FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Davaria Pty Limited v 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd (No 13) [2023] FCA 84

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The further hearing of the proceedings be adjourned to a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J:

1 These reasons concern two representative proceedings.

2 The first, VID180/2018 (the 180 Proceeding), concerns claims brought against 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd (7-Eleven), Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) and 7-Eleven Inc (a Texas Corporation) by franchisees of 7-Eleven stores. The applicants in that proceeding are Davaria Pty Ltd (Davaria Co) and Kaizenworld Pty Ltd (Kaizenworld).

3 The second, VID182/2018 (the 182 Proceeding), concerns claims brought by the natural person principals and guarantors of corporate franchisees against 7-Eleven and ANZ. The applicants are Pareshkumar Davaria (Mr Davaria) and Khushbu Davaria (Ms Davaria), who are the principals of Davaria Co, and Jatinder Singh (Mr Singh) and Suman Kaur (Ms Kaur), who are the principals of Kaizenworld.

4 The proceedings were set down for trial before Middleton J on 9 August 2021 on an estimate of 10 weeks.

5 The proceedings were mediated in June and July 2021 before the Honourable Susan Crennan AC QC, a former justice of the High Court of Australia.

6 On 3 August 2021, Mr Davaria, Ms Davaria, Mr Singh and Ms Kaur entered into settlement deeds with ANZ.

7 On 4 August 2021, a Settlement Deed was executed between Davaria Co and Kaizenworld, on their own behalf and on behalf of the group members in the 180 Proceeding, and the applicants’ directors/shareholders (Mr Davaria, Ms Davaria, Mr Singh, and Ms Kaur) on their own behalf and on behalf of the group members in the 182 Proceeding; Levitt Robinson Solicitors (Levitt Robinson); Galactic Seven Eleven Litigation Holdings LLC (Galactic or the funder) and 7-Eleven.

8 The parties agreed to settle the proceedings for $98 million.

9 By application dated 11 August 2021, subsequently amended on 17 December 2021 and 12 May 2022, made pursuant to s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), the applicants sought court approval of the settlement of the proceedings on the terms as agreed by the parties in the Settlement Deed, including for payment by 7-Eleven of the Settlement Sum to be distributed in accordance with the Settlement Scheme, set out in the Confidential Affidavit of Mr Brett Imlay sworn 23 August 2021 (Approval Application).

10 By interlocutory applications dated 22 October 2021, Galactic sought, among other things: (i) approval of a payment to it in the amount of $24.5 million (being 25% of the $98 million settlement sum) in the form of a common fund order, plus (ii) reimbursement for legal costs incurred and paid of approximately $20 million (and return of its security for costs which was paid into Court).

11 By their Further Amended Interlocutory Application for settlement approval dated 12 May 2022 the applicants sought a fund equalisation order, as follows:

17A. If the Court does not make [a common fund] order at the request of Galactic … then pursuant to sections 33V and (or alternatively) 33ZF of the [Federal Court of Australia Act], each of the group members who apply for and receive any payment out of the Settlement Sum in accordance with the Settlement Scheme (Settlement Scheme Payment) be required to contribute to the Funder’s Portion (as described below), to be determined as follows:

(a) the total of the Settlement Scheme Payments to be paid to all group members who have signed litigation funding agreements (Funded Group Members) with Galactic in relation this proceeding (LFAs) shall be computed;

(b) the sum of 35% of the sum in subparagraph (a) shall be computed (the Funder’s Portion);

(c) all group members who have not signed LFAs (Unfunded Group Members) and Funded Group Members shall be required to contribute an amount to the Funder’s Portion (including any Enhanced Funder’s Portion as described in subparagraph (d) below), so that an equal percentage of the Settlement Scheme Payment is paid by the Funded Group Members and Unfunded Group Members, with the calculation of that contribution made by the Administrator of the Settlement Scheme; and

(d) to the extent that any contribution by Unfunded Group Members increases Settlement Payments to Funded Group Members and so requires that Funded Group Members pay further monies to Galactic under the terms of the LFAs, and thereby increase the Funder’s Portion (Enhanced Funder’s Portion), the Unfunded Group Members shall each be required to contribute a further percentage of their Settlement Scheme Payments so that ultimately each of the Funded Group Members and Unfunded Group Members contribute equally to the Enhanced Funder’s Portion, and a calculation of that contribution and equal percentage shall be made by the Administrator of the Settlement Scheme.

17B The Administrator be authorised to pay to Galactic the Funder’s Portion including any applicable Enhanced Funder’s Portion, or such other amount as the Court deems fair and reasonable, out of the Settlement Sum in discharge of Galactic’s entitlements under the LFAs.

12 On 16 November 2021, I listed the applications for hearing to commence on 28 March 2022.

13 After a three day hearing, on 31 March 2022 I made the following orders (among others):

Approval of the settlement

1. Pursuant to sections 33V and 33ZF of the FCA Act that the settlement of this proceeding as against 7-Eleven be approved on the terms set out in:

a. the Class Action Settlement Deed dated 4 August 2021 between:

i. the Applicants (Davaria Pty Ltd and Kaizenworld Pty Ltd), on their own behalf and on behalf of the Group Members, and the Applicants’ directors/shareholders (Mr Pareshkumar Davaria, Ms Khushbu Pareshkumar Davaria, Mr Jatinder Pal Singh, and Ms Suman Meet Kaur) on their own behalf and on behalf of the group members in proceeding VID182/2018;

ii. Levitt Robinson;

iii. Galactic; and

iv. 7-Eleven; and

b. The Settlement Scheme annexed to these orders.

Administration of the settlement scheme

2. Steven Nicols of the accounting firm Nicols & Brien be appointed as the Administrator of the Settlement Scheme.

Payment of the settlement sum

3. 7-Eleven to pay the Settlement Sum of $98,000,000 to a trust account nominated by the Administrator within 14 days of the date on which:

a. the appeal period in respect of paragraph 1 of these orders (Approval Order) has expired without any appeal or application for leave to appeal having been filed; or

b. any orders from an appeal from the Approval Order have been Approved.

In this order, “Finally Approved” means that an application for leave to appeal or an appeal from the Approval Order has been filed and the ultimate outcome of that appeal (including any subsequent appeal or application for leave to appeal) is that the Approval Order is upheld or an order materially similar or substantially equivalent to the Approval Order is made.

Security for costs

4. The security for 7-Eleven’s costs and any interest thereon held in the Federal Court’s high-interest bearing account be paid to Levitt Robinson’s trust account, to be returned to Galactic forthwith, and the Registry is so directed.

Confidentiality orders

5. In addition to Order 1 of the Court made on 15 February 2022, pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the FCA Act, until further order of the Court, in order to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the documents in the Consolidated Confidentiality Schedule as Annexure A to these orders be treated as confidential, not be published or made available and not be disclosed to any person or entity except as permitted by the relevant party identified with respect to the relevant document as set out in the Consolidated Confidentiality Schedule or by order of the Court.

Costs orders

6. There be no order as to the costs of the proceeding as between the Applicants and 7-Eleven.

7. All existing costs orders in favour of the Applicants as against 7-Eleven, or in favour of 7-Eleven as against the Applicants, be vacated.

Consequential orders

8. Pursuant to section 33ZF of the FCA Act or otherwise, the Applicants be authorised nunc pro tunc on behalf of the Group Members bound by these orders to enter into and to give effect to the Class Action Settlement Deed and the obligations, rights, releases and transactions contemplated in it for and on behalf of those Group Members.

The reasons for the making of those orders are to be found in Davaria Pty Ltd v 7-Eleven Stores Pty Ltd (No 11) [2022] FCA 331.

14 The proceedings were adjourned to dates in April and May 2022 for consideration of matters relevant to s 33V(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act.

15 Mr D Pritchard SC appeared with Mr P Tucker, Mr NYH Li and Mr A Rizk for the applicants. Mr RG Craig QC appeared with Mr AN McRobert for 7-Eleven. Mr SG Finch SC appeared with Mr DTW Wong for the funder. And Mr JA Redwood SC appeared with Mr RK Jameson as the court appointed contradictor. Ms E Harris also appeared to assist the court in relation to her various costs reports in her capacity as referee.

16 It was agreed that it would be preferable for me to publish these reasons and then permit the parties to confer in relation to the form of the orders to be made to give effect to those reasons, before resuming any further hearing.

17 The applicants relied on the following evidence:

(1) affidavits of Stewart Alan Levitt, the Senior Partner of Levitt Robinson who had the ultimate conduct and carriage of the matter for the applicants, sworn:

(a) 13 March 2018;

(b) 1 December 2020;

(c) 14 October 2021 (including a confidential version);

(d) 28 October 2021;

(e) 16 December 2021;

(f) 17 December 2021 (including a confidential version);

(2) affidavits of Brett Richard Imlay, Special Counsel at Levitt Robinson, sworn:

(a) 30 September 2020;

(b) 26 November 2020;

(c) 25 January 2021;

(d) 17 May 2021;

(e) 23 August 2021 (including a confidential version);

(f) 6 October 2021 (including a confidential version);

(g) 13 October 2021 (including a confidential version);

(h) 20 October 2021 (confidential);

(i) 25 October 2021;

(j) 17 December 2021 (including a confidential version);

(k) 12 May 2022;

(3) affidavits of Jermir Schan Jehangir Punthakey, a solicitor at Levitt Robinson, sworn:

(a) 6 September 2019;

(b) 10 December 2019;

(c) 5 June 2020;

(d) 24 July 2020;

(e) 3 November 2021 (including a confidential version);

(f) 15 November 2021;

(g) 25 March 2022;

(h) 28 March 2022 (including a confidential version);

(i) 21 April 2022 (including a confidential version);

(4) affidavit of Steven Nicols, the administrator of the settlement scheme, sworn 30 March 2022;

(5) affidavits of Pareshkumar Chhaganlal Davaria, sworn:

(a) 21 October 2020

(b) 12 November 2021 (including a confidential version);

(6) affidavits of Jatinder Pal Singh sworn:

(a) 13 October 2020;

(b) 12 November 2021 (including a confidential version);

(7) affidavits of the following other franchisees:

(a) Sushil Kumar Sharma sworn 19 December 2018; 8 July 2019; 6 September 2019; 16 November 2021;

(b) Kirandeep Singh sworn 28 June 2019;

(c) Sajjadur Rahman sworn 26 June 2019;

(d) Atulkumar Nagjibhai Patel sworn 3 July 2019;

(e) Kailas Pujar sworn 4 July 2019;

(f) Nanette Wang sworn 4 July 2019;

(g) Ambika Nand sworn 6 April 2021 and a further affidavit affirmed 23 March 2022 (including a confidential version)

(h) Harjit Singh Salhan sworn 12 April 2021; and

(8) affidavit of Christopher David Hart, a remuneration consultant engaged by Levitt Robinson to prepare a report in connection with the applicants’ additional remuneration arising out of their hours worked, affirmed 12 May 2021.

18 7-Eleven relied on the following evidence:

(1) affidavits of Nigel David Jones, a Partner of Norton Rose Fulbright Australia, the solicitors for 7-Eleven, affirmed:

(a) 10 December 2020;

(b) 14 May 2021;

(c) 14 June 2021;

(d) 29 October 2021 (including a confidential version);

(e) 3 February 2022;

(f) 23 March 2022;

(2) affidavit of Abdul Muhit Ridwan Alam, a Group Reporting Analyst employed by 7-Eleven, affirmed 4 June 2021 (including a confidential version);

19 At the hearing on 22 April 2022, I agreed that I would make an order that on a date that was seven days after payment of the settlement sum, the proceeding would be dismissed as against 7-Eleven. On 2 May 2022, I made an order in those terms. On 2 June 2022, the first respondent made payment of the settlement sum. Accordingly, on 10 June 2022, I made an order dismissing the proceeding against 7-Eleven.

20 The funder relied on two affidavits of Fredrick Schulman, the Managing Director of Galactic, sworn 21 October 2021 and 1 February 2022 respectively. The latter was confidential.

21 Elizabeth Mary Harris was appointed as a referee pursuant to orders made on 15 September 2021. Ms Harris swore six affidavits, annexing four costs reports relevant to the applications (which are discussed at [136] below) and a further report pursuant to orders made on 11 October 2022 (see [325] below).

22 The contradictor also sought to rely on an affidavit of Ambika Nand, a franchisee. Mr Nand lodged an objection to the funding commission and legal costs, and gave evidence about his involvement with the proceedings and his reasons for objecting to the settlement. However, as I explain at [199] of these reasons, I accept that his objection can be properly put to one side.

23 7-Eleven objected to some parts of the applicants’ and the funder’s evidence. By agreement between the parties, certain passages of affidavits were not read, and others were admitted subject to s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) as either submissions, evidence of the deponent’s state or mind, or evidence of the deponent’s understanding of another person’s state of mind. The evidence the subject of those limitations was ultimately of little relevance.

24 The contradictor also objected to Mr Imlay’s 12 May 2022 affidavit. I deal with those objections at [307]-[309] below.

25 The funder and the contradictor also relied on expert evidence from Mr Houston and Mr McGing respectively.

26 A confidential opinion from the applicants’ counsel, being the same counsel who appeared for the applicants at the hearing, was also in evidence. It was an exhibit to the confidential affidavit of Mr Imlay sworn 20 October 2021. A supplementary confidential opinion was also filed, but it was not material.

27 The confidential opinion, in substance, expressed the following general opinions, which are not in themselves confidential.

28 As to the fairness and reasonableness of the proposed settlement, counsel expressed the opinion that the proposed settlement was fair and reasonable as between:

(a) the applicants and group members (on the one hand) and the respondent (on the other); and

(b) group members.

29 Counsel also expressed the opinion that the proposed settlement distribution scheme was fair and reasonable.

30 Counsel also considered that the settlement sum and proposed distribution of those funds, fairly reflected:

(a) the complexities, prospects and risks associated with the claims made in the proceedings;

(b) the time, cost and vicissitudes of a rigorously defended trial of those claims, and the potential costs associated with further hearings for groups members (including the potential for appeals);

(c) the losses and burdens (and benefits) that group members have suffered (or enjoyed) in the course of operating their franchises; and

(d) acknowledgment of the applicants’ costs of conducting the proceedings to date, and of administering the proposed scheme of distributing the Settlement Sum.

31 Counsel said that they had arrived at those opinions upon a frank assessment of:

(a) the applicants’ prospects of success in proving liability and damages (or entitlement to compensation or other favourable relief), and of group members generally;

(b) the exigencies of litigation generally, and specifically in respect of the proceedings; and

(c) the limited number of common questions that could be determined at trial for the benefit of all group members.

32 Counsels’ opinions in matters of this kind are kept confidential to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice.

33 That is so, including because such opinions routinely contain matters that are the subject of lawyer-client privilege. As the Victorian Court of Appeal (Tate, Whelan and Niall JJA) said in Botsman v Bolitho (2018) 57 VR 68 at 125 [270], [272]:

It is a common feature of an approval application for a compromise of a group proceeding that counsel for each of the parties will provide a confidential advice to the court that candidly exposes the strength and weakness of the competing contentions and explains why, in the opinion of counsel, the settlement is appropriate.

…

The candid exposure of the strengths and weaknesses of the lawyer’s own case is essential to the utility of the advice in the court’s deliberations. In principle, there is a sound reason for the maintenance of confidentiality over such opinions.

34 In Camilleri v The Trust Company (Nominees) Ltd [2015] FCA 1468 at [35], Moshinsky J said that there were several factors that may give courts confidence in relying on the confidential opinions of counsel, each of which is applicable in the circumstances of these proceedings:

(a) the proceedings are at a very advanced stage, with all the lay and expert evidence already filed.

(b) the settlement occurred virtually on the eve of the trial, which places the parties and their lawyers in a good position to assess the strengths and weaknesses of their cases.

(c) the lawyers who have expressed the opinions are very familiar with the detail of the case.

(d) the opinions are well constructed and reasoned, giving the court confidence in the opinions they express.

35 The following submissions were relied on:

(1) by the applicants:

(a) outline of submissions dated 14 October 2021;

(b) further outline of submissions dated 21 December 2021 (AS2);

(c) submissions in reply on confidentiality dated 14 February 2022 (AS3);

(d) submissions in reply dated 25 March 2022 (AS4);

(e) outline of supplementary submissions dated 14 April 2022 (AS5);

(f) a document entitled “Applicants’ note on intended submission of contradictor in respect of the FEO” dated 22 April 2022;

(g) submissions concerning admission of the affidavit of Brett Imlay sworn 12 May 2022 dated 23 May 2022;

(h) a supplementary note in reply in relation to the FEO calculation dated 24 May 2022;

(2) by 7-Eleven:

(a) outline of submissions dated 29 October 2021 (RS1);

(b) outline of submissions dated 15 November 2021;

(c) submissions on confidentiality dated 3 February 2022; and

(d) reply submissions dated 23 March 2022;

(3) the funder’s submissions dated 22 October 2021;

(4) by the Contradictor:

(a) preliminary outline of submissions dated 12 November 2021;

(b) submissions on confidentiality dated 6 December 2021;

(c) outline of submissions on confidentiality and the further settlement notice dated 7 February 2022;

(d) outline of submissions on proposed timetabling orders dated 14 February 2022;

(e) further outline of submissions dated 9 March 2022 (CS3);

(f) outline of submissions dated 14 March 2022;

(g) response to applicants’ submissions of 14 March 2022, dated 15 March 2022;

(h) a document entitled “Findings sought and not sought from the Court in respect of the evidence of Stewart Levitt” dated 11 April 2022;

(i) submissions regarding the applicants’ application for leave to re-open and the affidavit of Brett Imlay sworn 12 May 2022 dated 23 May 2022;

36 These reasons address these agreed questions:

(1) Is the proposed settlement distribution fair and reasonable inter se among group members or different categories of group members in both proceeding VID 180 and proceeding VID 182? The answer to that question turns on the following sub-questions:

(a) Is the allocation of the net settlement proceeds of 60% to proceeding VID 180 and 40% to proceeding VID 182 within a rational range?

(b) Is the allocation for the proceeding VID 180 claims of 80% for VID 180 Loss Claims and 20% for Rebates Claims within a rational range?

(c) Are the relative weightings for the VID 180 Loss Claims and the VID 182 Claims of 100%, 33% and zero rational insofar as they are based on: (i) limitation risk for franchisees who entered into a franchise agreement prior to 21 February 2012; (ii) whether the franchisee sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015; or (iii) whether the franchisee entered their franchise agreement after 1 October 2015?

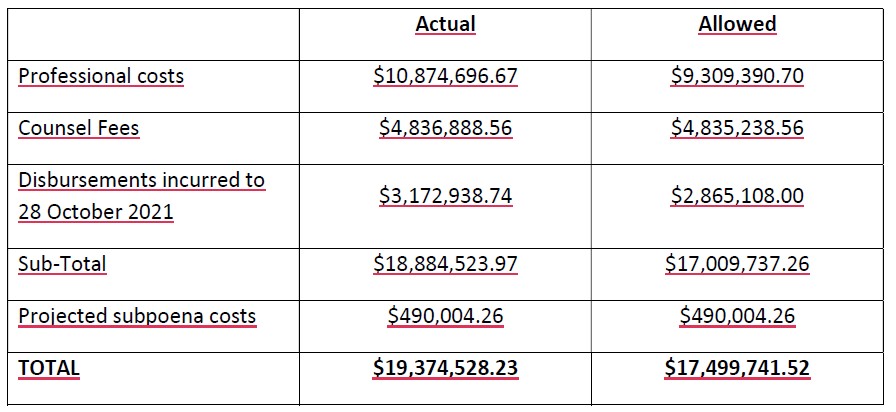

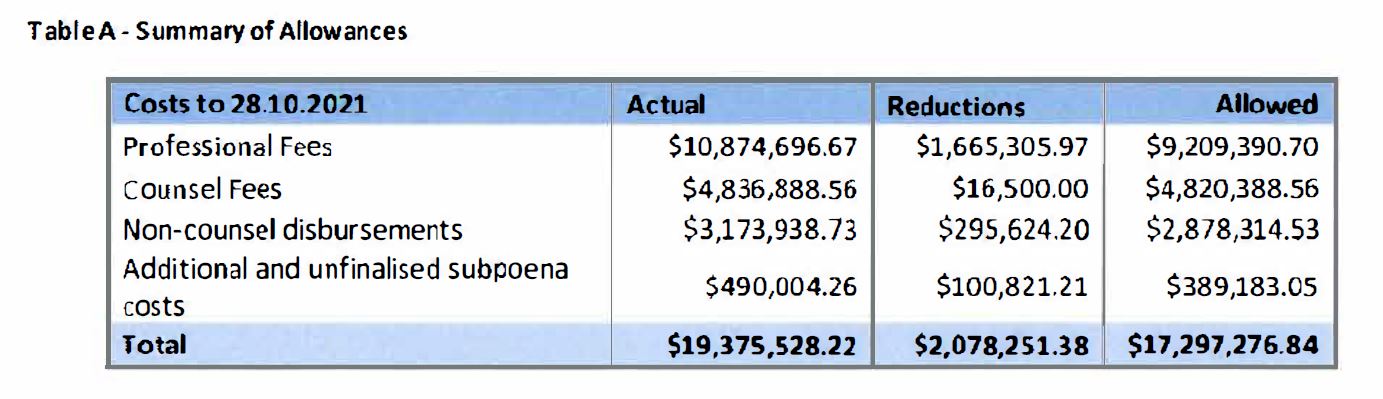

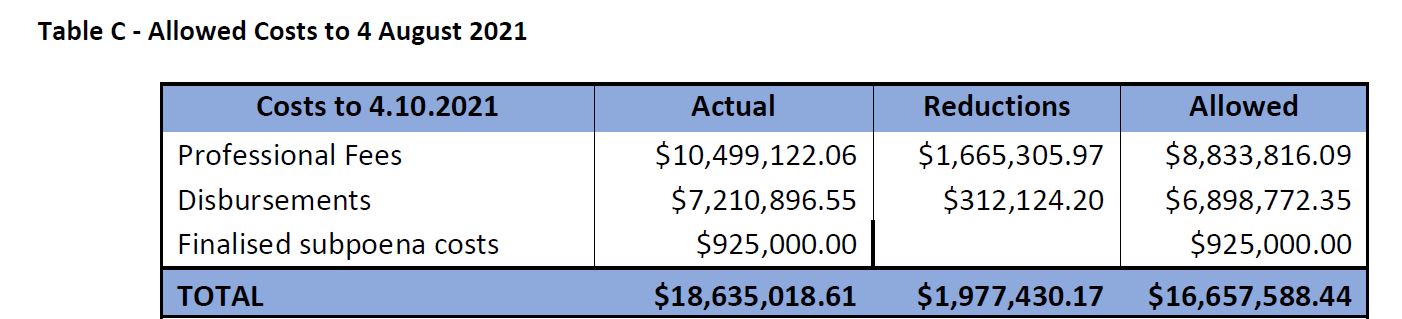

(2) Are the legal costs of $16,657,588.44 incurred in the proceedings up to 4 August 2021 (being the date of the settlement agreement), as assessed by the costs referee, and sought to be recovered from the settlement sum, reasonable?

(3) Are the total legal costs, or any substantial part or category of those costs, proportionate to the expected benefits to be obtained in incurring those costs, and what are the consequences (if any)?

(4) Should each of the costs reports of the costs referee be adopted, varied or rejected, in whole or in part, or be the subject of other order(s) by the Court pursuant to s 54A of the Federal Court of Australia Act?

(5) Was there adequate disclosure and monitoring of legal costs throughout the proceedings, and what are the consequences (if any) if there was not?

(6) Were there any deferred fee arrangements in place between Levitt Robinson and Galactic in relation to legal costs, and what are the consequences (if any) if there were?

(7) Does the court have the power to make a CFO of the kind sought under s 33V(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act, or in its equitable jurisdiction under s 5(2)?

(8) If the court has power to make a CFO of the kind sought, should it make such an order in its discretion in these circumstances?

(9) If the court considers such an order should be made in its discretion, is 25% of the gross settlement proceeds a fair and reasonable amount?

(10) What is the appropriate methodology to determine a fair and reasonable funding commission and what is the relevance in that regard of the expert reports of Mr Houston and Mr McGing to the Court’s determination of a fair and reasonable funding commission?

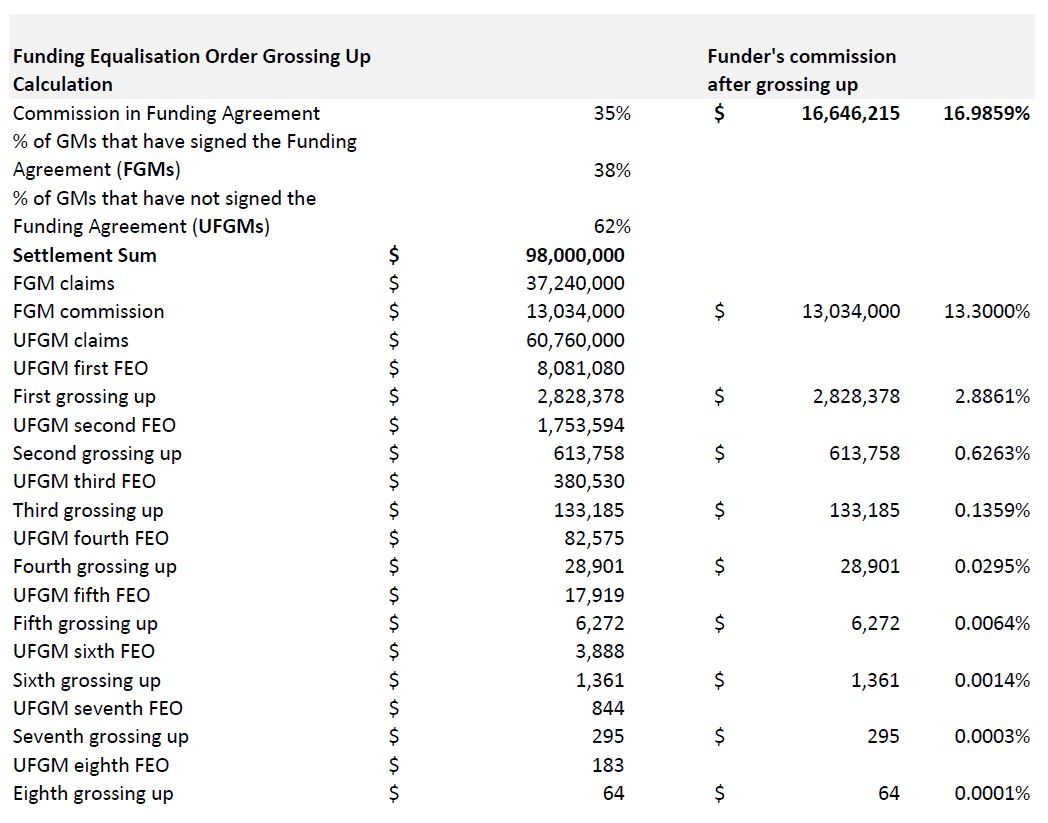

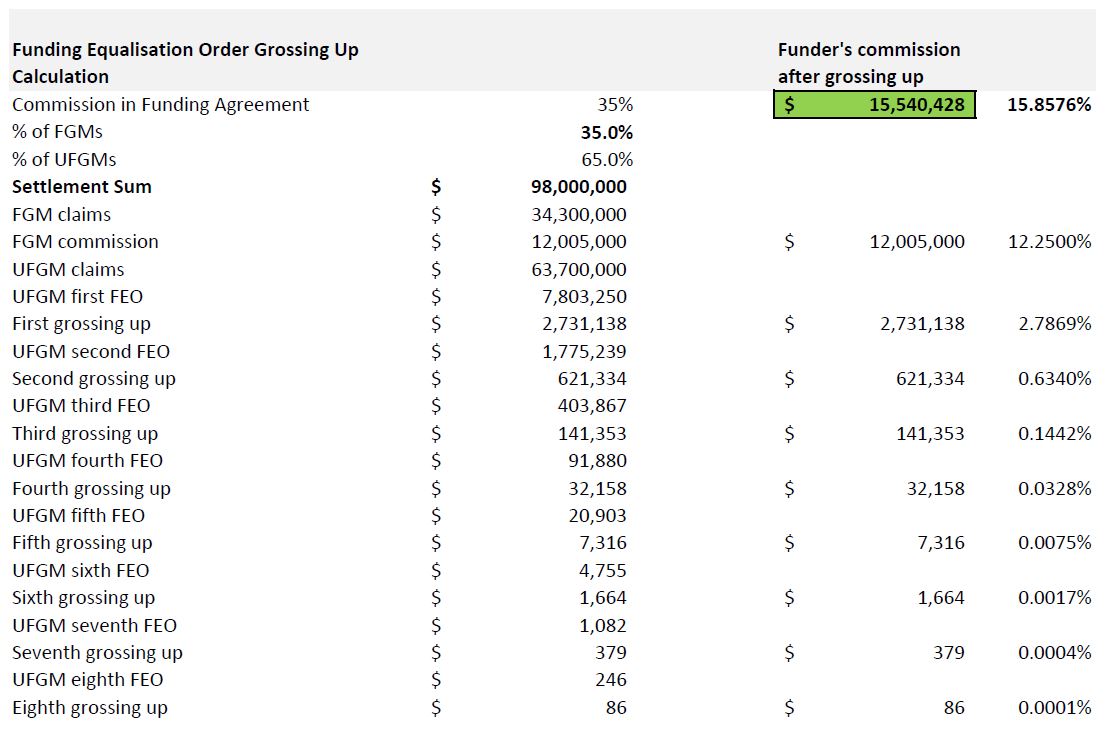

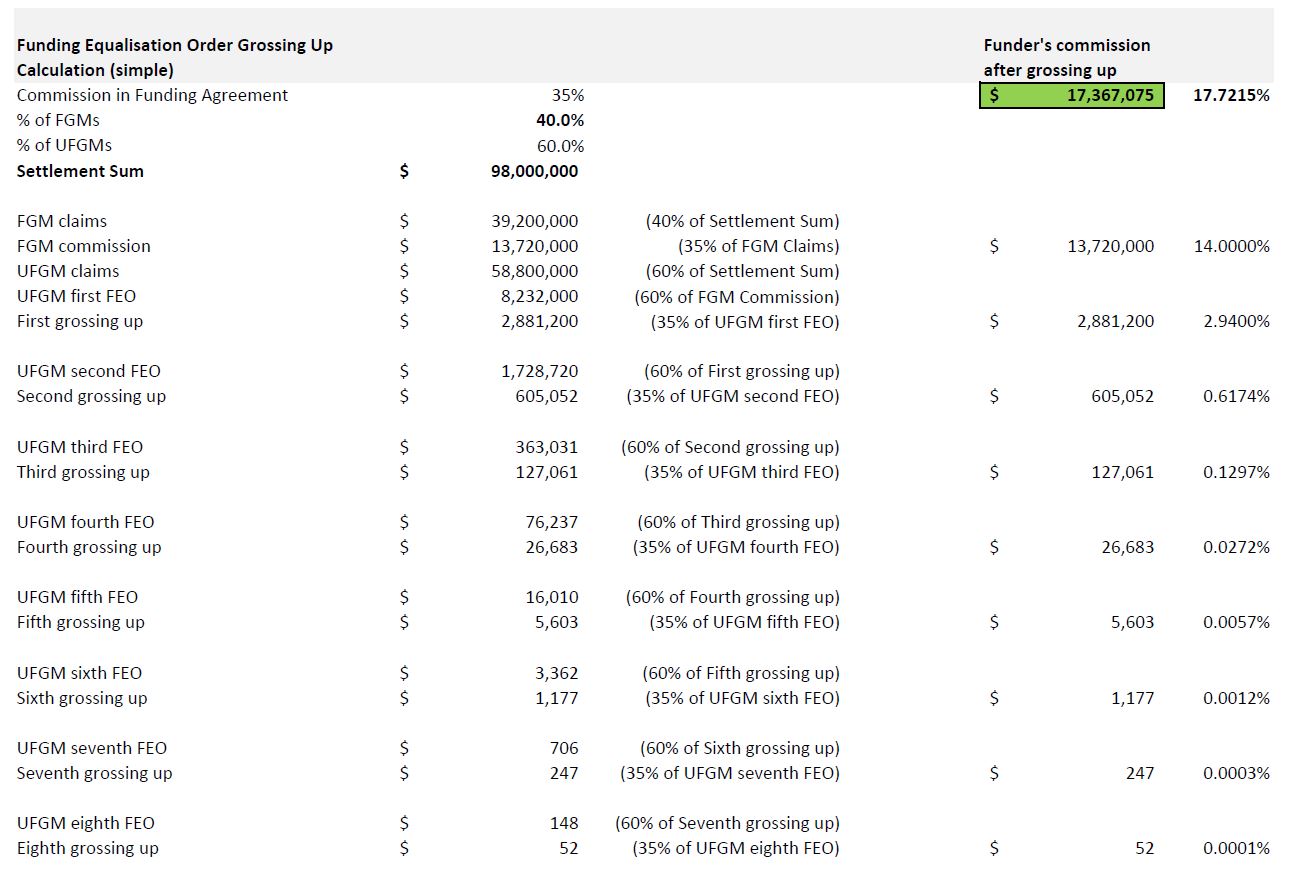

(11) If the court declines to make a CFO in these circumstances, should a FEO otherwise be made and, if so, what is, or should be, the aggregate amount of any FEO? The answer to that question turns on the following sub-questions:

(a) Does the court need to be satisfied as to Galactic’s asserted contractual rights under the funding agreements in order to make a FEO and, if yes, was there sufficient evidence adduced about the existence of binding funding agreements?

(b) To what extent (if at all) is Galactic entitled to a “gross-up” funding commission if a FEO is made?

(12) Are the costs of the solicitors for the applicants in respect of these approval applications reasonable?

(13) Does the costs referee’s reference extend to reviewing the reasonableness of the contradictor’s costs? Should it?

37 Because the answers to questions (1) and (11) turn on the answers to their respective sub-questions, when I get to them, I will deal with each of those sub-questions first.

NATURE OF THE CLAIMS MADE IN THE PROCEEDINGS

38 The matters set out under this heading are derived from a statement of agreed facts dated 26 May 2022. In what follows, I have adopted most of the extensive definitional terms used by the parties in that document.

39 In the 180 Proceeding, Davaria Co and Kaizenworld made four types of claim that related to their entry into a standard form franchise agreement with 7-Eleven.

40 First, there were claims for breach of contract by reason of 7-Eleven’s merchandise supply and inventory practices that were alleged to contravene one or more express or implied terms of the Franchise Agreement (together described as the “C-Store claims”), including:

(a) allegations that 7-Eleven did not obtain the lowest price or prices reasonably obtainable from Suppliers using its best endeavours (Best Endeavours Wholesale Price);

(b) requiring franchisees to purchase merchandise (Merchandise) for sale at 7-Eleven stores (Stores) through an online portal (Portal) from essentially one supplier, C-Store (an arm or related entity of Metcash Limited (Metcash)), whose prices were alleged to be in excess of the Best Endeavours Wholesale Price (this conduct described as “C-Store Practices”);

(c) subjecting Franchisees to:

(i) 7-Eleven’s automatic Merchandise ordering system, which generated Merchandise orders for Stores automatically (Suggested Orders) which was alleged to include excessive or unwarranted quantities and types of Merchandise;

(ii) allegedly unreasonable stock auditing practices;

(iii) allegedly unreasonable credit management and cashflow practices, through 7-Eleven’s Open Account system;

(this conduct is described as “Inventory Practices”)

(iv) an alleged failure to account to Franchisees in respect of rebates (Rebates) collected by 7-Eleven from Suppliers that related to Merchandise purchases made by Franchisees (Purchases).

41 Secondly, there were claims of misleading or deceptive conduct, by 7-Eleven allegedly:

(a) understating the true payroll cost of a 7-Eleven store by providing prospective Franchisees with average Store financial statements for Stores at State and national level (Average Store Financials) and financial statements for specific Stores (Individual Store Financials) that allegedly understated the payroll costs associated with operating a Store if employees were to have been paid in accordance with their lawful entitlements (Future Average Payroll Cost Representation);

(b) misstating that the Average Store Financials and Store Financials for the Campbelltown Store were accurate (Average Store Financials Accuracy Representation and Campbelltown Store Financials Accuracy Representation);

(c) overstating Stores’ true value (Goodwill Value Representation) by providing an allegedly inappropriate formula for the calculation of goodwill associated with Stores (Goodwill Formula) that was premised on a multiple of the annual gross income from Stores’ trading (Gross Income Multiple) and which had no regard to a Store’s operating costs;

(d) misrepresenting that Franchisees would be able to sell the goodwill in their franchise in the future to an incoming franchisee on the Gross Income Multiple (Renewal Representation);

(e) misstating that franchisees did not have an obligation to contribute to an advertising fund (Fund) (Advertising Fund Representation);

(f) misstating that 7-Eleven would enter into favourable agreements with Suppliers for the supply of Merchandise, based on volumes of Merchandise ordered by 7-Eleven or Franchisees (Volume Pricing Representation);

(g) misstating that 7-Eleven would provide franchisees with an extensive list of Suppliers and Merchandise from which franchisees could choose product lines to range in their Store (7-Eleven Supplier Representation).

42 Thirdly, there were claims for loss arising from 7-Eleven’s alleged breach of s 51ACB of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (previously s 51AD of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)), by reason of 7-Eleven’s alleged non-compliance with its disclosure obligations under the relevant industry codes (Relevant Codes), stemming from the provision of information in disclosure documents alleged to be inadequate under the Relevant Codes (Code Disclosure Documents).

43 Fourthly, there were claims for loss arising from 7-Eleven’s allegedly unconscionable conduct, including allegations that:

(a) 7-Eleven made the representations that constituted the alleged misleading or deceptive conduct (Alleged Misleading or Deceptive Conduct);

(b) 7-Eleven knew: that Stores could not be operated profitably if all labour hours were remunerated at Award wages, but nonetheless promoted, by the Alleged Misleading or Deceptive Conduct, the purchase of Stores franchises; and that (notwithstanding) franchisees invested substantial capital and borrowed significant monies (usually from ANZ Bank) to acquire a Store franchise, the franchisees often had little or no understanding of Australian labour laws or Award obligations (at least until late in their Franchisee training with 7-Eleven, when Franchisees had committed to purchasing their Store franchise) and often also allegedly had reduced facility with the English language;

(c) franchisees were (consequently) obliged to supply their own unpaid labour in their Stores and, or alternatively, engage in unlawful employment practices, in order to survive financially;

(d) franchisees were also subject to C-Store Practices and Inventory Practices whilst they operated their Store franchises, 7-Eleven’s control over their Store operations and 7-Eleven’s control of the Open Account and Franchisees’ access to funds — all of which was alleged to further impede Franchisees’ ability to trade profitably or to “run their own business”; and

(e) franchisees were reliant upon 7-Eleven continuing to provide allegedly inaccurate information to prospective Franchisees in order for an existing Franchisee to recover and/or make a gain on their investment when they exit 7-Eleven’s franchise system.

44 The applicants alleged that, by reason of the above, 7-Eleven engaged in unfair tactics and acted without good faith.

45 7-Eleven denied the allegations that were made against it.

46 It was agreed before me that before they settled (subject to court approval), the proceedings were “vigorously contested”. As Mr Craig QC for 7-Eleven put it at the hearing on 30 March 2022, “[t]he litigation was deserving of that overused phrase ‘hard fought and vigorously defended’. There were at least 12 decisions of an interlocutory nature handed down by Middleton J, one application for leave to appeal to the Full Court, and … one referral to the Full Court on the question of power to make a common fund order”.

47 The Settlement Deed provides that 7-Eleven denies liability and makes no admission as to liability.

48 The 182 Proceeding was said to be “ancillary” to the 180 Proceeding, because it substantially relied on the facts pleaded in the 180 Proceeding to establish an entitlement to compensation for the natural persons who were Nominated Directors under the Franchise Agreements or guarantors of Franchisee’s obligations under the Franchisee Agreements or ANZ loans (Guarantors).

49 The 180 Proceeding was commenced by Originating Application and Statement of Claim, both dated 20 February 2018.

50 The pleadings in the 180 Proceeding were subsequently amended. Their final iteration was contained in the Third Further Amended Originating Application and the Third Further Amended Statement of Claim (3FASOC).

51 The 182 Proceeding was commenced by Originating Application and Concise Statement, both dated 20 February 2018.

52 The pleadings in the 182 Proceeding were subsequently amended. Their final iteration was contained in the Third Further Amended Originating Application and the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim (2FASOC).

MATTERS RELEVANT TO LIMITATIONS ISSUES (AND WEIGHTING OF CLAIMS MADE BY GROUP MEMBERS IN THE SETTLEMENT SCHEME)

53 The matters set out under this heading are also derived from the statement of agreed facts.

54 The applicants in both proceedings bring claims for breach of contract and damages pursuant to ss 236, 237 and 243 of Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act (the Australian Consumer Law) and ss 82, 87(1) and 87(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act (previously ss 82 and 87 of the Trade Practices Act).

55 Sub-section 236(2) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that an action for damages under sub-section 236(1) “may be commenced at any time within 6 years after the day on which the cause of action that relates to the conduct accrued”. Sub-section 82(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act (previously of the Trade Practices Act) provides for the same limitation for an action for damages under sub-section 82(1).

56 Sub-section 237(3)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that an application under s 237(1)(a)(i) for orders against a person that was engaged in a contravention of certain provisions of the Australian Consumer Law “may be made at any time within 6 years after the day on which … the cause of action that relates to the conduct referred to in that subsection accrued”.

57 The date that is six years prior to the commencement of the proceedings here is 20 February 2012.

58 An issue ventilated during the hearing of the Approval Applications was whether this date represented the correct date from which to assess the limitation defence advanced by 7-Eleven in the proceedings. That question is relevant because the proposed Settlement Scheme seeks to differentiate between claims said to be affected by the limitation period, and those which are not.

59 Under the Settlement Scheme proposed by the applicants in the amended interlocutory applications dated 12 May 2022:

(a) 60% of the net Settlement Sum available for distribution to eligible group members (VID 180 Settlement Sum) will be distributed to eligible group members in the 180 Proceeding (Eligible VID 180 Group Members); and

(b) 40% of the net Settlement Sum available for distribution to eligible group members (VID 182 Settlement Sum) will be distributed to eligible group members in the 182 Proceeding (Eligible VID 182 Group Members).

60 Under that proposed Settlement Scheme:

(a) The VID 180 Settlement Sum will be distributed to Eligible VID 180 Group Members having regard to the following claims that could have been made by those group members: Claims made in respect of monies lost in connection with acquiring a franchise (VID 180 Loss Claims); and Claims that 7-Eleven was obliged (and failed) to account to Franchisees for rebates received by 7-Eleven from merchandise vendors (Rebates Claims).

(b) Different relative weightings will be applied in the Settlement Scheme to the VID 180 Loss Claims of all Eligible VID 180 Group Members, having regard to: the date when the franchisee entered into their Franchise Agreement to acquire their franchise; and the date when the franchisee sold or disposed of the franchise (if they have sold or disposed of it).

61 Under that proposed Settlement Scheme:

(a) The VID 182 Settlement Sum will be distributed to Eligible VID 182 Group Members upon an assessment of the claims made by those group members (VID 182 Claims), having regard to: the hours the Eligible VID 182 Group Member spent in operating the relevant 7-Eleven store(s); the payment they received for those hours of work; and what additional monies the Eligible VID 182 Group Member might have been able to earn rather than devoting their time to operating the relevant 7-Eleven store(s).

(b) Different relative weightings will be applied to VID 182 Claims having regard to:

the date when Eligible VID 182 Group Members became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement, or became Guarantors under an ANZ Bank loan contract; and the date when the relevant franchisee sold or disposed of the franchise(s) (or if the franchisee still retains the franchise(s)).

Time from when the limitations period might run and the time from which a franchisee acquiring a store is unlikely to have suffered a loss

62 The applicants allege that, for a period commencing on a date unknown to the applicants but ending in about late November 2015, 7-Eleven supplied guidance that goodwill for a store was 2.1x - 2.7x “Total Retail Income” (Goodwill Guidance).

63 Commencing on 29 August 2015, a series of articles were published in newspapers and online over several days concerning allegations of widespread wage underpayment within the 7-Eleven system.

64 On 31 August 2015, an episode of a program broadcast on free-to-air television called “Four Corners” and entitled “7-Eleven: The Price of Convenience”, also alleged widespread wage underpayment within the 7-Eleven system.

65 7-Eleven then appointed an independent panel to review underpayment claims. Approximately $173 million was paid to employees of 7-Eleven franchisees as part of the wage compensation program that resulted from the review. The Board also oversaw changes to 7-Eleven’s Store Agreements with franchisees across the network designed to offset the expected increase in their payroll costs. The changes were referred to by various names, including the “New Deal”, “New Model”, “MIG” and “MGI Guarantee” and were contained in variation agreements which provided non-fuel stores with a minimum level of Gross Income of $340,000 per annum and fuel stores with a minimum level of $310,000 per annum.

66 7-Eleven had ceased supplying the Goodwill Guidance by November 2015.

MATTERS RELEVANT TO THE MAKING OF A FUNDING EQUALISATION ORDER

67 There are 678 group members in the 180 Proceeding, including the two lead applicants, representing 811 stores (inclusive of the three stores operated by the lead applicants) and 1,232 group members in the 182 Proceeding, including the four lead applicants.

68 In his 12 May 2022 affidavit Mr Imlay deposed, and it was not disputed, that as at that date:

(a) there were 678 VID 180 Group Members, inclusive of the two lead applicants;

(b) there were 202 VID 180 Funded Group Members (ie those who signed funding agreements), which amounted to about 29.8% of the 678 VID 180 Group Members;

(c) the 678 VID 180 Group Members represented 811 VID 180 Stores, inclusive of the lead applicants);

(d) the 202 VID 180 Funded Group Members represented 251 VID 180 Funded Stores, which amounted to 30.9% of the 811 VID 180 Stores;

(e) of the 811 VID 180 Stores, after removing stores operated by entities that were deregistered (with no intention to reinstate them) and stores operated by entities that provided releases to 7-Eleven, there were 487 VID 180 Stores Without Releases, of which under the proposed Settlement Scheme: 144 had a 100% weighting; 172 had a 33% weighting; and 171 were zero-weighted;

(f) there were therefore 316 (144 + 172) VID 180 Loss Claim Stores, being VID 180 Stores of registered companies or individuals, without releases, that have valuable loss claims;

(g) of the 251 VID 180 Funded Stores, there were 190 VID 180 Funded Stores Without Releases, of which under the proposed Settlement Scheme: 58 had a 100% weighting, which amounted to 40% of the 144 VID 180 Stores Without Releases with a 100% weighting; 74 had a 33% weighting, which amounted to 43% of the 172 VID 180 Stores Without Releases with a 33% weighting; and 58 were zero-weighted, which amounted to 34% of the 171 VID 180 Stores Without Releases that are zero-weighted;

(h) there were therefore 132 (58 + 74) Funded VID 180 Loss Claim Stores, being VID 180 Loss Claim Stores operated by entities that had signed the funding agreement, which amounted to 41.7% of the 316 VID 180 Loss Claim Stores (132/316);

(i) there were about 1,232 VID 182 Group Members;

(j) there were about 316 VID 182 Funded Group Members (inclusive of the four lead applicants), which amounted to 25.6% of the 1,232 VID 182 Group Members (1,228 plus the four lead applicants in VID 182).

CONSIDERATION – QUESTIONS TO BE DECIDED

Question (1): Is the proposed settlement distribution fair and reasonable inter se among group members or different categories of group members in both proceeding VID 180 and proceeding VID 182?

69 In reviewing whether the settlement is fair and reasonable inter se among group members or different categories of group members in both proceedings, the court is primarily concerned to ensure that the interests of the lead applicants, or group member clients of the applicants’ solicitors, are not being preferred over the interests of other group members. See eg Camilleri v The Trust Company (Nominees) Ltd [2015] FCA 1468 at [5(e)] (Moshinsky J); Blairgowrie Trading Ltd v Allco Finance Group Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 330; (2017) 343 ALR 476 at 500 [85] (Beach J).

70 As Moshinsky J said in Camilleri at [40]-[41]:

… [A]s in many representative proceedings, the manner in which the settlement sum is to be distributed requires assumptions to be adopted and judgment calls to be made. There are different classes of claimants within the body of group members here, and it is necessary to arrive at some model that fairly and reasonably divides the settlement sum between those classes, recognising the differences in their respective claims. There is no single approach which alone can qualify as reasonable for sharing the fixed pool of funds among the claimants. Inevitably, adjustments in a given approach will be favourable for certain group members at the expense of others.

The question, therefore, can only be whether the model is within the bounds of fairness and reasonableness in its attempts to balance what are, unavoidably, conflicts between the interests of the different claimants.

Question (1)(a): Is the allocation of the net settlement proceeds of 60% to proceeding VID 180 and 40% to proceeding VID 182 within a rational range?

71 Under paragraph 24 of the Proposed Settlement Scheme, the Estimated Net Settlement Sum is to be divided amongst both proceedings VID 180 and VID 182 as follows:

(a) 60% to VID 180 eligible group members; and

(b) 40% to VID 182 eligible group members.

72 An “eligible group member” is a group member who has registered for the Settlement Scheme in accordance with its terms, and who has either not entered into a release with 7-Eleven or who has entered into a release but that release is determined by an independent barrister to be ineffective in accordance with the terms of the settlement scheme.

73 The contradictor submitted that VID 180 losses arise by reason of a “no transaction” case, and that by comparison “there is greater speculation involved in respect of VID182 claims which losses are to be calculated by reference to the ability of a director of a 7-Eleven franchisee who worked in-store to obtain alternative employment over the same time-period earning award wage rates, and who would have been prepared to work as hard elsewhere (capped at 70 hours) per week as they worked at their store”.

74 The contradictor suggested that “there are several other difficulties affecting the VID182 claim”, in particular that the loss claimed is less orthodox and more speculative, and that its prospects of success were, in the contradictor’s view, “low to very low and significantly worse than the VID180 proceeding”.

75 Accordingly, the contradictor submitted that:

[the] “60:40 allocation is very difficult to reconcile with a fair and rational assessment of the prospects for the VID 182 claim. It is respectfully submitted that a more rational allocation would be 80% to VID180 and 20% to VID182 (at its highest). We are not convinced … that there would have been a link between the loss claims in VID180 and VID182 which tends to reduce the significance of the split as between the two proceedings. For one thing, we are not satisfied the current state of the evidence on these applications justifies that reasoning. If anything, as 7-Eleven submit, we think issues of double recovery would inflict the VID182 proceeding and work in the opposite direction.

76 In the course of oral argument, the contradictor summarised his position this way:

So in respect of VID180, what I wanted to emphasise is that we’re not saying that the prospects are hopeless or poor, but for the reasons we’ve identified, we consider that VID180 was significantly better because it was a more orthodox claim, easier causation route, not as susceptible to individual circumstances – not so variable, in that regard.

…

And one only needs to think about some – and this isn’t, again, to be critical but some of the claims in terms of lost time with grandchildren and leisure and so on – now, that may be perfectly appropriate, but those are very difficult issues of quantification and far more difficult issues of quantification, we say, than affected the VID180 claim.

… [S]o we say that there’s just too great a degree of disconformity, on an assessment of all the material – that is what my learned friends have said – 7-Eleven’s perspective, the state of evidence as it existed at the time of settlement between VID180 and VID182, to justify an allocation of 60/40 and we think an allocation of 80/20 is not better but significantly better and accepting these are matters of judgment – fine judgment – we think that your Honour would be justified in making that kind of adjustment in the circumstances.

77 The applicants submitted to the contrary. Their submissions were as follows.

78 The applicants pleaded case in the 180 Proceeding was that they, and some or all, of the other franchisees would be unable to operate their store profitably and maintain their Minimum Net Worth unless the principals (and/or their family members) worked in that store without pay for an unreasonable and unsociable number of hours each week and/or covered night and weekend shifts without pay (or engaged family members to do so).

79 In the 182 Proceeding, it is alleged that had the franchisee not been induced into acquiring their franchise, then VID 182 Group Members would not have worked in their store for no wages, or lower wages and lower income than they would have earned from continuing their former (or from pursuing other) employment; or otherwise, they did not have the use and enjoyment (and so lost the benefit) of the hours that they worked in their stores.

80 The applicants do not accept the contradictor’s view of the hurdle facing VID 182 Group Members. They submitted in that regard as follows:

Accepting (as the Contradictor apparently does …) that the entry into the franchise gives rise to the Net Worth Trap, is that circumstance which caused VID182 group members to work excessive and unreasonable hours, and lose the ability to use those hours as they otherwise might have chosen (be it in other employment, or having those hours to spend in leisurely pursuits). It is not the case that VID182 group members suffered no loss if they were not to prove that they could have been employed elsewhere at a higher rate of pay. The Net Worth Trap left VID182 group members with no choice but to work in their stores for little or no pay. Even those persons who might have chosen not to work, and instead to use their time in a manner of leisure (as Mr Singh, for example, deposes) are entitled to be compensated, by virtue of being forced into working hours that they did not choose to in order to keep their franchise afloat. In addition, having invested a considerable sum by way of franchise fee (usually in excess of $100,000) and typically funded the investment with a high-leverage business loan (see 3FASOC [106(e)]), VID182 group members could not simply sell the business at or near the goodwill price paid without wearing a considerable loss. Instead, the VID182 group members were put in the unenviable position of continuing to run the store until the sales (and consequently, the goodwill price) increased to allow a sale that would allow a sufficient return on the investment.

To stipulate that proof of more valuable employment must first be demonstrated is to say that VID182 group members have no loss by providing their time for free or for little compensation in circumstances where they had no choice. At the least, those persons are entitled to be paid what they would have been paid by undertaking the same work for a third party at award rates (as the Proposed Settlement Scheme contemplates).

(Emphasis in original)

81 The applicants advanced two other reasons not to adopt the weighting of 80:20 of the Net Settlement Sum as between VID 180 and VID 182 proposed by the contradictor.

82 First, it was submitted, “the Net Worth Trap creates a “yin-yang” relationship with profits earned by stores … the less the [f]ranchisee principal and their family members are paid through payroll, the higher the “profit” of the franchise, which in turn decreases the amount paid under VID180 and increases the amount paid under VID182. That provides sound reason to maintain substantial parity of the Net Settlement Sum between VID180 and VID182”.

83 Secondly, it was submitted, there are a substantially greater number of VID 182 Group Members than VID 180 Group Members, 1228 versus 676 (a ratio of approximately 1.8:1), and which have estimated to produce 865 and 397 compensable claims respectively (a ratio of approximately 2.18:1). The Proposed Settlement Scheme contemplates a cap of 70 hours per week and a payment based on average hourly award wages, less income actually received.

84 The contradictor agreed (in part of the transcript set out above at [76]), that questions of this sort are matters of fine judgment. They are questions about which reasonable minds may differ. Here, as I have already mentioned, counsel for the applicants prepared a detailed confidential opinion setting out many reasons why the split they propose between the two proceedings is reasonable.

85 The contradictor posited a different, although not radically different, split.

86 So I am faced with a situation where experienced counsel take a different view of the world on matters of fine judgment. I have weighed the competing submissions in the balance, but it seems to me that I am quite unable to say that the 60/40 split proposed by the applicants, to adopt Moshinsky J’s words in Camilleri at [40]-[41], is not “within the bounds of fairness and reasonableness in its attempts to balance what are, unavoidably, conflicts between the interests of the different claimants”.

87 It is critical to keep the appropriate test in mind when assessing whether a particular term of a proposed settlement is fair and reasonable. In making such assessments it is emphatically not the case that something resembling a “mini-trial” of the proceedings, or issues in them, is to be conducted. To do so would plunge the settlement process into a de facto version of the very world that it is designed to avoid, and would be bound to work substantial unfairness to respondents in cases like this, where they cease being parties once the global settlement figure is approved.

88 For those reasons, the answer to question (1)(a) is: yes.

Question (1)(b): Is the allocation for the proceeding VID 180 claims of 80% for VID 180 Loss Claims and 20% for Rebates Claims within a rational range?

89 As to the 60% allocated to VID 180 then further being divided as to 80% for VID 180 Loss Claims and 20% for Rebates Claims, the contradictor submitted that “there would be force in a division of 90% to VID 180 Loss Claims and no more than 10% for Rebate Claims … Arguably, the Rebate Claims were too inchoate and speculative to be ascribed anything by way of distribution but we have real difficulty in an allocation any higher than 10% based on a fair assessment of the prospects of this claim. Nor are we able to accept that it is rational to ascribe a greater allocation to the Rebates Claim on the basis that it provides a foundation for all eligible group members to receive a financial benefit from the settlement. That strikes us as rather arbitrary”.

90 The applicants submitted to the contrary as follows:

The Rebates Claim had its genesis in the provision of information by 7-Eleven in August 2019, in response to a letter dated 5 June 2019 issued by the Applicants’ lawyers in which complaint was made about the paucity of information provided by 7-Eleven as to rebates. The responsive letter from 7-Eleven’s lawyers provided information that indicated that rebates were applied not only to a promotional or marketing fund, but that there existed other “Guaranteed” rebates and “Purchases Promo Rebates Shares” (presumably collected by 7-Eleven) in respect of purchases made by Franchisees.

Upon receipt of that information, inquiries of the Applicants’ retail pricing expert and the Applicants were made, in response to which:

(a) the Applicants said they had never received any similar document from 7-Eleven that set out that information; and

(b) the retail pricing expert stated that he was not able to discern the true nature of the rebates, or the basis on which the rebates had been provided, from the information provided by 7-Eleven.

On 28 October 2019 a request was made to 7-Eleven’s lawyers for more information, which letter included the foundational elements of the accounting obligation underpinning the Rebates Claim. By letter dated 18 December 2019, the request for further information was largely rejected by 7-Eleven’s lawyers.

The entitlement to the remedy of an account involves the existence of an accounting relationship between the applicant and the accounting party, and that the applicant is entitled to a sum from the accounting party but the applicant is uncertain as to what that sum is. The terms of the Franchise Agreement provide the foundation for the accounting relationship. 7-Eleven’s refusal to provide information as to rebates it received in respect of purchases made by Franchisees founded the need for an account. The fact that Franchisees were paying for goods under agreements arranged by 7-Eleven at prices higher than supermarket retail prices for the same goods provided a proper foundation to assert that Rebates were not being passed on to Franchisees (and particularly if it were the case that 7-Eleven had in fact negotiated appropriately favourable pricing with suppliers).

The subpoenas subsequently issued by the Applicants to Metcash and major suppliers were targeted in accordance with what the Applicants’ retail pricing expert informed the Applicants he needed to analyse the rebates. The information was sought on the basis that it would indicate that 7-Eleven had not negotiated appropriately favourable pricing and, or alternatively, that 7-Eleven was not passing on the economic benefit of rebates to Franchisees.

Virtually uniformly, third party subpoenaed suppliers of 7-Eleven required confidentiality undertakings, and in most cases, more circumscribed categories of information were negotiated for production.

Metcash stood in a category of its own, as 7-Eleven’s “primary” supplier. Metcash revealed (through applications resisting production under subpoena) that:

(a) it sold approximately $700M in goods to 7-Eleven franchisees in the 2018 year;

(b) Metcash’s business model was built on sharing a portion of rebates that it obtained from product suppliers with Metcash’s customers;

(c) its rebate arrangements with suppliers were complex and negotiated frequently; and

(d) Metcash shared relatively few rebates with 7-Eleven, because 7-Eleven had its own direct relationship with major suppliers of goods sold in 7-Eleven stores.

Metcash treated the terms of trade with its suppliers with secrecy and, consequently, provided information to the Applicants with reluctance (following two contested hearings) and over an extended period, because to retrieve the relevant information involved reviewing a large quantity of emails.

The institution of the Rebates Claim led to the filing by 7-Eleven of the affidavit of Abdul Ridwan Alam affirmed 4 June 2021 (Alam Affidavit), which contained information concerning rebates that had never before been provided by 7-Eleven. That affidavit revealed the extent of the rebates received by 7-Eleven and … further reason to believe that 7-Eleven had not passed on to Franchisees the full extent of rebates to which they were entitled. At this time, the Applicants’ retail pricing expert was reviewing the material received from suppliers and Metcash ….

…

In agreeing to the settlement figure of $98M, the Applicants considered that the Rebates Claim deserved (and was attributed) a value that is reflected in the 12% weighting (20% of 60%) that has been ascribed to the Rebates Claim in the Proposed Settlement Scheme.

…

Nothing in CS3 causes the Applicants to retreat from the weighting afforded to the Rebates Claim in the Proposed Settlement Scheme, from the utility of pursuing the Rebates Claim …

(Footnotes omitted).

91 Again, these are questions about which reasonable minds may properly differ. And here the differential proposed by the contradictor is not large. It is well within a “tolerance”. And the applicants make a detailed case for why they say their counsel’s opinion is within the range. In my view, the spilt proposed by the applicants is within the bounds of fairness and reasonableness in its attempts to balance the unavoidable conflicts between the interests of the different claimants.

92 For those reasons, the answer to question (1)(b) is: yes.

Question (1)(c): Are the relative weightings for the VID 180 Loss Claims and the VID 182 Claims of 100%, 33% and zero rational insofar as they are based on: (i) limitation risk for franchisees who entered into a franchise agreement prior to 21 February 2012; (ii) whether the franchisee sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015; or (iii) whether the franchisee entered their franchise agreement after 1 October 2015?

93 The gist of the contradictor’s submission as to (i) was that “the limitation issue is more finely balanced” than the applicants would have it and that there was “a cogent available argument that those group members who entered into Franchise Agreements prior to 21 February 2012 are not statute-barred, and a weighting of 50% more rationally and fairly reflects the risks associated with this issue”.

94 The contradictor further submitted as to (ii) that:

[A] relative weighting of 33.33% to loss claims of group members who sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015 appears irrational. It is very difficult to understand how those group members could have suffered any significant loss and have claims of any substantive value. A zero weighting should apply to those claims.

95 Again, quite correctly with respect, the contradictor accepted that “weightings cannot be approached with mathematical exactitude and that a margin of appreciation should be allowed for weightings falling within a rational range”.

96 The contradictor did not make any separate submissions as to (iii).

97 The weightings in respect of the VID 180 Loss Claims are:

(1) A relative weighting of 100% will be applied to VID 180 Loss Claims for Eligible VID 180 Group Members whose Franchise Agreement was entered into on or after 21 February 2012, and the franchise was sold or disposed of after 1 October 2015 or is still retained by the Eligible Group Member.

(2) A relative weighting of 33.3% will be applied to VID 180 Loss Claims for Eligible VID 180 Group Members whose Franchise Agreement was entered into before 21 February 2012, and the franchise was sold or disposed of after 1 October 2015 or is still retained by the Eligible Group Member.

(3) A relative weighting of 33.3% will be applied to VID 180 Loss Claims for Eligible VID 180 Group Members whose Franchise Agreement was entered into on or after 21 February 2012, and the franchise was sold or disposed of before 1 October 2015.

98 A relative weighting of zero will be applied to VID 180 Loss Claims for Eligible VID 180 Group Members whose Franchise Agreement was entered into before 21 February 2012, and the franchise was sold or disposed of before 1 October 2015 or was entered into after 1 October 2015.

99 There is no weighting in respect of the Rebate Claims. As the contradictor said, that is presumably the case in part because in respect of claims for breach of contract the limitation period commences from the date of breach.

100 The same weightings are applied in respect of the VID 182 Claims (with some differences to the terms of those weightings to account for the varied claims) as follows:

(1) A relative weighting of 100% will be applied to the VID 182 Claims made by Eligible VID 182 Group Members who became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement entered on or after 21 February 2012, or who became Guarantors under a Bank Loan Contract on or after 21 February 2012, and where either the 7-Eleven store franchise the subject of that Franchise Agreement was sold or disposed of after 1 October 2015 or the Franchisee still retains that franchise.

(2) A relative weighting of 33.3% will be applied to the VID 182 Claims made by Eligible VID 182 Group Members who became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement entered before 21 February 2012, or who became Guarantors under a Bank Loan Contract before 21 February 2012, and where either the 7-Eleven store franchise the subject of that Franchise Agreement was sold or disposed of after 1 October 2015 or the Franchisee still retains that franchise.

(3) A relative weighting of 33.3% will be applied to the VID 182 Claims made by Eligible VID 182 Group Members who became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement entered on or after 21 February 2012, or who became Guarantors under a Bank Loan Contract on or after 21 February 2012, and where the 7-Eleven store franchise the subject of that Franchise Agreement was disposed of before 1 October 2015.

(4) A relative weighting of zero will be applied to the VID 182 Claims made by Eligible VID 182 Group Members who became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement entered, or who became Guarantors under a Bank Loan Contract before 21 February 2012, and where the 7-Eleven store franchise the subject of that Franchise Agreement was disposed of before 1 October 2015 or who became Nominated Directors or Guarantors under a Franchise Agreement that was entered into after 1 October 2015, or who became Guarantors under a Bank Loan Contract after 1 October 2015.

101 The contradictor helpfully summarised the rationale for the weightings as follows.

102 In respect of franchisees who entered into a franchise agreement prior to 21 February 2012, the contradictor submitted that their claims are or would be at risk of being defeated by a successful limitation defence, which is advanced by 7-Eleven in its VID 180 Defence to the 3FASOC at [105A] and [121A] and in its VID 182 Defence to the 2FASOC at, principally, [19], which paragraphs were in these terms:

VID180

105A It says in further response to paragraphs 41 to 105 of the FASOC:

(a) that any Franchisee who entered into a Franchise Agreement before 20 February 2012 (or, in respect of the Goodwill Value Representation Contravention, before 2 March 2014) is statute barred from maintaining a cause of action:

(i) under section 237 or 243 of the ACL pursuant to sub-section 237(3) of the ACL; and

(ii) under section 236 of the ACL pursuant to sub-section 236(2) of the ACL; and

(iii) under sections 82 or 87 of the CCA or the TPA pursuant to sub-section 82(2) and 87(1CA) of the TPA or CCA;

(b) that the Second Applicant is statute barred from maintaining the Goodwill Value Representation Contravention, it having entered into the South Melbourne Store Franchise Agreement on 2 October 2013.

121A It says in further response to paragraphs 106 to 121 of the FASOC, that any Franchisee who entered into a Franchise Agreement before 20 February 2012 is statute barred from maintaining a cause of action:

(a) under section 236 of the ACL, pursuant to section 236(2) of the ACL;

(b) under section 237 or 243 of the ACL, pursuant to section 237(3) of the ACL;

(c) under sections 82 or 87 of the CCA or the TPA (to the extent applicable) pursuant to sub-section 82(2) and 87(1CA) of the TPA or CCA;

(d) under section 12GF of the ASIC Act, pursuant to section 12GF(2) of the ASIC Act; and

(e) under section 12GM of the ASIC Act, pursuant to section 12GM(5) of the ASIC Act.

VID182

19. To the whole of the SOC, it says:

(a) that save, for where a defence is pleaded, further and/or particular defences may be available to it in respect of a Nominated Director’s or Guarantor’s claims, which cannot be determined until after the Nominated Director or Guarantor has been identified; and

(b) any Nominated Director who entered into a Franchise Agreement before 20 February 2012 (or, in respect of the Goodwill Value Representation Contravention and the Renewal Representation Contravention, before 2 March 2014) and any Guarantors who entered into Guarantees before 20 February 2012 (or, in respect of the Goodwill Value Representation Contravention and the Renewal Representation Contravention, before 2 March 2014) are statute barred from maintaining a cause of action:

(i) under section 236 of the ACL pursuant to section 236(2) of the ACL;

(ii) under section 237 or 243 of the ACL, pursuant to section 237(3) of the ACL;

(iii) under section 82 or 87 of the TPA pursuant to section 82(2) or 87(1CA) of the TPA, alternatively section 82(2) or 87(1CA) of the ACL;

(iv) under section 12GF of the [Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act)], pursuant to section 12GF(2) of the ASIC Act; and

(v) under section 12GM of the ASIC Act, pursuant to section 12GM(5) of the ASIC Act.

103 In respect of franchisees who entered into their franchise agreements after 1 October 2015 (ie after 7-Eleven abandoned the Goodwill Formula), many of the representations said to give rise to the misleading or deceptive conduct (including the Goodwill Value Representations) had ceased by this time, and therefore it is said that those franchisees would not be entitled to relief in respect of those representations.

104 The contradictor submitted that the limitation issue is largely a legal issue, that I am in a position to assess its merits, and that I should reach a view about it.

105 The contradictor’s submission on the limitation issue was as follows.

106 The limitation defence was pleaded by 7-Eleven only in respect of the claims of misleading or deceptive conduct and unconscionability, under which the only relief sought is relief pursuant to ss 236 and 237 (and 243) of the Australian Consumer Law (and its analogues under the Trade Practices Act and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth)).

107 The relevant time limits in relation to such claims are that any action may be commenced at any time within 6 years after the day which the cause of action that relates to the conduct accrued. See eg Australian Consumer Law ss 236(2), 237(3)(a).

108 Both the applicants and 7-Eleven in their submissions submitted that the loss and damage in respect of the VID 180 Loss Claims and the VID 182 Claims accrued, for the purpose of ss 236 and 237 of the Australian Consumer Law, at the time of entering into the franchise agreements. That is because, it was submitted, when the franchisees were induced by misleading or deceptive and/or unconscionable conduct to enter into the franchise agreements, the true value of the franchises were in fact less than the purchase price paid for by franchisees. 7-Eleven put the argument this way:

For the purpose of sections 236 and 237, the cause of action accrues when damage is first suffered, regardless of whether the damage is then discovered or discoverable. A claimant pursuing the statutory action is responsible for formulating how such loss or damage as they claim to have suffered is to be identified. Damage being an element of the cause of action, a new cause of action generally does not arise in respect of different and separate items of loss and damage, there being, instead, only a single cause of action. “Once an applicant has suffered loss or damage relevant to the claim, time begins to run, even if damage continues to grow”.

…

In short, the applicants’ case was a ‘purchase of an asset at over value case’. On the case as pleaded, the applicants and Group Members bought something which was worth less than what they had agreed to pay and did pay. If that is so, then a Group Member could have brought a claim immediately after entering into their Store Agreement – their cause of action under sections 236 and 237 of the ACL would have accrued because they, on the basis of the allegations made, “had suffered an actual loss” at that time.

109 After citing and discussing passages from Bodycorp Repairers Pty Ltd v Holding Redlich [2018] VSCA 17 setting out and relying upon the principles propounded by the High Court in each of Hawkins v Clayton (1988) 164 CLR 539, Wardley Australia Ltd v Western Australia (1992) 175 CLR 514 and Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd (2004) 216 CLR 388, and extensively from the judgment of Thawley J in Han Jing Pty Ltd v Nestle Australia Ltd [2021] FCA 143 at [30]-[31] and [44]-[45], the contradictor submitted:

[W]e consider there is a cogent alternative argument available to these group members that their claims are not statute-barred. It bears emphasis that limitation issues very much turn on the particular circumstances of the case. Analogies and generalisations by reference to otherwise decided cases only take the analysis so far. Importantly, as the High Court emphasised in Wardley, a general consideration is always whether it is unjust or unreasonable to expect a plaintiff to have commenced proceedings at a particular point in time. There is more than an air of unreality in the idea that group members should be expected to have commenced proceedings (let alone any group proceeding) against 7-Eleven shortly after entry into the Franchise Agreements.

More fundamentally, in the unusual circumstances of this case, we respectfully submit that there is considerable force in the argument that the loss here did not fully manifest until certain critical external events or circumstances came to pass; in particular, until after the public revelation of widespread underpayment within the 7-Eleven franchise system, the resulting abandonment of the Goodwill Formula, and the pre-existing market for exchange of franchisees under 7-Eleven’s direction and influence on a state of affairs uninfluenced by true payroll costs.

110 After setting out passages from the judgment of Brennan J (as he then was) in Wardley at 536-538, the contradictor’s submission continued:

It is strongly arguable in these particular circumstances that the die was not cast upon entry into the Franchise Agreement. The ‘adverse balance’ flowing from the entry into the Franchise Agreements did not transpire, and may never have transpired, until 7-Eleven altered the fundamental basis upon which exchange of franchisees occurred by abandoning the Goodwill Formula consequential upon the media reporting as to systemic underpayment within the system. Up until that point, group members who acquired a franchise prior to 21 February 2012 could have sold their franchise to an incoming franchisee for no loss; and indeed for a capital gain.

We think this argument also has the appeal of common sense and fairness. It is not reasonable and just to expect group members to have commenced claims shortly after entering into the Franchise Agreements, or well before the critical events of August-October 2015. This outcome is also consistent with the remedial and consumer context and purpose of the ACL. The shut out group members who entered into Franchise Agreements before 21 February 2012 from bringing claims against 7-Eleven under the ACL when the concrete foundation for the claims did not transpire until August-October 2015 is not consistent with the remedial purpose of the statute. Nor do we do think this argument is necessarily inconsistent with the no-transaction case and an assessment of true value at acquisition. The issues are not coterminous. One is a measure of loss; the other is an assessment of the time by which it was reasonable to have expected a claim to have been brought. In saying this, we recognise that for some franchisees there may be facts and circumstances individual to them that lessen the merits of their position on this issue. Davaria Co might fall into that category.

…

[W]e consider it appropriate for the Court to adjust this weighting if it agrees with the Contradictor’s submission that the assessment of “highly likely” (or a discount of 66.67%) is clearly a too pessimistic view of prospects on the limitation issue. Overall, our assessment of the issue is that there are reasonable arguments in either direction and a 50% weighting better reflects the difficulty of the issue and the prospects of these group members overcoming the limitation argument.

111 In response, the applicants’ counsel said that they “examined this issue extensively in [their] Confidential Opinion, and maintain[ed] their views there expressed”, that the matter “points more persuasively to a weighting of 33% rather than 50%”.

112 The opinion is confidential, so I cannot in these reasons set out the detail of counsel’s reasoning that led them so to conclude, for reasons explained above at [26]-[34]. But as the contradictor recognised, questions of the assessment of weightings and related risks are ones that are inherently likely to give rise to reasonable minds differing on the figure that they choose to reflect their risk assessment – or to repeat his words, “the Contradictor recognises weightings cannot be approached with mathematical exactitude and that a margin of appreciation should be allowed for weightings falling within a rational range”.

113 In my view, as the contradictor’s comprehensive and helpful submissions on the point made clear, questions of when causes of action accrue in cases involving facts of the type relevant here, are often not straightforward.

114 In part of his submission that I did not set out above, the contradictor submitted that the Victorian Court of Appeal did not state the law correctly when it said that a cause of action accrues when damage is first suffered, regardless of whether the damage is then discovered or discoverable, and that the true position is much more fact dependent, for reasons explained in detail by Thawley J in Han Jing.

115 Although the contradictor invited me to resolve the legal question thrown up by that submission, among others, I decline to do so. As the contradictor recognised, the true issue here is whether, taking into account the vagaries, uncertainties and intricacies of the relevant law concerning the accrual of a cause of action in cases of this type, the weightings proposed by the applicants are within the appropriate range. In my view, they are.

116 But in any event, courts have long cautioned against deciding limitation questions in the abstract or absent a full hearing. As Mason CJ, Dawson, Gaudron, and McHugh JJ said in Wardley at 533:

We should, however, state in the plainest of terms that we regard it as undesirable that limitation questions of the kind under consideration [s 82 of the Trade Practices Act] should be decided in interlocutory proceedings in advance of the hearing of the action, except in the clearest of cases. Generally speaking, in such proceedings, insufficient is known of the damage sustained by the plaintiff and of the circumstances in which it was sustained to justify a confident answer to the question.

117 In my view, it is equally undesirable to decide an issue such as whether a decision of a superior court is correctly decided in the context of a class action settlement approval application, in particular where the underlying issues are both factually and legally complex.

Group Members who sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015

118 The contradictor’s submission on this point was as follows.

119 Under the proposed weightings a relative weighting of 33% would be applied to those group members who entered into a franchise agreement on or after 21 February 2012 (ie not affected by any limitation issue) but sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015. In other words, the weightings treat the prospects of those who sold or disposed of their franchise before 1 October 2015 the same as those group members who entered Franchise Agreements before 21 February 2012. The contradictor submitted that “this is not rational. The risks associated with the limitation issue are not equivalent to the risks of those selling before 1 October 2015 having suffered no loss”.

120 The contradictor submitted that he had “grave difficulty in understanding how those who sold their franchise prior to 1 October 2015 could have suffered any substantial loss as they were able to sell their franchise under the prevailing Goodwill Formula mechanism unaffected by the events which followed”. The submission continued:

We are aware of no evidence identifying instances where group members who sold prior 1 October 2015 did so for a price significantly less than what they paid for that franchise after 21 February 2012. 7-Eleven (at RS1 [7.2]) appear[ed] to proceed on the hypothesis that those who were able to sell prior to 1 October 2015 can have suffered no loss. In the absence of further explanation and evidence … we find it hard to disagree with this assessment. If that is correct, it is not rational to ascribe a 33% weighting to this cohort. They should have a relative weighting of zero to reflect the very poor prospects of their claims.

121 The applicants countered that the contradictor’s approach was “too simplistic”, and contended as follows: