Federal Court of Australia

MF Lady Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Henry Morgan Limited [2022] FCA 978

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The defendant be wound up pursuant to s 461(1)(k) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) on the ground that it is just and equitable that the company be wound up.

2. Ian Niccol and Vincent Pirina are appointed as the joint and several liquidators of the defendant.

3. The plaintiffs' costs of this application are costs in the winding up of the defendant.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[3] | |

[3] | |

[5] | |

[9] | |

[13] | |

[16] | |

[21] | |

[35] | |

[35] | |

[38] | |

[44] | |

[59] | |

[62] | |

[65] | |

[68] | |

[70] | |

[80] | |

[101] | |

[101] | |

[110] | |

[111] | |

[111] | |

[113] | |

[135] | |

Transactions in relation to connected companies in late 2016 | [139] |

[146] | |

[146] | |

[149] | |

[157] | |

[160] | |

[165] | |

[173] | |

[177] | |

[177] | |

[178] | |

[191] | |

[195] | |

[201] | |

[215] | |

[219] | |

[221] | |

[222] | |

[223] | |

[224] | |

[228] | |

[229] | |

[234] | |

[236] | |

[239] | |

[246] | |

[254] | |

[254] | |

[259] | |

[263] | |

[264] | |

[268] | |

[279] | |

[292] | |

[299] | |

[304] | |

[307] | |

Resolutions concerning changes in Investment Mandate or purpose | [319] |

[331] | |

[340] | |

[344] | |

Whether plaintiffs are acting unreasonably in not pursuing another remedy | [349] |

[358] | |

[360] | |

[361] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

1 Henry Morgan Limited (HML) is a public company which, until 3 February 2020, was listed on the Australian Securities Exchange Ltd (ASX). The plaintiffs apply for it to be wound up pursuant to s 461(1)(f) or s 461(1)(k) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), that is, on a ground that can be broadly described as oppression, or on the ground that it is just and equitable. HML opposes the application.

2 For the following reasons, an order winding HML up will be made.

Background to the corporate group

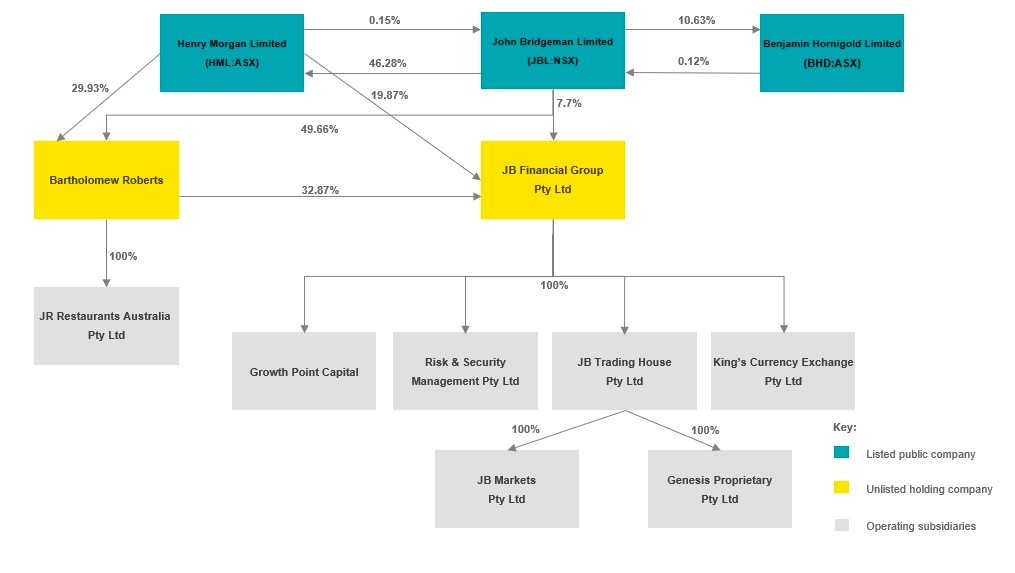

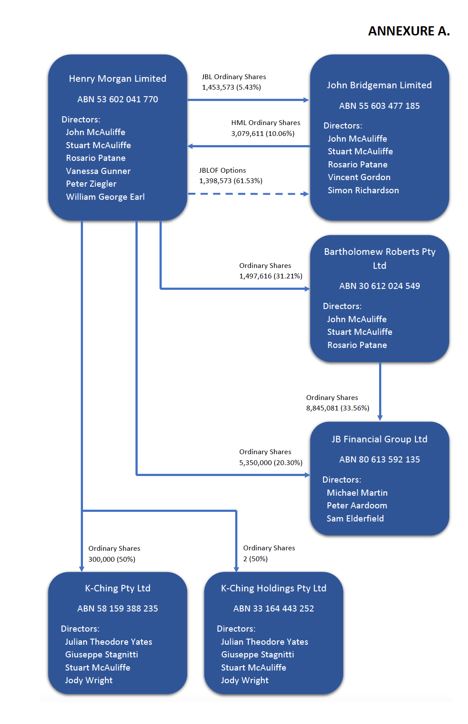

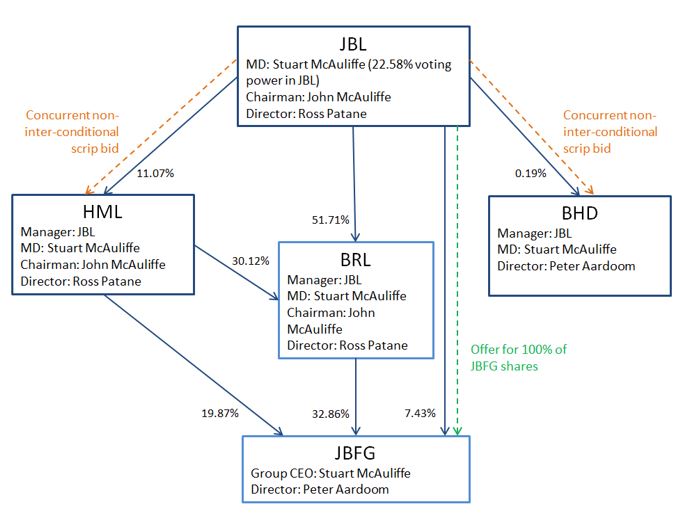

3 HML is part of a complex corporate group, which is best described by means of the following diagram. The diagram is taken from a report dated 13 December 2019 that was prepared by administrators of one of the companies in the group, JB Financial Group Pty Ltd (JBFG):

Diagram 1 - corporate group structure

4 Neither party contested the accuracy of the diagram. However the question of the relationships between the various companies, including whether they were relationships of control, was controversial. Describing the companies as a corporate group implies no finding that they are, for example, 'holding companies' or 'subsidiaries' of each other as those terms are defined in the Corporations Act. At this point it is simply convenient to group the companies together for the purpose of this judgment.

5 According to the New Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol 8 (15th ed, 1993), Sir Henry Morgan was a 'Welsh buccaneer, most famous of the adventurers who plundered Spain's Caribbean colonies during the late 17th century'. Henry Morgan Ltd was incorporated on 26 September 2014. In late 2015 it made an initial public offering of its shares, together with one option for every share issued. The prospectus for that public offering described it as an unlisted investment company which sought to become a listed investment company on the ASX.

6 The prospectus referred to a 'Management Services Agreement' with John Bridgeman Limited (JBL, the company in the centre of the top row of Diagram 1) into which HML had entered on 12 March 2015. The agreement was said to relate to the provision of investment management services to HML.

7 The public offering closed on 17 December 2015, having raised $15.6 million. The official quotation of the issued shares in HML on the ASX commenced on Friday 5 February 2016. It appears that approximately $15 million in further funds were raised by reason of the conversion of options over subsequent years.

8 On 9 June 2017, all of HML's securities were suspended from quotation on the ASX, in circumstances that will be described below. From around June 2018, HML began to ask ASX to lift the suspension. Substantial correspondence between HML and ASX ensued, which will also be described further below. On 30 May 2019, ASX expressed the view that it would be inappropriate to reinstate the securities of HML to trading until the outcome of certain investigations by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) were known. ASX removed HML from its official list on 3 February 2020.

9 The book International Criminals Past and Present (Frederic Boutet, Walter Mostyn trans, Hutchinson & Co, 1930) records that '[c]onspicuous among those pirates of the seventeenth century were the strange beings who were known as the Kings of Madagascar, and of whom James Avery became the most famous' (at 124). Avery had many aliases, including Henry Every, Long Ben and Captain Bridgeman, and so went by the name of John Bridgeman: Encylopaedia Britannica (online). John Bridgeman Limited, that is, JBL, is a public company. It was listed on the National Stock Exchange of Australia (NSX). That listing was, however, suspended on 1 October 2019, because the company failed to lodge its audited financial statements for FYE 2019 (although the securities had originally been suspended on 10 April 2019). On 23 October 2020 the NSX removed JBL from its official list which, according to NSX, was due to the non-payment of annual listing fees for FYE 2021 (this judgment will use the convention 'FYE' to designate the financial year ending on 30 June in the relevant year).

10 Up to at least the end of FYE 2018, the main business of JBL was investment management and, as has been said, it was party to an agreement for it to provide services of that kind to HML. JBL not only acted as the investment manager for HML, as at 16 June 2021 (the date of Mr McAuliffe's first affidavit in this proceeding) it held a 46.28% interest in HML.

11 International Criminals Past and Present describes Bartholomew Roberts as 'undeniably the greatest pirate captain of his time', and leader of the 'most formidable gang of pirates that ruled the waves in the eighteenth century' (at 172, 176). Bartholomew Roberts Pty Ltd is another company in the group (in the second row of Diagram 1). JBL was also the manager of investments for Bartholomew Roberts Pty Ltd and, as at 13 December 2019, JBL held a 49.66% interest in that company. HML also held a 29.93% interest in Bartholomew Roberts Pty Ltd as at 13 December 2019.

12 Benjamin Hornigold was one of a 'powerful and insolent' group of pirates in the Bahamas though after receiving a pardon he 'was back at sea; but this time in the service of law and order' engaged 'in hunting down his former associates': Caribbean Pirates (Warren Alleyne, Macmillan Education, 1986) at 32, 33, 36. JBL is also the manager of investments for Benjamin Hornigold Limited (BHD), the other company at the top of Diagram 1. BHD is listed on the ASX.

13 Diagram 1 shows that between them, HML, JBL and Bartholomew Roberts held approximately 60% of the issued shares in JBFG as at 13 December 2019.

14 It can also be seen from Diagram 1 that JBFG directly and indirectly held 100% of the shares in a number of subsidiary companies, including King's Currency Exchange Pty Ltd and Growth Point Capital Pty Ltd, subsequently known as Capital Credit Pty Ltd (Capital Credit). According to the plaintiffs' submissions, holding those shares was its predominant function.

15 Receivers were appointed to JBFG on 28 October 2019, and on 19 November 2019 it was placed into voluntary administration. On 5 August 2020 it went into liquidation.

16 Stuart McAuliffe is the Managing Director of HML and has been since it was incorporated on 26 September 2014. He is also a director of JBL; in fact, since 8 January 2015 he has been JBL's Managing Director and Chief Investment Officer.

17 Between 15 December 2016 and 21 February 2018, Mr McAuliffe was also a director of JBFG, and between 8 May 2017 and 3 November 2019 he was the Group Chief Executive Officer of that company.

18 Between 28 September 2016 and 12 June 2019, Mr McAuliffe was also a director of BHD. He was appointed executive chairman of BHD in or about February 2017 and resigned as a director of BHD on 12 June 2019.

19 Also, since 22 April 2016, Mr McAuliffe has been a director of Bartholomew Roberts.

20 Also, between at least August 2016 and April 2019, Stuart McAuliffe's father John McAuliffe, and one Rosario (Ross) Patane were directors of each of HML, JBL and Bartholomew Roberts. (Save where necessary for clarity, I will generally call Stuart McAuliffe 'Mr McAuliffe' in this judgment, and will refer to John McAuliffe by name.)

The proceeding, the pleadings and the issues

21 The first plaintiff commenced this proceeding on 24 December 2020. The second plaintiffs were joined as parties on 10 November 2021. The matter went to trial over two days on 13 and 14 December 2021. Final written closing submissions were filed by the plaintiffs on 20 January 2021. HML made an application to reopen which was heard and dismissed on 30 June 2022, for reasons that will be given below.

22 The plaintiffs are shareholders in HML; in the case of the first plaintiff, as a beneficial owner through custodian arrangements and in the case of the second plaintiffs as registered shareholders. By the time of trial, no point was taken as to the plaintiffs' standing to apply to wind the company up.

23 The matter proceeded on pleadings. However several potentially significant developments occurred after the close of pleadings, and these were the subject of evidence filed shortly before trial which was largely admitted by consent. Counsel for the parties accepted in closing that the issues at trial had changed since the pleadings and that the parties were content to deal with those issues in substance, and that was also manifest throughout the course of submissions. For that reason it is not necessary to describe the pleadings in great detail. They are mainly relevant here for the purposes of identifying factual matters that are not in dispute.

24 For the most part HML does not dispute the underlying facts on which the plaintiffs rely. Most of those facts are matters of public record, such as the contents of the prospectus for the initial public offering, the share registry initially engaged by HML, the holding of annual general meetings (AGMs), and the release of reports to the ASX. In broad terms the parties joined issue on whether the company should be wound up by reference to the following alleged matters:

(a) HML's failure to conform with the purposes or objects stated in the prospectus under which it raised funds from investors;

(b) related party transactions, at least some of which have caused HML to suffer loss; and

(c) various concerns that could be classified as compliance concerns (which is neither to minimise nor to emphasise their importance, if established), namely HML's lack of a share registry, its failure to maintain the required number of directors, its failure to hold AGMs, its failure to publish financial reports and its failure to maintain a registered office or principal place of business. The plaintiffs submit that these issues have been rectified only belatedly, and for the most part not at all.

25 In relation to the compliance concerns, the plaintiffs submit that HML has displayed a cavalier attitude to the requirements to lodge accounts and the delay is not adequately explained. They also submit that the unaudited accounts that had been provided by the time of the hearing give rise to real concern about whether HML is insolvent. The plaintiffs also point to what they say was a large number of statutory notices and requests from ASX and ASIC.

26 Other alleged matters on which the plaintiffs relied in closing to submit that HML should be wound up were as follows:

(1) The 'substratum' of HML has collapsed. It had been marketed to shareholders as a listed investment company but it was no longer listed and had engaged in no trading activity for the last two years. Its now stated purpose is instead to pursue litigation opportunities, chiefly (perhaps only) against ASX. The plaintiffs say that is entirely outside the common understanding of members when the company was formed and listed.

(2) HML's affairs were being conducted in a manner that was oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to or unfairly discriminatory against a member or members or in a manner that was contrary to the interests of members as a whole. The plaintiffs relied in particular on an extraordinary general meeting that was held on 3 December 2021 (EGM), which they say was conducted in an oppressive manner, and on various loans and other transactions with related parties, on the lack of trading activities and the failure to maintain appropriate standards of corporate governance.

27 A theme which underlies many of these allegations and the plaintiffs' case as a whole should also be mentioned. It is that Mr McAuliffe is alleged to have been in substantial control of HML, JBL and JBFG, which in turn informs the plaintiffs' characterisation of various transactions as related party transactions. But, the plaintiffs submit (and HML agrees), it is neither necessary nor appropriate for the Court to make findings of contraventions of the Corporations Act in relation to alleged related party transactions at this time. It is enough, according to the plaintiffs, that the fact and complexity of the transactions, along with the lack of an apparent return to HML, 'point to a real need to investigate the affairs of HML'. The plaintiffs submit that the most appropriate person to do that is a liquidator.

28 For HML's part, while it accepts that there have been shortcomings in relation to its administration and management, and compliance with some of its Corporations Act obligations, it submits that it has made serious efforts to address those issues, that most of those issues have been addressed, and there is a serious and credible plan to rectify the remaining issues in the short-term future. And so, as a result of that, HML submits that the Court should not be satisfied that the just and equitable ground has been made out to warrant the drastic remedy of winding up the company.

29 HML points to evidence that the compliance and governance failures have been rectified or are in the process of being rectified. It also relies on the EGM of 3 December 2020, at which a special resolution for a members' voluntary winding up was defeated, with about three quarters of the votes cast being votes against. It submits that the loss of capital invested is a risk that every contributory takes when they invest in a company.

30 HML disputes the submission that it is defunct or dormant. It points to lines of credit it has obtained from Mr McAuliffe on which it can draw down to fund the ongoing activities including litigation against ASX. It says that the company has been 'undergoing a rebuilding period, of consolidation and change'. It also denies that there has been any failure of substratum in the sense of a departure from its original purpose that would justify winding up. It points to what it says is shareholder approval at the EGM of a change to its purpose to being an unlisted investment company. It submits that it is open to it and reasonable for it to undergo 'a period of consolidation', including by the realisation and recovery of assets through litigation, before turning again to investment activities.

31 HML disputes that Mr McAuliffe was in a position to control HML or the other entities said to be related parties. It also says that the plaintiffs' submission about how the Court should approach findings on that issue is properly made. That is, HML agrees with the plaintiffs that it is neither necessary nor appropriate for the Court to make findings of contraventions of the Corporations Act in relation to the alleged related party transactions on which the plaintiffs rely. While it denies the plaintiffs' allegations, it mounts no real rebuttal of the proposition that an investigation into those transactions is warranted. It submits, however, that the appropriate entity to make that investigation is ASIC, not a liquidator.

32 In relation to oppression, HML characterises the plaintiffs' complaints as reflecting unhappiness with commercial decisions that have been made by management, unhappiness with being outvoted by majority shareholders, unhappiness that the capital they invested in HML has been diminished, and unhappiness with its delisting. According to HML, none of those things amounts to oppression and they do not justify the winding up of the company.

33 HML also submits that s 467(4) of the Corporations Act means that the Court should not make a winding up order. That section concerns circumstances where plaintiffs are acting unreasonably in seeking to have the company wound up, instead of pursuing other remedies that would be available.

34 Much of the rest of this judgment will consist of a chronological account of the evidence relevant to the plaintiffs' allegations, making observations and findings along the way with the above areas of dispute in mind. I will then reach conclusions about whether HML should be wound up because it is just and equitable to do so, or because its affairs have been conducted oppressively. But it will be helpful first to review the statutory provisions and the principles that the Court must apply, and also necessary to give reasons for the dismissal of two interlocutory applications HML brought which were disposed of at or after trial.

35 Section 461(1) of the Corporations Act provides that the Court may order the winding up of a company if, relevantly:

(f) affairs of the company are being conducted in a manner that is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, a member or members or in a manner that is contrary to the interests of the members as a whole; or

…

(k) the Court is of opinion that it is just and equitable that the company be wound up.

36 Section 462(2)(c) confers standing to apply for such an order upon contributories, where a contributory is defined in s 9 to include a holder of fully paid shares in the company. As I have said, there is no issue about the plaintiffs' standing to make this application.

37 Section 467(4), on which HML relies, provides as follows:

Where the application is made by members as contributories on the ground that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up or that the directors have acted in a manner that appears to be unfair or unjust to other members, the Court, if it is of the opinion that:

(a) the applicants are entitled to relief either by winding up the company or by some other means; and

(b) in the absence of any other remedy it would be just and equitable that the company should be wound up;

must make a winding up order unless it is also of the opinion that some other remedy is available to the applicants and that they are acting unreasonably in seeking to have the company wound up instead of pursuing that other remedy.

38 The plaintiffs base the application principally on the just and equitable ground. That is potentially broad in scope. In In Re Straw Products Pty Ltd [1942] VLR 222 at 223, Mann CJ said:

Facts rendering it just and equitable that a company should be wound up cannot be resolved into categories. Cases upon the subject are to be read with this always in mind. They merely illustrate the diversity of the circumstances calling for an exercise of the Court's discretion in winding up a company because it is just and equitable so to do.

See also Ebrahimi v Westbourne Galleries Ltd [1973] AC 360 at 374-375 (Lord Wilberforce). The classes of conduct which justify the winding up of a company on the just and equitable ground are not closed, and each application will depend upon the circumstances of the particular case: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v ActiveSuper Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 234 at [19] (Gordon J).

39 It can, however, be said that 'at the foundation of applications for winding up, on the "just and equitable" rule, there must lie a justifiable lack of confidence in the conduct and management of the company's affairs': Loch v John Blackwood Ltd [1924] AC 783 at 788 (Lord Shaw). Three general fundamental principles are relevant to that consideration: a lack of confidence in the conduct and management of the affairs of the company; a demonstrated risk to the public interest that warrants protection; and reluctance on the part of the courts to wind up a solvent company: ActiveSuper at [20] quoting Australian Securities and Investments Commission v ABC Fund Managers Ltd [2001] VSC 383 at [119] (Warren J).

40 In relation to the first of these, in ActiveSuper at [21] Gordon J said (quoting from Galanopoulos v Moustafa [2010] VSC 380 at [32] and citing other authorities as well) that:

… a lack of confidence may arise where, 'after examining the entire conduct of the affairs of the company' the Court cannot have confidence in 'the propensity of the controllers to comply with obligations, including the keeping of books, records and documents, and looking after the affairs of the company'.

41 In relation to the second consideration, Gordon J said at [23] (citations omitted):

… a risk to the public interest may take several forms. For example, a winding up order may be necessary to ensure investor protection or where a company has not carried on its business candidly and in a straightforward manner with the public. Alternatively, it might be justified in order to prevent and condemn repeated breaches of the law.

42 The public interest justifies intervention where, among other things, it is required for investor protection and where there have been regular or repeated breaches of the law: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Chase Capital Management Pty Ltd [2001] WASC 27 at [75] (Owen J).

43 I will return to the third consideration, solvency, below.

Failure of company's purpose and failure of substratum

44 It may be appropriate to wind a company up on the just and equitable ground 'where it is impossible to carry on the company's business because the "substratum of the company" has failed or, in other words, it has become impossible for the company to achieve the purpose for which it was formed': Re CNPR Ltd [2018] NSWSC 989 at [9] (Black J).

45 HML submits that the '"failure of substratum" factor is limited to circumstances where it is an impossibility for the company to fulfil its original purpose' (original emphasis). It relied on Re CNPR, on CIC Insurance Ltd (prov liq apptd) v Hannan & Co Pty Ltd [2001] NSWSC 437, and on Kingjade Holdings Pty Ltd v Pineridge Nominees Pty Ltd (1997) 15 ACLC 910. But Re CNPR was an essentially uncontested case (the company was itself the applicant) where, in terms quoted above, the Court said only that it may be appropriate to wind the company up when it had become impossible to carry on the company's business or impossible to achieve its purpose. CIC Insurance was also uncontested (the company's sole shareholder was the applicant) and was based on corporate paralysis, because there was no one willing to serve as director, not on a failure of substratum or purpose. In Kingjade, the rule ultimately depended on approval of a 1964 journal article in which the doctrine of winding up on just and equitable grounds was reduced to three principles:

(1) where initially it is, or later becomes, impossible to achieve the object for which the company was formed;

(2) where it has become impossible to carry on the business of the company;

(3) where there has been serious fraud, misconduct or oppression in regards to the affairs of the company.

[BH McPherson, 'Winding Up on the "Just and Equitable" Ground' (1964) 27(3) Modern Law Review 282]

To reduce the breadth of the term to those principles is, with respect, inconsistent with the broader course of authority on the just and equitable ground described above.

46 The true approach appears in Menhennitt J's comprehensive summary of the principles in Re Tivoli Freeholds Ltd [1972] VR 445. At 468 (point (4)) his Honour stated the basic principle as follows (citations removed):

It has been recognized that it may be just and equitable to wind a company up if the company engages in acts which are entirely outside what can fairly be regarded as having been within the general intention and common understanding of the members when they became members. The cases on loss or failures of substratum are an illustration of this more basic concept. This more basic concept is not, it appears to me, confined to cases of 'partnership' companies or 'main object' companies. Whilst it may be easier to find the general intention and common understanding in those cases I can see no reason in principle why it should be confined to such cases and I am not aware of any decision that it is so confined.

47 The following discussion of authority in Re Tivoli Freeholds at 469 (point (5)) is also relevant in this case:

But where, even although a company could still pursue its original objects, whether they be main or paramount objects or not, if in fact the matter has gone beyond intention and the company had in fact embarked upon a course which, even although it is within power, is quite outside and different from what was originally commonly intended and understood, then it appears to me that it may be just and equitable to wind up a company. The case of Re National Portland Cement Co. Ltd., [1930] N.Z.L.R. 564, was one in which a main object had never been pursued for five years and it was then proposed to pursue a subsidiary object. However, it appears to me that Myers, C.J., was stating a principle which can have general application when he said at p. 572: 'The most that can be said by the directors is that if their present proposed experiment of hydrating lime is successful they may be able to secure capital to carry out the main object for which the company was established. It seems to me that this really involves an abandonment of the primary object of the company, and that the shareholders who have taken up contributing shares are being asked to leave their money in a venture different altogether from that to which they have subscribed.'

At 471 (at point (7)) his Honour described it as a 'question of equity between a company and its shareholders'.

48 In fact there are many cases where there has been held to be a failure of substratum even though the circumstances fall short of impossibility of fulfilment of the company's original purpose. The tenor of many of those cases is that something fundamental to the company's business has fallen away: see e.g. Hillig v Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council [2006] NSWSC 1371 at [36] (failure of substratum once trustee company's assets transferred to beneficiary company, overturned on appeal but not on this point: Hillig v Darkinjung Pty Ltd [2008] NSWCA 75); Commonwealth v ABC2 Group Pty Ltd (court-apptd recs and mgrs apptd) [2009] NSWSC 1442 at [39] (failure of substratum of company used to run and sell childcare centres as going concerns, once sales made); Nassar v Innovative Precasters Group Pty Ltd [2009] NSWSC 342 at [72] (expiry of licence to use patent).

49 Once again, the truth is that it is a matter of degree. Obviously, not every departure from a company's stated or commonly intended objects will justify its winding up; in many cases, even very substantial departures will not attract that consequence. The Court must make sensible allowances for the fact that the circumstances of a company will change over time, and so too may its objects and purposes: see Haselgrove v Lavender Estates Pty Ltd [2009] NSWSC 1076 at [81] (Ward J). Sometimes, the span of time will be considerable indeed, such as the near century involved in Re New South Wales Leagues' Club Ltd [2014] NSWSC 1610.

50 Nor, obviously enough, will every difficulty the company experiences in carrying on its business put it at risk of a just and equitable winding up; a realistic chance that the difficulties will resolve, and the company will be able to carry on, may make that undesirable. The just and equitable outcome will depend on all the relevant facts in the circumstances of the particular case.

51 Another submission HML makes is that the prime source to use for determining the purpose of a company is its memorandum of association or constitution. It cited Re Tivoli Freeholds at 471 (point (8)), where Menhennitt J said:

All the authorities appear to me to recognize that the prime source for ascertaining the general intention and common understanding of the members is the company's memorandum of association which among other things states its objects.

52 Counsel for HML also relied on a 1991 case (Strong v J Brough & Son (Strathfield) Pty Ltd (1991) 5 ACSR 296 at 300) which in turn relied on a 1980 decision (Re Johnson Corporation Ltd [1980] 2 NSWLR 681) for the principle that 'one does not look at the prospectus to find the main object, but one looks at the memorandum of association'.

53 But that asserted principle implies an assumption that the company will have a memorandum of association that does state its objects. While that assumption was no doubt sound in 1972 or 1980, it is not any longer. The LexisNexis service, Australian Corporation Practice (online), summarises the contemporary position as follows (at [7.075]):

The company's constitution may specify the objects of the company: s 125(2). Originally companies were required to provide an objects clause in their memorandum of association. This was abolished in 1981 when companies were granted the legal capacity of an individual: s 124. The abolition of the doctrine of ultra vires in its application to companies, achieved by ss 124-125, has largely circumvented the need for object clauses, other than for the companies noted below.

Object clauses will generally only be included in a company's constitution where this is required by law or otherwise necessary in order for the company to qualify for the applicable tax concessions …

54 In Re Tivoli Freeholds (at 468, point (3)) Menhennitt J acknowledged that in having regard to previous decided cases in relation to the just and equitable ground, 'it would be necessary to have regard to changing circumstances and developments in relation to company practices including any relevant changes in the law'. At 471 (point (7)) his Honour said that regard should be had to all relevant developments including changes in the law. It has since been recognised that changes in the corporations legislation have borne directly upon the significance to be attributed to the public purposes served historically by the documents making up a company's constitution: Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd v Coopers Brewery Ltd [2005] FCA 1812 at [75] (Finn J) approved in Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd v Coopers Brewery Ltd [2006] FCAFC 144; (2006) 156 FCR 1.

55 It is true that in Strong, decided in 1991, Young J was considering a company which had no objects stated in its memorandum of association, and his Honour held, citing Re Johnson Corporation, that it was doubtful how far a prospectus would be determinative. But I do not consider that Strong is clear authority that one looks to the constitution rather than a prospectus to determine the company's objects or purposes. The relevant observations were obiter dicta: there was no prospectus in Strong, and in any event it was not a winding up case, but a case about whether, on the construction of a provision of the articles of association, the directors were authorised to dispose of the company's main business. Further, in relation to Re Johnson Corporation, Young J describes Needham J as saying that one does not look at the prospectus to find the main object, but one looks at the memorandum of association. But Young J was, with respect, not accurately stating Needham J's view. What Needham J in fact said in Re Johnson Corporation (at 689-690) was:

It is, in my opinion, still an open question whether, in determining whether a company has main objects and, if so, what they are, the court may go outside the memorandum of association. It could be argued that a prospectus issued at the time of incorporation could be examined, although, I hasten to add, there is authority against that proposition.

56 In my opinion that question, while open in 1980, is no longer open now more than 40 years later. In Registered Clubs Association of NSW v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2016] NSWSC 835, McCallum J said at [18]:

Implicitly, the Corporations Act contemplates the possibility that a company will have neither a constitution nor stated objects. Plainly, in such a case, the ascertainment of the objects for which the company was formed would require inquiry beyond the documents by which it was formed, potentially extending to consider its activities and published statements since incorporation (what the company had said and done).

57 Even in Re Tivoli Freeholds in 1972, Menhennitt J seemed to accept the potential relevance of prospectuses for the purposes of identifying the objects of the company: see 472 (point (9)), although his Honour also acknowledged authority to the contrary. His Honour held that:

a basic consideration is that the material being looked at must establish something general or common to all members and this consideration of itself precludes something passing between only the company and a particular shareholder unless it can be concluded that it was a matter common to all shareholders.

58 Similarly, in Strong Young J said that 'one looks to "the general intention and common understanding of the members"'. A prospectus on the basis of which most members provide funds to subscribe for shares can meet that criterion. In a just and equitable winding up, which will always depend on the particular circumstances of the case, there can be no rigid rule against having regard to a prospectus to determine the purpose for which a company was formed. In my view it is open to the Court to put weight on documents, such as the prospectus under which the bulk of the funds employed by a company have been raised, in order to ascertain what was, in truth, generally intended and understood among members who subscribed to shares on the basis of that prospectus.

Relevance of breaches of the law

59 On the subject of regular or repeated breaches of the law (Chase Capital Management, see above) relevant breaches may include breaches of directors' duties, inadequacy of accounts and record keeping, and failure to comply with legal requirements with respect to financial records and reports: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Merlin Diamonds Ltd [2019] FCA 1546 at [107] (O'Bryan J); Pages Property Investments Pty Ltd v Boros [2020] NSWSC 1270 at [203] (Black J, overturned in Boros v Pages Property Investments Pty Ltd [2021] NSWCA 288 but not on this point). On this subject HML relied on cases including Gregor v British-Israel-World Federation [2002] NSWSC 12, where failure to comply with statutory requirements for financial and directors' reports was held at [146] to be 'an additional but not independently weighty ground supporting the making of a winding up order', and Gognos Holdings Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2018] QCA 181, where non-lodgement of financial reports for eight to nine years, when the reporting had still not been brought up to date, did justify winding up. But each of these cases turned on their own facts, and they do not give rise to any rigid rules as to when non-compliance is, or is not, enough to justify a winding up order.

60 Observations in Gognos by McMurdo JA (Sofronoff P and Gotterson JA agreeing) do, however, provide guidance on how the Court is to approach a situation, which has arisen in this case, where the defendant company seeks to rectify non-compliance shortly before trial. His Honour said at [98]:

The task for the judge was to assess the nature and extent of the risks to the public interest from these companies being allowed to continue, given their lamentable history of mismanagement and misconduct. Ultimately, it was common ground that as things stood just a few weeks or days from the trial, there was a compelling case for the companies to be wound up. Her Honour had to consider whether the risk to the public interest had been eliminated, or at least reduced to an acceptable level, by what had been put in place at the eleventh hour.

That is the approach I will follow here.

61 In relation to breaches of the Corporations Act generally, a serious issue may exist to justify intervention even where the Court has not reached a final conclusion as to whether particular alleged breaches have been established: see Chase Capital Management at [77]. In many cases it will not be necessary or appropriate to reach any final conclusion. As I have already indicated, in this case both sides effectively embraced that proposition. So, for example, in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Uglii Corporation Ltd [2016] FCA 1099 at [78], Davies J found it relevant to the just and equitable ground that a lack of evidence to support certain substantial cash flow projections was a matter warranting independent investigation by an external controller.

62 As to s 461(1)(f) of the Corporations Act, concerning oppression, the plaintiffs submit, and HML does not contest, that the principles that have been developed in relation to remedies for oppressive conduct, as found in s 232 of the Corporations Act, may be applied to cases of winding up. In Hylepin Pty Ltd v Doshay Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 201; (2021) 288 FCR 104 at [124]-[130], the Full Court (Markovic, Banks-Smith and Anderson JJ) summarised as follows, with apparent approval, the review of those principles conducted by the primary judge (O'Bryan J):

[124] The primary judge commenced a review of the oppression principles under s 232(e) by noting that 'oppressive to, unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against' is a compound expression: Hillam v Ample Source International Ltd (No 2) (2012) 202 FCR 336 at [4].

[125] His Honour referred to Re Ledir Enterprises Pty Ltd (2013) 96 ACSR 1, where Black J observed at [178], and having referred to various authorities including Wayde v New South Wales Rugby League Ltd (1985) 180 CLR 459, that the phrase in s 232(e) is concerned with 'commercial unfairness'; or 'a departure from the standards of fair dealing, or where a decision has been made so as to impose a disadvantage, disability or burden on the plaintiff that, according to ordinary standards of reasonableness and fair dealing, is unfair'.

[126] The primary judge cited the statement of Brennan J in Wayde (at 472-473) that the relevant test as to unfairness in the context of oppression is 'whether reasonable directors, possessing any special skill, knowledge or acumen possessed by the directors and having in mind the importance of furthering the corporate object on the one hand and the disadvantage, disability or burden which their decision will impose on a member on the other, would have decided that it was unfair to make that decision'. Whether there has been unfairness in the requisite sense is to be judged objectively: Wayde at 472-473. To those references we would add that the section requires proof of oppression or proof of unfairness. Proof of mere prejudice to or discrimination against a member is insufficient to attract the court's jurisdiction to intervene: Wayde at 472.

[127] His Honour also cited the test as to unfairness as described in Catalano v Managing Australia Destinations Pty Ltd (2014) 314 ALR 62 at [9], being whether 'objectively in the eyes of a commercial bystander there has been unfairness, namely conduct that is so unfair that reasonable directors who consider the matter would not have thought the decision fair'.

[128] It was noted that mismanagement alone does not constitute oppression, and a court is concerned 'to avoid an unwarranted assumption of the responsibility for management of the company': Wayde at 467 (Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ).

[129] Turning to s 232(d), the primary judge said that whether conduct is 'contrary to the interests of the members as a whole' is also objectively ascertained, citing Goozee v Graphic World Group Holdings Pty Ltd (2002) 170 FLR 451 at [42]-[44], and is determined by an assessment of whether the conduct adheres to 'accepted standards of corporate behaviour' or is in accordance with how reasonable directors would act in attending to the affairs of the company.

[130] Further, the primary judge noted that although s 232 is not subject to any limitation period, and a court may grant relief even if the oppressive conduct has ceased, a court has a broad discretion as to remedy, citing Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [65] (French CJ), [182] (Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

63 In Hylepin at [133]-[135] the Full Court held that it was necessary to look to the cumulative effect of the whole course of conduct, in overview, since (at [136]) 'depending on the circumstances, an accumulation of conduct, even where none of the separate matters of conduct is found to be oppressive, may have that result'.

64 HML submits, and I accept, that the mere fact that a member of a company has lost confidence in the manner in which the company's affairs are being conducted does not lead to the conclusion that the member is oppressed, and nor does mere dissatisfaction with or disapproval of the conduct of the company's affairs; nor does even a fundamental disagreement with a decision made by majority shareholders and directors (by itself) amount to oppression: see John J Starr (Real Estate) Pty Ltd v Robert R Andrew (A'asia) Pty Ltd (1991) 6 ACSR 63 at 6; Shelton v National Roads and Motorists Association Ltd [2004] FCA 1393 at [24] (Tamberlin J).

65 As for the winding up of a solvent company, in Hillam v Ample Source International Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCAFC 73; (2012) 202 FCR 336 at [70] (Emmett, Jacobson and Buchanan JJ) it was held that there is no presumption against this, although:

the warnings given in the authorities, that an order to wind up a solvent company is an extreme step, are warnings which should be borne in mind … An order to wind up a solvent company may often be too extreme a step to take (and therefore not justified or appropriate) but that is very different from proceeding upon any 'principle' or assumption that a winding up order of a solvent company is inappropriate. No such implication arises from s 232 or s 233 of the Act, or should be made in those terms. The real question is whether a winding up order was appropriate to deal with and address the grounds for relief which had been established. The answer to that question must be found in the facts of the particular case.

These comments were made in the context of a remedy of winding up being sought under the provisions of the Corporations Act concerning oppressive conduct, but there is no reason to think they do not apply more broadly.

66 It is notable that in the principal case to which the Full Court in Hillam referred before reaching the above conclusion, Cumberland Holdings Ltd v Washington H Soul Pattinson & Co Ltd (1977) 13 ALR 561, the warning was against the winding up of 'a successful and prosperous company and one which is properly managed' (at 566). This confirms what would be evident from the broad evaluative nature of the statutory criteria in any event, namely that it is a matter of degree. Obviously, a court will be more reluctant to wind up a successful, prosperous and properly managed company than it will be to wind up a company of doubtful solvency and dubious management practices. So a stronger case may be required where the company is prosperous, but solvency per se is no bar to the appointment of a liquidator, particularly where there have been serious and ongoing breaches of the Corporations Act: ActiveSuper at [24].

67 As will be seen, HML does not defend the case on the basis that the strength of its financial position meant that it would be an extreme step to order its winding up. It submits that this is a neutral factor. Nevertheless, the Court must keep in mind the interests of creditors and members of the company as a whole and the considerations just outlined remain relevant to the exercise of the discretion.

68 HML relies on s 467(4) of the Corporations Act to submit that an order for winding up would not be appropriate. That sub-section, which is set out above, requires the Court to make a winding up order, relevantly on the just and equitable ground, if it is satisfied of the necessary matters, but then provides for an exception that lifts that requirement, if the Court 'is also of the opinion that some other remedy is available to the applicants and that they are acting unreasonably in seeking to have the company wound up instead of pursuing that other remedy'. So it imposes a mandatory duty on the Court to make a winding-up order with a discretion not to make one if certain conditions are satisfied: Vujnovich v Vujnovich [1989] 3 NZLR 513 at 518-519, applied to s 467(4) in Asia Pacific Joint Mining Pty Ltd v Allways Resources Holdings Pty Ltd [2018] QCA 48; [2018] 3 Qd R 520 at [96] (Jackson J). 'Other remedy' in s 467(4) is not restricted to a legal remedy in the sense of a cause of action but is to be understood in the wider sense of a course of action otherwise open to the party: Host-Plus Pty Ltd v Australian Hotels Association [2003] VSC 145 at [67] (Hansen J).

69 The onus is on the defendant to establish that this exception is made out: Asia Pacific Joint Mining at [43] (McMurdo JA, Gotterson JA and Jackson J agreeing). The question of whether an applicant is acting unreasonably requires an objective assessment of the applicant's preference for a winding up order: Asia Pacific Joint Mining at [45]. In Asia Pacific Joint Mining at [47] McMurdo JA said (footnotes omitted):

The evident purpose of the proviso in s 467(4) is to avoid the extreme step of a winding up if there is an alternative and adequate remedy. Consequently a winding up will be ordered if there is no other remedy which is adequate, in that it would redress the consequences of the facts and circumstances which are the basis for relief. This is another way of saying what McPherson J said in Re Dalkeith Investments Pty Ltd [(1984) 9 ACLR 247] about the statutory predecessor of s 467(4) namely 'that winding up is to be regarded as a remedy of last resort and [one] which ought not to be granted if some other less drastic form of relief is available and appropriate.' In referring to a winding up as 'drastic form of relief', McPherson J was referring to the far reaching consequences of a winding up. In referring to an alternative form of relief which was 'appropriate', his Honour was referring to what was necessary, in the interests of the applicant, to redress the consequences of the relevant events and circumstances.

Application to set aside a subpoena

70 Before turning to describe the evidence it is convenient to give reasons for a decision that was made at trial concerning an application to set aside a subpoena. It will also then be necessary to give reasons for the dismissal of an application to reopen that HML made after trial.

71 As has been indicated, the trial commenced on 13 December 2021. On 8 December 2021, that is, three business days before, an affidavit of Mr McAuliffe was filed that set out a substantial amount of new evidence that was not covered in his first affidavit, which had been filed in accordance with pre-trial directions on 16 June 2021. Some of the evidence in the second affidavit appears to have been intended to bring the Court up to date about developments since the first affidavit. There was no objection to reliance on the affidavit and the evidence in it will be considered below.

72 However the late date of filing of the second affidavit was relevant to the subpoena, because the plaintiffs applied for its issue on the same day, that is, 8 December 2021. It was addressed to Mr McAuliffe and sought the production of documents in two categories:

For the period from 1 October 2021 to 6 December 2021, a copy of any bank statement for any account held (either individually or jointly) in your name that records:

1 the transfer of funds by you to Henry Morgan Limited ACN 602 041 770; and / or

2 the funds available to you.

73 The first of these was not in issue. The application to set the subpoena aside concerned the second. A registrar gave leave to issue the subpoena and it came to be returnable before me at the commencement of the trial on 13 December 2021. At that time counsel for HML, acting on instructions from Mr McAuliffe, applied to set aside the subpoena to the extent of that disputed ground. I dismissed the application and said I would give reasons as part of this judgment.

74 Mr McAuliffe sought the setting aside of the subpoena on the grounds of oppression and lack of a legitimate forensic purpose, that is, relevance. The oppression ground was based on things said from the bar table to the effect that Mr McAuliffe's funds were held in 12 different accounts, some in Australian dollars, some in various different foreign currencies, and they included futures contracts. It was said that it would be time consuming to collate the relevant bank statements in order to comply with a subpoena that was served only one clear business day before the commencement of the trial, at a time when Mr McAuliffe needed to prepare for the hearing and had other personal and work commitments.

75 As to relevance, counsel for Mr McAuliffe submitted that HML did not put its solvency in issue as a factor against the winding up order sought. He submitted that at most the company's solvency position was a neutral factor in relation to the winding up sought on just and equitable grounds. While HML is relying on some funding from Mr McAuliffe, and there is evidence about the current position of the funds he has provided, the possible extent of any future funding he is to provide is not an issue before the Court. Evidence in Mr McAuliffe's second affidavit is to the effect that he was providing funding of up to $410,000 to HML for the purposes of working capital and funding of up to $2 million for the purposes of conducting litigation. Counsel for the plaintiffs said, in reply to Mr McAuliffe's submissions, that he would be submitting that the financial statements for HML (that were also annexed to Mr McAuliffe's second affidavit) demonstrated that HML will be insolvent without Mr McAuliffe's ongoing financial support, so that Mr McAuliffe's ability to provide that support was relevant. Counsel indicated from the bar table that the subpoena was directly prompted by Mr McAuliffe's second affidavit which explained the timing of issue of the subpoena.

76 I did not accept either of the bases that HML advanced as warranting the setting aside of the subpoena. The short time for responding to the subpoena was a function of the fact that an affidavit from Mr McAuliffe deposing to his funding of HML was only filed on 8 December 2021. The application for the issue of the subpoena was made on the same day. As for the submission that there were a large number of bank accounts and it would be difficult to comply, that was not supported by evidence and in any event the subpoena only required the production of bank statements. It appeared to me to be quite feasible for Mr McAuliffe to locate such bank statements as were in his possession, custody or power for the purpose of production to the Court. In the circumstances I was prepared to permit him to do so overnight, between the two days on which the matter was listed for hearing. Although that was a short period of time, it was a function of the lateness with which the question of the funding of HML's ongoing activities was raised.

77 As for the relevance objection, the threshold is one of apparent relevance which is not necessarily at the level required for the material to be admitted into evidence: see the summary of principles in Harvard Nominees Pty Ltd v Tiller [2019] FCA 1672 at [3]-[6] and the authorities referred to there. I understood counsel's submission about relevance to be to the effect that Mr McAuliffe had already provided financial support to HML, so Mr McAuliffe's ability to provide further amounts in the future was not relevant. But there was no clear evidence that the advances promised had been drawn down, whether fully or at all, and it is inherently unlikely from the legal activity described below that the $2 million line of credit taken out to support the activity of potential litigation against ASX has been fully utilised.

78 As will be set out below, on HML's case that potential litigation is a substantial rationale for its ongoing existence. It is also clear that HML will not be able to engage in this activity unless it obtains funding to do so. The $2 million line of credit appears to have been taken out for that purpose. No substantial source of funding for potential litigation other than Mr McAuliffe has been suggested in the evidence; while HML has raised some funds from investors, there is no evidence that this money was raised to fund the litigation, and one of those investors has been Mr McAuliffe himself, and the amounts raised have not been nearly as large as the line of credit. The only potential defendant named is ASX, in connection with its decision to suspend HML's securities from trading and its refusal to approve the release of meeting materials in respect of a proposed transaction involving JBFG (each of which will be described further in these reasons). It can be expected that to pursue successful litigation of that kind against a defendant such as ASX will cost the best part of the $2 million that Mr McAuliffe has promised, if not all of it. Mr McAuliffe's ability to fund litigation in future therefore satisfied the test of apparent relevance required to justify the issue of a subpoena.

79 For those reasons, the subpoena was not set aside. And despite what was said from the bar table, on the second day of trial Mr McAuliffe ended up complying with the subpoena by producing only one bank statement in connection with only one bank account. His counsel (that is, counsel for HML) stated on the second day that the instructions that he had been given before he made his submissions on the first day were incorrect because 'Mr McAuliffe had misunderstood the breadth of the subpoena'.

80 As has been said, the hearing finished and judgment was reserved on 14 December 2021, although the parties filed further written closing submissions with the last of those received on 20 January 2022. On 26 May 2022, HML filed an interlocutory application to reopen its case in order to adduce further evidence in an affidavit of Mr McAuliffe of the same date. The plaintiffs opposed the application and at a hearing on 30 June 2022 I dismissed it. These are my reasons.

81 Other than an up to date company extract for HML, the further evidence in Mr McAuliffe's affidavit of 26 May 2022 was three annual reports for HML for FYE 2019, FYE 2020 and FYE 2021, which had been lodged with ASIC on 26 May 2022. These included accounts that had been audited by Pitcher Partners. As will be seen below, annual reports and audited reports for those years were outstanding at the time of the substantive hearing.

82 On 27 June 2022 Mr McAuliffe swore a further affidavit by which HML sought to adduce evidence that HML had convened an AGM to be held on 25 July 2022.

83 HML submitted that the annual reports amounted to highly probative evidence, primarily because the audited accounts, and the fact of their filing with ASIC, went to two issues that it submitted would be central to the Court's decision, namely the company's compliance with the Corporations Act and its financial position. HML submitted that this meant that it would be in the interests of justice to admit the evidence as it would probably affect the outcome of the case. While HML accepted that it would be necessary to show that it could not, by reasonable diligence, have adduced the evidence earlier, it submitted that this was the case here, as the audited accounts were not in existence at the time of the hearing. HML submitted that the prejudice to the plaintiffs would be minimal. It suggested that the matters the plaintiffs would need to follow up would be discrete.

84 The plaintiffs disagreed with that, having put on evidence in an affidavit of Michael Catchpoole, one of their solicitors, affirmed on 7 June 2022, as to further work they would need to do. This would include subpoenas to HML's accountants (Pilot Partners) and its auditors (Pitcher Partners) for the production of their working files in order to seek to understand a number of important differences between the audited accounts of May 2022 and the unaudited ones produced in December 2021 which were in evidence at the hearing. The plaintiffs submitted that they would then need to cross examine Mr McAuliffe on the differences and on the reasons for the further delay in producing the audited reports (noting that, as will emerge, the evidence at hearing was that Pitcher Partners had expected to complete the audits by 28 January 2022). The plaintiffs would also seek to subpoena JBL, Mr McAuliffe and another company, Tetue Pty Ltd, to seek to understand a particular transaction which appears to have converted a deficiency in shareholders' equity and working capital, as shown in the unaudited accounts, to a surplus, as shown in the audited accounts. I will describe the evidence about that transaction shortly. They would also need to obtain documentary evidence about a further placement of shares referred to in the annual reports that appears to have taken place in May 2022.

85 The plaintiffs also submitted that the annual reports could have been produced prior to the hearing and that it was a 'commercial and forensic choice' not to arrange for their inclusion in HML's case. They submitted that the reasons given for the delay were unsatisfactory. They also submitted that the expiry of possible limitation periods for taking action in respect of certain transactions were approaching so that excessive delay would prejudice them, assuming that a liquidator is appointed.

86 As to the applicable principles in an application to reopen, it is convenient to repeat the summary I gave in Frigger v Trenfield (No 7) [2020] FCA 1740 at [22]-[24]:

The power is discretionary: Urban Transport Authority of New South Wales v Nweiser (1992) 28 NSWLR 471 at 474; Commonwealth of Australia v Davis Samuel Pty Ltd (No 7) [2013] ACTSC 146; (2013) 282 FLR 1 at [1578]. The ultimate question is where the interests of justice lie: Inspector-General in Bankruptcy v Bradshaw [2006] FCA 22 at [24] (Kenny J); Telstra Corporation Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2008] FCA 1436; (2008) 171 FCR 174 at [208] (Lindgren J); Spotlight Pty Ltd v NCON Australia Ltd [2012] VSCA 232; (2012) 46 VR 1 at [26].

Broadly speaking, there are four recognised classes of cases where leave to reopen may be given, although the classes are not closed: (1) fresh evidence; (2) inadvertent error; (3) mistaken apprehension of the facts; and (4) mistaken apprehension of the law: Bradshaw at [24] (Kenny J); Spotlight at [25]-[26].

Likely prejudice to the party resisting the application will be relevant: Nweiser at 478. So will the public interest in the timely conclusion of litigation: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2006] NSWSC 826; (2006) 235 ALR 587 at [18]. The probability that the additional evidence will affect the result is also relevant: Telstra at [209]. If success in reopening is not likely to make any difference to the outcome of the trial, that would weigh against putting the parties and the court to the delay, trouble and expenditure of resources involved in reopening.

87 Relevant to that last point, HML submitted that one factor that guides the court's discretion is whether the further evidence, if accepted, would probably affect the result of the case. It seems to me, however, that the Court cannot assume that the evidence will be accepted. The probability that the evidence will be accepted as true (if admitted) is relevant to the probability that it will affect the result. In any event, counsel for HML agreed that in deciding the application to reopen, it was necessary for the Court to make a preliminary assessment of the likelihood that the new evidence will affect the case.

88 Also relevant are the following observations in Spotlight Pty Ltd v NCON Australia Ltd [2012] VSCA 232; (2012) 46 VR 1 at [17]-[18] (Harper and Tate JJA and Beach AJA, footnotes omitted):

There are good reasons why the circumstances must be exceptional before a court may allow a case, having been closed and judgment reserved, to be re-opened. The need for finality in litigation is one. It is no answer to this point to say that the further evidence sought to be adduced by the respondent in this case is confined to the quantum of damages. Were applications to re-open to be allowed almost as of course, such applications would be regularly made. That would add enormously to inefficiencies in the administration of justice, even if the re-opened hearing was strictly confined. The discipline which ought to attend the conduct of litigation by highly competent litigators would also inevitably decline.

The very strict rule that, subject to any applicable process of appeal or review, the presentation of their cases by parties to litigation must conclude with the end of the trial, has another important justification. It is that, very often, the boundaries of the re-opened issues would be hard to define and as difficult to protect. The re-opened hearing would then be bedevilled by arguments about whether one party or the other was seeking to take advantage of the re-opening to polish parts of its case which were more or less within the scope of the re-opened proceeding but not clearly on one side or the other of the prescribed limits.

89 I dismissed the application to reopen on the basis of these principles, and because I did not consider that the evidence to be adduced was likely to affect the result. My specific reasons were as follows.

90 First, there was no reason to doubt or second guess Mr Catchpoole's affidavit to the effect that the plaintiff would seek to subpoena a number of people or entities to investigate the new developments disclosed in the annual reports. What that reveals is that, decisive or not, the new evidence would open up a range of issues going both to the financial position of HML and to further transactions in which it has engaged. The application would be a prime example of one where, in the words used in Spotlight, 'the boundaries of the re-opened issues would be hard to define and as difficult to protect'.

91 Second, the particular transaction involving Tetue Pty Ltd was likely to raise further concerns. The transaction is described in the annual report for FYE 2021 (also in the reports for the prior years) as a post reporting period development. It concerns debts between HML and JBL. A debt of approximately $2.4 million owed to HML by JBL (described in more detail in the narrative of the evidence below) was valued at nil in the unaudited accounts for FYE 2019, but in the audited accounts was given full value. According to the FYE 2021 annual report, that was because of the following transaction:

On 5 May 2022, Henry Morgan Limited entered into a Deed of Assignment & Novation with Stuart McAuliffe, Tetue Pty Ltd and John Bridgeman Limited to offset amounts payables [sic] and receivable between the above-mentioned parties. As set out in the notes to the financial statements, the balance of any net loans receivable will be repaid from funds held in trust with the Company's legal counsel.

92 The note to the 'Loans and Receivables' section in the accounts then said:

(a) On 8 August 2018 the Company made a loan of $2,411,000 to JBL for a term of one year at 11.5% pa interest. On 28 June 2019 the term of the loan was extended to 31 March 2021.

As of 5 May 2022 the Loan to John Bridgeman Limited is subject to rights of set-off of liabilities as set out in:

• Note 6 Trade and Other payables, being Accrued expenses of $194,883 (2020: $73,333) and Other payables - JBL of $1,172,008 (2020: $1,172,008);

• Note 7 Borrowings, being loans from Stuart McAuliffe $343,916 (2020: $85,261).

Whilst the net amount receivable from John Bridgeman Limited as at 30 June 2021 of $603,751 is past due, it has not been impaired on the basis of these funds being transferred to the Company's legal counsel trust account on 25 May 2022.

93 A company search of Tetue Pty Ltd that is in evidence on the interlocutory application shows its sole director is one Brett James McAuliffe and its previous directors include Stuart McAuliffe, John McAuliffe and a Barbara Joan McAuliffe. In short, this evidence, if admitted, would raise yet another transaction with connected parties which the plaintiffs would submit requires investigation. The evidence to be adduced by HML on any reopening would be limited to the new annual reports, so there would be no further explanation of the transactions in evidence. It would be necessary, as Mr Catchpoole's evidence showed, for the plaintiffs to investigate by the issue of more subpoenas and test HML's claims by further cross examination of Mr McAuliffe.

94 Also in relation to solvency, the directors noted in the annual report for FYE 2021 (also in the reports for the prior years):

The continuation of the Company as a going concern is largely dependent on the Company's ability to:

• maintain forecast expense levels;

• raise additional capital and funding, of which $410,000 was raised subsequent to 30 June 2021 (refer note 10); and

• have funds continued to be advanced from one of its Directors to allow it to maintain its solvency and allow it to pay its debts as and when they fall due.

These conditions give rise to a material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt of the Company's ability to continue as a going concern. Should the above actions not generate the expected cash flow, the Company may be required to realise assets and extinguish liabilities other than in the normal course of business and at amounts that differ from those stated in the financial statements. The report does not include any adjustments relating to the recoverability and classification of recorded assets amounts and classification of liabilities that might be necessary should the Company not continue as a going concern.

95 It therefore appeared to me that the evidence sought to be adduced would raise further questions about transactions with connected parties and about the solvency of HML. There was some confusion at the hearing of the application to reopen as to the significance of the issue of solvency to the case, but in his written closing submissions filed in December 2021 counsel for HML said:

the court need not make any specific finding as [to] the solvency of the company, as [HML] does not submit that this case falls within the category of cases where courts have held that the strength of solvency of a company was such that it would be an extreme case to order a winding up. In the present case, it is submitted that solvency would be a neutral factor in the Court's decision.

That being so, it appears unlikely that admitting the audited accounts would significantly improve HML's case. Despite the apparent change in net assets that they record, they are hardly likely to rise to the level of establishing a strong case for solvency. HML did not put the application on the basis of any proposed change of such significance in the nature of its case. Rather, it was put on the basis that the new evidence was highly relevant to the case as framed by the time that judgment was reserved.

96 Nor would the less contestable fact that the audits and annual reports had been completed be likely to change the result; while it might be relevant that it has put an end to certain defaults in legislative compliance, it cannot erase the very long delay before that occurred, and the concerns about the management of HML the delay might raise.

97 I therefore did not consider it likely that the evidence would affect the result. I did consider it likely that admitting the evidence would lead to significant delay in the resolution of the proceeding by opening up new areas of inquiry. Those considerations, together with the systemic importance of holding parties to the closing of their cases in all but exceptional circumstances, led me to conclude that it would not be in the interests of justice to permit reopening.

98 In reaching that conclusion I placed no weight on the plaintiffs' argument based on limitation periods. Those periods have been approaching for some time and it would have been within the plaintiffs' power to inform the Court earlier and take appropriate procedural steps to ensure that the limitation periods would not expire. I note HML's submission that the plaintiffs here made deliberate forensic decisions to obtain extensive discovery, issue numerous subpoenas and engage in lengthy cross examination exploring the affairs of the company in depth, when they could have brought an application for a just and equitable winding up framed in simpler terms which would have led to a quicker result. The volume of evidence about to be addressed in this judgment goes some way to bearing that submission out.

99 I also did not place any weight on the plaintiffs' argument that the annual reports were not really fresh evidence, because they could have been prepared earlier. I agree that any unexplained delay is relevant to the question of whether it is just and equitable to wind up HML, but how it impacts on the different discretion to permit the reopening of the trial is not something that is necessary to decide in the present case. Nor did I put any weight on a submission made by the plaintiffs that it was open to infer that HML deliberately waited to complete the audits and make the application to reopen specifically to disrupt the orderly resolution of the matter. I did not consider that the evidence supported that inference.

100 I did, however, put some weight on the plaintiffs' submission that HML could have sought an adjournment of the hearing pending the production of the annual reports. The audit was expected to be concluded as soon as 28 January 2022, noting that final submissions did not come in until 20 January 2022. The option of an adjournment application was raised in discussion between the bar and the bench at the hearing, but was not taken, instead leaving any developments after the hearing to depend on an application to reopen, as has in fact occurred. It was appropriate to hold that decision not to seek an adjournment against HML's application, given the importance of holding parties to some finality in the closing of their cases.

101 It is convenient to start the discussion of the evidence by making some observations about the evidence of Mr McAuliffe, as he was the only witness from whom HML adduced evidence and the only person who gave oral evidence in the proceeding.

102 Mr McAuliffe was 51 years of age when he gave evidence. He holds a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Queensland, a Graduate Diploma of Legal Studies from the Queensland University of Technology, and a Masters of Education from Bond University. Between 2007 and 2014 he was an Associate Professor in finance and investment analysis at Bond University. Between 2012 and 2015 he was investment manager for the Aliom Managed Futures Fund No 1, a 'wholesale investment fund'. His various positions at HML and other companies are identified above and below. According to Mr McAuliffe, those roles as director or CEO of companies have given him approximately seven years of experience managing listed and unlisted investment companies and managing all aspects of their operations.

103 I found Mr McAuliffe to be an unsatisfactory witness. His approach to his cross examination tended to be obstructive and, beyond that, to have an unreal quality. For example, he accepted that HML, JBL, BHD, Bartholomew Roberts and JBFG were all located at the same Brisbane CBD address, which had been notified to ASIC as their business premises, but asserted that 'the operational [sic] of the company was with the independent directors, and they weren't located there'. He accepted that the companies all had interests in each other, including that HML was the largest shareholder in JBFG. He accepted that there were various loans between the different companies. He appeared to accept that they used the same accounting staff, although he sought to qualify that by saying 'Some internal people were - were the same; although, I don't know if that's really exactly accurate, because not every person worked on - on - on every company'. He accepted that JBL was the investment manager for HML, and that: his role at JBL was investment manager; he was also the Managing Director of JBL; and that he had oversight of its business. He accepted that he was a director of JBL along with his father and Mr Patane, and that he has a 22% shareholding in JBL. He accepted that JBL provided office services and corporate support to HML. And yet he did not accept the common sense proposition that HML was 'part of a wider group of companies which appears to be referred to variously as the JBL Group'.

104 There were also several examples of Mr McAuliffe's refusal to accept propositions that were evidently true. One was that he did not agree that since it was listed, HML had a relatively consistent experience of complaints from ASIC and ASX. The history about to be recounted shows that was plainly so. Nor would he accept that a number of matters raised by ASX and ASIC remained unresolved.

105 Another example occurred when Mr McAuliffe was shown meeting logs apparently prepared by KPMG during the audit of various companies. He was listed as having been present at several of the meetings. But he refused to accept that he was at any of the meetings or to confirm whether he considered the records of discussion accurate, because he had not seen the KPMG notes before. When pressed he said 'Well, it's - it's possible even if I was present, I was present for part of it, and that - and that was it'. There is no reason to think that the KPMG audit personnel who prepared the meeting logs were mistaken in thinking that Mr McAuliffe attended the meetings; in the normal course of events the logs prepared by auditors on such occasions would be accurate in that regard. It would be one thing for a witness in his position to say that he did not remember specific meetings; that would be plausible. But to refuse to accept that he was at a particular meeting recorded in the working papers of the company's own auditors, and then to grudgingly accept as a possibility that if he was present it was only for part of the meeting, is to give evidence in an evasive way.

106 The following passage, about the transaction in which HML advanced approximately $2.4 million to JBL, is another example of the combination of unreality and obstruction that marked much of Mr McAuliffe's cross examination:

So as best you can recall, how was it that HML could finance this transaction, given that it had cash of 11-odd thousand dollars, as best you can recall?---I wasn't a party to extending it, so I don't - - -

No. I know you weren't a party - sorry. Sorry, Mr McAuliffe?---You're asking me to comment on a meeting of independent directors that I wasn't present at. I don't know.

But you were a director of HML. You're not arguing with me about that, correct?---What I'm arguing with me - with you about is if we have legal advice and company secretarial advice to not participate in a transaction, then I don't.

Mr McAuliffe, is it your evidence that you've got no idea how it was that HML was to finance this transaction, given that it had - appears that it had cash equivalents of 11-odd thousand dollars?---Well, what I'm telling you is I'm not privy to a meeting I wasn't at.

Did you regard this loan to JBL of 2.4-odd million as an authorised investment? And you know what I mean by that: one that was authorised for the purpose of the JBL management agreement?---No, because no loans were done under the JBL management agreement. They were done only by the independent directors.

You would agree that this kind of transaction was not the kind of investment that was envisaged by HML's prospectus. You would agree with that?---Not necessarily.

Well, you would agree that this transaction is not one that is an investment in listed equities?---It's not … list with equities, but it wasn't done under JBL's management group.

You would agree that this transaction wasn't one that comprised an investment in global exchange traded futures contracts. You would agree with that?---I would agree with that.

You would agree with that?---Yes.

107 In cross examination, Mr McAuliffe also sought to deploy the separate legal existence of different companies as a way of avoiding the need to give candid answers to questions. Some instances of that appear in the history recounted below. An example is as follows:

And then, you will see there's reference to the loan to - sorry - John Bridgeman, at the top?---I see it.

And what was that loan for?---I don't know.

Mr McAuliffe, you're the group CEO of this company, JBFG?---But you're not asking me in that capacity, you're asking me in my capacity as a director of Henry Morgan.

I'm asking you if you can tell me, given your roles across these companies, what you understood this transaction with JBL was?---I believe there's a dispute about that.

Between who?---Between JBL and JBFG.

What, a current dispute between the liquidator of JBFG and JBL, is that what you're saying?---That's what I'm saying.