Federal Court of Australia

Casey v DePuy International Ltd (Appeal from Independent Counsel) [2023] FCA 254

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent JOHNSON & JOHNSON MEDICAL PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 March 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties provide a short minute of order containing a suitable declaration and an order under s 33V(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) within 7 days.

2. The Respondents pay Ms Davidson’s costs of the application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

Introduction

1 This is an appeal on an error of law under an Amended Deed of Settlement (‘the Deed’) which provided for the settlement of a class action. The settlement was approved by this Court under s 33V(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (‘FCA Act’). The lead Applicant in the class action alleged that a prosthesis designed to be fitted during total knee replacement surgery was neither fit for purpose nor of merchantable quality. The Deed did not involve the payment of a global sum for the class but instead made provision for: (a) a mechanism by which the eligibility of group members to receive compensation of different grades could be determined; and (b) another mechanism for the determination of that compensation having regard to the grade of eligibility. This latter mechanism was contained in a document entitled the ‘Compensation Protocol’ which was to have effect between the parties to the settlement by virtue of certain provisions of the Deed. The Compensation Protocol contemplated a two-stage process. In the first stage, the eligible group member would seek a nominated amount of compensation and provide supporting documentation to the Respondents (i.e. the manufacturer of the prosthesis and its supplier and distributor): cls 6.1-6.5. If the Respondents agreed with the amount, then this would be the amount of compensation. On the other hand, if there was a dispute about the amount of compensation, the dispute would proceed to the second stage and be referred to a person known as the Independent Counsel for determination: cl 6.7. The Independent Counsel was a barrister who the parties agreed on. The Independent Counsel’s decision would bind the Respondents and the eligible group member.

2 Some provision for further dispute about the determination of the Independent Counsel was provided for in the Deed. Clause 15.7 of the Compensation Protocol provides that a person who is entitled to compensation under the Compensation Protocol may apply to this Court ‘in respect of any point of law arising from the implementation of this Compensation Protocol’. Clause 10.6(e) also makes clear that there can be no appeal from any determination by the Independent Counsel under the Compensation Protocol other than in relation to an error of law. The parties proceeded on the basis that these two clauses permitted either party to commence a proceeding in this Court’s original jurisdiction to determine the appeal contemplated by the clauses and that that appeal was limited to issues of law.

3 Ms Davidson is one of the group members in the class action who has been determined to be eligible for compensation. She lodged an application for compensation under the Compensation Protocol. The Respondents did not accept the amount claimed and the claim was referred to the Independent Counsel for determination. He made his determination on 3 August 2022. He concluded that Ms Davidson was entitled to $1,106,473.80. Ms Davidson wishes to see this amount increased and submits that the Independent Counsel made an error of law in rejecting part of her claim. She has therefore filed an interlocutory application in the original class action proceeding seeking a declaration that the decision is affected by an error of law and is not binding upon her.

Jurisdiction

4 The first question in the appeal is whether this Court has any jurisdiction to entertain the interlocutory application. Both parties submitted that the Court does have jurisdiction. The fact that the parties agree that the Court has jurisdiction does not, however, entail that it does. There is, in my view, a question as to whether parties may, by means of a deed of settlement, confer jurisdiction on this Court. This matters because it is the first duty of a court to satisfy itself that it has jurisdiction: Re Nash (No 2) [2017] HCA 52; 263 CLR 443 at [16] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane and Edelman JJ; Federated Engine-Drivers’ and Firemen’s Association of Australasia v Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (1911) 12 CLR 398 at 415 per Griffith CJ. Consequently the question of jurisdiction must be determined in the first instance regardless of the parties’ views.

5 Under s 77(i) of the Constitution, the Parliament may make laws ‘defining the jurisdiction of any federal court other than the High Court’ with respect to any of the matters with which the High Court is invested under s 75 or with which it may be invested under s 76. Relevantly, the High Court may be invested with jurisdiction in any matter ‘arising under any laws made by the Parliament’: s 76(ii). Thus, under s 77(i), the Parliament may make laws investing this Court with jurisdiction in matters arising under a law made by the Parliament and has, in fact, done so in the form of s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (‘Judiciary Act’).

6 It is correspondingly established that within the federal system it is not possible to confer jurisdiction on this Court other than in respect of the matters set out in ss 75 and 76 of the Constitution: Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally [1999] HCA 27; 198 CLR 511. Consequently, a state legislature cannot confer jurisdiction on this Court. Largely for the same reason, it is beyond the power of private parties by contract to confer jurisdiction on a federal court either. Neither party disputed these propositions. It is therefore necessary to identify some feature of the present application that brings the matter underlying it within federal jurisdiction. Ms Davidson and the Respondents identified the present matter as arising under a law of the Parliament (i.e. s 76(ii)) although they differed as to the identity of the law.

7 For Ms Davidson, it was said that the orders made by this Court under s 33V(1) of the FCA Act approving the settlement had the effect that the matter arose under s 33V(1). For the Respondents, on the other hand, it was submitted that the matter arose under ss 74B and 74D of the former Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (‘TPA’). It was under these provisions that the lead Applicant had sued the Respondents claiming against them that they had manufactured or supplied in Australia prostheses which were neither fit for purpose nor of merchantable quality. That proceeding remained on foot, so the submission went, because the orders approving the settlement were interlocutory in nature. As I understood it, the point was that the original proceeding remained in some way on foot so that the appeal under cl 15.7 of the Compensation Protocol might be seen as part of that suit.

8 Dealing then with Ms Davidson’s submission that the Court has jurisdiction because of the orders made under s 33V(1), the settlement was approved by this Court on 4 December 2012: Casey v DePuy International Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 1370 per Buchanan J. The orders made that day dealt with a number of machinery matters but the approval was provided for in Order 1:

1. Pursuant to sections 33V(1) and 33ZF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act), the settlement of the proceeding is approved on the terms set out in:

(a) the amended settlement agreement dated 19 November 2012 between the applicant and the respondents in annexure RG-8 to the affidavit of Rebecca Gilsenan affirmed on 20 November 2012 (Gilsenan Affidavit);

(b) the “Liability Protocol” in annexure RG-9 to the Gilsenan Affidavit; and

(c) the “Compensation Protocol” in annexure RG-10 to the Gilsenan Affidavit.

9 Clause 5.1 of the Deed provided for a ‘Liability Protocol’ under which the eligibility of group members for compensation of different grades was to be determined. It also provided for the Compensation Protocol under which the amounts of compensation due to eligible group members would be determined. Under cls 6 and 7 of the Deed, the Respondents agreed to pay certain costs and expenses upon the submission of documentation and particulars. Under cl 8.1, the group members agreed that the Deed could be pleaded ‘as a complete defence by any party or Group Member to any action, suit, or proceedings commenced, continued or taken by another party or Group Member or on their behalf in relation to the subject matter of this Proceeding, in contravention of the provisions of this agreement’. By cl 3.1, the Deed was subject to the Court’s approval under s 33V(1) and, if that approval were refused, the Deed was treated as never having been made: cl 3.2. The Deed was signed by Ms Casey as the lead Applicant on behalf of the group members and by the representatives of both Respondents.

10 Section 33V of the FCA Act provides:

33V Settlement and discontinuance—representative proceeding

(1) A representative proceeding may not be settled or discontinued without the approval of the Court.

(2) If the Court gives such an approval, it may make such orders as are just with respect to the distribution of any money paid under a settlement or paid into the Court.

11 Buchanan J approved the settlement as contained in the Deed, the Liability Protocol and the Compensation Protocol pursuant to s 33V(1). Whilst s 33V(2) would have authorised an order requiring the distribution of any moneys recovered under the settlement, it was, as I have already noted, a particular feature of this settlement that there was no settlement fund. Rather, the Respondents agreed to process claims the subject of the proceeding in accordance with the Liability Protocol and Compensation Protocol.

12 It is evident that both the Deed and the Compensation Protocol assumed that the Respondents would pay any amount determined to be due although neither contains an express stipulation to that effect. By the same token, the orders of Buchanan J do not include an order under s 33V(2), requiring the Respondents to pay any amounts determined under the Compensation Protocol to the relevant eligible applicant. Had such an order been made, the liability of the Respondents to Ms Davidson under the Compensation Protocol would have arisen directly under that order. In such a circumstance, it would be clear that this Court had jurisdiction to determine whether its own order had been carried into effect and, if not, to make supplemental orders to bring about that result. In that case, a proceeding in this Court alleging an error of law by the Independent Counsel would have arisen directly under the Court’s own order and therefore directly under s 33V(2). However, this is not the order which was made and neither party sought to have this Court make an order nunc pro tunc under s 33V(2).

13 Viewed as a private contract, I have no doubt that cl 15.7 could not be effective to confer jurisdiction on this Court to hear the appeal to which it refers. The question then becomes whether the fact that the Deed could have no legal consequences until such time as leave was granted under s 33V(1) means that it can be said that the appeal provided for in cl 15.7 is a matter arising under s 33V(1).

14 A matter may properly be said to arise under a federal law if the right or duty ‘owes its existence to Federal law or depends upon Federal law for its enforcement’: R v Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration; Ex parte Barrett (1945) 70 CLR 141 at 154 (‘Barrett’); LNC Industries Ltd v BMW (Australia) Ltd (1983) 151 CLR 575 at 581. I do not think that the right to appeal under cl 15.7 can plausibly be said to owe its existence to s 33V(1). Leave under s 33V(1) merely lifted a prohibition on the rights of the parties to enter into a private contract. It did not become thereby the source of those rights.

15 On the other hand, it may be said that the right to appeal under cl 15.7 does depend on federal law for its enforcement. Without a grant of leave under s 33V(1), the Deed is unenforceable. It was only once leave was granted that the terms of the Deed (and cl 15.7 of the Compensation Protocol) had any legal effect. This proposition may be tested by asking how the matter might hypothetically have been pursued had there been an order for pleadings. If Ms Davidson had filed a statement of claim pleading cl 15.7 as the source of her right to approach this Court to set aside the decision of the Independent Counsel, any plea by the Respondents that the Deed was unenforceable would have been met by a reply pleading s 33V(1). Another way of looking at the matter might be this: cl 3.1 of the Deed (and with it the two protocols) would have had no legal effect if a grant of leave were not secured under s 33V(1). Consequently, the issue of s 33V(1) could have been raised by Ms Davidson in any pleading by her of a statement of claim. For example, it would have been open to her to aver that the Compensation Protocol took effect because of the Deed, that the Deed was legally ineffective without a grant of leave under s 33V(1), and that there had been such a grant of leave with the consequence that the Compensation Protocol gave rise to rights and liabilities including cl 15.7.

16 Whilst the form of pleadings and the relief claimed are not definitive of whether a claim is in federal jurisdiction, I consider it persuasive that it is possible to conceive of a form of the current proceeding in which s 33V(1) would have been pleaded by Ms Davidson.

17 In that regard, the present situation is not unlike that which arose in Barrett. There the rules of a union became binding only once the union was registered under the provisions of the then Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth). As Latham CJ observed at 151: ‘the rules as rules of the organization derive their force from the Act, and, therefore, a controversy as to the observance or performance of the rules is a matter arising under the Act’. The same may be said here. The Deed derives its legal efficacy from the fact that the Court has granted leave to the parties to settle the proceedings on its terms under s 33V(1). So viewed, s 33V(1) is an indispensable element to its enforcement.

18 For those reasons, I think the better view is that an appeal to this Court under the terms of a deed of settlement, which forms part of a settlement in respect of which this Court has granted its leave under s 33V(1), is a matter arising under s 33V(1) and is therefore within this Court’s jurisdiction conferred by s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act.

19 However, this view is reasonably contestable. That being so, a safer course in the present proceeding would be, I think, for this Court now to make orders under s 33V(2) requiring the Respondents to pay eligible applicants any amounts determined to be due in accordance with the Compensation Protocol. This was the solution which commended itself to Jessup J in Darwalla Milling Co Pty Ltd v F Hoffman-La Roche Ltd (No 2) [2006] FCA 1388; 236 ALR 322 at [96] (‘Darwalla’). What his Honour said there was this:

The settlement scheme reserves a limited role to the court. This is consistent with the fact that the proceeding itself will remain on foot until the distribution of the settlement sum has been completed in accordance with the scheme. For the court to have the kind of role proposed (such as dealing with issues of law which arise out of assessment reviews), it is necessary that there be a juridical basis for the court’s intervention. Merely to have approved the distribution of an agreed sum as between group members, according to the settlement scheme, would not, in my view, provide such a basis. The applicants propose that the court should, having approved the settlement, make orders that the settlement fund be distributed, and administered generally, in accordance with the settlement scheme. They submitted that such an order might be made under s 33V(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act (1976), which provides:

(2) If the Court gives such an approval, it may make such orders as are just with respect to the distribution of any money paid under a settlement or paid into the Court.

I agree that this subsection would provide the court with power to make an order of the kind proposed. I consider that the limited role which is proposed for the court in the settlement scheme is appropriate in the context of the administration of the scheme as a whole. Although the distribution of moneys to group members under the settlement scheme will finally settle the claims of those members which were raised in the proceeding, the orders under s 33V(2) should, in my view, be regarded as interlocutory, since, as between the applicants and the respondents, they do not dispose of the proceeding.

20 Ms Davidson submitted in this Court that Darwalla assisted her contention that this Court had jurisdiction to entertain an appeal under cl 15.7. I do not agree. To the contrary, his Honour identified that the absence of an order under s 33V(2) quite possibly meant that the Court would not have jurisdiction. Although I have arrived at the view that the Court does have jurisdiction even without an order under s 33V(2), Jessup J’s tentative view to the contrary only underscores my concerns about the possible fragility of my own conclusion. In that regard, whilst I would not depart from anything said by Jessup J without anxious consideration, his Honour’s observations on this occasion were strictly an obiter dictum made after less than full argument. I think the better view is that the order under s 33V(1) approving the settlement in the terms of the Deed and the two protocols is sufficient to mean that an appeal under cl 15.7 is in federal jurisdiction.

21 However, in order to put the matter beyond doubt, it would be appropriate to make an order under s 33V(2) requiring the Respondents to pay compensation to eligible group members in accordance with the Compensation Protocol. This order should be retroactive to the date of the orders made by Buchanan J. I will leave the drafting of this order to the parties.

22 It is not necessary in that circumstance to consider the Respondents’ submission that an appeal under cl 15.7 also arises under ss 74B and 74D of the TPA or that jurisdiction arises because the s 33V(1) orders were interlocutory.

The Error Alleged By Ms Davidson

23 The issues before the Independent Counsel were extensive and complex and were resolved by him by a thorough and lengthy set of reasons. The appeal focusses on a single issue which occupied a relatively small portion of those reasons. Neither party contends that the Independent Counsel made any other errors of law in his determination of the large number of other issues with which he had to deal.

24 What is the error? There is a complexity in Ms Davidson’s case inasmuch as the original implantation in her of the prosthesis during a total knee replacement procedure on 21 May 2008 was itself done as a consequence of an earlier workplace injury suffered on 4 February 2001 when Ms Davidson fell at her work.

25 In the class action, the lead Applicant alleged that the prosthesis was neither fit for purpose nor of merchantable quality. In due course, Ms Davidson developed difficulties arising from the prosthesis. She underwent further procedures and treatments including, eventually, the removal of the prosthesis.

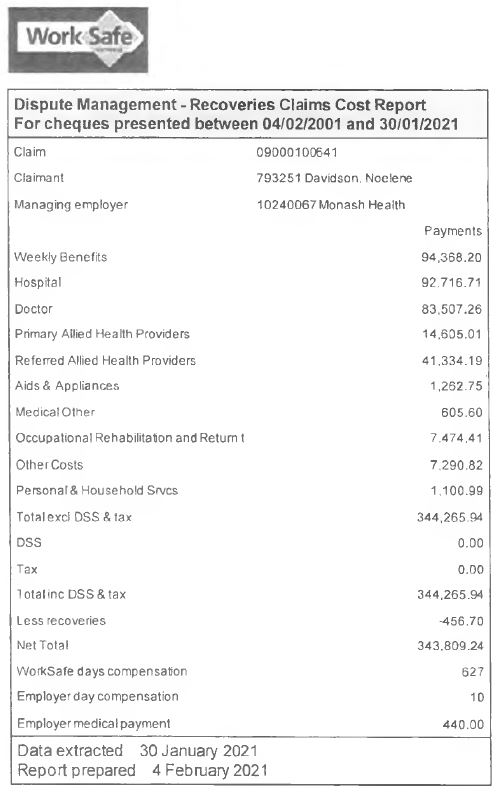

26 Without dwelling on the statutory detail at this stage, it suffices for present purposes to know that the relevant workers’ compensation body was WorkSafe Victoria (‘WorkSafe’) or its statutory predecessors. At all times it has paid Ms Davidson’s out of pocket expenses arising from the original fall. These included not only the cost of the knee replacement surgery but also the subsequent procedures and treatments resulting from the implantation of the prosthesis. At no time has it been necessary for Ms Davidson to establish any fault element for her entitlement in order to have these expenses paid for her because the scheme administered by WorkSafe is a no-fault scheme.

27 Before the Independent Counsel, Ms Davidson contended that if she recovered compensation from the Respondents under the terms of the Compensation Protocol for the expenses which WorkSafe had paid in consequence of the implantation of the prosthesis, then she would become liable to WorkSafe under s 85(6) of the Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic) (‘ACA’). The question is whether s 85(6) did in fact operate in that way. There is an irrelevant issue as to the version of s 85(6) which applies since it has undergone some changes over time. Ms Davidson and the Independent Counsel proceeded on the basis that the relevant version was the current version. The Respondents approached the matter on the basis that it was s 85(6) as it stood at 2001 which was the relevant version. It is not necessary to determine this issue. The differences between the two versions of s 85(6) are not material to any issue in this case. I will use the current version of the legislation since, as will be seen, the events which enliven its operation have not yet occurred.

28 Section 85(6) provides:

If a person—

(a) receives compensation under this Act in respect of any injury; and

(b) subsequently obtains damages or an award of damages, accepts a payment into court or settles or compromises a claim in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia)—

the Authority, employer or a self-insurer shall be entitled to recover from that person the amount of compensation paid under this Act or an amount equal to the damages or payment obtained or made, settled or compromised whichever is the lesser amount.

29 It will be seen that the language of s 85(6) requires that the compensation received should have been ‘in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria’. It is not in dispute that the implantation of the prosthesis took place in Victoria. Nor is it in dispute that, in the event that Ms Davidson recovers compensation from the Respondents, it is properly to be characterised as the compromise of a claim under ss 74B and 74D of the former TPA. Those are laws of the Commonwealth. The immediate question which arose before the Independent Counsel was whether a claim under a law of the Commonwealth is properly to be characterised as a claim under the law of a place ‘outside Victoria’.

30 Those words in s 85(6) take as their point of departure that whatever a ‘place’ might be, it is a concept which must have laws under which a claim may be made. Whatever the boundaries of that concept are, it is clear that they include a state or territory of the federation and, it may be accepted, the Commonwealth itself. That being so, s 85(6) requires one to ask whether the Commonwealth is ‘outside’ Victoria. Certainly all those parts of the Commonwealth which are outside Victoria may be said to be so and, in that sense, at least a part of the Commonwealth may be said to be outside Victoria.

31 On the other hand, that part of the Commonwealth which is located in Victoria cannot be said to be outside Victoria. In a sense, the Commonwealth is therefore both within and outside of Victoria. It appears to me therefore that the expression ‘outside Victoria’ is ambiguous in relation to the Commonwealth. The ambiguity is whether it means ‘wholly outside’ or merely ‘outside to some extent’. The question which therefore arises is how this ambiguity is to be resolved. This is an issue of statutory construction. It is useful now to examine s 85 in its full terms:

85 Entitlement to damages outside Victoria

(1) This section shall apply where an injury is caused to or suffered by a worker which gives the worker a right of action under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia) in circumstances which would otherwise have entitled the worker or the worker’s dependants to compensation under this Act.

(2) Subject to subsection (3), if—

(a) damages has not been paid or recovered; and

(b) judgment for damages has not been given or entered—

in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia), the worker or in the case of the death of the worker the worker's dependants shall be entitled to compensation under this Act as if there were no right of action under the law of any place outside Victoria.

(3) A person who has a right of action in respect of an injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia) shall not be entitled to claim compensation in respect of the injury under this Act if in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria—

(a) the person has been paid or recovered any amount of damages;

(b) judgment for damages has been given or entered;

(c) any payment into court has been accepted;

(d) there has been a settlement or compromise of any claim; or

(e) any action for damages is pending.

(4) If—

(a) damages has been paid or recovered; or

(b) judgment for damages has been given or entered—

in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia) the worker or in the case of the death of the worker the worker's dependants shall not be entitled to compensation under this Act.

(5) The worker or in the case of the death of the worker the worker's dependants shall not be entitled to compensation under this Act if a payment into court has been accepted by the worker or the worker's dependants in proceedings or a settlement or compromise of a claim has been made in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia).

(6) If a person—

(a) receives compensation under this Act in respect of any injury; and

(b) subsequently obtains damages or an award of damages, accepts a payment into court or settles or compromises a claim in respect of the injury under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia)—

the Authority, employer or a self-insurer shall be entitled to recover from that person the amount of compensation paid under this Act or an amount equal to the damages or payment obtained or made, settled or compromised whichever is the lesser amount.

(7) Any dispute under subsection (6) shall be determined by a court of competent jurisdiction.

(8) Unless a worker produces satisfactory evidence to the contrary, any amount recovered or to be recovered by a worker under the law of any place outside Victoria (whether within or outside Australia) as damages in respect of an injury shall be presumed to be damages for the same injury in respect of which the worker claims compensation or a right of action under this Act.

32 It will be seen that the idea of a claim under the law of a place outside Victoria permeates the entire provision. Viewed as a whole, it is evident that the provision intends to regulate the relationship between rights to workers’ compensation under the ACA and rights to claim compensation under the laws of other places. Subsection (3) erects a bar on compensation under the ACA where a person under the law of a place outside Victoria recovers damages, obtains judgment, settles such a claim or even where such a claim is merely pending. Provided sub-s (3) is not engaged, sub-s (2) permits a claim for compensation under the ACA to be made. Subsection (4) appears to be otiose. Satisfaction of either of sub-ss (4)(a) or (b) would also satisfy sub-ss (3)(a) or (b). Subsection (5) also appears to be otiose in light of sub-ss (3)(c) and (d). Subsection (6) then creates a right of recovery by WorkSafe or an employer against a person who has received compensation.

33 Pausing there, if the Commonwealth is not to be regarded as a place outside Victoria, the consequence of sub-s (3) is that a person may commence a proceeding under Commonwealth law seeking compensation and, at the same time, seek and receive compensation under the ACA. This is because the bar in sub-s (3)(e) would not apply even though the suit under Commonwealth law was pending. Having received compensation, for example from WorkSafe, under the ACA the person could then obtain a judgment in the suit under Commonwealth law and there would be no right of recovery by WorkSafe out of the fruits of that judgment under sub-s (6).

34 It strikes me as highly unlikely that this is what the Victorian Parliament intended. It would mean that WorkSafe could recover the payments made by it under the ACA from the amounts of compensation recovered by a person under the law of any of the states and territories but not of the Commonwealth. Having regard to the economic imperatives which drive workers’ compensation legislation it is difficult to see why the Parliament would intend such an outcome.

35 Returning then to the ambiguity I referred to above, sub-s (3) persuades me that in s 85, the Commonwealth is a place ‘outside Victoria’ to avoid the anomalous outcome to which I have just referred. That is, the expression ‘outside Victoria’ means ‘outside to some extent’. It therefore bears the same meaning in s 85(6). This was also the conclusion reached by the Victorian Supreme Court in Victorian WorkCover Authority v Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd [2013] VSC 720; 283 FLR 242 at [87]-[89] and [91] per Bell J. Although my reasoning differs to an extent from that of Bell J’s, the result is the same.

36 Returning then to the decision of the Independent Counsel, he reached this conclusion at [573]:

The purpose the s 85 of the ACA is reasonably clear. The section applies in the situation where a worker is injured in a place outside Victoria in circumstances that, had the worker been injured in Victoria, would have entitled the worker to damages under the ACA. The nature of Mrs Davidson’s clearly does not fall within the ambit of the operation of s 85 of the ACA.

37 In light of the foregoing, this was erroneous. Section 85(6) is not concerned with where the injury physically takes place. It is concerned with the location of the legal system under which the compensation is sought.

38 However, the Respondents submitted that the conclusion that s 85(6) did not apply to Ms Davidson was nevertheless correct even if the Commonwealth were ‘outside Victoria’. There were three steps in the submission. First, they drew attention to s 85(1) which specifies when s 85 applies. In particular they noted that the injury referred to had to be an injury which could give rise to a claim for compensation under the ACA. Although the word ‘otherwise’ in sub-s (1) is problematic inasmuch as it assumes that compensation under the ACA would not be available where a person has a right of action under the law of a place outside Victoria, I am prepared to assume, as the Respondents suggest, that the provision should be read as if that word was not there.

39 Secondly, they observed that the injury being discussed was necessarily the injury suffered by Ms Davidson on the implantation of the prosthesis in 2008, not her initial fall at work in February 2001. I accept this. Ms Davidson’s claim is about the loss caused to her by the implantation of the prosthesis which arose under the laws of the Commonwealth.

40 Thirdly, it was then submitted that the implantation of the prosthesis could not have given rise to a right to compensation under the ACA because she did not suffer the injury in her capacity as a worker. I reject this submission. The ACA has at all times permitted a person to recover compensation for an injury which arises out of or in the course of their employment. At the time of Ms Davidson’s initial fall, s 82(1) provided:

If there is caused to a worker an injury arising out of or in the course of any employment and if the worker’s employment was a significant contributing factor the worker shall be entitled to compensation in accordance with this Act.

41 Subsequently, the Accident Compensation and Transport Accident Acts (Amendment) Act 2003 (Vic) amended s 82(1) of the ACA to remove the requirement that the person’s employment should also be a significant contributing factor to the injury. The current form of s 82(1) reads in these terms:

If there is caused to a worker an injury arising out of or in the course of any employment, the worker shall be entitled to compensation in accordance with this Act.

42 In Ms Davidson’s case, I do not think that these provisions operate differently. If Ms Davidson had not suffered her workplace injury, she would never have had the knee replacement surgery nor, therefore, the implantation of the prosthesis. Under either provision, the question which arises is therefore whether the injury constituted by the implantation of the prosthesis is one which may be said to arise out of or in the course of her employment. In any event, the Respondents did not submit that Ms Davidson was not entitled to workers’ compensation for the implantation of the prosthesis and it is abundantly apparent that WorkSafe has always accepted that she is.

43 The submission that the injury was not suffered by Ms Davidson in her capacity as a worker does not therefore align with the statutory language. The correct question is whether the injury was suffered ‘in the course of any employment’. That concept is explicated at length in s 83 which is a deeming provision. The current form of s 83(1)(d) (which remains the same as the 2001 version) provides:

(1) An injury to a worker is deemed to arise out of or in the course of employment for the purposes of section 82(1) and 82(2) if the injury occurs—

…

(d) while the worker is in attendance at any place for the purpose of obtaining a medical certificate, receiving medical, surgical or hospital advice, attention or treatment, receiving a personal and household service or an occupational rehabilitation service or receiving a payment of compensation in connection with any injury for which the worker is entitled to receive compensation or for the purpose of submitting to a medical examination required by or under this Act.

44 The injury constituted by the implantation of the prosthesis took place in a hospital in Victoria while obtaining surgical treatment. The surgical treatment took place in connection with Ms Davidson’s original fall. The original fall was an injury for which she was entitled to receive compensation under the ACA. The effect of s 83(1)(d) is therefore that the implantation of the prosthesis is taken to be an injury which arose in the course of her employment. When fed back into s 82(1), this conclusion inevitably entails that Ms Davidson was entitled to workers’ compensation for the injury suffered as a result of the implantation of the prosthesis.

45 The Respondents submitted that the opposite conclusion should be reached because of the New South Wales Court of Appeal’s decision in Hood Constructions Pty Ltd v Nicholas (1987) 9 NSWLR 60 (‘Hood’). That case was concerned with a provision dealing with the situation where the worker’s injury gave rise to a right to workers’ compensation against one person and some other legal liability in a second person. It permitted the worker to sue both persons but prevented them from keeping both the workers’ compensation and any damages awarded. The appeal was concerned with a situation not unlike Ms Davidson’s. The worker was injured at work and as part of his treatment for that injury was injected with a substance which gave him chemical meningitis. The question in the appeal was whether the second injury was caught by this provision so that worker was barred from recovering both workers’ compensation and damages. It was held that he was not.

46 The provision was s 64(1)(a) of the then Workers’ Compensation Act 1926 (NSW):

(1) Where the injury for which compensation is payable under this Act was caused under circumstances creating a legal liability in some person other than the employer to pay damages in respect thereof —

(a) the worker may take proceedings both against that person to recover damages and against any person liable to pay compensation under this Act for such compensation, but shall not be entitled to retain both damages and compensation.

If the worker recovers firstly compensation and secondly such damages he shall be liable to repay to his employer out of such damages the amount of compensation which the employer has paid in respect of the worker’s injury under this Act, and the worker shall not be entitled to any further compensation.

47 The conclusion was that the reference to ‘the injury for which the compensation is payable’ was a reference to the first injury rather than the second and that this was so even though the worker could recover workers’ compensation for the second injury. Each member of the Court of Appeal thought it necessary to identify ‘the injury’ for which compensation was payable and each thought that it was the initial injury and not the subsequent maiming at the hands of the doctor: see, eg, Hood at 68 per Hope JA, 76 per Mahoney JA, and 79 per Priestley JA.

48 However, s 85(1) of the ACA does not operate by reference to the concept of the ‘the injury for which compensation is payable’ and this reasoning is not apposite. Rather, its criterion of operation is ‘an injury’ in respect of which compensation is payable. Since the reasoning of the Court of Appeal turned on the words ‘the injury’ and s 85(1) uses the language ‘an injury’, I do not accept that Hood assists the Respondents.

49 Accordingly, I do not accept the Respondents’ submission that s 85 does not apply to Ms Davidson’s situation. For completeness, I should note that the Respondents also submitted that a similar approach should be taken for s 85(6) itself. Here the point was that the injury referred to in s 85(6)(a) had to be the same injury as referred to in s 85(6)(b). I accept this but I do not accept the Respondents’ submission that the injury constituted by the implantation of the prosthesis was not an injury falling within s 85(6)(a) for the reasons I have already given; in short, it was an injury for which compensation was payable under the ACA.

50 Returning to the Independent Counsel’s decision that s 85(6) did not apply because the injury was suffered in Victoria, this remains erroneous in result. That is to say, I do not accept that ss 85(1) or 85(6) provide an alternative route to the same conclusion reached by the Independent Counsel, untarnished by legal error.

51 I would therefore uphold the first error.

The Error Alleged By the Respondents

52 Ms Davidson’s claim, in its final form, was that she was entitled to compensation under cl 5.4 of the Compensation Protocol by reason of her liability under s 85(6) of the ACA. Clause 5.4 provides:

The Respondents will pay reasonable out-of-pocket expenses incurred and/or paid and/or to be paid by an Eligible Group Member or by a Third Party on behalf of an Eligible Group Member.

53 In relation to cl 5.4, the Independent Counsel reached these conclusions at [569]-[571]:

569. The first point to make is that the Compensation Protocol is an agreement between Mrs Davidson and DePuy. The Compensation Protocol cannot be interpreted in a way which subverts or interferes with the operation of the relevant substantive law. The Compensation Protocol must be read subject to the substantive law. The substantive law must prevail.

570. The relevant clauses of the Compensation Protocol contemplate circumstances in which there is an obligation on an Eligible Group Member to repay amounts received from a third party to that third party. As DePuy has recognised in its supplementary submissions, one such obligation arises under the Health and Other Services (Compensation) Act 1995 (Cth) to repay payments made by Medicare. That recognition is given effect to by DePuy’s acceptance of the claim made by Mrs Davidson in relation to payments made to her by Medicare payments.

571. I agree with the submissions of DePuy that in accordance with the relevant substantive law, Mrs Davidson does not presently have, and will not have in the future, an obligation to repay workers compensation payments made to her by WorkSafe Victoria. This is addressed in more detail below. In the circumstances, cl 5.3 and 5.4 of the Compensation Protocol have no application in relation workers compensation payments received by Mrs Davidson.

54 The reasoning here appears to be: (a) cl 5.4 cannot override statute law; (b) cl 5.4 could be enlivened where, for example, Medicare benefits were paid; and (c) Ms Davidson had no obligation, and will not have an obligation, to repay WorkSafe under s 85(6) of the ACA. There may be, I think, an unarticulated step between (b) and (c) to the effect that cl 5.4 only applies where the eligible group member has a legal liability. It is possible to read [570] as reaching towards that conclusion without quite stating it. However, it must be the case that the Independent Counsel reasoned this way because [571] proceeds on the basis that cl 5.4 was not satisfied because Ms Davidson did not have a present or future obligation to repay WorkSafe.

55 In this Court, the Respondents challenged this reasoning disputing the conclusion that cl 5.4 could be enlivened merely by the existence of an obligation to repay. Instead, they submitted that cl 5.4 should be construed so that it was enlivened only where it was shown that the third party was seeking to recover the out of pocket expenses from the eligible group member. Alternatively, they contended for an implied term to the same effect.

56 It is necessary to begin with two observations about cls 5.1-5.4. First, there is no dispute that WorkSafe is a third party within the meaning of cl 5.3. Secondly, cls 5.1 and 5.2 are explicit that only losses actually suffered by an eligible group member may be recovered. However, cl 5.4 is not subject to such a limitation. Literally, it permits an eligible group member to recover from the Respondents payments which have been made by a third party on their behalf regardless of whether the eligible group member has any legal obligation to the third party to repay those payments.

57 The Respondents submit that cl 5.4 should not be construed literally and that recovery under it should not be permitted unless the eligible group member demonstrates that the third party is seeking to recover the out of pocket expenses from the eligible group member.

58 The Respondents advanced three reasons why cl 5.4 should be read in this way. First, cls 5.1 and 5.2 laid out the general principle on which compensation was to be paid. This principle was that compensation was to be paid for losses suffered. Clause 5.4 was to be understood as a subordinate statement about liability to pay financial losses and as such is subject to that principle. To the extent that cl 5.4 appeared to transgress the principle stated in cls 5.1 and 5.2 it was to be read down.

59 Secondly, it was submitted that if construed literally, cl 5.4 would operate so as to permit an eligible group member to recover compensation twice. If a third party paid an out of pocket expense on behalf of an eligible group member but had no legal right to recoup the repayment out of any moneys paid by the Respondents for those out of pocket expenses, then the eligible group member would be enriched rather than compensated. This was because the eligible group member would retain the benefit of having had the out of pocket expense paid by the third party and would at the same time receive an amount of money for the same expenses from the Respondents. It was submitted that this was an example of double recovery and that a contract ought to be construed so as to avoid double recovery where possible.

60 Thirdly, it was submitted in the alternative that there was an implied term by law in the Compensation Protocol to the effect that a claim could only be made under cl 5.4 if an eligible group member established that the third party was going to recover the out of pocket expenses from him or her: T24.29-31.

61 In relation to the first and second submissions, I accept that an eligible group member cannot recover from the Respondents out of pocket expenses paid on his or her behalf by a third party unless the eligible group member is subject to a legal liability to repay those expenses to the third party in the event of receiving compensation for them from the Respondents. However, I would not go so far as to say, as the Respondents do, that recovery under cl 5.4 is not possible unless the eligible group member proves that the third party is in fact going to recover the out of pocket expenses from the eligible group member.

62 Clause 5.4 is part of a section of the Compensation Protocol which is evidently intended to provide compensation for financial losses flowing from the implantation of a prosthesis in an eligible group member. I do not read cl 5.4 as departing from the principle that what an eligible group member is to be compensated for is loss suffered. Thus whilst cl 5.4 literally permits payment of an out of pocket expense which has been paid for by a third party where the third party has no corresponding right of recoupment from the eligible group member, I do not accept that cl 5.4 is so broad. Properly construed cl 5.4 only permits recovery of out of pocket expenses paid on behalf of an eligible group member by a third party where the third party has a legal entitlement to recoup those payments out of any compensation for those amounts paid by the Respondents to the eligible group member. I read cl 5.4 this way because it is subordinate to the general principle stated in cls 5.1 and 5.2 and is to be read subject to that principle.

63 But neither the principle that only losses may be recovered nor a constructional aversion to double compensation requires acceptance of the more ambitious submission advanced by the Respondents that cl 5.4 is only enlivened if the third party is in fact going to recover the out of pocket expenses from the eligible group member.

64 As to the necessity for there to be loss, there is no doubt that the incurring of a liability to repay a third party, such as WorkSafe, is a species of loss. The Respondents, however, submit that Ms Davidson has no liability to WorkSafe until it seeks to recover the amounts of compensation it has paid. I do not accept this submission. Section 85(6) confers on WorkSafe an entitlement to recover from Ms Davidson the amount of compensation paid. In contribution statutes, an entitlement to recover compensation from another person has long been held to accrue on the event which enlivens the entitlement to contribution (cf. when the entitlement is actually sought by the claimant). For example, s 5(1)(c) of the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1946 (NSW) provides:

5 Proceedings against and contribution between joint and several tort-feasors

(1) Where damage is suffered by any person as a result of a tort (whether a crime or not):

…

(c) any tort-feasor liable in respect of that damage may recover contribution from any other tort-feasor who is, or would if sued have been, liable in respect of the same damage, whether as a joint tort-feasor or otherwise, so, however, that no person shall be entitled to recover contribution under this section from any person entitled to be indemnified by that person in respect of the liability in respect of which the contribution is sought.

65 The right created by s 5(1)(c) on its enlivenment is an entitlement in the tortfeasor to recover contribution from another tortfeasor. The language used is ‘may recover contribution from any other tort-feasor’. It has been held in relation to s 5(1)(c) that the cause of action created by it accrues for limitation purposes only when the judgment is given against the first tortfeasor seeking contribution: James Hardie & Co Pty Ltd v Seltsam Pty Ltd [1998] HCA 78; 196 CLR 53 at [30] (‘James Hardie’). This does not seem relevantly different to s 85(6).

66 Under s 85(6), the event which will trigger WorkSafe’s entitlement to recoup compensation it paid on Ms Davidson’s behalf is the settlement of Ms Davidson’s claim against the Respondents under Commonwealth law (i.e. s 85(6)(b)), where the settlement relates to injuries for which compensation has been paid under the ACA.

67 The concept of ‘settlement’ in this context requires some explanation. As I have explained above, the class action was settled on the terms of the Deed approved by this Court under s 33V(1) of the FCA Act. However, the terms of the Deed did not, at that time, settle Ms Davidson’s claims the subject of this proceeding for further steps were yet required to be taken before an amount of compensation could be calculated. In Ms Davidson’s case, those steps have included the activation of the Independent Counsel process. Once the Independent Counsel produces a figure for compensation under the terms of the Compensation Protocol and makes a decision, it is at that legal moment that Ms Davidson’s claim will have been settled within the meaning of s 85(6)(b) for it is only at that moment that the elaborate contractual machinery of the Deed will result in an obligation in the Respondents to pay Ms Davidson a compensation figure.

68 Since the implantation of the prosthesis was an injury for which compensation was paid to her, it follows that at the moment the Independent Counsel determines Ms Davidson’s claim against the Respondents, the right of recoupment in WorkSafe will arise.

69 Applying the reasoning in James Hardie, it follows that at the moment the Independent Counsel made his decision, and not before, WorkSafe possessed a cause of action against Ms Davidson and she had a corresponding liability. The existence of this liability in no way depends on WorkSafe making a demand. In fact, because the liability is for a liquidated sum it constitutes a debt. As Mellish LJ observed in Ex parte Kemp; In Re Fastnedge (1874) LR 9 Ch App 383 at 387, subject to context, a debt prima facie ‘would include all sums certain which any person is legally liable to pay, whether such sums had become actually payable or not’: see also Clyne v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1981) 150 CLR 1 at 15 per Mason J; Coles Myer Finance Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1993) 176 CLR 640 at 679 per McHugh J.

70 As a footnote to the question of whether Ms Davidson has a liability to WorkSafe, it useful to observe a timing problem which potentially exists. It is implicit in the preceding analysis that Ms Davidson’s liability arises at the moment that the Independent Counsel determines that she is entitled to compensation for the implantation of the prosthesis. It may legitimately be questioned how, immediately before that determination, the Independent Counsel could determine that she was entitled to be compensated for that liability since, by definition, the liability could only come into existence at the moment of the decision.

71 The answer to this conundrum, in my view, is that the Independent Counsel is entitled, in determining the quantum of the Respondents’ liability to Ms Davidson, to take into account the fact that his act in determining her claim will, at the moment of determination, result in the creation in her of a liability to WorkSafe under s 85(6). As a matter of formality, although his reasons are prepared in the form of a draft, it is the formal making of the decision in her favour which constitutes the settlement for the purposes of s 85(6). That being so, there can be no objection if the draft decision includes an element compensating her for a loss which will only be suffered when the decision is delivered. This does not involve the Independent Counsel awarding compensation for loss which will only be suffered in the future. Rather, it involves the determination of the compensation taking into account the legal impact the decision immediately has under s 85(6).

72 As to double compensation, no double compensation occurs where an eligible group member is awarded compensation from the Respondents for out of pocket expenses paid by a third party where a group member incurs simultaneously a liability to repay to the third party. The entitlement to compensation is a credit in the eligible group member’s balance sheet and the liability to the third party is an unsatisfied liability appearing as a debit. There is no double compensation in such a state of affairs.

73 It is true that if subsequently it becomes clear that the third party is not going to enforce the currently existing liability, then double compensation will occur. This, however, is not a function of the fact that the Respondents have paid the compensation. Rather, it is a consequence of the workers’ compensation entity deciding not to collect its debts.

74 I therefore do not accept that cl 5.4 should be construed in the manner suggested by the Respondents.

75 I also do not accept the alternative submission that there exists an implied term that achieves the same outcome as the Respondents’ construction. As I would construe cl 5.4 it is sufficient for the eligible group member to come under a legal liability to refund the out of pocket expenses to the third party. The implied term goes somewhat further and would require the group member to establish that the third party is, as a matter of fact, going to recover the out of pocket expenses from them. The Respondents submitted that such a term would be implied by law, satisfying the five conditions set out by the Privy Council in BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings (1977) 180 CLR 266 at 283 and adopted by the High Court in Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority of New South Wales (1982) 149 CLR 337 at 347 per Mason J. These are:

(1) it must be reasonable and equitable;

(2) it must be necessary to give business efficacy to the contract, so that no term will be implied if the contract is effective without it;

(3) it must be so obvious that ‘it goes without saying’;

(4) it must be capable of clear expression; and

(5) it must not contradict any express term of the contract.

76 I do not accept that the proposed term is so obvious that it goes without saying. The problem at hand is the fact that the mere existence of a liability to the third party does not necessarily entail that the third party is going to enforce that liability. It may be readily enough imagined that in some circumstances the liability may not be enforced. One situation where this would be so would arise where an eligible group member did not inform the third party that he or she had received compensation from the Respondents for the out of pocket expenses paid by the third party. In that situation it may be inferred that the third party would not seek to enforce the liability because it would be unaware of its existence. Another such situation would arise where the third party overlooked the existence of the liability through administrative misadventure.

77 These occurrences are matters which could, no doubt, happen but since they concern events which necessarily post-date the decision of the Independent Counsel under the Compensation Protocol, proof of them would involve proof of future events. The question which arises is therefore who should have to prove what. Under the Respondents’ proposed implied term it would be the eligible group member who would be required to prove that the third party was going to seek to enforce the liability. But the problem could equally be addressed by requiring the Respondents to prove that the third party would not seek to enforce the liability. Either approach would solve the problem.

78 Credible arguments may be made in support of both solutions. For example, it is the eligible group member who may be seen as being required to prove the existence of his or her loss. So viewed, resort to ordinary concepts of trial procedure might suggest that it should be the eligible group member who needs to prove that the third party is going to seek recovery. No doubt, it is that sentiment which underpins the Respondents’ position in this litigation.

79 On the other hand, ordinary trial procedure might also suggest that the eligible group member in fact proves loss on the demonstration of the existence of the liability. On this view, it would be an affirmative matter of defence for the Respondents to prove that the liability established by the eligible group member had a book value of $0 by demonstrating that the third party was not going to seek to enforce it.

80 Both of these approaches are conceivable responses to the problem thrown up by the possibility that a third party may not enforce a recoupment entitlement which it has. For myself, the latter is more plausible than the former since the existence of the liability is undoubtedly a species of loss. However, even if one approach seems more probable than the other, the fact that there are two such views means that it is impossible to say that either is so obvious that it goes without saying. It follows that the term suggested by the Respondents is not one which would by implied by law.

81 I therefore reject the Respondents’ submissions about the operation of cl 5.4.

Should the Independent Counsel have dealt with the section 85(6) claim at all?

82 The Respondents next submitted that the Independent Counsel ought not to have embarked on a consideration of Ms Davidson’s contentions about s 85(6) because she had not relied upon it in her initial claim.

83 There is no dispute that Ms Davidson did not raise s 85(6) until the delivery of her supplementary submissions contained in the body of an email that post-dated the exchange of submissions before the Independent Counsel. In her submissions in chief, she had indicated that she relied upon s 138 of the ACA as the source of her obligation to repay WorkSafe. Without wasting time on s 138, it is clear that this could not be correct, which was pointed out by the Respondents in their submissions in response. In response, Ms Davidson’s solicitors then flagged reliance upon s 85(6) in an email dated 15 February 2022. The Respondents replied by an email dated 17 February 2022 by which they submitted, amongst other things, that the claim was not appropriate for determination by the Independent Counsel because it had not gone through the initial claim process under cl 6 of the Compensation Protocol which had denied them the opportunity of seeking particulars, information or documents from Ms Davidson and third parties.

84 As will be clear from the discussion of s 85(6) above, the Independent Counsel resolved the matter by concluding that s 85(6) had no application to Ms Davidson’s situation since the implantation of the prosthesis had occurred in Victoria. He therefore decided there was no need to resolve this submission of the Respondents although he did indicate at [582] that had it been necessary, he would have concluded that the claim for workers’ compensation payments ‘should appropriately have been raised and addressed in accordance with cl 6 of the Compensation Protocol’.

85 The relevant clauses of the Compensation Protocol are cls 6.2, 6.4 and 6.5:

6.2 Within three months of receiving notification in accordance with clause 6.1, the Eligible Group Member's lawyer will provide the following information and documents (Claim Documents) to NRA in so far as they are relevant:

(a) particulars of any lost income, sick leave, other leave, superannuation or other economic loss claimed and documents in support of such a claim;

(b) particulars of out-of-pocket expenses and documents in support of such a claim;

(c) particulars of the cost of any care or services, other than Gratuitous Care, and documents in support of any claim for the cost of such care;

(d) any relevant Notice of Charge under the Health & Other Services (Compensation) Act 1995 (Cth);

(e) any relevant notice served by Centrelink, workers compensation authority or insurer or other government department or related entity;

(f) any other relevant documents in support of the Eligible Group Member’s claim.

…

6.4 If the Claim Documents submitted by the Eligible Group Member are considered by the Respondents to be insufficient to enable an assessment of the Eligible Group Member’s claim, within one month of receiving the Claim Documents the Respondents will request clarification of the Claim Documents and/or seek further particulars from the Group Member’s lawyer and the Group Member's lawyer will endeavour to provide clarification and/or particulars.

6.5 If, after receiving clarification and/or particulars from the Eligible Group Member’s lawyer pursuant to clause 6.4, the Respondents maintain that the Claim Documents are insufficient to enable an assessment of the Eligible Group Member’s claim:

(a) the Respondents:

(i) may, within one month, request documents or particulars from a third party and the Eligible Group Member will provide any authorities to the Respondents that are necessary to facilitate such requests; and if so

(ii) will request that the documents first be sent to the Eligible Group Member’s lawyer, who will have five days from the date of receipt to notify the Respondents of any claim for legal professional privilege and who will otherwise forward the documents (other than the privileged documents) to the Respondents; and

(b) the Eligible Group Member may make a notification under clause 3.4(a) despite any earlier determination about the Category that is applicable to the Eligible Group Member; and

(c) within one month of the Eligible Group Member’s Claim Documents being finalised in accordance with clauses 6.2, 6.3, 6.4 or 6.5(a) (as applicable), the Respondents may request the Eligible Group Member to attend any reasonable medical examination/s:

(i) the Respondents will arrange for the examination/s to occur as soon as possible but in any event within six months of the request made to the Eligible Group Member;

(ii) the Eligible Group Member must attend the examination/s and the Eligible Group Member’s failure to do so without good reason will result in the Eligible Group Member’s claim being suspended until such time as they agree to attend the examination/s; and

(iii) any report obtained by the Respondents as a result of such examination/s is to be provided to the Eligible Group Member’s lawyer as soon as is practicable after receipt by the Respondents or either one of them.

86 It will be seen that cl 6.2 permits the making of the claim and requires particulars thereof to be provided and supporting documentation. Clause 6.4 allows the Respondents to seek further particulars of the claim, and cl 6.5 permits them thereafter to request documents from third parties.

87 On 1 December 2017, Ms Davidson by her solicitors made a claim under cl 6.2 by a letter bearing that date. The claim was voluminous running to many thousands of pages and dealt with many topics. The documents were divided in 19 categories. Category 18 was entitled ‘Annotated Allianz statement of benefits’. The covering letter accompanying the claim documents said under the heading ‘5. Workers’ Compensation Insurer’:

All items marked on the enclosed Allianz statement of benefits appear to relate to the failure of Mrs Davidson’s Affected Implant. Please review the statement of benefits and advise us whether the Respondent’s dispute liability for any marked items.

88 Attached to the claim letter was another document headed ‘Summary of Claim’: CB 113. Under the heading ‘Other Third Party Repayment’ (CB 116) it was said that Ms Davidson had an obligation to reimburse Allianz (i.e. the authorised agent of WorkSafe) in the amount of $96,234.21. The nature of this obligation was not identified. Also attached to the letter was a table of non-compensation payments made by WorkSafe (‘the 2017 Table’): CB 1131. This was the complete list of third party payments that WorkSafe had paid on Ms Davidson’s behalf from 21 May 2008 to 13 April 2017. The list is long. A tick has been placed next to the payments for which Ms Davidson was making a claim.

89 I was not taken to any aspect of this initial claim which included a reference on Ms Davidson’s part to liability to WorkSafe under s 85(6). I therefore accept the Respondents’ submission that Ms Davidson did not raise the operation of s 85(6) in her claim documents.

90 Returning to cl 6.2, it will be seen that she had agreed to provide the Respondents with particulars of out of pocket expenses and documents in support of such a claim (sub-cl (b)). In her claim, Ms Davidson did not particularise the above WorkSafe expenses now sought as ‘out of pocket expenses’. She did make a claim for out of pocket expenses (CB 115) but this was limited to an amount of $1,576.18 in respect of various medications (CB 118-119) and $1,720.07 for some other expenses relating to travel: CB 132-133. In her claim summary she also made claims for other financial losses such as past gratuitous care and a claim for some future out of pocket expenses but none of these included a claim that the payments made by WorkSafe were out of pocket expenses.

91 As I have explained, as a matter of construction the payments made by WorkSafe were, in fact, out of pocket expenses within the meaning of cl 5.4 and should have been particularised as such in the claim document. Instead, they appear to have been provided as ‘other relevant documents’ under cl 6.2(f).

92 The correct position is therefore this: a claim for compensation for the payments made by WorkSafe was a claim for out of pocket expenses within the meaning of cl 5.4. In her claim to the Respondents, Ms Davidson should have included these payments as a claim for out of pocket expenses. She was required to provide particulars of that claim by cl 6.2(b). Had the claim been particularised, she ought to have indicated at least that they were payments which had been made on her behalf by WorkSafe and she ought to have provided the documents on which this claim was based. However, these matters were disclosed in the claim albeit under the wrong heading. The Respondents do not suggest that they were prejudiced by the fact that the WorkSafe payments were disclosed to them under cl 6.2(f) rather than under cl 6.2(b). In any event, such a submission would have been untenable.

93 It is debatable whether Ms Davidson’s obligation to provide particulars under cl 6.2(b) of the out of pocket expenses extended to informing the Respondents that her liability to repay these expenses would arise from the operation of s 85(6). Making the assumption that this is a matter which ought to have been particularised, it also follows that it was a matter of which the Respondents could subsequently have sought particulars under cl 6.4. I was not taken to any evidence of a request for such a particular.

94 However, it is clear that the Respondents did seek particulars of the claim in relation to the WorkSafe out of pocket expenses. This is known because on 28 August 2020, Ms Davidson’s solicitors provided particulars of them by email: CB 2178. I was not taken by either party to the request to which this email is a response. The Court Book is 5,502 pages long and I have not been able to locate it myself. The email was as follows:

Dear Carly,

Mrs Davidson was not under an obligation to provide particulars of her worker’s compensation claim in her claim documents.

The payments relate to her workplace injury on 4 February 2001.

The weekly benefits/settlements totalling $97,545.20 were paid to Mrs Davidson when she was unable to work between approximately February 2001 – September 2003.

The medical & like ($131,271.05), hospital ($80,704.10) and rehabilitation ($8,221.83) expenses all relate to medical and allied services treatments which have been ongoing since her initial workplace injury.

The claimant expenses ($6,514.49) relate to medications and travel costs which have been ongoing since her workplace injury.

The pain and suffering ($400,000) compensation was paid to Mrs Davidson in lump sum on approximately 24 July 2007.

As set out above, since the settlement of Mrs Davidson’s worker’s compensation claim she has continued to receive ongoing medical benefits (including claimant expenses) from her worker’s compensation insurer. She has not been entitled to any other ongoing benefits.

As previously advised, Mrs Davidson’s worker’s compensation insurer is seeking reimbursement of medical benefits incurred as a result of the failure of her affected implant.

We look forward to receiving an offer pursuant to clause 6.6 of the Compensation Protocol as soon as is practicable.

Kind regards,

Katherine McCallum

95 I infer from this email that it was sent in response to a request under cl 6.4. The email makes clear that WorkSafe was seeking reimbursement and that Ms Davidson was claiming an entitlement to have the out of pocket expenses paid by the Respondents. I was not taken to any further correspondence following this email.

96 The procedural prejudice to which the Respondents now point is that they have been denied the opportunity to seek particulars or documents from WorkSafe under cl 6.5(a)(i) because s 85(6) was only raised before the Independent Counsel. I do not accept this submission. The Respondents knew from 28 August 2020 that Ms Davidson was claiming that WorkSafe was seeking recovery of the payments it had made. At that point, they could have asked Ms Davidson to provide evidence in support of that contention but I was not taken to any evidence that they did. They did not need to know anything about s 85(6) to make that request. They could also have enlivened the process in cl 6.5(1)(a) and requested from WorkSafe any information or documents about that matter. I was not taken to any evidence that they did that either.

97 Once that is appreciated, it becomes apparent that the suggested lost opportunity to request information or documents from WorkSafe is a self-inflicted wound. I therefore do not accept that the Respondents have suffered any procedural prejudice by reason of this aspect of the matter.

98 This is not the end of the issue, however. It then becomes necessary to identify why this situation might have meant that the Independent Counsel ought not to have to have proceeded to consider the s 85(6) question. Neither before the Independent Counsel nor this Court did the Respondents identify a legal basis for why the Independent Counsel ought not to have considered the s 85(6) question. For example, it was not put that the Independent Counsel’s jurisdiction was strictly limited to the claim which was initially made. Had such an argument been put it would have made the question of whether the Respondents were prejudiced irrelevant.

99 I do not accept, and it was not put, that the provisions of the Compensation Protocol delimited the jurisdiction of the Independent Counsel only to arguments which were made in the initial claim. Rather, under cl 10.6(d) his jurisdiction was put in these terms:

Independent Counsel will make a determination concerning any items in dispute and will provide a written assessment to the Eligible Group Member’s lawyer and NRA within one month of receiving the Eligible Group Member’s Claim Documents.

100 This demonstrates that as long as an item of the claim was in dispute, the jurisdiction of the Independent Counsel with respect to the claim was at large. Nor do I accept that the inability now for the Respondents to seek documents or information from WorkSafe under cl 6.5(a)(i) is indicative that the Independent Counsel had no jurisdiction. A more conventional interpretation would be that the Respondents are living with the consequence of their own failure to pin Ms Davidson down by asking her for particulars of the email of 28 August 2020.

101 On the other hand, if the Respondents’ contention is not to be seen as a jurisdictional argument but rather as some species of procedural entitlement, it becomes necessary to identify what that entitlement might be. I do not think that it can be said that Ms Davidson waived her entitlement to rely upon s 85(6) by not relying upon it in her initial claim for she was not at that time confronted by a choice between inconsistent legal paths between which she was bound to choose. Clause 6.2 required only of her that she identify the out of pocket expenses together with particulars and relevant documentation. Even assuming she should have mentioned s 85(6) as a particular, I do not think that it could be said that by not doing so she had waived any entitlement to rely upon it. Ordinarily, where a particular is not provided the allegation which it supports remains at large. I do not see why it would be any different under cl 6.2 especially where cl 6.4 gave the Respondents an orthodox right to seek further particulars. More is this so where Ms Davidson actively signalled on 28 August 2020 that WorkSafe was seeking reimbursement.

102 Nor do I accept that it can be said that by saying nothing about s 85(6) she had, in some way, elected not to rely upon it. Were that so, it would entail that she had elected to abandon the claim for the out of pocket expenses. However, one matter which is clear is that she was plainly pursuing an entitlement to recover the WorkSafe out of pocket expenses from the Respondents.

103 That leaves the possibility of an estoppel by representation. There are, however, two problems with such an estoppel. The first is that Ms Davidson did not make any representation in her initial claim about the legal basis of her liability to WorkSafe. The second is that even if she had made such a representation, I do not think that the Respondents can demonstrate that they relied upon the representation to their prejudice. The cause of their inability to make a request of WorkSafe under cl 6.5(1)(a) was their own failure to do so after receipt of the email of 28 August 2020.

104 For those reasons, I do not accept that the Independent Counsel could have rejected Ms Davidson’s claim under s 85(6) on the basis that she had not mentioned it in her initial claim. I do not think that the Independent Counsel in fact formed a view on this topic although I do accept that he indicated that if it mattered he thought that Ms Davidson should have raised the matter in her initial claim. I do not read that statement as a determination of this issue. As such, the Respondents’ submission needs to take the form of a contention that the Independent Counsel erred in law in not concluding that Ms Davidson was not permitted to raise s 85(6) before him. In that form, I reject the submission for the reasons I have given. Alternatively, if the statement at [582] is in fact a finding that Ms Davidson was not permitted to rely upon s 85(6) then, in my view, the statement discloses an error of law for the same reasons. In either case, the Respondents’ submission about this matter in this Court does not succeed. The Independent Counsel was obliged to deal with Ms Davidson’s contentions about s 85(6).

Did Ms Davidson fail to prove that the out of pocket expenses claimed were causally linked to the implantation of the prosthesis?

105 On 30 November 2021, Ms Davidson’s solicitors forwarded to the Independent Counsel her initial claim and a copy of the Compensation Protocol (as was required by the terms of the Compensation Protocol). Amongst the documentation provided by the solicitors to the Independent Counsel was the 2017 Table, sent as part of Ms Davidson’s claim to the Respondents, setting out all of the payments which WorkSafe had made on Ms Davidson’s behalf. As I have explained above at [88], she did not seek to recover all of these. The solicitors for Ms Davidson had annotated the table with ticks setting out the payments in respect of which she sought recovery.

106 It is apparent from this table that at the time of Ms Davidson’s initial claim to the Respondents in 2017, she had made a claim for recovery of an amount of $96,234.21 representing payments made on her behalf by WorkSafe which she claimed were causally connected to the implantation of the prosthesis.

107 On 21 December 2021, Ms Davidson’s solicitors then made a submission on her behalf to the Independent Counsel: CB 5216. The submission contained a section headed ‘WorkSafe Victoria’. The submission said this at [8.1]:

WorkSafe Victoria is seeking reimbursement for expenses it incurred on behalf of Mrs Davidson as a result of the failure of the Affected Implant pursuant to section 138 of the Accident Compensation Act 1985 (Vic).

108 The submission set out (as part of an attached costs report) expenses ‘incurred by WorkSafe Victoria as a consequence of the failure of the Affected Implant’ and explained by reference to seven categories what the payments related to. For example, the first category referred to a class of expenses resulting from ‘surgeries necessitated by the failure of the Affected Implant’. Although the claim made to the Respondents in the 2017 Table had been $96,234.21, by 2021, the claim had increased to $116,597.27.

109 On 4 February 2022, the Respondents put on a submission in response. The submission dealt with the position of WorkSafe in section 8. The submission made a number of points which included:

(a) A number of payments had been incurred before Ms Davidson had manifested any symptoms associated with the implantation of the prosthesis. One example was a payment of $900.44 made before there were any issues with the prosthesis.

(b) A number of payments did not have sufficient detail to allow one to identify whether there was a link with the implantation of the prosthesis. For example, there were chemist charges where it was not stated what medications had been purchased.

(c) A number of the payments were for treatments which could not be said to relate only to treatment for the issues flowing from the implantation of the prosthesis. For example, a payment of $17,830.65 in respect of Ms Davidson’s ongoing consultation with her psychologist was instanced.

(d) Ms Davidson had not discharged her evidentiary onus of proving that the payments related to the failure of the implanted prosthesis.