FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Taylor v Killer Queen, LLC (No 5) [2023] FCA 364

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

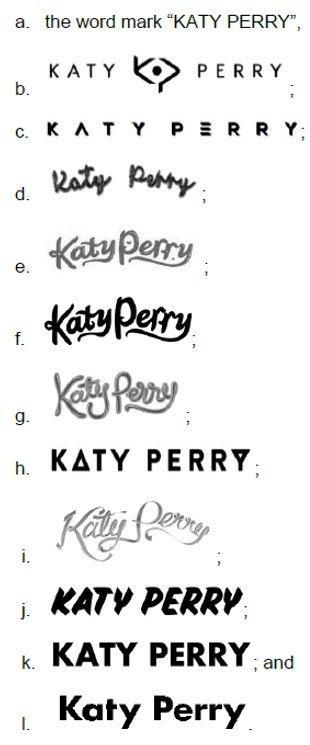

1. The parties are to confer and within 14 days of the making of these Orders provide to the Associate to Markovic J proposed orders giving effect to these reasons.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the proposed orders referred to in Order 1 above, including the appropriate order as to costs, the areas of disagreement should be set out in mark up in the draft to be provided.

3. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), and on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the documents listed in Schedule 1 to these Orders are to be treated as confidential and are not to be disclosed to any person other than the parties to this proceeding, their legal representatives and to the Court for the purpose of this proceeding.

4. Order 3 above is to remain in place:

(a) in relation to the document at item 6 of Schedule 1 until 31 December 2023; and

(b) in relation to the balance of the documents itemised in Schedule 1 until 31 December 2026.

5. The proceeding be listed for case management hearing on 10 May 2023 at 9.30 am AEST.

6. The text of the reasons for judgment published today is to be published and disclosed only to the parties and their legal advisors.

7. By 4.00 pm AEST on 26 April 2023 the parties are to inform the Associate to Markovic J whether:

(a) the proposed redactions (shown in yellow highlight) to paragraphs [478], [533] and [536] of the reasons published in accordance with Order 6 above are to be maintained having regard to Orders 3 and 4 above; and

(b) they propose any further redactions as a result of Orders 3 and 4 above.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

8. The reasons for judgment will be published on 27 April 2023 at midday AEST and any redactions made in the reasons are made in accordance with Orders 3 and 4 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Schedule 1

# | Document | Category |

1 | Agreement between Killer Queen LLC and Purrfect Ventures LLC dated 16 September 2016 | 1 |

2 | Agreement between Purrfect Ventures LLC and GBG USA Inc dated 16 September 2016 | 1 |

3 | Agreement between DMG and Second Respondent dated 22 October 2004 | 1 |

4 | GBG e-commerce and URL rights acknowledgement, confirmation and consent letter dated 1 December 2017 | 1 |

5 | Email between Epic Rights and DMG dated 10 March 2020 | 1 |

6 | List of Katy Perry branded merchandise in Australia by Epic Rights | 2 |

7 | Confidential Exhibit SJ-6 – Membership Interest Purchase Agreement between GBG USA Inc and Hudson Fund, LLC | 1 |

8 | List of goods (Excel version included in electronic court book) | 3 |

9 | List of goods – additional goods | 3 |

10 | Agreement between Bravado International Group Merchandising Services, Inc. and H&M Hennes & Mauritz GBC AB | 1 |

11 | Operating Agreement of Purrfect Ventures LLC | 1 |

12 | Agreement between UMG Commercial Services, Inc dba Universal Music Group Brands and Killer Queen, LLC | 1 |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MARKOVIC J:

1 This is a tale of two women, two teenage dreams and one name.

2 The applicant, Katie Jane Taylor, is a fashion designer. She is the registered owner of Australian trade mark no. 1264761 for the word KATIE PERRY (Applicant’s Mark) which is registered in class 25 for “clothes” (Registered Goods) with a priority date of 29 September 2008 (Priority Date). Ms Taylor has designed and sold clothes under the brand name “KATIE PERRY” since about 2007.

3 The second respondent, Katheryn Hudson, is a music artist and performer. In 2002 she adopted the name Katy Perry for the purposes of her professional music career and associated commercial merchandise licensing activities and, since that time, she has used that name for those purposes. I will refer to Katy Perry in these reasons as Ms Hudson. The first, third and fourth respondents to the proceeding are respectively Killer Queen, LLC, Kitty Purry, Inc and Purrfect Ventures LLC. As explained below, they are companies associated with Ms Hudson.

4 How Ms Taylor and Ms Hudson each came to be known by, and to use, the same name in their respective commercial activities, albeit with different spelling, is set out below. Suffice to say it is that fact that has led to this proceeding.

5 In summary, Ms Taylor alleges that the respondents have imported for sale, distributed, advertised, promoted, marketed, offered for sale, supplied, sold and/or manufactured in Australia, or to people in Australia, the Registered Goods bearing the word mark KATY PERRY and the other marks set out at [7] of her further amended statement of claim (FASOC) (see [267] below) (collectively, Katy Perry Mark) and further, or in the alternative, that the respondents have participated in a common design with certain retailers to carry out those acts. Ms Taylor alleges that by that conduct the respondents have infringed the Applicant’s Mark pursuant to s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act) or are liable as joint tortfeasors in the direct infringement of either some of the respondents or relevant third parties.

6 The respondents have filed a cross-claim seeking cancellation of the Applicant’s Mark pursuant to s 88(1)(a) of the TM Act on the grounds set out in s 88(2)(a), relying on ss 60, 42 and 43, and s 88(2)(c) of the TM Act.

7 On 7 April 2020 I made an order pursuant to r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that all issues of liability, entitlement to additional damages for alleged trade mark infringement and all claims for declaratory and injunctive relief be heard and determined separately from, and prior to, all other issues and claims in the proceeding: see Taylor v Killer Queen LLC [2020] FCA 444. These reasons address those issues.

8 Putting aside the experts called by the parties in relation to the question of whether particular items of apparel are clothes or goods of the same description as clothes (see [288]-[376] below), there were only two witnesses.

9 Ms Taylor relied on her own evidence and the respondents relied on evidence given by Steven Jensen, a partner of Direct Management Group Inc (DMG), a talent management agency which has managed, and continues to manage, Ms Hudson’s career. Ms Hudson did not give evidence. Ms Taylor’s and Mr Jensen’s evidence, which respectively chronicles Ms Taylor’s and Ms Hudson’s careers and the development of their “brands”, insofar as it is relevant, is set out below. Both Ms Taylor and Mr Jensen were extensively cross-examined.

10 The respondents submitted that Ms Taylor was not a truthful witness and that the Court should not rely on her evidence except where it is against her interests or independently corroborated by documents in evidence. They set out aspects of Ms Taylor’s evidence which they submitted demonstrated her dishonesty. Those aspects principally concern events which took place in 2009 and I address them, where relevant, below including by making findings as to whether her evidence is accepted. However, I am not prepared to reject all of Ms Taylor’s evidence, except where it is against her interests or corroborated by documents in evidence, as urged by the respondents.

11 The events which led to this proceeding commenced many years ago. Ms Taylor did her best to recall them and, given that a significant period of time has passed since some of the relevant events took place, I accept that she may have been confused in some aspects of her recollection. As a general observation, my impression of Ms Taylor was that she was somewhat naïve, prone to a level of exaggeration and opportunistic. It became clear on a number of occasions that Ms Taylor attempted to fashion her evidence in a manner that she believed would best assist her case, rather than giving full and frank evidence to the Court. On other occasions, she was evasive in responding to questions put to her in cross-examination. On yet other occasions Ms Taylor gave answers to questions that could not be accepted, particularly in the face of other contemporaneous material. Although this approach by Ms Taylor to her evidence served to undermine my overall impression of her as a witness, it has not led me to reject the whole of her evidence.

1.1 Ms Taylor – background and early career

12 Ms Taylor was born Katie Jane Perry. Her biological father is Brian Perry and her mother is Suzanne Mary Skillen. Ms Taylor’s parents separated when she was 18 months old and her biological father did not play a large role in the early part of her life. Thus while growing up Ms Taylor adopted her step-father’s last name, Howell, and for much of her life she was referred to as Katie Howell, although she never formally changed her legal name to Howell.

13 Ms Taylor had a falling out with her step-father and, in the early 2000’s, “reached out” to her biological father and sought to have a relationship with him. Ms Taylor’s evidence was that, as a result, since about 2006 she has referred to herself as “Katie Perry”. Despite that evidence, in cross-examination, a number of matters became apparent.

14 First, Mr Taylor only referred to herself as Katie Perry socially, that is, among her friends, and for example, when making restaurant bookings, but remained as Katie Howell in legal documents. According to Ms Taylor at that time and at least until 2008, when she first became aware of Ms Hudson (see [127] below), she went by two names.

15 Secondly, at the time she left her job at David Jones in 2007 (see [49] below), Ms Taylor was still known to her work colleagues as Katie Howell, despite having decided in 2006 to refer to herself as Katie Perry. Ms Taylor explained that when she first took on the role at David Jones she was Katie Howell and that it “would have been weird” for her staff if she suddenly changed names so she remained as Katie Howell while at David Jones.

16 Thirdly, there was evidence that Ms Taylor continued to use the name Katie Howell beyond 2006 including in relation to services acquired and documents relating to her fashion business. Ms Taylor said that this was either because the documents were legal documents or because she went by both names, “Katie Howell” and “Katie Perry”.

17 In March 2015, following her marriage to Matthew Taylor, Ms Taylor changed her legal name to “Katie Jane Taylor”.

18 Ms Taylor wanted to be a fashion designer since she was 11 years old. She studied at the Fashion Business Institute and in 2003 she completed a Fashion Industry Certificate IV.

19 Ms Taylor has always worked in retail and fashion and, until she started her own fashion label, had the following roles:

sales assistant at Browns, South Molton Street, London (1999);

assistant store manager at Jag, Warringah, New South Wales (NSW) (2000);

buyer and store manager at Activate Pro Shop, Bondi, St Leonards, Mosman and Parramatta, NSW (2001-2002);

store manager at Oroton, Paddington and Centre Point, NSW (2003-2005); and

menswear sales manager working in executive menswear and with buyers’ agents in order to determine what menswear to stock at David Jones in Chatswood and Warringah, NSW (2005-2007).

1.2 Ms Hudson – background and early career

20 As set out above, the principal witness for the respondents was Mr Jensen, a partner of DMG which has its principal place of business in Los Angeles, California, United States of America (US or USA). Mr Jensen founded DMG with his partner, Martin Kirkup, in April 1985. A third partner, Bradford Cobb, joined DMG in 1998.

21 DMG manages artists’ careers or other talents with a view to assisting in achievement of their commercial and career goals. Other managers, agents and firms are responsible for other aspects of support and services required by the artists or talents including creative, processing engagements and work for which they are booked, marketing and sales, publicity, accounting, legal and tax services and so on. DMG works closely with the other managers, agents and firms providing services in carrying out its role.

22 Mr Jensen was introduced to Ms Hudson in 2004 by his business partner, Mr Cobb. At the time she was introduced as Katy Perry. Prior to meeting Ms Hudson Mr Jensen understood, from research he had undertaken in relation to her early career as well as publicity he had read, that Ms Hudson had adopted the name “Katy Perry” as her professional or stage name in about 2002.

23 Since July 2004, when Ms Hudson was about 19 years old, DMG has acted exclusively as her talent manager. Since that time, Mr Jensen, together with Messrs Kirkup and Cobb, has taken various steps to plan for and implement the development of Ms Hudson’s career as a successful music artist including engaging other relevant service providers as required, securing commercial opportunities for her, carrying out various actions and providing advice. Mr Jensen explained that each of his and Messrs Kirkup and Cobb’s respective roles overlap in that they each know what the others are doing but that, in terms of responsibilities, Mr Kirkup is concerned with marketing and record label interaction, Mr Cobb oversees the music aspect of Ms Hudson’s career and he is involved in Ms Hudson’s brand affiliations, real estate purchases and touring.

24 In undertaking his role as talent manager Mr Jensen has kept in regular and frequent contact with Ms Hudson, by calls and meetings, to discuss strategy for managing her career and to keep her informed of the actions DMG is taking. He also texts Ms Hudson regularly.

25 Ms Hudson has been active as a music artist since at least 2000. As a teenager she performed gospel music and in 2001 she entered into a music recording contract with Red Hill Records, the “youth” division of a Christian entertainment company, Pamplin. Pamplin ceased to operate and Red Hill Records closed in December 2001.

26 Mr Jensen understands, given his role as Ms Hudson’s talent manager, that during 2001 Ms Hudson released an album titled “Katy Hudson” which included the single “Trust in Me” which placed at number 17 on the Radio & Records Christian Rock Chart.

27 From September to November 2001 Ms Hudson toured the US and performed as an opening act on the Christian music artist Phil Joel’s tour, “The Strangely Normal Tour”.

28 In 2002 Ms Hudson moved to Los Angeles and adopted her stage name “Katy Perry”. This is a combination of the shortened form of her first name, Katheryn, and her mother’s maiden name, Perry, and was adopted to avoid confusion between her and the actress Kate Hudson.

29 Prior to DMG commencing as Ms Hudson’s manager in 2004 the recording label Java, affiliated with The Island Def Jam Music Group and music producer Glen Ballard, was Ms Hudson’s record company for a short period. During that time although Ms Hudson recorded music, it was not released as an album.

30 In 2004 Ms Hudson provided the background vocals for the song “Old Habits Die Hard” by Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones which was featured as track one on the album “Alfie”. The album won the 2005 Golden Globe Award for best original song at the 62nd Annual Golden Globe Awards.

31 From the time that DMG started to represent Ms Hudson there was substantial activity associated with the planning and development of her career, including writing and production of music and seeking performing and recording opportunities. Mr Jensen was closely involved in those activities. At that time Colombia Records was already in place as Ms Hudson’s record company and work was proceeding on an album with Ms Hudson as one of two lead singers with the band “Matrix” although, the album was never released. The relationship with Colombia Records came to an end because of creative differences, including over Ms Hudson’s ambition for a career as a solo performing artist.

32 In October 2004 Ms Hudson was featured in an article titled “The Next Big Thing” in Blender magazine, a US music industry publication.

33 On 24 May 2005 Ms Hudson’s unreleased single “Simple” featured as track 11 on the soundtrack to the “Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants” released by Colombia Records. In 2005 Ms Hudson released a music video for “Simple”. The video currently has over five million views on a fan account on YouTube uploaded in 2007.

34 The “Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants” movie was released in Australia on 23 June 2005. It ranked as number eight on its opening and in its second weekend in cinemas. According to a website “Box Office Mojo”, which Mr Jensen described as an Amazon-owned box office revenue tracking website, the movie grossed just over US $1.3 million in Australia.

35 In November 2005 Ms Hudson collaborated with Payable On Death (P.O.D.), an American Christian “nu metal” band on its single titled “Goodbye for Now” and was featured in the music video for the song. In January 2006 the band, together with Ms Hudson, performed the single on “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno”.

36 Ms Hudson featured in a music video for the single “Cupid’s Chokehold” by US rock band “Gym Class Heroes” which was released on 28 November 2006.

1.3 Killer Queen, Kitty Purry and Purrfect Ventures

37 Killer Queen was incorporated on 27 August 2009 in California with Ms Hudson as its sole shareholder and officer. On 16 December 2011 Ms Hudson and Killer Queen entered into a deed of assignment pursuant to the terms of which Ms Hudson assigned to Killer Queen all of her “rights, titles and interests in and to” the trade marks and service marks and the federal registration and US and international registrations and applications listed in schedule A to the deed.

38 Kitty Purry was incorporated on 23 April 2008 in California. In its statement of information filed in 2016 it describes its business as “Entertainment – Music Touring”. Ms Hudson is the sole director, chief executive officer, secretary, chief financial officer and shareholder of Kitty Purry.

39 Purrfect Ventures was incorporated on 7 September 2016 in Delaware. Its initial members were Killer Queen and GBG USA Inc. As described at [234] below, in 2021 Hudson Fund, LLC, a company incorporated in 2016 with Ms Hudson as its sole member, acquired GBG’s shares in Purrfect Ventures.

1.4 Ms Taylor starts her own fashion label

40 In 2007, after leaving her role at David Jones, Ms Taylor started her own fashion label, a decision which was inspired by her travels in Italy the preceding year.

41 From the outset Ms Taylor had a clear vision of what she wanted her label to be; she wanted to design luxurious loungewear. She was aware, from working in retail and her experience buying clothes, that there was a niche market at the time for this type of garment. Ms Taylor described loungewear as “garments which are comfortable enough to be worn at home, but sufficiently aesthetic to be seen out and about in”. She wanted to create garments that women could dress up or down and which they felt good in “no matter their shape, age or size”. While Ms Taylor initially planned to design garments for women, she ultimately intended to expand her label into menswear.

42 Ms Taylor wanted to ensure that the process of designing and manufacturing her clothing was kept in Australia. She thought that a “Made in Australia” aspect of the brand that she wished to build would be an asset. It would help to show the sustainability of the label and to reduce the carbon footprint in production of the garments, which would be an attractive quality for the brand. Ms Taylor wanted to have control over all aspects of the manufacturing process to ensure the quality of the garments. Having them made in Australia would allow her to have greater control and oversight of the goods produced which she thought would ultimately make her business easier to run.

43 Ms Taylor was aware that having her garments manufactured in Australia would cost more but she considered that the quality and sustainability of the goods and the positive qualities of the brand would outweigh the costs and allow her to charge more for her clothing.

44 Another important aspect of Ms Taylor’s business was that she intended to donate a proportion of its proceeds to an Australian charity. Ms Taylor wanted her business to have a positive impact on the community and she thought that this would also confirm the positive identity which she wished for the brand. Since inception the “KATIE PERRY” label has donated to a number of charities including Lucca Leadership Charity, bushfire appeals, breast cancer events and refugee organisations.

45 Ms Taylor described the process she has adopted since 2007 to produce her garments. It is not necessary to set it out in detail but in summary it involves Ms Taylor sketching the garment, preparing more detailed line drawings, instructing a pattern maker to create a pattern from her line drawings, sourcing the fabrics, having a sample made, finalising the pattern and sewing the garment. Ms Taylor described it as an iterative process which includes testing the fit of the garment on a model or mannequin.

46 On 19 December 2006, prior to leaving her job at David Jones, Ms Taylor began to take steps to establish her business. She registered an Australian business number (ABN) under the name “PALMS”, which was the name she initially chose for her label as a nod to her mother’s shop. However, in either December 2006 or January 2007 she was dissuaded from using the name “PALMS” by a friend, Christina Andoniou, who told her that it made her think of old people in Florida. As this was not the image Ms Taylor wished to convey she decided instead to use her name, “Katie Perry”. Ms Taylor was aware that numerous designers used their own names for their brands, citing for example Carla Zampatti, Collette Dinnigan, Leona Edmiston and Oscar de la Renta. At the time Ms Taylor did not want her label to be associated with the name Katie Howell given her falling out with her stepfather.

47 Ms Taylor cannot now recall precisely when in 2007 she decided to change the name of her business from “PALMS” to “KATIE PERRY”. However, she believes that it must have been sometime before April 2007 as on 5 April 2007 she applied to register the business name “Katie Perry”, which was subsequently registered on 12 April 2007. For reasons which Ms Taylor cannot now recall she did not update the trading name associated with her ABN to “KATIE PERRY” until 7 August 2007.

48 On 2 May 2007 Ms Taylor registered a domain name for her business at www.katieperry.com.au. Ms Taylor had originally wanted to register the domain name www.katieperry.com because she dreamt of her brand going global. However, upon undertaking a search in about late April or early May 2007 that domain name appeared to be registered to a woman in the United Kingdom (UK) and, to this day, is still registered to that person. As she could not register the latter domain name Ms Taylor chose to register the Australian domain.

49 Ms Taylor left David Jones in February 2007. She thought that it would probably take some time to set up her new business. She was not only seeking to become a fashion designer but was also going to be running her own business and, until that time, Ms Taylor had only ever worked for others. Accordingly, after leaving her full time employment, in order to still earn money, Ms Taylor worked casually as a receptionist at a waxing salon and devoted her spare time to building her business. She estimated that in 2007 she spent about 30 hours per week developing her label and her business.

50 As this was the first time Ms Taylor was creating a business she sought out business training and, on 20 July 2007, she attended a business course for people starting their own businesses at Mosman Evening College. At the course Ms Taylor met other people who were in the same position as her including Manush Farhang who was also starting his own fashion label. Ms Taylor became friends with Mr Farhang and they helped each other out as they sought to establish their respective businesses.

51 On 21 August 2007 Ms Taylor registered an email address, katie.perry7@gmail.com. In her business, Ms Taylor used that email address as well as two emails associated with her domain name: info@katieperry.com.au and katie@katieperry.com.au.

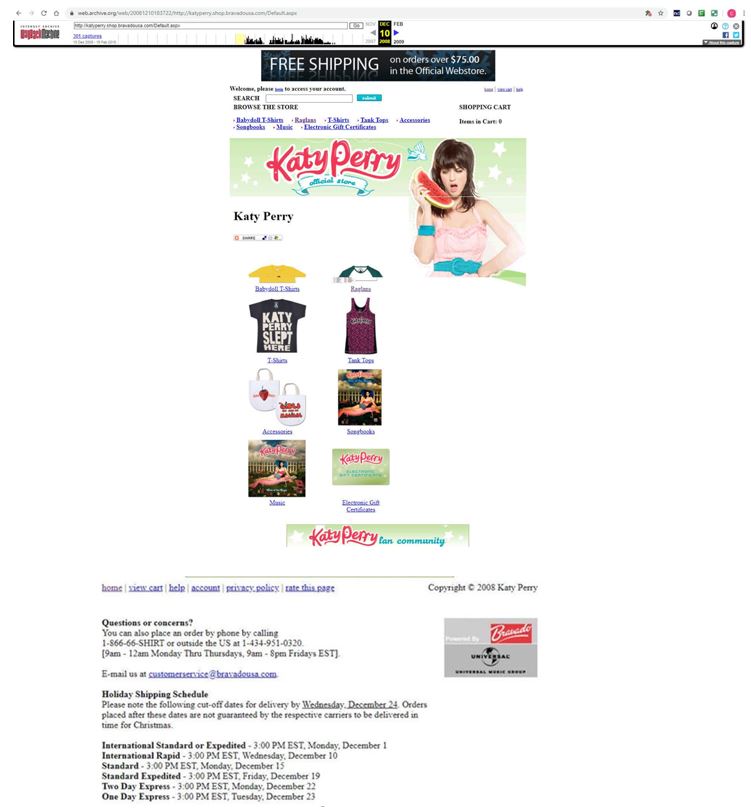

1.5 Ms Taylor makes her first application for registration of a trade mark

52 On 29 August 2007 Ms Taylor attended an IP Australia business course at which she learnt about the process for, and importance of, applying for trade marks and designs for her business and about copyright. At about this time she also engaged Three Dimensional Communication to design business cards, letterhead and swing tags for her garments.

53 On 13 September 2007 Ms Taylor applied to register a trade mark for a fancy logo based on the logo on her business card. The prominent feature of the logo was the words “KATIE PERRY” in cursive font. She applied for registration of the trade mark in class 42 for “clothing and fashion designing” (First KP Trade Mark). At the time Ms Taylor had not appreciated that goods and services belong to different classes. It was only in 2008 that she came to understand that in order to obtain better protection she should seek to register a mark in relation to clothes which were the type of goods she intended to sell.

54 By letter dated 4 January 2008 IP Australia informed Ms Taylor that her trade mark application no. 1198609 for the First KP Trade Mark had cleared the examination stage of the registration process and that it would be advertised on 17 January 2008, which would commence the three month opposition period. The letter noted that if Ms Taylor paid the registration fee of $250 by 17 July 2008 and no one raised an objection within the three month opposition period, or sought an extension of time in which to do so, IP Australia would automatically register the First KP Trade Mark when that period expired. IP Australia also warned that if the registration fee was not paid by 17 July 2008, the trade mark application would lapse.

1.6 Launching the Katie Perry label – October to November 2007

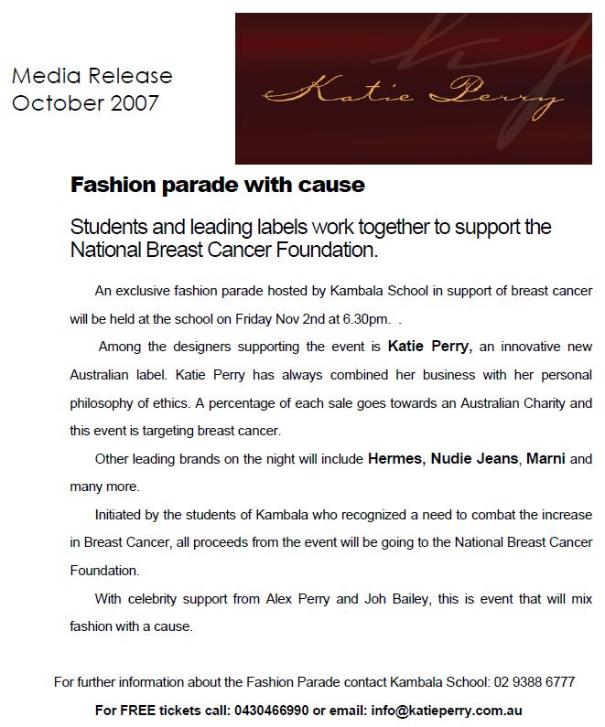

55 In about October 2007 a friend of Ms Taylor’s, Cameron Paulinich, who was a gardener at Kambala School, a private girls school in Sydney, informed Ms Taylor that the students were hosting a fashion parade to raise money for charity and asked her if she wished to be involved. The event was titled “Catwalk for a Cure” and was to raise money for the National Breast Cancer Foundation. Ms Taylor’s name was put forward as a potential designer and she was selected to dress some of the students for the parade. By that time Ms Taylor had finalised several designs, but had not yet produced her garments at scale. She had only one or two of each style made up which she was using as samples to locate a suitable production house. Nonetheless Ms Taylor considered the Kambala fashion parade to be a great opportunity to promote the “KATIE PERRY” brand and her designs so she agreed to debut them at the event. On 31 October 2007, prior to the fashion parade, Ms Taylor sent a press release to Radio Northern Beaches and New Woman Magazine about the launch of her label which provided:

56 The Kambala parade took place on 2 November 2007. Ms Taylor considered it to be a success and posted about the event on her personal Facebook page. Ms Taylor did not set up a Facebook page for the “KATIE PERRY” brand until 8 January 2009.

57 The Kambala parade generated interest in Ms Taylor’s brand and she received verbal inquiries asking where her garments were available. Ms Taylor gave evidence that, given her inexperience, she was not as prepared as she should have been and was not in a position to take full advantage of the interest at the time. She had not yet ramped up production as she had not been able to locate a suitable production house nor had she set up a website at her registered domain name.

1.7 Ms Taylor establishes a production chain

58 As set out at [42] above, Ms Taylor wished to have her garments made in Australia. When starting out Ms Taylor found it very difficult to identify a suitable production house to manufacture her garments on a relatively small scale using her preferred fabric which was both reliable and reasonable in price. As a result, when Ms Taylor first commenced production she retained different people for each step of the production process, including pattern makers, fabric suppliers, cutters and manufacturers.

59 In order to gauge interest in garment colours and styles and to determine what to produce, on 15 November 2007 Ms Taylor undertook a survey of her friends and acquaintances. By the end of 2007 she was ready to produce her designs at volume but she still needed a production house willing to make the clothes in the smaller quantities required. After making enquiries, she identified a suitable candidate and from 2008 she began working with Kim Phung and his production house.

60 Ms Hudson’s career was also developing.

61 In about April 2007 Ms Hudson changed her record company to Virgin which was then owned by EMI. It merged with Capitol Records when Universal Music acquired EMI in 2012. Mr Jensen considered this to be a major development in Ms Hudson’s career because, based on discussions at the time with executives at Virgin, he understood it was committed to the development of Ms Hudson’s career as a solo artist which was her career ambition.

62 From that time there was increased activity associated with Ms Hudson’s career, in which Mr Jensen was closely involved, including continued writing, production and recording of music, promotion of Ms Hudson and her music and planning for commercial opportunities.

63 In November 2007, in advance of the planned release of a Katy Perry album, Ms Hudson’s single “Ur So Gay” and music video was digitally released on the youth oriented social media website, MySpace. It was immediately very popular and, without active promotion, it “went viral”. An Extended Play (EP) including the single was subsequently released and from 15 January 2008 was available for purchase (in a compact disk (CD)).

64 After its release the “Ur So Gay” single received publicity in:

(1) the US Out Magazine online in an article titled “You probably think this song is about you” dated 19 November 2007;

(2) the US McClatchy Tribune Business newspaper online, which was accessible in Australia from 5 December 2001, in an article titled “Katy Perry makes Bay Area debut: New Year’s show introduces buzz-worthy up-and-comer” dated 28 December 2007;

(3) the US Billboard Magazine online, which was accessible in Australia from 8 January 1994, in an article titled “The Billboard Reviews Singles” dated 12 January 2008; and

(4) a radio interview on the Johnjay & Rich Radio show on Phoenix’s 104.7 KISS FM station in April 2008 in which the artist Madonna mentioned Ms Hudson’s “Ur So Gay” single. A transcript of that interview prepared by the respondents’ lawyers includes the following exchange between Madonna and the two presenters:

Presenter 2: Do you have something geeky on your iPod that you love that you wouldn’t admit to many people?

Madonna: Geeky?

Presenter 2: Yeah, something that is not yours but just kind of out of context for you.

Madonna: Well I have a favourite song right now

Presenter 1: What’s that?

Madonna: It’s called … it’s called ‘Ur so gay and you don’t even like boys’

Presenter 2: [Laughing] That sounds awesome.

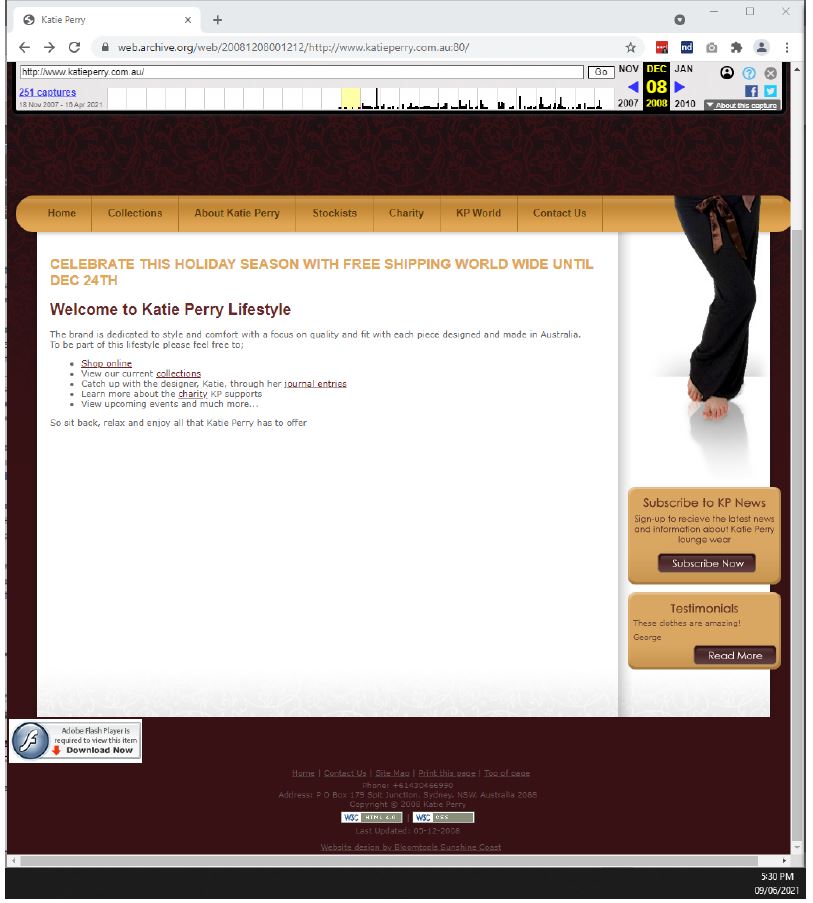

Presenter 1: That might be a song about me.

Madonna: Have you heard it?

Presenter 2: Is it…

Madonna: You have to hear it.

Presenter 2: Is it a children’s song?

Madonna: It’s by an artist called Katy Perry

Presenter 2: Let me look it up.

Presenter 1: Look it up while we see if we can find it

Madonna: Oh it’s so good. Check it out on iTunes.

Presenter 1: Sounds like the story of my life.

Presenter 3: Jesus John.

Presenter 2: Katy Perry.

65 According to Mr Jensen the “Ur So Gay” single was successful in several countries including the US, with over 500,000 sales and Gold Certification by the Recording Industry Association of America, and Brazil, with over 100,000 sales and a Platinum Certification by Pro-Musica Brazil. In 2008 the “Ur So Gay” single also peaked at number one on the American Billboard Hot Dance Single Sales Chart.

66 In late 2007 Mr Jensen observed that Ms Hudson’s popularity started to grow in Australia. This growth continued with the release of Ms Hudson’s singles in early 2008 and her album in June 2008, as described below. From at least early 2008 Mr Jensen considered that Australia was going to be an important market for Ms Hudson’s career.

67 In January 2008, in response to the positive reception and attention given to the “Ur So Gay” single, a seven inch vinyl version of it was released. It was available for purchase and was used on behalf of Ms Hudson as promotional merchandise.

68 From early 2008 Mr Jensen and others involved in the development and management of Ms Hudson’s career planned for her to undertake a number of promotional and performance activities before a worldwide concert tour scheduled to take place in 2009.

69 In addition in early 2008 Ms Hudson was invited to perform in the US summer at the “Warped Tour”, a US rock music tour which has operated since 1995, usually at outdoor venues, with a strong emphasis on punk rock. Its major sponsor has traditionally been the Vans skateboard shoe brand and the tour is often called the “Vans Warped Tour”. The “Warped Tour” later toured to some overseas countries.

70 On 8 April 2008 Ms Hudson performed the “Ur So Gay” single live on “Last Call with Carson Daly”, a US television variety program.

71 In April 2008 Mr Jensen was touring Australia with artist k.d.lang. While here he met with Michael Coppel, an Australian concert promoter. Mr Jensen mentioned Ms Hudson to Mr Coppel informing him that he should “look out for this artist”. Mr Jensen recalls that he said words to the following effect to Mr Coppel:

I encourage you to take note of Katy Perry. Let me know if you wish to be in touch with Katy’s local Australia record label EMI.

72 On 17 June 2008 Ms Hudson released her second studio album “One of the Boys” which included the song “Ur So Gay” and the singles “I Kissed a Girl”, “Hot n Cold”, “Thinking of You” and “Waking Up in Vegas”. The “One of the Boys” album and those singles ranked on international music charts. Following its release the album attracted media attention including in a number of Australian online publications such as:

(1) The Daily Telegraph newspaper, available in NSW, Australian Capital Territory and Queensland, which featured an article titled “Listen up: Album of the week”, dated 31 July 2008, which, among others, reviewed “One of the Boys”;

(2) The Herald Sun newspaper which featured an article titled “from gospel to gay” dated 7 August 2008;

(3) The Adelaide Advertiser newspaper which featured an article titled “Miss versatility” dated 7 August 2008;

(4) The Sunday Age newspaper which featured an article titled “One of the Boys: Reviews - CDs” dated 10 August 2008;

(5) The Brisbane Courier Mail newspaper which featured an article titled “CD Reviews” dated 14 August 2008, which included a review of the “One of the Boys” album;

(6) The Age newspaper which featured an article titled “One of the Boys: Music” dated 15 August 2008;

(7) The Brisbane Sunday Mail newspaper which featured an article titled “[POP] One of the Boys Katy Perry” dated 17 August 2008;

(8) The Townsville Bulletin newspaper which featured an article titled “cds: The title track is fitful and energetic and the lyrics tell of Katy Perry’s desire to be one of the girls not one of the boys” dated 21 August 2008;

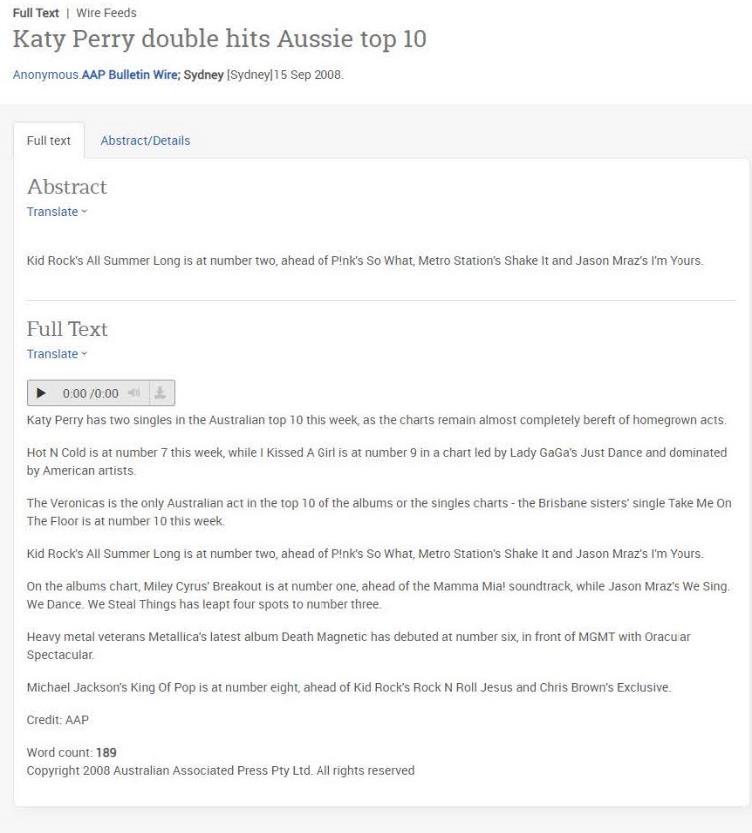

(9) The AAP Bulletin Wire newspaper which featured an article titled “Katy Perry double hits Aussie top 10” dated 15 September 2008; and

(10) The Gold Coast Bulletin newspaper featured an article titled “CD Reviews” dated 16 September 2008 which included a review of “One of the Boys” album.

73 In anticipation of Ms Hudson’s participation in the “Warped Tour” Mr Jensen pursued merchandising opportunities. In addition:

(1) on 12 June 2008 he caused an application to register “KATY PERRY” as a trade mark for apparel in class 25 to be lodged in the US; and

(2) on 26 June 2008 he caused an application to register “KATY PERRY” as a trade mark for music, CDs and other goods in class 9 and for entertainment and other services in class 41 to be lodged in the US.

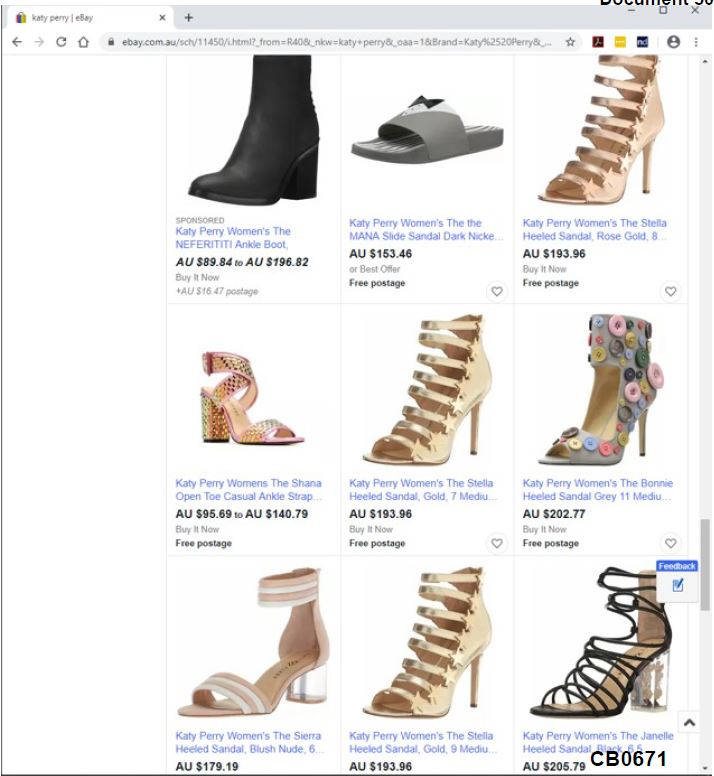

74 Mr Jensen and his colleagues at DMG arranged for a range of “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise to be specially designed and produced for the “Warped Tour” by a US company called Chaser. This included various clothing items and other merchandise including heart shaped glasses, lip balm (cherry chapsticks) and tote bags. At each concert during the tour there would be an official “Warped Tour” merchandise booth where fans could buy merchandise from the various bands who were performing. Mr Jensen and his colleagues at DMG planned and arranged for the Katy Perry section of the merchandise sales area to be colourful, fruit themed and “girly”, making it distinctive and different from the merchandise offered by other bands. An image of Ms Hudson at the “Warped Tour” “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise booth taken from a YouTube video appears below:

75 The “Warped Tour” commenced on 20 June 2008 in Pomona, California and ended on 17 August 2008 in Carsen, California. Mr Jensen attended some of the concerts and was otherwise kept informed by the tour manager and Mr Cobb, who also attended a number of the concerts, about all aspects of Ms Hudson’s performances, promotional events and merchandise. Ms Hudson performed about 40 concerts, performing on the main stage on every date of the tour except for 10 and 11 July 2008. On 20 June 2008, at the beginning of the “Warped Tour”, Ms Hudson performed her single “I Kissed a Girl”.

76 During the northern hemisphere summer of 2008 Ms Hudson’s commercial and career momentum increased. Mr Jensen observed that: Ms Hudson was very popular on the “Warped Tour”, attracting large audiences that sought out her performances; at the time her three singles, including “I Kissed a Girl”, were popular on radio and received extensive airplay; and, while the album “One of the Boys” was slower to gain sales following its release in 2008, it was ultimately successful. The “End of year chart – top 100 singles in 2008” published by the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) shows that for 2008 Ms Hudson’s single “I Kissed a Girl” was at number six and her single “Hot n Cold” was at number 16.

77 During Ms Hudson’s 2008 performances and promotional appearances Mr Jensen observed that she was popular across a wide cross section of people, including teenage boys and girls. In 2008 Ms Hudson’s popularity quickly spread internationally including because of international coverage of her performances on the “Warped Tour” and because of the popularity of the singles she had released, including “I Kissed a Girl”, on radio in a number of countries such as the UK, Japan, Germany, France, Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Spain, Russia and South America.

78 Mr Jensen together with, among others, his partners and staff members at DMG and executives and staff members of the record company, proceeded in the northern hemisphere summer of 2008 with planning a substantial North American and international promotional tour for Ms Hudson during which she would undertake a range of scheduled events promoting her album. They included personal appearances, radio and television interviews, meet and greets with fans, small venue concert appearances, meeting local record label personnel and events aimed generally at increasing Ms Hudson’s visibility. The overseas markets for the tour included the UK, Canada, Germany, Spain, Mexico and Australia, as explained below, with the visits to take place in the last few months of 2008. During the tour, the concert dates in countries where Ms Hudson was to perform during her 2009 worldwide tour were to be announced.

79 In the course of 2008 Ms Hudson received publicity in Australian newspapers and magazines including The Age, The Brisbane Courier Mail, The Sunday Herald, The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and The Canberra Times. For example an article appearing in The AAP Bulletin Wire Australian newspaper dated 15 September 2008 reported:

80 Given Mr Jensen’s view about the importance of the Australian market to Ms Hudson’s career, by mid 2008 he considered that the next logical step was for her to include Australia in her 2008 promotional tour and in the itinerary for the 2009 world concert tour.

81 In July 2008 Mr Jensen corresponded with Mr Coppel by email in relation to Ms Hudson and her upcoming promotional visit to Australia and anticipated concert tour. An email dated 22 July 2008 with subject “Re: Katy Perry” from Mr Jensen to Mr Coppel included:

I am thrilled that you will be our promoter for Katy Perry in Australia. You’ll recall that I mentioned Katy to you when we ran into each other at the Intercontinental in Sydney. We have been managing Katy for the past four years, taking the time to develop her and set up the album for release. She might seem like an ‘overnight sensation’ to the outside world, but it’s been a long and involved road to get to where we are today. As you probably know, she’s doing incredibly well in North America and it’s now starting to ‘take off’ in the rest of the world. The success of the single, ‘I Kissed A Girl’ in Australia is phenomenal. And, we have high hopes for the album release on August 2. Needless to say, we’re very excited.

Katy is an edgy pop artist with a long career ahead if we do this right. She wrote (or co-wrote) all the songs on the album. She is a very determined woman, has a compelling personality, is sexy and extremely talented. You’ll know what I mean when you meet her .... she’s infectious and ambitious!

Again, I’m thrilled that you will be our ‘promoter’ partner in Australia, and we look forward to working together to build Katy’s concert career. I know Emma is in contact regarding the showcase gigs in October, and please know that management is available to help in any way possible. You’ll see Bradford Cobb, Katy’s primary manager at Direct Management, when he’s with Katy during the promotion trip. You’ll remember that Bradford was with the B-52’s when they played the Hordern Pavilion for you several years ago. I’m copying Bradford on this email so you have his contact information.

Cheers,

Steve

82 In August 2008 Messrs Jensen and Coppel exchanged further emails about Ms Hudson’s album debut on the Australian album charts, which came in at number 12.

1.9 The development of KATY PERRY merchandise

83 By July 2008, based on Ms Hudson’s success, her increasing popularity and in anticipation of her global concert tour, Mr Jensen considered that there was a significant commercial opportunity for sales, including online sales, of “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise. Accordingly, he commenced planning and carrying out various activities to take advantage of that commercial opportunity in all countries where Ms Hudson was popular at the time, including Australia.

84 From July to September 2008 Mr Jensen was involved in the planning and preparation for Ms Hudson’s promotional tour in 2008 and subsequent world concert tour in 2009, including her travel to and touring in Australia. At the same time Mr Jensen was also involved in activities related to promoting commercial opportunities for “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise. As to the latter Mr Jensen had Australia in mind as a market of interest and importance and considered that “KATY PERRY” branded apparel and other merchandise would be popular and would sell well in Australia including at concert venues, retail stores and online.

85 In July 2008 Mr Jensen commenced discussions in relation to “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise with Tom Donnell of Bravado International Group Inc., a merchandise company that operated in the music industry. In these reasons, I will refer to that company and any of its related entities, including Bravado International Group Merchandising Services, Inc, as Bravado. Bravado’s role was to arrange merchandise designs for approval and, when approved, to arrange for the manufacture and distribution of licensed merchandise for advertising and sale, including through other intermediaries and resuppliers.

86 Having worked with Bravado and Mr Donnell for 15 years, Mr Jensen was aware that Bravado provided branded merchandise to distributors for resupply to retailers including the supply of mass market merchandise to department stores for retail sale to consumers. The branded merchandise was advertised by the retailers and through other promotional activities and was offered for sale and sold to members of the public by the retailers.

87 In or about 2008 or 2009, before her first world concert tour, Mr Jensen introduced Ms Hudson to Mr Donnell and his colleagues at Bravado, including those involved in the design of products. Mr Jensen recalls that he had discussions with Ms Hudson about his prior experiences working with Bravado and that Ms Hudson accepted his recommendation that they work with Mr Donnell and Bravado.

88 Following the development of the internet in the 1990s, it was also Mr Jensen’s experience that branded merchandise was sold to members of the public through websites, where orders could be placed electronically or by calling an advertised telephone number. Since at least the late 1990s this was another channel of sales used by Bravado and Mr Jensen for artists for their branded merchandise.

89 By email sent on 22 August 2008 Mr Donnell provided Mr Jensen and others with proposed “I Kissed a Girl” designs noting that there would be “a few more to choose from in the master presentation coming next week”. Mr Jensen responded indicating that he and Mr Cobb would review the designs over the weekend and asked “[h]ow fast could we get this ready?”. By email dated 23 August 2008 Mr Donnell responded in the following terms (as written):

We will release to sell the day it’s approved on paper. About one week to sample and then a week to manufacture. Retailers and Etailers will determine distribution timeline, but would think product will land in the market four weeks from approval. Seems like a long time, but the key is circulating approved designs. Once buyers know have something to buy, they will lock in and wait for product to arrive.

90 By email dated 6 September 2008 from Shannon Biliske of Bravado to, among others, Messrs Jensen and Cobb, Ms Biliske provided the initial merchandise design concepts for “Katy Perry”. There followed an exchange of emails with feedback about the proposed online store.

91 By email dated 9 September 2008 David Weekes of Red Octopus contacted Mr Cobb inquiring if DMG was interested in enlisting its help with merchandise production or sales for Ms Hudson’s upcoming Australian tour. Mr Jensen forwarded Mr Weekes’ email to Mr Coppel. By email dated 11 September 2008 with subject “merchandise for Katy Perry’s upcoming Australian tour” Mr Coppel responded to Mr Jensen in the following terms (as written):

I’ve never heard of Red Octopus, and I think Derek is out of the business, isn’t he?

I have an on-going merch deal with Simon Lonergan at TSP, who handles any of my tours for which I have merch rights, as well as a bunch of major acts ((including RHCP, Pearl Jam, The Police, RATM, Christine Aguillera, Gwen Stefani etc), as well as local artists and start up club tours.

He has his own T shirt printing factories so can do quick turnaround and good pricing.

So I’m happy to sort out any merch requirements you have for the promo shows on a straight split of net income, if that suits?

92 On 11 September 2008 Mr Jensen sent an email with subject “katy perry retail merch” to Mr Donnell, among others, which included:

I don’t want to shock you, but we have one design approved for retail sale and should have one or two more by tomorrow. The approved design is attached. Let’s get rolling on this one.

sj

93 On 16 September 2008 Mr Jensen sent a further email to, among others, Mr Donnell with subject “Katy Perry/Approved t-shirt” which included:

The attached t-shirt is now approved for retail. I’d especially like to get this out in the UK, Europe, Australia and Japan quickly. How do we do that?

Let’s talk today about ‘where we’re at’ on retain merch. I’m in Cologne and available on my cell, XXX.XXX XXXX.

Cheers,

Steve

94 At the time Mr Jensen and his colleagues at DMG were also organising a “Katy Perry” doll (Katy Doll). The Katy Doll was designed by a Taiwanese/Canadian artist and fashion designer, Jason Wu, and made and sold by New York toy maker Integrity Toys. It was dressed in a belted gold mini dress and was inspired by the outfit Ms Hudson wore in the “I Kissed a Girl” music video. Only around 500 Katy Dolls were made and around 150 of them were distributed within the record industry for giveaways. It is now a collectible item. Mr Jensen recalls that in 2008 Ms Hudson ran a sweepstakes competition on her MySpace page and the winner was given a Katy Doll. The Katy Doll was available for purchase in late September 2008 on the Integrity Toys official website and was sold out on pre-orders as at 10 October 2008.

1.9.1 Launch of the Katy Perry webstore

95 On 24 September 2008 Mr Donnell informed Mr Jensen by email that the “Katy Perry web store” was live and ready to be linked to Ms Hudson’s homepage and provided a link. Mr Jensen reviewed the link and provided feedback by return email. Mr Jensen understood that launch of the webstore meant that “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise, including t-shirts and other apparel and merchandise, would be advertised, offered for sale and available for purchase from Bravado either online or by telephone order which could be placed from outside the US including by members of the public in Australia.

96 The evidence as to when the website went live was unclear. Initially Mr Jensen said that he understood it was from 24 September 2008. But that cannot be so given Mr Jensen’s email of 24 September 2008 requesting changes to the site and subsequent material shown to him. Indeed, in cross-examination Mr Jensen ultimately accepted that the webstore went live and was publicly available in early October 2008 and I find that to be so.

97 A screenshot, obtained from the Wayback Machine as at 10 December 2008, showing the “Katy Perry” webstore at katyperry.shop.bravadousa.com (Bravado Website) appears below:

98 Mr Jensen recalls that a few days after the “Katy Perry” webstore went live on the Bravado Website it also went live on Ms Hudson’s own website via a link which, in turn, automatically linked to the Bravado Website. Relevantly, an announcement dated 7 October 2008 on Ms Hudson’s official site provides:

Katy’s Webstore is Now Live!

Shop Katy Perry!

Click here to go to Katy’s official webstore now

Mr Jensen understood that members of the public from any country around the world, including Australia, who could access Ms Hudson’s website were able to purchase “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise through it.

1.9.2 Initial arrangements with Bravado

99 On 18 November 2008 Mr Donnell provided DMG with an updated confidential proposal for the distribution and sale worldwide for Ms Hudson’s upcoming world tour of “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise (November 2008 Proposal). A formal contract was not entered into with Bravado until 2011 (see [204] below). Until that time the terms set out in the November 2008 Proposal were treated by DMG and Bravado as binding and, according to Mr Jensen, they conducted themselves generally in accordance with the terms of that proposal until such time as they entered into a contract in 2011. The November 2008 Proposal set out the terms for the distribution and sale of merchandise including the percentage royalties payable in each tour country, which included Australia, and definitions of the terms “Tour Sales” and “Tour Profits”.

100 As set out below, “KATY PERRY” branded merchandise continued to be developed and sold. It was not in dispute that Ms Hudson was closely involved in the selection and approval of designs and items of merchandise to be offered for sale generally and in particular geographic regions.

1.10 Ms Hudson’s promotional tour – 2008

101 On 9 September 2008 Ms Hudson commenced her promotional tour in the UK. The other countries included in the promotional tour were France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, Mexico and Australia. In each of the European cities to which she travelled Ms Hudson appeared and performed on television programs and at radio stations, was interviewed by magazines and news publications and participated in interviews and fan meet and greets. The tour was the subject of media in the UK, France and Spain.

102 In September 2008, before Ms Hudson’s arrival in Australia, there was publicity about her intended visit and the fact that she would be performing concerts in Sydney and Melbourne, with tickets going on sale on 12 September 2008. The Australian leg of the promotional tour ran from 10 to 14 October 2008. There were a number of articles published about Ms Hudson while she was in Australia during that period.

103 In an email dated 15 October 2008, with subject “Katy Perry is a true star…”, from Glenn Dickie, EMI Music Australia Label Manager Capitol & Virgin to, among others, Mr Jensen, Mr Dickie reported on the Australian leg of Ms Hudson’s promotional tour. His email included:

While Katy has been here we have covered nearly every major TV, Press and Radio in both Australia and New Zealand, had paparazzi fights that were caught on film and two rocking’ shows (with Melbourne 10 tickets off selling out) that really showed that Katy’s got the live skills to pay the bills and won a lot of sceptics over.

All of our hard work and attention to Katy and One Of The Boys is paying off as we are now GOLD on One Of The Boys continuing on from our platinum sales plus sales of I Kissed A Girl. Congratulations to everyone locally and internationally for this excellent achievement. Now it’s time to get to platinum!!!

We still have lots of TV, radio and press interviews to roll out over the coming weeks including what we expect to be great live reviews as well as Sunday nights ROVE performance that will air in New Zealand on Friday night.

…

TV advertising starts from next week to back up the tour and we should see One Of The Boys heading up the charts. One Of The Boys will be One Of The Must have Albums of this Christmas.

…

1.11 Filing of the application for registration of the Applicant’s Mark

104 As at 2008 Ms Taylor did not realise that she had not paid the registration fee for the First KP Trade Mark. An Australian trade mark search for trade mark application no. AU1198609 shows that the trade mark was advertised on 17 January 2008 but that it lapsed on 17 July 2008. It also shows that on 19 June 2008 “Registration Fee Reminder” correspondence was sent but on 2 July 2008 that correspondence was returned to sender. Ms Taylor explained that at that time she was no longer residing at the address she had used to apply for registration of the First KP Trade Mark and thus did not receive the reminder correspondence.

105 On 9 July 2008 Ms Taylor sent an email to IP Australia requesting a change of address to her PO Box in Spit Junction, NSW.

106 In about August 2008 it occurred to Ms Taylor that she had not yet paid the registration fee for the First KP Trade Mark. She called IP Australia and was informed that she could still register her mark but that she would have to pay late fees in addition to paying the registration fee.

107 It was at about this time or shortly thereafter that Mr Farhang informed Ms Taylor that he was going to apply for another trade mark in class 25. He advised Ms Taylor that she should do so too and that she should apply for a word mark because it would give her more protection if she wished to change her logo later. Following that discussion Ms Taylor made a decision to apply for a word mark in class 25. However, as her business was small and self-funded she did not consider that she could maintain two trade marks. Accordingly she decided to let the First KP Trade Mark application lapse and on 29 September 2008 she applied for registration of the word mark “KATIE PERRY” in class 25 for clothes, i.e. the Applicant’s Mark.

108 By letter dated 7 October 2008 IP Australia notified Ms Taylor that her trade mark application for the word mark “KATIE PERRY” had been received and filed as trade mark application no. 1264761 with a filing date of 29 September 2008.

109 On 18 December 2008 Ms Taylor received an early notice of acceptance from IP Australia for her word mark “KATIE PERRY”. IP Australia noted that trade mark application no. 1264761 had passed the examination stage and that the next step was advertising in order to give other people an opportunity to oppose registration of the trade mark.

1.12 The KATIE PERRY fashion label - 2008 to 2009

110 In or about May to June 2008 Ms Taylor was part of the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme, a government program for a Certificate IV in Business. Through this program Ms Taylor attended seminars in relation to small business management and, as part of the program, she prepared a business plan for her KATIE PERRY label.

111 Since 2007 Ms Taylor has accumulated a database of over 200 people. She sent Katie Perry newsletters on a monthly basis to the contacts in her database. The newsletter bore her logo, a message from her in relation to the brand and some images. In it she shared news about the progress of, and any updates on, the brand and made announcements about where she was going to be, what she was going to be doing, new products and so on.

112 In the early stages of development of her brand Ms Taylor considered wholesaling to high end boutiques and visited stores and events in preparation. For example, in September 2007 she attended Melbourne Fashion Week for inspiration, to undertake market research and to seek out boutiques she could potentially approach. Ms Taylor also considered selling goods at Paddington Markets, in Paddington, NSW. She wished to grow organically and use the markets as a launch pad to get customer feedback. At the time Ms Taylor considered Paddington to be a fashion hub and, prior to working at David Jones, had been the store manager at the Oroton store located in Paddington, across the road from the markets. She observed that the markets, which were open every Saturday, always had high foot traffic from both local and overseas visitors and she frequently visited there during her lunch break so she knew of the types of stalls that were there and the demographics of the customers. Ms Taylor understood that Paddington Markets focussed on high quality Australian made brands, Australian made fashion, jewellery and accessories and she considered that her Australian luxury loungewear would be well accepted at the markets.

113 Along with having physical presence Ms Taylor also planned to sell her garments through an e-commerce website. Although she had wanted to set up a website, since registering her domain name she could not do so until sometime later for two reasons. First, she needed the garments to be produced at volume and ready to be sold. Secondly, as far as she was aware e-commerce was not big with Australian suppliers and consumers at the time which meant that developing a suitable website with e-commerce facilities was not inexpensive. Therefore Ms Taylor decided to develop the website in stages.

114 In late 2007 Ms Taylor engaged Tanveer Kalani to prepare a landing page for her website. From January 2008 she worked with Mr Kalani to set up the website. For most of 2008, while it went through a number of variations, the website was fairly rudimentary. It was a “splash” screen with the Applicant’s Mark, and had details about the brand and contact details. There was no e-commerce facility. As at 18 July 2008 the website appeared as follows:

115 On 16 May 2008 Ms Taylor received a letter of approval from Paddington Markets accepting her application for registration as a stallholder.

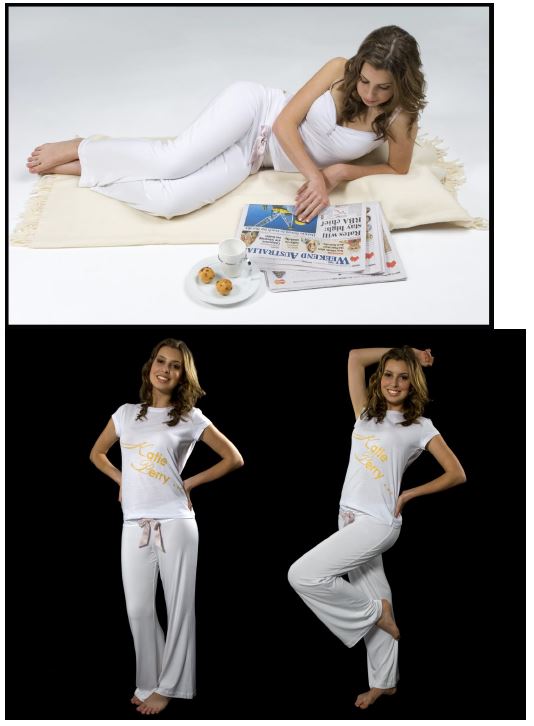

116 By July 2008 high volume manufacturing of Ms Taylor’s collection was complete. Thus on 18 July 2008 Ms Taylor organised and supervised a photoshoot of the collection. One of the main reasons for obtaining high quality professional photos was for use on the online store. Copies of the photographs which were taken at the time were in evidence before me and included:

117 In anticipation of opening her Paddington Markets stall Ms Taylor organised for Eftpos merchant facilities with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and on 22 July 2008 was provided with a merchant facility number.

118 Ms Taylor opened her stall at Paddington Markets for the first time on Saturday, 2 August 2008. Although she had originally intended to have a stall there for only a few months, she maintained her stall at the market for around seven years.

119 In August 2008 Ms Taylor engaged David Waters of DJW Designs to set up an e-commerce website. From August to December 2008 she worked with Mr Waters to design and create a comprehensive website with e-commerce facilities and a platform where she could share more about herself and her brand through a blog.

120 By November 2008 Ms Taylor outgrew working from home and rented a storage unit. At that time she was also nominated as a finalist for the 2threads Fashion Awards in the “best up and coming designer” category.

121 In order to promote her brand Ms Taylor attended, and was part of, as many fashion related events as possible. In 2008 one of the main events in which she participated was the Duke of Edinburgh Award’s fundraising event, “Dressed to Kilt – a Tartan Fashion Extravaganza” held on 19 November 2008 at Doltone House, Jones Bay Wharf, NSW. Ms Taylor was asked by the organisers to design a garment with the theme “a touch of tartan” and her garment, along with those of other designers, was showcased and auctioned at the charity event.

122 By early December 2008 Ms Taylor’s website was up and running with an online store. To celebrate the launch she ran a promotion for the month of December for all online purchases. A copy of the website at www.katieperry.com.au as taken from the Wayback Machine appears as follows:

123 Ms Taylor also applied for and was allocated a stand to participate at the “Fashion Exposed” trade show to be held at the Sydney Exhibition Centre in March 2009. Ms Taylor had a stall showcasing her latest range of KATIE PERRY clothing. She spoke to numerous retailers hoping to have her label sold in their boutiques and, as a result, “picked up” a boutique in Kiama called “Classy Lady”. Unfortunately, as the boutique did not pay Ms Taylor for the stock it purchased from her, in about October 2009 Ms Taylor had to retrieve the leftover stock. Given this experience Ms Taylor decided to change her focus away from wholesaling. Although her clothing was still stocked in “Mushroom Boutique” in Queensland and in another local store, she no longer actively sought to wholesale her range but focussed her attention on her own stores.

124 Ms Taylor looked for a showroom which she could also use as a workspace, retail space, display room and for promotional events. On 1 April 2009 she signed a lease for a showroom at 2/87 Avenue Road, Mosman, NSW and on 4 June 2009 she launched the opening of the showroom with an event where she showcased and sold items from her collection.

125 Generally Ms Taylor would set up the showroom from Monday to Friday, opening it to the public from Tuesday to Thursday. If clients wished to attend at a different time they were able to make a private booking. On Saturdays she continued to sell her clothing at Paddington Markets. Ms Taylor’s showroom was on the second floor of the building at 2/87 Avenue Road, Mosman and she hung the clothes on the shop front. There was “KATIE PERRY” signage on the window, a “KATIE PERRY” light box on the street, which also displayed Ms Taylor’s website address, and another “KATIE PERRY” sign on the wall at the entrance to the steps which led to the showroom, which also displayed her website address. Even now people occasionally ask Ms Taylor questions about the showroom in Mosman. A photo showing the signage which appeared at the showroom appears below:

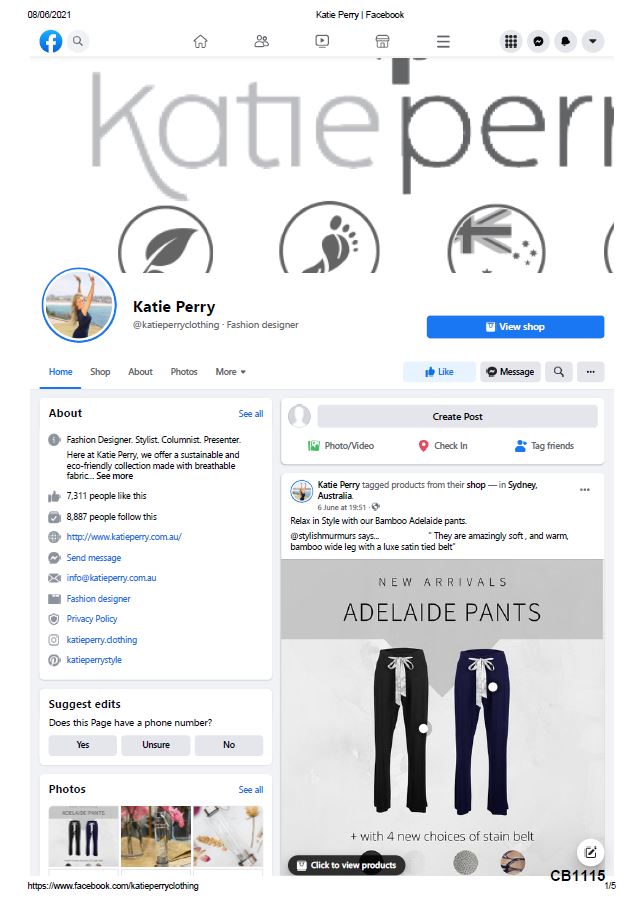

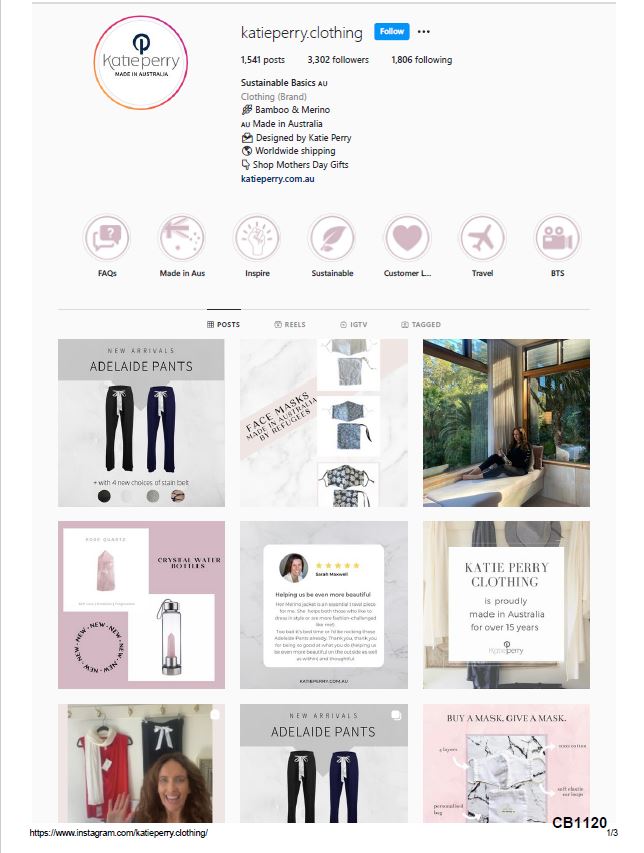

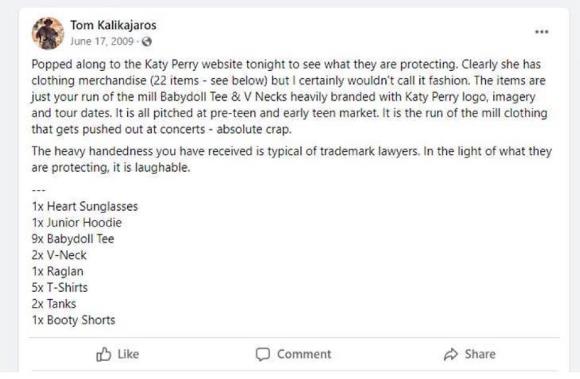

126 Since 2007 Ms Taylor has also actively posted on various social media platforms including Facebook and Instagram. Initially she promoted the “KATIE PERRY” brand on her personal Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/katietaylor30. On 8 January 2009 she established a Facebook page for her business at https://www.facebook.com/katieperryclothing/. Ms Taylor continues to share and promote her brand through Facebook and now has a “shop” tab where people can view various items and access them by a link to her website. In about 2013 Ms Taylor also set up an Instagram account for her clothing brand at https://www.instagram.com/katieperry.clothing/. Ms Taylor usually tries to upload a post on Facebook or Instagram every few days. Extracts from the “KATIE PERRY” Facebook and Instagram pages, printed as at 8 June 2021, are as follows:

Facebook:

Instagram:

1.13 Ms Taylor first hears about Ms Hudson

127 Ms Taylor first heard of Ms Hudson in July 2008. She was listening to the radio and heard Ms Hudson’s name and her song “I Kissed a Girl”. Ms Taylor bought the song on iTunes because she wanted to support an artist who had the same name as her. At the time she did not intend to listen to the song and she does not recall that she did so often, if at all. Ms Hudson’s style of music was not to Ms Taylor’s liking and she has never bought any of her songs again.

128 Prior to June 2009, when she received the correspondence described below, Ms Taylor:

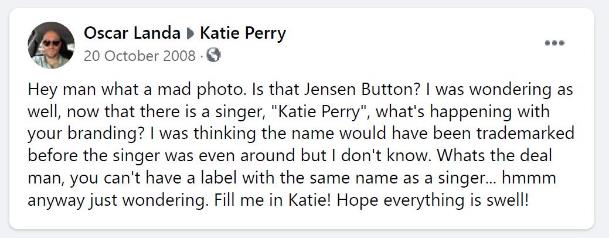

(1) did not recall anyone ever mentioning Ms Hudson, her songs, her concerts or tours to her, whether or not with a reference to her own brand. But, in February 2021, in the course of reviewing documents for the purpose of this proceeding Ms Taylor found a Facebook post dated 20 October 2008 on her Facebook page about Ms Hudson. It was posted by Oscar Landa, a friend of Ms Taylor’s brother who Ms Taylor does not know well. A copy of the Facebook post, which Ms Taylor does not recall seeing prior to February 2021 and to which she did not respond, appears below:

(2) had not considered, or even thought about, Ms Hudson as a potential threat to her business. To the extent Ms Taylor considered Ms Hudson at all, she has no recollection of thinking there would be any issues between them but she thinks it is more likely that she simply did not turn her mind to Ms Hudson at the time.

1.14 Mr Jensen becomes aware of Ms Taylor’s application for the Applicant’s Mark

129 In about May 2009 Mr Jensen became aware, from the US lawyers acting for Ms Hudson, of Ms Taylor’s application for registration of the Applicant’s Mark for “clothes” in Australia. Mr Jensen was concerned that Ms Taylor’s purpose may have been to attempt to obtain a financial advantage from Ms Hudson who, at that time, was scheduled to be in Australia as part of her world concert tour in August 2009.

1.15 Correspondence between Ms Hudson and Ms Taylor

130 In May 2009 Mr Jensen authorised the US lawyers for Ms Hudson, who acted on his instructions, to send a cease and desist letter to Ms Taylor in order to attempt to stop Ms Taylor’s application for registration of the Applicant’s Mark. Those lawyers, in turn, instructed Australian trade mark attorneys, Fisher Adams Kelly, to send the letter.

131 At some point in the period 5 to 8 June 2009, shortly after the launch of her showroom, Ms Taylor received a letter from Fisher Adams Kelly dated 21 May 2009 (21 May 2009 Letter). Ms Taylor recalls being surrounded by empty champagne glasses from the showroom launch party when she read it. The 21 May 2009 Letter, which was marked “without prejudice”, included:

We act for Katy Perry of XXXX (“Our Client”), born Katheryn Elizabeth Hudson is an internationally known American singer, songwriter and musician whose career commenced in 2001. In particular, Our Client rose to fame in 2007 with her internet hit “Ur So Gay” and with her international debut “I Kissed a Girl”.

An extract taken from the “Wikipedia” website, in respect of Our Client on 20 May 2009 is enclosed.

NB: The “Wikipedia” extract can be obtained by entering either “Katy Perry” or “Katie Perry”.

Legislation:

Sections 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Commonwealth) provide as follows:

…

Your Activities:

Any use, by yourself, or anyone authorized by you, of the trade mark “Katie Perry”, in respect of “clothes” (or other goods), is liable to mislead or deceive consumers into believing that the goods were manufactured by, or under the authority of, Our Client, (Section 52;) or that the goods have the “sponsorship, approval or affiliation” of Our Client (Paragraph 53 (d)).

NB: “Katie Perry” has identical appeal to the ear as “Katy Perry”: and the respective marks are “substantially identical” to the eye.

…

Undertakings:

Our Client, therefore, requires that you give the following written undertakings by the close of business on Friday 29 May 2009:

(1) You will immediately withdraw Australian Trade Mark Application 1264761;

(2) You will immediately withdraw from sale, clothes (or any other goods) bearing the “KATIE PERRY” trade mark;

(3) You will immediately withdraw any advertising in relation to the “KATIE PERRY” trade mark, including withdrawing any websites or links thereto in respect to the KATIE PERRY trade mark; and

(4) You will not, in the future, use any trade mark or name “substantially identical or deceptively similar to “KATIE PERRY” or “KATY PERRY”.

Your acceptance of the above Undertakings can be affected by executing the “Acceptance of Undertakings” on the duplicate copy of this letter and returning same to us by the deadline.

Should you fail to give the written Undertakings, Our Client shall be entitled to take any such action as is considered appropriate to protect her reputation, without further notice to yourself.

132 Ms Taylor recalls that she cried upon reading the 21 May 2009 Letter. She feared that she was going to lose everything she had worked so hard to build. She had never received a letter in that form from lawyers before and she thought they were going to take everything from her.

133 Ms Taylor was aware that another letter dated 8 May 2009 had been sent by Fisher Adams Kelly to her PO Box address which enclosed a notice of opposition to the registration of the Applicant’s Mark. However, the first letter Ms Taylor recalls reading was the 21 May 2009 Letter. Ms Taylor explained that she did not check her PO Box very often and when she did, she would open all the mail at once. She had picked up the 21 May 2009 Letter because it was distinctive as it was in a large express post envelope. Ms Taylor was also aware that Ms Hudson had filed an application for an extension of time to file the notice of opposition (Extension of Time Application) at the time that she filed the notice of opposition.

1.16 Events leading up to registration of the Applicant’s Mark

134 Ms Taylor arranged to meet with Justin Betar, a lawyer to whom she had been introduced. At the time she recalls that Mr Betar said words to her to the following effect:

You’ve got a really good case, but this is going to cost you $20,000 and unless you have $20,000 to fight this, you should shut up shop now.

Ms Taylor did not have that type of money to spend on legal fees and so did not engage Mr Betar.

135 Ms Taylor felt intimidated and distressed by the ordeal. The legal world was foreign to her and she found even speaking to a lawyer intimidating. She felt as though she was being bullied into signing everything away when she had not done anything wrong. She did not want to give up on her label, which she loved, and decided that she was not going to do so without a fight. Ms Taylor had applied for her trade marks because that was recommended to her in the courses that she had attended. She never had Ms Hudson in mind when she planned, or worked on, any aspect of her business or when she filed her trade mark applications. Ms Taylor took, and still takes pride in, her label being Australian owned and 100% made in Australia, which she felt was always a significant aspect of the brand’s identity and one of her biggest marketing points. Having her Australian brand associated with an American singer was not what she wanted and she did not consider it to be positive for her business.

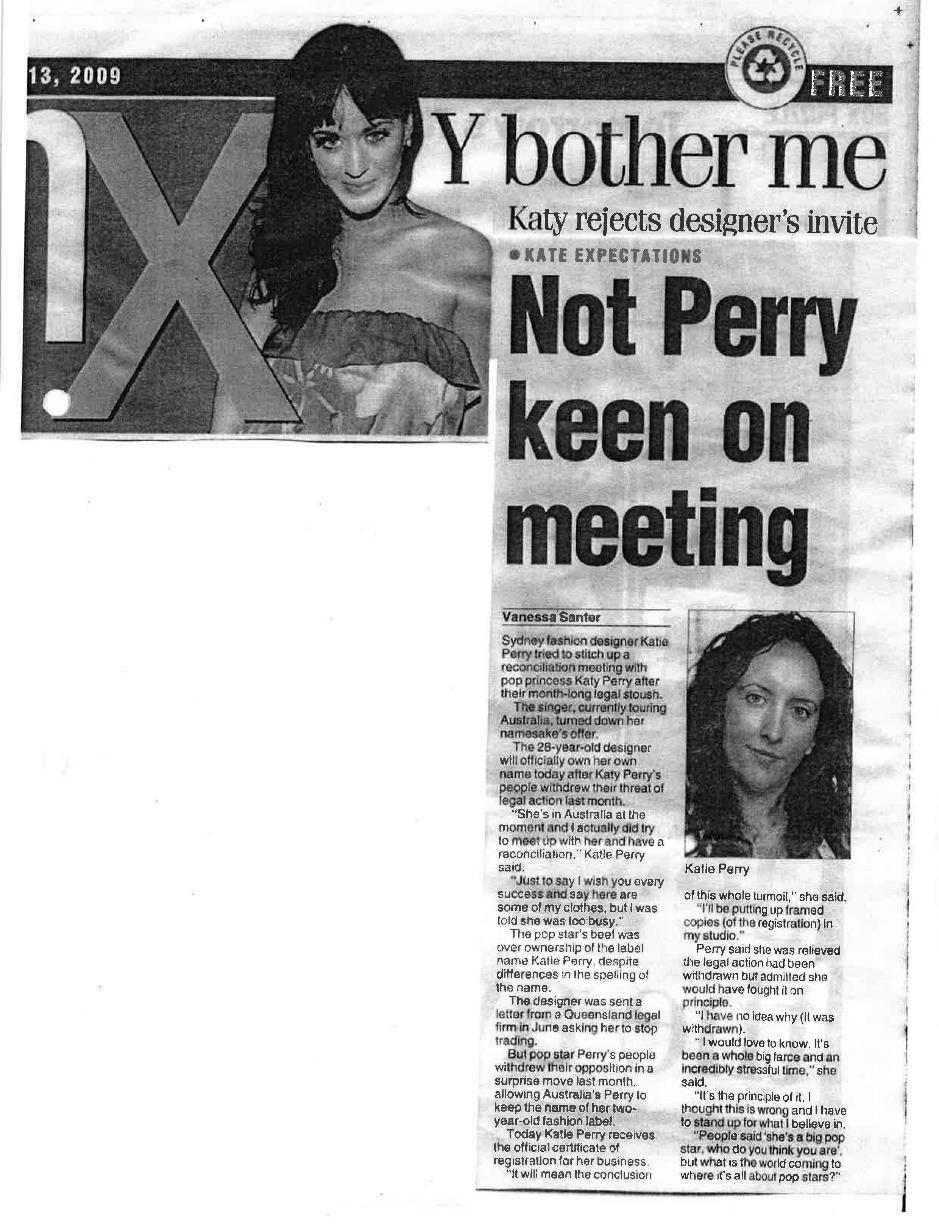

136 Ms Taylor sought guidance from her business mentor, Graham Lawrence, about the 21 May 2009 Letter. He referred Ms Taylor to a journalist he knew at The Australian newspaper, Lara Sinclair. Ms Taylor thought that Ms Sinclair would be interested in her story because the 21 May 2009 Letter had been sent on behalf of Ms Hudson and because it was about a small business being “up against” a singer. On 16 June 2009 the following article authored by Ms Sinclair (Australian Article) was published in The Australian:

The Australian Article was also published on News.com.au, was picked up by a number of media outlets both in Australia and internationally and MTV News published an article based on it.

137 Ms Taylor purchased a copy of The Australian Newspaper which she retained. She said that she “skim read” Ms Sinclair’s article at the time of its publication and agreed that it was “highly likely” that she read those parts of the article to which she was taken in cross-examination including commentary from:

(1) Trevor Choy, a trade mark lawyer, that “[f]ashion is a common area into which celebrities launch brands” and that “[a] lot of US popstars are moving into all sorts of merchandising, … [c]lothing is an obvious one for popstars”; and

(2) Trish Nicol, a fashion publicist, that “the singer had a feminine fashion style that would lend itself to a label of her own”.

However, Ms Taylor did not accept that when she read those parts of the article she understood that it was likely that in the future Ms Hudson would sell clothing under her own KATY PERRY brand in Australia.

138 Despite that, Ms Taylor accepted that as at September 2008, prior to Ms Hudson travelling to Australia on her promotional tour, she likely knew that music artists sold clothing bearing their names at concerts. She said that she did not think about whether Ms Hudson would be selling clothing of that type at her concerts but, had she turned her mind to it, it would have been readily apparent that Ms Hudson would do so.

139 On 16 June 2009 Ms Taylor received an email with the subject “The trademark issue” from Caroline Thomson, who has since become a friend of Ms Taylor’s. Ms Thomson’s email of that date is lengthy but includes:

Hi Katie,

I am David Thomson’s partner, who you know from the NEIS course.

He has just shown me the news report on the legal issue with the trademark and Katy Perry.

I was so angry with what they have done, that I felt the need to write to you. I know David is also dropping you an email, as we both see it as so unfair and really want to let you know we support you and will do anything we can to help.

…

I noticed on the news websites that Katy Perry herself said back in March she was looking at launching her own clothes line. Hence, the whole objection to your trademark I guess and trying to intimidate you to stop trading.

Ms Taylor accepted that she would have read Ms Thomson’s email on receipt. So much is apparent from Ms Taylor’s response of the same date. Thus, at least from that time, Ms Taylor must have been aware of Ms Hudson’s intention to launch a clothing line.

140 The email exchanges between Ms Taylor and Ms Thomson continued. On 17 June 2009 Ms Thomson sent Ms Taylor an email in which Ms Thomson set out her thoughts on a proposal for a petition. The email concluded in the following way (as written):

I believe Katy Perry is meant to coming out here in August as well so it will be interesting to see what reception she gets after you get going missus!!! Go for it!

141 Once again Ms Taylor accepted that she read Ms Thomson’s email some time after receipt on 17 June 2009 and before she responded to it on 28 June 2009. Ms Taylor also accepted that from that time she knew that Ms Hudson would be touring Australia in August 2009 but she said that she did not know what the purpose of the tour was, i.e. as a concert tour or some other form of promotional tour, and she did not consider whether Ms Hudson would be selling promotional merchandise while in Australia.

142 Also on 16 June 2009 Ms Taylor sent out a newsletter with links to some of the articles that had been published. The newsletter included (as written):

For Katie,

I need your support!

My Australian owned and Australian made label is under threat.

Lawyers, acting for the US Popstar Katy Perry (real name Katheryn Hudson), are attempting to stop me trading under my real name.

See the articles below for the details.

USA Popstar against the Australian label.

Katy Perry vs KATIE PERRY

As you can imagine after all the hardwork and loce I had put into my label it’s very scary.

As you can imagine, after all the hardwork and love I had put into my label, this is all very scary. However, I am determined to fight for the right to use my long established name (although I refuse to let you in on the secret of my age......)

Please support me, and all small Australian businesses, in our efforts against the Goliath’s of this world.

Stay True,

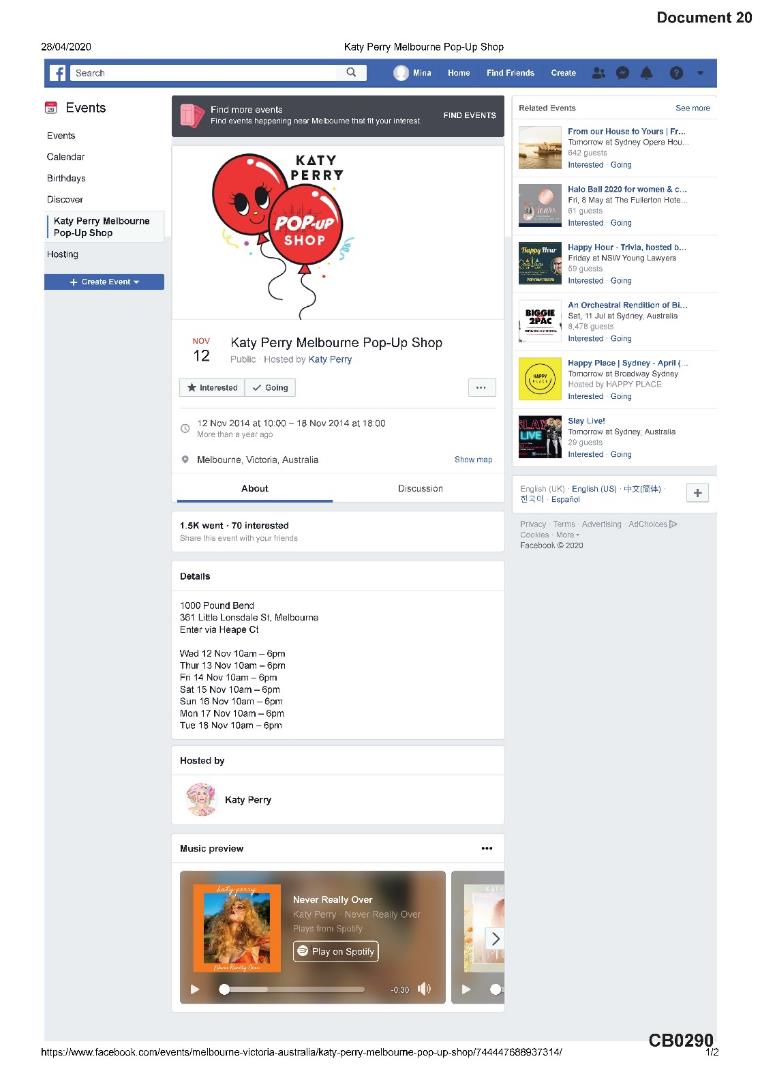

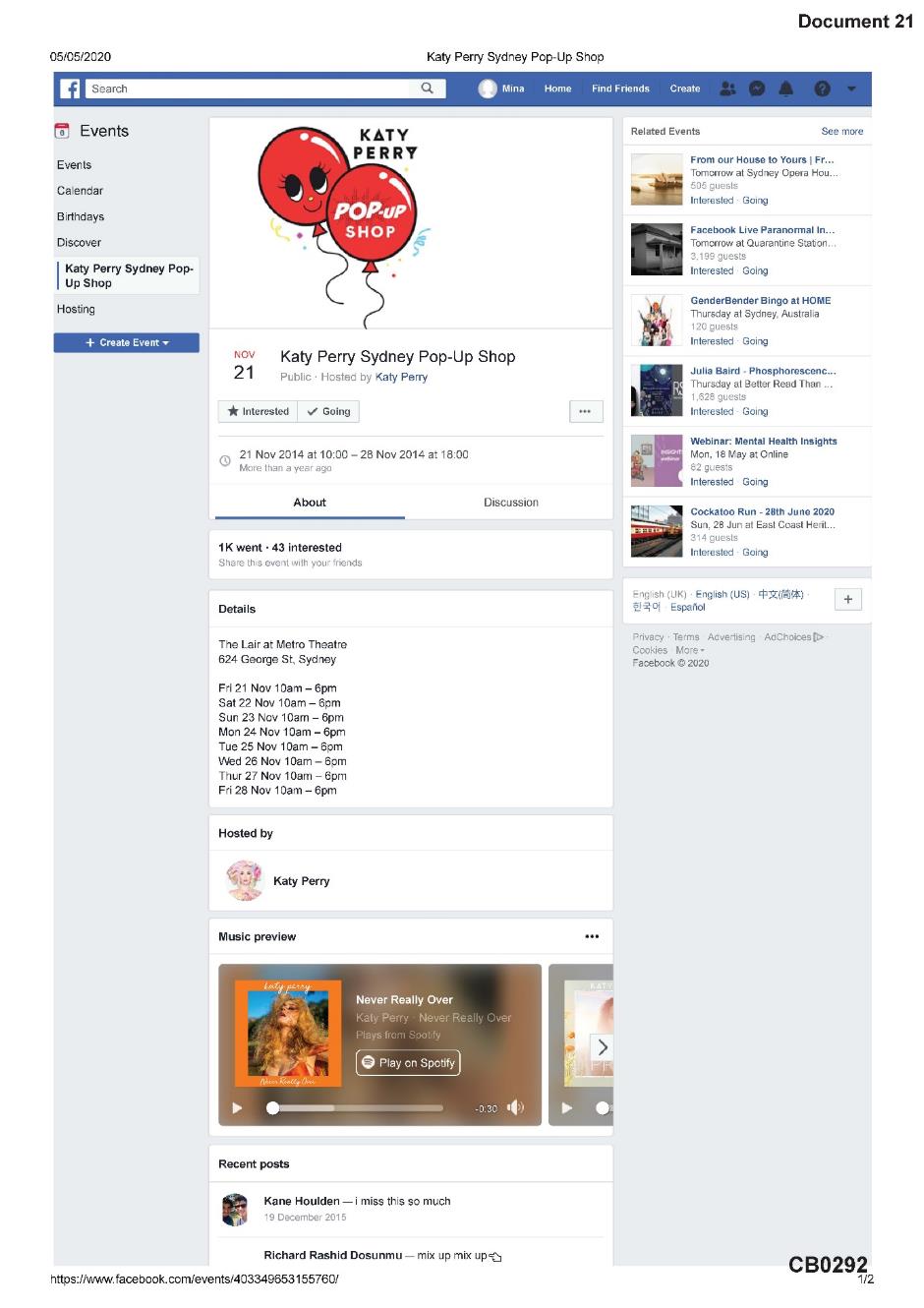

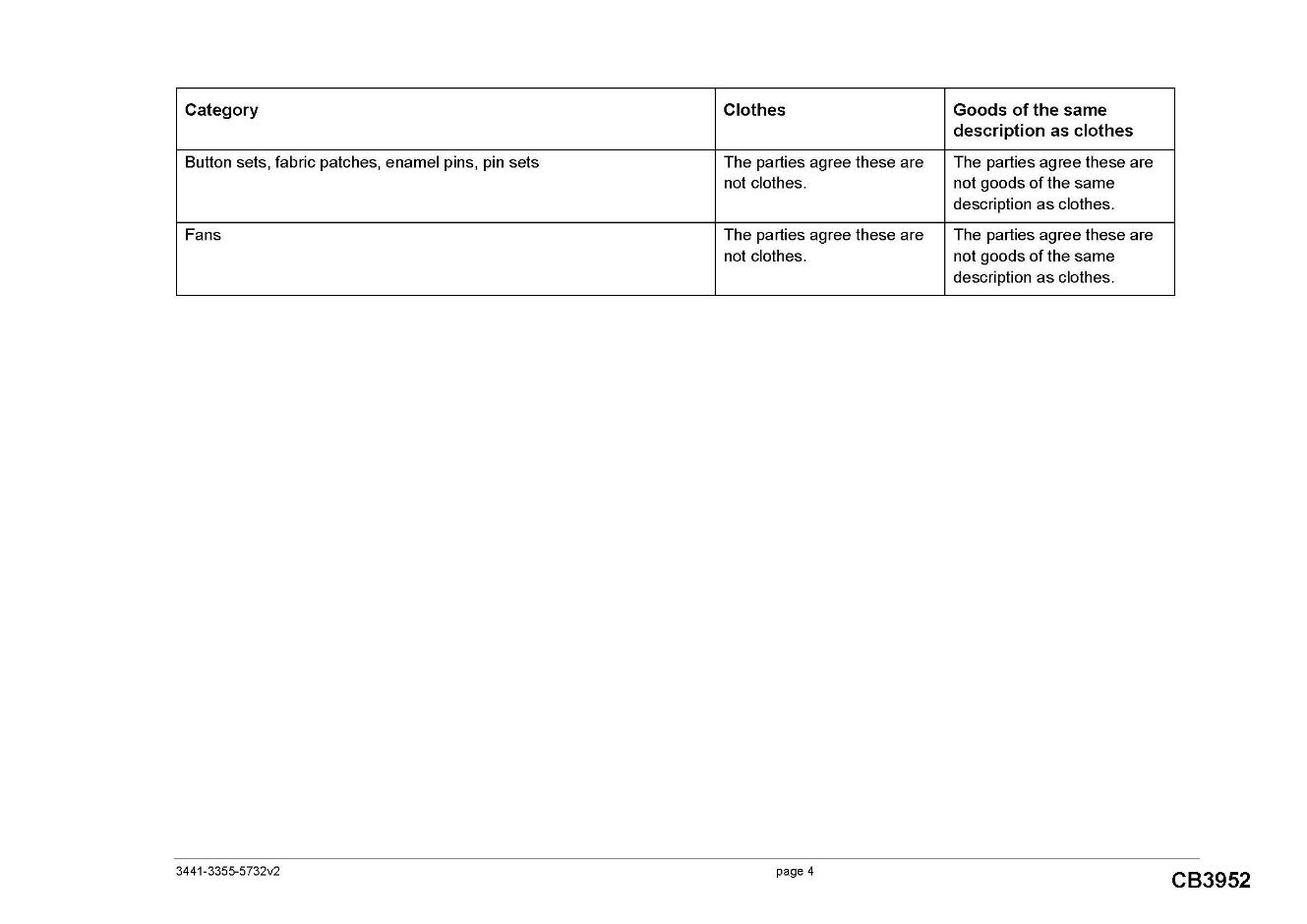

Katie Perry