Federal Court of Australia

Tayar v Feldman [2022] FCA 1432

ORDERS

Applicant and others named in the Schedule | ||

AND: | First Respondent MR YOSEF FELDMAN Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The orders made on 21 July 2022 be affirmed.

2. The interim application filed by the respondents on 11 August 2022 is dismissed.

3. The respondents are to pay the applicant’s costs of the interim application.

4. If the trustees of the respondents’ bankrupt estate wish to make any application in relation to their costs of the interim application they are to file and serve any such application on or before 7 December 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 On 21 July 2022, on the application of the applicant, Corey Tayar (who is also known by his Hebrew name Shabsi Tayar), a registrar of this Court made an order, among others, that the estates of each of the respondents, Pinchus Feldman and Yosef Feldman, be sequestrated under the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth). Jonathan Kingsley Colbran and Gregory Bruce Dudley are the Trustees of the respondents’ bankrupt estates.

2 On 11 August 2022 the respondents filed an interim application seeking a review pursuant to s 35A(5) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) of the exercise of the power by the registrar in this proceeding and an order under s 153B of the Bankruptcy Act that their bankruptcies be annulled.

3 On 1 September 2022 I granted leave to the Trustees pursuant to r 2.03 of the Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) to be heard in the proceeding without becoming a party. The Trustees did not seek to take an active role in the proceeding but, as officers of the Court and in the performance of their statutory duties pursuant to the Bankruptcy Act, sought to assist the Court in relation to the performance of their role as trustees and the administration of the respondents’ estates. The trustees also made submissions in relation to the consequential orders that should be made pursuant to s 35A(6) of the Federal Court Act in relation to their remuneration and costs in the event that I determined to dismiss the amended creditor’s petition and set aside the sequestration order.

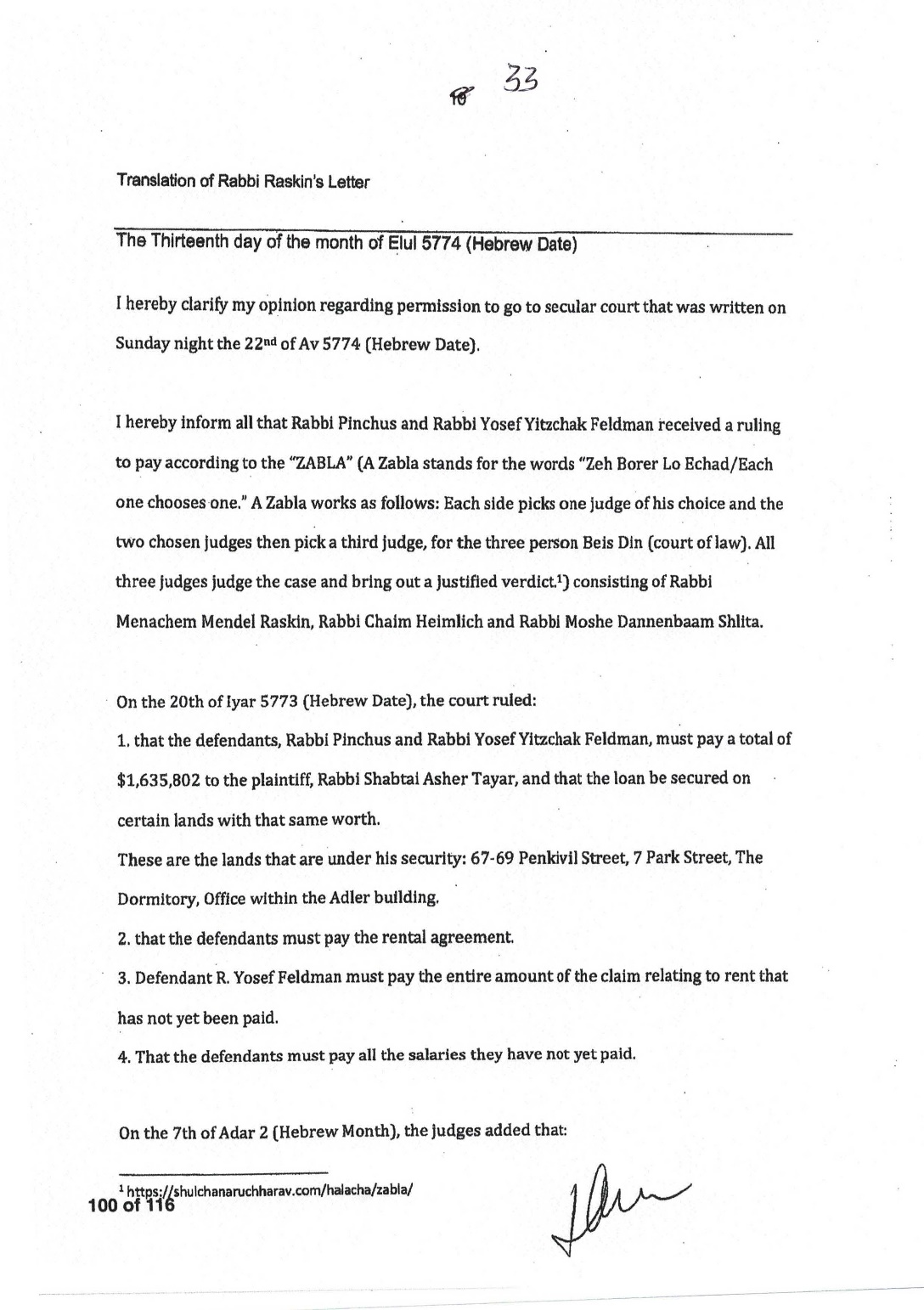

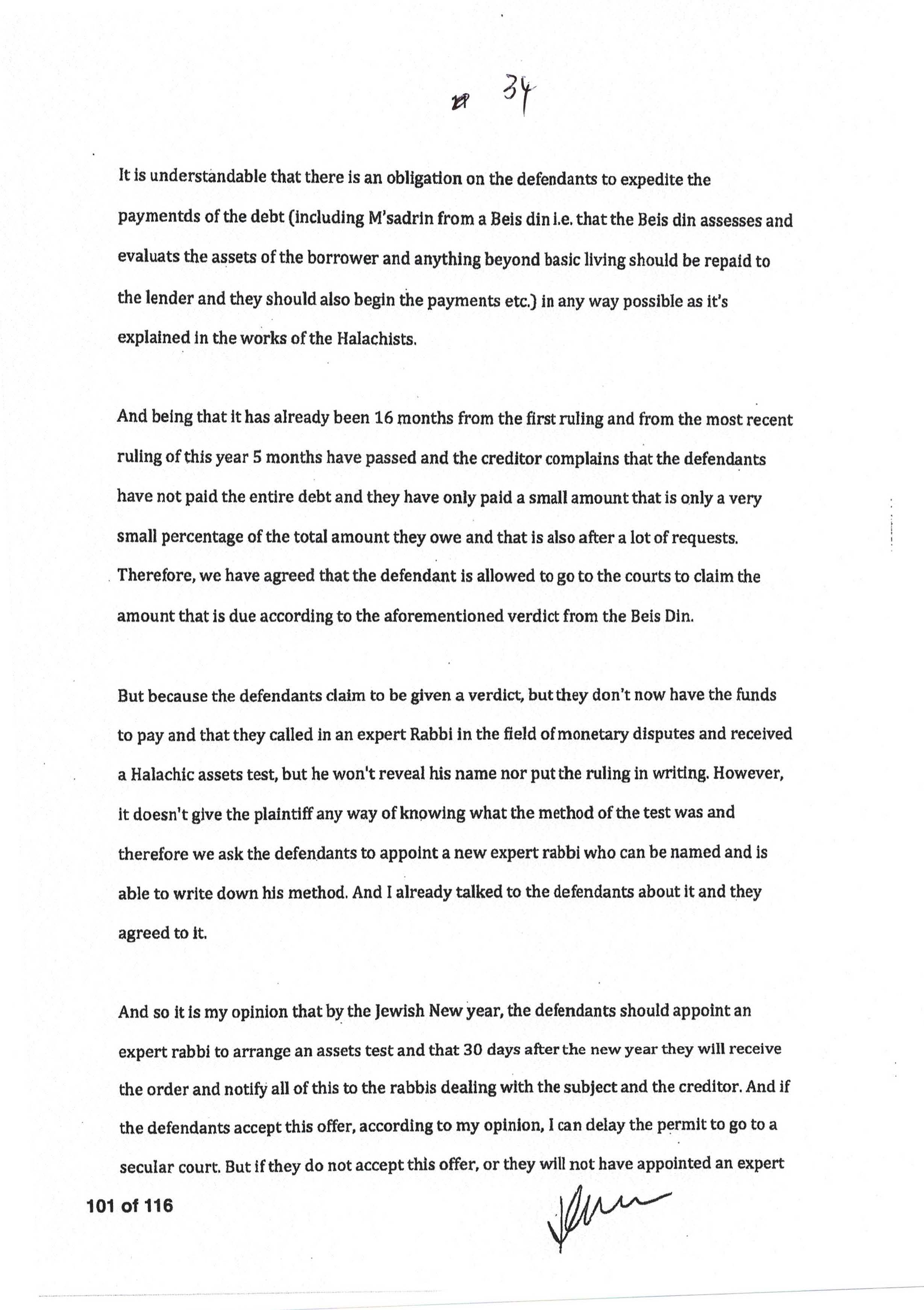

4 At the hearing the respondents informed the Court that they only pressed the first prayer for relief in their interim application, namely the application for review of the sequestration order made by a registrar of this Court.

5 Before proceeding further it is convenient to set out the nature of the jurisdiction being exercised by the Court on this application in which the respondents seek a review of the exercise of delegated power by a registrar of this Court. Relevantly, in Bechara v Bates (2021) 286 FCR 166 at [17] a Full Court of this Court (Allsop CJ, Markovic and Colvin JJ) said:

The nature of a review under s 104(3) of the Circuit Court Act and under s 35A(6) of the Federal Court Act of an order made by a registrar (often but not always in the context of the review of the making of a sequestration order in bankruptcy) has been the subject of a significant number of decisions of this Court. All are consistent. To underpin the validity of the delegation of judicial power of the Commonwealth to a non-judicial court officer there must be a rehearing de novo before a judge of the Court (whether Circuit Court or Federal Court). The review does not hinge, or focus, upon error in the decision of the registrar. It is a hearing de novo, in which the matter is considered afresh on the evidence and on the law at the time of the review, that is at the time of the hearing de novo. The importance of the de novo rehearing is Constitutional, being the supervisory condition that enables judicial power to be delegated to a registrar. All the jurisprudence stems from this requirement marked out by the High Court in the landmark decision in 1991 of Harris v Caladine 172 CLR 84, which is discussed in many of the cases referred to below.

background

6 The first respondent, Pinchus Feldman, is the father of the second respondent, Yosef Feldman. They and the applicant, Rabbi Tayar, are rabbis and are each adherents to the Chabad Lubavitch movement, an orthodox Hasidic movement within Judaism.

7 As well as being a rabbi, Rabbi Tayar has the credentials of “Yodin Yodin” which demonstrate his expertise in Jewish commercial law and has established “Mehadr Beis Din Tribunal” in Melbourne which hears commercial disputes.

8 Some of the facts set out below were the subject of findings in Tayar v Feldman [2020] VSC 66 at [19]-[26]. To the extent that is so, I do not understand them to be in dispute. I also set out below the circumstances in which the proceeding which gave rise to that decision arose.

9 Rabbi Tayar worked at the Yeshivah Centre in Flood Street, Bondi, New South Wales which was operated by the respondents. While working there he made a series of advances to the respondents for the purposes of meeting the ongoing expenses of the centre.

10 As described by the respondents, in or about 2010 the parties entered into a series of complicated commercial transactions. As part of the arrangement to advance funds five parcels of land owned by the respondents and others were pledged to Rabbi Tayar. They were to be returned if the advances were repaid. This arrangement, by which a person who advances the funds is categorised as an investor seeking to derive profit from investing capital, rather than as a lender seeking to derive interest from a loan, is known in Hebrew as “Heter Isko” or “Isko”.

11 A number of disputes arose between the parties: Rabbi Tayar claimed that the advances he made had not been repaid; there was a dispute about whether the respondents had authority to pledge the parcels of land referred to in the preceding paragraph on behalf of all of the owners; there was a dispute about the non-payment of rent on Rabbi Tayar’s home by the respondents. Rabbi Tayar asserted that the respondents had agreed to pay the rent as the advances he had made to them had exhausted his funds to do so; and there was a dispute in relation to non-payment of salary for work done by Rabbi Tayar and of redundancy payments.

The parties agree to proceed to arbitration

12 On or about 4 March 2013 Rabbi Tayar and the respondents entered into an agreement to refer the disputes which had arisen between them to arbitration (Arbitration Agreement). That agreement provided that:

(1) the arbitration was to be conducted by a panel of three rabbis, Rabbis Heimlich, Donenbaum and Raskin (together referred to as the Arbitral Panel), in accordance with the principles of orthodox Jewish law known as “Halacha”. The members of the Arbitral Panel were also parties to the Arbitration Agreement;

(2) the Arbitral Panel was appointed to determine the “Disputed Matters” which were described in Sch 1 to the Arbitration Agreement which, in turn, provided that (as written):

The matters to be determined by the Arbitral Panel are to be determined by the Statement of Claim, Statement of Defence and Cross Claim (if any) and the Reply and Deference to Cross Claim (if any) to be filed in the arbitration as directed by the Arbitral Panel.

(3) the Arbitral Panel was to act as an arbitral tribunal under the Commercial Arbitration Act 2011 (Vic); and

(4) the Arbitration Agreement was governed by the laws in force in Victoria.

13 There were five claims which were considered by the Arbitral Panel. In the proceeding before the Supreme Court of Victoria, there was no dispute that those claims were the subject of evidence and submissions before the Arbitral Panel and that the respondents were afforded procedural fairness in relation to them: see Tayar v Feldman at [36].

14 On 9 May 2013 the Arbitral Panel published its award and reasons for the award to the parties. The award provided:

The Court has decided the proceedings to be held in the Holy Language [Hebrew], Yiddish and English, as required for proceedings and evidence etc, as well as due to the fact those languages are understandable both to the court and the parties involved, also the court decision will be delivered to the parties in the Holy Language[.]

Parts of the decision mainly based on claims frankly made by the Parties on a court hearing and on the claims expressed orally on the second hearing of the Court (as the Court was unable to approve the claims sent and written via email).

Claim 1 — the claim on the whole property or a part thereof located at 67&69 Penkivil Street, 7 Park Street, Office within the Adler Building, Dormitory Building

Court decision: The mentioned properties remain in possession of the defendants and nevertheless the defendants are obliged to pay the amount of $1,635,802 to the plaintiff. However, the lender retains a lien on the properties up to the value of the aforementioned amount.

Claim 2 — the claim regarding $17,815.47 pcm rental agreement

Court decision: The defendants must pay the entire amount of the rental agreement $17,815.47 pcm, as agreed between the parties initially (including all outstanding payments, which have not been paid completely yet). This obligation continues until the defendants pay the entire above mentioned amount mentioned in claim 1. Regarding the monthly payments from that time till [sic] September 2013, it depends on the details of initially made agreement and needs further clarification by the Court.

Claim 3 — the claim of apartment rental payment of $850 per week

Court decision: Mr Joseph Feldman must pay the entire amount of the claim related to the rent that has not yet been paid.

Claim 4 — the claim regarding salary

Court decision: The defendants must pay the entire amount of the salary (that has not yet been paid) to the plaintiff for all the time of his service at the office etc, but not for the time after he resigned from work.

Claim 5 — the claim regarding redundancy payments

Court decision: At the moment, the defendants are exempt from compensating the plaintiff.

15 On 2 March 2014 the Arbitral Panel sent a letter to the parties (supplemental award) correcting the award, which included:

Whereas there are impediments and delays for the Parties to proceed before the Court of Torah due to a number of reasons, we hereby declare and confirm the decision which has been issued taking into account the law as well as the principle of compromise and honesty, as it is understood by the Court, as well as world judicial practice and the Arbitration Agreement, as follows: the Court Decision made on day 29 of the month of lyar year 5773, 9 May 2013 is valid (there is only one typographical error in claim 3 and it has been amended, stating that the apartment rent is $850 per week [and not per month])

The defendants must pay the amounts stated in the Court Decision as soon as possible.

We hereby sign this document on the day 30 of the month of Adar I, year 5774, 2 March 2014 in Melbourne

Events following publication of the award

16 On 9 May 2014 Rabbi Raskin, a member of the Arbitral Panel, sent a letter in Hebrew to the parties on behalf of all members of the Arbitral Panel (First Raskin Letter). A translation of that letter provides:

By the Grace of G-d

7 Adar Beis 5774

In honour of the claimant R' Shabsi Tayar and the respondents R' Pinchos and R' Yosef Feldman

Since the arbitrators are finding it difficult to continue with a further Din Torah on this topic for numerous reasons, and we also stipulated before we began that we do not accept upon ourselves to bring the judgement to actualization, or to be involved in Mesadrin etc, and therefore it's on you to search for another Beis Din to organise this.

It is self-understood the great obligation on the respondents to quickly pay off the debt etc, (including Mesadrin, beginning to pay the debt etc) whatever is possible as explained in the books of the Poskim.

And since the arbitrators invested plenty of effort and time (without compensation), and therefore it is our request that you don’t disturb the arbitrators any further from today onwards. And you have something urgent to be in contact with the arbitrators please turn to R' Binyomin Koppel head of the community of Adass Yisroel.

17 In relation to the First Raskin Letter, Rabbi Tayar explained that:

(1) 7 Adar 5774 is the Hebrew date for 9 May 2014;

(2) “Din Torah” means Jewish legal proceedings;

(3) “Beis Din” (also referred to as a Beth Din) is a Jewish arbitral tribunal usually comprised of three rabbis;

(4) “Mesadrin” is a process by which a Beth Din investigates the assets and liabilities of a debtor to determine how the amount owed should be paid and what assets the debtor can retain; and

(5) “Poskim” means Jewish judges throughout the centuries.

18 The question of whether the parties had agreed to and subsequently engaged in a Mesadrin is at the heart of the grounds of opposition relied on by the respondents. It is thus convenient at this stage to set out the evidence which explains that process. There was no expert evidence about the way in which a Mesadrin operates. However, each of Rabbis Tayar and Yosef Feldman gave evidence of their understanding of the process.

19 As set out at [17] above, according to Rabbi Tayar, a Mesadrin is a process by which a Beth Din, which is a Jewish arbitral tribunal, investigates the assets and liabilities of a debtor to determine how an amount owed should be paid and what assets the debtor can retain. Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s evidence was that an integral part of Jewish bankruptcy law is that there must be a “Mesadrin” which he described as an arrangement of how to pay and deal with the debt including the sale of the debtor’s property in order to repay it. This would be determined by the Beth Din unless agreed upon by the parties.

20 According to Rabbi Yosef Feldman, he and, I infer, Rabbi Pinchus Feldman underwent a Mesadrin. Although the timing is not clear, it seems, based on Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s evidence, that at some time after the First Raskin Letter, the respondents engaged in a Mesadrin. However, it is also plain from Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s evidence that they did so without disclosing to Rabbi Tayar the identity of the “judge” who advised them at that time or, indeed, that at least as far as they were concerned they had undergone a Mesadrin. However, Rabbi Yosef Feldman deposed that the rabbi who provided the advice for the Mesadrin at that time is now amenable to the disclosure of his identity. The rabbi in question is Rabbi Mordechai Gutnick AM who is Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s uncle and Rabbi Pinchus Feldman’s brother in law. A letter dated 14 March 2022 from Rabbi Gutnick addressed to “whom it may concern” includes:

About 8 years ago I was consulted regarding a dispute between Rabbi Tayar (RT) and the Rabbis Feldman (the RF). It had been agreed by all parties to settle their dispute by a Beth Din arbitration panel. The result of that arbitration was that the RF were required to pay RT a certain amount of money. However, the RF claimed they did not have the amount determined. I was informed that the Beth Din arbitration panel thereupon further directed that the way to deal with his outcome was through Jewish law bankruptcy procedures. This essentially required that all assets not required for basic daily living needs and expenses were to be liquidated and the resulting amount was to be paid to the plaintiff, RT. In addition, the defendants, the RF, were to then pay a further set amount at determined intervals gleaned from future income, over and above their basic living expenses, until the debt was paid in full.

It was my understanding that the original Beth Din panel did not wish to accept the responsibility for the assessment of assets or the future repayment options and so referred the parties to seek the input of another Beth Din panel or another mutually acceptable method of assessment, in order to determine the value of any assets and any future payment amounts and intervals, that would be in accordance with applicable Jewish law.

I was contacted by the defendants, the RF, at the time and I advised on a process of repayment that, to the best of my knowledge, had subsequently been accepted by both parties. It basically was agreed that the defendants had no assets that could effectively be liquidated and that they would pay a set amount, as determined and agreed on between the parties, on a regular basis. To the best of my knowledge this has been adhered to over the many years since the agreement was finalised.

I am now informed that RT had decided to register the outstanding debt at this time in order to leave him with the possibility that he could institute legal bankruptcy proceedings, with permission from a Jewish Beth Din panel, if the RF don’t continue to pay as per the current agreement.

There is, however, a serious claim being made by the RF that permission to institute civil bankruptcy proceeding would not be permitted in this case and at this time. This is based on the original ruling of the Beth Din arbitration panel (and is also based on the application of Jewish bankruptcy law generally) to the effect that, as long as the RF continued paying the amounts due as per the agreed undertaking currently in force and observed unchallenged over the all these years, the original payment agreement and schedule still stands.

I am further informed, however, that, after the registering of the debt, RT is now taking the RF to court in order to institute bankruptcy proceedings - notwithstanding the claim of the defendants that the conditions of the original agreement as instituted in accordance with the original Beth Din arbitration are still very much extant. The RF assure me that they have continued paying all this time until very recently when the RF notified RT that whatever finances are needed to defend these proceedings would need to be taken off the regular payments as they simply don't have enough for both.

It is my considered opinion therefore, that, according to Jewish law and indeed according to the ruling of the original Beth Din arbitration panel, it would be prohibited by Jewish law for the plaintiff, RT, to commence civil bankruptcy proceedings unless he can verify before a Beth Din panel that the RF do indeed have assets or additional income that they did not, or have not, declared accurately or have otherwise reneged on the original agreement. RT would then need to receive that Beth Din panel’s permission to proceed with civil bankruptcy proceedings accordingly.

I may not be in possession of all the details involved in this case and I acknowledge that I am related to the defendants. Accordingly, I am not issuing a binding, firm ruling on this matter. However, I certainly take the opportunity to strongly urge both parties to remove the matter from civil court at this time and, as expected by Jewish law, to refer the dispute to a mutually acceptable Beth Din panel and agree to abide by its decision and ruling - all in accordance with the ruling following the original arbitration conducted by the original Beth Din panel.

If there is any way that I can assist in providing further information or detail on Jewish law issues, please do not hesitate to contact me.

21 It is not clear for what purpose Rabbi Gutnick’s letter was relied on.

22 At one point it was suggested by counsel for the respondents that the letter was relied on as expert evidence on the issue of whether Rabbi Tayar could institute a proceeding in this Court to bankrupt the respondents given that there had been a Mesadrin or alternatively an agreement that the parties should engage in a Mesadrin. However, there are a number of reasons why the letter cannot be relied on for that purpose. Putting to one side his lack of independence they include that Rabbi Gutnick has not been qualified as an expert, there is no evidence of his credentials or his area of expertise nor has he acknowledged receipt of the Court’s Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT) or the Harmonised Expert Witness Code of Conduct.

23 At another point in the course of the hearing it was suggested that Rabbi Gutnick’s letter supports the respondents’ contention that there was a Mesadrin at some time between 9 May 2014, the date of the First Raskin Letter, and September 2014 (see the letter set out at [30] below). However, Rabbi Gutncik’s letter goes no higher than to state that he was contacted by the respondents and that he advised on a repayment plan. He states that he believes that his advice was accepted by both sides without explaining the basis for that belief.

24 Rabbi Yosef Feldman said that he understood that the parties had reached a Mesadrin. For the following reasons, that evidence is difficult to accept.

25 First, Rabbi Yosef Feldman does not set out who constituted the tribunal for the purpose of determining the Mesadrin. On his own evidence a Mesadrin is usually determined by a Beth Din i.e. an arbitral panel constituted by rabbis or by “an expert judge”, who I infer is a rabbi appointed for that purpose. Nor does he say what was determined at the Mesadrin or if and how Rabbi Tayar was involved.

26 Secondly, I do not accept Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s understanding that a Mesadrin had been reached because of the advice given by Rabbi Gutnick. On Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s evidence Rabbi Gutnick gave his advice on an anonymous basis and, to the extent it was given, it was only provided to the respondents and not communicated to Rabbi Tayar. To that end, I accept Rabbi Tayar’s evidence that he was not aware that a tribunal was ever appointed for the purpose of a Mesadrin. That evidence is entirely consistent with Rabbi Yosef Feldman’s evidence that Rabbi Gutnick’s identity was kept secret as was, it seems, any advice that he gave.

27 Thirdly, that the respondents made some payments to Rabbi Tayar, by paying his wife sums of money from time to time (see [35] – [37] below), does not lead to a conclusion that there was a Mesadrin. The payments were irregular. Rabbi Yosef Feldman described them as payments of at least $180 per week and “all up probably around 150k”. But no record of the amounts and times of payment and the total in fact paid was provided to the Court nor was there any evidence which would permit me to draw a conclusion that the payments were made pursuant to a Mesadrin of which both parties were aware and by which they felt bound as opposed to the payments being made by the respondents because of their obligation to make payment of the amount owing under the award.

28 Rabbi Tayar felt he had a religious duty to give the respondents an opportunity to pay him without the necessity for civil enforcement proceedings. He therefore approached Rabbi Raskin and three other rabbis, who were not part of the arbitral tribunal. However, their attempts to arrange payment failed.

29 On 18 August 2014 Rabbi Tayar received permission from the four rabbis referred to in the preceding paragraph to escalate the matter to a secular court. The permission was in a form of a document in Hebrew. According to Rabbi Tayar the penultimate paragraph of the document when translated into English provided:

And therefore according to what the Alter Rebbe says in his code of Jewish law (laws of damages at the end of section 6), we give permission to Rabbi [Tayar] above to turn to the civil courts to save what belongs to us according to our holy Torah.

30 In a letter dated 8 September 2014 from Rabbi Raskin (Second Raskin Letter) to the parties and the three rabbis who were signatories to the permission, Rabbi Raskin wrote, as translated from Hebrew into English by Rabbi Tayar, with some explanation included and denoted in brackets:

31 The Second Raskin Letter supports the finding made above that the advice given by Rabbi Gutnick did not constitute a Mesadrin which bound Rabbi Tayar. So much is evident from Rabbi Raskin’s observation that the rabbi called in by the respondents would not reveal his identity nor put his ruling in writing so that Rabbi Tayar would have no way of understanding the test which was applied. Rabbi Raskin thus asked the respondents to appoint a new expert rabbi who could record his ruling and his reasons or methodology and to do so by Jewish new year.

32 Rabbi Tayar is not aware of whether the procedure referred to in the Second Raskin Letter was undertaken and is unaware of what kind of “Halachic” test was performed, if any at all. He does not know whether the respondents’ assets were removed from their possession and whether they were made to take the Halachic oath that all future assets that come into their possession would be immediately handed over to him. In other words, Rabbi Tayar has no knowledge of the respondents undertaking the steps referred to in the Second Raskin Letter. One might expect that if they did, the name of the rabbi appointed would have been disclosed to Rabbi Tayar (and the Arbitral Panel as requested by Rabbi Raskin in his letter) and that the decision and methodology applied would have been reduced to writing and provided to Rabbi Tayar.

33 Nor does Rabbi Tayar recall having any discussions about a Mesadrin with the respondents following receipt of the Second Raskin Letter. He never participated in, approved of or was informed by anyone about the election of any particular rabbi for the purpose of a Mesadrin.

34 Rabbi Tayar felt that he had fulfilled his religious duty to ask rabbis for permission to enforce the award in the civil courts and that he was given that permission. Further, to the extent that the operation of the Permission may have been deferred or suspended by the Second Raskin Letter, there is no evidence that the respondents undertook the steps set out in that letter by the specified time, namely the Jewish new year such that Rabbi Tayar would be prevented from proceeding in accordance with it.

35 It did not appear to be in dispute that between the date on which the award was handed down and the commencement of the proceeding by Rabbi Tayar in the Supreme Court of Victoria described below, Rabbi Yosef Feldman paid a sum of money, estimated by Rabbi Tayar to be between approximately $80,000 and $120,000, to Rabbi Tayar’s wife. However, the nature of the payments was in dispute.

36 According to Rabbi Tayar, on numerous occasions Rabbi Yosef Feldman denied owing Rabbi Tayar any money, informed Rabbi Tayar’s wife that the payments were for charitable purposes and never informed Rabbi Tayar that these payments were part of a Mesadrin procedure.

37 According to Rabbi Yosef Feldman he made the payments over a period of eight years. Even though according to Jewish law he was not obliged to pay, he made the payments because he felt morally compelled to do so. He said he stopped making payments because Rabbi Tayar’s wife told him to do so and because he needed those funds to bring the proceeding to set aside the bankruptcy notice which was served on him and his father. In contradistinction to that evidence, Rabbi Yosef Feldman suggests that the payments were made pursuant to the Mesadrin which he says took place, overseen by Rabbi Gutnick. But as I have already found to be the case, while Rabbi Gutnick may have given advice to the respondents, Rabbi Tayar was unaware of the content and author of that advice. As far as Rabbi Tayar was aware there was no Mesadrin at that time nor at any time after the Second Raskin Letter.

38 As set out below, ultimately the amount paid by the respondents was taken into account by the Supreme Court of Victoria in considering the question of enforcement of the award.

Rabbi Tayar commences a proceeding in the Supreme Court of Victoria

39 On 6 May 2019 Rabbi Tayar commenced proceeding S ECI 2019 1970 in the Supreme Court of Victoria seeking an order pursuant to s 35 of the Commercial Arbitration Act in relation to the award (Supreme Court Proceeding). The respondents were the respondents to that proceeding. By interlocutory application they sought orders pursuant to s 36 of the Commercial Arbitration Act refusing recognition or enforcement of the award.

40 The proceeding came before Justice Lyons for hearing. At [2] of Tayar v Feldman his Honour described the award the subject of the Supreme Court Proceeding as follows:

The Award relates to payment of moneys pursuant to three successful claims determined at arbitration owed to the Applicant by the Respondents, Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and his son Rabbi Yosef Feldman. Those claims, accounting for adjustments of amounts already paid, accrue to an award of $1,849,570.02. The claims that the Applicant seeks to enforce (adopting the numbering used in the Award) are:

2.1 repayment of loans advanced to the Respondents and interest totalling $1,635,802.00 (‘Claim 1’) less an adjustment of $120,400 already paid;

2.2 an amount of $320,168.02 which the Applicant deposes is the ‘intended amount awarded’ for outstanding rental payments owed by the Respondents to the Applicant (it is unclear to what property the rental agreement relates) (‘Claim 2’); and

2.3 an amount of $14,000.00 which the Applicant deposes is the ‘intended amount awarded’ for outstanding salary payments (‘Claim 4’).

His Honour noted that there were two other claims determined as part of the award but which Rabbi Tayar did not seek to enforce.

41 In the Supreme Court Proceeding Lyons J found that claims 1 and 2 described above were “domestic commercial arbitrations” under the Commercial Arbitration Act and that the court was entitled to enforce the award in respect of claim 1 only: see Tayar v Feldman at [124]-[126]. Justice Lyons found that the respondents had not established the grounds set out in s 36 of the Commercial Arbitration Act in relation to claim 1: see Tayar v Feldman at [128]-[139]. His Honour considered the balance of the matters raised by the respondents pursuant to s 36 of the Commercial Arbitration Act and concluded that he would refuse to enforce the award in respect of claims 2 and 4: see Tayar v Feldman at [159].

42 Justice Lyons concluded that the monetary component of claim 1 of the award should be enforced. His Honour found that the amount to be awarded in respect of that claim should be adjusted to take into account the amounts acknowledged by Rabbi Tayar as having already been paid by the respondents. Thus the amount to be enforced was $1,515,402.02: see Tayar v Feldman at [169]-[171].

43 Orders were made in the Supreme Court Proceeding (Supreme Court Orders) including relevantly that:

1. Pursuant to s 35 of the Commercial Arbitration Act 2011 (Vic), the Respondents pay the Applicant the sum of $1,515,402.02 in respect of Claim 1 of the Award made by the Arbitrators dated 9 May 2013.

2. For the avoidance of doubt, the Respondents pay the Applicant interest on the amount in order 1 (or any parts thereof that remain outstanding) pursuant to s 101 of the Supreme Court Act 1986 (Vic).

44 The Supreme Court Orders were the subject of an appeal to the Victorian Court of Appeal and an application for special leave to appeal in the High Court of Australia, both of which were unsuccessful.

The bankruptcy notice

45 On 18 November 2021 bankruptcy notice BN254781 addressed to Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman claiming a total amount of $1,751,793.53 was issued by the Official Receiver. The amount claimed in the bankruptcy notice was made up of the amount the subject of the Supreme Court Orders including interest payable up to 17 November 2021 less amounts received. The bankruptcy notice required the respondents to pay the amount claimed in it within 21 days after the date of its service to Rabbi Tayar at the office of his solicitor, Dov Silberman, or to make arrangements to Rabbi Tayar’s satisfaction for settlement of the debt.

46 On 24 November 2021 a sealed copy of the bankruptcy notice was personally served on Rabbi Yosef Feldman and on 3 December 2021 a sealed copy of the bankruptcy notice was personally served on Rabbi Pinchus Feldman.

47 On 15 December 2021 the respondents commenced proceeding VID 748 of 2021 seeking to set aside the bankruptcy notice. That application was dismissed.

The creditor’s petition

48 On 4 May 2022 an amended creditor’s petition was filed with the Court.

49 On 19 May 2022 Rabbi Pinchus Feldman was personally served with, among other things, the amended creditor’s petition and on 3 June 2022 Rabbi Yosef Feldman was personally served with, among other things, the amended creditor’s petition.

50 On 14 June 2022 the respondents filed a notice stating grounds of opposition to application, interim application or petition (Notice of Grounds of Opposition).

51 As set out at [1] above on 21 July 2022 a sequestration order was made by a registrar of this Court in relation to the estates of each of Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman. It is the exercise of that power which is the subject of the present application for review.

Proof of matters in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act

52 According to Rabbi Tayar as at 15 November 2022:

(1) he was owed $1,923,903.06, made up of the amount owing as at 18 November 2021, being the date of issuing the bankruptcy notice to the respondents, of $1,751,793.53 plus interest of $173,739.53 and less the sum of $1,630 which had been paid since that date; and

(2) there was no agreement or other arrangement with either or both of the respondents to pay any or all of the amount owing to Rabbi Tayar by instalments or to postpone the enforcement of any or all of the debt.

53 On 16 November 2022 Mr Silberman, Rabbi Tayar’s lawyer, undertook a search of the National Personal Insolvency Index for each of Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman. It revealed that there were no extant creditor’s petitions in relation to either of them, other than the amended creditor’s petition, that although they are now undischarged bankrupts by reason of the orders made by the registrar, neither Rabbi Pinchus Feldman nor Rabbi Yosef Feldman was a bankrupt at the time those orders were made nor had they (or have they subsequently) entered into a debt agreement in relation to the judgment debt the subject of the bankruptcy notice which founded the act of bankruptcy.

the notice of grounds of opposition

54 In their Notice of Grounds of Opposition, the respondents raise the following grounds (as written):

1. According to the final judgement of the arbitration, Corey Stephen Tayar (“CST”) must agree to a “Mesadrin” (Jewish bankruptcy process) and has implicitly agreed to one through his acceptance of about $150,000.00 over the years, which was in accordance with the “Mesadrin” and not requesting a further “Mesadrin” with a Jewish court.

2. If CST rejects the way this “Mesadrin” agreement took place, he should, as per the final arbitration judgement (as annexed hereto in annexure 1), apply for another “Mesadrin”, rather than going to bankruptcy court.

3. In any event, the ruling of the arbitrators wasn’t finalized according to Jewish law and shouldn’t be binding. As they heard our appeal, but they didn’t want to respond to it as they didn’t have the energy or time and therefore it is unconscionable that any legal bankruptcy takes place before the appeal is dealt with, which puts in doubt the entire debt. The main judge, Rabbi Raskin, has agreed that and therefore, if the bankruptcy occurs, natural justice isn’t being served here until they deal with the appeal and rule accordingly

legislative framework

55 Section 43 of the Bankruptcy Act empowers the Court to make a sequestration order against the estate of a debtor where:

(1) a petition is presented by a creditor;

(2) the debtor has committed an act of bankruptcy; and

(3) at the time he or she did so the debtor was, among other things, personally present or ordinarily resident in Australia.

56 Section 40 of the Bankruptcy Act relevantly provides:

Acts of bankruptcy

(1) A debtor commits an act of bankruptcy in each of the following cases:

…

(g) if a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order, being a judgment or order the execution of which has not been stayed, has served on the debtor in Australia or, by leave of the Court, elsewhere, a bankruptcy notice under this Act and the debtor does not:

(i) where the notice was served in Australia—within the time fixed for compliance with the notice; or

(ii) where the notice was served elsewhere—within the time specified by the order giving leave to effect the service;

comply with the requirements of the notice or satisfy the Court that he or she has a counter‑claim, set‑off or cross demand equal to or exceeding the amount of the judgment debt or sum payable under the final order, as the case may be, being a counter‑claim, set‑off or cross demand that he or she could not have set up in the action or proceeding in which the judgment or order was obtained;

…

57 Section 52 of the Bankruptcy Act relevantly provides:

(1) At the hearing of a creditor's petition, the Court shall require proof of:

(a) the matters stated in the petition (for which purpose the Court may accept the affidavit verifying the petition as sufficient);

(b) service of the petition; and

(c) the fact that the debt or debts on which the petitioning creditor relies is or are still owing;

and, if it is satisfied with the proof of those matters, may make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

…

(2) If the Court is not satisfied with the proof of any of those matters, or is satisfied by the debtor:

(a) that he or she is able to pay his or her debts; or

(b) that for other sufficient cause a sequestration order ought not to be made;

it may dismiss the petition.

consideration

Satisfaction of the matters in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act

58 Based on the evidence relied on by Rabbi Tayar, I am satisfied of, among other requirements, the matters set out in s 43 and s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. That is, I am satisfied that:

(1) the bankruptcy notice has been served on each of Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman;

(2) each of Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman has committed an act of bankruptcy in that they have each failed to comply with the requirements of the bankruptcy notice within 21 days after the date of service of it on them;

(3) the amended creditor’s petition is in the proper form as required by s 47(1A) of the Bankruptcy Act;

(4) the debt owed to Rabbi Tayar exceeds the statutory minimum as required by s 44(1) of the Bankruptcy Act;

(5) the creditor’s petition has been presented within six months of the date of commission of the act of bankruptcy as required by s 44(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act;

(6) the amended creditor’s petition, which included the affidavit verifying [4] of the petition, has been served on each of Rabbi Pinchus Feldman and Rabbi Yosef Feldman as required by r 4.02 and r 4.04 of the Bankruptcy Rules; and

(7) subject to the matter considered below, that the debt on which the amended creditor’s petition relies is still owing.

59 This means that Rabbi Tayar, as petitioning creditor, has a “prima facie right” to a sequestration order: see Stratton v Bowles (No 2) [2015] FCA 43; 12 ABC(NS) 404 at [27] (Beach J). However, there is discretion to refuse to make such an order if the debtor satisfies the Court of either of the matters set out in s 52(2) of the Bankruptcy Act.

Section 52(2) of the Bankruptcy Act

60 I turn then to consider the matters raised in the Notice of Grounds of Opposition and whether, in light of those grounds, the respondents have established either of those matters. Before doing so, I note that the respondents do not, either in their Notice of Grounds of Opposition or in their evidence, seek to rely on s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act and to establish their solvency. Indeed when expressly asked, counsel for the respondents eschewed any reliance on s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. Further, the evidence before me reinforces that position in that Rabbi Yosef Feldman says, on at least one occasion, that he and Rabbi Pinchus Feldman do not have the income or assets to pay the amount sought in the bankruptcy notice.

Respondents’ submissions

61 The respondents submitted that there was a mutual understanding between the parties that Jewish Law, as understood by the parties in accordance with Chabad and orthodox customs, was paramount and took precedence over secular law, particularly in relation to commercial disputes. They said that it was impermissible for parties to go first to a civil court; that it is a last resort when all avenues of Jewish law are exhausted. They contended that the existence of a debt as well as its enforcement is to be determined in accordance with Jewish law, as understood by adherents of the Chabad movement.

62 The respondents submitted that from a legal perspective the authority of the Beth Din and the Jewish rabbinical court is voluntary. They accepted that the Beth Din has no real powers of enforcement other than for those who voluntarily accept its authority; that a person who is no longer orthodox, or who chooses not to be part of the Chabad movement, could ignore its rulings without any ramifications, other than communal pressures; and that a person could refuse to accept the authority of the Beth Din for any reason.

63 The respondents submitted that they understood that when Rabbi Tayar commenced the Supreme Court Proceeding, he did so to protect his position, and that he commenced that proceeding in aid of Jewish law. The respondents observed that under Jewish law there is no time limit to enforce a debt and that a person has an ongoing obligation to repay a debt which does not cease while, in contrast, it is uncontroversial that under Australian law there are limitation periods for almost all causes of action.

64 The respondents submitted that in that context it was understood by the parties that Rabbi Tayar might seek a judgment in a civil court to protect his position so that his ability to enforce the award would not become barred by a limitation period and, in that way, a judgment debt in a civil court is in aid of Jewish law. The respondents submitted that Rabbi Yosef Feldman approached his uncle, Rabbi Gutnick, and that he believed Rabbi Gutnick had organised a Mesadrin. They submitted that at all relevant times they were “severely lacking in financial means” and were unable to repay the debt owing to Rabbi Tayar other than in small instalments.

65 The respondents submitted that they do not accept the validity of the decision by the Beth Din in relation to the debt (i.e. the decision of the Arbitral Panel), but decided not to appeal the decision or to take the matter to another Beth Din. This was because they accepted that they were, in some way, morally obligated to repay Rabbi Tayar although they disputed the quantum of the debt and the basis upon which it was determined to be payable by the Beth Din.

66 The respondents submitted that as they were, at all material times, “severely lacking in funds and assets” and had no capacity to repay the debt, they commenced paying small periodic payments into Rabbi Tayar’s wife’s account. They understood these payments to be in accordance with a Mesadrin. The respondents submitted that prior to commencing the Supreme Court Proceeding Rabbi Tayar did not assert that there was no valid Mesadrin and did not suggest that there should be another Mesadrin. They contended that at all times it was open to Rabbi Tayar to either challenge the Mesadrin that they asserted had taken place or, alternatively, to seek a further Mesadrin.

67 The respondents submitted that while there was a challenge to the validity to the adjudication by the Beth Din in the Supreme Court Proceeding, this Court, in determining whether to make a sequestration order, must consider different factors. They contended that the only relevant question in the Supreme Court Proceeding was whether or not there was a debt owing. They submitted that the argument proceeded on the basis that the only matter for that court to determine was whether the award of the Arbitral Panel was valid having regard to principles of procedural fairness relevant to the Commercial Arbitration Act. They said that the substance of the debt and matters relevant to its enforcement, such as whether or not there was a Mesadrin, were not raised in that proceeding nor examined.

68 The respondents submitted that they do not seek in this Court to revisit the validity of the debt by going behind the Supreme Court Orders and the judgment of the Supreme Court of Victoria. Rather, they contended that the manner in which the Beth Din came to its original decision was so lacking in due process and adequacy, when compared to how any Australian court exercising civil jurisdiction would have dealt with the matter, that an inference can be drawn that at all times the parties understood that Jewish law would be paramount in all aspects of the case, including enforcement. The respondents submitted that the evidence shows that all dealings between the parties proceeded on the basis of a common understanding about the fact that Jewish law was paramount and that there is a common understanding about how Jewish law operates in conjunction with secular law.

69 The respondents submitted that there is evidence that the parties felt that Rabbi Raskin was responsible for giving permission to them if they wished to go to a secular court. They submitted that the Beth Din appeared to be exerting at least some level of control over the parties’ ability to go to secular court and that the award under the Commercial Arbitration Act must be seen in this context.

70 The respondents observed that Rabbi Tayar gave evidence that he declined to agree to enter into a Mesadrin with the respondents and only sought that the Beth Din determine whether there was a debt and if so the quantum of that debt. The respondents submitted that given this fact it would be an abuse of process for Rabbi Tayar on the one hand to seek the benefit of the ruling by the Beth Din but thereafter to decline to participate in a Mesadrin which, based on the evidence, must be understood as an integral part of the process. They contended that Rabbi Tayar has, in his actions, taken advantage of the respondents in circumstances where they are both members of Chabad and by, on the one hand, seeking adjudication by a Beth Din and, on the other, thereafter declining to accept a Mesadrin.

71 The respondents submitted that even if Rabbi Tayar states he never agreed to a Mesadrin it is clear from the dealings between the parties that any agreement to go to the Beth Din to determine the matter would implicitly entail that all matters between them be determined by the Beth Din including how the debt would be repaid. The respondents submitted they are currently prepared to undergo a further Mesadrin, they have no assets in any event and the sequestration order is essentially futile.

72 In their oral submissions, the respondents submitted that the parties to the proceeding are members of the Lubavitch community, a known Jewish orthodox community, and that when one looks at the totality of the evidence it is clear that the parties agreed to deal with this dispute from start to finish in accordance with Jewish law. The respondents put their case on a number of alternative bases. They said it is either:

(1) an abuse of process for Rabbi Tayar to rely on the amended creditor’s petition and seek a sequestration order; or

(2) there is a collateral contract between the parties by which they agreed to deal with the question of enforcement of the award under Jewish law; or

(3) Rabbi Tayar is estopped from denying that enforcement should be dealt with under Jewish law; or

(4) it could be a case of unilateral mistake in contract.

73 The respondents did not make any detailed submissions in support of these alternative bases, either as to the applicable law or by an analysis of the facts which would support a finding of, for example, a collateral contract, estoppel, unilateral mistake or abuse of process. Rather, the respondents submitted that the Court would decline to enforce the Supreme Court Orders in this jurisdiction based on the dealings between the parties because one of those alternatives was made out.

74 The respondents contended that it was clear from the dealings between the parties that there is no time frame for payment of the amount found to be payable in the award and there is in fact evidence, in the supplemental award, that the debt must be paid “as soon as possible”. They said that the fact that there is no timeframe attached to the award is entirely in accordance with Jewish law and ties into the concept of Mesadrin. The requirement is to pay as soon as possible and if one does not have the money to pay, one simply has to do the best one can. The respondents submitted that is what “as soon as possible” means in this context.

75 The respondents also submitted that it is apparent from the First Raskin Letter that the Arbitral Panel understood that there would be a Mesadrin after they handed down their award. The respondents said that reference was a sufficient basis on which to conclude that there is a collateral agreement between the parties to that effect. The respondents submitted that the fact that the parties foresaw entering into a Mesadrin was reinforced by Rabbi Tayar seeking permission to go to a civil court.

76 The respondents submitted that if the Court did not find there was a collateral contract by which they had agreed that the matter should proceed in accordance with Jewish law or that there was some form or estoppel, then it was open to find, in the alternative, that Rabbi Tayar acted in a way that caused the respondents to believe that they were going to be guided under Jewish law in all aspects of the matter but, contrary to that, proceeded to enforce the award by invoking the Bankruptcy Act.

Have the respondents established “other sufficient cause” for the purposes of s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act?

77 The respondents rely on s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act and seek to satisfy the Court that there is other sufficient cause which would lead me to exercise my discretion to dismiss the amended creditor’s petition.

78 In Totev v Sfar [2006] FCA 470; (2006) 230 ALR 236 at [37] Allsop J (as his Honour then was) observed the following about the meaning of “other sufficient cause” as used in s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act:

On proof of the matters in s 52(1) of the Act, the Court will generally proceed to make an order for sequestration. It is for the debtor to persuade the Court that the public interest in the dealing with the insolvent debtor and the rights of individual creditors are outweighed by other considerations: Cain v Whyte (1933) 48 CLR 639 at 645-6 and 648. In Cain v Whyte, the judgment of Henchman J sitting as the judge in bankruptcy for the District of Southern Queensland was approved by Rich, Starke, Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ. At 645-46 Henchman J was recorded as saying the following:

…Mr. Philp, however, argues that the Court has a discretion even though the proofs that I have alluded to have been made. He suggests that in the present case “other sufficient cause” exists, within the meaning of sec. 56 (3) (b), which throws upon me an obligation to dismiss, or gives me a discretion to dismiss, the petition. I agree that the sections do leave a certain amount of discretion in the Bankruptcy Judge (see secs. 54, 56 (2) and 56 (3)), and I do not agree with the argument put forward by Mr. Graham that the words “other sufficient cause” should be limited to the one case where the Court is satisfied that the petition is put forward solely for some collateral illegitimate end, and not for the purpose of securing the equal distribution of the available assets amongst the creditors. To my mind, the High Court of Australia did not intend to put a limit on the meaning of the words “other sufficient cause” in Dowling v. Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society (1915) 20 CLR 509, and I do not propose to be the first to say that such wide words as “other sufficient cause” are necessarily limited to meaning a cause in the nature of fraud or abuse of the provisions of the bankruptcy law. I can well conceive that “other sufficient cause” might arise in connection with any particular case. To my mind, it is the duty of the Bankruptcy Judge to examine in each case, if the question is raised, whether there is other sufficient cause than the fact that the debtor is able to pay his debts in full, for refusing to make an order.

I rule then that I am fully entitled to examine the contention put forward by Mr. Philp on behalf of the debtor that there is, in the present case, other sufficient cause sufficient to justify the dismissal of this petition. I approach that question with the full appreciation that, prima facie, on proof of the matters mentioned in sec. 56(2), the Court will proceed to make an order for sequestration, and that it is for the debtor to show some cause overriding the interest of the public in the stopping of unremunerative trading, and the rights of individual creditors who are unable to get their debts paid to them as they become due. Something has to be put before the Court to outweigh those considerations before it can be said that sufficient cause is shown against the making of a sequestration order. …

79 As his Honour also observed (at [40]) it is for the debtor, in this case the respondents, to show “other sufficient cause” and (at [44]) that the discretion to be exercised in s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act is a broad one and is informed by public interest considerations in dealing with insolvents.

80 With that context I turn to consider the respondents’ grounds in their Notice of Grounds of Opposition.

81 Grounds 1 and 2 of the Notice of Grounds of Opposition can be considered together. By those grounds the respondents, in effect, contend that the Supreme Court Orders cannot presently, (or indeed ever) be enforced. This is because Rabbi Tayar must agree to a Mesadrin, before he can take steps to bankrupt them, and has implicitly agreed to a Mesadrin by his acceptance of the payments made to date by the respondents or, if Rabbi Tayar contends that there has been no Mesadrin, he should apply for another Mesadrin rather than invoking the procedures under the Bankruptcy Act.

82 While not expressly stated to be the case and despite the respondents’ contention that they do not ask this Court to go behind the judgment in Tayar v Feldman, at the heart of these grounds (and ground 3) is a contention that the amount the subject of the Supreme Court Orders is not presently owing. If that is so then the discretion in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act to make a sequestration order is not enlivened or, alternatively, that fact, if established, could be sufficient to establish “other sufficient cause” for the purposes of s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act. If that is so, then on one analysis and noting that the respondents did not in fact seek to do so, the question that arises is whether the Court should go behind the judgment given in the Supreme Court Proceeding in order to consider whether the Supreme Court Orders establish the amount truly owing to Rabbi Tayar.

83 Relevantly, in Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Ltd v Compton (2017) 261 CLR 132 at [54] a majority of the High Court (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Nettle JJ) said:

In point of principle, scrutiny by a Bankruptcy Court of the debt propounded by a judgment creditor seeking a sequestration order in no sense involves an attempt to impeach the judgment. A Bankruptcy Court is not concerned with whether the judgment should be set aside as upon an appeal, or even as a default judgment or a judgment obtained by fraud may be set aside; nor is a Bankruptcy Court concerned to deny the effect of the judgment as “res judicata” between the parties to it. A Bankruptcy Court is not concerned to prevent the judgment creditor from invoking the ordinary processes of execution available under the general law. Rather, a Bankruptcy Court is concerned with whether the debt on which it is based is truly a basis for the making of a sequestration order. A Bankruptcy Court has a statutory duty to be “satisfied” as to the existence of the petitioning creditor’s debt; a creditor should not be able to make a person bankrupt on a debt which is not provable.

(Footnote omitted.)

84 At [68]-[70] the majority continued:

68 For the purposes of s 52 of the Act, a judgment may usually be taken to be sufficient evidence of a debt in that a judgment against a debtor in favour of a creditor obtained after a trial is, generally speaking, a reliable indication of the true state of indebtedness as between creditor and debtor. Indeed, such a judgment can usually be expected to provide the most reliable statement of the debt humanly attainable because the ordinary processes of the adversarial system provide a practical guarantee of reliability. The testing of the relative merits of a claim and counterclaim under the rigours of adversarial litigation will usually establish the true state of accounts as between the parties to the proceedings. Accordingly, a Bankruptcy Court will usually have no occasion to investigate whether the judgment debt is a true reflection of the real debt. But where the merits of a claim and counterclaim have not been tested in adversarial litigation, a judgment debt will not have this practical guarantee of reliability.

69 In Petrie v Redmond, Latham CJ, with whom Rich and McTiernan JJ agreed, said that the Bankruptcy Court:

“is entitled to go behind the judgment and inquire into the validity of the debt where there has been fraud, collusion or miscarriage of justice. … Also the court looks with suspicion on consent judgments and default judgments. … The Bankruptcy Court does not examine every judgment debt. Special circumstances must be established before it will do so. It is impossible to lay down any general rule.”

70 The first two sentences of that passage were cited with evident approval by Dixon, Williams, Webb and Kitto JJ in Corney v Brien. The passage was explicitly concerned with consent judgments and default judgments. As a matter of practical experience, these are the sorts of cases in which third parties can be expected to be disadvantaged by the making of a sequestration order based on a judgment which was not the outcome of the rigorous processes of adversarial litigation. The same concern may also arise in a case where the judgment was obtained in circumstances which suggest a failure on the part of the judgment debtor to present his or her case on its merits in the litigation that led to the judgment.

(Footnotes omitted.)

85 In this case, I am satisfied that the Supreme Court Orders establish that there is a debt truly owing to Rabbi Tayar. My reasons for reaching that conclusion follow.

86 As set out at [12] above, the parties entered into the Arbitration Agreement and appointed the Arbitral Panel to determine the “Disputed Matters” in the manner set out in that agreement. That was the extent of the role of the Arbitral Panel under the Arbitration Agreement. Its role did not extend to enforcement of any award that they issued. I pause to note that any submission to the contrary or suggestion that the Arbitral Panel was charged by the parties to concern themselves with questions of enforcement must be rejected.

87 The Arbitration Agreement also provided that the Arbitral Panel is to act as an arbitral panel under the Commercial Arbitration Act and that the agreement is governed by the laws in force in Victoria.

88 Given that context, it is necessary to consider the terms of the Commercial Arbitration Act. Relevantly, s 1AC of that Act provides that the paramount object of that Act is “to facilitate the fair and final resolution of commercial disputes by impartial arbitral tribunals without unnecessary delay or expense”.

89 Part 7 of the Commercial Arbitration Act is titled “recourse against award”. Section 34 concerns an application for setting aside an arbitral award. It provides:

(1) Recourse to the Court against an arbitral award may be made only by an application for setting aside in accordance with subsections (2) and (3) or by an appeal under section 34A.

Note: The Model Law does not provide for appeals under section 34A.

(2) An arbitral award may be set aside by the Court only if—

(a) the party making the application furnishes proof that—

(i) a party to the arbitration agreement referred to in section 7 was under some incapacity; or the arbitration agreement is not valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it or, failing any indication in it, under the law of this State; or

(ii) the party making the application was not given proper notice of the appointment of an arbitral tribunal or of the arbitral proceedings or was otherwise unable to present the party's case; or

(iii) the award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration, or contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration, provided that, if the decisions on matters submitted to arbitration can be separated from those not so submitted, only that part of the award which contains decisions on matters not submitted to arbitration may be set aside; or

(iv) the composition of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties, unless such agreement was in conflict with a provision of this Act from which the parties cannot derogate, or, failing such agreement, was not in accordance with this Act; or

(b) the Court finds that—

(i) the subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law of this State; or

(ii) the award is in conflict with the public policy of this State.

90 Section 34(3) requires that an application to set aside an arbitral award be made within three months from the date on which the party making the application has received the award or, where a request has been made under s 33 of the Commercial Arbitration Act, from the date on which that request was disposed of by the arbitral tribunal. Section 33 permits a party, with notice to the other party, to request an arbitral tribunal to correct any errors in the award, such as clerical, typographical or similar errors, or to request the tribunal to provide an interpretation on a specific point or part of the award. There is no evidence that any such request was made here. Nor is there any evidence that any application was brought pursuant to s 34 of the Commercial Arbitration Act to set aside the award.

91 Similarly, the respondents have not sought to contend that any of the matters set out in s 34(2) of the Commercial Arbitration Act arise. They do not contend that there is any basis under the Commercial Arbitration Act to have the award set aside and, in any event, even if they did so, they would be significantly out of time to bring such an application in the proper forum, the Supreme Court of Victoria.

92 Section 34A of the Commercial Arbitration Act provides for an appeal to the Supreme Court of Victoria on a question of law arising out of an award if the parties agree, before the end of the appeal period referred to in s 34A(6), that an appeal may be made under that section and the court grants leave. The appeal period referred to in s 34A(6) is the same as that which applies under s 34(3), namely three months from the date on which the party bringing the appeal received the award or, from the date on which any request under s 33 of the Act has been disposed of by the arbitral tribunal. Once again, there is no evidence that any appeal for the purposes of s 34A on a question of law was brought by the respondents or that they intend to bring such an appeal.

93 I turn then to Part 8 of the Commercial Arbitration Act which concerns recognition and enforcement of awards and which includes s 35 and s 36. Applications under those sections were considered in the Supreme Court Proceeding.

94 Relevantly, s 35(1) of the Commercial Arbitration Act provides:

An arbitral award, irrespective of the State or Territory in which it was made, is to be recognised in this State as binding and, on application in writing to the Court, is to be enforced subject to the provisions of this section and section 36.

95 Section 36 of the Commercial Arbitration Act sets out the grounds on which recognition or enforcement of an arbitral award may be refused by the Court. Those grounds are as follows:

(1) Recognition or enforcement of an arbitral award, irrespective of the State or Territory in which it was made, may be refused only—

(a) at the request of the party against whom it is invoked, if that party furnishes to the Court proof that—

(i) a party to the arbitration agreement was under some incapacity, or the arbitration agreement is not valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it or, failing any indication in it, under the law of the State or Territory where the award was made; or

(ii) the party against whom the award is invoked was not given proper notice of the appointment of an arbitrator or of the arbitral proceedings or was otherwise unable to present the party's case; or

(iii) the award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration, or it contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration, provided that, if the decisions on matters submitted to arbitration can be separated from those not so submitted, that part of the award which contains decisions on matters submitted to arbitration may be recognised and enforced; or

(iv) the composition of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties or, failing such agreement, was not in accordance with the law of the State or Territory where the arbitration took place; or

(v) the award has not yet become binding on the parties or has been set aside or suspended by a court of the State or Territory in which, or under the law of which, that award was made; or

(b) if the Court finds that—

(i) the subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law of this State; or

(ii) the recognition or enforcement of the award would be contrary to the public policy of this State.

96 In Tayar v Feldman Lyons J considered Rabbi Tayar’s application under s 35 of the Commercial Arbitration Act to recognise or enforce the award and the respondents’ application under s 36 of that Act that recognition or enforcement of the award be refused. In that regard the respondents relied on s 36(1)(a)(i), (ii) and (iv). As set out above, after considering the parties’ submissions, Lyons J concluded that, while the court was entitled to enforce the award in respect of claims 1 and 2, it could not enforce the award in respect of claim 2.

97 His Honour considered the respondents’ submissions in response to the application under s 35 of the Arbitration Act for recognition or enforcement of the award and those in support of their application pursuant to s 36 of the Commercial Arbitration Act. As to the latter Lyons J concluded that the respondents had made out their grounds under s 36 in relation to claims 2 and 4 considered by the Arbitral Panel and that therefore the Court could not recognise or enforce the award in respect of those claims under s 35 of the Commercial Arbitration Act. That was because the reasons of the Arbitral Panel did not provide a means for calculating the amounts in respect of claims 2 and 4.

98 As set out at [44] above there was an appeal to the Victorian Court of Appeal from the Supreme Court Orders which was dismissed and a subsequent application for special leave to appeal to the High Court which was refused.

99 In the circumstances, I do not think that there is a basis upon which the Court would go behind the judgment which resulted in the Supreme Court Orders. Those orders were not made by consent nor were they entered as a result of default judgment. There was a contested hearing between the parties, as well as an appeal, on the application for recognition and enforcement under s 35 of the Commercial Arbitration Act. The parties were represented. They were able to make their applications and submissions, albeit within the confines of the Commercial Arbitration Act, which relevantly governed the proceeding before the Arbitral Panel. There can be no suggestion, let alone a finding, that the respondents were not able to present their case on the merits in the Supreme Court Proceeding.

100 The alternative way in which the respondents sought to establish other sufficient cause for the purposes of s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act was to contend that the debt was not presently payable and/or a sequestration order should not be made because the parties have agreed to address the question of enforcement by application of Jewish law and by submitting to the Mesadrin procedure.

101 Both Rabbi Tayar and each of the respondents are orthodox Jews. As the evidence establishes, and likely because of their adherence to the orthodox principles of Judaism, they elected to have their commercial dispute determined by a Beth Din by reference to principles of Jewish law (known as Halacha). As set out at [12] above, pursuant to the Arbitration Agreement the Arbitral Panel was appointed to determine the “Disputed Matters”. They, in turn, were to be defined by, among other things, the statement of claim, defence and any cross-claim, filed in the arbitration. However, while no such documents were provided to the Arbitral Panel: see Tayar v Feldman at [33], the Arbitral Panel identified the claims which it determined. Based on that definition, the award and the evidence before me it is clear that the Arbitral Panel was not appointed to address questions relating to, or processes of enforcement of any award issued by it in relation to the Disputed Matters.

102 Further, it does not follow that, because of their faith and their adherence to orthodox principles, all issues that arise between them are to be resolved according to Jewish law. In cross-examination Rabbi Tayar did not accept that the process the parties embarked upon to resolve their dispute involved the Arbitral Panel or another Beth Din dealing with how the debt the subject of an award would be paid according to Jewish law. Rather his evidence was that was possible, but not necessarily so. Rabbi Tayar gave further evidence explaining his answer. He said that the stricter view is that the parties should first try to deal with the question of enforcement of an award internally. If that fails, in that one party refuses to take part in or comply with the Mesadrin process, then the rabbis who are aiding in and overseeing that process will give Halachic permission to approach a secular court.

103 As to whether permission is required to take a matter to a secular court, Rabbi Tayar explained that there are two views: one is that following the issuing of an award by a Beth Din a party can immediately go to a secular court for the purposes of enforcement without first seeking permission; and the other is that before going to a secular court for the purposes of enforcement permission should be sought. The latter shows respect for the Jewish religion and the authorities. Rabbi Tayar explained that he always follows the more stringent (second) approach.

104 In other words it is apparent that while the Mesadrin process may be favoured by members of the orthodox Jewish community, it is not obligatory. There is no bar to approaching a secular court for the purposes of enforcement of an award given by a Beth Din.

105 Finally, the respondents have not established that there was an agreement (or collateral contract) that the question of enforcement be dealt with by a Mesadrin or that a Mesadrin took place.

106 As to the former there is no evidence that would lead me to that conclusion or to conclude that Rabbi Tayar is estopped from undertaking enforcement processes in the secular courts or that the respondents can rely on unilateral mistake or to find that this proceeding is an abuse of process. The evidence supports the contrary conclusion. First, the terms of the Arbitration Agreement limit the maters to be addressed by the Arbitral Panel to the Disputed Matters. Secondly, to the extent that the Arbitral Panel’s supplemental award required the amounts stated in the award to be paid by the respondents “as soon as possible” this did not mean that the Arbitral Panel was considering enforcement or payment terms. Rather, it seems that the Arbitral Panel was simply stating that the debt was immediately due and payable and should be paid. Thirdly, the First Raskin Letter makes it clear that the Arbitral Panel’s role was not to “bring the judgment to actualization, or to be involved in Mesadrin etc”. Fourthly, Rabbi Tayar gave the respondents an opportunity to pay the amount owing because he felt he had a religious duty to do so (see [28] above) and because of his adherence to a stricter view of how to address enforcement (see [103] above). There is no evidence that he did so because he had entered into any agreement which restricted enforcement to a Mesadrin procedure. Fifthly, the permission was issued. Finally, the Second Raskin Letter does no more than to give the respondents an opportunity to arrange a Mesadrin presided over by a rabbi or rabbis made known to Rabbi Tayar and involving a transparent process. That letter did no more than to “delay” the permission in order to give the respondents time to embark on the process set out in it. There is no evidence that the respondents did so or that Rabbi Tayar agreed to any different process.

107 As to the latter, as set out at [24]-[27] above, the evidence does not establish that there has been a Mesadrin.

108 Accordingly, grounds 1 and 2 of the Notice of Grounds of Opposition are not made out.

109 By ground 3 of the Notice of Grounds of Opposition, the respondents contend that the ruling of the Arbitral Panel was not final and should not be binding. The Arbitral Panel heard but did not wish to respond to the respondents’ appeal as it did not “have the energy or time” to do so. The respondents submitted it would be unconscionable for the bankruptcy to proceed before the appeal, which puts in issue the debt on which the Supreme Court Orders are based.

110 No express submissions were made about this ground. However, having regard to the evidence before me it is not made out for two reasons.

111 Firstly, as set out at [39]-[43] above, the award issued by the Arbitral Panel has been recognised pursuant to the Commercial Arbitration Act. The Supreme Court Orders are accordingly final orders and are enforceable.

112 Secondly, insofar as the respondents assert that they filed an appeal in relation to the award, the evidence before me, given by Rabbi Yosef Feldman, was that both the respondents and Rabbi Tayar sought to appeal the award but on 10 October 2013 the respondents were told by the Arbitral Panel that it rejected the application to appeal, that it proposed to terminate the current proceeding and recommended that the respondents start afresh with the appointment of a new arbitral panel or that the parties execute a new arbitration agreement appointing the Arbitral Panel to start the proceeding again. This evidence does not establish that the Arbitral Panel deferred hearing the appeal because it “did not have the energy or the time”. At its highest the evidence establishes how the respondents should proceed if they wished to pursue an appeal or rehearing by the Arbitral Panel or a differently constituted panel (i.e. Beth Din). Nor did the respondents bring any application pursuant to s 34A of the Commercial Arbitration Act (see [92] above). To that end, Rabbi Yosef Feldman acknowledged he could have sought to appeal the award in a civil court because the arbitration “lacked natural justice” but he “didn’t want to take the Rabbis to court”.

113 As I am satisfied of the matters set out in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act and the respondents have not made any of the grounds in their Notice of Grounds of Opposition, I would make a sequestration order in relation to the estates of each of the respondents. As a registrar of this Court made such an order on 21 July 2022, I will affirm the orders made at that time and dismiss the respondents’ interim application filed on 11 August 2022.

114 In those circumstances it is not necessary to consider the Trustees’ submissions in relation to their remuneration and costs incurred to date in administering the respondents’ bankrupt estates.

115 As the respondents have been unsuccessful they should pay Rabbi Tayar’s costs of the interim application, as agreed or taxed. For clarity, I note that those costs are payable having regard to the priority regime in s 109(1) of the Bankruptcy Act.

116 The Trustees were granted leave to be heard pursuant to r 2.03 of the Bankruptcy Rules and appeared to assist the Court. In the circumstances I do not intend to make an order for payment of their costs on this application. If the Trustees wish to make any application in relation to their costs of the interim application I will grant them leave to file and serve any such application within seven days of the publication of these reasons.

117 I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and seventeen (117) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |

Associate:

Schedule of Parties

VID 235 of 2022 | |

Mr Jonathon Kingsley Colbran | |

Interested Person: | Mr Gregory Bruce Dudley |