Federal Court of Australia

Tipakalippa v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2022] FCA 1121

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | NATIONAL OFFSHORE PETROLEUM SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY First Respondent SANTOS NA BAROSSA PTY LTD (ACN 109 974 932) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The decision made by the First Respondent on 14 March 2022 pursuant to reg 10(1)(a) of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth) to accept the Barossa Development Drilling and Completions Environment Plan (Document No: BAD-200-0003 Revision 3, dated 11 February 2022) is set aside.

2. On the basis that on or before 5 pm on 22 September 2022 the Second Respondent extends to 6 October 2022 the undertaking provided to the Court and referred to at [19] and [20] of the Court’s Reasons for Judgment, order 1 shall not take effect until 6 October 2022.

3. Costs are reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[21] | |

[22] | |

[29] | |

[54] | |

Reasonable Satisfaction as a Jurisdictional Precondition – Applicable Principles | [65] |

[79] | |

[90] | |

[90] | |

[108] | |

[125] | |

[127] | |

[173] | |

[264] | |

[276] | |

[277] | |

[281] | |

[289] | |

[290] |

BROMBERG J:

1 This is an application for judicial review of a decision (Decision) of a delegate of the first respondent, the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA). NOPSEMA is an independent statutory authority established under s 645 of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth). NOPSEMA regulates offshore petroleum activities in Australian waters and its functions relevantly include accepting an environment plan pursuant to reg 10(1)(a) of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth). By the Decision purportedly made under reg 10(1)(a), NOPSEMA accepted an environment plan (the Drilling EP) submitted by the second respondent, Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd, under reg 9 of the Regulations. NOPSEMA may only accept an environment plan it if is “reasonably satisfied” that the plan meets the criteria specified in the Regulations, including that the plan demonstrates that the “titleholder” (in this case Santos) has carried out the consultations required by the Regulations and in particular reg 11A.

2 The legal effect of NOPSEMA’s acceptance of the Drilling EP, assuming it to be valid, was that Santos was permitted to carry out the petroleum activity detailed by the Drilling EP (Activity). Without such an acceptance the carrying out of the Activity would constitute an offence of strict liability under reg 6 of the Regulations.

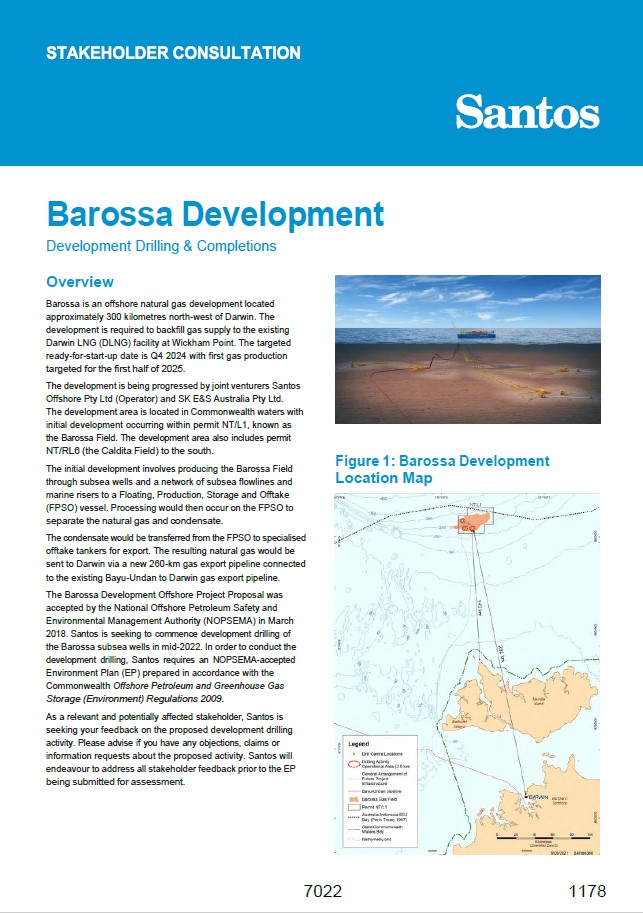

3 The Activity under the Drilling EP is part of a wider project known as the “Barossa Project”, the focus of which is an offshore gas-condensate field in the Timor Sea known as the “Barossa Field”. Santos intends to exploit that field using a floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) facility, subsea production system, supporting in-field infrastructure and a gas export pipeline connected to an existing Bayu-Undan pipeline in Commonwealth waters. The Barossa Field is the subject of “Petroleum Production Licence NT/L1” held by Santos. As the holder of the Licence, Santos is a “petroleum titleholder”, and therefore a “titleholder”, within the meaning of the Regulations.

4 The Barossa Project initially proposes to exploit an area of the Barossa Field referred to in the Drilling EP as the “Operational Area” located approximately 300 km north of Darwin and 138 km north of the Tiwi Islands. The Barossa Project aims to provide a new source of natural gas for approximately 20 years to Santos’ existing onshore Darwin Liquefied Natural Gas facility at Wickham Point.

5 Under the Drilling EP, Santos proposes to conduct a “drilling and completions campaign”, which entails the drilling and completion of up to eight production wells using a semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit (MODU). The Activity is intended to take place between 2022 and 2025, with the Drilling EP noting that drilling activities were expected to commence in the second quarter of 2022. Each well is expected to take approximately 90 days to drill. The entire drilling campaign is expected to take approximately 18 months subject to weather and operational performance. By way of an overview, the Drilling EP states that the operations or works which are to take place entirely within the Operational Area include the following:

movement of the MODU within the Operational Area (including the entry and exit of the area);

MODU and vessel commissioning and demobilising activities (eg, equipment testing, tank flushing and cleaning, inventory management, etc.);

deployment and recovery of the MODU anchors and mooring lines (including potential for pre-lay anchors);

riserless drilling;

drilling with a conventional closed-circulating fluid system and riserless mud recovery;

installation of casing strings;

drilling using water-based and non-aqueous drilling fluid systems;

installation and operation of a blow-out preventer;

cementing;

well completions, including perforating and well flowback (ie, sampling, clean up, and flaring);

installation of Christmas trees;

contingency activities such as side-track drilling, re-drilling sections, re-spud and abandonment;

well intervention;

ongoing well inspection, maintenance and management; and

general operations associated with the use of a MODU, vessels, helicopters and remotely operated vehicles within the Operational Area.

6 It is intended that the drilling and completions campaign will be followed by the installation of project facilities comprising the FPSO facility, subsea production system, supporting in-field infrastructure and the gas export pipeline mentioned earlier. The intention is that the FPSO facility will store and offload condensate to vessels for transportation to market and will also treat and export dry gas through a new pipeline that is proposed to connect into the existing Bayu-Undan to Darwin pipeline located in Commonwealth waters to the north-west of Darwin.

7 The Tiwi Islands are located in the Timor Sea, approximately 80 km north of Darwin. The Tiwi Islands comprise two main islands, Bathurst Island and Melville Island and several smaller islands. The traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands are comprised of eight clans, one of which is the Munupi clan. The traditional land of the Munupi clan extends to the northern-most reaches of the Tiwi Islands, located on the north-western peninsula of Melville Island and includes Seagull Island located approximately 4.4 km to the north of the northern-most point of Melville Island, known as Imalu Point. The traditional land of the Munupi clan is the geographically closest land to the Operational Area.

8 The applicant, Dennis Murphy Tipakalippa, is an elder, senior law man and traditional owner of the Munupi clan. He lives on the Tiwi Islands, was raised there, and has always lived at Pirlangimpi and at his homelands in the northern beaches of Munupi country. He is connected to Munupi country through his father’s family.

9 Mr Tipakalippa complains that he and the Munupi clan were not consulted by Santos in relation to the Drilling EP. Broadly speaking, his principal claim relies upon reg 11A which provides that in the course of preparing an environment plan a “titleholder” must consult each “relevant person”, being a person “whose functions, interests or activities may be affected by the activities to be carried out under the environment plan”.

10 Mr Tipakalippa claims that he and the Munupi clan, as well as other traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands, have “sea country” in the Timor Sea to the north of the Tiwi Islands, extending to and beyond the Operational Area. Their asserted rights to that sea country are based upon longstanding spiritual connections as well as traditional hunting and gathering activities in which they and their ancestors have engaged. Mr Tipakalippa claims that those interests and activities were referred to in the Drilling EP. In circumstances where the Drilling EP did not show that Mr Tipakalippa, others of the Munupi clan or indeed any of the traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands were consulted, Mr Tipakalippa claims that the decision-maker could not have been “reasonably satisfied” (as was required by reg 10(1) read with regs 10A(g) and 11A of the Regulations) that the Drilling EP “demonstrates” that Santos “has carried out the consultations” required by reg 11A.

11 What I have described as Mr Tipakalippa’s principal claim was the subject of ground 1 of the grounds of review specified in Mr Tipakalippa’s Amended Originating Application as follows:

[NOPSEMA] did not have jurisdiction to make the Decision because [it] could not have been reasonably satisfied that the Drilling EP demonstrated that the consultation required by regulations 10A and 11A of the [Regulations] was carried out.

12 This ground raises the question of whether a precondition to the valid acceptance of the Drilling EP was infected by legal error. The relevant precondition is that NOPSEMA is “reasonably satisfied” that the Drilling EP meets the criteria set out in reg 10A (reg 10(1)), a sub-set of which is the consultation criteria in reg 11A.

13 The applicable legal principles which I am required to apply to answer that question are complex and will be further explained below. It is important, however, to appreciate at the outset, that Mr Tipakalippa must establish more than that NOPSEMA came to a wrong conclusion in relation to whether consultation with him and other traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands was carried out by Santos in accordance with the Regulations. Broadly stated, Mr Tipakalippa must demonstrate that NOPSEMA, in the words of Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ in Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2018) 264 CLR 123 at [34], failed to “proceed reasonably and on a correct understanding and application of the applicable law”.

14 Santos opposed Mr Tipakalippa’s application. In the light of the principles in R v Australian Broadcasting Tribunal; Ex parte Hardiman (1980) 144 CLR 13, NOPSEMA made submissions in relation to its powers and procedures.

15 For the reasons which follow, Mr Tipakalippa has succeeded on ground 1 of his application. He has established that NOPSEMA was not lawfully satisfied that the Drilling EP meets the criteria required by the Regulations and in particular that the Drilling EP demonstrates that Santos consulted with each person that it was required by the Regulations to consult with. The consequence of that is that a necessary precondition of the acceptance of the Drilling EP by NOPSEMA did not exist and the acceptance (or permission) given by NOPSEMA was legally invalid. NOPSEMA’s decision to accept the Drilling EP must therefore be set aside.

16 By the second ground of his application, Mr Tipakalippa contended that:

[Santos] submitted the Drilling EP without having carried out the consultations required by regulations 10A and 11A of the [Regulations].

17 For the reasons I will explain, Mr Tipakalippa’s second ground is misconceived and fails at its threshold.

18 Before closing this somewhat lengthy introduction, I should say that the evidence and submissions provided by the parties was received during an expedited trial held partly on the Tiwi Islands and partly in Darwin on 22-26 August 2022. The expedited trial could not have taken place without the cooperative spirit in which it was conducted by the parties and their legal representatives, for which I am grateful.

19 The expedited trial followed a hearing held on 13 July 2022 of an unsuccessful application made by Mr Tipakalippa for interim relief (see Tipakalippa v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority [2022] FCA 838). On or about 17 July 2022, Santos commenced drilling the first of the wells to be drilled in the Operational Area under the Drilling EP. At the end of the expedited trial with the drilling of the first well not yet complete, in circumstances where Mr Tipakalippa threatened to renew his application for interim relief pending the delivery of my judgment and where the Court had indicated that it would try and accommodate the prompt delivery of judgment, Santos proffered an undertaking to the Court in the following terms:

[Santos] hereby undertakes to the Court that, in carrying out drilling activities for the Barossa Project, it will not, prior to 17 September 2022:

a) cause any well to intersect with the Barossa reservoir ‘Elang C’, being the gas and condensate reservoir located in the Barossa field within Petroleum Production Licence NT/L1; or

b) commence drilling any new well or wells in accordance with the [Drilling EP].

20 On 15 September 2022, this undertaking was extended and has effect until 22 September 2022.

LEGISLATIVE/REGULATORY FRAMEWORK & APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES

21 This section outlines the legislative provisions upon which Mr Tipakalippa’s claim for relief is founded before turning to the statutory and regulatory scheme for the acceptance of an environment plan proposing an offshore petroleum activity.

The ADJR Act, the Judiciary Act and the Relief Claimed

22 Mr Tipakalippa’s application for judicial review is made pursuant to section 5(1) of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) and sections 39B(1) & (1A) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).

23 Section 5(1) of the ADJR Act provides that a person who is “aggrieved by a decision” to which the ADJR Act applies may apply to this Court for an order of review in respect of a decision. The decisions to which the ADJR Act apply are defined under s 3 of the ADJR Act to mean:

… a decision of an administrative character made, proposed to be made, or required to be made (whether in the exercise of a discretion or not and whether before or after the commencement of this definition) … under an enactment...

That the Decision is a decision to which the ADJR Act applies is not in contest.

24 The definition of a person “aggrieved by a decision” under the ADJR Act relevantly includes a person whose interests are adversely affected by the decision. Mr Tipakalippa’s standing to bring this proceeding under the ADJR Act or under the Judiciary Act is not in contest.

25 The grounds upon which an aggrieved person may seek review of a decision are outlined in s 5 of the ADJR Act and relevantly include that:

(i) procedures that were required by law to be observed in connection with the making of the decision were not observed (s 5(1)(b));

(ii) the person who purported to make the decision did not have jurisdiction to make the decision (s 5(1)(c));

(iii) the decision was not authorized by the enactment in pursuance of which it was purported to be made (s 5(1)(d));

(iv) that the making of the decision was an improper exercise of the power conferred by the enactment in pursuance of which it was purported to be made (s 5(1)(e)); and

(v) the decision involved an error of law, whether or not the error appears on the record of the decision (s 5(1)(f)).

26 By his Amended Originating Application, Mr Tipakalippa seeks judicial review of NOPSEMA’s decision under s 5(1)(c), (d) and (f) of the ADJR Act in relation to ground 1 and under s 5(1)(b) of the ADJR Act in relation to ground 2. Although Mr Tipakalippa in his written opening submissions and oral opening submissions also raised s 5(1)(e) of the ADJR Act in passing as a ground of review within ground 1, that went beyond his pleaded case but makes no material difference to it, and I have not regarded it as forming part of ground 1 to be decided in this case.

27 Section 39B of the Judiciary Act relevantly provides that the original jurisdiction of this Court includes jurisdiction with respect to any matter in which a writ of mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer or officers of the Commonwealth (s 39B(1)). The original jurisdiction of the Court also includes jurisdiction in any matter “arising under any laws made by the Parliament, other than a matter in respect of which a criminal prosecution is instituted or any other criminal matter” (s 39B(1A)(c)). These provisions vest in the Court the entirety of the jurisdiction which s 75(v) of the Constitution vests in the High Court: Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Richard Walter Pty Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 168.

28 By his Amended Originating Application, Mr Tipakalippa seeks the following orders:

(i) A declaration that the Decision is invalid and [be] set aside, alternatively, an order pursuant to s 16(1)(a) of the ADJR Act, quashing or setting aside the Decision, or a part of the Decision, with effect from the date of the order or from such earlier or later date as the Court specifies.

(ii) An order in the nature of prohibition and/or an injunction under s 39B of the Judiciary Act, alternatively, s 16(1)(d) of the ADJR Act, prohibiting or restraining NOPSEMA and Santos from doing any act or thing pursuant to the Decision, on a final basis, and on an interim, or interlocutory basis pending final judgment or orders following trial.

29 It is convenient to set out here the relevant statutory and regulatory scheme for the acceptance of an environment plan and the steps in the process of obtaining NOPSEMA’s approval to undertake offshore “petroleum activities”. The same scheme applies in relation to offshore “greenhouse gas activities”. I will set out chronologically the provisions of relevance and to some extent emphasise those provisions of heightened significance to the contest between the parties as to the proper legal construction of the Regulations.

30 The object of the Act is to provide an effective regulatory framework for petroleum exploration and recovery and the injection and storage of greenhouse gas substances in offshore areas (s 3). The Regulations are made under the Act.

31 The object of the Regulations as specified by reg 3, is as follows:

The object of these Regulations is to ensure that any petroleum activity or greenhouse gas activity carried out in an offshore area is:

(a) carried out in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development set out in section 3A of the EPBC Act; and

(b) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level.

32 Section 3A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) to which the object of the Regulations refers, identifies the following principles as “principles of ecologically sustainable development” (emphasis added):

(a) decision-making processes should effectively integrate both long-term and short-term economic, environmental, social and equitable considerations;

(b) if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

(c) the principle of inter-generational equity—that the present generation should ensure that the health, diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations;

(d) the conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity should be a fundamental consideration in decision-making;

(e) improved valuation, pricing and incentive mechanisms should be promoted.

The term “environment” is defined in the EPBC Act (s 528) consistently with the definition of “environment” in the Regulations which is set out below at [35].

33 Regulation 4 defines various terms used in the Regulations under the qualification that “unless the contrary intention appears” a defined term has its defined meaning.

34 Regulation 4 defines “activity” to mean “a petroleum activity or a greenhouse gas activity”. “Petroleum activity” is defined to mean:

operations or works in an offshore area undertaken for the purpose of:

(a) exercising a right conferred on a petroleum titleholder under the Act by a petroleum title; or

(b) discharging an obligation imposed on a petroleum titleholder by the Act or a legislative instrument under the Act.

35 The term “environment” is defined as (emphasis added):

(a) ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities; and

(b) natural and physical resources; and

(c) the qualities and characteristics of locations, places and areas; and

(d) the heritage value of places;

and includes

(e) the social, economic and cultural features of the matters mentioned in paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and (d).

36 Regulation 4 also states that the term “relevant person” has the meaning given by reg 11A(1) which is extracted below at [47].

37 Regulation 6(1) provides that it is an offence for a titleholder to undertake an activity if there is no environment plan in force for the activity. As mentioned above, this is an offence of strict liability (reg 6(1A)). Regulation 7(1)(a) provides that it is an offence for a titleholder to undertake an activity in a way that is contrary to the environment plan in force for the activity. This is also an offence of strict liability (reg 7(1A)).

38 Regulation 9(1) provides that, before commencing an activity, a titleholder must submit an environment plan for the activity to NOPSEMA. The environment plan must be in writing (reg 9(6)) and must “set out the full text of any response by a relevant person to consultation under reg 11A in the course of preparation of the plan” in the “sensitive information” part of the plan (reg 9(8)).

39 Regulation 9AA requires that within 5 business days of the submission of an environment plan to NOPSEMA, NOPSEMA must decide provisionally whether the plan includes material apparently addressing all of the contents of an environment plan required by the Regulations. Regulation 9AB provides that once NOPSEMA has made a provisional decision under reg 9AA, NOPSEMA must publish on its website as soon as practicable the environment plan as well as other specified details. Only if the environment plan in question is a “seismic or exploratory drilling environment plan” is NOPSEMA required to also publish an invitation for public comment on the plan in accordance with reg 11B.

40 Regulation 9AC provides that if NOPSEMA’s provisional decision under reg 9AA is that the environment plan does not include material apparently addressing all of the requirements as to the contents of the environment plan specified by Div 2.3, NOPSEMA must give the titleholder a written notice identifying the provisions of Div 2.3 that appear not to be addressed by the plan and inviting the titleholder to modify the plan and resubmit it.

41 Regulation 9A also provides a power for NOPSEMA to request further information. By that regulation where an environment plan is submitted, NOPSEMA “may request the titleholder to provide further written information about any matter required by these Regulations to be included in an environment plan” (emphasis added). The request made must be in writing and set out each matter for which information is requested and specify a reasonable period within which the information is to be provided. A titleholder, in providing the information requested by NOPSEMA, must resubmit to NOPSEMA the environment plan with the new information incorporated. NOPSEMA is required to have regard to the information that was requested by it and provided by the titleholder in a resubmitted environment plan.

42 Regulation 10(1) deals with acceptance by NOPSEMA of an environment plan as follows (emphasis added):

(1) Within 30 days after the day described in subregulation (1A) for an environment plan submitted by a titleholder:

(a) if the Regulator is reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in regulation 10A, the Regulator must accept the plan; or

(b) if the Regulator is not reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in regulation 10A, the Regulator must give the titleholder notice in writing under subregulation (2); or

(c) if the Regulator is unable to make a decision on the environment plan within the 30 day period, the Regulator must give the titleholder notice in writing and set out a proposed timetable for consideration of the plan.

43 What a notice of the kind referred to in reg 10(1)(b) must do is the subject of reg 10(2). A notice to a titleholder must state that NOPSEMA is not reasonably satisfied that the environment plan submitted meets the criteria set out in reg 10A and identify the criteria set out in that regulation about which NOPSEMA is not reasonably satisfied and set a date by which the titleholder may resubmit the plan.

44 Regulation 10(4) then provides that within 30 days after the modified plan has been submitted, if NOPSEMA is reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in reg 10A, NOPSEMA must accept the plan or, if NOPSEMA is still not reasonably satisfied that the plan meets the criteria in reg 10A, NOPSEMA must give the titleholder a further notice under reg 10(2), or refuse to accept the plan or, under reg 10(6) accept the plan in part for a particular stage of the activity and/or accept the plan subject to limitations or conditions applying to operations for the activity. Alternatively, under reg 10(4)(c) if NOPSEMA is unable to make a decision on the environment plan within the 30 day period, NOPSEMA must give the titleholder notice in writing and set out a proposed timetable for consideration of the plan.

45 The criteria for NOPSEMA’s acceptance of an environment plan are set out in reg 10A (emphasis added):

For regulation 10, the criteria for acceptance of an environment plan are that the plan:

(a) is appropriate for the nature and scale of the activity; and

(b) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level; and

(d) provides for appropriate environmental performance outcomes, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria; and

(e) includes an appropriate implementation strategy and monitoring, recording and reporting arrangements; and

(f) does not involve the activity or part of the activity, other than arrangements for environmental monitoring or for responding to an emergency, being undertaken in any part of a declared World Heritage property within the meaning of the EPBC Act; and

(g) demonstrates that:

(i) the titleholder has carried out the consultations required by Division 2.2A; and

(ii) the measures (if any) that the titleholder has adopted, or proposes to adopt, because of the consultations are appropriate; and

(h) complies with the Act and the regulations.

46 Regulation 11 relevantly provides that NOPSEMA must give the titleholder notice in writing of its decision to accept or refuse the environment plan, or to accept the environment plan in part for a particular stage of the activity, or subject to limitations and conditions. A notice of decision to refuse the environment plan, or to accept the environment plan in part for a particular stage of the activity, or subject to limitations and conditions (under reg 11(1)(b) or (c)) must set out “the terms of the decision and the reasons for it” (reg 11(2)(a)). The requirement for reasons does not appear to also apply to a notice given under reg 11(1)(a) of a decision to accept the environment plan. As soon as practicable after giving the notice of the decision to the titleholder, NOPSEMA must publish on its website a description of the decision and, if the decision was to accept the environment plan (in whole or in part), must also publish the environment plan with the sensitive information part removed. Furthermore, within 10 days of receiving NOPSEMA’s notice that the environment plan has been accepted, the titleholder must submit a summary of the accepted plan to NOPSEMA for public disclosure. That summary must include material from the environment plan including the location of the activity and a description of “the receiving environment”, the “details of environmental impacts and risks” as well as “details of consultation already undertaken, and plans for ongoing consultation”. As soon as practicable after receiving a summary, NOPSEMA must publish it on its website.

47 Division 2.2A of the Regulations (to which reg 10A(g)(1) refers) contains only one regulation, being reg 11A. Regulation 11A(1) specifies each of the persons (relevant persons) with whom the titleholder must consult (emphasis added):

(1) In the course of preparing an environment plan, or a revision of an environment plan, a titleholder must consult each of the following (a relevant person):

(a) each Department or agency of the Commonwealth to which the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan, may be relevant;

(b) each Department or agency of a State or the Northern Territory to which the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan, may be relevant;

(c) the Department of the responsible State Minister, or the responsible Northern Territory Minister;

(d) a person or organisation whose functions, interests or activities may be affected by the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan;

(e) any other person or organisation that the titleholder considers relevant.

48 Regulations 11A(2) to (4) specify how consultation is to occur (emphasis added):

(2) For the purpose of the consultation, the titleholder must give each relevant person sufficient information to allow the relevant person to make an informed assessment of the possible consequences of the activity on the functions, interests or activities of the relevant person.

(3) The titleholder must allow a relevant person a reasonable period for the consultation.

(4) The titleholder must tell each relevant person the titleholder consults that:

(a) the relevant person may request that particular information the relevant person provides in the consultation not be published; and

(b) information subject to such a request is not to be published under this Part.

49 Division 2.3 then deals with the contents of an environment plan. Regulation 12 provides that an environment plan must include the matters set out in regs 13, 14, 15 and 16. Reg 13(1) and (2) provide that an environment plan must contain a “comprehensive description of the activity” as well as “describe the existing environment that may be affected by the activity…and include details of the particular relevant values and sensitivities (if any) of that environment”. The Note appearing under reg 13(2) refers to the definition of “environment” in reg 4 and emphasises that the definition “includes its social, economic and cultural features”.

50 Regulation 13(3) then provides:

(3) Without limiting paragraph (2)(b), particular relevant values and sensitivities may include any of the following:

(a) the world heritage values of a declared World Heritage property within the meaning of the EPBC Act;

(b) the national heritage values of a National Heritage place within the meaning of that Act;

(c) the ecological character of a declared Ramsar wetland within the meaning of that Act;

(d) the presence of a listed threatened species or listed threatened ecological community within the meaning of that Act;

(e) the presence of a listed migratory species within the meaning of that Act;

(f) any values and sensitivities that exist in, or in relation to, part or all of:

(i) a Commonwealth marine area within the meaning of that Act; or

(ii) Commonwealth land within the meaning of that Act.

51 Regulation 13(5) provides that the environment plan must include “details of the environmental impacts and risks for the activity” and “an evaluation of all the impacts and risks, appropriate to the nature and scale of each impact or risk” as well as “details of the control measures that will be used to reduce the impacts and risks of the activity to as low as reasonably practicable and an acceptable level”. To avoid doubt, reg 13(6) provides that the evaluation of all of the impacts and risks, required by reg 13(5)(b) “must evaluate all the environmental impacts and risks arising directly or indirectly from…all operations of the activity”.

52 Regulation 14 is concerned with an implementation strategy for the environment plan and requires that the plan must contain such a strategy. Under reg 14(9) the implementation strategy must provide for “appropriate consultation” with relevant authorities of the Commonwealth, a state or territory and “other relevant interested persons or organisations”.

53 Lastly, reg 16(b) provides for “other information” the environment plan must contain, relevantly (emphasis added):

The environment plan must contain the following:

…

(b) a report on all consultations under regulation 11A of any relevant person by the titleholder, that contains:

(i) a summary of each response made by a relevant person; and

(ii) an assessment of the merits of any objection or claim about the adverse impact of each activity to which the environment plan relates; and

(iii) a statement of the titleholder’s response, or proposed response, if any, to each objection or claim; and

(iv) a copy of the full text of any response by a relevant person;

…

The Key Events in the Assessment Process of the Drilling EP

54 Having set out the regulatory process, it is convenient to turn to an overview of the key events in the process of NOPSEMA’s acceptance of the Drilling EP. The following events have been largely taken from the decision-maker’s Statement of Reasons (Reasons) to which I shall shortly return. The decision-maker was a delegate of the CEO of NOPSEMA. For convenience I will, unless the context suggests otherwise, refer to the decision-maker as NOPSEMA or the delegate.

55 On 6 October 2021, Santos submitted the Drilling EP, being the first submitted version of that document which the material before the delegate referred to as “Revision 1” (Drilling EP (Revision 1)).

56 On 15 October 2021, the Drilling EP (Revision 1) was found to be complete for assessment in accordance with reg 9AA and was published by NOPSEMA on NOPSEMA’s website in accordance with reg 9AB.

57 On 25 October 2021, NOPSEMA issued Santos with a letter advising of a change of the assessment timeframe under reg 10(1)(c), with the assessment date to be completed by 29 November 2021.

58 On 29 November 2021, NOPSEMA requested that Santos provide further written information under reg 9A. That correspondence, to which I will return, included amongst other matters a request for further information in relation to the consultation carried out by Santos.

59 In response to the request from NOPSEMA to provide further information, Santos resubmitted the environmental plan on 30 December 2021. This revised version was referred to as “Revision 2” and dated 24 December 2021.

60 On 24 January 2022, Santos was again requested to provide further written information by NOPSEMA under reg 9A. In response to that request, Santos resubmitted the Drilling EP on 14 February 2022 in a document referred to as “Revision 3” and dated 11 February 2022. It is that version of the Drilling EP which I have referred to as the Drilling EP.

61 After further assessment by the NOPSEMA assessment team, of which I will say more shortly, on 14 March 2022 the delegate accepted the assessment team’s recommendation that the Drilling EP met all the acceptance criteria set out in reg 10A of the Regulations. Notice of that decision was provided in writing to Santos on 14 March 2022 in accordance with reg 11(1).

62 On 6 May 2022, NOPSEMA published the Reasons.

63 The Reasons, which I discuss further below, contain a conclusion at [53] thereof as follows (emphasis added):

In accordance with regulation 10 and based on the available facts and evidence, NOPSEMA was reasonably satisfied that the [Drilling EP] met the following criteria set out in sub-regulation 10A of the [Regulations]:

a. the [Drilling EP] is appropriate for the nature and scale of the activity; and

b. the [Drilling EP] demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

c. the [Drilling EP] provides for appropriate [environmental performance outcomes], [environmental performance standards] and measurement criteria; and

d. the [Drilling EP] includes an appropriate implementation strategy and monitoring, recording and reporting arrangements; and

e. the [Drilling EP] does not involve the activity or part of the activity, other than arrangements for environmental monitoring or for responding to an emergency, being undertaken in any part of a declared World Heritage property within the meaning of the EPBC Act; and

f. the [Drilling EP] demonstrates that:

i. the titleholder has carried out the consultations required by Division 2.2A; and

ii. the measures (if any) that the titleholder has adopted, or proposes to adopt, because of the consultations are appropriate; and

g. the [Drilling EP] complies with the Act and the regulations.

64 It is the emphasised finding made at para (f) of [53] of the Reasons that Mr Tipakalippa contends is infected with legal error. Before assessing the contentions made about the asserted error, it is convenient that I first outline the legal principles to be applied in that assessment.

Reasonable Satisfaction as a Jurisdictional Precondition – Applicable Principles

65 It is not in contest in relation to ground 1, that the jurisdictional precondition for the exercise of NOPSEMA’s power to accept an environment plan is that NOPSEMA “is reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in reg 10A” (reg 10(1)(a)). If the requisite satisfaction is not lawfully formed the precondition for the exercise of power will not exist. As the Full Court (Allsop CJ, Besanko and O’Callaghan JJ) said in Djokovic v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2022] FCAFC 3; (2022) 397 ALR 1 at [21]:

In such a case the precondition for the exercise of the power will not exist and the decision will be unlawful and will be set aside. That is, the lawful satisfaction is a jurisdictional precondition, a form of jurisdictional fact, for the exercise of the power or discretion: Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu (1999) 197 CLR 611; 162 ALR 577; 54 ALD 289; [1999] HCA 21 (Eshetu) at [131] and the cases cited at footnote 109.

66 The applicable principles for assessing whether a decision-maker had the state of satisfaction required by statute as a precondition of jurisdiction, are broadly encapsulated by the observation of Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ in Hossain at [34] that the “[f]ormation of the [decision-maker’s] state of satisfaction or of non-satisfaction is in each case conditioned by a requirement that the [decision-maker] … must proceed reasonably and on a correct understanding and application of the applicable law”. For that proposition their Honours referred to a number of authorities including the survey of authorities provided by Gummow J in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu (1999) 197 CLR 611, in which (at [133]) his Honour relied upon the following seminal observations of Latham CJ in R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd (1944) 69 CLR 407 (at 430, 432):

[W]here the existence of a particular opinion is made a condition of the exercise of power, legislation conferring the power is treated as referring to an opinion which is such that it can be formed by a reasonable man who correctly understands the meaning of the law under which he acts. If it is shown that the opinion actually formed is not an opinion of this character, then the necessary opinion does not exist.

…

It should be emphasised that the application of the principle now under discussion does not mean that the court substitutes its opinion for the opinion of the person or authority in question. What the court does do is to inquire whether the opinion required by the relevant legislative provision has really been formed. If the opinion which was in fact formed was reached by taking into account irrelevant considerations or by otherwise misconstruing the terms of the relevant legislation, then it must be held that the opinion required has not been formed. In that event the basis for the exercise of power is absent, just as if it were shown that the opinion was arbitrary, capricious, irrational, or not bona fide.

67 Other forms of error beyond those mentioned by Latham CJ may also infect a state of satisfaction which is a jurisdictional prerequisite to the exercise of a power or discretion. Relevantly to the issues raised in this case, a failure to consider a matter that the statute required be considered may also undermine the lawfulness of the state of satisfaction required. So much is apparent from the observation made by the Full Court (Bromberg, Katzmann and O’Callaghan JJ) in One Key Workforce Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union and Another (2018) 262 FCR 527 at [109]:

Where, as here, a statute vests a power in, or imposes a duty on, an administrative decision-maker to do something upon reaching a state of satisfaction and matters the statute requires the decision-maker to take into account are not considered, as a matter of law the requisite state of satisfaction is not reached and the Court may grant relief: Avon Downs Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1949) 78 CLR 353 at 360 (Dixon J); Buck v Bavone (1976) 135 CLR 110 at 118-119 (Gibbs J) (approved by Brennan CJ, Toohey, McHugh and Gummow JJ in Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Wu Shan Liang (1996) 185 CLR 259 at 275); Saeed v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2010) 241 CLR 252 at [54].

68 The Full Court went on to observe at [118]:

Alternatively, as the CFMEU submitted, the Commissioner’s error might be regarded as an error of the kind referred to by the High Court in R v Australian Stevedoring Industry Board; Ex parte Melbourne Stevedoring Company Pty Ltd (1953) 88 CLR 100 at 120. In that case, where an order was made for prohibition under s 75(v) of the Constitution, the Court observed that the inadequacy of the material before the tribunal was not itself a ground for prohibition but “a circumstance which may support the inference” that the tribunal applied the wrong test, was not really satisfied of the requisite matters, or misconceived the purpose of the function committed to it. In circumstances such as these, the Court said, “it is but a short step to the conclusion that in truth the power has not arisen because the conditions for its exercise do not exist in law and in fact”.

69 Of the many authorities to which reference may be made, I have found One Key and the authorities referred to in the passages just quoted, particularly helpful. The nature of the task required to form the requisite state of satisfaction in that case, an assessment as to whether a communication required to have been made was made is somewhat analogous to the task here required of NOPSEMA by the Regulations. In One Key, a jurisdictional precondition for the approval by the Fair Work Commission of an enterprise agreement made under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) was the Fair Work Commission’s satisfaction that, in making the agreement with its employees, the employer had taken all reasonable steps to ensure that the terms of the agreement and the effect of those terms had been explained to the relevant employees.

70 Whilst it is not necessary to set out a comprehensive taxonomy of the kinds of errors which may invalidate a state of satisfaction as a jurisdictional precondition, it needs to be observed that legal unreasonableness is an applicable form of error. As the learned authors state in Aronson M, Groves M, Weeks G, Judicial review of administrative action and government liability (7th ed, Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia Limited, 2022) at [6.30] p 275, so much was made implicit in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Li (2013) 249 CLR 332 but explicit in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW (2018) 264 CLR 541 (at [6]-[9] Kiefel CJ; [55] Gageler J and [81]-[83] Nettle and Gordon JJ).

71 The availability of legal unreasonableness as a ground is also recognised by the Full Court in Djokovic (see at [29]-[35]) and by Murphy and O’Bryan JJ, with whom Snaden J relevantly agreed, in BFH16 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2020) 274 FCR 532 at [28]-[30] (Murphy and O’Bryan JJ) and at [63] (Snaden J).

72 Whether the legal standard imposed by the requirement that the decision-maker proceed reasonably is enhanced by the Regulations’ requirement that NOPSEMA be “reasonably satisfied”, was the subject of some contest between the parties. That debate occurred in the context of the observation made by Gageler J in SZVFW at [53] to the effect that the governing law may supply its own standard of reasonableness and the example there given of a higher standard supplied by a law which provides that a power may only be exercised upon the repository of the power being satisfied that there are “reasonable grounds” for its exercise.

73 Santos, on two bases, sought to reject the proposition that some higher standard was here required by the limitation imposed on the exercise of NOPSEMA’s power by the words “reasonably satisfied”. First, Santos contended that the word “reasonably” adds nothing that would not be implied just as it is implicit in the conferral of a discretionary power that the power is to be exercised reasonably. Second, Santos sought to distinguish the observation made by Gageler J as an observation about a “reasonable grounds” requirement and not a “reasonably satisfied” requirement.

74 To my mind, in relation to the assessment task of the kind required of NOPSEMA (which I consider further below) the words “reasonably satisfied” are directed at the standard of satisfaction that NOPSEMA must apply in making the assessment required of it. By parity of reasoning with what Gray and Lee JJ observed in Goldie v Commonwealth (2002) 117 FCR 566 at [5]-[6] about the phrase “reasonably suspects”, where it is that “reasonably satisfied” lies on the spectrum between certainty and irrationality is to be construed contextually by reference to the circumstances of the case including the scheme which has imposed that standard. It would not be correct to presume, as the debate before me seemed to do, that legal unreasonableness has some fixed standard. Legal unreasonableness is fact dependent and, by reference to the statutory task required of a decision-maker may be applied more stringently in some cases than in others: see SZVFW at [84] (Nettle and Gordon JJ). The point is that a requirement of “reasonable satisfaction” and the requirement that a decision-maker proceed reasonably are not unrelated. The first feeds into the second and the standard of reasonableness required will be set by their combination and governed by the requirements or objectives of the scheme in question.

75 The nature of the task required of a decision-maker in reaching a state of satisfaction will also have a bearing upon whether the decision-maker proceeded reasonably. It will be more difficult to establish unreasonableness where the state of satisfaction is to be reached by a task which requires significant subjectivity such as in relation to “a matter of opinion or policy or taste”: Buck v Bavone (1976) 135 CLR 110 at 118-119 (Gibbs J).

76 Two further observations need to be made here in relation to the appropriate approach to be taken on the judicial review of the lawfulness of a state of satisfaction. First, as a matter of proof, the burden falls on Mr Tipakalippa to show why the state of satisfaction in fact formed by NOPSEMA was not a lawful state of “reasonable satisfaction”: see Ellis v Central Land Council (2019) 267 FCR 339 at [121] (Barker, Griffiths, White JJ).

77 Second, in an assessment of whether a decision was beyond power because it was legally unreasonable “[w]here reasons are provided they will be a focal point for that assessment”: SZVFW at [84] (Nettle and Gordon JJ). I see no reason why the same approach is not apposite in a case involving the judicial review of the lawfulness of a state of satisfaction. I made an observation to that effect in Australian Workers’ Union v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 9) [2019] FCA 1671; 168 ALD 11 at [94], and at [95] I there referred to a passage in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Singh (2014) 231 FCR 437 (Allsop CJ, Robertson and Mortimer JJ) at [47] which has been cited by many authorities (see for example, Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Haq [2019] FCAFC 7 at [35] (Griffiths J with whom Gleeson J agreed) and at [91]-[97] (Colvin J)) including some involving the judicial review of the lawfulness of a state of satisfaction (see for example, BPV17 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2022] FCA 157 (Nicholas J)). The Court in Singh at [47] observed that:

where there are reasons for the exercise of a power, it is those reasons to which a supervising court should look in order to understand why the power was exercised as it was. The “intelligible justification” must lie within the reasons the decision-maker gave for the exercise of the power — at least, when a discretionary power is involved. That is because it is the decision-maker in whom Parliament has reposed the choice, and it is the explanation given by the decision-maker for why the choice was made as it was which should inform review by a supervising court.

78 By analogy, where there are reasons which provide an understanding as to how and why a state of satisfaction was reached, a supervising court should look to those reasons to understand why the power was exercised as it was. It is the reasoning actually utilised by the decision-maker as the basis for the satisfaction reached, that ordinarily must supply the lawfulness of that satisfaction because it is the satisfaction of the decision-maker upon which Parliament has preconditioned the exercise of the power.

79 It is necessary to properly appreciate what NOPSEMA was required to do in order to lawfully form the satisfaction which preconditions its power of acceptance. The regulatory task required by NOPSEMA is obviously to be assessed by reference to the Regulations.

80 The requisite satisfaction is stated in reg 10(1)(a), NOPSEMA must be “reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in regulation 10A”. That overall satisfaction entails the need for NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied in relation to each criterion set out in reg 10A including, relevantly, at reg 10A(g) which requires that the environment plan “demonstrat[e] that … the titleholder has carried out the consultations required by Division 2.2A”. For relevant purposes, that in turn and by reference to reg 11A (being the only provision in Div 2.2A), entails the need for NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied that the environment plan demonstrates that in the course of preparing the environment plan the titleholder consulted each “relevant person” falling within the descriptions in paras (a)-(e) of reg 11A(1) in the manner required by reg 11A(2)-(4).

81 The requirement that the titleholder “must consult with each” relevant person is a requirement to consult with each and every relevant person. The text of reg 11A, including the multiple references made to “each relevant person” make that requirement clear. No party contended to the contrary. All the parties contended that reg 11A requires each and every relevant person to be consulted.

82 Given that the obligation imposed by reg 11A is that every relevant person must be consulted, NOPSEMA’s regulatory task includes an assessment of whether the environment plan “demonstrates” that every relevant person was consulted. That issue must be considered by NOPSEMA in order for NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied that the environment plan demonstrates that the consultations required to be carried out by reg 11A have been carried out. It follows that that consideration is not only a relevant consideration but is a consideration that the Regulations require NOPSEMA to take into account: One Key at [109]. Or in other words, that is a task or inquiry which the Regulations require NOPSEMA to engage in and perform. I will label that inquiry the “universe of relevant persons inquiry” and will return to deal with how it was performed in relation to the Drilling EP, because central to each aspect of ground 1 of Mr Tipakalippa’s application is that NOPSEMA erroneously performed that task resulting in its non-performance at law, thus depriving NOPSEMA’s state of satisfaction of its legal validity.

83 Next, because reg 11A(2)-(4) deals with the manner in which consultation must occur or what must be done in the consultation, NOPSEMA is tasked with assessing whether the environment plan demonstrates that consultations have occurred in the manner required. For the same reasons as earlier expressed, that is also a consideration that the Regulations require NOPSEMA to take into account.

84 It is necessary to observe that each of those considerations or tasks essentially involves a factual assessment as to what the environment plan demonstrates by reference to facts asserted in the environment plan in relation to which questions of law, as to the proper construction of the Regulations, may be raised. Although the assessment will lead to a state of satisfaction or what may be described as an opinion being formed, the assessment task itself does not involve subjective content like the formation of an opinion, consideration of policy or a value-laden evaluation.

85 It is also necessary to observe that in performing each of the consultation criteria tasks which I have described, NOPSEMA may (without apparent restriction) request further information of the titleholder pursuant to reg 9A. Opportunities are also effectively provided to titleholders to provide further information about a criteria of which NOPSEMA is not reasonably satisfied by the provisions of reg 10. In each case, where further information is provided, the environment plan must be revised and resubmitted so as to maintain the nature of the assessment exercise as an exercise based upon whether the environment plan meets the requisite criteria.

86 Lastly, I need to make some observations about the extent to which the consultation requirements imposed by the Regulations are of importance to the fulfilment of its objectives. I do so in part to provide a general context for all of the issues I need to address, but in particular because an understanding of the extent of the importance of the consultation tasks I have identified may assist to inform the consideration of whether NOPSEMA proceeded reasonably as well as, relatedly, to inform the standard of satisfaction which the scheme intends by the requirement of “reasonable satisfaction”.

87 That “each” relevant person must be consulted in an informed manner, of itself speaks to the importance of consultation in the scheme for the acceptance of an environment plan. There are other indicators of the important function which consultation seems to be intended to have. The importance of consultation is to be understood in light of the objects of the Regulations which relevantly seek to ensure that any petroleum activity is carried out in a manner which reduces to as low as reasonably practicable and to an acceptable level, the environmental impacts and risks of the activity the subject of an environment plan (reg 3). That objective is pursued in the context of the “environment” relevantly including “the social, economic and cultural features” of “people and communities” (reg 4).

88 It can hardly be doubted that it was considered that people who may be affected by the petroleum activity are well placed to assist in informing an assessment process with the objective of minimising harm to them and their social, economic and cultural interests and activities. This is especially so in the context of an assessment process which largely depends upon information provided by the proponent of the activity, which is not adversarial and where there is no contradictor. The consultation required by the scheme is seemingly important for two further reasons. First, because it will inform the proponent of measures that the proponent may take to mitigate the adverse environmental effects that the petroleum activity may otherwise cause. Second, because it will better inform NOPSEMA in its assessment process of the potential adverse impacts of the proposed activity, the persons who may be affected by those adverse impacts and the measures that are available to mitigate them. So much seems apparent from the criteria in reg 10A(g)(ii) which requires NOPSEMA’s satisfaction that the environment plan demonstrates that “the measures (if any) that the titleholder has adopted, or proposes to adopt, because of the consultations are appropriate”. This is also apparent from the requirement made by reg 16 that the environment plan contain a report on “all consultations under regulation 11A of any relevant person” including “a copy of the full text of any response by a relevant person”.

89 It is also worth noting that the Regulations were amended in 2019 by the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Amendment (Consultation and Transparency) Regulations 2019 (Cth) (Amendment Regulations). There were several amendments within the Amendment Regulations including the introduction of the concept of “sensitive information”, the requirement for the publication of submitted environment plans under reg 9AB, and the requirement in Division 2.2B for public consultation with respect to seismic and exploratory drilling environment plans. Relevantly to the above analysis, the Explanatory Statement for the Amendment Regulations explicitly supports the first reason above at [88] as it emphasises the importance of the titleholder being able to take into account comments from relevant persons “during the development of the [environment] plan” (see page 12 of the Explanatory Statement). The heading for Div 2.2A was accordingly changed from “Division 2.2A – Consultation” to “Division 2.2A – Consultation in preparing an environment plan” (emphasis added).

90 The content of the Drilling EP is of critical significance to all of the issues I need to determine. Where I need to address specific content I will do so when dealing with the particular issue to which that content is relevant. To put the specific content in its proper context the following is provided by way of background.

91 The Drilling EP is a large document of some 354 pages in the main document and 590 pages including its appendices A to G. The document is divided into nine chapters covering several topics each of which purports to address various criteria set out within the Regulations.

92 Chapter 1 is headed “Introduction”. This chapter provides a summary of the Drilling EP, an overview of the Activity describing at a general level the works Santos proposes to undertake under the Drilling EP, an explanation of the purpose of the Drilling EP and details of the titleholder.

93 Chapter 2 is headed “Activity description”. This chapter contains an overview and description of the Activity referring to reg 13(1). It describes the equipment to be used for conducting the Activity and the well construction design and method including detailed descriptions of the various materials to be used and managed during well construction and completions. The activities included in the Drilling EP are described in section 2.1. This section also discusses emergency response and well suspension procedures.

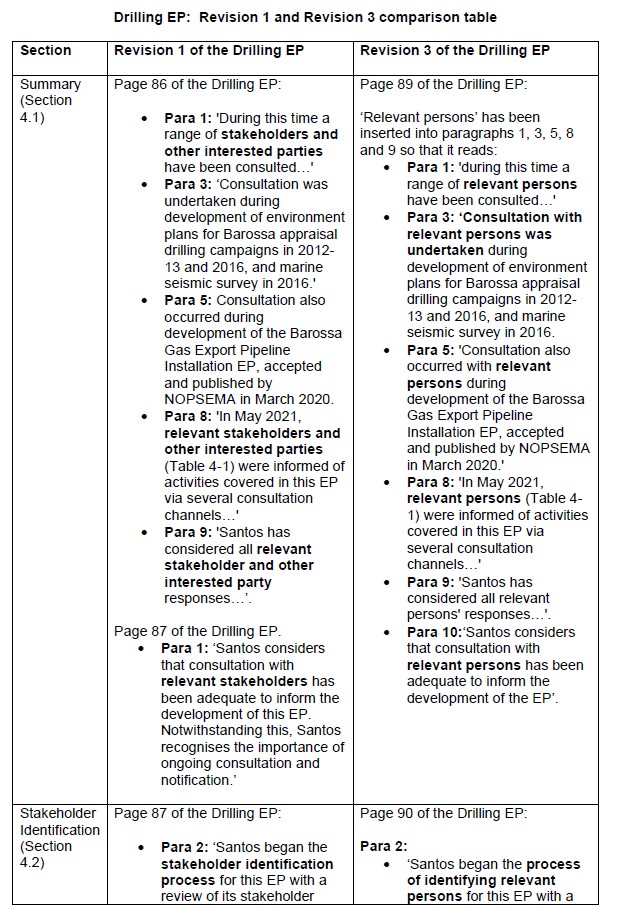

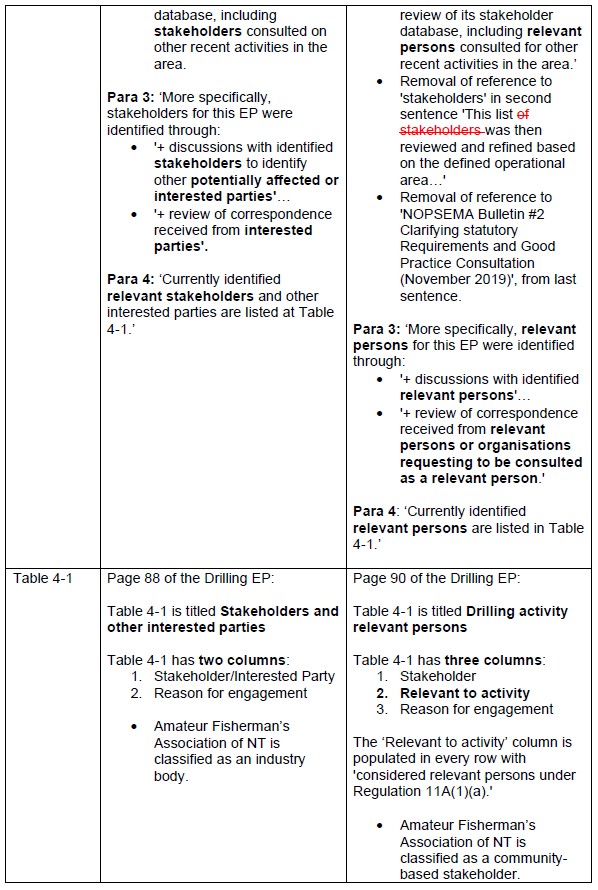

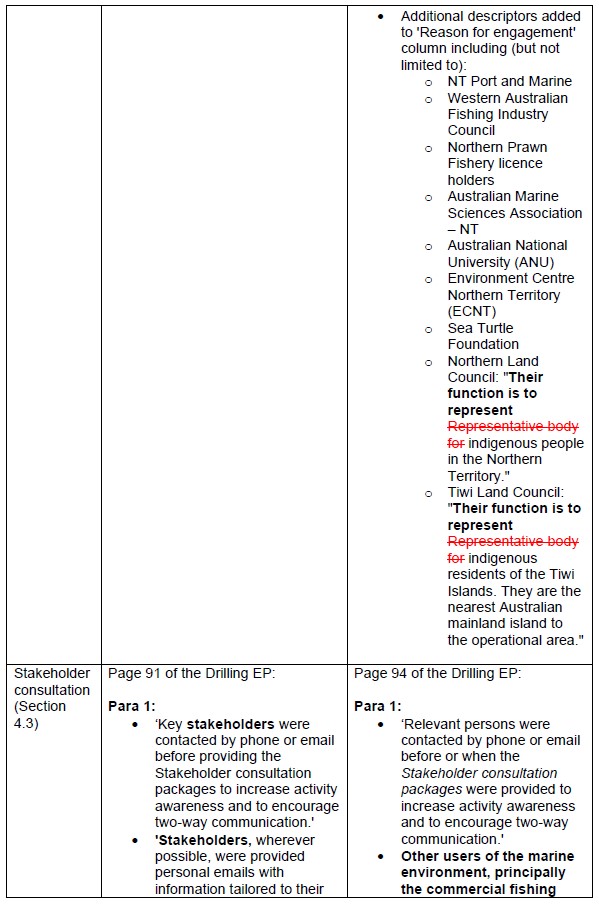

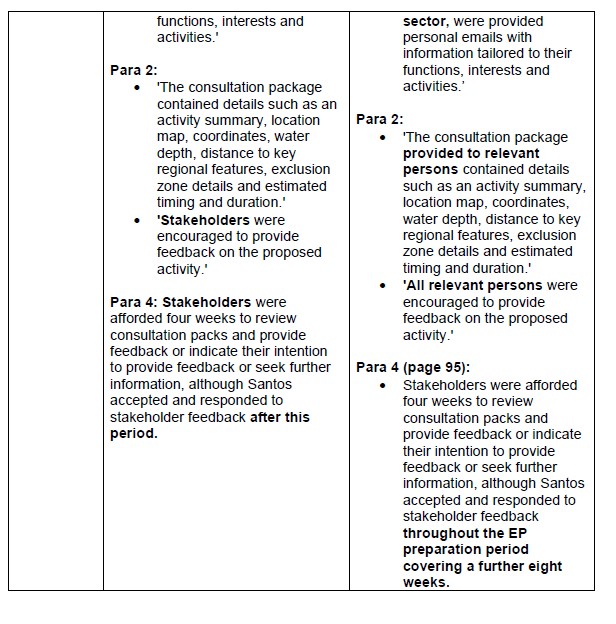

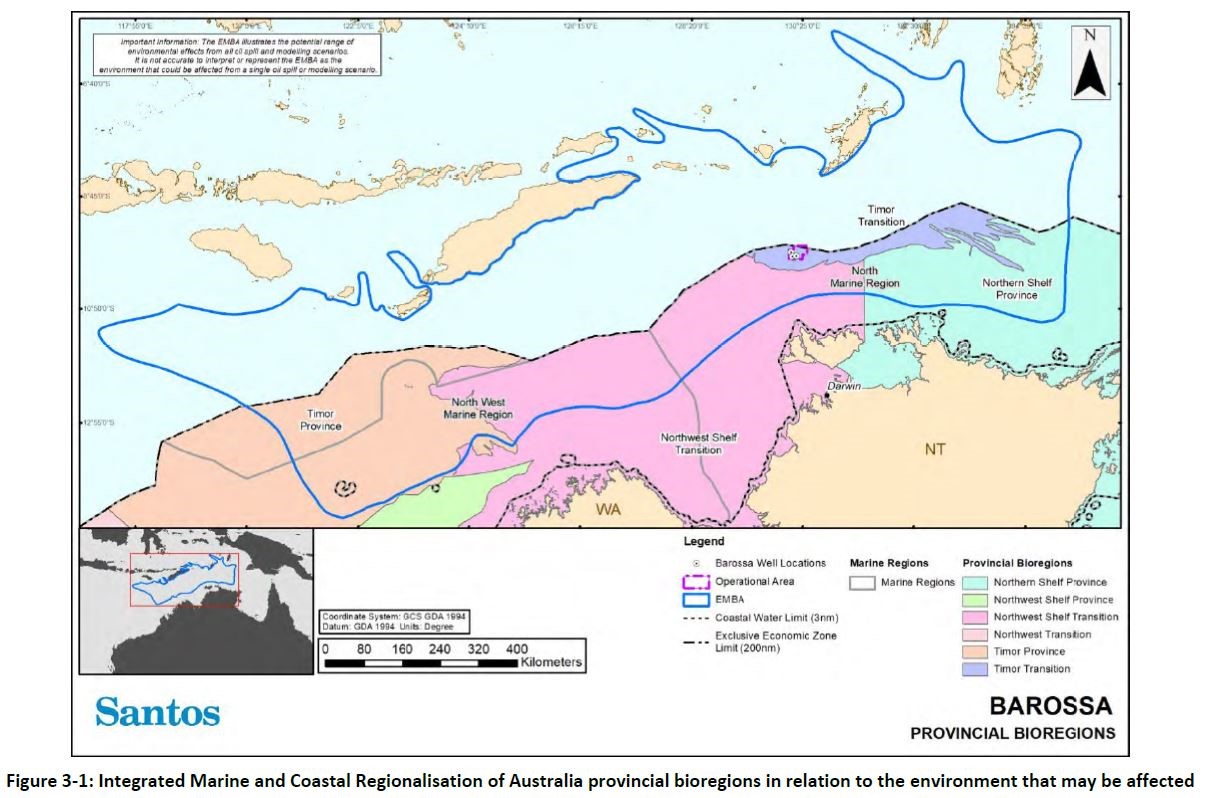

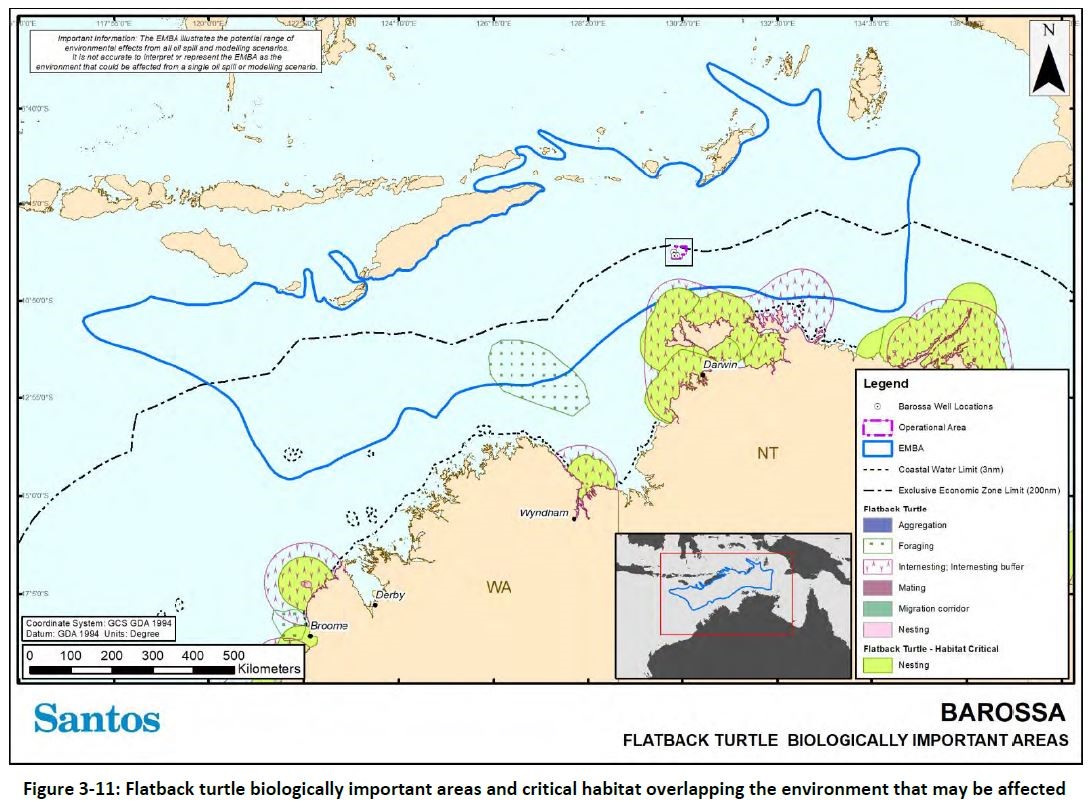

94 Chapter 3 is headed “Description of the environment”. This chapter provides a description of the “existing environment that may be affected”, a requirement under reg 13(2). This is referred to in the Drilling EP as the “EMBA”. This chapter explains that “stochastic hydrocarbon dispersion and fate modelling” was undertaken to identify “the worst-case spill scenario for the operational area”, section 3.1.1 states that this was undertaken “to inform [the creation of] the EMBA”. The Drilling EP contains several figures depicting the EMBA in relation to various risk and impact analysis. Figure 3-1 shown below depicts the EMBA which is defined using a blue line with various marine regions and bioregions noted. Section 3.1.1 states that the “EMBA boundary was identified using low exposure values which are not considered to be representative of a biological impact, but they are adequate for identifying the full range of environmental receptors that might be contacted by surface and/or subsurface hydrocarbons…and a visible sheen”.

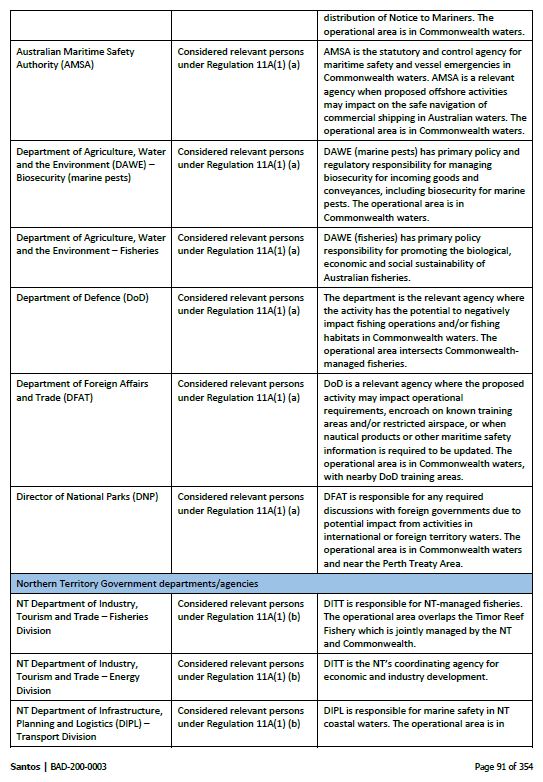

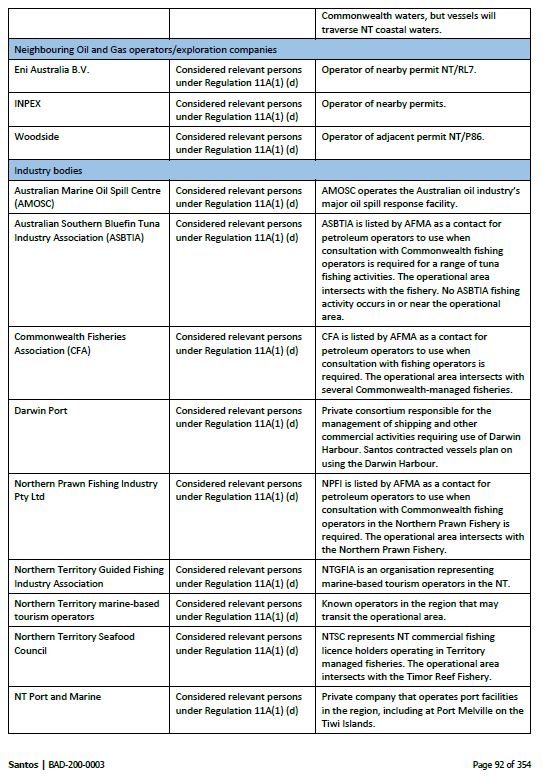

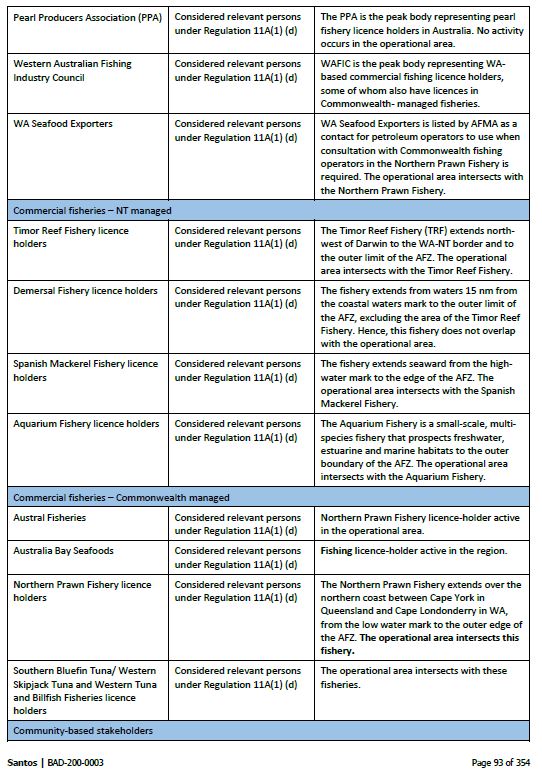

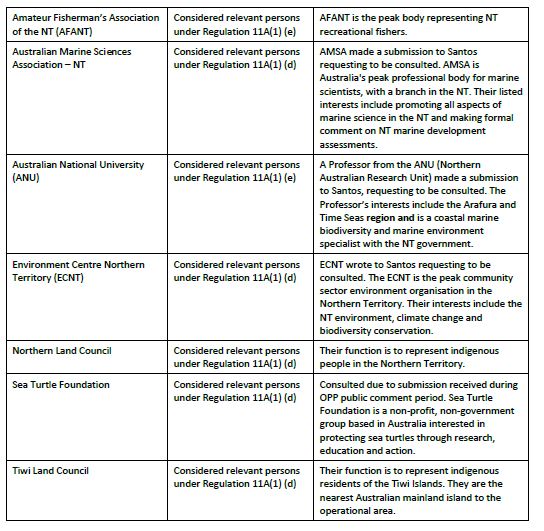

95 Chapter 4 is headed “Stakeholder consultation”. The issues I need to resolve are principally concerned with the information in this chapter which will be discussed in further detail shortly. For now, it is worth noting that this chapter purports to provide a description of the process used by Santos to identify relevant persons and the consultation of those identified as relevant persons (under reg 11A(1)(a) to (e)) who are also referred to in the Drilling EP as “stakeholders”. It also contains an assessment of stakeholder objections and claims, by reference to reg 16(b).

96 Chapter 5 is headed “Impact and risk assessment methodology”. This chapter discusses the environmental and risk assessment process undertaken to assess planned and unplanned events that will or may occur during the Activity. The methodology describes planned activities as “impacts” and unplanned events as “risks” to be assessed. The methodology seeks to address the requirements of reg 13(5) and (6) dealing with the evaluation of the environmental impacts and risks for the Activity and which also requires details of the control measures that will be used to reduce the impacts and risks of the Activity to as low as reasonably practicable and at an acceptable level.

97 Chapter 6 is headed “Planned activities risk and impact assessment”. This chapter details the actual assessment undertaken by Santos of the impacts discussed in the methodology set out in chapter 5 and describes the results of the impact assessment. The chapter further seeks to address the matters in reg 13(5) and (6) discussed above, and reg 13(7) which, in broad terms, stipulates that an environment plan must set “environmental performance standards” for the control measures used to reduce the impacts and risks of an activity and set out “environmental performance outcomes” against which the performance of the titleholder in protecting the environment is to be measured. It details that Santos held activity-specific environmental assessment workshops in June 2021 (discussed in chapter 5) which identified eight causes of environmental impact associated with the planned activities to be undertaken in the Operational Area, being: (i) noise emissions, (ii) light emissions, (iii) atmospheric emissions, (iv) seabed and benthic habitat disturbance, (v) interaction with other marine users, (vi) operational discharges, (vii) drilling and completions discharges, and (viii) contingency spill response operations.

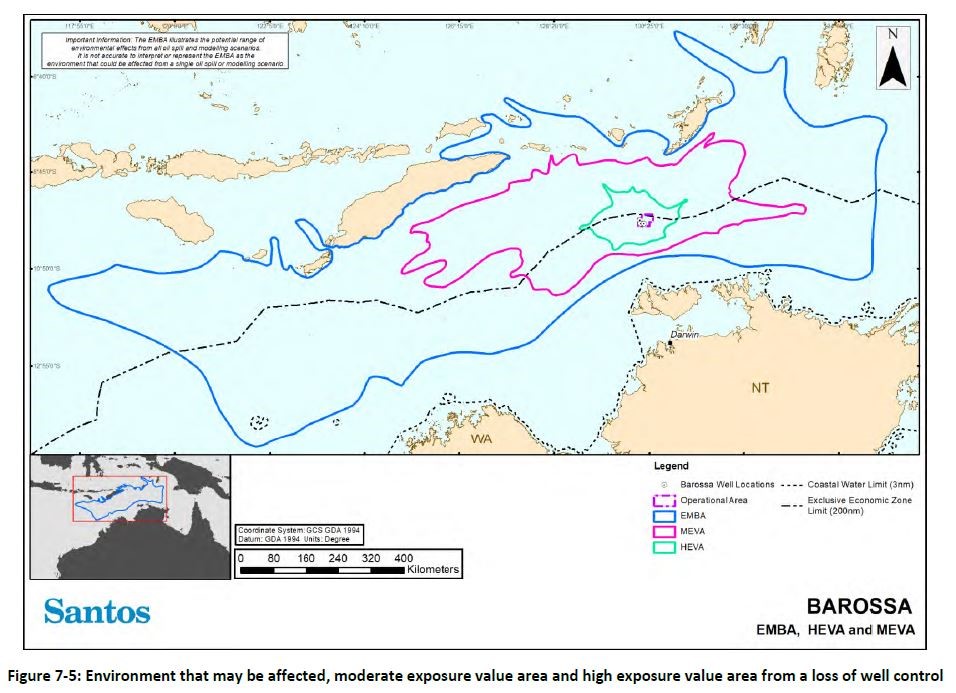

98 Chapter 7 is headed “Unplanned events risk and impact assessment”. This chapter details the assessment undertaken by Santos of the risks discussed in the methodology set out in Chapter 5 and describes the results of the risk assessment. The chapter seeks to address the matters in reg 13(5), (6) and (7). Santos’ activity-specific environmental assessment workshops identified seven environmental risks associated with unplanned events which could occur as a result of the Activity. These are: (i) release of solid objects, (ii) introduction of invasive marine species, (iii) marine fauna interaction, (iv) non-hydrocarbon and chemicals release (surface) liquids, (v) hydrocarbon spill – condensate, (vi) hydrocarbon spill – marine diesel and (vii) minor hydrocarbon release (surface and subsea). This chapter also features maps and analysis depicting and discussing the environment that may be affected by the risks identified and the range of consequences that could occur, for example, from hydrocarbon spill events. At section 7.5 the chapter discusses potential sources of unplanned release of hydrocarbons which include “loss of well control” and “vessel collision” resulting in a spill of hydrocarbons into the sea. At section 7.5.1.1, the Drilling EP notes that in the worst case, a subsea loss of well control event could result in a release of “Barossa condensate [identified as a hydrocarbon at section 7.5.3.1] over 90 days”. The Drilling EP notes at section 7.5.4 that to inform the environmental assessment, exposure values that “may be representative of biological impact have also been identified”. These are referred to as “moderate exposure values” (defined by the MEVA in purple) and “high exposure values” (defined by the HEVA in aqua) and are shown in Figure 7-5 reproduced below.

99 Chapter 8 is headed “Implementation strategy”. This chapter discusses the implementation strategy developed by Santos for the Activity, including a description of Santos’ “management system” which is described as a “a framework of policies, standards, processes, procedures, tools and control measures” to ensure, the environmental impacts and risks of the Activity continue to be identified and reduced to a level that is as low as reasonably practicable. The implementation strategy is described by reference to the requirements for an implementation strategy under reg 14. This chapter outlines the leadership, accountability and responsibility for the implementation, management and review of the Drilling EP. It also discusses workforce training and competency, emergency preparedness and response, incident reporting, investigation and follow-up, reporting notifications, document management protocols and audit and inspections procedures.

100 Chapter 9 contains references to the sources cited within the Drilling EP.

101 Appendices A to G are referred to within the main Drilling EP document and deal with the following matters:

(a) Appendix A – Santos’ Environment, Health and Safety Policy

(b) Appendix B – Legislative Requirements Relevant to the Activity

(c) Appendix C – Barossa Development Values and Sensitivities of the Marine and Coastal Environment

(d) Appendix D – EPBC Act Protected Matters Searches

(e) Appendix E – Stakeholder Consultation Records

(f) Appendix F – Santos’ Environment Consequences Descriptors

(g) Appendix G – Spill Modelling Results Summary (Maximum Values Across All Seasons and Water Depths)

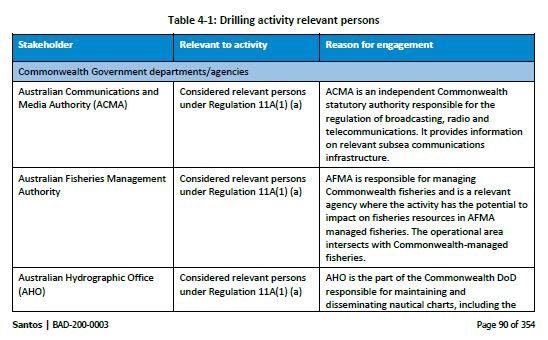

102 As earlier mentioned, the subject of chapter 4 is consultation. Some parts thereof need to be closely considered and are considered by reference to the issues I need to address at [141]-[172]. However, in order to put the specific content in relation to consultation in context, it is helpful to refer mainly by way of background to the other content of chapter 4. Chapter 4 states that the “[s]takeholder consultation on petroleum activities within the Barossa permit area and surrounds has been ongoing since 2004”. The chapter provides a summary of the consultations with those persons Santos identified as “relevant persons” for the purpose of preparing the Drilling EP and purports to outline the process of “stakeholder identification” and the assessment of objections and claims received from relevant persons. A summary of the engagement with relevant persons is provided at section 4.1 and relevantly includes the following text (emphasis in original):

Consultation on the Barossa Development Drilling and Completions EP (this EP) was undertaken in 2019, but the EP was not submitted to NOPSEMA at this time.

Due to the time that had elapsed since the previous consultation, Santos elected to consult again before submission of the EP.

In May 2021, relevant persons (Table 4-1) were informed of activities covered in this EP via several consultation channels, including:

• meetings in May and June 2021

• distribution of the Barossa Development Drilling and Completions Stakeholder Consultation Package in June 2021 (Appendix E).

• distribution of the Barossa Development Drilling and Completions Additional Information for Commercial Fishers Package in June 2021 (Appendix E).

Santos has considered all relevant persons’ responses and assessed the merits of all objections and claims about the potential impacts and risks of the proposed activities. The process adopted to assess these objections and claims is outlined in Section 4.3. A summary of Santos’ response statements to the objections and claims is provided in Table 4-2.

Santos considers that consultation with relevant persons has been adequate to inform the development of this EP. Notwithstanding this, Santos recognises the importance of ongoing consultation and notification.

103 Section 4.2 is later extensively considered at [141]-[157]. Section 4.2 (including Table 4-1) is set out as Annexure 1 to these reasons.

104 Section 4.3 describes how relevant persons were contacted, relevantly stating:

Relevant persons were contacted by phone or email before or when the Stakeholder consultation packages were provided to increase activity awareness and encourage two-way communication. Other users of the marine environment, principally the commercial fishing sector, were provided personal emails with information tailored to their functions, interests and activities.

The consultation package provided to relevant persons contained details such as an activity summary, location map, coordinates, water depth, distance to key regional features, exclusion zone details and estimated timing and duration. The consultation package also outlined relevant potential risks and impacts together with a summary of selected management control measures. All relevant persons were encouraged to provide feedback on the proposed activity.

Commercial fishers were provided additional information specific to the fishery within which they operate. Individual fishing licence holders, as identified through sourced data and in consultation with fisheries organisations, were provided the Stakeholder consultation package and Additional information for commercial fishers package by email or post.

Stakeholders were afforded four weeks to review consultation packs and provide feedback or indicate their intention to provide feedback or seek further information, although Santos accepted and responded to stakeholder feedback throughout the EP preparation period covering a further eight weeks.

105 I will later address one of the responses made by Santos to the claims made by Mr Tipakalippa that the Drilling EP demonstrates that any consultation that may have been required with the traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands was done through consultation of the Tiwi Land Council (TLC). For that discussion and Mr Tipakalippa’s response, that if the TLC was consulted it was not consulted in the informed manner required by reg 11A(2), it is necessary to see the information provided to the TLC by Santos. Annexure 2 to these reasons contains a copy of a “stakeholder consultation package” provided to the TLC and to all persons Santos identified as relevant persons. That material, which is included in Appendix E of the Drilling EP, comprised the “Q2 2021 Barossa Quarterly Update” and a pro forma email distributed on 11 June 2021. In addition to the material in Annexure 2, commercial fishers were provided with “additional information specific to the fishery within which they operate” which was identified through “sourced data” and in consultation with commercial fishers’ organisations. That additional information provided detailed information about the impact of the Activity on various fisheries within or adjacent to the EMBA.

106 At section 4.4 and within Table 4-2 Santos provided its summary of its assessment of “all comments received from relevant persons” and noted the processes adopted to address objections and claims from relevant persons.

107 At the conclusion of chapter 4, the Drilling EP describes future intended consultation on the Activity.

The process for acceptance of the Drilling EP

108 The Reasons explain (at [18]) that the Drilling EP was assessed by staff of NOPSEMA who formed an “assessment team”. The assessment team comprised “a decision-maker” (it is not clear whether that is an intended reference to the delegate ), a “lead assessor” and “environment technical specialists” with expert knowledge in environmental and marine science relevant to offshore oil and gas activities and their associated impacts and risks. The Reasons go on to state:

The assessment included a general assessment of the whole EP and detailed topic assessments of the EP content, as follows:

a. Matters protected under Part 3 of the EPBC Act.

b. Consultation with a focus on adequacy of consultation with relevant persons.

c. Unplanned emissions and discharge scope with a focus on the adequacy of arrangements and capability for timely and effective source control response to a low [sic] of well control event.

109 At [19] of the Reasons, the delegate stated that the decision-maker “accepted the assessment team’s recommendations that the [Drilling EP] submission meets all the acceptance criteria set out in regulation 10A of the [Regulations]”. The delegate further stated that in deciding to accept “the [Drilling EP] for the activity, I have considered the findings and agree with the conclusions made by the assessment team in relation to the general assessment and each topic assessment”.

110 Mr Cameron Charles Grebe, who is the Head of the Division for Environment, Renewables and Decommissioning at NOPSEMA and gave evidence on its behalf, deposed that the delegate was a delegate of the Chief Executive Officer of NOPSEMA. Mr Grebe himself had some oversight over the assessment process as part of his role by which he has overall responsibility for NOPSEMA’s regulation of environmental management across offshore activities in Commonwealth waters. He deposed that NOPSEMA uses a database known as the “Regulatory Management System” (RMS) for recording information about its assessment of each environment plan. For each assessment process a file is created in that database, with standard fields that are populated in the course of the assessment, including a record of assessment findings of the assessment team which, according to Mr Grebe, is an iterative record that includes findings and observations made from time to time over the assessment process. He further deposed that the bundle of documents titled ‘Bundle of material before the decision-maker filed pursuant to orders made on 17 June 2022’ and produced by NOPSEMA in the proceeding contain a document entitled “Assessment Findings” (Assessment Findings document). That document was produced by extracting the assessment team’s findings from the relevant database and then setting those out in a table format. Mr Grebe deposed that because of the iterative nature of the relevant field in the RMS database, the Assessment Findings document includes entries from members of the assessment team over the course of the assessment, at various points in time, including before and after the provision of further information by Santos.

111 Over some fifty-four paragraphs, the Reasons explain the assessment process for the Drilling EP and set out the findings (generally made at a high level) by reference to the criteria in the Regulations. The “key materials” considered in making the decision are listed at [20] and include various “NOPSEMA [e]nvironment plan assessment policies guidelines and guidance”. Of these and of relevance to a matter I need to consider is a document entitled “NOPSEMA Environment plan content requirements guidance note” (Content Requirement Guidance Note).

112 It is not necessary to refer to the Reasons in respect of each of the criteria assessed. For the issues I need to address, it is sufficient to refer to aspects of the Reasons dealing with reg 13 which requires an environment plan to, inter alia, describe the environment that may be affected including the particular “values and sensitivities” of that environment and the “details of the environmental impacts and risks for the activity”. It is also necessary to refer to the way the Reasons deal with the consultation criteria.

113 At [26] of the Reasons and addressing the Drilling EP’s description of the environment, the Reasons state that NOPSEMA found that “a thorough description of the physical and biological environment and details of relevant values and sensitivities that may be affected” by the Activity had been provided. The Reasons also note that the description of the environment included the Operational Area as well as an extended area titled “Environment that may be affected (EMBA)”. NOPSEMA also state that the EMBA “has been conservatively defined based on stochastic modelling for an unmitigated worst case oil pollution incident to low exposure values consistent with the matters set out in NOPSEMA Bulletin – Oil spill modelling”.

114 The values and sensitivities within the Operational Area were identified including the presence of listed threatened species. The values and sensitivities within the EMBA that it was said “may be affected” were also said to have been identified and described in the Drilling EP. The Reasons describe those as follows (emphasis added):

i. Australian Marine Parks including the Oceanic Shoals Marine Park, Arafura Marine Park, Ashmore Reef Marine Park, Cartier Island Marine Park.