FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd trading as Database Consultants Australia (No 8) [2023] FCA 182

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant bring in draft minutes of order reflecting the conclusions in these reasons and the parties will be heard as to the terms of the orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO J:

Introduction

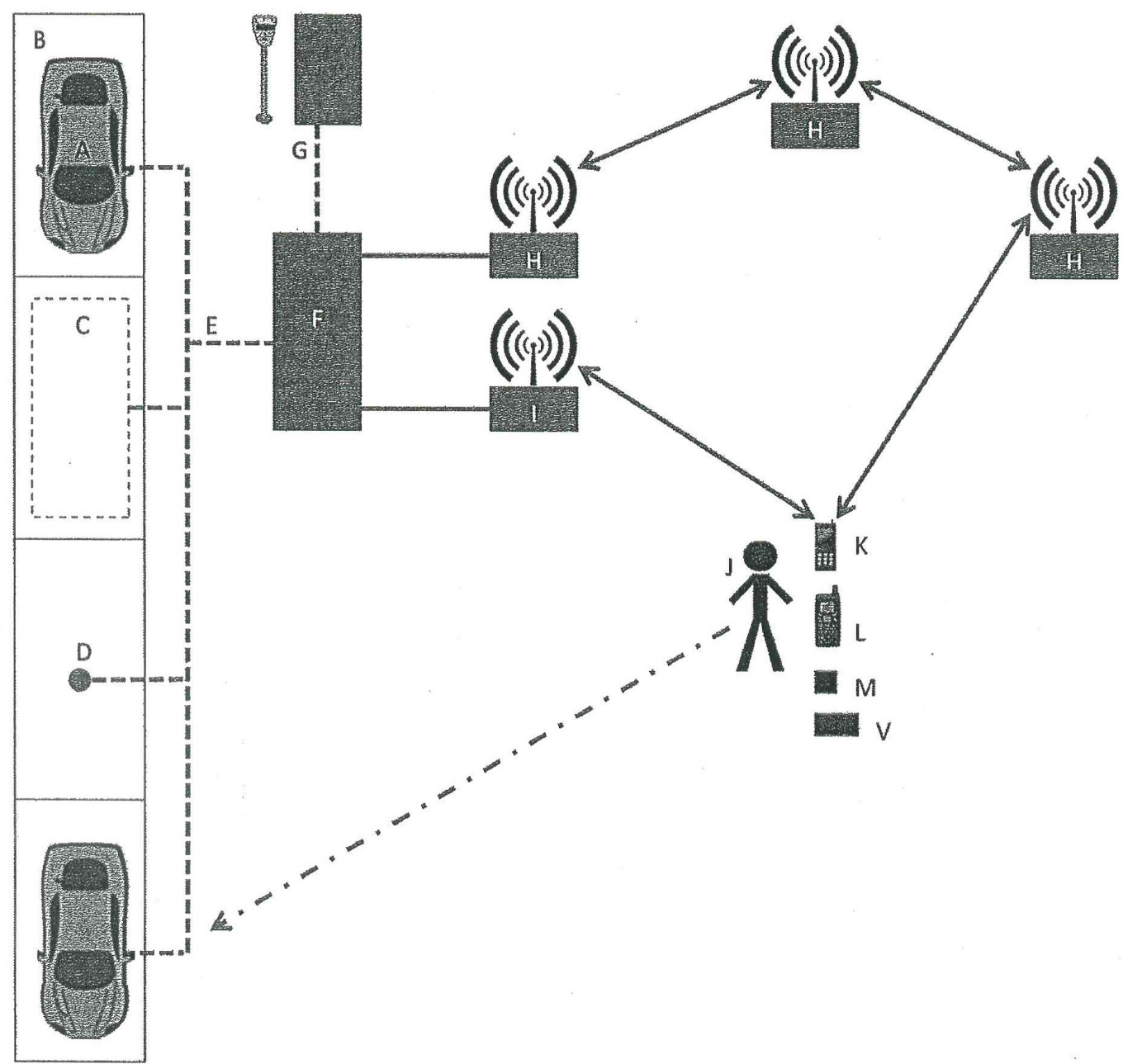

1 Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited (VMS) is the registered owner of two patents. The first patent is Australian Patent No. 2005243110 and bears the title “Method, apparatus and system for parking overstay detection” (the First Patent). The second patent is Australian Patent No. 2011204924 (the Second Patent) and has the same title. The invention is for identifying the overstay of a vehicle in a parking space and involves a battery-powered subterraneous detection apparatus (DA) to detect the presence of a vehicle in a parking space, the storage of data in that apparatus and the wireless transmission of that data to a data collection apparatus (DCA) and the indication by that device to an operator of identified instances of vehicle overstay in a parking space. The DCA may be portable and may retrieve data from the DA whilst the DCA is located in a moving vehicle. The wireless retrieval of data from the DA may be performed in response to receipt of a wireless wake-up signal from a DCA.

2 In earlier periods of time, the DA was referred to as a vehicle detection unit (VDU) or an in-ground unit (IGU). In earlier periods of time, the DCA was referred to as a drive-by enforcement vehicle (DEV) or the in-vehicle unit (IVU) and may consist of a handheld unit (HHU) and a transient middle tier (TMT) which is a belt-worn device which communicates with the HHU by Bluetooth.

3 VMS has brought a proceeding in this Court against SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (t/a Database Consultants Australia) (SARB) and the City of Melbourne (CoM) for relief in relation to alleged infringements of the patents.

4 The claim by VMS against SARB is that it has directly and indirectly infringed claims in the First Patent and claims in the Second Patent by its conduct in connection with vehicle detection sensors, systems and methods known as PinForce. There are three versions of SARB’s PinForce Sensors, PinForce Systems and PinForce Methods. The First PinForce Sensor and First PinForce System was made, sold, used and kept by SARB and the subject of authorisation by SARB to local government councils to use, between approximately October 2007 and December 2016 (PinForce Version 1). Between approximately January 2016 and December 2016, PinForce Version 1 was progressively upgraded to the Third PinForce Sensor and Third PinForce System.

5 The Second PinForce Sensor and Second PinForce System was made, sold, used and kept by SARB and the subject of authorisation by SARB to local government councils to use, between approximately November 2014 and December 2016 (PinForce Version 2). Between approximately November and December 2016, PinForce Version 2 was progressively upgraded to the Third PinForce Sensor and Third PinForce System.

6 The Third PinForce Sensor and Third PinForce System was made, sold, used and kept by SARB and the subject of authorisation by SARB to local government councils to use from approximately December 2014 (PinForce Version 3).

7 VMS seeks declarations, injunctions, orders for delivery up, damages or an account of profits and additional damages under s 122(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) against SARB.

8 The relief which VMS seeks against CoM is similar, although the relief is based on claims of direct infringement by CoM.

9 On 6 April 2020, the Court made the following orders in this proceeding:

1. Pursuant to r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the quantum of any pecuniary relief be heard and determined separately from, and after, the determination of all issues of liability for infringement and patent validity.

2. For the avoidance of doubt:

(a) the issues of liability for infringement include all questions of liability for authorisation of any infringement, of liability for additional damages and any question of innocent infringement under s 123 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth);

(b) the issues of quantum include the quantum of any additional damages and the allegations of double-recovery that are pleaded in paragraphs 10(b) and 11(b) of the First Respondent’s Defence filed 28 February 2020 and paragraphs 18(d) and 19(e) of the Second Respondent’s Defence filed 28 February 2020.

10 With respect to paragraph 2(a) of the orders, the following matters should be noted. The authorisation of infringements are actionable by reason of s 13 of the Act and VMS’s case is that SARB has authorised local government councils to use the PinForce Sensors and the PinForce Systems and that SARB has, in Australia, authorised other persons to use the PinForce Sensors and the PinForce Systems in one or more methods for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. As I have said, the claim for additional damages is made under s 122(1A) of the Act and is made against both respondents and under the orders, the Court is to determine liability for additional damages at this stage, but the quantum thereof (assuming liability for additional damages is established) is to be determined at a later stage. With respect to innocent infringement under s 123 of the Act, that is a basis upon which a Court may refuse relief by way of damages or an account of profits. The defence was raised by CoM in its Amended Defence, but it was not pursued by CoM in closing submissions and need not be considered any further.

11 With respect to paragraph 2(b) of the orders, the following matters should be noted. The allegations of double recovery are made by both SARB and CoM. The allegations are based on a Deed of Release dated 18 June 2014. SARB alleges in its Further Amended Defence that in relation to the PinForce Sensors and PinForce Systems, VMS has already been compensated under the Deed of Release for loss and damage alleged to arise from the supply or use of the PinForce Sensors and PinForce Systems which were sold or supplied by SARB prior to 9 May 2013, “including in respect of allegations arising from the use of those PinForce Sensors and PinForce Systems after that date”. SARB advances a similar plea in response to the alleged infringement of PinForce Methods. CoM advances equivalent pleas in its Amended Defence. The issue of double recovery is, like the quantum of additional damages (assuming liability for additional damages is established), to be determined at a later stage.

12 SARB has filed a Notice of Cross-Claim in which it seeks orders from the Court under s 138(3) of the Act revoking the First Patent and the Second Patent. SARB did not press in its closing submissions all of its pleaded grounds of invalidity.

13 The infringement issues of which there were four include issues of construction.

14 The first issue raises the meaning of “wake-up signal” in certain claims in the patents and whether PinForce Version 1 and PinForce Version 2 used a wake-up signal.

15 The second issue raises the construction of certain claims in the First Patent and whether the claims include a method or system where the determination of vehicle overstay is made by the DCA instead of the DA, it being accepted that in the case of PinForce Version 3, all capability of determining vehicle overstay in the DA has been removed and vehicle overstay is determined by the DCA.

16 The third issue raises a question as to the infringing acts for which SARB is liable because it has authorised those acts, or because it is a joint tortfeasor in relation to these acts. It is also necessary to consider in this context the construction of the Deed of Release dated 18 June 2014.

17 The final issue is whether SARB and CoM are liable for additional damages under s 122(1A) of the Act.

18 The grounds of invalidity which were pursued by SARB in its closing submissions are as follows:

(1) In relation to both patents, a failure to describe in the complete specification the best method known to VMS of performing the invention (s 40(2)(a));

(2) In relation to both patents, a failure by VMS to describe the invention fully (s 40(2)(a));

(3) In relation to both patents, a claim that VMS was not the inventor, or the sole inventor, of the invention and did not derive title from the inventor under s 15 of the Act and is not entitled to the First Patent or the Second Patent and it is just and equitable that the patents be revoked under s 138(3) of the Act;

(4) In relation to both patents, and in respect of those claims that do not involve the use of wake-up signals (i.e., claims 1 and 6–10 (to the extent they depend on claim 1) and 30–32 of the First Patent and claims 1–25 and 27–29 of the Second Patent), the claims are not fairly based on the matter described in the specification (s 40(3));

(5) In relation to both patents, the “invention” lacks an inventive step having regard to common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the earliest priority date of the claims (s 18(1)(b)(ii)). In relation to this ground, SARB relies only on common general knowledge and does not rely on any information of the kind identified in s 7(3) of the Act;

(6) In relation to the First Patent and if, contrary to earlier contentions made by SARB, claims 21–23 and 28–32 encompass a system in which the DCA determines vehicle overstay, then the First Patent, or at least those claims in the First Patent, should be revoked because:

(a) the Patent or those claims were obtained by false suggestion or misrepresentation (s 138(3)(d)); and

(b) they lack clarity and therefore do not comply with s 40(3); and

(c) they lack definition and therefore do not comply with s 40(2)(b).

19 CoM adopted SARB’s submissions in relation to infringement and invalidity. CoM confined its closing submissions (written and oral) to the reasons it contends an award of additional damages should not be made against it.

20 The relevant version of the Act and Regulations for the purpose of this proceeding is that in force prior to the amendments made to the Act by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (the Raising the Bar Act) and the Intellectual Property Legislation Amendment (Raising the Bar) Regulations 2013 (No 1) (Cth).

The First Patent

21 The complete specification of the First Patent was published and became open for public inspection on 24 November 2005. The application for the First Patent was made on 9 May 2005 and the patent was sealed on 13 March 2008. The priority date for the claims in the First Patent is 17 May 2004. The inventor named in the First Patent is Mr Fraser John Welch.

22 The First Patent identifies the field of the invention as relating to parking violations and, more particularly, to the detection of vehicles that overstay a defined time interval in parking spaces.

23 In the section in the specification entitled “Background”, the traditional methods of detecting vehicles that have exceeded the time limit of a parking space are described. A traditional method of placing a chalk mark on the tyre of a vehicle in a parking space and then returning at a later time to check if any of the vehicles with “chalked” tyres are still parked is described. The inefficiencies and disadvantages said to be associated with that method are identified and then a statement is made that a need thus exists for a method, an apparatus and a system that overcomes, or at least ameliorates, one or more of the described disadvantages.

24 In the “Summary” section in the specification, three aspects of the invention are described. Those descriptions of aspects of the invention correspond with claims 1, 11 and 21 respectively.

25 The first aspect is the provision of a method performed by a subterraneous DA for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. The method comprises the steps of detecting the presence of a vehicle in the parking space, processing and storing data relating to the presence of the vehicle in the parking space, determining whether the vehicle has overstayed a defined duration in the parking space, and wirelessly transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

26 The second aspect is the provision of a battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. The apparatus comprises a detector adapted to detect the presence of a vehicle in the parking space, a processor coupled to the detector for processing and storing data received from the detector, and determining whether the vehicle has overstayed a defined duration in the parking space, a radio receiver coupled to the processor for receiving wake-up signals, and a radio transmitter coupled to the processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

27 The third aspect is the provision of a system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces. The system comprises a plurality of battery-powered DAs for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces when subterraneously installed, and a DCA for wirelessly retrieving data from the plurality of battery-powered detecting apparatuses. The DCA comprises a radio transmitter for transmitting wake-up signals to ones of the plurality of battery-powered DAs, a radio receiver for receiving data from woken-up ones of the plurality of battery-powered DAs, a memory unit for storing data and instructions to be performed by a processing unit, and a processing unit coupled to the radio transmitter, the radio receiver and the memory unit. The processing unit is programmed to process data received via the radio receiver and to indicate instances of vehicle overstay to an operator. The data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay in the respective parking space.

28 The specification then contains the following passages (on p 3) which were the subject of expert evidence and of submissions by the parties:

Repeated wireless wake-up of a detection apparatus is typically performed irregularly with respect to time depending on the presence of a data collection device. Wireless retrieval of data may be performed in response to wireless wake-up of a detection apparatus. Overstay of a vehicle in a parking space may be determined at the detection apparatus by processing data received from the detector.

The data collection apparatus may be portable and may retrieve the data from the detection apparatus whilst the data collection apparatus is located in a moving vehicle. Data relating to presence of a vehicle may comprise presence duration of the vehicle in the parking space, movements of the vehicle in and out of the parking space with corresponding time-stamp information, and/or an indication of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space. Vehicle presence detection may be performed by a magnetometer that detects changes in the earth’s magnetic field caused by presence or absence of a vehicle in the parking space. The detection apparatus may be encased in a self-contained, sealed housing for subterraneous installation in a parking space. The radio transmitter and/or radio receiver may operate in the ultra-high frequency (UHF) band and may jointly be practised as a transceiver.

29 The specification contains nine drawings, diagrams or figures which are described in the specification.

30 The body of the specification states that a “small number of embodiments are described hereinafter, by way of example only, with reference to the accompanying drawings” and contains the following brief description of the drawings, diagrams or figures:

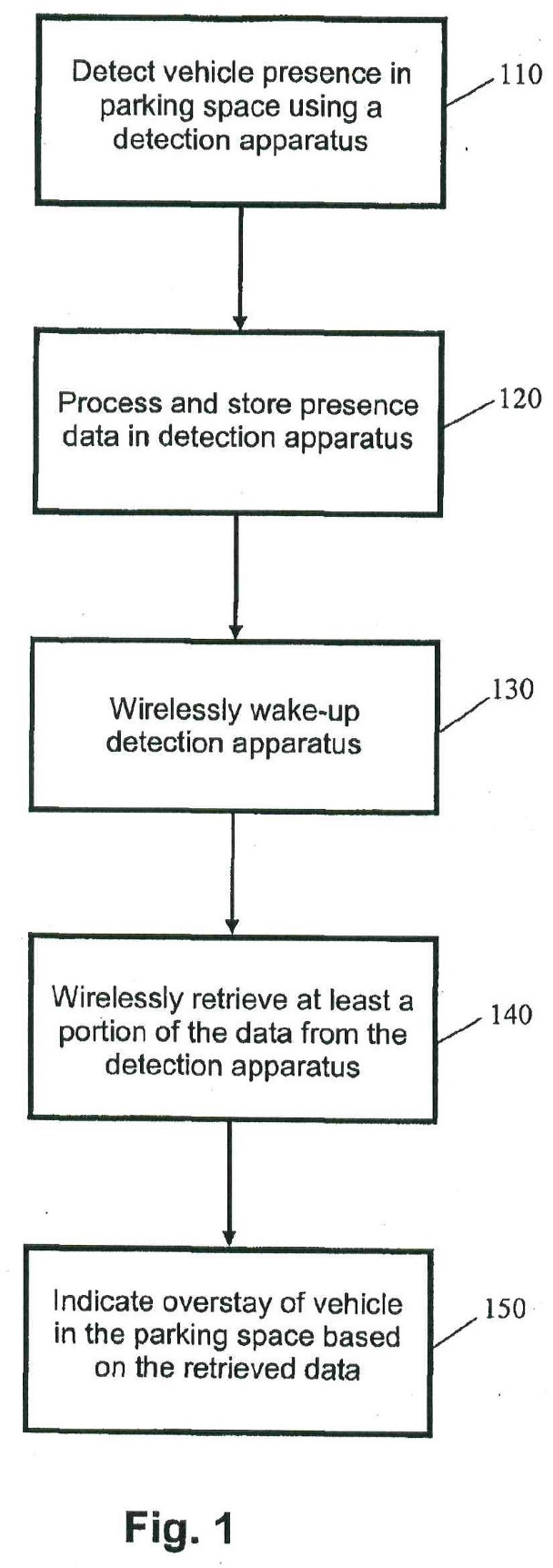

Fig. 1 is a flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space;

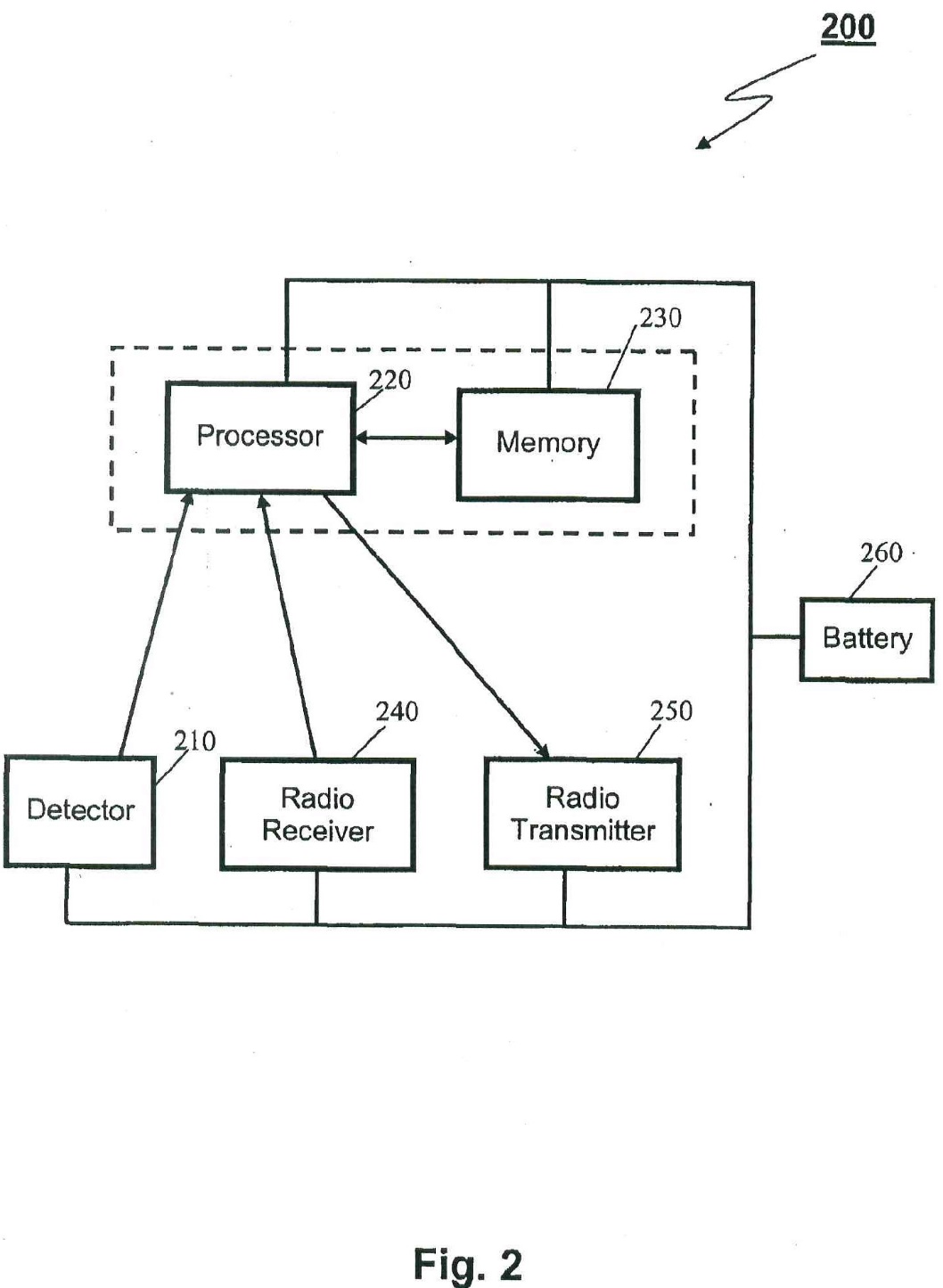

Fig. 2 is a block diagram of a detection apparatus for monitoring presence of a vehicle in a parking space;

Fig. 3 is a block diagram of a data collection apparatus for retrieving data from one or more detection apparatuses;

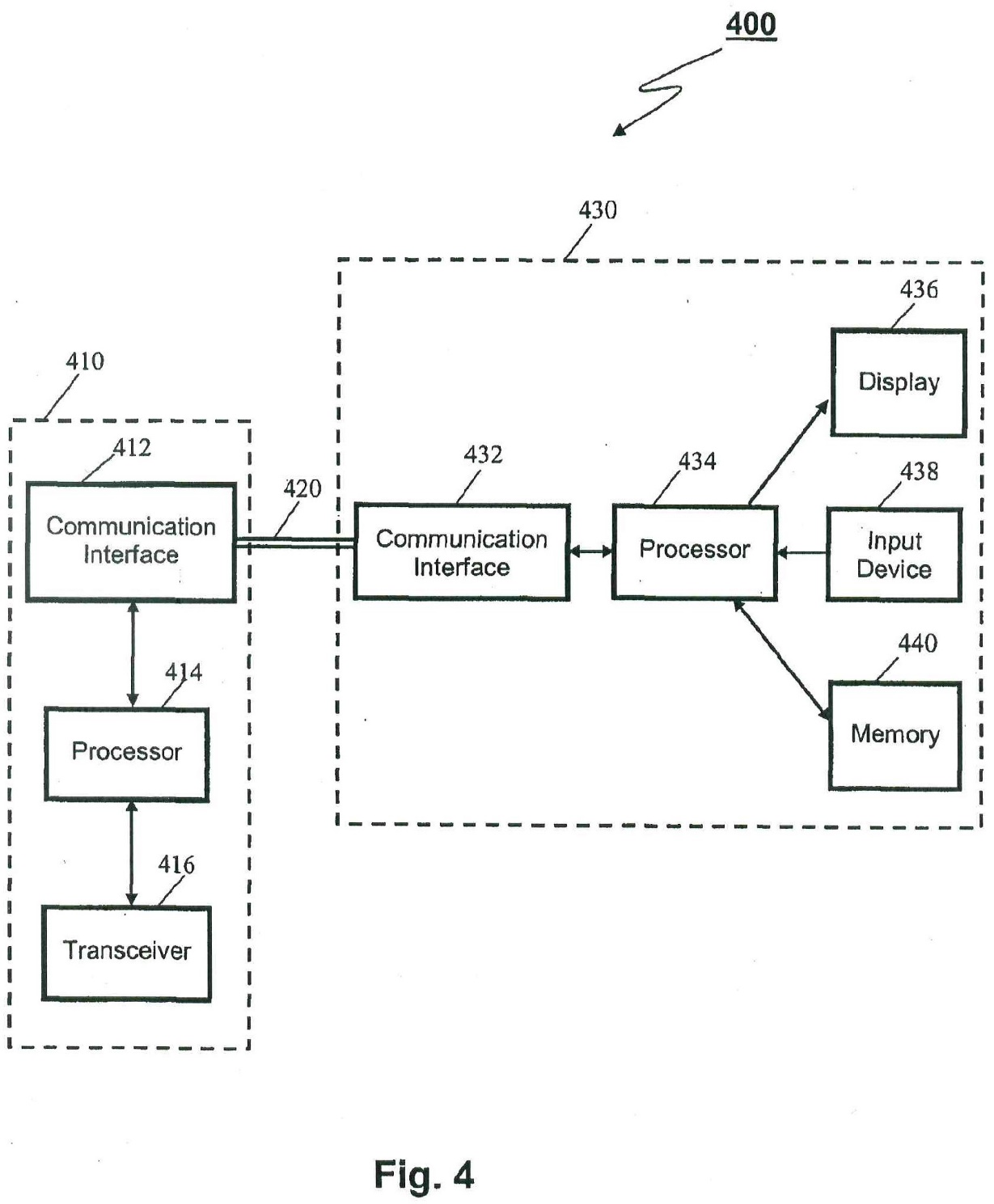

Fig. 4 is block diagram of another data collection apparatus for retrieving data from one or more detection apparatuses;

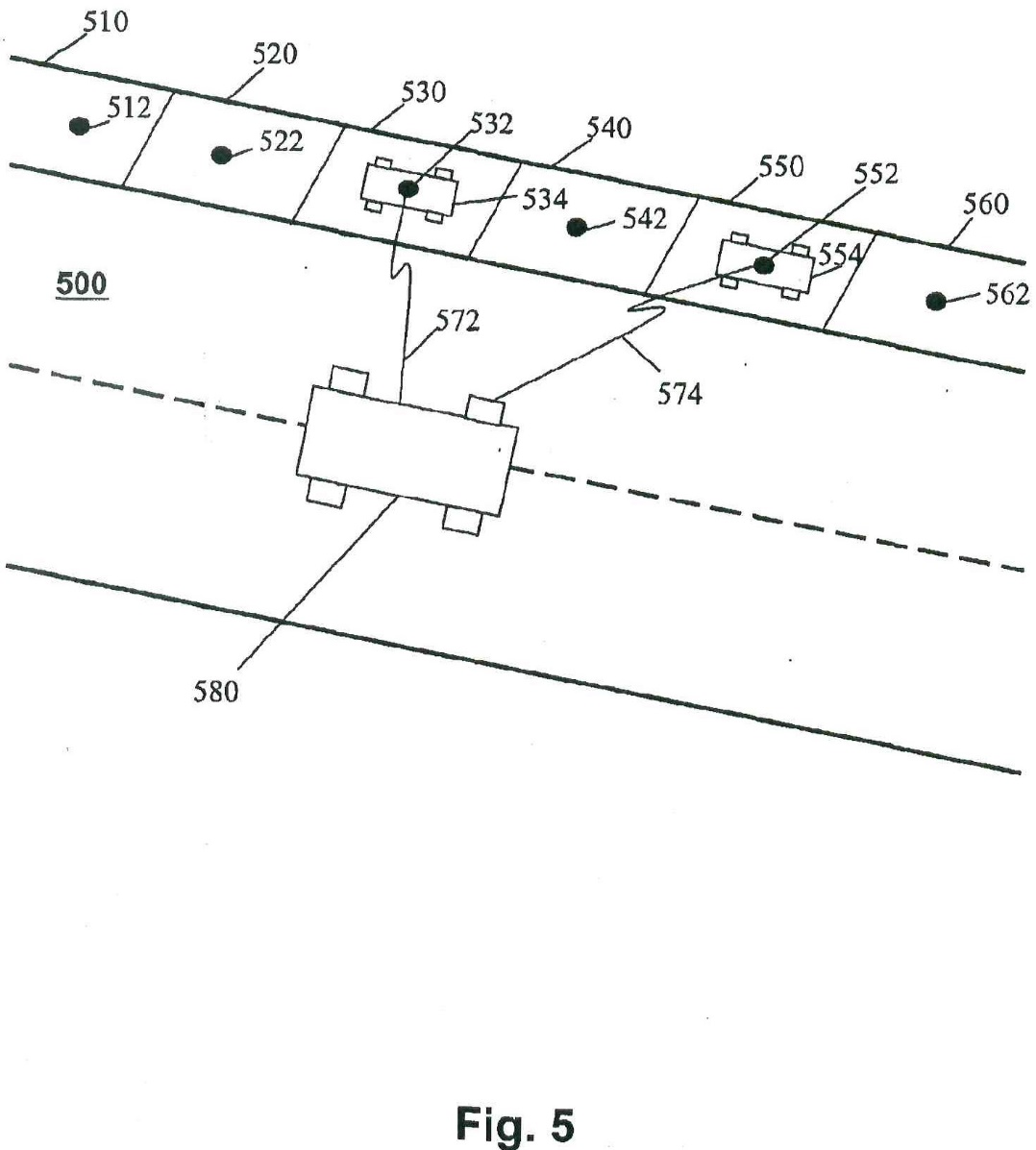

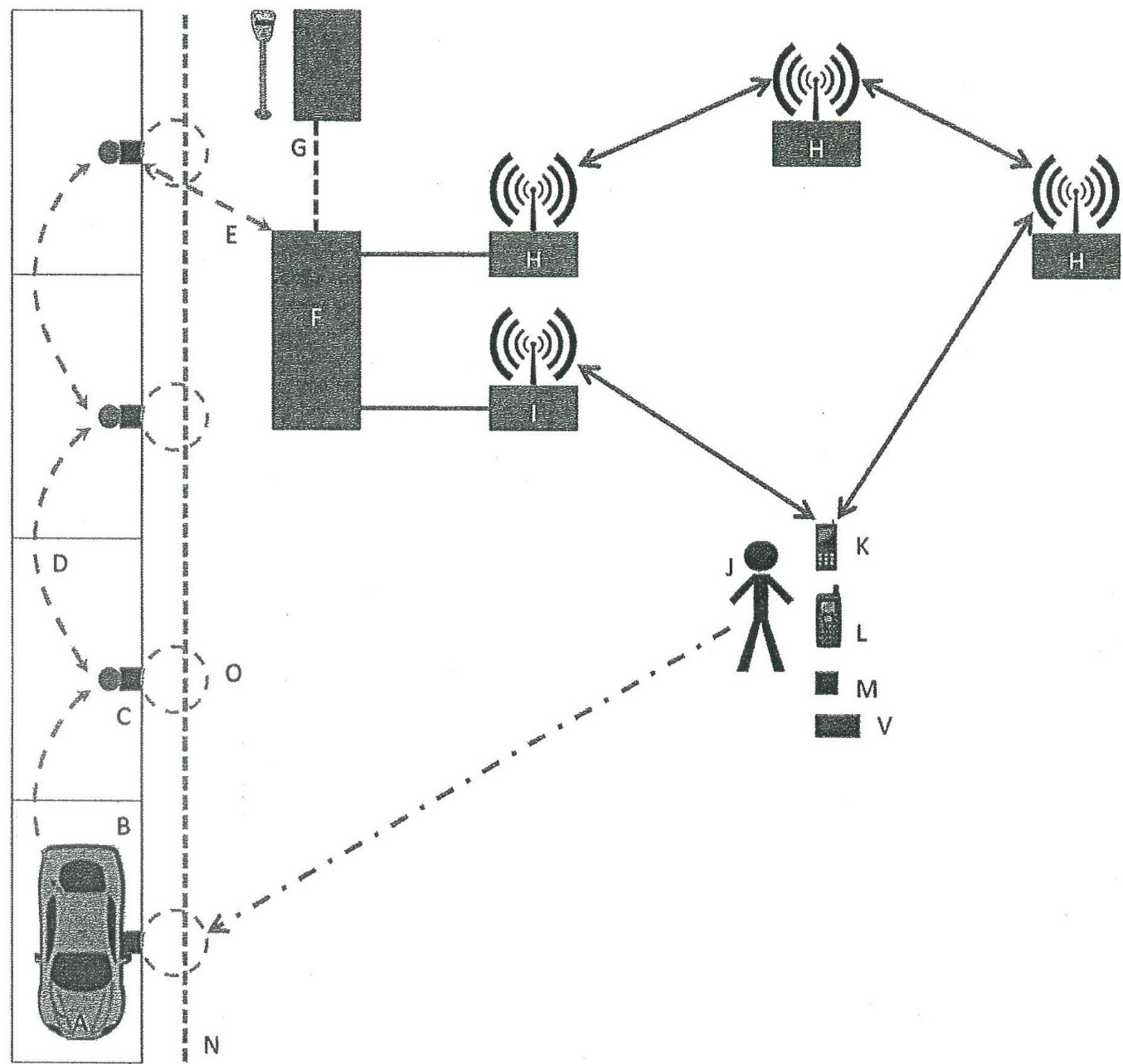

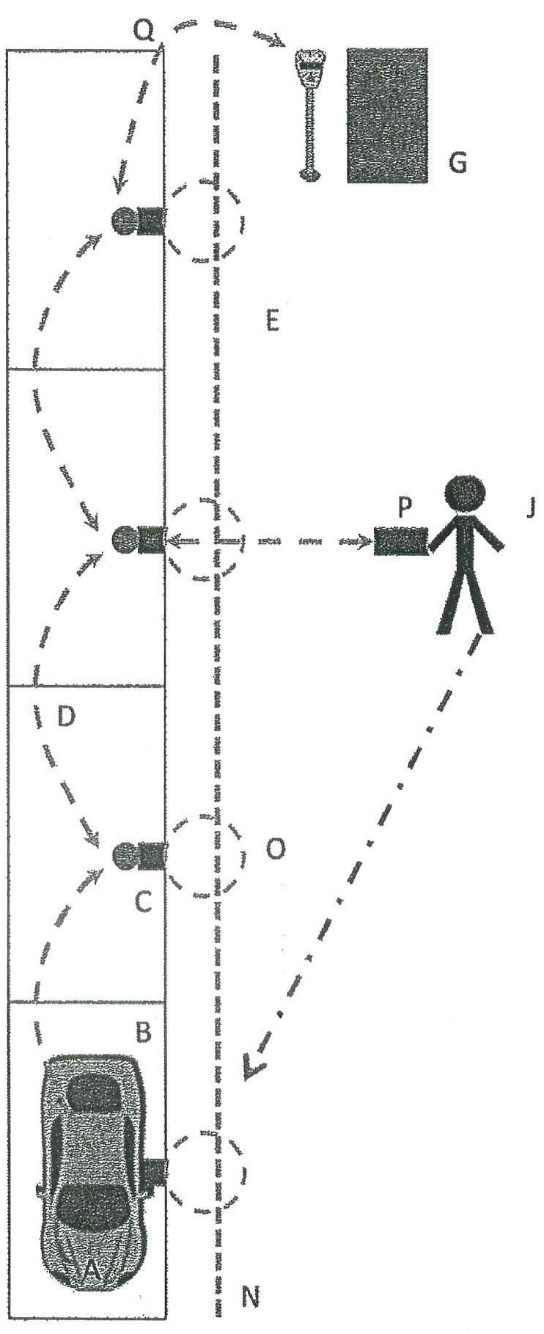

Fig. 5 is a schematic diagram of a system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces;

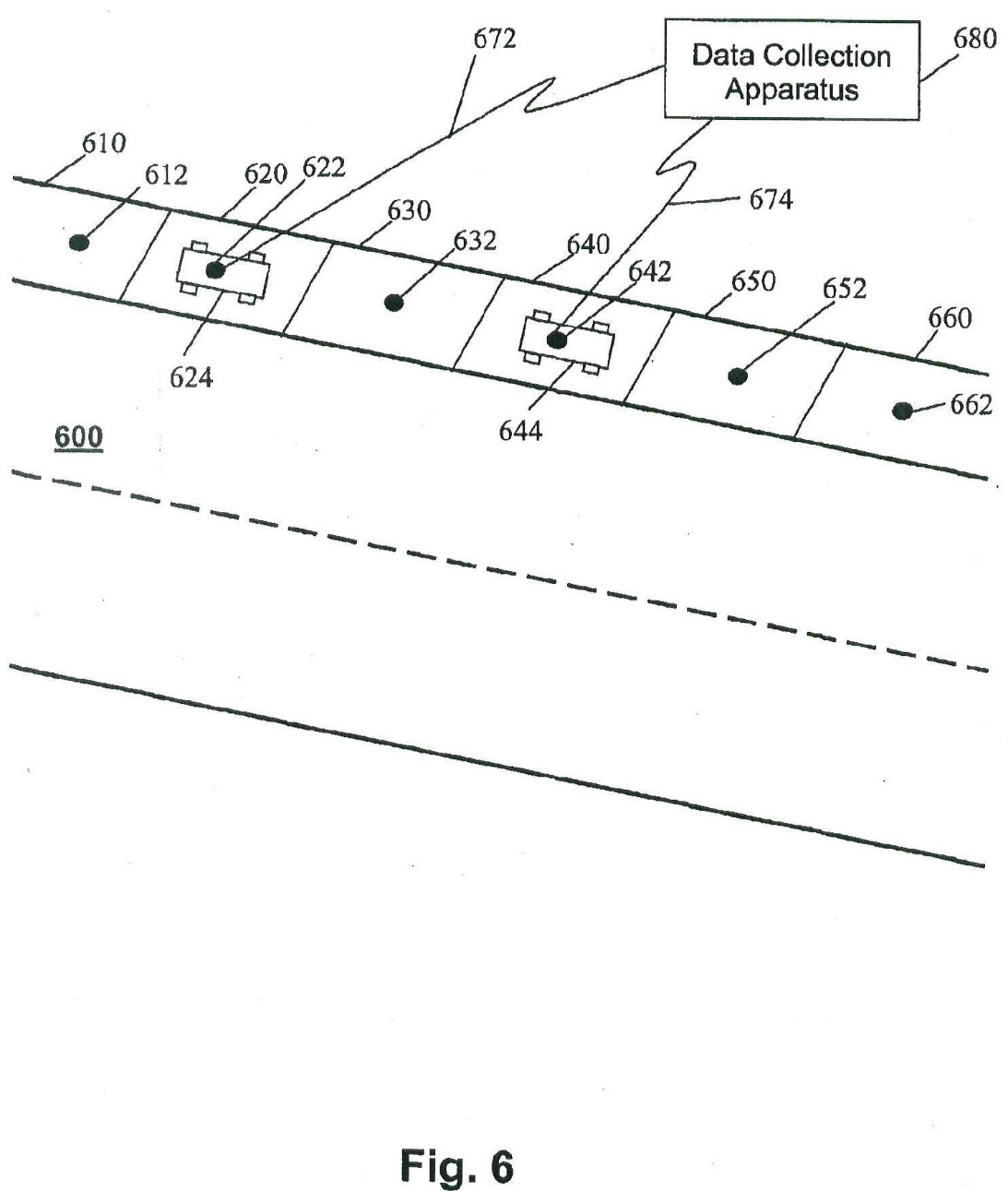

Fig. 6 is a schematic diagram of another system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces;

Fig. 7 is a schematic diagram of a further system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces;

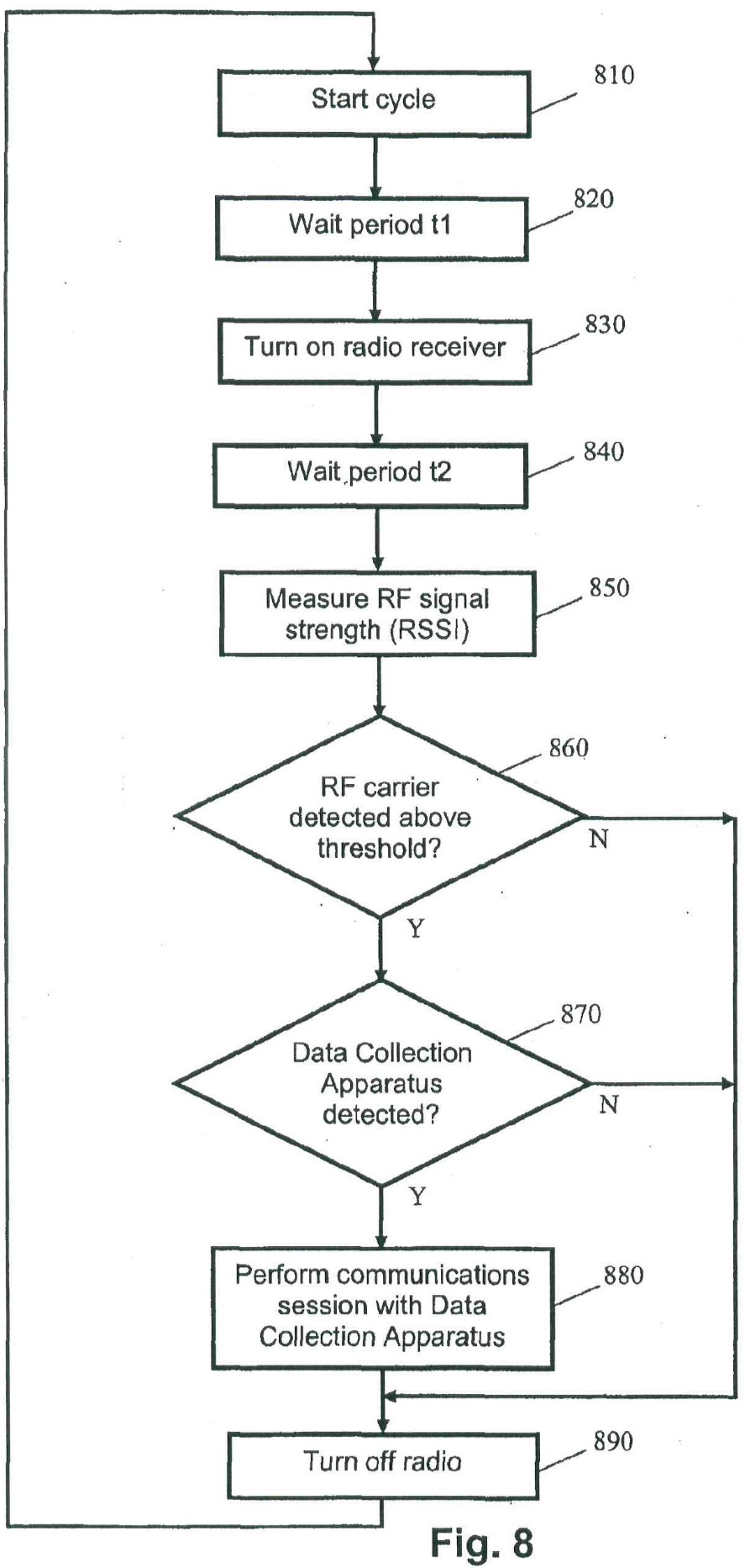

Fig. 8 is a flow diagram of a method of operating a detection apparatus according to an embodiment of the present invention; and

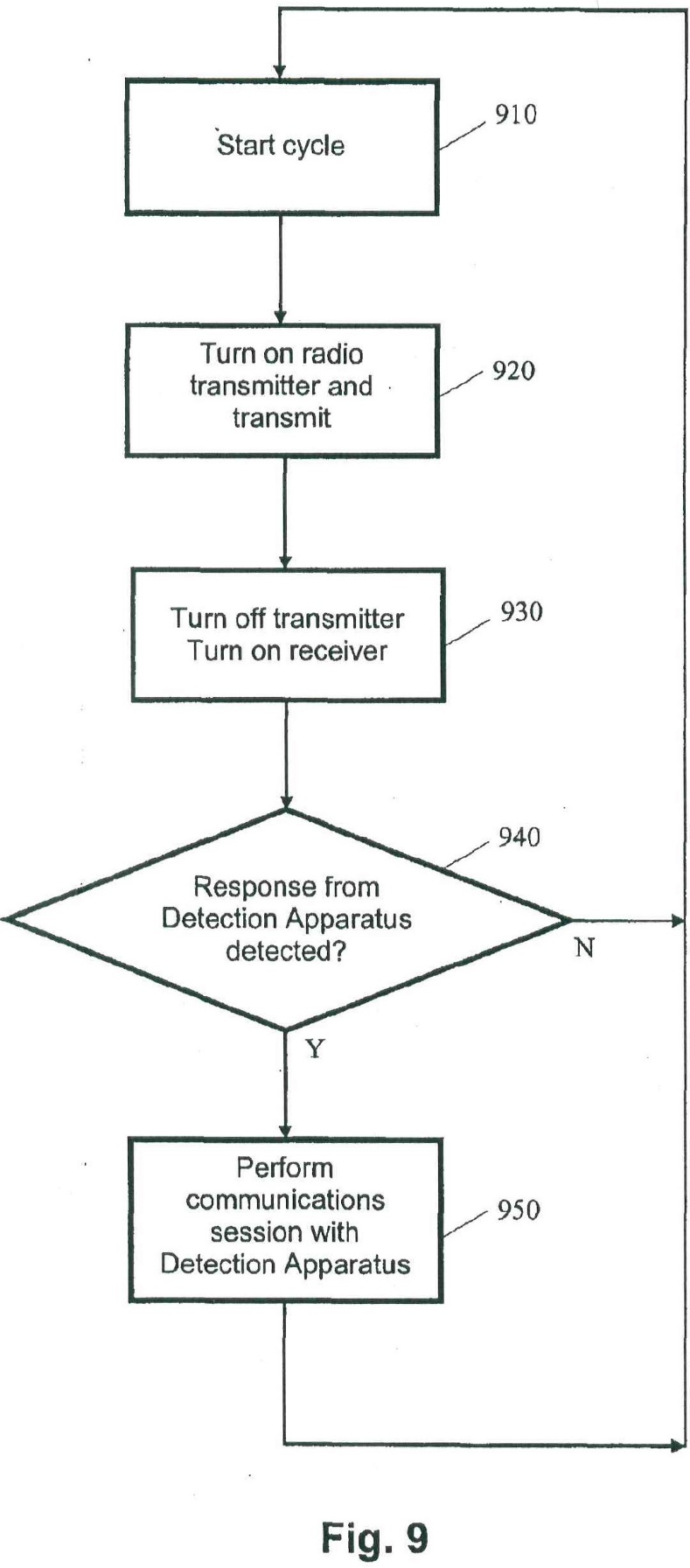

Fig. 9 is a flow diagram of a method of operating a collection apparatus according to an embodiment of the present invention.

31 Figures 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9 are as follows:

32 A detailed description of the methods, apparatuses and systems largely by reference to the figures, extends over approximately 10 pages in the specification. In light of the issues between the parties, it is necessary to set out the following passages:

In relation to Figure 1

Page 4

Fig. 1 is a flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. Presence of a vehicle in the parking space is detected using a detection apparatus in step 110. Data relating to presence of the vehicle is processed and stored in the detection apparatus at step 120. The detection apparatus is wirelessly woken-up at step 130 and at least a portion of the data is retrieved from the detection apparatus at step 140. Overstay of the vehicle in the parking space is indicated based on the retrieved data at step 150.

In relation to Figure 2

Fig. 2 is a block diagram of an apparatus 200 for monitoring presence of a vehicle in a parking space. ….

Page 5

The radio receiver 240 and radio transmitter 250 are practised as a 433 MHz ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio transceiver for transmitting and receiving radio signals to and from a data collection apparatus, respectively. Various UHF transceivers may be practised such as the Micrel MICRF501 transceiver, which requires to be turned on for approximately 1ms before RF carrier energy can be detected. However, persons skilled in the art would readily understand that other types of transmitters, receivers or transceivers may be practised such as low frequency (LF) transceivers. Other UHF frequencies may also be practised such as in frequency bands commonly used for low powered devices, including 868 MHz, 915 MHz and 2.4 GHz.

The battery 260 comprises a lithium manganese dioxide (LiMnO2) battery, which may be capable of providing the apparatus 200 with 5 to 10 years of continuous operation. Again, persons skilled in the art would readily understand that various other battery types may be practised in place of a LiMnO2 battery.

Page 6

The apparatus 200 generally operates in a low-power mode while detecting vehicle movements and presence in a corresponding parking space, which may be practised on a continuous or periodic (e.g., interrupt driven) basis to conserve battery life. Although the radio receiver 240 of the apparatus 200 consumes a small amount of power (relative to other radio receivers), the radio receiver 240 is only turned on for the shortest possible time duration at regular intervals to detect the presence of a data collection apparatus. At other times, the radio receiver 240 is turned off to conserve battery life.

…

In one embodiment, the apparatus 200 determines and maintains three primary types of information:

• Current Status

The current status of the parking space in terms of vehicle presence (i.e., present or not present) and the amount of time the space has remained in the present state.

• Historical Vehicle Movements

Page 7

A record of each vehicle movement in the parking space including the date and time of the movement.

• Overstay Situation

Detected when a vehicle remains in said parking space for a duration longer than a defined time interval.

The apparatus 200 may optionally be programmed with information relating to the hours of operation and parking time limits that apply to an associated parking space based on the time of day and day of week. Decisions concerning overstay can thus be made by the apparatus 200 based on different time limits that may apply to the parking space at different times.

Information may also be downloaded to the apparatus 200 using a radio receiver in the apparatus 200. The same radio receiver as used for receiving wake-up signals or a separate radio receiver may be used for this purpose. The downloaded information may comprise, but is not limited to:

• application firmware for the apparatus 200,

• a table of operating hours and time limits (time of day and day of week) applicable to an associated parking space,

• operating parameters for the apparatus 200, and

• information for updating or synchronising the real-time clock with a more accurate real-time source.

Alternatively, decisions relating to vehicle overstay can be made by a data collection apparatus that collects data from the apparatus 200 via a radio communication link rather than by the apparatus 200.

…

In relation to Figure 4

Page 9

A data collection apparatus transmits a wake-up signal (e.g., RF carrier followed by a defined message) and listens for valid responses from detection apparatuses. If no response is received from a detection apparatus, the data collection apparatus repeatedly transmits the wake-up signal.

…

In relation to Figure 6

Page 10

Fig. 6 is a schematic diagram of another system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces. Fig. 6 shows detection apparatuses 612, 622, … 662 installed in parking spaces 610, 620, …, 660, respectively. Vehicles 624 and 644 are parked in parking spaces 620 and 640, respectively. Detection apparatuses 622 and 642 are shown in radio communication with a data collection device 680 by means of jagged lines 672 and 674, respectively. The data collection device 680 may be of fixed location remote from the parking spaces 610 620, …, 660 or may comprise a hand-held portable apparatus carried by a pedestrian enforcement officer.

…

In relation to Figure 8

Page 11

Fig. 8 is a flow diagram of a method of operating a detection apparatus such the apparatus 200 in Fig. 2. A cycle of operation begins at step 810. After a wait period of duration t1 at step 820, the radio receiver is turned on at step 830. After a further wait period of duration t2 at step 840, for the radio receiver to stabilise, the received radio frequency signal strength (RSSI) is measured at step 850. At step 860, a determination is made whether the signal strength of a detected RF carrier is larger than a defined threshold. If an RF carrier of sufficient signal strength is detected (Y), a determination is made at step 870 whether the RF carrier relates to a data collection apparatus. If a data collection apparatus is detected (Y), a communications session between the detector apparatus and the data collection apparatus occurs at step 880. Such a session typically involves transmission and reception by both the detector apparatus and the data collection apparatus. The radio receiver and transmitter are turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

If an RF carrier of sufficient signal strength is not detected (N), at step 860, the radio receiver is turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

If a data collection apparatus is not detected (N), at step 870, the radio receiver is turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

The duration t2 is determined according to the type of radio receiver used and is typically of the order of 1 millisecond. Setting the duration t1 to 250 milliseconds implies an on:off duty cycle of 1:250. A typical low-power receiver may consume 5 to 10mA in receiver mode and the average power consumption of the data collection apparatus detection process is thus 20 to 40 µA.

33 Again, in light of the issues between the parties, it is necessary to set out the following claims in the First Patent:

1. A method performed by a subterraneous detection apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method comprising the steps of:

detecting presence of a vehicle in said parking space;

processing and storing data relating to presence of said vehicle in said parking space;

determining whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space; and

wirelessly transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

2. The method of claim 1, wherein said step of wirelessly transmitting is performed in response to receipt of a wireless wake-up signal.

3. The method of claim 2, wherein wireless wake-up signals are received irregularly with respect to time.

…

8. The method of claim 1 or claim 2, comprising the further step of determining an overstay duration of the vehicle in said parking space and storing a record thereof.

…

11. A battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus comprising:

a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in the parking space;

a processor coupled to said detector, said processor adapted to process and store data received from said detector and to determine whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space;

a radio receiver coupled to said processor for receiving wake-up signals; and

a radio transmitter coupled to said processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

…

21. A system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces, said system comprising:

a plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces when subterraneously installed; and

a data collection apparatus for wirelessly retrieving data from said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses, said data collection apparatus comprising:

a radio transmitter for transmitting wake-up signals to ones of said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses;

a radio receiver for receiving data from woken-up ones of said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses;

a memory unit for storing data and instructions to be performed by a processing unit; and

a processing unit coupled to said radio transmitter, said radio receiver and said memory unit;

said processing unit programmed to process said data received via said radio receiver and to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator;

said data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space.

22. The system of claim 21, wherein said data is received from one of said battery-powered detection apparatuses in response to receipt of a wake-up signal transmitted from said data collection apparatus.

23. The system of claim 22, wherein said data collection apparatus is portable.

…

28. The battery-powered apparatus of claim 11, wherein said radio receiver is only turned on to receive said wake-up signals for short durations to conserve power in said battery-powered detection apparatus.

29. The method claim 1, comprising the further step of selectively enabling receipt of said wake-up signal for short durations to conserve power in said subterraneous detection apparatus.

30. A method performed by a subterraneous detection apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

31. A battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

32. A system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces, said system substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

The Second Patent

34 The complete specification for the Second Patent was published and became open to the public for inspection on 11 August 2011. The application for the patent was made on 21 July 2011 and the patent was sealed on 4 February 2016. The priority date for the claims in the Second Patent is (as with the claims in the First Patent) 17 May 2004. The inventor named in the Second Patent is Mr Fraser John Welch.

35 The Second Patent describes the invention in very similar terms to the description of the invention in the First Patent. The different consistory clauses in the Second Patent reflect the different language of the claims. The nine drawings, diagrams or figures in the Second Patent are identical to the nine drawings or figures in the First Patent.

36 Again, in light of the issues between the parties, it is necessary to set out the following claims in the Second Patent:

1. A method for identifying vehicles that overstay a parking time limit associated with a parking space, said method comprising the steps of:

detecting presence of a vehicle in said parking space using a battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing;

processing and storing, in said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing, data relating to presence of said vehicle in said parking space;

determining from said stored data by said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing and independently of any parking payment system, whether said vehicle has overstayed said parking time limit associated with said parking space;

detecting presence of a data collection apparatus within wireless communication range of said detection apparatus; and

when presence of said data collection apparatus is detected, wirelessly transmitting from said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing, data relating to an identified instance of said vehicle overstaying said parking time limit associated with said parking space.

…

10. A battery-powered apparatus for identifying vehicles that overstay a parking time limit associated with a parking space, said apparatus comprising:

a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in said parking space;

a processor coupled to said detector, said processor adapted to process and store data received from said detector and to determine from said data and independently of any parking payment system whether said vehicle has overstayed a parking time limit associated with said parking space;

a radio receiver coupled to said processor for receiving radio signals from a data collection apparatus; and

a radio transmitter coupled to said processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of said vehicles overstaying said parking time limit associated with said parking space;

wherein said battery powered apparatus is encased in a self-contained, sealed housing.

…

25. A method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method comprising the steps of:

detecting presence of a vehicle in said parking space using a battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing;

processing and storing, in said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing, data relating to presence of said vehicle in said parking space;

determining from said stored data by said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing and independently of any parking payment system, whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space; and

wirelessly transmitting, from said battery-powered apparatus encased in a self-contained, sealed housing, data relating to an identified instance of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

26. An apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus comprising:

a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in the parking space;

a processor coupled to said detector, said processor adapted to process and store data received from said detector and to determine from said data and independently of any parking payment system whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space;

a radio receiver coupled to said processor for receiving wake-up signals; and

a radio transmitter coupled to said processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space; and

a battery for providing power to said detector, processor, radio receiver, and radio transmitter;

wherein said apparatus is encased in a self-contained, sealed housing.

27. A method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method comprising the steps of:

detecting presence of a vehicle in said parking space using a battery-powered apparatus;

processing and storing, in said battery-powered apparatus, data relating to presence of said vehicle in said parking space;

determining from said stored data by said battery-powered apparatus and independently of any parking payment system, whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space; and

wirelessly transmitting, from said battery-powered apparatus, data relating to an identified instance of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

28. An apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus comprising:

a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in the parking space;

a processor coupled to said detector, said processor adapted to process and store data received from said detector and to determine from said data and independently of any parking payment system whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space;

a radio transmitter coupled to said processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space; and

a battery for providing power to said detector, processor, and radio transmitter;

The Decision of this Court in 2013

37 VMS was the registered owner of Innovation Patent No 2010101354 which bears the title “Method, apparatus and system for parking overstay detection”. The Innovation Patent was certified on 14 January 2011. The complete application for the patent was filed on 2 December 2010 as a divisional application of Patent Application No. 2008200089 (the Parent Application). The Parent Application was filed on 8 January 2008 as a divisional application of the First Patent. The Innovation Patent expired on 9 May 2013.

38 VMS instituted a proceeding in this Court against SARB alleging that the supply of SARB’s VDU known as the PinForce Sentinel VDU which was used in a method for detecting the overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, infringed the claims in the Innovation Patent. The Court upheld the validity of the Innovation Patent and found that the claims had been infringed by SARB (Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (trading as Database Consultants Australia) (No 2) [2013] FCA 395; (2013) 101 IPR 496 (VMS 2013)).

39 A construction issue resolved by the Court in VMS 2013 was whether the PinForce Sentinel VDU had a radio receiver for receiving wake-up signals within claim 2 of the Innovation Patent. Claim 2 of the Innovation Patent and claim 26 of the Second Patent are in identical terms. The Court described the PinForce Sentinel VDU in detail. The Court found that it infringed claim 2 of the Innovation Patent.

40 As I have said, an issue arises in this proceeding as to the meaning of “wake-up signal” in claims in the First Patent and the Second Patent and whether PinForce Version 1 and PinForce Version 2 wirelessly transmits data in response to receipt of a wireless wake-up signal. VMS filed a Reply in this proceeding in which it alleged that by reason of the findings in VMS 2013, an estoppel in relation to that issue arose against SARB. The plea of issue estoppel is no longer pressed by VMS. VMS now submits that the findings in VMS 2013 are highly persuasive.

41 The decision in VMS 2013 is relevant in another respect. In this proceeding, SARB contends that for the purposes of claims 1, 6–10 (insofar as they depend on claim 1) and 30–32 of the First Patent and claims 1–25 and 27–29 of the Second Patent, there is no real and reasonably clear disclosure of a system/apparatus/method in which the DA communicates with the DCA without the aid of wake-up signals and, in those circumstances, those claims are not fairly based. VMS contends that a “materially identical argument” was put to this Court in VMS 2013 and rejected by the Court.

42 There was an appeal to the Full Court of this Court against the orders made in VMS 2013 and the appeal was heard. However, the proceeding was resolved before judgment was delivered when VMS and SARB entered into the Deed of Release dated 18 June 2014.

The Infringement Issues

43 The infringement issues raise issues as to the proper construction of claims in the patents. The principles of claim construction are well established and are not in dispute in this case. In the circumstances, it is sufficient to set out the statement of those principles by the Full Court of this Court in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; (2005) 222 ALR 155; (2005) 65 IPR 86 (at [67]):

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corp Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-486; the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–486.

Issue 1

44 The first issue raises the meaning of “wake-up signal” in certain claims in the patents and whether PinForce Version 1 and PinForce Version 2 used a wake-up signal.

45 A wake-up signal is referred to in two contexts in the First Patent. First, it is referred to in the context of a step being performed in response to receipt of a wireless wake-up signal, that step being the wireless transmission of data relating to identified instances of overstay of a vehicle in a parking space as in claim 2 of the First Patent. The second is as an integer of the DA being a radio receiver coupled to the processor (previously identified) for receiving wake-up signals as in claim 11 in the First Patent and claim 26 in the Second Patent.

46 VMS adduced evidence from Mr Tony Spirovski. Mr Spirovski is an electrical engineer. He is the sole employee or consultant of a consulting company that specialises in electronics design. He is a qualified electrical engineer who has specialised in working with sensing devices, RF (radio frequency) communications and communication devices concerned with the generation, transmission, processing, exchange and storage of data. He has had a long involvement as an independent expert witness in disputes between VMS and SARB.

47 SARB adduced evidence from Mr Jefferson Harcourt. Mr Harcourt has an Associate Diploma of Mechanical Engineering (Manufacturing) and a Bachelor of Engineering (Honours) in Electronics and Communication Engineering. He sets out his work history in his affidavit at considerable length. It is not necessary for me to repeat it. I accept that he has specialised knowledge in the field of electronics and communications engineering technologies.

48 Each expert provided lengthy affidavits dealing with the issues of infringement and invalidity. They then participated in a conference of experts in which they addressed a number of agreed questions. A joint experts’ report (JER) was prepared. The experts then gave evidence in this proceeding in a joint session of evidence over a period of three days. There was no challenge to the expertise of either witness, although SARB made a general challenge to Mr Spirovski’s evidence which I will address later in these reasons.

49 The experts were asked in the conference of experts to identify any points of agreement or disagreement between them regarding their understanding of the term “wake-up signal” in the claims in the First Patent and the Second Patent (being claims 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 21, 22, 28 and 29 in the First Patent and claim 26 in the Second Patent) in light of the specifications of the First Patent and the Second Patent respectively.

50 In the JER, the experts indicated that they agreed that the term “wake-up signal” is somewhat confusing in that the processor and receiver in the DA are active in order to receive the wake-up signal. They agreed that rather, the wake-up signal acts as a keep awake signal to alert the DA to the presence of the DCA within radio communications range and that when the wake-up signal is received, the DA and the DCA engage in a communications session.

51 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Spirovski made the following observations. A wake-up signal within the meaning of the claims in the First Patent is a wireless radio signal that is transmitted by a transient DCA to notify a data detection apparatus that it is within radio communications range. The effect of the wake-up signal is to halt the data detection apparatus’ power-saving operating cycle which involves the processor and transceiver being in various states of activity and inactivity, and to keep the processor and radio receiver in an active state, once the DCA is within range, in order to have a communications session with the DCA.

52 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Harcourt made the following observations. A wake-up signal initiates change in a system’s power state from a sleep state to a run or active state. In a sleep state, the device is in, or close to, hibernation. The device may “wake” to perform certain routine tasks, and return to sleep. In the case of both patents, the “wake-up signal” is not waking the device from a typical sleep state, but rather initiates a communications session between the IGU and the HHU (TMT and HHU). The IGU is already awake as it must be awake to receive and process messages from the HHU. The wake-up signal would have been better labelled as an “initiate communications request” or “HHU beacon”, as it is not technically waking the IGU (DA) up.

53 The experts were also asked to address in the conference of experts any points of agreement or disagreement between them regarding whether PinForce Version 1 uses a wake-up signal as claimed in claims 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, 21, 22, 28 and 29 of the First Patent and claim 26 of the Second Patent.

54 In the JER, the experts indicated that they disagreed as to the signal which acts as the “wake-up signal” within the meaning of the claims in the First Patent. It followed that they disagreed as to which device is sending the wake-up signal.

55 Mr Spirovski expressed the opinion that the [REDACTED] informs the IGU that the TMT is within radio communications range. The effect of receiving the [REDACTED] causes the processor and transceiver in the IGU to [REDACTED]. The [REDACTED] is synonymous with the wake-up signal in the First Patent. The use of a wake-up signal in the form of a [REDACTED].

56 Mr Harcourt expressed the view that claim 2 of the First Patent discloses that the IGU will wirelessly transmit data in response to a wake-up signal sent by the DCA. The transfer of data is thus initiated by the DCA which sends the so-called “wake-up signal”. [REDACTED]

57 It is convenient to note at this point that the notion of performing a communications session is identified in Fig 8 (at step 880) and in Fig 9 (at step 950). It should also be noted that in VMS 2013 (at [79]), Yates J considered the meaning of wake-up signals within claim 2 of the Innovation Patent and said that they are:

signals that are sent wirelessly by a data collection apparatus to a detection apparatus that, upon receipt by the detection apparatus, activate it to engage in a communications session with the data collection apparatus, in which the detection apparatus wirelessly transmits data relating to identified instances of overstay of a vehicle in a parking space.

58 VMS submits that the following matters are common ground between it and SARB as to the operation of PinForce Version 1. First, PinForce Version 1 has a battery-powered DA that identifies overstay, by the use of a magnetic sensor, the readings of which are used to detect vehicle presence and which is coupled to a microprocessor in a module that includes, inter alia, a radio transceiver. [REDACTED].

59 In VMS 2013, the Court set out the process in the case of the PinForce Sentinel VDU which takes place when the DA attempts to communicate with a TMT. The Court’s description was relied on by VMS in this case although, at the same time, I did not understand VMS to dispute the description contained in SARB’s outline of closing written submissions which is set out below (at [63]). The description of the process given by the Court in VMS 2013 (at [90]) is as follows:

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

60 [REDACTED].

61 In VMS 2013, the Court held that SARB’s PinForce Sentinel VDU possessed all of the essential features of claim 2 in the Innovation Patent.

62 Mr Stephen Toal is the Director of Development at SARB and he is one of three main shareholders in the company, including as he put it, through entities controlled by him. He has approximately 37 years’ experience in software development, “working primarily for system vendors developing and supplying off-the-shelf systems and consulting to large corporate clients”. His work history includes leading SARB’s design team in developing the “PinForce Sentinel” vehicle detection and parking management system from 2006 to 2012. Mr Toal gave evidence in this case as he had in VMS 2013.

63 SARB set out a description of the process in its outline of closing written submissions on infringement. That description is based on the evidence of Mr Toal and various documents. It is an accurate description of the process and, as I have said, I did not understand VMS to dispute that that is the case. It is as follows:

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

(Footnotes omitted.)

64 VMS submits in this case that while Mr Toal provides additional evidence of the information contained in the [REDACTED] and how the communications session is established between the DA and the DCA when there is a violation or pending violation, neither of those matters should lead to a different conclusion in this case from the conclusion reached by the Court in VMS 2013. VMS makes the point that the information provided in the [REDACTED] from the DA was not identified with any precision in VMS 2013. In his evidence in re-examination in VMS 2013, Mr Toal said that the key piece of information was the reason for connecting. He said that there was also other information about how much parking event data has been collected, and other fields. He said:

I don’t recall all of them off the top of my head.

65 Mr Toal said he believed it was the information set out in the VDU functional specification.

66 In his evidence before this Court, Mr Harcourt agreed that the [REDACTED]. He agreed that while some information was included in the [REDACTED].

67 Mr Spirovski did not consider that the [REDACTED].

68 Mr Harcourt expressed the opinion that Mr Spirovski’s opinion was incorrect and that it was flawed by reason of his consideration of the Zigbee protocol. In response, Mr Spirovski said the following:

This has nothing to do with the Zigbee protocol. [REDACTED]

69 Mr Spirovski was cross-examined at some length about the extent to which he had relied on his knowledge of the Zigbee protocol in formulating his opinion. The Zigbee protocol is a global standard that relates to wireless networking and it relates to the products which have a similar functionality to SARB’s products. Mr Spirovski described the Zigbee protocol as a framework that specifically relates to the construction of mesh networks and low power devices and it is targeted towards a particular class of device. He agreed that a fair way to describe it was that it provides the “broad communications architecture”. Mr Spirovski was taken through paragraphs in his affidavit which referred to the Zigbee protocol. He expressed a number of opinions in para 125 of his first affidavit based on his knowledge of the Zigbee protocol and two product specifications, specification 1.0 and specification 2.0. He was taken to Mr Toal’s evidence about the communications protocol actually adopted by SARB. He was asked to assume that Mr Toal’s evidence is correct. He was also taken to the Verified Product and Method Description verified on 24 April 2020 (VPMD). He agreed that some of the opinions he expressed were incorrect on the assumption that Mr Toal’s description of how the process worked was correct. For example, he gave the following evidence:

MR CAINE: So that lays to rest, does it not, the evidence you give about what might be a logical design choice in 127. It’s simply not a feature of the version 1 SARB product.

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes. It’s – the logic aspect of it has to do with needlessly sending additional data. But that’s – that’s a logical perspective based on how I would design a system. If Mr Toal’s evidence says it’s done otherwise, then it’s done otherwise.

70 The criticism of Mr Spirovski’s approach went further than this and I deal with the additional criticisms of Mr Spirovski’s approach below. VMS submits that SARB’s criticism of Mr Spirovski in terms of his reliance on the Zigbee protocol and the functional specifications “goes nowhere” because Mr Spirovski has based his opinions, or has also based his opinions, on more fundamental considerations.

71 VMS submits that the [REDACTED]. VMS submits that I should reach the same conclusions as the Court did in VMS 2013.

72 As I have already said, the Court in VMS 2013 noted that [REDACTED]

[REDACTED].

73 The Court then noted that the evidence before the Court was unclear as to precisely what part of the overstay information was included in the [REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

74 The key point put by SARB in response to VMS’s submissions was expressed by it in various ways. It submits that it is the [REDACTED] containing the connection information which initiates the communications between the DCA and the DA. It submits that the DA initiates communications with the DCA. It submits that the [REDACTED] is in and of itself a communication that contains useful data, including overstay information and it is the initial transmission in the sequence of transmissions and responses. SARB submits that the DA and the DCA have already engaged in a communications session before the DCA sends its response.

75 SARB submits that the decision in VMS 2013 should not be followed because the Court in that case did not have the benefit of Mr Toal’s evidence about the connection information contained in the [REDACTED] and details of how the communications session is established between the DA and the DCA and details of how the PinForce Version 1 departed from the [REDACTED]. SARB submits that a proper understanding of these matters is essential to the correct conclusion that the PinForce Version 1 did not use a wake-up signal as claimed. SARB refers to Fig 8 and the significance of performing a communications session and submits that the crucial point is, in effect, which of the two devices initiates the communications session. SARB submits that that is the [REDACTED] containing the connection information which initiates the communications session.

76 SARB submits that the wake-up scheme of the invention as revealed in the claims is that it is the DCA which initiates the communications session and that that is not the case with the PinForce Version 1. SARB refers to the significance of the communications session to the decision in VMS 2013. It submits that this Court has fresh evidence from Mr Toal and, furthermore, that the opinions of Mr Spirovski have been shown to be flawed.

77 In my opinion, the essence of the Court’s reasoning in VMS 2013 applies having regard to the evidence advanced in this case and, with respect, that reasoning is correct. The notion of which device initiates the communications session was a matter raised before the Court in VMS 2013. For example, in paras 45 and 46 in confidential exhibit STO1 referred to in the affidavit of Mr Toal affirmed on 22 December 2011, the following appears:

45 In [13(c)] Mr Spirovski also states:

[REDACTED];

46 This is also incorrect. The VDU [REDACTED].

78 In my opinion, as VMS submits, reference to “initial communication” or “initiating the communications session” is irrelevant because neither of those matters is referred to in the claims and it is not the communications session that is the subject of the claims. The communications session which is the subject of the claims is that which follows the wake-up signal. Furthermore, data related to identified instances of overstay of a vehicle, in that magnetic data is undoubtedly data that relates to identified instances of overstay of the vehicle, is transmitted in response to receipt of a wireless wake-up signal.

79 In my opinion, the PinForce Version 1 (and the PinForce Version 2) infringes claims 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 21, 22, 28 and 29 of the First Patent and claim 26 of the Second Patent and the contention by SARB that PinForce Version 1 does not involve the use of a wake-up signal or provide for data to be transmitted when a DCA is detected, should be rejected.

80 SARB raised a separate point which appears to be correct and that is that PinForce Version 1 and PinForce Version 2 do not infringe claim 8 in the First Patent because the DA does not involve the further step of determining an overstay duration of the vehicle in the said parking space (emphasis added).

81 Before leaving this section of the reasons, I will address by way of a summary a submission made by SARB that seems to bear upon Mr Spirovski’s approach to giving evidence in relation to this issue and, as I would apprehend it, other issues in the case. SARB submits that Mr Spirovski speculated on the basis that SARB had used the Zigbee protocol in circumstances where he knew when he made his affidavit that Mr Toal had given evidence in 2011 that SARB’s DAs only utilised a subset of the Zigbee protocol. Furthermore, SARB submits that Mr Spirovski’s evidence did not reflect the VPMD or Mr Toal’s 2011 evidence, both of which Mr Spirovski had to hand when he made his affidavit. SARB submits that Mr Spirovski was aware from Mr Toal’s 2011 evidence that the SARB functional specifications did not accurately describe PinForce Version 1. The submission seemed to be that Mr Spirovski proceeded on a basis he knew to be incorrect. I reject that submission.

82 SARB referred to the fact that in Mr Spirovski’s first affidavit in this proceeding, he said that he was provided with, and had read, affidavits sworn in the VMS 2013 proceedings. One of those affidavits was an affidavit of Mr Spirovski himself sworn on 27 February 2012 in which he said:

Zigbee standard

22. In paragraphs 31 to 33 of Confidential Exhibit ST02, Mr Toal states that I may have assumed that [REDACTED]

83 Counsel for VMS took me through the history of the matter. He started with a redacted document dated 22 December 2009 and a second redacted document dated on various dates in 2009 (VDU Technical Specification). Counsel submits that that was all Mr Spirovski had at the beginning of 2020. VMS was then given an unverified VPMD and then a verified VPMD which contained marked up a number of additions. VMS asked to look at the underlying documents and received the various functional specifications and specifications set out in a table in para 100 of Mr Spirovski’s first affidavit.

84 Counsel took me to para 115 and following of Mr Spirovski’s affidavit where he sets out his instructions which were to consider the function and specifications of 1.0 to 3.1 and to describe the process by which the IGU and the TMT establish a communications session. Mr Spirovski was asked to assume that the documents relate to the PinForce Version 1. There are a number of references to the Zigbee protocol in the documents. VMS prepared a 24 page document which, among other things, linked paragraphs in Mr Spirovski’s affidavit with paragraphs in the Sentinel Functional specifications. I do not propose to go through this document in detail. It is sufficient that I do not consider that Mr Spirovski prepared his evidence on a basis which he knew to be wrong (see transcript pp 758–761, 779–781).

Issue 2

85 The second issue raises the construction of certain claims in the First Patent and whether the claims include a method or system where the determination of vehicle overstay is made by the DCA instead of the DA.

86 It is agreed between the experts that in the case of PinForce Version 3, all capability of determining overstay in the DA has been removed. Vehicle overstay is determined by the HHU. The issue is whether, on the correct construction of claims 21–23 and 28–32 of the First Patent, either the DA or the DCA can make the determination that a vehicle has overstayed. VMS’s case is that on the correct construction of those claims, either the DA or the DCA can make the determination that a vehicle has overstayed. SARB’s case is that those claims are restricted to systems or methods in which the DA, and only the DA, makes the determination that a vehicle has overstayed.

87 In the joint conference of experts, the experts addressed this issue as an issue involving proper construction of the claims and an issue as to whether PinForce Version 3 fell within the terms of the claims as so construed. As there is no dispute about how the PinForce Version 3 operates in this respect, the issue is, in essence, one of construction.

88 With respect to the construction of the claims, the experts were asked to identify any points of agreement or disagreement between them regarding their understanding of which component(s) of the system or method claimed are responsible for determining overstay of vehicles in parking spaces within claims 21–23 and 28–32 of the First Patent.

89 The experts agreed that the system as disclosed in the First Patent is capable of determining overstay in the DCA. However, they disagree as to whether claims 21–23 and 28–32 of the First Patent indicate that the DCA performs the overstay determination.

90 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Spirovski made the following observations. He said that in order to determine overstay, the system needs to have the following information: (1) the arrival time of the vehicle; (2) the identification of the parking space; (3) the parking time rules associated with that parking space; and (4) the current time. The First Patent discloses a DCA that has all of the means necessary for determining overstay within the apparatus. The First Patent also discloses a system where the DA is operated in a reduced capacity that transmits a subset of the necessary information to the DCA and the DCA is used to determine overstay of the vehicle as part of the system. In this context, Mr Spirovski referred to p 7 lines 21–23 of the First Patent, which is set out above, but which I repeat here for convenience:

Alternatively, decisions relating to vehicle overstay can be made by a data collection apparatus that collects data from the apparatus 200 via a radio communication link rather than by the apparatus 200.

91 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Harcourt made the following observations. He said that claim 21 of the First Patent states that the vehicle detector (i.e., the DA) determines overstay. The passage on p 7 lines 21–23 of the First Patent states that decisions relating to overstay can be made by a HHU. The meaning which Mr Harcourt gives to this passage is that overstay is still determined in the IGU (DA), but decisions relating to the information can be made in the DCA or HHU. Mr Harcourt’s opinion is that the system could theoretically support the determination of overstay outside the DA, but the First Patent clearly states that the DA determines overstay. Mr Harcourt expresses the opinion that “considerable thought” is required in order to decide how overstay could be determined in the DCA or HHU and the First Patent is silent on that matter.

92 The experts were also asked to address in the joint conference of experts any points of agreement or disagreement between them regarding their understanding of Figs 1 to 9 of the First Patent, including by reference to the description of those figures in the specification.

93 The experts agreed that, in the case of Fig 1, the DCA indicates overstay based on retrieved data stored in the DA. However, they disagree as to whether the retrieved data already contains a determination of overstay made by the DA. They agree on the meaning and description of the other figures.

94 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Spirovski made the following observations. Fig 1 is a general system overview of overstay determination and the figure discloses that at least the vehicle presence data is stored in the DA and later retrieved by the DCA. The figure allows for an overstay determination to be made by either the DA or the DCA.

95 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Harcourt made the following observations. In the case of the method shown in Fig 1, overstay is determined by the DA and this information is then retrieved by the DCA and indicated on the HHU based on the retrieved data (Mr Harcourt’s emphasis). There is no reference in the figure to other data sources and Mr Harcourt states that he can only infer that all data relating to overstay is retrieved from the DA. Mr Harcourt expresses the opinion that the word “indicated” means to “pass through information” and display it to a user. There is no mention of further processing or calculation with respect to the data, which Mr Harcourt believes would have been described in the First Patent if that was a feature of the system.

96 The experts were asked to identify in the joint conference of experts any points of agreement or disagreement between them as to whether the PinForce Version 3 is, in substance, the same as, or different to, the embodiments shown in Figs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9 in the First Patent. They agreed in regards to the embodiments in Figs 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9 in the First Patent, that the PinForce Version 3 is substantially the same as the system in the First Patent. They disagree that PinForce Version 3 in regards to the embodiment shown in Fig 1 in the First Patent is substantially the same as the system of the First Patent.

97 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Spirovski made the following observations. PinForce Version 3 is the same in substance as the system of the First Patent operating in the configuration where the DCA determines overstay. Mr Spirovski refers to and relies upon his comments with respect to the construction of claims 21–23 and 28–32 of the First Patent (see [90] above). Mr Spirovski agrees that the DA in the PinForce Version 3 cannot determine overstay.

98 In addition to the joint observations, Mr Harcourt made the following observations. Step 150 in Fig 1 reads as overstay indicated based on the retrieved data from the DA (IGU). There is no reference to retrieving data from anywhere else so the retrieved data must therefore include overstay information. It follows, according to Mr Harcourt, that Fig 1 does not match in substance the PinForce Version 3.

99 Finally, the experts were asked to identify in the joint conference of experts any points of agreement or disagreement between them with respect to the related question of whether PinForce Version 3 has all of the features of the system claimed in claim 21 of the First Patent. The experts referred to their previous comments. In addition, they noted that they agree that the system as disclosed in the First Patent is capable of determining overstay in the DCA. However, they disagree as to whether claim 21 of the First Patent discloses that the DCA performs the overstay determination.

100 Before turning to consider first, the proper construction of claim 21 and whether it includes a system in which vehicle overstay is determined in the DCA and then, if not, the same question in relation to the omnibus claims (claims 30–32), it is necessary to highlight certain evidence given by the experts.

101 The third aspect of the invention is the consistory clauses for claim 21 and is described above (at [27]).

102 Mr Spirovski was cross-examined by counsel for SARB about the scope of the third aspect of the invention. He gave the following evidence:

MR CAINE: And just by way of broad overview, you will see that set out on page 2 are three aspects of the invention. The first one is a method, the second one in the middle paragraph is an apparatus, and the third one is a system. Do you see that?

MR SPIROVSKI: Looking. So method, apparatus and the system. Yes.

MR CAINE: Okay. And is it your understanding that the invention has those three aspects as described on pages 2 and 3?

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes.

103 Mr Spirovski then agreed that, in the case of the first aspect (method) and the second aspect (apparatus), the determination of vehicle overstay takes place in the DA.

104 Mr Spirovski was then taken through the elements of the third aspect and he gave the following evidence:

MR CAINE: So what is being described there is that the data apparatuses have determined or calculated that there have been identified instances of vehicle overstay.

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes, in that summary.

MR CAINE: Yes. And the processing unit in the data-collection apparatus is programmed to process those instances of vehicle overstay - - -

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes.

MR CAINE: - - - and to indicate those instances to an operator – an end user such as a parking officer.

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes.

MR CAINE: And that means that the data-collection apparatus will pass on the information from the – sorry – it will pass on the information to the end user that it has received from the detection apparatus.

MR SPIROVSKI: It – it says to process. It doesn’t indicate what processing is done and exactly what is passed on or – or determined from – from the received data.

MR CAINE: So let’s just take that step by step. It’s telling you that the data received is data from the detection apparatus which has previously determined whether there is vehicle overstay.

MR SPIROVSKI: Yes.

MR CAINE: And then what the data-collection apparatus is doing is to pass on, that is, to indicate instances of vehicle overstay that it has received from the detection apparatus.

MR SPIROVSKI: That’s some of the data, yes, but as a summary it doesn’t include any detail as to what is being processed.

MR CAINE: No. But what’s it not saying is that the data-collection apparatus is itself calculating or determining vehicle overstay.

MR SPIROVSKI: Not there it isn’t, no.

105 Counsel for SARB returned to the topic the next day in order to clarify one of Mr Spirovski’s answers. Mr Spirovski gave the following evidence:

MR CAINE: Thank you. All I wish to do, Mr Spirovski, is just clarify one question and answer between you and I. At transcript page 403, towards the bottom of the page at about line 42, I asked you a question about the data-collection apparatus and some of its features, and then at the top of page 404 I said:

The processing unit is programmed to process the data it receives from the detection apparatus –

and at this stage I’m walking through the third aspect of the invention. I refer there to the data that’s received from the detection apparatus and you say “yes”. And then I say:

And that data provided by the detection apparatuses is data that relates to identified instances of overstay –

and you say “yes”. And then the question I put to you is:

So what is being described there is that the data apparatuses have determined or calculated that there have been identified instances of vehicle overstay.

Now, what I wanted to ask you was did you – and you say:

Yes, in that summary.

First of all, that summary was the third aspect that we were talking about – third aspect of the invention?

MR SPIROVSKI: .....

MR CAINE: And did you understand my question when I referred to data apparatuses to mean the detection apparatuses had determined or calculated identified instances of vehicle overstay or would your answer be the same had I referred to detection apparatuses rather than data apparatuses, which was inelegant?

MR SPIROVSKI: Detection apparatuses.

106 SARB submits that it is significant in terms of the proper construction of claim 21 that Mr Spirovski agreed that in the system described in the consistory clause for claim 21, the determination of vehicle overstay is made in the DA.

107 Mr Spirovski did make it clear on a number of occasions that his opinion was that the description of the third aspect of the invention was only a summary and a description of one embodiment of the invention. He did not resile from his opinion that the relevant claims in the First Patent included a system or method in which vehicle overstay was determined by the DCA. He made it clear that his opinion was based on the specification as a whole.

108 Mr Spirovski referred to a number of passages in the specification of the First Patent in support of his opinion that a product, system and method wherein the determination of vehicle overstay is made in the DCA is within the terms of claim 21 or the omnibus claims.

109 First, he referred to the passage on p 3 of the First Patent which is set out above (at [28]) and which I repeat here for convenience:

Overstay of a vehicle in a parking space may be determined at the detection apparatus by processing data received from the detector.

Mr Spirovski relies on the fact that the word may has been used in this passage and the use of that word carries the implication that overstay of a vehicle may not be determined in the DA.

110 Secondly, Mr Spirovski referred to the passage on p 3 of the First Patent which again, is set out above (at [28]) and which I repeat here for convenience:

The data collection apparatus may be portable and may retrieve the data from the detection apparatus whilst the data collection apparatus is located in a moving vehicle. Data relating to presence of a vehicle may comprise presence duration of the vehicle in the parking space, movements of the vehicle in and out of the parking space with corresponding time-stamp information, and/or an indication of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

Mr Spirovski placed emphasis on the use of and/or in the above passage. He interprets the passage to mean that the DA may, for example, send data relating to the presence duration of the vehicle in the parking space and movements of the vehicle in and out of the parking space with corresponding time-stamp information, but not data which includes an indication of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space. In those circumstances, the DCA would have to determine the overstay of the vehicle.

111 SARB submits in response to this interpretation of the passage that the passage can be read in a way which gives it work to do, but is quite neutral with respect to the present issue. The DA may send only an indication of the overstay of the vehicle in the parking space and not the other information or it may send the first two types of information, but not the third because there is no overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

112 Thirdly, Mr Spirovski places great reliance on the passage at p 7 lines 21–23 of the First Patent which is set out above (at [90]) in support of his opinion. This passage appears in the detailed description of Fig 2 which is a block diagram of a DA (or IGU) designated 200. The figure does not show or refer to the DCA.

113 Mr Spirovski expresses the opinion that there is nothing in claim 21 or Fig 1 which precludes the determination of vehicle overstay by the DCA. There is no statement that the determination of vehicle overstay can only be made by the DA. Step 150 in Fig 1 refers to “[i]ndicate overstay of vehicle in the parking space based on the retrieved data”. The ordinary mean of “indicate” is to show or to make known. Step 140 in Fig 1 is described as the wireless retrieval of at least portion of the data from the DA and that accommodates the determination of vehicle overstay by the DCA. The argument, as I understand it, is that if the receiving device is receiving only portion of the data, it then is doing something with the data and not simply receiving it. Mr Spirovski said that, in his opinion, there is nothing in Fig 1 to indicate where vehicle overstay is determined. Mr Spirovski said that there would be no difficulty with the DCA determining vehicle overstay. The hardware of the DA and the DCA is the same irrespective of where vehicle overstay is determined and the software programming necessary to implement either option would be “straightforward and routine”. He said in his oral evidence that the decision made by the DCA would be made in the same way as the DA, “using the same equations”.

114 Mr Harcourt does not consider the passage relied on by Mr Spirovski on p 7 lines 21–23 of the First Patent has the significance to the present issue that Mr Spirovski attributes to it. He expresses the opinion that the reference in the passage to “decisions relating to vehicle overstay” does not mean determinations of vehicle overstay, but rather, decisions made subsequent to determinations of vehicle overstay. It became apparent in Mr Harcourt’s cross-examination that he had in mind, at least in part, decisions made not by the DCA, but by the parking officer. As I understand it, Mr Harcourt’s opinion is that the passage deals with decisions made by the DA “being overruled or perhaps upheld”. He gave the following example:

… even if the device is broken and the operator – the parking officer is confident that the vehicle has, indeed, been there for a long time and overstayed, may issue the fine regardless of what the VDU tells him or her.

115 Mr Harcourt points to what he says is a further difficulty with Mr Spirovski’s construction of the passage on p 7 lines 21–23 of the specification and that is there is no indication anywhere in the specification as to how the DCA would make determinations of vehicle overstay. Mr Harcourt disagrees with the suggestion by VMS that it can be readily concluded that vehicle overstay would be determined by the DCA in the same way it would be determined by the DA. Mr Harcourt also disagreed with the suggestion by VMS that there was nothing sophisticated about the programming of the DCA. This point is linked to Mr Harcourt’s opinion that the system disclosed in the First Patent is capable of determining vehicle overstay in the DCA. Mr Harcourt explained that this was theoretically the case, but not practically the case because, as he explained in his oral evidence, there is no information in the specification as to how that could be done in circumstances in which there are many indications in the specification that vehicle overstay is determined by the DA.

116 In forming his opinion that the passage relied on by Mr Spirovski is not dealing with determinations of vehicle overstay, Mr Harcourt also relies on the fact that Fig 2 in the detailed description of which the passage appears, does not show the determination of vehicle overstay by a DCA. That is true as Fig 2 is a representation of the DA.

117 Mr Harcourt agreed in cross-examination that there is nothing in Fig 1 that “explicitly confines the determination of overstay to the detection apparatus” and that vehicle overstay could be determined in the DCA.