Federal Court of Australia

Brick Lane Brewing Co Pty Ltd v Torquay Beverage Co Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 66

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | TORQUAY BEVERAGE COMPANY PTY LTD First Respondent BETTER BEER COMPANY PTY LTD Second Respondent MIGHTY CRAFT LTD Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding.

3. There be liberty to apply for a variation of order 2 within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[3] | |

[11] | |

[22] | |

[28] | |

[28] | |

[38] | |

[42] | |

[50] | |

Development, promotion, sale and reputation of the Sidewinder range | [50] |

[65] | |

[75] | |

The circumstances in which the products are offered to the public | [76] |

[78] | |

[83] | |

[91] | |

[91] | |

[97] | |

[115] | |

[] |

STEWART J:

1 The applicant makes a claim of misleading or deceptive conduct and misleading or false representations against the respondents based on their promotion and sale of beer and ginger beer, branded as “Better Beer”, in similar get-up to that used by the applicant for the promotion and sale of its beer, branded as “Sidewinder”. The claim relies on ss 18 and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). There is no passing-off claim. The applicant seeks declarations, injunctions, delivery up, corrective advertising, damages and other relief.

2 As will be seen, the applicant’s Sidewinder brand was announced publicly about five days before the respondents’ Better Beer brand, and although the get-up used for each has many similar features, each was developed independently of the other. The first Sidewinder product was available for sale to consumers nearly three months before the first Better Beer product. The products essentially built their reputations in the market side by side. For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that despite the applicant having got its get-up and product into the market first, its claim fails.

3 The applicant is Brick Lane Brewing Co Pty Ltd. It is a brewing company that has manufactured, distributed, advertised and sold beer since 2017. It has a production facility that includes a warehouse, logistics facility, hospitality business and head office located at Dandenong South, Victoria, an office and hospitality business at the Queen Victoria Market in Melbourne and a warehouse and office facilities in Brisbane.

4 Brick Lane has more than 60 full-time employees and a number of contract staff. It supplies its products to over 2000 hospitality venues and alcohol distributors across Australia. The distributors include well-known national distributors such as Dan Murphy’s, BWS Liquor, Liquorland, First Choice Liquor, Vintage Cellars and ALDI supermarkets as well as a number of independent retailers. It also supplies its beer products at its own two hospitality venues, restaurants and bars, events and festivals, and through its online store.

5 From around September 2020, Brick Lane started to develop a new range of no and low alcohol beer which came to be known as the Sidewinder range. The Sidewinder range was launched in 2021 comprising two products, namely the Sidewinder Hazy Pale, being a 1.1% ABV (alcohol by volume) low alcohol beer sold in cans, and the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe, being a maximum 0.5% ABV ultra-low alcohol extra pale ale sold in cans.

6 Although I will come back to the detail, by way of introduction it can be said that the Sidewinder range was launched by a media release on 21 July 2021. The media release included an image of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale can. Sales of the Hazy Pale commenced in August 2021 and of the XPA Deluxe in December 2021.

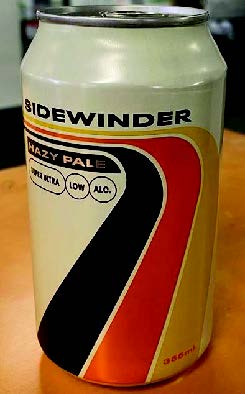

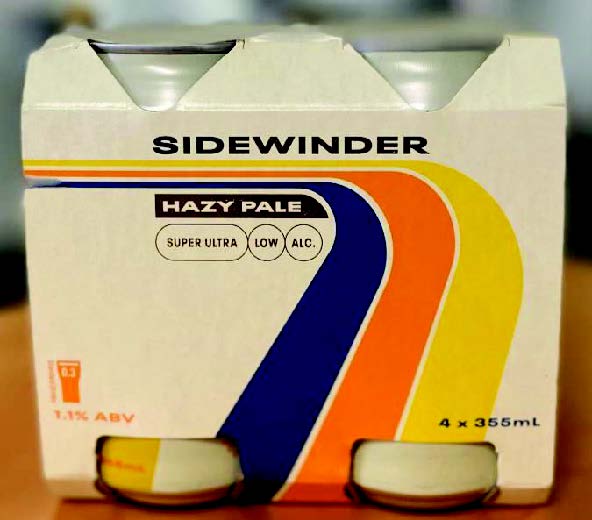

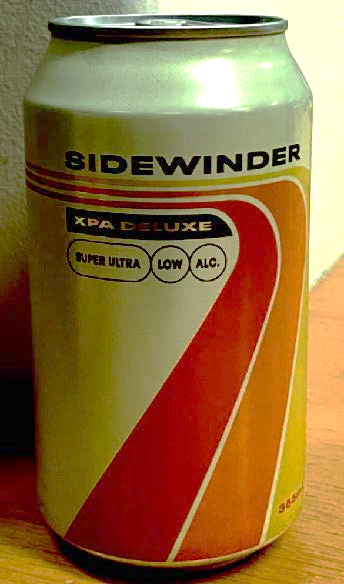

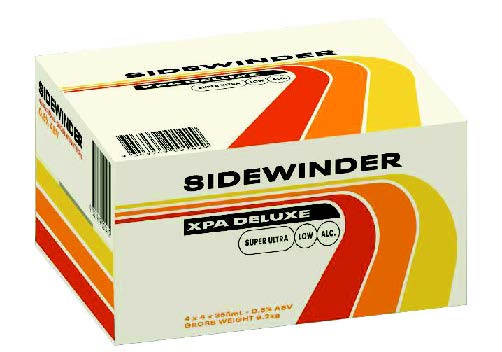

7 The cans and packaging of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale are depicted at Figures 1 to 3 in the Schedule to these reasons for judgment and the cans and packaging of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe are depicted in Figures 4 to 6.

8 The get-up of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale has the following features:

(1) an off-white 355 ml can;

(2) an off-white cardboard cluster and case (where sold by cluster or case);

(3) a curving flared striped design (on the can, cluster and case) in blue and shades of yellow and orange with the dominant flared part of the stripes being vertically aligned;

(4) the use of horizontal black lettering for the Sidewinder name and horizontal off-white lettering against a black background for the name of the particular product on the can and case (the lettering, or background to the lettering, being silver on the cluster packaging); and

(5) the use of a sans serif typeface in upper case for the “Sidewinder” lettering.

9 The get-up of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe is the same save for the name of the particular product and that the three stripes are in shades of orange and yellow.

10 All the packaging for both Sidewinder products is clearly marked in easily legible script that the products are “SUPER ULTRA LOW ALC”.

The respondents and Better Beer

11 The first respondent is Torquay Beverage Co Pty Ltd. It is a producer of alcoholic beverages including beer, the registrant of the domain name www.betterbeer.com.au and the applicant for a number of Better Beer trademark registrations. Its principal place of business is in Torquay, Victoria.

12 The second respondent is Better Beer Co Pty Ltd. It was formed to be 60% owned by Torquay and 40% owned by The Inspired Unemployed as a vehicle for the launch and sale of a new beer branded as Better Beer. The Inspired Unemployed are two Australian comedians and social media influencers, Matt Ford and Jack Steele.

13 The third respondent is Mighty Craft Ltd, a listed public company that describes itself as a craft beverage “accelerator” with a nationally diversified portfolio of craft beverages.

14 On 26 July 2021, Mighty Craft made an announcement to the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) that it had partnered with Torquay and The Inspired Unemployed to form Better Beer Co and launch a new beer branded as Better Beer. It was explained in evidence that Mighty Craft was predominantly responsible for sales and distribution with Torquay essentially doing marketing and the day-to-day operation of the business. The Inspired Unemployed were also accountable for marketing and public relations to support the launch and ongoing sales of Better Beer. The ASX announcement included an image of a can of Better Beer.

15 Better Beer is a no carbohydrate full (alcohol) strength lager, ie, 4.2% ABV.

16 Production of Better Beer lager commenced under contract by Australian Beer Company Pty Ltd in August 2021. Retail sales of Better Beer lager in 355 ml cans commenced in late October 2021 and in 330 ml bottles (stubbies) in mid-December 2021.

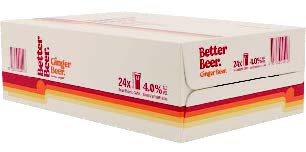

17 The respondents also developed a low sugar alcoholic (ie, 4% ABV) ginger beer sold in cans branded as Better Beer Ginger Beer. Production and sale of the ginger beer product commenced in about April 2022.

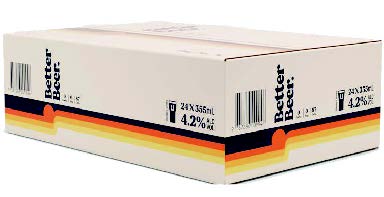

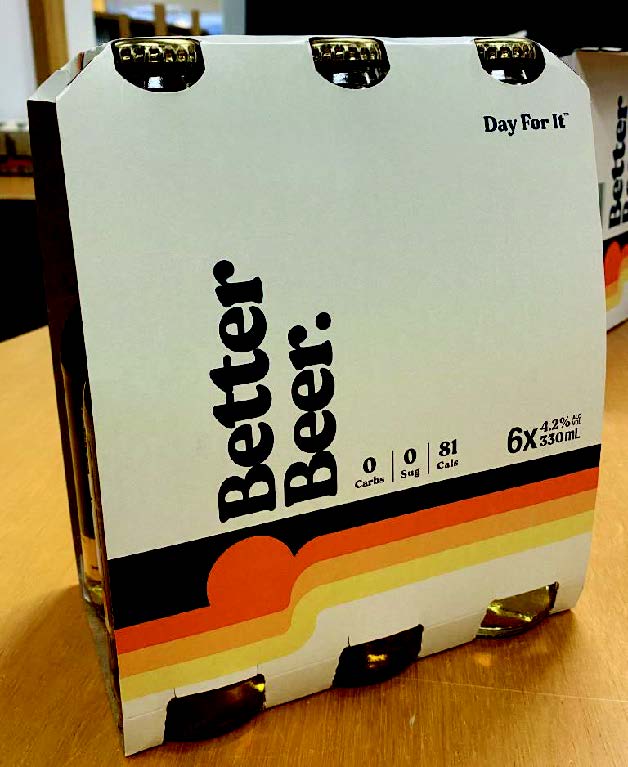

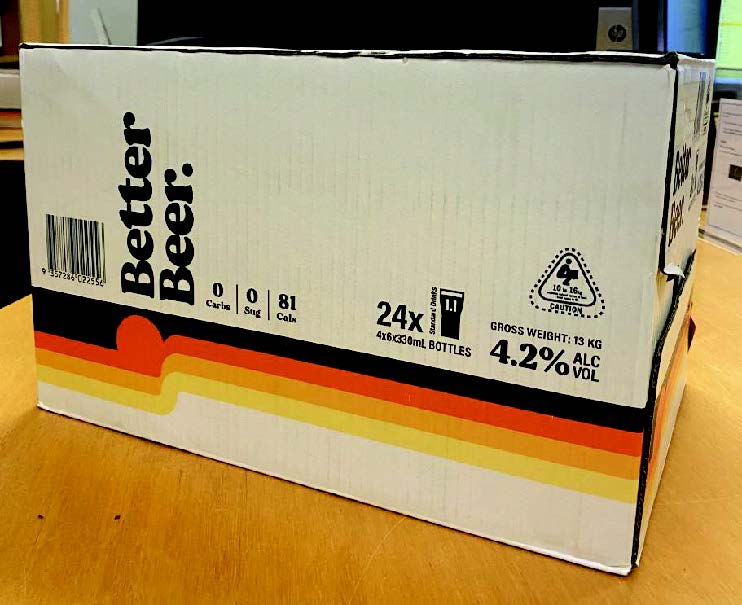

18 The cans and packaging of Better Beer lager are depicted at Figures 7 to 9 in the Schedule to these reasons for judgment and the cans and packaging of Better Beer ginger beer are depicted in Figures 10 to 12. The Better Beer lager bottles and packaging are depicted in Figures 13 to 15 in the Schedule.

19 The get-up of the Better Beer lager has the following features:

(1) an off-white 355 ml can (save for the bottled product);

(2) off-white cardboard cluster and case (where sold by cluster or case);

(3) a curving non-flared striped design (on the can, bottle, cluster and case) in blue and shades of orange and yellow with the stripes oriented horizontally; and

(4) the use of dark blue lettering for the product name, the lettering being rotated vertically; and

(5) the use of a serif typeface in title case for the “Better Beer” lettering.

20 All the packaging is clearly marked in easily legible script that the product is “0 Carbs ǀ 0 Sug ǀ 87 Cals” (81 calories in the case of the bottled lager) and “4.2% ALC VOL”.

21 The get-up of the Better Beer ginger beer is the same, save that the blue stripe and dark blue lettering is replaced with a stripe and lettering in a burnt orange or maroon colour. The packaging is clearly marked in easily legible script that the product is “Lower sugar” and “4.0% ALC VOL”.

22 Brick Lane pleads that the conduct of the respondents in packaging and promoting their Better Beer lager and ginger beer products has induced or is capable of inducing consumers into error by:

(1) mistaking the Better Beer lager product in cans and/or bottles for the Sidewinder Hazy Pale product or vice versa;

(2) mistaking the Better Beer ginger beer product for the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe product or vice versa;

(3) mistaking the Better Beer products as being products in the Sidewinder range or vice versa; and/or

(4) mistaking the Better Beer products as being low or no alcohol beverages.

23 The conduct of the respondents is thus said to be misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, within the meaning of s 18(1) of the ACL.

24 Brick Lane also pleads that by their conduct the respondents have falsely, misleadingly or deceptively represented to consumers that:

(1) the Better Beer product in cans and/or bottles is the Sidewinder Hazy Pale product or another product in the Sidewinder range;

(2) the Better Beer ginger beer product is the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe product or another product in the Sidewinder range;

(3) the Better Beer products are manufactured by the manufacturer of the Sidewinder products;

(4) the Better Beer products are associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by the manufacturer of the Sidewinder products; and

(5) one or more of the respondents is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by Brick Lane.

25 The representations by the respondents are thus said to be false or misleading with regard to the products or the respondents having sponsorship, approval, affiliation or characteristics which they do not have contrary to s 29(1)(g) and (h) of the ACL.

26 Brick Lane pleads that the conduct of the respondents was made in trade or commerce and that to the extent that any of the respondents did not directly engage in the conduct, they aided, abetted, counselled, procured, induced or were knowingly concerned in or a party to the conduct by one or more of the other respondents within s 75B of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Those matters are uncontroversial.

27 Brick Lane rightly accepts that the s 29 case does not really add anything to the s 18 case, and that if the s 18 case is not made out then the s 29 case will also fail. For that reason, I will not deal with the position in relation to s 29 in any detail.

The statutory provisions and general principles

28 Section 18 of the ACL provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. Section 29(1) of the ACL provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or the use of goods, make a false or misleading representation in respect of certain matters. Section 29(1)(g) identifies those matters with regard to goods as including the goods having particular sponsorship, approval or characteristics, and s 29(1)(h) identifies the matters as including that the person making the representation has particular sponsorship, approval or affiliation.

29 Section 18 is intended to protect members of the public in their capacity as consumers of goods and services: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture v Puxu [1982] HCA 44; 149 CLR 191 at 202 per Mason J. Liability imposed by s 18 is unrelated to fault; a corporation which has acted honestly and reasonably may nevertheless be restrained by injunction and liable to pay damages: Parkdale at 197 per Gibbs CJ.

30 Section 18 of the ACL is not limited to misleading or deceptive representations. Rather, the focus is on the extent to which the conduct of the defendant, considered in light of all relevant circumstances, is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. See Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ.

31 Conduct is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error: ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ. The threshold “likely to be” is satisfied where there is a real and not remote possibility that conduct will mislead or deceive: ACCC v Employsure Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 142; 392 ALR 205 at [89] per Rares, Murphy and Abraham JJ. Conduct causing confusion or uncertainty in the sense that members of the public might have cause to wonder whether the two products might have come from the same source is not necessarily misleading and deceptive conduct; the question is whether a consumer is likely to be misled or deceived: S & I Publishing Pty Ltd v Australian Surf Life Saver Pty Ltd [1998] FCA 1463; 88 FCR 354 at 362 per Hill, R D Nicholson and Emmett JJ; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 104; 247 FCR 570 (Verrocchi FCAFC) at [62] per Nicholas, Murphy and Beach JJ.

32 There is no requirement that “a not insignificant number” of reasonable persons within the relevant class would be misled or deceived: Trivago NV v ACCC [2020] FCAFC 185; 384 ALR 496 at [192]-[193] per Middleton, McKerracher and Jackson JJ, ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; 278 FCR 450 at [23] and Employsure at [108].

33 The question whether conduct has a tendency to lead a person into error is an objective question of fact for the court to determine on the basis of the conduct of the defendant as a whole viewed in the context of all relevant surrounding facts and circumstances: Campbell at [102]. The conduct is tested as against the ordinary or reasonable member of the public or relevant section of the public to whom the conduct is directed: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [102]-[103] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

34 In considering whether consumers are likely to be misled or deceived, it is necessary to consider the conduct against all the surrounding circumstances, including:

(1) the strength of the applicant’s reputation, and the extent of distribution of its products;

(2) the strength of the respondent’s reputation, and the extent to which the respondent has undertaken any advertising of its product;

(3) the nature and extent of the differences between the products, including whether the products are directly competing;

(4) the circumstances in which the products are offered to the public; and

(5) whether the respondent has copied the applicant’s product or has intentionally adopted prominent features and characteristics of the applicant’s product.

(See Verrocchi FCAFC at [69].)

35 In many cases it will be necessary to consider the class of persons to whom the representation was directed: S & I Publishing Pty Ltd at 362. Reasonable members of a class include “the inexperienced as well as experienced, and the gullible as well as astute” but does not include “persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests”: Parkdale at 199.

36 Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom particular conduct has been directed, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained of has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief is granted. See Campomar at [103].

37 Evidence that members of the public have actually been misled or deceived by the conduct complained of is not an essential element to a claim under s 18 of the ACL, nor is it conclusive: Parkdale at 198-199. Such evidence is of “peripheral value”: McWilliam’s Wines Pty Ltd v McDonald’s System of Australia Pty Ltd [1980] FCA 188; 33 ALR 394 at 399 per Smithers J, approved in Parkdale at 198-199. As French J said in State Government Insurance Corporation v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales [1991] FCA 198; 28 FCR 511 at 529:

Generally speaking, in cases of alleged misleading or deceptive conduct which is analogous to passing-off, evidence from consumers that they have been misled by the impugned conduct is of limited utility. It has no statistical significance and the court cannot draw inferences from it that any section or fraction of the population will have similar reactions. But if the inference is open, independently of such testimonial evidence, that the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then it may be that the evidence of consumers that they have been misled can strengthen that inference.

See also Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 170; 42 ALR 177 at 202; Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 234 at [94]-[95]; Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Caroline Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 403; 349 ALR 598 (Homart FCA) at [32]. Notwithstanding the dicta on the admissibility of such evidence, it does not appear that in any of the decided get-up cases has evidence of actual confusion been used to reach a conclusion of misleading or deceptive conduct. The most recent example is Natural Raw C Pty Ltd v Maicap Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 51 at [24]-[28] and [45] per Nicholas J.

38 Where, as in the present case, the conduct that is said to be misleading or deceptive, or to amount to a representation that is false or misleading or deceptive, is the adoption and use of a particular get-up for the marketing and sale of a product, a question arises as to the extent to which it is necessary for the applicant to show that its get-up enjoys some reputation amongst the public or the relevant sector of the public.

39 In Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd Careline Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 105; 264 FCR 422 (Homart FCAFC) at [8] it was held by Murphy, Gleeson and Markovic JJ that it is not necessary for an applicant to demonstrate “a particular reputation” in order to prove misleading or deceptive conduct. With reference to Woodtree Pty Ltd v Zheng [2007] FCA 1922; 164 FCR 369 at [34], it was said that it is not necessary for an applicant to establish any reputation at all, but rather the question is whether consumers are likely to be misled or deceived by the respondent’s conduct. Observing (at [9]) that “the assessment of the impugned conduct is not done in a vacuum”, the Full Court in Homart FCAFC quoted from Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 70; 159 FCR 397 at [99] per Black CJ, Emmett and Middleton JJ:

Whether or not there is a requirement for some exclusive reputation as an element in the common law tort of passing off, there is no such requirement in relation to Part V of the Trade Practices Act. The question is not whether an applicant has shown a sufficient reputation in a particular get-up or name. The question is whether the use of the particular get-up or name by an alleged wrongdoer in relation to his product is likely to mislead or deceive persons familiar with the claimant’s product to believe that the two products are associated, having regard to the state of the knowledge of consumers in Australia of the claimant’s product.

(My emphasis.)

40 The words that I have emphasised demonstrate that although it might be said that a particular reputation is not necessary, it is nevertheless necessary that there is some association in the mind of the relevant sector of the public between the applicant’s product and its get-up such that confusion might arise from the use of the same or a similar get-up in relation to the respondent’s product. Without the pre-existence of such an association, it could not be said that the use by the respondent of the same or a similar get-up suggests a misleading or deceptive association. The inquiry does not proceed on the assumption that the hypothetical consumer member of the relevant class is familiar with the applicant’s product; that is required to be established.

41 As explained by Perram J in Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 606; 81 IPR 354 at [22], the claim requires the identification of features of the applicant’s packaging (referred to as “get-up”) that are known to the public mind as the springboard for the argument that consumers are deceived by a particular imitation. This was accepted by the Full Court on appeal: Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 174; 84 IPR 12 at [11] per Emmett, Bennett and Edmonds JJ. See also Interlego AG v Croner Trading Pty Ltd [1992] FCA 992; 39 FCR 348 at 387 per Gummow J (Black CJ and Lockhart J agreeing): “… reputation and likelihood of deception are distinct issues, the first proceeding the second, so that if the plaintiff fails on reputation that is the end of the case.” In Verrocchi FCAFC at [64] it was said that “it is usually necessary to establish a relevant reputation in the get-up that has become distinctive of the relevant business or products”, but it is not necessary to establish an exclusive reputation.

42 The question arises as to the relevant date at which the assessment as to the impugned conduct being misleading or deceptive, or as likely to mislead or deceive, should be undertaken. Brick Lane submits that the relevant date to assess an applicant’s reputation in a get-up is “the date on which the impugned products become available to consumers”. The respondents, in contrast, submit that the relevant date “is the date on which the respondents’ impugned conduct commenced”, that conduct being the promotion of their product. As will be seen, there is some significance in this difference in the present case because the respondents commenced using the impugned get-up in a public-facing way in July 2021 whereas their products did not become available to consumers until October 2021. In the intervening period, any reputation that Brick Lane had in its relevant get-up increased considerably.

43 The submission on behalf of Brick Lane that the relevant date is the date on which the respondents’ products became available to consumers is not supported by authority or logic. Particular conduct can be misleading or deceptive by the association that it suggests between the respondents’ get-up and the applicant and its products. That conduct, being the use of the respondents’ get-up in a public-facing way in the promotion of its products, does not depend on the products already being available for sale. When a promotion precedes the availability of the promoted product for sale, the promotion can still be misleading or deceptive in the association that it suggests between the promoted product and some other unrelated and already available product. It is not uncommon for a variety of products, for example films, television series, sports and entertainment events, motor vehicles and so on, to be advertised and promoted before the products, or tickets for the products, are available to be bought.

44 Brick Lane accepts that the relevant date is the date of the commencement of the impugned conduct, but it says that that conduct necessarily involves the sale, or the availability for sale, of the competing product because otherwise there is no relevant harm to protect consumers against; they are protected by the ACL from misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce and until they can purchase the relevant product by acting on being misled or deceived, there is no harm from which to protect them. The fallacy of that submission is exposed by considering whether, on the assumption that the respondents’ Better Beer get-up is misleading and deceptively similar to the Sidewinder get-up, Brick Lane would have been entitled to an injunction restraining the respondents from advertising, marketing and promoting Better Beer using that get-up in the lead up to the product being available for sale. Leaving aside any questions of discretion, I see no reason why Brick Lane would not have been entitled to an injunction in those circumstances, the requisites for an injunction against unlawful conduct not being dependent on the product already being available for sale. That is reflected, in part at least, in the terms of the injunction that Brick Lane seeks which is to restrain the respondents from “advertising, marketing [and] promoting … any beer product … by reference to the Impugned Packaging”. The same can be said for the declaration sought by Brick Lane, ie, that by “advertising” and “marketing” the Better Beer products in the impugned packaging, the respondents engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

45 It is true that there are authorities that say that the relevant date is the date on which the relevant product became available to consumers (eg, Hansen Beverage Co v Bickfords [2008] FCA 406; 75 IPR 505 at [52]), or which say that the relevant date is the date of the commencement of the impugned conduct where that conduct includes or coincides with the making of the relevant product available to consumers (eg, Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; 275 ALR 526 at [334] and Homart FCA at [24]). However, in those cases the impugned conduct did not precede the availability of the product to consumers. It was thus not necessary in those cases to decide the point in question and, consequently, they are not authorities against the respondents’ submission.

46 In a passing-off action, the plaintiff must establish its reputation as at the date of the commencement of the conduct that is complained of: Norman Kark Publications Ltd v Odhams Press Ltd [1962] 1 WLR 380 at 386. In Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Pub Squash Co Pty Ltd (1980) 2 NSWLR 851 at 861G, it was held by the Privy Council in an appeal from the Supreme Court of New South Wales that that was the date that the defendant commenced marketing its product. That was a period of a few months before “full-scale production” of the product (see the advice of the Board at 855G), and there is nothing in the reasoning to suggest that the product was available to the public on the day that marketing commenced, or that the availability of the product for sale to the public was a necessary part of the impugned conduct. As a matter of principle and logic, that reasoning would also apply to an ACL ss 18 and 29 claim.

47 In In-N-Out Burgers Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 193; 377 ALR 116 at [181], Katzmann J held that the relevant date for the determination of the applicant’s reputation for the purposes of a misleading and deceptive conduct claim is the date that the impugned conduct began. In that case, that was the date on which the respondent’s “Down-N-Out” Facebook page was launched (at [181]). From earlier in the judgment (at [40]-[41] and [46]) it is apparent that the Facebook page was launched a week or two before the relevant product was available to consumers. That approach to the relevant date was not challenged in the appeal which was decided on the basis that the relevant date was when use of the impugned product name commenced and not the later date when the store was opened to customers: Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-n-Out Burgers Inc [2020] FCAFC 235; 385 ALR 514 at [2] and [113] per Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ.

48 Where, as here, the marketing and promotion of the respondents’ product using the impugned get-up was antecedent to the availability of the product for sale, the relevant date is when the respondents’ public-facing activities using that get-up commenced and not when the respondent’s product became available for sale to consumers. That is when the impugned conduct commenced.

49 For reasons I will come to, the relevant date for the case in relation to Sidewinder Hazy Pale is 26 July 2021 being the date of Mighty Craft’s announcement of the launch of Better Beer to the ASX. The relevant date for the case in relation to Sidewinder XPA Deluxe is April 2022 being the date that the respondents launched their Better Beer ginger beer.

Development, promotion, sale and reputation of the Sidewinder range

50 Brick Lane started working on a no to low alcohol beer range in September 2020. From late November 2020, concepts for the new range were developed. By February 2021, a mood board for the proposed new Sidewinder range had been developed and sent to a design agency for further development. The mood board included the ultimate brand “Sidewinder” as well as the concept of three curved stripes in the colours that are reflected in the ultimate packaging (as depicted in Figures 1 to 6 in the Schedule). The name Sidewinder was chosen as a reference to 1960s and 70s jet boats and the stripes are a reference to GT racing stripes featured on muscle cars and jet boats from that era. A “retro” feel or mood was apparently sought.

51 In May 2021, Brick Lane submitted copies of the final mock-ups for the cans and packaging to Brick Lane’s can manufacturer and its two packaging manufacturers.

52 Mr Hall, Brick Lane’s head of brand and innovation, testified that he chose the name Sidewinder. The name struck him as being particularly captivating, having power, energy and uniqueness. He also described it as evoking freedom, excitement, possibility and fun, even hedonism, as a deliberate counterpoint to the compromise that drinking no or low alcohol beer might otherwise represent. Mr Hall regarded the curved flared striped design as being unique in the beer market.

53 On 9 July 2021, Brick Lane registered the Instagram handle @sidewinderlife and the domain name www.sidewinder.com.au. With reference to correspondence about the content and launch of the Sidewinder Instagram account, Mr Hall accepted that the Instagram page did not “go live” until 30 July 2021. Mr Bowker, however, explained that the account was publicly accessible from inception as no privacy settings were ever applied to it, and that from that time the profile picture showed a Sidewinder Hazy Pale can. He was not challenged on that and I accept it. As explained by Mr Bowker, Mr Hall’s reference to “going live” is properly to be understood as a reference to content being posted to the account page, rather than the inception of the account and anything included from that time in the profile.

54 In an email on 27 July 2021, there is a reference to the page still being prepared to be launched, and in an email late on 30 July 2021, a particular curved depiction of the can was chosen over a flat version and the “bio” for the page was approved. Also on 30 July, the first images were posted to the page, being a series of nine images as “tiles” (ie, intended to be viewed 3 x 3 as a single image) which together showed a “skater-girl” and no part of the Sidewinder get-up. Mr Hall accepted that prior to that point the choice of profile photograph and the wording of the bio had not yet been finalised and that the launch of the page was still imminent. As explained, that is to be understood as a reference to when material would first be posted to the page.

55 In any event, the attachments to the email on 30 July reflect that at that time the page had only nine followers. According to Mr Bowker, he was one of them as he followed the page after receiving an email about it on 12 July. It seems probable that the nine followers, or most of them, were accounts of people associated with Brick Lane. Prior to 30 July no content had been posted to the page and the level of public engagement at that point must have been negligible. It was only on 4 August that an image of the Hazy Pale can was posted to the page, as opposed to being reflected in the small profile picture.

56 In the meanwhile, on 21 July 2021, Brick Lane’s public relations agency published a media release about the launch of the Sidewinder range. The media release announced that Sidewinder Hazy Pale would be available through speciality retailers, restaurants and bars and in all Dan Murphy’s stores nationally from 2 August, and that it was the first to be released in the Sidewinder range of low alcohol beers. The media release included images of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale can showing its get-up.

57 The media release was sent to 77 addressees – freelance journalists in the food and drink area as well as journalists at a number of prominent publications that cover those topics. There was also an invitation to the journalists to attend an online tasting event on 10 August 2021. The media release generated at least one article that was published before 26 July 2021. That was on 23 July 2021 in Drinks Digest. The article included images showing the Sidewinder Hazy Pale can get-up. The “reach” of the article was reported by Brick Lane’s public relations company to be 905 people, although it is not revealed how that number was arrived at or how many of those people saw or read the article before 26 July.

58 On 29 July 2021, on Brick Lane’s separate Instagram account, a 16 second video of the coloured striped curves was published with the explanation that “A tastier way of life is on the horizon!” but there was no explicit identification of that with the Sidewinder brand – it was in effect a teaser of what was to come, and did in fact come, in the following days. On 4 August 2021, a follow-up 16 second video was posted on the account. It showed the Sidewinder Hazy Pale can including all its relevant get-up.

59 The records show that in July 2021, small quantities of Sidewinder Hazy Pale were sold to liquor wholesalers and retailers. It is not apparent from the evidence when in the month the sales were made, or when the product that was the subject of those sales was made available for sale to consumers – save that the record of sales by Dan Murphy’s to customers shows no sales in July and a very small volume of sales in August. Given that evidence, the announcement on 21 July that the product would be available to consumers from 2 August, and Brick Lane’s Mr Bowker’s evidence that the first sales of Hazy Pale to the public were on 3 August, I find that the first retail sales of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale were on 3 August 2021.

60 On the above evidence, I find that up to and including 26 July 2021 there was very limited exposure of Brick Lane’s Sidewinder range get-up to consumers. All that there was was the media release to 77 journalists, many of whom can be taken to be consumers of beer as well as being journalists, one article in Drinks Digest with no evidence of how widely it was read by the relevant date, a newly formed and barely followed Instagram account showing part of the get-up in the tiny profile picture, and very few, if any, sales of the product. The product was essentially unavailable to consumers until 2 August. The exposure of the get-up to the relevant sector of the public, namely consumers of beer, was accordingly very limited, and that sector’s state of knowledge of the get-up and its features was minimal.

61 After 26 July 2021, Brick Lane’s activities to promote the Sidewinder range, first the Hazy Pale and later the XPA Deluxe, intensified. There were further media articles arising from the 21 July media release, samples of Hazy Pale were dispatched to the recipients of the media release, there was an online tasting, the Sidewinder Instagram and Facebook pages went live, Hazy Pale was promoted on Brick Lane’s website from 2 August, an electronic direct mail containing images of the Hazy Pale product was sent to more than 8,400 recipients, an intensive digital advertising campaign was implemented between 6 September and 8 November 2021, a large billboard was erected on a major arterial road in Melbourne between 27 September and 8 November 2021, and 345 digital or static panels were placed in bus shelters outside convenience stores in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and the Gold Coast between October and December 2021. The records also show that, despite some fluctuations, sales of the product increased over time. I accept that by late-October 2021, the Sidewinder get-up had established something of a reputation amongst consumers of beer, although it remained a very small player and most consumers of beer are unlikely to have encountered it.

62 However, as already explained, I consider 26 July 2021 to be the relevant date to assess the state of knowledge of Brick Lane’s Sidewinder get-up in the relevant sector of the public with the result that the activities after that date are not relevant.

63 The exception to that arises from Brick Lane’s case in relation to the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe product and Better Beer ginger beer. On one view, it is necessary to consider the state of knowledge of the XPA Deluxe get-up in the market when the Better Beer ginger beer was launched in April 2022. However, the case was not presented that way. Moreover, the XPA Deluxe product is part of the Sidewinder range with a get-up that has distinct features in common across the range. The same is true of the Better Beer range. The result is that the case on the XPA Deluxe product is likely to succeed or fail with the case on the Hazy Pale. I will come to those questions, but in the meantime, and for completeness, I will deal with the development and promotion of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe.

64 The evidence is that the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe was promoted from 3 December 2021 and available for sale from 6 December 2021. The promotion included an electronic direct mail on 6 December 2021 to 10,751 recipients, being the subscribers to Brick Lane’s database at the time. The direct mail included images of XPA Deluxe cans and an image of an XPA Deluxe can next to a Hazy Pale can where the similarities between them demonstrate that they are part of the same range. Significant quantities of XPA Deluxe were sold to consumers between December 2021 and April 2022. I accept that by April 2022, the XPA Deluxe get-up had established something of a reputation amongst consumers of beer although, as with the Hazy Pale, it remained a very small player. Even at that time, most consumers of beer are not likely to have encountered the XPA Deluxe get-up.

Development, promotion and sale of the Better Beer range

65 In January 2021, Torquay commenced the design process for a new “zero carb” beer product which later came to be known as Better Beer. By 23 March 2021, Torquay’s external designer had provided a design for the Better Beer get-up in substantially the same form as that which was ultimately adopted and used as depicted in the photographs at Figures 7 to 9 in the Schedule.

66 On 13 July 2021, Torquay provided approval for the artwork for the Better Beer cans to its can manufacturer. On 19 July 2021, Torquay made a purchase order with the manufacturer for 350,000 cans. On 21 July 2021, Torquay paid the manufacturer for the cans.

67 On 20 and 21 July 2021, Torquay issued purchase orders to Australian Beer Company Pty Ltd for 13,200 cardboard cartons and 54,000 cardboard six-pack wraps for the Better Beer product.

68 On 21 July 2021, Torquay’s general manager, Mr Cogger, created a Facebook page for Better Beer and uploaded the page’s profile image as an image of the Better Beer logo including the name Better Beer and the curved stripes. There is, however, no evidence of how many, if any, people viewed the Facebook page between then and 26 July 2021.

69 As mentioned, on 26 July 2021, Mighty Craft formally announcement the launch of Better Beer to the ASX and on its pre-existing Instagram page. The ASX announcement and the Instagram post included an image of the Better Beer can including the material elements of the get-up, being the brand name Better Beer and the coloured curved stripe design, and that the product would be released in October 2021 in partnership with The Inspired Unemployed.

70 The material content of the ASX announcement was republished in a number of industry publications, each of which displayed the depiction of the Better Beer can. These included in Beer & Brewer and Drinks Trade on 26 July 2021, and an Instagram post by @beerandbrewer on the same day. Brick Lane’s public relations agency reported to it, and Mr Bowker of Brick Lane accepted in cross-examination, that at that time articles in Beer & Brewer had a “reach” of 13,000 people and articles in Drinks Trade had a “reach” of 27,000 people. Once again, it is not apparent how those figures were arrived at. It can nevertheless be accepted that the reach of those articles was significant in the industry.

71 The ASX announcement and the immediate reporting on the announcement makes 26 July 2021 the date on which the respondents first presented the essential features of their Better Beer get-up to the public in a material way. Although they had committed to that get-up behind-the-scenes much earlier (eg, by ordering and paying for the cans and packaging), that is the date on which their product was publicly announced and it is therefore the relevant date for the purpose of assessing whether their use of that get-up is misleading or deceptive, or conveys false representations, relative to Brick Lane’s Sidewinder get-up, taking into account the state of knowledge of the latter in the relevant sector of the public at that time.

72 On 24 August 2021, Australian Beer Company Pty Ltd commenced canning Better Beer lager for Torquay, the brewing process having started some weeks before that. Retail sales of Better Beer lager commenced in late October 2021. On about 15 December 2021, Better Beer lager was launched in glass bottle packaging using essentially the same get-up.

73 On 8 April 2022, Torquay launched its Better Beer ginger beer. The Better Beer ginger beer packaging was also designed by reference to, and is consistent with, the design of the Better Beer lager packaging, save that it incorporates a different colour scheme, being orange and yellow, and it includes the words “Ginger Beer. Lower sugar”.

74 As would be expected, Better Beer lager, and subsequently Better Beer ginger beer, were the subject of substantial marketing campaigns from the time of their launch. There was a major Better Beer campaign in the middle of November 2021. The Inspired Unemployed, who have a substantial social media presence, contributed to the marketing of Better Beer and the popularisation of the name. The marketing campaigns and sales figures show Better Beer to be a successful brand that quickly established itself in the market.

75 For ease of reference, the material dates can be summarised as follows:

21 July 2021 Sidewinder Hazy Pale publicly announced by press release

26 July 2021 Better Beer lager publicly announced by ASX announcement

3 August 2021 Sidewinder Hazy Pale sales to consumers commenced

Late October 2021 Better Beer lager retail sales commenced

3 December 2021 Sidewinder XPA Deluxe publicly launched

6 December 2021 Sidewinder XPA Deluxe retail sales commenced

18 April 2022 Better Beer ginger beer launched.

The circumstances in which the products are offered to the public

76 Brick Lane’s products are directed to consumers of beer who are interested in no or low alcohol beer, and the respondents’ products are directed to consumers of beer and ginger beer who are interested in low carbohydrate beer and ginger beer. There is some evidence that these types of products might be categorised together as options for the health-conscious, although there is also evidence that retailers classify non-alcoholic beer separately from “light” or low carbohydrate beer. There is also conflicting evidence about what a “craft” beer is and whether the products in this case are in that category, or whether they are in an “alternative” category. Generally, the categorisations appear to be inconsistent – there is no clear convention that defines the different categories.

77 Brick Lane’s and the respondents’ relevant products are sold in national licensed retail outlets such as Dan Murphy’s and BWS. They are also sold through online stores operated by those and other retailers. The products are generally presented in their cluster packaging and their case packaging, although they might also appear as individual cans or bottles. Sales are predominantly in clusters or cases.

The parties’ knowledge of each other’s plans

78 Brick Lane makes no claim that the respondents copied its design. The parties accept that the two designs were developed independently of each other, without one party having knowledge of the other party’s intended design. As the events identified above demonstrate, the designs were developed not only independently but also concurrently. What then occurred is that Brick Lane made its design public five days before the respondents made their design public, and the Sidewinder product became available to consumers nearly three months before the Better Beer product.

79 The public announcement of the launch of Better Beer by way of the ASX announcement and the Instagram post on 26 July 2021 immediately came to the attention of Brick Lane. The response of Mr Hall, Brick Lane’s head of brand and innovation, at the time was that he was “spewing” but that there was “no turning back now” and that Brick Lane would “blow them outta the water with a cracking fully integrated comms plan”. Mr Johnson, the creative director of Brick Lane’s design agency, responded by saying that it was as though the respondents had “copied the concept”. Mr Bowker, Brick Lane’s managing director, considered that “the two designs have a very similar look and feel”. Ms Harp Kennealy, Brick Lane’s marketing director, considered that “there are different purchase triggers for those choosing low/no carb like this [ie, Better Beer] at 4.5% ABV vs 1.1%”.

80 Mr Cogger, Torquay’s general manager, said in his evidence in chief that he first became aware of the Sidewinder product in about August 2021 from an Instagram post. However, he accepted in cross-examination that he would have seen the brief video of the striped curves posted on Brick Lane’s Instagram account on 29 July 2021 on or about that date. He also accepted that he saw the 4 August 2021 video on or about that date. That is accordingly the date from which it can be taken that Torquay was aware of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale and its branding or get-up. By that time, the respondents were substantially committed to their get-up including by the can and packaging orders that they had placed and their own public announcements.

81 Mr Cogger became aware of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe product at the time of its launch in early December 2021.

82 Despite recognising similarities between the get-up of the Sidewinder products and the Better Beer products, Mr Cogger accepted that the respondents did nothing to further distinguish the products once they knew about the Sidewinder products. Mr Cogger also accepted that there were “definitely similarities between the colour schemes” of the Hazy Pale and Better Beer lager products and that the orange colours used for the XPA Deluxe and Better Beer ginger beer products “have some resemblance”.

83 Brick Lane sought to prove incidents of actual confusion by consumers between the Sidewinder and Better Beer products because of the similar get-ups. It relies on two separate incidents which it submits amount to evidence of such confusion.

84 The first incident is explained in the evidence of Mr Emans, the Experience Manager for Brick Lane. He explained that there is an annual “Great Australasian Beer SpecTAPular” craft beer festival, known as the GABS Festival, which is one of the world’s largest craft beer festivals. In May 2022, the GABS Festival was held in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. Mr Emans attended and operated the Brick Lane stall at the GABS Sydney event which featured the Sidewinder get-up. He promoted and facilitated tastings of the Sidewinder range with the attendees at the event.

85 Late one afternoon as he was cleaning the Brick Lane stall, Mr Emans was approached by a male cleaner who was attending to the area generally. Mr Emans gave the cleaner a few samples of the Sidewinder range of low alcohol beer and they had a conversation in which the cleaner said “Woah, that’s so great that you guys from Better Beer are doing low-alcoholic options now.”

86 Brick Lane submits that the inference arising from the incident is that the man was led into error so as to believe that Better Beer products were associated with or part of the range of Brick Lane’s products. It is said that the confusion arises solely because the respondents have marketed a beer in strikingly similar get-up to the Sidewinder beer.

87 The second incident is explained in the evidence of Mr Lampard, an area manager for Brick Lane. Mr Lampard’s role includes visiting Dan Murphy’s stores in his area on a monthly to quarterly basis to meet with store representatives to discuss Brick Lane’s products.

88 On 31 January 2022, Mr Lampard attended the Dan Murphy’s Parkwood store on the Gold Coast in Queensland. He entered the store carrying a four-pack cluster of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale product and approached a Dan Murphy’s staff member, showing him the cluster and saying that he was from Brick Lane and wanted to discuss the minimum product levels for Sidewinder. The staff member said that they had the product on display and led Mr Lampard to a display of the canned Better Beer lager product. The Sidewinder product was stocked in the store, but at a different place, namely in the low alcohol fridge section.

89 Brick Lane submits that the inference arising from the incident is that the Dan Murphy’s staff member confused the Sidewinder and Better Beer products. It is said that a Dan Murphy’s staff member is likely to be better informed about the different products than an ordinary consumer would be, such that the incident gives rise to an inference that consumers would be confused about the two products being associated because of their similar get-up.

90 Both incidents reflect a person being confused between the Sidewinder and Better Beer products. Although there is no direct evidence as to the reason for the confusion, the relevant person in each case not having been a witness, there does not appear to be any credible reason for the confusion other than the similarity in the get-ups of the different products. For that reason, I infer that the cleaner at the GABS Sydney event and the Dan Murphy’s Parkwood staff member were at least momentarily confused between the Sidewinder and Better Beer products because of the similarity of their get-ups.

91 The respondents emphasise that the Sidewinder products are no or low alcohol products whereas the Better Beer products are full alcohol but low carbohydrate products. They submit that these are different segments of the beer market. They rely in particular on the statement by Ms Harp Kennealy (referred to at [79] above) that the purchase triggers in each market segment are different. On that basis they submit that the relevant class of person in considering Brick Lane’s claim is consumers purchasing no or low alcohol beer.

92 I accept that the market segments are different. However, I do not consider that that is particularly significant. The reality is that consumers considering possible purchases online or in a retail store are faced with an extraordinary array of beer products that vary in many different respects. Those include with respect to alcohol (full strength, mid-strength and no or low or ultra-low) and carbohydrate (low carb or light) content, as well as in many other ways including as to the type of beer (eg, lager, pale ale, IPA, XPA, stout, pilsner, wheat beer, craft or not craft, draught, etc.) and the origin (eg, domestic or imported). The relevant information is presented in a variety of different ways, and the ways in which the products are categorised or grouped for presentation for sale may vary considerably. Also, particular brands, of which Sidewinder and Better Beer serve as good examples, may have many different beer types in their range which are branded similarly.

93 In the circumstances, if two products had identical get-ups but were in different segments of the beer market, I have no doubt that consumers would be likely to be confused differentiating them or to consider that they are related; the fact of them being in different segments would not prevent that or even particularly detract from it.

94 Also, although no alcohol and low carbohydrate products may be considered as separate segments of the market, together they might be considered as part of a “health-conscious” segment. That that is so is demonstrated by the fact that a low alcohol Better Beer lager was introduced by the respondents in June 2022. That product is part of the Better Beer range although it is not specifically the subject of complaint in this case. It is nevertheless promoted by the respondents as another health-conscious beer choice. In short, there are many instances of related products being in different segments of the market, of which the Better Beer low carbohydrate and low alcohol products are prime examples. This shows that it would be wrong to consider this case on the basis of identifying a hypothetical consumer in only one segment of the market. A broader approach is necessary.

95 It follows that in my view the relevant class of persons is consumers purchasing beer. The fact of the products being in different segments of the beer market will be relevant to whether or not such consumers might be confused, to which I will come, but it does not particularly affect the identification of the relevant class.

96 The respondents’ submit that alcoholic ginger beer is in a different segment of the market to the Hazy Pale and XPA Deluxe beers and that this is relevant in assessing any likelihood of deception. I accept that beer and alcoholic ginger beer are different products and that they may be bought or consumed by different people. However, the evidence shows that alcoholic ginger beer and beer tend to be categorised and sold together. For example, the Dan Murphy’s webpage for beer includes more than 30 alcoholic ginger beers. Many brewers of beer, including both Brick Lane and Torquay, and very well-known brewers such as James Squire, also brew and sell alcoholic ginger beer. So, while the difference between beer and alcoholic ginger beer may have some bearing on the likelihood of deception arising from similar get-ups, I do not accept that it is material.

Misleading or deceptive, or false?

97 The first reason why Brick Lane’s claim in respect of the Sidewinder Hazy Pale product must fail is that at the relevant time, being 26 July 2021, there was no appreciable knowledge amongst members of the relevant class of the Sidewinder get-up. That is to say, the hypothetical member of the class of consumers purchasing beer is not likely to have any familiarity with the Sidewinder get-up with the result that on seeing the Better Beer get-up they would not be likely to confuse it with the Sidewinder get-up. As it was explained by Burley J in Homart FCA at [125], “it takes a strong case” to establish a reputation that the get-up relied on is associated by consumers with the relevant product. Put differently, even assuming a strong similarity in the respective get-ups, the hypothetical consumer is not likely to be misled or deceived into thinking that the two products are associated if they do not readily associate the applicant’s product’s get-up with the applicant or its product.

98 The essentials of what occurred in this case are that, entirely independently of each other, each side of the case simultaneously developed a get-up for a new beer product and both get-ups were presented to and promoted in the market at almost the same time – only days apart. The happenstance of Brick Lane having won the race – a race that neither it nor the respondents knew that they were in – by only a few days does not give it the right to stop the respondents from using their get-up or to claim damages. That is because in the intervening period Brick Lane had not established any appreciable reputation for its get-up. Without that, its claim must fail: Interlego at 387.

99 The position with regard to Brick Lane’s claim in respect of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe is a little different. That is because by April 2022, when the Better Beer ginger beer was launched, the common features of the Sidewinder get-up and the particular features of the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe get-up had been in the market for a long time – since 21 July 2021 in respect of the former and 3 December 2021 in respect of the latter. I consider that by April 2022 those features had developed a reputation such that the hypothetical consumer might be considered to have a familiarity with them on coming across the Better Beer ginger beer get-up. However, the hypothetical consumer would also by that time have familiarity with the common features of the Better Beer lager get-up. That is because the Better Beer lager get-up had been in the market since 26 July 2021 and considerable quantities of Better Beer had been sold on the back of extensive promotion. Thus, the hypothetical consumer’s familiarity with both get-ups must be taken into account in considering any likelihood of confusion.

100 Turning now to the differences and similarities between the relevant products’ get-up, the first observation is that each product bears a distinctive brand name – Sidewinder and Better Beer. Not surprisingly, Mr Hall’s evidence was that the Sidewinder brand name is distinctive, unique and powerful. There is no reason to disagree with that assessment notwithstanding that not everyone encountering the name may associate it with 70s jet boats – they may think of air-to-air missiles or snakes or something else equally distinctive and memorable. Equally, Better Beer is a distinctive brand name. Brick Lane submitted that because it is descriptive it is weak, but I do not accept that. It is alliterative and catchy. Moreover, Sidewinder and Better Beer are rendered in quite different styles of typeface – sans serif and serif respectively. They look and feel very different. They do not have visual or phonetic similarities such as were material to the reasoning in Homart FCA at [195(b)].

101 Brick Lane submits that the name Better Beer suggests that it is “better-for-you” beer, ie, a more healthy option and therefore likely to contribute to any confusion with Brick Lane’s product which as a no or low alcohol product is also a more healthy choice. It seems to me that the hypothetical reasonable beer consumer is likely, at least initially, to understand the name Better Beer to be saying that the particular beer is better, ie, better than other beers in terms of taste and enjoyment. I accept that on seeing that it is a low carbohydrate beer, particularly in the context of its promotion that emphasises that choosing it is a better health choice, the reasonable consumer would understand the name to be suggesting that it is “better-for-you” beer. However, I do not accept that that would in any material way contribute to confusion between the parties’ respective products for the reasons that follow.

102 The relevance of the observations about the products’ names is that in a get-up case a difference in the name of a product can be compelling, and in most cases it is likely to be: Homart FCA at [192]. For example, different product names in the context of otherwise very similar get-ups was compelling in distinguishing the products in Natural Raw C at [53]. As was explained by Gibbs CJ in Parkdale at 199, “if an article is properly labelled as to show the name of the manufacturer or the source of the article its close resemblance to another article will not mislead an ordinary reasonable member of the public”. The same is true if there is a close resemblance in the get-up of the articles, other than the names or labels. Given the distinctive names, as I have described, the other features of the get-up would have to be particularly close in resemblance, if not identical, for the get-ups as a whole, including the names, to be misleading or deceptively similar.

103 In that regard, and against Brick Lane’s urging in reliance on Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths [1999] FCA 1020; 93 FCR 365 at [33] per French J (Tamberlin J agreeing), I give no particular significance to the fact that an examiner of trademarks considered that the similarity of the colours and the visual similarity of the shared three coloured stripe element of a mark sought to be registered by Torquay and the colours in Brick Lane’s trademark showing the blue, orange and yellow flared curved stripes are likely to cause consumers familiar with the latter mark to infer a shared trade origin of the goods under the former mark. That is because the relevant marks that were compared, considered and contrasted by the examiner of trademarks did not incorporate the distinctive different brand names which are part of the get-up of Better Beer and Sidewinder that are before me in the present case.

104 In any event, it is doubtful that evidence of the examiner’s opinion is admissible as it does not come within the confines of the relevant dictum in Woolworths which is with regard to the admissibility of the Registrar’s opinion on the question of deceptive similarity in an appeal from the Registrar’s decision with regard to the registration of a trade mark. Section 76(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) renders the examiner’s opinion on the likelihood of confusion arising from similarities in the parties’ respective get-ups inadmissible opinion evidence in this case.

105 I nevertheless accept that there are distinct similarities between the relevant get-ups, noting that the cluster and case packaging offers the clearest comparison of the get-ups and is the form most likely to be seen by consumers on contemplating a purchase. The three-curved stripe design with very similar if not identical colouring as between the Hazy Pale and the Better Beer lager, and the XPA Deluxe and the Better Beer ginger beer, against an off-white background is striking. The respondents point out that the Sidewinder design has flared stripes whereas the Better Beer stripes are non-flared, and that the relevant people associated with Brick Lane considered the flared design to be special and even unique in the context of a beer product. I accept that difference, as well as that the Sidewinder stripes are predominantly vertical whereas the Better Beer stripes are predominantly horizontal, but these differences do not seem to detract particularly from the similarity of the designs. The spontaneous responses of the people associated with Brick Lane on first seeing the Better Beer design, as detailed above, supports the conclusion that the designs are strikingly similar – although the principal concern at that time appears to be that the design might have been copied.

106 Brick Lane places some emphasis on beer being a fast moving consumer good at a relatively low price (between $16 and $20 per cluster), in contrast to the expensive designer lounge suites in Parkdale, and submits that consumers are therefore not likely to give much attention to, or spend much time on, deciding on their purchase. From this, Brick Lane submits that the hypothetical consumer with some familiarity with Sidewinder is more likely to be confused into thinking that Better Beer is associated with it in some way on seeing the Better Beer get-up.

107 However, given the plethora of different types and styles of beer in the Australian market, and there being no evidence that they are consistently categorised and grouped in their presentation to consumers, whether online or in retail outlets, the point is easily overstated. It is precisely because of the huge variety in beers and the way in which they are presented that the hypothetical reasonable beer purchaser is likely to have to pay close attention to just what it is that they are taking off the shelf, or clicking on, to ensure that they get what they want. There’s a lot to choose from, and a lot to look out for. A consumer wanting a low alcohol beer will be disappointed to find that they had erroneously bought a low carbohydrate full strength alcohol beer, and vice versa. Someone wanting a lager or a pilsner will be disappointed if they erroneously walk out with a pale ale, and so on.

108 Brick Lane references the often quoted statement by Lord Macnaghten in Montgomery v Thompson [1891] AC 217 at 225 that “thirsty folk want beer, not explanations” in support of its point. That much may be accepted, but there is no suggestion in that case that consumers were faced with a bewildering array of options. There had been one brewery in the town of Stone making and selling Stone Ales for hundreds of years when the defendant established a new brewery in the town and sought to name it Stone Brewery selling Stone Ales. It was in the context of the suggestion that the defendant might distinguish its products in some way but still call them Stone Ales that Lord Macnaghten coined the famous aphorism. For the reasons I have given, that case is very different from the present. Indeed, it rather confirms the significance of a product’s name in identifying the product for consumers rather than other possible features of the get-up.

109 The short point is that the hypothetical reasonable consumer of beer must be taken to take reasonable care of their own interests. That includes paying enough attention to what they are buying in a crowded and bewildering market so as to be able to distinguish between low alcohol and low carbohydrate products and to notice the names of the relevant products. I do not see that consumer fleetingly taking something from the shelf, or clicking on an icon, because of some similarity of colouring and design that they might remember from a previous purchase. That is particularly so in the present case given the distinctly different names and the clarity of the statements on the packaging as to the different nature of the products, ie, low alcohol and low carbohydrate.

110 Brick Lane also places some emphasis on both Sidewinder and Better Beer being sold in 355 ml cans which were described by Mr Bowker in an email when he first saw the Better Beer get-up as being “very unusual”. Counsel for Brick Lane submitted that most beer is sold in 330 ml glass bottles or 375 ml cans. I accept that the size of the can, if it were an uncommon size, could form a distinctive part of the get-up. However, I am not persuaded by Mr Bowker’s one-off remark in an email that 355 ml cans are very unusual. A printout of the Dan Murphy’s online store page for beers shows that approximately 50 of the 894 different beers, of which a large number are in any event sold in bottles, are sold in 355 ml cans. There is no basis on which the “very unusual” characterisation can be justified in light of those figures and there is no evidence specifically directed to the question whether a 355 ml can is especially unusual, or that in this case it is particularly distinctive. I am not sure that consumers pay much attention to the difference between a 355 ml or 375 ml can – only a tablespoon or modest sip’s difference, and if they were that attentive then they would likely also notice the name and nature (ie, low alcohol or low carbohydrate) of the beer that they are purchasing. I simply do not see, and therefore do not place, any significance in the can size.

111 For the same reasons, I do not see any particular significance in the different format of the packing of the products as emphasised by the respondents, namely in clusters of four cans and cases of 16 cans in the case of Sidewinder, and in clusters of six cans and cases of 24 cans in the case of Better Beer in cans. Those do not seem to me to be particularly distinctive features of the products’ get-ups.

112 I have considered the evidence of actual confusion in the market above. As explained there, I accept that there is evidence of actual confusion. However, that evidence does not go all that far. In both cases the relevant observer – the cleaner at the GABS festival and the Dan Murphy’s employee – had only a fleeting observation of the Sidewinder get-up. They were, at most, momentarily confused about the products, but were not misled or deceived in a material sense, eg, by being led to purchase the wrong product. In any event, on the authorities the two isolated incidents are statistically insignificant and of peripheral value and can only be used to support a finding that the relevant conduct is objectively misleading or deceptive and not to reach such a finding.

113 Taking all of the above matters into consideration, I am not satisfied that the hypothetical reasonable consumer of beer would at the relevant date have had any particular familiarity with Brick Lane’s Sidewinder get-up, but even if they did, they would not have been likely to be misled by the similarity of the respondents’ Better Beer get-up to the Sidewinder get-up into thinking that the products were in some way associated. As explained, that arises in particular from the distinctive names used for the different products as well as the differences between the get-ups and the features of the relevant market.

114 That ultimate conclusion applies equally to the XPA Deluxe / Better Beer ginger beer case as it does to the Hazy Pale / Better Beer lager. Although by April 2022, when the ginger beer was launched, it can be accepted that the Sidewinder XPA Deluxe had a reasonably established reputation such that the reasonable beer consumer can be taken to have some familiarity with the XPA Deluxe get-up, by that time that consumer would also have familiarity with the Sidewinder Hazy Pale get-up and the Better Beer lager get-up. As both the Sidewinder and Better Beer brands were reasonably established by then, the consumer would not be likely to confuse them as a consequence of the similarities in their respective get-ups.

115 On account of having found that the respondents’ relevant conduct was not misleading or deceptive, and did not falsely represent any relevant association between the parties’ respective products, the proceeding falls to be dismissed.

116 I am not aware of any reason why the usual rule with regard to costs should not apply, and the applicant should therefore pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding. However, since I have not heard the parties on costs, in the event that there is some relevant matter with regard to costs that may justify a different order, the party contending for such an order can apply for a variation of the costs order within 14 days.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and sixteen (116) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Stewart. |

Associate:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15