FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Scholz (No 2) [2022] FCA 1542

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter is listed for a case management hearing at 9.30am on 31 January 2023.

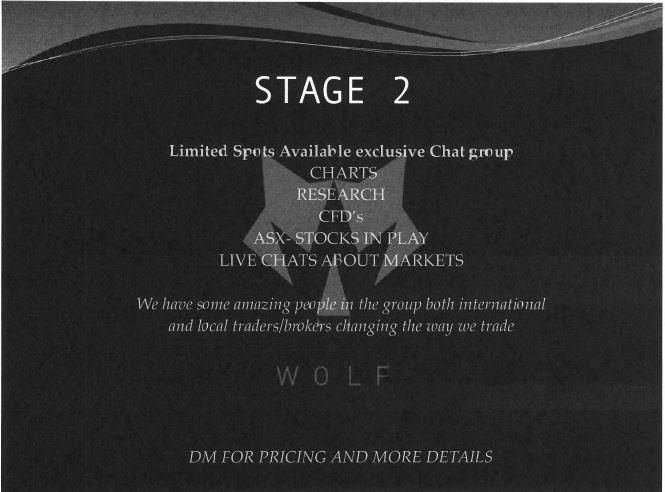

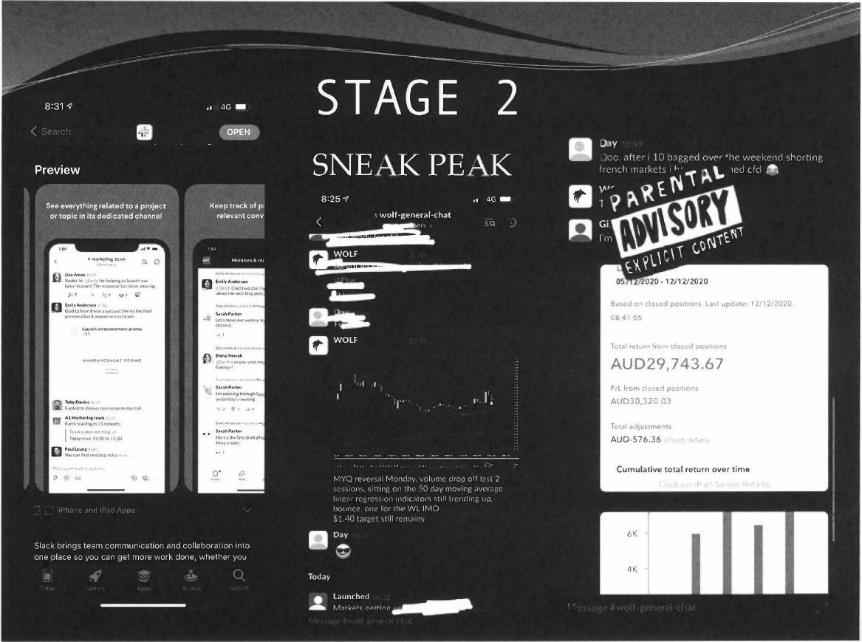

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DOWNES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) alleges that, contrary to s 911A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), the defendant, Mr Tyson Scholz, carried on a financial services business between at least early 2020 and November 2021 (relevant period) without an Australian financial services licence.

2 The central issue in this proceeding was not whether Mr Scholz was carrying on a business (he was) or whether he had the required licence (he did not), but whether he was carrying on a financial services business.

3 The business carried on by Mr Scholz evolved during the relevant period. From about March 2020, Mr Scholz posted positive stories (being posts viewable for only 24 hours) about particular companies on an Instagram account, which often indicated that he had acquired shares in that company or that he thought that shares in that company would be a good investment. A likely consequence of his conduct was that it would influence viewers of his stories to acquire the shares and his shareholding would increase in value when that occurred. He knew this, admitting to Mr Danny Chen in June 2020 that he used Instagram to engage in a “clever way of pumping” (that is, increasing the price of shares). Mr Scholz told Mr Chen, “We should get positions” (that is, buy particular shares) and “let the word out”, also saying, “Only thing is I can’t charge them” and “That’s why [I] can get away with it”.

4 Mr Scholz changed his Instagram “handle” or user name to ‘asxwolf_ts’ and adopted the persona of the “ASX Wolf”. This persona, by which he held himself out as being a successful trader of shares on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), was emphasised by the use of wolf images on Instagram as well as various references to himself as the “wolf”.

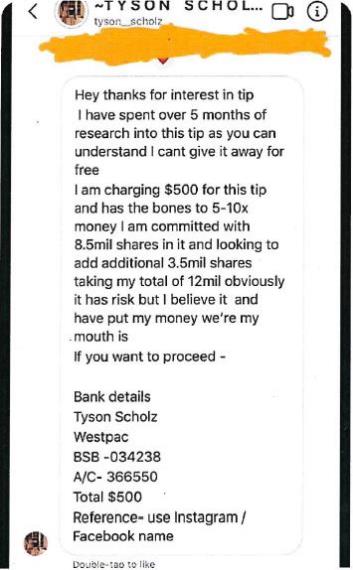

5 By no later than mid-2020, Mr Scholz was engaged in selling private “tips” about shares to clients for $500.

6 Mr Scholz also promoted on Instagram and ran seminars designed to teach attendees about how to trade on the ASX. He charged $500 for these seminars, which were held over Zoom or in person at Mr Scholz’s residence in Queensland. Mr Scholz used direct messaging within Instagram to facilitate payment for the seminars, and to promote the seminars including by stating, “10 years of my trading career has been rolled into this package”. Deposits of $500 were made into Mr Scholz’s bank account from March 2020.

7 In the seminars, Mr Scholz also, on occasion, expressed views about shares in particular companies, which coincided with references to those shares being made in stories posted on the Instagram account.

8 The seminars were described by Mr Scholz as “Stage 1” with attendees being encouraged by him to progress to “Stage 2”, which was an online group on Discord in which messages were exchanged by members about share trades. All members were anonymous except for Mr Scholz (who used a wolf avatar) and members paid $1,000 a year to participate. Stage 2 was also promoted on Instagram, and Mr Scholz used direct messaging within Instagram to facilitate payment for Stage 2 and to encourage prospective members to join. For example, some of these direct messages stated that Mr Scholz offered Stage 2 as an “extra add on”.

9 Mr Scholz described the Discord group in direct messages sent via Instagram as the “Wolf mentorship channel”. It was also known as the “Black Wolf Pit Channel”, and members were required to agree to specific rules devised by Mr Scholz.

10 Mr Scholz expressed numerous views via the Black Wolf Pit Channel about whether particular shares should be acquired or sold, and when, and at what price – both to the group as well as in direct messages exchanged with group members, who sometimes asked for his particular guidance and advice as to what they should do about certain shares.

11 The members of Stage 2 were also given advance notice by Mr Scholz of a share recommendation which he was planning to post in a story on the Instagram account. In this way, Mr Scholz was seeking to influence the members of Stage 2 as to their decision in relation to those shares, but also doing the same thing to readers of the story on the Instagram account.

12 The business then commenced to offer “Stage 3” which was promoted on Instagram as being “Master Class Technical”. Little is known about this stage of the business.

13 For the following reasons, ASIC has established that Mr Scholz contravened s 911A Corporations Act.

STRUCTURE OF REASONS

14 A significant proportion of the hearing was occupied with submissions on procedure and objections to evidence which were taken by Mr Scholz, and some rulings were made during the hearing with others deferred until delivery of this judgment.

15 A decision was also delivered prior to the commencement of the second day of the hearing which provided reasons for the exclusion of opinion evidence sought to be relied upon by ASIC: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Scholz [2022] FCA 1188. ASIC did not attempt to repair the deficiencies in this evidence or to tender alternative opinion evidence.

16 Taking into account these matters, these reasons are structured as follows:

(1) reasons for refusing ASIC’s application to vacate an order made on 7 June 2022 in which the question of liability was ordered to be heard separately from the question of relief;

(2) reasons for admission of evidence obtained by ASIC through execution of search warrants;

(3) rulings on remaining objections to evidence taken and maintained by Mr Scholz;

(4) consideration of Mr Scholz’s complaint about lack of particularisation;

(5) whether there has been a contravention of s 911A Corporations Act;

(6) whether there has been a contravention of s 911B Corporations Act;

(7) disposition.

APPLICATION TO VACATE ORDER

17 Before addressing the issues which arise in this case, it is necessary to provide reasons for refusing what was an informal application by ASIC on the first day of the hearing to vacate an order made on 7 June 2022 that the question of liability be heard separately from the question of relief (7 June order).

18 The proposal that the 7 June order be vacated was made through ASIC’s outline of opening submissions filed on 27 September 2022 (being a week before the liability hearing).

19 It is relevant to consider how the 7 June order came to be made. For the case management hearing held on that date, Mr Scholz had proposed draft orders which included an order that there be a separate hearing on liability.

20 When counsel for ASIC was asked at the hearing on 7 June whether ASIC opposed Mr Scholz’s proposal to have a separate hearing on liability, it was submitted (twice) that the proposed order was opposed but that ASIC did not have a “particularly strong view”. In light of ASIC’s desultory opposition to the order, and as a separate hearing on liability is not uncommon in regulatory matters, the order sought by Mr Scholz was made.

21 ASIC accepted that Mr Scholz had made forensic decisions and prepared for the hearing commencing on 4 October 2022 on the basis that it would be a separate hearing on liability.

22 For these reasons, had the 7 June order been vacated on the first day of the hearing as sought by ASIC, the prejudice to Mr Scholz is self-evident.

23 To address this prejudice, ASIC submitted that, should Mr Scholz wish to rely on further evidence, the matter could be adjourned part heard to a date to be fixed and that, in the interim, Mr Scholz could file and serve further evidence. ASIC submitted that this would have the advantage that one judgment on all relevant issues would be delivered at an earlier time. However, I was not persuaded that such an advantage, even if it could have been achieved, would overcome the prejudice to Mr Scholz if this course had been adopted. Nor was I persuaded that there was any advantage in terms of efficiency or timeliness of the kind described by ASIC. Instead, there was a danger that the hearing would be transformed into a tangled procedural mess.

24 For these reasons, I refused to vacate the 7 June order.

EVIDENCE OBTAINED PURSUANT TO SEARCH WARRANTS

Overview

25 On 16 November 2021, three search warrants relating to Mr Scholz were issued under Part IAA Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), being:

(1) a warrant issued for the search of Mr Scholz;

(2) a warrant issued for Mr Scholz’s premises; and

(3) a warrant issued for Mr Scholz’s car,

(together, the search warrants).

26 Evidential material obtained as a consequence of the execution of the search warrants and therefore seized under Part IAA Crimes Act formed a significant part of ASIC’s evidence at the hearing. This evidence, and other evidence which built upon the seized documents, was the subject of objection by Mr Scholz.

27 That objection was not accepted, and the evidence was admitted. The reasons for that admission are as follows.

Relevant legislation

28 Section 3ZQU Crimes Act as modified by s 39H Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (s 3ZQU) relevantly provides as follows:

3ZQU Purposes for which things may be used and shared

(1) A constable or Commonwealth officer may use, or make available to a member of ASIC or an ASIC staff member to use, a thing seized under this Part for the purpose of the performance of ASIC’s functions or duties or the exercise of its powers.

(2) Without limiting the scope of subsection (1), a constable or Commonwealth officer may use, or make available to a person covered under subsection (3) to use, a thing seized under this Part for the purpose of any or all of the following if it is necessary to do so for that purpose:

(a) preventing or investigating any of the following:

(i) a breach of an offence provision;

(ii) a breach of a civil penalty provision;

(iii) a breach of an obligation (whether under statute or otherwise), other than an obligation of a private nature (such as an obligation under a contract, deed, trust or similar arrangement);

(b) prosecuting a breach of an offence provision;

(c) prosecuting a breach of a civil penalty provision;

(d) taking administrative action, or seeking an order of a court or tribunal (within the meaning of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001), in response to a breach of an obligation (whether under statute or otherwise), other than an obligation of a private nature (such as an obligation under a contract, deed, trust or similar arrangement).

29 Pursuant to s 3 Crimes Act, “Commonwealth officer” means a person holding office under, or employed by, the Commonwealth and includes certain persons, which no party submitted was relevant to the facts of this case. ASIC submitted, and I agree, that a Commonwealth officer includes Commonwealth employees who work within ASIC. Mr Scholz did not submit otherwise.

Objection taken by Mr Scholz

30 It was not disputed by Mr Scholz that the search warrant material which had been seized under the search warrants was “a thing seized under this Part” within the meaning of s 3ZQU(1). That this is so is apparent from the face of the search warrants themselves.

31 However, it was disputed by Mr Scholz that ASIC could rely upon the search warrant material pursuant to s 3ZQU.

Reasons for admission of search warrant material

32 The words of s 3ZQU(1) are not ambiguous, and Mr Scholz did not submit that they were. Rather, they provide, by clear words, that a Commonwealth officer may use, or make available to a member of ASIC or an ASIC staff member to use, a thing which has been seized. The only condition which is imposed is that this is done for the purpose of the performance of ASIC’s functions or duties or the exercise of its powers.

33 The central provision relied upon by ASIC in this proceeding is s 911A Corporations Act, which relevantly provides that a person who carries on a financial services business in this jurisdiction must hold an Australian financial services licence covering the provision of the financial services. Section 911A is a provision within Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act.

34 Section 1101B Corporations Act empowers ASIC to apply for “such order, or orders” as the Court “thinks fit” if it appears to the Court that, amongst other things, a person has contravened a provision of Chapter 7.

35 Section 1324 Corporations Act empowers ASIC to apply for an injunction where a person has engaged or is proposing to engage in conduct that constituted, constitutes or would constitute a contravention of the Corporations Act.

36 By this proceeding, ASIC seeks orders pursuant to ss 1101B and 1324 Corporations Act. The use which it sought to make of the search warrant material was to establish that Mr Scholz has contravened a provision of the Corporations Act, within Chapter 7 of that Act, so as to establish the basis to obtain this statutory relief. It follows that ASIC was seeking to deploy the search warrant material in the exercise of its powers as conferred on it by the Corporations Act. Section 3ZQU(1) therefore enables ASIC to use the search warrant material for this purpose.

37 Contrary to Mr Scholz’s submission, ASIC does not rely on the opening words to s 3ZQU(2) as conferring on it “unlimited power”. Rather, the use to which ASIC seeks to put the search warrant material, being to seek an injunction under ss 1101B and 1324 Corporations Act, falls squarely within s 3ZQU(1), which provision is confined to the lawful performance of ASIC’s functions or duties or the exercise of its powers.

38 Further, the opening words of s 3ZQU(2), being “[w]ithout limiting the scope of subsection (1)” could not be more plain in that they convey that s 3ZQU(2) is not intended to limit the scope of s 3ZQU(1).

39 This means that, if there is an exercise of power by ASIC (for example) which does not fall within one of the listed purposes of s 3ZQU(2), it would be captured by s 3ZQU(1). It follows that it is not necessary that ASIC’s purpose in using the search warrant material falls within one of the listed purposes in s 3ZQU(2), as submitted on behalf of Mr Scholz, because such an approach would do the opposite to what is stated expressly – namely, it would be to limit the scope of s 3ZQU(1).

40 Senior counsel for Mr Scholz pointed to the words “if it is necessary to do so” in s 3ZQU(2) as supporting a construction which limits the width of s 3ZQU(1) because to do otherwise would mean that those words have no work to do. By a related submission, it was also submitted that, to use the search warrant material, ASIC must establish at the time of tender that it is necessary for it to use the material in the manner proposed.

41 No authority was cited in support of these submissions, and none exists.

42 The proper construction of s 3ZQU means that these submissions must be rejected.

43 That is because s 3ZQU(1) is a standalone provision. It is also expressly not limited by s 3ZQU(2). Section 3ZQU(1) does not contain any requirement that ASIC establish that it is “necessary” to use the search warrant material for any particular purpose; all that is required is that the purpose for which ASIC uses the search warrant material is the performance of ASIC’s functions or duties or the exercise of its powers. In these circumstances, a submission that particular words used in s 3ZQU(2) “limit the width” of s 3ZQU(1), and that ASIC must establish that it is necessary to use the search warrant material for a purpose stated in s 3ZQU(2) before it can be tendered successfully, cannot be accepted because to do so would have the effect of limiting the scope of s 3ZQU(1), being something which s 3ZQU(2) states expressly should not be done.

44 Mr Scholz concluded his objection to the search warrant material by submitting “that a strict approach to the construction of, and compliance with, statutory provisions authorising the issue and execution of search warrants”, is applicable to s 3ZQU by reference to the principle of legality, that these provisions do not provide ASIC with “irresistible clearness” or “clear words or those of necessary intendment” that would permit reliance by ASIC on the search warrant material at the liability hearing and that s 3ZQU does not displace in express terms the decisions of Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich (2005) 52 ACSR 374; [2005] NSWSC 62 at [262], [305] (Austin J) and Williams v Keelty (2001) 111 FCR 175; [2001] FCA 1301 at [233] (Hely J) and their application to liability proceedings.

45 The principle of legality is a well-accepted principle of statutory construction that a provision should not be construed in a way which would “overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law, without expressing its intention with irresistible clearness”: Lee v New South Wales Crime Commission (2013) 251 CLR 196; [2013] HCA 39 at [171] per Kiefel J (as her Honour then was) citing Al-Kateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562; [2004] HCA 37 at [19] and Potter v Minahan [1908] HCA 63; (1908) 7 CLR 277 at 304.

46 However, the principle of legality is of little assistance where Parliament has expressed, by clear words or necessary implication, a statutory intention to abrogate or restrict a fundamental freedom or principle: Lee at [55]–[56] (French CJ), [313]–[314] (Gageler and Keane JJ); Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police v Luppino (2021) 284 FCR 233; [2021] FCAFC 43 at [214] (Wigney and Abraham JJ) citing X7 v Australian Crime Commission (2013) 248 CLR 92; [2013] HCA 29 at [24], [119], [125], [158]. That is the position here.

47 The clear words of s 3ZQU manifest the intention of the legislature to exclude or minimise any rights which Mr Scholz might otherwise have by unambiguously authorising the use of materials obtained pursuant to a search warrant for the purpose of performing ASIC’s powers and functions.

48 Finally, the decisions of Rich and Williams do not assist Mr Scholz because each of these cases was about the use or disclosure of documents seized under a search warrant under the preceding provisions of the Crimes Act. As is apparent from the legislation, the relevant provisions have been modified so as to expressly confer a broad power on ASIC in relation to the use of evidence obtained under a search warrant. That has the consequence that these single judge decisions which interpreted earlier and differently worded legislation do not assist in the interpretation of the legislation in this case.

RULINGS ON REMAINING OBJECTIONS TO EVIDENCE

Complaint received by ASIC

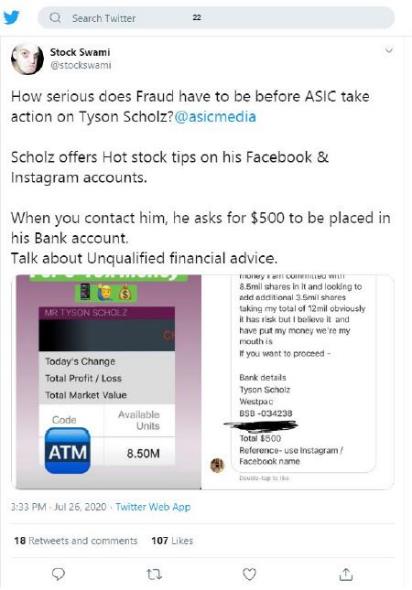

49 Mr Scholz objected to the admission of a copy of an email received by ASIC from a Senior Market Analyst, Surveillance, at ASX which attached a tweet from ‘Stock Swami’. The attached tweet is extracted here:

50 In support of its admission into evidence, ASIC relied upon s 69(1) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), which relevantly provides:

69 Exception: business records

(1) This section applies to a document that:

(a) either:

(i) is or forms part of the records belonging to or kept by a person, body or organisation in the course of, or for the purposes of, a business; or

(ii) at any time was or formed part of such a record; and

(b) contains a previous representation made or recorded in the document in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business.

51 Mr Scholz accepted that the email from ASX which attached the tweet is a document that forms part of ASIC’s records which has been kept by it for the purposes of its business within the meaning of s 69(1)(a)(i).

52 However, Mr Scholz submitted, and I agree, that the tweet does not contain a previous representation made or recorded in the course of, or for the purposes of, ASIC’s business, with the consequence that s 69(1)(b) is not satisfied. In particular, the fact that ‘Stock Swami’ chose to tag ASIC in the tweet does not have the consequence that the representation was made for the purposes of ASIC’s business.

53 As such, the evidence which is comprised of the tweet will not be admitted by reason of the hearsay rule: s 59 Evidence Act.

54 Although ASIC sought to tender it for a non-hearsay purpose, in the event that s 69 was found not to be satisfied, it will not be admitted for such a purpose, as it would not be relevant evidence: s 56(2) Evidence Act.

WeChat messages

55 A hearsay objection was also taken to evidence contained in the affidavit of Mr Kavanagh affirmed 20 May 2022 (second Kavanagh affidavit) relating to and extracting WeChat messages between Mr Scholz and Mr Chen.

56 The extracts contained in the body of the second Kavanagh affidavit were as follows:

# | Time | From | Message |

8 June 2020 | |||

534 | 03.19 PM | Tyson Scholz |

|

535 | 03.19 PM | Tyson Scholz | This was another dud[e] |

… | |||

540 | 03.19 PM | Tyson Scholz | Yea I told him course that day |

541 | 03.19 PM | Tyson Scholz | I said oh I like this company |

542 | 03.20 PM | Tyson Scholz | As long as people make money that’s all that matter |

… | |||

563 | 03.21 PM | Tyson Scholz | Just have to be slick about it |

564 | 03.21 PM | Tyson Scholz | And careful |

565 | 03.21 PM | Tyson Scholz | Hence why very clever how I do it |

566 | 03.22 PM | Tyson Scholz | I just say I Beleive in stock and I am in |

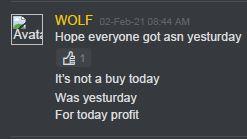

… | |||

568 | 03.22 PM | Tyson Scholz | And very vague at best |

569 | 03.22 PM | Tyson Scholz | So nothing can come back |

570 | 03.22 PM | Tyson Scholz | Even if they screen shot |

9 June 2020 | |||

588 | 08.23 AM | Tyson Scholz | I have clever way of pumping |

… | |||

596 | 09.20 AM | Danny | Whats clever way to pump? |

597 | 09.20 AM | Tyson Scholz | Just congrats a mate who has been in it lol |

598 | 09.21 AM | Tyson Scholz | From start haha |

599 | 09.21 AM | Tyson Scholz | Have a look at my starry |

600 | 09.21 AM | Tyson Scholz | Story |

601 | 09.21 AM | Tyson Scholz | Insta |

602 | 09.22 AM | Tyson Scholz | Not saying buy or anything just say how good it is lol |

14 June 2020 | |||

911 | 02.36 PM | Tyson Scholz | I might do a wow post on insta on Monday morning if it comes up |

912 | 02.36 PM | Danny | Yeah definitely, hype it up |

913 | 02.36 PM | Tyson Scholz | And say wow well done MYQ |

… | |||

916 | 02.38 PM | Tyson Scholz | I will get my HC guy ready |

917 | 02.38 PM | Tyson Scholz | As I can’t be seen in HC or twitter promote |

918 | 02.38 PM | Tyson Scholz | Insta is ok |

919 | 02.38 PM | Tyson Scholz | Different audience |

19 June 2020 | |||

1072 | 10.28 AM | Tyson Scholz |

|

1073 | 10.28 AM | Tyson Scholz | Haha a person that did course |

1074 | 10.28 AM | Danny | hahaha very nice |

1075 | 10.28 AM | Danny | keep building the group |

1076 | 10.28 AM | Danny | get a nice pump and dump crew |

1077 | 10.29 AM | Tyson Scholz | Yea have a cool audience now |

1078 | 10.29 AM | Danny | heheheh its pretty awesome |

1079 | 10.29 AM | Danny | we find the good stocks, grab em first |

1080 | 10.29 AM | Danny | get info on the ones we can |

1081 | 10.30 AM | Danny | everyone wins, we just win more |

1082 | 10.30 AM | Tyson Scholz | Yea can do a group one |

1083 | 10.30 AM | Tyson Scholz | We should get positions |

1084 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | And let the word out |

1085 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | Only thing is I can’t charge them |

1086 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | That’s why can get away with it |

1087 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | Atm |

1088 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | Am saying I love this stock etc |

1089 | 10.31 AM | Tyson Scholz | On my feed I am not saying u have to buy lol |

1090 | 10.32 AM | Danny | yeah we dont need to charge em |

1091 | 10.32 AM | Danny | we make more than enough from the group anyway lol |

1092 | 10.32 AM | Danny | yeah |

1093 | 10.33 AM | Tyson Scholz | Will keep doing what doign for now |

1094 | 10.33 AM | Danny | yeah its working |

1095 | 10.33 AM | Tyson Scholz | And see if can have survivors out other end |

1096 | 10.33 AM | Tyson Scholz | That’s what I am testing |

1097 | 10.33 AM | Danny | the best ones are the ones when we know news is coming and easy to pump lol, myq is actually perfect for it |

1098 | 10.33 AM | Danny | Yeah |

1099 | 10.34 AM | Tyson Scholz | Yea they get excited when they can buy 5k worth |

1100 | 10.34 AM | Danny | Hahahah |

1101 | 10.35 AM | Tyson Scholz |

|

1102 | 10.35 AM | Tyson Scholz | That’s on insta we migrate to what’s app |

1103 | 10.35 AM | Danny | Hahahahah |

57 In response, ASIC relied on the exception contained in s 81 Evidence Act, which provides:

81 Hearsay and opinion rules: exception for admissions and related representations

(1) The hearsay rule and the opinion rule do not apply to evidence of an admission.

(2) The hearsay rule and the opinion rule do not apply to evidence of a previous representation:

(a) that was made in relation to an admission at the time the admission was made, or shortly before or after that time; and

(b) to which it is reasonably necessary to refer in order to understand the admission.

58 The Dictionary to the Evidence Act provides:

admission means a previous representation that is:

(a) made by a person who is or becomes a party to a proceeding (including a defendant in a criminal proceeding); and

(b) adverse to the person’s interest in the outcome of the proceeding.

59 Section 88 Evidence Act provides:

88 Proof of admissions

For the purpose of determining whether evidence of an admission is admissible, the court is to find that a particular person made the admission if it is reasonably open to find that he or she made the admission.

60 In this case, it is reasonably open to find that the statements made in the WeChat messages (and which are attributed to him) were made by Mr Scholz. That is because the WeChat messages were recovered pursuant to the search warrants from a mobile telephone in Mr Scholz’s possession, and Mr Kavanagh’s unchallenged evidence was that “[i]nformation held by ASIC causes me to believe these messages [were] between the Defendant and Danny Chen.”

61 As to whether the representations by Mr Scholz were adverse to Mr Scholz’s interest in the outcome of this proceeding, the extracts demonstrate that Mr Scholz was, and was intending to, make recommendations about the purchase of shares on social media which he knew would influence the buying behaviour of others. They are therefore admissions within s 81(1) Evidence Act.

62 The surrounding statements contained in the WeChat extracts which were not made by Mr Scholz or which do not amount to admissions are also admissible because they were contemporaneous and it is reasonably necessary to refer to them in order to understand the admissions: s 81(2) Evidence Act.

63 A complaint was made by Mr Scholz that there was no attempt by ASIC to call Mr Chen to give evidence, with reference being made to s 82(a) Evidence Act. Section 82 provides:

82 Exclusion of evidence of admissions that is not first-hand

Section 81 does not prevent the application of the hearsay rule to evidence of an admission unless:

(a) it is given by a person who saw, heard or otherwise perceived the admission being made; or

(b) it is a document in which the admission is made.

64 However, this objection is without substance when regard is had to s 82(b) Evidence Act, which applies in this case as the WeChat messages (in which the admissions were made) constitute a document within the meaning of the Evidence Act.

65 For these reasons, the extracts of the WeChat messages between Mr Scholz and Mr Chen which are contained in the second Kavanagh affidavit will be admitted.

COMPLAINT THAT ASIC’S CASE WAS INSUFFICIENTLY PARTICULARISED

66 Along with the extensive objections to ASIC’s evidence, Mr Scholz commenced his defence of the case against him by complaining in opening submissions that ASIC’s case as to what is alleged is or was Mr Scholz’s “financial services business” was “anything but precise”. Mr Scholz also complained that ASIC’s case on how he was said to have given financial product advice was “similarly insufficient and imprecise”. It was submitted that, “Nor is there any identification of the particular financial products which are allegedly relevant, or of the decisions of persons with respect to those products”. Reference was made to a request for particulars by Mr Scholz on 9 March 2022 and the response from ASIC dated 6 May 2022.

67 No application was brought by Mr Scholz seeking an order that ASIC provide further and better particulars of the allegations against him. None was brought prior to the hearing on liability, or even at the hearing itself.

68 This was so, notwithstanding that Mr Scholz’s complaint in his opening submissions was raised with his counsel prior to ASIC opening its case orally. The following exchange occurred:

HER HONOUR: - - - Mr Dick’s side, in their submissions, complains about particulars. Now, do I do anything with that, Mr Dick, or is that just a – can I just ignore that?

MR DICK: Well, it’s only – yes. I wanted to flag it, your Honour, because - - -

HER HONOUR: Well, where does it go?

MR DICK: It goes to this, I suppose: that your Honour might then be expecting if ASIC hasn’t really particularised the way in which my client is said to have contravened, having regard to this mass of evidence and Wolf Chats and things, that we would be expecting that to be addressed in opening so that that would enable me to focus my cross-examination on what I understand the real issues are. It’s true we didn’t come back to your Honour after we got the lack of particulars because we were told it’s all going to be in the evidence. We’ve looked at all the evidence, and, I mean, we understand broadly what ASIC is complaining about, but, for example, is ASIC saying that the stage 1 aspect of what my client was doing, that is, the seminar – is that a breach? Is that a contravention of 911A? And if it is, in what respects?

And then when we come to the stage 2 – or we come to the Instagram posts. Is it alleged that putting pictures on the Instagram where the whole world can apparently access it – is that breaching 911A? And then lastly with the Discord, which is the so-called stage 2. What precisely is being advanced by ASIC, particularly in circumstances where I think there’s only one witness that they’ve called that actually participated in stage 2? So they are the sorts of matters – and, obviously, I can wait till my closing submission and say, well, we’re still none the wiser, but we wanted to raise it in opening because we thought it would assist your Honour and all of us to understand better what the case really is.

HER HONOUR: All right. But at the moment, nothing is being sought from me in terms of the complaint about particulars.

MR DICK: No. It’s just for your Honour to note.

HER HONOUR: All right. But if the opening is inadequate – not adequate for your purposes, that’s a matter for you what you do about it.

MR DICK: Yes. Well, I mean, I can’t really ask your Honour to summarily dismiss the case. I don’t think the cases are so generous to mean that I could do that, but – so I think that’s the highest that I can put it at this stage.

HER HONOUR: Well, no, but, I mean, if your concern is that your client doesn’t know the case against him - - -

MR DICK: Yes.

HER HONOUR: - - - then that’s something that probably can’t wait till closing.

MR DICK: No. No, I accept that.

…

MR DICK: No, but it may well be after the opening that we consider our position further and make an application, your Honour.

69 After senior counsel for ASIC concluded ASIC’s oral opening submissions, no issue was raised by Mr Scholz by way of further complaint to the effect that he did not understand the case against him.

WHETHER CONTRAVENTION OF SECTION 911A CORPORATIONS ACT

Issues

70 Section 911A(1) Corporations Act relevantly provides that:

911A Need for an Australian financial services licence

(1) Subject to this section, a person who carries on a financial services business in this jurisdiction must hold an Australian financial services licence covering the provision of the financial services.

71 The following are the substantive issues to be addressed:

(1) whether Mr Scholz carried on a financial services business within the meaning of s 911A Corporations Act;

(2) whether the exemption in s 911A(2)(eb) Corporations Act applies.

Whether Mr Scholz carried on a financial services business

Relevant facts

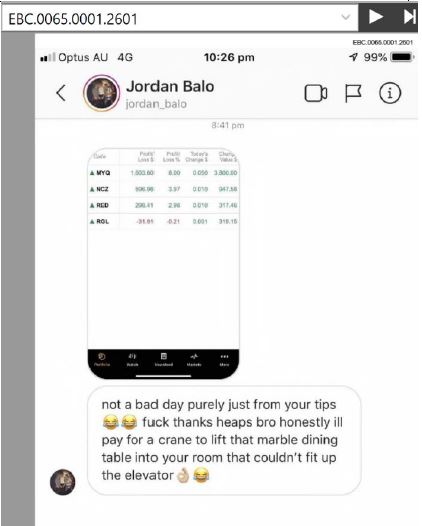

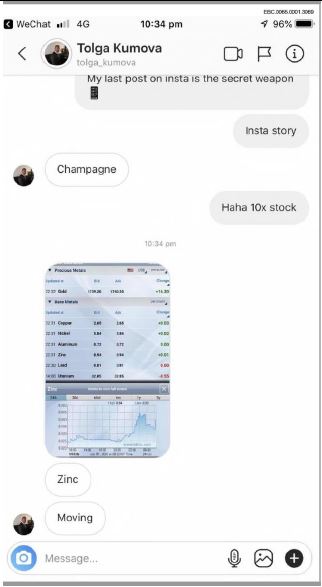

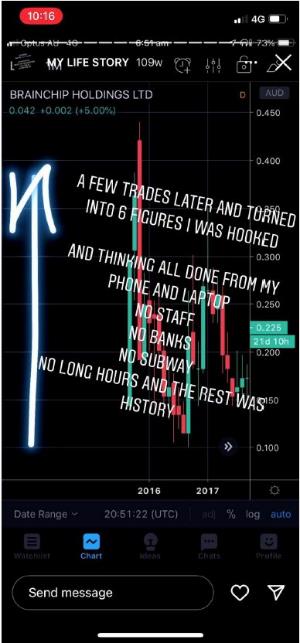

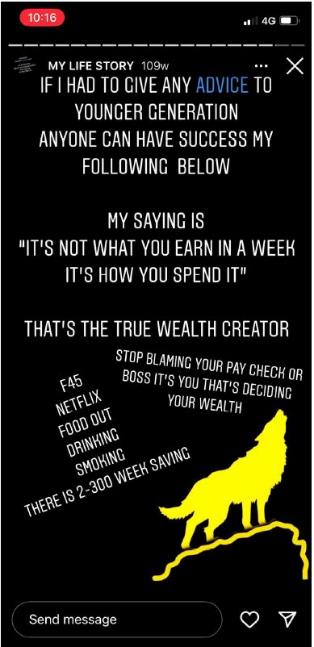

72 Throughout the relevant period, Mr Scholz held the Instagram account on which he published posts and stories. One such story contained information about how Mr Scholz had become a self-made success story through trading on the ASX. The life story included the following images, and sought to encourage people to follow Mr Scholz on his Instagram account:

73 Mr Scholz also posted numerous photographs and stories on the Instagram account which depicted himself enjoying a lavish lifestyle. The impression given by these posts and stories was that this lifestyle had been achieved by Mr Scholz as a consequence of his share trading on the ASX. These posts appeared to be designed to encourage followers to see Mr Scholz as an expert in share trading who had achieved significant success.

74 Such a conclusion is fortified by the fact that the Instagram account also utilised sponsored posts, which is a form of advertising on Instagram and which sought to entice people to follow Mr Scholz on the Instagram account. One example of a sponsored post depicted a Ferrari driving and drifting toward a bottle of champagne, with the post directing the viewer to the Instagram account operated by Mr Scholz.

75 In 2020, Mr Scholz changed his “handle” or user name on Instagram to ‘asxwolf_ts’ and began to hold himself out as being the “ASX Wolf”. The reference to ASX Wolf is an allusion to the infamous “Wolf of Wall Street”; again, the adoption of this persona appeared intended to convey that Mr Scholz was an expert in share trading on the ASX. By 21 October 2021, the Instagram account had approximately 21,900 followers.

76 Mr Scholz also used various images or logos on some of the posts and stories on the Instagram account, which reinforced his status as the ASX Wolf:

77 During the relevant period, Mr Scholz posted stories on the Instagram account about shares in particular companies. Although these stories appeared for no longer than 24 hours, there was no evidence to support the submission by Mr Scholz that the length of time that each story was pictured on the screen was reduced by the number of stories posted by Mr Scholz (even if that is relevant, which it is not).

78 These stories were usually not in a form of being a direct recommendation that readers should buy shares, but were more subtle. Nevertheless, the underlying message was that Mr Scholz was recommending the acquisition of the shares referred to in the stories. Having regard to Mr Scholz’s exchanges with Mr Chen, he was aware that his stories on the Instagram account would be likely to influence others in relation to the shares but he considered that this approach was “slick” and “very clever” so that “nothing can come back”.

79 By way of example, these stories appeared on the Instagram account:

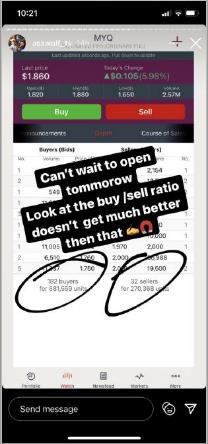

80 As another example, these stories also appeared on the Instagram account:

81 Although it might be said that these stories were posted for ‘free’ for anyone to read and therefore did not form part of any financial services business operated by him, it is objectively unlikely that Mr Scholz posted these stories for no gain to himself.

82 As observed above, a likely consequence of these stories being posted on Instagram was that it would influence viewers of his stories to acquire the shares in question and Mr Scholz’s shareholding would increase in value when that occurred. He knew this, effectively admitting to Mr Chen in June 2020 that he used “Insta” as a “clever way of pumping” (which is a reference to increasing the price of shares). Mr Scholz boasted, “Not saying buy or anything just say how good it is lol” (with “lol” being an acronym for “laugh out loud”).

83 Mr Scholz told Mr Chen, “We should get positions” (that is, buy particular shares) and “let the word out”, also saying, “Am saying I love this stock etc” and “On my feed I am not saying u have to buy lol”. In the context, the reference to “feed” was a reference to Instagram. Mr Chen told Mr Scholz that “we [don’t] need to charge [them]” as “we make more than enough from the group anyway lol”. Mr Chen had also observed earlier in their exchange, “everyone wins, we just win more”.

84 By March 2020, Mr Scholz promoted on Instagram and commenced to hold seminars designed to teach attendees about how to trade on the share market.

85 An example of such an advertisement is as follows:

86 Witnesses called by ASIC, namely Mr Daniel Borrowman, Mr Jayden Redmond, Mr Andrew Geard, and Mr Antonio Worner, saw advertisements on the Instagram account in relation to the Stage 1 seminar. They exchanged direct messages with Mr Scholz on Instagram who provided them with information about the seminars in those messages. They each then paid $500 to attend the seminar, as did Mr Daniel Hunter (who was also called by ASIC).

87 Instagram was therefore used by Mr Scholz as a promotional tool for the seminars, as well as a means to exchange information with potential attendees of the seminars, including for the purposes of obtaining payment of the fee.

88 From March 2020, Mr Scholz received numerous payments of $500 into his bank account. Some of these deposits included references which indicated that they were payments for the Stage 1 seminar (such as “trading webinar” on 27 March 2020 and “webinar” on 17 April 2020).

89 The seminars were held in person as well as via Zoom. Almost all of the content of these seminars was provision of general information about how to undertake share trading. Mr Scholz also, on occasion, made statements during the seminars about shares in particular companies.

90 For example, in a seminar which was the subject of a video played during the hearing, Mr Scholz stated the following about a particular company which was in a trading halt:

Trading halts just mean that they’re looking to close a deal or there’s something really big coming. So … I wouldn’t be buying on the pump, because it’ll probably gap up to something like, really high. Or, it could tank depending on the news.

…

So, just wait for your re-entries. Don’t buy on – just ‘cause you see 20 percent up, you know what I mean? So, you’ve got to really be disciplined. But, I think this – this companies got a really good future long term …

…

91 In the same seminar, Mr Scholz stated about another company:

But, to be honest with you, I probably wouldn’t buy that, to be honest.

92 In the same seminar, Mr Scholz said this about a different company:

Whatever you want to do. But scour – I'd even look at the AGY, because that might be a buy soon.

…

Once that starts to trend down into the green again, maybe look at that because you may be able to double your money pretty quick there, too …

93 During the seminar attended by Mr Hunter in December 2020, Mr Scholz commented to the following effect:

Take AGY as an example for fundamental analysis and the weight of the top 20 shareholders

There are several family members among the top 20 shareholders

If it was 20 complete strangers owning the shares that would be a negative indicator for the success of that investment. Because if people are paid in income regardless of the success of the company, then they are less motivated to make it work

Because it's family, they are more motivated which makes the investments safer. When a family owns the company and is entrenched in the company, they will rally in bad times to protect their investments and their business

I invested in AGY. This is a good investment.

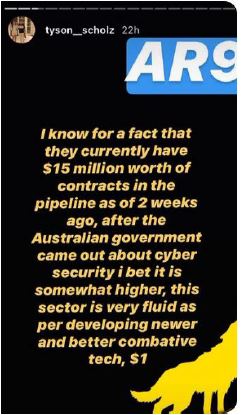

94 Mr Scholz also made statements of this kind during this seminar about a company called AR9:

This stock is an example of a strong stock;

It's at a good place to buy in because the potential for growth in the short term is good.

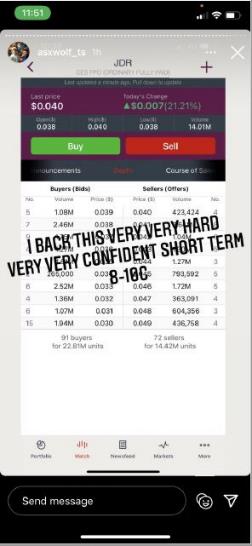

95 Mr Scholz also posted stories on Instagram about AR9. For example:

96 During cross-examination, Mr Hunter identified that he had learned about AR9 “in both the seminar and in various Instagram posts” of which he became more aware after following Mr Scholz on Instagram. He said that he “put weight towards” Mr Scholz’s posts regarding the stock, saying that the nature of the posts “seemed to place a particular amount of time sensitivity and pressure on entering the market with that stock for perceived future success in the short-term”.

97 Mr Borrowman saw stories posted on the Instagram account around August 2020 about SI6 in which Mr Scholz would “[push] shares in SI6 quite heavily”.

98 Mr Scholz also made comments to this effect in relation to SI6 in the seminar attended by Mr Hunter in December 2020:

I have invested quite heavily in that company;

I am in the top 20 shareholders;

This is a company that is undervalued;

I am taking advantage of this time in the market to accumulate stock before the price goes up;

I have an association with the upper management of the company;

SI6 is a good investment.

99 Again, in December 2020, Mr Scholz posted a story on Instagram about SI6, which stated words to this effect:

it is about to blow …

awaiting results now is the time to come in.

once that comes it is all gonna go.

100 That Mr Scholz was referring to the same shares in seminars that he was posting stories about on Instagram supports ASIC’s case that Mr Scholz made recommendations during the seminars about particular shares which he predicted would improve in value, rather than citing these companies as practical examples for teaching purposes.

101 As well as posting stories about shares on the Instagram account, Mr Scholz provided his tips about shares in private.

102 In the WeChat exchange between Mr Scholz and Mr Chen on 19 June 2020, Mr Scholz sent to Mr Chen a screenshot of a direct message to Mr Scholz from a person named “Jordan Balo”. In his message, Mr Balo referred to tips given by Mr Scholz and expressed gratitude. Mr Scholz states that this message was from “a person that did course” which I infer is a reference to the Stage 1 seminars. It is unclear whether Mr Scholz gave the shares tips during or after the seminar attended by Mr Balo, but it is plain that Mr Balo had been the beneficiary of Mr Scholz’s tips which were likely to have been given in relation to the companies which appear in the screenshot in his Instagram message to Mr Scholz. Mr Jordan Balo deposited two amounts of $1,000 into Mr Scholz’s bank account, one in August 2020 and one in December 2020.

103 Through Instagram, Mr Scholz provided information to people about how to pay for his private share tips. For example, the following is a message sent by Mr Scholz:

104 The reference in the private message for the person to “use Instagram/Facebook name” indicates that Mr Scholz was using Instagram to derive income from providing these tips.

105 In July 2020, Mr Scholz received five payments of $500 into his bank account with a description which included the word “tip” such as “Jesse stokes Instagram tip” and “Mitch gee stock tip”.

106 By late 2020, the seminars were described by Mr Scholz as being Stage 1 with Stage 2 and Stage 3 also being promoted on the Instagram account.

107 Stage 2 was one year of access to the “Black Wolf Pit Channel” on a social media platform called Discord and with an annual cost of $1,000.

108 Stage 3 was also promoted on the Instagram account as being “Master Class Technical”.

109 The explicit references to the different “stages” indicates that these stages formed part of one business, rather than any stage being a separate business in its own right. Further, the reference to Stages 1, 2 and 3 is suggestive of a progression by the participant from one stage to the next.

110 The Black Wolf Pit Channel or Stage 2 was also promoted by Mr Scholz during the Stage 1 seminars, including by slides in a PowerPoint presentation:

111 The second PowerPoint slide above shows, under the words “SNEAK PEAK”, the “WOLF” (that is, Mr Scholz) posting a message on “wolf-general-chat” which gives a price target for shares in a company, MYQ. This demonstrates that part of what is being promoted in the Stage 1 seminars was that Mr Scholz (aka WOLF) would provide share advice within Stage 2.

112 Mr Hunter’s unchallenged evidence was that Mr Scholz said during the Stage 1 seminar attended by him, “if you want to take it further to the next level, then you can enquire about the stage 2 group”. Mr Scholz also promoted Stage 2 in direct messages to Mr Hunter on Instagram following the seminar, describing Stage 2 as an extra add on.

113 Mr Geard’s unchallenged evidence was that, towards the end of the seminar attended by him, Mr Scholz said words to the effect “if you sign up, you will get access to a Discord chat which will provide more information about shares”.

114 As well as Stage 2 being called the Black Wolf Pit Channel, Mr Scholz used a wolf avatar and the identifier “WOLF” when communicating in group chats and “ASX_WOLF_PIT” when communicating in private one-on-one chats.

115 As can be seen, the avatar matched one of the logos used in some of the stories on the Instagram account:

116 Mr Scholz also controlled who accessed the Black Wolf Pit Channel, and those who were granted access were required to abide by rules which Mr Scholz stipulated.

117 One of those rules appeared to recognise that financial advice would be given, stating as follows:

Disclaimer Persons accessing this information before relying on any information contained. It is also considered general advice. Neither your personal objectives, financial situation nor needs have been taken into consideration. Accordingly, you should consider how appropriate the advice (if any) is to those objectives, financial situation and needs, before acting on the advice.

118 Mr Scholz made recommendations and gave advice to participants in the Black Wolf Pit Channel about whether they should buy, sell or sit on shareholdings, either as part of the group chat or through direct messaging – for instance “it’s def a buy this one”. He also expressed opinions about specific shares, including what he considered was likely to happen to the share price (e.g. “this could really get traction”), and what he thought were factors which might influence the share price, or the value of the company.

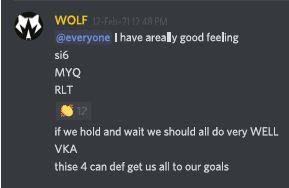

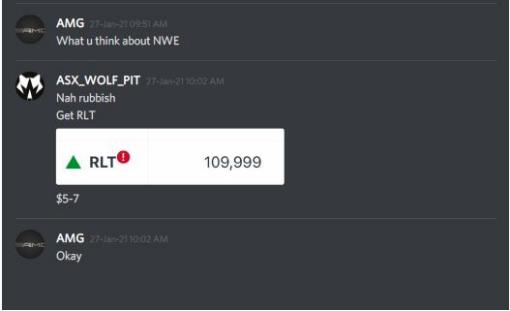

119 Examples of messages from Mr Scholz which appeared in the Black Wolf Pit Channel are as follows:

120 Mr Scholz also made recommendations and gave advice about shares in direct messages to participants in the Black Wolf Pit Channel.

121 These are two examples:

122 Mr Scholz also recommended purchasing shares to members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel prior to “dropping” a recommendation about those shares on Instagram. For example:

(1) on 3 February 2021, Mr Scholz said in the Black Wolf Pit Channel:

@everyone

Going to do a plug on PNN

On the gram

Another user explained:

Plug means he’s releasing it to his ig followers in 20 mins. We all get heads up first.

(2) on 16 February 2021:

(a) at 11.07am, Mr Scholz posted a screenshot of share prices for “MBK” on his Instagram account with a comment written across “Took 2mil of this just now”;

(b) at 11.32am, “Brandon M” stated in the Black Wolf Pit Channel about “MBK” that “Yeah @WOLF brought and put on his gram so people jumping on”. One minute later, “WOLF” said “Yea I grabbed some But it’s to late for group”;

(3) on 17 February 2021, in the “Black Wolf Chat Channel – General Chat-Banter” channel, the following exchange occurred:

Stacky: Hey @WOLF you posted earlier about May is that the one you are promoting on ig?

[Mr Scholz]: I havnt told INSTA about MAY will throw that up Tommrow Is everyone set in him

…

[Mr Scholz]: @everyone will announce MAY tomorrow. It’s solid.

Ghost: At lunch time?

[Mr Scholz]: Let’s do 2.00 QLD TIME INSTA

…

[Mr Scholz]: Put

As people will smash them selves To pieces

So I would rather keep that as it will be up to u all to take profits

Like I did say tofay [sic] I took some VKa Off table.

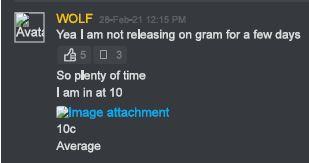

(4) between 26 February to 2 March 2021:

(a) on 26 February 2021 during a Discord chat, Mr Scholz wrote “I am thinking of dropping MGU on gram today? Thoughts”, to which other users replied “Not yet”, “Mmmm nah” and “Let us accumulate”. Mr Scholz gave a “thumbs up” to those comments;

(b) on 28 February 2021 during a Discord chat, Mr Scholz said, in relation to “MGU” and “MGUO”, “Yea I am not releasing on gram for a few days”;

(c) on 2 March 2021, Mr Scholz referred to “MGU” on his Instagram account, stating “This one proper scares me what could do It actually ticks most of my boxes”.

123 This demonstrates another manner in which stories posted on the Instagram account by Mr Scholz formed a part of Mr Scholz’s business. In this way, both he and the members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel could “win”, with the price of their shares likely to increase once the story appeared on Instagram.

124 During the period from 26 October 2020 and 4 August 2021, a total of $1,156,500 was received in Mr Scholz’s bank accounts in increments of $500, $1,000 and $1,500, comprised of:

(1) $571,000 received in Mr Scholz’s Westpac Cash Investment Account with narrations such as “stock trading course”, “ASXcourse”, “trade course”, “ASX groupchat” and “mentorship asx”;

(2) $7,500 received in Mr Scholz’s Westpac eSaver account, containing narrations including “Stage 3”;

(3) $578,000 received in Mr Scholz’s NAB account, with narrations such as “stage 1”, “stage 2”, “ASX course stage 1”, “Insta” and “asx wolf trading course”.

Relevant legislation

125 A financial services business is a business of providing financial services: s 761A Corporations Act.

126 Relevantly to this case, a “financial service” is provided by a person if they “provide financial product advice”: s 766A(1)(a) Corporations Act.

127 Section 766B(1) Corporations Act provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Chapter, financial product advice means a recommendation or a statement of opinion, or a report of either of those things, that:

(a) is intended to influence a person or persons in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product or class of financial products, or an interest in a particular financial product or class of financial products; or

(b) could reasonably be regarded as being intended to have such an influence.

128 A “financial product” includes shares in a body corporate: ss 9, 92, 764A(1) Corporations Act.

129 It does not matter if only one part of the business is comprised of providing financial services. That is because s 19 Corporations Act provides that:

A reference to a business of a particular kind includes a reference to a business of that kind that is part of, or is carried on in conjunction with, any other business.

Whether Mr Scholz gave financial product advice

130 ASIC contended that Mr Scholz gave financial product advice throughout the relevant period by way of stories posted on the Instagram account, through tips which he gave to clients privately, in the Stage 1 seminars, and in the Black Wolf Pit Channel, both in group messages and in direct messages.

131 Each of these will now be considered.

Stories on Instagram account

132 By stories posted on the Instagram account during the relevant period, Mr Scholz expressed opinions about particular shares, but usually without giving any direct encouragement to anyone to buy those shares. For example, his stories referred to the fact that he had acquired particular shares or he made positive statements about a company.

133 Contrary to the submission by Mr Scholz, the posting of such stories by him in his guise as the ASX Wolf, in the context of the other posts on the Instagram account and having regard to the content of these stories, constituted a recommendation or expression of a statement of opinion within the meaning s 766B(1) Corporations Act. That is because, through his lifestyle posts and “life story” posts on the Instagram account, Mr Scholz had established a reputation as a successful share trader who had the ability to identify worthwhile companies in which an investment should be made. It did not matter that the stories did not contain any overt recommendation to acquire the shares: it was enough that Mr Scholz referred to a company or its shares in the stories, which was usually done in a way which indicated that he liked that company.

134 Further, the posting of these stories was intended, or was reasonably capable of being regarded as intended, to influence persons in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product – namely, investing in the shares of the company referred to in the stories.

135 Mr Scholz’s intention was usually apparent from the stories themselves; that is, it was apparent from the content of the stories that Mr Scholz intended to exert such influence.

136 Further, were it needed, Mr Scholz admitted to such an intention in the WeChat messages with Mr Chen and in his messages to the members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel.

137 Finally, the posting of stories about companies occasionally coincided with those companies being referred to in Stage 1 seminars, which reinforced the messages given in those seminars about those companies. This also supports a finding that Mr Scholz had the relevant intention.

138 For these reasons, Mr Scholz posted stories on Instagram during the relevant period which constituted financial product advice within the meaning of s 766B(1) Corporations Act.

Private share tips

139 The evidence established that Mr Scholz was likely to have provided private tips about shares in particular companies to clients, including paying customers. Contrary to the submissions by Mr Scholz, it is objectively unlikely that a client would pay $500 for a generic tip about how to trade on the ASX.

140 Further, the screenshot of the message from Mr Balo showed the price of shares in particular companies which tends to indicate that Mr Balo had received tips from Mr Scholz in relation to those companies.

141 However, as there is no evidence of the content of the communications by Mr Scholz to any recipient of the private tips, or the circumstances in which any share tip was communicated, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that Mr Scholz gave financial product advice through such private share tips within the meaning of s 766B(1) Corporations Act.

Stage 1 seminars

142 The evidence established that Mr Scholz did, on occasion, express opinions about particular companies during the course of the Stage 1 seminars. Examples of when this occurred are set out above.

143 Having regard to their content, the statements made by Mr Scholz during the seminars were reasonably capable of being regarded as intended to influence persons in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product – whether and when to invest in the shares of the company referred to in his statements.

144 This is especially the case where Mr Scholz’s references to particular companies coincided with the posting of stories about those companies on the Instagram account.

145 For these reasons, Mr Scholz made statements during the Stage 1 seminars which constituted financial product advice within the meaning of s 766B(1) Corporations Act.

Black Wolf Pit Channel

146 The evidence established that Mr Scholz also, on numerous occasions, expressed opinions and made recommendations about shares in particular companies both in group messages and in direct messages on the Black Wolf Pit Channel. Examples of when this occurred are set out above.

147 It is evident from their content that Mr Scholz intended that his various messages about particular shares be relied upon by the recipients. The evidence was replete with examples of Mr Scholz’s attempts to influence others as to what they should do in relation to particular shares, and Mr Scholz did not give evidence to contradict the overwhelming inference that this was his intention.

148 For these reasons, Mr Scholz made statements in group messages and in direct messages on the Black Wolf Pit Channel which constituted financial product advice within the meaning of s 766B(1) Corporations Act.

Whether Mr Scholz carried on a financial services business

149 The manner in which Mr Scholz conducted his activities as the ASX Wolf through Instagram, the seminars and the Black Wolf Pit Channel had many features of a commercial enterprise, and constituted a business. These activities were conducted using particular branding and marks associated with the ASX Wolf, in relation to which Mr Scholz cultivated an image of a successful share trader (including through lifestyle and sponsored posts on the Instagram account); the respective stages of the business were promoted and were interrelated (for example, Stage 1 seminar participants were encouraged to progress to Stage 2); the overall operations were continuous and systematic; the transactions engaged in by Mr Scholz were commercial in nature, and there was a profit making purpose: see e.g. Hungier v Grace [1972] HCA 42; (1972) 127 CLR 210 at 216–217; PP Consultants Pty Limited v Finance Sector Union of Australia (2000) 201 CLR 648; [2000] HCA 59 at [12]; Puzey v Commissioner of Taxation (2003) 131 FCR 244; [2003] FCAFC 197 at [48].

150 Further, the financial product advice given by Mr Scholz formed an integral part of this business. The advice which was given by him was not a one off but formed part of the continuous and systemic business operations by which Mr Scholz derived profit. In particular:

(1) the stories posted on Instagram served a number of commercial purposes within the business. They were used by Mr Scholz to increase the value of his shares and, from about late 2020, the shares held by members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel. They were also used to reinforce the financial product advice given during Stage 1 seminars. Finally, these stories attracted customers to the business and were a form of indirect promotion of Stages 1, 2 and 3;

(2) the recommendations and expressions of opinion which were conveyed by Mr Scholz in the Stage 1 seminars also served a commercial purpose in that they either acted as an enticement to attendees to sign up to the Black Wolf Pit Channel in order to obtain further such advice from Mr Scholz or they constituted the equivalent of posting stories on Instagram for his own benefit and, later, for the benefit of the members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel;

(3) in the Black Wolf Pit Channel, Mr Scholz gave financial product advice which he conveyed in group messages as well as direct messages, and which he also “dropped” on the Instagram account after he had encouraged the members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel to acquire those shares.

151 Mr Scholz submitted that he was not carrying on a financial services business because any financial product advice given by him was given in the course of his business, relying on the decision of Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd (2002) 41 ACSR 561; [2002] NSWSC 310 at [77] and submitting that:

[i]t is important in this regard to distinguish between carrying on a business in the course of which advice is given about securities, and carrying on a business of advising other people about securities.

152 However, the legislation which was considered in Pegasus was in different terms to the Corporations Act. In Pegasus, Davies AJ was considering whether an investment advice business was being carried on, which was defined in the legislation as being a business of advising other persons about securities or a business in the course of which the person publishes securities reports: see [71]. That gives rise to different considerations to those which arise under s 911A(1) when read in conjunction with ss 19, 766A(1)(a) and 766B(1) Corporations Act. As a consequence, the reasoning in Pegasus does not assist Mr Scholz.

153 For these reasons, Mr Scholz carried on a financial services business within the meaning of s 911A Corporations Act from March 2020 to November 2021.

Section 911A(2)(eb) exemption

154 By his Concise Response, Mr Scholz alleged that, even if he had carried on a financial services business (as found above), he was exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence as his conduct was captured by s 911A(2)(eb) Corporations Act.

155 Section 911A(2)(eb) provides:

(2) However, a person is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence for a financial service they provide in any of the following circumstances:

…

(eb) the service is the provision of general advice and all of the following apply:

(i) the advice is provided in the course of, or by means of, transmissions that the person makes by means of an information service (see subsection (6)), or that are made by means of an information service that the person owns, operates or makes available;

(ii) the transmissions are generally available to the public;

(iii) the sole or principal purpose of the transmissions is not the provision of financial product advice;

156 As this exemption was raised by Mr Scholz by his Concise Response and as its existence relies upon the proof of additional or special facts, the burden of proving that it applied was upon Mr Scholz: Vines v Djordjevitch [1955] HCA 19; (1955) 91 CLR 512 at 519–520 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Webb, Fullagar and Kitto JJ):

[If an enactment] expresses an exculpation, justification, excuse, ground of defeasance or exclusion which assumes the existence of the general or primary grounds from which the liability or right arises but denies the right or liability in a particular case by reason of additional or special facts, then it is evident that such an enactment supplies considerations of substance for placing the burden of proof on the party seeking to rely upon the additional or special matter: …

(citations omitted)

Whether general advice

157 Section 766B(4) Corporations Act provides that general advice is “financial product advice that is not personal advice.” Personal advice is advice that is given or directed to a person in circumstances where the provider has considered one or more of the person’s objectives, financial situation and needs, or a reasonable person might expect the provider to have considered one or more of these matters: s 766B(3) Corporations Act.

158 As accepted by ASIC, there was no evidence that any advice which Mr Scholz gave constituted personal advice, with the consequence that the financial service provided by Mr Scholz was the provision of general advice.

Whether advice provided in the course of, or by means of, transmissions made by means of an information service

159 Relevantly to this case, the second issue is whether the advice was provided in the course of, or by means of, transmissions that Mr Scholz made by means of an information service.

160 Section 911A(6) provides:

(6) In this section:

information service means:

(a) a broadcasting service; or

(b) an interactive or broadcast videotext or teletext service or a similar service; or

(c) an online database service or a similar service; or

(d) any other service identified in regulations made for the purpose of this paragraph.

161 Regulation 7.6.01B(6) Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) relevantly provides:

(6) For paragraph 911A(6)(d) of the Act, each of the following services is an information service:

…

(c) a service provided by the Internet.

162 It was accepted by ASIC that the advice given by Mr Scholz on Instagram and over Zoom (in respect of the Stage 1 seminars) and Discord (via the Black Wolf Pit Channel) was provided in the course of, or by means of, transmissions that Mr Scholz made by means of an information service, being a service provided by the internet.

163 While there is no evidence that the private share tips provided by Mr Scholz, being those for which he charged a fee, were provided through a service provided by the internet, the evidence did not establish that these tips constituted financial product advice.

164 Therefore, it was established that the general advice provided by Mr Scholz was provided in the course of, or by means of, transmissions that Mr Scholz made by means of an information service.

Whether transmissions were generally available to the public

165 It was accepted by ASIC that, as the Instagram account was able to be accessed by the public (including through a general internet search), the transmissions made by Mr Scholz on that account were generally available to the public within the meaning of s 911A(2)(eb)(ii).

166 As to the transmissions on Zoom (Stage 1 seminars) and general chats and posts by Mr Scholz on Discord (Black Wolf Pit Channel), these were not able to be accessed by the public in the same way as Instagram. Both of these platforms required the payment of an agreed fee, and the agreement by Mr Scholz to permit each person to access the transmissions, and provision by him of access to each particular person. Further, proposed members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel were required to agree to the “WOLF PIT CHANNEL RULES” and the power to approve and remove members and to otherwise regulate the conduct of members of the Black Wolf Pit Channel lay solely with Mr Scholz, operating under the names “WOLF” and “ASX_WOLF_PIT”.

167 Notwithstanding these matters, Mr Scholz maintained that the transmissions on Zoom and Discord were generally available to the public and sought to contrast s 911A(2)(eb)(ii) with s 911A(2)(ea)(ii). Emphasis was placed on the fact that, in the latter section, the exception for general advice provided by way of newspapers in that subsection expressly applies only if “the newspaper or periodical is generally available to the public otherwise than only on subscription” (emphasis in submissions).

168 As s 911A(2)(ea)(ii) excludes subscription only services, this supports a conclusion that such services can be considered to be generally available to the public for the purpose of s 911A(2)(eb)(ii). Such an interpretation appears to be correct when regard is had to reg 7.6.01B(5) Corporations Regulations, which provides:

(5) A reference in subparagraph 911A(2)(eb)(ii) of the Act to transmissions that are generally available to the public includes transmissions provided as part of a subscription service within the meaning of the Broadcasting Services Act 1992.

169 ASIC submitted that “Mr Scholz was not delivering a subscription broadcasting service or information service; this is not an apt way of characterising either the Stage 1 seminars or the Stage 2 Black Wolf [Pit] Channel”.

170 However, the scope of s 911A(2)(eb)(ii) is not confined to such services and, when read in the context of s 911A(2)(ea)(ii) and reg 7.6.01B(5), the words “generally available to the public” appear intended to capture transmissions provided as part of an internet service which are made available to the public even if a member of the public must pay, enter a contractual arrangement or otherwise subscribe for that access.

171 It follows that the transmissions made by Mr Scholz on Zoom in the Stage 1 seminars and in the group chats on the Black Wolf Pit Channel were generally available to the public.

172 However, the direct messages between Mr Scholz and an individual member of the Black Wolf Pit Channel were not able to be accessed by other members of the Stage 2 group, let alone the public. On any view, these transmissions were not generally available to the public, but were private exchanges between Mr Scholz and another person.

173 Therefore, it was not established that all transmissions made by Mr Scholz were generally available to the public.

Sole or principal purpose of the transmissions

174 The final issue is whether the sole or principal purpose of the transmissions that Mr Scholz made was not the provision of financial product advice.

175 As submitted by Mr Scholz, the distinction drawn by the wording of s 911A(2)(eb)(i) between the advice which is provided by the person and the transmissions that the person makes means that, when considering the sole or principal purpose of the transmissions for the purpose of s 911A(2)(eb)(iii), regard must be had to the transmissions that the person makes as a whole and not only to the particular transmissions by that person which contain the financial product advice.

176 Having regard to the transmissions made by Mr Scholz on the Instagram account (such as various lifestyle posts) and in the Stage 1 seminars, the evidence established that the transmissions by Mr Scholz on the Instagram account and on Zoom were not made for the sole or principal purpose of providing financial product advice.

177 However, the evidence did not establish that the principal purpose of the transmissions by Mr Scholz in the Black Wolf Pit Channel (including by direct messaging) was not the provision of financial product advice. In these circumstances, s 911A(2)(eb)(iii) was not satisfied.

178 Indeed, the evidence was replete with examples of Mr Scholz expressing opinions and making recommendations about the purchase of shares by transmissions made by him on the Black Wolf Pit Channel. Importantly, no suggestion was made in cross-examination of any witness called by ASIC that there existed other transmissions made by Mr Scholz within the Black Wolf Pit Channel which did not contain financial product advice. These matters provide a further reason to conclude that s 911A(2)(eb)(iii) was not satisfied.

179 Therefore, it was not established that the sole or principal purpose of the transmissions by Mr Scholz was not the provision of financial product advice.

Whether regulated disclosure failure

180 ASIC contended that, even if Mr Scholz could satisfy the requirements of s 911A(2)(eb), he could nonetheless not rely on the exception to the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence as he had failed to comply with the requirements of reg 7.6.01B(1) Corporations Regulations.

181 Section 911A(5)(a) Corporations Act provides:

(5) The exemption under paragraph (2)(ea), (eb) … may apply unconditionally or subject to conditions:

(a) in the case of the exemption under paragraph (2)(ea), (eb) or (ec), or an exemption under paragraph (2)(k)—specified in regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph; or

…

182 Regulation 7.6.01B Corporations Regulations relevantly provides:

(1) For paragraph 911A(5)(a) of the Act, the exemptions from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence provided for in paragraphs 911A(2)(ea), (eb) and (ec) apply subject to the condition that a person mentioned in any of those paragraphs, or a representative of a person mentioned in any of those paragraphs, who provides financial product advice states the following matters, to the extent to which they would reasonably be expected to influence, or be capable of influencing, the provision of the financial product advice:

(a) any remuneration the person or the person’s representative is to receive for providing the advice;

…

183 ASIC relied on the existence of a consulting agreement between Jaydar Resources Limited and a company called ‘EWolf Enterprises’.

184 However, notwithstanding that Mr Scholz was a director and secretary of EWolf Enterprises during the relevant period, that alone does not establish that Mr Scholz received any remuneration for the provision of the financial product advice given by him, and nor was it demonstrated by ASIC that EWolf Enterprises was a representative of Mr Scholz.

185 ASIC therefore failed to demonstrate Mr Scholz did not comply with the requirements of reg 7.6.01B(1) Corporations Regulations.

Conclusion

186 The evidence did not establish that the exemption in s 911A(2)(eb) applied with the consequence that Mr Scholz was required by s 911A(1) Corporations Act to hold an Australian financial services licence for the purposes of carrying on his financial services business.

WHETHER CONTRAVENTION OF SECTION 911B CORPORATIONS ACT

187 By amendments made to its Concise Statement during the hearing, which were not opposed, ASIC notified an intention to apply for an injunction which, amongst other things, restrained Mr Scholz from directly or indirectly carrying on a financial services business in Australia in contravention of s 911B Corporations Act.

188 ASIC did not make any submissions as to the basis upon which it sought to allege that s 911B had been contravened, or the evidence which supported a finding of contravention of that provision. As s 911B has a number of alternative factual bases for it to be engaged, ASIC’s case in this regard cannot be assumed. For this reason, no finding of contravention of s 911B Corporations Act will be made, assuming that remained something which ASIC sought.

DISPOSITION

189 For these reasons, Mr Scholz contravened s 911A Corporations Act by carrying on a financial services business between March 2020 and November 2021 without an Australian financial services licence.

190 A case management hearing will be held on 31 January 2023 to progress the proceeding to a further hearing at which the remaining issues will be determined, including costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and ninety (190) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Downes. |