FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Konami Australia Pty Limited (No 3) [2022] FCA 1373

Table of Corrections | |

[172] insert the words “and claimed” in eighth sentence | |

[183] substitute “with” for “without” in the first sentence | |

[250] amend last sentence to read “… a significant market for EGMs that included a standard game only, which EGMs …” | |

[255] delete the word “configurable” in the first sentence | |

[475] delete the words “in the 2021 year” in the last sentence | |

Confidential information in [504], [505], [509], [510] and [560] has been redacted |

ORDERS

ARISTOCRAT TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 001 660 715) Applicant | ||

AND: | KONAMI AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 076 298 158) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties’ external legal representatives and accounting experts confer for the purpose of calculating:

(a) the amounts (exclusive of interest) that the respondent is required to pay in profits and damages in accordance with the reasons for judgment published today (Reasons); and

(b) interest pursuant to s 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that takes into account, in the case of profits, the financial year in which they were made and, in the case of damages, the financial year in which the NCCs were supplied.

2. The parties are to notify the Associate to Nicholas J as soon as practicable if:

(a) there is any disagreement in relation to the calculations referred to in order 1;

(b) there is any disagreement in relation to the appropriate form of costs order; or

(c) the parties or the accounting experts seek clarification of any ruling in the Reasons.

3. Up to and including 12 December 2022 or until further order, and subject to order 4, the disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the text of the Reasons be prohibited, other than to and as between:

(a) the external legal representatives of the parties;

(b) any independent expert retained by the parties; and

(c) Court staff.

4. Notwithstanding order 3, the external legal representatives of the parties may disclose to their respective clients (the parties):

(a) the substance of the Reasons; and

(b) so much of the text of the Reasons;

that does not disclose any facts or information in the Reasons which are the subject of orders 2, 3 and 4 of the Orders made on 13 March 2020 (Suppression Orders).

5. On or before 2 December 2022, so as to permit publication of the Reasons, the parties are to confer regarding the following:

(a) what, if any, redactions ought be made in respect of any confidential information in the Reasons having regard to the Suppression Orders; and

(b) whether the Suppression Orders ought be varied and, if so, what variations should be made.

6. On or before 7 December 2022, the parties are to file and serve:

(a) a joint statement setting out the matters in order 5 above which are agreed between them;

(b) failing agreement on any matters in order 5 above, competing orders, redactions (if necessary) and short submissions (limited to 2 pages) in support of their respective positions;

(c) any affidavit evidence to be relied on in support of any application for orders restricting publication of any part of the Reasons.

7. The proceeding be fixed for further hearing at 9.30am on 12 December 2022 for the purpose of making final orders and any further interlocutory orders restricting publication of any part of the Reasons.

8. Each party is given liberty to apply on 3 days’ notice.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NICHOLAS J:

1 These reasons concern the quantification of the profits for which the respondent (“Konami”) is liable to account to the applicant (“Aristocrat”) in respect of certain infringements of Australian Patent No 754689 (“the 689 Patent”) and Aristocrat’s entitlement to damages in respect of other infringements of the 689 Patent. The relevant infringements occurred in the period from August 2005 to August 2017.

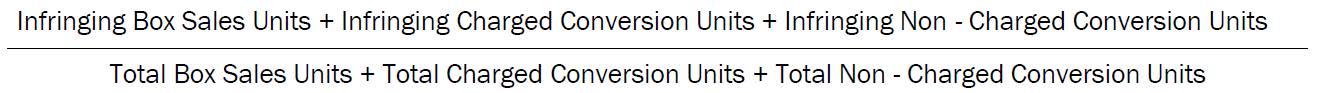

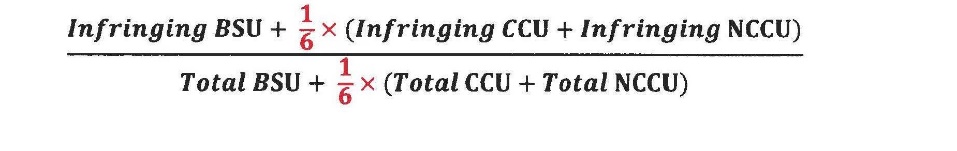

2 The largest component of Aristocrat’s claim concerns profits made by Konami from the sale of 6,931 electronic gaming machines (“EGMs”) on which infringing games were installed and 4,647 conversions for the installation of an infringing game on an existing EGM. The damages claim is concerned with conversions made by Konami without charge. Each of these were referred to in evidence as a “no charge conversion” or a “NCC”. There were 7,380 no charge conversions in respect of which Aristocrat claims both compensatory and additional damages.

3 Findings of validity and infringement were made at an earlier stage of this proceeding: Aristocrat Technologies of Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 (“Konami 1”). On 5 August 2015 declarations and an injunction were granted and the Court also ordered an inquiry as to damages or profits in respect of Konami’s infringement of the 689 Patent. Konami’s appeal against those orders was dismissed by a Full Court on 12 August 2016: Konami Australia Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd (2016) 119 IPR 402; [2016] FCAFC 103 (“Konami 2”).

4 With regard to the account of profits claim, there is a significant dispute between the parties as to whether or not the revenue received by Konami should be apportioned to reflect what Konami says is the fair and reasonable measure of the role played by the invention (which Konami says in substance is “the trigger” mechanism) in generating the profits made by Konami from the 689 Games. It is fair to say that Konami contends that the contribution made by the trigger mechanism to those profits was slight.

5 Aristocrat contends that apportionment is not available in this case and that after allowing for what Aristocrat concedes to be properly deductible expenditure, an amount of approximately $80 million (exclusive of interest) should be awarded in respect of the account of profits. Konami says that only a small fraction of that amount should be awarded.

6 In respect of those infringements where Konami did not receive any revenue (the NCCs) Aristocrat claims damages under s 122 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) of approximately $14 million on a reasonable royalty basis ($1,900 multiplied by 7,380 NCCs) and an unspecified sum by way of additional damages. Aristocrat also claims compensatory damages for breach by Konami of a licence agreement entered into between Aristocrat and Konami on 24 June 2011 (“the Konami Licence”). Konami says that no damages (whether compensatory or additional) should be awarded in respect of the NCCs.

The declaratory, injunctive and other relief

7 On 5 August 2015, the infringement declaration made was in these terms:

1. The Respondent has infringed:

(a) claims 1 – 4, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 37, 38, 43, 55 and 56 of Australian Patent 754689 (“689 Patent”) by exploiting the gaming machine product and/or a gaming machine system comprising a bank of linked or networked gaming machines under or by reference to the name Free Spin Dragons; and

(b) claims 1 – 4, 16, 25, 27, 28, 37, 43 and 55 of the 689 Patent by exploiting the gaming machine products and/or a gaming machine system comprising a bank of linked or networked gaming machines under or by reference to the names High Velocity Grand Prix, King’s Reward and any jackpot game operating under the “Cash Carriage” brand,

collectively referred to in these orders as the “Infringing 689 Products”.

8 The injunction granted was in these terms:

The Respondent, whether by itself, its directors, its servants, agents or otherwise, is restrained in Australia from infringing claims 1 – 4, 16, 17, 25, 27, 28, 37, 38, 43, 55 and 56 of the 689 Patent during its term and, without limiting the foregoing, the Respondent, whether by itself, its directors, its servants, agents or otherwise, is restrained in Australia during the term of the 689 Patent from, without the licence or authority of the Applicant:

(a) making, hiring, selling or otherwise disposing of, or offering to make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described;

(b) using or importing the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described;

(c) keeping the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described for the purposes of doing any of the acts referred to in (a) and (b);

(d) using the method of the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described; and

(e) authorising others to use the method of the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described.

9 There was also an order for an inquiry as to damages or profits in these terms:

9. There be an inquiry as to damages or profits in respect of the Respondent’s infringement of the 689 Patent by the Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described and as to damages in respect of the Respondent’s breach of contract, such inquiry to be listed for directions before Justice Nicholas on a date and time to be fixed after the determination of any appeal from these orders.

10 On 1 September 2017 Aristocrat gave notice of its election as follows:

Where Konami generated revenue from the supply of the 689 Games, Aristocrat elects to claim Konami’s profits referable to those supplies; and

Where Konami asserts it supplied 689 Games on a “no charge” basis and did not generate revenue, Aristocrat elects to claim damages referable to those supplies.

Konami did not challenge the validity of the mixed nature of the election which it appears to have regarded as open in light of the decision in LED Builders Pty Ltd v Eagle Homes Pty Ltd (1999) 44 IPR 24 (Lindgren J). However, the mixed nature of the election has given rise to various complexities including whether any damages awarded in respect of the manufacture and supply of NCCs should be treated as allowable expenditure in calculating the profit made by Konami from the revenue generating supplies of the 689 Games.

11 The claims infringed by Konami were in the following terms:

1. A random prize awarding feature to selectively provide a feature outcome on a gaming console, the console being arranged to offer a feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition, the console including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console.

2. The prize awarding feature of claim 1, wherein the trigger condition is determined by an event having a probability related both to expected turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console and the credits bet on the respective game.

3. The prize awarding feature of claim 1 or 2, wherein the console is arranged to play a main game, during which testing for the trigger condition will occur, and the feature outcome initiated by the trigger condition is the awarding of one or more feature games.

4. The prize awarding feature of claim 3, wherein the main game is a standard game normally offered on the console and each feature game is a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize.

…

16. The prize awarding feature as claimed in any one of the preceding claims wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of winning a major prize than in the main game.

17. The prize awarding feature as claimed in claim 16, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

…

25. A gaming console including a prize awarding feature to produce a feature outcome, the console being arranged to offer the feature outcome when a game has achieved a trigger condition and including trigger means arranged to test for the trigger condition and to initiate the feature outcome when the trigger condition occurs, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console.

…

27. The gaming console of claim 25 or 26, wherein the console is arranged to play a main game, during which testing for the trigger condition will occur, and the feature outcome initiated by the trigger condition is the awarding of a feature game.

28. The gaming console of claim 27, wherein the main game is a standard game normally offered on the console and the feature game is a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize.

…

37. The gaming console as claimed in any one of claims 25 to 36, wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of success than the main game.

38. The gaming console as claimed in claim 37, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

…

43. A method of awarding a prize on a gaming console, the console being arranged to offer a feature outcome when the game has achieved a trigger condition, the method including testing for the trigger condition and when the trigger condition occurs offering the feature outcome, the trigger condition being determined by an event having a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger condition on the respective console.

…

55. The method as claimed in any one of claims 43 to 54, wherein the feature outcome is a simplified game having a higher probability of success than the main game.

56. The method as claimed in claim 55, wherein the feature game provides a plurality of pseudo-reels with a restricted number of different symbols on each reel and a jackpot is activated if after spinning the reels the same symbol appears on a win line of each reel.

12 Claims 1–4, 16 and 17 are what I will refer to as “the Feature Game Claims”. These are the claims that specify the trigger condition which determines when the feature outcome selectively provided by a random prize awarding feature on the gaming console is triggered. The trigger condition as described in claim 1, is determined by an event having a probability related to expected turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger conditions on the console and, in claim 2, the credits bet on the respective game. Claims 25, 27–28, 37 and 38 are what I will refer to as “the Gaming Console Claims” which are to gaming consoles including a prize awarding feature that produces a feature outcome when the trigger condition is achieved. In essence, the trigger condition described in the Gaming Console Claims is the same as that described in one or more of the Feature Game Claims. Claims 43, 55 and 56 are method claims (the “Method Claims”) which claim a method of awarding a prize on a gaming console by offering a feature outcome that is triggered by the trigger condition referred to in claim 1.

13 The working relationship defined in claims 1 and 2 is between the feature outcome, the trigger and a gaming console. A gaming console must be arranged to offer a feature outcome and to include a means of testing for the presence of the trigger condition. Subject to it being capable of performing those functions, any gaming console will suffice.

14 Claim 3 also requires that the console be arranged to play a main game during which testing for the trigger condition will occur and that the feature outcome is the awarding of one or more “feature games”. In this context a “feature game” is the award of an additional game (which game is the “feature outcome”) in which a player may then win a prize (e.g. a jackpot): see Konami 1 at [96]. Claim 4 also requires that the feature game is a jackpot game associated with a special jackpot prize. Claim 4 therefore limits the claim to a particular type of feature game.

15 Claim 16 also requires that the feature outcome be a simplified game in which there is a higher probability of winning a major prize than in the main (or base) game.

16 Claim 17 also requires that the feature game (i.e. the prize awarding feature referred to in the earlier claims) includes a number of spinnable “pseudo-reels” and specifies a combination that will activate a jackpot. I note that only one of the Infringing 689 Products referred to in the declaration (Free Spin Dragons) was held to infringe that claim.

17 Claim 25 is the first of the Gaming Console Claims. Rather than describing a prize awarding feature to provide a feature outcome on a gaming console as in claim 1, it describes a gaming console that includes such a prize awarding feature. The remaining Gaming Console Claims 27, 28, 37 and 38 broadly correspond with Feature Game Claims 3, 4, 16 and 17. Claim 43 describes a method of awarding a prize on a gaming console that corresponds with claim 1. Claims 55 and 56 refer to the method claimed in claim 43 but introduce the further limitations found in claims 16 and 17.

18 It was suggested in Aristocrat’s submissions that the Feature Game Claims were, on their proper construction, not only to feature games with the relevant trigger condition, but also to the gaming consoles themselves. I do not think that is correct. The Feature Game Claims, it is true, describe aspects of the gaming console on which the random prize awarding feature is installed. But I regard the description of the gaming console in the claim as a description of the conditions in which the random prize awarding feature is to operate. On this view, the Feature Game Claims are directed to random prize awarding features for use on a gaming console rather than (unlike the Gaming Console Claims) gaming consoles on which the prize awarding feature is installed. This construction reflects the language of the Feature Game Claims particularly when read in the context of the Gaming Console Claims which claim a gaming console including the relevant feature game. In this respect, claims 1 and 25 are, at least in their form, directed to different things.

19 Bradley Spencer Robertson is the Director of Sales Australia for Aristocrat. Mr Robertson worked at Aristocrat from 2005 to 2008, and then again from 2012. From 2008 to early 2011 Mr Robertson worked for the New Zealand arm of Aristocrat, before moving to Sydney and working for eBet in early 2011 and Azure Gaming in late 2011. Mr Robertson’s professional background includes working in the hotel and club industries as well as being a sales representative for Konami between 2000 and 2005.

20 Mr Robertson made one affidavit and was cross examined. His affidavit addressed the Hyperlink games and the sale of those games, factors relating to the sale of EGMs to venues, factors influencing the purchase of EGMs, the player experience and the 689 Games. His affidavit also provided evidence on the success of the Hyperlink games in the gaming industry, through a series of graphs. Mr Robertson responded to the affidavit evidence of Mr Cutmore, Mr Martin, Mr Pocock, Mr Primmer and Mr Wohlsen.

21 Natalie Jane Bryant is the Studio Quality and Process Director for Aristocrat and has been employed by Aristocrat since 1997. Ms Bryant has worked in various positions at Aristocrat including Principal Game Designer, Intellectual Property Officer, Manager – Game Development Process and Process Design and Compliance Director. Prior to working at Aristocrat Ms Bryant worked for GTest, a subsidiary of Gaming Laboratories International, which is an accredited testing facility for gaming products including the hardware and software used in EGMs.

22 Ms Bryant made one affidavit and was cross examined. In her affidavit Ms Bryant gave evidence concerning the development and commercialisation of the Hyperlink games and their impact and success. In her affidavit Ms Bryant also provided her opinion concerning the relationship between the integers of the Hyperlink games and the integers of the claims of the 689 Patent. She also explained the physical parts of an EGM cabinet, game development and approval, the use of alternative feature games, alternative triggers and what she believes drives the sale of an EGM. Ms Bryant also responded to the evidence of Mr Crosby and Mr G Duffy in relation to (inter alia) different types of trigger mechanisms.

23 Neil Phillip Spencer is the Managing Director of Gaming Consultants International. Mr Spencer has a Bachelor’s Degree in Applied Science (Physics and Computer Science) and 30 years’ experience in the gaming industry. He has acted as an advisor for some of the largest gaming venues in Australia, including Crown Resorts. When acting as both a consultant and full time employee of Crown Resorts, Mr Spencer was involved in the assessments and evaluation of EGM products sold by a range of vendors. He was also involved in the development of the regulatory regime for EGMs in Australia.

24 Mr Spencer made two affidavits and was cross examined. In his first affidavit Mr Spencer gave evidence on the state of the EGM market prior to the development of Hyperlink games, including the limitations of linked progressive and mystery jackpot machines. He also provided his recollection and views on the introduction and performance of the Hyperlink games and gave evidence of their popularity at Crown Resorts’ casinos in the years following their introduction. He stated in his first affidavit that the Hyperlink technology was “revolutionary” and “changed the industry significantly.” He also responded to the affidavit evidence of Mr Wohlsen and Mr J Duffy. In his affidavit Mr Spencer indicated that he did not agree with Mr J Duffy’s analysis of the role of the 689 trigger in generating sales, including Mr J Duffy’s use of what he referred to as the “80:20 rule”.

25 Dawna Kathleen Wright is an accounting expert. Ms Wright is a chartered accountant and Senior Managing Director and leader for Australia of the Forensic Accounting and Advisory Services practice at FTI Consulting Pty Ltd. Ms Wright has more than 25 years of training and experience in firms of chartered accountants, of which more than 15 years have included providing forensic services. Ms Wright made two affidavits and also produced a joint expert report with Mr Ross. She gave oral evidence in a concurrent session with Mr Ross.

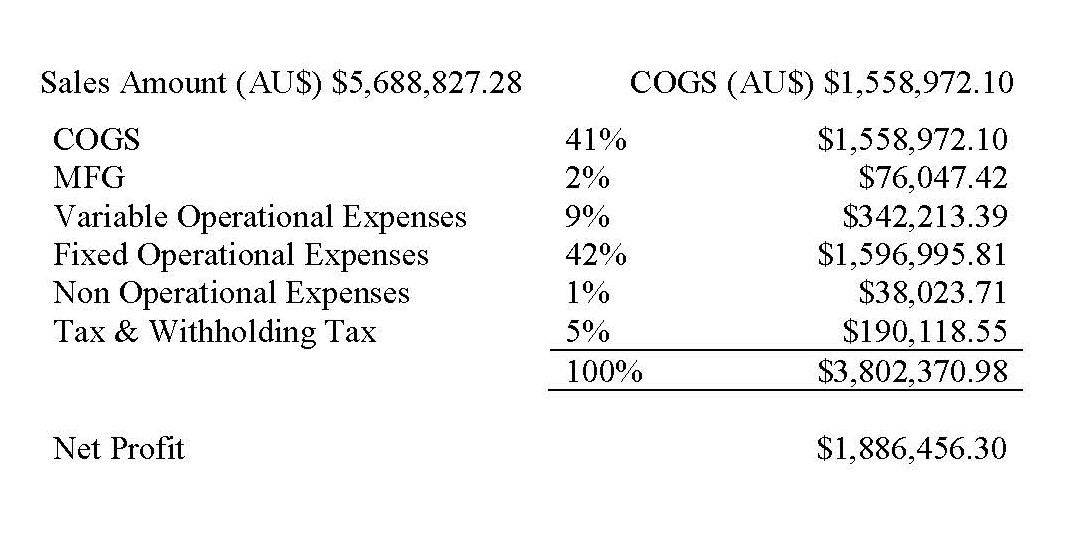

26 Annexed to the first of Ms Wright’s affidavits is her expert report. She was instructed to calculate the “Infringing Games Profit” under two specific scenarios, one including the cost of NCCs and the other excluding the cost of NCCs. Ms Wright indicated in her report that the main area of disagreement between she and Mr Ross related to the allocation of costs to the infringing products including, in particular, whether, and if so how, fixed costs should be allocated to the infringing products. In her second affidavit Ms Wright responds to various matters raised by Mr Ross.

27 Mitchell Alexander Bowen has held a variety of roles at Aristocrat including, since January 2017 as the Managing Director ANZ and International. He made two affidavits and was cross-examined. His affidavit evidence was directed to the importance attached by Aristocrat to research and development and the commercial success of the Hyperlink games which he describes as “an exceptionally well performing technology for Aristocrat”. According to Mr Bowen, Aristocrat is not generally prepared to licence its most commercially significant technology. However, he produced various agreements in which Aristocrat had granted such licences including the Konami Licence and various other licence agreements referred to later in these reasons.

28 Timothy Heberden is a business valuer and an intellectual property valuer. Mr Heberden made two affidavits and produced a joint expert report with Mr Halligan. Mr Heberden gave his oral evidence in a concurrent session with Mr Halligan. He has 20 years’ experience in the valuation of intangible assets, the determination of royalty rates, and the provision of advice regarding the monetisation of intellectual property rights. He holds degrees in commerce, accounting and a post-graduate degree in business administration. He is a partner in the Valuations Team at Deloitte Financial Advisory Pty Ltd and was previously a Director of Glasshouse Advisory Pty Ltd (“Glasshouse Advisory”). He is a registered business valuer and chartered accountant. He is the author of a number of publications concerned with valuation including a chapter called “Royalty Determination and the Valuation of IP” in a book entitled “International Licensing and Technology Transfer: Practice and the Law”. In his oral evidence he was taken to that chapter where there appears some discussion concerning a valuation “rule of thumb”, but not one that he purported to apply in this case.

29 Mr Heberden was provided with a copy of the Konami Licence and various other licence agreements. For the purpose of preparing his report he also undertook research which led him to identify a number of other licence agreements at least some of which he considered relevant to the determination of a reasonable royalty rate. Mr Heberden ultimately concluded that the Konami Licence was the most useful comparator for the purpose of assessing a reasonable royalty rate in the case of the NCCs in respect of which Aristocrat sought damages.

30 George Mokdsi is an experienced patent searcher and researcher. He described himself in his affidavit as Global IP Analytics Manager of Glasshouse Advisory but now works in his own firm as a patent analyst and researcher. He holds a PhD in Organic Chemistry awarded in 2000. Between 2000 and 2005 he worked as a patent searcher. Between 2005 and 2017 he worked with Griffith Hack. Glasshouse Advisory is an affiliate of Griffith Hack, the firm that acted for Aristocrat in relation to the 689 Patent at the liability hearing before me. He made one affidavit and was cross examined. Dr Mokdsi sought to determine what he called the “commercial significance” of the 689 Patent using patent analytics. I refer in greater detail to Dr Mokdsi’s instructions, methodology, and conclusions later in these reasons.

31 Peter John Madden is the National Lead Partner of the International Tax Advisory Group at KPMG Australia. He is a tax lawyer and chartered accountant who has practiced in the taxation field since 1983. He made one affidavit and was not cross-examined. He gave evidence concerning whether Konami would be entitled to a tax deduction in respect of any payment that Konami may be required to make to Aristocrat pursuant to an order made in this proceeding.

32 Isaac Bishara is the Accounting Manager and Inventory Accountant for Konami. Prior to working at Konami Mr Bishara worked at Aristocrat for approximately 10 years during which he held a number of positions including Global Management Accountant for Research and Development. In this role he was responsible for the budget for research and development and game design for Aristocrat. Mr Bishara has worked at Konami since 2008 where he has also held a number of positions including Sales Administration Manager and Purchasing Manager. In his current role, Mr Bishara is responsible for Konami’s accounting systems. He manages the general ledger and the preparation of financial statements and reports to management on financial results.

33 Mr Bishara made two affidavits and was cross examined. In his first affidavit, he explained Konami’s business and accounting methods, how Konami accounts for revenue, the different types of machine sales and conversion sales, and the different circumstances in which a no charge conversion may occur. He also explained the various costs and expenses associated with manufacturing, how various figures relating to the cost of manufacture are calculated, and outlined the various fixed and variable operational expenses. Mr Bishara’s second affidavit makes some clarifications to his first affidavit.

34 Gerard Thomas Crosby is the Group Manager of Product Development at Konami and has held this position since 2007. He has worked at Konami since 1999. As the Group Manager of Product Development Mr Crosby is responsible for making decisions about which games Konami will develop. This includes reviewing and approving game concepts, supervising the development of games, and deciding whether a game should be commercialised once it is developed and has obtained regulatory approval. Mr Crosby is named as an inventor in various patents which have been granted to Konami in the gaming field.

35 Mr Crosby made one affidavit and was cross examined. In his affidavit he explained the different components of an EGM as well as the different types of games. He also explained the process of developing games generally and when and how the 689 Games were developed. In his affidavit Mr Crosby also gave evidence as to what he believed Konami would have done had it not utilised the 689 trigger and how this may have affected the resources allocated to the research and development of new products and impacted the number of gaming products manufactured by Konami during the relevant period.

36 Robert James Cutmore was a Queensland based Sales Executive at Konami from 1999 to 2013. In that role Mr Cutmore sold EGMs to clubs and venues, reported to clubs and venues on the performance of Konami’s EGMs and made suggestions where necessary to improve the performance of Konami’s EGMs. From about 2014 to September 2015 Mr Cutmore was the Chief Operating Officer of the Broncos League Club where he was responsible for managing the gaming floor including purchasing gaming machines and making decisions in relation to the conversion of games.

37 Mr Cutmore made two affidavits and was cross examined. In his first affidavit Mr Cutmore explained the way in which he sold Konami EGMs and conversions to venues, and the factors that he emphasised when doing so. From the perspective of someone who had been responsible for purchasing EGMs, managing gaming floors and having conversations with purchasers of EGMs, Mr Cutmore provided evidence in his first affidavit on characteristics that are important to the purchase of gaming machines and what factors draw players to particular machines. In his first affidavit Mr Cutmore also provided evidence concerning the relative importance of the trigger type to sales of the infringing products.

38 Gregory Michael Duffy (who I refer to in these reasons as Mr G Duffy) was the former Technical Compliance Manager at Konami. Mr G Duffy worked at Konami from 2001 to 2019, during which time he worked in a variety of roles including Technical Compliance Coordinator, Game Design Manager and Content Manager. In Mr G Duffy’s role as Technical Compliance Manager he was responsible for testing, product approval and compliance submissions. In this capacity, he worked with accredited testing facilities and regulatory bodies across Australia, New Zealand, Asia and South Africa. When in the Game Design Manager and Content Manager roles, Mr G Duffy was involved in the development of approximately 300-500 games. In the Technical Compliance roles he was involved in evaluating and preparing compliance documentation for a similar number of additional games.

39 Mr G Duffy made one affidavit and was cross examined. In his affidavit he explained the process of game development and gave evidence as to the cost of game development, breaking down costs and time estimates including for development, compliance, and testing. He provided this estimate for the development of a range of different types of products including new products and modifications of existing products. In his affidavit Mr G Duffy provided evidence on the proportion of time that different features take to develop as well as evidence on the different types of features. He also provided evidence in his affidavit on possible alternatives to the 689 trigger.

40 Michael Anthony Martin is the Queensland State Manager of Konami and has been in this role since 2014. Prior to that he worked as a sales representative at Konami and for a number of different clubs. In his current role, Mr Martin manages five sales representatives and assists them in creating sales strategies, setting and achieving budgets and sales targets, and promoting new products. Mr Martin also acts as a sales representative to casinos and large hotel groups.

41 Mr Martin made two affidavits and was cross examined. In his first affidavit Mr Martin gave evidence concerning the factors that were, in his experience, significant to the selling of EGMs. His first affidavit also included evidence concerning the role of the 689 trigger in the sale of EGMs. His second affidavit related to the additional damages claim and explained how he gave notice to various venues that Konami could no longer licence the 689 Games, he also explained the immediate responses of representatives of various venues to this notice.

42 Damien James Pocock is a Sales Executive at Konami, selling EGMs and games to hotels and clubs between the Gold Coast, Queensland and Kempsey, NSW. Mr Pocock has been in this role since 2013. He has worked in the entertainment and gaming industry for over 20 years working at various clubs as well as for other companies including Jupiter’s Network Gaming licensed monitoring business (now known as Maxgaming), Ainsworth Gaming Technology, Star Games and Voyager Games.

43 Mr Pocock made two affidavits and was cross examined. In his first affidavit Mr Pocock gave evidence of his practice when dealing with venues in relation to the sale of EGMs. In his first affidavit he also gave evidence concerning the characteristics that are important to the sale of EGMs and the importance of the 689 trigger in sales of EGMs and conversions. Mr Pocock’s second affidavit, relevant to the additional damages, explained how he became aware of the dispute between Aristocrat and Konami over the 689 Patent and details conversations with members of various venues regarding ceasing to use the 689 Games.

44 Paul Christopher Primmer is the owner and operator of South Coast Gaming Machines Pty Ltd which is an independent sales agent for Konami. Mr Primmer has been working in the gaming industry for approximately 25 years as a sales agent, and has been an independent sales representative for Konami since March 1998. Mr Primmer made two affidavits and was cross examined. Mr Primmer gave evidence on his experience of the sales process and the factors involved in the sale of EGMs. His second affidavit related to the additional damages claim and explained how he went about notifying specific clients of their options once he was informed that clients had to cease using the 689 Games.

45 Jason Quayle is the IT Manager for Konami and has been in this role since 2003. Mr Quayle has worked at Konami since 2000 and was a Product Development Assistant in the research and development department between 2000 and 2005, acting as a liaison between Konami’s Japanese headquarters and Australia. In his current role, Mr Quayle is responsible for patent and trade mark clearances in relation to proposed games and a significant component of his role is concerned with management, data collection and reporting in the sales and research and development areas.

46 Mr Quayle made five affidavits that were read in evidence. Mr Quayle’s exhibits include a detailed spreadsheet which he created summarising information in relation to Konami’s sales. Mr Quayle’s evidence also detailed the number of sales made, the numbers of NCCs supplied, including a breakdown of the different types of NCCs supplied. The evidence also includes six other affidavits made by Mr Quayle that were served by Konami pursuant to orders made prior to Aristocrat making its election. Mr Quayle was cross-examined.

47 John Stewart Duffy (who I refer to in these reasons as Mr J Duffy) is the president and CEO of Fortunam Studios Inc, which together with Gold Coin Studios is creating casino games for the online real money market. Prior to assuming this role, Mr J Duffy had 25 years of experience in game design and development, engineering, compliance, quality assurance and production with IGT, where he worked from 1993 to 2017. At IGT Mr J Duffy maintained a number of positions including Vice President and Executive Director of IGT (US) and Executive General Manager of IGT (Australia).

48 Mr J Duffy made three affidavits and was cross examined. An exhibit to Mr J Duffy’s first affidavit is his April 2018 report, in which he provides his opinion concerning the role of the 689 trigger in the sale of the infringing products and its relative importance in comparison with other factors that may contribute to sales. In his report, Mr J Duffy outlined the key factors that operators consider when purchasing games. His report also includes an analysis aimed at quantifying the relative importance of the 689 trigger. I refer to Mr J Duffy’s analysis and his written and oral evidence in more detail later in these reasons.

49 Andrew Murray Ross is a Chartered Accountant and Partner of KordaMentha with over 30 years of experience in the provision of financial advice, valuation and forensic accounting. Mr Ross has worked at a number of accounting firms including Arthur Anderson, Ernst & Young and Ferrier Hodgson and has significant experience in providing expert evidence in legal proceedings. Mr Ross made three affidavits and produced a joint expert report with Ms Wright. He gave oral evidence in a concurrent session with Ms Wright.

50 Mr Ross’ first affidavit included as an exhibit his April 2018 expert report. In this report Mr Ross calculated the profits made by Konami attributable to the infringing sales. Mr Ross’ second affidavit included as an exhibit his April 2019 expert report. This report responded to the evidence of Ms Wright. Mr Ross’ third affidavit exhibited electronic copies of documents referred to by him in his first report. I refer to Mr Ross’ analysis and his written and oral evidence in more detail later in these reasons.

51 Geoffrey Wohlsen is the director of Dickson Wohlsen Strategies and is a business analyst and economist specialising in the leisure and entertainment sector. Mr Wohlsen has previously worked in the Strategic Planning and Economic Development division of KPMG where he specialised in the provision of services in the leisure and entertainment sectors and was a key part of a team dedicated to delivering services to not-for-profit community gaming clubs, hotels, casinos, gaming corporations, liquor and gaming and industry representative bodies. After KPMG, Mr Wohlsen worked at CMP Consulting, a small consulting practice that serviced the not-for-profit community gaming club, hotel and casino sectors and then worked as a sole-trader providing consulting services to those sectors. While practicing as a sole-trader, Mr Wohlsen was a shareholder in the development and commercialisation of the industry business intelligence tool Club Data Online. Mr Wohlsen has completed many strategic and business plans for clubs and casinos in Australia.

52 Mr Wohlsen made two affidavits and was cross examined. Exhibited to Mr Wohlsen’s first affidavit is his April 2018 report. In this report Mr Wohlsen considered whether the trigger that infringed the 689 Patent had a role in the sale of the affected games and identified the relative importance of the infringing trigger mechanism. In doing this, Mr Wohlsen’s report considered the history of the Australian market and described the various factors relevant to EGM play and purchases. Mr Wohlsen provided data on Konami’s market share, the manufacture and sale of affected EGMs and conversions in NSW and Queensland and the performance of affected and not affected games in the market place in NSW and Queensland.

53 Thomas Anthony Jingoli is Director, Executive Vice-President and Chief Commercial Officer of Konami Gaming Inc. Mr Jingoli also acts as Compliance Officer for Konami. He made one affidavit and was cross-examined. He gave evidence concerning his dealings with Mr Kieran Power of Aristocrat in 2011 in relation to Konami’s Mystical Temple game, related correspondence between Konami and Aristocrat, the proceeding commenced by Aristocrat against Konami in March of 2011, and his involvement in the negotiation of the Konami Licence.

54 Brendan Patrick Halligan is a Chartered Accountant and a principal of Halligan & Co, a specialised forensic accounting and valuation practice. Mr Halligan made two affidavits and prepared a joint expert report with Mr Heberden. He gave oral evidence in a joint session with Mr Heberden. Mr Halligan’s evidence was directed to the question of what is a reasonable royalty rate for the NCCs the subject of Aristocrat’s damages claim. He considered the matter of comparable licence agreements and explained why he did not regard the Konami Licence as an appropriate comparator. He considered that the most appropriate comparators were the Shuffle Master Licence (discussed below) pursuant to which Aristocrat licensed the 341 Patent to Shuffle Master Australasia Pty Ltd and the Neurizon Licence (also discussed below) pursuant to which Neurizon licensed to a subsidiary of Konami the prize awarding system the subject of the 299 Patent.

55 Paul King is Senior Tax Counsel at Minter Ellison. He is a tax lawyer and chartered accountant with many years of experience in the taxation field. He made one affidavit and was not cross-examined. He responded to Mr Madden’s affidavit concerning the tax implications for Konami arising out of any payment by Konami to Aristocrat pursuant to an order made in this proceeding. He also considered whether calculating the amount of that payment on a pre-tax basis could unfairly disadvantage Konami.

56 Affidavits made by various other witnesses (who were not cross-examined) were also read and relied on. These include affidavits by Mr Warren Paul Jowett, Mr John Dominic Lee read by Aristocrat, and Ms Claire Slunecko read by Konami.

57 The key parts of an EGM are the cabinet, the platform and the games. The cabinet is the physical box and associated hardware in which a platform is installed. The platform is a combination of computer hardware and software which enables the operation of a game on the EGM. Konami supplied various platforms and compatible cabinets in the period 1998 to 2016. The platforms included the Tasman (1998), Endeavour (2001), K2V (2006), and KP3 (2012) platforms. The cabinets manufactured by Konami during the same period included the Tasman (1998), Endeavour (2001), K2V (2006), and The Podium (2009) cabinets. The earlier cabinets and platforms (Tasman and Endeavour) were developed and named alongside each other. Later cabinets and platforms were developed and named separately. This made it possible for a prospective customer of Konami to upgrade the platform of their EGM to the newest generation while retaining their existing cabinet.

58 A single cabinet design will typically have multiple variations. Although the basic design remains the same, the dimensions of the variations differ. The variations include “high boy”, “low boy”, “casino top” and “slant top” cabinets. Customers can choose a variation that best meets their requirements (e.g. with regard to space).

59 A “standard game” (sometimes called “a standalone game”) is a game that is not paired with a feature game. A standard game usually has its own “feature” or “features” such as free games. The experts drew a distinction between a standard game and a base game. As Ms Bryant explained in her oral evidence:

…[M]ost games these days have a feature element. So within the standard game there will be a base game which is generally spinning reels where you would spin up combinations of symbols and they will pay prizes. There are usually another feature element which, in a lot of cases, for example, would be free games where a certain combination trigger might – that comes up in the base game will take you into a – a feature game event. Free games, or – or something to that effect…So when I refer to a standard game I’m talking about the base game and any standard game feature within the standard game.

60 A base game is one that is paired with a feature game. The combination of a base game (including any features) and a feature game is sometimes referred to as a complete game. The base game is the game which the player starts when placing a bet. The reels then spin and the player is awarded a prize based on the combination of symbols that appear on the reels when they have stopped. Like a standard game, a base game usually has its own features. Most of the player's time is spent playing the base game (including any won free games).

61 A feature game is a game that is additional to a base game. The feature game is not a standalone game and cannot be played without first playing the base game it is paired with and achieving a predetermined condition within the base game. A common example of a feature game is one that pays a progressive jackpot to the player (a “progressive feature game” or “progressive”).

62 A jackpot is the “top” prize, or set of prizes that a player can win and both the base game and feature game can award a jackpot prize. A jackpot or feature that is awarded based on a combination of symbols is referred to as a symbol driven jackpot or feature. There are other ways in which jackpots or features may be triggered. Mystery jackpots are triggered by a means other than a combination of symbols known to the player. Most jackpots are progressive jackpots in which the amount of the jackpot increases as further bets are made until the jackpot is awarded.

63 The term “linked progressive” refers to a progressive jackpot or features associated with a number of machines that are linked together to contribute to a progressive jackpot. The linked progressive jackpot is a combined jackpot (or series of jackpots) which increases as amounts are bet on the linked machines until the jackpot is won by a player of one of them. Usually there are a large number of machines involved although, in some smaller venues, the numbers may be considerably smaller. Linked progressives can include “wide area progressives” in which machines are linked across multiple venues. As the name implies, Hyperlink games are typically linked progressive jackpots (or simply “linked progressives”) that are played on a series of linked machines. There is also a complete game known as a standalone progressive which is played on a machine that has a progressive jackpot but that is not linked to any other machine.

64 There are various types of trigger mechanisms that can be used for the purpose of the triggering of an event such as the award of a prize or the initiation of a feature game. Examples of triggers that can be used for this purpose include symbol driven triggers (in which an event is triggered based on the player achieving a predefined combination of symbols); range mystery triggers (in which an event is triggered based on an accrued value reaching a predefined threshold calculated by the machine but hidden from the player); random triggers (in which an event is triggered based on an outcome of a random number generator for each play of the game); and conditional triggers (in which an event is triggered based on satisfying another predefined condition). An example of a conditional trigger is one in which a feature game is triggered if the player does not receive a prize in the course of playing the base game.

65 The trigger mechanism, or trigger, forms part of the game software that drives the EGM. The trigger is essentially a set of rules (which may be represented as a formula or other mathematical statement) that determine the conditions which will result in the award of a feature (the feature game) or the outcome of the feature (the feature outcome) which might be a free game, a jackpot or some other prize.

66 A number of affidavits were made in this proceeding by Mr J Quayle as the authorised representative of Konami setting out details of what are referred to in the affidavits as the infringing “689 Games”. These affidavits were filed by Konami pursuant to orders made by the Court for the purposes of informing Aristocrat’s election. The names of the 689 Games, which Konami accepts infringed are:

(a) Cash Carriage

(b) King’s Reward

(c) Free Spin Dragons

(d) High Velocity Grand Prix

(e) Rapid Fire

(f) Rapid Fire Grand Prix

(g) Full Steam Express

(h) Caribbean Jackpot

(i) Free Spin Festival

(j) Free Game Festival

(k) Free Spin Safari

(l) Round One

(m) Rock Around the Clock

(n) Pirate’s Jackpot

(o) Catch Me

67 Of those 689 Games, four (Free Spin Dragons, High Velocity Grand Prix, Rapid Fire Grand Prix and Catch Me) are games played on a number of linked gaming machines. All of the 689 Games are “feature games” (as opposed to standard or base games) or, in the language of the relevant claims, “[a] random prize awarding feature to selectively provide a feature outcome on a gaming console …”. Other terms used in the evidence to describe a gaming console are poker machine, gaming machine or EGM. Although there exist gaming machines that are not electronic gaming machines, all of the gaming machines relevant to this stage of the proceeding are electronic gaming machines.

68 Other 689 Games were identified by Konami which it agreed should be included in the inquiry. These are the Queensland versions of the following games:

(a) Cash Carriage Mystery

(b) Dollar Power

(c) Fortune Garden

(d) Lucky Garden

(e) Money Dragon

(f) Wildfire (on the K2V Platform only)

(g) Sport of Kings 2

69 An example of a linked 689 Game is Rapid Fire Grand Prix. A promotional brochure produced by Konami which includes material on this game describes it as a symbol driven linked progressive. According to the brochure:

Any 3 or more rapid fire symbols will trigger the feature to win either the MAXI or MINI Jackpot.

When the feature is won the RAPID FIRE engine on the LCD revs up to display the winning jackpot.

There are a wide selection of RAPID FIRE jackpot parameters available to suit your venue and configurable with your chosen denomination and game.

70 The brochure also refers to different base games. It shows a gaming machine with Rapid Fire Grand Prix and Wild Tiki as the base game.

71 Rapid Fire is an example of a feature game with a standalone progressive jackpot. According to the brochure for Rapid Fire, it is a “standalone symbol driven progressive”. The description in the brochure for Rapid Fire is otherwise the same as for Rapid Fire Grand Prix.

72 The 689 Games were not sold separately by Konami. The 689 Games were supplied as either part of a “box” or a “conversion kit”. The box included the software for both the base game and the 689 Game. It also included all relevant hardware, including display panels on which images associated with both the base and feature games are projected, and audio facilities which emit sounds associated with the base and feature games. Conversion kits were used to install new software for a base game and a 689 Game on an existing EGM. They included, depending on the type of conversion, the storage device, the software and artwork.

73 Games and gaming machines must be approved by the relevant State regulatory authority before they can be supplied for use in a gaming venue. The evidence includes examples of approval documentation including gaming machine profiles. An example of a gaming machine profile for EGMs (Konami’s Endeavour cabinets) on which one of the 689 Games (Rapid Fire 2) was installed is in evidence. It identifies the main components and peripheral devices in the gaming machine by part number and manufacturer and shows that Konami’s Endeavour cabinets included LCD monitors, control units, memory units, interface units, communications boards, connector boards, AC power units, DC power units, communications power units, coin validators, banknote stackers and acceptors, coin hoppers and validators, and ticket printers.

74 The principal issues to be decided in relation to Aristocrat’s claim for profits are as follows:

(1) Whether and, if so, to what extent, the profits otherwise payable to Aristocrat should be reduced by way of apportionment.

(2) Whether it is appropriate to include the costs of the NCCs in calculating profits derived by Konami in exploiting the 689 Games in circumstances where these were supplied at no charge.

(3) Whether and, if so, to what extent, Konami’s claims for deductions in respect of various categories of overheads which are disputed by Aristocrat should be allowed. The disputed deductions include amounts falling within the following categories:

(a) product development;

(b) general administration;

(c) employment (excluding compliance);

(d) employment (including compliance);

(e) licencing; and

(f) other expenses.

(4) Whether losses made by Konami on the sale of EGMs and conversion kits incorporating the 689 Games in the financial years 2009 and 2016 can be offset against profits made in other years.

(5) Whether in calculating the profits to be awarded to Aristocrat allowance should be made for income tax paid by Konami on the relevant profits.

There is also a question as to whether Konami is entitled to claim a deduction in respect of any damages payable in respect of NCCs.

75 It is convenient to deal with two threshold arguments regarding apportionment raised by Aristocrat based on findings made, and the declaration and injunction granted, in Konami 1.

The manner of manufacture finding

76 Aristocrat referred to the Court’s characterisation of the invention in Konami 1 at [223]. Aristocrat’s submission was, in effect, that the Court’s characterisation of the invention in Konami 1 at [223] constitutes a finding that the Gaming Console Claims are to inventions that are, in substance, new and useful gaming machines and that, in light of that finding, it is not open to the Court to accept Konami’s submission that the substance of the invention is to the trigger. I will refer to the relevant finding as “the manner of manufacture finding”.

77 The manner of manufacture finding was made in the context of a submission that the substance of the invention was to no more than an idea which, if that were the true nature of the invention, would be inherently unpatentable. The submission that what was claimed was a “mere idea” was rejected. I said in Konami 1 at [223]:

A mere idea that does not translate into a claim for a new and useful result is not within the concept of a manner of manufacture because it involves no more than “mere discovery” or “discovery without invention” compare NRDC at CLR 264; IPR 66. However, the inventions claimed in the 689 patent are not “mere ideas” but new and useful gaming machines and new and useful methods of operation producing new and improved results.

The reference to National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252 at 264 is to the page in the judgment of Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ at which their Honours referred to “… discovery without invention either because the discovery is of some piece of abstract information without any suggestion of a practical application of it to a useful end, or because its application lies outside the realm of ‘manufacture’”.

78 The finding in Konami 1 was that the claims were to more than a mere idea and were instead to (inter alia) new and useful gaming machines and new and useful methods of operation producing new and improved results. For the purpose of disposing of Konami’s “mere idea” argument it was unnecessary to make any more specific findings as to what it was about the gaming consoles referred to in the claims that rendered them both new and useful gaming machines. However, for the purpose of determining the correctness of Aristocrat’s argument based on the manner of manufacture finding, it is necessary to elaborate on that finding further by reference to other findings made in Konami 1.

79 The common general knowledge was considered in Konami 1. As is apparent from [30]-[31], the common general knowledge included EGMs capable of operating on a standalone basis or as a part of a network with the following: consoles that include means to make selections and play games; games with primary or base games; games with secondary or bonus features; games with triggers; games with jackpots; games with symbol driven jackpots; games with progressive jackpots; and games with mystery jackpots. These matters were common general knowledge whether considered on an individual or a collective basis. Hence, there was, for example, nothing new or inventive at the priority date in an EGM which could be operated on a standalone basis or as part of a network that included a primary or base game, a secondary or bonus feature game, and symbol driven progressive jackpots.

80 The nature of progressive jackpots and mystery jackpots was considered in Konami 1 at [35]:

Progressive jackpots operate by accumulating contributions from turnover on machines that contribute to the building of the jackpot (that is the prize or award). Mystery jackpots are a type of progressive jackpot. With a mystery jackpot, a lucky number is electronically selected from a designated range and held in secret. A counter is then activated starting at the lowest value of the designated range. As play ensues, a percentage of each wager is added to the count, and the new count is compared against the secretly held lucky number. If a match occurs, the player whose wager caused the match is awarded the jackpot.

81 There were other findings made in Konami 1 in the context of Konami’s contention that the invention as claimed did not involve an inventive step that are also relevant to the proper characterisations of the invention. In particular, it was held at [210] - [212] that the invention described and claimed in the 689 Patent solved two problems associated with progressive jackpots.

82 The first of these problems was the fact that the probability of a player winning a feature jackpot was independent of the amount wagered by the player. This was a problem affecting both standalone EGMs and those forming part of a network. The second problem was known as “swamping” and was related to patterns of play in which players would cease play on their EGMs once a progressive jackpot had been triggered by a player on another EGM on the same network and not resume play until a later time at which the chance of winning the next progressive jackpot had materially increased. As explained in Konami 1 at [36]:

Progressive jackpots suffer from a disadvantage due to the manner in which turnover is accumulated. This results in some people not playing the gaming machines once the jackpot is awarded until a significant amount of additional play takes place, and the turnover count has increased to a point at which they consider it more likely that they will win a large prize and therefore worthwhile to play. Once a substantial period of time had passed without a jackpot being awarded, professional gamblers will then move in and commence play and “swamp” the machines.

83 These problems were described more colourfully in Konami 2. Perram J (with whom Besanko and Jagot JJ agreed) said at [7]-[8]:

[7] There are thought to be some problems with progressive jackpots. To begin with, as a measure to ensure that the jackpot is sufficiently large to be enticing very often the machine is set so that the jackpot cannot go off for a pre-determined number of games after it has last gone off. This is achieved by ensuring that the random number is generated within a range which starts at a higher number, eg, 49-999. On such a machine, the jackpot cannot go off until it has been played at least 50 times. This initial period is sometimes referred to as the ‘dead zone’. The enticement of a decent sized jackpot, however, contains within it the seeds of discontentment too. Players who are playing for the jackpot are all too prone to reason that once the machine has gone off it will not go off again for some time (while the machine traverses the dead zone) and hence that there is no point playing. Correlatively, once a machine has not gone off for a while a similar class of player tends to ‘swamp’ the machine. This problem is known as the ‘swamping’ problem.

[8] Another problem is that the players who are playing for the jackpot have no rational incentive to bet more than the minimum amount on each game because the counter is increased by only one no matter what the size of the bet. Mention of the ‘take out’ has been made above. As the trial judge explained (at [45]), each machine is set to return on average over time a specified percentage of credits bet back to the players and, indeed, this is required by law. So, for example, a machine may be set to return, on average, 80% of the money which is wagered upon it. The converse of that is, of course, that the machine keeps the other 20%. It follows, in a straightforward fashion, that the profits of the operator are a linear function of the amount which is wagered on the machine. The progressive jackpot, therefore, provides an incentive for players to act in a way which diminishes the potential profits of the operator.

84 The problem of swamping might affect a standalone EGM in that a player might abandon the machine after winning a progressive jackpot on a feature game before returning to it after other players had, by their play on the same EGM, increased the probability of the feature jackpot being triggered for a second time. But it is clear that the problem of swamping was far more significant in the case of network systems involving multiple EGMs, multiple players, larger turnover and larger progressive jackpots.

85 It is apparent from the findings made in Konami 1 that the invention as claimed in the Gaming Console Claims was a new gaming machine that included the prize awarding feature referred to in the claims which used a trigger that addressed the two problems which were found to be present in the prior art. The gaming machines were new and useful because they included a feature game with a trigger that overcame those problems. I do not consider that the manner of manufacture finding requires the Court to hold, when determining the extent of the benefit obtained by Konami from its exploitation of the invention, that the invention was a new EGM without considering what it was that made the EGM new and useful.

86 Aristocrat also relied upon the form of the declaratory and injunctive relief that was granted. It submitted that the scope of the declaration and the injunction determines the scope of the infringer’s liability to account for profits. It submitted that the scope of an account of profits should correspond with the scope of the injunction and extend to an account of the profits made by Konami by reason of the acts, the repetition of which is restrained by the injunction. Aristocrat referred to Nokia Corporation v Liu (2009) 179 FCR 422 (“Nokia”), a trade mark case in which the Full Court (Finn, Sundberg and Edmonds JJ) said at [36]:

The link between the manner of infringement found — and often enjoined — and the subsequent award of relief by way of damages (or an account) is reflected in the notion that:

the scope of the inquiry as to damages corresponds to that of the injunction

See National Broach & Machine Company v Churchill Gear Machines Ltd [1965] 1 WLR 1199 at 1204-1205; or as put in Kerly (at 19-131):

The proper form of an order for an inquiry as to damages occasioned by the infringement of a mark is, therefore, what damage (if any) has the claimant sustained by reason of the acts, repetition of which is restrained by the judgment.

See also the form of the orders in AG Spalding 30 RPC at 400.

87 Aristocrat also referred to another trade mark case, Elecon Australia v PIV Drives (2010) 93 IPR 174 (“Elecon”) where the Full Court (Emmett, Perram and Yates JJ) said at [47]:

The scope of an inquiry as to damages, and, it would follow, an account of profits, normally corresponds to the width of the injunction that is granted (see National Broach and Machine Co v Churchill Gear Machines Ltd [1965] 1 WLR 1199 at 1204–05; 2 All ER 961 at 965; [1965] RPC 516 at 529, Nokia at [34]–[36]). Here, the injunction is in broad terms, unconfined by reference to particular infringements or, indeed, any form of infringement. The declaration is similarly unconfined.

88 Aristocrat submitted that, applying the principle in Nokia and Elecon, the scope of the account of profits in this case extends to that which is attributable to the exploitation of “Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems however described”, as restrained by the injunction. It submitted that those profits are the whole of Konami’s net profits attributable to the 689 Games including profits made on the sale of every component of the 689 Games. It also submitted if Konami wished to limit the invention and the pecuniary relief to a profit made on the sale of the trigger, it was open to Konami to challenge the validity of the infringed claims, including on s 40 grounds, or to argue for a more limited form of the injunctive relief. Aristocrat argued that Konami is in effect attempting to re-litigate the form of the declaratory and injunctive relief, which it cannot now do.

89 The declaration recorded that Konami had infringed the specified claims of the 689 Patent by exploiting “the gaming machine product and/or gaming machine system comprising a bank of linked or networked gaming machines” identified by various names. One of the games, Freespin Dragons, infringed all of the relevant claims and the other games referred to in the declaration infringed most of them. The form of the injunction picks up the definition of the “Infringing 689 Products” and restrained Konami from (inter alia) making or selling Infringing 689 Products or any identical gaming machine products or gaming machine systems.

90 The declaration and injunction were in a form agreed to by the parties following the publication of Konami 1. Those reasons for judgment do not deal with any issue of apportionment. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that the parties understood that a declaration and injunction in that form would preclude any argument in relation to apportionment.

91 Although the declaration refers to the particular gaming products or systems that were found to have infringed, neither party suggested that the account of profits was limited to profits resulting from the particular games referred to in the declaration and it appears to have been agreed between them that the profits for which Konami must account should include those resulting from its exploitation of other infringing games. That agreement reflects the approach that was recognised and approved in Nokia (a trade mark case) in which it was held that the scope of the inquiry as to damages was, in that case, not limited to loss arising from specific and particularised instances of infringement.

92 In Nokia, the Full Court referred to “the notion that … the scope of the inquiry as to damages corresponds to that of the injunction”. In the course of its consideration of that matter, the Full Court referred to the judgment of the English Court of Appeal in National Broach and Machine Co v Churchill Gear Machines Ltd [1965] 1 WLR 1199 at 1204–1205 (a confidential information case) and the form of the orders in AG Spalding & Bros v AW Gamage Ltd (1913) 30 RPC 388 at 400 (a passing off case). Each of those cases recognised that the scope of the inquiry as to damages corresponded to the scope of the injunctive relief and that it was appropriate to order an inquiry as to damages sustained by reason of the acts, the repetition of which was restrained by the injunction. Neither was concerned with patent infringement or any question of apportionment. In my opinion, none of the authorities relied on by Aristocrat support the contention that the form of orders made in this case precludes apportionment.

93 The logic of Aristocrat’s argument based on the form of orders is that because the injunction restrained the sale of certain gaming machines, it is entitled to recover profits on the sale of all such gaming machines made prior to the imposition of the restraint. But if it is accepted that apportionment is available in respect of an infringement of the Feature Game Claims, it would follow that an injunction restraining the sale of a gaming machine which infringed those claims should not preclude the Court from apportioning profits if it considered that it was otherwise appropriate to do so. So far as the Gaming Console Claims are concerned, there is no reason why the form of the orders made should preclude the Court from allowing apportionment of profits were it to consider that it was otherwise appropriate to do so. The effect of the injunction granted was to (inter alia) preclude the supply of gaming machines with the proportional trigger. As Konami submitted, supply of the gaming machines with a different trigger would not have infringed any of the claims and the injunction would not bite. I do not think the form of the injunction granted has any bearing on whether or not apportionment is available in this case.

Analysis of the parties’ submissions and relevant authorities

94 It is useful before turning to consider the facts of this case in greater detail to refer to the parties’ key submissions in relation to the nature of an account of profits and the law with respect to apportionment in the context of that remedy.

95 Both parties referred in detail to the well-known decision of Windeyer J in Colbeam Palmer Ltd v Stock Affiliates Pty Ltd (1968) 122 CLR 25 (“Colbeam Palmer”). This was a case in which an account of profits was ordered in respect of the defendant’s infringement of a registered trade mark for the word “CRAFTMASTER” by his use of the words “Craft Master” on painting sets. The case did not involve any allegation of passing off. Windeyer J said at 32:

“The distinction between an account of profits and damages is that by the former the infringer is required to give up his ill-gotten gains to the party whose rights he has infringed: by the latter he is required to compensate the party wronged for the loss he has suffered. The two computations can obviously yield different results, for a plaintiff’s loss is not to be measured by the defendant’s gain, nor a defendant’s gain by the plaintiff’s loss. Either may be greater, or less, than the other. If a plaintiff elects to take an inquiry as to damages the loss to him of profits which he might have made may be a substantial element of his claim: see Mayne on Damages, 11th ed (1946), p 71 note. But what a plaintiff might have made had the defendant not invaded his rights is by no means the same thing as what the defendant did make by doing so.”

96 Windeyer J distinguished the facts of the case before him from those in which a patent had been infringed. His Honour said at 37:

It was suggested that the defendant's profit should be measured by the difference between the amount it received for painting sets bearing the trade mark and the amount it had paid to obtain them. The account taken when a patent has been infringed was suggested as an analogy. But to my mind there is an important distinction. If the infringer of a patent sells an article made wholly in accordance with the invention and thereby obtains more than it cost him to make or acquire it, he is accountable for the difference as profit. That is because he has infringed the patentee's monopoly right to make, use, exercise and vend the invention. But in the case of a registered trade mark, infringement consists in the unauthorized use of the mark in the course of trade in relation to goods in respect of which it is registered. The profit for which the infringer of a trade mark must account is thus not the profit he made from selling the article itself but, as the ordinary form of order shews, the profit made in selling it under the trade mark. This creates a difficulty in taking the account–a difficulty which also arises sometimes in cases of patents for improvements: see e.g. Goodlet v. Fowler [(1876) 14 S.C.R. (N.S.W.) 496.].

97 His Honour continued as follows at 42-43:

“What the defendant must account for is what it made by its wrongful use of the plaintiffs’ property. The plaintiffs’ property is in the mark, not in the painting sets. The true rule, I consider, is that a person who wrongly uses another man's industrial property - patent, copyright, trade mark - is accountable for any profits which he makes which are attributable to his use of the property which was not his. An early form of the order in a patent case is for “an account of all profits actually made by the defendant by means of the infringement”: Elwood v. Christy [(1865) 18 C.B. (N.S.) 494].

Lord Kinnear in the Court of Session in Scotland sufficiently summarized the course of earlier decisions when he said “and there certainly is a great deal of authority for saying that where only a part of a complex machine is protected by a patent, the infringer cannot be made liable for the aggregate profit derived from the entire machine, as if that were the profit he had made by the use of the patent”: United Horsenail Co. v. Stewart & Co. [(1886) 3 R.P.C. 139, at p. 143]. And in the same case on appeal Lord Watson said that in a patent action, if the patentee elects to have profits instead of damages, “it becomes material to ascertain how much of his invention was actually appropriated, in order to determine what proportion of the net profits realized by the infringer was attributable to its use. It would be unreasonable to give the patentee profits which were not earned by the use of his invention”: United Horse-Shoe and Nail Co. Ltd. v. Stewart & Co. [(1888) 13 App. Cas. 401, at pp. 412, 413; 5 R.P.C. 260, at pp. 266, 267]. In trade mark cases it has been generally accepted ever since Cartier v. Carlile [(1862) 31 Beav. 292 [54 E.R. 1151]] (a common law trade mark) that what a plaintiff who establishes infringement is entitled to is the profit attributable to the use of the mark, and no more.

It has been recognized that it may be very difficult sometimes to establish how much of the total net profit which an infringer has made by sales of his goods is to be attributed to his selling them under another man's mark. That problem, the apportionment of a total profit, has been discussed many times, most recently so far as I am aware in Canada: Dubiner v. Cheerio Toys & Games Ltd [(1966) 55 D.L.R. (2d) 420, at pp. 434, 435]. It is similar to the difficulty, to which I have alluded above, of a patent infringed by the incorporation or use of a patented invention or process as a part of a larger machine or process. The same questions and the same difficulty in accounting for profits or assessing damages can also arise if a copyright is infringed by the publication of copyright material as part only of a larger work: e.g. Baily v. Taylor [(1829) 1 Russ. & My. 73 [39 E.R. 28]]; Blackie & Sons Ltd. v. Lothian Book Publishing Co. Pty. Ltd [(1921) 29 C.L.R. 396.].

If one man makes profits by the use or sale of some thing, and that whole thing came into existence by reason of his wrongful use of another man's property in a patent, design or copyright, the difficulty disappears and the case is then, generally speaking, simple. In such a case the infringer must account for all the profits which he thus made.”

98 Aristocrat placed emphasis on the last paragraph of this extract from Windeyer J’s judgment. It submitted that his Honour made clear that, if the whole thing had been supplied in breach of a patent, then the infringer would be liable to account to the patentee for the profit made as a result of such supply. In the case of the infringing EGMs sold by Konami, Aristocrat says that it must account for the whole of the profit made from those sales. In this context, it placed considerable reliance on claims 25, 27, 28 and 37, each of which is for a gaming console including the relevant prize awarding feature.

99 Aristocrat also placed reliance on the decision of the High Court in Dart Industries Inc v The Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 179 CLR 101 (“Dart”). This was a case arising from rulings made by the primary judge in relation to the taking of an account for infringements of a patent for press button seals for the sealing of plastic kitchen containers. The argument before the primary judge (Dart Industries Inc v Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1990) 20 IPR 144, King J) and, before the Full Court of the Federal Court (Decor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1991) 33 FCR 397, Sheppard, Burchett and Heerey JJ), concerned two questions. The first, which was the subject of the appeal to the High Court, concerned the infringer’s overheads, and whether it was proper to make any allowance for them in calculating the relevant profit.

100 The second matter, which was the subject of an application for leave to cross-appeal to the High Court, concerned the question of whether the infringers were liable to account for their profit in relation to the whole container which they had made or supplied or whether they were merely obliged to account for profits made in respect of making or supplying the infringing component only (i.e. the press button seal). If that question had been answered in the respondents’ favour, then some apportionment would have had to be made. It should be noted, however, as Aristocrat emphasised, that the infringed claims were not for the whole container, but merely the press button seal.

101 The majority of the High Court dismissed the application for leave to cross-appeal. The majority (Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Toohey JJ) said at 120-121: