FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 DECEMBER 2022 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Between approximately 20 June 2018 and 31 August 2020, the respondent, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL); and

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to price in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL,

by displaying on the Uber app and the Uber website, in respect of the UberTaxi product available via the Uber platform, an estimated fare range for an UberTaxi trip, and thereby representing to consumers that the price that the consumer would pay for a taxicab booked through UberTaxi would likely be in the displayed fare range, when in fact the price of the taxicab was not likely to be in the displayed fare range and the actual price was likely to be less than the lower range of the estimate of that fare range.

2. Between approximately 8 December 2017 and 20 September 2021, the respondent, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) made false or misleading representations with respect to price in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL,

by displaying on the Uber app and the Uber website to consumers who:

(i) had booked an UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort or UberPool ride through the Uber platform; and

(ii) had subsequently selected the “Cancel Trip” option during a period in which UBV’s terms and conditions or cancellation policies provided for a free cancellation,

a message stating that they may be charged a small fee when in fact such consumers would not be charged a fee if they cancelled their trip during the free cancellation period.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3. The respondent be restrained for a period of three years from the date of this order, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise, in trade or commerce in connection with the supply or possible supply or promotion of rideshare services, from making any representation to the effect that a consumer may be charged a cancellation fee in circumstances where the relevant terms and conditions or cancellation policies applicable in Australia to the rideshare services stipulate that the consumer would not be charged a cancellation fee.

4. Within 30 days of the date of this order, the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties in the amounts of:

(a) $3 million in respect of the respondent’s contraventions of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL set out in the declaration at paragraph 1 above; and

(b) $18 million in respect of the respondent’s contraventions of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL set out in the declaration at paragraph 2 above.

5. Within five days of the date of this order, the respondent publish, or cause to be published, at its own expense, a colour copy of a corrective notice in the form provided at Annexure A on the website located at https://www.uber.com/au/en/ and ensure that such corrective notice:

(a) is maintained on that website for a period of 30 days from the date of this order;

(b) is viewable immediately on a computer screen upon access to https://www.uber.com/au/en/;

(c) is crawlable (ie, its contents may be indexed by a search engine); and

(d) of a size that consists of at least 40% of the images on the screen utilising a “modal” pop-up window.

6. The respondent, at its own expense:

(a) establish and implement an Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program in the form provided at Annexure B to be undertaken by:

(i) senior management and marketing employees of Uber Australia Pty Ltd involved in the Rides business; and

(ii) such employees of the respondent making determinations as to the messaging in respect of the Rides business in the Uber app which is displayed to Australian consumers,

being a program designed to minimise the respondent’s risk of future contraventions of ss 18 and 29 of the ACL;

(b) maintain and continue to implement the Australian Consumer Law Compliance Program referred to in sub-paragraph 6(a) for a period of three years from the date of this order; and

(c) comply with the requirements regarding the provision of Compliance Program documents to the ACCC, for a period of three years from the date of this order.

7. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, fixed in the amount of $200,000, within 30 days of the date of this order.

8. Pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice), for a period of five years from the date of this order (subject to any further order of the Court):

(a) the figures referred to in:

(i) the second column of the table in paragraph 21, the columns entitled “Average consumer fare”, “Average service fee” and “Average variable contribution” of the table in paragraph 38, the percentages referred to in paragraph 40, the columns entitled “Average consumer fare”, “Average service fee” and “Average variable contribution” of the table in paragraph 41, the percentages referred to in paragraph 44, the figures referred to in paragraph 53, the figures referred to in paragraphs 61(a), 61(b) and 61(c) and the percentage referred to in paragraph 62 of the supplementary statement of agreed facts filed on 21 September 2022;

(ii) the second column of the table in paragraph 9 of the affidavit of Sebastien Serge Dupont affirmed on 21 September 2022;

(iii) the columns entitled “Average consumer fare”, “Average service fee” and “Average variable contribution” of the tables in paragraphs 11 and 15 of the affidavit of Sashikant Dash affirmed on 23 September 2022; and

(iv) the dollar amounts in paragraph 19(a), the percentages referred to in paragraph 19(d), the dollar amount in paragraph 21, the percentages and dollar amounts (with the exception of the final two percentages) in paragraph 24, the figures in paragraphs 27(a) and 27(b), the number of weeks specified in paragraph 44(c), the dollar amounts in the final sentence of paragraph 45 and the dollar amounts and number of days referred to in footnote 20 (with the exception of “$26 million” referred to in the final daily calculation) of the ACCC’s supplementary submissions on penalty dated 21 September 2022,

(together, the Confidential Information) are to be treated confidentially and will not appear in any transcript or judgment in the proceedings other than in a confidential copy of the transcript or judgment which shall only be made available to those persons permitted by these orders to have access to the relevant Confidential Information; and

(b) no person is to have access to the Confidential Information pursuant to r 2.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), other than those persons who are permitted by these orders to have access to the Confidential Information.

9. The following persons have unrestricted access to the Confidential Information provided such persons keep that material confidential in accordance with these orders:

(a) Court staff and any person assisting the Court;

(b) the parties to the proceedings; and

(c) any persons assisting the parties to the proceedings, to the extent required for the purposes of providing that assistance, including barristers and external solicitors retained by the parties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CORRECTIVE NOTICE

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

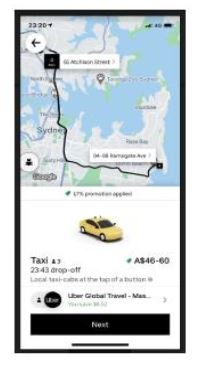

[insert Uber logo]

Misleading Representations by Uber B.V.

Following proceedings commenced by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), the Federal Court has declared that Uber B.V. (UBV) contravened the Australian Consumer Law by making false or misleading representations and engaging in false or misleading conduct as follows:

● between 20 June 2018 to 31 August 2020, UBV displayed on the Uber app and the Uber website, an estimated fare range for UberTaxi trips booked through the Uber platform, and thereby represented to consumers that the price the consumer would pay for a taxi booked through UberTaxi would likely be in the displayed fare range, when in fact the actual price paid by riders was likely to be less than the lower range of the fare estimate; and

● between 8 December 2017 to 20 September 2021, UBV displayed on the Uber app and the Uber website to consumers who booked an UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort or UberPool ride and had subsequently selected the “Cancel Trip” option during a period in which UBV’s terms and conditions or cancellation policies provided for a free cancellation, a message stating that they may be charged a small fee, when in fact such consumers would not be charged a fee if they cancelled during the free cancellation period.

These proceedings were settled by consent. The Court ordered UBV to:

• pay a penalty of $21 million and make a $200,000 contribution towards the ACCC’s costs;

• implement an Australian Consumer Law compliance program;

• refrain from making similar representations to the Cancellation Representation; and

• issue this corrective notice.

Further information about the Court’s decision can be found on the website of the Federal Court of Australia and in the ACCC’s media release at [link].

Annexure B

CONSUMER LAW COMPLIANCE PROGRAM

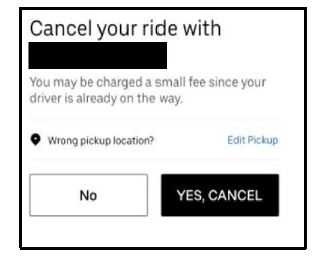

Pursuant to an order by the Federal Court dated 29 November 2022 (Order), Uber B.V. (UBV) will establish a Consumer Law Compliance Program (Compliance Program) that complies with each of the requirements below. Where requirements are relevant to Uber Australia Pty Ltd (UAPL), UBV will procure and will be responsible for ensuring UAPL’s compliance with those requirements.

Appointments

1. Within 90 days of the date of the Order, UBV will appoint a director or a senior manager of Uber’s business, or an individual with the position title of “Director” (or a position of greater seniority) in Uber’s Ethics and Compliance team, with suitable qualifications or experience in corporate compliance as a Compliance Officer to be responsible for the development, implementation and maintenance of the Compliance Program (the Compliance Officer).

2. Within 90 days of the date of the Order, UBV will appoint a suitably qualified, internal or external, compliance professional with expertise in consumer law (the Compliance Advisor).

3. UBV will instruct the Compliance Advisor to conduct a consumer law risk assessment in respect of the rideshare business provided via the Uber Platform in Australia (Australian Rides business) within 90 days of being appointed as the Compliance Advisor (Risk Assessment).

4. UBV will use its best endeavours to ensure that the Risk Assessment, which is to be recorded in a written report (Risk Assessment Report):

4.1. identifies the areas associated with the Australian Rides business where UBV is at risk of breaching section 18 of Part 2.1 and/or section 29 of Part 3.1 (Division 1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) which is Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) in respect of representations to consumers (i.e. riders);

4.2. assesses the likelihood of these breaches occurring;

4.3. identifies where there may be gaps in UBV’s existing procedures for managing the risk of these breaches; and

4.4. provides recommendations for any action to be taken by UBV having regard to the above assessment.

Compliance Officer Training

5. UBV will ensure that within 90 days of appointment pursuant to paragraph 1 its Compliance Officer attends practical training focusing on sections 18 and 29 of the ACL.

6. UBV will ensure that the training is administered by a suitably qualified compliance professional or legal practitioner with expertise in Australian consumer law.

Compliance Policy

7. Within 30 days of the date of the Order, UBV will issue a policy statement outlining UBV’s commitment to compliance with the ACL in respect of the Australian Rides business (Compliance Policy).

8. The Compliance Policy will:

8.1. contain a statement of commitment to compliance with the ACL;

8.2. contain an outline of how commitment to ACL compliance will be realised within UBV;

8.3. contain a requirement for UBV and UAPL employees to report any Compliance Program related issues and ACL compliance concerns to the Compliance Officer; and

8.4. contain a guarantee that whistleblowers with consumer law compliance concerns will not be prosecuted or disadvantaged in any way and that their reports will be kept confidential and secure.

9. A copy of the Compliance Policy will be provided to:

9.1. all members of the Executive Leadership team at UBV;

9.2. all UBV employees making determinations as to the messaging in respect of the Uber Rides business in the Uber app which is displayed to Australian consumers; and

9.3. all employees of UAPL involved in the Australian Rides business.

Whistleblower Protection

10. The Compliance Program will include whistleblower protection mechanisms to protect those coming forward with consumer law complaints which will be developed and implemented within 180 days from the date of the Order.

11. UBV will use its best endeavours to ensure that these mechanisms are consistent with AS 8004:2003 Whistleblower protection programs for entities, tailored as required to UBV’s circumstances.

Staff Training

12. The Compliance Program will include a requirement for regular (at least once a year) training (Staff Training) to raise awareness of consumer compliance issues for:

12.1. UBV employees making determinations as to the messaging in respect of the Australian Rides business in the Uber app which is displayed to Australian consumers; and

12.2. senior management and marketing employees of UAPL involved in the Australian Rides business.

13. UBV will ensure that the Staff Training is conducted by a suitably qualified compliance professional or legal practitioner with expertise in Australian consumer law.

14. UBV will ensure the Staff Training is conducted for a period of three (3) years from the date of the Order.

Reports to Board/Senior Management

15. UBV will ensure that its Compliance Officer reports to its Board or relevant governing body every 6 months on the continuing effectiveness of the Compliance Program for a period of three (3) years from the date of the Order.

Compliance Review

16. UBV will, at its own expense, cause an annual review of the Compliance Program (Review) to be carried out in accordance with each of the following requirements:

16.1. Scope of Review – the Review should be broad and rigorous enough to provide UBV with:

a) a verification that UBV has established a Compliance Program that complies with each of the requirements detailed in paragraphs 1 – 15 above; and

b) the Compliance Reports detailed at paragraph 20 below.

16.2. Independent Reviewer – each Review is to be carried out by a suitably qualified, independent compliance professional with expertise in Australian consumer law (Reviewer). The Reviewer will qualify as independent on the basis that he or she:

a) did not design or implement the Compliance Program;

b) is not a present or past employee or director of UBV, UAPL, or any other entity in the Uber group;

c) has not acted and does not act for, and does not consult and has not consulted to, UBV, UAPL, or any other entity in the Uber group in any consumer law related matters, other than performing Reviews under this Compliance Program; and

d) has no significant shareholding or other interests in UBV, UAPL, or any other entity in the Uber group.

16.3. Evidence – UBV will use its best endeavours to ensure that each Review is conducted on the basis that the Reviewer has access to all relevant sources of information in UBV’s possession or control related to the Australian Rides business, including without limitation:

a) the ability to make enquiries of any officers, employees, representatives and agents of UBV and UAPL;

b) documents relating to the Risk Assessment, including the Risk Assessment Report;

c) documents relating to the Compliance Program, including documents relevant to the Compliance Policy and Staff Training; and

d) any reports made by a Compliance Officer to the Board or senior management regarding the Compliance Program.

17. The first Review must be completed within one (1) year of the date of the Order. The second Review must be completed within two (2) years of the date of the Order. The third Review must be completed within three (3) years of the date of the Order.

18. There is no expectation that the Independent Reviewer would attend (in person) any offices outside of Australia.

Compliance Reports

19. UBV will use its best endeavours to ensure that, within 30 days of the completion of a Review, the Reviewer includes the following findings of the Review in a report provided to UBV (Compliance Report):

19.1. whether the Compliance Program includes all the elements detailed in this Annexure and, if not, what elements need to be included or further developed;

19.2. whether the Compliance Program adequately covers the parties and areas identified in the Risk Assessment and, if not, what needs to be further addressed;

19.3. whether the Staff Training is effective and, if not, what aspects need to be further developed;

19.4. whether UBV is able to provide confidentiality and security to consumer law whistleblowers and whether employees are aware of the whistleblower protection mechanisms; and

19.5. whether there are any material deficiencies in the Compliance Program, or whether there are or have been any instances of Material Failure and, if so, recommendations for rectifying the Material Failure.

Responses to Compliance Reports

20. UBV will ensure that its Compliance Officer, within 14 days of receiving the Compliance Report:

20.1. provides the Compliance Report to its Board or relevant governing body; and

20.2. where a Material Failure has been identified by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report, provides a report to its Board or relevant governing body identifying how UBV can implement any recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report to rectify the Material Failure.

21. UBV will use its best endeavours to implement promptly (with due regard to technical or engineering requirements) and with due diligence any recommendations made by the Reviewer in a Compliance Report to address a Material Failure.

Provision of Compliance Program documents to the ACCC

22. UBV will maintain records of and store all documents relating to and constituting the Compliance Program for a period not less than 3 years from the date of the Order.

23. If requested by the ACCC during the period of 3 years, UBV will, at its own expense, cause to be produced and provided to the ACCC copies of all documents constituting the Compliance Program including:

23.1. the Compliance Policy;

23.2. the Risk Assessment Report;

23.3. Staff Training materials;

23.4. all Compliance Reports that have been completed at the time of the request;

23.5. copies of the reports to the Board and/or senior management referred to in paragraphs 15 and 20.

Material failure

24. In this Annexure, “Material Failure” means a failure, that is non-trivial and which is ongoing or continued for a significant period of time, to:

24.1. incorporate a requirement of this Annexure in the design of the Compliance Program; or

24.2. comply with a fundamental obligation in the implementation of the Compliance Program, for example, if no Staff Training has been conducted within the Annual Review period.

O’BRYAN J:

Introduction

1 The respondent, Uber B.V. (UBV), is a company incorporated in the Netherlands. It is a subsidiary of Uber Technologies, Inc (Uber Tech), which is the parent or ultimate holding company in the Uber corporate group (Uber Group). The Uber Group conducts a global technology business. Companies within the Uber Group offer a number of services including a proprietary technology platform that enables independent providers of rideshare services (the Uber drivers) to transact with consumer passenger (riders) (Uber platform). Put simply, the Uber platform connects riders with drivers. In Australia, UBV makes available the Uber platform to consumers (ie, riders) via a mobile device application (Uber app), which can be downloaded by consumers in Australia via the Apple App Store (for iOS) and the Google Play Store (for Android), and via the Uber website located at www.uber.com (Uber website).

2 On 26 April 2022, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) filed an originating process supported by an affidavit of Andrew Riordan, a Partner of Norton Rose Fulbright, solicitors for the ACCC. The ACCC alleged that UBV engaged in conduct which contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law, as contained in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Act). The parties agreed to a resolution of the proceeding, including penalty, prior to its commencement. To that end, the parties filed:

(a) a statement of agreed facts and admissions dated 26 April 2022 setting out the facts agreed between the parties pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and the admissions made by UBV; and

(b) joint submissions on relief dated 26 April 2022 (and subsequently amended on 21 July 2022).

3 By the agreed facts, UBV admitted two categories of conduct which contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law.

4 First, UBV admitted that, between 20 June 2018 and 31 August 2020, it made false or misleading representations and engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct by representing to consumers that the price the consumer would pay for a taxicab requested via the Uber app or Uber website through the option labelled “Taxi” would likely be in the displayed fare range, when the actual price was likely to be less than the lower range of that displayed fare range (the UberTaxi Representation). It is important to emphasise that UBV over-estimated the fare at the time of booking, and the consumer ultimately paid a lower fare. The agreed facts included the following:

(a) the UberTaxi service, by which consumers could request rides from drivers of taxicabs who had agreements with Uber, was offered in Sydney (only) between approximately June 2013 and 31 August 2020;

(b) during the period of contravening conduct (20 June 2018 until 31 August 2020), consumers took a total of approximately 128,853 UberTaxi trips which represented less than 1% of total Uber rideshare trips taken in Sydney in that period; and

(c) the fare estimate provided at the time of booking the UberTaxi trip was an over-estimate approximately 89% of the time.

5 Second, UBV admitted that, from 8 December 2017 until 20 September 2021, it made false or misleading representations and engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct with respect to the display of inaccurate messages to consumers who selected an option to “Cancel Trip” during a free cancellation period, by representing to those consumers that they may be charged a small fee if they chose to cancel their trip when that was not the case (the Cancellation Representation). It is important to emphasise that UBV did not in fact charge consumers a cancellation fee when it was not entitled to do so. Its contravention involved the communication of an incorrect statement that consumers may be charged a small fee when that was not the case. The agreed facts included the following:

(a) in respect of trips booked using the UberX, Uber Premier and Uber Comfort services in the period from 1 December 2018 until 17 August 2021, consumers selected an option to “Cancel Trip” during a free cancellation period and received the incorrect cancellation message in respect of approximately 7.39 million trips, but only 27,313 trips were ultimately not cancelled; and

(b) in respect of trips booked using the UberPool service in the period from 3 April 2018 until 2 September 2021, approximately 74,559 consumers selected an option to “Cancel Trip” during a free cancellation period and received the incorrect cancellation message, but only 332 consumers elected not to cancel the trip.

6 The parties also filed proposed consent orders as the means of resolving the proceeding. The proposed orders provide for:

(a) declarations of the admitted contraventions by UBV pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act);

(b) the payment by UBV of total pecuniary penalties of $26 million ($8 million in respect of the UberTaxi Representation and $18 million in respect of the Cancellation Representation);

(c) an injunction pursuant to s 232 of the Australian Consumer Law restraining UBV from making any representation to the effect that a consumer may be charged a cancellation fee in circumstances where relevant terms and conditions or cancellation policies applicable in Australia state that the consumer would not be charged a cancellation fee;

(d) the publication by UBV of a corrective notice on its website;

(e) the establishment and implementation of an Australian Consumer Law compliance program by UBV; and

(f) a contribution by UBV to the ACCC’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding fixed in the sum of $200,000.

7 Apart from the proposed pecuniary penalty, the proposed orders are relatively uncontroversial.

8 The Court is empowered by s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law to impose a pecuniary penalty in respect of contraventions of s 29 in such amount as the Court determines to be appropriate, subject to specified statutory maximums. In proceedings brought by the ACCC against a respondent seeking the imposition of a pecuniary penalty under s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law (or s 76 of the Act), there is a long-standing practice, approved by the Court, for the respondent to resolve the proceeding by making admissions of contravention, and for the parties jointly to propose a penalty to be imposed by the Court. In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (FWBII), the High Court confirmed that, subject to the Court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to the facts and their consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances, it is consistent with principle and highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and impose the proposed penalty (at [58] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ). As the plurality observed (at [46]):

… there is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings … the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

9 In the earlier decisions of the Full Federal Court in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (NW Frozen Foods) at 290-291 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; ATPR 41-993 (Mobil Oil) at [51] per Branson, Sackville and Gyles JJ, which were approved by the High Court in FWBII, it was observed that, because fixing the quantum of a civil penalty is not an exact science, there is a permissible range in which courts have acknowledged that a particular figure cannot necessarily be said to be more appropriate than another. The question for the Court is whether the agreed figure proposed by the parties is appropriate in the circumstances of the case. The Court will not reject the agreed figure simply because it would have been disposed to select some other figure, provided the agreed figure is within what the Court considers to be the permissible range. However, the agreement of the parties cannot bind the Court to impose a penalty which it does not consider to be appropriate: Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2021) 284 FCR 24 (Volkswagen) at [125] per Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ.

10 As was made clear in each of NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil, the parties must provide the Court with evidence that will enable the Court to fully and properly exercise its statutory power to impose a penalty that is appropriate. As stated by the Full Court in NW Frozen Foods (at 298), it is the Court which bears the responsibility for the imposition of pecuniary penalties and “justice should be done in the light, with the relevant facts exposed to view”. In FWBII, the plurality explained that it is to be expected that the regulator (here, the ACCC) will be in a position to offer informed submissions as to the effects of the contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance (at [60], endorsing earlier statements made in NW Frozen Foods at 290-295). It is the role of the Court to scrutinise the evidence adduced by the parties. As observed by the Full Court in Mobil Oil (at [58]):

The Court, if it considers that the evidence or information before it is inadequate to form a view as to whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, may request the parties to provide additional evidence or information or verify the information provided. If they do not provide the information or verification requested, the Court may well not be satisfied that the proposed penalty is within the range.

11 The pecuniary penalties proposed by the parties in the present case are very substantial, being $26 million in aggregate. In order to assess the appropriateness of penalties of that magnitude, the Court requires evidence of a substantive kind that addresses the considerations that are relevant to the assessment of penalty. In the present case, the evidence initially adduced in support of the proposed penalty was grossly inadequate. Further, the joint submissions to the Court in support of the proposed penalties did not adequately explain how the figures had been arrived at. It is necessary to say something more at the outset about the evidentiary shortcomings in the present case.

12 As recently reiterated by the High Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 175 ALD 383 (Pattinson), deterrence is the primary, if not sole, objective for the imposition of civil penalties (at [15], [40]-[41] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ; see also FWBII at [55] and [59] and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG) at [65] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). A penalty is appropriate if it is no more than is reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions of a like kind by the respondent or by others (Pattinson at [9]). For that purpose, the penalty must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by the offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business (Singtel Optus v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 (Singtel Optus) at [62]-[63] per Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ, cited with approval in TPG at [66] and in Pattinson at [17]).

13 The level of penalty required to achieve the objective of deterrence in a given case depends upon the facts and circumstances of the case. There are a range of factual matters that are generally relevant to the assessment of penalty and they are enumerated and considered later in these reasons. However, the mandatory statutory considerations will ordinarily have great significance. For the purposes of the present case, those mandatory considerations are specified in s 224(2) of the Australian Consumer Law in the following terms:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission;

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Ch 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

14 Consideration (a) requires the Court to have regard to the nature and extent of the contravening conduct and any loss or damage suffered as a result. The importance, indeed centrality, of this consideration in the assessment of penalties is readily apparent. The objective of the Australian Consumer Law is to enhance the welfare of Australians through the promotion of competition and fair trading and provision for consumer protection (as per s 2 of the Act). The Australian Consumer Law advances that objective in two principal ways. First, it prohibits a range of conduct in trade or commerce that has the potential to cause financial, physical or personal harm to consumers or other businesses in a supply chain. Second, it prohibits a range of conduct in trade or commerce that unfairly damages competitors or competition, including particularly the prohibition against misleading and deceptive conduct. The objective of the prohibitions is to protect Australians against harm caused by certain types of conduct in trade or commerce. As recognised by consideration (a), the starting point for the assessment of penalty is therefore an assessment of the nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the nature and extent of the harm, or the potential for harm, caused by the contravening conduct.

15 It is important to emphasise that the words “loss” and “damage” in s 224(2)(a) should not be given a narrow meaning, limited to financial harm. Section 13 of the Australian Consumer Law stipulates that loss and damage includes injury. In the context of s 236 (which provides for the recovery of loss and damage caused by contravening conduct), loss and damage has been held to include personal injury and mental stress. In determining an appropriate penalty in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 4) [2022] FCA 942 (Google (No 4)), the Court had regard to the harm caused to individuals’ privacy by reason of the contravening conduct (see at [39]-[40]). In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft [2019] FCA 2166, the Court had regard to the environmental damage caused by the misleading conduct. As Foster J put it (at [235]):

The consequence of VWAG’s contravening conduct was that 57,082 diesel-powered Volkswagen-branded vehicles were let loose on Australian roads at the behest of VWAG and for reasons of profit in circumstances where those vehicles would emit NOx in substantially higher quantities than was permitted under ADR 79.

16 The evidence initially adduced by the parties in the present case established the number of misleading communications made to consumers by the respondent, but provided no information concerning the value of the commerce affected, or the value of financial harm potentially suffered by consumers or other persons, or any other form of harm suffered by any person. This left the Court in the position of speculating whether any harm was suffered and, if so, whether the harm was significant or trivial.

17 Consideration (b) requires the Court to have regard to the circumstances in which the contravening conduct occurred. As the objective of imposing a penalty is deterrence, under this consideration the Court is principally concerned with facts that explain the causes of the contravening conduct; in particular, whether the contravening conduct was deliberate and motivated by the potential for financial gain from the contravening conduct or, conversely, whether the contravening conduct was the result of inadvertence or negligent inattention to compliance. A highly relevant consideration in that regard is whether the respondent made or had the potential to make a financial gain from the contravening conduct and the quantum of any such gain.

18 The evidence initially adduced by the parties in the present case provided no information as to the potential for financial gain by the respondent from the contravening conduct. Further, on the question of the deliberateness or otherwise of the contravening conduct, the evidence took the form of conclusory statements, at the highest level of generality, to the effect that “certain employees” knew that the communications were incorrect. The evidence lacked a quality that would enable proper consideration by the Court.

19 Consideration (c) requires the Court to have regard to previous occasions on which the respondent has been found by a court to have engaged in similar conduct. The relevance of that consideration to the objective of deterrence is readily apparent. In the present case, the parties agreed that there were no such occasions.

20 As the language of s 224(2) makes clear, considerations (a), (b) and (c) are not the only matters that may be relevant to the assessment of penalty in a given case. The factors enumerated by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; ATPR 41-076 (CSR) have long been regarded as relevant considerations (subject to the circumstances of the particular case) and were endorsed by the majority in Pattinson (at [18] and [44]). In discussing those factors, the majority in Pattinson observed (at [46]-[47], in the context of s 546 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth)):

46 … It is important to recall that an “appropriate” penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case. A contravention may be a “one-off” result of inadvertence by the contravenor rather than the latest instance of the contravenor’s pursuit of a strategy of deliberate recalcitrance in order to have its way. There may also be cases, for example, where a contravention has occurred through ignorance of the law on the part of a union official, or where the official responsible for a deliberate breach has been disciplined by the union. In such cases, a modest penalty, if any, may reasonably be thought to be sufficient to provide effective deterrence against further contraventions.

47 The penalty that is appropriate to protect the public interest by deterring future contraventions of the Act may also be moderated by taking into account other factors of the kind adverted to by French J in CSR. For example, where those responsible for a contravention of the Act express genuine remorse for the contravention, it might be considered appropriate to impose only a moderate penalty because no more would be necessary to incentivise the contravenors to remain mindful of their remorse and their public expressions of that remorse to the court. Similarly, where the occasion in which a contravention occurred is unlikely to arise in the future because of changes in the membership of an industrial organisation, a modest penalty may be appropriate having regard to the reduced risk of future contraventions.

21 The importance and centrality of the considerations in paras (a), (b) and (c) of s 224(2) of the Australian Consumer Law to the objective of deterrence is clear, and the considerations should be addressed by evidence that is sufficiently detailed to enable the Court to assess those matters properly. Prior to the hearing of the proceeding, I requested the parties to address in more detail, by evidence and submissions:

(a) the nature, extent and quantification of any loss suffered by any person as a result of the admitted contraventions; and

(b) the profit earned by the Australian Uber business in the period of the admitted contraventions.

22 On 21 July 2022, the parties filed supplementary joint submissions addressing those matters and an affidavit of Patrick Francis Clark, a partner of Herbert Smith Freehills (solicitors for UBV) addressing the second of the two matters. The material filed was underwhelming. The affidavit exhibited extracts of the financial statements for Uber Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (Uber Australia Holdings), the parent company for all Australian Uber entities. The extracts consisted of a few pages only and rendered it impossible to obtain a full understanding of the financial statements. The supplementary joint submissions largely repeated matters stated in the submissions originally filed with little, if any, new information.

23 At the hearing on 25 July 2022, I informed the parties that I considered that the evidence before the Court did not provide support for the quantum of penalties proposed by the parties by agreement. Some of the basic information that was not before the Court included the average cost to the consumer of Uber rideshare trips (ie, the consumer fares) in the relevant period and the average gains to Uber from rideshare trips (which could be measured in terms of service fee revenue or operating profit) in the relevant period. The UberTaxi Representation, by overstating the likely fare to be charged to consumers, might have had the effect of suppressing demand for that Uber service, but the evidence did not attempt to quantify the extent of the overestimation of the likely fare and therefore the likely extent of the suppression of demand; nor did it attempt to quantify the likely consequences for consumers, Uber or taxi drivers from the suppression of demand. The Cancellation Representation, by stating that consumers may pay a small fee for cancelling a booking when that would not occur, would be expected to lead a proportion of consumers to alter their decision and not proceed with the cancellation and perhaps deter future cancellations, but the evidence did not even include the quantum of the cancellation fee that was charged by Uber during the relevant period. The evidence showed that a very small percentage of consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option and received an incorrect communication about a cancellation fee in fact altered their choice (less than 0.5%). Even for those trips which were taken, there was no evidence about the cost to the consumer (the consumer fare) or the gain to Uber.

24 At the hearing, the ACCC submitted that the Court could be satisfied that the penalty proposed by the parties was appropriate for three principal reasons. First, having regard to the number of acts that constitute contraventions (each communication to a consumer constituting a contravening act), the statutory maximum penalty was in the trillions of dollars. Second, Uber is a very large corporate group with global revenues measured in the billions of dollars and Australian revenues increasing over the relevant period to approximately $1 billion (albeit, the Australian rideshare business incurred losses in the financial years 2017 and 2018, a profit of $1.58 million in 2019 and $6.96 million in 2020). Third, the penalty was jointly proposed by the parties and the Court could therefore be satisfied that the penalty was not so high as to be oppressive. In that regard, the ACCC placed reliance on the recent decision of the High Court in Pattinson in which the High Court reiterated that the purpose of a civil penalty is primarily the promotion of the public interest in compliance with the provisions of the Act by the deterrence of further contraventions of the Act, and that the determination of penalty is not constrained by notions of proportionality drawn from the criminal law (at [9], [10] and [38]).

25 It can be accepted that each of the three matters relied on by the ACCC are relevant considerations in the assessment of penalty. On their own, however, they provide a wholly inadequate foundation for the determination of a penalty under s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law. The decision of the High Court in Pattinson does not suggest the contrary, referring to the range of factors that may be relevant to the assessment of the appropriate penalty that is required for deterrence (at [19], [46] and [47]). The Court’s statutory task of determining an appropriate penalty for the relevant acts of contravention requires it to arrive at a figure (or range of figures) that it considers is reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions of a like kind. The Court can only perform that task with at least information concerning the factors listed in s 224(2): the nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the potential harm caused or likely to be caused by the contravening conduct (both in terms of potential harm to consumers or other persons); the likely causes of the contravening conduct (whether that be financial benefit to the respondent or inattention); and the respondent’s history of compliance with the Australian Consumer Law. In the absence of information of that kind, the three matters relied on by the ACCC are not informative of the quantum of penalty required for deterrence. A brief explication of that last point follows.

26 In relation to the statutory maximum penalty, it is important to observe that the maximum is applicable to each contravening act or omission. In the case of false or misleading statements made in a standard form to consumers in connection with the supply of consumer products, each false or misleading statement made to an individual consumer is a separate contravention of the Australian Consumer Law in respect of which a penalty may be imposed under s 224. The present case is typical of many cases coming before the Court involving false or misleading statements made in connection with the supply of consumer products (here, a rideshare service) having a small or modest value but supplied in very large quantities, often in the millions. Through a number of amendments in recent years, the maximum penalty that may be imposed by the Court for each act or omission that is a contravention of a provision of Pt 3-1 of the Australian Consumer Law has been increased. In respect of the period of contravening conduct in this proceeding, the following maximum penalties applied for each contravening act or omission:

(a) before 1 September 2018, $1.1 million; and

(b) from 1 September 2018, the greater of:

(i) $10 million;

(ii) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the contravening corporation obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission, three times the value of the benefit; and

(iii) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit, 10% of the annual turnover of the contravening corporation.

27 Thus, the maximum penalty for each false or misleading statement may be in excess of $1 million (and potentially many multiples of that figure), but the false or misleading statement may relate to the supply of a consumer product of modest value (for example, $10.00). If the false or misleading statement is repeated on thousands or millions of occasions in connection with the supply of the consumer product, the maximum penalty very quickly becomes stratospheric (and, in a practical sense, somewhat meaningless). As discussed later in these reasons, the maximum penalty for the UberTaxi Representations would be in the order of several trillion dollars and the maximum penalty for the Cancellation Representations would be in excess of one hundred trillion dollars. While recognising that the concepts of totality and course of conduct are applicable in such cases, the point remains that s 224 is applicable to a wide range of commercial transactions some of which may have very low values and some of which may have very high values. In taking account of the maximum penalty as a relevant consideration in the assessment of penalty in a given case, it is necessary to consider all of the features of the contravening conduct including particularly the nature and extent of potential harm caused by the contravening conduct. Such an approach accords with the following explanation provided by the Full Federal Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) (at [155]-[156], citations omitted):

155 The reasoning in Markarian about the need to have regard to the maximum penalty when considering the quantum of a penalty has been accepted to apply to civil penalties in numerous decisions of this Court both at first instance and on appeal. As Markarian makes clear, the maximum penalty, while important, is but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied.

156 Care must be taken to ensure that the maximum penalty is not applied mechanically, instead of it being treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one. Put another way, a contravention that is objectively in the mid-range of objective seriousness may not, for that reason alone, transpose into a penalty range somewhere in the middle between zero and the maximum penalty. Similarly, just because a contravention is towards either end of the spectrum of contraventions of its kind does not mean that the penalty must be towards the bottom or top of the range respectively. However, ordinarily there must be some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed.

28 After citing the above passage with approval, the majority in Pattinson continued (at [54]-[55]):

54 Two aspects of the Full Court’s reasoning in this passage from Reckitt Benckiser deserve particular emphasis here. The first is their Honours’ recognition that the maximum penalty is “but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied” and must be treated “as one of a number of relevant factors”. As has already been seen, other factors relevant for the purposes of the civil penalty regime include those identified by French J in CSR.

55 The second point is that the maximum penalty does not constrain the exercise of the discretion under s 546 (or its analogues in other Commonwealth legislation), beyond requiring “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”. This relationship of “reasonableness” may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravenor as well as by the circumstances of the conduct involved in the contravention. That is so because either set of circumstances may have a bearing upon the extent of the need for deterrence in the penalty to be imposed. And these categories of circumstances may overlap.

29 In relation to the size and financial position of the respondent, for a long time it has been accepted that the quantum required to achieve the object of deterrence will be larger where the Court is setting a penalty for a company with vast resources: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265; 215 ALR 301 at [39] per Goldberg J. To the same effect, the majority in Pattinson observed (at [60]) that, all other things being equal, a greater financial incentive will be necessary to persuade a well-resourced contravenor to abide by the law (rather than to adhere to its preferred policy) than will be necessary to persuade a poorly resourced contravenor that its unlawful policy preference is not sustainable. However, the majority in Pattinson also made clear that both the circumstances of the contravenor and the circumstances of the contravention may be relevant to the assessment of the level of penalty required to achieve deterrence (at [55]-[56]). Again, it is not possible to assess the appropriate penalty to achieve deterrence by reference to the financial size of the respondent without attention to the nature, extent and circumstances of the contravening conduct, including particularly the harm caused or potential harm that might have been caused by the contravening conduct.

30 In relation to the fact that the penalty was jointly proposed by the parties, that fact alone cannot support a conclusion that the proposed penalty is not oppressive as that word is used in the authorities. In this context, oppressive is not a subjective notion. It is merely an antonym for a penalty that is appropriate; that is, a penalty that is sufficient to satisfy the object of deterrence. As stated by Burchett and Kiefel JJ in NW Frozen Foods (at 293):

… insistence upon the deterrent quality of a penalty should be balanced by insistence that it ‘not be so high as to be oppressive’. Plainly, if deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression.

31 In Pattinson, the majority explained (at [41] and [46]) that an “appropriate” penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case. It follows that the fact that a respondent has agreed to the proposed penalty does not lead to a conclusion, for that reason alone, that the proposed penalty is appropriate and not oppressive. As the authorities referred to earlier make clear, even where an agreed or jointly proposed penalty is put to the Court as part of a settlement, the task of the Court remains to determine the appropriate penalty pursuant to s 224(2): FWBII at [57]; Volkswagen at [123]. This requires the Court to be persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to the facts and their consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances.

32 Immediately following the hearing, on 26 July 2022, the Court invited the parties to adduce further evidence to address a number of questions relating to the contravening conduct to assist the Court in its consideration of the penalties proposed by the parties. The questions focussed on the value of commerce affected by the contravening conduct both in terms of potential harm to consumers or other businesses and potential gains to Uber and Uber’s awareness of the contravening conduct. It took the parties many weeks to compile the further evidence. I infer that the evidence sought by the Court had not previously been sought by the ACCC and was not in its possession, calling into question the basis upon which the proposed penalties had been arrived at by the ACCC. The parties filed further evidentiary materials and supporting submissions between 21 and 26 September 2022, including particularly a supplementary statement of agreed facts and admissions dated 21 September 2022 and supplementary submissions on penalty filed by the ACCC. During October 2022, the parties also filed an application for confidentiality orders in respect of certain business information together with supporting material, and also filed a revised form of orders sought by consent. I have accepted the application for confidentiality and will not reproduce the information in these reasons.

33 In the supplementary submissions, the ACCC acknowledged that the agreed penalties that had been proposed by the parties were not based on financial harm to consumers. The ACCC submitted that “consumer harm is but one of a number of factors used to inform a multifactorial investigation in the process of the ‘instinctive synthesis’ used to determine an appropriate penalty” and that “the absence of quantifiable consumer harm should not be given undue weight in the penalty analysis”. In support of those submissions, the ACCC relied upon cases in which the extent of harm was difficult to quantify, or where the nature of harm was non-financial (such as privacy concerns in Google (No 4)) or where the financial harm caused by the contravening conduct had been remediated by the contravenor (such as Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corp Ltd [2021] FCA 502; 392 ALR 614). The submissions involved a confusion of principles. It can be accepted that the object of the prohibitions in the Australian Consumer Law is to protect Australians (whether consumers or businesses) against physical and personal harm as well as financial harm; that different types of harm may be difficult to quantify in financial terms, but constitute material harm to be taken into account; and that the fact that the contravenor has remediated financial harm does not obviate the need for pecuniary penalties. None of those propositions, nor the cases cited by the ACCC in its supplementary submissions, negative a conclusion, founded upon s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law, that the nature and extent of actual or potential harm caused by the contravening conduct is a central consideration in the assessment of penalty. It is not appropriate to impose severe penalties under the Australian Consumer Law in respect of contravening conduct that has no potential to cause harm (of some kind) to Australians.

34 The ACCC’s supplementary submissions concluded with two submissions which require specific comment. First, the ACCC submitted that “there is a non-quantifiable harm if large corporations make widespread misrepresentations on a large scale for lengthy periods of time in circumstances where they were aware or should have been aware that the messaging was incorrect or inaccurate”. It is not entirely clear what the ACCC meant by that submission. The fact that a misrepresentation is made does not, of itself, establish harm to Australians. It can be accepted, though, that widespread misrepresentations in trade or commerce have the potential to distort consumer or business choices, harming competition and efficient markets and potentially harming consumers. In each case, though, the Court is required to assess the nature and extent of harm that will or may be caused by the contravening conduct. That can be done even if the quantification of the harm is difficult and requires broad or rough estimation. In my view, the recurrent theme in the ACCC’s submissions, that the Court does not need to be concerned whether harm to Australians was likely to be caused by the contravening conduct, is wrong in principle.

35 Second, the ACCC submitted that “were the Court to be concerned about the relationship between the penalties for each course of conduct … the appropriate course would still be to impose total penalties of $26 million, by imposing higher total penalties for the Cancellation Representations and lowering those for the UberTaxi Representations by a corresponding amount”. The submission does not reflect a principled basis on which to determine penalties. As the parties acknowledged, the UberTaxi Representations and the Cancellation Representations involved distinct and non-overlapping conduct relating to different aspects of the Uber platform. This is not a case in which penalties can, in one sense, be apportioned between contravening acts that are interrelated and perhaps part of a single course of conduct. It is necessary for the Court to consider the conduct relating to the UberTaxi Representations and the Cancellation Representations separately and determine appropriate penalties for each.

36 For the reasons that follow, I consider that the penalty jointly proposed by the parties in respect of the UberTaxi Representations greatly exceeds any amount that I consider to be appropriate having regard to the mandatory statutory considerations and all other relevant considerations. I consider an aggregate penalty of $3 million to be appropriate in respect of that course of conduct. Conversely, I am satisfied that the penalty jointly proposed by the parties in respect of the Cancellation Representations is within a range of penalties that I consider to be appropriate, albeit at the higher end of the range. I will therefore order an aggregate penalty of $18 million in respect of that course of conduct.

37 This is an unusual case in which the Court has determined that the appropriate penalty to be imposed is less than the penalty jointly proposed by the parties (including the respondent). It should be reiterated that, in imposing penalties under s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law, the Court does not simply approve the parties’ agreement. The Court is required by statute to impose only a penalty that is appropriate. The proper exercise of the statutory function is important not only for the case being decided, but also for the precedential value the decision may have in the future application of the law. It is unnecessary and unhelpful to speculate about why the respondent may have agreed to a penalty that is higher than the Court considers to be appropriate. The respondent’s agreement does not excuse the Court from performing the task required by the statute. The conclusion reached in this case should not be understood as any reduction in the Court’s resolve to impose penalties that are appropriate to achieve the statutory objective of deterring contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law. It reflects the application of the statutory criteria and the applicable principles to the circumstances of this case.

The statutory prohibitions

38 The ACCC alleges that UBV engaged in conduct which contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law. The relevant provisions, and principles governing their application, are set out below.

39 Section 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law relevantly provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

40 Section 29(1) of the Australian Consumer Law relevantly provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services;

41 There is no significant difference between the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” in s 18 and “misleading” in s 29(1): see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] per Gordon J (regarding the equivalent provisions in the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)), cited with approval in respect of the Australian Consumer Law provisions in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 at [40] per Allsop CJ, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1369 at [60] per White J, and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 367; 391 ALR 346 at [113] per Thawley J.

42 The principles applicable to determining whether conduct contravenes s 18 are well known. Similar principles govern the application of s 29: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd (t/as Activ8me) [2019] FCA 384; 136 ACSR 80 at [13] per Middleton J. The central question arising under each provision is whether the impugned conduct or representation, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error: TPG at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1409 at [236] per Griffiths J. Knowledge of the falsity or misleading nature of a representation is not necessary to make out a contravention of ss 18 or 29 of the Australian Consumer Law; the sections are concerned with the actual or likely effects or consequences of the conduct or representations: Gill v Ethicon Sarl (No 5) [2019] FCA 1905 at [3556] per Katzmann J, citing Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Limited (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 per Stephen J, 232 per Jacobs J and 234 per Murphy J.

Admitted contraventions

43 A summary of the relevant background facts and admissions regarding UBV’s contravening conduct, drawn from the agreed facts and supplementary agreed facts, is set out below.

Uber’s Australian business

44 As stated earlier, Uber Tech is the parent or ultimate holding company in the Uber Group. Uber Tech is incorporated in the State of Delaware and its principal executive offices are located in San Francisco, California. Uber Tech is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

45 The Uber Group conducts a global technology business. Companies within the Uber Group offer a number of services including the Uber platform that enables Uber drivers to transact with riders, who are their customers, in Australia and elsewhere.

46 The respondent, UBV, is a subsidiary of Uber Tech. In Australia, UBV makes available the Uber platform to consumers (ie, riders) via the Uber app and the Uber website. This is done pursuant to a technology licence from Uber Tech (prior to April 2019, via a related corporate entity, Uber International B.V. and, following April 2019, directly with UBV). UBV is the contracting party for consumers (riders) that access or use the Uber app and Uber website in Australia.

47 Uber Australia Holdings, also a subsidiary of Uber Tech, is the parent company for all Australian Uber entities. Drivers in Australia willing to provide rideshare services enter into an agreement with a subsidiary of Uber Australia Holdings (Uber Pacific Pty Ltd in the case of drivers who offered the UberTaxi product and Rasier Pacific Pty Ltd in the case of drivers offering other products such as UberX). Pursuant to that agreement, Uber provides lead generation services to drivers and, on behalf of drivers, arranges for the collection of the fare charged by the driver to the rider. The fare is then remitted to the driver, less a service fee payable to Uber for the provision of its services to the driver.

48 Uber Australia Pty Ltd (Uber Australia) is a subsidiary of Uber Australia Holdings and the entity within the Uber Group that employs all Uber personnel based in Australia. Uber Australia also plays a role in operating the Uber app in Australia for the purposes of providing marketing and support services to other Uber entities in Australia. Uber Tech makes certain technologies available to Uber Australia to operate the Uber app in Australia and provides various platforms which enable Uber Australia to configure and manage specific elements of the Uber app, including product settings, pricing and matching of drivers and riders in Australia. Since March 2021, the Uber website has been fully managed through a regional self-service model, whereby employees of Uber Australia (with applicable training and access) can edit existing website content. Uber Australia also engages third party processors to assist with the collection and processing of fares paid by consumers. Uber Australia directs the third party processors to settle collected funds into a bank account held by UBV from which they are then distributed to drivers (less the service fee charged by Uber).

49 The revenue recorded by Uber Australia Holdings (on a consolidated basis) is derived from the provision of services to Uber’s partners. In the case of ridesharing, the relevant partners are drivers. The ridesharing revenue recorded by Uber Australia Holdings is primarily derived from the service fees paid by drivers to Uber. Consumer fares are earned by drivers and are not recorded as revenue of Uber. Uber Australia Holdings also derives revenue from other services such as Uber Eats.

UberTaxi Representations

50 Between approximately June 2013 and 31 August 2020, consumers in metropolitan Sydney could choose an option labelled “Taxi”, which was available on the Uber platform (UberTaxi). Through UberTaxi, consumers could request rides from drivers of taxicabs who had agreements with Uber to receive booking requests from consumers through the Uber app and Uber website.

51 From 1 December 2017, in respect of UberTaxi, the Uber app and the Uber website displayed to consumers an estimated fare range for a requested trip (UberTaxi fare range). The UberTaxi fare range was displayed to a consumer after the consumer entered a destination address and confirmed the pickup location. An example of how this appeared on the Uber platform is shown below.

52 To request rideshare services using UberTaxi, the consumer was required to select the “Taxi” option and tap or click on a “CONFIRM TAXI” button. An example of the screen which was displayed to the consumer once the UberTaxi option was selected is displayed below.

53 The UberTaxi fare range was calculated using a function or algorithm (UberTaxi fare algorithm). Uber Tech was responsible for the development and maintenance of the UberTaxi fare algorithm.

54 In or around June 2018, there was a global update of fare estimate algorithms for UberTaxi. That update also applied to fare estimate algorithms for other Uber platform options.

55 From 20 June 2018, the UberTaxi fare algorithm calculated the UberTaxi fare range by applying time and distance multipliers to calculate a lower range estimate figure and a higher range estimate figure (the Wayfare algorithm). Prior to 20 June 2018, different time and distance multipliers were applied.

56 The UberTaxi fare actually charged by the driver was calculated on the basis of a time or distance multiplier, depending on the speed of the vehicle.

57 The Wayfare algorithm was an inaccurate estimator of the fare to be charged. Its use resulted in UberTaxi fare ranges published or displayed by UBV on the Uber app and the Uber website being higher than the actual fare in most circumstances in Australia. UBV did not monitor, and no other entity or entities in the Uber Group monitored, the functionality of the Wayfare algorithm to ensure the accuracy of the estimates produced by the Wayfare algorithm in Australia.

58 All consumers who took an UberTaxi trip paid the actual fare applicable to their trip, based on the relevant time or distance calculations, rather than the amount estimated by the Wayfare algorithm.

59 UberTaxi represented a very small percentage of Uber rideshare services available in Sydney, and the usage of the UberTaxi service in Sydney substantially declined between 2017 and 2020. In 2017, UberTaxi trips accounted for approximately 1% of total Uber rideshare trips in Sydney, with an average of approximately 28,000 trips per month. At the beginning of 2020, UberTaxi rideshare trips accounted for only around 0.1% of all Uber trips in Sydney.

60 The extent of the inaccuracy in the Wayfare algorithm only became apparent to UBV on or around 24 July 2020 after an Uber entity in Australia received a statutory notice from the ACCC. As the service was not being utilised to any material extent, and as a result of the issues raised by the ACCC and the difficulties associated with UberTaxi estimates (as discussed further below), Uber discontinued UberTaxi on 31 August 2020.

61 In respect of the foregoing matters, UBV admitted that:

(a) during the period 20 June 2018 until 31 August 2020, by displaying the UberTaxi fare range to consumers via the Uber app and the Uber website, UBV represented to Australian consumers that the price that the consumer would pay for a taxicab booked through UberTaxi would likely be within the displayed fare range (the UberTaxi Representation);

(b) the UberTaxi Representation was false or misleading, or likely to mislead or deceive by reason of the fact that the price of a taxicab booked through UberTaxi was not likely to be within the displayed fare range, and the actual price was likely to be less than the lower range of the estimate of that fare range;

(c) insofar as the UberTaxi Representation was a representation as to a future matter, UBV did not have reasonable grounds for making that representation; and

(d) by making the UberTaxi Representation it engaged in conduct in trade or commerce in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law.

Cancellation Warning Representations

62 Consumers who book a rideshare service via the Uber app or the Uber website are able to cancel their booking by selecting an option to “Cancel Trip”.

63 From at least 8 December 2017, when a consumer using the Uber app or the Uber website selected an option to “Cancel Trip” after requesting a trip, the Uber app or the Uber website displayed a message to the consumer asking the consumer to either confirm the cancellation request or continue the trip.

64 From at least 8 December 2017 until September 2021, certain consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option were shown a cancellation message, before the consumer either confirmed the cancellation request or continued the trip, which stated (with minor grammatical variations over time): “You may be charged a small fee since your driver is already on the way” (the cancellation warning).

65 An example of how the cancellation warnings appeared to consumers is extracted below.

66 From at least 8 December 2017, Uber Tech was responsible for the determination, maintenance and control of cancellation messages displayed via the Uber app and the Uber website, including the cancellation warning.

67 From at least 8 December 2017, UBV’s terms and conditions relating to the use of the Uber app and Uber website provided that, if certain conditions were met, the consumer may be charged a fee if the consumer elected to cancel a booked service. The relevant conditions were contained in Uber’s cancellation policies, which comprised a number of documents that were published on the Uber website and were accessible within the Uber app (together, the cancellation policy). Pursuant to Uber’s cancellation policy, whether or not a cancellation fee applied depended upon the time elapsed between the consumer being matched with a driver and the time of the consumer cancellation.

68 From at least 8 December 2017, for UberX, Uber Premier and Uber Comfort, the cancellation policy specified that a consumer was entitled to cancel a trip without charge if the consumer cancelled the trip within five minutes of a driver accepting the trip. At all relevant times for UberPool, the cancellation policy specified that a consumer was entitled to cancel an UberPool request without charge if the consumer cancelled within 60 seconds of being matched with a driver, provided that the consumer did not cancel another UberPool request immediately prior. Those periods are referred to in these reasons as the free cancellation period. UBV did not have the legal right to charge a consumer (on behalf of the driver) a fee for cancelling an UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort or UberPool request during the applicable free cancellation period.

69 At all relevant times, the cancellation fees in respect of UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort and UberPool services were fixed fees (ie, the fees did not vary upon any projected time or cost of a trip). The fees varied between the type of services (UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort and UberPool) and the city in which the service was to be provided, and ranged between a high of $10 and a low of $6). Of the cancellation fee charged, 20 to 25% (exclusive of GST) was retained by Uber (as a service fee charged to the driver) and the balance was paid to the driver whose trip was cancelled.

70 From at least 8 December 2017 until September 2021, the cancellation messaging displayed to consumers on the Uber app and the Uber website did not differentiate between consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option during the applicable free cancellation period and those who selected the “Cancel Trip” option after the expiry of the applicable period. As a result, consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option during the applicable free cancellation period received the cancellation warning. Despite receiving the cancellation warning, however, no cancellation fees were charged to consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option during the applicable free cancellation period.

71 From at least March 2018, Uber Tech had the technical capability to display differentiated cancellation messaging to consumers reflecting whether or not the consumer would in fact be charged a cancellation fee, which would have allowed UBV to display accurate cancellation messages to consumers. Notwithstanding these matters, Uber Tech did not, and UBV did not cause or request Uber Tech to, update or modify the cancellation messages displayed to consumers to ensure the accuracy of cancellation messages displayed to consumers in Australia prior to September 2021.

72 In or about September 2021, Uber Tech updated or modified the cancellation messages displayed to consumers in Australia, so that the Uber app and Uber website did not display a cancellation warning to consumers using UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort and UberPool who selected an option to “Cancel Trip” during the applicable free cancellation period.

73 In respect of the foregoing matters, UBV admitted that:

(a) during the period 8 December 2017 until 20 September 2021, by displaying the cancellation warnings to consumers who selected the “Cancel Trip” option during the applicable free cancellation period in respect of UberX, Uber Premier, Uber Comfort and UberPool services, UBV represented to consumers that they may be charged a fee if they chose to cancel their trip (the Cancellation Representation);

(b) the Cancellation Representation was false or misleading, or likely to mislead or deceive, in that consumers would not be charged a fee if they chose to cancel their trip during the applicable free cancellation period; and

(c) by making the Cancellation Representation, it engaged in conduct in trade or commerce in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law.

Pecuniary penalties

Applicable principles

74 The applicable principles governing the Court’s consideration of penalties jointly proposed by the parties, and the determination of penalties to be imposed, have been set out earlier in these reasons. The following matters are highlighted.