Federal Court of Australia

Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 10) [2023] FCA 228

ORDERS

NSD 1590 of 2012 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | KATHRYN GILL First Applicant DIANE DAWSON Second Applicant ANN SANDERS Third Applicant | |

AND: | ETHICON SÀRL First Respondent ETHICON, INC. Second Respondent JOHNSON & JOHNSON MEDICAL PTY LIMITED (ACN 000 160 403) Third Respondent | |

NSD 310 of 2021 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | LISA TALBOT Applicant | |

AND: | ETHICON SÀRL First Respondent ETHICON, INC. Second Respondent JOHNSON & JOHNSON MEDICAL PTY LIMITED (ACN 000 160 403) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 33V(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), the settlement of the proceedings between the parties on the terms set out in the settlement deed executed 10 November 2022 be approved.

2. The settlement approval in order 1 is subject to the separate and later determination of what orders should be made as are just with respect to the distribution of the money paid under the settlement pursuant to s 33V(2) of the FCA Act.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE OF REASONS

1 Before the Court are two applications pursuant to s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) for approval of a proposed settlement in the following open class representative proceedings: Gill & Ors v Ethicon Sàrl & Ors (NSD 1590 of 2012) (Gill Proceeding); and Talbot v Ethicon Sàrl & Ors (NSD 310 of 2021) (Talbot Proceeding).

2 The parties have agreed upon a sum of $300,000,000 to settle all group member claims and liabilities across both proceedings. Notwithstanding some hesitation, I have decided to approve the settlement sum, but I have not agreed to make the orders initially proposed by the applicants.

3 My usual practice with s 33V applications is to deliver judgment ex tempore or as promptly as possible, so as to give certainty to group members. I decided not to take my usual course in the circumstances of this case for four reasons.

4 First, the overall settlement sum is not, for reasons I will explain, sufficiently generous as to be self-evidently fair, given the failure of Ethicon Sàrl, Ethicon, Inc., and Johnson & Johnson Medical Pty Ltd (together, Ethicon) in their opposition to the claims advanced both at the initial trial and on appeal in the Gill Proceeding. One can readily understand a group member rationally forming the impression that this is litigation where big-pocketed respondents have taken every point (including points eventually shown to be contrary to the true position and wholly devoid of merit) and dragged out the dispute interminably, only to be rewarded at the eleventh hour by a proposed settlement which reduces Ethicon’s likely exposure – with the group members then having to discount the amount to which they are likely entitled and pick up a substantial part of the tab for costs. But, as I will explain, this view needs to be somewhat tempered upon close analysis.

5 Secondly, the settlement approval application came before the Court contemporaneously with a s 33V application in another class action in my docket, namely Debra Fowkes v Boston Scientific Corporation & Anor (NSD 244 of 2021) (Fowkes Proceeding). The Fowkes Proceeding is a class action brought against the manufacturers of pelvic “mesh” devices designed to alleviate pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). While there are important differences between the proceedings, many of the factual and legal issues overlap. In particular, the solicitors for the applicants and the Court received a large number of objections from group members in both proceedings. This partial overlap made it appropriate to deliver judgment in both matters on the same date: see Fowkes v Boston Scientific Corporation [2023] FCA 230.

6 The third reason, somewhat connected to the first, relates to complications and well-founded concerns that arose as to the distribution of money paid under the settlement.

7 The legal representatives for the applicants in both proceedings, Shine Lawyers (Shine) obtained a very substantial amount pursuant to adverse costs orders. But they also seek payment out of the proposed settlement sum on account of unpaid past cost and disbursements, including, novelly, an amount referable to interest payable on a disbursement funding facility. Given the likely scrutiny as to costs on the settlement application, I granted leave for Shine to be separately represented.

8 As it stands, notwithstanding Shine has already been paid, pursuant to existing costs orders, a sum of $41,313,575.73 (and, as I understand it, a further unspecified costs awarded upon dismissal of the special leave application), it now seeks further amounts for past costs and disbursements of $38,131,096.53 (comprising $37,459,569.29 for unrecovered fees and disbursements in the Gill Proceeding and $671,527.24 for unrecovered fees and disbursements in the Talbot Proceeding). Moreover, Shine seeks an amount of $26,030,878 to meet the interest accrued on the disbursement funding facility.

9 Needless to say, these sums are immense. I am no stranger to the reality that big litigation costs big money. But central to the Court’s duty to protect the interests of class members is judicial oversight of legal costs and disbursements. I must be satisfied that the further amount of costs proposed to be deducted from the settlement sum is a just deduction. If the costs-inclusive settlement is approved, every cent paid to the solicitors is a cent not paid to group members.

10 But past costs are not the only issue. The present proposal for settlement names two of Shine’s practice leaders as scheme administrators. This is common practice. This is despite me explaining elsewhere that the assumption that solicitors for applicants in proceedings brought under Pt IVA of the FCA Act should become scheme administrators by default is a notion which needs to be exploded: Lifeplan Australia Friendly Society Limited v S&P Global Inc (Formerly McGraw- Hill Financial, Inc) (A Company Incorporated in New York) [2018] FCA 379 (at [52]–[54]).

11 The concerns I ventilated in Lifeplan were picked up in Recommendation 9 of the Australian Law Reform Commission’s (ALRC) report Integrity, Fairness and Efficiency—An Inquiry into Class Action Proceedings and Third-Party Litigation Funders (Report 134, December 2018) (at [5.35]–[5.39]) (ALRC Report). The ALRC recommended that Pt 15 of the Class Actions Practice Note (GPN-CA) include a clause that the Court may tender settlement administration, and include processes that the Court may adopt when tendering settlement administration.

12 Here, when settlement subject to documentation and Court approval was struck on 9 September 2022, Shine made an Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) announcement pursuant to ASX Listing Rule 3.1 (which provides that once an entity is or becomes aware of information that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s securities, the entity must immediately tell the ASX that information). That announcement provided that “[s]ubject to the timing of the Court’s approval, cash is expected to be positively impacted in FY23”. Regrettably, as I explain below, this anxiety to inform the market as to the expectation of the material augmentation of revenue for Shine was not matched by an anxiety in ensuring the settlement documentation was completed quickly, thus triggering an obligation for the $300,000,000 to be paid and causing interest to accrue for the benefit of group members.

13 Shine estimated that the “[t]otal costs of administration of the settlement scheme” would be up to $36,860,750. On any view, being appointed administrator of a scheme of this scope presents a significant commercial opportunity. It seems passing strange that it should continue to be assumed that the Court would just allow such a commercial opportunity to be taken by the solicitors acting for the applicants without exploring whether there were other cheaper and better ways to distribute the settlement sum justly among group members.

14 Even though this exploration might be contrary to the interests of Shine, one would have thought at least exploring such options would have been consistent with the duties of the representative applicants to group members. But it was only over their opposition that I made orders on 21 December 2022 providing for a tender process to take place to enable consideration of alternative settlement schemes and alternative settlement administrators.

15 As I explain in separate reasons delivered at the same time as this judgment (Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 11) [2023] FCA 229), I have already seen enough to confirm my initial (wholly unremarkable view) that competition is likely to produce a better outcome for group members when it comes to price and assist in fastening upon the optimal way of distributing the funds. In any event, these issues as to past and future costs and disbursements are matters worthy of further exploration and close consideration.

16 As a result, on the final day of hearing, I bifurcated the settlement approval process, such that in the event that settlement is approved, I will determine the distribution of funds paid under the settlement at a later date. This approach is consistent with the text of s 33V. Sections 33V(1) and 33V(2) confer two distinct, but related, powers: first, to approve the settlement; and, secondly, if the approval is given, to approve the distribution of payments made under the settlement: Davis v Quintis Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) [2022] FCA 806 (at [3] per Lee J); Botsman v Bolitho [2018] VSCA 278; (2018) 57 VR 68 (at 111 [198]–[203] per Tate, Whelan and Niall JJA); Davaria Pty Ltd v 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 183; (2020) 281 FCR 501 (at 506–507 [23] per Lee J, with whom Middleton and Moshinsky JJ agreed).

17 Fourthly, and importantly, another reason for reserving was because the Court heard numerous accounts of women who have suffered and continue to suffer an array of physical, psychological and psychosocial difficulties. Certainty and closure are especially important in a case of this kind, which (remarkably) has now been on foot for over a decade, and in respect of which common liability findings have already been made (and are now beyond challenge following an unsuccessful Full Court appeal and special leave application). But it was appropriate to take some time to reflect on these accounts and satisfy myself that what is proposed is fair for those women who are group members and have suffered greatly.

18 In dealing with the settlement, these reasons are divided as follows:

B Litigation History;

C The Proposed Settlement;

D Notification and Reactions to the Proposed Settlement;

E Relevant Principles;

F Fairness and Reasonableness of the Proposed Settlement; and

G Conclusion and Orders.

B LITIGATION HISTORY

B.1 The Gill Proceeding

19 An originating application and statement of claim were filed in the Gill Proceeding over a decade ago, culminating in a complex and hard fought initial trial before Katzmann J, which commenced at the beginning of July 2017 and concluded in late February 2018.

20 At the initial trial, the applicants alleged that Ethicon:

(1) negligently failed to evaluate the implants designed to be surgically implanted in women to alleviate POP or SUI prior to their release on the market; negligently failed to conduct post-market evaluations of the products; and negligently failed to warn of the risk of complications (Negligence Claims);

(2) contravened various statutory norms which render manufacturers liable to compensate consumers in relation to products which are defective, not fit for purpose and/or not of merchantable quality (Product Liability Claims); and

(3) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in the course of marketing and supplying the implants (Misleading Conduct Claims).

21 Justice Katzmann delivered reasons in November 2019, finding that the applicants succeeded on the Negligence Claims, Product Liability Claims and Misleading Conduct Claims: Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 5) [2019] FCA 1905.

22 Ethicon appealed to the Full Court of this Court from the judgments in Gill (No 5) and Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 6) [2020] FCA 279 (concerning a contest as to the form of the common questions and injunctive relief), raising seventeen grounds of appeal: Ethicon Sàrl v Gill [2021] FCAFC 29; (2021) 288 FCR 338. The appeal was wholly unsuccessful, as was an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court: Ethicon Sàrl v Gill [2021] HCATrans 187. The lead applicants were not only successful in their individual claims, but importantly for present purposes, were also successful in securing favourable answers to common issues on behalf of group members.

B.2 The Talbot Proceeding

23 The Talbot Proceeding was commenced on 7 April 2021 to bring the same claims brought in the Gill Proceeding against Ethicon for the benefit of women who suffered a complication on or after 4 July 2017 (being the day after the cut-off date for class closure in the Gill Proceeding).

24 On 24 March 2022, I entered orders for the benefit of group members in the Talbot Proceeding who had received an implant on or before 30 June 2020, including liability findings based on the answers to common questions in the Gill Proceeding.

25 Although Ethicon acknowledges that the lead applicants in the Gill Proceeding have each established their claims against it, Ethicon does not admit that any other group member will establish their personal claim. Further, Ethicon does not admit the quantum of any damages or compensation order that any group member asserts they may obtain, and denies it is liable to pay damages to any group member in the Talbot Proceeding who had an implant after 30 June 2020.

B.3 The Reference Process

26 One aspect of the management of this case assumed prominence in the lead up to and over the course of hearing the s 33V applications. On 22 March 2022, I made orders pursuant to s 54A of the FCA Act appointing experienced senior counsel to act as a referee and report on the outcome of a limited (but hopefully representative) set of potential group member claims.

27 As I have explained in great detail elsewhere (see, in particular, Kadam v MiiResorts Group 1 Pty Ltd (No 4) [2017] FCA 1139; (2017) 252 FCR 298 (at 307–314 [35]–[63]) and CPB Contractors Pty Ltd v Celsus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 2112; (2018) 268 FCR 590 (at 597–300 [26]–[35])), references have long been adopted as a way of ensuring that discrete issues in litigation are determined with maximum efficiency. Section 54A of the FCA Act and Div 28.6 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) set out a reference regime under which the Court retains control at all stages in order to “ensure that the cost of justice remains proportionate to the relief being sought”: Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Second Reading Speech, 3 December 2008, 12296 (The Hon Robert McClelland, MP).

28 I appointed a referee to identify a set of paradigm cases for determination, in respect of which the referee would produce a report to guide the assessment of individual cases to supplement the findings of Katzmann J. My intention was to have a “master” reference report which, if adopted, would then be followed by multiple, subsequent, streamlined references to inquire into and report upon individual claims of group members.

29 Regrettably, the “master” reference process has not proceeded with the celerity I had anticipated. Despite my intention it be conducted as quickly and efficiently as possible, it was soon bogged down. For present purposes, there is no need to go into the reasons or assign blame. It suffices to note that with considerable hesitation on my part (and for reasons explained below at [39]) the reference was suspended pending the determination of the settlement approval application.

B.4 The Section 33V Application

30 The path to the proposed settlement was, as with apparently everything in this litigation, long and winding.

31 The parties to the Gill Proceeding first went to mediation in 2016, following orders made by Murphy J. A number of settlement offers were made and rejected. The initial trial went ahead and Katzmann J ordered the parties to mediate after the hearing, again to no avail. I am told that settlement negotiations and discussions recommenced in May 2020. A mediation took place and was eventually terminated on or about 22 June 2020. The Full Court delivered judgment on 5 March 2021.

32 All was quiet while Ethicon pursued its special leave application, until about February 2022, when Shine was informed that Ethicon was interested in once again trying to settle the Gill Proceeding and, by this time, the Talbot Proceeding. Negotiations took place in New York in late June and early July 2022, followed by negotiations in Sydney in August 2022. Ms Rebecca Jancauskas, a solicitor at Shine with carriage of this matter until late 2022, gave evidence that after the August negotiations, the parties “progressed the negotiations further” and, by 9 September 2022, had agreed upon a settlement subject to documentation and approval.

33 Shine wrote to my Chambers informing me of the “in-principle” settlement and requesting the Court contact the referee concerning this development. I instructed my Associate to respond stating the referee should only be consulted in the event the settlement is approved by the Court, and that I would list the matter upon the filing of the applications pursuant to s 33V of the FCA Act. The parties then sought the matter be relisted in order “to provide an update on the progress of the reference”.

34 I listed the matter for a case management hearing on the earliest possible date, which was 7 October 2022.

35 The upshot of that case management hearing was twofold.

36 First, I expressed regret at the fact that I had received no substantive details from the parties as to the proposed settlement, notwithstanding the fact that the “in-principle” agreement had been reached about a month earlier. I requested the parties send me a copy of the draft deed during the hearing or, at the very least, a copy of the heads of agreement, so that I might understand the structure of the proposed settlement: T3.17–4.28. Although initially resisted, after a brief adjournment, a copy of a draft deed was provided by the solicitors for the applicants to my Associate and to the respondent for the first time.

37 Upon an initial review of the draft deed, it was apparent that virtually nothing had been done towards preparing the deed. My investigations in the days following revealed that the draft deed provided on 7 October 2022 was, but for a few amendments, identical to the deed dated 12 July 2022 provided by the parties in the Fowkes Proceeding. Indeed, the draft deed provided to me was still dated “July 2022” and still made reference to Herbert Smith Freehills, the respondent’s solicitors in the Fowkes Proceeding.

38 Obviously enough, this was all unsatisfactory. I ordered the applicants to put on an affidavit and appear before me again on 10 October 2022 to explain the terms of the heads of agreement and the steps taken since entry into the heads of agreement to progress the completion of documentation.

39 Secondly, I acceded to an application to suspend the reference pending the determination of the foreshadowed s 33V applications, although this was not a decision I took lightly. I indicated that the continuation of the reference would give me comfort in forming a view as to whether the proposed settlement was fair and reasonable.

40 In any event, a month later, on 10 November 2022, the parties to both proceedings executed a Deed of Settlement (Settlement Deed), and the s 33V applications were set down for hearing.

B.5 Appointment of Contradictors

41 I determined to appoint experienced counsel as amici curiae to perform the role of contradictors.

42 The role of a Court-appointed contradictor is to put forward all reasonably arguable competing positions on behalf of, and for the benefit of, group members. Appointing a contradictor is not a panacea for all the nuances and difficulties of the settlement approval process. But it can be a useful tool in ensuring “both that justice is done and is seen to be done”: J Kirk SC (as his Honour then was), ‘The Case for Contradictors in Approving Class Action Settlements’ (2018) 92 Australian Law Journal 716 (at 729).

43 Two reasons informed my decision. The first was the experience of my Chambers in hearing the s 33V application in the Fowkes Proceeding, in relation to which I considered but ultimately determined not to appoint a contradictor. Both before and after hearing that application, my Associate was inundated with communications from group members. While I was happy for my staff to receive and respond to these communications, a number of practical difficulties ensued, including the need to compile and provide the responses received to the parties to avoid the risk of unfair prejudice.

44 Secondly, in this case, there were aspects of the material initially put before the Court which seemed to me to give insufficient weight to the fact the group members already had the benefit of common liability findings and assumed the counterfactual to settlement would be individualised curial hearings of group member claims in the traditional way. Additionally, there are considerable benefits to appointing a contradictor where there is a risk of a conflict: ALRC Report (at [5.27]). Shine has an obvious financial interest in the settlement being approved, and the Court’s requirement to assess the level of legal costs claimed for the work undertaken and to be undertaken was likely to be controversial: see Kelly v Willmott Forests Ltd (in liq) (No 5) [2017] FCA 689 (at [108] per Murphy J).

45 As will be seen, the work of the contradictors was commendable and served to guide the Court through voluminous statistical and other material, including representations by group members.

C THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

46 A recurring theme in the oral and written objections received by the Court was a lack of understanding of the terms of the proposed settlement by group members. My intention in this section is to step through the proposal as clearly as possible.

C.1 Settlement Sum

47 Subject to the Court’s approval, Ethicon agrees to pay $300,000,000 to settle all group member claims and liabilities in respect of both the Gill Proceeding and the Talbot Proceeding. It is proposed that the sum be held in an interest-bearing bank account to create a settlement fund.

48 It is proposed that that fund be used to pay for:

(1) the applicants’ costs to date, including solicitor/client costs (to the extent those costs have not been met by previous costs orders);

(2) disbursement liabilities, including those arising under the disbursement funding facility used to fund part of the cost of conducting the Gill Proceeding;

(3) the costs of administering the settlement scheme; and

(4) recovery amounts to third parties (for example, Medicare and private health insurers).

49 Orders were sought which would have had the effect that no payments are to be made to group members out of the settlement fund until amounts that must be reimbursed to third parties who have made payments for the benefit of the group members are paid from the settlement fund.

50 Shine estimates that recovery amounts could be in the order of $26,112,546.20. The Court was told that this figure may be lowered as Shine intends to seek to reach bulk payment arrangements with third party payers to increase the net funds available for distribution to group members.

51 When clarification was sought, it eventually became apparent that not accounting for interest accrued, if I was to approve the settlement on the terms originally proposed, and if the recovery amounts do not change, an estimated $174,433,640.30 would be left in group members’ pockets.

C.2 Releases

52 The Settlement Deed provides appropriate releases. They are no wider than the claims common to group members and there are no indemnities in favour of the respondents.

C.3 Scheme Administration

53 As noted above, it was proposed that the scheme administrators be the solicitors at Shine with carriage of the proceedings, Ms Janice Saddler and Ms Jancauskas. However, following their departure from Shine, the applicants now seek leave to appoint two other highly experienced Shine solicitors, Mr Craig Allsopp and Ms Vicky Antzoulatos.

54 Given the tender process I ordered (discussed above at [14]) there is little point in setting out the terms of the settlement scheme proposed by Shine. This will avoid confusion, in particular among group members, as to what falls to be determined at this stage.

55 One exception which should be mentioned is the proposal in the current settlement scheme to exclude claims which would likely result in a non-economic loss claim which is less than 15% of a “most extreme case”, as understood under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Competition and Consumer Act). The statute provides that a “most extreme case” is a case “in which the plaintiff suffers non-economic loss of the gravest conceivable kind”: s 87P(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act.

56 This aspect of the proposed settlement scheme is relevant to the question before the Court insofar as the calculations of funds potentially payable to group members proceed on the assumption that women who do not meet the 15% threshold will not be compensated.

D NOTIFICATION AND REACTIONS TO THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

D.1 Notification

57 Pursuant to ss 33X, 33Y and 33ZF of the FCA Act, I approved the Notice of Proposed Settlement (Notice) on 16 November 2022 for distribution to all registrants by email or post, as well as its publication on a website dedicated to the settlement, www.jjmeshclassaction.com.au, and by requesting the administrators of a number of Facebook support groups to post a link to the Notice. The approved Settlement Overview was also to be published on www.jjmeshclassaction.com.au.

58 The final form of the Notice and Settlement Overview differ considerably from the drafts provided to the Court by Shine. I was required to make considerable amendments. The first was generally to simplify and shorten the documents to make them more accessible to their intended readers. Secondly, the Notice was, regrettably, opaque in an important respect and I added an explanation of the amount actually likely to be available to group members. Both drafts stated only that Ethicon “will pay the amount of $300,000,000.00 for the purpose of a Settlement Fund being established”, omitting other crucial details. Thirdly, I provided the direct contact details of the contradictors, removing the proposal that group members send objections to Shine to be passed on to the contradictors. Relatedly, I clarified somewhat the role of the contradictors and the opportunity for group members to attend the hearing either in person or remotely.

D.2 The Reaction of the Class

59 The reaction of the class to the proposed settlement is one of many factors to be taken into account on an s 33V application: Williams v FAI Home Security Pty Ltd (No 4) [2000] FCA 1925; (2000) 180 ALR 459 (at 465 [19] per Goldberg J).

60 The offer to provide objections and attend the hearing was taken up with fervour. Hundreds of group members attended the Court in person or using Microsoft Teams. Approximately 250 written objections had been received by the close of evidence, and 13 registrants made oral objections in open Court on the first day of hearing (5 December 2022).

61 I am grateful to each registrant who took the time to write to or address the Court. It was impossible not to be affected by the poignant stories told. The intimate, human element of this settlement approval application loomed large at all times.

62 In this case, the involvement of the contradictors ensured that this information was conveyed efficiently and with appropriate regard for considerations of procedural fairness. The contradictors were rigorous in their approach to reviewing, compiling and responding to objections from registrants. Accordingly, contrary to the approach taken in Fowkes v Boston Scientific (at [60]–[93]), I have eschewed setting out specific representations provided to the Court and provide instead the following summary of the material. It goes without saying that in doing so, I do not intend to diminish the importance of the individual oral and written submissions provided to the Court which were (by consent) received into evidence, read and taken into account.

63 The solicitor instructing the contradictors, Mr Robert Ishak, put on a lengthy affidavit summarising group member responses and objections received: at a specially-created contradictor email address; over the phone; by way of email to my Associate; and by Shine. Mr Ishak helpfully summarised those responses into 16 categories as follows:

Nature of Response | Number of Non-Unique Responses | |

1 | The Settlement Sum is not enough – pain and suffering | 114 |

2 | Average individual payments does not reflect out-of-pocket compensation claimed | 68 |

3 | Settlement amount is not sufficient to cover ongoing costs | 68 |

4 | The settlement represents a compromise of the Group Members’ claims in favour of the Applicants and/or lawyers | 65 |

5 | The deduction of the Recovery Amounts/splitting the settlement between the group will leave little left for the Group Member | 55 |

6 | Does not agree with settlement but requests further information | 28 |

7 | Johnson & Johnson has no recoverability issues and therefore should pay more | 15 |

8 | The settlement terms are vague | 14 |

9 | Comparatively low to other Johnson & Johnson settlements or other personal injury class action settlements | 11 |

10 | Does not agree with how eligibility is determined | 10 |

11 | Shine’s fees should not be paid out of settlement | 8 |

12 | The Applicants won, so this represents a compromise | 4 |

13 | Not enough time to consider whether to object | 3 |

14 | Enquiry requesting further information regarding the proposed settlement (and no express objection) | 80 |

15 | Statement of personal circumstances or other information relevant [to the] proceeding; no specific grounds provided | 16 |

16 | Other – Comments with no query/objection or no comments made | 43 |

64 I am satisfied that these sixteen categories capture the concerns repeatedly put forward. I wish only to add the following by way of elaboration.

65 In relation to Category 1, “The Settlement Sum is not enough – pain and suffering”, registrants objected to the proposed settlement sum on the basis that it does not compensate physical, psychological and psychosocial harm caused by the mesh. Broken or damaged relationships with partners and children, for example, were cited repeatedly.

66 As to Category 2 and Category 3 (“Average individual payments does not reflect out-of-pocket compensation claimed” and “Settlement amount is not sufficient to cover ongoing costs” respectively), numerous objectors expressed distress at the fact that they have already paid to treat their complications, and that there are ongoing costs incurred that will not be covered by the proposed sum. An excerpt from a category three objection reads as follows:

I am 49 years old and have no idea how I am going to afford this care for the rest of my life.

I am a single mum so don’t have another income to fall back on.

I don’t believe that the amount of money I get will come close to helping for the next 30 odd years of health care.

I have resigned myself to the fact that we will never see any money for the pain & suffering we have endured, but I would like some security that my health costs will be affordable in the years to come.

67 The prevalence of Category 4 objections (“The settlement represents a compromise of the group members’ claims in favour of the applicants and/or lawyers”) reflects concerns that under the terms of the settlement, group members will be required to accept less than their claim amount in circumstances where the lead applicants in the Gill Proceeding have received a proportionally greater amount of compensation for their claims and that Shine will receive a large percentage of their outstanding costs.

68 Against the wave of objections received is the trickle of three affidavits put on by the applicants in support of the settlement, two from lead applicants and a third from a sample group member who participated in the reference. Those women express concerns about engaging in a “protracted” reference process, having their compensation eclipsed by the costs of the reference and of paying refunds to third parties. The prevailing tenor is that settlement avoids or substantially lessens the distress which would be suffered in the process of answering questions asked by the respondents or the referee, undergoing physical examinations to prove aspects of their claim, preparing statements and so forth.

E RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

69 In Fowkes v Boston Scientific (at [31]–[45]), I detailed the principles informing the discretion to be exercised under s 33V at length. In view of that summary, it is only necessary to draw out a few points of particular importance in this case.

70 First, the Court’s “principal task is to assess whether the compromise is a fair and reasonable compromise of the claims made on behalf of the group members”: Lopez v Star World Enterprises [1999] FCA 104; (1999) ATPR 41-678 (at 42,670 per Finkelstein J). The Court has a duty to scrutinise the terms of the settlement and determine whether the proposal, though acceptable to a representative party, accommodates the interests and circumstances of the broader pool of group members.

71 Secondly, there are no mandatory considerations, rather factors which the Court will “usually be required to address”: Class Actions Practice Note (at [14.3]–[14.4]). Those factors include, as outlined in the Class Actions Practice Note (at [14.4]):

(a) the complexity and likely duration of the litigation;

(b) the reaction of the class to the settlement;

(c) the stage of the proceedings;

(d) the risks of establishing liability;

(e) the risks of establishing loss or damage;

(f) the risks of maintaining a class action;

(g) the ability of the respondent to withstand a greater judgment;

(h) the range of reasonableness of the settlement in light of the best recovery;

(i) the range of reasonableness of the settlement in light of all the attendant risks of litigation; and

(j) the terms of any advice received from counsel and/or from any independent expert in relation to the issues which arise in the proceeding.

72 Thirdly, there will rarely be one single or obvious way in which a settlement should be framed, either between the claimants and the respondents (inter partes aspects) or in relation to sharing the compensation among claimants (the inter se aspects). Relatedly, and importantly for present purposes, it must be recognised that reasonableness is a range. The question is whether the proposed settlement falls within that range; it is not the task of the Court to second-guess or go behind the tactical or other decisions made by the applicant’s legal representatives.

73 Fourthly, although I have deferred dealing with any deductions from the settlement fund, it is well to record why I have done so. It is central to the Court’s duty to protect the interests of class members is judicial oversight of legal costs and disbursements. As I said in Liverpool City Council v McGraw-Hill Financial, Inc [2018] FCA 1289 (at [66]), the Court must satisfy itself of the reasonableness of the amounts charged and proposed to be deducted from the settlement sum. The rationale is that the settlement power in s 33V must be interpreted and applied in promotion of the overarching purpose of civil litigation in this Court. The Court must account for a peculiar “asymmetry” in the assessment of costs in representative proceedings, as explained by Murphy J in Petersen Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Bank of Queensland Limited (No 3) [2018] FCA 1842; (2018) 132 ACSR 258 (at 277 [88]):

… because (a) the applicant’s solicitor is in a more dominant position vis-a vis a class member than in a solicitor-client relationship in individual litigation; (b) class members are commonly not told about the mounting costs as they are incurred and they suffer a significant information asymmetry in that regard; (c) it is not necessary for class members to retain the applicant’s solicitor and commonly they do not, yet they are usually made liable for a pro rata share of the costs; (d) even where class members retain the applicant’s solicitor they do not provide instructions as to the running of the class action and have no control over the quantum of costs, yet they are usually made liable for a pro rata share of the costs; (e) class members are unlikely to pay much attention to legal costs because they are usually only payable upon success and from the successful outcome; (f) it is usually not until after settlement is achieved that class members are told the total costs claimed, but they are not told (and it is commonly very difficult to accurately estimate) what their pro rata share of the costs will be; and (g) the Court has a protective role in relation to class members’ interests.

74 The costs and disbursements (including the costs associated with the financing of disbursements) in this case are very high and must, in the circumstances of this case, be the subject of close but proportionate scrutiny.

F FAIRNESS AND REASONABLENESS OF THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

75 Rather than rehearse the material before the Court by reference to the Class Actions Practice Note, given the discretionary, multifactorial task before me, the following section of these reasons canvasses a number of factors which I consider to be of particular relevance, drawing upon the submissions of the parties and the contradictors, counsel’s confidential opinions, and the evidence before the Court.

F.1 The Settlement Sum

76 At the heart of the question of whether the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable between the parties and between potential claimants is the adequacy of the settlement sum.

F.1.1 Arrival at the Settlement Sum

77 Substantial contest surrounded the cogency of the evidence relied upon by the applicants, in particular the affidavit of Ms Jancauskas affirmed 16 November 2022 (Jancauskas Affidavit) (which underpins the confidential opinion of the applicants’ counsel) to arrive at the proposed settlement sum.

78 That affidavit outlines the applicants’ efforts to understand the characteristics of the group member cohort and the potential value of their claims, including by selecting a sample group, categorising the sampled claims into “bands” and working out the likely distribution of the larger group of registrants by reference to these categories. The result was a series of notional compensation payment figures which the applicants characterise as “at the lower to medium end of a reasonable range”: Jancauskas Affidavit (at [121]–[122]).

79 Ms Jancauskas identifies the starting point for her assessment as being the advice received from Dr Sarah Whitehouse, a biostatistician, who took a randomised sample of 499 potential group members in the Gill Proceeding (from a total cohort of 11,610 registrants) said to be statistically representative of the cohort of registrants. In coming to the notional compensation figures, Ms Jancauskas relied upon only 273 of the 499 sample registrants owing to a number of practical issues, including: (1) no evidence was obtained to establish that 121 of the registrants have or had an implant the subject of the proceedings; (2) a further 42 registrants could not be contacted or withdrew from the proceedings; and (3) a further 63 either have not experienced complications or their complications arose after the relevant cut-off dates.

80 The total value of the applicants’ individual estimates of sample group member claims is $21,161,603.77. The estimates for sample group members were then stratified into bands. Next, a notional damages figure was attributed to each band, using an estimate of the claim relative to a “most extreme case” under the Competition and Consumer Act. Ms Jancauskas deposed that the notional damages amounts were attributed to the bands having regard to past and future treatment expenses. Notional amounts for economic loss and costs of care were also accounted for in the higher value damages band. The rationale for this was that the more severe a case, the more likely there will be care required and economic loss suffered.

81 The bands were adjusted and readjusted over the course of settlement discussions.

82 Ultimately, Ms Jancauskas undertook the task of attempting to work out the amount which may be distributed to women likely to be group members if the total amount available for distribution is in the order of approximately $200,000,000. This figure was chosen on the assumption that approximately $100,000,000 would be paid to Shine for unpaid costs and disbursements (though, of course, that is an entirely separate question).

83 For completeness, it should be said that the calculations were subject to an order made on 16 December 2022 pursuant to s 37AF(1) of the FCA Act, that the material not be disclosed until the final disposition of the proceedings on the grounds specified in s 37AG(1)(a) of the FCA Act.

84 Significant time was spent with these figures at the hearing on 16 February 2023. I informed senior counsel for the applicants that unless the applicants sought to be heard to the contrary, I was minded to include that information in the judgment for the benefit of group members. The statutory scheme for compensation for economic loss is highly complex and its limits very strict; it is beneficial to reproduce the figures so that group members can appreciate what the evidence reveals. In any event, senior counsel explained that the applicants had sought the information to be kept confidential in order to preserve the position of group members should the settlement be rejected. In short, I consider it is necessary I detail the calculations to explain my decision properly and group members, particularly those who opposed the settlement, are entitled to be fully apprised on the material put before the Court unless it is truly necessary it be suppressed. Suppression orders previously made will be varied accordingly.

85 The following table is taken from the Jancauskas Affidavit:

Table 1

Band | Notional damages | Proportion | Total Potential Group Members | Total Damages per Band |

Tape | ||||

Low | $7,500 | 45% | 2771 | $20,782,500 |

Medium | $25,000 | 26% | 1601 | $40,025,000 |

High | $100,000 | 4% | 246 | $24,600,000 |

Extraordinary | $500,000 | 0% | 0 | $ - |

Mesh | ||||

Low | $7,500 | 8% | 493 | $3,697,500 |

Medium | $25,000 | 10% | 616 | $15,400,000 |

High | $100,000 | 6% | 308 | $30,800,000 |

Extraordinary | $500,000 | 2% | 123 | $61,500,000 |

Total | 100% | 6,158 | $196,805,000 | |

86 I will add that the correlation between the bands and the “most extreme case” metric in the Competition and Consumer Act is as follows:

(1) Low – 15%–20% of the most extreme case;

(2) Medium – 21%–32% of the most extreme case;

(3) High – 33%–39% of the most extreme case; and

(4) Extraordinary – 40% + of the most extreme case (which category would include, for completeness, a group member in Mrs Gill’s position).

87 The contradictors identified two issues with these figures: first, whether the evidence relied upon in order to arrive at the figures in fact supports the contention that the settlement sum is fair and reasonable; and secondly, and relatedly, whether the applicants applied the correct legislative framework to assess the size of potential group members’ claims.

F.1.2 Adequacy of Numerical Evidence

88 The contradictors’ criticisms of the numerical evidence are as follows.

89 First, it is said that Ms Jancauskas’ evidence as to the characteristics of potential group members appears to be based on extrapolation from a reduced subset of 273 of the 499 registrants identified by Dr Whitehouse. Dr Whitehouse’s report does not address whether the reduced sample group of 273 registrants used by Ms Jancauskas in her final calculations is statistically representative of the total cohort of registrants, not least the larger body of potential group members. On this basis, on the first day of the hearing, the contradictors submitted it would be appropriate for the Court to require the applicants to provide further evidence from Dr Whitehouse addressing whether the 273 registrants actually used are statistically representative of the total cohort, and whether the manner in which Ms Jancauskas extrapolates figures based on those 273 registrants is reasonable.

90 At my direction, and in advance of the final day of hearing on 16 February 2023, the applicants took the following steps to allay the contradictors’ concerns. First, they obtained a supplementary report by Dr Whitehouse in which Dr Whitehouse confirms that the approach taken by Ms Jancauskas in her analysis is statistically valid. Moreover, the applicants point to the fact that Dr Whitehouse produced slightly higher estimates for likely group member numbers and recommended that some consideration be given to the adoption of a range of likely estimates in lieu of landing on a single figure as an estimate. This was the course taken by Ms Jancauskas. Secondly, the applicants sought to justify Ms Jancauskas’ extrapolative method with evidence from Ms Saddler, who confirmed that in her experience, Ms Jancauskas’ extrapolation of a statistically representative sample of claims is an orthodox and practical approach in the context of the settlement of a large personal injury class action: Affidavit of Ms Saddler sworn 19 December 2022 (at [35]).

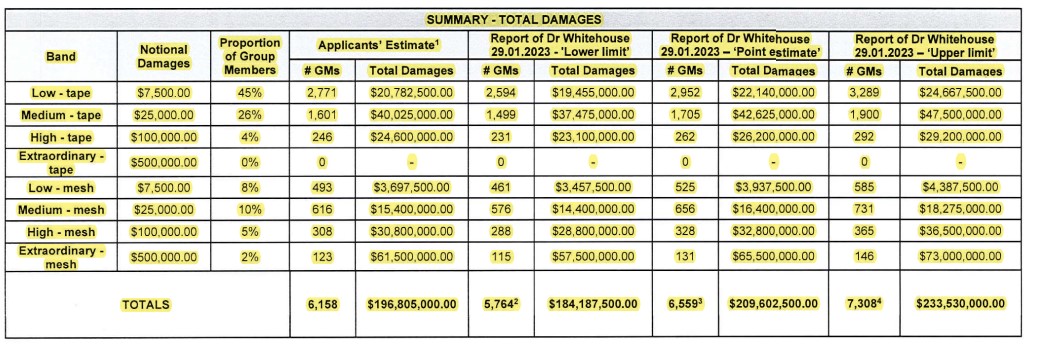

91 Accordingly, the applicants contend that the calculations undertaken by Ms Jancauskas, in the light of the estimations provided in Dr Whitehouse’s reports, reveal that eligible group members will have damages entitlements at the lower end of the reasonableness range. So much is demonstrated by the following table produced by the applicants, which compares the applicants’ estimates against the “lower limit”, “point” and “upper limit” estimates of Dr Whitehouse (compare, in particular, the “totals” figures in the bottom row):

Table 2

92 For ease of reference, it is well here to set out the available interest on the settlement sum. After a number of requests, the applicants drew the Court’s attention to the interest payable on the total amounts in Table 2, which adjusts the “totals” as follows:

(1) Applicants’ estimate: $202,434,153.58;

(2) Dr Whitehouse’s “lower limit”: $189,456,427.38;

(3) Dr Whitehouse’s “point estimate”: $215,597,470.32; and

(4) Dr Whitehouse’s “upper limit”: $240,209,044.43.

93 The second criticism levelled by the contradictors is that the figures reached do not make adequate allowance for economic loss claims. In this regard, the contradictors stepped through the figures as follows:

(1) the Jancauskas Affidavit (at [114]–[116]) explains that Ms Jancauskas’ assessment includes amounts for economic loss, which are likely only to be present in higher value claims. Ms Jancauskas deposed that the average quantum of economic loss claims is $138,623.47;

(2) applying the average quantum of economic loss claims to the “point estimate” number of group members with economic loss claims renders a total of close to $60,000,000; and

(3) applying the average quantum of economic loss claims to the “upper limit” estimate number of group members with economic loss claims renders a total of close to $103,000,000.

94 It is said that no adequate allowance for these claims is made in Table 2: in her supplementary report, Dr Whitehouse indicates that the “point estimate” of total damages for economic loss includes an amount of only $24,900,000 for economic loss (instead of nearly $60,000,000), while the “upper limit” estimate of total damages includes an amount of only $27,740,000 for economic loss (instead of nearly $103,000,000).

95 It appears, however, that the contradictors were labouring under an understandable misapprehension, initially shared by me. As it turns out, the average quantum of economic loss figure is a weighted average, rather than an arithmetic average. This means that the calculations account for the number of group members in each band. In the end, I am satisfied that an allowance for economic loss claims is made in the proposed figures.

96 Thirdly, the contradictors submit that the calculations relied upon do not allow for the possibility that the notional damages awarded might be higher or lower than Ms Jancauskas’ estimates, nor does it include allowance for the possibility that the percentage of group members in different severity bands might differ from Ms Jancauskas’ estimates. It is said that the figures proceed on an assumption that the “notional damages” and “proportion” are correct.

97 It should be said here that, perhaps unsurprisingly, the applicants’ conclusions are broadly consistent with, but higher than, the calculations undertaken by the respondents in the course of settlement negotiations.

98 The affidavit of Mr Zane Reister, general counsel at Ethicon in the United States, sworn 30 November 2022, traces the work done by the respondents following receipt of the available medical records of persons in the subset of 499 registrants. For completeness, it should be noted that the respondents did not have the advantage of the totality of the Whitehouse Report and other evidence when conducting these calculations. On the respondents’ analysis:

(1) 191 registrants in the sample group provided no evidence of any pleaded complication related to an Ethicon implant. This, of itself, is significant because it demonstrates that a number of registrants do not in fact qualify as group members in these proceedings;

(2) 354 of the 499 registrants (comprising the 121 registrants who did not appear to have a relevant implant, the 42 registrants who could not be contacted or requested to withdraw, and the 191 registrants in (1) above) were not likely to be eligible for compensation;

(3) the medical records of approximately one third of the cohort of registrants potentially eligible for compensation suggest that their complication is unlikely to reach the threshold to be awarded general damages under the federal statutory scheme; and

(4) in many instances, the medical records of the registrants who may be awarded general damages disclosed that there were objectively reasonable alternative causes (that existed both prior to and after the implant) of the claimed complication.

99 The respondents also put on evidence that extrapolating this analysis to all 10,743 potential group members (noting there is some doubt as to whether 1,723 of the 10,743 individuals are group members):

(1) approximately 7,520 individuals will likely not be eligible for compensation;

(2) approximately 967 individuals will not reach the threshold to be awarded general damages under the federal statutory scheme; and

(3) approximately 2,256 individuals may receive compensation, including for general damages, but there will be, in many instances, objectively reasonable alternative causes for the complication.

100 Of those potentially eligible to receive compensation, approximately 14% were eligible for compensation in a range assessed as “low” (predominantly comprising claimants who had undergone one revision surgery); approximately 5% of claimants were eligible for compensation in a range assessed as “medium” (predominantly comprising claimants who had undergone two revision surgeries); and approximately 1% of claimants were eligible for compensation in a range assessed as “high” (predominantly comprising claimants who had undergone three or more revision surgeries).

101 As will be seen, these conclusions are more conservative than Ms Jancauskas’ conclusions. The respondents also observed the analysis of medical records outlined in the Jancauskas Affidavit is consistent with what the respondents have experienced in the resolution of pelvic mesh claim cohorts in the United States and other jurisdictions.

F.1.3 Legislative Framework Applied to Potential Claims

102 The second issue identified by the contradictors is that the size of potential group members’ claims has been assessed in accordance with Pt VIB of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (Trade Practices Act) and Pt VIB of the Competition and Consumer Act.

103 The criticism is advanced by the contradictors because: (1) the provisions of the Trade Practices Act and Competition and Consumer Act apply only to group members’ product liability and misleading conduct claims, not a group members’ negligence claims; and (2) while the provisions of the Trade Practices Act and Competition and Consumer Act prevent recovery by group members whose non-economic loss claims are less than 15% of the notional “most extreme case”, the provisions of the applicable state and territory legislation (excepting NSW) applying to group members’ negligence claims do not. It is said that the effect of Ms Jancauskas’ approach is to exclude from consideration all potential group members’ negligence claims, notwithstanding that given the answers to common questions, those claims are viable.

104 The contradictors pointed to the fact that an applicant in the Gill Proceeding was entitled to twice as much under state legislation for her claim as she was under the Trade Practices Act. This is said to illustrate the fact that there is likely to be a material understatement of group members’ non-economic loss claims in the tables above.

F.1.4 Comparison with Best Recovery

105 The Court will usually be required to assess the range of reasonableness of the settlement in the light of the best recovery. This is a consideration of real importance in this case.

106 Importantly, by way of context, there are limits on the amounts a Court may award in respect of various heads of damage.

107 In the case of the Product Liability Claims and the Misleading Conduct Claims, the relevant provisions are contained in Pt VIB of the Competition and Consumer Act and Pt VIB of the Trade Practices Act, as the case may be. For ease of reference, I will refer only to the provisions engaged under the Competition and Consumer Act, noting that the provisions engaged by this litigation are not materially different whether it is the predecessor Act (the Trade Practices Act) or the Competition and Consumer Act which applies.

108 As to the Negligence Claims, the applicable limits are set out in the various State and Territory Acts – there is no uniform national regime: Gill (No 5) (at [4889] per Katzmann J).

Non-economic Loss: Product Liability and Misleading Conduct Claims

109 A Court must not award as personal injury damages for non-economic loss an amount that exceeds the amount permitted under Pt VIB of the Competition and Consumer Act: s 87L of the Competition and Consumer Act. As at September 2022, the maximum amount that can be awarded for non-economic loss is $396,800, as mandated by s 87M.

110 As outlined above (at [55]), whether an award for non-economic loss is available, and, if so, the value of the non-economic loss claim, are determined by reference to the concept of a “most extreme case”: see s 87P(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act. The maximum available amount of damages for non-economic loss is only available in a most extreme case: s 87P(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act.

111 For all other cases, the approach taken is as follows.

112 Where the non-economic loss suffered is less than 15% of a most extreme case, the Court must not award personal injury damages for non-economic loss: s 87S of the Competition and Consumer Act.

113 For cases where the non-economic loss suffered is at least 15%, but less than 33% of a most extreme case, the Court must not award more than the amount which exceeds that permitted in the following table:

Severity of the non-economic loss (as a proportion of a most extreme case) | Damages for non-economic loss (as a proportion of the maximum amount of damages for non-economic loss) |

15% | 1% |

16% | 1.5% |

17% | 2% |

18% | 2.5% |

19% | 3% |

20% | 3.5% |

21% | 4% |

22% | 4.5% |

23% | 5% |

24% | 5.5% |

25% | 6.5% |

26% | 8% |

27% | 10% |

28% | 14% |

29% | 18% |

30% | 23% |

31% | 26% |

32% | 30% |

114 If the non-economic loss suffered is at least 33% but less than 100% of a most extreme case, the Court must not award an amount that exceeds the applicable percentage of the maximum amount of damages for non-economic loss: s 87Q of the Competition and Consumer Act.

115 Section 87ZA mandates that interest must not be awarded on non-economic loss damages.

116 To put these figures in perspective, the following examples give some indication of the approach a Court may apply to a group member’s claim (recognising, of course, that each case turns on its own facts).

117 First, as surprising as it may seem to a non-personal injuries lawyer, applying the current maximum payable for a most extreme case, if a group member suffers non-economic loss equivalent to 20% of a most extreme case, they would be awarded $13,888. No amount of interest would be available to them.

118 Secondly, if a group member suffers non-economic loss equivalent to 30% of a most extreme case, they would be awarded $91,264 (with no interest).

119 A third example is the compensation that was available to Mrs Gill. Mrs Gill’s non-economic loss was found to be 45% of a most extreme case: Gill (No 5) (at [5068]). She had, by the time of the trial, undergone three mesh removal surgeries and a further surgery (which Ethicon accepted was caused by her implant): Gill (No 5) (at [4918]). The surgeries resulted in recurrent prolapse: Gill (No 5) (at [4931]).

120 The Court found that Mrs Gill suffered from an array of “terrible” physical and psychological maladies: Gill (No 5) (at [4918], [4931], [4981]). Mrs Gill was found to have suffered pain in her pelvis, coccyx, her groin, her lower back, her vagina and her rectum, which was caused by her implant, subsequent mesh infection, mesh erosions or exposure, and the surgery undertaken to treat the exposures: Gill (No 5) (at [4931]). She suffered dyspareunia and nausea with orgasm: Gill (No 5) (at [4981]). In her evidence to the Court, Mrs Gill described the pain she suffered after her implant surgery as being of three kinds (see Gill (No 5) (at [3936])):

(1) constant, aching pain in the region of her coccyx (which she rated at 6 out of 10 in severity);

(2) sporadic severe pain akin to period pain with coughing or on sudden movements (of such an intensity that she could not speak and at times struggled to breathe and had to lie down to let it pass, rated at 8 or 9 out of 10); and

(3) “terrible” pain on defaecation, fluctuating in intensity, but with a difficult bowel movement around 9 out of 10 in severity, leaving her unable to talk or concentrate and requiring her to focus on breathing. The pain built up and then peaked and lasted from one to five minutes. She needed to sit or lie very still “until the waves of pain, cramps and spasms. subsided”. She compared it to the feeling of labour pains near the coccyx. She said that it felt like her coccyx was being pushed against so hard that it was going to crack.

121 Mrs Gill was found to have suffered aggravation of an underlying depression caused by her implant and consequent complications. She was also found to have developed a generalised anxiety disorder in response to the complications and revision surgery: Gill (No 5) (at [5027]).

122 At the time judgment was entered, had Mrs Gill elected to take a compensation order under the Competition and Consumer Act, her non-economic loss award would have been $157,840.

Non-economic Loss: Negligence

123 The law which applies as to the amounts which may be awarded for non-economic loss is determined by reference to the law of the place where the wrong occurred: John Pfeiffer Pty Ltd v Rogerson [2000] HCA 36; (2000) 203 CLR 503 (at 544 [100] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ). This means that the cap which applies to a group member’s claim depends upon where that group member had their surgery.

124 The limits on general damages and non-economic loss awards which may be made are subject to exclusions and caps but will generally be higher than the awards available under the Competition and Consumer Act. The caps and limits which apply are set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

125 Mrs Gill’s case demonstrates the impact of these location-based differences. Had Mrs Gill had her surgery in New South Wales, for example, there would be no material difference in her personal injury damages for non-economic loss if judgment was given on her negligence claim or claim under the Competition and Consumer Act: Gill (No 5) (at [5050]). However, as her surgery took place in Western Australia, the application of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) meant that Mrs Gill was awarded $325,000 for non-economic loss on the basis of her negligence claim: Gill (No 5) (at [5068]).

126 After considering Mrs Gill’s harrowing story, one might be forgiven for expressing disbelief that she received only $325,000 for non-economic loss. But this is a reality that cannot be fixed by going back to the drawing board and negotiating a new settlement; it cannot be fixed by proceeding to individual liability determinations – it is the reality of the system in which claims of this kind operate and are determined.

Economic Loss

127 Limits on economic loss awards are likely to have a limited impact on group members, given a lower number of registrants have reported economic loss than non-economic loss. Limits apply whether under the Commonwealth or State and Territory regimes.

128 Section 87U of the Competition and Consumer Act requires that, when determining personal injury damages for economic loss under that Act, the Court must disregard the amount by which the claimant’s gross weekly earnings during any quarter would (but for the personal injury in question) have exceeded: (1) if, at the time the award was made, the amount of average weekly earnings for the quarter was ascertainable – an amount that is twice the amount of average weekly earnings for the quarter; or (2) if: (a) at the time the award was made, the amount of average weekly earnings for the quarter was not ascertainable; or (b) the award was made during, or before the start of, the quarter; an amount that is twice the amount of average weekly earnings for the quarter that, at the time the award was made, was the most recent quarter for which the amount of average weekly earnings was ascertainable.

129 Average weekly earnings is defined in s 87V of the Competition and Consumer Act. As at the date of the hearing, twice the average weekly earnings as defined was $2,689.40.

130 As to negligence claims, in broad strokes, the position under the respective State and Territory statutes is that once economic loss is ascertained, a discount is then applied to account for the uncertainties which attend the hypothetical situation in which a group member would have earned income. This results in a notional economic loss figure, to which caps are then applied. As at the date of the hearing, the caps were as follows:

(1) Australian Capital Territory: s 98 of the Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT) requires the Court to disregard loss of earnings above a limit of three times average weekly earnings in a week (as defined in s 98). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $6,298.80;

(2) New South Wales: s 12 of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) requires the Court to disregard the amount (if any) by which the claimant’s gross weekly earnings would (but for the injury or death) have exceeded an amount that is three times the amount of average weekly earnings at the date of the award (as defined in s 12(3)). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,370.00;

(3) Northern Territory: s 20 of the Personal Injuries (Liabilities and Damages) Act 2003 (NT) requires the Court to disregard the amount (if any) by which the injured person's gross weekly earnings would, but for the personal injury, have exceeded an amount that is three times average weekly earnings as published before 1 January preceding the date on which the assessment is made (as defined by s 18 of the Act). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,130.90;

(4) Queensland: pursuant to s 54 of the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld), in making an award of damages for loss of earnings, including in a dependency claim, the maximum award a Court may make is for an amount equal to the present value of three times average weekly earnings for each week of the period of loss of earnings (as defined in Schedule 2 to the Act). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,115.30;

(5) South Australia: s 54 of the Civil Liability Act 1936 (SA) provides that the total damages for loss of earning capacity (excluding interest awarded on damages for any past loss) are not to exceed the prescribed maximum. Currently, the prescribed maximum is $3,540,070.00;

(6) Tasmania: s 25 of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (Tas) prescribes caps on economic loss in relation to lost superannuation by reference to the maximum percentage required by law to be paid as superannuation contribution. Section 26 of that Act provides that the Court must not award damages for loss of earning capacity on the basis the person was, or may have been capable of, earning income at greater than three times the adult average weekly earnings as last published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics before damages are awarded (as defined in s 3 of the Act). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,309.40;

(7) Victoria: s 28F of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) provides that the maximum amount of damages that may be awarded for each week of the period of loss of earnings is an amount that is three times the amount of average weekly earnings at the date of the award (as defined in s 28F(3)). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,252.10; and

(8) Western Australia: s 11 of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) provides that in assessing damages for loss of earnings, the Court is to disregard earnings lost to the extent that they would have accrued at a rate of more than three times the average weekly earnings at the date of the award (as defined in s 11(3) of the Act). Currently, three times the average weekly earnings as defined is $5,811.90.

F.1.5 Consideration

131 In the end, I have formed the view that the proposed settlement sum is within the range of fair and reasonable outcomes, albeit at the lowest end of that scale. But I am troubled by this settlement.

132 The reasonableness of the headline figure is far from obvious. Ethicon lost, and its defence was devoid of merit. Its actions put the group members through much delay and further suffering (leaving aside any individual causation issues as to their initial suffering that may exist). The group members have the benefit of favourable answers to common questions. Calculations have been done which downplay the amount that may be recovered in negligence. This reality is most glaring in counsel’s confidential opinion, where, at my request, counsel set out a rough estimate of the amounts available if it is assumed that all members of the potential group member cohort could obtain an award of damages proportionately equivalent to the average sum obtained by the lead applicants in the Gill Proceeding.

133 It is immediately apparent that if eligible women could bring their claims forward in uniform categories (which, of course, they cannot, but I make this assumption for the sake of the exercise), and those women were ultimately able to establish claims proportionately equivalent to the average amount achieved by the applicants in the Gill Proceeding, they would be entitled to substantially greater amounts than they will receive if the net amount available is in the order of $200,000,000.

134 But, as counsel recognised, attempts to compare the proposed settlement against figures extrapolated from the outcome for the applicants in Gill (No 5) is not the only or even a correct measure of ascertaining the fairness and reasonableness of the settlement sum. Furthermore, it is inaccurate, and can be misleading, to assume that the global settlement figure can be divided by an assumed total number of group members as a method of reckoning the fairness or outcome of the proposed settlement.

135 The settlement sum is by nature a compromise. Obvious practical difficulties exist in attempting to estimate the compensation payable to group members. The details of the claims of the group member cohort are unknown, and without extensive further work, practically unknowable by reason of the unique claims of each group member, and the large variation in the severity of the complications suffered by group members. Any figures arrived at in the absence of detailed further work will necessarily be “rubbery”, based on reasoned estimation and extrapolation. But that is the best that can be done without further time consuming and expensive work being conducted, which the settlement seeks to avoid.

136 I am conscious some group members will be upset. All I can say as I have thought very carefully about whether approval should be given. But my job is to be objective, particularly in a case such as this one, where the personal injury suffered is of such a deeply personal and intimate kind, that reduction of pain and suffering to a figure may indeed seem a large compromise, even if that figure is the best recovery available.

137 In the end, I accept Ms Jancauskas’ calculations and the evidence underpinning them as a good faith attempt to calculate the loss arising from the statutory claims while building in a price to be paid to avoid an adversarial process against an exceptionally well-resourced opponent with a determination and appetite for defending its position. On the calculations presented to the Court, it will be possible to provide a sizable amount of compensation to each participating group member. That does not mean the amount received will be equal to what might be obtained in a “best case scenario” borne out through persistence in this litigation; but there are things which settlement offers that would otherwise not be available through further litigation. The most important of these are certainty, “closure”, the avoidance of further delay, and the not inconsiderable further vexation that would result in proving claims (however streamlined I made the reference process).

138 I am satisfied, on balance, that the calculations undertaken by the applicants’ legal representatives provide as accurate an account of group membership as is possible at this stage in the lifecycle of a class action, owing to two factors. First, to be a group member, it is not sufficient that a woman has received an implant or have suffered an adverse consequence as a result of the insertion of an implant. A group member is a woman who has been implanted, during surgery performed in Australia, with an Ethicon implant and who has suffered a particular pleaded complication by the applicable cut-off date: Ethicon Sàrl v Gill (at 403 [37]–[38] per Allsop CJ, Murphy and Lee JJ). Secondly, and relatedly, the Gill and Talbot Proceedings have had the benefit of a robust registration process. A great deal of information was at the parties’ disposal, and was evidently applied in settlement negotiations.

139 I remain concerned as to the choice by the applicants to adopt the Competition and Consumer Act damages regime but accept it was open as being practical. Although ungenerous, at least is a universal regime which may be applied across the whole cohort of group members, providing an outcome which can be efficiently administered and is to be understood as a compromise in the interests of inter se fairness. This view was taken by Wigney J in Stanford v DePuy International Ltd (No 6) [2016] FCA 1452 (at [142]), where his Honour accepted that adopting the Competition and Consumer Act regime, as opposed to state based legislation that may have been applicable to claims in negligence, was “eminently sensible and reasonable” and “resulted in a uniform basis of assessment that avoided the potentially arbitrary and disparate results based on the state in which a particular group member may have been supplied” with the implant in question. Adopting a uniform regime has also been described as the usual approach in settlement distribution schemes for mass tort and product liability class actions elsewhere: see R Gilsenan and M Legg, Australian Class Action Settlement Distribution Scheme Design (IMF Bentham Class Action Research Initiative Report No 1, 1 June 2017) (at 18) (IMF Bentham Report).

140 Finally, my concerns are somewhat assuaged by the fact that the real problem in the settlement (such as it is) is not the headline figure, but the amounts to be deducted from the fund before the balance goes to group members. The figures set out in the tables above demonstrate that the headline figure can reasonably accommodate the total value of group members’ claims, which is estimated to be within the range of $184,187,500 (lower limit) to $233,530,000 (upper limit). But I am comforted by the fact that I can guard against unjust deductions. Precisely how far along on the spectrum of reasonableness the settlement ultimately sits will depend on the distribution of funds to scheme administrators and the applicants’ lawyers. That is, the lower the amount paid to Shine and paid to the scheme administrators, the higher the settlement will sit within the range. For the reasons explained above, I am satisfied that approval of the settlement sum can be quarantined from approval of distributions, and any order I make approving the settlement sum will be subject to the separate and later determination of what orders should be made as are just with respect to the distribution.

F.2 Exclusion of Claims of Less Than 15% of a Most Extreme Case

141 I should mention a further matter. The current settlement arrangement (and the calculations explained above) proposes to exclude claims which likely result in a non-economic loss claim less than 15% of a “most extreme case”.

142 The contradictors assert that unfairness is done to group members whose claims are excluded because they do not exceed the 15% threshold, despite the fact that they have viable claims in negligence, given the answers to common questions determined by Katzmann J.

143 Given the likelihood that, in a litigated context, compensation for a claimant with a claim which is less than 15% of a most extreme case will be limited, it is fair and reasonable that group members who cannot establish a claim of 15% or more of a most extreme case are not able to participate in the settlement scheme.

144 As explained by the applicants, it is likely that if group members who do not meet the 15% threshold are included, the award of damages in negligence would simply trigger liabilities to third party payers. The effect of this is that there would be little, if any, compensation paid directly to the group member.

F.3 Counterfactual: Reference Process

145 Although I have touched on it above, because of the time devoted to it in submissions (and because it was an aspect of the way the settlement was justified which did cause me some concern), I wish to deal separately with the situation group members would have found themselves in, in the event settlement was not approved.

146 Individual assessment though a contested curial process conducted in the traditional way would be unworkable (despite it being contemplated, at least initially, by the applicants). The most likely alternative to a proposed settlement is the course I proposed by way of draft orders sent to the parties on 17 January 2023. Those draft orders provided for the reference process to be resumed and, once complete for the 12 selected cases, the referee’s determinations to be provided to numerous other panel referees. It was intended that the Court would:

(1) consider whether to adopt or reject the referee’s report;

(2) settle a notice to be sent to confirmed group members to notify them that their names have been provided to the Court and seeking confirmation of their intention to participate in an assessment; and

(3) appoint panels of referees pursuant to ss 33ZF, 37P(2) and 54A of the FCA Act and Div 28.6 of the FCR to conduct inquiries and prepare a report in relation to each registered group member.

147 The panel of referees would have regard to guidance provided by the judgments of the primary judge and the Full Court in this matter and referee’s assessments report. It would be intended that the individual assessments will be conducted in a way which provides procedural fairness to the parties, but without the involvement of lawyers for either party. Independent counsel and solicitors would, however, assist the panel of referees.

148 The costs of an individual assessment would not be payable until the conclusion of that assessment. Costs would be determined by the relevant referee by reference as to whether any sum assessed is better or worse than any individual offer of settlement made to the registered group members and any other relevant consideration.