Federal Court of Australia

Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NSW) v Allianz Australia Insurance Limited (Liability Judgment) [2023] FCA 190

ORDERS

UNITING CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA PROPERTY TRUST (NSW) Applicant | ||

AND: | ALLIANZ AUSTRALIA INSURANCE LIMITED (ACN 000 122 850) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 MARCH 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties provide to the Associate to Justice Lee agreed short minutes of order reflecting these reasons (or, failing agreement, competing short minutes of order and submissions limited to five pages) within seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION

1 This matter involves a claim by the applicant insured, the Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NSW) (UCPT), on the respondent insurer, Allianz Australia Insurance Limited (Allianz), in relation to historic claims of sexual and physical abuse. The claims have their genesis in policies dating back to 1999, with conduct relevant to the issues in dispute dating back to the 1970s.

2 The UCPT is a corporation constituted under s 12(1) of the Uniting Church in Australia Act 1977 (NSW) (UCA Act). It is one of the various bodies or organs falling under the umbrella of an unincorporated association, being the Protestant church known as the “Uniting Church in Australia” (UCA).

3 A number of schools operated by the UCPT have been connected with historic claims of sexual and physical abuse by former students. Knox Grammar School (KGS), one of the schools operated by the UCPT, has been the subject of number of allegations, including that former teachers and staff of the school sexually and physically abused former students. The events are alleged to have occurred up to around four decades ago.

4 The UCPT was one of many insureds under various professional indemnity policies (Policies) underwritten by Allianz, formerly MMI Insurance Limited (MMI). The Policies provided continuous insurance cover to UCA and its various bodies and organs, including the UCPT, for a twelve-year period from 31 March 1999 to 31 March 2011 (Period). The Policies were part of a broader national programme of insurance with Allianz, which was organised for the UCA and its constituent bodies by its brokers, J & H Marsh & McLennan (Marsh) and, from 15 December 2008, Willis Australia Ltd (Willis).

5 The fulcrum of the UCPT’s case is that over the course of the Period, it notified Allianz of facts that might give rise to claims within the meaning of s 40(3) of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (Act). Section 40(3) modifies the operation of certain contracts of insurance by extending the cover of the relevant policy to indemnify the insured in respect of a claim made after the policy period, provided the insurer was notified in writing of facts which might give rise to the claim as soon as was reasonably practicable. The UCPT submits that by operation of s 40(3), the Policies are engaged and it is entitled to indemnity because the facts it notified to Allianz over the course of the Period concerned sexual or physical abuse involving former students, teachers and staff of KGS, which might give rise to claims against the UCPT, and which were notified as soon as was reasonably practicable after the UCPT became aware of those facts.

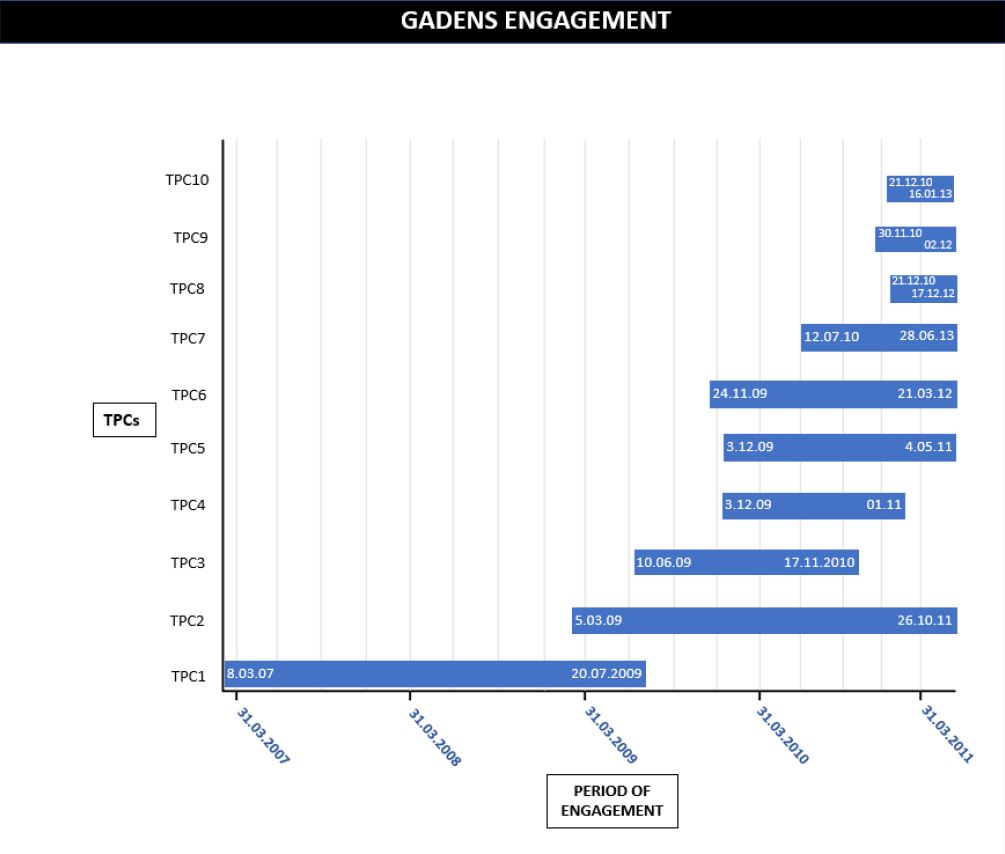

6 The notifications relied upon by the UCPT comprise: multiple specific notifications given throughout the Period; four “bulk notifications” given in 2009, 2010 and 2011 (Bulk Notifications); and a notification given in February 2011 known as the “alleged perpetrator” notification (AP Notification). It is said that the notifications correspond to claims made by third-party claimants (TPCs) who allege that they suffered sexual or physical abuse from one or more staff members of KGS or alleged perpetrators (APs). As at the date of this proceeding, some 53 claims by TPCs have emerged. A number of potential third-party claimants (PTPCs) have also been identified who, according to the UCPT, may claim that they suffered sexual or physical abuse at KGS by one or more APs.

7 Allianz initially indemnified the UCPT under the Policies for twelve claims made against the UCPT by various TPCs. Indemnity for the last claim was accepted on 26 September 2012. In addition, up until 19 May 2014, Allianz indemnified the UCPT in respect of all claims of sexual and physical abuse relating to one or more APs notified to it by way of notified claims or circumstances during the Period. However, after 19 May 2014, Allianz has either declined indemnity or otherwise reserved its rights in respect of all claims arising from those notified facts and circumstances.

8 Accordingly, the UCPT now seeks indemnity and consequential orders in respect of liabilities incurred out of the settlement of claims by TPCs, and declaratory relief in respect of potential claims that may be made against the UCPT by known and unknown PTPCs who may allege that they suffered sexual or physical abuse by former teachers or staff of KGS.

9 The balance of these reasons is set out in the following structure:

Section B will outline the relevant factual background and evidence, and findings will be made in large part based upon the statement of agreed facts prepared in accordance with s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (EA);

Section C will address some procedural matters, including with respect to suppression orders made in this proceeding and separate questions for determination;

Section D will set out the agreed factual and legal issues for determination, and provide an overview of how the issues arise and interrelate;

Section E will address issues concerning the engagement of the Policies, including principles applicable to s 40(3) of the Act, the role of a firm of solicitors, Gadens, and s 54 of the Act;

Section F will deal with exclusions 6 and 7 in the Policies and address issues relating to the knowledge of the UCPT;

Section G will address issues of estoppel, waiver, election and utmost good faith; and

Section H will address the question of relief.

B FACTUAL BACKGROUND

10 Before discovery closed, there was some ambiguity as to the number of witnesses that would be called (if any) by the parties, and the matter was set down for hearing with a provisional estimate of three to four weeks. As it turns out, due to a refinement of the issues, the hearing proceeded solely on the documentary record, and was concluded within eight days.

11 With that said, in the light of the scope of the UCPT’s case, the relevant period upon which it is founded, and the reliance on the documentary record, the evidence filed in this proceeding by both parties was considerable. In order to limit the scope of the evidence, I required the legal representatives for both parties to attempt to agree upon all relevant non-contentious facts prior to preparing evidence that would be the subject of dispute. Although this process was somewhat delayed, a statement of agreed facts was prepared, and a final version was provided to the Court on the conclusion of the hearing. That finalised version of the statement of agreed facts document was admitted into evidence (Agreed Facts or AF) with each fact being an “agreed fact” within the meaning of s 191 of the EA.

12 The Agreed Facts document is a useful one and I am grateful for the constructive way in which the parties engaged in the conferral and drafting process, which was consistent with their duties to narrow the scope of the factual issues required to be the subject of affidavit evidence or the tender of documents. I trust this course did not cause unnecessary cost – but the result was worth it – in other words, as Sir Henry (“Chips”) Channon once wrote, there was a Methodist in my madness.

13 In the present case, the helpful working hypothesis of paying close regard to the contemporaneous documents is of importance. However, the factual issues are not in substantial contest between the parties; what is in contest are the inferences and conclusions (both factual and legal) that are to be drawn from various contemporaneous communications, records and other documents.

14 In accordance with this view, the factual findings that follow are made upon an admixture of the Agreed Facts, material drawn from contemporaneous documents (which, as I noted earlier, has largely not been challenged in a significant way) as well as inferences drawn from any communications and documents.

B.1 The Uniting Church in Australia

15 It is necessary to begin by canvassing the structure of the UCA, so as to appreciate how the UCPT, KGS and other constituent bodies of the UCA sit within that architecture. A brief overview will be given, before turning to the relevant legislative background and various constituent bodies making up the UCA.

B.1.1 Overview

16 Despite being an unincorporated association, the UCA has a highly formalised and complex governance structure, which has its origins in statute. It is principally administered by two bodies, the Assembly and the Synods.

17 The Assembly is the national governing body of the UCA. It is empowered to make guiding decisions on the tasks and authority to be exercised by councils of the Church, amend the constitution of the UCA (UCA Constitution), and delegate to any council any of the authority vested in it by the UCA Constitution. The Synods, broadly speaking, correspond to the various States and Territories of Australia in which the UCA operates. They constitute councils of the UCA and are delegated various administrative functions by the Assembly, subject to its direction. The Synods operate through a standing committee, a general secretary and various boards which are responsible for administering aspects of the UCA’s mission, including in relation to education, finance and Church property.

18 The UCPT (and its equivalents in each State and Territory) are statutory corporations, which supplement the administrative functions of the Assembly and the Synods. The UCPT is required to hold, manage, administer and otherwise deal with property held in trust for the UCA in accordance with the regulations, directions and resolutions of the Assembly. In addition, the UCPT and its equivalents are the legal entities to sue, or be sued, on behalf of the Synods or any agency of the UCA, or in relation to trust property.

19 Uniting Resources (formerly the Board of Finance and Property) also supplements the administrative functions of the Assembly and Synod by (among other things) making recommendations to the Synod regarding policy, facilitating the use and coordination of Church resources, and providing services when the Synod deems it necessary. The functions of Uniting Resources extend to insurance. It is responsible for establishing policies and procedures, maintaining an insurance fund, and maintaining adequate reserves.

20 The Assembly, the Synod Standing Committee and each of the boards are non-legal entities with fluctuating memberships. The UCA also operates many services (which it refers to as “institutions”) across a wide spectrum of industries, including aged care, medicine, education, childcare and hospitality. KGS, an unincorporated association, is one such institution.

B.1.2 The Legislative Background

21 The legislative scheme underpinning the structure of the UCA finds expression in separate but similar enactments in each State and Territory (UCA Acts).

22 By s 6 of the UCA Act, the Congregational Union of Australia, the Methodist Church of Australasia and the Presbyterian Church of Australia are united in accordance with the basis of union contained in Sch 2. By cl 15 of the basis of union, the Church was to ensure that its constitution made provision for its various organs, including the Congregation, the Council of Elders or Leaders’ Meeting, the Assembly, the Synod and the Presbytery.

23 As noted earlier, the most important of these organs are the Assembly and the Synod, both of which are recognised in the UCA Acts: see, for example, UCA Act, Sch 2, cll 16(c)–(e).

B.1.3 The UCPT

24 By s 12(1) of the UCA Act, the UCPT was established as a statutory corporation. The members of the UCPT consist of those prescribed in s 12(1), being statutorily designated officials (or appointees) of the Synod.

25 Significantly, s 13 empowers the UCPT to acquire, hold, deal with and dispose of the property that it is required to hold in trust for the UCA. By s 13(3) of the UCA Act, the UCPT is required to hold, manage, administer, and otherwise deal with trust property in accordance with the regulations, directions, and resolutions of the Assembly.

26 The UCA Acts contain cognate provisions to establish an operational statutory corporation in the relevant State or Territory, which is conferred equivalent powers, and bestowed with equivalent functions, to that of the UCPT. This enables the legal title to all UCA property to be vested in the appropriate property trust for that jurisdiction.

27 Importantly, the property trusts are the legal entities to sue, or be sued on behalf of, the Synods or any agency of the UCA, or in relation to trust property.

B.1.4 The Assembly

28 The Assembly is the national governing body of the UCA.

29 By ss 9 and 10 of the UCA Act, the Assembly is empowered to amend and repeal the UCA Constitution, or adopt a new constitution, consistent with the basis of union. Clause 38 of the UCA Constitution provides that:

the Assembly shall have determining responsibility in matters of doctrine, worship, government and discipline, including the promotion of the Church’s mission, the establishment of standards for theological education and the reception of Ministers from other denominations, and is empowered to make final decisions on all matters committed to it by this Constitution;

30 The Assembly has the power, inter alia, to make guiding decisions on the tasks and authority to be exercised by councils of the Church, create or dissolve Synods, provide for the control and management of the property and funds vested in the Church, and to delegate to any other council any of the authorities vested in the Assembly: UCA Constitution, cl 38(b).

B.1.5 The Synod and the Synod Standing Committee

31 The Synod is defined in s 5 of the UCA Act by reference to cl 15(d) of the basis of union, which in turn is reproduced in Sch 2 to the UCA Act. It has responsibility for, among other things, the general oversight, direction and administration of the Church’s worship, witness and service in the region allotted to it.

32 Both the Assembly and the Synod are vested with rule-making powers: cll 62 and 63 of the UCA Constitution. The Assembly has invoked this power by promulgating regulations (Assembly Regulations).

33 The Assembly Regulations make provision for the Synod to be further responsible for, inter alia, the “effective supervision of property matters” (cl 3.5.53), “making Synod by-laws” (cl 3.5.12(k)) and “appointing a Standing Committee” (cl 3.5.43). Only members of the Synod are eligible to be members of the Synod Standing Committee (cl 3.7.4.1). That committee, in turn, is composed of, among others, the moderator and the general secretary.

34 The Synod is also invested with powers with respect to Church institutions. The term “institution” is defined as “any body whether incorporated or unincorporated established by or on behalf of the Church … or in which the Church participates for a religious, educational, charitable, commercial or other purpose” (cl 3.5.34). KGS is one such institution.

35 By cl 4.9.1 of the Assembly Regulations, the relevant property trust in each State or Territory (in NSW, the UCPT) is empowered to sue or be sued in its name on behalf of the Church, any agency of the Church or in relation to trust property.

36 The Synod itself is empowered to make its own rules and by-laws provided they are consistent with the UCA Constitution and the Assembly Regulations (Synod by-laws): UCA Constitution, cl 63.

37 Each Synod elects a moderator. The moderator has a pastoral and advisory leadership role in his or her Synod: Synod by-laws, cl N3.23.1–N3.23.9. The moderator (unlike the general secretary) has limited formal powers with respect to the day to day administration or governance of the relevant Synod.

B.1.6 The General Secretary of the Synod

38 Each Synod also appoints a general secretary who fulfils, in substance, the responsibilities of a chief executive officer. The general secretary is an ex officio member of the Synod Standing Committee (that is, the Council of Synod): Synod by-laws, cl N3.24.2(a).

39 The Synod by-laws make provision for the role and functions of the general secretary, which includes the duty, among other things, “to inform [the] Synod and the Council of Synod on matters affecting or likely to affect the Church” and “to maintain communication with Boards and their officers in order to foster the implementation of decisions of policies of Synod and the Council of Synod”: Synod by-laws, cl N3.24.1–N3.24.3.

B.1.7 Uniting Resources

40 Uniting Resources (formerly the Board of Finance and Property) is established under Synod by-law N3.31.2. The by-laws provide for the board of each Synod to be responsible to its respective Synod for the determination of the board’s policy and its activities: Synod by-laws cl N3.31–N3.3.56.

41 Broadly speaking, those activities are divided into three areas: property; finance, accounting and funds; and office and computer services.

42 Within the finance, accounting and funds activity area, the functions of Uniting Resources extend to insurance: Synod by-laws, cl N3.34.1B. In that respect, Uniting Resources’ functions include, among other things:

(1) implementing and supervising Assembly Regulations and Synod by-laws relating to finance and funds: cl N3.34.1B(i);

(2) gathering information from Synod boards and agencies and the Assembly to the extent necessary to enable the Synod budget committee to determine the Synod budget: cl N3.34.1B(ii);

(3) administering the decisions of the Synod budget committee: cl N3.34.1B(iii);

(4) exercising the general oversight and management of such Synod funds as may be determined by Synod, including the insurance fund: cl N3.34.1B(iv); and

(5) in conjunction with the Synod property trust, managing and administering all property which vests or has vested in the UCPT and which is not the responsibility of any parish, presbytery, board or other body of the Church under or pursuant to any regulation or by-law or decision of the Synod: cl N3.34.1B(viii).

43 By cl N3.31.7B of the Synod by-laws, the membership of United Resources includes, among others, members of the property trust, being the moderator, the general secretary and the property officer of the Synod.

44 The membership of the executive committee of Uniting Resources is also prescribed by cl N3.34.2 of the Synod by-laws, and includes the general secretary of the Synod and the executive director of Uniting Resources.

B.1.8 Knox Grammar School

45 KGS at all material times was an unincorporated association, without any separate legal personality. It is governed by a constitution (KGS Constitution) which has been amended from time to time. From at least 1998, cl 5 of the KGS Constitution provided that ultimate control of KGS was to vest in the Synod.

46 The KGS Constitution otherwise provided for the following matters:

(1) all real and personal property of KGS was to be held and managed in accordance with the UCA Act, the Assembly Regulations and Synod by-laws (cl 4);

(2) subject to the ultimate control of the Synod, the management of KGS would be carried out by a council of between twelve and fifteen persons, whose members were to be appointed by the Synod (cl 6(a));

(3) the council would meet at least quarterly (cl 12(a));

(4) the council would be empowered to appoint committees and to delegate powers to the committees in such a manner as it may determine (cl 21); and

(5) the council may, from time to time, appoint, suspend or dismiss a principal (that is, the headmaster), who was to be responsible for the general administration and daily operation of KGS and for the implementation of decisions of the council (cl 11).

47 The UCPT throughout the Period was the owner of the business name “Knox Grammar School”, and held an ABN in the name of the UCPT trading as KGS.

B.2 The Policies

48 Over the Period, Allianz (or, for the policy years 1999–2000 and 2000–2001, Allianz’s predecessor MMI) issued 19 policies of professional indemnity insurance to the UCA that are the subject of this proceeding. Those policies were organised for UCA and its various bodies and entities by its broker, Marsh, and, later, Willis.

49 Those 19 policies of professional indemnity insurance are as follows:

(1) 1999–2000 MMI Policy;

(2) 1999–2000 HIH Excess Policy;

(3) 1999–2000 MMI Excess Policy (shared risk with HIH);

(4) 2000–2001 MMI Policy;

(5) 2000–2001 MMI Excess Policy;

(6) 2001–2002 Allianz Policy;

(7) 2002–2003 Allianz Policy;

(8) 2002–2003 Allianz First Excess Policy;

(9) 2002–2003 Allianz Second Excess Policy;

(10) 2003–2004 Allianz Primary Policy;

(11) 2003–2004 Allianz Buy Down Policy;

(12) 2004–2005 Allianz Primary Policy;

(13) 2004–2005 Allianz Buy Down Policy;

(14) 2005–2006 Allianz Policy;

(15) 2006–2007 Allianz Policy;

(16) 2007–2008 Allianz Policy;

(17) 2008–2009 Allianz Policy;

(18) 2009–2010 Allianz Policy; and

(19) 2010–2011 Allianz Policy.

50 By way of a broad overview, Allianz provided continuous insurance cover to the UCA and its various bodies and organs, including the UCPT, over the Period. The period of cover for each year of insurance was defined in the policies of insurance as a “Period of Insurance”.

51 In total, there were twelve successive periods of insurance from 31 March 1999 to 31 March 2011 (Periods of Insurance).

52 During the Periods of Insurance, the terms of the various conditions, exclusions and extensions of the Policies were amended from time to time (set out in Annexure A to these reasons). Although each of the policies are not identical, their terms share many substantive similarities. Relevant differences are identified below.

B.2.1 The Insured

53 In each policy, the “Insured” was defined to include, among other entities, the UCPT.

54 The 1999–2000 policy described the name of the Insured as “The Uniting Church in Australia as stated in the attached Policy Wording”. There was a change as between the policy years 1999–2000 and 2008–2009 on the one hand, and the policy years 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 on the other. The former wording was as follows (taken from the 2008–2009 policy):

Name of Insured: The Uniting Church in Australia, including:

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NSW)

• The Uniting Church (NSW) Trust Association

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Victoria)

• The Uniting Church in Australia (Australian Capital Territory) Property Trust

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Tas)

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (N.T)

• The Uniting Church Council of Mission Trust Association

• The United Theological College

• National Assembly

and including all those entities listed in the Directories of The Uniting Church in Australia, Synods of Victoria and Tasmania, NSW/ACT/NT and Northern Synod and all other entities under the Uniting Church's effective management control or for which the Uniting Church is responsible and all their subsidiary companies and related corporations as defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (including those acquired during the period of insurance) for their respective rights and interests but excluding;

• Epworth Foundation (Epworth Hospital)

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Q.)

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (South Australia)

• The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Western Australia)

• Haileybury College (Victoria)

• Newington College (NSW)

• Presbyterian Ladies College (WA)

[Annexure A included: “(c) Any person who is, becomes or ceases to be, during the Period of Insurance, a director, executive officer, employee, partner, voluntary worker, counsellor, councillor, representative, delegate, committee member, member, member in association, adherent, minister, deaconess or lay pastor of the Insured, adherent of the Insured … but only whilst acting within the scope of their duties or activities; …]

55 The latter wording, taken from the 2009–2010 policy, was as follows:

The Insured: The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NSW)

The Uniting Church (NSW) Trust Association Limited

The Uniting Church in Australia (Australian Capital Territory) Property Trust

The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NT.)

Uniting Church Council of Mission Trust Association

Uniting Financial Services

The Uniting Church in Australia National Assembly

The Uniting Church in Australia Synod of NSW and The ACT

The Uniting Church in Australia - Northern Synod

And including all those entities listed in the directories of The Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of New South Wales and ACT and the Northern Synod and all other entities under the Uniting Church’s effective management control or for which the Uniting Church is responsible and all their subsidiary and related corporations as defined under Australian Corporations Law (including those acquired during the Period of Insurance).

But excluding:

• Wesley Mission t/as Wesley Private Hospital

• Wesley Mission t/as Wandene Private Hospital

56 Although the drafting of the insuring clause was amended from time to time, the insuring clause in each policy was to the effect that, subject to the Insured’s payment of the relevant premium, Allianz agreed to indemnify the Insured, up to any applicable “Limit of Indemnity” or “Sublimit” (including for sexual misconduct) in each policy, against all sums which the Insured became legally liable to pay as a result of any claim or claims first made against the Insured during a Period of Insurance and reported to Allianz during that period for breach of professional duty arising out of any negligence.

B.2.2 Conditions

57 Condition 1 in each policy was that upon the making of a claim against the Insured, the Insured shall notify Allianz in writing as soon as reasonably practicable after the claim was made and provide to Allianz whatever information relating to the claim that was in the Insured’s possession. That was the language of condition 1 for the policy years in force from 31 March 2004 to 31 March 2011.

58 Before that time, condition 1 expressly permitted notification of any allegation or the discovery of any circumstance which indicated the possibility of a claim arising.

59 Condition 1 in the 1999–2000, 2000–2001 and 2001–2002 policies was in the following terms:

Upon the making of a claim against the Insured, or the making of any allegation or the discovery of any circumstance which indicates the possibility of a claim arising, the Insured shall notify the Company in writing immediately and shall provide to the company whatever information relating to the claim or possible claim is in the Insured’s possession.

If during the Period of Insurance the Insured becomes aware of any circumstance which may subsequently give rise to a claim against the Insured and during the Period of Insurance gives written notice to the Company of such circumstance, any claim which may subsequently be made against the Insured arising out of that circumstance shall be deemed for the purposes of this policy to have been made during the Period of Insurance.

For the purpose of this condition only, “the Insured” shall mean “the General Secretary of the Synod”.

60 In the 2002–2003 and 2003–2004 policies, condition 1 was amended to read:

Upon the making of a claim against the Insured, or the making of any allegation or the discovery of any circumstance arising, the Insured shall notify the Company in writing immediately and provide to the Company whatever information relating to the claim or possible claim is in the Insured’s possession. For the purpose of this condition only, “the Insured” shall mean “the General Secretary of the Synod”.

61 For the various policies in force in the period from 31 March 2004 to 31 March 2011, the clause was again amended such that condition 1 only provided for the notification of claims, as opposed to claims or circumstances that may give rise to a claim. The clause was again amended in the 2004–2005 policy to read:

Upon the making of a Claim against the Insured, the Insured shall notify the Company in writing as soon as practicable after the Claim is made and shall provide to the Company whatever information relating to the Claim that is in the Insured’s possession.

For the purposes of this condition only, “the Insured” shall mean “the General Secretary of the Synod”.

62 The clause was again amended in the 2005–2006 policy (and in the later policies) to read:

Upon the making of a claim against the Insured, the Insured shall notify the Company in writing as soon as practicable after the Claim is made but during the period of insurance and shall provide to the Company whatever information relating to the claim that is in the Insured’s possession.

For the purposes of this condition only, “the Insured” shall mean “the General Secretary of the Synod”.

B.2.3 Exclusions 6 and 7

63 In each policy, exclusions 6 and 7 provided (with some minor differences in the wording) that:

This policy does not cover any liability for or arising directly or indirectly from:

…

6. Retroactive Date

any act, error or omission committed or alleged to have been committed prior to the retroactive date, if any, specified in the Schedule;

7. Prior Claims & Circumstances

any Claim, fact, circumstance or occurrence;

a. in respect of which notice has been given to [Allianz] or any other insurer under a previous insurance policy, or

b. disclosed or communicated to [Allianz] in the proposal or declaration or otherwise before the commencement of the Period of Insurance, or

c. of which the Insured is aware before the commencement of the Period of Insurance, which may give rise to a claim.

This exclusion is independent of and shall not affect [Allianz]’s other rights regarding misrepresentation and non-disclosure.

64 The “retroactive date” was stated in the relevant policy schedule (in this case in the 2009–2010 policy) to be “Unlimited (excluding known claims and circumstances).”

65 It is uncontroversial as between the parties that exclusion 6 has no operation independent of exclusion 7.

B.2.4 Continuous cover

66 From the 2007–2008 policy year, cover was further extended by means of a continuous cover clause. Where a continuous cover clause is engaged, cover is provided under the terms of the policy in which the claim is made, but only to the extent that Allianz would have been obliged to indemnify the UCPT under the terms and conditions of the policy in effect during the period of the policy in which the failure to notify the relevant facts or circumstances occurred.

67 During the policy years 2007–2008, 2009–2010 and 2010–2011, the insurance policies contained continuous cover clauses to the following effect:

1. We agree to indemnify you against civil liability arising from any claim that is first made against you during the period of cover and is notified to us during the period of cover, that arises out of facts or circumstances which first became known to you prior to the period of cover where:

a) we were your professional indemnity insurer at the time the facts or circumstances first became known to you (the “previous policy period”) and have continued to be your professional indemnity insurer from then until the date of actual notification; and

b) but for your failure to notify us of the facts or circumstances during the previous policy period, you would have been entitled to indemnity under a previous policy issued by us; and

c) but for the exclusion in clause 16 you would be entitled to indemnity under this policy; and

d) you have not committed or attempted to commit fraudulent non-disclosure or fraudulent misrepresentation.

2. We are only liable to indemnify you to the extent that we would have been obliged to indemnify you under the terms and conditions of the policy in effect during the previous policy period. We may reduce our liability to you by the amount that fairly represents the extent to which we have been prejudiced as a result of the late notification.

(Emphasis in original)

68 The presence of the continuous cover clauses in the 2007–2008, 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 policies bears upon the issue of which policy each claim falls given the earlier notification of facts and circumstances (including in respect of the supplementary or “top-up” claims arising out of the same facts and circumstances). In turn, this raises issues in relation to, inter alia, provisions for erosion, aggregation, limits and deductibles, which are provided for in the various policies (set out in Annexure A).

69 At this stage of the proceeding, however, it is only necessary to determine whether, as a matter of principle, the claims are the subject of a proper claim for indemnity (that is, whether one or more policies respond to the facts and circumstances notified to Allianz over the course of the Period). Ancillary questions of how various conditions in the Policies providing for, among other things, limits, erosion, reinstatement and deductibles colour each claim for indemnity (including supplementary or “top-up” claims for indemnity relating to TPCs 1–11) are more appropriately dealt with at the quantum and relief stage of the proceeding.

70 It is now appropriate to turn to make findings as to the relevant background facts.

B.3 Initial Allegations

71 On 30 June 1999, after the 1999–2000 policy had commenced, Mr Peter Crawley (then headmaster of KGS) received a letter from a former student (PTPC1) expressing disappointment at his son not receiving a scholarship to attend KGS.

72 The letter went on to make an allegation of sexual abuse of PTPC1 and others, by an unnamed housemaster at KGS sometime between 1972 and 1977. No alleged offender was specifically identified. The Legal & Technical Manager of MMI, Ms Helen Brennan, made amendments to a draft letter Mr Crawley had prepared in response to PTPC1’s letter. Ms Brennan’s amendments were enclosed with her facsimile dated 9 August 1999 to Ms Maureen Stanistreet of Marsh.

73 On 10 November 1999, Mr Bernard Dennis of Marsh sent a letter to Mr Steve Piening of the NSW Synod attaching a “Guidelines for Reportable Incidents”, which was prepared following discussions between Marsh and MMI to prepare “a Protocol for notification of claims of a ‘sexual misconduct’ nature”.

74 On 14 February 2000, Mr John Cameron (then Finance Director of KGS) sought “declarations” from various staff at KGS, including Mr Crawley and Adrian Nisbett (AP1) in his capacity as Director of Students.

75 On 16 February 2000, the KGS council met and minutes of that meeting were taken. The KGS council passed a resolution concerning the insurance declaration, declaring there were no claims, nor claims circumstances of which it was aware, which would give rise to claims.

76 On 17 February 2000, Mr Cameron signed an insurance declaration on behalf of “Knox Grammar School (The Uniting Church in Australia)”. The declaration provided:

We confirm that there are no known claims or claims circumstances that have not as yet been reported to the General Secretary of the Synod.

77 On the next day, the Uniting Church’s “Insurance Advisory Committee” met and discussed the importance of “sweeps” for potential claims that “properly identify incidents that might give rise to claims” and the “ramifications of late reporting”.

78 On 1 March 2000, Mr Cameron provided copies of the 16 February 2000 KGS Council minutes, and the 17 February 2000 declaration from “Knox Grammar School (The Uniting Church in Australia)”, to Mr Mein of the UCA.

79 On 2 March 2000, Mr Crawley signed two documents. In the first document, which was written on the KGS letterhead, although was not addressed to any identified person, he wrote:

This is to certify that the names known for possible claims are:

[AP15]

Damien Vance [AP2]

Christopher Fotis [AP9]

80 The second document was another insurance declaration on behalf of “Knox Grammar School (The Uniting Church in Australia)” in similar terms to that notified on 17 February 2000.

81 On 3 March 2000, Mr Cameron sent Mr Piening by facsimile a letter that he had received further information. He stated that “[t]here are no known claims, however there appears to be some potential for claim(s) to arise” and “I have therefore sent to you by mail names known for possible claims”.

82 On 24 March 2000, Mr Piening wrote a letter to Mr Dennis, advising as to possible claim matters from Knox arising from internal sweeps, stating, among other things, that there were rumours about the departure of three teachers, namely AP15, Vance and Fotis.

83 During the Periods of Insurance between the years 2000 and 2003, further insurance declarations were requested and completed by Mr Crawley, confirming that there were no known claims or claims circumstances that had not as yet been reported to the general secretary of the Synod.

B.4 The LKA Investigations and Reports

B.4.1 The First LKA Report

84 At 4pm on 31 March 2003, the 2002–2003 policy expired, and the 2003–2004 policy commenced.

85 On 20 November 2003, Mr Crawley received a complaint from TPC1’s mother about the conduct of Nisbett towards her son. A note of the conversation records that the complaint was that Nisbett had TPC1 over for dinner at his home and offered him alcohol, cigarettes and a hug. The note specifies that “no accusation of molestation or any other form of sexual abuse” was made.

86 Following the complaint, Mr Crawley caused investigations to be undertaken, including engaging LKA Risk Services Pty Ltd (LKA). In turn, LKA engaged Mr Grahame Wilson, a licensed private investigator, to conduct the investigation. Mr Crawley’s procurement of the LKA investigation was first made known to the NSW Ombudsman on 21 November 2003 (noted in a subsequent letter to the NSW Ombudsman from the KGS headmaster (then, Mr John Weeks) dated 26 February 2004).

87 On 4 December 2003, Mr Wilson finalised his report and accompanying materials dated 4 December 2003, which he addressed and provided to Mr Crawley on or about that same date (LKA1 or 2003 LKA Reports and Materials).

88 LKA1 comprises 21 documents and spans more than 120 pages. It contains, among other things, file notes, contemporaneous notes provided by Mr Crawley, correspondence with the NSW Ombudsman, interview plans and transcripts, an analysis of evidence, a risk assessment, and investigation protocols.

89 On 17 December 2003, Mr Cameron sent an email to Mr Piening. The email concerned the complaint by TPC1’s mother to the headmaster, Mr Crawley, regarding the “inappropriate behaviour” of Nisbett, including, among other things, that Nisbett took her son back to his apartment alone.

90 On 18 December 2003, Mr Piening forwarded a summary of the allegations against Nisbett to Mr Dennis of Marsh. Mr Piening wrote:

This is an initial report, and hopefully Knox will put together a more formal report quickly.

I am not sure if you think this email is an adequate report on this potentially serious incident.

Q, how do teachers (and students) in this enlightened age get into these situations? Are the kids stupid or that way inclined and parents do not accept they are likely that way.

Please do not send my comments on to insurers if you use the initial message.

91 Two memoranda dated 18 December 2003 addressed to Ms Vivian Kontos of Allianz, from Ms Stanistreet of Marsh, relating to the potential claim by the mother of TPC1, are in evidence.

92 The first is in respect of a professional indemnity claim (2003 PI Memo) and the second is in respect of a directors and officers claim (2003 DO Memo) (collectively, the 2003 Memo). The copy of the 2003 PI Memo includes hand-written amendments and annotations, including to the reference number and the amount of the deductable.

93 A further memorandum, dated 16 January 2004, relating to the potential claim by the mother of TPC1 also appears in evidence (2004 Memo).

94 In early 2004, there was a change of headmaster at KGS. The new headmaster was Mr John Weeks.

95 On 15 January 2004, in email communications involving Mr Martin Gooding (KGS), Mr Cameron and Mr Piening, there were references to the allegations of TPC1 against Nisbett, as well as an “independent investigator” and an “investigator’s report”. The correspondence concluded with: “need to brief John Weeks on this, and ensure that the report/action is taken, and that the Ombudsman is notified”.

96 On 27 January 2004, Mr Cameron had discussions with PTPC41 regarding Nisbett, including, among other things, the “behavioural issues that might give rise to concern” and “the Boarding House ‘murmurings’ relating to Nisbett”.

97 On 24 February 2004, Mr Cameron emailed Mr Piening with an “extract from our [KGS] last Council Meeting minutes”, confirming that there were no claims or potential claims, “other than those previously advised”.

B.4.2 Further Investigations

98 On 25 February 2004, Mr Cameron attended a meeting at the Association of Independent Schools. Among the attendees were Mr Weeks, Mr Grahame Mapp (Chairperson of KGS) and Mr Wilson. In his file note of the meeting, Mr Wilson wrote:

They advised that, during the Headmaster’s discussions with senior staff regarding outcomes from the investigation I conducted at the end of 2003, information regarding possible allegations of child abuse against Adrian Nisbett dating back to the ’80s had been received.

99 Mr Wilson also noted that he was “instructed to conduct a further investigation relating to these possible allegations”.

100 That same day, Mr Wilson made a file note indicating he identified PTPC3 as a student potentially affected, and noted risk management issues.

101 In early 2004, Mr Wilson was then engaged to conduct a further and more detailed investigation into Nisbett on behalf of LKA and KGS.

102 On 26 February 2004, Mr Weeks reported to the NSW Ombudsman “to advise of allegations received by me concerning a member of staff at Knox Grammar School”. The member of staff was Nisbett, and the alleged behaviour by him included “groping and touching of boys private parts whilst working in the photographic darkroom at the Boarding House”. Mr Weeks noted the details of the 2003 LKA Reports and Materials and said that it was as a result of that earlier investigation that the allegations had surfaced. Mr Weeks also noted that he had “contacted the Association of Independent Schools”, and had engaged LKA again.

103 On 27 February 2004, Mr Weeks contacted Mr Wilson seeking an update regarding the investigation, and sought Mr Wilson’s advice “on risk”.

104 On 2 March 2004, Mr Wilson spoke to PTPC41 about his concerns about being interviewed and the potential for retaliation.

105 On 4 March 2004, Mr Wilson telephoned Mr Pearson to arrange a meeting. Mr Pearson anticipated that the call concerned Nisbett, and stated that he wrote a report about Nisbett for the previous KGS headmaster, Dr Ian Paterson.

106 On 8 March 2004, Mr Wilson met with Mr Pearson for the purposes of the investigation, and conducted an interview, which was taped and later transcribed.

107 On 13 March 2004, Mr Wilson interviewed Dr Paterson regarding his investigation into Nisbett. Sometime prior to 18 March 2004, Dr Paterson arranged a meeting with Mr Weeks following his interview with Mr Wilson.

108 On 18 March 2004, Mr Weeks telephoned Mr Wilson to advise him of the meeting, including various matters remembered by Dr Paterson and discussions between Ms Kim Walton, the deputy headmaster of KGS, and Nisbett following Nisbett being informed of the “new investigation”.

109 Over the following days, Mr Wilson conducted interviews with Mr Gooding, Mr Les Harvey, Mr Norrie Cannon and the ex-chaplain, Mr Ross Godfrey. Following these interviews, Mr Wilson contacted Mr Weeks to discuss the general progress of the investigation and details of the interviews.

110 On 27 March 2004, Mr Wilson interviewed Dr Paterson at his home for a second time. After the interview, Dr Paterson asked Mr Wilson about the risks of litigation. Mr Wilson also pressed the importance of locating Mr Pearson’s report.

111 On 29 March 2004, Mr Piening called Mr Dennis. There are two file notes of this conversation from Mr Dennis. In the first file note, Mr Dennis wrote:

UCA (SP) 29/3

Knox – report re: teacher took boy home

– goes back a long way (like Kinross)

– awful things happened

– meeting with teacher this week (confront)

– want him to leave

– no claims

– grooming boys for the future

112 In the second file note, Mr Dennis wrote:

PI Incident – Knox Grammar / Mrs [TPC1’s mother]

Steve called to advise having been briefed further on this matter by Knox Grammar. Knox’s enquiries indicate inappropriate behaviour by teacher going back quite some time. Knox (John Cameron and John Weeks – the new headmaster) are meeting with the teacher this week and will likely ask him to resign. They have consulted with Teachers Union.

Steve said there is no indication of any claims at this time. He said it seems the teacher may have been “grooming” boys for the future.

113 On 30 March 2004, Mr Wilson telephoned Mr Weeks to provide an update on his interview with Dr Paterson and the progress of investigation, and asked him to check staff files of Vance (AP2) and Fotis (AP9).

114 On 31 March 2004, Mr Wilson drafted a letter addressed to Nisbett detailing the (then) 16 allegations made against him.

115 At 4pm on that same day, the 2003–2004 policy expired, and the 2004–2005 policy commenced.

116 On 1 April 2004, Mr Wilson attended KGS and met with Mr Weeks. Mr Wilson provided him with a copy of the draft letter to Nisbett. Mr Weeks provided Mr Wilson with files relating to Vance and Fotis. Mr Wilson asked about Craig Treloar (AP3), and Mr Weeks agreed to obtain Treloar’s file for Mr Wilson.

117 On 7 April 2004, Mr Wilson contacted Mr Weeks’ secretary to obtain Treloar’s file. That same day, Mr Wilson interviewed Nisbett.

118 On 15 April 2004, Mr Dennis followed up with Mr Piening regarding their 29 March conversation, stating:

Further our phone conversation on 29/3/04, have you heard from Knox concerning the outcome of the meeting they proposed having with Mr Nisbett that week? If you have heard nothing further would you please follow-up with Knox to determine the current position.

119 On 19 April 2004, Mr Dennis wrote to Mr Piening:

Steve,

I have discussed these type of reports further with my Finpro colleagues. They have commented that the changed conditions affecting the insurance market are also evident in respect of insurers attitude towards the reporting of circumstances that could give rise to a claim. In this regard, insurers have tightened their requirements in recent times and now require brief details and some form of identification (not necessarily names) before they will accept a report as a formal notification of circumstances which could give rise to a claim. I am advised that provision only of a reference number and an accompanying statement that it relates to an allegation of sexual misconduct involving a minister will not be accepted by insurers as a notification.

I appreciate that this is a very sensitive matter for the Church and you may choose not to disclose the required information while preliminary investigations are underway. However, as you are aware, under a “claims made” policy, if brief details of the matter are not notified to insurers during the period of insurance, there is always the possibility that the policy conditions may be breached by a claim arising after the renewal date (or perhaps after several renewals have passed).

Could I have your thoughts on this issue.

120 On 21 April 2004, Mr Wilson conducted a second interview with Mr Cannon, seeking information concerning other possible witnesses he had nominated.

121 On 23 April 2004, Mr Weeks contacted Mr Wilson, who provided an update on the investigation, including the difficulties involved due to missing documentation. On 27 April 2004, Mr Cannon left Mr Wilson a message saying he had spoken with TPC2, and suggested that Mr Wilson contact TPC2.

122 On 29 April 2004, Mr Wilson interviewed TPC2. During the interview, TPC2 made a new allegation against Nisbett concerning an incident occurring in or about 1986.

123 On the same day, Mr Wilson contacted Mr Pearson to confirm details regarding the investigation. During this discussion, the two both agreed that they had “some awareness of [AP2] but would not discuss this further”. Mr Wilson also telephoned Mr Weeks and advised him of the new allegation against Nisbett by TPC2 and provided the general context of the allegation.

124 During the discussion, it was agreed that Nisbett needed to be informed of this new allegation as soon as possible, and a further letter of allegation was prepared. Mr Wilson provided that letter to Mr Nisbett on or about 30 April 2004, and subsequently called him to inform him of the letter and to arrange a further interview in order to give Nisbett a chance to respond.

125 On 4 May 2004, Mr Wilson interviewed Nisbett regarding the new allegation. Following the interview, Mr Wilson contacted Mr Weeks to provide a brief update on the investigation and made an appointment to meet him on the afternoon of 7 May to deliver the investigation report.

B.4.3 The Second LKA Report

126 On 7 May 2004, Mr Wilson finalised his further investigation report and materials dated 7 May 2004 (LKA2 or 2004 LKA Reports and Materials) which he addressed and provided to Mr Weeks on or about that date.

127 LKA2 itself spans over 1,500 pages and comprises the following documents:

(1) “Risk Services Investigation Report” dated 7 May 2004;

(2) “Supplementary Risk Assessment Report” dated 7 May 2004; and

(3) “Investigation File 240134” (comprising four volumes).

128 Despite its length, it is worth setting out the executive summary that appears in LKA2:

Late in 2003 allegations were made against [Nisbett] in relation to his conduct towards a student of Knox Grammar School, [TPC1]. The report of this investigation was provided to the Headmaster at the time, Peter Crawley.

The current Headmaster, John Weeks, took up his position at the beginning of 2004. While he was reviewing the findings of the 2003 investigation, he was made aware of allegations relating to [Nisbett’s] conduct in or around 1986. These allegations had not been made known during the 2003 investigation.

Mr. Weeks sought advice from The Association of Independent Schools and they in turn took advice from the NSW Ombudsman. It was determined that the information from the past constituted allegations under the Ombudsman Act and an investigation was required.

We were instructed to undertake the investigation on 25 February, 2004.

The allegations appeared to relate to a pattern of behaviour which could be characterised as grooming. [Nisbett] was the Housemaster of a boarding house Ewan, that catered for the equivalent of Years 11 and 12 boys today. An investigation had been carried out in 1986 and [Nisbett] was allegedly removed from his position at Ewan House by the Headmaster at the time, Dr. Ian Paterson.

After a period of time [Nisbett] became a member of staff at another boarding house, “Kooyong” that catered for the same age group of boys as Ewan House. During the course of our investigation, allegations were also made regarding [Nisbett's] conduct at Kooyong House and at Cadet Camps.

This very complex matter has involved the face to face interviewing of 8 people. Two interviewees were interviewed twice and [Nisbett] was interviewed twice. These interviews created approximately 350 pages of transcript that have been analysed.

A huge amount of documentation has been collected and analysed during the course of the investigation.

The allegations were detailed in formal letters to [Nisbett] on 31 March, 2004 (FOLIO 1087) and 30 April, 2004 (FOLIO 1124)[.]

The Association of Independent Schools N.S.W. and The NSW/ACT Independent Education Union Recommended Protocols for Internal Investigative and Disciplinary Proceedings “2001 have been followed (refer FOLIO 2166).

The definition of child abuse from page 22 of the Ombudsman Act 1974 (FOLIO 2165) has been applied.

This report contains preliminary findings in terms of the protocols for all allegations.

129 On 9 and 11 June 2004, and on 12 July 2004, Mr Weeks provided information to the NSW Ombudsman, which included documents comprising LKA2.

130 On 19 July 2004, the NSW Ombudsman acknowledged receipt of this information.

131 On 16 June 2004, LKA2 was tabled at a KGS council meeting. The minutes of the meeting provide:

1. [Nisbett] Matter.

The report to the School by Mr. Grahame Wilson of Lee Kelly & Associates on the allegations against [Nisbett] has been received and actioned on.

In his report Mr. Wilson found that “There is sufficient evidence to sustain an allegation that [Nisbett] behaved in a way which constituted grooming in the sexual abuse context and that he failed to meet the professional standards expected of him as an employee of Knox Grammar School. I find that the matter requires disciplinary action.”

From a risk perspective Mr. Wilson considered [Nisbett] an extreme risk to the students, the reputation of the School and to his own reputation.

Upon receiving the report, [Nisbett] was informed of its findings and given time to respond. This he did in writing denying the claims but indicating no desire to fight them nor offer any new evidence.

As a result [Nisbett] will leave the employment of Knox Grammar School on 18 June. He will take Long Service Leave until Easter 2005 at which time his position at Knox will be formally concluded.

In line with Child Protection Legislation both the Ombudsman and the Commission for Children and Youth Protection have been notified of the outcome of this investigation.

I believe, that in the absence of any claims against the School, the matter now closed.

132 On 9 and 11 June 2004, and on 12 July 2004 (in all cases after receipt of the 2004 LKA Reports and Materials on 7 May 2004) Mr Weeks provided further information to the NSW Ombudsman, which included documents comprising the 2004 LKA Reports and Materials.

133 On 9 November 2004, Mr John Oldmeadow (Executive Director of UCA NSW Synod) sent an email to Mr Weeks. The subject was PTPC41. Mr Oldmeadow wrote:

As regards to his [PTPC41’s] information about the other matters within the school, I am unclear about how much more information he has. In the conversations he appears to alternate between inferring there is more and, as he did today, claiming that he had passed on everything to his superiors at the school (although some of this information may have been well before your time as Headmaster).

I pressed him to consider providing anything more and he reiterated that he had passed on everything at some time or other.

My feeling is that the key area where he may have been able to assist is in the provision of names of others who may have more information but at this time he is not willing to involve others. His final assertion was that he had given all the information that he had at the time each event happened and that it should be on the record in the school somewhere.

If he doesn’t change his mind, and I think such a change is unlikely, l believe that we / you have done all that is possible to pursue any and all references or hints of untoward or illegal activity at the school recently or in the distant past. [PTPC41] has provided much detail to you and the investigator previously, I don’t think there is much more that you or the school or even the police can do to pursue this at this time. I may make a follow up call to [PTPC41] in several weeks, in the meantime, I think the matter rests and the meeting on Friday 18th will not take place.

134 On 28 January 2005, Ms Patricia Gough (KGS bursar) signed a “Professional Indemnity Insurance Proposal” of even date on behalf of the “Uniting Church in Australia (NSW Synod)”, “Professional Business: Knox Grammar School”. Ms Gough recorded her role in that document as “Office Manager”.

135 At 4pm on 31 March 2005, the 2004–2005 policy expired, and the 2005–2006 policy commenced.

136 On 30 January 2006, Ms Gough signed an insurance declaration for KGS. The document was headed: “Name of Presbytery/Institution: Knox Grammar School”, and “The Uniting Church in Australia”. The document recorded that there are “no known claims or claims circumstances that have not as yet been reported to the General Secretary of the Synod”.

137 At 4pm on 31 March 2006, the 2005–2006 policy expired, and the 2006–2007 policy commenced.

B.5 Further Allegations and Arrests

138 In late 2006, Mr Weeks was told by Mr Pearson of an incident in 1988 where a year seven boarder had watched a pornographic video with Treloar.

139 Mr Pearson said that the matter had been investigated at the time and raised with Dr Paterson, who immediately “sacked” Treloar. As it turns out, this decision was later reversed, and Treloar was in fact still employed by KGS. Mr Weeks conducted an internal investigation and learned from the deputy head of the KGS preparatory school, Mr Bob Thomas, that Treloar had been stood down for six months but reinstated at the start of 1989.

140 In December 2006, TPC1’s mother called Mr Weeks and made allegations against Nisbett of sexual assault of TPC1.

141 On 13 December 2006, Mr Oldmeadow emailed Mr Piening (copying Mr Weeks) noting a call from Mr Weeks “to update me on the situation regarding an alleged sexual assault by a student”. That update was that the student had left the school and that TPC1’s “mother … mentioned the possibility of compensation”. Mr Oldmeadow’s email also noted that the incident had been the subject of an earlier report to the Uniting Church.

142 On 14 December 2006, Ms Stanistreet forwarded that email to Ms Kontos under the following covering email:

This circumstance was notified to you under the D&0 and P/I policies by mem dated 18 December 2003. I do not have your reference for either file.

An update was then forwarded 16 January 2004.

As no further information was received from the school our files were closed in May 2005.

The attached email has now been received and it appears that there may be some activity on this matter in future.

If you have any comments, or file references, please advise

(Emphasis added).

143 The reference to the “memo dated 18 December 2003” and the later “update” is to the 2003 Memo and the 2004 Memo.

144 On 15 December 2006, Ms Kontos sent an email to Ms Stanistreet regarding TPC1’s claim, stating that she could not find a reference to the original notification dated 18 December 2003, and requesting that copies of that memo and the update of 16 January 2004 be forwarded to her.

145 Ms Stanistreet replied at 1:43pm, writing: “Attached is a copy of my initial memo 18.12.2003 and the up date [sic] 16.01.2004.” Attached to the email were two PDFs (with filenames “memo 18.12.03.pdf” and “memo 16.1.04.pdf”). Ms Kontos replied on 15 December 2006 to advise that she had opened a claims file at Allianz and allocated a reference number.

146 Allianz draws on these communications, and the absence of any reference numbers for the notifications, to contend that the Court should infer that the 2003 Memo and the 2004 Memo were first provided to Ms Kontos (and therefore Allianz) by Ms Stanistreet on 15 December 2006. The UCPT submits the memoranda must have been sent on 18 December 2003 and 16 January 2004 respectively due to, among other things, Ms Stanistreet’s contemporaneous reference to the 2003 Memo as having been “Advised 18 December 2003”. It will be necessary to return to this factual dispute later in these reasons.

147 On 31 January 2007, Mr Oldmeadow emailed Mr Weeks regarding TPC1’s claim, noting that by that time Mr Weeks had “notified [the] School Council, the Uniting Church and the Ombudsman” about TPC1’s claim.

148 On 1 February 2007, Mr Dennis emailed Ms Stanistreet, attaching a file note prepared by the NSW Synod’s board of education in respect of the developments regarding the new allegations. That email also noted:

During the course of the investigation carried out by Graham Wilson on behalf of Knox Grammar School, another person (presumably a former student) came forward to report that he was also molested by [Nisbett]. Scott was informed that this person does not want to pursue the matter.

149 On 2 February 2007, Ms Stanistreet forwarded an email chain to Ms Kontos, including the above emails regarding TPC1’s allegations.

150 On 28 February 2007, TPC1’s solicitor sent a letter of demand addressed to Mr Weeks.

151 On 7 March 2007, Ms Stanistreet forwarded the letter of demand to Ms Kontos, stating “UCA would be pleased if you would involve Wendy Blacker from Gadens”. On the same date, Ms Kontos sent an email to Ms Wendy Blacker, a partner at Gadens, attaching a copy of the letter of demand, stating: “the Insured has specifically asked us to retain you to assist with the above matter. We would also be very pleased if you would act for the Insured in responding to the claim”. Ms Blacker replied to Ms Kontos confirming receipt of the instructions.

152 On 7 March 2007, Gadens was appointed to act for the UCPT as insured and Allianz as insurer in defence of TPC1’s claim. Ms Blacker had the principal carriage of these engagements.

153 On 15 March 2007, Inspector Elizabeth Cullen of NSW Police and Mr Weeks had a telephone conversation in which Inspector Cullen said: “I hope these people don’t still work at Knox – Nisbett [AP1], Barratt [AP5], Stewart [AP4] and Treloar [AP3]”.

154 On 16 March 2007, Ms Blacker prepared a draft letter of advice addressed to Ms Kontos. The report provided a summary outline of facts and legal advice regarding TPC1’s claim, and stated (among other things):

It appears the School arranged for an investigation to be carried out in respect of the matter [alleged by TPC1]. During the conduct of the investigation another student came forward with allegations concerning a sexual assault perpetrated by [Nisbett]. We are not currently in possession of any details concerning this other student, nor do we know (definitively) whether that other student intends to make a claim against the insured. However, in respect of this last point we note that an email dated 1 February 2007 from Mr Bernard Dennis to Ms Maureen Stanistreet indicates that the other student does not wish to pursue the matter.

155 On 21 March 2007, the KGS council held a private meeting to discuss the allegations against Nisbett. At that meeting, Mr Weeks spoke of his conversation with Inspector Cullen.

156 At 4pm on 31 March 2007, the 2006–2007 policy expired, and the 2007–2008 policy commenced.

157 On 4 April 2007, Mr Oldmeadow emailed Ms Blacker, copying Mr Driscoll and Mr Weeks.

158 In that email, Mr Oldmeadow states, among other things, that there is a “significant deposit of information and documentation held at Knox”, and invited Ms Blacker to “visit the school and examine the material onsite”.

159 On 10 April 2007, according to timesheet records, Ms Blacker attended KGS “to inspect documents” for over six hours.

160 It is necessary to pause here to say something about Ms Blacker’s involvement at this early stage. As I said during the hearing, whatever the catalyst for Mr Oldmeadow’s email to Ms Blacker on 4 April 2007 may have been, I would infer that Ms Blacker’s initial report dated 16 March 2007 was not sent and that Mr Oldmeadow had not received a copy of it: T378.30–46. Indeed, it was intended as a purely internal document which (according to Gadens internal records discovered by Allianz) had been superseded by the advice that was in fact sent on 9 June 2007. Furthermore, Mr Oldmeadow’s response in the first paragraph of his letter, which states “I understand that you have been appointed to pursue the matter at Knox Grammar School concerning [TPC1]” is consistent with him not having received Ms Blacker’s initial draft advice.

161 Returning to the narrative, on 9 June 2007, Ms Blacker provided a legal advice on behalf of Gadens to Ms Kontos in respect of TPC1’s claim. It is necessary to set out its contents:

This matter concerns allegations of a sexual assault committed in late 2002 by [Nisbett] on [TPC1]. The precise nature of the assault is not known, however it has been reported by the Claimant's mother to the Headmaster to include oral sex.

Apparently no criminal charges have been laid against [Nisbett] although the police are aware of the allegations that are the subject of the Claimant's claim against the School and are attempting to locate him …

When the incident was brought to the School's attention, it investigated the incident and reported it to the authorities, as it has a statutory obligation to do.

The investigation of the incident was hampered because the Claimant originally refused to provide any information and then subsequently did not provide a consistent version of events. Initially the Claimant alleged that [Nisbett] offered him alcohol, cigarettes and a hug. Subsequently the Claimant alleged that [Nisbett] sexually assaulted him. The School has no means by which it can establish the truth of the allegations. For present purposes it has, therefore, accepted that the Claimant's version of events as being accurate.

[Nisbett] has been under a cloud in relation to prior conduct. During the 1980's up to 1990 the then General Duties Master, Stuart Pearson, whose role also included disciplinarian, conducted ongoing enquiries and an investigation into [Nisbett] conduct that culminated in a ten page report being submitted to the then Headmaster and [Nisbett] being removed from his position of Boarding Master of Ewen House and promoted to the position of Director of Studies. The rationale for the promotion appears to have been that the position of Director of Studies provided less opportunity for intimate contact with pupils.

The enquiries resulted in the following observations and allegations being made by third parties against [Nisbett]. [The footnote “2” stated “ibid” refers back to the Statement dated 8 March 2004 by Mr Pearson reporting on the allegations]

(a) [Nisbett] favoured certain pupils in terms of allocation of tasks.

(b) [Nisbett] spent time along with certain pupils: pupils were invited into boarding house masters' rooms for hours at a time while the door to the room was closed.

(c) [Nisbett] befriended certain boys and became their confidante; [Nisbett] had intimate conversations with certain pupils, extracting confidential and personal information from the pupils.

(d) [Nisbett] offered pupils alcohol and tobacco.

(e) [Nisbett] touched certain pupils in an inappropriate manner.

Mr Pearson satisfied himself that the allegations were true, with the exception of inappropriate touching of pupils by [Nisbett]. Mr Pearson was unable to establish the truth of this allegation …

In or about 1990, a former pupil of the School reported that he was one of the pupils that had been invited into [Nisbett’s] room. He reported that while in [Nisbett’s] room [Nisbett] showed him pornographic material (including homosexual material) and asked the pupil: … do you like men? Do you have any feelings for men? The pupil claimed that he was invited into the room on about six occasions and on each occasion the level of exposure to pornographic and homosexual material increased. The pupil was also offered alcohol and tobacco. He denied that there was ever physical contact between him and [Nisbett], or that [Nisbett] ever invited such contact.

This was not the only pupil that reported to Mr Pearson that he was in [Nisbett’s] room.

The then Headmaster instructed Mr Pearson to: … keep a very close watching brief over [Nisbett], which included Mr Pearson conducting a search of [Nisbett’s] room in the absence of [Nisbett]. The search did not disclose anything untoward. In relation to his enquiries and investigation, Mr Pearson said:

... I found no evidence of sexual assault. I found heaps of innuendo and heaps of allegations and my concerns were that what I was watching was an escalating pattern occurring over years, where he would initially favour boys, then he'd treat boys as special, as special cases, invite them into his room. Ask them or invite them, were they interested in this lifestyle, a homosexual lifestyle. If they said no, then that was fine, if they said yes, I don’t know what happened because I never found a boy who came to me who was prepared to say, ‘I] [sic] said yes’.

Despite the foregoing, the School determined that there were insufficient grounds for dismissing [Nisbett] …

The evidence justified lawful dismissal … the following breaches combined would have been sufficient grounds for dismissal.

(a) [Nisbett] failed to exercise appropriate professional judgment when he:

(i) favoured pupils; and

(ii) invited and entertained pupils in his room.

(b) [Nisbett] engaged in unprofessional conduct when he:

(i) offered pupils alcohols and tobacco; and

(ii) showed pupils pornographic materials.

[Nisbett’s] conduct was a serious breach of School policy. Even if (a)(i), and (b)(i) and (b)(ii) could not be demonstrated, it seems the school would have been able to readily establish that [Nisbett] was inviting pupils into his room behind a closed door for extended periods. It could have acted on this, at the very least by way of warning. …

It was not necessary for the conduct to amount to criminal conduct to be grounds for dismissal … Dismissal may have been achieved through a serious of warnings … commencing when the conduct was first disclosed. Alternatively, dismissal could have been effected when the conduct was subsequently reported first hand in or about 1990. The School had an ongoing obligation to its pupils …

The alleged incident [involving Nisbett] did not come to the attention of the School until the latter part of 2003.

Upon coming to the attention of the then Headmaster …. [the Headmaster] arranged for an independent investigation to be carried out by Mr Grahame Wilson and reported the matter to the NSW Ombudsman … Mr Wilson obtained statements from relevant persons during the course of the investigation, however, the Claimant and his family declined a request to provide a statement …

Subsequent to that investigation, the Claimant’s mother informed the School about the alleged sexual assault … upon receipt of this information, the authorities were notified and Mr Wilson conducted a further investigation …

During the conduct of the further investigation another pupil came forward with allegations concerning an alleged sexual assault perpetrated by [Nisbett]. We are not currently in possession of any details concerning this other pupil, nor do we know (definitively) whether the other pupil intends to make a claim against the School. …

162 An amended copy of this advice was later reissued on 15 June 2007. In that letter of advice, Ms Blacker advised that she anticipated that TPC1 would “expand his claim to include allegations of negligence against KGS, and if he does this, the School will be at risk of being found liable in negligence, subject to the nature of those allegations”.

163 On 1 August 2007, Mr Weeks received a letter from Mr Thomas acknowledging that he knew that Treloar had shown a pornographic video to a student or students in 1988. On the same day, Mr Pearson sent a letter to Mr Weeks, along with a copy of what Mr Pearson believed was the video confiscated from Treloar in 1988. In the letter, Mr Pearson provided his recollection of events, stating that it was “clear to me that [Treloar] had attempted to have a sexual encounter with this lad”.

164 In or around late 2007, Mr Weeks gave a notification to the NSW Ombudsman. That notification stated:

4. Details of alleged victims

The following names appear on the Police warrant seeking information from school files. The School assumes therefore that they are either alleged victims or alleges witnesses:

…

5. Details of the allegations(s)

Members of the NSW Police arrived at the School, and charged the alleged person. He is now in custody, and school files pertaining-to the charges were produced by the school in response to a warrant. The School assumes that there is more than one incident, but that information in a definitive sense is with the Police. The school will provide details when submitting Part B.

The School understands that the charges are of a sexual nature, possibly sexual assault.

Please note that a video, allegedly shown to students in 1988, was delivered to the School in late 2007. On the advice of the Ombudsman, this, and relevant information, was taken to Beth Cullen of the Sex Crimes Unit at Parramatta. This is now with the Police.

165 On 27 November 2007, Gadens provided a further letter of advice in respect of TPC1’s claim addressed to Mr Karl Adra of Allianz.

166 On 2 December 2007, Ms Blacker emailed Ms Stanistreet, stating:

During the course of acting in this matter it has become evident that there may well be other incidents that potentially could give rise to claims, although I think from your email correspondence you are already aware of this. I will also alert Allianz and let the Church know that I have done so. The Church is aware of this.

167 At 4pm on 31 March 2008, the 2007–2008 policy expired, and the 2008–2009 policy commenced.

168 From November 2008, Claims Management Australasia Pty Ltd (CMA) provided claims management services to UCA and its various bodies and entities. During the period over which cover was engaged, CMA assisted with notifying claims as well as facts and circumstances which may give rise to claims. From time to time, claims management protocols were agreed between UCA/CMA and Allianz.

169 On 18 December 2008, Ms Blacker sent pre-mediation advice to Mr Adra regarding TPC1’s claim. On the same day, the UCPT and TPC1 settle TPC1’s claim.

170 In February 2009, the NSW Police made a series of arrests of current and former teachers of KGS, including Nisbett, Treloar and Barrie Stewart (AP4), as part of “Strike Force Arika”.

171 On 17 February 2009, Mr Emerson sent Mr Adra an email with a media report in relation to the arrest of Treloar.

172 On 18 February 2009, Mr Adra sent an email to Ms Barker of CMA, stating:

As per our conversation we will register the notification of the potentail [sic] sexual abuse claims under the professional [sic] Indemnity policy 96–0966596 PLP.

…

For now our mains concerrn [sic] as always is the UCA’s & Knox Grammar’s reputation. These potential notifications will be treated as 1 notification for the time being as we have very little information regarding the claimants, however later they will be separated into 2 claims being 2 different incidents as more information comes to hand.. [sic]

These claims if followed through by the claimants after the criminal proceedings especially if the teacher is found to be guilty, have the potentail [sic] to exceed the deductible and hence I would recommend that Wendy Blacker of Gadens be instructed to look after these matters should they emerge. She has good experience with sexual abuse matters and has dealt previously with Knox.

173 On 19 February 2009, Ms Blacker sent Mr Adra an email with a media report in relation to the arrests of Treloar and Stewart.

174 On 24 February 2009, Mr Emerson sent an email to Mr Adra, requesting that his email be treated as a notification of potential sexual abuse claims by three persons arrested over allegations at KGS. The reference to a third arrest concerned the arrest of Nisbett. Mr Adra responded to the email on the same day, confirming that the notification had been given a claim number.

175 On 2 March 2009, Ms Blacker sent a letter of engagement to Mr Dwane Feehely (in his capacity as Manager Insurance and Property Services, Uniting Resources – Property Services). In the letter, Ms Blacker stated that Gadens had been “instructed to do all things necessary to advise you in relation to the above matter”, which she described as “The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (NSW) ats Knox Grammar School”. The file reference was recorded to be: “Our reference Wendy Blacker:shd 29601178”.

176 On 6 March 2009, Mr Adra sent Ms Marleny Vargas of Allianz an email and an attachment in relation to TPC2. The attachment was a letter from TPC2 to Mr Weeks, expressing his deep concern “as to the conduct of KGS through the course of the investigation in 2004.”

B.6 The Bulk Notifications

B.6.1 The First and Second Bulk Notifications

177 By two letters dated 31 March 2009, Mr Emerson emailed Mr Adra purporting to notify Allianz of “circumstances that could give rise to claims”. The first letter was sent at 9:50am (first bulk notification) and the second letter was sent at 4:21pm (second bulk notification).

178 The claims were identified as “likely to be claims relating to: psychiatric injury and/or physical injury arising from physical assault, sexual assault, trespass to person, breach of fiduciary duty and/or negligence”. A number of potential claimants were identified in the letter under three classifications:

(1) “persons who have expressed an intention to seek redress”;