FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Invisalign Australia Pty Limited v SmileDirectClub LLC [2023] FCA 395

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant be granted leave to file and serve the Amended Concise Statement in the form set out in Annexure A to the proposed minutes of order received by the Court on 31 October 2022.

2. The applicant’s claim be dismissed.

3. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the claim, to be fixed by way of an agreed lump sum or, in default of agreement, by way of a lump sum fixed by a Registrar.

4. The cross-claimant’s cross-claim be dismissed.

5. The cross-claimant pay the cross-respondent’s costs of the cross-claim, to be fixed by way of an agreed lump sum or, in default of agreement, by way of a lump sum fixed by a Registrar.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANDERSON J:

[1] | |

[14] | |

[16] | |

[22] | |

Rulings on objections to the evidence of Mr David Cristofaro | [43] |

[82] | |

[85] | |

[93] | |

[94] | |

[95] | |

[95] | |

[103] | |

[106] | |

[109] | |

[111] | |

[114] | |

[117] | |

[136] | |

[141] | |

[145] | |

[150] | |

[155] | |

[159] | |

[159] | |

[166] | |

[175] | |

[175] | |

[180] | |

[220] | |

[220] | |

[224] | |

[228] | |

[235] | |

[244] | |

[259] | |

[269] | |

[274] | |

[277] | |

[284] | |

[294] | |

[310] | |

[326] | |

[327] | |

[329] | |

[330] | |

[331] | |

[337] | |

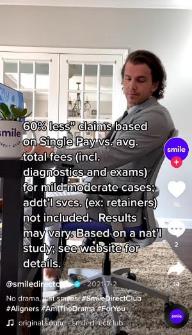

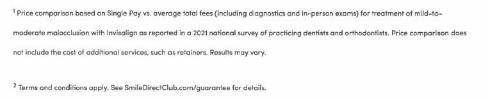

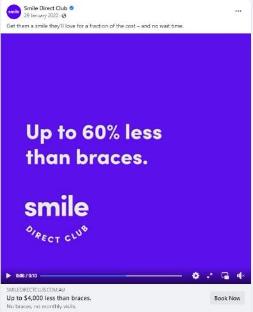

“Up to 60% less than braces” claim on the SDC Australian Website | [339] |

[347] | |

[350] | |

[355] | |

[359] | |

[360] | |

[362] | |

[405] | |

[407] | |

[412] | |

[416] | |

[419] | |

[421] | |

[423] | |

[427] | |

[433] | |

[443] | |

[501] | |

[502] | |

[527] | |

[544] | |

[562] | |

[568] | |

[570] | |

[587] | |

[613] | |

[617] | |

[618] | |

[630] | |

[646] | |

[650] | |

[655] | |

[658] | |

[665] | |

[674] | |

Role of general dentists in diagnostic assessment of patients | [678] |

[681] | |

[692] | |

[697] | |

[698] | |

[699] | |

[699] | |

[718] | |

[731] | |

[733] | |

[733] | |

[739] | |

[740] | |

[741] | |

[742] | |

[743] | |

[778] | |

[785] | |

[799] | |

[803] | |

[815] | |

[819] | |

[825] | |

[831] | |

[837] | |

[873] | |

[874] | |

[883] | |

[887] | |

[891] | |

[893] | |

Representations alleged to have been made by Invisalign in the DIY article | [898] |

[901] | |

SDC’s contention that the “representations” were made by Invisalign | [907] |

[915] | |

[932] | |

[973] | |

[981] | |

[1002] | |

[1009] |

1 The applicant (Invisalign) and the respondents (collectively, SDC) are competing providers of clear aligner teeth straightening products in Australia. Invisalign alleges that SDC has engaged in false, misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to certain promotional material that it has published with respect to its clear aligners (SDC aligners). The promotional material that is the subject of Invisalign’s claim is listed in Annexure A to the Concise Statement (CS), which was later amended under Annexure A to the Amended Concise Statement (Amended CS). This promotional material was then further particularised in Schedule 1 to Invisalign’s closing submissions, which is annexed to these reasons for judgment at Annexure C.

2 The second respondent (SDC AU) has brought a cross-claim against Invisalign. SDC AU alleges that Invisalign has published or caused to be published material which is false, misleading or deceptive.

3 Both the claim and cross-claim are brought pursuant to ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL).

4 This dispute revolves around two companies that offer clear aligner teeth straightening treatment.

5 Invisalign commenced operating in Australia in late 2001 and was the first supplier of clear aligners in Australia. SDC commenced operating in Australia from about 29 May 2019.

6 Clear aligners are teeth straightening products that are designed to gradually move and straighten a patient’s teeth over the course of a number of months. Clear aligners are seen as an alternative to braces and take the form of subtle, transparent mouthguards that are custom fit to each patient’s teeth.

7 Invisalign aligners and the dental treatment that is involved with it (Invisalign Aligner Treatment) is provided by dentists and/or orthodontists who supply the treatment to patients.

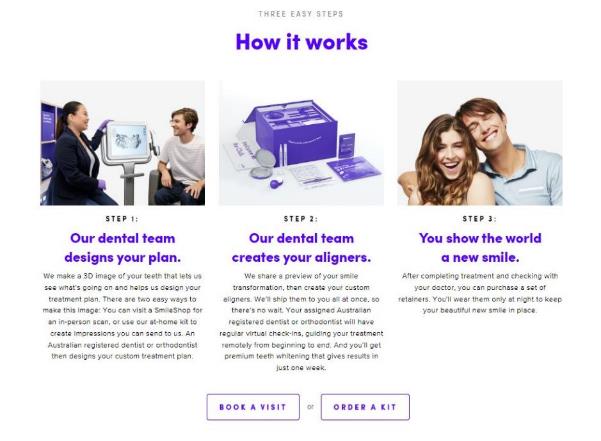

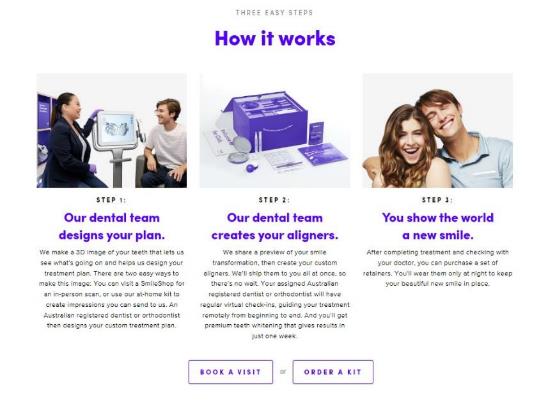

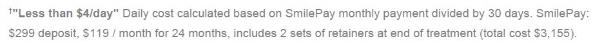

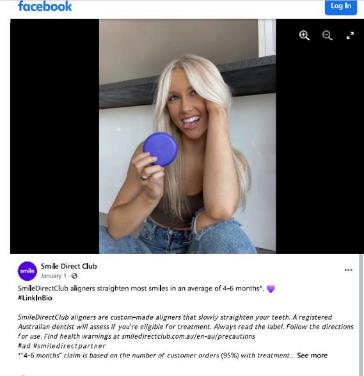

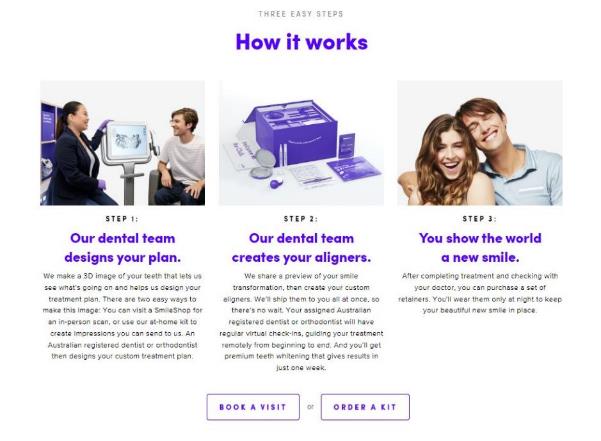

8 SDC aligners and the treatment that is involved with it (SDC Aligner Treatment) is supplied by SDC to customers at the direction of, and under the supervision and control of, an Australian registered dentist or orthodontist (Affiliated Dentists) via a web-portal administered by SDC (SDC Platform).

9 Invisalign, by its Amended CS, contends that SDC, in the course of promoting and marketing its SDC Aligner Treatment, made the following representations which it alleges are false, misleading or deceptive or are likely to mislead or deceive:

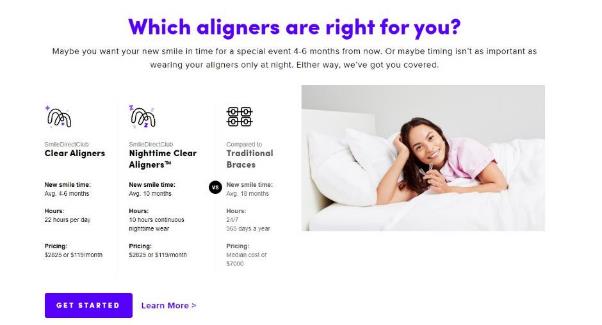

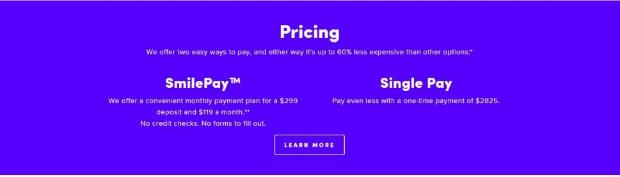

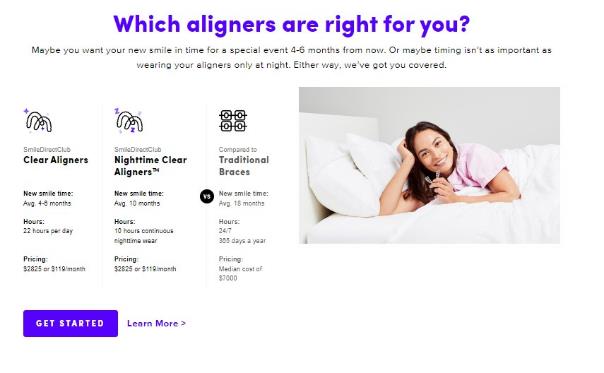

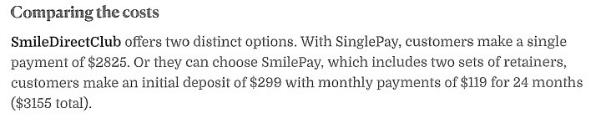

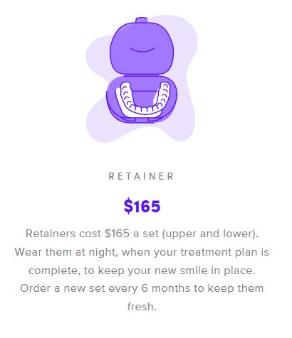

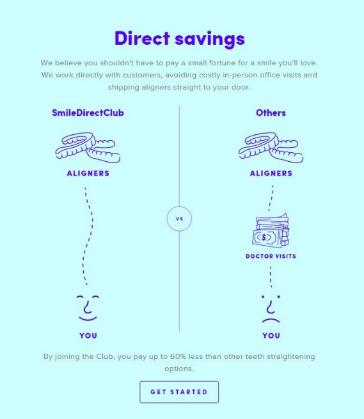

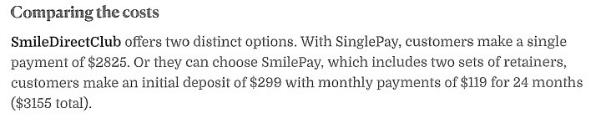

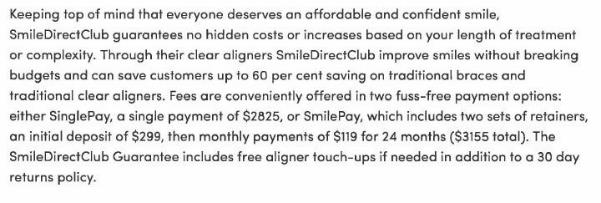

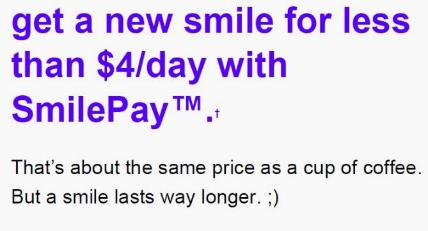

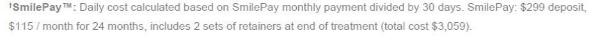

(a) the total cost associated with treatment with SDC aligners is either $2,825 for upfront payment or $3,155 by instalments (Total Cost Representation);

(b) the total cost associated with treatment with SDC aligners is less than $4 a day for the duration of treatment (or alternatively for the duration of a 90 day to 6-month treatment) (Less than $4 a Day Representation);

(c) various representations set out at Amended CS [19] to the general effect that SDC Aligner Treatment is of comparable efficacy to treatment with traditional orthodontic treatment (being treatment from a dentist or orthodontist with an orthodontic appliance such as braces or Invisalign aligners) for all, or at least a majority of, patients (Comparable Treatment Representations);

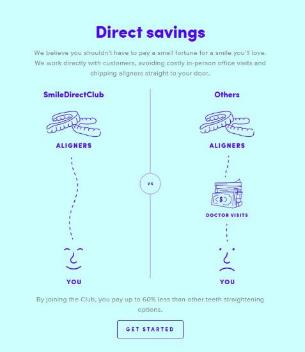

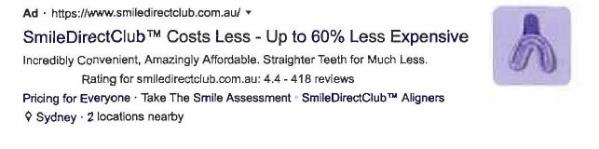

(d) various representations set out at Amened CS [20] to the effect that SDC Aligner Treatment is less expensive or ‘60% less’ or ‘up to 60% less’ expensive in all instances or alternatively for equivalent treatments obtained from an orthodontist or dentist such as braces or Invisalign (Price Comparison Representations);

(e) SDC Aligner Treatment provides a comprehensive solution to all orthodontic issues or alternatively all non-severe issues (Comprehensive Solution Representation); and

(f) SDC Aligner Treatment provides a comprehensive orthodontic solution to all orthodontic issues or alternatively all non-severe issues at significantly less cost than that of equivalent treatments with braces or Invisalign (Lower Cost Representation).

10 SDC AU, by its cross-claim, alleges that Invisalign made a number of representations about about the comfort, predictability and treatment time associated with its clear aligners (Invisalign aligners), that were false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of ss 18 and 29 of the ACL.

11 SDC AU, by its cross-claim, also alleges that Invisalign has made certain representations about SDC aligners which are false, misleading or deceptive. SDC AU alleges that these representations were made in an “advertorial” published by a number of news outlets entitled, “DIY teeth straightening kits – Should you try this at home?” (DIY article). The DIY article was “created in partnership” with Invisalign. SDC AU alleges that the DIY article, without mentioning SDC by name, makes various statements which it contends the ordinary and reasonable consumer would understand as referring to SDC aligners.

12 SDC AU contends that the DIY article impliedly represents, inter alia, that SDC Aligner Treatment does not involve oversight by a dentist. SDC AU contends that the representations are false, misleading or deceptive as SDC Aligner Treatment is supplied by SDC to customers at the direction, and under the supervision and control of, Affiliated Dentists using the SDC Platform.

13 For the sake of completeness, these reasons for judgment will refer to “consumers”, “customers” and “patients”, however each of these groups are used interchangeably and refer to the same group.

RULINGS ON AMENDED CONCISE STATEMENT AND EVIDENCE

14 Before turning to the evidence, I will deal with certain outstanding issues which remain from the trial and which were articulated in the parties’ joint note to the Court which my chambers received on 7 December 2022.

15 These outstanding issues are:

(a) Invisalign’s Amended CS;

(b) Schedule 1 to Invisalign’s closing written submissions, including the affidavit evidence of Ms Jaimie Maree Wolbers as well as the material in annexure JMW-4 (exhibits 73 and 74); and

(c) the evidence of Mr Cristofaro.

Invisalign’s Amended Concise Statement

16 Invisalign, in its closing written submissions, attached an Amended CS in which it sought to add the words “60% less, or further or alternatively” to the existing Price Comparison Representations allegations pleaded in sub-paragraphs 20(c) and (d), which Invisalign submitted reflected the case, as opened (T60.16-30), and ultimately run, by Invisalign.

17 SDC opposed the amendment to the CS on the basis that it substantially amended the case as pleaded under the Price Comparison Representations and would require SDC to adduce further and better pricing survey evidence. SDC also opposed the amendment on the basis that there has been no explanation for the delay in seeking to amend the CS until closing submissions were filed.

18 The Court’s power to grant leave to amend is broad and has the remedial objective of ensuring that any defect in the pleading is cured and that the real questions that are the subject of the controversy are properly agitated: Caason Investments Pty Ltd v Cao [2015] FCAFC 94; 236 FCR 322 (Caason) at [20] (Gilmour and Foster JJ) and AON Risk Services Australia Ltd v Australian National University [2009] HCA 27; 239 CLR 175 at [14]. The power to grant leave to amend must be exercised in a “way that best promotes the Court’s overarching purpose to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible”: Caason at [19].

19 Leave to amend should generally be granted unless the proposed amendment is futile, including, for example, because the issue sought to be raised by the amendment has no reasonable prospect of success, or will be liable to be struck out as not raising a reasonable cause of action, or where the amendment would cause substantial prejudice or injustice to the opposing party in a way that cannot be compensated by an award of costs: Caason at [21] and KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 at [110]-[111] (Wigney, Anastassiou and Jackson JJ).

20 I am satisfied that the amendment to the CS is minor in nature and reflects the manner in which Invisalign ran its case, as such the amendment will be allowed.

21 I am also satisfied that granting the amendment will not cause any prejudice or injustice to SDC and that it facilitates the just resolution of the disputes as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

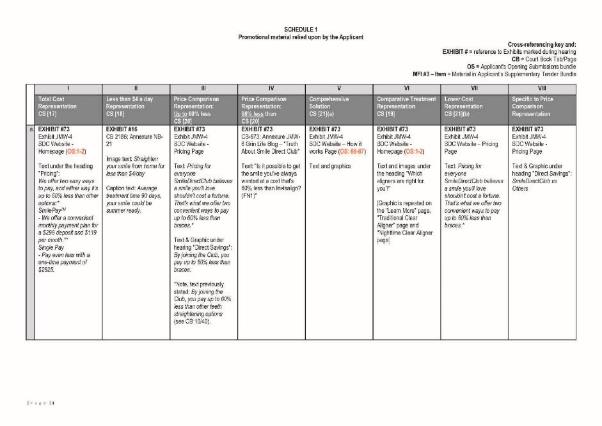

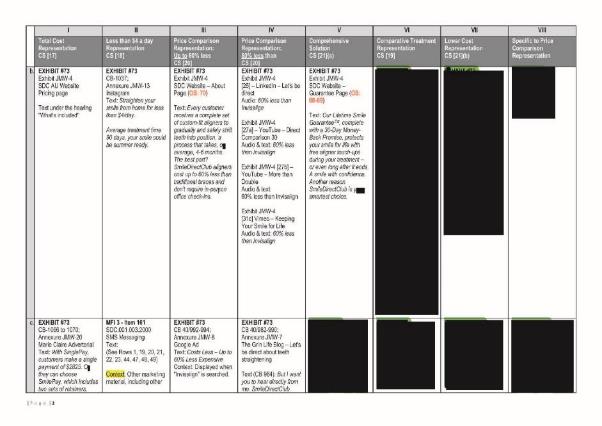

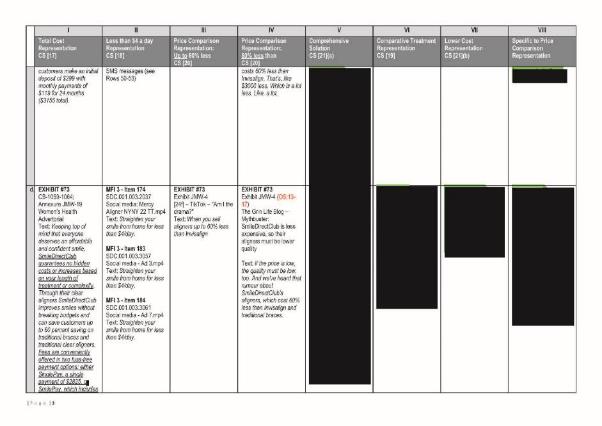

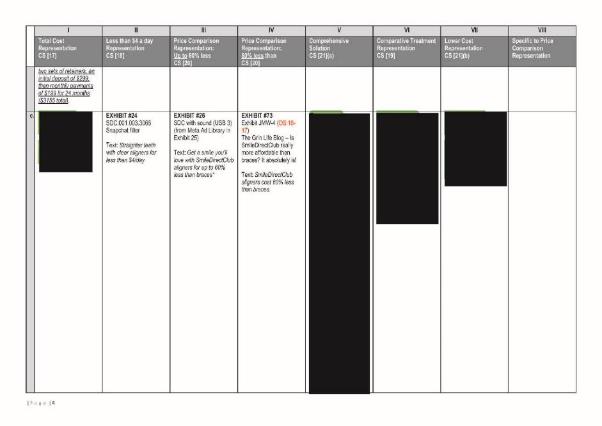

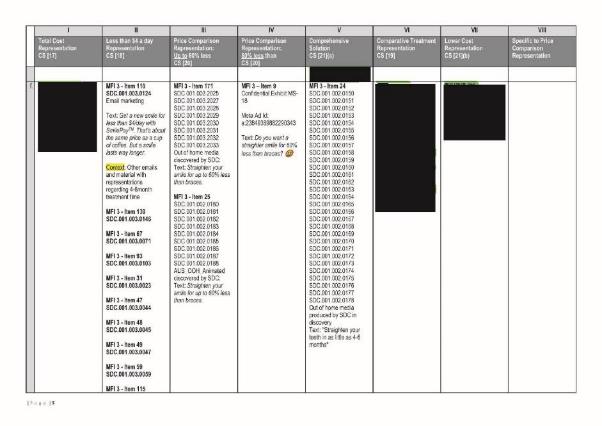

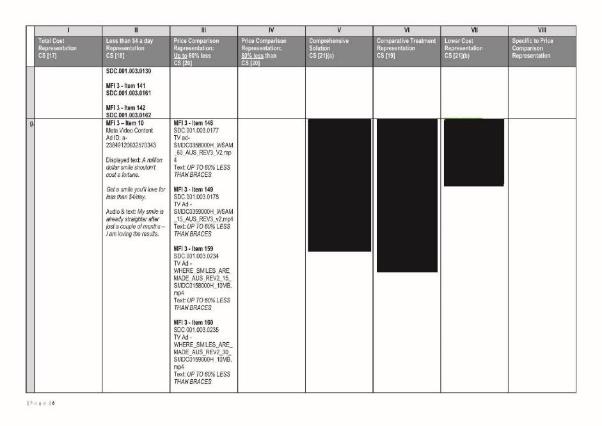

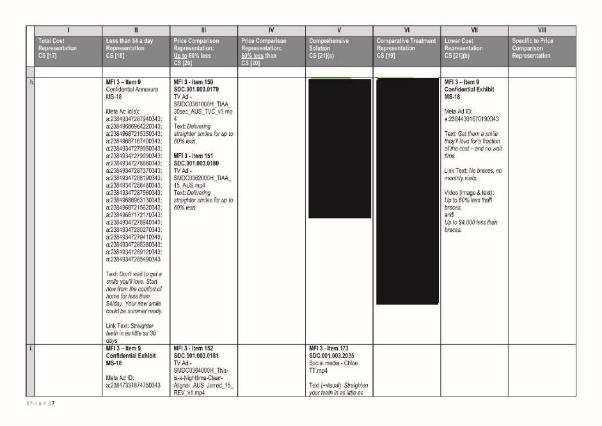

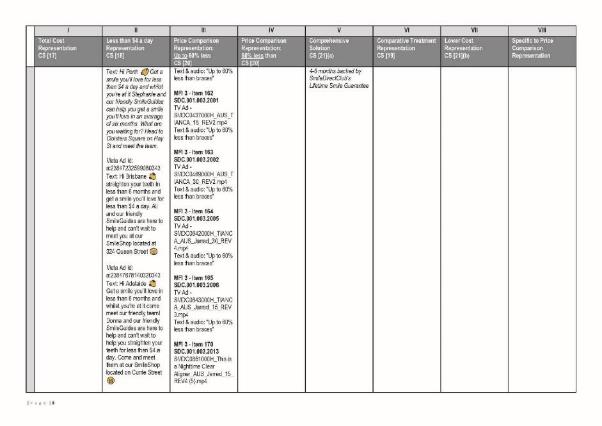

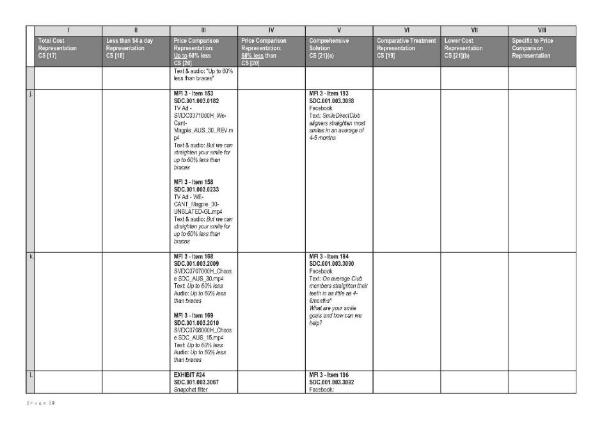

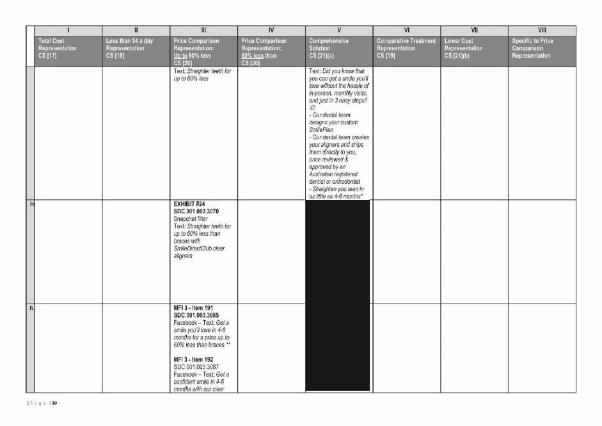

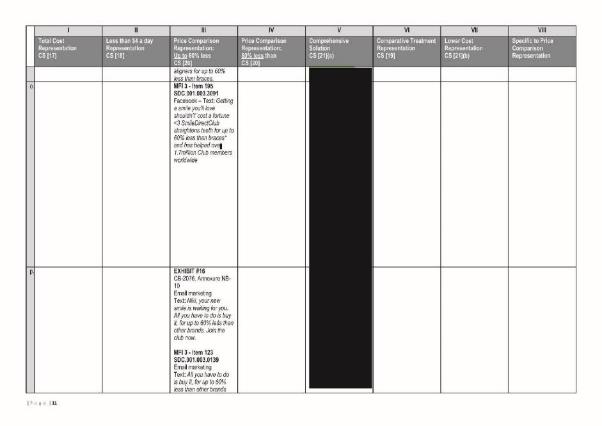

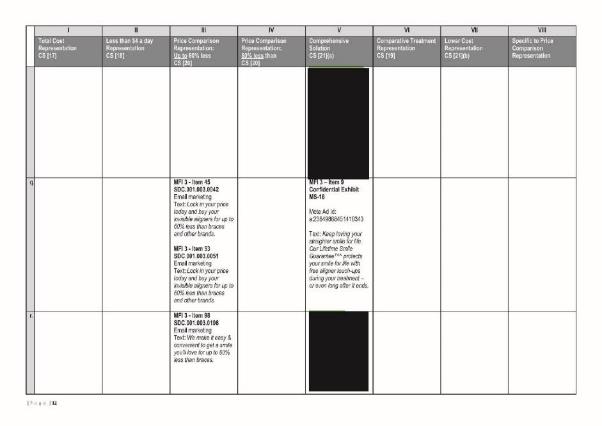

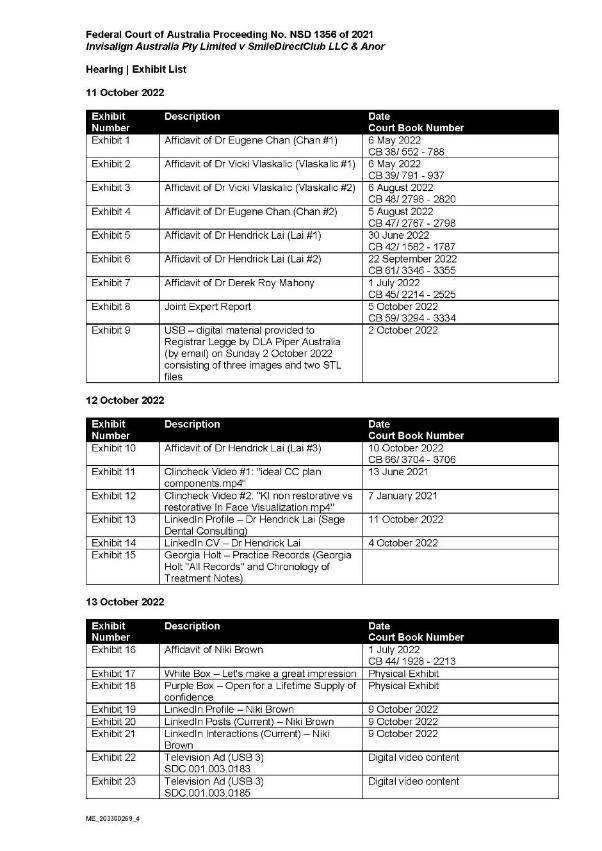

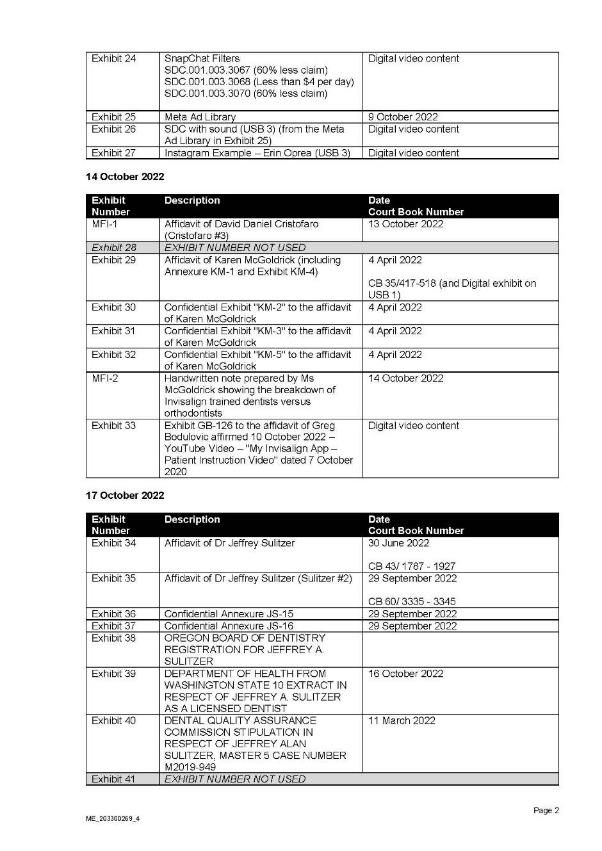

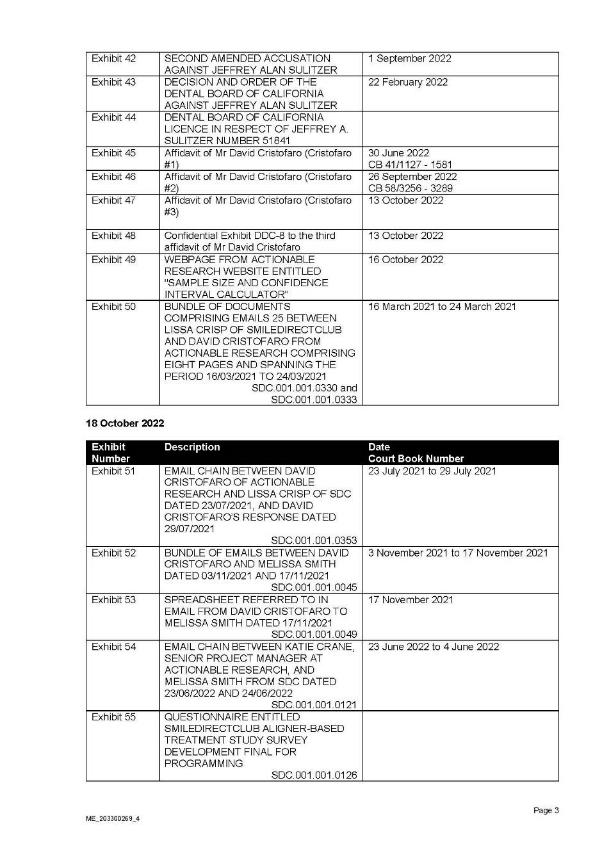

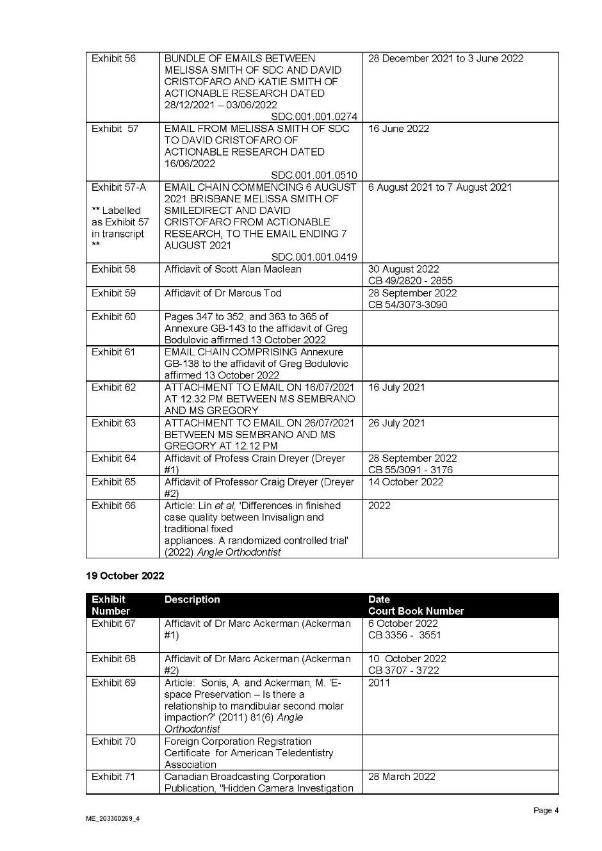

Schedule 1 to Invisalign’s Closing Written Submissions

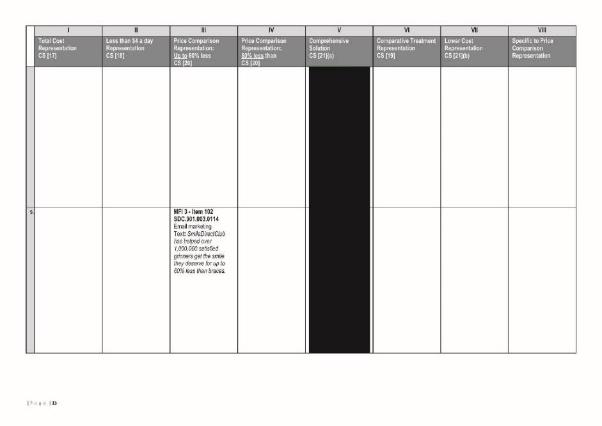

22 Invisalign’s closing submissions include a Schedule 1, entitled, “Promotional material relied upon by the Applicant”. This Schedule 1 sets out, in table form, the promotional material exhibited to the affidavit of Jaimie Maree Wolbers sworn 4 April 2022 and annexure JMW-4, being a USB containing digital promotional material of SDC. On day eight of the trial, on 19 October 2022, I provisionally admitted the affidavit of Jaimie Maree Wolbers sworn 4 April 2022 and annexure JMW-4 and marked it exhibit 73, subject to an objection by SDC: T658.20-660.05.

23 Invisalign seeks to rely upon the promotional material identified in Schedule 1 to its written submissions in support of its claim. As stated above in these reasons at [1], this promotional material is annexed to these reasons for judgment at Annexure C (Annexure C or Schedule 1).

24 Invisalign accepts that the promotional material itemised in Annexure C contains material which goes beyond that identified in Annexure A to the Amended CS.

25 SDC objects to the admission into evidence of certain material identified in Annexure C, which was shaded in green in the version of Annexure C which was annexed to SDC’s closing written submissions. The material that was shaded in green is now redacted in the Annexure C to these reasons for judgment. The basis of SDC’s objection to this material that was shaded in green was that it goes well beyond Invisalign’s pleaded case as identified in the Amended CS and its Annexure A.

26 The promotional material falls into two categories.

27 First, material that contains the same, or substantially the same, statements as those in Annexure A. These statements do not fall outside Invisalign’s pleaded case. Second, promotional material that contains other unpleaded statements which, in SDC’s submission, falls outside Invisalign’s pleaded case.

28 This second category is the promotional material that was shaded in green in the version of Schedule 1 which was annexed to SDC’s written closing submissions.

29 SDC submits that Invisalign should not be permitted, at such a late stage of the proceeding, to tender and rely upon this additional promotional material. That is so, in SDC’s submission, for two reasons.

30 First, Invisalign’s closing submissions failed to squarely assert which of the many statements are said to convey the particular representations alleged. SDC also submits that it is not apparent what Invisalign was referring to in column VII of Schedule 1 entitled “Specific to Price Comparison Representation”.

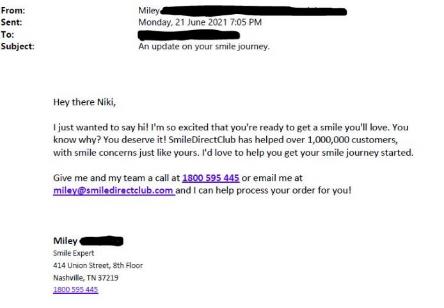

31 Second, SDC submits that Invisalign has provided no explanation for the delay in identifying the new statements contained in Schedule 1 which were highlighted in green. SDC submits that with the exception of a relatively confined number of Facebook and Instagram advertisements that were produced during discovery and made available to Invisalign on 17 September 2022, the remainder of the promotional material referred to in Schedule 1 is taken from Ms Wolbers’ affidavit sworn 4 April 2022, annexure JMW-4 and the affidavit of Ms Niki Brown affirmed 1 July 2022.

32 SDC submits that Invisalign has been on notice of this additional promotional material for an extended period of time and has not sought to amend its claim. SDC submits that Invisalign is seeking to amend the Amended CS and its Annexure A by replacing it with Schedule 1, without any explanation as to why this was not done earlier and prior to the commencement of the hearing.

33 SDC submits that to permit Invisalign to tender the promotional material which is exhibit JMW-4 to Ms Wolbers’ affidavit sworn on 4 April 2022 for the first time in closing submissions is procedurally irregular and unfair. SDC submits that the new promotional material has no probative value in circumstances where it does not reflect the pleaded statements in Annexure A to the Amended CS.

34 Invisalign submits that SDC has been on notice since it filed and served Ms Wolbers’ affidavit sworn 4 April 2022 and that Invisalign confirmed, by letter dated 28 June 2022, that it intended to rely upon all of the material in Ms Wolbers’ affidavit as well as relevant promotional material that came to light during the course of the proceeding.

35 Invisalign submits that paragraph 15 of the Amended CS expressly stated that Annexure A to the Amended CS was a “sample” of the material ultimately to be relied upon and that Invisalign intended to rely on the entirety of the material in Ms Wolbers’ affidavit sworn on 4 April 2022 and any other relevant promotional material that came to light through discovery.

36 Invisalign contends that a concise statement is not a pleading and that as a consequence it is not required to expose issues in dispute to the same level of detail as in a pleading: Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2021] FCAFC 121; 396 ALR 27 per McKerracher and Colvin JJ at [140]-[150].

37 I will not admit into evidence those portions of Schedule 1 which were highlighted in green by SDC, and which are now redacted in Annexure C to these reasons. The additional promotional material goes beyond the scope of the Amended CS and Annexure A

38 Whilst an applicant may not be limited to matters strictly referred to in a concise statement, a respondent is entitled to fair disclosure of the case it is required to meet.

39 In my view, it is unfair for Invisalign, in its closing submissions, to seek to rely upon additional promotional material and to expand the scope of the evidence in circumstances where Invisalign has refused to provide particulars identifying the statements upon which it relies in the additional promotional material. This is particularly the case in circumstances where on 28 June 2022, SDC’s instructing solicitors wrote to Invisalign’s solicitors seeking to understand the relevance of the additional promotional material and how Invisalign put its case. At no point prior to closing submissions has Invisalign provided notice to SDC of the new statements contained in Schedule 1 upon which it now seeks to rely.

40 Invisalign has also failed to identify, in its closing submissions, which of the many statements are said to convey the representations alleged.

41 In those circumstances, in my view, it is unfair and prejudicial to SDC to admit into evidence the promotional material shaded in green which contain statements beyond those identified in the Amended CS and Annexure A.

42 It is also not apparent what Invisalign is referring to by column VIII entitled “Specific to price comparison representation”. The material in this column will also be ruled inadmissible.

Rulings on objections to the evidence of Mr David Cristofaro

43 Mr Cristofaro tendered three affidavits into evidence:

(a) the affidavit of Mr Cristofaro dated 30 June 2022 (first Cristofaro Affidavit), marked exhibit 45;

(b) the affidavit of Mr Cristofaro dated 26 September 2022 (second Cristofaro Affidavit), marked exhibit 46; and

(c) the affidavit of Mr Cristofaro dated 13 October 2022 (third Cristofaro Affidavit), marked exhibit 47,

(collectively, the Cristofaro Affidavits).

44 Mr Cristofaro’s evidence is relevant to the pricing claims made by Invisalign in the Amended CS, in particular, the Price Comparison Representations at Amended CS [20].

45 Invisalign objects to each of the three Cristofaro affidavits on the basis that the evidence given by Mr Cristofaro does not comply with s 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) and on the basis that aspects of his evidence is hearsay, conclusory and should be excluded pursuant to s 135 of the Evidence Act.

46 SDC filed written submissions on 11 October 2022 in support of the admission into evidence of the first and second Cristofaro Affidavits. Invisalign on 13 October 2022, filed written submissions objecting to the admission into evidence of the first and second Cristofaro Affidavits. On 13 and 14 October 2022, I heard oral argument from the parties as to the objections to Mr Cristofaro's evidence as contained in the first and second Cristofaro Affidavits together with the third Cristofaro Affidavit.

47 On 14 October 2022, I ruled that the first and second Cristofaro Affidavits be admitted into evidence (T407.8-16). At that time I informed counsel that I will publish my reasons for making that ruling in due course. On Monday, 17 October 2022, I heard brief oral argument from counsel for Invisalign seeking to object to admissibility of the third Cristofaro Affidavit on the same basis as the previous two affidavits. I informed counsel that the third Cristofaro Affidavit will be admitted into evidence, and that I will also publish my reasons for making that ruling in due course.

48 I now provide my reasons for the rulings made in respect of the Cristofaro Affidavits.

49 Mr Cristofaro is the principal of Actionable Research, a market research firm that he founded in 2002 in the USA that has clients including Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Roche and Invisalign’s parent company, Align Technologies, Inc.

50 Actionable Research specialises in providing primary research for participants in the oral care industry, including all facets of oral health care delivery. Actionable Research has conducted over 140 research projects involving dentists and orthodontists in numerous jurisdictions around the world, including Australia. Mr Cristofaro has personally been involved in the design of the research, the sampling for the surveys, and the analysis of the data.

51 Mr Cristofaro has written the survey and interview guide for approximately 70 percent of the studies conducted by Actionable Research. He also regularly moderates market research focus groups and conducts one-on-one interviews with dentists and orthodontists in order to inform his understanding of the dental and orthodontic industry and so as to appropriately design survey questions.

52 SDC submits that Mr Cristofaro gives evidence of fact about a market research survey he conducted (Actionable Study) and the responses given to the Study. SDC submits that Actionable Research was retained by SDC prior to the commencement of these proceedings in May 2021, to conduct market research into the prices charged for professional teeth straightening by dentists and orthodontists using braces and clear aligner treatment in Australia. In order to conduct this research, Mr Cristofaro developed a questionnaire (Questionnaire) and oversaw a team at Actionable Research that conducted the Study.

53 The first Cristofaro Affidavit sets out the relevant methodology and results of the Actionable Study, including:

(a) the study participants and sample size: [15]-[17], [22];

(b) the screening criteria used when selecting participants for the study: [18]-[21];

(c) the demographics of the study participants, including their geographic location, their years of experience, the types of dental procedures they performed and the number of case starts per year in their practice: [24]-[34]; and

(d) the results of the Actionable Study in relation to pricing habits for braces and clear aligners: [35]-[51].

54 The first Cristofaro Affidavit annexes the raw data containing the responses obtained to the Questionnaire (exhibit DDC-2) (Raw Data), which is a 300 page document. The affidavit also annexes:

(a) the questions asked of dentists and orthodontists (exhibit DDC-1);

(b) an Excel spreadsheet which calculates whether the average price reported in the Survey correlates to 60% less than Invisalign and braces (Calculation Spreadsheet) (exhibit DDC-3); and

(c) two reports created during the course of preparing Mr Cristofaro's evidence which describe the results of the Actionable Study in respect of braces (Braces Report) (exhibit DDC-4) and Invisalign aligners (Invisalign Report) (exhibit DDC-5).

55 Invisalign has been provided with an electronic version of the Raw Data in response to a request made for it.

56 SDC submits that in respect of the First Cristofaro Affidavit, Mr Cristofaro provides a factual account of the processes he followed to conduct the Study and analyse and record its results, as well as the results of the Actionable Study.

57 SDC submits that the Second Cristofaro Affidavit was filed in reply to Invisalign's evidence (specifically the affidavit of Mr MacLean which calls into question the methodology of the Actionable Study) and further exposes Mr Cristofaro’s methodology in conducting the Actionable Study. In particular, it addresses:

(a) the selection of participants for the Actionable Study (Study Participants), including how Actionable Research has developed its database of dentists and orthodontists in Australia and its practices in conducting market research: [8]-[26];

(b) testing of the results of the Actionable Study to account for geographic spread of dentists and orthodontists in Australia, to respond to criticisms of Mr MacLean: [27]-[32];

(c) description of how Mr Cristofaro calculated the sample size of the Actionable Study: [33]-[43];

(d) the financial contribution offered for participation in the Actionable Study: [44];

(e) the nature of the questions asked in the Questionnaire, including the lack of pilot study: [45]-[50]; and

(f) whether it was appropriate to “trim” the results of the Actionable Study to remove outliers: [51]-[52].

58 Invisalign objects to parts of Mr Cristofaro’s evidence on the basis that it is hearsay.

59 SDC submits that some paragraphs to which the hearsay objection is advanced are not hearsay. These are:

(a) [11]-[12] of the first Cristofaro Affidavit contain evidence of fact about the circumstances in which Actionable Research was retained by SDC and the instructions provided;

(b) [15]-[16] of the first Cristofaro Affidavit again contain evidence of fact, this time about how Actionable Research identified potential Study Participants and invited them to participate in the Actionable Study;

(c) [9]-[10] of the second Cristofaro Affidavit is factual evidence describing how Actionable Research developed its database of dentists and orthodontists in Australia;

(d) [12] of the second Cristofaro Affidavit is factual evidence about how dentists were invited to participate in the Actionable Study; and

(e) [20]-[26] of the second Affidavit is factual evidence about the Study Participants and their demographics, as well as some opinions offered about the sufficiency of the sample.

60 SDC submits that there are no prior representations contained in the above paragraphs.

61 Invisalign submits that the results of the Actionable Study that are recorded in [2] and [26]-[33] are hearsay and inadmissible. SDC accepts that insofar as Mr Cristofaro reports the answers given by dentists and orthodontists to the Questionnaire, this evidence is hearsay. However, SDC submits that the evidence is admissible as it falls within one of the exceptions to the hearsay rule.

62 SDC relies upon s 69 of the Evidence Act being the business records exception. SDC submits that the Raw Data are records belonging to or kept by Actionable Research in the course of completing the Actionable Study. The Actionable Study was conducted for the purpose of its business. The previous representations, being the responses from the participating dentists, were kept for the purpose of Actionable Research conducting the Actionable Study. In SDC’s submission, the Raw Data is a business record to which s 69 of the Evidence Act applies.

63 SDC further submits that s 69(2) of the Evidence Act provides that the hearsay rule does not apply to the document if the representation was made:

(a) by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact; or

(b) on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact.

64 Here, SDC submits that the Study Participants were dentists and orthodontists in Australia.

65 SDC submits that the Study Participants responded to questions about pricing for particular treatments at their own practices. As such, SDC submits that the representations were made on the basis of information directly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact.

66 Accordingly, SDC submits that the answers to the Actionable Study recorded in the first Cristofaro Affidavit, including the Raw Data, are business records of Actionable Research and admissible pursuant to s 69 of the Evidence Act.

67 SDC further submits that two further exceptions to the hearsay rule apply. First, s 64(2) of the Evidence Act provides an exception to the hearsay rule in civil proceedings where the maker is available, where it would cause undue expense or undue delay, or would not be reasonably practicable, to call the person who made the representation to give evidence. Here, SDC submits that the makers of the representations would be the 73 individual dentists and orthodontists who responded to the survey. SDC submits that to call that evidence first hand would require affidavits from each of those dentists and orthodontists and would cause undue expense, delay and would not be reasonably practicable.

68 Secondly, s 66A of the Evidence Act contains an exception for contemporaneous statements about a person's knowledge. SDC submits that the Raw Data records contemporaneous statements about the Study Participants’ knowledge about their experience, practices and pricing, given at a time prior to the proceedings brought by Invisalign against SDC.

69 Thirdly, SDC submits that insofar as the Raw Data is admissible, so too are Mr Cristofaro’s explanations of the results contained in his affidavit. Mr Cristofaro’s evidence simply summarises the evidence contained in the Raw Data, which spans some 300 pages.

70 SDC submits that s 29(4) of the Evidence Act provides that evidence may be adduced as explanatory material that aids comprehension of other evidence.

71 SDC submits that in the first Cristofaro Affidavit, Mr Cristofaro simply explains what is shown by the Raw Data in respect of particular categories of answers.

72 Fourthly, SDC submits that in relation to [36]-[50] of the second Cristofaro Affidavit, the evidence contained in these paragraphs relates to Mr Cristofaro's use of an online calculator to calculate an appropriate sample size for the Actionable Study.

73 SDC submits that the evidence in [36]-[50] of the second Cristofaro Affidavit, falls into two categories. First, [36] is evidence of the witness' direct knowledge of the formula used on the UBC Power Calculator website. Paragraphs [37] to [38] provide an explanation of the terms used in that formula and in SDC's submission, are not hearsay.

74 Second, [39] describes the process that Mr Cristofaro followed when using the UBC Power Calculator. SDC submits that this is not hearsay because it provides direct evidence of his processes. Similarly, SDC submits that [40] again provides direct evidence of the result generated by the calculator.

75 In relation to [40], SDC submits that it falls within s 146 of the Evidence Act. That section applies where a document is produced by a device or process and is tendered by a party who asserts that, in producing the document or thing, the device or process has produced a particular outcome. If it is reasonably open to find that the device or process is one that, or is of a kind that, if properly used, ordinarily produces that outcome, it is presumed (unless evidence sufficient to raise doubt about the presumption is adduced) that, in producing the document or thing on the occasion in question, the device or process produced that outcome. SDC submits Mr Cristofaro that explained the information he input into the calculator (at [39]) and produced a screenshot of the results generated by the calculator (at [40]). This, in SDC’s submission, is sufficient to meet the presumption in s 146 that the calculator produced the results in that paragraph.

76 Invisalign also objects to the first Cristofaro Affidavit on the basis that it does not comply with the Court’s Survey Evidence Practice Note (GPN-SURV) (Survey Evidence Practice Note). SDC submits that the Survey Evidence Practice Note is directed to the design of surveys conducted specifically for the litigation in which it is proposed to be used to address a particular issue in the proceedings (most commonly involving intellectual property disputes): Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2018] FCA 1459 at [32].

77 SDC submits that the Actionable Study was conducted well before the commencement of proceedings and therefore cannot be assessed against the standards in the Survey Evidence Practice Note. Insofar as Invisalign objects to any opinion expressed by Mr Cristofaro about the Actionable Study and its results on the basis of his expertise, SDC submits that this objection is answered by Mr Cristofaro’s experience in conducting studies of this kind and in this industry. SDC submits that Mr Cristofaro has conducted market research surveys for around 20 years, and has been involved in around 100 surveys of dentists and orthodontists. SDC submits that he therefore has "specialised knowledge" based on his experience to bring him within s 79 of the Evidence Act and is qualified to offer his opinion about the adequacy of the Actionable Study.

78 Invisalign also objects to Mr Cristofaro’s evidence on the basis that he has not adopted the Expert Witness Code of Conduct.

79 SDC submits that the Expert Witness Code of Conduct and the Survey Evidence Practice Note have no application in this case where a witness, here Mr Cristofaro, has prepared a report prior to the commencement of litigation at a time when he or she was not retained to provide an independent opinion to the Court. SDC submits that Mr Cristofaro and Actionable Research were retained prior to litigation commencing for the purpose of carrying out their survey and were therefore not "retained" to give opinion evidence in the proceeding. In any event, SDC submits that non-compliance with the Expert Witness Code of Conduct does not mandate exclusion of the evidence. Rather, the issue is whether non-compliance gives rise to a reason to exclude the evidence pursuant to s 135 of the Evidence Act.

80 Invisalign also seeks to exclude Mr Cristofaro’s evidence on the basis that its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might (a) be unfairly prejudicial to a party, (b) be misleading or confusing, or (c) cause or result in undue waste of time.

81 Mr Cristofaro’s affidavits purport to give evidence of an online survey undertaken by Actionable Research pertaining to various matters including the price of clear aligner therapy and braces. In his affidavits, Mr Cristofaro refers to this as the "engaged study". Invisalign’s overarching objection to Mr Cristofaro’s affidavits is threefold:

(a) the Raw Data and the reports, opinions and conclusions that are derived from the Raw Data are relied on for a hearsay purpose and are inadmissible under s 59 of the Evidence Act;

(b) much of this material also amounts to opinion evidence which should be excluded under s 76 of the Evidence Act, given that the conditions of expert opinion evidence under s 79 of the Act are not met, and in any event, SDC has expressly said that Mr Cristofaro is not an expert witness; and

(c) while it seems that there may have been earlier versions of some of these materials, the versions of the Actionable Research reports and the Calculations included in the first Cristofaro Affidavit were prepared for the purpose of this proceeding. For this and other reasons, the evidence should be excluded under s 135 of the Evidence Act.

Section 69 Evidence Act – Business Records

82 Invisalign submits that the authorities consistently distinguish between the "business records" and the "products" of a business. Invisalign's submission is that only the former fall within s 69 of the Evidence Act. Invisalign submits that the Raw Data and all the records and conclusions derived from that data, are the products of Actionable Researcher's business as a market research firm.

83 Invisalign relies upon the decisions of Roach v Page (No 15) [2013] NSWSC 939 per Sperling J and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand (No 1) [2012] FCA 1355; 207 FCR 448 for the proposition that published output of a business in literary form such as books, magazines and newspapers are not "business records", but rather, are "products of the business", falling outside the business records exception in s 69(1) of the Evidence Act.

84 Invisalign also relies upon the decision of Middleton J in Hanson Beverage Co v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 406; 75 IPR 505 at [110], [114], [131]-[133] where his Honour determined that television rating data (which Invisalign submits is analogous material to the Raw Data in the present case) did not fall within the business records exception to s 69(2) of the Evidence Act and were not admitted into evidence. Middleton J concluded that the ratings data were the "product of a business" and not a business record.

Consideration of objections to Mr Cristofaro’s evidence

85 The proposition that "output" or "product" of a business falls outside the business records exception in s 69 of the Evidence Act has been doubted, and rejected, in more recent authorities on the basis that s 69(1) includes records "kept … for the purposes of a business": Southern Cross Airports v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2011] NSWSC 347 (Southern Cross) per Gzelle J at 41-44 and Rodney Jane Racing Pty Ltd v Monster Energy Company [2019] FCA 923; 142 IPR 275 (Rodney Jane) per O’Bryan J at 175-176.

86 Similarly in Charan v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] VSC 3 at [463], Forrest J stated:

…the distinction between 'product' and 'records' is problematic. It does not appear in the text of s 69(1). The language used in the provision is broad and appears to encompass any documents kept by a person, body or organisation 'in the course of, or for the purposes of' a business. To exclude documents that are part of the records of an organisation, however generated and for whatever purpose under this provision (as opposed to a subsequent discretionary exclusion under s 135) involves, I think, an artificial distinction not covered by the wording of the section.

(Emphasis added)

87 In Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co. KG Arzneimittel v Coombe International Ltd [2020] FCA; 149 IPR 1 39 at [112]-[134] (Dr Wolff), the relevant question before Stewart J was whether various survey reports were admissible as an exception to the hearsay rule: at [112]-[134].

88 The surveys were commissioned and obtained by the parties to the proceedings, prior to the commencement of proceedings, for the purpose of the conduct of their businesses. In relation to the reports, Stewart J noted at [122]:

Material common elements of all the reports are the following. First, they were commissioned by the relevant owner of the brand from specialist professional survey companies. Secondly, they record respondents' responses or answers to survey questions, or other feedback from the respondents. Thirdly, they aggregate particular responses and produce, or calculate, some statistical outcomes. Fourthly, they were commissioned in the course of the business of the owner of the brand for the purpose of the conduct of its business (i.e. in order to be able to rely on the information in the reports in taking business decisions), and they were produced by the survey companies in the course of their business. Fifthly, they were kept or stored as part of the records or archives of the commissioning company and (presumably) the survey company.

89 Stewart J did not accept that the survey reports were the “products of the business”. Rather, “guided by the provisions of s 69”, his Honour held that “the survey reports form part of the records belonging to or kept by [Combe or Combe Asia-Pacific] in the course of, or for the purposes of, a business” (at [131]-[132]). Stewart J admitted the survey reports and concluded in respect of whether the reports formed part of the records belonging to the business:

Clearly they do. They were commissioned for the purpose of the business of the owner of the brand in each case, with the intention that they would be relied on in various ways including in devising advertising campaigns and, possibly, in developing and marketing products. Whilst they do not record the activities of the business, they are records produced for the purpose of those activities. They were intended to be relied upon by the business, and there is no reason to suppose that the hearsay statements recorded in the report are other than accurate.

(Emphasis added)

90 Likewise in the present case, the survey was commissioned by SDC prior to the commencement of the proceedings, for the purpose of SDC's business and was intended to be relied on by SDC in its business activities: first Cristofaro Affidavit at [11]-[12].

91 The survey was carried by Actionable Research and the survey data collected in the ordinary course of Actionable Research business: Dr Wolff at [122]. There is no reason to suppose that the hearsay statements contained in the data are other than accurate responses. I am of the view that the survey data falls within the clear and unequivocal meaning of the words in s 69(1) of the Evidence Act and is admissible as an exception to the hearsay rule.

92 Each of the first, second and third Cristofaro Affidavits will be admitted into evidence.

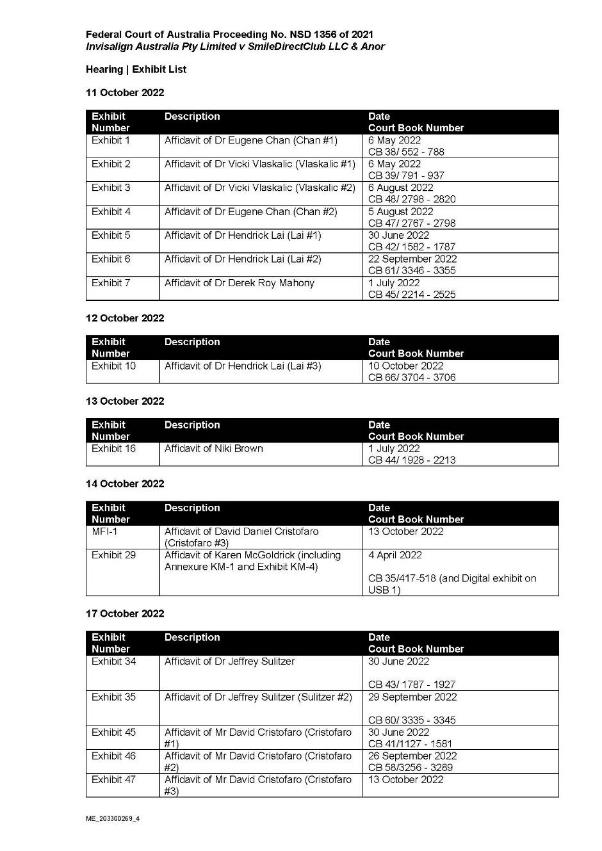

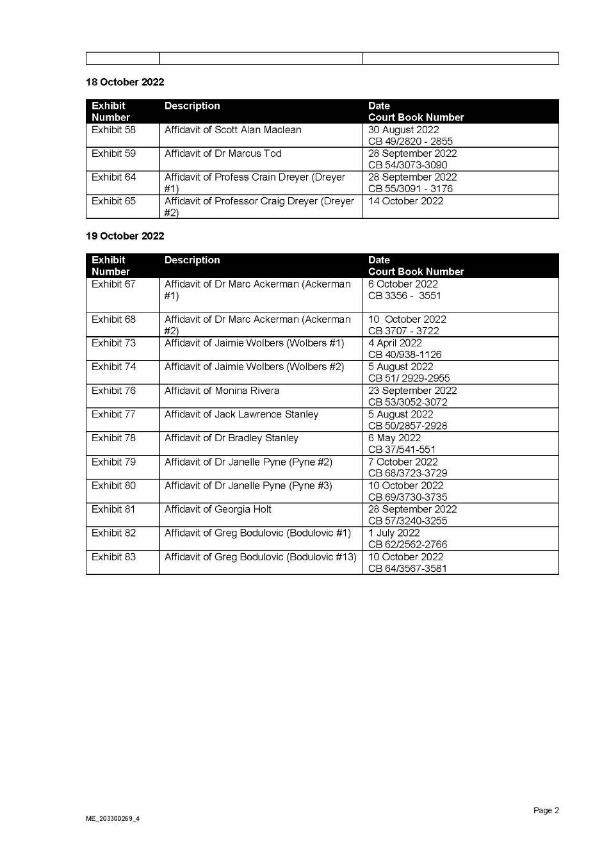

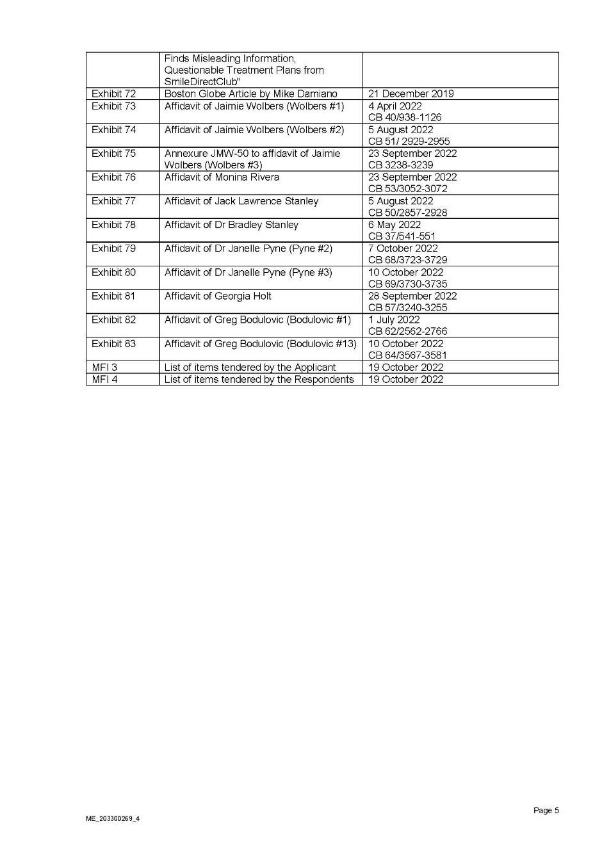

93 A list of the affidavits tendered by the parties are in Annexure A to these reasons for judgment.

94 Invisalign tendered affidavit evidence from a number of witnesses, some of whom were not required to attend for cross-examination. That evidence may be summarised as follows.

95 Ms Karen McGoldrick is the Managing Director of Invisalign in Australia and New Zealand.

96 Ms McGoldrick affirmed one affidavit dated 4 April 2022, which was tendered in evidence and marked exhibit 29.

97 Ms McGoldrick deposed to her significant experience as a company director, having spent 28 years working in various directorship positions at Unilever, immediately prior to commencing as the Managing Director at Invisalign in August 2015.

98 In her current role, Ms McGoldrick is responsible for leading, managing and directing Invisalign’s business in Australia and New Zealand.

99 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence about the background to Invisalign, the Invisalign system and Invisalign treatment in Australia. Ms McGoldrick’s evidence on these topics can be summarised as follows.

100 Invisalign Australia is the Australian subsidiary of Align Technology, Inc. (Align Technology), a global medical device company whose corporate headquarters is located in the United States of America (USA).

101 Since about December 2001, clear dental aligners, under the Invisalign brand name and trade mark, forming an orthodontic appliance treatment system (the Invisalign system) have been available in Australia.

102 At the time of the lnvisalign system’s launch in Australia in 2001, Align Technology already had eight international sales offices in the United States, Europe and Latin America, and had over 30,000 patients that were receiving treatment using the Invisalign system. Invisalign also has around 10,000 doctors trained and certified to prescribe the Invisalign system.

103 The Invisalign system was originally designed and created by Align Technology in 1997, with a vision to design an orthodontic treatment system that could be offered by doctors to their patients as an aesthetic and comfortable alternative to traditional fixed braces. No metal or ceramic brackets nor wires are used as part of the Invisalign system.

104 Since about 2011, following the acquisition of Cadent Holdings, Inc., Align Technology has also been the supplier of the iTero intraoral scanner (iTero scanner), which doctors can use to take 3D scans of a patient’s teeth and gums.

105 The current version of the Invisalign system features:

(a) the use of a series of clear removable aligners, worn over a patient’s teeth, that gently move teeth to a desired final position in order to correct or treat malocclusion;

(b) the clear aligners are made with “SmartTrack” material, a proprietary and multilayer orthodontic aligner material;

(c) “attachments” which are nearly always prescribed by the treating doctor as part of a patient's treatment plan, depending on the patient's individual circumstances. Attachments are small pieces of enamel-coloured composite which the doctor fixes onto the patient's teeth to help the aligner grip the teeth providing additional force and greater control over the movement of teeth than clear aligners alone. The combination of attachments in a treatment plan are custom designed for the individual patient's treatment; and

(d) depending on the patient’s individual circumstances, the treating doctor may also use orthodontic elastics with the lnvisalign system.

Registration of the Invisalign system in Australia

106 Invisalign Australia is the sponsor, for the purposes of registration with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), of the Invisalign system in Australia.

107 In 2018, in anticipation of the likely regulatory developments in Australia, Invisalign Australia took steps to register the Invisalign system as a class I medical device with TGA.

108 Invisalign Australia holds the following registrations under the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) for the Invisalign system:

109 Since 2018, Invisalign has offered a number of different treatment options and packages to trained doctors to offer to Invisalign customers. These were:

(a) Invisalign Clear Aligners Express package;

(b) Invisalign Clear Aligners Lite package;

(c) Invisalign Clear Aligners Moderate package;

(d) Invisalign Clear Aligners Comprehensive package;

(e) Invisalign First Comprehensive package;

(f) Invisalign System Comprehensive Phase 2 package; and

(g) Invisalign Go,

(collectively, the Invisalign Treatment Packages).

110 Ms McGoldrick, in her affidavit, described each of the Invisalign Treatment Packages and the type of customers that would fit within a particular package. In short compass, each of the Invisalign Treatment Packages differ based on the idiosyncratic requirements of the level of aesthetic correction required by the customer (such as the amount of tooth movement required, the level of teeth spacing, crowding, malocclusion, as well as the age of the patient).

111 Invisalign Australia only supplies the Invisalign Treatment Packages to eligible doctors who have received training in the use of the Invisalign system.

112 Since 2001, Invisalign Australia has continued to offer training courses in Australia, which is offered by the Invisalign Australia team as well as other independent practitioners. There are three training courses that Invisalign Australia offers:

(a) the Invisalign Fundamentals training course, which is targeted at dentists to use the Invisalign system and is best designed for dentists and orthodontists that have existing teeth straightening experience;

(b) the Invisalign Go Fundamentals training course, which is targeted at general dentists that have little to no teeth straightening experience; and

(c) the Invisalign Ignite training course, which is targeted at dentists that have previous experience using Invisalign Go, but wish to expand their treatment repertoire to include the full suite of Invisalign Treatment Packages,

(each a Training Course, collectively, the Training Courses).

113 Ms McGoldrick, in her affidavit, described each of the Training Courses.

Marketing and promotion of the Invisalign system

114 Since the launch of the Invisalign system in Australia in 2001, Invisalign Australia has promoted its brand and the Invisalign system in Australia through consumer marketing and marketing which specifically targets doctors.

115 With respect to consumer marketing, Invisalign Australia has, since at least 2016, advertised and promoted its products in Australia through a number of channels, including the following:

(a) the Invisalign Australia website located at www.invisalign.com.au;

(b) television;

(c) radio;

(d) print;

(e) social media;

(f) digital channels;

(g) out-of-home advertising commonly by way of digital panels at retail;

(h) shopping centres and gyms; and

(i) interactive customer experiences offered through the Invisalign Centre and popups in Westfield shopping centres.

116 Invisalign also sponsors events in Australia such as the Mercedes Benz Fashion Week in 2019. Ms McGoldrick deposed that advertising its brand at events such as Mercedes Benz Fashion Week offers increased media exposure and further promotes awareness of its products.

Cross-examination of Ms McGoldrick

117 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence that in order to provide Invisalign Aligner Treatment in Australia and indeed, to complete the Training Courses, it was a requirement that the course attendee was a dentist or an orthodontist.

118 Ms McGoldrick was asked about the Invisalign Go Fundamentals training course. Ms McGoldrick explained that the Invisalign Go Fundamentals training course is designed for dentists with little to no teeth straightening experience for simple teeth straightening cases, and involves a full day course. Once the dentist has completed this course, they are able to provide the Invisalign Go treatment in Australia.

119 Ms McGoldrick was asked about the Invisalign Fundamentals training course. Ms McGoldrick explained that this course is for dentists (more particularly, those dentists that have some experience in teeth straightening and have confidence in orthodontic treatment planning) and is designed to enable the dentist to use the full suite of the Invisalign Treatment Packages in Australia, once they have completed the Training Course.

120 Ms McGoldrick explained that the ClinCheck software is the system by which Invisalign interacts with the dentists and orthodontists that have completed one of its Training Courses. Once a dentist or orthodontist has completed a Training Course they are then an Invisalign provider (Invisalign provider).

121 After a dentist has completed the Invisalign Fundamentals training course they are then able to access the ClinCheck software, and that dentist, now an Invisalign provider, is able to access and order the full range of Invisalign Treatment Packages from within the system. Whereas a dentist that has completed the Invisalign Go Fundamentals training course is only able to order the Invisalign Go product through the ClinCheck system.

122 The Invisalign provider is then able to submit information to Invisalign through the ClinCheck system under what is called a “prescription form”. Then, based on the information that is provided within the prescription form, Invisalign, through its ClinCheck system, produces a 3D treatment plan with the help of certain Invisalign technicians (Invisalign technicians). Ms McGoldrick explained that these Invisalign technicians are based in Costa Rica and do not have Australian dental or orthodontic qualifications.

123 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence that Invisalign leaves the process of patient diagnosis entirely up to its Invisalign providers. Ms McGoldrick explained that the ClinCheck software allows Invisalign providers to approve or modify the 3D treatment plan that is generated. Any updates or modifications to these plans can be made by the Invisalign provider in minutes, or less. This process can also be done live, such that the Invisalign provider can work with the Invisalign technician in real time to update or modify the 3D treatment plan at their direction. Ms McGoldrick stated that Invisalign providers are encouraged to use the ClinCheck system in this way to speed up the turnaround time for customers.

124 Ms McGoldrick outlined, in further detail, the process surrounding the use of the ClinCheck system. Ms McGoldrick illustrated how, once an Invisalign provider has diagnosed a patient, they will then complete a treatment form and will enter the patient’s records into the system. These treatment forms are then sent to the Invisalign technicians in Costa Rica who then create the 3D treatment plan for that patient. The 3D treatment plan is then sent back to the Invisalign provider for their review to enable them to make sure that it is in line with the patient’s objectives for treatment. Ms McGoldrick gave evidence that there is usually a series of modifications that the Invisalign provider will make and send back to the Invisalign technician. Ms McGoldrick told the Court that, on average, an Invisalign provider will make three modifications to a patient’s treatment plan. Ms McGoldrick was able to provide this average based on data that is stored within the ClinCheck system. This process occurs until the Invisalign provider is satisfied with the treatment plan.

125 Ms McGoldrick was asked about the number of Invisalign providers in Australia. This information is confidential in nature, however Ms McGoldrick provided a confidential note to the Court, marked MFI-2, which contained the breakdown of these figures.

126 Ms McGoldrick was asked about Invisalign Virtual Care. Ms McGoldrick was played part of a YouTube video entitled “My Invisalign App – patient instruction video” published 7 October 2020, and marked exhibit 33. This YouTube video was annexure GB-126 to the affidavit of Greg Bodulovic affirmed on 10 October 2022. Exhibit 33 is an instructional video which shows the viewer how to use Invisalign’s mobile app (My Invisalign App or Invisalign Virtual Care). A screenshot of part of this video is extracted directly below.

127 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence that Invisalign Virtual Care allows Invisalign providers to monitor the progress of their patients’ Invisalign Aligner Treatment virtually. This is able to be done because Invisalign Virtual Care enables patients to take photos and videos of themselves and upload these photos directly to the My Invisalign App, which can be accessed by the Invisalign provider. The Invisalign provider can then respond to the patient through the app and can also review the progress photos that they receive via the My Invisalign App.

128 Ms McGoldrick was asked about the TGA process undertaken by Invisalign, with particular emphasis on the registration of its products that are registered on the ARTG. Ms McGoldrick gave evidence about the two ARTG identifiers that are each registered as “Medical Device Class 1” on the ARTG. Ms McGoldrick explained that the TGA changed their guidelines and in order to ensure that Invisalign complied with the TGA, Invisalign registered these products as medical devices on 23 November 2020.

129 Ms McGoldrick explained that the “sponsor” of these ARTG registrations was Invisalign Australia Pty Ltd, which means that this entity is the supplier of the product in Australia. Ms McGoldrick gave evidence that these ARTG registered products are subject to certain conditions. Ms McGoldrick, under cross-examination, stated that one of the conditions that has been imposed upon Invisalign is that it, as the sponsor, must report any adverse events which patients experience as a result of being treated with the Invisalign system to the TGA.

130 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence about Invisalign’s consumer marketing. Ms McGoldrick conceded that SDC’s brand is reasonably well-known in Australia and that, in her view, it has become reasonably well-known to Australian consumers that SDC offers a direct to consumer model. Ms McGoldrick agreed that the price of SDC aligners has become reasonably well-known to Australian consumers.

131 Ms McGoldrick was taken to the DIY article and was shown a sentence on the ultimate page of the article which reads:

Invisalign wants to ensure Australians considering teeth straightening know the facts, what to ask and what they’re getting, so they created the Be Clear on the Facts.

132 The above text is hyperlinked, such that when one clicks on the words “Be Clear on the Facts”, they are taken to Invisalign’s website and, in particular, to its webpage entitled “Be Clear on the Facts”, which Ms McGoldrick told the Court she is familiar with.

133 Ms McGoldrick identified that the DIY article would have been “driven” by Invisalign’s marketing team.

134 Ms McGoldrick gave evidence about Invisalign’s review committee. Ms McGoldrick explained that the review committee consists of a marketing representative, a legal representative and a clinical representative and they meet weekly to review material to ensure that it complies with all of these different areas before material gets published and before they take it to the consumer. Ms McGoldrick stated that she was not involved in any of the committee’s meetings in respect of the DIY article.

135 I find Ms McGoldrick to be a truthful witness whose evidence I accept.

136 Dr Stanley swore one affidavit dated 6 May 2022, which was tendered in evidence and marked as exhibit 78.

137 Dr Brad Stanley is an Australian registered dentist with more than 30 years of dental practice experience. Dr Stanley gave evidence relating to the pricing of treatment using the Invisalign system.

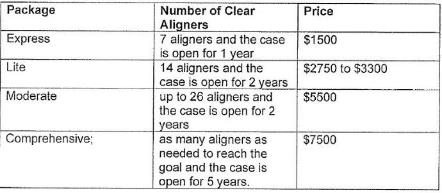

138 Dr Stanley deposed to the prices that he charges patients at his practice for the provision of Invisalign Aligner Treatment. Dr Stanley outlined how these prices vary depending upon the complexity of a patient’s treatment plan and the number of clear aligners that are needed to achieve the programmed treatment outcomes. The pricing structure adopted in Dr Stanley’s practice falls into four tiers, which are:

139 The price for each package includes the following products and services:

(a) initial diagnostic assessment which includes an intraoral exam and diagnostic record taking (including radiographs, photographs and an intraoral scan);

(b) treatment planning;

(c) an appointment to place attachments and fit the aligners;

(d) an in-person consultation approximately every 4 weeks to monitor the patient’s progress; and

(e) fixed or removable retainers following completion of treatment.

140 Dr Stanley was not called for cross-examination.

141 Ms Jaimie Maree Wolbers is the solicitor employed by MinterEllison, the solicitors for Invisalign. Ms Wolbers gave evidence relating to SDC marketing material she had obtained by taking internet and other web-based searches.

142 Ms Wolbers swore two affidavits that were tendered in evidence. The first was dated 4 April 2022 and marked exhibit 73. The second was dated 5 August 2022 and marked exhibit 74.

143 Ms Wolbers’ affidavits detail searches which she and MinterEllison conducted. These searches related to:

(a) SDC company information;

(b) SDC website information as well as SDC’s social media webpages;

(c) SDC’s advertisements and advertorial content;

(d) Google search engine results for various terms including “DIY teeth straightening” among other things;

(e) advertorial content of other similar aligner brands;

(f) Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) media releases; and

(g) the Orthodontics Australia webpage.

144 Ms Wolbers was not called for cross-examination.

145 Mr Jack Laurence Stanley is a solicitor employed by MinterEllison, the solicitors for Invisalign.

146 Mr Stanley affirmed one affidavit dated 5 August 2022, which was tendered in evidence and marked exhibit 77.

147 Mr Stanley’s affidavit provided a response to the affidavit of Mr Greg Bodulovic dated 1 July 2022.

148 Mr Stanley deposed to searches he made with respect to webpages that were referenced in Mr Bodulovic’s affidavit at [24] and [25] and shown at annexure GB-30. These searches were produced in order to negate any inference that Mr Bodulovic might have made to suggest that patients of dentists and orthodontists who utilise “DentalMonitoring”, (which is a remote monitoring solution that enables dentists and orthodontists to view the progress made by their patients by allowing patients to scan their teeth and take intraoral images with DentalMonitoring’s proprietary ScanBox Pro Device. The patient can then upload these images to the patient app for their dentist to view). Mr Stanley provided copies of screenshots which were annexed to his affidavit.

149 Mr Stanley was not called for cross-examination.

150 Dr Vicki Vlaskalic is a practising orthodontist who owns and operates her own practice and is also a clinical instructor in the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Melbourne. Dr Vlaskalic is a Clinical Consultant to Invisalign. Dr Vlaskalic gave expert evidence relating to orthodontic treatment in Australia, including the use of clear aligner therapy and evidence relating to the price of treatment.

151 Dr Vlaskalic prepared two affidavits which were tendered in evidence. Dr Vlaskalic’s first affidavit sworn 6 May 2022, was marked as exhibit 2; and her second affidavit sworn 6 August 2022, was marked as exhibit 3. Dr Vlaskalic participated in an expert conference which produced a joint expert report dated 5 October 2022, which was tendered in evidence and marked exhibit 8 (Joint Expert Report). Dr Vlaskalic also gave concurrent evidence with the other dental and orthodontic experts called to give evidence in the proceeding.

152 Dr Vlaskalic, in her affidavit evidence, provided an overview of:

(a) the concept of malocclusion, and her understanding of the phrase “mild to moderate malocclusion”;

(b) the basic biomechanics that are involved in moving teeth;

(c) the objectives of orthodontic treatment as well as the diagnostic and treatment planning processes that are involved in orthodontic practice; and

(d) clear aligner therapy in further detail, including the background to clear aligner therapy;

(e) the “Consent and History”, the “Pricing Page”, the “Night time Clear Aligners” and the “Smile Assessment” pages of the SDC’s website.

153 Dr Vlaskalic also provided a response to certain matters raised and opinions expressed in affidavits of Dr Derek Mahony, Dr Hendrick Lai and Dr Jeffrey Sulitzer.

154 Dr Vlaskalic’s affidavit evidence ran 169 pages, including annexures. Ultimately the issues between the experts were narrowly defined, which is exemplified by the Joint Expert Report and the evidence that was given in the expert conclave. I deal with Dr Vlaskalic’s evidence in greater detail below.

155 Dr Eugene Chan is a practising orthodontist who owns and operates his own orthodontic practice. Dr Chan has been appointed by the Dental Board of Australia as an arbitration consultant regarding complaints or concerns raised relating to dental and orthodontic practitioners. Dr Chan is also a clinical consultant to Invisalign. Dr Chan provided expert evidence pertaining to orthodontic treatment in Australia, including the use of clear aligner therapy and evidence relating to the price of treatment. Dr Chan prepared two affidavits which were tendered in evidence. Dr Chan’s first affidavit sworn 6 May 2022, was tendered in evidence and marked as exhibit 1; and his second affidavit sworn 5 August 2022, was marked as exhibit 4. Dr Chan also gave concurrent evidence with the other dental and orthodontic experts called to give evidence in the proceeding.

156 Dr Chan, in his affidavit evidence, provided an overview of:

(a) the orthodontic profession in Australia, including the educational and other requirements for registration as an orthodontist, and also the professional standards that orthodontists practicing in Australia are expected to meet;

(b) general concepts relating to the underlying anatomy and biology that guide orthodontic treatment and practice;

(c) malocclusion, its definition and meaning;

(d) the biomechanical principles that guide tooth movement, as they apply to orthodontic treatments;

(e) the type of orthodontic treatments available in Australia and commonly used in orthodontic practice;

(f) the process of patient assessment and diagnosis in orthodontic treatment, including where clear aligners are used;

(g) the factors that are considered in orthodontic treatment planning and implementation, including choice of orthodontic appliance, use of attachments in clear aligner therapy, and obtaining consent to treatment;

(h) how the outcomes of orthodontic treatment are measured and evaluated;

(i) how Dr Chan manages patients who present with requests for cosmetic-only treatment, (treatment that corrects the aesthetic aspects of their malocclusion without addressing co-existing functional problems);

(j) how Dr Chan uses Invisalign clear aligners in his practice;

(k) the cost of treatment using braces, Invisalign Aligner Treatment, or other clear aligners for treatment of a simple correction of overcrowding or spacing issues involving the front six upper and/or lower teeth; and

(l) his awareness of SDC Aligner Treatment and how it is marketed.

157 Dr Chan also provided a response to certain matters raised and opinions expressed in affidavits of Dr Derek Mahony, Dr Hendrick Lai and Dr Jeffrey Sulitzer.

158 Dr Chan's affidavit evidence ran 270 pages, including annexures. Ultimately the issues between the experts were narrowly defined, which is exemplified by the Joint Expert Report and the evidence that was given in the expert conclave. I deal with Dr Chan’s evidence in greater detail below.

159 Mr Alan Scott MacLean is a marketing research and data analyst and is the Principal and Director of Nulink Analytics Pty Ltd (Nulink Analytics). Mr MacLean was retained by MinterEllison, the solicitors for Invisalign, to provide an expert opinion in relation to the market research Actionable Study undertaken by SDC’s marketing analytics expert, Mr David Cristofaro and his company, Actionable Research.

160 By way of brief background, Mr Cristofaro, conducted the Actionable Study that surveyed 73 Australian dentists and orthodontists about their pricing. Mr Cristofaro, in the first Cristofaro Affidavit, identified the objectives for the Actionable Study. These were:

(a) to determine the average case numbers of a representative sample of general dentists and orthodontists in full-time practice in Australia;

(b) to understand the Study Participants’ usage of aligner-based treatment products from different companies;

(c) to determine the average price charged for aligner-based treatment and fixed appliances (namely braces) and the price charged most often (the mode price charged) as a function of treatment method, condition severity, and other relevant factors;

(d) to determine the criteria used by dentists and orthodontists to determine pricing for treatment of their aligner-based and fixed appliance-based cases; and

(e) to determine the difference between the amounts charged by dentists and orthodontists for aligner-based and fixed appliance-based cases and the amounts patients pay for these services.

161 Mr Cristofaro’s Actionable Study identified that the overall average fee charged for braces in treating mild to moderate malocclusion at the time of the data collection in July 2021 was $6,939 and the overall median fee was $7,100. Mr Cristofaro identified that the overall average fee charged for treatment using Invisalign Aligner Treatment for mild to moderate malocclusion was $6,926 and the overall median fee was $7,000. Mr Cristofaro found that the average and median prices were higher for severe malocclusion. Mr Cristofaro also identified that the fees charged for treating mild to moderate malocclusion by braces ranged from $3,500 to $9,180, whereas Invisalign Aligner Treatment ranged from $4,500 to $9,500.

162 Mr MacLean affirmed one affidavit dated 30 August 2022, which was tendered in evidence and marked exhibit 58 (MacLean Affidavit).

163 Mr MacLean deposed to his experience in marketing research and data analytics. Mr MacLean outlined how in order to design and implement any survey for the purpose of achieving the objectives identified above at, the following matters, at a minimum, are essential to achieve any kind of reliability in the interpretation of results:

(a) the interviewed sample needs to be representative of the target population or able to be reweighted so as to represent the target population;

(b) an appropriate sample size needs to be determined. In this regard, the considerations elucidated by William G. Cochran in 'Sampling Techniques, 2nd Edition' (1963, John Wiley & Sons Ltd) need to be followed, which includes the need to achieve a balance between the reliability in the results and controlling the costs of the work to be undertaken;

(c) questions asked during the interview need to be unambiguously understood by respondents in order for them to frame their responses correctly, as detailed by Sudman, Bradburn, and Schwartz in ‘Thinking about answers – the Application of Cognitive Processes to Survey Methodology’ (1996, Jossey-Bass Publishers). This could be achieved, for example, through both the pre-piloting and piloting of the survey instruments and procedures;

(d) objectives of the project need to be sufficiently clear to allow the appropriate questions to be asked in the appropriate manner;

(e) prior to analysis, results should always be cleaned to remove “speeders” (respondents who answer too quick to sensibly be responding to the survey questions), and “flatliners” – (respondents who show little or no variation across their answers to the questions (e.g. answering 5, 5, 5, 5 for all questions)); and

(f) the assumptions underlying the statistical tests utilised in the analysis need to be sustainable. For example, the “t-test” assumes at least approximate normality in the distribution of the target metrics within the population.

164 Mr MacLean provided evidence about the financial contribution that was offered as part of Mr Cristofaro’s survey. Mr MacLean’s evidence was that he understood that the Study participants in Mr Cristofaro’s Actionable Study were offered a “small financial contribution” to complete the Questionnaire in order to “increase the response rate to the Actionable Study”. Mr MacLean identified that he had not been told the amount of that financial contribution. Mr MacLean’s evidence was that the level of financial contribution can be an important factor in determining whether the Study Participants have been influenced in their willingness to participate in the questionnaire. This is because, in Mr MacLean’s view, if the financial contribution offered is well below a professional’s usual hourly rate, it may negatively affect a professional’s willingness to be interviewed or participate in a survey which can be an obstacle in obtaining the requisite number of respondents for the survey. Further, for those who agree to participate, it may affect the time and care that the individual devotes to answering the survey.

165 In relation to the Questionnaire that was used in the survey that Mr Cristofaro sent out to the Study Participants, Mr MacLean provided the following comments:

(a) it does not appear that Actionable Research conducted a pilot survey before proceeding with the questionnaire. It is best practice to conduct a pilot first, or at least to run through the questions that one intends to ask with a handful of potential respondents;

(b) you cannot in general assume that people understand the questions being asked in questionnaires. Particularly in the absence of a pilot, and given Survey Participants are not being guided through the questionnaire;

(c) the questions in the Questionnaire, relating to prices charged, use terms such as “the fee you charged most often”, “average fees”, “range of fees”, and “minimum and maximum price”. It is unclear why the Study Participants were asked questions in relation to the fees they charge in all of these different ways. In particular, it is unclear why Actionable Research has asked for the fee charged most often as well as the average fee charged. A questionnaire designed to elicit information about prices charged, in order to prompt the most accurate responses, should include instead questions along the lines of: “of the fees you charged, what is the minimum, what is the maximum and what is the average?”. In Mr Maclean’s experience, there would also be a risk of respondent fatigue at this stage of the Questionnaire. Mr MacLean explained that respondent fatigue is a “well-documented phenomenon” that occurs when Study Participants become tired of the survey task and the quality of the responses they provide begins to deteriorate which can lead to unreliable results. It occurs when Study Participants’ attention and motivation drop toward later sections of a questionnaire, particularly in circumstances where the questions become repetitive and/or the cognitive load is large. In order to reduce survey fatigue, it is critical to design questionnaires to be as engaging and efficient as possible; and

(d) when an online market research questionnaire asks participants for details of prices they have charged or have paid, participants do not usually consult their records to determine what they charged or paid but rather answer from their recollection. The answers are ultimately their guess, and perhaps their best/educated guess. Mr MacLean stated that the Study Participants would likely have completed the Questionnaire from their recollection rather than actually consulting their records which may have negatively affected the accuracy of the results.

Cross-examination of Mr MacLean

166 Mr MacLean was taken to [19] of the MacLean Affidavit, which sets out the minimum essential features, that in Mr MacLean’s view, are required in order to achieve reliable results in a survey of the kind conducted by Mr Cristofaro. Mr MacLean was taken to [19(c)] of the MacLean Affidavit, where he provides his view that “questions which were asked during the interview need to be unambiguously understood by respondents in order for them to frame their responses correctly”. It was put to Mr MacLean that he had not undertaken any assessment or testing of the survey questions in issue in this proceeding to see whether they were unambiguously understood by the respondents. Mr MacLean agreed that he had not done so.

167 Mr MacLean was taken to [44(f)] of the Maclean Affidavit, where Mr MacLean commented on the questions in Mr Cristofaro’s questionnaire in relation to the fees charged by dentists and orthodontists. Mr MacLean was taken to [44(f)] of the MacLean Affidavit in which he cited the proposition that “respondent fatigue is a well-document phenomenon” which occurs when survey participants become tired of the task and their answer begin to deteriorate, and stated, with respect to Mr Cristofaro’s Questionnaire that:

In my experience there would also be a risk of respondent fatigue at this stage of the questionnaire.

168 Mr Maclean was asked whether he had undertaken any independent assessment of whether the Study Participants did, in fact, experience respondent fatigue in answering the survey questions. Mr MacLean confirmed that he had not done so.

169 Mr MacLean was taken to [41] of the Maclean Affidavit, where he provides evidence in relation to the financial contributions that were offered to Study Participants. Mr MacLean was taken to the following part of this paragraph:

For instance, if the financial contribution offered is well below a professional's usual hourly rate, in my experience, it may negatively affect a professional's willingness to be interviewed or participate in a survey. This can therefore be an obstacle in obtaining the requisite number of respondents for the survey and, further, for those who agree to participate, it may affect the time and care that the individual devotes to answering the survey.

170 Mr MacLean was asked if he had conducted any independent assessment or analysis of whether the financial contributions that were made in relation to Mr Cristofaro’s survey did indeed affect the results. Mr MacLean conceded that he had not done so.

171 Mr MacLean accepted that, as a statistician, he had not undertaken any survey involving dentists or orthodontists.

172 Mr MacLean was taken to [19(b)] of the MacLean Affidavit, where he stated that one of the essential features of designing a survey that is reliable is to ensure that an appropriate sample size is determined which achieves a balance between reliability in the results and the cost of the survey being undertaken. Mr MacLean explained that, in general terms a larger sample size equates to a more reliable estimate, derived from the sample. Mr MacLean gave evidence that this needs to be balanced with the costs associated with achieving the result, as each extra interview that is conducted bares a cost, and therefore surveyors are subject to budgetary constraints. Mr MacLean stated that the factors that he set out at [19] of the MacLean Affidavit represent best practice in conducting a survey, but are not the requirements to create a “perfect study”.

173 Mr MacLean accepted that he did not conduct any independent analysis as to whether the respondents just addressed their responses.

174 Mr MacLean was an honest and forthright witness who made appropriate concessions during cross-examination. I accept his evidence.

175 Dr Marcus Tod is a registered and practising orthodontist and a partner at Ethos Orthodontics in Brisbane, Australia. Dr Tod affirmed one affidavit dated 28 September 2022, which was tendered in evidence as exhibit 59 (Tod Affidavit).

176 Dr Tod deposed that he had received a request from Ms Sadie Gregory, in which she asked Dr Tod if he would be willing to speak to www.news.com.au in relation to the DIY article, which he agreed to do.

177 Dr Tod stated that he was interviewed on the phone for around 30 minutes by Ms Pilar Mitchell, a journalist whom he understood was associated with www.news.com.au.

178 Dr Tod stated that during that interview, Ms Mitchell asked him a number of questions relating to individuals undertaking their own dental or orthodontic treatment, including teeth straightening, teeth whitening, veneers and tooth filing. Dr Tod deposed that he did not receive any payment, compensation, or consideration from Invisalign Australia or any other person for participating in the interview.