FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 5) [2022] FCA 1475

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) First Respondent JASON THOMAS ELLIS Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 December 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter is listed for hearing on the question of remedies at 10:15 am on 3 April 2023 on an estimated duration of two days.

2. By 27 January 2023, the applicant file and serve any application for discovery from the respondents on the question of remedies.

3. By 3 February 2023, the respondents notify the applicant of any objection to discovery, and provide discovery in any category (or part of a category) that is not objected to.

4. Any dispute with respect to discovery will be heard on a date to be fixed.

5. By 10 March 2023, the applicant file and serve:

(a) proposed orders it will seek at the remedies hearing;

(b) outline submissions limited to 15 pages; and

(c) any witness statements and a list of documents on which it intends to rely at the remedies hearing which are additional to the evidence already adduced in the proceeding.

6. By 20 March 2023, each of the respondents file and serve:

(a) any proposed orders they will seek at the remedies hearing;

(b) outline submissions limited to 15 pages; and

(c) any witness statements and a list of documents on which they intend to rely at the remedies hearing which are additional to the evidence already adduced in the proceeding.

7. Any party may apply to vary orders 1 to 6 above by filing and serving an application within 14 days of the date of these orders together with an outline submission in support limited to 5 pages and any evidence relied upon.

8. If an application is made under order 7, any other party may file a responsive outline submission limited to 5 pages and any evidence relied upon by 20 January 2023.

9. Any application made under order 7 will be determined on the papers unless any party states in their outline submissions that they seek an oral hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

O’BRYAN J:

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) alleges that each of the first respondent, BlueScope Steel Limited (BlueScope), and the second respondent, Jason Thomas Ellis (Mr Ellis), attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia to contravene s 44ZZRJ of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Act) by making arrangements or arriving at understandings with BlueScope that contained cartel provisions within the meaning of s 44ZZRD of the Act. The type of cartel provision alleged by the ACCC is colloquially referred to as a “price fixing” provision and is defined by s 44ZZRD(2). The ACCC alleges that this conduct occurred during a 10 month period from September 2013 to approximately June 2014 (which I will refer to as the “relevant period”).

2 At the time of the alleged conduct, s 44ZZRJ prohibited a corporation from making a contract or arrangement or arriving at an understanding that contains a cartel provision. Relevantly, s 44ZZRD provided that a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is a cartel provision if two conditions are satisfied: first, in respect of a price fixing provision, the provision has the purpose or has or is likely to have the effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price for goods supplied or likely to be supplied by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; second, two or more of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding are or are likely to be in competition with each other in relation to the supply of those goods.

3 Flat steel products are used in a wide variety of industries within the construction and manufacturing sectors. They are produced from a material known as “steel slab” and are supplied in a number of product categories.

4 Flat steel products sold in Australia are either manufactured in Australia by BlueScope or manufactured by steel mills in other countries and imported into Australia. In the relevant period, BlueScope was the only manufacturer of flat steel products located in Australia. The division of BlueScope responsible for the manufacture and sale of flat steel products was called the BlueScope Coated Industrial Products Australia division. In these reasons, I will refer to that division as “BlueScope CIPA”, or simply “CIPA”.

5 There are two main functional levels of the market for flat steel products: manufacture/importation and distribution. BlueScope (directly and through subsidiaries) is both a manufacturer and distributor of flat steel products. A number of companies conduct business in Australia as importers of flat steel products manufactured by overseas steel mills, and are referred to as import traders. A number of other companies conduct business in Australia as distributors of flat steel products. Some of those companies acquire steel predominantly from BlueScope (and are referred to as BlueScope aligned – or franchised – distributors); others acquire steel predominantly from import traders (and are referred to as non-aligned distributors).

6 By 2013, due to a worldwide over-supply of steel and lower demand for steel in the wake of the global financial crisis, steel prices in Australia were low and BlueScope and distributors were under financial pressure. Many countries, including Australia, became increasingly protectionist in relation to their local steel industries, which led to an increase in anti-dumping applications. The ACCC’s allegations centre upon a commercial strategy, allegedly devised by Mr Ellis who had recently returned to Australia and rejoined BlueScope’s Australian operations, to alleviate the consequences of the intense competition arising from this downturn in the market.

7 The ACCC alleges that, by in or around September 2013, Mr Ellis had devised a strategy (referred to as the “benchmarking strategy”, the “recommended resale price strategy” or the “RRP strategy”) to increase the value to BlueScope and its distributors of sales of flat steel products. The strategy was for BlueScope to publish a recommended resale price which was to be used by BlueScope, BlueScope’s distributors and import traders as a benchmark for raising their prices for the supply of flat steel products in Australia. In referring to the strategy, many witnesses used the expression “recommended retail price” instead of “recommended resale price” both in contemporaneous correspondence and in giving evidence. It is clear that the witnesses were referring to the same strategy, and the phrases were being used interchangeably. In a commercial context, there is no material difference in meaning between the two phrases. When referring to the strategy in these reasons (as opposed to the evidence of specific witnesses), I will use the expression “recommended resale price”, being the expression used by Mr Ellis and which was ultimately used in certain of CIPA’s price lists for the supply of flat steel products to distributors from December 2013 onwards. These reasons also use the common abbreviation “RRP” for recommended resale price.

8 The ACCC further alleges that Mr Ellis devised a strategy for addressing competition from overseas steel manufacturers, being to restrict the volume of imported steel coming into Australia and to persuade overseas steel manufacturers to increase the price at which they sold flat steel products to Australian import traders. The ACCC says that the strategy also involved threatening to make anti-dumping applications against overseas steel manufacturers unless the price at which they sold flat steel products in Australia increased.

9 The ACCC contends that, by these strategies, BlueScope and Mr Ellis sought to control or maintain the price of flat steel products supplied or likely to be supplied by BlueScope and distributors in the Australian market. It alleges that, in carrying out these strategies, BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce arrangements or understandings containing a cartel provision with certain steel suppliers, being seven Australian distributors, one import trader and one overseas steel manufacturer, within the meaning of s 76(1)(d) of the Act. In these reasons, I will refer to the objects of the alleged attempts collectively as the “counterparties”.

10 The words “arrangement” and “understanding” are statutory words that have different shades of meaning, as discussed below. Broadly, an understanding is less formal than an arrangement. In these reasons, I will use the word “understanding” when referring to the ACCC’s allegations of attempts to induce price fixing arrangements or understandings, in part as an abbreviation and in part because the evidence does not suggest that BlueScope or Mr Ellis attempted to induce an arrangement.

11 The ACCC does not allege that the attempts were successful. No understandings were ultimately arrived at. In some instances, the evidence suggests that BlueScope’s proposal, whatever its ultimate characterisation under the Act, was rebuffed because the counterparties believed that the proposal would or might involve a contravention of the law. In other instances, the proposal was ignored because the competitive pressure from imported steel made BlueScope’s proposal commercially unviable.

12 The ACCC seeks a range of remedies including declaratory relief, an order for the payment of pecuniary penalties to the Commonwealth pursuant to s 76 of the Act and an order that Mr Ellis be disqualified from managing a corporation under s 86E of the Act.

13 The trial was generally confined to issues of liability. As noted below, the ACCC adduced evidence in support of an allegation that, at all material times from at least 11 October 2013, the Chief Executive Officer of BlueScope Australia and New Zealand (BANZ), Mark Vassella, was aware of certain aspects of the conduct constituting the alleged attempts to induce the unlawful understandings. It is appropriate to make findings in respect of that allegation even though it does not relate to any issue of liability.

14 The trial was conducted in the second half of 2021 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. For that reason, the trial was conducted using video-conference technology. Witnesses gave evidence and were cross-examined via that medium.

15 The preparation of these reasons has taken a considerable period of time. This was due to the wide range of allegations that were contested in the proceeding and the extent of the evidence adduced to address all contested issues. I note, though, that my findings with respect to the credit of all witnesses who gave evidence were prepared during or shortly after the trial of the proceeding.

16 For the reasons that follow, I find the majority of the ACCC’s allegations proved. I find that during the relevant period BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia, being seven Australian distributors, one import trader and one overseas steel manufacturer, to contravene s 44ZZRJ by arriving at an understanding that contained cartel provisions, within the meaning of s 76(1)(d) of the Act.

17 This section of the reasons identifies the principal factual allegations that are in dispute in the proceeding.

18 By way of overview, in their respective defences BlueScope and Mr Ellis denied all of the ACCC’s allegations concerning attempts to induce unlawful understandings. BlueScope and Mr Ellis also contested aspects of the ACCC’s allegations concerning the steel products the subject of the alleged attempts and the structure of the market for the manufacture and distribution of those products, including the nature and extent of competition between BlueScope, distributors, overseas manufacturers and import traders.

19 The range of matters put in issue by BlueScope and Mr Ellis greatly extended the evidence required to be adduced in the case and the length of the trial. In my view, most of the contentions advanced on behalf of BlueScope and Mr Ellis concerning the market for flat steel products and BlueScope’s competitors in Australia lacked substance. The witnesses in the proceeding, including BlueScope’s own employees, readily identified BlueScope’s competitors and confirmed most of the ACCC’s allegations concerning the structure of the market for the manufacture and distribution of flat steel products. It is troubling, to say the least, that the ACCC’s allegations, denied by BlueScope, were largely confirmed by a contemporaneous document, prepared by BlueScope, and submitted by BlueScope to the ACCC in connection with an application for informal clearance of a merger. I allowed the tender of the document over BlueScope’s objections (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 1147 (BlueScope (No 3)) at [17]-[33]). Ultimately, there was only one substantive issue in the proceeding that was truly contentious: whether the impugned conduct of Mr Ellis and other representatives of BlueScope rose to the level of an attempt to induce a price fixing understanding.

The market for flat steel products

20 In its pleading, the ACCC defined flat steel products as hot rolled coil, cold rolled coil, steel plate, sheet steel and metallic coated and painted products. The respondents say that the ACCC’s classification of flat steel products is incorrect and that flat steel products generally include products in the following categories: steel plate, hot rolled coil, cold rolled coil, sheet steel, metallic coated sheet and coil and painted sheet and coil. Ultimately, the evidence shows that the differences in the parties’ terminology is of no moment.

21 The ACCC alleged that there was demand for flat steel products in Australia by steel users who did not intend to re-supply those products (being manufacturers who use flat steel products in their business) and by distributors who acquired flat steel products and then resupplied those products to either steel users or other distributors. The respondents say that the ACCC’s description of demand is incomplete in two respects. First, the respondents say that the category of steel users can be further divided between larger manufacturers whose large purchase volumes made it economic and practical to acquire flat steel products directly from BlueScope or import traders and smaller manufacturers who typically purchased flat steel products in smaller volumes and often had different service requirements from larger manufacturers (such as shorter lead times, processing services and/or stock management services that made it uneconomic or impractical to acquire those products directly from BlueScope or import traders). Second, the respondents say that distributors typically performed further processing services required by their customers (including slitting and shearing) and typically supplied their customers with a range of value-added services such as shorter lead times, stock management services, low minimum volumes and other product support.

22 With respect to the supply side of the market, it was common ground that:

(a) BlueScope carried on business in Australia as a manufacturer of, amongst other things, steel slab (which is a raw material that is an input to manufacturing flat steel products) and various flat steel products. BlueScope supplied flat steel products in Australia to its wholly owned subsidiary, BlueScope Distribution Pty Ltd (BlueScope Distribution), other distributors and some steel users.

(b) BlueScope Distribution operated nationally as a distributor of flat steel products in Australia and traded under business names including Sheet Metal Supplies (SMS), Impact Steel and BlueScope Distribution (which I will refer to as BSD to distinguish it from the corporate entity, BlueScope Distribution).

(c) Flat steel products manufactured by overseas steel mills were imported into Australia by a category of trading companies referred to by the parties as import traders. In turn, import traders supplied the imported products to distributors or steel users.

(d) New Zealand Steel Limited (NZ Steel), also a wholly owned subsidiary of BlueScope, manufactured various flat steel products in New Zealand which it supplied to New Zealand Steel (Australia) Pty Ltd (NZSA), another wholly owned subsidiary of BlueScope. NZSA operated as a steel trader for flat steel products in Australia supplying distributors and occasionally steel users.

(e) Overseas steel manufacturers that supplied import traders included:

(i) Shang Chen Steel Co Ltd and Shang Shing Industrial Co Ltd (together, Shang Shing), which were related companies that manufactured flat steel products in Taiwan;

(ii) Yieh Phui Enterprise Co. Ltd (Yieh Phui), which manufactured flat steel products in Taiwan; and

(iii) JSW Steel Ltd (JSW), which manufactured flat steel products in India.

(f) Distributors who acquired flat steel products from BlueScope CIPA or NZSA included:

(i) Southern Steel Group Pty Limited (Southern Steel) and its wholly owned subsidiaries including Southern Sheet & Coil Pty Ltd (Southern Sheet & Coil), Southern Steel Supplies Pty Ltd (Southern Steel Supplies), Surdex Steel Pty Limited (Surdex Steel) and Brice Metals Australia Pty Limited (Brice Metals);

(ii) Arrium Limited (Arrium) and its wholly owned subsidiary OneSteel Trading Pty Ltd (OneSteel) which operated two separate business units known respectively as OneSteel Metalcentre and OneSteel Sheet & Coil (the latter of which was acquired by BlueScope on 1 April 2014);

(iii) CMC Steel Distribution Pty Ltd (CMC Steel);

(iv) Apex Steel Pty Ltd (Apex Steel);

(v) Selection Steel Trading Pty Ltd (Selection Steel);

(vi) Celhurst Pty Ltd trading as Selwood Steel (Selwood Steel); and

(vii) Vulcan Steel Pty Ltd (Vulcan Steel).

23 The ACCC alleged that import traders acquired flat steel products from overseas steel manufacturers and supplied the products to distributors and steel users in Australia. The respondents said that import traders typically did not operate as distributors of flat steel products in Australia or supply flat steel processing services.

24 The ACCC further alleged that each of Wright Steel (Sales) Pty Ltd (Wright Steel) and Citic Australia Commodity Trading Pty Ltd (Citic) was an import trader, either in its own right or jointly with the other as parties to an unincorporated joint venture (the Wright Steel-Citic JV). That was not admitted by the respondents.

25 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times:

(a) BlueScope CIPA and NZSA were in competition with overseas steel manufacturers for the supply of flat steel products to distributors and steel users in Australia; and

(b) BlueScope CIPA, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA were in competition with distributors for the supply of flat steel products in Australia to steel users.

26 The respondents admitted that BlueScope Distribution (through the SMS and Impact Steel divisions) was in competition with other distributors of flat steel products for the supply of some flat steel products to some distribution customers in Australia, but otherwise contested the ACCC’s allegation concerning competition. The principal issues in dispute were whether:

(a) BlueScope CIPA and NZSA were in competition with the overseas steel manufacturer Yieh Phui (as opposed to the import trader – Wright Steel/Citic – which imported Yieh Phui’s flat steel products into Australia); and

(b) BlueScope CIPA was in competition with distributors for the supply of flat steel products to steel users.

27 The ACCC’s allegations concern the conduct of a number of BlueScope employees. The parties prepared a dramatis personae listing the persons referred to in the proceeding and their positions of employment at the relevant time. It is common ground that the following persons held the following positions in the relevant period:

(a) Mr Vassella was employed by BlueScope as the Chief Executive Officer of BANZ;

(b) Mr Ellis was employed by BlueScope as General Manager, Sales & Marketing for CIPA;

(c) Matthew Hennessy was employed by BlueScope as Executive, National Sales Manager, Distribution for CIPA;

(d) Brian Kelso was employed by BlueScope as a National Account Manager (with responsibility for the OneSteel account) and as Queensland Sales Manager (with responsibility for the sheet and coil divisions of Vulcan Steel and Queensland Sheet and Coil);

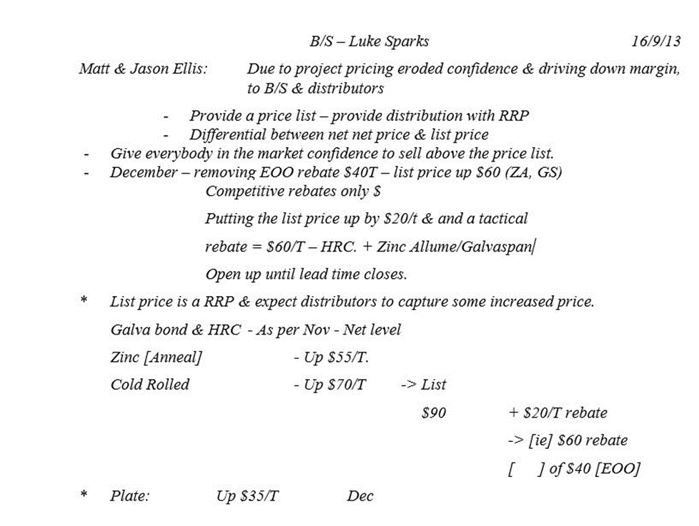

(e) Luke Sparks was employed by BlueScope as the National Account Manager and Sales Manager for South Australia and Northern Territory (and with responsibility for the Southern Steel account);

(f) Troy Gent was employed by BlueScope as Sales Manager for New South Wales (with responsibility for CMC Steel) and Acting Sales Manager for Victoria and Tasmania (with responsibility for BlueScope Distribution);

(g) Denzil Whitfield was employed by BlueScope as an Account Manager based in Victoria (with responsibility for the CMC Steel, OneSteel and Surdex Steel accounts in Victoria); and

(h) Graham Unicomb was employed by BlueScope as a Pricing Manager Distribution, CIPA.

28 In respect of Mr Gent, the ACCC alleged that he had responsibility for Selection Steel, whereas BlueScope said that he only acquired that responsibility from approximately July 2014.

29 In respect of Dieter Schulz, the ACCC alleged that he was employed by BlueScope as the President of the International Markets Group, whereas BlueScope said he was employed by a related company, BlueScope Buildings North America.

30 The ACCC alleged that the conduct of each of the above employees relied upon in the statement of claim was conduct undertaken in the course of their employment and, as a consequence, each acted on BlueScope’s behalf and within the actual or apparent scope of their authority with respect to the conduct. The respondents generally denied that allegation; however, Mr Ellis admitted that he engaged in conduct in the course of his employment.

31 The ACCC further alleged that, at all material times, Mr Hennessy, Mr Sparks, Mr Gent, Mr Whitfield, Mr Kelso, Mr Schulz and Mr Unicomb acted at the direction of Mr Ellis with respect to their conduct as alleged in the statement of claim. The respondents denied that allegation.

BlueScope’s strategies to increase prices for flat steel products in Australia

32 The ACCC alleged that, by in or around September 2013, Mr Ellis (in his new role within CIPA) had developed a strategy to increase the value to BlueScope and distributors of sales of flat steel products in Australia (the benchmarking strategy). The benchmarking strategy comprised:

(a) providing distributors with a suggested or recommended resale price for flat steel products that would be or was higher than the market price before the implementation of the benchmarking strategy;

(b) persuading distributors to use the suggested or recommended resale price to set the price at which those distributors would sell flat steel products to steel users if BlueScope caused BlueScope Distribution and NZSA to price in accordance with the suggested or recommended resale price; and

(c) causing BlueScope Distribution and NZSA to set their prices for flat steel products in accordance with the suggested or recommended resale price, including by limiting the use and availability of tactical pricing.

33 The ACCC alleged that, prior to the introduction of the benchmarking strategy in September 2013, BlueScope had sold flat steel products to BlueScope Distribution, OneSteel, Southern Steel and CMC Steel at additional discounts in order to assist those distributors reduce their prices and meet competition, which was referred to as “tactical pricing”.

34 In its pleading, the ACCC refers to the suggested or recommended resale price as the “pricing information”. I prefer to use the term “CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists” (or “CIPA’s price lists” in shorthand) as that term better describes the documents given by BlueScope to distributors and import traders that is the subject of the allegations.

35 The ACCC further alleged that, between 29 August 2013 and February 2014, Mr Ellis developed a strategy for addressing competition from overseas steel manufacturers whereby he and other BlueScope employees directed by him, on behalf of BlueScope, would seek to:

(a) restrict the volume of imported steel coming into Australia;

(b) persuade overseas steel manufacturers to increase the price at which they sold flat steel products to distributors in Australia; and/or

(c) threaten to make anti-dumping applications against jurisdictions in which overseas steel manufacturers were based unless the price at which they sold flat steel products to distributors in Australia was increased.

36 The respondents denied those allegations.

Attempts to induce arrangements and/or understandings with domestic competitors

37 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce eight domestic suppliers of flat steel products in Australia (seven being distributors and one being an import trader of flat steel products, which were alleged to have been in competition with one or more of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA) to arrive at separate understandings with BlueScope which contained cartel provisions within the meaning of s 44ZZRD(1), being provisions which would have had the purpose or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price for flat steel products supplied, or likely to be supplied, by one or more of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution, NZSA or the competitor concerned. It was common ground that, by the operation of s 44ZZRC, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA would be taken to be a party to any understanding reached by BlueScope (as they were related bodies corporate). The ACCC alleged that reaching the understandings would have involved a contravention of s 44ZZRJ of the Act and that, as a result, the attempts to induce the competitors to arrive at those understandings are subject to the imposition of a pecuniary penalty under s 76(1)(d).

38 Those allegations were denied by the respondents.

39 The ACCC alleged that each of BlueScope and Mr Ellis engaged in the attempts within the meaning of s 76(1)(d) of the Act. In the case of BlueScope, the ACCC alleged that the conduct and state of mind of Mr Ellis and certain employees referred to below should be deemed to be the conduct and state of mind of BlueScope by virtue of ss 84(1) and (2) of the Act respectively. In the case of Mr Ellis, the ACCC relied on Mr Ellis’s own conduct and state of mind, including conduct consisting of Mr Ellis directing other employees to undertake certain actions.

40 The principal allegations for each of the alleged understandings are as follows.

41 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce Wright Steel and/or Citic to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that Wright Steel and/or Citic (either in their own right or acting jointly through the Wright Steel-Citic JV) would sell flat steel products to distributors in Australia at increased prices by reference to CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists;

(b) that Wright Steel would take steps to cause other import traders to sell flat steel products to distributors in Australia at increased prices by reference to CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists; and/or

(c) that BlueScope and NZSA would sell flat steel products to distributors in Australia at increased prices by reference to CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists,

(the Wright Steel understanding).

42 The ACCC alleged that at all material times, Wright Steel and/or Citic (either in their own right or acting jointly through the Wright Steel-Citic JV) were in competition with at least one of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and/or steel users.

43 The ACCC alleged that the conduct constituting the attempt comprised:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis to Griff Wright at a dinner meeting at the Crown Casino complex on 12 September 2013, also attended by Mr Hennessy; and

(b) directions given by Mr Ellis in September and October 2013 for NZSA to increase the prices at which it sold flat steel products to distributors in Australia.

44 In respect of its allegations against each of BlueScope and Mr Ellis concerning the Wright Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the conduct and state of mind of Mr Ellis.

Selection Steel, Apex Steel, Southern Steel and Vulcan Steel understandings

45 The ACCC alleges that each of BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce each of Selection Steel, Apex Steel, Southern Steel and Vulcan Steel to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that the relevant distributor would use CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists as a benchmark when selling flat steel products to steel users in Australia;

(b) that BlueScope would limit the use of tactical pricing;

(c) that BlueScope would increase the price that it sold flat steel products to BlueScope Distribution and NZSA; and/or

(d) that BlueScope Distribution and NZSA would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia in accordance with CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists,

(respectively, the Selection Steel understanding, the Apex Steel understanding, the Southern Steel understanding, and the Vulcan Steel understanding).

46 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times, each of Selection Steel, Apex Steel, Southern Steel and Vulcan Steel respectively was in competition with at least one of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and/or steel users in Australia.

47 In respect of each of the alleged understandings, the ACCC relies on:

(a) statements made by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy at a meeting held at the ParkRoyal Hotel at Melbourne Airport on 6 September 2013 (the Melbourne Airport meeting) with Rod Gregory of Selection Steel, Joe Calleja of Apex Steel, Peter Smaller of Southern Steel and Peter Wells of Vulcan Steel;

(b) directions given by Mr Ellis to Mr Hennessy on or around 13 September 2013 to release CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists for December 2013 to distributors and to speak to distributors to get them to use the price lists to set the price at which they sold flat steel products to steel users;

(c) statements made and directions given by Mr Hennessy at a CIPA meeting held on 16 September 2013 between the Pricing Managers (including Mr Unicomb) and the Account Managers for each of CMC Steel, OneSteel, Southern Steel and BlueScope Distribution (including Messrs Gent, Kelso and Sparks), particularly in relation to the preparation of what the ACCC referred to as “an internal price list” for products to be supplied in December 2013 (a label that does not adequately describe the nature of this document, which I address later in these reasons and refer to as the “December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet”);

(d) directions given by Mr Ellis to Mr Hennessy on or around 16 September 2013 to circulate the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet to BlueScope Distribution and other distributors and to discuss the benchmarking strategy with them.

48 In respect of the Selection Steel understanding, the ACCC also relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting at BlueScope’s office in Mount Waverley in August or September 2013 attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Gary Collis and Mr Gregory of Selection Steel;

(b) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Messrs Collis and Gregory of Selection Steel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet and a conversation between Mr Hennessy and Mr Collis on that day about the price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(c) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to representatives of Selection Steel on 19 September 2013 attaching CIPA’s Distribution Market price list for December 2013; and

(d) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Mr Collis of Selection Steel on 8 January 2014 attaching CIPA’s Distribution Market price list for March 2014.

49 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the Selection Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Unicomb and the state of mind of Messrs Ellis and Hennessy. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the conduct of Mr Ellis including alleged directions given to Mr Hennessy.

50 In respect of the Apex Steel understanding, the ACCC also relies on:

(a) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Mr Calleja of Apex Steel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet and a conversation between Mr Hennessy and Mr Calleja on that day about the price lists and the benchmarking strategy; and

(b) the provision of CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists to Apex Steel by BlueScope on 23 December 2013, 5 February 2014, 7 March 2014, 2 April 2014, 6 May 2014 and 2 June 2014.

51 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the Apex Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Unicomb and the alleged state of mind of Messrs Ellis and Hennessy. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis and Hennessy.

52 In respect of the Southern Steel understanding, the ACCC also relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting at Southern Steel’s office in Bankstown, New South Wales, on 2 September 2013 attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and James (Jim) Larkin of Southern Steel;

(b) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting at a coffee shop in Double Bay in Sydney on 4 September 2013 attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Kevin Smaller and Peter Smaller of Southern Steel;

(c) a conversation between Mr Sparks of BlueScope and Dave Lander of Southern Steel on 16 September 2013 about CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(d) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to representatives of Southern Steel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet; and

(e) the provision of CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists to Southern Steel by BlueScope on 20 December 2013, 5 February 2014, 5 March 2014, 1 April 2014, 30 April 2014 and 30 May 2014.

53 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the Southern Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Unicomb and Sparks and the alleged state of mind of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Sparks. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Mr Ellis including alleged directions given to Mr Hennessy.

54 In respect of the Vulcan Steel understanding, the ACCC also relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Jon Gousmett and Adrian Casey of Vulcan Steel which occurred during the Australian Steel Institute Conference on the Gold Coast on 9 and 10 September 2013;

(b) a conversation between Mr Kelso of BlueScope and one or more representatives of Vulcan Steel on or around 16 September 2013 about CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(c) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Mr Casey of Vulcan Steel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet and a conversation between Mr Hennessy and Mr Casey on that day about the price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(d) a further conversation between Mr Kelso of BlueScope and David Millard and Andrew Moss of Vulcan Steel on 18 September 2013 about BlueScope’s price list and the benchmarking strategy;

(e) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Mr Casey of Vulcan Steel on 19 September 2013 attaching CIPA’s Distribution Market price list; and

(f) the provision of CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists to Vulcan Steel by BlueScope on 6 January 2014, 13 February 2014, 13 March 2014, 7 April 2014, 6 May 2014 and 5 June 2014.

55 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the Southern Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Unicomb and Kelso and the alleged state of mind of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Kelso. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Mr Ellis including alleged directions given to Mr Hennessy.

56 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce Selwood Steel to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that Selwood Steel would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia at a higher price than it was doing at that time;

(b) that Selwood Steel would benchmark its prices based on CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists;

(c) that BlueScope would provide Selwood Steel with the opportunity to purchase BlueScope’s flat steel products on a transactional basis; and/or

(d) that BlueScope Distribution and NZSA would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia in accordance with CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists,

(the Selwood Steel understanding).

57 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times, Selwood Steel was in competition with at least one of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and/or steel users in Australia.

58 In respect of the Selwood Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting held at Selwood Steel’s premises in Victoria on 30 October 2013 attended by Messrs Ellis and Whitfield of BlueScope and Dale Wood of Selwood Steel; and

(b) an email sent by Mr Whitfield to Mr Wood of Selwood Steel on 12 November 2013 attaching CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists.

59 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the Selwood Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct and state of mind of Messrs Ellis and Whitfield. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Mr Ellis.

60 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce CMC Steel to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that BlueScope Distribution and NZSA would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia in accordance with CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists;

(b) that BlueScope would reduce its tactical pricing; and/or

(c) that CMC Steel would use CIPA’s Distribution Market price lists as a benchmark for setting prices for the sale by CMC Steel of flat steel products to steel users in Australia,

(the CMC Steel understanding).

61 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times, CMC Steel was in competition with at least one of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and steel users in Australia.

62 In respect of the CMC Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Matthew (Matt) Stedman and Glenn Simpkin of CMC Steel which occurred during the Australian Steel Institute Conference on the Gold Coast on 9 and 10 September 2013;

(b) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to representatives of CMC Steel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet;

(c) a telephone conversation or conversations between Mr Ellis and Neil Lobb of CMC Steel on a date or dates between October 2013 and April 2014 about CIPA’s price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(d) an email sent by Mr Gent of BlueScope to Mr Lobb of CMC Steel on 27 November 2013 stating that competitors of CMC Steel had already implemented the price increases;

(e) an email sent by Mr Gent of BlueScope to Mr Lobb and Nick Klingos of CMC Steel on 21 March 2014 attaching copies of letters sent by BlueScope Distribution to steel users setting out an increase in the price at which BlueScope Distribution intended to sell flat steel products to them;

(f) an email sent by Mr Gent of BlueScope to Mr Lobb of CMC Steel forwarding an email from SMS (a division of BlueScope Distribution) recording that it had provided letters to customers with its new tonne rates and had not had too much backlash, however the competitors of SMS had not yet sent prices out; and

(g) the provision of CIPA’s price lists to CMC Steel by BlueScope on 20 December 2013, 7 February 2014, 7 March 2014, 1 April 2014, 30 April 2014 and 30 May 2014.

63 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the CMC Steel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Unicomb and Gent and the alleged state of mind of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Gent. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Mr Ellis including alleged directions given to Mr Hennessy.

64 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce OneSteel to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that OneSteel would use CIPA’s price lists as a benchmark when selling flat steel products to steel users in Australia; and/or

(b) that BlueScope Distribution and NZSA would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia in accordance with CIPA’s price lists,

(the OneSteel understanding).

65 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times, OneSteel was in competition with at least one of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and steel users in Australia.

66 In respect of the OneSteel understanding, the ACCC relies on:

(a) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Mark Lewin of OneSteel which occurred during the Australian Steel Institute Conference on the Gold Coast on 9 and 10 September 2013;

(b) a conversation between Mr Kelso of BlueScope and David Bolzan of OneSteel on 12 September 2013 about CIPA’s price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(c) statements made by Mr Ellis at a meeting attended by Messrs Ellis and Hennessy of BlueScope and Michael Lambourne and Bruce Birchall of OneSteel at the Qantas Meeting Rooms at Sydney Airport on 13 September 2013 about CIPA’s price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(d) a conversation between Mr Kelso of BlueScope and one or more representatives of OneSteel on 16 September 2013 about CIPA’s price lists and the benchmarking strategy;

(e) an email sent by Mr Hennessy to Mr Birchall and Glenn Szecsodi of OneSteel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet;

(f) an email sent by Mr Kelso to Messrs Lewin and Bolzan of OneSteel on 17 September 2013 attaching a version of the December 2013 Benchmark spreadsheet; and

(g) the provision of CIPA’s price lists to OneSteel by BlueScope on 20 December 2013, 4 February 2014, 6 March 2014, 2 April 2014, 30 April 2014 and 2 June 2014.

67 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope concerning the OneSteel understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Unicomb and Kelso and the alleged state of mind of Messrs Ellis, Hennessy and Kelso. In respect of its allegations against Mr Ellis, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct of Mr Ellis including alleged directions given to Mr Hennessy.

Attempts to induce arrangements and/or understandings with an overseas steel manufacturer – Yieh Phui

68 The ACCC alleged that, on 26 February 2014, Mr Ellis, together with other representatives of BlueScope, attended a meeting with representatives of Yieh Phui at the offices of Yieh Phui in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and that, at that meeting, BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce Yieh Phui to arrive at an understanding with BlueScope which included one or more of the following provisions:

(a) that Yieh Phui would sell flat steel products to import traders at a higher price than it was doing at the time of the Yieh Phui meeting;

(b) that Yieh Phui would raise the price at which it sold flat steel products to import traders by reference to CIPA’s price lists in order to increase the profitability of both Yieh Phui and BlueScope;

(c) that BlueScope would be taking anti-dumping measures against any overseas steel manufacturer that it considered was selling flat steel products into Australia at a price that was too low; and/or

(d) that BlueScope Distribution would sell flat steel products to steel users in Australia in accordance with CIPA’s price lists,

(the Yieh Phui understanding).

69 The ACCC alleged that, at all material times, Yieh Phui was in competition with at least one of BlueScope and NZSA in relation to the supply of flat steel products to distributors and steel users in Australia.

70 In respect of its allegations against each of BlueScope and Mr Ellis concerning the Yieh Phui understanding, the ACCC relies on the alleged conduct and state of mind of Mr Ellis.

Involvement of BlueScope senior management

71 For the purposes of penalty, but not liability, the ACCC alleged that at all material times from at least 11 October 2013, Mr Vassella was aware of certain aspects of the conduct constituting the alleged attempts to induce the unlawful understandings. Evidence was adduced in support of that allegation and it is therefore appropriate to make findings even though the trial concerned issues of liability only.

C. APPLICABLE LEGAL PRINCIPLES

Relevant legislative provisions

72 The following legislative provisions, relevant to the proceeding, are stated as in force at the time of the impugned conduct.

73 The ACCC seeks pecuniary penalties against BlueScope and Mr Ellis under s 76(1)(d) of the Act. Section 76(1) relevantly provided as follows:

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened any of the following provisions:

(i) a provision of Part IV (other than section 44ZZRF or 44ZZRG);

(iii) … ; or

(b) has attempted to contravene such a provision; or

(c) has aided, abetted, counselled or procured a person to contravene such a provision; or

(d) has induced, or attempted to induce, a person, whether by threats or promises or otherwise, to contravene such a provision; or

(e) has been in any way, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention by a person of such a provision; or

(f) has conspired with others to contravene such a provision;

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Part or Part XIB to have engaged in any similar conduct.

74 As set out earlier, the ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia to contravene s 44ZZRJ of the Act by arriving at understandings that contained a cartel provision within the meaning of s 44ZZRD of the Act. The type of cartel provision alleged by the ACCC is a “price fixing” provision as defined by s 44ZZRD(2).

75 Section 44ZZRJ provided as follows:

A corporation contravenes this section if:

(a) the corporation makes a contract or arrangement, or arrives at an understanding; and

(b) the contract, arrangement or understanding contains a cartel provision.

76 The phrase “arrive at”, in relation to an understanding, was defined in s 4(1) as including reach or enter into. In these reasons, I have used those expressions interchangeably.

77 For completeness, I note that s 44ZZRK(1) provided as follows:

(1) A corporation contravenes this section if:

(a) a contract, arrangement or understanding contains a cartel provision; and

(b) the corporation gives effect to the cartel provision.

78 Section 44ZZRD relevantly provided as follows:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is a cartel provision if:

(a) either of the following conditions is satisfied in relation to the provision:

(i) the purpose/effect condition set out in subsection (2);

(ii) the purpose condition set out in subsection (3); and

(b) the competition condition set out in subsection (4) is satisfied in relation to the provision.

Purpose/effect condition

(2) The purpose/effect condition is satisfied if the provision has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of directly or indirectly:

(a) fixing, controlling or maintaining; or

(b) providing for the fixing, controlling or maintaining of;

the price for, or a discount, allowance, rebate or credit in relation to:

(c) goods or services supplied, or likely to be supplied, by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

…

Note 1: The purpose/effect condition can be satisfied when a provision is considered with related provisions — see subsection (8).

Note 2: Party has an extended meaning — see section 44ZZRC.

…

Competition condition

(4) The competition condition is satisfied if at least 2 of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding:

(a) are or are likely to be; or

(b) but for any contract, arrangement or understanding, would be or would be likely to be;

in competition with each other in relation to:

(c) if paragraph (2)(c) … applies in relation to a supply, or likely supply, of goods or services — the supply of those goods or services; or

…

Note: Party has an extended meaning — see section 44ZZRC.

…

Recommending prices etc.

(6) For the purposes of this Division, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is not taken:

(a) to have the purpose mentioned in subsection (2); or

(b) to have, or be likely to have, the effect mentioned in subsection (2);

by reason only that it recommends, or provides for the recommending of, a price, discount, allowance, rebate or credit.

…

Purpose/effect of a provision

(10) For the purposes of this Division, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is not to be taken not to have the purpose, or not to have or to be likely to have the effect, mentioned in subsection (2) by reason only of:

(a) the form of the provision; or

(b) the form of the contract, arrangement or understanding; or

(c) any description given to the provision, or to the contract, arrangement or understanding, by the parties.

…

79 The following words, which appeared in s 44ZZRD, were defined in the Act as follows:

(a) the word “provision”, in relation to an understanding, was defined in s 4 as meaning any matter forming part of the understanding;

(b) the word “competition” was defined in s 4 as including (relevantly) competition from imported goods; and

(c) the word “likely”, in relation to (relevantly) the supply of goods, was defined in s 44ZZRB as including a possibility that is not remote.

80 Section 4F(1) is a deeming provision in relation to the purpose of a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding. It relevantly provided as follows:

(1) For the purposes of this Act:

(a) a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding or of a proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or a covenant or a proposed covenant, shall be deemed to have had, or to have, a particular purpose if:

(i) the provision was included in the contract, arrangement or understanding or is to be included in the proposed contract, arrangement or understanding, or the covenant was required to be given or the proposed covenant is to be required to be given, as the case may be, for that purpose or for purposes that included or include that purpose; and

(ii) that purpose was or is a substantial purpose…

…

81 Section 44ZZRC extended the meaning of being a party to a contract, arrangement or understanding. It provided as follows:

For the purposes of this Division, if a body corporate is a party to a contract, arrangement or understanding (otherwise than because of this section), each body corporate related to that body corporate is taken to be a party to that contract, arrangement or understanding.

82 Combining the various elements of the statutory provisions, the ACCC must establish that:

(a) BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia to arrive at understandings;

(b) each understanding was to contain a provision that had the purpose, or had or was likely to have had the effect, of directly or indirectly, fixing, controlling or maintaining or providing for the fixing, controlling or maintaining of the price for, or a discount, allowance, rebate or credit in relation to, goods supplied, or likely to be supplied, by any or all of the parties to the understanding; and

(c) at least two of the entities that were to be parties to each understanding were or were likely to have been, or but for the understanding, would have been or would be likely to have been in competition with each other in relation to the supply of the goods the subject of the provision.

83 Each of the statutory elements has been the subject of extensive judicial analysis, which is discussed below.

Attempt to induce a person to contravene

84 The meaning of the words “attempt” and “induce” in the context of s 76 of the Act have been discussed in a number of cases. In considering those cases, it is important to bear in mind the context in which the words are used within s 76(1). Relevantly, s 76(1) empowers the Court to impose a pecuniary penalty in respect of the following categories of conduct: where a person has contravened a provision of Pt IV (s 76(1)(a)); where a person has attempted to contravene such a provision (s 76(1)(b)); where a person has induced a person to contravene such a provision (s 76(1)(d)); and where a person has attempted to induce a person to contravene such a provision (also s 76(1)(d)). The present case is concerned with the fourth context – an attempt to induce a person to contravene. When reading the decided cases, it is important to bear in mind the specific provision and conduct relied upon, and the legal reasoning that is applicable to that provision and conduct.

85 It is uncontroversial that, in both paras (b) and (d) of s 76(1), an attempt has two elements – conduct and intention: see Trade Practices Commission v Tubemakers of Australia Ltd [1983] FCA 99; 47 ALR 719 (Tubemakers) at 735-737 per Toohey J and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Egg Corporation Ltd (2017) 254 FCR 311 (Australian Egg Corporation) at [92] per Besanko, Foster and Yates JJ.

86 In the context of s 76(1)(b), the conduct necessary to constitute an “attempt to contravene” a provision of Pt IV has been described as a step towards the commission of the contravention which is immediately and not merely remotely connected with it: Tubemakers at 736 per Toohey J. Conduct which is merely preparatory to committing the contravention does not suffice: Trade Practices Commission v Parkfield Operations Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 534 (Parkfield) at 538-539 per Bowen CJ, Smithers and Morling JJ.

87 The common law requirement that, in order to constitute an attempt, conduct must be more than merely preparatory to the commission of the offence or contravention has been considered in many cases. The requirement has also been adopted as the relevant test of the conduct element of an attempt in s 11.1 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code, being the Schedule to the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) (which, at the relevant time, was applicable to the criminal offences of making a contract, arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision – prohibited by s 44ZZRF – and giving effect to a cartel provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding – prohibited by s 44ZZRG). Relevantly, subss 11.1(1) and (2) stipulate that:

(1) A person who attempts to commit an offence commits the offence of attempting to commit that offence and is punishable as if the offence attempted had been committed.

(2) For the person to be guilty, the person’s conduct must be more than merely preparatory to the commission of the offence. The question whether conduct is more than merely preparatory to the commission of the offence is one of fact.

88 The meaning of “more than merely preparatory” in s 11.1 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code was considered by the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal in Inegbedion v The Queen [2013] NSWCCA 291. Justice Rothman (with whom Hoeben CJ at CL and McCallum J agreed) said (at [17]):

Over and above the proof of an intention to commit the crime alleged, the Crown must also prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the accused, with that intention, performed some act that went towards the commission of the offence, which act was more than merely preparatory of the crime and was immediately connected with the commission of that crime, having no reasonable purpose other than its commission.

89 In Holliday v The Queen (2016) 12 ACTLR 16, the Court of Appeal of the Australian Capital Territory considered the meaning of the same phrase as adopted in s 44(2) of the Criminal Code 2002 (ACT). Chief Justice Murrell referred to the above statement of Rothman J with apparent approval (at [52]). Justice Wigney observed (at [124]-[125]):

124 The conduct referred to by the Crown and the trial judge was capable of being conduct that was more than “merely preparatory” to the commission of the offence of perverting the course of justice. In his summing up, the trial judge used the expression “immediately connected” as a means of explaining or describing the element that the conduct be more than merely preparatory. That expression appears to have been derived from the judgment of Rothman J (with whom Hoeben CJ at CL agreed) in Inegbedion v The Queen [2013] NSWCCA 291 at [17] in relation to the similar provision in s 11.1 of the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth). Another expression that has been used in the authorities to describe or explain the requirement that conduct be “more than merely preparatory” is “sufficiently proximate” to the intended commission of the crime: see Britten v Alpogut [1987] VR 929 at 935; Onuorah at 10 [30].

125 It is perhaps doubtful whether it is useful to put a gloss on the words used in s 44(2) of the Criminal Code. The words “merely preparatory” are ordinary English words that a jury could readily comprehend. It is perhaps not desirable, and probably not possible, to formulate a single test for determining when conduct may be more than merely preparatory. Much will depend on the nature and elements of the substantive offence in question and the facts and circumstances of the particular case. It is ultimately a question of fact for the jury. In the circumstances of Mr Holliday’s case, it is sufficient to say that, if the jury found that Mr Holliday drafted, typed and printed the letter containing the instruction and provided that letter to Mr Powell, it was at least open to the jury to find that those acts were more than merely preparatory to the offence of perverting the course of justice.

90 The tests for the conduct element of an attempt as stated in Tubemakers and Parkfield were referred to with approval by the Full Court in Australian Egg Corporation at [93]. Tubemakers and Parkfield concerned an alleged attempt to contravene a provision of Pt IV, for which a penalty was imposed under s 76(1)(b) of the Act. In contrast, Australian Egg Corporation concerned an attempt to induce a person to contravene a provision of Pt IV, for which a penalty was imposed under s 76(1)(d). The Full Court in Australian Egg Corporation did not comment on the different statutory context, and the different conduct at which the attempt must be directed. Nevertheless, in the context of an attempt to induce a person to contravene, it would seem to be appropriate to refer to the conduct element as requiring a step towards the inducement of the contravention which is more than merely preparatory of the inducement to contravene and which is immediately and not merely remotely connected with the inducement to contravene.

91 The meaning of the word “induce” in s 76(1)(d) and related provisions has been considered in a number of cases. In Yorke v Lucas (1983) 49 ALR 672 (affirmed on appeal: Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 (Yorke v Lucas)), the Full Court said in obiter remarks that inducing a contravention within the meaning of s 75B(b) of the Act (now s 75B(1)(b)) connotes some act of compulsion by force or threat of force or some act of persuasion or stimulation (at 681). Those observations are consistent with the statutory language which, in both ss 75B(1)(b) and 76(1)(d), indicates that an inducement may be “by threats or promises or otherwise”.

92 In Heating Centre Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1986) 9 FCR 153 (Heating Centre), the Full Court considered the meaning of the phrase “inducing or attempting to induce” in the context of s 96(3)(b) of the Act concerned with the practice of resale price maintenance (prohibited by s 48 of the Act). Justice Pincus (with whom Lockhart and Wilcox JJ agreed) concluded (at 164):

Next, it is necessary to consider whether the conversation falls within par (b), properly construed; that is directed against inducing or attempting to induce people not to sell at less than the price specified, where the goods come directly or otherwise from the inducer. Counsel argued that there must be an “inducement” as that word is commonly used in the law. It is true that the word ordinarily refers to some proffered advantage or disadvantage, promised or threatened, to follow from following or failing to follow a stipulated course of action. There is no reason, however, to read into par (b) a necessity to find that anything is offered in exchange, so to speak, for not discounting; mere persuasion, with no promise or threat, may well be an attempt to induce.

93 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v J McPhee & Son (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 3) [1998] FCA 200, Heerey J referred to the dictionary definitions of the word “induce” as “to lead or move by persuasion or influence, as to some action or state of mind” (Macquarie Dictionary) or “to lead (a person) by persuasion or some influence to some action, condition, belief, etc” (Shorter Oxford).

94 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SIP Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCA 824; ATPR 41-877 (SIP Australia), Goldberg J observed (at [112]):

An attempt to induce particular conduct can take a number of forms. As is made clear by s 76(1)(d) of the Act, an inducement may occur although no threat or promise is involved. Section 76(1)(d) of the Act empowers a court to impose a penalty where a person has induced or attempted to induce a person to contravene a provision of the Act “whether by threats or promises or otherwise”. What is required for an inducement is that there be an affirmative or positive act or course of conduct directed to the person who is said to be the object of the inducement. Accordingly “mere persuasion, with no promise or threat, may well be an attempt to induce”: The Heating Centre Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1986) 9 FCR 153 at 164. See also Yorke v Lucas (1983) 49 ALR 672, at 681 682 (affirmed on appeal (1985) 158 CLR 661). …

95 The Full Court in Australian Egg Corporation referred to the above statements in Heating Centre and SIP Australia with approval (at [93]).

96 The respondents drew a distinction between persuading a competitor to increase their price and persuading a competitor to arrive at an understanding containing a provision that they will increase their price. The respondents argued that conduct in the first category is lawful while conduct in the second is unlawful. The distinction can be accepted in theory but is likely to be a fine one in practice. For example, if competitor A says to competitor B that competitor B should increase its prices because they are unprofitable, that might be characterised as mere persuasion (in the form of a persuasive argument) to increase prices and may not involve an inducement to reach an understanding and a contravention of the law. An illustration of such conduct is given by the findings in Trade Practices Commission v Service Station Association Ltd (1992) 109 ALR 465 (Service Station Association) (see at 488 per Heerey J) (upheld on appeal in Trade Practices Commission v Service Station Association Ltd (1993) 44 FCR 206 (Service Station Association (Full Court)) at 224-225, 238 per Lockhart J, Spender and Lee JJ agreeing). However, an added statement that competitor A is intending to do likewise may, in appropriate circumstances, be characterised as an attempt to persuade competitor B to arrive at an understanding to increase prices. Further, as Heerey J observed in that case (at 488), the objective likelihood of particular conduct producing a particular result (viz, arrive at an understanding) is relevant to ascertaining what was intended by the conduct (referring to the observations of Windeyer J in Vallance v The Queen (1961) 108 CLR 56 at 82).

97 In Parkfield, the Full Court concluded (at 539) that an attempt to contravene does not need to have reached an advanced stage before it comes within the purview of s 76(1)(b). In respect of an attempt to induce a contravention within s 76(1)(d), the Full Court said that it is not necessary for any arrangement to be in place, or readily able to be effected – it is sufficient that the respondents sought to persuade the counterparties to enter into an arrangement to increase prices (also at 539). Those statements were approved by the Full Court in Australian Egg Corporation (at [94]):

For the purposes of both elements of an attempt, that is to say intention and conduct, it is not necessary for the precise terms of the proposed arrangement or understanding to have been formulated. This point was made by the Full Court in Parkfield Operations (at 539) and another way of putting the point is that it is not necessary for an attempt to be made out to establish that the relevant conduct had reached an advanced stage. Having said this, it is perhaps trite to note that the more advanced the conduct, the more likely it is that the inference of the necessary intention will be drawn.

98 The relevant intention that must be established is an intention to bring about that which is attempted: Tubemakers at 737 and 743 per Toohey J. However, it is unnecessary to show that the respondent expected that the understanding would be arrived at: Tubemakers at 736 per Toohey J. Those statements were referred to with approval by the Full Court in Australian Egg Corporation at [92], where the Full Court formulated the requisite intention as “to bring about the proscribed result which in this case is the making of an arrangement or the reaching of an understanding within s 44ZZRJ”. As noted above, Tubemakers concerned an attempt to contravene a provision of Pt IV within the meaning of s 76(1)(b), whereas Australian Egg Corporation (like this case) concerned an attempt to induce a person to contravene a provision of Pt IV within the meaning of s 76(1)(d). In the context of an attempt to induce a person to arrive at an understanding containing certain provisions, it would seem to be appropriate to refer to the intention element as requiring an intention to induce the person to arrive at that understanding. Otherwise, the distinction between the conduct described in paras (b) and (d) of s 76(1) would be lost. In practice, though, there will not be any material difference between the two descriptions of the requisite intent – the conduct, involving inducement, must be intentionally directed to the making of an arrangement or the reaching of an understanding.

99 It is unnecessary to show that the respondents knew that the contemplated understanding was unlawful. However, knowledge of the essential facts that would have rendered the alleged understanding unlawful is necessary before there can be intent: Giorgianni v The Queen (1985) 156 CLR 473 at 505 per Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ; Yorke v Lucas at 667 per Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ; Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 (Rural Press (HC)) at [48] per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ.

100 The ACCC alleged that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia to arrive at arrangements or understandings that contained a cartel provision.

101 The meaning of the words “arrangement” and “understanding” in s 45 of the Act should now be regarded as well established. The meaning given to those terms has not altered in any material way since the earliest case brought under the Act, the decision of the Australian Industrial Court (Joske, Smithers and Evatt JJ) in Top Performance Motors Pty Ltd v Ira Berk (Qld) Pty Ltd (1975) 24 FLR 286 (Top Performance Motors) (which considered the original form of s 45 of the Act, prohibiting contracts, arrangements and understandings in restraint of trade or commerce).

102 The applicable principles, established by the cases, can be stated as follows:

(a) The terms “contract”, “arrangement” and “understanding” in s 45 of the Act represent “a spectrum of consensual dealings”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (2007) 160 FCR 321 (Leahy) at [24] per Gray J. In many decisions, no distinction is drawn between the terms “arrangement” and “understanding”, although in a number of cases there is a recognition that the statutory language of “arrives at an understanding” connotes a less precise consensus than “makes an arrangement”: see for example Trade Practices Commission v TNT Management Pty Ltd (1985) 6 FCR 1 (TNT) at 25 per Franki J; Leahy at [27]; and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (No 4) [2017] FCA 1590; 353 ALR 460 (Colgate-Palmolive) at [49] per Wigney J (affirmed on appeal in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 83 at [53] per Middleton, Perram and Bromwich JJ).

(b) Each of the terms “arrangement” and “understanding” requires a meeting of minds or consensus between the parties to the arrangement or understanding that they will conduct themselves in accordance with the subject matter of the arrangement or understanding: Top Performance Motors at 291 per Smithers J, applying Re British Basic Slag Ltd’s Agreements [1963] 1 WLR 727 (Re British Basic Slag) at 746 per Diplock LJ. The reasoning of Smithers J has been referred to with approval and adopted in numerous decisions including Trade Practices Commission v Nicholas Enterprises Pty Ltd (No 2) (1979) 40 FLR 83 (Nicholas Enterprises) at 90 per Fisher J (upheld on appeal in Morphett Arms Hotel Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1980) 30 ALR 88 (Morphett Arms) per Bowen CJ, Brennan and Deane JJ); Trade Practices Commission v Email Ltd (1980) 31 ALR 53 (Email) at 55-56 per Lockhart J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CC (NSW) Pty Ltd (No 8) (1999) 92 FCR 375 (ACCC v CC) at [135]-[141] per Lindgren J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Amcor Printing Papers Group Ltd [2000] FCA 17; 169 ALR 344 (Amcor Printing) at [75] per Sackville J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (2003) 129 FCR 339 at [409] per Heerey and Sackville JJ, Emmett J agreeing in that regard; Leahy at [28] per Gray J; Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 162 FCR 466 (CEEEIPPAS v ACCC) at [150] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ; and Country Care Group Pty Ltd v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) (2020) 275 FCR 342 (Country Care) at [60] per Allsop CJ, Wigney and Abraham JJ.

(c) By way of further explication, an “arrangement” and “understanding” requires that the parties to the understanding have, by words or conduct, aroused an expectation in each that they will conduct themselves in accordance with the subject matter of the arrangement or understanding. The expectation must be more than a mere hope, belief or prediction that, as a matter of fact, a person will conduct themselves in the future in a particular way. The expectation must arise out of the dealings between the parties which has resulted in what can alternatively be called the assumption of an obligation, the giving of an assurance or undertaking, or a meeting of minds, that they will act in in the future in a particular way: see Nicholas Enterprises at 89 per Fisher J; ACCC v CC at [141] per Lindgren J; Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 118 FCR 236 (Rural Press) at [79] per Whitlam, Sackville and Gyles JJ; Apco Service Stations Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2005) 159 FCR 452 (Apco) at [45] per Heerey, Hely and Gyles JJ; Leahy at [35]-[38] per Gray J; and Country Care at [60] per Allsop CJ, Wigney and Abraham JJ.

(d) As an arrangement or understanding is not binding on the parties in law (indeed, an arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision is unlawful), the parties are inevitably free to withdraw from it and act inconsistently with it, notwithstanding their consent to it: TNT at 24 per Franki J (referring to the joint judgment of Gibbs and Mason JJ in Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Lutovi Investments Pty Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 434 at 444); Leahy at [34] per Gray J.

(e) Conduct which founds an understanding can be arrived at by words or conduct and may be tacit: Leahy at [28] per Gray J: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd [2014] FCA 1157; 319 ALR 388 (Air New Zealand) at [463(1) and (3)] per Perram J (overturned on appeal in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v PT Garuda Indonesia Ltd (2016) 244 FCR 190 (PT Garuda) but without criticism of his Honour’s statement of principles in respect of “arrangement or understanding”); Australian Egg Corporation at [95] per Besanko, Foster and Yates JJ; Colgate-Palmolive at [50] per Wigney J (affirmed on appeal).

(f) The existence of an arrangement or understanding can be inferred from circumstantial evidence, including the course of dealings between the putative parties which might provide the occasion for the formation of an arrangement or understanding, their trading conduct and its consistency with the putative arrangement or understanding, and any attempt to enforce compliance with the putative arrangement or understanding: R v Associated Northern Collieries (1911) 14 CLR 387 at 400 per Isaacs J; TNT at 24 per Franki J (referring to the observations of Fisher J, with whom Brennan and Deane JJ agreed, in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Cooper Brookes (Wollongong) Pty Ltd (1979) 41 FLR 277 at 301-302); Email at 55-56 per Lockhart J; Service Station Association at 485 per Heerey J (upheld on appeal in Service Station Association (Full Court)); CEEEIPPAS v ACCC at [136] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ.

(g) Although in business it might be expected that a person would not make an arrangement or understanding in the absence of reciprocal or mutual obligations, that has never been authoritatively held to be a necessary element of an arrangement or understanding prohibited by s 45: Morphett Arms at 91-92 per Bowen CJ, Brennan and Deane JJ (qualifying the Court’s agreement with the applicable principles stated by Fisher J in Nicholas Enterprises); Email at 64 per Lockhart J; Service Station Association (Full Court) at 231 per Lockhart J and at 238 per Spender and Lee JJ; Amcor Printing at [75] per Sackville J; Australian Egg Corporation at [96] per Besanko, Foster and Yates JJ. It can be added that a requirement of reciprocal or mutual obligations would be difficult to reconcile with the terms of ss 44ZZRJ and 44ZZRK which refer to a contract, arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision, and the terms of ss 44ZZRD which defines a cartel provision as being binding on any of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding.

103 The use of the word “obligation” to explain the conception of an “understanding” within the meaning of the Act has the potential to cause confusion, particularly for business people. The word “obligation” is most commonly associated with the law of contract and is usually understood as conveying a legal obligation. In contrast, an understanding containing a cartel provision is unlawful, creates no legal obligations, will often be arrived at in secret and with stealth and may break down through cheating (non-compliance) or parties resiling from the understanding.