Federal Court of Australia

Abbott v Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1390

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and on or before 7 December 2022 file draft orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment delivered today and in default of agreement draft orders marked up to show any disagreements and written submissions limited to 3 pages.

2. The proceeding stand over to 9 December 2022 for the making of final orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

1 This is a representative proceeding under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). It concerns a vaccine, EquivacHeV Hendra virus vaccine (Equivac HeV), developed by the respondent, Zoetis Australia Pty Limited, which until about March 2013 was called Pfizer Animal Health Pty Limited, in conjunction with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and others, to provide immunity for horses against the zoonotic (ie: capable of being transmitted from animals to humans) virus of the henipavirus family. That virus has taken the eponymous name Hendra virus (or HeV) from the Brisbane suburb where it first became evident in 1994. On that occasion, a number of racehorses and a veterinarian died and a veterinary nurse suffered long-term effects from HeV.

2 There are approximately 900,000 domesticated, and an unknown number of feral, horses in Australia. Equivac HeV has proved particularly effective in providing immunity to vaccinated horses.

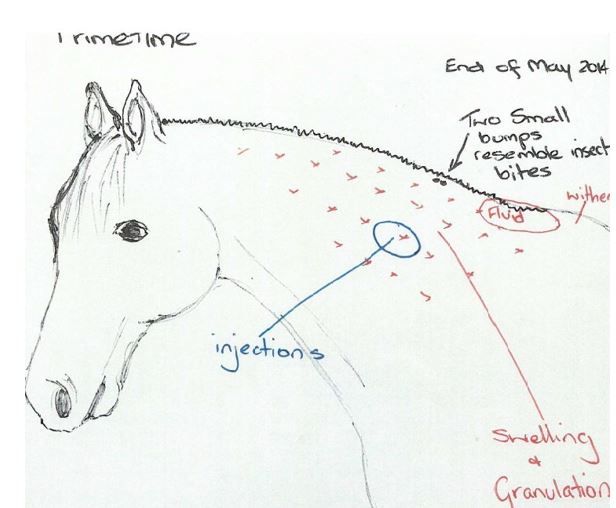

3 The applicant representative party, Rachael Abbott, is a stockperson who owned a number of horses, including the mare, Primetime, which was vaccinated with an initial injection and a booster injection of Equivac HeV in, respectively, July and August 2014. In addition, commencing in July 2013, a sample group member, Kelly Hinton, had her horses, including Quinn, a gypsy cob stallion, vaccinated.

4 Ms Abbott claims that Primetime suffered enduring adverse physical conditions as side effects resulting from the administration of Equivac HeV. Ms Hinton claims that Quinn died within five days after receiving his fifth vaccination on 28 January 2016, again, as a result of the vaccination itself.

5 The applicant claims that over the relevant period, between 10 August 2012 and 20 March 2018, Zoetis engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), by making three representations, that she pleaded as the geographic spread, the no serious side effects and the all horses representations in a number of different publications. (For brevity and because nothing turns on it in this proceeding, in these reasons I will use the shorthand expression “misleading” to encapsulate the various permutations in s 18(1)).

6 In addition, the applicant claims that during the relevant period, Zoetis guaranteed to consumers, within the meaning of s 54(1) and (2) of the ACL, that Equivac HeV was of acceptable quality. The applicant claims compensation under s 236 of the ACL. The group members are all persons who suffered loss or damage or personal injury in the relevant period because of Zoetis’ alleged conduct in contravention of ss 18(1) or 54(2) of the ACL.

7 The essential issues are whether, first, each of the representations on which the applicant relies was conveyed by the publications identified, secondly, it was, in fact, incorrect or misleading or deceptive and, thirdly, to the extent that it was made with respect to a future matter within the meaning of s 4 of the ACL, Zoetis had reasonable grounds for making it, as it contends.

8 The three representations as pleaded in the second further amended statement of claim and the particulars of publications in which the applicant alleged they were conveyed as pressed at trial (with the shorthand names of the publications by which each was conveyed) are:

(1) The geographic spread representation

From 2 March 2013 and throughout the relevant period, Zoetis represented to the Class that there was a serious risk of horses contracting Hendra in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present.

Particulars

The representation was contained, separately and together, in:

(a) the 2013 fact sheet;

(b) the March 2013 media release;

(c) the mythbusting pamphlet;

(d) the September 2013 seminar;

(e) the Horses 4 Horses website information; and

(f) the every horse owner pamphlet.

(2) The no serious side effects representation

From 10 August 2012 and throughout the relevant period, Zoetis represented to the class that Equivac HeV had no serious side effects.

Particulars

The representation was contained, separately and together, in:

(a) the first and second permit disclosures;

(b) the registration module;

(d) the third permit disclosure;

(c) the mythbusting pamphlet;

…

(f) the Horses 4 Horses website information;

(g) the facts about HeV pamphlet; and

(h) the Equestrian Life letter.

(3) The all horses representation

From 2 March 2013 and throughout the relevant period, Zoetis represented to the class that all horses in Australia should be treated with Equivac HeV.

Particulars

(a) The representation was made expressly in the 2013 fact sheet and March 2013 media release.

(b) Further to (a), the representation was contained in the registration module materials and Equestrian Life letter.

9 I will describe the contents of each of the particularised and pressed publications below when considering whether each representation was conveyed to an ordinary, reasonable member of the class. Ms Abbott pleaded that she relied on each of the representations whereas Ms Hinton pleaded that she relied only on the geographic spread and no serious side effect representations.

10 If the no serious side effects representation is true, the claim under s 54(1) and (2) of the ACL necessarily fails and, likewise, if that representation was untrue, the guarantee will succeed. In addition, it is necessary to consider what, if any, damages Ms Abbott and Ms Hinton have been able to prove.

11 Relevantly, the ACL provided during the relevant period:

4 Misleading representations with respect to future matters

(1) If:

(a) a person makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act); and

(b) the person does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation;

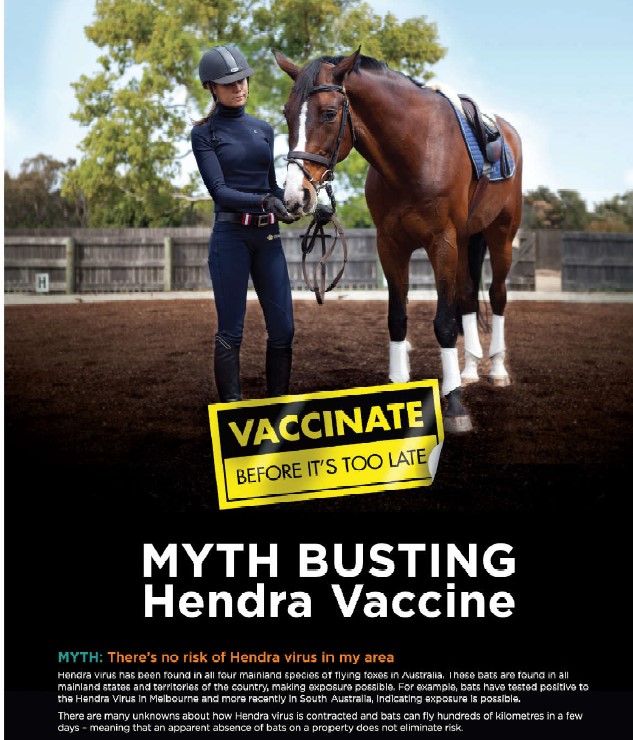

the representation is taken, for the purposes of this Schedule, to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made with respect to a future matter by:

(a) a party to the proceeding; or

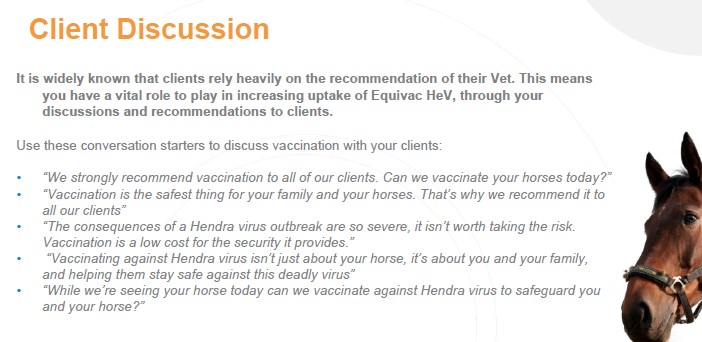

(b) any other person;

the party or other person is taken not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation, unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the person who made the representation is taken to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the person who made the representation had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

(4) Subsection (1) does not limit by implication the meaning of a reference in this Schedule to:

(a) a misleading representation; or

(b) a representation that is misleading in a material particular; or

(c) conduct that is misleading or is likely or liable to mislead;

and, in particular, does not imply that a representation that a person makes with respect to any future matter is not misleading merely because the person has reasonable grounds for making the representation.

…

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

54 Guarantee as to acceptable quality

(1) If:

(a) a person supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods are of acceptable quality.

(2) Goods are of acceptable quality if they are as:

(a) fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied; and

(b) acceptable in appearance and finish; and

(c) free from defects; and

(d) safe; and

(e) durable;

as a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods), would regard as acceptable having regard to the matters in subsection (3).

(3) The matters for the purposes of subsection (2) are:

(a) the nature of the goods; and

(b) the price of the goods (if relevant); and

(c) any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods; and

(d) any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods; and

(e) any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods.

12 Zoetis is, together with its associated company, Zoetis Australia Research and Manufacturing Pty Limited, an Australian subsidiary of a global veterinary pharmaceutical business, Zoetis Inc. Previously, Zoetis had formed part of the Pfizer Animal Health business prior to Pfizer divesting itself of its Zoetis businesses.

13 Equivac HeV is an award-winning veterinary medicine. The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (also called APVMA) registered Equivac HeV on 4 August 2015 in the Register of Agricultural and Veterinary Commercial Products under s 20(2) in the Schedule to the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code Act 1994 (Cth) (the Agvet Code). Before this, from the launch of the product on 10 August 2012 until its registration, the Authority had granted Zoetis three minor use permits under s 112 of the Agvet Code that strictly controlled the use and distribution of Equivac HeV to horses.

14 The Authority required Zoetis, as a condition of each of the permits, to label, and include a leaflet in, the container in which it supplied Equivac HeV, that contained certain information referred to as the first, second or third permit disclosures, as to possible side effects of vaccination on which the applicant relies as conveying the no serious side effects representation. Until the Authority registered Equivac HeV, the permits only allowed Zoetis to distribute the vaccine to registered veterinary surgeons (veterinarians or vets), who had to administer it.

15 The applicant alleged that each of the labels and leaflets for permit PER13510, issued for the period 10 August 2012 to 3 August 2014 (the first permit), permit PER14876, issued for the period 4 August 2014 to 4 August 2015 (the second permit), and the superseding permit PER14887, issued for the period 31 March 2015 to 4 August 2015 (the third permit), conveyed the no serious side effects representation, as I explain later.

16 It was common ground that a large number of publications accompanied great public controversy and discussion about the Hendra virus since its discovery in 1994 with the tragic results that I have mentioned.

17 Earlier in this proceeding, Lee J ordered that Professor Michael Ward PhD; DVSc, FACVSc be appointed as an expert referee. Professor Ward was a registered specialist in veterinary epidemiology. The referee had to report about:

the risk of horses contracting HeV in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present;

the nature and magnitude of that risk, as well as the state of knowledge of transmission of HeV from flying foxes to horses, between horses and from horses to humans;

the state of knowledge of the geographic distribution and movement of flying fox species;

which species of flying fox was or were capable of transmitting HeV to horses in Australia; and

what factors affected the nature and magnitude of the risk of HeV being passed from flying fox to flying fox, flying foxes to horses, horses to horses and horses to humans.

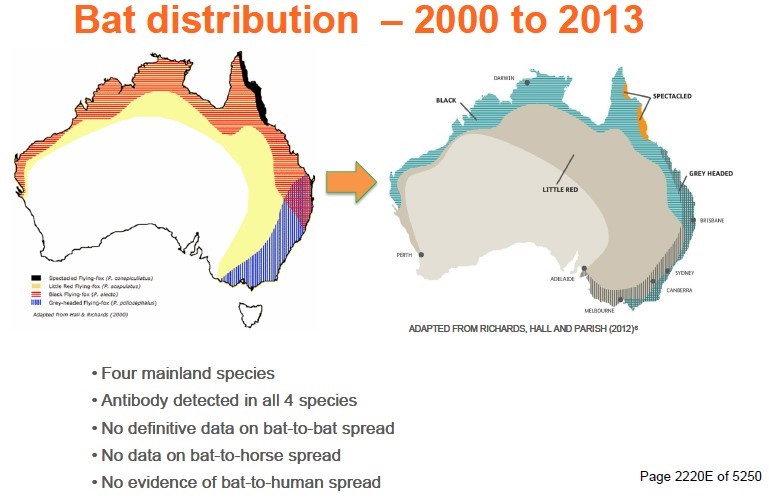

18 Professor Ward made a report, dated 11 September 2020, which became an exhibit. He supplemented the report with answers to further questions which the parties posed through the Court. Professor Ward opined, and I find, that during the relevant period:

(1) there was a risk of horses contracting HeV, whether directly from flying foxes or otherwise, in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present;

(2) the magnitude of the risk of horses contracting HeV in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present primarily was dependent on the presence of two species, Pteropus (or P.) alecto and Pteropus (or P.) conspicillatus, being the black and spectacled flying fox;

(3) the magnitude of the risk ranged from very low, or about 1 to 2 per 10,000, within the Hendra area (defined as the area where the horses had suffered HeV infection, namely the coastal strip from Far North Queensland, and on the eastern side of the Great Dividing Range in tropical areas of Queensland to the mid North Coast of New South Wales and, in one instance, in Southern Queensland) to negligible or extremely low outside the Hendra area, namely, or about 1 or 2 per 1,000,000;

(4) except for the transmission of HeV from horses to humans during the relevant period, the state of knowledge of the means of transmission of the virus between flying foxes, from flying foxes to horses and between horses was poor;

(5) there was good knowledge of the geographic distribution of flying fox species and fair knowledge of their local and long-distance movements. A scientific consensus developed that the black and spectacled varieties were the flying fox species more likely to be capable of transmitting HeV to horses in Australia; and

(6) a range of factors was proposed that might affect the nature and magnitude of the risk of HeV being passed from flying fox to flying fox and from flying foxes to horses, but there was a lack of scientific consensus. In contrast, there was a consensus that the transmission of the virus from horses to horses and from horses to humans depended on very close contact with an infectious horse.

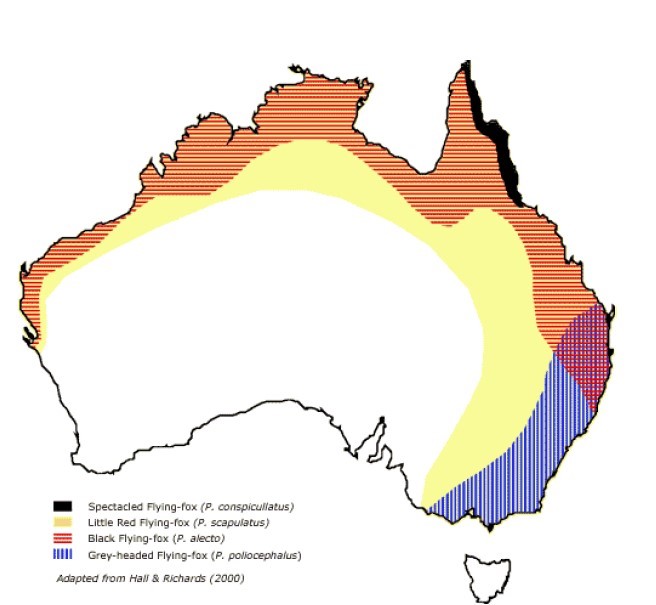

19 Professor Ward’s view, on which the parties largely proceeded, was that there was a risk throughout those areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present, as depicted on the map below that summarised the distribution of the four species, of both horses and humans contracting HeV, but that the risk outside the Hendra area was extremely low, but still present.

20 During the course of the hearing, Zoetis sought to have Professor Ward comment on provisional and speculative results released by some researchers, in a document entitled “Horses as Sentinels Research”, which suggested that another species of flying fox, other than the black or spectacled ones, carried a slightly different variant of the Hendra virus. Professor Ward said that he was generally aware at the time he wrote his report that research into this topic was progressing, but he was not aware of its content or of its provisional findings and had not taken those into account.

21 The researchers hypothesised that, at the stage their research had reached, the grey-headed flying fox might intermittently cause a variant of HeV to be transmitted or spillover into other species, such as horses and humans. They stated that they had speculated that different strains of HeV could predominate in different species of flying fox. However, at that stage, their work had not been formulated into a paper, far less peer reviewed.

22 In those circumstances, I formed the view that it would not be appropriate to have the referee report on that material, or to allow it to be introduced into evidence, because the applicant would not be able to meet it. It may well be that if and when that research matures into a more concrete form, some of the conclusions that I reach may need reconsideration in another context.

4.2.1 The applicant’s lay witnesses

23 Ms Abbott had been a stockperson for her working life. She had experience in handling horses, cattle, and, as a lay person, veterinary products to treat livestock. She had certification and training in farm safety and feeding cattle. She had also competed, with some success, in stockhorse handling competitions. Part of her working experience had involved her riding her own horses as a pen rider. She explained that this required her to ride through numerous pens of between 150 to 250 cattle to check on their apparent health, the amount of feed and water, and identify any that were in need of attention. She said that, as a pen rider, ultimately she needed to check about 5000 head daily and spent about three minutes in each pen. To do this, she needed a good, healthy horse, called a stockhorse. Ms Abbott obviously cared deeply about her horses, as was apparent when she gave evidence.

24 Ms Hinton has a master’s degree in business administration and, at the time of the trial, was studying for a master of financial planning degree. She had a lifelong interest in horses, having begun riding when she was six years old, and had her own horse at about 15. She bought her first horse as an adult when she was 18 and has owned horses ever since. She and her husband, David Hinton, traded as a horse stud partnership from about August 2008 under the name Dellifay Gypsy Cobs and Performance Horses.

25 Dr Richard L’Estrange graduated as a bachelor of veterinary science from the University of Queensland in 1987. He became a member of the Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists in veterinary pharmacology in 2008 and studied vaccinology and pharmacology to pass the examination for that qualification. He worked in private practice in Queensland and the United Kingdom from graduation until 2010 when he began employment with Pfizer. In 2012, he became responsible for Pfizer’s equine products portfolio, including Equivac HeV.

26 Dr Phillip Lehrbach was a technological expert in vaccines and biological products. He obtained degrees of bachelor of science from the University of Sydney in 1974, a doctor of philosophy from the University of Melbourne in 1980, a master of business administration from the University of Technology, Sydney, and a master of medical science drug development from the University of New South Wales in 2005. He worked on post-doctoral research fellowships in the 1980s at the Universities of Edinburgh (in molecular biology) and Geneva (in medical biochemistry). He also lectured at the Universities of Sydney and New South Wales on molecular biology and its influence on the development of animal health vaccines, as well as authoring or co-authoring over 60 peer reviewed articles on topics of molecular biology, animal health vaccines and microbial genetics. He also had roles assisting governmental bodies. He worked in senior positions in companies that eventually became part of the Pfizer group in October 2009. In 2010, he became director of regulatory affairs Asia-Pacific.

27 Dr John Messer, in 2012, was Zoetis’ regulatory affairs manager. Dr Messer was experienced in collecting data and investigating adverse reaction reports for the purpose of Zoetis’ pharmacovigilance of its products. He graduated as a bachelor of veterinary science in 1990 and then practised as a vet in Australia and the United Kingdom for about 12 years, predominantly with farm animals, including horses. As part of his practice, from time to time, he vaccinated horses. In December 2002, he began working with the German multinational, Bayer, as a product support veterinarian and eventually became a technical development manager. His roles at Zoetis required him to deal with consumers, vets and the Authority in respect of, among other matters, pharmacovigilance. He began working for Zoetis in 2011. During 2011 to 2013, as regulatory affairs manager, he worked under Dr David Chudleigh who until late 2013 was Zoetis’ departmental director new product developments, regulatory and scientific affairs and whose role included being in charge of pharmacovigilance, including for Equivac HeV. Dr Messer succeeded to Dr Chudleigh’s position.

28 Pharmacovigilance involves the assessment of reports of clinical signs that an animal presents in a temporal association with the earlier administration of a vaccine or medication and an assessment, based on the known pharmacology and toxicity of the introduced product or the likelihood that it may have caused the clinical sign to present.

29 There were three expert witnesses, Associate Professor Ben Sykes, who was called by the applicant, Dr Charles El-Hage and Professor Josh Slater, who were called by Zoetis. Each prepared individual reports and they all prepared a joint report and gave concurrent evidence.

30 Associate Professor Sykes has numerous tertiary qualifications including degrees as a bachelor of veterinary medicine and surgery and of science from Murdoch University, master’s degrees in science, from the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, and business administration from the University of Liverpool and a doctor of veterinary pharmacology from the University of Queensland. He had over 20 years’ clinical experience as a veterinarian with particular focus on high performance horses and large animal internal medicine. His research had focussed on gastrointestinal diseases of horses. He had taught at numerous universities around the world and was, at the time of the trial, an associate professor at Massey University in New Zealand. He also holds diplomas from both the European College of Equine Internal Medicine and the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, which are the highest internationally recognised veterinary internal medicine qualifications.

31 Dr El-Hage is a bachelor of veterinary science with honours and a doctor of philosophy (in infectious diseases focussed on equine immunology and vaccinations) from the University of Melbourne. He is a member of the Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists (Equine Medicine). He had been a lecturer in clinical sciences at the University of Melbourne since 2006 and since 2012 had taught students for the degree of doctor of veterinary science. He practised for 16 years from 1984 as a clinician, mainly with horses, in Australia and overseas. He also carries out research.

32 Professor Slater is a bachelor of veterinary medicine and surgery from the University of Edinburgh, and a doctor of philosophy in equine virology from the University of Cambridge. He also holds a diploma from the European College of Equine Internal Medicine. He was a lecturer, then senior lecturer, in equine medicine at Cambridge and professor of equine clinical studies for 13 years at the Royal Veterinary College of the University of London. Since 2019, he has been a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Melbourne. At London, he was director of the equine referral hospital responsible for all aspects of the College’s clinical activities, treating animals referred to it by general practitioners, as well as leading its research and teaching programs. He specialised in research into equine infectious diseases, particularly equine influenza and equine strangles in collaboration with other institutes in the United Kingdom, United States of America, and Melbourne. Strangles is a bacterial infection that affects a horse’s upper respiratory system (in its head, neck and throat), causing its lymph glands to swell and compress its respiratory tract, restricting its ability to breathe and, as it were, strangling it. Professor Slater was a research group leader and supervised doctoral and masters students. At London, he led and had overall responsibility for its specialist and medical team. In that role, he performed surgeries and treated horses.

33 In terms of its chemical structure, Equivac HeV is relatively simple. It consists of an antigen, being a genetically engineered, but inert, copy of the G protein on the surface of the living HeV, a biological adjuvant, excipients (that give each dose bulk but are neutral substances), and a preservative.

34 The G protein in the antigen replicates the part of the virus that binds to cells within the horse’s body on infection. On the past and present understanding of the operation of the vaccine, it is necessary for a booster injection to be given 21 days after the first administration and, thereafter, every six months to maintain the horse’s immunity. The purpose of the vaccine is to introduce the G protein in its inert form into the horse’s immune system and generate an immune response, leading to immunity.

35 The second ingredient of Equivac HeV is a biological adjuvant. An adjuvant stimulates the immune response in the animal when the inoculation occurs. The adjuvant used in Equivac HeV is a particular immune stimulating complex (ISCOM) known as the ISCOMatrix, and it, together with the excipients and the preservative, are all also used in the Equivac equine flu vaccine. The only difference between Equivac HeV and Equivac is the antigen in each.

36 As is common in human experiences, from time to time, horses also will develop a side effect, being an injection site reaction, at the area where the body reacts to the introduction of the vaccine by generating an immune response. Naturally, the questions of whether there are other side effects from the administration of any vaccine, what their nature is and what risks they present to the organism, are critical to any person making an informed choice about the wisdom or otherwise of vaccinating.

37 When Zoetis originally submitted Equivac HeV for registration by the Authority, it based its data on the results of a very small clinical trial of only about 30 horses. That was why the Authority required, as a condition of each of the three permits that it issued, that the vaccine be administered only by vets, and that any clinical signs or adverse reactions had to be reported to Zoetis or the Authority by those vets or horse owners.

38 As the evidence made clear, horses suffer a variety of illnesses and other apparent ailments or conditions that occur with regularity, some of which are also manifestations of clinical signs of HeV itself, and others of reactions, or potential reactions, to the administration of one or more vaccines.

5. Was each representation conveyed?

39 At the outset, it is necessary to consider whether each of the representations was conveyed by each particular publication on which the applicant relied. Over the course of the relevant period, knowledge developed about, first, HeV itself and its geographic spread, in terms of published instances of infections of horses or humans and, secondly, the actual or possible side effects of Equivac HeV were appearing as clinical signs or adverse reactions in horses in a temporal, but coincidental, relationship to, or as a result of, the administration of the vaccine. Thus, a publication may have been accurate at one time but rendered inaccurate later by new experiences.

40 Each of the 12 publications was made to a somewhat different audience. Some, such as the three permit disclosures that the Authority required be made on the label or in a leaflet with which the vaccine was distributed for use, were made primarily or probably exclusively to veterinarians. Others, such as Zoetis’ publicity materials, were made to the general public, but more particularly to group members and other persons in the equine industry and those who owned horses or whose business involved horses, such as farms or feedlots, who were, or were likely to be, interested in protecting themselves and or their horses or businesses from any adverse impact or risk that HeV posed or might pose. Thus, Zoetis made the 12 publications to wide but diffuse audiences comprised of members of the public as well as, in some cases, a more limited audience that primarily included veterinarians.

41 Whether or not each of the 12 publications on which the applicant relied conveyed one or more of the three representations is a question of fact that must be addressed in the context of the surrounding circumstances: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 84-85 [100]-[101] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ; see too: H Lundbeck A/S v Sandoz Pty Ltd (2022) 399 ALR 184 at 199 [69] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Steward and Gleeson JJ.

42 The evaluation of whether a particular publication conveyed to its audience one or more of the three representations as alleged has to be undertaken by considering whether an ordinary reasonable member of the class comprised of that particular audience would have so understood it: Nike 202 CLR at 85 [102]; see too Ethicon Sarl v Gill (2021) 288 FCR 338 at 516-519 [798]-[810] per Jagot, Murphy and Lee JJ. Importantly, s 18(1) of the ACL does not relieve a person to whom a publication is made, that is alleged to convey a representation that is misleading, from taking reasonable care of, or for, his or her or its own interests: Nike 202 CLR at 85 [102]-[103], applying Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199 per Gibbs CJ and 210-211 per Mason J.

43 Thus, in each case of publication on which the applicant relies, the question is whether the effect of the communication to reasonable members of the class to whom it was made was to convey to them the relevant representation or representations: Nike 202 CLR at 85 [103].

44 I will describe each publication in the chronological sequence in which it was made before turning to whether it conveyed any representation the applicant alleged it did and then its accuracy.

5.1 The first permit disclosure

45 The first permit, which was in force for two years from 3 August 2012, restricted the use of Equivac HeV to vets who had been accredited by completing the Equivac HeV module (which comprised the registration module on which the applicant also relied in respect of conveying the no serious side effects and all horses representations). The first permit required Pfizer (as Zoetis was then named) to supply the Equivac HeV vaccine in a container that complied with the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code Regulations 1995 (Cth) and was labelled in the manner that the permit specified, including a statement: “READ ENCLOSED LEAFLET”. Pfizer and veterinarians had to maintain records of, among other matters, each vaccinated horse, its owner and any reported adverse reaction, including lack of efficacy, resulting from use of the vaccine. Pfizer had to fully investigate and report all adverse reactions to the Authority within 48 hours of receiving a report of an adverse reaction. The form of the leaflet that was part of the first permit stated:

Side Effects

Transient swelling may develop at the site of vaccination in some horses but should resolve within one week without treatment.

46 The leaflet also described the safety trials that Pfizer had conducted that founded the statements about the then-known side effect. It stated that the safety profile of Equivac HeV had been assessed in completely randomised, negatively controlled safety trials in foals and adult horses. The foals had remained healthy throughout the study and there was no evidence of decreased appetite, altered demeanour or abnormal gait. One animal in the vaccinated control group had a higher short-lived rectal temperature following a double dose that resolved by the following morning. Another demonstrated marked pyrexia (ie: increased temperature) at the same time, which, the leaflet stated, indicated that the event might not have been vaccine related. It said 3.4% of adult horses in the vaccinated group had an injection site reaction following the first dose and 34.5% had one the day after the second dose, but seven days after the second dose, all of those reactions had resolved apart from one small lesion in a particular horse that may not have been vaccine related. The leaflet stated there were no systemic vaccine reactions or other abnormal reactions to the vaccine and no adverse events had been reported in the course of the study.

47 Dr L’Estrange said that Equivac HeV went into use in about November 2012.

48 Shortly after Equivac HeV’s public release, Zoetis (then still called Pfizer), the CSIRO, through its Australian Animal Health Laboratory, the Australian Veterinary Association (AVA), Equine Veterinarians Australia and two bodies based in the United States of America, the Henry M Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences published a document headed “Hendra Virus Fact Sheet” (the 2013 fact sheet).

49 The 2013 fact sheet said that HeV was a deadly disease found exclusively in Australia that was transmitted from flying fox to horse, horse to horse and horse to people, having first been discovered in 1994 in the Brisbane suburb of Hendra. It stated:

The virus occurs naturally in flying fox populations across most Australian states and territories with the potential for the disease to appear wherever there are flying fox colonies.

(emphasis added)

50 The 2013 fact sheet said that since 1994, HeV had claimed the lives of 81 horses with more than 30 of those deaths recorded in 2011 and 2012. It stated that of seven confirmed cases of HeV infection in humans, four persons had died, with the most recent death occurring in August 2009. It stated:

Why is the Hendra virus a concern for Australian horse owners?

While the prevalence is low, the Hendra virus is one of Australia’s most lethal viruses. 75 per cent of horses infected with the virus die as a result of the disease, usually within the first two days of showing signs of illness.

The Hendra virus is just as deadly to the humans that come into close contact with infected horses. 57 per cent of humans diagnosed with the disease have died.

How is the Hendra virus spread?

It is thought that horses contract the Hendra virus by ingesting food or water contaminated with infected flying fox body fluids and excretions. The virus can then be passed onto humans if they come into contact with an infected horse’s nasal discharge, blood, saliva or urine.

(emphasis added)

51 The 2013 fact sheet said that, to date, no evidence supported direct or zoonotic transmission or spillover from flying foxes to humans. It stated that clinical signs of HeV infection in horses included, but were not limited to, acute onset of illness, increased body temperature, shifting of weight between legs, depression, increased respiratory rate, nasal discharge, head tilting or circling, muscle twitching and urinary incontinence. The 2013 fact sheet said that ways to reduce the risk of infection in horses included increasing hygiene and cleaning practices, moving horse feed and water containers that were beneath trees to be under shelter so as to avoid potential contamination by flying fox fluids, cleaning and disinfecting all equipment such as halters, lead ropes and twitches, that had been exposed to horses’ bodily fluids, before use on other animals and quarantining any horse thought to be infected. It continued:

How can horse owners and vets protect themselves and others from infection?

In keeping with the Australian Veterinary Association’s policy briefing on the Hendra virus horse vaccine (Equivac® HeV), it is strongly recommended that all horses in Australia are vaccinated against Hendra virus to protect humans from its potentially fatal outcome.

(emphasis added; footnotes omitted)

5.3 The March 2013 media release

52 On 20 March 2013, Zoetis issued a media release, in which it identified itself as formally having changed its name from Pfizer and confirmed its ongoing commitment to educating the equine industry and making Equivac HeV available to horse owners. It stated that:

Zoetis recognised that HeV continued to be a public health concern, “as it is an unpredictable virus that can cause disease and death in both humans and horses.”

Zoetis was working closely with key equine industry members, government bodies and veterinary wholesalers to promote a Hendra vaccination month in April 2013, ongoing education of vets and horse owners, and:

The CSIRO have recently completed a duration of immunity study and greater flexibility around the administration of the vaccine by vets in the near future is a possibility. Additionally, the latest safety data shows that Equivac HeV has exceptionally low incidence of adverse events, with 0.2% of horses displaying minor events.

Equivac HeV vaccine continues to be crucial to breaking the cycle of Hendra virus transmission from flying foxes to horses and then people.

As such, Zoetis remains committed to making the vaccine available in Australia and to supporting veterinarians in their efforts to control Hendra virus. Zoetis also supports the Australian Veterinarian Association’s position that all horses in Australia should be vaccinated against Hendra to reduce equine and human infection.

(emphasis added)

53 Next, in about March 2013, Zoetis produced a two-page pamphlet entitled “Myth Busting Hendra Vaccine” (the myth busting pamphlet). The front page of the pamphlet had a photo of a young woman feeding her horse, under which, in bold yellow and black, appeared the wording, “Vaccinate before it’s too late”. The format of the myth busting pamphlet was to state a myth and then provide Zoetis’ response. The front side relevantly appeared as below:

54 The myth at the bottom of the front page read:

MYTH: There’s no risk of Hendra virus in my area

Hendra virus has been found in all four mainland species of flying foxes in Australia. These bats are found in all mainland states and territories of the country, making exposure possible. For example, bats have tested positive to the Hendra Virus in Melbourne and more recently in South Australia, indicating exposure is possible.

There are many unknowns about how Hendra virus is contracted and bats can fly hundreds of kilometres in a few days – meaning that an apparent absence of bats on a property does not eliminate risk.

55 In addition, on the reverse page of the pamphlet, among other matters, there appeared:

MYTH: The vaccine isn’t safe

Data from the first 24,500 does of the Hendra vaccine administered to horses resulted in only 58 reports from horse owners and veterinarians, with 53 horses categorised as having had a side-effect. The majority of these reports involved injection site swellings, which is not uncommon with any injection in a horse. The adverse event rate to date is approximately 0.22%, placing it in-line with the expected adverse event rate for most vaccines. None of the side-effects reported were serious, and all resolved.

(emphasis added)

56 After about May 2013, and over 25,000 doses in the first six months of use, Zoetis issued an online module to already accredited vets entitled “NEW Hendra virus e-learning module: An update on Equivac HeV vaccine” (the registration module). The registration module stated that:

the module was designed to bring addressees up to date with recent developments on the duration of immunity, the safety, as well as the administration protocol, of Equivac HeV and an update on HeV itself;

Hendra Virus Update

As of 28th April 2013 there have been two confirmed cases of Hendra virus in 2013.

One horse was infected near Mackay, in January 2013.

One horse was infected in the Tablelands area of North Queensland in February 2013.

A Hendra-positive bat was discovered in Adelaide in January 2013, meaning Hendra positive bats are now known to be in six states or territories around Australia.

because clients heavily relied on a vet’s recommendation, vets should recommend vaccination to their clients by saying, among other things, that:

it was “the safest thing for your family and your horses”; and

“[t]he consequences of a Hendra virus outbreak are so severe, it isn’t worth taking the risk. Vaccination is a low cost for the security it provides”;

the AVA’s recommendation was to vaccinate all horses against HeV to protect them and humans from its potentially fatal outcome.

57 The registration module included multiple choice questions based on the information it contained, including about the adverse reaction rate from the first 25,000 doses.

5.6 The September 2013 seminar

58 In September 2013, Dr L’Estrange approved the 30 slides entitled “Hendra virus and the Hendra virus vaccine” for Zoetis staff to use in the September 2013 seminar, which included:

59 The applicant relied on the statement in the slide above, that the antibody had been detected in all four species of flying fox, as conveying the geographic spread representation.

60 The next slide was interactive and set out a timeline from the discovery of HeV in 1994 to 2013, which had details of occurrences of HeV including each location, the numbers of deaths and infected humans and horses in each occurrence and observations of symptoms. The following slide was as below:

61 Other slides described the research from which Equivac HeV resulted, the protocol for administering it, including reference to the first permit, Zoetis’ Health4Horses webpage, that enabled veterinarians to register and check vaccination of a horse using its microchip number, a summary of the results of clinical studies, details of the numbers of vets accredited to administer the vaccine and numbers of vaccinated horses. Zoetis presented the reader with further slides that recorded “current stakeholder positions”, including statements:

“The AVA believes that all horses should be vaccinated against the Hendra virus” under the heading “Reducing Hendra risk”,

recommending vaccination of horses by then Queensland Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, the Hon John McVeigh MLA, Racing Queensland, and the New South Wales and Queensland Governments’ biosecurity agencies, and

Equestrian New South Wales’ mandate that any horse attending any event in that State had to be vaccinated with Equivac HeV as of 1 January 2014.

5.7 The Health4Horses website information

62 On 10 October 2013, Zoetis posted on its Health4Horses webpage a page headed “Widespread Risk” with a subheading “Hendra Virus: Presumed Transmission Pathway” (the Health4Horses website information). The page reproduced a flying fox distribution map that was similar to those at [19] and [58] above. Above the map, this page stated:

Hendra virus can occur wherever there is overlap of flying foxes and horses. Because of the large distances that flying foxes travel, Hendra virus outbreaks could occur across a large proportion of the country.

(emphasis added)

63 Underneath the map, the page stated: “Bats carrying the Hendra virus are present in six states or territories around Australia”.

5.8 The every horse owner pamphlet

64 In December 2013, Zoetis published a pamphlet headed “Hendra Vaccination: What every Australian horse owner needs to know” (the every horse owner pamphlet). The pamphlet stated, among other matters:

65 After a page entitled “The enormous impact of Hendra virus” that discussed the fatality rate and health consequences for the three humans who survived the virus and the effect of infection on those in the equine industry, the next page appeared as below:

66 The remainder of the every horse owner pamphlet identified the signs of HeV in horses and humans and urged that vaccination was the best protection against it.

5.9 The second permit disclosure

67 The second permit continued the restrictions on the administration and use of Equivac HeV and the requirements to report and investigate fully all adverse reactions that the first permit had imposed. The second permit expanded the content of the leaflet under the side effects heading to the following:

Side Effects

Transient swelling may develop at the site of vaccination in some horses but should resolve within one week without treatment.

In some horses transient post-vaccination reactions including injection site reaction, pain, increase in body temperature, lethargy, inappetance [sic], and muscle stiffness have also been observed. Rarely reported symptoms have included urticaria, mild peripheral oedema and mild transient colic. Symptoms may vary in severity and on some occasions may require veterinary intervention.

Systemic allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis are thought to occur rarely with all vaccines and may require parenteral treatment with adrenaline, corticosteroid and antihistamine as appropriate and should be followed with appropriate supportive therapy.

(emphasis added)

68 Urticaria is hives or small swelling under the skin, and colic is a general term for abdominal pain. Oedema is swelling. I have discussed urticaria, colic and oedema below in dealing with the expert evidence at [240]-[251]. Inappetence is loss of appetite. The leaflet included substantially the same information as to the safety profile of Equivac HeV as in the first permit’s leaflet.

5.10 The facts about HeV pamphlet

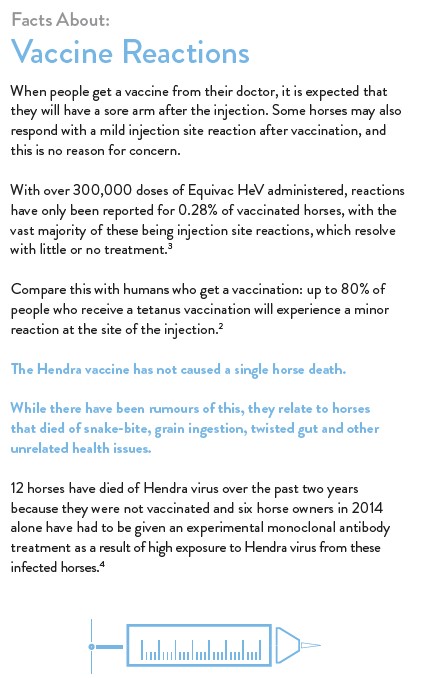

69 In about December 2014, Zoetis published as part of its Health4Horses series a two page pamphlet headed: “Facts About: The Hendra vaccine” (the facts about HeV pamphlet). The applicant relies on this pamphlet as conveying the no serious side effects representation.

70 The pamphlet outlined on the left hand side of the front page the research studies and testing of Equivac HeV that provided the basis of the Authority’s grant of the permit for its use. It told the reader that in the field studies, “the only reactions seen were temporary injection site swellings in some horses”.

71 The front page then stated on its right hand side:

72 Across the foot of its front page, the pamphlet stated the following:

“The Hendra vaccine has been subject to the same level of rigorous safety and efficacy testing as other vaccines on the equine market.”

Dr Deborah Middleton: Research Team Leader and Senior Veterinary Pathologist, CSIRO

73 On the reverse page of the pamphlet, Zoetis explained that it had an obligation to report suspected reactions to the Authority and it advised horse owners to report to their vet, Zoetis or the Authority any suspected reaction to the Equivac HeV.

74 The reverse page had quotes attributed to, first, Dr Padraig Kelly, the resident veterinarian of Coolmore stud in the Hunter Valley in New South Wales and, secondly, Megan Jones, an Olympic silver medal winner, who operated a stud farm in the Adelaide Hills. Both recommended vaccinating horses with Equivac HeV. In his quote, Dr Kelly expressly acknowledged that the Hunter Valley “is not located in a high-risk area, [but] we deem it prudent to be proactive in terms of protecting against the risks posed by the disease”. The quote did not refer to any reaction of a horse at Coolmore stud. Ms Jones stated that in the Adelaide Hills, “there is a risk of Hendra virus from fruit bats. In addition, a number of our horses and our clients’ horses travel interstate for competitions, which also poses a risk”. She said that her stud was not prepared to take a risk of contracting HeV and that they had “seen only one minor site reaction, which was temporary and not threatening to the horse’s health”.

75 A summary at the foot of the reverse page of the facts about HeV pamphlet stated:

5.11 The third permit disclosure

76 The third permit again continued the restrictions on the administration and use of Equivac HeV as well as the requirements for Zoetis to report and investigate fully all adverse reactions that the first and second permits had imposed. The description of side effects that had to be stated in the leaflet was slightly, but not materially, different to that required in the second permit. I have highlighted the changes below, namely from “Rarely reported symptoms” to “Additional reported clinical signs”, “Symptoms” to “Clinical signs” and, where the ellipsis is in the last paragraph, the deletion from the side effects stated in the second permit leaflet in [67] above of “are thought to occur rarely with all vaccines and”):

Side Effects

Transient swelling may develop at the site of vaccination in some horses but should resolve within one week without treatment.

In some horses transient post-vaccination reactions including injection site reaction, pain, increase in body temperature, lethargy, inappetence, and muscle stiffness have also been observed. Additional reported clinical signs have included urticaria, sweating, mild peripheral oedema and mild transient colic. Clinical signs may vary in severity and occasionally may require veterinary intervention.

Systemic allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis […] may require parenteral treatment with adrenaline, corticosteroid and antihistamine as appropriate and should be followed with appropriate supportive therapy.

(emphasis added)

5.12 The Equestrian Life letter

77 The January 2016 issue of Equestrian Life Australia Magazine published Dr L’Estrange’s letter to its editor dated 2 November 2015. He appeared to be responding to a single critic’s views that the magazine had published in its November/December 2015 edition. Dr L’Estrange wrote:

Hendra virus is a deadly zoonotic disease that has killed four people and nearly 100 horses.

Its incidence is increasing. In the past five years, there have been more than 40 spillover events in Queensland and New South Wales. In every case, at least one horse dies. I have witnessed the devastating effects this virus has on those involved: the fear of exposure, an agonising 30-day wait to be cleared, and the regret expressed by owners that they didn’t protect themselves, their families, friends and horses with vaccination.

Hendra virus is rare, but its symptoms in horses are non-specific and easily mistaken for common conditions. Some horses appear to have colic, others may simply go off their feed or appear lethargic. There have even been infected horses without any noticeable symptoms. Veterinarians face the difficulty of diagnosis, suiting up and suiting down in full PPE in heat and humidity, unable to leave behind medications and warning owners to stay away from a horse that probably will not have Hendra but where the safety-first approach must be paramount. Communication from Queensland government authorities to veterinarians recently has been to the effect that “if Hendra cannot be ruled out, then it must be ruled in.”

…

In 2014, six horse owners had exposure to Hendra virus considered so extreme they were offered an experimental treatment in a Brisbane hospital. The treatment is administered intravenously, with adrenalin at the ready, in case of anaphylaxis.

This year, workplace health and safety prosecutions were commenced against three veterinarians who were accused of not maintaining a safe workplace. Horses they treated turned out to have Hendra virus.

Veterinarians face a real threat to their health and now a legal threat to their livelihoods when diagnosing and treating unvaccinated horses. Veterinarians, of course, are not the only people with workplace health and safety obligations, which is why sporting bodies, event organisers and others often conclude that vaccination is an obvious, sensible precaution.

The Hendra vaccine became available in late 2012 following ground-breaking work by the CSIRO, Zoetis and international research partners. As part of the original permit, veterinarians were required to report every suspected adverse event, and every dose has been documented and administered by a veterinarian.

Zoetis assesses each report received and classifies it as to the likelihood of the symptoms reported being attributable to vaccine administration. All reports are conveyed to the APVMA which makes an independent assessment.

(emphasis added)

78 Dr L’Estrange continued:

I have personally examined every adverse event report concerning the Hendra vaccine received by Zoetis. The majority are typical of the experiences many people have with human vaccines: temporary soreness or swelling around the injection site, sometimes a temperature, or being off colour for a day or so. Phenylbutazone (bute) is commonly recommended by veterinarians for the treatment of horses experiencing an adverse reaction or as a preventative for horses that have previously experienced a reaction, but is not recommended for horses that have not experienced a reaction.

Australia’s very thorough regulator had the benefit of seeing the adverse report data generated from 350,000 doses administered as part of the registration application. The APVMA was satisfied as to the safety of the vaccine and proceeded to register it. The vaccine is demonstrably safe and effective. It is widely used as a health and safety tool by owners, breeders and the mounted units of state police forces.

(emphasis added)

Everyone involved with horses in Australia is fortunate to have a safe, high quality vaccine to help protect against a deadly virus. The Hendra vaccine deserves wider use to protect horses, veterinarians, owners and their families.

Owners should speak with their veterinarian in order to make a sensible and informed decision as to whether to vaccinate their horses.

(emphasis added)

6. Was the geographic spread representation (there was a serious risk of horses contracting Hendra in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present) conveyed?

6.1 The applicant’s submissions

80 The applicant argued that each of the following six publications (the geographic spread publications) read separately and together conveyed the geographic spread representation, namely, the 2013 fact sheet, the March 2013 media release, the myth busting pamphlet, the September 2013 seminar, the Health4Horses website information, and the every horse owner pamphlet.

81 The applicant argued that each of the geographic spread publications misrepresented the nature and degree of the risk of horses contracting HeV. She contended that each of the six publications falsely asserted the magnitude of the risk as being “a serious risk of horses contracting Hendra in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present” (emphasis added). She contended that, as Professor Ward’s report made clear, the risk was extremely low outside the Hendra area, indeed, “miniscule”, being 1 or 2 in 1,000,000. She asserted that each of the six publications had overpitched the magnitude of the risk of horses catching HeV both in and out of the Hendra area. She argued that the referee’s finding that, even in the Hendra area, the risk of a horse being infected with HeV was only 1 or 2 in 10,000, and that in 25 years no horse outside the Hendra area had been infected, rendered the geographic spread representation misleading.

82 The applicant contended that in the myth busting pamphlet, Zoetis’ campaign reached its high watermark by impelling owners to “Vaccinate before it’s too late”, based on the fear that a horse could catch the virus anywhere in Australia and so put both the animal and those humans who came in contact with it at risk. The prompt to take immediate action, she claimed, was reinforced by the statement that wherever bats were the serious risk existed that they could carry and spread the virus.

83 The applicant also relied on the unqualified statement in the every horse owner pamphlet as to the areas in which bats can be found. That pamphlet was focused on, and directed to, horse owners.

84 The applicant claimed that each of the six geographic spread publications conveyed misleadingly that, wherever flying foxes were present in Australia, there was a serious risk that a horse could become infected with HeV and that the horse owner should therefore vaccinate their horse to prevent that serious risk maturing. She contended that the six publications conveyed that because all species of flying fox carried HeV, were thought to be the means by which horses became infected and were present throughout Australia, the risk of equine infection was “serious”. She submitted that the miniscule magnitude of the risk, as found by the referee, was never communicated to the public, including group members. She asserted that the group members had been “entitled to know the magnitude of the risk before they wasted their money” on paying for vaccination or treatment of horses that suffered an adverse side effect from it.

85 The applicant argued that because Chinchilla was just on the west side, but not west, of the Great Dividing Range, and was the place furthest to the west where there had been a confirmed HeV infection, it was misleading for Zoetis to represent that there was a serious or significant risk in the vast land mass to the west of the Great Dividing Range. She contended that it was syllogistic for the geographic spread publications to posit that, because HeV occurred naturally in flying foxes and they were present across most States and Territories, therefore there was a serious risk of infection wherever they were without adverting to the fact that no cases had been detected outside the Hendra area.

86 She argued that, for example, Agriculture Victoria had published “An Assessment of the Hendra virus Situation in Victoria” on 12 July 2011 in which it stated that there had been no cases of HeV infection in any horse in Victoria. The applicant asserted that, in approximately June 2013, the Chief Veterinarian of Victoria had asserted to a vet in private practice in Maffra, a dairy district in that State, that “IT WONT [sic] BE HENDRA, we don’t get hendra in Victoria”, as Dr L’Estrange had recorded in an email dated 26 June 2013 to officers in the Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. She argued that the Victorian Chief Veterinarian “knew of the real level of risk” in that State and that Zoetis ignored this information in its publications, such as in the heading “Widespread Risk”, on the Health4Horses website information that it posted on 10 October 2013.

87 The applicant also contended that Zoetis did not have reasonable grounds for making the geographic spread representation to the extent that it was made with respect to any future matter within the meaning of s 4 of the ACL. The applicant argued that contemporaneous scientific literature, of which Zoetis was aware, confirmed that no cases of HeV had occurred outside the Hendra area and that the risk of the virus being transmitted (or there being a spillover) from flying foxes to horses or humans was sporadic and connected to an outbreak in a colony. She cited the abstract of a paper entitled “Hendra Virus Infection Dynamics in Australian Fruit Bats” by H Field and others published in December 2011. The abstract stated that the researchers’ findings showed that flying fox HeV excretions occurred periodically, “rather than continuously, and in geographically disparate flying fox populations in the state of Queensland”. The applicant argued that this, and similar publications which Dr L’Estrange had read before writing or approving the geographic spread publications, had identified HeV infections as only having ever occurred in the Hendra area, so that the generalised expression in those publications in respect of the risk of HeV infection wherever bats were found was misleading. She also contended that the geographic spread publications were misleading because there had been no known case of horse to horse transmission of HeV infection, yet the publications, such as the every horse owner pamphlet, suggested that this was possible (see [65] above). The applicant accepted that the transmission mechanism for HeV to horses was unknown, but she contended that the geographic spread publications’ “elevat[ion of] speculation to a statement of fact is misleading”.

88 The issue is whether the geographic spread publications convey that “there was a serious risk of horses contracting Hendra in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present”?

89 Mason J explained in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40 at 47-48, with the agreement of Stephen J and Aickin J, what the perception and evaluation of the nature of a risk involves in ordinary human experience (on which a jury would have to act) as:

The perception of the reasonable man’s response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have. It is only when these matters are balanced out that the tribunal of fact can confidently assert what is the standard of response to be ascribed to the reasonable man placed in the defendant’s position.

The considerations to which I have referred indicate that a risk of injury which is remote in the sense that it is extremely unlikely to occur may nevertheless constitute a foreseeable risk. A risk which is not far-fetched or fanciful is real and therefore foreseeable. But, as we have seen, the existence of a foreseeable risk of injury does not in itself dispose of the question of breach of duty. The magnitude of the risk and its degree of probability remain to be considered with other relevant factors.

(emphasis added)

90 In my opinion, the 2013 fact sheet explained in a balanced way that the prevalence of the virus was low but that, if a horse became infected with HeV, there were life threatening consequences for the animal and any human who came into contact with it that had to be considered and prevented. It conveyed that the reason for this was not because, necessarily, there was a real possibility of a horse contracting HeV anywhere in Australia where flying foxes were present but because, although there was some possibility of that occurring, the gravity of the consequences were that event to occur would be severe.

91 The ordinary reasonable member of the class or other reader (whom I will describe in these reasons as the ordinary reasonable reader or the reader) would have read the 2013 fact sheet as a whole.

92 The reader would have read in it that since 1994, HeV had claimed the lives of 81 horses, which comprised 75% of the total number of horses infected. The 2013 fact sheet said in terms that “the prevalence is low” but that HeV “is one of Australia’s most lethal viruses”. The thrust of the 2013 fact sheet was that the risk of infection was small, but real, and connected to flying foxes in which HeV occurs naturally. The reader would have understood that HeV infections in horses and humans were very rare but were likely to be deadly when they did occur.

93 The 2013 fact sheet conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader that the risks of equine HeV infection and potential horse and human transmission would be minimised by vaccinating horses with the new Equivac HeV. The reader would have understood the 2013 fact sheet to say that the magnitude of the risk maturing into an infection is very slight, but not fanciful or far-fetched, and that if there were an infection the consequences would be serious.

94 The ordinary reasonable reader would have understood that prior outbreaks of HeV had been the subject of considerable publicity and public concern but that those outbreaks were rare. The 2013 fact sheet accurately conveyed the consequences of past HeV outbreaks and the fact that while only 81 horses had died since 1994, over 30 of those deaths had occurred in the previous two years (in 2011 and 2012).

95 The ordinary reasonable reader of the 2013 fact sheet would have understood from it that, over the previous 18 years, the consequences of horses and humans contracting HeV were extremely grave and that the risk of that happening, while not large, was real wherever flying foxes could travel. This was the basis for the recommendation of Zoetis (then named Pfizer) and its co-publishers (the CSIRO, the AVA, Equine Veterinarians Australia and the two United States medical bodies) that all horses in Australia be vaccinated to protect humans from HeV’s potentially fatal outcome.

96 I reject the applicant’s argument that, based on the referee’s findings, the magnitude of the risk that a horse (or human) could contract HeV, even in the Hendra area, precluded any suggestion that the risk, in the sense of the magnitude of the risk occurring (as opposed to its consequences if it did), was “weighty” or “grave” or “threatening” (see the definitions of “serious” in Macquarie Dictionary Online: sense 5, Oxford English Dictionary online: senses 3a, b).

97 In my opinion, the 2013 fact sheet did not convey the geographic spread representation. That is because the ordinary reasonable reader would not have understood it to be saying that the magnitude of the risk of horses contracting HeV in all areas of Australia was a “serious risk” in the sense which the applicant asserted. The publication conveyed in a balanced way that there was a real, albeit very low, risk but it was one which merited the precaution of vaccination rather than taking the chance of the potential serious or dire consequences of inaction.

6.2.2 The March 2013 media release

98 The March 2013 media release made the point that HeV continued to remain a health concern and “an unpredictable virus that can cause disease and death in both humans and horses.” Equivac HeV was “crucial to breaking the cycle of Hendra virus transmission from flying foxes to horses and then people”. Zoetis said in it that it supported the recommendation of the AVA that all horses ought be vaccinated (as set out at [52] above).

99 The ordinary reasonable reader would not have understood the March 2013 media release as conveying that there was a “serious risk”, in terms of magnitude of the likelihood of horses catching the disease, in the sense on which the applicant relied.

100 I am of opinion that the applicant’s reading of the 2013 March media release is strained and far-fetched. The reader would have understood it to convey that inoculating horses with Equivac HeV would provide protection against the possibility that, although unpredictable, HeV could infect them and, through that mechanism, humans. The reader would not have read it as conveying that there was a “serious” risk of a horse contracting HeV.

101 It is important to distinguish between what is a real, foreseeable risk of a serious consequence occurring if a horse became infected with HeV, on the one hand, and the magnitude or degree of probability of that risk occurring, on the other. This is the point that Mason J made in Shirt 146 CLR at 47-48 in the passage I have quoted in [89] above. The applicant’s attempt to discern the geographic spread representation as conveyed in the March 2013 media release (and the other geographic spread publications) distorts the distinction. The publication was stating a truism in recounting to the reader that HeV is a virus that can cause disease and death and, as such, is a serious matter of concern for persons employed in the equine industry in Australia.

6.2.3 The myth busting pamphlet

102 The myth busting pamphlet stated in terms on the first page (see [53] above):

There are many unknowns about how Hendra virus is contracted and bats can fly hundreds of kilometres in a few days – meaning that an apparent absence of bats on a property does not eliminate risk.

(emphasis added)

103 The applicant also relied on the injunction to “Vaccinate before it’s too late” as conveying that there was risk of considerable magnitude in all areas in which flying foxes were present.

104 In my opinion, the ordinary reasonable reader of the myth busting pamphlet would have understood it to be conveying that, in terms of the old adage, it is better to be sure than sorry. The pamphlet made clear that there were many unknowns about how HeV is contracted. It stated the fact that bats are found in, and can travel across, large areas of Australia where horses could be present.

105 The reader would also have been aware, particularly since a horse owner is likely to have followed stories about HeV and horses over the course of the previous 18 years, that the virus had caused known infections very rarely but that on those occasions there had been deleterious consequences.

106 In that context, the reader would have understood the pamphlet to be doing no more than asserting, as an advertisement by Zoetis, that, now that a vaccine was available, it was better to vaccinate one’s horse now rather than to regret the realisation of the risk that HeV might appear on the owner’s property and affect his or her horse. The reader would not understand the myth busting pamphlet to be saying that there was a risk of considerable or significant magnitude in all areas of Australia that horses would contract HeV. Rather, it was saying that no one knows whether or not the virus is able to be transmitted in all areas of Australia where there are bats, so that, as a matter of common sense, it would be prudent to use the new vaccine that could eliminate the risk entirely.

6.2.4 The September 2013 seminar

107 The slides, read as a whole, conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader that “Australian flying fox populations coincide with the areas of greatest risk for Hendra virus” and that flying foxes were a natural host for HeV. The slides informed readers, accurately, that HeV antibodies are present in all four mainland species of flying fox, but that there was no definitive data on how the disease spread from bat to bat; no data as to how it spread from bat to horse and no evidence of it spreading from bats to humans. The seminar slides set out a brief history of the virus from 1994 to a case that had appeared in 2013 in Mackay in the Tablelands area of Queensland. It noted that there had been about 30 occurrences affecting a total of around 80 horses over the 19-year timeframe including two large outbreaks, one in 1994 in which 14 of the 20 horses affected died, and one of the two people infected had died, and the second in 2008 in Redlands in Queensland where four of the five horses infected had died and one of two people infected had died.

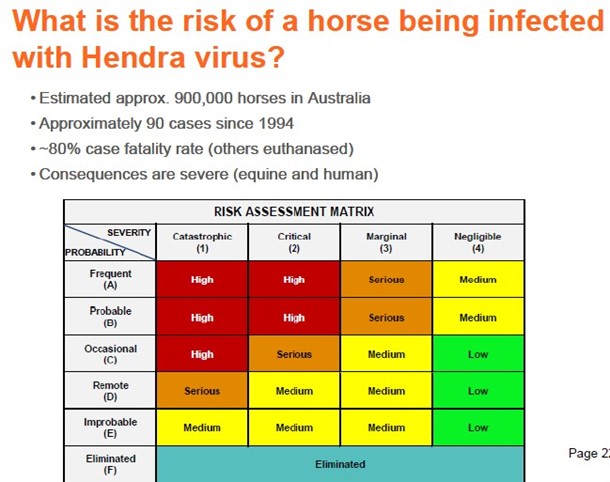

108 The slide headed “What is the risk of a horse being infected with Hendra virus?” (see [60] above) stated that there were approximately 900,000 horses in Australia, 90 cases since 1994, with an 80% fatality rate, and other horses had had to be euthanised that had come into contact with the deceased horses.

109 The ordinary reasonable reader of the September 2013 seminar slides would not have understood them to convey that there was a substantial or serious risk that horses could contract HeV in all areas of Australia. Such a construction would be fanciful. The reader would know that, if there had only been about 90 cases in 30 outbreaks, including the two larger ones in Hendra and Redlands, over the preceding period of 19 years, equine HeV infection was an extremely rare event, apparently somewhat random and connected to the presence of flying foxes in the area. The ordinary reasonable person would not have understood that the September 2013 seminar conveyed the geographic spread representation.

6.2.5 The Health4Horses website information

110 The Health4Horses website information had a heading “Widespread Risk” and a subheading “Hendra Virus: Presumed Transmission Pathway” that informed the reader that HeV “can occur wherever there is overlap of flying foxes and horses” and that, because flying foxes have a wide geographic presence, outbreaks of HeV could occur across a large proportion of Australia.

111 Those statements were accurate and did not inflate, to “a serious risk”, the magnitude of the real and foreseeable possibility that horses could contract HeV. Rather, as with the other geographic spread publications, the website information conveyed, in a balanced way, that there was a real, but unpredictable, risk of an outbreak of HeV where flying foxes were present and the reader might wish, as a matter of common sense, to guard against it by vaccinating his or her horses.

6.2.6 The every horse owner pamphlet

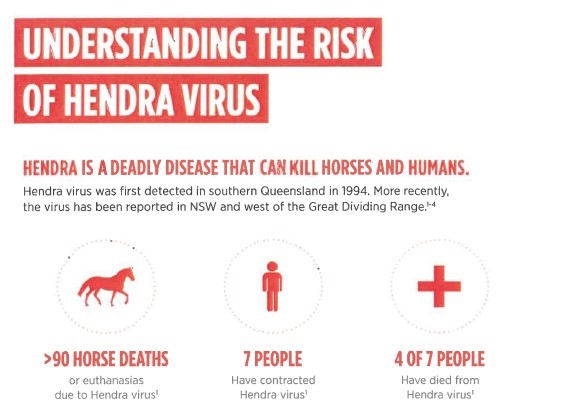

112 The every horse owner pamphlet identified that HeV had caused over 90 horse deaths (directly or because of the need to euthanise) and that, of seven people infected, four of them had died.

113 The ordinary reasonable reader of the pamphlet would not have understood it to convey that there was a serious risk throughout Australia of horses contracting HeV. Like the other geographic spread publications, the pamphlet was factually accurate in stating how all species of flying fox carried HeV, outbreaks were rare and had occurred sporadically but randomly in Queensland and more recently in New South Wales and west of the Great Dividing Range. The reader would have understood that, among other things, the pamphlet conveyed that movement of horses could also pose a risk of spreading infection from HeV. It quoted Associate Professor James Gilkerson, the director of the Centre for Equine Infectious Diseases at the University of Melbourne, as saying:

This is an endemic disease. It is not going away … The best way to protect ourselves and the best way to protect our horses is to have the horses vaccinated.

(emphasis added)

114 In my opinion, that was a statement of obvious common sense and captured what the ordinary reasonable reader of the pamphlet would have understood it to be saying, namely, that as a matter of common sense, Equivac HeV could eliminate any risk of the uncommon and random chance that there could be an outbreak of HeV which would put not only the horses but humans who came into contact with them in peril of serious consequences, including death.

115 For the reasons above, I am not satisfied that any of the geographic spread publications, read in isolation or together, conveyed the geographic spread representation.

116 I reject the applicant’s argument that, because the geographic spread publications failed to convey to the reader that between 1994 and 2012, there had been no case of any horse contracting HeV outside the Hendra area, the absence of such a qualification would have led the reader to believe that the magnitude of the risk was serious, being far greater than was the reality.

117 If I am wrong and the omission of some further definition of the risks in and out of the Hendra area, of the nature that the referee’s report specified, in any of the geographic spread publications caused the geographic spread representation to be conveyed, that omission could not amount to conduct that contravened s 18(1) of the ACL. That is because, in making a considered decision whether to vaccinate one or more horses, an owner or a vet or other group member can be expected to do more than act on the vaccine vendor’s self-promotion. An ordinary reasonable member of the class is not a person who would make an impulsive decision to vaccinate his or her horse without reflection or thought.

118 A consumer who looks at furniture that resembles another manufacturer’s product can be expected to look more closely for any distinguishing marks or labels as part of making a considered decision whether to buy. The person cannot say that he or she was misled by a mark where the label identifies the maker: Puxu 149 CLR at 199, 210-211. As Mason J said of such a decision (at 211):

taking into account the importance both financially and aesthetically of the relevant furniture, my conclusion is that a purchaser who considered it important to acquire Post and Rail “Contour” furniture could reasonably be expected to look for and find the label or to take comparable steps, such as inquiring of a salesman, to ensure that furniture from the “Contour” range was being purchased.

(emphasis added)

Similarly, Gibbs CJ said (at 199):

Although it is true, as has often been said, that ordinarily a class of consumers may include the inexperienced as well as the experienced, and the gullible as well as the astute, the section must in my opinion be regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class. The heavy burdens which the section creates cannot have been intended to be imposed for the benefit of persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. What is reasonable will of course depend on all the circumstances. The persons likely to be affected in the present case, the potential purchasers of a suite of furniture costing about $1,500, would, if acting reasonably, look for a label, brand or mark if they were concerned to buy a suite of particular manufacture.

The conduct of a defendant must be viewed as a whole. It would be wrong to select some words or act, which, alone, would be likely to mislead if those words or acts, when viewed in their context, were not capable of misleading.

(emphasis added)

119 In my opinion, the geographic spread publications conveyed only that there was a real risk of horses contracting HeV in all areas of Australia in which flying foxes were present. As Professor Ward’s report found, that was correct, bearing in mind that the risk was nonetheless real and could be guarded against. The publications did not convey the magnitude of the risk as “serious” or suggest that there was any significant probability of it occurring. Rather, the thrust of the geographic spread publications’ discussions of the risk was to recognise its unforeseeability, the randomness and rarity of its occurrence over the preceding years since 1994 in juxtaposition with the very serious consequences that HeV infection posed for horses and humans if and when it did occur.