FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Daly (Liability Hearing) [2023] FCA 290

Table of Corrections | |

10 January 2024 | Paragraph 362: Insert “(Mr Williams)” after the word “approved”. Insert “(Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams)” after the two occurrences of the word “executed”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent PAUL NIELSEN Second Respondent PAUL ANTHONY RAFTERY (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 3 APril 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 17 April 2023, the parties are to confer and propose short minutes setting out timetabling orders for the preparation of the hearing concerning relief and provide a copy to the Associate to Cheeseman J.

2. Costs be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHEESEMAN J

1 In these civil penalty proceedings, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) seeks declaratory relief, pecuniary penalties and disqualification orders in relation to the alleged contravention of ss 601FD(1)(b), (c), (e), (f) and 601FD(3) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by four respondents in relation to their conduct as officers of Endeavour Securities (Australia) Ltd (in liquidation) (ACN 079 988 819), the responsible entity of the Investport Income Opportunity Fund, a registered managed investment scheme. These reasons are addressed to the issue of liability only.

2 The proceeding arises in the context of two managed investment schemes. Both bore the same name – the Investport Income Opportunity Fund – and were referred to by the same acronym – IIOF. The earlier of the two schemes was an unregistered managed investment scheme for which Linchpin Capital Group Ltd (ACN 163 992 961) was responsible. The other scheme was registered. To distinguish between the two, I will refer to them as the Unregistered Scheme and the Registered Scheme.

3 The Registered Scheme is necessarily the focus of the allegations of contravention of ss 601FD(1) and (3) of the Act, which impose duties on the officers of responsible entities of registered schemes.

4 Endeavour raised about $17.3 million in the Registered Scheme from 131 investors pursuant to three product disclosure statements (PDS), issued on 27 April 2015, 1 October 2015 and 24 June 2016, the First PDS, Second PDS and Third PDS respectively. About 95% of the funds raised in the Registered Scheme were transferred to Linchpin as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme.

5 Unless context otherwise dictates, all references to Endeavour are to Endeavour acting in its capacity as the responsible entity for the Registered Scheme. Linchpin was described as the responsible entity and acted as the trustee of the Unregistered Scheme. I will refer to Linchpin as the trustee of the Unregistered Scheme. Again, unless context otherwise dictates, all references to Linchpin are to Linchpin acting in this capacity with respect to the Unregistered Scheme.

6 On 7 August 2018, Mr Jason Mark Tracy and Mr David Orr of Deloitte were appointed as interim Receivers of the property of: Linchpin; the Unregistered Scheme; and the Registered Scheme: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Linchpin Capital Group Ltd [2018] FCA 1104 (ASIC v Linchpin).

7 After obtaining interlocutory relief, ASIC brought proceedings against Linchpin and Endeavour which were, to the extent possible, resolved by agreement, and by orders entered on 15 March 2019: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Linchpin Capital Group Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 398 (ASIC v Linchpin (No 2)). The respondents to the present proceeding were not parties to the proceedings against Linchpin and Endeavour.

8 In ASIC v Linchpin (No 2) declarations were made in respect of Endeavour’s contravention of s 208 (as modified by s 601LC) — engaging in related party transactions without member approval; s 601FC(1)(b) — failing to exercise reasonable care and skill as responsible entity of the Registered Scheme; s 601FC(1)(c) — failing to act in the best interests of the members of the Registered Scheme; s 601FC(1)(h) — failing to comply with its compliance plan; s 601FC(1)(j) — failing to ensure that the property of the Registered Scheme was valued at regular intervals; s 601FC(1)(k) — failing to ensure that payments were made out of scheme property in accordance with the Act; s 912A(1)(a) — failing to ensure that the financial services it provided in respect of the Registered Scheme were provided efficiently and fairly; s 912A(1)(aa) — failing to have in place adequate arrangements for the management of conflicts of interest; ss 1013D(1)(f) and 1013E — failing to identify, in the Second PDS and the Third PDS, the nature of the related party transactions which had been entered into prior to issuing those PDS; and s 1017B(1) — failing to identify to the Registered Scheme members the nature and extent of the related party transactions that were entered into following the issue of the First, Second and Third PDS. Declarations were also made in respect of Linchpin’s contraventions of the Act including, inter alia, contravention of s 601ED(5) — failure to register the Unregistered Scheme and 601ED(5) of the Act — operating an unregistered managed investment scheme.

9 On 15 March 2019, Mr Tracy and Mr Orr were appointed as the joint and several liquidators of Linchpin and Endeavour (pursuant to s 461(1)(k)) and as the responsible persons for winding up the funds of the Registered Scheme (pursuant to s 601ND(1)(a)) and the Unregistered Scheme (pursuant to s 601EE(2) of the Act).

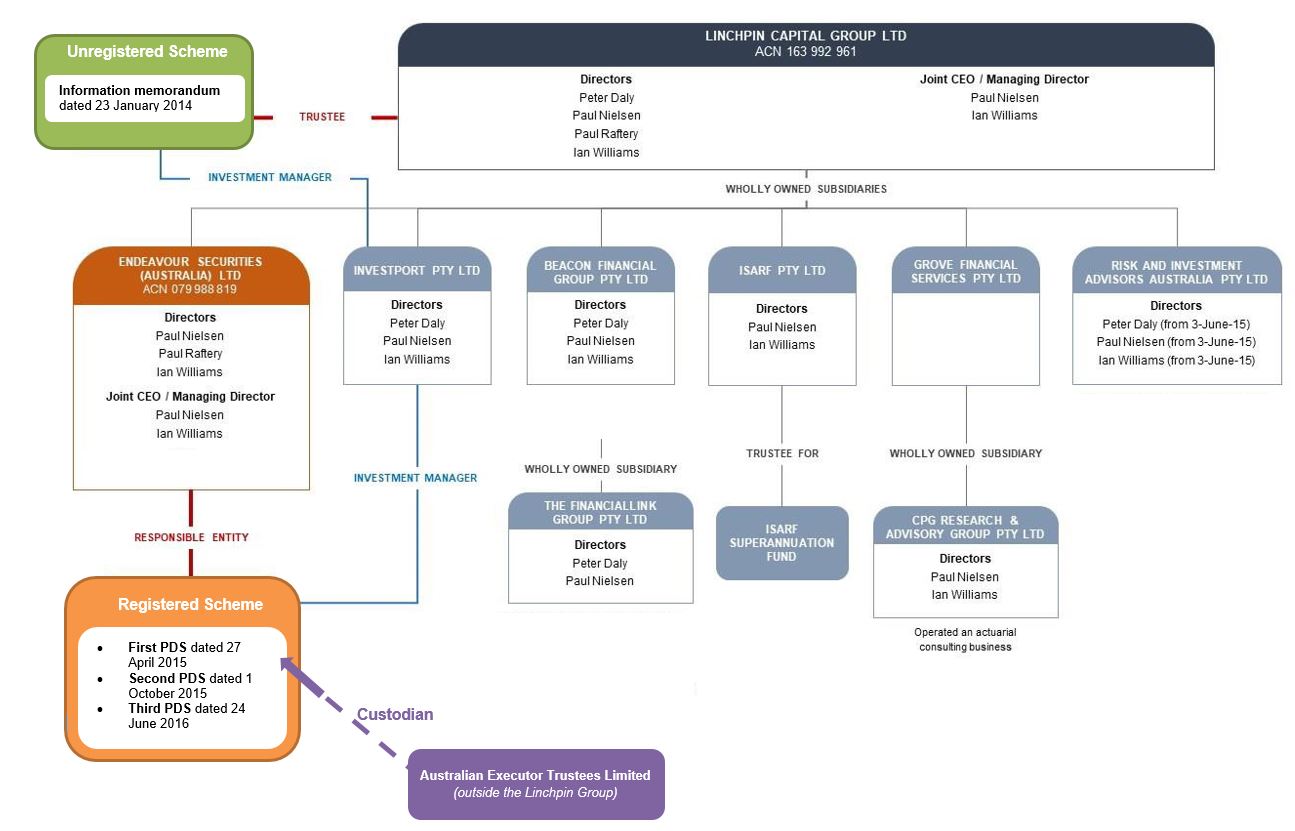

10 Endeavour was acquired by Linchpin in December 2014. All four respondents were directors of Linchpin throughout the whole of the relevant period. A structural diagram of Linchpin and its relevant related entities (collectively, the Linchpin Group), and the Registered Scheme and Unregistered Scheme is included as Schedule A to these reasons.

11 Mr Paul Nielsen, Mr Paul Raftery and Mr Ian Williams, the second, third and fourth respondents respectively, were directors of Endeavour during the whole of the relevant period, 1 April 2015 to 7 August 2018. Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams acted as joint chief executive officers and managing directors of Endeavour for the whole of the relevant period.

12 Mr Peter Daly, the first respondent, was not appointed as a director of Endeavour. ASIC contends that Mr Daly was relevantly an officer of Endeavour within the meaning of para (b)(i) and (ii) of the definition of “officer” in s 9 of the Act because he was a person who made, or participated in, making decisions that affected the whole, or a substantial part, of the business of Endeavour, or had the capacity to significantly affect Endeavour’s financial standing.

13 At the commencement of the liability hearing, Mr Nielsen, Mr Raftery and Mr Williams by their respective counsel confirmed that they did not contest ASIC’s entitlement to declaratory relief on the basis that the evidence led by ASIC established to the requisite standard of proof that they each had contravened s 601FD(1) of the Act as alleged.

14 Mr Daly was legally represented at the hearing. He was the only respondent who took an active part in the liability hearing. In his defence, Mr Daly denied that he was an officer of Endeavour. He also sought to defend the allegations against him on the basis of his contention that ASIC’s claim against him was inadequately pleaded and that ASIC had not established a causative link between his conduct and the relevant contraventions of the Act. At the conclusion of ASIC’s case, Mr Daly elected to exercise his privilege against exposure to a penalty. Accordingly, he did not go into evidence.

15 Conscious of the consequences that follow in the context of these civil penalty proceedings, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that ASIC has established that the respondents contravened ss 601FD(1)(b), (c), (e), (f) and 601FD(3) of the Act, in the manner set out within.

16 In finding against Mr Daly, and again, conscious of the consequence of doing so in the present context, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that ASIC has established that Mr Daly was an officer of Endeavour from at least 1 April 2015 to 7 August 2018.

17 I will hear from the parties on the relief that should follow as a consequence of my findings on liability.

18 Before moving to the facts, it is useful to first address the legislative framework for the regulation of managed investment schemes.

19 Section 9 of the Act defines “managed investment scheme” as follows:

(a) a scheme that has the following features:

(i) people contribute money or money’s worth as consideration to acquire rights (interests) to benefits produced by the scheme (whether the rights are actual, prospective or contingent and whether they are enforceable or not);

(ii) any of the contributions are to be pooled, or used in a common enterprise, to produce financial benefits, or benefits consisting of rights or interests in property, for the people (the members) who hold interests in the scheme (whether as contributors to the scheme or as people who have acquired interests from holders);

(iii) the members do not have day-to-day control over the operation of the scheme (whether or not they have the right to be consulted or to give directions)…

20 Chapter 5C of the Act contains provisions relating to the registration and operation of managed investment schemes. To register a managed investment scheme, a person must lodge an application with ASIC together with, relevantly, a copy of the scheme’s constitution and compliance plan: s 601EA. ASIC must register the scheme within 14 days of lodgement of the application, unless it appears to ASIC, inter alia, that the constitution and compliance plan do not meet the requirements specified in the Act: s 601EB.

21 The requirements for a scheme’s constitution are set out in Part 5C.3 of the Act. Section 601GA(1) provides that the constitution of a registered scheme must make adequate provision for, inter alia, the powers of the responsible entity in relation to making investments of, or otherwise dealing with, the scheme property. The constitution of a registered scheme must be contained in a document that is legally enforceable as between the members and the responsible entity: s 601GB.

22 The requirements of the scheme’s compliance plan are in Part 5C.4 of the Act. The compliance plan must set out adequate measures that the responsible entity is to apply in operating the scheme to ensure compliance with the Act and the scheme’s constitution: s 601HA(1). Compliance with the plan must be audited by a registered company auditor, an audit firm or an authorised audit company: s 601HG.

23 A registered managed investment scheme must have a responsible entity, which in turn must be a public company that holds an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) authorising it to operate a managed investment scheme: s 601FA. The responsible entity of a registered scheme is to operate the scheme and perform the functions conferred on it by the scheme’s constitution and the Act: s 601FB(1). The responsible entity holds scheme property on trust for scheme members: s 601FC(2). In effect, the responsible entity is tasked with acting as a professional trustee in relation to the scheme property.

24 The duties of a responsible entity are prescribed by s 601FC(1). The duties imposed directly on the responsible entity by s 601FC(1) are mirrored in s 601FD(1), which imposes duties on officers of a responsible entity. This is the critical provision in issue in this proceeding.

25 The duties imposed by s 601FD(1) that ASIC alleges that each of the respondents contravened in various ways are:

Duties of officers of responsible entity

(1) An officer of the responsible entity of a registered scheme must:

…

(b) exercise the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they were in the officer’s position; and

(c) act in the best interests of the members and, if there is a conflict between the members’ interests and the interests of the responsible entity, give priority to the members’ interests; and

…

(e) not make improper use of their position as an officer to gain, directly or indirectly, an advantage for themselves or for any other person or to cause detriment to the members of the scheme; and

(f) take all steps that a reasonable person would take, if they were in the officer’s position, to ensure that the responsible entity complies with:

(i) this Act; and

(ii) any conditions imposed on the responsible entity’s Australian financial services licence; and

(iii) the scheme’s constitution; and

(iv) the scheme’s compliance plan.

26 In the context of the obligations imposed by s 601FD(1)(f), it is relevant to note that the Act imposes obligations in respect of PDS issued in respect of financial products. The obligation to issue a PDS in respect of financial products is imposed by s 1012A. Relevantly, a PDS must contain such information about the following matters as a person would reasonably require for the purpose of making a decision, as a retail client, as to whether to acquire the relevant financial product:

(a) any significant risks associated with holding the product: s 1013D(1)(c);

(b) the cost of the product, any amounts that will or may be payable by a holder of the product in respect of the product after its acquisition, and – if the amounts paid in respect of the financial product and the amounts paid in respect of other financial products are paid into a common fund – any amounts that will or may be deducted from the fund by way of fees, expenses, or charges: s 1013D(1)(d);

(c) any other significant characteristics or features of the product, or of the rights, terms, conditions and obligations attaching to the product: s 1013D(1)(f); and

(d) any other matter that might reasonably be expected to have a material influence on the decision of a reasonable person, as a retail client, whether to acquire the product: s 1013E.

27 Issuers of financial products must notify the holders of their products of any material change to a matter, or any significant event that affects a matter, being a matter that would have been required to be specified in a PDS for the financial product prepared on the day before the change or event occurs, and certain changes, events and matters as may be specified in the regulations: s 1017B(1A)(a), (b). A notice given pursuant to s 1017B(1) must contain all the information that is reasonably necessary for the holder to understand the nature and effect of the relevant changes or events: s 1017B(4).

28 A duty of an officer of the responsible entity under s 601FD(1) overrides any conflicting duty the officer has under Part 2D.1 of the Act, which prescribes the duties and powers of directors and other officers and employees of corporations generally: s 601FD(2).

29 Section 601FD(3) provides that a contravention of s 601FD(1) is also a contravention of s 601FD(3), which is a civil penalty provision: s 1317E.

30 The evidence tendered at the liability hearing was voluminous, comprising approximately 15 volumes of documentary material. Broadly, it was drawn from the following sources.

31 ASIC’s affidavit evidence was comprised of:

(a) Three affidavits of Ms Anne Elizabeth Gubbins, solicitor at ASIC, dated 30 April 2021, 29 November 2021, and 11 February 2022;

(b) Two affidavits of Mr Tracy in his capacity as Receiver and liquidator, described above, dated 30 April 2021 and 22 February 2022; and

(c) Two affidavits of Ms Tegan Harris, director, formerly senior associate, at Gadens Lawyers, solicitors for ASIC, dated 30 April 2021 and 29 November 2021.

32 In January 2018, ASIC commenced a formal investigation into suspected contraventions of the Act by Linchpin, Endeavour, other entities related to Linchpin, and the officers, employees, agents and associated entities of those companies. Ms Gubbins deposes to and puts into evidence the results of various searches conducted by ASIC in the course of its investigation and the responses received by ASIC to compulsory notices issued by it under the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). In her third affidavit, Ms Gubbins clarifies, inter alia, certain matters in respect of the responses ASIC received to compulsory notices issued by it. Ms Gubbins was briefly cross-examined by Mr Daly’s counsel at the liability hearing.

33 Mr Tracy’s first affidavit, inter alia, annexes a joint report prepared by him and Mr Orr, in their capacities as the Receivers, for the purpose of the receivership and winding up proceedings, (Receivers’ Report). In that report, Mr Tracy and Mr Orr identify the way in which funds invested in both the Registered and Unregistered Schemes were applied. Mr Tracy described the key foundation of the Receivers’ Report as being a full reconciliation of the bank accounts of both the schemes. In order to fulfil the scope of the report as dictated by the orders of the Court, Mr Tracy considered it necessary to look at the source of all funds within each of the schemes and the use to which those funds had been put. In his second affidavit, Mr Tracy provides some further explanation of the process he undertook in reaching certain conclusions in the Receivers’ Report and exhibits additional key documents relied upon by him in preparing that report. Mr Tracy was briefly cross-examined by Mr Daly’s counsel at the liability hearing.

34 Ms Harris’ evidence went to the processes undertaken by ASIC’s solicitors to identify and distil documents relevant to the proceeding, including by conducting and supervising key word searches across the documents obtained by ASIC under various compulsory notices. ASIC relies on her evidence in support of an inference that certain things which ASIC contends should have been done were not done because no documents were produced in answer to notices directed to those things. Ms Harris was not cross-examined.

35 A feature of the evidence was that, notwithstanding an extensive investigation by ASIC, which included the administration of statutory notices to many varied entities, there were clear deficiencies in the documentary record relating to both schemes and the way in which they were managed. The nature of many of the deficiencies, in combination with the responses to statutory notices, causes me to infer that the record-keeping for both schemes was inadequate. There was, at the very least, a blurring of the proper demarcation between the two schemes in the way in which such records as were kept, were maintained. Particular deficiencies in the record-keeping of the schemes are addressed where relevant below.

FACT-FINDING – APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES

36 Before turning to consider the evidence, it is convenient to address the principles applicable to fact finding in the present context.

Standard of satisfaction on balance of probabilities

37 In proceedings such as these, involving civil penalty, for ASIC to succeed, I must reach a state of satisfaction or actual persuasion, on the balance of probabilities, while taking into account the seriousness of the allegations and the consequences which will follow if the contraventions are established. Section 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), which is the statutory expression of the principle in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336, provides:

(2) Without limiting the matters that the court may take into account in deciding whether it is so satisfied, it is to take into account:

(a) the nature of the cause of action or defence; and

(b) the nature of the subject‑matter of the proceeding; and

(c) the gravity of the matters alleged.

38 The application of s 140(2) of the Evidence Act and the principles applicable to inferential fact-finding, were canvassed by Lee J in a civil penalty context in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Getswift [2021] FCA 1384 at [118] to [122] and at [1897] to [1899]. It is not necessary for me to reproduce his Honour’s detailed analysis. I draw the following principles from it:

(1) The Court must reach a state of actual persuasion of the occurrence of an alleged contravention;

(2) The specific factual allegations are paramount when considering the gravity of the matters alleged, not the examination of any cause of action or issues in the abstract;

(3) Where there is no direct evidence of a fact alleged, the Court need not have entire satisfaction as to the true state of affairs — a case may be advanced on the basis of circumstantial evidence which, taken in combination with other directly proven facts, may form an adequate basis for making the ultimate factual finding;

(4) Circumstances raising a more probable inference in favour of the facts alleged may satisfy the civil standard of proof, notwithstanding that the conclusion may fall short of certainty; and

(5) Whether an inference is open to be drawn invites consideration of the combined weight or force of circumstantial facts, rather than a discrete consideration of each fact.

39 I adopt and apply those principles here.

Are Jones v Dunkel inferences available against the respondents?

40 Having reserved his position until the close of ASIC’s case, Mr Daly ultimately elected not to give evidence. ASIC contends that, in the context of civil penalty proceedings, and in circumstances where Mr Daly has not waived his privilege against self-exposure to a penalty, the rule in Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 applies. ASIC submits that the Court can, and should, draw Jones v Dunkel inferences against Mr Daly on a number of factual matters upon which he did not give evidence but would be expected to have knowledge. The inference for which ASIC contends is that Mr Daly’s evidence on certain matters, on which he could have, but did not, give evidence, would not have assisted his defence. Mr Daly did not make submissions on this issue. ASIC did not address submissions on this issue to the position of the other respondents. The same issue arises in relation to them as well as Mr Daly.

41 In Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; 243 CLR 361, Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ said at [63] to [64] (footnotes omitted):

The rule in Jones v Dunkel is that the unexplained failure by a party to call a witness may in appropriate circumstances support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case. That is particularly so where it is the party which is the uncalled witness. The failure to call a witness may also permit the court to draw, with greater confidence, any inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness, if that uncalled witness appears to be in a position to cast light on whether the inference should be drawn. These principles have been extended from instances where a witness has not been called at all to instances where a witness has been called but not questioned on particular topics. Where counsel for a party has refrained from asking a witness whom that party has called particular questions on an issue, the court will be less likely to draw inferences favourable to that party from other evidence in relation to that issue. That problem did not arise here. The plaintiff's counsel did ask the plaintiff relevant questions.

The rule in Jones v Dunkel permits an inference, not that evidence not called by a party would have been adverse to the party, but that it would not have assisted the party...

42 The drawing of Jones v Dunkel inferences, if appropriate, in civil penalty proceedings where there is an available claim for penalty privilege has been confirmed by the Full Court: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 at [74] to [76]; Adams v Director of Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2017] FCAFC 228; 258 FCR 257 at [147].

43 I will address the particular inferences which I consider it appropriate to draw against each of the respondents in considering the substantive issues to which they relate.

44 On the basis of the body of evidence outlined above, and applying the approach to fact-finding outlined above, I make the following findings of fact.

45 As noted above, the relevant period is from 1 April 2015 to 7 August 2018.

46 The significance of 1 April 2015 is that it is the date of a circular resolution of a committee that ASIC contends set the overarching investment strategy of the Registered Scheme. The committee was variously referred to as the “Credit Committee”, the “Lending Committee” and / or the “Investment Committee”. For reasons which I will develop, I find that these names were used interchangeably and there was in fact only one committee, which was referred to variously by each or a combination of these names. Mr Daly conceded that the terms “Credit Committee”, “Investment Committee” and “Lending Committee” each referred to the same committee notwithstanding the use of different names. I will refer to this committee as the Investment Committee. In doing so, I note that nothing turns on the name by which the committee was known. The central contest for the purpose of Mr Daly’s defence is whether, from about 1 April 2015, the committee operated with respect to the Registered Scheme as well as the Unregistered Scheme.

47 The end of the relevant period is marked by the appointment of the Receivers.

48 The structure and operations of the Linchpin Group prior to 1 April 2015 provides necessary context to what occurred during the relevant period. It is useful to begin by examining the period before the acquisition by Linchpin of Endeavour in about December 2014, before moving to the relevant period.

49 A feature of the pre-Endeavour period is the operation of the Unregistered Scheme within the Linchpin Group. On about 22 January 2014, Linchpin issued an Information Memorandum (IM), offering units in the Unregistered Scheme to investors. Excluding the amount received from the Registered Scheme, the total amount invested in the Unregistered Scheme was about $5.4 million, which was received from 46 investors between January 2014 and June 2015. There were three redemptions from the Unregistered Scheme resulting in net investor funds of about $5.2 million. During this period, Linchpin as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme commenced making loans using the pooled funds administered in the Unregistered Scheme.

50 The second period follows the acquisition of Endeavour by Linchpin in around December 2014. Prior to Endeavour being acquired by Linchpin, Endeavour was already the responsible entity for the Registered Scheme, then known by another name. The Registered Scheme was inactive at the time of the acquisition by Linchpin. The evidence in relation to the Registered Scheme in the pre-Linchpin period is sparse. It was named the “Endeavour Hi-Yield Fund”. The Registered Scheme is referred to as having had “a limited operating history” in all the PDS issued after Linchpin acquired Endeavour. The “Minutes of a Compliance Committee Meeting” of 15 April 2015 record that the directors of Endeavour had resolved to “activate” the Registered Scheme, using the same name as that used for the Unregistered Scheme. The Endeavour Compliance Committee is addressed in detail below.

Funds raised in the Registered Scheme

51 As mentioned above, during the period after it was acquired by Linchpin, Endeavour raised about $17.3 million in the Registered Scheme from 131 investors pursuant to the three PDS it issued.

52 The vast majority of investors in the Registered Scheme acquired units as retail clients. Only four investors contributed over $500,000 and accordingly were not retail investors within the meaning of s 761G(7)(a) of the Act and reg 7.1.18(2) of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth). Based on the presumption in the Act that a person to whom a financial product or service is provided as a retail client, is taken to acquire that product or service as a retail client, the remaining 127 investors acquired the relevant financial products as retail clients: s 761G(1).

Investment mandate – diversified, secured, income-producing

53 A key feature of the descriptions included in the IM in respect of the Unregistered Scheme and in each of the PDS in respect of the Registered Scheme was the emphasis on the diversification of the investment of the pooled funds administered in each scheme. Further, that loans made using the pooled funds would be secured and income producing.

Funds passed by Endeavour to Linchpin

54 The pooled funds received in the Registered Scheme were passed by Endeavour to Linchpin, as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, or to others on behalf of Linchpin. The basis upon which funds from the Registered Scheme were provided to, or for the benefit of, Linchpin, as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, was not adequately documented. The inadequacy of the documentation has resulted in a lack of precision as to whether the funds advanced by the Registered Scheme were invested in units in the Unregistered Scheme, or lent to Linchpin as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, or a combination of both. This issue is addressed in greater detail below.

55 I interpolate to note that ASIC frames its case to accommodate this uncertainty. ASIC’s primary position, in closing submissions, was that the funds advanced by the Registered Scheme were invested in units in the Unregistered Scheme. For the purpose of the present proceeding, nothing turns on the resolution of this uncertainty. ASIC contends that the respondents’ contraventions are established on both alternatives.

56 Linchpin applied the funds received from Endeavour principally to making loans to itself and to others. The loans made by Linchpin as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, including in the period before Linchpin acquired Endeavour, fell into three broad categories, each of which is addressed in more detail below. I will refer to the loans collectively as the Unregistered Scheme Loans.

57 The first category comprises loans to entities in the Linchpin Group (Linchpin Entity Loans). The total amount of Linchpin Entity Loans was approximately $14.8 million, comprising five loans to five different entities in the Linchpin Group. The findings of fact that I make in respect of each of these loans are summarised in Schedule B to these reasons.

58 In Schedule B, I make findings as to the identity of the borrowers for each of the Linchpin Entity Loans, the loan and security documentation executed in respect of each loan, the applicable loan limits, including, where applicable, in relation to variations thereto, and the identity of the respondents who executed the relevant documentation on behalf of Linchpin in its capacity as trustee for the Unregistered Scheme. I further make findings in relation to the date on which the relevant loans were approved by the Investment Committee by circular resolution and the identity of the respondents who signed the relevant circular resolutions.

59 The second category is loans to advisers operating as authorised representatives, individual or corporate, of AFSL holders within the Linchpin Group (Adviser Loans). The total amount of Adviser Loans was approximately $6.3 million, comprising 18 loans to 17 different entities. The findings of fact that I make in respect of each of the Adviser Loans are summarised in Schedule C to these reasons.

60 In Schedule C, I make findings as to the identity of the borrowers for each of the Adviser Loans, the loan and security documentation executed in respect of each loan, the applicable loan limits, including, where applicable, in relation to variations thereto, and the identity of the respondents who executed the relevant documentation on behalf of Linchpin in its capacity as trustee for the Unregistered Scheme. I also make findings as to the existence and extent of adviser relationships between particular borrowers and entitles in the Linchpin Group, particularly Financiallink Group Pty Ltd and Risk and Investment Advisers Australia Pty Ltd (RIAA). I further make findings in relation to the date on which the relevant loans were approved by the Investment Committee by circular resolution and the identity of the respondents who signed the relevant circular resolutions.

61 The third category comprises loans made to each of Mr Daly and Mr Raftery, both directors of Linchpin (Linchpin Director Loans). The Linchpin Director Loans were in the total amount of about $100,000 with about $70,000 lent to Mr Daly and about $30,000 lent to Mr Raftery. The findings of fact that I make in respect of each of the Linchpin Director Loans are summarised in Schedule D to these reasons.

62 In Schedule D, I make findings as to the details of each of the Linchpin Director Loans, the dates of execution of the loan and security documents and variations thereto, and the identity of the respondents who executed the relevant documentation on behalf of Linchpin in its capacity as trustee for the Unregistered Scheme. I further make findings in relation to the date on which the relevant loans were approved by the Investment Committee by circular resolution and the identity of the respondents who signed the relevant circular resolutions.

63 During the whole of the relevant period, Endeavour had in place written policies that purported to regulate its operations, including with respect to its role as the responsible entity of the Registered Scheme. The purpose of these policies was to ensure that Endeavour complied with the Act, including relevantly, the obligations imposed in respect of transactions involving related parties.

64 I now turn to consider the evidence in greater detail.

Structure and operation of Linchpin Group pre-Endeavour acquisition

65 Relevantly, the Linchpin Group provided a range of financial products, as well as funds management, investment advisory and consulting services. As at August 2018, it had 413 authorised representatives under s 761A of the Act, and four of its group entities held an AFSL. Linchpin itself was a corporate authorised representative under an AFSL.

66 The Linchpin Group relevantly included the following companies:

(1) Endeavour;

(2) Investport Pty Ltd (IPL);

(3) Beacon Financial Group Pty Ltd (Beacon);

(4) ISARF Pty Ltd (ISARF);

(5) CPG Research & Advisory Group Pty Ltd (CPG);

(6) RIAA; and

(7) Financiallink.

67 Linchpin was either the direct or ultimate holding company of these entities. The respondents, in varying combinations, acted as the directors of these entities during the relevant period. Each of the respondents was a director of Linchpin. As mentioned, Mr Nielsen, Mr Raftery and Mr Williams were directors of Endeavour. Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams acted as joint chief executive officers and managing directors of both Linchpin and Endeavour. Mr Daly, Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams were each directors of IPL and Beacon and, from 3 June 2015, RIAA. Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams were directors of CPG and Mr Daly and Mr Nielsen were directors of Financiallink: see Schedule A.

68 As noted, with the exception of Mr Daly, the respondents were each directors of Linchpin and Endeavour, appointed as follows and continuing for the whole of the relevant period:

(1) Paul Nielsen: Linchpin – 28 May 2013;

Endeavour – 8 December 2014;

(2) Paul Raftery: Linchpin – 28 May 2013;

Endeavour – 8 December 2014;

(3) Ian Williams: Linchpin – 28 May 2013;

Endeavour – 8 December 2014.

69 Mr Daly became a director of Linchpin on 2 October 2013 and continued as a director for the whole of the relevant period.

70 As mentioned above, a central issue in dispute between ASIC and Mr Daly is whether, notwithstanding that Mr Daly was not formally appointed as one of the directors of Endeavour, his role was such that he fell within the statutory definition of an officer during the relevant period.

The Unregistered Scheme in the period before the Endeavour acquisition

71 On about 22 January 2014, by a trust deed poll entitled the Investport Income Opportunity Fund Constitution, Linchpin established the Unregistered Scheme. Linchpin was described as the “Responsible Entity” and acted as the first trustee. IPL was appointed as the manager of the Unregistered Scheme pursuant to the provisions of a management agreement dated 22 January 2014.

72 On about 23 January 2014, Linchpin issued the IM, offering units in the Unregistered Scheme to investors. The IM relevantly provided that:

(1) Linchpin was the responsible entity of the Unregistered Scheme and IPL was the fund’s manager;

(2) up to 20 initial investors were invited to invest in the Unregistered Scheme

(3) there were three investment options: a one year option with a return rate of 8.25% per annum; a two year option with a return rate of 8.5% per annum; or a three year option with a return rate of 8.75% per annum;

(4) the minimum total subscription was $5 million with a maximum target of $10 million. Over subscriptions could be accepted if IPL received additional lending submissions that were in accordance with the fund’s mandate;

(5) Linchpin would deposit and deal with the investors’ funds pursuant to “this offer”;

(6) distributions would be paid quarterly;

(7) each unit in the Unregistered Scheme would be initially issued by Linchpin for an application price of $1.00;

(8) the offer of units was expressed to be made pursuant to s 911A(2)(b) of the Act; and

(9) the offer of units was available only to “Wholesale / Experienced Investors” and it was stated that for this reason a PDS in accordance with Division 2 of Part 7.9 of the Act was not required.

73 In the IM, a statement was included as to an intention to issue a retail PDS once the scheme had been registered with the ASIC and after the “wholesale fund” commenced. Notwithstanding the reference to the issue of a “retail PDS”, which was to be registered with ASIC, there is no evidence of any retail PDS being issued by Linchpin. The three relevant PDS were issued by Endeavour in connection with the Registered Scheme.

74 The total amount of funds invested pursuant to the IM by investors, excluding funds received from Endeavour was approximately $5.4 million received from 46 investors. If the funds received from Endeavour are treated as an investment in the Unregistered Scheme the total amount invested would increase by approximately $16.5 million.

75 In section 3 of the IM — “Fund Summary” — the “Investment Strategy” was summarised in the following terms:

To invest funds progressively that achieves a diversified loan portfolio across property and corporate sectors on a secured basis that are income producing. The lending policy and process is outlined in the Lending Manual.

The Fund also seeks to hold cash and cash equivalents to generate income and provide liquidity to the Fund.

76 The only versions of the “Lending Manual” in evidence are manuals which postdate the IM and which I infer comprise what, from at least March 2016, became a composite Lending Manual in respect of both the Unregistered Scheme and Registered Scheme. That there was a version of the Lending Manual which was issued in around February 2014, proximate to the issue of the IM, is evident from the version logs maintained in the later versions of the manual. There is no copy of the February 2014 version of the Lending Manual in evidence. None was produced to ASIC in answer to compulsory notices, the terms of which covered the February 2014 version of the manual. The facts I have found in relation to the Lending Manual are addressed in detail below.

77 Section 3 of the IM also included a summary description of section 5 —“Investment Universe”:

The Fund invests in the full spectrum of direct property and corporate loans that includes, but not limited to:

• Construction and development and sub-division of residential, commercial, industrial and retail property

• Purchase of residential / retail / commercial / industrial premises that are primarily serviced by rental income generated.

• Short term funding for businesses supported by appropriate real property security or security interest.

• Lease finance arrangements for business equipment

• Corporate debt

• Business acquisition finance Excess funds can be invested in Government & corporate rated bonds, bank bills, commercial paper, fixed interest managed investments and mortgaged backed and asset backed securities.

The Fund may also invest in derivatives for investment & hedging purposes.

78 Section 5 of the IM detailed the investment strategy of the Unregistered Scheme in the following terms:

The Fund is an Unregistered Managed Investment Scheme that pools investors’ monies together.

The Fund will lend part or all of those pooled monies to qualified and approved borrowers that fulfil the Funds investment criteria.

The Manager is assisted in its selection and managerial duties by its Credit Committee. This committee comprises a team of qualified and experienced experts, which utilise their pooled knowledge and expertise to review the prospects of the likelihood of the financial success of the typical and preferred projects such as:

• Construction and development and sub-division of residential, commercial, industrial and retail property

• Purchase of residential / retail / commercial / industrial premises that are primarily serviced by rental income generated by the property.

• Short term funding for businesses supported by appropriate real property security or security interest.

• Lease finance arrangements for business equipment

• Corporate debt

• Business acquisition finance

• Managed Investments

• Corporate lending,

• Margin lending, and

• Leasing.

The Fund will invest in a range of diversified assets. The Fund will invest in predominantly mortgages in particular commercial and development loans, secured by registered mortgages, commercial and corporate loans secured by registered fixed and floating charges and / all economic contractual interests. The Fund may also make loans to or invest in similar Managed Investment Schemes and in cash held on deposit with Banks or other financial institutions.

Those loans will be:

• Secured by either registered mortgages and / or security interest and,

• Any other additional securities required by the Credit Committee. Those additional securities may be in the nature of floating and / or fixed debenture charges, guarantees and / or the provision of collateral securities.

• Invested in cash.

79 Clause 9.6 of the IM provided “[w]e may invest in both listed, unlisted, registered and unregistered, managed investment schemes”. The content of, at least, the versions of the Lending Manual from March 2016 were more proscriptive in relation to investment in unregistered managed investment schemes – see paragraphs [135] to [146] below.

Loans by Unregistered Scheme (pre-Endeavour acquisition)

80 Linchpin made some of the Unregistered Scheme Loans before it acquired Endeavour and before the Registered Scheme was activated, including certain of the Linchpin Entity Loans (then with a combined total limit of $6 million) and one of the Adviser Loans (then with a limit of $220,000).

81 By circular resolution dated 10 February 2014, signed by Mr Daly, Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams, the Investment Committee approved a loan facility of $3 million for each of Beacon and Linchpin, respectively, the Beacon Loan and Linchpin Loan. The loan deeds were executed by Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams on behalf of Linchpin as lender and, in the case of the Linchpin Loan, as borrower as well. As noted, Mr Daly, Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams were directors of Linchpin and Beacon and members of the Investment Committee, which at this time, assisted IPL in the management of the Unregistered Scheme. Both loans were progressively drawn down. Between 4 February 2014 and 1 April 2015, advances were made from the Unregistered Scheme to or on behalf of Beacon and Linchpin, pursuant to the respective loan agreements. These advances were approved by circular resolution of the Investment Committee. Mr Daly signed many of these circular resolutions in this period.

82 The Linchpin Loan and the Beacon Loan were both subject to variations. The limits of the Linchpin Loan was ultimately increased to $6 million. The limit of the Beacon Loan was ultimately increased to $5 million. The details of the variations of these loans are set out in Schedule B.

83 By circular resolution of the Investment Committee dated 10 December 2014, Mr Daly, Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams approved the first of the Adviser Loans to Alps Network Pty Ltd, Mr Peter Larkin and Mr Lance Miekle in the sum of $220,000. The loan deed is undated. It was executed by Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams on behalf of Linchpin. The loan was drawn down on about 24 December 2014.

84 This loan was subject to variations which ultimately increased the limit to $760,000. The details of this loan are set out in Schedule C.

85 The aggregate amount of these three loan facilities at the time they were entered into was about $6.2 million. The amount Linchpin had agreed to advance under these loans exceeded the total amount invested in Unregistered Scheme at the time Linchpin committed to the loans, which was about $5.4 million.

86 The Beacon Loan Deed was entered into on or around 10 February 2014. It recorded that the purpose of the Beacon Loan was for Beacon “to finance the acquisition of additional books of financial planning clients and the general expansion of its business”.

87 The Beacon Loan was ostensibly secured pursuant to the Specific Security Agreement (Shares) dated 10 February 2014 (the Beacon SSA). As with the Beacon Loan Deed, Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams executed the Beacon SSA on behalf of both parties, in their capacities as directors of Beacon and Linchpin. The Beacon SSA relevantly provided that Beacon granted to Linchpin a security interest over “Share Assets”, identified as shares held by Beacon in itself, Financiallink, CCS Operations Pty Ltd, Interactive Mortgage & Finance Pty Ltd, and B Property Group Pty Ltd.

88 The purported security was not perfected by timely registration on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR). The Beacon SSA was executed on about 10 February 2014 but no security was registered on the PPSR in respect of the Beacon Loan Deed until 26 September 2016. On that date, a PPSR registration was created identifying Beacon as the grantor of security. The PPSR registration was scheduled to lapse on 30 June 2017 regardless of whether the secured moneys had been repaid. The PPSR registration did in fact lapse on this date.

89 At the time the Beacon Loan was approved, and the relevant documents were executed, Beacon did not own shares in itself, and was likely precluded from doing so under s 259A of the Act. Beacon could not grant a meaningful security interest over shares it purported to hold in itself, notwithstanding the terms of the Beacon SSA. Linchpin did not obtain a valuation in respect of the value of the remaining shares offered as security under the Beacon SSA and did not obtain any form of security over the business assets the acquisition of which was said to be the purpose of the loan.

90 The Linchpin Loan Deed was entered into on about 1 August 2014. Linchpin executed the Linchpin Loan Deed as lender, in its capacity as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, and as borrower, on behalf of itself. The Linchpin Loan Deed records the purpose of the loan as being for Linchpin “to fund the expansion of its business”.

91 Like the Beacon Loan, the Linchpin Loan was ostensibly secured via a separate agreement – the Specific Security Agreement (Shares) (the Linchpin SSA). Mr Nielsen and Mr Williams executed the Linchpin SSA on behalf of Linchpin in its respective capacities as grantor in its own right, and as secured party in its capacity as trustee of the Registered Scheme.

92 As with the Beacon SSA, the Linchpin SSA relevantly provided that Linchpin in its capacity as “Grantor” granted itself in its capacity as the “Secured Party” a security interest over shares held by Linchpin in itself, as well as a fixed and floating charge over all shares held by Linchpin in its subsidiaries.

93 The problems identified above in respect of the Beacon SSA are also evident in relation to purported security given under the Linchpin SSA, including in relation to the late PPSR registration and the lapsing of the registration.

94 In around December 2014, Linchpin acquired Endeavour. Mr Nielsen, Mr Raftery and Mr Williams were appointed as its directors. As mentioned, at the time of the acquisition, Endeavour was the responsible entity of a registered managed investment scheme named the “Endeavour Hi-Yield Fund”.

95 On or about 25 March 2015, the name of the Endeavour Hi-Yield Fund was changed to “Investport Income Opportunity Fund”, which was the same name as that of the Unregistered Scheme. That is how the Registered Scheme and the Unregistered Scheme came to have the same name. The Unregistered Scheme was referred to in some of the contemporaneous documents as the “old IIOF” fund, whereas the Registered Scheme was referred to as the “new IIOF” fund.

96 Endeavour continued as the responsible entity of the Registered Scheme, and Linchpin continued as the responsible entity and trustee of the Unregistered Scheme. Australian Executor Trustees Limited (AET), a company outside the Linchpin Group, was the custodian for the purposes of the Registered Scheme.

97 An important component of ASIC’s case is the allegation that, from about 1 April 2015, there was a single investment committee that made decisions as to the use of the pooled funds in both the Registered Scheme and the Unregistered Scheme. As noted above, the relevant committee was variously referred to as the “Credit Committee”, the “Lending Committee” and or the “Investment Committee”. These names were used interchangeably but there was in fact only one committee.

98 Mr Daly submitted that he was a member of the Investment Committee of the Unregistered Scheme only. Further, that ASIC bore the onus of establishing that this committee acted as a single committee in respect of the use of the pooled funds in both the schemes and not, as he contends, as a decision-maker only in relation to the Unregistered Scheme. The principal submission advanced by Mr Daly was that ASIC had not established, to the requisite standard, that the Investment Committee acted as the decision making body in respect of the use of the funds in both schemes.

99 I am satisfied on the evidence that ASIC is correct in its contention that the Investment Committee, which had operated as the relevant committee for the Unregistered Scheme, operated from 1 April 2015 as the committee responsible for making decisions in relation to the use of funds in both the Registered Scheme and the Unregistered Scheme.

100 I am further satisfied that each of the respondents was a member of the Investment Committee in the relevant period. Mr Daly and Mr Williams were each members from at least around 1 April 2015 until around 7 August 2018. Mr Nielsen was a member from at least around 1 April 2015 until around December 2016. Mr Raftery is also alleged by ASIC to have been a member of the Investment Committee from at least around 1 April 2015 until around 7 August 2018. He did not admit that allegation in his defence. He has not sought to be heard on that allegation in the liability hearing because of the stance he took on the first day of the hearing. Even so, I am not satisfied that ASIC has established that Mr Raftery was a member of the Investment Committee from at least April 2015. ASIC did not identify any documents which supported its contention that Mr Raftery was a member of the Investment Committee from April 2015. On the evidence before me, Mr Raftery first signed circular resolutions of the Investment Committee in January 2017. He signed the balance of the circular resolutions that are in evidence. Accordingly, I find that Mr Raftery was a member of the Investment Committee from at least about January 2017. It appears that he replaced Mr Nielsen on the Investment Committee. In making these findings, on the basis of the evidence in these proceedings, and taking into account the gravity of the consequences in the present context, I feel an actual persuasion that these findings are correct for the reasons which I will develop.

101 In addition to the respondents, Mr Andrew Blanchette was also a member of the Investment Committee, or at least attended meetings of the Investment Committee, in the period 10 February 2014 to 31 July 2015. Mr Blanchette was a director of Beacon from 31 May 2013 to 25 July 2013, and was Beacon’s chief operating officer as at July 2015. Mr Blanchette appears to have been employed by Beacon until at least around 26 November 2016 as “Head of Endeavour Super”. I infer from the evidence that Mr Blanchette resigned from this role around 26 November 2016, but was expected for a period thereafter to continue “communicating professionally with advisers directly approached”. He was not called as a witness in the proceedings. In cross-examination, Ms Gubbins confirmed that ASIC had not interviewed or issued notices to Mr Blanchette. Mr Daly contends that ASIC’s failure to call Mr Blanchette is significant. I will return to this submission below.

102 In order to explain why I have concluded that during the relevant period the Investment Committee made the investment decisions for both the Unregistered Scheme and the Registered Scheme, it is necessary to first set out my findings in relation to the activation and operation of the Registered Scheme.

The Circular Resolution of 1 April 2015

103 In anticipation of the issue of the First PDS, the Investment Committee approved an overarching investment strategy by circular resolution dated 1 April 2015 in relation to both the Unregistered Scheme and the Registered Scheme (the 1 April 2015 Resolution). The strategy which was approved provided for Endeavour to transfer the funds invested in the Registered Scheme to the Unregistered Scheme, and that Linchpin, as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme, would in turn lend those funds in accordance with the investment mandate of the Registered Scheme. The 1 April 2015 Resolution was addressed to and signed by each of Mr Daly, Mr Nielsen, Mr Williams and Mr Blanchette. It was in the following terms:

The Lending Committee is requested by Circular Resolution to note and approve the following:

(1) With the launch of the new IIOF PDS the committee notes the following loan facilities are in place with IIOF (old)

(a) Loan Facility to Beacon of $3M

(b) Loan Facility to [Linchpin] of $3M

(2) These funds are being drawn progressively.

(3) As AET does not be provide loans, loans will continue to be undertaken through IIOF (old).

(4) IIOF (new) will invest in IIOF (old). These funds will be lent by old in accordance with the investment mandate of the IIOF (new).

104 The reference to “IIOF (old)” in the above extract is a reference to the Unregistered Scheme and the reference to “IIOF (new)” is a reference to the Registered Scheme.

105 Consistent with there being a single Investment Committee for both the Registered Scheme and the Unregistered Scheme, the 1 April 2015 Resolution identified a strategy for the joint future operation of the two funds.

106 The Investment Committee commenced functioning as a decision maker in respect of the strategy to be employed with respect to both schemes prior to the formal establishment of the Registered Scheme and in anticipation of the Registered Scheme receiving an influx of funds pursuant to the First PDS. The Investment Committee continued to function in this way in relation to the funds received pursuant to the Second and Third PDS until the Receivers were appointed.

107 The terms of the 1 April 2015 Resolution make it plain that the Investment Committee was considering the present operation of the Unregistered Scheme and the future operation of both schemes. Pursuant to this strategy, funds were raised through the Registered Scheme and then “invested” in the Unregistered Scheme before being loaned out by Linchpin as trustee of the Unregistered Scheme. The strategy described in the 1 April 2015 Resolution was directed to the funds being lent by the Unregistered Scheme in accordance with the investment mandate of the Registered Scheme, which was subsequently published in the PDS which incorporated Endeavour’s written policies. Mr Daly was provided with the final version of the First PDS on 27 April 2015, the day it was issued. The investment strategy across the two schemes appears on the face of the 1 April 2015 Resolution to be directed to circumventing the constraint identified in respect of AET.

108 In practice, and consistently with the overarching strategy promulgated in the 1 April 2015 Resolution, the funds passed from Endeavour and the Registered Scheme to Linchpin and the Unregistered Scheme and were then lent by Linchpin by way of the Unregistered Scheme Loans. On occasion the funds flowed directly from Endeavour to an Unregistered Scheme Loan borrower. That the funds were transferred on behalf of Linchpin is evident in the fact that the corresponding loan agreements were between the Unregistered Scheme Loan borrower and Linchpin, not Endeavour.

109 The documentary trail in respect of the 1 April 2015 Resolution does not disclose any paper submitted to the Investment Committee, by way of analysis or recommendation, which supported the approval of the proposed resolution. The 1 April 2015 Resolution does not on its face record any consideration by the Investment Committee as to whether investment by the Registered Scheme in the Unregistered Scheme was considered to be in accordance with the investment mandate of the Registered Scheme; or in the best interests of unit holders in the Registered Scheme. Similarly, in the circular resolutions of the Investment Committee approving Linchpin making or increasing the limit of the Unregistered Scheme Loans, there is no evidence that the Investment Committee considered whether the loans accorded with the mandate of the Registered Scheme as per the strategy approved by the 1 April 2015 Resolution.

110 As noted, none of the respondents on the Investment Committee at this time gave evidence. I infer that the evidence that Mr Daly, Mr Williams and Mr Nielsen could have given on this issue as members of the Investment Committee would not have assisted their respective defences. I further note that Mr Nielsen, Mr Williams and Mr Raftery do not contest liability in circumstances where the 1 April 2015 Resolution is a central tenet of ASIC’s case. I further infer that any evidence that Mr Williams, Mr Nielsen and Mr Raftery could have given on this issue as directors of Endeavour would not have assisted them. Mr Blanchette was not called as a witness by either ASIC or Mr Daly.

111 To further explain my reasons for reaching the conclusion that from 1 April 2015 the Investment Committee was responsible for making investment decisions in relation to both schemes, it is next relevant to address in more detail the evidence in relation to the Registered Scheme.

112 As noted above, Endeavour issued three PDS in respect of the Registered Scheme between April 2015 and June 2016. Endeavour was the responsible entity, IPL was the investment manager and AET was the custodian.

113 Each PDS refers to Endeavour being the responsible entity pursuant to the Registered Scheme’s constitution dated 4 October 2006, as amended, and to IPL being appointed as the investment manager pursuant to a management agreement dated 30 March 2015, as amended. A summary of the constitution and the management agreement was included in each PDS.

114 ASIC received a notification of change to the constitution on 10 March 2015, which made minor amendments to the constitution. On 1 May 2015, ASIC received a notification of Endeavour’s intention to replace the constitution. The constitution as it applied from 1 May 2015 was in evidence.

115 The management agreement in evidence is dated 2 April 2015. It provided that Endeavour appoints and authorises IPL and its authorised representatives (if any) to issue, vary and dispose of interests in the unit trust and that Endeavour would issue, vary or dispose of interests accordingly. IPL was required to maintain an AFSL that covered its activities in this regard.

116 The three PDS are similar, but not identical, in many respects to the IM issued in respect of the Unregistered Scheme. Like the IM, the PDS emphasised that the relevant investments would be diversified, secured and income-producing. For example, in the IM it was stated that “[t]he Fund will invest in a range of diversified assets” and in each PDS, it was stated that “[t]he Fund will invest in a diversified range of loans”. The investment strategy was described in the IM as being to “invest funds progressively that achieves a diversified loan portfolio across property and corporate sectors on a secured basis that are income producing. The lending policy and process is outlined in the Lending Manual”. Each PDS described the investment strategy as being to “invest funds progressively that achieves a diversified loan portfolio across property and corporate sectors on a secured basis that are income producing” and further stated that such “loans may be held directly by the Fund or held through another fund in which the Fund has invested.”

117 Like the IM, each PDS included a statement to the effect that Endeavour, as the responsible entity of the Registered Scheme, “may invest in both listed, unlisted, registered and unregistered managed investment schemes”, notwithstanding that, from at least March 2016, the Lending Manual was more proscriptive in this regard. The Lending Manual provided that “[u]nder the Compliance Plan of [Endeavour] the Manager has the ability to invest funds in another Managed Investment Scheme, provided that the other scheme is registered under Chapter 5C of the Corporations Law”. The first step in the procedure for investing funds in another managed investment scheme required that “[Endeavour] must be satisfied that the proposed Managed Investment Scheme is registered under Chapter 5C of the [Act]”.

118 The First PDS was issued on 27 April 2015.

119 The price and terms of the investment offered in the First PDS were the same as those for the Unregistered Scheme, as set out above.

120 In section 3 of the First PDS, the question, “Who can invest?” is posed and answered in the following terms “Wholesale Investors and other investors who meet the minimum investment criteria”.

121 Similarly to the IM, the First PDS included statements to the effect that the strategy of the Registered Scheme would be to invest in a range of diversified assets on a secured basis. The scheme’s “Investment Strategy” was described as follows:

To invest funds progressively that achieves a diversified loan portfolio across property and corporate sectors on a secured basis that are income producing. These loans may be held directly by the Fund or held through another fund in which the Fund has invested.

The Fund also seeks to hold cash and cash equivalents to generate income and provide liquidity to the Fund.

122 Section 3 of the First PDS states that Endeavour will lend invested monies to “Primary Target Borrowers” amongst others:

[Endeavour] and [IPL] will amongst other types of lending target loans to assist financial planners to buy client books to expand their businesses. These planners will always be part of the Linchpin Capital / Beacon Financial dealer universe when we approve a loan and must remain with the Group during the term of the loan.

We will take security over the client books of the planner’s existing business as well as the new client book alongside usual Director’s guarantees and corporate fixed and floating charges.

A borrower will be required to remain part of the dealer group while the loan is outstanding. This gives the lender direct access to the adviser’s revenue as all planner revenue passes through the dealer group.

Loans will be subject to interest rates approximating overdraft rates and this should allow the returns from the Fund to be stronger than traditional mortgage funds.

123 Clauses 5.3 and 5.4 of the First PDS relevantly provided:

5.1 The Fund is a Registered Managed Investment Scheme (ARSN 121 875 009) that pools investors’ monies together.

5.2 The Fund will lend part or all of those pooled monies to qualified and approved borrowers that fulfil the Fund’s investment criteria.

5.3 The RE is assisted in its investment selection and managerial duties by the Investment Manager and its Credit Committee. This Committee comprises a team of qualified and experienced lending professionals, which utilise their pooled knowledge and expertise to review the prospects of the financial success of a typical and preferred project such as:

• Short term funding for businesses supported by appropriate real property security or security interest,

• Lease finance arrangements for business equipment,

• Corporate debt,

• Business acquisition finance,

• Managed investments,

• Corporate lending,

• Construction and development and sub-division of residential, commercial, Industrial and retail property,

• Purchase of residential / retail / commercial / industrial premises that are primarily serviced by rental income generated by the property,

• Margin lending; and

• Leasing.

The Fund will invest in a diversified range of loans. The Fund will invest in predominantly commercial and corporate loans able to be secured by registered fixed and floating charges, non-residential mortgages such as commercial and development loans, secured by registered mortgages; and other types of economic contractual interests. The Fund may also make loans to, or invest in similar Managed Investment Schemes and in cash held on deposit with Banks or other financial institutions.

5.4 Those loans will be:

• Capable of being secured by either registered mortgages or registered security interests, and any other additional securities required by the Credit Committee. Those additional securities may be in the nature of fixed and floating charges, debenture charges, business, director and personal guarantees and the provision of collateral securities.

• Invested in cash, cash equivalents, bank and term deposits, bonds.

124 The First PDS relevantly stated under the heading “Related Party Transactions and Conflict of Interest Risk” (in cl 10.2):

All transactions with the [Linchpin Group of companies] (including the Investment Manager) will be conducted on arm’s length terms and will only be entered where the Investment Manager (or such other LPCG entity) has demonstrated to the Responsible Entity that the transactions are based on arm’s length terms…

Any related party transaction or other transaction giving rise to a conflict will be undertaken in accordance with the Responsible Entity’s related party and conflict of interest policies (see Section 13.10 for further details).

125 The additional information relating to conflicts of interest and related party transactions is in fact contained in cl 13.8 (second appearing), not cl 13.10:

Endeavour may and will have related party relationship with the Fund Manager, its agents and potentially borrowers from the Fund. In the unlikely event that any such conflict may arise in principal then Endeavour would so advise the Credit Committee of such relationship prior to its considering any application where a related party relationship exists.

Subject to the Corporations Act, Endeavour and its associates may:

• Hold Units in the Fund;

• Deal with the assets of the Fund;

• Enter into any contract or transaction with the Fund, or any Unit Holder, and retain for its own benefit any profits or other benefits derived from such contract or transaction; and

• From time to time, act as Responsible Entity in relation to any other Fund.

From time to time the Fund may invest in, or lend to, investment schemes managed by Endeavour or its Related Parties, or invest in other Authorised Investments issued or managed by Endeavour or its Related Parties, in this regard, Endeavour adopts an ‘arms length’ approach to the assessment of transactions on commercial terms whether they are related party transactions or not.

Endeavour has a Conflicts of Interest and Related Party Transactions Policy which sets out procedures for reporting and managing, conflicts and related party transactions. The procedures include:

• Identifying conflicts and related party transactions

• Avoiding conflicts and related party transactions where possible

• Disclosure of conflicts and related party transactions

• Managing conflicts and related party transactions.

All conflict of interests and related-party transactions are recorded in the Conflicts of Interest and Related Party Transaction register.

126 The First PDS expressly identified that the directors of Endeavour (being Mr Nielsen, Mr Raftery and Mr Williams) had consented to and authorised the issue of the First PDS.

127 On or around 1 October 2015, Endeavour issued a Second PDS in materially the same terms as the First PDS. The description of “Who can invest?” in section 3, was changed to “experienced investors who meet the minimum investment criteria”, instead of what had been included in the First PDS – “wholesale investors and other investors who meet the minimum investment criteria”. The Second PDS was otherwise in terms materially similar to the terms outlined above in respect of the First PDS.

128 The Second PDS also expressly identified that the directors of Endeavour had consented to and authorised the issue of the Second PDS.

129 On or around 24 June 2016, Endeavour issued the Third PDS, which was materially in the same terms as the First and Second PDS. The description of “Who can invest?” in section 3 was again changed, this time to “experienced and retail investors who meet the minimum investment criteria” (emphasis added). The description of “Primary Target Borrowers” in section 3 was amended to read:

From time to time, the offer to borrow for business purposes, subject to all relevant securities, guarantees and external audit assessment, may extend to qualified Authorised Representatives of [FinancialLink], or [RIAA];

130 Clause 5.3, which in each PDS provided information in relation to the Registered Scheme’s typical and preferred projects, was amended to add:

The [sic] Endeavour as the Responsible Entity (RE) is assisted in its investment selection and managerial duties by the Investport Pty Ltd as Investment Manager and the Credit Committee. This Committee comprises a team of qualified and experienced finance professionals, which utilise their pooled knowledge and expertise to review the prospects of the financial success of a typical and preferred projects and borrowers such as:

• Borrowers that meet the terms and conditions as assessed by the Credit Committee and clearly defined in the Lending Manual, Borrowers from time to time may include Industry related applicants, Financial Services professionals such as, Financial Planners, Finance Brokers, Accountants, Real Estate Agents…

131 There were otherwise no material changes to cll 5.1 to 5.6 in the Third PDS.

132 The Third PDS also expressly identified that the directors of Endeavour had consented to and authorised the issue of the Third PDS.

133 The Third PDS was also approved by Mr Daly, in an email exchange with Mr Williams, Mr Nielsen and Mr Raftery on 28 June 2016.

134 I now turn to consider the evidence in relation to Endeavour’s written policies.

135 Endeavour had a Lending Manual that applied in respect of investments made by the Registered Scheme. The Lending Manual defined the “core policies and procedures constituting the minimum basis for assessing and managing the risk inherent in property development and property finance loans, corporate loans, capital equipment finance, margin lending and leasing transactions and other secured lending transactions”. The Lending Manual and its appendixes formed part of “the overall framework of [Endeavour’s] credit standard”. Any deviation from the Lending Manual required prior approval from the “Credit Committee” or its delegate. As already noted, the reference to the “Credit Committee” in the Lending Manual are properly understood as a reference to the Investment Committee, which performed the function of the “Credit Committee”. The Lending Manual was to be read with other corporate manuals issued from time to time.

136 As noted above, the Third PDS provided that borrowers were required to meet the terms and conditions as assessed by the Credit Committee and as defined in the Lending Manual. The First and Second PDS do not refer to the Lending Manual, but make reference to Endeavour and IPL applying “lending criteria and security requirements for corporate loans”.

137 There are three versions of the Lending Manual in evidence. All three of the manuals have a front sheet with the title:

Endeavour Securities (Australia) Limited

Investport Income Opportunity Fund

LENDING MANUAL

138 Two of the manuals are identical and have a version log on the front page with three dates: February 2014, March 2016 and March 2017. I will refer to this version as the version issued in March 2017. The third version appears to be an earlier iteration of the manual. It has a version log with the dates February 2014 and March 2016. I will refer to this version as the version issued in March 2016.

139 A copy of the version issued in March 2017 was produced by Endeavour in response to an ASIC notice, which required production of Endeavour’s lending manual as updated in the period 1 July 2015 to 5 December 2017.

140 Another copy of this same version was produced by Linchpin in answer to an ASIC notice that required production of the lending manual for the Unregistered Scheme in the period 1 January 2014 to 2 May 2018.

141 As mentioned, the date of February 2014, which is the first date in the version logs on each of the Lending Manuals that are in evidence, is proximate to the time Linchpin published the IM. There is, however, no copy of the Lending Manual as it stood at February 2014 in evidence. The earliest version of the Lending Manual in evidence is the version issued in March 2016.

142 On the evidence before me, it is not possible to determine what changes were made to the Lending Manual between the version in February 2014 and the version issued in March 2016 save in one minor respect. Given that Endeavour was not acquired by Linchpin until about December 2014, I infer that the February 2014 version of the Lending Manual would not have included the name of Endeavour on the front sheet.

143 Based on the above, having particular regard to the fact that Linchpin produced the Lending Manual in answer to a notice calling for the lending manual for the Unregistered Scheme in the period 1 January 2014 to 2 May 2018, and that there was a version issued proximate to the date of issue of the IM, I infer that the Lending Manual for the Unregistered Scheme was the progenitor of the Lending Manual for the Registered Scheme. I further infer that over time the Lending Manual became a composite manual that applied to both the Unregistered Scheme and the Registered Scheme. On this basis, I find that the three Lending Manuals in evidence each applied in the context of both the Registered Scheme and the Unregistered Scheme after March 2016.

144 Relevantly, each of the Lending Manuals in evidence included policies in relation to investment in other managed investment schemes. Both the March 2016 and the March 2017 versions of the Lending Manual provided:

8. Investment in Other Managed Investment Schemes

Under the Compliance Plan of [Endeavour] the Manager has the ability to invest in another Managed Investment Scheme, provided that the other scheme is registered under Chapter 5C of the Corporations Law. It is at the discretion of [Endeavour] how it wishes to invest the funds received from investors, so to this end, if it is seen fit to invest funds with another registered scheme the following requirements must be satisfied.

8.1 Procedure for Investing Funds in another Managed Investment Scheme

The following procedure is to be followed:

1. [Endeavour] must be satisfied that the proposed Managed Investment Scheme is registered under Chapter 5C of the Corporations Law.

2. [Endeavour] must satisfy itself that the scheme is a Mortgage Investment Scheme dealing only in first mortgages over property of the nature detailed in [Endeavour’s] disclosure document.

3. The term of any investment in the other Scheme must not exceed two years.

4. [Endeavour] must obtain a copy of the Scheme disclosure document and complete the required application form which must be accepted by the Manager of that Scheme.

5. [Endeavour] Credit Committee will minute the decision stating that the investment is in the best interests of investors.

…

8.3 Related Parties

[Endeavour] may lend Fund money to provide loans to, or make investments in, any related party subject to normal banking covenants and full disclosure in the Conflicts of Interest Register.

145 Clause 8.3 of the Lending Manual issued in March 2017 was expanded to include the following text at the end of the clause:

Financial Planners and mortgage brokers

• Assessment and approvals of financial planners acquiring other financial planning books of Beacon planners / Brokers are an interactive process.

Assessment & review of Beacon Group Financial Planners encompasses accessing electronic files maintained for AFSL / ACL licencing and statutory purposes, and the engagement of key Beacon staff:

1) Compliance check and discussions with the State Managers / Business Development Managers