FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hastie Group Limited (in liq) v Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd (Formerly Brookfield Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd) (No 3) [2022] FCA 1280

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and thereafter by 2pm on 18 November 2022 file and serve any agreed minutes of orders reflecting the reasons of the Court, or in default of agreement, separate minutes of orders and short written submissions (of no longer than five pages).

2. A case management hearing is listed at 10.15am on 23 November 2022 to the extent desired by the Court or any party if the orders are not determined by the Court on the papers.

3. Unless otherwise ordered by the Court on its own motion or otherwise requested by any party, the orders of the Court will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 237 of 2022 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF HASTIE GROUP LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 122 803 040) | ||

HASTIE GROUP LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) ACN 122 803 040 First Plaintiff | ||

CRAIG DAVID CROSBIE (IN HIS CAPACITY AS LIQUIDATOR OF THE FIRST AND THIRD TO SIXTEENTH APPLICANTS) Second Plaintiff | ||

ACN 008 700 178 PTY LTD (IN LIQUIDATION) (FORMERLY DIRECT ENGINEERING SERVICES PTY LTD) (and others named in the Schedule) Third Plaintiff | ||

order made by: | MIDDLETON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 November 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and thereafter by 2pm on 18 November 2022 file and serve any agreed minutes of orders reflecting the reasons of the Court, or in default of agreement, separate minutes of orders and short written submissions (of no longer than five pages).

2. A case management hearing is listed at 10.15am on 23 November 2022 to the extent desired by the Court or any party if the orders are not determined by the Court on the papers.

3. Unless otherwise ordered by the Court on its own motion or otherwise requested by any party, the orders of the Court will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MIDDLETON J:

[1] | |

[9] | |

[22] | |

[22] | |

[33] | |

[38] | |

[45] | |

[48] | |

[57] | |

Applicants’ application for leave to file amended reply to John Holland | [60] |

[75] | |

[83] | |

[90] | |

[105] | |

[120] | |

[121] | |

[123] | |

[132] | |

DISCUSSION OF THE APPLICANTS’ OVERARCHING SUBMISSIONS REGARDING CHAPTER 5 OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT | [147] |

[184] | |

[187] | |

Applicants’ Submissions on Common Issues in Receivables Case | [209] |

[215] | |

[215] | |

[239] | |

[247] | |

[255] | |

[266] | |

[269] | |

An explanation of performance bonds in the form of bank guarantees | [269] |

[295] | |

John Holland “Project F: Sydney Desalination Plant” Agreement | [318] |

Specific clauses concerning the Respondent’s recourse to the bank guarantees | [322] |

[332] | |

[351] | |

Applicants’ Submissions on Common Issues in Bank Guarantee Case | [355] |

[368] | |

Summary of contractual instruments and relevant actions taken after the Appointment Date | [369] |

[370] | |

[376] | |

[394] | |

Does the Act relevantly void any transactions or dispositions in these proceedings? | [408] |

[420] | |

[425] | |

[433] | |

[444] | |

[444] | |

[454] | |

[460] |

1 These two proceedings concern the liquidation of the Hastie Group of companies, which comprises the First Applicant and a number of its wholly owned subsidiaries. The Hastie Group, which was headquartered in Australia, ran a business of providing mechanical, electrical and plumbing services in a number of countries.

2 On 28 May 2012 (the ‘Appointment Date’), voluntary administrators were appointed in respect of the Hastie Group companies party to the main proceeding (VID1277 of 2017) (the ‘Hastie Entities’, being the First and Fifth to Twenty-Second Applicants), and by 31 January 2013, the creditors of the Hastie Entities resolved to voluntarily wind up those companies. The Applicants (the Hastie Entities and their liquidators) commenced the main proceeding in this Court in November 2017 seeking its assistance to recover property and to assert rights held by the Hastie Entities as against a number of construction companies (being the Respondents in the main proceeding) who had separately entered into agreements with various Hastie Entities in respect of various construction projects (the ‘subcontracts’).

3 I will return separately to the other proceeding (VID237 of 2022, the ‘winding up proceeding’) later in these reasons, which was only commenced in April 2022. Until I deal separately with that winding up proceeding, my reasons only concern the main proceeding.

4 The Applicants allege that the Respondents failed to pay to the Hastie Entities the cumulative sum of $60 million in “receivables” owing as at 28 May 2012 (the ‘Receivables Case’). The Applicants further allege that after the Appointment Date, the Respondents impermissibly drew the cumulative sum of $63.5 million on performance guarantees (also referred to as “bank guarantees” or “performance bonds”) which were purchased by the Hastie Entities and provided to each of the Respondents as an alternative to the retention of monies from progress payments under their respective subcontracts (the ‘Bank Guarantee Case’). The Applicants assert that the monies owed in receivables and the monies drawn down by the Respondents on the bank guarantees are each property of the Hastie Entity which performed the work under the subcontract and purchased and provided the bank guarantee. The now sole Liquidator of the Hastie Entities (the Second Applicant) seeks to recover those monies in order to apply them in satisfaction of the liabilities of each of the Hastie Entities in accordance with Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the ‘Corporations Act’ or the ‘Act’), that is, to priority creditors such as Hastie Entity former employees first, and then on a pari passu basis among remaining unsecured creditors.

5 In total, the Applicants seek to recover approximately $120 million for the benefit of its creditors, but this judgment is not concerned with the quantum of that sum. The trial in the main proceeding throughout March to May 2022 (the “liability trial”) was only concerned with the liability issue of whether the Applicants are entitled in principle to the recovery of the property in question in this case and to the rights they assert as against the Respondents. The matters of principle as between the Applicants and each Respondent are broadly the same. Although there are differences in their respective contractual arrangements, those differences do not produce a relevantly different result on the principal common issues.

6 The Respondents’ respective positions against the Applicants’ Receivables Case and Bank Guarantee Case are broadly aligned. In respect of the Receivables Case, the Respondents assert first, that no valid receivables were ever owing under the relevant subcontract. Second, if a receivable is owing, they are entitled to set-off that amount (pursuant to s 553C of the Act) against monies owed by the Hastie Entity to the respective Respondent under the relevant subcontract by reason of the loss and damage it has suffered by the Hastie Entity being unable to complete the works under the subcontract. Third, some of the Respondents also contend that the limitation period for the relevant Hastie Entity’s claim to recover the receivables has expired.

7 Each of the Respondents contends that the value of their claims against the relevant Hastie Entity is greater than the amount of the unpaid receivables alleged by the Applicants and the amount of the guarantee proceeds held by them.

8 In respect of the Bank Guarantee Case, the Respondents deny the Applicants have any proprietary rights in the proceeds of the respective guarantees. Accordingly, their position is that the Applicants’ recourse to various provisions of Chapter 5 of the Act is not applicable. In addition, some of the Respondents also contend that the limitation period for the relevant Hastie Entity’s claim to recover the proceeds of the guarantees has expired.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

9 Before the Appointment Date, Hastie Group Limited (the First Applicant) was a public company listed on the Australian Securities Exchanges, and was the parent company of a number of wholly owned subsidiaries (43 subsidiaries, as at the Appointment Date).

10 The Hastie Group carried on the business of providing mechanical, electrical and plumbing services in countries including Australia, and through its various subsidiaries, was engaged in performing works on a number of building projects or had performed works on completed projects. The Hastie Entities in these proceedings entered into major long-term building subcontracts with head builders, being the Respondents, on large-scale multimillion dollar projects around Australia.

11 Pursuant to those subcontracts, the Hastie Entities undertook services and rendered progress payment claims or invoices to the respective Respondents, the amounts in relation to which were owing to the Hastie Entities as at the Appointment Date.

12 As part of each subcontract, the Hastie Entities were required to secure their performance, and in respect of each Respondent, this was done by way of bank guarantee issued to the Respondent. As is normal commercial practice, each Hastie Entity held a “bank guarantee facility” with the issuing bank for the purpose of its issuing bank guarantees to beneficiaries, and the bank guarantee itself was entered into by way of a separate agreement between the issuing bank and the respective Respondent beneficiary.

13 It is also relevant to note that the Hastie Group had in place a Deed of Cross-Guarantee dated 30 June 2005, under which each ‘Group Entity’ defined under the deed would guarantee to a ‘Creditor’ (as defined) the payment in full of any debt payable by another Group Entity

14 On 28 May 2012, Messrs Crosbie, Carson and McEvoy were appointed as voluntary administrators of the companies in the Hastie Group, including the Hastie Entities.

15 After the Appointment Date, the Respondents each failed or refused to pay the amounts owing as at the Appointment Date. Instead, each Respondent:

(a) elected to terminate or suspend performance of their respective subcontracts;

(b) stated that they had or would incur costs and expenses to have other providers perform the services the Hastie Entities now could not perform, and asserted an entitlement to set-off against the amount sought by the relevant Hastie Entity; and

(c) either retained the bank guarantee provided by the relevant Hastie Entity despite a request for its return, or ‘called’ on the bank guarantee, resulting in the issuing bank drawing down on the guarantee and providing the proceeds to the Respondent.

16 On 30 and 31 January 2013, the creditors of the Hastie Entities resolved that each of those companies be wound up and the administrators were appointed as liquidators of each company.

17 On 14 November 2017, the Applicants commenced proceedings in this Court as against twenty-nine respondents. The claims as against some of those respondents have since been discontinued.

18 It is unnecessary to detail comprehensively the procedural history of these proceedings. It is sufficient to refer briefly to two previous judgments which I delivered in the case management of the main proceeding.

19 First, in my reasons for judgment on 22 December 2020, I granted leave to the Applicants to file an amended originating process and pleading, and found on an interlocutory basis for the purposes of allowing the main proceeding to continue to trial that the receivable debt and bank guarantee claims as amended were covered sufficiently in the initial originating process and pleading such that they were not “new claims”: Hastie Group Limited (in liq) v Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd (Formerly Brookfield Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd) [2020] FCA 1824 (Hastie Interlocutory Decision) at [18], [22].

20 Second, on 27 October 2021, as the Twelfth and Thirteenth Respondents (together, ‘Grocon’) had by that time entered external administration and were subject to a deed of company arrangement, I granted leave under s 444E(3) of the Act for the Applicants to proceed against them in respect of specific issues.

21 I will now turn to the Applicants’ claims in the main proceeding.

22 The Applicants’ claims as against all of the Respondents were initially contained in the Concise Statement filed on 14 November 2017 and the Points of Claim filed on 13 July 2018. I will detail the procedural history of the pleadings later in these reasons when I come to the issue of limitation of actions. The Applicants now rely on their Second Further Amended Originating Process filed on 3 March 2021 and the following Points of Claim filed as against each individual group of Respondents (I note that the various “Further Amended Points of Claim” referred to below are not referred to in the Second Further Amended Originating Process, but I granted leave to file those during the trial and they were relied upon by the Applicants in their submissions):

(1) the Further Amended Points of Claim filed 22 March 2022 as against the First and Second Respondents (‘Multiplex’);

(2) the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Third Respondent, the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Fourth and Thirtieth Respondents, and the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Fifth Respondent (those respondents together, ‘Lendlease’);

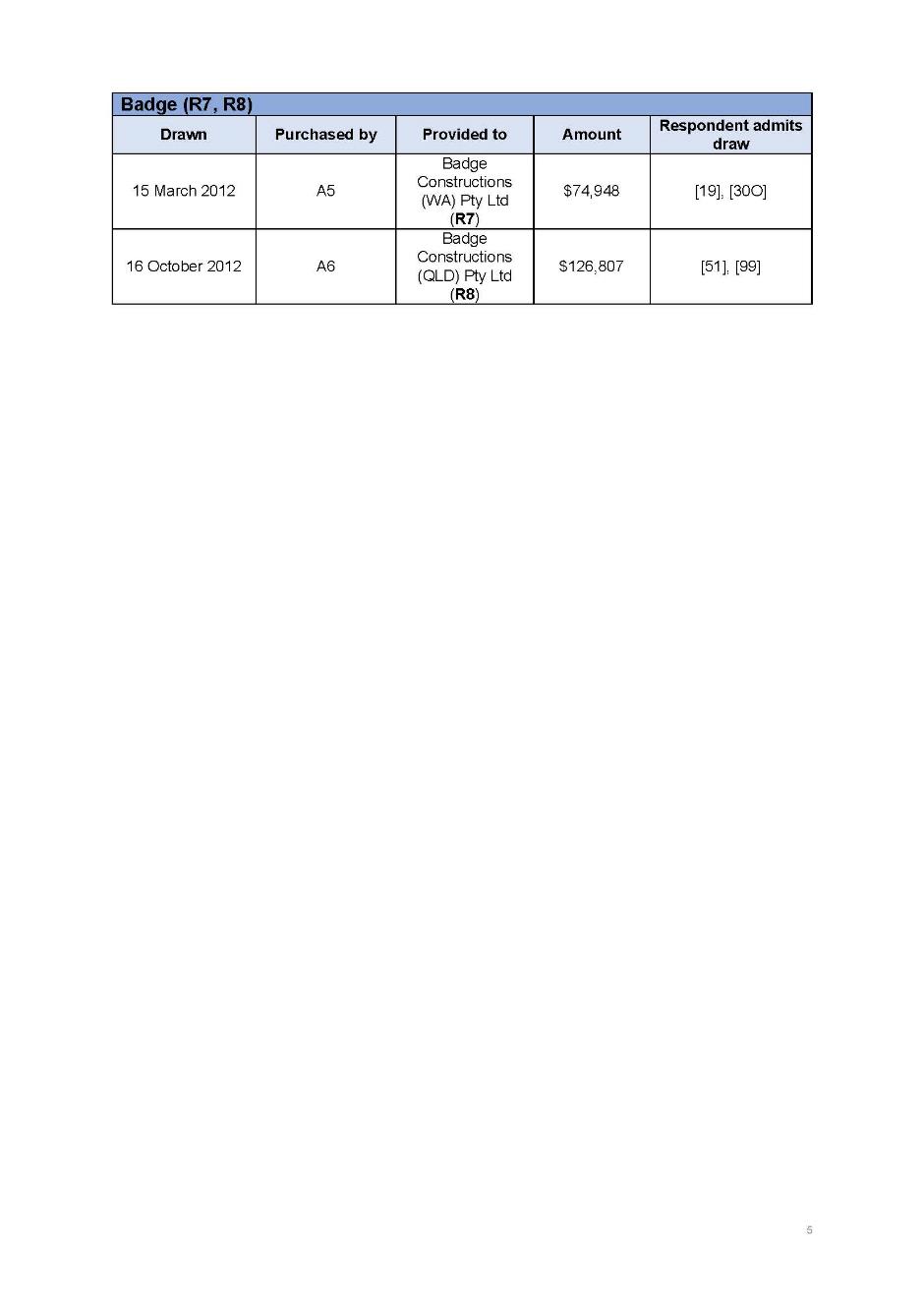

(3) the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Seventh and Eighth Respondents (‘Badge’);

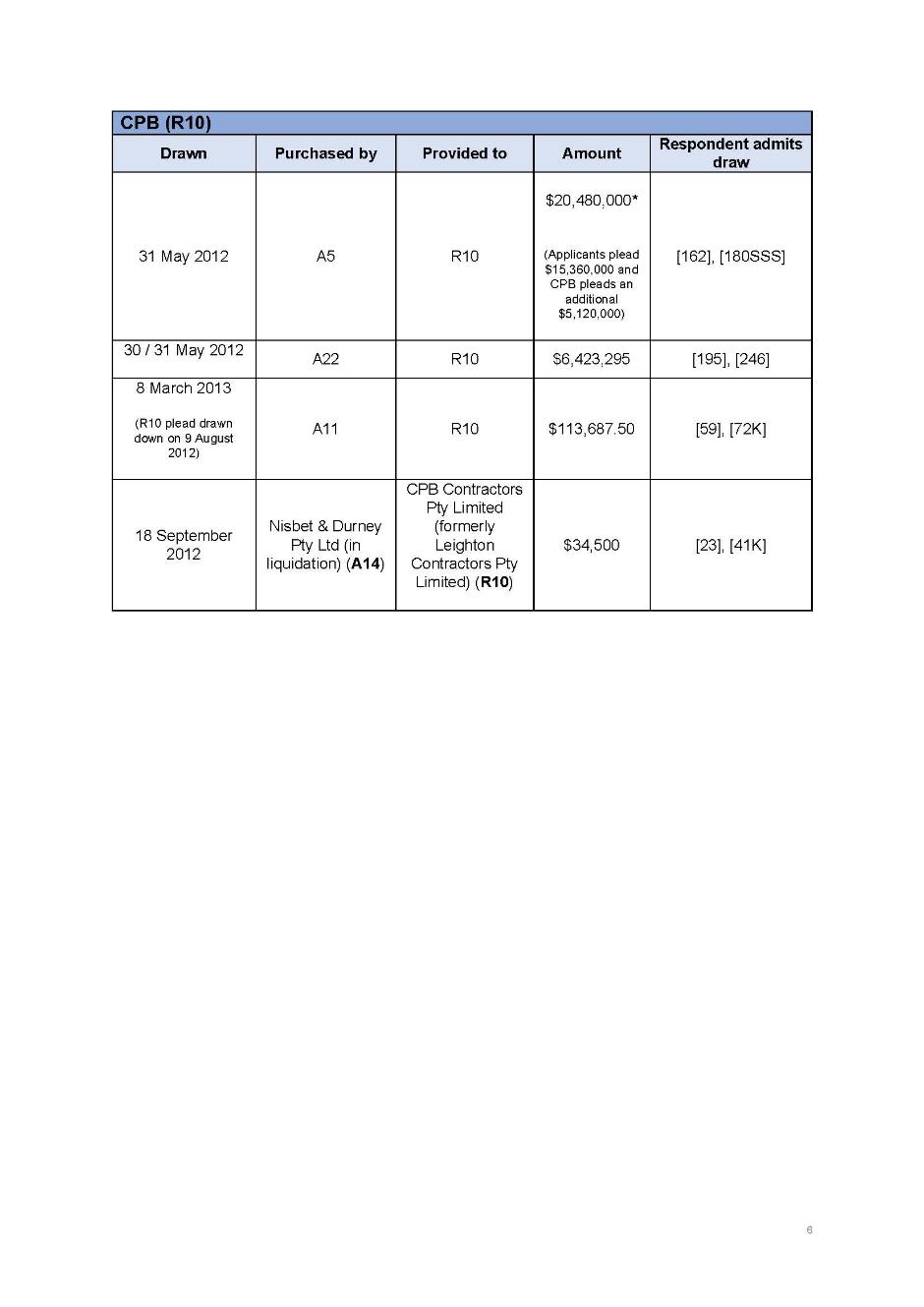

(4) the Further Amended Points of Claim filed 6 April 2022 as against the Tenth Respondent (‘CPB’);

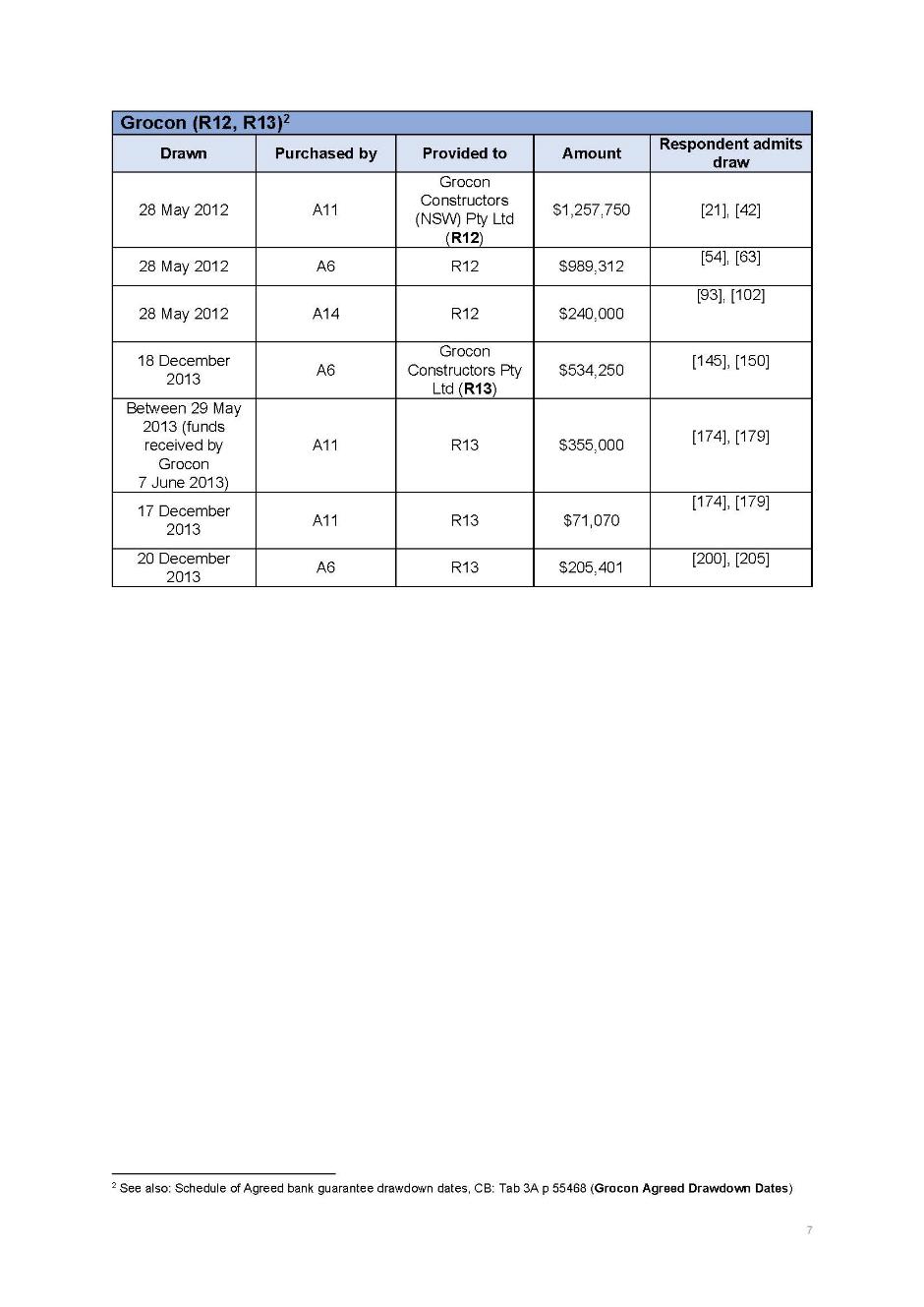

(5) the Further Amended Concise Statement filed 26 February 2021 as against the Twelfth and Thirteenth Respondents (Grocon);

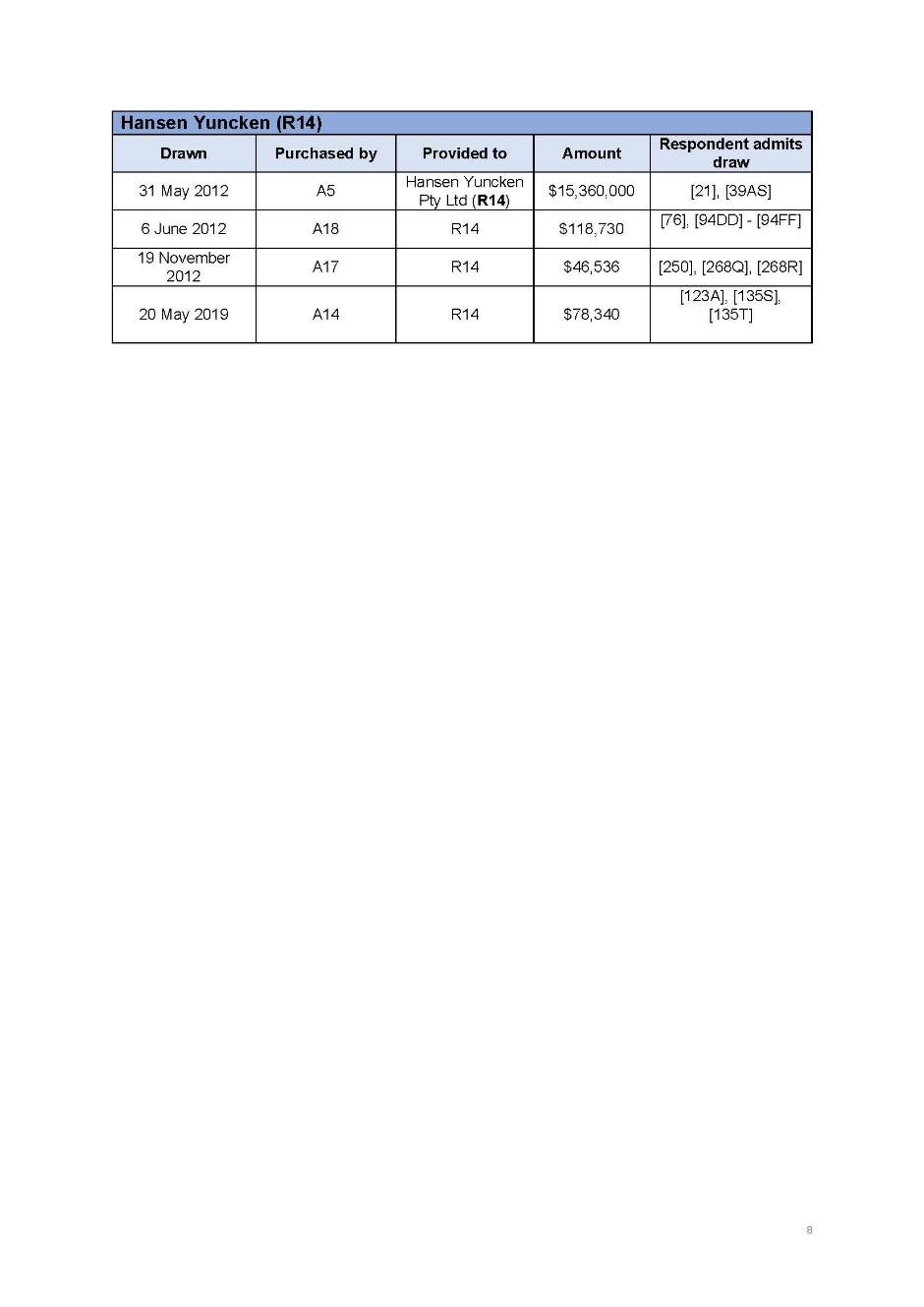

(6) the Further Amended Points of Claim filed 29 March 2022 as against the Fourteenth Respondent (‘Hansen Yuncken’);

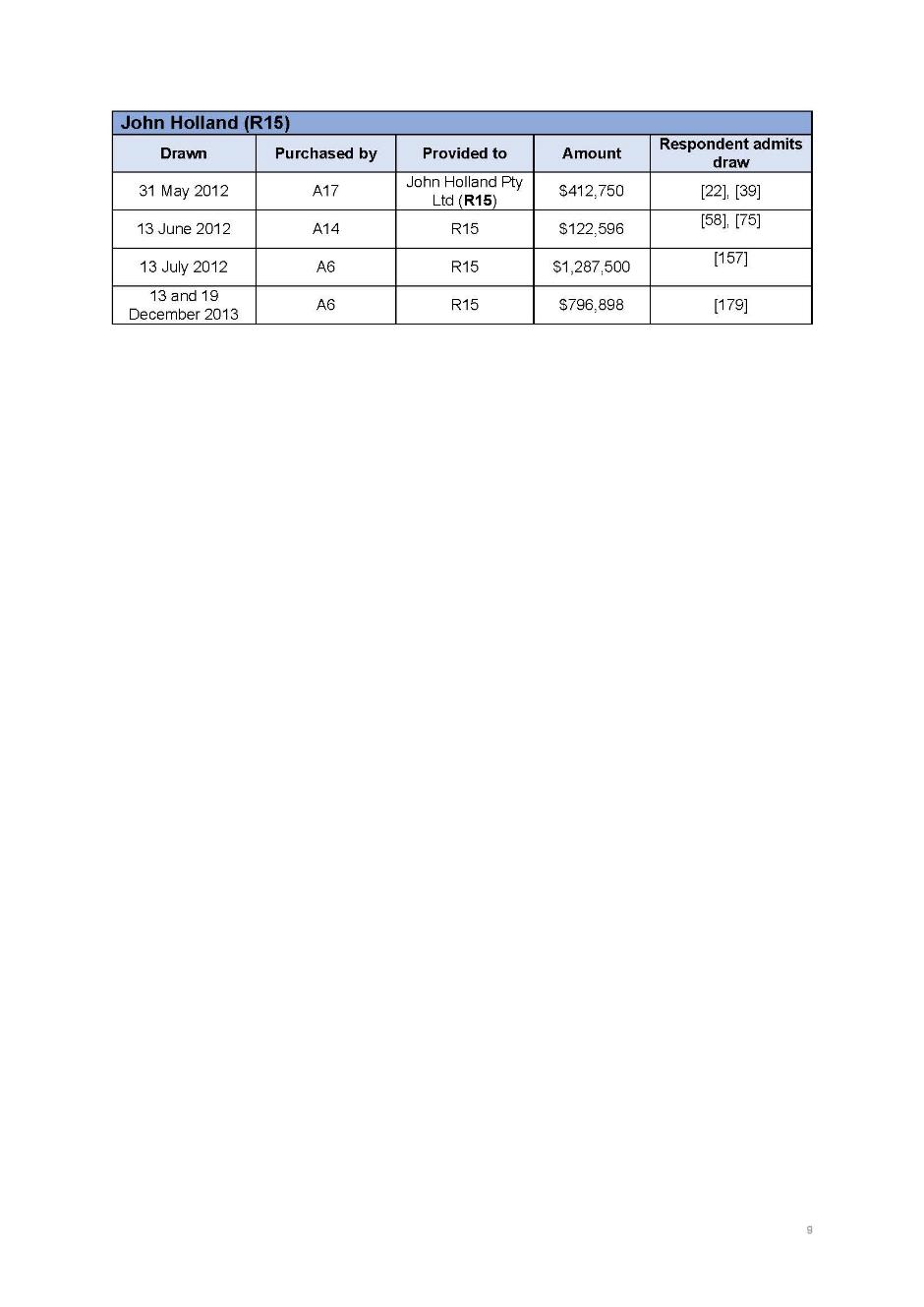

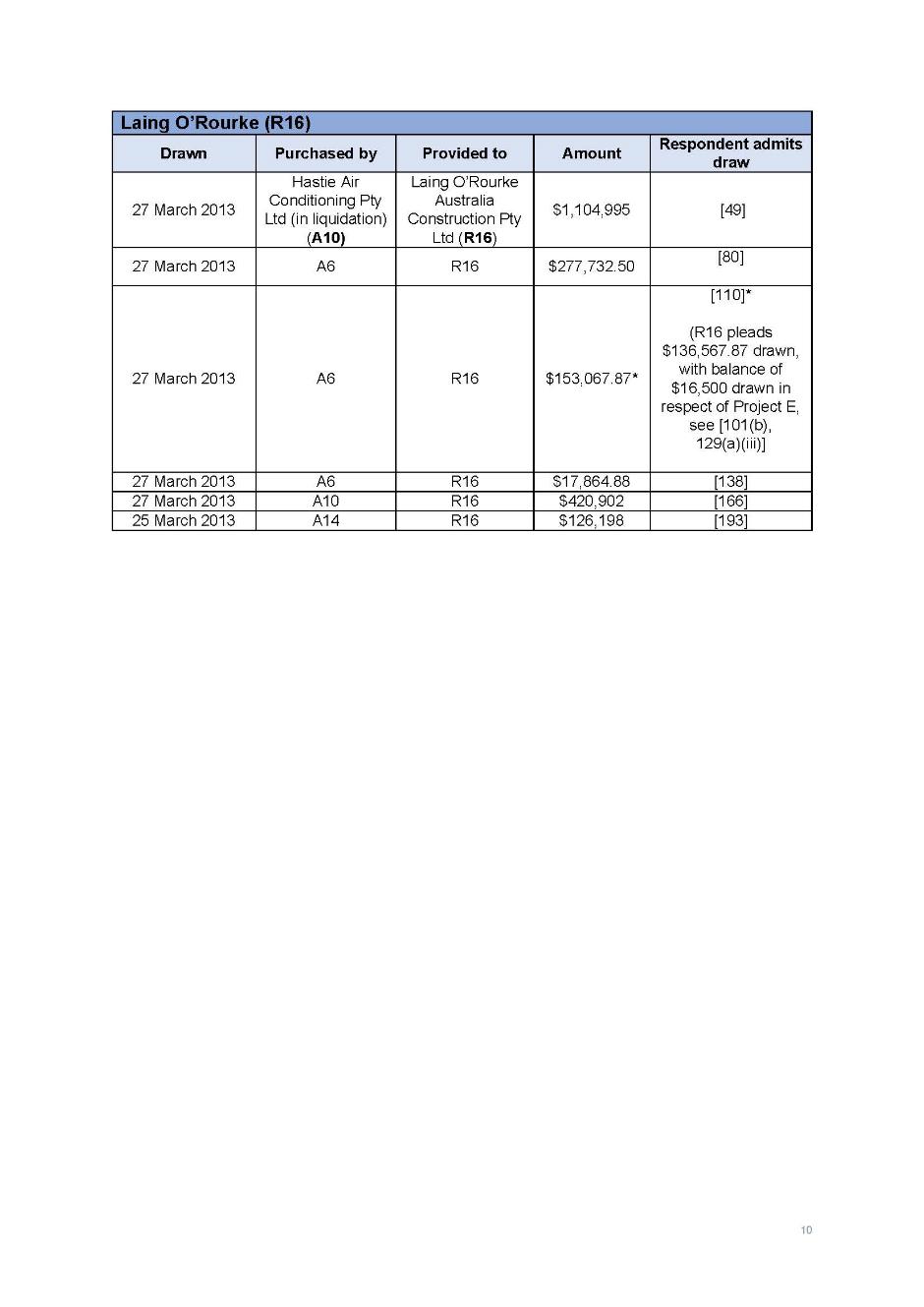

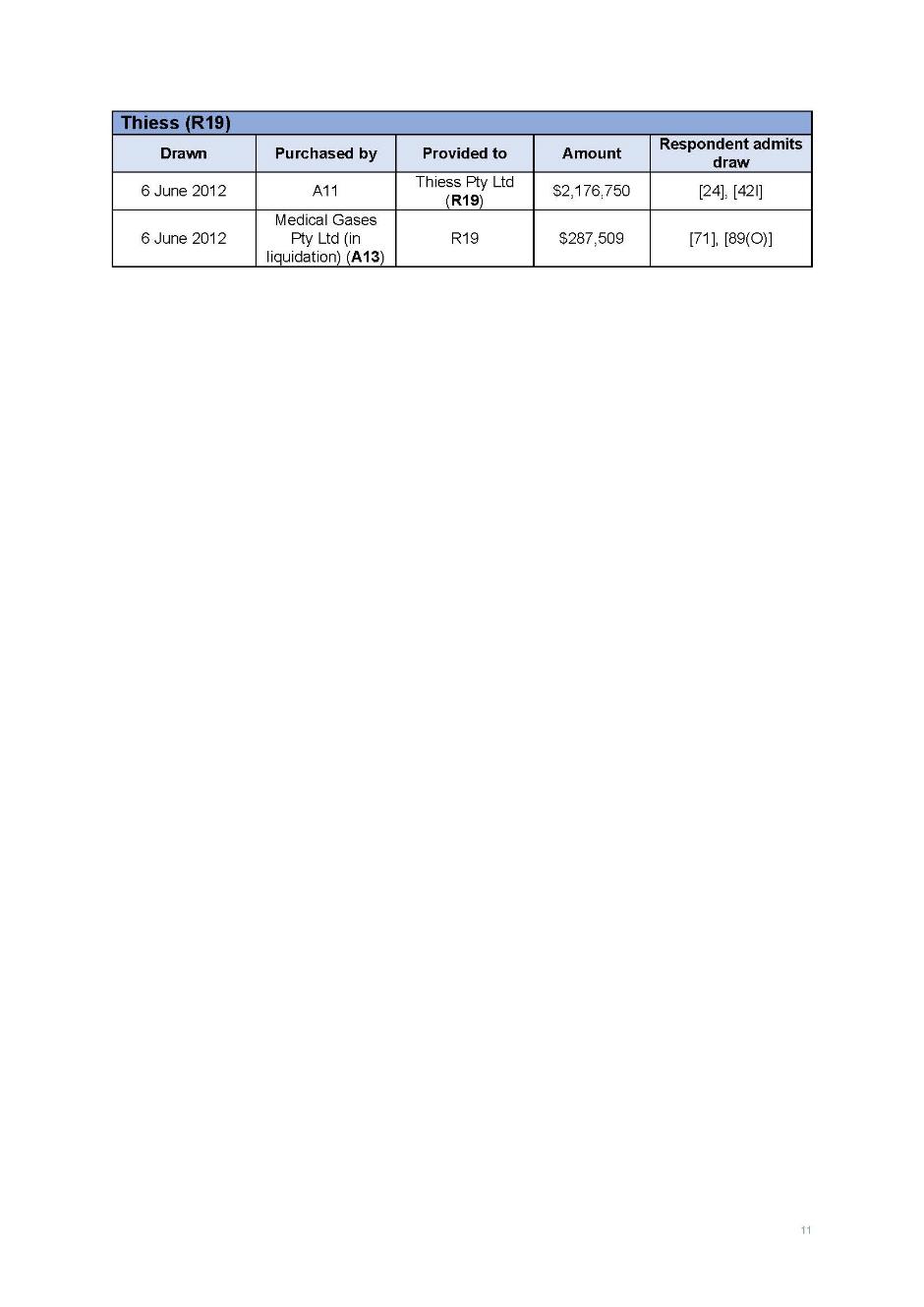

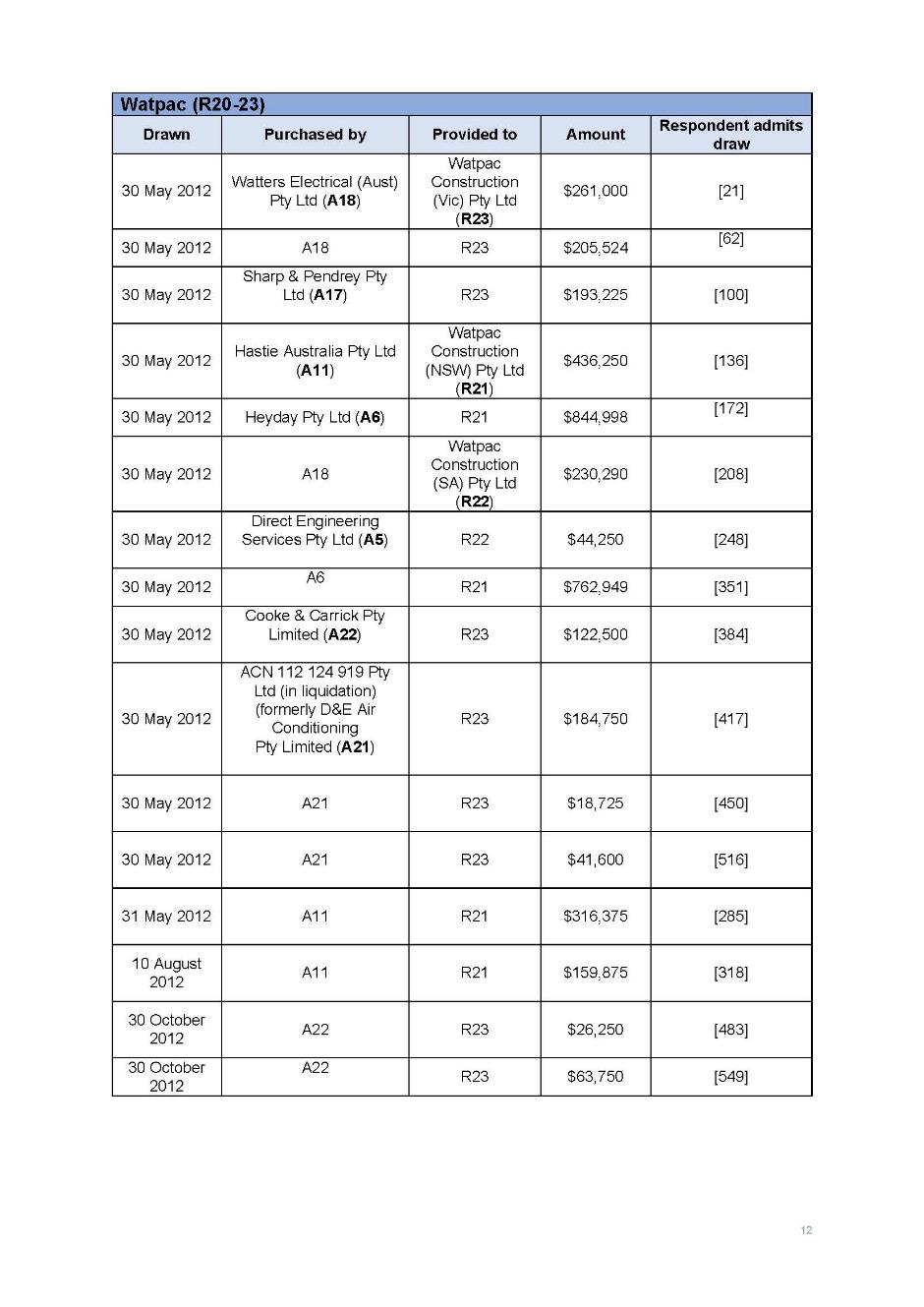

(7) the Amended Points of Claim filed 10 March 2021 as against the Fifteenth Respondent (‘John Holland’);

(8) the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Sixteenth Respondent (‘Laing O’Rourke’);

(9) the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Nineteenth Respondent (‘Thiess’);

(10) the Further Amended Concise Statement filed 26 February 2021 as against the Twenty-First to Twenty-Third Respondents (‘Watpac’); and

(11) the Amended Points of Claim filed 26 February 2021 as against the Twenty-Fifth Respondent (‘Scentre’).

23 I shall briefly outline the Concise Statement filed 14 November 2017 as against the Respondents for the purpose of indicating the claims made against the Respondent as at that date. Although the Applicants no longer rely on the Concise Statement or initial Points of Claim, those pleadings are relevant to the limitation period issues raised by certain Respondents.

24 The Concise Statement summarised the Receivables Case and the Bank Guarantee Case as follows, noting however that the Receivables Case and the Bank Guarantee Case are not completely separate, as they share elements and the two cases are not separated in the Applicants’ pleadings. It is convenient to refer to these as separate cases, as the issues for determination were framed in that way.

4 The assets of the Hastie Group of companies include invoices or progress payment claims issued prior to or in respect of work completed prior to 28 May 2012 by the Hastie Group of companies to each of the Respondents identified in Annexure 1 in the amount set out therein.

5 Each of the Respondents has refused to make payment and asserted an entitlement to set-off against the amount sought, an alleged indebtedness.

6 Further or alternatively, several of the Respondents have on or after 28 May 2012 called upon or failed to return bank guarantees issued in favour of those Respondents by various banks at the request of members of the Hastie Group of companies prior to 28 May 2012 (refer Annexure 1).

7 In consequence of the said Respondents having called upon the various Bank Guarantees as alleged, the liabilities of the Hastie Group of companies have been increased after 28 May 2012 by at least $69,279,263.43.

8 The liquidators contend that in consequence of the operation of the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) (PPSA) none of the Respondents are entitled to set-off under s 553C of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) (the no mutuality proposition).

9 Further or alternatively, the liquidators contend that the bank guarantee creditors are not, and were not, entitled to call upon the bank guarantees until such time as their claims have been admitted in the liquidations, alternatively at all.

25 The Applicants no longer press the “no mutuality proposition” referred to at [8] above, which was based on a Supreme Court of Western Australia decision at that time before it was overturned on appeal: Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd v Forge Group Power Pty Ltd (in liq) (receivers and managers appointed) [2017] WASC 152; (2017) 52 WAR 90 (Forge First Instance).

26 I shall now outline the structure of the various Points of Claim filed against each group of Respondents so as to indicate the commonality of the issues as between the various Respondents. I will note any significant individual issues that arise as against only one or some of the Respondents separately later in this section.

27 Each Points of Claim filed is divided into sections pertaining to particular project subcontracts between the relevant Hastie Entity and Respondent. In respect of each project subcontract, the Applicants set out the following matters:

(a) the terms of the subcontract;

(b) the relevant bank guarantee provided to the Respondent;

(c) the relevant Hastie Entity’s payment claims under that subcontract, and therefore the total receivables claim for work performed under the subcontract;

(d) the subsisting legal position under the Act at the time of the Hastie Entity’s entering into voluntary administration;

(e) the Respondent’s termination or suspension of performance under the subcontract, and the Respondent’s calling on and drawing down of the bank guarantee (or alternatively, failure to return the bank guarantee);

(f) the effect and application of the Act in relation to the Respondent’s calling on and drawing down of the bank guarantee, pursuant to the Act’s regime in relation to voluntary administration and winding up;

(g) the relevant Hastie Entity’s total claimed debt as against the Respondent and its demand for payment made to the Respondent;

(h) the Respondent’s failure to pay the amount demanded and failure to provide evidence to establish its claim for which it asserts an entitlement to set-off; and

(i) on the premises of the above, the Respondent’s liability to the Hastie Entity or Liquidator.

28 The relief sought under the Applicants’ Second Further Amended Originating Process filed on 3 March 2021 consisted of orders that each Respondent pay to the Applicants certain amounts claimed in the respective Points of Claim. However, the trial of the main proceeding was split between liability and quantum by orders made on 1 October 2021, so that the trial commencing on 15 March 2022 only concerned the liability issues.

29 Given this bifurcation of the proceeding, the relief sought by the Applicants at this liability trial differed from the orders sought in the Second Further Amended Originating Process, and instead the relief sought was in the form of orders and directions to the Liquidator as to the winding up of the Hastie Entities. I will discuss these later in this section. However, it is important not to lose sight of the ultimate aim of the Liquidator in commencing and continuing these proceedings: namely, to recover money so as to be distributed in accordance with the Act.

30 To some extent, during the course of the trial, the Applicants also raised arguments and issues that were not canvassed in their pleadings, the agreed common issues in the liability trial or their opening written submissions. Each Respondent complained about the impermissible and unfair departure by the Applicants from the agreed common issues, the pleadings and the relief originally sought in the Applicants’ Second Further Amended Originating Process.

31 For the reasons which will become apparent, I do not need to delve into these complaints. There is no doubt there has been a re-casting of issues, some arising from concessions or an appreciation by the Applicants of some difficulties with their case. The main proceeding has changed over the years in its focus, particularly after the Hastie Interlocutory Decision in 2020 when the preliminary question regarding the “no mutuality proposition” in reliance on Forge First Instance fell away. However, each Respondent has been able to deal with the re-casting, which was primarily focussed on the appropriate relief. The underlying legal analysis by the parties, refined and expanded on from time to time by the Applicants, has remained constant in the reliance by the Applicants on their view of the overriding operation of the Corporations Act (which view I have rejected in these reasons).

32 I shall now set out the Applicants’ claims against the Respondents as contained in their Points of Claim in greater detail.

33 Although the subcontracts are different for each Respondent, and the subcontracts for each project for each Respondent are also not always the same, the subcontracts are relevantly similar as between each Respondent. At this point, it is convenient to summarise the basic content of relevant terms of the subcontracts as set out in the Points of Claim as against each group of Respondents. The relevant terms of each subcontract are comprehensively set out by the Applicants in Schedule A to their closing written submissions dated 6 May 2022, which subject to some minor matters were agreed with by the Respondents for the purposes of the liability phase of the main proceeding. I have proceeded on the basis of this agreement for the purposes of the liability trial.

34 First, the fundamental obligations under each of the subcontracts were that the relevant Hastie Entity was to perform the works under the subcontract, and the Respondent was to pay the contract sum.

35 Second, each subcontract required some form of performance security to be provided by the Hastie Entity to the Respondent. Generally, each subcontract included the option of the Hastie Entity providing a “retention amount” to the Respondent (a cash amount to be held by the Respondent) or an “unconditional undertaking” or guarantee provided by a bank or financial institution in the same amount (ie a bank guarantee). Generally, under each of the subcontracts, the Respondents elected or received a bank guarantee. Each subcontract included terms in relation to the release of the security and other terms concerning the legal rights and interests arising in relation to the security.

36 Third, each subcontract provided for a mechanism by which the Hastie Entity would submit payment claims to the Respondent for work performed. Under most subcontracts, the Respondent would then assess the claims and issue a payment schedule. Generally, each subcontract also provided for a mechanism by which the Respondent could set-off any amounts due to the Hastie Entity or have recourse to the security provided as described above against amounts which the Hastie Entity were liable to pay to the Respondent.

37 Fourth, generally each subcontract provided for a right of termination upon appointment of an administrator to the Hastie Entity or a right to take relevant work out of the hands of the Hastie Entity, and permitted the Respondent to employ other persons to carry out and complete the works.

The bank guarantees provided to the Respondents

38 As stated earlier, the bank guarantees provided to the Respondents were issued by an issuing bank. The issuing bank in each case had entered into a facility agreement with the relevant Hastie Entity to provide the bank guarantee facility to the Hastie Entity. This arrangement is separate to the bank guarantee itself.

39 The bank guarantees in this proceeding were issued pursuant to one of the following bank guarantee facility agreements with an issuing bank:

(a) a Multi-Option Facility Agreement between Hastie Group Limited and ANZ Bank on or about 1 April 2008;

(b) a Facility Agreement between Hastie Group Limited and NAB on or about 1 April 2008;

(c) a Facility Agreement between Hastie Group Limited and Westpac on or about 1 April 2008, as varied and restated on or about 29 June 2010;

(d) a Standstill Facilities Agreement between Hastie Group Limited and the ANZ Bank on or about 11 April 2011, as varied and restated on or about 11 May 2011; and

(e) a Syndicated Facility Agreement (or ‘SFA’) between Hastie Group Limited and various banks, including the ANZ Bank and Westpac, on or about 7 June 2011, as varied and restated on or about 10 April 2012.

40 In each Points of Claim, the Applicants referred to the following features of the relevant bank guarantee facility agreement applicable to each respondent:

(a) the issuing bank agreed to make available to the relevant Hastie Entity financial accommodation by way of bank guarantees in the form provided in the facility agreement;

(b) upon issue of a bank guarantee by the issuing bank, the Hastie Entity became liable to pay to the issuing bank an issuance fee (commonly being a percentage of the face value of the bank guarantee); and

(c) upon demand for payment under a bank guarantee by the recipient, the Hastie Entity became liable to pay (immediately or within a certain period of time) all amounts paid out by the issuing bank, together with any costs, liability or loss incurred by the issuing bank in paying out the financial accommodation.

41 The Applicants’ submissions made particular reference to the terms of the SFA, which will be set out in detail later in these reasons.

42 Again, although the bank guarantees issued to each Respondent were not substantively identical, and the bank guarantees in respect of each project for each Respondent were also not always substantively identical, the bank guarantees were relevantly similar as between each Respondent.

43 The Points of Claim as against each Respondent sets out each bank guarantee issued and provided to each Respondent, and asserts that upon issue of the bank guarantees, the relevant Hastie Entity became liable to repay to the issuing bank as loans any amounts paid out upon the guarantees (plus interest and other costs).

44 The Applicants then contend that at all material times from the date of issue of the bank guarantee, each bank guarantee was an asset of the relevant Hastie Entity or the Hastie Group, being financial accommodation which had been purchased from the issuing bank, and was property of the relevant Hastie Entity within s 9 of the Act.

Payment claims and receivables

45 For each project, the Applicants assert that the relevant Hastie Entity performed the services and did the works under the relevant subcontract, and submitted payment claims or issued invoices for amounts due for the work completed, pursuant to the subcontract. Under most of the contractual regimes, the relevant Respondent then issued payment schedules in response to those payment claims.

46 The aggregate outstanding amount of such payment claims and invoices payable to the relevant Hastie Entity prior to entering administration is referred to as the “receivable” for each project. The Applicants assert that each receivable was an asset of the relevant Hastie Entity as at the Appointment Date.

47 As noted earlier, given the bifurcation of the liability and quantum in this proceeding, the amounts claimed in the Points of Claim and the underlying payment claims, schedules and invoices do not need to be considered in detail in these reasons. Rather, certain of these documents were accepted into evidence on an indicative basis to the extent necessary for the determination of the liability issues of the Applicants’ Receivables Case.

The effect and application of the Corporations Act

48 The Appointment Date on which each Hastie Entity entered voluntary administration under s 436A of the Act – being 28 May 2012 for each of the Hastie Entities – brought certain consequences under the Act. For example, as at the Appointment Date, s 440D of the Act immediately denied each Respondent any entitlement to begin or continue a proceeding in a Court against a Hastie Entity or in relation to any of its property except with the administrators’ written consent or the leave of the Court.

49 None of the Respondents was a “secured creditor” of any Hastie Entity at the Appointment Date within the meaning of s 9 of the Act. Each Respondent was therefore an unsecured creditor.

50 It is then contended that each Respondent who presented and drew down on their bank guarantee, without the consent of the administrators and without notifying the administrators of its intent to do so, did not obtain any proprietary interest in nor any immediate entitlement to the amount drawn down and received from the issuing bank, which remained at all times and remains the property or money of the relevant Hastie Entity.

51 In particular, it is contended that, by the Respondent engaging (or rather, as finally submitted by the end of the trial by the Applicants, by the issuing bank engaging) in a transaction or dealing affecting property of the Hastie Entity under administration, the call or draw down on the bank guarantee was void by virtue of s 437D.

52 It is then contended that the winding up of the Hastie Entities by creditors’ resolution pursuant to s 439C(c) of the Act – on 30 or 31 January 2013 – also brought certain consequences under the Act, being that:

(a) each Respondent is prohibited by s 500(2) of the Act from bringing proceedings against a Hastie Entity to secure an order transferring to the Respondent proprietorship over the amount drawn down on the bank guarantees;

(b) having regard to s 553 of the Act (and Chapter 5 of the Act generally), each Respondent is required to seek to be admitted to proof in the external administration of the Hastie Entity in respect of any claims against the Hastie Entity arising from or connected with the relevant subcontract;

(c) pursuant to s 474 of the Act, the Liquidator must take into his custody or control the amount drawn down by each Respondent under the bank guarantee, and each Respondent must immediately return that amount to the Liquidator;

(d) pursuant to s 506 of the Act, the Liquidator is entitled to exercise any of the powers the Act confers on a Liquidator in a winding up in insolvency;

(e) each Respondent is subject to ss 555, 556 and 560 of the Act, which give effect to the pari passu principle and the priority payments regime, and because of which each Respondent is prohibited from using the proceeds of the bank guarantee to satisfy its claims against the Hastie Entity; and

(f) as elaborated in the Applicants’ submissions (but not specifically referred to in any of the Points of Claim), s 468 of the Act has the effect of voiding any disposition of property of the Hastie Entity made after the Appointment Date, including each Respondent’s draw down of the bank guarantees.

53 On the above premises, the Applicants contend that the Liquidator is entitled to an order that the Respondents return to the Liquidator the debt owed to the Hastie Entities (being receivables owed and the proceeds of the bank guarantees which were drawn down).

54 Each Points of Claim refers to the Liquidator’s demand for payment on each Respondent in relation to each debt owed in respect of each relevant project subcontract.

55 In response to the Liquidators’ demand for payment, each Respondent refused to pay the amount demanded and asserted its own rights and entitlements under the subcontract. The Applicants contend that each Respondent has failed to provide evidence to the Liquidators that:

(a) it has paid amounts to third parties to complete the works to be performed by the Hastie Entity under the relevant subcontract that are more than what the Respondent owes to the Hastie Entity;

(b) such amounts or costs paid to third parties are or could be a claim against the Hastie Entity within the meaning of ss 553(1) and 553C(1) of the Act; and

(c) such amounts or costs are or could be amounts for which the Hastie Entity is liable to the Respondent under or in connection with the relevant subcontract.

56 Accordingly, the Applicants assert that each Respondent remains liable to pay its outstanding debts to the Hastie Entities.

57 As part of the case management of the main proceeding, the parties were asked to agree and file a List of Issues in respect of each group of Respondents. From the Court’s point of view, this was to focus the collective minds of all those participating in the liability trial on the main issues really in dispute. However, at all times it was made clear that the ultimate determination of the issues in dispute ought to be resolved by the “pleadings” (I use quotations here because of the quasi-pleading status of concise statements and points of claim in this Court). Nevertheless, when the trial of the main proceeding was split between liability and quantum by orders made on 1 October 2021, those orders referred to the various Lists of Issues filed in respect of each group of Respondents. Whilst there are some issues which pertain only to particular Respondents, the common issues for the liability trial in the main proceeding were as follows (as summarised in the Applicants’ closing submissions, and which I will refer to in these reasons as the ‘Common Issues’). Because of those orders made on 1 October 2021, a number of the issues in the various Lists of Issues were not to be determined at the liability trial, including issues as to the amount of any alleged set-offs or as to the final quantum of each claim.

A. Receivables

(a) Issue 1: The subcontracts between the Hastie Entity and each respondent and the terms of same. (the” subcontract issue”) The framing of this issue does not identify any question to be resolved. However, to the extent that the identification of the relevant subcontracts is in dispute, whether any particular subcontracts ought to be treated as “representative”, and whether particular contractual provisions are required to be interpreted as a matter of general understanding prior to the determination of the issues that follow, I consider them as falling under this issue 1.

(b) Issue 3: Whether the liquidator is statute-barred from getting in the receivables. (the receivables limitation defence)

(c) Issue 4: Are each of the allegations of set-off “claims” within the meaning of s 553 of the Act? (the “claims issue”).

(d) Issue 5: Have there been mutual dealings between each Hastie Entity and a Respondent who wants to have a claim admitted against that Hastie Entity to come within s 553C of the Act? (the “mutuality issue”). By the end of the trial of the main proceeding, it was accepted by the Applicants that mutuality was satisfied, but mutuality still remained in dispute in relation to the Respondents’ claims under the Deed of Cross-Guarantee.

(e) Issue 7: Whether as and from 28 May 2012, s 553C of the Act applied exclusively to any “claim” founding a “set-off” alleged against a Hastie Entity? (the “s 553C exclusivity issue”). This question is framed as one of statutory exclusivity, but the Applicants’ submissions on this issue went also to whether s 553C requires that the set-off accounting be exclusively determined by the Liquidator.

(f) Issue 7a: A further issue which was included in only some of the Lists of Issues but implicit where not included, and which related to an additional aspect of the s 553C exclusivity issue mentioned above, was: whether each respondent is entitled to deduct or set-off monies which it owed to each Hastie Entity as at 28 May 2012 any “loss and damage” that is a “claim” within s 553? (which I shall call the “automatic set-off issue”)

B. Proceeds of the bank guarantees

(g) Issue 8: Did the terms of each subcontract confer any proprietary interest in the monies drawn or any entitlement to treat those monies as the Respondent’s own funds? (the “property in proceeds question”).

(h) Issues 9 & 10: Whether the purchase of each bank guarantee by the Hastie Entity amounted to “financial accommodation” and created a chose in action between the Hastie Entity and the bank? (the “chose in action question”).

(i) Issue 11: Whether the credit (to the Respondent’s bank account) and debit (to the Hastie Entity’s loan account with the issuing bank) which happened in consequence of the guarantee being drawn by the Respondent were causally and transactionally linked? (the “causal and transactional link question”).

(j) Issues 12 & 13: Was the drawdown on the bank guarantees void by reason of s 437D of the Act? (the “void transaction/disposition question”). It is to be noted that the Applicants’ submissions also include s 468 of the Act within the scope of this issue, which is resisted by the Respondents.

(k) Issues 14 & 15: Can the Respondents retain the guarantee proceeds and can those proceeds be used to pay their “claims” in the face of s 555 and 556 of the Act? (the “retainer of the guarantee proceeds question”).

(l) Issue 16: Did the Liquidator bring an action to recover the guarantee proceeds by filing this proceeding on 14 November 2017? (the “guarantee proceeds limitation defence”).

58 I note that the various Lists of Issues were formulated by the Applicants and were not agreed to in their entirety by the Respondents, some of whom made submissions regarding the precise scope and formulation of the particular issues. However, recalling my earlier comments about the purpose of the listing of issues for the liability trial, for the purposes of my reasons, it is convenient to deal with the Common Issues as framed above.

59 Other issues specific to particular Respondents shall be dealt with as they arise in my substantive reasons as to each of the issues.

Applicants’ application for leave to file amended reply to John Holland

60 It is convenient to deal here with one outstanding “pleading issue” raised during the course of the hearing of the liability trial. The Applicants sought leave to rely on an Amended Reply served on 12 May 2022. The proposed Amended Reply primarily sought to raise a claim based on an estoppel or election defence.

61 The new reply claims raised in the Amended Reply concern only the Airport Link Project (‘Project E’). The claims respond to John Holland’s defence that the contractual claims of the relevant Hastie Entity on this Project (Heyday) are defeated by clauses 10.7 and 10.8 of the relevant contract (‘Airport Link Agreement’).

62 In my view, as formulated the proposed Amended Reply (other than paragraph 10) fails to disclose an arguable claim. For that reason, leave to amend the reply other than paragraph 10 will be refused. John Holland does not oppose paragraph 10 being pleaded by way of reply.

63 Before explaining the reasons for my view in relation to the other paragraphs of the proposed Amended Reply, it is useful to set out some relevant background.

64 On 8 March 2022, John Holland served its written submissions in relation to the hearing commencing on 15 March 2022. Schedule 2 to the submissions raised various contractual defences to the Applicants’ claims (including in relation to Project E).

65 On 29 April 2022, John Holland served on the Applicants a proposed Amended Defence. The proposed amendments included reliance on clauses 10.7 and 10.8 of the Airport Link Agreement.

66 On 11 May 2022, John Holland was granted leave, without opposition, to file in Court its Amended Defence.

67 On 12 May 2022, the Applicants served on John Holland a proposed Amended Reply which asserted that by election and estoppel John Holland was prevented from seeking to rely on clauses 10.7 or 10.8 of the Airport Link Agreement to deny a liability to pay the Liquidator the unpaid invoice sum of $567,773.24, and that these provisions were unenforceable.

68 John Holland contends that both the proposed election and estoppel defence and the proposed “penalty” defence are “so untenable that it cannot possibly succeed” (see King v Patrick Projects Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1110 at [15]) and so that the amendments should not be allowed.

69 Putting aside the procedural matters, apart from paragraph 10, the other pleas in the proposed Amended Reply are without sufficient particularity to be permitted.

70 As to the waiver or election plea, the only basis of this plea seems to be that the original Defence of John Holland to the Applicants’ Points of Claim did not raise the newly relied upon clauses of the Airport Link Agreement in its original reply. As Deane J said in the Commonwealth v Verwayen (1990) 170 CLR 394 (Verwayen) at 447 (and see also 408-409 and 414 per Mason CJ; 426-427 per Brennan J; 456-457 per Dawson J; 464-465 per Toohey J; 485-486 per Gaudron J; 498-499 per McHugh J):

In the ordinary case where a party to litigation amends a pleading to raise a new defence or to assert a new claim, questions of estoppel do not arise. The effect of earlier pleadings will be merely to reflect the particular party’s then intentions in relation to the conduct of the action and the other party will not be justified in assuming that subsequent amendment will not be made. Nor, in such a case, will amendment of the pleadings and subsequent conduct of the proceedings on the basis of the amendment give rise to any suggestion of unconscionable conduct on the part of the amending party. It will involve no more than the exercise of the right to seek to raise additional matters of claim or defence in accordance with the procedures laid down for that purpose.

71 Therefore, without more, the plea of the Applicants in their proposed Amended Reply would fail.

72 As to the allegation that John Holland would obtain a gain by the operation of clauses 10.7 and 10.8 that is “extravagant and unconscionable and out of all proportion to John Holland’s legitimate interest”, this has not been particularised at all, and on its face does not arise on the face of the Airport Link Agreement. Again, without more, the plea of a “penalty” (if that is the essence of the allegation) would fail.

73 At this stage of the proceedings, I will not allow such un-particularised pleas to be introduced by way of Amended Reply.

74 I will grant leave to the Applicants to file the Amended Reply other than the pleas in paragraphs 5 to 9 and 11.

75 As I have alluded to previously, the approach of the Applicants altered during the course of the liability trial. I will return to this issue at the end of these reasons.

76 The orders now sought by the Applicants at this liability trial are annexed to these reasons as an Appendix. I shall summarise the orders as sought below. It is appropriate to focus on these orders now sought as to determining the future conduct of the main proceeding. However, in determining whether there is any liability to the Hastie Entities, and as I have stressed already, the basis of analysis must be upon the pleadings, assisted by the various Lists of Issues and the submissions finally adopted by the Applicants.

77 The orders sought were under three headings for the purposes of the future conduct of the proceedings, being:

(1) Advice as to admission of claims in each winding up;

(2) Advice as to future conduct of the winding up; and

(3) Directions to Liquidator for further conduct of the windings up.

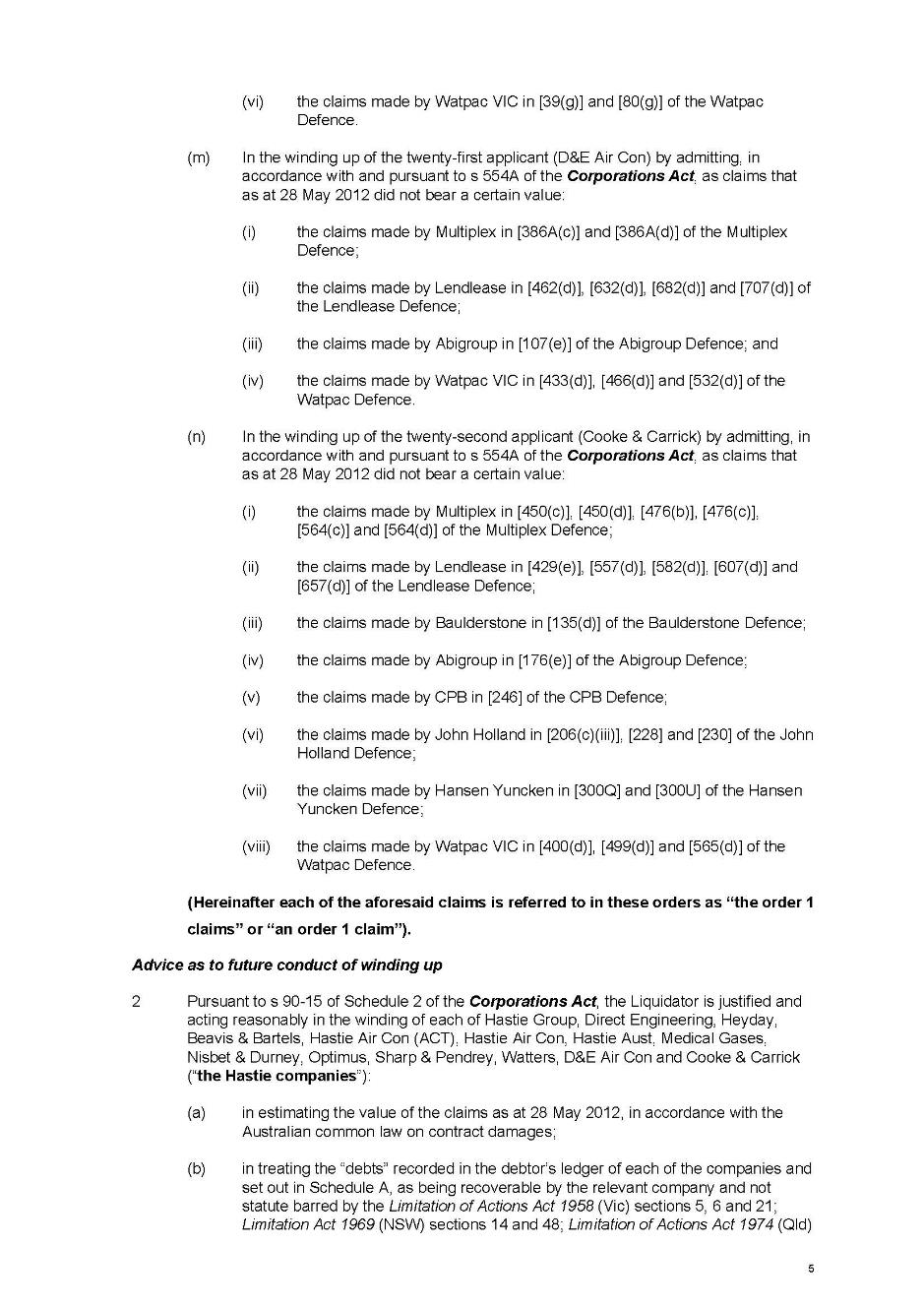

78 First, the orders sought under proposed order 1 were that, pursuant to s 90-15 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations), being Sch 2 to the Act, the Liquidator is justified and acting reasonably in the winding up of each Hastie Entity by admitting the claims made by the Respondents in their respective pleadings as claims that as at the Appointment Date did not bear a certain value (that is, they are of uncertain value: see s 554A of the Act).

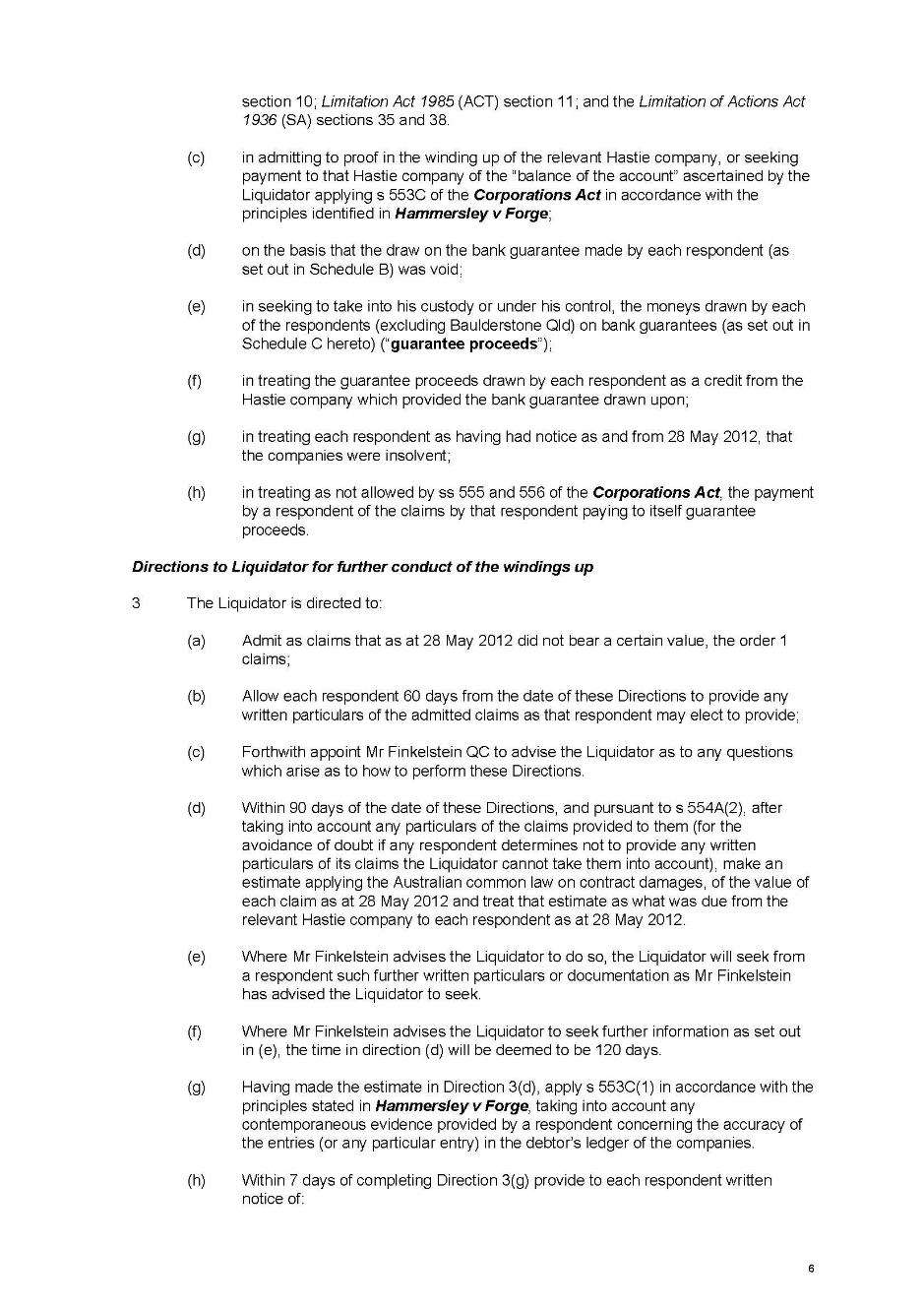

79 Second, the orders sought under proposed order 2 were that the Liquidator is justified and acting reasonably in the winding up of each Hastie Entity:

(a) in estimating the value of the Respondents’ claims as at the Appointment Date in accordance with the Australian common law on contract damages;

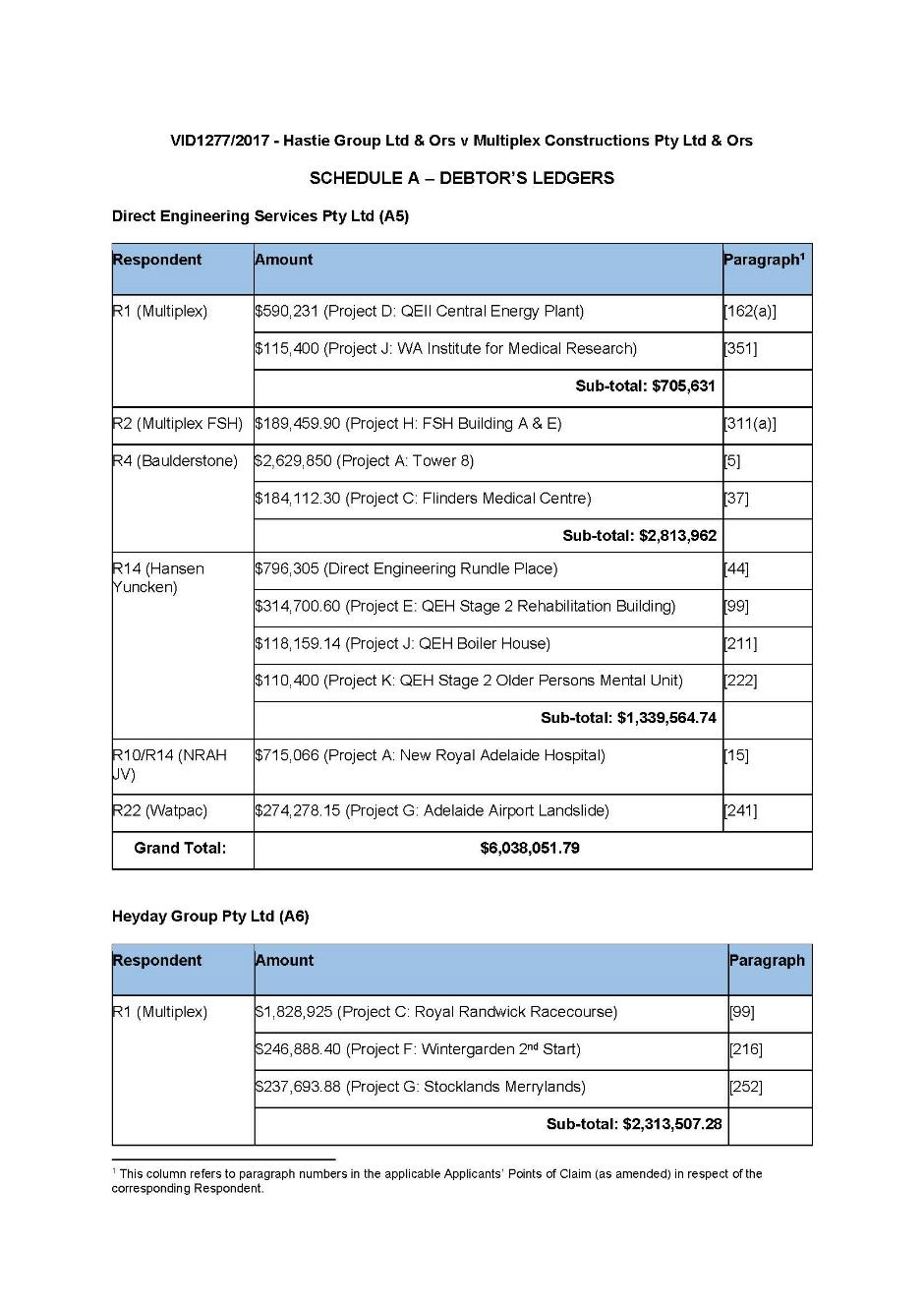

(b) in treating the “debts” recorded in the debtor’s ledger of each of the Hastie Entities as being recoverable by the relevant company and not statute barred;

(c) in admitting to proof in the winding up of the Hastie Entity, or seeking payment to that Hastie Entity of the “balance of the account” ascertained by the Liquidator applying s 553C of the Act in accordance with the principles in Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd v Forge Group Power Pty Ltd (in liq) (Receivers and Managers appointed) [2018] WASCA 163; (2018) 53 WAR 325 (Forge).

(d) on the basis that the draw on the bank guarantee made by each Respondent was void;

(e) in seeking to take into his custody or under his control, the moneys drawn by each Respondent (excluding Baulderstone Qld) on bank guarantees (the “guarantee proceeds”);

(f) in treating the guarantee proceeds drawn by each Respondent as a credit from the Hastie Entity which provided the bank guarantee drawn upon;

(g) in treating each Respondent as having had notice as and from the Appointment Date, that the Hastie Entities were insolvent;

(h) in treating as not allowed by ss 555 and 556 of the Act, the payment by a Respondent of the claims by that Respondent paying to itself guarantee proceeds.

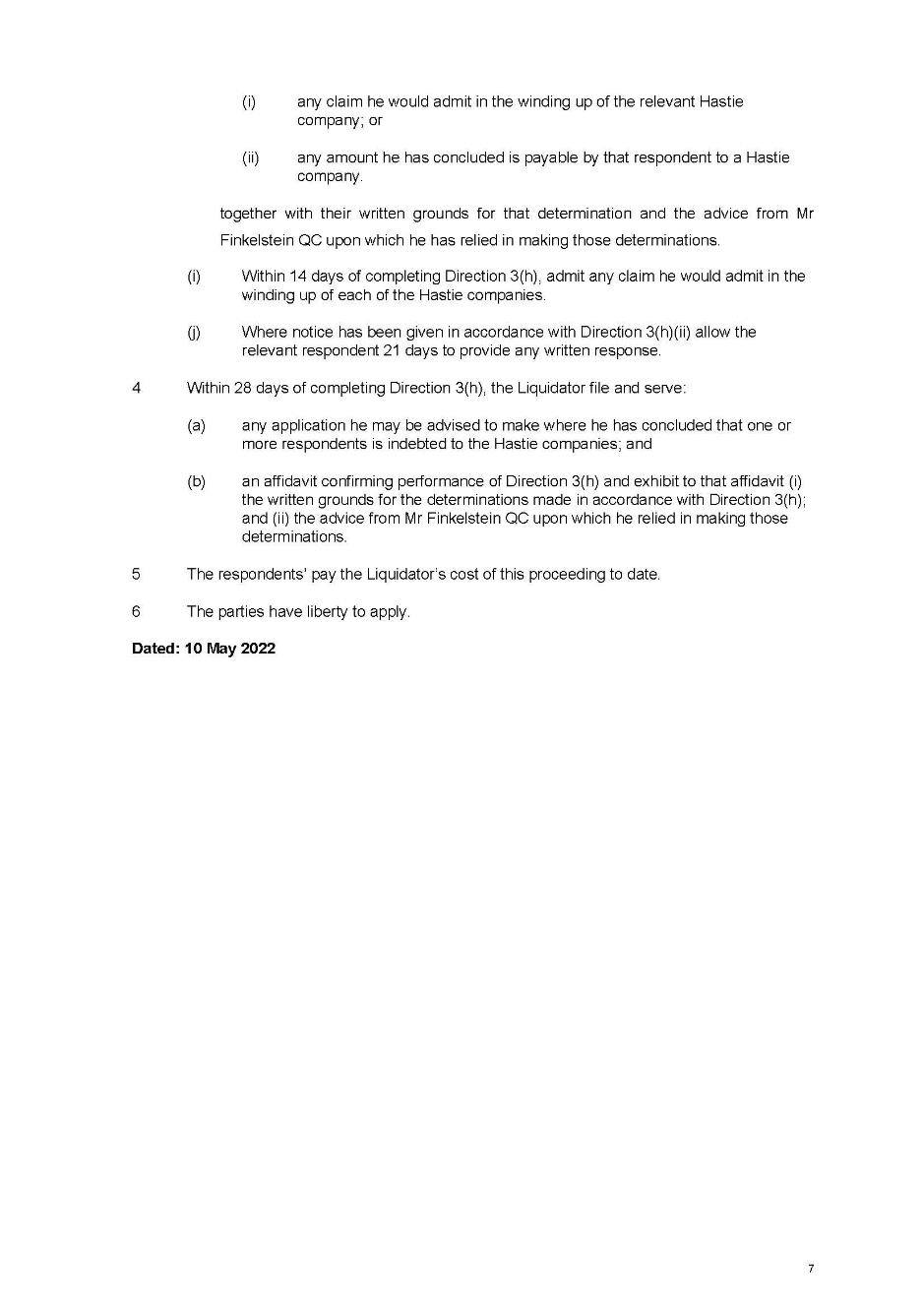

80 Third, the orders sought under proposed orders 3 and 4 were that the Liquidator is directed to admit the order 1 claims as claims not bearing a certain value and then follow a prescribed mechanism by which, among other things:

(a) each Respondent could provide particulars as to their admitted claims;

(b) the Liquidator would estimate the value of the Respondents’ claims;

(c) the Liquidator could receive advice from a King’s Counsel as to any questions which arise as to how to perform the directions;

(d) the Liquidator would determine to admit or not admit the Respondents’ claims; and

(e) the Liquidator would be entitled to file and serve any court application in respect of a Respondent’s indebtedness to a Hastie Entity.

81 In summary therefore, the Applicants sought orders that would confirm their interpretation of the application of the Act, require the Respondents to participate in the proof of debt process for each Hastie Entity and allow the Liquidator to commence new proceedings against any Respondent in respect of any indebtedness determined following the proof of debt process.

82 Finally, I note that no injunction or restraining order (final or interlocutory) is specifically sought in these proceedings to prevent any Respondent from “calling on” any bank guarantee not already called on.

Evidence in the main proceeding

83 During the trial of the main proceeding, I decided that various aspects of the pleadings would effectively be treated as fact for the purposes of the liability trial. In particular, the Court proceeded on the basis that the facts pleaded by the Applicants formed the basis of their claims concerning the operation of the Corporations Act, and the questions relating to the limitation defences.

84 There were a number of objections to evidence by the parties, but in the end, the parties either came to an agreement to allow certain evidence to be tendered for the purposes of the liability trial or the Court admitted the evidence subject to relevance. It is unnecessary for me to specifically refer to each of these items of evidence as I have in the course of these reasons referred to the evidence that is relevant and determinative of the issues that are required to be considered in this liability trial.

85 Further, the Court received the following evidence:

(a) the contracts between each Respondent and each Hastie Entity (including, where no formal contract was entered into, correspondence said to constitute a contract), as summarised at Schedule A to the Applicants’ Closing Submissions dated 7 May 2022;

(b) various other contracts relevant to the main proceeding, such as certain facilities agreements entered into between the Hastie Group and various banks, and the Deed of Cross-Guarantee;

(c) the bank guarantees relevant to the main proceeding which were issued to each Respondent;

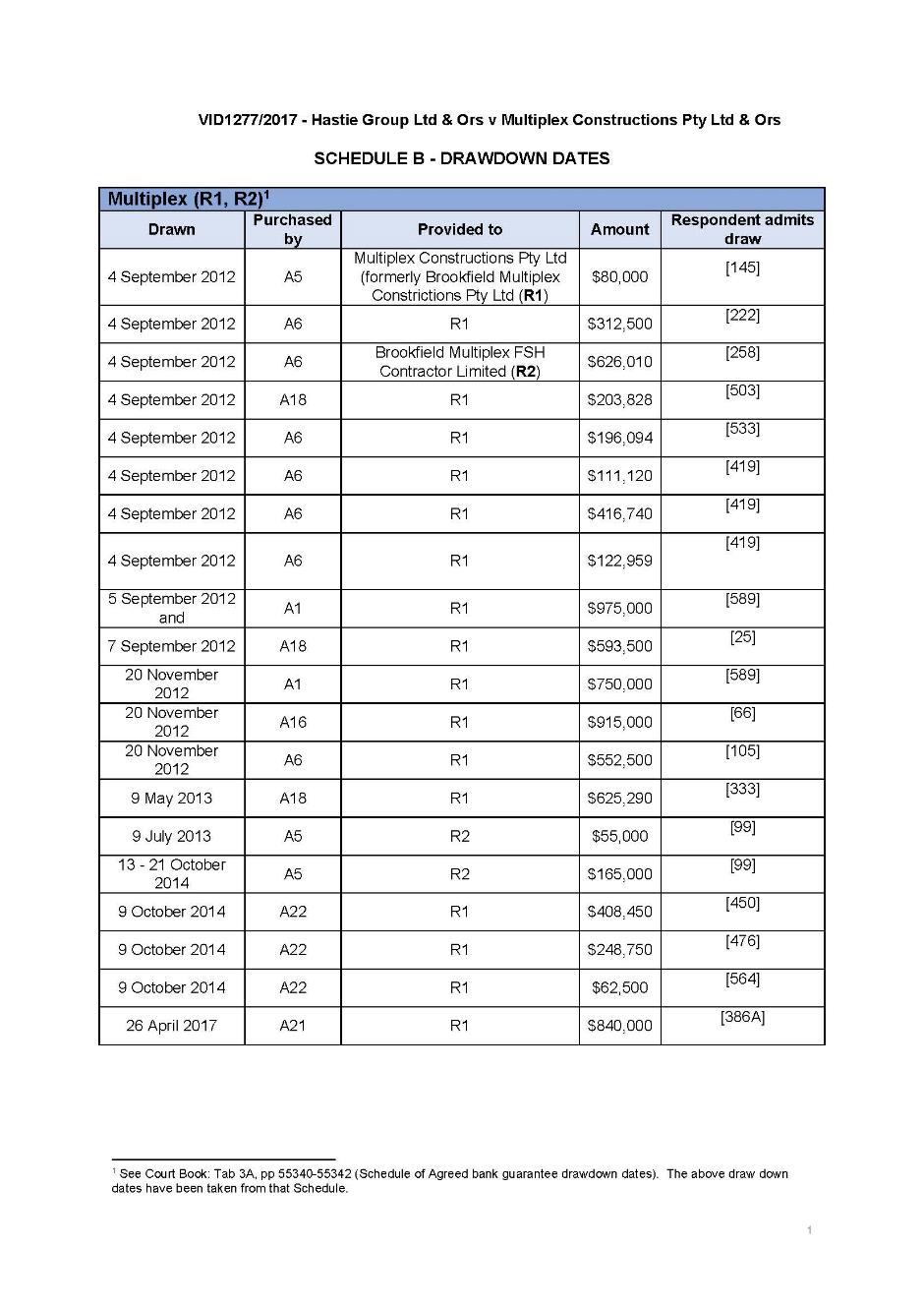

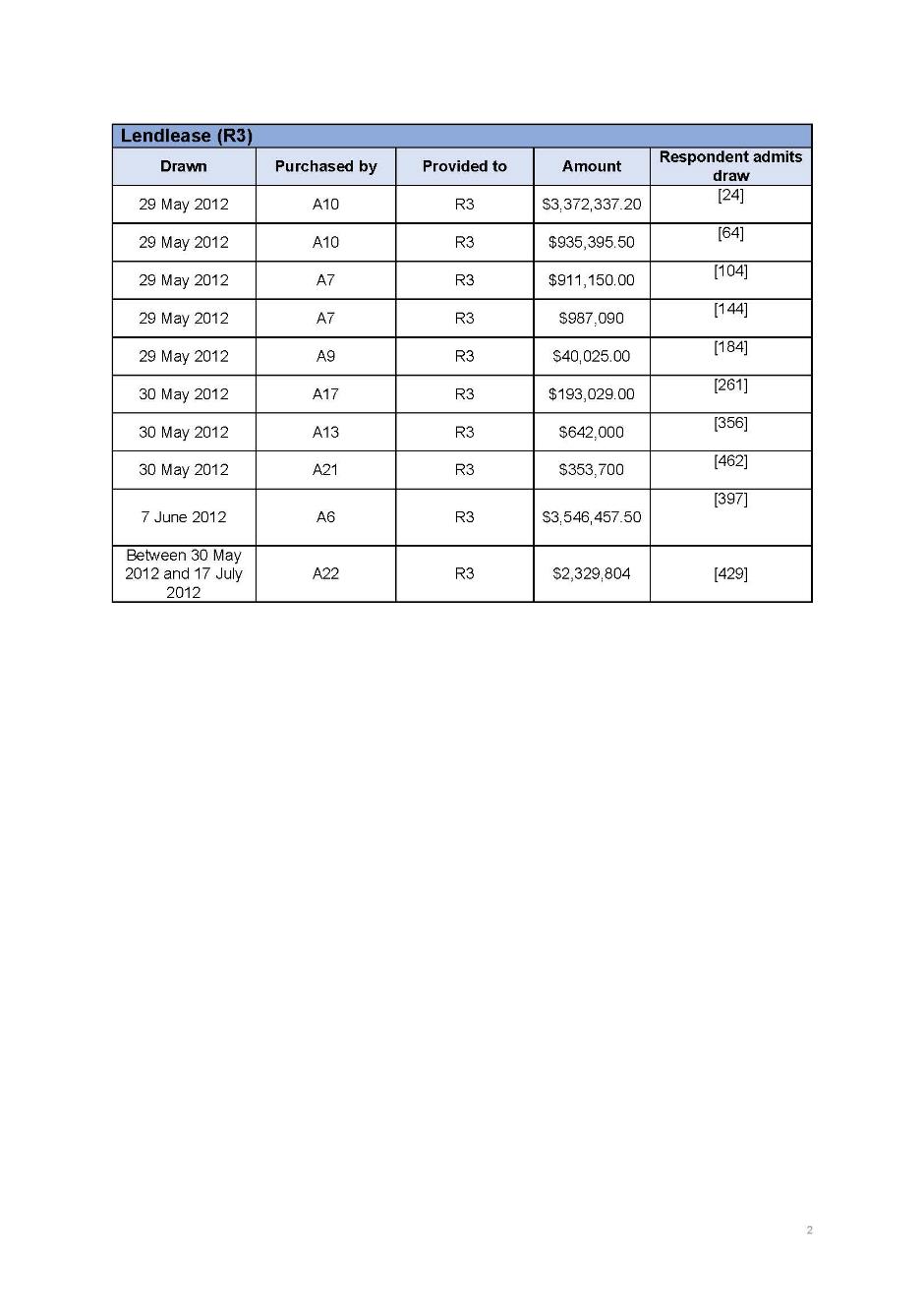

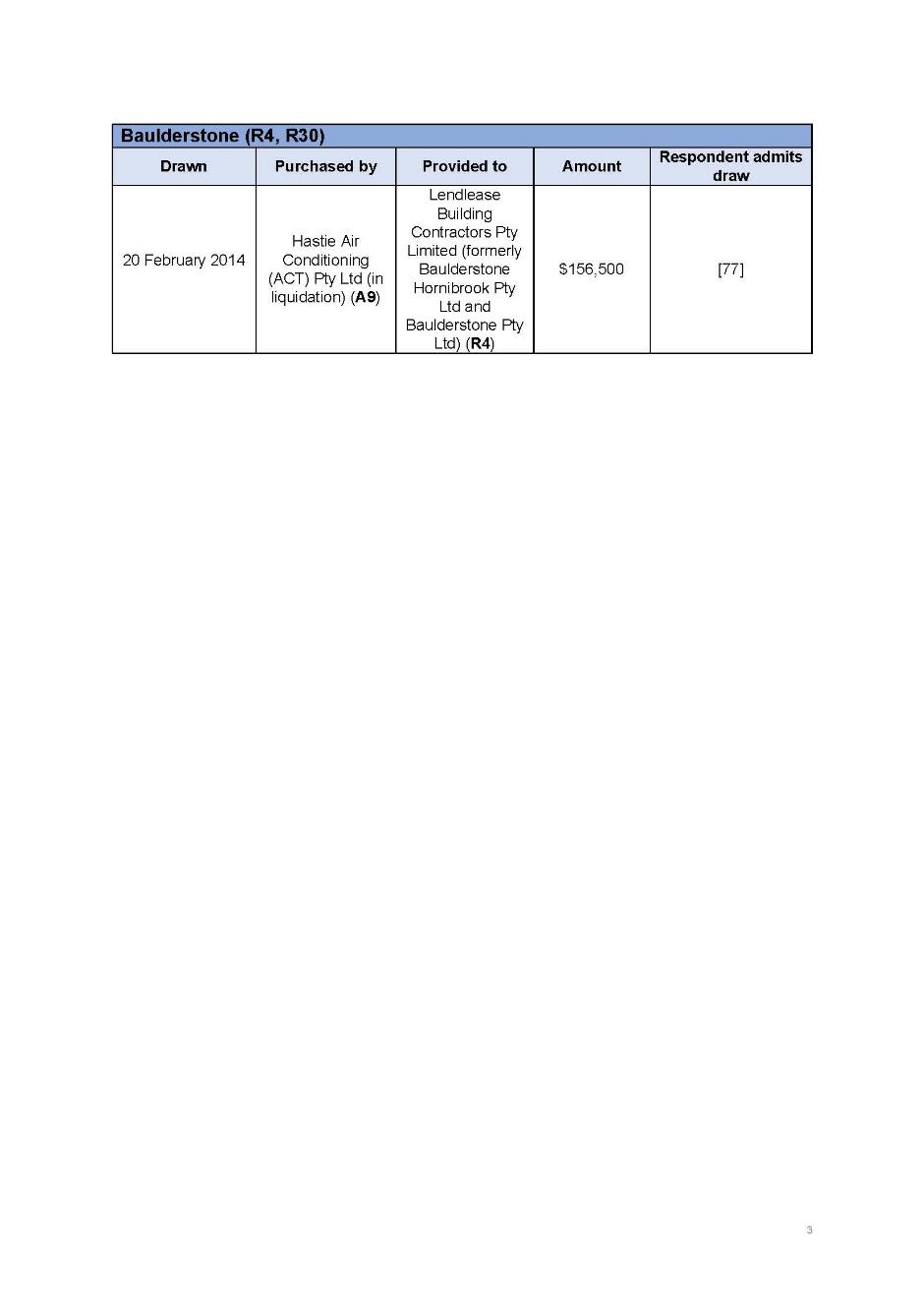

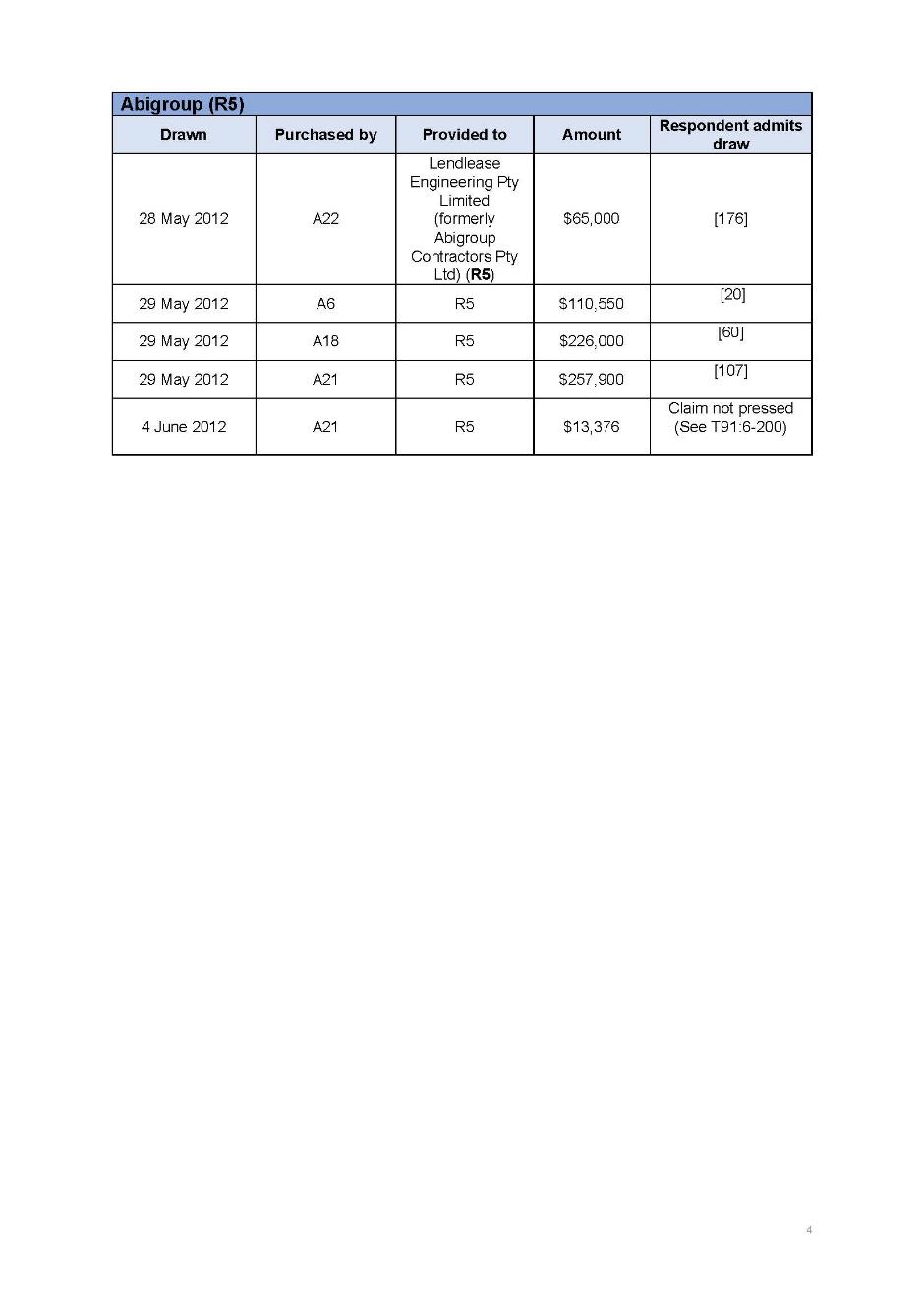

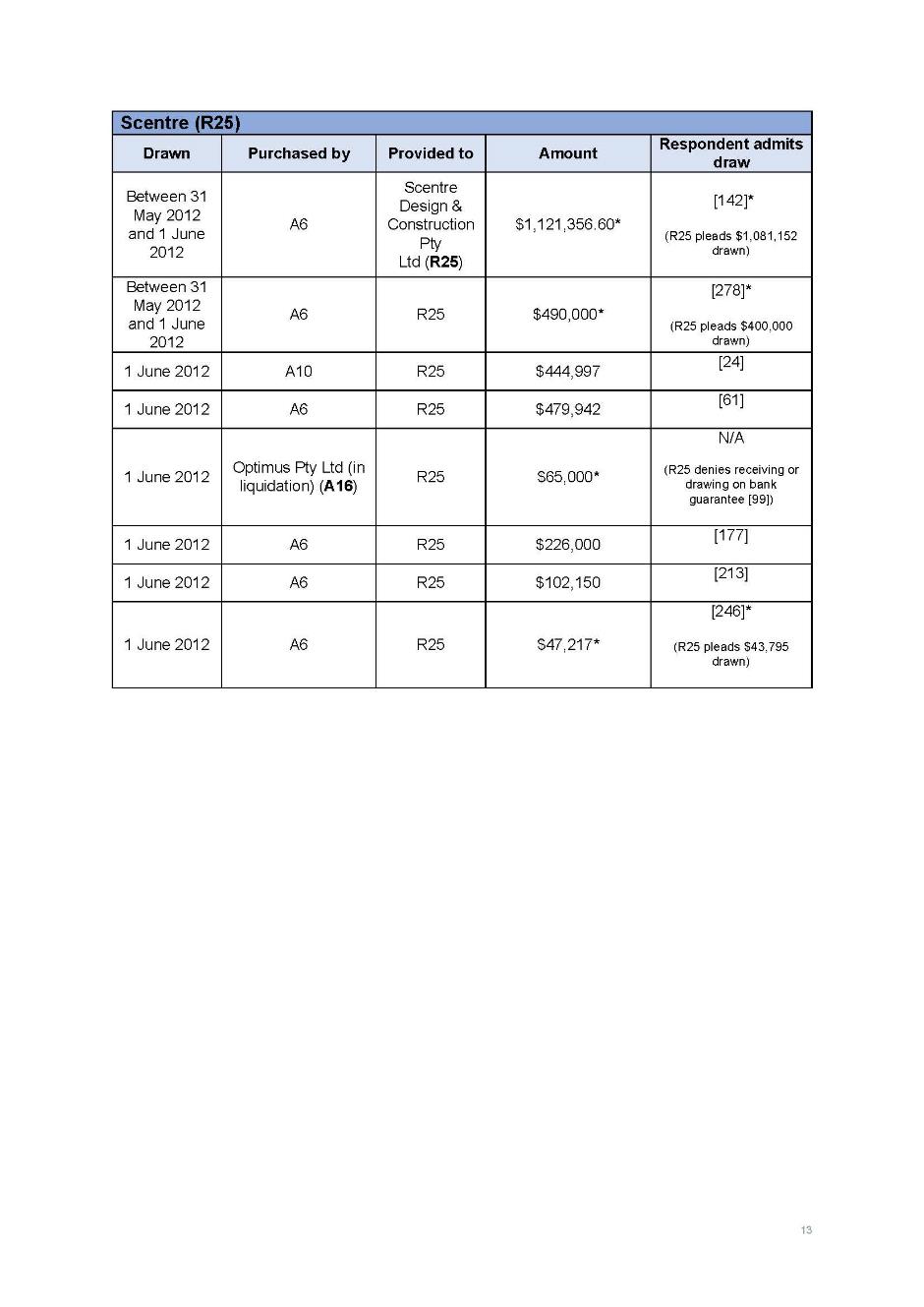

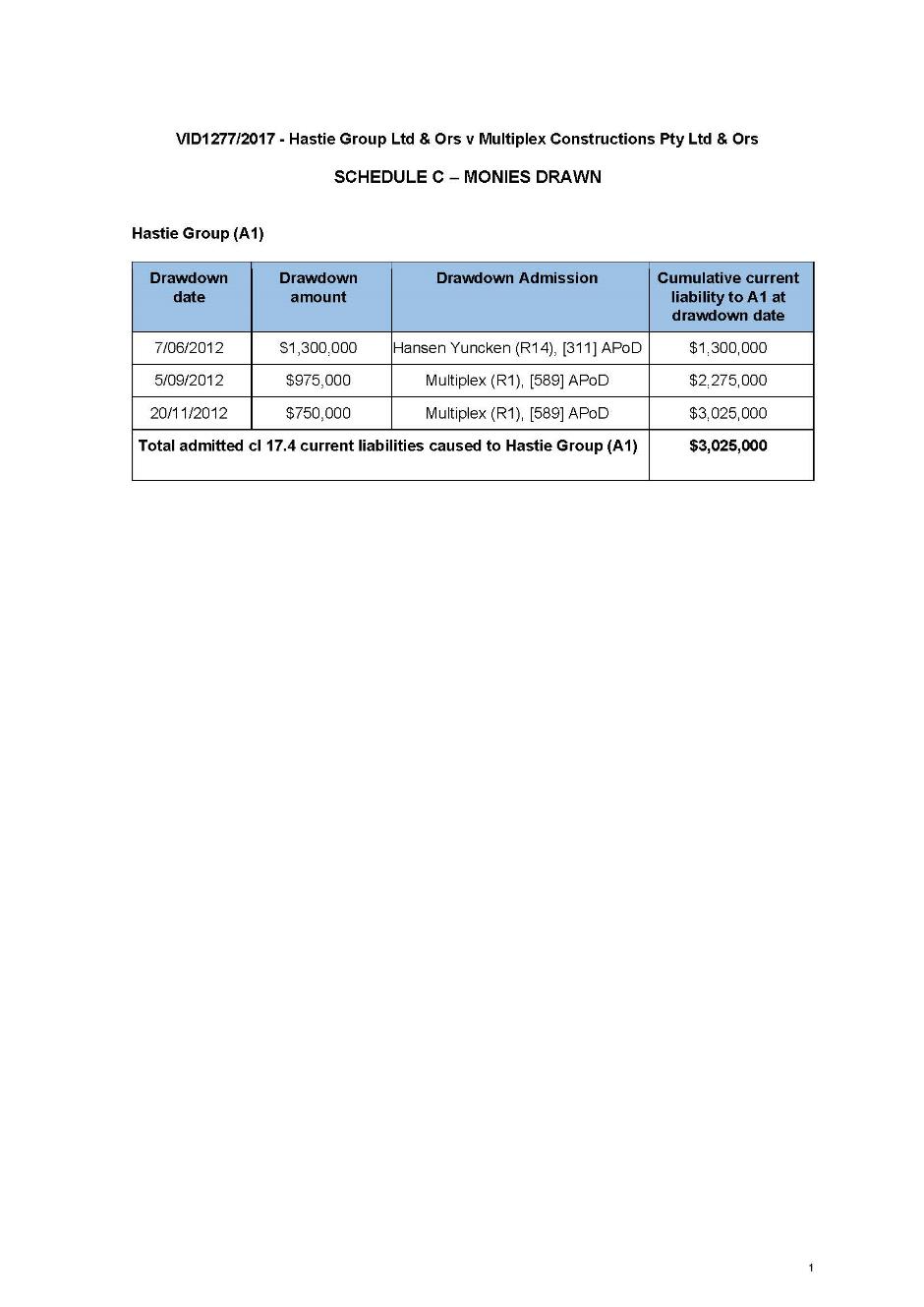

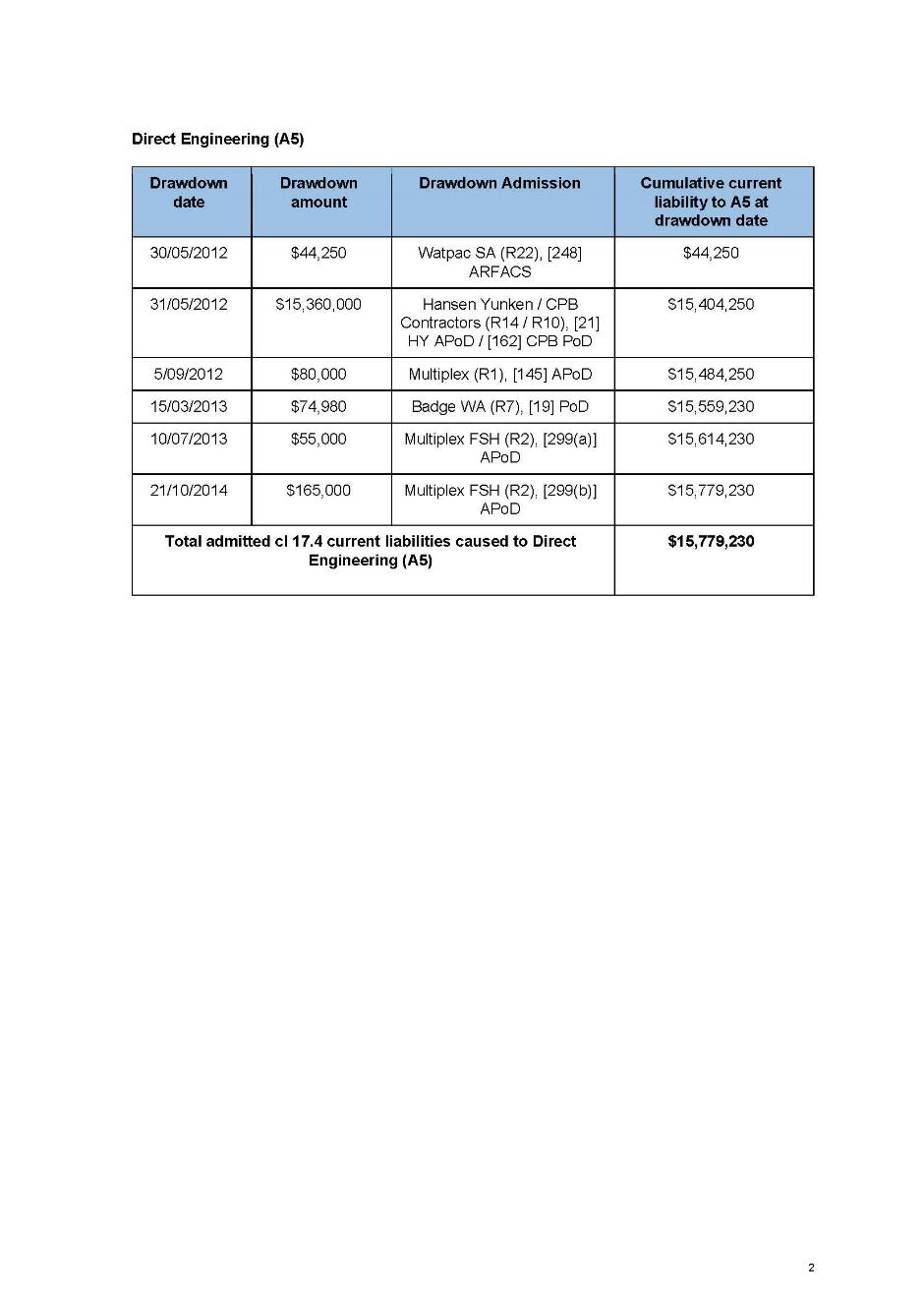

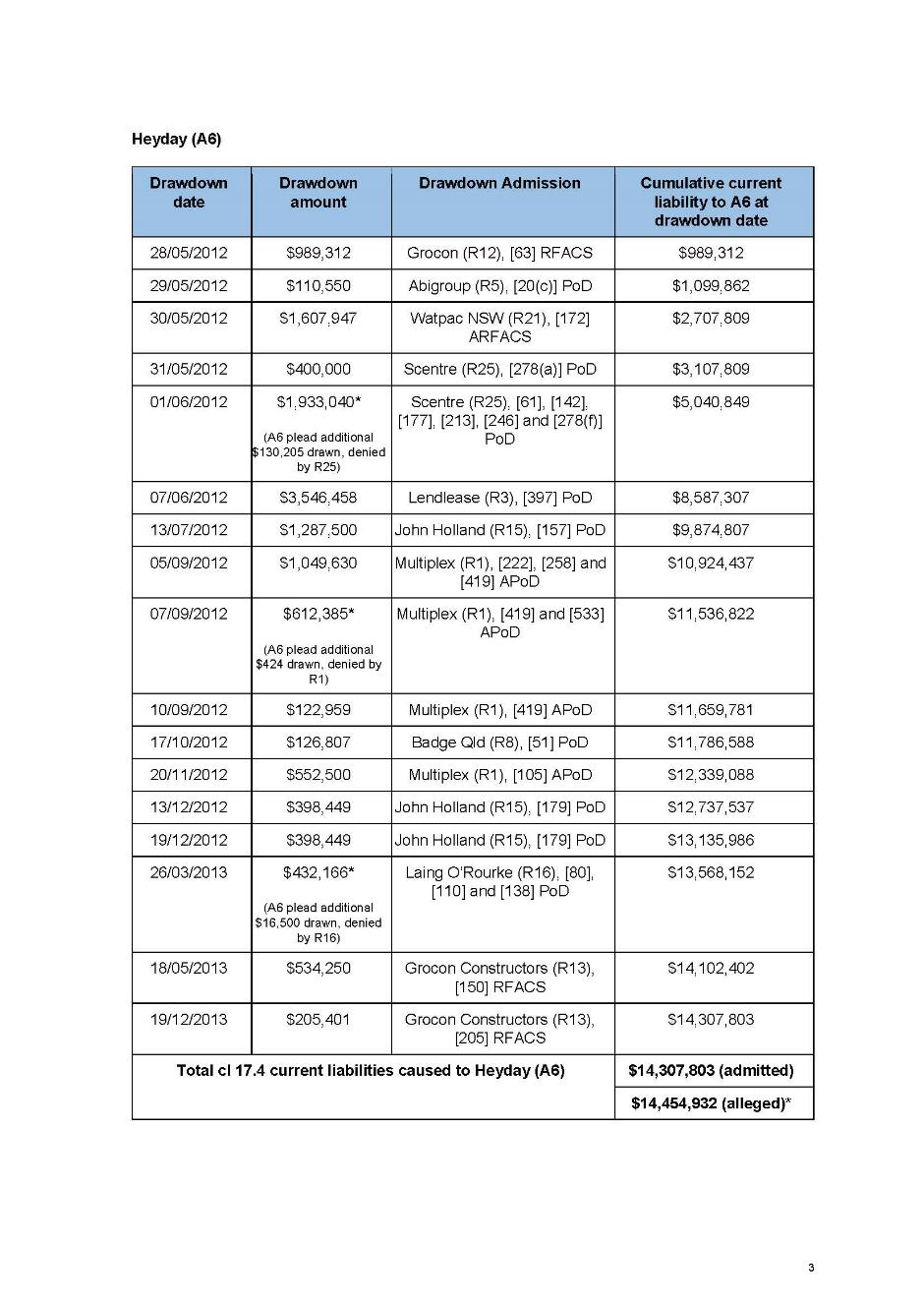

(d) the date of recourse and amount drawn by each Respondent on the bank guarantees provided by each Hastie Entity, set out at Schedule B to the Applicants’ Closing Submissions dated 7 May 2022;

(e) the status of each project subcontract, including whether the subcontract was terminated (and date thereof), or taken out of the hands of the Hastie Entity (and date thereof), or treated as having been terminated, set out at Schedule C to the Applicants’ Closing Submissions dated 7 May 2022; and

(f) further documents tendered by agreement between the Applicants and each Respondent, such as relevant contractual notices pursuant to the abovementioned contracts, correspondence between the parties and limited affidavit evidence in relation to certain contracts.

86 Where a contract sought to be relied upon by the Applicants is not available and not put in evidence before the Court, I cannot and do not infer that such an alleged contract existed, or that its terms were identical to or similar to the other contracts before the Court. The Applicants may still be able to rely on s 1305 of the Act as prima facie evidence of their claims, even if a contract is not available. I refer later in these reasons to s 1305 and its operation.

87 Further, there is an issue concerning the contracts entered into between Multiplex and the Hastie Entities in relation to “Project K – Sydney Water HQ” and the so-called “Global Bonds” (being certain bank guarantees issued by ANZ to Multiplex in relation to Hastie Australia).

88 Evidence was tendered concerning the terms of the contract relating to the Sydney Water HQ project: see the affidavit of David Kenneth Cooksley sworn 1 February 2022 on behalf of Multiplex. There can be no doubt that an agreement was reached as to the Sydney Water HQ project via email correspondence (for example, as to price), but no formal contract was in evidence. I make no findings for the purposes of this main proceeding as to any specific terms as to payment, other than accepting the Applicants’ pleaded date when the receivables claimed were due and payable.

89 As to the “Global Bonds”, I proceed to accept the written bank guarantees at annexures DKC-41 and DKC-42 of the said affidavit of Mr Cooksley. Otherwise, there is no sufficient evidence produced to the Court to prove that Multiplex and Hastie Australia entered into an agreement in which Hastie Australia agreed to provide unconditional bank guarantees on behalf of and to secure performance by Hastie Australia and each subsidiary of the Hastie Group for works subcontracted to them by Multiplex regarding projects located in New South Wales, as pleaded by Multiplex: see [584] of Multiplex’s Amended Points of Defence.

PRINCIPAL CONCLUSIONS TO THE COMMON ISSUES

90 I shall now set out my principal conclusions as to the issues that require determination following the liability trial of the main proceeding, by reference to the Common Issues detailed earlier in these reasons.

Issue 1: The subcontracts between the Hastie Entities and each respondent

91 The relevant subcontracts were identified by the parties and were not in dispute, with the exception of certain contracts in relation to Multiplex which were not in formal written form and so were partly-written and partly-oral, and certain contracts that were not available to the parties and so the terms of which the Applicants sought to infer, each of which I referred to in the previous section of these reasons. To the extent necessary for the determination of the Common Issues, each of the relevant subcontracts has been considered for the purposes of these reasons and the effect of their operation demonstrated mainly by reference to an example subcontract involving Multiplex (the First Respondent). Where any of the relevant subcontracts are substantively different or produce a substantively different outcome for the purposes of these proceedings, this is discussed in my reasons.

Issue 3: Whether Hastie Entities’ Receivables Case statute-barred

92 The Hastie Entities’ claims, as detailed in the Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement and the Originating Process filed on 14 November 2017, were relevantly made on 14 November 2017. To the extent each such claim was made within the six-year limitation period applicable to each of those claims, the claims are not statute-barred. To the extent that any other claims of the Hastie Entities were not made on 14 November 2017 but were made after that date (for example, by the filing of the Applicants’ Points of Claim on 13 July 2018), the claims are statute-barred unless those claims were made within the six-year limitation period applicable to each claim.

Issue 4: Whether respondents have “claims” pursuant to s 553C of the Act

93 The Respondents’ contractual claims against the Hastie Entities pursuant to their respective subcontracts – asserted after the Appointment Date but the circumstances giving rise to which existed before the Appointment Date – are “claims” within the meaning of s 553 and therefore s 553C of the Act which may be set-off in accordance with s 553C.

94 However, the Respondents’ assertions of their entitlement to set-off pursuant to s 553C are not in themselves “claims” within the meaning of s 553.

Issue 5: Whether mutuality pursuant to s 553C of the Act

95 By the end of the trial, it was not in dispute that mutuality was satisfied for the purposes of s 553C in respect of the Respondents’ claims against the Hastie Entities pursuant to the respective subcontracts. I accept that such claims were mutual within the meaning of s 553C.

96 In addition, the Respondents’ claims against the Hastie Entities insofar as they are made pursuant to the Deed of Cross-Guarantee also satisfy the mutuality requirement imposed by s 553C.

Issue 7: Whether s 553C of the Act applies exclusively to the parties’ claims

97 It is not necessary to resolve the question as to whether set-off pursuant to s 553C of the Act applies exclusively to each of the Respondents’ claims in the main proceeding, and in particular, to the exclusion of any entitlement to contractual set-off that may have been asserted by a Respondent prior to the winding up of the Hastie Entities.

Issue 7a: Whether s 553C of the Act applies automatically with respect to the parties’ claims

98 The Respondents are each entitled to the benefit of the application of set-off pursuant to the principles set out in s 553C in the winding up of the Hastie Entities, and such entitlement is not dependent on any precondition of lodging a proof of debt in the winding up, or on the determination of the liquidator as to the application of s 553C set-off in respect of the relevant claims.

Issue 8: Whether respondents have proprietary interest in bank guarantee proceeds

99 By virtue of the various contractual instruments in relation to the bank guarantees, the Respondents were conferred proprietary interests in not only the physical bank guarantee instruments, but more importantly, the proceeds of the bank guarantees drawn down (once those proceeds were received by the Respondents).

Issues 9-10: Whether Hastie Entities had proprietary interests in relation to bank guarantees

100 Having regard to the various contractual instruments in relation to the bank guarantees, the Hastie Entities did not possess proprietary interests in relation to the bank guarantees that relevantly affect the proprietary interests of the Respondents in the proceeds of the bank guarantees drawn down. Any proprietary interests or rights of action that the Hastie Entities possess or once possessed as “choses in action” or “things in action” are of no consequence or utility for the purposes of the Hastie Entities’ claims against the Respondents.

Issue 11: Whether causal and transactional link between respondents’ credit of the bank guarantee proceeds and Hastie Entities’ debits

101 The Hastie Entities do not possess any proprietary interest in the bank guarantee proceeds by virtue of any “causal and transactional link” between the respondents’ credit of the bank guarantee proceeds drawn down and the corresponding “debit” arising from the Hastie Entities’ crystallised liabilities to the issuing banks pursuant to the facility agreements between the Hastie Entities and the banks.

Issues 12-13: Whether drawdown of bank guarantees voided by ss 437D or 468 of the Act

102 The Respondents’ drawdowns of the bank guarantees are not voided by either of ss 437D or 468 of the Act.

Issues 14-15: Whether respondents are entitled to retain the guarantee proceeds

103 The Respondents are not otherwise restrained from retaining the bank guarantee proceeds by virtue of ss 555 and 556 of the Act, or Chapter 5 of the Act generally, and so they are entitled to retain the bank guarantee proceeds subject to the final accounting of the respective claims of the Hastie Entities and the Respondents, following which it can be determined whether there are any surplus proceeds which the Respondents must account for and repay to the Hastie Entities.

Issue 16: Whether Hastie Entities’ Bank Guarantee Case statute-barred

104 The Hastie Entities’ claim against Baulderstone Qld Pty Ltd (the Thirtieth Respondent), as contained in the Amended Points of Claim against the Fourth and Thirtieth Respondents filed 26 February 2021, was made on that date and is pleaded pursuant to a deed of release. To the extent that this claim was made within the twelve-year limitation period applicable to a claim upon a deed or specialty, it is not statute-barred. To the extent that the other Hastie Entities’ claims were relevantly made on 14 November 2017 by way of Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement and the Originating Process filed on 14 November 2017, the claims are not statute-barred if those claims were made within the six-year limitation period applicable to each claim. To the extent that any other claims of the Hastie Entities were not made on 14 November 2017 but were made after that date (for example, by the filing of the Applicants’ Points of Claim on 13 July 2018), the claims are statute-barred unless those claims were made within the six-year limitation period applicable to each claim.

CONSIDERATION OF ISSUES CONCERNING LIMITATION OF ACTIONS

105 Before turning to the substantive issues in the proceeding, I will address the Respondents’ contentions that the Hastie Entities’ claims are statute-barred by reasons of various statutes of limitations (Issues 3 and 16 of the Common Issues).

106 The Applicants set out the relevant Receivables Case claim dates in their pleadings. These dates are the dates that I adopt for the purposes the determining the limitation issue in relation to the Receivables Case.

107 The Applicants also produced a schedule to their written closing submissions setting out the relevant Bank Guarantee Case claim dates. Some of these Bank Guarantee Case claim dates were in contention, but not relevantly for the purposes of the limitation issue raised by the Respondents. I proceed to determine the limitation of actions defences in relation to the Bank Guarantee Case by reference to this schedule. However, where there are dates in contention and recorded by each of the Respondents in their written submissions, having considered the underlying documents, I accept the Respondents’ dates. Therefore, if any issues arise as to the application of these reasons to the relevant guarantee claim dates, then the correct dates are those submitted by each Respondent. However, as I say, in my view and in light of my approach, whether any competing date is chosen, there is no difference in the application of the principles to apply.

108 The following principles apply to the determination of the limitation of actions defences raised by the Respondents. The relevant State Limitations Acts referred to by the parties and agreed are applicable by operation of ss 79 and 80 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). I interpolate also that whilst there was some mention by Counsel for the Applicants that there may well be a running account and so the limitation of actions defences could not be dealt with at this stage, there is no evidence (either admitted into evidence or sought to be admitted into evidence) or any suggestion in any of the material before me that there was any running account in relation to any of the relevant subcontracts. This is certainly not the way in which the Applicants have presented their case in the main proceeding or sought to prove the relevant debts.

109 As to the Bank Guarantee Case, the position is straight forward. The relevant accrual of the cause of action is the drawdown date or failure to return date pleaded by the Applicants, as the case may be. Even if the guarantee is a deed, as the Hastie Entities’ claims are not made pursuant to the guarantee, the limitation period is six years from the date of draw down or breach of the failure to return obligation.

110 Now, turning to the Receivables Case, the general principles are as follows. For breach of contract, which will include failure to abide by a contractual term or obligation to pay or perform, time accrues once that failure occurs. The same limitation period of six years applies unless any specific contract is a deed (where a limitation period of twelve or fifteen years applies, depending on the State jurisdiction). Generally, in an action for repayment of a debt, the action accrues on failure to comply with the valid demand for repayment, being at the relevant date for repayment. In the case of breach of multiple promises in one contract (eg periodical payments) a new cause of action arises every time a payment becomes payable and is not paid. In most cases this will not be difficult to determine. The difficulties encountered in a different context (like in Verwayen) do not arise in this main proceeding.

111 As to the receivables, the Applicants plead relevant dates on the basis that these can be proved, primarily by reference to books of accounts and reliance on s 1305 of the Act. For the purpose of determining the operation of the limitation of actions defences, the issue of whether or not the pre-conditions that may arise in relation to the obligation to pay need not arise for determination having regard to the basis of the Applicants’ own case. Where the claims are not statute barred, and will proceed to quantification, then it will may be necessary to determine whether these pre-conditions were satisfied. If the Applicants continue to rely on the books of accounts and s 1305, the onus will be on the Respondents to demonstrate the amounts are not owing and the prima facie position is displaced. The important point for this part of the main proceeding is that the parties have proceeded (largely by agreement) to treat the relevant dates pleaded by the Applicants as maintainable and the basis upon which they seek payment and relief.

112 The real issue of some debate is whether sufficient material facts were pleaded at the commencement of the main proceeding in relation to the various claims now pressed against each Respondent. This involves in the main proceeding a question of the ambit of the Originating Process filed on 14 November 2017. I interpolate that to the extent that claims are not made in the latest Points of Claim against each Respondent, and were made previously, they are treated as abandoned.

113 By order of the Court dated 29 January 2021, the Respondents had reserved to them the position to argue the relevant date for the operation of the relevant limitation period. Each Respondent took the opportunity to make submissions on this issue, essentially re-arguing the matters raised at an earlier interlocutory stage. I now confirm the approach and conclusions I reached in the interlocutory application relevant to these issues: see Hastie Interlocutory Decision especially at [20]-[22] and [41]-[57].

114 I stress that the claims made are limited to those referred to in Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement referred to in the Originating Process filed on 14 November 2017 by reference to the relevant Respondent and Hastie Entity. In my view, Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement does bring to the attention of each Respondent referred to therein the relevant key issues and key facts for determination, and the essential relief sought. However, this is limited to the various builder groups, project names and the reference to the particular debts and bank guarantees referred to in Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement. Therefore, if any claim is subsequently sought to be brought outside those referred to in Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement and is otherwise not within the six-year period from which the claim arises, the Applicants cannot rely upon the date of 14 November 2017 as the date of the commencement of that claim. For example, if a Hastie Entity’s debt claim arose as at 14 July 2012 (because a payment was asserted to be due and payable as at 14 July 2012), then if that claim was contained in the Applicants’ Points of Claim filed on 13 July 2018 but not in Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement, it would not be statute-barred.

115 On this basis, as long as the Applicants’ claim is within the scope of Annexure 1 to the Concise Statement, the limitation period only operates to prevent the Hastie Entities from pursuing the receivables and guarantee claims where the claim sought to be raised arose earlier than six years from 14 November 2017. The schedule relied upon by the Applicants and their pleading will indicate the relevant date for each claim for the parties to apply those principles. (I again note that the different dates raised by the Respondents make no difference to the application of the principles).

116 It will be apparent I do not accept the detailed arguments of the Respondents as to when the claims were later made by the Hastie Entities by way of amended concise statements or points of claim, as once it is concluded that they were sufficiently raised on 14 November 2017, the other various dates raised by the Respondents are of no consequence.

117 I need make mention of Baulderstone Qld Pty Ltd, who was only joined on 29 January 2021 pursuant to the following order:

1. Pursuant to rule 9.05 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Federal Court Rules), Baulderstone Qld Pty Ltd (Baulderstone Qld) be joined as a Respondent to these proceedings, noting that, pursuant to r 9.05(3) of the Federal Court Rules, the proceedings against Baulderstone Qld is taken to have started on the date of these orders.

118 Even in light of this order, the Hastie Entities’ pleaded claim against Baulderstone Qld Pty Ltd would not be statute barred to the extent that the claim (as pleaded) is an action upon a deed of release. This is because the relevant limitation period for an action upon a deed or specialty under the applicable State Limitation Act is twelve years.

119 I also note that an issue arose as to the applicable limitation period in relation to the Applicants’ claims against Grocon in relation to the subcontract referred to as the “Project A – Hastie Australia 161-163 Castlereagh Street” Deed. This is the only subcontract brought to the Court’s attention that was on its face made as a deed. There was some argument as to whether the claims made against Grocon in this main proceeding were made under the deed (in which case they may be subject to the twelve-year limitation period under the applicable State Limitation Act) or were merely property or debt claims (in which case the six-year limitation period would apply). In light of my reasons as to the Bank Guarantee Case which disposes of the issues relevant to Grocon in this liability trial, it is not necessary for me to determine this issue as to the applicable limitation period.

120 I now turn to the various relevant provisions of Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act and to some aspects of their operation.

Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act

121 Chapter 5 of the Act implements the statutory scheme in relation to the external administration of companies. In particular issue in these proceedings is Part 5.3A in relation to the voluntary administration of a company, and the various Parts of Chapter 5 concerning the winding up of a company.

122 I shall set out the relevant provisions for these proceedings.

Voluntary administration under the Act

123 First, s 435A sets out the objects of Part 5.3A:

The object of this Part, and Schedule 2 to the extent that it relates to this Part, is to provide for the business, property and affairs of an insolvent company to be administered in a way that:

(a) maximises the chances of the company, or as much as possible of its business, continuing in existence; or

(b) if it is not possible for the company or its business to continue in existence -- results in a better return for the company's creditors and members than would result from an immediate winding up of the company.

124 Section 435C provides that the administration of the company begins when an administrator is appointed.

125 Section 437D makes void dealings or transactions affecting the property of the company without the administrator’s consent or leave of the court. This section is central to the Bank Guarantee Case, so I set it out in full:

437D Only administrator can deal with company’s property

(1) This section applies where:

(a) a company under administration purports to enter into; or

(b) a person purports to enter into, on behalf of a company under administration;

a transaction or dealing affecting property of the company.

(2) The transaction or dealing is void unless:

(a) the administrator entered into it on the company’s behalf; or

(b) the administrator consented to it in writing before it was entered into; or

(c) it was entered into under an order of the Court.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply to a payment made:

(a) by an Australian ADI out of an account kept by the company with the ADI; and

(b) in good faith and in the ordinary course of the ADI’s banking business; and

(c) after the administration began and on or before the day on which:

(i) the administrator gives to the ADI (under subsection 450A(3) or otherwise) written notice of the appointment that began the administration; or

(ii) the administrator complies with paragraph 450A(1)(b) in relation to that appointment;

whichever happens first.

(4) Subsection (2) has effect subject to an order that the Court makes after the purported transaction or dealing.

…

126 Section 440B prevents the holders of various rights in relation to property of the company from exercising such rights without the administrator’s consent or leave of the court, relevantly providing:

440B Restrictions on exercise of third party property rights

General rule

(1) During the administration of a company, the restrictions set out in the table at the end of this section apply in relation to the exercise of the rights of a person (the third party) in property of the company, or other property used or occupied by, or in the possession of, the company, as set out in the table.

Note: The property of the company includes any PPSA retention of title property of the company (see section 435B).

…

Restrictions on exercise of third party rights | ||

Item | If the third party is … | then … |

1 | a secured party in relation to property of the company, and is not otherwise covered by this table | the third party cannot enforce the security interest. |

2 | a secured party in relation to a possessory security interest in the property of the company | the third party cannot sell the property, or otherwise enforce the security interest. |

3 | a lessor of property used or occupied by, or in the possession of, the company, including a secured party (a PPSA secured party) in relation to a PPSA security interest in goods arising out of a lease of the goods | the following restrictions apply: (a) distress for rent must not be carried out against the property; (b) the third party cannot take possession of the property or otherwise recover it; (c) if the third party is a PPSA secured party—the third party cannot otherwise enforce the security interest. |

4 | an owner (other than a lessor) of property used or occupied by, or in the possession of, the company, including a secured party (a PPSA secured party) in relation to a PPSA security interest in the property | the following restrictions apply: (a) the third party cannot take possession of the property or otherwise recover it; (b) if the third party is a PPSA secured party—the third party cannot otherwise enforce the security interest. |

127 Section 440D stays proceedings against the company or in relation to any of its property without the administrator’s consent or leave of the court, relevantly providing:

440D Stay of proceedings

(1) During the administration of a company, a proceeding in a court against the company or in relation to any of its property cannot be begun or proceeded with, except:

(a) with the administrator’s written consent; or

(b) with the leave of the Court and in accordance with such terms (if any) as the Court imposes.

128 Section 440F prevents enforcement processes against property of the company except with the leave of the court.

129 Division 7 of Part 5.3A sets out various provisions relevant to the rights of parties holding security interests to enforce or take action against property of the company, despite ss 440B and 440F. For example, s 441A concerns the rights of secured parties who have a security interest in respect of the “whole, or substantially the whole, of the property of a company under administration”, and s 441B concerns the rights of secured parties who commence enforcement of their security interests before the administration commences.

130 Section 447A grants the Court general powers to make orders as it think appropriate about how Pt 5.3A is to operate in relation to a particular company.

131 Section 447B grants power to the Court to make orders to protect the interests of a company’s creditors while the company is under administration.

132 Chapter 5 provides for various forms of winding up of a company. Relevantly to these proceedings:

(a) Pt 5.4 relates to ‘Winding up in insolvency’.

(b) Pt 5.4B relates to ‘Winding up in insolvency or by the Court’. It contains various provisions relevant to those forms of winding up.

(c) Pt 5.5 relates to ‘Voluntary winding up’. Each of the liquidations of the Hastie Entities occurred by reason of a creditors’ voluntary winding up. It is to be noted that a company may be insolvent, yet enter liquidation by way of a voluntary winding up, rather than an order of the Court that the company be wound up in insolvency.

(d) Pt 5.6 relates to ‘Winding up generally’.

133 Although the Hastie Entities have been voluntarily wound up, certain provisions in Pt 5.4 and Pt 5.4B apply to a voluntary winding up by reason of s 506(1)(b), which states that a liquidator in a voluntary winding up may “exercise any of the powers that this Act confers on a liquidator in a winding up in insolvency or by the Court”.

134 It is not necessary to set the provisions out in full, but the effect of s 513A to 513C is that where a voluntary administration is in effect prior to a winding up ordered by the Court or a voluntary winding up, the winding up is taken to have commenced on the day on which the voluntary administration began.

135 Section 474 of the Act concerns the custody and vesting of a company’s property, providing:

(1) If a company is being wound up in insolvency or by the Court, or a provisional liquidator of a company has been appointed:

(a) in a case in which a liquidator or provisional liquidator has been appointed — the liquidator or provisional liquidator must take into his or her custody, or under his or her control, all the property which is, or which appears to be, property of the company; or

…

Note: Section 465 extends the meaning of the property of the company to include PPSA retention of title property, if the security interest in the property has vested in the company in certain situations.

(2) The Court may, on the application of the liquidator, by order direct that all or any part of the property of the company vests in the liquidator and thereupon the property to which the order relates vests accordingly and the liquidator may, after giving such indemnity (if any) as the Court directs, bring, or may defend, any action or other legal proceeding that relates to that property or that it is necessary to bring or defend for the purpose of effectually winding up the company and recovering its property.

136 It has not been said that any relevant vesting order under s 474(2) has been made in respect of any property of a Hastie Entity.

137 Section 478 deals with the liquidators duty to collect and apply the company’s property in discharging the company’s liabilities or debts, providing:

(1) As soon as practicable after the Court orders that a company be wound up, the liquidator must:

(a) cause the company’s property to be collected and applied in discharging the company’s liabilities…

138 Section 506 sets out the central powers and obligations of a liquidator in a voluntary winding up, relevantly providing:

(1) The liquidator may:

…