FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited [2022] FCA 1324

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | NATIONAL AUSTRALIA BANK LIMITED ACN 004 044 937 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The claims in paragraph 1 of the Originating Application relating to alleged misleading or deceptive conduct, the making of false and misleading representations, and alleged breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) are dismissed.

2. It is declared that in the period from January 2017 until July 2018, the National Australia Bank by its conduct of continuing to charge Periodic Payment Fees to customers in circumstances where it knew that it had no contractual entitlement to do so and omitting to inform its customers as to the wrongful charging or suggest that they review any such fees debited to their accounts, engaged in conduct in trade or commerce and in connection with the supply of financial services that was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable in contravention of s 12CB(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

3. The parties are to be heard on what other relief, if any, ought to be granted consequent upon the determinations made in the reasons for judgment published herewith.

4. The parties are to be heard on the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DERRINGTON J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In the period between 20 July 2007 and 22 February 2019, the National Australia Bank (NAB) wrongly overcharged certain of its customers on at least 1,608,575 transactions. The overcharging related to the amounts which NAB debited its customers’ accounts for fees for causing periodic payments to be made from their accounts. It has since remedied the overcharging where it has been able to do so, and otherwise relinquished any benefit which it might have derived. To the date of the hearing it had voluntarily, by way of compensation, paid in excess of $8.3 million to affected customers. By the current proceedings the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) seeks declarations that during specific periods prior to 22 February 2019, NAB’s conduct in relation to the overcharging amounted to misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act), to the making of a false or misleading representation in contravention of s 12DB of the ASIC Act, or to unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 12CB of the ASIC Act. It also seeks declarations that the conduct had the result that NAB contravened s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that its financial services were provided “efficiently, honestly and fairly”. Consequential to these, it seeks the imposition of penalties and other relief.

2 The factual circumstances in which the overcharging occurred and NAB’s attempts to rectify or remedy it, have been agreed between the parties, and are set out in a lengthy statement of agreed facts pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). Despite that, as the issues raised in the action turn to some extent on inferences which are to be drawn from the agreed facts, it is necessary to set them out in full, and they appear as paragraphs 4 to 233 hereof. The numerous attachments to the statement of agreed facts are not reproduced, but will be referred to as and when necessary.

3 The hearing proceeded upon those agreed facts and none of the witnesses who swore affidavits in the proceeding was required for cross-examination.

The agreed facts

NAB overview

4 At the date of filing, NAB is one of the five largest listed companies by market capitalisation in Australia.

5 As at close of market on 22 February 2021, NAB’s market capitalisation was approximately $81 billion.

6 As at 30 June 2020, NAB’s total assets exceeded $866 billion.

7 NAB at all material times held Australian financial services licence number 230686.

Periodical payments

8 For at least the account types referenced in paragraph 9 below, “periodical payments” are recurring payments that are set up by a NAB employee at the request of a NAB customer (being the sending account-holder in the recurring payment transaction). Recurring payments can also be set up by a NAB customer themselves, without the assistance of a NAB employee (for example, using NAB internet banking portal), but such arrangements are not referred to as “periodical payments”. Examples of such periodical payments included payments from a customer’s savings account to a home loan account to meet monthly mortgage repayments or to a third party for rent.

9 Between (relevantly) at least 20 July 2007 and 22 February 2019 (the Relevant Period), NAB offered the periodical payments service to customers who held (relevantly):

9.1 the 13 personal account types, identified in Annexure C.

9.2 the 7 business account types, identified in Annexure B.

10 At all times during the Relevant Period, NAB had adopted the Code of Banking Practice (as amended from time to time) published by the Australian Banking Association and which applied to NAB’s personal banking and business banking accounts.

Relevant customer fees NAB charged for periodical payments

11 The claim made in the proceeding concerns fees charged by NAB for successful periodical payments (PP Fees) that NAB charged to customers who held personal or business accounts (as explained in paragraphs 46-48), including one or more of the accounts identified in paragraph 9 above (the Relevant Accounts) during the Relevant Period.

Establishing a periodical payment at NAB

12 During the Relevant Period, periodical payments could be requested by a customer in a NAB branch or by telephone call or email.

13 Subject to paragraph 14 below, to establish a periodical payment for the Relevant Accounts, NAB’s instruction manuals to staff specified that the customer was required to sign a completed Periodical Payment Authority Form (PPA Form) to authorise the periodical payment from their account. A copy of the PPA Form that was in use at all times during the Relevant Period is attached as Attachment 1.

14 In some instances, a separate periodical payment authority (namely, not the PPA Form) was embedded in some loan contracts and used to establish and authorise periodical payments in respect of those loans. However, the number of customers who set up a periodical payment through a loan contract is limited.

15 The relevant process to create a periodical payment during the Relevant Period was as follows (subject to the exception in paragraph 14):

15.1 The PPA Form was typically filled out by a NAB employee, but could also be filled in by the customer, or by the two of them working collaboratively. It could be filled out by hand, or electronically.

15.2 The PPA Form had a section entitled “Periodical payment fee indicator”. The options in this section corresponded to the “PP Fee Indicator” which NAB employee was required to select in NAB’s Electronic Branch Online Business System (eBOBS) to specify whether the periodical payment in question was subject to, or exempt from, a PP Fee. The PP Fee Indicator was selected when NAB employee was setting up the periodical payment arrangement through a screen in eBOBS titled “Periodical Payment New” (PP Setup Screen). The PP Fee Indicators in use during the Relevant Period were a series of numbers (from 1 to 7) that would set a particular PP Fee or PP Fee Exemption in respect of the periodical payment in question, and are set out in Annexure D.

15.3 NAB employee was to ensure that the correct PP Fee Indicator had been selected for the periodical payment in question (both in the PPA Form and in eBOBS).

15.4 NAB’s instruction manuals to staff specified that the customer was required to sign the PPA Form in order to authorise the commencement of the periodical payment from their account.

15.5 Using the contents of the executed PPA Form, NAB employee manually selected a PP Fee Indicator in eBOBS to establish a periodical payment in NAB’s systems, either by using a drop-down menu in eBOBS, or by typing the relevant PP Fee Indicator number into eBOBS.

15.6 Once a PP Fee Indicator was set in respect of a particular periodical payment, NAB would charge the corresponding PP Fee (if any) in respect of each occurrence of that payment, unless or until NAB amended the PP Fee Indicator for that transaction (amendment was required to be made manually using eBOBS in the same manner as when the periodical payment was established).

15.7 During the Relevant Period, there was a “help screen” accessible to NAB employees within the PP Setup Screen in eBOBS, which provided an explanation of the PP Fee Indicator when establishing a periodical payment arrangement. There were also similar “help screens” with explanatory information available for all fields in eBOBs for establishing a periodical payment arrangement, which were accessible from within the PP Setup Screen.

15.8 Further, at all times during the Relevant Period, NAB employees and customers could access and review the Personal Fees Guide and the Business Fees Guide, which contained the details of the PP Fees and PP Fee Exemptions.

Customer entitlement to exemptions

16 NAB offered bank accounts to its customers on standard contractual terms and conditions throughout the Relevant Period. NAB’s standard contractual terms and conditions provided that NAB was entitled to charge a fee upon each occurrence of a periodical payment, unless a fee exemption applied (PP Fee Exemption).

17 During the Relevant Period, the standard terms and conditions that governed the operation of periodical payments for the personal and business banking accounts that are the subject of this proceeding were contained in the following documents (as amended from time to time):

17.1 general terms and conditions concerning personal and business banking products, being:

17.1.1 the “Personal Transaction and Savings Products Terms and Conditions” (Personal Product Terms); and

17.1.2 the “NAB Business Products Terms and Conditions” (Business Product Terms).

17.2 fees guides concerning personal banking and business banking products, being:

17.2.1 “A Guide to Fees and Charges – Personal Banking Fees” (Personal Fees Guide); and

17.2.2 “Business Banking Fees – A Guide to Fees and Charges” (Business Fees Guide);

(together, the Fees Guides).

18 A summary of the Fees Guides which identifies the PP Fees and PP Fee Exemptions relevant to the fees incorrectly charged in this case to the Relevant Accounts for personal banking and business banking are identified in Annexure B.

19 Subject to paragraph 20, during the Relevant Period, NAB’s Fees Guides for the Relevant Accounts provided that NAB was entitled to charge $1.80 for periodical payments to other accounts within NAB, and $5.30 for periodical payments to accounts at another bank / financial institution.

20 NAB’s terms and conditions for the Relevant Accounts also provided that customers would be entitled to a PP Fee Exemption for certain transactions during the Relevant Period as follows:

20.1 for personal banking customers, PP Fee Exemptions applied from personal accounts, identified in Annexure C, to certain types of accounts identified in Annexure B; and

20.2 for business banking customers, PP Fee Exemptions applied from certain types of business accounts identified in Annexure B to business loans.

21 During the Relevant Period, where a customer was entitled to a PP Fee Exemption under NAB’s terms and conditions, NAB did not have an entitlement to charge the customer a PP Fee.

22 NAB’s Personal Product Terms identified the personal accounts from which a periodical payment could be made in a table headed “Product Comparison Table – Features and Benefits” under a section with a heading “Key Information” and a subheading “Account Access”. The relevant sending accounts were denoted in this subsection by a “tick” in relation to “periodical payments”. A copy of an example extract of NAB’s Personal Product Terms during the Relevant Period is attached as Attachment 2.

23 All NAB personal account types from which a periodical payment could be made were entitled to the PP Fee Exemptions specified in the Personal Fees Guide when they met the criteria. The Personal Fees Guide identified the types of receiving accounts or scenarios in which a customer would either be entitled to a PP Fee Exemption, or would be charged a PP Fee.

24 NAB’s Business Fees Guide identified the types of business accounts that were entitled to PP Fee Exemptions for periodical payment arrangements to business loans. Those same business accounts were also identified in NAB’s Business Product Terms. The Business Fees Guide specified that they were to be charged $1.80 (for periodical payment arrangements from those accounts to other accounts within NAB) and $5.30 (for periodical payment arrangements from those accounts to accounts at another financial institution).

25 NAB is unable to locate any written or electronic notice provided to customers during the Relevant Period in accordance with its terms and conditions advising that a PP Fee Exemption or PP Fee would be changed (eg removing the exemption entitlement).

26 In the absence of any such notice, customers continued to be entitled to the PP Fee Exemptions or PP Fees that were in place at the time they established their periodical payment arrangement unless the arrangement was amended. If a periodical payment arrangement was amended by changing the sending or receiving account this could have affected the PP Fee Exemptions or PP Fees that applied.

27 The Personal Product Terms for each of the personal banking accounts from 23 May 2008 and the Business Product Terms for each of the business banking accounts from 30 July 2009 (including the Relevant Accounts) contained a term to the effect that customers were required to check their account statements, and to notify NAB of any transactions for which the information recorded was suspected to be, or might be, incorrect. These standard terms are extracted in a table set out in Annexure E.

NAB notification of charges to customers

28 The manner in which periodical payments and any corresponding PP Fees charged were recorded in relevant customer account statements did not change during the Relevant Period and is explained below. Passbook accounts that operated differently are discussed at the end of this section.

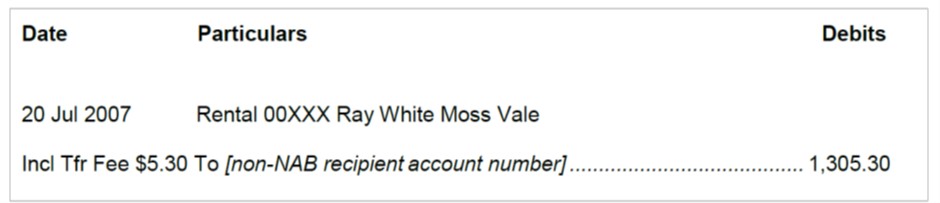

29 When NAB charged a PP Fee to a customer, that fee would be shown on the customer’s account statement as “Incl Tfr Fee $[amount of PP Fee]” against the transfer of funds transaction.

30 The statement entry relating to the periodical payment also included the following information:

30.1 date of the periodical payment transaction;

30.2 description of the periodical payment transaction utilising information supplied by the customer when the transaction was established;

30.3 the account number of the recipient of the periodical payment; and

30.4 the total amount of the periodical payment transaction in question (including any PP Fee charged).

31 An example of a narration, taken from an account statement for a National Cheque Account (with personal identifying information removed) and referring to a periodical payment made to a non-NAB account for which no PP Fee Exemption applied, is as follows:

32 During the Relevant Period, all account statements for the Relevant Accounts (except Passbook accounts, which are addressed separately below) included the following text:

Explanatory Notes

Please check all entries and report any apparent error or possible unauthorised transaction immediately.

We may subsequently adjust debits and credits, which may result in a change to your account balance to accurately reflect the obligations between us.

For information on resolving problems or disputes, contact us on 1800 152 015, or ask at any NAB branch.

33 The narrations which appeared on customer bank statements when Relevant Accounts were charged a PP Fee included the text set out in Annexure A under the heading “notification text”. A copy of an example bank statement, which has been redacted to remove personal identifiable information, is attached as Attachment 3.

34 The bank account statements did not contain any other explanation of the reason why the PP Fee was charged otherwise than summarised in paragraphs 29 to 31 above or any information about the circumstances in which the customer would be entitled to a PP Fee Exemption or the amounts of PP Fees to be charged in particular circumstances.

35 During the Relevant Period, the bank statements did not include PP Fees in the “Transaction Summary” or “Monthly Transaction Summary” part of the bank statement which (when present) provides to customers a summary of the product-related fees and charges levied against the account.

36 PP Fees were not recorded in the “Transaction Summary” or “Monthly Transaction Summary” sections of relevant account statements during the Relevant Period because these sections of NAB account statements concerned product-related fees, being fees incurred in the daily operation of a particular account product (as set out in section 1 of NAB’s Personal Fees Guide and Business Fees Guide).

37 NAB does not consider periodical payments as a “product”. They are discretionary transactions arranged at the request of a customer. Fees charged by NAB in relation to discretionary transactions like periodical payments are only recorded by NAB in the body of the account statement against the relevant transaction.

38 The process was different for customers with NAB “Passbook” accounts during the Relevant Period. Passbook account transactions were printed in the customer’s passbook when it was presented to a NAB branch, rather than being the subject of account statements sent to a customer. Periodical payments and any corresponding PP Fees that were charged in respect of those payments were printed in customer passbooks in the same format as described above on pages with the following note at the bottom of each page on which transactions could be recorded: “Please check entries before leaving the branch”.

Amount charged by NAB for each fee

39 During the Relevant Period, there were potentially two ways in which error on the part of a NAB employee during the process of establishing a periodical payment could give rise to the charging of an incorrect PP Fee to the customer:

39.1 NAB employee selected an incorrect “Periodical payment fee indicator” in the PPA Form; and

39.2 NAB employee entered an incorrect PP Fee Indicator into eBOBS (whether on the basis of an incorrectly completed PPA Form, or otherwise).

40 As a result, from at least 20 July 2007 to 22 February 2019, NAB charged some customers either:

40.1 a PP Fee of $1.80 or $5.30 when they were entitled to a PP Fee Exemption under NAB’s standard terms; or

40.2 a PP Fee of $5.30 when the correct fee under NAB’s standard terms was $1.80.

41 The incorrect PP Fees charged to customers during the Relevant Period are referenced in paragraph 137 below.

42 An incorrect PP Fee Indicator would not necessarily cause an incorrect PP Fee to be charged because, as set out in Annexure D, some PP Fee Indicators caused the same PP Fee to be charged (for example, PP Fee Indicators 1, 2, 4 and 5). Further, at the stage of making inputs into eBOBS, NAB staff could identify and correct an error in the PP Fee Indicator recorded on the PPA Form.

43 The incorrect charging did not cease entirely until NAB removed PP Fees for all periodical payments on 22 February 2019.

NAB’s overcharging of PP Fees

44 During the Relevant Period, NAB charged PP Fees that it was not entitled to charge under its standard contractual terms (PP Fees overcharging). Between 25 February 2015 and 22 February 2019 (Penalty Period), NAB engaged in PP Fees overcharging on at least 195,305 occasions with a total value of $365,454.60 involving 4,874 personal banking customers and 913 business banking customers.

45 Annexure A sets out information on the value and number of occasions on which NAB engaged in PP Fees overcharging during the Penalty Period.

46 For personal accounts during the Penalty Period, Annexure A reflects PP Fees incorrectly charged from NAB Classic Banking, NAB Retirement, NAB Gold Banking-Private and NAB Reward Saver accounts (identified in Annexure C) to:

46.1 the types of accounts identified in Annexure B for personal banking where NAB charged customers $5.30 or $1.80 when it should have applied a PP Fee Exemption (where the charge / fee is identified as “Free”); and

46.2 other accounts at the same or other NAB branch where NAB charged a customer $5.30 when it should have charged $1.80.

47 For business accounts during the Penalty Period, Annexure A reflects PP Fees incorrectly charged from NAB Business Everyday Account ($0 and $10 Monthly Fee Option), NAB Business Cheque Account (including $0 and $10 Monthly Fee Option), NAB Business Management Account and NAB Farm Management Account (as identified in Annexure B) to:

47.1 business loans where NAB charged customers $5.30 or $1.80 when it should have applied a PP Fee Exemption; and

47.2 accounts at the same branch or another branch where NAB charged customers $5.30 when it should have charged customers $1.80.

48 For the period between 20 July 2007 and 24 February 2015, NAB incorrectly charged customers for PP Fees as follows:

48.1 for periodical payments from some personal accounts, including those identified in Annexure C, that were subject to the Personal Fees Guide to:

48.1.1 the types of accounts identified in Annexure B for personal banking where NAB charged customers $5.30 or $1.80 when it should have applied a PP Fee Exemption (where the charge / fee is identified as “Free”); and

48.1.2 other accounts at the same or other NAB branch where NAB charged a customer $5.30 when it should have charged $1.80.

48.2 for periodical payments from some business accounts, including those identified in Annexure B, that were subject to the Business Fees Guide to:

48.2.1 business loans where NAB charged customers $5.30 or $1.80 when it should have applied a PP Fee Exemption; and

48.2.2 accounts at the same branch or another branch where NAB charged customers $5.30 when it should have charged customers $1.80.

49 The rates at which PP Fees were charged incorrectly at relevant times are approximately as follows:

49.1 Between 20 July 2007 and 31 December 2007, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 95,388 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 3.17% of periodical payment transactions between 20 July 2007 and 31 December 2007.

49.2 In 2008, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 210,399 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 3.20% of periodical payment transactions in 2008.

49.3 In 2009, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 207,560 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 3.27% of periodical payment transactions in 2009.

49.4 In 2010, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 202,750 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 3.31% of periodical payment transactions in 2010.

49.5 In 2011, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 189,257 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 3.25% of periodical payment transactions in 2011.

49.6 In 2012, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 166,413 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 2.98% of periodical payment transactions in 2012.

49.7 In 2013, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 139,004 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 2.66% of periodical payment transactions in 2013.

49.8 In 2014, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 108,893 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 2.12% of periodical payment transactions in 2014.

49.9 In 2015, PP Fees were incorrectly charged in relation to 95,191 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 1.92% of periodical payment transactions in 2015.

49.10 In 2016, PP Fees were charged incorrectly in relation to 82,416 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 1.80% of periodical payment transactions in 2016.

49.11 In 2017, PP Fees were charged incorrectly in relation to 72,641 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 1.78% of periodical payment transactions in 2017.

49.12 In 2018, PP Fees were charged incorrectly in relation to 37,385 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 1.02% of periodical payment transactions in 2018.

49.13 Over the Relevant Period, PP Fees were charged incorrectly in relation to 1,608,575 periodical payment transactions, which reflected 2.61% of periodical payment transactions over this period.

NAB’s identification and investigation of PP Fees overcharging

50 On 5 September 2016, ASIC issued a media release, stating that ANZ would refund $25.8m (plus interest) to 376,570 retail accounts and 17,230 business accounts, on the basis that ANZ had failed to disclose to customers when certain periodical payment fees would be charged. Specifically, the media release stated that ANZ’s terms and conditions had defined periodical payments as transactions “to another person or business”, in circumstances where ANZ had also been charging fees for periodical payments made between accounts held in a customer’s own name.

51 In response to that media release, in September 2016, NAB’s consumer banking and business banking Deposits teams commenced a review of periodical payment fees charged by NAB.

52 NAB employees with primary responsibility for the review at this time were:

52.1 Ms Su Jen Lee (Manager, Management Assurance, Deposits);

52.2 Ms Kay Hung (Product Consultant, Business Transaction Accounts);

52.3 Mr John Hur (Product Manager, Business Transaction Accounts);

52.4 Mr Richard Winkett (Head of Product, Business Transactions & Consumer Solutions); and

52.5 Mr Mark Siddall (Senior Legal Counsel).

53 The first step involved a review of NAB’s terms and conditions relating to periodical payments and PP Fees.

54 NAB determined that its terms and conditions properly disclosed its PP Fee charges to customers in respect of periodical payments (namely, its terms and conditions did not suffer from the same issues as those experienced by ANZ in respect of periodical payments, as referred to in the 5 September 2016 media release).

55 Subsequently, in September 2016, NAB commenced the second step in the review, which involved sample testing of approximately 25 randomly selected customer account statements recording periodical payment transactions to determine whether PP Fees had been correctly charged in those cases (Sample Testing). NAB concluded its Sample Testing in late October 2016.

56 The Sample Testing identified instances involving both personal banking and business banking accounts where a PP Fee Exemption had not been correctly applied (in other words, the customer’s account statement recorded that a PP Fee had been charged in connection with a periodical payment transaction to which a PP Fee Exemption applied).

57 On 25 October 2016, Mr Winkett emailed Mr Brendan White (General Manager, Deposits) (copying Mr Hur and Ms Hung – other members of the Deposits team with responsibility for the review) stating that:

>> Periodical payments from a NAB business transaction account to a NAB business loan should be transaction fee exempt

>> Bankers need to manually exempt these transactions from PP Fees, we have found evidence of this not occurring

>> Size / # customers impacted is not known at this stage but we do know our F&C back to 2004 had exempt these PP transactions from these fees.

>> This has been identified during a review Kay has undertaken of disclosures / charging following a recent refund at ANZ.

It is important to note this issue is not as broad as the ANZ event (in that we are comfortable in our disclosures) but will take us a couple of weeks to size the impact.

58 On the same date, Ms Hung created an entry in Riskmart (NAB’s event management system) titled “Overcharging of periodical payment fees for business transaction accounts”.

59 On 27 October 2016, Ms Sophia Yeung (Graduate, Segment Performance, Consumer Transactions) sent a meeting invite titled “Periodic Payment Fees – Next Steps” to Mr Ryan Buckley (Consultant, Product Management, Consumer Deposits), Ms Hung, Ms Carlene Comfort (Senior Analyst, Deposits Lend & Transactions Support Team) and Ms Lee that stated “Both business and consumers have identified issues relating to PP fee not being exempted as shown on the T&Cs. Let’s discuss next steps and possible solutions for both the areas”.

60 On 28 October 2016, Ms Lee emailed Ms Jane Francis (Head of Operational Risk and Compliance, Deposits and Transaction Services) and Ms Claire Plummer (Manager, Operational Risk & Compliance, Consumer Lending) stating that:

… Deposits have identified that for Business Transaction Accounts, periodical payment fees have been charged in scenarios when they shouldn’t have been charged due to bankers failing to manually waive fees. We have since determined that periodical payment fees have also been charged on consumer deposit accounts under similar scenarios … We will be expanding the event to also include Consumer Transaction Accounts as the root cause for both issues is the same … Deposits is currently in the process of performing additional analysis to determine number of customers impacted and value of fees which may need to be refunded. A meeting has been organised with Product Support (assisting with the data extraction process) to discuss next steps.

61 Ms Francis responded on the same date stating “It’s likely we’ll be calling a SERP”.

62 Because NAB’s Sample Testing identified some instances of customers being incorrectly charged PP Fees, NAB identified at this point in time that there was a risk it was overcharging some other customers for PP Fees.

63 As a result of the Sample Testing by the end of October 2016, some NAB employees were aware that there were instances where PP Fees had been charged in error to some business banking and personal banking customers, (including the employees who were party to the correspondence described in paragraphs 57 to 60 above) and that NAB Deposits team was working to determine the number of customers impacted and the value of PP Fees that needed to be refunded.

64 At the time Ms Francis was responsible for deciding whether to refer the findings of the Sample Testing to NAB’s Significant Events Review Panel (SERP), being the body within NAB that, at November 2016, would determine whether an incident was reportable to ASIC under s 912D of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).

65 On 7 November 2016, Ms Francis determined not to refer the matter to SERP because:

65.1 NAB had determined that its terms and conditions properly disclosed NAB’s approach to charging PP Fees; and

65.2 although the Sample Testing had identified instances where a PP Fee Exemption had not been correctly applied, the extent of any incorrect charging was not known.

66 Ms Francis directed that the decision not to refer the matter to SERP should remain under review as the investigation into the extent of the issue progressed, with a view to considering taking the matter to SERP at a later stage.

67 At that time, NAB believed that the total of all PP Fees charged over the previous four years was only $64,000 in revenue.

68 It was not until 20 June 2018 that the PP Fees overcharging was determined by SERP to be reportable under s 912D of the Corporations Act.

69 On 4 November 2016, Ms Plummer sent an email to Mr Winkett, Mr Gordon Long (Head of Product Management, Domestic Payments), Ms Deanne Keetelaar (General Manager, Transaction Products & Payments) and others stating “Appears overcharge has been happening since March 1999” in the context of outlining the notes taken in relation to a meeting for “PP Charging Issue – SERP”.

70 In about December 2016, NAB commenced an investigation for the purpose of determining the extent to which PP Fees had been charged incorrectly, and to ultimately remediate impacted customers. To the best of NAB’s knowledge the investigation was commenced at the direction of Ms Keetelaar and / or Mr Long. In around December 2016, Mr Long left NAB.

71 At this time responsibility for the investigation was allocated to NAB’s Payments team as the “product owners” of periodical payments.

72 The core investigating team initially comprised three employees from NAB’s Payments team. Ms Alida Macalister (Head of Product International Payments and Channels) had day-to-day responsibility for the investigation and was supported by Ms Hillary Ruffell (Product Manager, Payment Channels) and Ms Blessing Mayowe (Consultant, Payments & Channels) who both reported to her. It did not include Ms Hung or the other NAB staff who initially had primary responsibility for review of periodical payment fees charged by NAB identified in paragraph 52.

73 On 1 December 2016, Ms Plummer sent a meeting invitation to Ms Macalister, Ms Ruffell, Ms Jaime Russell (Senior Consultant, Management Assurance, Deposits & Transaction Services), Mr Winkett, Ms Lee and Ms Francis with the subject “PP charging issue – handover to new Payments resources”. Ms Plummer’s email relevantly stated:

With Gordon Long leaving NAB I am keen for you to provide subject matter expert background and context to Hilary and Alida to ensure adequate PP understanding, and remediation is undertaken.

74 Ms Plummer’s meeting invite dated 1 December attached “background emails”. This included an email chain containing a copy of the email referred to in paragraph 69, which relevantly stated “Appears overcharge has been happening since March 1999”. The meeting invitation was for an in person meeting on 13 December 2016 at 11.30am. Ahead of the meeting, Ms Macalister responded to Ms Plummer’s meeting invite asking for “dial in details”.

75 The General Manager, Payments was ultimately responsible for management of the investigation and had authority to make decisions on proposed courses of action. Ms Keetelaar was in this role in December 2016, when the Payments team took over responsibility for the investigation, and remained in the role until 10 March 2017, when she left NAB. Mr Michael Starkey was in the role in an acting capacity between 11 March 2017 and 23 May 2017. Mr Paul Franklin was in the role from 29 May 2017 to the end of the Relevant Period.

76 Updates on the progress of the investigation were also provided from time-to-time to NAB’s Payments Risk Management Forum (PRMF), a risk management committee that convened monthly to discuss and action compliance and risk matters relating to NAB’s Payments team. The PRMF was chaired by the General Manager, Payments.

77 At around this time, the investigating team formed the view that the PP Fees overcharging could only affect customers who had established a PP Fee arrangement from 2014.

78 The reason for that view was that those employees believed that the PP Fee structure in operation at the time had been introduced in terms and conditions dated in 2014.

79 NAB’s investigation used data extracted from the system that stores certain datasets associated with periodical payments (the Authority Payments Master File) (Master File) to identify instances of incorrect PP Fees.

80 NAB staff who were investigating the issue and developing the process to identify and remediate impacted customers initially identified those customers using two point in time data extracts created by NAB in September 2016 and January 2018.

81 Progress with developing a process to identify and remediate all impacted customers was hampered by limitations in the Master File data. In particular, that data:

81.1 recorded PP Fee Indicators in effect as at the date of extraction, but did not include historical data (namely, about how PP Fees had been charged in the past in respect of particular periodical payments);

81.2 did not record the structure of historical periodical payment arrangements (i.e. Sending / receiving account and payment frequency) to enable NAB to determine whether an arrangement recorded in a Master File extract had been structured differently in the past;

81.3 did not include reliable data showing the commencement dates of the periodical payment arrangements recorded in the data; and

81.4 did not include a full set of data for some periodical payment arrangements.

82 NAB staff investigating the issue did not know it could retrieve the data recording historical periodical payments and related PP Fees charged to customers using NAB’s “Statement Transaction” system. This data source was ultimately identified in around February 2019.

83 Because NAB investigating team did not know it could retrieve historical periodical payments as described above in paragraph 82, the investigating team focused on attempting to overcome the limitations in the Master File data. While the investigating team ultimately did develop a remediation methodology utilising the Master File data, it was impacted by most of the limitations described in paragraph 81 above, which the investigating team was not able to overcome.

84 Between the end of October 2016 and January 2017, some of the correspondence between NAB employees about the identification and investigation of the PP Fees overcharging included:

84.1 On 25 October 2016, Mr Winkett advised Mr White through the email described in paragraph 57 above that there was a “new risk / refund event in relation to periodical payment transaction fees” and noted that:

>> Periodical payments from a NAB business transaction account to a NAB business loan should be transaction fee exempt

>> Bankers need to manually exempt these transactions from PP Fees, we have found evidence of this not occurring.

84.2 On 28 October 2016, Ms Lee advised Ms Francis through the email described in paragraph 60 above that since she was first advised that business transaction accounts had been charged periodical payment fees “where they shouldn’t have been”, they had also determined that periodical payment fees had been charged on consumer accounts under similar scenarios. Ms Francis responded that “It’s likely we’ll be calling a SERP”.

84.3 On 4 November 2016, a meeting was held between NAB employees in relation to the “PP Charging Issue” and considering a SERP, which included Ms Keetelaar, Mr Long and Mr Winkett.

84.4 On 8 November 2016, Ms Ruffell forwarded an email to Mr Long and Ms Keetelaar which recorded that NAB’s revenue from PP Fees for the last four financial years (FY13 to FY16) was “64k an average of $15k per annum”. On 14 November 2016, Mr Long sent an email in reply which relevantly stated: “Looking at recent numbers, may as well just waive the fee for all customers going forward. Revenue is not worth trying to control in my view ($30k pa)”. Ms Keetelaar replied: “Agreed”.

84.5 On 15 November 2016, there was a meeting of the Deposits Risk Management Forum which was attended by a number of NAB employees, including Mr White. The meeting pack provided to the attendees included an update headed “Incorrect charging of Periodical Payment Fees” which stated:

In response to ANZ’s recent periodical payments disclosure issue, Deposits undertook a review to confirm that: a) periodical payment fee disclosures were sufficient b) periodical payment fees charged align to the disclosures. Whilst the review confirmed that the disclosures were adequate, it identified that bankers have failed to follow internal process and waive the periodical payment fees in certain scenarios. For example, when a periodical payment is established from either a Business Everyday Account ($0 and $10) or a Farm Management Account to any NAB Business loan, the periodical payment fee should be exempt. Pending the outcomes of further data/analysis, CRO have determined that a Significant Event Reporting Panel (SERP) is not required for now. Should a SERP be subsequently required, it is acknowledged that this will be under Transaction Product & Payments (and not Deposits) as they have since been confirmed as the Product Owners of Periodical Payments. Deposits will continue working with Transaction Product & Payments to manage the event.

84.6 On 14 December 2016, Ms Plummer circulated action items from a periodical payments meeting to Ms Ruffell, Ms Macalister, Ms Francis, Mr Winkett, Ms Russell and others noting the agreed actions were as follows:

Blessing: Send out ‘PP – need to know’ awareness comms to frontline in Dec 2016 and again in Feb 2017.

Sophia: Contact Carlene Comfort to filter on data that should be exempt from PP, but incurred charges; design a report that can be used regularly to detect any overcharging in the future. Include Blessing in discussions.

Alida: Contact Major Refunds Team to extract 18 months of PP data, so we can expand analysis from 6 months to 2 years of data. Obtain any refund recommendations from the team.

84.7 On 15 December 2016, Ms Plummer circulated another email in relation to action items from the same periodical payment meeting and relevantly stated:

Actions have been amended as per feedback, thank you:

…

Sophia: Contact Carlene for a list of each product code and cycle code, so that the Payments team can better understand how to filter the data in the spreadsheets

…

84.8 On 15 December 2016, Mr Jason Webster (Consumer Products & Services) sent a meeting invitation to Ms Macalister and Ms Mayowe with the subject “Refund PP / DDR discussion”, which relevantly stated:

Note –

We have 2 types of authority payment transactions (DDR’s “pull” and Periodic Payments “Push”)

My team already have some data available on Periodic payments that we provided deposits team recently, so if a decision is made to refund all these fees, it will be a large Refund.

84.9 On 3 January 2017, Mr Webster sent an email to Ms Macalister, Ms Mayowe and Ms Comfort, which relevantly stated:

Minutes / actions from December Refund check in

…

2) Blessing to confirm dates of T&Cs relating to any potential refund

3) Data: (32Mg file.. If you need it let me know)

-SR67364 P Payments extract as at 30/11/2016

- 196K NAB PP’s / 16K Non Nab PP’s

- 172K (of 196K Nab ones) had zero fee charged as per excel snapshot below

4) Jason to investigate timeframes of how long “Closed PP data” is stored on ledgers

5) Blessing / Alida to set up next steps meeting once any formal refund has been confirmed.

85 On or around 20 February 2017, a draft of the “Need to Know” article referred to above in paragraph 84.6 was finalised. The article was designed by the investigating team with a view to improving awareness of staff in NAB’s retail branches around the application of the PP Fee. However, the article was not finalised and sent to retail branch staff because NAB’s Retail Communication Team, which sends communications to retail branch staff, advised that the Need to Know article was not suitable for publication because such articles are reserved for advising retail branch staff of changes relevant to their roles, whereas the purpose of the proposed article was to remind retail branch staff of existing procedures.

86 Between March and May 2017, five months after NAB first identified there was a risk it was overcharging some customers PP Fees, the investigating team sought assistance from other NAB employees to determine whether the task of identifying incorrect PP Fee charges could be assisted by utilising data stored in NAB’s Global Data Warehouse system (GDW). In particular:

86.1 On 15 March 2017, Mr Stuart Murray (Senior Analyst, Product Delivery & Support, Customer Products & Services) sent an email to Ms Macalister which explained that sourcing transaction data from GDW may assist with identifying incorrect PP Fee charges and that a resource with GDW expertise would be needed to track down the bulk, if not all, of the data.

86.2 On 20 March 2017, Ms Macalister sent an email to Ms Amber Barrow (Senior Consultant, Management Information, Payments) which stated:

We are trying to work out who has been overcharged but it seems that no one has the skill set to help us. Can you have a look at the explanation below and let me know where else i should be trying? Is it something you are able to do, or where else do i find this skill set. It must be rocket science!

86.3 On 19 May 2017, Ms Macalister sent an email to Mr Andreas Haggren (Senior Consultant, Data Scientist) which stated:

We are struggling to find someone with the skills to work out who has been overcharged, and we have been advised that the data should sourced [sic] from actual transaction data via GDW.

…

We would like your guidance on what is actually possible as there seems to be very limited GDW understanding out there.

87 Ms Barrow and Mr Haggren both attempted to identify incorrect PP Fee charges using data sourced from GDW but were unsuccessful.

88 On 17 May 2017, Ms Mayowe and Ms Macalister corresponded about NAB’s revenue from PP Fees and whether NAB should cease charging PP Fees, which relevantly included:

Ms Mayowe: “I think we should re-visit Hillary’s idea donating [sic] a specified amount to charity.

I am still working on analysing the revenue for Periodical Payments to see what the effect will be on our revenue.

This is what I’ve found out so far:

• For the last 4 years we’ve earned 64k which is an average of $15k per annum for periodical payments made from one NAB acc to another NAB acc ($1.80 per transaction).

• What I am yet to find out is how much revenue we receive for periodical payments made from a NAB acc to another FI ($5.30 per transaction). Kum is to provide me with data”

Ms Macalister responded: “Blessing, I am agreeing with you now. Maybe no charge for DDs. What do other banks do and does Hillary agree? (good time to get rid of it as we are doing FY18 planning at the moment).”

Ms Mayowe responded: “I’ll do some research on how other banks charge for PP’s not DD.

• Periodical Payment is a transfer of funds that we make on a regular basis at the customer’s request from one account to another specific account.

• A direct debit is a transfer of funds from a customer’s account drawn under a direct debit request you have given a third party.

Hillary is happy to forego the revenue as this will constantly be an issue unless there are system changes to eBobs.

89 On 18 July 2017, Ms Macalister advised the PRMF that the investigating team had not been able to develop a methodology for identifying customers who had incurred incorrect periodical payment fee charges. She proposed to make a donation to charity instead.

90 The PRMF did not accept the proposal to make a charitable donation in lieu of remediation.

91 On 18 July 2017, Mr Nick de Crespigny (GM Risk, Business Lending and Deposits and Transaction Services), who had attended the PRMF meeting on that date, sent an email to Ms Alena Wang (Manager, Operational Risk and Compliance, Deposits and Transaction Services) reporting on the meeting, which relevantly stated:

Initial view is that we can’t extract the data - but there was some disagreement on the call about whether a greater level of effort would allow us to extract the data. Preliminary estimates of $15k seem very low.

92 The reference in Mr de Crespigny’s email to “estimates of $15k” related to the assessment of NAB’s annual revenue from PP Fees.

93 Subsequently, at a PRMF Meeting on 27 September 2017, approximately ten months after NAB first identified there was a risk it was overcharging some customers PP Fees, the investigating team presented a paper which described the challenges being faced in obtaining reliable data to determine the extent of any incorrect charges associated with PP Fee Exemptions.

94 The PRMF directed that further resources be allocated to attempt to overcome the data challenges.

95 In October 2017, following the PRMF’s direction, Ms Mayowe, one of the members of the investigating team was replaced by a more senior consultant, Mr Kris Prasad (Product Transformation Consultant, Payments).

96 Between October and November 2017, Mr Prasad developed a methodology to utilise the Master File data extract obtained in September 2016 to identify the periodical payment arrangements with incorrect PP Fee configurations.

97 On 26 October 2017, Mr Prasad sent an email to Ms Macalister reporting that his analysis (utilising the Master File data referenced above) had found 3,455 out of a total of 196,306 periodical payment arrangements (1.76%) were “overcharged”, broken down as follows:

97.1 3,316 periodical payment arrangements were charged $1.80 instead of $0;

97.2 132 periodical payment arrangements were charged $5.30 instead of $1.80;

97.3 9 periodical payment arrangements were charged $5.30 instead of $0.

98 The Master File data that Mr Prasad used did not record any actual fee ‘charges’. It recorded the fee configurations that applied to the periodical payment arrangements at the date the Master File extract was obtained, which enabled an inference to be made that incorrect charges had occurred.

99 On 30 October 2017, prior to a PRMF meeting scheduled on that day, Ms Macalister sent a document to the members of the PRMF which contained an amended version of Mr Prasad’s analysis in table form. The analysis identified that the forecast annualised revenue from periodical payment fees exceeded $1.5m. The analysis also identified that the forecast annualised revenue from periodical payment fees overcharged was $509,738.

100 On 27 November 2017, Mr Grant Duthie transferred into NAB Payments team from another team within NAB and took over responsibility from Mr Prasad for progressing the investigation. One of the first tasks assigned to Mr Duthie was to interrogate the reliability of the initial estimate provided to the investigating team of the annual revenue from periodical payments. Mr Duthie also worked with Mr Prasad to peer review his analysis of incorrect charges.

101 On 6 December 2017, over a year after NAB first identified there was a risk it was overcharging some customers PP Fees, Mr Duthie sent an email to Ms Macalister (copied to others) which stated:

I spent some time with Kris today to run through his analysis, logic, findings and assumptions. So some of the call outs around the customer impact (as at November 2016) of the periodical payments:

* 3,227 customers we believe have been overcharged

* 147k estimated unique remitters (based on unique account names) that have set up periodical payments set up [sic] in eBOBS

* $152k is the estimated amount that customers have been overcharged for periodical payments per annum (1.76% of total periodical payments volume)

* $1.14M is the estimated total revenue NAB earns each year from periodical payments fees.

102 One of the reasons that the overcharged amount was expressed as an estimate was that the Master File data extract utilised for the analysis did not contain reliable data recording the start date of each periodical payment arrangement to enable an assessment of how long an incorrect PP Fee Indicator identified in that data may have been in place for. As noted above at paragraph 83, the investigation team was focused on data recorded in the Master File extract because it did not know it could retrieve the data recording historical periodical payments.

103 In relation to the estimate that NAB’s total annual revenue from PP Fees was $1.4m, Ms Macalister sent an email to Mr Duthie dated 10 December 2017 which stated:

This seems like a lot compared to the estimates Hillary came up with initially.

104 On 15 December 2017, Mr Duthie forwarded an email to Mr Kum Chau (Senior Analyst, Performance Management (Non Traded), Customer Products & Services Finance) containing an analysis Mr Chau had performed in November 2016 to determine that NAB’s revenue from periodical payments averaged $15,000 per annum. Mr Duthie stated that he “…wanted to understand how we calculated this data as well and get any assumptions…”.

105 On 19 December 2017, Mr Chau sent an email to Mr Duthie referring to data which “appears to relate to periodical payments where the revenue for FY17 is $1.4m” and stated that he was “trying to get the transaction details for these transactions, which I should hopefully be able to send you later today”.

106 On 20 December 2017, Mr Chau sent a further email to Mr Duthie advising that, subject to certain assumptions, NAB’s revenue from periodical payment transactions in FY17 was $817,339.20.

107 On 10 January 2018, Mr Duthie sent an email to Ms Macalister which included the following statement regarding the further PP Fee revenue data provided by Mr Chau:

I have also included Kum Chau’s emails with the recent P&L that shows $1.4M associated with PPs and some other misc. Products and then his workings that showed the figure might be closer to $800k.

108 On 31 January 2018, Ms Macalister sent an email to Ms Russell in relation to the “periodic payment remediation”, which relevantly stated:

- someone new has started in the support team (previously Major refunds) who has been able to understand the data better & changed some of the outcomes -around 3000 currently impacted (ie have been overcharged). We are unable to determine historical periodic payments incorrectly charged. - We are unable to tell how long these periodic payments have been in force for and therefore, the total amount that should be repaid to each customer. On an annual basis. It is approx. $152,000 pa. T&Cs were changed in 2014 so payments in place before then were not overcharged. -We propose refunding customers 1 years’ worth of fees but some of them may complain because their PPs have been in place longer than that. -we have also identified that all the revenue comes into our PU and is worth approx. $800k pa, declining by 17% pa. Therefore any remediation will need to come out of our cost centre -need to make a decision on how much to remediate customers – max of 3 years??? And will do in in the next few months ...

109 On 5 February 2018, a meeting pack was emailed to the members of the PRMF for a meeting on 6 February 2018. It included the following update in relation to periodical payments:

Around 3000 currently impacted (i.e. Have been overcharged). We are unable to determine to historical periodic payments incorrectly charged. We are unable to tell how long these periodic payments have been in force for and therefore, the total amount that should be repaid to each customer. On an annual basis. It is approx. $152,000 pa. T&Cs were changed in 2014 so payments in place before then were not overcharged.

Status & Next Steps

Decision required on how much to remediate customers & which actions will be implemented to prevent reoccurrence.

110 In February 2018, approximately one year and three months after NAB first identified there was a risk it was overcharging some customers PP Fees, Mr Duthie requested assistance from NAB’s GDW Production Support team to determine, utilising GDW data, the start date, end date and (where applicable) amendment date of the periodical payments identified in the Master File data as having incorrect PP Fee Indicators.

111 In February and March 2018, an analyst from the GDW Production Support team extracted and provided this information to Mr Duthie.

112 The investigating team believed that the commencement dates supplied by the analyst for periodical payment arrangements that commenced prior to 2014 were unreliable. This affected the approach NAB took to calculating the remediation amounts paid to customers whose periodical payment arrangement commenced prior to 2014. This is explained further in paragraphs 127 and 129 below.

113 On 23 March 2018, NAB employees discovered that the relevant terms and conditions were amended in February 2002 and the PP Fees in operation at that time had in fact been in force since then.

114 As a result, from this time NAB knew that the risk it was overcharging some customers PP Fees existed from at least February 2002.

115 After this discovery on 23 March 2018, the following events occurred:

115.1 On 26 March 2018, Mr Duthie sent an email to Ms Macalister which referred to his understanding that start dates obtained for periodical payment arrangements commencing prior to 2014 were unreliable and stated “Based on the poor data quality here, I don’t believe we should be remediating any customer with a pp starting pre-2014”. On 29 March 2018, Ms Macalister replied to Mr Duthie’s email and said she agreed with this approach;

115.2 On 28 April 2018, members of the investigating team presented a paper to the PRMF stating that: “If a periodical payment commenced before 2014, the arrangement start date is not reliable as it is mixed with the account start date and therefore we cannot calculate refunds for these customers properly. Customers with periodical payments commence [sic] before 2014 will have their fees corrected, but will not be refunded”; and

115.3 On 20 June 2018, Ms Macalister reported on the outcome of the SERP meeting and wrote that: “Action for us to engage Jocelyn Turner who can provide FOS guidelines for remediation of customers, particularly pre 2014 where we cannot reliably calculate the amount. There was a consensus that some attempt must be made to remediate these customers”.

116 NAB undertook the steps in paragraph 115 above based on a view that the data available to it about establishment dates for periodical payment arrangements prior to 2014 was unreliable, and so it initially calculated remediation for customers whose arrangement had been in place since prior to 2014 for a maximum period of seven years from October 2011. NAB applied this approach to the design of its “Initial Remediation Program”, which is described in more detail commencing at paragraph 121 below.

117 In July 2018, NAB started making remediation payments to some customers impacted by the PP Fees overcharging and writing to impacted former customers of NAB identifying that the customer had been incorrectly charged a PP Fee and asking the customer to nominate an account into which their refund amount could be paid.

118 By February 2019, NAB had identified a potential approach to retrieve the historical periodical payments and related fees charged to customers whereby the data was available from 1 August 2001 to the present from its “Statement Transaction” system. The Statement Transaction data recorded historical periodical payment transactions and the associated PP Fees that had been charged over time (and accordingly, was not affected by the same “point in time” limitations as the data extracted from the Master File).

NAB notifications to ASIC

119 On 4 July 2018, NAB notified ASIC of the PP Fees overcharging by a breach report to ASIC related to those customers within the scope of NAB’s Initial Remediation Program, being customers identified from the September 2016 and January 2018 Master File data extracts.

120 On 28 February 2019, NAB informed ASIC that it had identified a potential approach to access the data required to identify all customers who had been overcharged PP Fees in the period from August 2001 and that it was investigating this possibility:

…as a matter of the highest priority for the purpose of developing a new methodology for undertaking a supplementary remediation program” which was intended to “identify all periodical payments for which a fee was incorrectly charged for the period 1 August 2001 to present, without the need to adopt assumptions as was considered to be necessary when relying on the data sources used previously.

NAB’s remediation to customers

Initial Remediation Program

121 On 13 July 2018, NAB commenced remediation payments to customers (Initial Remediation Program).

122 Payments under the Initial Remediation Program were processed in two tranches. The first tranche of payments was processed on 13 July 2018. The second tranche was processed on 26 October 2018.

123 NAB remediated at least 4,579 customers a total of $688,318.41 under the Initial Remediation Program (including compensatory interest to reflect the “time value of money”). This excludes the amounts that NAB remediated as part of its monthly exception reporting process, which commenced on 28 June 2018 and is described in paragraphs 130 to 132 below.

124 The customers within the scope of the Initial Remediation Program were identified from two point in time Master File data sets extracted by NAB in September 2016 and January 2018.

125 The Master File data was used to design the Initial Remediation Program.

126 The Initial Remediation Program was undertaken on the basis of a number of assumptions.

127 For customers identified as having a periodical payment arrangement with an incorrect PP Fee configuration and whose arrangement had been in place since 2014, NAB assumed that the incorrect fee configuration had been in place since the PP arrangement commenced, even if the arrangement had been amended and the incorrect configuration may have only been in place since the amendment date.

128 For customers identified as having a periodical payment arrangement with an incorrect PP Fee configuration and whose arrangement had been in place before 2014, NAB applied the following approach:

128.1 if the periodical payment arrangement had been amended, it was assumed that the incorrect fee configuration had commenced on the date of that amendment;

128.2 if there were multiple amendments, it was assumed that the incorrect fee configuration had commenced on the date of the most recent amendment;

128.3 if the periodical payment had not been amended, it was assumed that the incorrect fee configuration had been in place since the customer’s account was opened; and

128.4 if the date identified by the above process was earlier than 26 October 2011, NAB remediated from 26 October 2011 (reflecting a maximum remediation period of seven years between 26 October 2011 and 26 October 2018).

129 The approach described in paragraph 128 above was implemented due to NAB’s understanding that the data available to it about establishment dates for periodical payment arrangements commencing prior to 2014 was unreliable. In around February 2019, in the course of responding to a statutory notice issued by ASIC, NAB identified that its understanding was incorrect and that the commencement date data utilised for the purpose of the Initial Remediation Program was reliable in relation to periodical payments commencing both before and after 2014.

Exception Reporting Process

130 On 28 June 2018, NAB obtained a data extract from the Master File and utilised it to commence an ‘exception reporting’ process which NAB undertook on a monthly basis.

131 The purpose of the exception reporting process was to identify incorrect PP Fees on a monthly basis, so that these matters could be corrected and impacted customers remediated.

132 NAB prepared the first exception report in July 2018 and continued the exception reporting process until March 2019 (to reflect that NAB ceased charging PP Fees on 22 February 2019).

133 NAB remediated customers a further $10,045.29 during this period for incorrect PP Fee charges identified through the monthly exception reporting process.

Supplementary Remediation Program

134 From at least 28 February 2019, NAB employees were aware they could potentially access the data required to identify all customers who had been overcharged PP Fees, potentially enabling it to remediate customers who were affected by the overcharging as far back as August 2001.

135 On 12 September 2019, NAB sent an email to ASIC confirming that it had finalised the design of a methodology for a supplementary remediation program utilising this data.

136 The objective of the program is to remediate all customers who incurred an incorrect PP Fee charge between 1 August 2001 (being the start date of the available data) and 22 February 2019, and who had not been (or had not been fully) remediated pursuant to the Initial Remediation Program (Supplementary Remediation Program).

137 As at June 2020, NAB had paid or intended to pay remediation in the amount of approximately $2,693,210 (plus compensatory interest) in respect of 1,448,417 transactions for PP Fees charged during the Relevant Period as part of its Supplementary Remediation Program.

138 NAB divided the Supplementary Remediation Program into tranches and payments to impacted customers within the first tranche commenced on 10 December 2019.

139 As at 4 December 2020, NAB had paid $7,714,314.48 under the Supplementary Remediation Program and some payments were still to occur.

140 The total amount of remediation payable by NAB through the Supplementary Remediation Program, in relation to incorrect PP Fee charges between 1 August 2001 and 22 February 2019, is $10,053,767.66 (including compensatory interest). This amount is payable to 70,265 current and former customers.

141 As at 20 April 2022, NAB had paid $8,362,639.54 of the total remediation amount to affected customers.

External assistance

142 By way of an engagement letter dated 3 April 2019, NAB engaged PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to provide assistance with its Supplementary Remediation Program. The objectives of the engagement were stated in an engagement letter in the following terms:

The objectives of this Engagement Contract are to ensure that NAB’s customer remediation program is appropriate, that it is executed correctly, and that NAB has done the right thing by its customers.

In particular, the purpose of the review is to ensure that NAB’s methodology for identifying impacted customers is accurate, and that its customer remediation program is properly designed and correctly executed.

143 The scope of PwC’s engagement includes reviewing and validating NAB’s approach to:

143.1 identifying all incorrectly charged periodical payment fees in NAB’s available data;

143.2 quantifying the remediation to be paid to customers for incorrectly charged periodical payment fees, including NAB’s methodology for calculating the compensatory interest added to remediation payments; and

143.3 executing the remediation payment process.

144 To date PwC has issued reports stating that it considers:

144.1 NAB’s methodology for identifying impacted customers is accurate, and that its customer remediation program is properly designed; and

144.2 NAB has quantified the required compensation payments for customers correctly and made allowance for compensatory interest appropriately.

Unpaid remediation

145 NAB has not remediated all customers who were overcharged PP Fees as remediation payments have not been made to customers in the following circumstances:

145.1 customers who were identified in NAB’s Supplementary Remediation Program, are a former customer, and are to be paid remediation less than $20. In those circumstances, NAB has not attempted to make payments and has stated that it intends to pay the amount directly to charity without attempting to contact the customer at the conclusion of NAB’s Supplementary Remediation Program; and

145.2 if a remediation amount of $20 or more is due to a current or former customer who does not hold a NAB account into which the remediation payment can be made, and NAB does not receive a response to its attempts to communicate with the customer about their entitlement utilising the contact details NAB holds on file (if any), or does not hold contact details on file. In those circumstances, NAB has stated that it will pay the remediation amount to charity if the amount is less than $500, and to ASIC as unclaimed moneys if the amount is more than $500.

146 ASIC’s Regulatory Guide 256 issued on 15 September 2016 says:

RG 256.135 Where the amount of compensation to be paid to a client is below $20 and the client cannot be compensated without significant effort on your part—for example, because the client no longer holds an account with you—you may instead make a community service payment by paying the amount to an appropriate organisation (which will generally be not for-profit) to fund activities that could be characterised as a community service. You may wish to consult ASIC on which organisations may be appropriate to pay this amount to. You must not profit from the misconduct or other compliance failure.

Note: See Regulatory Guide 100 Enforceable undertakings (RG 100) for further information about community service obligations.

147 If an affected customer contacts NAB after their remediation amount has been paid to charity or to ASIC as unclaimed moneys, NAB has stated that the customer will still be entitled to payment of the remediation amount. In the circumstance where a customer’s remediation has been paid to charity, NAB has stated that it will still remediate that customer.

NAB’s systems

NAB’s systems and processes in relation to periodical payment arrangements

148 Paragraph 15 above describes the process for NAB staff to create a periodical payment arrangement during the Relevant Period. As noted above, NAB had “help screens” accessible to NAB employees within the PP Setup Screen in eBOBS, which provided an explanation of the PP Fee Indicator when establishing a periodical payment arrangement. Further, NAB staff could review the Personal Fees Guide and Business Fees Guide, which contained the details of the PP Fees and PP Fee Exemptions.

149 Between 20 July 2007 and July 2018, NAB did not have any system or process in place to detect (and if detected, correct) whether a periodical payment arrangement had been established incorrectly.

150 As noted above at paragraph 33 and demonstrated by Attachment 3, NAB’s account statements did not advise customers whether a customer was entitled to a PP Fee Exemption, or whether the PP Fee Exemption had not been applied.

151 As noted above at paragraph 132, between July 2018 and March 2019, NAB remediated customers it identified as being incorrectly charged through its monthly exception reporting process.

152 NAB’s reliance on monthly extracts of the “point in time” Master File data for this process meant that incorrect PP Fee charging may not have been identified in circumstances including where:

152.1 the underlying periodical payment arrangement was established and then cancelled in the time between monthly exception reports being generated; and

152.2 the incorrect PP Fee charging was identified and corrected in the time between monthly exception reports being generated.

153 NAB admits that the monthly exception reporting process could have been implemented earlier than July 2018 because it relied on the methodology designed by Mr Prasad between October and November 2017 for utilising data extracted from the Master File to identify periodical payment arrangements with incorrect PP Fee configurations.

154 NAB’s monthly exception reporting process did not eliminate overcharging of PP Fees. It primarily identified the PP Fee overcharging after it occurred so that NAB could remedy incorrect PP Fee configurations when identified and remediate impacted customers.

155 Prior to 22 February 2019, NAB did not change its systems in relation to the PP Fees to eliminate instances of overcharging of PP Fees.

156 Prior to 22 February 2019, NAB investigated ceasing to charge PP Fees altogether (being the solution ultimately adopted by NAB).

157 On 22 February 2019, NAB ceased to charge customers PP Fees.

158 During the Relevant Period, NAB’s systems and processes did not detect or prevent all wrongful charging of PP Fees when it did occur. NAB implemented the exception reporting process during the Relevant Period but, as explained at paragraph 152 above, it may not have identified all incorrect PP Fee charges.

NAB’s systems and processes in relation to data

159 As noted above in paragraph 82, NAB staff investigating the issue and conducting the Initial Remediation Program did not know they could retrieve the historical PP Fees charged to customers using NAB’s “Statement Transaction” system. The ability to do this was ultimately identified in around February 2019. Because of this when NAB’s investigating team developed the Initial Remediation Program the team focused on attempting to overcome the limitations in the Master File data.

160 As at 5 November 2018, NAB’s understanding was that there were no data sources available that would have enabled NAB to:

160.1 identify the structure of historical periodical payment arrangements (i.e. Sending / receiving account and payment frequency) to determine whether an arrangement recorded in a Master File extract had been structured differently in the past;

160.2 identify details of historical PP Fee configurations to determine whether an incorrect fee configuration had been configured correctly in the past and vice versa;

160.3 identify reliable commencement dates for relevant periodical payment arrangements commencing before 1 January 2014;

160.4 fill in the gaps in the Master File extracts where data was missing for some periodical payment arrangements.

161 NAB identified the Statement Transaction data as a result of investigations commencing in around January 2019 for the purpose of responding to a question in a statutory notice issued by ASIC.

162 Between December 2016 and February 2019, the employees undertaking the work to identify the customers who were affected by the PP Fees overcharging:

162.1 did not identify the Statement Transaction data, as noted above in paragraph 159. This is partly because they did not have the skills to be able to identify or obtain this data. This is noted in two emails from Ms Macalister dated 4 and 19 May 2017, where she stated that “the payments team does not have the skill to work out who has been overcharged” and that they “are struggling to find someone with the skills to work out who has been overcharged”;

162.2 incorrectly thought that the data challenges were insurmountable because they did not identify that the Statement Transaction system could be used to remediate impacted customers and they continued to focus on the Master File data; and

162.3 incorrectly thought that NAB did not have the data to be able to reliably identify the start date of the pre-2014 periodical payment arrangements because they did not identify that the Statement Transaction system could be used to remediate impacted customers and / or because they did not make further enquiries about the data that was available.

163 Through the Sample Testing NAB identified instances of PP Fees overcharging in October 2016, but due to the issues identified in paragraphs 159 and 162 above:

163.1 NAB was not able to commence developing the Supplementary Remediation Program to identify and remediate all impacted customers until around February 2019 (when the Statement Transaction data was identified);

163.2 NAB did not commence remediating affected customers until July 2018, and as at 30 June 2021, NAB continues to remediate affected customers.

164 Until 22 February 2019 NAB continued to charge PP Fees and continued to cause harm in instances where it charged customers incorrectly for those fees.

165 NAB’s systems and processes did not result in NAB identifying and remediating, during the Relevant Period, all customers affected by wrongful charging of PP Fees.

Harm

166 NAB customers who incurred the PP Fee charges referenced in paragraph 137 above suffered financial loss and inconvenience because they were required to pay PP Fees that NAB was not entitled to charge.

167 NAB implemented the Initial Remediation Program and the Supplementary Remediation Program to address the financial loss and inconvenience to customers.

168 NAB has not compensated all customers who were incorrectly charged PP Fees for the reasons set out in paragraph 145 above.

169 Payments under the Supplementary Remediation Program are continuing. As at 17 September 2021, remediation totalling $1,698,337.30 (including interest) had not been paid to 18,220 affected customers because of the matters described at paragraph 145.

170 A total of 72 of the affected customers referenced in paragraph 169 above incurred incorrect PP Fee charges in the period between 1 January 2017 and 28 June 2018 (being the date NAB obtained a data extract from the Master File which it utilised to commence the exception reporting process). These 72 customers were charged a collective total of $1,610.10 incorrect PP Fees during that period.

NAB’s investigation of solutions to address incorrect PP Fee charging

171 In September 2017, Ms Macalister presented a paper titled “PP Refund Discussion Paper” to the PRMF.

172 The paper detailed the current status of NAB’s investigations into the periodical payment issue. Under the sub-heading “Our Actions” the paper noted the potential system changes and associated costs that could be involved, in the following terms:

…

2. Investigation into implementing a systems fix to prevent PP fees being charged to the excluded accounts would be costly ~$1.5M(High level estimate. (Requires EBOBS systems)

3. If we were to remove the fee altogether we would still require a PP to remove from ebobs and change process for bankers etc. – Still need to investigate what the requirements would cost.

173 In this context, the reference to requiring a “PP” was a reference to the need to submit a “Project Proposal” to request a change to NAB’s systems rather than being a reference to a periodical payment.

174 As stated in paragraph 99 above, on 30 October 2017 Ms Macalister sent a document to the members of the PRMF which contained an amended version of Mr Prasad’s analysis of incorrect PP Fee charging. The document also included a section headed “Eliminate root cause”, which stated: