Federal Court of Australia

Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Joyce [2022] FCA 1423

ORDERS

COMMONWEALTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS Prosecutor | ||

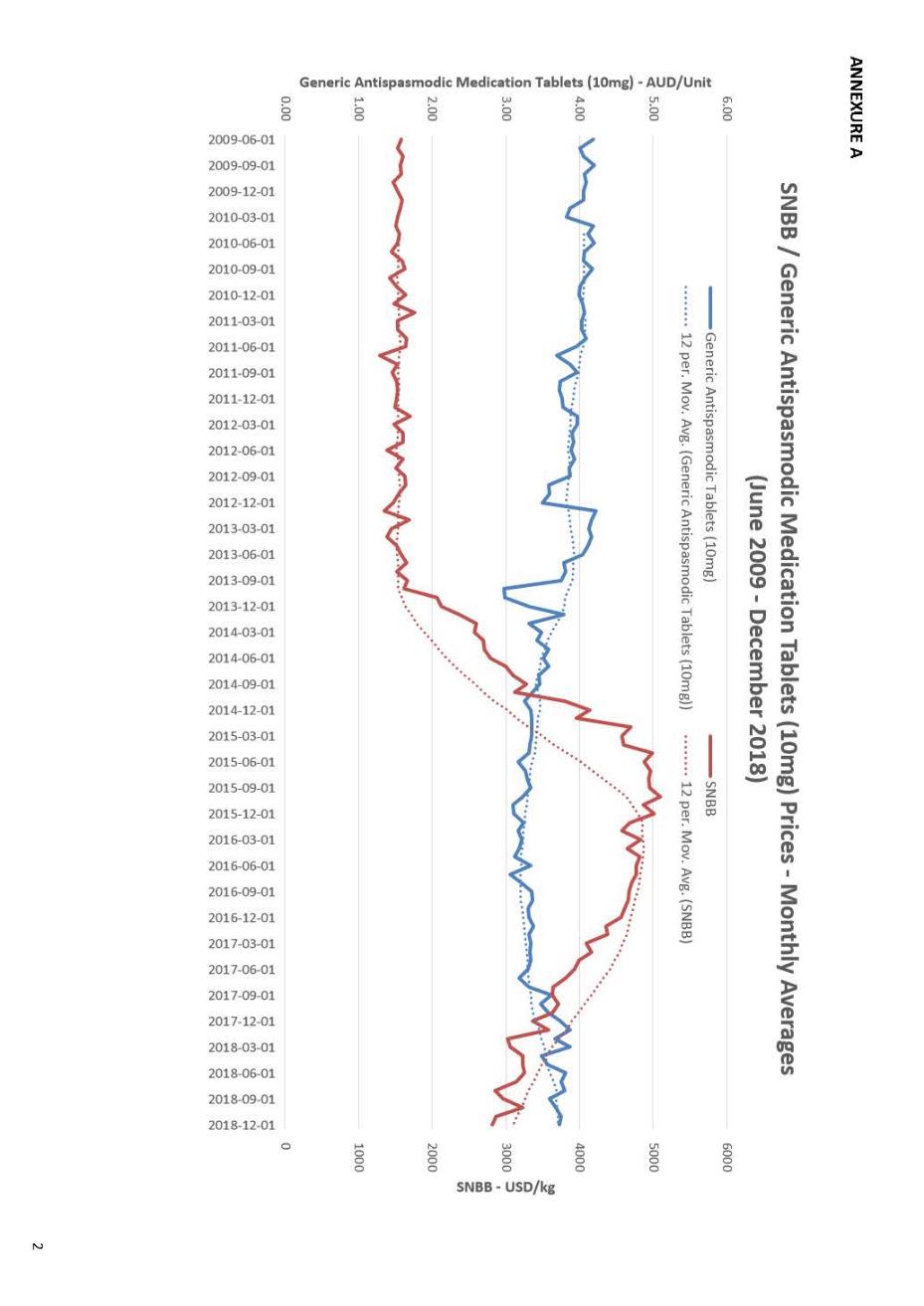

AND: | Offender

| |

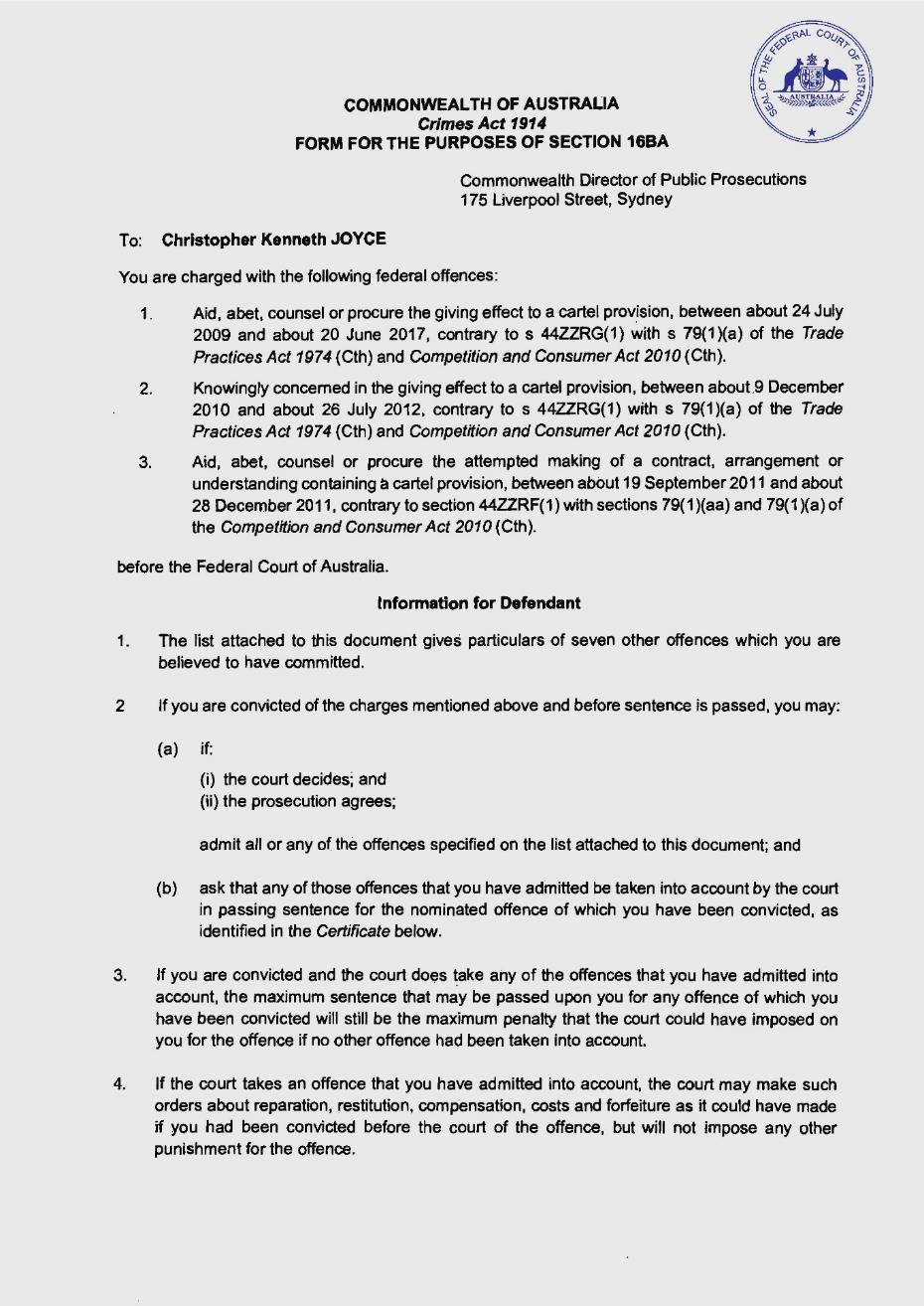

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 November 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Christopher Kenneth Joyce is convicted of Charge 1, Charge 2 and Charge 3 of the indictment attached as Annexure A.

2. Christopher Kenneth Joyce is sentenced to an aggregate sentence of 32 months imprisonment.

3. Pursuant to s 7(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW), the sentence be served by way of intensive correction in the community.

4. The standard conditions prescribed by s 73 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) apply, that is:

(a) Christopher Kenneth Joyce must not commit an offence; and

(b) Christopher Kenneth Joyce must submit to supervision by a community corrections officer.

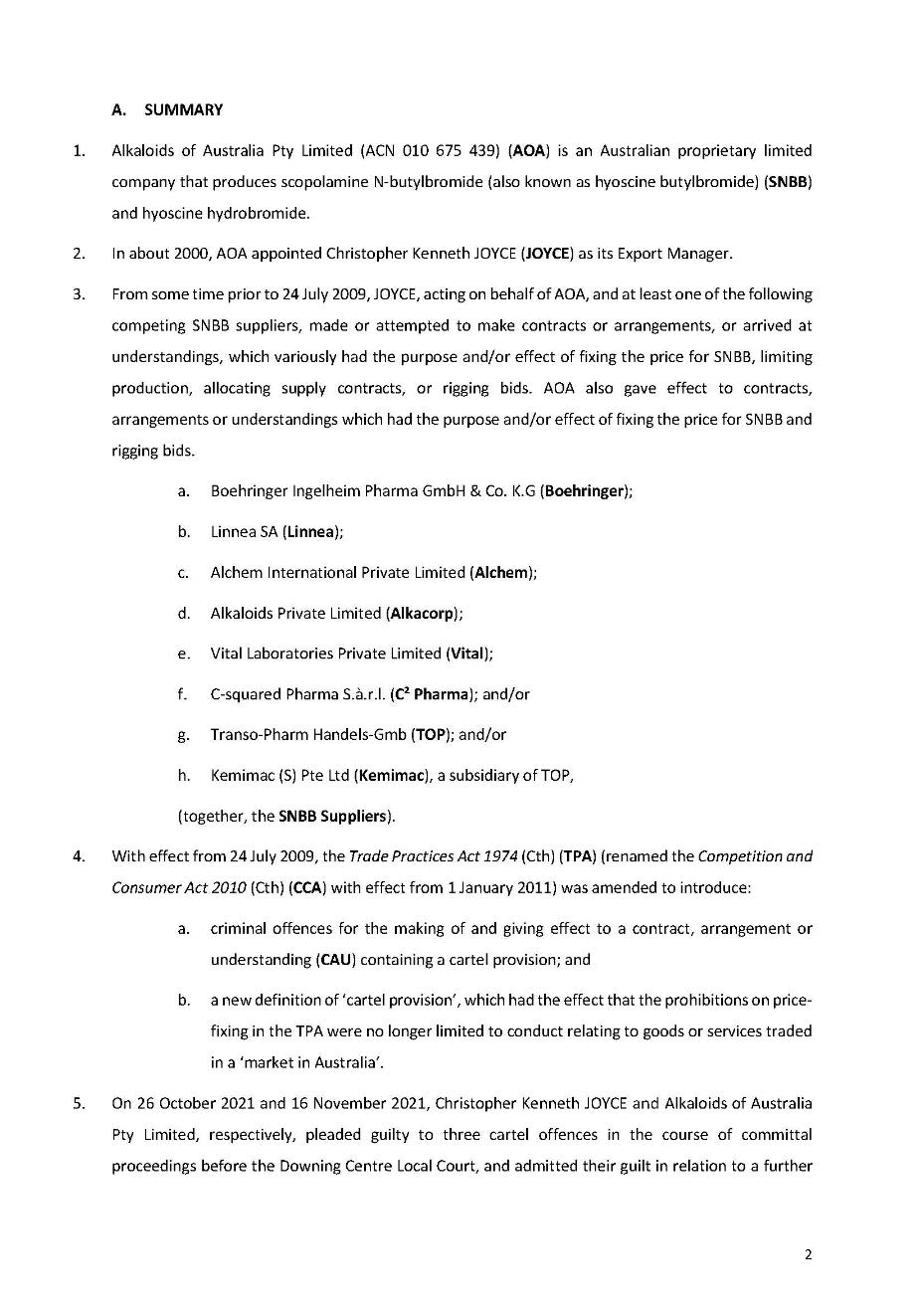

5. The following additional condition applies:

(a) Christopher Kenneth Joyce must perform community service work for 400 hours.

6. Christopher Kenneth Joyce is to report to the City Community Corrections Office as soon as practicable after but not later than 7 days after the date of this order.

7. Christopher Kenneth Joyce is fined the sum of $50,000.

8. Christopher Kenneth Joyce is disqualified from managing corporations, pursuant to s 86E(1A) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) for a period that begins on the date of this order and ends on 29 November 2027.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ABRAHAM J:

1 Christopher Kenneth Joyce is to be sentenced for cartel offences contrary to the provisions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) and Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) which relate to a number of contracts, arrangements or understandings (CAUs) given effect to or attempted to be made during the course of Mr Joyce’s work as the Export Manager for Alkaloids of Australia Pty Limited (AOA). Mr Joyce also admits seven additional offences under the TPA and CCA that are to be taken into account.

Background

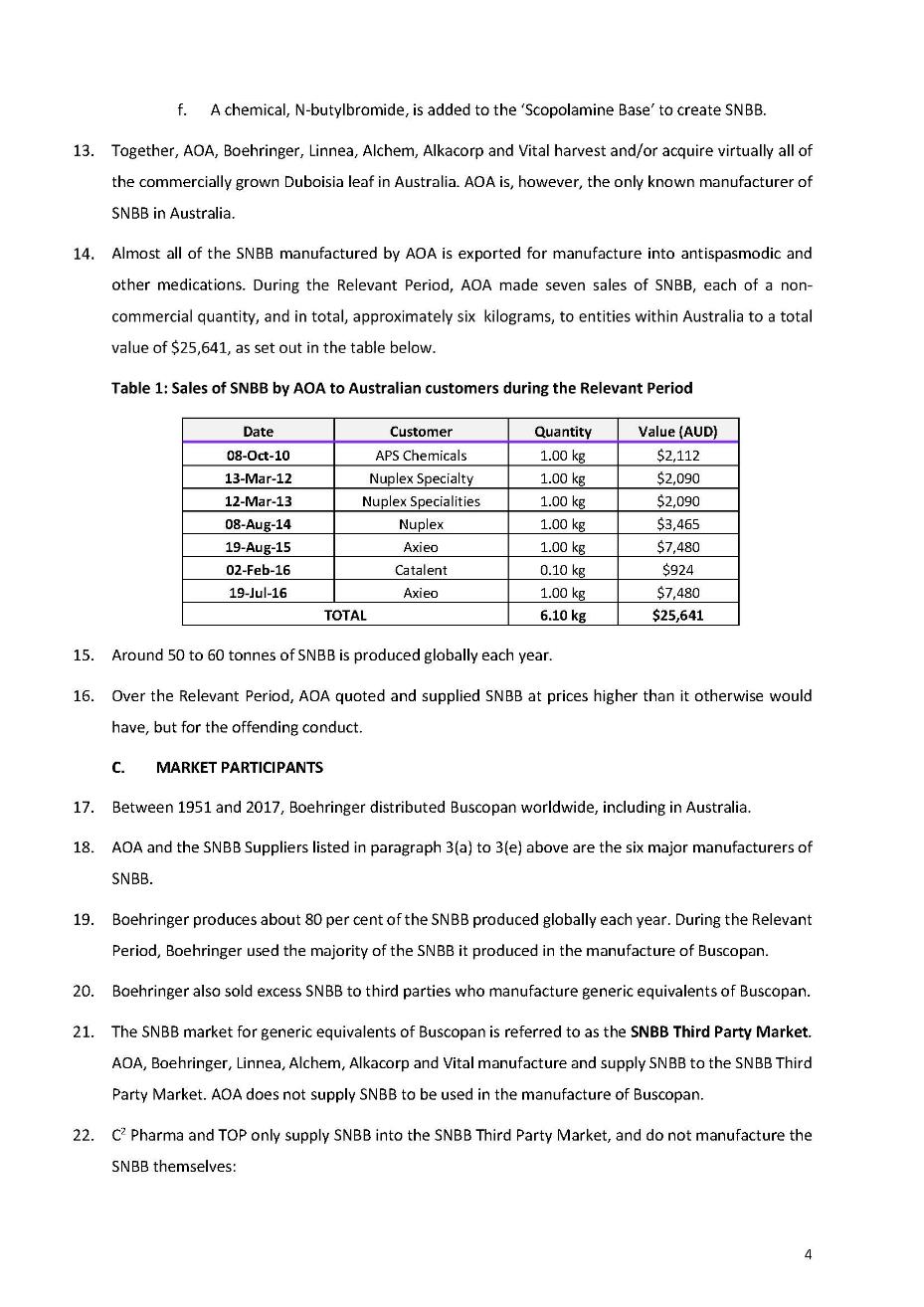

2 AOA is an Australian company which produces scopolamine N-butylbromide (also known as hyoscine butylbromide) (SNBB) and hyoscine hydrobromide. SNBB is manufactured from the alkaloid scopolamine (also known as hyoscine), which is extracted from plants, including the native Duboisia plant. SNBB is the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in some medications used to treat abdominal pain, oesophageal spasms, renal colic and bladder spasms. SNBB is sold as the API of an antispasmodic medication under the brand name Buscopan and in generic antispasmodic and other medications.

3 Almost all of the SNBB manufactured by AOA is exported for manufacture into antispasmodic and other medications. From 24 July 2009 to 19 December 2018 (the Relevant Period), AOA sold approximately 29 tonnes of SNBB. Of this, approximately 6 kg of SNBB was sold by AOA to Australian customers, to a total value of $25,641. There is no material market for SNBB in Australia.

4 Medications containing SNBB (SNBB medications) are purchased in Australia. During the Relevant Period, SNBB was the API used in 33 medications approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for sale in Australia and registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. During the periods in which AOA gave effect to the CAUs in relation to the supply of SNBB, the three major wholesalers sold $2,821,509.24 worth of generic SNBB medications (that is, excluding Buscopan) to Australian pharmacies.

5 From sometime prior to 24 July 2009, Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA and at least one of its competitor SNBB suppliers, made or attempted to make CAUs, which variously had the purpose and/or effect of fixing the price for SNBB, limiting production, allocating supply contracts, or rigging bids. AOA also gave effect to CAUs which had the purpose and/or effect of fixing the price for SNBB and rigging bids. The competing SNBB suppliers were: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. K.G (Boehringer); Linnea SA (Linnea); Alchem International Private Limited (Alchem); Alkaloids Private Limited (Alkacorp); Vital Laboratories Private Limited (Vital); C-squared Pharma S.à.r.l. (C² Pharma); and/or Transo-Pharm Handels-Gmb (TOP); and/or Kemimac (S) Pte Ltd (Kemimac), a subsidiary of TOP.

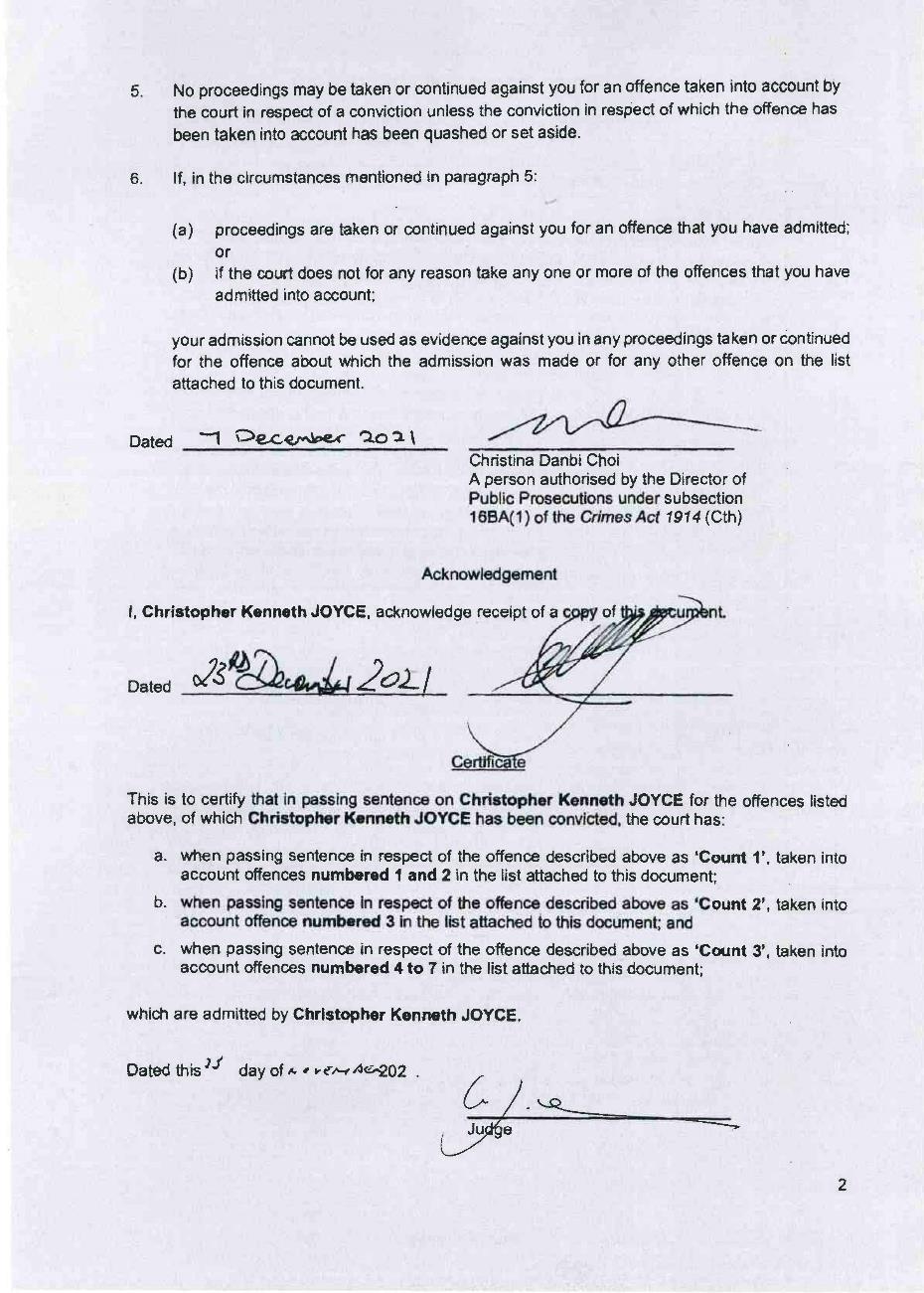

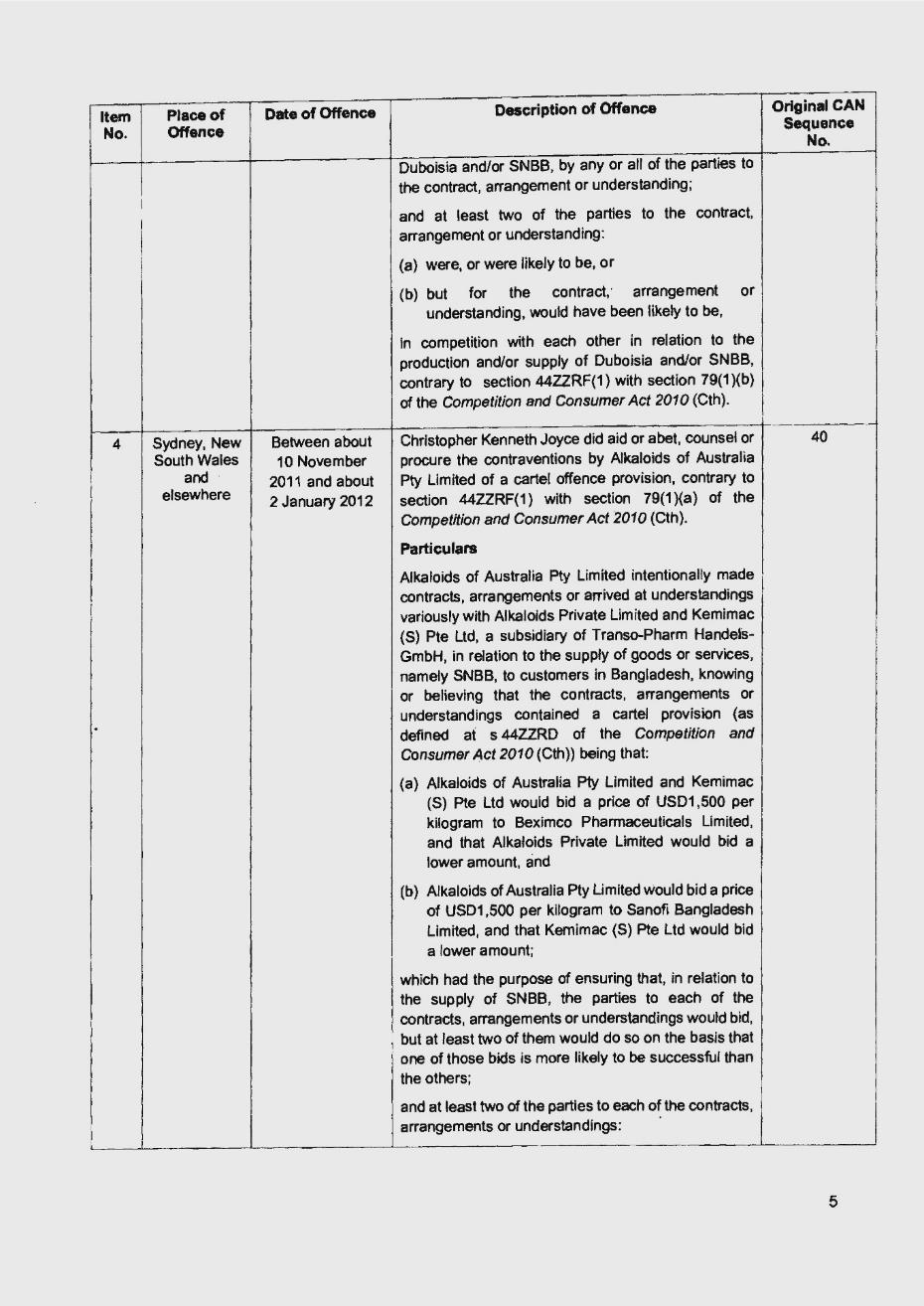

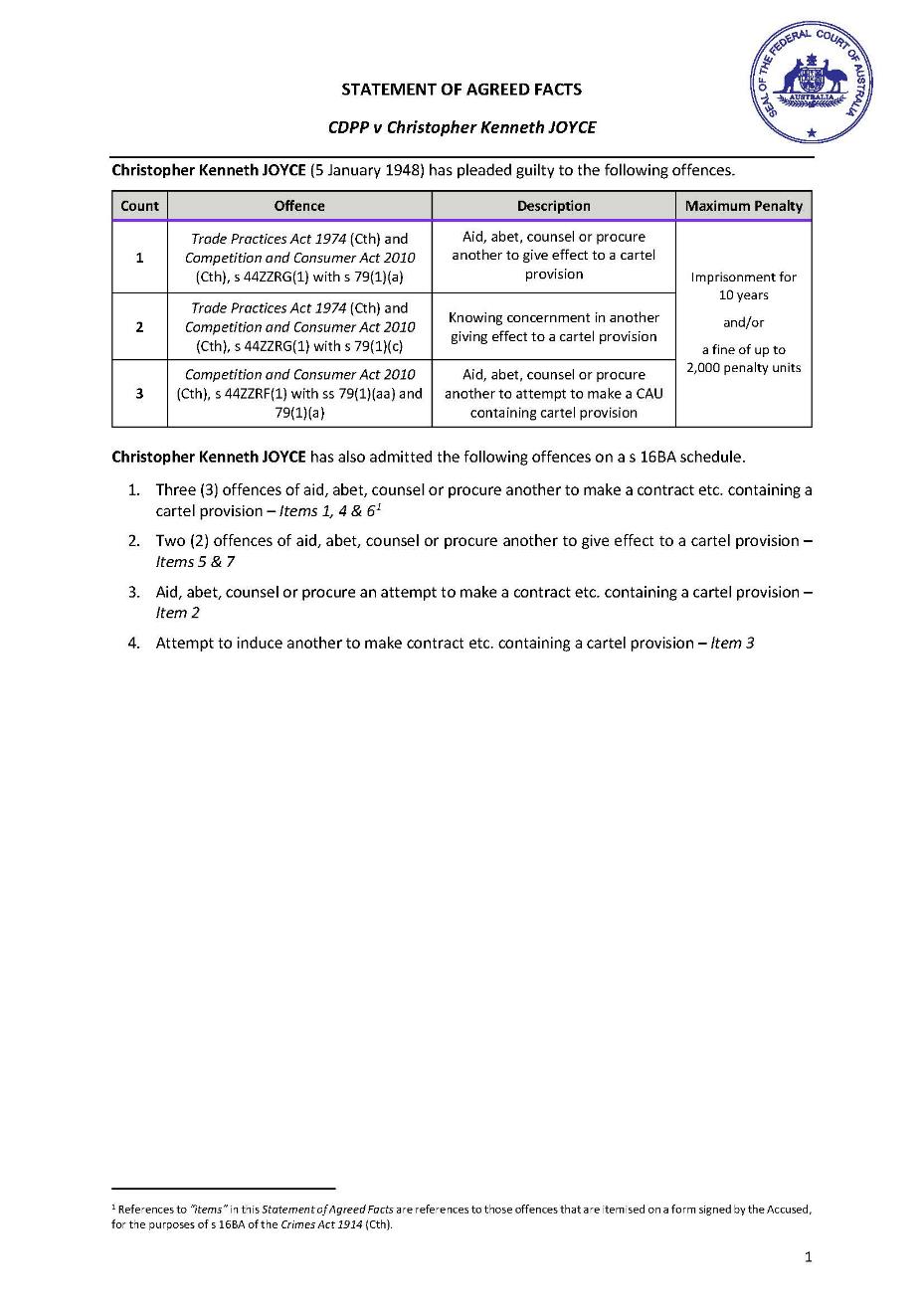

6 On 26 October 2021, during the course of committal proceedings in the Local Court of New South Wales, Mr Joyce pleaded guilty to: one count of aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring AOA giving effect to a CAU; one count of being knowingly concerned in AOA intentionally giving effect to a CAU; and one count of aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring AOA’s attempt to make a CAU. Mr Joyce also admitted his guilt in relation to a further seven cartel offences on a schedule (the Schedule), pursuant to s 16BA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) (Crimes Act). On 16 September 2022, those guilty pleas were affirmed on arraignment in this Court. The indictment and the Schedule are attached to these reasons as Annexure A. For present purposes, it is sufficient to summarise the counts and offences on the Schedule as follows.

Offences

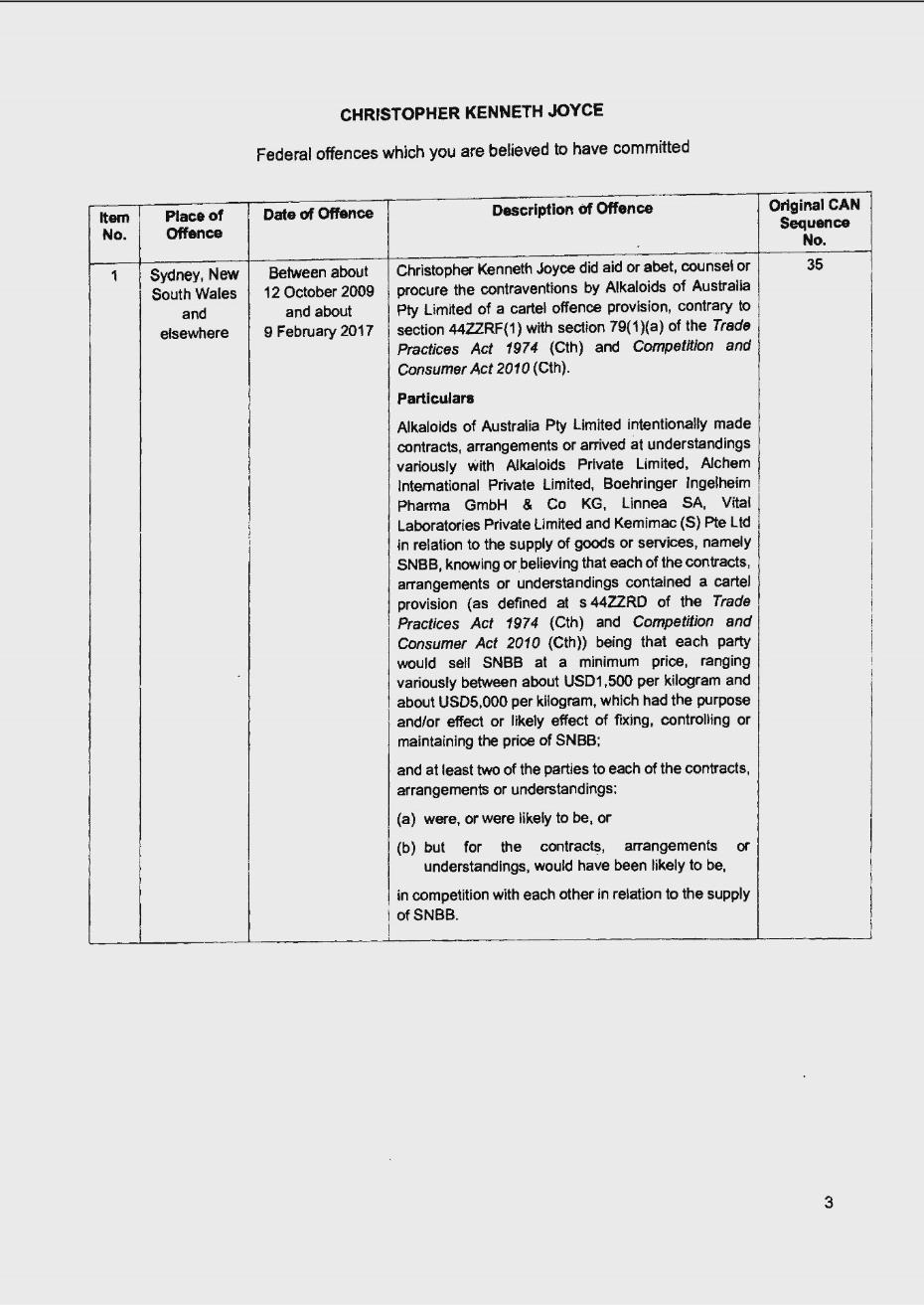

7 Count 1 relates to conduct between about 24 July 2009 and about 20 June 2017, when AOA intentionally gave effect to CAUs reached variously with Alkacorp, Alchem, Boehringer, Linnea, Vital and Kemimac that the parties to each of the CAUs would sell SNBB at a minimum price, variously ranging between about USD1,500 per kilogram and about USD5,000 per kilogram, knowing or believing that the cartel provisions had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB. Mr Joyce aided, abetted, counselled or procured AOA’s contravening conduct, contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the TPA and CCA. This count is a rolled up offence which involves AOA giving effect to seven price fixing provisions in different CAUs with competitors over a number of years. Although it is one count, the offending involves multiple acts of criminality and a course of conduct.

8 In addition, in sentencing for this count, Mr Joyce asks this Court to take into account two further offences: between about 12 October 2009 and about 9 February 2017 AOA made a CAU, aided or abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce; and between about 20 June 2017 and about 28 July 2017 AOA attempted to make a CAU, aided, abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce. These offences are included in the Schedule as Item 1, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the TPA and CCA, and Item 2, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(aa) of the CCA. Again, Item 1 is a rolled up count which relates to the making of six of the CAUs to which effect was given in Count 1.

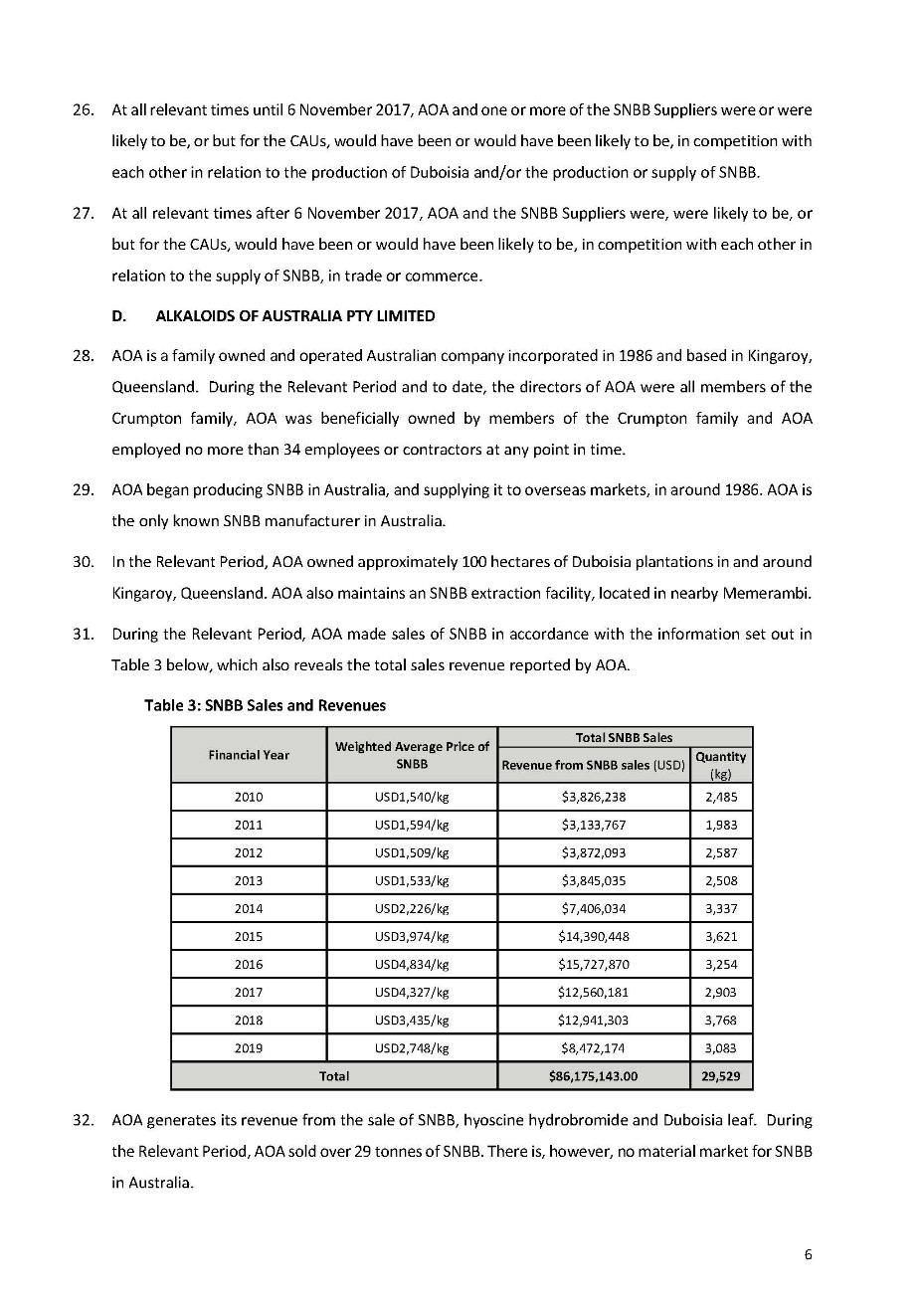

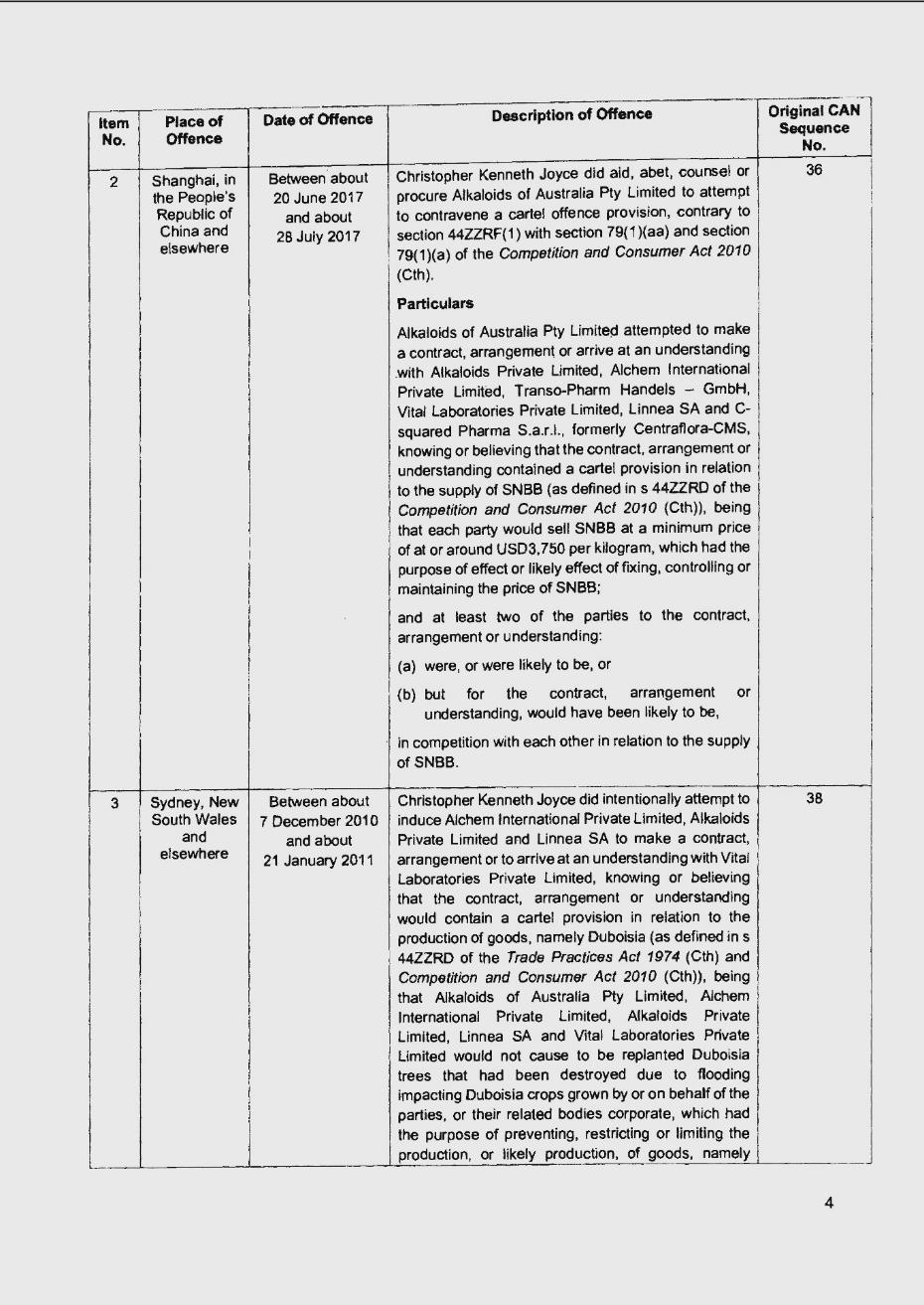

9 Count 2 occurred between about 9 December 2010 and about 26 July 2012, when AOA intentionally gave effect to a cartel provision in relation to the supply of SNBB, contained in a CAU made between Alkacorp, Boehringer, Linnea, AOA and Alchem, being that Alkacorp and/or Alchem, or subsidiaries thereof, would acquire the entire supply of Duboisia leaves from a grower named David Thamm, and obtain a commitment from him that he would not grow or produce, or cause any Duboisia to be grown or otherwise produced, on his Memerambi property, knowing or believing that the cartel provision had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB. Mr Joyce was knowingly concerned in AOA’s contravention, contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) with s 79(1)(c) of the TPA and CCA.

10 In addition, in sentencing for this count, Mr Joyce asks this Court to take into account an offence, contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(b) of the CCA, that between about 7 December 2010 and about 21 January 2011, he attempted to induce others into making a CAU: Item 3 on the Schedule.

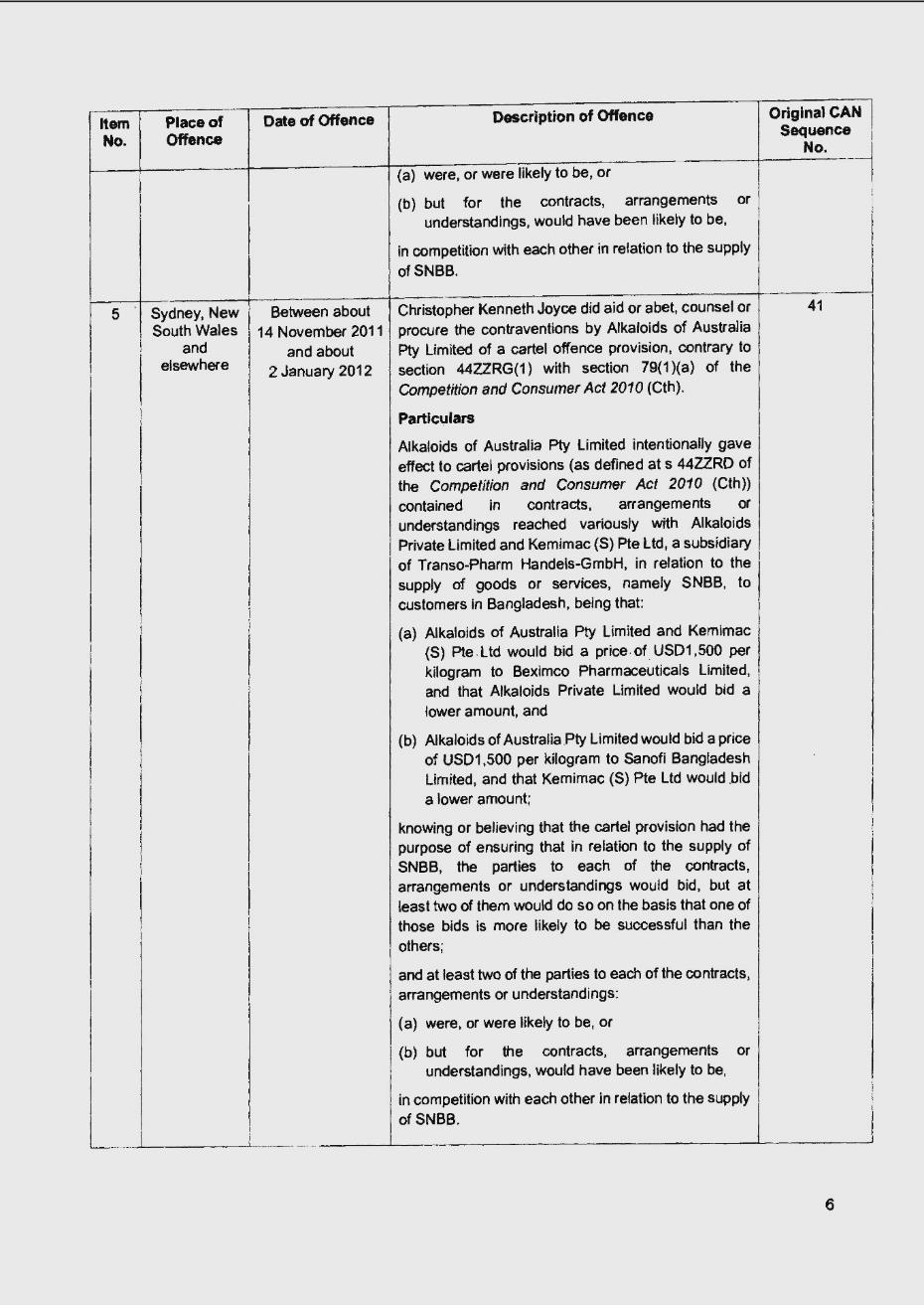

11 Count 3 occurred between about 19 September 2011 and about 28 December 2011, when AOA attempted to make a CAU with Alkacorp and Kemimac knowing or believing that it contained cartel provisions in relation to the supply of SNBB, that: each party would sell SNBB in accordance with a pricing structure inversely tiered on the basis of the quantity to be supplied, with a minimum price of no lower than USD1,500 per kilogram, to customers in Bangladesh, which had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB; and the supply contracts in respect of the likely acquisitions of SNBB by Fisions (Bangladesh) Ltd, Opsonin Pharma Ltd and Essential Drugs Company Limited would be allocated variously to AOA, Alkacorp, and Kemimac which had the purpose of allocating between any or all of the parties to the CAU SNBB, from any or all of the parties to the CAU, and/or had the purpose and/or effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of SNBB. Mr Joyce aided, abetted, counselled or procured this attempt by AOA, contrary to s 44ZRF(1) with ss 79(1)(aa) and 79(1)(a) of the CCA.

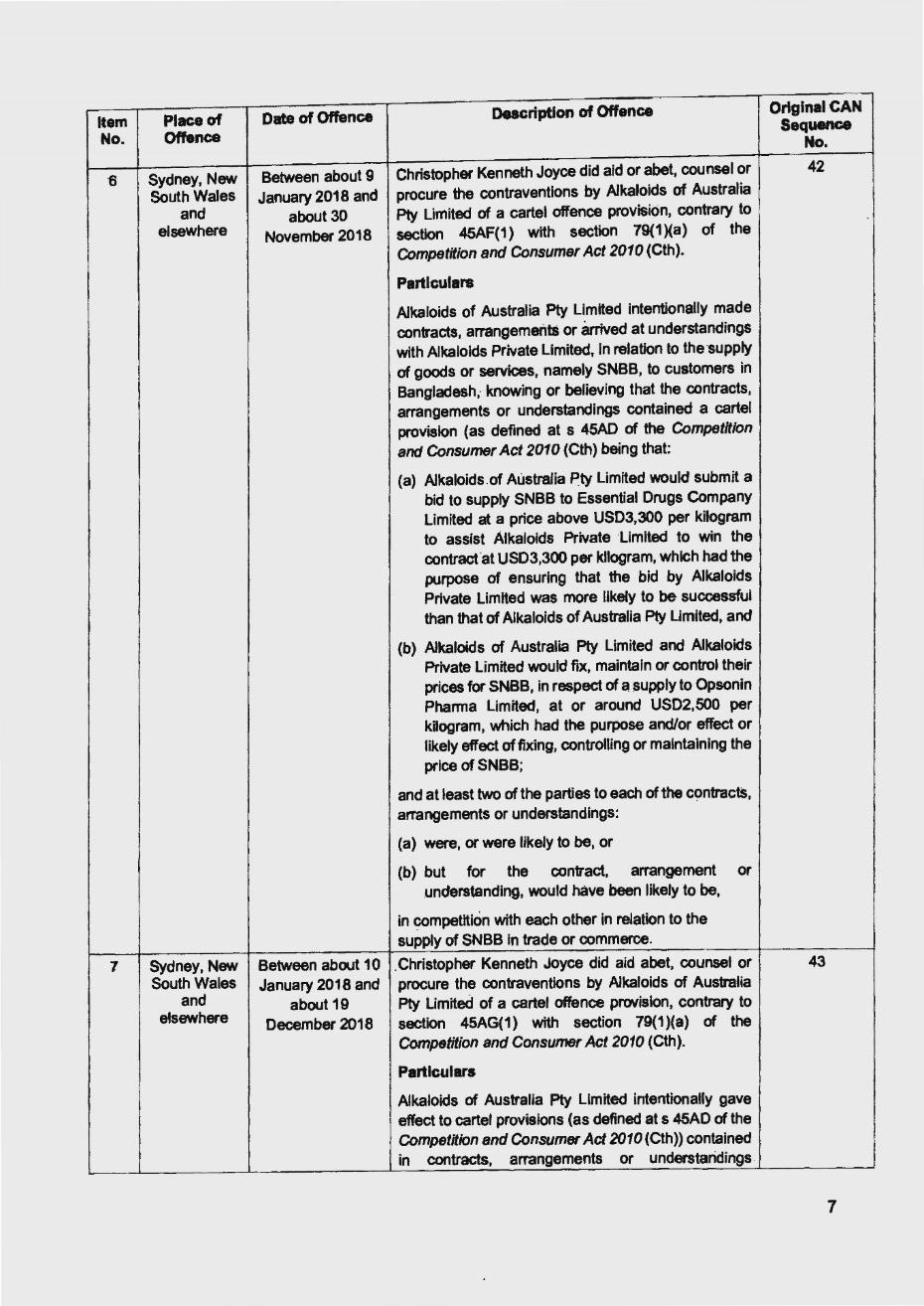

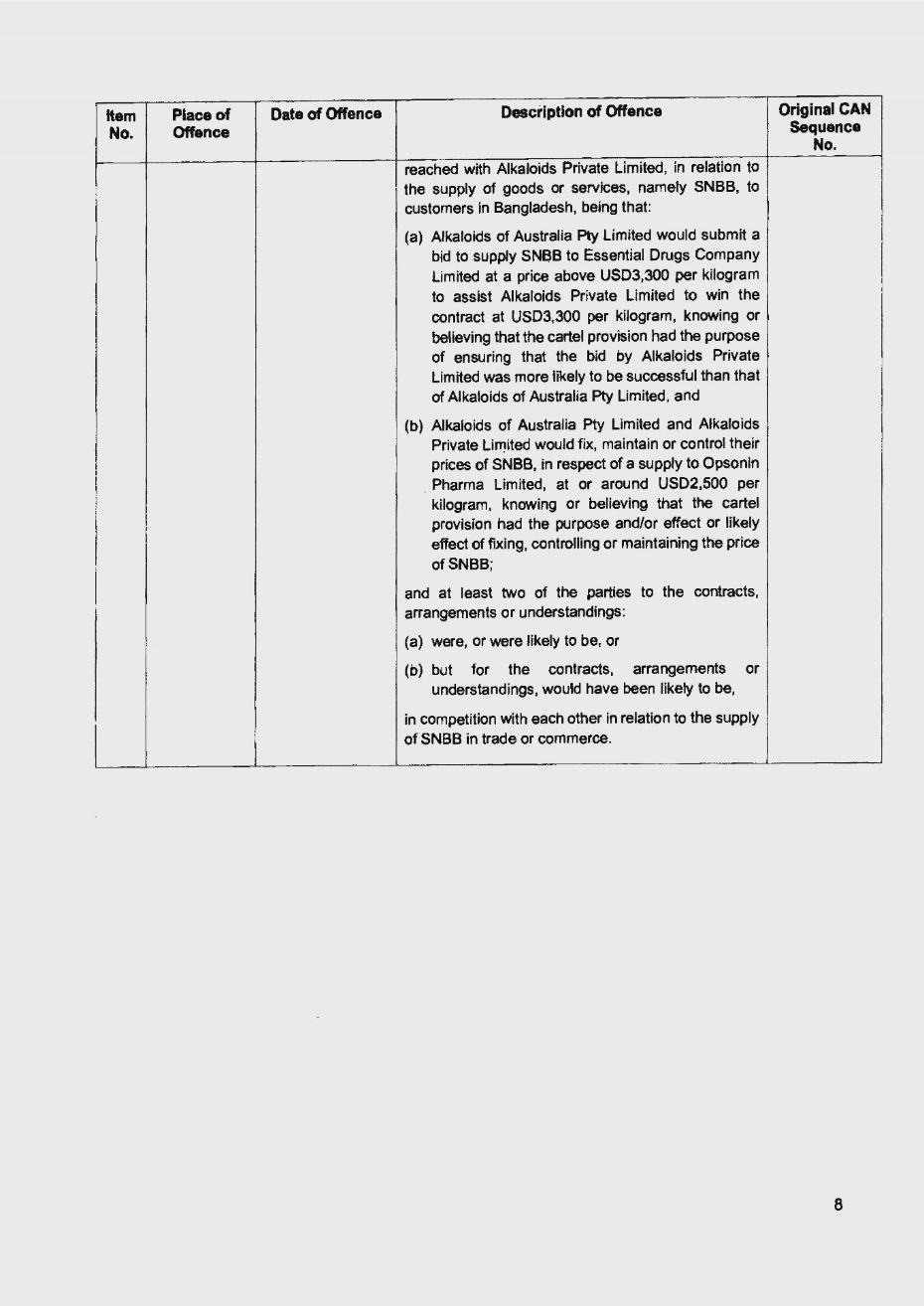

12 In addition, in sentencing for this count, Mr Joyce asks this Court to take into account four further offences that: first, between about 10 November 2011 and about 2 January 2012, AOA made a CAU aided or abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce (contrary to s 44ZZRF(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the CCA); second, between about 14 November 2011 and about 2 January 2012, AOA gave effect to cartel provisions aided or abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce (contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the CCA); third, between about 9 January 2018 and about 30 November 2018, AOA intentionally made CAUs aided or abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce (contrary to s 45AF(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the CCA); and fourth, between about 10 January 2018 and about 19 December 2018, AOA gave effect to cartel provisions aided, abetted, counselled or procured by Mr Joyce (contrary to s 45AG(1) with s 79(1)(a) of the CCA).

13 Mr Joyce’s contravening conduct spans 9.5 years, although it is not alleged that AOA gave effect to any CAU in relation to the supply of SNBB between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 within that period. The offending conduct involved the six major manufacturers of SNBB. One of those manufacturers, Boehringer, produced around 80 percent of the SNBB produced globally each year. Boehringer supplied 65 percent to 75 percent of the SNBB for generic equivalents. As a result of the CAUs, the price of the SNBB sold and quoted was higher than it otherwise would have been but for that conduct.

14 Before addressing the facts in more detail, it is appropriate to refer to the relevant sentencing principles.

Sentencing principles

15 Mr Joyce is to be sentenced for aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring cartel offences committed by AOA (counts 1 and 3) and being knowingly concerned in a cartel offence (count 2), which is an extension of criminal responsibility by force of s 79(1) of the CCA. An accessory within any of the paragraphs of s 79(1) “is taken to have contravened” the relevant cartel offence provision.

16 In respect to the culpability of an aider and abettor, the High Court observed in GAS v The Queen; SJK v The Queen [2004] HCA 22; (2004) 217 CLR 198 at [23]:

… it is not a universal principle that the culpability of an aider and abettor is less than that of a principal offender… A manipulative or dominant aider and abettor may be more culpable than a principal. And even when aiders and abettors are less culpable, the degree of difference will depend upon the circumstances of the particular case.

17 The Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (the Director) submitted that given the role of Mr Joyce in the offending, his culpability is, in effect, the same as AOA. That is, he was the company for the purposes of the offending. Given the basis of liability for the company relies on the acts of Mr Joyce, in the circumstances of this case, there is no relevant difference in Mr Joyce’s culpability on account of his offences being via an extension of criminal liability. I accept that his role in the offences was, accordingly, at the same level as that of the principal offender, AOA.

18 Mr Joyce is to be sentenced in accordance with Pt 1B of the Crimes Act, which requires that the sentence imposed by the Court be of a “severity appropriate in all the circumstances of the offence”: s 16A(1) of the Crimes Act.

19 In determining the sentence to be passed, in addition to any other matters, the Court must take into account the matters set out in s 16A(2) as far as they are relevant and known to the Court. This list relevantly includes: the nature and circumstances of the offence: s 16A(2)(a); if the offence forms part of a course of conduct consisting of a series of criminal acts of the same or a similar character, that course of conduct: s 16A(2)(c); any injury, loss or damage resulting from the offence: s 16A(2)(e); the degree to which the person has shown contrition for the offence: s 16A(2)(f); if the person has pleaded guilty to the charge in respect of the offence, that fact, the timing of the plea, and the degree to which that fact and the timing of the plea resulted in any benefit to the community, or any victim of, or witness to, the offence: s 16A(2)(g); the degree to which the person has cooperated with law enforcement agencies in the investigation of the offence or of other offences: s 16A(2)(h); the deterrent effect that any sentence or order under consideration may have on the offender: s 16A(2)(j) (specific deterrence); the deterrent effect that any sentence or order under consideration may have on other persons: s 16A(2)(ja) (general deterrence); the need to ensure that the person is adequately punished for the offence: s 16A(2)(k); the character, antecedents, age, means and physical and mental condition of the person: s 16A(2)(m); if the person’s standing in the community was used by the person to aid in the commission of the offence, that fact as a reason for aggravating the seriousness of the criminal behaviour to which the offence relates: s 16A(2)(ma); the prospects of rehabilitation of the person: s 16A(2)(n); and the probable effect that any sentence or order under consideration would have on any of the person’s family or dependents: s 16A(2)(p).

20 In Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha [2017] FCA 876; (2017) 254 FCR 235 at [220] (NYK) and later in Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2019] FCA 1170; (2019) 137 ACSR 75 at [279]-[281] (K-Line) and Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS [2021] FCA 52; (2021) 386 ALR 98 at [174]-[175] (WWO), Wigney J recognised that some guidance as to relevant sentencing factors in this context can be gained from civil penalty cases in respect to cartel conduct. In those cases, his Honour referred to the convenient summary of the principles in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2016] FCA 1516; (2016) 118 ACSR 124 (ANZ). Particularly relevant are [86]-[87]:

[86] In general terms, the factors that may be relevant when fixing a pecuniary penalty may conveniently be categorised according to whether they relate to the objective nature and serious [sic] of the offending conduct, or concern the particular circumstances of the contravenor in question (what sentencing judges commonly refer to as the offender’s “subjectives” or the “subjective circumstances”).

[87] The factors relating to the objective seriousness of the contravention include: the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate, covert or reckless conduct, as opposed to negligence or carelessness; whether the contravention comprised isolated conduct, or was systematic or occurred over a period of time; if the contravenor is a corporation, the seniority of the officers responsible for the contravention; the existence, within the corporation, of compliance systems and whether there was a culture of compliance at the corporation; the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties; and the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention.

21 As I observed in Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Vina Money Transfer Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 665 (Vina Money Transfer) at [109], although there are differences between the civil process and the criminal process, the factors referred to in ANZ are not surprising, and are really matters of common sense, given the nature of cartel offences: also see WWO at [175]. That said, care must be taken in considering these factors (and the potential weight to be attached to them) in a criminal context, given the different principles which apply in criminal sentencing: see, for example, Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 175 ALD 383 at [105].

22 The sentencing process involves the judge weighing all the relevant circumstances and making a judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence. It involves the balancing of many different and conflicting features: Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [75] (Wong). This has been described as a process of “instinctive synthesis”, namely, as described by McHugh J in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [51] (Markarian), “the method of sentencing by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case”.

23 That said, general deterrence is of particular importance given the nature of cartel offending, which like other “white collar” offending is difficult to detect, investigate and prosecute successfully: Vina Money Transfer at [110]-[112]; NYK at [273]-[274].

24 As general deterrence is ordinarily a primary sentencing consideration for such offending, factors personal to the offender such as good character and other mitigatory factors are necessarily afforded less weight than they otherwise might be: Vina Money Transfer at [112]; and Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Page [2006] VSCA 224 at [37] (Page).

25 It is important to recall that in sentencing, a court may not take into account facts adverse to the interests of the offender unless those facts are established beyond reasonable doubt. For facts in favour of the offender, it is enough that those facts are proved on the balance of probabilities: R v Olbrich [1999] HCA 54; (1999) 199 CLR 270 at [27]. The onus is on the offender to establish those mitigating factors. That said, as noted above at [19], s 16A of the Crimes Act requires that those matters be taken into account so far as they are “relevant and known to the court”. That phrase is not to be construed as imposing a universal requirement that matters urged in sentencing hearings be either formally proved or admitted: Weininger v The Queen [2003] HCA 14; (2003) 212 CLR 629 at [21]-[22].

26 It is also important to recall the approach a court is to take when sentencing for a rolled up count. A rolled up count is a count in which more than one contravention of the relevant offence provision, or more than one episode of criminality, is particularised as part of the charge. Count 1 is a rolled up count. This approach is adopted in some cases where there is a guilty plea, and where there is consent of the offender’s counsel, for otherwise the counts would be regarded as duplicitous: R v Jones [2004] VSCA 68 at [13] (Jones); NYK at [206]-[207]. The maximum penalty for the offence remains the same as if it were a single offence. However, the objective criminality of the offence is greater for the offender than if there was only one count: Jones at [13]; NYK at [207].

27 Relevantly, in K-Line, Wigney J observed at [270]:

[270] In sentencing a rolled-up charge, the Court is required to assess the criminality of an offender’s conduct as particularised. The issue for the Court on sentence is the criminality disclosed by the offence, not the number of charges: R v Knight [2004] NSWCCA 145 at [25]-[26]. The more contraventions or episodes of criminality that form part of the rolled-up charge, the more objectively serious the offence is likely to be: R v Richard [2011] NSWSC 866 at [65(f)]; R v Glynatsis [2013] NSWCCA 131; 230 A Crim R 99 at [66]; R v De Leeuw [2015] NSWCCA 183 at [116]. That said, the maximum penalty for the rolled-up charge is the maximum penalty for one offence, not the aggregate of the penalties for what could have been charged as separate offences: R v Richard at [105]; R v Donald [2013] NSWCCA 238 at [85].

28 In WWO, Wigney J further observed at [227]-[230]:

[227] The objective of taking other offences into account pursuant to provisions such as s 16BA of the Crimes Act is to ensure that the sentence imposed “is one which best meets the situation”: AG’s Application at [30]. The Court takes into account the other offences “with a view to increasing the penalty that would otherwise be appropriate for the particular offence” for which the offender is to be sentenced: AG’s Application at [42]. The increased penalty is effectively the product of the Court giving greater weight to two elements in the sentencing process: the first being the need for personal deterrence, as the commission of other offences will frequently indicate that the accused has engaged in a course of conduct; the second being “the community’s entitlement to extract retribution for serious offences when there are offences for which no punishment has in fact been imposed”: AG’s Application at [42]. The additional penalty as a result of taking the s 16BA offences into account will not necessarily be small; sometimes it will be substantial: AG’s Application at [18].

[228] The manner and degree to which other offences, which are taken into account pursuant to provisions such as s 16BA of the Crimes Act, can impinge upon elements relevant to the sentencing process will depend on a range of other factors pertinent to those elements and the weight to be given to them in the overall sentencing task. For that reason it will rarely be appropriate for a sentencing judge to attempt to quantify the effect on the sentence of taking those other offences into account: AG’s Application at [44].

[229] Section 16BA must be applied having regard to the basic common law principle that no one should be punished for an offence of which he or she has not been convicted. Section 16BA offences constitute an admission of guilt only: there is, relevantly, no conviction: AG’s Application at [23]. It follows that in taking the s 16BA offences into account, the sentencing judge is not imposing any punishment for those offences: AG’s Application at [29]. Rather, when taking the other (s 16BA) offences into account, the Court is concerned and concerned only with imposing a sentence for “the principal offence”; it is no part of the task of the sentencing court to determine appropriate sentences for s 16BA offences or to determine the overall sentence that would be appropriate for all the offences and then apply a “discount” for the use of the procedure under s 16BA: AG’s Application at [39]. The use of the s 16BA procedure, however, will generally result in a lower effective sentence than would have been imposed if the offender had been separately sentenced for the s 16BA offences: AG’s Application at [34].

[230] The Court is given an overriding discretion to refuse to accede to the wishes of the prosecution and the offender in terms of the utilisation of the s 16BA procedure: AG’s Application at [47]. That is a wide discretion which “should not be confined by the identification of a list of situations in which it should not be exercised”: AG’s Application at [48].

29 It may be expected that use of the procedure set out in s 16BA will result in a lower effective sentence than would have been imposed if an offender had been sentenced for the principal offence and separately sentenced for each of the offences included in the s 16BA schedule. That said, “[i]t does not follow, however, that the increase to the penalty as a result of taking the two s 16BA offences into account will necessarily be small”: WWO at [233].

30 The maximum penalty for each offence in this case is a term of imprisonment not exceeding 10 years or a fine not exceeding 2,000 penalty units (which equates to $220,000), or both: s 79(1)(e) of the TPA and CCA. Mr Joyce accepted that no penalty other than imprisonment is appropriate. The issue is whether any of it ought to be immediately served, or how it ought to be served.

31 In this regard, in Markarian, the plurality observed at [31]:

[31] … careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

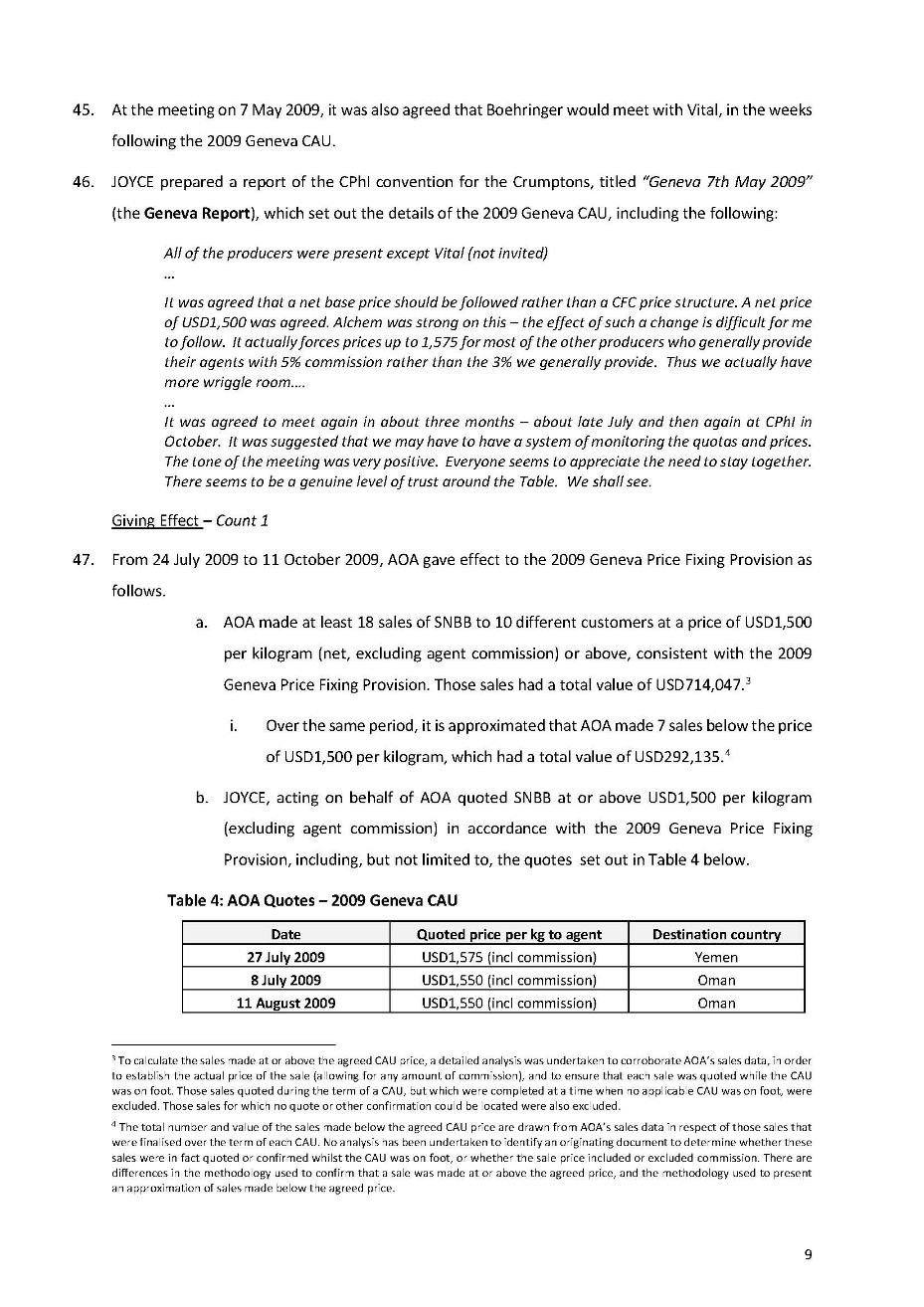

Evidence relied on by Mr Joyce

32 Mr Joyce read the following affidavits and tendered the following statements:

(1) affidavit of Christopher Kenneth Joyce affirmed 5 August 2022;

(2) affidavit of Stephen Charles Kroker sworn 27 April 2022;

(3) statement of Julie Marie Bird dated 3 August 2022;

(4) statement of Jolyon Burnett dated 2 August 2022;

(5) statement of Richard Hamilton Fisher dated 5 August 2022;

(6) statement of David Lindsay Crawford dated 1 August 2022;

(7) statement of Chris Lee dated 10 August 2022;

(8) statement of Long (Laurence) Ma dated 25 July 2022;

(9) statement of Peter Hall McLean dated 22 July 2022;

(10) statement of Trevor Ranford dated 1 August 2022; and

(11) statement of Barbara Wilby dated 4 August 2022.

33 Primarily they were directed to Mr Joyce’s good character, and the impact these proceedings have had on him. In addition, Mr Kroker’s affidavit addresses a conversation he had with Mr Joyce, between 1993 and 1995, regarding his “views on a trade practices issue”.

Mr Joyce’s evidence

34 As noted above, Mr Joyce provided an affidavit, affirmed 5 August 2022. He was required for cross-examination. Before that commenced, Mr Joyce was asked some brief questions in chief.

35 The focus of the cross-examination was Mr Joyce’s assertion in his affidavit that he was not aware that the offending conduct was unlawful, as it related to goods exported from Australia. He stated in his affidavit that he first became aware the activities of the cartelists may have been contrary to Australian law when the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) raided his office on 17 September 2019. Mr Joyce’s state of mind was a significant matter relied on in his written submissions to, inter alia, support that his conduct was less morally culpable. Notably, Mr Joyce’s affidavit was silent on his state of mind as to the lawfulness of the conduct in respect to Count 2 (which occurred in Australia). The basis relied on by Mr Joyce that goods were exported, could not apply to that count. Mr Joyce gave additional evidence in chief on that topic.

36 Mr Joyce admitted in cross-examination that at the time of the conduct that forms the basis of Counts 1 and 3, he considered it was improper conduct. In respect to Count 2, at the time of the conduct he considered it was improper, unethical and probably unlawful (although he did not know what law it was contrary to). Those concessions are significantly more than what was in Mr Joyce’s affidavit. As conceded by his counsel, they detracted from the submission he had advanced in writing, as to his moral culpability.

37 Although Mr Joyce submitted that he should be assessed as having been candid in his evidence, as a general proposition, I do not accept that. It may be accepted on some topics that he was candid. However, on some topics he sought to minimise his conduct. To give three examples.

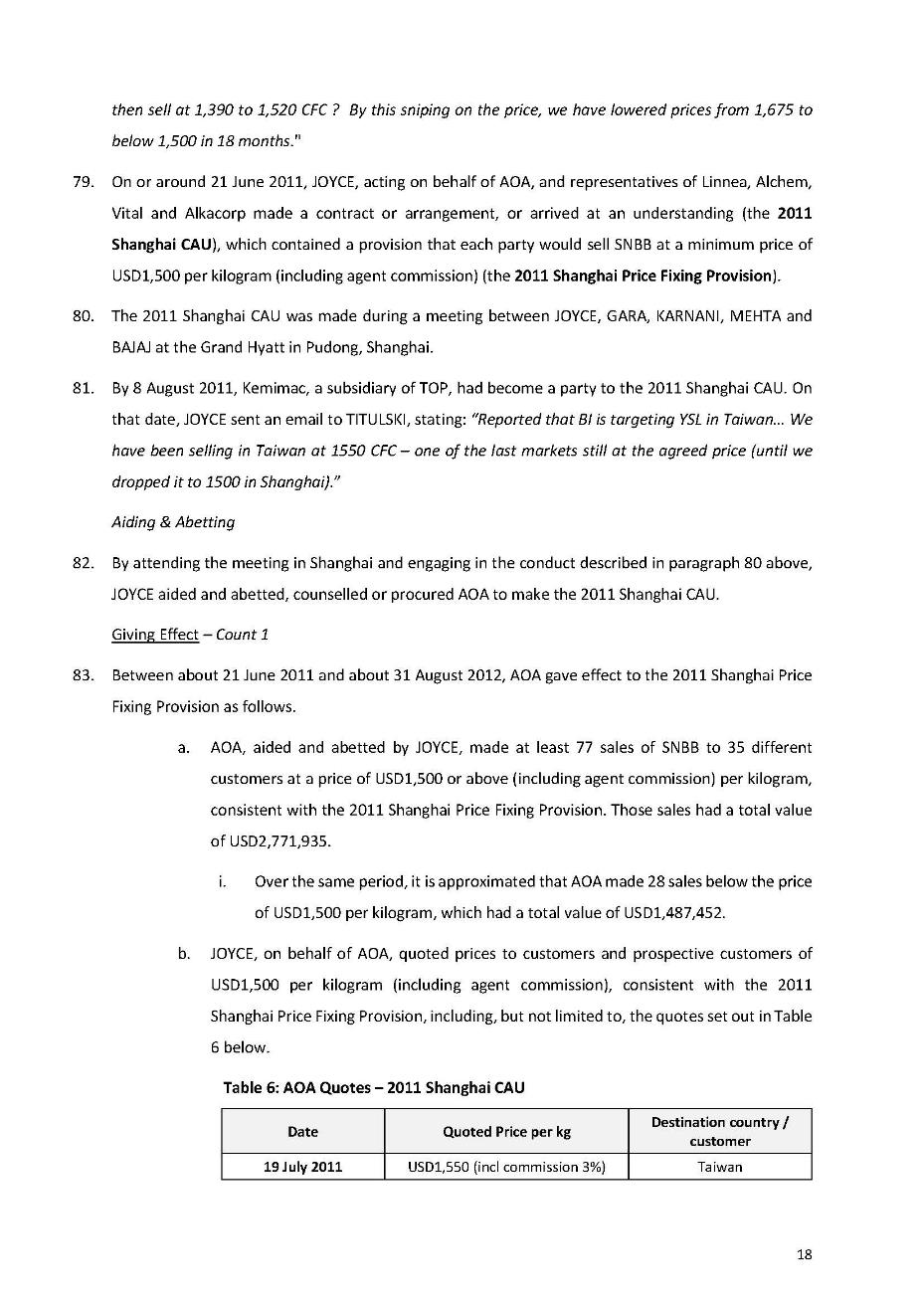

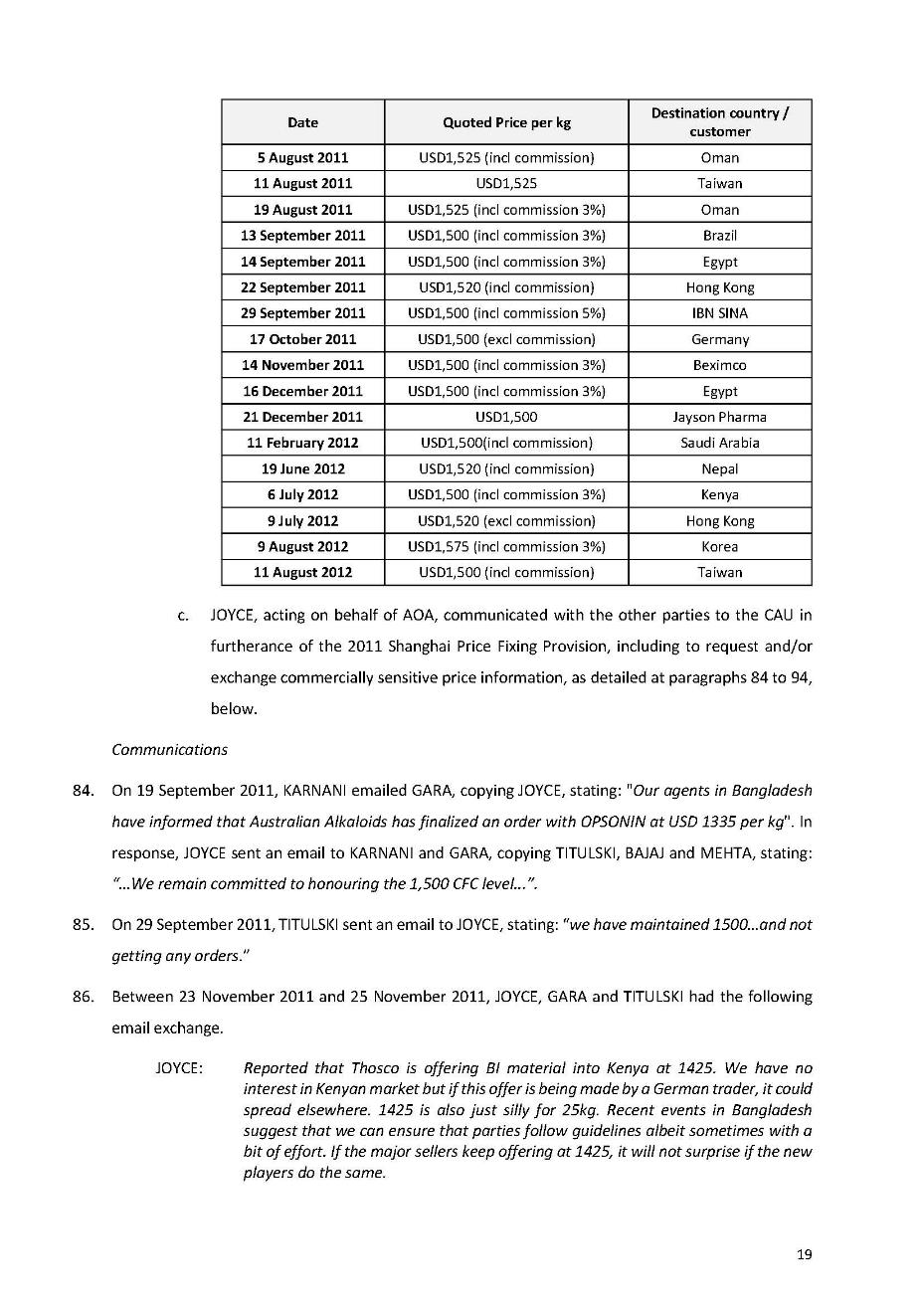

38 First, in respect to Count 2, in examination in chief, Mr Joyce gave evidence that at the time he considered the conduct to be improper, and probably unlawful (although he did not know what law it was contrary to). Mr Joyce’s answers in cross-examination on this topic were unsatisfactory. He initially denied having said that he thought the conduct was probably unlawful, before conceding that he had said that but it related to his current state of mind. That evidence could not be accepted, as he had pleaded guilty to the offence (and therefore at the time he gave evidence knew the conduct to be unlawful). He then returned to the position taken in examination in chief, admitting that was his state of mind at the time of the offending conduct. Mr Joyce’s counsel attempted to attribute any inconsistencies in his evidence to a number of possible factors, including his age and the stress of giving evidence in the particular circumstances. Making allowances for such matters, I nonetheless do not accept they were the basis of this inconsistency. Mr Joyce was well aware of the significance of this issue. Rather, considered in the context of all his evidence generally, the inconsistency reflects an attempt on his part to diminish his responsibility.

39 Second, in the same vein, I do not accept Mr Joyce’s evidence that he did not turn his mind to the issue of lawfulness of the conduct in the countries AOA was exporting to, or his denials that, at times, he was concerned about the legality of the conduct. An example of the latter is his evidence as to the circumstances of his conversation with Mr Kroker, which occurred in a casual social context (for example, a dinner or a barbeque). This conversation was sometime between 1993 and 1995 and in the context where Mr Joyce had known Mr Kroker, a competition lawyer, for some time. Mr Joyce raised with him, what he now accepts he knew was an unusual and improper business practice. The compelling inference in the circumstances is that Mr Joyce was concerned about the lawfulness of the conduct and sought reassurance. Mr Joyce’s evidence that he raised the topic as casual conversation, in effect for enjoyment, cannot be accepted. Mr Joyce’s denial that he raised the topic because of concerns he held as to the lawfulness of the conduct, is implausible. In any event, any advice was informally given and was not definitive, as is apparent by its terms. So much was accepted by Mr Joyce. Moreover, if he was concerned about the legality of the conduct, as he contends, he would have obtained legal advice outside the context of a casual social occasion at some stage over the many years over which the conduct was undertaken.

40 Third, Mr Joyce’s answers to questions in cross-examination suggest that he undertook the conduct for financial gain. Although Mr Joyce ultimately admitted that was a motive, albeit a limited one, it took a number of questions to elicit that admission. The questions had been clear and direct.

41 Each of these examples reflect an attempt by Mr Joyce to diminish his responsibility.

42 Despite the concession referred to above as to the informal nature of the advice from Mr Kroker, that conversation is the basis on which he purportedly founded his view that the conduct was not unlawful. Mr Joyce’s counsel described the factual basis for Mr Joyce’s belief as to lawfulness as “feeble”. On Mr Joyce’s case as advanced in submissions, the belief was also based on a conversation with Mr Hannaford, the CEO and Managing Director of Joe White Maltings Ltd, who passed on advice from another board member who was a partner of a law firm. The advice passed on was said to indicate there was no problem with the arrangements because no other Australian companies were involved. That conversation was not focussed on in oral submissions. The conversation occurred in 1988 or 1989, was at best second hand hearsay, and again was not definitive advice. The purported basis for Mr Joyce’s view was therefore not proper or reasonable. In any event, that purported view as to lawfulness could not apply to his conduct in respect to Count 2.

43 Mr Joyce gave evidence accepting that he should have obtained advice. He did not provide any explanation, or adequate explanation as to why he did not. Moreover, it begs the question of why a person in his position (also considering the extent of his involvement in other businesses), who believed the conduct was improper, did not do so.

44 Mr Joyce chose not to get any legal advice. When he returned to work with AOA in 2009, he did so that knowing the improper practice was still in place. He did not seek any advice at that time, even though many years had passed since the informal advices he relied on were given. This is in a context where he knew that laws had changed in the nut industry, in which he also worked. After there was more than a two year gap in the offending conduct between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015, Mr Joyce recommenced the same practices without apparent question. Mr Joyce points to an email he sent to his solicitor directly after the ACCC raids which states, inter alia, “[t]here is no conspiracy to my knowledge. Even if there where [sic] hyoscine butylbromide is only sold internationally … My understanding of the Trade Practices Act is that it only covers domestic Australian activities?”. This was said to be evidence of state of mind. However, as explained above, it is difficult to accept that a person in his position could consider there was a proper or reasonable basis for that belief. If Mr Joyce was genuinely concerned about the lawfulness of the conduct, as he said, he would have obtained legal advice.

45 I am satisfied Mr Joyce undertook this conduct believing it was improper and, in respect to Count 2, unethical and probably unlawful. He went ahead regardless. I accept the Director’s submission that Mr Joyce undertook the conduct being reckless as to whether it was unlawful. I am satisfied that Mr Joyce was not concerned about AOA’s customers or how this conduct impacted on others. Rather, he was indifferent as to the effect. He, with the other cartelists, had been undertaking this conduct undetected and for financial benefit for such a long time, he wanted the position to continue.

46 That said, I accept Mr Joyce’s evidence as to the impact these proceedings have had on him, including that he has felt “[d]eep humiliation, guilt and regret”.

The nature and circumstances of the offending

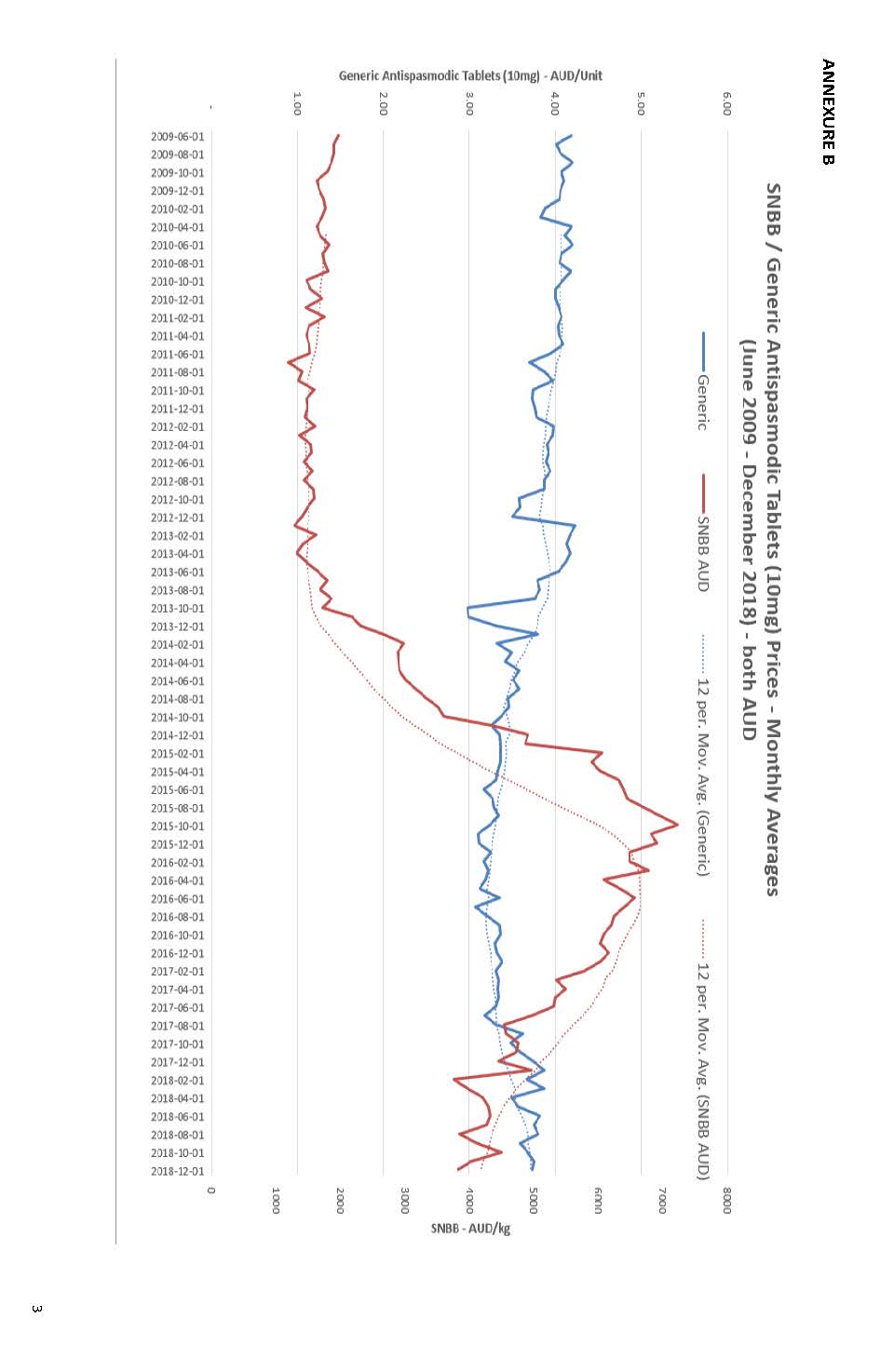

47 This matter proceeded by way of a statement of agreed facts (SOAF), a copy of which is attached to this judgment as Annexure B.

48 Before addressing the particular counts it is appropriate to make some general observations.

49 These offences were committed over a substantial period of time, reflective of an ongoing course of anti-competitive conduct.

50 AOA is a family owned and operated Australian company incorporated in 1986 and based in Kingaroy, Queensland. During the Relevant Period and to date: the directors of AOA are all members of the Crumpton family; AOA is beneficially owned by members of the Crumpton family; and AOA employs no more than 34 employees or contractors at any point in time. At various times the directors have included Glenn Crumpton, John Crumpton and Sonie Crumpton.

51 AOA began producing SNBB in Australia, and supplying it to overseas markets, in around 1986. AOA is the only known SNBB manufacturer in Australia. In the Relevant Period, AOA owned approximately 100 hectares of Duboisia plantations in and around Kingaroy. AOA also maintains an SNBB extraction facility, located in nearby Memerambi.

52 AOA generates its revenue from the sale of SNBB, hyoscine hydrobromide and Duboisia leaf.

53 During the Relevant Period, AOA sold over 29 tonnes of SNBB. Of this, approximately 6 kg of SNBB was sold by AOA to Australian customers.

54 During the period between 2012 and 2016, natural weather events and other supply issues affected the price of SNBB.

55 From the figures in SOAF [31], it is apparent that revenue from SNBB sales accounted for a substantial proportion of all revenue generated by AOA.

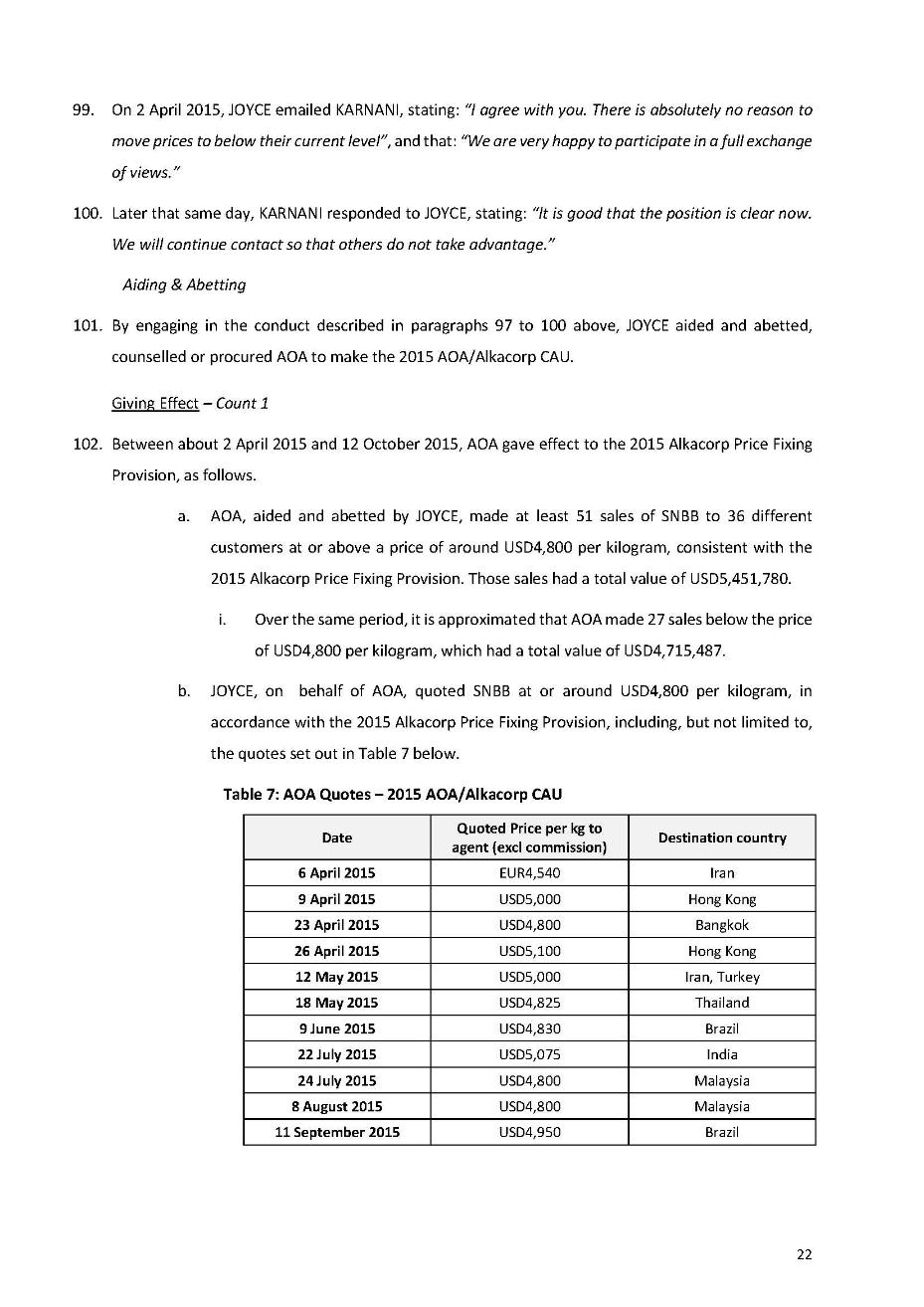

56 As previously explained, throughout the Relevant Period, Mr Joyce was AOA’s Export Manager, with responsibility for all aspects of the marketing and sale of SNBB produced by AOA, including deciding the price at which SNBB was sold. He was an independent contractor. At all material times, he acted within the scope of his actual authority as Export Manager, and with the authority of the Crumptons. As reflected in the SOAF, Mr Joyce kept the Crumptons informed of matters relating to the marketing and sale of SNBB, including the pricing arrangements with other SNBB Suppliers.

57 Mr Joyce was paid a monthly retainer of $9,500 and a commission of 2 percent of AOA’s SNBB sales revenue. Between 1 July 2009 and 30 June 2017, after meeting his expenses, Mr Joyce received in the order of $1,450,000 in respect of his role with AOA, ranging between $22,439 in FY2011 and $430,250 in FY2016.

Count 1: Giving effect to a CAU

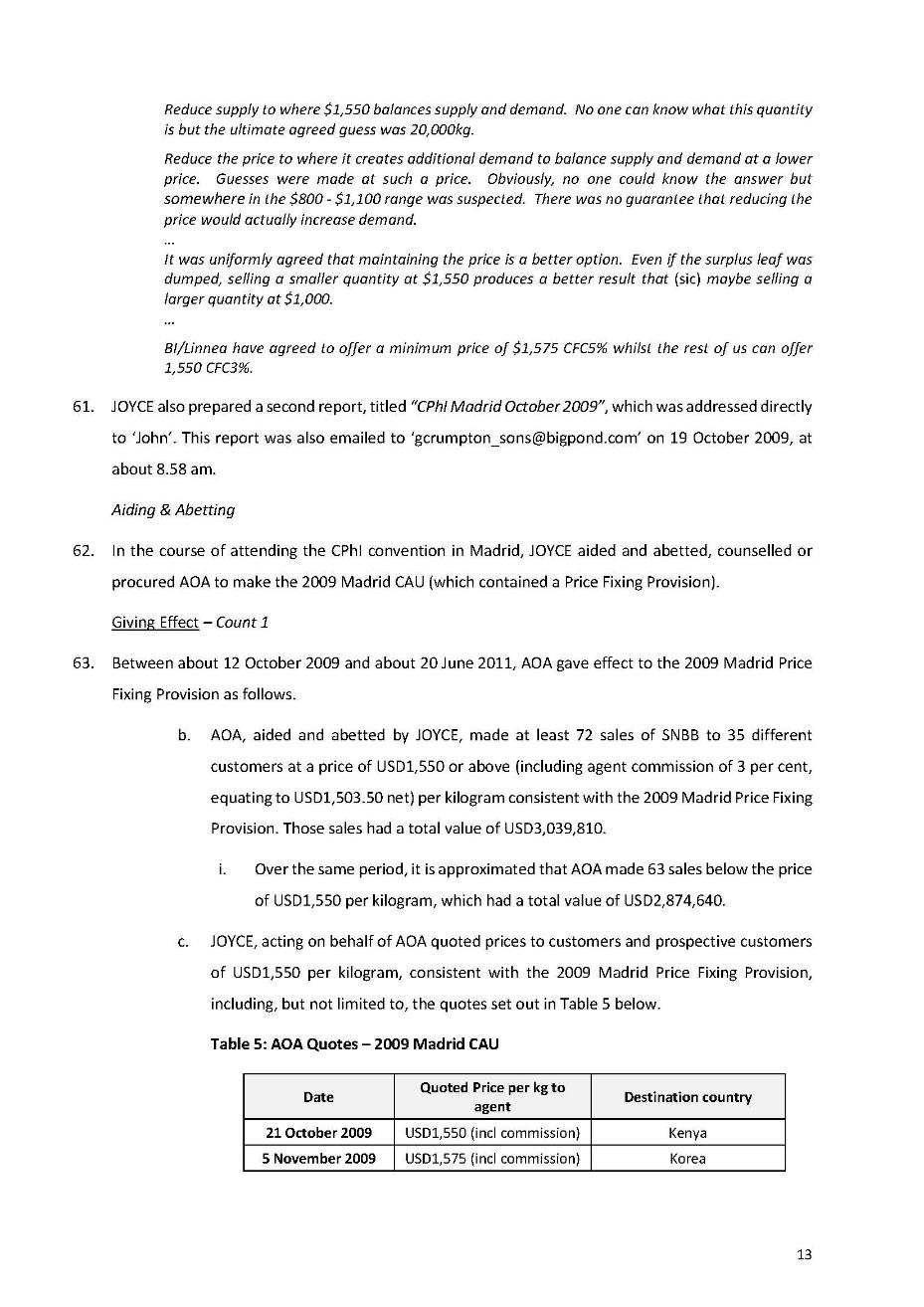

58 This rolled up count encompasses Mr Joyce aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring AOA giving effect to seven different CAUs containing price fixing provisions. As reflected in the SOAF, the seven price fixing provisions have titles for ease of reference to assist, which reflect, in most cases, the location where the arrangement was made. Those names are 2009 Geneva CAU: SOAF [44]-[55]; 2009 Madrid CAU: SOAF [56]-[76]; 2011 Shanghai CAU: SOAF [77]-[95]; 2015 AOA/Alkacorp CAU: [96]-[103]; 2015 Madrid CAU: SOAF [104]-[120]; 2016 Sydney CAU: SOAF [121]-[136]; and 2017 AOA/Alkacorp/Linnea CAU: [137]-[149].

59 On this count, Items 1 and 2 of the Schedule are to be taken into account. Item 1 is also rolled up, and includes aiding or abetting, counselling or procuring the making of six CAUs, namely the last six CAUs referred to immediately above (the first agreement was made before the conduct was made a criminal offence).

60 The offending conduct involved six of the major manufacturers of SNBB (Boehringer, Linnea, Alchem, Alkacorp, Vital and AOA), who between them produce Buscopan and supply the SNBB used to manufacture the vast majority of its generic equivalents. The offending conduct raised the price of SNBB, which potentially affected SNBB customers around the world. It may be safely inferred that SNBB medications were available for sale to Australian pharmacies.

61 The offending the subject of the count occurred during a period spanning about 7 years, 10 months and 27 days (between 24 July 2009 and 31 August 2012, and 31 March 2015 and 20 June 2017), noting as above that it is not alleged AOA gave effect to the CAU between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 (meaning the period of offending is reduced to 5 years 3 months and 26 days), with a further 38 days once the additional admitted offending in Items 1 and 2 of the Schedule are considered. The offending conduct was on foot since before the charge period commenced on 24 July 2009. The Director accepted that Mr Joyce is not to be punished for conduct prior to the charge period, and it does not aggravate the offence. It provides background in respect to giving effect to the 2009 Geneva CAU. It also reinforces that the offending conduct was not anomalous.

62 In respect to each of the seven CAUs, the SOAF contains, inter alia, facts as to: the number of sales made; and the occasions on which AOA gave effect to the relevant CAU by quoting the price in accordance with the CAU. In respect to each CAU, Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA, communicated with the other parties to the CAU in furtherance of the relevant price fixing provision, including to request and/or exchange commercially sensitive price information.

63 Taking the first CAU, the 2009 Geneva CAU, as an example.

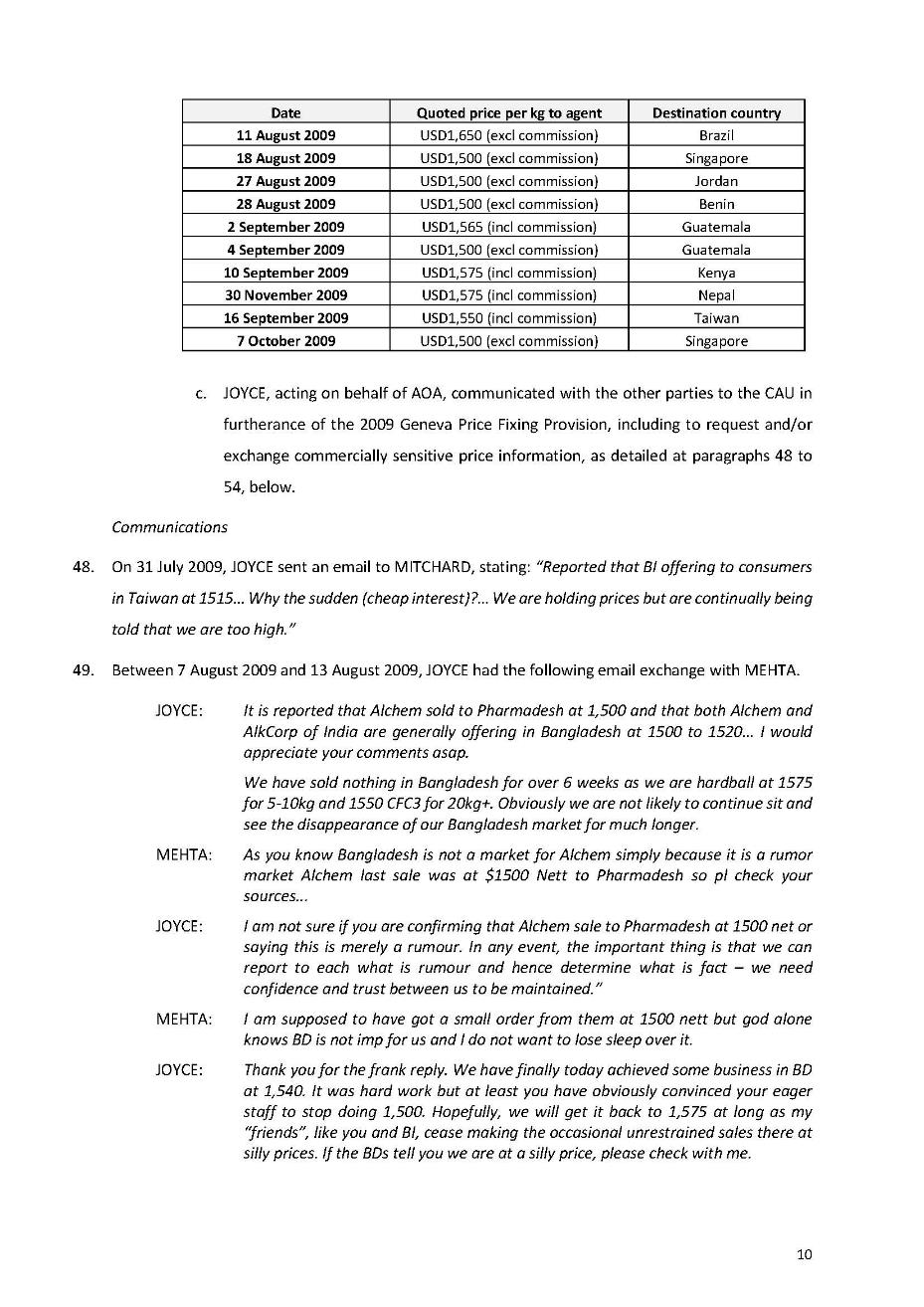

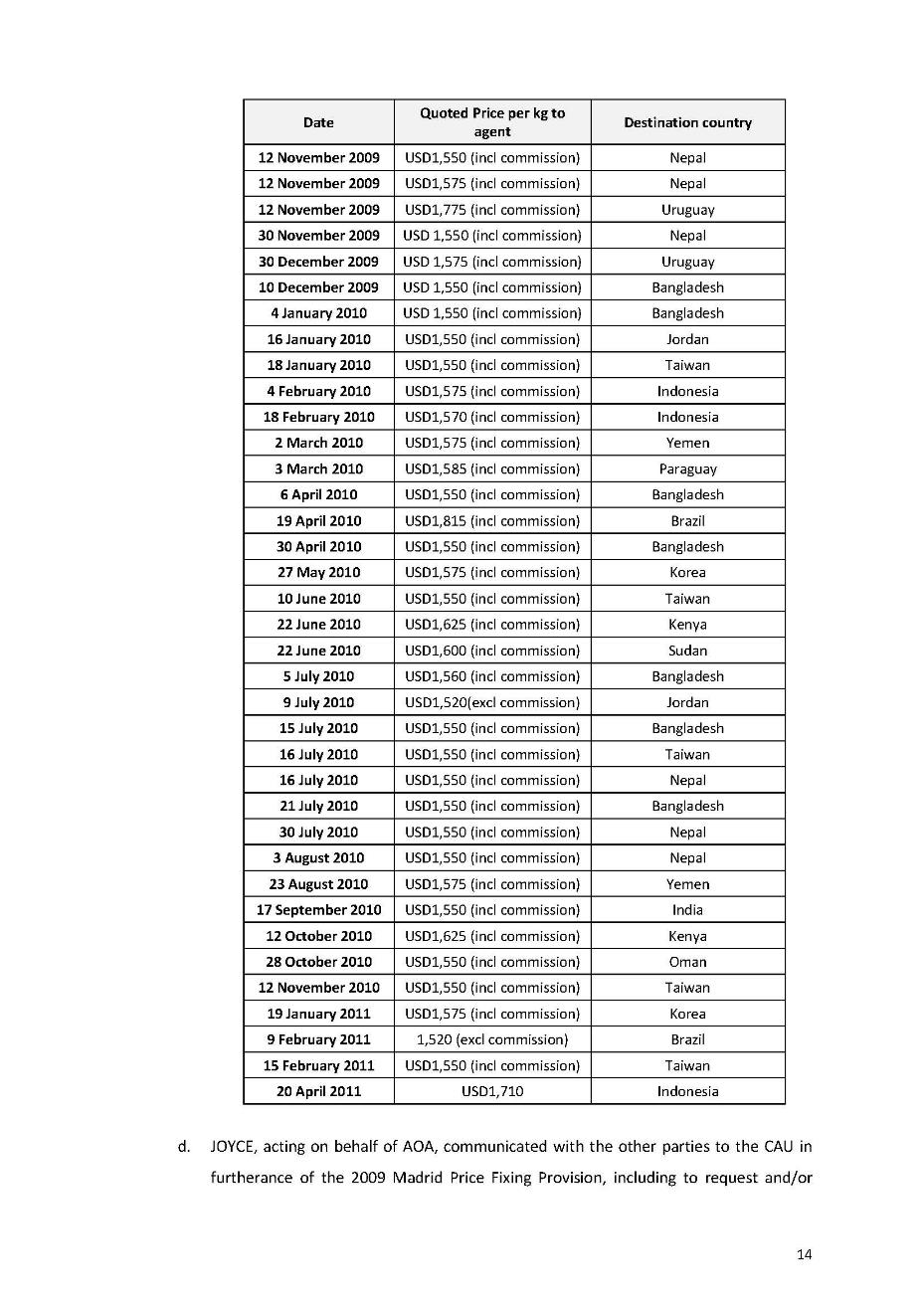

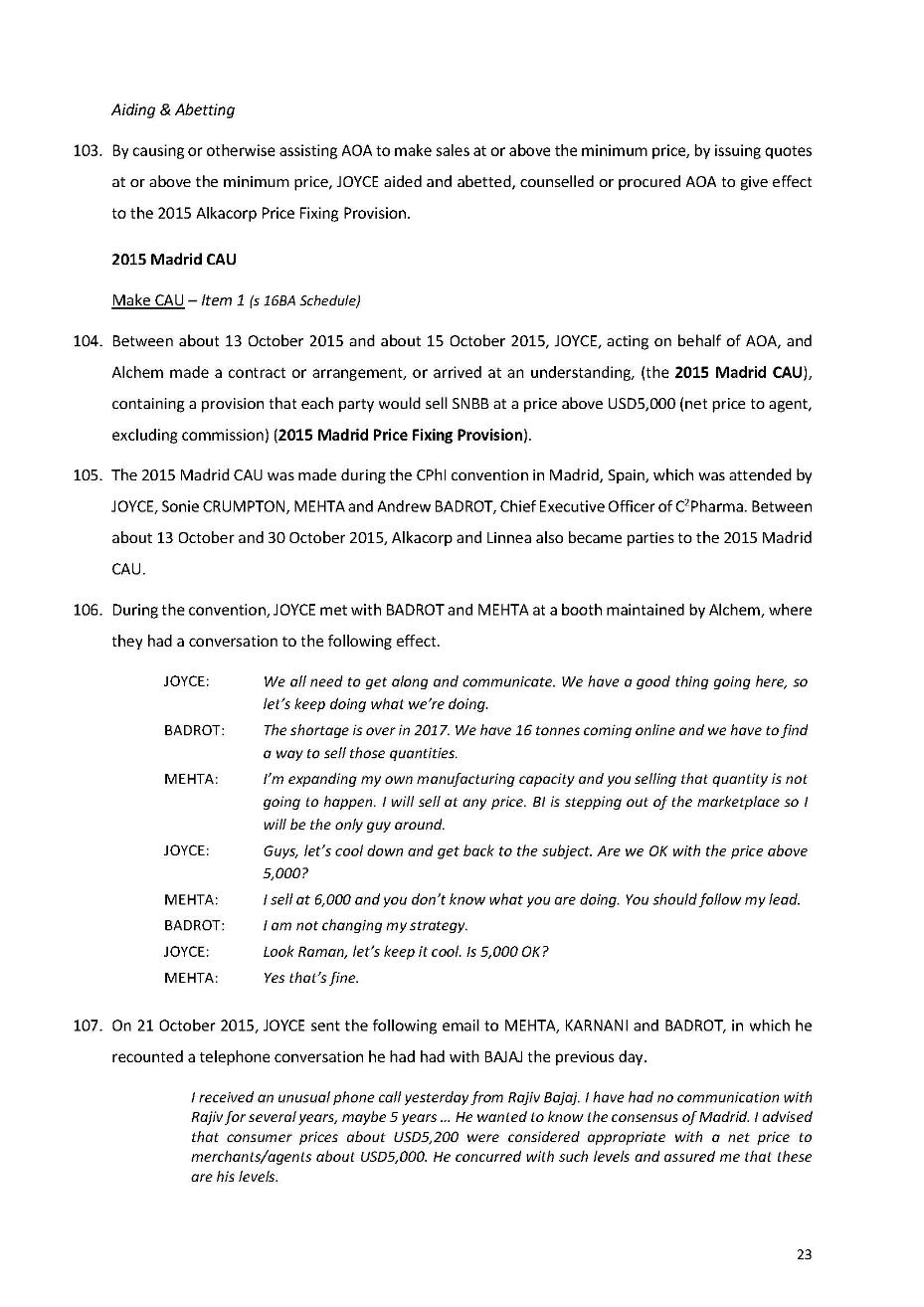

64 Between 24 July 2009 and 11 October 2009, AOA gave effect to a provision contained in the 2009 Geneva CAU which stated that each party to the CAU would sell SNBB at a minimum price of USD1,500 per kilogram (2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision). During that time AOA, aided and abetted by Mr Joyce, made at least 18 sales of SNBB to 10 different customers at a price of USD1,500 per kilogram (net, excluding agent commission) or above. Those sales had a total value of USD714,047. Mr Joyce, acting on behalf of AOA, quoted SNBB at or above USD1,500 per kilogram (excluding agent commission) in accordance with the 2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision. The quotes in the below table have been identified as giving effect to the 2009 Geneva Price Fixing Provision in the SOAF at [47]:

Date | Quoted price per kg to agent | Destination country |

27 July 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Yemen |

8 July 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Oman |

11 August 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Oman |

11 August 2009 | USD1,650 (excl commission) | Brazil |

18 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Singapore |

27 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Jordan |

28 August 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Benin |

2 September 2009 | USD1,565 (incl commission) | Guatemala |

4 September 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Guatemala |

10 September 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Kenya |

30 November 2009 | USD1,575 (incl commission) | Nepal |

16 September 2009 | USD1,550 (incl commission) | Taiwan |

7 October 2009 | USD1,500 (excl commission) | Singapore |

65 As explained in Vina Money Transfer at [123], any one act which is undertaken to give effect to a CAU, constitutes an offence. It follows that an offence is committed each time a person engages in conduct which gives effect to a cartel provision: also see NYK at [205].

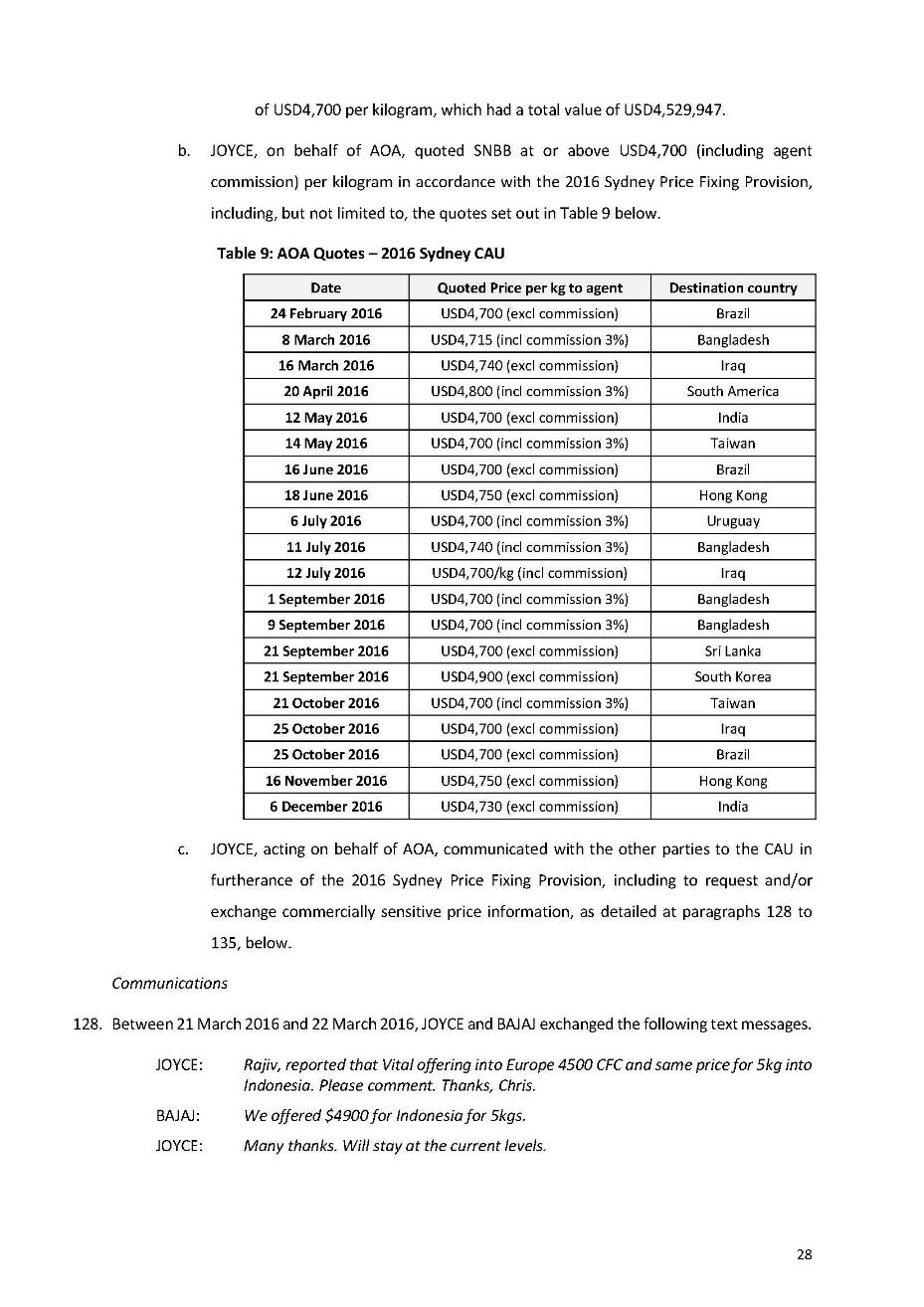

66 The SOAF refers to many acts, as demonstrated by the table at [64] above. The number of times the CAU was given effect to varies in respect to each CAU covered by this count, as reflected in the SOAF at [63], [83], [102], [111], [127] and [146]. Depending on the nature of the CAU being given effect to, the number of acts of giving effect to it may impact on the seriousness of the offending. In this case, it reflects that an ongoing course of conduct was undertaken in implementing the relevant CAU.

67 The range of destination countries for which the quotes were made giving effect to the CAUs is also illustrated in the table above at [64] (which is consistent with the broad range of destination countries involved in the other CAUs the subject of this count). It illustrates that each of these CAUs relates to a global cartel. It also reflects the breadth of the international impact or reach of Mr Joyce’s conduct.

68 It is appropriate at this stage to also refer to the agreed fact that over the same period of this CAU, it is approximated that AOA made seven sales below the price of USD1,500 per kilogram, which had a total value of USD$292,135: SOAF [47(a)(i)]. Similar agreed facts exist in relation to each of the CAUs: SOAF [63(a)(i)], [83(a)(i)], [102(a)(i)], [111(a)(i)], [127(a)(i)] and [146(a)(i)].

69 Mr Joyce actively monitored and policed other parties’ adherence to price fixing agreements (who were also competitors of AOA) and sought to hold them to the arrangement. Mr Joyce was forceful in advocating compliance. This was accomplished, for example, through local agents or distributors in each country who reported the prices being quoted by others back to Mr Joyce. If Mr Joyce suspected a departure from the CAU, he would follow up by email. The SOAF also reflects that meetings were held and that Mr Joyce’s counterparts in the CAUs would similarly police compliance.

70 For example, in relation to the 2009 Geneva CAU, the following extracts from the SOAF illustrate the policing undertaken by Mr Joyce to ensure other parties to the CAU acted pursuant to it:

[49] Between 7 August 2009 and 13 August 2009, JOYCE had an email exchange with MEHTA that included the following statements.

JOYCE: It is reported that Alchem sold to Pharmadesh at 1,500 and that both Alchem and AlkCorp of India are generally offering in Bangladesh at 1500 to 1520… I would appreciate your comments asap.

We have sold nothing in Bangladesh for over 6 weeks as we are hardball at 1575 for 5-10kg and 1550 CFC3 for 20kg+. Obviously we are not likely to continue sit and see the disappearance of our Bangladesh market for much longer.

MEHTA: As you know Bangladesh is not a market for Alchem simply because it is a rumor market Alchem last sale was at $1500 Nett to Pharmadesh so pl check your sources

JOYCE: I am not sure if you are confirming that Alchem sale to Pharmadesh at 1500 net or saying this is merely a rumour. In any event, the important thing is that we can report to each what is rumour and hence determine what is fact – we need confidence and trust between us to be maintained.”

MEHTA: I am supposed to have got a small order from them at 1500 nett but god alone knows BD is not imp for us and I do not want to lose sleep over it.

JOYCE: Thank you for the frank reply. We have finally today achieved some business in BD at 1,540. It was hard work but at least you have obviously convinced your eager staff to stop doing 1,500. Hopefully, we will get it back to 1,575 at long as my “friends”, like you and BI, cease making the occasional unrestrained sales there at silly prices. If the BDs tell you we are at a silly price, please check with me.

…

[51] On 12 August 2009, JOYCE exchanged the following emails with GARA, having forwarded an email from a distributor reporting that Linnea was selling at between USD l,400 and 1,420/kg in Taiwan.

JOYCE: I have received the following from our Taiwan agent… I assume that it is not correct, but I sure you would like to know that people are talking about you.

…

PS. Thanks for laying off in Nepal, we are now happily achieving 1,575 for 5-10kg. Hopefully, we can get this back to 1600.

GARA: Had no sales nor offers for long, long time to Taiwan. Our minimum price is and remain USD 1575 and sometimes for large quantities USD 1550… as you can imagine we are getting similar stories using your name.

…

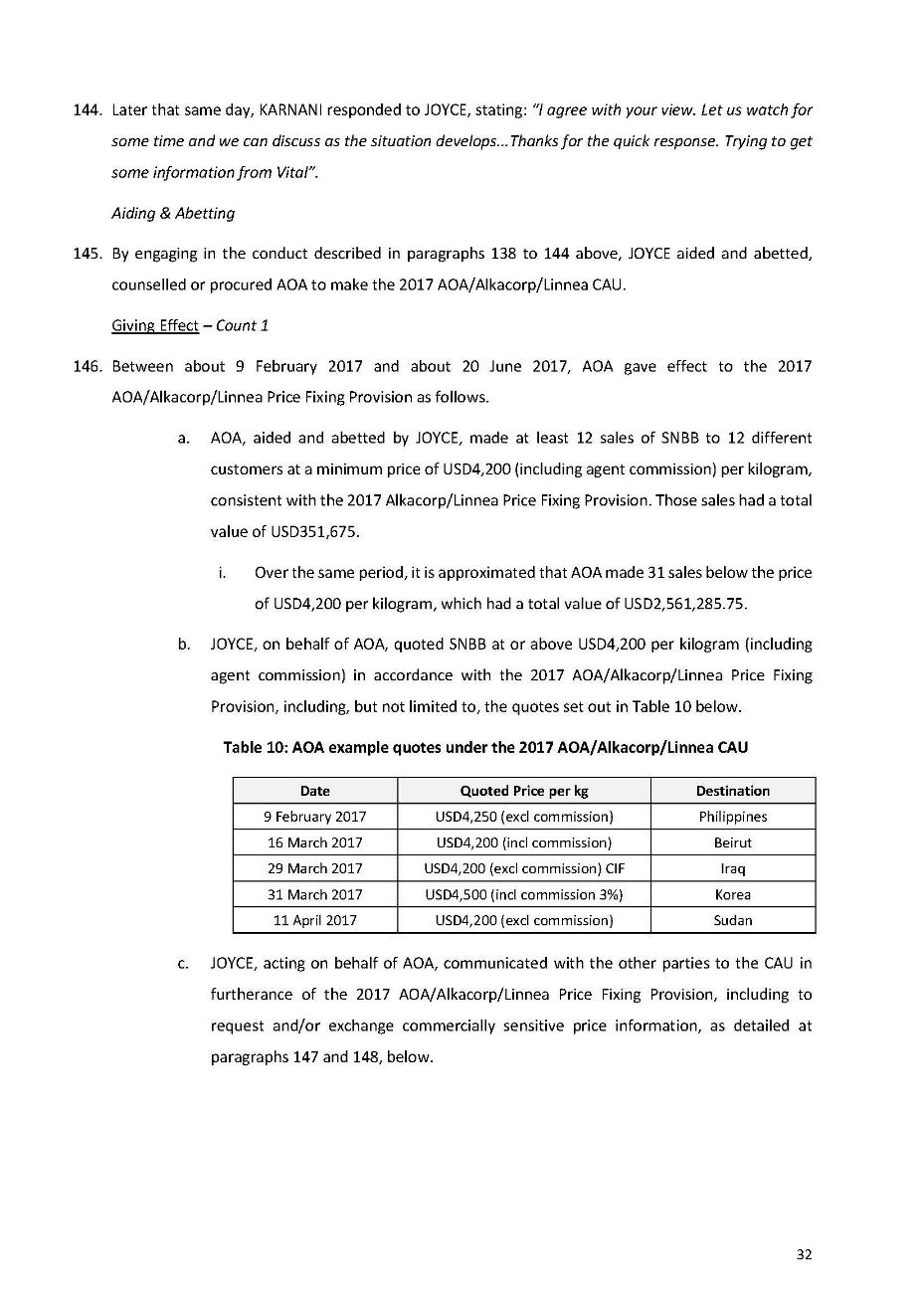

[53] On 14 September 2009, MITCHARD sent an email to JOYCE, forwarding a report from a third party that AOA had offered to sell at USD1,455/kg to Sanofi Aventis. By way of reply, JOYCE forwarded an earlier email he had sent to SPOENEMANN.

Interestingly, I sent the email below to Hellmuth earlier tonight.

We offered to Sanofi at 1550 CFC3% three weeks ago… you will note that Kemimac is allegedly at 1500/1520 (not 1450!!). We obtained the last Sanofi business three months ago at 1540 after weeks of being told that Kemiac and Linnae were much cheaper and that we had to go to 1500. We stayed at 1550, we finally agreed to 1540 to allow them to save some face.

…

I think we just have to stand…

[54] The following day, JOYCE sent an email to MITCHARD, copying SPOENEMANN, forwarding an email from a distributor reporting that Kemimac had offered to sell at USD1500/kg to Sanofi Aventis, stating: “You will note that our agent says Kemimac is cheap at 1500/1520. At least you are higher than the reported 1455 that we are offering at!!! Please confirm what you are doing”. Later that day, MITCHARD sent the following reply: “I instructed Kemimac to do 1550 ...”.

71 These communications are typical of what occurred in in relation to each of the CAUs the subject of this count.

72 Parties to the CAUs were also concerned that non-compliance in one market might affect others. For example, in relation to the 2011 Shanghai CAU:

[90] In the course of email exchange with TITULSKI in late July 2012, JOYCE stated that: “We really need to stop these silly prices in Bangladesh. Sooner or later, they will spill over into other markets”.

73 The Director submitted that the relevant two items of additional offending in the Schedule reinforce the enduring nature of the arrangements and Mr Joyce’s active participation in AOA’s offending. That was said to represent additional criminality that should be reflected in the sentence imposed for this offence and elevate the importance of specific deterrence.

74 As referred to above, Item 1 concerns aiding or abetting, counselling or procuring the making of six of the CAUs that were subsequently given effect to, which are the subject of Count 1.

75 Although there is some overlap in the offending, there is an additional criminality. Item 1 demonstrates Mr Joyce’s active involvement in making the CAUs which were then given effect. A cartel can be given effect to by a person without their having been involved in its making. Once that is appreciated, it can readily be accepted that Mr Joyce’s conduct in making the CAUs reflects additional criminality. Further, the active role taken by Mr Joyce is evident from the SOAF. The conduct which gave rise to the offences was deliberate.

76 Item 2 is different, in that it involves an attempt to make a CAU between about 20 June 2017 and about 28 July 2017. It appears that a CAU did not materialise because others were unwilling to agree. The Director submitted that it demonstrates that, as late as mid-2017, Mr Joyce was still perpetuating AOA’s attempts to engage in the same kind of cartel conduct.

77 Mr Joyce submitted that: he was not the instigator of the arrangements; they were in place prior to his involvement in the industry; and they continued in the absence of his involvement. So much may be accepted. Although, as submitted by the Director, the only arrangements for which Mr Joyce is to be sentenced are those which he aided, abetted, counselled or procured.

78 Mr Joyce also submitted that this offence was below mid-range in terms of seriousness. In reply, the Director took issue with that characterisation, submitting that it was mid to high range. That said, both parties recognised the inherent difficulties in putting such a label on the conduct, and the usefulness of that approach.

79 I make the following additional observations regarding Count 1.

80 First, the offending conduct in this count occurred over a very significant period of time and can only be characterised as deliberate and systematic.

81 Second, Mr Joyce, was actively involved in policing and enforcing compliance with the CAUs.

82 Third, as explained above, the CAUs were repeatedly given effect to, in giving quotes in various countries. This conduct raised the price of SNBB.

83 Fourth, there was an ongoing course of conduct in respect to each CAU, with it being given effect to until the next CAU was made, with the exception of the gap between 1 September 2012 and 31 March 2015 (see [61] above).

84 Fifth, I accept that the offending conduct was covert in nature, which is typical of cartel conduct. It was not published to and would not have been readily apparent to the market.

85 Sixth, the conduct admitted to in the Schedule adds to the criminality of the conduct in this count, in that it reinforces Mr Joyce’s willingness to be actively involved in the CAUs, as well as their enduring nature. It illustrates the scale and scope of his conduct.

Count 2: Giving effect to a CAU

86 There is a dispute between the parties as to the characterisation of the conduct the subject of this count. Although the facts are agreed, what is said can be drawn from them as to Mr Joyce’s role is in issue. This count was particularly prominent in oral submissions because, as explained above, Mr Joyce ultimately accepted he knew the conduct involved was probably unlawful. Further, the advice Mr Joyce purportedly relied on as to the lawfulness of the conduct, on any scenario, could not apply to this count.

87 The primary difference between the parties is that Mr Joyce submitted that he was not involved in the making of the CAU to which effect was given, and he is not charged with that. Mr Joyce submitted that the CAU was communicated to him after it had been made and that he did not have any contact with Mr Thamm. The Director submitted that on the agreed facts, although Mr Joyce may not have been involved in the making of the ultimate CAU, he was nonetheless involved in the lead up to it. It also submitted that a failure to consider the surrounding circumstances would be to consider the offence in a vacuum.

88 It is to be recalled that this offending involved five of the major manufacturers of SNBB, who between them produce Buscopan and supply SNBB to manufacturers of the vast majority of its generic equivalents. It targeted an Australian grower of Duboisia, Mr Thamm, seeking to eliminate him as a competitor. The CAU involved: Alkacorp entering into an agreement with Mr Thamm; Alkacorp acquiring his equipment; and a compensation payment from AOA to Alkacorp. The purpose of acquiring the entire crop and securing a commitment from Mr Thamm not to grow or produce any further Duboisia was to prevent him (or any other person through him) supplying Duboisia to a third party who intended to enter the market (Sarv Biotech), thereby preventing that third party from becoming the “seventh player” and putting downward pressure on prices.

89 It is trite that Mr Joyce is not to be sentenced for any offence with which he is not charged. As Mr Joyce emphasised, he is to be sentenced for knowingly giving effect to the CAU that materialised and is the subject of Count 2. That said, the circumstances in which that offence was committed are a relevant consideration in assessing the offence. It may be accepted that on the agreed facts Mr Joyce was not involved in making the CAU to which effect was given. However, that is not the complete picture. It is apparent that the discussion between the relevant parties as to the potential options for dealing with Mr Thamm evolved over time. It can be accepted that the SOAF reflects that Mr Joyce was concerned about addressing the issue of Mr Thamm and the effect he had on the competition in the market. It can also be accepted that Mr Joyce provided suggestions as to ways to deal with Mr Thamm, all directed to eliminating competition, in order to prevent a seventh SNBB competitor entering the market and upsetting the price status quo. That is part of the context in which the CAU arose.

90 The fact that Mr Joyce did not have direct contact with Mr Thamm does not diminish the significance of his conduct. Nor does the fact he did not personally make the payment to Alkacorp because he checked with John Crumpton as to whether AOA had made the payment, actively ensuring that AOA fulfilled its obligation. Properly read, and in context, Mr Joyce’s characterisation of the conduct as “simply passing on communications to John Crumpton about payment and seeking confirmation of whether payment had been made”, is to understate his role. Mr Joyce had full knowledge of the CAU when he gave effect to it. In that context, the SOAF at [179] records the following communication by Mr Joyce with others involved in the cartel:

Thank you for your summary of the situation… I will take this opportunity to restate our position:

1. We bear our share of the costs of the harvester/drier purchase and our share of the Thamm crop

2. We will continue to support the decisions of the group, even if we happen to be holding a minority view.

I would also like to state our assessment of the dangers in the current situation of the duboisia/hyoscine markets… A new player entering the game. This situation is being dealt with by the acquisition of the dryer and the Thamm crop as far as the current potential market entrant is concerned…

91 Although it is only the latter part of the proposal, being that Mr Thamm would not grow or produce Duboisia in the future, that gives rise to the charged offence, in light of the above communication, Mr Joyce supported whatever activities the group determined was necessary. In accordance with the arrangement, he sent an email on 15 April 2011, to Alkacorp, Alchem and Linnea, stating “We do all need to settle with Mr Karnani [Alkacorp]. His efforts are well appreciated by all of us. How much and when?”: SOAF [180].

92 The surrounding circumstances reflect the deliberate nature of Mr Joyce’s conduct in Count 2 and the extent to which he was knowingly concerned in giving effect to it.

93 Mr Joyce submitted that the conduct the subject of this count was not sophisticated because Alkacorp drove the arrangements with Mr Thamm, with Mr Joyce having a far more limited role. He also submitted that it was less serious than Count 1, and could be characterised as well below mid-range in terms of seriousness.

94 The offending in this count occurred over about 1 year and 7 months. Although it is of a different nature to that in Count 1, the motivation underpinning it was the same. The offending occurred while Count 1 was on foot. It occurred over a relatively long period of time, albeit, there was no activity by Mr Joyce giving effect to it for periods of time. Given the nature of the CAU and Mr Joyce’s conduct giving effect to it, this does not detract from its seriousness. Mr Joyce’s commitment to giving effect to it continued throughout that period.

95 I note that during this period, Mr Joyce undertook the conduct in Item 3 of the Schedule. Namely, intentionally attempting to induce, between 7 December 2010 and 21 January 2011, Alchem, Alkacorp and Linnea to make a CAU with Vital, containing a provision that the parties would not cause to be replanted Duboisia trees that had been destroyed due to flooding and were grown by or on behalf of the parties, or their related bodies corporate, which had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the production, or likely production of Duboisia and/or SNBB. Vital represented a significant threat to the parties’ ability to maintain the price of SNBB by limiting the production of Duboisia.

96 It is unclear from the SOAF why the attempt failed. I note the last communication recorded is from Mr Joyce to Linnea on 20 January 2011, which includes the following, “[t]his is a unique opportunity that should not be missed. The number of [D]uboisia trees will be significantly reduced although we do not know at this time by how many. There needs to be a commitment NOT to replant dead trees and orchards”: SOAF [198].

97 It is apparent from the SOAF that the opportunity being referred to arose as a result of major flooding in Queensland.

98 Item 3 reflects additional criminality and highlights Mr Joyce’s active involvement in persuading others to agree to cartel conduct.

99 Although this conduct is different to that in Count 1, the object was the same. It reflects on the breadth of the actions taken by Mr Joyce to achieve his aim. Again, the conduct was deliberate. There was a level of sophistication.

Count 3: Attempt to enter a CAU

100 The conduct the subject of this count occurred over about three months, although the relevant admitted offending in Items 4 to 7 of the Schedule falls within a much larger date range.

101 The 2011 Attempted Bangladesh CAU that is the subject of Count 3 would have been with Alkacorp, which was one of the major manufacturers of SNBB, and Kemimac, which is not itself a manufacturer. The CAU was to have two cartel provisions: a price fixing provision and a provision which allocated supply contracts between the participants.

102 The offending conduct was systematic and deliberate, involving a degree of sophistication. It took place by discussions in person in Germany, and by email. Again, the conduct was covert in the sense that there is nothing to suggest the market was aware of it.

103 This count is not as serious as the offending the subject of the other counts, but I accept the Director’s submission that it was nevertheless significant.

104 A number of admitted offences which add to the criminality of this count are to be taken into account. These items occurred over an extended period, the last being 19 December 2018. Items 4 and 5 involve two CAUs containing bid rigging provisions, with Mr Joyce aiding or abetting, counselling or procuring the making of each (rolled up as Item 4) and aiding or abetting, counselling or procuring the giving effect to each (rolled up as Item 5). Items 6 and 7 similarly concern two further CAUs, one containing a bid rigging provision and a price fixing provision, with Mr Joyce aiding or abetting, counselling or procuring the making of and aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the giving effect to each (being rolled up into the two items). Mr Joyce submitted that the conduct the subject of these items reflected two distinct periods of offending, with the conduct the subject of Items 4 and 5 overlapping with the existing price fixing agreement in place between the parties and the subject of Count 1 and Item 1. Nonetheless, Mr Joyce accepted that the items add to the seriousness of the offending in Count 3.

105 A number of matters relevant to the offences in all three counts require further consideration.

Benefit attributable to the conduct

106 The whole point of price fixing and market sharing is to obtain the benefit of prices greater than those which would be obtained in a competitive market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visy Industries Holdings Pty Ltd (No 3) [2007] FCA 1617; (2007) 244 ALR 673 at [314] per Heerey J (Visy Industries). This conduct was engaged in by AOA, through Mr Joyce, for the purpose of financial gain.

107 The fact that it is not possible to quantify precisely the profit or other financial benefit derived by giving effect to a CAU does not lessen or mitigate the seriousness of its offending conduct: WWO at [223]. Moreover, as Wigney J aptly observed in K-Line at [307]:

[307] It may also be inferred that the offending conduct may have given rise to less direct and tangible benefits to K-Line, including benefits derived from the increased certainty arising from stable market shares and customer allocations and the absence of any, or any aggressive, price competition.

108 And see NYK at [247].

109 A motive for Mr Joyce was also financial benefit to him. Mr Joyce’s evidence on this topic was rather unsatisfactory because he failed, on a number of occasions, to answer questions put to him: see above at [40]. Mr Joyce ultimately accepted that part of his motive in undertaking this conduct, albeit a limited one, was for financial benefit to himself. He stated that his prime motives were to: “do a good job” for AOA, a company he worked for; continue using his exporting and sales skills; and ensure that the company made a good profit, for which he would be adequately rewarded.

110 It can be accepted that Mr Joyce earned substantial wages from his work with AOA. In addition to the monthly retainer he received, he earned a commission of 2 percent of AOA’s SNBB sales revenue, being about $1,723,502.86, and AOA’s conduct ultimately led to it being able to charge higher prices. I accept that Mr Joyce benefited financially from his offending conduct.

Injury, loss or damage resulting from the offences

111 Mr Joyce accepted that generally, cartel conduct is presumed to have an anti-competitive effect for the reasons identified by Wigney J in WWO at [170].

112 That said, it was submitted that the extent to which the cartel conduct was connected to Australia, and had implications for the Australian economy, is relevant to the assessment of the objective seriousness of the offence. Mr Joyce submitted that there was no connection between the cartel conduct and the price of SNBB medications in Australia. He accepted that the offending conduct resulted in AOA quoting and supplying SNBB at prices higher than it otherwise would have in the export market but for the offending conduct. Accordingly, the cartel conduct had an effect on SNBB customers in the export market. However, he submitted that due to the small amount of sales of SNBB to Australian consumers, the connection of the offending to Australia was very limited. The fact that the cartel conduct did not have an impact on Australian consumers was said to diminish the objective seriousness of the offence. Although there was a focus on the connection to Australia, Mr Joyce accepted that there was harm caused overseas as a result of the CAUs, which was not irrelevant. It was also accepted the effect on Australia’s business reputation is relevant. Specifically, it was accepted that Australia’s “reputation as a society that promotes the free market and discourages those who engage in anti-competitive conduct from our shores is relevant” and that this reputation was detrimentally affected.

113 The Director accepted that almost a hundred percent of the SNBB manufactured was exported and in that sense, the effect of the cartel was in the export market, and it cannot be established beyond reasonable doubt that there was an effect on prices of SNBB medications sold in Australia. It was submitted however, that does not significantly diminish the objective seriousness of the offence.

114 Mr Joyce also noted that courts have had regard to the industry in question, submitting that the level of strategic importance of the nut industry (as compared to, for example, oil or freight) lessens the objective seriousness of the offending. I note that the concept of strategic importance of the industry the subject of the conduct is not found in the CCA. In any event, as submitted by the Director, the industry in question directly affects the welfare of Australians as it relates to an active ingredient in medicines. It follows that the nature of the industry is strategically important.

115 As to the prices, the Director submitted that it is impossible to compare the effects of the cartel arrangements against a counterfactual scenario where the conduct did not occur because of the multiplicity of factors that may have borne upon prices. The Director submitted that the longstanding and widespread nature of the offending would have distorted the market for SNBB (and derivative markets for SNBB medications). Prices, quality and range of services throughout the market could realistically have been different but for the conduct. It is wrong, therefore, to proceed as if sales not subject to the cartel arrangements were not likely to be affected by them. It is also wrong to stop the assessment at 19 December 2018. Given the longstanding and widespread nature of the offending, it is improbable that the market for SNBB (and derivative markets for SNBB medications) would have snapped back to a state unaffected by the cartel arrangements upon the offending ceasing or at any point in time when there was no cartel agreement being given effect. The Director submitted that it does not follow from the fact the pricing for SNBB medications decreased that the offending conduct had no anticompetitive effect, either generally or in Australia. It does not negate the possibility that the decreased price of SNBB medications in real terms could have been all the greater but for the cartel conduct. I accept that submission.

116 Moreover, any effect or purported lack thereof on SNBB prices is entirely fortuitous. There is no evidence that Mr Joyce had any concern at all as to the impact of his conduct, including on the prices of SNBB medications or the quantity of SNBB medications that would end up in Australia.

117 The Director did not dispute that the extent of the conduct’s connection with Australia is relevant to the assessment of its objective seriousness, but submitted that is not to say that loss or harm caused to overseas customers is unimportant. The Director submitted that s 2 of the CCA refers to “the welfare of Australians” and noted that cartels are corrosive to the economy generally and to international confidence in Australian businesses. General deterrence remains important (see also [124]-[128] below).

118 It is appropriate to recall that in the context of considering the application of s 16A(2)(d) and (e) of the Crimes Act in WWO, Wigney J stated at [242]:

[242] It would be wrong, however, to approach this offence as if it were a victimless offence, simply because no specific individual or quantified loss can be identified. The cartel offence in s 44ZZRG(1) is part of a suite of provisions in the CCA that are designed to protect the integrity of Australia’s markets and economic system: see also s 2 of the CCA. Australia’s economy, like other free-market economies, is based on the philosophy that private enterprise and competition will foster productivity, efficiencies and innovation for the greater good of the economy and the community generally. Cartel conduct, like other anti-competitive behaviour, is inimical to, destructive of and may lead to a loss of public confidence in, Australia’s markets and economic system. That is so even where the conduct, as here, is eventually uncovered and punished.

119 And see K-Line at [313] to similar effect, and Vina Money Transfer citing the passage with approval at [113]. Cartel conduct is inimical and destructive of public confidence in Australia’s markets and economic system generally.

120 Breaches of Australia’s competition laws are destructive of competition on which the market economy depends. It is recognised that it is in the nature of the cartel conduct to protect inefficiency and cause market distortions. That is so even when the direct purchasers of the goods and services are located outside of Australia. Cartel conduct engaged in by Australian businesses is corrosive to the economy generally and to international confidence in Australian businesses. That necessarily impacts on the Australian economy and the welfare of Australians. Competition enhances the welfare of Australians.

121 As referred to above, the Director accepted the particular relevance of loss or damage in Australia. There is no basis to assess the loss or damage outside Australia. Suffice to say that there must have been a loss as foreign customers lost the ability to enjoy the potential benefits of competition between AOA and its competitors. This occurred over a substantial period of time. It is readily apparent that it resulted in customers paying, at least at times, higher SNBB prices than there would have been but for the CAUs. In any event, given the lack of information about the extent of the loss or damage, it can only be taken into account at the level of generality described above.

122 As to Count 2, in so far as Mr Joyce submitted that the effect was the same as that of the other conduct because AOA did not compete with Mr Thamm, the submission is too narrow. The offending in Count 2 directly impacted Australia by removing a Duboisia grower. Further, although Mr Thamm was not a competitor to AOA in respect to SNBB, the effect of the CAU was to take out a potential supplier of Duboisia to a competitor who would not form part of the cartel arrangements. The additional competitor sought to be prevented, a “seventh player”, would have put downward pressure on prices. The CAU the subject of Count 2 was therefore given effect to preserve the effectiveness of the cartel conduct the subject of Count 1. Taking out a potential supplier in Australia has a distortive effect on the Australian economy. Duboisia plants, from which SNBB is derived, grow in volume in Australia and Brazil. In that context, there is a real likelihood that lessening competition at the SNBB level would also have had consequential impacts upon Duboisia growers in Australia.

Seniority of those involved

123 Mr Joyce was the most senior AOA representative in charge of exports. With AOA’s authority, he had responsibility for all aspects of the marketing and sale of SNBB produced by AOA. He has said he “was responsible to make all of the sales; execute all of the necessary export documentation; supervise the actual shipment; and to oversee the collection of the sales proceeds”. He also agreed that he “pretty much did everything on behalf of AOA in relation to the marketing and sales of the product hyoscine”: SOAF [36].

124 Although AOA may not have provided oversight or had a culture of compliance, it should be expected that as a senior representative of a company undertaking such a role that Mr Joyce ensure he, and the company, comply with Australian competition law.

Deterrence

125 Every case must be determined on its own facts. Nonetheless, and in that context, guidance can be given about the accommodation that is to be made between the various sentencing considerations in s 16A of the Crimes Act, and in the requirement that the severity of the sentence be appropriate in all the circumstances: Wong at [71].

126 As noted above at [23], it has been recognised that ordinarily general deterrence plays a weighty role in offending of this nature.

127 In K-Line, Wigney J observed at [358]-[359]:

[358] First, as has already been noted, cartel conduct is notoriously difficult to detect, investigate and prosecute. It often involves large and sophisticated corporate offenders who can deploy their considerable resources and position to minimise the risk of detection. It is well accepted that general deterrence is a weighty consideration in sentencing for offences which are difficult to detect and investigate. The importance of general deterrence has also been accepted in imposing penalties for anti-competitive conduct in the civil penalty context.

[359] Second, cartel conduct is an essentially economic or commercial crime that generally involves the offender weighing up whether the benefit or profit from the conduct is likely to outweigh the risks of detection and punishment. Sentences imposed for such offences should be set so that others who may engage in such a weighing exercise will come to appreciate that the risks are likely to outweigh the benefits: that the likely penalty will be such that it could not be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business. This consideration has also been accepted in the civil penalty context.

128 Properly read, such observations do not to detract from the proposition that they must be applied to the individual circumstances of a case: cf Totaan v R [2022] NSWCCA 75; (2022) 400 ALR 578 at [98]-[100] (Totaan). As the Director submitted, what was said in Totaan plainly does not mean that in some cases general deterrence (and/or denunciation, punishment and retribution) will play a more dominant role in the instinctive synthesis.

129 There are features of this offending which lead to general deterrence being a primary sentencing consideration, for example: its nature as a long standing deliberate systemic course of conduct; that it was undertaken for financial gain; and difficulties in detection, investigation and prosecution of these offences. Mr Joyce accepted that general deterrence was a significant sentencing factor and a primary consideration.

130 On the other hand, for the reasons given below (see, for example, [153]-[155]), in addressing subjective features of Mr Joyce’s case, I accept that specific deterrence has less of a role to play in imposing his sentence.

Guilty plea

131 The Court is required to take into account not only the fact of the plea of guilty, but also its timing and the degree to which the timing resulted in any benefit to the community or any victim of, or witness to, the offence: s 16A(2)(g). This requires the Court to take into account the utilitarian effect of the plea, in addition to any subjective significance that may flow from it (for example, as a reflection of remorse or contrition, or a willingness to facilitate the course of justice). The utilitarian value involves an objective assessment to be undertaken. On the other hand, if an offender has demonstrated contrition involving facilitating the course of justice as evidenced by the plea, this is a subjective factor and involves an enquiry as to the attitude of the offender and an assessment of contrition. It may be taken into account in the offender’s favour: s 16A(2)(f), see Bae v R [2020] NSWCCA 35 at [55]-[57] (Bae); Khalid v R [2020] NSWCCA 73; (2020) 102 NSWLR 160 at [88]. Although there is no requirement in the Crimes Act to specify or quantify the reduction given for the guilty plea, it has become the practice in some states to do so (NSW, for example, but cf Victoria). It follows, though, that the failure to do so is not an error.

132 Following the introduction of s 16A(2)(g), its operation was considered by Johnson J in Bae (with whom Bell P and Walton J agreed), who concluded at [57]:

[57] The utilitarian value of a plea of guilty is an objective factor to be considered and preferably quantified (Xiao v R at [280]; Huang v R (2018) 332 FLR 158; [2018] NSWCCA 70 at [9], [49], [55]), with the subjective side involving demonstration of contrition to be an unquantified factor assisting the offender on sentence as part of the process of instinctive synthesis, but with the sentencing court guarding against double counting of these aspects in a manner favourable to the offender.

133 The approach described in Bae has repeatedly been applied.

134 The advantage of specifying the reduction for the utilitarian value of the plea is that it recognises the degree of discount for the step taken, and provides, inter alia, guidance to others as to the possible impact of a plea of guilty on the sentencing process. It also provides transparency in the sentencing process, as it is (with assistance to law enforcement authorities) the only aspect of the sentencing process where a discount is given. Other factors, both mitigatory and otherwise, are weighed in the instinctive synthesis sentencing process.

135 The Director submitted that the fact that an offender has pleaded guilty may itself be evidence of contrition. It was also accepted that Mr Joyce’s guilty plea evidences a subjective willingness to facilitate the course of justice, remorse and contrition. However, the Director also submitted that the nature of the explicit communications set out in the SOAF indicated that the prosecution case was strong and the guilty pleas were a recognition of the inevitable. Mr Joyce did not accept the latter submission given the complexity of matters of this kind.

136 Mr Joyce entered guilty pleas on 26 October 2021, in the Downing Centre Local Court. The Director accepted that these guilty pleas were entered at an early stage and have resulted in a utilitarian benefit to both the community and witnesses in avoiding the need for a trial, which is likely to have been a great cost to the community given the number of offences and the complexity of cartel offences.