FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Schiff v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 336

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | NINE NETWORK AUSTRALIA PTY LTD First Respondent THE AGE COMPANY PTY LTD Second Respondent NICHOLAS MCKENZIE (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 April 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave to file a Further Amended Defence in the form annexed to the respondents’ Interlocutory Application dated 20 March 2023 and marked “A” be refused.

2. The respondents be given leave to re-plead paragraphs 13 and 14 and the particulars of justification.

3. Any re-pleading of the proposed Further Amended Defence be provided to the applicant by 12 May 2023.

4. The matter be stood over to 19 May 2023 at 9.30am for a further case management hearing before me.

5. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the interlocutory application dated 20 March 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKMAN J

Introduction

1 In Schiff v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 1120, Jagot J decided certain separate questions in these proceedings. Relevantly to the present dispute, Jagot J concluded that the television broadcast which is the subject of the proceedings conveys the following imputations:

Imputation 8.1 (by permitting his bank, Euro Pacific, to be used as a vehicle for around one hundred Australian customers to commit tax evasion, Schiff facilitated the theft of millions of dollars from the Australian people).

Imputation 8.2 (Schiff orchestrated an illegal tax evasion scheme).

Imputation 8.3 (Schiff committed tax fraud).

Imputation 8.4 (Schiff knowingly facilitates tax fraud, in that he established his bank, Euro Pacific, in Puerto Rico for the purpose of enabling his customers to illegally hide their money from tax authorities).

Imputation 8.5 (Schiff knowingly assisted around one hundred Australians to illegally evade their tax obligations).

Imputation 8.11 (through his bank Euro Pacific, Schiff poses a grave organised crime threat to Australia).

Imputation 8.12 (Schiff is such an unscrupulous individual that he has no qualms about doing business with criminals and money launderers).

2 Jagot J also concluded that the newspaper article which is the subject of the proceedings does not convey any of the pleaded imputations. The respondents seek leave to amend their Amended Defence in light of Jagot J’s conclusions on the separate questions. In addition, there is an extant application dated 2 May 2022 by the applicant to strike out parts of the respondents’ Defence. It is accepted by the parties, and indeed has been urged upon me by the respondents, that the strike out application should be dealt with as a matter of substance by reference to the application to file the proposed Further Amended Defence. Accordingly, I have before me at present an application by an Interlocutory Application by the respondents to file a Further Amended Defence, which is dated 20 March 2023. The parties are agreed that I should deal with that application on the basis that it subsumes the substantive complaint about paragraphs 13, 14(a), (b) and (d) of the Defence and the earlier versions of the particulars of justification. The applicant opposes the grant of leave to file the proposed Further Amended Defence on the principal grounds that the particulars of justification are defective, and also that even if one assumes that all the particulars were proved at the trial, the defence of justification would still fail.

3 In addition, there is an issue between the parties as to whether the proceedings should be dismissed against the second respondent, The Age Company Pty Ltd, or alternatively that there be judgment for the second respondent. That application arises out of Jagot J’s conclusion that the newspaper article does not convey any of the pleaded imputations, that being an article published by The Age Company Pty Ltd.

Legal Principles

4 It is accepted by the parties that the relevant principles pertaining to the pleading of a justification defence are those set out by Wigney J in Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 357; (2018) 359 ALR 473 at [42]-[54], [99] and [172]-[174], cited with approval by the Full Court in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 at [132]. Those principles may be summarised as follows:

(a) The power to strike out pleadings or portions of pleadings on the basis that no reasonable cause of action or defence is disclosed is discretionary, and should be employed sparingly and only in a clear case, lest a party be deprived of a case which in justice it ought to be able to bring.

(b) Rule 16.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) provides that the party must state in a pleading the necessary particulars of each claim, defence or other matter pleaded by the party. The degree of particularity required by this general obligation depends on the circumstances of the case and the nature of the allegations.

(c) Particulars provided in support of a defence of justification must be shown to be capable of proving the truth of the defamatory meaning sought to be justified. In this regard, caution must be exercised because in determining the strike out application it is necessary to make factual evaluations which are difficult to render within the context of an interlocutory hearing pitched at the low threshold of showing arguability. The need for caution also arises because the particulars are simply a summary of the relevant facts and are therefore unlikely to be as fulsome as the evidence that may ultimately be led to prove those facts. In approaching the strike out application, the court must determine whether the particulars that have been provided, taken at their highest, are capable of proving the truth of the defamatory imputations that are sought to be justified. In assessing the sufficiency of the particulars, it is also necessary to have regard to the cumulative effect of the particulars.

(d) The particulars provided in support of a defence of justification must also be sufficiently specific and precise to enable a claimant to know the case they are required to meet. In this regard a defendant must specify the particulars of truth relied on with the same precision as an indictment. Like an accused in a criminal proceeding, a plaintiff in a defamation action is entitled to be put on notice of the precise particulars of the facts or allegations that are said to be true. The need for precision in a defamation case is perhaps even more acute, given that ordinarily the plaintiff gives evidence first. The relevant issue is not how much information is provided in the particulars, but whether the information that is given is sufficient to give the plaintiff or applicant in a defamation action sufficient notice of exactly what the defendant or respondent alleges against him or her in the context of a defence of justification.

(e) In order to prove the substantial truth of an imputation, it is necessary to prove that every material part of the imputation is true.

(f) A defendant who pleads justification must do so on the basis of the information which it has in its possession when the defence is delivered and is not permitted to undertake a fishing expedition in the hope of finding something in support of its plea. However, that does not mean that the factual basis provided in support of the defence cannot be augmented after properly invoking the forensic processes of the court. The distinction is between a case in which the defendant is unable to state any facts to support the defence (requiring discovery and interrogatories to find out if he has a defence, which is not permitted) and a case in which the pleaded facts are spare, but capable of sustaining the defence.

5 To these principles may be added the proposition that although the defendant must establish that every material part of the imputation was true, this does not mean that the defendant has to prove the truth of every detail of the words established as defamatory. Rather, the defence of substantial truth is concerned with meeting the sting of the defamation: see Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Mohammed [2010] NSWCA 335; (2010) 278 ALR 232 at [138] (McColl JA); O’Brien v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2017] NSWCA 338; (2017) 97 NSWLR 1 at [172] (McColl JA). It should also be noted that the meanings conveyed by a defamatory publication must be construed in their context: see Greek Herald Pty Ltd v Nikolopoulos [2002] NSWCA 41; (2002) 54 NSWLR 165 at [21]-[27] (Mason P).

6 In addition, I note that r 16.43 of the Rules requires that a party who pleads a condition of mind (including knowledge and any fraudulent intention) must state in the pleading particulars of the facts on which the party relies.

7 The relevant version of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act) that applies to these proceedings is the version which existed before the amendments to that legislation which commenced on 1 July 2021. The defence of justification is set out in s 25 as follows:

It is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that the defamatory imputations carried by the matter of which the plaintiff complains are substantially true.

8 “Substantially true” is defined in s 4 as meaning “true in substance or not materially different from the truth”.

The Proposed Further Amended Defence

9 As the respondent submits, some of its proposed amendments seek no more than to bring the pleading into line with the conclusions expressed by Jagot J on the separate questions. The proposed amendments to paragraphs 8, 9 and 10 are of this nature and there is no opposition to those amendments.

10 The controversy concerns paragraphs 13 and 14 of the proposed Further Amended Defence, and the particulars of justification provided in support of paragraph 13. In its present proposed form, paragraph 13 reads as follows:

Further and in the alternative, the Respondents say that in so far as, and to the extent that, the Court has found that the Segment [being the television broadcast] was published of and concerning the Applicant and was defamatory of him in its natural and ordinary meaning, as bearing the imputations in paragraphs 8.1-8.5 and 8.11-8.12 of the Statement of Claim the Respondents rely on the following defences:

(a) Justification – section 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act)

Each of the imputations in sub-paragraphs 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.11 and 8.12 of the Statement of Claim is substantially true.

11 Paragraph 14 in its present proposed form provides as follows:

Further and in the alternative, if (which is denied) the Applicant suffered any damage as a result of the publication of any of the matters complained of and/or any of the imputations pleaded in paragraph 8 of the Statement of Claim, then the Respondents will rely upon the following facts and matters in mitigation of such damage:

(a) the substantial truth of the imputations (or so many of them as are established by the Respondents to be substantially true);

(b) the facts, matters and circumstances proved in evidence in support of the defences pleaded in this defence;

(c) the circumstances in which it is proved that the matters complained of were published; and

(d) the background context to (a) to (c) above.

Are the particulars of justification defective?

12 It is convenient to adopt the applicant’s division of the particulars of justification into three categories: particulars 1-34B and 34H-39 (relating to the establishment and promotion of the Euro Pacific Bank (Bank)), particulars 34C-34G and 40-56 (allegations about certain customers of the bank) and particulars 57-70 (regulatory investigations). I set out below the relevant particulars in relation to each of those categories, together with my reasoning concerning those particulars.

Particulars 1-34B and 34H-39 (Establishment and Promotion of the Bank)

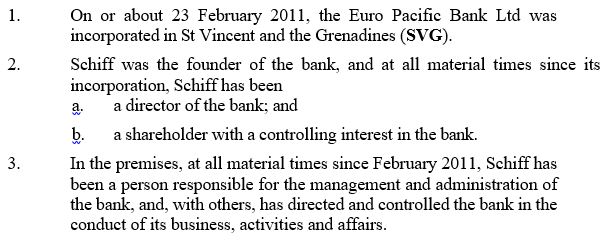

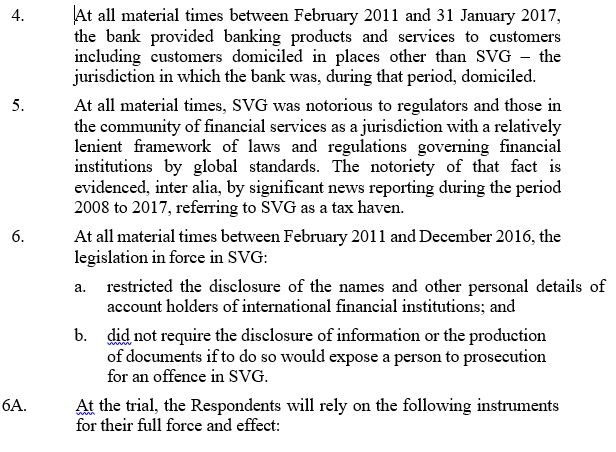

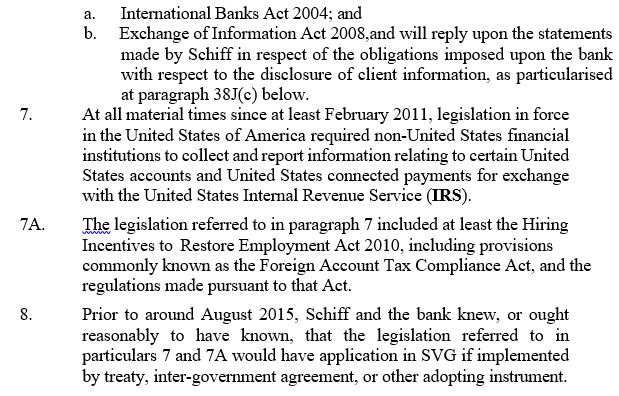

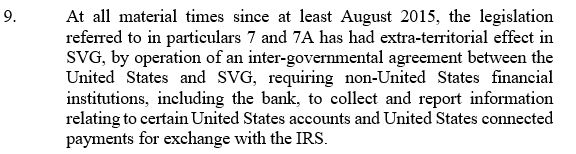

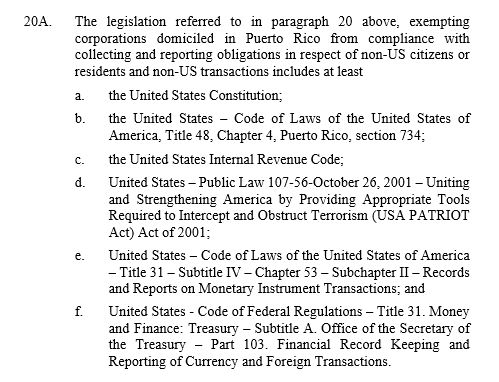

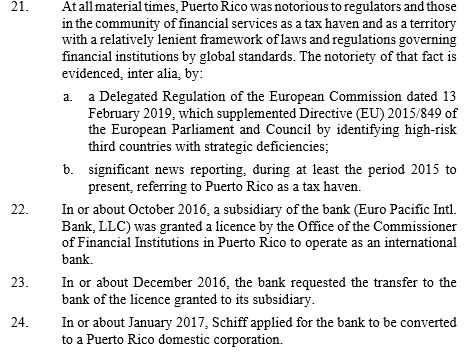

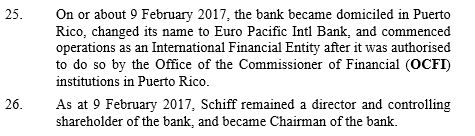

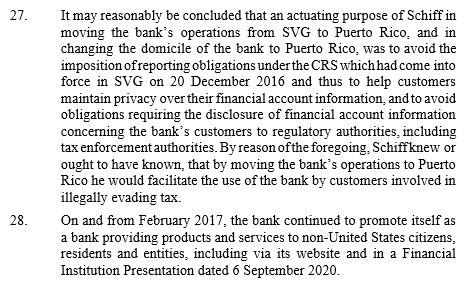

13 The relevant particulars are as follows:

14 These particulars contain a series of allegations about the establishment of the Bank, first in St Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG) (particular 1) and then in Puerto Rico (particulars 24-25), the manner in which the Bank’s services were promoted (particulars 10-10A, 28-37A), and Mr Schiff’s personal views on taxation (particulars 38-38J).

15 The applicant first criticises these particulars for not identifying Mr Schiff’s precise role within the Bank. The applicant refers to particular 3 where it is alleged that Mr Schiff has at all times been a “person responsible for the management and administration of the bank, and, with others, has directed and controlled the bank”. The submission is made that these particulars do not specify the nature or extent of Mr Schiff’s responsibilities, or his relationship with the others who direct and control the Bank and the division of responsibilities between them. The applicant submits that the problem occurs again at particular 10(a), where it is alleged that the Bank represented that “the bank was founded by Schiff, and its structure and benefits were attributable in part to Schiff’s input as a founder”. It is submitted that this allegation begs questions as to the nature and extent of Mr Schiff’s input and which specific part of the structure and benefits of the Bank were attributable to his input.

16 While I accept that there is a degree of imprecision in relation to those matters, in my opinion these particulars are sufficiently specific and precise to enable the applicant to know the case he is required to meet. It is to be noted that particular 2 refers to Mr Schiff as the founder of the Bank and, at all material times, having been a director and a shareholder with a controlling interest. In addition, particular 36 states that Mr Schiff “has represented to the world at large that he was the founder of the bank, that he holds a controlling interest in the bank, and that he controls and runs the bank, and that he makes decisions regarding the bank’s operations”. It is sufficiently clear that the respondents will contend at the trial that Mr Schiff ultimately controls the decision making of the Bank. It should be noted, however, that the particulars do not suggest that Mr Schiff was engaged in every operational matter concerning the Bank’s day-to-day administration, or that he was familiar with any of its customers or with the Bank’s processes for accepting customers.

17 The applicant next draws attention to the emphasis placed by the particulars on the assertion that SVG and Puerto Rico are jurisdictions with “a relatively lenient framework of laws and regulations governing financial institutions by global standards”: particulars 5, 19-21. From this, the applicant submits, the respondents invite the following inferences:

(a) That an actuating purpose of Mr Schiff in establishing the Bank in SVG was to promote the products and services of the Bank “to persons who wish to maintain privacy over their financial account information from the government and agencies responsible for enforcing tax avoidance and anti-money laundering laws and regulations”: particular 13;

(b) That Mr Schiff intended to attract business from those who wish to maintain privacy over their financial account information: particulars 14 and 33;

(c) That Mr Schiff “knew that those persons would include tax evaders and other criminals seeking to take advantage of the fact that the bank was not subject to tax reporting obligations”: particulars 14 and 33;

(d) That an actuating purpose of Mr Schiff in moving the Bank from SVG to Puerto Rico was to help customers maintain privacy over their financial account information and to avoid disclosure obligations to regulatory authorities: particular 27; and

(e) That Mr Schiff “knew or ought to have known that, by moving the bank’s operations to Puerto Rico, he would facilitate the use of the bank by customers involved in illegally evading tax”: particular 27.

I note at this point that Senior Counsel for the respondent in the course of his oral submissions did not press the words “ought to have known” in particular 27.

18 The applicant submits that the foundation for these inferences is, in substance, simply the fact that Mr Schiff chose to establish the Bank in jurisdictions which may have been perceived as having a favourable regulatory environment from the perspective of privacy. That is, the applicant submits, Mr Schiff is said to have taken advantage of benefits which were legitimately available under the laws of those jurisdictions. The respondent says that the foundation for those inferences is more than the establishment of the Bank in tax havens, and also includes the promotion of the features of banking in those jurisdictions, which features would be attractive to customers looking to cheat tax and use the Bank as a vehicle to commit crimes, being features which were promoted by the Bank: particulars 10, 10A, 31, 31A, and 32.

19 In my opinion, even taking into account the respondents’ submission as to a broader basis for those inferences, the applicant is correct in his submission that these particulars do not suggest that the benefits which Mr Schiff is alleged to have taken advantage of were not lawfully available under the laws of the relevant jurisdictions, namely SVG and Puerto Rico. The question then arises, taking the particulars at their highest, whether it should be inferred that Mr Schiff knew that the Bank’s customers would include tax evaders and other criminals (particulars 14 and 33) and that Mr Schiff knew that by moving the Bank’s operations to Puerto Rico, he would facilitate the use of the Bank by customers involved in illegally evading tax (particular 27). The knowledge alleged in paragraphs 14 and 33 is said to arise from particulars 2 and 3 (ie Schiff’s direction and control of the Bank) and the statements made by Schiff particularised in paragraphs 38A to 38J (ie promoting tax avoidance). I read the latter references as also being intended to refer to particular 38, although that is not expressly stated. The knowledge alleged in particular 27 is said to be based on the reason for moving the Bank from SVG to Puerto Rico being avoidance of reporting obligations under the CRS. While I accept that the particulars would provide a basis for an allegation that Mr Schiff should have been aware that tax evaders might be amongst the customers, or that he could facilitate tax evasion by establishing the Bank in those jurisdictions, I do not regard the particulars as providing a basis for alleging that Mr Schiff actually knew that those things would in fact occur; that is, as a matter of probability. That strikes me as a substantially different matter from the question of mere possibilities of what might occur, and would require more by way of factual basis than is currently provided in the particulars.

20 That point became starker during oral argument in which Senior Counsel for the respondents stated repeatedly that the respondents’ case was that Mr Schiff knew that it was “inevitable” that a sub-set of the Bank’s customers would be tax evaders and other criminals: T47.10-48.40; T50.25-51.2; T51.47-52.5; T55.43-45; and T117.2-9. The word “inevitable” does not appear in any of particulars 14, 27 and 33, but if that is the allegation then the particulars must allege facts which demonstrate that inevitability. As presently formulated, the particulars fall short of that demanding contention.

21 I should note that the applicant also makes the criticism that the particulars do not demonstrate that the only relevant benefit conferred by the applicable jurisdictions was avoidance of tax reporting obligations, and that the particulars failed to exclude the possibility that there was some other reason for incorporating the Bank in those jurisdictions, such as lower tax rates or reduced compliance costs. I do not regard that as a valid objection. The particulars do amount to an allegation as to a substantial purpose of Mr Schiff, which I regard as sufficient.

22 The final criticism made by the applicant concerning these particulars relates to the public statements by Mr Schiff in which he is said to have expressed views antipathetic to the legitimacy of taxation (particulars 38-38J), which then culminate in an inference expressed in particular 39 that it may reasonably be concluded that:

(a) Schiff endorses, permits and condones avoidance of the payment of tax;

(b) Schiff, at all material times, has known that the Bank provides a vehicle for its customers to illegally avoid the payment of tax, with minimal risk of enforcement action.

The applicant contends that those serious allegations do not follow from the basis set out in the particulars. Whether Mr Schiff has expressed political views antipathetic to taxation does not support an assertion that he in fact endorses, permits and condones the illegal avoidance of tax in practice, or that he knows as a fact that this occurs through the medium of his bank.

23 In my opinion, that submission is well founded. None of the statements in particulars 38-38J condone or encourage illegal conduct, as distinct from the lawful minimisation of tax liabilities, together with some political views (such as those in sub-paragraphs 38(a) and (d)) which would widely be regarded as idiosyncratic, extreme and possibly irrational. The way in which particular 39 is expressed is infelicitous, in that tax avoidance is ordinarily understood to refer to transactions which comply with the letter of the relevant revenue law, whereas tax evasion is ordinarily understood to refer to the illegal non-payment of tax. Paragraph 39(a) thus alleges no more than that Schiff encourages the lawful minimisation of tax, and paragraph 39(b) is internally contradictory in alleging the illegal minimisation of tax permitted by the letter of the law. That is a matter of expression in particular 39 which might readily be cured. However, the real problem with particular 39 is more fundamental and concerns the inadequacy of the matters particularised at 38-38J to support the inference which is alleged in particular 39(b). In saying that, I have taken into account the principle referred to above that the cumulative effect of the particulars must be considered. I have also taken into account that the word “foregoing” at the beginning of particular 39 may be intended to refer to everything alleged in particulars 1-38J, although that literal meaning is not clear from the context.

Particulars 34C-34G and 40-56 (Allegations about Certain Customers of the Bank)

24 Particulars 34C-34G and 40-56 are in the following terms:

25 These particulars make specific allegations about three of the Bank’s customers: Gunnar Helgason, Simon Anquetil and Michael Wilson.

26 In relation to Mr Helgason, it is alleged that he told a Bank Referral Agent that “he was not fond of tax reporting”, and that “part of his motivation for joining the Bank was to avoid paying tax in his local jurisdiction”: particular 34E. I do not accept the applicant’s criticism that particular 34E is not adequately particularised because the words allegedly used by Mr Helgason are not set out with specificity and no date is given for this alleged conversation. However, the applicant also submits that while it is alleged that Mr Helgason opened a Euro Pacific account (particular 34F), the pleading is completely silent as to: (a) whether Mr Helgason actually did avoid paying tax in his local jurisdiction; (b) if so, whether he actually used a Euro Pacific account to do so; and (c) if so, how the Euro Pacific account facilitated any such tax avoidance. I agree with the applicant’s submission, and would add that these particulars proceed on the erroneous basis that there is something intrinsically nefarious about avoiding tax, despite that being a reference in its ordinary and natural meaning to lawful conduct. The respondents submit that whether or not Mr Helgason achieved his objective of avoiding the payment of tax, is not a matter which the respondents will seek to prove at trial; rather, the respondents will seek to establish that the Bank’s vetting processes were inadequate to prevent a person like Mr Helgason from opening an account (particular 34G). It is not clear to me that such an allegation goes any further than what is, in effect, a negligence case against the Bank for not implementing adequate precautions. While the respondents also draw attention to particulars 34H-35A, I do not read those particulars as elevating the allegations to a different moral plane than that of negligence. Senior Counsel sought to argue that the Bank’s processes for vetting and accepting customers involved wilful blindness or recklessness as to who those customers were (T49.19-20; T52.12-28; and T54.30-55.37), but accepted that there is no such allegation in the particulars. It may be doubted whether such an allegation would be sufficient in any event to support a defence of justification in light of Jagot J’s comments at [102] that the imputations are pitched at a higher level than Mr Schiff being wilfully blind or reckless. Further, particular 54 appears to treat Mr Helgason as a person engaged in criminal activity (like Mr Anquetil and Mr Wilson). That is a most egregious breach of proper pleading, given that Mr Helgason is not alleged to have done, or attempted to do, anything unlawful under the laws of any jurisdiction.

27 In relation to Mr Anquetil, the applicant submits that the only allegations are that he was guilty of a major tax fraud conspiracy (particulars 40-45), and that for a period which coincided with the criminal proceedings against him (but not when he actually committed the crimes), he was a customer of the Bank (particular 46). The applicant submits there is no allegation that his Euro Pacific account actually had anything at all to do with the commission of these crimes, or that the money in his Euro Pacific bank account was derived from his criminal conduct, or that the amount of “in excess of $1,000,000” was deposited in that account. I agree with those submissions.

28 In relation to Mr Wilson, the applicant submits that the only allegations are that he was guilty of wire fraud (particular 49), and that in 2017 he held a Euro Pacific account (particular 51). The applicant submits that there is no allegation that the Euro Pacific account had anything to do with the commission of this fraud. Further, the applicant submits that, on the face of the particulars, Euro Pacific could not possibly have had anything to do with the fraud, because the fraud is alleged to have taken place in 2008-2010 (particular 48(a)) whereas Euro Pacific was not incorporated until 2011 (particular 1). I agree with those submissions. Senior Counsel for the respondents submitted that Mr Wilson deposited the proceeds of his crimes in his Euro Pacific bank account, but accepted that the particulars (including particular 49) do not say that: T61.10-17.

29 The applicant submits that there is no allegation in the pleading that Mr Schiff personally knew anything whatsoever about Mr Helgason, Mr Anquetil or Mr Wilson, their activities, or the fact that they were three of many thousands of customers of the Bank. The applicant submits that in the absence of particulars supporting the attribution of such knowledge, the allegation at particular 53 that “the bank was prepared to have criminals and tax cheats as customers” cannot properly be made. I agree with those submissions, and I would add that even if someone in the Bank had that knowledge of these three customers, particular 53 goes nowhere unless that knowledge can be attributed in some way to Mr Schiff. The respondents appear to accept that it has not particularised any allegation that Mr Schiff personally knew or ought to have known anything at all about Mr Helgason, Mr Anquetil or Mr Wilson, or their activities.

30 Particular 55 alleges that Mr Schiff actually knew that:

(a) the Bank was being used and would be used as a vehicle for customers to commit tax fraud, and as a vehicle for criminals to hide and launder the proceeds of crime; and

(b) the provision of secret bank accounts and encrypted communication would assist tax cheats and criminals in their criminal endeavours.

31 The applicant submits that given what precedes it, there is no proper basis for that very serious allegation. The applicant submits that the particulars do not identify a single instance in which a customer of the Bank actually used his or her Euro Pacific account to engage in tax evasion or tax fraud, let alone to Mr Schiff’s knowledge. I agree with those submissions.

Particulars 57-70 (Regulatory Investigations)

32 Particulars 57-70 provide as follows:

33 The applicant refers to the assertion in particular 59 that the purpose of Operation Atlantis was to stop the Bank from being used by its customers “to engage in illegal tax evasion and money laundering”. The applicant submits that the particulars do not identify a single instance in which a customer of the Bank did use it to engage in illegal tax evasion or money laundering. That submission, in my opinion, is correct. The applicant also submits that the pleading does not establish any basis for asserting that this was in fact the purpose of Operation Atlantis, which also appears to me to be well founded. Most importantly, the applicant submits that even if that purpose was as alleged, the fact that the group known as the J5 was investigating the Bank for that purpose would not of itself be capable of establishing that the conduct in question actually did occur. That submission should be accepted. The fact that suspicions or opinions of guilt are held by regulatory or investigative bodies cannot establish guilt as a matter of truth.

34 The applicant then draws attention to the allegation that around 100 Australians who were customers of the Bank were “targeted” as part of Operation Atlantis (particulars 60-61). The applicant submits that there is no particularity as to what “targeted” means, what conduct on the part of those customers caused them to be targeted, or whether that conduct had anything whatsoever to do with the Bank. That submission in my view is well founded. The investigation of around 100 Australian customers is irrelevant; what must be established is that they were actually guilty of tax evasion.

35 The applicant then refers to the allegation that the Australian Taxation Office scrutinised over 100 cases concerning Australians who happen to be customers of the Bank, and imposed tax penalties, “in some, but not all, of those 100 cases”: particular 66(b). The applicant submits that the particulars do not state how many cases in fact resulted in tax penalties, or why those penalties were imposed, or whether it had anything at all to do with those Australians’ use of Euro Pacific accounts. That submission in my view is well founded.

36 The applicant also submits that it is apparent from the allegations in particular 64 that the OCFI investigation had nothing to do with the Bank facilitating actual tax evasion and tax fraud by customers. That submission seems to me to be too strongly put, however I accept the applicant’s submission that particular 64 does tend to indicate that the findings of the OCFI pertained to the Bank’s risk management practices, deficient earnings and capital levels, and inaccurate accounting and due diligence. The applicant draws attention to particular 64(e) which alleges the OCFI made findings in relation to the Bank’s money laundering and customer due diligence program, but does not allege a finding of actual tax evasion or tax fraud by the Bank, or that Mr Schiff had knowledge of this. In my opinion that submission is correct. There also appears to be a tension between the use of the words “critically deficient” towards the beginning of particular 64, in contrast to the milder adjective “inadequate” used in paragraph 64(e).

37 The applicant submits correctly that particular 67 does not identify which aspect of Puerto Rican law the applicant admitted knowledge of the Bank not having complied with.

38 As to particular 69, the applicant submits that the allegation does not specify how the investigations of the Bank’s customers are said to involve the Bank or, more relevantly, Mr Schiff. The applicant submits that it has been well over three years since Operation Atlantis commenced yet no particular has been alleged of any finding, charge or conviction of any kind against Mr Schiff. The one conviction referred to in particular 69 is that of a customer from the Netherlands, but the charge is unspecified as to its the connection (if any) to the Bank or to Mr Schiff. Those submissions are well founded.

39 Particular 70(a) alleges deliberateness in the Bank’s maintenance of inadequate compliance procedures to prevent money laundering or tax evasion. However, there is no basis in the particulars for elevating to that level what appears to be an allegation of carelessness in particular 64.

40 Particular 70(b) alleges unlawful conduct by Australian customers of the Bank, and criminal conduct by one Australian customer, but does not allege that this conduct was connected in any way with the accounts with Euro Pacific or that Mr Schiff had any knowledge of the customers or their conduct. Particular 70(c) implicitly assumes such knowledge on the part of Mr Schiff, but does not allege that knowledge, nor is there any sufficient basis in the particulars for such an allegation.

41 Accordingly, for the reasons given above, the particulars of justification provided in the proposed Further Amended Defence are defective. For that reason, leave to file that proposed pleading should be refused.

42 I turn now to consider whether, even if the particulars were not treated as defective, and were all assumed to be established at the trial, the defence of justification would still fail.

Do the particulars (if assumed to be established) provide a defence of justification?

43 This ground of objection to the proposed pleading requires a comparison between the imputations which have been found by Jagot J to have been conveyed by the television broadcast with the propositions of fact alleged in the particulars. In doing so, I will assume that any reasonable argument as to the meaning of those imputations is resolved in favour of the respondents’ contentions, and that the particulars are taken at their highest.

Imputation 8.1

44 Imputation 8.1 is that by permitting his bank, Euro Pacific, to be used as a vehicle for around 100 Australian customers to commit tax evasion, Schiff facilitated the theft of millions of dollars from the Australian people.

45 Putting to one side the issue of what state of mind on the part of Mr Schiff may be raised by this imputation, the propositions that around 100 Australian customers have used Euro Pacific bank to commit tax evasion, and millions of dollars have thereby been unlawfully taken from the Australian people, are material parts of the imputation. Senior Counsel for the respondents accepted that there is no particular that around 100 Australian customers were tax evaders (T29.39-30.7) and submitted that the figure of around 100 Australian customers is not part of the “sting” of the imputation. Senior Counsel for the respondents accepted, however, that the monetary amount of millions of dollars is part of the sting (T30-34). I am unable to draw such a distinction. The sting of the defamation includes the size and scale referred to which are relevant to the gravity of the imputation. The size and scale are measured in two ways: by headcount of customers and by total monetary amount. The proposed particulars refer only to one Australian customer of the Bank as having been guilty of an offence relating to tax, namely Mr Anquetil. Not even Mr Anquetil is alleged to have used his Euro Pacific account in engaging in that conduct. Particular 42(b) expresses the amount of the proceeds of his criminal conduct as “in excess of $1,000,000”, which does not amount on its face to “millions of dollars”. Particular 66 refers only to investigations by the ATO, but does not allege the fact of tax evasion by anyone in any amount. Accordingly, in my opinion, taken at their highest, the proposed particulars are incapable of providing a defence of justification for this imputation. That conclusion would be sufficient on its own for the whole of the defence of justification in relation to all the imputations found by Jagot J to be struck out: Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCAFC 119 at [7]-[16] (Rares J, Wigney and Lee JJ agreeing).

46 It is not necessary for me to consider what mental element (if any) is implicit in the word “facilitated”, and whether the proposed particulars are sufficient for that purpose. I note, however, that in oral submissions, Senior Counsel for the respondents accepted that one cannot be said to facilitate something without knowing or intending that one is doing so (T22.36-39)

Imputation 8.2

47 Imputation 8.2 is that Schiff orchestrated an illegal tax evasion scheme.

48 Used in this figurative sense, “orchestrated” means combined harmoniously like instruments in an orchestra. That is necessarily a reference to intentional conduct directed to a particular purpose and the actual achievement of that purpose. As Jagot J said of this imputation at [70]:

He intended Euro Pacific bank to be used by tax evaders. His clients include Australians who are ‘wealthy crooks’ who avoid paying their share of tax by using, amongst others, Euro Pacific bank …. The ordinary, reasonable viewer would not take a lawyer’s view of Mr Schiff orchestrating an illegal tax evasion scheme as requiring Mr Schiff’s knowing involvement in specific instances of tax evasion by known persons. They would understand that if Mr Schiff founded and runs Euro Pacific bank at least in part to facilitate the use of the bank by customers involved in illegally evading tax and the bank is so used, then Mr Schiff orchestrated an illegal tax evasion scheme.

49 I read the words “to facilitate” in the last sentence as meaning “in order to facilitate” or “with the purpose of facilitating”. The penultimate sentence deals with the lack of any requirement of knowing involvement in specific instances of tax evasion by known persons, and the last sentence relates to a more generalised purpose and intention.

50 There is no particular that Mr Schiff had such a purpose or intention. Particulars 14, 27, 33, 39, 55 and 70(a) are the closest the particulars come to that allegation. However, the purpose alleged in particulars 14, 27 and 33 is only as to attracting and permitting custom from persons who wished to maintain privacy over their financial account information. The knowledge alleged (albeit defectively) in particulars 14, 27, 33, 39 and 55 may be a starting point for an allegation of intention or purpose, but is not in itself sufficient. Particular 70(a), which I have also found to be defective, goes no further than a purpose of attracting global custom from persons including tax evaders and money launderers, but that falls short of an allegation that such persons were in fact induced to become customers by that alleged attraction.

51 Further, as Jagot J’s reasoning at [70] makes clear, imputation 8.2 conveys that the Bank was actually used for an illegal tax evasion scheme. The particulars refer to only one customer of the Bank as having been guilty of tax-related offences, namely Mr Anquetil (particulars 42-43). Another customer, Mr Wilson, is said to have been guilty of wire fraud (particulars 48-49), but not of tax evasion. Another unnamed customer in the Netherlands is said to have been convicted (particular 69), but the pleading does not identify his crimes or whether they were related to tax evasion. In none of these cases, including that of Mr Anquetil, is there any suggestion that bank accounts at Euro Pacific played any role at all in the criminal conduct.

52 The particulars on their face therefore fall short of supporting a defence of justification for this imputation.

Imputation 8.3

53 Imputation 8.3 is that Schiff committed tax fraud.

54 In relation to this imputation, Jagot J said at [71]:

The ordinary, reasonable viewer would understand that a person who has intentionally permitted the bank which he owns, runs and is responsible for to be used for tax evasion must have committed tax fraud. Such a person would not distinguish (or think about) any difference between knowingly and intentionally facilitating other people to commit tax fraud and personally committing tax fraud in relation to one’s own money.

55 For the reasons given in relation to imputation 8.2, the particulars do not go so far as to allege that Mr Schiff did “intentionally” permit his bank to be so used. Nor do the particulars allege that the Bank was actually used for tax evasion. Accordingly, the particulars cannot support a defence of justification for this imputation.

Imputation 8.4

56 Imputation 8.4 is that Schiff knowingly facilitates tax fraud, in that he established his bank, Euro Pacific, in Puerto Rico, for the purpose of enabling his customers to illegally hide their money from tax authorities.

57 Particulars 27 and 33, which I have found to be defective, in substance correspond to the language used in expressing this imputation after the words “in that”. If I had not found particulars 27 and 33 to be defective, then I would have concluded that those particulars, taken at their highest, were capable of supporting a defence of justification for imputation 8.4 on the most favourable construction to the respondents of that imputation.

Imputation 8.5

58 Imputation 8.5 is that Schiff knowingly assisted around 100 Australians to illegally evade their tax obligations.

59 For the reasons given in relation to imputation 8.1, the particulars do not support a defence of justification for this imputation for any customer at all, let alone around 100 Australians.

Imputation 8.11

60 Imputation 8.11 is that through his bank, Euro Pacific, Schiff poses a grave organised crime threat to Australia.

61 Particulars 62 and 63 allege in substance that ACIC as the relevant regulatory body believes that Euro Pacific is a serious organised crime threat to Australia. ACIC’s belief does not establish the truth of that belief.

62 The word “threat” is capable of a variety of meanings. In the context of a contagious disease, “threat” was treated as interchangeable with “risk” in LCA Marrickville Pty Ltd v Swiss Re International SE [2022] FCAFC 17; (2022) 290 FCR 435, eg at [545]-[546]. In other contexts, “threat” may require a declaration of an intention to punish or hurt. In the present case, the expression “poses a threat” has the natural and ordinary meaning of presenting a risk.

63 The applicant submitted that the concept of a threat requires a likelihood of the relevant subject matter occurring, rather than a mere possibility. However, the applicant accepts that for present purposes I should adopt any reasonably arguable construction of the imputation which is most favourable to the respondents (T71.33-43). On that approach, if it were not for the defects in the particulars identified above, I would have found that the particulars on their face, and bearing in mind their cumulative effect, are capable of supporting a defence of justification for imputation 8.11.

Imputation 8.12

64 Imputation 8.12 is that Schiff is such an unscrupulous individual that he has no qualms about doing business with criminals and money launderers.

65 A defence of justification would require particulars of actual knowledge by Schiff that he is doing business with criminals and money launderers, and is unconcerned about that. If I had not found particulars 14, 27, 33, 39, 55 and 70 to be defective, then I would have found that the cumulative effect of the proposed particulars was capable of supporting a defence of justification for this imputation.

Conclusion on Defence of Justification

66 Accordingly, leave to rely on paragraph 13 of the proposed Further Amended Defence should be refused, together with the particulars provided for the defence of justification as set out in the proposed Further Amended Defence.

67 In my opinion, the respondents should have leave to re-plead paragraph 13 and the particulars of justification. Although this is the third attempt by the respondents to plead their defence, the applicant’s substantive challenge to the defence of justification has not been heard and decided until now. In my opinion, the respondents should have a further opportunity, taking into account my reasons as to the shortcomings of their pleading, to plead a defence of justification, as well as mitigation of damages, if they are instructed to do so. While this may prejudice the applicant in terms of the prolongation of the proceedings, and (as a speculative possibility) in terms of the amount of security for costs, any such prejudice is outweighed in my opinion by the necessity in the interests of justice of affording the respondents a further opportunity to re-formulate their defence.

Paragraph 14: Mitigation of Damages

68 In relation to the mitigation of damages, the respondents rely on: (a) the substantial truth of such of the imputations as are ultimately proved to be true; (b) matters proved in support of the defences; and (c) the circumstances in which it is proved that the matters complained of were published: paragraph 14(a)-(c).

69 The respondents accept that if the Court refuses leave for the defence of justification in paragraph 13 and its particulars, it follows that leave would be refused for sub-paragraph 14(a)-(b).

70 As to paragraph 14(c), the applicant does not complain about this aspect of the pleading.

71 Sub-paragraph 14(d) relies upon background context material as a factor in mitigation of damages pursuant to s 38 of the Defamation Act. This is an invocation of the so-called “Burstein principle”, recognised in Burstein v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 1 WLR 579. No particulars are given in the current proposed Further Amended Defence as to what is said to be the relevant background context other than a generalised reference to the proposed particulars of justification, which I have rejected. In Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 550; (2018) 359 ALR 564 at [45], Wigney J said that mere resort to the label “directly relevant background context” is not sufficient as a pleading. Leave to rely on sub-paragraph 14(d) should be refused in the absence of particulars, with leave to re-plead. Although the submissions at this interlocutory hearing dealt with the constraints which apply in invoking the Burstein principle, this is not the occasion for determining what aspects of the current proposed particulars of justification are capable of being re-fashioned for the purpose of mitigation of damages.

The Position of the Second Respondent

72 As indicated above, the second respondent (The Age Company Pty Ltd) seeks an order that the proceedings be dismissed against it or alternatively that judgment be entered in its favour. The basis of that application is that the second respondent was the publisher of the newspaper article but not the television broadcast, and Jagot J found that the article does not convey any of the pleaded imputations.

73 The applicant points out that in the Statement of Claim, Mr Schiff pleaded that each of Mr McKenzie, Mr Grieve and Mr Toser was a journalist with responsibility for the publication of the television broadcast, and it is alleged that each of them was “an employee or agent of the first respondent and the second respondent” (paragraphs 4 to 6 of the Statement of Claim). The applicant says that in each case, he did not differentiate whether they were employees or agents of one company or the other because, prior to discovery, the applicant had no way of knowing which was applicable in each individual’s case. The respondents admitted the allegations contained in the relevant paragraphs of the Statement of Claim, without making clear whether each individual was an employee of the first respondent or an employee of the second respondent.

74 The applicant submits that, in light of the allegation that the three journalists were responsible for the publication of the broadcast, and by reason of the admission by the respondents that the second respondent employed each of those individuals, it follows that the second respondent is, as a matter of law, vicariously liable for their torts. The applicant submits that it does not matter that there is no express pleading that the corporate respondents are vicariously liable for the wrongs of their employees, being a proposition of law so obvious that it does not need an express pleading.

75 In my view, in the light of the current state of the pleadings, there is no basis for the summary disposal (whether by way of dismissal or judgment) of the proceedings against the second respondent. The matter can be addressed subsequently if it emerges on the pleadings that there is no longer any issue concerning the potential liability of the second respondent.

Conclusion

76 Accordingly, the orders which I make are as follows:

(1) Leave to file a Further Amended Defence in the form annexed to the respondents’ Interlocutory Application dated 20 March 2023 and marked “A” be refused.

(2) The respondents be given leave to re-plead paragraphs 13 and 14 and the particulars of justification.

(3) Any re-pleading of the proposed Further Amended Defence be provided to the applicant by 12 May 2023.

(4) The matter be stood over to 19 May 2023 at 9.30am for a further case management hearing before me.

(5) The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the interlocutory application dated 20 March 2023.

I certify that the preceding seventy-six (76) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Jackman. |

Associate:

NSD 1086 of 2021 | |

CHARLOTTE GRIEVE | |

Fifth Respondent: | JOEL TOZER |