FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fair Work Ombudsman v DTF World Square Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2023] FCA 201

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties agree upon orders giving effect to these reasons.

2. The matter be listed for case management of the remaining questions at 9:30am on 6 April 2023.

3. There be liberty to apply on two (2) days’ notice.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KATZMANN J:

1 This proceeding concerns numerous alleged contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (Regulations) by two related companies operating restaurants in Sydney and Melbourne which trade under the name “Din Tai Fung” (DTF). The two companies, DTF (World Square) Pty Ltd (DTF (WS)) and Selden Farlane Lachlan Investments Pty Ltd (Selden), are members of the DTF group of companies. A glossary of select terms appears at the end of these reasons.

2 The Fair Work Ombudsman (Ombudsman) alleges that the two companies (the Employers) contravened several provisions of the FW Act. The alleged contraventions arose out of the Employers’ practices of paying employees below award rates and of keeping false or misleading records with the apparent object of concealing the underpayments. Some of the alleged contraventions are said to be “serious contraventions” within the meaning of s 557A of the FW Act.

3 The Ombudsman considers that three individuals were involved in many or all of the alleged contraventions and in her original pleading alleged that each had therefore also contravened the FW Act. The Ombudsman was unable to serve the first of these individuals, Dendy Harjanto (the third respondent), and discontinued the proceeding against him. The remaining two, who are the fourth and fifth respondents respectively, are Hannah (aka Vera) Handoko and Sinthiana (aka Sinthia) Parmenas.

4 The case relates to a particular cohort of employees. The employees in question (the Employees) worked at restaurants in Sydney and Melbourne during the period from 6 July 2014 to 30 June 2018 (the contravention period). With one exception, the contraventions are alleged to have taken place in the period 5 November 2017 to 30 June 2018 (the assessed period). The exception relates to one employee, Guoyong (aka Jet) Liu. The contraventions affecting him allegedly occurred during the period 6 July 2014 to 5 May 2018 (the Liu period).

5 The Ombudsman seeks declaratory relief and orders that the Employers pay compensation to the Employees together with interest and superannuation contributions on behalf of them to their nominated superannuation funds. She also seeks orders that the Employers, Ms Handoko, and Ms Parmenas pay pecuniary penalties.

6 This judgment is concerned with the question of liability only. An order was made on 21 September 2021 that the question of liability be determined separately from all other questions arising in the proceeding.

7 On 18 May 2022, after the Ombudsman served her evidence, the time within which the respondents were required to file and serve their evidence had expired, and after hearing dates had been fixed, both DTF (WS) and Selden went into voluntary liquidation. Leave to proceed against them was granted last year: Fair Work Ombudsman v DTF World Square Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 724. The liquidators chose not to defend the proceeding. Consequently, the only active respondents were Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas. They did not challenge or contest the Ombudsman’s case against the Employers. And, although they vigorously resisted the making of adverse findings against them, they elected not to give evidence.

8 The Ombudsman read affidavits from eight witnesses, only three of whom were required for cross-examination.

9 Those witnesses who were not required for cross-examination were:

(1) Luke Russell Thomas, a Fair Work Inspector, employed as an Assistant Director in the Compliance and Enforcement Group in the Office of the Ombudsman, who supervised the investigation between 15 January 2019 and 4 June 2020;

(2) Melvin Paul, a lawyer in the Office of the Ombudsman and a former Fair Work Inspector;

(3) Peter Richter, a Taskforce Investigator for the Large Corporates Branch in the Compliance and Enforcement Group of the Office of the Ombudsman and a Fair Work Inspector;

(4) Ronnie Wong, an Assistant Team Leader in the Calculations Team in the Ombudsman’s Office; and

(5) Monica Zhang, a Fair Work Inspector.

10 Mr Thomas deposed to the course of the investigation, including site visits and requests for production of documents. Most of the documentary evidence was exhibited to his first affidavit (Ex LRT-1). Exhibit LRT-1 included documents produced to the Ombudsman by the Department of Home Affairs and by the Employers themselves. Mr Paul deposed to an interview he attended with another Fair Work Inspector (FWI), FWI Colalancia, and Ms Parmenas. Ms Zhang deposed to an interview conducted by two other FWIs and Mr Harjanto on 9 October 2019 at which she was present. Mr Richter deposed to a site visit he undertook at the Head Office of DTF (WS) on 12 December 2017. Mr Wong calculated the amounts of the alleged underpayments.

11 The witnesses who were required for cross-examination were Qiyin Lin, Mr Liu, and Anthony Tandra.

12 Ms Lin and Mr Liu are former employees of DTF (WS). Mr Tandra was employed by DTF (WS) as a payroll officer from 11 July 2016 until about March 2018. His main responsibility was to process the fortnightly payroll for each of the companies in the DTF Group. I gave Mr Tandra a certificate under s 128 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act), which prevents the evidence the subject of the certificate from being used against him in any proceeding in an Australian court, save for a criminal proceeding related to the giving of false evidence.

13 As the Ombudsman submitted, the cross-examination did not challenge the veracity of their evidence (or, for that matter, its reliability). Indeed, in some respects the cross-examination confirmed and advanced their evidence.

14 Before DTF (WS) and Selden went into liquidation, the parties agreed on some facts and a statement of agreed facts was admitted into evidence.

15 The respondents adduced no evidence. Two affidavits filed by the respondents in May 2022 were not read.

16 Any respondent is entitled to remain silent. That said, however, in a civil case, the unexplained failure of a party to give evidence or call witnesses may lead to an inference that the missing evidence or absent witness would not have assisted that party’s case: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 308 (Kitto J); 312 (Menzies J); and 321 (Windeyer J). The Court may take that circumstance into account in deciding whether to accept particular evidence that relates to a matter on which the absent witness could have spoken: JD Heydon, Cross on Evidence (13th ed., LexisNexis, 2021) at [1215]. Moreover, in a civil case evidence the witness might have contradicted can be accepted more readily if the respondent fails to give evidence: Jones v Dunkel at 312 (Menzies J); and 321 (Windeyer J); RPS v The Queen (2000) 199 CLR 620 at [26] (Gaudron A-CJ, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). And any inference favourable to the other party for which there is a foundation in the evidence can more comfortably be drawn: Jones v Dunkel at 308 (Kitto J); and 312 (Menzies J). It does not matter that the party who could have called the evidence does not bear the burden of proof. As Rich J put it in Insurance Commissioner v Joyce (1948) 77 CLR 39 at 49, “when circumstances are proved indicating a conclusion and the only party who can give direct evidence of the matter prefers the well of the court to the witness box a court is entitled to be bold”.

17 A Jones v Dunkel inference cannot fill gaps in the evidence and cannot convert conjecture or suspicion into inference: Jones v Dunkel at 313 (Menzies J). But, if the inference is drawn, it can “weigh the scales, however slightly, in favour of the opposing party”: Adler v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2003] NSWCA 131; 21 ACLC 1810; 46 ACSR 504; 179 FLR 1 at [649] (Giles JA, with whom Mason P and Beazley JA agreed at [1] and [2] respectively).

18 Moreover, as Heydon observed in Cases and Materials on Evidence (Butterworths, 1975) at 62:

[A] party’s failure to give any satisfactory explanation of a prima facie case against him may suggest that the case is sound, either because silence is assent — an implied admission, or because it shows a consciousness of guilt or liability, or because inferences from the prima facie case, being unchallenged, are thereby strengthened. The presumption is the stronger where the facts are particularly within his knowledge.

19 Here, none of the respondents offered an explanation for their failure to give evidence or call witnesses. The fact that this is a proceeding for a pecuniary penalty is not a satisfactory explanation: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; 41 ACSR 72; 20 ACLC 576; 168 FLR 253 (ASIC v Adler) at [504] (Santow J); appeal dismissed in Adler at [664]–[669]. As counsel for Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas accepted, reliance on the penalty privilege does not prevent the Court from drawing an adverse inference. Only a witness can invoke the privilege against self-incrimination and then only under oath or affirmation: Chong v CC Containers Pty Ltd (2015) 49 VR 402 at [236] (Redlich, Santamaria and Kyrou JJA).

20 Having regard to the positions Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas held in the companies and the fact that they were parties to the proceeding, the absence of evidence from them is particularly significant. As Street J observed in Dilosa v Latec Finance Pty Ltd (1966) 84 WN (Pt 1) (NSW) 557 at 582, in a passage cited by Santow J in ASIC v Adler at [448]:

The inference which a Court can properly draw in the absence of a witness, where such absence is not satisfactorily accounted for, is that nothing which this witness could say would assist the case of the party who would normally have been expected to have called that witness. The significance of this inference differs according to the closeness of the relationship of the absent witness with the party against whom the inference is sought to be propounded. Where the absent witness is a party himself then considerable importance may well attach to the inference. Similarly, the inference is significant if the absent witness is, as in the present case, a person who … was personally engaged in the transactions in question and who was in fact present at Court during part of the hearing …

21 Much of the Ombudsman’s evidence was uncontroversial. It is convenient at this point to set out some of those uncontroversial facts.

22 The following matters were either agreed or not disputed.

23 At all material times both DTF (WS) and Selden were “constitutional corporations” within the meaning of s 12 of the FW Act and “national system employers” within the meaning of s 14 of the Act. They were among a number of “related entities” within the meaning of s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), operating restaurants in Australia under the “Din Tai Fung” brand.

24 At all material times DTF (WS) employed people to work at three restaurants, specialising in Taiwanese food. The restaurants were located at Shop 1104 World Square Shopping Centre, 664 George Street, Sydney (World Square Restaurant); the Emporium Shopping Centre, Level 4, 287 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne (Emporium Restaurant); and at Westfield Shopping Centre, Level 3, 1 Anderson Street, Chatswood NSW (Chatswood Restaurant). Each of the three restaurants provided sit-down services with meals primarily intended for consumption within the restaurants’ premises.

25 At all such times DTF (WS) also employed people in an office at 15 Shirlow Street, Marrickville where administrative, human resources and payroll management functions were performed on behalf of the DTF Group (DTF Head Office).

26 Mr Harjanto was a director of DTF (WS) and Selden throughout the relevant periods. All the evidence indicates that he was at the apex of the management of the restaurants.

27 Ms Handoko was the General Manager of the DTF Group and DTF (WS) at this time.

28 Ms Parmenas worked for the DTF Group as HR Coordinator or HR Manager. She informed FWIs Colalancia and Paul, and I accept, that she started in February 2015.

29 The following matters were agreed.

30 DTF (WS) employed the following employees (DTF (WS) Employees) at least for the periods mentioned:

Guoyong Liu from 6 July 2014 to 5 May 2018 (the Liu period);

Eliyani Eliyani from 17 November 2017 to 2 June 2018;

Ery Ery for the assessed period;

Kenny Kenny for the assessed period;

Qiyin Lin from 5 November 2017 to 2 June 2018;

Renpeng Liang for the assessed period;

Rong Xue for the assessed period;

Santy Kam for the assessed period;

Tingli Qiu from 5 November 2017 to 19 May 2018;

Wynne Elysia Wijaya for the assessed period;

Yovika Tonang Toe for the assessed period; and

Zhizi Xu from 5 November 2017 to 30 December 2017.

31 Selden employed the following employees (Selden Employees) for at least the following periods:

Henghui Chen from 5 November 2017 to 10 February 2018;

Meng Joo Low from 5 November 2017 to 21 December 2017;

Nianna Chandra Goi for the assessed period;

Tu Dat Huy for the assessed period; and

Yinhu Zheng for the assessed period.

32 Each of the Employees was a “national system employee” within the meaning of s 13 of the FW Act.

33 At all material times, Mr Liu, Mr Kenny, Ms Lin and Ms Xue (Full-time Employees) were employed pursuant to written employment contracts with DTF (WS) that included a term that the employee’s contracted hours would be based on a weekly cycle of 38 hours. Each of the Full-time Employees was resident in Australia on a visa sponsored by DTF (WS).

34 During the assessed period, Ms Eliyani, Mr Ery, Mr Liang, Ms Kam, Ms Qiu, Ms Wijaya, Ms Toe, Ms Xue and all of the Selden Employees (collectively, the Casual Employees) worked hours which varied each fortnight; did not have reasonably predictable hours of work; worked without a firm advanced commitment by their employer as to their days or hours of work; did not receive any paid annual leave or personal leave; and did not have a written part-time agreement with DTF (WS). The Selden Employees worked at the Emporium Restaurant.

35 The Employers paid the Employees on a fortnightly basis. In certain fortnights during the contravention period, each of the Employers made “adjustments” to the total amount paid to the Employees during that fortnightly pay period.

36 Before 6 May 2018, DTF (WS) paid the wages of the Full-time Employees (with the exception of Mr Liu) each fortnight using a combination of electronic funds transfer (EFT) and cash. DTF (WS) paid Mr Liu’s wages each fortnight using a combination of EFT and cash, but on at least one occasion paid him solely by cash, and on other occasions, paid him solely by EFT. After 6 May 2018, DTF (WS) paid the Full-time Employees’ wages each fortnight solely by EFT.

37 Before 22 April 2018, the Employers paid the Casual Employees’ wages each fortnight by a combination of EFT and cash, solely in cash or solely by EFT. After this time, wages were paid each fortnight solely by EFT.

38 The only Employees who gave evidence were Mr Liu and Ms Lin. I make the following findings based on their unchallenged evidence.

39 Mr Liu was employed by DTF (WS) from about March 2011 to 5 May 2018. When he started, he was a student and worked about two or three days a week as a kitchen hand. He was later promoted to supervisor and became the second-in-charge of the kitchen at the World Square Restaurant. After he completed his studies, DTF (WS) sponsored him for a subclass 457 visa (a temporary work visa for employees of approved employers for up to four years). DTF (WS) arranged for him to receive training from Culinary Solutions Australia and on 10 March 2014 he acquired Certificates III and IV in Asian Cookery. He was given an employment contract dated 13 March 2014 in which his position was described as “cook”. His base salary was recorded as $58,240, payable monthly in arrears. His hours of work were said to be “based on a weekly cycle of 38 hours with applicable benefits being calculated on those hours”. The contract was signed by Ms Handoko and Mr Liu.

40 That same year, a new DTF restaurant opened at Greenwood Plaza in North Sydney. Mr Liu was appointed head of the back kitchen and was responsible for managing staff there. Later that year (no later than 6 July 2014), he moved to the Chatswood Restaurant where he filled the same role. In that position he supervised kitchen staff, cooked food, prepared rosters and oversaw food preparation to the required standards of the DTF business. He also interviewed and trained new staff.

41 Despite the terms of his contract, Mr Liu was told by both Ms Handoko and Kitty Li (sometimes misspelt as “Lee”), the manager of the Chatswood Restaurant, that as “sponsored staff” he had to work 55 hours a week. Mr Harjanto told him the same thing. Mr Liu was also given to understand that he should not take more than one day off a week. Both Ms Li and Ms Handoko told him he had to work additional hours when he included more than one day off per week in his schedule. This was because, unless he worked six days, he could not meet the 55 hour requirement.

42 Mr Liu found it “hard and tiring” to work the long hours required of him. He said the restaurants in which he worked were very busy and there were often “lots of customers” waiting in line. As he was not meant to have more than one day off a week, he was not able to spend time with his family and young son. He struggled during this time. He found it “really stressful” and felt like he was “selling [himself] for the job”.

43 As I mentioned earlier, Mr Liu was paid using a combination of EFT and cash. Each fortnight when he was paid the cash portion of his salary, he signed a form called a Staff Received Payment (SRP) form. Sometimes it was Ms Handoko who handed him the cash in an envelope and had him sign the SRP form. At other times, it was Ms Li or Ms Parmenas.

44 Mr Liu was not paid extra for working overtime, evenings, split shifts, weekends or public holidays.

45 Mr Liu’s employment came to an end as a result of an email he sent to Ms Parmenas and Ms Handoko on 1 May 2018, while the Ombudsman’s investigation was under way. The same month he made a complaint to the Ombudsman about his working conditions.

46 While the email did not offer an explanation for his departure, in his affidavit Mr Liu indicated that it occurred in the following circumstances. When his four year contract was due to expire, Ms Handoko told him “face to face” that his application for sponsorship (for permanent residency) had been approved but on “one condition”, namely, that he “must work for DTF for 10 more years”. She went on to say:

The salary remains unchanged but not all of the weekly salary is given to you. I want to leave part of it in the company to make sure that you don’t quit without PR [permanent residency]. This is Dendy’s decision. Other sponsored staff accept this agreement.

47 Shortly after a visit from “Fair Work”, staff from the Chatswood Restaurant including Mr Liu attended a video conference with Mr Harjanto. During that meeting Mr Harjanto said words to the following effect:

All the leaders: you can’t put the timetable on the wall. Only the leader can see the files. They can’t be public for all staff so they can’t take photos.

48 Around the same time Ms Li directed Mr Liu not to make the schedule (roster) public. She told him that it needs to be kept “somewhere that only we can see it”. She continued:

When Fair Trading [presumably she meant the Fair Work Ombudsman] come we have to lie to them. The working hours for the student can’t be more than 20 hours per week.

49 Ms Lin began working for DTF (WS) in October 2010 as a casual employee while on a student visa. She worked in the kitchen at the World Square Restaurant and occasionally helped out at other “stores”. Like Mr Liu, Ms Lin later acquired a subclass 457 visa, sponsored by DTF (WS) who paid for her to participate in a course following which she obtained Certificates III and IV in Asian Cookery from Culinary Solutions Australia. Ms Lin signed an employment contract dated 9 April 2014 and became a Full-time Employee. Her position was described as “cook”. Her base salary was recorded as $54,340, payable monthly in arrears. Her hours of work were said to be “based on a weekly cycle of 38 hours with applicable benefits being calculated on those hours”. The contract was signed by Ms Handoko and Ms Lin. According to a letter sent by Ms Handoko to the “457 visa section” of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection on 16 May 2014, Ms Lin would be required to work side by side with the other cook at the World Square Restaurant.

50 From about the middle of 2014 Ms Lin occupied the position of Front Kitchen Leader at DTF’s Greenwood restaurant in North Sydney. She was responsible for managing the quality of the food at the restaurant. She supervised and directed more junior staff, prepared food, and arranged rosters for other restaurants. During the assessed period, Ms Lin was working as the Front Kitchen Leader at the Emporium Restaurant in Melbourne. In that role she cooked food and supervised and directed kitchen staff.

51 Ms Lin was paid a salary, part of which was paid into her bank account (by EFT) and the balance was paid in cash, usually every second Friday. Ms Xue (known as Rita) was a “store manager” at the Emporium Restaurant when Ms Lin worked there and she paid her the cash component of her salary.

52 Although her contract recorded that she would be working 38 hours per week, at around the time she was sponsored for the visa she was told by Doddy Doddy (Ms Parmenas’s predecessor as HR manager) that she needed to work 55 hours a week. In around February 2018, after the investigation by the Ombudsman had commenced and the first site visit had taken place, the hours Ms Lin was required to work changed to 50. She normally worked weekends and public holidays. Her evidence as to the requirement to work first a 55 hour week and later a 50 hour week is corroborated by WhatsApp message exchanges involving Mr Doddy (until around 20 May 2016) and Mr Tandra exhibited to her affidavit on 30 November 2015, 24 January 2018, and 21 February 2018. Ms Lin deposed that the same number was used by DTF’s payroll and HR staff.

53 At times Ms Lin worked in excess of 55 hours a week but was not paid for the excess hours. Nor was she given time off in lieu.

54 The parties agreed that the Restaurant Industry Award 2010 (Restaurant Award) covered and applied to both DTF (WS) and Selden, that each of them fell within the definition of the “restaurant industry” in cl 3.1 of the Restaurant Award, and that the Employees performed work within the classifications listed in Schedule B of the Restaurant Award.

55 Mr Tandra gave evidence, among other things, about the payroll system and the record-keeping practices of the DTF Group, including the roles played by Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas. The resolution of a number of issues in the case largely turns on Mr Tandra’s evidence. The evidence itself was uncontroversial. The only controversy concerned a finding the Ombudsman asked the Court to make, based in part on that evidence.

56 Mr Tandra struck me as an honest witness. No suggestion to the contrary was put to him in cross-examination or advanced on behalf of the active respondents in submissions. There is no reason why I should not accept his evidence and I do. I make the following findings based on that evidence.

57 Ms Parmenas was Mr Tandra’s immediate supervisor. When he started work for DTF (WS) Mr Tandra received (verbal) instructions from Ms Parmenas about how to operate DTF’s payroll system and the process he was to follow in administering the payroll. In cross-examination, Mr Tandra said that he took over the payroll job from Ms Parmenas. Mr Tandra sat next to Ms Parmenas in the open plan office and they often spoke to each other during the working day. On more than one occasion, Ms Parmenas assisted Mr Tandra with his payroll duties by entering data into the system herself. Although Ms Handoko was her immediate supervisor, Ms Parmenas also reported directly to Mr Harjanto.

58 The payroll process included making records regarding the hours worked by, and amounts paid to, employees.

59 The records included both accurate and inaccurate records.

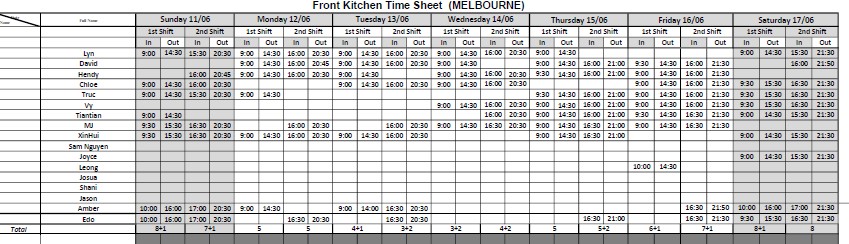

60 At the beginning and end of each working day and at the beginning and end of each break from work, the employees were required to scan their fingerprints into fingerprint scanning machines (fingerprint scanners) at the restaurants in which they worked. Provided the employees remembered to scan in and out at the right time, the machine would record the times their shifts and breaks started and finished.

61 The first step in processing the payroll was downloading the timesheet records from the fingerprint scanners (fingerprint timesheets). The fingerprint timesheets recorded the hours and times worked by employees. Ms Tandra then created a copy of the Excel file that contained all the fingerprint timesheets and SRP forms from the previous pay run and from that document created a new Excel file for use in the new pay run. He inserted the data he had downloaded from the fingerprint scanners into this new Excel file, making only formatting adjustments so that the data was more easily legible and comprehensible. He then calculated the wages payable to the employees based on the employees’ hourly rates of pay or fortnightly salaries, which were drawn from an Excel document on the DTF Head Office system called the Master Payroll document.

62 If Mr Tandra detected what seemed to be errors in data downloaded from the fingerprint scanners to the fingerprint timesheets, such as a significant difference between the hours worked and the rostered shifts or the failure to record a break, his practice was to contact the store manager or staff member directly. If he was informed that the employee in question had forgotten to sign out or to record a break, Mr Tandra would obtain the details of the break or sign-out times and amend the record of hours worked on the fingerprint timesheet. From time to time, managers would independently contact Mr Tandra by email to let him know that the data in the fingerprint scanners needed to be corrected and he would make the corrections. If the maximum time allowed for breaks was 10 minutes, he would insert a break of that length unless otherwise authorised by the store manager or employee concerned. He never altered an entry generated by the fingerprint scanners without first confirming the correct times with them.

Staff Received Payment Forms (SRP forms)

63 The second step in the payroll process was the creation of the SRP forms. The SRP forms recorded the total hours worked by employees each fortnight, the total amounts paid to employees in a fortnight, and the components of the total paid by EFT and in cash. Once these forms were generated, they were provided to the relevant store manager, who was responsible for asking each of the Employees to sign the form once they had been paid. The signed forms were returned to DTF Head Office.

The ADP and MYOB Payroll Systems

64 The third step in the payroll process was the creation of records using the payroll software systems used by DTF. When he began working for the DTF business in July 2016, the software that was used was provided by the company known as ADP. Between September and December 2017 DTF switched from ADP to MYOB.

65 Throughout the time he worked for DTF, in accordance with Ms Parmenas’s instructions and following her example, Mr Tandra would enter hours into the payroll systems that were different from those the employees actually worked. As he explained it:

The Payroll System Hours for the full-time employees were 76 hours per fortnight regardless of how many hours they actually worked. I used this number because it was the practice I was told by Sinthia [Parmenas] when I started at DTF. I don’t remember how the Payroll System Hours for the casual employees were determined, but I do recall that they were less than the hours the causal employees would actually work.

When I used the ADP Payroll system, my practice was to download an ADP Payroll sheet and insert the Payroll System Hours into it, rather than the number of hours the employee in fact worked.

When I used the MYOB payroll system, my practice was to insert the Payroll System Hours into the system directly.

66 During the time DTF used the ADP payroll system, Mr Tandra also generated ADP e-timesheets and when the business switched to MYOB, MYOB e-timesheets. The hours set in these documents were not correct as they recorded the Payroll System Hours rather than the hours actually worked by the employees.

ADP payroll journals and MYOB pay run summaries

67 The information in the e-timesheets was used to create ADP payroll journals and MYOB pay run summaries. Mr Tandra’s practice was to cause these documents to be generated from the payroll system each fortnight. They contained the same errors as the e-timesheets. Consequently, neither the hours worked nor the hourly pay rates recorded in them were correct. Regardless of the hours they actually worked, casual employees were paid the hourly rates set out in the Master Payroll and full-time employees were paid the fortnightly salary set out in that document. Further, in fortnights in which employees were paid a “balance” amount in cash, the “TAX INC”, “GROSS” and “NET” (or in the case of the MYOB pay run summaries the “Gross” and “Take Home”) amounts shown in these records were incorrect as they did not include the amounts paid in cash to the employees. The payroll software did not calculate tax payable on the “balance” amounts paid in cash to employees.

68 The above errors were replicated in the pay slips as they contained the information that Mr Tandra, and at times Ms Parmenas, had entered into the ADP or MYOB software. The ADP pay slips were posted to the DTF Head Office by ADP for distribution to employees. The MYOB pay slips were generated electronically and were either sent to employees by email or accessed by the employees logging onto MYOB themselves.

69 Mr Tandra’s evidence about the false information in the pay slips was corroborated by Mr Liu and Ms Lin.

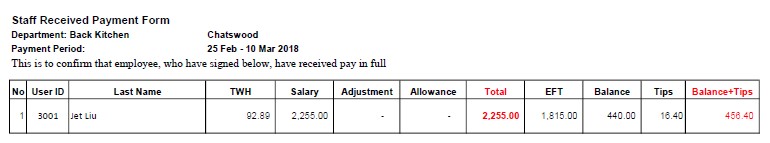

70 Mr Liu deposed that the hours on the pay slips did not match the hours he actually worked and the payments they recorded did not correspond to the payments he received. He pointed, by way of example, to a pay slip he received for the period 25 February to 10 March 2018 (Ex GL-1 p 54), which recorded that:

he was paid a normal hourly rate of $29.96 although he was not paid by the hour but was paid a flat salary that did not change according to the hours he worked;

he worked 76 hours that fortnight when his SRP form for the same period (Ex GL-1 p 56) shows that he worked 92.89 hours; and

he received take home pay of $1,815 which corresponds to the amount in the EFT column of the SRP form but ignores the amounts he was paid in cash, which are recorded in the “Balance+Tips” columns of the SRP form.

71 This is the pay slip:

72 In contrast, this is the SRP form for the same period:

73 Mr Liu explained that “TWH” refers to total working hours, “EFT” to the amount transferred to his bank by electronic funds transfer, and the “Balance” to the remaining part of his salary that he would be paid separately in cash. “Balance+Tips” was the total amount of cash that he received during the pay period. He said it was “the standard practice” that the “Balance+Tips” were paid in cash.

74 Mr Liu deposed that with rare exceptions, throughout the time he worked at DTF the SRP forms appeared to accurately reflect the hours he worked and the amounts he was paid. He said that sometimes staff for whom he was responsible complained that some of their hours had not been recorded in their SRP forms. In those cases, Mr Liu would check the schedules and, if he agreed, he or the staff member would send a message to Ms Parmenas or Ms Li to have the form corrected. He added that no-one ever suggested that too many hours had been recorded on a SRP form in relation to any employee.

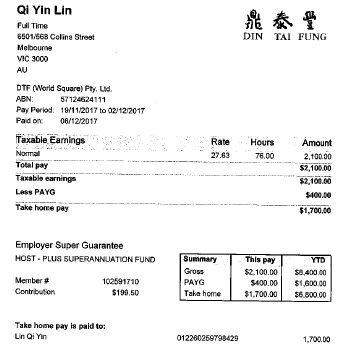

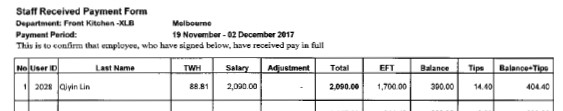

75 Ms Lin also deposed that the information in the pay slips was not correct in that they did not record the hours she actually worked and the amounts recorded were different from the amounts she received. She offered as an example a pay slip bearing her name for the period 19 November to 2 December 2017 (Ex QYL-1 p 129), which recorded that:

her normal hourly rate was $27.63 when she was not paid per hour but a flat salary that did not change according to the hours she worked;

she worked 76 hours that fortnight when her SRP form for the same period (Ex QYL-1 p 114) shows that she worked 88.81 hours; and

she received take home pay of $1,700 which corresponds to the amount in the EFT column of the SRP form but ignores the amounts she was paid in cash, which are recorded in the “Balance+Tips” columns of the SRP form.

76 This is the pay slip:

77 In contrast, this is what the SRP form showed for the same period:

78 After Mr Tandra had been working at DTF “for a little while”, each fortnight, before the employees were paid, he prepared a payroll report and provided it to Ms Parmenas, who would then hand it to Ms Handoko to review. The payroll reports included the SRP forms.

79 At some stage, there was a change to the process of approving the payroll such that every pay run had to be approved by Mr Harjanto.

80 Throughout the time Mr Tandra worked for DTF, the business paid its employees’ wages using a combination of EFT and cash.

81 Once the payroll records had been created, unless Ms Parmenas told him otherwise, Mr Tandra would process the employees’ EFT payments for the EFT amounts in the SRP forms.

82 The employees received the rest of their wages in cash. The process, as described by Mr Tandra, was as follows. Each fortnight, Mr Tandra took enough cash to pay the employees from the Head Office to each of the Sydney stores. He carried it with him in a backpack. He visited seven stores in a day, travelling around Sydney from store to store by train. The amount varied each fortnight from about $160,000 to $200,000. The cash was divided into bundles, with one bundle for each store. Mr Tandra would hand over the amount of cash owing to the employees of that store to each store manager for distribution. On occasions, he and Ms Parmenas would share the burden, dividing the cash and restaurants between them. In a telephone interview with FWI Colalancia on 10 July 2019, attended by FWI Paul and an Indonesian interpreter, Ms Parmenas reported that until August 2018 she processed the cash payments by taking the cash to the stores for the store managers to distribute. She said that Frendy Frendy, the accountant for the DTF Group, would give her the cash and she would put it into envelopes and drop them off at the stores.

83 Mr Tandra deposed that DTF would also make pay as you go (PAYG) withholding payments on behalf of the employees.

84 Mr Tandra testified that Mr Frendy would liaise with someone in the Emporium Restaurant in Melbourne to distribute the cash portion of the salaries to employees there.

85 Cross-examination was brief. At no point was it put to Mr Tandra that any aspect of his evidence was false. Mr Tandra confirmed that employees were being paid the wrong amounts and that he knew that the records he was generating were incorrect. He said that the system was in place when he started with DTF.

86 Pursuant to s 712 of the FW Act, FWIs Hunter and Paul served a number of notices to produce on DTF (WS), Selden, and Safford Farris Kieran Investments Pty Ltd (Safford), another entity in the DTF Group. The notices were issued on 29 March 2018, 10 September 2018, and 3 December 2018. They required the production of records or documents relating to the employment of 22 employees (including the 17 the subject of this proceeding).

87 The records produced in response to those notices included the SRP forms, documents entitled “Payroll $” (payroll tables) which included records of the Payroll Hourly Rates and the Payroll Salaries, and Westpac online banking records entitled “Payment Details” which recorded the amounts paid to the employees by EFT each fortnight (Westpac EFT receipts). It was an agreed fact that these documents accurately record what they purport to record.

88 The records produced also included pay slips, ADP payroll journals, ADP and MYOB e-timesheets, and MYOB pay run summaries. The pay slips and ADP payroll journals purport to record the rates of remuneration paid to the Employees (reg 3.33(1)(a)) and the loadings and penalty rates paid to the Employees (reg 3.33(3)). The pay slips, ADP payroll journals and MYOB pay run summaries purport to record the gross and net amounts paid to the Employees (reg 3.33(1)(b)). The pay slips, ADP and MYOB e-timesheets, and the ADP payroll journals also purport to record the hours worked by the Casual Employees (reg 3.33(2)). The Ombudsman contends that these records contained information that was false to the knowledge of the respondents.

THE BURDEN AND STANDARD OF PROOF

89 Before going any further, I should say something about the burden and standard of proof.

90 Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas submitted that “it is clearly a matter for the [Ombudsman] to persuade the Court as to each of the contraventions having regard to the level of proof or confidence required in Briginshaw v Briginshaw [(1938) 60 CLR 336] and s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995”. They argued that “findings as to a contravention of the [FW Act] are not findings lightly to be made”, citing Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Hall [2017] FCA 274; 269 IR 1 at [20] per Flick J. So much may be accepted.

91 With one qualification, the burden of proof rests with the Ombudsman. The qualification relates to the contraventions alleged to have taken place on and from 15 September 2017 when s 557C of the FW Act commenced. Section 557C shifts the burden of proof to the employer in a proceeding relating to a contravention by an employer of certain civil remedy provisions of the Act in circumstances in which, relevantly, the employer was required to make and keep records or to give a pay slip and, absent a reasonable excuse, the employer failed to comply with the requirement. The provision reflects a legislative policy that an employer should not be able to take advantage of its failure to make or keep certain records to defeat a claim that it has underpaid its employees, see for example: Gallagher v AAG Labour Services Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1753 at [18] (Jackson J).

92 Section 557C relevantly provides as follows:

Presumption where records not provided

(1) If:

(a) in proceedings relating to a contravention by an employer of a civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (3), an applicant makes an allegation in relation to a matter; and

(b) the employer was required:

(i) by subsection 535(1) or (2) to make and keep a record; or

(ii) by regulations made for the purposes of subsection 535(3) to make available for inspection a record; or

(iii) by subsection 536(1) or (2) to give a pay slip;

in relation to the matter; and

(c) the employer failed to comply with the requirement;

the employer has the burden of disproving the allegation.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply if the employer provides a reasonable excuse as to why there has not been compliance with subsection 557C(1)(b).

(3) The civil remedy provisions are the following:

(a) subsection 44(1) (which deals with contraventions of the National Employment Standards);

(b) section 45 (which deals with contraventions of modern awards);

…

(j) any other civil remedy provisions prescribed by the regulations.

93 As Colvin J explained in Ghimire v Karriview Management Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 1627; 290 IR 331 at [14], it is the legal, not merely the evidential, burden of proof which shifts to the employer:

Section 557C provides for more than an evidentiary burden on the defaulting employer when it comes to an absence of records. It is not a mere reversal of the evidentiary onus. Further, it is not a provision, for example, that operates to deem a matter to be proved in the absence of evidence to the contrary. In such cases, an issue may arise as to whether the obligation is to adduce some evidence which raises a genuine issue as to whether the matter occurred or whether the burden of disproving the matter falls on the party who disputes the matter. Rather, s 557C states expressly that the defaulting employer bears the burden of disproving the allegation. It is a provision concerned with the overall burden of proof.

94 Thus, as his Honour went on to say at [16], if the evidence adduced by the employer is insufficient to disprove the allegation on the balance of probabilities, then the effect of s 557C is that the claim must be upheld.

95 A contravention of a civil remedy provision is not an offence: FW Act, s 549. A court is required to apply the rules of evidence and procedure for civil matters when hearing proceedings relating to a contravention: FW Act, s 551. The standard of proof in a civil matter is proof on the balance of probabilities. The strength of the evidence necessary to discharge the burden may vary according to what is sought to be proved: Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd (1992) 67 ALJR 170 at 171 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ). Thus, in deciding whether that standard has been met, s 140 of the Evidence Act requires a court to take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject matter of the proceeding; and the gravity of the matters alleged. Section 140 is, in effect, an enactment of some of the principles explained by Dixon J in Briginshaw at 361–2:

Except upon criminal issues to be proved by the prosecution, it is enough that the affirmative of an allegation is made out to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. But reasonable satisfaction is not a state of mind that is attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved. The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. In such matters “reasonable satisfaction” should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences.

96 In Neat Holdings at 171 the plurality observed that authoritative statements have often been made to the effect that clear, cogent or strict proof is required where so serious a matter as fraud is to be found. Referring to Briginshaw at 362, their Honours emphasised that such statements are not to be understood as directed to the standard of proof. Rather, they are to be understood as a reflection of “a conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct” and a judicial approach that a court should not lightly find a party to civil litigation guilty of such conduct.

97 The Ombudsman identified five “threshold issues” arising from the pleadings:

(1) whether the conduct and the states of mind of Mr Harjanto, Ms Handoko, Ms Parmenas, Mr Tandra and any other payroll officer/s are attributable to the two companies as pleaded at [9] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC);

(2) whether the Employees performed work at the restaurants and in the roles and duties pleaded in the FASOC [12];

(3) whether the Employees fell within the Restaurant Award classifications set out in the “Classification” column of Annexure A to the FASOC (FASOC [26]);

(4) whether the Employers calculated the amounts payable to the Employees and paid the Employees on the basis pleaded at [16]-[19] of the FASOC (relating to the hourly rates for the Casual Employees and the Payroll Salaries for the Full-time Employees, PAYG withholding rates, and different rates); and

(5) whether the fingerprint timesheets accurately recorded the following information:

(a) the times the Employees scanned into work and scanned out of work;

(b) the total hours the Employees worked in a day, and in a fortnight;

(c) in respect of the Casual Employees, an hourly rate of pay;

(d) an amount described as “Total Pay” for the fortnight; and

(e) the component of the “Total Pay” amount paid by EFT.

Is the conduct and state of mind of each of Mr Harjanto, Ms Handoko, Ms Parmenas, Mr Tandra and any other payroll officers attributable to DTF (WS) and Selden?

98 The answer to this question is yes. That is the effect of s 793 of the FW Act, which, at all material times relevantly provided as follows:

Liability of bodies corporate

Conduct of a body corporate

(1) Any conduct engaged in on behalf of a body corporate:

(a) by an officer, employee or agent (an official) of the body within the scope of his or her actual or apparent authority; or

(b) by any other person at the direction or with the consent or agreement (whether express or implied) of an official of the body, if the giving of the direction, consent or agreement is within the scope of the actual or apparent authority of the official;

is taken, for the purposes of this Act and the procedural rules, to have been engaged in also by the body.

State of mind of a body corporate

(2) If, for the purposes of this Act or the procedural rules, it is necessary to establish the state of mind of a body corporate in relation to particular conduct, it is enough to show:

(a) that the conduct was engaged in by a person referred to in paragraph (1)(a) or (b); and

(b) that the person had that state of mind.

Meaning of state of mind

(3) The state of mind of a person includes:

(a) the knowledge, intention, opinion, belief or purpose of the person; and

(b) the person’s reasons for the intention, opinion, belief or purpose.

…

(5) In this section, employee has its ordinary meaning.

99 Thus, the liability of a body corporate depends on the conduct in which its officers, employees or agents engaged (provided it is within the scope of their actual or apparent authority) and their conduct is taken for the purposes of the FW Act to have been engaged in also by the body corporate. Further, if it is necessary to establish the state of mind of the body corporate, it is sufficient to show that a particular officer, employee or agent had that state of mind. In other words, s 793 operates so that the conduct and state of mind of an officer, employee or agent of a body corporate are attributed to the body corporate for the contravention concerned. See Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (The Bruce Highway Caloundra to Sunshine Upgrade Case) (2020) 281 FCR 365 at [45]–[46] (Reeves and O’Callaghan JJ).

100 Having regard to the work they performed, Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas were either employees or agents of DTF (WS) and agents of Selden, Mr Tandra was an employee of DTF (WS) and an agent of Selden, and any other payroll officers were at least agents of DTF (WS) and Selden.

Did the Employees in question perform work at the restaurant and, if so, did they perform the roles and duties pleaded?

Did the Employees fall within the pleaded classifications in the Restaurant Award?

101 In their defences the respondents denied that the Employees performed work at the three restaurants and that they performed the roles and duties pleaded by the Ombudsman. In the statement of agreed facts the respondents admitted that the Employees were employed by the relevant employer during the alleged periods and that the Employers employed the Employees to perform work at their restaurants. But they denied that the Employees performed work at the particular restaurants and in the roles and duties pleaded.

102 The nature of the work they are alleged to have performed was described in a table in Annexure A to the FASOC. I have broken up the table to separate the Employees of the two companies and elevated Mr Liu to the first row of the DTF (WS) table:

Table A: DTF (WS) Employees

Employee | Restaurant | Role and duties | Qualifications | Award classification |

Guoyong Liu | World Square Chatswood | Cook Head of the kitchen at the Chatswood Restaurant. Responsible for supervising kitchen staff, cooking hot food (such as noodles, wok based dishes and soups) and overseeing the preparation of dishes to the DTF Group’s required standards and specifications. | Certificate III and Certificate IV in Asian Cookery from Culinary Solutions Australia dated 10 March 2014 | B.3.8 Cook grade 5 (tradesperson) |

Eliyani Eliyani | World Square | Front of House Staff Taking customers’ orders, serving food and beverages, preparing itemised cheques and accepting payments. Sometimes performing additional duties such as escorting customers to tables, serving customers seated at counters and setting up and cleaning tables. (Wait Staff Duties) | N/A | B.2.2: Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Ery Ery | World Square | Cook Cooking hot food such as noodles, wok based dishes and soups. Preparing all of the ingredients for these dishes to the DTF Group’s required standards and specifications. Managing incoming orders and effectively prioritising all of his tasks (Cook Duties). | N/A | B.3.4: Cook grade 1 |

Kenny Kenny | Emporium | Restaurant Manager Coordinating daily restaurant operations, including food delivery and service, maximizing customer satisfaction and responding efficiently and accurately to customer complaints. (Restaurant Manager Duties) | Diploma of Leadership and Management from International Institute of Leadership and Management dated 12 October 2015 | B.2.5 Food and beverage supervisor – Level 5 |

Qiyin Lin | Emporium | Cook Supervising and directing kitchen staff preparing food. Checking the food produced to ensure it meets the DTF Group’s required standards. | Certificate III and Certificate IV in Asian Cookery from Culinary Solutions Australia dated 10 March 2014 | B.3.7 Cook grade 4 (tradesperson) |

Renpeng Liang | World Square | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | N/A | B.2.2: Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Rong Xue | Emporium | Restaurant Manager Restaurant Manager Duties | Diploma of Management from iBN College dated 16 September 2012 Advanced Diploma of Management from iBN College dated 17 March 2013 Certificate IV in Accounting from Australian Ideal College dated 27 October 2014 Diploma of Accounting from Australian Ideal College dated 15 December 2014 | B.2.5: Food and beverage supervisor –Level 5 |

Santy Kam | World Square | Dumpling Maker Leader Supervising and directing staff who are preparing dumplings. Checking each of the dumplings staff produce to ensure they meet the DTF Group’s required standards. | N/A | B.3.4 Cook grade 1 |

Tingli Qiu | World Square | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | N/A | B.2.2: Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Wynne Elysia Wijaya | World Square | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | N/A | B.2.2: Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Yovika Tonang Toe | World Square | Dishwasher Assisting in dishwashing area and ensuring that all of the utensils and plates are washed and clean. | N/A | B.3.1 Kitchen attendant grade 1 |

Zhizi Xu | World Square | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | N/A | B.2.2: Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Table B: Selden Employees

Employee | Restaurant | Role and duties | Qualifications | Award classification |

Henghui Chen | Emporium | Cook Cook duties | Certificate IV in Commercial Cookery | B.3.6 Cook grade 3 (tradesperson) |

Meng Joo Low | Emporium | Dumpling maker Making dough, filling and wrapping dumplings, steaming food and deep frying food. | N/A | B.3.4 Cook grade 1 |

Nianna Chandra Goi | Emporium | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | N/A | B.2.2 Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

Tu Dat Huy | Emporium | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | Advanced Diploma of Hospitality from William Angliss Institute | B.2.4 Food and beverage attendant grade 4 (tradesperson) |

Yinhu Zheng | Emporium | Front of House Staff Wait Staff Duties | B.2.2 Food and beverage attendant grade 2 |

103 For the reasons set out below at [177]–[206], I am satisfied that the description of the roles and duties in Annexure A to the FASOC is an accurate summary and that, having regard to those matters and the extent, if any, of the Employees’ qualifications, the Restaurant Award classifications for which the Ombudsman contended are appropriate.

Did the Employers calculate the amounts payable to the Employees, and pay the Employees, on the basis pleaded at FASOC [16]-[19]?

104 In [16] of the FASOC the Ombudsman pleaded that DTF (WS) calculated the amounts payable to the Casual Employees on the basis of particular hourly rates (WS Payroll Hourly Rates) and the Full-time Employees on the basis of particular salaries (Payroll Salaries) and Selden did so on the basis of particular hourly rates (Selden Payroll Hourly Rates). In [17] the Ombudsman pleaded that the Employers withheld PAYG withholding amounts in certain fortnightly periods, which are listed in Annexure E to the FASOC. In [18] the Ombudsman pleaded that in certain fortnights during the contravention periods, set out in Annexures F and G, each of the Employers paid the Casual Employees for a different number of hours from those they in fact worked, made adjustments to the total amounts paid to the Employees during that fortnightly pay period, and paid the Casual Employees amounts in addition to the WS Payroll Hourly Rates and Selden Hourly Rates (collectively, the Payroll Hourly Rates). The actual amounts paid to the Employees were set out in [19].

105 The Payroll Hourly Rates and Payroll Salaries are contained in the Payroll Tables in Ex LRT-1, which were amongst the documents produced to the Ombudsman in response to the notices to produce. The rates contained in those documents are reproduced in the tables appearing at FASOC [16]. No objections were pressed with respect to this evidence and FWI Thomas was not cross-examined.

106 The evidence as to the PAYG withholding amounts pleaded at FASOC [17] is found in the pay slips, payroll reports, ADP payroll journals and MYOB pay run summaries for the Employees and, in Mr Liu and Ms Lin’s case, also in the PAYG payment summaries.

107 In any event, no objections were taken to the affidavit of Mr Wong in which he calculated the underpayments based on this evidence or to the methodology he employed and he was not cross-examined.

108 Since the evidence of FWI Thomas and Mr Wong was not challenged and was ultimately admitted without objection and there is no evidence to the contrary, there is no good reason why I should not accept it and I do.

Do the fingerprint timesheets accurately record the matters they purport to record?

109 There is a wealth of evidence to show that the Employees recorded their hours of work by the use of fingerprint scanning machines. Not only did Mr Tandra, Mr Liu and Ms Lin give evidence to this effect but other employees reported the same thing to Fair Work inspectors at site visits. On 12 December 2017, for example, Hui Wei, who was in charge of purchasing for the DTF business at that time, told FWI Richter on a visit to the DTF Head Office that actual hours worked were recorded by employees “clock[ing] in and out with a thumbprint”. Several other employees told him the same thing. FWI Richter took a photograph of a fingerprint scanner and photographs were also taken of fingerprint scanners at the Emporium Restaurant and the World Square Restaurant the same day. FWI Hunter’s notes of her interview with Ms Parmenas confirm that actual hours worked were recorded by “fingerprint[ing] all staff”.

110 All respondents disputed the accuracy of the fingerprint timesheets. Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas submitted that the fact that Mr Tandra transferred, and from time to time amended, the data produced by the fingerprint scanners meant that the fingerprint timesheets were not primary records of the hours worked by the Employees and the Court cannot have the requisite level of confidence in their accuracy. I reject that submission. The fact that Mr Tandra amended the data produced by the fingerprint scanners after checking with the restaurant managers does not mean that they were not primary records of the hours employees worked nor does it affect the reliability of the information contained in the fingerprint timesheets. The “Din Tai Fung Australia Rules”, exhibited to Mr Liu’s affidavit, required employees who forgot “to do the fingerprint” in accordance with the protocols, to report their omissions to their “department leaders” so that the information could be recorded. In the absence of any challenge to Mr Tandra’s evidence and any evidence to the contrary, the fingerprint timesheets are the best evidence of the matters they purport to record and the Court is entitled to give weight to them. The fact that Mr Tandra went to the trouble to check the accuracy of the data makes the information in the fingerprint timesheets more, not less, reliable.

RECORD KEEPING AND PAY SLIP CONTRAVENTIONS

111 Section 535 of the FW Act provides that:

Employer obligations in relation to employee records

(1) An employer must make, and keep for 7 years, employee records of the kind prescribed by the regulations in relation to each of its employees.

Note This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

(2) The records must:

(a) if a form is prescribed by the regulations—be in that form; and

(b) include any information prescribed by the regulations.

Note This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

(3) The regulations may provide for the inspection of those records.

Note: If an employer fails to comply with subsection (1), (2) or (3), the employer may bear the burden of disproving allegations in proceedings relating to a contravention of certain civil remedy provisions: see section 557C.

(4) An employer must not make or keep a record for the purposes of this section that the employer knows is false or misleading.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

(5) Subsection (4) does not apply if the record is not false or misleading in a material particular.

112 Subsections (4) and (5) and the note to subs (3) were inserted by the Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Act 2017 (Cth) (Protecting Vulnerable Workers Amendment Act) and commenced on 15 September 2017.

113 Regulation 3.44(1), which was repealed with effect from 21 December 2017, provided:

An employer must ensure that a record that the employer is required to keep under the Act or these Regulations is not false or misleading to the employer’s knowledge.

Note: Subregulation (1) is a civil remedy provision to which Part 4-1 of the Act applies. Division 4 of Part 4-1 of the Act deals with infringement notices relating to alleged contraventions of civil remedy provisions.

114 For the purposes of s 535(1), reg 3.31(1) provides that an employee record must be legible, in the English language, and in a form that is readily accessible to an inspector.

115 Regulation 3.33 provides:

Records—pay

(1) For subsection 535(1) of the Act, a kind of employee record that an employer must make and keep is a record that specifies:

(a) the rate of remuneration paid to the employee; and

(b) the gross and net amounts paid to the employee; and

(c) any deductions made from the gross amount paid to the employee.

(2) If the employee is a casual or irregular part-time employee who is guaranteed a rate of pay set by reference to a period of time worked, the record must set out the hours worked by the employee.

(3) If the employee is entitled to be paid:

(a) an incentive-based payment; or

(b) a bonus; or

(c) a loading; or

(d) a penalty rate; or

(e) another monetary allowance or separately identifiable entitlement;

the record must set out details of the payment, bonus, loading, rate, allowance or entitlement.

Note: Subsection 535(1) of the Act is a civil remedy provision. Section 558 of the Act and Division 4 of Part 4-1 deal with infringement notices relating to alleged contraventions of civil remedy provisions.

116 Regulation 3.34 provides:

Records—overtime

For subsection 535(1) of the Act, if a penalty rate or loading (however described) must be paid for overtime hours actually worked by an employee, a kind of employee record that the employer must make and keep is a record that specifies:

(a) the number of overtime hours worked by the employee during each day; or

(b) when the employee started and ceased working overtime hours.

Note: Subsection 535(1) of the Act is a civil remedy provision. Section 558 of the Act and Division 4 of Part 4-1 deal with infringement notices relating to alleged contraventions of civil remedy provisions.

117 Section 536 deals specifically with pay slips. It relevantly provides:

Employer obligations in relation to pay slips

(1) An employer must give a pay slip to each of its employees within one working day of paying an amount to the employee in relation to the performance of work.

Note 1 This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

…

(2) The pay slip must:

(a) if a form is prescribed by the regulations—be in that form; and

(b) include any information prescribed by the regulations.

Note 1: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

Note 2: If an employer fails to comply with subsection (1) or (2), the employer may bear the burden of disproving allegations in proceedings relating to a contravention of certain civil remedy provisions: see section 557C.

(3) An employer must not give a pay slip for the purposes of this section that the employer knows is false or misleading.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1)

(4) Subsection (3) does not apply if the pay slip is not false or misleading in a material particular.

118 Regulations 3.45 and 3.46 prescribe the form and content of the pay slips.

119 Regulation 3.45 provides that for s 536(2)(b), a pay slip must be in electronic form or hard copy.

120 Regulation 3.46 stipulates:

Pay slips—content

(1) For paragraph 536(2)(b) of the Act, a pay slip must specify:

(a) the employer’s name; and

(b) the employee’s name; and

(c) the period to which the pay slip relates; and

(d) the date on which the payment to which the pay slip relates was made; and

(e) the gross amount of the payment; and

(f) the net amount of the payment; and

(g) any amount paid to the employee that is a bonus, loading, allowance, penalty rate, incentive-based payment or other separately identifiable entitlement; and

(h) on and after 1 January 2010—the Australian Business Number (if any) of the employer.

(2) If an amount is deducted from the gross amount of the payment, the pay slip must also include the name, or the name and number, of the fund or account into which the deduction was paid.

(3) If the employee is paid at an hourly rate of pay, the pay slip must also include:

(a) the rate of pay for the employee’s ordinary hours (however described); and

(b) the number of hours in that period for which the employee was employed at that rate; and

(c) the amount of the payment made at that rate.

(4) If the employee is paid at an annual rate of pay, the pay slip must also include the rate as at the latest date to which the payment relates.

(5) If the employer is required to make superannuation contributions for the benefit of the employee, the pay slip must also include:

(a) the amount of each contribution that the employer made during the period to which the pay slip relates, and the name, or the name and number, of any fund to which the contribution was made; or

(b) the amounts of contributions that the employer is liable to make in relation to the period to which the pay slip relates, and the name, or the name and number, of any fund to which the contributions will be made.

Contraventions of s 535(4) of the FW Act and reg 3.44(1) – False or Misleading Records Contraventions

Pay slips

121 The Ombudsman pleaded (at FASOC [38]) that, at all material times before 6 May 2018, the pay slips produced with respect to the Full-time Employees recorded that those employees:

(1) worked different hours in total than they in fact worked;

(2) were paid an hourly rate of pay when in fact they were paid a flat fortnightly salary regardless of the hours they worked; and

(3) were paid particular gross and net payments which were inaccurate on each occasion the employees were paid partly in cash.

122 The Ombudsman also pleaded (at FASOC [39]) that at all material times before 25 March 2018, the pay slips produced with respect to the Casual Employees recorded that those employees:

(1) worked different (and fewer) hours than those they in fact worked;

(2) were paid base hourly rates of pay that:

(a) were higher than the Payroll Hourly Rates;

(b) from 5 November to 30 December 2017 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Hospitality Industry (General) Award 2010 (Hospitality Award) and from 31 December 2017 to 25 March 2018 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Restaurant Award; and

(c) were different from the rates they were actually paid;

(3) were paid penalty rates of pay for hours worked on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays that from 5 November to 30 December 2017 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Hospitality Award and from 31 December 2017 to 25 March 2018 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Restaurant Award; and

(4) were paid particular gross and net payments, which were inaccurate on each occasion when the Casual Employees were paid amounts in cash.

123 The Ombudsman alleged (at FASOC [40]–[42]) that:

(1) the ADP e-timesheets produced in the period from 5 November to 2 December 2017 recorded that the Selden Employees worked fewer hours than they in fact worked;

(2) the ADP payroll journals produced in respect of Mr Liu in the period before 7 October 2017 recorded that Mr Liu:

(a) worked different hours from those he in fact worked;

(b) was paid an hourly rate of pay, when he was in fact paid a flat fortnightly salary regardless of how many hours he worked; and

(c) was paid particular gross and net payments which were inaccurate on each occasion when Mr Liu was paid amounts in cash.

(3) the ADP payroll journals produced in respect of the Selden Employees in the period 5 November 2017 to 27 January 2018 recorded that the Selden Employees:

(a) worked fewer hours than they in fact worked;

(b) were paid base hourly rates of pay that:

(i) were higher than the Selden Payroll Hourly Rates;

(ii) from 5 November to 30 December 2017 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Hospitality Award and from 31 December 2017 to 27 January 2018 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Restaurant Award;

(iii) were different from the rates they were actually paid;

(c) were paid penalty rates of pay for hours worked on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays that from 5 November to 30 December 2017 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Hospitality Award and from 31 December 2017 to 27 January 2018 were consistent with the hourly rates of pay specified in the Restaurant Award, when those penalty rates were not in fact paid; and

(d) were paid particular gross and net payments which were inaccurate on each occasion that the Selden Employees were paid amounts in cash.

124 The Ombudsman alleged (at FASOC [43]–[46]) that:

(1) at all material times before 6 May 2018 the MYOB e-timesheets produced with respect to the Full-time Employees recorded that they worked different hours from those they actually worked;

(2) at all material times before 25 March 2018 the MYOB e-timesheets produced with respect to the Casual Employees recorded that they worked fewer hours than they actually worked;

(3) at all material times before 6 May 2018 the MYOB pay run summaries produced with respect to the Full-time Employees recorded that they were paid particular gross and net payments which were inaccurate on each occasion they were paid amounts in cash.

(4) at all material times before 22 April 2018 the MYOB pay run summaries produced with respect to the Casual Employees recorded that they were paid particular gross and net payments which were inaccurate on each occasion they were paid additional amounts in cash.

125 For the reasons set out above, the Ombudsman claims that the pay slips, ADP records and MYOB records (the inaccurate records) were false or misleading in material particulars (FASOC [54]).

126 The Ombudsman alleged that the inaccurate records were created at the DTF Head Office and, where they relate to the same fortnightly pay period, were created by the same employees of the DTF group and in accordance with procedures approved, in part at least, by Ms Handoko, Ms Parmenas, Mr Tandra and/or other payroll officers. For the period from February 2015 to 30 June 2018, she alleges that the records were created by Mr Tandra and/or other payroll officers, under the supervision of Ms Parmenas. The Ombudsman alleges that the records made and kept in relation to Mr Liu and the DTF (WS) Employees were made and kept by DTF (WS) or an agent on its behalf and the records made and kept in relation to the Selden Employees were made and kept by Selden or by an agent on that company’s behalf.

127 The Ombudsman claimed that at all material times Mr Harjanto, Ms Handoko, Ms Parmenas, Mr Tandra and/or the payroll officers knew that these records were false or misleading and therefore so did DTF (WS) and Selden.

128 Consequently, she pleaded (at FASOC [57]–[59]) that:

(1) DTF (WS) contravened s 535(4) and reg 3.44(1) of the FW Act by knowingly making and keeping false or misleading records of:

(a) the rate of remuneration paid to the DTF (WS) Employees;

(b) the gross and net amounts paid to the DTF (WS) Employees;

(c) the hours worked by the Casual DTF (WS) employees; and

(d) the loadings and penalty rates paid to the Casual DTF (WS) employees.

(2) Selden contravened s 535(4) of the Act by knowingly making and keeping false or misleading records for the Selden Employees of:

(e) the rate of remuneration paid to the Selden Employees;

(f) the gross and net amounts paid to the Selden Employees;

(g) the hours worked by the Selden Employees; and

(h) the loadings and penalty rates paid to the Selden Employees.

129 I am satisfied that each of these allegations has been proved. The Employees were not paid the rates of remuneration, the gross and net amounts or the loadings and penalty rates recorded in the inaccurate records. Mr Tandra’s evidence in this respect was clear, unequivocal, unchallenged and undisputed. Mr Liu and Ms Lin confirmed critical aspects of it and their evidence was not disputed either. Further, it was an agreed fact that the SRP forms are accurate records. It necessarily follows that, to the extent that the information they contain differs from the information in the inaccurate records, these records are false and misleading. They represent that the Employees were paid amounts that they were not paid.

130 I also take into account the fact that Ms Parmenas and Ms Handoko and, for that matter, Mr Harjanto would have been in a position to contradict Mr Tandra’s account if it were false.

131 I find that the false and misleading records were created by Mr Tandra, an employee of DTF (WS) and an agent of Selden, on their behalf, within the scope of his actual authority and on instructions from his supervisor, Ms Parmenas. Mr Tandra knew they were false or misleading because he knew they were created using incorrect rates and incorrect working hours. By reason of s 793 of the FW Act, Mr Tandra’s conduct is also taken to have been engaged in by DTF (WS) and Selden and, in effect, his knowledge is attributed to them. It follows that DTF (WS) and Selden each knew that these documents were false and misleading. Since the false and misleading records continued to be produced after Mr Tandra left the employ of DTF, it is to be inferred that whoever took over his responsibilities maintained these practices.

132 Mr Tandra did not devise these practices. He followed Ms Parmenas’s instructions. When he started work for DTF Ms Parmenas instructed him on how to operate the payroll system and the process he was to follow in administering the payroll, which included the making of the false and misleading records. For the first month, she asked him to observe the process. From time to time, she helped him with the payroll. She told FWI Hunter that she was the person who created the employee records and that she processed the wages for the employees when Mr Tandra was away.

133 Having regard to s 793, the conduct and knowledge of Ms Parmenas is also attributed to the Employers.

134 For these reasons, I find that DTF (WS) and Selden each contravened s 535(4) and reg 3.44(1) as alleged.

Contraventions of s 535(1) of the FW Act

135 The second part of the Ombudsman’s claim with respect to record keeping is that the Employers failed to make and keep certain records in contravention of s 535(1) of the FW Act.

136 First, the Ombudsman alleged that at all material times before 22 April 2018 in respect of the Casual Employees and 6 May 2018 in respect of the Full-time Employees, during each fortnightly pay period in which each of the Employers paid an Employee by EFT and cash and remitted a PAYG amount on behalf of the Employee (identified in Annexure J to the FASOC), each of the Employers:

(a) failed to make and keep a record of the actual rates of remuneration paid to the employees, contrary to reg 3.33(1)(a), and

(b) the actual gross amount paid to them, contrary to reg 3.33(1)(b).

137 This allegation is made out. As the Ombudsman submitted, the records produced by the Employers do not include records of the actual rates of remuneration paid to the Employees as required by reg 3.33(1)(a) or the actual gross amounts paid to them as required by reg 3.33(1)(b) on each occasion in the relevant periods in which the Employees were paid by EFT and cash. The SRP forms only recorded the net amounts. The fingerprint timesheets, of course, only recorded the hours worked. While the Employers did make and keep records which purported to record the rates of remuneration and the gross and net amounts paid to the Employees, those records were false in that they purported to record that information but the information they recorded did not correspond to the rates or amounts actually paid.

138 Second, the Ombudsman alleged that, during the periods indicated below, DTF (WS) failed to keep a record of the net amounts paid to the following DTF (WS) employees:

(a) Ms Eliyani, from 3 December 2017 to 24 February 2018 (for which period no SRP forms or fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(b) Mr Ery, from 11 February to 24 February 2018 (for which period no SRP forms or fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(c) Mr Liu, from 30 July to 12 August 2017 and from 22 October to 2 December 2017 (for which periods no SRP forms, fingerprint timesheets or payroll tables were produced).

139 Third, the Ombudsman alleged that Selden failed to keep a record of the net amounts paid to Mr Dat Huy from 3 to 16 June 2018 (for which period Selden failed to produce SRP forms or fingerprint timesheets).

140 These allegations are also made out. Annexure I to the FASOC records, in tabular form, the pay slips, SRP forms, ADP and MYOB e-timesheets, payroll tables, ADP payroll journals, fingerprint timesheets, MYOB pay run summaries and Westpac EFT receipts produced by the Employers and/or Safford, indicating which were or were not produced for each fortnight. It was an agreed fact that the records were produced in those fortnights in which a cross appears in the table in Annexure I. In each of the periods listed above in relation to Ms Eliyani, Mr Ery and Mr Liu no cross appears, indicating that no records were produced in any of those periods. In an in-person interview with FWI Hunter at the DTF Head Office on 17 December 2021, Ms Parmenas was asked whether she had received records relating to cash payments made to employees that were signed by the employees who received the payments. Ms Parmenas replied that she had, “but not for several months”, and when FWI Hunter asked to see the records Ms Parmenas told her she had thrown them out.

141 As the Ombudsman further alleged, during the periods indicated below, the Employers failed to keep a record of the number of overtime hours worked each day by the Employees listed below and when they started and ceased working overtime hours:

(a) Ms Eliyani, from 14 January to 2 June 2018 (for which period no fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(b) Mr Ery, from 11 to 24 February 2018 (for which period no fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(c) Mr Liu, from 30 July to 12 August 2017 and 6 November to 2 December 2017 (for which period no fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(d) Ms Qiu, from 8 to 21 April 2018 (for which period no fingerprint timesheets were produced);

(e) Ms Wijaya, from 8 to 21 April 2018 (for which period no fingerprint timesheets were produced).