Federal Court of Australia

Kilmallock (ACT) Pty Ltd v World Blinds Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1472

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for interlocutory relief be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the interlocutory application.

3. The proceeding be listed for case management on 18 November 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

(Revised from the transcript)

RARES J:

1 This is an application for an interlocutory injunction by one competitor against another in the sale of a type of blind, window shade or curtain. The applicant, Kilmallock (ACT) Pty Ltd (which trades under the name of Pacific Wholesale Distributors), sells its blinds under the name “Veri shades”. Kilmallock is an established business. Kilmallock’s blinds use a patented connector product that it acquires under arrangements it has with its Korean suppliers. Kilmallock is the registered owner of seven innovation patents. The relevant patent for the purposes of the application for interlocutory relief is Australian innovation patent number 2015101931 (the 931 patent).

2 The 931 patent was filed on 31 December 2015 and is titled “Connector for blind-type curtain and blind-type curtain comprising same”. It has priority dates of 15 January 2015 and 30 December 2015, tied to the PCT patents in Korean filings from which it derives. The 931 patent was granted on 31 October 2018 and certified on 12 June 2019. It expires on 31 December 2023, subject to the payment of renewal fees. The 931 patent was the subject of re-examination at the suit of a person presently unknown in the period between May 2020 and March 2021, during which Kilmallock made some amendments that are not presently relevant.

3 The respondents are World Blinds Australia Pty Ltd, Viewlux Pty Ltd, trading as World Blinds Newcastle, Ciani Qld Pty Ltd, trading as World Blinds Queensland, Kiwani Pty Ltd, trading as World Blinds ACT, Moo Yeul Ryu, also known as “Joseph”, Sangwoo Kwak, Young Mi Kim and Ki Wan Aron Kim. The parties have conducted the present argument on the basis that the principal and driving force of the respondents is Mr Ryu.

The alleged patent infringement

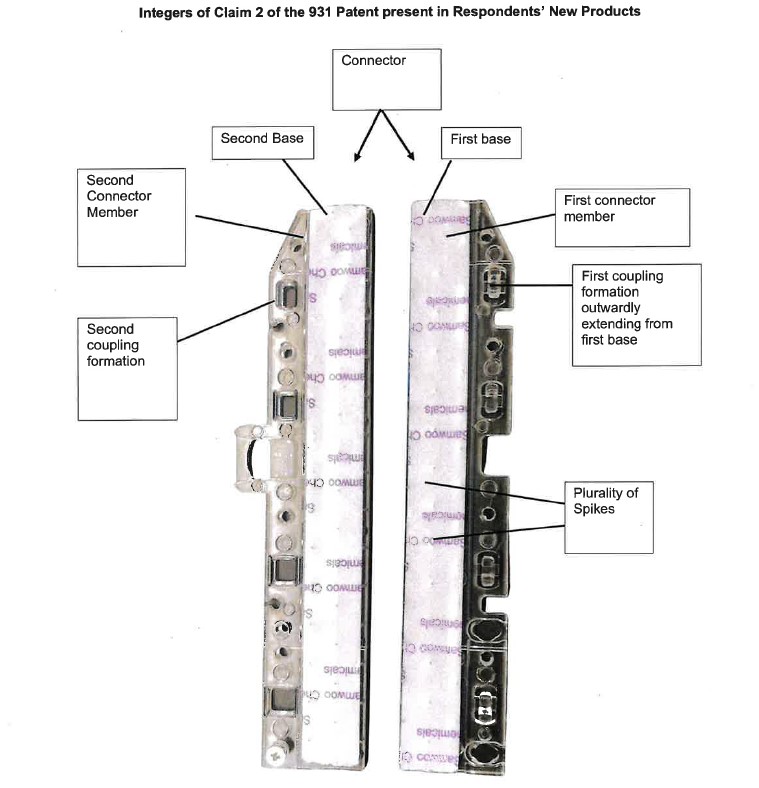

4 After some preliminary skirmishing in the proceeding, the respondents have admitted that they have been selling their product, comprising a connector for blinds or curtains, and that it infringes claims 1 and 2 of the 931 patent (the accused product). Those claims are:

1. A connector for a blind-type curtain, the connector including:

a first connector member for location on a first side of a blind-type curtain part, the first connector member having (i) a first base, and (ii) a first coupling formation outwardly extending from the first base;

a second connector member operatively associated with the first connector member and operatively adapted for location on an opposite side of the blind-type curtain part, the second connector member having (i) a second base, and (ii) a second coupling formation operatively adapted for detachable attachment to the first coupling formation such that the first and second connector members are operatively adapted (i) to be attached to each other to secure the connector to the blind-type curtain, and (ii) to be detached and separated from each other when the connector is to be removed from the blind-type curtain; and

a rail connector operatively associated with the first and second connector members and operatively adapted to secure the first and second connector members to a curtain rail, the rail connector including (a) a rail portion adapted for connection to the curtain rail, and (b) a stem adapted for attachment to the rail portion at one end and attachment to the first and second connector members at another end, the stem being adapted to undergo pivotal movement about a vertical axis whereby rotation of the stem causes pivotal movement of the first and second connector members about the vertical axis.

2. A connector according to claim 1, wherein the first connector member includes a plurality of spikes.

5 Essentially, the connector device, as claimed, consists of male and female parts that are able to be interlocked over fabric, comprising the blind fabric or material, so as to hold it in place while a connecting part is placed over or around, and is moveable along a curtain rail. The male and female parts are described in the illustration below:

The issue

6 The respondents assert that, despite their infringement of the two claims, first, the claims lack novelty within the meaning of s 7(4) and (5)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), secondly, there is no sufficient prima facie case to support the grant of an interlocutory injunction, and thirdly, the balance of convenience favours maintaining the status quo, in particular, by reason of the existence in the market of similar or identical infringing products to the accused product for a considerable period of years before 27 September 2022, when Kilmallock commenced this proceeding, and Kilmallock’s delay in enforcing its rights before that.

Background

7 The parties put on a considerable volume of evidence for the present hearing, but the facts presently necessary for the purpose of considering interlocutory relief are centred on the nature of the respondents’ challenges to the validity of the 931 patent and where the balance of convenience lies.

8 Immediately prior to establishing the respondent companies, Mr Ryu was involved with his brother-in-law, Kwang Min Park, in companies that traded, among others, under the corporate name Ciani Pty Ltd and business names related to it.

9 Earlier, in May 2014, Mr Ryu was trading in his own account. He asserted that he began importing and selling blind products called Curvers from World Blinds Co Ltd that operated in South Korea (World Blinds Korea).

10 The chief executive officer of World Blinds Korea, Jun-Seok Cho, has made two affidavits. Mr Cho gave evidence that he had been chief executive officer of World Blinds Korea since 2006. He said that, from May 2014, his company began exporting Curvers products to Mr Ryu in Australia. He attached a ledger showing such sales including products in 2014 that the respondents say match, or should be inferred to include, Curvers blinds that came to be installed in the Sydney home of Vicki Syrras in December 2014.

The saga of Ms Syrras’ Blinds

11 Ms Syrras gave evidence that, in about November 2014, her son recommended replacing some old blinds in her home and introduced her to his neighbour, Mr Ryu, as a person who operated the business of selling and installing such blinds and curtains. She recalled that she thought it was a good idea that the family home be improved before the forthcoming 2014 Christmas. She said that in about mid-December 2014, after earlier taking measurements, Mr Ryu came back to her house and installed the new vertical blinds there.

12 After that simple domestic event, in October 2022 Ms Syrras became embroiled in a series of visits by persons interested in the state of her blinds for the purposes of this proceeding and her blinds have wound up being tendered as an exhibit.

13 The connector pieces at the top of Ms Syrras’ blinds, as they currently exist, comprise separate male and female pieces. However, the male and female pieces were manufactured in a mould in which they had been joined by a thin line of plastic between and at the top of each so as to make it possible to fold them over to join the two together. The way in which Ms Syrras’ blinds are configured has the male piece affixed by glue at one end of a length of curtain and, at the other end of the length of curtain, the female piece is also affixed by glue to the fabric which is then able to be moved across so that the male and female pieces can be joined together leaving a length of curtain hanging down but fixed between the two.

14 The principal of Kilmallock, Peter Taylor, made an affidavit in which he identified the features of the connector in Ms Syrras’ blinds as being similar to that used in a blind known as the Anna Ripple blind. However, Mr Taylor was mistaken in that conclusion. This was because the Anna Ripple blind, although having a male and female connector of a similar kind to that in Ms Syrras’ blinds, also had metal riveting that held the male and female pieces together, a feature which is not present in her blinds, the accused product or the 931 patent. The Anna Ripple blinds’ fixture mechanism leaves the male and female parts connected at the top by the original piece of thin plastic that formed part of their being extended together in the mould when produced.

15 Mr Cho’s and Mr Ryu’s evidence was that the blinds as supplied in 2014 by World Blinds Korea to Mr Ryu and since came in a form in which the male and female parts of the connector pieces had been separated in Korea and they were then packed in a roll of the blind fabric for later assembly with the connector pieces at a distance apart. This meant that both male and female pieces when packed in Korea were spaced at a considerable horizontal distance from each other, and the base of the blind was then rolled vertically towards the top, where the male and female parts were left separated, until the blind came to be assembled in Australia.

16 The solicitor and experienced patent attorney acting for Kilmallock, Johann Meyer, said that he recognised photographs of Ms Syrras’ blinds’ connector as being substantially the same as that Mr Taylor had instructed him was the Anna Ripple connector. He looked at the photographs annexed to Ms Syrras’ affidavit, that she made on 19 October 2022, and reviewed the photographs of the same product in Mr Ryu’s affidavit, which Mr Meyer noted were identical. Mr Meyer said that the first thing that struck him was that the connector components, that is the male and female parts, had been separated along the former join of the thin plastic hinge. He also observed in the photograph that the edges of the hinge portions were rough and broken as if they had been snapped or cut apart.

17 Mr Meyer then visited Ms Syrras’ house. He obtained her permission to inspect and take photographs of the connector pieces of her blinds while they were still hanging happily in her lounge room. He said that he removed a single connector clip from the curtain rail and found it easy to detach its male and female pieces from each other without causing damage to the connector clip. He said that he had observed that the connector clip was made from moulded plastic and had two hinges, being a first and second connector base, which were connected by the two hinges at the top of the connector and that that was the same connector on Ms Syrras’ blinds as shown in the photograph annexed to Mr Ryu’s affidavit. But Mr Meyer said that in the photographs, to his observation, the hinges were joined and intact.

18 Mr Meyer also observed that, for some reason, the majority of the connector clips on Ms Syrras’ blinds were cream-coloured, but there were some clear clips that were similar to a later product produced in about 2016 that did not have a hinge and consisted of separate male and female parts that did not originally come from a mould in which they had been joined together by a hinge.

19 After Mr Meyer made his affidavit on 31 October 2022, Mr Ryu made an affidavit on 1 November 2022. Mr Ryu asserted that no connector pieces in the blinds at Ms Syrras’ house were joined by a hinge in the sense of the male and female parts being connected by a hinge and that he knew this to be the case because he had never received the accused products that he sold in the form where the male and female parts were joined by a hinge at the top.

20 Mr Ryu had attended Ms Syrras’ residence on 30 October 2022 and made a video, which was shown in evidence. The video depicted him separating the male and female parts on some of the blinds in situ in which there was no hinge joining the pieces, and did not show him breaking any hinge in opening the two parts. He said that he had not broken any clips or hinges, including those at Ms Syrras’ house.

21 On the day following Mr Ryu’s visit to Ms Syrras’ house, Hang Young Ko, the solicitor for the respondents, visited Ms Syrras and, with her permission and the assistance of another solicitor, removed her blinds, causing a forensic redecoration so that they could be tendered physically today in Court. It is common ground that in the state in which the blinds were removed, there was no intact hinge connecting the male and female parts on them.

Kilmallock’s submissions about Ms Syrras’ Blinds

22 Kilmallock asserted that the sequence of events affecting Ms Syrras’ blinds suggested that, at the time of or immediately after Mr Meyer’s visual observations on his visit, the hinges were undamaged and connected the male and female parts in her blinds while in her house, but that, during his visit on 31 October 2022, Mr Ryu or others must have broken or caused the separation of some or all of the hinges then present. Kilmallock contended that Mr Ryu did this or caused this to occur in an effort to support his case of lack of novelty before the priority dates in 2015 on the basis that the installation of Ms Syrras’ blinds had occurred prior to Christmas 2014. Kilmallock also asserted that Mr Cho’s affidavits failed to exhibit any brochures or photographs of the stock of connectors that World Blinds Korea supplied in and prior to 2014, even though it was the manufacturer. Essentially, Kilmallock argued that Mr Ryu and the respondents’ businesses now controlled by him, and World Blinds Korea, as their supplier, were seeking to make a fraudulent case of lack of novelty.

23 The resolution of the issue of whether or not, as a matter of fact, the male and female connectors were or were not joined by a hinge at the time of the priority dates would be fatal to one side’s case or the other, in the sense that if there were in the market unhinged or unjoined male and female connector parts, such as the respondents say Mr Ryu supplied to Ms Syrras before Christmas 2014, the 931 patent lacks novelty. Alternatively, if the male and female parts on Mrs Syrras’ blinds were hinged when supplied to her, the defence of lack of novelty necessarily fails, and the admitted infringement will then be unanswered.

The evidence of Kilmallock’s delay

24 On 10 December 2019, Mr Meyer’s firm, Meyer West IP, wrote to Ciani Sydney Pty Ltd claiming infringement of several of Kilmallock’s patents, seeking undertakings that the conduct would cease and advising that, failing receipt of those undertakings by 19 December 2019, Kilmallock would be seeking interlocutory injunctive relief. The letter did not allege infringement of the 931 patent, but related to three other patents in issue in this proceeding, and did not make any claims against Mr Ryu or any of the current personal respondents. It is common ground that this letter came to Mr Ryu’s contemporaneous attention in his capacity as a then-principal of the Ciani businesses.

25 After that letter went unanswered, on 21 January 2020, Mr Meyer caused it to be emailed to other entities associated with Ciani Sydney, but again received no response. On 8 April 2020, he sent a further email attaching the 10 December 2019 letter to Ciani Newcastle and yet again received no response.

26 On 28 May 2020, Meyer West IP sent a letter addressed to nine persons, including Mr Ryu, Mr Park and various Ciani companies, alleging infringement of three other patents the subject of this proceeding (but not the 931 patent) and attached a draft statement of claim. Mr Ryu took the attitude that it was not necessary to respond to any of the letters of demand and no response arrived. As I have noted, the Commissioner then undertook a re-examination of the patent, ultimately leaving it in place with some not presently relevant amendments.

27 In May 2021, Mr Ryu had a falling out with his brother-in-law Min Park, who was also a co-director and shareholder in Ciani Pty Limited. Mr Ryu then incorporated World Blinds Australia.

28 In February 2022, Mr Ryu resigned as a director of Ciani.

29 In late March or early April 2022, Mr Taylor contacted Mr Meyer, informing him that Ciani had made contact and suggested a meeting at their offices in Lidcombe. Mr Taylor asked Mr Meyer to come to the meeting with him.

30 On 5 April 2022, Mr Taylor and Mr Meyer met at the Lidcombe office of Ciani with Min Park, Andrew “Andy” Park, the managing director of another company, Dae Sang Techroll Australia Pty Ltd, and two other persons connected with a business trading as Blind Fairy. During the meeting, Mr Meyer and Mr Taylor appear to have become aware of the existence of Mr Ryu’s new company World Blinds Australia, and that it was part of a group in which Mr Kwak was also involved dealing in the accused product, about which they were negotiating with Ciani. Mr Meyer and Mr Taylor said that, during the meeting, they learnt that Mr Ryu and his new group were sourcing products from World Blinds Korea through a number of companies and that Mr Ryu was asserted to be “the mastermind” and “running the show at Ciani” before his departure. Min Park asserted that his own role involved the production of blind products at Ciani and asserted that he was not involved in its active management but that, as a result of the falling out, Mr Ryu had “played him” and was now competing with his business. Andrew Park told Mr Meyer and Mr Taylor at the meeting that he had been told that Mr Ryu was telling concerned customers that he, Mr Ryu, had used and installed Curvers products well before the patents were filed and that the earlier use would provide a defence against any infringement action being taken by Kilmallock.

31 Mr Meyer said that he understood that the information about the patents and the allegations of patent infringement of the Curvers product, being the accused product, “had been making the rounds in industry and that Joseph [Mr Ryu] was placating customers with the story of having used Curvers products while working with Andy”.

32 Kilmallock adduced evidence that the respondents’ businesses sell the accused Curvers product, which is a later model to that used in Ms Syrras’ home but has the same essential infringing features for present purposes, at a very substantial discount to the price which Kilmallock charges customers. There is also evidence that, in a trap purchase at one of the respondents’ businesses, the salesperson offered to supply the accused product at a cheaper price for cash than that in a written quotation.

33 Following the 5 April 2022 meeting, Kilmallock reached a settlement with Ciani. Ciani gave undertakings not to infringe Kilmallock’s patents, the details of which are not relevant save that Ciani no longer trades in the accused product or ones that are alleged to infringe Kilmallock’s patents.

34 Mr Taylor and Mr Meyer then set about collecting material to deal with the new information that Mr Ryu had established the respondents’ businesses.

35 On 27 May 2022 Meyer West IP sent a letter addressed to each of the respondents that alleged each was infringing seven patents, including the 931 patent. The letter explained in some detail why there was an alleged infringement and demanded undertakings that the respondents cease infringing by 16 June 2022, failing which, the letter threatened, Kilmallock would seek injunctions and other relief from the Court, including on an interlocutory basis.

36 The 27 May 2022 letter remained unanswered until 21 June 2022 when Strathfield Law, Mr Ko’s firm and the solicitors for the respondents, wrote to Meyer West IP saying that they had recently been instructed, but could not reply by 16 June 2022 and hoped to be in a position to do so by 30 June 2022. Thereafter, Mr Ko, on behalf of his clients, sought further requests for extension which Kilmallock granted.

37 Finally, on 12 August 2022, Strathfield Law wrote to Meyer West IP and joined issue with Kilmallock’s claims. That letter stated that, since at least mid-2014, the respondents had been importing and selling Curvers products that embodied the relevant alleged infringing features of the accused product. It attached a sales ledger of World Blinds Korea for sales to Mr Ryu, as a sole trader, in the 2014 calendar year. The letter alleged that the respondents had several other defences that are no longer pressed and refused to provide the undertakings sought.

38 On 27 September 2022, Kilmallock commenced this proceeding and sought an order for short service. That led to the application for interlocutory relief being fixed before me today.

Kilmalock’s submissions ON relief

39 Kilmallock argued, as noted above, that there is a strong inference to be drawn that the respondents engaged in fraudulent conduct because of the alleged alteration of the physical characteristics of the connecting pieces by the destruction of the hinges in all of Ms Syrras’ blinds’ connectors, so as to enhance the respondents’ prospects of the success of their defence based on lack of novelty. Kilmallock contended that, having regard to the admission of infringement, the strength of Kilmallock’s prima facie case warranted the grant of an interlocutory injunction. It offered the usual undertaking as to damages. It submitted that it had acted promptly but needed to take an appropriate period of time in which to investigate and articulate its case against the respondents. Kilmallock argued that it needed some time particularly in light of Mr Ryu’s changes of position and the fact that it had not previously made allegations against the individual respondents, including Mr Ryu, in its earlier letters of demand, that it had not followed up by taking any proceedings as threatened, at any time prior to 27 September 2022.

40 Kilmallock contended that it would suffer irreparable or substantial prejudice because the 931 patent has only another 14 months to run and the respondents are significantly undercutting its prices, so as to require Kilmallock to meet the market by lowering its own prices and reducing its profit margins. It submitted that on the evidence the respondents’ capacity to pay any damages that might be awarded for the 14 months in which it sought interlocutory relief is questionable and that damages would not be an adequate remedy. It argued that it is entitled to seek the enforcement of its statutory monopoly as patentee and that its market position would be affected adversely were the respondents allowed to trade with the infringing accused product. It contended that it would never recover an adequate amount of damages, particularly given difficulties in proof, in circumstances where the respondents were making cash sales of the accused product that may not be reflected in any documentary accounts that the respondents may keep.

41 Kilmallock submitted that there was no evidence that the respondents would be significantly inconvenienced or damaged if they had to seek an alternative supplier of products that did not infringe and that the balance of convenience favoured the preservation of its rights as patentee, given that it may never be compensated properly or at all for the harm done if an interlocutory injunction were not granted, and ultimately it were found entitled to relief.

Consideration

42 The findings that I have expressed above are simply findings on the basis of the untested evidence of each side, as put forward in affidavits to which I was taken without the benefit of any witness being subjected to cross-examination, far less, given the allegations of fraud, the parties being able to test witnesses in the witness box or me having any opportunity to observe or them. Therefore, nothing in these reasons reflects any ultimate or concluded finding or view that I have reached on the issues between the parties. Such concluded findings will only be possible once all the material on which each side relies has been admitted into evidence at the trial. There was no relevant objection taken for the purposes of the hearing today as to the form of evidence, its relevance or admissibility on a final hearing.

43 In Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57 at 68 [19], Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreed with the explanation of the organising principles for the grant of an interlocutory injunction that Gummow and Hayne JJ gave (at 81-84 [65]-[72]). In particular, their Honours applied and affirmed the principles in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618 which, importantly, involved a claim for an interlocutory injunction in a patent case (unlike O’Neill 227 CLR 57 which was a claim for an interlocutory injunction in a defamation proceeding). Gummow and Hayne JJ said (227 CLR at 81-82 [65]):

The relevant principles in Australia are those explained in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd ((1968) 118 CLR 618). This Court (Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ) said that on such applications the court addresses itself to two main inquiries and continued ((1968) 118 CLR 618 at 622-623):

“The first is whether the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case, in the sense that if the evidence remains as it is there is a probability that at the trial of the action the plaintiff will be held entitled to relief … The second inquiry is … whether the inconvenience or injury which the plaintiff would be likely to suffer if an injunction were refused outweighs or is outweighed by the injury which the defendant would suffer if an injunction were granted.”

By using the phrase “prima facie case”, their Honours did not mean that the plaintiff must show that it is more probable than not that at trial the plaintiff will succeed; it is sufficient that the plaintiff show a sufficient likelihood of success to justify in the circumstances the preservation of the status quo pending the trial. That this was the sense in which the Court was referring to the notion of a prima facie case is apparent from an observation to that effect made by Kitto J in the course of argument ((1968) 118 CLR 618 at 620). With reference to the first inquiry, the Court continued, in a statement of central importance for this appeal ((1968) 118 CLR 618 at 622):

“How strong the probability needs to be depends, no doubt, upon the nature of the rights [the plaintiff] asserts and the practical consequences likely to flow from the order he seeks.”

44 Importantly, in Beecham 118 CLR at 623-624, the Court said:

The first of these inquiries in the present case is not complicated by the special considerations which generally arise in a patent action where there is a substantial issue to be tried as to the validity of the patent. In such an action the plaintiff's prima facie case must be a strong one so far as the question of validity is concerned, for he asserts a monopoly and must give more proof of the right he claims than is afforded by the mere granting of the patent: Smith v. Grigg Ltd. [1924] 1 KB 655 per Atkin L.J. [1924] 1 KB, at p 659 ; Bonnella v. Espir (1926) 43 RPC 159. The general practice in that kind of case has long been to refuse an interlocutory injunction unless either the patent has already been judicially held to be valid or it has stood unchallenged for a long period: Smith v. Grigg Ltd. [1924] 1 KB 655, at p 658. Even if the patent is an old one – which for this purpose is generally taken to mean more than six years old– it has been said that an interlocutory injunction will generally be refused provided that the defendant shows by evidence "some ground" for supposing that he has a chance of successfully disputing the validity of the patent at the trial: Marshall and the Lace Web Spring Co. Ltd. v Crown Bedding Co. Ltd. (1929) 46 RPC 267, at p 269.

45 In Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 217 FCR 238, Dowsett, Foster and Yates JJ also discussed the principles for grant of interlocutory injunctions in patent cases, obviously applying Beecham 118 CLR 618. They said that the assessment of harm to the plaintiff, if there were no injunction, and the prejudice or harm to the defendant, if one were granted, was at the heart of the basket of discretionary considerations that have to be addressed and weighed as part of the Court’s consideration of the balance of convenience and justice (217 FCR at 260 [62]). They emphasised that the determination of whether or not interlocutory relief ought be granted involved a weighing process that required consideration of the principles or inquiries specified in Beecham 118 CLR 618 and affirmed in O’Neill 227 CLR 57.

46 In Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2019) 139 IPR 409, Jagot, Yates and Moshinsky JJ considered a situation somewhat similar in principle to the position here, where there was a prima facie case of infringement and a defence of lack of novelty. They noted, agreeing with the primary judge, that it was axiomatic that a valid patent could not be infringed and that the question of the strength of a lack of novelty argument on an interlocutory hearing could be determinative of the availability of injunctive relief. They upheld the primary judge’s decision based on his view (that was necessarily, as here, provisional, because of the interlocutory character of the hearing) that while the patentee’s case was not unarguable and that the evidence might be different at a final hearing, it did not warrant the grant of an interlocutory injunction.

47 Here, I anticipate that the allegations of fraud that Kilmallock will seek to propound and prove at the final hearing will need to be established by substantial evidence to the degree of satisfaction on the balance of probabilities in light of the principles in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and those in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362-353 per Dixon J.

48 I am satisfied that, on the evidence in its current, early state, the respondents have shown “some ground” for supposing that they have a chance of successfully disputing the validity of the patent at the trial, on the basis of the evidence relating to the features of Ms Syrras’ blinds. That being so, even though the 931 patent has been in force for a few years, the principle is that generally an interlocutory injunction will be refused, because the evidence adduced by the respondents is sufficient for supposing they have such a chance of a successful defence: Beecham 118 CLR at 624.

49 Moreover, I am not satisfied that the balance of convenience favours the grant of interlocutory relief. Although the conduct of the respondents can only be complained of since a time between mid-2021 and February 2022 in which Mr Ryu and his colleagues established their businesses after the falling out with his brother-in-law, Kilmallock has been trading, and able to trade, in an environment where, since at least late 2019, it was asserting that Ciani had been infringing various of its patents yet it had taken no action to bring proceedings to vindicate or protect its asserted patent rights. While it was entitled to investigate and bring a properly formulated claim against the present respondents, after learning of their separation from Ciani at the meeting of 5 April 2022, Kilmallock had been able to conduct its business without suggesting or demonstrating that it had suffered some irreparable harm, substantial loss or inconvenience, beyond its assertions that it has had to lower its prices to meet the market affected by its competitors’ conduct. I have borne in mind that that conduct must have included the earlier conduct of Ciani prior to the respondents’ entry into the competitive arena and the undertaking that Ciani gave in April 2022 to no longer to conduct its previous business of selling their version of the accused product.

50 In all of the circumstances, I am of opinion that it is not appropriate to grant Kilmallock an interlocutory injunction. Damages are likely to be an effective remedy, even though it is likely, given the present scale of the forensic battle, that a final hearing and judgment cannot be expected before the expiry of the 931 patent in light of the volume of work necessary to prove or defend the current allegations of fraud and lack of novelty.

Conclusion

51 For these reasons, I am of opinion the application for an interlocutory injunction should be dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding fifty-one (51) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Rares. |

Associate:

NSD 821 of 2022 | |

KIWANI PTY LTD (ACN 617 745 945) T/AS WORLD BLINDS ACT | |

Fifth Respondent: | MOO YEUL RYU |

Sixth Respondent: | SANGWOO KWAK |

Seventh Respondent: | YOUNG MI KIM |

Eighth Respondent: | KI WAN ARON KIM |