Federal Court of Australia

Sheehy v Nuix Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 56

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating process is to be dismissed.

2. Within 14 days of these orders, the parties provide, by email, to the Associate of Halley J agreed or competing orders for costs.

3. In the event of competing orders, the parties also provide short written submissions and any affidavit evidence in support of their respective positions.

4. The making of costs orders be dealt with on the papers unless either party seeks an oral hearing, in which event that is to be communicated in the email referred to in Order 2.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[15] | |

[15] | |

[20] | |

[21] | |

[28] | |

[33] | |

[41] | |

[45] | |

[48] | |

[54] | |

[54] | |

[56] | |

[65] | |

Failure to sell Nuix by 2010 and 2011 share acquisition by Macquarie | [73] |

[77] | |

[80] | |

[88] | |

[93] | |

[94] | |

[101] | |

[102] | |

[102] | |

[104] | |

[104] | |

[111] | |

[114] | |

[123] | |

[130] | |

[130] | |

[136] | |

[138] | |

[142] | |

[145] | |

[145] | |

[145] | |

[150] | |

[153] | |

[153] | |

[157] | |

[165] | |

[165] | |

[168] | |

[176] | |

[176] | |

[189] | |

[213] | |

[213] | |

[216] | |

[216] | |

[222] | |

[229] | |

[233] | |

[239] | |

[239] | |

[245] | |

[248] | |

[253] | |

[255] | |

[257] | |

[259] | |

[261] | |

[266] | |

[269] | |

[272] | |

[281] | |

[290] | |

[299] | |

[310] | |

[310] | |

[311] | |

[316] | |

[322] | |

[330] | |

[341] | |

[341] | |

[342] | |

[344] | |

[348] | |

[349] | |

[352] | |

[356] | |

[359] | |

[364] | |

[364] | |

[367] | |

[367] | |

[369] | |

[371] | |

[385] | |

[385] | |

[387] | |

[388] | |

[392] | |

[392] | |

[402] | |

[405] | |

[405] | |

[408] | |

[414] | |

[415] | |

[416] | |

[416] | |

[417] | |

[420] | |

[427] | |

[430] | |

[430] | |

[438] | |

[448] | |

[448] | |

[451] | |

[454] | |

[457] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

HALLEY J:

1 Between 2006 and 2017, the applicant, Mr Edward Maurice Sheehy (Mr Sheehy), was the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the respondent, Nuix Pty Ltd (Nuix).

2 In 2008, as part of a renegotiation of his remuneration package, Mr Sheehy was granted options over shares in Nuix (2008 Options) that were exercisable upon the sale of the business of Nuix (2008 Option Agreement).

3 In late 2016, Nuix undertook a “share split” by which each of its existing shares was subdivided into 50 shares (Share Split).

4 During the same period in which Nuix undertook the Share Split, Macquarie Capital Group Limited (Macquarie) acquired a majority interest in Nuix, partly by purchasing and exercising approximately 20% of the 2008 Options from Mr Sheehy. Macquarie was able to exercise the 2008 Options it had acquired from Mr Sheehy because of a resolution of the Nuix board waiving any pre-conditions to the exercise of the options.

5 On 9 December 2016, Mr Sheehy received an amount of $10,354,467 from Macquarie from the sale of 20% of the 2008 Options and other options and resigned as the CEO of Nuix with effect from 27 January 2017.

6 In 2018, Mr Sheehy brought proceedings in the Supreme Court of New South Wales seeking a declaration that the 453,273 2008 Options that he had retained (Remaining 2008 Options) were exercisable in the event of a sale of the business of Nuix and for an order that the Nuix options register (Options Register) be corrected to record that the Remaining 2008 Options remained exercisable (2018 Proceedings). Nuix agreed to resolve the 2018 Proceedings on the basis that it would update the Options Register to record that the 453,273 Remaining 2008 Options were still capable of being exercised and that both parties pay their own costs. This agreement was recorded in a consent judgment entered on 26 November 2019 (Consent Judgment).

7 In December 2020, Nuix conducted an initial public offering (IPO) on the ASX which led to a significant reduction in Macquarie’s shareholding in Nuix.

8 In January 2021, Mr Sheehy provided Nuix with a notice seeking to exercise the Remaining 2008 Options on the basis that the IPO and the changes in the shareholding of Nuix constituted a sale of the business of Nuix (Option Exercise Notice). This contention was disputed by Nuix and it did not accept the Option Exercise Notice.

9 In these proceedings Mr Sheehy now seeks damages or compensation from Nuix arising from its refusal to accept the effect of the Share Split on the Remaining 2008 Options, the fact that they were exercisable and to issue shares in Nuix in accordance with those options. In refusing to accept the Option Exercise Notice, Mr Sheehy contends that Nuix has breached the 2008 Option Agreement, acted oppressively and engaged in unconscionable conduct.

10 Those contentions are rejected by Nuix and moreover, it contends that Mr Sheehy is precluded from raising those claims in this proceeding by reason of the Consent Judgment in the 2018 Proceedings.

11 These proceedings give rise to the following principal issues:

(a) given the terms of the Consent Judgment, is Mr Sheehy precluded by reason of res judicata/cause of action estoppel, issue estoppel, Anshun estoppel or abuse of process from advancing the causes of action that he is seeking to pursue in these proceedings;

(b) should a term be implied into the 2008 Option Agreement to the effect that, in the event of a share split, there is to be a proportionate adjustment to the conversion ratio between options and shares, either as an implication from the express terms of the agreement or because it is necessary to give business efficacy to the agreement;

(c) are the changes in the shareholding of Nuix, effected by the IPO, sufficient to constitute a sale of the business of Nuix for the purpose of enlivening the preconditions in the 2008 Option Agreement for the exercise of the Remaining 2008 Options;

(d) did Nuix breach the 2008 Option Agreement by not accepting the Option Exercise Notice;

(e) was the conduct of Nuix in not accepting the Option Exercise Notice oppressive, contrary to s 232 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act);

(f) was the conduct of Nuix in not accepting the Option Exercise Notice unconscionable contrary to s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL); and

(g) if Mr Sheehy has established that Nuix has breached the 2008 Option Agreement or, has otherwise contravened s 232 of the Corporations Act, or has contravened s 21 of the ACL, what damages or compensation should be awarded to Mr Sheehy.

12 There are two fundamental and insurmountable hurdles to the claims that Mr Sheehy seeks to pursue in these proceedings. First, Mr Sheehy, after the Share Split had occurred, sought and obtained pursuant to the Consent Judgment, a declaration in the 2018 Proceedings that the 453,273 Remaining 2008 Options that he held were exercisable in accordance with the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement and the Options Register be corrected to reflect that declaration. Second, pursuant to the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement, the Remaining 2008 Options were only able to be exercised on a sale of the business of Nuix.

13 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that Mr Sheehy is precluded by the doctrine of Anshun estoppel from pursuing the causes of action that he seeks to advance in these proceedings.

14 I am otherwise persuaded that the implied term that Mr Sheehy seeks should be implied into the 2008 Option Agreement but there has been no breach of that agreement because there has been no sale of the business of Nuix. I am not persuaded that the conduct of Nuix in not accepting the Option Exercise Notice was oppressive contrary to s 232 of the Corporations Act or unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21 of the ACL. If, contrary to these findings, Nuix had breached the 2008 Option Agreement or acted oppressively or unconscionably, I have determined that the value of the Nuix shares that Mr Sheehy would have been issued if the Option Exercise Notice had been accepted by Nuix for the purposes of determining the damages or compensation to which Mr Sheehy would have been entitled is best reflected in the valuation undertaken by Mr Michael Potter, the expert forensic accountant relied upon by Nuix, for the fourth scenario he was asked to consider.

15 Mr Sheehy gave evidence of the circumstances in which he entered into the 2008 Option Agreement and the background to the incentives provided to him. This evidence included the growth of the business of Nuix, the transactions between Nuix and Macquarie in 2011 and 2016, the sale to Macquarie in December 2016 of 30,000 options that had been issued to him with a grant date of 13 June 2006 and an exercise price of $0.85 (2006 Options) and some 20% of the 2008 Options. Mr Sheehy gave further evidence regarding the circumstances of his resignation as the CEO of Nuix, his knowledge and participation in the Share Split and the commencement and settlement of the 2018 Proceedings.

16 Mr Sheehy was cross-examined. He found the task of directly answering questions challenging. He was prone to becoming argumentative and non-responsive as illustrated in the following exchange:

Do you see that?---Yes, I see that.

And those were the instructions that you had given to Deutsch Miller at the time about your understanding of the effect of the share split on your options and those of all other Nuix share and option holders; correct?---Yes, and no. I hate to be confusing, but Deutsch Miller - - -

Let me just break it down for you, Mr – – –

HIS HONOUR: Had you finished your answer?---I was trying to explain why I said yes and no.

I think a yes and no answer probably does require an immediate explanation for it to be of any sense?---Deutsch Miller are a great law firm, but they didn’t understand the intricacies of options and shares, so hence the reason why – one of the reasons why I changed law firms by this case.

Well, that’s not really an answer to the question that was asked of you?---Oh, okay, sorry. And the question then is – I apologise.

MR DARKE: This paragraph, Mr Sheehy, reflects the instructions that you gave to Deutsch Miller about what you understood to be the effect of the share split on your options; correct?---Yes.

17 When pressed further by Mr Darke SC, who appeared for Nuix, as to how he gave instructions to his solicitors, Deutsch Miller, to state to Nuix that the number of the Remaining 2008 Options should be multiplied by 50 and the exercise price divided by 50, contrary to the position he was now advancing in these proceedings, he gave the following argumentative evidence:

That statement of how the share split would apply to your options, accorded with your instructions to Deutsch Miller, didn’t it?---That’s how they wrote it up, yes.

Yes. And - - -

HIS HONOUR: That’s not an answer to the question?---Sorry.

We are not interested in what they wrote up. We know what was written up; it’s in the letter. That wasn’t the question that was asked by Mr Darke. Answer Mr Darke’s question?---Yes, Mr Darke.

MR DARKE: The words that appear in brackets:

Our client’s options will be multiplied by 50 and the exercise price will be divided by 50.

Accorded with your instructions to Deutsch Miller; correct?---Yes. Yes and no again. I mean, there was multiple ways it was described over the - - -

I’m not asking you, Mr Sheehy, about how it was described?---Okay.

I’m asking you about the instructions you gave to Deutsch Miller. And the instructions you gave to Deutsch Miller were that the number of your options will be multiplied by 50, and the exercise price would be divided by 50 as a result of the share split; correct?---Yes.

And that was your state of mind at the time; correct?---I was of two states of mind because both – in my mind, both got to the same place. Whether you had 50 times the number of options then you had a one to one change, or you had a one to 50 share split and they both got to the same place.

Mr Sheehy - - -?---So, you could say yes.

If you had been in two states of mind at the time, as you just said, you would have instructed Deutsch Miller to describe the effect of the share split on your options in 35 those two alternative ways, wouldn’t you?---Sorry to be contrarian but no, I wouldn’t. Because they both ended up in the same place as having 22.X million shares. They – I wouldn’t have.

Mr Sheehy, you gave Deutsch Miller explicit instructions about how you understood the share split to affect your options; correct?---I gave them instructions.

Explicit instructions; correct?---I asked them to work out what happened. I wouldn’t have said – I didn’t sit down and give them a lecture on how share and option splits work. But, you know, I thought it was pretty obvious.

18 I accept that generally, Mr Sheehy was seeking to answer questions truthfully but at times his evidence was not only affected by the adversarial manner in which it was given but also by the extent to which it was inconsistent with the apparent logic of events or contemporaneous documents. This inconsistency was particularly evident in his evidence about his knowledge of the content of the capitalisation tables and option registers of Nuix, his knowledge of the Share Split and its likely impact on the Remaining 2008 Options and the reasons why he had not advanced in the 2018 Proceedings the claims he now seeks to raise in these proceedings.

19 In all the circumstances, I did not disregard but I treated with caution the evidence, both written and oral, given by Mr Sheehy in these proceedings.

20 The respondent relied on the following witnesses.

21 Mr David Standen is an Executive Director of Macquarie. In the period between June 2011 and November 2020 he was a non-executive director of Nuix.

22 Mr Standen gave evidence of his involvement with the co-founder of Nuix, Dr Tony Castagna, who had previously been a consultant to Macquarie, and the circumstances of Macquarie’s initial investment in Nuix, the Share Split and the October 2016 transaction whereby Macquarie acquired 20% of all shares and options held by participating Nuix employees, for approximately $20 million (Macquarie 2016 Transaction). In particular, Mr Standen gave evidence of his understanding as to whether, absent a waiver from Nuix, the options that Macquarie acquired from Mr Sheehy were exercisable and the relationship between the transaction and Mr Sheehy’s resignation from Nuix. He also gave evidence of his knowledge and involvement in the settlement of the 2018 Proceedings including the basis on which Nuix agreed to the terms of the Consent Judgment.

23 Mr Standen was cross-examined.

24 The principal focus of the cross-examination of Mr Standen by Mr Jackman SC (as his Honour then was), who appeared for Mr Sheehy, was a challenge to his evidence that although Macquarie had agreed to pay approximately $7 million for the 2008 Options from Mr Sheehy, Mr Standen believed at the time they were purchased that they could not be exercised because they had expired. The cross-examination included the following somewhat colourful exchange:

Now, on your evidence, Mr Standen, Mr Sheehy’s options issued under the letter of 5 17 September 2008, in order to be exercised, required something to have happened by the end of 2010; correct?---Yes.

And it was now 2016; correct?---Yes.

Right. And, to your understanding, then, the options had expired or lapsed?---Yes.

Right. And, in effect, they were dead. Yes?---I don’t know if that’s – whatever word you want to use. I mean, what can I say here.

But among Macquarie’s many skills is the not the ability to bring the dead back to life, is it?---Look, again, I don’t know what word you want to use, but, yes.

25 Mr Standen otherwise gave evidence that the apparent contradiction was that the “real substance and intention” of Macquarie’s acquisition of 86,727 of the 2008 Options and the 2006 Options from Mr Sheehy was a “golden handshake” on an ex gratia basis so that he “would leave on good terms and support the business going forward in a productive way.” He explained that this was the commercial purpose of the transaction and that Macquarie had only agreed to proceed on the basis that Nuix would waive the preconditions to the exercise of the options, which included for the Remaining 2008 Options that there had been a sale of the business of Nuix.

26 I accept Mr Standen’s evidence, albeit that his subjective belief as to the status of the Remaining 2008 Options was at best of marginal relevance to the matters that I had to determine. It was consistent with the contemporaneous Nuix board minutes formally waiving any preconditions to the exercise of the options to be acquired by Macquarie from Mr Sheehy and the entries in Nuix’s capitalisation tables and option registers recording that the options had been exercised or surrendered. It was also consistent with the apparent logic of events, as Mr Sheehy resigned on the day he entered into the option sale agreement with Macquarie and Macquarie immediately exercised the options and acquired a majority interest in Nuix.

27 In the circumstances, the credit challenge to Mr Standen’s evidence did not cause me to doubt the accuracy or truthfulness of Mr Sheehy’s oral and written evidence.

28 Mr Daniel Phillips is an executive director of Macquarie. He was appointed as a non-executive director of Nuix in 2011.

29 Mr Phillips gave evidence of Macquarie’s initial investment in Nuix in 2011, his understanding of the status of the 2008 Options, his involvement in the Macquarie 2016 Transaction, his knowledge of the “increasing friction” between Mr Sheehy and the Board of Nuix and the circumstances in which Macquarie agreed to purchase 2008 Options from Mr Sheehy. Mr Phillips also gave evidence of the reasons why Nuix agreed to a resolution of the 2018 Proceedings on the basis of the Consent Judgment and the time that would have been necessary for Mr Sheehy to have been issued with shares in Nuix and for the shares to then be sold, if Nuix had accepted the validity of his purported exercise of the Remaining 2008 Options on 27 January 2021.

30 Mr Phillips was cross-examined.

31 Much of the cross-examination of Mr Phillips was directed at his evidence concerning the Macquarie 2016 Transaction. It was clearly evident from the cross-examination of Mr Phillips that his knowledge of the status of the 2008 Options at the time of the Macquarie 2016 Transaction was very limited and that Mr Standen had principal carriage of the transaction for Macquarie.

32 The concessions made by Mr Phillips in the course of his cross-examination as to the extent of his knowledge of relevant events were readily provided. I am satisfied these concessions did not reflect on the reliability of other relevant evidence that he gave of matters in which he had direct knowledge. In particular, the reasons why Macquarie acquired 2008 Options from Mr Sheehy as part of the Macquarie 2016 Transaction and the basis on which Nuix agreed to the Consent Judgment.

33 Mr Damian Smith was the interim CEO of Nuix between June 2005 and June 2006 and a non-executive director of Nuix between 2005 and 2011. He resigned as a director of Nuix on 31 May 2011.

34 Mr Smith gave evidence about his involvement in the appointment of Mr Sheehy as the CEO of Nuix in 2006, Mr Sheehy’s 2006 employment contract, the background to and negotiation of the remuneration arrangements with Mr Sheehy that culminated in the 2008 Option Agreement and the initial investment by Macquarie in Nuix in 2011.

35 Mr Smith was cross-examined.

36 The principal focus of the cross-examination of Mr Smith was his statement in paragraph 6 of his affidavit that he had a conversation with Mr Sheehy at the time of the negotiation of the 2008 Option Agreement in which he stated words to the effect:

The board wants to incentivise you to help find a sale of the entire business.

37 Prior to being taken to this paragraph in his cross-examination by Mr Jackman, Mr Smith gave the following evidence:

You understood my questions to relate to the fact that words such as “whole” or “entire” or similar adjectives were not used by either you or Mr Sheehy in any correspondence in negotiating the option agreement?---In these documents; that’s correct.

Yes. And you don’t remember any other document which used words such as “whole” or “entire” in describing the sale of the business of Nuix?---I don’t recall any other documents that haven’t been shown to me regardless.

And you don’t recall any conversation between you and Mr Sheehy in negotiating the option agreement in which words such as “whole” or “entire” were used in relation to the sale of the business; correct?---I cannot specifically recall that phrase. Specifically, no.

38 Prior to this exchange with his cross-examiner, Mr Smith presented as an attentive, careful and responsive witness. It was therefore of some concern that immediately after being taken to paragraph 6 of his affidavit, he gave the following evidence:

You don’t actually recall the word “entire” being used, do you?---Sorry, I misunderstood your previous question. You know, I recall – I don’t recall a document that used those words. I don’t recall any other documents that aren’t in these various folders.

No?---I do recall that conversation, and, again, that’s certainly my recollection throughout, that that was my intention.

Mr Smith, you understood my question a moment ago to relate to conversations between you and Mr Sheehy, not documents?---Sorry, I misunderstood.

Is English your first language, Mr Smith?---It is. I’m sorry. I just misunderstood the question.

39 Given this evidence, I am not persuaded that Mr Smith has any specific recollection of using the word “entire business” in discussions with Mr Sheehy about the incentives he was being provided to sell the business of Nuix. There was no ambiguity in Mr Jackman’s questions. The use of the language of a sale of the “entire business”, given there was no suggestion that Nuix operated more than one business, appears strained and objectively unlikely to have been used. I accept that Mr Smith was discussing what he understood to be a sale of the whole of the business of Nuix but I do not accept that he used the specific words “whole of” or “entire” to describe the scope of the business to be sold. There was no contemporaneous document or testimonial evidence to the effect that any consideration was ever given at the time of the negotiation of the 2008 Option Agreement to any sale of anything other than the business as a whole, let alone the provision of any incentive to Mr Sheehy to sell less than the whole of the business. Hence, there would not appear to have been any reason to emphasise “whole of” or “entire” in discussions about the sale of the business of Nuix.

40 I otherwise accepted as truthful and reliable the evidence given by Mr Smith. It was of relatively limited compass and it was consistent with, and did not seek to travel materially beyond, the contemporaneous documents and the apparent logic of events.

41 Ms Cassandra Rochay (née Bell, as she was at the time of affirming her affidavit) is the Head of Risk at Nuix. She gave evidence regarding the maintenance of the Options Register, maintained in the form of an excel spreadsheet entitled “Capitalisation Table”. She gave evidence that the Options Register was initially maintained by Mr Sheehy, who then delegated responsibility of that task to herself and another Nuix employee, Mr Stephen Doyle.

42 Ms Rochay also gave evidence in her affidavit regarding the Macquarie 2016 Transaction and her understanding of how this transaction affected Mr Sheehy’s options, her involvement in the Share Split, the provision of a version of the Options Register to Mr Sheehy in the course of the 2018 Proceedings, the resolution of the 2018 Proceedings culminating in the Consent Judgment and the Nuix “Employee Options Plans”.

43 Ms Rochay was cross-examined.

44 She directly answered the questions that were put to her in a considered and careful manner. Her answers in cross-examination and her affidavit evidence were consistent with both contemporaneous documents and the apparent logic of events. I had no reason to doubt the accuracy or truthfulness of her answers.

45 Mr Michael Egan is the company secretary of Nuix. He was appointed to that role on 9 October 2020.

46 Mr Egan gave evidence of the receipt by Nuix of the notice of the purported exercise by Mr Sheehy of the Remaining 2008 Options on 27 January 2021. He also gave evidence of the steps that Nuix would have had to take to issue Nuix shares to Mr Sheehy and arrange for them to be listed on the ASX, including the time it would likely take to complete each of those steps, if Nuix had accepted the exercise notice was valid.

47 Mr Egan was not required for cross-examination.

48 Both Mr Sheehy and Nuix advanced expert evidence directed at the likely sale prices that Mr Sheehy could have expected to receive in various scenarios had Nuix accepted his purported exercise of the Remaining 2008 Options on 27 January 2021 and Mr Sheehy had then sold on the ASX the Nuix shares that he would have been issued.

49 Mr Sheehy relied on a report from Ms Julie Planinic, a forensic accountant and a director of Lonergan Edwards, dated 13 December 2021.

50 Nuix relied on a report from Mr Michael Potter, a forensic accountant and a director of Axiom Forensics, dated 14 April 2022.

51 The experts prepared a joint report and gave concurrent evidence in the course of the hearing in what has colloquially been referred to as a “hot tub”.

52 Both the joint report and the evidence given by the experts concurrently at the hearing, together with the comprehensive and detailed reports prepared by each of them, demonstrated that other than with respect to some ultimately minor matters of emphasis, particularly on “blockage discounts”, the only substantive disagreements between them on the sale prices that Mr Sheehy could have expected to have achieved on the various scenarios that the experts were asked to consider were driven by assumptions as to the length of time it would take for the shares to be sold.

53 I consider in more detail the evidence given by the experts later in these reasons in addressing what damages Mr Sheehy might have expected to have been awarded had he otherwise been successful in establishing the causes of action that he seeks to advance in these proceedings.

54 Nuix was founded by Mr Jim McInerney. He died in 2004 and his wife, Agnes McInerney, inherited ownership of Nuix.

55 In late 2005, a group of six investors invested approximately $510,000 in Nuix (Angel Investors) to fund its recapitalisation and restructuring.

56 On 12 June 2006, Mr Sheehy commenced employment with Nuix as its CEO. The Chairman of Nuix at that time was Mr Tony Castagna who remained the Chairman until 2021, apart from a period between 2013 and 2015 when the Chairman was Mr David Standen.

57 Mr Sheehy was employed pursuant to a written agreement in the form of a letter from Mr Castagna dated 12 April 2006 and signed by Mr Sheehy on 19 June 2006 (Employment Contract).

58 The total compensation package offered in the Employment Contract comprised a guaranteed cash component, an “at-risk” bonus and an equity participation. The “at-risk” bonus comprised a sales bonus and a separate profitability bonus.

59 The Employment Contract provided, under the heading “Equity participation”, that Mr Sheehy would be:

…offered the opportunity to purchase 30,000 shares, or 3% of the issued capital in the company via an options scheme. The terms and conditions for these stock options will be provided to you in a separate document, but the essential terms will be:

• Vesting over 36 months, commencing June 2006

• 12-month “cliff” for vesting, such that should you leave prior to June 2007, no stock options would vest

• 12 month “accelerated” vesting in the event of a change of control of the company

• 90-day period after your departure from the company in which you may exercise these options …

60 Under the heading “Equity participation”, the Employment Contract also provided that Mr Sheehy may be granted an additional 25,000 fully-paid shares at the discretion of the Nuix Board.

61 The Employment Contract stated the compensation package “provides a strong incentive for [Mr Sheehy] to unlock the value inherent in the opportunity” available to Nuix.

62 Mr Sheehy subsequently received an “Offer to Take up Options Under the Employee Option Plan (EOP)” dated 23 July 2007 (2007 Offer). Mr Sheehy was invited to apply for the 2006 Options under the Employee Option Plan Rules of Nuix dated 17 July 2007 (EOP Rules) on the terms and conditions set out in the 2007 Offer. The options were stated to be otherwise subject to the EOP Rules. The options were exercisable for five years after the date on which they vested.

63 The EOP Rules provided:

(a) for the accelerated vesting of options in the event of a “Change of Control event”, which “denotes an event where 51% of the company’s Shareholding changes ownership” (cl. 11); and

(b) that in the event of a “reorganisation of the capital of the Company the terms of the Options shall be reorganised in accordance with the relevant re-organisation plan as at the date of reorganisation” (cl. 10.1).

64 On 23 July 2007, Mr Sheehy accepted the 2007 Offer.

65 The Employment Contract was due to be reviewed at the end of the 2007 financial year.

66 On 17 September 2008, a further remuneration arrangement was ultimately agreed between Mr Sheehy and Nuix pursuant to the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement.

67 The 2008 Option Agreement was in the form of a letter from Mr Castagna and Mr Smith that Mr Sheehy signed as received and accepted on 17 September 2008.

68 The 2008 Option Agreement commenced by acknowledging the work that Mr Sheehy had done, in particular, the “growth and focus you have brought to the CEO role”.

69 It then relevantly provided as follows:

The package we are proposing is one that unambiguously aligns your incentives with those of existing shareholders. In particular, it provides very strong incentives for you to look for a sale event for Nuix before the end of 2010; a sale event at particular valuations during this time will see you enjoy a significant reward.

We are therefore pleased to offer you a new package as follows:

l) An unrestricted stock grant of 75,000 shares, vesting immediately. I know you are aware that there will likely be tax consequences for you on this grant, and that you acknowledge these tax consequences will be borne by you.

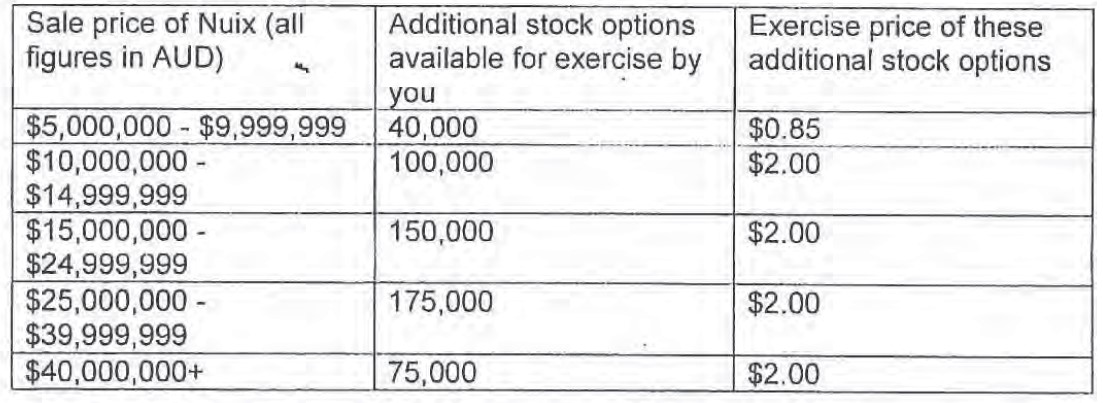

2) A series of “call options” over Nuix stock, exercisable in the event of a sale of the business at particular prices. Note that these options are only exercisable in the event of a sale; a valuation of the business in the context of an additional funding round will not trigger the call option. These call options will be structured as follows:

Note that these stock options are both incremental and cumulative; meaning, by way of example, that a sale price of $10,000,000 would see you able to exercise options to purchase 40,000 shares at $0.85 PLUS 100,000 shares at $2.00.

Please note that the $2.00 exercise price is in - place for all new option grants since 2007; however, given the time taken to negotiate this package, we acknowledge that you would have normally received an additional stock option grant on the 12-month anniversary of your employment in June 2007. This grant would have been at the previous $0.85 exercise price, and so this will prevail for the first 40,000 additional options.

…

3) You will also receive a cash bonus, in the event of a sale in excess of certain$ thresholds before certain nominated dates as follows:

• For a sale in excess of $10,000,000 on or before 31 December 2009, you will receive a cash bonus (pre-tax) equivalent to 20% of the total cash gain (net of exercise price but pre-tax) you receive from the sale via your equity ownership.

• For a sale in excess of $20,000,000 on or before 31 December 2010, you will receive a cash bonus (pre-tax) equivalent to 20% of the total cash gain (net of exercise price but pre-tax) you receive from the sale via your equity ownership.

4) Please note that your equity position (unrestricted stock and options) has been expressed in absolute terms, not as a relative % of the company. Obviously, should additional financing rounds take place, and the total number of shares outstanding increase, your relative % ownership will decline, but the absolute number of shares & options held (and the $ thresholds for exercise) will remain constant.

70 The 2008 Option Agreement concluded:

Eddie, let me again indicate the strong support you enjoy from the Board. We hope the package as outlined in this email [sic] reinforces that support and provides you with clear incentives to grow the business and achieve the sale event that the current shareholders seek.

71 The 2008 Option Agreement was not stated to be subject to the EOP Rules, including any provision linking the exercise of the options to a change of control or any provision for the reorganisation of the terms of the options upon reorganisation of Nuix’s share capital.

72 On 17 September 2008, Mr Sheehy was issued with the 2008 Options, being 540,000 call options issued pursuant to the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement.

Failure to sell Nuix by 2010 and 2011 share acquisition by Macquarie

73 The business of Nuix was not sold by 31 December 2010.

74 On 18 May 2011, the Angel Investors, other than Ferodale Limited (Ferodale), entered into a subscription and share purchase agreement with Macquarie Group Capital Limited for the sale of all of their Nuix shares to Macquarie.

75 On 31 May 2011, Macquarie paid approximately $8 million in consideration for the transfer of the Nuix shares from the Angel Investors. Macquarie also invested a further $2.5 million in return for the issuance of new shares. At this point, Macquarie became the largest shareholder in Nuix.

76 On 9 June 2011, Mr Standen and Mr Phillips were appointed to the Nuix Board.

2016 payment to Mr Sheehy and his resignation

77 In October 2016, Macquarie made an offer to acquire 20% of all shares and options held by Nuix employees, for approximately $20 million pursuant to the Macquarie 2016 Transaction.

78 On 18 October 2016, the Nuix board considered and approved the Macquarie 2016 Transaction. The Nuix board also passed a resolution at the board meeting held on that day waiving any option exercise conditions as part of its approval of the Macquarie 2016 Transaction.

79 As part of the Macquarie 2016 Transaction, Mr Sheehy sold all of the 2006 Options and 86,727 of the 2008 Options to Macquarie in exchange for a payment from Macquarie of $10,354,467. This sale left Mr Sheehy with the Remaining 2008 Options totalling 453,273 options. Macquarie immediately exercised the 2006 Options and the 2008 Options that it had purchased from Mr Sheehy and was issued with shares by Nuix in accordance with those options.

Share Split and resignation of Mr Sheehy

80 On 29 November 2016, the directors of Nuix, including Mr Sheehy, formally passed a resolution to propose the Share Split to existing shareholders of Nuix for their approval. The Share Split provided for a division of the ordinary shares of Nuix pursuant to the mechanism contained in s 254H of the Corporations Act so that each ordinary share would be subdivided into 50 ordinary shares. This resolution formalised an agreement between the Nuix directors, including Mr Sheehy, in August 2016 that was recorded in a document entitled “Resolution by signed minute” and emailed to Nuix board members on 12 August 2016 (Share Split board resolution).

81 On 5 December 2016, Mr Sheehy signed the Share Split board resolution.

82 On 9 December 2016, Mr Sheehy received the payment of $10,354,467 from Macquarie and resigned from his employment with Nuix, with effect from 27 January 2017.

83 On 15 December 2016, the Share Split was approved by Nuix shareholders.

84 On 14 March 2017, the Share Split was completed.

85 The Share Split was implemented due to the high price of Nuix shares (at that time $100 per share), the impact of a high share price on the recruitment of staff and on the ability of Nuix to conduct an IPO.

86 In preparation for the Share Split, Mr Castagna appeared in a webinar to staff to explain its effect on their shares and options (Webinar). In the course of that Webinar he stated that:

…we are going to do a 50 to 1 share split. Those of you who have already got options will get a letter from us saying - advising you of the split - and what that means is that, if I just use a very simple example; for every one option that you have, post-split – post the 50 to 1 split - you will have 50 share options. So, for every one share option that you have you will be able to translate that into 50.

and

but essentially applying the principle of fairness and equity nothing changes as a result of the split because what we are really saying is the size of the cake is the same instead of having fat - one fat slice you have got –you have got 50 slices that add up to the same one fat slice - they are just thinner slices - the addition of each of those 50 slices ends up being the same as the slice had you got only one.

87 Mr Castagna also gave a PowerPoint presentation at a series of Town Hall meetings relating to the Share Split (Town Hall Meetings). The slides for that presentation included two worked examples in which the number of options were multiplied by 50 and the equivalent price to exercise the options was divided by 50. The slides included statements that “the relative price ratio remains unchanged” as a result of the Share Split, and that “the pre & post split total price to exercise remains unchanged”.

88 On 22 May 2018, Mr Sheehy commenced the 2018 Proceedings in the Commercial List of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

89 In the 2018 Proceedings, Mr Sheehy relevantly sought (in his Summons):

1 A declaration that 453,273 options granted over unissued shares of the defendant that the plaintiff holds (Options) are exercisable by the Plaintiff on the occurrence of a sale of the defendant’s business in accordance with the agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant made on or around 17 September 2008.

2 An order under section 175(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) that the defendant correct its register to record the Options.

90 On 7 November 2019, Mr Sheehy made an offer to settle the 2018 Proceedings (Settlement Offer).

91 On 21 November 2019, Nuix accepted the Settlement Offer.

92 On 26 November 2019, the Supreme Court made declarations and orders in the terms of prayers 1 and 2 of Mr Sheehy’s Summons pursuant to the Consent Judgment.

Commencement of these proceedings

93 On 26 October 2020, Mr Sheehy commenced these proceedings.

94 On 18 November 2020 Nuix issued a prospectus in relation to an IPO of its shares.

95 The total number of shares to be issued and transferred under the IPO was 179.5 million and the total number of shares in Nuix on completion would be 317.3 million.

96 As at the date that the prospectus for the IPO was issued, Macquarie held 76.2% of the shares in Nuix and 66.1% of the shares on a fully diluted basis (that is existing shares and shares to be issued on the exercise of options).

97 On completion, Macquarie would hold 30.1% of the shares in Nuix and 30.0% on a fully diluted basis. New investors in the IPO would hold 55.8% of the shares in Nuix and 55.4% of the shares on a fully diluted basis.

98 On 20 November 2020, Mr Sheehy’s solicitors sent a letter to Nuix's solicitors indicating that he intended to exercise the Remaining 2008 Options.

99 On 3 December 2020, Nuix’s solicitors stated in response to Mr Sheehy’s solicitors that there had not been a sale of Nuix for the purposes of his purported exercise of the Remaining 2008 Options, with the result that those options were not exercisable.

100 On 4 December 2020, the IPO proceeded and Nuix was listed on the ASX.

Purported exercise of the Remaining 2008 Options

101 On 27 January 2021, Mr Sheehy provided Nuix with the Option Exercise Notice in relation to the Remaining 2008 Options. This was rejected by Nuix on 2 February 2021.

102 Nuix relies on res judicata/cause of action estoppel, issue estoppel, Anshun estoppel and abuse of process preclusionary defences that it alleges arise from the Consent Judgment in the 2018 Proceedings.

103 It is necessary to address the potential application of these defences before considering the substantive claims that Mr Sheehy seeks to advance in these proceedings. If Nuix can establish any of these defences, then the claims made by Mr Sheehy must be dismissed or, to the extent that the defences may be established with respect to some of the claims advanced by Mr Sheehy, then those claims must be dismissed.

Res judicata/cause of action estoppel

104 Res judicata/cause of action estoppel (or “claim estoppel”) requires both that a “claim to a right or obligation” was asserted in a prior proceeding and that the claim was finally determined in that proceeding. It operates “to preclude assertion in a subsequent proceeding of a claim to a right or obligation which was asserted in the proceeding and which was determined by the judgment”: Tomlinson v Ramsey Food Processing Pty Limited (2015) 256 CLR 507; [2015] HCA 28 (Tomlinson) at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ) (see also [20] regarding res judicata); Clayton v Bant (2020) 272 CLR 1; [2020] HCA 44 (Clayton) at [29] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ).

105 Consent judgments attract the operation of the doctrine of res judicata/cause of action estoppel: Chamberlain v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1988) 164 CLR 502; [1988] HCA 21 (Chamberlain) at 505 (Brennan J), 508 (Deane, Toohey and Gaudron JJ), 512 (Dawson J); see also Somanader v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2000] FCA 1192 at [36] (Merkel J). So, too, do declarations: Spautz v Butterworth (1996) 41 NSWLR 1 at 20.

106 In Re South American and Mexican Co; ex parte Bank of England [1895] 1 Ch 37 (South American and Mexican Co), a matter where a consent order for financial provision was held to bar a further application by the former wife, Lord Herschell, LC stated at 50:

The truth is, a judgment by consent is intended to put a stop to litigation between the parties just as much as is a judgment which results from the decision of the Court after the matter has been fought out to the end. And I think it would be very mischievous if one were not to give a fair and reasonable interpretation to such judgments, and were to allow questions that were really involved in the action to be fought over again in a subsequent action.

107 The focus of cause of action estoppel is on “substance rather than form”: Trawl Industries of Australia Pty Ltd v Effem Foods Pty Ltd (In Liq) (1992) 36 FCR 406 (Trawl Industries) at 418 (Gummow J); cited with approval in Clayton at [34] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ) and [68] (Edelman J). Absolute identity between the sources and incidents of rights asserted or capable of being asserted is not required. There need only be “substantial correspondence” or that the rights are “of a substantially equivalent nature and cover substantially the same subject matter”: Clayton at [34] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ).

108 In Trawl Industries, Gummow J held that the dismissal of a claim for misleading or deceptive conduct under ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TP Act) gave rise to a cause of action estoppel against a claim in negligence. The applicant had previously brought proceedings in negligence based on some of the same representations, and sought damages measured in the same way and in the same quantum as in the subsequent proceedings. Gummow J stated at 422:

In my view, Effem has made out its case of cause of action estoppel against Trawl. This is so, even though no claim previously was made in negligence. The substance of the controversy embraces such a claim. The gist of the recovery sought both in negligence and for contravention of the TP Act is the same.

…

109 To similar effect, in Zavodnyik v Alex Constructions Pty Ltd (2005) 67 NSWLR 457; [2005] NSWCA 438 (Zavodnyik) a builder’s claim in restitution was barred by cause of action estoppel by reason of the dismissal of the builder’s earlier claim in contract: [30], [31], [33] (Handley JA, Mason P and Latham J agreeing). And in Lee v Kim (2006) 68 NSWLR 433; [2006] NSWCA 384 (Lee), Handley JA (Beazley and Santow JJA agreeing) found that a cause of action estoppel arose where a party, having failed in a claim for defamation based on the publication of material in two issues of a newspaper, sought to later sue for the publication of other material in the same issues (said to convey the same defamatory implications): at [27]. That was so despite the fact that the causes of action were technically different: see [15]-[17].

110 In considering whether cause of action estoppel arises, it is irrelevant whether the plaintiff knew, when he brought the first action, the facts on which he relies in the second: Honeywood v Munnings (2006) 67 NSWLR 466; [2006] NSWCA 215 at [11]-[19] (Handley JA, Giles JA and Hislop J agreeing); French & Anor v NPM Group P/L [2008] QCA 217 at [47]-[54].

111 Mr Sheehy submits that the “claim to a right or obligation” in the 2018 Proceedings was the claim that the Remaining 2008 Options continued to exist contrary to the contention by Nuix that they had expired.

112 More specifically, Mr Sheehy submits that the claim was that Nuix was in breach of contract because it had refused to recognise the continued existence of the options. He submits that claim was determined by the declaration in paragraph 1 of the Consent Judgment that the options “are exercisable by the plaintiff on the occurrence of a sale of the defendant’s business”. He submits that this declaration said nothing about the particular terms of the Remaining 2008 Options.

113 Mr Sheehy submits that his claim that the options had not expired and continued to exist was the claim that merged in the Consent Judgment. He submits that each of the breach of contract, oppression and unconscionability claims in the present proceedings are entirely different.

114 Nuix relies on three matters to establish that Mr Sheehy’s claim in these proceedings that he is entitled to 22,663,650 shares is precluded by cause of action estoppel.

115 First, Nuix submits that Mr Sheehy’s claim to hold a particular number of options following the Share Split (the claim brought in the 2018 Proceedings) is substantively equivalent to his claim to be entitled to a particular number of shares on exercise of his options (the claim brought in these proceedings).

116 Nuix submits that the 2018 Proceedings dealt with one of the “two ways” the Share Split could be applied to Mr Sheehy’s Remaining 2008 Options. The 2018 Proceedings necessarily involved the effect of the Share Split on Mr Sheehy’s Remaining 2008 Options because one of the ways the Share Split could arguably affect those options was by multiplying their number and Mr Sheehy was seeking a declaration as to the number of options he held post the Share Split. It follows that the substantively equivalent claim Mr Sheehy now makes as to the effect of the Share Split on the Remaining 2008 Options - namely, that it multiplied the number of shares to which those options entitle him - was also part of that controversy.

117 It submits that this has the consequence that Mr Sheehy’s claimed entitlement to 22,663,650 shares is, as a matter of substance, the same as the claim determined by the 2018 Proceedings. The “substance of the controversy” litigated in the 2018 Proceedings “embrace[d]” the claim Mr Sheehy now makes. It submits that claim is thereby precluded by cause of action estoppel.

118 Second, Nuix submits that, by reason of Order 2 in the Consent Judgment (prayer 2 of Mr Sheehy’s Summons in the 2018 Proceedings), Nuix was required to rectify its Options Register to record that Mr Sheehy held 453,273 options (Rectification Order). Pursuant to s 170 of the Corporations Act, a company’s options register must contain particular information, including the number of shares over which the options were granted and the exercise price of the options: s 170(1)(d) and (h). It submits that as such, the Rectification Order required Nuix to specify these matters in its register with respect to the Remaining 2008 Options and must, therefore, have determined them. The order cannot have required Nuix to breach s 170 of the Corporations Act by including incomplete information on the Options Register.

119 Moreover, Nuix submits that the Consent Judgment must be understood in light of Mr Sheehy’s contentions in the Commercial List Statement in the 2018 Proceedings (CLS). In particular, that the Rectification Order encompassed details of Mr Sheehy’s options is reflected in the terms of the CLS at [14(b)], where Mr Sheehy stated that the order would require Nuix to record “accurate particulars of the Remaining Sheehy Options in Nuix’s register of options”.

120 Nuix submits that is reinforced by the fact that Mr Sheehy: (a) pleaded that he held 453,273 options (CLS at [9]); (b) particularised the 2008 Option Agreement in support of a term that those options existed and were exercisable (CLS at [5]); and (c) pleaded the requisite particulars of those options in the CLS at [5], by particularising cl 2 of the 2008 Option Agreement (excluding the final paragraph). That part of the 2008 Option Agreement recorded the exercise price for the options (in the third column of the table) and that one option entitled Mr Sheehy to one share (by the text at the bottom of the table, read together with the table itself).

121 Third, Nuix submits that the declaration made by the Consent Judgment stated that the Remaining 2008 Options were exercisable by him “on the occurrence of the sale of the defendant’s business in accordance with the agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant made on or around 17 September 2008”. By doing so, the declaration in the Consent Judgment determined that the 2008 Option Agreement: (a) contained the terms pleaded and particularised in the CLS at [5]; and (b) had terms which were express or implied by law only, as particularised in the CLS at [4].

122 Nuix submits that in view of these matters, the Court determined by the Consent Judgment, not only that Mr Sheehy’s options remained in existence, but also their number (453,273), exercise prices (being those set out in the third column of the table in the 2008 Option Agreement), and number of shares over which they were granted (one share for each option). As a matter of res judicata, Mr Sheehy’s claimed rights with respect to those matters therefore merged in the Consent Judgment. In terms of cause of action estoppel, Mr Sheehy’s claim in this proceeding to an entitlement to 22,663,650 shares upon exercise of his options is precluded or estopped.

123 The claim or right determined by the declaration in the Consent Judgment was whether the 453,273 options granted to Mr Sheehy remained exercisable by him on the sale of the business of Nuix in accordance with the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement. The order for the correction of the Options Register in the Consent Judgment was ancillary to that declaration. It did not expand or qualify the claim or right determined by the declaration.

124 The claims and rights the subject of these proceedings are directed not at the continued existence of the Remaining 2008 Options but rather at the number of shares over which the options can be exercised given the 50 for 1 share split and whether there had relevantly been a “sale of the business” of Nuix in late 2020. Unlike Trawl Industries, Zavodnyik and Lee this is not a case where an applicant is seeking to advance a new cause of action based on the same conduct that had been relied upon and determined in a prior proceeding.

125 There was no “substantial correspondence” between a right to exercise an option and the determination of a conversion ratio from options to shares following a share split. Nor are those discrete rights “of a substantially similar nature and cover substantially the same subject matter”. The substance of the controversy in the 2018 Proceedings was the continuing existence of the Remaining 2008 Options, not their conversion ratio into Nuix shares.

126 I accept that a method by which a share split might typically be addressed in order to prevent prejudice to an option holder would be to multiply the number of options they hold and to preserve the existing conversion ratio. I also accept that the Consent Judgment necessarily precluded Mr Sheehy from advancing any case in these proceedings that the number of options that he held following the Share Split could be multiplied by 50 to reflect the impact of the Share Split. I do not accept, however, that this incidental or consequential effect of the Consent Judgment on claims or rights that Mr Sheehy might subsequently pursue against Nuix had the consequence of expanding the controversy litigated in the 2018 Proceedings to the claims now advanced by Mr Sheehy in these proceedings.

127 Nor do I accept that the pleading and particularisation of the 2008 Option Agreement in the CLS can expand the controversy litigated in the 2018 Proceedings. An order to correct a register to reflect the specific claim or right the subject of a declaration cannot expand the controversy beyond the terms of the declaration. Nor can the identification in a declaration of the agreement under which options are to be exercised have that effect. The Consent Judgment necessarily by its terms determined the number of options that Mr Sheehy held following the Share Split. It did not determine their exercise price nor the number of shares over which they were granted. The controversy was limited to whether Mr Sheehy could still exercise the Remaining 2008 Options.

128 For these reasons, I am satisfied that the claims made by Mr Sheehy in these proceedings are not precluded by cause of action estoppel or the doctrine of res judicata.

129 Issue estoppel is a principle whereby “judicial determination directly involving an issue of fact or of law disposes once for all of the issue, so that it cannot afterwards be raised between the same parties or their privies”: Blair v Curran (1939) 62 CLR 464; [1939] HCA 23 at 531 (Dixon J) cited with approval in Tomlinson at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ). Issue estoppel can arise even where the causes of action in the two proceedings are entirely different: Jackson v Goldsmith (1950) 81 CLR 446; [1950] HCA 22 (Jackson) at 467 (Fullagar J). Issue estoppel similarly involves consideration of substance over form: see Ku-Ring-Gai Council v Ichor Constructions Pty Ltd [2014] NSWSC 1534 at [33] (Stevenson J); Tomlinson at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ); Clayton at [34] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ).

130 Unlike res judicata where only the actual record is generally relevant, any material may be looked at which will show what issues were raised and decided: Jackson at 467 (Fullagar J).

131 Consent judgments can give rise to issue estoppel: Robinson v Deep Investments Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 232; (2018) 364 ALR (Robinson) at [137] (Jagot and Colvin JJ); Commissioner of Taxation v Day (2007) 164 FCR 250; [2007] FCAFC 193 at [15] (Spender J, Edmond J agreeing); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (No 2) (2001) 119 FCR 1; [2001] FCA 1861 at [1148] (Goldberg J); Ekes v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2014] NSWCA 336 (Ekes) at [111] (Bathurst CJ, Beazley P and Emmett JA agreeing); Habib v Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd [2009] NSWCA 231 at [186] (and the authorities cited therein) (McColl JA, Giles and Campbell JJA agreeing); Makhoul v Barnes (1995) 60 FCR 572 at 582 (Hill, Cooper and Branson JJ); and NHB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Corry (No 7) [2021] NSWSC 741 at [400], [402], [414] (Bell P).

132 In Robinson, Jagot and Colvin JJ observed at [137] that, when considering the extent to which a consent judgment may give rise to an issue estoppel:

…there must be an inquiry as to the issues that were determined by the consent judgment and any issue estoppel only arises to the extent that the consent determined a particular issue.

133 In that case, the Court was directly concerned with the effect of a consent judgment (although ultimately decided the dispute on the basis that the subsequent proceedings were an abuse of process).

134 In considering the extent of issue estoppel arising from a consent judgment, the subjective motivations of the parties to the consent judgment are irrelevant and the question of its effect is objective (however regard can be had to the background leading up to the order): Ekes at [114]-[115] (Bathurst CJ, Beazley P and Emmett JA agreeing).

135 Mr Sheehy submits that issue estoppel cannot exist without a full determination on the merits: Zetta Jet Pte Ltd v The Ship "Dragon Pearl" (No 2) (2018) 265 FCR 290 (Zetta) at [20] (Allsop CJ, Moshinsky and Colvin JJ). He submits that as there was no reasoned judgment on the merits underpinning the Consent Judgment, therefore, the doctrine of issue estoppel has no role to play in this case.

136 Mr Sheehy submits that, moreover, and in any event, it remains unclear from Nuix’s submissions what issue it contends was resolved in the 2018 Proceedings so as to give rise to an issue estoppel. He submits that the issues of how the 2008 Option Agreement is to operate in the event of a share split, how the Share Split affects his rights under the 2008 Option Agreement and whether the shares are exercisable were not considered or resolved at all in the 2018 Proceedings.

137 Nuix submits that the 2019 Consent Judgment necessarily determined (a) the number of options Mr Sheehy held post Share Split (being 453,273) and (b) the number of shares Mr Sheehy was entitled to on exercise of his options (by reason of the matters that it relied upon to establish cause of action estoppel).

138 Nuix submits that it is clear that in making the Rectification Order, the Court must have decided the number of shares over which the options were granted and the exercise price of the options (as matters required to be specified pursuant to s 170(1)(d) and (h) of the Corporations Act).

139 Nuix submits that in considering the issues decided by the 2019 Consent Judgment, the Court should also give, if anything, greater weight to the terms of the CLS, including the allegations that:

(a) the Rectification Order would require Nuix to record “accurate particulars of the Remaining Sheehy Options in Nuix’s register of options”: [14(b)]; he held 453,273 options (CLS at [9]);

(b) the 2008 Option Agreement supported a term that those options existed and were exercisable (particulars to [5]); and

(c) the requisite particulars of those options were those set out in cl 2 of the 2008 Option Agreement, which recorded the exercise price for the options (in the third column of the table) and that one option entitled Mr Sheehy to one share (by the text at the bottom of the table, read together with the table itself) (particulars to [5]).

140 Nuix submits that in circumstances where the Consent Judgment reflected identically all of the relief claimed by Mr Sheehy in the Summons, the CLS provides a strong indication of the issues that it determined.

141 The contentions advanced by Nuix in support of its issue estoppel case largely replicate those that it advances in support of its cause of action/res judicata case. Those contentions are no more persuasive for issue estoppel.

142 The making of the Rectification Order in the context of the specific requirements of ss 170(1)(d) and (h) of the Corporations Act did not carry with it any necessary implication that the issues determined in the 2018 Proceedings travelled beyond the Consent Judgment.

143 The declaration in the Consent Judgment was in the same terms as the declaration sought in the Summons. It addressed only the issue as to whether the Remaining 2008 Options held by Mr Sheehy remained exercisable in accordance with the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement. It did not address the question of the applicable conversion ratio post the Share Split. That was not an issue that was raised or sought to be litigated in the 2018 Proceedings.

Anshun estoppel and abuse of process

144 As the High Court explained in Port of Melbourne Authority v Anshun Pty Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 589; [1981] HCA 45 (Port of Melbourne) at 598, what has become known as Anshun estoppel:

…operates to preclude the assertion of a claim, or the raising of an issue of fact or law, if that claim or issue was so connected with the subject matter of the first proceeding as to have made it unreasonable in the context of that first proceeding for the claim not to have been made or the issue not to have been raised in that proceeding.

145 The question of unreasonableness is derived significantly from the matter being “so relevant” to the subject matter of the first proceeding: Champerslife Pty Ltd v Manojlovski (2010) 75 NSWLR 245; [2010] NSWCA 33 (Champerslife) at [3] (Allsop P, as his Honour then was). The determination of unreasonableness in that sense involves at least two related assessments; namely, “was the matter so relevant that it can be said to have been unreasonable not to rely upon it in the first proceeding?”: Champerslife at [3] (Allsop P).

146 The broad merits-based or value judgment to which Allsop P referred in Champerslife is not at large. It is to be directed to the making of those two related assessments. Thus, a close connection between the facts in separate sets of proceedings may make it unreasonable not to have agitated the issue in the earlier proceedings: Accord Pacific Holdings Pty Ltd v Gleeson as Liquidator of Accord Pacific Land Pty Ltd (in liq) [2011] NSWSC 1021 at [137] (Ward J, as her Honour then was) and the cases cited therein.

147 In deciding the question, the onus is on the party asserting the estoppel to prove that the other party’s choice to refrain from asserting the claim or raising the issue, in the course of the first proceeding, was unreasonable: Clayton at [30] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ); Preston v Nikolaidis [2021] NSWSC 36 at [271] (Williams J). To this end, “any facts which bear upon the reasonableness of the conduct in question are admissible”: Beck v Weinstock [2012] NSWCA 289at [73] (Campbell JA, McColl and Meagher JJA agreeing). As was said in Port of Melbourne at 603 (and recently cited with approval in Clayton at [31] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ)):

there are a variety of circumstances ... why a party may justifiably refrain from litigating an issue in one proceeding yet wish to litigate the issue in other proceedings eg expense, importance of the particular issue, motivations extraneous to the actual litigation, to mention but a few.

148 Anshun estoppel arises even where the omission in the earlier proceedings was due to negligence, inadvertence or even accident: Henderson v Henderson [1843] 67 ER 313 at 319; Port of Melbourne at 598. Relatedly, a deficiency in legal advice is not a matter that can be taken into account in determining whether an Anshun estoppel arises: Donnelly v Kempsey Local Aboriginal Land Council [2020] NSWSC 1548 at [98] (Williams J).

149 Abuse of process may be invoked in areas in which estoppels also apply, although it is “inherently broader and more flexible than estoppel”: Tomlinson at [22], [25] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ). For example, the failure to make a claim or raise an issue in an earlier proceeding, which ought reasonably to have been made or raised in the earlier proceeding, can constitute an abuse of process even where the earlier proceeding might not have given rise to an estoppel: Tomlinson at [26] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ); Walton v Gardiner (1993) 177 CLR 378; [1993] HCA 77 at 393 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ) and the authorities cited therein.

150 The circumstances when the Court will have the power to stay proceedings as an abuse of the process of the Court are incapable of being distilled into closed categories. Rather, the Court’s power can be enlivened in circumstances “where the use of the court’s procedures occasion unjustifiable oppression to a party, or where the use serves to bring the administration of justice into disrepute”: UBS AG v Tyne (2018) 265 CLR 77; [2018] HCA 45 at [1] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ); Tomlinson at [25].

151 The onus of satisfying the Court that there is an abuse of process is a “heavy one” and it falls on the party asserting the abuse of process: Williams v Spaultz (1992) 174 CLR 509; [1992] HCA 34 at 529 (Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ); Goldsmith v Sperrings Ltd [1977] 1 WLR 478 at 498 (Scarman LJ).

Requirements for Anshun estoppel

152 Mr Sheehy submits that Anshun estoppel is a “true estoppel” and therefore, it can only apply if the party asserting the estoppel relied on the state of affairs giving rise to the estoppel to its detriment or it would be unconscionable for the other party to resile from an expectation that it had created: see Sidhu v Van Dyke (2014) 251 CLR 505; [2014] HCA 19 (Sidhu) at [1]-[2], [58], [61] and [77] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ). In this regard, Mr Sheehy submits that the use of the language of “true estoppel” in the context of Anshun estoppel in Tomlinson at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ) and in Rogers v The Queen (1994) 181 CLR 251; [1994] HCA 42 (Rogers) at 275 (Deane and Gaudron JJ) must have been intended to mean that some form of reliance is required to make good the estoppel.

153 Mr Sheehy submits that Nuix has not established any form of detrimental reliance sufficient to give rise to an Anshun estoppel.

154 Mr Sheehy submits that the Nuix decision-makers in the 2018 Proceedings were “plainly well-aware” that he did not intend to compromise his rights in relation to the Share Split. He points to the email sent by Mr Castagna on 27 November 2019 after Nuix entered into the Consent Judgment (Castagna November 2019 Email), and in particular, that the compromise for 1/50th of the original amount was “most surprising” and “I have no doubt we will hear the screams of angst from Eddie in the fullness of time” and the response from Mr Krupczak, Nuix’s then general counsel, that it was “truly unbelievable”. He submits that none of the parties to these communications was called to give evidence in these proceedings and therefore, the Court should conclude that the true position was that Nuix was well aware that he was not intending to give up any rights in relation to the impact of the Share Split on the Remaining 2008 Options. Mr Sheehy submits that this conclusion would have been obvious to any reasonable person involved in the settlement of the 2018 Proceedings.

155 Mr Sheehy submits that, in the circumstances, it cannot be said that Nuix believed that he was electing not to proceed with his claims in relation to the Share Split at the time that he settled the 2018 Proceedings or relied on any such assumption. Hence for the purposes of Anshun estoppel there is no basis for Nuix to contend that it would be unreasonable for him to pursue his present claims.

156 Mr Sheehy submits that it was not unreasonable for him to have not raised the issue of the Share Split in the 2018 Proceedings for the following reasons.

157 First, the 2018 Proceedings were narrowly confined to the issue of whether the Remaining 2008 Options continued to exist or not and the present claims concern an “entirely different feature” of the 2008 Option Agreement.

158 Second, there was nothing to suggest to him that there could be any issue between him and Nuix about the application of the Share Split to the 2008 Options. He submits that during the 2018 Proceedings, Nuix disclosed extracts from the Options Register as it stood at a specific date in 2017 to him. He submits that in those extracts it was expressly noted that the Remaining 2008 Options, like the options of other option-holders, resulted in the number of shares associated with each option being multiplied by 50 post the Share Split in Column N, albeit those extracts wrongly recorded that the Remaining 2008 Options had been forfeited. He submits that these documents demonstrate that there was no dispute as to the shares associated with his options being multiplied by 50. He further submits that there was no reason for him to conclude that the Share Split was something that needed to be determined in the 2018 Proceedings.

159 Third, the number of 2008 Options he held were not determined adversely to him in the 2018 Proceedings. He obtained exactly what he sought in the 2018 Proceedings, namely confirmation that the Remaining 2008 Options remained in existence.

160 Fourth, the defence of Nuix to the 2018 Proceedings was “always a hopeless one” and was “in reality yet another contrivance and was of no value to Nuix whatsoever”. No weight should be given to Nuix’s claim that its defence in the 2018 Proceedings, that the Remaining 2008 Options had expired, could also have been relied upon in these proceedings, had it not been extinguished by the Consent Judgment. In any event, it is not clear that that any of Nuix’s relevant decision makers genuinely believed that the Remaining 2008 Options had expired, as evidenced by an email from Mr Castagna dated 27 November 2019 to Nuix executives. Mr Castagna’s affidavit was not read and it should be inferred that his evidence would not have assisted Nuix’s case.

161 He submits that Mr Standen’s evidence in cross-examination, that he believed the Remaining 2008 Options had expired when the business of Nuix was not sold by late 2010, was “entirely inconsistent with all of the contemporaneous documentation”. Mr Sheehy also points to the evidence of Mr Phillips in cross-examination in which he “largely stepped back” from the evidence he had given in his affidavit that he had held a similar belief.

162 Fifth, it is not correct to contend that he had advanced no good reason for not raising his present claims in the 2018 Proceedings. Neither party raised the effect of the Share Split on the Remaining 2008 Options in the 2018 Proceedings. Mr Sheehy’s evidence in cross-examination, in these proceedings, that if he had turned his mind to the effect of the Share Split in the course of the 2018 Proceedings he would have believed he held 22 million of the Remaining 2008 Options with an exercise price of 4 cents was explicable in the context of his current claims because it was only “one of the two interpretations you can have” and “one of the two ways it works”.

163 Sixth, despite the earlier 2018 Proceedings and the present proceedings both being concerned with the terms of the 2008 Option Agreement, this fact does not support an estoppel. The way in which Nuix recorded the Remaining 2008 Options in the Options Register following the Consent Judgment showed that the 2018 Proceedings did not resolve critical issues in relation to those options.

Requirements for Anshun estoppel

164 Nuix submits that the High Court’s decisions in Tomlinson and Rogers do not suggest that a characterisation of Anshun estoppel as a “true estoppel” imports any requirement as to detrimental reliance. It submits that the requirements of Anshun estoppel have been addressed by the High Court on a number of occasions, including in Tomlinson at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ); Clayton at [30] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ) and in Port of Melbourne. It submits that on none of those occasions has detrimental reliance been identified as a matter that must be proved.

165 Nuix submits that Anshun estoppel is “[f]ounded on the twin policies of ensuring finality in litigation (thereby promoting respect for and efficient use of courts as well as avoiding inconsistent judgments) and of ensuring fairness to litigants (by sparing them the stress and expense of duplicative proceedings)”: Clayton at [34] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Gageler JJ). It submits that neither of these policies suggests that establishing detrimental reliance is a necessary element to Anshun estoppel. Rather, Anshun estoppel proceeds on the premise that detriment will inevitably arise if litigants are permitted to act inconsistently with these policies.

166 Nuix submits that the statements made by the High Court in Tomlinson and Rogers that Anshun estoppel was a “true estoppel” must be understood in context. In both cases a distinction was being drawn between res judicata and the common law doctrine of estoppel in relation to judicial determinations, which were characterised as “true estoppels”.

Relevance and reasonableness

167 Nuix submits that the 2018 Proceedings and Mr Sheehy’s claims in this proceeding are so closely connected it was unreasonable for Mr Sheehy not to have raised them earlier. It relies on the following principal matters in support of that contention.

168 First, Mr Sheehy’s claim regarding the number of shares he is entitled to is merely an alternative formulation of the claim determined in the 2018 Proceedings. Mr Sheehy himself emphasised in oral evidence that there were two ways the Share Split could have applied to the Remaining 2008 Options, with his options being multiplied by 50 being one of them (“one of the two ways it works”). Importantly, Mr Sheehy accepted that, holding that view, if he had thought in the 2018 Proceedings about the Share Split and its effects on his options, he would have appreciated the need to amend his Summons to claim a larger number of options.

169 Second, both sets of claims concern the terms of the same agreement and features of the options granted under that agreement.

170 Third, both sets of claims concern matters that should have been recorded in the Options Register with respect to the Remaining 2008 Options. Both seek orders that the Option Register be corrected. The orders are sought by reference to events that pre-date the 2018 Proceedings.

171 Fourth, Nuix’s defence to the 2018 Proceedings would also be a defence to Mr Sheehy’s claims in this proceeding (i.e. if the options had expired or ceased to exist they would not be exercisable and no shares would be granted).

172 Fifth, no good reason has been offered for Mr Sheehy’s failure to advance the claims made in these proceedings in the 2018 Proceedings. The only explanation he has provided is to the effect that he did not turn his mind to the impact of the Share Split on the Remaining 2008 Options, and was not told of the risks. Indeed, he accepted in oral evidence that, if he had thought about the Share Split and its effects on his options in the 2018 Proceedings, he would have appreciated the need to amend his Summons to claim a larger number of options. Mr Sheehy is an adequate proxy for a reasonable litigant and he accepted that, but for his own inadvertence, in the 2018 Proceedings he would have claimed that his 2008 Options had the benefit of the Share Split. That is evidence of what a reasonable litigant would have done in the circumstances.

173 Sixth, it is unsurprising that Nuix had not raised any dispute with Mr Sheehy prior to the commencement of the 2018 Proceedings as to the application of the Share Split to the Remaining 2008 Options, given its position that the options had expired. That no dispute was on foot was the result only of Mr Sheehy failing to assert a claim to a higher number of options or shares – Mr Sheehy cannot rely upon the very failure that founds Anshun estoppel to defeat it.

174 Seventh, the contention advanced by Mr Sheehy that the Court cannot be satisfied that Nuix would not have settled the 2018 Proceedings on the terms that it did if Mr Sheehy had made the same claims in those proceedings as he makes in this one, is both irrelevant and untenable. As outlined earlier in these reasons, Nuix submits that it is irrelevant because detrimental reliance is not a necessary element of Anshun estoppel. It submits that it is untenable because (a) any subjective belief as to whether Nuix would have settled the proceedings on that basis cannot be relevant as to whether it was unreasonable for Mr Sheehy not to raise the claims he is now advancing in these proceedings in the earlier 2018 Proceedings; and (b) in circumstances where Nuix is defending the present proceedings it defies credulity to suggest it may have conceded the claims had they been raised in the 2018 Proceedings.

Requirements for Anshun estoppel

175 Contrary to the position advanced by Mr Sheehy, I do not accept that it is necessary to prove detrimental reliance as an additional and discrete element in order to establish an Anshun estoppel.

176 In Tomlinson, the plurality identified the three forms of preclusionary estoppel recognised by the common law of Australia at [22] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ). After addressing “cause of action estoppel” and “issue estoppel”, the plurality stated with respect to Anshun estoppel, that: