Federal Court of Australia

Redbubble Ltd v Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Limited [2022] FCA 1039

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The following orders in Federal Court of Australia Proceeding No QUD 403 of 2020 be stayed pending determination of this appeal or until further order:

(a) orders 1 and 2 made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022;

(b) order 3 made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022, subject to the following conditions:

(i) The Court notes that Redbubble has paid $78,250 into the trust account of the solicitors for the Appellant, Allens.

(ii) Subject to any further order of the Court, Allens is not to release those funds from its trust account before 5pm on the day of the delivery of the judgment in this appeal.

(iii) If the appeal proceeding:

A. is resolved such that order 3 made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022 is affirmed, the funds are to be paid to, or at the direction of, the First Respondent within 48 hours of the time to which paragraph (ii) above refers;

B. is resolved such that order 3 made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022 is overturned, the funds may be paid to, or at the direction of, the Appellant; or

C. does not resolve the question of damages wholly in favour of any of the parties, the funds are to be paid or released in accordance with the orders of the Court or as agreed between the parties; and

(c) order 4 made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022.

2. Subject to Orders 3 and 4 hereof, pending determination of this appeal or further order, the Appellant, by itself, its servants or agents, and without the licence of the First Respondent or the Second Respondent, be restrained from:

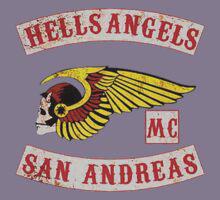

(a) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

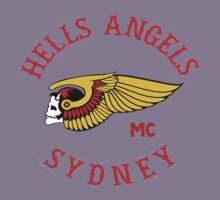

(b) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 723219 and 1257992 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

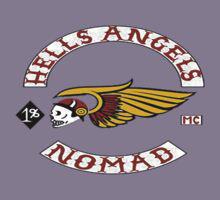

(c) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(d) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(e) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(f) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(g) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(h) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(i) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered;

(j) using the following image, or an image that is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the following image, as a trade mark in Australia in relation to the goods or services in which trade marks 526530, 723219, 1257992, 723463 and 1257993 are registered, and insofar as those trade marks remain registered.

3. The appellant will not be in breach of order 2 if:

(a) it maintains a system involving the surveillance of its website at www.redbubble.com (the Website) and the removal of images or other writing that might infringe the marks referred to in order 2 hereof which is no less rigorous than that which it had in place as at 24 August 2022 and is referred to in the affidavit of Mr Joel Barrett of that date as “Proactive Moderation”; and

(b) within seven days of an image to which order 2 refers being identified on the website by the Appellants or its servants or agents, the Appellant removes the image from the Website.

4. Notwithstanding Order 3, the Appellant will be in breach of Order 2 if on the First Respondent or the Second Respondent or both of them becoming aware of an image to which Order 2 refers being available on the Website, notifying the Appellant of the image by sending an email to dmca@redbubble.com (or such other email address as notified by Appellant in writing from time to time):

(a) with the subject field ‘Hells Angels Complaint’;

(b) identifying the image by reference to the location of the image on the Website in the form http://www.redbubble.com/people/[username]/works/[work number and name]; and

(c) stating that the First Respondent and/or the Second Respondent considers that the image would breach order 2,

the Appellant fails to remove the image or images from the Website within seven days of such email.

5. The Appellant is to prosecute the appeal expeditiously.

6. The costs of the application for a stay are reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DERRINGTON J:

Introduction

1 This is an application by Redbubble Limited (Redbubble) which is an appellant in this Court in proceedings QUD 282 of 2022 in which it seeks to appeal against:

(a) the orders made by Greenwood J on 19 July 2022 (July 2022 Orders) in Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Ltd v Redbubble Limited (No 5) [2022] FCA 837 (Main Judgment); and

(b) the orders made by Jagot J on 16 March 2022 (March 2022 Orders) Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Ltd v Redbubble Limited (No 4) (2022) 166 IPR 144 (Release Judgment).

2 The present application is made pursuant to r 36.08(2) or r 41.03 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (the Rules) for:

(a) a stay of orders 1 and 2 of the July 2022 Orders (2022 Injunctions);

(b) a stay of order 3 of the July 2022 Orders (Damages Award); and

(c) a stay of order 4 of the July 2022 Orders and order 2 of the March 2022 Orders (Costs Orders).

3 Redbubble also seeks an order against the respondents to the appeal for the production of communications between their solicitors and this Court which, without notice to it, resulted in the amendment of orders granting the 2022 Injunctions. It should be noted that the respondents to the appeal are Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (Australia) Pty Ltd (HAMC AU), which is the authorised user of certain registered trade marks which are owned by the registered owner Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporation (HAMC). Although both are represented by the same solicitors, HAMC, which was a necessary party to the proceedings pursuant to s 26(2) the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act), has filed a submitting appearance.

4 To a very real extent the focus of the present application concerned the appropriateness of the making of the 2022 Injunctions.

The urgency of the application

5 It should be noted that HAMC AU has recently filed its own interlocutory application in which it seeks orders that Redbubble be punished for contempt of the 2022 Injunctions. The statement of charge filed in the Court makes a charge only against Redbubble and no other person. As will become apparent, the July 2022 Orders made by Greenwood J were altered on 4 August 2022 by the insertion of a penal notice. A draft of the order incorporating the penal notice had been sent to the Court with the request that the order be made in that form. That draft added the name of Mr Ilczynski, the CEO of Redbubble, as a person who was obliged to obey the orders even though the 2022 Injunctions were not made against him. Amended orders were made in that form. The Court was advised that HAMC AU has sought to serve Mr Ilczynski with the orders, albeit without success. Nevertheless, the fact that HAMC AU has alleged that Redbubble is acting in breach of the terms of the 2022 Injunctions, that such contraventions amount to a contempt of court, and that fines should be imposed for such breaches, gives added significance and urgency to the present application. If the assertions underpinning HAMC AU’s allegations are correct, very significant consequences will follow if the orders are not stayed.

6 It may well have been the result of the urgency with which this matter was brought on that the submissions made to the Court were advanced at a high degree of generality. There is nothing pejorative in that statement which is merely a description of how the application unfolded. Nevertheless, it was somewhat difficult to ascertain from the submissions whether they were directed to the veracity of the decision from which the appeal has been made or the issue of the balance of convenience. That said, the written submissions of Mr Eliades for HAMC AU focused almost entirely on the latter and it will be assumed that they were directed to that issue.

Background

7 The appeals raised by Redbubble arise in the context of historic disputation between it and the respondents, HAMC AU and HAMC.

8 In broad terms, Redbubble operates an online platform through which goods are provided. It is not, however, a traditional supplier of goods. It and its related entities operate what is called an “online marketplace” at the web address of www.redbubble.com. That website operates by bringing together parties (referred to as “the Sellers”), who can upload and commercialise their artwork, and other persons who wish to acquire it. The Sellers are able to choose the artwork which they upload to the platform, the products to which the artworks might be printed or applied, and the titles, description and “tags” for the artwork on the website. Persons (referred to as “Purchasers”) interested in acquiring products with the artwork can choose the design or picture of their choice and the item to which it is applied and place an order for it. It appears that Redbubble facilitates that transaction including payment. Through a process, which was not entirely pellucid, the order is filled by a third party (referred to as a “Fulfiller”) and another third party (referred to as “the Shipper”) causes the package to be delivered.

9 There are, apparently, a number of other websites which supply similar services.

10 The evidence before the Court disclosed that there are some 49,200,000 pieces of artwork on the Redbubble website, and that number increases by about an average of 97,900 per day. This is relevant to the level of control which Redbubble might have with respect to the images which are displayed on its website, as it seems that it is not an infrequent occurrence that third parties, acting as Sellers, upload images or designs which infringe the intellectual property rights of others. This has occurred in relation to designs or artworks in which HAMC AU and HAMC have an interest, and that conduct has been the source of the disputation between them and Redbubble.

11 The sale and purchase transactions are automated and brought into effect by various software systems on Redbubble’s servers located in the United States of America. There is no substantial human intervention on the part of Redbubble although it charges a fixed service fee for each sale which occurs from the platform. The evidence discloses that the packages delivered by the Shippers are decorated with Redbubble’s livery and designs.

Prevention of copyright and trademark infringements

12 As mentioned, there has been a history of disputation between the parties arising from unauthorised uploads of artistic work to the Redbubble website which infringe the trade marks or other intellectual property rights of HAMC AU and or HAMC.

13 The first proceedings between Redbubble on the one hand and HAMC AU and HAMC on the other, commenced in around 2015 (the 2015 Proceeding) and resulted in a judgment by Greenwood J on 15 March 2019: Hells Angels Motorcycle Corp (Australia) Pty Ltd v Redbubble Ltd (2019) 369 ALR 408: in favour of HAMC AU and HAMC. It was held that the presence on Redbubble’s website of certain images which infringed HAMC AU and or HAMC’s intellectual property rights constituted a use of the images in Australia by Redbubble. It was further held that Redbubble was a primary infringer of the trade marks and HAMC AU was entitled to nominal damages for the infringement. There was no appeal from that decision.

14 Subsequent to the commencement of the 2015 Proceeding, Redbubble undertook steps to prevent the uploading or presence of images or designs on its website which infringed or might have infringed the intellectual property rights of HAMC AU and HAMC. The evidence shows that it emphasises to all Sellers that any content uploaded to its platform must not infringe third party intellectual property rights. Nevertheless, it is obvious that platforms such as Redbubble’s are open to abuse by third parties who ignore that directive. In order to counteract this type of activity Redbubble adopted a range of processes designed to prevent, mitigate and penalise such conduct. They include:

(a) the application of software to capture certain artworks before they can be publicly viewed on the website;

(b) regularly screening the website for infringing artworks. In particular, since the dispute with HAMC AU commenced, Redbubble has proactively removed artworks which it believes that HAMC AU might consider as involving an infringement of its rights and Redbubble has developed software tools to assist with that task; and

(c) consistently taking steps to improve its software capability and increasing the number of employees devoted to the screening process.

15 The evidence discloses that some millions of dollars have been spent on technology and software development every year in the implementation of these steps and that Redbubble is expanding and improving those techniques each year. In its written submissions Redbubble refers to these steps as “Proactive Moderation” and that expression is adopted in these reasons although it should not be thought that it carries any implication other than being a descriptor.

16 Redbubble’s Proactive Moderation has met with some success. Since March 2015 it has removed from its website more than 4,000 artworks which it believes HAMC AU might consider an infringement of its interest in certain registered trade marks, and it has taken that action without receiving complaint from any person. Additionally, on any occasion when HAMC AU has made a complaint that there has been an infringement of trade marks in which it has a relevant interest, Redbubble has acted promptly to remove any offending artwork or image.

17 This evidence is not disputed although as HAMC AU correctly identifies, it is evident that the Proactive Moderation was not sufficient to prevent all of the infringements of the trade marks in which it has an interest. Over time, further examples of allegedly infringing uploads were identified by HAMC AU and a second proceeding was commenced by HAMC AU in 2020 (the 2020 Proceedings).

The 2020 Proceedings

18 The 2020 Proceedings concerned eleven so-called infringing artworks which Sellers had uploaded to the Redbubble website. They were identified as examples 1 to 11. Although HAMC AU discovered these examples 1 to 11 on the Redbubble website, it did not immediately inform Redbubble of their existence such that the latter might take immediate steps to remove them. Rather, it took no action for an extended period of time and engaged in trap purchases of products with those artworks on several occasions. The first complaint which Redbubble received from HAMC AU about some of the alleged infringements occurred when the Originating Application which commenced the 2020 Proceedings was served on it on 4 January 2021. However, Mr Eliades for HAMC AU explained that the non-disclosure of these infringements to Redbubble was deliberate as it generated evidence of the apparent lack of efficacy of Redbubble’s Proactive Moderation. That would appear to be an acceptable explanation and, particularly so, in circumstances where Redbubble had asserted or, at least, suggested that its measures to prevent third parties from uploading infringing material were appropriately effective.

19 Redbubble has analysed each of the alleged infringements which were the subject of the 2020 Proceedings and has identified the circumstances in which they were uploaded. It is relevant that none of them were uploaded in Australia, that many were on the website for less than a fortnight and a number, albeit not all, were removed as a result of Redbubble’s Proactive Moderation. It is relevant that the only sales in Australia were to a person called “Mr Gavin Hansen” who was an agent of HAMC AU and tasked with conducting trap purchases for the purposes of the litigation.

20 The 2020 Proceedings resulted in judgment for HAMC AU with several orders being made. These were the July 2022 Orders referred to above and included:

(a) a declaration that Redbubble had used the sign “Hells Angels” in several of the examples and its use constituted infringing “use” pursuant to s 120(1) of the Act;

(b) a declaration that Redbubble had used the depiction of the “winged death head” (the device) in some of the example contraventions which constituted an infringement for the purposes of s 120(1) of the Act;

(c) injunctions restraining Redbubble from infringing the trademark “Hells Angels” or the device;

(d) an order that Redbubble pay damages assessed in the sum of $78,250; and

(e) an order that Redbubble pay the costs of the proceedings.

21 The day on which the orders of Greenwood J were made, 19 July 2022, was the day of his Honour’s retirement from the Bench. As is discussed below, this assumes some importance in relation to some of the issues now raised by Redbubble.

22 On 4 August 2022, the July 2022 Orders of Greenwood J were amended by Logan J by, inter alia, the inclusion of a penal notice. The amendment was given retrospective effect in that the orders of 19 July were reissued, purportedly as being effective as of that date, together with the penal notice. The circumstances in which that occurred are as follows:

(a) On 22 July 2022, the firm Bradley Rees Hogan which acted for HAMC AU and HAMC wrote to the Court seeking to have the orders endorsed in accordance with r 41.06 of the Rules and enclosed certain draft orders;

(b) The enclosed draft included the orders of Greenwood J together with a penal notice directed to Redbubble and Mr Michael Ilczynski who was Redbubble’s then Chief Executive Officer;

(c) There was correspondence between the firm Bradley Rees Hogan and the Federal Court in relation to the issuing of the orders with the penal notice.

(d) On 4 August 2022, Logan J made an order that Greenwood J’s July 2022 Orders be amended to include the penal notice and that the amended order be served on the respondents to the 2020 Proceedings being Redbubble and HAMC.

23 It is not in dispute that Mr Ilczynski had not been made aware of the application to have a penal notice directed to him and nor is it in dispute he had no opportunity to make submissions in that respect.

24 On 19 August 2022, Redbubble filed an appeal against the July 2022 Orders made by Greenwood J. The substance of the grounds of that appeal are considered later.

25 Subsequently on 29 August 2022, HAMC AU served on Redbubble its application for contempt of court relying on breaches of the orders made by Greenwood J and amended by Logan J. It was filed on 23 August 2022 but not served until 29 August 2022. It relies upon two allegedly infringing artworks which are referred to as examples 12 and 13. Of these it can be said, as a consequence of Redbubble’s preliminary investigation, that:

(a) neither example 12 nor 13 was uploaded by a user in Australia;

(b) example 12 was uploaded on 8 July 2021 and example 13 on 11 July 2022;

(c) the only sales to purchasers in Australia of examples 12 and 13 were to a Mr Shannon O’Neill who was an agent of HAMC AU, tasked with conducting trap purchases;

(d) the software used by Redbubble did not capture example 12 by image matching technology, apparently because the image had not been previously uploaded;

(e) the software did not capture example 13 due to a technical issue which was rectified on 20 July 2022; and

(f) Redbubble’s searches by keywords did not capture examples 12 and 13 as neither their titles nor tags contained the words “Hells Angels” and the title to example 12 involved an unusual misspelling in that “Hells” was misspelled “Helles”.

26 From the evidence it seems that the locating of examples 12 and 13 on the website by HAMC AU took some significant time, being at least 15 hours. This, was apparently a consequence of the misspelling in example 12 and the use of a particular name in example 13. The circumstances in which Mr O’Neill, who discovered the existence of examples 12 and 13, engaged in his search of the Redbubble platform were not fully explained.

27 Redbubble asserts, and it seems to be accepted, that HAMC AU has not shared any list of the keywords which the latter uses to search the Redbubble website and nor has HAMC AU taken up Redbubble’s offers to work with it to optimise the latter’s techniques for detecting and excluding any artwork which might infringe HAMC AU’s intellectual property.

28 The evidence also shows that Redbubble acted promptly to remove examples 12 and 13 from the website on becoming aware of their presence and subsequently modified its software and list of search keywords so as to detect any future similar infringements.

29 As is apparent from these circumstances, including the existence of HAMC AU’s application to punish Redbubble for contempt, the issue of whether the orders of Greenwood J (as modified by Logan J) should be stayed involves some urgency. If the orders stand, Redbubble may be in contempt of the Court’s orders and may be punished as a result. If they are stayed pending the appeal no further contempt will occur. Mr Eliades submitted that the contempt application only seeks the imposition of fines such that the impact of any breach may be relatively minor. That submission should be rejected. A contempt of a court order is a serious matter in and of itself. It is not minimised merely because the party seeking relief does not seek committal or sequestration of property. Even so, the imposition of a penalty for a repeated and prolonged breach may well be substantial.

The alleged release

30 In the course of the interlocutory steps of the 2020 Proceedings, Redbubble sought to raise an additional defence to the effect that it had been released from any liability in respect of the alleged infringements. This was said arise as a result of an agreement for release which had been entered into between HAMC as the registered owner of the marks in question and a company named as TeePublic, an entity which is apparently related to Redbubble. The release granted by HAMC extended to Redbubble. The application to raise this defence was refused by Greenwood J although an appeal from that refusal was allowed by consent: Redbubble Ltd v Hells Angels Motorcycle Corp (Australia) Pty Ltd (2021) 163 IPR 491. However, as a result of the foundation of Greenwood J’s conclusions leading to the refusal of leave to amend the defence, the determination of whether Redbubble was entitled to the benefit of the release was allocated to Jagot J. Her Honour held: Hells Angels Motorcycle Corp (Australia) Pty Ltd v Redbubble Ltd (No 4) (2022) 166 IPR 144: that Redbubble had been released by the agreement, but not in relation to the use of the marks on its website. As a result, for the purposes of the 2020 Proceedings that defence failed.

31 It should be mentioned that Redbubble does not rely upon any alleged deficiency in the reasons of Jagot J for the purposes of the present application even though it has appealed from the whole of it in its Notice of Appeal.

Relevant principles

Legislation

32 The application is made under rr 36.08 and 41.03 of the Rules.

33 Rule 36.08 of the Rules states:

(1) An appeal does not:

(a) operate as a stay of execution or a stay of any proceedings under the judgment subject to the appeal; or

(b) invalidate any proceedings already taken.

(2) However, an appellant or interested person may apply to the Court for an order to stay the execution of the proceeding until the appeal is heard and determined.

(3) An application may be made under subrule (2) even though the court from which the appeal is brought has previously refused an application of a similar kind.

34 Rule 41.03 of the Rules states:

A party bound by a judgment or order may apply to the Court for an order that the judgment or order be stayed.

Note: The party may rely on events occurring after the judgment or order takes effect.

Principles

35 The principles to be applied in relation to applications pursuant to r 36.08(2) of the Rules were summarised in Stefanovski v Digital Central Australia (Assets) Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1121 (Stefanovski) at [4]:

(a) A court should not be easily disposed to delaying the enforcement of a judgment obtained after a trial. Prima facie, the successful party at trial is entitled to the fruits of their judgment. In particular, judgments of the trial division should not be treated merely as provisional and, following a trial the successful party should generally have an unfettered entitlement to enforce their judgment;

(b) However, the provisions permitting the Court to grant a stay pending the determination of an appeal exist to prevent possible injustice arising from the enforcement of a judgment which might subsequently be overturned;

(c) It is not necessary for a party seeking a stay to show “special” or “exceptional” circumstances. All that needs to be shown is that the applicant has demonstrated that the case is an appropriate one for the exercise of the discretion in their favour (see Powerflex Services Pty Ltd v Data Access Corporation (1996) 67 FCR 65 and Re Middle Harbour Investment (in liq) (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales (CA), 15 December 1976));

(d) The applicant for a stay must necessarily provide sound reasons to justify a suspension of the successful party’s right to recover judgment (see McBride v Sandland No.2 (1918) 25 CLR 369, 374; Powerflex Services Pty Ltd v Data Access Corporation (1996) 67 FCR 65, 66);

(e) Necessarily, the applicant will need to establish that their appeal has some merit to it. They are not obliged to demonstrate that the appeal will be successful, or that success is more probable than not. The degree of confidence which a court needs to have in the appeal’s prospects will most likely vary with all of the circumstances of the case including the potential prejudice which might be suffered by the parties as the result of the granting or refusal of the stay. That said, where an appellant can demonstrate that they have substantial prospects on appeal, that will be a significant factor in favour of granting a stay.

(f) Although the applicant for a stay must necessarily establish the grounds of their application by admissible evidence, it must be kept steadily in mind that much of the evidence will relate to events which may occur in the future. Necessarily, the evidence produced must provide an appropriately sound foundation on which a court may assess the risk of those future events occurring. In that respect, for the purposes of establishing that the circumstances warrant the granting of a stay, the applicant must not leave the situation in a state of mere “speculation” or “argument”.

(g) A significant factor in any discretionary consideration is whether there is a real risk or probability that a successful appellant would be deprived of the fruits of their appeal if a stay is not granted (see Scarborough v Lew’s Junction Stores Pty Ltd (1963) VR 129, 130). That consideration extends to the circumstances where there is a real risk that it will not be possible for the successful appellant to be substantially restored to its former position if judgment is executed against it (see Cellante v G Kallis Industries (1991) 2 VR 653);

(h) Conversely, there is a strong reason for refusing a stay where it is established that there is a real risk that the granting of a stay may prevent the successful party at trial from obtaining the full benefits of their judgment if the appeal is unsuccessful.

36 Similarly, in Viagogo AG v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCA 175 it was said at [10] – [12]:

10. Rule 36.08 confers a broad discretion. Generally, there must be demonstrated “a reason or an appropriate case” to warrant the exercise of discretion in favour of granting a stay. It is not necessary to establish special or exceptional circumstances for the grant of a stay: Powerflex Services Pty Ltd v Data Access Corp [1996] FCA 460; (1996) 67 FCR 65 at 66.

11. Two questions must be considered: first, is there an arguable point on the proposed appeal: Nolten v Groeneveld Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1494 (Nolten) at [24] or some “rational prospect of success” in relation to any of the grounds of appeal: Burns v AMP Finance Ltd [2005] FCA 761 at [5]; and second, does the balance of convenience favour the grant of a stay: Nolten at [24], [46].

12. The party seeking the order bears the onus of demonstrating a proper basis for a stay, which must be fair to all parties: Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corporation Ltd (receivers appointed) (1985) 2 NSWLR 685 (Alexander) at 695. That party must demonstrate that there is a real risk that it will suffer prejudice or damage if a stay is not granted, which will not be redressed by a successful appeal: Kalifair Pty Ltd v Digi-Tech (Australia) Ltd, McLean Tecnic Pty Ltd v Digi-Tech (Australia) Ltd [2002] NSWCA 383; (2002) 55 NSWLR 737 (Kalifair) at [18]; Flight Centre Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2014] FCA 658 (Flight Centre) at [9(f)]. This requirement will be satisfied if a successful appeal will be rendered nugatory unless a stay is granted: Ali v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCA 860 at [11]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BMW (Australia) Ltd (No 2) [2003] FCA 864 (BMW) at [5]; Alexander at 695; Kalifair at [18].

37 It is also appropriate to notice the observations of McKerracher J in Ali v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCA 860 [11], where his Honour relied upon the observations in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BMW (Australia) Limited (No 2) [2003] FCA 864 where Finkelstein J said:

The principles which govern a court’s discretion in granting a stay pending the determination of an appeal are well known: see generally Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corporation Ltd (Receivers Appointed) (1985) 2 NSWLR 685. Although it is not possible to state exhaustively the considerations that may be taken into account in the exercise of this discretion, it is appropriate that I mention those that bear on this application. The general rule is that a stay will be granted where there is a likelihood that a successful appeal will be rendered nugatory: Wilson v Church (No.2) (1879) 12 Ch D 454, 458. A court will also consider the balance of convenience and the competing rights of the parties as well as whether either party will be prejudiced by the stay: The Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company Limited v The Commonwealth [No.3] (1913) 16 CLR 384, 386; Philip Morris (Australia) Ltd v Nixon [1999] FCA 1281 at [17]. Even though a judge will generally not be required to speculate about the appellants prospects of success, it is well established that a stay will not be granted in the absence of arguable grounds of appeal, or if the appeal is not bona fide: J C Scott Constructions v Mermaid Waters Tavern Pty Ltd (No. 1) [1983] 2 Qd R 243, 248; Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corporation Ltd (Receivers Appointed) (1985) 2 NSWLR 685, 695. It necessarily follows that a stay will not be granted if an appeal has no prospect of success: Australian Workers’ Union v Pilkington (Aust) Ltd (2000) 101 FCR 35, 43.

Merits of the appeal

38 As is apparent from the written submissions filed by the parties for the purposes of the application, little attention was given to the initial question of the merits or prospects of the appeal. Nevertheless, the issues that were raised are rendered slightly more complex by reason of the circumstances of the 11 examples of infringement which were the foundation of the causes of action in the 2020 Proceedings. Redbubble had previously admitted, in relation to examples 1 to 7, that similar conduct by it constituted a use of the trademarks under the Act. The same admissions did not apply in relation to examples 8 to 11. For that reason different defences were raised as between these two groups of alleged infringements and, necessarily, different issues arise on the appeal.

39 Ground 1 of Redbubble’s appeal seeks to raise significant questions in relation to the contraventions in respect of examples 8 to 11, the answers to which are far from self-evident. In particular, it seeks to assert that the appearance of any infringing images on its website in conjunction with the goods to which they might be applied, did not constitute either a use of the trade mark within the meaning of s 120(1) of the Act or an infringement by it. The issues underpinning this ground include whether the mere storing and displaying of images on servers in the United States of America could amount to conduct which involves any engagement with a trader or consumer in Australia with respect to any goods which are essential matters in order for a “use” to occur. Although this issue was determined against Redbubble by the primary judge, it is a point on which reasonable minds might differ as his Honour’s reasons reveal. Similar considerations arise around whether the evidence of the trap purchasers provides a useful guide to the events which might involve the ordinary Australian consumer. Redbubble seeks also to agitate whether the test for infringement as articulated by the learned primary judge was correct. It has always maintained that merely engaging in the conduct of its marketplace website did not constitute an infringement. It is far from clear that there could only be one answer to that question.

40 By ground 2 Redbubble raises the issue of whether, in the circumstances, examples 8 to 11 were in any practical sense available to an ordinary consumer in Australia. If not, there was no basis for finding that they had been used by Redbubble in the course of trade in or within Australia. The basis for this ground is that the artistic works the subject of examples 8 to 11 could only have been found via extensive searches on Redbubble’s website and it was most unlikely that such searches would be engaged in by an ordinary Australian consumer, rather than a person dedicated to searching for examples of the marks in respect of which HAMC AU was an authorised user. There is substance to that ground of appeal and, in particular, because the evidence reveals that no one in Australia had sought to acquire merchandise with those marks on it. Redbubble also seek to agitate the point that given the difficulty of locating such marks and the speed with which they were removed, it cannot be said that they were, in any practical sense, available to an ordinary consumer in Australia.

41 By ground 3 Redbubble asserts that, in the circumstances of this case, the infringements, if they occurred, were of such a minimal nature that they ought to be disregarded. Albeit an unusual submission, it is not without some merit given the manner in which the alleged infringements occurred.

42 Additionally, Redbubble asserts that the learned primary judge erred in making an award of damages. It advances a number of reasons for this including that HAMC AU did not, by evidence or otherwise, demonstrate that it or HAMC had suffered any loss by reason of the alleged impugned conduct. From this it asserts that the amounts awarded were not supported by any evidence. Similarly, it seeks to appeal against the award of damages made pursuant to s 126(2) of the Act in the sum of $70,000 on the grounds that the requirements of that section had not been satisfied. That, in part, is a legal argument. There is no need at this point to detail it in full. It suffices to observe that there is a case to be made that the damages were not available under s 126(2) in the particular circumstances of the case. It is an unusual circumstance of this case that neither HAMC AU nor HAMC apparently have sought to commercialise the marks in question. They simply seek to restrict their use to persons who are members of their own or their associated motorcycle clubs. Redbubble also relies upon the fact that the primary judge seemed to accept that its business model only provides a platform for others to engage in trade and it is those third parties who engage in infringing conduct. His Honour had held that Redbubble did not upload any content found to be infringing. In relation to this ground Redbubble also relies on the primary judge’s failure to take account of the nature and extent to which Redbubble went to prevent infringements from occurring.

43 By ground 7 Redbubble seeks to appeal against the grant of the 2022 Injunctions in the terms in which they were made. In part, this ground of appeal relies upon some of that which has already been said as to whether or not any infringement occurred. However, Redbubble additionally asserts that the scope of the injunctions granted are vastly in excess of what is required to prevent infringement. The terms of the injunctions were as follows:

1. Redbubble is restrained whether by itself, its officers, servants or agents or otherwise howsoever, from using the sign “Hells Angels” as depicted in Examples 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 of Attachment C to the reasons and as depicted in Examples 8, 9, 10 and 11 of Attachment D to the reasons, or any sign substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, a sign bearing the words “Hells Angels”, on the website operated by Redbubble in relation to trade in goods to which the sign can be applied, where such goods are goods in respect of which Trade Mark No. 526530, Trade Mark No. 723219 and Trade Mark No. 1257992 is registered.

2. Redbubble is restrained whether by itself, its officers, servants or agents or otherwise howsoever, from using the sign being the device described in Declaration 2 of these declarations and orders as depicted in Examples 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 of Attachment C to the reasons and as depicted in Examples 8, 9, 10 and 11 of Attachment D to the reasons, or any sign substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, a sign consisting of the device, on the website operated by Redbubble in relation to trade in goods to which the sign can be applied, where such goods are goods in respect of which Trade Mark No. 526530, Trade Mark No. 723463 and Trade Mark No. 1257993 is registered.

44 As was explained above, the learned primary judge had held that the appearance of the infringing marks on Redbubble’s website were a use by it and that use resulted in an infringement. The injunctions appear to be directed to that “use” within the meaning of the Act.

45 Mr Cobden SC submitted that the injunctions so granted are what might be referred to as “obey the law” injunctions, in the sense that they are framed in terms of requiring compliance with the Act. He further submitted that there exists a lively debate in the authorities as to whether such injunctions should be granted in trademark cases as opposed to patent cases. There is an arguable point in relation to this issue. In Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation (No 2) (2019) 147 IPR 386 (Calidad v Seiko Epson) consideration was given to the diverging views as to whether the several statements in the leading texts on trade mark law in Australia were in error in suggesting that granting an injunction in general form “should probably be regarded as inappropriate”. Their Honours disagreed with that proposition in relation to either trade marks or patent infringement although, as Mr Cobden SC rightly submitted, that case was concerned with only a patent infringement. He further submitted that there was some inconsistency with the earlier decision of the Full Court (Bennett, Katzmann and Davies JJ) in Christian v Societe Des Produits Nestle SA (No 2) (2015) 327 ALR 630, 667 – 668 [182] (Christian v Nestle) which doubted whether injunctions should be granted where they only have the effect of exposing a respondent to the risk of contempt if there is non-compliance, rather than leaving the owner of the intellectual property rights with the entitlement to commence further proceedings for any subsequent breach. The obiter observations in Calidad v Seiko Epson at 396 [48] – [49] disagreeing with this view do not rise as high as concluding that the view is plainly wrong.

46 In these circumstances it can be accepted that there exists some disagreement in the authorities as to the appropriate scope of an injunction which might be granted in cases such as the present and it follows there is some real substance in this aspect of Redbubble’s appeal as well.

47 It is, perhaps, a good example of the difficulties associated with the particular form of injunctive relief granted in the present case that the 2022 Injunctions are in terms which prevent Redbubble using images or artistic works which had been determined did not infringe the rights of HAMC AU and HAMC. A number of images and works are referenced in Redbubble’s written submissions. The terms of the injunctions granted also prevent the use of the marks even if the use of such is not “as a trade mark”. It was not submitted by HAMC AU that these criticisms of the scope of the injunction were in error.

48 Finally, Redbubble seeks to appeal on the question of costs. It claims that it was not given an opportunity to be heard on that question and, in particular, that it was denied the opportunity to make arguments including with respect to the operation of the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth) and r 40.08(a) of the Rules. It also advances the contention that the claim by HAMC AU in the 2020 Proceedings was for damages in an amount of at least $1 million, but the award fell substantially short that amount. Indeed it was only about 7% - 8% of the claim. It was submitted that this issue in relation to the question of costs arose as a consequence of Greenwood J delivering his judgment and making orders at 4:15pm on the last day of his Honour’s tenure on the Court and, unfortunately, his Honour seemingly overlooked that Redbubble had sought to reserve its position on costs. There was no substantive submission made on behalf of HAMC AU that Redbubble’s appeal in relation to this ground was not solidly founded.

49 Redbubble also seeks to appeal from the decision of Jagot J however, as has been mentioned, its prospects of success in that appeal are not relied upon for the purposes of the stay application.

50 Given the foregoing there are more than sufficient grounds on which to conclude that Redbubble’s appeal has some merits to it. Indeed, in the absence of any submissions from HAMC AU in relation to a number of the grounds of appeal it is possible to conclude that Redbubble has not insignificant prospects of success with respect to, at least, part of the appeal.

The balance of convenience

51 The main area of contention between the parties concerned whether the balance of convenience favoured the granting of the stay. Redbubble has indicated it is willing to submit to a form of injunction in relation to the use of the marks of HAMC AU for the purposes of securing the latter’s position pending the determination of the appeal. It submitted that an appropriate injunction would restrain it from using the several marks which were the subject of the 2020 Proceedings in relation to goods and services. However, the form of the injunction proposed by it was subject to two matters. The first was that it would not be breached if, when an image that infringes any of the marks appears on the Redbubble website, it is removed within seven days of being uploaded. The second was that the injunction was subject to HAMC AU and HAMC, on becoming aware of any infringing images on the Redbubble website, notifying Redbubble by providing specific information about the infringement. This matter was to be subject to the further proviso that Redbubble would only be in breach of the injunction if it failed to remove the infringing image within seven days of being notified of it.

52 It was submitted on behalf of HAMC AU that the scope of the proposed consent injunction was insufficient because it did not provide an unqualified undertaking not to use the marks of HAMC AU and HAMC and this, so the submission went, was essential. In support of this submission, Mr Eliades referred to Tamberlin J’s decision in Esco Corporation v PAC Mining Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1018 [20] (Esco Corporation v PAC Mining). That was a case concerned with the granting of a stay of a judgment which had concluded that the successful applicant’s patent had been infringed. Mr Cobden SC for Redbubble submitted that injunctions granted in relation to patent infringements are usually stricter than those granted in cases involving the infringement of other intellectual property rights. He further submitted that in Esco Corporation v PAC Mining Tamberlin J did not require, as a condition of the granting of a stay, an undertaking that there would be no infringement of the successful applicant’s patent. On the contrary, the learned judge stayed his final orders granting injunctions pending the appeal, but did so on the respondent’s undertaking that it would, inter alia, “keep accurate records of sales, shall not destroy any records in relation to their business, shall not dispose of or encumber any assets otherwise than in the ordinary course of business”. That was indeed the effect of his Honour’s orders. As Mr Cobden SC submitted, this had the effect that until the hearing of the appeal the respondent was able to pursue its business on the basis that the injunction had not been granted. It was submitted that this had the effect that the respondent could “infringe the patent willy-nilly”. That is, with respect, an overstatement. All it meant was that the respondent was not restrained by an order of the Court from infringing the patent. If its appeal was ultimately unsuccessful, the respondent would nevertheless have infringed the applicant’s rights and would be required to remedy any such breach.

53 For the purposes of the present application it is relevant that in Esco Corporation v PAC Mining Tamberlin J stayed the final injunctive relief on the undertaking offered with the result being that any infringements in the period to the determination of the appeal would not constitute a contempt of the Court’s order. Here, there is no undertaking to keep accounts although that is immaterial given that the interests of HAMC AU and HAMC do not concern the commercial exploitation of their marks. The undertakings or consent injunctions offered do, however, provide a measure of protection for HAMC AU and HAMC by requiring Redbubble to act on the identification of any infringing work located on its website. Mr Eliades submitted that Redbubble’s proffered consent injunction is insufficient in that it relates to certain specific marks which were the subject of the 2020 Proceedings and no more. Therefore, if an image which was no more than a slight modification to the marks as identified were uploaded to the Redbubble website, the injunction would be of no utility. Mr Eliades provided the example of one of the marks which Greenwood J had held had been infringed, being altered to remove the “s” from the word “Angels”. He submitted that the uploading of such an image would not infringe the proposed consent injunctions. There is force in that submission. It may be the case that persons with a malevolent intent to upload infringing works might slightly alter the images which they offer to sell in order to avoid whatever safeguards there may be on Redbubble’s website. The example referred to by Mr Eliades would suggest this to be so. In the course of the hearing Mr Cobden SC suggested that the wording of the proposed consent injunctions could be widened. There is merit in that and any injunction made as part of an order for a stay should extend to any marks which are “substantially identical with or deceptively similar to” those which have already been identified.

54 It was submitted by Mr Eliades that the proposed interim injunctions offer no protection for HAMC AU and HAMC and that Redbubble was unwilling to cease infringing their marks such that their rights will be severely impacted. That overstates the position. HAMC AU and HAMC’s rights in relation to their marks retain the protection provided by the Act, entitling them to recover from Redbubble for any infringement. Importantly, this is not a case where any infringement by Redbubble arises as a result of any intentional act on its part. If there is an infringement it occurs as the result of the intentionally dishonest acts of third parties who seek to derive a profit from breaching HAMC AU and HAMC marks, albeit by utilising Redbubble’s platform. It is a misstatement to suggest that Redbubble is unwilling to cease the conduct which is alleged to constitute infringing conduct. The evidence of the steps it has taken to date to prevent the uploading of any potentially infringing material, referred to here as the Proactive Moderation, was not questioned and nor was the veracity of its intention in undertaking these tasks. In addition, although there is no question that HAMC AU and HAMC are entitled to protect their interest in the marks, they both suffer no economic loss consequent upon any infringement in the sense that they are not deprived of income which they would otherwise have made. Their sole interest is to prevent persons who are not members of their clubs from wearing or displaying their insignia or the device. Whilst that entitlement exists and should be protected, necessarily the lack of any desire to commercially exploit the marks has the consequence that no economic loss will be sustained if an infringement occurs.

55 Mr Eliades also submitted that the proposed orders, which require that Redbubble be notified by HAMC AU or HAMC of the existence of potentially infringing items on the website, “removes the right to rely on further infringements after the date of Justice Greenwood’s orders and raises the only option for HAMC to take action to enforce its right in commencing yet a third proceeding for infringement”. This too can be rejected. HAMC AU is entitled to pursue remedies under the Act as it has done previously. The only effect of the orders is that Redbubble will not be in contempt of the Court’s extant orders if, assuming the conclusions of the primary judge are correct, additional infringing works are uploaded to its website. Moreover, the orders are interim and only operate until the determination of Redbubble’s appeal.

56 However, a justifiable complaint is made that the proposed orders would have the effect that the non-compliance can only arise if HAMC AU and or HAMC continue to monitor the Redbubble website. On the basis of the form of the proposed orders Redbubble would be entitled to abandon those steps which it had previously undertaken to detect and remove potentially infringing marks from its website and simply await the receipt of a complaint from HAMC AU or HAMC. In support of this submission Mr Eliades relied upon the observations of the learned primary judge (at [135]) to the effect that he did:

… not accept that a party otherwise establishing infringing conduct on the part of a respondent ought to be denied a remedy on the footing that if infringing conduct does occur, the real remedy upon which an applicant should rely is that the applicant or its solicitor should draw the infringing conduct to the attention of Redbubble as and when it occurs and Redbubble will take steps to moderate or remove the uploaded material, as an adjunct to the steps Mr Toy describes in his affidavit …

57 However, those comments refer to the form of the final orders made following the hearing. They are not relevant to the terms of an undertaking or consent injunction seeking to preserve the status quo as best as is possible pending the appeal. In any event, it is unlikely that the intended effect of Redbubble’s proposed orders was that the removal of any offending material would be conditional upon it being brought to the attention of Redbubble by HAMC AU. Nevertheless, it must be made clear that a condition of the granting of the stay should be the maintenance of the regime which has been referred to in the course of this application as Redbubble’s Proactive Moderation. In the affidavit material before the Court it was evident that Redbubble intended to continue these monitoring systems in any event. Such systems have been previously successful in detecting and removing a substantial number of potentially infringing works and there is no reason why Redbubble should not maintain that system until the appeal has been determined, at least. Any stay should be subject to the maintenance of the status quo which has existed previously in relation to the detection and removal of potentially infringing items. This obligation to preserve the Proactive Moderation systems must necessarily be linked with the requirement to remove any image within seven days of detection.

58 Although these measures provide some level of protection, it is appropriate to include as part of the interim injunctive relief the arrangements proposed by Redbubble which afford HAMC AU and HAMC the opportunity to notify of the existence of any infringing marks on the website. This, however, does not impose any obligation on HAMC AU or HAMC to search the Redbubble data base and Redbubble’s own processes are likely to detect most potential infringements. On the other hand it is apparent from the evidence that HAMC AU and HAMC have previously been assiduous in scrutinising the website and there is nothing to suggest that they will cease doing so. On the assumption that this will continue it is appropriate that Redbubble be required to actively respond to any notification which it receives of such an infringement. However, unlike the proposed orders sought by Redbubble, the obligation to respond positively to such notifications should be in addition to the obligation to maintain the system of Proactive Moderation at its current level. The notification of the infringements should not be a condition of the obligation on Redbubble to maintain surveillance of its data bases.

59 Submissions were made as to the effect of the decision in Calidad v Seiko Epson in relation to the issue of the balance of convenience. That case has been discussed previously and its details do not require repetition. Nevertheless, it is necessary to observe that it was concerned with the form of final injunctions. Here, in the consideration of the balance of convenience, the Court is concerned with whether any undertaking or consent injunction provides a sufficient level of protection to HAMC AU which has secured a favourable verdict at the trial. It seemed to be the position of HAMC AU, as it was advanced by Mr Eliades, that the price to be paid for a stay of the orders of Greenwood J was Redbubble’s submission to an interim injunction in a form generally similar to that granted in in Calidad v Seiko Epson. That would lead to the somewhat aberrant result that there would be no effective stay at all. The final injunction would simply be replaced with an interim one of the same effect. The purpose of the interim injunctions to which Redbubble consents in this case is that they are to act in lieu of an undertaking which might otherwise have been given. Such undertakings are usually required to minimise the damage which the successful party might suffer on the assumption that the first instance decision is correct. On that basis the injunctions which have been identified above in these reasons are adequate to substantially protect the interests of HAMC AU and HAMC pending the outcome of the appeal.

60 It was further submitted that Redbubble’s efforts to prevent additional alleged infringements were “untrustworthy”. It seemed to be suggested that the occurrence of additional potential infringements, which it should be accepted for the purposes of this application did occur, had the result that the Proactive Moderation was insufficient to protect the interests of HAMC AU and HAMC such that the interim injunctions should be made in broader terms: Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Sharman Networks Ltd (2006) 150 FCR 110 [43]. Yet again, the matters in that case related to the form of final injunctions rather than the type of appropriate interim protection which should exist whilst the initial orders are stayed. In any event, the evidence establishes that some 4,000 artworks which might potentially infringe the marks in which HAMC AU and HAMC have an interest have been detected and removed, as opposed to a relatively small number which have evaded that detection. That rather suggests that Redbubble’s Proactive Moderation is generally successful in protecting HAMC AU and HAMC’s interests, albeit that those entities would obviously prefer that no infringement occur. The evidence does not warrant the conclusion that the efforts by Redbubble to detect and remove potentially infringing artwork can be described as “untrustworthy”.

61 Finally, as is discussed below, Redbubble has agreed to pay into the trust account of its solicitor the sum of $78,250 to be paid at the direction of the Court. This secures the receipt of compensation by HAMC AU should the appeal not be successful.

Conclusion on the balance of convenience in relation to the injunctive relief

62 For the foregoing reasons the balance of convenience obviously favours the granting of the stay subject to the form of injunctive relief to which reference has been made. The steps required of Redbubble are likely to substantially protect the interests of HAMC AU and HAMC which are not concerned with the economic exploitation of their marks and will not suffer economic loss were some infringements to occur. That is not to diminish their entitlement to protect the marks in respect of which they have an interest, but it is relevant to the consequences of the orders presently sought.

Stay of payment of damages

63 Redbubble also seeks a stay of the order requiring it to pay damages in the amount of $78,250. It was submitted that if that amount was paid to HAMC AU there is a real risk that Redbubble would be unable to recover that sum if the damages award is ultimately overturned or reduced on appeal. In the circumstances there are sufficient grounds to justify a stay of the award of damages. They are:

(a) That there is sufficient doubt as to the foundation of the conclusion that Redbubble infringed the interests of HAMC AU in the relevant trade marks;

(b) The award of damages by Greenwood J was not made on the basis of any economic loss sustained by HAMC AU but pursuant to s 126(1)(b) of the Act as a mark of the Court’s disapproval of the infringements. In that sense, if the stay is ordered HAMC AU will not be out of pocket in respect of funds which it would otherwise have earned from its marks;

(c) Redbubble has taken steps to secure the sum of $78,250 for HAMC AU by paying that amount into the trust account of its solicitors to be applied at the direction of the Court. Whilst HAMC AU submitted that the funds should be paid into its own solicitor’s trust account there is no real difference between the two repositories of the funds;

(d) HAMC AU has a share capital of only $100;

(e) In the 2015 Proceeding, HAMC AU made submissions to the Court to the effect that it would be unable to provide security for costs of more than $30,000 and it therefore appears to be relatively impecunious;

(f) As part of that security for costs dispute, HAMC AU relied upon evidence in which Mr Mark Nelms, who was its sole director and secretary at the time and who remains a director, represented that HAMC AU had no “real estate in Australia or outside Australia or … any others assets of substantial value” (apart from the copyright in a particular image of a skull, which HAMC AU had not valued); and

(g) ASIC proposed to deregister HAMC AU, on 6 March 2018 and again on 23 February 2021, under sections 601AB(1) or (1A) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

64 There was a suggestion that HAMC AU was intending to use the receipt of damages for the purposes of meeting its costs of litigation with its own legal representatives, but there was very little evidence that it requires these funds for that purpose. It has been an active litigator against Redbubble over a number of years and there is nothing to suggest that it is unable to pay its legal representatives as and when it needs.

Costs orders

65 As has been mentioned, Redbubble seeks to appeal the costs orders made by Greenwood J on the basis that it was not given an opportunity to be heard in relation to costs. There were no substantive submissions made on behalf of HAMC AU in relation to this ground and the issue appears to have arisen in the unusual circumstances in which the learned primary judge handed down his reasons and made his orders.

66 Given the financial circumstances of HAMC AU which are referred to above and the consequential likelihood that it may be unable to repay the costs if the appeal is successful, there is sufficient reason to stay the orders as to costs pending the appeal’s determination.

67 Redbubble also sought a stay of the costs orders made by Jagot J in relation to that part of the proceedings dealt with by her Honour. However, the substance of the submissions was merely that it would be more convenient were all of the cost orders to be dealt with contemporaneously. Although that may well be undoubtedly true, it offers no basis on which the costs awarded in favour of HAMC AU by her Honour should be stayed. That relief is refused.

Amendment of orders of the Court

68 Redbubble also sought a mandatory final injunction requiring HAMC AU to provide to it all documents relating to the circumstances in which it secured the insertion of the Penal Notice into the orders of Greenwood J of 19 July 2022 which also added the name of Mr Ilczynski. Whilst the circumstances in which that occurred raise some potential concerns, it is not presently relevant to any issue in the proceedings. Interlocutory injunctions can only be used in support of final relief and not for the purposes of inquiring into peripheral matters. The relief in relation to the correspondence with the Court should also be refused.

69 In relation to this matter, it must be noted that the solicitor for HAMC AU, Mr Peter Bolam, deposed to the circumstances in which the amendments to the orders were made and attached the apparently relevant correspondence. There is more than sufficient information disclosed in that affidavit to permit Redbubble to ascertain what had occurred and nothing further is required in this respect in any event.

Costs

70 Although Redbubble has had substantial success on this application, it may be that it will be ultimately unsuccessful on the appeal. If that were to be the case there is no reason why it should automatically recover the costs of this application despite the opposition by HAMC AU and HAMC. In those circumstances the costs of the stay application should be reserved to the Full Court which determines the appeal.

I certify that the preceding seventy (70) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Derrington. |

Associate: