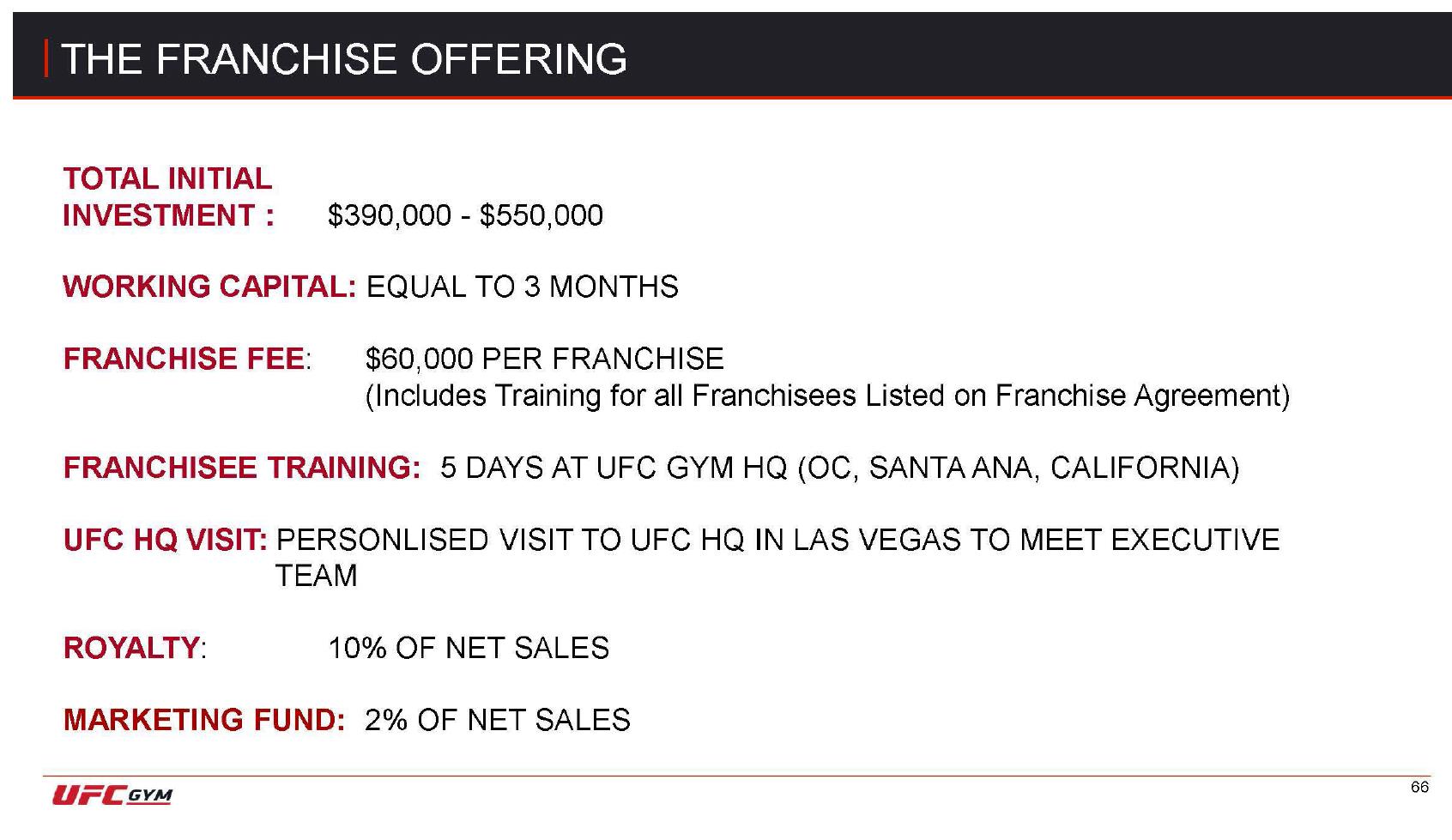

72 Slide 66 was headed “The Franchise Offering”:

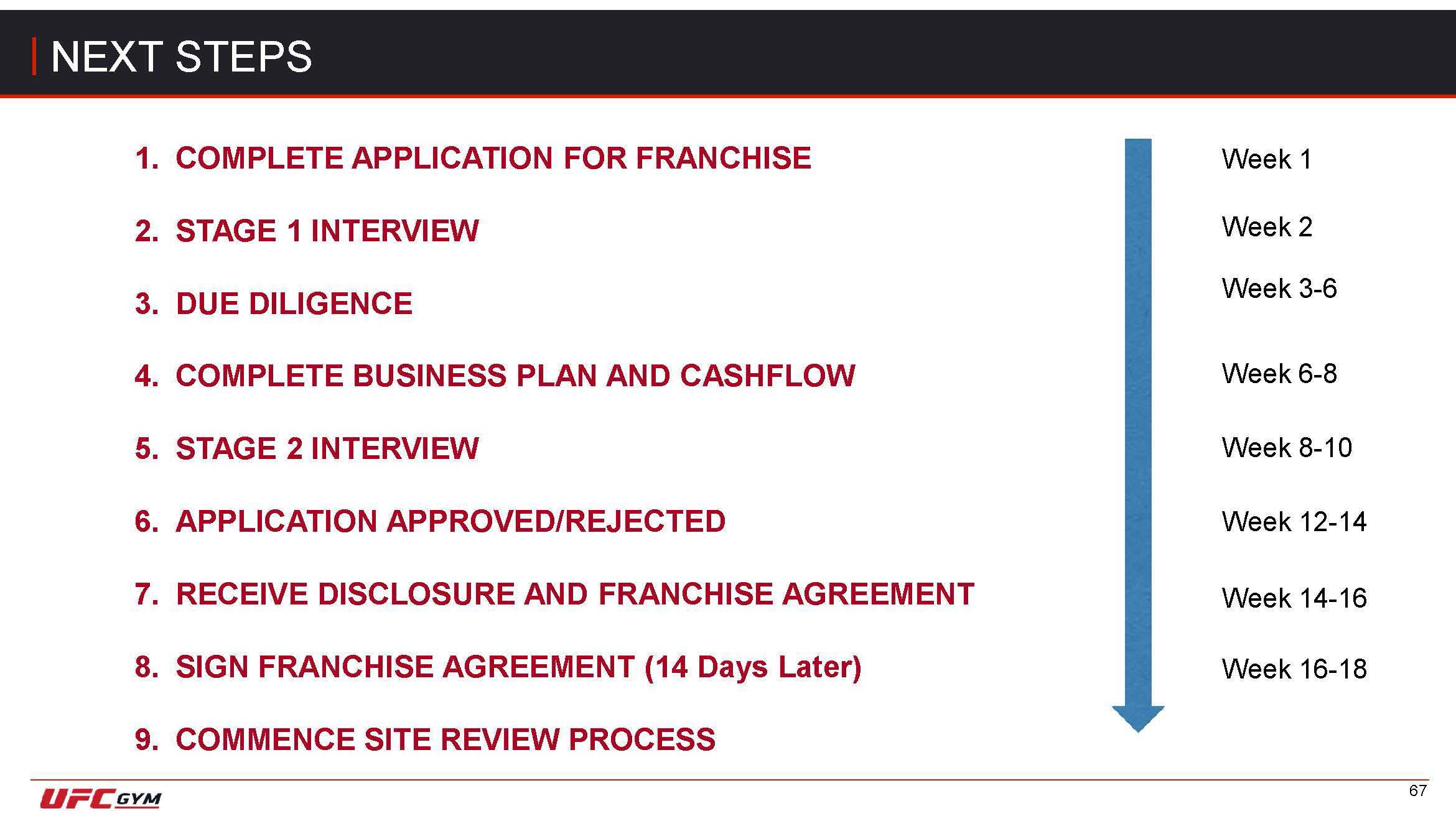

73 Slide 67 was entitled “Next Steps” and set out a time line for the various stages of an application:

74 Mr K Girgis gave evidence that the presentation was given mostly by Mr Hagemrad, with Mr Husseini occasionally commenting. He stated that there was a question and answers session after the presentation. Mr K Girgis’s first affidavit included:

10 During the presentation Maz [Hagemrad] said words to the effect that:

(a) franchises for UFC Gym would be able to be established for startup costs in the range of $500,000 to $800,000;

(b) the projected figures of $500,000 to $800,000 would be inclusive of all equipment and fit-out costs, franchise fees, training and working capital.

75 Mr S Girgis’s first affidavit included:

7 During the presentation Maz said words to the effect:

(a) franchises for UFC Gym would be able to be established for startup costs in the range of $500 ,000 to $800,000;

(b) the estimate of $500,000 to $800,000 was inclusive of all equipment and fitout costs, with the fitout being about $250,000 to $300,000 and $200,000 to $250,000 depending on the fitout costs.

8 In answer to questions from Karim [Girgis], Maz said words to the effect:

(a) they would need to check with US head office as to the brand of equipment;

(b) the weekly membership cost was $30 per week;

(c) the maximum space was about 1000 square metres;

(d) there would be about 8 to 12 personal trainers and coaches.

76 Mr Hagemrad denied making a representation as set out in [10(a)] of Mr K Girgis’s affidavit and [7(a)] of Mr S Girgis’s affidavit.

77 Mr K Girgis’s first affidavit also included:

11 In the question and answer session, I asked the following questions, which were answered by Maz or Sam [Husseini]:

Karim: How much is the fitout expense?

Maz: About $250,000 to $300,000 depending on club size.

Karim: What about the equipment costs?

Maz: About $200,000 to $250,000.

Karim: What brand of equipment will be used, because this seems relatively cheap compared to my previous experience with Jetts Fitness?

Sam: Ahh, not 100% sure. We will confirm that with the US head office.

Karim: The total startup costs of opening a Jetts club of around 300 square metres is about $500,000, so the costs seems a bit low to me. Do you think this is accurate?

Maz: Considering the size variance of 800 square metres to 1200 square metres, the franchise fee and working capital, a club over 1000 square metres would be most likely to be anywhere from $500,000 to $800,000.

Karim: What is the weekly membership cost?

Maz: About $30 per week.

Karim: What is the maximum number of members a club can have?

Maz: We generally go by 1 member per 1 square metre of space, so 1000 square metres is 1000 members.

Karim: How many staff are required? And the wage expense?

Maz: Full-timers are 1 General Manager, 2 sales, 1 reception manager and another 3 or 4 casual receptionists.

Karim: How many trainers are required? PT’s and MMA coaches?

Maz: 8 to 12 total.

78 Mr Chau’s first affidavit stated the following about the meeting:

7 The presenters at the Hyatt on behalf of the franchisor were Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini. The presentations included slides. Afterwards there were questions and answers, during which Karim asked some questions answered by Maz and Sam. I did not ask any questions of relevance.

8 Karim asked Maz and Sam questions about:

(a) the size of the gym and number of members - we were told it depends, but the ideal size is about 1 member for 1 sqm;

(b) the costs of the fitout - about $250,000 to $300,000

(c) the cost of the equipment - about $200,000 to $250,000

(d) the brand of the equipment - they did not know the answer to this question;

(e) numbers of staff; and

(f) membership charges - $30 / week.

9 During the presentation Maz Hagemrad said that the investment would be $390,000 to $550,000 plus 3 months working capital and a $60,000 franchise fee, plus the costs of training in the United States.

10 In the questions afterwards, Karim asked Maz further about costs. Maz said that there was a variance in costs for clubs between 800 to 1200 sqm, and with a franchise fee and working capital, a club over 1000 sqm would be likely to be between $500,000 to $800,00[0]. He said that this figure included equipment and fit-out costs.

79 Mr Hagemrad stated that he could not recall being asked questions by Mr K Girgis, but could recall general discussion by those in the room. He denied stating that the maximum space was 1000 square metres, this being inconsistent with slide 55. He also denied stating that he would need to check with US head office about the brand of equipment, as they had “full autonomy in Australia to select equipment manufacturers”. Mr Hagemrad’s first affidavit included:

12 I do not recall being asked a question about costs of the “fit out” or “the equipment” and I deny that I gave the figures referred to in paragraph 8 of the Chau affidavit and paragraph 7 of the Sherif affidavit. The only figures I referred to during the Perth presentation were those set out in my slides. I do not recall being asked any question by Karim Girgis, or anyone else, which referred to a “Jetts club” or any other gymnasium business.

80 Mr Husseini’s first affidavit included:

8 I refer to paragraph 8 of the Sherif affidavit and paragraph 11 of the Karim affidavit. Maz made the presentation on his own and I did not speak during it. At the end of the presentation there was a time for questions from the attendees. I joined Maz for the question time. I recall Karim asked a question about the equipment cost and I said words to the effect "the equipment will be on an operating lease but we have not yet selected an equipment supplier." I deny that I said we need to check with the US head office, as the US head office had nothing to do with which equipment company we chose. This was the only question I recall answering. I deny any question was asked by Karim about "fit out expense". I do not recall being asked any question by Karim Girgis, which referred to a "Jetts club", or any other gymnasium business.

81 It was put to Mr Chau in cross-examination that the only thing Mr Husseini said at the Hyatt presentation was: “The equipment will be on an operating lease, but we have not yet selected an equipment supplier”. Mr Chau responded: “No, I don’t – I don’t know. I don’t remember what he said”.

82 In cross-examination, Mr Husseini accepted that UFG had not decided what brand of equipment to use: T563. He accepted that his recollection of the event was not good. He did recall Mr K Girgis asking about equipment costs: T563.4.

83 I do not accept that Mr Husseini said that the equipment would be on an operating lease. There was no contemporaneous document which suggested that, as the time, it was contemplated recommending that equipment should be leased. If Mr Husseini had said what he claimed, the relevant cost would have been discussed and the cost would have been provided for in the cash flows which were prepared in June 2016. The cash flows which were prepared contained no provision for hire purchases or equipment “leases” in the nature of hire purchases.

10 February 2016: Cash Flow Template

84 In early February 2016, Mr Chau had a telephone conversation with Mr Husseini in which Mr Husseini said that he wanted to discuss the opportunity with UFG. Mr Chau stated that they – Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau – needed further information in particular regarding the projected cash flow. Mr Husseini stated that that he would send a cash flow template.

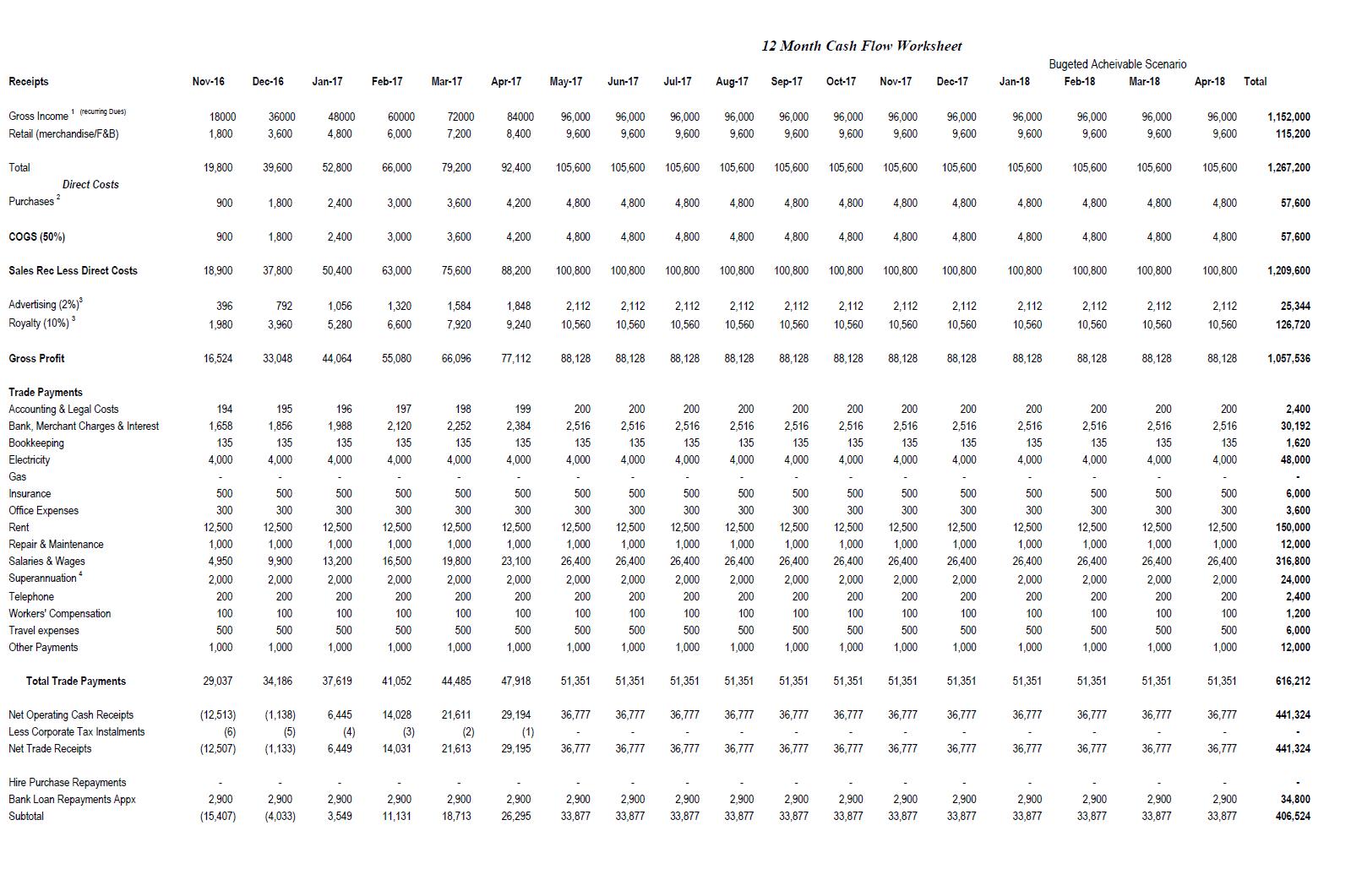

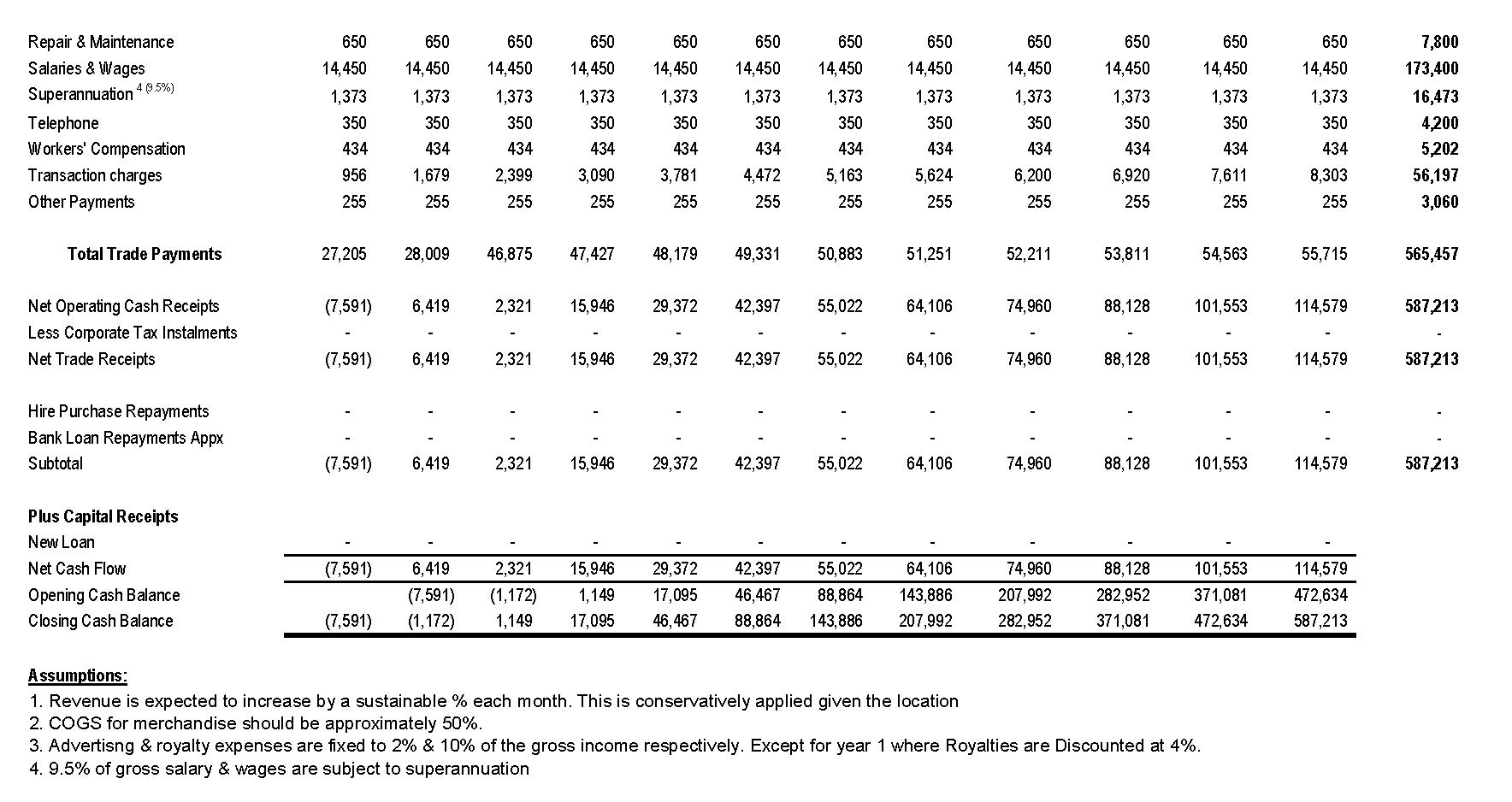

85 Mr Husseini sent an email to Mr Chau on 10 February 2016 attaching a template for a 12-month cash flow (Cash Flow Template). It was an excel worksheet. It contained formulas for the cost of goods sold (50%) and for advertising (2%) and royalties (10%). The template contained excel instructions to add the monthly numbers to provide a yearly total. At the end, it stated:

Assumptions:

1. Gross income is expected to increase by a sustainable 3% each month. This is conservatively applied given the location

2. COGS for merchandise should be approximately 50%.

3. Advertis[i]ng & royalty expenses are fixed to 2% & 10% of the gross income respectively.

4. 9.5% of gross salary & wages are subject to superannuation

86 The Cash Flow Template did not contain amounts for any item of income or expense.

31 March 2016: First Disclosure Document

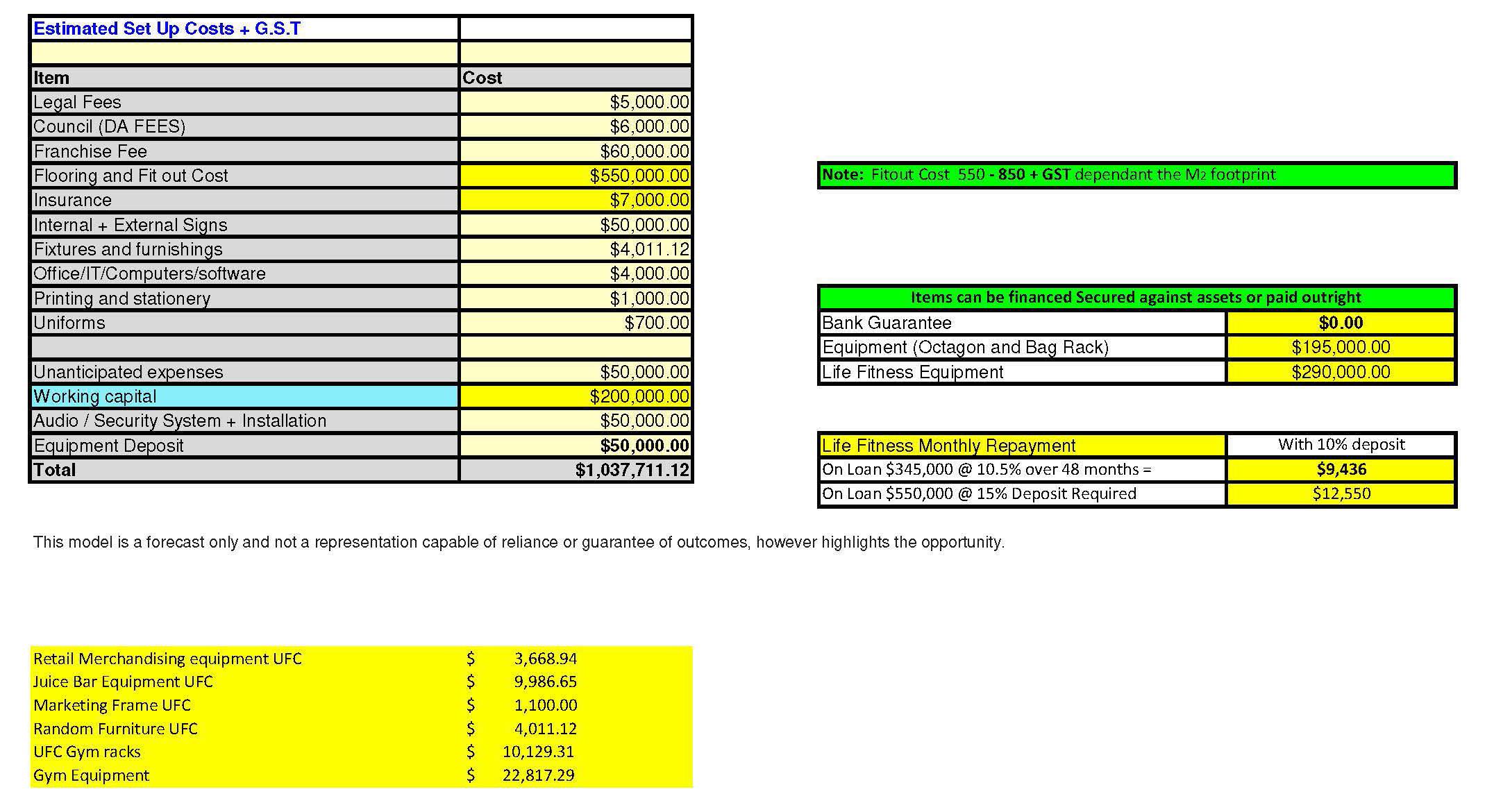

87 The First Disclosure Document (defined below) was dated 31 March 2016. It was not sent to Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau at this time. It was signed by Mr Husseini, but prepared by Mr Hagemrad. Tables 1 to 3 of Schedule 5 are set out at [159] to [161] below. At this point, it is relevant to note that Table 1 of Schedule 5 of the First Disclosure Document which addressed “Establishment Costs” referred to the “lease or purchase of equipment” in the range $250,000 to $350,000 and to “building, construction and fitout costs” in the range “$190,000 to $360,000 (approx 300 psm)”. Table 1 also referred to other expenditure as part of “Establishment Costs” including working capital of $35,000 to $65,000 and travel expenses for training of between $20,000 to $30,000.

88 In the First Disclosure Document, Mr Hagemrad referred in cl 3.1 to his significant experience as a Subway franchisee. Clause 4.1 required disclosure of proceedings against a franchisor director if those proceedings involved (amongst other things) an allegation of a contravention of trade practices law or misconduct. One point of such a clause is to enable prospective franchisees to make an informed decision about whether or not the franchisor and its directors and associates are the kinds of people with which the franchisee wishes to have an ongoing commercial relationship of trust and confidence.

89 The First Disclosure Document, which Mr Hagemrad prepared, answered “Not Applicable” to cl 4.1.

90 In fact, as at 31 March 2016, Mr Hagemrad was a respondent in proceedings in this Court brought by Mr Shah in which Mr Shah alleged that Mr Hagemrad and one Mr Allouche fraudulently inflated the sales figures for a Subway franchise in Haymarket before offering it for sale. The case was run as a s 18 ACL claim but it was “founded on the proposition that Mr Hagemrad and Mr Allouche deliberately and dishonestly created fake sales that were included in sales records upon which they knew prospective purchasers would rely”: Shah v Hagemrad [2018] FCA 91 at [2]. Ultimately, Nicholas J rejected as false Mr Hagemrad’s evidence that the Haymarket franchise was profitable: at [94]. His Honour concluded that Mr Hagemrad knew of the fake sales and that those sales were “created” in order falsely to inflate sales figures so that a better price for the Haymarket franchise could be obtained when it came to be sold: at [101].

91 Of course, the judgment in those proceedings is not admissible in these proceedings as evidence of the existence of facts in issue in those proceedings.

92 What is important for present purposes is that Mr Hagemrad knew he was required to make a disclosure of the litigation in the First Disclosure Document and, indeed, in each of the disclosure documents given in relation to each of the three franchises the subject of this litigation. He did not. His failure to do so reflects poorly on his credit.

13 April 2016: Skype meeting

93 A Skype meeting was held on 13 April 2016 between Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis, Mr Chau, Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini. In his first affidavit, Mr K Girgis stated:

14 During this Skype meeting Maz said words to the effect:

(a) a UFC Gym franchise would be able to be established for startup costs in the range of $500,000 to $800,000;

(b) the range of startup costs was based on the size of the premises, with larger premises being at the higher end of the range.

15 We also discussed the application process, including having to provide personal financials and business experience, the variety of classes offered. Staff responsibilities, martial arts coaches, which was forecast as $50 per hour rates, insurance costs and travel expenses, training in the US.

16 Maz said in particular words to the effect, “Martial arts coaches fees are essentially covered by the PT rent so you don’t really have to pay for martial arts coaches”.

94 Mr S Girgis did not give evidence about this meeting.

95 In his first affidavit, Mr Chau stated:

On 13 April 2016 we had an initial Skype meeting with Karim, Sherif and myself on Skype with Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini. During this Skype meeting Maz said again that a UFC Gym franchise would be able to be established for startup costs in the range of $500,000 to $800,000. He said that this range of startup costs was based on the size of the gym, with larger gyms being at the higher end of the range.

96 Mr K Girgis and Mr Chau were both cross-examined on the similarities between their affidavits in this respect.

97 In his first affidavit, Mr Hagemrad stated:

During that video conference I agree that I said words to the effect “the start-up costs are likely to be between $500,000 and $800,000”. By that time, I had obtained more information about potential set-up costs for a UFC Gym. I also said words to the effect “The setup costs will vary depending on the site size, location and age of the premises, and a range of other variables”. I deny I said words to the effect “Martial arts coaches fees are essentially covered by the PT rent so you don’t really have to pay for Martial arts coaches”. The call was to discuss their franchise application, not detailed specifics about business operations.

98 In cross-examination in relation to the Skype meeting on 13 April 2016, Mr K Girgis stated that he understood Mr Hagemrad to be predicting the actual costs, or making a statement about what the actual costs would be, rather than expressing his existing opinion as to the likely costs. Mr K Girgis confirmed that he had an actual recollection of what was said by Mr Hagemrad in this regard: T131-3.

99 Mr Chau accepted that he could not remember word for word what was said during the Skype meeting: T295.20. His evidence at 295 included:

Was the wording in paragraph 19 of your affidavit provided to you by your lawyers?---I believe they would have, yes, done some – whatever to it.

What Mr Hagemrad said at this conference was words to the effect of that the start-up costs are likely to be between $500,000 and $800,000. Do you accept that that is a more correct version of what Mr Hagemrad said?---I do not recall the exact words, so I – I can’t say.

Would it be fair to say that you do not specifically recall the words “would be” being used?---That’s fair.

100 In cross-examination, Mr Hagemrad stated that he had a recollection of the meeting, but not the specifics: T473.20. He recalled mentioning the amounts of $500,000 and $800,000.

101 After the Skype meeting on 13 April 2016, Mr Hagemrad sent an email to Mr Chau, copied to Mr K Girgis and Mr S Girgis, which attached a “New Application Form” and a “Business Plan Template”. The Business Plan Template required the prospective franchisee to insert a variety of information, including information about the proposed management of the business and a “SWOT” analysis.

16 May 2016: Email from Life Fitness

102 On 16 May 2016, Mr Aaron Oman, the Commercial Accounts Manager of Life Fitness sent an email to Mr Hagemrad and Mr Dimas. He attached a concept floor plan for a gym of 850 square metres and an “equipment proposal” for the concept. The equipment proposal provided two quotes. The difference in quotes related to whether the “Discover SE” or “Integrity” line of Life Fitness products was chosen. The total cost of Life Fitness and Hammer Strength equipment if the “Integrity” line were chosen was $269,971.35, including GST of $24,542.85. The total cost of Life Fitness and Hammer Strength equipment if the “Discover SE” line were chosen was $315,159.35, including GST of $28,650.85. Both quotes included a “lease” option over a 48 month term ($6,440.34 and $7,470.58 per month respectively).

103 The email included the following at the end:

Lastly and most importantly, we would like to meet and discuss the first NSW site. I have spoken with Paul and we would like to work with you on the initial facility in Western Sydney, as a preferred supplier. Whilst we are unable to provide the products to you at no charge, we are interested in supplying them at our cost, with no margin added.

We feel that the facility is going to be a key site for you and we have no doubt that Life Fitness and Hammer Strength products, will improve your exposure in this region. We already supply a number of large western Sydney facilities and the majority of attendees are familiar with our brand and quality of product.

In addition to the discounted pricing, we would also look to offer you a discounted rate of internal finance, to assist the group in your infancy. By financing with Fitness Equipment Finance, your capital expenditure will not be tied up with equipment, keeping funds free for your initial growth.

I believe you have your eye on a couple of sites at the moment, that may be suitable. If this is the case, we would like to prepare a proposed layout and equipment proposal based on the proposed location.

104 On 18 May 2016, Mr Chau emailed Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini stating that he, Mr K Girgis and Mr S Girgis were completing the cash flow.

9 June 2016: Draft Business Plan and Draft Cash Flow

105 On 9 June 2016, Mr Chau sent an email to Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini attaching a completed Draft Business Plan, a completed draft 12-month cash flow worksheet (Draft Cash Flow) and resumes and other information about Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau. Mr Chau’s email asked the recipients to have a look at the attachments so that they could be discussed before they were submitted.

106 The Draft Business Plan identified the management team as Mr S Girgis, Mr K Girgis and Mr Chau. It attached resumes and other information for each. These are addressed below. It described the roles of the management team in the following way:

Sherif Girgis - Managing Director

Sherif will be the main operator of the business and be the director who will be the business full time.

Amber Chia - Assistant Manager/ trainer

Amber who is Sherif’s partner will assist in running the business and is also a qualified trainer

Karim Girgis - Support and Training

Karim is a very experienced trainer and experienced business owner and will provide support to Sherif and Amber

Paul Chau - Financial and business management

Paul has vast experience in the fitness industry as a business owner and also in finance and management and will assist in all aspects of the business including strategy and marketing

In addition to the key stakeholders above we plan on recruiting an experienced General Manager to operate the business.

107 The Draft Business Plan contained a SWOT analysis. The Draft Business Plan contained a section entitled “Strategies” which addressed various matters including goals. One of the goals was achieving breakeven membership numbers within 6 months of operation and “capacity membership” within 12 months of operation.

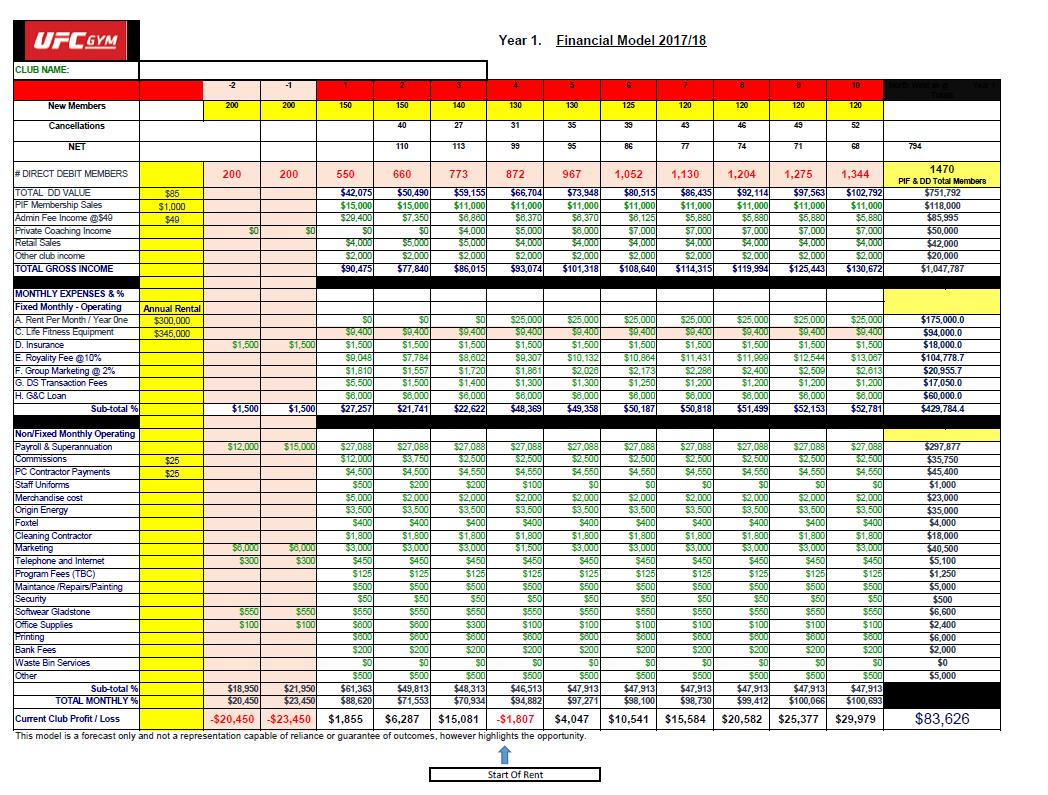

108 The Draft Cash Flow was prepared primarily by Mr Chau from the Cash Flow Template. It covered the period May 2017 to April 2018. It forecast $96,000 in gross income per month. This was based on 800 members paying $30 per week, yielding $1,152,000 in gross income over the 12 month period. The Draft Cash Flow contained an expense for interest at $1,458 per month, totalling $17,496 for the year. The Draft Cash Flow also contained a row for “Hire Purchase Repayments”. This row contained no expense.

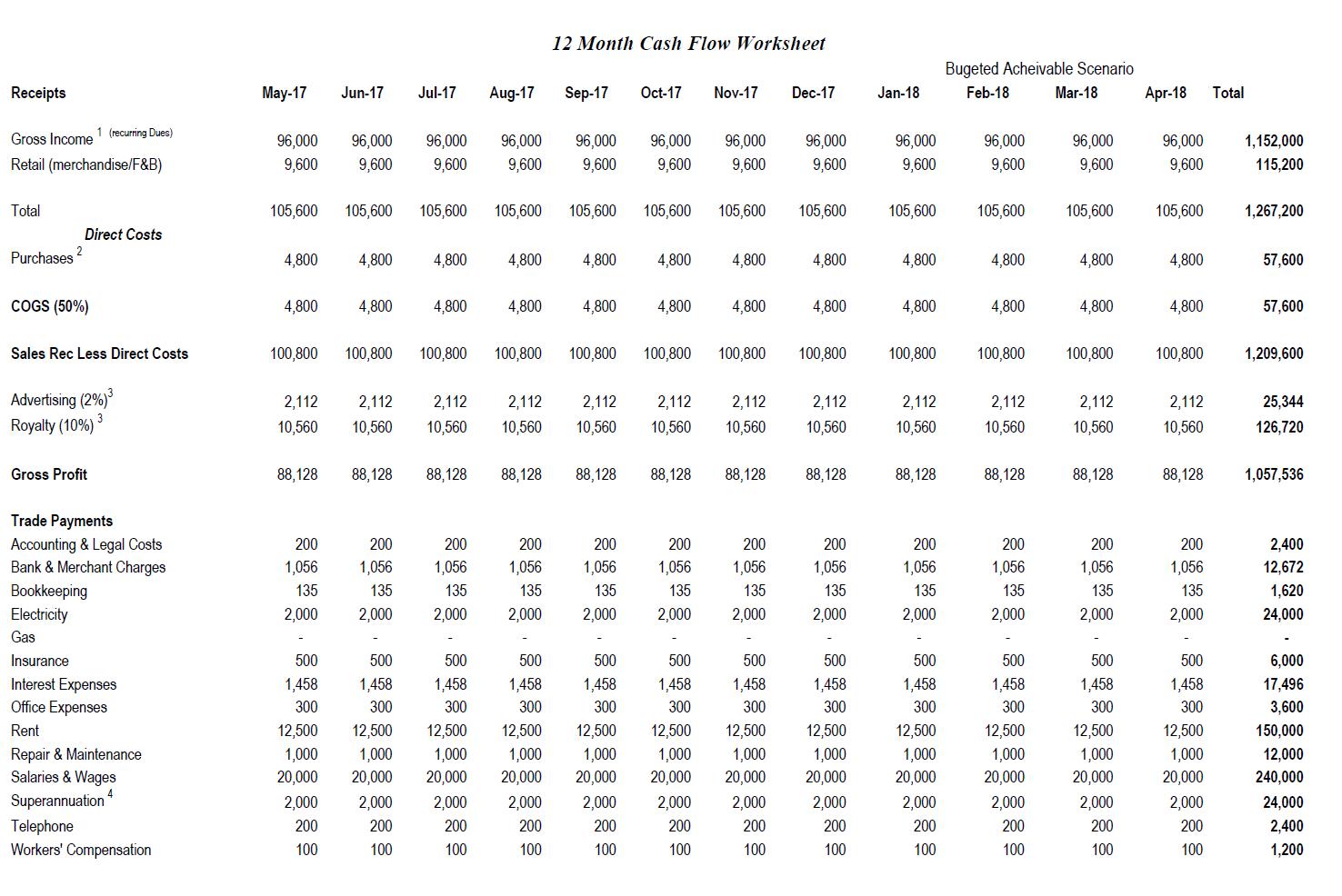

109 The Draft Cash Flow was as follows:

110 Consistently with what is indicated at the end of the Draft Cash Flow, Mr Chau stated that the interest expense was calculated on a borrowing of half of the start-up costs ($250,000), which was stated in the Draft Cash Flow to total $500,000: T233. As to “gross income”, he stated at T233:

[W]e got the information that we should, like, work on one person per square metre capacity and it’s always – we were always under the impression that we would be operating a 1000 square metre facility and that the weekly dues would be $30 a week; that information, we got from Maz. Also speaking to Maz, he recommended that we use an 80 per cent capacity as an achievable, I guess, result within the first 12 months, so I plugged that in, put the formula in, and that’s how we came up with that figure.

111 Mr Chau was cross-examined about [17] of his affidavit, in which he had stated that 80% capacity had come from the Hyatt presentation and later emails. Mr Chau accepted that the information was not contained in any email communication before 9 June 2016: T265.13 He accepted that it was not mentioned as having been something discussed at the Hyatt presentation on 19 January 2016: T265.29.

112 Mr Chau gave evidence that the information came from a conversation between Mr Chau and Mr Hagemrad. His evidence included:

Are you able to identify specifically – are you able to identify more specifically when Mr Hagemrad – when you say Mr Hagemrad said this to you?---It was on a call, but I can’t recall the exact date.

Was anyone else involved in that call?---I don’t think so.

You accept that you make no mention of this in your first affidavit. Correct?---Correct.

And do you also accept that you make no mention of it in your second affidavit. Correct?---Correct.

…

The truth of the matter, Mr Chau, is this. You sitting here now, in the witness box, you have no recollection of Mr Hagemrad saying to you anything about 80 per cent capacity or 800 members when you prepared the cashflow document send on 9 June 2016. That’s the case, isn’t it?---I recall him advising us that that would be an achievable target for the first 12 months. In terms of the cashflow, this is the first time I’ve received a blank template from all the previous franchises. They’ve given us a model and I complete it as best I could and then, with their guidance. So yes, he – he did say that.

…

And what I’m putting to you is, sitting here, giving evidence to his Honour, you have no real recollection of Mr Hagemrad having said to you seven years ago anything about 80 per cent capacity or 80 members when you prepared the cashflow document. That’s the case, isn’t it?---I do remember that. That’s where I got the figure from.

113 Mr Hagemrad accepted that he had stated that one could work with one person per square metre at some time between April and June 2016: T502, 503.

114 I think it likely that Mr Hagemrad mentioned the figure of one person per square metre before the meeting on 9 June 2016. I accept that this is why the figure was used by Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau in preparing their draft cash flow. Mr K Girgis thought it was as early as at the Hyatt presentation. I accept that Mr Hagemrad is likely either to have said to use an 80% capacity or to have agreed it was reasonable to use 80% in the Draft Cash Flow.

115 As to “retail trade”, Mr K Girgis stated:

[A]gain, through discussions with Maz, I believe there’s an email where I asked what is the, I guess, expected retail revenue, which he replied for conservativeness, use 10 per cent, so that’s how I came up with that figure.

116 He noted that the “COGS” (costs of goods sold) and “Advertising” and “Royalty” were prepopulated formulas. Interpolating, these were calculated automatically by the excel spreadsheet from the income inputs.

117 As to the various expenses, Mr Chau gave the following evidence in oral evidence before cross-examination:

“Accounting and Legal Costs”: I – I kind of knew how much I pay my accountant, so that’s how we came up with that figure. No legal costs were, I guess, included in that; it was all really accounting.

“Bank & Merchant Charges”: just from, I guess, experience in my past businesses, that was put in at one per cent.

“Bookkeeping”: again, I know how much I pay my bookkeeper.

“Electricity” and “Insurance”: was based on, you know, I’ve run facilities that are about 300 square metres and we – I looked at that and said, you know, this is x times larger, so that’s how I kind of came up with that figure. The same with insurance.

“Interest Expenses”: was calculated as a – at the bottom of that spreadsheet it states that we were always expecting to borrow 50 per cent of the start-up costs, which, at the time, we expected to be 500K, so 250K was the borrowing amount at the interest of [at] the time of approximately seven per cent over a seven-year term and that’s how I calculated that figure.

“Office Expenses”: Again, office was just based off what I had kind of known in the past and extrapolated that.

“Rent”: The rental amount came from Maz. He said based on, I think, warehouse or bulky goods at around $150 a square metre and that’s how we came up with that figure.

“Repairs and Maintenance”: again, just based on what I knew was expecting.

“Salaries & Wages”: again, came from – there’s an email between me and – between Maz and I about what to expect for staff. And at the bottom of the page, it was based on a full-time GM, a full-time fitness director, two sales consultants and some bonuses. So I – that’s how I calculated that figure.

“Superannuation”: Super is a percentage of wages, which is, you know, the standard.

“Telephone”, “Workers’ Compensation” and “Travel Expenses”: And then same with telephone, that was just based off what I knew was – I guess how much phone and internet was at that time. And same with Workers’ Comp and travel was based on, you know, having to travel to – travel to the US for training.

118 Mr K Girgis stated that 800 members was included in the Draft Cash Flow by him, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau on the basis that it represented 80% of an anticipated membership of 1000 for a 1000 square metre premises. Mr K Girgis accepted that the assumption underlying the model was that there would be 800 members from the first month of operations: T.73.30. Mr K Girgis accepted that he was relying on his experience and the experience of Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau in forecasting gross income: T.74.36. He stated, however, that he also relied on what Mr Hagemrad had said at the presentation on 19 January 2016 that the maximum number of members was 1 per square metre: T.74.7.

119 Mr K Girgis agreed that, at this time, he was aware that neither Mr Hagemrad nor Mr Husseini had operated a gym; that they were located in Sydney; and that there was no UFC gym yet operating in Australia: T.84.6.

120 Mr S Girgis gave evidence in cross-examination that Mr Chau was the “numbers guy”: T189.17; T190.6. He could not recall what input he had into the Draft Cash Flow, although accepted he would have had input: T190.

15 June 2016: Second Skype meeting

121 On 15 June 2016, Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau met with Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini on Skype. The Draft Cash Flow was discussed. The parties were in dispute as to what was said during the Skype conference.

122 In his first affidavit, Mr Chau stated:

23 On 15 June 2016 Karim, Sherif and I had a Skype meeting with Maz and Sam, during which we discussed the completed cash flow projections. We went through the figures in the cash flow spreadsheet.

24 Maz said that the figures were generally correct, but we needed to make some changes to the spreadsheet, including for rental cost at $150 sqm, and changing income projections to provide for a start-up phase which included a two-month “presale” period. Maz said that we should assume that members will increase at 150 new members initially and then 100 members per month going forward.

25 Following this Skype meeting I updated the cash flow spreadsheet given the changes required by Maz and on 17 June 2016 Sherif sent an updated version to Maz by email. …

123 Mr Chau was cross-examined about [24] and his statement that Mr Hagemrad told him to change the Draft Cash Flow to include rent at $150 per square metre. It was pointed out that the amount of $150 per square metre had been used in the Draft Cash Flow and was the same in the Updated Cash Flow provided on 17 June 2016 (defined below): T272-3. His evidence at T273-4 included:

You had allowed rent at $150 per square metre, Mr Chau, before you spoke to Mr Hagemrad on 15 June 2016, correct?---Yes, correct. That was based on the Hyatt.

Do you need to correct what you say in paragraph 24, about Mr Hagemrad telling you on 15 June 2016 to include rental cost at $150 per square metre?---No. He did say that. I’m assuming it was just confirming that it was correct.

Well, what you say in paragraph 24 of your affidavit is that Mr Hagemrad told you to include rent at $150 per square metre. That’s what you say in paragraph 24 of your affidavit, correct?---That’s correct. Yes.

By 15 June 2016 - - -?---I - - -

- - - you had already included rent - - -?---Yes.

- - - at $150 per square metre?---I believe he was – he was just reiterating that that was the correct figure.

Well, that’s not what you say in your affidavit, Mr Chau, is it?---Yes. It’s – I assume that’s – that’s what he meant.

Mr Chau, my question to you was in your affidavit, you said Mr Hagemrad told you to include rent at $150 per square metre. That’s what you say, isn’t it?---That’s correct. That’s what it says in the affidavit.

You’re now saying that he said something different, correct?---No. I’m not saying he said something different. The – he did say that the rent is at $150 per square metre on the call, so I assume he’s reiterating that that is the correct figure.

Mr Chau, you have no real recollection of this conversation, do you?---No, I do. I definitely do. Yes. That was - - -

In your affidavit, you say that Mr Hagemrad told you to include something in the cash flow document which you had already included. That’s the case, isn’t it?---He reiterated that it was $150 a square metre, or he said that it was 150 per square metre is what we should be anticipating.

124 The difficulty with Mr Chau’s evidence is that [24] of his affidavit states that Mr Hagemrad told him to change the amount of $150 per square metre. It is not reasonably read as stating that Mr Hagemrad reiterated the figure. There would be no reason for Mr Hagemrad to have done that.

125 In his first affidavit, Mr K Girgis stated:

17 On 15 June 2016 we had a second Skype meeting with Maz Hagemrad and Sam Husseini. During this meeting we discussed the business plan and the cash flow projections in detail.

18 During this meeting Maz and Sam said that the income projections should be adjusted for a pre-sale phase and then operations where I [sic] the pre-sale phase we should assume membership increasing 150 per month and then 100 per month.

19 After this Skype meeting, Paul updated the cash flow spreadsheet and this was sent to Maz on 17 June 2016, as set out in Paul’s affidavit.

126 During cross-examination, Mr K Girgis readily and appropriately conceded that the words “and Sam” should be deleted from [18] of his affidavit. He agreed that what had been said was said by Mr Hagemrad.

127 Mr Hagemrad’s affidavit evidence included:

18 I refer to paragraphs 17 and 18 of the Karim affidavit and paragraphs 23 and 24 of the Chau affidavit. A video conference was held via “Skype” with Paul, Karim and Sherif on 15 June 2016. During that video conference I deny I made any statement about the “figures” of the applicants or whether they were “correct”. I recall saying words to the effect “The business plan and cashflow are for the purpose of getting franchisee approval from the US. They will review your background experience, net worth, business plan detail and your understanding of a cashflow projection”. I deny I said to the applicants “you should assume that members will increase at 150 new members initially and then 100 members per month going forward”. I do not recall any discussion about anticipated membership growth in that meeting as at that time no UFC Gym had opened in Australia and those type of projections were something I would have deferred to Jason Laurence given his experience with opening new gyms … In relation to the [cashflow] spreadsheet, I do recall saying during the Skype call words to the effect “I think just inserting the same figures across all months of the cashflow would likely raise concerns with the US franchisor. It would show a lack of the basic understanding of building a business plan.” However, I did not suggest any specific figures for the cashflow spreadsheet.

128 In his second affidavit, Mr Chau stated:

9 As to paragraph 18 [of Mr Hagemrad’s affidavit], one of the purposes of the Skype call was to go through the business plan and cashflow that was to be submitted to the US. During the call Maz specifically said words to the effect that we should make changes including a ramp up of growth during pre-sales and after opening. I had no experience with a big box gym like UFC so I was relying on Maz to provide guidance as to the figures. Maz told us the presales figures we used in the cashflow spreadsheet.

129 In his reply affidavit, Mr K Girgis stated:

11 As to paragraph 18, both Maz and Sam said words to the effect that the figures were correct and in line with “their model”. Maz said words to the effect:

(a) both the cashflow and business plan needed to be accurate for them to be approved by the US and themselves (which I took to mean Maz, Sam, John and Jim);

(b) we should assume that the initial growth would be 150 members per month and then 100 members per month after that, he said that first year growth would be consistent because the members sign onto a 12-month contract;

(c) he would review the documents to be sent to the US for approval.

130 There was extensive cross-examination on the opening sentence of this paragraph. It was suggested that Mr K Girgis would have included the first sentence in his first affidavit if he truly had a recollection to the effect stated. Mr K Girgis agreed that he had read Mr Chau’s affidavit when making his reply affidavit. Mr Chau’s affidavit contained evidence to similar effect as the first sentence of [11] of Mr K Girgis’s reply affidavit.

131 In cross-examination, Mr Hagemrad denied going through the Draft Cash Flow line by line: T474.11. Mr Hagemrad stated he could not recall whether he said to Mr K Girgis, Mr S Girgis and Mr Chau that “the figures [were] generally correct”: T474.45. He thought he may have discussed a pre-sale period of about two months: T475.2. He also stated that “pre-sale at that point in time wasn’t part of my fitness knowledge” T474.20.

132 Mr Hagemrad accepted that he had stated that using the same figures across all months might raise concerns when the application came to being assessed by the Master Franchisor in the USA: T474.40. This might also be explained by the desire expressed in the Cash Flow Template’s Assumption 1 that “gross income is expected to increase by a sustainable 3% each month”.

133 In cross-examination, Mr Husseini first stated that the particular line items in the Draft Cash Flow were not discussed individually; they were discussed “holistically, not item by item”: T564.1. He then agreed that some line items were discussed but he could not remember which ones: T564.8.

134 On balance, I consider it unlikely that Mr Hagemrad stated that the figures were “correct”, in the sense of conveying that all of the figures in the cash flow worksheet were correct.

135 It was also suggested to Mr K Girgis in cross-examination that Mr Hagemrad had not stated to use 150 members per month initially and then 100 members. It was put to him, and he readily agreed, that there was no contemporaneous note to that effect.

136 In cross-examination, Mr Hagemrad denied that he recommended using 150 new members per month initially and then 100: T474.28; 474.34. Mr Hagemrad was cross-examined about his statement at [18] of his first affidavit that he would not have stated to use 150 members initially for reasons including that “those type of projections were something I would have deferred to Jason Laurence given his experience with opening new gyms”. Mr Laurence had not commenced his role with UFC at this time. As noted earlier, his contract provided for him to start on 1 July 2016 or later agreed and Mr Laurence’s evidence was that he started in October 2016.

137 A revised cash flow was sent by Mr S Girgis two days later and this used 150 members for the first month (November 2016), 300 for the second month (December 2016) and then increasing by 100 a month, reaching 800 members by May 2017.

138 On balance, it is likely that Mr Hagemrad suggested the change to using 150 members in each of the first two months in the Skype meeting.

17 June 2016: Updated Business Plan and Updated Cash Flow

139 On 17 June 2016, Mr S Girgis sent an email to Mr Hagemrad and Mr Husseini attaching an “updated business plan and cash flow”. The amendments to the business plan included a statement that it “will take time and money” to establish a UFC Gym in Australia.

140 Item 2 of the analysis of “Strengths” now provided the following comment:

Karim and Sherif have vast experience in business and in the fitness industry and currently own and operate multiple successful businesses. These skills are transferable to the UFC gym venture and therefore we understand how to effectively implement strategy and operate a business of this nature

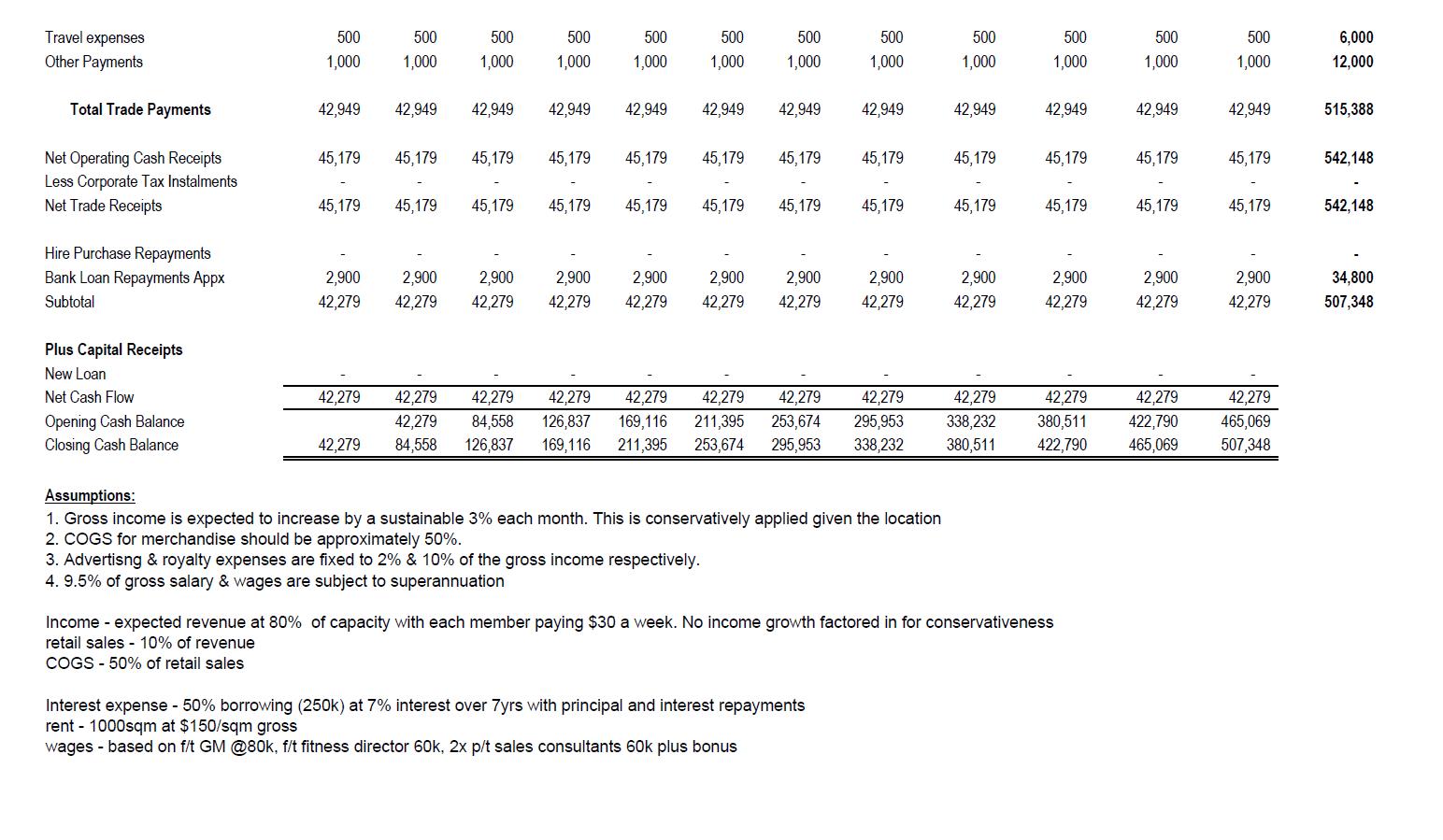

141 The cash flow worksheet attached to the email of 17 June 2016 was updated by Mr Chau (Updated Cash Flow). It was as follows:

142 Mr Chau gave evidence that the main changes to the Draft Cash Flow were to: (a) include a ramp-up or pre-sale period; (b) electricity; and (c) wages. His evidence at T234 was:

Can I ask you to explain what changes you made from the last version of the cashflow to this one and why?---Sure, okay. Again, from just from the top, probably one of the biggest changes was after discussion in the Skype call with Maz, was that he said we would need to have a – a ramp-up or presale period, which made sense, and he said, “Expect to grow at 150 members for the first two months of presale,” and then we would open and then expect, like, a 100-member growth from there, and that’s what I had inputted until we reached that 80 – 80 per cent capacity, which was from the previous spreadsheet. That was one of the major changes. The other major change was the electricity amount. He said we probably were underbudgeting for electricity, and that’s why it has been increased there to double what we were expecting. And finally, in terms of wages, he said we should aim for a 25 per cent of gross, and that’s what I’ve inputted to account for, you know, the ramp-up period and then when – when we become operational. I think they’re the three major changes from that spreadsheet. Yes, that’s – they’re the changes.

143 The Draft Cash Flow and the Updated Cash Flow both include a projection of total revenue in the sum of $1,267,200, comprising total gross income from fees ($1,152,000) and retail sales ($115,200). The main change to receipts was to include a pre-sales phase commencing in November 2016.

144 The main changes to the expenses were to:

double the cost of electricity from $24,000 to $48,000;

increase “Salaries & Wages” from $240,000 per year to $316,800 per year;

merge (although not quite exactly) what had been “Bank, Merchant Charges & Interest” and “Interest” in the Updated Cash Flow, rather than having them as separate line items.

145 The Updated Cash Flow continued to contain a row for “Hire Purchase Repayments”, which contained no expense, consistently with the fact that no-one had suggested equipment would be on operating lease. The “Superannuation” row contained an error because it continued to show a fixed amount of $2000 per month (as depicted in the Draft Cash Flow) when it should have increased in line with the updated increase to “Salaries & Wages”. The end result was that “Net Trade Receipts” which had been $542,148 in the Draft Cash Flow reduced to $441,324 in the Updated Cash Flow.

24 June 2016: Emails from Life Fitness to Mr Hagemrad

146 On 24 June 2016 at 10.02pm, Mr Oman of Life Fitness sent an email to Mr Hagemrad, with the subject “Email 1 – Wetherill Park”, which included:

Firstly, thanks for the walk through at the site today. I am really positive about the future of UFC here with sites like these in the mix. As discussed today, I feel that it will be easy to sell a 800m2 club to a potential franchisee, when walking through the Wetherill Park club. The product list is scalable and there are some simple changes that can be made to the different training zones to fit a smaller location. Hopefully Wetherill Park will be complete with Hammer Strength and Life Fitness products, as I am sure they will play an important part in the growth of the brand here in Australia.

I have attached a revised proposal for Wetherill Park with this email. There aren't many changes to the equipment list, except for the added Tiyr and Multi Plyo Boxes. The big addition is the deferment of payments for 4 months on the finance. I have approval from my CEO to deliver the goods with a single initial payment. The 4 months following the installation of the goods, will see a hold placed on your finance with no payments due. After these 4 months have passed, the finance will recommence with 47 more repayments to be made to complete the contract.

…

I will send you a separate email about the Franchisee pricing, but I have made some changes as we had discussed this afternoon.