Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2022] FCA 1476

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[12] | |

[12] | |

Google’s objections to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s evidence | [26] |

[41] | |

[52] | |

[53] | |

[56] | |

[63] | |

[64] | |

[67] | |

[71] | |

[74] | |

[80] | |

[84] | |

[89] | |

[123] | |

[134] | |

[150] | |

[150] | |

[150] | |

[163] | |

[164] | |

[165] | |

[177] | |

[186] | |

[222] | |

[225] | |

[227] | |

[237] | |

[257] | |

[259] | |

[260] | |

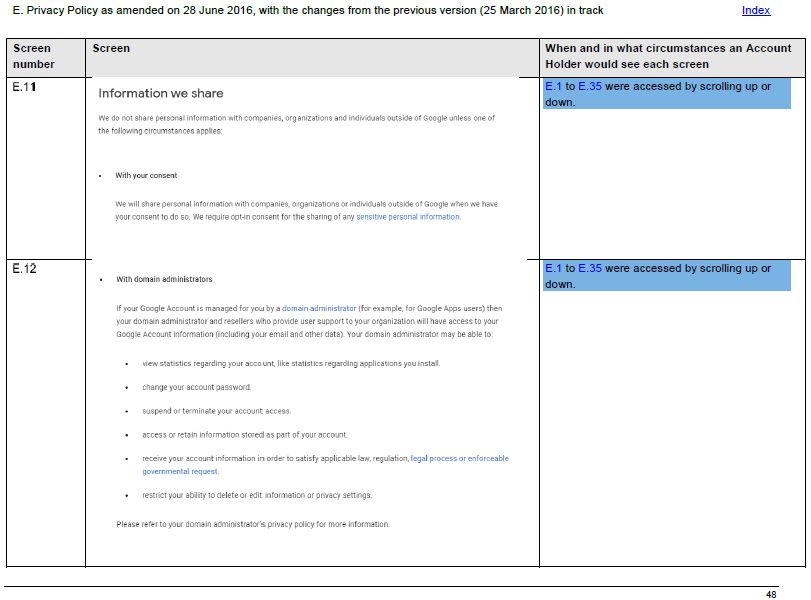

The Commission’s case based on the Explicit Consent Representation | [269] |

[271] | |

[291] |

YATES J:

1 The applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the Commission), alleges that the respondent, Google LLC (Google), contravened the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL) (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) by:

(a) engaging in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, contrary to s 18 of the ACL;

(b) making false or misleading representations about the services it provided concerning the performance characteristics, uses, or benefits of those services, contrary to s 29(1)(g) of the ACL;

(c) making false or misleading representations about the services it provided in relation to the existence, exclusion or effect of a right, contrary to s 29(1)(m) of the ACL; and

(d) engaging in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of the services it provided, contrary to s 34 of the ACL.

2 The Commission seeks, amongst other relief, declarations, pecuniary penalties, redress and publication orders, and compliance orders.

3 The conduct in question is alleged to have occurred in the period between 28 June 2016 and at least 10 December 2018 (the relevant period) in connection with a global project which was known within Google as, variously, “Narnia 2.0”, “NS”, “N20” or, simply, “Narnia” (Narnia 2.0). In implementing the project, Google sought the permission of its account holders (Account Holders) to make changes to the settings in their Google Accounts which, if agreed to, authorised Google to:

(a) combine or associate Account Holders’ personal information with their activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps, in addition to combining or associating Account Holders’ personal information with their activity on Google Services;

(b) allow that combined or associated information to be used to create or generate Account-based Advertising for Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps; and

(c) deliver Account-based Advertising to signed-in Account Holders on both Google Services and Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps on any of their devices.

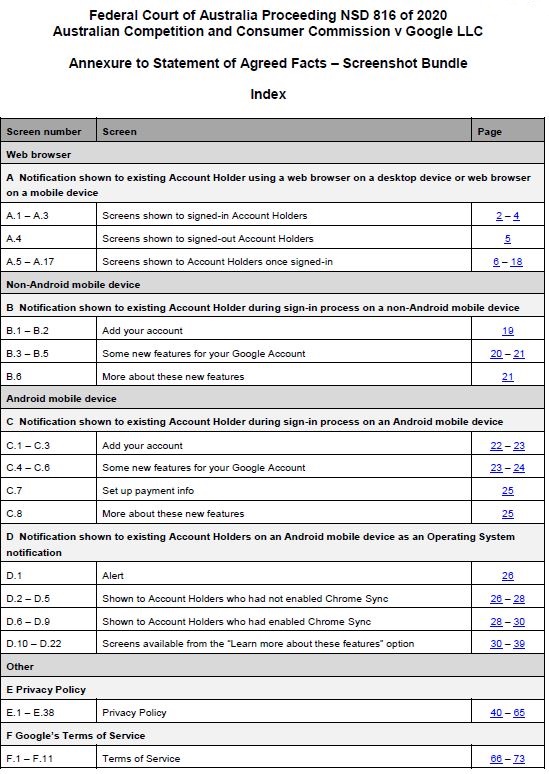

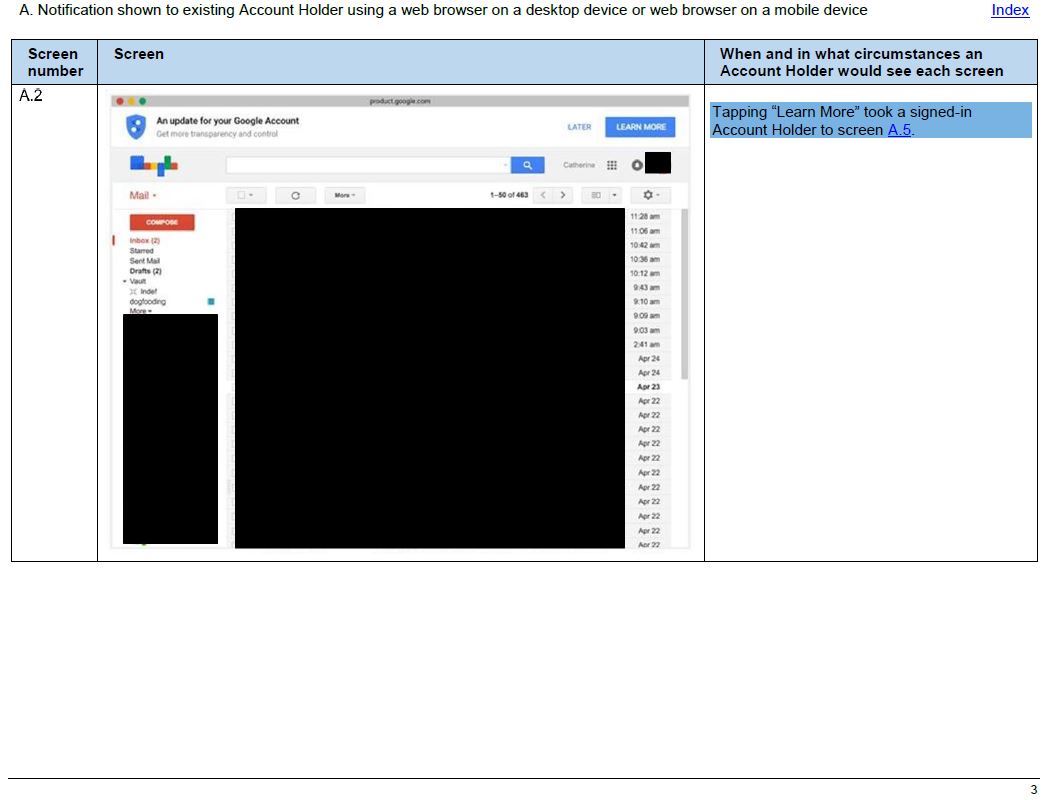

4 In order to obtain permission to make these changes, Google displayed a notification on the desktop and mobile devices of its Account Holders who had signed-in to their Google Accounts and who had already enabled various settings in respect of those accounts (the Notification). The Notification appeared in different ways depending on the Account Holder’s device and the Google Service that was being used at the time. I will discuss the form and content of the Notification in greater detail below: [89] – [122].

5 The Commission’s case is that the Notification failed to inform, or adequately inform, Account Holders that Google was seeking consent to undertake the activities referred to above and that, according to the Commission, Google had made a change to its Privacy Policy (which I discuss below) (the Notification conduct).

6 The Commission alleges that, as a consequence, Google engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18(1)), and which was liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 34).

7 The Commission also alleges that, by displaying the Notification, Google represented that it was only seeking the consent of Account Holders to “turn on” new features that would result in:

(a) more information being visible in Account Holders’ Google Accounts, making it easier to review and control that information; and

(b) Google using that information to make advertisements across the internet more relevant to Account Holders,

(the Notification Representations).

8 The Commission alleges that, as a consequence, Google made a false or misleading representation as to the performance characteristics, uses or benefits of Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 29(1)(g)), and engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18(1)) or was liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 34).

9 As to the changes to Google’s Privacy Policy, the Commission alleges that, in the face of an express statement that it would not reduce Account Holders’ rights under the policy without Account Holders’ explicit consent (the Explicit Consent Representation), Google did, in fact, reduce those rights in three ways.

10 The Commission alleges that, as a consequence, Google made a false or misleading representation as to the performance characteristics, uses or benefits of Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 29(1)(g)), and made a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of a right in relation to Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 29(1)(m)). The Commission also alleges that, as a consequence, Google engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18(1)) and was liable to mislead the public as to the nature or characteristics of Account Holders’ Google Accounts and Google Services (s 34).

11 For the following reasons, I am not satisfied that the Commission has established that Google contravened the ACL as alleged.

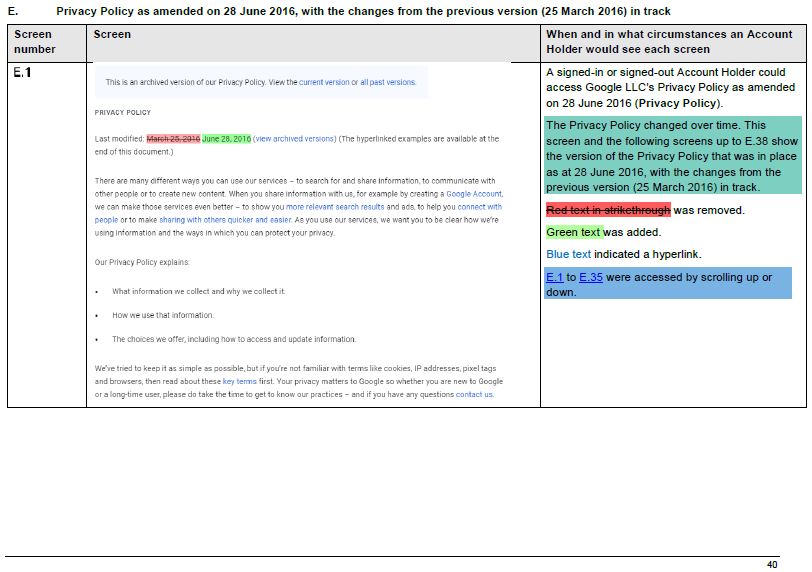

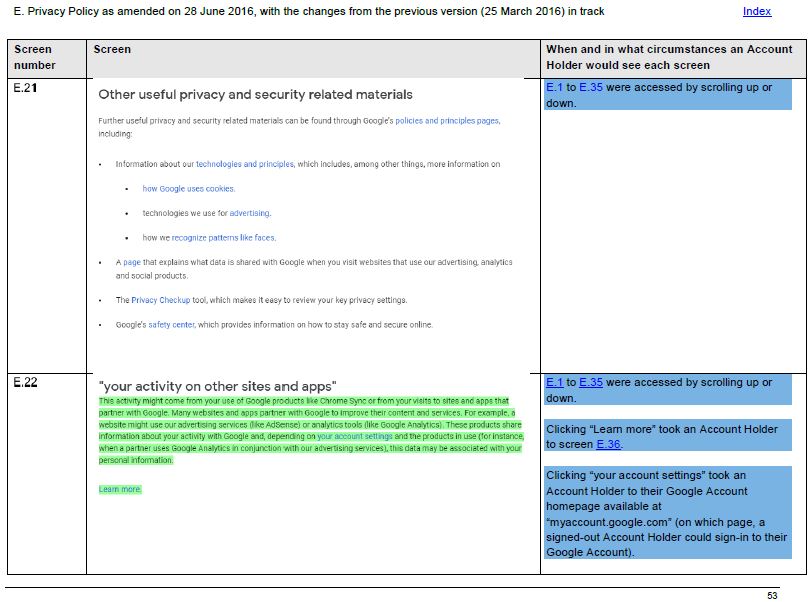

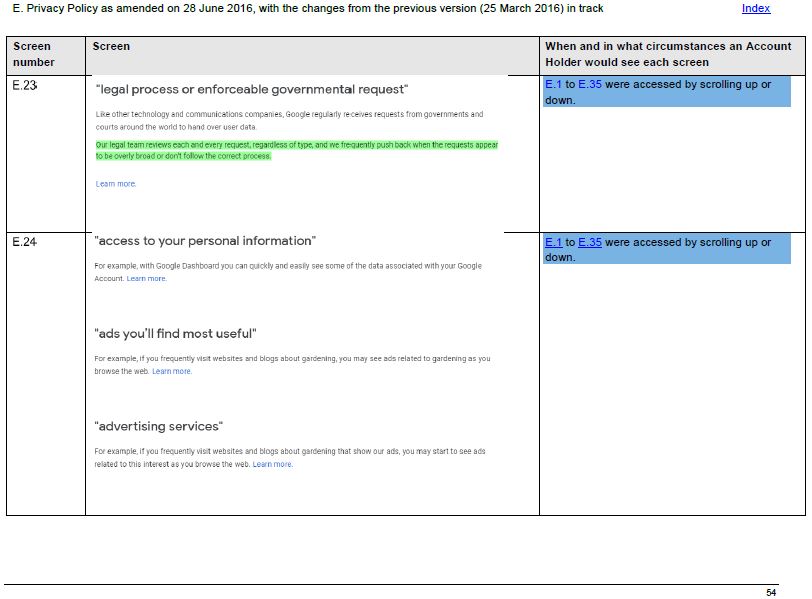

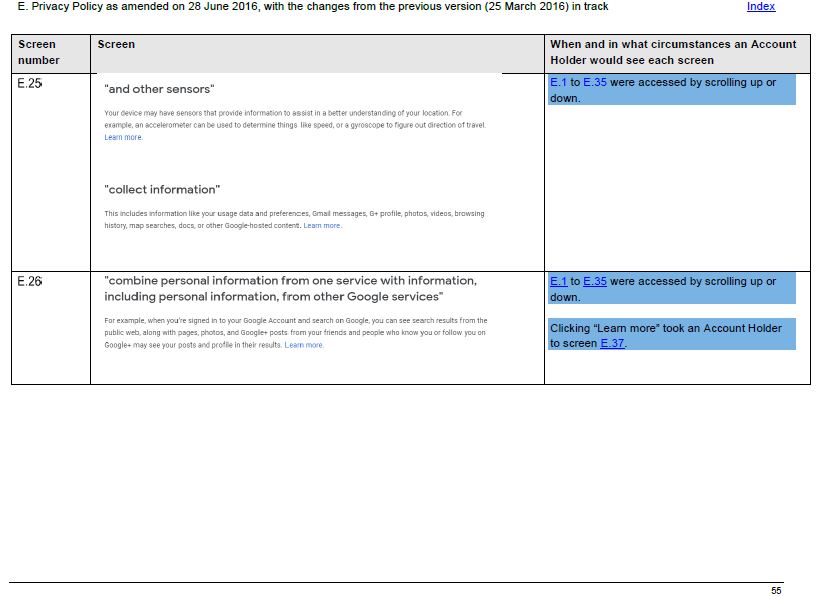

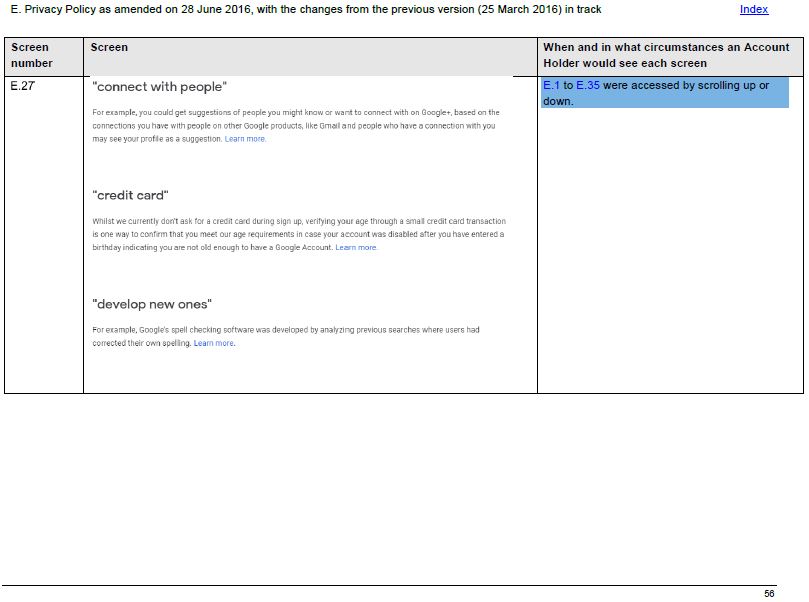

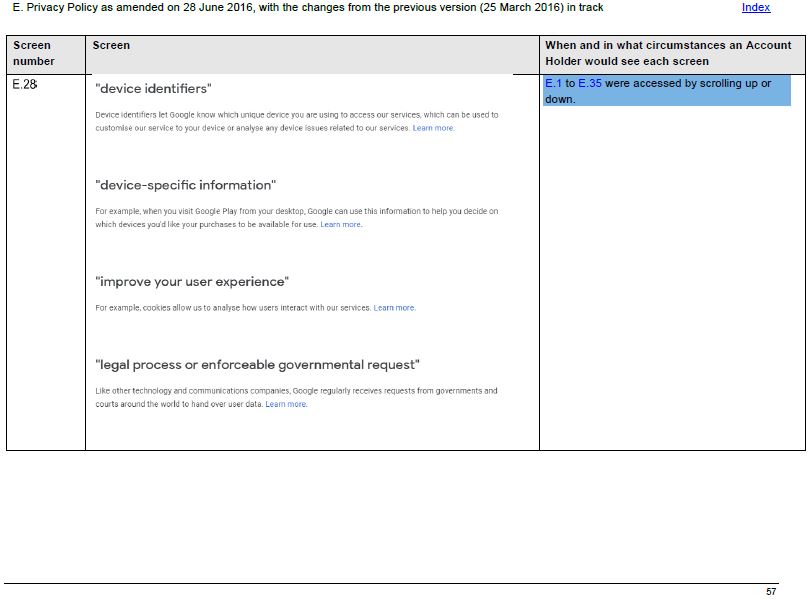

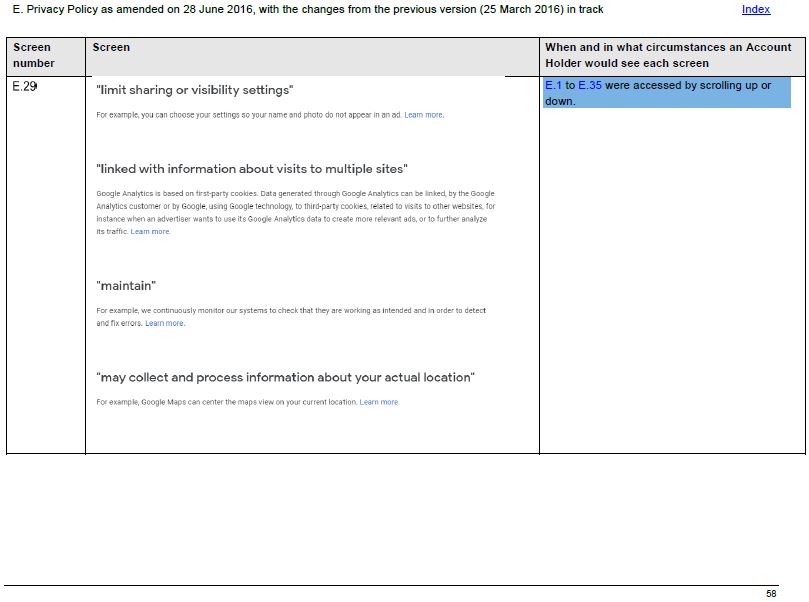

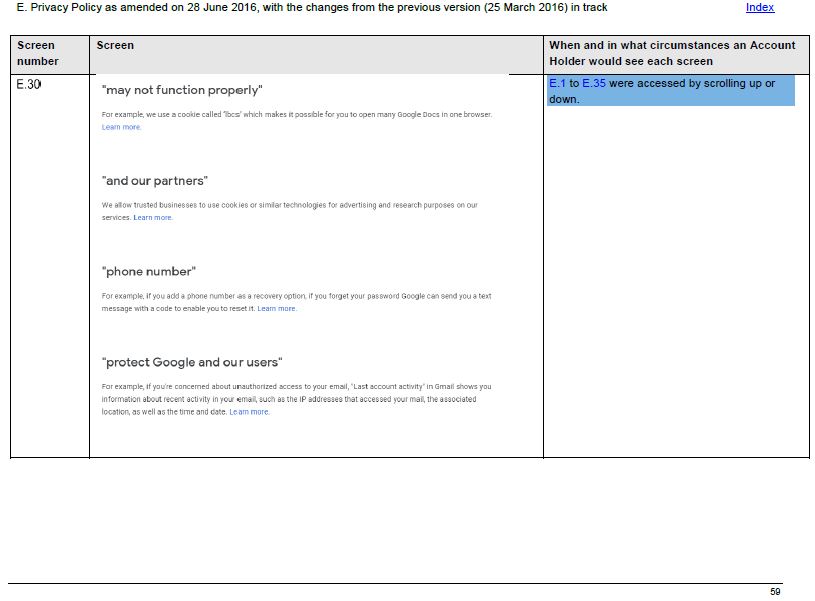

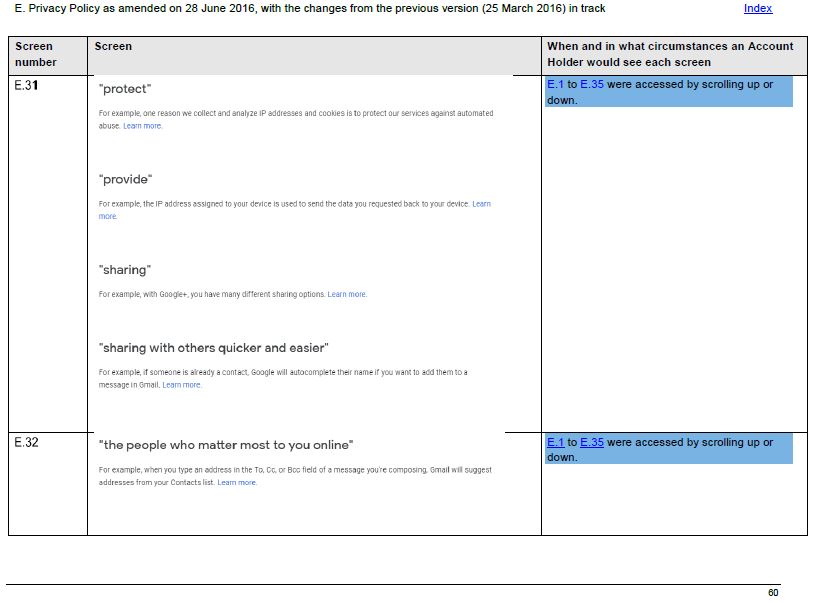

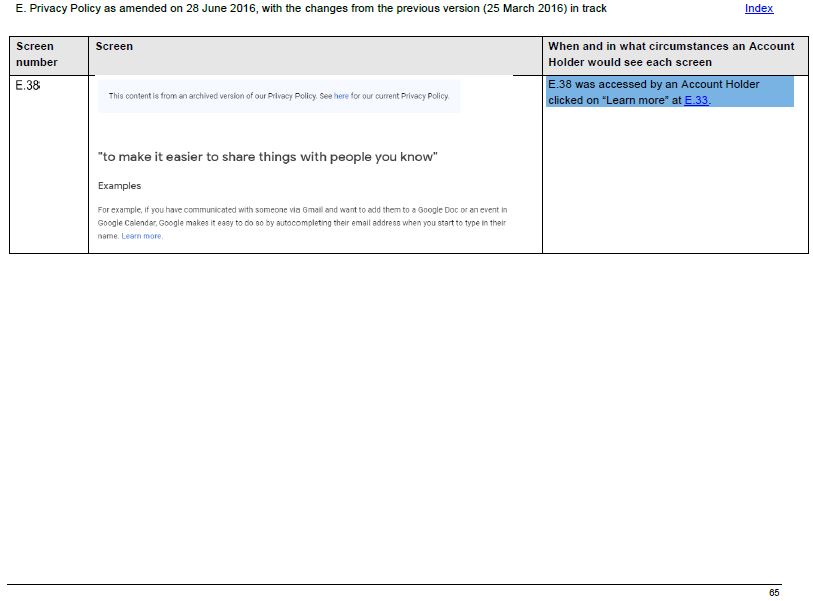

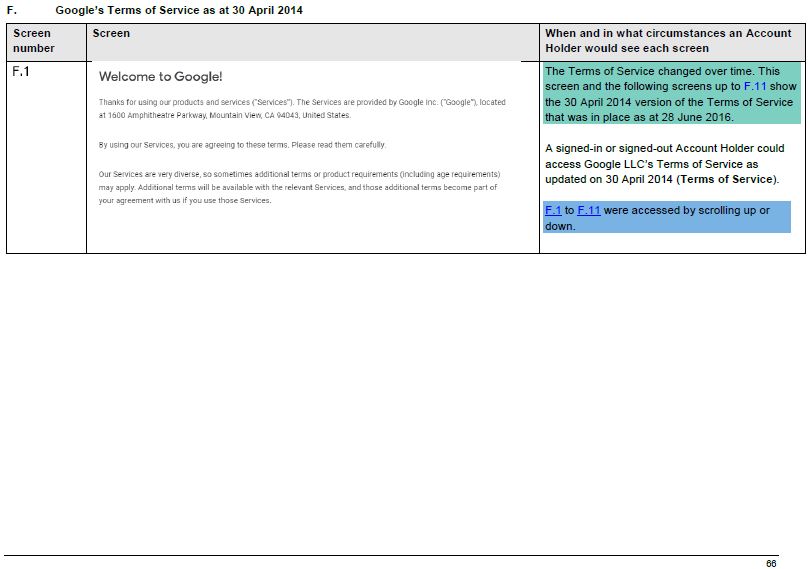

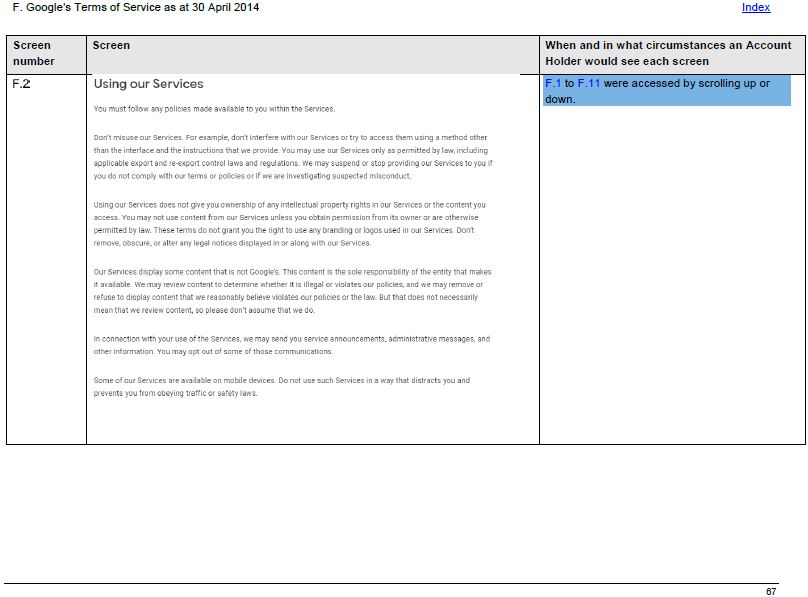

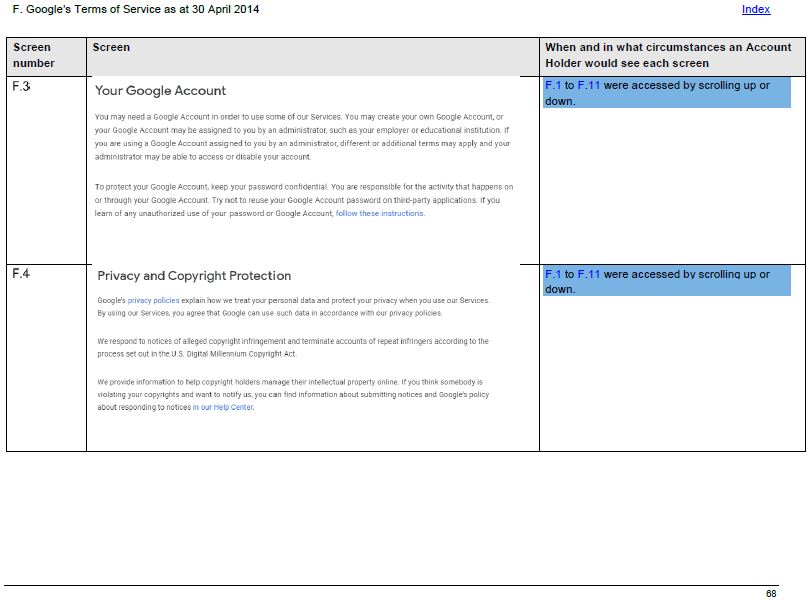

12 The evidence comprises a Statement of Agreed Facts dated 12 March 2021, prepared pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act), and a number of documentary tenders. The Statement of Agreed Facts annexes a collection of screenshots depicting the various forms in which the Notification was given to Account Holders, Google’s Privacy Policy, and Google’s Terms of Service (the Screenshot Bundle). I have reproduced the Screenshot Bundle in Schedule A to these reasons.

13 Each party also called expert evidence. The Commission called Associate Professor Elise Payzan-LeNestour. Google called Professor John List.

14 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour is a behavioural scientist who undertook her PhD research at the Swiss Finance Institute at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in 2009 in Neurofinance. She completed the first part of her PhD at the London School of Economics.

15 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour commenced as a Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in the School of Banking and Finance in 2010, and was promoted to the position of Associate Professor in 2018. She currently teaches in the Behavioural Finance course offered at undergraduate and Masters levels at the UNSW Business School.

16 As explained by Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour, Neurofinance is a new kind of behavioural economics that consists of integrating insights from psychological research into economic science. She explained that, while standard behavioural economics focuses on describing how individuals behave, Neurofinance addresses the origins of observed behaviour at the neurobiological level.

17 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour also described Neurofinance as a subfield of Neuroeconomics, which involves “the application of insights from decision neuroscience to predict economic behaviour both at the individual and collective/aggregate levels”.

18 According to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour, her expertise in Neurofinance encompassed all that concerns individual decision-making under uncertainty: that is, how individuals acquire and process information to form an opinion when they have to decide under uncertainty, and how they make a decision on the basis of their opinion.

19 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour prepared two reports, dated 26 July 2021 (first report) and 3 September 2021 (second report) respectively. Her second report responded to a report prepared by Professor List.

20 Among other appointments, Professor List is the Kenneth C. Griffin Distinguished Service Professor in Economics at the University of Chicago and the Distinguished John Mitchell Professor of Economics in the Research School of Economics at Australian National University. He has a PhD in Economics. He is the recipient of a number of Honorary Doctorates. In addition to his academic responsibilities, Professor List is currently the Chief Economist at Lyft Inc. and a Senior Consultant at Compass Lexecon.

21 Professor List said that his research makes extensive use of behavioural economics and experimental economics to evaluate a wide variety of issues, including how individuals make decisions, the external validity of behavioural and experimental economic analysis, the valuation of environmental amenities, education outcomes, and charitable giving.

22 Professor List has received numerous awards for his scholarship, including being named in the “Top 25 Behavioural Economists” by TheBestSchool.org.

23 Professor List’s report is dated 9 August 2021. It responded to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report.

24 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour and Professor List prepared a Joint Expert Report. They gave their oral evidence concurrently.

25 No consumer evidence (from Account Holders) was called.

Google’s objections to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s evidence

26 At the commencement of the hearing, Google objected to the admissibility of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports and to her comments in the Joint Expert Report. Amongst other objections, Google raised a number of “global” objections.

27 One “global” objection was that the questions asked of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour (to which her first report was directed) sought an opinion that was not based, wholly or substantially, on her “specialised knowledge”, within the meaning of s 79 of the Evidence Act.

28 There were two aspects to this objection. The first aspect was that Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s opinions were based on her own, non-expert reading of the Notification. The second aspect was that Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report was directed, in part, to answering a particular question by reference to “the principles applying to information acquisition and processing in the context of navigating through screens on a desktop or mobile device”. Google submitted that Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour had no specialised knowledge in relation to that particular matter, and had referred to no such principles in her reports.

29 This objection was made in the following context. On 15 September 2021, I made orders by consent that provided for the convening of a joint conference of experts to prepare a joint report identifying, in summary form, the principal areas of agreement between them, and the principal areas of disagreement between them (including the reasons for that disagreement). The joint report was also to identify whether, and in what respects, the experts’ respective opinions departed from the opinions they had expressed in their reports.

30 By the time these orders were made, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s two reports had been served. Professor List’s responding report had also been served. Significantly, at that time, Google had not raised any objection that the opinions expressed in Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s two reports were not based wholly or substantially on her specialised knowledge.

31 Pursuant to the orders made on 15 September 2021, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour and Professor List met, online, on 5 October 2021 and 15 October 2021, and prepared the Joint Expert Report.

32 The first time that an objection to the admissibility of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports was raised with the Court was in Google’s written opening submissions dated 22 November 2021, five business days before the commencement of the final hearing.

33 Section 192A of the Evidence Act provides the facility for the Court to give a ruling on the admissibility of evidence, in advance of that evidence being adduced, should the Court consider it appropriate to do so. Google did not seek to use that facility, even though the basis for objecting to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports, on the ground that the opinions she expressed were not based wholly or substantially on specialised knowledge, must have been apparent to it relatively shortly after the service of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report in July 2021.

34 There is an oddity in objecting to the admissibility of opinion evidence, on the basis that the opinion is not wholly or substantially based on specialised knowledge, after the party objecting to the evidence has not only engaged, substantively, with the opinion by filing a responding expert’s report, but has also engaged with the opinion through participation, without objection, in a conference of experts directed to preparing a joint report of the kind sought by the orders made on 15 September 2021.

35 The objection that Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s opinions were not based wholly or substantially on her specialised knowledge was not clear cut—although, as I explain in a later section of these reasons, I accept that her opinions proceeded from her own, non-expert reading of the Notification.

36 Google made other “global” objections to the admissibility of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports, including that, should the Court come to the view that Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour had specialised knowledge relevant to the determination of the matters in issue in the proceeding, her opinions: (a) were not expressed in a manner which permitted the Court to be satisfied that they were based on that specialised knowledge; and (b) trespassed beyond the matters pleaded in the Amended Concise Statement. Once again, the basis for these objections would also have been apparent to Google relatively shortly after the service of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report in July 2021.

37 It is important to note that success on any of these objections would not have led, necessarily, to the rejection of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports, or her comments in the Joint Expert Report, in their entirety.

38 At the time when these objections were raised in opening, I expressed my concern that, in order to rule on them, it would be necessary for me to have a deep understanding of not only Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report (which was complex), but also Professor List’s responding report, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s second report, and the Joint Expert Report. I was concerned that dealing with Google’s “global” objections at that time would be a significant undertaking that would adversely impact on the trial schedule. I suggested that the better course, in the present case, was to admit all the expert evidence, leaving it to the parties to address me in closing submissions on the weight I should give it.

39 Google expressed its concern that, if it acquiesced in that course, it might be taken as consenting to an “enlarged case” which, it contended, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour had addressed. In response, I made it clear that I would not countenance any suggestion that the case that Google was required to meet was something other than the case presented in the Amended Concise Statement.

40 In light of that indication, Google did not proceed with its objections. Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s reports, and her comments in the Joint Expert Report, were admitted into evidence accordingly.

41 As the parties recognised, the present case does not involve any novel question of law. The relevant legal principles are well-settled. Nevertheless, the Commission called in aid the following uncontentious principles.

42 First, conduct will be misleading or deceptive if it induces or is capable of inducing error or has a tendency to lead into error: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 (TPG) at [39].

43 Secondly, whether particular conduct is misleading or deceptive is a question of fact to be determined having regard to the context in which the conduct takes place and the surrounding facts and circumstances: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd [1982] HCA 44; 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 198 – 199; Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Limited (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202.

44 In this connection, the Commission submitted that the assessment of Google’s conduct should not be limited to the text of the Notification. Rather, regard should be had to all the surrounding facts and circumstances. The Commission submitted that this included Google’s business records which, the Commission submitted, revealed that the Notification was designed to maximise the number of people who clicked “I AGREE”. The Commission submitted that the Notification was not designed to maximise the number of people who understood the implications of agreeing to Notification. I observe, however, that no such allegation is made in the Amended Concise Statement.

45 Thirdly, the Commission submitted that half-truths may amount to misleading representations. In this connection, the Commission referred to the following passage in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1047 (LG Electronics) at [53]:

53 It can readily be accepted that a half a truth may be worse than a blatant lie. A half-truth may beguile the receiver of the half-truth into a false sense that he or she is receiving the whole truth and nothing but the truth – and hence is under the understanding, and reasonable and legitimate expectation, that the person giving the information is presenting all the information necessary for the recipient to act accordingly.

46 Fourthly, the Commission submitted that the conduct in question must be considered by reference to the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct.

47 The Commission relied on the following passage from Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; 278 FCR 450 at [22(e)]:

22 The applicable principles concerning the statutory prohibition of misleading or deceptive conduct (and closely related prohibitions) in the ACL are well known and there was no dispute between the parties concerning those principles. The central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 200 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 (Campomar) at [98]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG Internet) at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; Campbell at [25] per French CJ. A number of subsidiary principles, directed to the central question, have been developed:

…

(e) … where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]–[105]; Google at [7] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

48 Fifthly, and relatedly, the Commission submitted that it is not necessary to approach the analysis of the conduct in question by isolating one hypothetical person within the class who had one response or reaction to the conduct to determine whether there has been a contravention: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 367; 391 ALR 346 at [87] – [98].

49 In relation to s 18 of the ACL, Google also referred to the first and fourth principles noted above. In addition, it submitted that while conduct which has a tendency to lead a consumer into error might be misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, the causing of confusion or questioning is insufficient: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [39]. Further, it submitted that whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is a question of fact to be determined objectively. Google accepted that there was no need for the Commission to prove that any person was actually misled or deceived (Puxu at 199) or that Google acted with an intention to mislead or deceive (TPG at [56]).

50 Google submitted that, where conduct is directed to the public at large, or to a section of the public, rather than to identified individuals, the conduct in question should be tested against an ordinary or reasonable member of that class, disregarding assumptions by persons whose reactions are extreme or fanciful. The class does not include consumers who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests: Puxu at 199; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [105].

51 Finally, Google submitted that, where the Court is concerned to ascertain the mental impression created by a number of representations conveyed by one communication, it is wrong to attempt to analyse the separate effect of each representation. Rather, the conduct must be viewed as a whole. Viewing isolated parts of the conduct “invites error”: Puxu at 199; Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; 218 CLR 592 at [109]; Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [102]; TPG at [52].

52 To appreciate the significance of the changes that Google sought to introduce by Narnia 2.0, it is necessary to understand the nature of the various services that Google provides; the settings presently relevant to the use of Google Accounts by signed-in Account Holders; the information in relation to Account Holders which, before the relevant period, Google was entitled to collect and store; and the information which, before the relevant period, Google was entitled to combine or associate with other information.

53 To create an account with Google (a Google Account), a person is required to create a username and password and to provide personal information, such as the person’s name and date of birth. The person is prompted to provide additional personal information, such as the person’s gender and location. The person is also required to accept Google’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. The Account Holder’s personal information is then associated with that person’s Google Account.

54 Google supplies a range of services which include an internet search engine (Google Search); a mapping service (Google Maps); an email service (Gmail); an online video platform (YouTube); an online entertainment store (Google Play); and an internet web browser (Google Chrome) (together, Google Services).

55 Some Google Services, like Gmail and Google Play, require Account Holders to be signed-in to their Google Account to use the service. Other Google Services, such as YouTube and Google Maps, can be used without a Google Account, but may have reduced functionality if an Account Holder is not signed-in to their Google Account when using the service.

56 Google provides online display advertising and analytics services to individuals and businesses. Google derives the majority of its revenue from these services.

57 Online display advertising services connect website and app publishers to advertisers for the purposes of utilising advertising space. The services match the criteria of advertisers with the criteria of the website or app publishers, so as to display advertisements that are likely to be of interest to the person viewing the website or app in question.

58 For present purposes, online display advertising may be classified as Pseudonymous Advertising or Account-based Advertising.

59 Pseudonymous Advertising is informed by the pseudonymous usage history of a particular browser on a particular computer or particular mobile device. The usage history is collected from the browser used on a computer via “cookies” or from the mobile device using equivalent technology.

60 Cookies are small pieces of text sent to a user’s browser by the website that is being visited. The cookies can be configured to record a unique identifier that helps a website remember information about a user’s visit using a particular browser and enables content or advertisements to be delivered (“served”) to users of that browser based on those visits. Cookies (and the equivalent technology on mobile devices and apps) do not require a Google Account to function.

61 Pseudonymous Advertising is tailored to an individual user only to a limited extent. It is informed only by the usage history of a particular browser on a particular computer or particular mobile device. There may be more than one user of the particular browser on the particular computer or the particular mobile device. Further, a person’s usage of their browser on, say, a work computer cannot inform the advertising served to that person on their home computer.

62 Account-based Advertising is informed by information that includes account activity (such as IP address, time/date, URL and advertisements served) stored in an Account Holder’s account. Once again, this information is recorded via cookies on browsers, or equivalent technology (in the case of mobile devices). Unlike Pseudonymous Advertising, Account-based Advertising serves advertisements regardless of the device used. For example, in relation to Google Accounts, Account-based Advertising on an Account Holder’s personal mobile phone or home computer may be informed by that person’s usage on their work computer or mobile phone, if that person is signed-in to their Google Account on all of those devices and has other relevant settings enabled.

Relevant settings and the storage of information

63 The following settings in respect of Account Holders’ Google Accounts are relevant to the present case:

(a) the WAA (Web and App Activity) Setting;

(b) the Ad Personalisation Setting;

(c) the Chrome Sync Setting; and

(d) the SWAA (Supplemental Web & App) Setting.

The WAA and Ad Personalisation Settings

64 The WAA Setting and the Ad Personalisation Setting are enabled by default during the sign-up process for a Google Account. When enabled, the WAA Setting permits Google to store, in association with the Account Holder’s Google Account, information about the activity of the signed-in Account Holder across Google Services, including:

(a) searches in Google Search;

(b) activity in Google Maps;

(c) activity in Google Play;

(d) articles read in Google News;

(e) commands given to Google Assistant and its response;

(f) any advertisements clicked on by the Account Holder; and

(g) data such as an Account Holder’s location, language and IP address.

65 When the Ad Personalisation Setting is also enabled, Google is permitted to deliver Account-based Advertising using that information to the signed-in Account Holder across Google Services.

66 This was the position both before and after 28 June 2016. It is important to note that, both before and after 28 June 2016, Account Holders could access, manage, and therefore change, their WAA Setting and Ad Personalisation Setting.

67 The SWAA Setting can only be enabled if the WAA setting is enabled.

68 If enabled, the SWAA Setting permits Google to associate with the Account Holder’s Google Account, information that includes: (a) certain app data from Android devices on which the Account Holder is signed-in (such as, whether the Account Holder has viewed multiple pages or sections of an app); and (b) the Account Holder’s Chrome internet browsing history (if the Chrome Sync Setting is enabled and the Account Holder has chosen to “sync” that person’s Chrome internet browsing history, as to which see [71] – [73] below).

69 This was the position both before and after 28 June 2016. Once again, it is important to note that, both before and after 28 June 2016, Account Holders could access, manage, and therefore change, their SWAA Setting.

70 Prior to 28 June 2016, information stored because the SWAA Setting was enabled (excluding information collected via the Google Mobile Ads SDK), was not used by Google to serve Account-based Advertising on Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps. However, I infer that this information could be used to serve Pseudonymous Advertising on Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps.

71 The Chrome Sync Setting enables Account Holders to choose whether Google can associate various aspects of their use of the Chrome internet browser with their Google Accounts, including their Chrome internet browsing history and other “synced” information (for example, bookmarks, passwords, and other settings on the their devices).

72 This was the position both before and after 28 June 2016.

73 During the relevant period, information stored because Chrome Sync was enabled was not used by Google to serve either Pseudonymous Advertising or Account-based Advertising on Google Partner Websites or Google Partner Apps. I infer it could, however, be used to serve advertisements to Account Holders on Google Services.

Other collection and storage of information

74 If websites elect to use Google advertising cookie technology, Google collects information (as Account Holders’ browser settings permit) about users’ and Account Holders’ internet browsing activities on Google Partner Websites via cookies set in the doubleclick.net web domain. This information is stored on a pseudonymous basis in association with an identifier unique to a user’s browser.

75 This was the position both before and after 28 June 2016.

76 If apps elect to use Google Mobile Advertising technology, Google collects information (as Account Holders’ browser settings permit) about users’ and Account Holders’ activities on third-party mobile device-based apps (such as in-app purchases, and views and interactions with in-app advertisements) using the Google Mobile Ads SDK (software development kit).

77 Before 28 June 2016, information collected using the Google Mobile Ads SDK was stored by Google on a pseudonymous basis in association with an identifier unique to the mobile device used, and was used by Google to deliver Pseudonymous Advertising on Google Partner Apps subsequently accessed using that mobile device. The information was not stored by Google in association with Account Holders’ Google Accounts (or any other personal information) without their consent, and was not used to serve Account-based Advertising.

78 This remained the position after 28 June 2016 if Account Holders did not turn on the “new features” in response to the Notification.

79 Prior to 28 June 2016, Google did not combine the information it collected about Account Holders’ activities on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps with personal information in Account Holders’ Google Accounts, unless Account Holders enabled and permitted Google to do so by means of the Chrome Sync Setting and/or the SWAA Setting.

80 Before 28 June 2016, if the WAA and Ad Personalisation Settings were enabled (as they were by default), Google was permitted to serve Account-based Advertising to Account Holders across Google Services using information based on their activity on Google Services.

81 In addition, if the SWAA Setting was enabled, prior to 28 June 2016, Google was permitted to associate supplementary information with Account Holders’ Google Accounts, which included certain app data and, if the Chrome Sync Setting was enabled and Account Holders had chosen to “sync” data, certain other data including their Chrome internet browsing history, to serve advertisements to them on Google Services.

82 Further, information collected by Google using the Google Mobile Ads SDK was stored by Google on a pseudonymous basis. This information was used by Google to serve Pseudonymous Advertising on Google Partner Apps subsequently accessed using the mobile device.

83 Therefore, before 28 June 2016, the only place where Account-based Advertising was served was on Google Services.

Changes sought to be introduced by Narnia 2.0

84 An internal Google document dated 18 July 2016 described the key goals of Narnia 2.0 as including:

• Holistic identity - Unifying our view of users’ cross-device identity and data across Google’s advertising and consumer products around GAIA. For display ads, we will enable GAIA-Keyed Serving (GKS) for millions of third party properties where Google’s display systems serves ads (e.g. NYTimes, BBC, Farmville, Weather.com’s app etc.).

• Informed consent - Obtaining users’ opt-in consent to unify Display Ads and Google identity per Google’s privacy policy. This consent is the legal and privacy foundation for GAIA-keyed serving, making it the lynchpin of Narnia 2. We get informed consent as part of the new account sign-up process, and via the “consent bump” for existing accounts.

• Better controls - Improving transparency and control for users over how Google uses their data across all their devices. With a signed-in experience, we can be much more transparent sharing user activity and exposing detailed controls. Without signed-in, we never know if a machine is shared. And these controls work only on a single browser or mobile device.

• Improved ad offerings - Building better ads products. Since significant user data at Google is GAIA-keyed data, leveraging this data for display ads will provide opportunities for improved personalization. Moreover, new ads capabilities, such as click-to-buy ads that connect to a user’s Google account, become possible in a GAIA-keyed system. Note: Our Moment of Consent (MOC) launch includes no substantial changes to our ad offerings -- these will come later.

85 The fundamental change introduced by Narnia 2.0, with the Account Holder’s explicit consent, was to expand the use of Account-based Advertising to Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps, taking into consideration information about the Account Holder’s activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps stored by Google in association with personal information in the Account Holder’s Google Account.

86 Specifically, if the Account Holder agreed to the proposed changes, the WAA Setting and the Ad Personalisation Setting were enabled to permit Google to serve Account-based Advertising using the information described at [64] above (i.e., information about the activity of a signed-in Account Holder across Google Services) across Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps as well as across Google Services.

87 Further, the SWAA Setting (which sat below the WAA Setting) was enabled to permit Google to associate, with the Account Holder’s Google Account, information from Third Party Websites visited when the Account Holder was signed-in to their Google Account, as well as the information referred to at [64] above. From 28 June 2016, this information also included information collected via the Google Mobile Ads SDK. The information stored (because the SWAA Setting was enabled) could be used by Google to serve Account-based Advertising on Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps.

88 For new Account Holders (i.e., persons who signed up for a Google Account from 28 June 2016), these changes were enabled by default. The present case, however, is only concerned with the position of those persons who were Account Holders as at 28 June 2016.

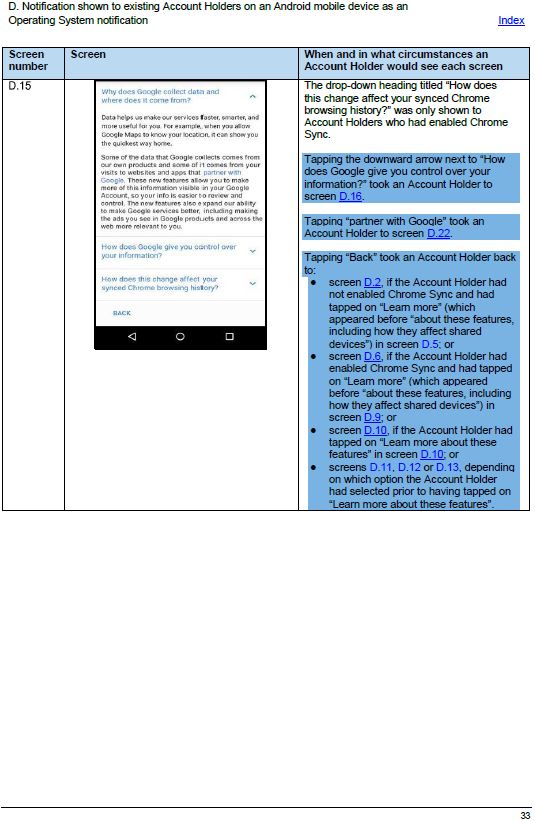

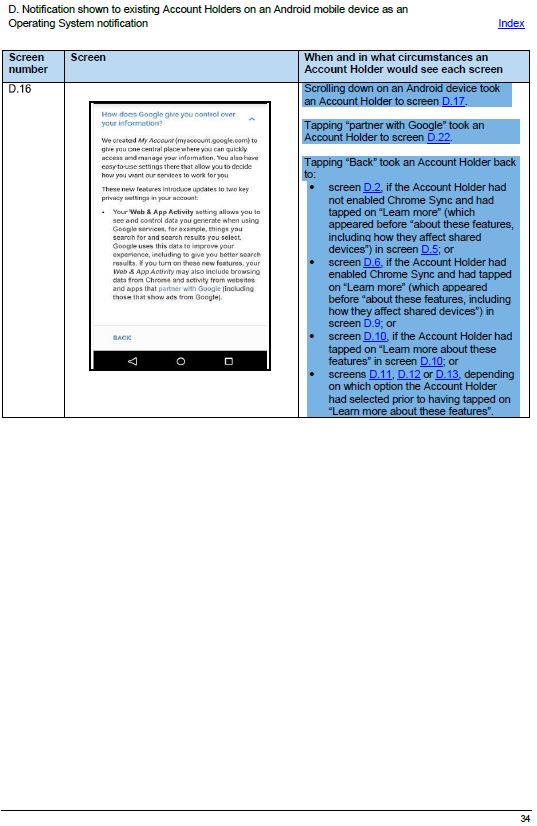

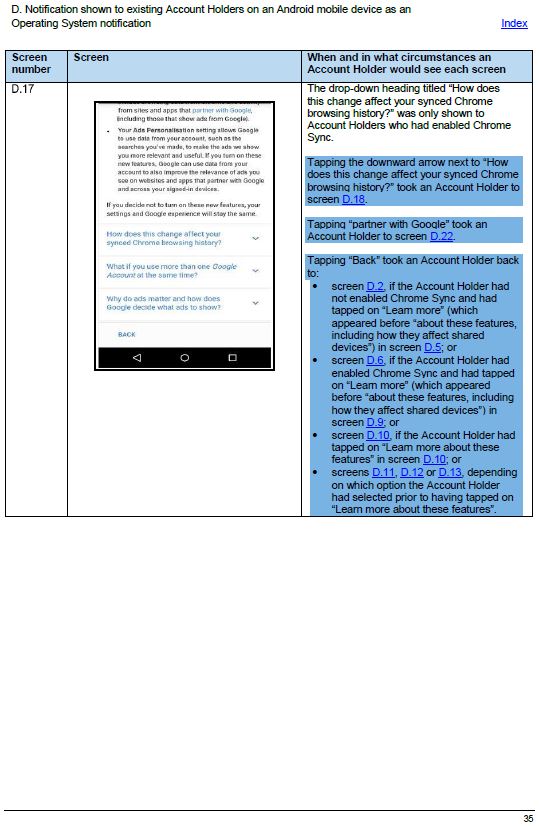

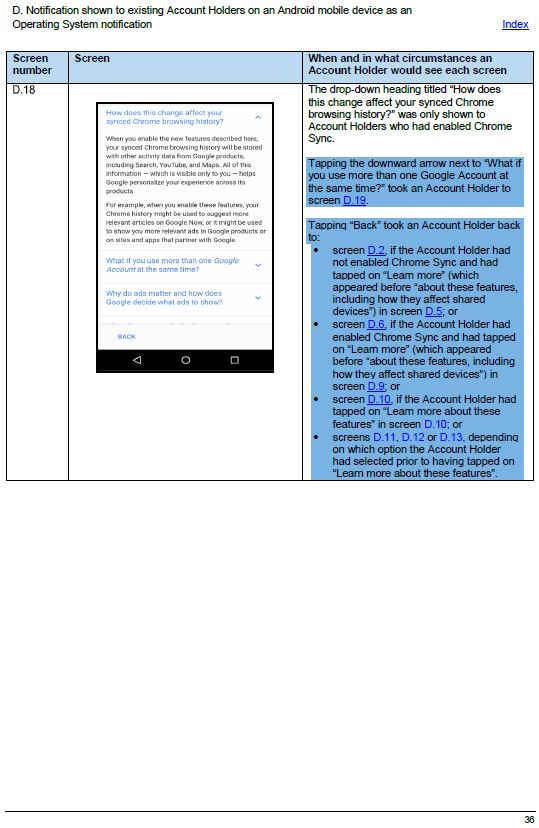

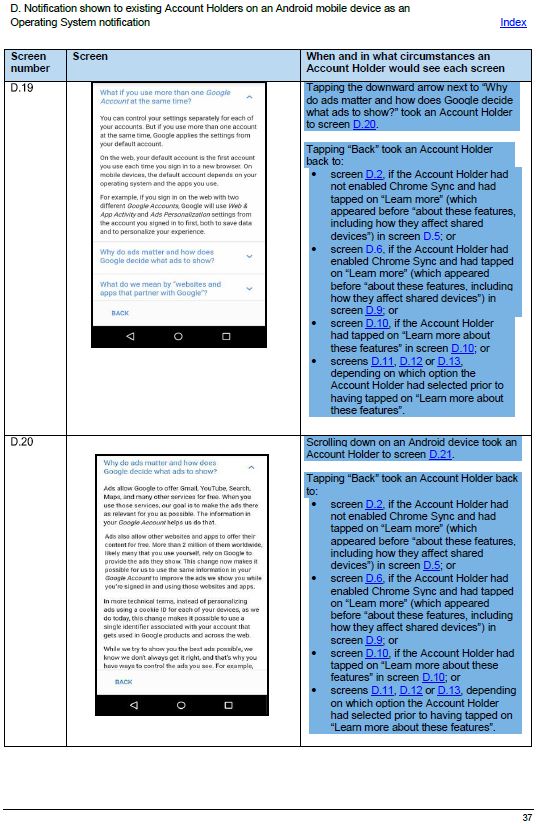

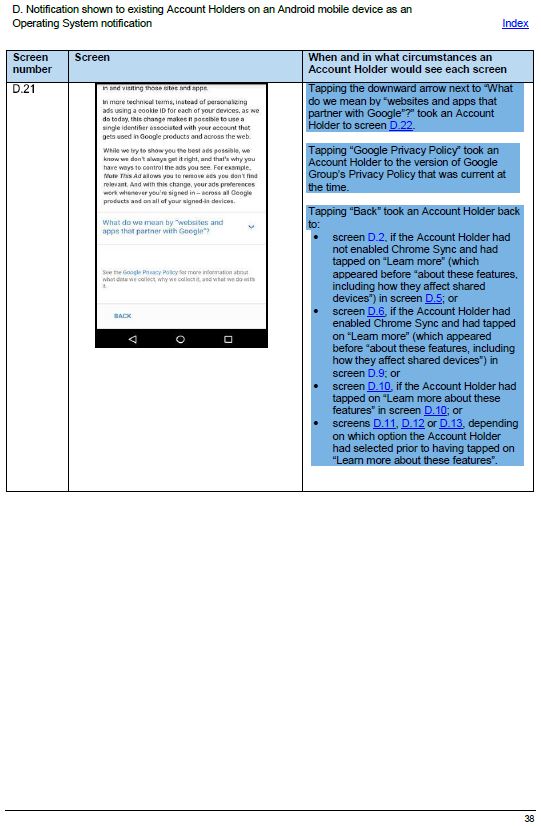

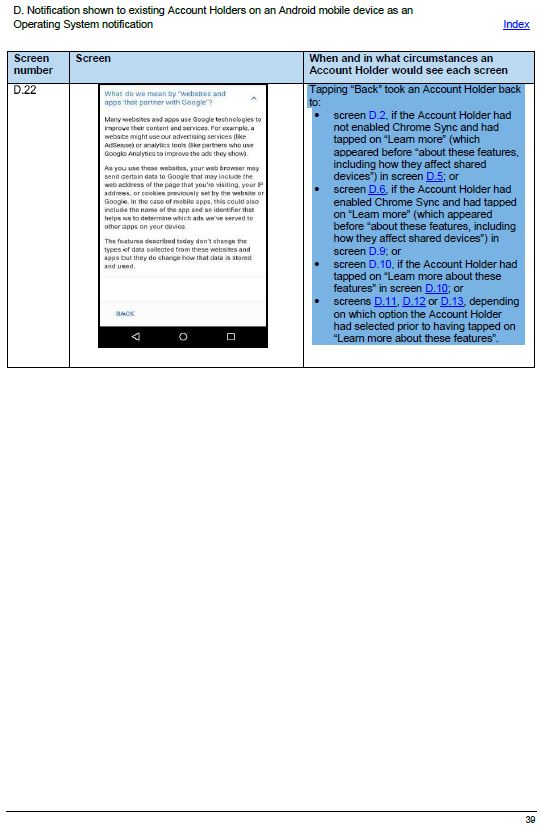

89 As I have said, the Notification appeared in different ways, depending on the Account Holder’s device and the Google Service they were using at the time.

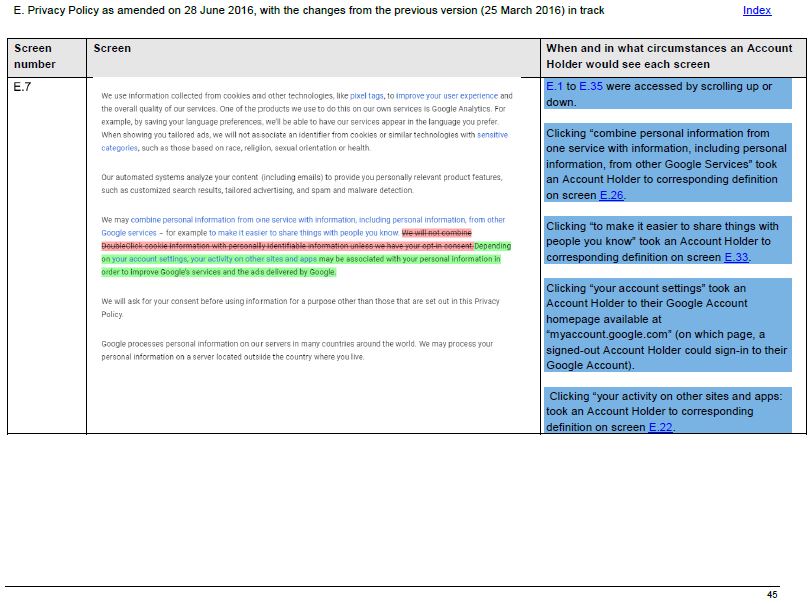

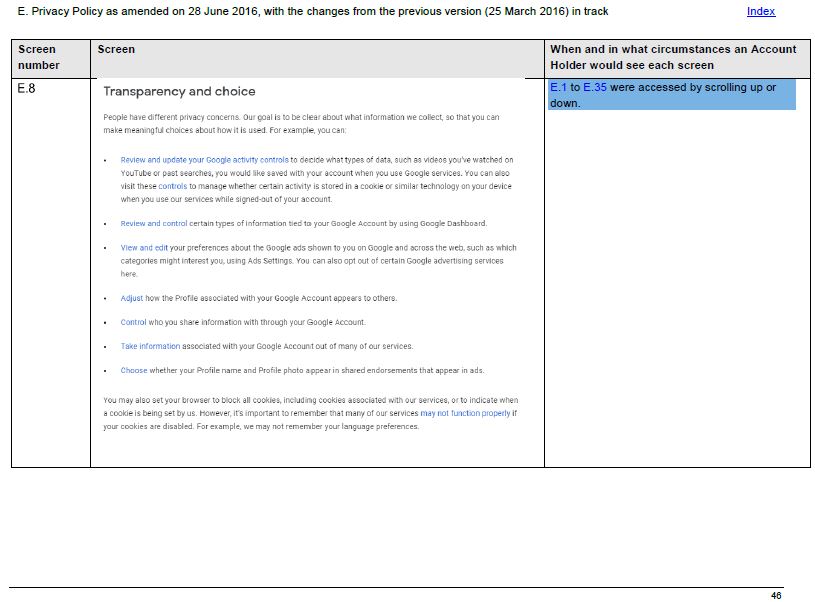

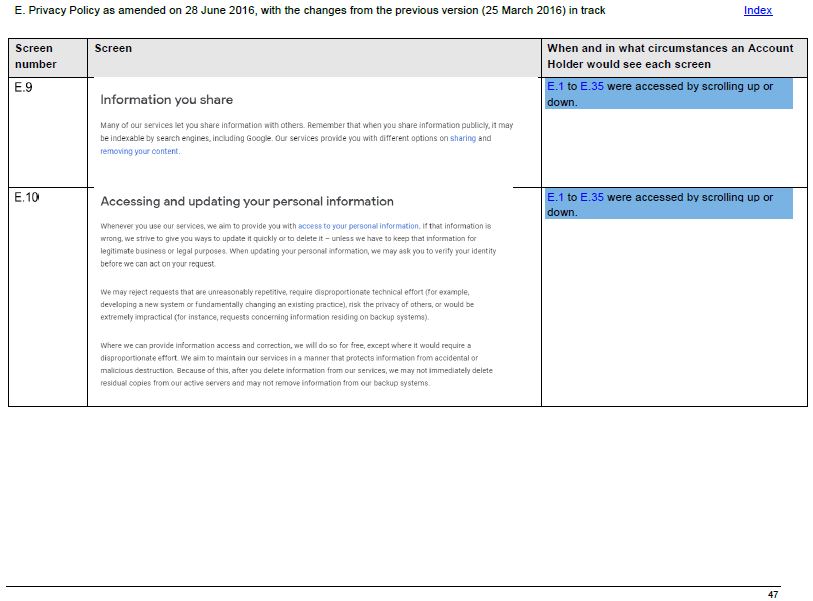

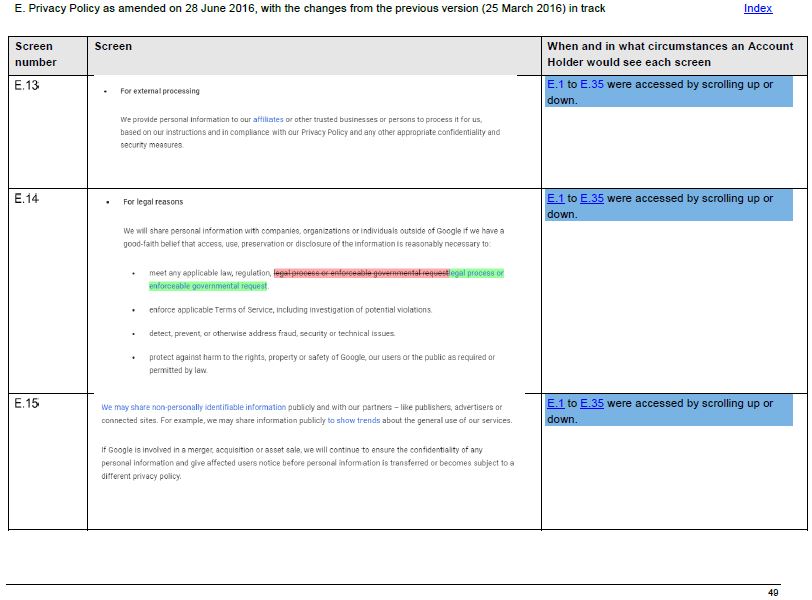

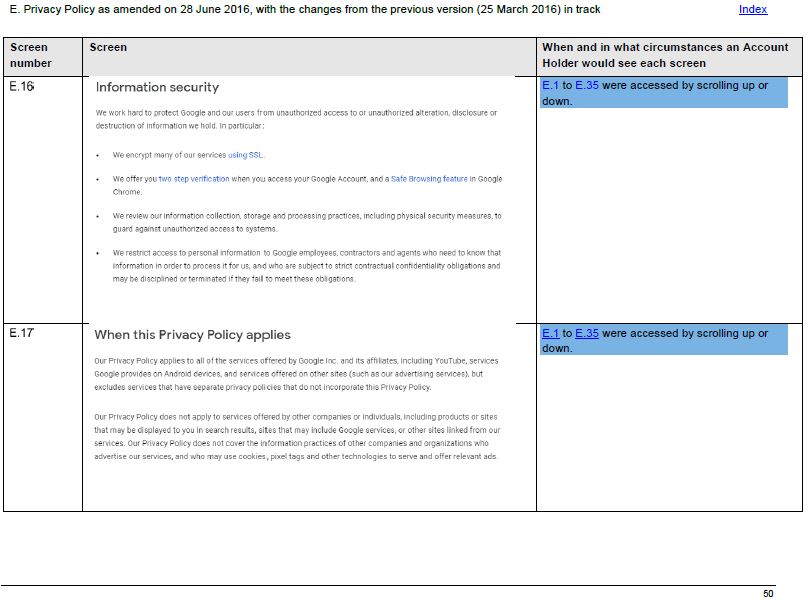

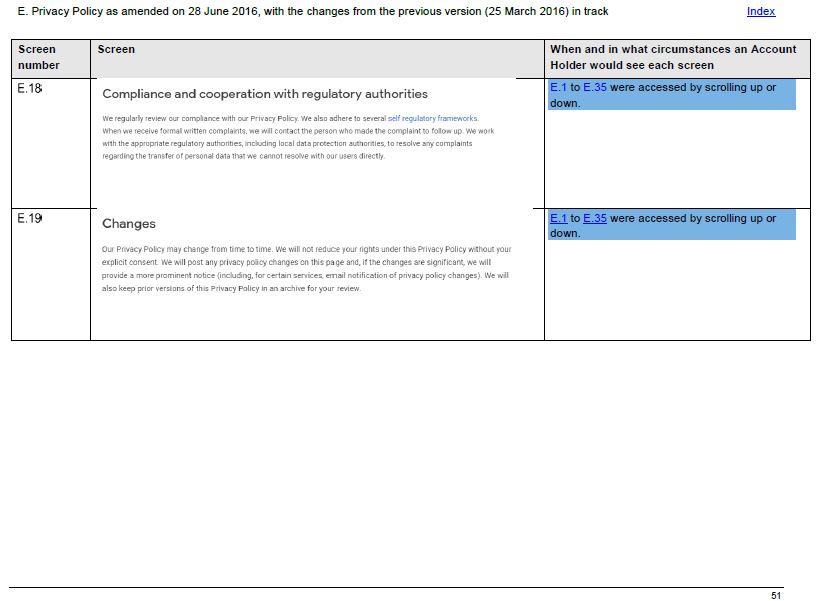

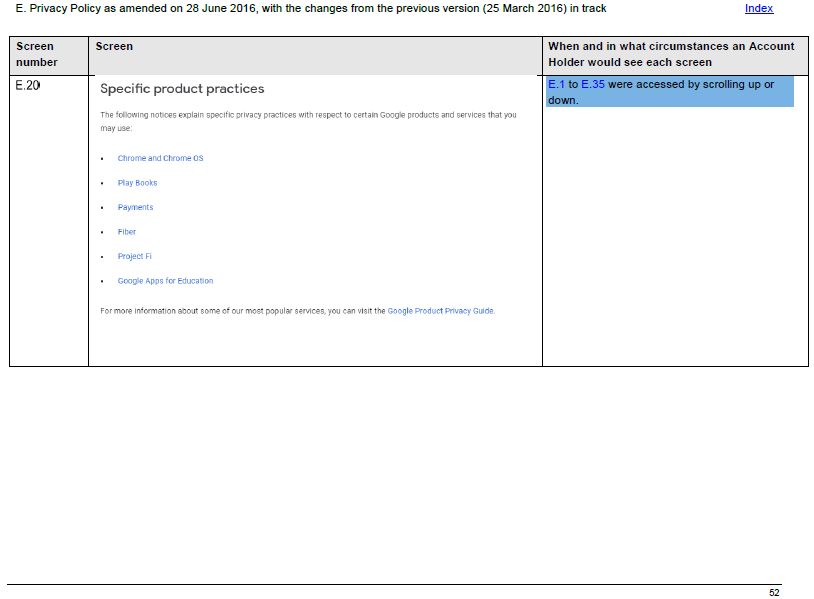

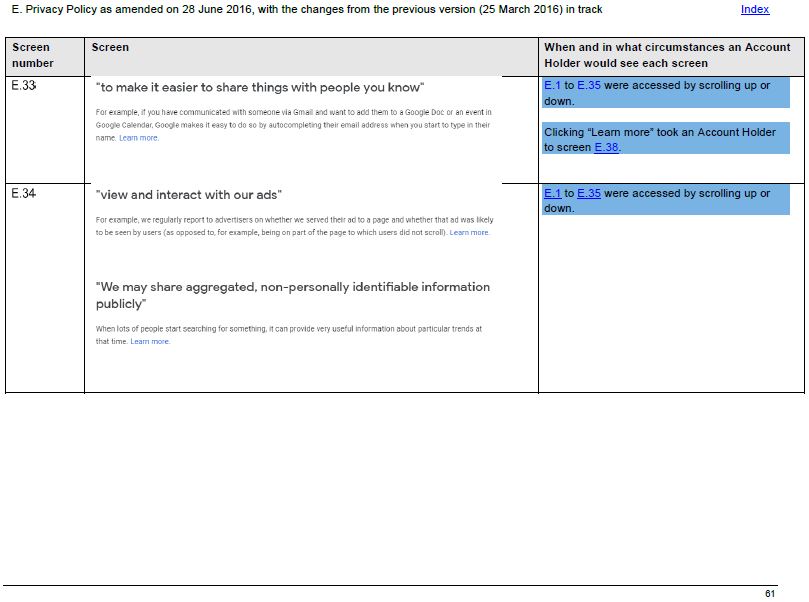

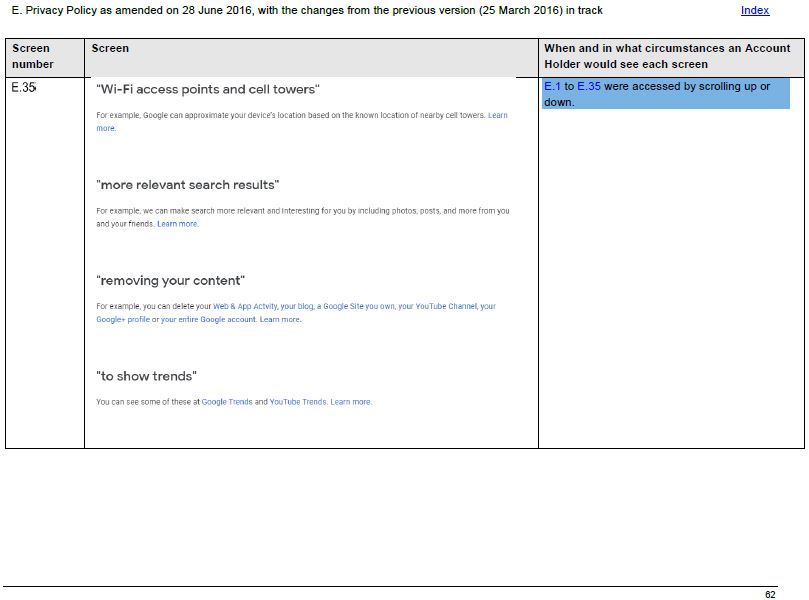

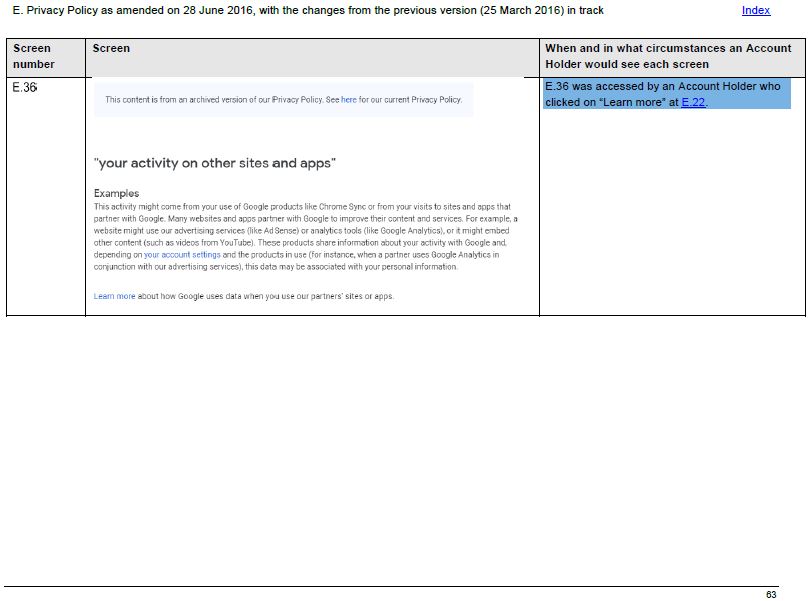

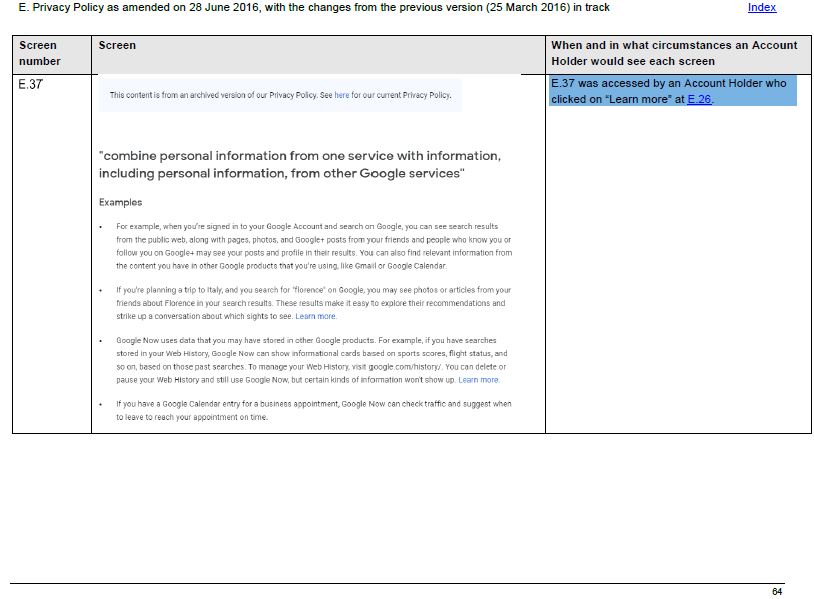

90 The Screenshot Bundle shows the various forms in which the Notification was given to an existing Account Holder:

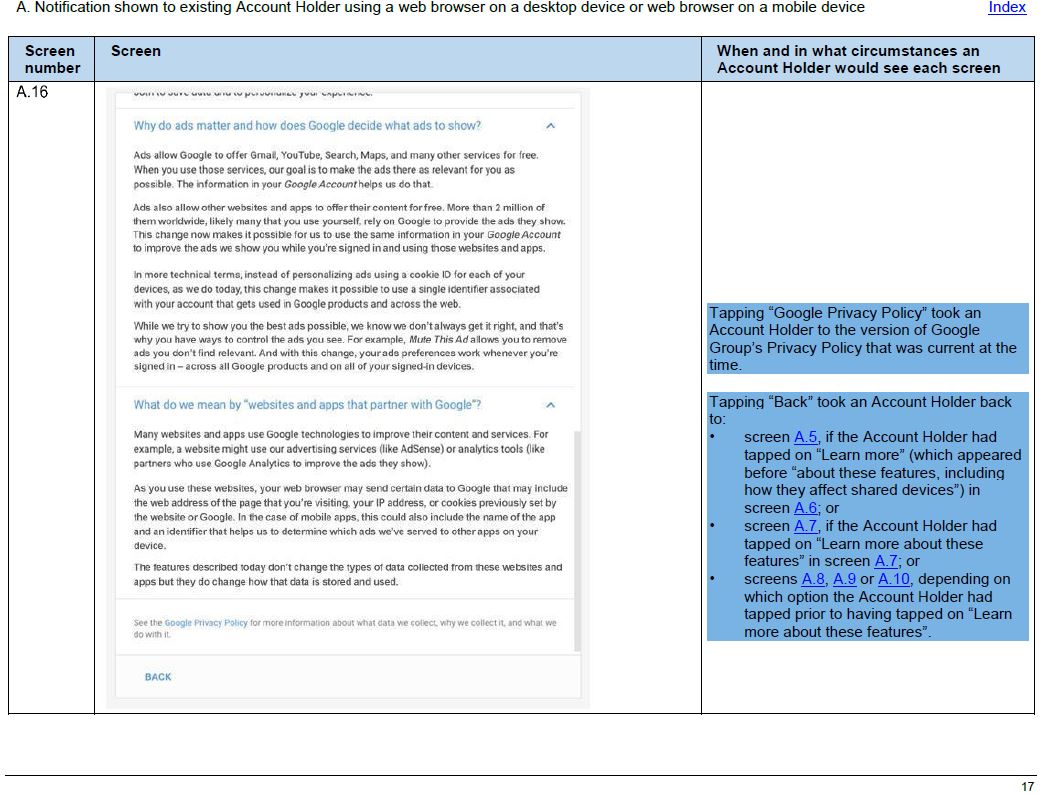

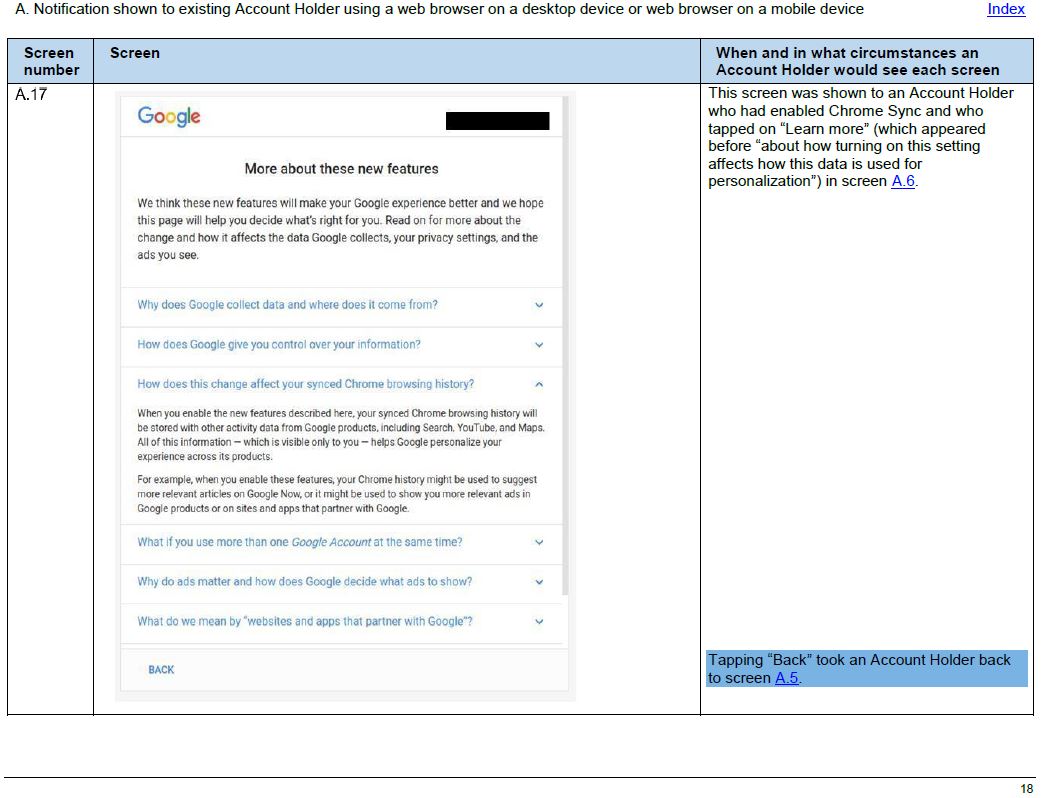

(a) using a web browser on a desktop device or web browser on a mobile device (screens A.1 – A.4 were the screens shown to signed-in Account Holders and screens A.5 – A.17 were the screens shown to Account Holders once signed-in);

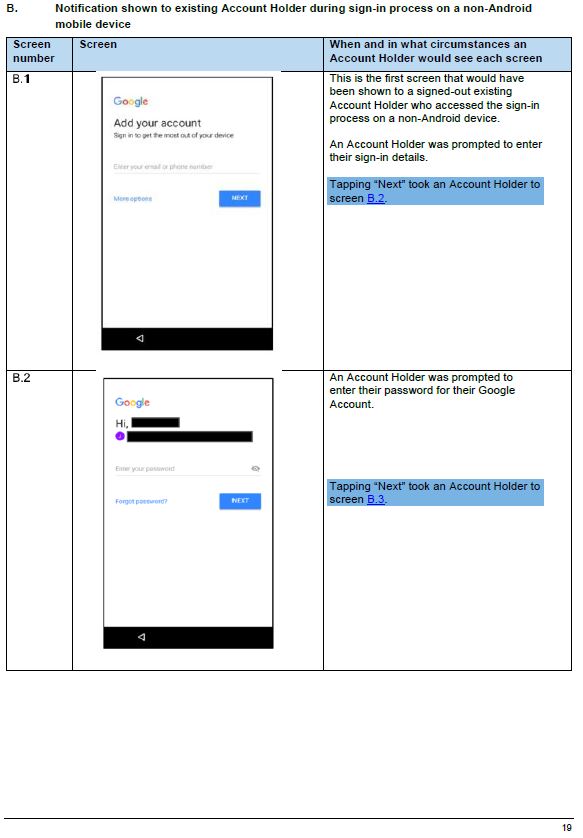

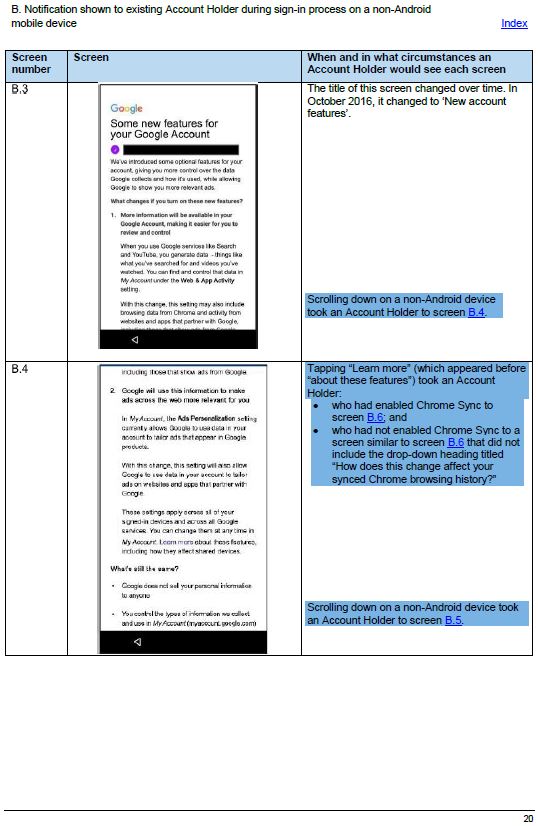

(b) during the sign-in process on a non-Android mobile device (screens B.1 – B.6);

(c) during the sign-in process on an Android mobile device (screens C.1 – C.8); and

(d) on an Android mobile device as an Operating System notification (screens D.1 – D.22).

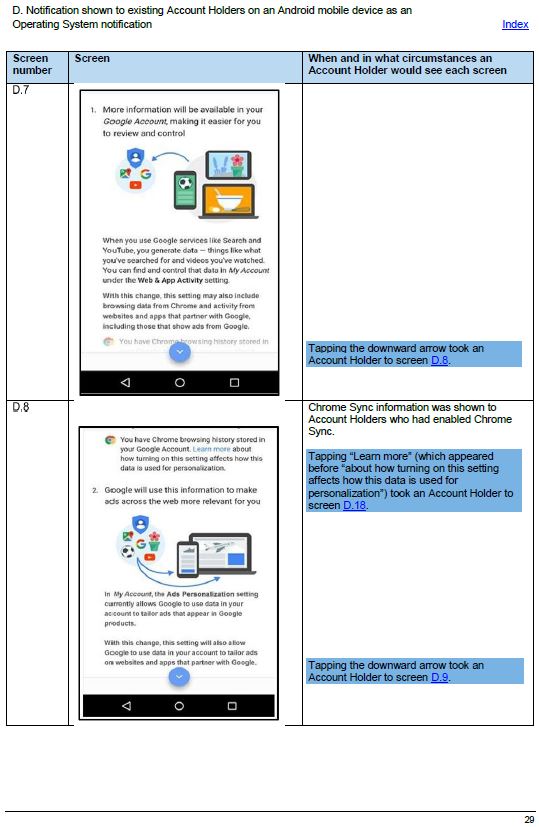

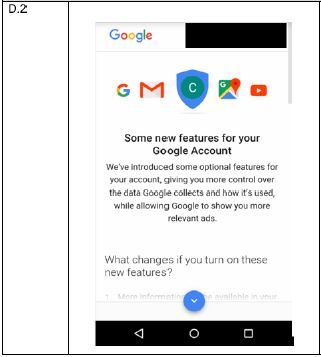

91 The parties advanced screens D.2 – D.5 as representative of the “main body” of the Notification (i.e., that part of the Notification that appeared to Account Holders without the Account Holder clicking additional links). Although four screens are depicted, screens D.2 – D.5 represent, in fact, one page through which Account Holders were required to scroll. This appears to have been the inevitable consequence of limited screen real estate. This page was referred to by the parties and expert witnesses as page 1 of the Notification:

92 Page 1 of the Notification commences with the heading “Some new features for your Google Account” (screen D.2). Icons for the Google Services are depicted above the heading.

93 The text proceeds by referring to the fact that there are some new features for the Account Holder’s Google Account that are “optional” features. The text conveys that the optional features concern how Google collects and uses data, and the control which the Account Holder has in respect of that data. The text also conveys that this relates to advertisements that Google shows to the Account Holder.

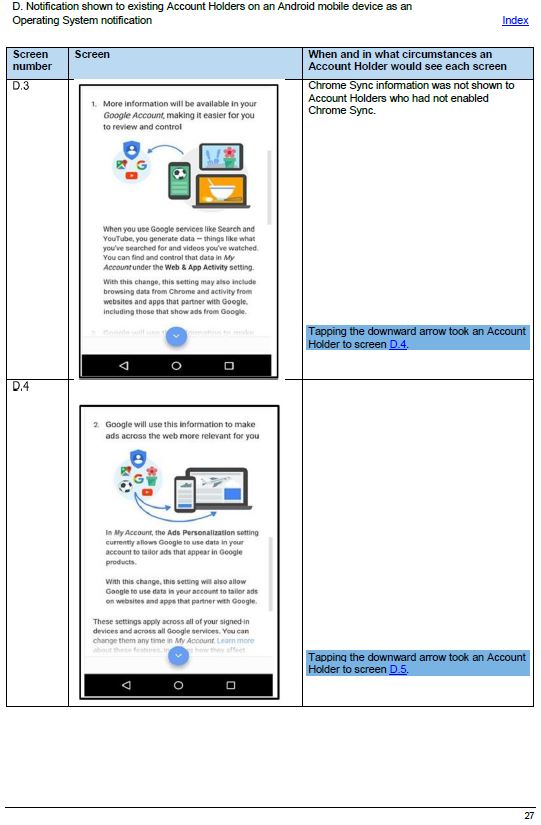

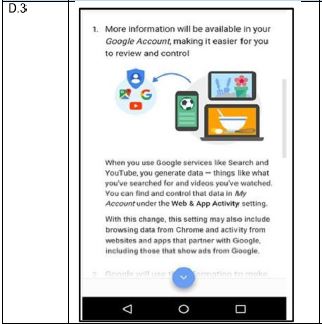

94 The question is posed: “What changes if you turn on these new features?” The use of the word “if” reiterates that the new features are optional for the Account Holder. As the Account Holder scrolls down page 1, the question is answered by reference to the numbered headings depicted in screens D.3 and D.4 and the text appearing under those headings.

95 The first numbered heading (screen D.3) refers to the fact that, if the Account Holder turns on the new features, more information will be available in the Account Holder’s account which, it is said, will make it easier for the Account Holder to review and control. The reference to the availability of “more” information in the Account Holder’s Google account is then explained.

96 In this connection, the Account Holder is told that, when they use Google Services, data is generated and that this data can be found and controlled by the Account Holder using the WAA Setting. Importantly, however, the Account Holder is also told that, “with this change”—clearly a reference to the change for which Google was seeking consent—other data may be included, namely the Account Holder’s browsing data from Chrome and data from their activity on websites and apps that partner with Google, including those that show ads from Google. It is important to note that, here, Google is addressing the Account Holder personally and referring to the Account Holder’s personal activity, not someone else’s browsing activity.

97 The diagram under the first numbered heading shows data from the Account Holder’s browsing activity on a mobile phone, tablet device, and a computer going into the Account Holder’s Google Account. The Account Holder’s Google Account is represented by some of the icons that depict Google Services, as well as the Google Account Holder icon (or “avatar”) itself.

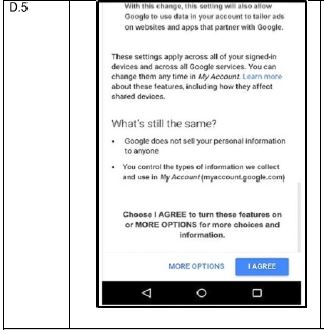

98 The second numbered heading (screen D.4) tells the Account Holder that “this information” (obviously meaning all the information collected by Google as discussed in relation to the first numbered heading) will be used by Google to “make ads across the web more relevant for you [the Account Holder]”.

99 As to this, the Account Holder is told that the Ad Personalisation Setting “currently” allows Google to use data in the Account Holder’s account to tailor ads that appear in Google “products”. This is a reference (although not by name) to the Account-based Advertising served by Google when the Account Holder is using Google Services.

100 Importantly, however, the Account Holder is told that, “with this change” the Ad Personalisation Setting will allow Google to use the data in the Account Holder’s Google Account to tailor advertisements on websites and apps that partner with Google. In other words, if the Account Holder turns on the new features, all the data that would then be available in the Account Holder’s Google Account will also be used in this way.

101 The diagram under the second numbered heading shows the expanded data in the Account Holder’s Google Account serving advertisements to a mobile phone and a computer (representing the Account Holder’s signed-in devices).

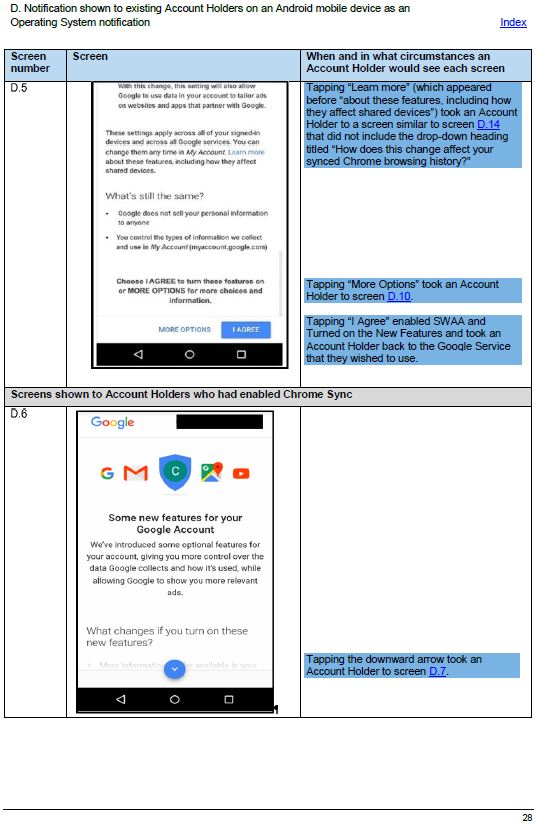

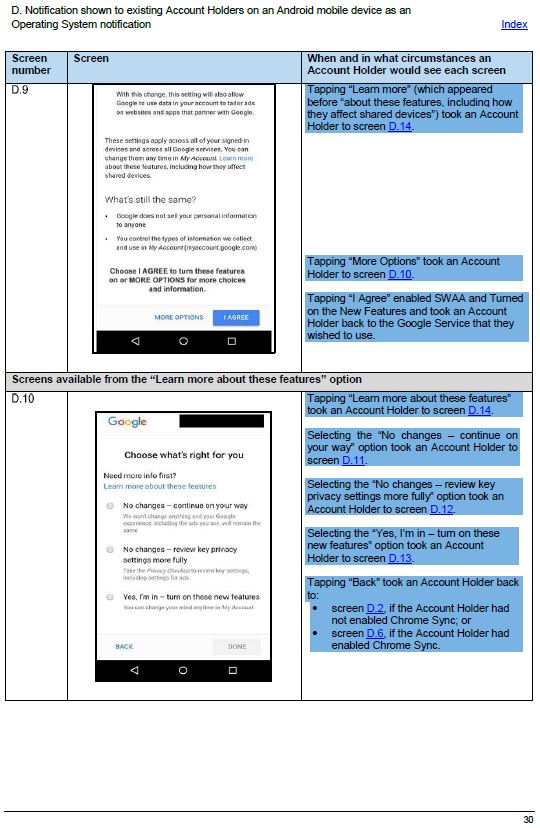

102 The Account Holder is also told that these settings will apply across all of their signed-in devices, but that “you [the Account Holder] can change them [the settings] at any time” (screens D.4 and D.5).

103 Then, the question is posed: “What’s still the same?” The Account Holder is told that the practice of their personal information not being sold to anyone, and their ability to control the types of information Google collects and uses, will remain the same.

104 Finally, the Account Holder is told to choose the “I AGREE” button to turn on the new features or to click the “MORE OPTIONS” button for “more choices and information”.

105 I have used screens D.2 – D.5 as the starting point for my analysis of the Notification. It is appropriate that I record the following further facts concerning the form and structure of the Notification in the various forms in which it was provided to Account Holders.

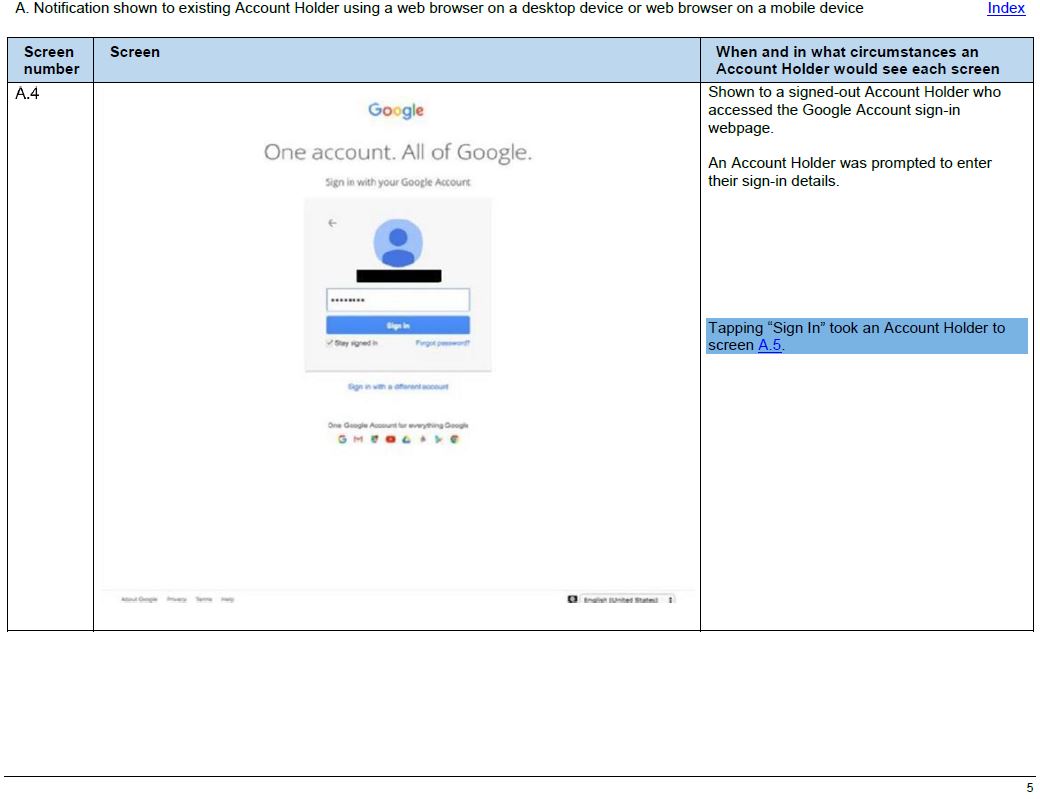

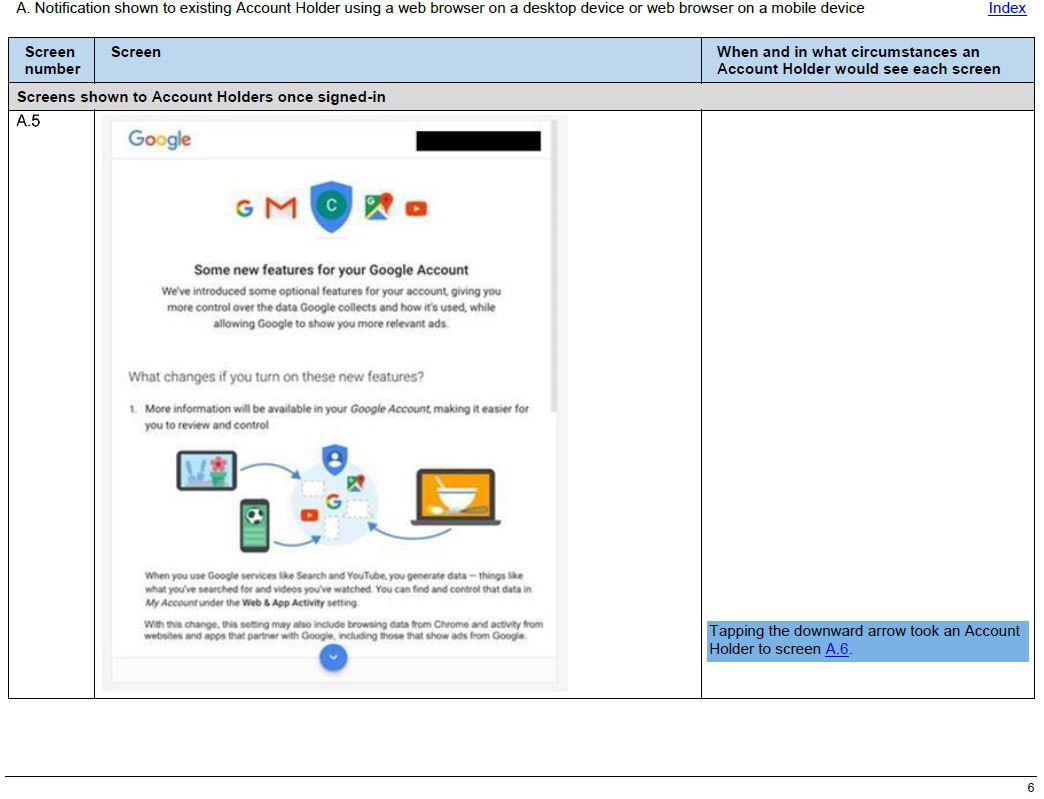

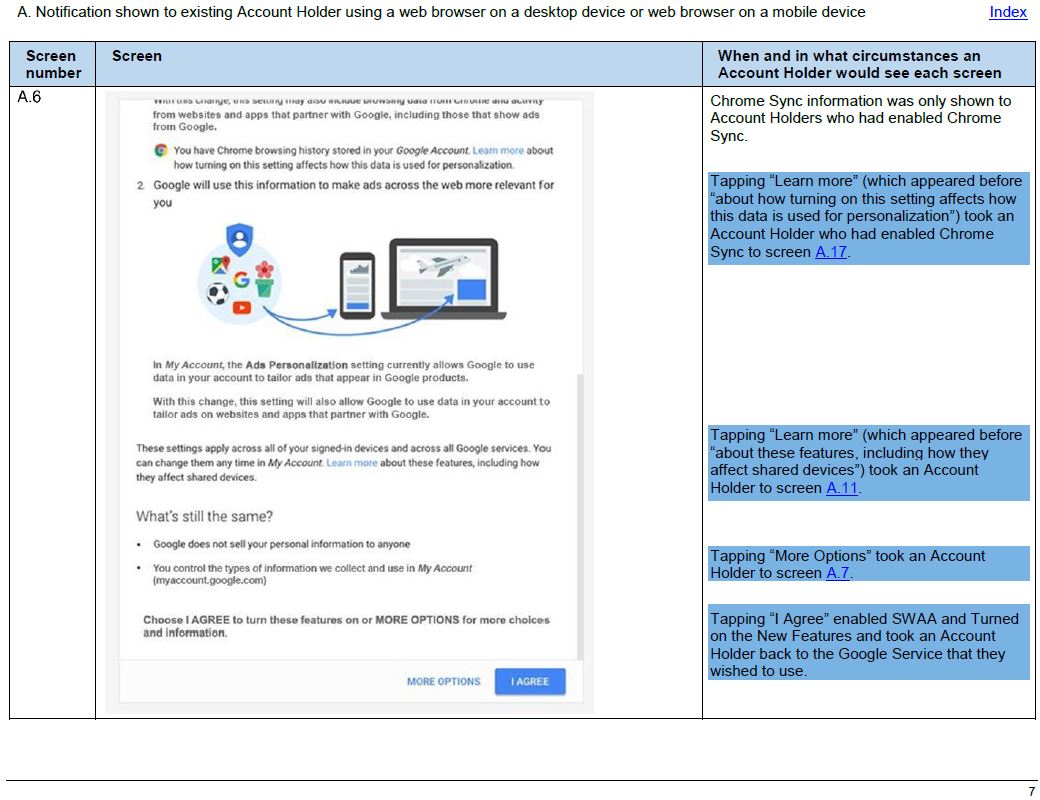

106 Signed-in Account Holders using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device received an alert shown in screens A.1 – A.3 of the Screenshot Bundle. If Account Holders chose “Learn More”, they were shown the Notification in screens A.5 and A.6. However, Account Holders did not have to choose “Learn More”. Account Holders could navigate away from the alert.

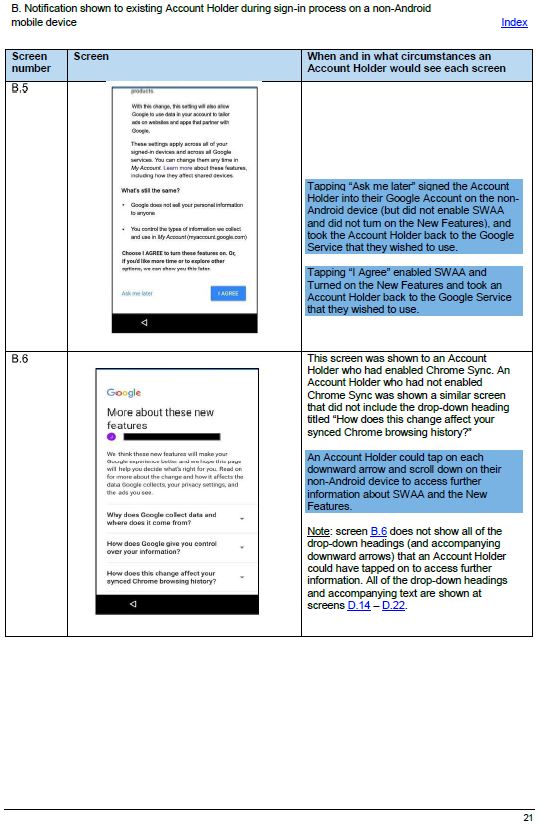

107 Account Holders with a non-Android device were shown the Notification in screens B.3 – B.5 during the sign-in process to their Google Accounts.

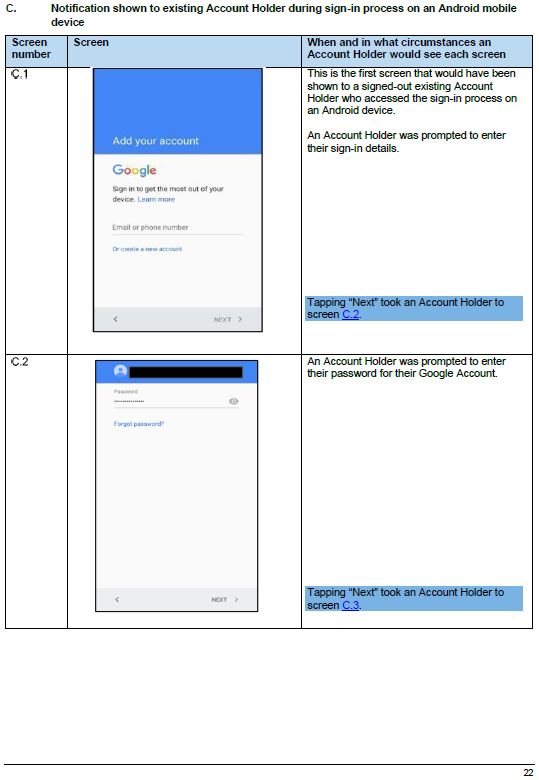

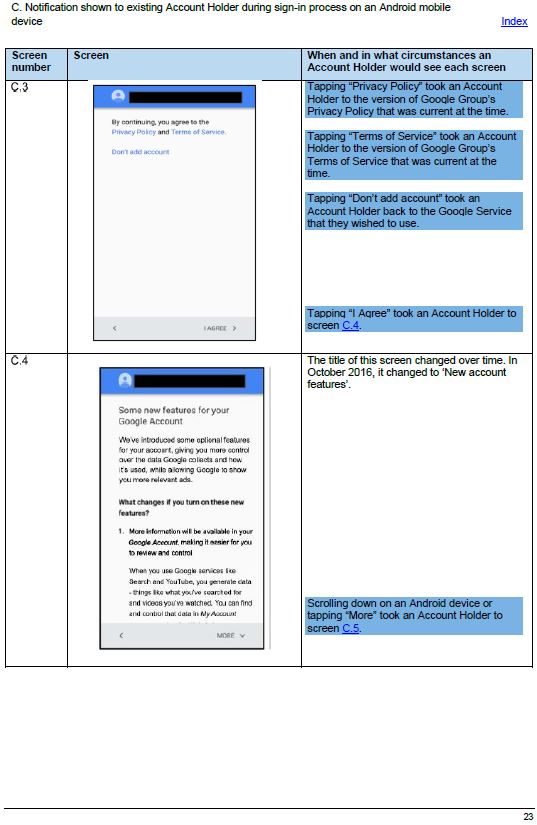

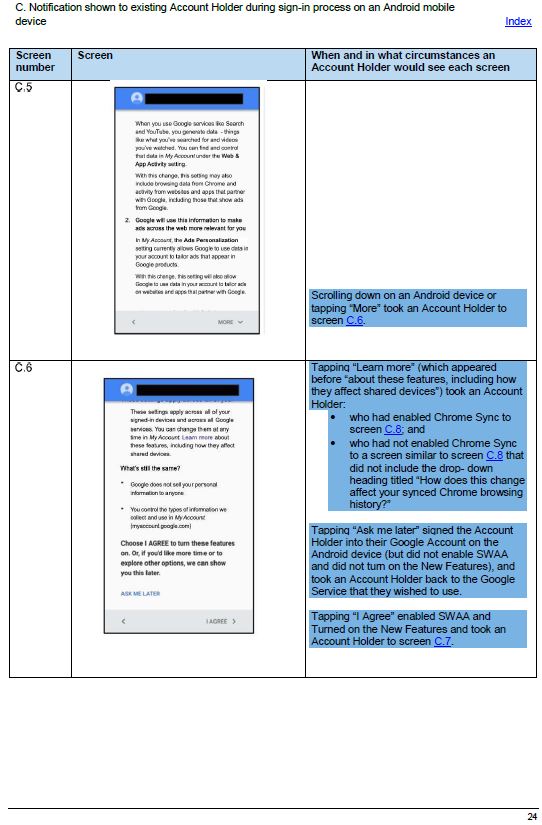

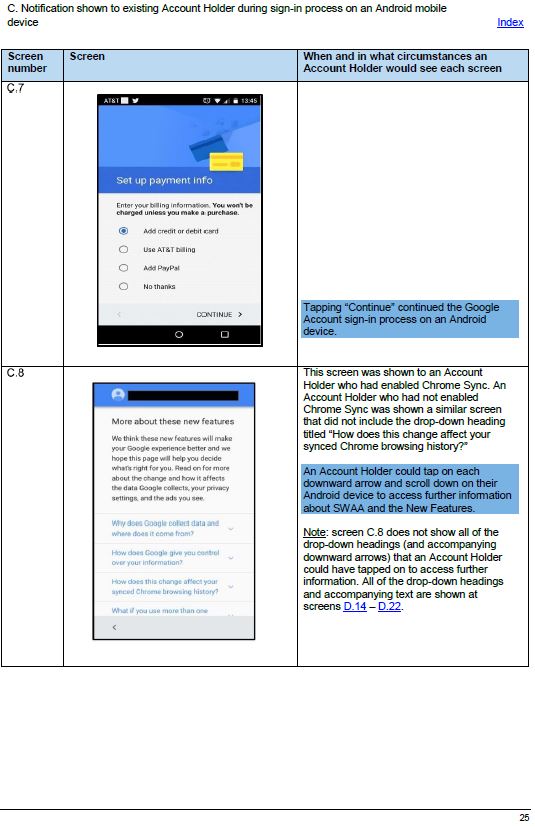

108 Account Holders with a mobile device using the Android Operating System (Android device) were shown the Notification in screens C.4 – C.6 during the sign-in process to their Google Account.

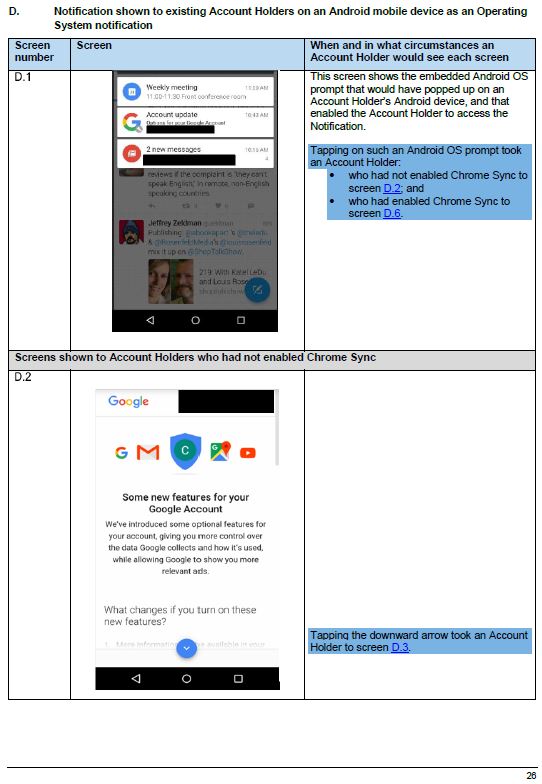

109 Account Holders with an Android device may have been alerted to the Notification with an Android Operating System prompt shown in screen D.1 of the Screenshot Bundle. If Account Holders tapped on the prompt, they were shown the Notification set out in screens D.2 – D.5 (for Account Holders who had not enabled the Chrome Sync Setting) or screens D.6 – D.9 (for Account Holders who had enabled the Chrome Sync Setting).

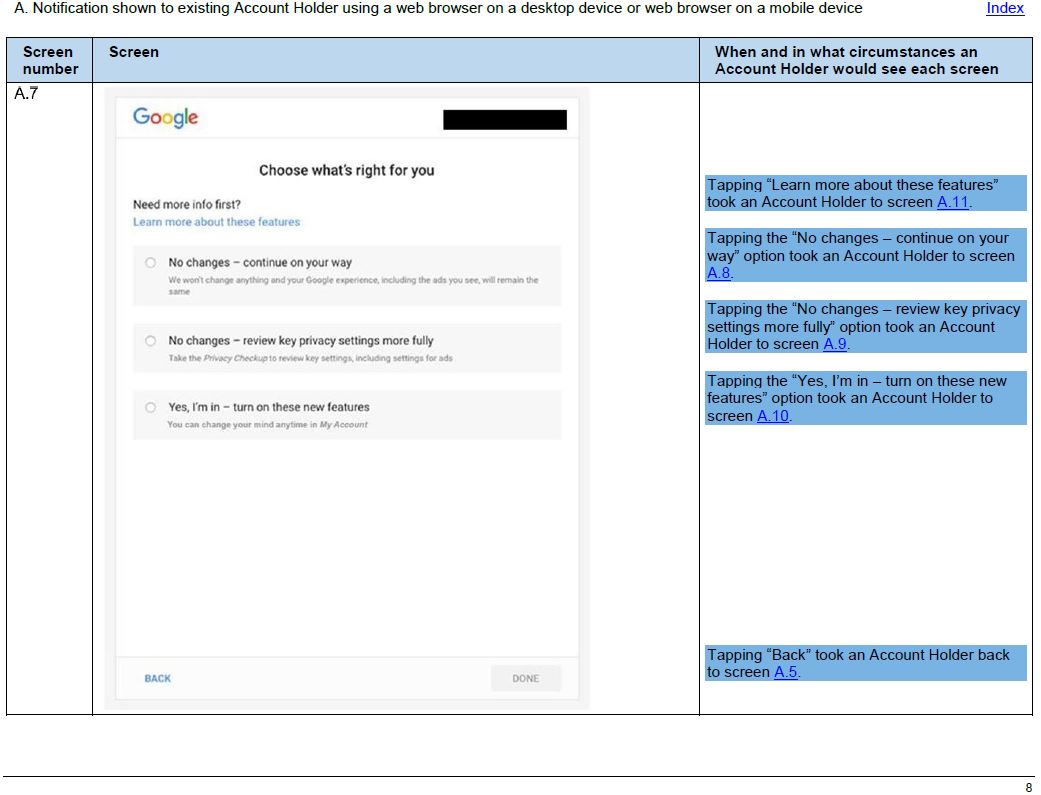

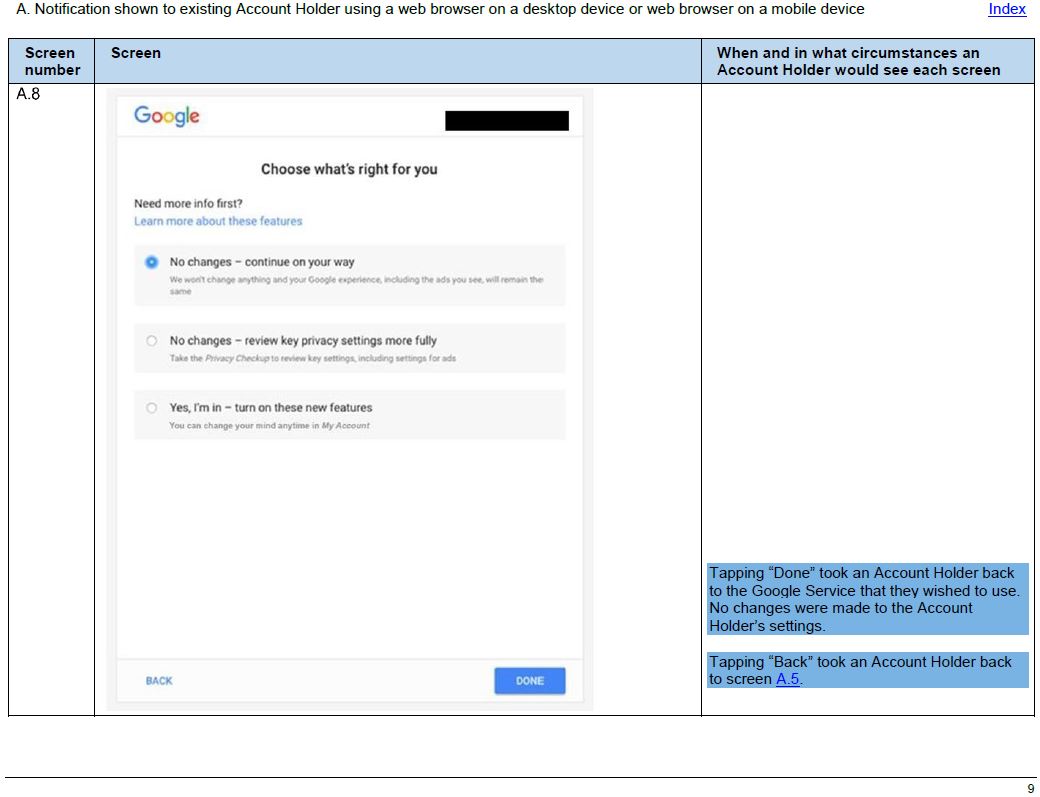

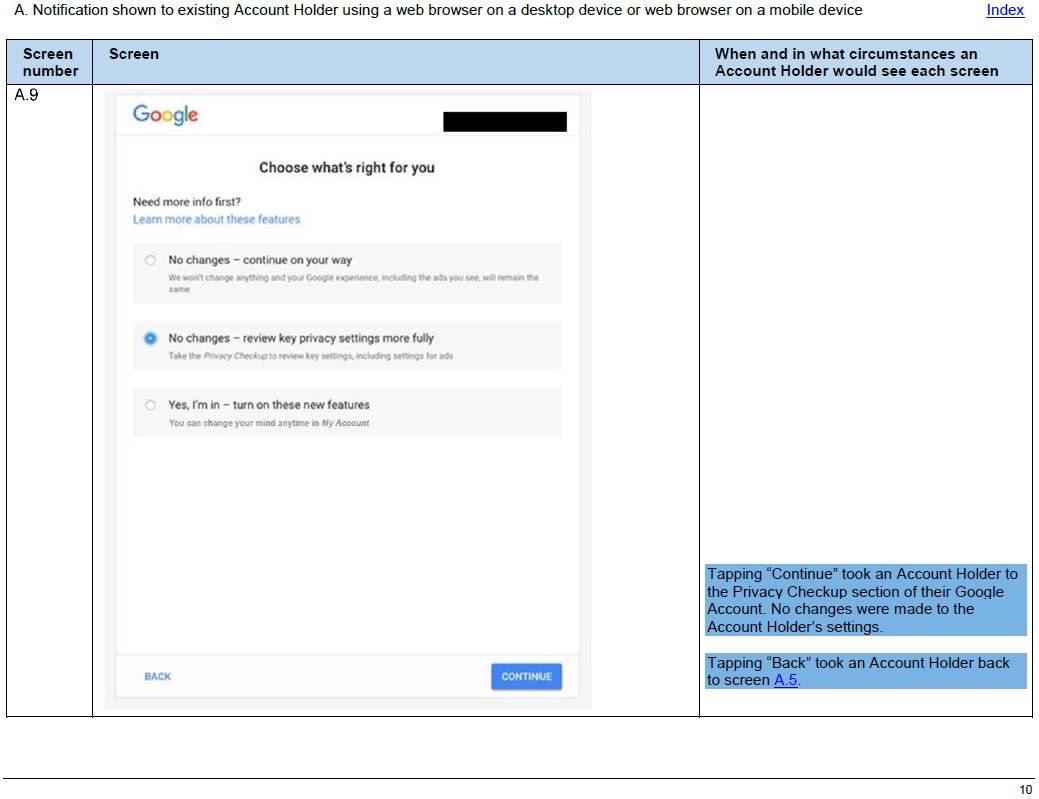

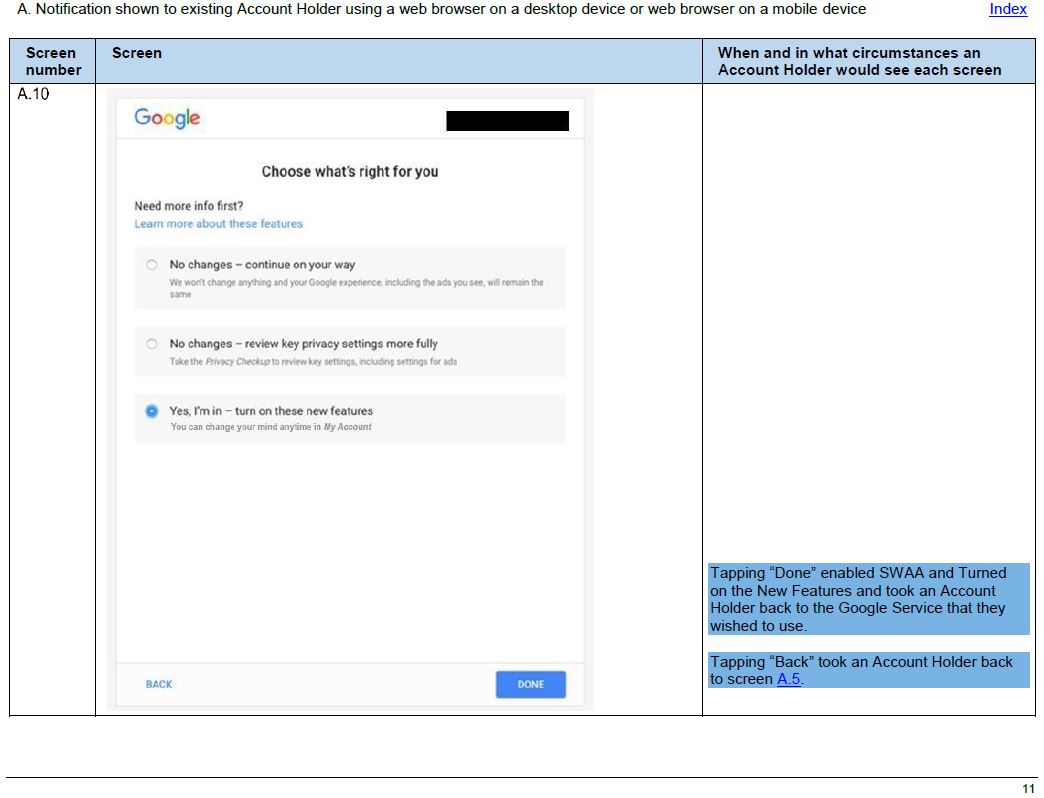

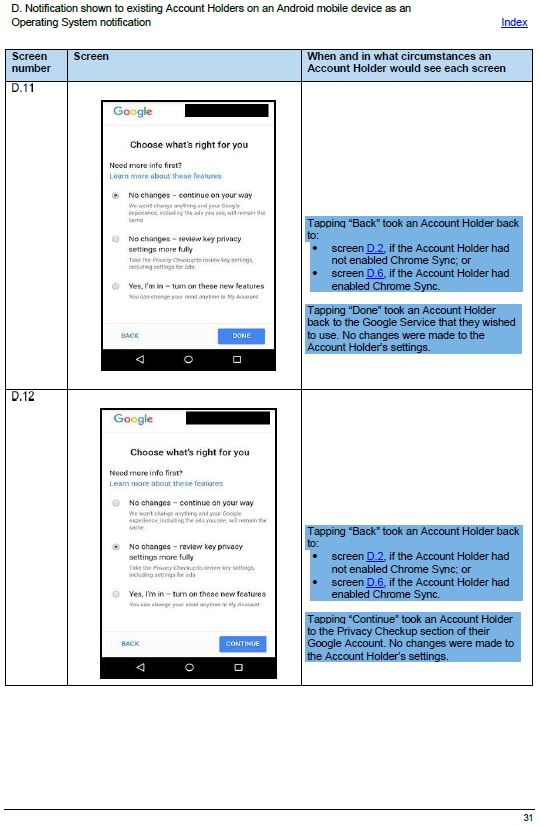

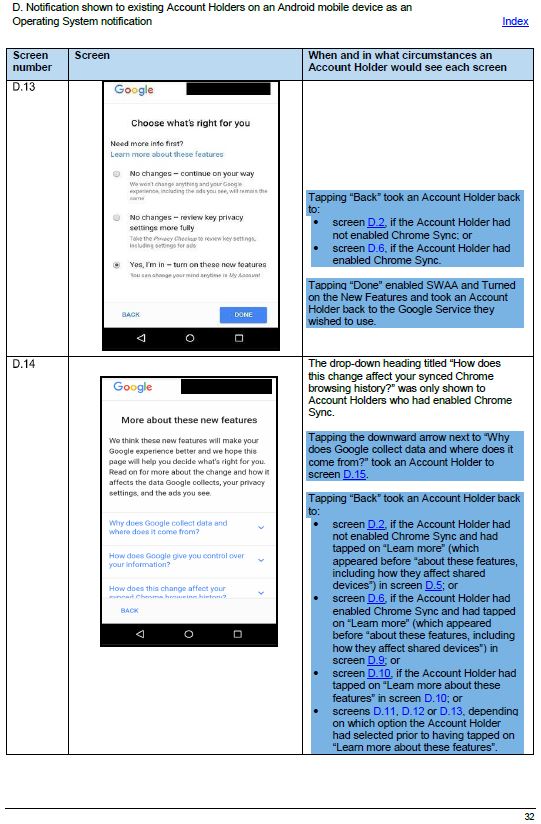

110 If Account Holders selected “MORE OPTIONS”—as shown in screen A.6 (for Account Holders using a web browser on a desktop or a web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device)), screen D.5 (for Account Holders using an Android device who had not enabled Chrome Sync and saw the Notification as an Operating System notification), and screen D.9 (for Account Holders using an Android device who had enabled Chrome Sync and saw the Notification as an Operating System notification)—they were shown a new page titled “Choose what’s right for you”, which contained a link titled “Learn more about these features”.

111 For Account Holders:

(a) who were using a web browser on a desktop or mobile device (including a non-Android device), this was shown in screen A.7; or

(b) who were using an Android device, this was shown in screen D.10.

112 Account Holders who were shown the Notification in the form of screens B.3 – B.5 (i.e. the Notification shown to existing Account Holders during the sign-in process on a non-Android device) and screens C.4 – C.6 (i.e. the Notification shown to existing Account Holders during the sign-in process on an Android device), were given the option to select “Ask me later” (rather than “MORE OPTIONS”).

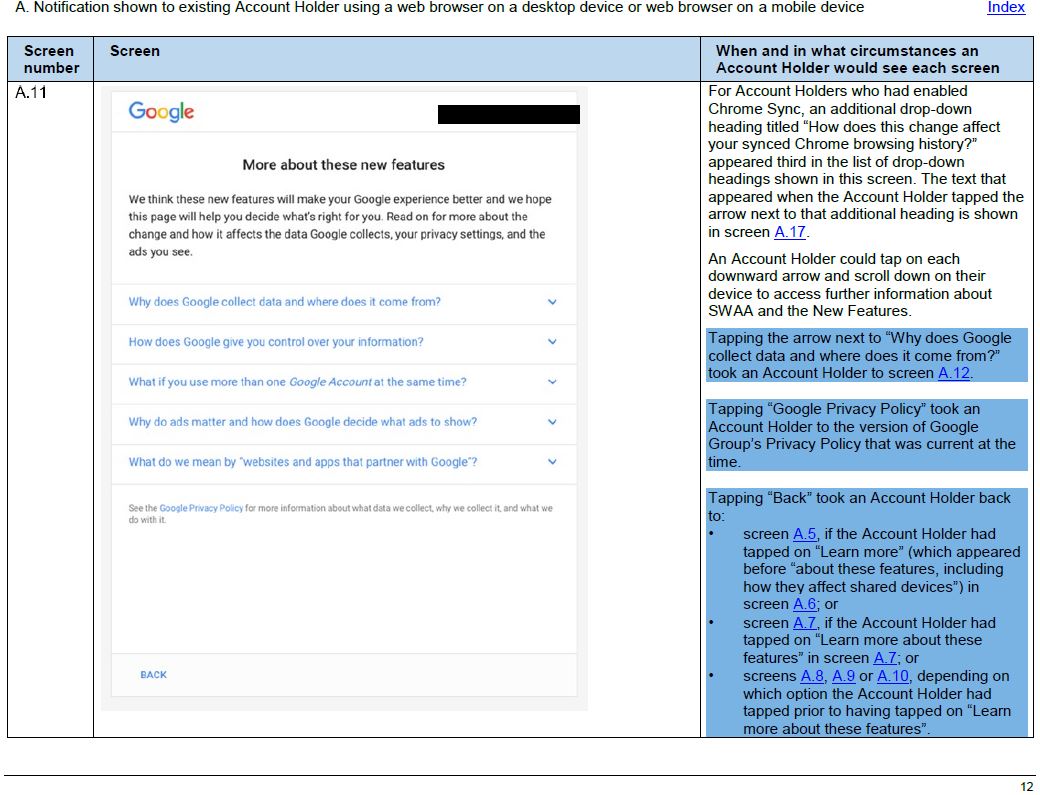

113 If Account Holders selected “Learn more about these features”, as contained in screen A.7 (for Account Holders who were using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device)), and screen D.10 (for Account Holders using an Android device and who saw the Notification as an Operating System notification), they were shown a new webpage titled “More about these new features”, which provided them with links to obtain additional information.

114 For Account Holders:

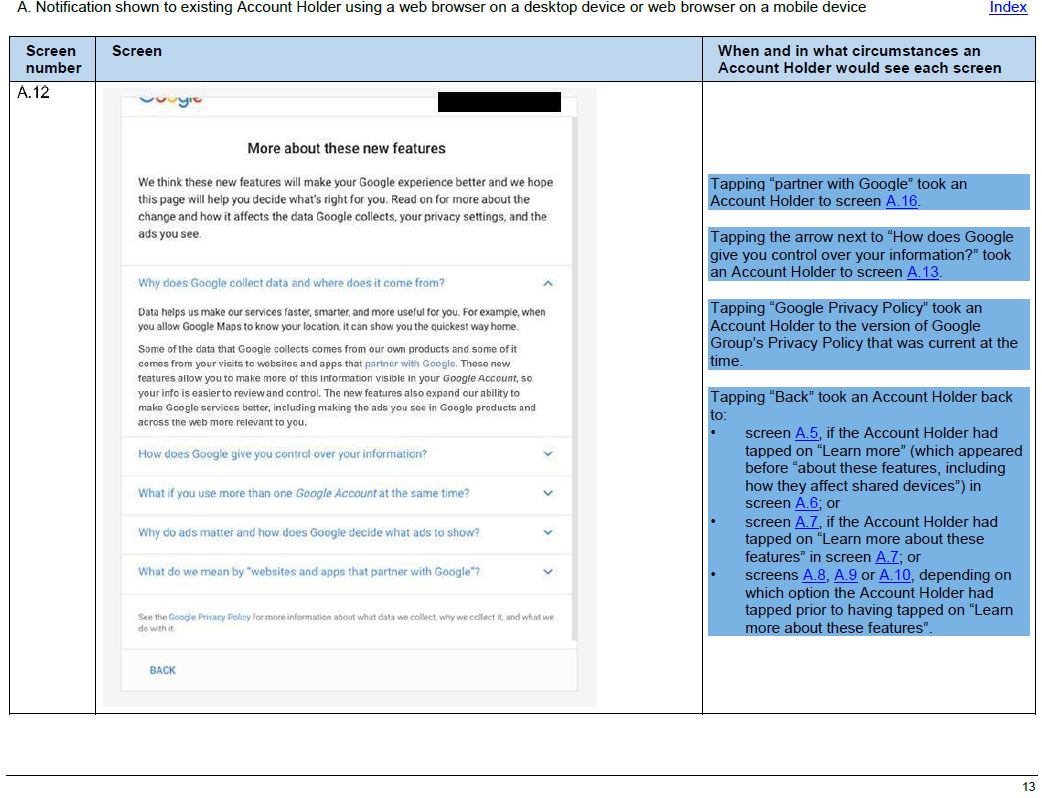

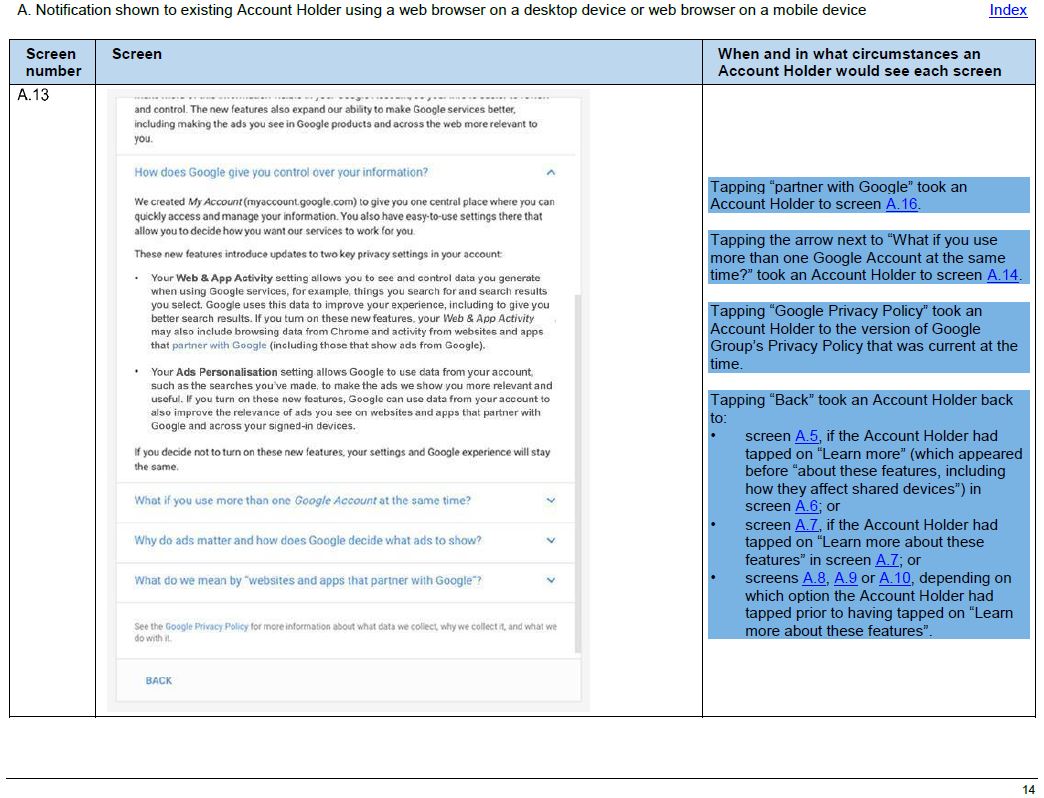

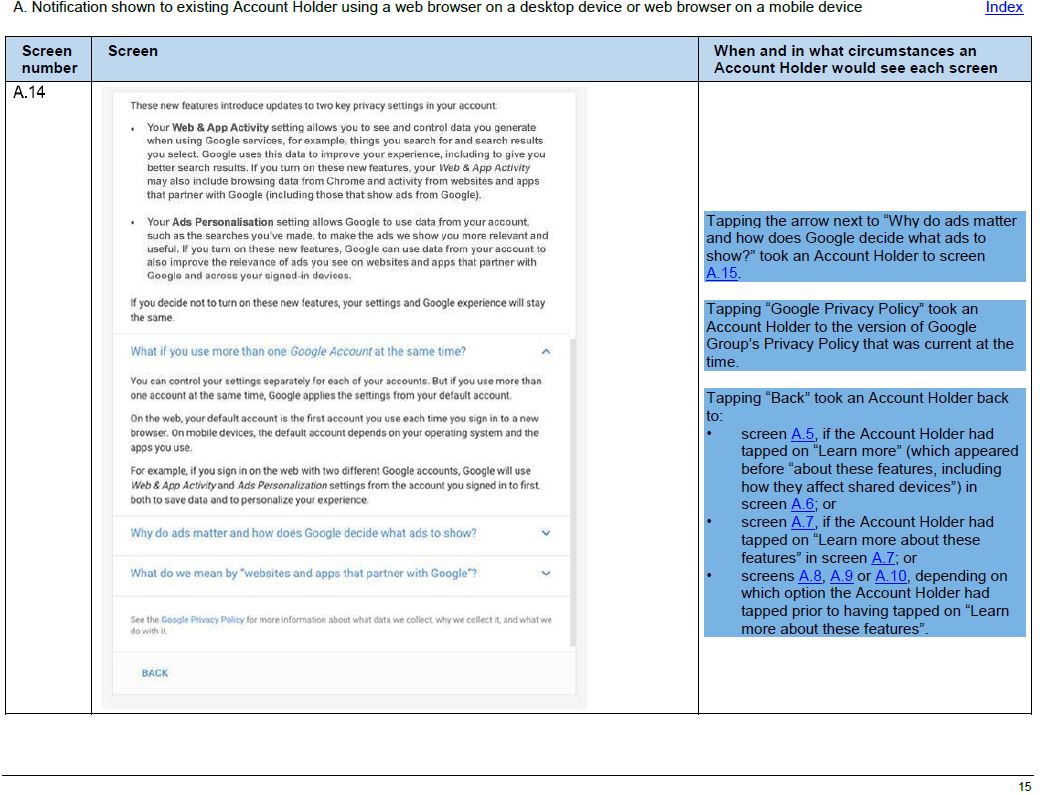

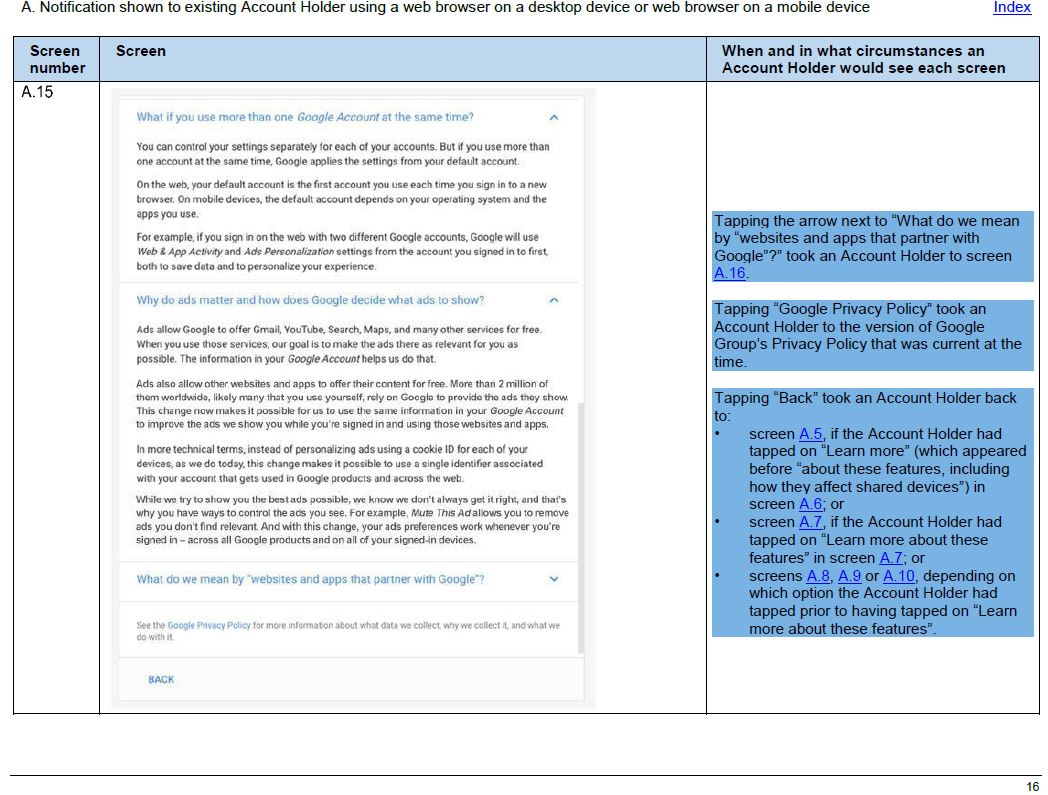

(a) using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device), this was shown in screen A.11; and

(b) using an Android device, this was shown in screen D.14.

115 After reviewing the “Choose what’s right for you” page, on screen A.7 (for Account Holders using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device)) and screen D.10 (for Account Holders using an Android device and who saw the Notification as an Operating System notification), Account Holders could select “BACK” to return to the Notification, as displayed on screen A.5 (shown to Account Holders once signed-in), screen D.2 (if the Account holder had not enabled Chrome Sync), or screen D.6 (if the Account Holder had enabled Chrome Sync), or they could select one of the three options listed and click “Done” or “Continue”.

116 Account Holders selecting one of the three options on the “Choose what’s right for you” page:

(a) using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device), were shown screens A.8 – A.10;

(b) using an Android device were shown screens D.11 – D.13.

117 Similarly, if Account Holders clicked on “Learn more” (which appeared before “about these features” and under the subheading “2. Google will use this information to make ads across the web more relevant for you”) in screen A.6 (for Account Holders who were using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device)), screen B.4 (for Account Holders using a non-Android device and who were shown the Notification during the sign-in process), screen C.6 (for Account Holders using an Android device and who were shown the Notification during the sign-in process), screen D.5 (for Account Holders using an Android device who had not enabled Chrome Sync and who saw the Notification as an Operating System notification), and screen D.9 (for Account Holders using an Android device who enabled Chrome Sync and who saw the Notification as an Operating System notification), they were shown the webpage titled “More about these new features”.

118 For Account Holders:

(a) using a web browser on a desktop or web browser on a mobile device (including a non-Android device), this was shown in screen A.11;

(b) using a non-Android device who had enabled Chrome Sync, this was shown in screen B.6 (Account Holders using a non-Android device who had not enabled Chrome Sync, were shown a screen similar to B.6 that did not include the drop-down heading titled “How does this change affect your synced Chrome browsing history?”); and

(c) using an Android device who had enabled Chrome Sync, this was shown in screens C.8 and D.14 (Account Holders using an Android device who had not enabled Chrome Sync, were shown a screen similar to C.8 and D.14 that did not include the drop-down heading titled “How does this change affect your synced Chrome browsing history?”).

119 If Account Holders selected “I AGREE” to the Notification, changes were made to their settings that permitted Google to combine the information it collected about their activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps with their personal information. These changes included:

(a) the SWAA Setting being enabled or the functionality of the SWAA Setting being expanded (if the Account Holder had already enabled the SWAA Setting); and

(b) a new feature of the Ad Personalisation Setting (i.e. a checkbox labelled “Also use your activity & information from Google services to personalize ads on websites and apps that partner with Google to show ads”) being enabled that permitted Google to serve Account-based Advertising on Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps to the Account Holder.

120 In relation to Account Holders who clicked “I Agree” or “Yes, I’m in – turn on these new features” and “Done” to accept the new features, Google considered itself authorised to:

(a) combine or associate Account Holders’ personal information with their activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps, in addition to combining or associating their personal information with their activity on Google Services; and

(b) allow that combined or associated information to be used to create or generate Account-based Advertising for Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps; and

(c) deliver Account-based Advertising to signed-in Account Holders on both Google Services and Google Partner Websites and Google Partner Apps on any of their devices.

121 An internal Google document makes clear what Google was trying to convey to Account Holders by the Notification:

We’re trying to emphasize a couple key points that we really want the user to understand.

⸰ First, that a user’s activity information on 3rd party sites and apps will now be associated with their account and not, say, a browser cookie or mobile identifier.

⸰ And second, that their account information, including this “web traversal” or “app traversal” data, will be used to improve the ads the user sees on 3rd party sites and apps.

122 As Senior Counsel for the Commission put the matter in closing submissions (with reference to this document):

The debate between us is that we say the [N]otification did not actually tell users that that was what was happening.

123 The Commission’s case on the Notification has two aspects—the Notification Conduct and the Notification Representations.

124 The case with respect to the Notification Conduct is advanced in the Commission’s Amended Concise Statement as one of omission:

26 In relation to Account Holders who clicked “I Agree” or “Yes, I’m in – turn on these new features” and “Done” to accept the ‘new features’ (Turned on the New Features), Google considered itself authorised to:

(a) combine or associate the Account Holder’s personal information with their activity on Third Party Websites and Apps, in addition to combining or associating the Account Holder’s personal information with their activity on Google Services;

(b) allow that combined or associated information to be used to create or generate personalised advertisements for Google Partner Websites and Apps; and

(c) deliver those advertisements to signed in Account Holders on both Google Services and Google Partner Websites and Apps on any device.

27 By the Notification, Google failed to inform, or adequately inform, Account Holders that:

(a) Google had made the June 2016 Privacy Update to the Privacy Policy; and

(b) Google was seeking the Account Holder’s consent to be able to undertake the matters set out in paragraph 26 above,

(the Notification Conduct).

125 The Commission contends that Google’s conduct, in publishing the Notification, was misleading or deceptive in that it had the tendency to lead to a reasonable and legitimate expectation or understanding by Account Holders that the information being presented about the positive changes to their access to the data that Google was collecting, was all the information that was necessary for them to consider.

126 In opening its case, the Commission advanced five principal submissions in support of this contention.

127 First, the Commission submitted that the Notification did not say that Google would now combine the personal information in Account Holders’ Google Accounts with information about their activities on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps. The Commission submitted that, although Account Holders were told that “more information will be available in your Google Account, making it easier for you to review and control” and that “Google would use this information to make ads across the web more relevant for you” (see, for example, screens D.3 and D.4), Google did not explain that the additional data it would be collecting would be data about the Account Holder’s activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps. The Commission also submitted that Google did not explain that it could serve more targeted advertisements because it was collecting that information and combining it with the Account Holder’s personal information.

128 Secondly, the Commission submitted that the “new features” to which the Notification referred (see, for example, screen D.2) were described “beneficially to the Account Holder”. The Commission submitted that, by framing the Account Holder’s choice in this way, Google suggested that the changes were for the sole benefit of the Account Holder, such that adopting the changes would enhance the Account Holder’s use of Google without any cost or effect on the Account Holder more specifically. The Commission did not expand on what the other “cost or effect” was beyond the fact that Google would be using the combined information to show the Account Holder “more relevant ads”. The significance of this submission to the case articulated in the Amended Concise Statement is not apparent.

129 Thirdly, and relatedly, the Commission submitted that the language used to describe the detail of the first feature (“more information will be available in your Google Account, making it easier for you to review and control”) would have left Account Holders with the impression that the change was about the Account Holder’s access to information and data that Google was already collecting, and not that Google was collecting and combining additional information and data. In other words, the Notification did not indicate that the “more information” was information that Google had not previously associated with the Account Holder’s Google Account. Rather, the suggestion was that this was information that had not previously been available to the Account Holder to review.

130 Fourthly, the Commission submitted that, to the extent that Google informed Account Holders that their activities on other sites and apps would be associated with their personal information, it was only framed as beneficial for the second feature, namely “in order to improve Google’s services and the ads delivered by Google”. Once again, the Commission did not expand on this submission. Its significance to the case articulated in the Amended Concise Statement is not apparent.

131 Fifthly, the Commission submitted that the Notification did not inform Account Holders that there was a change to Google’s Privacy Policy. As I have noted, there is no dispute about this fact. There is, however, a dispute as to the effect of the June 2016 Privacy Update—a matter to which I will return.

132 In support of its submissions, the Commission relied on certain findings recorded in internal Google documents about the user testing which Google undertook as part of Narnia 2.0, and on the evidence given by Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour.

133 It is convenient to turn to that evidence now.

134 The Commission tendered certain documents that Google had produced in response to compulsory notices and orders for discovery. These documents reveal that, in the period before June 2016, Google perceived that there was significant commercial value in being able to combine the data available to it about Account Holders’ activity on Google Services with the data available to it about those Account Holders’ activity on Third Party Websites and Third Party Apps. Google saw its (then) inability to combine and use this data as limiting the scope of the advertising services it could provide to advertisers.

135 These constraints stemmed from Google’s adherence to a previous commitment given by DoubleClick Inc—a supplier of ad-serving technology services which Google acquired in 2008—not to combine a user’s web-traversal cookie data with their personally identifiable information, without obtaining the user’s explicit consent. Narnia 2.0 sought to overcome this constraint, so as to enable Google to expand its ability to serve Account-based Advertising to Account Holders.

136 An aspect of Narnia 2.0 was the development of a “Consent Bump” (i.e., a notification directed to Account Holders seeking their consent to Google combining and using all this information). Obtaining Account Holders’ consent was, obviously, a matter of commercial significance for Google. The documents reveal that, by obtaining Account Holders’ consents, Google would increase its advertising revenue significantly.

137 Google carried out extensive market research and user testing in relation to the text and format of the “Consent Bump”. This testing was carried out in the United States of America, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom in 2015 and 2016 to ascertain: (a) users’ feelings about the changes, including the way in which data was to be collected and stored; (b) users’ comprehension of the notification that was being tested as the “Consent Bump”; and (c) the design and format of a “Consent Bump” that would make it more likely that users would “click” on the option to agree. In one document, Google expressed its aim as being to “Maximise conversion”. It was “Designing for Consent”.

138 The Commission places reliance on Google’s analysis and conclusions in respect of the user testing it was carrying out. In particular, it points to findings (expressed in various documents) that:

(a) participants did not have a good understanding of the information and data that existed across their various devices and the existing user control settings before the proposed changes;

(b) most users did not understand that the change would result in a combination of their data;

(c) in the absence of a clear yes/no choice, users felt that they did not have a choice whether or not to agree to the notification; and

(d) participants paid limited attention to the text of the Consent Bump, and most participants continued without reading the text closely.

139 However, the text and format of the Consent Bump developed over time in response to this testing and Google’s analysis of the test results.

140 The Commission appears to suggest that, in designing the text and format of the Consent Bump, Google was acting untowardly. For example, it relies not only on the fact that Google was “Designing for Consent” but also on the fact that, as versions of the “Consent Bump” involved, Google removed references to its Privacy Policy and to the word “privacy”. The Commission suggests these references were removed because testing indicated that Account Holders were less likely to consent to the proposed changes when the text of the notification referred to a change that affected their privacy.

141 The Commission contends that Google was designing the “Consent Bump” to maximise the number of Account Holders who checked “I AGREE” rather than to maximise the number of Account Holders who understood the implications of agreeing to the changes that were proposed. The Commission seeks to derive support for this contention from Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s evidence, which I discuss in the next section of these reasons.

142 It was here that the Commission advanced the uncontroversial proposition that a half-truth may be a misleading representation: LG Electronics at [53]. This precept is the cornerstone of the Commission’s case in respect of the Notification Conduct.

143 I should say now that I am not persuaded that, in designing the “Consent Bump”, Google was acting in an untoward way. Google does not dispute that it was in its interests for Account Holders to respond to the Notification by consenting to the changes that Google wanted to implement. However, as Google points out, it is hardly surprising that it wanted Account Holders to consent. The fact that Google was seeking that consent must have been apparent to Account Holders on reading the Notification. Plainly, that is what the Notification was asking Account Holders to do—to consent to the changes that Google wanted to implement. That said, Account Holders were given the choice as to whether they should give consent.

144 On the basis of other documents tendered by the Commission, I am satisfied that, in “Designing for Consent”, Google was seeking to design a “Consent Bump” which gave Account Holders the information necessary to understand the changes that Google wanted to make so that, if consent was given, it was given on an appropriately informed basis. For example, in relation to the document in which Google expressed its desire to “Maximise conversion”, Google also referred, unequivocally, to its objective to obtain “informed consent”.

145 I also observe that, in “Designing for Consent”, with the objective of obtaining informed consent, Google recognised that its Account Holders comprised a range of individuals who it classified as “Skippers, Skimmers and Readers”. The documents reveal that Google understood that the “Consent Bump” had to be worded so as to cater for all these individuals.

146 Google’s appreciation that its Account Holders comprised “Skippers, Skimmers and Readers” explains why the Notification was presented in a way that provided links to enable Account Holders to obtain more information in relation to Google’s proposal, should that have been their desire when considering the Notification. In its internal documents, Google described this as presenting a “layered story”. This is a pithy way of explaining the cascading form of the Notification, with the increasing levels of detail described at [89] – [122] above.

147 In a document entitled “Narnia 2.0 Town Halls; Sridhar Intro: Transparency, Control, and an Identity-based Platform for Display Advertising”, Google explained:

…we’ve found through research that the group of users who don’t immediately want to agree are a nuanced group. So instead of offering a simple “no”, we’ve developed a few options that we feel will best address the desires of these users:

… First, some users may need additional details around how this new option works - what data we’re talking about, how their controls work, and more. Users who read this information are now empowered to make a better choice. Of course, there are some users who want to get on their way - selecting “no” and moving on is the first choice we offer here. And for some users, the best thing we can do for them is give them the option to view these changes in context by taking them to the Privacy Checkup …

148 In a document entitled “Comm Doc: Signed-In Ads (Global Consent) Messaging for Sales”, Google summarised the final results of its testing:

We’ve done extensive qualitative testing of the consent flow around the world, and the testing suggests that many users will choose to try out the new experience, though some users will decline. The ratios will vary regionally based on users’ attitudes about Google, privacy, and advertising. Our goal is simply to explain the update as clearly as we can and let users make a choice. We hope most will give the new approach a try, but it’s important that those who aren’t comfortable with the change have the chance to keep things the way they are.

149 In relation to the Notification Conduct, the only question is whether, by omission, Google’s conduct in asking for consent, through the medium of the Notification, was misleading or deceptive (or likely to mislead or deceive), or liable to mislead the public, in the specific ways alleged by the Commission in the Amended Concise Statement.

Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report

Behavioural science principles

150 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s first report proceeded on the basis of 12 identified principles. She described these principles as well-established behavioural science principles which were “most obviously relevant” to understanding the decision-making of users navigating the webpages of the Notification relevant to the claims made in this proceeding. Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that the conceptual framework used throughout her first report reflected the state-of-the-art in behavioural science.

151 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour explained that economics has long revolved around the “Homo economicus” model, which depicts an idealistic view of humans as emotion-free creatures setting goals and pursuing them with limitless capacity for rationality and using all available information and resources. She explained that this model reflects a simplifying strategy to deal with human behaviour by expelling all psychological notions from economic theory.

152 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour then described the emergence of the field of behavioural economics from work carried out in the late 1960s which exposed the failures of the Homo economicus model in predicting individual behaviour. Behavioural economics incorporates insights from human psychology into economic analysis, providing economists with a richer set of analytical and experimental tools for understanding and predicting human behaviour.

153 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour explained that one basic notion in behavioural science is that decision-making is a dual process comprising information acquisition and information processing on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the process of making decisions on the basis of opinions that have been formed. Contrary to the idolised figure of Homo economicus, who has automatic access to all available information in his surroundings, processes that information optimally to form his opinions, and always makes optimal decisions (in the sense of utility maximisation) for a given set of beliefs, humans are vulnerable to a number of behavioural biases which are widespread, and often difficult for them to intuit. Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour explained that this implies that people’s choices often do not reflect their true preferences—they would like to behave differently if they knew about their biases. It also implies that people’s choices are manipulable (i.e., they can be altered) through designing the decision-making environment in particular ways—in other words, people can be “nudged” in their decision-making.

154 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour identified three principles relevant to information acquisition:

(a) Principle 1 – limited information recording;

(b) Principle 2 – information overload; and

(c) Principle 3 – limited attention.

155 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that the key contextual determinants in relation to information acquisition are:

(a) with reference to Principle 1, time and the nature of the information provided to the agent: agents stop acquiring information earlier under time constraints, and they prioritise sources of information that are quicker for the brain to record;

(b) with reference to Principle 2, complexity: providing more information often means that less information is, in effect, acquired; and

(c) with reference to Principle 3, salience: salient (“attention-grabbing”) information is attended at the expense of potentially more relevant information; for example, headings in bold and vivid images will catch attention.

156 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour identified three principles relevant to information processing:

(a) Principle 4 – limited memory and “recency bias”;

(b) Principle 5 – reinforcement learning; and

(c) Principle 6 – belief perseverance and “anchoring bias”.

157 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that there are four important determinants of the nature of the beliefs held by a person at a given point in time, and the extent to which those beliefs are correct:

(a) with reference to Principle 4, the nature of the information recently provided to the person;

(b) with reference to Principle 5, whether the person’s environment is stable;

(c) also with reference to Principle 5, and in the case of a changing environment, whether the person has been primed to recognise a change in their environment; and

(d) with reference Principle 6, the nature of the information initially provided to the person.

158 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour identified four principles relevant to the decision process:

(a) Principle 7 – limited deliberation;

(b) Principle 8 – default option bias;

(c) Principle 9 – decoy/contrast effect and the context-dependence of perception; and

(d) Principle 10 – framing effects.

159 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that there are four key determinants of the choice made by a person on the basis of their opinions:

(a) with reference to Principle 7, the time pressure felt by the agent;

(b) with reference to Principle 8, the default option in the choice set;

(c) with reference to Principle 9 – the nature of the other options present in the choice set; and

(d) with reference to Principle 10 – whether the information presenting the choice set is positive or negative.

160 These considerations imply that two decision-makers, sharing the same opinion (i.e., their assessment of the situation is strictly identical) will likely make a different decision if they decide under different degrees of time pressure, different choices, and different “framing”.

161 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that all the principles she had identified share three essential characteristics: (a) they are systematic (and hence predictable); (b) they are ingrained (i.e., they are rooted in neurobiology); and (c) they are counter-intuitive (people are typically unaware of the biases and, even when they are told about them, they are still susceptible to them and cannot spot them when they are happening).

162 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour identified two further principles:

(a) Principle 11 – “nudge”: a strategy for changing human behaviour on the basis of a scientific understanding of how humans behave (such as through the deployment of Principle 8 (default option bias)); and

(b) Principle 12 – interindividual differences (although Principles 1 – 11 apply to all persons, it is important to account for interindividual differences when studying individual decision-making).

Observations on the form and content of the Notification

163 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour then made a series of 15 observations about aspects of the form and content of the Notification and the June 2016 Privacy Update. These observations were based on Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s own reading and personal understanding of the Notification and the June 2016 Privacy Update. Importantly, she accepted that her observations were not based on any expertise in textual analysis. As Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour put it, her observations were based on, simply, “precise reading”. It is not necessary for me to list Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s observations.

The questions advanced for consideration

164 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour then addressed two questions which were advanced by the Commission in these terms:

(a) Based on your specialised knowledge and training, and by reference to the principles applying to information acquisition and processing in the context of navigating through screens on a desktop or mobile device, what are the matters, elements or factors that may have influenced Account Holders when navigating the Notification as set out in sections A, B, C and D in Annexure A to the Statement of Agreed Facts? (first question)

(b) Based on your specialised knowledge and training, and by reference to the principles applying to decision-making in the context of navigating through screens on a desktop or mobile device, what are the matters, elements or factors that may have influenced Account Holders when making decisions in respect of the Notification as set out in sections A, B, C and D in Annexure A to the Statement of Agreed Facts? (second question)

165 As to the first question, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour expressed the following ultimate conclusion:

In my opinion … it is highly likely that many if not most users clicked ‘I AGREE’ on the first page of the Notification without knowing what they were agreeing to, because the ‘what’ was not explained anywhere in the Notification, and it is unlikely that users would realise it (the missing information) given the human tendency to expedite the information acquisition process. Besides, it is likely that many users—including internet-savvy users—were misled by the way the proposed change was described in the Notification, and that they agreed to something different from the actual change intended by Google. Specifically, it is likely that users agreed to Google turning on new functionalities to improve their experience and that they did not realise that by agreeing, they were giving their consent to the change intended by Google, which concerned their privacy.

166 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour explained this conclusion over a number of pages in her report. In doing so, she referred to the principles she had discussed earlier in her report in conjunction with the observations she had made about the form and content of the Notification and the June 2016 Privacy Update. I note, again, that her observations in this regard were not based on any expertise in textual analysis. Moreover, when one reads Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s analysis, it is clear that it contains her personal (non-expert) expectations of what the Notification and the June 2016 Privacy Update preferably should have said. It is important to bear this in mind when considering a number of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s conclusions, such as that the headings used by Google were “misleading in reality” or contradicted other information that was given in the Notification.

167 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s analysis commences with the controversial proposition that Account Holders were not informed of the “Nature of the Change”, which she defined as “Google’s move on 28 June 2016 to start combining personal information in consumers’ Google Accounts with information about those individuals’ activities on Third-Party Websites and Apps”. I also observe, for present purposes, that this is not a complete statement of the proposed changes.

168 From that starting point, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour then expressed a number of conclusions, most significantly the probabilistic headline conclusion that it was “highly likely” that “most users” would not have clicked on the links provided to access more information. She conjectured that this was because, in her view: (a) “one would expect” that a “significant number” of users, before clicking “I AGREE” on page 1 of the Notification, did not ask themselves whether they were sufficiently informed about the proposed change; and (b) for those users who did ask themselves whether they were sufficiently informed, “one has reasons to believe” that “the large majority” of users gathered that they knew enough about the proposed change to make a decision. As to the latter, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said that it was “highly likely” that users were either mistaken in thinking that they knew what the proposed change was about or simply trusted Google (according to Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour, despite not understanding what the proposed change was).

169 It is important to note at the outset that, although Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour explained her conclusions by reference to the principles she had discussed earlier, there is no evidence that, in relation to Account Holders’ understanding of the Notification, all those principles were, as a matter of fact, brought into play or had the various causal effects or consequences for which Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour contended. Her conclusions were, in fact, her hypotheses or, as she elsewhere described them, her conjecture or predictions.

170 Further, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s analysis incorporated unproven and, in some cases, generalised simplifying assumptions—for example, users “likely” had “limited time” and “limited willingness” to spend time on reading the Notification, or that it was “likely that many (if not most) users only read the headings …”. These assumptions may or may not be valid. The underlying facts, important to an acceptance of Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour’s analysis, are simply not known.

171 Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour expressed a number of other headline probabilistic conclusions, namely:

(a) where users would not have felt the need to learn more, it is “likely” that the “majority” of them would have failed to notice the link provided on page 1 of the Notification (a conclusion which, elsewhere in her first report, Associate Professor Payzan-LeNestour said was “highly likely”);

(b) for those who would have noticed the link, it is “almost certain” that they would not have clicked on it; and