FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kumova v Davison (No 2) [2023] FCA 1

Table of Corrections | |

17 February 2023 | In the table at paragraph 35 and the table at paragraph 80, “about New Century’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to capital raising” be replaced with “about the New Century Resource’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to the capital raising” |

17 February 2023 | In the table at paragraph 35, the heading at paragraph 68 and the table at paragraph 80, “manipulated share price of stocks to the benefit money launderers” be replaced with “manipulated the share price of stocks to the benefit of money launderers” |

17 February 2023 | In the table at paragraph 35, the table at paragraph 80, the table at paragraph 90, paragraph 234(2), the heading at paragraph 267 and paragraph 279, “an activity as disreputable as engaging in a drug syndicate” be replaced with “an activity that is as disreputable as engaging in a drug syndicate” |

17 February 2023 | In paragraph 148, “the pleaded representation has been proven to be apt” be replaced with “the pleaded representation has not been proven to be apt” |

17 February 2023 | In paragraph 339, “having closely observed the effect of this conduct of Mr Kumova” be replaced with “having closely observed the effect of this conduct on Mr Kumova” |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 8 February 2023, the parties bring in agreed or competing short minutes of order providing for:

(a) judgment to be awarded in favour of the applicant against the respondent on the amended statement of claim in the sum of $275,000 together with interest (at a rate of 3%) calculated to the date of entry of judgment; and

(b) a proposed form of injunction enjoining the respondent if such relief was to be granted.

2. The proceeding be stood over to 10 February 2023 at 10:15am to deal with the entry of judgment and all remaining issues.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

3. The respondent, through his solicitor, has given an undertaking to the Court that he and his servants and agents will take no steps to publish or republish the imputations that I have found to be conveyed until 4pm on 10 February 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION

1 This is a defamation case defended primarily on the basis of proving the existence of a “pump and dump” securities trading scheme.

2 The applicant, Mr Tolga Kumova, is an Australian investor in mining companies and sues the respondent, Mr Alan Davison, an ex-Swami, or religious ascetic, who is now engaged in the more prosaic activity of owning numerous internet domains and generating income from advertising revenue. More relevantly for present purposes, Mr Davison also operates a Twitter account at https://twitter.com/stockswami and has embraced the sobriquet “Stock Swami”. He publishes anonymously and his account features a phantasmal (and somewhat disconcerting) profile picture.

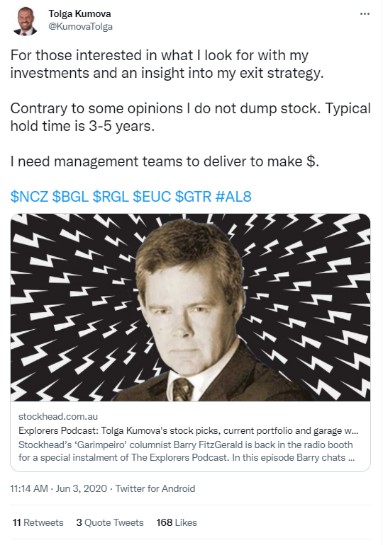

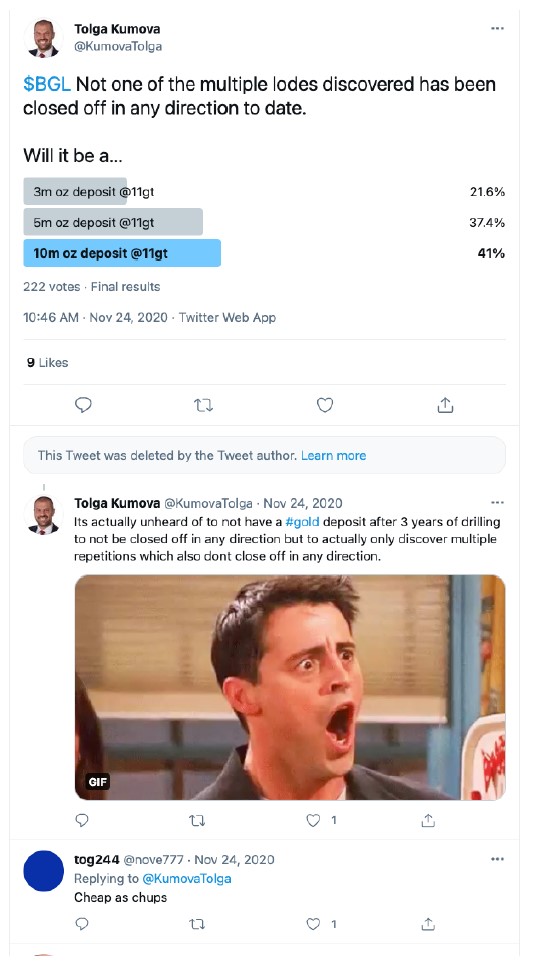

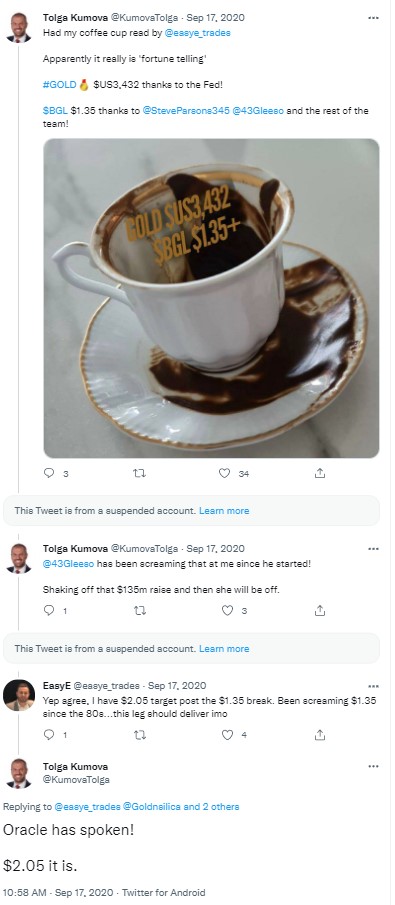

3 Mr Kumova is also a Twitter aficionado. His Twitter account is located at https://twitter.com/kumovatolga. He liked to tweet about his investments in mining stocks and his success in making money. His evidence was that he did so because he was “proud” of his material success. He also tweeted about an array of personal matters, including his family, sport, his polo club, politics and the COVID-19 pandemic.

4 The genesis of this dispute (and the core of the defence) is Mr Davison’s belief that some of the tweets posted by Mr Kumova were part of a deliberate strategy to mislead and deceive the investing public to further the financial interests of Mr Kumova.

5 It should be noted at the outset that Mr Davison was not tilting at windmills in being generally concerned about the real or potential misuse of social media to “ramp” securities. The misuse of social media prompted the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) (in ASIC warns of social media led ‘pump and dump’ campaigns (Media Release 21-256, 23 September 2021)) (ASIC Media Release) to warn of:

a concerning trend of social media posts being used to coordinate ‘pump and dump’ activity in listed stocks, which may amount to market manipulation in breach of the Corporations Act 2001.

‘Pump and dump’ activity occurs when a person buys shares in a company and starts an organised program[me] to seek to increase (or ‘pump’) the share price. They do this by using social media and online forums to create a sense of excitement in a stock or spread false news about the company’s prospects. They then sell (or ‘dump’) their shares and take a profit, and other shareholders suffer as the share price falls.

ASIC has recently observed blatant attempts to pump share prices, using posts on social media to announce a target stock, a designated time to buy and a target price or percentage gain to be reached before dumping the shares. In some cases, posts on social media forums may mislead subscribers by suggesting the activity is legal.

If an investor decides to buy shares as part of one of these campaigns, they may become the victim. The people behind the campaign may start dumping their shares and taking profits before they reach the target price.

Market manipulation is illegal. It can attract a fine of over $1 million and up to 15 years imprisonment. ASIC takes breaches of the market manipulation provisions seriously.

6 In recent weeks, Downes J found a social media user was carrying on a financial services business, which included posting positive stories about a company on an Instagram account. These stories often indicated that the social media user had acquired shares in that company or that he thought that shares would be a good investment. Her Honour found that a likely and knowing consequence of this conduct was that it would influence viewers of his stories to acquire shares and his shareholding would thus increase in value (a “clever way of pumping”): see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Scholz (No 2) [2022] FCA 1542 (at [1]–[13]). As an aside, the activities of the contravener in that case had also attracted the interest and criticism of Mr Davison: see ASIC v Scholz (at [49]–[52]).

7 This problem is not confined to Australia. In the United States, for example, fraudulent schemes to manipulate securities by publishing false and misleading information in online stock trading forums, on podcasts, and through Twitter accounts are well known.

8 Different forms of manipulation broadly described as “pump and dump” or “hype and dump” schemes have a common theme: insiders or promoters obtain ownership or control of a significant block of shares of a selected issuer by using their own accounts or nominees. They hype the shares to the public to generate artificial interest and cause the price to rise without disclosing an intention to sell. There is nothing particularly new about such market manipulation, but it has recently become easier to effectuate because the “pumper” can readily access social media to attempt to distort the market (perhaps in combination with others). Such a social media user may have a sufficient understanding of the dynamics of the medium to predict that followers will act based on their “pumping”, notwithstanding they might include a form of disclaimer on their profile to the effect they are not providing share recommendations or financial advice.

9 It is conduct that is difficult to regulate and, as ASIC has recognised, is insidious. When discovered, it is not only worthy of attention by the regulator, but also by those who commentate on financial markets. Speaking in the abstract, the financial media or a public commentator exposing market manipulation (and thereby prompting the regulator) might be thought to have social and economic utility. But the very seriousness of market manipulation in any form means that a public accusation of pumping and dumping or insider trading must be approached responsibly and with a degree of circumspection.

10 What also should be approached with care is boasting on Twitter or other social media about one’s sagacity in share trading and the prospects of companies in which one has an equity stake. Holding oneself out as a stock picking expert and being so “proud” of the success of a company with which one is associated that one feels the need (for some reason) to share that pride with strangers risks promoting the company’s shares to followers in a way that has the effect of generating demand for the company’s shares. In micro-cap or other thinly-traded securities, this conduct risks the creation of a false market. Given the apparent trend for promoters to engage in broadly similar social media conduct, but with a base motive to manipulate the market, it is easy to see why tweeting or posting about the alleged value of a company’s shares or assets, when you have a substantial interest in the company, can arouse suspicion.

11 For reasons I will explain, an aspect of Mr Kumova’s conduct examined in this case is troubling. But if one is going to make an allegation of illegal conduct, one must proceed warily. For the reasons explained below, Mr Davison did not prove the substantial truth of critical facts. He defamed Mr Kumova, and upon a review of the whole of the evidence he has no substantial truth or honest opinion defence. Accordingly, Mr Kumova is entitled to be vindicated and to be seen to be vindicated.

12 In explaining why, the balance of my reasons are divided into the following headings:

B Further Background;

C The Publications, Imputations and Mode of Publication;

D The Disputed Imputations and Meaning;

E The Defences Generally;

F Justification;

G Honest Opinion; and

H Relief.

B FURTHER BACKGROUND

13 The backdrop to this dispute is set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts (SAF) jointly filed by the parties pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) and received into evidence. The following section records my findings, in large part based upon that document.

B.1 Mr Kumova’s Business and Trading Activity

14 Mr Kumova boasts an extensive business and trading history. He has pursued investment opportunities in the junior mining sector since 2013, investing in numerous companies including Aston Minerals Limited (formerly known as European Cobalt Limited), Alderan Resources Limited, Bellevue Gold Limited (Bellevue Gold), Meteoric Resources NL, New Century Resources Limited (New Century) and Syrah Resources Limited (Syrah Resources). Mr Kumova has also held corporate director positions in a suite of mining companies.

15 Two companies are of especial importance to this case: Bellevue Gold and New Century.

Bellevue Gold

16 Bellevue Gold is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). The company is exploring and developing a high-grade underground gold mine in Western Australia.

17 In the period during which the impugned matters were published (September 2019 to June 2020), Bellevue Gold experienced considerable growth, notwithstanding the COVID-19 pandemic. The share price bottomed at around $0.28 in early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first broke out, but bounced back after BlackRock Asset Management took a $30,000,000 placement. As at the close of business on 27 May 2020, the company’s market capitalisation was $491,100,000 based on a $0.72 share price with an average daily volume of 3,000,000 shares. By 11 November 2020, Bellevue Gold’s market capitalisation was $1,175,900,000, based on a $1.40 share price with an average daily volume of 4,500,000 shares.

18 The largest shareholders in Bellevue Gold across the period included the following large institutional investors: 1832 Asset Management (a leading global gold fund), BlackRock Asset Management and VanEck (the largest gold exchange trade fund in the world): T342.19–21.

19 Mr Kumova first purchased shares in Bellevue Gold in about March 2017, at a time when they were trading for as low as three cents per share. Between July 2019 and March 2020, Mr Kumova disposed of a net 3,000,000 shares in Bellevue Gold. More particularly, on 5 July 2019, Mr Kumova sold 1,500,000 shares on market for $0.665 per share, totalling $997,500. He sold a further 200,000 shares on market on 11 November 2019 for just shy of $0.50 per share, and 200,000 shares on market on 16 December 2019 for just over $0.50 per share.

20 During the earliest stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, in late February 2020, Mr Kumova sold 389,498 shares for $0.60 per share and 810,502 shares for $0.6131 per share on market, culminating in a total sale of $730,617. As the full force of the pandemic was felt in March and April 2020, the Bellevue Gold share price collapsed. Mr Kumova took advantage of the drop, purchasing 100,000 shares on 19 March 2020 for $0.2850 per share. He sold those shares for $0.3150 per share the next day.

21 Mr Kumova did not sell Bellevue Gold shares again until 12 May 2020 when the share price had recovered to $0.59 per share. As at this date, Mr Kumova held 42,329,805 shares totalling $24,974,584 (based on the 12 May 2020 average sale price of $0.59).

22 By 25 June 2020, Mr Kumova’s remaining 39,432,401 shares were worth $46,727,395. On 15 July 2020, when Mr Kumova ceased being a substantial shareholder due to a dilution on 15 July 2020, he still held 38,132,401 shares.

23 Mr Kumova’s sales were disclosed to the market up until 30 July 2020. Mr Kumova also discussed his sales in a series of published interviews in 2020 and 2021.

24 Throughout the period over which the impugned matters were published, Mr Kumova had several offers to sell his total shares through Macquarie Bank or Canaccord Genuity Group Inc (Canaccord) on behalf of institutional investors. He declined those offers.

New Century

25 New Century is an Australian-based metal producer, also listed on the ASX. It operates the historic Century Mine in Mount Isa, Queensland, using hydraulic mining techniques to harvest and process zinc from tailings (the mineral waste that remains after the processing of ore to extract mineral concentrate).

26 Mr Kumova joined the board of New Century as a director in July 2017. With the encouragement of mining executive and investor Mr Evan Cranston, Mr Kumova capitalised upon what he perceived to be a “unique” deal and agreed to invest $2,500,000 in the company. He remained a director of New Century until July 2019.

27 Mr Kumova bought 16,666,666 fully paid shares and 30,000,000 options in New Century on 13 July 2017. At this time, New Century disclosed to the ASX that Mr Kumova had a shareholding of 5.64%.

28 On 1 May 2018, New Century had a large capital raising. It was heavily oversubscribed by institutional investors, and, as a result, New Century’s directors, including Mr Kumova, were not entitled to participate.

29 Instead, Mr Kumova purchased $1,250,000 of shares in New Century on market. New Century’s 2019 Annual Report records that Mr Kumova held 17,900,000 shares and 30,000,000 options in the company between 1 July 2018 and 17 July 2019. This investment did not change during this time, bookended by his resignation from the company.

B.2 Mr Kumova’s Twitter Account

30 Mr Kumova began operating a Twitter account in September 2017, generating increased (but still relatively modest) interest over time. From April 2019 to June 2022, Mr Kumova’s followers increased from approximately 4,500 to 27,500. As was put by his senior counsel, Mr Kumova is “no Kardashian”. But he was celebrated in the business media from time to time, including by featuring on the Australian Financial Review’s “Young Rich List”, as a figure having gone “from taxi driver’s son to $95 million business tycoon”: Tony Yoo, ‘From taxi driver’s son to $95 million business tycoon’, Yahoo! Finance (online, 1 April 2019).

31 Mr Kumova’s account profile read at all relevant times, “My tweets are my opinions. I am not a licenced financial advis[e]r and what I say should not be considered financial advice”. Notwithstanding what may be gleaned from the substance of Mr Kumova’s tweets and Twitter activity, nowhere on his Twitter profile did Mr Kumova identify himself as a director of Bellevue Gold, New Century, or any other company.

B.3 Mr Davison’s Twitter Account

32 At all material times, Mr Davison’s Twitter account also had a modest following compared to some. He had approximately 4,900 followers in December 2019, 6,800 followers in September 2020 and 7,500 followers by mid-June 2022.

33 Mr Davison gave evidence that he started the @stockswami account “to give [himself] a platform to provide commentary” on the ASX and related online forums. In his account profile, Mr Davison described the account as offering a “[c]ynical and [c]ranky take on the ASX professional company manipulators, I mean operators, making a play on [r]etail. They can [b]lock but they can’t stop the Swamo.”

C THE PUBLICATIONS, IMPUTATIONS AND MODE OF PUBLICATION

C.1 The Matters and Imputations

34 Mr Kumova sues upon six allegedly defamatory publications published on Twitter. Mr Davison admits to publishing the material part of each matter.

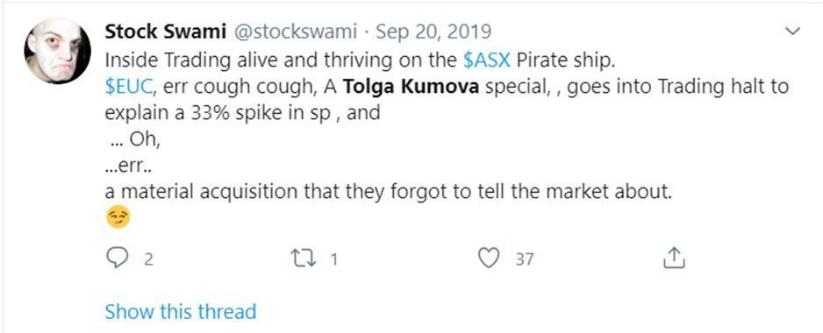

35 Identified in the table below are the publications and the alleged imputations (by the number of the paragraph in which they appear in the amended statement of claim). Also identified in the table is whether the conveyance of the imputation was actively disputed by Mr Davison by the end of the trial. Mr Davison belatedly conceded that each imputation, if carried, was defamatory (T664.5–8; T677.18):

First Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

Imputation 5(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Yes |

Imputation 5(b): Mr Kumova engaged in unlawful activity on the Australian [Securities] exchange | No |

Imputation 5(c): Mr Kumova misled the Australian share market | No |

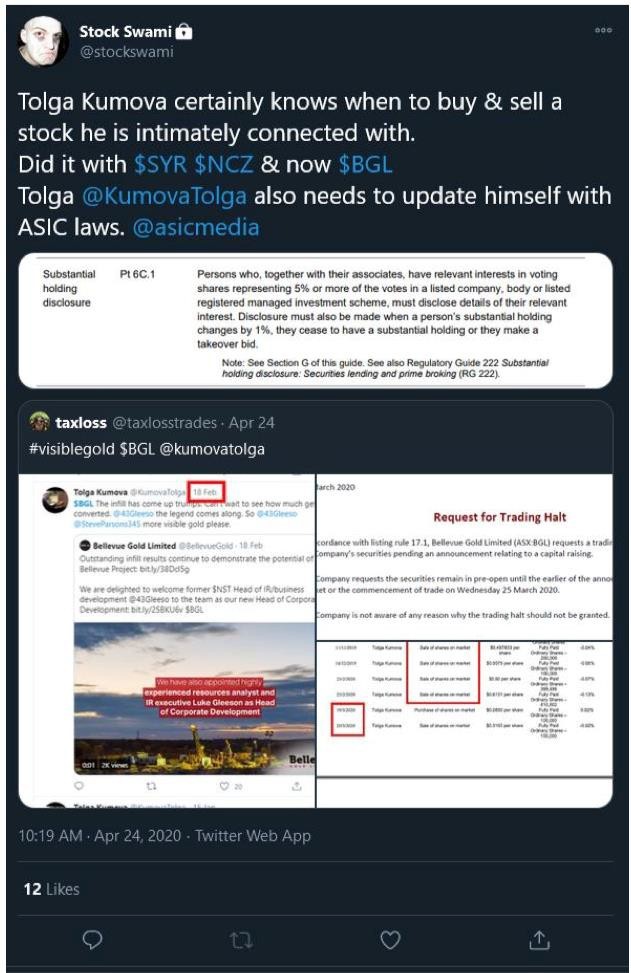

Second Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

Imputation 7(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Yes |

Imputation 7(b): Mr Kumova acted illegally by buying and selling stocks in a number of companies that he is intimately connected with | Yes |

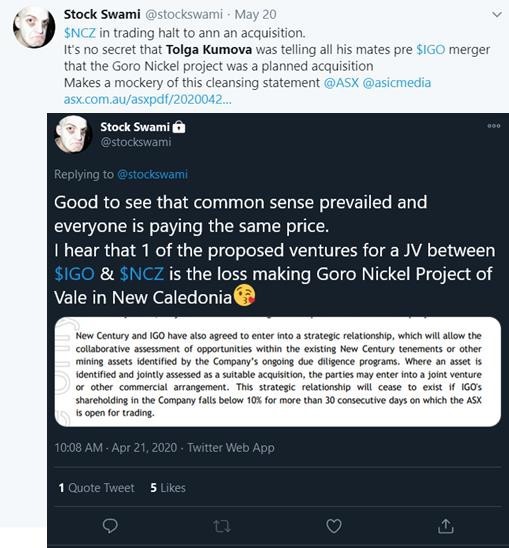

Third Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

Imputation 9(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Yes |

Imputation 9(b): Mr Kumova gave inside information about the New Century Resource’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to the capital raising involving IGO Limited | No |

Fourth Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

Imputation 11(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Yes |

Imputation 11(b): Mr Kumova gave inside information about the New Century Resource’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to the capital raising involving IGO Limited | No |

Imputation 11(c): Mr Kumova has a professional relationship with convicted tax evader Harry Hatch | Yes |

Imputation 11(d): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of stocks to the benefit of money launderers | Yes |

Imputation 11(e): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of Syrah Resources to the benefit of money launderers | Yes |

Imputation 11(f): Mr Kumova has manipulated the price of Syrah Resources to enable it to get into an ASX index | Yes |

Fifth Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

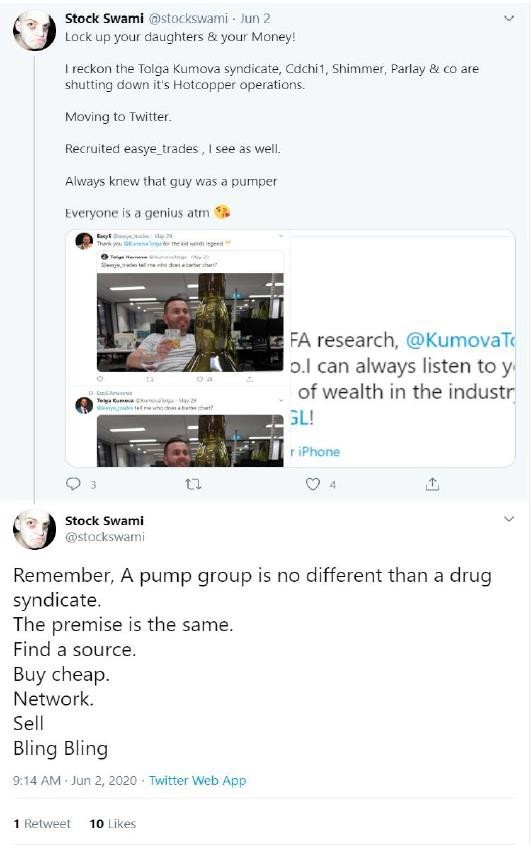

Imputation 13(a): Mr Kumova engaged in pump and dump schemes in the financial market | No |

Imputation 13(b): Mr Kumova engaged in an activity that is as disreputable as engaging in a drug syndicate | No |

Imputation 13(c): Mr Kumova has engaged in market manipulation | Yes |

Sixth Matter | |

| |

Imputation | Actively Disputed |

Imputation 15(a): Mr Kumova gave inside information to Assad Tannous | Yes |

C.2 Mode of Publication

36 As to the mode of publication of the matters, being the social media platform Twitter, the parties helpfully agreed on a number of facts: see SAF (at [23]–[44]). Many of these facts might be thought obvious, but some should be recorded as findings.

37 Twitter is free to access and use (at least it was free at the time material to this case). Twitter users can create content (by posting tweets) or consume content (by reading other users’ tweets). Twitter can be accessed from virtually any computer or device, through the website twitter.com or through the Twitter application, downloadable on mobile devices.

38 A user does not need a Twitter account to access Twitter and consume content on the platform. If a user establishes an account, the user is required to select a username known as a “handle”. Users can choose to “follow” others, that is, to subscribe to receive updates concerning their activity on Twitter.

39 Upon logging in, the user sees a real-time stream of tweets made, re-tweeted or shared from accounts that the user has chosen to follow, known as the “Twitter Home timeline”.

40 A user can also find content through the “Explore” tab function, which displays trending tweets and other tailored content, including from accounts the user does not follow. This content is generally selected by Twitter using a proprietary algorithm. According to Twitter’s “Help Cent[re]”, this additional content is selected “using a variety of signals”, including the other users and topics the user already follows, how popular the content is, and how people in the user’s network are interacting with it. Consequently, Twitter users who are interested in a particular subject matter may see tweets in their Twitter Home timeline related to matters they have engaged with in some way, from persons they do not follow.

41 Twitter allows its users to reply to, “like”, “retweet” and “quote tweet” other users’ tweets and share tweets of their own. Relevantly, a “retweet” is a reposting by one Twitter user (the “retweeter”) of another user’s tweet, while a “quote tweet” is a retweet with additional text or content added by the retweeter. Retweets and quote tweets are performed by clicking or tapping on the retweet icon and, in the case of a quote tweet, then adding any additional text or content.

42 Information about a tweet is displayed as follows:

43 Twitter Analytics records the level of engagement other Twitter users have had with a specific tweet. A metric used is “total engagement”, which reflects the total number of times users have interacted with a tweet, that is, clicked anywhere on the tweet, including on retweets, replies, follows, likes, links, hashtags, embedded media, the username and the profile photo.

D THE DISPUTED IMPUTATIONS AND MEANING

44 As noted above, Mr Davison denies that all but six of the pleaded imputations were conveyed and “does not contest” that the following imputations were carried: 5(b) and 5(c) (First Matter); 9(b) (Third Matter); 11(b) (Fourth Matter); and 13(a) and 13(b) (Fifth Matter).

45 One would think that not contesting issues would sensibly lead to the making of admissions consistently with the requirements of narrowing issues in accordance with s 37M(3) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), but Mr Davison still maintains that the “uncontested” imputations are matters for Mr Kumova to establish.

46 The principles as to meaning were unsurprisingly not in dispute and do not require, yet again, explication, save for in one respect: see, for example, Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 68; (2022) 400 ALR 56 (at 63–65 [28]–[31] per Rares J, with whom Wigney and Lee JJ agreed). The issue of how questions of meaning should be approached in the context of social media posts was recently considered in Bazzi v Dutton [2022] FCAFC 84; (2022) 289 FCR 1 (at 9–11 [29]–[33] per Rares and Rangiah JJ). In short, as with all questions as to meaning, context is everything. Several pointed things might be said about Twitter, but it is correct to observe that it is a conversational medium characterised by informality and, sometimes, the crude reduction of complex matters to their core elements. It would be wrong to engage in elaborate analysis of tweets; an impressionistic approach is required: Bazzi v Dutton (at 16 [62] per Wigney J). However, this impressionistic approach must take account of each tweet as a whole and the context in which the ordinary reasonable reader would read it, including matters of general knowledge and matters that were put before the reader via Twitter. As has been remarked, it is pre-eminently a medium whereby the ordinary reader reads and passes on. Consistently with these features of the platform, it was not disputed that where shorthand is used in a tweet (which is often the case), implication and innuendo are rife. This is exacerbated by the limited number of characters available to users for each tweet.

47 It should also be noted that relevant extrinsic facts, being the shorthand references to certain companies, the ASX and “sp” (meaning “share price”), are agreed: see, for example, SAF (at [46]–[48], [60], [63]–[65], [71]–[74], [80]–[85], [95]–[96]).

48 It is convenient then to deal with each of the imputations.

D.1 First Matter

Imputation 5(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading

49 Mr Davison submits that Imputation 5(a) is not conveyed by the First Matter. At worst, it is said, the reader would understand the charge to be a failure to procure “$EUC” (European Cobalt Limited) to disclose information concerning a material acquisition to the ASX, which information was used by others to their financial benefit. In Mr Davison’s view, it would be a strained or forced interpretation of the tweet to say it suggests Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading.

50 Mr Davison’s submissions must be rejected for three reasons. First, the only person identified in the tweet is Mr Kumova. The words “[i]nside [t]rading alive and thriving” are indubitably directed towards him. Secondly, the ordinary reasonable reader would understand the words “[i]nside [t]rading”, the reference to a “[t]rading halt” and a “33% spike in sp” to refer, plainly, to insider trading. This, coupled with the reference to the ASX as a “Pirate Ship”, necessarily conveys that illegal acts are taking place on the ASX. Thirdly, the assertion that such piracy is a “Tolga Kumova special” conveys the message that Mr Kumova engages in insider trading on the ASX. The tweet purports to address just one example of Mr Kumova’s improper tactics, “alive and thriving” and known by many, as implied by “err cough cough”.

51 The imputation is conveyed.

D.2 Second Matter

Imputation 7(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading

52 Mr Davison submits that the ordinary reasonable reader would understand the first sentence of the Second Matter (“Tolga Kumova certainly knows when to buy & sell a stock he is intimately connected with”) to be a mere observation as to the impeccable timing of Mr Kumova’s trades. Further, it is said that the final sentence (that Mr Kumova needs to “update himself with ASIC laws”) is no more than an observation that Mr Kumova needs to refamiliarise himself with his legal obligations to disclose his share trading activity as a substantial shareholder in Bellevue Gold. Central to Mr Davison’s submissions is that the Second Matter does not expressly mention inside information or use the words “insider trading”.

53 These submissions should be rejected: the imputation is conveyed.

54 The allegation that Mr Kumova knows precisely when to buy and sell stock he is “intimately connected with”, and that he has done so with three companies, conveys the meaning that Mr Kumova habitually misuses “intimate” information when trading. The phrase “intimately connected with” is pregnant with meaning. The ordinary reader would understand that phrase, in the context of the tweet as a whole, to be an allegation of insider trading, particularly having regard to the allegation that Mr Kumova needs to “update himself with ASIC laws”.

Imputation 7(b): Mr Kumova acted illegally by buying and selling stocks in a number of companies that he is intimately connected with

55 Mr Davison conceded this imputation is carried in oral address: T768.9–10. However, that concession is not recorded in the table prepared by Mr Davison’s solicitors summarising the contested imputations and defences finally pressed (Imputations and Defences Table) and is addressed (albeit briefly) in Mr Davison’s written closing submissions.

56 It suffices to say that the suggestion that Mr Kumova should “update himself with ASIC laws” implies non-compliance with those laws. It is suggested that Mr Kumova is not disclosing substantial shareholdings and has traded in shares improperly prior to the trading halt. This imputes unlawfulness in Mr Kumova’s trading practices. A pattern of behaviour is alleged in the reference to three companies. These elements culminate in the conveyance of Imputation 7(b): that Mr Kumova repeatedly acts unlawfully in relation to companies with which he is involved.

D.3 Third Matter

Imputation 9(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading

57 This tweet suggests that, despite the published “cleansing statement” for New Century, Mr Kumova has inside information in relation to the company and passed on the information to his friends. It is an agreed fact that readers of the Third Matter knew that a “cleansing statement” was an announcement to the ASX by a listed entity which “may disclose information to the market and confirms that no other undisclosed price sensitive information exists”: SAF (at [76]).

58 Mr Davison submits that there is a material difference between Mr Kumova giving inside information to “his mates”, and Mr Kumova himself engaging in insider trading.

59 There is no such meaningful difference. The moral or social standard by which the hypothetical referee would evaluate the tweet would not discriminate between Mr Kumova and “his mates”, other than that Mr Kumova, as the distributor of the inside information, is most at fault, or at least at the heart of the wrongdoing: Chau v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2021] FCA 44; (2021) 386 ALR 36 (at 46–47 [34]–[36] per Rares J).

60 Further, the assertion that the alleged trading halt “makes a mockery” of the cleansing statement implies that the cleansing statement was false. This means that the ordinary and reasonable reader of the Third Matter would understand that the information Mr Kumova was said to be telling his “mates” was undisclosed, price sensitive information. That reader would not distinguish between Mr Kumova as facilitator, and Mr Kumova as participant, not least when reading the Third Matter on Twitter, a platform engineered for fast-paced reading and engagement.

61 The imputation is conveyed.

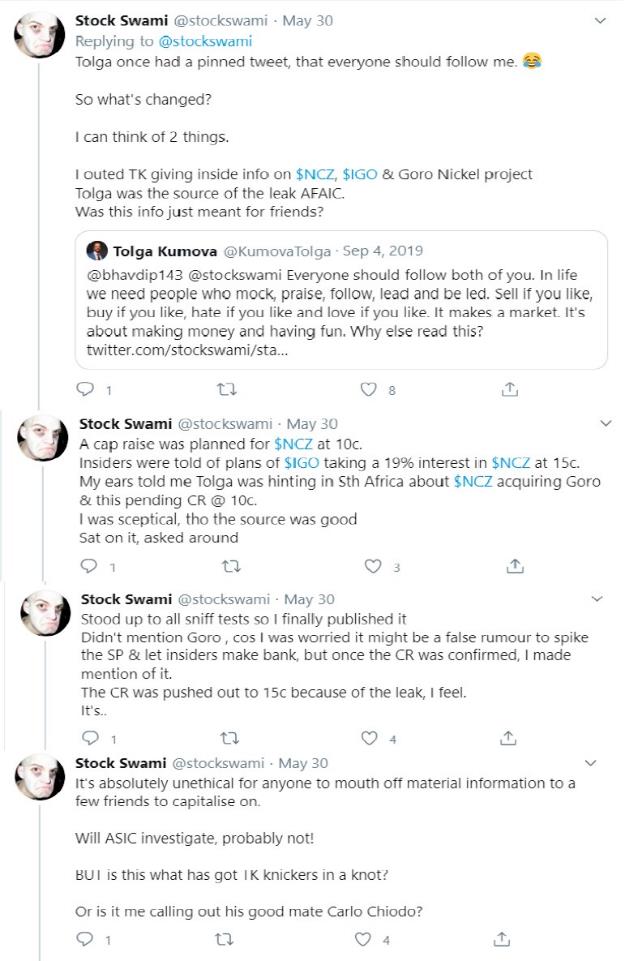

D.4 Fourth Matter

Imputation 11(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading

62 As with the Third Matter, Mr Davison asserts that the Fourth Matter concerns Mr Kumova relaying information to others, rather than using that information during his own share trading activity.

63 Again, as a matter of impression, there is no material difference for the ordinary reasonable reader between orchestrating a series of insider trades and making the trades themselves. The hypothetical referee would read the Fourth Matter and glean from it that Mr Kumova had been instrumental in the misuse of inside information.

64 The tweet claims, “I outed TK giving inside info […] Tolga was the source of the leak […] Was this info just meant for friends?” This is an assertion of fact: that Mr Kumova has previously been exposed as using insider information to benefit his friends. The question, “Was this info just meant for friends?” can be read in two ways, both defamatory. The first available reading (and the better view) is that the assertion that Mr Kumova held on to sensitive information and revealed it “just” to “friends” is an allegation of insider trading. Secondly, the question might be thought by some to insinuate that Mr Kumova shared the information beyond “just” his “friends”, to a broader pool. If I am required by authority to adopt one meaning, it would be the former.

65 Further, “Insiders were told of plans […] Tolga was hinting” and “let insiders make bank” imply that the “insiders” could make money from misconduct. The imputation of illegality is reinforced by the remaining allegations in the tweet which impute that Mr Kumova is engaged in a range of other nefarious conduct with his associates.

Imputation 11(c): Mr Kumova has a professional relationship with convicted tax evader Harry Hatch

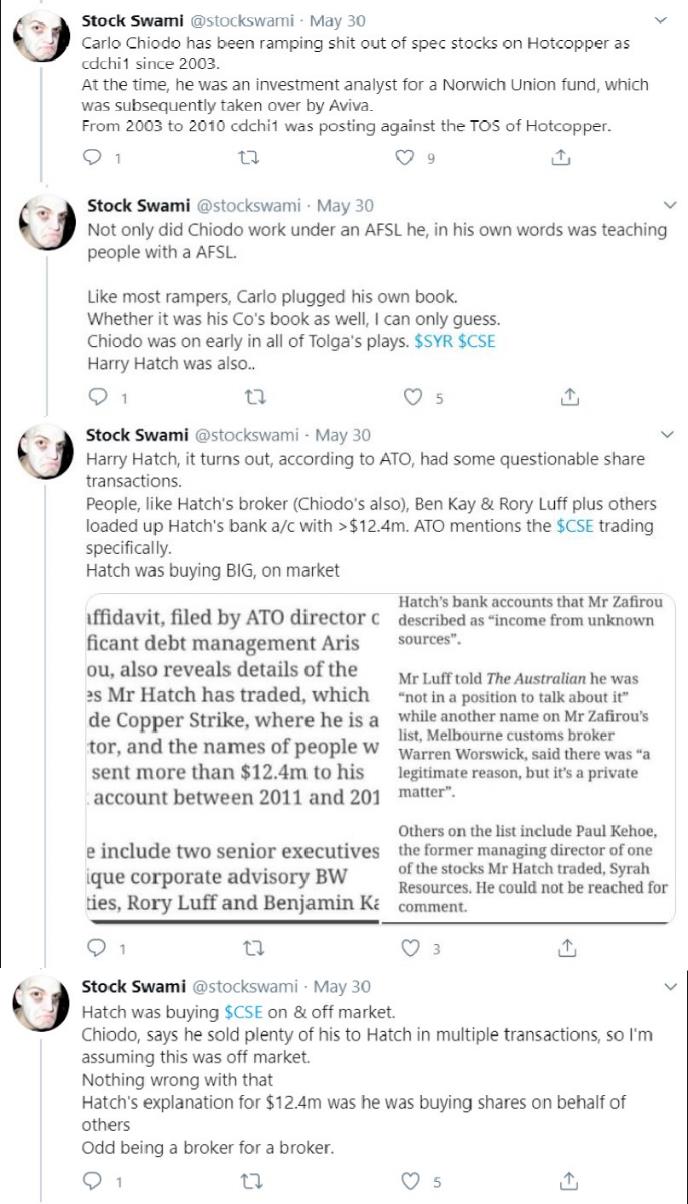

66 The entire purpose of the second half of the Fourth Matter is to impugn Mr Kumova by reason of his alleged association with Mr Carlo Chiodo and Mr Harry Hatch.

67 The screenshot of orders made in a Federal Court matter between the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation and Mr Hatch imputes that Mr Hatch has been found to have evaded paying millions of dollars of tax. The crux of the defamation is the innuendo, “But if TK can judge me by my association with porn… 😏”, an unfinished sentence which, if there was any doubt, is completed by Mr Davison when he questions why the “Press aren’t all over the story” and notifies the reader that he is applying to the Court for documents to provide more detail. Read in context, this suggests that additional documents from a reliable source may disclose a newsworthy story about Mr Kumova. The sting is not assuaged by Mr Davison’s assertion that his words do not “implicate anyone other than Hatch”.

Imputation 11(d): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of stocks to the benefit of money launderers

68 Mr Davison alleges that Mr Kumova’s case for Imputation 11(d) is built upon “inference upon inference and looking for the most well-hidden of meanings”. Mr Davison’s submission fails to recognise the way meaning is conveyed on a quick-fire, grapevine-like platform such as Twitter, especially in the light of the composition of the Fourth Matter, as a cascading series of retweets.

69 A hypothetical referee, scrolling through Twitter, would associate Mr Kumova with the conduct of Mr Chiodo, Mr Kumova’s alleged “good mate”, who has “been ramping the s*** out of spec stocks”. In fact, Mr Davison expressly invites the reader to do so: “Chiodo was on early in all of Tolga’s plays. $SYR $CSE Harry Hatch also”. It is then alleged that Mr Hatch undertook questionable share transactions, and that Mr Chiodo was selling to Mr Hatch, a chain of wrongdoing in which Mr Kumova is implicated: “[a] great way to launder money tho, or hide who’s been selling (manipulating)”.

70 Furthermore, “[one] theory is $SYR sp was manipulated to into an ASX index to sell into the institutions buying” is a suggestion Mr Kumova manipulated the price of shares in Syrah Resources. Given Syrah Resources is identified as one of Tolga’s “plays”, the implication is that Mr Kumova manipulated the share price of that company to assist either or both of Mr Chiodo and Mr Hatch.

Imputation 11(e): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of Syrah Resources to the benefit of money launderers

71 The fact that the relevant reference to manipulation of the “$SYR sp” is couched as being “[one] theory” does not detract from the meaning, given it is said without qualification in a publication that impugns Mr Kumova repeatedly. Although the ordinary reader is neither avid for scandal nor suspicious of mind, the meaning is clear when one has regard to the context as a whole. The money launderers are plainly suggested to be Mr Hatch and Mr Chiodo.

Imputation 11(f): Mr Kumova has manipulated the price of Syrah Resources to enable it to get into an ASX index

72 The reasoning is essentially the same as above: the imputation is conveyed.

D.5 Fifth Matter

Imputation 13(c): Mr Kumova has engaged in market manipulation

73 It is Mr Davison’s case that the Fifth Matter “says nothing about market manipulation”. Rather, he submits, it is concerned with “the selling of cheaply bought stock to an identified customer base for a profit”, which he characterises as market “exploitation” rather than manipulation.

74 This is a silly line to draw. To exploit the market by creating a “syndicate”, “find[ing] a source”, “buy[ing] cheap”, “network[ing]” and profiting as a result is to engage in a form of market manipulation as that concept is generally understood. Nowhere is the implication of market manipulation stronger than in the use of the terms “pumper” and “pump group”.

75 Although the meaning of the verb “pump” in this context is not an agreed fact, there did not emerge over the course of written and oral submissions any substantial difference in the parties’ understanding of the term. Mr Kumova asserts, and I agree, that “a pumper or a pump group is a person or persons who engages in market manipulation to increase a share price and enable profit to be made on the shares”. A definition to this effect is accepted by Mr Davison in his closing submissions, although elsewhere, Mr Davison adopts a different definition inconsistent with ordinary usage and understanding. It will be necessary to return to this issue below when considering the justification defence in Section F.6.

76 The present question is whether such a fact was notorious or was otherwise known to some readers of the Fifth Matter. It is a commonly used expression. Given the focus of Mr Davison’s Twitter account, it can be readily inferred that readers of that account (or at least many of them) had knowledge of what a “pumper” and a “pump group” are, and the connotations of market manipulation carried by these terms. He was, after all, the “Stock Swami”.

77 But even an atypical reader of the Fifth Matter who did not have a real understanding of the concept of “pumping” would understand it involved market manipulation. This is because of the appeal to readers to “lock up [their] money”, the comparison of a pump group to a drug syndicate and the explanation of the pumping process given at the end of the Fifth Matter.

D.6 Sixth Matter

Imputation 15(a): Mr Kumova gave inside information to Assad Tannous

78 The collocation of “Tolga Kumova giving info to mates… again?” and the ticker codes $NCZ (New Century) and $IGO (IGO Limited) would, in the mind of the ordinary reasonable reader, impute that the “info” relates to the companies and the trading of shares in those companies.

79 By retweeting a tweet by Mr Assad Tannous, Mr Davison puts an insidious spin on it. The tweet conveys both that Mr Kumova gave inside information to Mr Tannous on this occasion but also on other earlier occasions (“giving info to mates… again?”). Although Mr Davison uses a question mark, it is deployed in a rhetorical sense given the content of Mr Tannous’ tweet and the use of the ellipses. In any event, Mr Tannous is the only “mate” identified in the Sixth Matter, and the tweet accuses Mr Kumova of giving inside information “again”. The ordinary reasonable reader would understand the Sixth Matter to impute that Mr Kumova gave inside information to Mr Tannous, perhaps on more than one occasion.

D.7 Conclusions as to Meaning

80 The upshot of the foregoing is that the following imputations are conveyed:

First Matter | Imputation 5(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading |

Imputation 5(b): Mr Kumova engaged in unlawful activity on the Australian [Securities] Exchange | |

Imputation 5(c): Mr Kumova misled the Australian share market | |

Second Matter | Imputation 7(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading |

Imputation 7(b): Mr Kumova acted illegally by buying and selling stocks in a number of companies that he is intimately connected with | |

Third Matter | Imputation 9(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading |

Imputation 9(b): Mr Kumova gave inside information about the New Century Resource’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to the capital raising involving IGO Limited | |

Fourth Matter | Imputation 11(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading |

Imputation 11(b): Mr Kumova gave inside information about the New Century Resource’s acquisition of the Goro nickel mine prior to the capital raising involving IGO Limited | |

Imputation 11(c): Mr Kumova has a professional relationship with convicted tax evader Harry Hatch | |

Imputation 11(d): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of stocks to the benefit of money launderers | |

Imputation 11(e): Mr Kumova has manipulated the share price of Syrah Resources to the benefit of money launderers | |

Imputation 11(f): Mr Kumova has manipulated the price of Syrah Resources to enable it to get into an ASX index | |

Fifth Matter | Imputation 13(a): Mr Kumova engaged in pump and dump schemes in the financial market |

Imputation 13(b): Mr Kumova engaged in an activity that is as disreputable as engaging in a drug syndicate | |

Imputation 13(c): Mr Kumova has engaged in market manipulation | |

Sixth Matter | Imputation 15(a): Mr Kumova gave inside information to Assad Tannous |

81 Given the belated but inevitable concession that the pleaded meanings were defamatory of Mr Kumova, it then becomes necessary to turn to Mr Davison’s defences.

E THE DEFENCES GENERALLY

82 A different form of “pump and dump” took place in the conduct of Mr Davison’s defence.

83 In his further amended defence, Mr Davison had pleaded the following defences to each of the six matters:

(1) justification under s 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act);

(2) statutory qualified privilege under s 30 of the Defamation Act and qualified privileged at common law;

(3) honest opinion under s 31 of the Defamation Act and fair comment at common law;

(4) qualified privilege at common law based on reply to attack; and

(5) (remarkably) triviality under s 33 of the Defamation Act.

84 Mr Davison also asserted contextual truth under s 26 of the Defamation Act with respect to the Fifth Matter.

85 The bulk of Mr Davison’s defences fell away. It should have been obvious from the start that a number of these defences were untenable on the facts. Mr Davison is not an outlier in not pursuing pleaded defences following mature reflection. It seems that in defamation, in stark contrast to most commercial litigation, there is an entrenched persistence in joining issue and raising positive defences when there is an infirm basis for doing so.

86 Defamation cases are now commonly run in the Federal Court. Part VB of the FCA Act does not contain empty rhetoric. There is a statutory duty on practitioners to assist their clients in facilitating the just resolution of disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible: s 37N(2) of the FCA Act. This means that in preparing pleadings, it is necessary for both the solicitor on the record and the barrister settling the pleading to ensure contentions not bona fide in dispute are not put in issue, and to make sure untenable defences are not pleaded. The apparently persistent notion that defamation practitioners can just roll the arm over and plead defences like they are in a time warp that has transported them back to the 1970s needs to be exploded.

87 In any event, to obtain clarity as to what remained, at the conclusion of the hearing, I ordered Mr Davison to prepare two tables: the first being the Imputations and Defences Table referred to above; and the second outlining several representations alleged to have been made by Mr Kumova and primarily relevant to the justification defence.

88 This exercise confirmed that the residuum of Mr Davison’s defence asserts statutory justification with respect to the First, Second and Fifth Matters and (with respect to the Fifth Matter only) honest opinion pursuant to s 31 of the Defamation Act.

89 In his further amended reply, Mr Kumova alleges that Mr Davison did not honestly hold any of the opinions expressed in defeasance of the honest opinion defence as to the Fifth Matter.

90 Leaving aside questions of meaning, it is worthwhile reproducing the final metes and bounds of Mr Davison’s defence in the Imputations and Defences Table:

Matter | Imputation | Defence |

First Matter | 5(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Undefended |

5(b): Mr Kumova engaged in unlawful activity on the Australian [Securities] Exchange | Justification: FAD (at [43(2)]) | |

5(c): Mr Kumova misled the Australian share market | Justification: FAD (at [43(2)]) | |

Second Matter | 7(a): Mr Kumova engaged in insider trading | Undefended |

7(b): Mr Kumova acted illegally by buying and selling stocks in a number of companies that he is intimately connected with | Justification: FAD (at [44(2), (4)]) | |

Fifth Matter | 13(a): Mr Kumova engaged in pump and dump schemes in the financial market | Justification: FAD (at [46A]), relying on the facts pleaded at [43(2.1)–(2.5)] and [46A(1.1)–(1.2)]) |

13(b): Mr Kumova engaged in an activity that is as disreputable as engaging in a drug syndicate | Justification: FAD (at [46A(2)]), relying on the facts pleaded at [43(2.1)–(2.5)] and [46A(1.1)–(1.2)]) Honest opinion: FAD (at [61]) | |

13(c): Mr Kumova has engaged in market manipulation | Justification: FAD (at [46A(1(3))]), relying on FAD (at [43(2.1)–(2.5)] and [46A(1.1)–(1.2)] Honest opinion: FAD (at [61]) |

F JUSTIFICATION

F.1 General Principles

91 Section 25 of the Defamation Act provides as follows:

25 Defence of justification

It is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that the defamatory imputations carried by the matter of which the plaintiff complains are substantially true.

92 Mere restatement of the statutory language may seem trite, but it is important to re-emphasise that it is the defamatory imputations that must be proven to be substantially true.

93 The relevant principles informing consideration of the defence are very well known and do not require repetition. It suffices to mention four matters.

94 First, as I recently explained in Palmer v McGowan (No 5) [2022] FCA 893 (at [278]), “substantially true” is defined in s 4 as “true in substance or not materially different from the truth”. It is not necessary to establish that every part of an imputation is literally true; it is sufficient if the “sting” or gravamen of an imputation is true: see Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Kermode [2011] NSWCA 174; (2011) 81 NSWLR 157 (at 179 [86] per McColl JA, with whom Beazley and Giles JJA agreed).

95 Secondly, a defamatory imputation must be construed within the context in which it is conveyed: Greek Herald Pty Ltd v Nikolopoulos [2002] NSWCA 41; (2002) 54 NSWLR 165 (at 172–173 [21]–[27] per Mason P, with whom Wood CJ at CL agreed). The construction of the imputation in context must, in turn, inform what is required to prove the substantial truth of the imputation.

96 Thirdly, a potential misconception seemed at times to lurk below the surface during aspects of Mr Davison’s submissions, being the notion of a defence of so-called “partial justification”. It is now beyond doubt that a defence of justification requires a respondent to prove that each of the defamatory imputations conveyed by the matter was substantially true at the time of the publication: Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCAFC 119 (at [7]–[17] per Rares J, with whom Wigney and Lee JJ agreed). A defence justifying only part of a defamatory matter is no defence at all. In the context of this case, the necessary consequence is that given a justification defence is now not pressed in relation to all imputations conveyed by the First and Second Matters, it must fail. The Fifth Matter is different because justification is still pressed for all three imputations conveyed.

97 Fourthly, a connected question of importance in this case becomes: what is to be done with evidence of misconduct on the part of an applicant that does not suffice to make out a defence of justification? There was no dispute between the parties that such evidence may be considered on the question of damages, to the extent that it is directly relevant to the subject of the defamatory matters in the relevant “sector” of the applicant’s reputation.

98 This use of this evidence on damages was referred to in this case, as it is so often, as being in “mitigation” of damages. Although this jargon is very well-entrenched (and adopted in the Defamation Act), it seems to me to obscure what is going on. Some common factors in “mitigation” of damages are identified in s 38 of the Defamation Act (for example, an apology or other compensation). But this is not an exclusive list of factors (see s 38(2)), and does not include the concept with which we are presently concerned. Usually, of course, in other areas of the law, the term “mitigation” is used in the phrase “a plaintiff’s duty to mitigate” (albeit mistakenly, as there is no so-called duty, because claimants are completely free to act as they perceive to be in their best interests, but defendants are not liable for all loss suffered by claimants in consequence of so acting): Sotiros Shipping Inc and Aeco Maritime SA v Sameiet Solholt, The Solholt [1983] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 605 (at 608 per Donaldson MR); Borealis AB v Geogas Trading SA [2011] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 482; [2010] EWHC 2789 (Comm) (at [42]–[50] per Gross LJ). Such a factor might be best described as not being in “mitigation” of damage, but as simply a factor, among others, informing the Court’s assessment. The concept can be viewed through the prism of causation of loss as the use of such evidence is relevant to, and impacts upon, the actual, causally-related harm suffered.

99 But leaving aside terminology, there was no dispute as to the correct approach, which was usefully explained by Wigney J in Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 550; (2018) 359 ALR 564 (at 573 [32]–[33]):

32. In Warren v Random House Group Ltd [2009] QB 600; [2009] 2 All ER 245; [2008] EWCA Civ 834, the Court of Appeal of England and Wales explained the Burstein principle in the following terms (at [78]):

The decision of this court in Burstein v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 1 WLR 579; [2000] All ER (D) 2384; [2000] EWCA Civ 338, cited above, established two important interlocking propositions. (a) In relation to the court’s assessment of damages for libel it is open to a defendant to seek to rely upon such facts as fall within the “directly relevant background context” to the defamatory publication. See in particular the judgment of May LJ, at para 42. (b) It is illogical and undesirable that a defendant can seek to rely upon such facts in relation to such assessment only if he has presented them as part of a substantive defence to liability, in particular within a plea of justification of the publication. He can rely upon them as freestanding matters pleaded as relevant only to the assessment of damages: see in particular the judgment of May LJ, at para 47.

33. That rather simple statement of the propositions flowing from Burstein somewhat belies the uncertainty that has arisen concerning the application of those propositions. That uncertainty mainly revolves around the vague and unhelpful expression “directly relevant background context”. Judges are often rightly sceptical when the tender of evidence is sought to be justified on the basis that it provides “background” or “context”. Those words often conceal or obscure, rather than explain, whether or why the evidence is relevant. Careful attention to what was actually decided in Burstein, however, tends to remove some of the uncertainty.

100 The facts pleaded and proved in the light of Burstein v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 1 WLR 579; [2000] All ER (D) 2384 must, in Wigney J’s terms (at 577 [45]):

concern specific conduct that is directly relevant to either the subject matter of the alleged defamatory statement, or the claimant’s reputation in the part of his or her life the subject of the defamatory publication … courts, including this Court, must proceed with caution in applying Burstein, should guard against “extending too creatively” the concept of “directly relevant background”, and should subject the proposal to adduce facts under the Burstein principle to careful scrutiny. Mere resort to the label “directly relevant background context” will not suffice.

(Emphasis added).

101 The underlying rationale is to prevent trials such as this one from becoming “roving inquiries” into an applicant’s reputation, character or disposition: Burstein (at 596 [35] per May LJ); Speidel v Plato Films Ltd [1961] AC 1090 (at 1143–1144 per Lord Denning).

102 A further point should be made. Contravening conduct of Mr Kumova directly relevant to damages occurred well after the last matter sued upon. Despite Sugarman ACJ considering that defamation law is concerned with a person’s “actual” or “current” reputation as at the date of defamatory publication (see Rochfort v John Fairfax & Sons Limited [1972] 1 NSWLR 16 (at 22)), as was explained by McColl JA in Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Mahommed [2010] NSWCA 335; (2010) 278 ALR 232, like the continuing nature of damage to reputation that may occur after the defamation, any evidence of post-publication material going directly to reputation and otherwise admissible should be considered to ensure that the damages awarded in accordance with s 34 of the Defamation Act accurately reflect the applicant’s reputation at the time the damages are awarded (although, as noted above, any so-called Burstein use must be approached with caution and must be carefully confined (at 283 [245] per McColl JA, with whom Spigelman CJ, Beazley JA, McClellan CJ at CL and Bergin CJ in Eq agreed)).

F.2 The Problems with Mr Davison’s Case

103 With the above principles in mind, some problematic aspects of Mr Davison’s justification defence become apparent.

104 The defence to the First and Second Matters is primarily focussed on nine statements made by Mr Kumova in a series of tweets and interviews, all with respect to either Bellevue Gold or New Century. With respect to those entities, Mr Kumova is said to have: (a) engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act); and (b) made materially misleading statements and/or disseminated materially misleading information, in contravention of s 1041E of the Corporations Act. It is also said that Mr Kumova contravened s 671B of the Corporations Act by failing to disclose to the market changes in his shareholding in Bellevue Gold.

105 Mr Davison’s defence to the Fifth Matter asserts that Mr Kumova engaged in a pump and dump scheme in respect of Bellevue Gold. There was some confusion as to the evidence relied upon in respect of the Fifth Matter. As I understand the final position, however, Mr Davison relies on a series of bullish statements made by Mr Kumova (including the nine statements relied upon with respect to the First and Second Matters), as well as changes in Mr Kumova’s shareholding in Bellevue Gold.

106 In the end, the parties agree that evidence of specific conduct adduced in relation to the First and Second Matters (as opposed to my findings as to whether that conduct constituted contravention of a statutory norm) may be relevant to my assessment of damages. Notwithstanding this, Mr Davison submits that it is necessary for the Court to determine whether Mr Kumova contravened the statutory norms he invokes in pursuit of his defence. In his further submissions, he insists this is because an “essential element of the imputations sought to be justified is that the activity of [Mr Kumova] was unlawful”, and “there is a difference between conduct that is unethical or contrary to accepted standards and conduct that contravenes a statutory prescription regulating conduct”.

107 Although this last statement is undoubtedly correct, there is, with respect, an oversimplification in the submissions of Mr Davison on this topic.

108 For almost fifty years, the commercial life of this country has been regulated by a basic norm, now reflected in a bewildering array of statutory provisions, being that persons must not engage in conduct which is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive. The pervading influence of the provisions enacting this norm might be seen generally as a reflection of social attitudes that have heralded a retreat from legal formalism on several fronts and, in many ways, the existence of the norm reflects community expectations of acceptable commercial behaviour. But it is not as simple as that. There is a continuum of conduct that can contravene the norm: at one end, wicked, predatory, and highly immoral conduct; and at the other, guileless conduct, engaged in by someone trying to do their best, but which involved an innocent but factually mistaken representation.

109 Speaking broadly, it is generally the nature of the impugned conduct, not its legal characterisation that matters when it comes to judging a person’s reputation among ordinary, right-thinking persons.

110 Although it is correct, so far as it goes, that an “essential element” of the carried imputations is the unlawfulness of Mr Kumova’s conduct, it is unlawfulness of a certain type requiring moral blameworthiness that is relevant. The impugned matters primarily relate to wrongdoing involving a subjective intention to obtain a financial reward by saying something to the public about financial matters which is other than the objective truth.

111 Mr Davison pleads breaches of different norms with different elements. As I will explain, Mr Davison relies on conduct (which is said to be in contravention of ss 671B, 1041E and 1041H of the Corporations Act) as being relevant to damages. But any such relevance is primarily because of the conduct itself. The fact that some of this conduct may have involved contravention of a statutory norm without any subjective element is, by itself, somewhat beside the point. Similarly, although there is no bright line, when it comes to damages, to the extent the conduct involves a breach of a norm with a subjective element, what matters most (but not exclusively) is the reputational effect of that conduct, not its legal characterisation.

112 However, I have resolved to address the entirety of Mr Davison’s case as to contravention of the statutory norms given: (1) the need to survey the underlying evidence of the conduct in my assessment as to damages and the fact that the legal characterisation of the conduct is not irrelevant; (2) the centrality of the nine impugned statements and pleaded representations to Mr Davison’s submissions; and (3) their relevance to the meanings conveyed by the Fifth Matter, which Mr Davison seeks to justify.

113 As such, I will proceed by: (1) setting out the statutory norms invoked; (2) examining the evidence adduced and submissions made as to these statutory norms; and (3) considering Mr Davison’s defence to the Fifth Matter.

F.3 Relevant Statutory Norms

Misleading and Deceptive Conduct

114 Section 1041H of the Corporations Act prohibits a person from engaging in conduct in relation to a financial product or financial service that is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive. A financial product includes securities: ss 761A and 764A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

115 The principles applicable to s 1041H are well known, but it is well to set out what I said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GetSwift Limited (Liability Hearing) [2021] FCA 1384 (at [2109]–[2114]):

2109. A useful two-step analysis for misleading and deceptive conduct was provided by Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1904; (2007) 244 ALR 470 (at 474 [14]–[15]):

14. A two-step analysis is required. First, it is necessary to ask whether each or any of the pleaded representations is conveyed by the particular events complained of: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45; 169 ALR 677; 46 IPR 481; [2000] HCA 12 at [105] (Nike); National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2004) 49 ACSR 369; 61 IPR 420; [2004] ATPR 42000; [2004] FCAFC 90 at [18] per Dowsett J (with whom Jacobson and Bennett JJ agreed); Astrazeneca Pty Ltd v GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd [2006] ATPR 42-106; [2006] FCAFC 22 at [37].

15. Second, it is necessary to ask whether the representations conveyed are false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. This is a “quintessential question of fact”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra (2004) 208 ALR 459; [2004] FCA 987 at [49].

2110. Whether conduct is misleading or deceptive, or is likely to mislead or deceive, is a question of fact, determined by reference to the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances, and by having regard to the conduct as a whole: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; (2004) 218 CLR 592 (at 625 [109] per McHugh J); approved in Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; (2009) 238 CLR 304 (at 341–342 [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ). The test is objective and a court must determine that question for itself: Butcher (at 625 [109] per McHugh J); Campbell (at 341–342 [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

2111. As has been made clear in many cases, the central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency or is apt to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error, that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (at 198 per Gibbs CJ); Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (at 200 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ).

2112. The making of a false or misleading representation is, obviously enough, conduct that may be misleading or deceptive: Campbell (at 341–342 [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ). It follows that even though a person may have lacked any intention to mislead or deceive, they may be found to have engaged in conduct that is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 (at 228 per Stephen J, with whom Barwick CJ at 221 and Jacobs J at 232 agreed; at 234 per Murphy J).

2113. In this context, the word “likely” means a real and not remote chance that relevant persons will be misled or deceived: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (at 87 per Bowen CJ, Lockhart and Fitzgerald JJ).

2114. A statement that is literally true may nonetheless be misleading or deceptive: Hornsby (at 227 per Stephen J). Hence a document may be misleading, even if a full and perfect understanding of its contents would not create that effect: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) [2004] FCAFC 90; (2004) 49 ACSR 369 (at 378 [36] per Dowsett J).

116 Two points may be added by way of elaboration.

117 First, where the relevant conduct is directed to the public at large, rather than a specific individual, the Court is required to determine whether the “ordinary” or “reasonable” member of the class of individuals to whom the conduct was directed would be misled or deceived: see Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; (2013) 249 CLR 435 (at 443 [7] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ); Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 (at 85 [102] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

118 Secondly, Mr Davison invokes s 769C of the Corporations Act, which provides that for the purposes of Ch 7 of the Act, a representation is taken to be misleading if it is with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or refusing to do, any act) and is made without reasonable grounds. Of course, a representation will only be with respect to a future matter if it is in the nature of a promise, forecast, prediction or other like statement about something that will only transpire in the future – that is, a representation which is not capable of being proven to be true or false when made: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Group Ltd [2020] FCAFC 162; (2020) 281 FCR 108 (at 145–146 [132] per Foster, Wigney and Jackson JJ).

119 Unlike its analogue s 4 of the Australian Consumer Law (being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), s 769C does not deem the person making the representation not to have had reasonable grounds for making it unless that person adduces evidence to the contrary: see s 4(2) of the Australian Consumer Law. To the extent Mr Davison relies on allegations of contravening conduct as being relevant to his justification defence or as to damages, he is required to establish that the facts possessed by Mr Kumova did not provide reasonable grounds for the making of the representation: In the matter of Colorado Products Pty Ltd (in prov liq) [2014] NSWSC 789; (2014) 101 ACSR 233 (at 262 [88] per Black J).

Materially Misleading Statements and Information

120 Section 1041E relevantly provides:

1041E False or misleading statements

(1) A person must not (whether in this jurisdiction or elsewhere) make a statement, or disseminate information, if:

(a) the statement or information is false in a material particular or is materially misleading; and

(b) the statement or information is likely:

…

(ii) to induce persons in this jurisdiction to dispose of or acquire financial products; … and

(c) when the person makes the statement, or disseminates the information:

(i) the person does not care whether the statement or information is true or false; or

(ii) the person knows, or ought reasonably to have known, that the statement or information is false in a material particular or is materially misleading.

121 The most important distinction between ss 1041E and 1041H is well known and can be critical: s 1041E requires deliberate, negligent, or reckless conduct, whereas s 1041H imposes liability without any requirement of fault. More specifically, leaving aside issues going to jurisdiction, the elements of a contravention of s 1041E are that: (1) a person makes a statement or disseminates information; (2) that is false in a material particular or is materially misleading; and (3) is likely to (a) induce persons to apply for financial products; or (b) induce persons to dispose of or acquire financial products; or (4) is likely to have the effect of increasing, reducing, maintaining or stabilising the price for trading in financial products on a financial market; and (5) when making the statement or disseminating the information, the person (a) does not care whether the statement or information is true or false; or (b) knows or ought reasonably to have known that the statement or information is false in a material particular or is materially misleading.

122 It is not a section (like s 1041H) directed to conduct generally, but rather the making of a statement or the dissemination of specified information. Mr Davison’s pleading, which proceeds on the basis that s 1041E is directed to conduct (being the making of representations said to be conveyed by statements), elides this distinction.

123 Three further elements of the statutory text merit elaboration.

124 First, a statement is “materially misleading” if its likely effect is to induce investors to purchase a company’s securities: Australian Securities Commission v McLeod [2000] WASCA 101; (2000) 22 WAR 255 (at 265 [42] per Owen J). The Court is to ask whether inducement of the reader to act in an erroneous belief is a natural and probable result of a statement: McLeod (at 265 [42] per Owen J). This question is to be determined objectively.

125 Secondly, the word “likely” in s 1041E(1)(b) has the same meaning as in s 1041H, that is, a “real and not remote chance”: James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85 (at 128 [184] per Spigelman CJ, Beazley and Giles JJA). In James Hardie Industries, Spigelman CJ, Beazley and Giles JJA explained earlier authority where it was held that “likely” meant “more probably than not”: see also McLeod (at 266 [47] per Owen J); Australian Securities Commission v Nomura International plc (1998) 89 FCR 301 (at 395–396 per Sackville J). However, their Honours invoked the comment of Baroness Hale of Richmond in Boyle v SCA Packaging Ltd [2009] ICR 1056; [2009] 4 All ER 1181 (at 1075 [68]) that “Parliament can always use the word “probable” if that is what it means”.

126 The word “likely” is liable to change with the context in which it is used (Boughey v The Queen (1986) 161 CLR 10 (at 20 per Mason, Wilson and Deane JJ)), but, as pointed out by Edelman J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cassimatis (No 8) [2016] FCA 1023; (2016) 336 ALR 209 (at 330 [634]), it has long been established that conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a “real and not remote chance” it will mislead or deceive: Tillmanns Butcheries Pty Ltd v Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union (1979) 27 ALR 367 (at 380–381 per Bowen CJ, with whom Evatt J agreed). This is consistent with the meaning given to the word in analogous legislative contexts: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 77; (2020) 277 FCR 49 (at 115–116 [242]–[244] per Middleton and O’Bryan JJ).

127 Thirdly, as to the knowledge criterion in s 1041E(1)(c)(i), whether a person ought reasonably to have known that a statement is false in a material particular or is materially misleading is an objective question: Equititrust Limited (In Liq) (Receiver Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (Responsible Entity) v Equititrust Limited (In Liq) (Receiver Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed); In the Matter of Equititrust Limited (In Liq) (Receiver Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (No 5) [2018] FCA 11; (2018) 124 ACSR 115 (at 134–136 [88]–[103] per Foster J).

Information about Substantial Holdings

128 Finally, Mr Davison also alleges breaches by Mr Kumova of s 671B of the Corporations Act.

129 Section 671B requires that a person give information about substantial holdings to a listed company or the responsible entity for a listed registered scheme, and the relevant market operator, if:

(1) …

(a) the person begins to have, or ceases to have, a substantial holding in the company, scheme or fund; or

(b) the person has a substantial holding in the company, scheme or fund and there is a movement of at least 1% in their holding; or

(c) the person makes a takeover bid for securities of the company or scheme.

….

(8) A person commits an offence if the person contravenes subsection (1).

…

(9) A person commits an offence of strict liability if the person contravenes subsection (1).

130 The underlying policy is that shareholders of a listed company are entitled to know whether substantial holdings of shares exist which might enable a single individual or group to control a company’s destiny and, if so, who has such control: Australian Securities and Investments Commission, Relevant interests and substantial holding notices (Regulatory Guide 5, 27 August 2020) (at [5.287]).

F.4 The Impugned Statements and Alleged Representations

131 The Impugned Statements and Alleged Representations said to have been conveyed are as follows:

132 Before proceeding, it is necessary to explain in more detail three difficulties in Mr Davison’s pleading.

133 First, as noted above, Mr Davison elides the distinction between s 1041H, which turns on conduct (traditionally the conveying of a representation or an omission), and s 1041E, which turns on the statutory concepts of a statement or information. Specifically, he relies upon representations he has crafted with respect to both sections. This limits his case as to s 1041H to the pleaded representations, and makes his s 1041E case at best uncertain, in that it is not focussed on the statements themselves nor upon identified, pleaded “information”.

134 Following discussion with counsel for both parties during oral closing, and further written submissions on the issue, I have determined to hold Mr Davison to his pleaded representations for the purposes of s 1041H, but to approach his s 1041E case with reference to the statements themselves, not the pleaded representations. Despite some protests by Mr Kumova, I am of the view that this does not occasion any unfairness. A large part of oral and written submissions proceeded on this basis and, as it happens, it makes no difference to the result nor to the relief to be granted.

135 Secondly, as to s 1041H, the form of Mr Davison’s pleaded representations is often misdirected, given the nature and overall context of each Impugned Statement. For example, Mr Davison has pleaded five representations based on the notion that Mr Kumova was representing that he had reasonable grounds upon which to make a statement. There is a real artificiality about this approach to the characterisation of the statement and the tweets. These were not solemn announcements and cannot be divorced from the informal context in which they were made. A statement made in a prospectus, or in a company announcement to the ASX, or during a bilateral commercial negotiation, is very different from a statement posted on a social media platform or said during a discursive and relatively informal interview. As will be seen, the forensic choice to pitch the representations in this way has caused difficulties.

136 Thirdly, Mr Davison’s pleading asserts that each of the alleged representations was “partly express and partly implied” and a “continuing representation”. The former contention was not really raised in oral or written submissions, and it is sufficient that I direct my attention to the question as to whether the representation pleaded was conveyed. The assertion the representations were continuing was not developed, was not said to be relevant to the way the misleading and deceptive conduct case was ultimately put and need not be considered further.

F.4.1 Relevant Class

137 Both parties addressed the relevant class of persons to whom Mr Kumova’s impugned tweets and interviews were directed somewhat generally. Given each tweet was published by the same means, and both interviews were published on comparable websites, this was sensible, and it is appropriate to adopt the same course.

138 The tweets and the interviews were accessible by the public at large. With respect to the tweets, Mr Davison submits that the size of the relevant class of persons was considerable, relying on the agreed operation of Twitter as a platform, and on statements as to Mr Kumova’s public notoriety in publications in the Business Review Weekly and the Australian Financial Review. Aside from these factors, Mr Davison’s submissions rely on assertions at a high level of generality, including that there would have been a significant number of Twitter users aware of his reputation as an astute stock picker and interested in having free access to his views.

139 Similarly, it is said that the interviews were widely received as Mr Kumova tweeted links to them: SAF (at [115]–[116]). By reference to Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike (at 85 [102]–[103] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ), Mr Davison argues for a wide conception of the “ordinary or reasonable” member of the relevant class. He submits the Court should take “judicial notice” of the prominence of self-managed superannuation funds and the advent of online discount share brokers such as “Commsec” or “nabtrade”, being developments that have empowered individuals to take direct control of their investments. It is said the audience is also “self-selected” to some degree, narrowed to a group of individuals with a lack of professional engagement in or sophisticated understanding of share markets. As such, Mr Davison arrives at a definition of the relevant class as:

unsophisticated retail investors with no professional experience or relevant formal education in financial markets or share trading, and who were of varying intelligence and understanding (including inevitably some of less than average intelligence and background knowledge), and who were seeking to receive helpful, readily comprehensible and actionable information about stocks and share market investing.

140 But this is arbitrarily specific. The Court must approach this inquiry at a level of abstraction which accounts for the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct or representation is directed, and consider the likely effect of the conduct on hypothetical ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding extreme or fanciful responses: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 278 FCR 450 (at 458–459 [22] per Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ). The conception of the relevant class must account for the reality that the alleged representations were directed at persons with some interest in or knowledge of trading of this kind, balanced against the reality that Mr Kumova’s content was liable to appear on the Twitter Home timeline or Explore page (available to persons who have never sought out Mr Kumova’s profile or like profiles). Mr Kumova’s audience ought to be identified by adopting a level of generality somewhat like that adopted in Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486 (at 506 [36] per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Kiefel JJ), where the relevant class was said to comprise “investors (both present and possible future investors) and, perhaps, as some wider section of the commercial or business community”. Persons of varying levels of sophistication who used social media and were generally interested in shares or mining, seems to me a workable definition of the relevant class.

F.4.2 First Statement

141 The First Statement was made during a podcast interview with Mr Barry Fitzgerald, a journalist at Stockhead, a news service which reports on ASX-listed companies, on or about 28 May 2020. The podcast was part of Stockhead’s “Explorers Podcast” series.