FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kite (Trustee), in the matter of Murray (a Bankrupt) v Murray [2023] FCA 198

ORDERS

ROBERT JOHN KITE AS THE TRUSTEE OF THE PROPERTY OF JAMES EDWARD MURRAY, A BANKRUPT Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 6 April 2023, the parties are to confer and provide draft orders to the Associate to Justice Raper giving effect to these reasons including in relation to the question of costs of the proceeding.

2. If the parties cannot agree on the form of proposed orders as contemplated by Order 1:

(a) by 6 April 2023 they are each to provide the Associate to Justice Raper with a form of proposed orders giving effect to these reasons including in relation to the question of costs, and submissions, not exceeding five (5) pages in length; and

(b) the proceeding will be listed on a mutually convenient date for a case management hearing in order to resolve the form of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RAPER J

[1] | |

[3] | |

[4] | |

[7] | |

[19] | |

[24] | |

[41] | |

[44] | |

The purchase of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties | [53] |

[58] | |

[75] | |

[92] | |

The status of the bankrupt’s business in the 2014 financial year | [96] |

[105] | |

[106] | |

How was the purchase of the North Balgowlah property funded? | [111] |

The evidence of the respondent and bankrupt regarding intention | [124] |

The beneficial ownership of the North Balgowlah property: Was it a mistake? | [134] |

The contributions made by the bankrupt to the Seaforth Mortgages in 2014 | [141] |

[146] | |

[146] | |

[157] | |

[164] | |

[188] | |

[198] | |

[207] | |

[213] | |

Operation of resulting trusts and the presumption of advancement | [213] |

[222] | |

[231] | |

[231] | |

Were there “transfers of property” from the bankrupt to the respondent? | [236] |

Would the property have been available or probably available to creditors? | [245] |

[251] | |

[255] | |

[256] | |

[261] | |

[266] | |

[278] |

1 The applicant, Robert John Kite (the trustee), is the trustee in bankruptcy of the estate of James Edward Murray (the bankrupt). The trustee was appointed on 25 September 2017 upon the filing by the bankrupt of a debtor’s petition pursuant to s 55 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth). Mellissa Beverley Murray (the respondent) is the wife of the bankrupt.

2 The trustee claims:

(a) a 50% beneficial interest in the property at 25B Serpentine Crescent, North Balgowlah, in the State of New South Wales (the North Balgowlah property), either on the basis of:

(i) Part VI, Division 4A of the Bankruptcy Act (the s 139DA claim); or

(ii) ordinary “purchase money resulting trust principles” (the resulting trust claim); or

(b) failing those, monetary claims secured by charge upon the North Balgowlah property in respect of the bankrupt’s cash applied towards the property’s purchase and as a result of transactions entered into between 11 April 2014 and 28 November 2014, pursuant to ss 120 and/or 121 of the Bankruptcy Act (the alternative voidable transaction claims).

3 By amended application filed on 14 October 2022, the trustee claims the following primary and alternative relief:

1. A declaration that the Respondent holds the legal title to 25B Serpentine Crescent, North Balgowlah (“the Property”) on trust for the Applicant and the Respondent in equal shares.

2. An order that the Respondent transfer a 1/2 interest in the Property to the Applicant.

3. An order pursuant to section 139A and/or section 139DA of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (“the Act”) that the respondent transfer to the Applicant 50% of the Property.

4. In the alternative to the relied [sic] sought in prayers 1-3 above, a declaration that the Respondent holds the legal title to the Property on trust for the Applicant and the Respondent in the proportions to which the Respondent and James Edward Murray (“the Bankrupt”) contributed to the total purchase price of the Property.

5. In the alternative to the order sought in prayer 2 above, an order that the Respondent transfer to the Applicant the portion of the Property determined by the Court to be held on trust for the Applicant.

6. Further to the relief claimed in prayers 1 to 5 above, an order pursuant to section 66G of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW), that the Trustee and Erwin Rommel Alfonso (“the 66G Trustees”) be appointed as trustees for the sale of the Property.

7. An order that the Property immediately vest in the 66G Trustees as trustees for sale.

8. An order that the 66G Trustees be authorised and empowered to offer the Property for sale and to sell the Property by public auction with the power to fix a reserve price or alternatively to sell the property by private treaty at the best available price.

9. The 66G Trustees are empowered to make all necessary adjustments of rates and taxes on settlement of the sale of the Property.

10. The proceeds of sale of the Property are to be distributed in the following manner:

(a) First, to the 66G Trustees’ costs and expenses, including legal fees, valuation fees, agents fees and commission and any other expenses, of effecting the sale of the Property;

(b) Second, to the remuneration of the 66G Trustees with respect to the sale of the Property and disbursement of the proceeds thereof;

(c) Thirdly, to the mortgagee’s debt secured over the Property; and

(d) Finally, the balance of the proceeds of sale to the Trustee and the Respondent in equal shares or such other shares as the Court may determine.

11. Liberty to the parties to apply on two days’ notice with respect to any matter arising out of the sale of the Property or the distribution of the sale proceeds.

12. In the alternative to the relief sought in prayers 1-11 above a declaration that the payment of $252,690.13 to the Respondent from the sale proceeds of the Bankrupt’s interest in property [sic] known as unit 305/97 Boyce Road Maroubra, and unit 505/747 Anzac Parade, Maroubra, in the state of New South Wales is void against the Applicant pursuant to section 120 and/or section 121 of the Act.

13. In the alternative to the relief sought in prayers 1-11 above an order that the Respondent pay the Applicant the sum of $252,690.13.

14. An order that the Respondent pay interest on the amount in prayer 13 from 3 September 2018 at the rates provided for pursuant to s51 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

15. An order that the Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of these proceedings.

16. An order that the Property be charged with the payment to the Applicant of any amount payable pursuant to prayers 13 and 14 above.

17. Such further or other order as the court sees fit.

(Emphasis in original.)

Interaction between the respective claims

4 It was difficult, at hearing, to decipher the trustee’s position regarding his respective claims. The trustee’s position ultimately appeared to be as follows:

(a) the s 139DA claim was his primary claim; and

(b) there was no need to consider his resulting trust claim if he succeeded on his s 139DA claim where the Court declared a 50% interest.

5 However, it was unclear as to what the trustee’s position was with respect to maintaining the alternative voidable transaction claims.

6 For the reasons which follow (and to the extent that was necessary for all claims to be decided) my conclusions with respect to each claim are as follows:

(a) the trustee succeeds on his s 139DA claim but only to the extent of a 11% beneficial interest in the North Balgowlah property;

(b) the trustee does not succeed on his resulting trust claim; and

(c) in the alternative, the trustee succeeds on his voidable transaction claims.

7 The parties’ agreed chronological facts reveal the following.

8 In 1999, the bankrupt and the respondent began paying their earnings into and paying expenses out of joint bank accounts. In 2000, the bankrupt and the respondent were married. Until 2015, the bankrupt was the primary income earner and the respondent the primary carer of their children.

9 Over the years, the bankrupt and the respondent acquired several properties in New South Wales prior to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property, some jointly but some separately. Specifically:

(a) in 1999, the property known as 12 Austin Street, Fairlight and being folio identifier 1/841427 (the Fairlight property) was purchased for $637,000 in the names of the bankrupt and respondent jointly. The purchase monies were obtained from Ms Beverley Dew (the respondent’s mother) in the sum of $200,000 and by way of loan from Collins Securities. The Fairlight property was sold in May 2003;

(b) in 2002, the property known as 606 Sydney Road, Seaforth being folio identifier 19/9521 (the Seaforth property) was purchased in the sole name of the respondent. The Seaforth property was sold in April 2016;

(c) in 2005, the property known as Unit 305/97 Boyce Road, Maroubra being folio identifier 35/SP74405 (the Boyce Road property) was purchased in the sole name of the bankrupt. The Boyce Road property was sold in April 2014; and

(d) in 2008, the property known as Unit 505/747 Anzac Parade, Maroubra being folio identifier 63/SP79763 (the Anzac Parade property) was acquired with the bankrupt as 99% legal owner and the respondent as 1% legal owner. The Anzac Parade property was sold in September 2014.

10 The circumstances concerning the purchase of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties assume relevance in these proceedings because it is the proceeds of the sale of those properties which the trustee claims constitute a significant part of the relevant “financial contributions” for the purpose of the s 139DA(a) claim, which support his claim regarding his beneficial interest in the later purchase of the North Balgowlah property (described at [14] below), and which also form part of the basis for the voidable transaction claims. The other relevant transfers for the voidable transaction claims also included various payments between April and November 2014 towards the four mortgages on the Seaforth property (the Seaforth Mortgages).

11 In the period between the purchase of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties, in July 2007 the bankrupt borrowed funds in the amount of $75,875 through ABL Nominees Pty Ltd to invest in an agricultural investment scheme known as the “Great Southern 2007 High Value Timber Project” (the Scheme), which led to the bankrupt owing what ultimately came to be the primary debt in his bankruptcy, being some $305,499.06 (as at 18 October 2017), to the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank (the Bendigo Debt).

12 During the period up to the critical property transactions in 2014, the following events unfolded with respect to the Scheme: On 1 May 2009, Great Southern appointed a voluntary administrator. In August 2009, the bankrupt defaulted upon the Bendigo Debt, and demands were made upon him shortly afterwards to pay the Bendigo Debt in October and November 2009. Rather than pay the Bendigo Debt, the bankrupt participated in a class action from about 2010 challenging his liability for the underlying debt – no material further payments were ever made, such that the balance of the Bendigo Debt kept increasing from then onwards. The trial of that class action occurred between October 2012 and October 2013. Sometime between October 2013 and July 2014 or before, the bankrupt spoke to either his financial planner or advisor about the hearing of the class action, and was told that the hearing “hadn’t gone well”, “wasn’t going well” or that “it didn’t look good”.

13 On 11 April 2014, the net proceeds of sale from the sale of the Boyce Road property (totalling $330,211.31) were paid to a joint account operated by the bankrupt and the respondent ending in #4777 (the Joint Account). On 30 June 2014, Apscore International Pty Ltd (the bankrupt’s company) recorded accumulated losses of $6,243,566.46. On 23 July 2014, a settlement of the class action was reached, substantially providing for a confirmation of the group members’ loan obligations.

14 Then, a matter of days later, on 4 August 2014, the bankrupt and the respondent exchanged the contract for the purchase of the North Balgowlah property (the sale price was $1.8 million). Both the bankrupt and the respondent were named on the contract as purchasers. By sale settling on 9 September 2014, the bankrupt and the respondent sold the Anzac Parade property realising $110,310.05 of net proceeds, which were paid into the Joint Account.

15 The purchase settled on 28 November 2014, at which time title to the North Balgowlah property was taken solely in the respondent’s name (the reasons for which are addressed later in these reasons when considering the trustee’s resulting trust claim).

16 The purchase price, and the other costs of the purchase, were paid by way of:

(a) drawings totalling $197,773.86 from the Joint Account; and

(b) $1.7 million borrowed from the Commonwealth Bank by way of a loan in respect of which both the bankrupt and the respondent were principal borrowers.

17 In the period between April and November 2014, $54,916.27 was applied in payment of the Seaforth Mortgages (which was solely for the benefit of the respondent given that property was solely in her name).

18 After the drawings from the Joint Account put towards the heavily mortgaged North Balgowlah property and the Seaforth Mortgages, the Joint Account was essentially exhausted and the bankrupt was denuded of his assets. When the Bendigo Bank further called upon the Bendigo Debt after the conclusion of the class action the bankrupt pleaded poverty and sought time. The bankrupt was then ultimately sued and, after attempting to defend the proceedings brought against him, declared bankruptcy on 25 September 2017.

19 The factual dispute concerns, first, the purported beneficial ownership of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties, which the trustee submits to be the source of the funds used to purchase the North Balgowlah property.

20 In this respect, the trustee contends that the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties were beneficially owned in accordance with their legal title (namely by the bankrupt solely or substantially).

21 The respondent contends that, while the legal title should be accepted as reflecting beneficial title in respect of the Seaforth and North Balgowlah properties (that is, the properties where she was the sole legal owner), the legal titles should be disregarded in respect of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties where the bankrupt was the sole or predominant owner, such that they should instead be viewed as beneficially owned by both her and the bankrupt equally.

22 The trustee contends that the respondent’s position should not be accepted, but even if it is accepted it does not change the conclusion that the bulk of the cash contributed to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property came from the bankrupt.

23 The factual dispute thereafter concerns the intention of the bankrupt as to the reason(s) for the sale of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties and their intention regarding ownership of the North Balgowlah property.

24 A series of affidavits have been filed in the proceeding which are listed as follows:

(a) Mr Kite, the trustee, made on 17 December 2021;

(b) Mrs Murray, the respondent, made on 6 April 2022; and

(c) Mr Murray, the bankrupt, made on 6 April 2022.

25 Each of the witnesses were cross-examined.

26 With respect to Mr Kite, it was my observation that he answered the questions asked of him truthfully. The apparent purpose of his cross-examination was to reveal certain limitations in his evidence. First, as to the absence of evidence and assumption made by him as to when the bankrupt knew when the Supreme Court of Victoria would deliver its judgment in the class action. Mr Kite conceded, contrary to his evidence, that there was no evidence of the trial judge indicating “at the time” that the proceedings concluded on 24 October 2013 that judgement would be delivered on 25 July 2014. Rather, according to the judgment of Judd J (in relation to applications made by the class action group members under ss 33KA and 33ZF of the Supreme Court Act 1986 (Vic): see Clarke v Great Southern Finance Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] VSC 569 at [3]) Croft J notified the parties “shortly before 25 July 2014” of his Honour’s intention to deliver judgment on that day. Secondly, Mr Kite accepted that he had not: (a) undertaken a detailed analysis of the other accounts identified by him as being held by the respondent and the bankrupt; (b) taken into account the fact that in April 2016, the proceeds of the sale of the Seaforth property were used to repay the Seaforth Mortgages and reduce the mortgages over the North Balgowlah property; and (c) did not factor into his analysis the contributions made by Ms Dew.

27 The respondent gave evidence. Her cross-examination was relatively brief. Her responses were curt and largely without explanation. The respondent is tertiary educated, holding a Bachelor of Human Movement Studies, a Graduate Diploma of Education, a Graduate Certificate in Religious Education and a Masters in Education in Career Development. It was apparent that she had had involvement in and made many decisions as to how her and the bankrupt’s assets were held and their affairs structured. Indeed, it was the bankrupt’s evidence that the respondent would have, on her own, given instructions to their solicitors when purchasing one of the properties.

28 I note that the trustee’s case does not depend upon an acceptance or rejection of the respondent’s evidence. The trustee does not challenge her honesty but does submit that the Court should not “unreservedly accept” the respondent’s evidence as to long-ago events, and should look to the contemporary materials, objectively established facts, apparent logic of events and the respondent’s past examination before the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) to best ascertain the truth. I am of the view that this is an appropriate approach to her evidence.

29 The bankrupt gave evidence and was cross-examined more extensively. The bankrupt’s responses were often difficult to understand, to reconcile with the evidence and inconsistent with other responses in his testimony. It appeared from my observation of the bankrupt during his evidence that the bankrupt wanted to ensure that to the extent that his wife may have deposed to conversations (different from his recollection) he did not want to contradict her but at the same time he sought to confuse the evidence and to not make any concession which he considered would assist the trustee’s case. It appeared implausible that a person who had conducted his own business for many years, held the position of a company director and employed 22 staff, would have such a limited recall as to his investment decisions and the structuring of his uncomplicated affairs.

30 In making findings regarding the bankrupt’s intention regarding the purchase and sale of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties and his intention regarding the use of the proceeds of their sale and purchase of the North Balgowlah property, much turns upon his credit. I have, in this respect, formed a view adverse to his credit. I will, therefore, before setting out my findings as to the facts relevant to the present proceedings set out the discrepancies in the bankrupt’s evidence. It will explain why I formed this view in addition to my observations of his demeanour in the witness box.

31 Only one affidavit sworn by the bankrupt was filed in the respondent’s case. However, the bankrupt had been examined by the AFSA, almost a year before, on 5 May 2021 (the examination) pursuant to a s 77C notice for which he was required to answer all questions truthfully and not avoid any questions: s 267G of the Bankruptcy Act.

32 A consideration of the bankrupt’s answers to the questions under examination, his affidavit evidence and his oral evidence revealed the following.

33 Curiously, the bankrupt deposed in his affidavit to having a recollection of a number of conversations many years ago, which he claimed a year earlier under the examination, he had no recollection of. For example:

(a) The bankrupt stated under examination that he could not remember any specific discussions about the ownership of the Fairlight property, yet at [14] of his affidavit claims to recall conversations with the respondent discussing that the Fairlight property was to be solely owned by the respondent.

(b) The bankrupt claimed, under examination, that he could not remember anything about the mistake on the contract for the North Balgowlah property, including any specific conversation about changing the names on the contract yet at [51]–[52] of his affidavit the bankrupt says he recalls the mistake on the contract and having a conversation with the respondent about making sure it was changed and instructing his solicitor to change it.

34 Similarly, under examination, the bankrupt was unable to recall a number of important matters but now deposes to having such a recall. For example, the bankrupt was unable to recall, during the examination, why the legal title to the Boyce Road property was in his sole name and the Anzac Parade property split 99:1 between him and the respondent, or any conversations to that effect. The bankrupt also stated that the legal title may have been done this way “for an accounting reason” but was not sure what that reason might have been, only that he would have had advice from lawyers or accountants but could not recall any meetings in that regard.

35 The bankrupt then deposed in his affidavit, a year after the examination, that he recalled seeking his accountant’s advice for the best taxation benefits available from the investment properties, that a “financial advisor” had suggested he buy an investment property and that he and the respondent had discussed owning them together. The bankrupt conceded in cross-examination that he only remembered the gist of these conversations and identified that the “financial advisor” referred to was probably a finance broker by the name of Gerard Hanson who had advised him, along with another person from Bright Wealth, in relation to the Scheme – a fact he could not recall at the examination.

36 There were further inconsistences as between the bankrupt’s affidavit evidence, the examination and the evidence he gave under cross-examination as to the purported reason for the bankrupt divesting the only substantial assets in his name in 2014, namely the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties.

37 The bankrupt deposed in his affidavit that he sold the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties for the following four reasons:

• Payment for one of [his] daughter’s wedding

• Payment of the O’Donnell settlement

• Payment of an overseas trip for [Ms Dew]

• Payment of school fees.

38 Yet, the previous year when under examination, the bankrupt had given two reasons for the sales only, namely to pay Mr O’Donnell and to fund renovations of the Seaforth property.

39 Perhaps what was the most significant, was the bankrupt’s oral testimony under cross-examination regarding the circumstances leading to his business’ decline and the extent of the acuteness of his financial stress in 2014. It was my strong impression that the bankrupt was attempting to obfuscate from the obvious. As will be seen at [99] below, the bankrupt’s 18 July 2015 statutory declaration paints a very different picture from the one the bankrupt is now seeking to create (as he claimed under cross-examination) that his business suffered a “gradual” not sudden decline.

40 Finally, I found it very difficult to reconcile the bankrupt’s lack of apparent recall for why he purchased the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties, his confused recall regarding the obtaining of advice regarding them and the tax treatment of the properties. At the time, the bankrupt had only those two investment properties, he is a sophisticated business man. He has repeatedly structured his affairs in the most tax beneficial way he can for himself. The evidence regarding this finding and related findings are dealt with more fulsomely below.

Conclusions as to the bankrupt’s credit and findings

41 Not all of the inconsistencies in the bankrupt’s evidence have been reproduced above. I accept that in part, the inconsistencies may be explained by the passage of time since the relevant events and the fact that during the relevant period the bankrupt was no doubt under significant stress and distress given the demise of his business, the failure of the Scheme and the mounting debt associated with it. What they reveal is at the very least his evidence is unreliable in the absence of corroborative documentary evidence or where it was against his interest.

42 However, I am of the view, that by reason of these findings, and for the reasons dealt with more fully below at [136], that the bankrupt did sell the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties or at least used $197,773.86 from those sales in the purchase of the North Balgowlah property so as to secure those monies from creditors.

43 Ultimately, however, I have approached the evidence, largely in a manner consistent with that urged upon me by the trustee, on the following bases:

(a) the bankrupt’s and the respondent’s evidence largely concerned dealings and conversations, between eight and 17 years before deposing to their evidence, principally based on the fallibility of their own memory rather than contemporary records;

(b) the Court should place primary emphasis on the objective factual surrounding material and the inherent probabilities, together with the documentation tendered in evidence, rather than the asserted recollections of witnesses; and

(c) the trustee, necessarily by not having involvement in any of the underlying dealings giving rise to the proceedings, is not able to adduce direct evidence of those matters and the Court must take that into account when the respondent seeks to make something of the fact that the trustee has not been able to adduce direct evidence of those matters.

44 It is necessary to consider the evidence in some detail to resolve the questions at issue.

45 For the reasons which follow, it is my view that the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties were beneficially owned in accordance with their legal title.

46 The agreed facts reveal a number of pertinent matters leading up to the purchase of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties. First, the bankrupt and the respondent, from 1999, paid their earnings into and expenses out of joint bank accounts. Secondly, from the time that they were married until 2015, the bankrupt was the primary income earner and the respondent the primary carer of their children and working part-time. Thirdly, over the years they acquired several properties, some jointly and some separately. For example, their first property bought together in 1999, the Fairlight property, was purchased in both their names and then three years later, in 2002 the Seaforth property was purchased solely in the name of the respondent.

47 The respondent and the bankrupt both gave evidence to the effect that this change in position regarding ownership reflected the fact that the purchase monies for the Fairlight property were obtained from Ms Dew, in the sum of $200,000 (which the respondent stated was a loan to her only), as well as a loan from Collins Securities. The bankrupt gave evidence of an undated conversation he had with his solicitor requesting that “he draw up a loan agreement or document to protect” Ms Dew’s loan and annexed to his affidavit an unexecuted mortgage document which he “believe[d]” reflected the loan agreement.

48 In 1999, the respondent was then 24 years’ old and the bankrupt 44 years’ old. The bankrupt had previously been married with two daughters to that marriage.

49 The respondent gave evidence that she had expressed an intention in 1999, that the Fairlight property “[had] to be [her] house, as it will be bought with money from [her] mum” and had been “worried about any claim [the bankrupt’s] children might make if [he] own[ed] it, particularly if [he] die[s]”. The bankrupt deposed to there being various conversations between them in about 1999 and thereafter regarding the purchase and the respondent being concerned to secure her interest in the property so as to avoid any testamentary claim by the respondent’s daughters from his former marriage. It was their unchallenged evidence that she was unable to secure a loan by herself, as at that stage the respondent had only been working for a year and as a consequence the title was required to be in both their names.

50 According to the respondent, her and the bankrupt then decided to purchase a bigger home to live in and bought the Seaforth property and then sold the Fairlight property. When the Fairlight property was sold, the respondent gave evidence that the bank took most of the money from the sale and her mother’s loan was not repaid which she knew of at the time “and felt bad about it”.

51 When the Seaforth property was purchased, it was in both the respondent’s and the bankrupt’s names. It was their respective unchallenged evidence that when the respondent initially saw the purchase contract it was in both their names and the respondent demanded a change. At some point, thereafter, at the respondent’s instigation, there was a change “in the name of the purchaser” to be solely hers. No evidence was adduced by either party of the contracts of sale, transfer documents nor loan documentation save for correspondence from L.G. Parker & Co solicitors in February 2002 to both the respondent and the bankrupt and in March 2002 to the respondent confirming settlement.

52 What this evidence reveals is that the respondent was intimately involved in the decisions regarding property ownership from the inception of their relationship and in particular concerning decisions regarding who would be placed on the title and what the effect of that would be, i.e., the respondent’s evidence was to the effect that with respect to the Fairlight and the Seaforth properties that she wanted them in her name for two reasons: (a) to reflect the contribution made by her mother; and (b) to preserve them from any claim made by the bankrupt’s children from his first marriage.

The purchase of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties

53 By contrast, three years after the purchase of the Seaforth property, in 2005 the Boyce Road property was purchased with the bankrupt as sole legal owner and then in 2008 the Anzac Parade property was acquired with the bankrupt as 99% legal owner and the respondent as 1% legal owner. Relevantly, in the intervening period, between the purchases of these two properties, in July 2007, the bankrupt borrowed funds in the amount of $75,875, through ABL Nominees Pty Ltd, to invest in the Scheme. This uncontested sequence reveals that over the period from 2005 to 2008 the bankrupt was investing in a number of different ventures for which he held solely or substantially the title.

54 The purchase of these two properties is relevant to the ultimate dispute between the parties because part of the sale proceeds of these properties is, on the trustee’s case, said to form the contribution to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property. Therefore, the determination of the beneficial ownership of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties is relevant to the trustee’s resulting trust claim against the North Balgowlah property, the trustee’s s 139DA claim as it is said to comprise the “direct or indirect” source of the financial contribution, and his ss 120 and 121 claims.

55 The contemporaneous documentary evidence relating to the purchase of both properties revealed that the bankrupt was represented by solicitors on both occasions, who it may be inferred acted upon his instructions and from which it can be inferred that to the extent his interest is reflected in the title of both properties, it reflected intentional thought and consideration. This is consistent with what the bankrupt said during the examination regarding how the title of the properties was determined, and that the bankrupt “would have” had advice from lawyers and accountants about determining the title of the properties (as outlined above at [34]).

56 The bankrupt was the sole mortgagor for the Boyce Road property. Whereas both the bankrupt and the respondent were mortgagors for the Anzac Parade property. Not much can be made of this as there was no contemporaneous mortgage documentation in evidence save for a letter from the bankrupt’s solicitor, dated 11 August 2005, to the solicitor for the vendor regarding the difficulties the bankrupt had had regarding obtaining finance and related delay. The bankrupt stated in the examination, in answer to questions regarding the mortgages of both properties, that “they were pretty much self-sufficient”.

57 Relevant to one’s consideration of what may be drawn from this documentary evidence is what may be drawn from past documentary evidence – as is evident from the purchase of the Fairlight and Seaforth properties, over time the bankrupt and respondent made conscious decisions putting the properties in their sole or joint names.

58 Evidence of the tax treatment of the properties was limited and in my view does not support the conclusion for which the respondent contends, namely that the legal title of both properties should be disregarded and that both properties should be viewed as beneficially owned by both the respondent and bankrupt equally.

59 There is no evidence of the properties’ tax treatment at the time of acquisition. The only tax returns regarding the properties in evidence were for the financial years ending 30 June 2010 – 2017. Therefore, there were no returns until five years after the purchase of the Boyce Road property and two years after the purchase of the Anzac Parade property. Those tax returns revealed a 50/50 split in the rental income/loss for both properties. The bankrupt also provided a calculation from his accountant regarding the capital gain for the Boyce Road property (purportedly split as between the respondent and the bankrupt).

60 Ultimately, I am of the view that little can be gained from the evidence regarding the tax treatment of the properties for the following reasons. First, the respondent and the bankrupt gave scant (and partly inconsistent) evidence as to their treatment at all. Secondly, there were no contemporaneous tax return records in evidence. Thirdly, there was contemporaneous documentary evidence that in 2005 and later in 2008 that legal title remained predominantly in the bankrupt’s name. Fourthly, as late as 2013, when applying to refinance their existing mortgage on the Seaforth property, the bankrupt and the respondent, when relying on both properties as security for the loan, describe them as being owned in a manner consistent with their legal title.

61 There was affidavit and oral evidence, including cross-examination on this issue.

62 The respondent gave affidavit evidence regarding her and the bankrupt’s intention with respect to the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties to the effect that it was intended that they were to be held jointly by them. As will be revealed, this evidence was very scant in detail and comprised largely recall without supporting contemporaneous documentary evidence. This evidence must be assessed within the context of the objective facts revealed by the documentary evidence.

63 In the respondent’s affidavit, the respondent gave evidence of an undated conversation between herself and the bankrupt that the impetus of the “investment” activity was her idea to save money for the education of their own children (where by 2004 the respondent had had the first of their three children). By contrast, the bankrupt’s evidence was that it was his “financial advisor” who had suggested “[he] buy an investment property” (emphasis added). However, the bankrupt changed his evidence regarding the same under cross-examination.

64 The respondent gave evidence of a conversation in 2005 where the bankrupt told her that he had found a property but that the “first one” would need to be in his name so he could “negatively gear it”.

65 The respondent then deposed to the following, in three short paragraphs, regarding the processes associated with the purchase of both properties:

29. I recall signing new mortgage documents for both Sydney Road and unit 305 Anzac Parade. The builder provided two different specifications for colours carpet and other items. I reviewed these and made the selections to complete the building.

30. In 2006 I gave birth to our second child.

31. In about April 2008 James and I inspected unit 505 in Boyce Parade, Maroubra. We purchased it. I was registered as a 1% owner. I recall James told me “The bank requires your name on title.” After it was acquired I again I [sic] spent some of my time selecting the internal finishes that the builder made available and I arranged for the inclusion of an internal wall that converted the study nook into a small bedroom. We were using Infinity Properties to manage the unit and they arranged the tradesmen to complete the internal wall.

66 Under cross-examination, the respondent maintained that the legal title of both properties reflected professional advice for negative gearing purposes, the bankrupt’s income was higher and his income funded the mortgage.

67 The bankrupt deposed to the following regarding the purchase of the two properties, though there was cross-examination regarding paragraph [34] (dealt with below):

34. In about 2004 or 2005 I recall that Mellissa and I had a discussion in words to the effect:

“My financial advisor has suggested that I buy an investment property. To do that there will be a need to use the equity from Sydney Road.”

Mellissa said words to the effect:

“Yes. We can own them together. It will be good to have investment property [sic] together.”

35. We looked at buying two units in Maroubra off the plan. We saw a display unit together. Mellissa chose the colours and floor coverings. The two units were in the same complex but had different street addresses. They were purchased a couple of years apart because one took longer to build than the other.

36. The first unit purchased was apartment 305 in Anzac Pde Maroubra. This was in 2005. I cannot now recall exactly why my name only was on the contract. Annexed hereto from page 11-12 of the Exhibit and marked JEM 1 is a true copy of the settlement sheet noting the payout of the then mortgage over Seaforth so that it could be used as security for the purchase of the Anzac Parade property in my sole name.

37. …I recall seeking my accountant’s advice for the best taxation benefits available from the investment properties.

38. A second investment property was acquired by Mellissa and I at Boyce Road Maroubra in about 2008. Annexed at page 13-16 of the Exhibit marked JEM1 is a true copy of my solicitors settlement letter and settlement sheet.

(Emphasis in original.)

68 Despite the bankrupt deposing to having a conversation with his wife in which he stated that his “financial advisor” had suggested that he “buy” an investment property, the bankrupt changed his evidence under cross-examination claiming that he had not had a financial advisor, he remembered only having a “broker” and a “general conversation”. This was in stark contrast with what the bankrupt had said in the examination previously, where he had stated:

MR MULLETTE: And Boyce Road was purchased in your sole name, wasn’t it?

WITNESS: Yes, I believe so.

MR MULLETTE: And was there a particular reason for that?

WITNESS: I don’t remember, but there must have been, otherwise we wouldn’t have done it. So it would have been advice from the lawyers or from – from the accountants.

MR MULLETTE: Right. Without asking you to tell us what that advice was, do you have a specific recollection of receiving advice from any lawyer or accountant?

WITNESS: No. I don’t have a specific recollection of any meeting or none of that.

MR MULLETTE: Okay. And would it have been the case that Mellissa might not have been working at that stage in March 2005?

WITNESS: Don’t remember.

MR MULLETTE: Don’t remember? Okay. And the payment of the mortgage on Boyce Road, do you remember where those funds came from other than the rent?

WITNESS: Just the rent.

MR MULLETTE: Just the rent?

WITNESS: As far as I know.

MR MULLETTE: If there was a shortfall, because it probably was negatively geared for at least a while, wasn’t it?

WITNESS: I don’t remember.

69 In addition, as can be seen from the above exchange, the bankrupt also changed his evidence in his affidavit from that in the examination. In the examination he claimed to have “no specific recollection of any meeting” with any lawyer or accountant and had no memory of the reason for why the Boyce Road property was purchased in his name, but then in his affidavit, he claimed that he “recall[ed] seeking [his] accountant’s advice for the best taxation benefits available from the investment properties”. To then state under cross-examination repeatedly that he had no memory of whether he “negatively geared” the Boyce Road property, and to say he “didn’t believe” that he had received advice that he should negatively gear it seems unlikely. It is not as though the bankrupt had an extensive, complex property or investment portfolio. These were the only two “investment properties” he had at that time. The bankrupt was a company director, who managed a staff of 22 employees. He could not be said to be unsophisticated.

70 Both the respondent and the bankrupt deposed in their evidence to conversations in which they discussed the purchase of “investment properties” and that they would “own them together”. However, it is clear that regardless of whether these conversations occurred, what happened subsequently, displaces that intention: The properties were purchased either entirely or predominantly in the bankrupt’s name. I do not accept that despite this, it remained their “intention” that they be held jointly.

71 First, the respondent gave clear evidence that the reason for the change was so that the bankrupt could obtain a negative gearing benefit. I accept that this is what happened. I do not accept the bankrupt’s evidence that the properties were not purchased in his name for “negative gearing” purposes. If negative gearing was the “intention” then it is clear that the respondent and the bankrupt intended that he own the property to obtain a tax minimisation benefit. Secondly, I do not accept that the true intention was that it be held “50/50”. It is not consistent at all with the respondent’s conduct with respect to other properties. If she had had that intention, she would have required that she be on the title (in a manner reflecting her intention) as she required with other properties. The bankrupt conceded that if the Boyce Road property had intended to be held equally, the title could have been in both their names equally. The respondent tendered no contemporaneous documentary evidence to support her position. Thirdly, with respect to the purported conversation that arose in the bankrupt’s affidavit (at [34]) his evidence was entirely unreliable. The bankrupt conceded that this evidence was incorrect in other material respects as set out at [34]–[35] and [67]–[69] above, and as such I have significant doubts about its accuracy. Fourthly, the bankrupt claimed, under cross-examination, that he intended the investment to be “for his kids”. This does not align with the investment being for them to hold together jointly and even if it did, by reason of my view as to his credibility, I do not accept it was the reason.

72 Ultimately, I am not persuaded by the respondent’s nor the bankrupt’s evidence in the face of the documentary evidence and a consideration of their past and future conduct: The evidence revealed that the bankrupt and the respondent made deliberate, conscious decisions, where they were represented by solicitors on each occasion with respect to acquisitions and their title. Each of them were involved in the process and the respondent had been vocal in the past (regarding the Fairlight and Seaforth properties) to ensure (if possible) that certain properties were in her name. In the context of the first of these transactions, the bankrupt had received advice from someone that it would be wise for him to purchase an investment property that he would own solely, on account of the negative gearing benefits. It was uncontroversial that the bankrupt’s income was significantly higher than the respondent’s at the time, which is consistent with the same. Both the Anzac Parade and Boyce Road properties were acquired in a manner consistent with that intention.

73 I hold the same view with respect to the acquisition of the Anzac Parade property for the same reasons, noting additionally: First, the apparent agreement between the bankrupt and the respondent that the respondent would only take a 1% interest so as to retain the maximum negative gearing benefit while satisfying the lender’s requirement. Secondly, this course was consistent with that involving both the Boyce Road property purchase and the bankrupt’s sole participation in the Scheme. Thirdly, all three investments were undertaken with tax minimisation partly in mind. Fourthly, the respondent’s evidence was largely consistent with that of the trustee’s case, whereby the respondent’s scant evidence revealed that it was necessary for her to be on the Anzac Parade property’s title due to a requirement of “the bank” (extracted at [65] above); the respondent agreed that she knew she would only take a 1% interest in the property and it was based on professional advice, agreed it was her understanding that the reason for the title being put in this way was because it would maximise the negative gearing benefits for the benefit of the bankrupt and where the respondent agreed that if she and the bankrupt had intended to be 50/50 owners instead of 99/1 owners, they could have easily registered the property’s title on that basis instead.

74 Accordingly, for these reasons, it is my view that the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties were beneficially owned in accordance with their legal title.

The sale of the Anzac Parade and Boyce Road properties

75 As set out at [13] above, the agreed facts revealed that:

(a) on 11 April 2014, the net proceeds of sale from the sale of the Boyce Road property (totalling $330,211.31) were paid to the Joint Account; and

(b) on 9 September 2014, the bankrupt and the respondent sold the Anzac Parade property realising $110,310.05 of net proceeds, which were paid into the Joint Account.

76 An important issue, on the trustee’s case, was why the properties were sold given as at 2014, they were the only substantial assets in the bankrupt’s name.

77 The respondent gave no affidavit evidence as to the circumstances of the sale of the two properties. She was not cross-examined at all about why they were sold. The only cross-examination relating to their sale was that the respondent conceded that the proceeds of their sale was deposited into the Joint Account.

78 As referred to above at [37], in the bankrupt’s affidavit evidence, he deposed that the circumstances in which the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties were sold were:

• Payment for one of [his] daughter’s wedding

• Payment of the O’Donnell settlement

• Payment of an overseas trip for [Ms Dew]

• Payment of school fees.

79 The respondent and the bankrupt advanced no evidence that any payments of the kinds referred to above were made from the proceeds of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties. Whilst there is a reference to a “Wedding Payment” in the bank statements, the respondent and the bankrupt did not provide further evidence to substantiate that this payment was made from the sale proceeds of the properties.

80 Under cross-examination, the bankrupt disputed that the reasons for their sale were because he was in a hard place financially despite conceding that was what he had said in the examination and that it was the truth. Inconsistently, as referred to above at [36]–[38], the bankrupt had claimed in the examination that they were sold to pay for renovations and to pay his former business partner, Mr O’Donnell. For the reasons which follow, I do not find his explanation for their sale at all satisfactory.

81 With respect to the alleged “renovations”, the bankrupt provided no plausible evidence as what the renovations comprised, when they were to occur, whether the bankrupt did in fact carry them out and what they cost. To the extent that there was any evidence, the bankrupt claimed in his affidavit evidence that renovations were made to the North Balgowlah property in 2016 (two years after the sale of the two assets). The Boyce Road property was sold in April 2014, the contract for the North Balgowlah property was not entered into until August 2014, four months after its sale and where in the examination the bankrupt conceded the renovation would have had to have been for the Seaforth property.

82 In the examination, the bankrupt stated the reason the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties were sold in 2014 was because he and the respondent “needed renovation money” and he needed to pay Mr O’Donnell roughly $240,000 (which as will be seen below at [88] was $225,000). The bankrupt said he and the respondent did not intend to sell the investment properties at that time but he was “pushed into a hard place”. The bankrupt stated that even with selling the properties he did not have enough money to pay Mr O’Donnell so he borrowed $100,000 from Ms Dew and in exchange he signed over his shares in Apscore to Ms Dew. The bankrupt could not recall how much the renovation cost but said it was at least more than a $100,000.

83 During cross-examination, the bankrupt confirmed what he had previously said about being “pushed into a hard place”, however, there was no further questioning by the trustee as to the bankrupt’s previous contention that the sale of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties was effected in order to pay Mr O’Donnell and cover renovation costs or that it was for the reasons he deposed to in his affidavit (see above at [37] and [78]). The bankrupt only said later during cross-examination that the proceeds of the properties went to “other things” and did not concede that any of the monies were used to fund the purchase of the North Balgowlah property.

84 Based on this evidence, it is not consistent with the bankrupt’s contention of the purpose of the sale of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties that a large amount of those proceeds went towards the purchase of the North Balgowlah property (rather than as the bankrupt contends, towards renovations).

85 Further, I am not convinced that the sale of the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties was for the purpose of repaying Mr O’Donnell pursuant to the O’Donnell settlement.

86 There was very limited contemporaneous evidence as to the terms of settlement and the payments made to Mr O’Donnell. The parties accepted that by way of Deed of settlement, the bankrupt settled litigation commenced by Mr O’Donnell against Grand Canyon Technologies Pty Limited (GCT), Apscore and the bankrupt.

87 At the time the Deed was drawn up, Mr O’Donnell and the bankrupt were directors and shareholders of GCT. Mr O’Donnell remained a shareholder of Apscore but ceased to be a director in December 2000. The bankrupt was then a shareholder and the sole director of Apscore.

88 The terms of the settlement provided that, by way of the following instalments, GCT was to repay the debt of $225,000 to Mr O’Donnell (for which Apscore guaranteed and indemnified the payments):

(a) $10,000 within 28 days of executing and exchanging counterparts of the Deed;

(b) $50,000 on or before 17 May 2013;

(c) $50,000 on or before 17 May 2014;

(d) $55,000 on or before 17 May 2015;

(e) $60,000 on or before either (whichever was the latest date):

(i) 17 November 2015; or

(ii) The date on which Mr O’Donnell fully released GCT in respect of the prescribed “Security Interest” (created by the GCT Security Deed) and then registered the release on the Personal Properties Securities Register (PPSR); or

(iii) The date on which Mr O’Donnell fully released Apscore in respect of the prescribed “Security Interest” (created by the Apscore Security Deed) and then registered the release on the PPSR.

89 The bankrupt agreed that the settlement reflected in the draft settlement deed was the settlement struck, such that he owed (through Apscore and GCT) money to Mr O’Donnell.

90 If one accepts that the ultimate settlement comprised the above terms, the respondent tendered no contemporaneous evidence of any of the payments in fact being made throughout the relevant period. Further, Mr Murray conceded that Apscore had a continuing liability to pay the instalments to Mr O’Donnell as at 30 June 2014.

91 Rather for the reasons which follow, it is my view that the sale of the two properties occurred in 2014 to fund the North Balgowlah property and shield the bankrupt’s assets from creditors. A combination of the following considerations leads to this view: the plight of the class action, the status of the bankrupt’s finances and the events leading up to the purchase of North Balgowlah reveal the same.

92 As referred to above at [11], alongside the bankrupt’s investments in property above, the bankrupt became involved in the Scheme, which led to the bankrupt owing the Bendigo Debt. Relevantly, during the period up to the critical property transactions, in addition to the matters referred to at [12] above, after the bankrupt’s default on 20 October 2009, the bankrupt received a Notice of Demand from the Bendigo Bank which stated that he owed $76,664.32 and that the Bank “may issue legal proceedings against [him] without further notice”. Then on 16 November 2009, the bankrupt received a “Credit Listing – Final Warning” from the Bendigo Bank (which at the time of the examination the bankrupt had no recollection of receiving but did not dispute receipt).

93 The parties agreed to the following relevant fact as to the state of the bankrupt’s knowledge: Sometime between October 2013 and July 2014 or before the end of the case, the bankrupt spoke to either his financial planner or advisor about the hearing of the class action, and was told that the hearing “hadn’t gone well”, “wasn’t going well” or that “it didn’t look good”.

94 The bankrupt accepted under cross-examination that regardless of what anyone told him “at any time” that he “always knew there was, at least, a risk that [he] could lose … the class action”, and further:

MR EDNEY: But once you were told, “It doesn’t look good,” whenever the exact date must have been, you would have appreciated that that risk was substantial, can’t put a number on it but substantial?---What was substantial?

Sorry. The risk of losing, the risk that it could be a loss?---Yes.

95 Accordingly, the bankrupt must have known, at least by July 2014, that he was likely to have to repay the Bendigo Debt. This is a significant fact that has bearing on the bankrupt’s state of mind when he purchased the North Balgowlah property in early August, a month later.

The status of the bankrupt’s business in the 2014 financial year

96 In addition, at this very time when the bankrupt knew of the failed class action, on 30 June 2014, the bankrupt’s business Apscore recorded accumulated losses of $6,243,566.46.

97 During the bankrupt’s cross-examination, it was my impression that he sought to downplay the extent of his business’ stressors and financial problems in 2014. This, in turn, revealed serious questions as to why in the face of a significant loss in the class action and his business failing, he would denude himself of his only assets and purchase a new heavily mortgaged property.

98 The trustee tendered Apscore’s Financial Reports for the 2015 and 2017 financial years. They revealed the following:

(a) a loss of $218,852.90 in 2014 and $126,178.68 in 2015;

(b) a substantial decline in salaries and wages, $432,799.76 in 2014 and $125,258.10 in 2015; and

(c) substantial loans from Apscore to the bankrupt in 2012, 2013 and 2014 to the value of $523,150.57.

99 What was particularly telling was the bankrupt’s description in 2015 in a statutory declaration as to the reasons for his company’s decline and the suddenness and acuteness of it. He declared, on 18 July 2015, the following:

… Last year my company’s largest client, a mining services electrical contractor in Perth, suddenly and without notice cancelled a multi-million dollar development contract. As a result we have been haemorrhaging revenue and staff ever since. That company is down to two full time staff from 22 last year…

I have also been caught with a credit card debt slightly in excess of $126,000. I have negotiated pay down arrangements, which includes some debt relief, with 2 of the banks and I am currently in negotiations with the other two banks…

I believe that the Courts have now confirmed that I owe to the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank a considerable amount of money…

I do not want to be forced into bankruptcy but at this stage of my life there is only so much I can afford to do.

(Emphasis added.)

100 The reference to “[l]ast year” was accepted by the bankrupt to be 2014. It is clear from the 2015 Financial Statement that there was a substantial decline in wages and salaries in his business from 2014 to 2015. Further, the bankrupt’s tax returns indicated a decline in his “allowances/ earnings/ tips/ director’s fees” from $60,000 in the 2014 financial year to $37,000 in the 2015 financial year.

101 It is important to understand “when” in 2014 the financial stressors became apparent to the bankrupt. It was put to the bankrupt that the loss of the major client was in late 2013 or before the middle of 2014. The exchange was as follows:

MR EDNEY: Well, having been shown that and doing the best you can to recall, would you accept that the loss of your major customer occurred, probably, actually about late 2013 or before the middle of financial year ’14?---I recall it being gradual, though. I mean, it was just a cutdown [sic]. So eventually, they just stopped doing business with us.

It’s over the course of the 2014 financial year it’s winding down, correct?---Yes, from memory, yes.

And by the end of the 2014 financial year, it is – if not totally, it is at least mostly wound down, correct?---I’m not sure, but yes.

Okay. Not sure, but you definitely don’t have a – you don’t have any recollection that would mean you can say I’m wrong. Does that make sense?---Yes.

Sorry, it makes sense, or you agree with me, or both?---I agree with you, but I don’t have any recollection that would dispute that, no.

102 Regardless, the bankrupt ultimately accepted that over the course of the 2014 financial year his business had “significantly wound down”.

103 At the same time, the bankrupt owed his former business partner Mr O’Donnell $225,000 arising from the negotiated settlement of litigation (see above at [88]).

104 The respondent accepted under cross-examination that she was aware in mid-2014 that the bankrupt’s business had shrunk massively from having 22 employees to two, that the bankrupt had lost a major customer and was under significant financial stress. Her evidence was as follows:

MR EDNEY: You were aware – there is a time – and I put to you that it’s about mid-2014 – where James’ business had – I will say collapse but then I will clarify what I mean. It had shrunk massively. It had gone from being 22 employees to two?---Yes.

You remember that happened? He had lost his major customer; correct?---Yes.

He was – I will put in somewhat usual terms – under significant financial stress; correct?---Yes.

And at the time those things occurred, you have previously given evidence under examination that you recall him being […] incredibly low because of his difficult financial position. If you don’t recall that, tell me, and I can take you to it?---No, I recall.

Okay. But that’s the truth, isn’t it?---Yes.

And that was at about the time that you were buying what I will call the North Balgowlah property, wasn’t it?---Yes. Yes.

So you were aware at this time that he had at least […] sufficient financial difficulties that it was making him incredibly low?---Yes.

You would have appreciated that that meant there was a real risk that creditors could one day be coming knocking for anything in James’ name; correct?---Yes.

And that meant that allowing James’ name to go on the title to the North Balgowlah property put it at risk to claims by those creditors, didn’t it?---Well, it could, yes. I can say that.

And that’s the main reason why you made sure that it was in your name at the end of the day and not both names?---No, that is not the reason.

The purchase of the North Balgowlah property

105 The undisputed facts, set out above at [14]–[16], reveal that on about 4 August 2014, the bankrupt and the respondent entered into a contract to purchase the North Balgowlah property for $1.8 million, with both of them named on the contract as purchasers. The purchase price, and the other costs of the purchase, were paid by way of:

(a) drawings totalling $197,773.86 from the Joint Account; and

(b) $1.7 million borrowed from the Commonwealth Bank by way of a loan in respect of which both the bankrupt and the respondent were principal borrowers, and

(c) the purchase settled on 28 November 2014, at which time title to the North Balgowlah property was taken solely in the respondent’s name.

106 On 5 November 2014, the Commonwealth Bank loan to the bankrupt and the respondent for the purchase of the North Balgowlah property was approved.

107 The Commonwealth Bank loan application showed that the bankrupt and the respondent were approved to borrow $1.7 million from the Commonwealth Bank comprising the bulk of the $1.8 million purchase price for the North Balgowlah property.

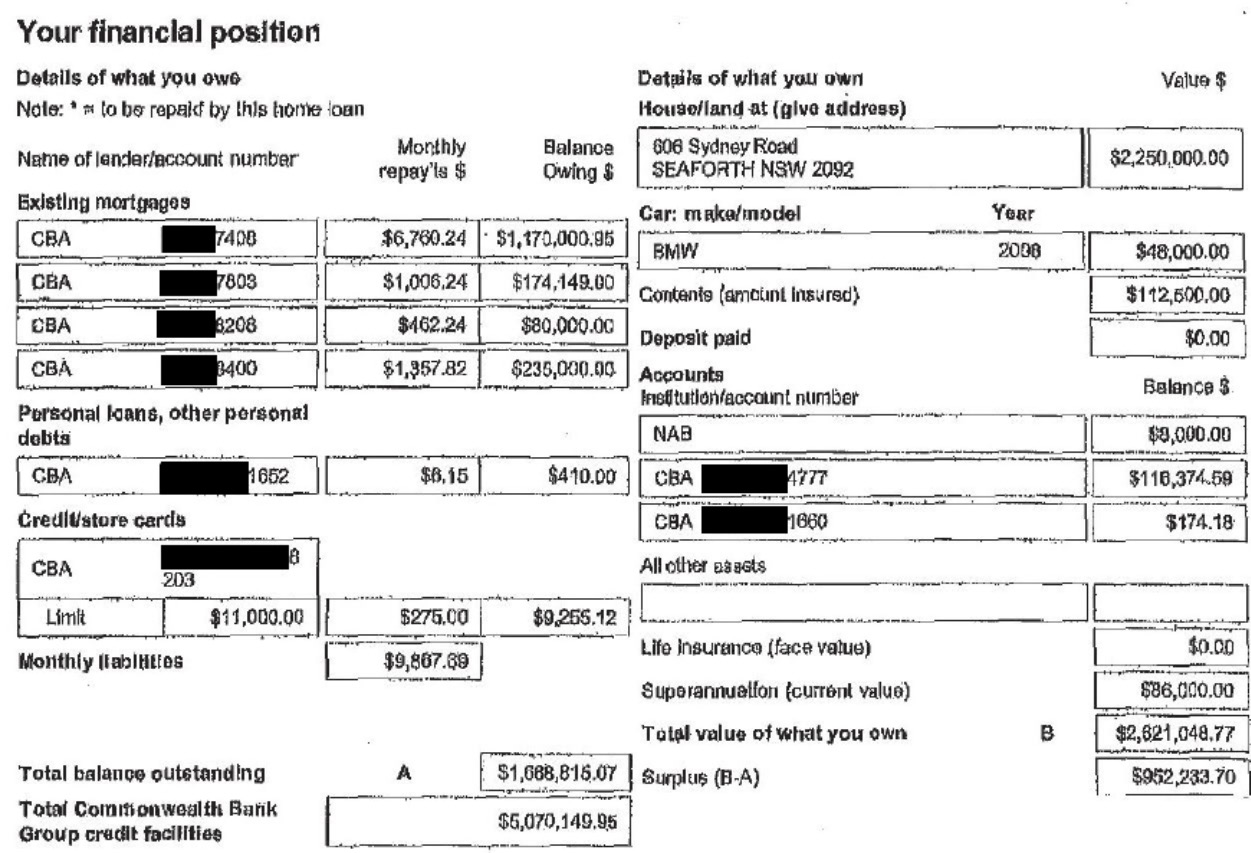

108 The loan application demonstrates the asset pool of the bankrupt and the respondent around the period between 29 October 2014 (the date recommended by the bank officer) and 5 November 2014 (the date approved by the bank officer). There were only three accounts comprising the bankrupt and the respondent’s savings listed on the loan application: a National Australia Bank (NAB) account with a balance of $8,000 (for which no account number was provided) and two Commonwealth Bank accounts – an account ending in #1660 with a balance of $174.18 and the Joint Account with a balance of $116,374.59 (consistent with the bank statement in evidence as at 4 November 2014). This is what the bankrupt and the respondent had represented to the Commonwealth Bank were their accounts at the time leading up to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property.

109 Accordingly, the respondent’s submission that there were numerous accounts for which the trustee needed to consider when analysing the bankrupt’s contributions to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property is not consistent with this contemporaneous documentary evidence. This is particularly so given that the documentation from the 2013 refinance application reflected the same picture (extracted at [122] below).

110 In relation to the the respondent’s equity in the Seaforth property, the loan application demonstrates that around the period between 29 October and 5 November 2014, the bankrupt and the respondent had four existing mortgages over the Seaforth property with the Commonwealth Bank. The Commonwealth Bank valued the Seaforth property as worth $2.25 million and the total balance owing on the mortgages was $1,659,149. The respondent’s equity was therefore $590,851 at that time.

How was the purchase of the North Balgowlah property funded?

111 A live dispute between the parties was whose funds were used to purchase the North Balgowlah property.

112 The evidence revealed that, as set out above, that apart from the Commonwealth Bank loan, the sole source of drawings totalling $197,773.86 used for the purchase came from the Joint Account.

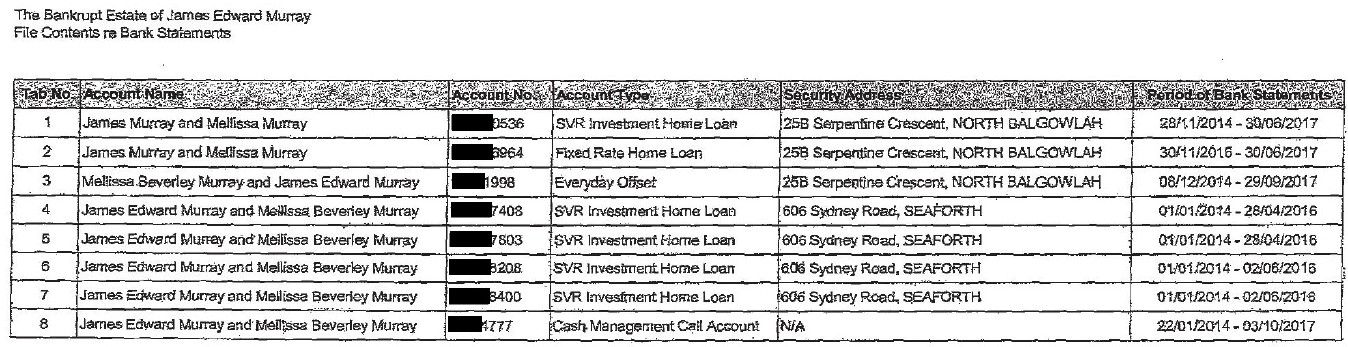

113 The trustee tendered the statements of the Joint Account for the period between 22 January 2014 and 3 October 2017.

114 The opening balance in the first Statement of Account was $1,156.47 and the closing balance for the last Statement of Account was $286.96.

115 A review of the statements of the Joint Account reveals that the only significant deposits and withdrawals from that account over the period between 22 January 2014 and 3 October 2017 were, first, the deposits associated with the sale of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties and secondly, the withdrawals for the purchase of the North Balgowlah property. I note there was a transfer of $60,000 from the Joint Account titled “Loan to Apscore” but there was no specific evidence or submission with respect to it from either party.

116 It was agreed that on 11 and 14 April 2014, funds from the sale of the Boyce Road property were deposited into the Joint Account in the sum of $330,067.31 (comprising $316,211.31 on 11 April 2014 and $13,856 on 14 April 2014).

117 It was also agreed that on 9 and 11 September 2014, funds from the sale of the Anzac Parade property were deposited into the Joint Account in the sum of $110,310.05 (comprising $63,393.05 on 9 September 2014 and $46,917 on 11 September 2014).

118 The parties agreed that ultimately $197,773.86 was contributed to the purchase of the property, which included legal fees and other expenses.

119 The respondent conceded under cross-examination that in the lead up to the sales of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties, so between 2012 and 2014, the bankrupt’s drawings from his business comprised the majority of the marital income and funded all the mortgages of their properties. The respondent accepted that the proceeds of sale of the Boyce Road and the Anzac Parade properties were paid into the Joint Account. Similarly, the bankrupt conceded, under cross-examination that the primary source of cash flowing into the marriage came from the bankrupt’s business and both their earnings went into the Joint Account.

120 Whilst the respondent and the bankrupt held at least two other savings/transactional accounts (an account with the NAB and a Commonwealth Bank account ending in #1660), it was clear from the 2014 loan application, that to the extent that they held any cash assets they were as contained in the Joint Account. They had represented to the Commonwealth Bank, around late October 2014, as part of their application for the North Balgowlah property that their entire cash assets were $124,548.77, as reflected in this snapshot from the loan application:

121 Accordingly, I find that as at the time of them applying for the 2014 mortgage and the completion of the purchase of the North Balgowlah property the funds came from the Joint Account and there were no other substantial funds available in other accounts.

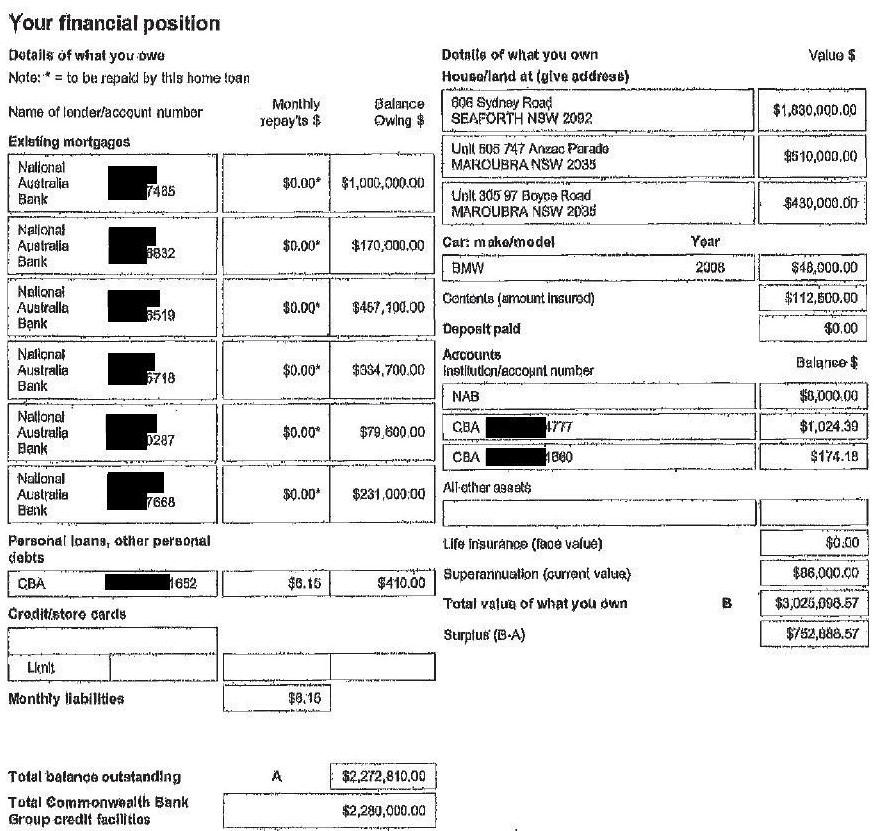

122 What was telling was if one looked back a year before to the bankrupt’s and the respondent’s “financial position” representations with respect to their 2013 refinance application:

123 It reveals the same, the bankrupt and the respondent had minimal cash reserves (and aside from the Joint Account the balance of the other two saving/transaction accounts was the same): Their combined assets comprised the Boyce Road, Anzac Parade and Seaforth properties.

The evidence of the respondent and bankrupt regarding intention

124 The respondent gave the following evidence with respect to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property. The respondent gave evidence of the fact that her mother had moved into the Seaforth property with them in 2012, her mother had lent the respondent and the bankrupt another $200,000 to pay for renovation works on that property; and by 2014 her mother had found it difficult to negotiate the stairs in their house.

125 This is consistent with the respondent’s previous conduct concerning the Fairlight and Seaforth properties, that there was an intention by both the respondent and the bankrupt that the North Balgowlah property would be solely owned by the respondent.

126 The respondent gave evidence that again (as with the Seaforth property), it was she that identified where the contract for the purchase of the North Balgowlah property was incorrectly in both their names and that she told them that she “need[ed]” the property in her name.

127 The respondent referred to the fact that at the time of the sale of the Seaforth property her and the bankrupt had paid her mother $100,000 “which [she] believed reflected the unpaid interest on the original and second loan”.

128 Both the respondent and the bankrupt gave evidence of discussions which prompted the bankrupt to take steps to amend the contract. The bankrupt deposed as follows:

Lindsay Parker acted on the purchase of North Balgowlah. I recall the contract for the purchase had Mellissa and me as the purchasers. I discussed this with Melissa in words to the following effect:

She said: “This house must be in my name. If something happens to you I do not want to have your daughters claiming against it I don’t trust them.”

I said “Of course. Your mum will have her granny flat safe from any of that if it is in your name. She has put so much money in.”

She said: “Exactly.”

(Emphasis in original.)

129 The respondent gave unchallenged evidence of a discussion at the same time as follows:

The contract for the purchase of Serpentine Cresent [sic] had both James’ name and my Name [sic] as the purchaser. James and I spoke about this in words to the following effect:

“James, we have done this again, I need the property in my name.”

James replied in words to the effect:

“Yes, you are right, we must have missed it, we must change it.”

Later James told me: “I sent an email to Lindsay Parker instructing him to change the contract into your name.”

(Emphasis in original.)

130 The bankrupt then sent an email to his solicitor, copied to the respondent, on 3 September 2014, stating the following:

…it appears that there has been a mistake made by me in the agreement to purchase the [North Balgowlah property]. It was always intended that the house would be in the name of [the respondent] alone not mine as well. Please affect the necessary documentation to have this matter fixed.

131 This email was sent almost three months before the sale completed on 28 November 2014.

132 Both the respondent and the bankrupt gave evidence that the preparation of the contract in both names and their signing of it was an oversight and a mistake respectively.

133 Six days after the bankrupt’s email to his solicitor, on 9 September 2014, settlement for the sale of the Anzac Parade property occurred. Proceeds of sale and deposit and the balance of the deposit, totalling $110,310.05, were paid into the Joint Account.

The beneficial ownership of the North Balgowlah property: Was it a mistake?

134 I accept that it was a mistake and that the bankrupt and the respondent intended that the North Balgowlah property be in the respondent’s name only.

135 I accept the respondent’s evidence, identified above, as to her intention regarding ownership of the North Balgowlah property and that she mistakenly signed the contract in both names. I accept her evidence on the basis that her conduct was consistent with her past conduct regarding the purchase of the Fairlight and Seaforth properties. The respondent had maintained a course of conduct where she had agitated for or obtained legal and beneficial title over the matrimonial home. The respondent maintained under cross-examination that it was a mistake and I accept her evidence. I accept also her evidence as to the reasons for why she intended the property to be in her name.

136 I also find that it was the bankrupt’s primary intention to place the North Balgowlah property in the respondent’s name and that it was mistake when the contract was entered into in both names. However, I am of the view that the bankrupt’s motivations for his wife holding legal title were different to those of the respondent and were to prevent the purchase monies and those monies paid towards the Seaforth Mortgages from becoming divisible to creditors.

137 For almost 10 years until 2014, the bankrupt had owned outright or substantially two properties in his own name. The bankrupt over that period had solely paid the mortgages on the Anzac Parade and Boyce Road properties. The bankrupt had been the sole contributor on the mortgages to the then marital home, the Seaforth property. As a consequence, up until the purchase of the North Balgowlah property the bankrupt had held two substantial assets in his name and had contributed solely to their growth. In the 2013 refinance application, as extracted at [122] above, the bankrupt had represented the Boyce Road and Anzac Parade properties’ combined worth to be $940,000 and the Seaforth property being worth $1,830,000. Accordingly, the bankrupt substantially owned assets (without accounting for the mortgages in all properties) in his own name, of not insignificant value when compared to the value of the Seaforth property. As at 30 June 2014 the bankrupt’s business was in financial peril and he was aware of the substantial debt he owed arising from the failed class action. Both the bankrupt and the respondent were aware of the significant financial strain the bankrupt was under. The respondent described the bankrupt at this point as being “incredibly low”. There was no change in circumstances between 4 August and 3 September 2014 to otherwise bring about the change. It reveals the “mistake”.

138 Furthermore, it was a “mistake’ in my view because the bankrupt intended that the relevant transfers were made by the bankrupt (including being put towards the purchase of the North Balgowlah, being intended to be in the respondent’s name) to defeat his creditors. This inference can be drawn from all of the evidence above but also because the only contribution made to the purchase of the North Balgowlah property was by the bankrupt as a result of the sale of the two properties that were in his name or substantially in his name and for which he had solely contributed towards. This fact contrasts with the circumstances in which the previous matrimonial homes were purchased. There was no evidence that the bankrupt had made any direct contribution at the time of purchase of a like kind previously.

139 There was also something very unusual about the conduct of the bankrupt and the respondent at this time – where despite them not having sold their current home, they would embark on a very risky exercise of purchasing another significant asset (with a mortgage of $1.7 million, almost 95% of the value of the property) at a time when the bankrupt’s business was in decline, he was under significant financial stress and he was aware of demands being made on the Bendigo Debt from the Bendigo Bank.

140 I do not accept the bankrupt’s denials as to him being motivated to shield the proceeds of these substantial assets from creditors. I found the bankrupt to be an unimpressive witness for the reasons identified above.

The contributions made by the bankrupt to the Seaforth Mortgages in 2014

141 The trustee relies on the following purported amounts paid from the Joint Account to the Seaforth Mortgages between 11 April and 28 November 2014 as forming part of the bases for his voidable transaction claims (as extracted from [24(b)(ii)] of his statement of claim):

Amounts Paid from Joint Account to Seaforth Mortgage 11 April 2014 to 28 November 2014 | |||

Date | Loan Account | Amount | Total |

28 April 2014 | 769837408 | 4,869.72 | |

769837803 | 1,070.25 | ||

769838400 | 977.99 | ||

769837208 [sic] | 332.93 | 7,250.89 | |

27 May 2014 | 769837408 | 4,712.06 | |

769837400 | 946.44 | ||

769837803 | 701.37 | ||

769837208 | 322.19 | 6,682.06 | |

27 June 2014 | 769837408 | 4,869.13 | |

769838400 | 977.99 | ||

769837803 | 724.75 | ||

769837208 | 332.93 | 6,904.8 | |

28 July 2014 | 769837408 | 4,712.06 | |

769838400 | 946.44 | ||

769837803 | 701.37 | ||

769837208 | 322.19 | 6,682.06 | |

27 August 2014 | 769837408 | 4,869.13 | |

769838400 | 977.99 | ||

769837803 | 724.75 | ||

769837208 | 332.93 | 6,904.8 | |

29 September 2014 | 769837408 | 4,869.13 | |

769838400 | 977.99 | ||

769837803 | 724.75 | ||

769837208 | 332.93 | 6,904.8 | |

27 October 2014 | 769837408 | 4,712.06 | |

769838400 | 946.44 | ||

769837803 | 701.37 | ||

769837208 | 322.19 | 6,682.06 | |

27 November 2014 | 769837408 | 4,869.13 | |

769838400 | 977.99 | ||

769837803 | 724.75 | ||

769837208 | 332.93 | 6,904.8 | |

Total | $54,916.27 | $54,916.27 | |

(Emphasis in original.)

142 The trustee asserts, and the respondent did not dispute, for the purposes of each of his claims, that the amounts comprise, in fact, contributions made by the bankrupt to the Seaforth Mortgages.

143 The evidence revealed that the claimed amounts were in fact drawn from the Joint Account to the Seaforth Mortgages.

144 The respondent and the bankrupt admitted the following, that until 2015: (a) the income from the bankrupt’s business was the primary source of the marital income; (b) the bankrupt admitted that whilst the Seaforth property was in the respondent’s name, the mortgage was paid out of the Joint Account and his income comprised the primary source of funds for paying that mortgage; (c) the respondent admitted that the Seaforth Mortgages were primarily serviced by the bankrupt’s income.