FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2022] FCA 1422

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA ACN 123 123 124 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 november 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The claims for the relief in the originating process are dismissed.

2. The plaintiff pay the defendant’s costs of the proceeding to be agreed or, failing agreement, to be taxed.

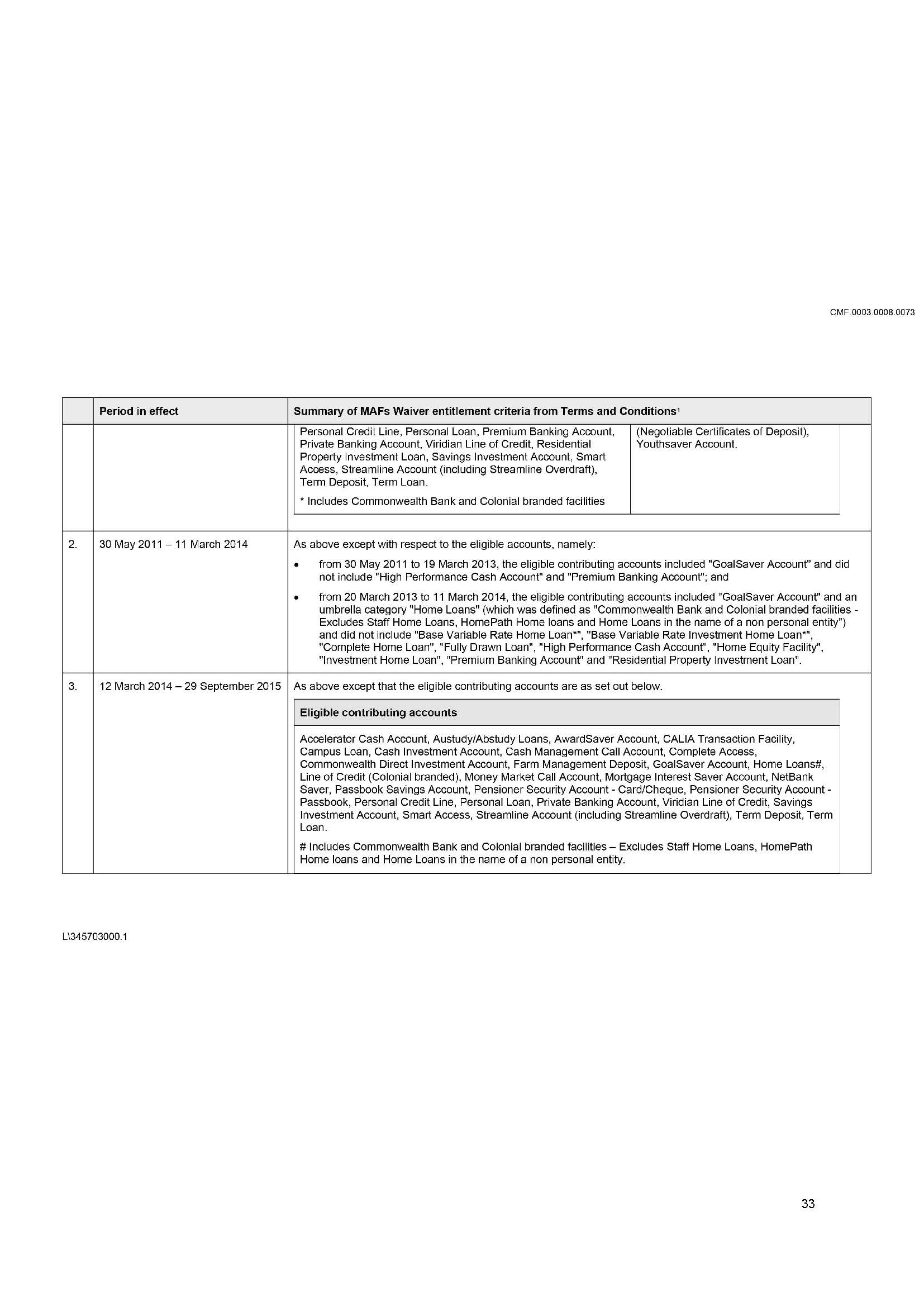

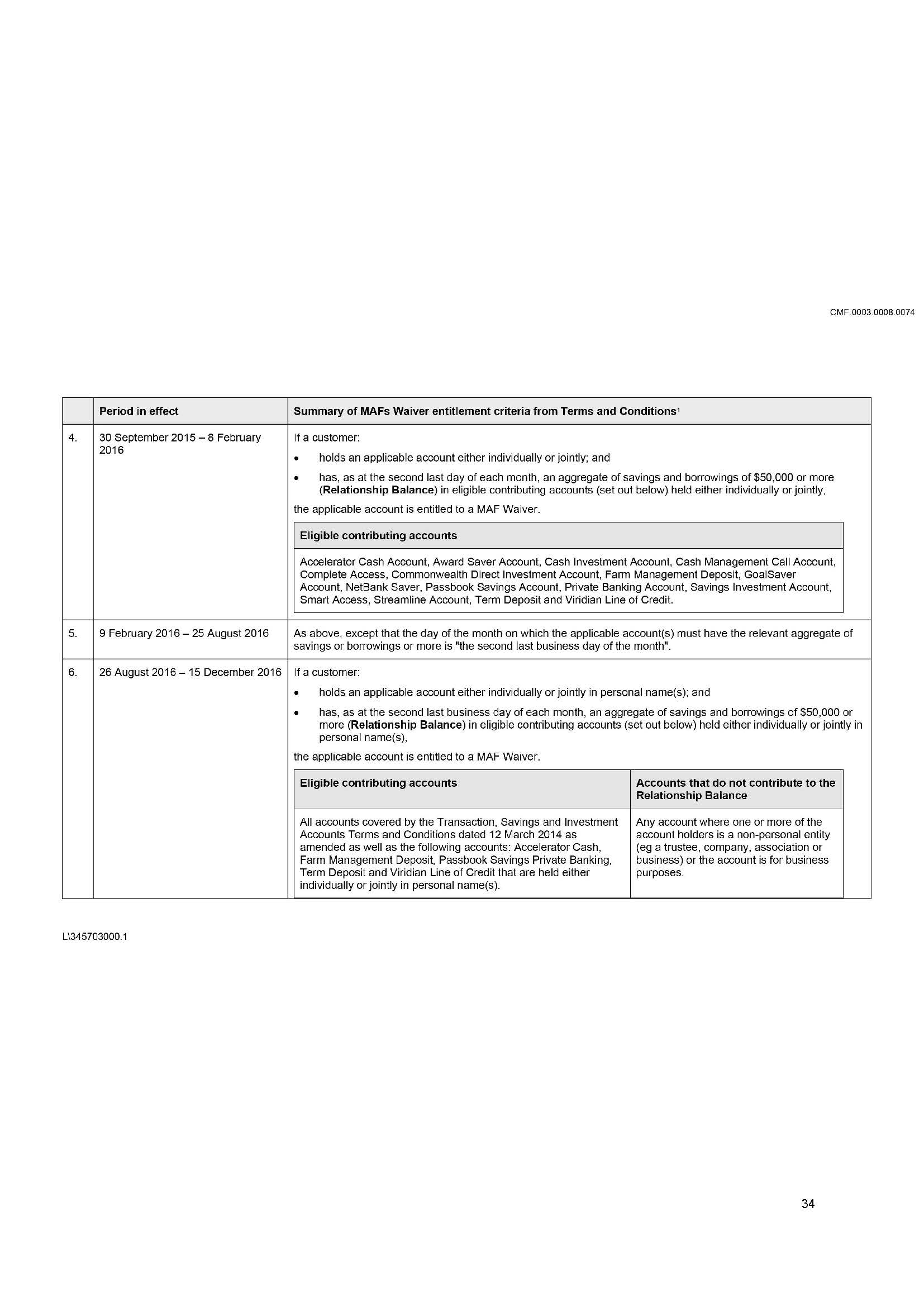

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DOWNES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The defendant (CBA) is a major Australian bank and the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence.

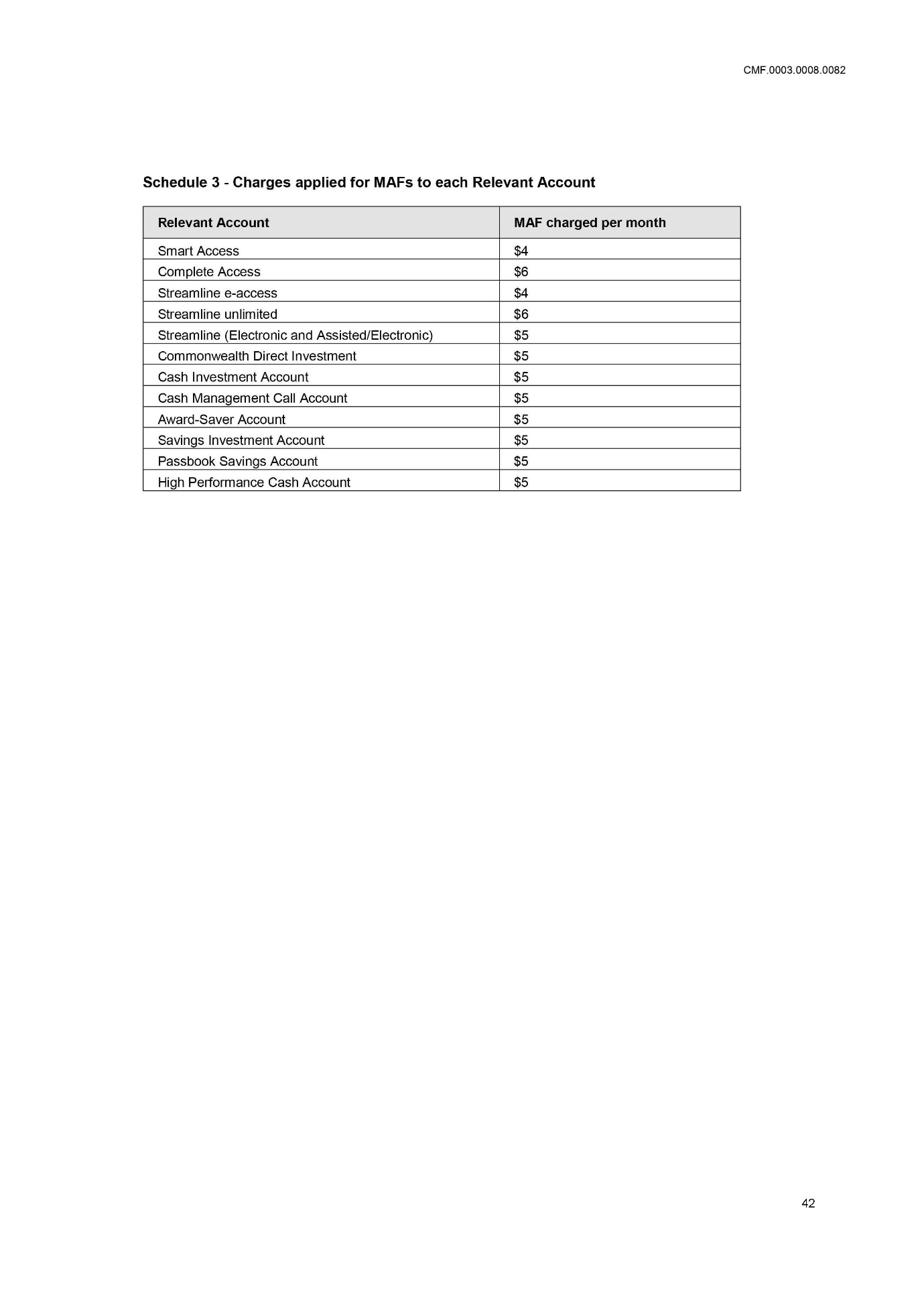

2 During the period from 1 June 2010 to 11 September 2019 (relevant period), CBA charged a monthly account fee (MAF) of between $4 and $6 on certain transaction accounts (described as the relevant accounts) in circumstances where the account-holder was contractually entitled to a waiver of the MAF. This occurred on at least seven million occasions and affected around 965,899 customers across more than 800,000 accounts.

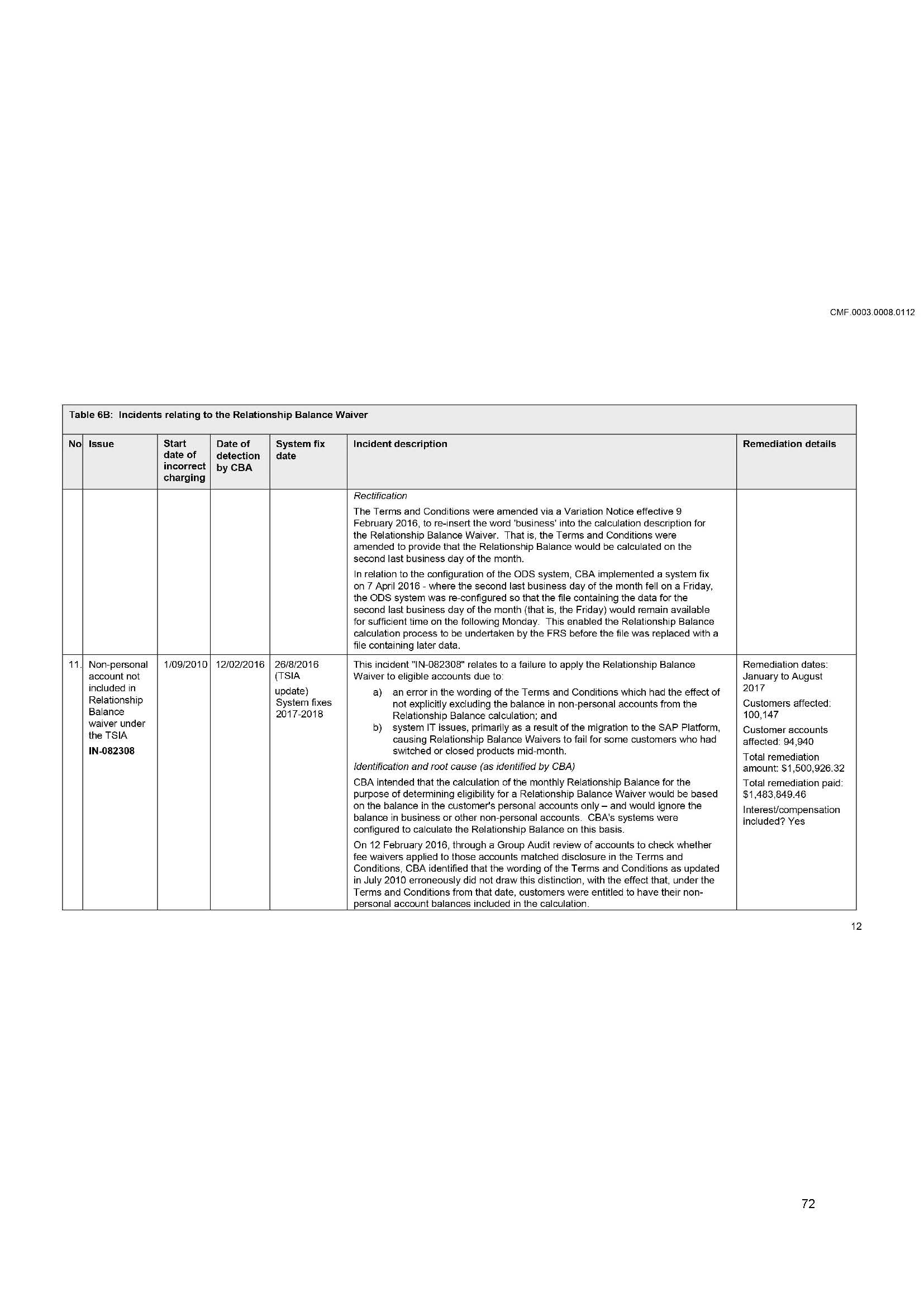

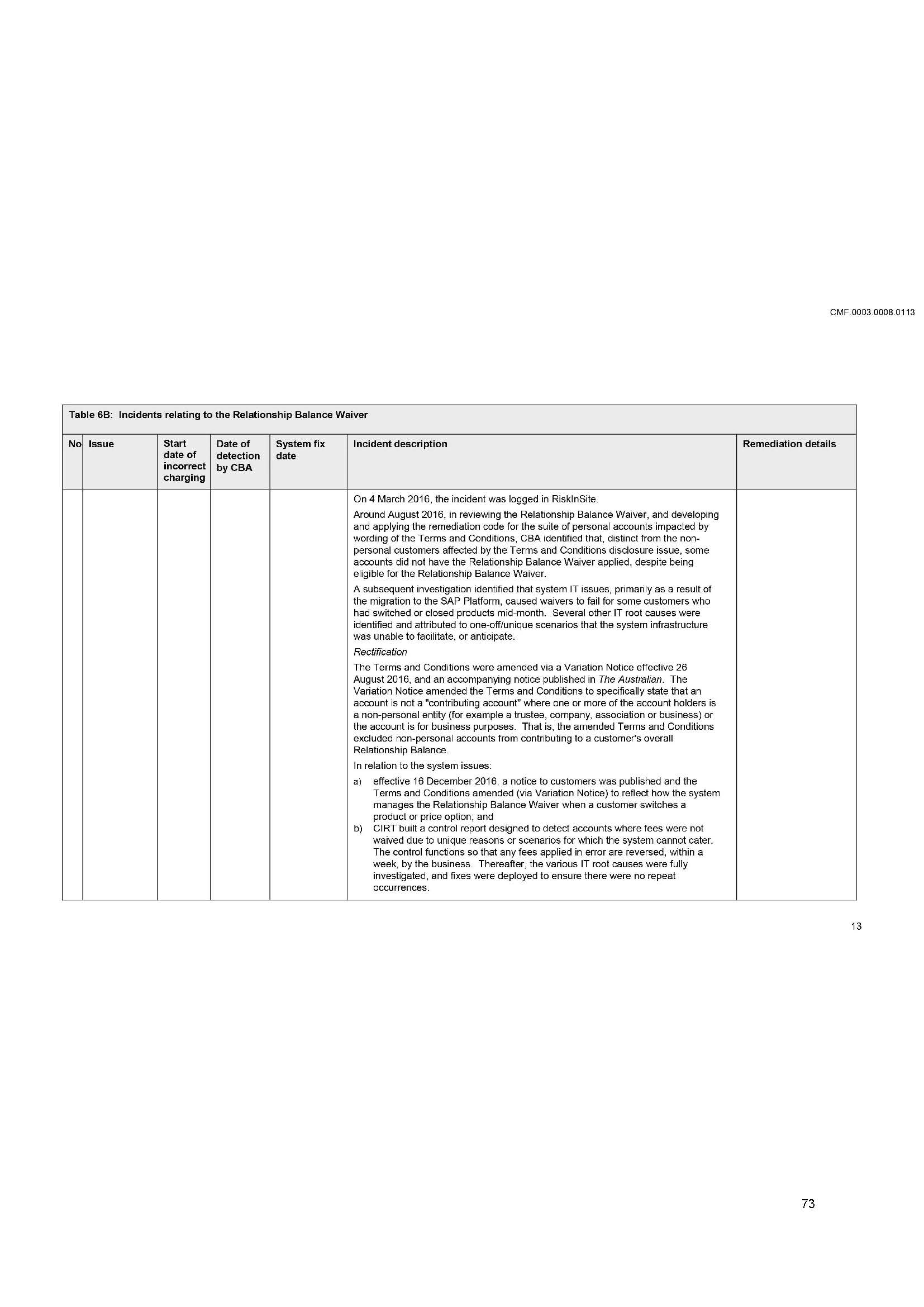

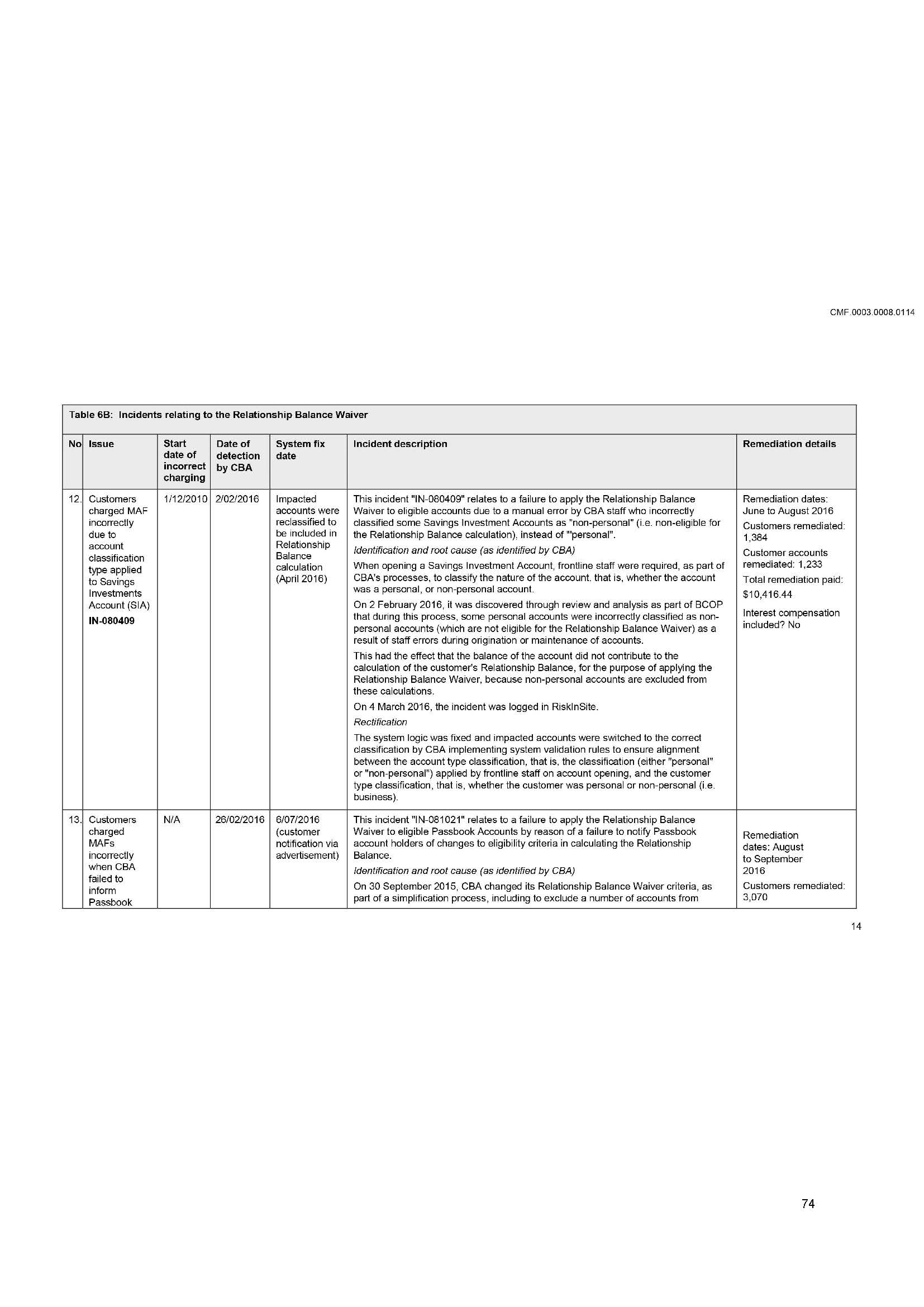

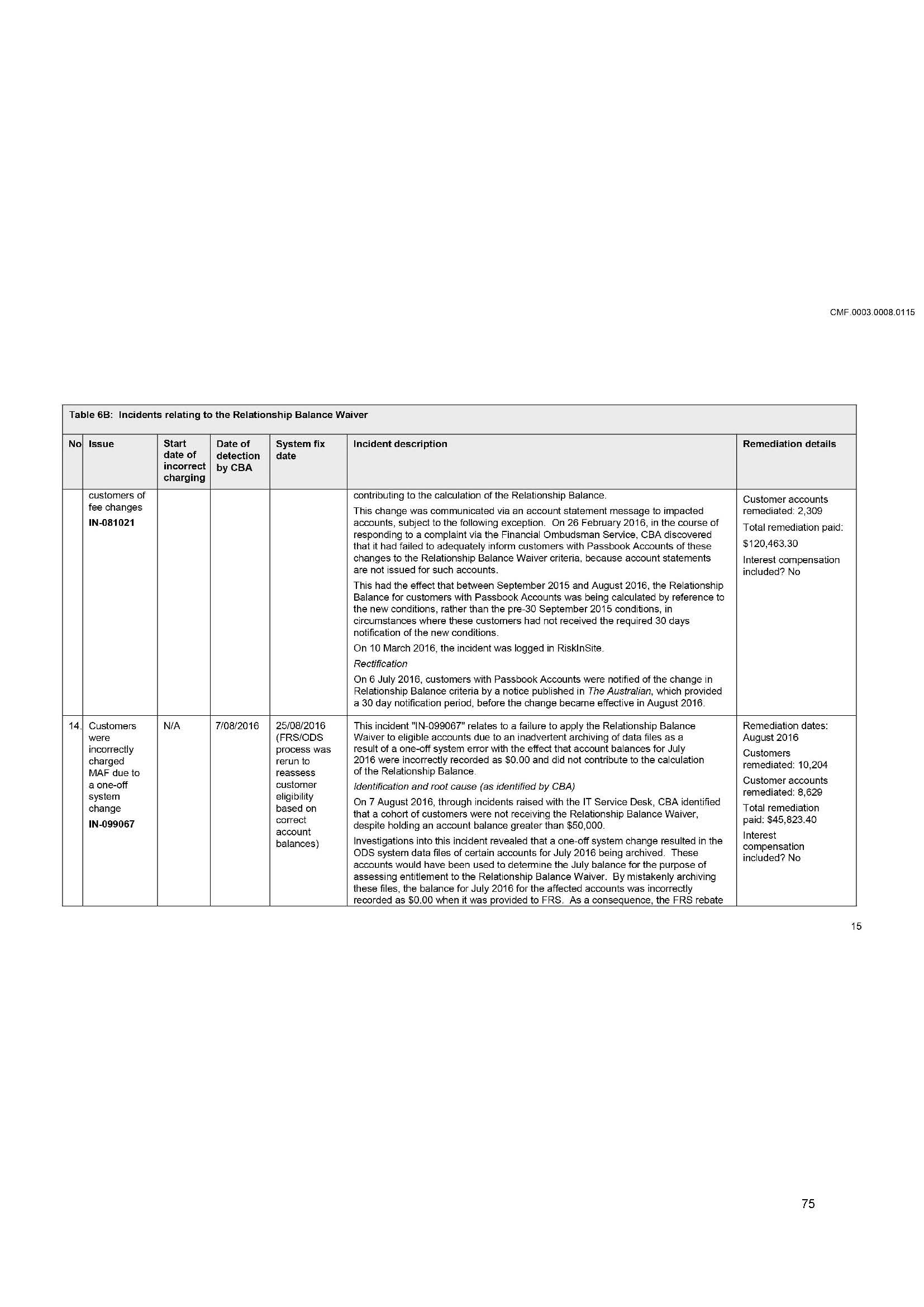

3 There were over 6.7 million relevant accounts as at 1 June 2010. During the relevant period, in excess of 14.8 million additional relevant accounts were subsequently opened, CBA charged a MAF to relevant accounts on approximately 215 million occasions and it applied a waiver of that fee on approximately 610 million occasions.

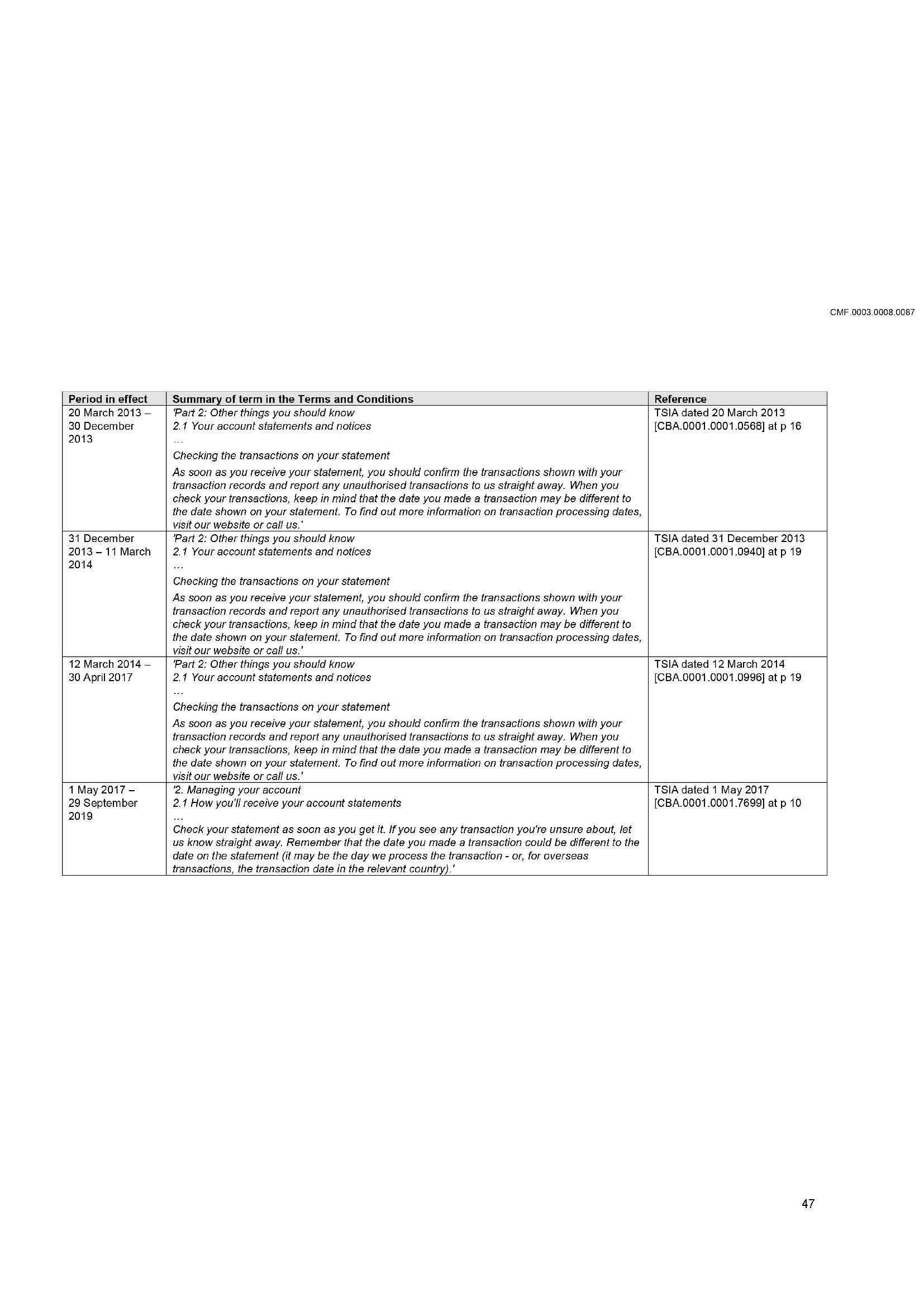

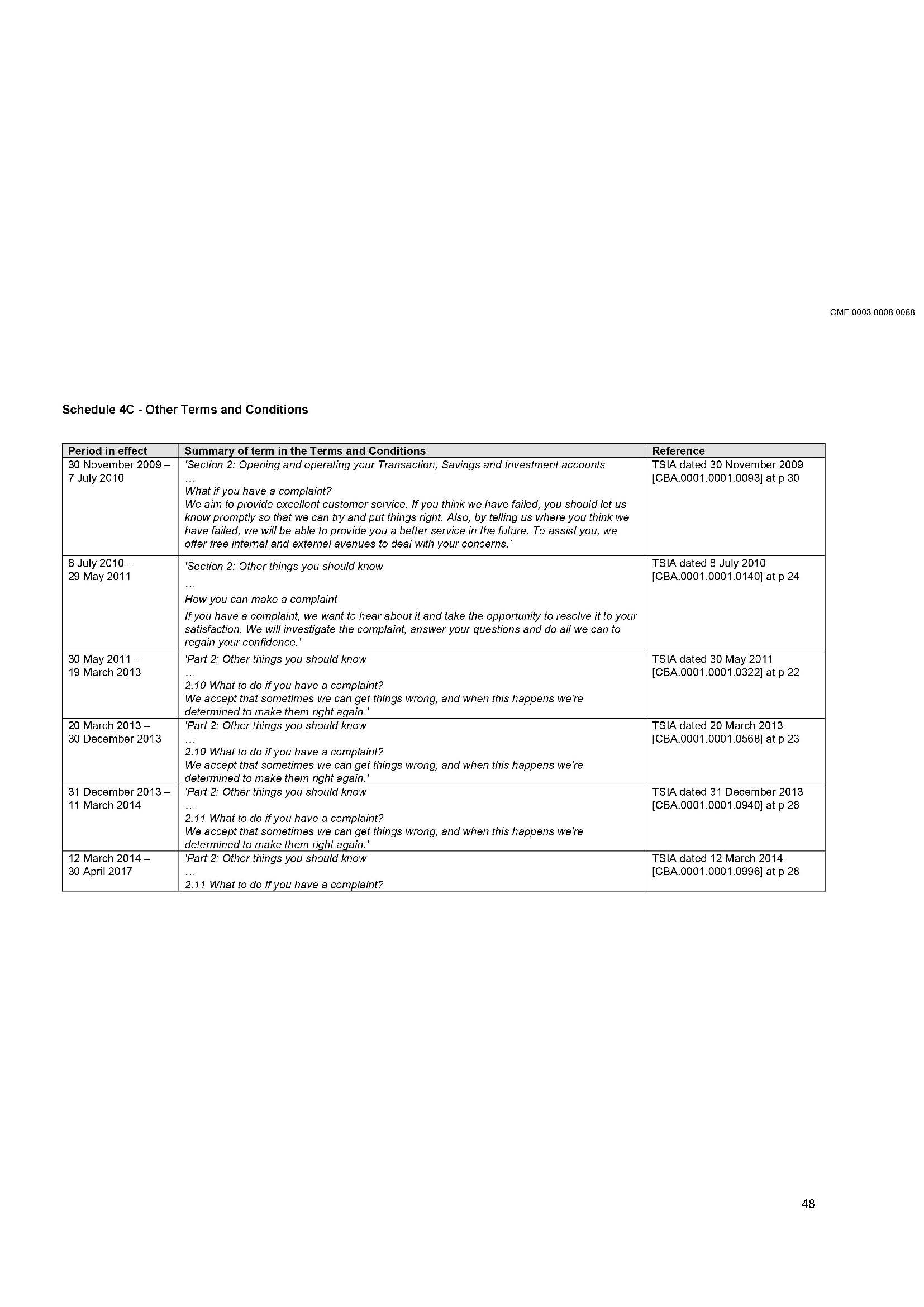

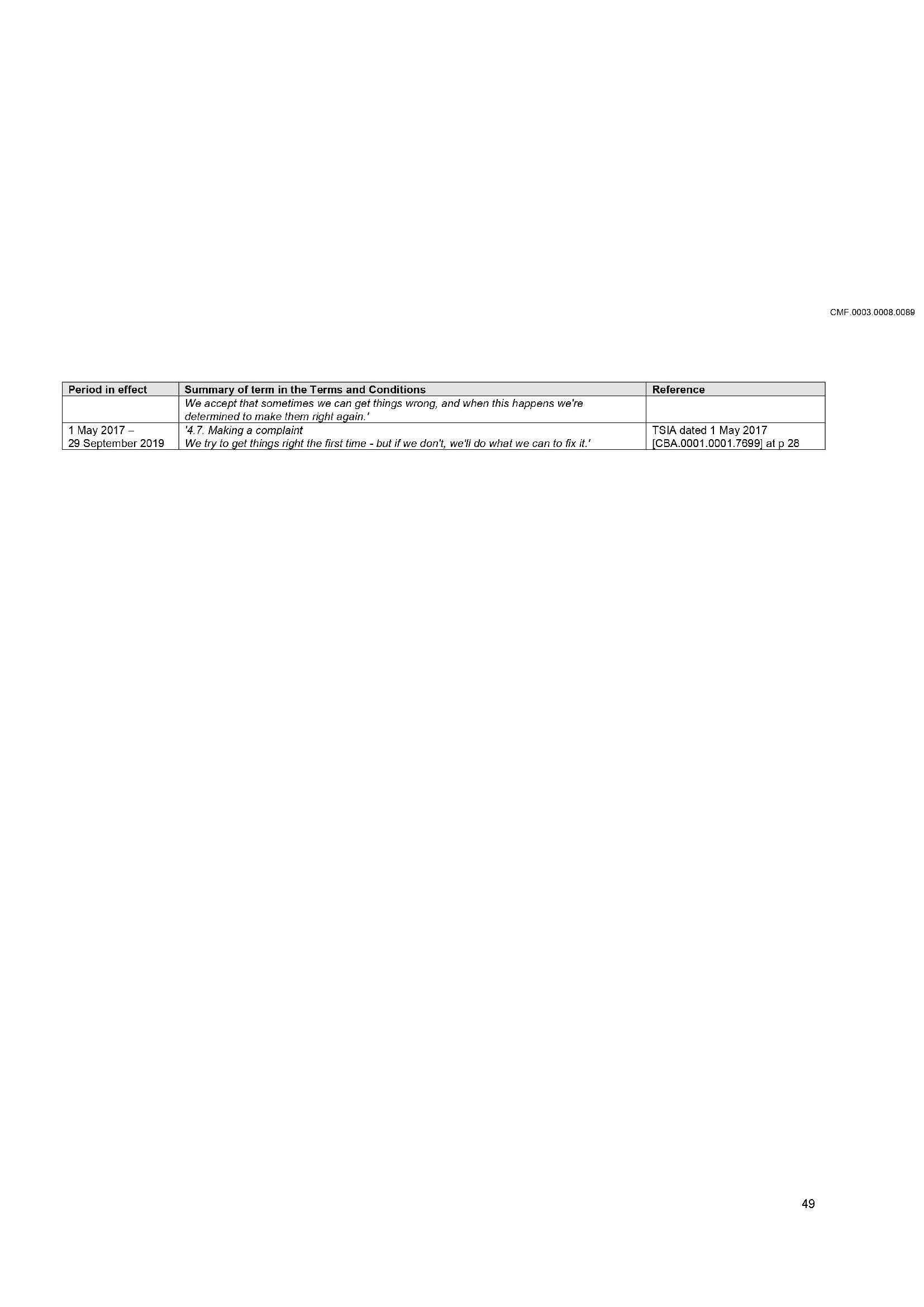

4 The contractual rights and obligations of CBA and its customers with respect to the charging of MAFs and the application of MAF waivers were contained in various documents. For the purposes of this proceeding, these documents were together defined as the Terms and Conditions. CBA provided customers with a copy of the applicable Terms and Conditions when an account was opened, and updated versions of those Terms and Conditions were also provided from time to time.

5 The Terms and Conditions provided that customers would be entitled to a MAF waiver if they satisfied specified eligibility criteria. The Terms and Conditions also contained words to the effect:

(1) that as soon as the customer received their statement, they should check and confirm the transactions shown and report any unauthorised transactions to CBA straight away; and

(2) with one exception, that CBA “accept[s] that sometimes we can get things wrong, and when this happens we’re determined to make them right again”.

6 From time to time, CBA also offered MAF waivers as part of discrete promotions or product offers. The documents relating to these promotions and product offers were also treated by the parties as forming part of the Terms and Conditions.

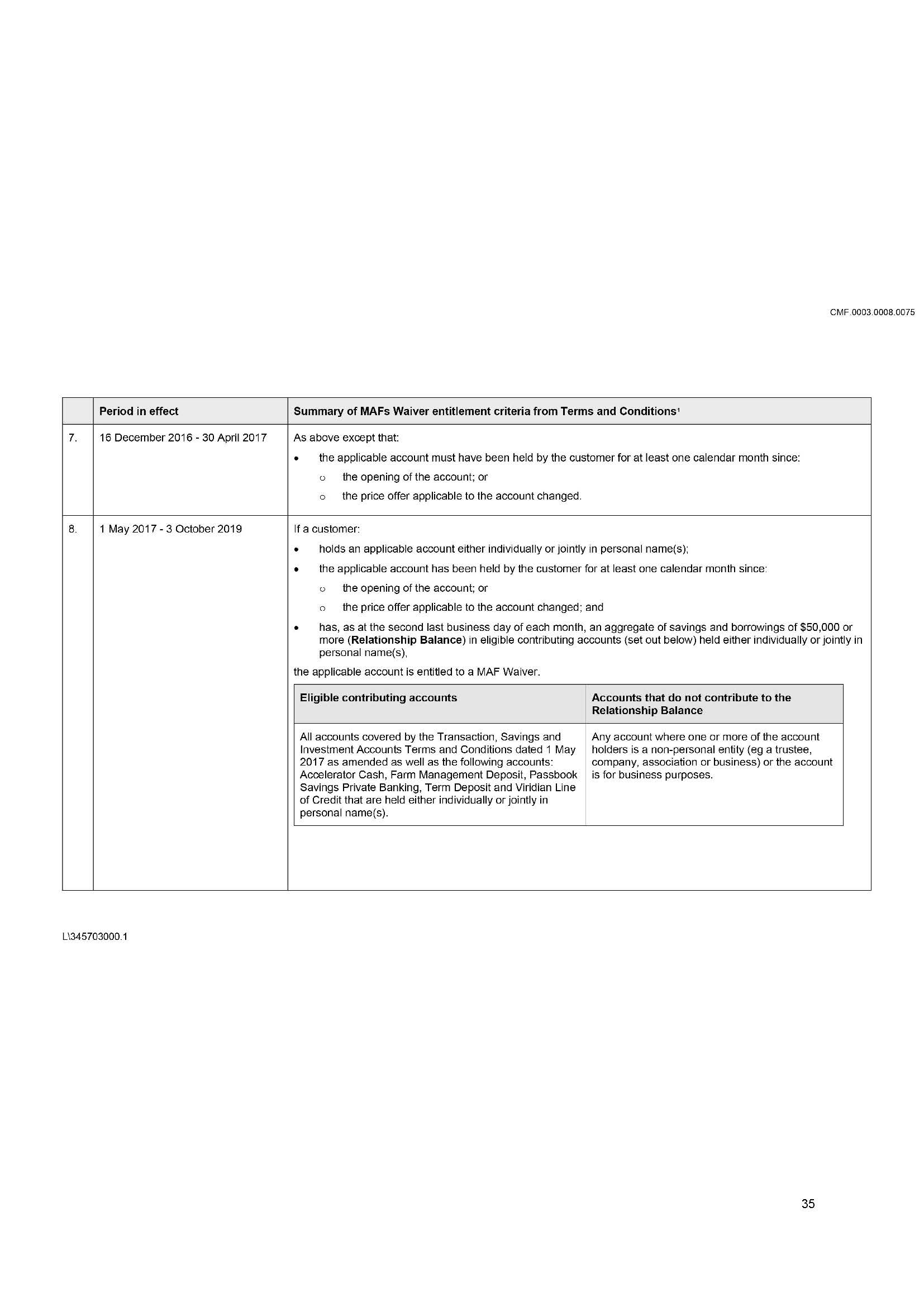

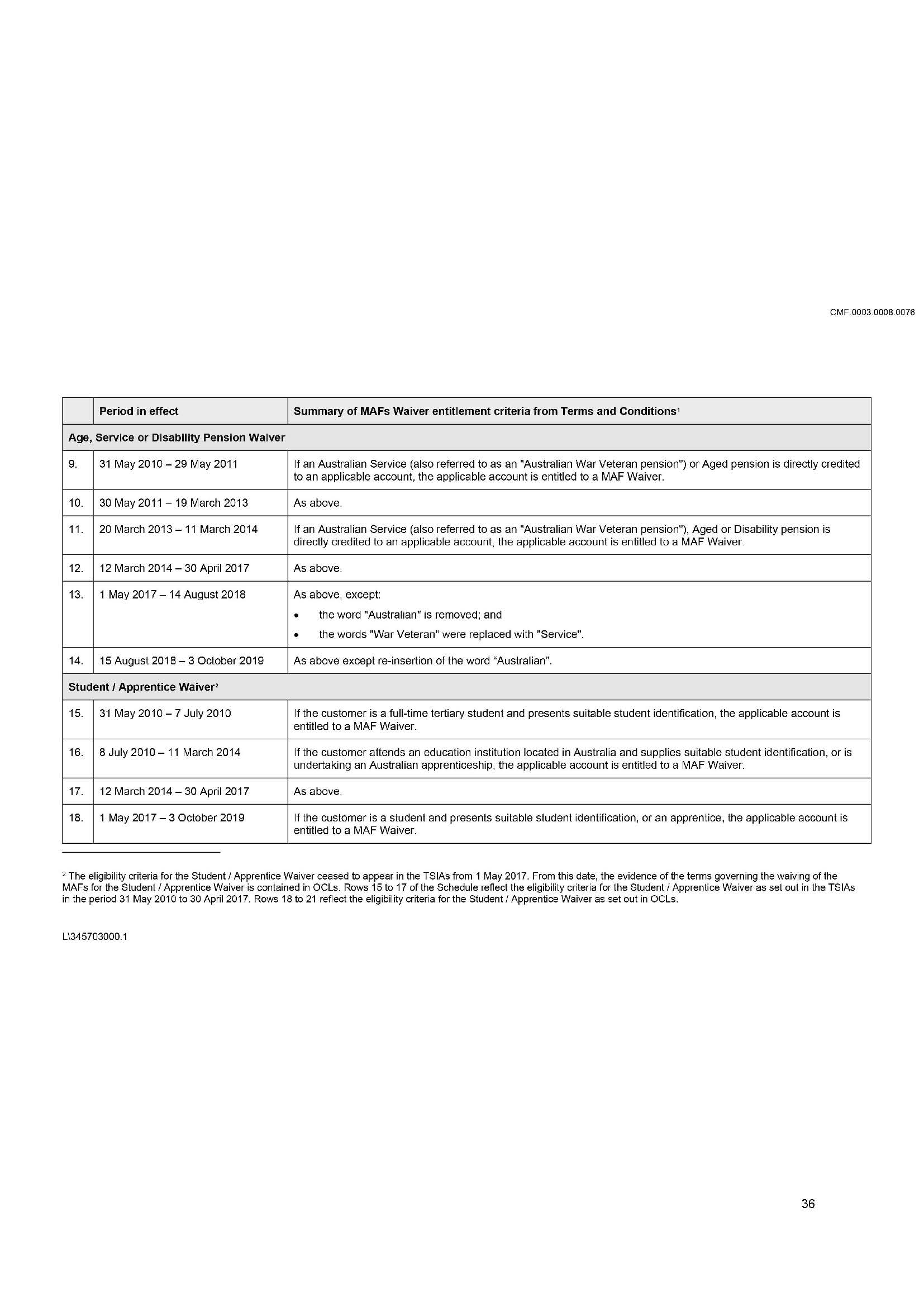

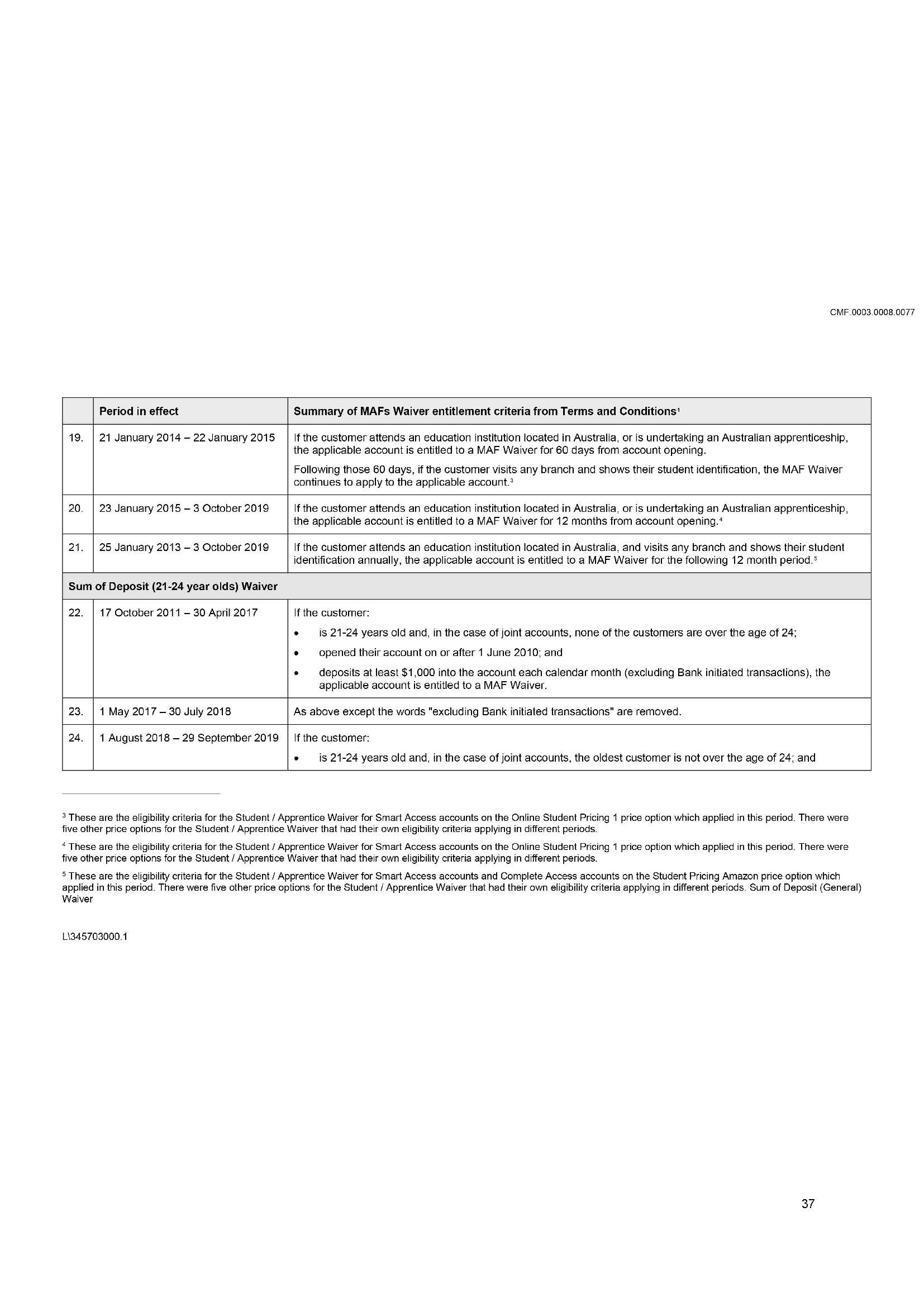

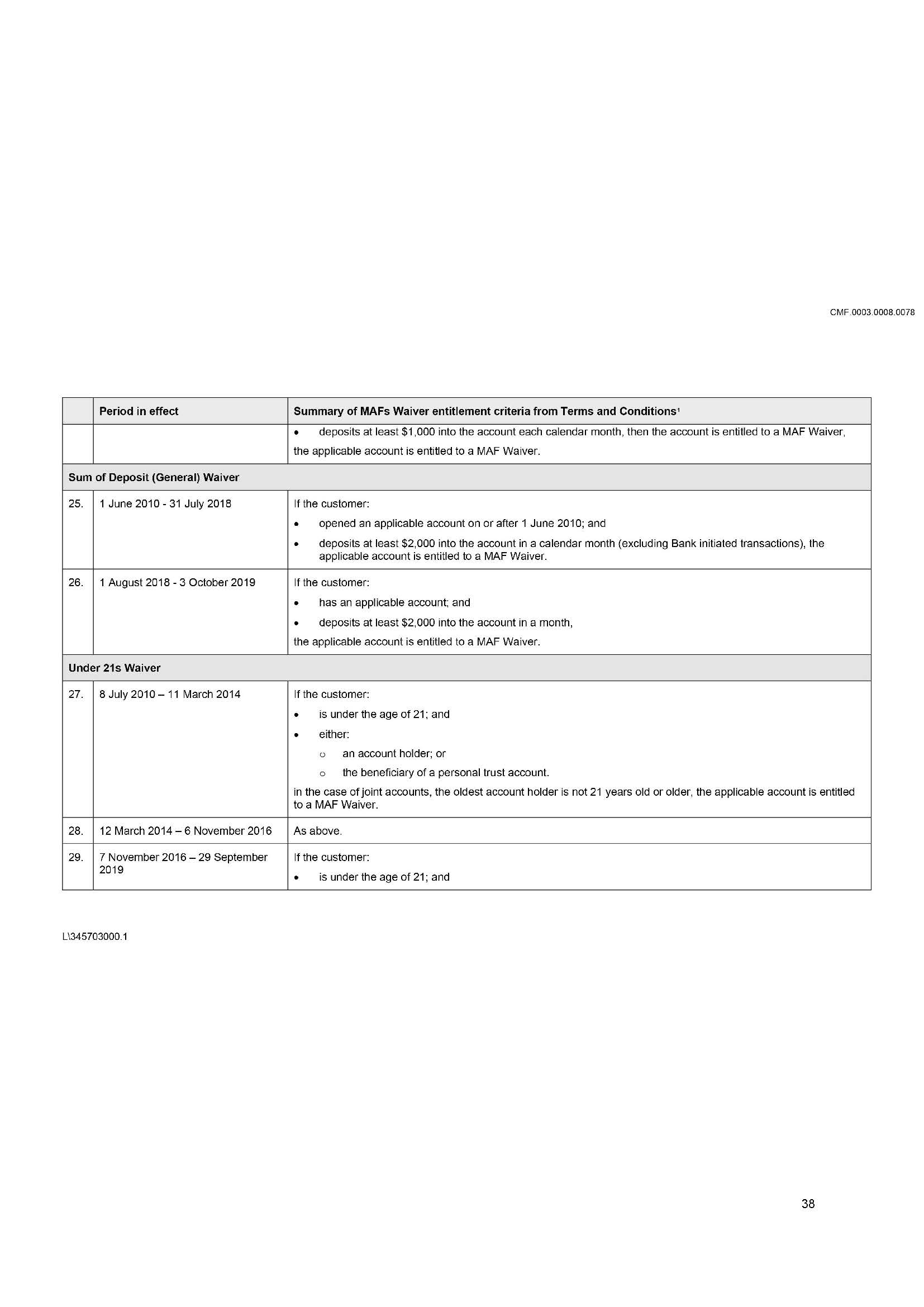

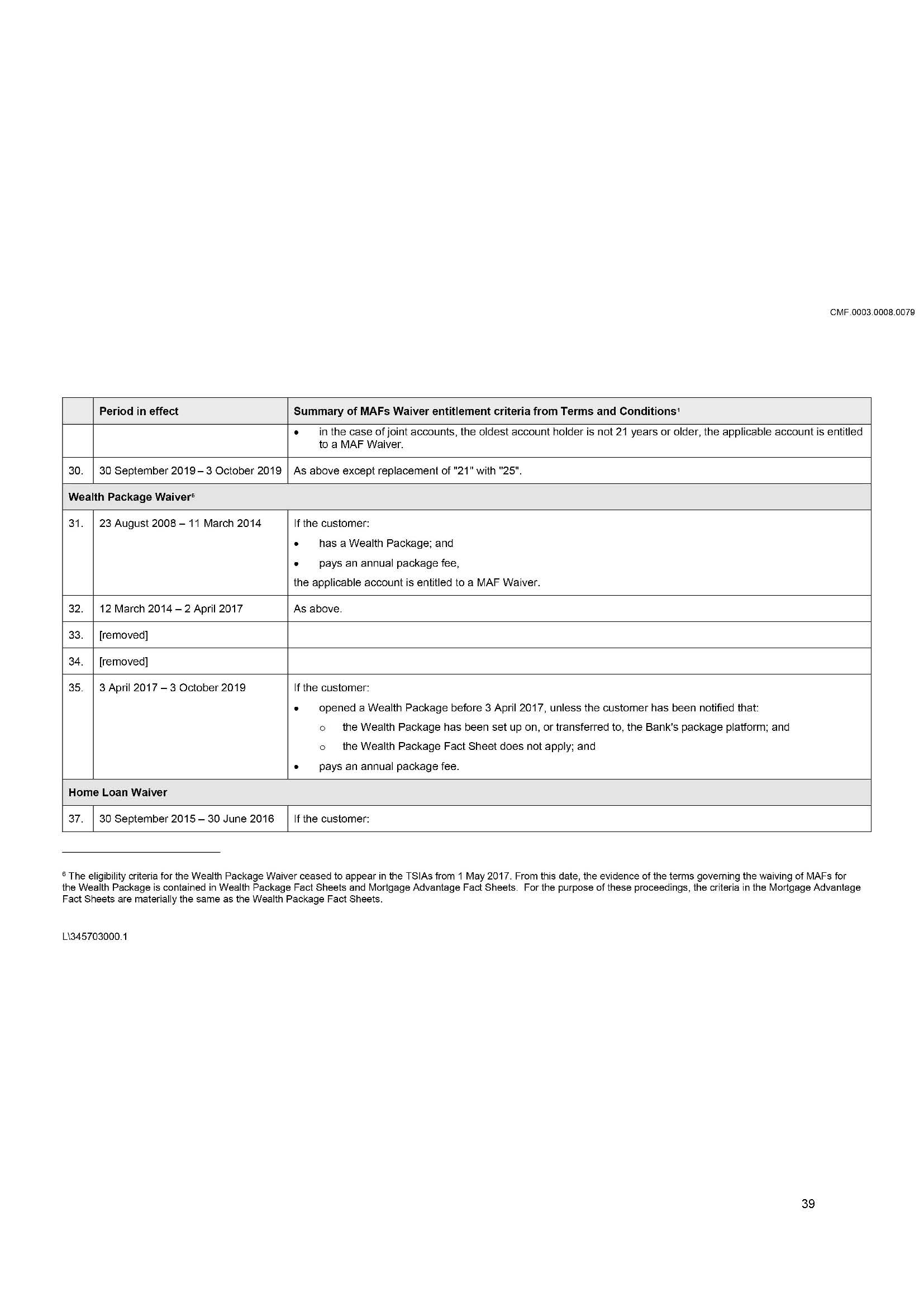

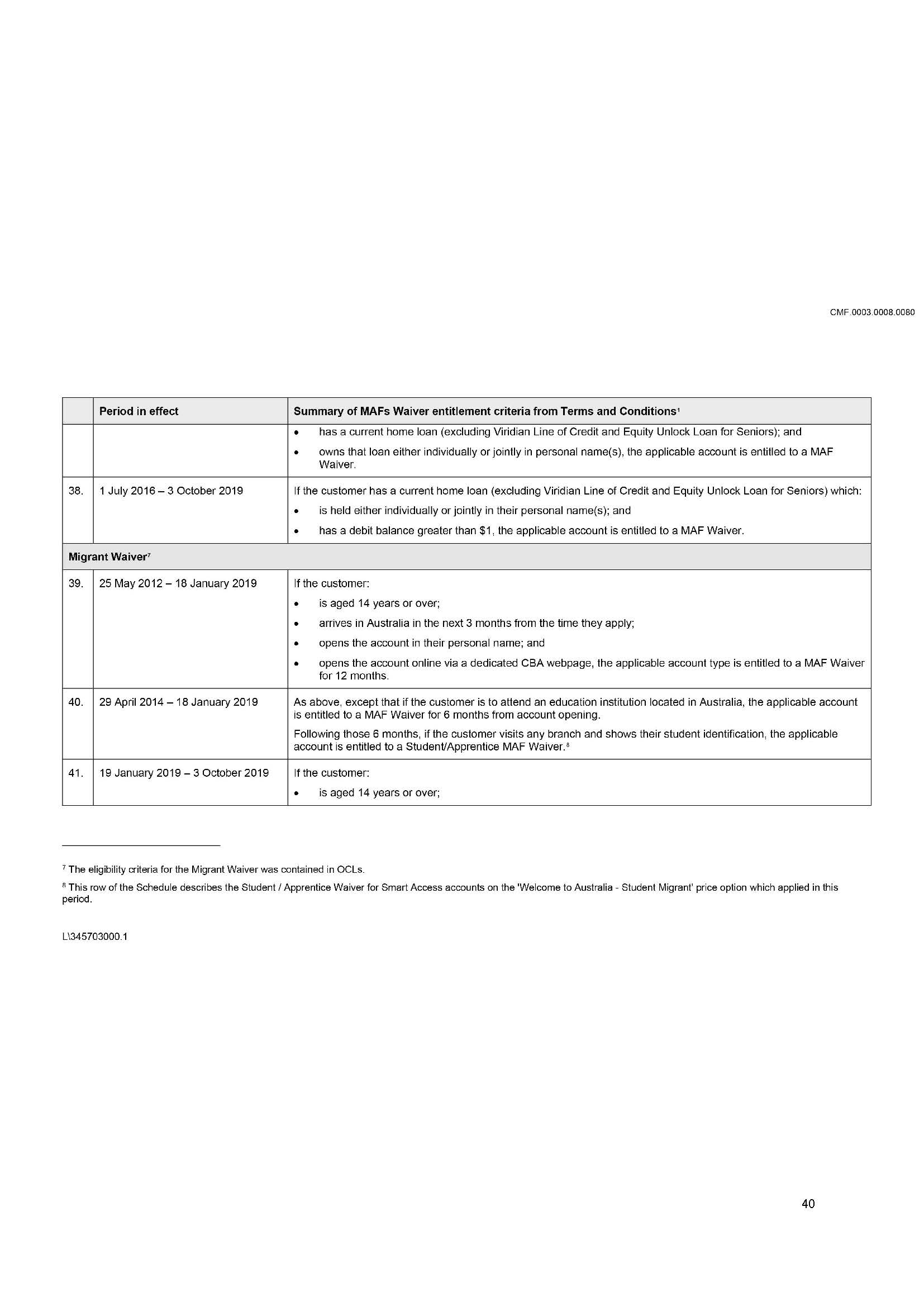

7 CBA offered different types of MAF waivers during the relevant period.

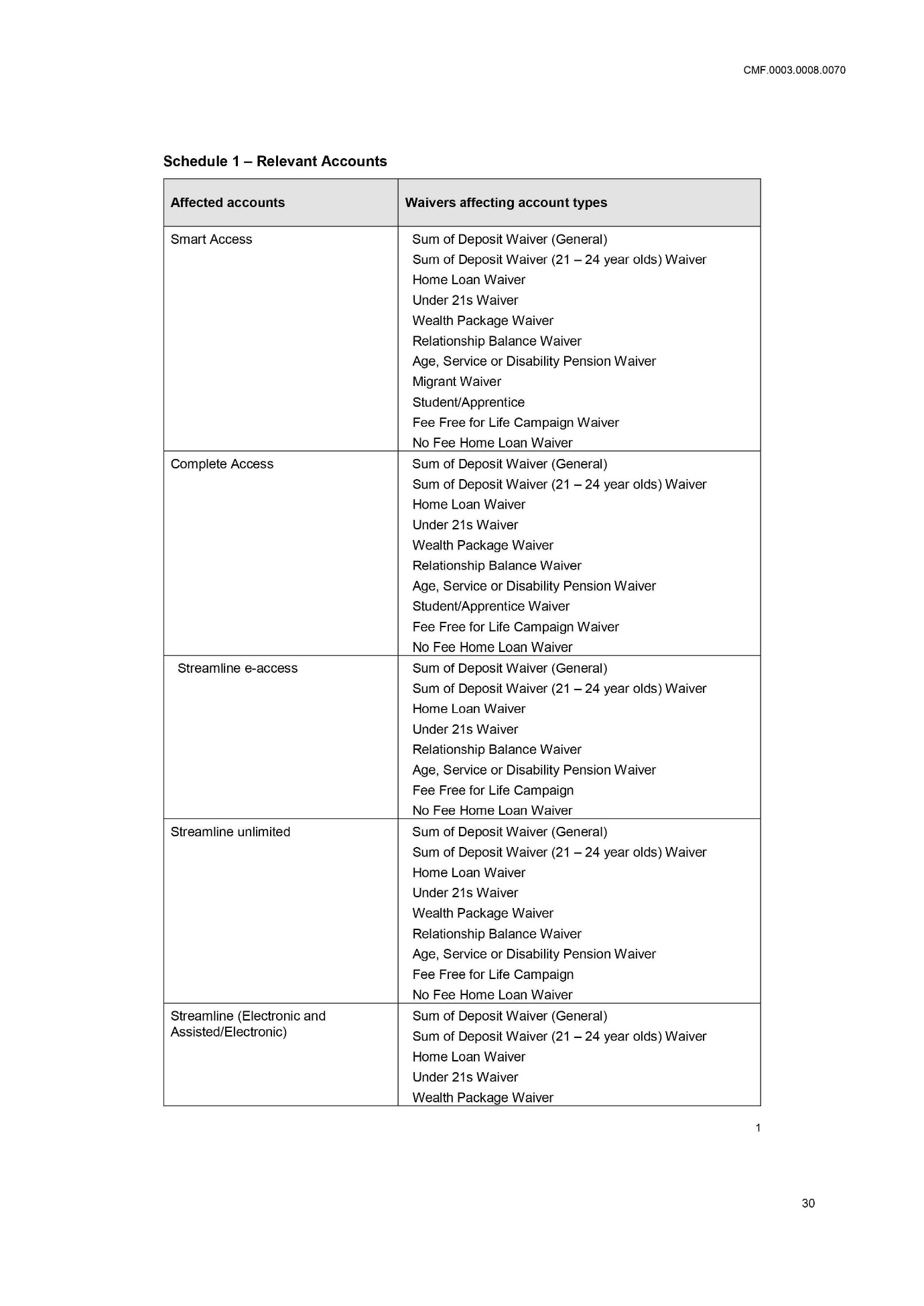

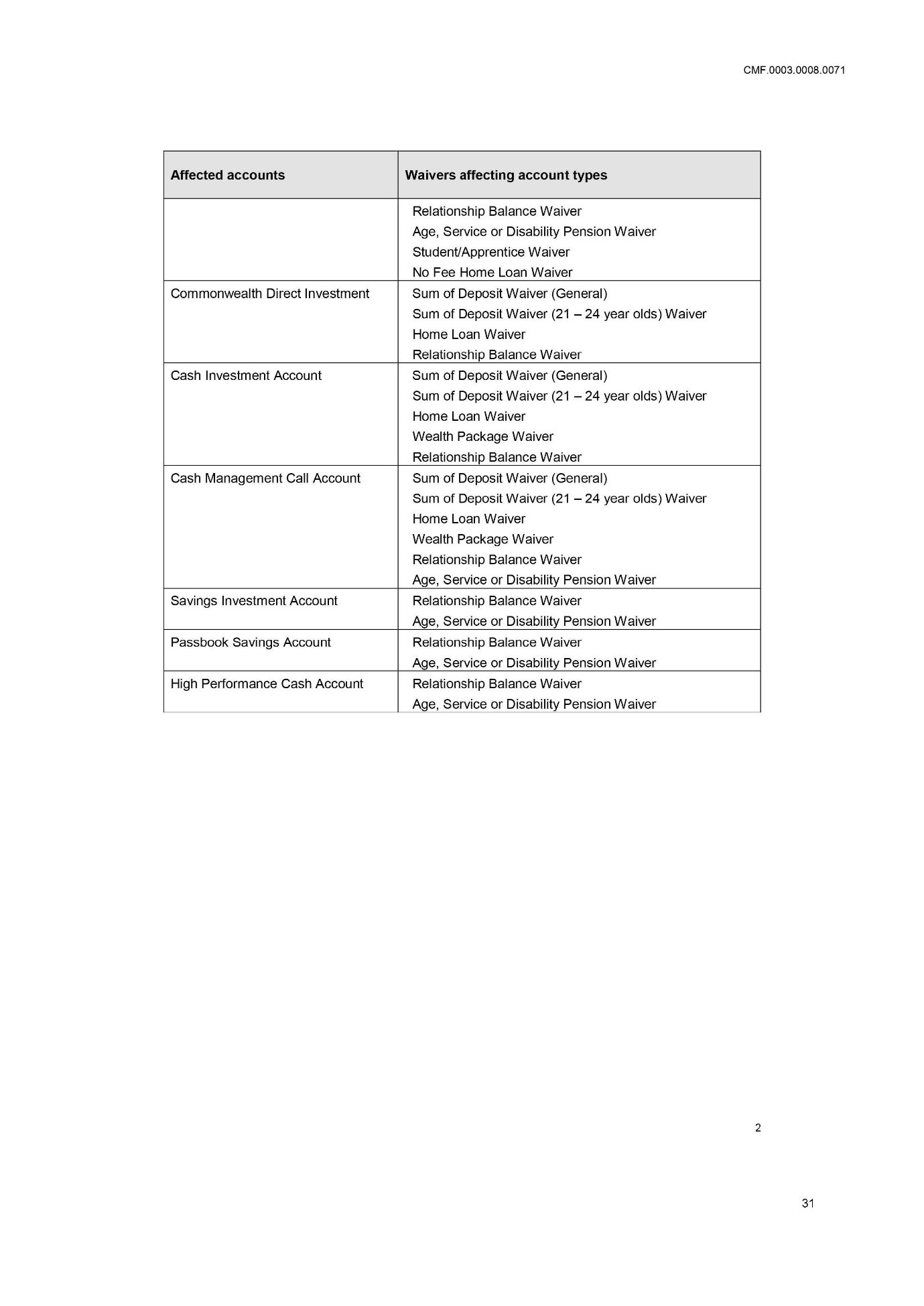

8 This proceeding concerns ten different types of MAF waiver, namely:

(1) Relationship Balance Waiver;

(2) Age, Service and Disability Waiver;

(3) Student / Apprentice Waiver;

(4) FFFL Campaign Waiver;

(5) Sum of Deposit Waiver, which was sub-categorised into “Sum of Deposit (General)” and “Sum of Deposit (21-24 year olds)”;

(6) Under 21s Waiver;

(7) Wealth Package Waiver;

(8) Home Loan Waiver;

(9) NFHL Waiver; and

(10) Migrant Waiver,

(described as the relevant MAF waivers).

9 Each of the relevant MAF waivers was subject to different eligibility criteria, which depended upon an assessment of the particular customer’s activity over a monthly period, such as the amount of savings and borrowings in contributing accounts as at the second last business day of each month or the amount deposited into the account each calendar month. In other cases, an eligible customer’s individual characteristics at a particular point in time entitled the customer to a MAF waiver, as in the case of the Student / Apprentice Waiver and the Under 21s Waiver. The application of any of the relevant MAF waivers during the relevant period therefore depended upon variables that were unique to the particular customer, that differed for each relevant MAF waiver and that could change from month to month.

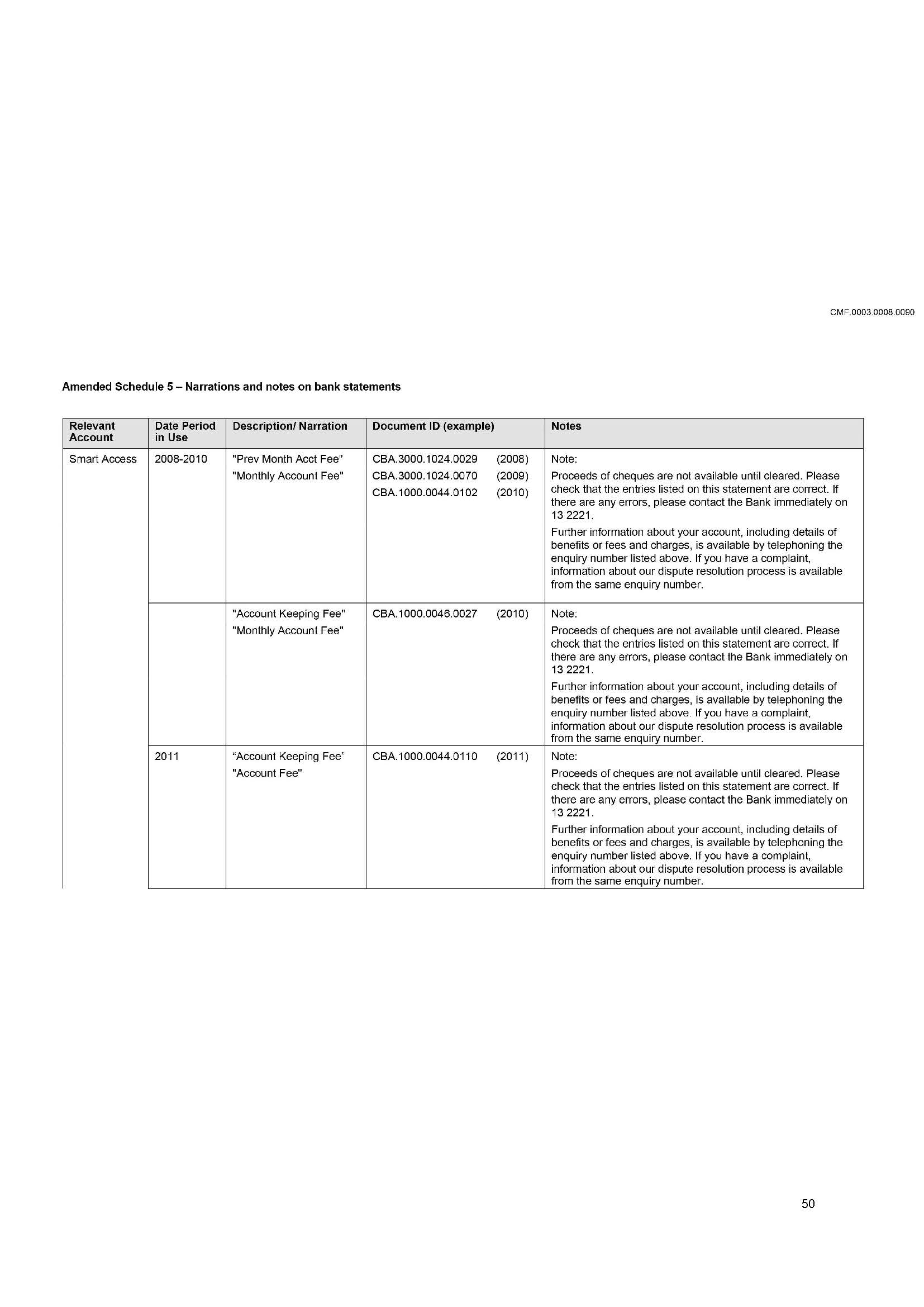

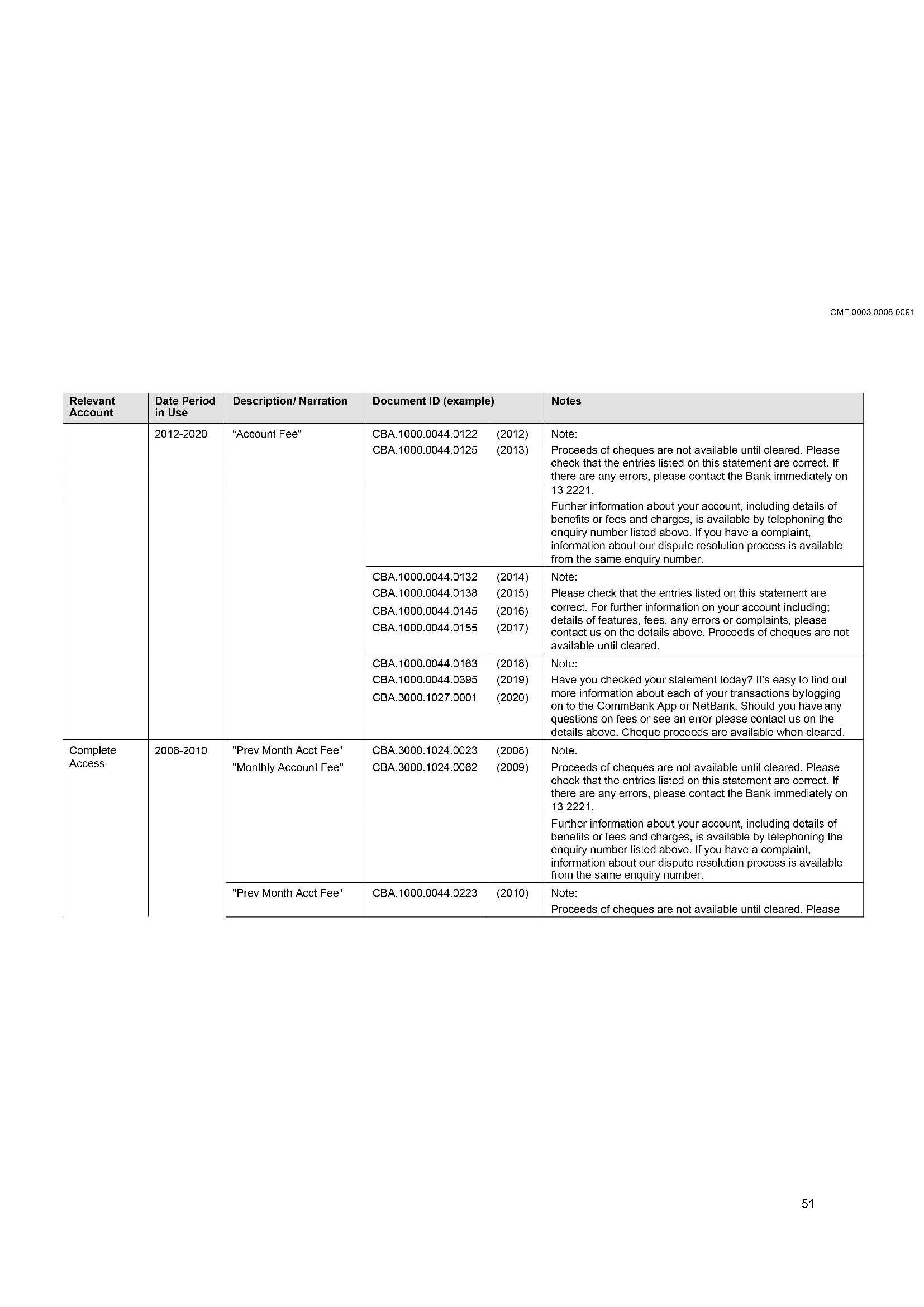

10 During the relevant period, the customer account statements which were issued to customers set out the transaction history on the account, identifying the date of a transaction, the amount debited or credited and a transaction description.

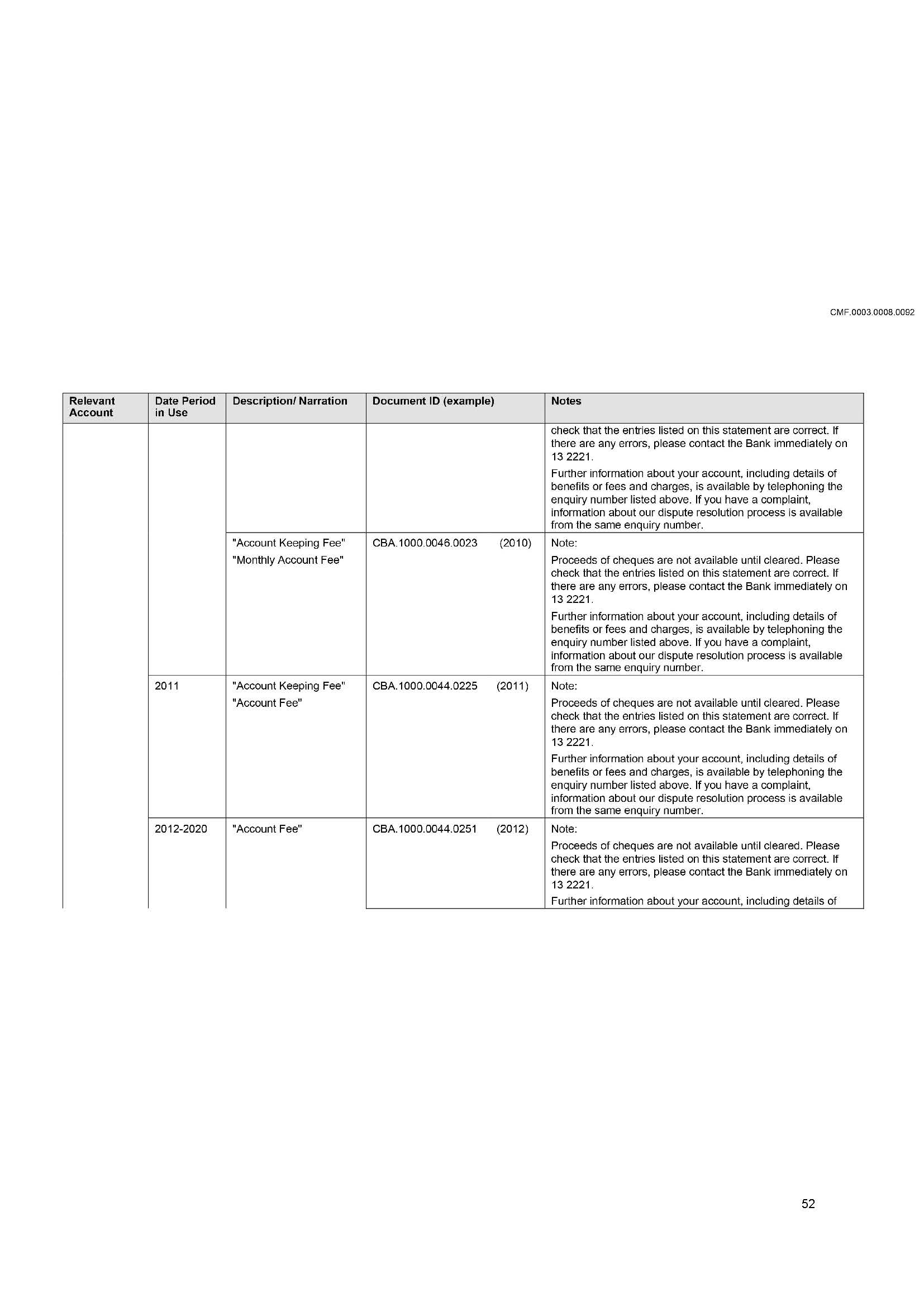

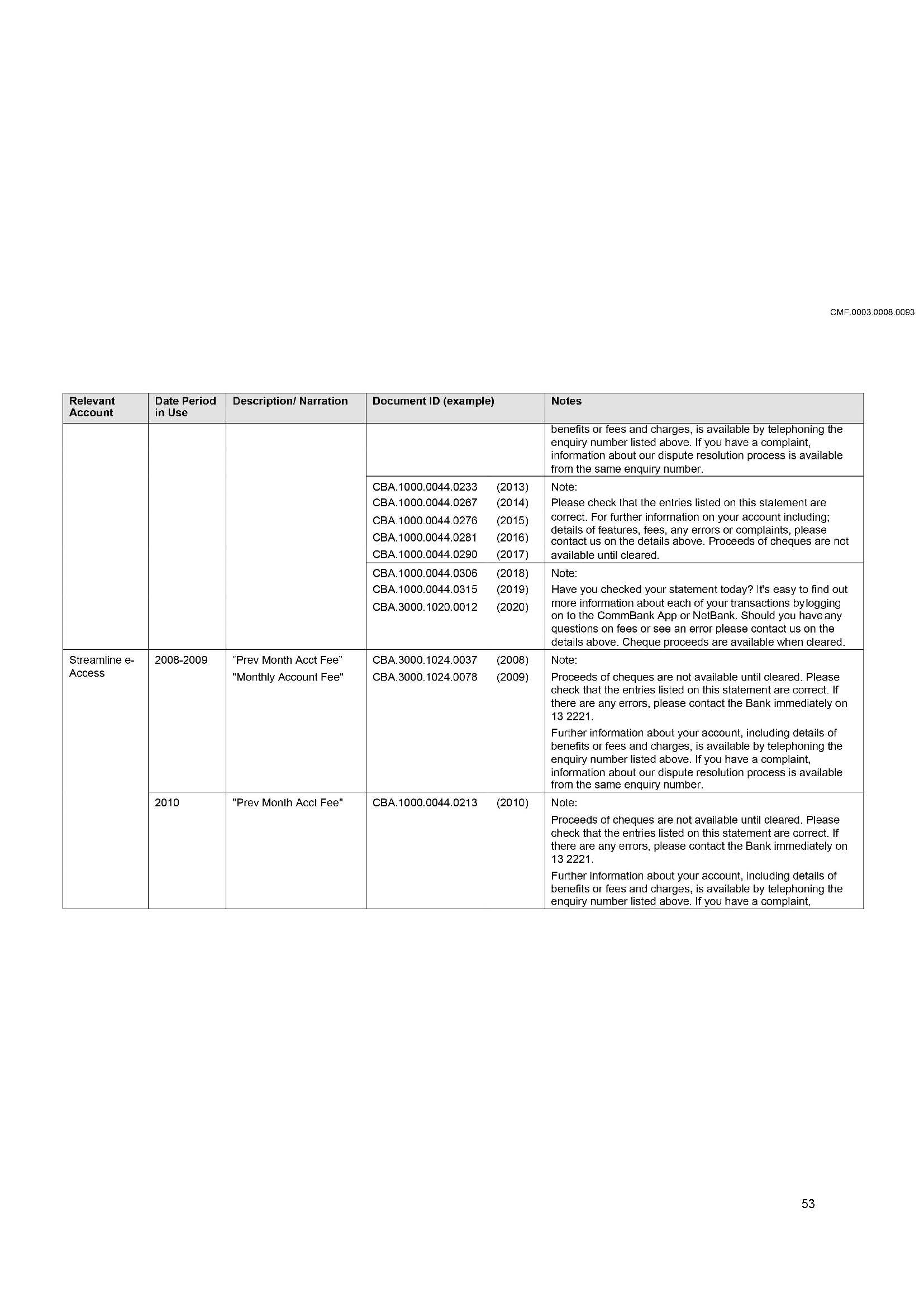

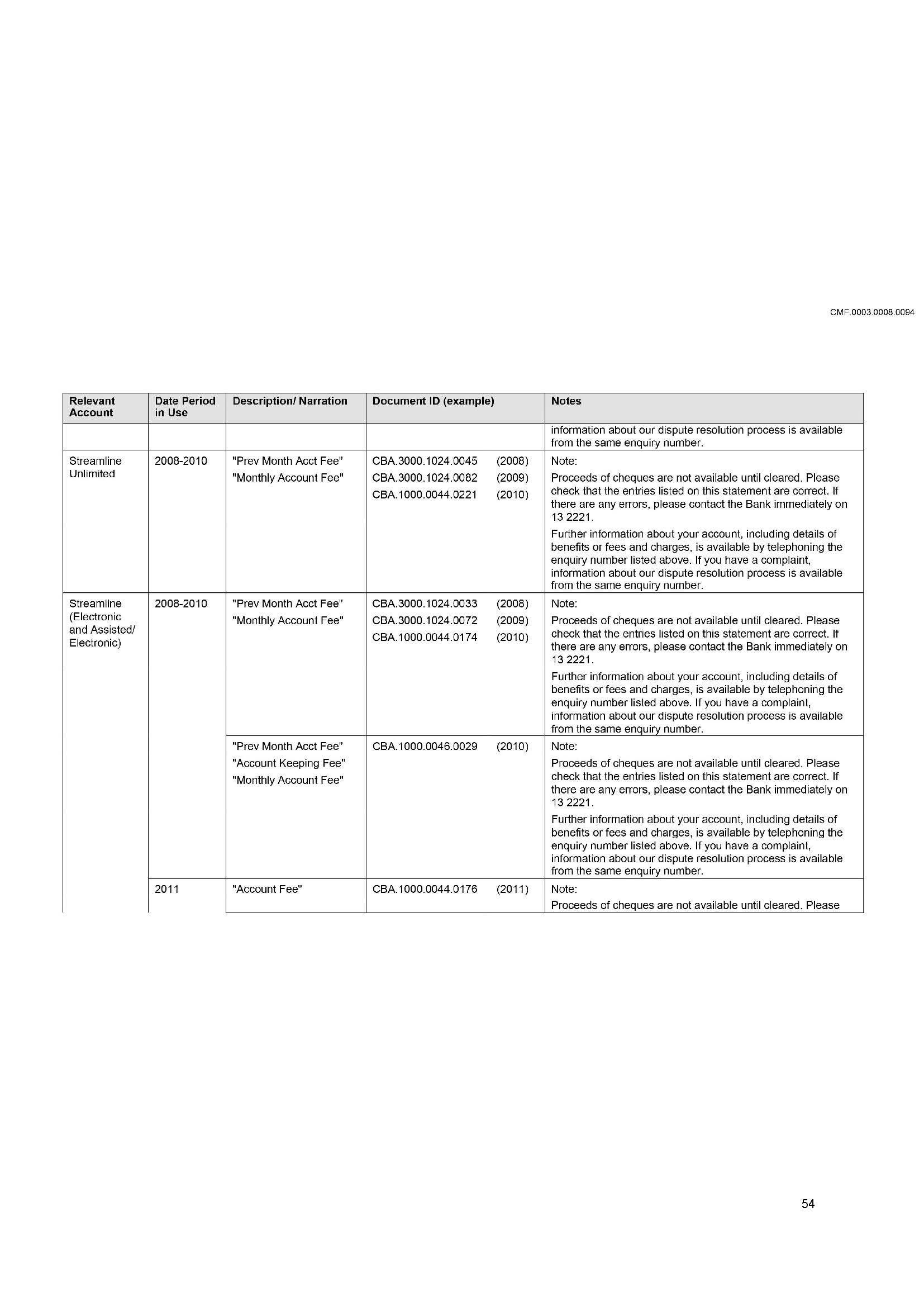

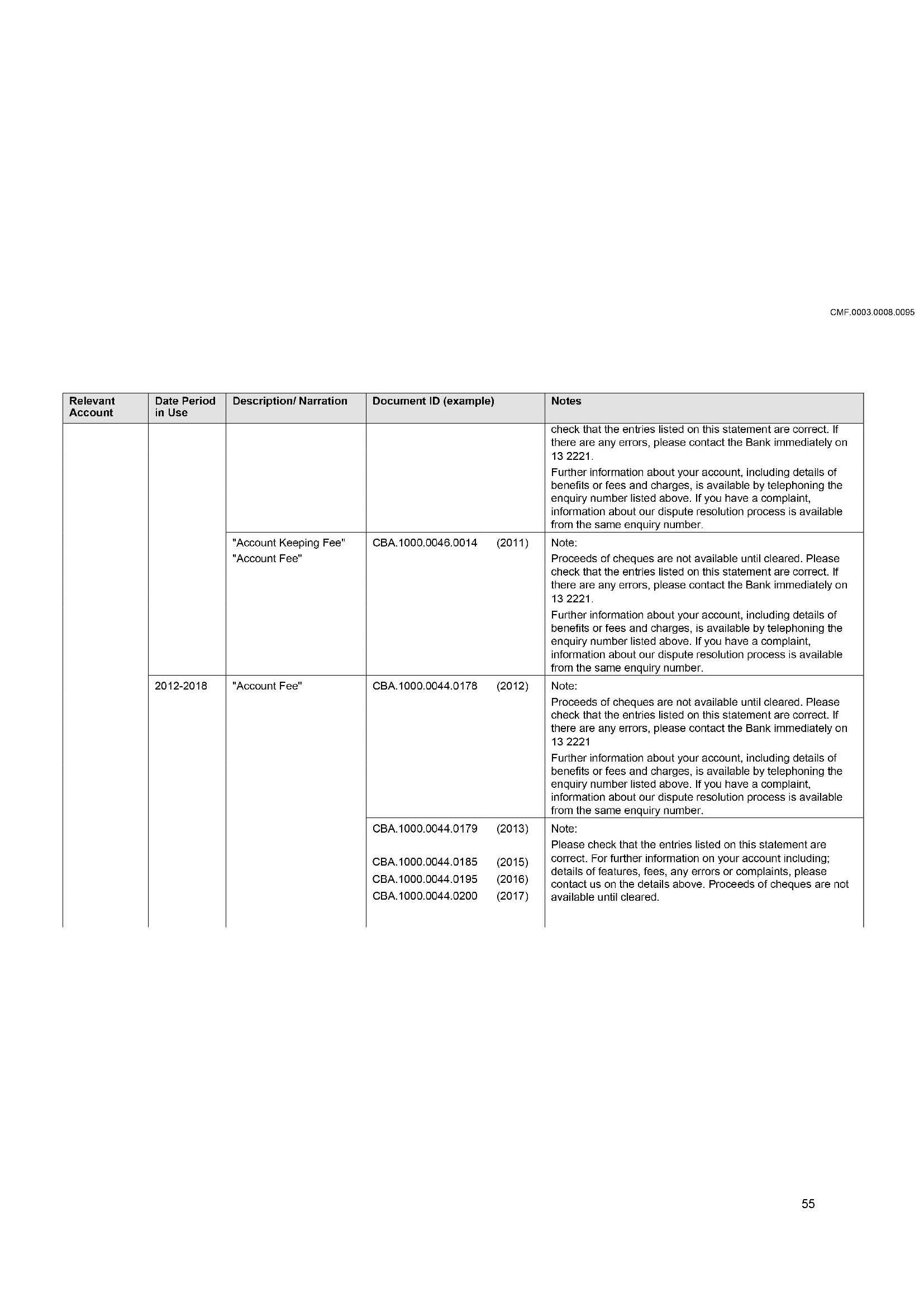

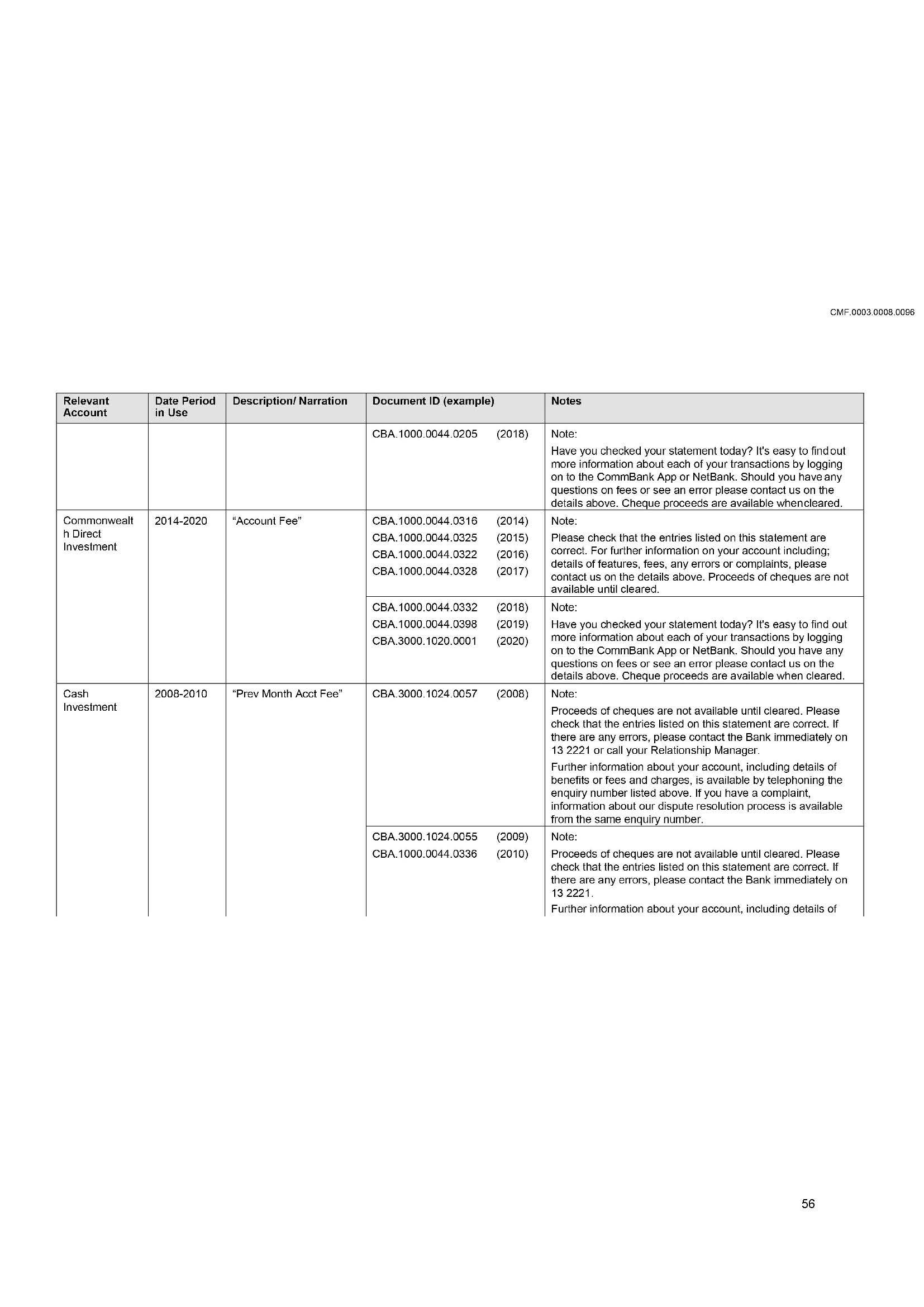

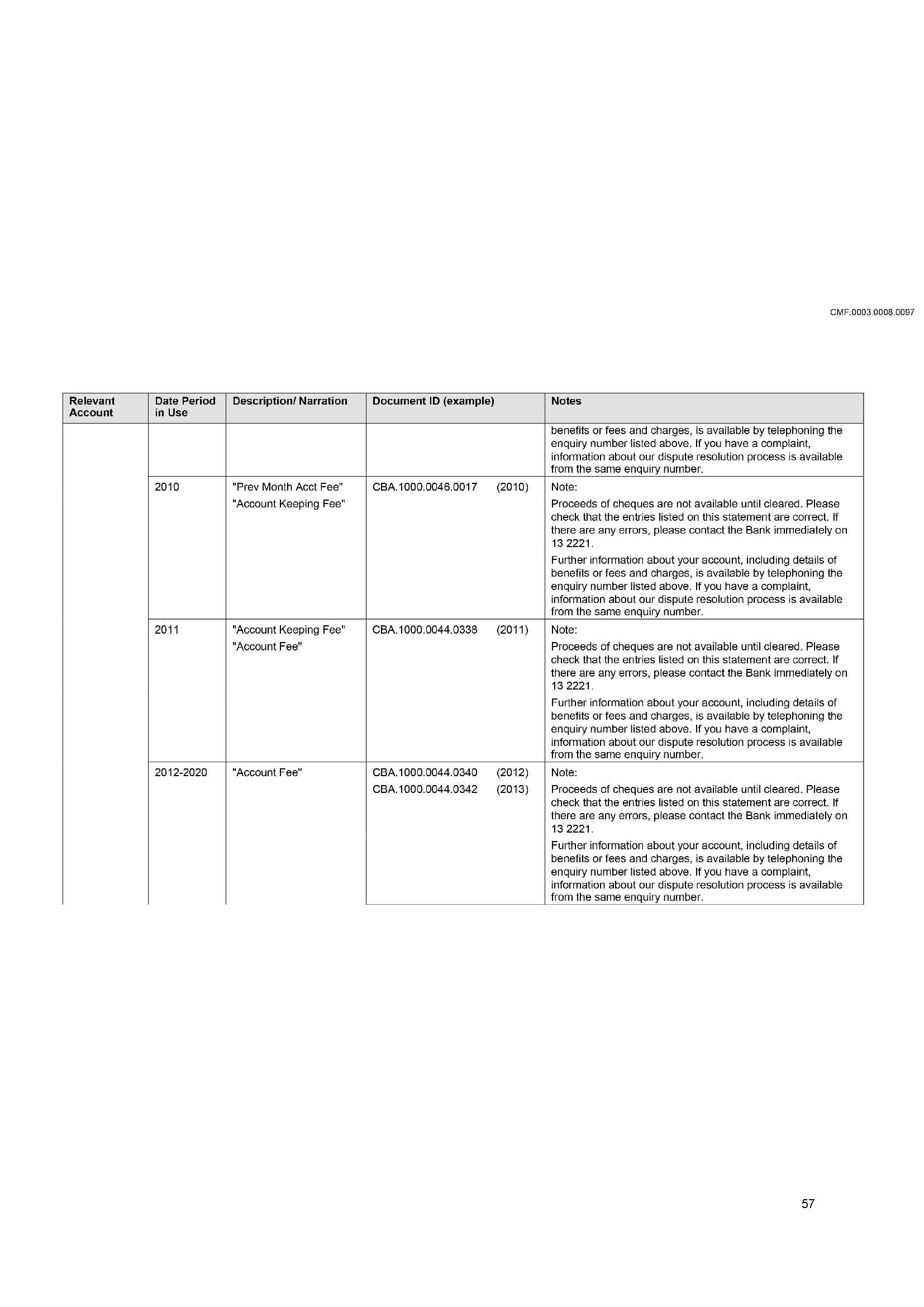

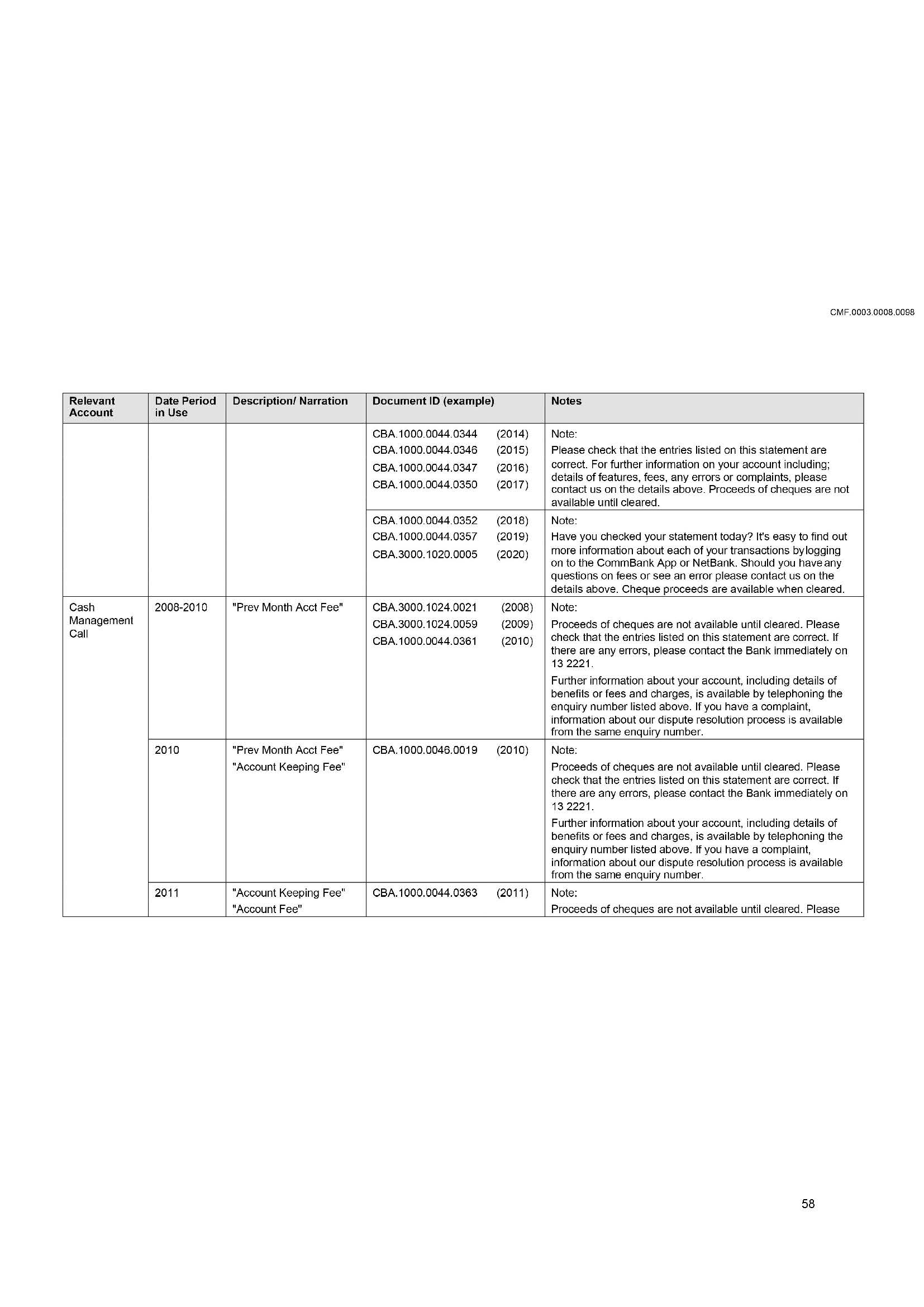

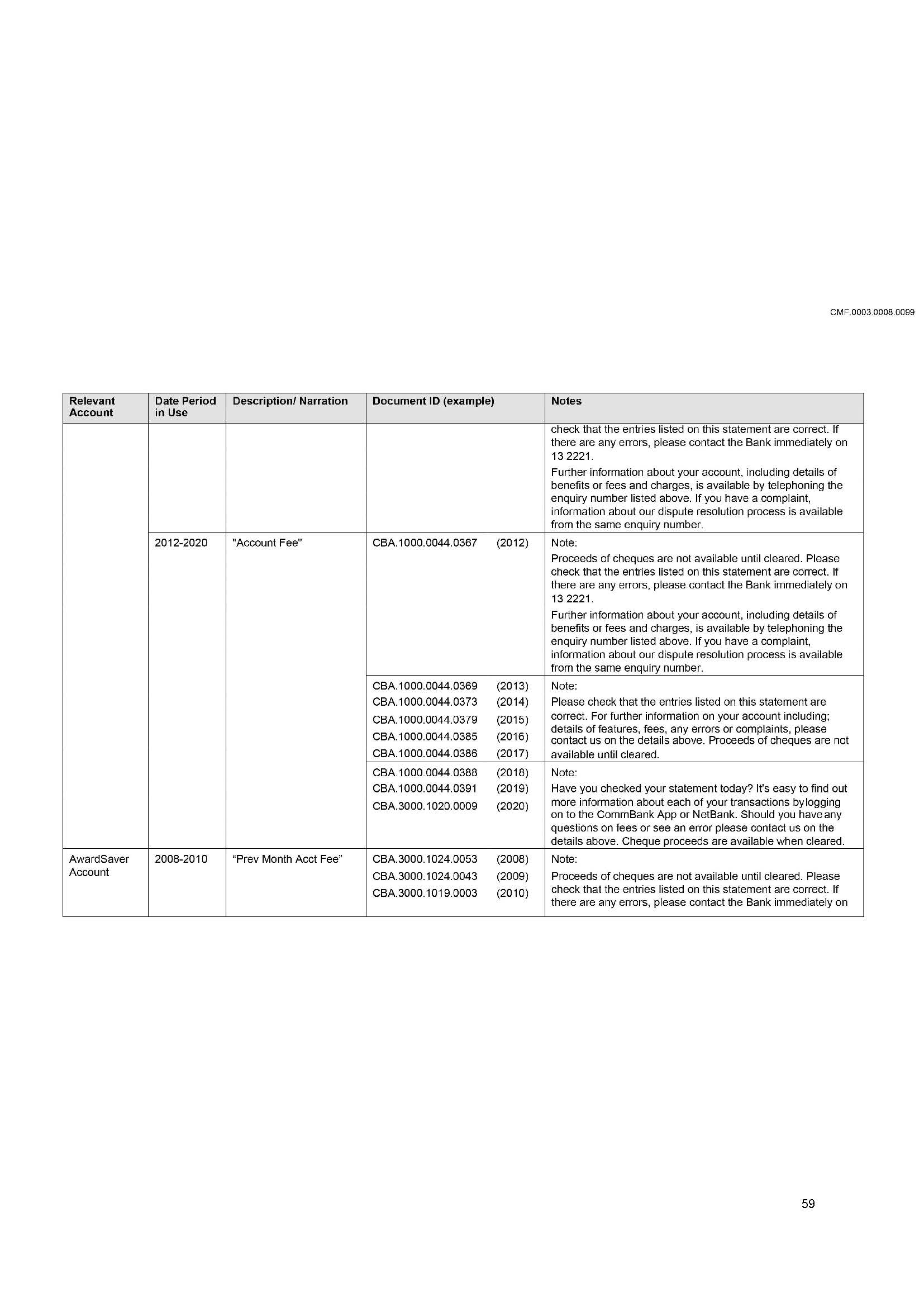

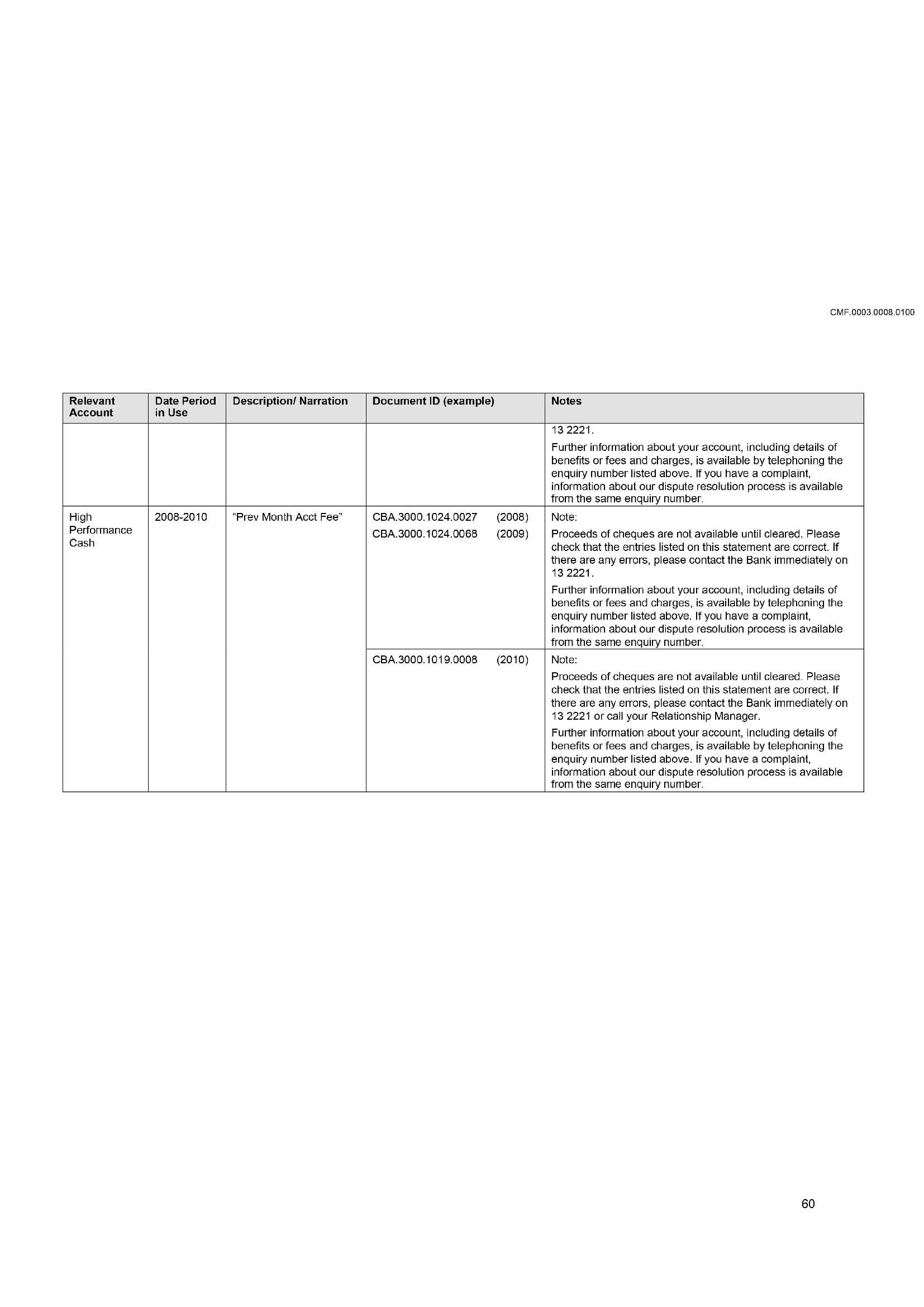

11 A MAF was described in customer account statements during the relevant period as a “Prev Month Acct Fee”, “Monthly Account Fee”, “Account Keeping Fee” or “Account Fee”.

12 The customer account statements contained a note on page 1 directing the customer to check that the entries listed in the statement are correct or to contact CBA immediately in the event of any errors in the statement. Examples of such notes included the following:

Example 1:

Note:

Proceeds of cheques are not available until cleared. Please check that the entries listed on this statement are correct. If there are any errors, please contact the Bank immediately on 13 2221.

Further information about your account, including details of benefits or fees and charges, is available by telephoning the enquiry number listed above. If you have a complaint, information about our dispute resolution process is available from the same enquiry number.

Example 2:

Note:

Please check that the entries listed on this statement are correct. For further information on your account including; details of features, fees, any errors or complaints, please contact us on the details above. Proceeds of cheques are not available until cleared.

Example 3:

Note:

Have you checked your statement today? It’s easy to find out more information about each of your transactions by logging on to the CommBank App or NetBank. Should you have any questions on fees or see an error please contact us on the details above. Cheque proceeds are available when cleared.

13 For the passbook accounts, CBA issued customers with a passbook which was generally required to be presented by customers in CBA branches for any deposit or withdrawal by the customer. For deposits by the customer, branch staff printed in a customer’s passbook the date of the deposit, a description of the transaction and the amount of the deposit. For withdrawals by the customer, branch staff printed in a customer’s passbook the amount of the withdrawal, the balance of the account and a verification comment (being a receipt number, or, if manually recorded, a branch stamp, for each transaction). Other transactions not initiated by the customer, such as account fees (including MAFs), were printed on the passbook when the customer presented it at a CBA branch.

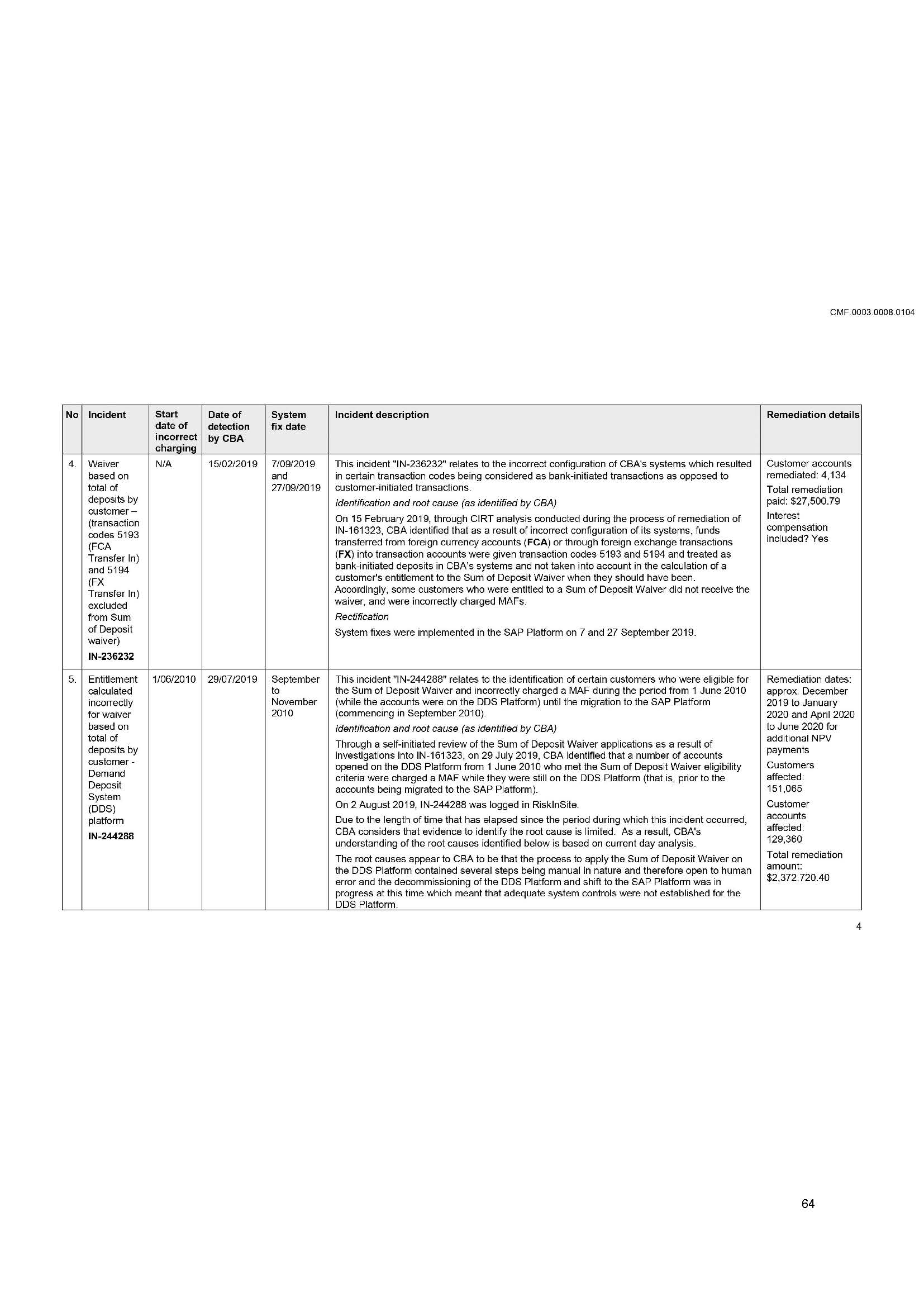

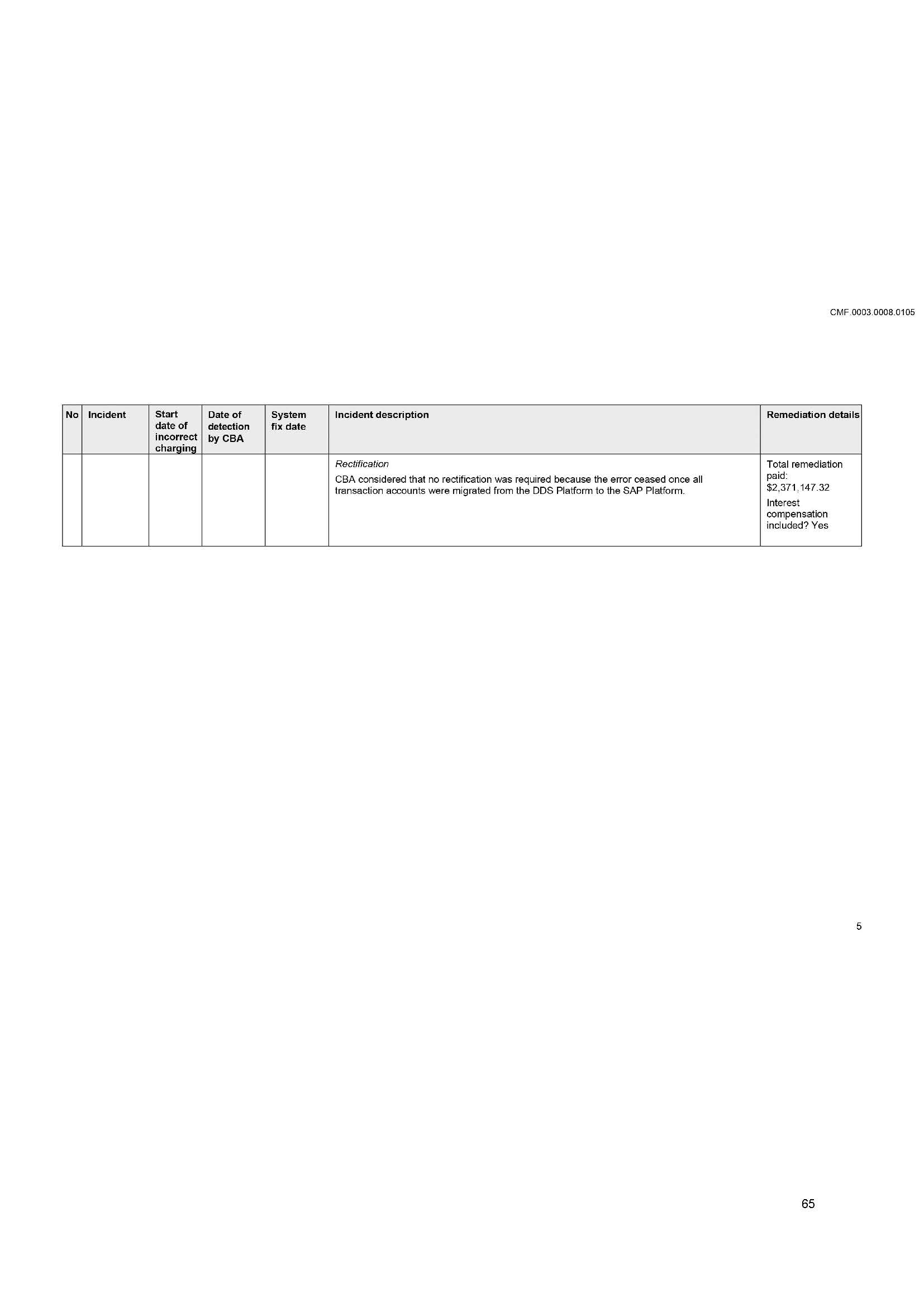

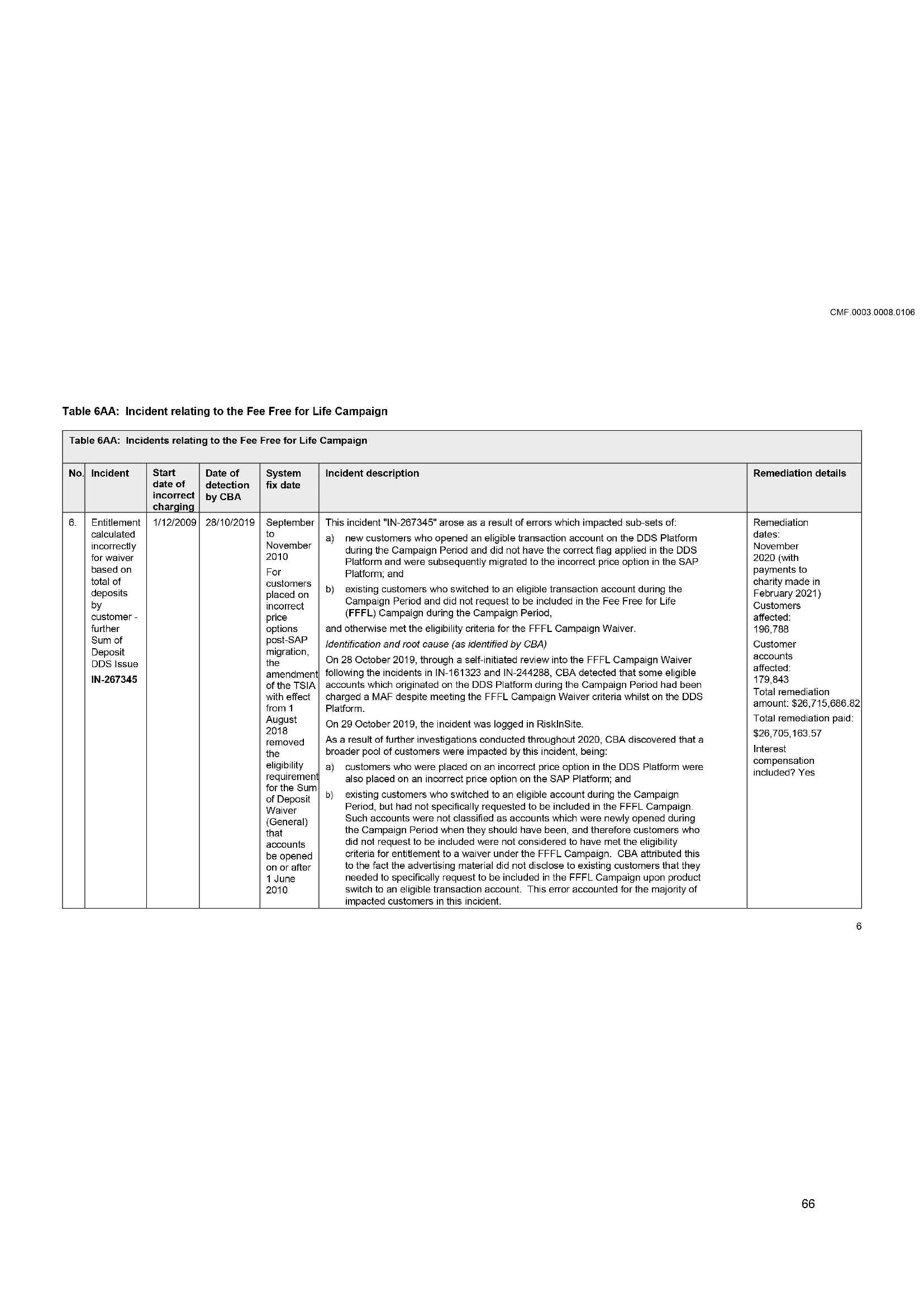

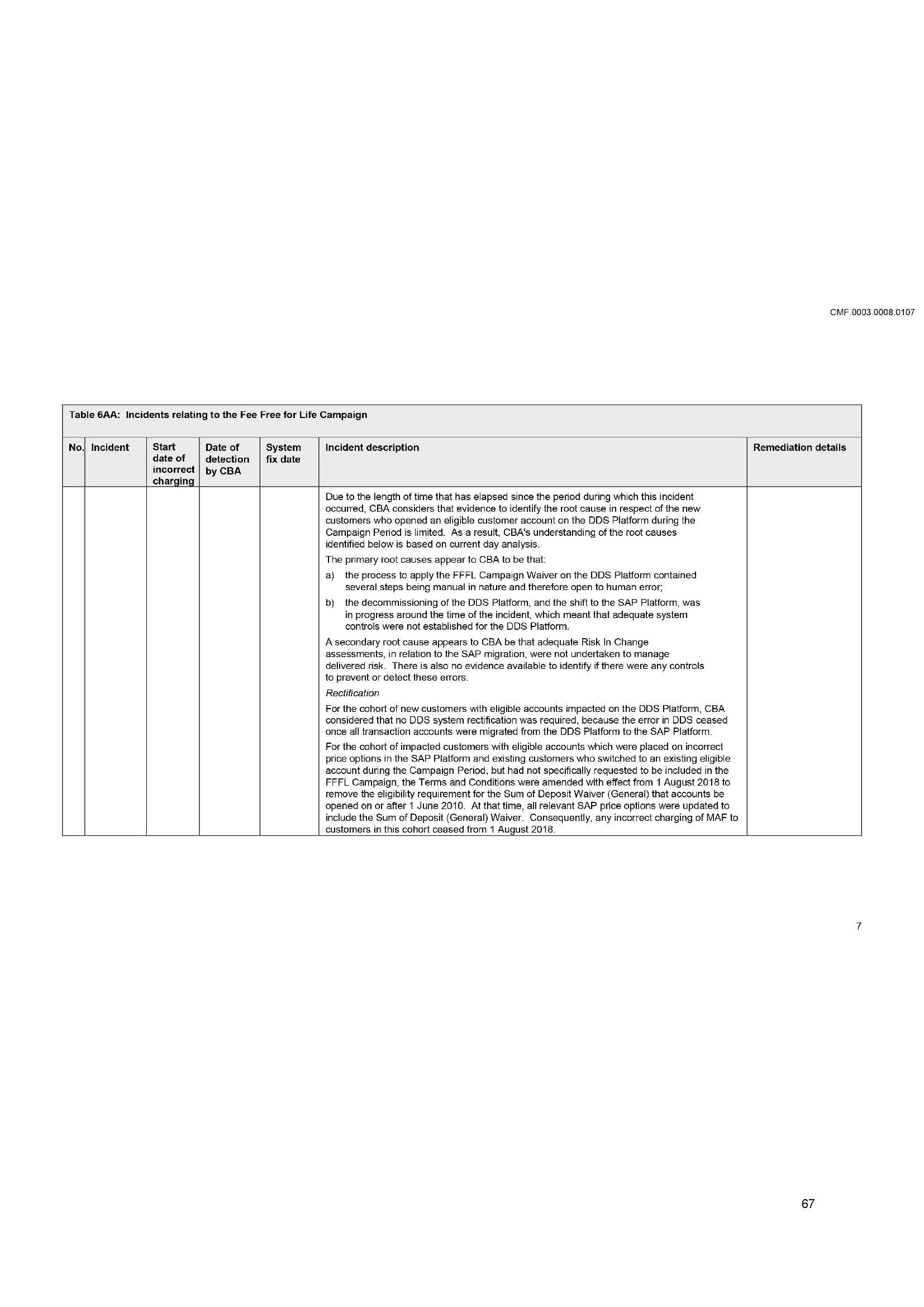

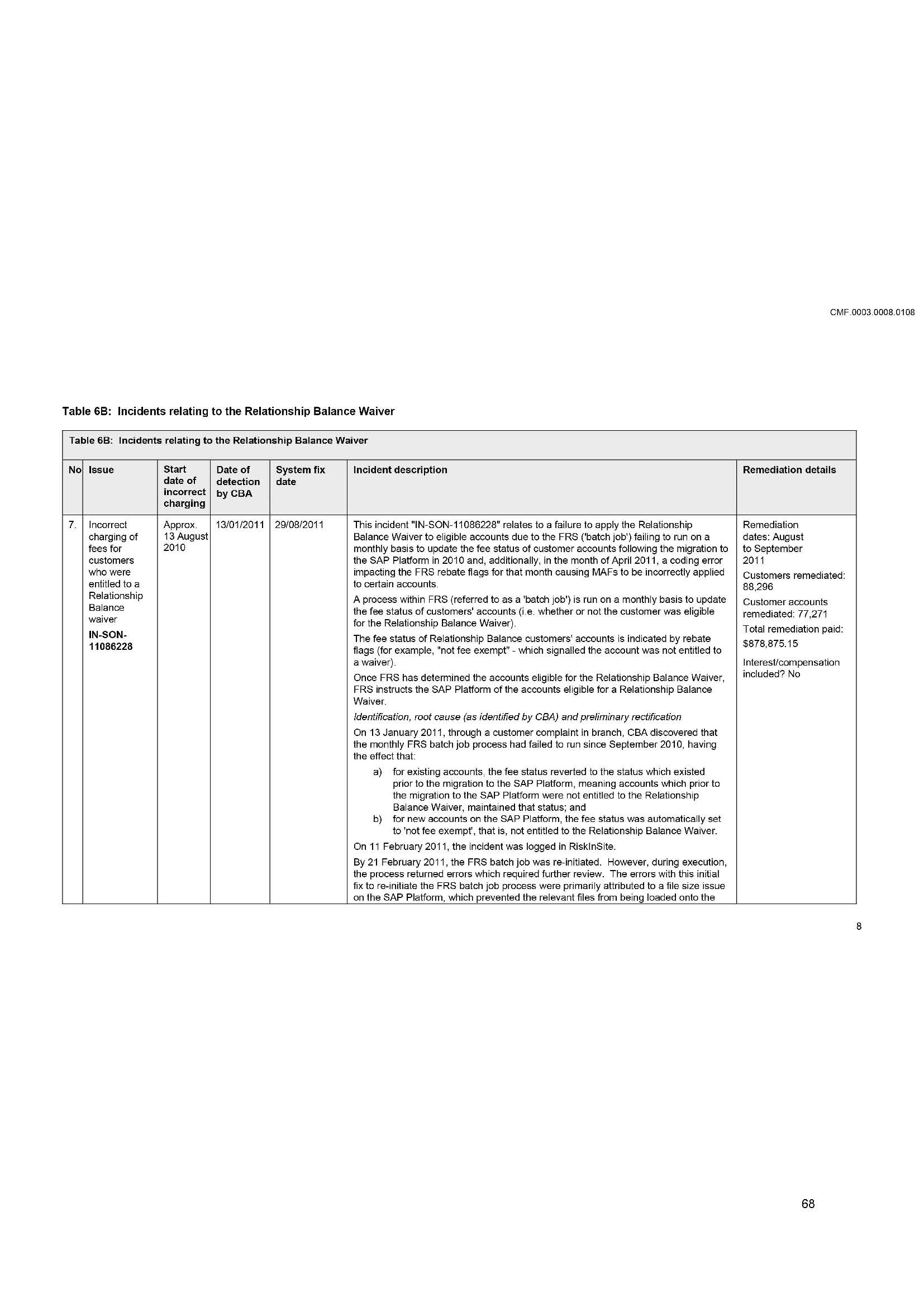

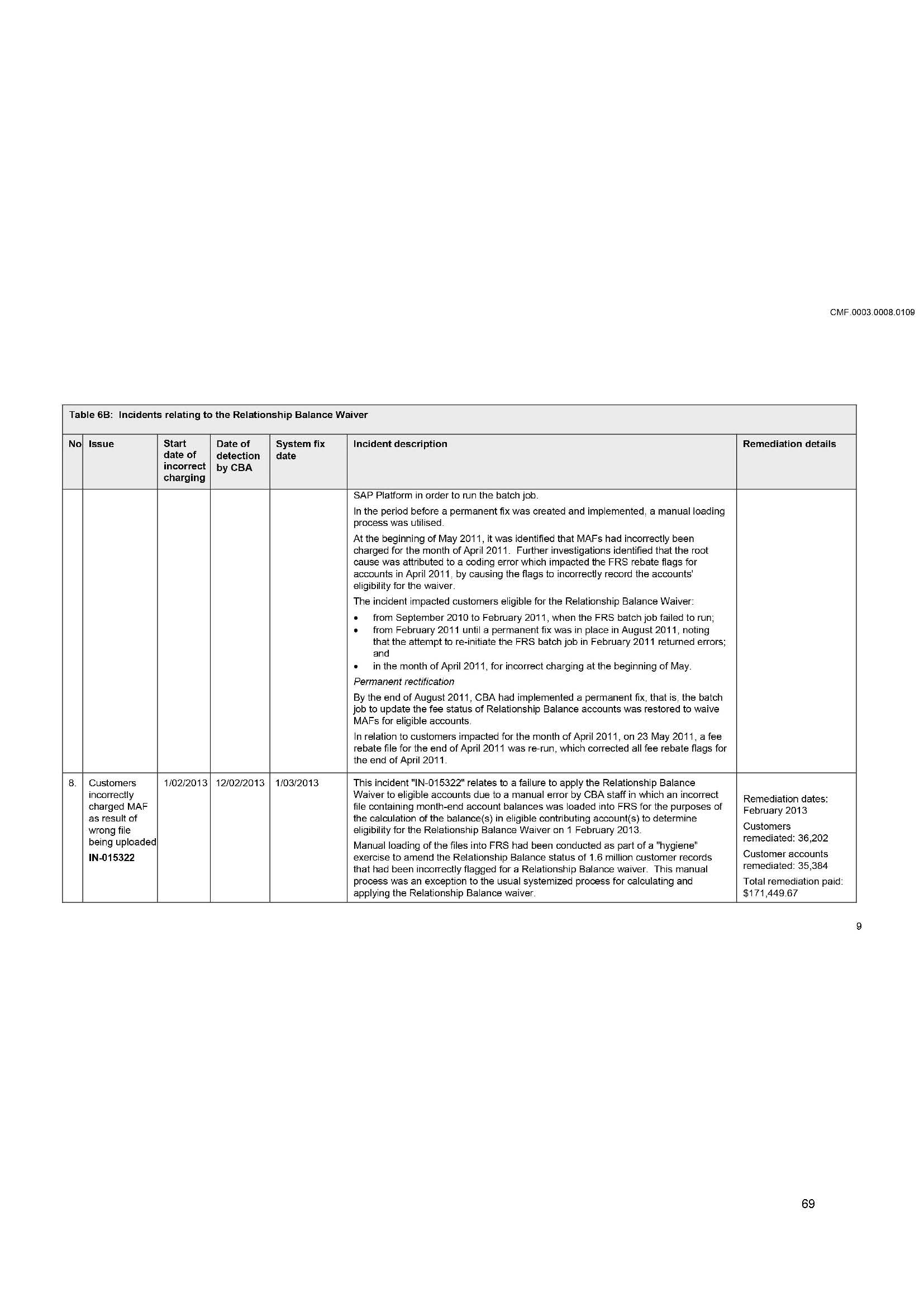

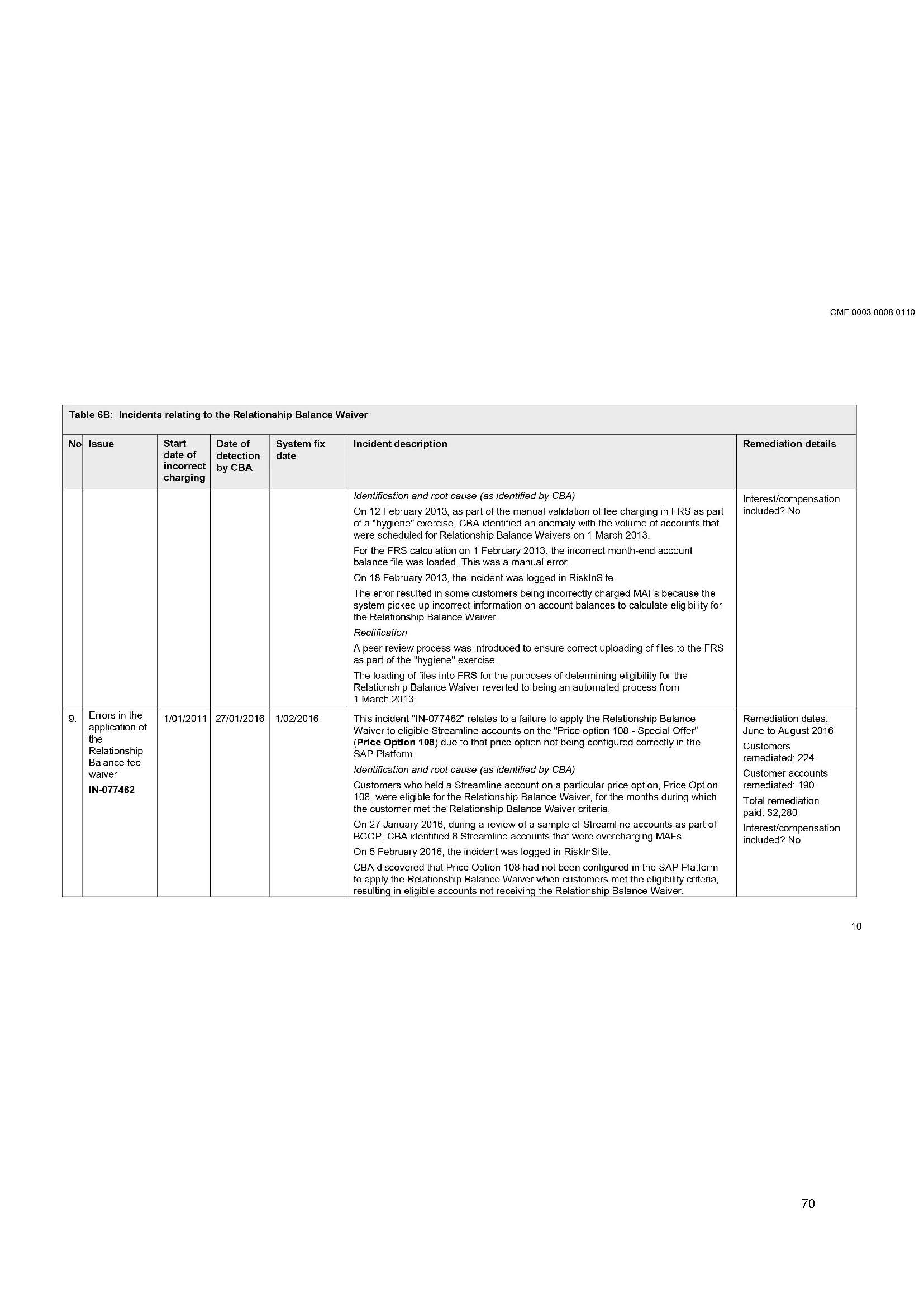

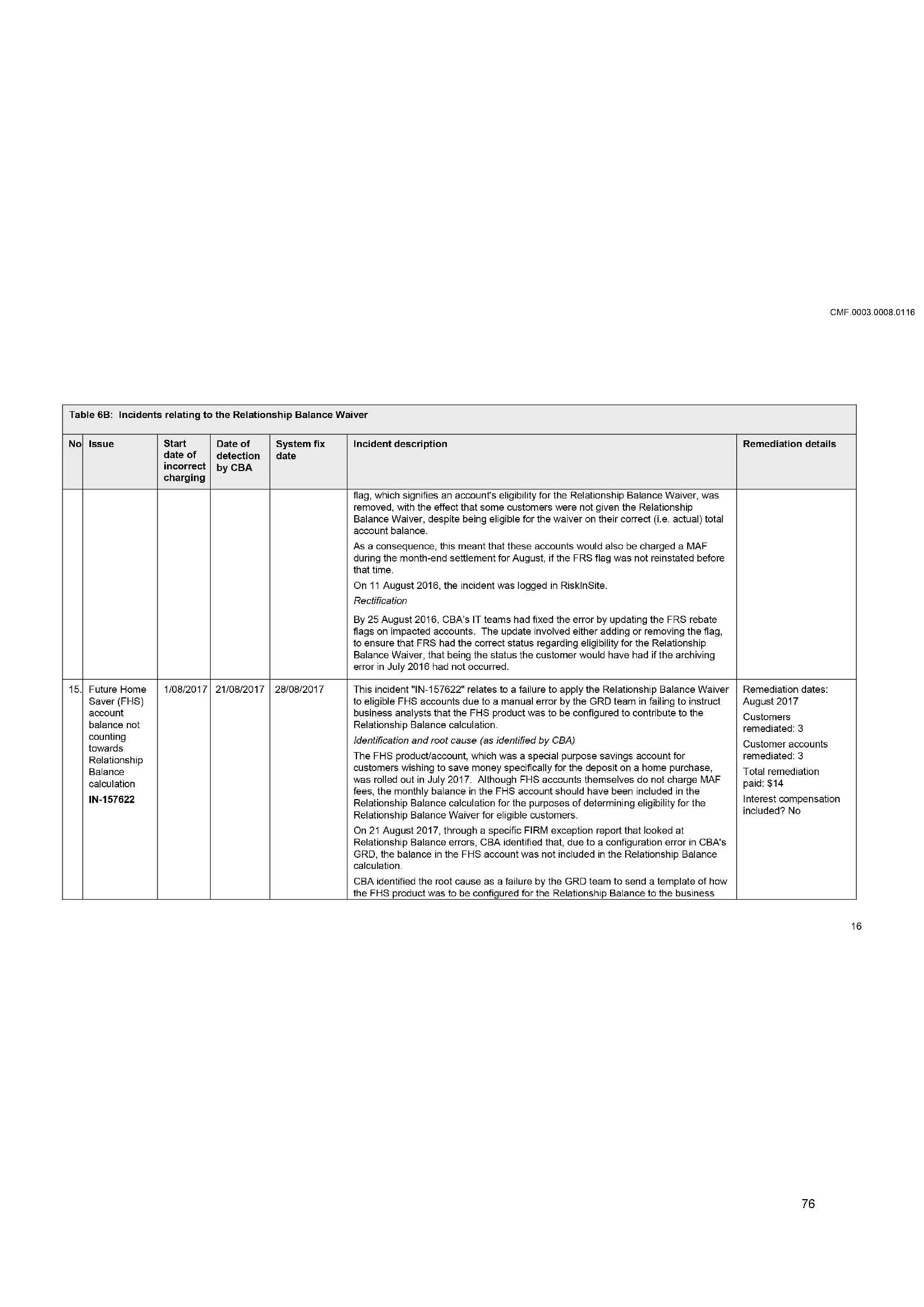

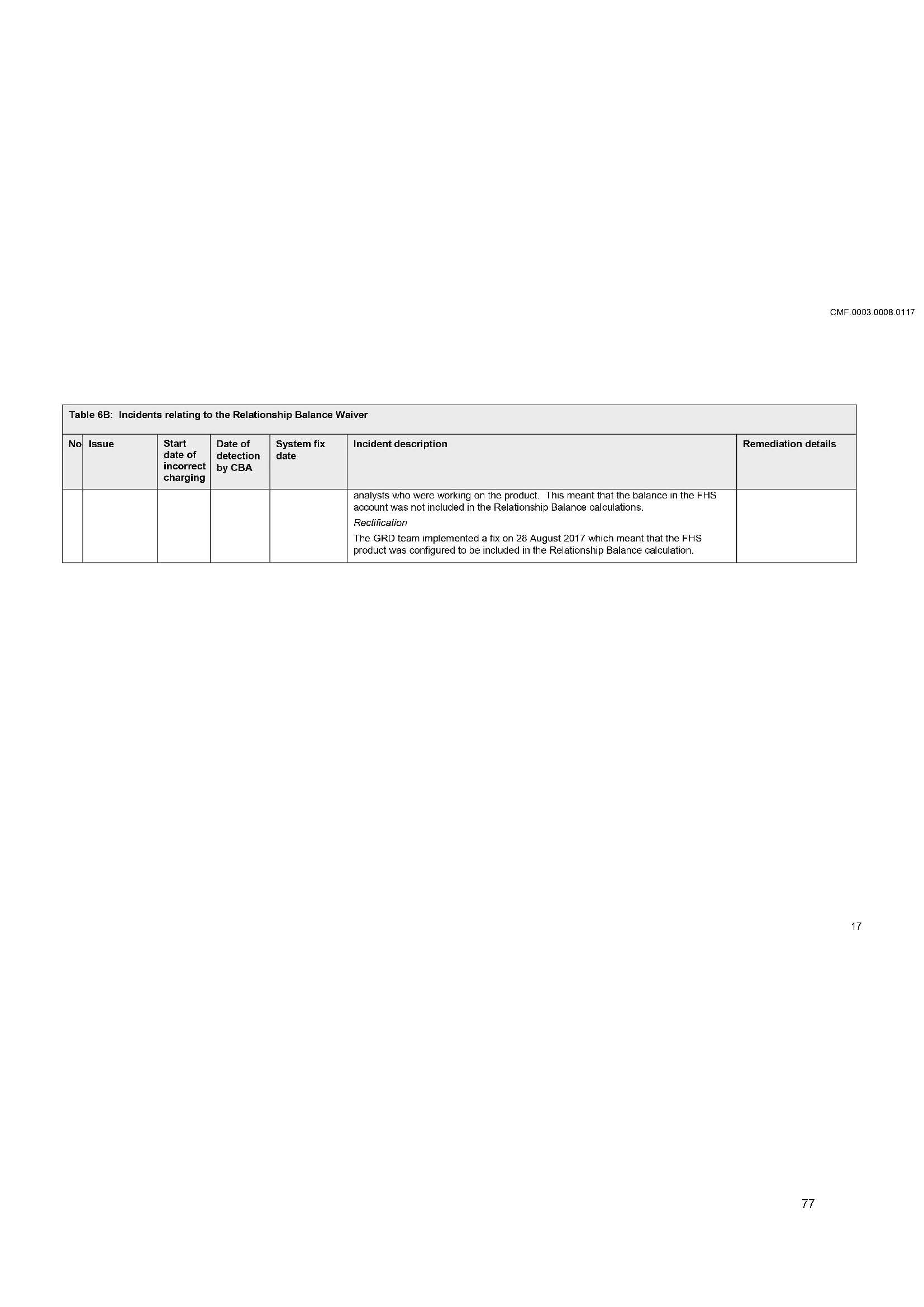

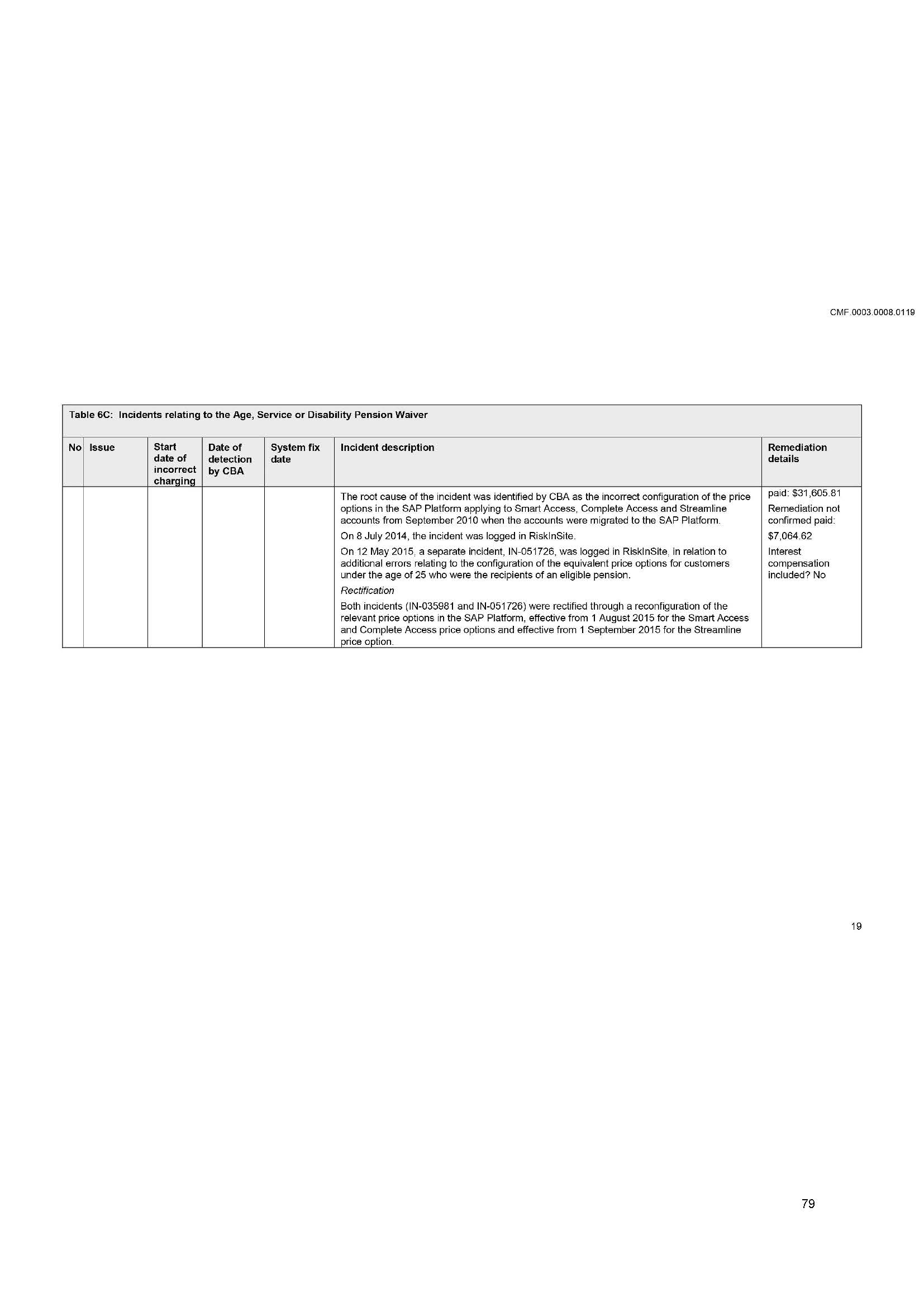

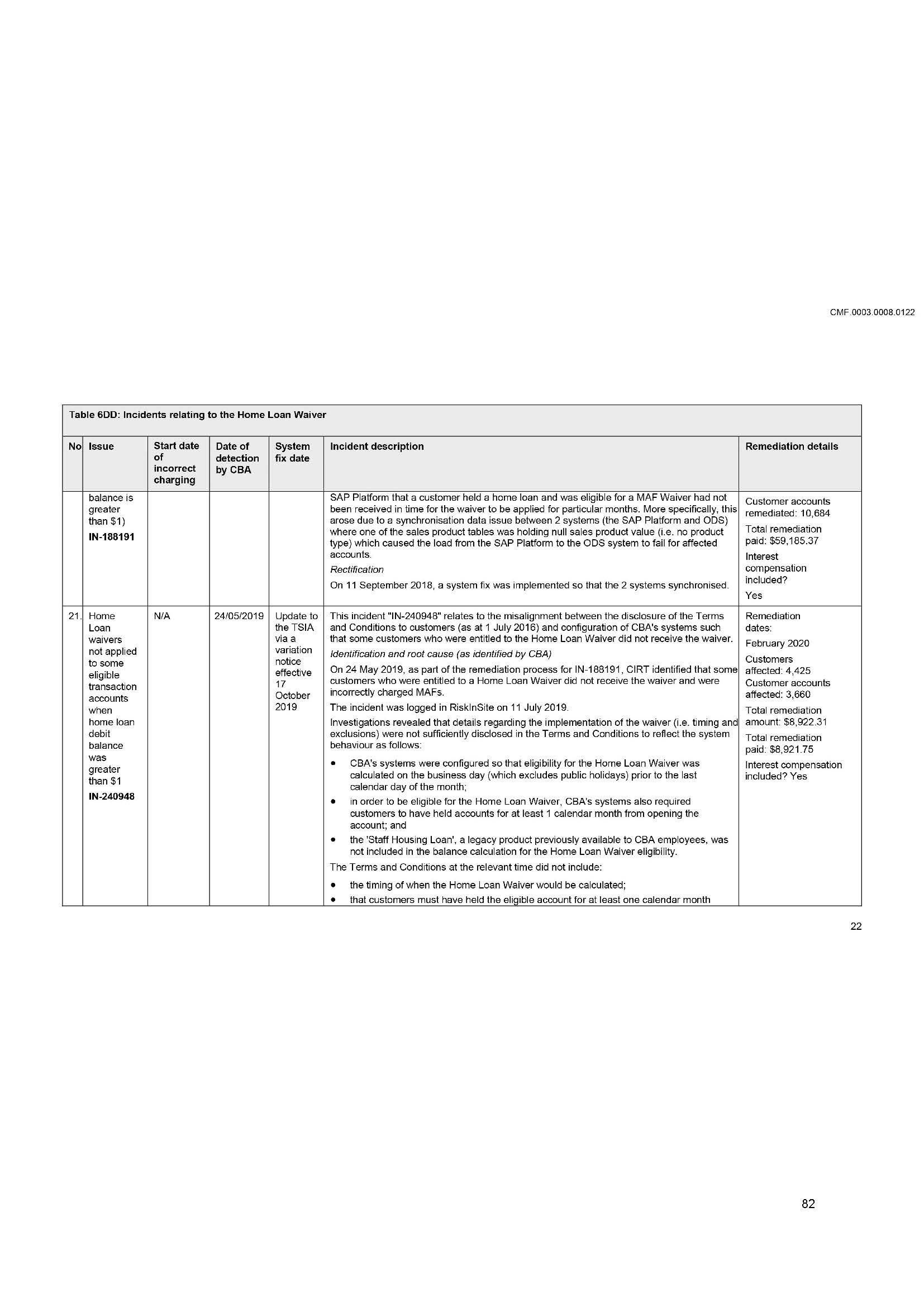

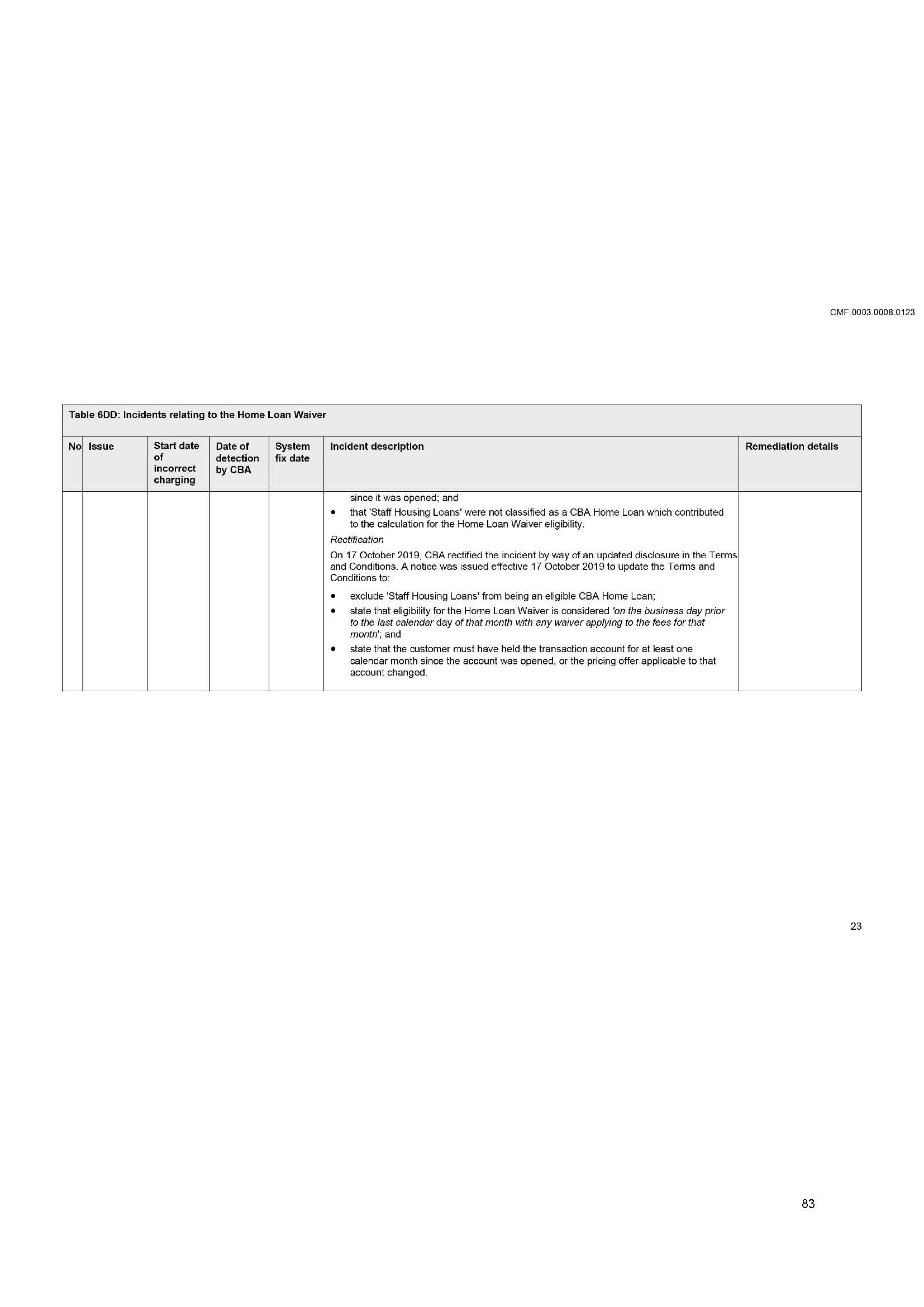

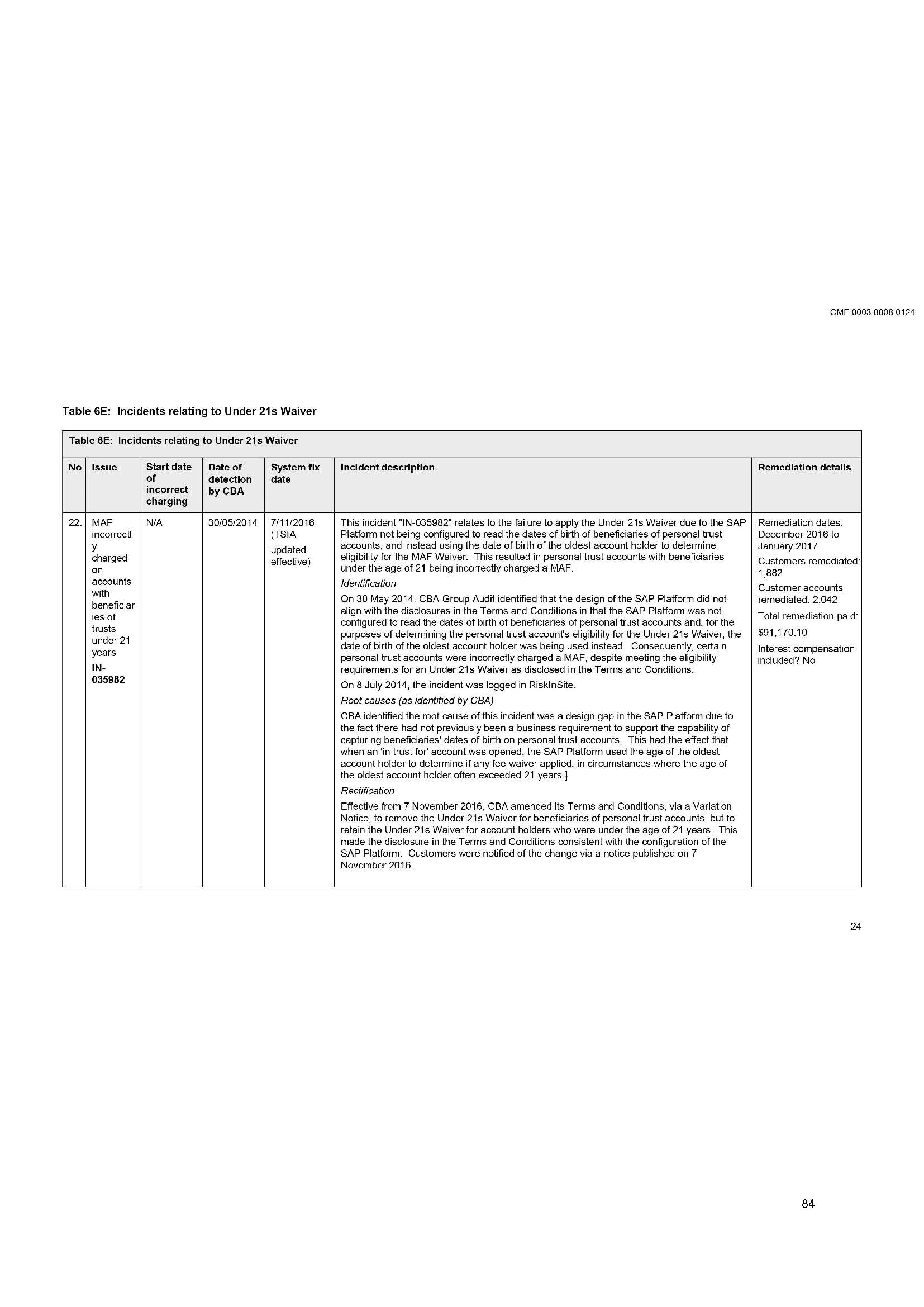

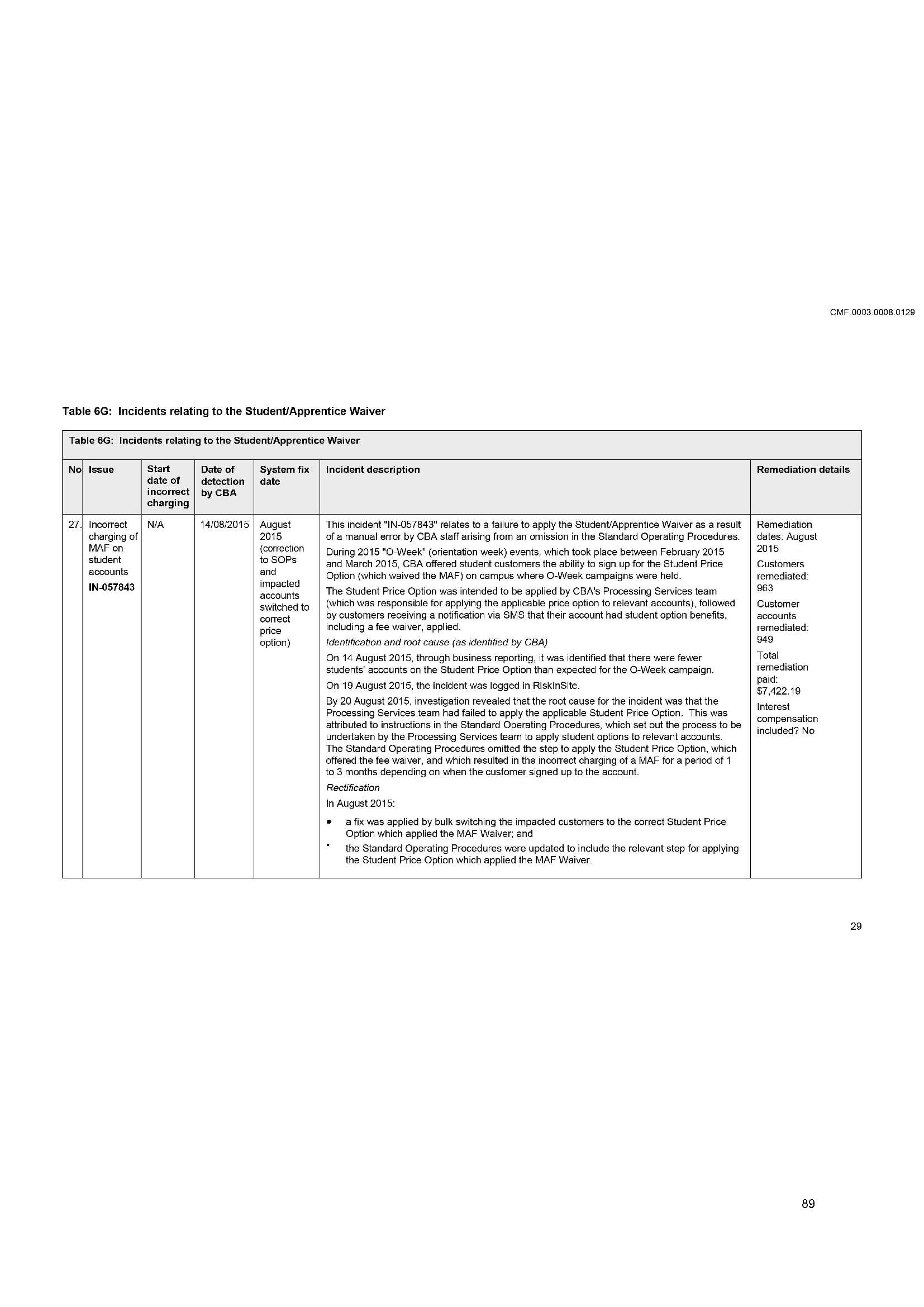

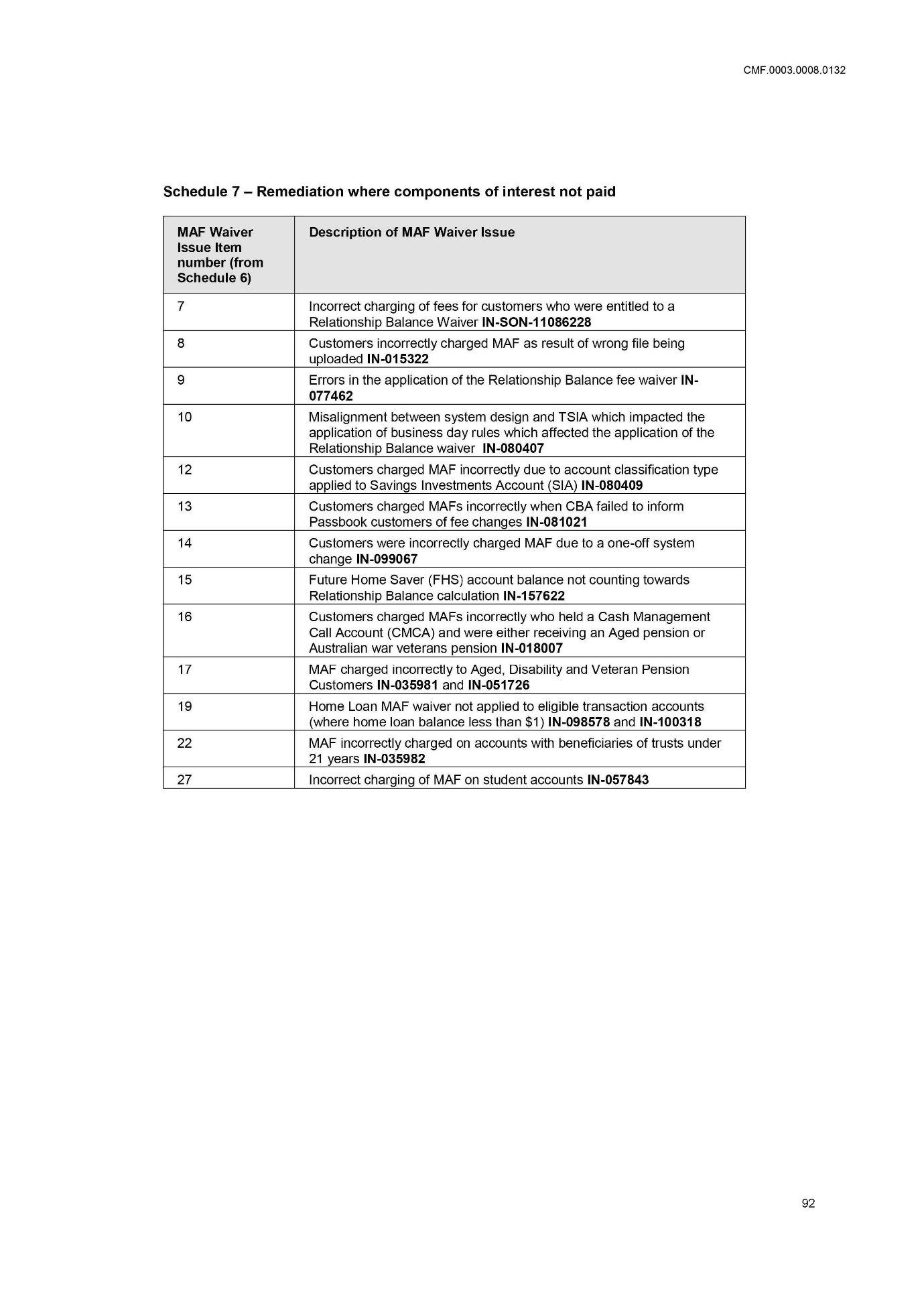

14 At different times during the relevant period, CBA identified at least 30 incidents in which MAF waivers were not applied. At those times, CBA logged the incidents in its relevant systems and separately investigated those incidents. This proceeding relates to 29 of those incidents which the parties described as the MAF Waiver Issues. Some of the MAF Waiver Issues involved manual errors by CBA staff.

15 Upon detection of each MAF Waiver Issue, CBA took steps to investigate the cause of the error; design, implement and test an appropriate mechanism to rectify that error and prevent its recurrence; identify all customers and customer accounts affected by the error in question; and remediate all affected customers (where possible).

16 CBA also sent correspondence to the plaintiff (ASIC) about its discovery of the MAF Waiver Issues. It also responded to notices issued by ASIC. ASIC’s case is based in part on the content of statements made by CBA in that correspondence.

17 CBA accepts that the MAF Waiver Issues should not have occurred. CBA received around $48 million (not including interest) during the relevant period for MAFs that were incorrectly charged. As at 13 September 2021, approximately $64,426,019 had been remediated to customers or paid to charity (where CBA was unable to make payments to customers).

THIS PROCEEDING

18 By its Concise Statement dated 31 March 2021, ASIC alleges that CBA contravened ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(e), (g) and (i) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). ASIC seeks declaratory relief, pecuniary penalty orders and associated relief.

19 Taking into account aspects of its case which were abandoned during the hearing, the primary legal grounds relied upon by ASIC for this relief are that:

(1) on each occasion that CBA notified the customer that a MAF had been charged, CBA impliedly represented to the customer that it had a contractual entitlement to charge the MAF. That contention, insofar as it pertains to customers who were eligible for a MAF waiver, underpins ASIC’s allegation that CBA engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 12DA ASIC Act and that it made a false or misleading representation concerning the existence or effect of a condition, right or remedy in contravention of s 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act. If established, such contraventions are also alleged to be a contravention of s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act. This part of ASIC’s case will be described as the charging and notification case;

(2) on each occasion that CBA entered into or varied a contract with customers, CBA impliedly represented that it had and would have adequate systems and processes in place to ensure that it could provide MAF waivers to eligible customers, when it did not have adequate systems and did not have reasonable grounds (within the meaning of s 12BB(1) ASIC Act) for stating that it would in the future have such systems, in contravention of any or all of ss 12DA, 12DB(1)(e) and 12DB(1)(g) ASIC Act, which, if established, is also alleged to be a contravention of s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act. This part of ASIC’s case will be described as the systems and processes case;

(3) CBA contravened s 912A(1)(a) Corporations Act by its conduct in each of (i) charging MAFs to customers who were eligible for a MAF waiver, (ii) continuing and maintaining systems and processes that were “not capable of ensuring compliance with obligations to customers”, and (iii) failing to undertake “an appropriate review of the multiple systemic issues that contributed to the ongoing failures of CBA’s systems to apply MAF Waivers”. This part of ASIC’s case will be described as the fairness and efficiency case.

20 By Order dated 30 April 2021, Derrington J ordered that all matters of liability be heard before matters of relief.

21 By its Concise Statement in Response dated 4 June 2021, CBA denied each contravention alleged by ASIC in the Concise Statement and its entitlement to the relief sought.

22 By way of overview on the substantive issues, it is the position of CBA that:

(1) as to the charging and notification case – in order for ASIC’s case to succeed, the Court would need to be persuaded that the notional customer reasonably understood that by wrongly charging a MAF and notifying a customer of that charge, CBA had unilaterally amended the terms of its bargain with the customer, inconsistently with the express terms of that bargain. It would also force a characterisation of the conduct of CBA that it had arbitrarily, for a significant minority of customers, resiled from its representations to the world that it would not charge a MAF to certain cohorts of customers, a representation which it continued to honour for the vast majority of customers in the same cohorts. CBA also submitted that the alleged representation cannot be reconciled with the prominent notation that appears on the customer account statements, directing the customer to check the statement and contact CBA if there appear to be any errors therein;

(2) as to the systems and processes case – even if the Court was to accept ASIC’s invitation to discern an actionable implied representation from CBA’s entry into contracts with customers, ASIC cannot establish that any such representation was false, misleading or deceptive, and whether such representation took an absolute form, or some lesser form as to “adequacy”. CBA submits that this is because, throughout the relevant period, CBA did in fact have in place adequate systems and processes for the provision of MAF waivers and it did in fact have reasonable grounds for making any representations that it would have such systems and processes in place in the future. CBA submits that, importantly, it is not disputed that CBA applied MAFs and MAF waivers in excess of 825 million times during the relevant period. The large number of failures that ASIC relies upon in this proceeding (approximately seven million) is a reflection not of some form of systemic failure, as alleged by ASIC, but of the magnitude of CBA’s business, the sheer length of the relevant period (111 months) and the aggregation by ASIC in this proceeding of discrete issues. CBA submits that the case for ASIC relies on some attempt by CBA to warrant a state of perfection, which is not only divorced from the reasonable reality of scale operations, but runs directly counter to the express representations CBA made to its customers acknowledging the possibility of errors and inviting them to be corrected if found;

(3) as to the fairness and efficiency case – CBA did not breach its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and ASIC has failed to articulate what necessary “things” CBA needed (but failed) to do in order to discharge that obligation.

23 On 14 September 2022, the parties filed an Amended Statement of Agreed Facts within the meaning of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). That document, with attachments, is an annexure to these reasons. To the extent that particular facts deserve emphasis, they will be referred to in these reasons.

24 The parties also filed a document which contained an agreed summary of the legal issues in dispute.

MATERIAL RELIED UPON

25 By its amended tender list, ASIC relied upon an affidavit of Ms Kelly Rodgers sworn on 7 March 2022. Ms Rodgers is a solicitor employed as a Senior Manager in Financial Services Enforcement with ASIC. Ms Rodgers’ affidavit exhibited documents which had been extracted from a database maintained by ASIC. ASIC relied on all such documents except for tabs 27 and 28 of exhibit KLR-1. Certain documents which formed part of the exhibit to her affidavit were the subject of successful objection by CBA.

26 Ms Rodgers was not required for cross-examination.

27 ASIC also relied upon the Modified Code of Banking Practice 2004, Code of Banking Practice 2013 and Banking Code of Practice 2019. CBA disputed the relevance of the fact that, at all times during the relevant period, CBA adopted the Code of Banking Practice (as amended from time to time) published by the Australian Banking Association and that the Code of Banking Practice is referred to in the Terms and Conditions which applied during the relevant period. However, it did not object to the tender of the documents, and addressed their impact on the case in their submissions.

28 CBA relied upon two affidavits as follows:

(1) affidavit of Ms Kate Crous sworn on 6 June 2022. Ms Crous is the Executive General Manager, Everyday Banking at CBA; and

(2) affidavit of Mr Daniel Tysoe sworn on 6 June 2022. Mr Tysoe is the Executive Manager, Digital Product Development at CBA.

29 Ms Crous and Mr Tysoe were cross-examined on their affidavits.

30 By its amended tender list, CBA also relied upon various customer account statements, together with a representative sample of the documents constituting the Terms and Conditions governing the accounts during the relevant period.

31 A contravention of ss 12DA and 12DB ASIC Act and s 912A Corporations Act is a civil wrong that must be proved on the balance of probabilities in accordance with s 140 Evidence Act.

32 That standard of proof is informed by s 140(2) Evidence Act, which requires the Court to take account of the nature of the cause of action, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged.

33 As stated by the Full Court in Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 162 FCR 466; [2007] FCAFC 132 at [30]–[31]:

The mandatory considerations which s 140(2) specifies reflect a legislative intention that a court must be mindful of the forensic context in forming an opinion as to its satisfaction about matters in evidence. Ordinarily, the more serious the consequences of what is contested in the litigation, the more a court will have regard to the strength and weakness of evidence before it in coming to a conclusion.

Even though he spoke of the common law position, Dixon J’s classic discussion in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361-363 of how the civil standard of proof operates appositely expresses the considerations which s 140(2) of the Evidence Act now requires a court to take into account. Dixon J emphasised that when the law requires proof of any fact, the tribunal must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence before it can be found. He pointed out that a mere mechanical comparison of probabilities independent of any belief in its reality, cannot justify the finding of a fact. But he recognised that …:

No doubt an opinion that a state of facts exists may be held according to indefinite gradations of certainty; and this has led to attempts to define exactly the certainty required by the law for various purposes. Fortunately, however, at common law no third standard of persuasion was definitively developed. Except upon criminal issues to be proved by the prosecution, it is enough that the affirmative of an allegation is made out to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. But reasonable satisfaction is not a state of mind that is attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved. The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. In such matters “reasonable satisfaction” should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences …

34 In deciding whether ASIC has proved its case, I have taken into account the considerations in s 140(2) Evidence Act being the nature of the cause of action, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged by ASIC. In particular, it is relevant to the latter consideration that penalties are sought by ASIC for the alleged contraventions of s 12DB(1) ASIC Act occurring after 1 April 2015 and s 912A(5A) Corporations Act (which entered into force on 13 March 2019).

WHAT IS ASIC’S CASE CONCERNING CBA’S SYSTEMS AND PROCESSES?

35 By the Concise Statement in Response, CBA described “the majority” of the allegations in the Concise Statement as “entirely unparticularised”. The complaint about lack of particularisation was made more than once in this document, especially concerning allegations that CBA did not have adequate systems and processes.

36 A further complaint about ASIC’s case was made in paragraph 4 of a letter from CBA’s solicitors dated 7 December 2021 as follows:

… we note that key aspects of ASIC’s case remain unparticularised, including with respect to the pleaded concept of “systems and processes” and the alleged “systemic issues” underpinning the MAF Waiver Issues. Those deficiencies are identified in CBA’s Concise Statement in Response, and have not been remedied to date.

37 By letter dated 9 May 2022, CBA’s solicitors wrote to ASIC, stating that CBA “repeats the matters outlined in the letter of 7 December 2021, in particular paragraphs 3, 4 and 5”.

38 The complaints about lack of particulars were repeated in CBA’s submissions filed on 30 September 2022.

39 These complaints were justified. The allegations that CBA’s “systems and processes” were not “adequate” to ensure that the MAF waivers would be applied (the systems and processes case) and that it did not continue and maintain systems and processes that were “capable of ensuring” that MAF waivers were applied (the fairness and efficiency case) were central to ASIC’s case, but were vague and ambiguous.

40 Notwithstanding the solicitors’ correspondence and submissions which were filed almost two weeks prior to the hearing, no particulars were provided by ASIC. This was in circumstances where ASIC did not file or notify an intention to rely upon any evidence, whether expert or otherwise, which identified any standard against which the “systems and processes” could be measured so it could be determined whether or not they were “adequate” and “capable”.

41 The reason for the lack of such evidence emerged during oral submissions on the first day of the hearing as follows:

HER HONOUR: Well, I noticed in the concise statement in response that some complaints were made about a lack of particularisation of particular allegations, and they seem to be said again in the opening submissions from the bank … – so, if we have a look at, just for example, paragraph 4 of the opening submissions from ASIC, on page 3, this phraseology appears in many places. It talks about “adequate systems”, and “adequate systems and processes”, and I just wanted to know what that means.

MR COUPER: Your Honour, what it means is this – and perhaps we can deal with it by reference to the 29 events, if I might call it that. With respect to each of those events, what was required was a computer system, and processes to utilise it, which caused the MAF waiver to be applied.

HER HONOUR: So, every time? 100 per cent? 100 per cent success? Is that the standard? I’m trying to understand what the standard is to say something is adequate or - - -

MR COUPER: Yes, that – we would say that’s the standard. But your Honour, if the bank is going to say, “You will receive this waiver” – so, take – if one takes a particular case – so, take an example – if one takes, for example, the cases where a customer was entitled to a waiver if they deposited $2000 per month into a relevant account, our submission is that, if that is the waiver which the Commonwealth Bank says would be applied in those circumstances, the bank needed to have in place a system – both a computer system and procedures related to that system – to ensure that that happened. It’s not good enough to say, “There’s a chance it will work,” or, “It’s fairly likely to work. We’re not really sure.” What is required, in our submission, is that, when the agreement is made by the bank, “We will waive this fee” – that it has systems in place which means it will waive the fee. And the same is apposite, in our respectful submission, to each of the categories of waiver set out in schedule 6 to the statement of agreed facts.

It’s not to the point, in our respectful submission, that there were different types of failure, because one is looking at a situation in which, as I say, there are a number of relevant accounts, and number of types of MAF waiver available, if I may use that term, and in each case if one focuses on the particular MAF waiver which the bank says to the customer, “This is what you will get,” then the bank was obliged to make sure that’s what the customer got, and a system which failed to make that happen was not an adequate system. That’s the passage [sic] the plaintiff advances, your Honour.

HER HONOUR: So, it is – you are contending for a 100 per cent success rate.

MR COUPER: Yes.

(emphasis added)

42 On the second day of the hearing, senior counsel for ASIC submitted as follows:

… As we apprehended, we accept this proposition that, where a party enters into a contract which requires its performance of an obligation, there is a representation that it is capable of performing the obligation and that it intends to do so, but we focus on “capable”.

In the context of this bank situation, there is no discernible difference between the bank saying we are capable of befalling [sic] our obligation to apply MAF waivers to your relevant account and the bank saying we have the systems and procedures in place which will ensure we apply that MAF waiver. They’re the same thing. …

In circumstances where the obligation to apply the MAF waiver in each case was an ongoing obligation, it’s a straightforward proposition, in our submission, that the implied representation goes beyond saying, well, we can do it now, but for some undefined reason, we might cease to be able to provide your contractual entitlement in the future. It’s the sensible proposition that what the bank is saying impliedly is we have and will continue to have the systems and processes in place so that our continuing ongoing obligation to give you MAF waivers will be met.

HER HONOUR: 100 per cent guarantee? … So you think a reasonable person reading the terms and conditions, if they do, would consider the bank was saying to them we guarantee you that we will apply the waiver? … Is that ASIC’s case?

MR COUPER: … We’re saying our case is, when the bank says to a customer, “You’re entitled to this MAFs waiver. We will ensure that you get it,” yes, that’s 100 per cent. …

(emphasis added)

ASIC’S RELIANCE ON COMMUNICATIONS FROM CBA

43 As part of its evidence to establish that CBA’s systems and processes were not “adequate” to ensure that the MAF waivers would be applied and that it did not continue and maintain systems and processes that were “capable of ensuring” that MAF waivers were applied, ASIC sought to tender and rely upon statements made by different senior representatives of CBA in its correspondence to ASIC commencing in 2014, including in responses provided by CBA to notices of direction under s 912C Corporations Act. These documents were the subject of objection by CBA.

44 ASIC relied on two documents in particular, being a s 912D notice sent by CBA to ASIC dated 14 June 2019 (14 June notice) and a statement in response to a notice of direction under s 912C Corporations Act dated 30 August 2019 (30 August statement).

45 The 14 June notice relevantly stated:

Updated breach details

We have previously reported to ASIC that certain MAF waiver criteria were not applied on some Smart Access and Complete Access Accounts (MAF Waiver Issue).

Our further investigations have revealed a number of additional instances of failures to correctly apply various MAF waiver criteria under our standard Transaction, Savings and Investment Account Terms and Conditions in addition to the failures identified in our Good Governance Notification dated 17 December 2018 and our notification of 23 May 2019 (Additional MAF Waiver Issues).

Consistent with our notification of 23 May 2019, we acknowledge that charging customers a MAF when we said it would be waived, combined with the time CBA took to detect the majority of these incidents and in some cases the length of the period over which the issue has occurred, constituted conduct which fell below the expected standard. In addition, the aggregate number of customers affected by the MAF Waiver Issue and the Additional MAF Waiver Issues, and the aggregate loss to those customers is a significant breach of section 912A(1)(a) for the purposes of section 912D of the Corporations Act.

For these same reasons we consider in this case we did not have appropriate compliance measures in place to prevent or otherwise detect earlier the MAF Waiver Issue and the Additional MAF Waiver Issues over the relevant period. Accordingly we also acknowledge that there has been a breach of CBA’s obligation to comply with a condition of our licence (section 912A(1)(b)) in respect of the MAF Waiver Issue and Additional MAF Waiver Issues, namely the obligation to establish and maintain compliance measures that ensure, as far as is reasonably practicable, that the licensee complies with the provisions of the financial services laws in respect of those issues.

(emphasis original)

46 The particular sentence in the 14 June notice on which ASIC wished to rely stated:

For these same reasons, we consider in this case we did not have appropriate compliance measures in place to prevent or otherwise detect earlier the MAF Waiver Issue and the Additional MAF Waiver Issues over the relevant period.

47 This statement was said by ASIC to be admissible as an admission of fact. Senior counsel for ASIC submitted that “[w]e don’t seek to rely upon any statement as an admission of law.”

48 The admission was relied upon, not only in relation to the matters referred to in the 14 June notice but also in relation to previously notified MAF waiver issues. It was also submitted by ASIC that notifications by CBA made after the 14 June notice were captured by this admission.

49 Although the 14 June notice made explicit reference to a letter dated 17 December 2018 and another s 912D notice dated 23 May 2019 (23 May notice), the statement in the 14 June notice did not contain any representation of fact as to CBA’s systems which extended beyond the MAF waiver issues referred to in that notice. In particular, the 14 June notice was concerned with instances of failure to correctly apply MAF waiver criteria in addition to the failures identified in the letter of 17 December 2018 and the 23 May notice.

50 Further, the critical sentence in the 14 June notice upon which ASIC relied as containing an admission stated that CBA considered that in this case (that is, as identified in that notice) “we did not have appropriate compliance measures in place”. When the statement is read in context, including the identification of the issues in that notice as being the “Additional MAF Waiver Issues”, ASIC’s submission that the “admission” contained in the 14 June notice extended to the failures to apply the MAF waiver as identified in the 17 December 2018 letter and 23 May notice (or any prior correspondence from CBA) is incorrect and cannot be accepted for this reason.

51 A further and more fundamental problem arises with ASIC’s characterisation of the critical sentence in the 14 June notice as being an admission of fact that CBA’s systems were not appropriate. It raises the obvious question – precisely what is being admitted by CBA? The reference to appropriate compliance measures means that the statement includes a conclusion that depends upon the application of a legal standard. As such, it provides no basis for a finding that CBA’s systems and processes were not appropriate at any particular time for the purposes of the allegations made in this proceeding: see Dovuro Pty Limited v Wilkins (2003) 215 CLR 317; [2003] HCA 51 at [67]–[71] (Gummow J, with whom McHugh and Heydon JJ agreed).

52 Further, the critical sentence in the 14 June notice begins with the words “For these same reasons” which is a reference to the preceding paragraph, which paragraph included admissions of contravention of the Corporations Act. Further, what follows the critical sentence in the same paragraph is a further admission of contravention. One cannot divorce these admissions of contravention which both infect and surround the critical sentence so as to erect a standalone admission of fact. To do so is artificial because, when read in context, the critical sentence is and forms part of an admission of contravention of s 912A Corporations Act and is therefore not an admission of fact.

53 Further, the purported admission of fact is a statement of opinion that “we consider” that we did not have “appropriate compliance measures”. But what does “appropriate” even mean? Against what standard are the compliance measures being compared? Is what CBA considers to be “appropriate” in the context of the 14 June notice the same thing as what ASIC contends is “adequate” in this proceeding? On what facts is this opinion based? Do these facts align with ASIC’s case in this proceeding? Even if it is admissible, no weight can be attached to this purported admission without knowing the answers to these questions.

54 It follows that the rejection of the critical sentence in the 14 June notice as being an admission of fact has the consequence that correspondence sent by CBA prior to and after this notice cannot be regarded as having been captured by this purported admission, contrary to ASIC’s submission in support of the admission of this correspondence. This justifies the exclusion of the correspondence dated 29 August 2014, 19 September 2014, 18 March 2016, 4 May 2016, 17 December 2018, 9 October 2019 and 13 November 2019 as well as the 23 May notice.

55 The 30 August statement contained statements at [8.8(d)] and [9.2] which ASIC also submitted were admissions of fact by CBA. The 30 August statement relevantly provided:

[Q8c]. [Provide] an explanation of why, at the time of making the Significant Breach Notification Decision (s912A(1)(b)), a second breach notification was issued.

…

Question 8(c)

8.1 While the May Breach Notification was being prepared, CBA received the May s912C Notice, on 22 May 2019.

8.2 The May s912C Notice required CBA to provide details of any instance where MAF waivers had not been correctly applied in the period 31 May 2010 to 22 May 2019 (the Additional MAF Waiver Issues) – including the detection, nature, rectification, impact and remediation of each of these Issues.

…

8.7 Of the 25 Additional MAF Waiver Issues identified:

(a) some had been the subject of previous breach reports to ASIC (being Items 5, 14, 22 and 24 as described at paragraph 6.5); and

(b) some of the issues had not been considered to be reportable, because, for example, they affected a small number of customers or had a minor financial impact (for example, each of Items 3, 9, 15 and 20 affected less than 1,000 customers and had a financial impact of under $8,000);

8.8 Having conducted this exercise, and considering further legal advice, CBA determined that:

(a) it had correctly reported some of the Additional MAF Waiver Issues to ASIC on the basis that they involved significant breaches;

(b) considered individually, the majority of the remaining Additional MAF Waiver Issues would not have been required to be the subject of a breach report; and

(c) however, viewed holistically, the Issues were significant because:

(i) customers were charged a MAF when CBA said it would be waived;

(ii) the time taken by CBA to detect the majority of the issues;

(iii) the period over which some of the Issues occurred;

(iv) the aggregate number of customers affected; and

(v) the aggregate loss to customers.

(d) for the same reasons, CBA concluded that its compliance measures in place to prevent or detect the issues were not appropriate.

8.9 On this basis, CBA made the June Breach Notification Decision.

[Q9]. Provide an explanation of why CBA had failed to realise the scale and scope of the MAF waiver issue prior to the Significant Breach Notification (s912A(1)(b)).

9.1 As described above and in the June Response and the July Response, the Issues had a number of different root causes and were detected through different mechanisms. In some instances, the cause of the failures to correctly apply a MAF waiver were one-off or manual errors, while in other cases there was a root cause that resulted in multiple problems manifesting separately. In some instances, these occurred years apart or in relation to different products.

9.2 As set out in the June Breach Notification, CBA considers that in this instance it did not have appropriate compliance measures in place to prevent or otherwise detect earlier the Issues.

(emphasis added; original emphasis omitted)

56 However, the reference to appropriate compliance measures again means that these statements include a conclusion that depends upon the application of a legal standard. This is especially so as the statement in [8.8(d)] is made following consideration of legal advice. The statement in [9.2] is a repetition of the conclusion in the 14 June notice, and so is not admissible for the same reasons that the conclusion in the 14 June notice is not admissible.

57 These statements are therefore not bare admissions of fact and they provide no basis for a finding that CBA’s systems and processes were not appropriate at any particular time for the purposes of the allegations made in this proceeding: see Dovuro at [67]–[71].

58 Further, the purported admissions of fact are statements of opinion. But again, these purported admissions raise obvious questions such as – what does “appropriate” mean? By what standard are the compliance measures compared? Is “appropriate” the same thing as “adequate”? On what facts is each opinion based? Do these facts align with ASIC’s case in this proceeding? Even if admissible, no weight can be attached to this evidence without knowing the answers to these questions.

59 It follows that the exclusion of [8.8(d)] and [9.2] in the 30 August statement from the evidence has the consequence that correspondence sent by CBA after this notice cannot be regarded as having been captured by these purported admissions, contrary to ASIC’s submission. This justifies the exclusion from the evidence of the statement issued by CBA dated 27 May 2020 and the attached appendix.

THE CHARGING AND NOTIFICATION CASE

ASIC’s allegations

60 ASIC alleges that on each occasion that CBA charged a MAF, and notified the customer of charging a MAF, CBA impliedly represented to the customer that it had a contractual entitlement to do so, when that was not the case.

61 Although the Concise Statement alleged that CBA also made an express representation on each such occasion, this allegation was abandoned by ASIC during the hearing.

62 The conduct on which ASIC relied by way of “notification” is each occasion that CBA issued a customer account statement to its customers recording that it had charged the MAF (or, where applicable, recorded this in a customer’s passbook).

63 In particular, it relied on the fact that the MAF was shown on the bank statement by the words, “Prev Month Acct Fee”, “Monthly Account Fee”, “Account Keeping Fee” or “Account Fee” and was similarly recorded in passbooks.

64 ASIC submits that the notification in a customer’s account statement or passbook that the customer’s money had been debited for the payment of a fee carried with it the implied representation that CBA was entitled to charge that fee.

65 ASIC contended that, on each of those occasions where CBA charged a MAF when it should have applied a MAF waiver, CBA engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive, and made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, right or remedy, in contravention of ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act.

66 ASIC also alleged, and this was not disputed, that CBA was acting in trade or commerce in connection with the supply of financial services when it engaged in such conduct.

Agreed legal issues

67 Taking into account ASIC’s modifications to its case as presented at the hearing, the first issue is whether CBA, by its conduct in charging a MAF to a customer and issuing a customer account statement to a customer who had been charged a MAF, made an implied representation that:

(1) it had a contractual entitlement to charge the MAF; and

(2) it was entitled to depart from its contractual promise that it would not charge a MAF on the relevant accounts where a customer had been promised a MAF waiver.

68 The second issue is whether, as CBA contends, the sole representation conveyed by customer account statements as regards MAFs was that a MAF of a particular amount had been deducted from the account in question on or around the nominated date, and that the customer should check whether that entry was correct and notify CBA in the event of any error.

69 The third issue is whether, if CBA made the implied representation as contended by ASIC (which CBA denies) in circumstances where the customer was entitled to a MAF waiver, CBA contravened either or both of ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act.

70 The final issue is whether CBA, by the conduct referred to in the previous paragraph (conduct which is alleged by ASIC but denied by CBA), breached its general obligation to comply with financial services laws in contravention of s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act.

The relevant legislation

71 Section 12DA(1) ASIC Act relevantly provided as follows:

12DA Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

72 At the commencement of the relevant period, there was no s 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act.

73 Section 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act (being the provision relied upon by ASIC and which came into force on 1 January 2011) relevantly provided as follows:

12DB False or misleading representations

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including an implied warranty under section 12ED).

74 While ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(i) respectively prohibit “misleading or deceptive conduct” and “false or misleading representations”, there is no material difference between the two expressions: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees Pty Ltd (2020) 147 ACSR 266; [2020] FCA 1306 at [47] (Yates J).

75 In relation to s 12DB(1) ASIC Act, the word “services” is defined to include “any rights … benefits, privileges or facilities that are, or are to be, provided, granted or conferred in trade or commerce”, subject to certain exceptions which are not presently relevant: s 12BA(1) ASIC Act.

76 The relevant principles in relation to the statutory prohibitions against misleading or deceptive conduct were helpfully summarised in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 278 FCR 450; [2020] FCAFC 130 (Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ). At [22], the Court stated:

[t]he central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): …

(citations omitted)

77 The Court identified a number of subsidiary principles, directed to the central question, as follows:

(a) First, conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility of it doing so: see Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87, referred to with apparent approval in Butcher at [112] by Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ; Noone v Operation Smile (Australia) Inc (2012) 38 VR 569 at [60] per Nettle JA (Warren CJ and Cavanough AJA agreeing at [33]).

(b) Second, it is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 per Stephen J (with whom Barwick CJ and Jacobs J agreed) and at 234 per Murphy J; Puxu at 197 per Gibbs CJ; Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 (Google) at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(c) Third, it is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Google at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ. Evidence that a person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive within the meaning of the statute. The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself: see Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ.

(d) Fourth, it is not sufficient if the conduct merely causes confusion: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ and 209-210 per Mason J; Campomar at [106]; Google at [8] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(e) Fifth, where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]-[105]; Google at [7] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

78 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Dover Financial Advisers Pty Ltd (2019) 140 ACSR 561; [2019] FCA 1932 at [99], O’Bryan J observed that:

In assessing whether conduct is likely to mislead or deceive, the courts have distinguished between two broad categories of conduct, being conduct that is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, and conduct that is directed to an identified individual. As explained by the High Court in Campomar, the question whether conduct in the former category is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction, where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class of persons to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful (at [101]–[105]). In Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435; 294 ALR 404; 99 IPR 197; [2013] HCA 1, French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was) confirmed that, in assessing the effect of conduct on a class of persons such as consumers who may range from the gullible to the astute, the Court must consider whether the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of that class would be misled or deceived (at [7]). In the case of conduct directed to an identified individual, it is unnecessary to approach the question at an abstract level; the Court is able to assess whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive in light of the objective circumstances, including the known characteristics of the individual concerned. However, in both cases, the relevant question is objective: whether the conduct has a sufficient tendency to induce error …

79 Where the statement is made to the public or a section of the public, the Court considers its effect upon ordinary or reasonable members of the class in question all of whom are presumed to take reasonable care to protect their own interests: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vocation Limited (In Liquidation) (2019) 136 ACSR 339; [2019] FCA 807 at [631]–[632] (Nicholas J).

80 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Limited (2007) 244 ALR 470; [2007] FCA 1904, Gordon J, in the context of considering s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), set out a two-step analysis for assessing misleading or deceptive conduct at [14]–[15] as follows:

The relevant legal principles have been well traversed by Australian courts. A two-step analysis is required. First, it is necessary to ask whether each or any of the pleaded representations is conveyed by the particular events complained of: …

Second, it is necessary to ask whether the representations conveyed are false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. This is a “quintessential question of fact”: …

(citations omitted)

81 This two-step analysis has been quoted with approval in a number of decisions of the Court: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GetSwift Limited (Liability Hearing) [2021] FCA 1384 at [2109]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2019] FCA 1039 at [84]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 992 at [288]; SPEL Environmental Pty Ltd v IES Stormwater Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 891 at [34].

82 In Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Dateline Imports Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 114 (Gilmour, McKerracher and Gleeson JJ), the Full Court cited the principles in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 (Gordon J) at [10] as being the “correct approach concerning representations of different types” in relation s 52 Trade Practices Act, and quoting at [179]:

2. … it would be wrong to select particular words or acts which although misleading in isolation do not have that character when viewed in context …

See also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited [2022] FCA 1324 at [239] (Derrington J) (ASIC v NAB).

83 This accords with the observations by McHugh J in Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited (2004) 218 CLR 592; [2004] HCA 60 at [109] (albeit in relation to s 52 Trade Practices Act):

… It invites error to look at isolated parts of the corporation’s conduct. The effect of any relevant statements or actions or any silence or inaction occurring in the context of a single course of conduct must be deduced from the whole course of conduct. Thus, where the alleged contravention of s 52 relates primarily to a document, the effect of the document must be examined in the context of the evidence as a whole. The court is not confined to examining the document in isolation. It must have regard to all the conduct of the corporation in relation to the document including the preparation and distribution of the document and any statement, action, silence or inaction in connection with the document.

(citations omitted)

84 Finally, s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act requires that a financial services licensee must comply with financial services laws, which includes ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act.

Consideration

85 ASIC submits that the ordinary or reasonable customer would know from the notation on the customer account statement that CBA had charged a fee. So much may be accepted.

86 ASIC then submits that, with that knowledge, a reasonable understanding of such a customer would be that a bank does not charge a fee unless it is entitled to do so. It submits that the alternative is that it is reasonable to expect a bank to take a customer’s money with no entitlement.

87 However, this ignores another alternative, being that a reasonable understanding of the ordinary and reasonable customer is that the fee has been or, at least, might have been charged in error.

88 The members of those classes of customers who entered a contract with CBA in relation to the relevant accounts are likely to be taking reasonable care of their own interests. They are also likely to have had their own personal experiences of, or otherwise be aware that there is at least some prospect of, computer systems malfunction, software design errors, and human error in relation to data input. They would be aware that CBA’s systems are computerised and that CBA’s processes involve human interaction with those systems. They would understand that customer account statements are generated by CBA’s computerised systems and, having regard to the size of CBA’s operations, are unlikely to have been reviewed by any of CBA’s personnel before being issued. They would also be aware that the systems and processes within large organisations such as banks are not and cannot be expected to be perfect all of the time; that all organisations (even banks), and the people within them, sometimes make mistakes and that, for a variety of reasons, a contractual promise by CBA to waive a fee otherwise payable in relation to their account might not translate into that fee being waived for reasons which may not involve any intentional conduct by CBA.

89 Further, the ordinary and reasonable customer would not view a customer account statement as an invoice, but as a record of transactions that have occurred on the account. The ordinary and reasonable customer understands that a customer account statement is sent to customers so that they may acquaint themselves with those transactions and satisfy themselves that no disputed transactions have occurred, either by error of the bank, or mistake or malfeasance by third parties.

90 For this reason, the facts of this case differ from those relied upon by ASIC, namely Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Limited (2018) ATPR 42–593; [2018] FCA 571 (Moshinsky J), Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus Mobile Pty Limited [2019] FCA 106 (Murphy J) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (Omnibus) (2022) 159 ACSR 381; [2022] FCA 515 (Beach J) (Westpac Omnibus). Further, each of these decisions involved determinations by agreement. In ASIC v NAB, where similar representations were alleged, ASIC also relied on these three decisions. As observed by Derrington J in that case at [292], “great care should be taken in relying on consent determinations, especially where the applicant is a regulator and any agreement as to statutory contravention might well have been motivated by extraneous factors”.

91 Another decision relied upon by ASIC is that of Allsop CJ in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (No 3) [2020] FCA 1421 in support of their case against CBA:

[13] … Despite all other features, the banker and customer relationship is at the heart of the economic system. It is a relationship based on contract, but, as the Code of Banking Practice reveals, it is founded on trust and good faith in a commercial sense.

[14] It would shock any customer to know that his or her bank took and was continuing to take his or her money in fees when it knew that there was a risk that it had no authority to do so, and without thereafter coming to a view that it did have that authority …

…

[17] … It is unrealistic to consider that there is other than a degree of consumer vulnerability in dealing with banks with carefully drawn contracts of adhesion which can be changed at will by the bank on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Contracts of adhesion are a central part of commercial life and much commerce could not be undertaken without them. They are not evil things in their own right. Nevertheless, they must be understood to be what they are, that is, standard forms drafted by the bank or the contracting commercial house, in these kinds of circumstances, on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. The customer can leave, of course, and they are free to do so, but the reality of commercial and consumer life is that the customer expects that the bank will at all times adhere, and adhere strictly and faithfully, to its contractual rights which it has chosen to express in its contract of adhesion.

92 However, this authority does not assist ASIC. This is not a case where it is alleged that CBA charged MAFs to customers when it knew that it had no contractual entitlement to do so, or charged MAFs “when it knew that there was a risk that it had no authority to do so, and without thereafter coming to a view that it did have that authority” (to use the words of Allsop CJ). While the customer expects that the bank will adhere to the terms of the contract, the ordinary and reasonable customer (as described above) does not expect perfection from a bank in the performance of its contract.

93 ASIC also submits that the understanding of the ordinary bank customer was reinforced by CBA’s adoption of the Code of Banking Practice during the relevant period, to which reference was made in the Terms and Conditions. Particular reliance was placed on the 2013 version of the Code which included the following under the heading, “Our key commitments and general obligations”:

We will act fairly and reasonably towards you in a consistent and ethical manner. In doing so we will consider your conduct, our conduct and the contract between us.

…

We will comply with all relevant laws relating to banking services.

(emphasis omitted)

94 ASIC submits that CBA’s adoption of the Code conveys to its customers that (among other things) it will not take their money unless it is entitled to do so (although this conduct was not relied upon as being a further representation). It also submits that CBA would not be acting “fairly, reasonably” and in an “ethical manner” if it took customers’ money with no entitlement to do so.

95 This means that, on ASIC’s case, members of those classes of customers who opened a relevant account with CBA would be aware of the Code, and its adoption by CBA (presumably through the Terms and Conditions). However, even if such customers were aware of the Code, it does not follow that they would be aware of its content. In any event, having regard to the characteristics of the class of customers referred to above and the content of the Code, they would not construe its adoption by CBA as some form of representation that no errors will ever be made by CBA, including in relation to the charging of fees: see also ASIC v NAB at [277].

96 There are further matters which tell against a finding that the implied representation was conveyed as alleged by ASIC.

97 First, customer account statements issued by CBA during the relevant period contained a note on the first page requesting that customers check that the entries listed in the statement were correct, and that they contact CBA immediately in the event of any errors. That notation enjoyed a prominent position at the top of the first page of the account statements.

98 This means that the very same document that is alleged to have conveyed the implied representation expressly put customers on notice that their account statement may contain incorrect or erroneous entries in a manner which was likely to have been seen by them.

99 In circumstances where CBA acknowledged the possibility of error in account statements and therefore contemplated the possibility of a MAF being debited incorrectly, the notional customer would not have been led to believe that CBA was representing as a matter of fact that it had correctly charged the fees identified in that statement. That is because one cannot properly infer that a document says a particular thing if there are statements in the document which are to the opposite effect: see Clarke (as trustee of the Clarke Family Trust) v Great Southern Finance Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (in liquidation) [2014] VSC 516 at [1333] (Croft J); see generally ASIC v NAB at [260]–[261].

100 Second, the Terms and Conditions during the relevant period expressly encouraged customers to check the transactions on their account statement upon receipt and report any unauthorised transactions to CBA. ASIC submitted that the notional customer would not understand the reference to transactions as including a reference to the charging of fees by CBA. However, the notional customer would not read the reference to transactions in such a narrow way, but would understand that they were being asked to check if the entries in the customer account statement were correct, including in relation to any debits such as fees.

101 This is especially as, except for the period between 1 June 2010 and 29 May 2011, the Terms and Conditions also contained an express statement to the effect that CBA “accept[s] that sometimes we can get things wrong, and when this happens we’re determined to make them right again” (emphasis added). By that express acceptance, CBA disclaimed any guarantee of perfect accuracy as regards the account statements or entries in the passbook.

102 Third, customers who met the contractual eligibility criteria for a MAF waiver were in a contractual relationship with CBA constituted by their acceptance of the Terms and Conditions. Pursuant to the Terms and Conditions, CBA represented to such customers that they would be exempt from paying a MAF on the basis that they were eligible for a waiver.

103 The implied representation alleged by ASIC is therefore inconsistent with CBA’s express contractual representations as to an eligible customer’s exemption from the payment of a MAF. This means that ASIC’s case carries with it a further implied representation that CBA was entitled unilaterally to resile from its earlier contractual promise as to the circumstances in which it would not charge a MAF and that it had in fact resiled from that contractual promise. ASIC appeared to accept this when it reached agreement with CBA about the legal issues, but did not make submissions to support this further implied representation. Yet it must succeed on both to succeed at all.

104 In any event, there was no such further implied representation. Having regard to the characteristics of the class of customers referred to above, the notional customer would not conclude that, by incorrectly charging a MAF and recording that charge in a computer-generated statement or passbook, CBA evinced an intention and expressed a positive right to act in a manner completely contrary to what it had promised in the written contract.

105 Instead, in all of the circumstances, the sole representation conveyed by customer account statements or a notation in a passbook as regards MAFs was that a MAF of a particular amount had been deducted from the account in question on or around the nominated date, and the customer should check whether that entry was correct and notify CBA in the event of any error.

Conclusion

106 For these reasons, ASIC failed to establish that, by its conduct in charging a MAF to a customer and issuing a customer account statement to a customer who had been charged a MAF (or notifying such a charge in a passbook), CBA made an implied representation that it had a contractual entitlement to charge the MAF and that it was entitled to depart from its contractual promise that it would not charge a MAF on the relevant accounts where a customer had been promised a MAF waiver.

107 As no implied representation was made by CBA as alleged, ASIC failed to establish that CBA contravened either ss 12DA or 12DB(1)(i) ASIC Act or that it breached its general obligation to comply with financial services laws in contravention of s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act.

THE SYSTEMS AND PROCESSES CASE

ASIC’s allegations

108 ASIC alleges that, on each occasion during the relevant period that CBA entered into a contract with a customer to establish a relevant account, by the customer’s acceptance of the Terms and Conditions, and each time CBA sent a customer an updated version of the Terms and Conditions during the relevant period after the customer had entered into the contract, CBA, on each occasion:

(1) made implied representations that it had, and would have adequate systems and processes in place to ensure that it could provide the MAF waivers where a customer satisfied the criteria specific to a relevant account contained in the Terms and Conditions; and

(2) made those implied representations when it did not have adequate systems and did not have reasonable grounds (within the meaning of s 12BB(1) of the ASIC Act) for stating it would have systems in the future to provide the benefits, and the price for services, in the form of MAF waivers,

in contravention of ss 12DA, 12DB(1)(e) and/or 12DB(1)(g) of the ASIC Act.

109 ASIC also alleged, and this was not disputed, that CBA was acting in trade or commerce in connection with the supply of financial services when it engaged in such conduct.

Agreed legal issues

110 The first issue is whether CBA, on each occasion during the relevant period that it:

(1) entered into a contract with a customer, by the customer’s acceptance of the Terms and Conditions; and

(2) sent a customer an updated version of the Terms and Conditions following the customer’s entry into a contract with CBA,

made implied representations that it had, and that it would have, adequate systems and processes in place to ensure that it could provide the MAF waivers where a customer satisfied the criteria specific to a relevant account contained in the Terms and Conditions.

111 Taking into account the submissions by ASIC at the hearing, as referred to above, the question is whether CBA conveyed an implied representation that its current systems and processes were capable of ensuring that the MAF waiver would be applied and that those systems and processes would always be so capable, without fail.

112 The second issue is whether by making such a representation, in circumstances where:

(1) CBA did not have adequate systems to provide MAF waivers (which ASIC alleges but CBA denies), and

(2) CBA did not have reasonable grounds for representing that it would have systems in the future to provide MAF waivers (which ASIC alleges but CBA denies),

CBA contravened ss 12DA, 12DB(1)(e) and/or 12DB(1)(g) of the ASIC Act.

113 The final issue is whether CBA, by the conduct referred to in the previous paragraph (conduct which is alleged by ASIC but denied by CBA), breached its general obligation to comply with financial services laws in contravention of s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act.

The relevant legislation

114 Section 12DA(1) ASIC Act relevantly provided as follows:

12DA Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

115 At the commencement of the relevant period, ss 12DB(1)(e) and 12DB(1)(g) ASIC Act did not exist in their current form.

116 Sections 12DB(1)(e) and 12DB(1)(g) (being the provisions relied upon by ASIC and which came into force on 1 January 2011) relevantly provided that:

12DB False or misleading representations

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

…

(e) make a false or misleading representation that services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristic, uses or benefits; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of services.

117 By reference to the terms of these provisions, it was contended by ASIC that the implied representations were false or misleading as to the benefits of services, and with respect to the price of services.

118 Here, the “financial services” were the relevant accounts offered by CBA. The term “benefit” is defined in s 9 Corporations Act as “any benefit, whether by way of payment of cash or otherwise”. The “benefit”, for the purposes of s 12DB(1)(e) is the entitlement for customers to receive MAF waivers when certain criteria are met. “Price” includes a “charge of any description”: s 12BA(1) ASIC Act. The “price of services”, for the purposes of s 12DB(1)(g), includes that the MAF will be waived when those criteria are met.

119 The general principles with respect to misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 12DA ASIC Act and false or misleading representations in contravention of s 12DB(1) ASIC Act have been addressed earlier in these reasons.

120 As to the application of these principles to the systems and processes case, additional considerations arise.

121 The divining of representations from the making of contractual promises and the entry into contracts is a task to be approached with caution and with an eye to all the facts and not by reference to implying representations mechanistically from equivalent promises: McGrath v Australian Naturalcare Products Pty Ltd (2008) 165 FCR 230; [2008] FCAFC 2 at [138] (Allsop J, as his Honour then was) which was cited with approval in Cash Bazaar Pty Ltd v RAA Consults Pty Ltd (No 2) (2020) 381 ALR 668; [2020] FCA 636 at [227] (Steward J). In a similar vein, Ormiston J (as his Honour then was) observed in Futuretronics International Pty Ltd v Gadzhis [1992] 2 VR 217 at 238 that:

… If a promissory statement is to be the subject of complaint, it is also necessary to ask how did it amount to misleading or deceptive conduct. It is wrong to view every contractual obligation as an unqualified promise to perform the stipulated act. Indeed it is rare that a contractual promise is not in some way qualified by some reciprocal obligation to be performed by the promisee or by some other circumstance. If the promise induced the other party to enter into the agreement, as one can readily accept it would, then it is that promise and the circumstances then surrounding it which must be examined. The promise can only be said to be misleading or deceptive if it was in some way inaccurate; otherwise every unfulfilled mutual contractual promise will constitute misleading or deceptive conduct, a consequence which I cannot believe those who drafted the Act intended. If intention be relevant, the promise may be misleading if the promisor had no intention to fulfil it at the time it was made and accepted. If intention be irrelevant, then the promise may be misleading if the promisor had no ability to perform it at that time. …

122 In Concrete Constructions Group v Litevale Pty Ltd (2002) 170 FLR 290; [2002] NSWSC 670 at [167]–[169], Mason P (as his Honour then was) cited Futuretronics with approval and observed that:

I readily accept that it will be comparatively easy to establish that a contracting party is implicitly representing a present intention to perform [the contract] according to its tenor. If the other party can establish causation and loss then damages should ensue, although there is usually little point in addressing such a claim because the law of contract will compensate the innocent party for the consequences of non-performance without even having to prove misleading intent from the inception.

But when one turns to an alleged implicit representation as to capacity to perform things are not so simple, nor should they be. There are policy reasons for restraint. The law arms the parties to a contract with rights to damages and other forms of relief if breach occurs or is threatened. A complex set of common law, equitable and statutory rights are superimposed on the terms of the bargain chosen by the parties. That bargain may have the simplicity as a contract to sell a loaf of bread or the complexity of a building agreement such as the one in question in this case.

Why should the parties be found or presumed to have intended more by what they expressly represented and understood? Of course, s 52 goes beyond intentionally misleading or deceptive conduct, but it does not follow that the innocent party understood or relied upon anything more than the express representations and the usually adequate consequences stemming from breach of them stemming from the law touching the mutually chosen regime, that is, contract.

123 An express contractual promise or representation will generally constitute an actionable implied misrepresentation only if the promisor had no intention or capability of carrying it out at the time that it was made: see, for example, Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd v FKP Limited [2008] FCA 1915 at [68]–[69]; Secure Parking Pty Ltd v Woollahra Municipal Council [2016] NSWCA 154 at [95]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cassimatis (No 8) (2016) 336 ALR 209; [2016] FCA 1023 at [661]–[662] (appeal dismissed: Cassimatis v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2020) 275 FCR 533; [2020] FCAFC 52); HTW Valuers (Central Qld) Pty Ltd v Astonland Pty Ltd (2004) 217 CLR 640; [2004] HCA 54 at [13]; Cash Bazaar at [228].

124 Finally, s 912A(1)(c) Corporations Act requires that a financial services licensee must comply with financial services laws, which includes ss 12DA(1), 12DB(1)(e) and 12DB(1)(g) ASIC Act.

Consideration

125 ASIC submits that the express statements in the Terms and Conditions, which contained the entitlement criteria for each of the relevant MAF waivers, amounted to the implied representations. It submitted that the ordinary customer would expect that, having stated in plain terms that it would not charge a MAF in certain circumstances, CBA would have adequate systems and processes in place to make good on that promise.

126 The implied representations alleged by ASIC go well beyond a representation that CBA had a present ability to fulfil its promise; they include a representation that CBA would ensure the fulfilment of the promise – in the sense of guaranteeing or making certain that it was carried out. That representation is alleged to have been conveyed in the absence of express agreement by the parties concerning the capabilities of CBA’s systems and processes, and in circumstances where the notional customer will have a remedy for breach of contract in the event that the promised waiver was not applied. ASIC failed to establish how the implied representations arose from CBA’s express promises in these circumstances.

127 Further, except for the period between 1 June 2010 and 29 May 2011, the Terms and Conditions also contained words to the effect that CBA “accept[s] that sometimes we can get things wrong, and when this happens we’re determined to make them right again”. This express acknowledgement that errors might be made by CBA in the performance of the contract with the customer negates the existence of the alleged implied representation. One does not impliedly represent an existing and future ability to perform a contract perfectly but, at the same time, expressly acknowledge the possibility of an error in that performance.

128 The express acknowledgement that sometimes CBA “get[s] things wrong” is, in any event, aligned with the understanding of the ordinary and reasonable member of the class of customers who entered the contracts with CBA. Having regard to the characteristics of the class of customers referred to above, a notional customer would not have been misled or deceived because they would not have regarded any such representation as being credible, even if it had been made.

129 In support of the systems and process case, ASIC relied upon the decision of Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790 (Beach J) (ASIC v CBA). It submitted that, whilst that matter proceeded on agreed facts, the Court accepted that certain brochures, the application form and the terms and conditions documents represented to each relevant customer to the effect that CBA had, and would continue to have, adequate systems and processes to ensure that customers received the benefits, fee waivers and interest rate discounts in accordance with the contractual documents. ASIC relied upon the conclusion by Beach J at [34] that:

On the basis of the agreed facts in my view there is little doubt that the elements of ss 12DB(1)(e) and (g) of the ASIC Act have been made out concerning the making of the representations and their falsity or misleading aspect.

130 However, ASIC v CBA is of no assistance to ASIC. That is because the representation alleged and accepted in that case arose in materially different circumstances (namely, where a promotional offer was made to a discrete subset of customers who were invited to pay consideration for certain benefits) and from a different set of contractual documents.

131 Further, that case proceeded on an agreed basis as to the facts, including the representations which had been conveyed. As observed by Beach J at [12], “Before turning to the detail I note that as sufficient factual matters have been agreed, I have not been required to determine any factual question on its merits”.

132 ASIC v CBA also proceeded on an agreed basis as to the legal characterisation of those agreed facts and the statutory contraventions ultimately alleged by ASIC. In those circumstances, the Court was not called upon to consider (much less determine) the application of the relevant principles to those materially different facts which had been agreed between the parties. In particular, Beach J referred to these admissions by CBA at [3]–[5].

133 On 26 October 2022, being after the hearing of this proceeding, the decision of Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2022] FCA 1251 (O’Callaghan J) (ASIC v ANZ) was handed down. This was also a determination by agreement between a regulator and a party. There are similarities with the facts of that case and this case in that it involved a bank failing to confer a promised contractual benefit on certain customers and ASIC alleged (and ANZ agreed) that on each occasion ANZ issued contractual documents, and an updated version of those documents, ANZ made implied representations that it had, and would continue to have, adequate systems and processes in place to administer the particular benefits on relevant products (as applicable) in accordance with the contractual documents: see, for example, [110] and [179].

134 However, ASIC v ANZ is also of no assistance. It proceeded on an agreed basis as to the facts, as well as the legal characterisation of those agreed facts and the statutory contraventions ultimately alleged by ASIC. It involved a different set of contractual documents to that being considered in this proceeding. Further, insofar as the case concerned an analysis of whether each implied representation in that case was misleading or deceptive, ANZ’s systems were substantially manual and therefore susceptible to human error: see [42] and [50]. By contrast, CBA did not have one singular “system” for waiving MAFs during the relevant period, but rather, a network of systems that worked to detect and give effect to a customer’s eligibility for a waiver, involving both manual and automated processes.