Federal Court of Australia

TCT Group Pty Ltd v Polaris IP Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1493

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and supply to the chambers of Justice Burley by 4pm on 1 February 2023 draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons and a timetable for further steps in the proceedings.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the draft short minutes of order referred to in order 1, the areas of disagreement should be set out in mark-up.

3. The proceedings be listed for a case management hearing at 9.30am on 2 February 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BURLEY J:

1 These proceedings concern innovation patent No AU 2020100485 (485 patent) entitled “Hinge” and innovation patent No AU 2020102918 (918 patent) also entitled “Hinge” (together, patents). Both claim 17 February 2016 as their priority date. Both patents concern hinges used for softly closing glass-panelled doors of the type typically used to access swimming pools. The patentee is Polaris IP Pty Ltd and the exclusive licensee is Glass Hardware Australia Pty Ltd.

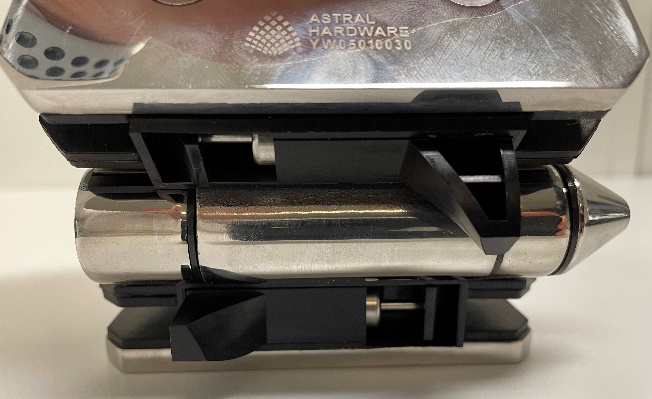

2 The applicants are TCT Group Pty Ltd and Astral Hardware Pty Ltd (collectively, TCT). They contend that the patents should be revoked pursuant to the terms of s 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) and that Polaris IP and Glass Hardware (collectively, Polaris) have made unjustified threats of patent infringement against them and their customers arising from their distribution and sale of hinges under the “Orion” brand (Orion hinges). The alleged threats are said by TCT to give rise to contraventions of s 128 of the Patents Act and ss 18 and 21 of Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL).

3 Polaris denies that the patents are invalid and denies making any unjustified threats.

4 Glass Hardware, as exclusive licensee of the patents, advances a cross-claim alleging that TCT Group and Astral are liable for patent infringement on the basis that the Orion hinges infringe the claims of the patents. More specifically, it alleges that the Orion glass-to-glass hinge (GTG hinge) infringes each of claims 1, 2 and 3 of the 485 patent and the 918 patent and that the Orion glass-to-wall (GTW hinge) infringes each of claims 4 and 5 of the 485 patent and the 918 patent. Polaris IP is not an applicant in the infringement cross-claim, but has been joined as a respondent to the cross-claim pursuant to s 120(2) of the Patents Act. Even so, whilst recognising this distinction, it is convenient to refer below to the cross-claimant as Polaris.

5 Polaris also pleads in its cross-claim that two individuals are liable for patent infringement being Liang Xue, who is a director and shareholder of TCT Group and a shareholder of Astral; and Xingying Chen, who is a director and the majority shareholder in Astral. In closing submissions, Glass Hardware abandoned its claim against Ms Chen.

6 By orders made on 25 May 2021, issues of liability were to be heard separately and before issues concerning the quantum of any pecuniary relief. Accordingly, this judgment addresses only questions of liability.

7 The parties agree that the version of the Patents Act that is applicable to the present dispute may be found in compilation no. 49 dated 26 August 2021. This has the consequence that the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (RTB Act) amendments apply to these proceedings.

1.2 Background information about the patents

8 The 485 patent was filed on 30 March 2020 and claims a priority date of 17 February 2016 from corresponding provisional application No 2016900547. It was certified on 19 June 2020.

9 The 918 patent was filed on 21 October 2020, amended on 23 December 2020 and certified on 28 January 2021. It also claims a priority date of 17 February 2016 from the provisional application.

10 The 918 patent lapsed on 31 August 2021 because of a failure to pay the renewal fee. Steps are apparently being made by Polaris to reinstate it to the Register, but nothing turns on that for the purpose of the present proceedings because the question of liability for infringement before 31 August 2021 remains for determination.

11 Each of the patents is a divisional of patent application No 2017201858 filed on 16 February 2017 (parent).

12 TCT advances the following five substantive grounds of invalidity in respect of each of the patents.

13 First, lack of novelty pursuant to s 7(1) of the Patents Act. It is not in dispute that TCT commenced selling the Orion hinges in January 2020. TCT contends that by operation of the Patents Act and the Patents Regulations 1990 (Cth) the priority date of the claims cannot be based on the filing date of either the provisional application or the parent, with the consequence that the priority dates for the 485 and 918 patents must be their dates of filing, which were 30 March 2020 and 21 October 2020 respectively. It is not in dispute that if this is so, the claims are anticipated by the earlier sale of Orion hinges.

14 Secondly, lack of full description because of a failure to comply with s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act.

15 Thirdly, lack of support because of a failure to comply with s 40(3) of the Patents Act.

16 Fourthly, if the priority date is not deferred, lack of novelty in the light of four prior art documents, being:

(a) international patent application No WO 2011/035499 A1 (WO499 patent);

(b) United States patent application No US 2012/0279015 (A1) (US015 patent);

(c) Chinese Utility Model No 203755860 (CN860 patent); and

(d) innovation patent No AU 2011101327 (AU327 patent).

17 Fifthly, lack of innovative step having regard to the common general knowledge and each of the prior art documents.

1.4 TCT’s unjustified threats and ACL claims

18 TCT contends that Polaris unjustifiably threatened in correspondence to bring an action against it, as well as its distributors and persons who are involved in the supply or promotion of the Orion hinges, in breach of s 128 of the Patents Act. It also contends, on the basis of the same correspondence, that Polaris engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in breach of ss 18 and 21 of the ACL.

1.5 The infringement cross-claim

19 In its amended cross-claim Glass Hardware contends that each of TCT Group, Astral and Mr Xue have infringed the patents in suit. In particular, it alleges that since 11 October 2019, the corporate cross-respondents (whom I shall continue to refer to collectively as TCT) manufactured or imported into Australia, and sold and supplied the Orion hinges in Australia.

20 The case against Mr Xue is based on the fact that he is the sole director and majority shareholder of TCT Group and also a director and shareholder of Astral. Polaris’ pleaded case alleges that Mr Xue is liable for authorising the infringing conduct of TCT Group and Astral and also as a joint tortfeasor with those companies. During the course of its closing written submissions TCT accepted that if the sale of the Orion hinges by either TCT Group or Astral is held to infringe, then it is open to the Court to find that Mr Xue authorised those infringements. In light of that concession, in its oral submissions Glass Hardware properly accepted that there was no utility in pressing its alternative claim against Mr Xue on the basis that he might also be a joint tortfeasor. The consequence is that if the Orion hinges are found to infringe a valid claim of the patents then it follows that Mr Xue will be found to have authorised that infringement.

21 Glass Hardware seeks additional damages in the event that infringement of the 485 patent is established.

22 Polaris submits that each of TCT Group, Glass Hardware and Mr Xue has engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the ACL as a result of the form of the packaging of the Orion hinges. Specifically, it contends that the packaging incorrectly contends that the hinges are the subject of particular patent and design rights in Australia.

23 This aspect of the case has been resolved by agreement and is not addressed further in these reasons.

24 For the reasons set out in more detail below, I have found that:

(1) the Orion hinges fall within the scope of the claims of each of the patents;

(2) the claims of neither the 485 patent nor the 918 patent are entitled to claim their priority date from the date of filing of the parent or the provisional application;

(3) by reason of the finding in (2), and the use and sale of the Orion hinges before the priority dates of 30 March 2020 and 21 October 2020, the claims of the 485 patent and the 918 lack novelty;

(4) the specifications of the 485 patent and the 918 patent also do not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the art within s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act;

(5) the claims of the 485 patent and the 918 patent are also not supported by matter disclosed in the specification within s 40(3) of the Patents Act;

(6) claims 1 and 4 of the 485 patent lack novelty in light of the disclosure of the US015 and CN860 patents;

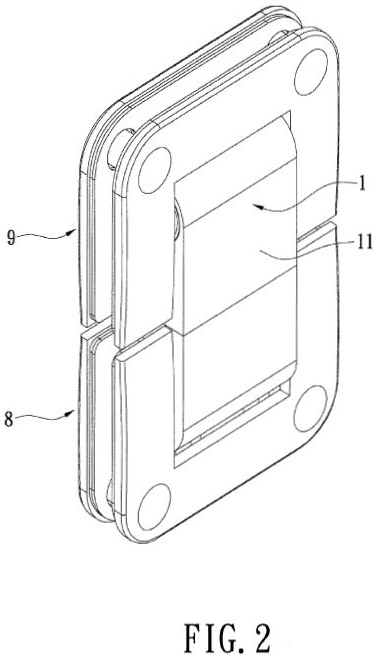

(7) all of the claims of the 485 patent lack an innovative step over the disclosure of the US015 patent;

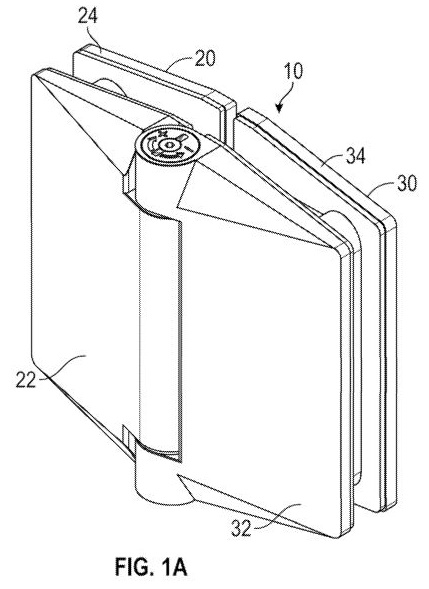

(8) otherwise the challenge to the validity of the 485 patent and the 918 patent on the basis of lack of novelty in the light of the WO499, US015, CN860 and AU327 patents and lack of innovative step on the basis of those prior art documents fails; and

(9) TCT succeeds in its claim for unjustified threats on the basis of the correspondence sent by the solicitors for Polaris to TCT and also to Glass Pro, but fails in its claim based on the same correspondence under s 18 of the ACL.

25 The result is that the claim for revocation of the patents must be allowed and that the cross-claim for patent infringement be dismissed. The matter will be relisted for the purpose of making final orders after allowing the parties time to confer and reach agreement as to the form of those orders, including as to costs.

26 William Hunter is a mechanical engineer. From 1986 until 1993 he held positions in companies engaged in the design of products that utilised hinges. From 1994 until 2001 he worked in his own product development company and designed many products and machines including hinges. Since then he has worked as an independent design consultant engaged in mechanical engineering design.

27 Mr Hunter was provided by the solicitors for TCT with copies of the parent, the provisional application, the 485 patent and the 918 patent. In his first affidavit he sets out what he understands to be the main concepts behind the hinge described in the parent, including the dampener feature. He then describes what he considers to be the disclosures of the 485 patent and the meaning of the claims, before comparing what he considers to be claimed in the 485 patent with the disclosure of the parent and the provisional application. He does the same exercise with the 918 patent. He then provides a review of what he considers to be the disclosure of (inter alia) the prior art documents and provides detailed claim charts that set out his view of the disclosure of the prior art documents when compared with the specific integers in the claims of the 485 and 918 patents. He then gives his opinion, relevant to the question of innovative step, as to whether or not the claims of the 485 and 918 patents vary from the information set out in the claim charts in ways “that make no substantial contribution to the working” of the inventions claimed.

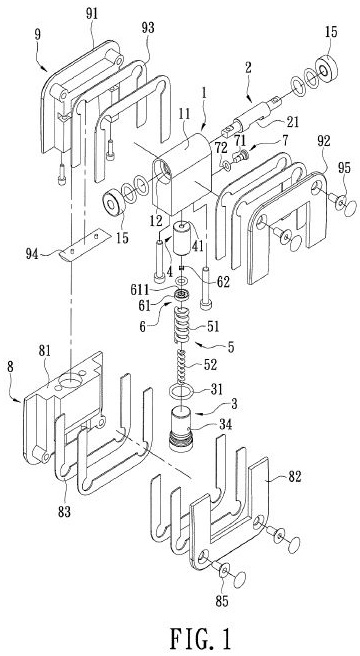

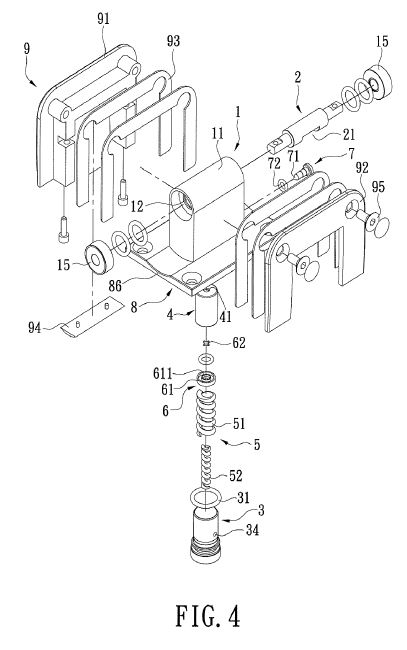

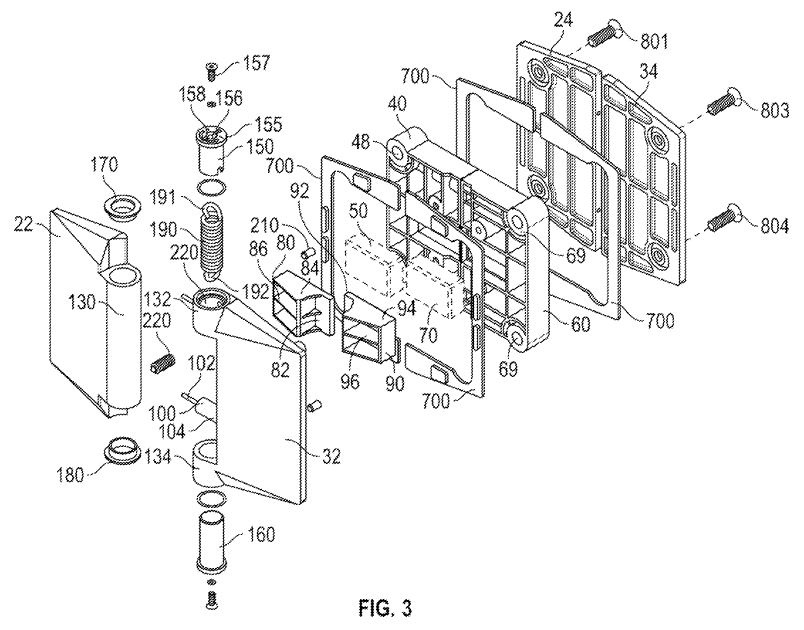

28 In his second affidavit Mr Hunter responds to the evidence of Mr Richardson, differing as to his understanding of the meaning of a number of the integers of the claims of the patents in suit for the purposes of infringement.

29 Mr Hunter joined with Mr Richardson in the preparation of a detailed joint expert report and participated in a concurrent evidence session with him, during which he was cross-examined.

30 Min Yee Won is the sales manager of Glass Pro Australia Pty Ltd, which he established with a business partner in 2018. He has been working in the glass industry since 2008. In his affidavit he gives evidence about his experience in the industry, his familiarity with the Polaris soft close hinges since 2013 and his company’s sales of Orion hinges. He also gives evidence about his reaction to receiving cease and desist letters from the solicitors acting for Polaris, Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers. He was cross-examined.

31 Weizhong Chen provides an English translation from Chinese of the CN860 and WO499 patents. He was not cross-examined.

32 Timothy Francis is a solicitor at Wrays Lawyers, who act for TCT. He affirmed an affidavit annexing a copy of Australian Standard AS 1926.1–2012 and related correspondence. He was not cross-examined.

33 Francis Bindschedler has been the general manager of Glass Hardware since November 2017 and prior to then held positions as sales executive from 2009 until 2014 and finance and operations manager from 2014 until 2017. He gives evidence about the operations of Glass Hardware and its dealings with TCT since 2012. He explains that in March 2012 Glass Hardware started purchasing glass products from TCT Group and how, after an approach from TCT Group in 2016, the two companies entered into negotiations for TCT Group to manufacture the Polaris 120 Series Hinges. He gives evidence that on 23 January 2018 Glass Hardware entered into a manufacturing agreement with TCT Group, which concluded in May 2019 with a final delivery of Polaris 120 Series Hinges. He explains that he regularly monitored the activities of Glass Hardware’s competitors which led him in October 2019 to learn that Glass Pro was promoting an Orion soft close hinge for sale. Mr Bindschedler gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

34 Jacqueline Chelebian is a solicitor at Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers. She annexes various documents and was not cross-examined.

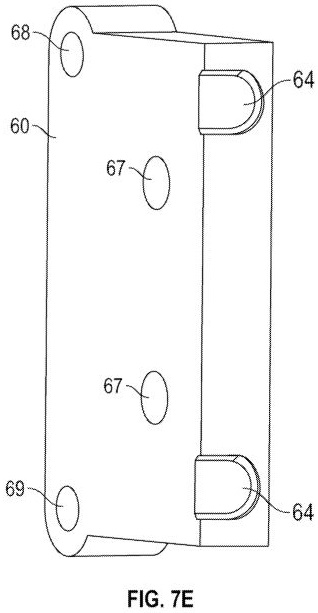

35 Alexander Richardson is an industrial designer and engineer who has been the managing director of Design Edge, an industrial design consultancy firm that he founded, since 1988. He has provided industrial design research and development, concept design, engineering detailing and manufacturing consultancy services to a wide range of industries. His work has involved the design of numerous types of hinges. He holds degrees in Mining Engineering and Arts (Industrial Design).

36 In his first affidavit, Mr Richardson provides his comments on his understanding of various phrases used in the 485 and 918 patents and gives his opinion that the features of the claims of those patents are embodied in the Orion hinges. In his second affidavit Mr Richardson notes that he has been provided with the parent, the provisional application and the 485 and 918 patents. He responds to certain questions asked of him in relation to the disclosure in those patents relevant to the s 40 case advanced by TCT. He also gives his opinion as to whether particular integers in the claims of 485 and 918 patents are present in the prior art documents.

37 Mr Richardson joined with Mr Hunter in the preparation of the joint expert report and also in a concurrent evidence session, during which he was cross-examined.

38 The body of the specification of each of the 485 and 918 patents is substantially the same, save for their claims and the consistory clauses contained in the summaries of the invention. It is convenient to describe their disclosure by reference to the specification of the 485 patent.

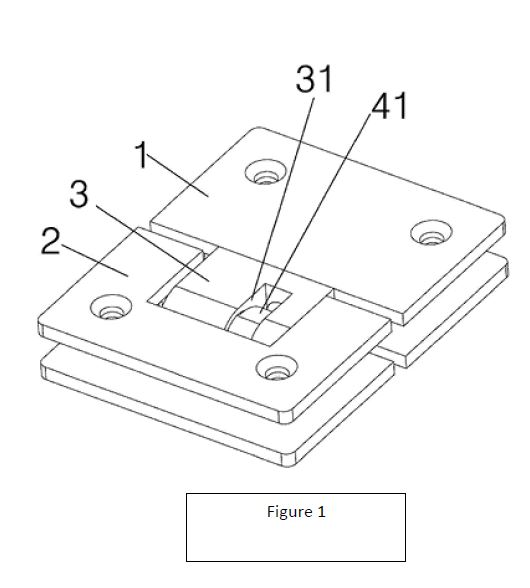

3.2 Disclosure of the 485 patent specification

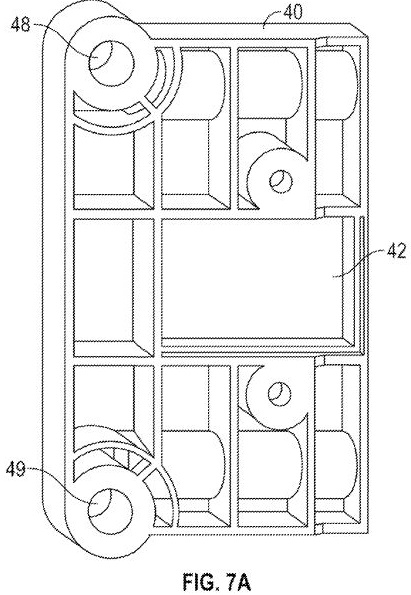

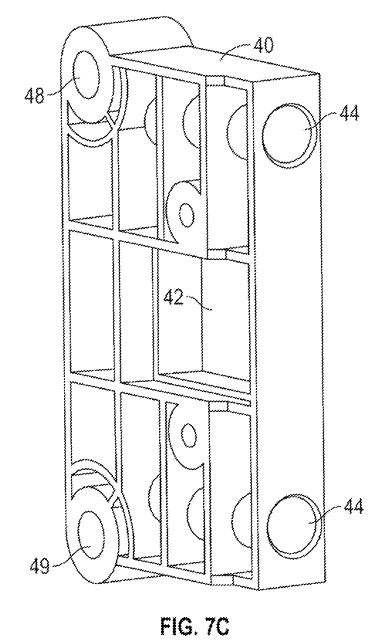

39 The specification commences by noting that it is a divisional application of the parent filed on 16 February 2017, and claims priority from the provisional application, which was filed on 17 February 2016. The contents of both related patents are incorporated in the specification.

40 The technical field of the invention is said to relate to a hinge.

41 The “Background” refers to WO 2009/018615 (615 patent) as describing a hinge including a mechanical biasing element, for example a spring, and a plurality of magnetic elements which bias and retain hinge members in a retained (for example, closed) position. The magnetic elements of that hinge were configured to have an overlapping arrangement in the closed position. The hinge was primarily designed for gates and showers which have a relatively significant weight and so the first and second magnetic elements were required to provide sufficient magnetic strength to bias the hinge toward the closed position, particularly when the spring may have suffered from mechanical wear. Dampeners were introduced into the hinge to control its closing action. These were orientated orthogonally (that is, perpendicular) relative to the plane of the hinge members such that the overlapping portion of the hinge would contact a protruding portion of the dampener when the hinge had nearly progressed to the closed position and would slowly retreat until the hinge progressed to the closed position. The specification says:

[0005] …However, despite the introduction of dampeners, structures such as glass panels of gates and shower doors could undergo significant vibration once the hinge progressed to the closed position. In particular, the structure would vibrate in a direction orthogonal to the plane of the glass panel of the structure. Over time, the vibration could lead to mechanical wear of the structure.

[0006] Furthermore, due to the dampeners being orientated orthogonally, the overall thickness of the hinge was relatively large to accommodate the dampeners which led to high manufacturing costs.

42 The specification notes that the requirement for magnets of sufficient strength led to the magnetic elements requiring a relatively large amount of space to be located within the hinge. The front hinge plate was designed to be relatively thick to accommodate the first magnetic element and, because of that element being located adjacent an outer face of the panel, the thickness of the first hinge member was accentuated. The front hinge plate of the second hinge member had the same thickness in order to be flush in the closed position. The specification goes on to say:

[0008] Whilst the hinge worked well to overcome problems associated with mechanical wear experienced by torsional springs in self closing hinges, new problems arose in relation to the panels of the hinged structure undergoing vibration after closing and the physical spatial constraints dictated by the size of the overlapping magnetic elements resulting in high manufacturing costs due to the amount of steel that was required to construct the hinge.

[0009] Therefore, there is a need to overcome or alleviate one or more of the above-mentioned problems or provide a useful alternative.

43 It may be seen that the specification discloses three identified difficulties with the prior art, the first being the vibration problem caused by vibration in a direction orthogonal to the plane of the glass panel, the second being the thickness problem caused by the orthogonal orientation of the dampeners relative to the plane of glass and also the thickness of the magnets, and the third being the manufacturing problem caused by the amount of steel used in the hinge.

44 Under the heading “Summary” the specification at [0011] sets out aspects and embodiments of the invention that are later reproduced in the claims. The first aspect of the invention is set out in [0011] and reproduces claim 1, which is set out in section 3.3 below.

45 Other embodiments are described in [0012]-[0016].

46 There follows a brief description of the figures which are provided “by way of example only” of embodiments of the invention, which are described by reference to 45 drawings.

47 The section entitled “Detailed Description of the Embodiments” commences by referring to an example of a hinge 10 in the glass-to-glass configuration in isometric drawing fig 1A:

48 The hinge 10 includes a first leaf assembly 20 hingedly coupled to a second leaf assembly 30, one or more biasing components 190 (shown in later figures as a spring, see [53] below) which bias the hinge toward a closed position, and one or more dampeners 100 (shown in fig 3 below) to slow movement of the first and second leaf assemblies 20, 30 to the closed position.

49 The specification says (emphasis added):

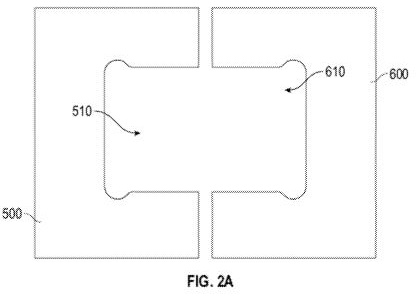

[0066] The first leaf assembly 20 includes a first front leaf component 22 coupled to a first rear leaf component 24 for accommodating therebetween a portion of a first panel 500 having a first cut-out section 510 as shown in Figure 2A. The first leaf assembly 20 further includes a first insert component 40 which is tight fittingly receivable within the first cut-out section 510 of the first panel 500.

50 The first insert component 40 is described in the specification to have “mouse ears” to fit within the cut-out part of the first panel 500, as shown in fig 2A. Figure 2A depicts the cut-outs which are respectively for the first insert 510 and second insert 610 as follows:

51 The second leaf assembly 30, which comprises part of the glass-to-glass embodiment, is described to have a similar arrangement.

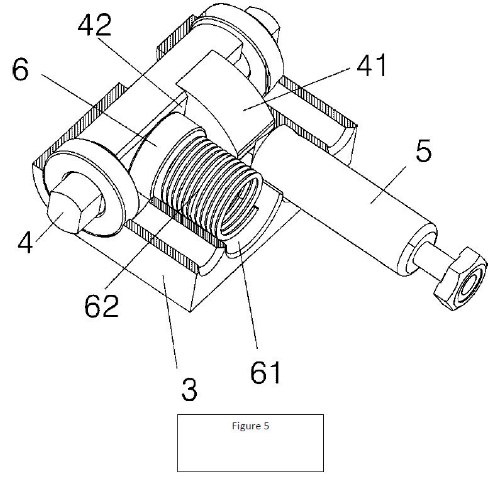

52 The specification describes a dampener in more detail:

[0069] A first portion 102 of each dampener 100 is secured or fixed within the first insert component 40 and a second portion 104 is configured to at least partially retract within the first insert component 40 when coming into contact with the second leaf assembly 30 during hinged movement toward the closed position under bias from the one or more biasing components 190. The second portion 104 of the dampener 100 extends and retracts along a longitudinal axis which is coplanar with the first panel 500.

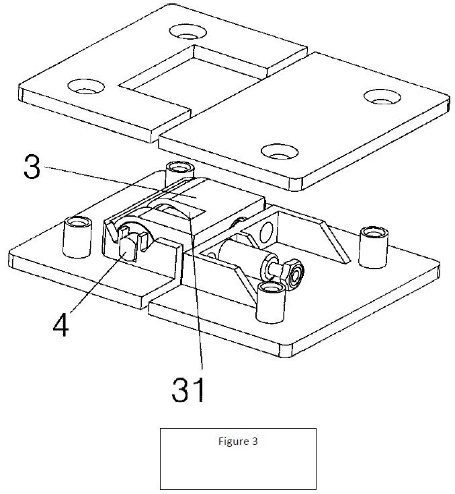

53 An exploded isometric view of hinge 10 in fig 1A is depicted in fig 3. It is quite complicated, but it may be seen that dampener 100 has a narrow, pin-like portion 102 and a larger cylindrical portion 104. Biasing spring 190 may be noted, and also the insert components 40 and 60 that have protrusions to match the mouse ears in the cut-out part of the panel:

54 The specification identifies advantages said to arise from the arrangement described:

[0070] Due to the longitudinal axis of the one or more dampeners 100 being coplanar with the first panel 500, any vibratory force is transferred in a direction parallel to the plane of the first panel 500. Due to the force being transferred along the plane of the first panel 500, the first panel 500 undergoes substantially little vibration resulting in a reduction in mechanical wear.

55 At [0071] the specification says that a first magnetic element 50 can be located in the first insert component 40 and a second magnetic element 70 can be located in the second insert component 60, being potential inclusions to provide an additional biasing component to the spring 190. The magnetic elements described in the specification are not referred to in the claims and played no significant part in the dispute between the parties.

56 The specification says:

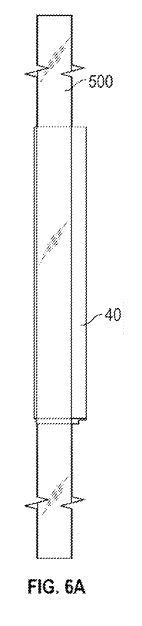

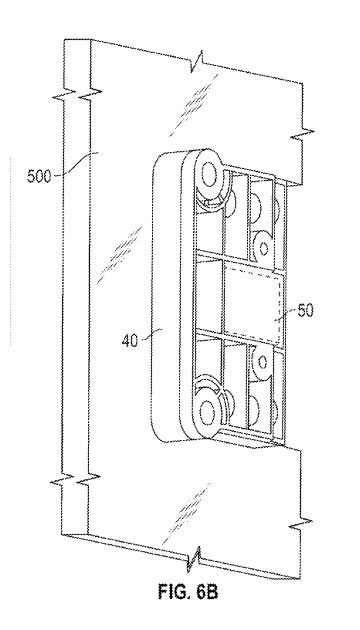

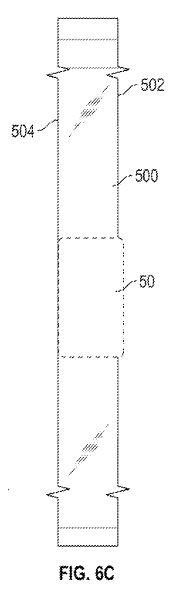

[0072] As shown in Figures 6A, 6B and 6C, a majority of the first insert component 40 is tight fittingly receivable by the first cut-out section 510 of the first panel 500 such that only a minority portion of the insert portion protrudes from the face of the first panel. …

57 Figures 6A, 6B and 6C are as follows:

|

|

|

58 The reference to “tight fittingly receivable” emphasises the fact that only a minority portion of the first insert component 40 protrudes from the face of the first panel.

59 The second leaf assembly has the same general arrangements, which are described at [0073]. It is to be noted that it is the first leaf assembly that has within the insert component dampeners located within hollows 44. In operation, in the open position those dampeners extend towards the second leaf assembly.

60 The specification states:

[0073] …As shown in Figure 7E, one or more striking surfaces 64 are provided by the second insert component 60, which the dampeners 100 strike when moving to the closed position, are located between opposing planes of the faces of the second panel 600 in order to achieve packing advantages….

61 The specification refers at [0075] to advantages said to arise from the design:

[0075] Due to the dampeners 100 being located between the planes of the opposing faces 502, 504 of the first panel 500, and optionally the first magnetic element 50 and the second magnetic element 70 being substantially located between opposing faces 502, 504, 602, 604, of the first and second panels 500, 600 respectively, the first leaf assembly 20 and the second leaf assembly 30 can be manufactured with a thinner profile meaning that the hinge 20 can be manufactured using less material…

62 The reference to the “thinner profile” is to be understood to be a comparison with the thicker profile used in the hinge arrangement of the prior art 615 patent, where the dampeners and magnetic elements were described as orientated orthogonally to the plane of the panels. By putting those elements between the planes of the opposing faces (that is, coplanar or parallel to the plane of the panel), the manufacturing problem of the prior art is said to be addressed.

63 The specification then refers again to fig 3 and notes:

[0077] …The first insert component 40 and second insert component 60 have a mouse ear shaped profile that corresponds to the mouse ear cut-out sections 510, 610 provided in the panels 500, 600 shown in Figure 2A. The mouse ear shaped corners of the first and second insert component 40, 60 contribute toward restricting rotational movement between the hinge 10 and the panels 500, 600. …

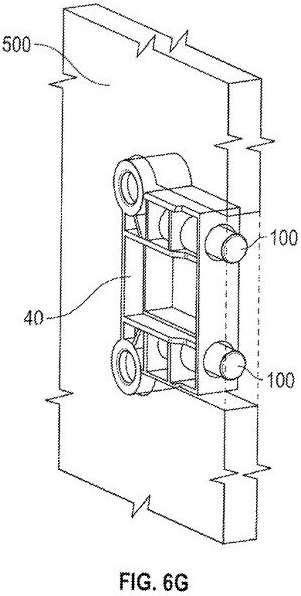

64 Figure 6G provides a perspective front view of the first insert component within the first cut-out section of the first panel, where it may be seen that dampener 100 is longitudinally aligned through hollows in the first insert component. The face of dampener 100, when in the extended position, meets with the chamfered face 64 of the second insert component as the hinge moves into the closed position, as shown in fig 7E, which is also depicted below:

|

|

65 Figures 7A and 7C are as follows:

|

|

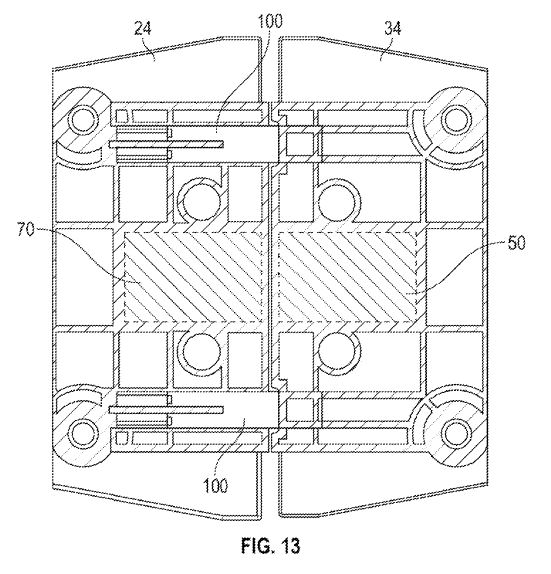

66 Figure 13 is as follows:

67 The description of the arrangement of the first insert component depicted in the above drawings was referred to at length in the evidence and the submissions and is reproduced in full below (this is [099] in the parent):

[0078] As shown in Figure 7A, 7B and 7C, the first insert component 40 includes a plurality of hollows 44 which have a longitudinal axis which is orthogonal to the hinge axis 290 and coplanar with the plane of the first panel 500. The hollows 44 are located along adjacent longitudinal edges of the cavity 42 for housing the first magnetic element 50. Each hollow 44 is configured to house at least a portion of a dampener 100 as shown in Figures 3 and 13 for reducing the speed which the hinge approaches the retained position. As shown in Figure 13, at least a portion 102 of each dampener 100 is located within a respective hollow 44 of the first insert component 40 and a second portion 104 of the dampener 100 at least partially retracts within the respective hollow 44 of the first insert component 40 when the second portion 104 of the dampener 100 comes into contact with the second insert component 60 during hinged movement towards the retained position. The second portion 104 of the dampener 100 extends and retracts along an axis which is coplanar with the first panel 500. The first portion 102 of the dampener 100 is a dampener pin which is coupled within a respective hollow 44 of the first insert component 40. Furthermore, the second portion 104 of the dampener 100 is a dampener body which at least partially extends from and at least partially retracts within the respective hollow 44 of the first insert component 40. As shown in Figure 13, the dampener pin 102 is substantially thinner than the dampener body 104. Due to the dampener pin 102 being secured within the respective hollow 44 and the dampener body 104 having a cross sectional profile which substantially corresponds to the cross-sectional profile of the respective hollow 44, the dampener pin 102 is less likely to deflect and bend during hinge movement toward the retained position. The substantially similar cross-sectional profiles between each dampener body 104 and the hollow 44 effectively acts as a guide such that each dampener body 104 receives therein the dampener pin 102 along the longitudinal axis of the respective hollow 44. As the orientation of the longitudinal axis of the one or more dampeners 100 is substantially coplanar with the first panel 500, the overall thickness of the hinge leaf component 20 can be reduced thereby providing material efficiencies in relation to manufacture of the hinge. Additionally, due to the orientation of the dampeners 100, a majority of the vibrational force experienced by the hinge 100 when approaching the retained position is transferred in a direction substantially parallel to the planes of the faces 502, 504, 602, 604 of the panels 500, 600 thereby reducing the stress on the panels when moving toward the retained position.

68 It may be noted from this passage that, first, the embodiment includes a description of the dampener arrangement that emphasises the steps taken in the design to ensure that the dampener pin is less likely to deflect and bend during closing. The evidence demonstrated that one concern for the person skilled in the art in developing such a hinge is to ensure that the dampener is not subject to undue lateral forces. Secondly, that the embodiment has an orientation of the longitudinal axis that is “substantially” rather than precisely coplanar with the first panel. Thirdly, the passage emphasises that “due to the orientation of the dampeners 100, a majority of the vibrational force experienced by the hinge 100 [sic, 10] when approaching the retained position is transferred in a direction substantially parallel to the planes…”.

69 There is no dispute that the orientation of the dampener 100 throughout this part of the specification is depicted and described as being orthogonal or substantially orthogonal to the hinge axis (orthogonal hinge arrangement).

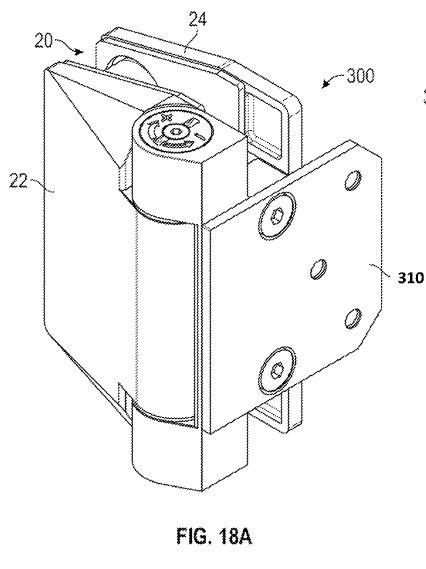

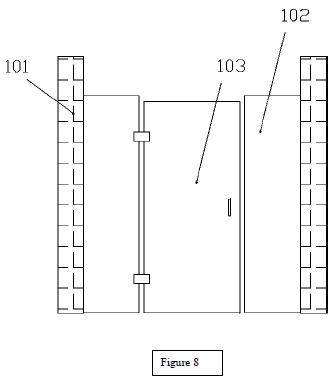

70 The specification then describes how the various components are fitted together, with additional detail provided of certain aspects of the embodiments described before addressing in some detail a glass-to-wall embodiment of the invention. It then describes the glass-to-wall embodiment of the invention by reference to hinge 300 in fig 18A:

71 The description explains the features of this embodiment, which does not involve a second leaf assembly, because the hinge is affixed to a mounting assembly 310 which is “hingedly coupled to the leaf assembly”. The specification provides in relation to the dampener of this arrangement:

[0093] The hinge 300 includes a dampener 100 to slow movement of the hinge 300 toward the retained position. The dampener 100 includes a first portion located within the insert component 40A and a second portion which at least partially retracts within the insert component 40A when coming into contact with the mounting assembly 310 during movement toward the retained position. The second portion of the dampener 100 extends and retracts along an axis which is parallel and coplanar with the panel 500. The first portion of the dampener 100 is a dampener pin which is coupled within a hollow 44 of the insert component 40A, and the second portion 394 of the dampener 390 is a dampener body which at least partially extends from and at least partially retracts within the hollow 44 of the insert component 40A.

72 The specification concludes by noting that the example hinges disclosed can be used for many applications, that modifications will be apparent to those skilled in the art without departing from the scope of the invention, and that, unless the context otherwise requires, the word “comprise” should be understood in its inclusive sense.

3.3 The claims of the 485 patent

73 The 485 patent has five claims. These are set out below with the integer numbers added.

74 Claim 1 encompasses a hinge with a glass-to-glass configuration and provides:

1.1 A hinge including:

1.2 a first leaf assembly including a first front leaf component coupled to a first rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a first panel having a first cut-out, 1.3 wherein the first leaf assembly further includes a first insert component located between the first front and rear leaf components, 1.4 wherein a portion of the first insert component is adapted to locate within the first cut-out;

1.5 a second leaf assembly hingedly connected to the first leaf assembly about a hinge axis, 1.6 said second leaf assembly including a second front leaf component coupled to a second rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a second panel having a second cut-out, 1.7 wherein the second leaf assembly further includes a second insert component located between the second front and rear leaf components, 1.8 wherein a portion of the second insert component is adapted to be located within the second cut-out;

1.9 a spring operatively coupled to the first and second leaf assemblies to bias the hinge to move from an open position to a closed position; and

1.10 a dampener, having a longitudinal dampener axis, said dampener at least partially housed within the first insert component and adapted to dampen movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position, 1.11 wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the first panel.

75 Claim 2 is for:

2.1 The hinge according to claim 1, 2.2 wherein the first insert component includes a first and second hole adapted to receive a first and second threaded stem of the first front leaf component, 2.3 wherein a first and second fastener are receivable through corresponding holes of the first rear leaf component and fasten with the first and second threaded stems respectively to secure the first front leaf component to the first rear leaf component.

76 Claim 3 is for:

3.1 The hinge according to claim 1, 3.2 wherein the hinge further includes an end cap coupled to an upper end of a barrel of the hinge, said end cap having an upper surface acutely angled relative to the hinge axis to prevent the end cap being used as a stepping surface.

77 Claim 4 is for:

4.1 A hinge including:

4.2 a leaf assembly including a front leaf component coupled to a rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a panel having a cut-out, 4.3 wherein the leaf assembly further includes an insert component located between the front and rear leaf components, 4.4 wherein a portion of the insert component is adapted to locate within the cut-out;

4.5 a mounting component for mounting said hinge, said mounting component hingedly connected to the leaf assembly about a hinge axis;

4.6 a spring operatively coupled to the leaf assembly and mounting component to bias the hinge to move from an open position to a closed position;

4.7 a dampener, having a longitudinal dampener axis, said dampener at least partially housed within the insert component and adapted to dampen movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position, wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the panel.

78 Claim 5 is for:

5.1 The hinge according to claim 4, 5.2 wherein the insert component includes a first and second hole adapted to receive a first and second threaded stem of the front leaf component, 5.3 wherein a first and second fastener are receivable through corresponding holes of the rear leaf component and fasten with the first and second threaded stems respectively to secure the front leaf component to the rear leaf component.

3.4 The claims of the 918 patent

79 As noted, the specification of the 918 patent is not materially different to that of the 485 patent, save that the summary of the invention and the claims differ.

80 It is not necessary for present purposes to address the summary of the invention. The claims are set out below with the relevant integers added.

81 Claim 1 provides:

1.1 A hinge including:

1.2 a first leaf assembly including a first front leaf component coupled to a first rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a first panel having a first cut-out, 1.3 wherein the first leaf assembly further includes a first insert component located between the first front and rear leaf components, 1.4 wherein a portion of the first insert component is adapted to locate within the first cut-out;

1.5 a second leaf assembly hingedly connected to the first leaf assembly about a hinge axis, 1.6 said second leaf assembly including a second front leaf component coupled to a second rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a second panel having a second cut-out, 1.7 wherein the second leaf assembly further includes a second insert component located between the second front and rear leaf components, 1.8 wherein a portion of the second insert component is adapted to be located within the second cut-out;

1.9 a spring operatively coupled to the first and second leaf assemblies to bias the hinge to move from an open position to a closed position, 1.10 wherein the spring has a longitudinal spring axis which is parallel with the hinge axis to operate as a torsion spring; and

1.11 a dampener, having a longitudinal dampener axis along which a portion of the dampener retracts during dampening, said dampener at least partially housed by the first insert component, 1.12 and wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and orientated substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the first panel;

1.13 wherein the second leaf assembly includes a striking surface to cooperate with the dampener to dampen spring induced movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position.

82 Claims 2 is for:

2.1 The hinge according to claim 1, 2.2 wherein the first insert component includes a first and second hole adapted to receive a first and second threaded stem of the first front leaf component, 2.3 wherein a first and second fastener are receivable through corresponding holes of the first rear leaf component and fasten with the first and second threaded stems respectively to secure the first front leaf component to the first rear leaf component.

83 Claim 3 is for:

3.1 The hinge according to claim 1, 3.2 wherein the hinge further includes an end cap coupled to an upper end of a barrel of the hinge, said end cap having an upper surface acutely angled relative to the hinge axis to prevent the end cap being used as a stepping surface.

84 Claim 4 is for:

4.1 A hinge including:

4.2 a leaf assembly including a front leaf component coupled to a rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a panel having a cut-out, 4.3 wherein the leaf assembly further includes an insert component located between the front and rear leaf components, 4.4 wherein a portion of the insert component is adapted to locate within the cut-out;

4.5 a mounting component for mounting said hinge, said mounting component hingedly connected to the leaf assembly about a hinge axis;

4.6 a spring operatively coupled to the leaf assembly and mounting component to bias the hinge to move from an open position to a closed position, 4.7 wherein the spring has a longitudinal spring axis which is parallel with the hinge axis to operate as a torsion spring; and

4.8 a dampener, having a longitudinal dampener axis along which a portion of the dampener retracts during dampening, said dampener at least partially housed by the insert component, 4.9 wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the panel;

4.10 wherein the mounting component includes a striking surface to cooperate with the dampener to dampen spring induced movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position.

85 Claim 5 is for:

5.1 The hinge according to claim 4, 5.2 wherein the insert component includes a first and second hole adapted to receive a first and second threaded stem of the front leaf component, 5.3 wherein a first and second fastener are receivable through corresponding holes of the rear leaf component and fasten with the first and second threaded stems respectively to secure the front leaf component to the rear leaf component.

86 There was no dispute that the skilled addressee of the patents in suit is a person engaged in, or who has experience in, the design of mechanical devices and, in particular, in respect of hinges used in domestic and commercial applications. Nor is there any dispute that Mr Hunter and Mr Richardson fall within that description.

87 The following questions of claim construction, which are relevant to a number of issues, require determination, namely the meaning of:

(a) “insert component” as it appears in integer 1.3 of claim 1 of each of the patents and subsidiary claims;

(b) “adapted to locate” as it appears in integers 1.4 and 4.4 of each of the patents; and

(c) “striking surface to cooperate with the dampener” as it appears in integers 1.13 and 4.10 of the 918 patent.

88 The principles of claim construction are not in dispute. They are conveniently set out in Jupiters v Neurizon [2005] FCAFC 90; 65 IPR 86 at [67] (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) as follows:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corp Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-486; the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–486.

4.2 The “insert component” integer

89 Claim 1 of each of the 485 and 918 patents provides as part of integer 1.3 that “the first leaf assembly further includes a first insert component located between the first front and rear leaf components” (emphasis added).

90 An “insert component” is also referred to in integers 1.4, 1.7, 1.8, 4.3 and 4.4 of the patents.

91 Polaris contends that the words “insert component” refer to a separately identifiable part that is assembled within the first and second leaf assemblies, and that when the hinge is assembled the “insert component” is a separate component located between the respective front and rear leaf components. It submits, based on Mr Richardson’s evidence, that the word “component” means “constituent part” and that the word “insert” is used as an adjective to describe a component that is being inserted between the front and rear leaf components.

92 TCT contends that the approach of Polaris involves impermissibly reading the word “separate” into the claim. Whilst the specification does envisage that in the preferred embodiment the insert component can be made of different material, TCT submits that the claim includes no language limiting the component to a separate entity. It submits that in engineering usage an “insert” can be a separate component, but it can also be a child component part of a parent component that is integral with one another. This was the view of Mr Hunter.

93 Claim 1 of the 485 patent provides suitable context for consideration of the words “insert component”. No party suggested that the words would have a different meaning in any other claim.

94 That claim describes the relationship between features in the hinge of the invention for a glass-to-glass embodiment. The constituent parts are to include a first leaf assembly, a second leaf assembly, a spring and a dampener.

95 The first leaf assembly includes a front leaf component coupled to a rear leaf component for accommodating between the two a portion of a panel, which has a cut-out (integer 1.2), and includes a “first insert component” which is located between the front and rear leaf components (integer 1.3) and a portion of that insert component is adapted to locate within the cut-out (integer 1.4).

96 The second leaf assembly is hingedly connected to the first leaf assembly and includes a front leaf component coupled to a rear leaf component for accommodating between the two a portion of a second panel, which has a cut-out (integer 1.6), and includes a “second insert component” which is “located between the front and rear components” (integer 1.7) a portion of which is adapted to locate within the cut-out (integer 1.8).

97 The spring is “operatively coupled” to the two leaf assemblies to bias the hinge to move from an open to a closed position (integer 1.9).

98 The dampener is described as having a longitudinal axis and being at least partially housed within the first insert component and adapted to dampen movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position (integer 1.10) “wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the first panel” (integer 1.11).

99 There was no suggestion in the evidence that the language of this claim had any technical meaning that could not be understood by reference to ordinary English usage.

100 The claim describes these four parts by reference to their relationship to each other and their functions, which together combine to result in a hinge. It does not purport to define how the hinge is to be manufactured or the materials from which it is to be made.

101 The word “component” in the claim is to be understood in its ordinary sense as being to describe a constituent part of the hinge. Such a component may be made up of multiple other parts and several components may make up a larger part of the hinge as a whole.

102 The words “insert component” in the claim serve to identify a part of the leaf assembly described, which is to be positioned between the front and rear leaves of the assembly. In that context, the word “insert” is not in my view to be understood as an adjective, as if it were a magazine inserted into a newspaper that is able to be separated from the whole or separately placed in (“inserted”) or removed. Rather, it identifies the part that is positioned between the front and rear leaves and in that sense is “inserted” or “sandwiched” between the two. The language of the claim does not specify one way or the other how this aspect of the leaf assembly is manufactured, but where the component is located. It may be a discrete part that is made and placed into the hinge, or it may in the final product be integral to either or both of the front and rear leaf components. When the hinge is assembled the insert component is physically located “between” the front and rear leaves regardless of whether it is a discrete part or integral to another. The requirement of the claim is that the insert component be situated between the two leaves and adapted to locate within the cut-out.

103 In my view the body of the specification supports this construction. The invention disclosed is directed to a hinge that addresses the prior art problems identified. Whilst it is true that the only embodiment described and depicted in the specification identifies that the insert component is a discrete part (see for example, fig 7C item 40), the specification makes clear that this is only one embodiment and that the person skilled in the art may work the invention in other ways.

104 Furthermore, at [0080] of the specification the patent states that “[p]referably the insert components 40, 60 are injection moulded components in order to further reduce the manufacturing costs of the hinge” (emphasis added). It is telling that where a component is to be manufactured in a particular way, the specification specifies as such. Whilst the outcome of that preference is that items 40 and 60 will be able to be separate “inserts”, the language of the claim does not require it.

4.3 “adapted to locate” integer

105 The words “adapted to locate” or “adapted to be located” are present in integers 1.4, 1.8 and 4.4 of each of the patents. The parties accept that the words will have the same meaning in all of the claims, and so their construction can be considered by reference to the language of claim 1 of the 485 patent.

106 Polaris contends that the words mean “formed to fit”, namely, that the insert component must have some correspondence or consistency of shape between it and the cut-out portion in the panel, while allowing for a degree of tolerance or leeway. This, it submits, is broadly equivalent to the expression “tight fittingly receivable”, which is used in the specification. It submits that the word “adapted” must be given work to do, and in the context of the specification as a whole it means “adapted” by reason of a correspondence or consistency of shape. It relies on the evidence of Mr Richardson.

107 TCT adopts the evidence of Mr Hunter to support a submission that the words “adapted to locate” encompass any relationship that allows a portion of the insert component to fit within the cavity formed by the cut-out. It notes that the words of the claim do not correlate with any language in the body of the specification, which refers to “tight fittingly receivable” only, and submits that where the patentee chooses to use different language in respect of the same integer, it should be understood that the patentee intended to refer to a different thing. Whilst the drawings in the patent depict the existence of small gaps between the insert component and the cut-out (e.g. fig 6G), this should not distract from the language of the claim. It submits that the word “adapted” must be given work to do, which “tight fittingly receivable” does not.

108 The word “adapted” in the phrase “adapted to locate within the first cut-out” in integer 1.4 is a relative term, “adapt” meaning, according to its ordinary usage, “to make suitable to requirements; adjust or modify fittingly”: Macquarie Dictionary (6th ed, 2013). The scope of the phrase “adapted to locate” is to be understood by reference to the role of the first insert component and the purpose that its location in the cut-out is to serve.

109 In that context, it is to be recalled that the insert component is part of a hinge mechanism that is fixed to a panel, typically of glass. When in the closed position, the hinge panel (or door) will align with another panel that will have a latch or similar arrangement to secure it. As Mr Richardson observed in his evidence, the first hinge leaf assembly must be adapted to locate “in order for the panel not to be loose in the first hinge leaf assembly to help prevent the panel from misaligning, moving, coming free or rotating for the invention to function successfully” and later “…[G]iven the context of mounting a hinge in a panel material, in my opinion, it would be obvious to anyone skilled in the art that ‘any shape or size’ is not preferable as the panel could misalign, move, come free or rotate relative to the hinge”. This view was shared by Mr Hunter.

110 This relationship is explained in the 485 patent, which says at [0077] by reference to fig 3 (emphasis added):

… The mouse ear shaped corners of the first and second insert components 40, 60 contribute toward restricting rotational movement between the hinge 10 and the panels 500, 600.

111 Whilst this description is provided in the context of a preferred embodiment, the experts’ evidence indicates that the need to avoid misalignment between the panels is applicable more generally. As Mr Richardson explained in his oral evidence, there were two aspects to the restriction of rotational movement. One is the hinge itself in relation to the panel. The other is the reality of an installed situation, being that there will be two hinges installed on a panel and accordingly the rotational movement will be significantly restricted. He noted that it is important for there to be some allowance for movement or adjustment in order to avoid misalignment and to ensure that the panel (such as a gate or glass door for a pool) is level with the rest of the fence and with the latch. Mr Richardson’s evidence was:

… there needs to be an allowance for an amount of adjustment, not a – a large amount. And that relationship, it’s – the tolerance relationship is compounded by the dimensional variation between the two cut-outs. So the formation of the cut-out in relation to the shape of the insert component, there’s an adapted to locate relationship that the insert component has a offset shape relative to the shape of the cut-out in the glass.

112 Furthermore, the experts agreed that the process of cutting glass panels needs to allow some variation, because there is necessarily a degree of variation in the dimensions of a cut-out, which is typically produced using a diamond tipped grinder wheel to score the glass and then snap it.

113 In my view the requirement in integers 1.4 and 4.4. that a portion of the first insert component be “adapted to locate within the first cut-out” cannot sensibly mean, as Mr Hunter contends, that it permits any relationship that allows a portion of the insert component merely to fit within the cavity formed by the cut-out. It has a more confined meaning which the skilled addressee would understand enabled the fitment to be suitable for purpose.

114 On the other hand, I do not consider the phrase to be synonymous with “tight fittingly receivable”, which is too narrow and necessitates a closer correlation between the insert component and the cut-out than its function would require. As Mr Richardson observed in his oral evidence, the relationships between a screw and a hole drilled for purpose or a piston in a cylinder in a car will be “tight fitting”, while the relationship between a house door and its frame will be relatively tight-fitting.

115 In my view the skilled reader would understand the phrase “adapted to locate” within the claim to mean that the insert component was sized to have a shape relationship between it and the cut-out for the purpose of enabling the hinge to be located or fitted in position. I do not understand it to mean that the insert must fit tightly within the cut-out such that there is little or no room for movement. That would be an impractical construction not required by the language of the claim.

4.4 “striking surface to cooperate with the dampener” integer

116 The following integers describe the operation of the dampener in claim 1 of the 918 patent (integers and emphasis added):

…[1.11] a dampener, having a longitudinal dampener axis along which a portion of the dampener retracts during dampening, said dampener at least partially housed by the first insert component, [1.12] and wherein said longitudinal dampener axis is disposed between and orientated substantially parallel with planes defined by respective opposing faces of the first panel; [1.13] wherein the second leaf assembly includes a striking surface to cooperate with the dampener to dampen spring induced movement of the hinge from the open position to the closed position.

117 A similarly worded integer appears in claim 4 at integer 4.10. The parties agree that the emphasised words will have the same meaning in both claims.

118 Two points arise, the first concerns the meaning of “striking surface” and the second the meaning of “to cooperate with the dampener”.

119 Polaris contends first, that the words “to cooperate with the dampener” in integer 1.13 include indirect action such as via an intermediate component and secondly, that the “striking surface” is something that must be “struck” by operation of something else in the hinge. It relies on the evidence of Mr Richardson to support the proposition that the hitting action of the “striking surface” in integer 1.13 may operate cooperatively on the dampener directly or alternatively through indirect contact via intermediate components operating between the dampener and the striking surface. Secondly, it submits that the definition of “strike” and “striking” means that a striking surface is a surface that is subject to impact from another object. The requirement that the striking surface “cooperate” with the dampener includes arrangements other than those with direct contact, including by an intermediate component.

120 TCT submits that the phrase requires that the dampener and the striking surface be in direct contact with each other. Whilst Mr Hunter agrees in his evidence that, considered in isolation, the words “to cooperate with the dampener” might be sufficiently broad to include the presence of intermediary components between the striking surface and the dampener, TCT contends that the 918 patent specification teaches that direct contact is required.

121 In answer to the second point, TCT contends that a “striking surface” describes a necessary feature of every hinge with a dampener. It contends that the language of the integer does not require the “striking surface” to be “hit” or “struck”. It relies on the evidence of Mr Hunter that “striking surface” is not a term of art and must be understood from the specification. He considers that the integer only requires that direct contact be made between the dampener and the striking surface and that accordingly the dampener and striking surface could be in contact throughout the door closure; no “striking” action is necessary.

122 In my view the words “to cooperate with the dampener” in integer 1.13 indicate that the striking surface does not need to be in direct contact with the dampener, but may interact indirectly with it, in order to achieve the effect of dampening the spring induced movement of the hinge. That is the plain meaning of the phrase “to cooperate with the dampener”. Whilst I accept that, leaving aside the consistory clause at [0011], there is no description of such an arrangement, the approach taken by TCT tends to read down the language of the claim by reference to the preferred embodiments. Nowhere does the specification purport to limit the word “cooperate” which, in its ordinary meaning, refers to a “joint operation or action”: Macquarie Dictionary (6th ed, 2013). Accordingly, in my view integer 1.13 is not to be understood to be confined to a direct interaction.

123 In my view, the approach taken by TCT in relation to “striking surface” deprives the word “striking” of content. Such approach is not to be preferred as a matter of construction. The consequence is that a dampener that is in continuous contact with the surface will not be in contact with a striking surface within the claim.

124 Glass Hardware contends that the GTG hinge infringes claims 1, 2 and 3 of each of the 485 and 918 patents and that the GTW hinge infringes claims 4 and 5 of each of those patents.

125 TCT’s position in relation to infringement changed during the course of the hearing, but ultimately the only issue between the parties in relation to infringement concerned whether integer 1.4 of claim 1 was present in the GTG hinge and whether integer 4.4 was present in the GTW hinge for both of the patents. Otherwise, TCT accepted that all of the integers of the claims of the patents are present in the Orion hinges.

126 Despite the narrowness of the dispute, it is convenient to commence with a full description of the Orion hinges.

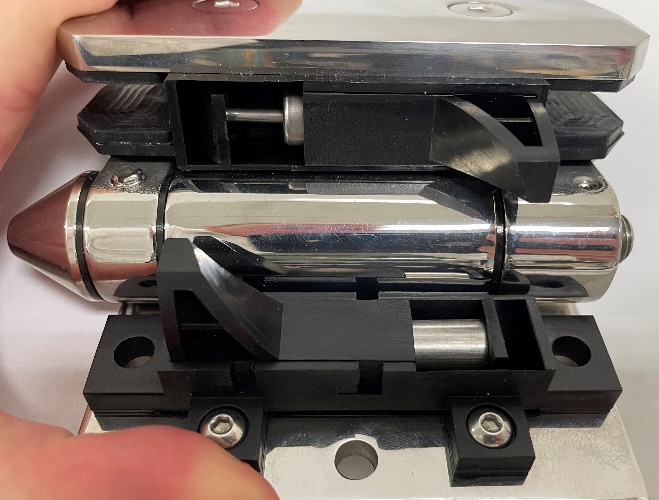

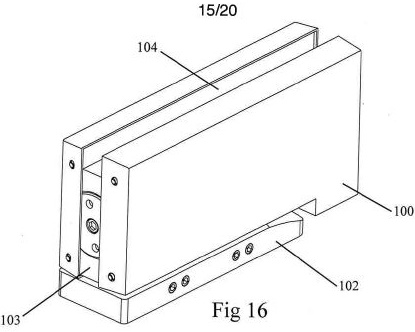

127 The impugned products were tendered in evidence. Images of the GTG and GTW products are set out below:

GTG | |

|

|

GTW | |

|

|

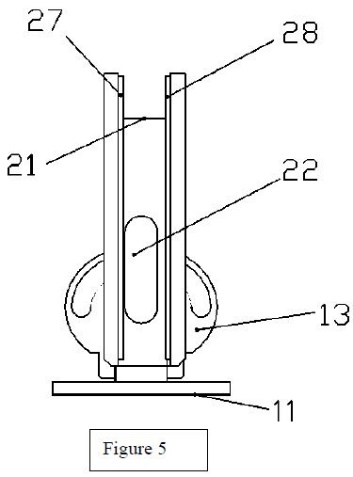

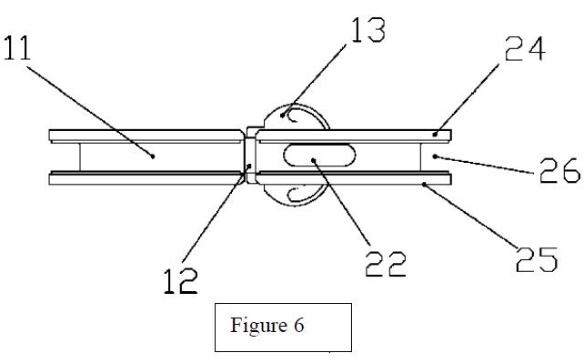

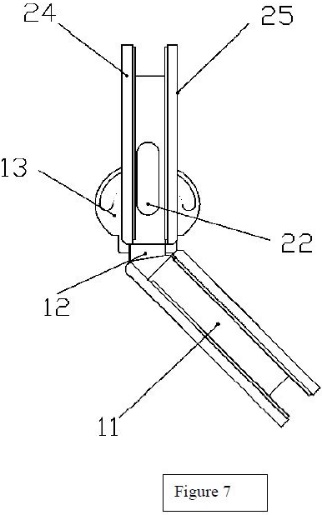

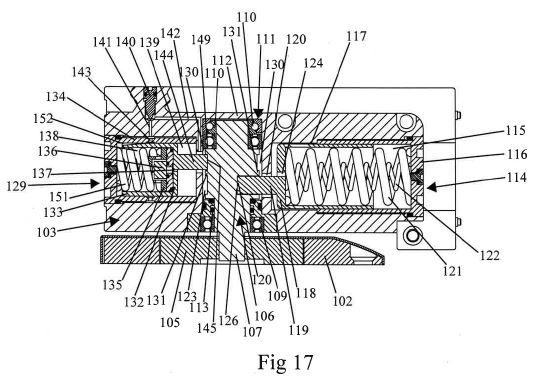

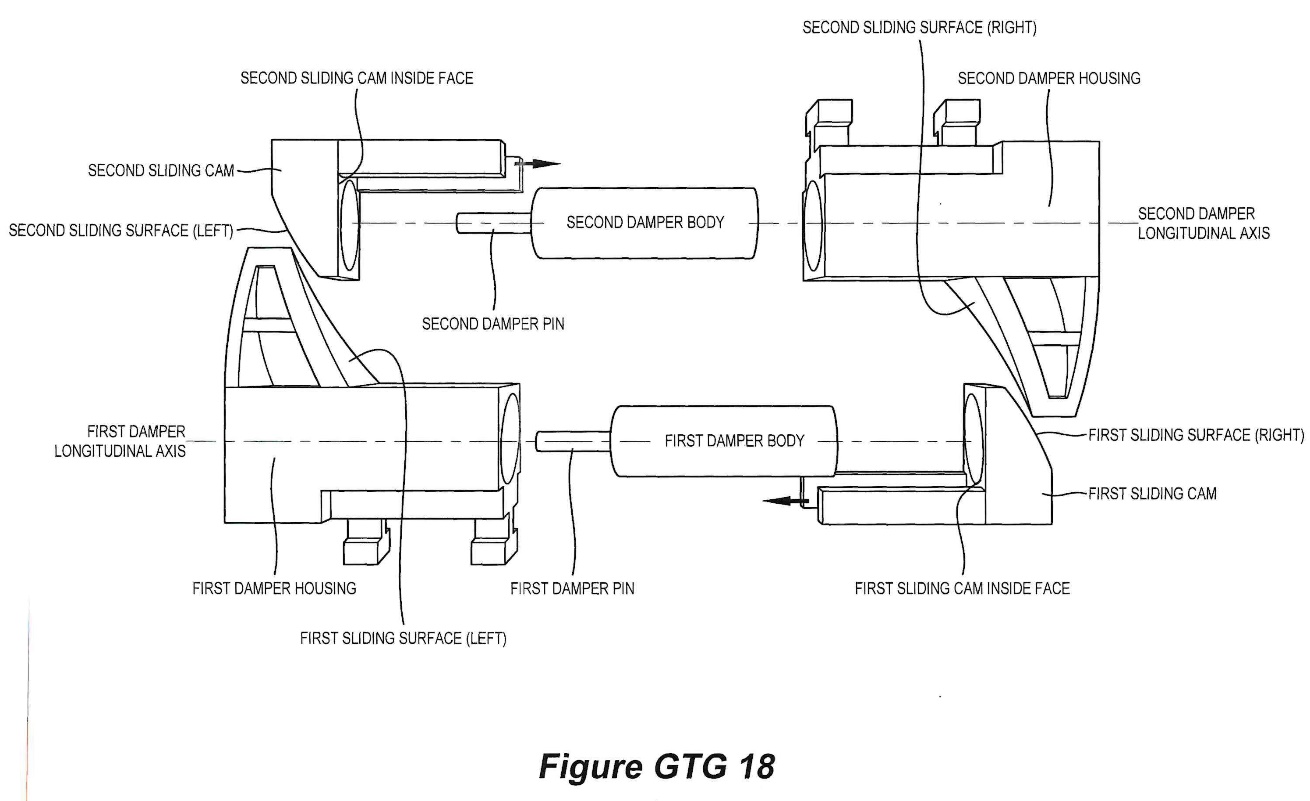

128 Exhibit C is a drawing of the dampening mechanism of the Orion GTG hinges:

129 Mr Hunter provided the following description of the apparatus:

21. … the dampeners in each of the Orion Hinges are actuated by a combination of interactions between several sliding surfaces external to the dampeners themselves … . That is, there is no direct contact between the dampener pin or body with a sliding surface provided by an opposite mounting assembly or second leaf assembly. Rather, each dampener is held within a dampener housing which slidingly locates within its respective insert. The insert contains a rectangular channel which houses the dampener in its dampener housing. A further component, which is a sliding cam, also slides in this same rectangular channel. The inside face of the sliding cam contacts the dampener (either the pin or the body) and causes the dampener to retract at approximately 35 degrees from the hinge’s fully closed position as the hinge is closing under spring bias …. The outside face of the sliding cam is actuated by an angled surface protruding from the dampener housing located in either the opposing leaf assembly (in the case of the GTG Hinge) or the mounting component (in the case of the GTW Hinge). Consequently, actuation of each dampener occurs via one intermediate sliding cam making contact with a sliding surface, which then in turn causes the dampener to retract. This arrangement ensures that only axial forces are transmitted to the dampener and the dampener pin does not receive any lateral forces.

5.3 Consideration of the adapted to locate issue

130 The first part of claim 1 of the 485 patent provides (integers and emphasis added):

1.1 A hinge including:

1.2 a first leaf assembly including a first front leaf component coupled to a first rear leaf component for accommodating therebetween a portion of a first panel having a first cut-out, 1.3 wherein the first leaf assembly further includes a first insert component located between the first front and rear leaf components, 1.4 wherein a portion of the first insert component is adapted to locate within the first cut-out;

131 I have in section 4.3 determined that within the emphasised phrase the words “adapted to locate” should be understood to mean that the insert component is sized to have a shape relationship between it and the cut-out for the purpose of enabling the hinge to be located or fitted in position. I do not consider that the phrase requires that the insert must be “tight fittingly receivable”.

132 Having reached this conclusion, I do not understand TCT to dispute that the insert component in the Orion hinges satisfies this integer. If I am wrong about that then, having regard to the analysis conducted by Mr Richardson of the Orion hinges, I am independently satisfied that the insert component of the Orion hinges falls within the scope of integer 1.4 (or 4.4) of both of the patents in suit. Accordingly, subject to the question of validity, the infringement case advanced by Polaris succeeds.

6. INTRODUCTION TO THE REVOCATION CASE

133 In its third further amended statement of claim, TCT contends that the patents are invalid for lack of sufficiency, lack of support, lack of novelty and lack of innovative step.

134 Part of the lack of novelty ground depends upon the contention that the claims are not entitled to a priority date earlier than the filing date of the patents. If that contention is correct, then as a result of my findings of infringement, the patents are anticipated by the Orion hinges and accordingly are invalid. It is convenient to first address the question of priority date before turning to the remaining grounds of invalidity advanced.

135 TCT pleads that the 485 patent and the 918 patent were both filed as divisional applications of the parent on 16 February 2017 and claim priority from the provisional application which was filed on 17 February 2016. Nothing turns on the difference in date between the parent and the provisional application as the disclosure of the two is essentially the same. Accordingly, in the reasons that follow I refer for convenience to the parent only.

136 TCT submits that by operation of s 43 of the Patents Act and the Regulations, the disclosure of the parent does not provide an adequate basis upon which to claim the earlier priority date, with the consequence that the priority date for the 485 patent will be deferred to the date that it was filed, being 30 March 2020, and the priority date for the 918 patent will be deferred until the date of its filing, being 21 October 2020.

137 In its statement of claim, TCT contends that the glass-to-glass and glass-to-wall hinges claimed in the 485 patent extend beyond that disclosed in the parent for several reasons. First, because the broadest disclosure of the parent describes a dampener feature of a specific operation in which the dampener is arranged to come into contact with the second leaf assembly during hinged movement towards the closed position (the coming into contact requirement). Secondly, because the parent discloses only an invention where the dampener partially extends from and retracts within a first insert component. Thirdly, because the orientation of the dampener feature is described in the parent to be orthogonal to the hinge axis, as set out in [0099] of that document (the orthogonal dampener requirement). Fourthly, because the broadest disclosure of the invention is that the first insert component is “tight fittingly receivable within the first cut-out section” of the first panel (the tight fitting requirement).

138 TCT contends that the claims of the 485 patent do not include any of these limitations. In closing submissions only the first, third and fourth reasons were pressed.

139 During closing submissions TCT abandoned a pleaded contention that amendments made to the 485 patent were not allowable.

140 TCT contends that the glass-to-glass and glass-to-wall hinges claimed in the 918 patent extend beyond the disclosure of the parent for the same reasons as those described for the 485 claims, with the additional contention that the parent discloses only a “striking surface” in the hinge located in the second insert component for an end of the dampener body to strike when moving toward the closed position with the dampener at least partially extending from and retracting within the hollow of the first insert component. It contends that the claims of the 918 patent do not possess that limitation (the striking surface requirement).

141 Polaris submits that the scope of the claims of each of the patents is sufficiently disclosed in the parent.

142 Section 43(1) of the Patents Act provides that each claim of a specification must have a priority date. If s 43(2A) applies to a claim, the priority date is the date determined under the Regulations: s 43(2)(a). Otherwise the priority date of a claim is the date of the filing of the specification: s 43(2)(b).

143 Section 43(2A) provides for a presently relevant exception:

(2A) This subsection applies to a claim if:

(a) prescribed circumstances apply in relation to the invention defined in the claim; and

(b) a prescribed document discloses, or a prescribed set of prescribed documents considered together disclose, the invention in the claim in a manner that is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art.

144 Chapter 3, Pt 1, Div 2 of the Regulations determines the priority date of a claim for s 43(2)(a) of the Patents Act: reg 3.12(1). Regulation 3.13D(4)(a), which falls within this part of the Regulations, provides that a prescribed circumstance within s 43(2A) of the Patents Act includes where the “specification containing the claim that defines the invention was filed for (i) a divisional application under s 79B”.

145 By reg 3.13D(4)(b), “the document mentioned in paragraph 1(b) is a prescribed document”. Paragraph (1)(b) says “the specification mentioned in subsection 79B(1) of the Act (the earlier specification) clearly discloses the invention in the claim”.

146 It follows that to be a prescribed document, the earlier specification (here, the parent) must (a) be an earlier specification mentioned in s 79B(1) of the Patents Act; and (b) “clearly disclose” the invention in the claim.

147 Regulation 3.12(4) provides:

In this Division, a document, or a set of documents considered together, clearly discloses an invention if the document, or set of documents, discloses the invention in a manner that is clear enough, and complete enough, for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art.

148 The requirement that a priority document clearly discloses an invention the subject of later claims is the same as that set out in s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act which provides:

40 Specifications

…

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art

149 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Bill 2011 [2012] (Cth) (RTB Bill) sets out the purpose for changes made to s 43 of the Patents Act. The prior test for determining the priority date was whether the claim was fairly based on the disclosure of the priority document. It says (at p 49):

The item amends paragraph 43(2)(b) to provide that, if prescribed circumstances apply in relation to the claim and the prescribed document discloses the invention claimed in that claim in a manner that is clear and compete enough for the claimed invention to be performed by a person skilled in the art, the priority date of the claim will be the date that is determined under the Regulations.…

150 The Explanatory Memorandum identifies two objectives for the change. The first is to maintain consistency between the requirement of s 40(2) and the requirement for priority. The second is to increase the transparency of the Patents Act.

151 The legislative language indicates the disclosure requirements under s 43 and the Regulations are the same as that under s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act.

152 In Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corporation v Wyeth LLC (No 3) [2020] FCA 1477; 155 IPR 1 at [511]-[514] and [523]-[526], I addressed the introduction of the current form of s 40(2)(a) into the Patents Act (by way of the RTB Act), the relevant secondary materials and the relationship that it bears to equivalent provisions in European and United Kingdom law. I said the following in relation to the manner in which the requirement under s 40(2)(a) has been applied in the United Kingdom by reference to “classical sufficiency”:

[524] In Mentor Corp v Hollister Inc (No 2) [1992] 7 WLUK 465; [1993] RPC 7 at 14, the Court of Appeal (per Lloyd LJ, with whom Stuart-Smith and Scott LJJ agreed) endorsed a passage from Aldous J at first instance (Mentor Corp v Hollister Inc [1991] 3 WLUK 167; FSR 557 at 562) who said:

The section requires the skilled man to be able to perform the invention, but does not lay down the limits as to the time and energy that the skilled man must spend seeking to perform the invention before it is insufficient. Clearly there must be a limit. The subsection, by using the words “clearly enough and completely enough”, contemplates that patent specifications need not set out every detail necessary for performance, but can leave the skilled man to use his skill to perform the invention. In so doing he must seek success. He should not be required to carry out any prolonged research, enquiry or experiment. He may need to carry out the ordinary methods of trial and error, which involve no inventive step and generally are necessary in applying the particular discovery to produce a practical result. In each case, it is a question of fact, depending on the nature of the invention, as to whether the steps needed to perform the invention are ordinary steps of trial and error which a skilled man would realise would be necessary and normal to produce a practical result.

[525] In Novartis AG v Johns & Johnson Medical Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 1039; [2011] E.C.C. 10, Jacob LJ said at [74]:

The heart of the test is: “Can the skilled person readily perform the invention over the whole area claimed without undue burden and without needing inventive skill?”

[526] In Terrell on the Law of Patents (19th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, London, 2020), at page 404 the learned editors (Sir Colin Birss et al) propose as a convenient summary of the elements of this aspect of classical insufficiency the following passage provided by Kitchin J (as his Lordship then was) in Eli Lilly v Human Genome Sciences [2008] 7 WLUK 978; RPC 29 at [239]:

The specification must disclose the invention clearly and completely enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the art. The key elements of this requirement which bear on the present case are these:

(i) the first step is to identify the invention and that is to be done by reading and construing the claims;

(ii) in the case of a product claim that means making or otherwise obtaining the product;

(iii) in the case of a process claim, it means working the process;

(iv) sufficiency of the disclosure must be assessed on the basis of the specification as a whole including the description and the claims;

(v) the disclosure is aimed at the skilled person who may use his common general knowledge to supplement the information contained in the specification;

(vi) the specification must be sufficient to allow the invention to be performed over the whole scope of the claim;

(vii) the specification must be sufficient to allow the invention to be so performed without undue burden.

153 The contrast between previous law applicable in the pre-RTB Act version of s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act and the present may be seen by reference to the decision of the Full Court in Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Apotex Pty Limited (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 26; 129 IPR 205 (Jagot, Yates, Burley JJ) at [99]-[113].

154 In considering the disclosure obligation, the first step is to construe the claims of the patent to determine the scope of the invention, the next is to construe the description (here, the content of the parent, and in the case of s 40(2)(a), the specification in suit) through the eyes of the person skilled in the art who is in possession of the common general knowledge. The final step is to consider whether the parent provides an enabling disclosure of all the things that fall within the scope of the claims: Cytec Industries Inc v Nalco Company [2021] FCA 970; 162 IPR 202 at [143]. The reference to “all things” that fall within the scope of the claims is to be understood by reference to a materiality consideration, having regard to the nature of the invention disclosed and described: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc v Kymab Ltd [2020] UKSC 27; RPC 22 at [56].

155 In Regeneron, the United Kingdom Supreme Court (Reed P, Hodge, Black, Briggs and Sales LJJ) considered the authorities relevant to the concepts of an enabling disclosure. Briggs LJ concluded as follows at [56] (Reed, Hodge and Sales LJJ agreeing):

Reflection upon those European and UK authorities yields the following principles:

(i) The requirement of sufficiency imposed by article 83 of the EPC exists to ensure that the extent of the monopoly conferred by the patent corresponds with the extent of the contribution which it makes to the art.

(ii) In the case of a product claim, the contribution to the art is the ability of the skilled person to make the product itself, rather than (if different) the invention.

(iii) Patentees are free to choose how widely to frame the range of products for which they claim protection. But they need to ensure that they make no broader claim than is enabled by their disclosure.

(iv) The disclosure required of the patentee is such as will, coupled with the common general knowledge existing as at the priority date, be sufficient to enable the skilled person to make substantially all the types or embodiments of products within the scope of the claim. That is what, in the context of a product claim, enablement means.

(v) A claim which seeks to protect products which cannot be made by the skilled person using the disclosure in the patent will, subject to de minimis or wholly irrelevant exceptions, be bound to exceed the contribution to the art made by the patent, measured as it must be at the priority date.