Federal Court of Australia

Papoutsakis v Prime Capital Securities Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 205

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | PRIME CAPITAL SECURITIES PTY LTD Respondent | |

MR ROBERT TENBENSEL IN HIS CAPACITY OF THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF ANTONIOS PAPOUTSAKIS Interested Person | ||

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for an extension of time, filed on 17 June 2022, to file a notice of appeal is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

HALLEY J:

1 This is an application under r 36.05 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) for an extension of time (Application) in which to appeal from orders dismissing an application made by the applicant, Mr Antonios Papoutsakis, to annul his bankruptcy: see Prime Capital Securities Pty Ltd v Papoutsakis [2021] FCCA 1594 (J).

2 The respondent, Prime Capital Securities Pty Ltd (PCS), is deregistered and has not participated in these proceedings. The trustee of Mr Papoutsakis’ estate, Mr Robert Tenbensel (Trustee), has participated in these proceedings as an interested person.

3 On 14 July 2021, the primary judge delivered written reasons and made an order that Mr Papoutsakis’ application for annulment of his bankruptcy be dismissed. Mr Papoutsakis was required to file any notice of appeal within 28 days after the date of the decision of the primary judge was delivered: r 36.03(a) of the Rules. Mr Papoutsakis did not file a complying notice of appeal within the time frame prescribed by r 36.03(a) of the Rules.

Background

4 On 1 August 2016, Mr Papoutsakis and his former wife, Ms Marietta Papoutsakis, signed a Prime Capital loan approval document (Loan Approval) as guarantors for a $500,000 loan to Papou Pty Ltd (Papou). Both Mr and Ms Papoutsakis were directors of Papou. Mr Papoutsakis also signed the Loan Approval on behalf of Papou. The signatures of Mr Papoutsakis on the Loan Approval were witnessed by the broker, Mr Steven Tsiakis of MBA Finance, who had arranged the loan for Papou. The loan to Papou did not proceed, however, and the principal amount was never advanced.

5 The Loan Approval included clauses providing that on the acceptance of the offer from Prime Capital a legally binding contract was created on the terms set out in the Loan Approval. Clause 18 of the Loan Approval also provided that if there was any withdrawal or the loan was not drawn within 30 days then the borrower and any guarantors were immediately required to pay all fees, costs and outlays payable pursuant to the Loan Approval and liquidated damages equivalent to one month’s interest at the “Lower Rate”.

6 On page 3 of the Loan Approval in the section entitled “Section 2.0 – Security”, the following four properties were stated to be required to secure the $500,000 proposed loan to Papou (Loan):

(a) 28 Shepherd Street, Sandy Bay – jointly owned by Mr and Ms Papoutsakis until the joint tenancy was severed on the date that Mr Papoutsakis was made bankrupt;

(b) 621-623 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay – owned by Papou Properties Pty Ltd as trustee of the Papoutsakis Family Trust;

(c) 644 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay – was owned by Mr Papoutsakis; and

(d) 1 Beach Road, Sandy Bay – was owned by Papou Properties Pty Ltd as trustee of the Papoutsakis Family Trust.

7 In the hearing before the primary judge Mr Papoutsakis and the Trustee relied on competing versions of the Loan Approval. The only material difference in the two versions of the Loan Approval is that in the version attached to an affidavit of Mr Papoutsakis sworn on 26 April 2022, three of the four properties to be provided by way of security are crossed out and some names or signatures have been inserted above the list of properties.

8 On 30 March 2017, Prime Capital issued an invoice to Papou in net amount of $26,606.63 (after deducting a payment received of $2,200 and providing for a discounted amount of $21,106.63 if it was paid by the due date of 6 April 2017) for application fees and expenses incurred in the course of arranging the loan and liquidated damages (Invoice). The Invoice was not paid.

9 Neither the Loan Approval nor the Invoice identified which particular Prime Capital entity was the party to the Loan.

10 PCS, a company within the Prime Capital group, subsequently commenced proceedings in the Local Court of New South Wales against Papou and Mr and Ms Papoutsakis.

11 On 24 July 2017, default judgment was entered against each of Papou and Mr and Ms Papoutsakis by reason of their failure to pay the Invoice (Disputed Debt).

12 On 29 September 2017, a bankruptcy notice was served on Mr Papoutsakis for a total debt of $28,969.05.

13 On 28 February 2018, PCS presented a creditor’s petition. Mr Papoutsakis did not file any notice stating grounds of opposition to the creditor’s petition or any evidence in support of any opposition.

14 On 21 May 2018, a sequestration order was made against Mr Papoutsakis’ estate (Sequestration Order).

15 Mr Papoutsakis is also a party to proceedings HBC 133 of 2018 which were commenced by Ms Papoutsakis in the Family Court of Australia (Family Court proceedings). In October 2022, Justice McClelland reserved judgment in the matter.

The primary judge’s reasons

Factual findings

16 Mr Papoutsakis commenced proceedings SYG 534 of 2018 in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (FCCA proceedings), as it then was, as a late application to review the Sequestration Order.

17 PCS did not participate in the FCCA proceedings. The Trustee participated as an interested person and provided a report pursuant to r 7.06 of the Federal Circuit Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth): at J [2].

18 The hearing occurred on 16 to 17 June 2021. At the hearing, Mr Papoutsakis “changed tack” and sought an annulment of his bankruptcy pursuant to s 153B(1) of the Bankruptcy Act 1996 (Cth) (Bankruptcy Act): at J [1].

19 The primary judge made the following observations and findings that provide important context to the circumstances surrounding the bankruptcy of Mr Papoutsakis and the exercise of any discretion to now annul his bankruptcy:

9 Mr Papoutsakis deposed that following the sequestration order his then-solicitors acted negligently and not in accordance with his instructions by responding to the Bankruptcy Notice outside the required time period. In his affidavit sworn 6 May 2021 Mr Papoutsakis deposed that the sequestration order dated 21 May 2018 was made in his absence and was made because his solicitor failed to attend court. However, in cross examination Mr Papoutsakis’s evidence was to the effect that he had only instructed his solicitors to assist him to obtain an adjournment of the creditor’s petition at its first return date and that he had been successful in obtaining that adjournment to 21 May 2018 with a related order that he file and serve any notice of ground of opposition and affidavit in support by 16 May 2018. His oral evidence was to the effect that once he had obtained the adjournment, he left the issue in the hands of the finance broker who had negotiated the PCS loan but that that person let him down. He agreed that he had been aware of the terms of the Court’s orders made at the first return date, that documents of the sort referred to in those orders were not filed and that he did not appear and was not represented on 21 May 2018, when the sequestration order was made.

10 Mr Papoutsakis said that in the first week of June 2018, with his solicitor, he met the Trustee and told him that he intended to have the bankruptcy annulled. On 23 October 2018 he incorrectly told the Trustee that an application to annul the bankruptcy had been filed. On 28 July 2020 he wrote to the Trustee saying that he intended to apply for an annulment.

11 In his affidavit of 6 May 2021, Mr Papoutsakis deposed that he met with his barrister on 10 October 2018 to sign a bankruptcy annulment application to be submitted to the Court. Two weeks later, the Trustee telephoned Mr Papoutsakis’s counsel, in his presence, to confirm that the application had been submitted but refused to provide Mr Papoutsakis with the details of their discussion. On about 10 January 2019 Mr Papoutsakis telephoned the Court and was informed that the application had not been received. Mr Papoutsakis deposed that he telephoned his counsel who said that he had forwarded the application to the Court for review prior to filing.

12 In his affidavit sworn 5 November 2020, Mr Papoutsakis deposed that he filed in the Local Court an application [to set aside the default judgment], but was advised by that court that the motion could not proceed because Capital Securities XVI Pty Ltd [sic] was in liquidation. In his oral evidence, Mr Papoutsakis identified his Local Court notice of motion to set aside the default judgment which bore a court stamp of 8 May 2019. In his affidavit sworn 5 November 2020, Mr Papoutsakis deposed that 30 days after having advised him that [the creditor plaintiff] was in liquidation, the Local Court notified him that it would not consider the matter without the Trustee’s consent. He also said that for a period a firm of solicitors in Sydney had acted for him in relation to that stage of the Local Court proceedings. Exhibit T14 is a copy of those solicitors’ tax invoice which recorded that they attended the motion’s return date on 30 May 2019 and a further hearing listing on 27 June 2019 but ceased to act in July 2019.

20 The primary judge found that the Trustee was a “credible and reliable witness” whilst Mr Papoutsakis was “not always an accurate historian”. The primary judge rejected a number of criticisms of the Trustee made by Mr Papoustakis, stating at J [43]:

His criticisms of the Trustee, largely to the effect that the Trustee was not administering the estate in a proper or business-like manner and was too interested in his fees, were not persuasive and seemed to overlook the complexities present in the administration of his estate, particularly by the contest in the Family Court.

21 The primary judge briefly but correctly identified the relevant principles to determine whether a bankruptcy should be annulled at J [44] and [61] and the relevant test for solvency at J [46].

The Disputed Debt

22 The primary judge addressed the Disputed Debt at J [47]-[53]. Given the submissions made by Mr Papoutsakis on this application, it is convenient to set out his Honour’s consideration of the Disputed Debt in full:

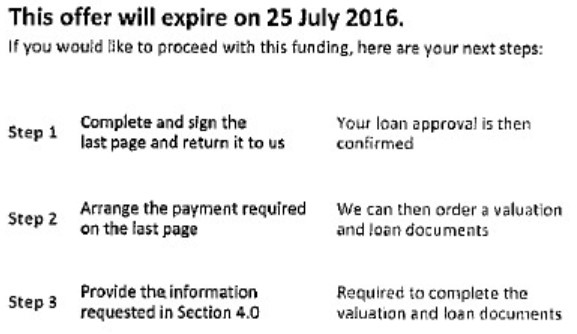

47 Mr Papoutsakis argued in his affidavit of 6 May 2021 that section 6.0 of the loan documents’ terms and conditions provided that three steps had to be completed to accept the loan approval and he deposed that only one of the three steps had been completed. The three steps referred to were:

48 Although the document was signed, steps 2 and 3, which concerned the payment of the application fee and provision of contact details for the borrower’s solicitor and for the person through whom access for a valuation would be arranged, were not completed. However, the relevant parts of the summary “Terms & Conditions” of the contract, extracted earlier in these reasons, provided that signature denoted acceptance of PCS’s offer and that that created “a legally binding contract between you and us”. That reflects the terms of the offer set out above, to the effect that signing and returning the documents “confirmed’ the loan approval, and other parts of the loan documents do not contradict what was said in the summary “Terms & Conditions”.

49 The formation of the contract did not, therefore, require anything more than return of a signed copy of the loan documents. Steps 2 and 3 were not preconditions to the entry into the contract but, properly understood, were obligations conditional upon that first step of acceptance having been taken. That being so, the fact that Papou Pty Ltd had not completed those second and third steps is of no relevant significance in circumstances where he it had, through Mr Papoutsakis, executed the agreement. The fact that those steps had not been completed did not affect the existence of the agreement with PCS.

50 Mr Papoutsakis further argued in his affidavits of 5 November 2020 and 6 May 2021 that:

(a) great doubt surrounds exactly which entity Papou Pty Ltd was dealing with when the Loan Approval was made;

(b) the name of the lender at the time the sequestration order was made seemed to be Prime Capital Mortgages Pty Ltd (which used to be called Prime Capital Securities and before it was deregistered on 5 July 2017 had the ABN 18 147 893 356 which appeared on the “Prime Capital” invoice of 30 March 2017;

(c) the various corporate entities that featured in his case and were associated with Prime Capital did not have the same identifying company or business numbers; and

(d) based on the information contained in Denton’s letter to the Trustee dated 19 June 2018, neither Capital Securities XV Pty Ltd nor Capital Securities XVI Pty Ltd, a related body corporate, should have initiated proceedings against him or Papou Pty Ltd.

51 The lack of clarity over the identity of the lender is a perplexing aspect of this case but, as the applicant for annulment, Mr Papoutsakis bore the onus of demonstrating that that issue was material to the question of his solvency on 21 May 2018. This he has failed to do. It has not been demonstrated that the plaintiff in the Local Court proceedings, who was the petitioning creditor in this proceeding, lacked standing, based on the loan agreement pleaded, to bring the Local Court proceedings.

52 In his written submissions, Mr Papoutsakis argued that he had never owed PCS any money as he had not gone through with the loan because PCS had not honoured the terms of their agreement. I am not persuaded by Mr Papoutsakis’s assertion that Papou Pty Ltd and he were not bound by an agreement with PCS and, specifically, not bound to pay the amount invoiced on 30 March 2017. In that connexion, I do not accept that the version of the loan documents annexed to Mr Papoutsakis’s affidavits of 5 November 2020 and 6 May 2021, which had fewer pages than the version supplied by Dentons to the Trustee, was what Papou Pty Ltd’s finance broker provided to PCS. Mr Papoutsakis gave unclear evidence concerning what document was supplied to PCS and he failed to explain how PCS came to have a version of it, as provided by Dentons to the Trustee, that was signed by him and his then-wife but which did not bear the striking out of three properties as his own copy did. The version of the loan documents provided by Dentons appears to be a clean and complete version of what Mr Papoutsakis adduced. The inference I draw is that it was that version of the documents that was given to PCS by the broker and that a loan agreement came into being at that time (“Loan Agreement”). The evidence does not support a conclusion that the version of the documents adduced by Mr Papoutsakis, with its additional manual alterations, was ever part of the negotiations with PCS or that that company was aware of it. I conclude that the version of the documents relied on by Mr Papoutsakis had no contractual significance.

53 That being so, if Papou Pty Ltd withdrew unilaterally from the transaction with PCS, as Mr Papoutsakis’s evidence indicates it did, the effect of the Loan Agreement’s terms quoted earlier is that Papou Pty Ltd, and in default Mr and Ms Papoutsakis, were liable for the amounts set out in the “Prime Capital” invoice of 30 March 2017.

Solvency

23 The primary judge relevantly referred to the following evidence from the Trustee on the question of Mr Papoutsakis’ solvency at J [29]:

Based on my investigations to date, I believe the Bankrupt may have been insolvent since 30 June 2013 (the last date of the first quarter in the DPN I refer to in subpara.g. below) for the following reasons:

a. The Bankrupt failed to pay water charges since December 2013, in respect of [644 Sandy Bay Road] a commercial property that he is the sole registered proprietor of

b. The Bankrupt failed to pay rates since August 2014, in respect of [644 Sandy Bay Road] and [28 Shepherd Street] being properties he is the registered proprietor of

c. The Bankrupt failed to pay land tax since November 2014, in respect of [644 Sandy Bay Road], a commercial property that he is the sole registered proprietor of

d. The Bankrupt, in his capacity as guarantor under a commercial lease agreement on the North Hobart Fresco store premises, failed to ensure rent obligations were met from 1 November 2015.

e. The Bankrupt, in his capacity as joint and several guarantor under a commercial sub-lease agreement on the Glenorchy Fresco store premises, failed to ensure rent obligations were met from 1 May 2017.

f. As joint and several guarantor and joint mortgagor, the Bankrupt failed to comply with a Notice of Default and Demand for Possession [of 28 Shepherd Street] under section 77 of the Land Titles Act 1980 (Land Titles Act) and remedy the default by the due date, being 6 January 2018;

g. The Bankrupt failed to pay superannuation guarantee obligations originally incurred by [Papou Pty Ltd] from the June quarter of 2013 to 30 June 2015, as required by a Director Penalty Notice (DPN) issued 29 March 2018.

24 The primary judge addressed the solvency of Mr Papoutsakis at J [54]-[57]. His Honour found that the emphasis that Mr Papoutsakis placed on the value of his real estate assets was, in large part, misplaced because illiquid assets do not support a finding of solvency unless they can be realised or borrowed against in a relatively short time frame: at J [55].

25 The primary judge considered that the evidence before him indicated that Mr Papoutsakis had not agreed to a sale of the Sandy Bay and Beach Road properties because he had an unrealistic opinion of their value which gives “no reason to be confident that he would have been willing to accept a fair market price for an asset were its sale necessary to provide ready money, even assuming that a sale could be effected quickly enough to meet the test of solvency”: at J [55]. The primary judge acknowledged that an alternative would have been to obtain funding against the security of the properties but Mr Papoutsakis had not led any evidence that “there was sufficient credit available to him sufficient that he could pay all his debts as they fell due”: at J [55].

26 Moreover, the primary judge stated that he was not aware of any income being generated from the family business at the Sandy Bay and Beach Road properties and found that “the practical value of assets that have been discussed is also clouded by the uncertainty introduced by the need to have regard to the potential division by the Family Court of the pool of matrimonial assets and the fact that Mr Papoutsakis’s share of that asset pool is undetermined.”: at J [57].

27 The primary judge was ultimately not persuaded for these reasons that Mr Papoutsakis was solvent when the Sequestration Order was made on 21 May 2018. The primary judge concluded at J [59] that for that reason, quite apart from the failure of Mr Papoutsakis to appear in Court to oppose the Sequestration Order or to file any notice of ground of opposition to the creditor’s petition, Mr Papoutsakis had not demonstrated that the Sequestration Order should not have been made.

Discretion

28 In light of the above finding, it was not necessary for the primary judge to consider whether, as a matter of discretion, the bankruptcy of Mr Papoutsakis should still be annulled. The primary judge, however, made the following observations in the event that he had otherwise concluded that the Sequestration Order should not have been made and he was required to consider the issue.

29 First, the primary judge considered that the FCCA proceedings had been commenced a “considerable time” after the Sequestration Order was made and that such a delay was “significant and material”: at J [62]. The primary judge was not persuaded by Mr Papoutsakis’ explanation for the delay in bringing the FCCA proceedings. Mr Papoutsakis attributed the delay to the “negligent inaction of his legal advisers [which] had hindered his attempts to set the sequestration order aside or to have the bankruptcy annulled”: at J [64]. The primary judge concluded that to the extent Mr Papoutsakis’ advisers had been “dilatory or ineffective” Mr Papoutsakis’ efforts to annul the bankruptcy “appear to have been sporadic and lacking in determination” and that Mr Papoutsakis could not avoid his “responsibility to protect his own interests by pressing [his legal advisers] into action”: at J [64].

30 Further, the primary judge did not accept Mr Papoutsakis’ claim that he was uninformed of his options to annul the bankruptcy, including by commencing the FCCA Proceedings, until 2020. The primary judge relied on Mr Papoutsakis’ evidence during the hearing that he had told the Trustee on 23 October 2018 that an application to annul the bankruptcy had been filed: at J [65].

31 The primary judge also had regard to the extent of the work done by the Trustee in relation to the proceeding and the inconvenience that would be imposed on Mr Papoutsakis’ unsecured creditors, should the bankruptcy be annulled: at J [62]-[63]. In particular, the primary judge noted that the unsecured creditors had “waited for years without access to the funds they are owed” and to annul the bankruptcy at this stage of the proceedings would require them to “put aside their proofs of debt and pursue their remedies afresh elsewhere”: at J [63].

32 Second, the primary judge rejected Mr Papoutsakis’ claim that the surplus from the sale of his two properties at 644 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay and 1 Beach Road, Sandy Bay could be applied to the Trustee’s fees and the debts of unsecured creditors because the funds formed part of the matrimonial pool of assets which remain the subject of the Family Court proceedings: at J [66].

33 Third, the primary judge was unable to conclude whether Mr Papoutsakis was solvent at the time of the FCCA proceedings due to the “inability to know how much of the matrimonial pool of assets Mr Papoutsakis will hold at the end of the Family Court proceeding”: at J [68]. The primary judge also held that Mr Papoutsakis had not demonstrated that creditors would receive a better outcome if the bankruptcy was annulled than if the administration of Mr Papoutsakis’ estate was completed: at J [69].

34 The primary judge concluded at J [70] that even if he had concluded that the Sequestration Order should not have been made, he would not have exercised the discretion to annul the bankruptcy of Mr Papoutsakis in circumstances:

where there has been a long and largely unexplained delay in bringing this proceeding, where an adequate proposal for paying the Trustee’s fees and expenses has not been made, where it has not been demonstrated that Mr Papoutsakis is presently solvent and where it would appear that creditors would not be better off with an annulment…

Legal principles

35 The principles which guide the Court’s discretion to allow an application for an extension of time within which to file a notice of appeal were restated by a Full Court of this Court in BQQ15 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 218 at [33] (Yates, Wheelahan and O’Bryan JJ):

Under rule 36.05, the Court may grant an extension of the time within which an appeal is to be filed. The principles applicable to the exercise of the Court’s discretion were set out in Hunter Valley Developments Pty Ltd v Cohen (1984) 3 FCR 344 at 348-9, which were adopted by the Full Federal Court in Parker v R [2002] FCAFC 133 at [6]:

(a) Applications for an extension of time are not to be granted unless it is proper to do so; the legislated time limits are not to be ignored.

(b) There must be some acceptable explanation for the delay.

(c) Any prejudice to the respondent in defending the proceedings that is caused by the delay is a material factor militating against the grant of an extension.

(d) The mere absence of prejudice to the respondent is not enough to justify the grant of an extension.

(e) The merits of the substantial application are to be taken into account in considering whether an extension is to be granted. Leave will not be granted where there are no reasonable prospects of success on the appeal: Kalanje v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2006] FCA 1618 at [5]. The applicant will have no real prospects of success where the case is devoid of merit or clearly fails; is hopeless; or is unarguable. In making an assessment the Court is not required to go into too great a detail, but is to “assess the merits in a fairly rough and ready way”: Jackamarra v Krakouer (1998) 195 CLR 516 at [7] – [9].

36 In Tuakeu v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCA 362, Farrell J relevantly stated at [32]:

Courts have generally taken the position that it is not an adequate reason for extensive delay that a person is not represented and is unaware that they have a right to appeal or to seek review of a decision. Nor is it an adequate reason that they do not know the time periods specified in legislation or the rules of the Court for initiating such processes.

37 In GOK18 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2021] FCAFC 169 (Collier, Rangiah and Derrington JJ) their Honours stated at [25]:

It appears that, from 7 November 2019, the applicant made several genuine attempts to obtain representation for the purpose of instituting an appeal, although he was experiencing financial hardship which hampered those efforts. Generally speaking, a party’s financial circumstances or difficulties alone are an insufficient excuse for delay and will not provide a justification for an extension of time: QAAH v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs [2004] FCAFC 9 [7]; SZKDC v Minister for Immigration & Citizenship [2008] FCA 164 [12].

38 In Robson v Body Corporate for Sanderling at Kings Beach CTS 2942 (2021) 286 FCR 494; [2021] FCAFC 143 at [36], Allsop CJ stated:

Also, I wish to emphasise what Colvin J has said in his reasons about the need for despatch in the dealing with matters in bankruptcy, in particular applications concerned with the invocation of the jurisdiction, including applications for review of registrars’ decisions concerned with such. The need for that despatch is part of the recognition of the public importance of a jurisdiction that affects all creditors and the status of the debtor and of the fact that the foundation of the jurisdiction is insolvency, not debt collection.

39 The following statements were made by Derrington J in Robson at [73] concerning the need for despatch in dealing with bankruptcy matters:

In the case of the exercise of the power to make a sequestration order on a creditor’s petition the need for a delegate to be conscious of these aspects of the exercise of delegated judicial power is heightened, as the circumstances of the present case illustrate. The nature of the power being exercised in such cases also heightens the need for any review to be conducted expeditiously and for there to be careful consideration on review as to whether it is appropriate to extend any time limit appropriately imposed in the interests of finality upon the bringing of any application for review of the exercise of the delegated judicial power. As to such time limits, at least where they are expressed by the judges of the Court in the exercise of their rule-making power and not by the exercise of a power conferred upon the Executive, they are consistent with the constitutional imperative for the provision of an opportunity for review: see Harrington v Lowe (1996) 190 CLR 311 at 321; 136 ALR 42 at 47; 20 Fam LR 145 at 150.

40 Section 153B of the Bankruptcy Act concerns annulment of a bankruptcy by the Court and provides:

153B Annulment by Court

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a sequestration order ought not to have been made or, in the case of a debtor’s petition, that the petition ought not to have been presented or ought not to have been accepted by the Official Receiver, the Court may make an order annulling the bankruptcy.

(2) In the case of a debtor’s petition, the order may be made whether or not the bankrupt was insolvent when the petition was presented.

(3) The trustee must, before the end of the period of 2 days beginning on the day the trustee becomes aware of the order, give to the Official Receiver a written certificate setting out the former bankrupt's name and bankruptcy number and the date of the annulment.

41 Section 154 of the Bankruptcy Act also relevantly provides:

154 Effect of annulment

(1) If the bankruptcy of a person (in this section called the former bankrupt) is annulled under this Division:

(a) all sales and dispositions of property and payments duly made, and all acts done, by the trustee or any person acting under the authority of the trustee or the Court before the annulment are taken to have been validly made or done; and

(b) the trustee may apply the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee in payment of the costs, charges and expenses of the administration of the bankruptcy, including the remuneration and expenses of the trustee; and

(c) subject to subsections (3), (6) and (7), the remainder (if any) of the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee reverts to the bankrupt.

…

The application for an extension of time

42 On 17 June 2022, Mr Papoutsakis filed the Application which was accompanied by an affidavit sworn by him on 26 April 2022 and a draft notice of appeal (Draft Notice of Appeal). In the Draft Notice of Appeal, Mr Papoutsakis set out 47 grounds of appeal.

43 In order to determine whether I should exercise my discretion to grant an extension of time to Mr Papoutsakis to file the Notice of Appeal it is necessary to consider first, Mr Papoutsakis’ explanation for the delay, second, any prejudice to the Trustee and unsecured creditors and third, the merits of the proposed appeal. I do so in turn below.

Consideration

Explanation for delay

44 Mr Papoutsakis gave evidence that the delay in filing the Notice of Appeal can be attributed to his ongoing health problems, lack of legal representation and lack of financial resources.

45 He gave evidence that his original notice of appeal was filed in August 2021 but was not accepted by the Hobart registry because he had mistakenly inserted the wrong date on the document and he was only made aware of the rejection when he contacted the registry to enquire whether the documents “had been filed and accepted”.

46 He also gave evidence that :

(a) both after and during his initial attempts to file the Notice of Appeal he had been “under enormous mental stress caused by the bankruptcy trustee, suffered a heart attack and endured sever [sic] health problems”;

(b) he had to start taking nine different medical tablets per day for his health conditions which made him “drowsy and unable to focus on mentally fatiguing tasks such as legal proceedings”; and

(c) his medical issues, coupled with the absence of any legal representation, had led to the delay in filing his appeal as he had “not been in a fit enough state to do so sooner”.

47 The ten month delay in filing the Notice of Appeal was significant. The generally expressed explanations provided by Mr Papoutsakis, at best, provided a partial, but incomplete explanation for the delay. Mr Papoutsakis was clearly aware of his right to appeal. The medical issues might explain some measure of delay but not ten months delay. The absence of legal representation and impecuniosity are also not matters that are sufficient to excuse delay or justify an extension of time within which to appeal.

48 Moreover, the notification by the Hobart registry of the rejection of the notice of appeal raises many unanswered questions, including, why there was a delay in following up the issue with the registry, what was the specific error that was alleged to have been made in the date and what was the reason for the subsequent delays in re-filing the notice of appeal. The following evidence given by Mr Papoutsakis in cross-examination did not relevantly assist in clarifying these matters:

MR GROVES: Can you take me to the date or dates in the document that you got wrong?

THE WITNESS: Yes. I – no. It’s not here. It’s not here. The reason – the reason is not here – this why I was saying to you before. The reason is not here is, as you realise, that the registry in Hobart is not fully occupied. Correct?

MR GROVES: No. I don’t - - -

THE WITNESS: Well, because you never go there. That’s why. I go there just about every week, and I know. Some days you go over there and – and you see none of the table. You – all you see is the security guards. That’s all you see. Right? Now, I have – I have done the – the first – the – the appeal for Cameron J. I have done it, and I have gave it to the clerk over there named Mark, which is not there now. He – he is not working there any more. He said to me, “Leave it here with me, Tony, and I will lodge them, stamp them, and I will give you a call.” I was wait for a month, month and a half. Nothing happened. So I have to go and see, and I say, “Mark, where is the documents?” He said, “What documents?” I said, “The documents I have gave you about a month and a half ago.” He say, “I can’t remember anything,” and that’s why I have to do it again.

49 For the foregoing reasons, I am not satisfied that Mr Papoutsakis has provided an adequate explanation for the ten month delay in filing his application for leave to appeal.

Prejudice

50 Although the Trustee submitted that he would not face any “specific prejudice” if an extension of time to file the application for leave to appeal was granted and he was required to participate in an appeal, he submitted that Mr Papoutsakis’ delay had caused “identifiable and seemingly irretrievable” prejudice to at least two of Mr Papoutsakis’ creditors. The Trustee submitted that Freshmax Australia Pty Ltd, one of the creditors, would not have settled its claims against Mr and Ms Papoutsakis if the bankruptcy was annulled. The Trustee also submitted that Ali Wong, another creditor, was unable to commence proceedings to recover debts owed by Mr Papoutsakis pursuant to s 58(3)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act, and such a claim would now be statute barred pursuant to s 4 of the Limitation Act 1974 (Tas).

51 The evidence relied upon by the Trustee was not sufficient to make any definitive findings as to prejudice. It can readily be inferred, however, that the positions of unsecured creditors of a bankrupt are likely to be prejudiced if they have compromised claims on the understanding that a person is a bankrupt. Further, they are likely to be prejudiced if they have relied on proofs of debt, rather than litigating matters, if by reason of the delay in the annulment of the bankruptcy those claims would now be subject to limitation issues.

Merits of the proposed appeal

52 It is readily apparent from the extensive, discursive, repetitive and argumentative proposed appeal grounds in the Draft Notice of Appeal that Mr Papoutsakis is in substance seeking to reargue the matters that he raised before the primary judge and that he has not discerned any appellable error in the primary judge’s approach. The proposed appeal grounds are not directed at establishing errors in the application by the primary judge of relevant principles and instead, seek to introduce new evidence or hypotheses that were not advanced before the primary judge. Moreover, the proposed grounds of appeal do not satisfy the “heavy onus” borne by an applicant under s 153B of the Bankruptcy Act and on a party to establish fraud in the context of the principles articulated in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336; [1938] HCA 34 at 362 (Dixon J) and s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). Nor do the proposed appeal grounds show any error in the primary judge’s discretionary decision to not annul Mr Papoutsakis’ bankruptcy: see House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499; [1936] HCA 40 at 505 (Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ).

53 The flaws in the overall approach taken by Mr Papoutsakis in the Draft Notice of Appeal is aptly illustrated in the first proposed ground of appeal which is in these terms:

The Judgement is biased in favour of the bankruptcy trustee and Prime Capital and I did not have a fair trial. His Honour factually misunderstood the evidence and facts in this matter which has led to a wrong decision. I seek leave to appeal the decision to correct the record and provide the Court with all available evidence required to make a fully informed and fair decision.

54 Central to many of the proposed grounds of appeal was the proposition that the Disputed Debt relied upon by PCS to obtain the Sequestration Order was procured by fraud as PCS was relying on a version of the Loan Approval that did not have the handwritten deletions to three of the four properties that had been inserted in the typed version of the Loan Approval. The allegation of fraud on the part of PCS was first raised in the Draft Notice of Appeal in proposed appeal ground 2(b) in these terms:

The unsigned Loan Approval document was the untrue document which Prime Capital substituted in place of the signed copy which included hand deletions of three properties, which were never agreed, mentioned or authorised to be offered as security for a loan. Prime Capital committed a criminal act against the borrowers, Marietta Papoutsakis, Papou Pty Ltd and Tony Papoutsakis. His Honour should have treated the version of the Loan Approval documents bearing signatures of Tony and Marietta Papoutsakis on page 3 in 'Section 2.0 - Security' as the true and correct version of the Loan Approval.

55 The allegation of fraud is repeated in proposed appeal grounds 15, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 32, 36, 41 and 45.

56 The significance of the alleged fraud to the bankruptcy of Mr Papoutsakis is advanced in proposed appeal grounds 39 and 40 where it is contended that:

I dispute the bankruptcy claim by Prime Capital and the decision made in error being based on wrong documents produced to this Court.

In all the circumstances, I should never have been made bankrupt in the first place. The bankruptcy was not legally correct or made. There was no debt and the terms and conditions of the Loan Offer was not valid due to the falsified documents by all the Prime Capital entities. The security given in Section 2.0 was amended in such a fundamental manner that the Loan Offer could not be accepted even if signed.

57 Relatedly, in the preceding proposed appeal grounds 37 and 38 it is contended that:

His Honour did not consider that no financial institution in Australia would accept the Loan Approval documents with the significant amendments to the terms which were not agreed by the parties.

If the Sequestration Order was never made, all the creditors would be paid in full and this was the reason I applied for a loan from Prime Capital via MBA Finance. However the loan did not proceed due to the terms of the loan offer not been accepted during negotiations. I ask the Honourable Court to reconsider my application.

58 The primary judge addressed at J [47]-[53] the facts relied upon by Mr Papoutsakis to advance his allegations of fraud on the part of PCS. The primary judge concluded that the complete version of the Loan Approval annexed to the affidavit of the Trustee which did not have three of the four properties crossed out was the version provided to PCS. On any reasonable view, it was open for the primary judge to have drawn that inference and conclude that there was nothing to suggest that PCS had engaged in any fraud or criminal act. The much more compelling inference is that after the Loan Approval was provided to PCS, a copy of that document was subsequently altered by a person crossing out the three properties.

59 It may well have been the case that Mr Papoutsakis did not give instructions to his broker for the security to extend to the three disputed properties. It may well also be the case that he may have a claim against his broker or his previous legal advisers, given the matters canvassed by the primary judge at J [9]-[12]. However, neither of these potential circumstances establishes that PCS acted fraudulently or that the Sequestration Order should have been set aside.

60 Nor does the evidence of Mr Papoutsakis before the primary judge concerning the Loan Approval establish that PCS acted fraudulently or that the Sequestration Order should have been set aside. The more plausible inference, if the oral evidence of Mr Papoutsakis is otherwise to be accepted, is that the broker failed to pass on to PCS the copy of the Loan Approval page with the three properties crossed out and instead substituted the original unsigned page listing the four properties for the page signed by Mr Papoutsakis.

61 In an affidavit sworn on 15 June 2021, Mr Papoutsakis gave evidence that the only Loan Approval that he received from PCS or his finance broker was “the document that I signed which crossed out 3 of my properties” (at J [8]). In his oral evidence before the primary judge, Mr Papoutsakis also gave the following evidence:

… I decided to get a loan so I said — he said to me he’s working for MBA Finance which is Master Builders Association. I said, okay, can you organise so I can get half a million dollars for working capital and he says no problem. And that’s how it was. I said to him only one property, … When I received these documents over here, they have three — they have three — four properties. I said I didn’t ask you for four properties, I asked you for one. He said, it doesn’t matter, he says. Just ….. three property sale and when these documents go to Prime Capital here in Sydney, they will adjust it in their proper documents to have only one. When the solicitor in Hobart called me to go and sign the papers, I noticed they have four properties in it ….. the solicitor ….. when I saw the documents they have four properties there on it, I said, look, I’m rejecting and my ex-wife was going to come and sign afterwards and I said when she comes, tell her not to sign because I’m rejecting the offer again because they didn’t honour my offer at the beginning: one property and not as four.

…

… They are the papers which I have signed for the loan which they’re not fully signed. They are being crossed out because they only have offer one property and not four. This is the reason I have crossed them off …

…

… I’ve been convinced by the MBA Finance that they would change the documents when the proper documents would come and they’ve never done it.

62 Again, if this evidence is accepted it only establishes that at the time that Mr Papoutsakis’ solicitor provided the Loan Approval to him for his signature (a) it had the four properties listed as the security that PCS required for the proposed loan to Papou, (b) for reasons that are not apparent, Mr and Ms Papoutsakis then signed or wrote their names under the list of parties to the proposed loan immediately above the list of the four properties, and (c) at the same time Mr Papoutsakis, or someone at his request, crossed out three of the four properties.

63 Relatedly, the Draft Notice of Appeal includes proposed grounds of appeal 2(c), 3, 28 and 45 directed at evidence that was either rejected by the primary judge or should now be permitted to be provided by the broker, Mr Tsiakis. The specific nature of the evidence that Mr Tsiakis might be able to give was not identified by Mr Papoutsakis. In a statutory declaration made on 11 November 2019, however, Mr Tsiakis stated that “it was never agreed to mortgage all properties for the securing of funds as the valuation on property to be mortgaged was only thirty percent of the funds required”. Again, even assuming that the evidence of Mr Papoutsakis as to the circumstances in which he signed the Loan Approval is accepted, this evidence only corroborates that evidence, namely that Mr Papoutsakis did not agree to mortgage all four properties. The critical questions are (a) which version of the Loan Approval was submitted to PCS, and (b) what discussions might the broker have had with PCS about the scope of the security to be provided. The evidence that the broker might have given, at least to the extent foreshadowed by Mr Papoutsakis, cannot establish that PCS ever received a copy of the page of the Loan Approval listing the four properties, with three properties ruled through, and bearing the names or signatures of Mr Papoutsakis and Ms Papoutsakis above the list of properties.

64 In addition, much of the Draft Notice of Appeal includes proposed grounds of appeal that seek to advance collateral attacks on the conduct of the Trustee rather than focusing on potential errors in the reasoning of the primary judge in determining not to annul the bankruptcy of Mr Papoutsakis. The collateral attacks on the Trustee included claims that the Trustee was attempting to sell properties at an undervalue, had unnecessarily prolonged the sale of properties, had acted in a careless and incompetent manner, had sworn a false affidavit and had incurred unnecessary costs and expense in his administration of the bankrupt estate of Mr Papoutsakis. These collateral attacks were principally made in proposed appeal grounds 1, 7(d), (e), (f) and (h), 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 31, 32 and 35.

65 Contrary to the proposed grounds of appeal, many of the matters in the Draft Notice of Appeal were in fact considered by the primary judge. For example, allegations that Mr Papoutsakis’ legal representatives had acted negligently as stated in proposed appeal ground 2(a) were considered at J [9] and allegations that several unsecured creditors were “firmly disputed” in the Supreme Court of Tasmania, corporate entities were the parties principally responsible for the debts and Mr Papoutsakis was “merely” a guarantor (proposed appeal ground 9) were considered at J [3], [13] and [36].

66 Other matters sought to be raised in the Draft Notice of Appeal were not contentious or did not concern evidence which was advanced before the primary judge. These include allegations that the tax invoice issued by PCS was invalid as the supplying entity was not registered for GST (proposed appeal ground 2(d)), Ms Papoutsakis would have paid all creditors over 3 years ago from her share of the matrimonial assets (proposed appeal ground 12), the primary judge should have found, in his discretion, that Mr Papoutsakis would have been entitled to 50% of the matrimonial assets (proposed appeal ground 33), there was an agreement reached between Ms Papoutsakis and the “lender” (proposed appeal ground 43(F)) and an amount of $252,000 superannuation was paid to the Australian Taxation Office in 2016 (proposed appeal ground 43(G)).

67 The remaining grounds of appeal were not the subject of any substantive submissions by Mr Papoutsakis. They appeared on their face not to contain cogent grounds of appeal nor identify error on issues that the primary judge was required to determine. In addition, some appeared to assume incorrect or incomprehensible legal propositions, such as that the Trustee did not allow Mr Papoutsakis any money to engage a solicitor which is alleged to be a “gross denial of natural justice” (proposed appeal ground 30), the primary judge failed to exercise “his discretion on all the facts in making [an/the] order annulling the bankruptcy” (proposed appeal grounds 34 and 47) and the primary judge “erred on all the facts to consider the assets available to the appellant as they fell due” (proposed appeal ground 46).

Conclusion

68 I am satisfied for the foregoing reasons that it is not in the interests of justice to grant an extension of time in which to appeal from the orders made by the primary judge. In my view, Mr Papoutsakis has not provided an adequate explanation for his delay in filing the application for leave to appeal but even if he had, the proposed grounds of appeal do not have reasonable prospects of success.

69 The Application is to be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding sixty-nine (69) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Halley. |

Associate: