FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

David on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 1430

ORDERS

LUI NED DAVID & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE SEA CLAIM APPLICANT (PART B) Applicant | ||

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 26 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MILTON SAVAGE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE KAURAREG PEOPLE #1 Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 10 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MILTON SAVAGE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE KAURAREG PEOPLE #2 Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 24 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MILTON SAVAGE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE KAURAREG PEOPLE #3 Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 114 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BERNARD RICHARD CHARLIE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE NORTHERN PENINSULA SEA CLAIM GROUP Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 115 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BERNARD RICHARD CHARLIE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE NORTH EASTERN PENINSULA SEA CLAIM GROUP Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

QUD 227 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | LUI NED DAVID & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL SEAS CLAIM (PART C) Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The Applicant in proceeding QUD26/2019 has made an application for a determination of native title (Kaurareg #1 Application).

B. The Applicant in proceeding QUD10/2019 has made an application for a determination of native title (Kaurareg #2 Application).

C. The Applicant in proceeding QUD24/2019 has made an application for a determination of native title (Kaurareg #3 Application).

D. The Applicant in proceeding QUD114/2017 has made an application for a determination of native title (Northern Peninsula Application).

E. The Applicant in proceeding QUD115/2017 has made an application for a determination of native title (North Eastern Peninsula Application).

F. The Applicant in proceeding QUD27/2019 has made an application for a determination of native title (TSRSC Part B Application).

G. The Applicant in proceeding QUD227/2022 has made an application for a determination of native title (TSRSC Part C Application).

H. As part of the case management timetable annexed to the Court’s orders of 27 July 2020, the land and waters covered by the Kaurareg #1 Application, the Kaurareg #2 Application, the Kaurareg #3 Application, the Northern Peninsula Application, the North Eastern Peninsula Application, and the TSRSC Part B Application, taken together, were discretely defined as the Western Overlap Area, the Eastern Overlap Area, and the Southern Overlap Area. By orders made on 11 August 2022, the case management timetable was amended to include the TSRSC Part C Application.

I. Parts of the Kaurareg #1 Application, the Kaurareg #3 Application, the TSRSC Part B Application and the TSRSC Part C Application overlap and are within the Western Overlap Area.

J. Parts of the Kaurareg #1 Application, the TSRSC Part B Application and the North Eastern Peninsula Application overlap and are within the Eastern Overlap Area.

K. The whole of the Northern Peninsula Application, and parts of the Kaurareg #2 Application, and the Kaurareg #3 Application overlap and are within the Southern Overlap Area to the west of Cape York.

L. Parts of the North Eastern Peninsula Application, parts of the TSRSC Part B Application and parts of the TSRSC Part C Application overlap and are within the Southern Overlap Area to the east of Cape York.

M. On 8 November 2022, the Court made orders under section 67(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) in respect of the Kaurareg #1 Application, the Kaurareg #2 Application, the Kaurareg #3 Application, the Northern Peninsula Application, the North Eastern Peninsula Application, the TSRSC Part B Application, and the TSRSC Part C Application, providing for them to be dealt with together.

N. By orders made on 8 November 2022, the area covered by the Northern Peninsula Application was administratively separated into:

(a) Part A, being onshore areas (Northern Peninsula Application (Part A)); and

(b) Part B, being offshore areas (Northern Peninsula Application (Part B)).

O. By orders made on 8 November 2022, the area covered by the North Eastern Peninsula Application was administratively separated into:

(a) Part A, being onshore areas (North Eastern Peninsula Application (Part A)); and

(b) Part B, being offshore areas (North Eastern Peninsula Application (Part B)).

P. This determination covers parts of the land or waters covered respectively by the Kaurareg #1 Application, the Kaurareg #2 Application, the Kaurareg #3 Application, the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the TSRSC Part B Application, and the TSRSC Part C Application.

Q. In relation to the Kaurareg #1 Application, the parties have agreed that:

(a) the application is to be dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters within the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below; and

(b) no determination is to be made at present in respect of the balance of the land or waters covered by the application.

R. In relation to the Kaurareg #2 Application, the parties have agreed that:

(a) the application is to be dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters within:

(i) the Ankamuthi Area, the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below; or

(ii) the balance of the land and waters in the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B) and North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B); and

(b) other than the land and waters within the Kaurareg Area, no determination is to be made at present in respect of the balance of the land or waters covered by the application.

S. In relation to the Kaurareg #3 Application, the parties have agreed that:

(a) the application is to be dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters within:

(i) the Ankamuthi Area, the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below; or

(ii) the balance of the land and waters in the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B) and North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B); and

(b) no determination is to be made at present in respect of the balance of the land or waters covered by the application.

T. In relation to the North Eastern Peninsula Application, the parties have agreed that:

(a) the application is to be dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters within the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area that are not also within the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below;

(b) a determination of native title is to be made for the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area; and

(c) no determination is to be made at present in respect of the balance of the land or waters covered by the application.

U. The parties have agreed that, in respect of the balance of the land or waters described in Schedule 6 and covered by the Kaurareg #2 Application, the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the TSRSC Part B Application and the TSRSC Part C Application, no determination is to be made at present.

V. The parties have filed in the Court agreements in writing made pursuant to section 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), in respect of the Kaurareg #1 Application, the Kaurareg #2 Application, the Kaurareg #3 Application, the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B), the TSRSC Part B Application, and the TSRSC Part C Application.

BEING SATISFIED that an order in the terms set out below is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court to do so, pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA)

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms proposed in these orders, despite any actual or arguable defect in the authorisation of the applicant in QUD 26 of 2019, QUD 10 of 2019, QUD 24 of 2019 or QUD 115 of 2017 to seek and agree to a consent determination pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

BY CONSENT THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (the determination).

2. The Kaurareg #1 Application is dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters that are within the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below.

3. The Kaurareg #2 Application is dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters that are within the:

(a) Ankamuthi Area, the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area, or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below; or

(b) the balance of the land and waters in the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B) and North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B).

4. The Kaurareg #3 Application is dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters that are within:

(a) the Ankamuthi Area, the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area, or the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below; or

(b) the balance of the land and waters in the Northern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B) and North Eastern Peninsula Application (Parts A and B).

5. The North Eastern Peninsula Application is dismissed to the extent that it covers any land or waters within the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area that are not also within the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area, as those areas are defined in order 9 below.

6. Each party to the proceeding is to bear its own costs.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

7. In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

Other words and expressions used in this determination have the same meanings as they have in Part 15 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

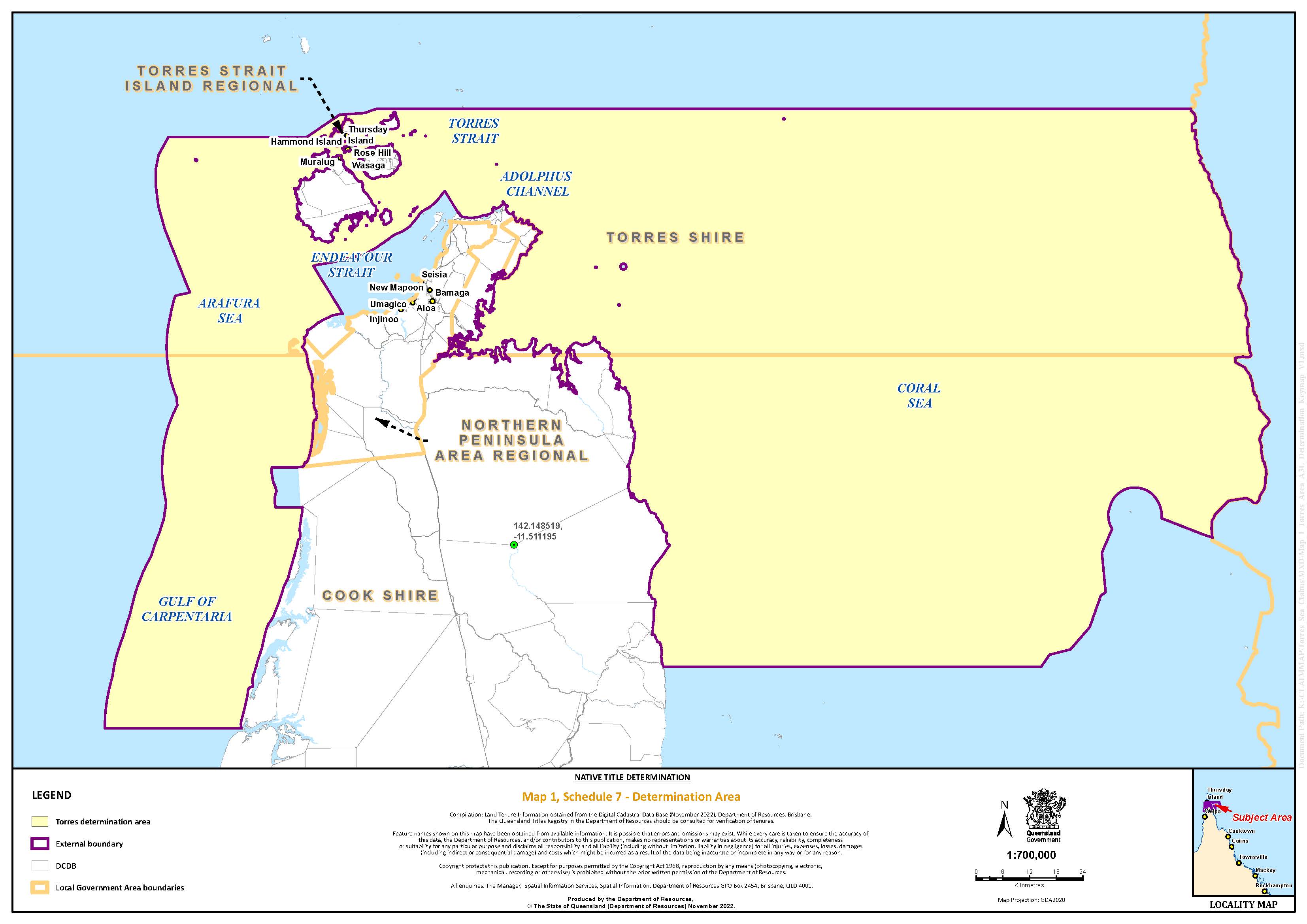

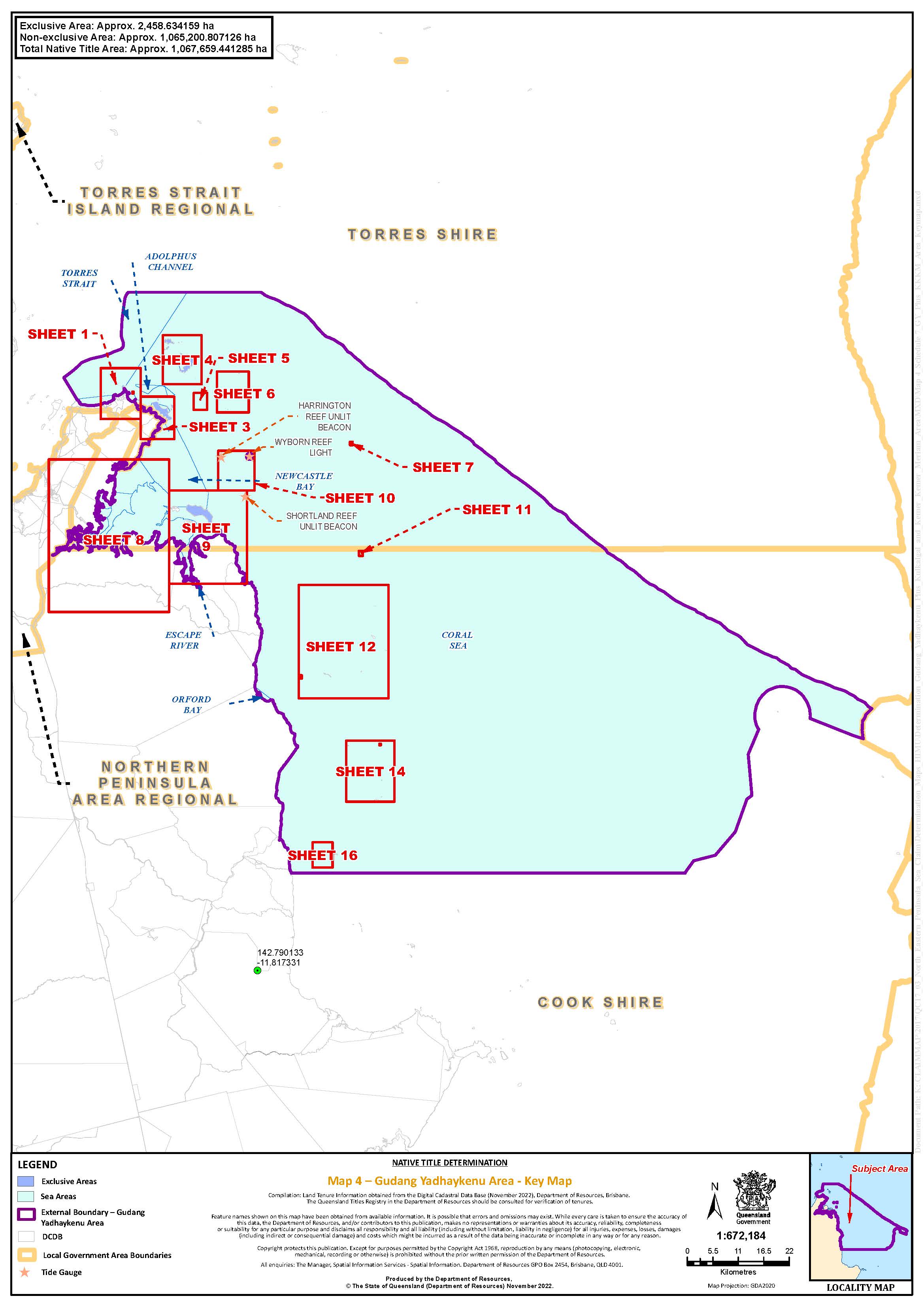

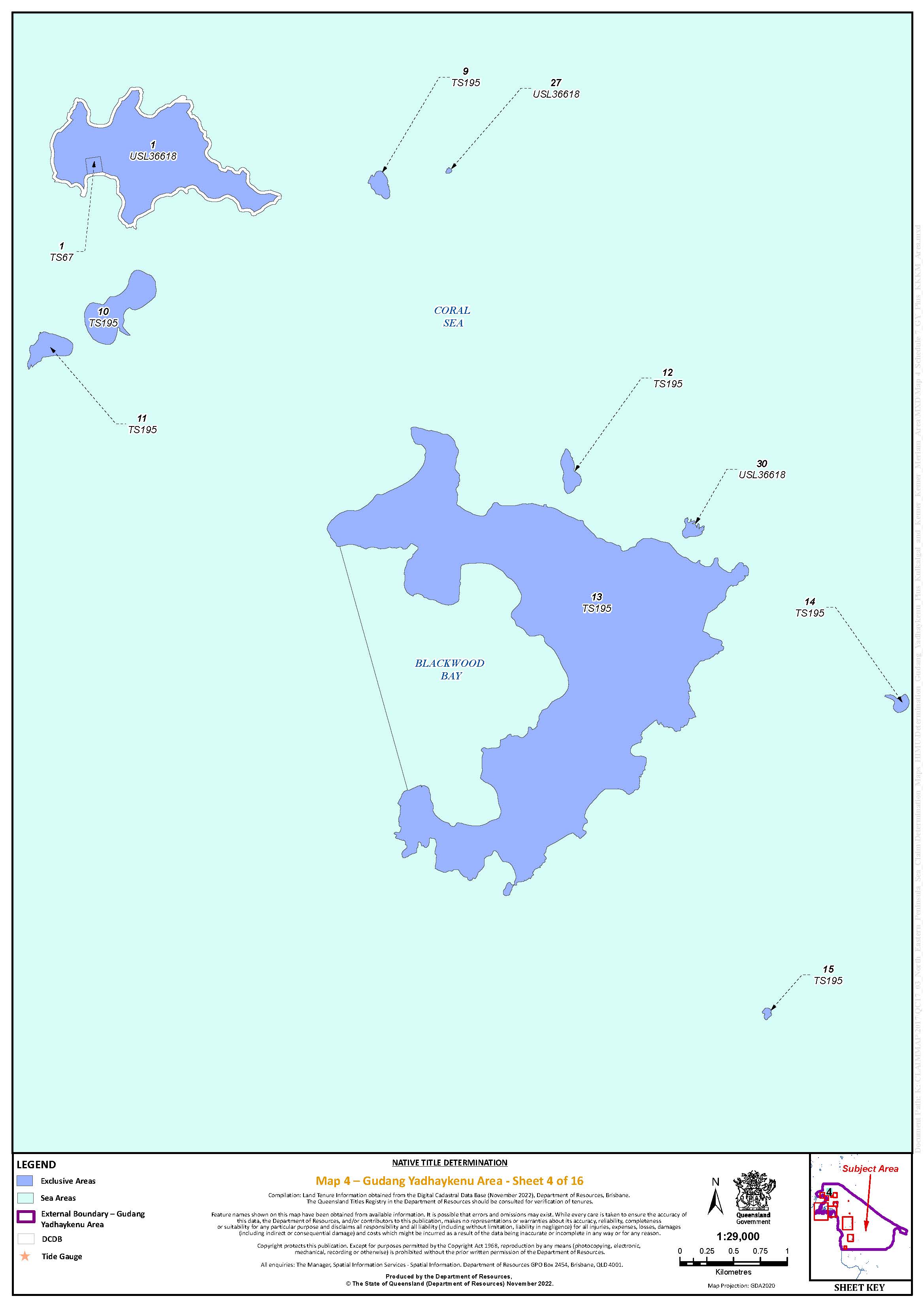

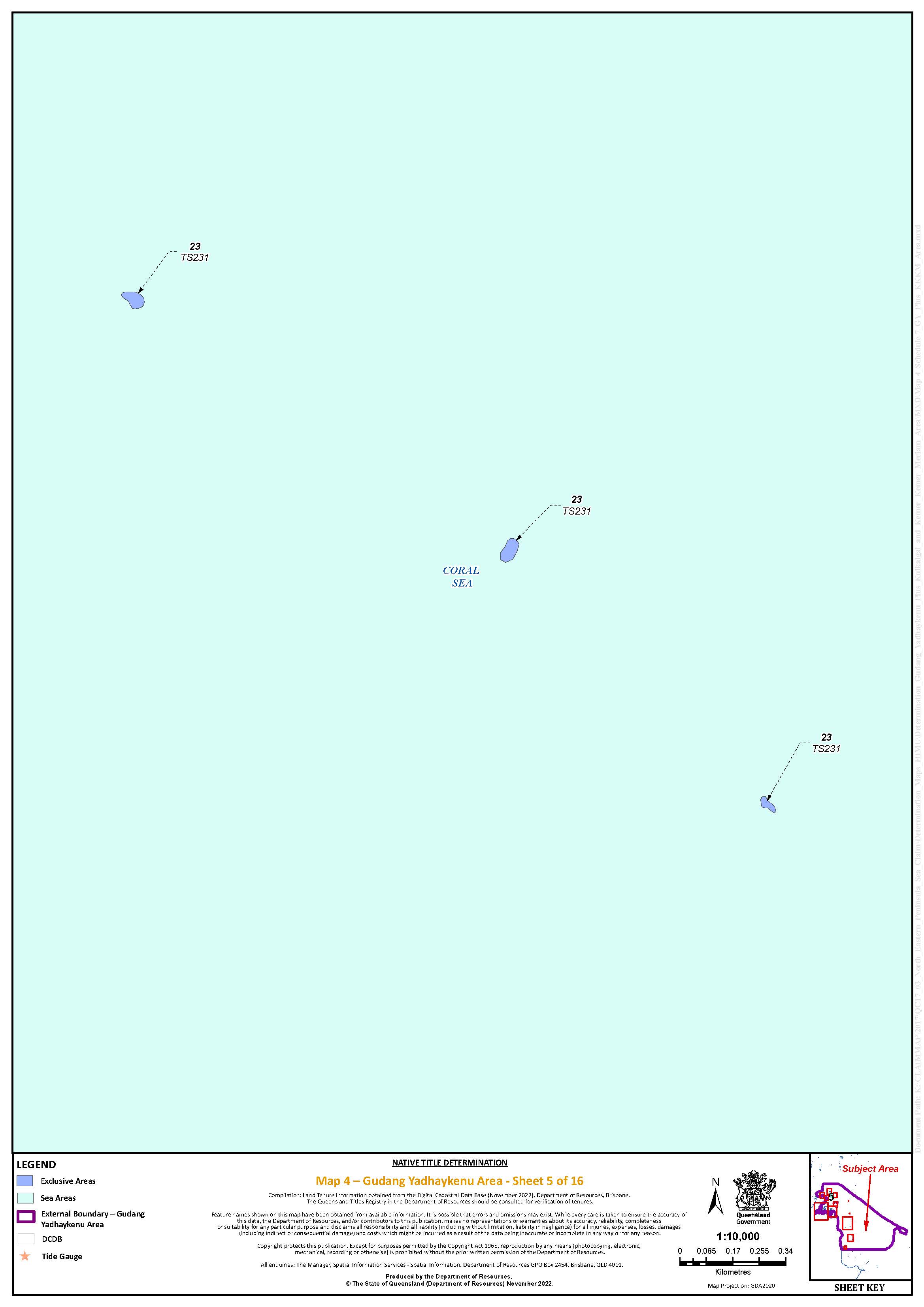

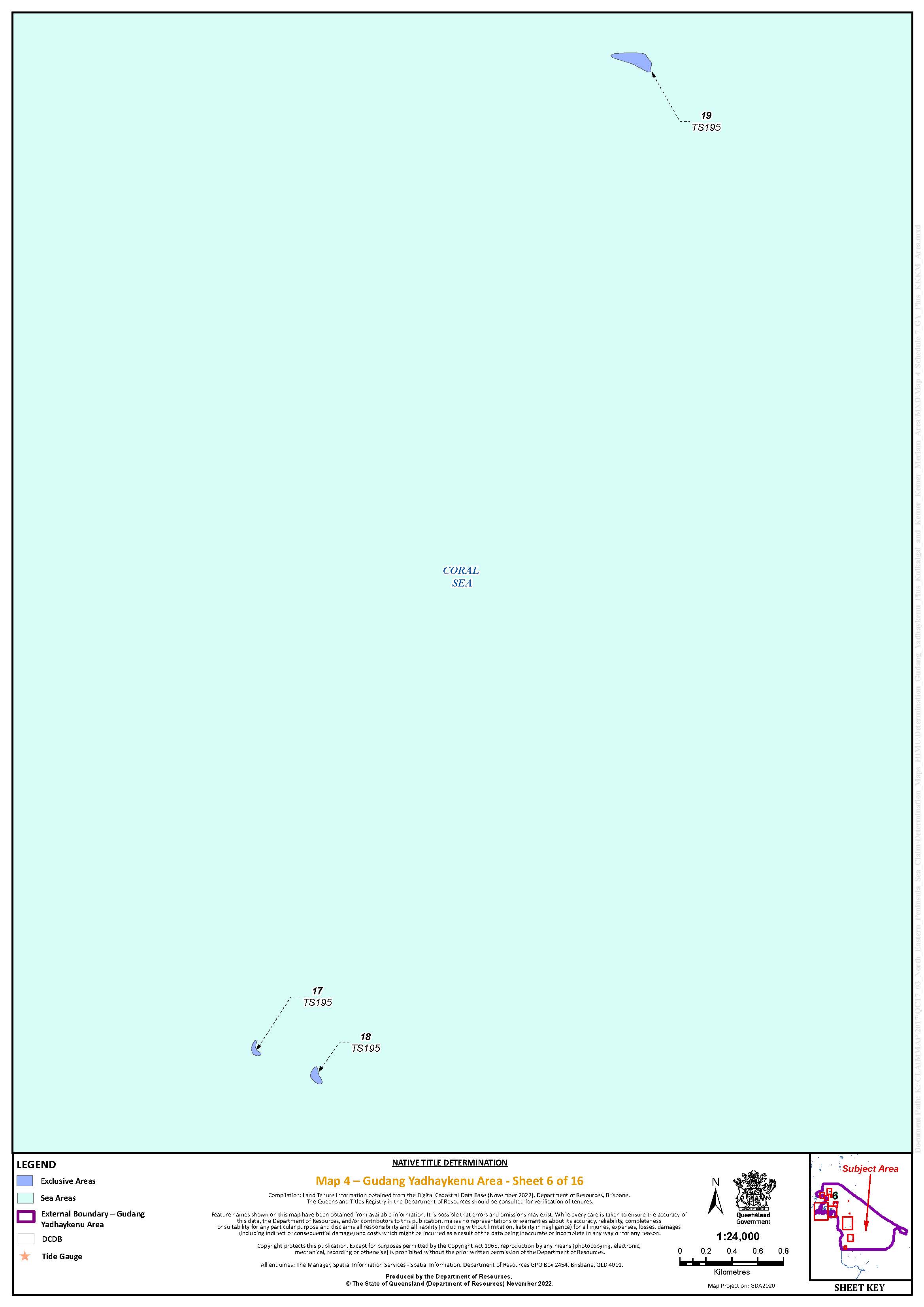

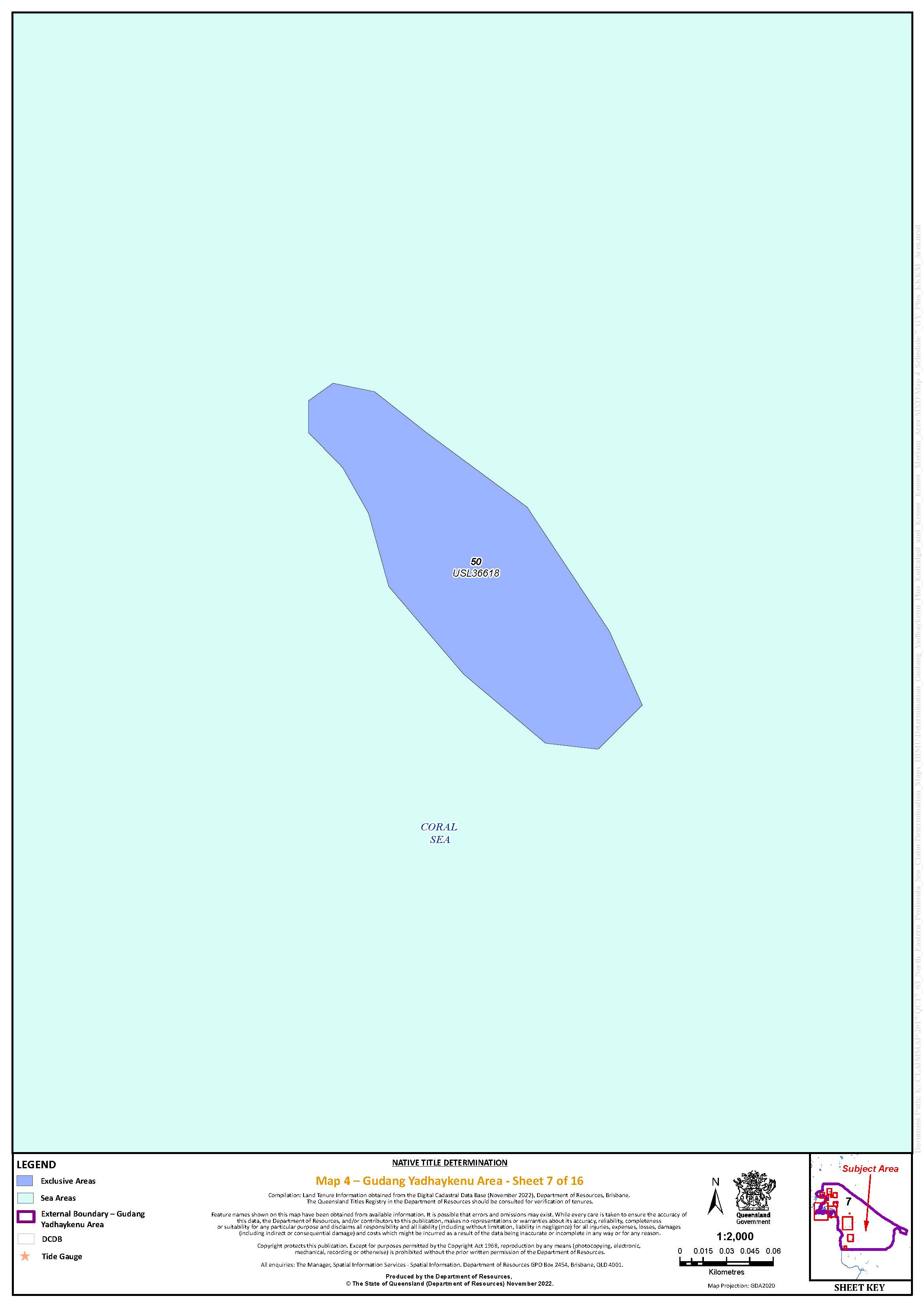

8. The Determination Area is the land and waters described in Schedule 5 and depicted in Map 1 of Schedule 7 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary (as described in Part 1 of Schedule 4), and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 6. To the extent of any inconsistency between the written description and the map, the written description prevails.

9. The Determination Area is comprised of the following Group Areas:

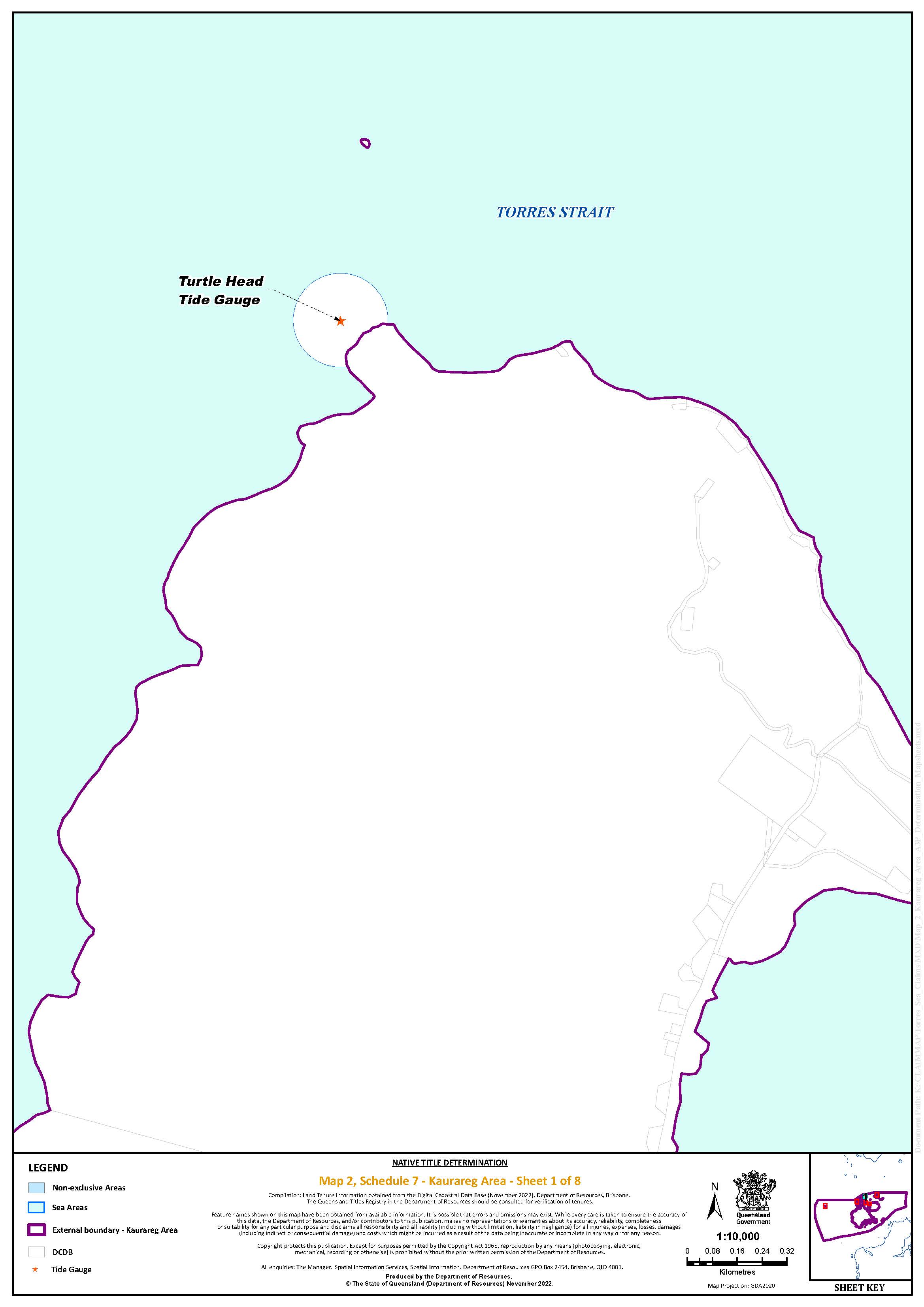

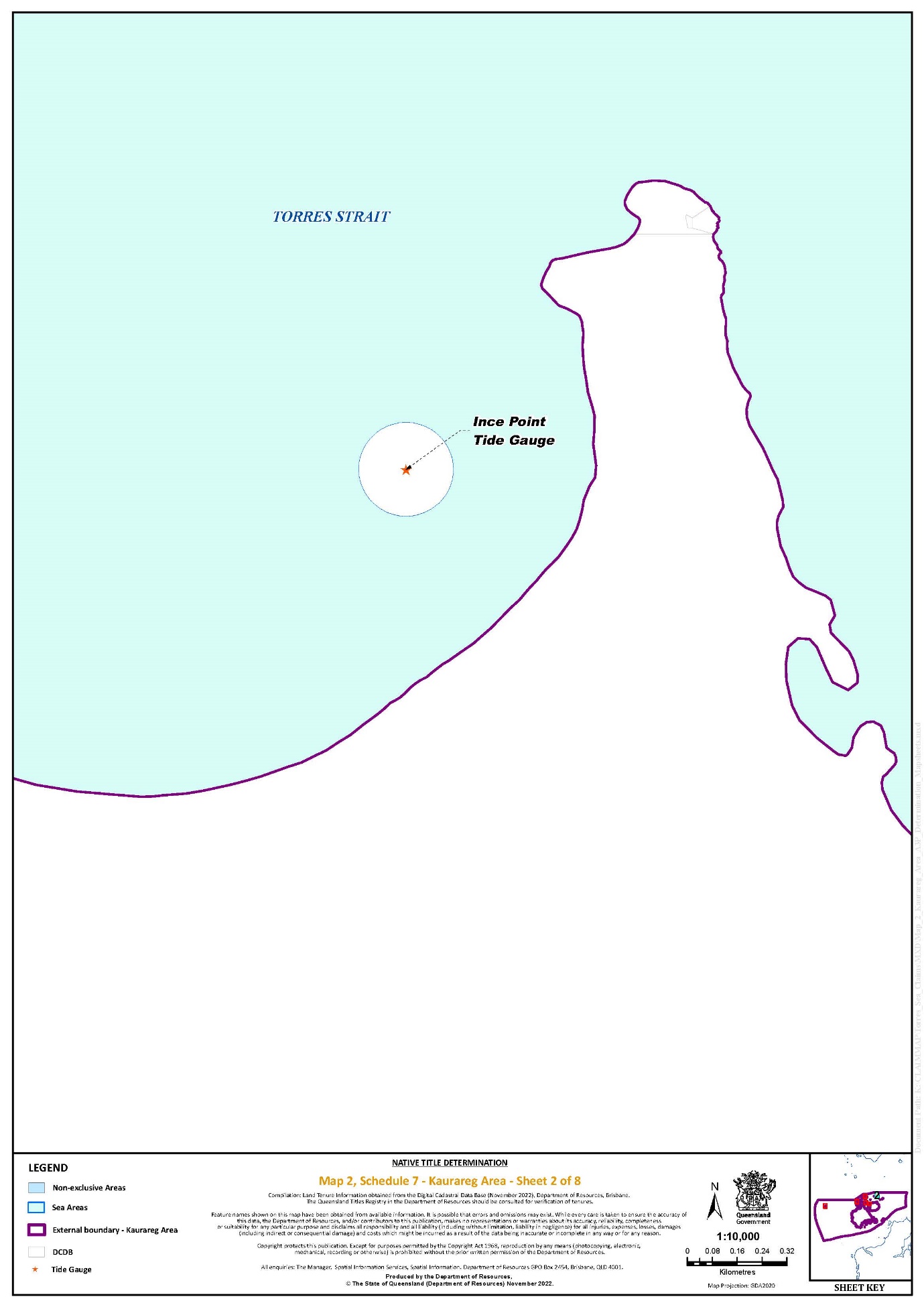

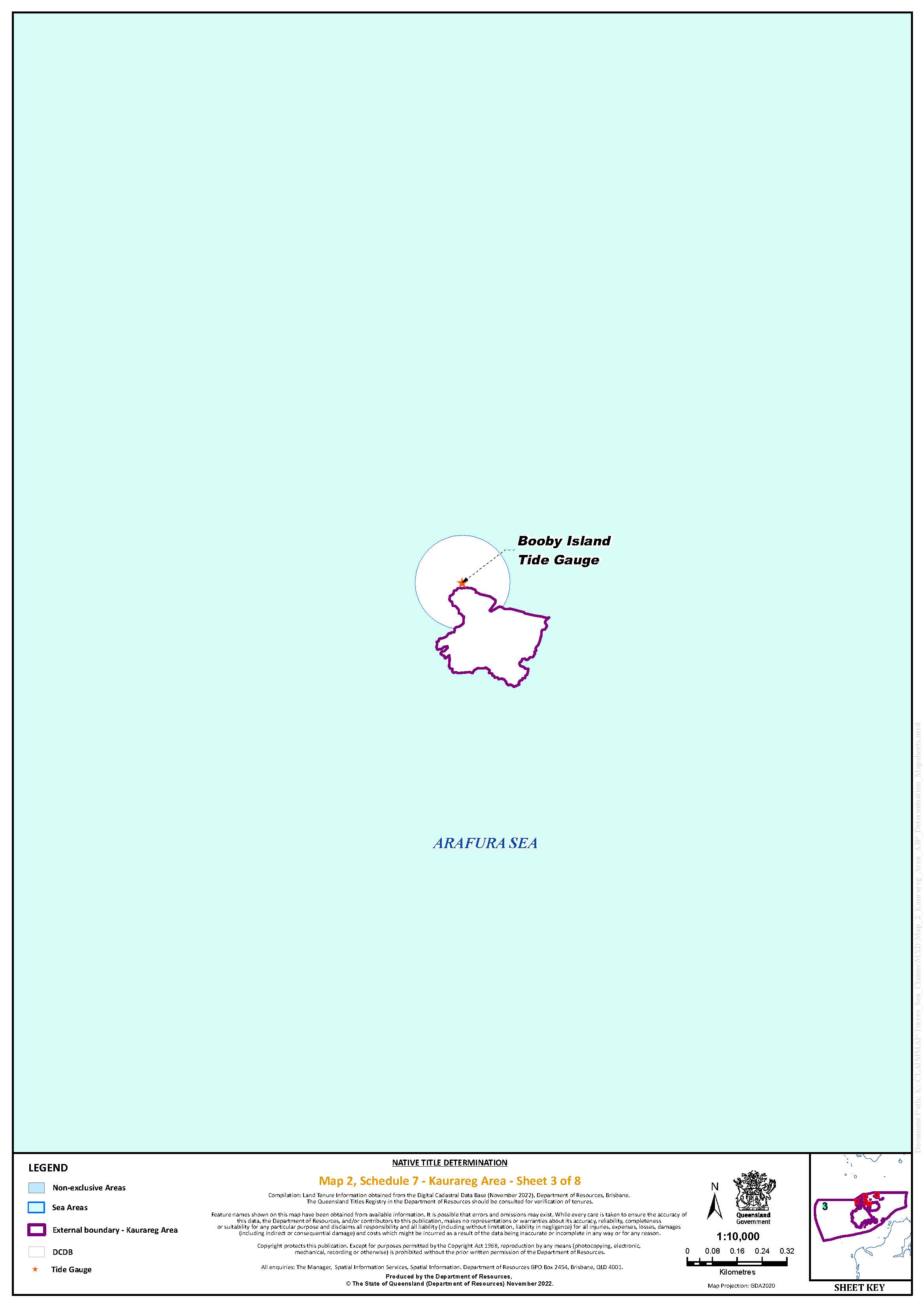

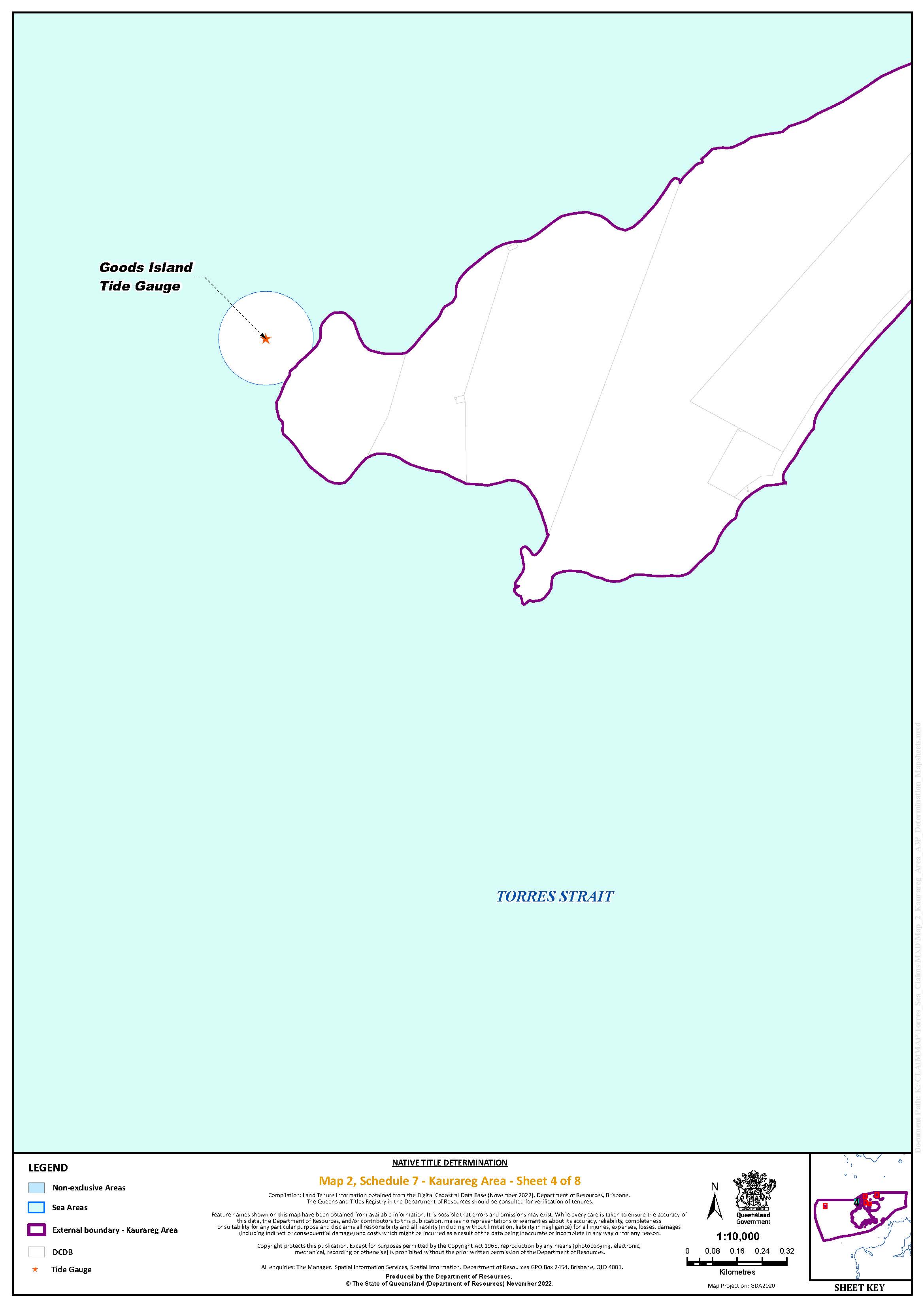

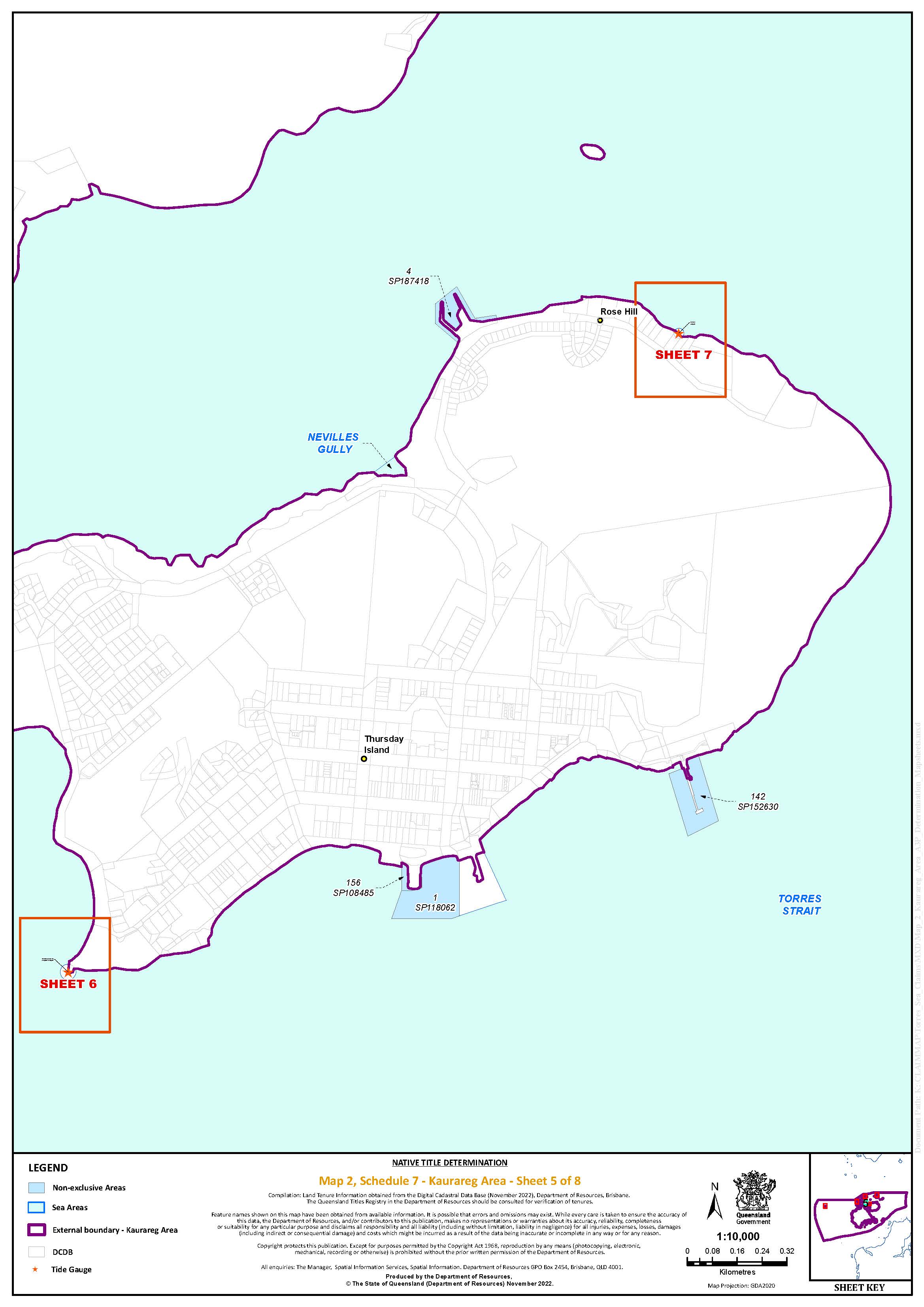

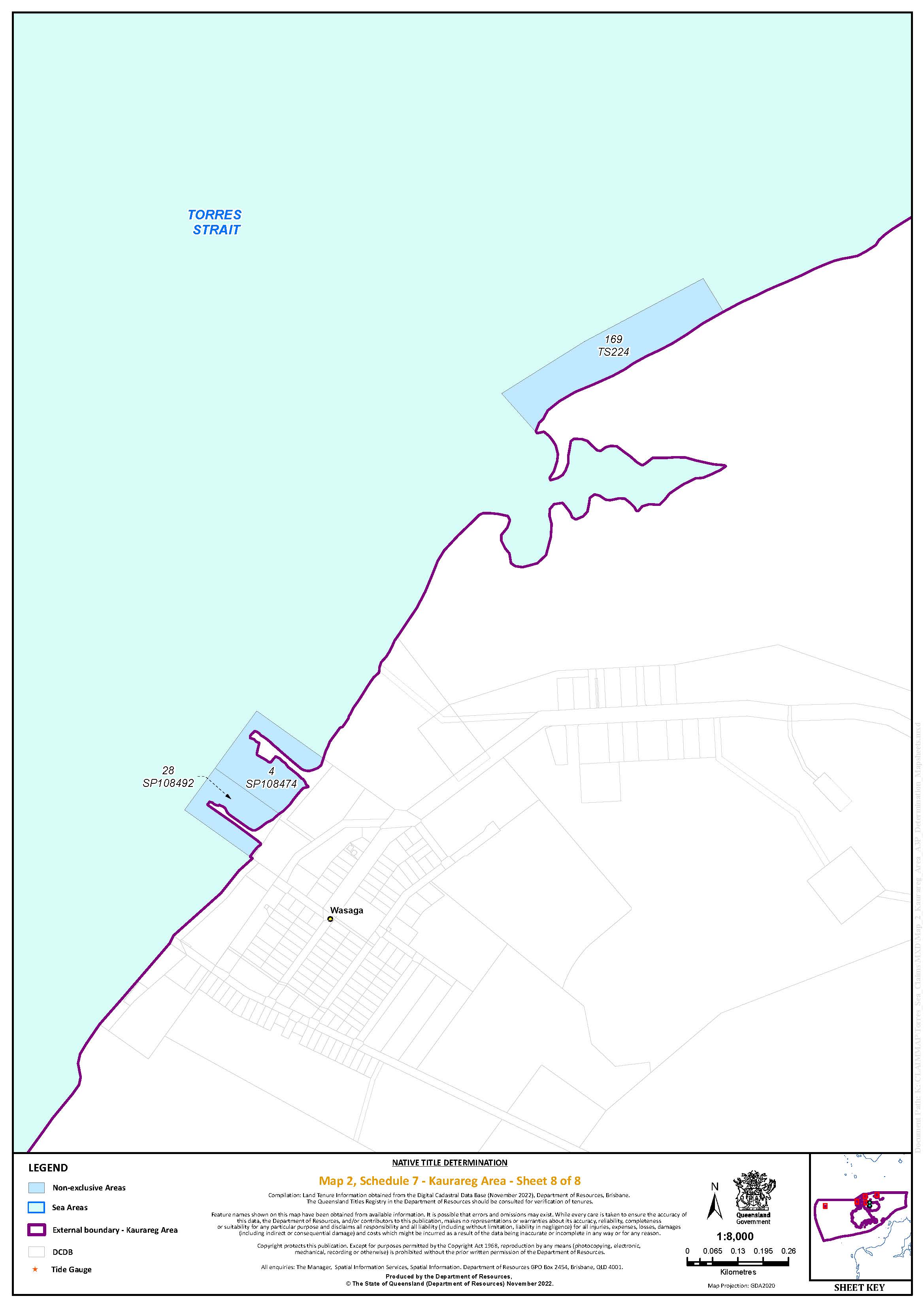

(a) the Kaurareg Area, being the land and waters described in Schedule 5 and depicted in Map 2 of Schedule 7 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary of the Kaurareg Area as described in Part 2 of Schedule 4, and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 6;

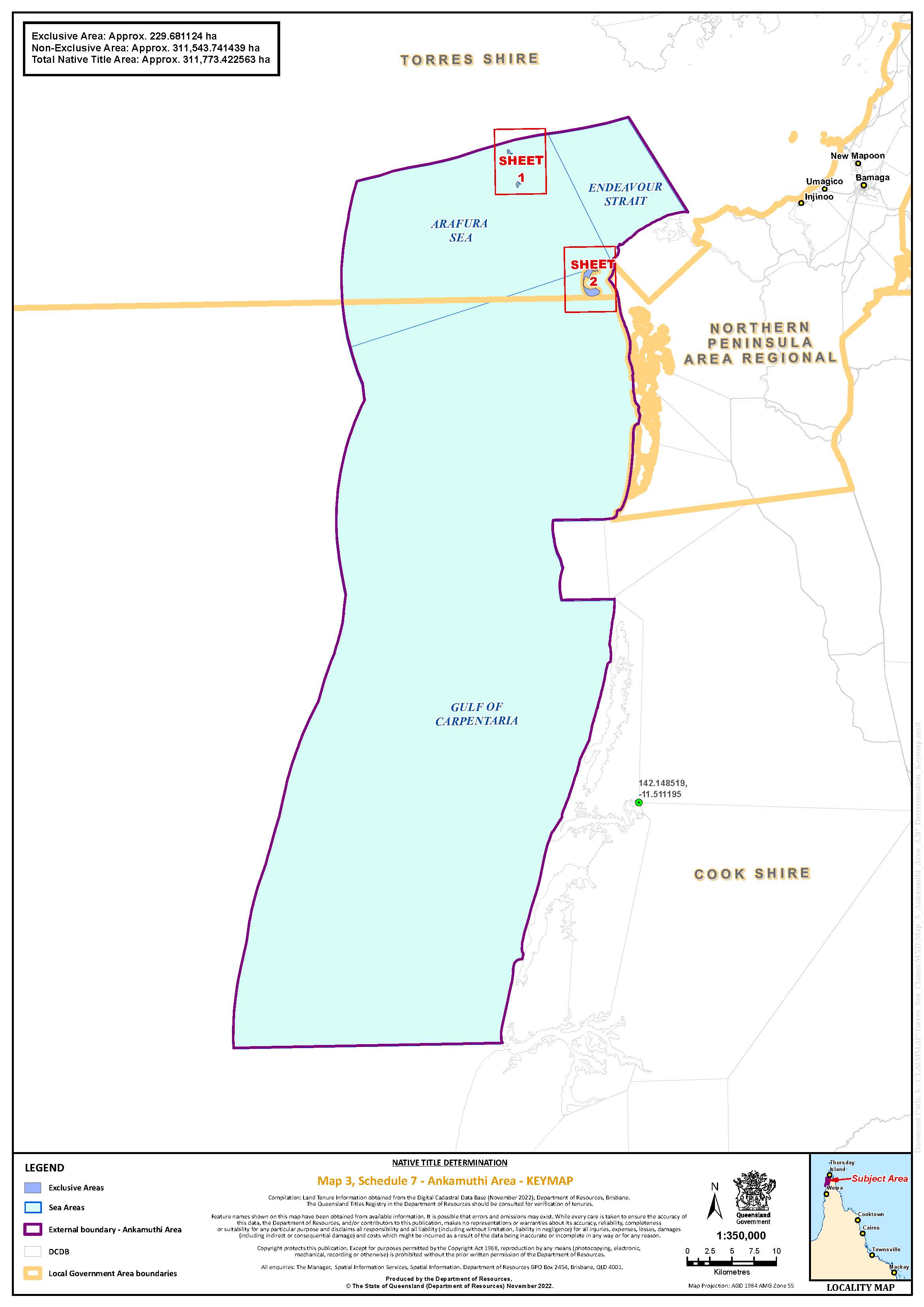

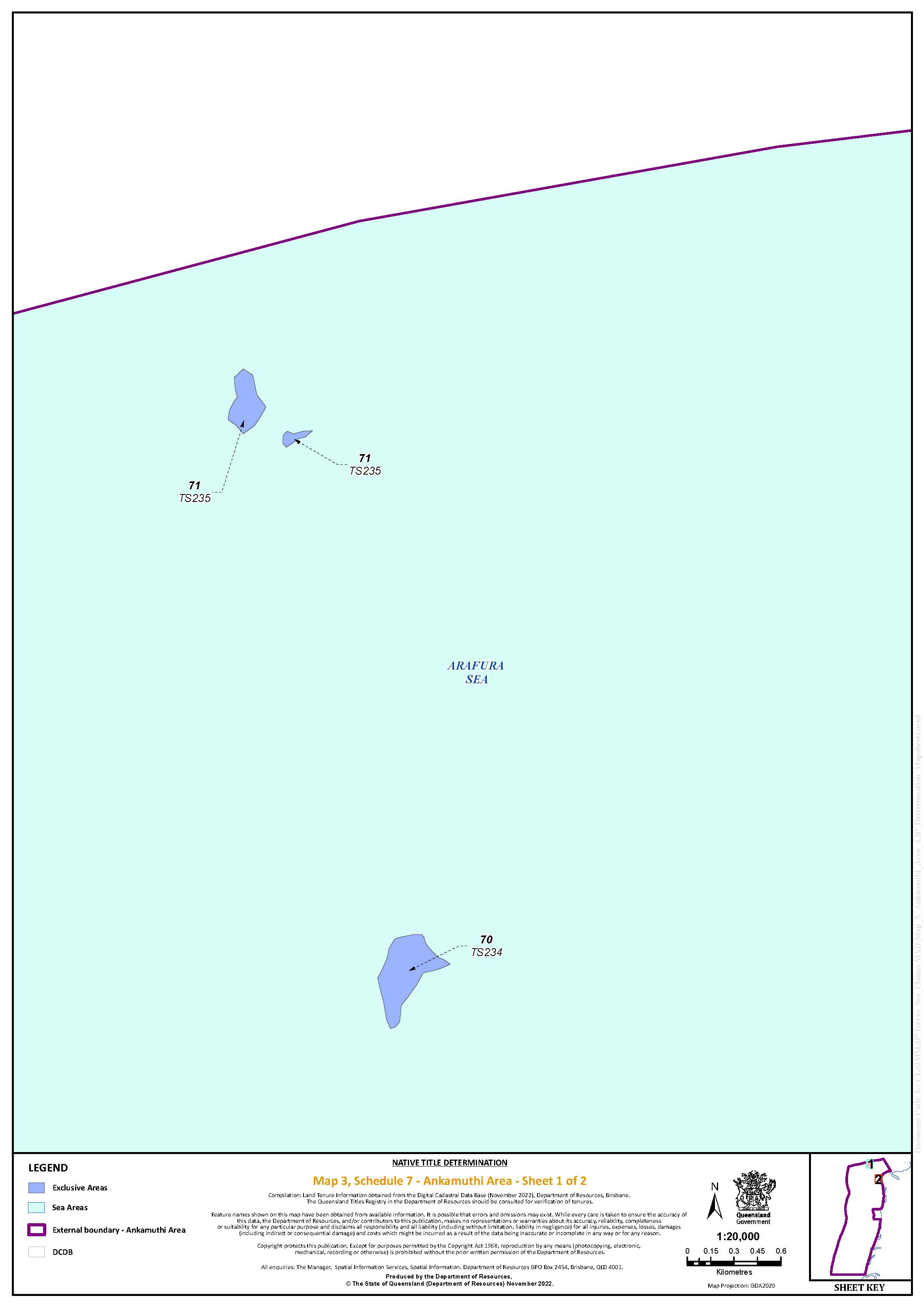

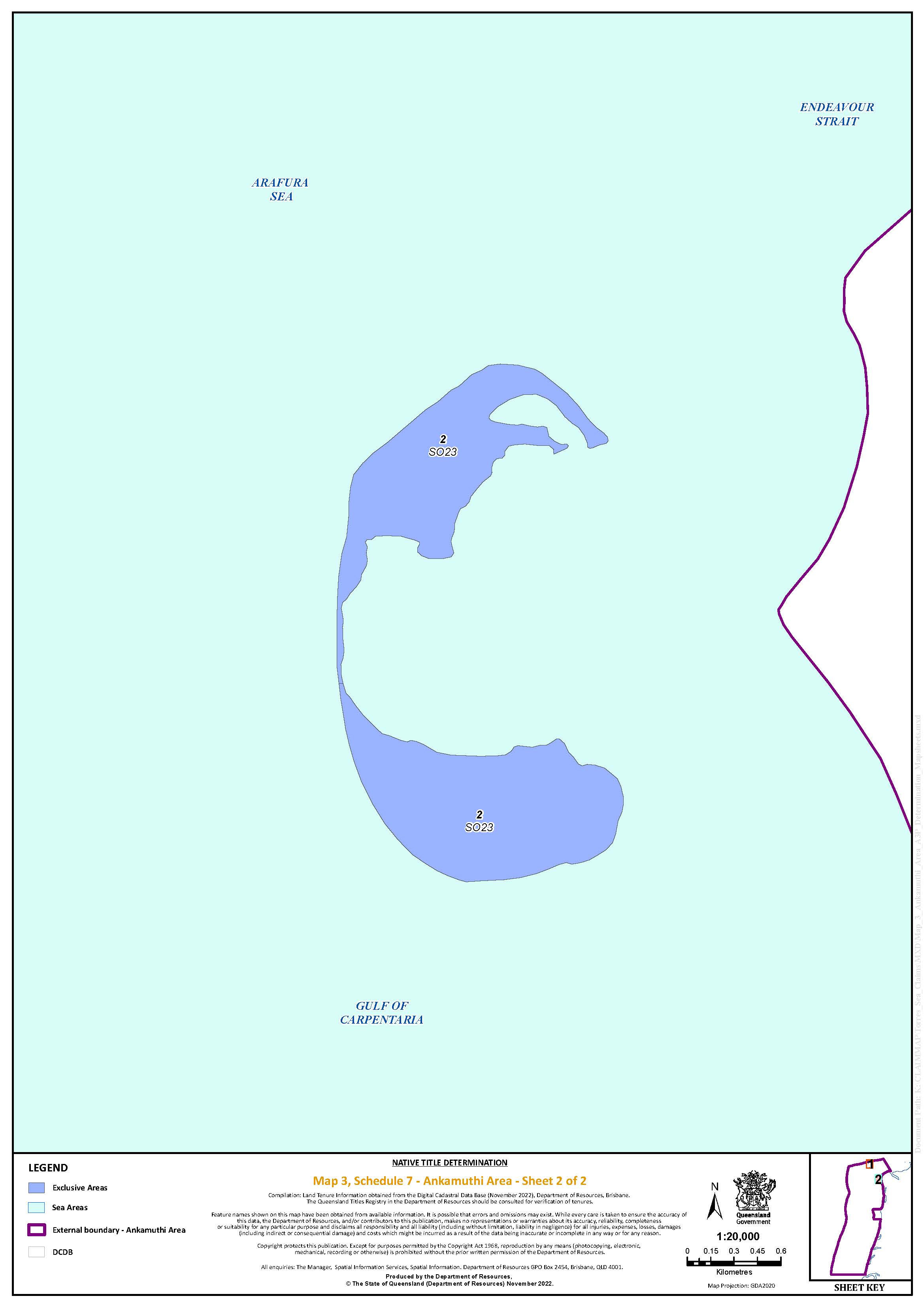

(b) the Ankamuthi Area, being the land and waters described in Schedule 5 and depicted in Map 3 of Schedule 7 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary of the Ankamuthi Area described in Part 3 of Schedule 4, and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 6;

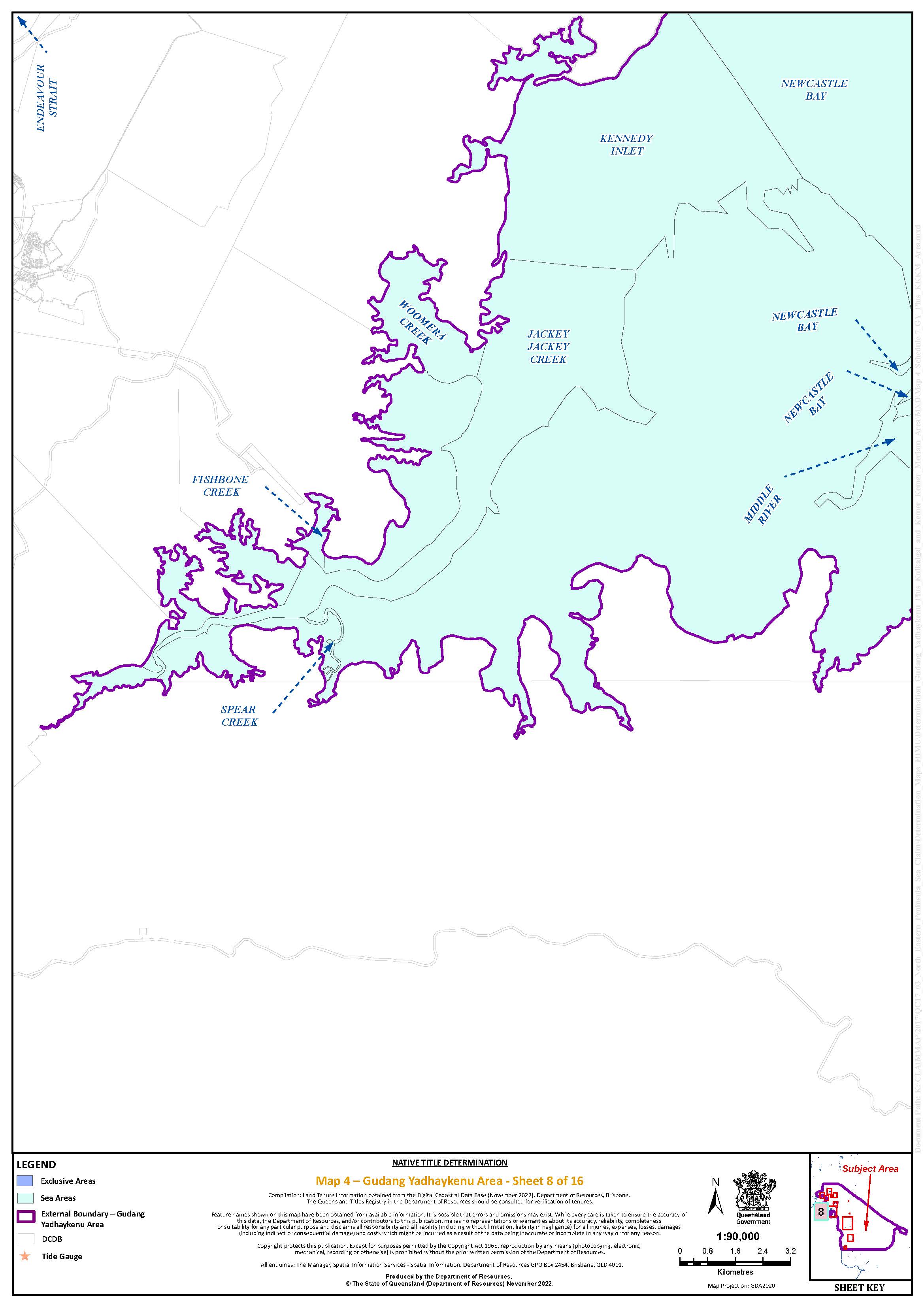

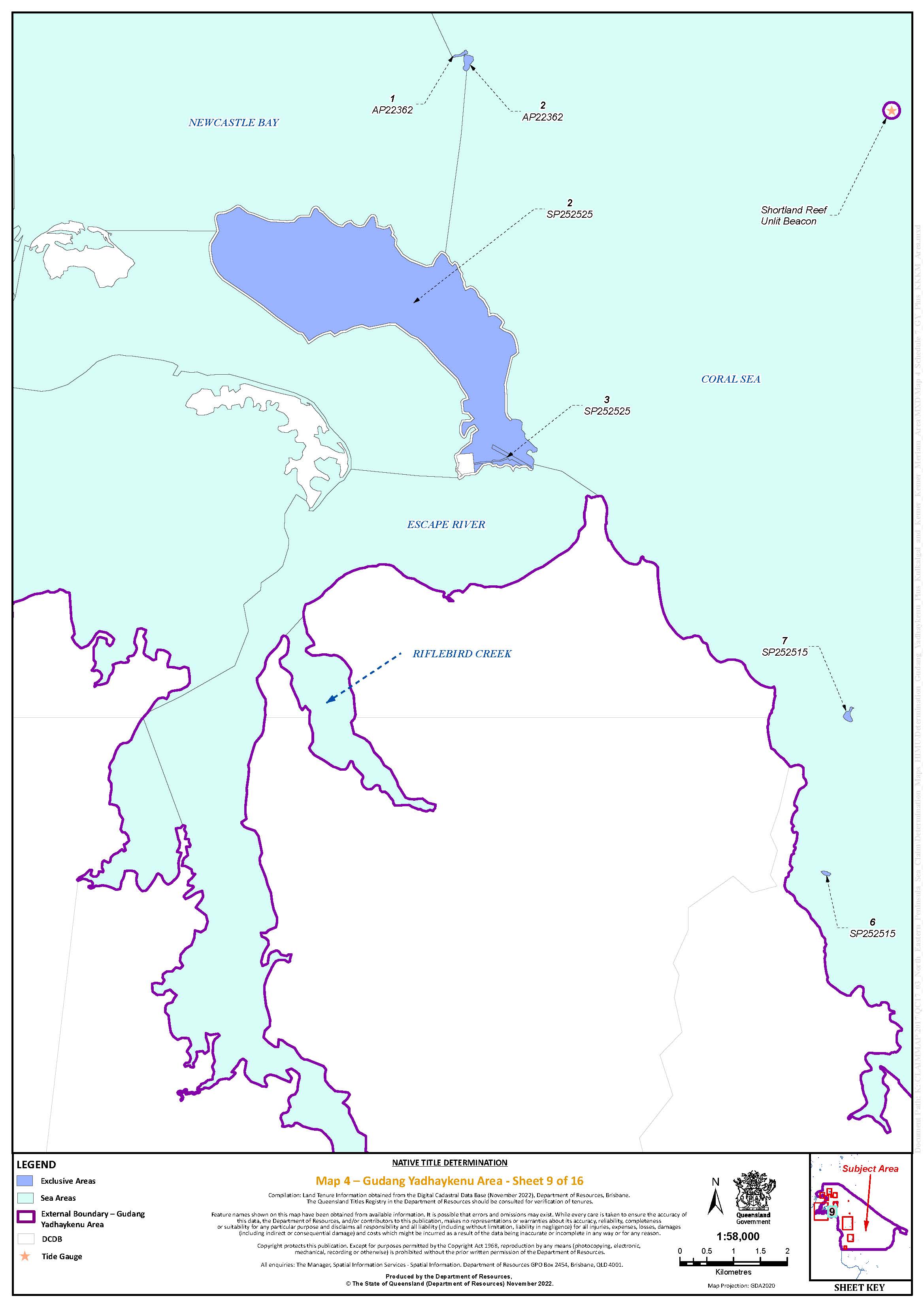

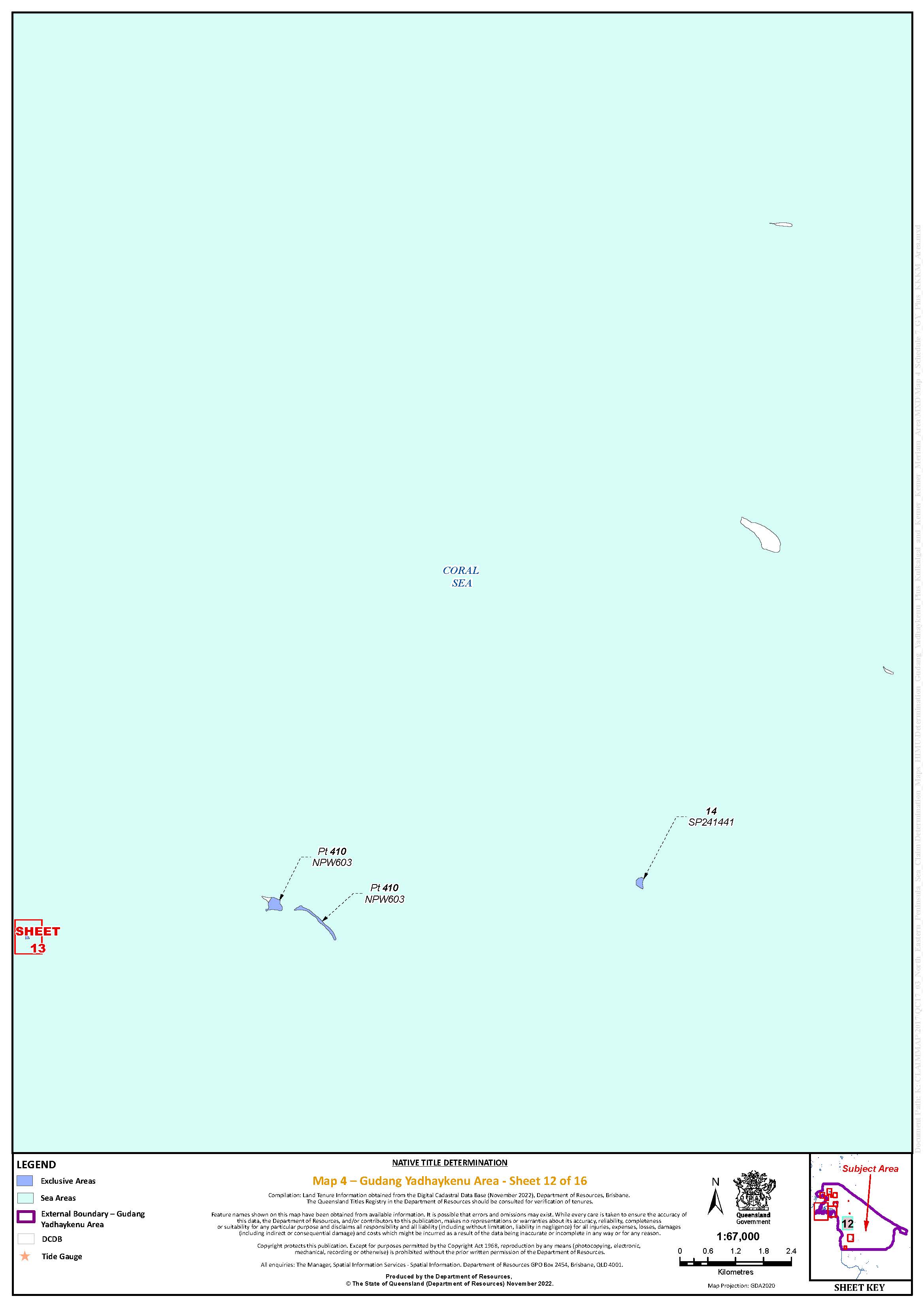

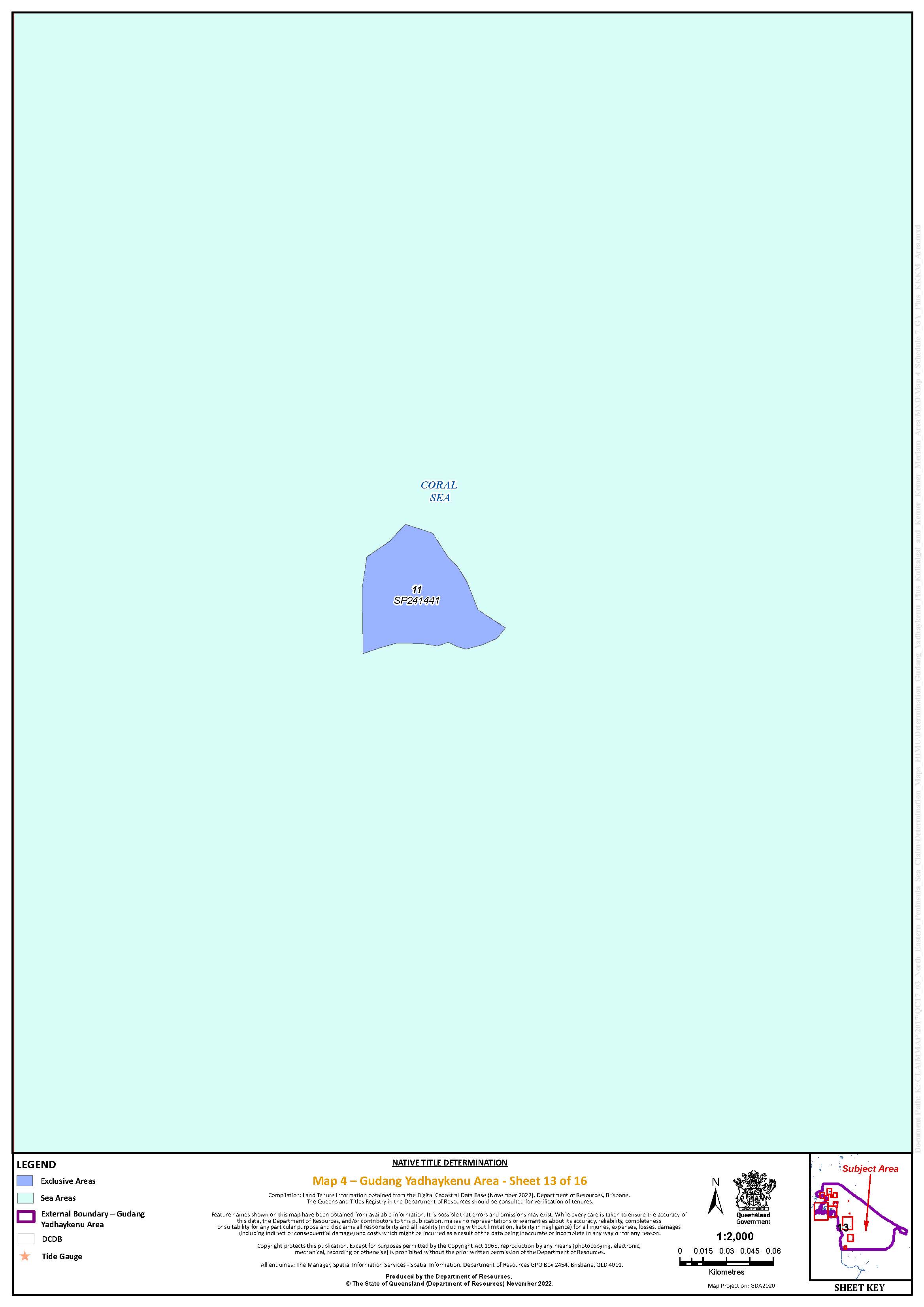

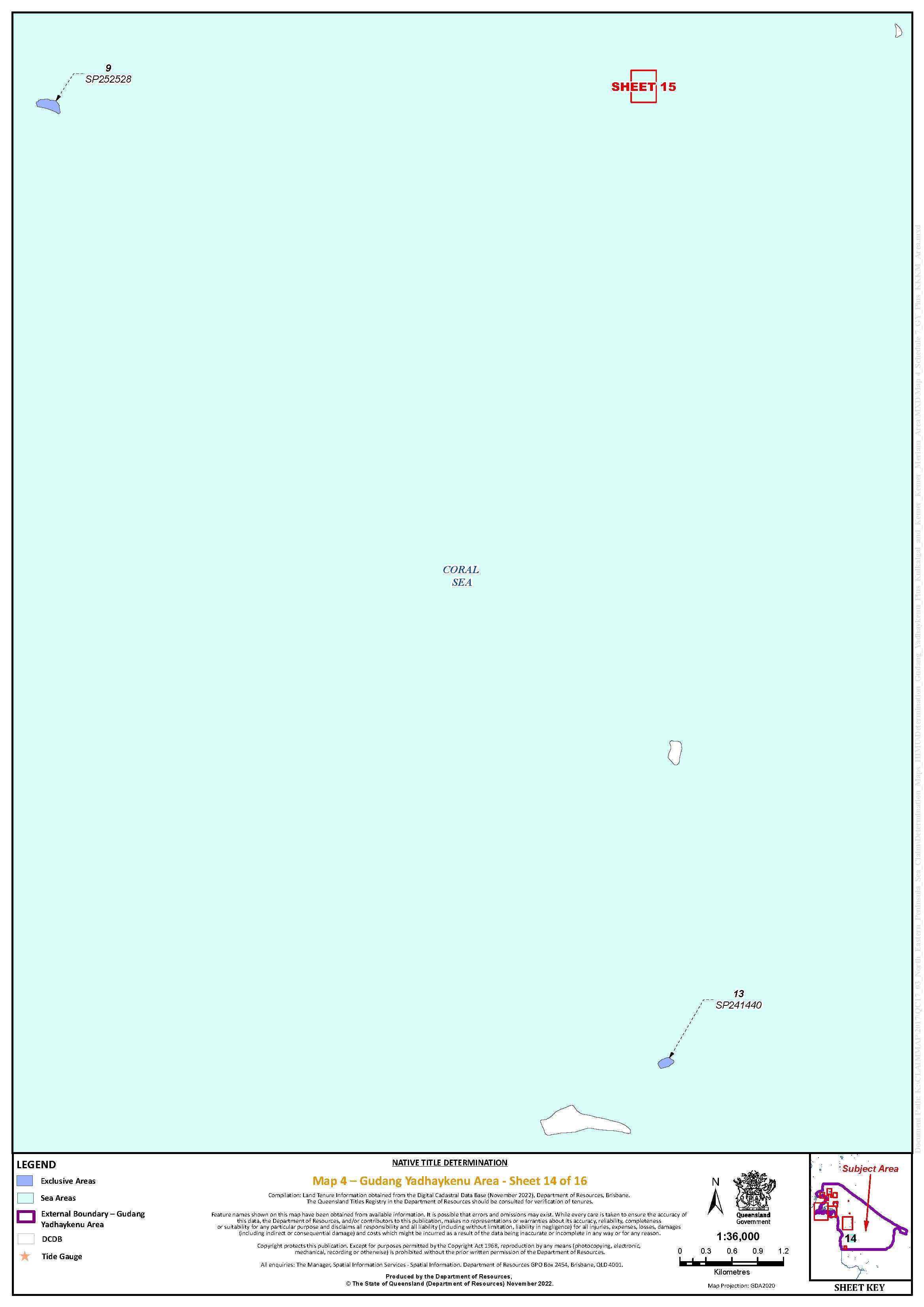

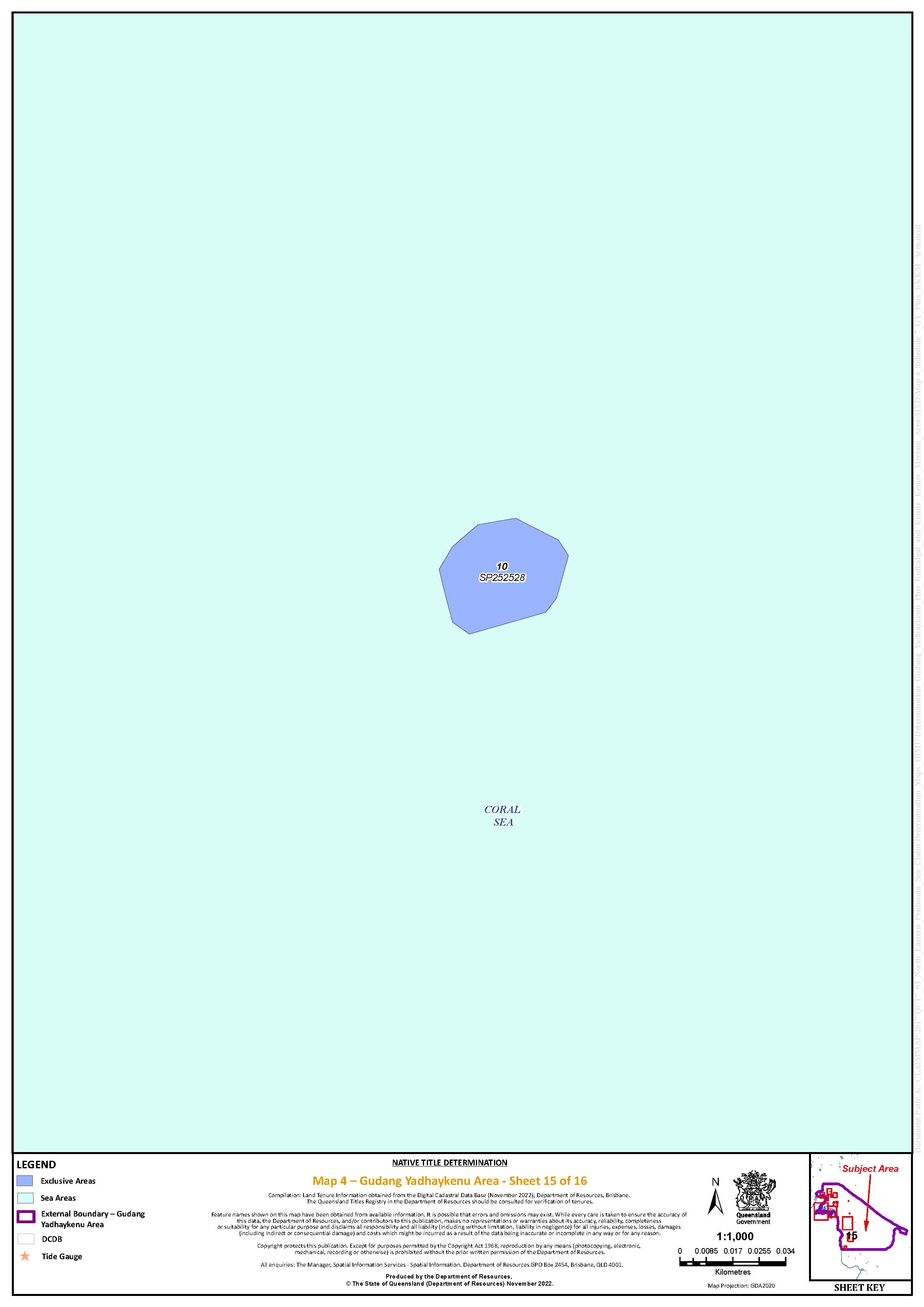

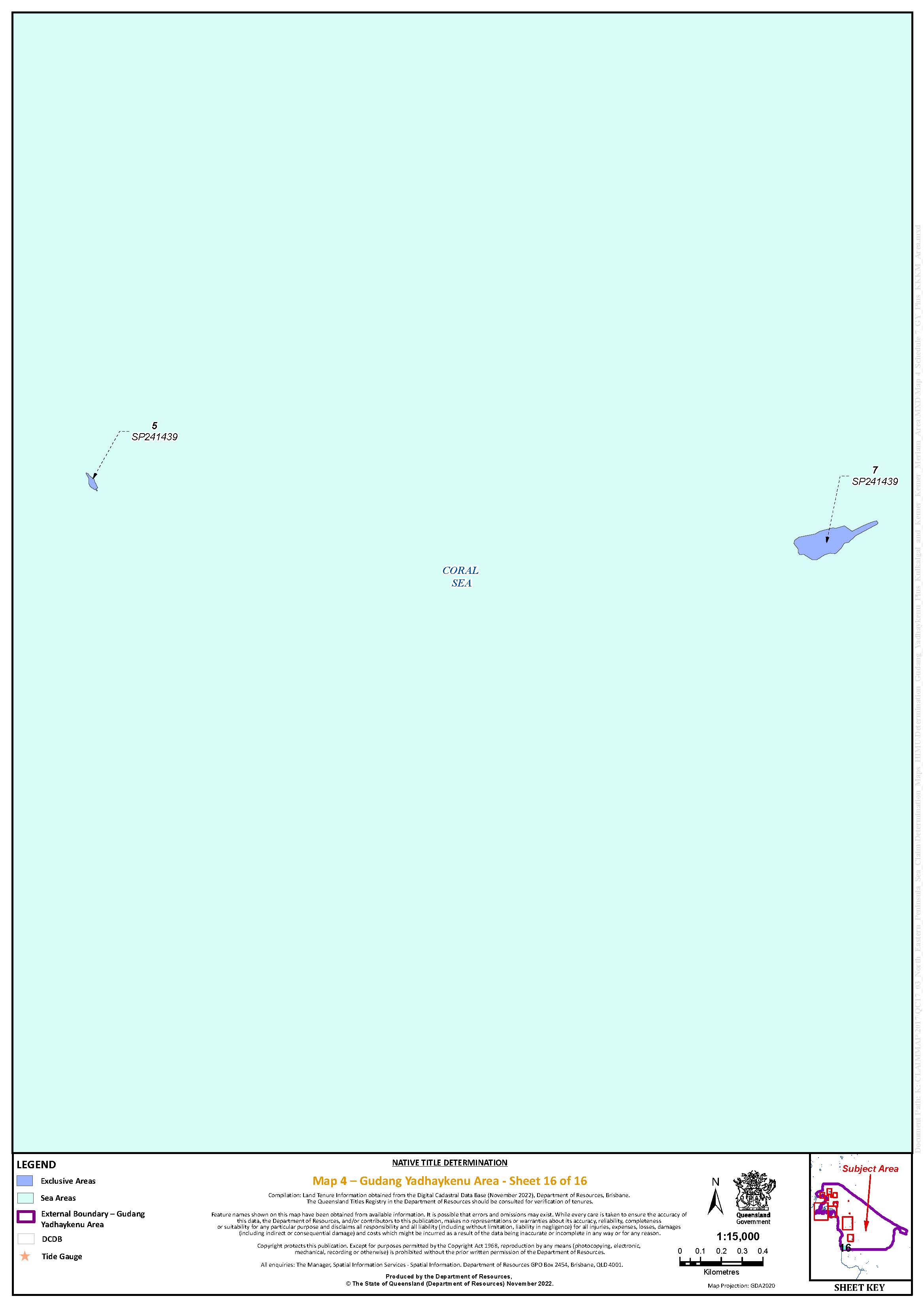

(c) the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area, being the land and waters described in Schedule 5 and depicted in Map 4 of Schedule 7 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary of the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area as described in Part 4 of Schedule 4, and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 6;

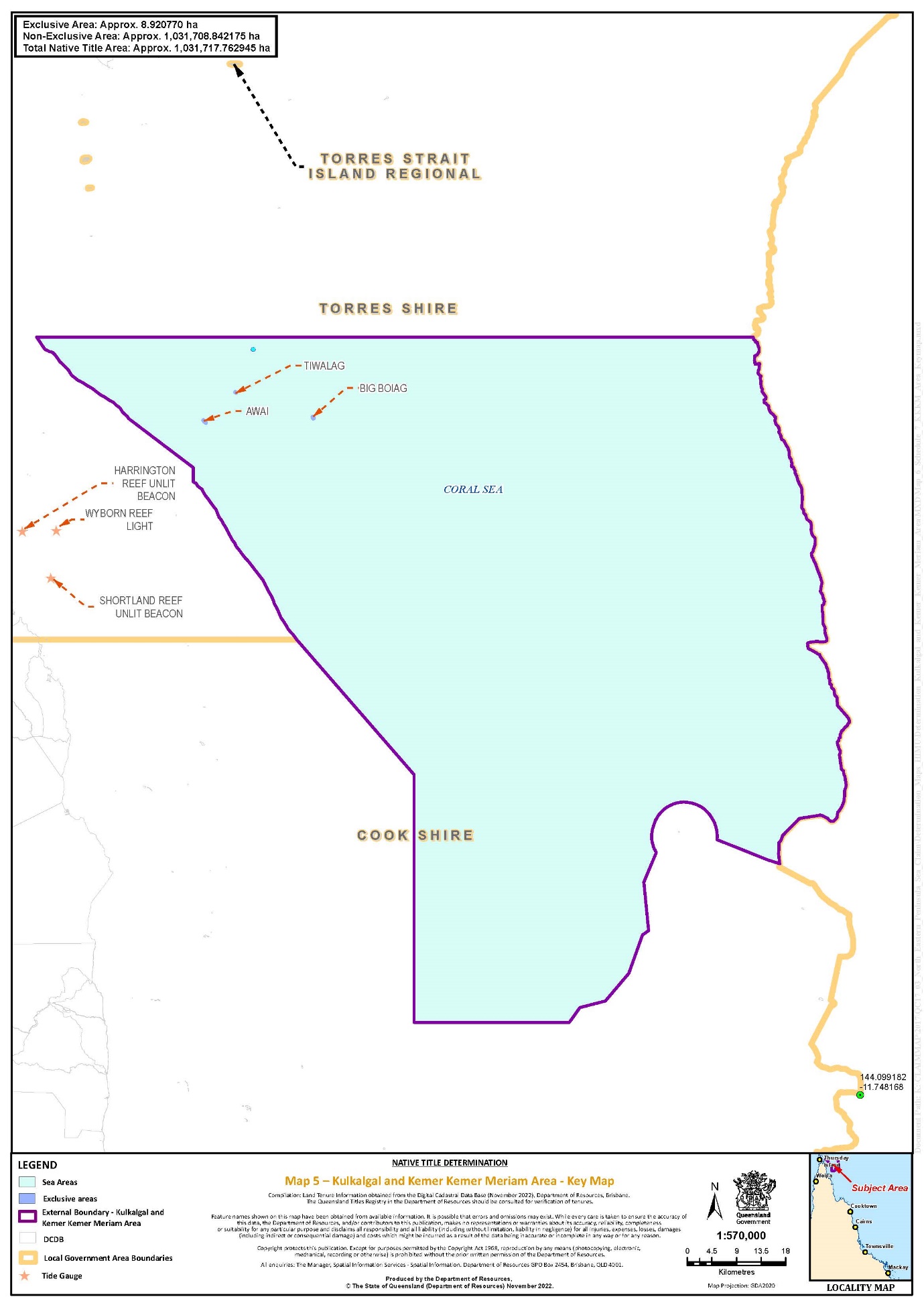

(d) the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area, being the land and waters described in Schedule 5 and depicted in Map 5 of Schedule 7 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary of the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area as described in Part 5 of Schedule 4, and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 6.

10. To the extent of any inconsistency between the written descriptions and the maps referred to in order 9 above, the written description prevails.

11. Native title exists in each of the Group Areas within the Determination Area.

12. Native title is held in each of the Group Areas within the Determination Area by one or more of the following Native Title Groups:

(a) the Kaurareg People, as defined in Section A of Schedule 1;

(b) the Ankamuthi People, as defined in Section B of Schedule 1;

(c) the Gudang Yadhaykenu People, as defined in Section C of Schedule 1;

(d) Kulkalgal, as defined in Section D of Schedule 1;

(e) Kemer Kemer Meriam, as defined in Section E of Schedule 1.

13. Native title in relation to each Group Area listed in order 9 above is held by the respective Native Title Group or Groups in accordance with Schedule 2.

14. Subject to orders 16, 17 and 18 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests held by each Native Title Group in relation to the land and waters of their respective part or parts of the Determination Area described in Part 1 of Schedule 5, are:

(a) other than in relation to Water, the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the area to the exclusion of all others; and

(b) in relation to Water, the non-exclusive rights to:

(i) hunt, fish and gather from the Water of the area;

(ii) take and use the Natural Resources of the Water in the area; and

(iii) take and use the Water of the area,

for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes.

15. Subject to orders 16, 17 and 18 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests held by each Native Title Group in relation to the land and waters of their respective part or parts of the Determination Area described in Part 2 of Schedule 5, are the non-exclusive rights to:

(a) access, to remain in and to use the area;

(b) access resources and to take for any purpose, resources in the area;

(c) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the Native Title Holders under their traditional laws and customs on the area and protect those places and areas from harm;

(d) be accompanied on to the area by those persons who, though not Native Title Holders, are:

(i) Spouses of Native Title Holders;

(ii) people who are members of the immediate family of a Spouse of a Native Title Holder; or

(iii) people reasonably required by the Native Title Holders under traditional law and custom for the performance of ceremonies or cultural activities on the area.

16. The native title rights and interests of each Native Title Group are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the respective Native Title Group.

17. The native title rights and interests referred to in orders 14(b) and 15 above do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

18. There are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld).

19. The nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the Determination Area (or respective parts thereof) are set out in Schedule 3.

20. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in orders 14 and 15 above and the other interests described in Schedule 3 (the Other Interests) is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by or held under the Other Interests may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(b) to the extent the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the Determination Area, the native title continues to exist in its entirety but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency for so long as the Other Interests exist; and

(c) the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or under, and done in accordance with, the Other Interests, or any activity that is associated with or incidental to such an activity, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LIST OF SCHEDULES

Schedule 1 – Native Title Groups

Schedule 2 – Description of which Group Areas are held by each Native Title Group

Schedule 3 – Other Interests in the Determination Area

Schedule 4 – External Boundaries

Schedule 5 – Description of Determination Areas

Schedule 6 – Areas Not Forming Part of the Determination Area

Schedule 7 – Maps of Determination Area

SCHEDULE 1 – NATIVE TITLE GROUPS

Section A: Kaurareg People

The Kaurareg People are the descendants of the Kaurareg People who were the traditional owners of the Kaurareg Area prior to the assertion of British sovereignty.

Section B: Ankamuthi People

The Ankamuthi People are the persons descended by birth or adoption from the following apical ancestors:

(a) Woobumu and Inmare;

(b) Bullock (father of Mamoose Pitt, husband of Rosie/Lena Braidley);

(c) Charlie Mamoose (father of Silas, Larry, Johnny and Harry Mamoose);

(d) Charlie Seven River;

(e) Toby Seven River (father of Jack Toby);

(f) Asai Charlie;

(g) Sam and Nellie (parents of George Stephen);

(h) Mammus/Mamoos/Mark/Mamoose plus his siblings Peter and Elizabeth;

(i) Charlie Maganu (husband of Sarah McDonnell);

(j) Polly (wife of Wautaba Charlie Ropeyarn).

Section C: Gudang Yadhaykenu People

The Gudang Yadhaykenu People are those Aboriginal persons who are descended by birth, or adoption in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Gudang Yadhaykenu People, from one or more of the following apical ancestors:

(a) Wymarra (Wymara Outaiakindi);

(b) Tchiako (aka Chaiku/Chakoo) & Baki (siblings);

(c) Peter Padhing Pablo;

(d) Mathew Charlie Gelapa;

(e) Annie Blanco;

(f) Ila-Ela;

(g) Woonduinagrun & Tariba (parents of Tom Redhead);

(h) Charlotte (spouse of Billy Doyle and Wilson Ware);

(i) Pijame and Daudi (sisters);

(j) Mother of Thompson Olwinjinkwi;

(k) Nara Jira Para.

Section D: Kulkalgal

(1) Kulkalgal is a collective term for the following island communities:

(a) Iamalgal (Iama);

(b) Masigalgal (Masig);

(c) Porumalgal (Poruma); and

(d) Warraberalgal (Warraber).

(2) The members of the island communities referred to in (1) above are, respectively, the descendants of:

(a) Iamalgal – Kebisu, Rusia, Ausa, Auda, Porrie Daniel, Gawadi, Kelam;

(b) Masigalgal – Aclan, Alau Messiah, Apelu, Asiah Messiah, Auara, Gewe Jack, Kudin, Ikasa, Maudar, Sidmu, Seregay, Tabu, Wabu;

(c) Porumalgal – Laieh, Gauid, Kalai, Wawa, Mapoo; and

(d) Warraber – Gagabe, Wawa, Mapoo, Baki, Ulud.

Section E: Kemer Kemer Meriam

(1) Kemer Kemer Meriam is a collective term for the following island communities:

(a) Meriam Le (Mer);

(b) Erubam Le (Erub); and

(c) Ugarem Le (Ugar).

(2) The members of the island communities referred to in (1) above are, respectively, the descendants of:

(a) Meriam Le – Kopam, Naisi, Sibari, Koiop, Ano, Apap, Kaidam, Dabor, Masig, Nipuri, Sogoi, Wada, Busei, Bauba, Kebekut, Dudei, Awas, Malo, Odoro, Barigud, Taroa, Diri, Sakauber, Mogar, Kopam, Maki/Salgar, Kebei, Wasalgi, Udai, Komagaigai, Gaidan, Wamo, Eba/Matul, Madi, Maber/Garau, Maii, Pagem/Naii, Paipa, Siboko, Bina, Bade/Bagari, Zaiar, Kuniam, Kober, Koim, Sipo, Sesei/Mokar, Marau/Daueme, Galeka, Mabo, Lag, Mele, Toik, Urpi, Keisur, Soroi, Ekai, Mononi/Babi, Darima, Tagai, Beiro, Geigi, Nosarem, Mano, Kogikep,Opiso, Polpol, Kawiri, Geigi, Sawi, Serib, Nunu, Imai, Kadal, Enemi, Aiwa, Emeni, Koit, Namu, Kauta, Balozi, Geigi, Daugiri;

(b) Erubam Le – Amani, Odi (I), Saimo, Narmalai, Nazir Mesepa, Meo, Deri, Ape, Odi (II), Demag, Rebes, Buli, Damui, Baigau, Dako, Malili, Nazir, Bambu, Dobam, Bobok, Nokep, Wadai, Arkerr Malili, Aukapim, Isaka, Kaigod, Kapen, Petelu, Ale, Epei, Bailat, Ema, Boggo Epei, Ikob, Annai, Eti, Aib, Wagai, Gedor, Dabad, Nazir, Kaupa, Nanai Pisupi, Sagiba, Nuku Idagi, Diwadi, Gewar, In, Aukapim, Timoto, Suere, Gemai, Pagai, Pai, Kapen, Kapen Kuk, Spia, Konai, Ani, Morabisi, Koreg, Kuri, Damu, Wasi, Gi, Mamai, Sesei (I), Kakai, Sesei (II), Sida, Maima, Wakaisu, Whaleboat, Supaiya, Tau, Ulud, Waisie, Wasada, Wimet, Mogi, Yart, Ziai, Assau, Oroki, Zib, Nazir, Gaiba; and

(c) Ugarem Le – Janny, Maima, Baniam, Jack Oroki.

SCHEDULE 2 – DESCRIPTION OF WHICH GROUP AREAS ARE HELD BY EACH NATIVE TITLE GROUP

[See Order 13]

The native title in relation to each Group Area of the Determination Area listed in Column 1 (whose description is referenced in Column 2 and map referenced in Column 3) is held by the respective Native Title Group or Groups listed in Column 4 (whose description is referenced in Column 5) for that respective Group Area.

Group Area | Group Area Description | Group Area Map | Native Title Group/s | Native Title Group Description/s |

Kaurareg Area | Order 9(a) | Map 2, Schedule 7 | Kaurareg People | Section A, Schedule 1 |

Ankamuthi Area | Order 9(b) | Map 3, Schedule 7 | Ankamuthi People | Section B, Schedule 1 |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Order 9(c) | Map 4, Schedule 7 | Gudang Yadhaykenu People | Section C, Schedule 1 |

Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area | Order 9(d) | Map 5, Schedule 7 | Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam (jointly) | Sections D and E, Schedule 1 |

SCHEDULE 3 – OTHER INTERESTS IN THE DETERMINATION AREA

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the Determination Area are the following as they exist as at the date of the determination.

1. The international right of innocent passage through the territorial sea.

2. The rights and interests of the parties under the Northern Cape York and Torres United Customary Rights and Permanent Arrangements Agreement signed on or before 12:00pm on 28 November 2022.

3. The rights and interests of the Commonwealth of Australia:

(a) in the West Cape York Marine Park, as defined by Part 8 of Schedule 3 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conversation (Commonwealth Marine Reserves) Proclamation 2013 (Cth);

(b) in the management of the West Cape York Marine Park, as set out in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Commonwealth Marine Reserves) Proclamation 2013 (Cth), including the rights and interests of the Director of National Parks; and

(c) under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth), Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth), and North Marine Parks Network Management Plan 2018 in relation to the West Cape York Marine Park, including the rights and interests of the Director of National Parks.

4. The rights and interests of the Commonwealth of Australia:

(a) in the Coral Sea Marine Park, as defined by Schedule 4 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conversation (Commonwealth Marine Reserves) Proclamation 2013 (Cth);

(b) in the management of the Coral Sea Marine Park, as set out in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Commonwealth Marine Reserves) Proclamation 2013 (Cth), including the rights and interests of the Director of National Parks; and

(c) under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth), Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth), and Coral Sea Management Plan 2018 in relation to the Coral Sea Marine Park, including the rights and interests of the Director of National Parks.

5. The rights and interests of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority in relation to plans of management made under the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth) and the Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984 (Cth), including for the Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery, Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery, Western Skipjack Fishery, Northern Prawn Fishery, Southern Bluefin Tuna Fishery, Torres Strait Beche-de-mer Fishery, Torres Strait Crab Fishery, Torres Strait Dugong Fishery, Torres Strait Finfish Fishery, Torres Strait Tropical Rock Lobster Fishery, Torres Strait Pearl Shell Fishery, Torres Strait Prawn Fishery, Torres Strait Trochus Fishery, Torres Strait Turtle Fishery, and Torres Strait Spanish Mackerel Fishery.

6. The rights and interests of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and any other person existing by reason of the force of operation of:

(a) the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 (Cth);

(b) the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Regulations 2019 (Cth);

(c) the Great Barrier Reef (Declaration of Amalgamated Marine Park Area) Proclamation 2004 (Cth); and

(d) the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 (Cth).

7. The rights and interests of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority as the owner, manager and/or operator of aids to navigation pursuant to section 190 of the Navigation Act 2012 (Cth) and in performing the functions of the Authority under section 6(1) of the Australian Maritime Safety Act 1990 (Cth) including to be a national marine safety regulator, to combat pollution in the marine environment and to provide a search and rescue service; and in particular as the owner, manager and/or operator of the following aids to navigation:

(a) the Gannet Passage Buoy (AN256) located at 10°35.4860' S; 141°52.4110' E;

(b) Gannet Passage WaveRider Buoy (AN606) located 10°35.4100' S; 141°52.1800' E;

(c) Larpent Bank Buoy (AN560) located 10°34.7089' S; 142°04.3541' E;

(d) Pullar Rock Buoy (AN180) located 10°30.4400' S; 142°15.5900' E;

(e) Herald Patches Buoy (AN301) located 10°30.1620' S; 142°21.5050' E;

(f) Mecca Reef Buoy (AN306) located 10°32.3250' S; 142°10.1420' E;

(g) Quetta Rock Buoy located 10°40.2500' S; 142°37.5000' E;

(h) Nardana Patches (AN307) Buoy located at 10°30.2850' S; 142°14.6290' E;

(i) Alert Patches aid to navigation (AN300) located at 10°29.8060' S; 142°21.1690' E;

(j) Alert Patches North Buoy (AN607) located at 10°473587’ S; 142°376642’ E;

(k) Harrison Rock Buoy located at 10°33.2140' S; 142°7.9570' E;

(l) Varzin Passage C1 (AN331) located at 10°32.4030' S ; 141°52.1650' E;

(m) Varzin Passage C2 (AN332) located at 10°32.1681' S; 141°51.9498' E;

(n) Varzin Passage C3 (AN333) located at 10°31.9110' S; 141°56.0649' E;

(o) Varzin Passage C4 (AN334) located at 10°31.5231' S; 141°56.7908' E;

(p) Varzin Passage WaveRider Buoy (AN599) located at 10°31.00000' S; 141°57.0000' E.

8. The rights and interests of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, pursuant to its powers and functions under the Australian Institute of Marine Science Act 1972 (Cth) as the owner, manager or operator of the weather station located at coordinates 10°55.4806’ S; 142°25.2531’ E.

9. The rights and interests of Far North Queensland Ports Corporation Limited (trading as Ports North) ACN 131 836 014 as the port authority for the Port of Kennedy (Thursday Island) and the Port of Skardon River and the provider of port services under Chapter 8 of the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld) and under the Transport Infrastructure (Ports) Regulation 2016 (Qld).

10. The rights and interests of the Torres Shire Council, Torres Strait Island Regional Council, Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council and Cook Shire Council under the Local Government Act and Local Government Regulations 2012 (Qld) for the respective parts of their Local Government Areas.

11. The rights and interests granted or available to RTA Weipa Pty Ltd (ACN 137 266 285), Rio Tinto Aluminium Limited (ACN 009 679 127) (and any successors in title) under the Comalco Agreement, including, but not limited to, rights and interests in relation to the “bauxite field” (as defined in clause 1 of the Comalco Agreement) and areas adjacent to or in the vicinity or outside of such bauxite field, where:

(a) "Comalco Act" means the Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation Pty Limited Agreement Act 1957 (Qld); and

(b) "Comalco Agreement" means the agreement in Schedule 1 to the Comalco Act, including as amended in accordance with such Act.

12. The rights and interests of the holders of any authority, permit, lease, licence or quota issued under the Fisheries Management Act 1991 (Cth) and the Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984 (Cth), including for the Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery, Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery, Western Skipjack Fishery, Northern Prawn Fishery, Southern Bluefin Tuna Fishery, Torres Strait Beche-de-mer Fishery, Torres Strait Crab Fishery, Torres Strait Dugong Fishery, Torres Strait Finfish Fishery, Torres Strait Tropical Rock Lobster Fishery, Torres Strait Pearl Shell Fishery, Torres Strait Prawn Fishery, Torres Strait Trochus Fishery, Torres Strait Turtle Fishery, and Torres Strait Spanish Mackerel Fishery.

13. The rights and interests of the State of Queensland or any other person existing by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State of Queensland, including those existing by reason of the following legislation or any regulation, statutory instrument, declaration, plan, authority, permit, lease or licence made, granted, issued or entered into under that legislation:

(a) the Fisheries Act 1994 (Qld);

(c) the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld);

(d) the Forestry Act 1959 (Qld);

(e) the Water Act 2000 (Qld);

(f) the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) or Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

(g) the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld);

(h) the Planning Act 2016 (Qld);

(i) the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld);

(j) the Fire and Emergency Services Act 1990 (Qld) or Ambulance Service Act 1991 (Qld);

(k) the Marine Parks Act 2004 (Qld);

(l) the Coastal Protection and Management Act 1995 (Qld);

(m) the Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994 (Qld); and

(n) the Transport Operations (Marine Pollution) Act 1995 (Qld).

14. The rights and interests of members of the public arising under the common law, including but not limited to the following:

(a) any subsisting public right to fish; and

(b) the public right to navigate.

15. So far as confirmed pursuant to s 212(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and s 18 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act (1993) (Qld) as at the date of this determination, any existing rights of the public to access and enjoy the following places in the Determination Area:

(a) waterways;

(b) beds and banks or foreshores of waterways;

(c) coastal waters;

(d) beaches; or

(e) areas that were public places at the end of 31 December 1993.

16. Any other rights and interests:

(a) held by the State of Queensland or Commonwealth of Australia; or

(b) existing by reason of the force and operation of the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth.

SCHEDULE 4 – EXTERNAL BOUNDARIES

Part 1 – External boundary of Determination Area

The determination area falls within the external boundary described as:

Commencing at the intersection of the southern boundary of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) with the eastern boundary of the Torres Shire Council Local Government Authority and extending generally southerly along the eastern boundaries of that Local Government Authority and the Cook Shire Council Local Government Authority to the northern boundary of the Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority at approximate Latitude 11.367295° South; then generally north westerly and generally south westerly along northern boundaries of that Marine Resource Agreement Area, approximated by the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

143.947742 | 11.361270 |

143.817141 | 11.309404 |

143.804758 | 11.309404 |

143.784275 | 11.298920 |

143.743375 | 11.397887 |

143.750958 | 11.477620 |

143.741208 | 11.484770 |

143.718592 | 11.548053 |

143.679808 | 11.593737 |

143.637692 | 11.604453 |

143.624542 | 11.622970 |

143.620474 | 11.628697 |

Then due west to the High Water Mark (at Captain Billy Landing); then generally northerly along that High Water Mark to an eastern corner of Lot 26 on NPW404 (about 520m south of Hunter Point), being a point on the external boundary of Area 1 of Native Title Determination QUD157/2011 Northern Cape York Group #1 (QCD2014/017); then generally northerly, generally westerly, generally north easterly, generally north westerly and generally south westerly along the external boundary of that native title determination to a point on the High Water Mark of the mainland at approximate Longitude 142.439405° East, Latitude 10.707819° South (being a point on the High Water Mark at Peak Point, about 17km north east of Seisia); then north westerly to Longitude 142.414081° East, Latitude 10.666402° South; then generally south westerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.411903 | 10.668136 |

142.407844 | 10.673561 |

142.405037 | 10.677602 |

142.400576 | 10.682504 |

142.395774 | 10.688253 |

142.391352 | 10.692639 |

142.384337 | 10.697673 |

142.382409 | 10.698764 |

142.368509 | 10.707439 |

142.366603 | 10.709057 |

142.361855 | 10.713892 |

142.359494 | 10.718169 |

142.343228 | 10.737603 |

142.334049 | 10.744291 |

142.332680 | 10.745314 |

142.324454 | 10.749383 |

142.319898 | 10.751406 |

142.314894 | 10.753420 |

142.306344 | 10.758448 |

142.302799 | 10.761454 |

142.299704 | 10.763950 |

142.295274 | 10.766929 |

142.288664 | 10.771372 |

142.283853 | 10.774809 |

142.277315 | 10.779202 |

142.269496 | 10.784048 |

142.257421 | 10.791251 |

142.250963 | 10.794583 |

142.243968 | 10.796463 |

142.233509 | 10.799272 |

142.223934 | 10.801599 |

142.216910 | 10.802512 |

142.213401 | 10.802967 |

142.202712 | 10.806688 |

142.182017 | 10.811269 |

142.157412 | 10.815331 |

142.148220 | 10.817764 |

Then south easterly to approximate Longitude 142.207696° East, Latitude 10.915040° South (being a point on the High Water Mark of the mainland at Van Spoult Head); then generally south westerly and generally southerly along that High Water Mark, crossing the mouths of any waterways between the seaward extremities of each of the opposite banks of each such waterway, to the intersection of the southern boundary of Lot 1 on SP120090 with the mouth of the Skardon River casement; then west to the intersection of a 30 kilometre buffer seaward from the High Water Mark of the mainland with Latitude 11.753658° South; then generally northerly along that 30 kilometre buffer to the intersection of the line joining Longitude 141.825674° East, Latitude 10.889081° South and Longitude 141.875261° East, Latitude 10.876652° South; then north easterly and generally northerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

141.875261 | 10.876652 |

141.893459 | 10.872617 |

141.898407 | 10.871008 |

141.894219 | 10.862271 |

141.847682 | 10.744509 |

141.834538 | 10.696874 |

141.829324 | 10.655291 |

141.829388 | 10.622364 |

141.834738 | 10.592893 |

Then north easterly to a corner of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) at approximate Longitude 141.854566° East, Latitude 10.556823° South; then generally easterly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.134470 | 10.556816 |

142.201137 | 10.511814 |

142.251138 | 10.508479 |

142.276138 | 10.500145 |

Then easterly to again a corner of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) at approximate Longitude 142.539358° East, Latitude 10.500147° South and then easterly along the southern boundary of that native title determination back to the commencement point.

Exclusions

This determination area does not include land and waters subject to:

• Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Indigenous Land Use Agreement (QI2006/044) as registered by the NNTT on 13 August 2007.

• Mining Lease ML 7024.

• Comalco Indigenous Land Use Agreement (QIA2001/002) as registered with the NNTT on 24 August 2001.

• Native title determination application QUD24/2019 Kaurareg People #3 filed in the Federal Court of Australia on 30 August 2010.

• All the area above High Water Mark (HWM) of Prince of Wales Island, Horn Island, Port Lihou Island, Tarilag Island and Zuna Island.

For the avoidance of any doubt, the Determination Area excludes any area subject to:

• Native title determination QUD6023/1998 Kaurareg People (Ngurupai) (QCD2001/001) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6024/1998 Kaurareg People (Murulag #1) (QCD2001/002) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6025/1998 Kaurareg People (Zuna) (QCD2001/003) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6026/1998 Kaurareg People (Murulag #2) (QCD2001/004) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6027/1998 Kaurareg People (Mipa, Tarilag, Yeta, Damaralag) (QCD2001/005) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6073/1998 Warraber People (QCD2000/004) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 7 July 2000.

Note

Data Reference and source

• External Boundary of Determination Area compiled by National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants.

• Local Government Authority data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), December 2021.

• Cadastre, Mining Lease and river casement data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), January 2022.

• Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region – Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2008.

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

Part 2 – External Boundary of the Kaurareg Area

The external boundary of the Kaurareg Area is described as:

Commencing at a corner of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) at approximate Longitude 142.539358° East, Latitude 10.500147° South and extending generally south westerly and generally northerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.537321 | 10.502230 |

142.534734 | 10.506243 |

142.533075 | 10.511943 |

142.531259 | 10.522655 |

142.527397 | 10.553357 |

142.526559 | 10.565071 |

142.526313 | 10.572951 |

142.525926 | 10.585381 |

142.528410 | 10.594063 |

142.529633 | 10.598616 |

142.529935 | 10.603137 |

142.529394 | 10.605634 |

142.528417 | 10.607624 |

142.525125 | 10.611089 |

142.518255 | 10.613540 |

142.510957 | 10.615980 |

142.500950 | 10.620358 |

142.488309 | 10.624699 |

142.478877 | 10.626607 |

142.474395 | 10.627559 |

142.468136 | 10.629469 |

142.465012 | 10.630419 |

142.460559 | 10.631846 |

142.454793 | 10.634223 |

142.449058 | 10.637068 |

142.446010 | 10.639616 |

142.444286 | 10.641799 |

142.433941 | 10.650695 |

142.426246 | 10.656713 |

142.411903 | 10.668136 |

142.407844 | 10.673561 |

142.405037 | 10.677602 |

142.400576 | 10.682504 |

142.395774 | 10.688253 |

142.391352 | 10.692639 |

142.384337 | 10.697673 |

142.382409 | 10.698764 |

142.368509 | 10.707439 |

142.366603 | 10.709057 |

142.361855 | 10.713892 |

142.359494 | 10.718169 |

142.343228 | 10.737603 |

142.334049 | 10.744291 |

142.332680 | 10.745314 |

142.324454 | 10.749383 |

142.319898 | 10.751406 |

142.314894 | 10.753420 |

142.306344 | 10.758448 |

142.302799 | 10.761454 |

142.299704 | 10.763950 |

142.295274 | 10.766929 |

142.288664 | 10.771372 |

142.283853 | 10.774809 |

142.277315 | 10.779202 |

142.269496 | 10.784048 |

142.257421 | 10.791251 |

142.250963 | 10.794583 |

142.243968 | 10.796463 |

142.233509 | 10.799272 |

142.223934 | 10.801599 |

142.216910 | 10.802512 |

142.213401 | 10.802967 |

142.202712 | 10.806688 |

142.182017 | 10.811269 |

142.157412 | 10.815331 |

142.126858 | 10.823417 |

142.104084 | 10.827794 |

142.079246 | 10.831641 |

142.055978 | 10.834488 |

142.031823 | 10.838772 |

141.992845 | 10.849188 |

141.973560 | 10.855277 |

141.960213 | 10.858517 |

141.944278 | 10.861728 |

141.921812 | 10.865350 |

141.906044 | 10.868522 |

141.898407 | 10.871008 |

141.894219 | 10.862271 |

141.847682 | 10.744509 |

141.834538 | 10.696874 |

141.829324 | 10.655291 |

141.829388 | 10.622364 |

141.834738 | 10.592893 |

Then north easterly to a corner of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) at approximate Longitude 141.854566° East, Latitude 10.556823° South; then generally easterly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.134470 | 10.556816 |

142.201137 | 10.511814 |

142.251138 | 10.508479 |

142.276138 | 10.500145 |

Then easterly back to the commencement point.

For the avoidance of any doubt, the Kaurareg Area excludes any area subject to:

• Native title determination application QUD24/2019 Kaurareg People #3 filed in the Federal Court of Australia on 30 August 2010.

• All the area above High Water Mark (HWM) of Prince of Wales Island, Horn Island, Port Lihou Island, Tarilag Island and Zuna Island.

• Native title determination QUD6023/1998 Kaurareg People (Ngurupai) (QCD2001/001) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6024/1998 Kaurareg People (Murulag #1) (QCD2001/002) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6025/1998 Kaurareg People (Zuna) (QCD2001/003) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6026/1998 Kaurareg People (Murulag #2) (QCD2001/004) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

• Native title determination QUD6027/1998 Kaurareg People (Mipa, Tarilag, Yeta, Damaralag) (QCD2001/005) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 May 2001.

Note

Data Reference and source

• Kaurareg Area boundary compiled by National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants.

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

Part 3 – External Boundary of the Ankamuthi Area

The external boundary of the Ankamuthi Area is described as:

Commencing at the intersection of the southern boundary of Lot 1 on SP120090 with the mouth of the Skardon River casement, being a point on the High Water Mark of the mainland and extending generally northerly along that High Water Mark, crossing the mouths of any waterways between the seaward extremities of each of the opposite banks of each such waterway, to approximate Longitude 142.207696° East, Latitude 10.915040° South (being a point on the High Water Mark of the mainland at Van Spoult Head); then north westerly to Longitude 142.148220° East, Latitude 10.817764° South, then generally south westerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.126858 | 10.823417 |

142.104084 | 10.827794 |

142.079246 | 10.831641 |

142.055978 | 10.834488 |

142.031823 | 10.838772 |

141.992845 | 10.849188 |

141.973560 | 10.855277 |

141.960213 | 10.858517 |

141.944278 | 10.861728 |

141.921812 | 10.865350 |

141.906044 | 10.868522 |

141.893459 | 10.872617 |

141.875261 | 10.876652 |

Then south westerly towards Longitude 141.825674° East, Latitude 10.889081° South until the intersection with a 30 kilometre buffer seaward from the High Water Mark of the mainland; then generally southerly along that 30 kilometre buffer to Latitude 11.753658° South and then east back to the commencement point.

Exclusions

The Ankamuthi Area does not include land and waters subject to:

Mining Lease ML 7024.

Comalco Indigenous Land Use Agreement (QIA2001/002) as registered by the NNTT on 24 August 2001.

Native title determination QUD157/2011 Northern Cape York Group #1 (QCD2014/017), as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 30 October 2014.

Native title determination QUD780/2016 Northern Cape York Group #3 (QCD2017/005), as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 26 July 2017.

Native title determination QUD6158/1998 Ankamuthi People (QCD2017/006), as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 26 July 2017.

Note

Data Reference and source

• Ankamuthi Area boundary compiled by National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants.

• Cadastre, Mining Lease and river casement data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), January 2022.

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

Part 4 – External Boundary of the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area

The external boundary of the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area is described as:

Commencing at a point on the High Water Mark of the mainland at approximate Longitude 142.439405° East, Latitude 10.707819° South (being a point on the High Water Mark at Peak Point, about 17km north east of Seisia), also being a point on the external boundary of Area 1 of Native Title Determination QUD157/2011 Northern Cape York Group #1 (QCD2014/017) and extending north westerly to Longitude 142.414081° East, Latitude 10.666402° South; then generally north easterly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.426246 | 10.656713 |

142.433941 | 10.650695 |

142.444286 | 10.641799 |

142.446010 | 10.639616 |

142.449058 | 10.637068 |

142.454793 | 10.634223 |

142.460559 | 10.631846 |

142.465012 | 10.630419 |

142.468136 | 10.629469 |

142.474395 | 10.627559 |

142.478877 | 10.626607 |

142.488309 | 10.624699 |

142.500950 | 10.620358 |

142.510957 | 10.615980 |

142.518255 | 10.613540 |

142.525125 | 10.611089 |

142.528417 | 10.607624 |

142.529394 | 10.605634 |

142.529935 | 10.603137 |

142.529633 | 10.598616 |

142.528410 | 10.594063 |

142.525926 | 10.585381 |

142.526313 | 10.572951 |

142.526559 | 10.565071 |

142.527397 | 10.553357 |

142.531259 | 10.522655 |

142.533075 | 10.511943 |

142.534734 | 10.506243 |

142.537321 | 10.502230 |

Then north easterly to a corner of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) at approximate Longitude 142.539358° East, Latitude 10.500147° South; then easterly along the southern boundary of that native title determination to Longitude 142.797073° East; then generally south easterly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

142.797100 | 10.500168 |

142.800459 | 10.502594 |

142.805938 | 10.506551 |

142.814950 | 10.510585 |

142.821047 | 10.512356 |

142.822106 | 10.512664 |

142.831096 | 10.516685 |

142.838309 | 10.520659 |

142.845512 | 10.524629 |

142.852641 | 10.526693 |

142.859830 | 10.530657 |

142.867008 | 10.534614 |

142.870595 | 10.536592 |

142.881339 | 10.542511 |

142.888547 | 10.548338 |

142.893985 | 10.554114 |

142.899413 | 10.559878 |

142.906685 | 10.569418 |

142.912088 | 10.575150 |

142.917481 | 10.580874 |

142.924613 | 10.586627 |

142.929896 | 10.588601 |

142.938707 | 10.592512 |

142.947545 | 10.598272 |

142.954590 | 10.602131 |

142.958145 | 10.605913 |

142.965277 | 10.615309 |

142.972294 | 10.619149 |

142.977595 | 10.624786 |

142.984620 | 10.630450 |

142.989875 | 10.634232 |

142.998657 | 10.643573 |

143.005643 | 10.649200 |

143.012596 | 10.652993 |

143.021300 | 10.660455 |

143.031709 | 10.667934 |

143.040360 | 10.673548 |

143.045555 | 10.679079 |

143.050741 | 10.684602 |

143.057628 | 10.688347 |

143.064512 | 10.693887 |

143.069666 | 10.697587 |

143.074815 | 10.701282 |

143.081670 | 10.705009 |

143.088518 | 10.708727 |

143.093643 | 10.714197 |

143.100472 | 10.717902 |

143.108987 | 10.725202 |

143.112393 | 10.727049 |

143.122586 | 10.734359 |

143.129364 | 10.739812 |

143.141218 | 10.747121 |

143.146304 | 10.748986 |

143.156444 | 10.754477 |

143.166545 | 10.761719 |

143.178316 | 10.768973 |

143.186704 | 10.774391 |

143.193385 | 10.779769 |

143.201747 | 10.785169 |

143.208404 | 10.790528 |

143.211675 | 10.795816 |

143.224980 | 10.804753 |

143.233240 | 10.811841 |

143.239844 | 10.817154 |

143.244801 | 10.820701 |

143.251387 | 10.825998 |

143.254604 | 10.831222 |

143.264475 | 10.838273 |

143.275946 | 10.847053 |

143.282479 | 10.852303 |

143.285713 | 10.855778 |

143.295570 | 10.861071 |

143.300463 | 10.864565 |

143.310234 | 10.871539 |

143.316716 | 10.876744 |

143.328447 | 10.885849 |

143.346804 | 10.900743 |

143.352301 | 10.906767 |

143.355964 | 10.910776 |

143.365266 | 10.918820 |

143.374717 | 10.924888 |

143.380517 | 10.926957 |

143.389951 | 10.933014 |

143.395222 | 10.940935 |

143.400655 | 10.946895 |

143.408066 | 10.952881 |

143.417273 | 10.960833 |

143.424660 | 10.966797 |

143.433835 | 10.974722 |

143.441197 | 10.980663 |

143.448555 | 10.986596 |

143.457872 | 10.992555 |

143.466984 | 11.000425 |

143.470359 | 11.006254 |

143.481607 | 11.012218 |

143.488904 | 11.018101 |

143.496387 | 11.022066 |

143.503665 | 11.027933 |

143.508967 | 11.033756 |

143.521918 | 11.041613 |

143.530920 | 11.049382 |

143.541660 | 11.059063 |

143.552584 | 11.066832 |

143.561951 | 11.070783 |

143.569147 | 11.076576 |

143.580239 | 11.082431 |

143.587410 | 11.088204 |

143.598257 | 11.095915 |

143.603673 | 11.099765 |

143.614714 | 11.105584 |

143.618391 | 11.107522 |

143.631365 | 11.113365 |

143.640655 | 11.117267 |

143.644093 | 11.121060 |

143.657030 | 11.126883 |

143.664114 | 11.132592 |

143.671659 | 11.134587 |

143.682614 | 11.140355 |

143.688205 | 11.142311 |

143.705138 | 11.157789 |

143.715023 | 11.162054 |

143.722868 | 11.166280 |

143.728675 | 11.170465 |

143.736215 | 11.178753 |

143.741861 | 11.184957 |

143.751693 | 11.189192 |

143.759495 | 11.193385 |

143.767281 | 11.197576 |

143.775066 | 11.201760 |

143.780978 | 11.203885 |

143.790768 | 11.208097 |

143.798690 | 11.210253 |

143.806291 | 11.216436 |

143.814039 | 11.220598 |

143.821780 | 11.224756 |

143.827330 | 11.230883 |

143.835223 | 11.233025 |

143.842769 | 11.239173 |

143.848468 | 11.243277 |

143.864041 | 11.249538 |

143.871733 | 11.253664 |

143.877586 | 11.255758 |

143.887457 | 11.257918 |

143.897139 | 11.262064 |

143.902982 | 11.264153 |

143.910643 | 11.268260 |

143.924318 | 11.272462 |

143.932154 | 11.274577 |

143.937786 | 11.278641 |

143.949230 | 11.284778 |

143.956649 | 11.290840 |

143.970068 | 11.296990 |

143.977263 | 11.304999 |

Then south easterly to the eastern boundary of the Cook Shire Council Local Government Authority at Latitude 11.309177° South; then generally southerly along the eastern boundary of that Local Government Authority to the northern boundary of the Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority at approximate Latitude 11.367295° South; then generally north westerly and generally south westerly along northern boundaries of that Marine Resource Agreement Area, approximated by the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

143.947742 | 11.361270 |

143.817141 | 11.309404 |

143.804758 | 11.309404 |

143.784275 | 11.298920 |

143.743375 | 11.397887 |

143.750958 | 11.477620 |

143.741208 | 11.484770 |

143.718592 | 11.548053 |

143.679808 | 11.593737 |

143.637692 | 11.604453 |

143.624542 | 11.622970 |

143.620474 | 11.628697 |

Then due west to the High Water Mark (at Captain Billy Landing); then generally northerly along that High Water Mark to an eastern corner of Lot 26 on NPW404 (about 520m south of Hunter Point), being a point on the external boundary of Area 1 of Native Title Determination QUD157/2011 Northern Cape York Group #1 (QCD2014/017); then generally northerly, generally westerly, generally north easterly, generally north westerly and generally south westerly along the external boundary of that native title determination back to the commencement point.

Exclusions

The Gudang Yadhaykenu Area does not include land and waters subject to:

Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Indigenous Land Use Agreement (QI2006/044) as registered by the NNTT on 13 August 2007.

For the avoidance of any doubt, the Gudang Yadhaykenu Area excludes any area subject to:

Native title determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 August 2010.

Native title determination QUD157/2011 Northern Cape York Group #1 (QCD2014/017) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 30 October 2014.

Data Reference and source

• Gudang Yadhaykenu Area boundary compiled by National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants.

• Local Government Authority data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), December 2021.

• Cadastre data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), January 2022.

• Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region – Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2008.

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

Part 5 – External Boundary of the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area

The external boundary of the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area is described as:

Commencing at the intersection of the southern boundary of Native Title Determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) with Longitude 142.743222° East and extending easterly along that determination boundary to the eastern boundary of the Torres Shire Council Local Government Authority; then generally southerly along the eastern boundaries of that Local Government Authority and the Cook Shire Council Local Government Authority to the northern boundary of the Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority at approximate Latitude 11.367295° South; then generally north westerly and generally south westerly along that agreement boundary, approximated by the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

143.947742 | 11.361270 |

143.817141 | 11.309404 |

143.804758 | 11.309404 |

143.784275 | 11.298920 |

143.743375 | 11.397887 |

143.750958 | 11.477620 |

143.741208 | 11.484770 |

143.718592 | 11.548053 |

143.679808 | 11.593737 |

143.637692 | 11.604453 |

143.624542 | 11.622970 |

143.620474 | 11.628697 |

Then west, north and generally north westerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

143.364800 | 11.628697 |

143.364800 | 11.220500 |

143.171400 | 10.998500 |

143.166038 | 10.990679 |

143.161664 | 10.986367 |

143.157271 | 10.980643 |

143.154321 | 10.974944 |

143.148432 | 10.966338 |

143.148217 | 10.966023 |

143.145481 | 10.962025 |

143.142495 | 10.954872 |

143.139502 | 10.947700 |

143.135040 | 10.940473 |

143.134717 | 10.939261 |

143.133509 | 10.934730 |

143.130493 | 10.927507 |

143.126004 | 10.920229 |

143.122992 | 10.914408 |

143.118463 | 10.905656 |

143.115435 | 10.899805 |

143.110929 | 10.893905 |

143.106415 | 10.887992 |

143.100384 | 10.880571 |

143.095852 | 10.874633 |

143.091305 | 10.868680 |

143.086779 | 10.864177 |

143.082217 | 10.858203 |

143.077646 | 10.852217 |

143.071541 | 10.844701 |

143.069955 | 10.840239 |

143.068033 | 10.837722 |

143.065354 | 10.834213 |

143.062234 | 10.828214 |

143.057542 | 10.819192 |

143.055974 | 10.816179 |

143.051302 | 10.808611 |

143.048555 | 10.803330 |

143.048154 | 10.802559 |

143.043502 | 10.796454 |

143.040297 | 10.788875 |

143.038671 | 10.784326 |

143.033993 | 10.778181 |

143.029304 | 10.772022 |

143.026157 | 10.767404 |

143.021452 | 10.761222 |

143.018293 | 10.756587 |

143.015081 | 10.750423 |

143.008889 | 10.745687 |

143.005713 | 10.741027 |

143.001112 | 10.738619 |

143.001111 | 10.715169 |

142.894661 | 10.634389 |

142.892627 | 10.630560 |

142.884569 | 10.623980 |

142.881135 | 10.617522 |

142.879887 | 10.616560 |

142.874684 | 10.612553 |

142.869769 | 10.607622 |

142.863387 | 10.604237 |

142.855351 | 10.599198 |

142.848948 | 10.595800 |

142.842440 | 10.590789 |

142.835921 | 10.585769 |

142.828236 | 10.580946 |

142.827833 | 10.580693 |

142.819730 | 10.575607 |

142.813279 | 10.572179 |

142.811393 | 10.571177 |

142.802508 | 10.564435 |

142.800138 | 10.562064 |

142.796576 | 10.555467 |

142.791542 | 10.550431 |

142.786501 | 10.545386 |

142.781453 | 10.540334 |

142.777957 | 10.535314 |

142.774461 | 10.530289 |

142.769384 | 10.525206 |

142.762964 | 10.523359 |

142.756418 | 10.519865 |

142.744017 | 10.501335 |

Then north westerly back to the commencement point.

Exclusions

This Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area does not include land and waters subject to:

Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Indigenous Land Use Agreement (QI2006/044) as registered by the NNTT on 13 August 2007.

Native title determination QUD6073/1998 Warraber People (QCD2000/004) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 7 July 2000.

For the avoidance of any doubt, the Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area excludes any area subject to:

Native title determination QUD6040/2001 Torres Strait Regional Sea Claim (QCD2010/003) as determined by the Federal Court of Australia on 23 August 2010.

Data Reference and source

• Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area boundary compiled by National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants.

• Local Government Authority data sourced from Department of Resources (QLD), December 2021.

• Wuthathi Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA) Region – Schedule 2 as defined by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 2008.

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey. Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

SCHEDULE 5 – DESCRIPTION OF DETERMINATION AREAS

All of the land and waters described in the following table and depicted in dark blue on the determination maps contained in Schedule 7:

Group Area | Area description (at the time of the determination) | Determination Map Sheet Reference | Note |

Ankamuthi Area | Lot 70 on Plan TS234 | Map 3, Sheet 1 of 2 | ~ |

Ankamuthi Area | Lot 71 on Plan TS235 | Map 3, Sheet 1 of 2 | ~ |

Ankamuthi Area | Lot 2 on Plan SO23 | Map 3, Sheet 2 of 2 | ~ |

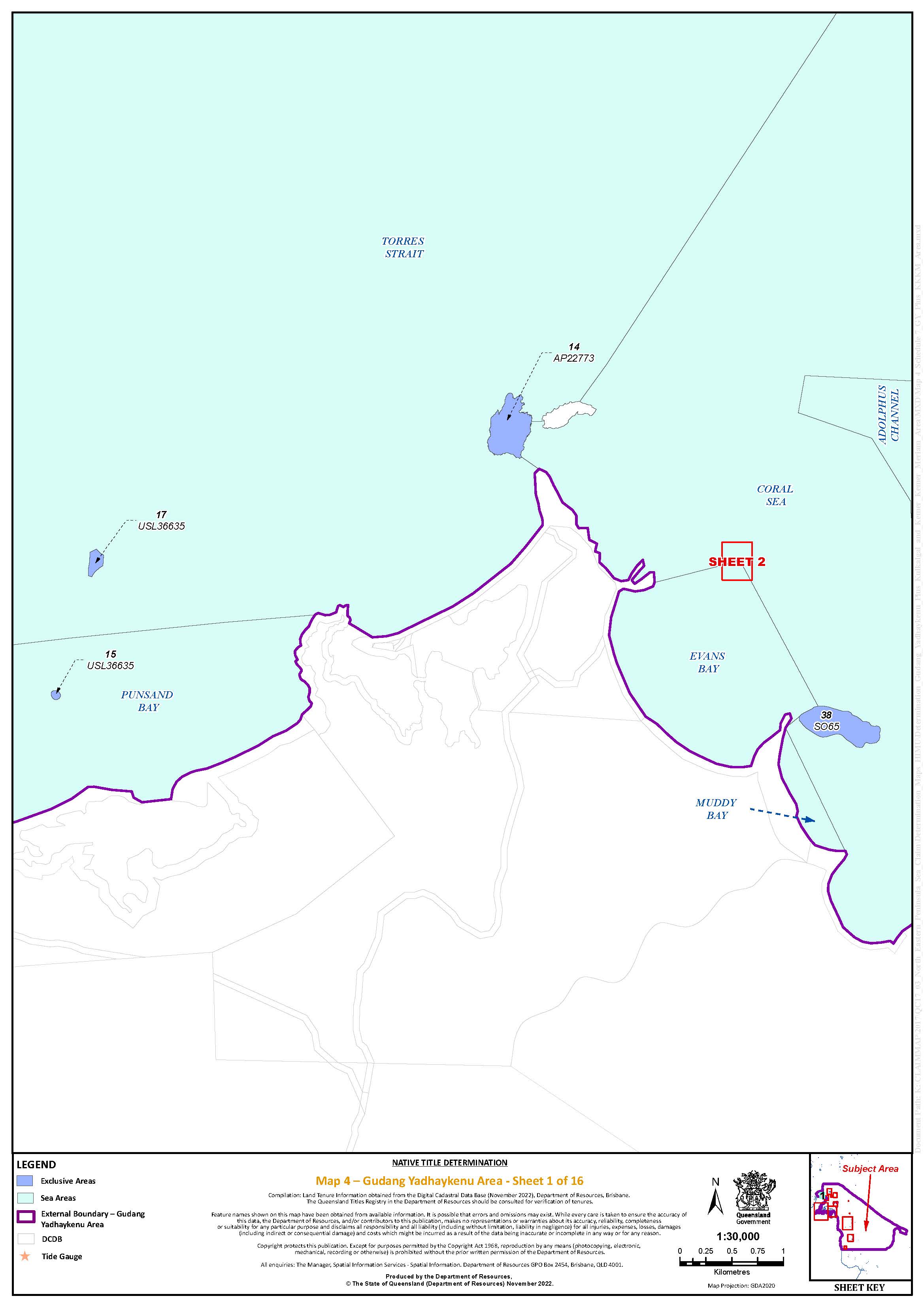

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 14 on Plan AP22773 | Map 4, Sheet 1 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 38 on Plan SO65 | Map 4, Sheet 1 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 15 on Plan USL36635 | Map 4, Sheet 1 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 17 on Plan USL36635 | Map 4, Sheet 1 of 16 | |

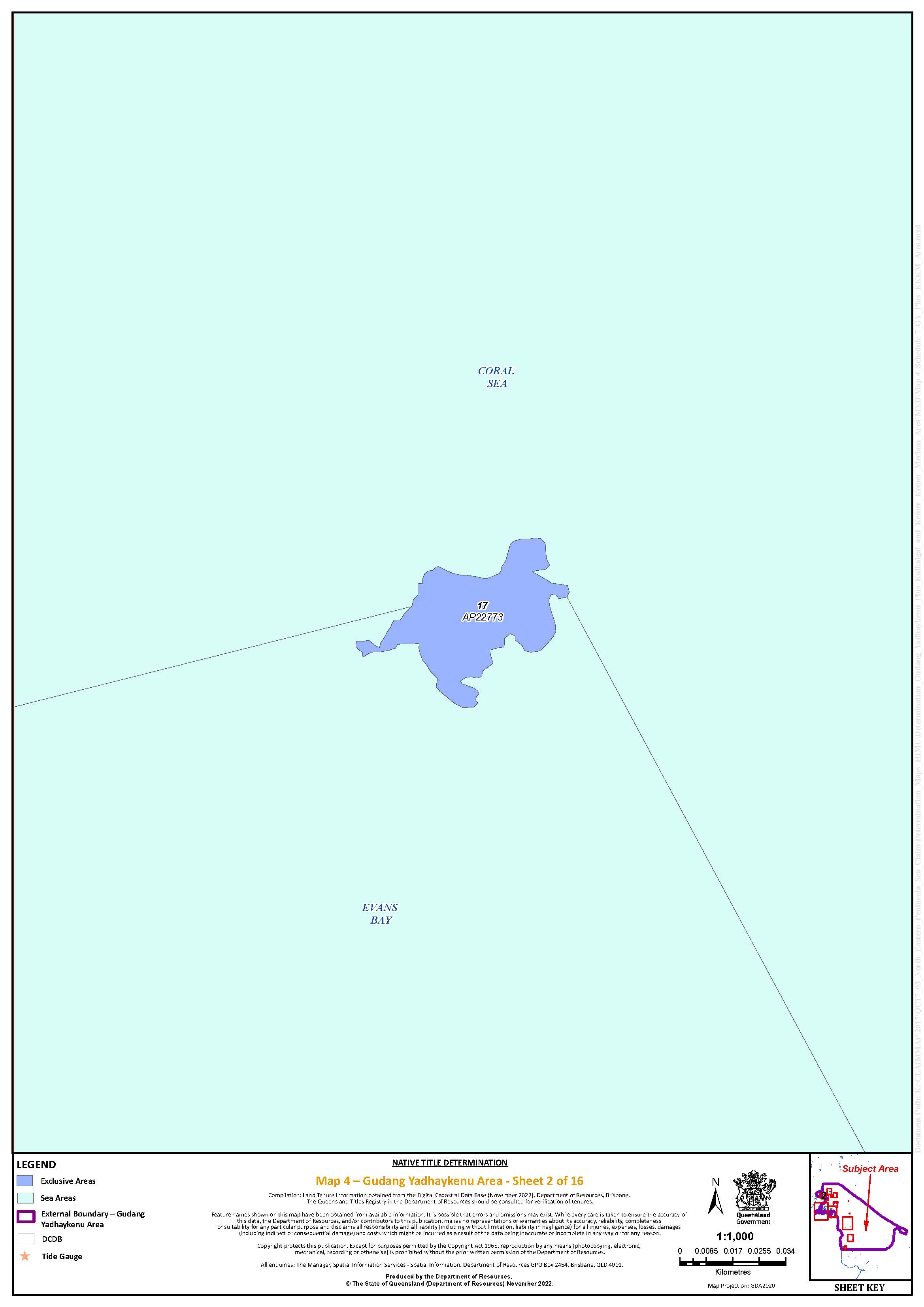

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 17 on Plan AP22773 | Map 4, Sheet 2 of 16 | |

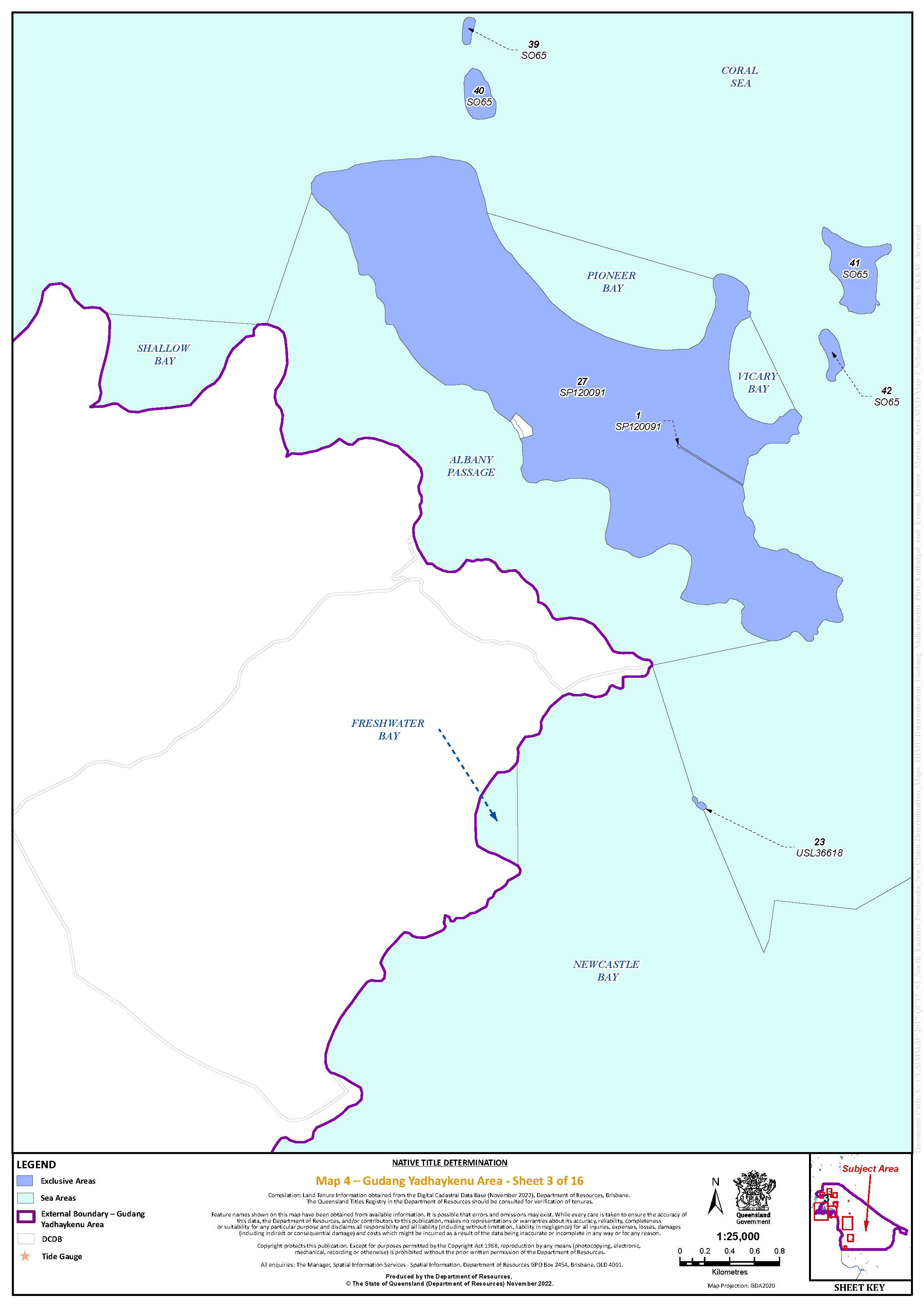

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 39 on Plan SO65 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 40 on Plan SO65 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 41 on Plan SO65 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 42 on Plan SO65 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 1 on Plan SP120091 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | ~ |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 27 on Plan SP120091 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | ~ |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 23 on Plan USL36618 | Map 4, Sheet 3 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 9 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 10 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 11 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 12 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 13 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | ~ |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 14 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 15 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 1 on Plan TS67 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | * |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 1 on Plan USL36618 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 27 on Plan USL36618 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 30 on Plan USL36618 | Map 4, Sheet 4 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 23 on Plan TS231 | Map 4, Sheet 5 of 16 | ~ |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 17 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 6 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 18 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 6 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 19 on Plan TS195 | Map 4, Sheet 6 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 50 on Plan USL36618 | Map 4, Sheet 7 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 1 on Plan AP22362 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 2 on Plan AP22362 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 6 on Plan SP252515 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 7 on Plan SP252515 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 2 on Plan SP252525 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | ~ |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 3 on Plan SP252525 | Map 4, Sheet 9 of 16 | ~ |

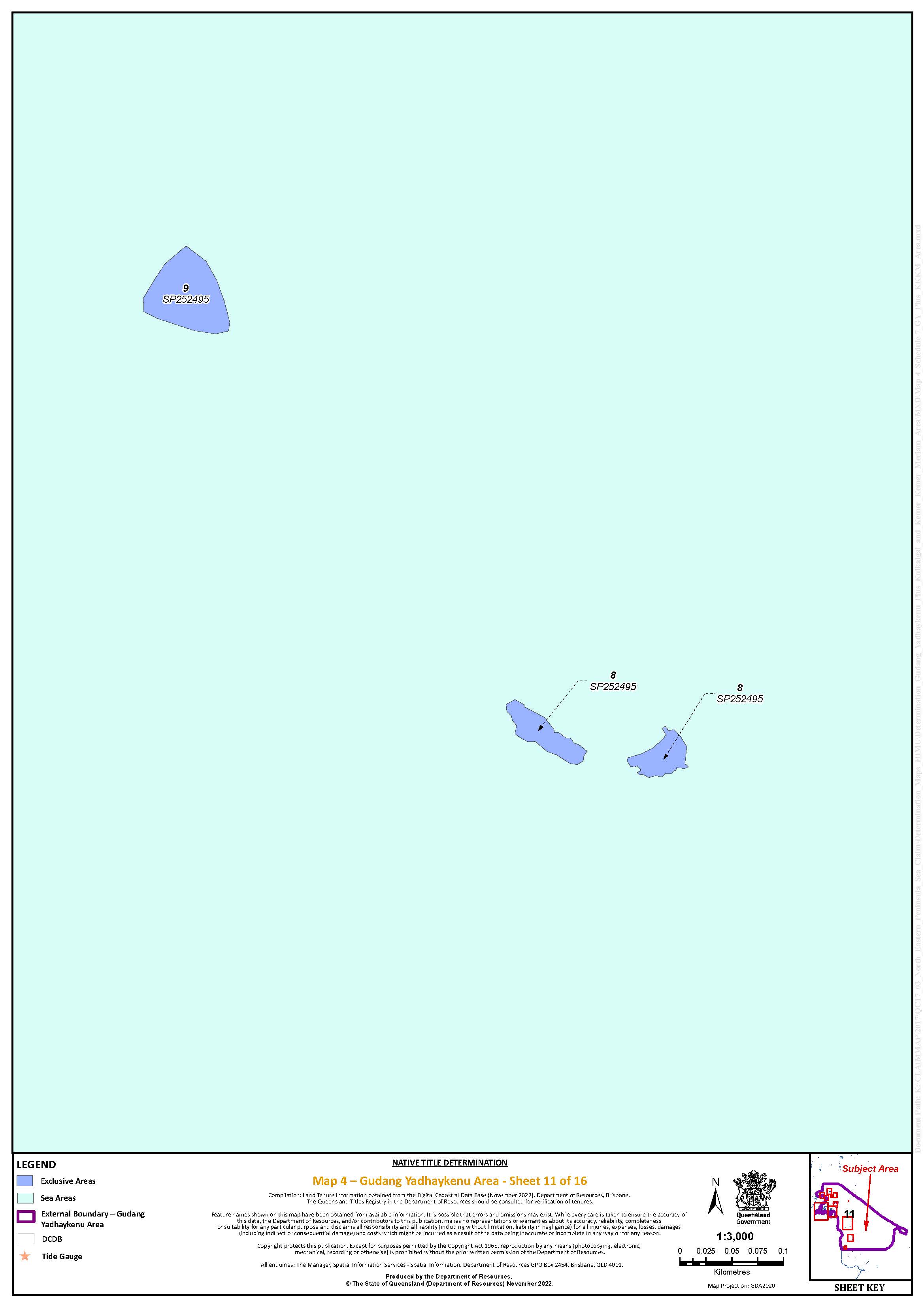

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 8 on Plan SP252495 | Map 4, Sheet 11 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 9 on Plan SP252495 | Map 4, Sheet 11 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | That part of Lot 410 on Plan NPW603 described as Denham Group National Park (Cairncross Island) excluding former Portion 1 on Plan SO10 | Map 4, Sheet 12 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 14 on Plan SP241441 | Map 4, Sheet 12 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 11 on Plan SP241441 | Map 4, Sheet 13 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 13 on Plan SP241440 | Map 4, Sheet 14 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 9 on Plan SP252528 | Map 4, Sheet 14 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 10 on Plan SP252528 | Map 4, Sheet 15 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 5 on Plan SP241439 | Map 4, Sheet 16 of 16 | |

Gudang Yadhaykenu Area | Lot 7 on Plan SP241439 | Map 4, Sheet 16 of 16 | |

Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area | Those parts, if any, of Awai (Pelican Sandbank), located in the vicinity of Longitude 143.019640° East, Latitude 10.638838° South, that are located on the landward side of the High Water Mark | Map 5, Key Map | ^ |

Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area | Those parts, if any, of Big Boiag (Koey Boiag), located in the vicinity of Longitude 143.198644° East, Latitude 10.632882° South, that are located on the landward side of the High Water Mark | Map 5, Key Map | ^ |

Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Area | Those parts, if any, of Tiwalag, located in the vicinity of Longitude 143.070823° East, Latitude 10.591019° South, that are located on the landward side of the High Water Mark | Map 5, Key Map | ^ |

~ denotes areas to which s 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies.

* denotes areas to which s 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies.

^ denotes areas that have not been surveyed at the date of the determination

Note for Kulkalgal and Kemer Kemer Meriam Areas

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022).

Part 2 — Non-Exclusive Areas (Offshore)

(a) all of the waters below the High Water Mark within the External Boundary and depicted in teal on the determination maps contained in Schedule 7; and

(b) all of the waters below the High Water Mark within the External Boundary and described in the following table and depicted in light blue on the determination maps contained in Schedule 7:

Group Area | Area description (at the time of the determination) | Determination Map Sheet Reference | Note |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 4 on Plan SP187418 | Map 2, Sheet 5 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 142 on Plan SP152630 | Map 2, Sheet 5 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 1 on Plan SP118062 | Map 2, Sheet 5 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 156 on Plan SP108485 | Map 2, Sheet 5 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 169 on Plan TS224 | Map 2, Sheet 8 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 4 on Plan SP108474 | Map 2, Sheet 8 of 8 | |

Kaurareg Area | Lot 28 on Plan SP108492 | Map 2, Sheet 8 of 8 |

SCHEDULE 6 – AREAS NOT FORMING PART OF THE DETERMINATION AREA

The following areas of land and waters are excluded from the Determination Area as described in Order 8.

1. Those lands and waters within the External Boundary which at the time the native title determination application was made were the subject of one or more Previous Exclusive Possession Acts, within the meaning of s 23B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) as they could not be claimed in accordance with s 61A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

2. Specifically, and to avoid any doubt, the land and waters described in (1) above includes:

(i) the Previous Exclusive Possession Acts described in ss 23B(2) and 23B(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to which s 20 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) applies, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied; and

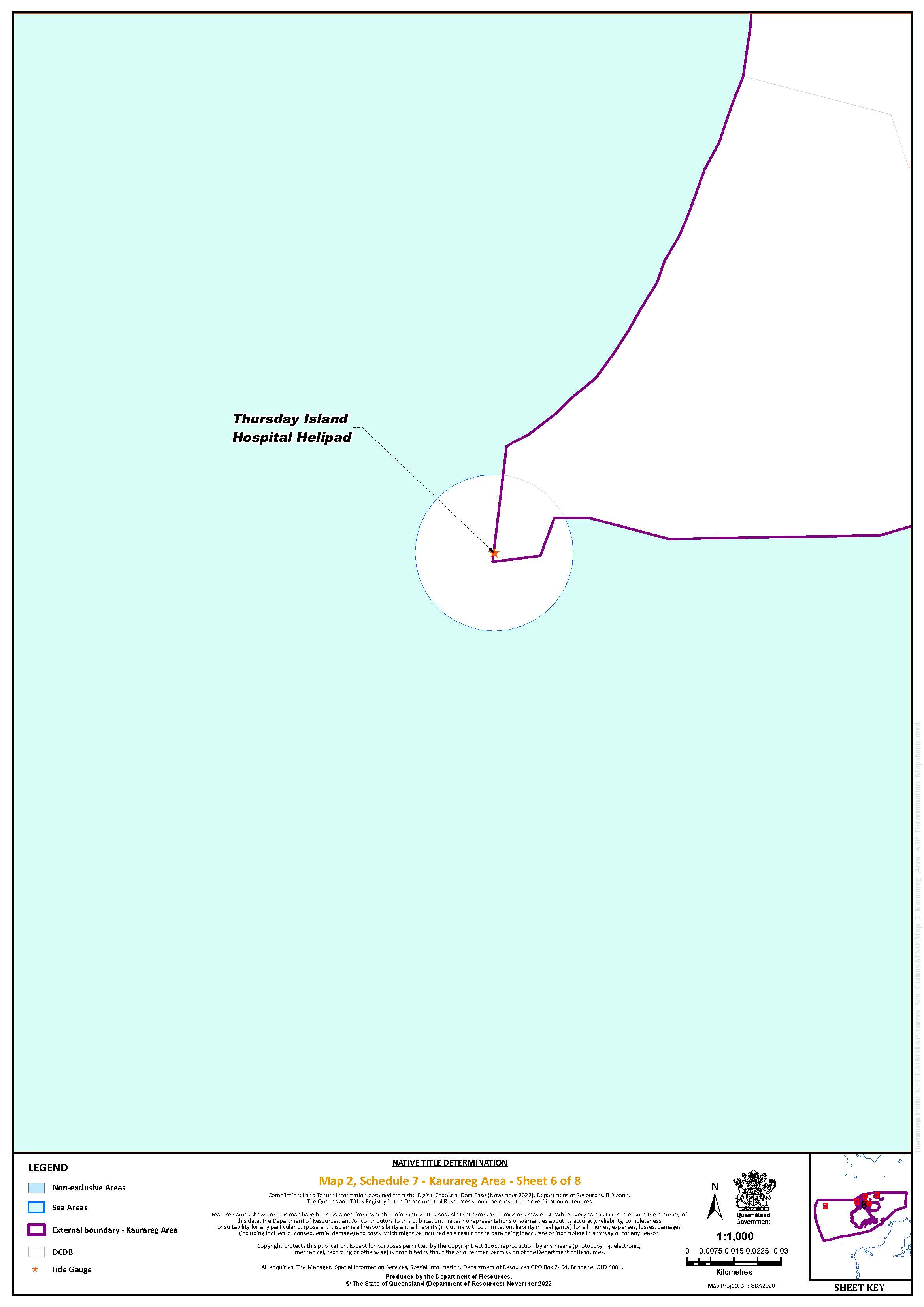

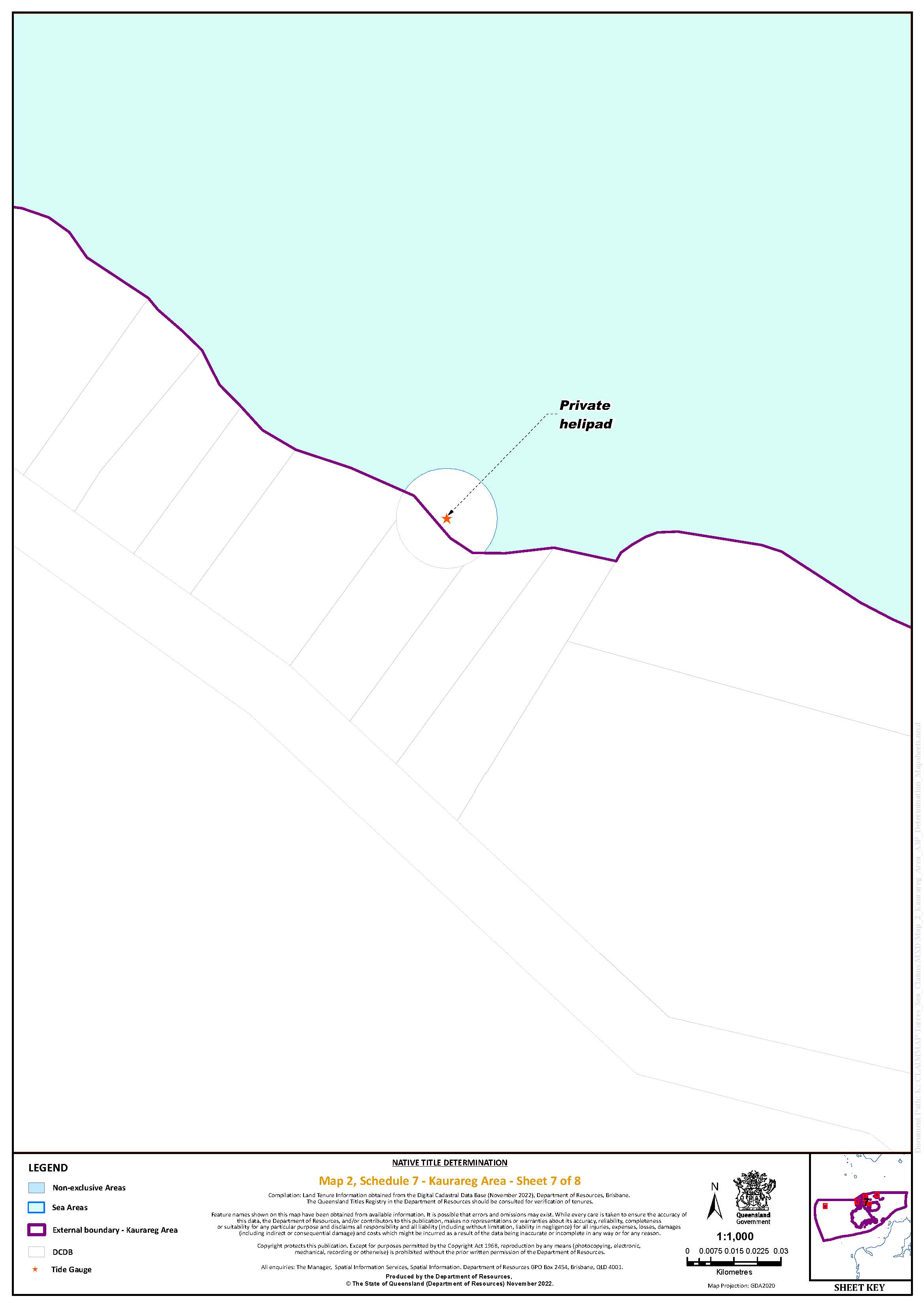

(ii) the land and waters on which any public work, as defined in s 253 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), is or was constructed, established or situated, and to which ss 23B(7) and 23C(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and to which s 21 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) applies, together with any adjacent land or waters in accordance with s 251D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

3. Those lands and waters within the External Boundary on which, at the time the native title determination application was made, public works were validly constructed, established or situated after 23 December 1996, where s 24JA of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies, and which wholly extinguished native title.

4. Those lands and waters within the External Boundary which, at the time the native title determination application was made, were the subject of one or more Pre-existing Rights Based Acts, within the meaning of s 24IB of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), which wholly extinguished native title.

5. The land and waters within the External Boundary in respect of which the parties have agreed that no determination is to be made at present and which are described in the following table:

Area description (at the time of the determination) |

Lot 140 on SP108487 |

Lot 191 on SP108475 |

Lot 11 on RP898338 |

Lot 12 on RP898338 |

Lot 1 on JD1 |

Lot 26 on NPW404 |

Lot 409 on NPW602 |

That part of Lot 410 on NPW603 formerly described as Portion 1 on Plan SO10 |

That part of Lot 410 on Plan NPW603 described as Denham Group National Park (Sinclair Islet, Milman Islet, Aplin Islet, Wallace Islet, Cholmondeley Islet and Boydong Island) |

Lot 18 on SP120091 |

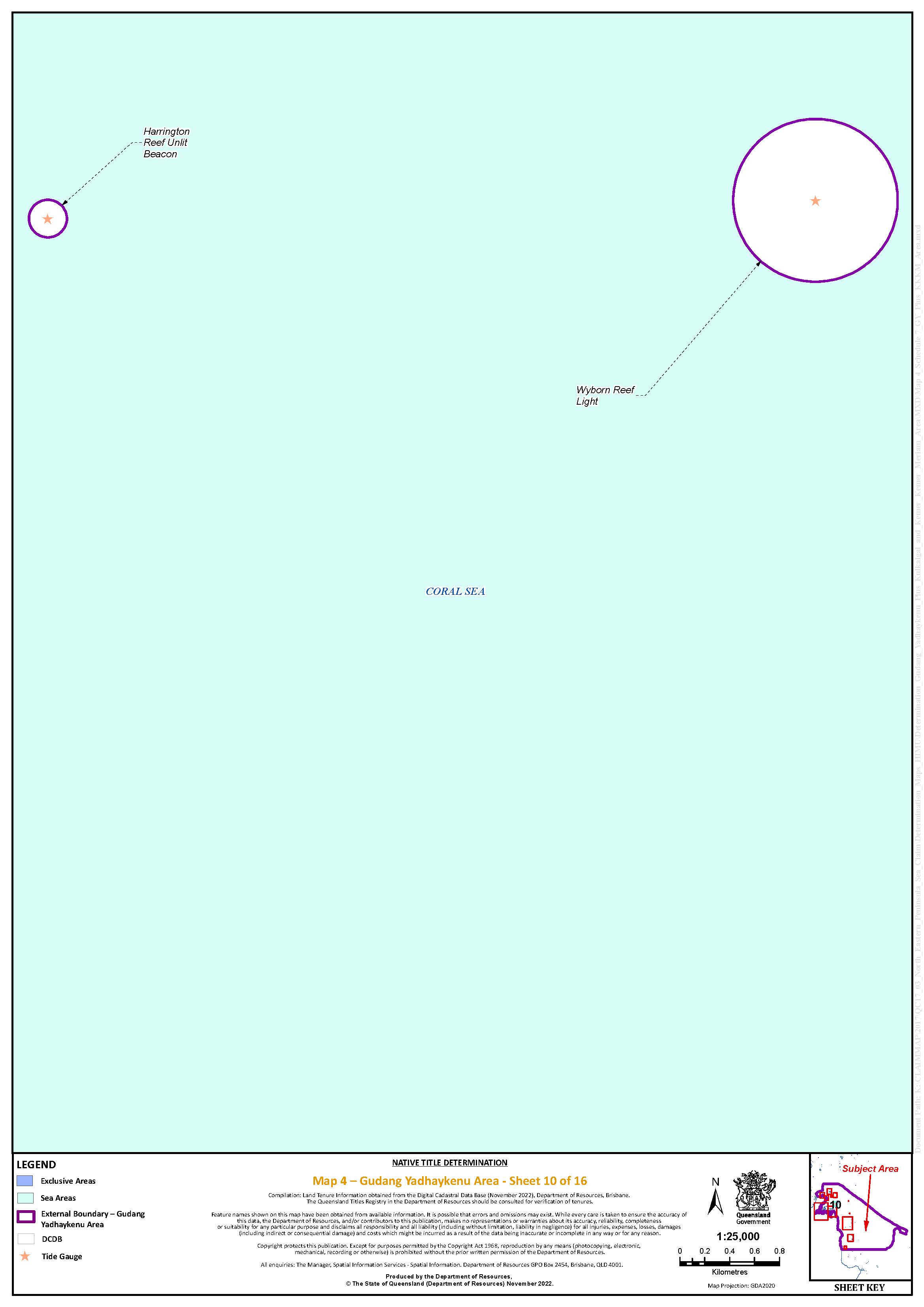

The area within a radius of 150 metres from the respective centre points of each Commonwealth asset as follows: Harrington Reef Unlit Beacon; approximate Longitude 142.719600° East, Latitude 10.820483° South (WGS84). Shortland Reef Unlit Beacon; approximate Longitude 142.766350° East, Latitude 10.896850° South (WGS84). The area within a radius of 650 metres from the respective centre points of each Commonwealth asset as follows: Wyborn Reef Light; approximate Longitude 142.775050° East, Latitude 10.819167° South (WGS84). Note Data Reference and source • Area boundary compiled by the National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants. • Commonwealth asset centre point details provided by the applicants. The Commonwealth have advised that AMSA maintains the coordinates in WGS84 for reasons relating to the international nature of shipping and navigation services. Reference datum Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time. Use of Coordinates Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey. Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022). |

The area within a radius of 150 metres from the respective centre points of each Commonwealth asset as follows: Booby Island Tide Gauge; approximate Longitude 141.910133° East, Latitude 10.602550° South (WGS84). Turtle Head Tide Gauge; approximate Longitude 142.213100° East, Latitude 10.520583° South (WGS84). Goods Island Tide Gauge; approximate Longitude 142.146650° East, Latitude 10.563350° South (WGS84). Ince Point Tide Gauge; approximate Longitude 142.304850° East, Latitude 10.514133° South (WGS84). Note Data Reference and source • Area boundary compiled by the National Native Title Tribunal based on information or instructions provided by the applicants. • Commonwealth asset centre point details provided by the applicants. The Commonwealth have advised that AMSA maintains the coordinates in WGS84 for reasons relating to the international nature of shipping and navigation services. Reference datum Geographical coordinates have been provided by the NNTT Geospatial Services and are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020), in decimal degrees and are based on the spatial reference data acquired from the various custodians at the time. Use of Coordinates Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome of the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey. Prepared by Geospatial Services, National Native Title Tribunal (28 September 2022) |