FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited [2022] FCA 1115

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

In the declarations and orders set out below, terms have the following meanings:

Affected Members means the AMPFP Affected Members, the Charter Affected Members and the Hillross Affected Members.

AFSL means Australian Financial Services Licence.

AMPFP Affected Members means 1,111 members of Flexible Super – Employer group plan that were previously entitled to receive general advice services by Authorised Representatives of AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited and from whom $282,453.01 in PSF was wrongfully deducted after the member’s employment had ceased with the relevant employer sponsor.

Authorised Representative has the meaning provided by s 761A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Charter Affected Members means 89 members of Flexible Super – Employer group plan that were previously entitled to receive general advice services by Authorised Representatives of Charter Financial Planning Limited and from whom $29,250.13 in PSF was wrongfully deducted after the member’s employment had ceased with the relevant employer sponsor.

Hillross Affected Members means 252 members of Flexible Super – Employer group plan that were previously entitled to receive general advice services by Authorised Representatives of Hillross Financial Services Limited and from whom $44,485.06 in PSF was wrongfully deducted after the member’s employment had ceased with the relevant employer sponsor.

PSF means plan service fees which were deducted from the accounts of members of Flexible Super – Employer group plan in consideration for general advice services to be provided by Authorised Representatives of either AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited or Hillross Financial Services Limited.

Relevant Period means the period between 31 July 2015 and 30 September 2018.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

AMP Financial Planning

1. During the Relevant Period, the first defendant, AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited (ACN 051 208 327), in trade or commerce accepted payments from AMPFP Affected Members for the provision of general advice services, which are financial services within the meaning of s 12DI(3)(a) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act), in circumstances where there were reasonable grounds for believing that AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited would not be able to supply the financial services to the Affected Members within the Relevant Period, and thereby contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act in respect of each payment accepted in this period.

2. AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to procure and administer a system that ensured that the deduction of PSFs from AMPFP Affected Members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of the AMPFP Affected Members’ employment and the date of notification; and

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from AMPFP Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

3. AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, by its conduct in contravening s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

Hillross Financial Services Limited

4. During the Relevant Period, the second defendant, Hillross Financial Services Limited (ACN 003 323 055), in trade or commerce accepted payments from Hillross Affected Members for the provision of general advice services, which are financial services within the meaning of s 12DI(3)(a) of the ASIC Act, in circumstances where there were reasonable grounds for believing that Hillross Financial Services Limited would not be able to supply the financial services to the Hillross Affected Members within the Relevant Period, and thereby contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act in respect of each payment accepted in this period.

5. Hillross Financial Services Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to procure and administer a system that ensured that the deduction of PSFs from Hillross Affected Members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of the Hillross Affected Members’ employment and the date of notification; and

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from Hillross Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

6. Hillross Financial Services Limited, by its conduct in contravening s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

Charter Financial Planning Limited

7. During the Relevant Period, the third defendant, Charter Financial Planning Limited (ACN 002 976 294), in trade or commerce accepted payment from Charter Affected Members for the provision of general advice services, which are financial services within the meaning of s 12DI(3)(a) of the ASIC Act, in circumstances where there were reasonable grounds for believing that Charter Financial Planning Limited would not be able to supply the financial services to the Charter Affected Members within the Relevant Period, and thereby contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act in respect of each payment accepted in this period.

8. Charter Financial Planning Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to procure and administer a system that ensured that the deduction of PSFs from Charter Affected Members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of the Charter Affected Members’ employment and the date of notification; and

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from Charter Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

9. Charter Financial Planning Limited, by its conduct in contravening s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

AMP Superannuation Limited

10. AMP Superannuation Limited (ACN 008 414 104), by:

(a) its conduct in:

(i) failing to exercise its powers under the outsourcing agreement with AMP Life Limited to effectively monitor and supervise the deduction of PSFs from Affected Members’ accounts; and

(ii) the deduction of PSFs from Affected Members’ accounts by the U2 System used to administer AMP Superannuation Limited’s products (which system was operated for AMP Superannuation Limited by AMP Life Limited, pursuant to the outsourcing agreement between those parties); and

(b) having knowledge of the continued deduction of PSFs from the Affected Members’ accounts after notification of their cessation of employment, and therefore knowledge of the contravening conduct in the Relevant Period,

was knowingly concerned in each of the contraventions of Hillross Financial Services Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited and AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act within the meaning of s 12GBA(1)(e) of the ASIC Act (as in force during the Relevant Period).

11. AMP Superannuation Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to adequately procure, administer and oversee a system that ensured the deduction of PSFs from a member’s account ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of member’s employment and the date of notification;

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

12. AMP Superannuation Limited, by its conduct in being knowingly concerned in the contraventions of Hillross Financial Services Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited and AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act within the meaning of s 12GBA(1)(e) of the ASIC Act (as in force during the Relevant Period), breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

AMP Life Limited

13. AMP Life Limited (ACN 079 300 379), by:

(a) its conduct in:

(i) facilitating the deduction of the PSFs from each Affected Member’s account as administrator and operator of the U2 System (which system was operated for AMP Superannuation Limited by AMP Life Limited, pursuant to the outsourcing agreement between those parties);

(ii) deducting PSFs from Affected Members’ accounts through the U2 System; and

(b) having knowledge:

(i) that there were reasonable grounds for believing that Hillross Financial Services Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited and AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited would not be able to provide the financial services to Affected Members within a specified period, or at all, after notification that the Affected Members had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor; and

(ii) of the continued deduction of PSFs from the Affected Members’ accounts after notification of their cessation of employment, and therefore knowledge of the contravening conduct in the Relevant Period,

was knowingly concerned in each of the contraventions of Hillross Financial Services Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited and AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act within the meaning of s 12GBA(1)(e) of the ASIC Act (as in force during the Relevant Period).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

14. The first defendant (AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $4,800,000 in respect of the contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act referred to in paragraph 1 of the declarations set out above.

15. The second defendant (Hillross Financial Services Limited) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $720,000 in respect of the contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act referred to in paragraph 4 of the declarations set out above.

16. The third defendant (Charter Financial Planning Limited) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $480,000 in respect of the contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act referred to in paragraph 7 of the declarations set out above.

17. The fourth defendant (AMP Superannuation Limited) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $2,500,000 in respect of its being knowingly concerned in contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act as referred to in paragraph 10 of the declarations set out above.

18. The fifth defendant (AMP Life Limited) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $6,000,000 in respect of its being knowingly concerned in contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act as referred to in paragraph 13 of the declarations set out above.

19. The pecuniary penalties referred to in paragraphs 14 to 18 are to be paid within 30 days of the date of this order.

20. Pursuant to s 12GLB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, within 30 days of this order, the first to fifth defendants publish, at their own expense, a written adverse publicity notice (Written Notice) in the terms set out in Annexure A to this order, by:

(a) for a period of no less than 90 days, maintaining a copy of the Written Notice, in font no less than 10 point, in an immediately visible area of the following web addresses:

(i) https://www.amp.com.au/;

(ii) http://www.hillross.com.au;

(the webpages)

(b) for a period of no less than 365 days, maintaining a copy of the Written Notice, in font no less than 10 point, in an immediately visible area of the webpages to appear after a person uses credentials to log into the secure online service via the ‘member’ or ‘employer’ sections of the webpage (to the extent applicable); and

(c) sending a copy of the Written Notice to any person who was a member of the Flexible Super – Employer group plan during the Relevant Period to the last known email or postal address of the member.

21. The first to fifth defendants pay the plaintiff’s costs of the proceeding, as agreed or assessed.

22. The originating application as against the sixth defendant be dismissed with no order as to costs.

ANNEXURE A: MISCONDUCT NOTICE

The Federal Court of Australia has ordered AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, Hillross Financial Services Limited, Charter Financial Planning Limited, AMP Superannuation Limited and AMP Life Limited (AMP Entities) to publish this misconduct notice:

On 20 September 2022, Justice Moshinsky of the Federal Court ordered the AMP Entities to pay a total pecuniary penalty of $14.5 million for charging 1,452 members of the AMP Flexible Super – Employer group plan (Flexible Super Plan) fees for no services.

The affected members of the Flexible Super Plan had been nominated by their employers to receive general advice services from financial planners with the AMP Entities in return for paying a fee called a Plan Service Fee (PSF) that was automatically deducted from their superannuation accounts on a regular basis. When members ceased employment with their employer-sponsors, they no longer had access to those general advice services and were therefore no longer liable to pay PSFs.

Between 31 July 2015 and 30 September 2018, the AMP Entities deducted $356,188.20 in PSFs from the superannuation accounts of members in circumstances where each of the AMP Entities were aware that the relevant member had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor, and therefore no general advice services could be provided to them.

The AMP Entities agree that they failed to have proper systems and compliance arrangements to ensure that the deduction of PSFs from affected members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and that they failed to refund the fees to members in a timely manner.

After reporting this conduct to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the AMP Group remediated $691,032.68 in fees and lost earnings to the Affected Members.

The AMP Entities acknowledge that their complaints monitoring systems and processes failed to identify the issue in a timely manner, which meant it took longer than it should have to rectify the issue.

Further information

The above conduct contravened the following financial services laws:

section 12DI(3) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth); and

section 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

For further information about the conduct, see the following links:

Statement of facts agreed between the parties to the proceeding [hyperlink];

Justice Moshinsky’s judgment on penalty [hyperlink]; and

ASIC media release [hyperlink].

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding concerns the charging of fees for no services during the period 31 July 2015 to 30 September 2018 (the Relevant Period). During that period, fees known as plan service fees (PSFs) were deducted from the superannuation accounts of certain members in circumstances where there was no entitlement to charge or deduct the fees.

2 The relevant superannuation plan was known as “Flexible Super”, which was an employer-sponsored superannuation product. Pursuant to the Flexible Super product rules, on a member ceasing employment with their employer-sponsor:

(a) the fifth defendant (AMP Life) received notification that the member had ceased employment;

(b) the member’s account was transferred out of the employer-sponsored group plan and into the retail category of Flexible Super;

(c) there was no entitlement to charge or deduct the PSF from the member’s account; and

(d) the PSF should have ceased being deducted from the member’s account.

3 However, during the Relevant Period, a total of $356,188.20 in PSFs was deducted from the superannuation accounts of 1,452 members (Affected Members) after AMP Life was notified of the cessation of the member’s employment.

4 The proceeding was commenced by the plaintiff (ASIC) by originating process and concise statement. The first to fifth defendants, which were all members of the AMP Limited (AMP) group of companies (the AMP Group) during the Relevant Period, are:

(a) AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited (AMP Financial Planning);

(b) Hillross Financial Services Limited (Hillross);

(c) Charter Financial Planning Limited (Charter);

(d) AMP Superannuation Limited (AMP Superannuation); and

(e) AMP Life.

5 The sixth defendant to the proceeding is AMP Services Limited. It is proposed by the parties that the proceeding against that defendant be dismissed. That defendant can therefore be put to one side for present purposes. I will refer to the first to fifth defendants as the defendants.

6 The defendants have admitted that they contravened the relevant provisions of the legislation. Specifically, it is agreed between the parties that:

(a) each of AMP Financial Planning, Hillross and Charter (together, the Advice Licensees) contravened s 12DI(3) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act) and s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth);

(b) each of AMP Superannuation and AMP Life was knowingly concerned in the Advice Licensees’ contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, within the meaning of s 12GBA(1)(e) of the ASIC Act (as in force during the Relevant Period); and

(c) AMP Superannuation contravened s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act.

7 Section 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, which is a civil penalty provision, provides that a person contravenes the section if:

(a) the person, in trade or commerce, accepts payment or other consideration for financial services; and

(b) at the time of acceptance, there are reasonable grounds for believing that the person will not be able to supply the financial services within the period specified by the person or, if no period is specified, within a reasonable time.

8 Section 912A of the Corporations Act was not a civil penalty provision during the Relevant Period. Section 912A(1)(a) provides that a financial services licensee must do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by the licence are provided efficiently, honestly, and fairly.

9 Section 912A(1)(c) provides that a financial services licensee must comply with the “financial services laws”. The expression “financial services laws” picks up s 12DI of the ASIC Act.

10 The parties have prepared a statement of agreed facts and admissions dated 27 April 2022 (the SOAF).

11 The parties are agreed on the form of declarations that should be made in respect of the contraventions. However, there is an issue between the parties as to the pecuniary penalties that should be imposed. ASIC contends that penalties totalling $17.5 million should be imposed. The defendants propose penalties totalling $4.6 million.

12 Apart from the issue of penalties, the parties are largely agreed on the form of other orders. There is a minor disagreement as to the form of an adverse publicity notice to be published by the defendants.

13 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that penalties totalling $14.5 million should be imposed on the defendants. In relation to the form of the adverse publicity notice, I consider the additional words proposed by the defendants should be included.

The hearing and the evidence

14 The proceeding was listed for a hearing on liability and penalty. There was no issue between the parties concerning liability, and the hearing focussed on the issue of penalty.

15 The material before the Court comprises the SOAF (including a bundle of documents) and a number of affidavits.

16 ASIC relies on two affidavits of Andrew Fleming, a senior lawyer in ASIC’s Financial Services Enforcement team, affirmed on 14 June 2022 and 8 July 2022. Parts of the affidavit of 14 June 2022 were not read.

17 The defendants rely on the following affidavits:

(a) an affidavit of Rachelle Taylor, Head of Customer Resolutions at AMP, sworn on 15 July 2022;

(b) an affidavit of Claudia Firmansjah, Head of Regulatory Response – Operations at AMP, affirmed on 15 July 2022;

(c) an affidavit of Allen Pavlek, a Senior Business Analyst at AMP, sworn on 10 August 2022;

(d) an affidavit of David John Clark, Director – Master Trust Product at AMP, affirmed on 15 July 2022; and

(e) an affidavit of Shamus Paul Toomey, General Counsel, Dispute Resolution and Regulatory Response at AMP, sworn on 26 July 2022.

18 There was no cross-examination of any of the deponents.

Factual findings

19 The following findings are based on the SOAF and the affidavit evidence.

The defendants

20 At all material times:

(a) AMP Financial Planning held an Australian Financial Service Licence (AFSL), which authorised it to carry on a financial services business pursuant to which it engaged authorised representatives as defined in s 761A of the Corporations Act (Authorised Representatives) to provide financial product advice for classes of financial products that included superannuation;

(b) Hillross held an AFSL, which authorised it to carry on a financial services business pursuant to which it engaged Authorised Representatives to provide financial product advice for classes of financial products that included superannuation;

(c) Charter held an AFSL, which authorised it to carry on a financial services business pursuant to which it engaged Authorised Representatives to provide financial product advice for classes of financial products that included superannuation;

(d) AMP Superannuation held an AFSL, which authorised it to carry on a financial services business of dealing in financial products, including by issuing superannuation products; and

(e) AMP Life held an AFSL, which authorised it to carry on a financial services business of dealing in financial products, including by issuing life insurance products, and applying for, acquiring, varying or disposing of a financial product on behalf of another person in respect of classes of products, including superannuation.

The Trusts and Flexible Super

21 During the Relevant Period, AMP Superannuation was the trustee of:

(a) the AMP Superannuation Savings Trust; and

(b) the AMP Retirement Trust,

(the Trusts).

22 Within the Trusts, AMP Superannuation offered retail and employer-sponsored superannuation products. One such employer-sponsored product was Flexible Super. The members who joined the group plan for that product were sponsored by their employers, who entered into the group plan on the members’ behalf.

23 Where employers opted in for members of their group plan in Flexible Super to receive general advice services, Authorised Representatives of each Advice Licensee provided those general advice services to members. The general advice services provided by Authorised Representatives included services such as employee seminars, email updates, policy committee attendance, ongoing phone support, and assistance with form completion.

24 Under the superannuation policies in respect of the Flexible Super group plan, AMP Life was entitled to deduct a PSF from members’ accounts, where their employer had opted them in to receive general advice services. The PSF was an ongoing monthly fee that was negotiated between the employer-sponsor and the Authorised Representative. It applied to members who joined a group plan before 30 June 2014.

25 AMP Financial Planning and Hillross were each a party to a Facilitation Agreement with AMP Life. During the Relevant Period, the arrangement between AMP Life and Charter operated in substantially the same way as the arrangements between AMP Life, AMP Financial Planning and Hillross. Pursuant to the terms of the Facilitation Agreements, AMP Life remitted a percentage of the PSFs deducted from members’ accounts to the Advice Licensees and the balance was remitted to the Authorised Representatives who provided the general advice services.

26 When a member ceased employment with his or her employer-sponsor, AMP Life received a notification to that effect. Upon receipt of the notification, the member was transferred to a retail plan by the operation of a rule in the product administration system.

27 Once AMP Life was notified that a member had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor, the member no longer had access to the general advice services being offered by the Authorised Representatives and was therefore no longer liable to pay the PSF.

28 As at 30 September 2018, there were 105,750 members in the Flexible Super product, of which 4,057 members had an employer who opted in to receive general advice services.

29 As noted in the Introduction to these reasons, pursuant to the Flexible Super product rules, on a member ceasing employment with their employer-sponsor:

(a) AMP Life received notification that the member had ceased employment;

(b) that member’s account was transferred out of the employer-sponsored group plan and into the retail category of Flexible Super;

(c) there was no entitlement to charge or deduct the PSF from that member’s account; and

(d) the PSF should have ceased being deducted from that member’s account.

30 The relevant product rule is clause 6.4 (Member Advice Fees and Plan Service Fees), which states in part:

The Plan Service Fee will not be charged in respect of a Member if AMP accepts a notice from a Participating Employer stating that a Member has ceased employment. A Participating Employer may change any Plan Service Fee by written agreement with the financial planner and by notice to the Trustee.

The wrongful deduction of PSFs

Overview

31 During the Relevant Period, a total of $356,188.20 in PSFs was deducted from the superannuation accounts of 1,452 members (referred to in these reasons as the “Affected Members”), after AMP Life was notified of the cessation of the member’s employment. No general advice services were provided to the Affected Members after the cessation of their employment, which were referable to, or which could justify the continued charging of, the PSF. There was therefore no entitlement to charge the PSF to the Affected Members.

32 Of the 1,452 Affected Members, 1,111 were members previously serviced by AMP Financial Planning Authorised Representatives, 252 were members previously serviced by Hillross Authorised Representatives and 89 were members previously serviced by Charter Authorised Representatives.

33 The total amount of $356,188.20 in PSFs wrongly deducted consisted of:

(a) $282,453.01 (approximately 79% of the total of $356,188.20) in respect of AMP Financial Planning members;

(b) $44,485.06 (approximately 12%) in respect of Hillross members; and

(c) $29,250.13 (approximately 8%) in respect of Charter members.

34 Of the $356,188.20 in PSFs wrongly deducted, $24,672.00 was retained by the Advice Licensees ($19,614.49 by AMP Financial Planning, $3,497.26 by Hillross and $1,560.25 by Charter), with the balance of $331,516.20 remitted to Authorised Representatives of the Advice Licensees.

AMP Life’s role in relation to the wrongful deductions

35 AMP Life was the administrator of AMP Superannuation’s superannuation products, performing administrative services in connection with the funds pursuant to contractual arrangements with AMP Superannuation.

36 It also had contractual arrangements in place with each Advice Licensee which facilitated the distribution of PSFs from members’ superannuation accounts to each Advice Licensee and their Authorised Representatives (being the Facilitation Agreements described above).

37 In performance of its administration of the Trusts and its contractual obligations with each Advice Licensee, AMP Life was the entity that deducted the PSF from members’ accounts and remitted it to the Advice Licensees. It was also primarily the entity that received complaints and queries from members and/or their advisers concerning the charging of the PSF, as detailed below.

38 AMP Life was typically notified of the Affected Member’s cessation of employment with their employer-sponsor by the employer-sponsor of the member. In some cases, the member notified their Authorised Representative, who then notified the employer-sponsor or AMP Life. In some other cases, the member notified AMP Life directly.

39 AMP Life typically sent a notification of the Affected Member’s cessation of employment to the applicable Authorised Representative of the Advice Licensee who was providing the general advice services, through a planner portal (a system used for communication, among other things).

40 The deduction of PSFs from Affected Members’ accounts was facilitated through the Ultimaas II (U2) Product Administration System (the U2 System), which was used to administer AMP Superannuation’s products and was operated for AMP Superannuation by AMP Life under an outsourcing agreement. The U2 System facilitated the continued deduction and charging of PSFs from an Affected Member’s account by AMP Life as the administrator of the funds.

AMP Superannuation’s role in relation to the wrongful deductions

41 Under an outsourcing agreement between AMP Superannuation and AMP Life, AMP Superannuation had powers to supervise and monitor AMP Life’s performance of its obligations:

(a) AMP Superannuation had power to obtain information from AMP Life about the provision of services to AMP Superannuation, the AMP Superannuation funds and the superannuation policies;

(b) AMP Superannuation had power to conduct on-site visits to AMP Life and obtain copies of any documents or information relating to the provision of services to AMP Superannuation; and

(c) AMP Superannuation had power to engage independent auditors to investigate AMP Life’s business activities relevant to the performance of its obligations under the agreement.

42 AMP Superannuation was the trustee of the funds and therefore had records in its possession that showed that:

(a) the Affected Members had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor, because the Affected Member had been transferred to the retail category of the relevant product; and

(b) PSFs continued to be deducted from the Affected Members’ accounts after they had been transferred to the retail category of the relevant product.

Advice Licensees’ role in relation to the wrongful deductions

43 Authorised Representatives were typically notified of the cessation of Affected Member’s employment by AMP Life as described above.

44 The PSF deducted after an Affected Member’s cessation of employment was recorded as revenue of the Advice Licensees.

45 Each Advice Licensee retained the portion of the PSFs which represented its licensee fees. The balance of the PSFs was distributed to the Authorised Representatives who were responsible for the provision of the general advice services.

46 The Advice Licensees, through their Authorised Representatives, did not (and could not) provide any general advice services to the Affected Members referable to the PSFs charged after notification that the Affected Members had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor.

The cause of the wrongful deductions

47 The evidence of Mr Clark establishes that the wrongful deductions stem from a computer coding error that occurred at about the time the Flexible Super – Employer group plan was introduced (in May 2010).

48 The exhibit to Mr Clark’s affidavit includes a document titled “Ultimaas II Application Documentation” (the U2 Application Document), which was prepared in 2010 to provide an overview to the Technology team of the business rules required to be coded into U2 for the Flexible Super product. The Flexible Super product was programmed into U2 after its introduction in or around May 2010.

49 Mr Clark gives evidence that U2 operates with “if this, then that” coding. That means that coding a rule into it causes the system to operate such that, when a particular event is recorded into the relevant field in U2, certain actions will automatically occur (or cease occurring) as a result. Rules that operate this way are identified in the U2 Application Document by the letter “R” followed by a four-digit number. The U2 Application Document states that:

If the member terminates employment, the PAF [sic: PSF] will no longer be charged to member’s account. R1744

50 Mr Clark gives evidence that, had Rule 1744 been coded into U2, a member who ceased employment with their employer-sponsor would no longer be charged a PSF.

51 Mr Clark gives evidence that, following an investigation into the issue in 2018, it was determined that the cause of the continued deduction of the PSF following “detachment” (that is, the member ceasing employment with the employer-sponsor) was a failure to code Rule 1744 in U2.

52 While the Court has evidence (summarised above) that the wrongful deductions arose because of a coding error, the evidence filed by the defendants does not provide any details about the how that error occurred and who was responsible for it.

53 Mr Clark gives evidence in paragraphs 48-50 of his affidavit about auditing and monitoring of U2 in relation to the Flexible Super – Employer product. He states that U2 was the subject of periodic and ad hoc audits and testing, including standard user acceptance testing (UAT) before the Flexible Super – Employer product was implemented. He states that the document at tab 25 of the exhibit to his affidavit sets out the test strategy in relation to the Flexible Super – Employer product. In particular, page 578 of the exhibit sets out the dates (in 2010) on which UAT was undertaken, as well as the dates on which various other tests were undertaken. Mr Clark states that the UAT involved a standard U2 user, from each of the relevant teams, undertaking testing of scenarios they were likely to encounter on a day-to-day basis. Mr Clark states that, in his experience, the specific UAT scenarios for each business unit are generally determined by the relevant business unit personnel, such as Business Analysts, Product, Master Trust Operations/Client Services and Finance.

54 I observe that this evidence is presented at a very general level, with no detail as to subsequent auditing and monitoring of the U2 system (and, in particular, the Flexible Super product) and no explanation as to why the auditing and monitoring did not pick up the coding error.

Complaints from members and advisers

Overview

55 AMP Life and AMP Financial Planning received many complaints from members and/or their advisers in relation to the continued deduction of PSFs after a member’s cessation of employment, as detailed below.

56 Each of the complaints was resolved at the time it was raised, through a refund of the PSFs wrongfully deducted from the relevant member’s account or (where applicable) manually removing the PSF from the member’s account.

57 The following table sets out details of complaints that were received from members and advisers in relation to PSFs charged through the Flexible Super group plan and how the complaints were resolved.

No. | Date | Complainant | Recipient | Nature of complain and outcome |

1. | 9 February 2015 | Member | AMP Life | Member (OS) complained that they had requested that PSFs be cancelled from July 2014, but PSFs continued to be charged. The complaint was resolved by providing OS with a refund of $18.71 and manually switching off the fee. |

2. | 23 December 2015 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to client (TT) after date of notification of employment termination on 20 September 2012. On 12 January 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing TT with a refund of $152.40 and manually switching off the fee. |

3. | 24 August 2016 | Member | AMP Life | Member (ECS) complained that PSF charged after date of notification of employment termination on 29 May 2014. On 12 September 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing ECS with a refund of $286.04 and manually switching off the fee. |

4. | 7 September 2016 | Member | AMP Life | Member (BP) complained that PSF charged after date of notification of employment termination on 20 March 2012. On 9 September 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing BP with a refund of $34.09 and manually switching off the fee. |

5. | 24 November 2016 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (BT) after date of notification of employment termination on 17 December 2012. On 25 November 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing BT with a refund of $194.75. The fee had already been switched off from 31 July 2016. BT was also the subject of the complaint made on 21 December 2017. |

6. | 25 November 2016 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (AJ) after date of notification of employment termination on 20 December 2013. On 29 November 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing AJ with a refund of $403.91 and manually switching off the fee. |

Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (AH) after date of notification of employment termination on 20 December 2013. On 29 November 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing AH with a refund of $175.45 and manually switching off the fee. | ||||

7. | 6 December 2016 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (MB) after date of notification of employment termination on 29 July 2016. On 12 December 2016, the complaint was resolved by providing MB with a refund of $43.97 and manually switching off the fee. |

8. | 28 April 2017 | Employee | AMP Life | Employee complained that PSF charged to member (DY) after date of notification of employment termination on 23 April 2015. On 22 May 2017, the complaint was resolved by providing DY with a refund of $146.25 and manually switching off the fee. |

9. | 17 August 2017 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (DAB) after date of notification of employment termination on 4 May 2017. On 21 August 2017, the complaint was resolved by providing DAB with a refund of $21.15 and manually switching off the fee. |

10. | 20 November 2017 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (JG) after date of notification of employment termination on 9 March 2017. On 22 November 2017, the complaint was resolved by providing JG with a refund of $147.77 and manually switching off the fee. |

Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (CJK) after date of notification of employment termination on 9 March 2017. On 22 November 2017, the complaint was resolved by providing CJK with a refund of $13.79 and manually switching off the fee. | ||||

11. | 21 December 2017 | Adviser | AMPFP | Adviser complained on behalf of 34 clients, 23 of whom were members of a Flexible Super group plan and who had PSFs charged after date of notification of employment termination of those members. 22 of these members were remediated in full at the time of the complaint. One member was remediated through the remediation program. |

12. | 15 March 2018 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (LS) after date of notification of employment termination on 4 September 2014. On 19 March 2018, the complaint was resolved by providing LS with a refund of $634.09 and manually switching off the fee. |

13. | 23 April 2018 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (JM) after date of notification of employment termination on 13 March 2014. The complaint was resolved by providing JM with a refund on 3 May 2018 and a further refund on 11 December 2018, totalling $73.02, and manually switching off the fee. |

Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (SW) after date of notification of employment termination on 13 and 19 March 2014. On 3 May 2018, the complaint was resolved by providing SW with a refund of $2.19 and manually switching of the fee. | ||||

14. | 24 April 2018 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser raised concern that PSF charged to two members (JM and SW) who were part of an employer plan but had left their employer-sponsor and joined a personal plan with AMP. This complaint triggered the investigation which led to the 26 June 2018 breach report in this matter. These members were remediated as part of AMP’s remediation program. |

15. | 7 June 2018 | Member | AMP Life | Member (CKF) complained that PSF charged after date of notification of employment termination on 31 March 2018. On 12 June 2018, the complaint was resolved by providing CKF with a refund of $105.64 and manually switching off the fee. |

16. | 1 August 2018 | Adviser | AMP Life / AMPFP | Adviser complained that PSF charged to member (EC) after date of notification of employment termination on 24 April 2014. On 27 August 2018, the complaint was resolved by providing EC with a refund of $198.39 and manually switching off the fee. |

17. | 27 August 2018 | Member | AMP Life | Member (DMB) complained that PSF charged after date of notification of employment termination on 20 April 2015. On 7 June 2019, the complaint was resolved by providing DMB with a refund of $2,308.54 and manually switching off the fee. |

58 In relation to complaints 1 to 13, despite the fact that each complaint related to the erroneous deduction of the PSF after a member ceased employment with the employer-sponsor, the systemic nature of the issue was not identified. It was not until after complaint 14, received on 24 April 2018, that steps were taken to investigate whether there was a systemic issue.

The 9 February 2015 complaint

59 Mr Pavlek provides evidence in his affidavit in relation to complaint 1 in the above table, which was made on 9 February 2015. In 2015, Mr Pavlek was a Business Support Analyst in the Business Support Team (BST) at AMP.

60 Mr Pavlek describes, at paragraph 8 of his affidavit, his typical workflow when working on coding issues in respect of product administration systems. This included: an employee lodging a “ticket” on the Management Incident Tracking Tool system (Mitts), which included information about the issue or problem being encountered; once a ticket was lodged on Mitts, it was allocated by a team manager to a member of the BST. The Mitts ticket for the 9 February 2015 complaint was allocated to Mr Pavlek.

61 Annexed to Mr Pavlek’s affidavit is a copy of a business process management system record relating to the Mitts ticket for the 9 February 2015 complaint. Mr Pavlek sets out, in paragraph 14 of his affidavit, the record for the 9 February 2015 complaint and his interpretation of the data. The following facts and matters emerge from that evidence:

(a) On 9 February 2015, an AMP employee (who I will refer to as ES), working in Operations/Platform & Corporate Support/Customer Service, created the Mitts ticket for the complaint. ES advised that she could not process a fee reversal/removal for a member, and requested that the fee be removed manually. The record contains the following data:

Call No 1916564 Log Date 9/02/2015 11:17AM Customer [ES] Organization Operations/Platform & Corporate Sup/Customer Servi Telephone 02 9768 7042 Service Type Ultimaas 2 Status Closed Configuration Item Priority 5 First/Response Esc Time Next Esc Time Problem Desc AP - FL 947418455 – Error “Ongoing Planner Service Fee is not allowed for Fee Sub Type POD” Objects Mitts 1374595 - Ongoing Planner Service Fee is not allowed for Fee Sub Type POD.msg42Kb Knowledge Articles (None)

(Emphasis added.)

Mr Pavlek’s evidence regarding the above data includes that he believes that “Sub Type POD” was the type of fee.

(b) On 12 February 2015, Mr Pavlek opened the ticket for initial investigation. On the same day, Mr Pavlek emailed ES with a potential solution. He states in his affidavit that he believes he proposed a “workaround”, being to remove the employer as “sponsoring employer”.

(c) On 16 February 2015, ES added a note that advised that the employer sponsorship could not be removed as the member had already been detached from the employer.

(d) On the same day, Mr Pavlek referred the ticket to AMP’s second line support (IT Production Support). Mr Pavlek referred IT Production Support to three previous tickets that likely related to the same or a similar issue (and providing the Mitts numbers for those tickets).

(e) On 25 March 2015, Andrew Reid (from IT Production Support) placed a note on the ticket, advising that the fee would be manually removed from the back end of the system. The record contains the following data:

25/03/2015 7:46 AM - Andrew Reid [Call Updated] Problem: FL 947418455 – Error “Ongoing Planner Service Fee is not allowed for Fee Sub Type POD” RCA: Known issue. An enhancement is required. Solution: Manually add ad new UFEEOH record for the Employment termination date and then add a UFEEOD record with code “Z”.

(Emphasis added.)

Mr Pavlek states in his affidavit that “RCA” means “Root Cause Analysis”. He states that he believes that where Mr Reid has written “enhancement required”, he has done so because, without an enhancement, if this issue (that is, the need to manually remove fee type POD for a particular member) arose again, the business user would be required to contact BST to implement the fix (as the business users did not have access to the back end of U2).

(f) On 25 March 2015, Mr Pavlek closed the ticket and sent an email to ES. Mr Pavlek states in his affidavit that, while he cannot recall specifically, based on his typical workflow, he expects that he would have advised ES that the ticket had been actioned, a manual workaround had been processed, and an enhancement was required to enable the business user to manually remove that fee type in the future.

62 Mr Pavlek states at paragraph 15 of his affidavit that he does not know whether the enhancement referred to above was implemented. He states that enhancements were dealt with by the Maintenance and Enhancements team (M&E team). He states at paragraph 16 that, without an enhancement being implemented, if this issue arose again for another individual member, the business user would be required to contact the BST to implement the fix (as the business users did not have access to the back end of U2). Mr Pavlek also gives the following evidence at paragraph 17 of his affidavit:

I have been told that these proceedings are about a U2 problem where there was a failure to code a rule that turned off plan service fees upon delink. During my time working in the BST, I operated on the assumption that the rules in U2 were correct. When resolving the Mitts ticket referred to above, my concern was the reason why the fee could not be turned off by the business user, not whether it was appropriate for the fee to be charged in the first place or following the member delinking.

63 I accept the evidence of Mr Pavlek, which was not challenged. However, it only goes so far. I make the following observations. First, the defendants have not called Mr Reid to give evidence (or indicated whether or not he is available to give evidence). It is unclear whether, in stating that this was a “[k]nown issue” and that an “enhancement” was required, Mr Reid was referring to an issue that business users could not manually remove the fee themselves (and an enhancement to address that issue), or to an issue that the PSF was being automatically deducted where it should not have been (and an enhancement to address that issue). Secondly, no one from the M&E team has been called to give evidence as to whether that team was requested to make an enhancement to address one or other or both of these issues. Thirdly, it seems that no one at AMP thought to ask why the PSF that was the subject of this ticket (or the three previous similar tickets) had been deducted in error – had this question be asked, the systemic issue may well have been identified much earlier than it was.

The 21 December 2017 complaint

64 Complaint 11 in the above table, which was made on 21 December 2017, was a complaint by an adviser on behalf of 34 clients, 23 of whom were members of a Flexible Super group plan and who had PSFs charged after the date of notification of employment termination of those members. Despite this complaint coming from an adviser and involving so many members, it still did not trigger an investigation as to whether there was a systemic issue.

AMP’s complaints handling system

65 Ms Taylor gives evidence in her affidavit about AMP’s complaints handling system during the Relevant Period. She states that complaints were handled within the business unit to which the complaints related – for example, a complaint relating to advice was generally handled by the complaints handling team within the advice business unit. That business unit was responsible for the receipt, recording, investigation, resolution and closure of complaints from both members/customers and advisers and self-reports from advisers.

66 In her affidavit, Ms Taylor states that, as acknowledged in the SOAF, between 2015 and 2018, AMP’s complaints monitoring system and processes did not identify in a timely manner that there was a systemic issue that resulted in the deduction of PSFs from the accounts of members in the Flexible Super – Employer group plan who had ceased employment with their employer-sponsors.

67 Ms Taylor expresses the opinion, which I accept, that the primary reasons why the complaints monitoring system did not detect this systemic issue until in or about April 2018 were as follows:

(a) The AMP Group did not have holistic oversight of complaints. There was no enterprise-wide sharing of complaints data, at a management level or frontline level, that would have enabled the analysis of that data to identify possible systemic issues. The complaints monitoring system across AMP was decentralised, in that different business units within AMP used different systems and processes to record and manage complaints, and these systems and processes were distinct from one another.

(b) There was no quality assurance of closed complaints to ensure that complaints were managed and resolved effectively and that any systemic issues were flagged.

Knowledge of the contravening conduct

68 As trustee of the Trusts with access to records indicating that Affected Members had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor, AMP Superannuation had knowledge of the continued deduction of PSFs from the Affected Members’ accounts and therefore knowledge of the contravening conduct in the Relevant Period.

69 Further, by reason of the complaints referred to above, and the records of these complaints, AMP Life and AMP Financial Planning knew that in the Relevant Period:

(a) the contravening conduct had occurred; and

(b) certain members and/or their advisers had complained about the contravening conduct and had received a refund in respect of such conduct.

Contraventions of the relevant provisions

70 The conduct the subject of this proceeding was in trade or commerce, and in connection with a financial product and a financial service, within the meaning of the Corporations Act and the ASIC Act. The general advice services provided by the Advice Licensees through their Authorised Representatives to the Affected Members was a service otherwise supplied in relation to a financial product.

71 The SOAF, at paragraphs 66-83, contains agreed facts establishing each element of the contraventions (or knowing involvement in the contraventions).

72 There were many thousands of contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act. A contravention by an Advice Licensee of s 12DI(3) occurred on each occasion a PSF was deducted from an Affected Member’s account. AMP Superannuation and AMP Life were involved in each and every contravention. This brings about the following calculations of the number of contraventions by each Advice Licensee and the number of contraventions in respect of which AMP Superannuation and AMP Life were knowingly concerned (as set out in ASIC’s submissions at paragraph 30, which I understand to be accepted by the defendants):

Defendant | Contraventions between 31 July 2015 and 30 June 2017 | Contraventions between 1 July 2017 and 30 September 2018 |

AMP Financial Planning | 34,681 | 8,957 |

Hillross | 5,685 | 1,038 |

Charter | 1,224 | 250 |

AMP Superannuation | 41,590 | 10,245 |

AMP Life | 41,590 | 10,245 |

73 Thus, the total number of contraventions by the Advice Licensees during the Relevant Period was 51,835. That figure was accepted by counsel for the defendants during the hearing (T77). AMP Superannuation and AMP Life were each involved in that number of contraventions.

Identification of the contravening conduct and rectification

74 On 24 April 2018, an Authorised Representative made a complaint to AMP. That complaint led AMP Life to make preliminary inquiries and to investigate members’ account records to determine whether the wrongful deduction of PSFs was a systemic issue.

75 On 18 May 2018, an incident was recorded on AMP’s incident management system, the Incident Management Database. Mr Clark states in his affidavit that he was the “Incident Owner” for the incident, meaning that he was the accountable business lead for the incident. Members of his team were the Incident Responsible Managers. Their role, and the investigation of the incident, are described at paragraphs 22-26 of Mr Clark’s affidavit.

76 As noted above, following its investigation, AMP Life determined that the cause of the continued deduction of the PSF following a member ceasing employment with the employer-sponsor was a failure to code Rule 1744 in the U2 System.

77 In May and June 2018, the issue was discussed internally at the Insurance, WSC & Group Functions Incident Working Group and then referred to the Insurance & Wealth Solutions Breach Review Committee, where AMP Superannuation became aware of the issue.

78 On 19 June 2018, the Advice Licensees were notified of the wrongful deduction of the PSFs and informed that steps were being taken to prevent such deductions.

79 In June 2018, AMP commenced a process to find a technological solution to ensure that PSFs were automatically removed from the accounts of members who had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor. As an interim step, it identified the accounts of members who had recently been transferred to a retail plan and manually removed the PSF from those members’ accounts before any further PSFs were deducted. In addition, AMP Superannuation began preparing a remediation plan that would address the compensation payable to impacted members, notification to those members, and the calculation of any loss of earnings. Breach reports were provided to ASIC.

80 In October 2018, AMP delivered a technology solution by which new code was written in the U2 System to prevent it from charging PSFs to members at the time that AMP Life was notified of cessation of employment. The effect of that fix was that the system automatically removed PSFs from the accounts of members who had ceased employment with their employer-sponsor.

81 In February 2019, following another review of the U2 System, AMP Superannuation and AMP Life determined that the deduction of PSFs should cease from the date of employment cessation, rather than from the date of notification of employment cessation (which may occur some time after the date of cessation). At this time, AMP began to develop a further technology release to give effect to that determination.

82 In May 2019, AMP implemented the further technology release to ensure that the deduction of PSFs ceased from the date of employment cessation (rather than from the date of notification). Under that release, a new code was written in the U2 System so that it automatically set the PSF to a zero value at the time of cessation of employment. That value was set retrospectively once AMP Life received notification of cessation of employment. The relevant member was then refunded where necessary.

83 In June 2019, AMP carried out testing to determine whether the system correctly identified all members whose employment had ceased and that the PSFs that they had been charged were recalculated and refunded where necessary. The results of the testing showed that PSFs had ceased being deducted from the accounts of members whose employment had ceased.

Remediation

84 During the period December 2018 to July 2019, the AMP Group conducted a remediation program under which it refunded PSFs charged to those affected (including sums reflecting the associated loss of performance).

85 Members other than the Affected Members were the subject of the remediation program as deduction of PSFs extended back to 1 September 2010. However, by reason of limitation periods, this proceeding is only concerned with the deduction of PSFs that occurred within the Relevant Period.

86 Pursuant to this remediation program:

(a) 2,555 superannuation accounts of members were refunded PSFs; and

(b) the AMP Group refunded a total amount of $928,494.20 to these members.

87 In relation to the Affected Members the subject of this proceeding:

(a) 1,452 members were refunded $554,950.58 in PSFs; and

(b) a total amount of $691,032.68 was paid to Affected Members (representing the $554,950.58 in PSFs plus loss of performance on those funds).

88 Each of the 1,452 Affected Members was fully remediated through AMP Group’s remediation program.

89 Further detail as to the remediation is provided in paragraphs 43-47 of Mr Clark’s affidavit.

Breach reports and updates to ASIC

90 The SOAF, at paragraphs 56-63, details various breach reports, and updates, provided by the defendants to ASIC in relation to the issues that are the subject of this proceeding. The SOAF, at paragraph 64, refers to notices issued by ASIC to the defendants for the production of documents and the responses to those notices.

Co-operation

91 The defendants co-operated with ASIC throughout the investigation leading to this proceeding, and also co-operated with ASIC in the preparation of the SOAF. They have admitted the contraventions of the relevant legislative provisions.

Improvements in systems

92 Ms Taylor gives evidence, in paragraphs 18-26 of her affidavit, that there have been significant developments and improvements in AMP’s complaints monitoring systems and processes since September 2018. I accept that evidence. I note also that AMP no longer charges PSFs on its superannuation products.

Size and circumstances of the defendants

93 The AMP Group is a wealth management company that, during the Relevant Period, offered a variety of financial solutions across financial advice, investment management, banking, life insurance, superannuation, retirement income and investing, to approximately 3.5 million customers in Australia and New Zealand.

94 In the 2018 financial year, being the last financial year that falls within the Relevant Period:

(a) AMP Superannuation was the trustee of 2,240,195 superannuation member accounts across the AMP Group;

(b) AMP Life administered the superannuation accounts of 922,446 members across the AMP Group;

(c) there were 1,345,462 superannuation member accounts linked to an Authorised Representative of AMP Financial Planning;

(d) there were 55,268 superannuation member accounts linked to an Authorised Representative of Hillross; and

(e) there were 54,259 superannuation member accounts linked to an Authorised Representative of Charter.

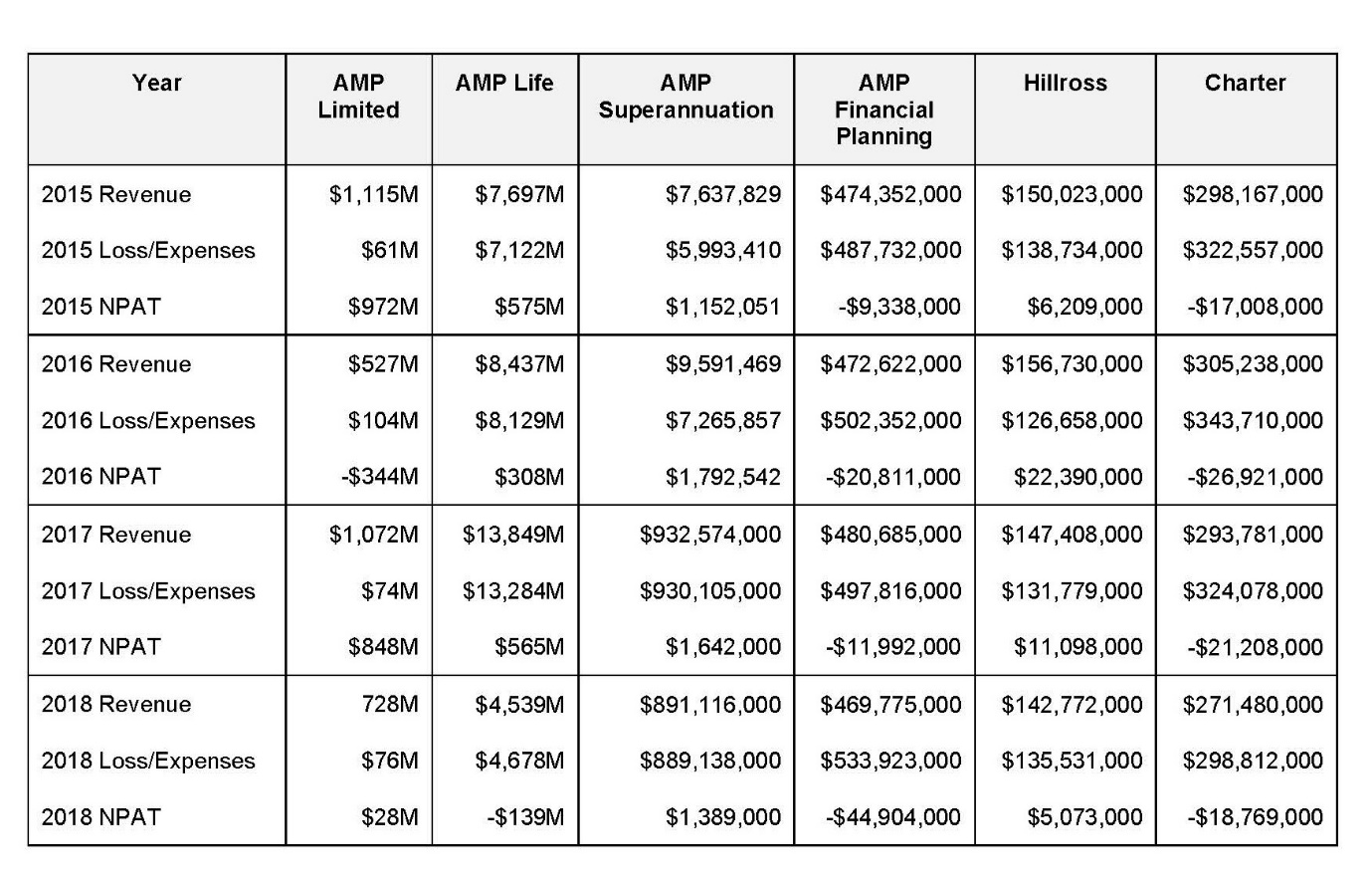

95 The table below outlines each entity’s revenue and net profit after tax (NPAT) throughout the years that fall within the Relevant Period:

Applicable principles

Section 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act

96 The terms of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act have been set out in the Introduction to these reasons. The elements of the provision were described by Beach J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (2022) 159 ACSR 381 (ASIC v Westpac) at [45]-[46]. His Honour also discussed, at [49]-[50], what must be shown to establish that a person has been “knowingly concerned” in a contravention of s 12DI(3).

Section 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act

97 The terms of s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act are set out in the Introduction, above. The principles relating to s 912A(1)(a) were discussed by Beach J in ASIC v Westpac at [60]-[66].

Declaratory relief

98 This Court has the power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

99 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68 (ABCC v CFMEU), the Full Court stated (at [90]):

The fact that the parties have agreed that a declaration of contravention should be made does not relieve the Court of the obligation to satisfy itself that the making of the declaration is appropriate. … It is not the role of the Court to merely rubber stamp orders that are agreed as between a regulator and a person who has admitted contravening a public statute.

(Citations omitted.)

The Full Court continued (at [93]):

Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions …

(Citations omitted.)

100 In Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421, Gibbs J stated (at 437-438) that before making declarations three requirements should be satisfied:

(a) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor.

Civil penalties

101 During the Relevant Period, s 12GBA of the ASIC Act provided in part:

12GBA Pecuniary penalties

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened a provision of Subdivision C, D [which includes s 12DI] or GC (other than section 12DA); or

…

(e) has been in any way, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention by a person of such a provision; or

…

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

(2) In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Subdivision [Subdivision G] to have engaged in any similar conduct.

…

(4) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more provisions referred to in paragraph (1)(a):

(a) a proceeding may be instituted under this Act against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of the provisions; but

(b) a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

102 The maximum pecuniary penalty in respect of a contravention of s 12DI(3) (or being knowingly concerned in a contravention of that provision) changed during the Relevant Period. For the period 31 July 2015 to 30 June 2017, the maximum was $1.8 million. For the period 1 July 2017 to 30 September 2018, the maximum was $2.1 million.

103 The principles applicable to the discretion to impose pecuniary penalties have been discussed in many cases. I refer to and adopt the summary of the principles in my judgment in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trivago N.V. (No 2) (2022) 159 ACSR 353 at [61]-[72]. For ease of reference, I set out the substance of part of that passage in the paragraphs below.

104 In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (the Agreed Penalties Case), the High Court emphasised that the primary purpose of civil penalties is to secure deterrence. In contrast to criminal sentences, they are not concerned with retribution and rehabilitation but are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: Agreed Penalties Case at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ; see also at [110] per Keane J. This point was also emphasised by the High Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 399 ALR 599 (Pattinson) at [15]-[16], [43], [45], [55] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ.

105 The plurality in Pattinson affirmed (at [18]) the well-known statements of French J, as his Honour then was, in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR ¶41-076; [1990] FCA 762 (CSR). In that case, his Honour listed several factors that informed the assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). His Honour stated:

The assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors which have been canvassed in the cases. These include the following:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

106 After setting out the above passage, the plurality in Pattinson stated at [19]:

It may readily be seen that this list of factors includes matters pertaining both to the character of the contravening conduct (such as factors 1 to 3) and to the character of the contravenor (such as factors 4, 5, 8 and 9). It is important, however, not to regard the list of possible relevant considerations as a “rigid catalogue of matters for attention” as if it were a legal checklist. The court’s task remains to determine what is an “appropriate” penalty in the circumstances of the particular case.

(Footnotes omitted.)

107 The plurality in Pattinson considered the role of the prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick in a civil penalty context, affirming (at [53]) the explanation provided by the Full Court of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [155]-[156]. See also Pattinson at [54]-[55].

108 In cases involving a very large number of contraventions, it may be unhelpful to seek to make a finding as to the precise number of contraventions, or to calculate a maximum aggregate penalty by reference to such a number: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [18] and [82] per Allsop CJ; ABCC v CFMEU at [143] per Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ.

109 It is relevant to refer to the course of conduct principle, which was considered by the Full Court of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [421]-[428]. The Full Court (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) stated at [424] that the course of conduct principle is a useful “tool” in the determination of appropriate civil penalties. The Full Court continued:

As we have already indicated, the principal object of the penalties imposed by s 76 of the [Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)] is that of specific and general deterrence. With this in mind, in a civil penalty context, the course of conduct principle can be conceived of as a recognition by the courts that the deterrent effect in respect of a civil penalty (at both a specific and general level) is measured by reference to the nature of the conduct for which it is imposed. It is therefore of paramount importance to identify whether multiple contraventions constitute a single course of conduct or separate instances of conduct, so as to ensure that an appropriate deterrent effect is achieved by the imposition of the penalty or penalties in respect of that particular conduct.

110 In relation to the course of conduct principle, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 (Hillside), Beach J stated at [25]:

… the “course of conduct” principle does not have paramountcy in the process of assessing an appropriate penalty. It cannot of itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions of the ACL. Further, its application and utility must be tailored to the circumstances. In some cases, the contravening conduct may involve many acts of contravention that affect a very large number of consumers and a large monetary value of commerce, but the conduct might be characterised as involving a single course of conduct. Contrastingly, in other cases, there may be a small number of contraventions, affecting few consumers and having small commercial significance, but the conduct might be characterised as involving several separate courses of conduct. It might be anomalous to apply the concept to the former scenario, yet be precluded from applying it to the latter scenario. The “course of conduct” principle cannot unduly fetter the proper application of s 224.

111 The above passage was cited with approval by the Full Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [141].

112 Where multiple separate penalties are to be imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the ‘totality principle’ requires the Court to make a ‘final check’ of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole. It will not necessarily result in a reduction. However, in cases where the Court believes that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too high, the Court should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are ‘just and appropriate’: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53 per Goldberg J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Energy Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 234 FCR 343 at [101]-[102] per Middleton J.

113 In determining the appropriate penalty, it is relevant to consider steps taken to ameliorate loss or damage (such as payment of compensation) as potentially mitigatory considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] ATPR ¶42-251; [2016] FCA 44 at [166]-[167] per Edelman J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 146 ALD 385; [2015] FCA 399 at [38] per White J.

114 Co-operation with authorities in the course of investigations and subsequent proceedings can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. The reduction reflects the fact that such co-operation: increases the likelihood of co-operation in future cases in a way that furthers the object of the legislation; frees up the regulator’s resources, thereby increasing the likelihood that other contravenors will be detected and brought to justice; and facilitates the course of justice: see, eg, Agreed Penalties Case at [46]; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293-294.

Application of principles to this case

Declarations

115 The parties propose that declarations be made (in summary) that:

(a) each of Advice Licensees contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act and s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act;

(b) each of AMP Superannuation and AMP Life was knowingly concerned in the Advice Licensees’ contraventions of s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, within the meaning of s 12GBA(1)(e) of the ASIC Act (as in force during the Relevant Period); and

(c) AMP Superannuation contravened s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act.

116 The proposed declarations are:

AMP Financial Planning

1. During the Relevant Period, the first defendant, AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited (ACN 051 208 327), in trade or commerce accepted payments from AMPFP Affected Members for the provision of general advice services, which are financial services within the meaning of s 12DI(3)(a) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act), in circumstances where there were reasonable grounds for believing that AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited would not be able to supply the financial services to the Affected Members within the Relevant Period, and thereby contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act in respect of each payment accepted in this period.

2. AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to procure and administer a system that ensured that the deduction of PSFs from AMPFP Affected Members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of the AMPFP Affected Members’ employment and the date of notification; and

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from AMPFP Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

3. AMP Financial Planning Proprietary Limited, by its conduct in contravening s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

Hillross Financial Services Limited

4. During the Relevant Period, the second defendant, Hillross Financial Services Limited (ACN 003 323 055), in trade or commerce accepted payments from Hillross Affected Members for the provision of general advice services, which are financial services within the meaning of s 12DI(3)(a) of the ASIC Act, in circumstances where there were reasonable grounds for believing that Hillross Financial Services Limited would not be able to supply the financial services to the Hillross Affected Members within the Relevant Period, and thereby contravened s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act in respect of each payment accepted in this period.

5. Hillross Financial Services Limited, by its conduct in:

(a) failing to procure and administer a system that ensured that the deduction of PSFs from Hillross Affected Members’ accounts ceased upon notification of cessation of employment and the remission of any fees deducted between the date of cessation of the Hillross Affected Members’ employment and the date of notification; and

(b) not having effective compliance arrangements in place to monitor and supervise the deduction and remission of PSFs from Hillross Affected Members’ accounts to Authorised Representatives,

breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

6. Hillross Financial Services Limited, by its conduct in contravening s 12DI(3) of the ASIC Act, breached its general obligation as a financial service licensee to comply with financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

Charter Financial Planning Limited