FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nona on behalf of the Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg Peoples (Warral & Ului) v State of Queensland (No 5) [2023] FCA 135

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The questions reserved for consideration be answered as follows:

Question (a)

(a) But for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so what, lands and waters of the claim area?

Answer

Yes, native title exists in all of the claim area.

Question (b)(i)

(b) In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(i) who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

Answer

The persons who hold the native title referred to in the answer to question (a) are the group members of the Badulgal and Mualgal Peoples, such group membership being determined in accordance with their traditional laws and customs.

Question (b)(ii)

(b) In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

…

(ii) what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

Answer

The Badulgal and Mualgal Peoples hold a single native title over the claim area, in the same way as they do over the islands in the determination in Nona and Manas v State of Queensland [2006] FCA 412.

The native title rights and interests are exclusive in nature.

2. The proceeding be listed for case management hearing in the week commencing 3 April 2023, at a date and time to be fixed in consultation with the parties.

3. On or before 4.00 pm (AEDT) two (2) working days before the case management hearing, the parties are to propose orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment dated 27 February 2023, including any proposed order relating to how the native title rights and interests in the claim area should be described in any determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 The Court’s orders and reasons arise from separate questions stated by the Court about two islands in the Western Torres Strait, Warral and Ului. There is presently a claim under s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) over these islands, on behalf of three groups. The claim is made on the basis that the native title to those islands is a shared title between the three groups, either as members of one “society” or (alternatively) as members of two “societies” which have under their customary laws shared the islands, since before colonisation. Those groups are the Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg Peoples. In these reasons, I will describe this as the shared ownership claim.

2 Since March 2020 there has been a challenge to the shared ownership claim, by five Badulgal men. They were joined as respondents to the shared ownership claim. Mediation has not been able to resolve the different views.

3 What has happened in this proceeding in some ways reflects the tragedy of having to recognise native title by fitting it into the straitjacket of Anglo-Australian law as reflected in the NTA, and the realities for First Nations peoples today in finding a way through that system. Eliziah Wasaga, a Kaurareg man, summed up in his evidence the long struggle and the tensions imposed by the native title system:

And so much has changed over the years that laws have changed. And, you know, when Mabo came into the sea it put a lot of effect on everybody. And it was only a case that was for, you know, Mer Island. But then that ricocheted globally. So, by giving power back to indigenous people, it was like a threat.

But all we wanted to do was just to manage our country and have rights to practise our – and exercise our cultural rights, you know? So – but also an identity factor because we’d identify ourselves as the Aboriginal people of this region and, you know, it’s been such a long, you know, struggle, because somebody gets into power and the policy changes. We’re governed by policy. It’s always hard. So the more we talk about policy, policy, our law is starting to, you know, get distance. And it’s not fair on our future generations. So we need to be, you know – we need to get all parties together. Let’s talk. And that’s proper way.

4 I have said this at the start of the reasons to emphasise that the Court is conscious of the tensions, and the apparent unfairness, the native title system can impose on First Nations peoples. The legal transformation wrought by Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 set Australia on a path towards recognising that land and waters on this continent have always belonged to First Nations peoples. The path is far from complete. And it can be torturous.

5 As all parties to the separate question proceeding acknowledged, the Court must decide not only whether the applicant has proven its case of shared ownership, but, if not, must also decide what the evidence establishes on the balance of probabilities is the correct answer to the separate questions about who has native title in Warral and Ului. If the Court finds the applicant has not discharged its burden of proof on the shared ownership claim, that does not mean the Court must dismiss the native title application. All parties accept that the Court should decide whether it is more likely than not that one or more of Badulgal, Mualgal or Kaurareg hold native title over Warral and Ului. All parties accept that the islands belong to one or more of these groups, and not to anyone else. The questions the Court must answer have been structured to allow for this possibility.

6 That said, the purpose of these separate questions is no wider than Warral and Ului. Given the state of claims and determinations in the Torres Strait and Northern Cape York region under the NTA, especially in the Western Torres Strait, I consider it is important the Court does not go further in its findings than is necessary to answer the questions posed and resolve the dispute over Warral and Ului. While some of the findings in these reasons may affect, or be seen to affect, other claims yet to be resolved, the Court’s findings are based on the evidence before it and the submissions made, all of which have been directed at what are narrower and different issues than those which may arise in some of the other claims.

7 The claim area tracks the land masses of Warral and Ului closely, but includes small islets along the north-western coast of Ului, as well as some beaches, and perhaps parts of sandbanks and reefs adjacent to each of those islands, but only as far as the mean high-water mark at spring time. Thus, it is treated as principally a claim to land, and not to the sea, nor to reefs below the mean high-water mark at spring time, a matter which is important to remember when reading the Court’s reasoning. Maps of Warral and Ului showing the claim area are at attachment 1 and attachment 2 to these reasons, respectively. These maps were tendered as agreed maps by the parties.

8 Native title in the sea around Warral and Ului – that is, areas below the mean high water mark at spring tide – has not been recognised yet under the NTA. Native title in the sea has been recognised in a significant area north of the claim area, under what was called the Torres Strait sea claim: Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v Commonwealth [2013] HCA 33; 250 CLR 209; Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 3) [2010] FCA 643; 204 FCR 1. The separation of the Torres Strait sea claim, which occurred during the trial of Akiba, into a Part A and a Part B claim, assumes some significance in this proceeding.

9 What was described as the Part B sea claim, and includes the sea around Warral and Ului, and the sea between those islands and Badu and Mua, and between Warral and Ului and the Kaurareg home islands, has not been determined. The Part B sea claim, and a number of other unresolved and partly overlapping sea claims, and one terrestrial claim, are currently being managed together with this proceeding (see Nona on behalf of the Badu People (Warral & Ului) v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 983 at [11]).

10 On 30 November 2022, native title was recognised by this Court in a large area of sea country mostly to the east of the current claim area, including large parts of the Part B sea claim. However, the sea around Warral and Ului, and indeed all of the sea in the western part of the Part B sea claim, was excluded from this determination, principally because of this current proceeding: see David on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 1430.

11 The first native title claim over Warral and Ului was filed on 4 March 2002 and eventually became this proceeding, QUD9/2019. Initially, the claim was made only on behalf of the Badulgal People. The Akiba claim had been filed in November 2001. In March 2002 a number of the home island and shared islands claims in the Western Torres Strait were filed within a few days of each other. On 28 November 2003, three Kaurareg respondents were joined to the (then) Badulgal claim over Warral and Ului. That joinder was on the basis that Kaurareg People asserted native title in the islands. This was consistent with the claims made by the Kaurareg People in Akiba to the sea extending north from their home islands and into the area of the sea between Warral and Ului, and Badu and Mua. No Mualgal people had sought to be joined as respondents at this point, but their assertion of interests in the islands was well understood in the region. Over the next decade or so, the home and shared islands claims were resolved, and the Akiba claim was litigated. The claim over Warral and Ului was not resolved.

12 On 17 March 2014, Greenwood J referred representatives of the Badulgal, the Mualgal and the Kaurareg Peoples to mediation in an attempt to resolve these disputes. As I noted in Nona at [13]-[15], this mediation was held in February 2015. The outcomes of the mediation included an agreement to amend the application and replace the applicant so as to reflect the shared ownership claim. In these reasons I will describe this as the 2015 agreement. The amended claimant application and the replacement of the applicant was authorised in February 2020, and the amended claim was certified by the Torres Strait Regional Authority in April 2020. It was the authorisation process that prompted the formal expression of disagreement from some within the Badulgal community.

13 On 4 March 2020, an interlocutory application was filed in this Court seeking orders to join five Badulgal men as respondents to this proceeding (the Badulgal respondents). The Badulgal respondents contended that under customary law, the islands of Warral and Ului were in the exclusive domain of the Badulgal, and the 2015 agreement and consequent shared ownership claim were wrong, and would lead to the diminishment of the Badulgal’s customary rights in favour of the Mualgal and Kaurareg Peoples.

14 On 15 July 2020, for the reasons set out in Nona, this Court granted leave to replace the applicant so that members of each of the three groups constituted the applicant, and leave to the newly constituted applicant to amend the s 61 application to make the shared ownership claim. The Court also granted the Badulgal respondents’ application for joinder.

15 The separate questions were stated in Nona on behalf of the Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg Peoples (Warral & Ului) v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 1353 (Nona (No 2)). The active parties on the separate question hearing were the applicant, the State, the Commonwealth and the Badulgal respondents.

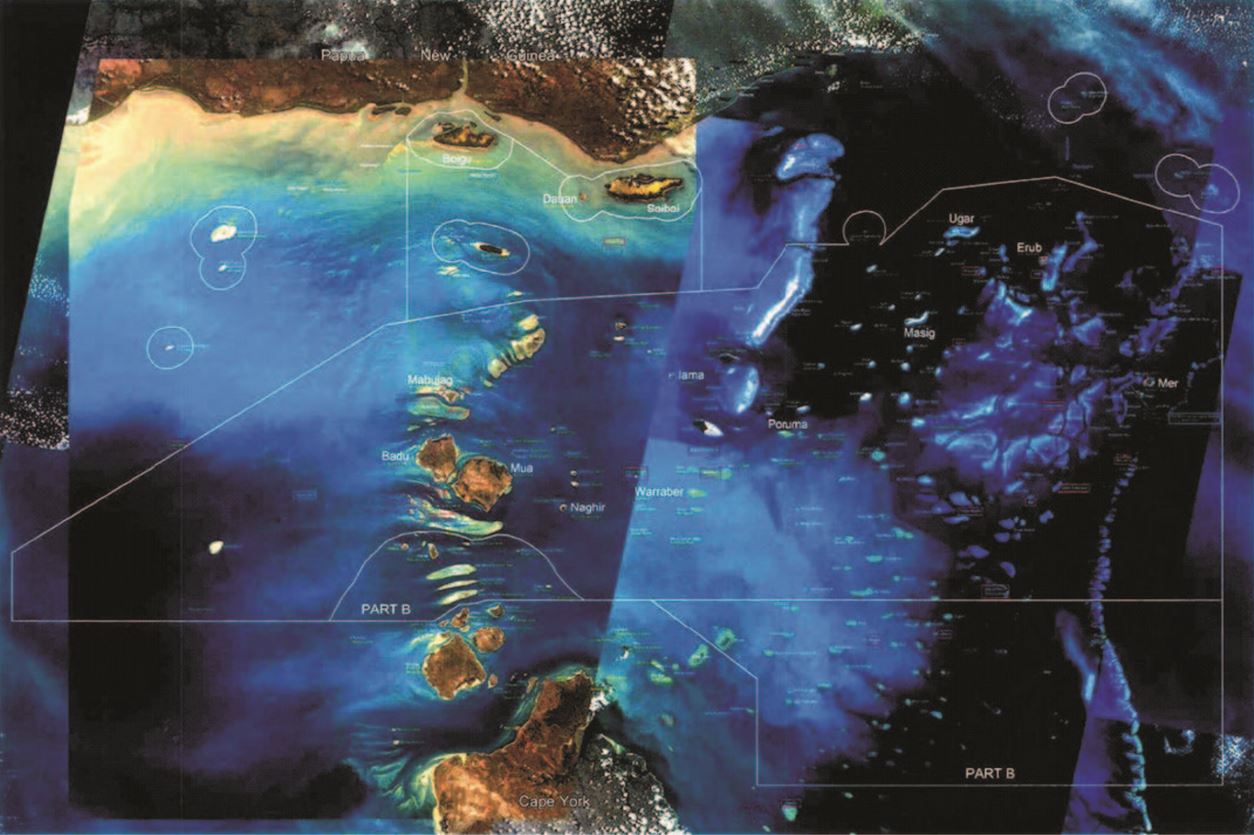

16 The wider regional area of the Western Torres Strait, as relevant to the evidence on the separate questions, can be seen in the agreed map at attachment 3, tendered in the separate question proceeding.

17 The separate questions were set out in full in paragraph 1 of the orders made by the Court in Nona (No 2):

Pursuant to rule 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the following questions are to be determined separately from any other questions in the proceeding (including questions arising under s 225(c), (d) and (e) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA)):

(a) but for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so what, lands and waters of the claim area?; and

(b) in relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(i) who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?; and

(ii) what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

18 All parties agreed this form of questions enabled the Court to make findings, and a determination of native title, on a basis other than the one in the shared ownership claim. For the reasons set out below, the Court has found native title exists in all of the claim area, and it is held by the Badulgal and Mualgal Peoples.

19 This trial has been challenging in terms of logistics. All parties, their witnesses and supporters, their legal representatives, the relevant representative bodies (TSRA and then Gur A Baradharaw Kod Sea and Land Council Torres Strait Islander Corporation) and their staff, have worked cooperatively and positively to make each stage of the trial run as smoothly and efficiently as it could. Careful attention has been paid by the TSRA and GBK to ensuring that members of the three communities could attend the separate question hearing. The Court expresses its gratitude to them all. The Court is grateful to the communities of each of Waiben, Mua and Badu for their warm hospitality during the conduct of the hearing. I express my personal gratitude to my Associates at various stages of the trial – Rosie Cham, Ganur Maynard, Michael McArdle and Sophie Ward, to Judicial Registrar Simon Grant and his assistant Melinda Carr, to the Court’s remote hearing officers Neil Warner and Jared Lane, and to Dave Oldland and Merryl Alexander from Transcript Australia. I also thank Wendy Chen, who provided proofing assistance over the weeks leading up to today. The Court is grateful to the owners and staff at the Cairns Business Hub (formerly known as the iiHub) for providing a culturally appropriate, comfortable and welcoming venue for the Cairns-based parts of the hearing.

20 The Court also extends its sincere gratitude to Mr Cyril Repu, from Mabuiag, who acted as an interpreter for the lay witnesses where required. This was an important and difficult undertaking, that required skill and concentration. Mr Repu performed his task with good humour and patience, affording respect to all witnesses, and the Court is grateful to him.

21 The Court acknowledges the cooperative and good natured way in which all legal representatives conducted the trial. Lastly, as I said on several occasions during the trial, the Court is conscious this proceeding has been very difficult at a deeply personal level for members of the three communities, and especially for witnesses. All conducted themselves with great respect and dignity for the most part. The Court is grateful for the respect and restraint shown by all those who participated in or observed the conduct of this proceeding.

22 These reasons commence with some matters of terminology. I then describe in brief terms the adversarial context for this proceeding and what it means for how the Court decides the answers to the separate questions. Next, I set out a summary of the evidence relied upon, and introduce all of the lay and expert witnesses who gave evidence. The documentary evidence was voluminous, and I give no more than a brief summary of the categories of documentary evidence before the Court. Where it is material to my findings, I refer to the documentary evidence later in my reasoning. Next, I turn to a conceptual matter which informs the overall approach I have taken, and the conclusions I have reached. A number of essentially historical factual matters must then be explained, especially about previous native title determinations in the region.

23 I then turn to some matters which involve some questions of law, and which are material to answering the separate questions. In this section, I work through in detail my findings about the nature and significance of the lay evidence given in Akiba. I also explain the matters I do not consider the Court needs to, or should, decide, even though some of them were the subject of submissions by one or more of the parties. Next, I explain my approach to some of the factual issues, and my approach to various categories of the evidence.

24 The final section of the reasons sets out my principal factual findings. There are two parts to that section. First, I set out my approach to, and findings on, certain factual matters that arose during the trial, each of which informs my reasoning on the key disputed questions of fact and the answers to the separate questions.

25 Second, I then turn to making ultimate factual findings necessary to the determination of the answers to the separate questions, on which the parties’ respective cases and submissions concentrated, and explain my answers to the separate questions.

26 In the terminology used in these reasons I have tried to be faithful to the lay evidence in particular, because that is the language used by the native title claimants themselves.

27 Some terms and descriptions are unavoidable, even though they carry the baggage of colonisation. For example, Eliziah Wasaga reminded the Court in his evidence that to identify as a “Torres Strait Islander” involves the use of a settler name, Torres.

Names used to identify the people of various home islands

28 In his supplementary report, Mr Ray Wood, one of the anthropologists called on behalf of the applicant, explains the usage of prefixes and suffixes to identify members of different home island groups. At [17]-[20] he explains:

Turning to Torres Strait social group nomenclature, group names consist of a stem and suffixes, the stem being either:

(i) the name of a home island; or

(ii) the personal name of a notable mythological figure.

To this is added a combination of suffixes which together mean ‘(people) of/belonging to/owners of’ that island or mythological figure. Original dialect variation is largely lost and the forms of the combinations are now standardized as -laig/-raig (singular or small group) and -lgal (mass plural, communal). The names denote not merely residence on an island, but ownership of it (see below). I note in the transcript that the Court is already familiar with Badulaig/Badulgal and Mualaig/Mualgal, and other examples are Purmalgal and Saibailaig, based on the home island names Badu, Mua, Purma (Poruma), and Saibai respectively.

Differing from these cases, the stem of the name now long written as ‘Kaurareg’ is not a placename, but derives from Kauraru, one of the names of the hero Waubin, and derived from kaura ‘bird (sp.),’ which in one version of the Waubin myth animates a headless body which grows into the giant body of Waubin. The origin of the name is thus a reference to the people of Kauraru alias Waubin. The Kaurareg were also often referred to by others as the Muralag people, after their core home island, a usage which Haddon and others before him picked up and followed.

‘Kaurareg’ is not the only group name based on that of a mythological personage. There is also the Central Islands name Kulkalaig/Kulkalgal, in which the stem Kulka is the personal name of a focal mythological hero Kulka from Cape York Peninsula who travelled through the Central Islands and settled at Aurid. The Central Islanders are called Kulkalgal after him. During the hearing Alick Tipoti (T849-15), Badhulaig, referred to the Kulkalgal (the transcript’s ‘Kulkulku’ at T673.15) as the Central Torres Strait Islands as still current usage.

A somewhat hybrid case is Goemulgal (aka Gumulgal), the stem of which is a placename on Mabuiag, Goemu, but also a reference to the mythological hero Kwoiam, for Goemu is the site where Kwoiam made his home, as Sydney Ray, a member of the Haddon expedition was told at Mabuiag (Haddon 1904:2). Goemulgal thus was often used as an indirect identifier of the Mabuiag people, and a higher level, Mabuiag and Badu together, as the people of/associated with Kwoiam. Wilkin (1904:286) observes that “Badu counted for all practical purposes as part of Mabuiag,” and at other points he and others use the name Goemulgal/ Gumulaig as a collective one for the Badu and Mabuiag people as single community, as in the passage I cite in Wood 2022 at [52].

(Footnotes omitted.)

29 When in these reasons I am describing the wider group of people from a particular home island, I use the terms Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg People.

30 For the people of Mabuiag, the island to the north of Badu, which features in the evidence at various points, some lay witnesses use the term Gumulgal, which is the term used by another of the applicant’s experts, Dr Murphy. However, other lay witnesses use Mabuiagulaig or Mabuiag People. In these reasons, I refer to the people of Mabuiag as the ‘Mabuiag People’.

31 There are English names for Warral and Ului which appear in some of the material, but which I otherwise do not use in these reasons. Dr Murphy in his 2015 connection report for Warral and Ului at [44] explains how these English names were assigned:

Ului was named West Island by Bligh in 1789, but he sighted it at a distance of 3 or 4 leagues (9-12 nautical miles) from the south by his own reckoning, and did not land there. Waral was named Hawkesbury’s Island by Edwards in 1791, but like Bligh with Ului, he named it from a distance and did not land there.

(Footnotes omitted.)

32 Dr Murphy repeated this explanation at [66] of his amended report in this proceeding.

33 The home islands of the Kaurareg People often remain identified by names given after colonisation. I have attempted in these reasons to use the Kaurareg names for their islands. Thus, I have used Waiben for Thursday Island, Ngurapai for Horn Island, Kirriri for Hammond Island and Muralag for Prince of Wales Island.

34 Where words are given different spellings in either the source materials, lay or expert evidence, or in prior judicial decisions, I have generally chosen the spellings consistent with prior judicial decisions.

35 There are various spellings for the names of some places. Mabuiag is spelled Maubiag in Dr Powell’s 1998 report. Ngurapai is spelled Ngurupai in Michael Southon’s 1997 report and by Drummond J in the Kaurareg determinations (Kaurareg People v State of Queensland [2001] FCA 657). Kirriri has sometimes been spelled as Kerriri in the academic documents tendered in evidence and appears as Kiriri in Mr Ray Wood’s 2022 report. Muralag has been spelled Murulag in previous decisions in this Court. For each of these place names, in these reasons I have used the spellings bolded above.

36 Warral is often spelled Waral. In Attachment 1 to Akiba it is spelled with one ‘r’. In his 2015 connection report, Dr Murphy spelled it as ‘Waral’ and Mr Wood also uses that spelling in his expert report. In the written outlines of evidence by lay witnesses filed by the applicant and respondents in this proceeding, however, ‘Warral’ is used. In these reasons, I have used ‘Warral’.

37 The island of Mua is sometimes spelled “Moa” in the materials. In his 2020 report, Dr Hitchcock states:

Mua is the correct language name for Moa Island, and the island is referred to as such throughout this report (see Powell 1998:4).

38 In these reasons I use ‘Mua’. That is also the spelling used in Akiba.

39 The name of the island(s) just to the north of Warral (on the map at attachment 1, shown as two main land forms), Sunswit, was often spelled differently in the material before the Court (as Sansuit, Sunsuit, or Sanswit). On the tendered maps, the spelling used is “Sunswit”, so I have adopted that spelling. I have also used the singular, as all the evidence did, even if geographically there may appear to be more than one landform on the agreed maps.

40 Muknab Rock, which is located to the south of Mua and east of Warral, is spelled in Akiba as “Mokanab”, on the map in map 7 of exhibit A1 as “Mukanab” and in the prior decision Manas v State of Queensland [2006] FCA 413 as “Muknab”. I have used ‘Muknab’.

41 Murabar or Murbayl, identified by the English name of Channel Island, was covered by the 2006 Mualgal determination (see [213] below), along with Muknab.

42 The spelling for the names of historical and mythological figures sometimes varies. The hero Kwiam is spelled Kwoiam in Akiba and is spelled in other sources as Kuiam. I have used ‘Kwiam’ in these reasons, as this is the spelling that accords with the lay witness evidence given in this proceeding.

43 There are various spellings for a central Kaurareg figure, Pithalai. Across a number of sources, his name is variously spelled Pithulai, Pihulai, Puthulai, Pitalai and Pithulay. I have used ‘Pithalai’ in these reasons, according with the lay evidence given in Akiba.

44 The Badulgal apical ancestors Waii and Sobai are referred to by various spellings in sources as Wai and Sorbai. I have used the ‘Waii’ and ‘Sobai’ spelling, as that accords with the spelling in the written outlines of evidence by the lay witnesses in this proceeding.

45 The people of Naghir have been referred to by the variants Kulkalgal, Kulkalagal, Kukalgal and Kulkulgal (see, for example, the 1997 Southon report and Mr Wood’s supplementary report). I have used ‘Kulkulgal’, as this spelling accords with the spelling used in Akiba.

46 In Akiba, Finn J used the term “Islander” and “Islanders” to refer to the members of the 13 communities in the Torres Strait who comprised the claimants in Part A.

47 In his Honour’s reasons, Finn J generally distinguishes between “Islanders” and “Pacific Islanders”, and sometimes uses the term “Torres Strait Islanders”. As I read the reasons, his Honour uses “Islanders” as a shorthand for “Torres Strait Islanders”. As his Honour acknowledges at [182], “Torres Strait Islanders” is a term defined in s 253 of the NTA as “a descendant of an indigenous inhabitant of the Torres Strait Islands”. The term “Torres Strait Islands” is not defined in the NTA. In attachment 1 to Akiba, Finn J lists the islands, islets, cays and reefs of the Torres Strait that are within the claim area, with their language and English names. His Honour includes the Kaurareg home islands such as Kirriri, Ngurapai, and Waiben, as well as Warral and Ului.

48 In discussing the parties’ alternative conceptions of “society” for the purposes of their arguments in Akiba, at [175] his Honour says:

During the hearing of this matter I directed the applicant to provide “a plain English description of the different possible societies” which could support the claims made by it. Five such societies were identified. They were, in descending order of scale and put in short form (omitting genealogical qualifications):

(i) the larger regional society which extends from the southern mainland coast of Papua New Guinea where it includes some people of that area; it includes all Torres Strait Islanders (including Kaurareg, whether or not they regard themselves as Torres Strait Islanders); and extends to the northern coast of Cape York Peninsula where it includes some people of that area.

(ii) the one society which is that body of persons who are Torres Strait Islanders, whether or not including Kaurareg — this is the applicant’s society though it does not disavow a larger regional society;

(iii) the two language groups, Eastern and Western — a grouping the applicant attributes to Haddon;

(iv) the Torres Strait Islanders of four regional cluster groups of islands — the Commonwealth’s societies; and

(v) the Torres Strait Islanders of each, several, inhabited island — the State’s societies.

(Original emphasis, citations omitted.)

49 It is tolerably clear, in my opinion, that at many points in his Honour’s reasons, Finn J uses the term “Islanders” inclusively of Kaurareg People, but not of any mainland peoples such as Gudang. See, for example, the narrative about governmental regulation at [45]-[50], which expressly includes Kaurareg.

50 I do not use the term ‘Islander’ very often in these reasons, although it is used frequently in the source material I extract. I do use ‘Torres Strait Islanders’ and I do so without positively excluding or including the Kaurareg People. I accept this is a sensitive issue. The evidence in this proceeding conveyed the strong Kaurareg self-identification as Aboriginal People rather than Torres Strait Islanders, notwithstanding close and sometimes multiple kinship connections with the Torres Strait, but this is not a matter I need make any findings about, and I make none.

51 A number of language terms will be used throughout these reasons, being unique concepts that are best expressed in their original terminology. I provide an explanation of them below.

52 Sarup – Many witnesses spoke of sarup. It was and remains a lived experience, and a lived apprehension about having to travel across the sea. Sarup denotes the state of being “stranded”, “stuck” or “shipwrecked” on an uninhabited island. Lay witnesses in the proceeding attest to a shared cultural practice of anticipating or provisioning for the possibility of people becoming sarup by practices of planting coconuts on islands so that if someone is sarup, they will have something to eat and drink. Fr Paul Tom described sarup this way:

Well, if there’s a coconut on the island, you have to be survive. You have to climb up without asking anybody, otherwise, who you going to ask? You know. When you on a position like that, anything you find on the beach growing, whether food or coconut, you have to knock it down because that’s the only food that you can eat when you sarup. I mean when you struggled, stranded.

53 Adhi – In the evidence in this proceeding, adhi were principally employed as a Kaurareg concept, though were referred to also by Mualaig and Badulaig witnesses. The adhi sites (adhilgal) may function as ‘mark posts’ or a ‘boundary mark’ demarcating the boundaries of country. Thomas Savage explained it is important to acknowledge and pay respect to adhi:

THOMAS SAVAGE: Because still is adhi, that adhi know is law and because it’s - for us Kaurareg it’s a must, you must acknowledge those adhi, that’s the law. There’s no way around it, no ifs and buts about it, that’s the law, yeah.

54 Respecting adhi is, as explained by Mr Savage, an essential practice of protocols of respect. It is like:

THOMAS SAVAGE: I go to your place I knock on your door. That’s … to you. That’s what we do.

55 Gud pasin – This concept is a shared one across the Torres Strait. It expresses notions of sharing with others, kindness, humility and respect. Some witnesses connected it to, or saw parallels with, Christian teachings, others did not. Eliziah Wasaga, a Kaurareg witness for the applicant, explains:

ELIZIAH WASAGA: Well, gud pasin is, you know, like – well, my grandmother taught me that – she talks about this thing called thubud system. Thubud system is like part of that kinship system, like, if you come to my country I look after you. I feed you. I house you. I clothe you. You know, I make you feel good. Because when I go to your country you got to return the favour. So that is the importance of that thubud system again that my grandmother taught me. But when that gud pasin become … it sort of complemented that and when you sort of complemented that – because I – as I grew older and I start to and understand, and I’d research and I’d read and, you know, when Christianity came in to this region, we were very badly impacted.

But when our people saw it – that these white men come with this boat and talks about the spiritual, we live the spiritual too. So we share. Because sharing represents love. And if you love, you give, and you get blessed.

56 Geiza Stow, a Badulgal witness for the applicant, describes gud pasin behaviour as follows:

GEIZA STOW: Well, it’s been handed down and it’s a respect gud pasin. That you do not go to a place without you know, they have got people on that place there so you would …

MS PHILLIPS: How does it make you feel when you do ---

GEIZA STOW: Because they will look after you and they will look after you while you there and then while you coming back. So that has been instilled, the values, that were handed down.

57 Tommy Tamwoy, a Badulgal witness for the respondents, puts gud pasin succinctly as:

TOMMY TAMWOY: It’s the respect for everybody and anybody.

58 Ailan pasin – This concept is connected to gud pasin. Some witnesses described it as the same concept. “Ailan” means “island”. In his evidence given in Akiba, the late Walter Nona explained it this way:

MR BLOWES: Alright. Now, what about the word “ailan pasin”? Is that - do you know those words, “ailan pasin”?

WALTER NONA: Yes.

MR BLOWES: And how do they fit in? What do they mean?

WALTER NONA: That mean – “ailan pasin”, got to follow - nearly the same. All the same. There’s gud pasin, mina paua. So the children can adopt that gud pasin. That’s what “ailan pasin” mean.

MR BLOWES: So when you said - you said ailan pasin, and you said mina paua. Are they the same things, or are they different things?

WALTER NONA: They’re the same things, yes.

59 Similarly, in her lay evidence given in Akiba, Lilian Bosun says:

Ailan pasin is the same as gud pasin. That’s respecting people and gud pasin is the same all across the Torres Strait.

60 Both ailan pasin and gud pasin are traditional concepts, as Finn J explained in Akiba at [238]-[239], rejecting a Commonwealth contention that they were Christian concepts:

In Anna Shnukal’s 2004 Dictionary of Torres Strait Creole, “ailan pasin”, a noun, is defined to mean “island fashion, island custom. The way Islanders have long done things”. “Gud pasin”, an adjective or an adverb (though often used in evidence as a noun), is defined to mean “polite, generous”. Almost all of the Islander witnesses addressed the subject of ailan pasin in their affidavits. Gud pasin is the recurrent formula used in their descriptions of it. While ailan pasin has not been the subject of discrete address in submissions, it warrants present mention. It reflects the outlook, the cast of mind, of the witnesses. It gives vitality and coherence to what otherwise is treated discretely in written submissions on laws and customs.

The Commonwealth has suggested that aspects of ailan pasin owe some debt to the activities of the London Missionary Society and to the Islanders’ embrace of Christianity. I consider its provenance clearly predates sovereignty. Such is the view of some number of the Islanders, for example, Kapua George Gutchen, Mareko Kebisu, Bully Saylor; see also Professor Beckett, 2008A, [79] ff and Professor Scott, 2008, [99]. Its practice in some respects, though, was probably affected before sovereignty in inter-island relations by suspicions born of warfare and raiding: see Beckett, 2008B, [13]; and after sovereignty, as a result of the demands and influences of church, government and the marine industries: Beckett, 2008A, [103].

61 Mina pawa – Alternatively transcribed as mina paua, this is an equivalent concept concerning right behaviour, including respectful sharing and generosity in relation to other people, especially people from other groups or that one does not know. In his lay evidence given in Akiba, excerpted at [367]-[368] below, the late Tom (Jack) Baira illustrates how this concept works in practice. In his lay evidence given in Akiba, Walter Nona succinctly sums up the concept as “the right way to go”:

MR BLOWES: Alright. And I just want to ask you one word - is there a language word mina paua?

WALTER NONA: Yes, that’s mina paua, that’s gud pasin.

MR BLOWES: Yes?

…

MR BLOWES: Yes. And what’s that mina paua got to do - has it got anything to do with thubud, anything to do with friend?

WALTER NONA: Well, that’s gud pasin, you know, so the children may see those mina paua to follow when they come - when they grow big, they have to follow the right way to go.

MR BLOWES: So that - - -

WALTER NONA: That’s what mina paua is.

MR BLOWES: That’s the right way to go.

WALTER NONA: Yes, right way to go.

62 Ronnie Nomoa in his evidence in this proceeding also explained mina pawa:

MR BLOWES: Yes. And when you talked about mina pawa and you were talking in there about the Kubin meeting in 2005 to Two Thousand and – or Two Thousand and Five or Six, and you gave the illustration of the $5 note, is the point of that, that if you and somebody asked you for $5, and you give it to them, you expect it back?

RONNIE NOM[O]A: No, because that’s mina pawa, a person who don’t know you, or person who know you, if he asks you for $5, you know he need money and you give it without replacing by, and that’s mina pawa. It belongs to people of Torres Strait.

MR BLOWES: Yes. And if at some later time you come across that man and you need $5 - - -

RONNIE NOM[O]A: It’s up to the person now. If he got to think he look at you, “Oh, this person who give me $5”, and if he give you back $5, well that’s up to him.

MR BLOWES: Okay. Alright. That’s a very generous custom.

RONNIE NOM[O]A: That’s our custom and it will never fade out.

63 Pithalai – Pithalai is an actor who features in the Waubin myth or narrative, which I discuss in detail in these reasons. The place Waubin narrative in Kaurareg traditional law and custom about rights to country is central to some of the issues arising in the separate questions.

64 Chuktalk – This activity is a norm practised again across the Torres Strait. It involves paying respect towards ancestors when approaching or visiting in certain places. Geiza Stow described it this way:

GEIZA STOW: We have always had values of when you go to another man’s place, you must acknowledge the ancestral place, and yamulin – chuck talk. Talk to them.

MS PHILLIPS: So if you go to Warral, what do you do?

GEIZA STOW: Even when you – before you land, you might be in the boat outside the water, you would face and talk to the land. Why I’m here. Whether you got dinghy full of people, or your family, that we come in peace and we are not going to disturb and we are not going to destroy anywhere.

MS PHILLIPS: And you used that phrase chuck talk?

GEIZA STOW: Yes.

MS PHILLIPS: What is chuck talk?

GEIZA STOW: Talk.

MS PHILLIPS: Who are you talking to?

GEIZA STOW: To the spirit of the place.

MS PHILLIPS: Whose spirits are there in that place?

GEIZA STOW: That place is all ancestral, it could be Badulgal, whoever went there or whoever went passing there, but we were always, passed down that you do not just walk in and walk out, you must respect, and this is the values that I was taught and I handed down to my kids.

MS PHILLIPS: Do they do that too?

GEIZA STOW: Yes.

65 Coming of the Light – Although this is an English expression, I include it here because it is used by Torres Strait Islanders. The phrase refers to the point in history when Christian missionaries established churches and missions in the Torres Strait. It is used to indicate the point in time when Christianity was introduced to Torres Strait Islanders.

Names of claimants and their ancestors

66 To make these reasons intelligible, it will be necessary to use the names of people who have died. I intend no disrespect by doing so. Where there are spelling discrepancies as to names, I have attempted to remain faithful to the lay evidence. For the names of people, living or deceased, I have made my best effort to be faithful to the way lay witnesses spelled their names, especially their spelling of those related to them.

67 The separate questions require the Court to examine the contemporary situation in respect of these islands, but the focus is really on what the situation was before colonisation. I prefer to use the term “before colonisation” or “pre-colonisation” to “pre-sovereignty” not because there can be any dispute about the assertion of British sovereignty, and its consequences, legal and factual, but rather because in my opinion an honest account of the history of this nation must include acknowledgement that what settlers did to First Nations peoples was to attempt to colonise them, subjugate them to a new and foreign system of law and government, including with regard to land ownership and tenure. Colonisation was neither wanted nor welcomed by First Nations peoples; it was imposed upon them, with tragic consequences, some of which have featured in the evidence in this proceeding, especially about the Kaurareg People.

“PROVING” NATIVE TITLE EXISTS AND SHOULD BE RECOGNISED

68 By the time of final submissions on the separate questions, all active parties agreed the answer to question (a) was ‘Yes’. On the evidence, that is plainly correct. Therefore, the real dispute is about who holds that native title, and on what basis.

69 This separate question trial occurs within an adversarial system of justice. The Court is not conducting an inquiry, but resolving a dispute between parties, and so the Court relies on the evidence and arguments presented by the parties. The parties make forensic decisions about what evidence to adduce. For example, what lay witnesses to call, and what documents to tender. They make forensic choices about what questions to ask of witnesses, and what not to ask. They choose what to emphasise, and not to emphasise.

70 The moving party – the applicant – has the burden of proof. An applicant party must give the Court enough evidence to persuade the Court on the balance of probabilities about what are the correct and relevant facts, and the conclusions to draw from them. This means the Court is deciding which facts are more likely than not to be the correct material facts.

71 In this proceeding, the applicant has the burden of proving the shared ownership claim. The Badulgal respondents do not have a legal burden of proof. Nor do the State or the Commonwealth. The Badulgal respondents correctly accepted they do have an evidentiary burden – that is, if they seek to persuade the Court that the applicant’s shared ownership case is wrong, and the islands belong only to Badulgal, they will need to persuade the Court of those propositions through the evidence.

72 The applicant and the Badulgal respondents relied on expert evidence as well as evidence from claimants. The role of expert witnesses in a proceeding is to assist the Court to understand evidence before it, and/or to explain matters to the Court, often matters about history, customary law and traditions, which may contribute to what the Court must decide. In doing so, they will express opinions about the facts they have gathered together.

73 Here, all four experts who gave evidence are anthropologists. Each is very experienced and the Court finds they gave their evidence in a genuine attempt to assist the Court. The Court does not have to agree with an expert’s views or opinions, even if the expert is highly qualified or experienced. The views and opinions of an anthropologist do not carry any greater weight than the evidence of the claim group members, just because they are anthropologists.

74 The Court must consider and weigh all the evidence put before it, and then decide two basic issues:

(a) Has the applicant proved it is more likely than not that native title in Warral and Ului is held jointly by the Kaurareg, Badulgal and Mualgal Peoples? If yes, then should the Court recognise a shared native title in Warral and Ului, or is there more than one native title between the three groups?

(b) If the applicant has not proven the shared ownership of Warral and Ului is more likely than not, then the Court must decide if the evidence shows it is more likely than not that native title is held by one, or more, of the Badulgal, Mualgal or Kaurareg People. If more than one group, then should the Court recognise this as a shared native title in Warral and Ului, or two separate native titles?

75 In this proceeding, one feature distinguishing it from many other native title cases is the important role of this Court’s previous decision in Akiba. The parties tendered a transcript of some of the witness evidence before the Court in Akiba, as well as relying on findings made in that case. There was some debate about what the tendered Akiba evidence proved, and what the Court’s findings in Akiba meant. In these reasons, I explain my conclusions about what was decided in Akiba, the relevance and weight of the evidence in Akiba tendered before this Court, and how much of the issues in this proceeding are determined by what the Court found in Akiba.

76 In its case management of this proceeding, the Court split the hearing of lay evidence and expert evidence in the trial of the separate question. The Court prioritised the lay evidence so as to understand how the claimants themselves explain their connection through traditional law and custom to the islands, and explain how their family and community histories of occupation and use of the islands, and the surrounding islands and waters, bear out or support the claims of native title. The Court’s view was that it would be assisted in understanding and evaluating the expert evidence if the lay evidence had been completed first. The Court’s expectation was that the experts would also be assisted by the lay evidence. That expectation did not prove to be entirely well-founded.

77 During the hearing of lay evidence, the Court undertook a view of Warral and Ului at the request of the applicant and the Badulgal respondents, because of the critical importance of the physical features of the islands and their surrounds to the parties’ evidence. The view was of considerable importance to my understanding of the evidence.

78 The hearing of the lay evidence commenced at the Waiben courthouse on Wednesday 6 October 2021, where the Court heard from the applicant’s Kaurareg witnesses over a span of three sitting days. After the weekend, the Court resumed on Monday 11 October at the community hall on the island of Mua, where the applicant’s Kaurareg lay evidence concluded and its two Mualgal witnesses gave evidence over two sitting days.

79 The Court conducted its view of the islands on Wednesday 13 and Thursday 14 October 2021.

80 The Court resumed lay evidence at the community hall on Badu, completing the applicant’s lay evidence with testimony from Badulgal witnesses on Friday 15, Saturday 16 and Monday 18 October 2021. The Badulgal respondents began their lay evidence at the same location on Tuesday 19 October 2021, and continued until the end of the Court’s final sitting day in the lay evidence hearing on Friday 22 October 2021.

Claim group members: the applicant

81 What follows are my findings of fact about each lay witnesses, their background, ancestors and relevant family relationships. I deal with the witnesses in the order in which they were called.

82 In the briefest of summaries, the lay evidence covered the following topics, aside from the family history and identification of each witness: travel to, and in the vicinity of, each of Warral and Ului both by the witnesses themselves and their families, and what they have been told about travel by their elders; the concept of sarup and the use of the islands for this purpose, but also the use of Sunswit; use of waters around the claim area, and the beaches in and outside the claim area, for gathering of marine resources; use of the land for gardens; the location of water and other resources in the claim area; who has rights to make gardens and/or build structures on the islands and who has done this; burning practices; stories said to be associated with the claim area, including the Waubin and Pithalai stories and the story of Waii and Sobai; the role of adhi; grave sites; historical accounts of clashes and warfare between various groups in the Western Islands; the removal of Kaurareg People to Mua; the concept of gud pasin; the concept of chuktalk; the work done in the Western Torres Strait by elders on pearl luggers and in the trocus and crayfishing industries; family relationships and connections between the people of Badu, Mua and the Kaurareg home islands, including aspects of culture and convention that are common among the groups; the Coming of the Light and what it meant for the practice of culture; the 2015 mediation and the concept of sharing of uninhabited islands.

83 I refer in more detail to the lay evidence in my findings.

84 Fr Paul Tom was the applicant’s first witness in the lay evidence hearing. He gave his evidence on Waiben. He identifies as Kaurareg and Mualaig. His father, Elikiam Tom, was a Kaurareg and Gudang man from Mount Adolphus, Muri Island. The Gudang People are from Cape York, and identify as Aboriginal. Fr Tom’s mother, Weiba Tom (née Makie), was a Mualaig woman from Mua.

85 Fr Tom’s paternal grandfather was the son of Tam Muri, from Muri, and Mudaunai, from the Kaurareg People. Mudaunai’s father was Koberis, who was the son of Makaku and Buia, from the Kaurareg People. Fr Tom’s evidence was that every Kaurareg person is a descendant of Makaku and Buia in one way or another.

86 Fr Tom was born in Kubin on Mua on 25 January 1947. This was a little more than 20 years after the Kaurareg People were forcibly removed to Mua by the Queensland government. In his 1997 report in support of the Kaurareg native title claims over some of their home islands, Michael Southon traces the forced removal of Kaurareg People from Kirriri to Mua, and some of the explanations given for it. I return to the forced removal later in these reasons.

87 Fr Tom attended school on Ngurapai and then on Waiben, where he completed grade 10 at the end of 1962. After his schooling, Fr Tom worked on pearl luggers in the Western Torres Strait, including the pearling grounds near Badu and northwest of Waiben. During this time, Fr Tom worked with members of the Nona family, from Badu. He moved to Townsville to work on the railways at the end of the 1964 pearling season. He married Rebecca Luffman, a Mualaig woman, in 1970, and moved around Queensland and Western Australia working in various jobs. Fr Tom returned to Kubin in 1986. He worked for the Kubin Council and was elected as a Councillor for Kubin in 1994, a role he held from that time until the Mua Island Council was amalgamated into the Torres Strait Islands Regional Council in 2007. Fr Tom was ordained as a deacon in the Anglican Church in 1999. He was ordained as a priest on 26 January 2015.

88 The applicant’s second lay witness was Thomas Ned Savage. He also gave his evidence on Waiben. His father, Nadaiaga Guy Savage, was a Mualaig and Kaurareg man born at Poid. Mr Savage’s paternal grandfather, Erimia Nagibu, was also Mualaig and Kaurareg, and his paternal grandmother, Bakari Kanai, was Mualaig. Mr Savage’s mother, Mrs Ellen Pia Savage (née Namai), has connections to several communities, including the Kaurareg People, Gudang and – by traditional adoption – the Mualgal.

89 Through his mother, Mr Savage is the grandson of Wees Nawia, an influential Kaurareg elder and a common relative of many of the applicant’s lay witnesses. Ultimately, Mr Savage traces his Kaurareg identity through to his great-great-great-grandfather, Makaku, who is one of the Kaurareg People’s apical ancestors, as Fr Tom explained.

90 Mr Savage was born on 16 April 1970 and grew up on Ngurapai, before attending primary school on Waiben. He completed primary school and started secondary school in Cape York, leaving in Year 9 to work as a bricklayer in Weipa, on the western side of the Cape York Peninsula. Mr Savage left Cape York to work as a builder’s labourer for the Kubin Community Council on Mua. He has since returned to Cape York, where he currently lives and works.

91 Enid Tom identifies as Kaurareg, and gave her evidence on Waiben. Her father was Billy Wasaga, a Kaurareg elder, the original first named applicant for the Kaurareg native title claims, and her mother was Alice Tom.

92 Ms Tom’s paternal grandfather was Wasaga Billy and her paternal grandmother was Tam Bosun. Ms Tom’s maternal grandfather was Elikiam Tom, which makes her in European terms the niece of Fr Paul Tom. Ms Tom’s maternal grandmother was Weiba Tom, from Kubin. Ms Tom’s evidence is that her Kaurareg ancestry is ultimately derived from Zagra, her paternal great-great-grandfather.

93 Ms Tom was born on 25 July 1962 on Waiben. She completed primary school on that island, but for secondary school moved to the Tablelands region southwest of Cairns. Her evidence is that nobody spoke her language in the Tablelands, so she became homesick and returned to Waiben after grade 10. She worked as a nurse on the island from 1979 until 1988, when she moved to Ngurapai to help establish a medical aid post there. At the end of 1988, Ms Tom moved to Darwin, where she would live for nine years, studying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s studies at university. She returned to the Torres Strait in 1997 to help with the Kaurareg native title claims, and worked for the Kaurareg prescribed body corporate after the Kaurareg native title determinations were made. She remains a director and an administrator of the Kaurareg Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, and now lives on Ngurapai.

94 Eliziah Wasaga identifies as Kaurareg, and gave his evidence on Waiben. His father, Samuel Wasaga, was a Kaurareg man and the first chairman of the Ngurapai Community Council. His mother, Lency Aken, was a Kaurareg and Mualaig woman. He was traditionally adopted by Eselina Nawie, a Kaurareg woman who traced her identity to the apical ancestor Bagie, but was taken back by his mother after his father’s death in 1974.

95 Mr Wasaga’s paternal grandfather was Wasaga Billy and his father’s mother was Tam Bosun, which makes Mr Wasaga in European terms the cousin of Enid Tom, but in Kaurareg custom, she is Mr Wasaga’s sister. Mr Wasaga’s maternal grandfather was Katua Namai, a Kaurareg man and a descendant of Makaku. His mother’s mother, Kaki Aken (née Kanai/Kaitap) was Mualaig and Mualgal.

96 Mr Wasaga was born on 10 April 1969 on Waiben but commenced his early schooling in Weipa. From 1975, Mr Wasaga lived with his biological mother in Townsville, where he completed primary school and started secondary school. Mr Wasaga left school to return to Ngurapai, where he lived with his traditional grandmother, Eselina Nawie. In the late 1980s, Mr Wasaga lived for a short time on Mabuiag Island with his uncle, Frank Genai. He married a Kaurareg and Gudang woman, Ivy Wasaga (née Rattler), and raised seven children on Ngurapai. Mr Wasaga studied Indigenous community management in Perth and now works as a mental health worker in Townsville. He was formerly the chairperson of the Kaiwalagal Aboriginal Corporation – a Kaurareg prescribed body corporate – and now holds the positions of director, secretary and public officer of the Kaurareg Native Title Aboriginal Corporation (RNTBC).

97 Naton Nawia identifies as Mualgal through his mother, Lizzie Nawia (née Savage), and Kaurareg through his father, Wees Nawia. Wees Nawia is a person whom the evidence, both oral and documentary, mentioned frequently in many contexts. Naton Nawia gave part of his evidence on Mua, part of his evidence on Ului, part of his evidence on Sunswit and part of his evidence on Badu. Mr Nawia is in European terms the uncle of Thomas Ned Savage and the brother of Lillian Bosun, who gave evidence in Akiba.

98 Mr Nawia’s paternal grandfather was Nawia Galgaberi and his paternal grandmother was Garagu, both of whom were Kaurareg. Mr Naiwa’s maternal grandfather was Aluwa Savage, from Mua, and his maternal grandmother was Matilda Stafford, an Aboriginal woman from the Queensland gulf country.

99 Mr Nawia was born on 10 November 1957 on Waiben. He was raised by his mother on Mua, where he attended primary school. After finishing school, Mr Nawia worked on pearling luggers around Waiben. When the pearling industry declined, Mr Nawia became a crayfisher, an occupation he had until his retirement about ten years ago.

100 Mr Nawia gave evidence about the trips he made to Warral and Ului, and the provenance of a Kaurareg song about travelling to Ului. He testified that the song originates from the heyday of the pearl lugging industry in the Western Islands.

101 Nazareth Adidi identifies as Italaig, which she explained is a name that some use for the people from Mua, the more common name being Mualgal. She was traditionally adopted by Wees Nawia and Lizzie Nawia (née Savage), which makes Mrs Adidi in European terms the sister of Naton Nawia and the aunt of Thomas Ned Savage. Mrs Adidi’s evidence was that all of the children of Wees and Lizzie Nawia were adopted. Mrs Adidi gave part of her evidence on Mua, part of her evidence on Ului, part on Sunswit and part on Badu.

102 Mrs Adidi was born on 6 September 1952 in Kubin and was raised there by her parents. She attended school on Mua, Waiben and Ngurapai. She married a Kaurareg man, James Kanai, who worked as a miner on Mua. In 1976, she and her husband moved to Townsville, where her husband worked with her biological uncle, Eddie Koiki Mabo, on land rights in the Torres Strait. Mrs Adidi worked in health care, and helped establish a centre that advocated for women’s rights and provided shelter to women escaping domestic violence. In 1990, her husband passed away, and she relocated to Waiben in 1992. Mrs Adidi remarried a man from Saibai Island, John Adidi, and studied theology and health care in Perth from 2004 to 2014. Mrs Adidi is now retired and lives on Waiben.

103 Mrs Warria identifies as Mualgal and Kaurareg, and she also considers herself part of the Badulgal community through her family. Mrs Warria gave part of her evidence on Mua, part on Ului, part on Sunswit and part on Badu. Her father was Oza Namai Bosun, whose mother, Bau Namai, was the daughter of Anu Namai, a Mualgal chief and descendant of the Mualgal ancestor Maga. Oza Namai Bosun’s father was Makeer Bosun, the son of the daughter of the chief of Kiriri (Hammond Island) – a Kaurareg man.

104 Mrs Warria’s mother is Lillian Bosun, who was adopted and raised by Wees Nawia and Lizzie Nawia (née Savage). Mrs Lillian Bosun gave evidence in the Akiba trial and some of her evidence has been tendered in this proceeding.

105 In European terms, Mrs Warria is the niece of Naton Nawia and Nazareth Adidi, and the cousin of Thomas Ned Savage. All these people were witnesses for the applicant.

106 Mrs Warria was born in 1967 on Waiben. She began primary school on Mua but, when she was still young, Mrs Warria was adopted to Ngailu Bani (from Mabuiag) and Cessa Bani (née Joe, from Badu). Mrs Warria moved to Badu to live with her adopted parents and spent much of her childhood on that island. She returned from Badu to her biological parents on Mua when her adopted father fell ill and moved to Waiben. She was sent to secondary school in Warwick, a town in southeast Queensland. Mrs Warria returned to the Torres Strait and married her husband, Milford ‘Moses’ Warria, who is from Masig, one of the central Torres Strait islands. With their children, Mr and Mrs Warria moved between Mua and Masig until 2009, when she settled on Mua.

107 Pastor Opeta James Kaitap identifies as Mualgal through his father, Suma. Suma Kaitap’s mother was Elion and his father was Inagi, both of whom were Mualgal. Pastor Kaitap’s mother was a Kaurareg woman named Joyce Kaitap (née Kanai). However, Pastor Kaitap explained that he does not identify as Kaurareg because, in his culture, a wife moves to her husband’s country. Therefore, Pastor Kaitap’s family stayed with his father’s side on Mua. Joyce Kaitap’s father was Opeta Kanai and her mother (Pastor Kaitap’s maternal grandmother) was Niceone Bosun, a sibling of Wees Nawia. Pastor Kaitap is thereby related to Naton Nawia, Nazareth Adidi, Thomas Ned Savage and Flora Warria. Pastor Kaitap gave part of his evidence on Ului, part on Sunswit, and part on Badu.

108 Pastor Kaitap was born on 22 January 1963 on Waiben. He was raised on Mua and attended primary school there. He moved to Townsville for secondary school and returned to the Torres Strait to work in the crayfish industry with his father and uncles, including around Dollar Reef and Warral. Pastor Kaitap now works as a machine operator and a religious pastor on Badu. He lives on Mua with his wife, Rita (née Nona, from Badu), with whom he has four children.

109 Mr Tipoti identifies as a Badulaig, and he gave his evidence on Badu. His mother was Phyllis Kusu and his father was Leniaso Tipoti, who was also known as Argan Besai, a Badulaig and Mabuiag man. Leniaso Tipoti’s mother was Dagum Tipoti, the daughter of Nomoa and Kaidi. Mr Tipoti’s paternal grandfather was Waipila Tipoti, the son of Kiriz and Alis Monday (also known as Alis Tipoti).

110 Mr Tipoti was born on 28 November 1975 on Waiben. He grew up on Badu and attended primary school there. He spent a lot of his childhood with his father, travelling around and between the islands and reefs of the Western Torres Strait, as well as to the island of Saibai, which lies further north. He learnt singing, dancing, art making, fishing and hunting on Badu, but moved to Waiben for schooling when he was about twelve years old. Mr Tipoti is now an internationally renowned professional artist, with tertiary qualifications from the Thursday Island TAFE, the Cairns TAFE and the Australian National University. Since October 2015 he has lived on Badu, where he produces art and works at the local art centre.

111 Geiza Stow identifies as a Badulaig, through her father, Aidan Laza, and she gave her evidence on Badu. Aidan Laza was the son of Bagari, a Badulaig man, and Tuigan, a woman from Saibai. Ms Stow’s mother, Naianga Blanket, was also Badulgal. Her maternal grandmother, Geiza Tamwoy, was a descendant of the Badulgal apical ancestor Sagul, and her maternal grandfather, Daniel Blanket, was a descendant of Wairu and Kaim.

112 Ms Stow was born on 17 June 1957 on Waiben. She grew up on Badu, attending primary school until grade 5, when she moved to Waiben. Ms Stow finished secondary school on Waiben in 1973, and completed a year of training at a TAFE college in Brisbane thereafter. She returned to Waiben and worked as a shop assistant for five years. She married her husband, Steven Stow, in 1982, and travelled around Queensland doing various jobs and completing further training at TAFE. During this time Mr and Ms Stow had four children, including Troy Laza, who is another witness for the applicant. Ms Stow divorced her husband in 1997 and returned to Badu in 1999 to be with her father. She worked as a housing officer for Badu Island Council for ten years. She currently works as a casual student welfare officer at the Badu School.

113 One aspect of Ms Stow’s evidence that became material during the trial was a map she told the Court about in her oral evidence, which she then produced. It was a very large map, rectangular in shape and all hand drawn. According to Ms Stow, the map was drawn by her father not long after the High Court decision in Mabo (No 2). A digital copy of the map was tendered as an exhibit in the hearing. I discuss the map in more detail later in these reasons.

114 Like his mother Ms Stow, Mr Troy Laza identifies as a Badulaig and gave his evidence on Badu. He was born on 11 March 1978 and is currently employed as the senior natural resource officer for the Torres Strait Islander Association’s western rangers division.

115 The applicant’s twelfth and final lay witness was Titom Nona, the first named member of the applicant. Mr Titom Nona identifies as Badulgal through his father, Philemon Nona, who was the son of Solomon Nona. He gave his evidence on Badu. Mr Titom Nona also considers that he could identify as Mualgal or Kaurareg through his mother’s side of his family tree. His mother was Flora Nona (née Savage), the daughter of Powanga Savage, who came from Mua, and Iaga Savage, who was originally from Normanton but moved to Mua with Powanga. His paternal grandfather was Solomon Nona.

116 Mr Titom Nona was born on 16 August 1957 on Waiben. He was raised on Badu and attended primary and secondary school there. After finishing grade 10, Mr Titom Nona fished for barramundi in Papua New Guinea for almost a year, and then worked as a crayfisher and on pearling luggers around the Western Torres Strait. He has lived on Badu for most of his life, and worked for the Australian Quarantine Service for 26 years.

The Badulgal respondents’ lay witnesses

117 Mr Nomoa is the third named Badulgal respondent. Mr Nomoa gave part of his evidence on Ului and Sunswit, and the remainder of his evidence on Badu.

118 Mr Nomoa’s mother’s name was Phoebe Lui, the daughter of a woman from Mornington Island named Daisy and a man from Samoa named Lui Samoa. His father’s name was Young Nomoa, the son of a woman named Koidei and a man named Numa (also known as Nomoa), both from Badu. Mr Nomoa ultimately traces his Badulgal heritage to the apical ancestor Uria.

119 Mr Nomoa was born on 10 August 1944 on Badu, in the bush of the centre of the island, where his family was relocated during the Second World War. In 1945, six months after the end of the war, Mr Nomoa and his family moved to the village of Wakaid, on the island’s south-eastern coast. He grew up in Circle V, which used to be known as Kona Village, where Mr Nomoa lived until his marriage in 1972. He was raised by his mother while his father worked on pearling luggers. Mr Nomoa worked his family’s gardens. He attended the Dogai school in Kona village until 1958, and began work on a pearling lugger after finishing grade 7; that is, when he was about fourteen. He worked the annual pearling seasons from April to January each year. After marriage, Mr Nomoa moved to Yallawar, on Badu, to be with his wife’s family. He moved into his current house on Badu in 2004, after his wife passed away. Mr Nomoa is now retired.

120 George Henry Nona is the second named Badulgal respondent. Mr George Nona gave part of his oral evidence on Sunswit, and the remainder on Badu.

121 Parts of Mr Nona’s evidence of his early family life are the subject of a suppression order.

122 Mr George Nona was born on 22 December 1971 on Waiben. He grew up in a house in Geia village, on Badu, and attended primary school on the island. He moved to Waiben to begin secondary school, and finished his secondary education in Redcliffe, a suburb in north-eastern metropolitan Brisbane. In early 1992, Mr George Nona went to Palm Island and then to Melbourne for tertiary studies. He worked for the Ipswich City Council in Brisbane, obtaining qualifications in bricklaying, but returned to Badu in 1998. In 2002, Mr George Nona researched traditional headdresses as an artist, living in Brisbane and Melbourne. He also spent two years living and researching art in Canberra. From 2008 to 2014, Mr George Nona lived on Kirriri (Hammond Island). He now lives permanently on Badu, working as an artist.

123 Mr Wolfgang Laza is not one of the Badulgal respondents, but he supports their contentions in this proceeding, although he is also a member of the applicant’s native title claim group. He gave his evidence on Badu.

124 Mr Wolfgang Laza’s father was Aidan Laza, which makes Mr Wolfgang Laza in European terms the brother of Geiza Stow. Mr Wolfgang Laza’s evidence was that Aidan Laza’s father’s name was Bagauer, who was the son of Bainu. I note the name “Bagauer” is slightly different to the name Ms Stow gave for her paternal grandfather, but nothing turns on this difference. According to Mr Wolfgang Laza, Bainu was the son of Wakie, who was the son of Baudu. Baudu’s father was Pithai, the son of the Badulgal apical ancestor Waii. In his evidence, Mr Wolfgang Laza traced his ancestry further back than Ms Stow did.

125 Mr Wolfgang Laza was born on 21 November 1965 on Waiben, but he was raised on Badu. When he was young, Mr Wolfgang Laza worked as a pearler in the Western Torres Strait, including in the area north-west of Ului. He started work for the Australian immigration authorities in 1996 and, aside from a period from 2000 to 2005, he has worked for the Australian Border Force ever since. He currently lives on Badu, on the same street as Mr Nomoa.

126 Pastor Walter Tamwoy is the fourth member of the Badulgal respondents. He gave his evidence on Badu.

127 Pastor Tamwoy’s father was Titom Tamwoy and his mother was Louisa Tamwoy (née Nona), both from Badu. His paternal grandfather was Taum, from Badu, and his paternal grandmother was Eccles, from Erub (Darnley Island). Taum’s father was Simi, a descendant of Pithi, from the Badulgal apical ancestors Waii and Sobai. Pastor Tamwoy’s mother’s father was Tipot (or Tipoti) Nona, from Samoa, and his father’s mother was Ugari Nona (née Usia), from Saibai.

128 Pastor Tamwoy was born on Badu on 11 March 1946. He was raised on the island and attended school there until 14 years of age. After school, he began work as a cook on pearling boats. At 16 or 17 years old, Pastor Tamwoy moved to mainland Queensland to work on the railways and in the fruit-picking industry. He then worked for eight years as a diver in the pearling industry, and then as a diver on crayfishing boats. In 1987, Pastor Tamwoy became a pastor in a Pentecostal church in Western Australia. He returned to Badu around 1991, where he still lives and works as a pastor today.

129 The Badulgal respondents’ fifth and final witness was Tommy Willie ‘Dinto’ Tamwoy. Mr Tommy Tamwoy is also the fifth member of the Badulgal respondents. He gave part of his oral testimony on Ului, and the remainder on Badu.

130 Mr Tommy Tamwoy’s parents were Titom and Louisa Tamwoy. He is the younger brother of Pastor Walter Tamwoy.

131 Mr Tommy Tamwoy was born on Waiben, but raised on Badu. He finished school when he was 14 or 15 years old, and started work as a deckhand on a pearling lugger. He worked throughout the islands of the Western Torres Strait, including at Cooks Reef, west of Ului. His work spanned many different luggers, including ones owned by Victor and Phillip Nona. In 1968, when he was about 21 years old, Mr Tommy Tamwoy moved to mainland Queensland to work on the railways. He continued this work on the mainland for about six years, which included a period of time in the Northern Territory. Mr Tommy Tamwoy returned to Badu in 1974 and has lived there ever since. He is now a crayfisher and although he was in his late seventies at trial, gave evidence that he still enjoys free-diving for crayfish.

132 The Court was invited by the applicants and the Badulgal respondents to undertake a view of several sites around Warral and Ului. The Court made an order pursuant to s 53 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) to facilitate this course of action. It was agreed that the view would be conducted from the decks of boats navigating around the islands. The parties’ counsel and several witnesses who were to indicate specific sites during the view all travelled on one boat, although at one point the Court party and accompanying persons moved from the ‘Court boat’ to the ‘State boat’. Other legal representatives and witnesses followed on other boats. Other witnesses and claim group members followed in their own boats. My associate prepared a record of the view, including photographs of the sites that were pointed out by witnesses, GPS locations of the boat and bearings of the photographs taken and summaries of the descriptions or notes of the witnesses that were given during the view. The parties reviewed the record and confirmed that they took no issue with its contents. The record was then marked as exhibit A58.

133 The view was conducted over two days. On 13 October 2021, after hearing evidence on Ului, the Court was shown a beach on Ului’s eastern coast, which Mrs Adidi said contains the site of a former garden and Mrs Warria said contains a picnic site. Slightly south of that site the Court was shown a site at which Mr Savage said he used to crayfish and Mrs Warria said her father used to crayfish.

134 On 14 October 2021, the Court was shown several sites around Warral. First, the Court was shown a beach on Warral’s north-eastern coast, which Mr Nawia said contains the site of a campsite he once visited with his father, and the site of a garden his father once had on Warral. Second, Mrs Adidi showed the Court a crayfishing area in the water east of a reef off the eastern coast of Warral. Third, Mrs Warria pointed out a site she claimed to be Warrior Lookout, located approximately in the middle of Warral’s eastern coast. Fourth, on the south-eastern part of the coast, Mr George Nona showed the Court a site he said once hosted a garden of his great-grandfather. Fifth, at Warral’s southern tip, the Court was shown the two rocks said to be part of the Pithalai story, about which there is a factual dispute in this proceeding.

135 One rock, pointed out by Mrs Warria, lies in the water. The evidence also describes this as Squat Rock. On attachment 1, especially by the inset, it can be seen as lying outside the claim area, in the water. At 12.14 pm, when the Court visited the site, the tide was high and only a small part of the rock could be seen. Thomas Savage pointed out the other rock said to be Pithalai, on the southern beach of Warral, and indicated to the Court that there is a design painted on that rock.

136 Sixth, after visiting the Pithalai rocks and while off the southern coast of Warral, Mr George Nona identified all islands visible from the Court boat’s deck. Starting facing northwest and turning clockwise, the islands were described as Badu, Mua, Murbayl, Naghir, Wednesday Island, Horn Island, Goodes Island, Prince of Wales Island, White Rocks and Booby Island. Seventh, viewing the beach immediately west of the Pithalai rocks, Mrs Warria pointed out square rocks that she said were painted with designs. Eighth, further west of that beach, Mr George Nomoa pointed out a bay that he claimed was once occupied by his grandfather, Jackonia, and a woman named Mary.

137 Ninth, while the boat was off the south-western coast of Warral, Mr Nomoa identified the islands visible from deck. Once again in a clockwise rotation starting while facing northwest, these islands were described as Ului, Salgai, Jerry Island, Dadalai, Football Island, Duncan Island, Kanig, Mabag, Jackson Island, Kulbai Kulbai, Zurath and Sunswit. Tenth, while facing the south-western coast of Warral, Mr George Nona pointed out what he claimed was Warrior Lookout or Turanagai Dagamurr. Eleventh, and finally, Mrs Warria pointed out a creek on Warral’s western coast, which Mrs Warria says leads to a bay on the north-western coast. Mrs Warria told the Court that her brother once caught a dugong to the north of the site, and brought it back to a beach on the other side of the bay.

138 There was no challenge to the qualifications and expertise of any of the anthropologists called by the applicant and the Badulgal respondents. That position means it is unnecessary to rehearse their respective qualifications. There were submissions made on behalf of the applicant contrasting the experience of Mr Wood, Dr Hitchcock and Dr Murphy in this region with the comparative lack of experience of Mr Leo. The experiential difference in this region as between Mr Leo and the other experts can be accepted. That does not necessarily make material parts of Mr Leo’s evidence any less persuasive, as I explain. Where appropriate, later in these reasons I refer to the experience of Mr Wood, Dr Hitchcock and Dr Murphy when discussing their opinions.

139 Mr Wood has worked as a linguistic researcher, an anthropologist and a consultant for various organisations, including the Cape York Land Council and the TSRA. Over the past 26 years, he has produced more than 40 anthropological reports in connection with native title claims in this Court, including reports in relation to Waiben, Muralag and other Kaurareg islands, and Mua. In the Expert Report he prepared for this proceeding, Mr Wood referred extensively to his 2015 Report on Kaurareg Rights and Interests in the Waral-Ului Islands and Waters. Mr Wood has extensive experience with the Kaurareg People.

140 Mr Wood’s opinion is that the Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg People form three parts of a single society, in the sense that term is used by the High Court in Yorta Yorta: see Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58; 214 CLR 422. He considers there is a single society spread across a wider body of Torres Strait communities and united by a shared cultural history, including a unitary body of laws and customs governing rights to lands and waters. Mr Wood could not identify anything in the body of laws and customs of the three claimant groups that is not common to all three. Even if the Badulgal acquired exclusive control of Warral and Ului by conquest (an assertion Mr Wood did not agree with), Mr Wood’s opinion is that the seizure of lands by force does not form part of the single body of law and custom that gives rise to rights in land and waters in the Torres Strait. His view was that the expropriation of land by force was “unthinkable” as between members of the same society.

141 Rather, Mr Wood’s view is that the disputes between the Badulgal, Mualgal and Kaurareg People are attributable to political and personal rifts that can be traced back to the 19th and early 20th century. The colonisation of the islands created inequalities of political power, wealth, prestige and self-confidence between the three communities, which are the real root of disputes between the Badulgal, the Mualgal and the Kaurareg People, rather than any pre-colonial history of land contest in the region. Mr Wood also found ample evidence in the documentary material and testimony of the applicant’s lay witnesses to support a finding that all three groups extensively used Warral and Ului prior to colonisation.