Federal Court of Australia

Strickland on behalf of the Maduwongga Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2023] FCA 270

ORDERS

MARJORIE MAY STRICKLAND AND ANNE JOYCE NUDDING Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Respondent CENTRAL DESERT NATIVE TITLE SERVICES LTD Respondent (and others named in the Schedule) | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate question is answered as follows: KB (the grandmother of the applicant) held rights and interests in those land and waters of the application which overlap with native title determination application WAD 91 of 2019 (Nyalpa Pirniku) under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert, and not under the normative system of a distinct land-holding group of which KB's descendants are the only identifiable surviving members.

2. The Nyalpa Pirniku respondent has liberty to apply in relation to costs until 4.00 pm AWST on 10 April 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

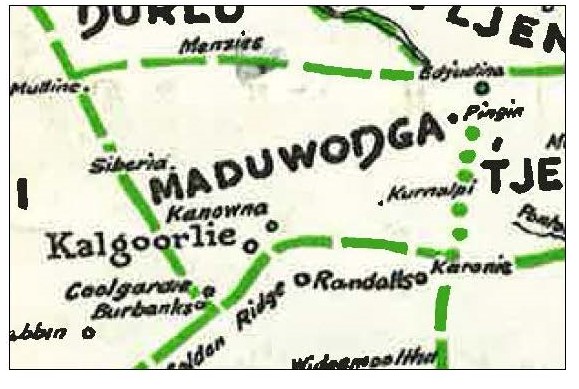

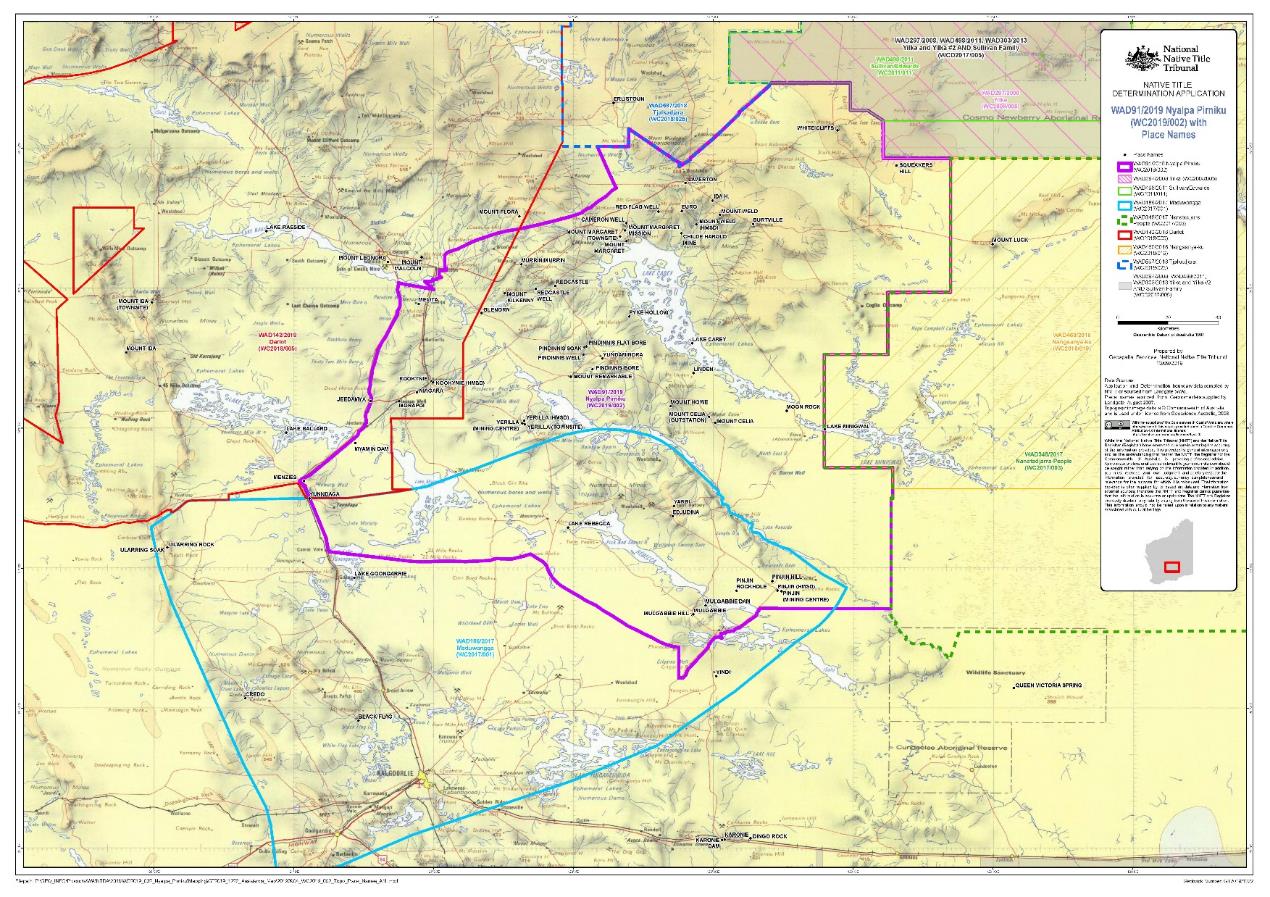

1 Marjorie Strickland and her sister, Joyce Nudding, are together the applicant in this native title claim. They contend that their grandmother, who at their request I will call KB, belonged to a group of people called the Maduwongga. On that basis, Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding seek a determination that they and others who are related to them hold native title rights and interests in relation to an area of land and waters in the Goldfields region of Western Australia. The area is approximately 25,473 km2, and stretches from its south-western corner near Coolgardie, Western Australia, to a north eastern boundary marked by the Edjudina Range. The claim group is comprised of the descendants of KB, whose grandchildren include Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding.

2 In a different proceeding, WAD 91 of 2019, another claim group, the Nyalpa Pirniku (NP claim group), seek a native title determination in their favour in respect of country which, again in broad terms, sits mainly to the north-east of the Maduwongga claim area, but also overlaps with the north-eastern third of that area. These reasons concern a separate question which is intended to determine a dispute between the Maduwongga applicant and the Nyalpa Pirniku respondent (NP respondent) which arises out of that overlap.

3 The question, which was posed in orders which Bromberg J made on 20 November 2019, is:

Did [KB] (the grandmother of the applicants in the Maduwongga Application [i.e. this proceeding, application WAD 186 of 2017]) hold rights and interests in those land and waters of the Maduwongga Application which overlap with native title determination application WAD 91 of 2019 (Nyalpa Pirniku) under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of:

(1) the Western Desert; or

(2) a distinct land-holding group of which KB's descendants are the only identifiable surviving members?

4 The members of the NP claim group contend that they have rights and interests in relation to the NP claim area under the traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert. And they accept that KB held rights and interests in the overlap area. So the issue raised by the separate question is: under which traditional laws and customs did KB have those rights and interests? Since KB is the apical ancestor of the members of the Maduwongga claim group, the answer will have significant implications for their claim.

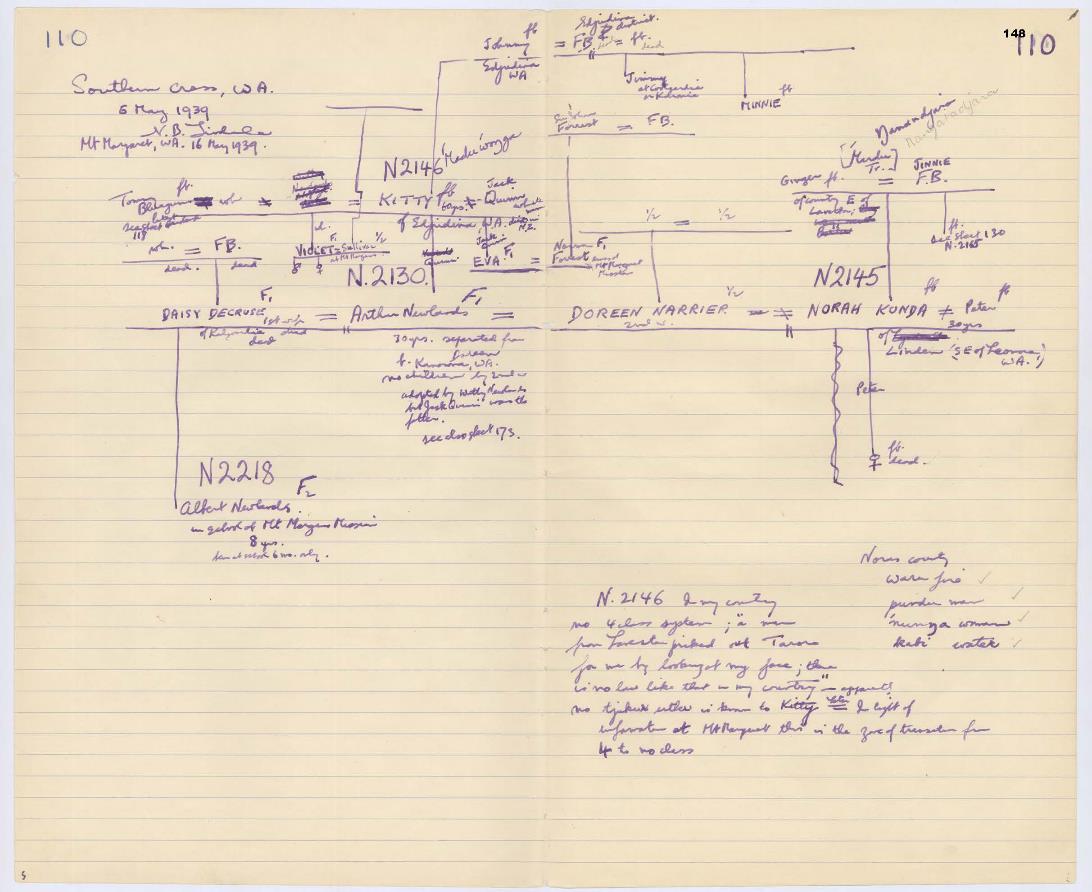

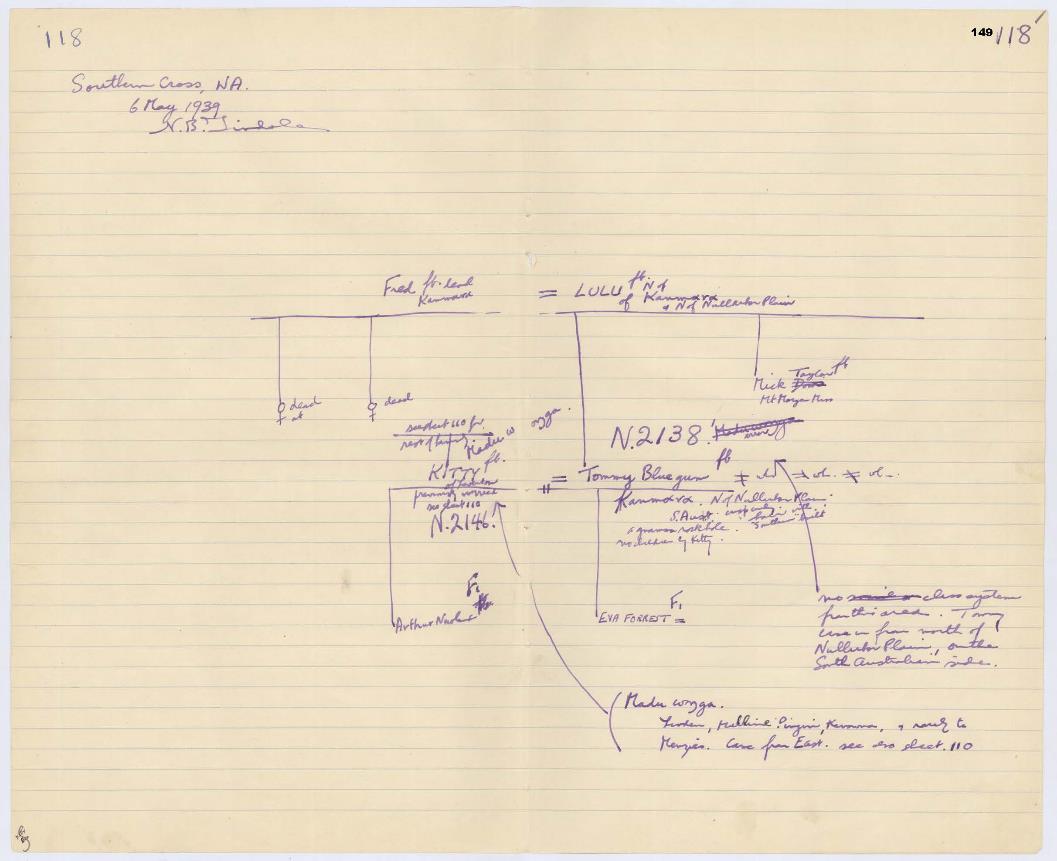

5 To put the question in its historical context, according to an estimate of KB's age given by the 20th century anthropologist Norman Tindale, KB was born in about 1880. She died in 1945. The Goldfields region began to experience European settlement in the 1890s and it is only from that time that there begin to be written records that could help identify the traditional laws and customs that were acknowledged and observed in the area. So because it focuses on KB, the question concerns the period of time from about 1890 until 1945.

6 It was common ground that in around 1892 to 1894, European settlement began to occur apace in the Goldfields, and that the laws and customs of the Aboriginal people who occupied that area just before that time may be taken to be the same as they were in 1829, when the British Crown asserted sovereignty over the area that is now Western Australia (see Western Australia v Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 373 at 429). That is supported by the opinion of the expert witnesses called in this case. I will call that later time of 1892 to 1894 (precision is unnecessary here) the time of effective sovereignty.

7 The parties who took an active role in relation to the separate question were the Maduwongga applicant, the NP respondent, the State of Western Australia and representatives of another Aboriginal claim group the Marlinyu Ghoorlie, whom I will call the MG respondent. That respondent in this proceeding is the applicant in a native title claim over an area which also overlaps with the Maduwongga claim area, but does not overlap with the NP claim area. The MG respondent took part on the basis that they have an interest in the answer to the separate question because, if it is answered unfavourably to the Maduwongga, that may have implications for the overlap between the Maduwongga and Marlinyu Ghoorlie claim areas.

8 For the following reasons, I have concluded that KB held rights and interests in relation to land and waters in the overlap area under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert, and not under the normative system of any distinct land-holding group of which KB's descendants are the only surviving members.

Some observations about the separate question

9 It is useful to make a few observations about the separate question at the outset. The first is that the question has been framed by reference to concepts that appear in the explication of the definitions of 'native title' and 'native title rights and interests' in s 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) which was given in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58; (2002) 214 CLR 422. It is convenient to set out s 223(1) now:

The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

10 The explication of this given in Yorta Yorta related in particular to s 223(1)(a) and concerned, among other things, the concepts of a society, defined as a body of persons united by their acknowledgment and observance of a body of laws and customs, and of rights and interests in relation to lands and waters being possessed under those traditional laws and customs: see Yorta Yorta at [47], [49] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, and Hayne JJ, McHugh and Callinan JJ agreeing). The separate question directs attention to those concepts, because it requires identification of which of two possible normative systems applied in the overlap area. It is common ground that the question requires KB to be placed in one of those systems.

11 However, it is not common ground that either of those systems actually existed. The respondents do not accept that during KB's time there was a distinctive society and system that could be designated as Maduwongga. And as will be seen, the Maduwongga applicant also sought to cast doubt over whether the existence of the relevant Western Desert society had been established.

12 While the separate question uses the term 'distinct land-holding group', rather than society, I proceed on the basis that whether the Maduwongga group is or is not distinct will depend on whether it constituted a society in the Yorta Yorta sense that was united by acknowledgment and observance of a body of laws and customs different to the body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the people of the Western Desert. By seeking a finding that they comprise a separate land-holding group, the Maduwongga are not saying that they were a defined group of people that held exclusive rights and interests in relation to particular country under a Western Desert normative system of broader application. They claim their own normative system.

13 The competing answer at (1) in the separate question was that contended for by all the respondents who took an active part in the issue. They contend that KB was not a member of any distinct Maduwongga society but was, rather, one of a number of persons who acknowledged a body of laws and observed a body of customs that were acknowledged and observed over a broader area of the Western Desert. No party suggested that KB acknowledged and observed laws and customs of both Maduwongga and Western Desert normative systems, or otherwise had some kind of dual identity or affiliation.

14 Second, as the discussion above suggests, the separate question can be read as implying that the issue is not whether KB held any native title rights and interests in the overlap area. And indeed, the parties to the proceeding who have participated in the determination of the separate question have not approached it on that basis. So what is at stake in the separate question is not whether KB's descendants, including Mrs Nudding and Mrs Strickland, hold any native title rights or interests in the overlap area. It is whether those people hold rights and interests to the exclusion of, or at least separably from, others who may claim under Western Desert laws, such as the members of the NP claim group.

15 Third, and that said, it must be recalled that a determination as to native title is a determination in rem that binds the whole world: Jango v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] FCAFC 101; (2007) 159 FCR 531 at [85]. So it is not enough that the parties to this proceeding do not contest that KB held native title rights and interests. The Court still needs to be satisfied of that on balance of probabilities, taking into account the nature of the cause of action and subject matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged: Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 140(1); Drill on behalf of the Purnululu Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 1510 at [768]. While the party with the onus of proof does not need to exclude or resolve all doubts, disconformities and possibilities, it must persuade the Court that the position for which it contends is more likely than not: Narrier v State of Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519 at [403].

16 Fourth, and on the subject of onus, the parties accepted that the onus is on the Maduwongga applicant to prove that the Maduwongga did constitute a distinct group holding native title rights and interests under a normative system of laws and customs that is to be distinguished from any system observed by the people of the Western Desert, and that the group included KB. Conversely, they also accepted that the onus was on the NP respondent to prove that KB in fact held native title rights and interests under a system of laws and customs of a broader Western Desert group. This is on the basis that it is a rule of evidence and of common sense that the burden of proof is on the party who asserts a fact, not the party who denies it: Drill at [789] citing Plaintiff M47/2018 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] HCA 17; (2019) 265 CLR 285 at [39]. That is not to say, of course, that the two matters are independent of each other. To the contrary, any increase in the probability that one of them is true necessarily reduces the probability that the other is.

17 Fifth, the separate question asks nothing about what has happened since KB's death, so there is no need for present purposes to determine whether any relevant laws and customs have continued to be observed since then or whether a continuous connection to country has been maintained. The separate question is not about ongoing acknowledgment and observance of laws and customs, or about ongoing connection to the land. Evidence about the circumstances after KB's death may, however, be relevant to inferences that need to be made about the position during her lifetime.

18 Finally, there was discussion in court between counsel for the parties and Bromberg J about the consequences if, contrary to the Maduwongga case, an affirmative answer is given to the first part of the separate question (at (1)). Senior counsel for the Maduwongga applicant confirmed to his Honour that if KB did hold rights and interests in the overlap area under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert, the Maduwongga application, that is this proceeding, should be dismissed. That was on the basis that an answer to that effect would mean that there was no separate land-holding group known as the Maduwongga. The State and the MG respondent confirmed at the same time that if that were the outcome, there should be no order as to the costs of the Maduwongga application (counsel for the NP respondent did not have instructions on the costs point at that time).

19 Before describing the parties' respective cases, it is convenient to comment on a few specific matters.

How 'Maduwongga' will be used in these reasons

20 The very existence of a people who can be identified as the Maduwongga is in issue in these proceedings. But it would be cumbersome to try to refer to the apical ancestor, KB, and her descendants in any other way. So I will generally use the term in these reasons to designate that group of people, that is, depending on context, one of the following: the present Maduwongga applicant; the present Maduwongga claim group; the ancestors, descent from whom the Maduwongga applicant says confers native title rights and interests in the Maduwongga claim area; and sometimes other people referred to in the evidence who may or may not be Maduwongga. So unless the context indicates otherwise (including at Section XII below), the use of the word 'Maduwongga' to designate a group of people in the course of considering and writing these reasons implies no concluded view about the issues in dispute. The same goes for the use of the word to designate other matters which are the subject of dispute, such the existence of Maduwongga laws and customs, a Maduwongga country or a Maduwongga language.

21 There was extensive reliance on evidence adduced in an earlier case, Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31. (I will use 'Wongatha' (unitalicised) to refer to the proceeding as distinct from Wongatha to refer to the reported reasons for decision.) In Wongatha Lindgren J determined a number of claims to land in the Goldfields, including a claim by the Maduwongga. Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding both gave evidence in that proceeding. Pursuant to s 86(1)(a) of the NTA, several passages from their evidence and from other lay evidence adduced in Wongatha were admitted into evidence in this proceeding, by consent.

22 I will weigh that evidence on the common sense basis that I did not observe the witnesses give it and that, while it included cross examination, I have not been apprised of the precise matters that were in issue and to which that cross examination went. That is, the evidence is presented to me shorn of a great deal of context, and as a result a cautious approach must be taken to it. That does not, however, mean that it is without value; no party in this proceeding submitted that the questions before Lindgren J in Wongatha were so different from the separate question here so as to rob the evidence of any value in this proceeding.

23 Some of the evidence in Wongatha was from witnesses who have since passed away and so could not give evidence in this proceeding. Where a witness did give evidence in this proceeding, I will tend to give it greater weight on the basis that the parties here did at least have an opportunity to test it. But as will be seen, with the exception of Mrs Nudding and Mrs Strickland, the cross examination of witnesses and hence the ability to observe them giving evidence orally was limited, so for the most part the comparison is between the written evidence of a witness here and the transcript of the testimony in Wongatha.

24 The outcome in Wongatha was that Lindgren J determined that the Maduwongga applicant in that case had not established its claim. The respondents who took part in the separate question do not say that that determination precludes the Maduwongga claim at the threshold, although they did seek to make forensic use of the claim and outcome in Wongatha as well as what they say are five other previous applications that Mrs Strickland and/or Mrs Nudding have brought in relation to some or all of the same area of land. The State's opening submissions sought to make extensive use of the findings of Lindgren J in Wongatha. But, as the Maduwongga applicant pointed out, no order had been made under s 86(1)(c) of the NTA for those findings to be adopted in this proceeding, and s 91 of the Evidence Act is a broad restriction on the admissibility of findings of fact in other proceedings. While the State made brief reference to certain findings in Wongatha in its closing submissions, it did not dispute the basis of the Maduwongga applicant's objection and it made no application for s 86(1)(c) of the NTA to be applied here. While the NP respondent did make an application under that provision, ultimately the application was not pressed. In what follows I have made my own findings based on the evidence and submissions in this proceeding, and have placed no reliance on Lindgren J's findings of fact in Wongatha.

Western Desert and the Western Desert Cultural Bloc

25 Much of the debate between the parties was couched in terms of whether the overlap area fell within the 'Western Desert Cultural Bloc' (WDCB). That term was coined by the anthropologist Ronald Berndt in his seminal 1959 article 'The Concept of "the Tribe" in the Western Desert of Australia' (1959) 30 Oceania 81-107. For Berndt, it described a large cluster of peoples inhabiting the Western Desert who had similar or related laws and customs. The Western Desert is a vast area which extends from eastern and north-eastern Western Australia into western South Australia.

26 I will generally, but not assiduously, avoid the terminology of the Western Desert Cultural Bloc or WDCB. I do not consider it useful to debate over a mid-20th century anthropological concept (see Narrier at [7]) and it is not the terminology used in the separate question. Where possible I will simply refer to peoples, laws and customs of the Western Desert. But this different terminology does not necessarily reflect disagreement with the substantive content of parties who spoke in terms of the WDCB.

Terminology, spelling and names

27 Words from Aboriginal languages will generally be italicised unless they are proper names used to designate individuals or groups. I will endeavour to use the spelling of the words that is given in the evidence adduced by the persons who speak (or claim to speak) the language. The spellings Walyen and Waljen were used interchangeably by the parties and in the lay evidence. Throughout these reasons the term Walyen will be used, following the practice of one of the expert witnesses, Dr John Morton.

28 I will generally refer to people by their surnames and title. Where people share the same surname, in order to avoid confusion I will generally simply refer to them by their full names without the title, although occasionally it will be preferable just to use first names to avoid unwieldy repetition. In none of this is any discourtesy or disrespect intended.

29 As far as the Court has been made aware, KB is the only deceased person whose name it is preferable not to use. If there are other deceased persons whom I have unknowingly named where I should not have, no offence is intended. Apart from one paragraph of a report of an expert witness, Dr Christine Mathieu, of March 2020, to which it is not necessary to refer, the Court has not been told that any of the evidence concerns matters that are gender restricted or subject to other sensitivities.

30 It will be necessary to use some terminology which is potentially offensive today, because it appears in the primary materials, by which I mean notes and other documents prepared by 20th century ethnographers and anthropologists such as Daisy Bates and Tindale. In doing so no disrespect or offence is intended.

III. THE PARTIES' CASES AND THE ISSUES ARISING

31 Each of the parties who took an active role in relation to the separate question filed a statement of facts and contentions (SOFAC) before the separate question was stated. But the focus provided by the separate question meant that the parties' contentions underwent some refinement, so it is appropriate to proceed largely by reference to the opening and closing submissions of the parties during that hearing. It is necessary to appreciate the way in which the parties ultimately put their cases: see AB (deceased) (on behalf of the Ngarla People) v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2012] FCA 1268 at [39] (Bennett J) and the authorities cited there. In any event, no party contended that there was any significant difference between those submissions and the SOFAC.

The Maduwongga applicant's case

32 The Maduwongga applicant's main contention is that KB held rights and interests in the land and waters within the Maduwongga claim area under a normative system of laws and customs relating to land tenure that was distinct from and antithetical to any normative system of laws and customs observed by the peoples of the Western Desert. It also contends that KB's descendants comprise the only identifiable surviving members of the group who hold rights and interests in the land and waters in the Maduwongga claim area.

33 According to the Maduwongga applicant's SOFAC, at effective sovereignty the claim area was occupied by a group of Aboriginal people who spoke the Maduwongga language and formed a 'socio-linguistic community'. This socio-linguistic community is said to have included the ancestors of Johnny, KB's father, and their descendants, including KB.

34 The group was held together, in accordance with a body of traditional laws and customs, by kinship ties established by descent and marriage. The Maduwongga applicant describes the ethno-historical expert evidence of Dr Christine Mathieu, on which it relies, as being to the effect that (Maduwongga applicant's SOFAC para 8):

Rule-based marriage relations, organised on the basis of an endogamous moiety system, structure a complex of hereditary social and cultural interdependence from which all economic and ceremonial rights and obligations to land are derived.

(It will be seen, however, that by the time of closing submissions the Maduwongga applicant sought to draw a sharp distinction between 'economic' rights and obligations and 'ceremonial' ones).

35 A moiety system exists when the society is divided into two groups. They can be vertical, determined by descent, or horizontal, breaking the society up into different, often alternating generations. It is an endogamous moiety system if people marry within their moiety. The Maduwongga applicant's SOFAC said that kinship, along with ecological knowledge of country obtained from ancestors, were the cultural foundations of land ownership under the body of laws and customs. By the time of closing submissions, the focus of the Maduwongga applicant's case was that the land tenure of members of the group was conferred under a system of laws and customs relating to birthplace, descent and marriage.

36 Specific laws and customs on which the Maduwongga applicant relies will be described in more detail below, but the following summary serves to highlight the main aspects:

(1) In the Maduwongga system of laws and customs, rights and interests in relation to the land and waters are obtained by descent (including child adoption) from an ancestor acknowledged to have been from that land and to have possessed rights and interests in relation to it.

(2) Members of the group have personal, family or district totems. However, this point did not really feature in the evidence.

(3) Male members of the group practise ritual initiation, although it would seem that the last initiated Maduwongga man was KB's son, Arthur Newland who died in 1987.

(4) Members of the group believe in the concept of tjukurrpa or Dreaming, and acknowledge and observe several Dreaming tracks that pass through the area. These are linked to the travels of ancestral beings and objects and have songs attached to them.

(5) Strangers must ask permission to have access to the land or must be accompanied by a person recognised as having rights or interests and knowledge of or authority in relation to the land.

(6) Members of the group have rights to hunt, gather, fish and take resources from the land and there are rules about the taking, preparation, use and sharing of those resources.

(7) There are laws and customs governing access to, protection of and responsibility for places of significance in the claim area, including behavioural requirements when approaching and entering those places. Rights in relation to ceremonial sites are, however, distinguished from rights and interests in relation to land. Initiation into knowledge about creation, songlines and stories gains ceremonial access to parts of country, but not access to hunting and resources without permission.

37 It is not immediately obvious how most of these matters serve to distinguish the Maduwongga normative system from the normative system observed in the Western Desert. But according to the Maduwongga applicant, there are two key points of distinction:

(1) In the Maduwongga system, rights to land are held on a communal basis arising out of marriages between individuals from contiguous estates and transmitted, as has been said, by descent, whereas in the Western Desert they are held on the basis of 'multiple pathways' concerning an individual's relationship to the land (which will be described below).

(2) In the Maduwongga system, there is no section system, whereas in the Western Desert social relations are governed by a four-section system.

38 Section systems are also referred to in the evidence and the anthropological literature variously as 'class', 'skin group' or 'skin' systems. In her first expert report filed on 8 November 2019 in this proceeding (Mathieu I), Dr Mathieu described a four-section system as one in which (para 112):

people belong to one of four classes which dictates who they should and should not marry: section x can only marry section y, and section a must marry section b. Individuals inherit their section membership on account of their parents' own class membership. The four-class system creates generational divisions, as well as a division between parallel (Mother's Sister's children/Father's Brother's children) and cross-cousins (Mother's Brother's children, Father's Sister's children).

39 The two key points of distinction on which the Maduwongga case relies are thus related, as the regulation of marriage relations is an important aspect of a section system (which can also be the basis of rules about other matters - see Section XI below). The respondents approached the case on the footing that these asserted features of the Maduwongga laws and customs would, if established, provide points of distinction between those laws and customs and those of the Western Desert normative system. However the respondents contended that the Maduwongga applicant failed to establish those features, and that this meant that their claim as a whole must fail.

40 The Maduwongga applicant sought to establish the existence of these key points of distinction mainly by means of expert evidence from Dr Mathieu. Dr Mathieu's opinion was to the effect that the territorial area of the Maduwongga is defined by a marriage system, in which at the time of effective sovereignty, the people between Edjudina and Coolgardie formed one 'marriage line' and were all relatives. In a concurrent expert evidence session Dr Mathieu described a marriage line as meaning that the people married between areas she had specified, to produce territorially contained marriage connections. Marriage classes corresponded to waterholes, implying a system of marriage exchange, based on territorial exogamy. According to a supplementary report of Dr Mathieu, filed on 11 March 2020 (Mathieu II), marriage exchange is an 'expression of reciprocity' (Mathieu II para 124). Over the course of generations, 'marriages between estate holders give individuals access to the entire aggregate [tribal] territory' which has implications for what Dr Mathieu calls primary and secondary rights (Mathieu II para 126). Marriage exchange rules thus determine who may marry whom and what rights and obligations, including in relation to land, are conferred as a result of those marriages.

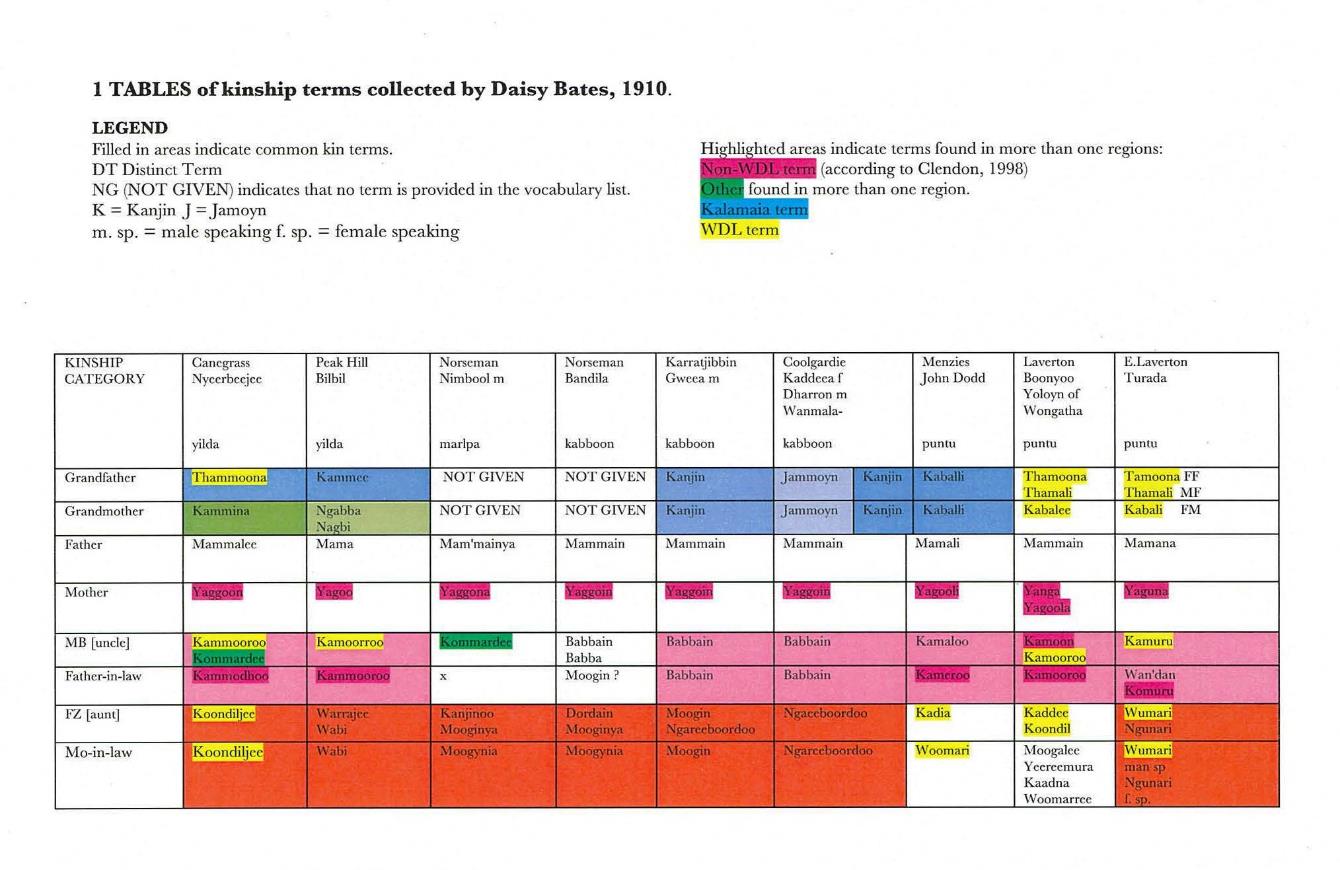

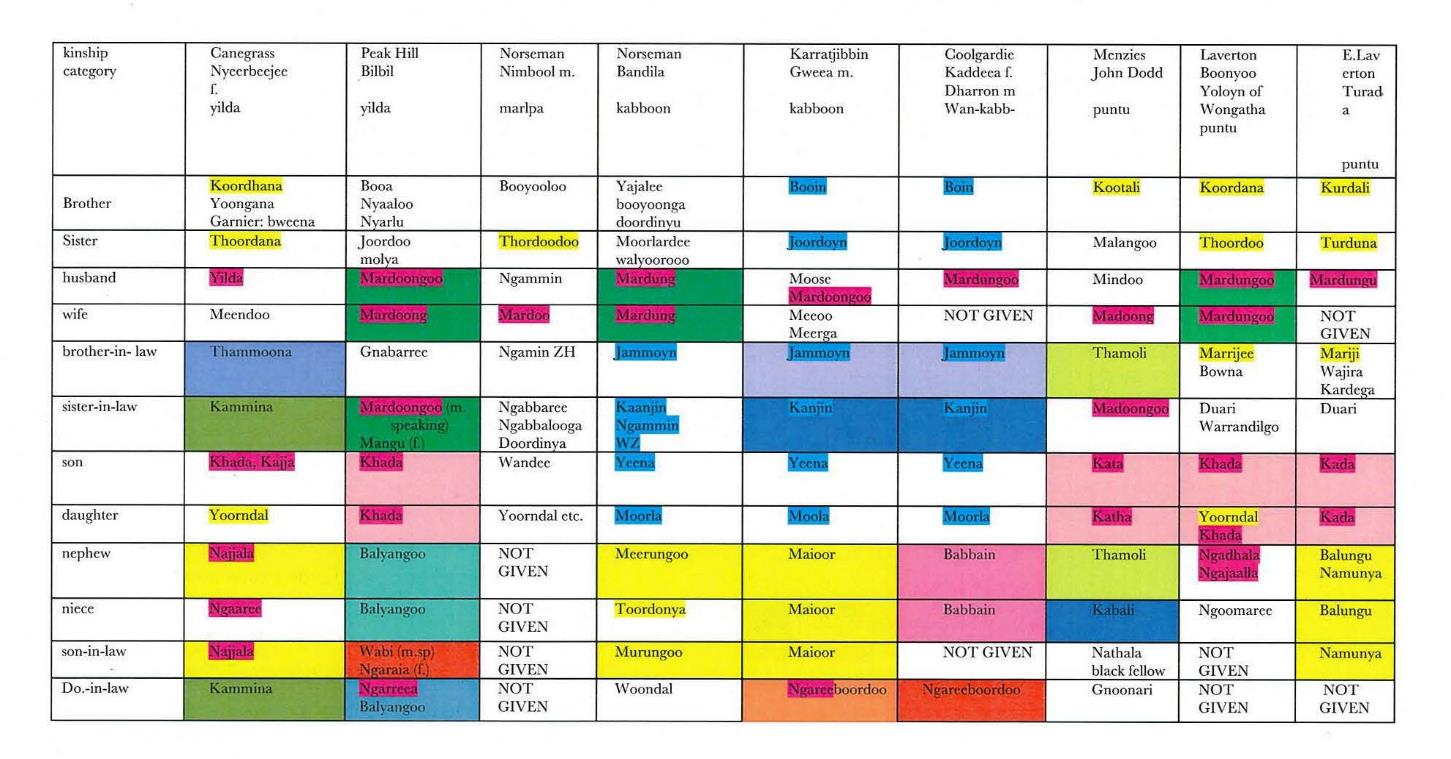

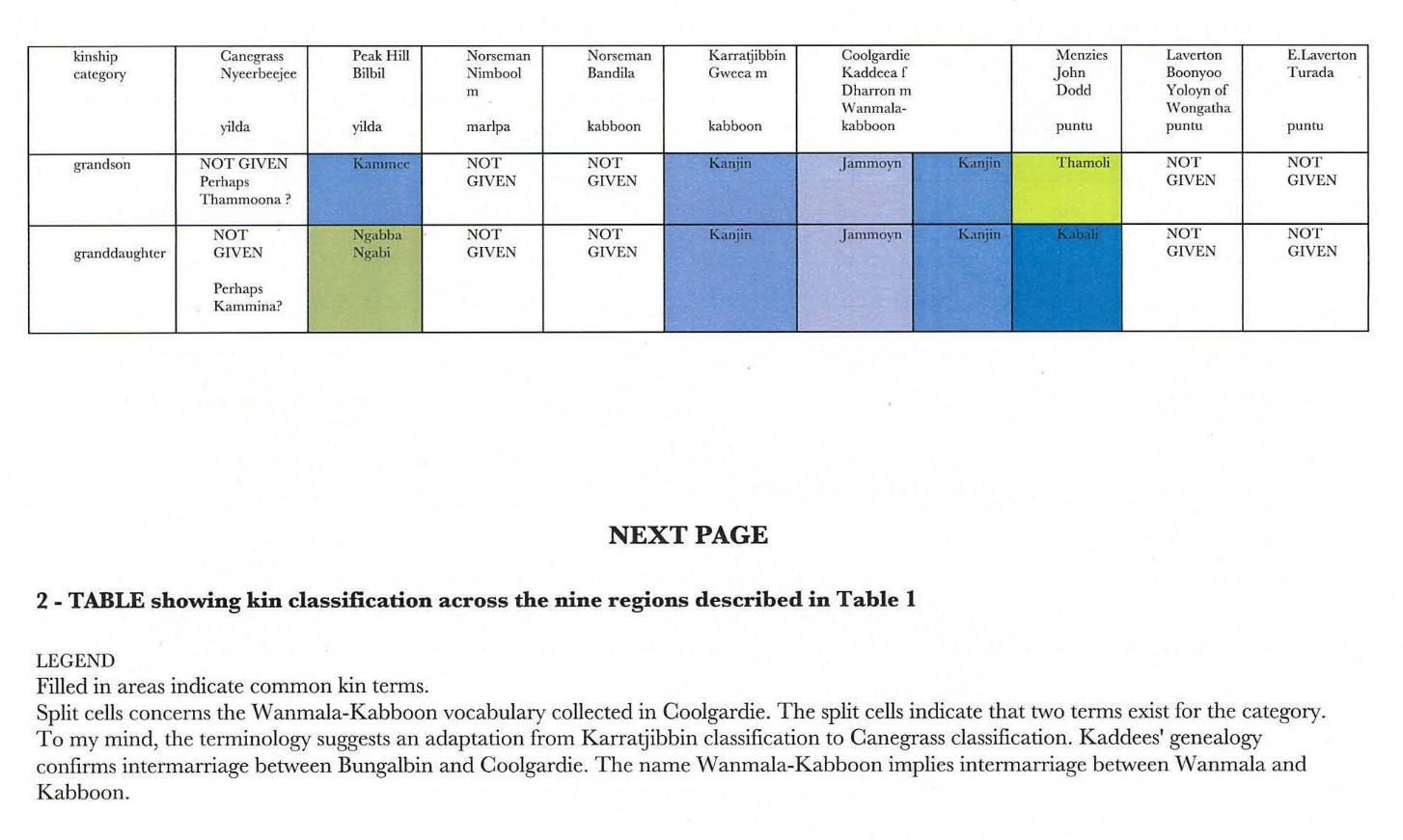

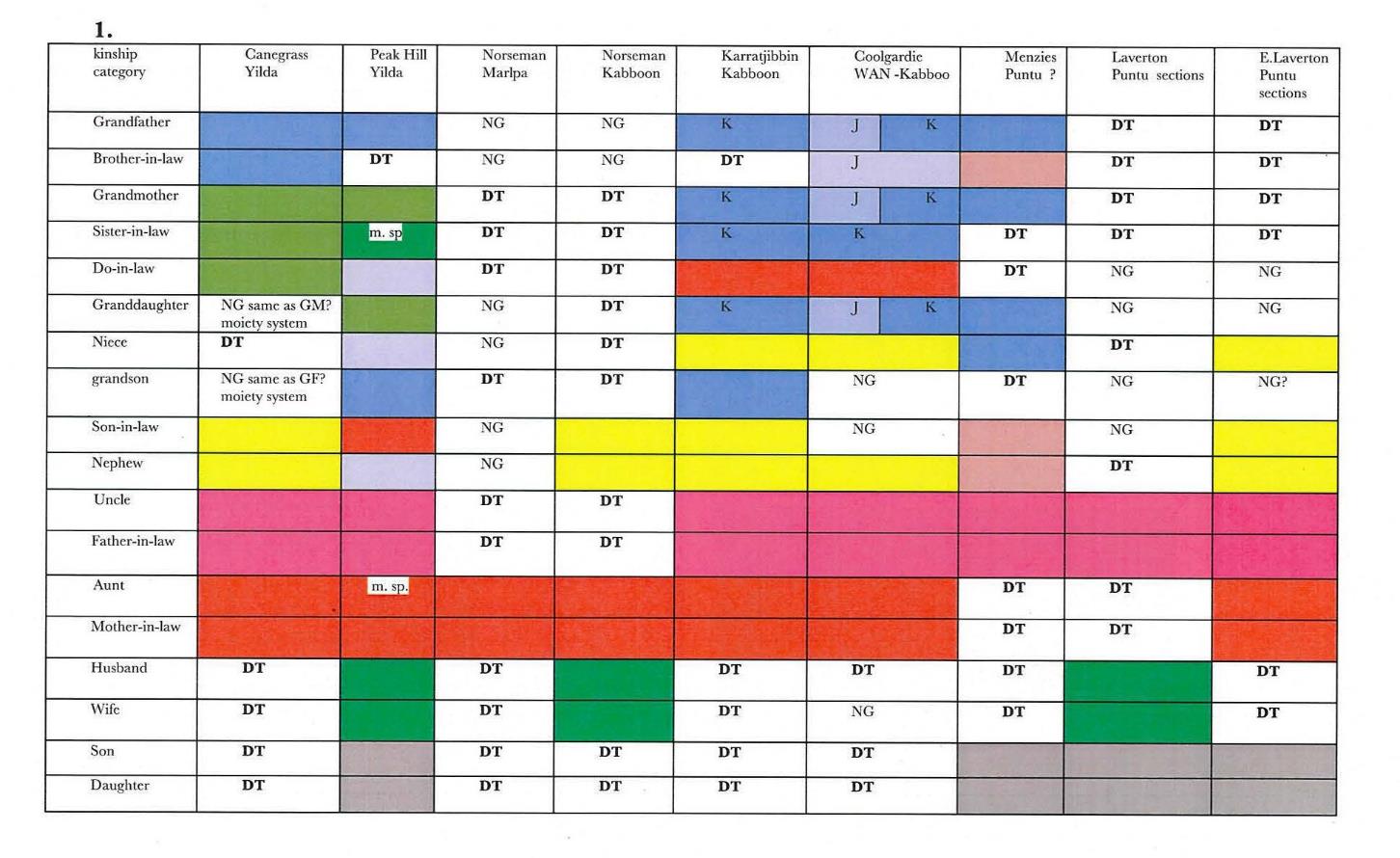

41 The Maduwongga applicant placed considerable reliance on Dr Mathieu's interpretation of kinship terms that were collected at Canegrass, a location approximately one third of the way south of Menzies on the way to Kalgoorlie. They were collected by the journalist and (untrained) ethnographer Daisy Bates in the early 20th century. The vocabulary used in the area was, Dr Mathieu says, consistent with an endogamous moiety system and so distinct from a four-class skin section system. Territorial patterns of marriage exchange are also said to be associated with birthplaces in the Maduwongga claim area.

Other matters said to distinguish the Maduwongga from Western Desert societies

42 In its written opening submissions, the Maduwongga applicant contends that the following further matters support the claim that the Maduwongga comprised a distinct land-holding group identified with the Maduwongga claim area:

(1) Self-identification, that is, the Maduwongga applicant says that KB called herself 'Maduwongga'.

(2) Territorial identification, in that KB identified the boundaries of her traditional country as an area that lies beyond the boundaries of the 'Western Desert Cultural Bloc' (see Section VIII below) and which is bounded on all sides with significant physiographic (that is, geological and topographical) and environmental features. These include what is said to be a natural geographic boundary between Maduwongga country and the country identified with the tribe known as the Walyen. That boundary is said to follow Lake Raeside and the Edjudina Range. It is also said to be a region where the predominantly eucalyptus vegetation and permanent water sources contrast with the drier mulga vegetation to the east of the Edjudina Range.

(3) Birth and association with the area: the Maduwongga applicant contends that KB was born at Edjudina, as were both of her parents and it says that she lived in the area and gave birth to all her children within the area.

(4) Language, in that KB, the Maduwongga applicant says, spoke a Western Desert language (WDL) with a southern influence. It says that while this was mutually intelligible to the people at Mt Margaret and Laverton, who also spoke WDL, it was perceived by those people as 'different'.

(5) Ritual membership, with responsibility for conducting rituals within the claim area being demarcated between those connected to Maduwongga country and others.

43 In relation to the third of these, all parties placed considerable importance on their competing versions of the duration and nature of KB's association with the overlap area and in particular Edjudina. As can be seen from the map attached to these reasons as Annexure A, that is a place some 20 km south-west of the north-eastern boundary of the Maduwongga claim area, which coincides with the Edjudina Range (a larger map of the overlap area was in use at trial but is too large scale to reproduce usefully in these reasons). It is also within the NP claim area and so within the overlap area. So both the Maduwongga claim group and the NP claim group claim to hold native title rights and interests in relation to the area around Edjudina.

44 The Maduwongga applicant says that KB's association with the claim area and the other matters referred to above support the conclusion that KB was a member of the Maduwongga society, being a society united by its observance of the laws and customs summarised above, and was not a member of any Western Desert society.

The relevance of Western Desert societies, laws and customs

45 While the Maduwongga applicant acknowledges a relationship between the Maduwongga and peoples of the Western Desert, it says that the relationship was primarily ritual in nature and not related to land tenure. The Maduwongga applicant also submitted that the term 'Western Desert Cultural Bloc' does not describe any specific society, but is rather a term by which anthropologists designate a number of peoples who have more in common with each other culturally and linguistically than they do with other groups.

46 Nevertheless, the Maduwongga applicant does not contest the description given in the NP respondent's SOFAC of the multiple pathways by which a person or group in the Western Desert Cultural Bloc comes to have rights and interests in relation to lands and waters. The Maduwongga applicant describes those pathways as follows:

(a) birth in or long association with the area, or a related tjukurrpa track, by a person or that person's ancestor;

(b) long term residence in the area;

(c) biological or socially recognised descent from persons with a connection to the area at effective sovereignty or the early decades of the 20th century;

(d) death or burial of a close relative in the area;

(e) caring for the country over a long term; and

(f) ceremonial responsibility for the area.

47 The Maduwongga applicant accepts the multiple pathways model in so far as it describes laws and customs followed generally by occupants of the Western Desert at sovereignty. It also accepts that if the traditional land holding rights for the overlap area were conferred under Western Desert laws and customs at the time of effective sovereignty, then KB would have accrued land rights in the Edjudina area in accordance with those laws and customs by virtue of her long-term association with and residence around Edjudina. But, the Maduwongga applicant says the NP respondent has failed to establish that the laws and customs governing the overlap area at effective sovereignty were Western Desert laws and customs. The Maduwongga applicant points out that only five of the persons identified as ancestors in the NP claim were born in the Maduwongga claim area. It says further that there is no evidence that any of the identified persons were associated with the overlap area prior to effective sovereignty.

48 The Maduwongga applicant accepts that tjukurrpa from the Western Desert pass over the Maduwongga claim area. But it seeks to draw a distinction between ceremonial and ritual knowledge and responsibilities connected to tjukurrpa, and rights to and interests in land, including the right to speak for country and to use resources. So, it contends, while there are watis (initiated men) from the NP claim group who have ceremonial responsibility for sites within the overlap area, and there are presently no watis in the Maduwongga claim group, that does not correlate with members of the NP claim group having rights to and interests in land in the overlap area.

49 It is worth noting at this point that while the Maduwongga applicant relies on aspects of the evidence of Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding, as well as the evidence of a wati of the Pilki people, Daniel (Stevie) Sinclair, in large part the propositions above, particularly with regard to Maduwongga laws and customs, depend on the expert evidence of Dr Mathieu.

50 There was no appreciable difference between the positions taken by the three respondents who took part in the separate question, that is the State, the NP respondent and the MG respondent. They were at one in saying that the Maduwongga applicant had not established the existence of any distinct Maduwongga society during KB's lifetime or at any other time. The NP respondent expressly adopted the State's submissions, as well as the MG respondent's submissions. The MG respondent largely adopted both the State's and the NP respondent's submissions. And the State adopted the NP respondent's and the MG respondent's submissions. So it is convenient to describe the respondents' cases together.

Whether there was a Maduwongga society

51 The State submits that the Maduwongga applicant's position runs counter to 'the vast majority' of Aboriginal evidence and anthropological and other expert evidence. It contends in particular that the views of the anthropological expert on whose evidence the NP respondent relies, Dr Morton, are to be preferred to those of Dr Mathieu. The State submits that Dr Mathieu's model of a distinct Maduwongga group, based on her interpretation of genealogical terms so as to construct a model of marriage relationships, is wrong. According to the State, Dr Mathieu has deduced the model (on an admittedly preliminary basis) based on limited and selective material that, in any event, does not support it. She is not a linguist and the data collected by Bates on which she has based her model is unreliable. It is likely that at least parts of it, which Dr Mathieu characterises as evidence of a distinctive Maduwongga model of marriage and kinship, in fact comes from WDL speakers. The State submits that Dr Mathieu's marriage line is incompatible with its apparent source in the writings of Bates. It is incompatible with evidence of how people said to belong to the Maduwongga actually married, including the evidence of Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding themselves. It is compatible with a skin or section system operating in the overlap area, including at Edjudina.

52 On the subject of KB's origins, the State's position is that she came originally from 'spinifex' country to the east of the overlap area; likely somewhere to the east of Laverton. The State says that KB and her family may well have obtained rights in the country around Edjudina, but that she did so under Western Desert laws and customs. The State agrees with the narrative given by Dr Morton, of KB and her family as Western Desert people who migrated into the overlap area in the late 19th century. It submits that Dr Mathieu's reliance on the material from Tindale's archives is narrow and selective, and when it is considered in the broader context of other material in the archive it does not support the claim that KB (and her father Johnny) was born at Edjudina. The MG respondent also made several submissions to the effect that some of Dr Mathieu's opinions were at odds with a common sense reading of Tindale's materials.

53 Once again, these submissions will be considered below in the context of all the evidence. The evidence includes the only records of the words of KB herself, being notes made by Tindale, or others working with him, of things she said in May 1939. That includes a statement to Tindale that in her country there was no four class system. The State says that the best explanation for this is that she is referring to the country she originally came from, where the section system did not reach until later. Both the State and the NP respondent place considerable weight on a journal entry by Tindale to the effect that the Maduwongga originally came from spinifex country to the east.

54 According to the respondents, the Maduwongga case relies heavily on Tindale's identification of a Maduwongga 'tribe'. The State submits, unequivocally, that Mrs Strickland first learned of 'Maduwongga' from Tindale. The MG respondent submits that Dr Mathieu relies heavily on the fact of Tindale having published a map in 1974 showing a Maduwongga territory, and contends that this reliance is misplaced. The State says that Tindale's designation of a separate Maduwongga group was wrong, being contrary to other 20th century and contemporary anthropology, his own field data, and the Aboriginal evidence. It is generally acknowledged in Australian anthropology that Tindale's tribal model is deficient in many respects and is not properly applicable in the Western Desert. Tindale is the only anthropologist to have identified the Maduwongga as a group, concept or term in or around the overlap area and, according to the State, this is not supported by his primary ethnographic data. The State points, too, to what it says is the ubiquity of the term, and similar terms, in the WDCB, with the word 'madu' simply being used in parts of the WDCB to refer to an Aboriginal person, rather than designating a land-holding group or tribe.

55 As to other points relied on by the Maduwongga applicant, the State says:

(1) KB and her descendants were and are WDL speakers whose asserted laws and customs are recognisably laws and customs of the Western Desert. The State says that while Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding asserted that their ancestors spoke a language called Maduwongga, all the evidence is to the contrary and the few remaining purported Maduwongga words that have been identified are in fact WDL words. In any event, within the Western Desert, linguistic groups are not the same as land-holding units. The MG respondent supported these contentions and said that if there was a distinct group that occupied the overlap area that spoke a WDL dialect, it is likely that the group observed Western Desert laws and customs.

(2) The State relies on evidence of several Aboriginal witnesses in Wongatha, including KB's now deceased grandson Albert Newland (whose relationship to KB the Maduwongga applicant now disputes) and others, who were unaware of a Maduwongga group.

56 The respondents also say that the case that Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding presented in Wongatha was that their claim group adhered to laws and customs of the Western Desert, which is inconsistent with the position they now advance on the separate question. The State refers to a number of matters where, it says, Mrs Strickland and Mrs Nudding gave evidence in Wongatha that contradicts the position the Maduwongga applicant now takes. Those instances will be considered in the course of the analysis of the evidence below.

57 The Maduwongga applicant says that this characterisation of the position Mrs Nudding and Mrs Strickland took in Wongatha is 'not entirely accurate' but does concede that in Wongatha they did submit that the relevant society under which they received rights and interests in land was the society of the Western Desert. They seek to explain that by saying that it was based on the view of the anthropologist they had retained at the time, Dr Edward McDonald, and that Dr Mathieu has since reached a different view.

Western Desert laws and customs in the overlap area

58 According to the State, the ethnographic and Aboriginal evidence demonstrates that the geographical area covered by Western Desert laws and customs includes all of the overlap area, which was and is occupied by Western Desert people. The State sets out 'ethnographic' sources, being late 19th century to mid-20th century accounts by lay and amateur observers and by professional anthropologists which, the State says, establish that the overlap area lay within the area of the WDCB. The State also points to the evidence in the separate question of several members of the NP claim group. The NP respondent supplements this by references to evidence from Aboriginal people in this proceeding and in Wongatha. I will leave a more detailed description of this aspect of the cases of the State and the NP respondent until Section XIII below, when I come to consider whether KB held rights and interests in relation to the overlap area under the traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert.

59 The NP respondent acknowledges that KB and her descendants possess rights and interests in the NP claim area, including the overlap area. But it says that members of its claim group had and have close associations with the overlap area. The NP respondent says that there is no basis on which the Maduwongga can assert exclusive rights and interests in the overlap area. Instead, they are (or should be) part of the larger NP claim group, which in turn is a subset of the broader Western Desert peoples.

60 The NP respondent submits that there can be different kinds of land-holding groups (a term used in the separate question) defined by different kinds of rights and interests in land; for example a right to speak for country or to be asked about country, as distinguished from rights to use country. It contends that the people of the Western Desert do comprise a society, in the sense of the term used in Yorta Yorta, that is, a group united by observance of a normative system of laws and customs. But within that society there can be land-holding groups being groups of persons who together have rights and interests in relation to an area of land (not the entire Western Desert). Members of the NP respondent refer to themselves as Wangkayi, being Western Desert people associated with the south-western part of the Western Desert, although not all Wangkayi are members of the NP claim group.

61 The NP respondent made two specific submissions that went beyond the submissions put by the State. The first is as to the significance of the association between the overlap area and Western Desert laws and customs concerning tjukurrpa and related ceremonies and sites. This, the NP respondent submits, is a compelling factor in favour of finding that the overlap area was associated with Western Desert laws and customs during KB's lifetime and that she held rights and interests in the overlap area under those laws and customs. The State's submissions and the NP respondent's submissions placed some emphasis on tjukurrpa as the foundation of those laws and customs. And according to the State, tjukurrpa and watis are key indicia of Western Desert laws and customs.

62 The NP respondent's submissions supplement this by addressing the Maduwongga applicant's contention that, while Western Desert 'Law business' and rituals are associated with the Maduwongga claim area, those ritual connections do not confer or come with rights to speak for country. The NP respondent accepts that wati who hold tjukurrpa associated with the overlap area and responsibility for related sites in the area may not have the right to speak for the area. But, the NP respondent says, the fact that wati from places as far away as Tjutjuntjarra (some 550 km north and east of Kalgoorlie, on the edge of the Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve) and Warburton (some 700 km north east of Kalgoorlie) hold tjukurrpa associated with the overlap area is a strong indicator that the overlap area is associated with Western Desert laws and customs. For reasons that will be developed below, the NP respondent says that this is in the regional nature of the laws and customs relating to tjukurrpa and the ceremonies conducted in relation to it.

63 The other main additional submission that the NP respondent makes concerns the skin or section systems. For reasons that will, once again, be set out in detail below, the NP respondent contends that there were different section systems in place throughout Western Australia, and in the overlap area that had a dynamic history. That is, the areas within which section systems generally were observed were moving and changing, as were the areas covered by specific section systems. Also, the systems themselves were changing as they met with each other and people intermarried.

64 The NP respondent characterises the expert evidence about section names in the overlap area around 1910 (when, according to Tindale's estimate, KB would have been around 30 years old) as showing a mixture of two kinds of section system as well as the endogamous moiety system. According to the NP respondent, this evidence provides no support for an opinion expressed by Dr Mathieu that although section names were in use around the Edjudina area, this was solely for the purpose of external relations and did not regulate internal relations. The NP respondent submits that the presence or absence of section systems does not distinguish KB or members of her family from other Aboriginal people who were present in the overlap area during her lifetime.

The Maduwongga applicant's submissions in reply

65 In closing submissions filed in reply, the Maduwongga applicant submitted that the NP respondent had not established on the balance of probabilities that Western Desert laws and customs were observed in the overlap area during KB's lifetime. It pointed to different ways in which the respondents, and Dr Morton, had identified the society out of which the allegedly relevant laws and customs arise, and which they define, as explained in Yorta Yorta at [49]-[50]. The Maduwongga applicant submits that neither dialect nor the presence of a section system permit the identification of a single society across the Western Desert.

66 The Maduwongga applicant also submits that the information available as to ties between people in the overlap area and people in the rest of the NP claim area at the time of effective sovereignty is limited, and insufficient to discharge the NP respondent's burden of proof on this point. It also says, as I have noted earlier, that to the extent that there were ties, they were of a ritual or ceremonial nature only and did not pertain to rights and interests in land.

IV. THE STRUCTURE OF THE REST OF THIS JUDGMENT

67 After considering the principles of law that apply to this matter, and making some general observations about the witnesses, these reasons address the issues that arise from the parties' contentions summarised above, in the following order:

(1) Section VII: The Maduwongga group. This will consider whether there was during KB's lifetime, an identifiable group of people called the Maduwongga. That question encompasses whether there were people who self-identified as such and whether other Aboriginal persons recognised the existence of the Maduwongga. That will require consideration of the significance of the first recorded use of the term in the context of the present matters by KB in 1939. It will address the evidence as to the composition of the group during KB's lifetime. Biographical sketches of its members will be given, along with an examination of some points of contention. It will be in this part of the judgment that the evidence about KB's biographical details and her own words will be considered, in particular the important question of where she was born. That is because the information that Tindale gathered about those matters substantially informed his view, and later that of Dr Mathieu. At this point I will also consider the respondents' arguments as to the size of the Maduwongga group in KB's time and the relevance of that.

(2) Section VIII: Maduwongga country. This section considers Tindale's mapping of the Maduwongga 'tribal' area in 1940 and 1974 and discrepancies between his maps and the data he took from his Aboriginal informants in 1939 and 1966. It canvasses the significant controversy on that subject which developed between the expert witnesses, and other ethnographic materials from the early 20th century on which the experts rely. It considers the significance of the physical and ecological features of the claim area that are said to demarcate it from other areas, including the Edjudina Range, which is said to form a natural boundary between the Maduwongga tribal territory and that of the Walyen. It also canvasses the Aboriginal evidence about KB's country and that of her descendants, as well as the association of Wangkayi or Walyen people with the overlap area.

(3) Section IX: Maduwongga language. This section concerns whether the dialect spoken by KB and her descendants serves as a marker of a society distinct from that of the Western Desert. It also canvasses the expert evidence about whether a distinct dialect identifies a distinct land-holding group.

(4) Section X: Maduwongga laws and customs. This will examine the lay and expert evidence about the existence and content of laws and customs said to be observed in the claim area by the Maduwongga, other than laws and customs to which I will give the broad description of kinship. The kinship laws not covered in this section deal with subjects including section systems and rules as to marriage. On the Maduwongga applicant's case, those laws relate directly to the ultimate issue of rights and interests in relation to land and waters. They are therefore crucial to the Maduwongga applicant's case, so they will be given their own section, following this one. This section however, will address the broad topic of differences between Maduwongga customs and those of the Wangkayi or Walyen people, as well as a number of specific topics: ritual and ceremonial practices; initiation in the Law; the role of tjukurrpa in Maduwongga laws and customs; laws and customs governing protection of and responsibility for places of significance; and spiritual beliefs. These topics are all more or less interrelated and are divided up this way chiefly for convenience of exposition. Some of these topics were said by the Maduwongga applicant to engage the distinction between ritual and ceremonial aspects of those places and rights and interests in relation to the land.

(5) Section XI: Laws and customs as to sections, marriage, descent and transmission of rights and interests in land. As just mentioned, the topic of the laws and customs said to be observed in the Maduwongga claim area as to kinship and the acquisition and transmission of rights and interests in relation to land by means of such laws and customs, has its own section because of the importance it assumed in the Maduwongga case. It will include consideration of the evidence about the presence or absence, and significance, of a sectional classification system in the claim area. And it will focus, in particular, on Dr Mathieu's evolving model of rights and interests in relation to land being transmitted and acquired by means of a 'closed connubium' in which endogamous marriage rules and related acquisition of 'estates' by descent are said to have resulted in 'primary' land rights moving and staying within the asserted Maduwongga group.

(6) Section XII: Was there a Maduwongga society? Drawing on the conclusions reached in previous sections, I will make findings about whether there was, during KB's lifetime, a Maduwongga society, in the Yorta Yorta sense of a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of a body of laws and customs, where those laws and customs were not the laws or customs of the Western Desert. This section of the judgment will explain why an affirmative answer cannot be given to the issue at the heart of the second part of the separate question, as to whether KB held rights and interests in the overlap area under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of such a distinct land-holding group.

(7) Section XIII: Were Western Desert laws and customs observed in the overlap area? By this point conclusions will have been reached about the existence of the Maduwongga as a distinct society, but it will then be necessary to address the other aspect of the separate question, namely whether KB held rights and interests in the overlap area under the normative system of traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert. This section will address the evidence, both lay and expert, as to the extent that laws and customs of the Western Desert were observed in the Maduwongga claim area. That will encompass:

(a) the extent to which it is necessary, for the purposes of determining the separate question, to identify a specific society that observed those relevant laws and customs in the Maduwongga claim area, and if it is necessary, how that society should be identified;

(b) the 'multiple pathways' model for the acquisition of land rights in the Western Desert';

(c) the significance of tjukurrpa, including the point of contention between the Maduwongga applicant and the respondents as to whether there is a meaningful distinction between the ceremonial and ritual aspects of tjukurrpa and its role (if any) in relation to rights and interests relating to land or waters;

(d) the ethnographic and anthropological evidence as to whether during KB's lifetime Western Desert laws and customs were acknowledged and observed in the overlap area; and

(e) where KB came from, that is, what the evidence reveals about where she was born and when and how she came to be associated with the overlap area.

(8) Section XIV: The answer to the separate question. This summarises the outcome by reference to the separate question.

68 It will become apparent to anyone charged with the task of reading these long reasons that the matters canvassed in Sections VII to XI are interrelated and interdependent, meaning it is necessary to defer making firm findings about the key issues until it is possible to consider them all together, in Section XII. That will not, however, deter me from making observations about the evidence along the way.

69 It is convenient to outline some of the established principles in relation to the identification of a distinct society united by common acknowledgement and observance of a normative body of laws and customs, as well as a few other evidentiary matters.

70 In Yorta Yorta at [49]-[50] Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ confirmed the central relationship between a body of laws and customs and the identification, as a society, of the group of persons who observe and acknowledge that body. At [49] their Honours said: 'Law and custom arise out of and, in important respects, go to define a particular society. In this context, "society'' is to be understood as a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of a body of law and customs'. Their Honours footnoted that observation with the following (emphasis added): 'We choose the word "society" rather than "community" to emphasise this close relationship between the identification of the group and the identification of the laws and customs of that group'.

71 That does not require a technical approach. In Northern Territory of Australia v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group [2005] FCAFC 135; (2005) 145 FCR 442 at [78] the Full Court said:

The concept of a 'society' in existence since sovereignty as the repository of traditional laws and customs in existence since that time derives from the reasoning in Yorta Yorta. The relevant ordinary meaning of society is 'a body of people forming a community or living under the same government' - Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. It does not require arcane construction. It is not a word which appears in the NT Act. It is a conceptual tool for use in its application. It does not introduce, into the judgments required by the NT Act, technical, jurisprudential or social scientific criteria for the classification of groups or aggregations of people as 'societies'. The introduction of such elements would potentially involve the application of criteria for the determination of native title rights and interests foreign to the language of the NT Act and confining its application in a way not warranted by its language or stated purposes.

72 The question posed by s 223(1)(b) of the NTA is whether Aboriginal people have a connection to the claim area by the traditional laws and customs referred to in s 223(1)(a). So even if they have ceased to comply with the laws and customs, for example if they no longer perform ceremonial responsibilities in relation to an area, the question would be whether, by those laws and customs, that means that they have ceased to have responsibilities (or rights and interests) in relation to the area: see De Rose v State of South Australia [2003] FCAFC 286; (2003) 133 FCR 325 at [313]-[314]; De Rose v State of South Australia (No 2) [2005] FCAFC 110; (2005) 145 FCR 290 at [63]-[64] (De Rose (No 2)); State of Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28; (2002) 213 CLR 1 at [64] (Ward HC).

73 Population shifts, in the sense of documented shifts of groups of persons into a claim area after sovereignty, do not necessarily lead to the conclusion that those persons or their descendants do not hold rights and interests in relation to the claim area under the normative system of traditional laws and customs that operated at sovereignty in the claim area. If the laws and customs of the Western Desert were observed in the claim area and provide for the acquisition of rights and interests by newcomers, not necessarily genealogically related to the inhabitants at sovereignty, those newcomers may still hold the rights and interests under the traditional laws and customs, if they have acquired those interests in a way acknowledged by those laws and customs: see De Rose at [220]-[268].

The relevance of cultural factors other than laws and customs

74 While the existence of a commonly observed body of laws and customs is central to the identification of the relevant society, it is not necessarily the only factor to which regard must be had. In Yorta Yorta Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ did not say that common observance of a body of laws and customs is the sole determinant of the existence of an identifiable society. They said it defines a society 'in important respects'. It is open to draw relevant inferences from evidence as to factors not directly linked to the existence and observance of laws and customs, such as language, self-identification and identification with a particular territory.

75 The relevance of that further 'constellation of factors' was considered by North and Mansfield JJ in Sampi on behalf of the Bardi and Jawi People v State of Western Australia [2010] FCAFC 26. There, the evidence established that there were distinctions between the Bardi and Jawi peoples of the Dampier Peninsula in terms of their languages, their self-identification (what they called themselves) and their identification with particular discrete territories. Nevertheless, the Full Court found that together, they comprised a single society because they observed the same body of laws and customs. At [67], after considering examples of the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses as to the common belief systems between the two peoples, their Honours held:

It remains necessary to consider the matters which the primary judge viewed as indicating that the Bardi and Jawi people constituted separate, albeit similar, societies at sovereignty. These matters, referred to by the primary judge as a 'constellation of factors', include the existence of distinct languages, the use of the self-referents Bardi and Jawi, and the existence of separate territories. When viewed against the evidence that the Bardi and Jawi people at sovereignty shared a single belief system on the fundamental matters of the creation and existence of rights and interests in land and waters, these factors have little significance and are not inconsistent with the existence of a single society.

76 Their Honours went on to consider differences in language (which they held to be 'at the level of dialect'), the use of the self-referents Bardi or Jawi, and territorial delineation. They then said at [71]:

The circumstances of each native title application are different. They depend heavily on the facts concerning the beliefs, histories, and practices of the particular native title claim group. It is therefore not normally useful to compare the facts in one case to the facts in others. However, the Court has ruled on quite a large variety of circumstances of native title claim groups so that certain lines have emerged between the characteristics of those groups which fall within the requirements laid down in Yorta Yorta and those which do not. Whilst it is not possible to push the comparisons too far, it is noteworthy that the Court has found in a number of cases that a native title claim group which adhered to an overarching set of fundamental beliefs constituted a society notwithstanding that the group was composed of people from different language groups or groups linked to specific areas within the larger territory which was the subject of the application.

77 Their Honours went on to consider several examples from previous decided cases. At [77] they said of a submission by the Bardi and Jawi people that the primary judge was not entitled to take the 'constellation of factors' into account:

Were it necessary to decide whether the primary judge was entitled to take into account the factors which he described as a 'constellation of factors' we would regard the argument of the Bardi and Jawi people as too widely stated. Whilst the ultimate fact to be proved by native title claimants is that they have been continuously united in their acknowledgement of laws and observance of customs, there are many subsidiary facts from which an inference may be drawn about that ultimate fact. It is too narrow to exclude from consideration factors which may bear on the existence of a normative system whilst not being direct evidence of the existence of that system. Indeed in the present case the array of factors relied upon by the Bardi and Jawi people themselves to demonstrate the existence of a single society at sovereignty highlights the point. They have not restricted themselves to factors which directly prove the existence of a normative system. For instance, the proof of the existence of songs about the sea is capable of showing that there were rules about the use of the sea even though the proof of the songs themselves is not proof of the law or custom.

78 So matters such as language and customs that do not pertain directly to rights and interests in relation to land can support inferences about the extent to which a given group of people have been united in their acknowledgement of laws and observance of customs. For that reason, and in view of the way in which the parties presented their cases, there will be extensive consideration of such matters in this judgment. Those matters must, however, be viewed as subsidiary to direct evidence that that the group shared a single belief system on the fundamental matters of the creation and existence of rights and interests in land and waters.

The asserted distinction between the ceremonial and ritual dimension and rights and interests in relation to land and waters

79 I have mentioned that the Maduwongga applicant distinguishes between ceremonial and ritual knowledge and responsibilities connected to tjukurrpa, and rights to and interests in land. However in this field it is necessary to take care before drawing any stark distinction of that kind. In Yanner v Eaton [1999] HCA 53; (1999) 201 CLR 351 at [38], Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ said (footnote omitted):

Native title rights and interests must be understood as what has been called 'a perception of socially constituted fact' as well as 'comprising various assortments of artificially defined jural right'. And an important aspect of the socially constituted fact of native title rights and interests that is recognised by the common law is the spiritual, cultural and social connection with the land.

80 Earlier in Yanner v Eaton, at [37], the majority quoted with approval the statements of Brennan J in R v Toohey; Ex parte Meneling Station Pty Ltd (1982) 158 CLR 327 at 358 that 'Aboriginal ownership is primarily a spiritual affair rather than a bundle of rights. Traditional Aboriginal land is not used or enjoyed only by those who have primary spiritual responsibility for it. Other Aboriginals or Aboriginal groups may have a spiritual responsibility for the same land or may be entitled to exercise some usufructuary right with respect to it'. Both a right to speak for country reflecting 'a higher order, religious or sacred imperative' and a more mundane right to use the land economically, are rights and interests in relation to land or waters' for the purposes of the NTA: Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2013] FCA 868 at [160] (Barker J).

81 The question of whether particular roles and responsibilities rooted in tjukurrpa give rise to rights and interests in relation to land or waters must of course be answered by reference to the evidence about the laws and customs of the particular people involved. In the context of a particular group of people, the High Court has recognised what is, at the same time, the difficulty of translating a spiritual relationship with the land into the language of rights and interests, and the necessity under the NTA of doing so. In Ward HC at [14], Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said:

As is now well recognised, the connection which Aboriginal peoples have with 'country' is essentially spiritual. In Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd [(1971) 17 FLR 141 at 167], Blackburn J said that: 'the fundamental truth about the aboriginals' relationship to the land is that whatever else it is, it is a religious relationship … There is an unquestioned scheme of things in which the spirit ancestors, the people of the clan, particular land and everything that exists on and in it, are organic parts of one indissoluble whole'. It is a relationship which sometimes is spoken of as having to care for, and being able to 'speak for', country. 'Speaking for' country is bound up with the idea that, at least in some circumstances, others should ask for permission to enter upon country or use it or enjoy its resources, but to focus only on the requirement that others seek permission for some activities would oversimplify the nature of the connection that the phrase seeks to capture. The difficulty of expressing a relationship between a community or group of Aboriginal people and the land in terms of rights and interests is evident. Yet that is required by the NTA. The spiritual or religious is translated into the legal. This requires the fragmentation of an integrated view of the ordering of affairs into rights and interests which are considered apart from the duties and obligations which go with them. The difficulties are not reduced by the inevitable tendency to think of rights and interests in relation to the land only in terms familiar to the common lawyer. …

82 And at [90] their Honours observed:

As we have said, it may be accepted that the right to be asked for permission and to speak for country is a core concept in traditional law and custom. As the primary judge's findings show, it is, however, not an exhaustive description of the rights and interests in relation to land that exist under that law and custom. It is wrong to see Aboriginal connection with land as reflected only in concepts of control of access to it. To speak of Aboriginal connection with 'country' in only those terms is to reduce a very complex relationship to a single dimension. It is to impose common law concepts of property on peoples and systems which saw the relationship between the community and the land very differently from the common lawyer.

83 These observations are a reminder that it is important not to permit a complex relationship between people and country with many dimensions to be fragmented too readily into a set of rights and interests in land and, say, a set of ceremonial rights and responsibilities. Consistently with that, in Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] FCAFC 178; (2007) 165 FCR 391 at [127], French, Branson and Sundberg JJ held:

It is not a necessary condition of the exclusivity of native title rights and interests in land or waters that the native title holders should, in their testimony, frame their claim to exclusivity as some sort of analogue of a proprietary right. In this connection we are concerned that his Honour's reference to usufructuary and proprietary rights, discussed earlier, may have led him to require some taxonomical threshold to be crossed before a finding of exclusivity could be made. It is not necessary to a finding of exclusivity in possession, use and occupation, that the native title claim group should assert a right to bar entry to their country on the basis that it is 'their country'. If control of access to country flows from spiritual necessity because of the harm that 'the country' will inflict upon unauthorised entry, that control can nevertheless support a characterisation of the native title rights and interests as exclusive. The relationship to country is essentially a 'spiritual affair'. …

84 So, for example, a right to care for, maintain and protect an area is capable of being a right or interest in relation to land or waters, even though it does not necessarily bring with it any right that would be recognised: Sampi at [118]-[125].

85 However, it is established that in order to be recognised by the common law of Australia, the laws and customs in question must have a normative content: Yorta Yorta at [38]. That is because only if the rules which together constitute the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed have a normative content will rights and interests arise: see Yorta Yorta at [42]. A law or custom has normative content if it imposes obligation or confers entitlement: Wongatha at [936]. See also Alyawarr at [75]:

The traditional laws or customs which are the source of the native title rights and interests must have a 'normative content'. They must derive 'from a body of norms or normative system - the body of norms or normative system that existed before sovereignty' (Yorta Yorta at [38]). This does not require fine distinctions to be drawn between legal rules and moral obligations. The interests may arise under both law and custom. There nevertheless must be some kind of 'rules' which have a 'normative content'. Absent such rules there may merely be observable behaviour patterns but no rights or interests in relation to the land.

86 So, for example, in Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Islanders of the Regional Seas Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 2) [2010] FCA 643; (2010) 204 FCR 1 at [173], Finn J adopted a working definition of 'custom' suited to the distinctive circumstances of that case as 'accepted and expected norms of behaviour, the departure from which attracts social sanction (often disapproval especially by elders)'.

87 It may be that the normative character of the laws and customs can be inferred from the fact that they are consistently observed, but care needs to be taken in that regard. In Ngarla at [283], Bennett J observed that (emphasis in original):

Yorta Yorta does not preclude the Court from drawing inferences as to the existence of a native title right or interest from conduct, including observable patterns of behaviour. If a right is based in the laws and customs of a normative society, whether the right has been exercised or whether the licence exists is a fact to be established. It may be established by inference from observable behaviour. However, care must be taken in relying on such inferences, as a native title right or interest, must have normative content.

A society and a land-holding group are not necessarily the same

88 It is well recognised that a society is not necessarily synonymous with a particular group that holds particular rights and interests under the body of laws and customs observed by the society. In Mabo v State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 62, Brennan J said: 'A communal native title enures for the benefit of the community as a whole and for the sub-groups and individuals within it who have particular rights and interests in the community's lands'. It is plain that the relevant society is not necessarily synonymous with a land-holding group and that there may be various groups and individuals within a given society who hold various different kinds and combinations of rights and interests in relation to particular stretches of land. In State of Western Australia v Ward [2000] FCA 191; (2000) 99 FCR 316 at [239], Beaumont and von Doussa JJ said (and were not overturned on this point in Ward HC):

The State contends that every relevant witness claimed to be either Miriuwung or Gajerrong, and a great majority of those who claimed to be Miriuwung gave evidence that they had a full array of rights only in an estate area. Those witnesses did not claim that other estate areas were their 'country'. To that point, the submission appears to be correct, but it does not follow that there is not now a Miriuwung and Gajerrong community which acknowledges and observes traditional laws and customs under which members of the community enjoy differing arrays of rights within and outside their particular family or estate country.

89 Wilcox, Sackville and Merkel JJ applied distinctions of this kind to the Western Desert in De Rose (No 2) at [38]-[39]:

It is hardly likely that the traditional laws and customs of Aboriginal peoples will themselves classify rights and interests in relation to land as 'communal', 'group' or 'individual'. The classification is a statutory construct, deriving from the language used in Mabo (No 2). If it is necessary for the purposes of proceedings under the NTA to distinguish between a claim to communal native title and a claim to group or individual native title rights and interests, the critical point appears to be that communal native title presupposes that the claim is made on behalf of a recognisable community of people, whose traditional laws and customs constitute the normative system under which rights and interests are created and acknowledged. That is, the traditional laws and customs are those of the very community which claims native title rights and interests. By contrast, group and individual native title rights and interests derive from a body of traditional laws and customs observed by a community, but are not necessarily claimed on behalf of the whole community. Indeed, they may not be claimed on behalf of any recognisable community at all, but on behalf of individuals who themselves have never constituted a cohesive, functioning community.