Federal Court of Australia

Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1424

File number(s): | NSD 1196 of 2021 |

Judgment of: | ABRAHAM J |

Date of judgment: | 29 November 2022 |

Catchwords: | CRIMINAL LAW – sentencing – cartel conduct – corporate offender pleaded guilty to two offences of giving effect to a cartel provision and one offence of attempting to make a contract, arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision – corporate offender admitted seven additional offences – where company generates revenue from sale of SNBB, hyoscine hydrobromide and Duboisia leaf |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) ss 2, 44ZZRF(1), 44ZZRG(1), 45AF(1), 45AG(1), 79(1)(aa) Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) ss 15A(1), 16A, 16BA Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) ss 44ZZRF(1), 44ZZRG(1) Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 10 |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 175 ALD 383 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Cement Australia [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) 258 FCR 312 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265; (2005) 215 ALR 301 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2016] FCA 1516; (2016) 118 ACSR 124 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Ltd [2008] FCA 1976; (2008) 253 ALR 89 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visy Industries Holdings Pty Ltd (No 3) [2007] FCA 1617; (2007) 244 ALR 673 Bae v R [2020] NSWCCA 35 CEO Customs v Labrador Liquor Wholesale Pty Ltd [2006] QCA 558; (2006) 65 ATR 547 Chief Executive of Customs v Jing [2007] NSWSC 1354 Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Vina Money Transfer Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 665 Darter v Diden [2006] SASC 152; (2006) 94 SASR 505 Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2019] FCA 1170; (2019) 137 ACSR 75 Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha [2017] FCA 876; (2017) 254 FCR 235 Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS [2021] FCA 52; (2021) 386 ALR 98 Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Page [2006] VSCA 224 Hamilton v Whitehead [1988] HCA 65; (1988) 166 CLR 121 Hili v The Queen; Jones v The Queen [2010] HCA 45; (2010) 242 CLR 520 Houghton v Arms [2006] HCA 59; (2006) 225 CLR 553 Imbornone v R [2017] NSWCCA 144 Jahandideh v R [2014] NSWCCA 178 Khalid v R [2020] NSWCCA 73; (2020) 102 NSWLR 160 Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59 R v Jones [2004] VSCA 68 R v Olbrich [1999] HCA 54; (1999) 199 CLR 270 R v Pham [2015] HCA 39; (2015) 256 CLR 550 R v Qutami [2001] NSWCCA 353; (2001) 127 A Crim R 369 Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1972] AC 153 Tyler v The Queen [207] NSWCCA 247; (2007) 173 A Crim R 458 Weininger v The Queen [2003] HCA 14; (2003) 212 CLR 629 Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Federal Crime and Related Proceedings |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Date of last submission/s: | 29 August 2022 |

5 September 2022 | |

Solicitor for the Prosecutor: | Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions |

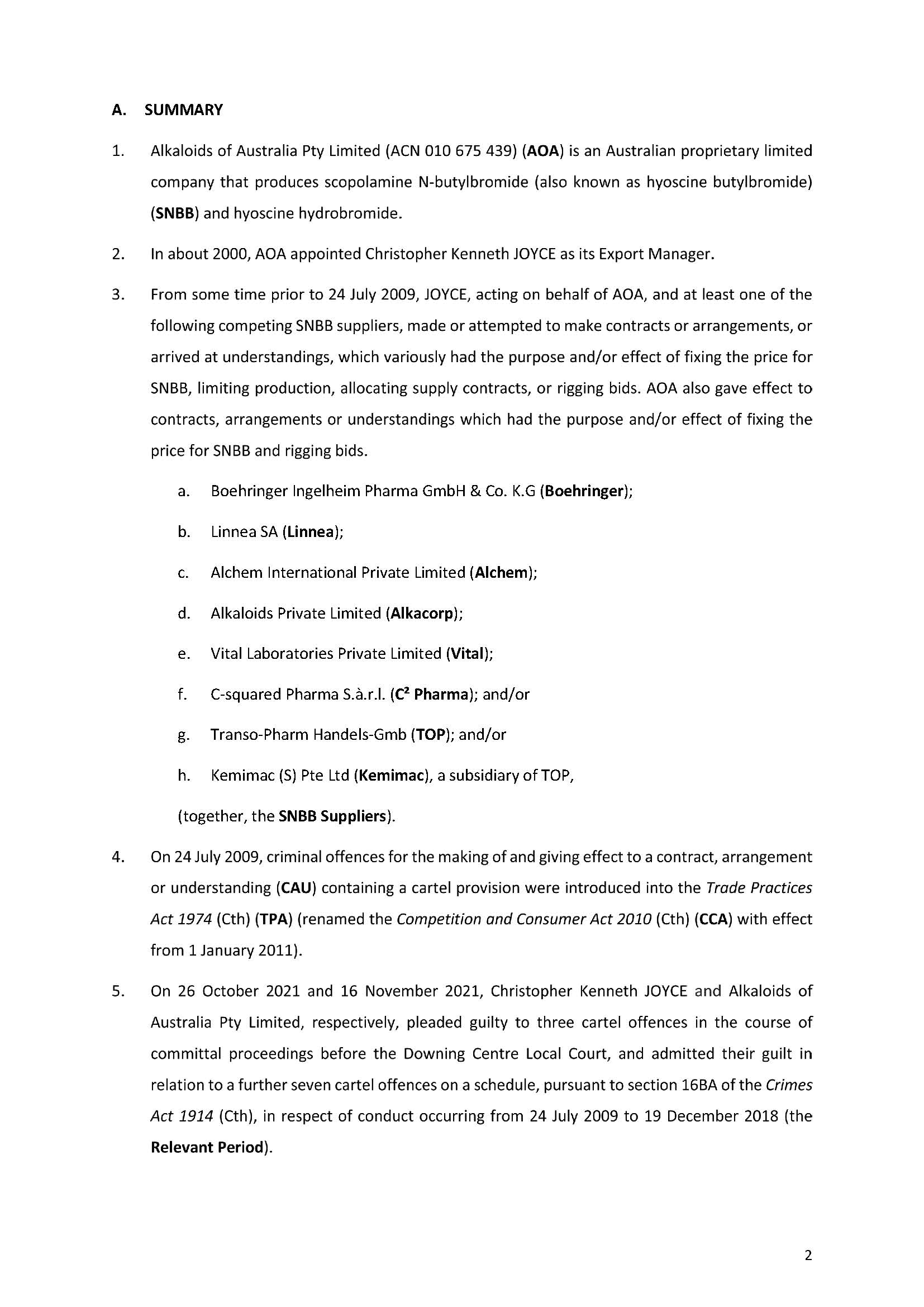

Counsel for the Offender: | Mr C Bannan with Mr E Kerkyasharian |

Solicitor for the Offender: | Ashurst |

ORDERS

COMMONWEALTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS Prosecutor | ||

AND: | ALKALOIDS OF AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Offender | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 november 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd is convicted of Charge 1, Charge 2 and Charge 3 of the indictment attached as Annexure A.

2. Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd in relation to Charge 1 is fined $1,500,000.

3. Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd in relation to Charge 2 is fined $375,000.

4. Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd in relation to Charge 3 is fined $112,500.

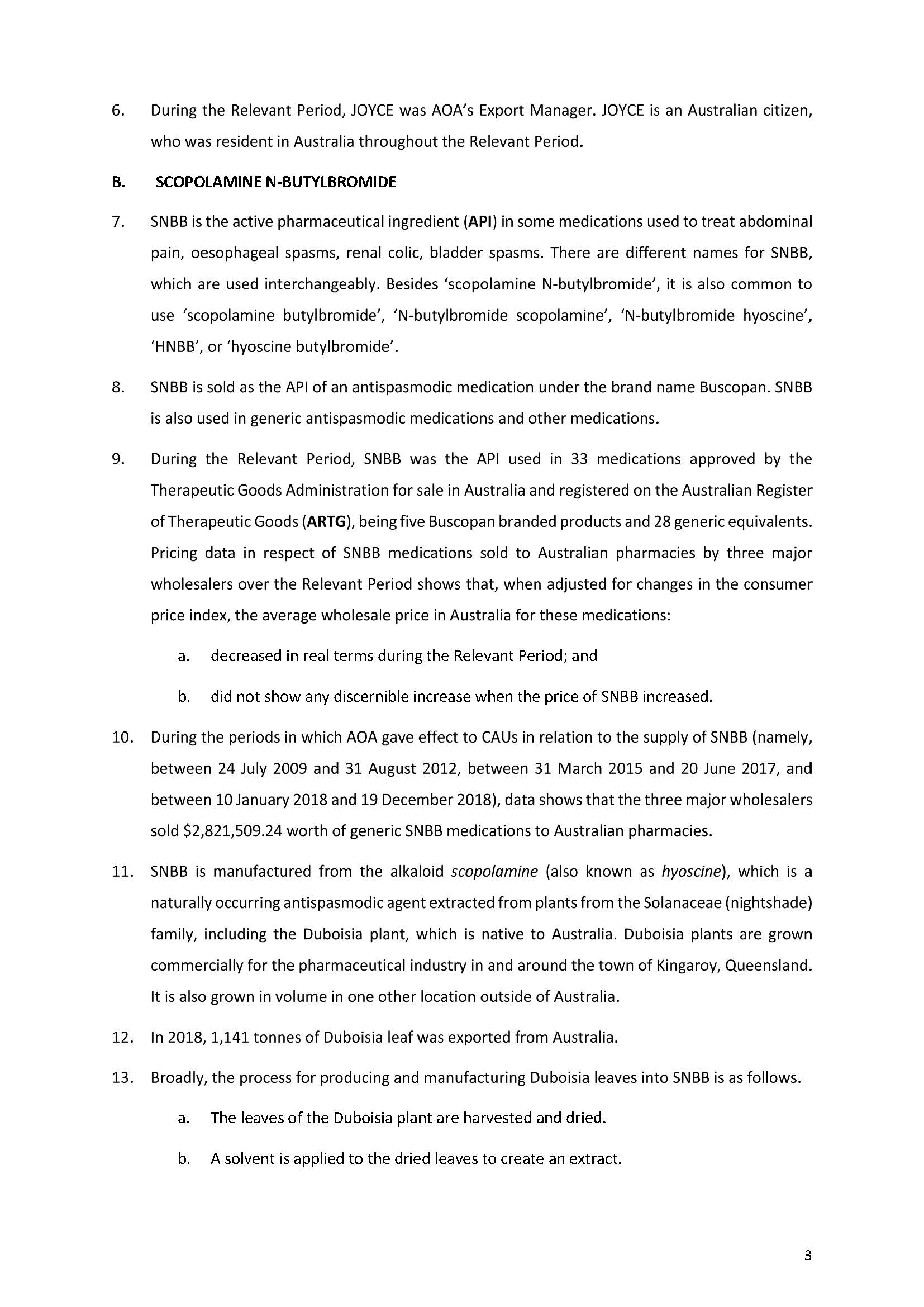

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ABRAHAM J:

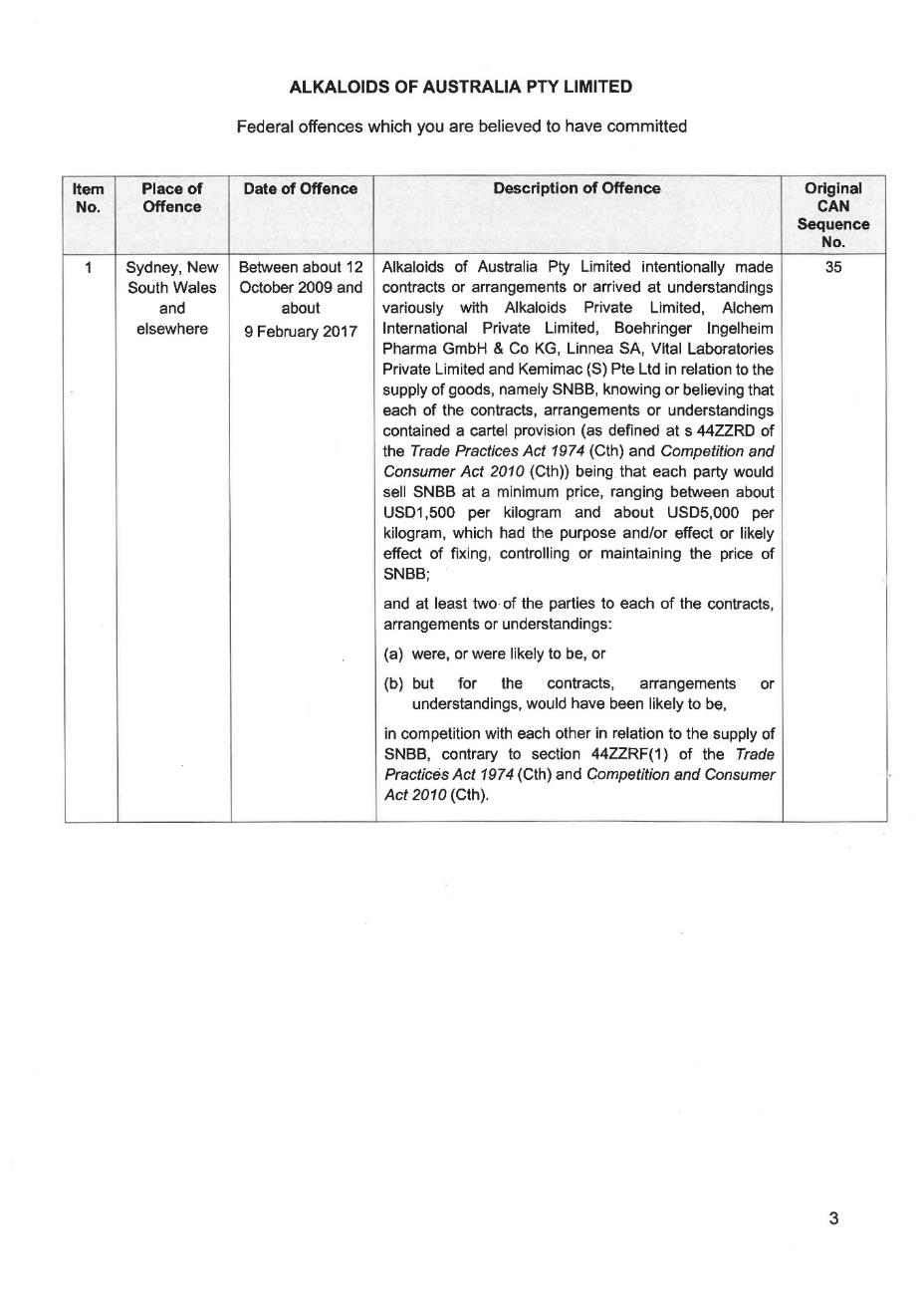

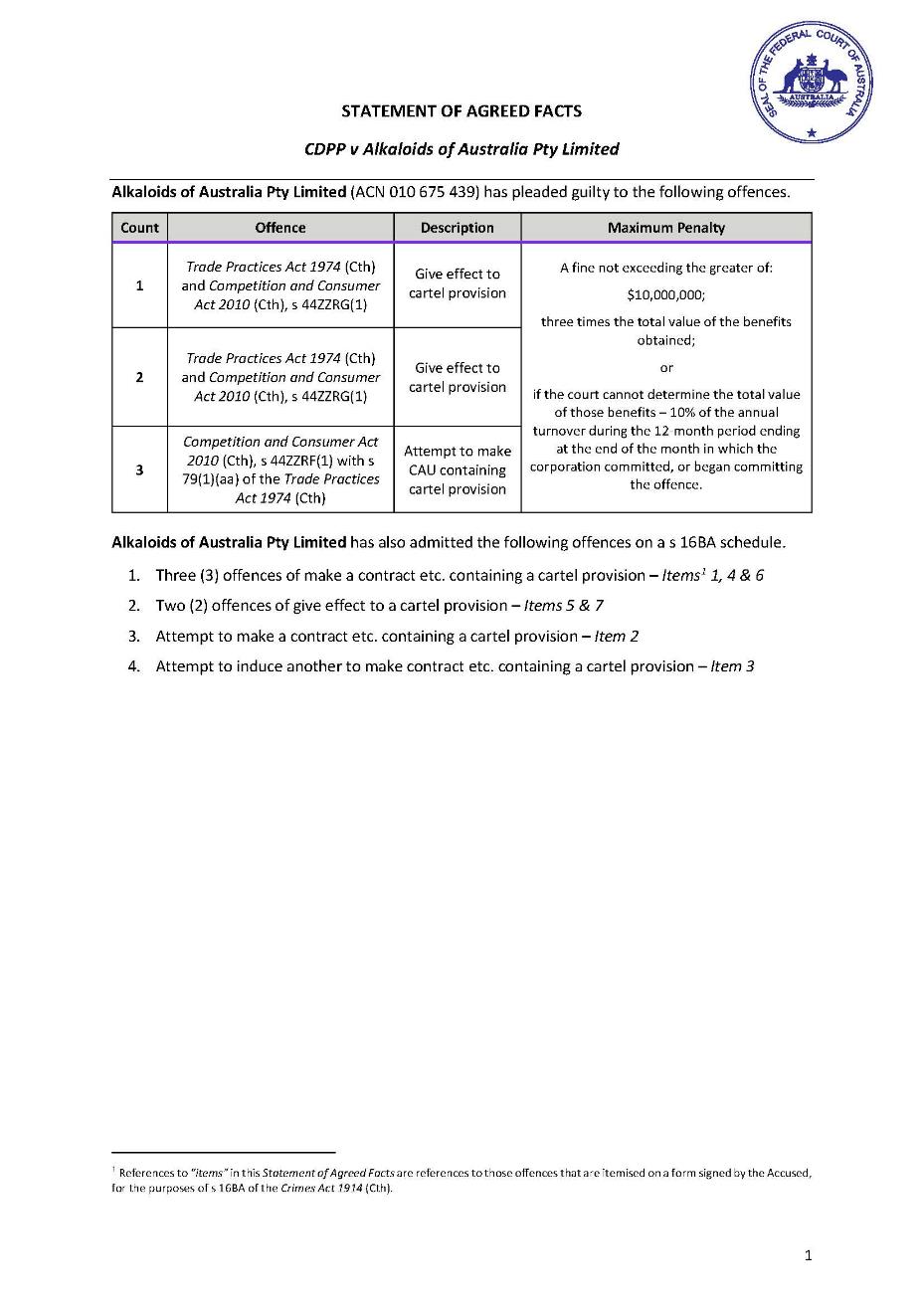

1 Alkaloids of Australia Pty Ltd (AOA) is to be sentenced for two offences of giving effect to a cartel provision, contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) and Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA), and one offence of attempting to make a contract, arrangement or understanding (CAU) containing a cartel provision, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(aa) of the CCA. AOA also admits seven additional offences under the TPA and CCA that are to be taken into account.

Background

2 AOA is an Australian company which produces scopolamine N-butylbromide (also known as hyoscine butylbromide) (SNBB) and hyoscine hydrobromide. SNBB is manufactured from the alkaloid scopolamine (also known as hyoscine), which is extracted from plants, including the native Duboisia plant. SNBB is the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in some medications used to treat abdominal pain, oesophageal spasms, renal colic and bladder spasms. SNBB is sold as the API of an antispasmodic medication under the brand name Buscopan and in generic antispasmodic and other medications.

3 Almost all of the SNBB manufactured by AOA is exported for manufacture into antispasmodic and other medications. From 24 July 2009 to 19 December 2018 (the Relevant Period), AOA sold approximately 29 tonnes of SNBB. Of this, approximately 6 kg of SNBB (0.02 percent) was sold by AOA to Australian customers, to a total value of $25,641. There is no material market for SNBB in Australia.

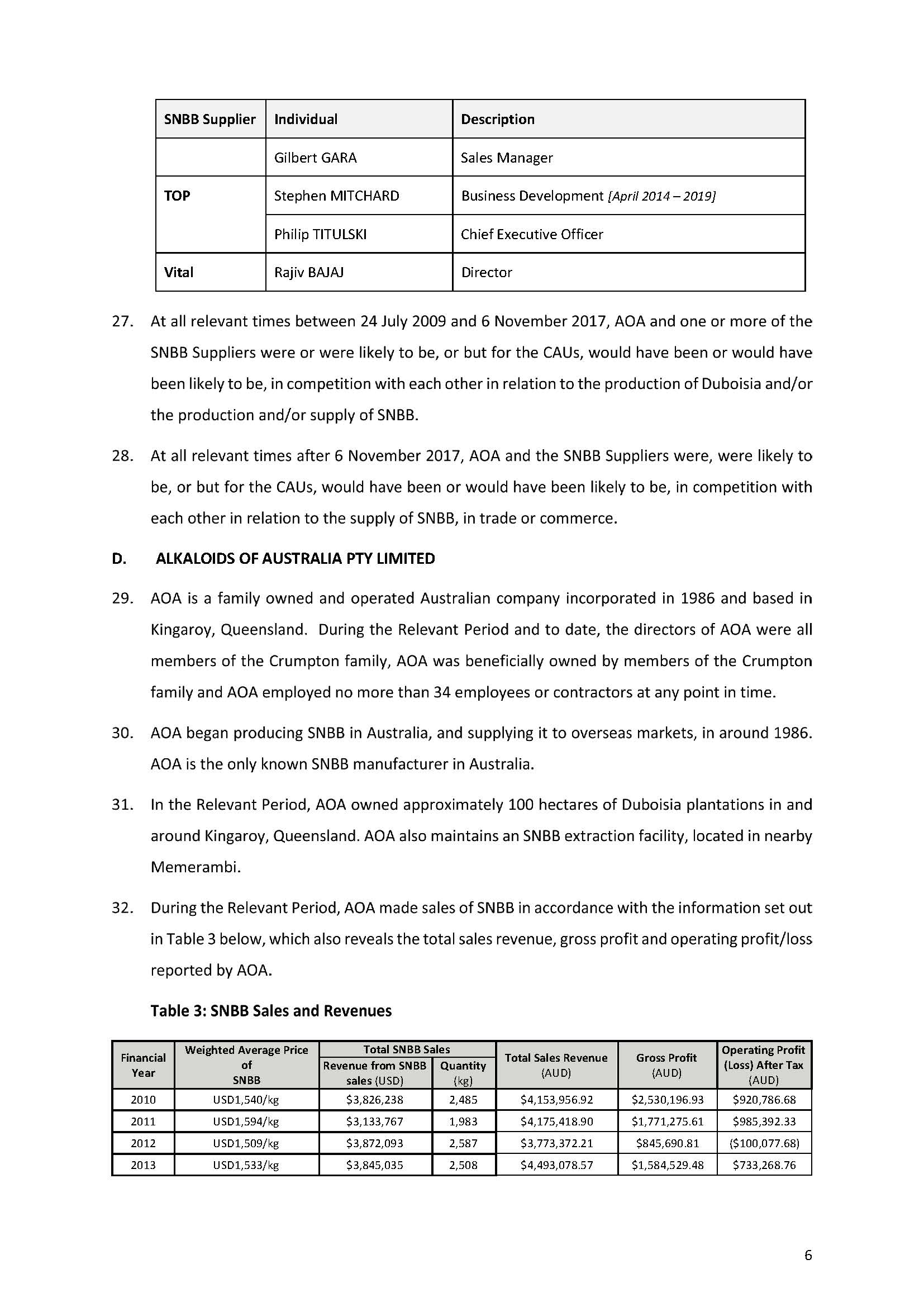

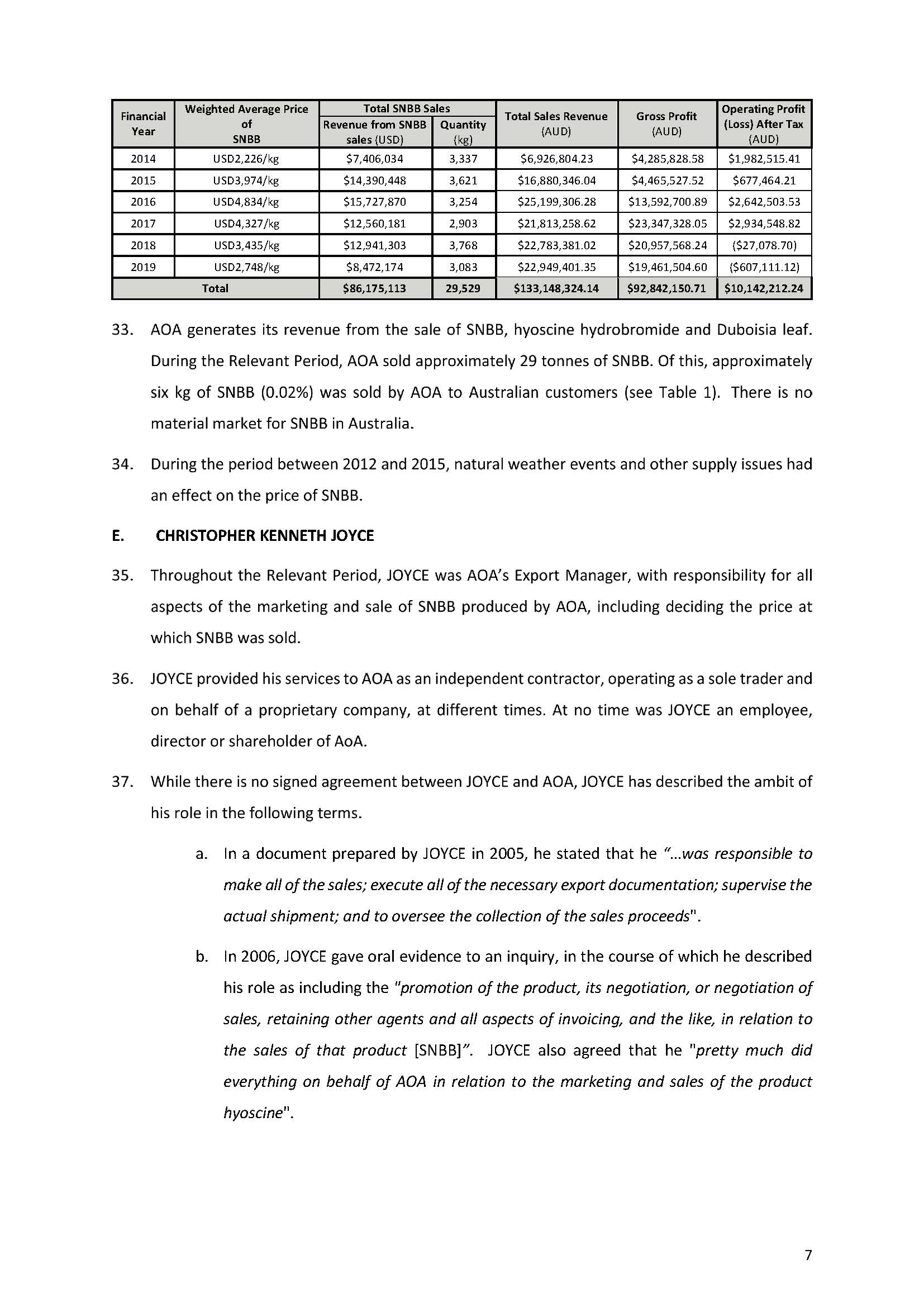

4 Medications containing SNBB (SNBB medications) are purchased in Australia. During the Relevant Period, SNBB was the API used in 33 medications approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for sale in Australia and registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. During the periods in which AOA gave effect to the CAUs in relation to the supply of SNBB, the three major wholesalers sold $2,821,509.24 worth of generic SNBB medications (that is, excluding Buscopan) to Australian pharmacies.

5 During the Relevant Period Christopher Kenneth Joyce was AOA’s Export Manager.

6 From sometime prior to 24 July 2009, Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA and at least one of its competitor SNBB suppliers, made or attempted to make CAUs, which variously had the purpose and/or effect of fixing the price for SNBB, limiting production, allocating supply contracts, or rigging bids. AOA also gave effect to CAUs which had the purpose and/or effect of fixing the price for SNBB and rigging bids. The competing SNBB suppliers were Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. K.G (Boehringer); Linnea SA (Linnea); Alchem International Private Limited (Alchem); Alkaloids Private Limited (Alkacorp); Vital Laboratories Private Limited (Vital); C-squared Pharma S.à.r.l. (C² Pharma); and/or Transo-Pharm Handels-Gmb (TOP); and/or Kemimac (S) Pte Ltd (Kemimac), a subsidiary of TOP.

7 AOA pleaded guilty to two counts of giving effect to a CAU and one count of attempting to make a CAU during the course of committal proceedings in the Local Court of New South Wales, and admitted their guilt in relation to a further seven cartel offences on a schedule (the Schedule), pursuant to s 16BA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) (Crimes Act). On 5 September 2022, those guilty pleas were affirmed on arraignment in this Court. The indictment and Schedule are attached to these reasons as Annexure A. For present purposes, it is sufficient to summarise the counts and offences on the Schedule as follows.

Offences

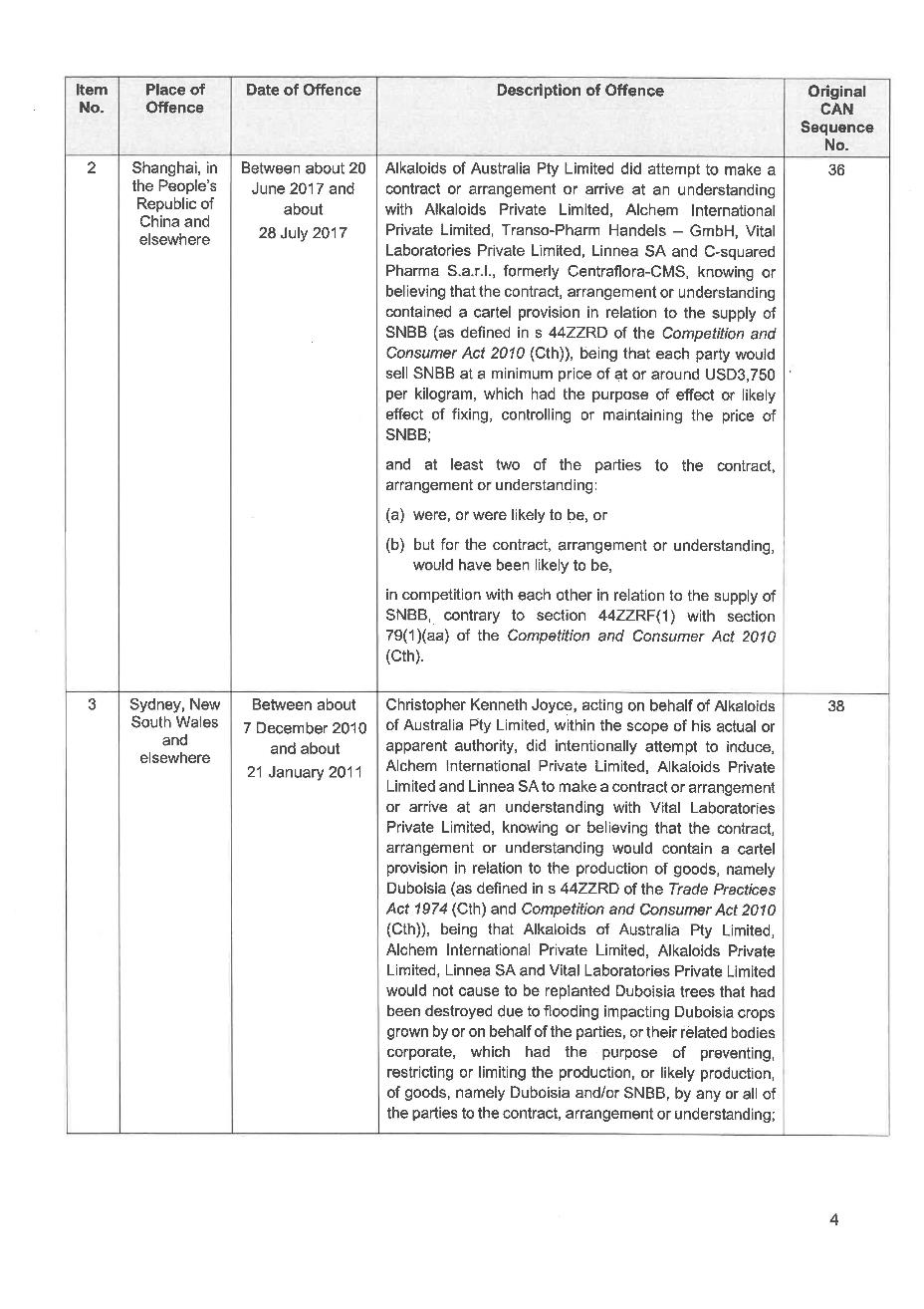

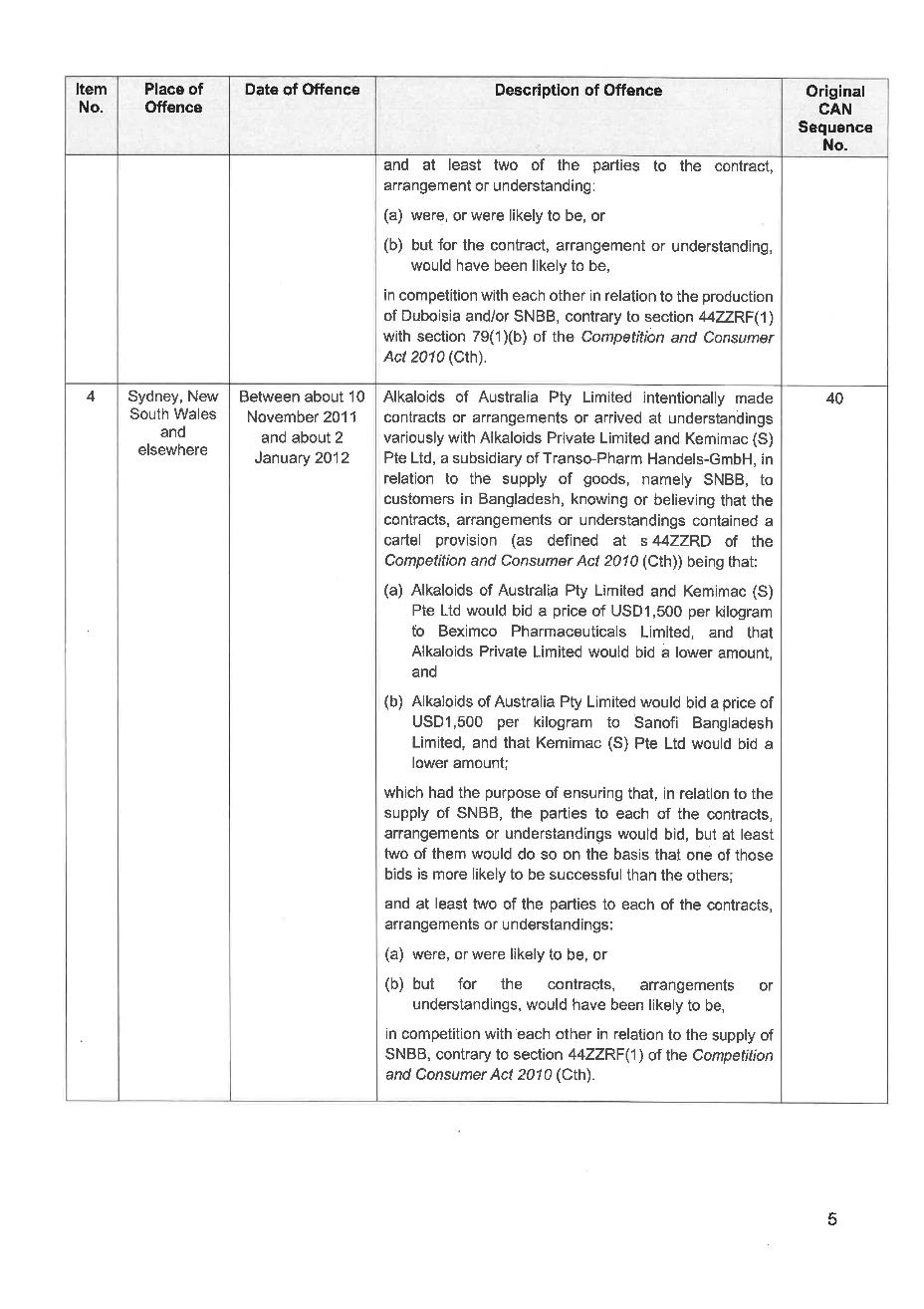

8 Count 1 relates to conduct between about 24 July 2009 and about 20 June 2017, when AOA intentionally gave effect to CAUs reached variously with Alkacorp, Alchem, Boehringer, Linnea, Vital and Kemimac that the parties to each of the CAUs would sell SNBB at a minimum price, variously ranging between about USD1,500 per kilogram and about USD5,000 per kilogram, knowing or believing that the cartel provisions had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB. This count is a rolled up offence which involves AOA giving effect to seven price fixing provisions in different CAUs with competitors over a number of years, contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the TPA and CCA. Although it is one count, the offending involves multiple acts of criminality and a course of conduct.

9 In addition, in sentencing for this count, AOA asks this Court to take into account two further offences: between about 12 October 2009 and about 9 February 2017 it made a CAU; and between about 20 June 2017 and about 28 July 2017 it attempted to make a CAU. These offences are included in the Schedule as Item 1, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) of the TPA and CCA, and Item 2, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(aa) of the CCA. Again, Item 1 is a rolled up count which relates to the making of each of six of the CAUs to which effect was given in Count 1.

10 Count 2 occurred between about 9 December 2010 and about 26 July 2012, when AOA, contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the TPA and CCA, intentionally gave effect to a cartel provision in relation to the supply of SNBB, contained in a CAU made between Alkacorp, Boehringer, Linnea, AOA and Alchem, being that Alkacorp and/or Alchem, or subsidiaries thereof, would acquire the entire supply of Duboisia leaves from a grower named David Thamm, and obtain a commitment from him that he would not grow or produce, or cause any Duboisia to be grown or otherwise produced, on his Memerambi property, knowing or believing that the cartel provision had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB.

11 In addition, in sentencing for this count, AOA asks this Court to take into account an offence, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(b) of the CCA, that between about 7 December 2010 and about 21 January 2011, it attempted to induce others into making a CAU: Item 3 on the Schedule.

12 Count 3 is that between about 19 September 2011 and about 28 December 2011, AOA attempted to make a CAU with Alkacorp and Kemimac knowing or believing that it contained cartel provisions in relation to the supply of SNBB, that: each party would sell SNBB in accordance with a pricing structure inversely tiered on the basis of the quantity to be supplied, with a minimum price of no lower than USD1,500 per kilogram, to customers in Bangladesh, which had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB; and the supply contracts in respect of the likely acquisitions of SNBB by Fisions (Bangladesh) Ltd, Opsonin Pharma Ltd and Essential Drugs Company Limited would be allocated variously to AOA, Alkacorp, and Kemimac which had the purpose of allocating between any or all of the parties to the CAU SNBB, from any or all of the parties to the CAU, and/or had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB. This conduct was contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(aa) of the CCA.

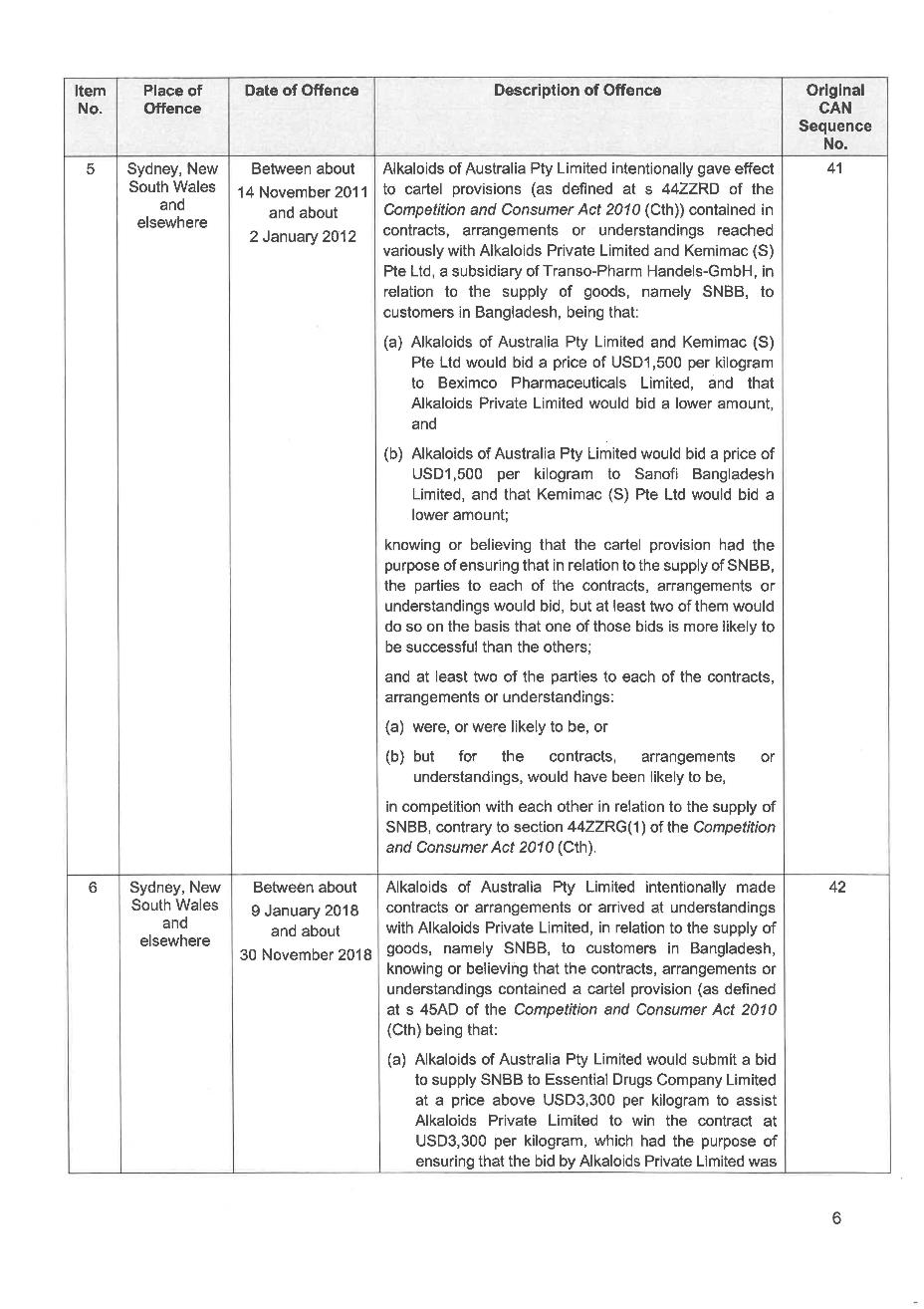

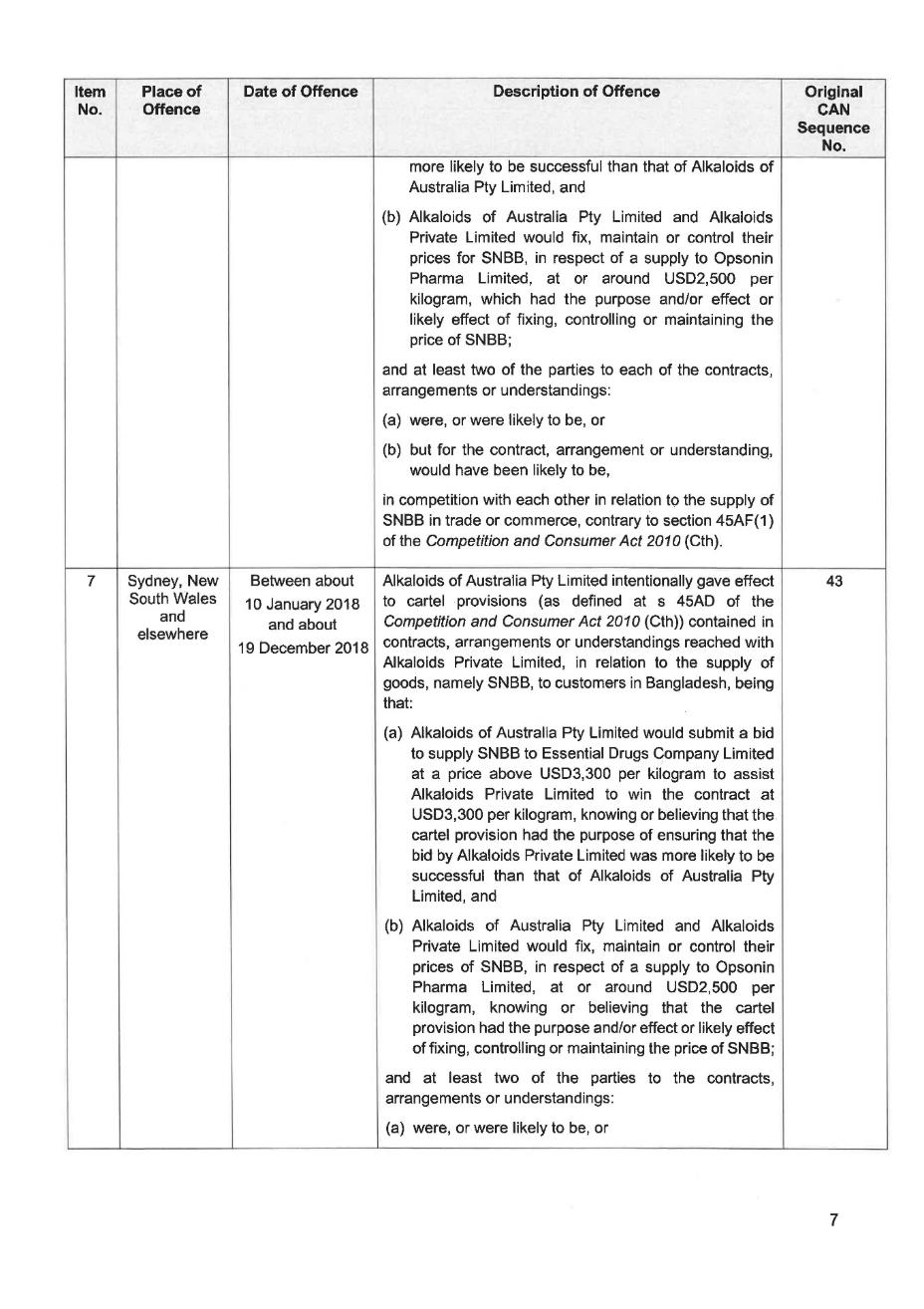

13 In addition, in sentencing for this count, AOA asks this Court to take into account four further offences that: between about 10 November 2011 and about 2 January 2012, it made a CAU (contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) of the CCA); between about 14 November 2011 and about 2 January 2012, it gave effect to cartel provisions (contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the CCA); between about 9 January 2018 and about 30 November 2018, it intentionally made CAUs (contrary to s 45AF(1) of the CCA); and between about 10 January 2018 and about 19 December 2018, it gave effect to cartel provisions (contrary to s 45AG(1) of the CCA).

14 AOA’s contravening conduct spans 9.5 years, although it is not alleged that AOA gave effect to any CAU in relation to the supply of SNBB between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 within that period. The offending conduct involved the six major manufacturers of SNBB. One of those manufacturers, Boehringer, produced around 80 percent of the SNBB produced globally each year. Boehringer supplied 65 percent to 70 percent of the SNBB for generic equivalents. As a result of the CAUs, the price of the relevant SNBB sold and quoted was higher than it otherwise would have been but for that conduct.

15 Before addressing the facts in more detail, it is appropriate to refer to the relevant sentencing principles.

Sentencing principles

16 The offender is to be sentenced in accordance with Part 1B of the Crimes Act, which requires that the sentence imposed by the Court be of a “severity appropriate in all the circumstances of the offence”: s 16A(1) of the Crimes Act.

17 In determining the sentence to be passed, in addition to any other matters, the Court must take into account the matters set out in s 16A(2) as far as they are relevant and known to the Court. This list relevantly includes: the nature and circumstances of the offence: s 16A(2)(a); if the offence forms part of a course of conduct consisting of a series of criminal acts of the same or a similar character, that course of conduct: s 16A(2)(c); any injury, loss or damage resulting from the offence: s 16A(2)(e); the degree to which the person has shown contrition for the offence: s 16A(2)(f); if the person has pleaded guilty to the charge in respect of the offence, that fact, the timing of the plea, and the degree to which that fact and the timing of the plea resulted in any benefit to the community, or any victim of, or witness to, the offence: s 16A(2)(g); the degree to which the person has cooperated with law enforcement agencies in the investigation of the offence or of other offences: s 16A(2)(h); the deterrent effect that any sentence or order under consideration may have on the offender: s 16A(2)(j) (specific deterrence); the deterrent effect that any sentence or order under consideration may have on other persons: s 16A(2)(ja) (general deterrence); the need to ensure that the person is adequately punished for the offence: s 16A(2)(k); the character, antecedents, age, means and physical and mental condition of the person: s 16A(2)(m); if the person’s standing in the community was used by the person to aid in the commission of the offence, that fact as a reason for aggravating the seriousness of the criminal behaviour to which the offence relates: s 16A(2)(ma); the prospects of rehabilitation of the person: s 16A(2)(n); and the probable effect that any sentence or order under consideration would have on any of the person’s family or dependents: s 16A(2)(p).

18 In Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha [2017] FCA 876; (2017) 254 FCR 235 (NYK) at [220] and later in Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2019] FCA 1170; (2019) 137 ACSR 75 (K-Line) at [279]-[281] and Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS [2021] FCA 52; (2021) 386 ALR 98 (WWO) at [174]-[175], Wigney J recognised that some guidance as to relevant sentencing factors in this context can be gained from civil penalty cases in respect to cartel conduct. In those cases, his Honour referred to the convenient summary of the principles in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2016] FCA 1516; (2016) 118 ACSR 124 (ANZ) at [86]-[89]:

[86] In general terms, the factors that may be relevant when fixing a pecuniary penalty may conveniently be categorised according to whether they relate to the objective nature and serious [sic] of the offending conduct, or concern the particular circumstances of the contravenor in question (what sentencing judges commonly refer to as the offender’s “subjectives” or the “subjective circumstances”).

[87] The factors relating to the objective seriousness of the contravention include: the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate, covert or reckless conduct, as opposed to negligence or carelessness; whether the contravention comprised isolated conduct, or was systematic or occurred over a period of time; if the contravenor is a corporation, the seniority of the officers responsible for the contravention; the existence, within the corporation, of compliance systems and whether there was a culture of compliance at the corporation; the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties; and the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention.

[88] The factors that concern the particular circumstances of the contravenor (where the contravenor is a corporation) generally include: the size and financial position of the contravening company; whether the company has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in the past; whether the company has improved or modified its compliance systems since the contravention; whether the company (through its senior officers) has demonstrated contrition and remorse; whether the company had disgorged any profit or benefit received as a result of the contravention, or made reparation; whether the company has cooperated with and assisted the relevant regulatory authority in the investigation and prosecution of the contravention; and whether the company has suffered any extra-curial punishment or detriment arising from the finding that it had contravened the law.

[89] The size of the contravening corporation does not of itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 at 559-561 [89]-[92]. The size of the corporation may, however, be particularly relevant in determining the size of the pecuniary penalty that would operate as an effective deterrent. The sum required to achieve that object will generally be larger where the company has vast resources: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265; 215 ALR 301 at 309 [39]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Apple Pty Limited [2012] FCA 646 at [38].

19 As I observed in Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Vina Money Transfer Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 665 (Vina Money Transfer) at [109], although there are differences between the civil process and the criminal process, the factors referred to in ANZ are not surprising, and are really matters of common sense, given the nature of cartel offences: also see WWO at [175]. That said, care must be taken in considering these factors (and the potential weight to be attached to them) in a criminal context, given the different principles which apply in criminal sentencing: see, for example, Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 175 ALD 383 at [105].

20 The sentencing process involves the judge weighing all the relevant circumstances and making a judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence. It involves the balancing of many different and conflicting features: Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [75] (Wong). This has been described as a process of “instinctive synthesis”, namely, as described by McHugh J in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [51] (Markarian), “the method of sentencing by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case”.

21 That said, general deterrence is of particular importance given the nature of cartel offending, which like other “white collar” offending is difficult to detect, investigate and prosecute successfully: Vina Money Transfer at [110]-[112]; NYK at [273]-[274].

22 As general deterrence is ordinarily a primary sentencing consideration for such offending, factors personal to the offender such as good character and other mitigatory factors are necessarily afforded less weight than they otherwise might be: Vina Money Transfer at [112]; and Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Page [2006] VSCA 224 at [37].

23 It is important to recall that in sentencing, a court may not take into account facts adverse to the interests of the offender unless those facts are established beyond reasonable doubt. For facts in favour of the offender, it is enough that those facts are proved on the balance of probabilities: R v Olbrich [1999] HCA 54; (1999) 199 CLR 270 at [27]. The onus is on the offender to establish those mitigating factors. That said, as noted above at [17], s 16A of the Crimes Act requires that those matters be taken into account so far as they are “relevant and known to the court”. That phrase is not to be construed as imposing a universal requirement that matters urged in sentencing hearings be either formally proved or admitted: Weininger v The Queen [2003] HCA 14; (2003) 212 CLR 629 at [21]-[22].

24 It is also important to recall the approach a court is to take when sentencing for a rolled up count. A rolled up count is a count in which more than one contravention of the relevant offence provision, or more than one episode of criminality, is particularised as part of the charge. Count 1 is a rolled up count. This approach is adopted in some cases where there is a guilty plea, and where there is consent of the offender’s counsel, for otherwise the counts would be regarded as duplicitous: R v Jones [2004] VSCA 68 at [13] (Jones); NYK at [206]-[207]. The maximum penalty for the offence remains the same as if it were a single offence. However, the objective criminality of the offence is greater for the offender than if there was only one count: Jones at [13]; NYK at [207].

25 Relevantly, in K-Line, Wigney J observed at [270]:

[270] In sentencing a rolled-up charge, the Court is required to assess the criminality of an offender’s conduct as particularised. The issue for the Court on sentence is the criminality disclosed by the offence, not the number of charges: R v Knight [2004] NSWCCA 145 at [25]-[26]. The more contraventions or episodes of criminality that form part of the rolled-up charge, the more objectively serious the offence is likely to be: R v Richard [2011] NSWSC 866 at [65(f)]; R v Glynatsis [2013] NSWCCA 131; 230 A Crim R 99 at [66]; R v De Leeuw [2015] NSWCCA 183 at [116]. That said, the maximum penalty for the rolled-up charge is the maximum penalty for one offence, not the aggregate of the penalties for what could have been charged as separate offences: R v Richard at [105]; R v Donald [2013] NSWCCA 238 at [85].

26 In WWO, Wigney J further observed at [227]-[230]:

[227] The objective of taking other offences into account pursuant to provisions such as s 16BA of the Crimes Act is to ensure that the sentence imposed “is one which best meets the situation”: AG’s Application at [30]. The Court takes into account the other offences “with a view to increasing the penalty that would otherwise be appropriate for the particular offence” for which the offender is to be sentenced: AG’s Application at [42]. The increased penalty is effectively the product of the Court giving greater weight to two elements in the sentencing process: the first being the need for personal deterrence, as the commission of other offences will frequently indicate that the accused has engaged in a course of conduct; the second being “the community’s entitlement to extract retribution for serious offences when there are offences for which no punishment has in fact been imposed”: AG’s Application at [42]. The additional penalty as a result of taking the s 16BA offences into account will not necessarily be small; sometimes it will be substantial: AG’s Application at [18].

[228] The manner and degree to which other offences, which are taken into account pursuant to provisions such as s 16BA of the Crimes Act, can impinge upon elements relevant to the sentencing process will depend on a range of other factors pertinent to those elements and the weight to be given to them in the overall sentencing task. For that reason it will rarely be appropriate for a sentencing judge to attempt to quantify the effect on the sentence of taking those other offences into account: AG’s Application at [44].

[229] Section 16BA must be applied having regard to the basic common law principle that no one should be punished for an offence of which he or she has not been convicted. Section 16BA offences constitute an admission of guilt only: there is, relevantly, no conviction: AG’s Application at [23]. It follows that in taking the s 16BA offences into account, the sentencing judge is not imposing any punishment for those offences: AG’s Application at [29]. Rather, when taking the other (s 16BA) offences into account, the Court is concerned and concerned only with imposing a sentence for “the principal offence”; it is no part of the task of the sentencing court to determine appropriate sentences for s 16BA offences or to determine the overall sentence that would be appropriate for all the offences and then apply a “discount” for the use of the procedure under s 16BA: AG’s Application at [39]. The use of the s 16BA procedure, however, will generally result in a lower effective sentence than would have been imposed if the offender had been separately sentenced for the s 16BA offences: AG’s Application at [34].

[230] The Court is given an overriding discretion to refuse to accede to the wishes of the prosecution and the offender in terms of the utilisation of the s 16BA procedure: AG’s Application at [47]. That is a wide discretion which “should not be confined by the identification of a list of situations in which it should not be exercised”: AG’s Application at [48].

27 It may be expected that use of the procedure set out in s 16BA will result in a lower effective sentence than would have been imposed if an offender had been sentenced for the principal offence and separately sentenced for each of the offences included in the s 16BA schedule. That said, “[i]t does not follow, however, that the increase to the penalty as a result of taking the two s 16BA offences into account will necessarily be small”: WWO at [233].

28 The parties agree that the maximum penalty for each offence in this case is $10,000,000 pursuant to ss 44ZZRF(3), 44ZZRG(3), 45AF(3) and 45AG(3) of the CCA, which provide:

Penalty

(3) An offence against subsection (1) is punishable on conviction by a fine not exceeding the greater of the following:

(a) $10,000,000;

(b) if the court can determine the total value of the benefits that:

(i) have been obtained by one or more persons; and

(ii) are reasonably attributable to the commission of the offence;

3 times that total value;

(c) if the court cannot determine the total value of those benefits—10% of the corporation’s annual turnover during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the corporation committed, or began committing, the offence.

29 The parties agree that the Court cannot determine the total value of the benefits obtained by AOA which are reasonably attributable to the commission of the offences and that 10 percent of AOA’s annual turnover in respect of the relevant 12 month periods is less than $10,000,000.

30 In this regard, in Markarian, the plurality observed at [31]:

[31] … careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

31 The tiered approach to the maximum penalty indicates that the Parliament views cartel conduct very seriously. In K-Line Wigney J said at [278]:

[278] It may equally be accepted that offences against s 44ZZRG(1) of the Competition Act specifically are objectively very serious. That is reflected in the maximum penalty for the offence, which is at least $10 million and may be considerably more in cases where the benefit derived from the offence was large, or the offender itself was a very large corporation with a high turnover.

The nature and circumstances of the offending

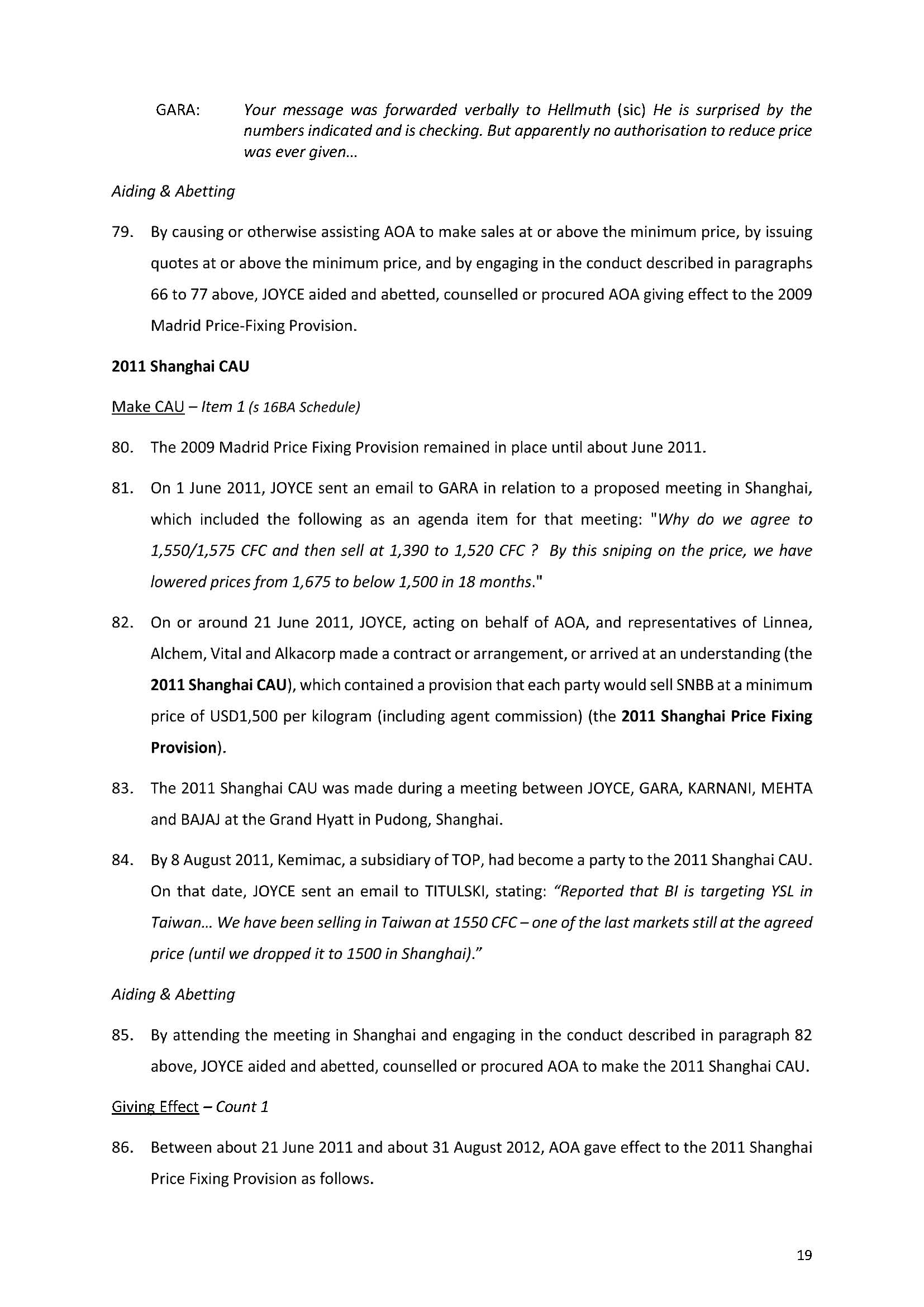

32 This matter proceeded by way of a statement of agreed facts (SOAF), a copy of which is attached to this judgment as Annexure B.

33 Before addressing the particular counts it is appropriate to make some general observations.

34 These offences were committed over a substantial period of time, reflective of an ongoing course of anti-competitive conduct.

35 AOA is a family owned and operated Australian company incorporated in 1986 and based in Kingaroy, Queensland. During the Relevant Period and to date: the directors of AOA are all members of the Crumpton family; AOA is beneficially owned by members of the Crumpton family; and AOA employs no more than 34 employees or contractors at any point in time. At various times the directors have included Glenn Crumpton, John Crumpton and Sonie Crumpton.

36 AOA began producing SNBB in Australia, and supplying it to overseas markets, in around 1986. AOA is the only known SNBB manufacturer in Australia. In the Relevant Period, AOA owned approximately 100 hectares of Duboisia plantations in and around Kingaroy. AOA also maintains an SNBB extraction facility, located in nearby Memerambi.

37 AOA generates its revenue from the sale of SNBB, hyoscine hydrobromide and Duboisia leaf.

38 During the Relevant Period, AOA sold approximately 29 tonnes of SNBB. Of this, approximately 6kg of SNBB (0.02 percent) was sold by AOA to Australian customers.

39 During the period between 2012 and 2015, natural weather events and other supply issues affected the price of SNBB.

40 From the figures in SOAF [32], it is apparent that revenue from SNBB sales accounted for a substantial proportion of all revenue generated by AOA.

41 As previously explained, throughout the Relevant Period, Mr Joyce was AOA’s Export Manager, with responsibility for all aspects of the marketing and sale of SNBB produced by AOA, including deciding the price at which SNBB was sold. He was an independent contractor. At all material times, he acted within the scope of his actual or apparent authority as Export Manager. Mr Joyce was paid a monthly retainer of AUD9,500 and a commission of 2 percent of AOA’s SNBB sales revenue.

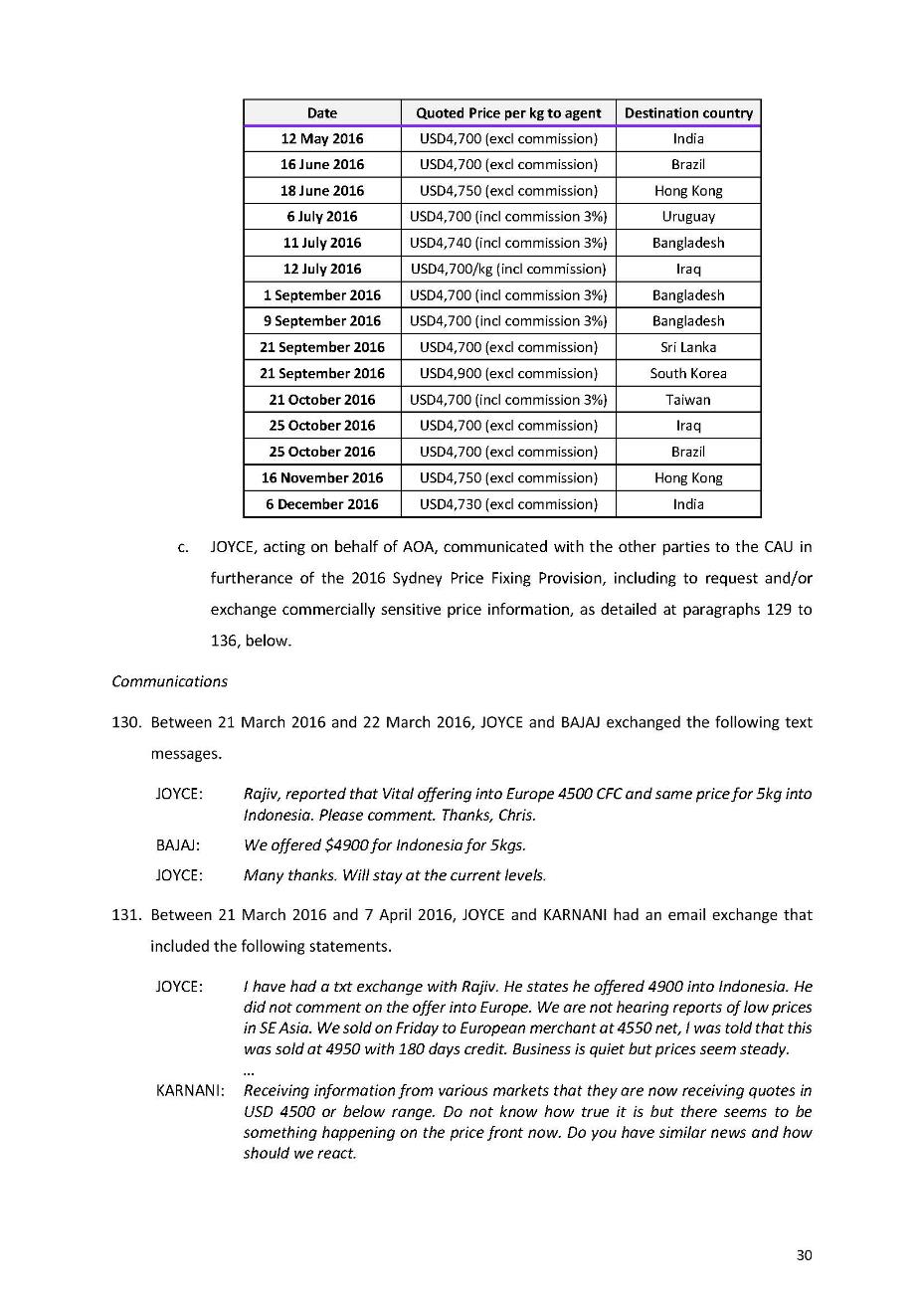

Count 1: Giving effect to a CAU

42 This rolled up count encompasses AOA giving effect to seven different CAUs containing price fixing provisions. As reflected in the SOAF, the seven price fixing provisions have titles for ease of reference to assist, which reflect, in most cases, the location where the arrangement was made. Those names are 2009 Geneva CAU: SOAF [49]-[57]; 2009 Madrid CAU: SOAF [66]-[78]; 2011 Shanghai CAU: SOAF [86]-[97]; 2015 AOA/Alkacorp CAU: [105]; 2015 Madrid CAU: SOAF [114]-[121]; 2016 Sydney CAU: SOAF [129]-[137]; and 2017 AOA/Alkacorp/Linnea CAU: [148]-[150].

43 On this count, Items 1 and 2 of the Schedule are to be taken into account. Item 1 is also rolled up, and includes six offences of making a CAU which coincide with the last six CAUs referred to immediately above (the first agreement was made before the conduct was made a criminal offence).

44 The offending conduct involved six of the major manufacturers of SNBB (Boehringer, Linnea, Alchem, Alkacorp, Vital and AOA), who between them produce Buscopan and supply the SNBB used to manufacture the vast majority of its generic equivalents. The offending conduct raised the price of SNBB, which potentially affected SNBB customers around the world. A significant amount of SNBB medications were sold to Australian pharmacies.

45 The offending the subject of the count occurred during a period spanning about 7 years, 10 months and 27 days (between 24 July 2009 and 31 August 2012, and 31 March 2015 and 20 June 2017), noting as above that it is not alleged AOA gave effect to the CAU between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 (meaning the period of offending is reduced to 5 years 3 months and 26 days), with a further 38 days once the additional admitted offending in Items 1 and 2 of the Schedule are considered. The offending conduct was on foot since before the charge period commenced on 24 July 2009. The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (the Director) accepted that AOA is not to be punished for conduct prior to the charge period, and it does not aggravate the offence, but it provides background in respect to giving effect to the 2009 Geneva CAU. It also reinforces that the offending conduct was not anomalous.

46 In respect to each of the seven CAUs, the SOAF contains, inter alia, facts as to: the number of sales made; and the occasions on which AOA gave effect to the relevant CAU by quoting the price in accordance with the CAU. In respect to each CAU, Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA, communicated with the other parties to the CAU in furtherance of the relevant price fixing provision, including to request and/or exchange commercially sensitive price information.

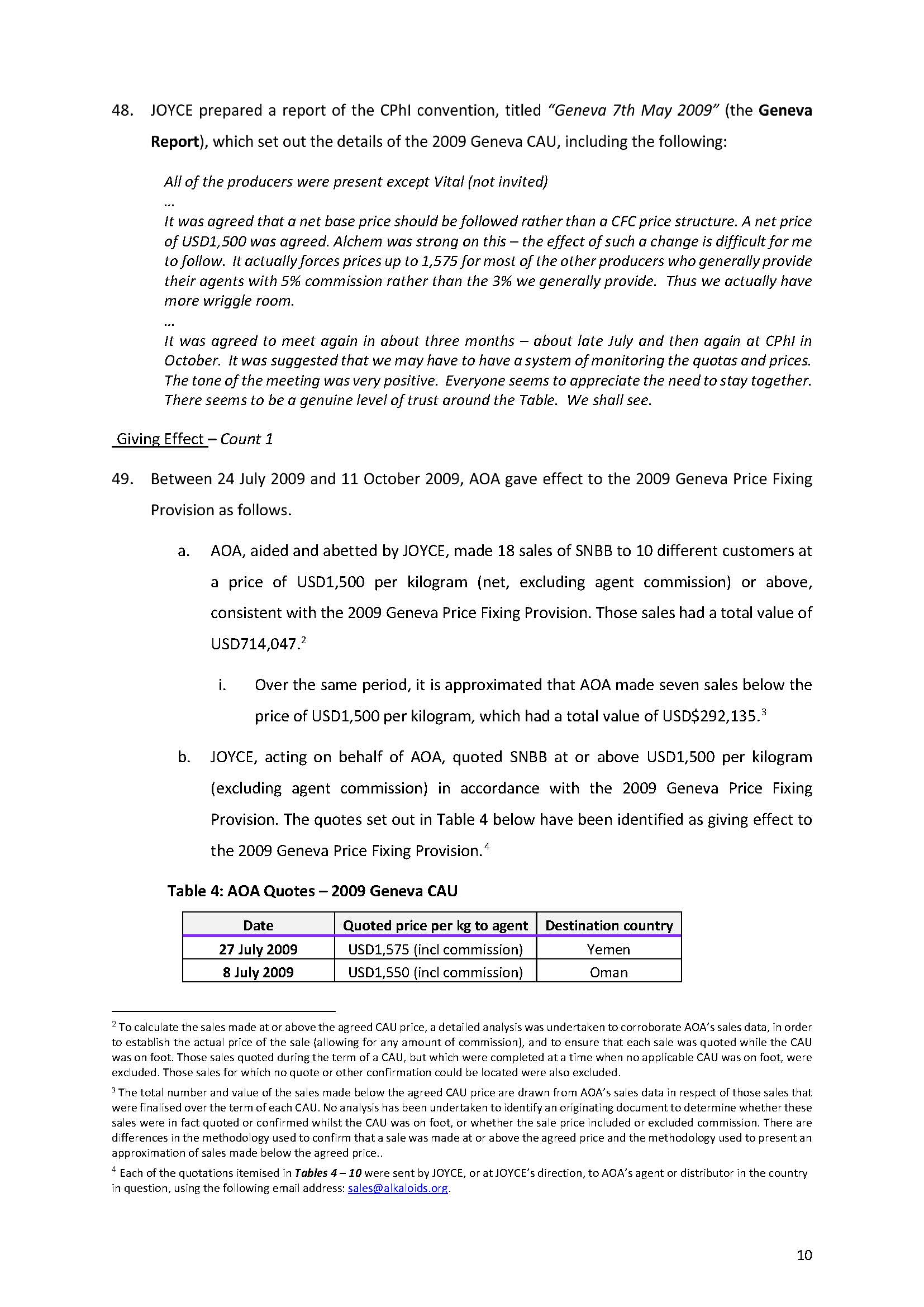

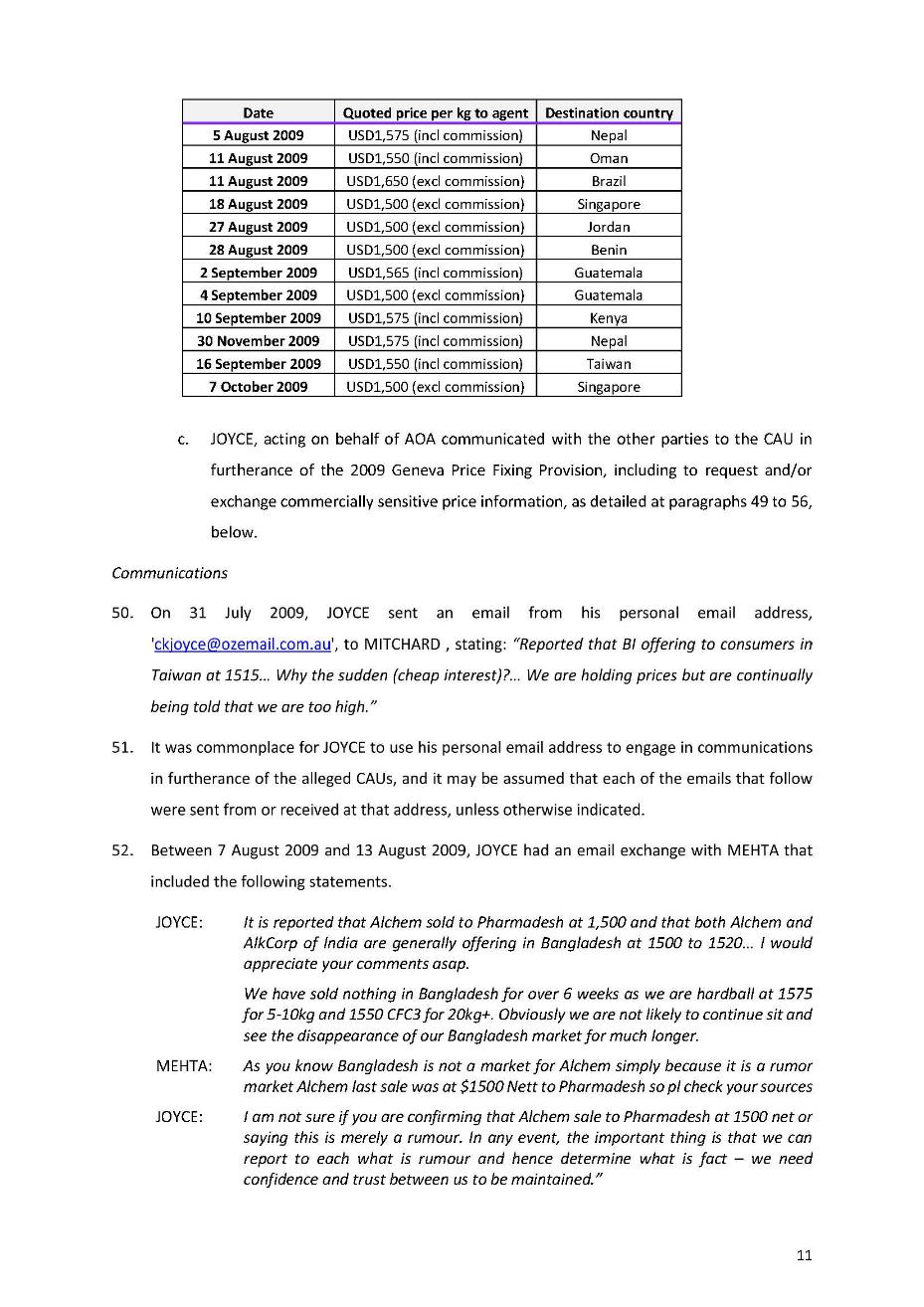

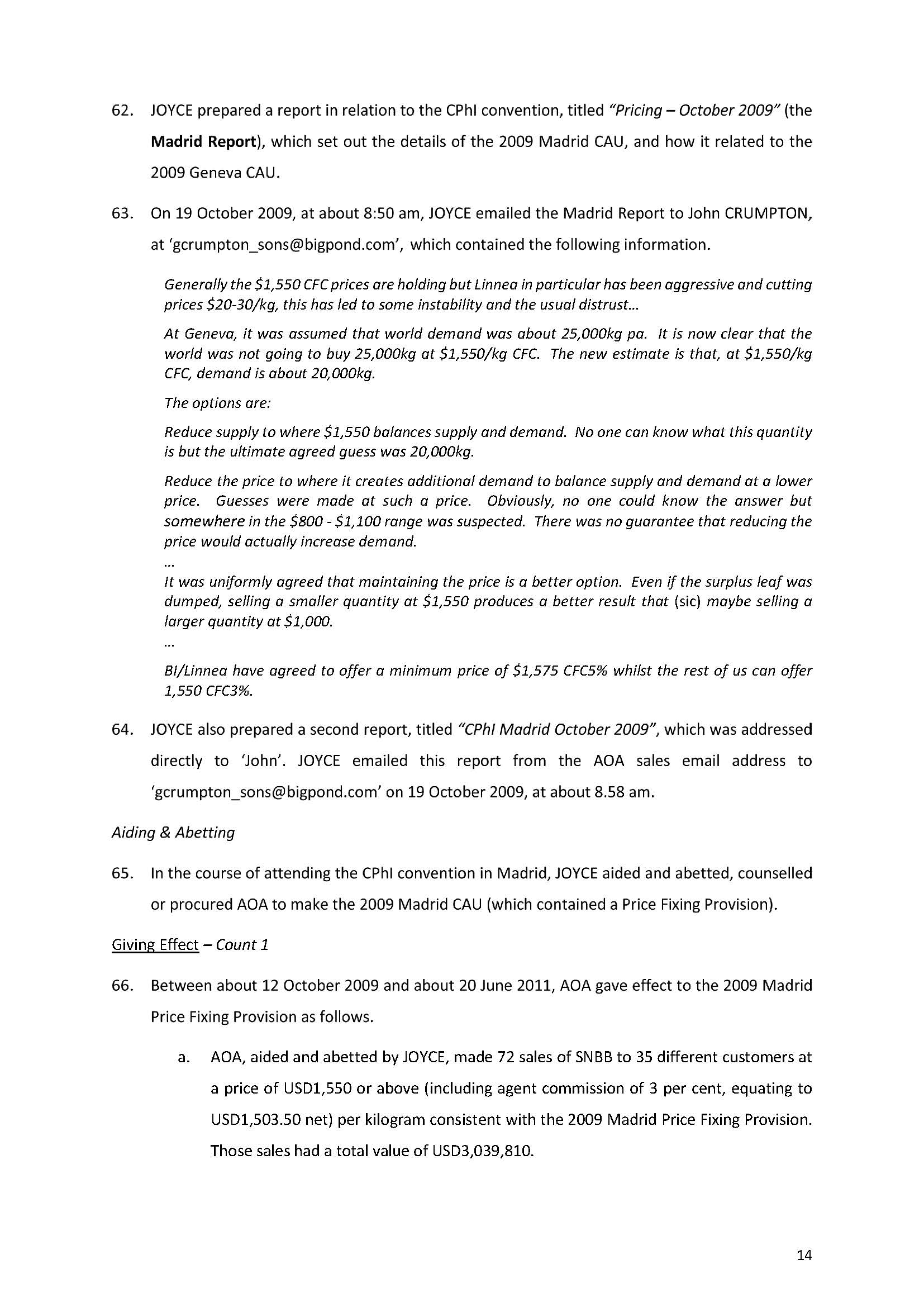

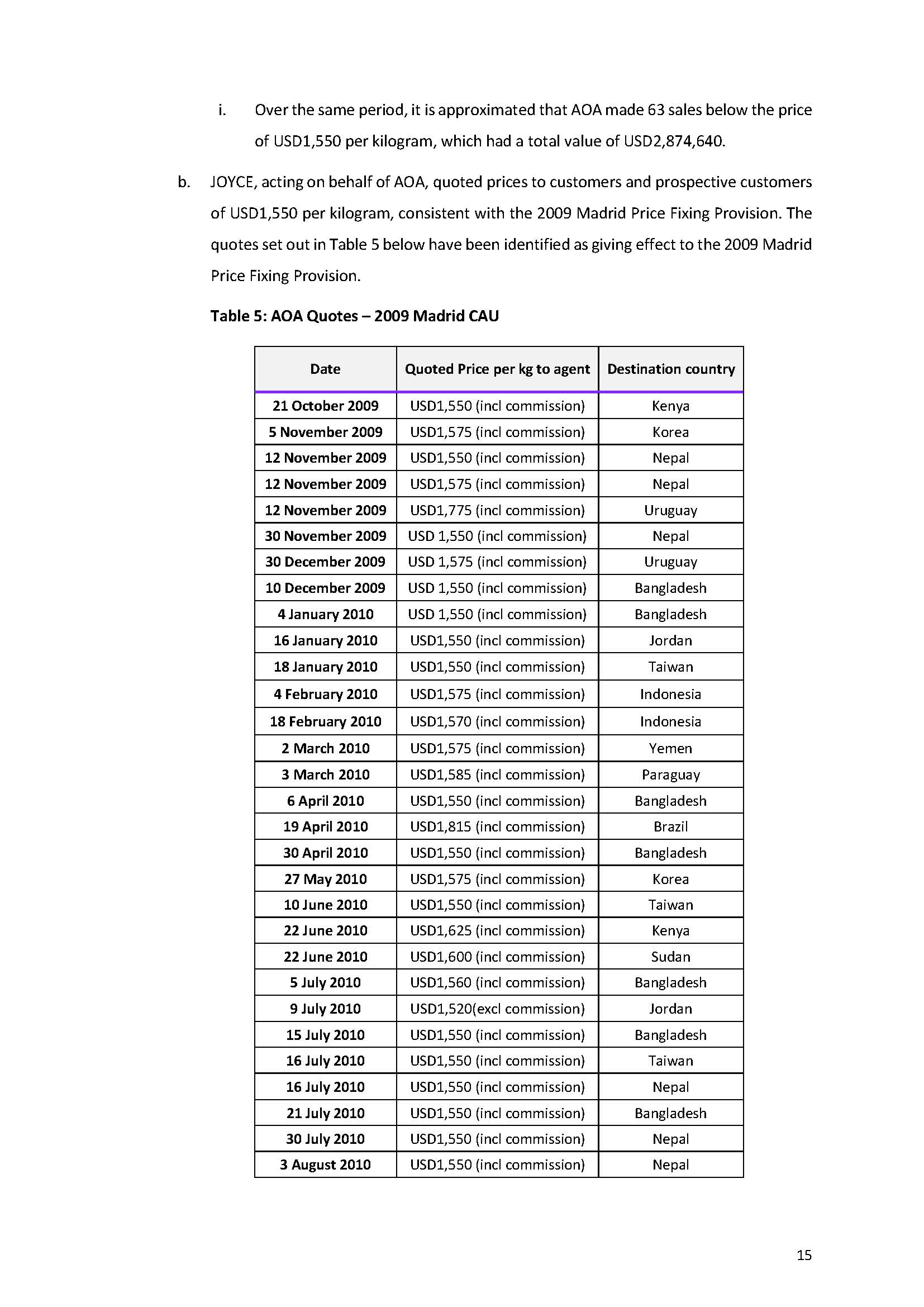

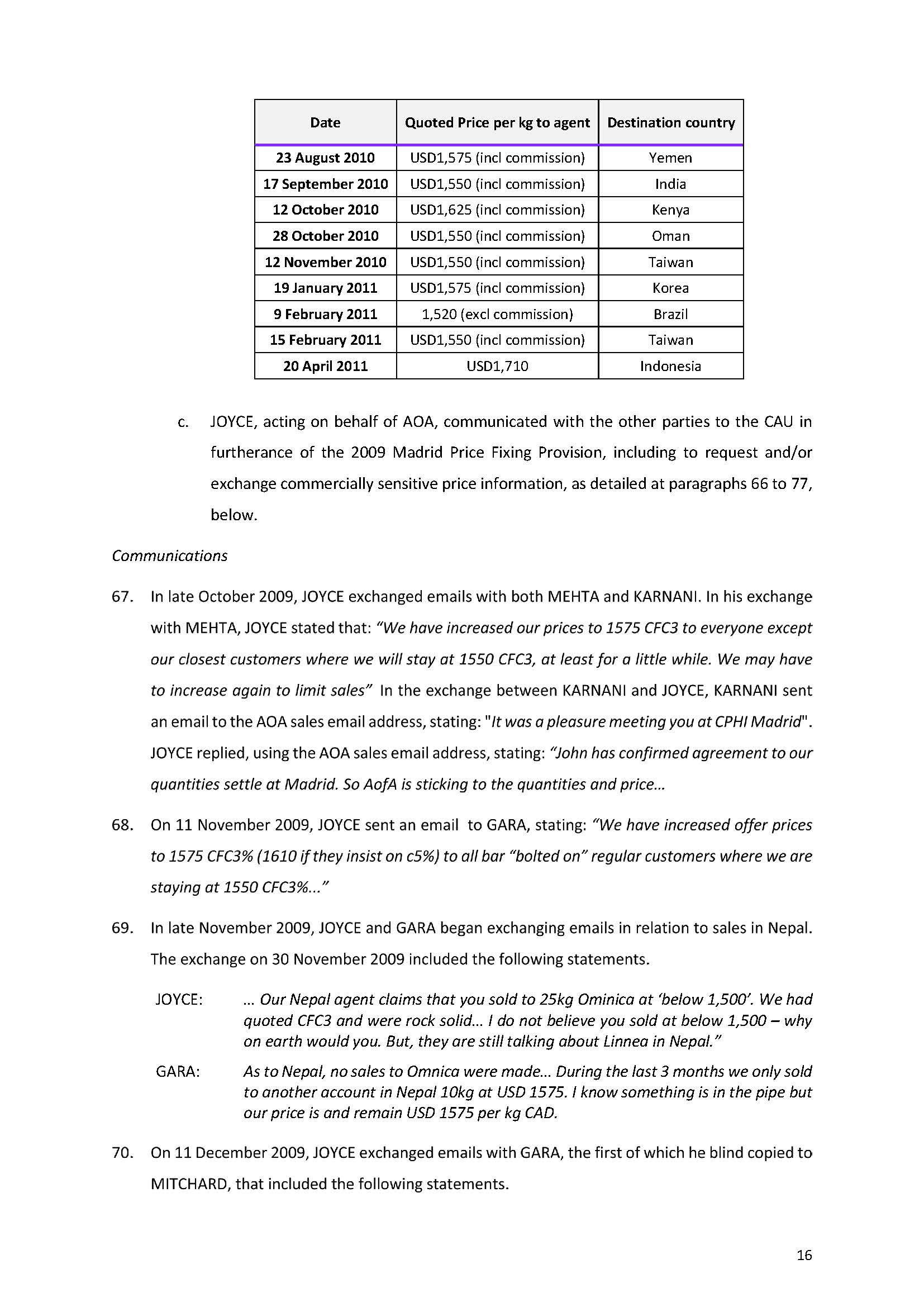

47 Taking the first CAU, the 2009 Geneva CAU, as an example.

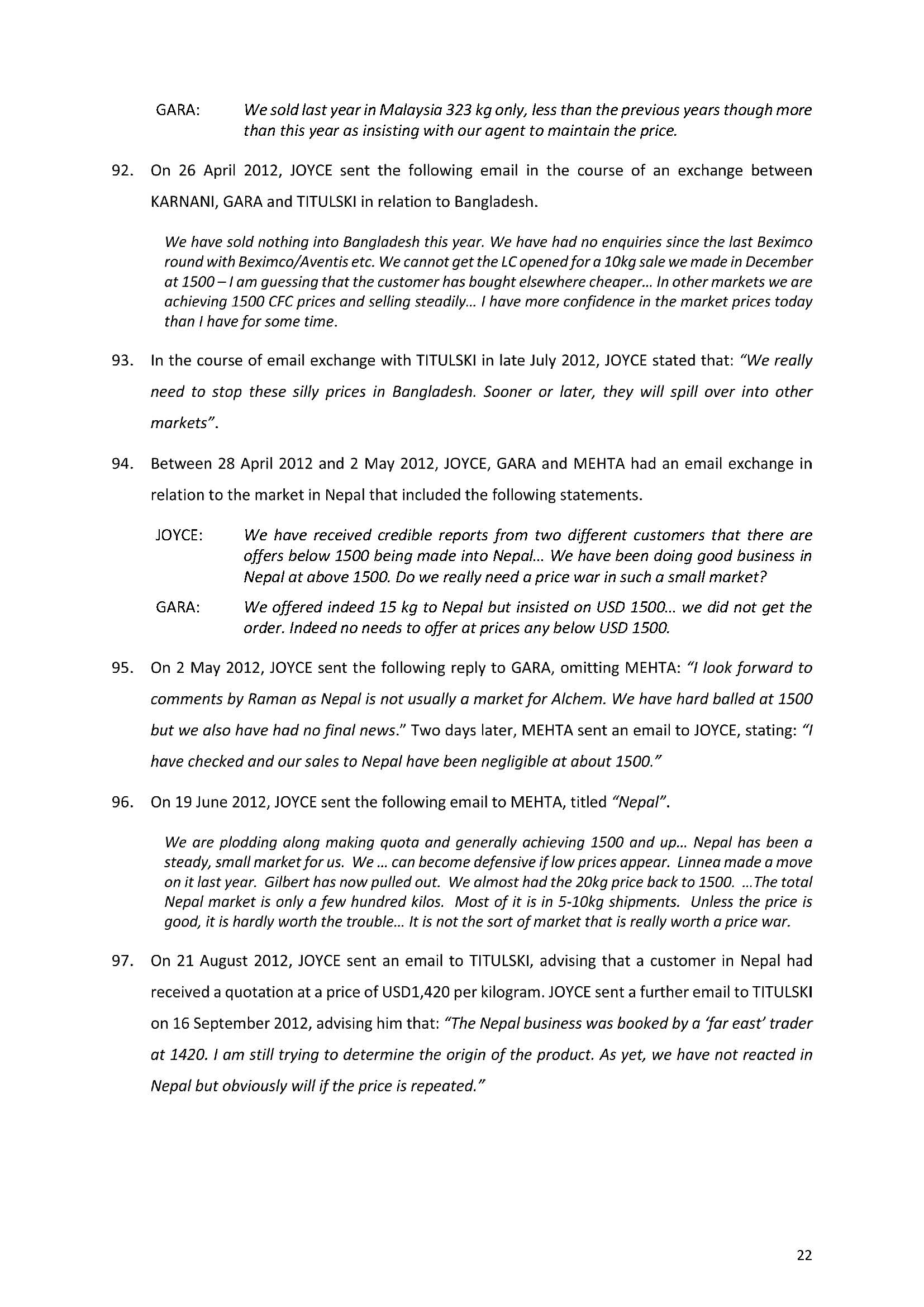

48 Between 24 July 2009 and 11 October 2009, AOA gave effect to a provision contained in the 2009 Geneva CAU which stated that each party to the CAU would sell SNBB at a minimum price of USD1,500 per kilogram (2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision). During that time AOA, aided and abetted by Mr Joyce, made 18 sales of SNBB to 10 different customers at a price of USD1,500 per kilogram (net, excluding agent commission) or above. Those sales had a total value of USD714,047. Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA, quoted SNBB at or above USD1,500 per kilogram (excluding agent commission) in accordance with the 2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision. The quotes in the below table have been identified as giving effect to the 2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision in the SOAF at [49]:

Date | Quoted price per kg to agent | Destination country |

27 July 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Yemen |

8 July 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Oman |

5 August 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Nepal |

11 August 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Oman |

11 August 2009 | USD1,650 (excl commission) | Brazil |

18 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Singapore |

27 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Jordan |

28 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Benin |

2 September 2009 | USD1,565 (incl commission) | Guatemala |

4 September 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Guatemala |

10 September 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Kenya |

30 November 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Nepal |

16 September 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Taiwan |

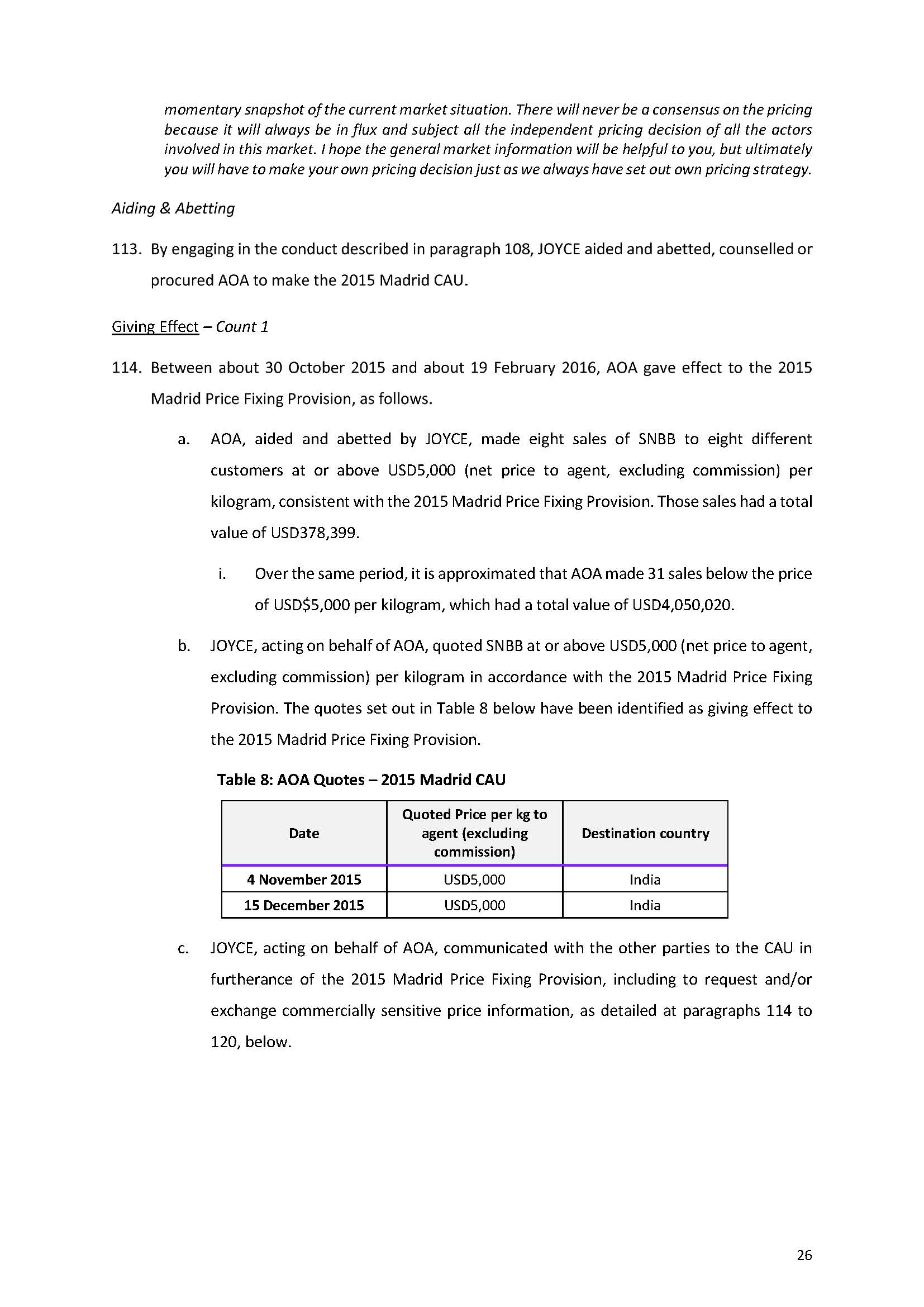

7 October 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Singapore |

49 As explained in Vina Money Transfer at [123], any one act which is undertaken to give effect to a CAU, constitutes an offence. It follows that an offence is committed each time a corporation engages in conduct which gives effect to a cartel provision: also see NYK at [205].

50 The SOAF refers to many acts, as demonstrated by the table at [48] above. The number of times the CAU was given effect to varies in respect to each CAU covered by this count, as reflected in the SOAF at [66], [86], [105], [114], [129] and [148]. Depending on the nature of the CAU being given effect to, the number of acts of giving effect to it may impact on the seriousness of the offending. In this case, it reflects that an ongoing course of conduct was undertaken, implementing the CAU.

51 The range of destination countries for which the quotes were made giving effect to the CAUs is also illustrated in the table above at [48] (which is consistent with the broad range of destination countries involved in the other CAUs the subject of this count). It illustrates that each of these CAUs is a global cartel. It also reflects the breadth of the international impact or reach of AOA’s conduct.

52 It is appropriate at this stage to also refer to the agreed fact that over the same period of this CAU, it is approximated that AOA made seven sales below the price of USD1,500 per kilogram, which had a total value of USD$292,135.3: SOAF [49(a)(i)]. Similar agreed facts exist in relation to each of the CAUs: SOAF [66(a)(i)], [86(a)(i)], [105(a)(i)], [114(a)(i)], [129(a)(i)] and [148(a)(i)]. AOA relies on these facts in mitigation of any sentence, as evidence that it did not always carry out or give effect to the CAU, but rather on occasions, cheated on the CAU. I return to this submission below at [60]-[63].

53 The parties to the CAUs, relevantly for AOA through Mr Joyce, having entered the agreements, actively monitored and policed the other parties’ (who were also their competitors) adherence to the price fixing agreements, and sought to hold them to the arrangement. Mr Joyce, on behalf of AOA, was forceful in advocating compliance. This was accomplished, for example, through local agents or distributors in each country who reported the prices being quoted by others back to Mr Joyce. If Mr Joyce suspected a departure from the CAU, he would follow up by email. The SOAF also reflects that meetings were held and that Mr Joyce’s counterparts in the CAUs would similarly police compliance.

54 For example, in relation to the 2009 Geneva CAU, the following extracts from the SOAF illustrate the policing undertaken by Mr Joyce to ensure other parties to the CAU acted pursuant to it:

[52] Between 7 August 2009 and 13 August 2009, JOYCE had an email exchange with MEHTA that included the following statements.

JOYCE: It is reported that Alchem sold to Pharmadesh at 1,500 and that both Alchem and AlkCorp of India are generally offering in Bangladesh at 1500 to 1520… I would appreciate your comments asap.

We have sold nothing in Bangladesh for over 6 weeks as we are hardball at 1575 for 5-10kg and 1550 CFC3 for 20kg+. Obviously we are not likely to continue sit and see the disappearance of our Bangladesh market for much longer.

MEHTA: As you know Bangladesh is not a market for Alchem simply because it is a rumor market Alchem last sale was at $1500 Nett to Pharmadesh so pl check your sources

JOYCE: I am not sure if you are confirming that Alchem sale to Pharmadesh at 1500 net or saying this is merely a rumour. In any event, the important thing is that we can report to each what is rumour and hence determine what is fact – we need confidence and trust between us to be maintained.”

MEHTA: I am supposed to have got a small order from them at 1500 nett but god alone knows BD is not imp for us and I do not want to lose sleep over it.

JOYCE: Thank you for the frank reply. We have finally today achieved some business in BD at 1,540. It was hard work but at least you have obviously convinced your eager staff to stop doing 1,500. Hopefully, we will get it back to 1,575 at long as my “friends”, like you and BI, cease making the occasional unrestrained sales there at silly prices. If the BDs tell you we are at a silly price, please check with me.

…

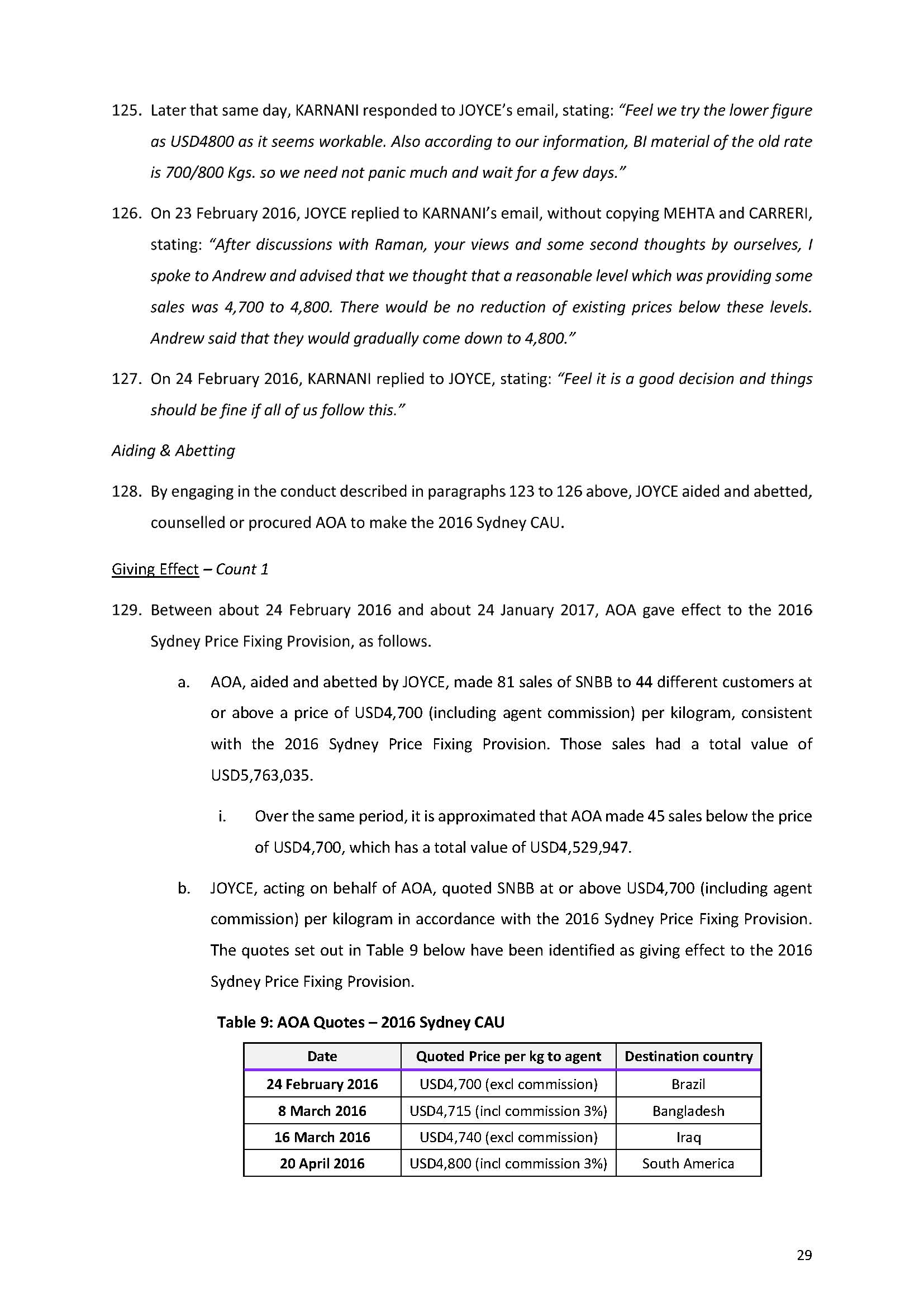

[54] On 12 August 2009, JOYCE exchanged emails with GARA that included the following statements, having forwarded an email from a distributor reporting that Linnea was selling at between USD l,400 and 1,420/kg in Taiwan.

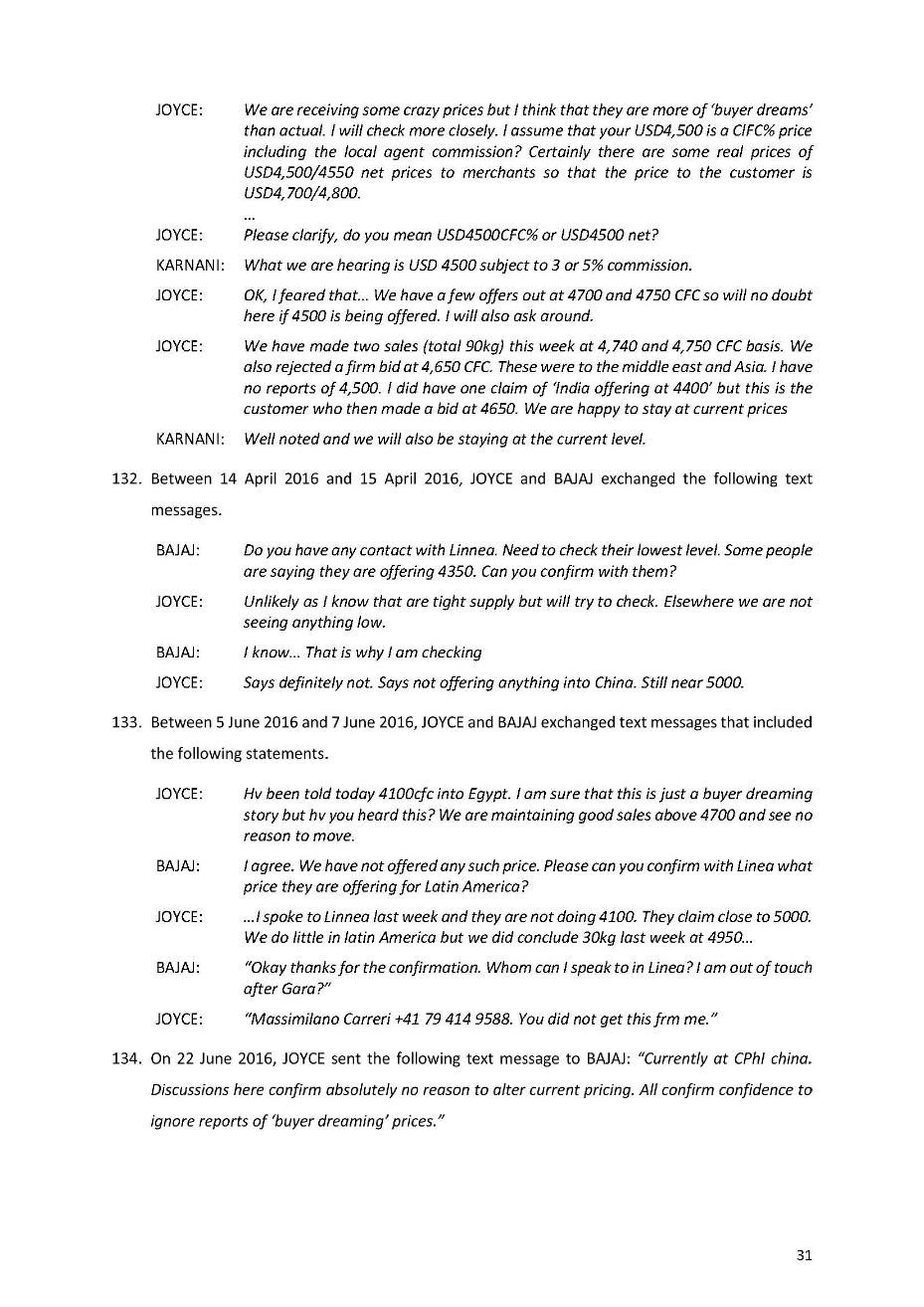

JOYCE: I have received the following from our Taiwan agent… I assume that it is not correct, but I sure you would like to know that people are talking about you.

…

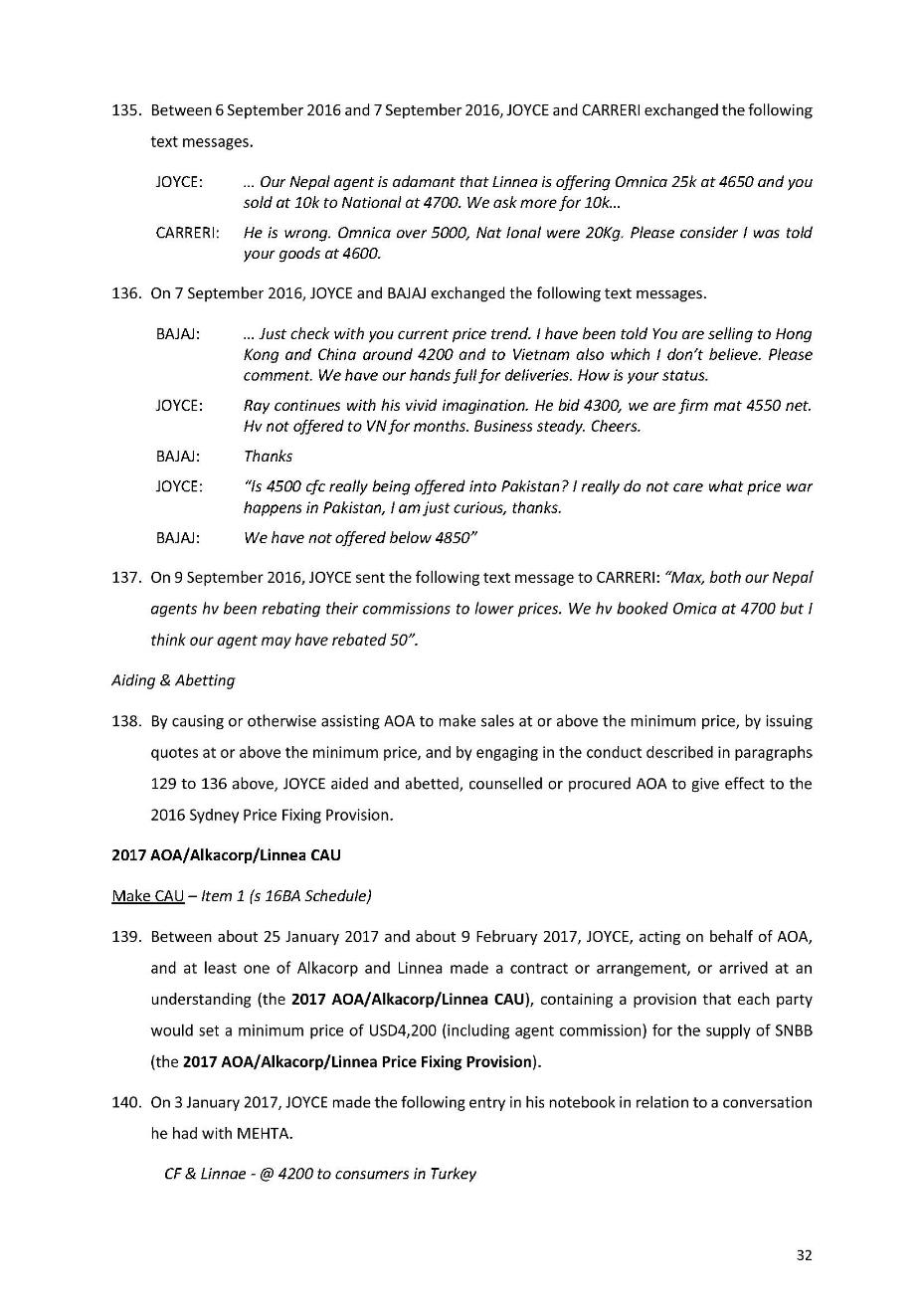

PS. Thanks for laying off in Nepal, we are now happily achieving 1,575 for 5-10kg. Hopefully, we can get this back to 1600.

GARA: Had no sales nor offers for long, long time to Taiwan. Our minimum price is and remain USD 1575 and sometimes for large quantities USD 1550… as you can imagine we are getting similar stories using your name.

…

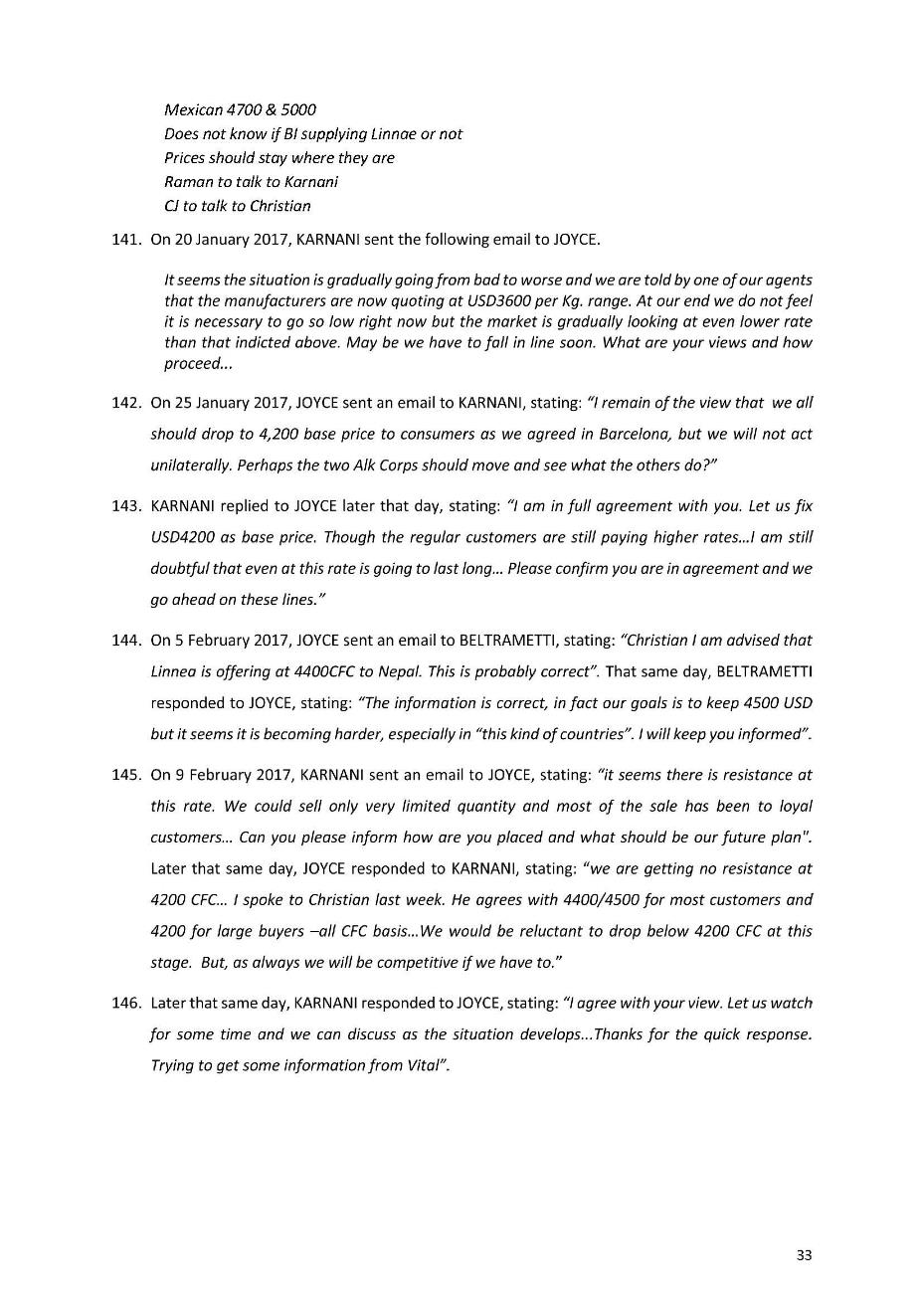

[56] On 14 September 2009, MITCHARD sent an email to JOYCE, forwarding a report from a third party that AOA had offered to sell at USD1,455/kg to Sanofi Aventis. By way of reply, JOYCE forwarded an earlier email he had sent to SPOENEMANN that included the following statements.

Interestingly, I sent the email below to Hellmuth earlier tonight.

We offered to Sanofi at 1550 CFC3% three weeks ago… you will note that Kemimac is allegedly at 1500/1520 (not 1450!!). We obtained the last Sanofi business three months ago at 1540 after weeks of being told that Kemiac and Linnae were much cheaper and that we had to go to 1500. We stayed at 1550, we finally agreed to 1540 to allow them to save some face.

…

I think we just have to stand…

[57] The following day, JOYCE sent an email to MITCHARD, copying SPOENEMANN, forwarding an email from a distributor reporting that Kemimac had offered to sell at USD1500/kg to Sanofi Aventis, that included the following statement: “You will note that our agent says Kemimac is cheap at 1500/1520. At least you are higher than the reported 1455 that we are offering at!!! Please confirm what you are doing”. Later that day, MITCHARD sent the following reply: “I instructed Kemimac to do 1550 ...”.

55 These communications are typical of what occurred in in relation to each of the CAUs the subject of this count.

56 Parties to the CAUs were also concerned that non-compliance in one market might affect others. For example, in relation to the 2011 Shanghai CAU:

[93] In the course of email exchange with TITULSKI in late July 2012, JOYCE stated that: “We really need to stop these silly prices in Bangladesh. Sooner or later, they will spill over into other markets”.

57 The Director submitted that the two items of additional offending on the Schedule to be taken into account represent additional criminality that should be reflected in the sentence imposed for this offence.

58 As referred to above, Item 1 concerns offences of making six of the CAUs that were subsequently given effect to, which are the subject of Count 1. AOA submitted that the additional criminality is limited because the offences on the Schedule are primarily reflective of the ongoing course of anti-competitive conduct engaged in by AOA during the Relevant Period, lessening the call for additional punishment. Although there is some overlap in the offending, there is an additional criminality. Item 1 demonstrates AOA’s active involvement in making the CAUs which were then given effect. A cartel can be given effect to by a person without their having been involved in its making. Once that is appreciated, it can readily be accepted from AOA’s admission that its conduct in making the CAUs reflects additional criminality. Further, the active role taken by AOA is evident from the SOAF. The conduct which gave rise to the offences was deliberate.

59 Item 2 is different, in that it is an attempt to make a CAU between about 20 June 2017 and about 28 July 2017. Although, as AOA submitted, the conduct the subject of Item 2 is objectively less serious than the conduct the subject of the counts, it nonetheless reflects additional criminality. It is a distinct offence. It appears that a CAU did not materialise because others were unwilling to agree.

60 Before leaving Count 1, it is appropriate to return to AOA’s submission that it cheated on the CAUs (by not uniformly complying with price fixing provisions), which it contends is a mitigating factor. AOA accepted in its written submissions that it did not contend that the extent of the cheating means that the offending conduct is necessarily less serious. The Director submitted that caution should be exercised when considering the figures proffered as to the sales said to be non-compliant with the CAUs. It was submitted that the total number and value of the sales made below the agreed CAU price were drawn from AOA’s sales data finalised over the term of each CAU, without identification of an originating document to determine whether the sales were in fact quoted or confirmed whilst the CAU was on foot, or whether the sale price included or excluded commission. There are differences in the methodology used to confirm that a sale was made at or above the agreed price and the methodology used to present an approximation of sales made below the agreed price. Those are proper matters of concern. That said, it may be accepted that there was some cheating on the CAUs. However, that does not assist AOA in any material way.

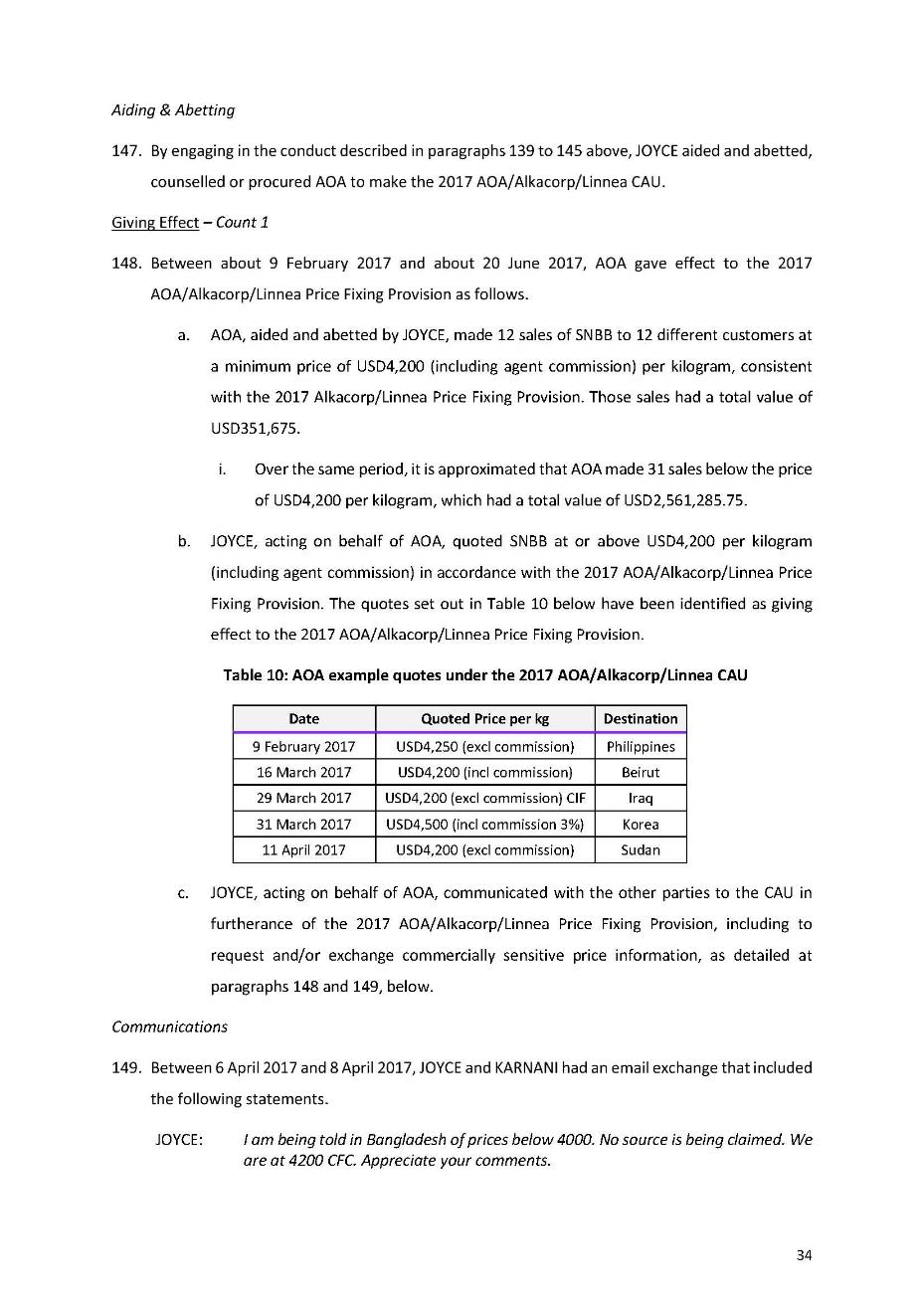

61 As observed by Wigney J in K-Line at [400], “cheating on a cartel should not generally be considered to be a significant mitigating circumstance”. In NYK his Honour observed at [231] that:

[231] … experience has shown that cheating between cartelists is a common feature of many cartels. Indeed, economic theory suggests that such conduct is economically rational. It is in the cartelist’s own self-interest to cheat on the cartel. They do not cheat for the benefit of the customer or consumer.

62 AOA attempted to distinguish K-Line on the basis that the cheating in that case was confined to isolated and minor instances, as opposed to what, it submitted, was more substantial cheating in this case. However, that submission fails to consider the description of the conduct in K-Line in the context of the broader conclusions made. The observation recited in the preceding paragraph from [231] of NYK is of general application. It is applicable regardless of the extent of the cheating.

63 Further, if the purported relevance of cheating is that it might suggest an offender is being disruptive of the implementation of a CAU, AOA’s actions are inconsistent with that. AOA actively encouraged and participated in the making and enforcement of the cartel. Moreover, AOA accepted that to ensure it succeeded in its cheating, it monitored other participants’ compliance with the CAU. This signifies that the price charged by AOA when cheating was necessarily affected by the agreed prices, which were artificially high as a result of the CAU. It follows that the competitive process was likely distorted, notwithstanding the cheating. As the Director submitted, there is no evidence that the prices charged by AOA inconsistently with the cartel arrangements were not affected by the collusion. The cheating was not done for the benefit of the customer, nor to promote competition. Accordingly, AOA’s cheating only highlights that its acts were motivated by financial gain and self-interest.

64 I make the following additional observations regarding Count 1.

65 First, I accept the Director’s submission that the offending conduct in this count occurred over a very significant period of time and can only be characterised as deliberate, systematic, and coordinated.

66 Second, AOA, through Mr Joyce, was actively involved in policing and enforcing compliance with the CAUs. That AOA did not give effect to the CAUs in every instance does not impact that characterisation.

67 Third, as explained above, the CAUs were repeatedly given effect to, in giving quotes in various countries. This conduct raised the price of SNBB.

68 Fourth, there was an ongoing course of conduct in respect to each CAU, with it being given effect to until the next CAU was made, with the exception of the gap between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 (see [45] above).

69 Fifth, I accept that the offending conduct was covert in nature, which is typical of cartel conduct. It was not published to and would not have been readily apparent to the market.

70 Sixth, the conduct admitted to in the Schedule adds to the criminality of the conduct in this count, in that it reinforces AOA’s willingness to be actively involved in the CAUs, as well as their enduring nature. It illustrates the scale and scope of AOA’s conduct.

Count 2: Giving effect to a CAU

71 AOA gave effect to a cartel provision with four other competitors to obtain Duboisia leaves from a particular Australian grower, David Thamm, and to obtain from him a commitment not to grow or produce Duboisia on his Memerambi property in Queensland.

72 This offending spanned about 1 year, 7 months and 17 days. The additional admitted offending in Item 3 of the Schedule falls within this date span. This period of time is shorter than Count 1, but I accept that it is nevertheless significant and prolonged.

73 The offending the subject of this count involved five of the major manufacturers of SNBB, who between them produce Buscopan and supply SNBB to manufacturers of the vast majority of its generic equivalents. The conduct targeted an Australian grower of Duboisia, seeking to eliminate him as a competitor. The CAU involved: Alkacorp entering into an agreement with Mr Thamm; Alkacorp acquiring Mr Thamm’s equipment; and a compensation payment from AOA to Alkacorp. The purpose of acquiring the entire crop and securing a commitment from Mr Thamm not to grow or produce any further Duboisia was to prevent him (or any other person through him) supplying Duboisia to a third party who intended to enter the market (Sarv Biotech), thereby preventing that third party from becoming the “seventh player” and putting downward pressure on prices.

74 The additional offending to be taken into account on this count is set out in Item 3 of the Schedule. Namely, an attempt between about 7 December 2010 and about 21 January 2011 by AOA to induce Alchem, Alkacorp and Linnea to make a CAU with Vital, containing a provision that the parties would not cause to be replanted Duboisia trees that had been destroyed due to flooding and were grown by or on behalf of the parties or their related bodies corporate, which had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the production, or likely production, of Duboisia and/or SNBB. It should be noted that Vital represented a significant threat to the parties’ ability to maintain the price of SNBB by limiting the production of Duboisia.

75 AOA submitted that the conduct the subject of Item 3 was objectively less serious than the conduct the subject of the counts, and that the additional criminality was limited. The Director submitted that Item 3 constituted a distinct offence that did not mature beyond an attempt only on account of the conduct of others. It is unclear from the SOAF why the attempt failed. I note the last communication recorded is from Mr Joyce to Linnea on 20 January 2011, including the following, “[t]his is a unique opportunity that should not be missed. The number of [D]uboisia trees will be significantly reduced although we do not know at this time by how many. There needs to be a commitment NOT to replant dead trees and orchards”: SOAF [200]. It is apparent from the SOAF that the opportunity being referred to arose as a result of major flooding in Queensland.

76 Item 3 does reflect additional criminality and highlights the active involvement by AOA in attempting to persuade others to agree to cartel conduct.

77 I make the following additional observations regarding Count 2.

78 First, the offending the subject of Count 2 spanned over a relatively long period of time. There was no activity by AOA giving effect to it for certain periods of time, but given the nature of the CAU and AOA’s conduct giving effect to it, those periods do not detract from its seriousness. Further, AOA’s commitment to giving effect to the CAU continued throughout those periods, as reflected by its conduct on either side of them.

79 Second, although this conduct is different to that in Count 1, AOA’s object was the same. It reflects on the breadth of the actions taken by AOA to achieve financial gains. Again, the conduct was systematic, deliberate, covert and there was a degree of sophistication.

Count 3: Attempt to make a CAU

80 The conduct the subject of this count occurred over about three months, although the admitted offending in Items 4 to 7 of the Schedule falls within a much larger date range.

81 The 2011 Attempted Bangladesh CAU that is the subject of Count 3 would have been with Alkacorp, which was one of the major manufacturers of SNBB, and Kemimac, which is not itself a manufacturer. The CAU was to have two cartel provisions: a price fixing provision; and a provision which allocated supply contracts between the participants.

82 The offending conduct was systematic and deliberate, involving a degree of sophistication. It took place by discussions in person in Germany, and by email. Again, the conduct was covert in the sense that there is nothing to suggest the market was aware of it.

83 This count is not as serious as the offending the subject of the other counts, but I accept the Director’s submission that it was nevertheless not insignificant.

84 A number of admitted offences which add to the criminality of this count are to be taken into account. These items occurred over an extended period, the last being 19 December 2018. Items 4 and 5 involve two CAUs containing bid rigging provisions, the making of each rolled up as Item 4 and the giving effect to each rolled up as Item 5. Items 6 and 7 similarly concern two further CAUs, one containing a bid rigging provision and the other a price fixing provision, the making of and giving effect to each being rolled up into the two items.

85 AOA submitted that the conduct the subject of these items was objectively less serious than the conduct the subject of the counts and that the additional criminality was limited, while the Director submitted that it represented distinct offending demonstrating a course of conduct. I accept the Director’s submission.

86 A number of matters relevant to the offences in all three counts require further consideration.

Benefit attributable to the conduct

87 The Director submitted that AOA engaged in the offending conduct for the purpose of financial gain, specifically, obtaining a benefit from higher SNBB prices than would have been charged in a competitive market. I accept that submission. As was also submitted by the Director, it is an agreed fact that the price of SNBB for each sale and quotation which was the subject of the CAUs was higher than it otherwise would have been, but for the conduct.

88 As explained above, AOA sold a substantial amount of SNBB during the years it engaged in cartel conduct the subject of the counts and the offending in the Schedule: see SOAF [32]. The whole point of price fixing and market sharing is to obtain the benefit of prices greater than those which would be obtained in a competitive market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visy Industries Holdings Pty Ltd (No 3) [2007] FCA 1617; (2007) 244 ALR 673 at [314] per Heerey J (Visy Industries). It may readily be inferred that AOA continued making and giving effect to the various CAUs, which involved monitoring and enforcing, because it was achieving that desired purpose.

89 The fact that it is not possible to quantify precisely the profit or other financial benefit derived by giving effect to a CAU, as in this case, does not lessen or mitigate the seriousness of offending conduct: WWO at [223]. Moreover, as Wigney J aptly observed in K-Line at [307]:

[307] It may also be inferred that the offending conduct may have given rise to less direct and tangible benefits to K-Line, including benefits derived from the increased certainty arising from stable market shares and customer allocations and the absence of any, or any aggressive, price competition.

90 Also see NYK at [247].

91 AOA submitted that the relevance of the benefit attributable to the conduct is limited, especially in circumstances where no quantification of the expected benefits is possible, citing, for example, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Cement Australia [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [446]-[447] (Cement Australia). I do not accept that submission. It is inconsistent with authority. Indeed, the nature of the offending and its sustained nature over an extensive period of time is what, at least in part, is destructive of the ability to reconstruct what would have occurred, but for the cartel conduct.

92 Nor do I accept AOA’s submission in this context, “that the benefit referrable to conduct in relation to commerce in Australia is either non-existent or de minimis, and the benefit relating to foreign commerce cannot be quantified, but is some unknown proportion of AOA’s revenue in relation to sales of SNBB to foreign customers that were the subject of the offending”. There is no basis to confine the relevant benefit to AOA to that derived from Australian customers: see below at [105]-[107].

93 It is the fact that this conduct was engaged in for the purpose of financial gain that is of significance. For example, in Cement Australia, Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ observed at [467]:

[467] We would accept that to achieve deterrence, both specific and general, a penalty must be sufficient to render inutile “the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention” (Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249 (Singtel Optus) at [63], cited with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG) at [66]). Moreover, we would also accept that the intention to profit from contravening conduct must be deterred even if it could be shown by the contravenor that no actual profit was made. Indeed, the higher the intended benefit (even if not actually received), the higher the penalty required to satisfy the objective of deterrence, all else being equal. Generally, we accept that “the sanction for the conduct [must be] substantial relative to the possible gain to be made from it” (our emphasis) (Reckitt Benckiser at [153]).

Injury, loss or damage resulting from the offences

94 AOA placed significant reliance on a submission that the conduct had no effect on Australian consumers. Emphasis was placed on the agreed fact that pricing data in respect of SNBB medications sold to Australian pharmacies by three major wholesalers over the Relevant Period shows that, when adjusted for changes in the consumer price index, the average wholesale price in Australia for these medications decreased in real terms during the Relevant Period and did not show any discernible increase when the price of SNBB increased.

95 AOA accepted that affected foreign customers lost the ability to enjoy the potential benefits of competition between AOA and its competitors. However, it submitted that AOA’s sales of SNBB in Australia during the Relevant Period were de minimis: AOA made a total of seven sales of SNBB, each of a non-commercial quantity, totalling approximately six kilograms (a total value of $25,641). This represents 0.02 percent of AOA’s total sales. AOA also stated that: there is no material market for SNBB in Australia; SNBB manufactured by AOA was not used in Buscopan, only generic SNBB medications; and the value of the sales of generic SNBB medications by wholesalers to pharmacies in Australia during the period in which AOA gave effect to the relevant CAUs was modest, with a total value of $2,821,509. It was therefore submitted that the high watermark of the total commerce that may have been affected in Australia, that is the total revenue affected (of which loss or damage could only ever be a proportion), is $2,847,150. It was also submitted that this likely overstates the figure as it almost certainly includes generic SNBB medications manufactured using SNBB sold by persons who were not parties to any cartel arrangement at the relevant time.

96 AOA submitted that care must be taken not to take the headline figure of $2,821,509 as the measure of the economic effect in Australia, which, if properly analysed, was said to be significantly less. That headline figure is the total amount of sales of generic SNBB medications by wholesalers to pharmacies in Australia over a period of more than 6 years (including SNBB medications supplied by all SNBB manufacturers, one of which is AOA), and the cost of SNBB comprises only a very small proportion of the total over the counter cost of SNBB medications. AOA submitted:

Let it be assumed that a generic SNBB medication contains 10mg of SNBB; that there are 20 tablets in a packet; and that the price of a packet of 20 tablets at Pharmacy Online is $5.99. Taking the average price of SNBB across the relevant period, $2,727 per kg (see [32] SOAF), the cost of the SNBB in a packet of 20 tablets is $0.55. It represents only 9.18% of the overall price. 9.18% of the total figure of $2,821,509 amounts to about $259,014 – a relatively small sum, of which only a portion could possibly have been affected by the offending conduct (given that this sum of $259,014 represents the entire cost of SNBB and not the extent to which the price may have been inflated by reason of the offending conduct).

97 AOA submitted the facts establish an upper bound for the anticompetitive effect in Australia, being some proportion of the $259,014 outlined above. AOA submitted that this is in stark contrast to Vina Money Transfer and NYK, as to the total value of Australian commerce affected by the cartel conduct.

98 In respect to Count 2, AOA submitted that, although there may be a loss of competition in overseas markets, removing a potential source of production of Duboisia leaves does not result in any loss or damage to the Australian economy. This was said to be because while there would have been an effect on competition in the overseas markets to which Duboisia leaves are sold, considering when and in what form Duboisia leaves come back into Australia shows that there would have been a negligible, if any, impact on the Australian economy. Any other effect was said to be speculative.

99 The Director does not dispute the figures referred to above at [95], but does dispute their significance. It was submitted that those figures do not tell the whole story and that it is impossible to compare the effects of the cartel arrangements against a counterfactual scenario where the conduct did not occur because of the multiplicity of factors that may have borne upon prices. The Director submitted that the longstanding and widespread nature of the offending would have distorted the market for SNBB and derivative markets for SNBB medications. It was said that prices, quality and range of services throughout the market could realistically have been different but for the conduct, meaning it is wrong to proceed as if sales not subject to the cartel arrangements were not likely to have been affected by them. It was also said to be wrong to stop the assessment at 19 December 2018 given the longstanding and widespread nature of the offending, which made it improbable that the market for SNBB and derivative markets for SNBB medications would have snapped back to a state unaffected by the cartel arrangements upon the offending ceasing or when there was no cartel agreement being given effect.

100 The Director submitted that it does not follow from the fact the pricing for the medication decreased that the offending conduct had no anticompetitive effect, either generally or in Australia. It was said not to negate the possibility that prices for SNBB medications would have been lower still absent the cartel conduct. I accept that submission.

101 The Director also submitted that cartel arrangements have a range of impacts on a market beyond the mere price of goods. The arrangements in this case were said to be longstanding and widespread and to have reduced competition. The benefits of competition can manifest in terms of lower prices but also in terms of higher quality and range of services. It is of the nature of cartel arrangements that they generate a real risk that these benefits will be denied. The Director also submitted, as noted above, that there is a possibility that prices for SNBB medications would have been lower still absent the cartel conduct.

102 The Director does not dispute that loss or harm to the Australian community is of central concern to the CCA and thus to the instinctive synthesis, but submitted that AOA’s submissions go too far in relying upon that importance to diminish the gravity of its offending. The Director submitted that s 2 of the CCA refers to “the welfare of Australians”, not just Australian “consumers”. Cartels are corrosive to the economy generally and to international confidence in Australian businesses. General deterrence was therefore said to remain important. To regard AOA’s conduct as less deserving of denunciation because it mostly affected overseas consumers was said to potentially allow such behaviours to take root and spill over to more domestic markets, which cannot be allowed. It was also submitted that the Crimes Act does not compel the Court to disregard victims who are overseas, nor does the CCA, citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Ltd [2008] FCA 1976; (2008) 253 ALR 89 at [39] (Qantas Airways) per Lindgren J:

[39] Nonetheless, the commission submits, and I accept, that over and above the jurisdictional connection required by s 5 of the Act, the degree of connection to Australia is relevant to the quantum of penalty. Section 2 of the Act states that the object of that Act is to enhance the welfare of Australians through the promotion of competition. Achievement of that objective is not inconsistent with preventing contraventions by Australian entities that injure non-Australians, but it is appropriate to focus primarily upon the effects of a contravention in Australia: compare the reference to “loss or damage” in s 76. Surcharges imposed on flights to and from Australia would be likely to have the most direct connection with loss or damage suffered by businesses or consumers in Australia.

103 The Director also submitted that the conduct the subject of Count 2 directly affected competition in Australia. Mr Thamm was an Australian grower. By eliminating him as a viable Australian source of Duboisia to other SNBB manufacturers, competition in Australia was said to be diminished. That was a direct injury to the Australian economy, including because it stultified the efficiency gains that competition would otherwise promote.

104 It was also submitted that the attempt which is the subject of Count 3 could have affected the sale of Duboisia by Australian growers had it been completed. It would have imposed a limit on the replanting of Duboisia trees.

105 It may be accepted that the direct victims of AOA’s offending conduct were primarily overseas customers to whom AOA exported SNBB. The vast majority of these victims are thus outside of Australia, and may have had little, if any, direct connection to Australia. It may also be accepted that loss or harm to the Australian community is of central concern to the CCA. However, it should be noted that it was common ground between the parties that the effect on overseas customers was relevant. The live issue was the significance and extent of each.

106 AOA’s submission is primarily premised on its calculations referred to above at [96], said to be the impact on the Australian consumers. It also relies on the limited amount of SNBB in SNBB medications, such that there will be no impact on the Australian consumer (because any increase in price of SNBB could not affect the price of SNBB medications). AOA also referred to the small amount of sales of SNBB in Australia during the Relevant Period.

107 AOA’s approach to assessing any loss or damage is unduly narrow and artificial.

108 It is appropriate to recall that in the context of considering the application of ss 16A(2)(d) and (e) of the Crimes Act in WWO, Wigney J stated at [242]:

[242] It would be wrong, however, to approach this offence as if it were a victimless offence, simply because no specific individual or quantified loss can be identified. The cartel offence in s 44ZZRG(1) is part of a suite of provisions in the CCA that are designed to protect the integrity of Australia’s markets and economic system: see also s 2 of the CCA. Australia’s economy, like other free-market economies, is based on the philosophy that private enterprise and competition will foster productivity, efficiencies and innovation for the greater good of the economy and the community generally. Cartel conduct, like other anti-competitive behaviour, is inimical to, destructive of and may lead to a loss of public confidence in, Australia’s markets and economic system. That is so even where the conduct, as here, is eventually uncovered and punished.

109 Also see K-Line at [313] to similar effect, and Vina Money Transfer citing the passage with approval at [113].

110 AOA’s submission is that those observations in WWO as to the inherent effects of cartel conduct do not apply in this case because the impact on the Australian economy is known, being confined to the impact of the price of SNBB on the price of generic SNBB medications in Australia. I do not accept that submission.

111 The inherent impact of cartel behaviour has also been discussed in the context of the need for general deterrence. The observations are apt in addressing this issue.

112 For example, in Visy Industries, Heerey J at [306]-[307] stated:

[306] Cartel behaviour of the kind with which this case is concerned is extremely destructive of the competition on which the prosperity of a free market economy depends. Often the profits can be immense, and the risk of detection slight. Of its nature, cartel behaviour is likely to occur in secret and between parties who seek mutual benefit…

[307] … Price fixing and market sharing are not offences committed by accident, or in a fit of passion. The law, and the way it is enforced, should convey to those disposed to engage in cartel behaviour that the consequences of discovery are likely to outweigh the benefits, and by a large margin.

113 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265; (2005) 215 ALR 301 at [47], Goldberg J accepted that very nature that the contravening conduct results in “distorted trade, created inefficiencies, wasted resources and resulted in a reduction in consumer and total welfare”.

114 The following was said in the second reading speech for the Bill introducing criminal offences for cartel conduct (Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 3 December 2008, 12,309 (Chris Bowen MP)):

Competition is the primary means of ensuring that consumers get the best product or service for the lowest price possible. Competition enhances Australia’s welfare generally, because the efficiencies it creates lead to improved productivity and ultimately increased standards of living.

Cartels are widely condemned as the most egregious forms of anticompetitive behaviour. At its heart, a cartel is an agreement between competitors not to compete. Cartel conduct harms consumers, businesses and the economy by increasing prices, reducing choice and distorting innovation processes.

The total annual cost of such conduct is difficult to quantify because the effects are dispersed and it is by its nature secretive, but it is likely to exceed many millions of dollars to the Australian economy each year, and many billions worldwide.

This bill makes much needed changes to the Trade Practices Act 1974 [since renamed as the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)] and will operate to deter cartel conduct by widening the range of regulatory responses available. Furthermore, it will bring Australia into line with its major trading partners and developed nations. In the international context, 15 OECD members, including the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, have criminal sanctions for cartel conduct.

115 I accept the Director’s submission that s 2 of the CCA refers to enhancing “the welfare of Australians” and not just Australian “consumers”. The latter, which was focused on by AOA, is a narrower concept.

116 As is apparent from the passages recited above, breaches of Australia’s competition laws are destructive of competition on which the market economy depends. It is recognised that it is in the nature of the cartel conduct to protect inefficiency and cause market distortions. That is so even when the direct purchasers of goods and services are located outside of Australia. Cartel conduct engaged in by Australian businesses is corrosive to the economy generally and to international confidence in Australian businesses. That necessarily impacts on the Australian economy and the welfare of Australians. On the other hand, competition enhances the welfare of Australians.

117 AOA’s submission fails to acknowledge the broader destructive impact of anti-competitive conduct. The narrowness of that submission is illustrated by the communication recited at [180] of the SOAF between AOA, Alchem, Alkacorp and Linea in relation to the CAU the subject of Count 2. In an email exchange it was stated: “… all the farmers have been advised that should the market collapse they will lose at least 50 cents per kilo of the leaf”. SNBB is derived from Duboisia plants, which are grown in Australia. In that context, as illustrated by that exchange, there was a real likelihood that lessening competition at the SNBB level of the market would have consequential impacts upon Duboisia growers in Australia.

118 This simply gives insight as to the breadth of impact of this anti-competitive conduct. It reflects that merely looking at the price of the generic SNBB medication eventually sold in Australia is unduly narrow.

119 Even leaving aside the broader impact of cartels, AOA’s analysis in respect to the effect on the prices of SNBB medications in Australia fails to grapple with the unknown factors determining those prices. The prices of other ingredients, and factors such as manufacturing costs all bear on the price. In other words, it is impossible to compare the effects of the cartel arrangements against a counterfactual scenario where the conduct did not occur because of the multiplicity of factors that may have borne upon prices. As explained above, the decreased price in real terms could have been greater but for the cartel conduct. Further, AOA’s approach fails to take into account any distortion of the price of SNBB based on the longstanding nature of the offending conduct.

120 The conclusion in WWO at [245], that “there was a risk that Australian consumers would be impacted in some way by the cartel behaviour”, as a minimum, similarly applies in this case. Contrary to AOA’s submission, that conclusion is not to reverse the onus of proof.

121 The limits of AOA’s analysis in respect to Count 1 are demonstrated by its reliance on a similar submission in respect to Count 2. AOA’s submission on Count 1 was that because SNBB only comprises approximately 10 percent of SNBB medications, any increase in its price can have no practical effect on the price of SNBB medications, and therefore on the Australian consumer. Its submission regarding Count 2 was that there would have been negligible, if any, impact on the Australian economy considering when and in what form Duboisia leaves come back into Australia. However, Count 2 involved a competitor being taken out of the market by a CAU, directly impacting the Australian economy. By eliminating Mr Thamm as a viable Australian source of Duboisia to other SNBB manufacturers, competition in Australia was diminished. That was a direct injury to the Australian economy, including because it stultified the efficiency gains that competition would otherwise promote. AOA, by confining in its submissions the impact to that experienced by consumers of generic SNBB medications, ignores that injury.

122 I accept the Director’s submissions that the CAUs in this case: were, on any view, longstanding; had widespread effect; and aimed to reduce competition. I also accept that benefits from competition can manifest in terms of both lower prices and higher quality and range of services.

123 Moreover, as AOA accepted, the effect of the conduct on overseas customers may also be a relevant consideration, and a matter that can be taken into account in the sentencing process. AOA accepted that affected foreign customers lost the ability to enjoy the potential benefits of competition between AOA and its competitors. The terms of ss 16A(2)(d) and (e) of the Crimes Act do not confine any to injury, loss or damage from offending, to Australia. Indeed, a consideration of Commonwealth offences to which the Crimes Act applies on sentence, reflect that a number of them, by their nature, are such that the impact must necessarily, at least in part, be felt overseas.

124 Further, Lindgren J’s observation in Qantas Airways at [39], that “[a]chievement of that objective [in the CCA] is not inconsistent with preventing contraventions by Australian entities that injure non-Australians, but it is appropriate to focus primarily upon the effects of a contravention in Australia” (see above at [102]), although not in the context of the Crimes Act, supports that conclusion.

125 That said, AOA submitted that the principal focus should be on loss or damage in Australia and, as referred to above, the Director accepted that loss or damage was central. There is no basis to assess the loss or damage outside Australia. Suffice to say that there was necessarily a loss because foreign customers lost the ability to enjoy the benefits of competition between AOA and its competitors over a substantial period of time. It is readily apparent that the CAUs being given effect to resulted in customers paying, at least at times, higher SNBB prices than there would have been but for the CAUs.

126 In so far as AOA referred to investigations that have been and are being undertaken in relation to its conduct in other jurisdictions, that fact does not advance its submissions on this topic. At this stage, AOA has not been charged or penalised in those jurisdictions. This is to be contrasted to the situation in NYK where penalties had been imposed overseas; see NYK at [276]-[283]. In any event, given the lack of information about the extent of the loss or damage overseas, it can only be taken into account at the level of generality described above.