FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave Funding) Corporation v Hitachi Construction Machinery (Australia) Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 68

ORDERS

COAL MINING INDUSTRY (LONG SERVICE LEAVE FUNDING) CORPORATION Applicant | ||

AND: | HITACHI CONSTRUCTION MACHINERY (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD (ACN 000 080 179) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to agreeing upon the form of the orders to be made by the Court to give effect to the reasons published today, and in the event of agreement, submit the orders to the Court where they will be made in their absence.

2. In the absence of agreement on the form of the appropriate orders by 17 February 2023:

(a) the applicant file and serve by 4pm (AEDT) on 17 February 2023 the form of orders it proposes to give effect to the Court’s judgment today;

(b) the respondent file and serve by 4pm (AEDT) on 22 February 2023 the form of orders it proposes to give effect to the Court’s judgment today.

3. The matter be adjourned until 28 February 2023 for consideration of the orders to be made and the subsequent timetabling of the remainder of the matter.

4. There be liberty to the parties to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 This application concerns whether the applicant (Coal LSL), a federal statutory corporation which administers the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) scheme (LSL scheme) is entitled to declaratory relief (relating to four employees of the respondent (Hitachi)) and the ordering of pecuniary penalties against Hitachi by reason of it having failed to pay the relevant levy associated with the accrual of long service leave to the applicant in respect of four employees of the respondent.

2 The applicant is responsible for the administration of the following legislation: the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Payroll Levy Act 1992 (Cth) (the Levy Act), the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Payroll Levy Collection Act 1992 (Cth) (the Collection Act), and the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Administration Act 1992 (Cth) (the Administration Act) (collectively referred to as the Scheme).

3 The Scheme constitutes a unique long service leave arrangement for the black coal mining industry whereby an employee accrues long service leave based on an employee’s service in that industry, rather than service with a particular employer.

4 The four relevant employees, who are the subject of the application, held the following positions with the respondent over the following periods:

Employee | Period employed by the Respondent | Role held | Where work performed |

Mr Garland | May to mid-June 2010 | Mechanical Fitter – performing bench repair work on dump truck “final drive” components | Muswellbrook branch |

June 2010 until Feb 2014, Nov 2017 until Dec 2020 | Mechanical Fitter – performing maintenance and repair work on Hitachi mining equipment | At various black coal mine sites | |

Feb 2014 until Nov 2017 | Shift Coordinator – supervise crews performing maintenance and repair work on the hydraulic loading shovel and dump trucks | At or about the Liddell mine (save for two months at the Glendell mine) | |

Mr Gee | Jan 2011 to Nov 2019 | Fitter – performing maintenance and repair work on Hitachi equipment | At or about the Liddell Mine (save for six months between 2016 and 2017 at the Glendell mine) |

Mr Stair | March 2014 to date | High voltage electrician (April 2014 to about 2019), maintaining and repairing hydraulic loading shovel and dump trucks and then from 2019 as a Team Leader of other employees and continuing to maintain and repair work on the hydraulic loading shovel and dump trucks. | At or about the Liddell mine |

Mr Cooper | April 2010 to Dec 2020 | Mechanical Fitter – performing maintenance and repair work on Hitachi mining equipment | At various black coal mining sites |

5 The respondent’s enterprise involves supplying new and used earthmoving and materials handling equipment, and after-sales maintenance support, to customers in a wide range of industries, including the black coal mining industry. Part of the reason for the disagreement between the parties, regarding the respondent’s employees being covered by this legislative scheme, is that the work the relevant employees were performing for the respondent’s black coal mining clients comprises only 2.6% of the total annual revenue of Hitachi’s enterprise. The respondent operates through a network of branches across Australia grouped into four geographical regions, the Eastern region being where the relevant employees were employed. The relevant Muswellbrook branch derives most of its revenue from black coal mining given its geographical location. By contrast, the Western region derives most of its revenue from iron ore mining.

6 The evidence in chief of all witnesses was given by affidavit.

7 The applicant led evidence from each of the relevant employees together with evidence from Mr Trent Sebbens, solicitor for the applicant. None of the applicant’s witnesses were required for cross-examination.

8 The respondent led evidence from Mr Stephen Smith (solicitor for the respondent), Mr Richard Trench (Service Manager), Mr Jason Gleeson (Regional General Manager – Eastern) and Mr Ricardo Moledo (Director – Product Support). Only Mr Gleeson and Mr Moledo were required for cross-examination. Whilst there are differences in the evidence of the witnesses, I am of the view that each witness gave their evidence honestly and endeavoured to assist the Court.

9 The first stage of the hearing, and for which these reasons are confined, concerns first questions of liability; and secondly the applicability of s 14(1)(d) of the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW).

10 The question of liability concerns whether the relevant employees comprise “eligible employees” within the meaning of s 4 of the Administration Act as follows:

eligible employee means:

(a) an employee who is employed in the black coal mining industry by an employer engaged in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine (limb (a)); or

(b) an employee who is employed in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are carried out at or about a place where black coal is mined and are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine (limb (b)); or

(c) an employee permanently employed with a mine rescue service for the purposes of the black coal mining industry; or

(d) a prescribed person who is employed in the black coal mining industry;

but does not include a person declared by the regulations not to be an eligible employee for the purposes of this Act.

(Descriptions for limbs (a) and (b) added; Emphasis in original.)

The three issues to be determined

11 The parties agree that there are three issues which require determination in these proceedings:

(1) Whether the relevant employees were “eligible employees” within limb (b) of the s 4 definition above, because they:

(a) were employed in the black coal mining industry;

(b) carried out their duties at or about a place where black coal is mined; and

(c) had duties which were directly connected with the day-to-day operation of a black coal mine.

(2) Whether the relevant employees were “eligible employees” within limb (a) of the s 4 definition above, because they:

(a) were employed in the black coal mining industry;

(b) were employed by an employer engaged in the black coal mining industry; and

(c) had duties directly connected with the day-to-day operation of a black coal mine.

(3) Whether any recovery of outstanding levies is subject to the limitation period prescribed in s 14(1)(d) of the Limitation Act.

12 For the reasons which follow, I conclude the following:

(1) The four employees were eligible employees within limb (b);

(2) The four employees were not eligible employees within limb (a); and

(3) The outstanding levies are not subject to the limitation period prescribed in s 14(1)(d) of the Limitation Act because the Scheme covers the field. If I had been required to, I would have found in the alternative that ss 10(3) applied and 18 of the Limitation Act did not apply.

13 The Commonwealth scheme for long service leave in the coal mining industry was first introduced in 1949 by way of the following legislation: the States Grants (Coal Mining Industry Long Service Leave) Act 1949 (Cth); Coal Excise Act 1949 (Cth); complementary legislation in participating States; and amendments to the Excise Tariff Act 1921 (Cth). The scheme then granted long service leave benefits to black coal miners under Federal awards made by the previous Coal Industry Tribunal. The scheme was operated by the Commonwealth collecting an excise per tonne of coal produced, and making grants to participating States for the reimbursement of employers.

14 In 1991, the scheme underwent substantial review leading to the introduction of the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave Funding) Act 1992 (Cth) (as the Administration Act was then called), the Levy Act, and the Collection Act, as well as the Coal Tariff Legislation Amendment Act 1992 (Cth) providing for the removal of the long service leave component of the excise duty on coal. It was at this time that the applicant was established, and entitlements were funded by an employer levy scheme, whereby a levy was imposed on wages paid to employees, and employers were reimbursed by the relevant State which was in turn reimbursed by a trust fund. Entitlements to long service leave under this scheme arose from Federal industry awards. Part of the reason for the imposition of the levy, as contained in the Explanatory Memorandum, Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Funding) Bill 1992, was by reason of the identification of a number of deficiencies within the Scheme including a $250.2 million unfunded liability for untaken long service leave as at 30 June 1990.

15 The Coal Act 1992 defined, in s 4, an “eligible employee” to mean:

(a) a person employed in the black coal mining industry under a relevant industrial instrument the duties of whose employment are carried out at or about a place where black coal is mined; or

(b) a person employed by a company that mines black coal the duties of whose employment (wherever they are carried out) and are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine; or

(c) a person permanently employed on a full-time basis in connection with a mine rescue service for the purposes of the black coal mining industry the duties of whose employment require him or her to be located at a mines rescue station; or

(d) any prescribed person who is, or is any person who is included in a prescribed class of persons who are, employed in the black coal mining industry;

but does not include:

(e) a person the duties of whose employment are performed in South Australia; or

(f) a person who is, or a person who is included in a class of person who are, declared by the regulations not be an eligible employee or eligible employees for the purposes of this Act.

16 Notably, the Coal Act 1992 did not require that the eligible employee be covered by a “relevant industrial instrument” in the “black coal mining industry”, given the employee could be covered by sub-ss (b) to (d). However, as a matter of substance, in large measure, the only other available source of entitlement came from sub-s (b) which required that the employer be limited to “a company that mines black coal the duties of whose employment (wherever they are carried out) and are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine”. It also did not contain a definition of “black coal mining industry”. Whilst an employee did not need to be employed in the “black coal mining industry”, they did need to be employed by “a company that mines black coal” (a more restrictive definition than in the current legislation).

17 From the commencement of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the FW Act) on 1 January 2010, Federal industry awards were superseded by modern awards under the FW Act. The FW Act precluded modern awards from containing long service leave terms, but existing award-based entitlements were preserved as a statutory entitlement under the National Employment Standards, pending development of national long service leave arrangements: ss 113, 155 of the FW Act.

18 By the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave Funding) Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) (2009 Amendment Act), provision was made to ensure that employers were entitled to reimbursement from the fund in respect of long service leave payments they made to employees pursuant to the preserved entitlements in the FW Act: s 44(3) of the Coal Act 1992 (as at 1 January 2010).

19 Notably, the 2009 Amendment Act amended the definition of “eligible employee” and introduced a definition of “black coal mining industry”, both of which have operated at all relevant times and continue to operate.

20 The 2009 Amendment Act amended the definition of an “eligible employee” to comprise:

(a) an employee who is employed in the black coal mining industry by an employer engaged in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine; or

(b) an employee who is employed in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are carried out at or about a place where black coal is mined and are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine; or

(c) an employee permanently employed in a mine rescue service for the purposes of the black coal mining industry; or

(d) a prescribed person declared by the regulations not to be an eligible employee for the purposes of this Act.

21 Accordingly, by reason of the FW Act amendments, a person could no longer fall within the definition of “eligible employee” by virtue of being covered by “a relevant industrial instrument”. Sub-section (a) was amended and replaced by a broader definition replacing the previous sub-ss (a) and (b).

22 However, the definition of “eligible employee” picked up, in part, the definition of “coal mining employees”, from cl 4.1(b) of the Black Coal Mining Industry Award 2010, the coverage provision in the Award. Clause 4.1 is extracted in full as follows:

4.1 This award applies to:

(a) employers of coal mining employees as defined in clause 4.1(b); and

(b) coal mining employees.

Coal mining employees are:

(i) employees who are employed in the black coal mining industry by an employer engaged in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine and who are employed in a classification or class of work in Schedule A—Production and Engineering Employees or Schedule B—Staff Employees of this award;

(ii) employees who are employed in the black coal mining industry, whose duties are carried out at or about a place where black coal is mined and are directly connected with the day to day operation of a black coal mine and who are employed in a classification or class of work in Schedule A—Production and Engineering Employees or Schedule B—Staff Employees of this award.

(Emphasis in original.)

23 Furthermore, the 2009 Amendment Act inserted a definition of “black coal mining industry” and is now defined as follows:

black coal mining industry has the same meaning as in the Black Coal Mining Industry Award 2010 as in force on 1 January 2010.

24 The Award defined, in cll 4.2 and 4.3, the “black coal mining industry” to have:

4.2 … the meaning applied by the courts and industrial tribunals, including the Coal Industry Tribunal. Subject to the foregoing, the black coal mining industry includes:

(a) the extraction or mining of black coal on a coal mining lease by means of underground or surface mining methods;

(b) the processing of black coal at a coal handling or coal processing plant on or adjacent to a coal mining lease;

(c) the transportation of black coal on a coal mining lease; and

(d) other work on a coal mining lease directly connected with the extraction, mining and processing of black coal.

4.3 The black coal mining industry does not include:

(a) the mining of brown coal in conjunction with the operation of a power station;

(b) the work of employees employed in head offices or corporate administration offices (but excluding work in town offices associated with the day-to-day operation of a local mine or mines) of employers engaged in the black coal mining industry;

(c) the operation of a coal export terminal;

(d) construction work on or adjacent to a coal mine site;

(e) catering and other domestic services;

(f) haulage of coal off a coal mining lease (unless such haulage is to wash plant or char plant in the vicinity of the mine); or

(g) the supply of shotfiring or other explosive services by an employer not otherwise engaged in the black coal mining industry.

NOTE: See, for example, decision of the Coal Industry Tribunal in Australian Collieries Staff Association and Queensland Coal Owners Association – No 20 of 1980, 22 February 1982 [Print CR 2997].

(Emphasis in bold in original; Emphasis in underline added.)

25 Justice White considered comprehensively, in Bis Industries Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2021] FCA 1374, at [43]–[75], the many court and tribunal decisions, before 2008 (when the Award was modernised and included reference to the meaning of “black coal mining” having the “same meaning” as those prior decisions). His Honour made a number of conclusions which could be drawn from those authorities about the term “black coal mining industry” and employment in that industry, at [76], which is extracted as follows:

This review of the authorities suggests that the following conclusions may be drawn about the term “black coal mining industry” and employment in that industry:

(a) the terms “coal mining industry” and “black coal mining industry” are not capable of clear definition: Drake-Brockman per Starke J at 59; R v Hickman at 614 (Dixon J). The difficulty of definition is reflected in cll 4.2 and 4.3 of the Black Coal Award;

(b) the industry is the production of black coal by mining operations. Those operations include the excavation of the coal from the seam; its removal from the pit; and the placement of coal on the surface in disposable form: Drake Brockman per Latham CJ at 56. This seems to be reflected in cl 4.2(a) of the Black Coal Award which states that the industry includes the extraction or mining of black coal on a coal mining lease by means of underground or surface mining methods;

(c) the industry does not include all the forms of subsequent processing, treatment or use of black coal (Drake-Brockman at 56) but does include its processing at a coal handling or processing plant on or adjacent to a coal mining lease (cl 4.2(c));

(d) the industry does include the transportation of black coal on a coal mining lease (cl 4.2(c)) but not the haulage of the coal away from the mine site: R v Hickman;

(e) the mere fact that the activities are carried on at a mine site does not necessarily mean that they are undertaken in the coal mining industry;

(f) correspondingly, the fact that activities in connection with coal mining operations are carried on at locations geographically separate from the coal mine will not necessarily mean that the activities are not part of the coal mining industry;

(g) the control exercised by the mine operator of the work is an important consideration (Thiess Repairs; Transfield Services; CQ Industries);

(h) whether particular employment is in the black coal mining industry is to be determined as a question of fact by consideration of the “substantial character” of the industrial enterprise in which the employer and the employee are concerned (Thiess Repairs per Latham CJ at 130-1, 135; Poon Bros Case at 454-5) and by consideration of the degree of connection or separateness between the activity in question and the mining operations (Thiess Repairs per Dixon J at 140-1; Colliery Staff Case at 16; Central West at [50]); and

(i) some activities associated with coal mines have not been regarded as part of the coal mining industry. These include:

(i) the haulage of the coal by an independent contractor from the mine to an offsite location: R v Hickman and see cl 4.3(f);

(ii) the maintenance of equipment used in a mine by employees of an entity separate from the mine operator which is undertaken in a workshop separate from, but adjacent to, the mine: Thiess Repairs; Transfield Services; and

(iii) the provision of catering and cleaning services to mining companies by the employees of independent contractors: Poon Bros Case at 454-5; Re Spotless and see cl 4.3(e).

(Emphasis in original.)

26 The Explanatory Memorandum, Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave Funding) Amendment Bill 2009 (Cth) described the purpose of the amendments to the Scheme to include, inter alia:

… to ensure that the scheme applies universally in the black coal mining industry from 1 January 2010:

• the definition of ‘black coal mining industry’ in the Funding Act (which flows through to related legislation) will be aligned with the definition in the Coal Award; and

• the current long service leave entitlements in the Coal Mining Industry (Production and Engineering) Consolidated Award 1997 (the main industry award) will be extended to all eligible employees who do not otherwise have an award-derived long service leave entitlement.

27 By the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Amendment Act 2011 (Cth) (2011 Amendment Act), the Scheme and the 2009 Amendment Act were further amended to provide a minimum long service leave entitlement for all eligible employees, establish a regime for transition from the Federal industry award-derived long service leave scheme, and rename the Administration Act to its present name. The statutory scheme has not relevantly changed since 2011.

28 The regime for transition from the Federal industry award-derived LSL scheme (preserved under s 113 of the FW Act in respect of award employees) also extended the scheme’s operation to non-award employees by Sch 2 of the 2009 Amendment Act to the new statutory LSL scheme established by the 2011 Amendment Act.

29 Additionally, the 2011 Amendment Act provided greater powers to Coal LSL for the purposes of ensuring compliance with the scheme. These powers included the power to require persons to produce information or documents and standing to pursue alleged contraventions of a civil penalty provision on behalf of the Commonwealth (explained further below).

30 The 2011 Amendment Act also renamed the Administration Act to its present name (the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Administration Act 1992 (Cth)).

Relevant legislative provisions

31 Entitlements to long service leave are prescribed under Pt 5A of the Administration Act. These entitlements are based on aggregate “qualifying service” as an “eligible employee” (s 39A(2) of the Administration Act).

32 Periods of unauthorised absence and certain periods of “unpaid leave” or “unpaid unauthorised absence” are excluded for the determination of qualifying service (s 39A(2) of the Administration Act). The service does not need to be continuous but may be aggregated in one or more period(s), with the long service leave entitlement arising based on cumulative service of 8 years, except if a break between periods of qualifying service is for a continuous period of 8 years of more (s 39A(4) of the Administration Act). Section 39A provides:

Part 5A—Entitlement to long service leave

Division 1—Entitlement, amount and grant etc.

39A Entitlement to long service leave

General rule

(1) If an eligible employee completes a period of qualifying service that is, or periods of qualifying service that add up to, at least 8 years, the employee is entitled to long service leave under this Part in respect of that period, or those periods, of qualifying service.

Meaning of qualifying service

(2) A period of qualifying service by an employee is a period during which the employee is an eligible employee of one or more employers, but does not include any of the following:

(a) a period of unauthorised absence;

(b) a period of unpaid leave or unpaid authorised absence, other than:

(i) a period of absence under Division 8 of Part 2-2 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (which deals with community service leave); or

(ii) a period of stand down under Part 3-5 of the Fair Work Act 2009, under an enterprise agreement that applies (within the meaning of that Act) to the employee, or under the employee’s contract of employment; or

(iii) a period during which the employee is absent from work because of a personal illness, or a personal injury, for which the employee is receiving compensation under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory that is about workers’ compensation or under an industrial instrument; or

(iv) a period of leave or absence of a kind prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this paragraph;

(c) if the employee ceases to be an eligible employee for a continuous period (a break period) of 8 years or more—any period before the break period during which the employee was an eligible employee;

(d) any period during which a waiver agreement is in effect between the employee and an employer;

(e) any other period of a kind prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this paragraph.

(3) For the purposes of subsection (2), if a casual employee is an eligible employee at any time during a week, the employee is taken to have been an eligible employee for the whole week.

Effect of break period once entitled to long service leave

(4) If:

(a) an employee ceases to be an eligible employee for a continuous period of 8 years or more; and

(b) at the time of so ceasing, the employee is entitled to long service leave under subsection (1) in respect of a period, or periods, of qualifying service (the employee’s previous qualifying service); and

(c) the employee becomes an eligible employee again;

paragraph (2)(c) does not apply in respect of the employee’s previous qualifying service.

(Emphasis in orginal.)

33 An eligible employee is entitled to 13 weeks leave for each 8 years of aggregate “qualifying service” in the black coal mining industry (ss 39A and 39AA of the Administration Act). The entitlement to leave is calculated in hours based on the working hours of the employee (s 39AA(2) of the Administration Act). Section 39AA provides:

39AA Amount of long service leave

(1) The number of hours of long service leave that an eligible employee is entitled to for a week of qualifying service completed by the employee is worked out using the formula in subsection (2).

(2) The formula is:

where:

working hours means:

(a) if the employee is a full-time employee at all times during the week—35 hours; or

(b) if the employee is a part-time employee at any time during the week—the lesser of the following amounts (or either of them if they are equal):

(i) the total number of ordinary hours of work of the employee as a part-time employee for the week;

(ii) 35 hours; or

(c) if the employee is a casual employee at any time during the week and paragraph (b) does not apply—the lesser of the following amounts (or either of them if they are equal):

(i) the total number of hours worked by the employee as a casual employee during the week;

(ii) 35 hours.

(Emphasis in original.)

34 Employees may apply for, and employers are required to grant, long service leave (subject to providing a written response if it is not to be granted) (s 39AB of the Administration Act). The leave must be taken in spells of no less than 14 days (s 39AB(2) of the Administration Act). An employee who takes long service leave is to be paid by their current employer for the period of long service leave taken (s 39AC of the Administration Act). The payment for the period of leave is equal to the base rate of pay, plus incentive-based payments and bonuses, that would have been payable during the period if the person was not on leave (s 39AC of the Administration Act).

35 The qualifying service and leave entitlements (which are recorded as “LSL credits”) of the eligible employee are recorded by the applicant (ss 7(da) and 39AB(5) of the Administration Act).

36 Section 39AB of the Administration Act provides:

39AB Grant of long service leave

(1) An eligible employee may apply, in writing, to his or her employer to take a period of long service leave.

(2) The employee may only apply to take a period of long service leave that:

(a) is a single continuous period of at least 14 days (being equivalent to a number of hours of long service leave as agreed with the employer); and

(b) does not exceed the employee’s LSL credit at the time the leave is to be taken.

Note: An employee is taken not to be on long service leave on public holidays and during certain other periods of absence (see section 39AE).

(3) As soon as practicable, but no later than 14 days after the application is made, the employer must give the employee a written response:

(a) stating whether or not the employer grants the long service leave; and

(b) if the employer refuses to grant the long service leave—giving details of the reasons for the refusal.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(4) The employer may refuse to grant long service leave only on reasonable business grounds.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

Meaning of LSL credit

(5) For the purposes of this section, the long service leave credit (LSL credit) of an eligible employee on a day (the calculation day) is the number of hours worked out as follows:

(a) first, add together the number of hours of long service leave that the employee is entitled to under section 39AA for each week of qualifying service completed by the employee before the calculation day;

(b) then, subtract the number of hours of long service leave (if any) previously granted to the employee under this section.

Note 1: The number of hours of long service leave that an employee is entitled to in respect of certain qualifying service may be affected by section 39CE.

Note 2: Division 4 of this Part provides other remedies for contraventions of civil penalty provisions.

(Emphasis in original.)

37 Employees may also be paid for long service leave if they cease to be an “eligible employee”, that is they are no longer employed in the black coal mining industry (s 39C of the Administration Act), and also in circumstances of ill health and retirement, redundancy, and death if relevant requirements are met (ss 39CA, 39CB and 39CC of the Administration Act).

38 An employer of an eligible employee, who grants leave and makes a payment for that leave, is reimbursed from the Fund for the payment (s 44 of the Administration Act). The reimbursement is made for the amount of long service leave hours (LSL credits) at the amount of eligible wages per hour, that is taken (cl 9 Employer Reimbursement Rules 2017 (Cth)). The calculation of eligible wages per hour is done by considering those hours the eligible employee received immediately before taking the leave, or if no longer employed then the amount immediately before the person left the employment (cl 9(1) Reimbursement Rules).

39 Accordingly, while an employer contributes a levy based on eligible wages for each month the eligible employee is employed, they will be reimbursed at the rate for the eligible wages at the time they are taken. The Fund is “pooled”, however the quantum of levy that an employer may have contributed for a particular eligible employee is not the same as the quantum of reimbursement that is made to the employer that grants and pays the leave. The amounts of levy contributed and the amounts which are reimbursed do not correspond.

40 The entitlements to long service leave under the Administration Act operate as “safety net” employment entitlements. The entitlements operate to the exclusion of provisions of the FW Act and State and Territory laws that deal with long service leave (ss 39E and 39EA of the Administration Act). Employees and employers may, however, agree to more generous entitlements under an industrial instrument (such as a modern award or enterprise agreement made under the FW Act) (s 39EB of the Administration Act). Sections 39E and 39EA provide:

Division 5—Relationship with other laws and industrial instruments

39E Relationship with the National Employment Standards

Despite section 61 of the Fair Work Act 2009, this Part applies in relation to eligible employees and their employers to the exclusion of Division 9 of Part 2-2 of that Act.

39EA Relationship with State and Territory long service leave laws

This Part applies in relation to eligible employees and their employers to the exclusion of a State or Territory law that deals with long service leave.

(Emphasis in original.)

41 Employers of “eligible employees” have a separate obligation to pay a levy under s 4 of the Levy Act, which the applicant submitted is “symbiotic with the obligation to grant and pay leave”:

Levy is imposed on eligible wages paid to eligible employees after the commencement of this Act.

42 The rate of the levy is prescribed as a percentage of the ‘eligible wages paid’, currently 2%: s 5 of the Levy Act; reg 6 of the Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave) Payroll Levy Regulations 2018 (Cth).

43 Importantly, liability for the levy rests with the “person who paid those wages”: s 6 of the Levy Act.

44 The Collection Act provides for the due date of payment of the levy and that an additional levy is payable by way of penalty if an amount of levy is not paid:

Subject to section 6, levy in respect of eligible wages paid to eligible employees for their employment during a month is payable at the end of the period within which a return is required by this Act to be made in respect of that month.

…

(1) If any levy remains unpaid on any day after the time when it became payable, or would apart from section 6 have become payable, additional levy is payable by way of penalty by the person liable to pay the levy, at the percentage applicable under subsection (2) in respect of that day, on the amount unpaid, computed from that time or, if under section 6 the Corporation has granted an extension of time for payment of the levy or has permitted payment of the levy to be made by instalments, from such date as the Corporation determines, not being a date before the date on which the levy was originally payable.

(2) The percentage applicable in respect of a day is 2 percentage points above the maximum indicator interest rate for that day, where:

maximum indicator interest rate, in relation to a day, means the higher or the highest, as the case may be, of the range of rates of interest per annum current on that day quoted by the Reserve Bank, on the basis of reports by each bank regarded by the Reserve Bank as a major trading bank operating in Australia, in respect of overdrafts of $100,000 or more.

(3) If judgment is given by, or entered in, a court for payment of:

(a) an amount of levy; or

(b) an amount that includes an amount of levy;

then:

(c) the levy is not taken, for the purposes of subsection (1), to have ceased to be payable merely because of the giving or entering of the judgment; and

(d) if the judgment debt carries interest, the additional levy that would, apart from this paragraph, be payable under this section in relation to the levy is, by force of this paragraph, reduced by:

(i) in a case to which paragraph (a) applies—the amount of the interest; or

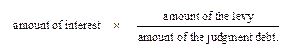

(ii) in a case to which paragraph (b) applies—the amount worked out in accordance with the formula:

(4) In this section:

bank includes, but is not limited to, a body corporate that is an ADI (authorised deposit-taking institution) for the purposes of the Banking Act 1959.

(Emphasis in original.)

45 For the purpose of determining the “eligible wages” of the “eligible employee” for which the levy is payable, the “eligible wages” comprise:

(a) For non-casual employees paid a base rate of pay (which has the same meaning as under the FW Act: s 3 of the Collection Act), the greater of:

(i) the “base rate of pay” including incentive-based payments and bonuses; or

(ii) 75% of the base rate of pay including incentive-based payments, bonuses, overtime and penalty rates and allowances (other than those for reimbursement of expenses) (s 3B(1) of the Collection Act);

(b) For non-casual employees paid an annual salary, the annual salary including incentive-based payments and bonuses, but excluding overtime, penalty rates and shift-loadings (s 3B(2) of the Collection Act); or

(c) For casual employees, the base rate of pay including incentive-based payments and bonuses (s 3B(3) of the Collection Act).

46 Section 9 of the Collection Act provides that the levy is a debt due to the Commonwealth:

9 Recovery of levy or additional levy

(1) An amount of levy, or an amount of additional levy under section 7, is a debt due to the Commonwealth, and payable:

(a) if the Corporation has given written notice to the person who is liable to pay the amount that a person specified in the notice is authorised, in lieu of the Corporation, to receive such an amount—to the specified person in such manner as is prescribed by the regulations or, if there are no such regulations, as that person directs; or

(b) otherwise—to the Corporation in such manner as is prescribed by the regulations or, if there are no such regulations, as the Board directs.

(2) An amount of levy, or an amount of additional levy under section 7, that is payable but has not been paid may be sued for and recovered by the Corporation or by the other person (if any) to whom the amount is payable, as the case may be, in any court of competent jurisdiction.

(3) The annual report prepared by the Board and given to the Minister under section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 for a period must include particulars of:

(a) any amounts paid to, or recovered by, the Corporation or another person under this section during the period; and

(b) any proceedings brought by the Corporation to recover an amount under subsection (2) during the period.

(Emphasis in original.)

47 In addition to the payment of the levy, employers of eligible employees must submit “returns”, and also annual audited reports to the applicant, confirming that the levy has been paid, pursuant to ss 5 and 10 of the Collection Act:

(1) A person who employs an eligible employee at any time during a month must, within 28 days after the end of that month, make a return in accordance with subsection (2) in respect of that month.

Civil penalty: 40 penalty units.

(2) A return for the purposes of this section:

(a) must be made:

(i) if the Corporation has given written notice to the person who is required to make the return that a person specified in the notice is authorised, in lieu of the Corporation, to receive returns under this section—to the specified person in such manner as is prescribed by the regulations or, if there are no such regulations, as that person directs; or

(ii) otherwise—to the Corporation in such manner as is prescribed by the regulations or, if there are no such regulations, as the Board directs; and

(b) must be in accordance with a form approved by the Board; and

(c) must contain such information as is required by that form.

(3) A person commits an offence of strict liability if the person contravenes subsection (1).

Penalty: 30 penalty units.

Note 1: For offences of strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

Note 2: For the physical elements of this offence, see subsection 3A(2) of this Act.

…

10 Requirement to give report to Corporation

(1) If a person employs an eligible employee at any time during a financial year, the person must, no later than 6 months after the end of the financial year, give to the Corporation a report prepared by an auditor that:

(a) states whether, in the opinion of the auditor, the person has paid all amounts of levy, or amounts of additional levy under section 7, that the person was required to pay in respect of the financial year; and

(b) if, in the opinion of the auditor, the person has not paid all amounts of such levy or additional levy—specifies in what respect and to what extent, in the opinion of the auditor, the person has not paid those amounts; and

(c) if, during the financial year, the person was paid an amount under Part 7 of the Administration Act—states whether, in the opinion of the auditor, the amount paid is correct; and

(d) includes reasons for the opinions contained in the report.

Civil penalty: 40 penalty units.

(2) A person commits an offence of strict liability if the person contravenes subsection (1).

Penalty: 30 penalty units.

Note 1: For offences of strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

Note 2: For the physical elements of this offence, see subsection 3A(2) of this Act.

48 When an employer makes a payment of long service leave under Pt 5A of the Administration Act to an employee, the employer is entitled to reimbursement from the applicant of the payment made in respect of the long service leave in accordance with the Reimbursement Rules. The basis for this reimbursement can be found in s 44 of the Administration Act and rr 8 to 10 of the Reimbursement Rules, which are extracted as follows:

44 Reimbursement for payments relating to long service leave

(1) If an employer makes a payment under Part 5A to a person who is or was an eligible employee, the Corporation must pay the employer out of the Fund the reimbursable amount the Board decides in accordance with the Employer Reimbursement Rules.

(2) If an employer makes a payment under Part 5A to the legal personal representative of a deceased person who is or was an eligible employee, the Corporation must pay the employer out of the Fund the reimbursable amount the Board decides in accordance with the Employer Reimbursement Rules.

Note: Section 52B provides that an application may be made to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal for review of a decision of the Board under subsection (1) or (2).

…

[Reimbursement Rules]

8 How does the Board decide the reimbursable amount for an employer?

(1) If the Corporation receives a claim from an employer for reimbursement under section 44 of the Act after the commencement of these Rules, the Board must decide the amount the employer is to be reimbursed by calculating that amount in accordance with:

(a) if the employer made a payment under Part 5A of the Act to an eligible employee – Rule 9 of these Rules; or

(b) if the employer made a payment under Part 5A of the Act to an eligible employee’s legal personal representative. – Rule 10 of these Rules.

(2) The Board is not required to deal separately with any part of a claim that relates to pre-2012 entitlements and any part of a claim relating to post-2012 entitlements.

9 How is the reimbursable amount for a payment to an eligible employee calculated?

(1) The reimbursable amount for a payment to an eligible employee is the amount worked out in accordance with the formula:

LSL paid x eligible wages amount per hour

where:

LSL paid means the hours (including any part of an hour) of long service leave entitlement paid for by the employer in respect of an eligible employee, not exceeding the hours of long service leave entitlement (including any part of an hour) recorded by the Corporation with respect to that employee, immediately prior to the date of payment by the employer and not including any hours for which a reimbursement has already been made;

eligible wages amount per hour means the amount per hour of the employee’s eligible wages:

(a) if the employee is employed by the employer at the time the payment is made – immediately before he or she was paid for, or commenced to take, the long service leave, or

(b) if the employee is not employed by the employer at the time the payment is made – immediately before he or she left their employment with that employer.

(2) If the amount calculated under subrule (1) is more than the amount actually paid to the eligible employee in respect of the employee’s long service leave entitlement, the reimbursable amount is taken to be the amount paid to the eligible employee.

10 How is the reimbursable amount for a payment to a legal personal representative calculated?

The reimbursable amount for an employer in respect of a payment made by the employer to an eligible employee's legal personal representative under either section 39C or 39CC of the Act is the amount that would have been the reimbursable amount for the employer if the payment had been made to the eligible employee under Rule 9.

(Emphasis in original.)

49 Mr Stephen Smith, Head of National Workplace Relations Policy for the Australian Industry Group, gave evidence regarding the negotiation and drafting history of the Award. In particular, he made reference to the opposition by the Ai Group and various unions to the inclusion in the Award coverage provision of, inter alia, maintenance and repair service contractors. Mr Smith referred to the comments made by the Full Bench with respect to the proposed Black Coal Award, in the Priority Stage Award Modernisation Decision [2008] AIRCFB 1000 at [156]–[157] that the “goal and intent [of the award]…should neither expand nor contract the reach of the key pre-reform awards both in relation to the kinds of employers to whom those awards apply and the extent to which the awards apply to such employers.” The Full Bench stated that they rejected “submissions that sought to have mechanical and electrical contractors invariably covered by awards other than the modern award for the black coal mining industry”. Paragraphs [156]–[157] were as follows:

156. We have, at this stage, acceded to the main submissions of the CFMEU and the CMIEG in relation to the coverage clause in the exposure draft and have generally reverted to the form of words in the draft clause agreed by the main coal industry parties. We note that the stated goal of the CFMEU and the CMIEG was to achieve a coverage clause that as closely as possible reflects the status quo in terms of the existing application of the key federal pre-reform awards both in relation to the kinds of employers to whom those awards apply and the extent to which the awards apply to such employers. We agree with that goal and intend that the award we have made should neither expand nor contract the reach of the key pre-reform awards both in relation to the kinds of employers to whom those awards apply and the extent to which the awards apply to such employers. It follows that we reject submissions that sought to have mechanical and electrical contractors invariably covered by awards other than the modern award for the black coal mining industry.

157. However, we are concerned that the clause as drafted is not simple to understand nor easy to apply. In particular, contractors who perform some work at or about coal mines may have difficulty in determining whether the award covers them. We acknowledge that significant attempts were made by the parties to agree on a form of words that described the industry in a clear and direct way. We intend to vary cl.4 before the award commences so that it contains a clearer description of the black coal mining industry albeit a description that reflects as closely as possible the status quo. We recognise that the difficulties in developing such a description are substantial and that this should not be done without further consultation with interested parties.

(Emphasis added.)

50 Despite the Australian Industrial Relations Commission recognising the need for greater clarity in the definition, no further refinement was made to the clause before the Award was made. What is telling from this extracted reasoning is that the Commission recognised, contrary to the submission of the Ai Group and others, that contractors performing “some work at or about coal mines” will be covered by the Award and did not engage directly, nor in the terms of the coverage clause define, clear boundaries which would exclude maintenance and repair contractors.

51 Mr Smith referred to attempts thereafter, to achieve greater clarity by the inclusion of the revised Note which the Commission made in its decision The Australian Industry Group [2012] FWA 9606, which is extracted as follows:

“NOTE: The coverage clause is intended to reflect the status quo which existed under key pre-modern awards in relation to the kinds of employers and employees to whom those awards applied and the extent to which the awards applied to such employers and employees.

An example of the types of issues and some of the case law to be considered when addressing coverage matters can be found in Australian Collieries Staff Association and Queensland Coal Owners Association – No. 20 of 1980, 22 February 1982 {Print CR2297} and in the Court decisions cited in this decision.”

52 However, I would observe that the Full Bench of the Commission did not, despite the urging of Mr Smith’s clients and others, narrow the definition of “black coal mining industry” such as to exclude “mechanical and electrical contractors” and specifically “rejected that submission” (as extracted at [49] above). To the extent that there was a “note” inserted later, it did not provide the “clarity” of the kind that the respondent now urges.

53 Mr Moledo, who has been employed by Hitachi for at least 14.5 years and currently holds the position of Director – Product Support of Hitachi, gave evidence as to the nature of Hitachi’s business and described it in the following terms:

(a) Hitachi’s business comprises the supply of “new and used earthmoving and materials handling equipment, and after-sales maintenance support, to customers in a wide range of industries” including inter alia various mining industries (not only the black coal mining industry). None of Hitachi’s branches sell or support machinery exclusively for one industry nor is any branch or workshop located on a mining lease. However, the revenue contribution differs between regions and branches due to the differing prevalence of various industries.

(b) All employees, save for some back office administrative staff, are employed by Hitachi.

(c) Hitachi’s enterprise is operated through company-owned branches, grouped geographically by regions, not by industries (see below at [242]).

(d) The branches are retail outlets which sell Hitachi machines and provide spare parts. Many branches have workshops attached where repair and maintenance services on those machines are provided.

(e) The “vast majority” of Hitachi’s contracts are for the sale of equipment and the supply of spare parts and only some are for service and maintenance.

(f) Hitachi holds three active “Mining related Maintenance and Repair Contracts (MARCs)” nationally, two related to the Liddell Mine and one related to the Boddington Mine. The MARCs provide that Hitachi bills customers on an agreed rate per the hours each machine is used, which covers servicing and schedule repairs, represented as invoiced contract revenue that is held in a central provision account. When service or repair work is required and performed, the relevant branch closes a work order which is then expensed to the provision account. This expense includes costs for labour, parts and other expenses.

(g) the branch expenses to the provision account, including labour, parts and other costs.

(h) Alongside its branch structure, Hitachi operates a centralised Construction Equipment Sales Division and a Mining Sales Division within its head office. The divisions are responsible for purchasing and pricing machinery, and liaising with manufacturing facilities. Hitachi also operates remanufacturing facilities at Muswellbrook, Perth and Brisbane, where parts and components are refurbished to particular specifications.

54 The respondent also relies on evidence of its revenue in the period of the financial years ending 31 March 2020, 2021 and 2022, and in particular Mr Moledo’s evidence that the sale of labour services to the black coal mining industry was only 2.6% of its total sales revenue during that 3 year period.

55 Under cross-examination, Mr Moledo accepted:

(a) that the predominant customers of the Muswellbrook Branch were in the black coal mining industry;

(b) that the Muswellbrook Branch services two large contracts, amongst others, called MARCs, directed to the Liddell mine;

(c) the vast majority of contracts entered into by the respondent, serviced by the Muswellbrook Branch, were for the provision of equipment and services to the black coal mining industry;

(d) the majority of the revenue generated out of the Muswellbrook Branch was from the black coal mining industry;

(e) labour needed to be available to work to a roster dictated by the client maintenance schedule; and

(f) the Muswellbrook Branch needed to employ and retain labour of a sufficient quantity to enable the Muswellbrook Branch to attend to its obligations under the contract.

56 Mr Gleeson, who has been employed by Hitachi for at least 10 years, currently holds the position of Regional General Manager – Eastern and was previously the Muswellbrook Branch Manager, gave evidence on Hitachi’s business in the Eastern region (which includes the Muswellbrook Branch). He described how Hitachi supplies machinery under both the Hitachi and Bell brands. He then described the Eastern region’s revenue from 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022 which comprised sale of construction ($41.4 million) and mining machinery ($21.4 million), service revenue ($109.5 million) including $34.4 million from the Muswellbrook Branch’s MARCs.

57 Mr Trench, who has been employed by Hitachi for at least 10 years and currently holds the position of Service Manager of the Muswellbrook Branch, gave evidence in particular about the proportion of Hitachi’s business that comprises the Muswellbrook Branch (which is the only branch Mr Trench has ever worked at). He described the nature of the Muswellbrook Branch in the following way:

(a) The Muswellbrook Branch supplies Hitachi machinery and spare parts to customers in the Hunter Valley and surrounding areas (including parts of western New South Wales), and provides maintenance on that machinery.

(b) Most of the Muswellbrook Branch’s customers are in the black coal mining industry, however it also supplies and services equipment to customers in the construction, rail, agricultural, plant hire, power and other industries. Insofar as Hitachi’s machinery is used on black coal mine sites, it is only used on open cut mines. Hitachi employees do not go underground in coal mines.

(c) There is a remanufacturing facility located on the same premises as the Muswellbrook Branch but it operates separately.

58 Both Mr Gleeson and Mr Trench gave evidence specifically regarding the relevant employees’ circumstances and responded to their evidence. This evidence is dealt with further below.

59 Mr Trent Sebbens, solicitor for the applicant, gave uncontested affidavit evidence regarding:

(a) online search results regarding how the respondent described its business, and particularly the mining portion of its business;

(b) the applicant’s issuing of a statutory Notice to Produce under s 52A of the Administration Act to the respondent and annexing documents produced by the respondent including an organisational chart and four MARCs; and

(c) the evidence of Mr Smith and in response, identified those Federal awards that had applied before the making of the Award as part of the award modernisation process.

60 Notably, his evidence extracted portions of the earlier coal mining awards which identified employees who were direct respondents in those awards (as they were then required to be) including contractors and service providers.

61 The remainder of the applicant’s evidence comprised the evidence of each of the relevant employees, which is summarised as follows.

62 Mr Garland is a Plant Mechanic who was employed by the respondent for over 10 years from May 2010 to December 2020. During his employment, his terms and conditions were covered by an employment contract (dated 16 April 2010) and a number of enterprise agreements.

63 Mr Garland identified “five distinct periods” in which he worked for the respondent in the following terms:

(a) for approximately six weeks after commencing employment, until about mid-June 2010, I performed work as a Plant Mechanic at Hitachi’s Muswellbrook branch workshop, located at 27-35 Thomas Mitchell Drive, Muswellbrook, New South Wales (Branch Workshop) (Period One);

(b) from about mid-June 2010 until about November 2013, I worked as a Plant Mechanic as part of a “field services” roster at a number of black coal mines in and around the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales (Period Two), see for example, the role recorded in the copy of a Hitachi organisational chart as at 1 July 2010 at Tab 6 of Exhibit BPG-1;

(c) from about November 2013 until about February 2014, I worked as a Plant Mechanic at the Liddell mine (Period Three);

(d) from about February 2014 until about November 2017, I primarily worked as a shift supervisor at the Liddell mine (Period Four); and

(e) from late around 2018 or early 2018 until my employment with Hitachi ended in about December 2020, I returned to working as a Plant Mechanic as part of a “field services” roster at a number of black coal mines in and around the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales (Period Five).

(Emphasis in original.)

64 During Period Two, Mr Garland repaired and maintained mining equipment at a range of black coal mine sites in and around the Hunter Valley region. All work was performed at these sites, save for approximately 1 to 2 shifts per month where no work was required to be performed at a mine site. Mr Garland would only attend the Muswellbrook Branch workshop, to drop off paper work, for safety training purposes and to occasionally collect parts for the machines requiring repair on the mine sites. Mr Garland worked the same shifts as the employees on the relevant mine site. During Period Three, Mr Garland was assigned by the respondent to work at the Liddell black coal mine site and performed the same kind of work as he had performed in Period Two. During Period Four, Mr Garland undertook work as a Shift Coordinator at Liddell, initially allocated to supervise shutdowns and later for the breakdown crew. Whilst his role primarily involved supervision, he did also, on occasion, undertake repair work himself. The work was undertaken on MARC machinery and usually performed at the main workshop on the Liddell mine site. At other times the work was performed “in the field at the mine site or in the mine pit itself”. During Period Five, Mr Garland returned to a “field service role” as a Plant Mechanic, where the work was substantially the same as to that during Period Two.

65 To the extent that his evidence was the subject of challenge (by the respondent through affidavit evidence and where Mr Garland was not required for cross-examination), it was: (a) regarding whether, during Period Two, he was employed as a “Shift Supervisor” or undertook “Shift Coordinator” work and remained employed as a mechanical fitter throughout his employment (nothing turns on this dispute); (b) whilst during Period Two, Mr Garland “worked predominantly at black coal mines”, according to Mr Trench, his job was to perform services for any customers in any industries and at any location to which Hitachi directed him”. According to Mr Trench: “The very same mechanical fitter employed under essentially the same contract and position description to perform exactly the same role in a Field Services team in Western Australia, would probably never set foot on a black coal mine site”; (c) a dispute about whether Mr Garland reported to mine site supervisors in addition to Hitachi supervisors (about which it does not appear ultimately that anything arises); and (d) a dispute as to whether Mr Garland performed “supplementary labour” on mine sites (again nothing turns on it).

66 Mr Gee was employed as a “Field Services Roster Fitter” with the respondent from January 2011 to November 2019. He described his work in the following way (which was unchallenged):

During the time that I worked for Hitachi, I was one of a number of employees of Hitachi who primarily worked on black coal mine sites in and around the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales, to perform or supervise maintenance and repair work on equipment such as excavators, trucks and bulldozers at those mines (being equipment which comprised both Hitachi equipment supplied to those mines, as well as other non-Hitachi equipment at those mines). These persons who worked primarily on black coal mine sites included both Hitachi employees who were based solely at a specific black coal mine, as well as Hitachi employees who formed part of “field service” rosters, whereby they travelled to different black coal mine sites for each roster at the direction of Hitachi management.

67 From about 18 January 2011, Mr Gee performed his duties as a “mechanic” at the Liddell mine site save for short periods at the Branch Workshop and a period of seven months when he worked at the Glendell mine site. At the Liddell mine site, Mr Gee worked in the main maintenance workshop alongside Liddell maintenance crew employees and also performed breakdown duties in the pit. There were three offices for Hitachi employees annexed to the main workshop for the Hitachi Site Manager, Hitachi Team Leader and the Supervisor.

68 There was limited dispute with respect to Mr Gee’s evidence, save by Mr Trench’s affidavit evidence, who disputed amongst other things: (a) whether Mr Gee was “supervised” by the Liddell Maintenance Supervisor (rather than the respondent’s supervisors); (b) the extent to which he was required to repair machinery and equipment other than that which was supplied by the respondent; (c) the extent to which he used Liddell’s tools rather than those of the respondent; (d) the extent to which the client determined what work to be performed under the MARC.

69 Mr Gee was not required for cross-examination.

70 Mr Stair has been employed by the respondent since March 2014 as a High Voltage Electrician. For the first month of his employment, he worked at the Branch Workshop, but thereafter only worked there on a small number of occasions each year, usually to attend safety-related presentations by the respondent. From April 2014, Mr Stair worked at the Liddell mine site performing high-voltage electrician work and his role was to perform the high voltage electrician work on the MARC Machinery at the Liddell site. From September 2019 onwards he also worked as a Team Leader supervising the work of crew members, assessing parts required to undertake work, ordering parts, and assessing whether particular work needed to be carried out on machinery. He described simply the three types of work performed by the respondent’s employees at the Liddell site being “servicing work” according to the servicing schedule, “breakdown work” performed on an as-needed basis and often carried out in the mining pit and “shutdown work”: After each 20,000 hours of use, the Hitachi dump trucks are placed in a “shut down” period during which components are replaced.

71 There was limited dispute with respect to his evidence from the respondent and he was not required for cross-examination.

72 From April 2010 until December 2020, Mr Cooper was employed by the respondent as a mechanical fitter. For approximately three weeks when Mr Cooper was first engaged by the respondent, he attended the Branch workshop. He thereafter predominantly worked as a mechanical fitter under the “field services” roster at a number of black coal mines in the Hunter Valley region, most frequently at the Liddell and Glendell mine sites.

73 He described the nature of his work in the following way:

The nature of the work I was required to perform varied from shift to shift, but broadly I was assigned to perform work of three types at black coal mine sites, being:

(a) assembly of new Hitachi machinery at the mine site to the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) specification (assembly work). I estimate that this comprised approximately 10% of my work;

(b) “rebuilds” of Hitachi machinery, and particularly dump trucks and excavators (rebuild work) that were located on mine sites. I estimate that this comprised approximately 40% of my work; and

(c) general maintenance, servicing and repair work as supplementary or role-replacement labour for the maintenance work teams at different mine sites. I estimate that this comprised approximately 50% of my work.

(Emphasis in original.)

74 There was limited dispute with respect to his evidence from the respondent and he also was not required for cross-examination.

75 A review of each of the relevant employees’ contracts reveals that they are largely identical, with the exception of Mr Stair’s contract which differs from the others in ways which are identified below.

76 The relevant employees’ contracts comprise the following: Their “Position” title is identified, with respect to each employee:

(a) Mr Garland, as “Roster Mechanical Fitter”;

(b) Mr Gee, as “Field Service Roster Fitter 1”;

(c) Mr Stair, as “High Voltage Electrician”; and

(d) Mr Cooper, as “Roster Mechanical Fitter”.

77 Whilst the Position title is identified (and different in each contract as identified in the preceding paragraph), no specific description is given for any of the Positions, save for the Position Description. Each contract provided as follows:

Your position is [XX]. You will be employed on a full time basis.

Your employment is subject to provision of proof of eligibility to work in Australia. You are required to provide proof of eligibility on commencement of employment by way of visa, passport, or birth or citizenship certificate.

Your current duties and responsibilities are contained in the Position Description in Schedule A, attached to this contract. You are also required to carry out other duties reasonably required by the Company that you are skilled and capable of performing. You may also be required to perform duties from time to time for the Company’s Related Entities.

The Company may alter your position, Position Description and responsibility in accordance with the needs of the business. You agree that the terms of this contract continue to apply unless varied in writing in accordance with this contract.

(Emphasis in original.)

78 Each of the employees was required to report to the Field Service Supervisor (save for Mr Stair who was required to report to the Project Manager).

79 The contracts of Messrs Gee, Garland and Cooper identified the “place of work” to be “27-29 Thomas Mitchell Dr, Muswellbrook NSW 2333”, described by each employee as the “Branch workshop” not the black coal mine sites where they in fact worked. Mr Stair’s contract identifies a different address (“27-35 Thomas Mitchell Drive, Muswellbrook NSW 2333”) as his “place of work”. Further each contract provides that the employees could be required “to work at other locations in accordance with the needs of the business” and employees “may be required to undertake intrastate, interstate or overseas travel” in the course of their employment.

80 Mr Stair’s contract also differs from the contracts of the other relevant employees in the following ways:

(a) Mr Stair’s probationary period is for 6 months, whilst the other relevant employees’ period of probation was 3 months. Further, Mr Stair’s contract omits the phrase (included in the other contracts) “[n]ormal qualifying period as legislated still applies”.

(b) Mr Stair’s hourly wage rate was different from that of the other relevant employees. Mr Stair’s wage is paid “with two weeks in arrears”, whilst the other relevant employees’ wages are paid “with one week current wage and one week in advance”.

(c) The “hours” clause in Mr Stair’s contract merely requires him to “be flexible with [his] hours of work patterns to suit either Monday-Friday or different roster arrangements that are in place to meet our business requirements”. However, the other relevant employees are required to work a roster “averaging 42 hours per week over 52 weeks”.

(d) Mr Stair’s “annual leave” clause explicitly excludes Leave Policy HR029 from his contract. This is not the case with the other relevant employees, with their contracts referring to Leave Policy HR029 but not excluding it. Further, Mr Stair’s “annual leave” clause contains a stipulation that requires him to take annual leave in the event that Hitachi has a shut down period, such as over Christmas, whilst the other relevant employees’ contracts do not contain this clause.

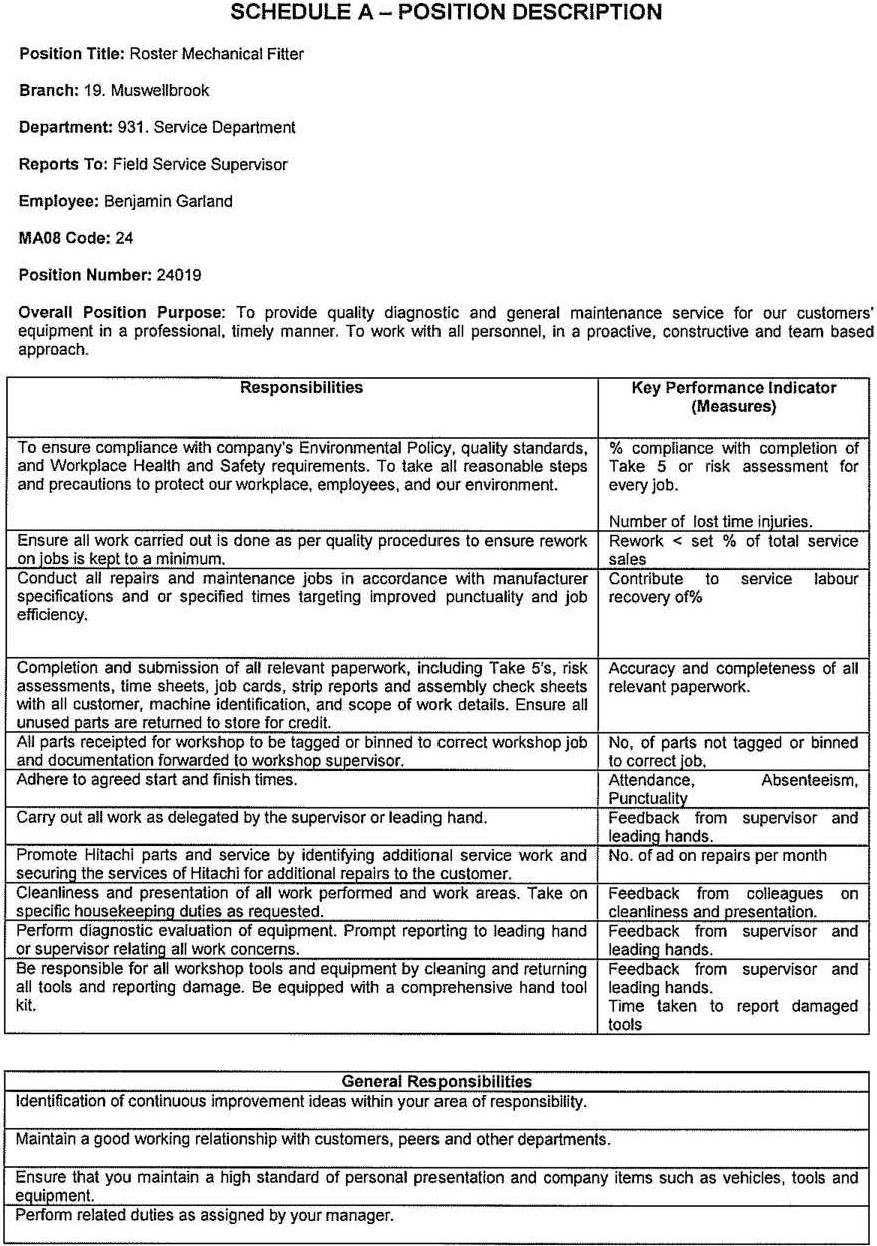

81 The generic “Position Description” is annexed in Schedule A to each contract in identical format. An example of Schedule A from Mr Garland’s contract is extracted as follows:

82 The following aspects of the Position Description are individualised in each contract: the employee’s name and position number, their position title, their department and the person to whom they report.

83 The Position Description then describes generically the “Overall Position Purpose” to be “[t]o provide quality diagnostic and general maintenance service for our customers’ equipment in a professional, timely manner…[and] [t]o work with all personnel, in a proactive, constructive and team based approach” and thereafter provides generic “Responsibilities” and “Key Performance Indicator[s]”.

84 Under the headings “Experience”, “Qualifications” and Customer”, the scant detail was as follows:

Common experience of the employees

85 As can be seen from the foregoing, each of the employees held different positions and worked at different locations on occasion. For example, Mr Stair was the only employee who worked at the Liddell Mine site for the entirety of his employment with the respondent. Messrs Garland, Gee and Cooper were engaged at a number of black coal mines. Mr Gee worked predominantly at the Liddell Mine apart from a short period at the Glendell Mine and in the Branch Workshop. Mr Cooper was engaged as a “mechanical fitter” on a “field services” roster, most frequently at the Liddell and Glendell mine sites.

86 The parties do not descend into the detail of the differing circumstances of each of the employees at each of the mine sites in their submissions so as to then suggest that any of them should be treated differently. They are treated as a homogenous group by both parties.

87 Some of the relevant employees’ evidence is quite detailed and specific as to a particular mine site, for example Mr Stair’s evidence with respect to the Liddell Mine site. However, this evidence has no relevance when determining whether the other relevant employees are “eligible employees” at other mine sites.

88 The evidence revealed the following common experience of the employees:

(a) save for when they were each initially employed (for a month or so) none of the employees worked at the “Location” identified in their contracts, namely the Branch Workshop;

(b) all the employees worked at either one or a range of black coal mine sites as directed by the respondent from time to time, working out of the site workshop or wherever on the mine site the equipment was located; and

(c) their work involved, depending on their skills and qualification, maintenance and repairs (primarily) of Hitachi equipment on the black coal mine sites.

89 The relevant employees were involved in three main forms of work performed at the mine sites being servicing, breakdown and shutdown work as identified at [70] and expanded upon below.

90 Servicing work required an outgoing crew to bring the relevant Hitachi machine into the main workshop at 3:00am and wash the machine in preparation for servicing, then it was for the incoming crew, who commenced the day shift at 6:30am, to carry out the servicing of the machine, which would ordinarily be completed within that day. Hitachi services the equipment based on a servicing schedule contained in documents described at the mine site as Hitachi technical or workshop manuals, which prescribe when machinery requires servicing based on the hours of use of the equipment. As part of the servicing, there are various checks and routine servicing tasks, which include electrical work, cleaning electrical cabinets and software upgrades.

91 Employees of the mine operator Liddell Coal Operations Pty Ltd (LCO) provided work orders to Hitachi planners for defects and upgrades that needed to be completed during the planned service. The work orders were done by way of a service sheet. If specific parts required servicing, or damage needed to be repaired that was not covered by the MARCs, Hitachi completed a specific work order for those relevant repairs/services and charged Glencore in addition to the usual MARC fees.

92 Broadly speaking, servicing work involved checking all functions of the machine, the movement in the machine’s pins as well as the machine’s steering, struts and suspension. The machine’s oil, oil filters, and hydraulic steering filters were changed. Replacement oil was provided by LCO, and grease screens were also cleaned. The relevant machine was also inspected to determine whether there were any cracks or oil leaks, which, if identified, were repaired.

93 Breakdown work comprises, as the nomenclature indicates, maintenance work where Hitachi equipment has broken down. Hitachi crew members are assigned to assist with breakdowns and usually work a 24/7 roster. Breakdown work is performed on an as-needed basis and is often carried out in the mining pit if it is not possible to move the relevant machinery. LCO maintains a two-way radio which is utilised to notify the service crews of breakdowns.

94 A breakdown crew consisted of a fitter and electrician, who travelled in a utility vehicle to the broken machine. The repairs were supervised by the LCO Mine Supervisor, and LCO employees often assisted with repair work.

95 Shutdown work occurs after each 20,000 hours of use of particular equipment. The Hitachi dump trucks are placed into a shutdown period during which components are replaced. The dump trucks are transported to the Hitachi workshop at Muswellbrook for this to occur and this process could take two to three weeks to complete. Mr Stair described mini-shutdowns, where major components of machinery were replaced, often during the night shift. Mr Gee gave evidence that shutdown work on dump trucks could take one month for each truck.

96 Mr Gee gave evidence that shutdown work usually occurred on site, however he recalled an occasion when dump trucks were returned to the Hitachi workshop.

97 Mr Garland gave evidence of what shutdown work entailed with respect to a “haul truck”. Shutdown work for a “haul truck” required removing the engine, pumps, final drives, axle drives and front hubs. These items were sent to the Branch workshop to be refurbished. The truck was then stripped down to its chassis, reassembled, and delivered. Any defects identified during this work were fixed. This work was predominantly performed by Hitachi employees, however sometimes fitters and mechanics engaged by the relevant mine site assisted with this work.

98 The uncontested evidence was that the relevant Hitachi machinery maintained by the relevant employees on the mine sites was ordinarily used to remove overburden and not black coal. Overburden comprises the material above the coal seam which needs to be removed from an open cut mine in order to gain access to the coal. In this case, the uncontested evidence was that the overburden was moved (using Hitachi machinery) to a dump located elsewhere on the mine site, which was usually an area that has already been excavated and mined and was being backfilled.

99 The respondent’s business included a “Field Service” team attached to each branch in each region of its business. Mr Gleeson and Mr Trench gave evidence as to the nature of the Field Service team, with Mr Trench’s evidence more specific to the team at the Muswellbrook Branch.

100 Mr Gleeson describes the Field Service team as responsible for servicing Hitachi equipment for customers “in the field” at customer sites.

101 Mr Gleeson identified the range of disciplines in the Field Service team who support all equipment types. However, the type of equipment differed based on the branch location as some machines are more commonly used in particular branch locations. Hitachi service technicians carry out assembly and commissioning work at the workshop or in the field (depending on the size and type of the machine) and these technicians are often involved in warranty work and ongoing maintenance.

102 Mr Gleeson described the work carried out by the Field Service Team in the Eastern region as comprising:

(a) Hitachi machinery assembly in Hitachi’s assembly yard at Muswellbrook;

(b) Hitachi machinery assembly in branch workshops (mostly for smaller machines);

(c) Hitachi machinery assembly on customer sites (for larger machines);

(d) commissioning and warranty work for Hitachi machinery on customer sites;

(e) maintenance and repair work on Hitachi machinery on customer sites;

(f) repairing Hitachi components and parts at branch workshops; and

(g) planned shutdown work involving replacing components at certain times.

103 Mr Trench further described the Muswellbrook Field Service team as follows: