FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Palmer v McGowan (No 5) [2022] FCA 893

ORDERS

Applicant / Cross-Respondent | ||

AND: | Respondent / Cross-Claimant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Judgment for the applicant against the respondent on the amended statement of claim in the sum of $5,000.

2. Judgment for the cross-claimant against the cross-respondent on the amended cross-claim in the sum of $20,000.

3. The applications for relief by way of an injunction enjoining the opposing party be dismissed.

4. The proceedings be adjourned to 10:15am on 11 August 2022 to deal with any issue as to the costs of the proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[5] | |

[7] | |

[12] | |

[13] | |

[19] | |

[24] | |

[26] | |

[33] | |

[37] | |

[38] | |

[42] | |

[46] | |

[47] | |

[47] | |

[52] | |

[69] | |

[73] | |

[79] | |

[81] | |

[84] | |

[87] | |

[90] | |

[95] | |

[100] | |

[106] | |

[111] | |

[117] | |

[120] | |

[122] | |

[140] | |

[146] | |

[159] | |

[160] | |

[161] | |

[167] | |

[181] | |

[181] | |

[185] | |

[200] | |

[225] | |

[227] | |

[234] | |

[251] | |

[275] | |

[276] | |

[277] | |

[279] | |

[281] | |

[285] | |

[295] | |

[316] | |

[317] | |

[324] | |

[325] | |

[325] | |

[331] | |

[337] | |

[344] | |

[349] | |

Reneging on the mediation agreement (Contextual Imputation 3) | [350] |

[352] | |

[359] | |

[364] | |

[372] | |

[373] | |

[374] | |

[380] | |

[395] | |

[403] | |

[406] | |

[407] | |

[411] | |

[412] | |

[424] | |

[425] | |

[430] | |

[436] | |

[436] | |

[441] | |

[450] | |

[466] | |

[467] | |

[467] | |

[471] | |

[485] | |

[486] | |

[487] | |

[489] | |

[490] | |

[494] | |

[495] | |

[516] | |

[518] | |

[522] | |

LEE J:

1 Enoch Powell once remarked: “for a politician to complain about the press, is like a ship’s captain complaining about the sea”. As these proceedings demonstrate, a politician litigating about the barbs of a political adversary might be considered a similarly futile exercise.

2 Both the applicant, Mr Palmer, and the respondent, Mr McGowan, have chosen to be part of the hurly-burly of political life. Many members of the public will have instinctive views about them absent any personal interaction. These views are likely to align with their broader political beliefs.

3 In the United States, if defamatory publications are made concerning a “public figure”, actual malice must be proved by clear and convincing evidence to obtain relief: New York Times Ltd v Sullivan 376 US 254 (1964) (at 279–280 per Brennan J delivering the opinion of the Court). But the law in Australia is different: it “rejects the extreme and semi-absolute protection of free speech and the free press that prevails, for constitutional reasons, in the United States”: Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill [2006] HCA 46; (2006) 227 CLR 57 (at 95–96 [114] per Kirby J). Hence, the law of defamation in this country deals differently with the tension between two important rights it seeks to balance: the right to freedom of expression and the right to reputation. But this does not mean that the law in this country does not recognise the significance of political speech in a liberal democracy. Indeed, in relatively recent times, the recognition of the importance of political speech has led to a special qualified privilege defence being developed: Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, although it was considered unsound to distinguish political discussion from discussion of other matters of serious public concern, a “Reynolds public interest defence” expanded the scope of protections to publications disseminated widely: see Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 2 AC 127 (at 204 per Lord Nicholls); but now see s 4, Defamation Act 2013 (UK).

4 It will be necessary to consider Lange in some detail below, because together with two other qualified privilege defences, these are the only bases upon which Mr McGowan seeks to defend the claim made by Mr Palmer. Although Mr Palmer resisted his characterisation as a “political figure”, in truth, these proceedings arise out of a prolonged and heated dispute between two political antagonists dealing, at least in large part, with matters best described as political. This reality presented a recurring challenge during all stages of these proceedings, including when dealing with both liability and damages.

5 Before moving to the substance of the claims, it is necessary to identify two contextual matters that dominate the background: first, the COVID-19 pandemic and the controversy as to the Western Australian “hard border”; and secondly, the enactment of the Iron Ore Processing (Mineralogy Pty Ltd) Agreement Amendment Act 2020 (WA) (Amendment Act).

6 The findings set out below as to these two topics are largely drawn from facts agreed by the parties for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

B.1 The COVID-19 Pandemic and the “Hard Border”

7 The COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020, and in April 2020, pursuant to the Emergency Management Act 2005 (WA) (Emergency Management Act), the Police Commissioner for Western Australia directed the closure of the Western Australian border save for exempt travellers, through the Quarantine (Closing the Border) Directions (WA) (Border Directions).

8 In May 2020, Mr and Mrs Palmer made applications to enter Western Australia. Both applications were refused. Mr Palmer, by his solicitor, sent a letter to Mr McGowan and the Police Commissioner, objecting to the refusal of the applications. Mr Palmer was invited by the State Solicitor’s Office to apply for a general travel exemption, but no application was made.

9 In late May 2020, Mr Palmer and Mineralogy Pty Ltd (Mineralogy), a company controlled and beneficially owned by Mr Palmer, commenced proceedings in the High Court against Western Australia and the Police Commissioner, seeking a declaration that the Emergency Management Act and/or the Border Directions were invalid on the basis they contravened s 92 of the Constitution (High Court Border Proceeding). The High Court Border Proceeding was defended.

10 In June 2020, the Attorney-General of the Commonwealth filed a Notice of Intervention in the High Court Border Proceeding, supporting the position of Mr Palmer and Mineralogy. Also in June, the High Court Border Proceeding was remitted to the Federal Court for the determination of relevant facts (Federal Court Border Proceeding). Dr Andrew Robertson, Chief Health Officer for Western Australia, gave evidence. In August 2020, Mr McGowan was notified by the then Prime Minister that the Commonwealth intended to withdraw its Notice of Intervention.

11 In late August 2020, the Federal Court Border Proceeding was concluded and, in November 2020, the High Court Border Proceeding was dismissed.

12 The events concerning the Amendment Act relate to an entirely different subject matter. To understand the importance of the Amendment Act to the current dispute, it is necessary to wade into the relevant history leading up to enactment.

13 Mineralogy holds a number of mining leases in the Pilbara district of Western Australia. In 1993, Western Australia commenced negotiations with Mineralogy to develop a State Agreement for industrial projects in the north of the State and, in December 2001, Mineralogy and other parties related to Mr Palmer, entered into an agreement with the then Premier, acting for and on behalf of the State and its instrumentalities (State Agreement).

14 The State Agreement was ratified by the Iron Ore Processing (Mineralogy Pty Ltd) Agreement Act 2002 (WA) (Iron Ore Processing Act), which came into operation in September 2002. The State Agreement is Schedule 1 to the Act. The Minister responsible for the administration of the Iron Ore Processing Act is also responsible for the administration of the State Agreement.

15 The purpose of the State Agreement was to facilitate the development of projects by Mineralogy, by itself or in conjunction with others, “for the purpose of promoting employment opportunity and industrial development in Western Australia”: Iron Ore Processing Act sch 1, r (d).

16 In August 2012, Mineralogy companies submitted a proposal to the Minister pursuant to the State Agreement, being the “Balmoral South Iron Ore Project Proposal” (BSIOP Proposal).

17 The State Agreement does not grant the Minister any power to reject, or to refuse outright to approve, a proposal submitted pursuant to the State Agreement: see Mineralogy Pty Ltd v The State of Western Australia [2005] WASCA 69 (at [4] per Roberts-Smith JA; [34], [58] per McLure JA with whom Steytler P agreed at [1]).

18 Notwithstanding these limitations, on September 2012, the then Minister notified Mineralogy of his refusal to consider the BSIOP Proposal, on the purported ground that it was not “a valid proposal”.

19 The Minister’s refusal to consider the BSIOP Proposal gave rise to a dispute to be resolved by arbitration. In 2013, a former High Court judge, the Hon Michael McHugh AC QC, was appointed as the arbitrator and an arbitration was subsequently conducted by him (First Arbitration). The First Arbitration resulted in an award being rendered in May 2014 (2014 Award). In the 2014 Award, Mr McHugh made findings and observations, which relevantly included the following:

(1) “The Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia had held that the Minister has no power to reject a proposal. He must approve it, defer a Proposal until a further proposal is submitted or require the Proposal to comply with such conditions as he thinks are reasonable” (at [9]);

(2) “It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the attempt to categorise the August 2012 submission as not being a proposal is an attempt to circumvent the Court of Appeal’s ruling that the Minister has no power to reject a proposal: Mineralogy Pty Ltd v Western Australia [2005] WASCA 69 at [58]” (at [57]);

(3) “It follows then that the August 2012 submission was a proposal for the purposes of the State Agreement. The Minister was required to deal with it under Clause 7 of [the State Agreement], which he has failed to do” (at [66]); and

(4) “The failure of the Minister to give a decision within that time means that he is in breach of the State Agreement and is liable in damages for any damage that [Mineralogy companies] may have suffered as the result of the breach” (at [67]).

20 The 2014 Award contained the following declaration:

Declare that the August 2012 Submission was a proposal submitted pursuant to clause 6 of the State Agreement with which the Minister was required to deal under clause 7(1) of the [State] Agreement.

21 The State did not legally challenge the 2014 Award, but subsequently asserted that it had exhausted the entitlement of Mineralogy and other Palmer-related parties to seek or obtain an award of damages, and that the parties could no longer pursue any such claim. The Minister also purported to impose some 46 “conditions precedent” on the BSIOP Proposal.

22 In October 2019, a second arbitral award (2019 Award) by Mr McHugh found that, contrary to the State’s contentions, Mineralogy and the Palmer-related parties remained entitled to pursue their claims for damages. Those claims for damages were for loss said to flow from: (1) the 2012 refusal by the Minister to accept the BSIOP Proposal as a valid proposal; and (2) the Minister’s purported imposition of 46 “conditions precedent” in 2014, which were alleged to be unreasonable and incapable of being imposed.

23 By late 2019, it had been agreed that Mr McHugh would hear and determine these claims for damages in a third arbitration (Third Arbitration).

24 In December 2019, directions were made as to the exchange of a Statement of Issues, Facts and Contentions, written statements of witnesses of fact and expert witness reports. Mr McHugh foreshadowed the making of further directions.

25 In June 2020, Mr McHugh directed that the Third Arbitration would be heard for 15 business days commencing at the end of November 2020. Relevantly, direction 10.4 provided that “[t]he Arbitrator shall deliver his award in the Arbitration on or before 12 February 2021”. The directions further provided that the parties attend a mediation by the end of October 2020 and “act in good faith towards each other” in respect of the mediation. In July 2020, an arbitration agreement was executed. Both the arbitration and the mediation were confidential.

The planning of the Amendment Act

26 Notwithstanding these events preparatory to and facilitating the Third Arbitration, Mr McGowan and Mr Quigley had already started work on what would become the Amendment Act.

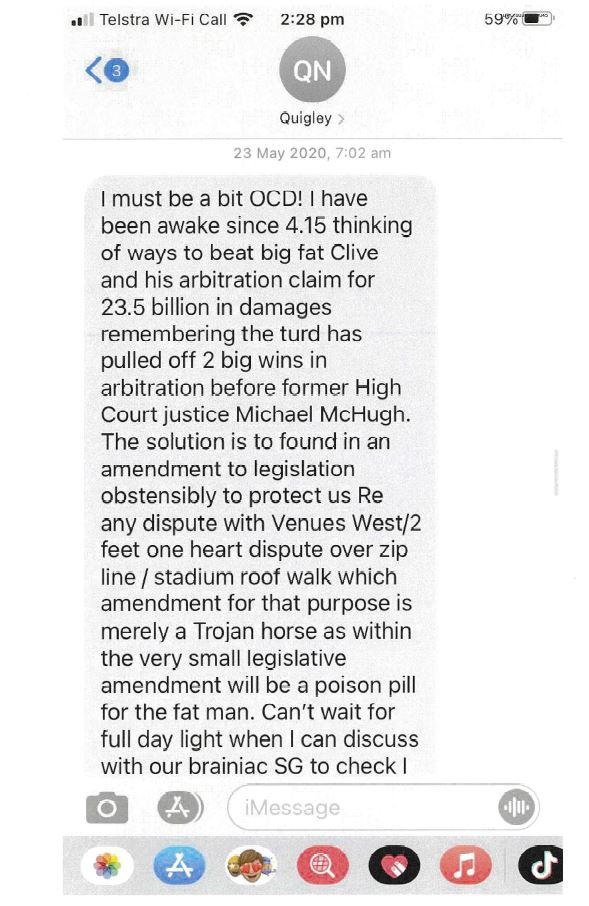

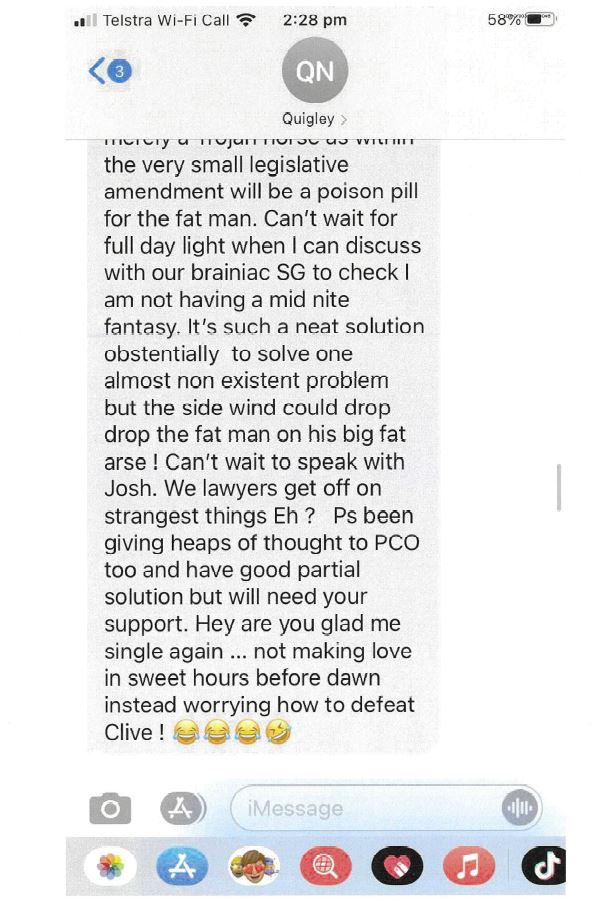

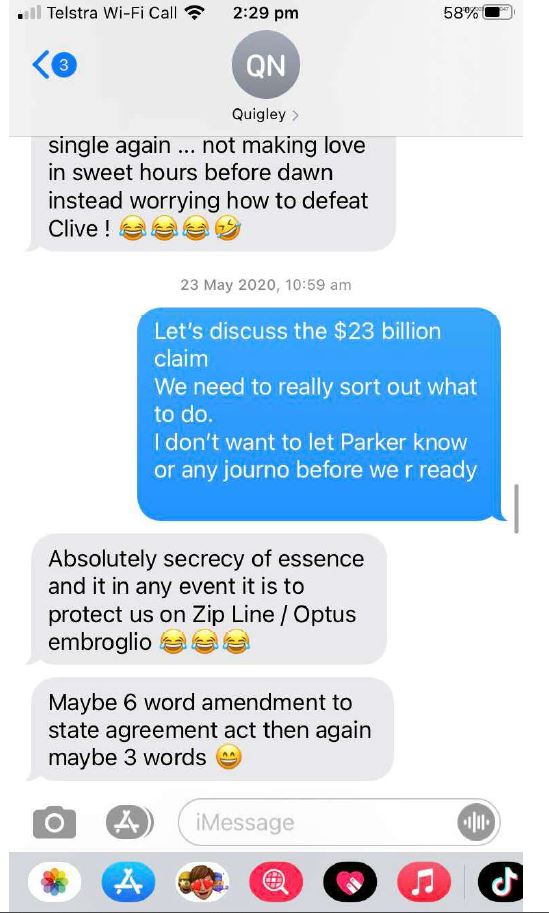

27 Mr McGowan said that from about March 2020, he and Mr Quigley were discussing the prospect of legislation as a means of dealing with the problem represented by Mr Palmer’s damages claim: T463.21–464.1. In late May, Mr Quigley and Mr McGowan had an SMS exchange in the following terms (reproduced in Annexure A):

Mr Quigley: I must be a bit OCD! I have been awake since 4.15 thinking of ways to beat big fat Clive and his arbitration claim for 23.5 billion in damages remembering the turd has pulled off 2 big wins in arbitration … The solution is to be found in an amendment to legislation obstensibly [sic] to protect us Re [the possibility of an unrelated dispute] … which amendment for that purpose is merely a Trojan horse as within the very small legislative amendment will be a poison pill for the fat man … It’s such a neat solution obstentially [sic] to solve one almost non existent problem but the side wind could drop drop the fat man on his big fat arse ! … Hey are you glad me single again … not making love in sweet hours before dawn instead worrying how to defeat Clive! 😂😂😂🤣

Mr McGowan: Let’s discuss the $23 billion claim

We need to really sort out what to do.

I don’t want to let Parker know or any journo before we r ready

Mr Quigley: Absolutely secrecy of essence … 😂😂😂

28 In July, Mr McGowan sent Mr Quigley an SMS in which he asked: “How’s our Bill Re legal action by Mr Palmer coming along[?]”. By the end of July, they were discussing the precise timing of its introduction into Parliament. The work in relation to this proposed legislation continued until just before 5pm on 11 August, when the bill that became the Amendment Act (Bill) was introduced in the Legislative Assembly.

29 The Bill moved through the Parliamentary process with the speed of summer lightning. It reached the Legislative Council on the morning of 13 August; passed the Legislative Council at about 10:35pm on the same day; and the Governor provided Royal Assent approximately 40 minutes later.

30 Other than Mr McGowan and Mr Quigley, and possibly one or two other Ministers, no member of Cabinet had any inkling of the Bill’s existence until a Cabinet meeting at 4:15pm on 11 August (45 minutes before the Bill was introduced). Backbenchers knew nothing of it until Mr Quigley rose to speak at 4:55pm on that day: T520.42–522.22.

31 It was common ground that the Amendment Act was extraordinary legislation. Among other things, it:

(1) terminated the relevant arbitration agreements (ss 10(5), 10(7));

(2) nullified both the 2014 Award and 2019 Award (ss 10(4), 10(6));

(3) terminated the Third Arbitration (ss 10(1)–(2));

(4) terminated the mediation agreement (s 10(2));

(5) granted immunity from the criminal law to “the State” (defined pursuant to s 7 so as to include Mr McGowan and others) in relation to “protected matters” (defined pursuant to s 7 to include any conduct “connected with” the preparation or enactment of the Amendment Act);

(6) extinguished freedom of information rights in relation to any document connected with any such “protected matter” (s 21(1)); and

(7) provided that no document connected with a “protected matter” was admissible or discoverable in any proceedings against “the State” (ss 18(5)–(6)).

32 It is, of course, uncontroversial that Mr McGowan approved the preparation, and supported the enactment, of the Amendment Act. He was also the responsible Minister for the State Agreement and thus for the Third Arbitration: T472.38–39.

33 On the day after the Bill was introduced by Mr Quigley, Mr McGowan and Mr Quigley gave a press conference at which Mr McGowan said in relation to the decision concerning the BSIOP Proposal:

I want to be clear on this. We believe Premier Colin Barnett took the right course of action to protect Western Australia at the time, as the proposal by Mr Palmer was flawed, and without appropriate detail.

34 Mr McGowan was no doubt making this statement for political effect, but it sits unhappily with the legal reality that what had been done in 2012 was impermissible and constituted a breach for which the State would be liable in damages. Mr McGowan’s characterisation of his predecessor’s actions as the “right course” was made notwithstanding the decision of Mineralogy v State of Western Australia (at [34], [58] per McLure JA, with whom Steytler P and Roberts-Smith JA agreed at [1] and [6] respectively), to which Mr McHugh referred in the 2014 Award.

35 On 13 August 2020, Mr Quigley gave a colourful radio interview on ABC Radio Perth, during which he purported to explain the tactics adopted in relation to the preparation of the Amendment Act:

(1) “it is like a complicated game of chess, but in no way is it a game. I certainly, together with the Premier, feel the heavy weight of responsibility on behalf of all Western Australians to repel this rapacious claim by this … by this … Palmer man”;

(2) “this is a game of tactics. Ah, Mr Palmer got … an Arbitrator’s award back in 2014 and in the intervening six years has failed to register the award. We … identified this weakness … in his position. And so we prepared legislation that terminates the arbitration, terminates it, full stop … the crucial part was it had to be terminated prior to … the arbitration being registered in the Supreme Court.”;

(3) “we kept it so tight and then brought it in at 5:00pm on Tuesday, after every court in the land was closed, and the doors were locked”;

(4) “Now, let me explain the legislation. The legislation in clause 10 and 11 terminates the arbitration, as of the time of introduction. So it terminates it as though the arbitration never happened. And the time … that termination begins, or becomes effective, is when I did my second reading speech on Tuesday evening. And it was too late for him to get to a court”;

(5) “And as I said to you, it is like, it is like a fight. And like my near neighbour, Danny Green says, you’ve just got to jab, jab, jab with your right, and move him over to the left, and then just knock him down with a right – a left hook. And what’s happened here is that Mark McGowan has been jab, jabbing away with insults, his lawyers have been busying themselves, were sending us back reams of defamation writs, when they should have been looking at the main game, of file – of registering the arbitration. And we got through in time. We got that legislation into the Assembly on Tuesday night while all the courts were locked”;

(6) “This is crucial that this bill is introduced and passed. And the academics and the other people can write about it afterwards, can analyse it afterwards, all they like for months to come. And criticise us, whatever. I don’t care. But we’ve got to unleash the left hook today. We’ve gotta knock [Mr Palmer] down, and knock him down today. There is too much at risk for all Western Australians, for namby pamby inquiries; “what does this word mean, what does that word mean?””; and

(7) “This legislation has been crafted over the last six weeks in secret by the best legal minds in this city. The Solicitor General of Western Australia, Mr Joshua Thomson, SC, our incredible State Solicitor, Mr Nick Egan, and his legal team at the State Solicitor’s Office. Mr Egan even left the office and worked at home to keep … the job secret, so that people in his own office wouldn’t know”.

36 With the background now explained, it is appropriate to turn to identifying the alleged defamatory publications.

C THE PLEADINGS AND PUBLICATIONS

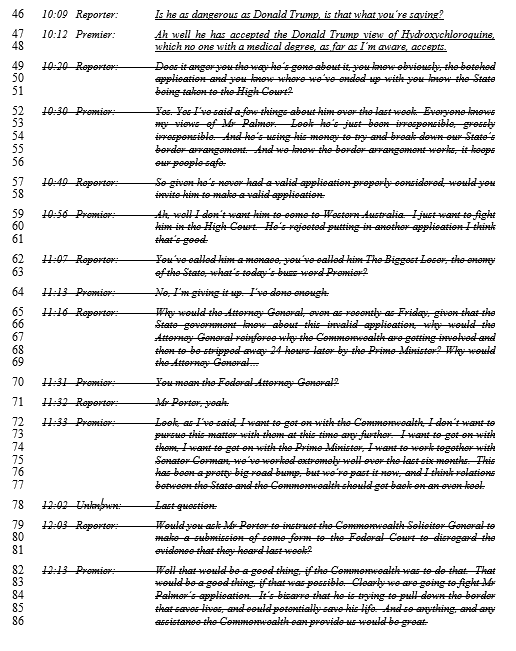

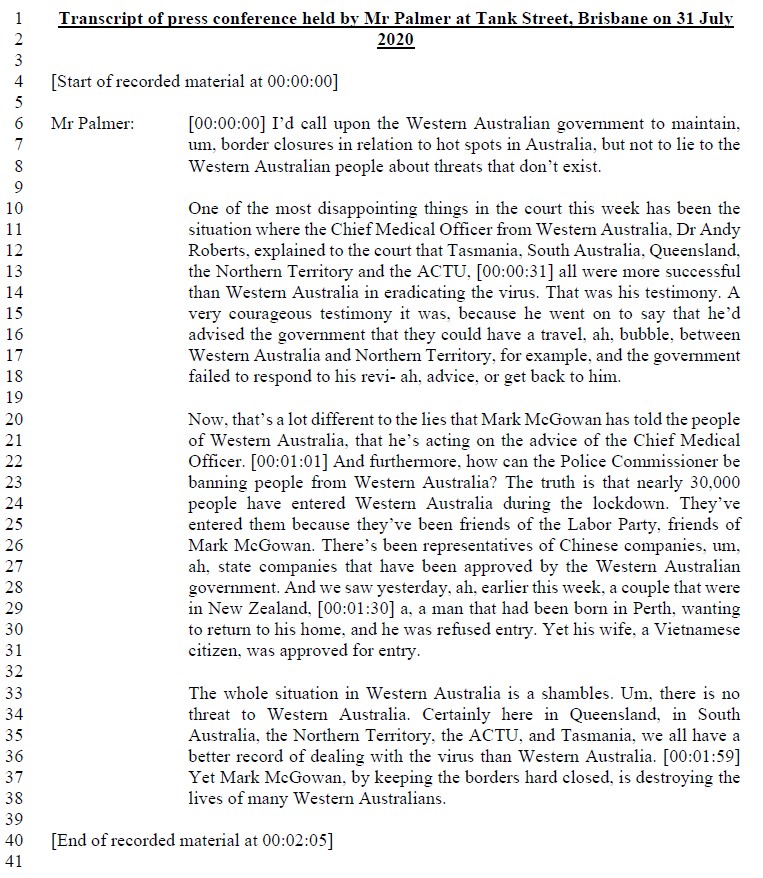

37 Mr Palmer commenced these proceedings in August 2020. He sues Mr McGowan on six alleged defamatory publications, all made in a two-week period between 31 July and 14 August 2020 (Primary Proceeding). By way of response, in September 2020, Mr McGowan filed a cross-claim, by which he sues Mr Palmer in respect of nine alleged defamatory publications (Cross-Claim).

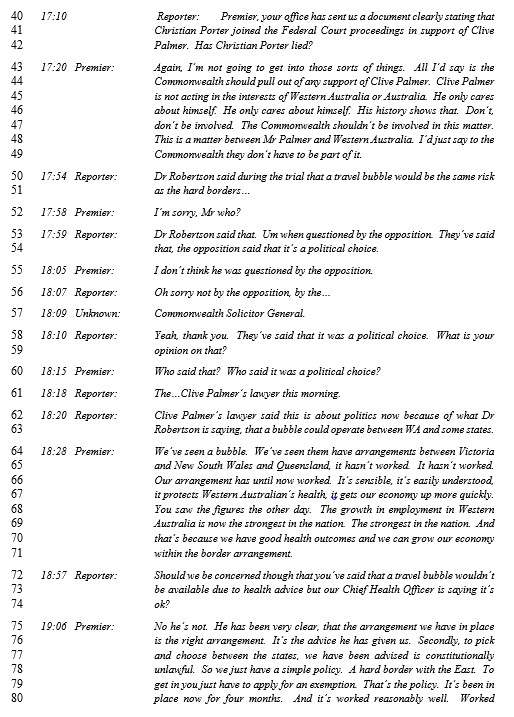

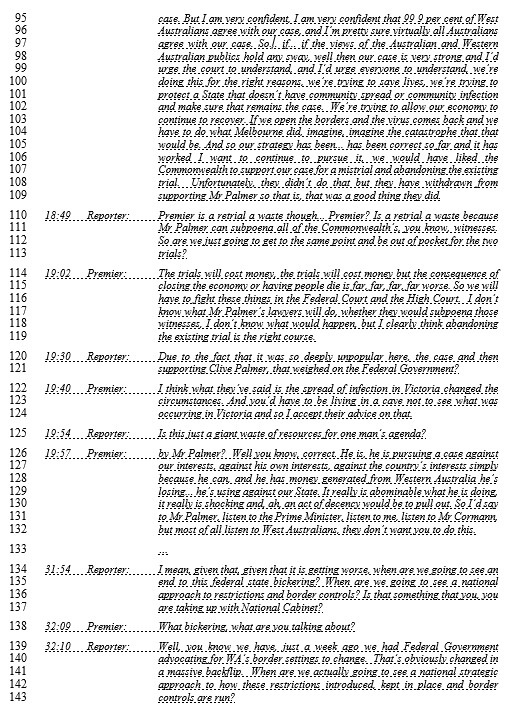

38 The six impugned publications by Mr McGowan are as follows:

(1) words spoken by Mr McGowan in a media briefing on 31 July (First Matter), republished on YouTube and the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH) website;

(2) words spoken by Mr McGowan at a different point in the same media briefing on 31 July (Second Matter), republished on the ABC website and substantially republished on the AAP website;

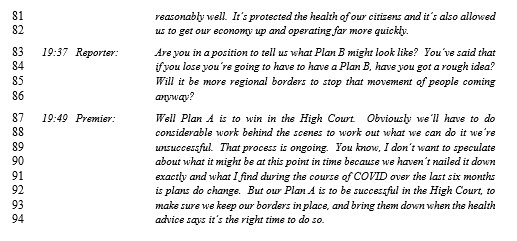

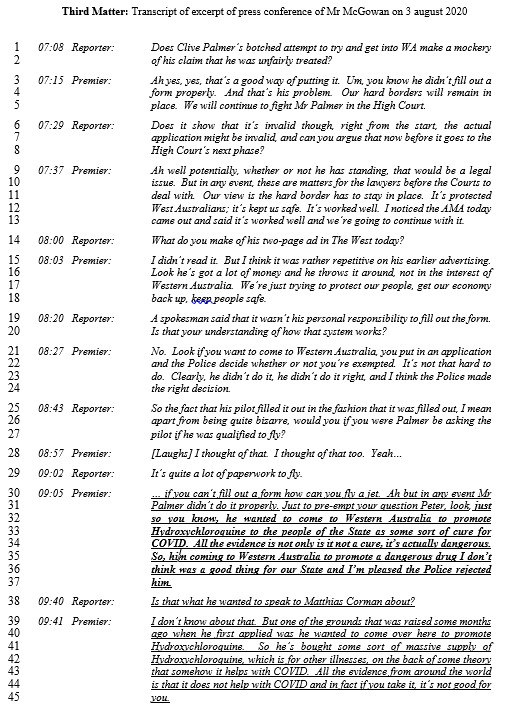

(3) words spoken by Mr McGowan in a media briefing on 3 August (Third Matter), republished on the AAP and Perth Now websites and partially on the Channel Seven website;

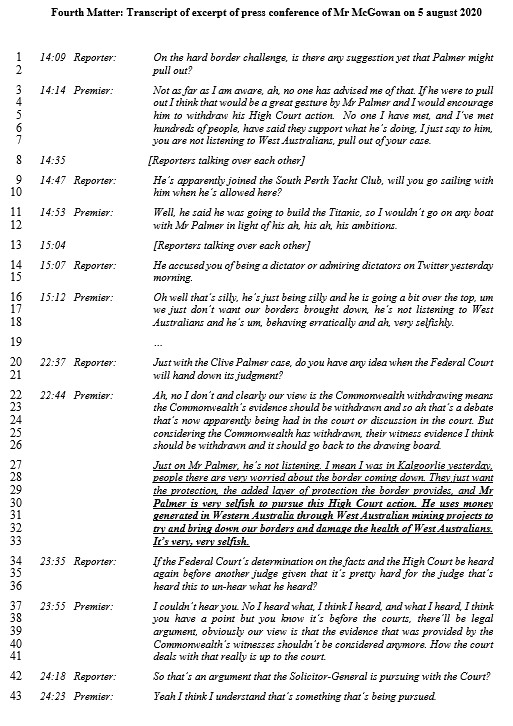

(4) words spoken by Mr McGowan in a media briefing on 5 August (Fourth Matter), republished on the WA Today Facebook page and substantially in the West Australian newspaper;

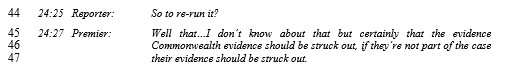

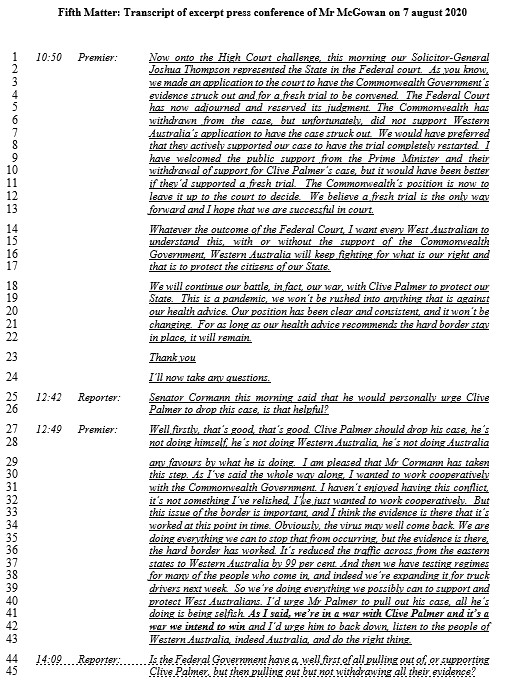

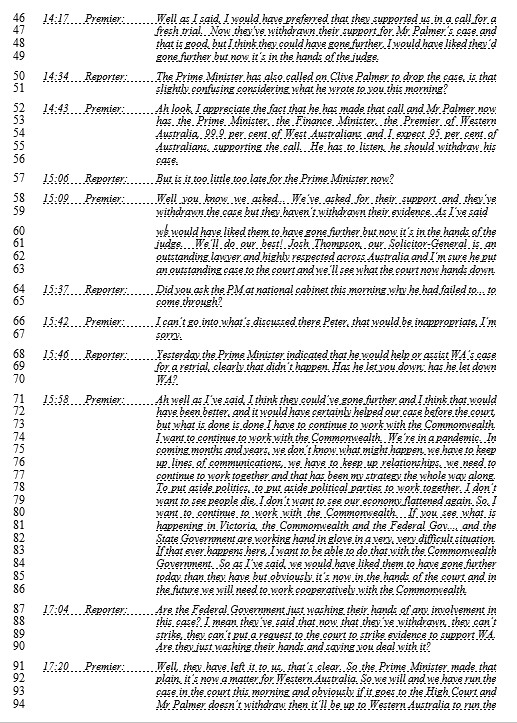

(5) words spoken by Mr McGowan in a media briefing on 7 August (Fifth Matter), republished on the Canberra Times website; and

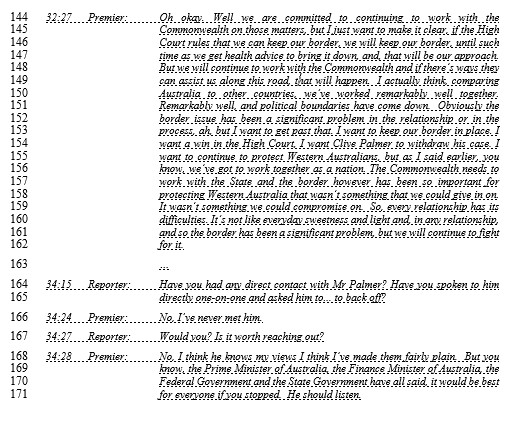

(6) a Facebook post uploaded to the Mark McGowan Facebook page on 14 August (Sixth Matter).

39 Transcripts of the First to Fifth Matters are located in Annexure B to these reasons, and the Sixth Matter is located in Annexure C).

40 Mr McGowan, in his further amended defence, pleads as follows:

(1) as to the first five matters, he admits that he spoke the pleaded words at the media briefings;

(2) he admits that he knew that some or all of what he said at those media briefings could be republished, but says that he did not intend just for those words to be republished, and that he had no control over their republication;

(3) for the most part he admits the specific republications pleaded in respect of the media briefings, but says that in some cases not all of the words appeared in the republication;

(4) he admits that he is responsible for the publication of the Sixth Matter;

(5) he denies that any of the matters were capable of conveying the pleaded imputations or that they were in fact conveyed, and initially denied that they were capable of carrying or in fact conveyed any meaning defamatory of Mr Palmer;

(6) he does not plead any defence of truth, in respect of any of the imputations; and

(7) his only substantive defence is to rely on three versions of qualified privilege: common law qualified privilege, statutory qualified privilege under s 30 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Act), and the particular species of qualified privilege concerned with publication of government or political matters, being a Lange defence.

41 Mr Palmer, in his reply, alleges malice in defeasance of all the qualified privilege defences.

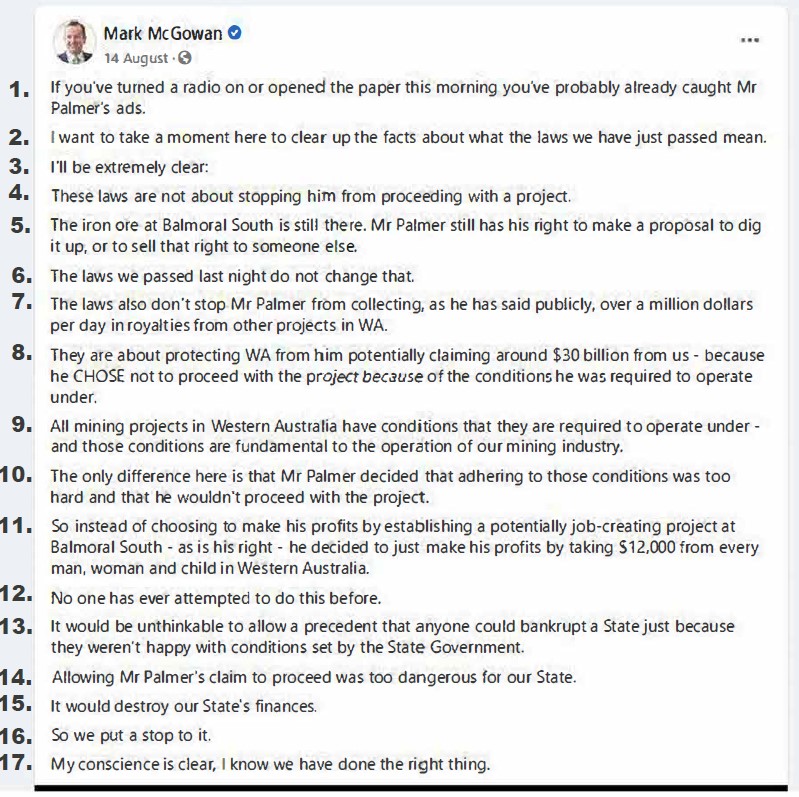

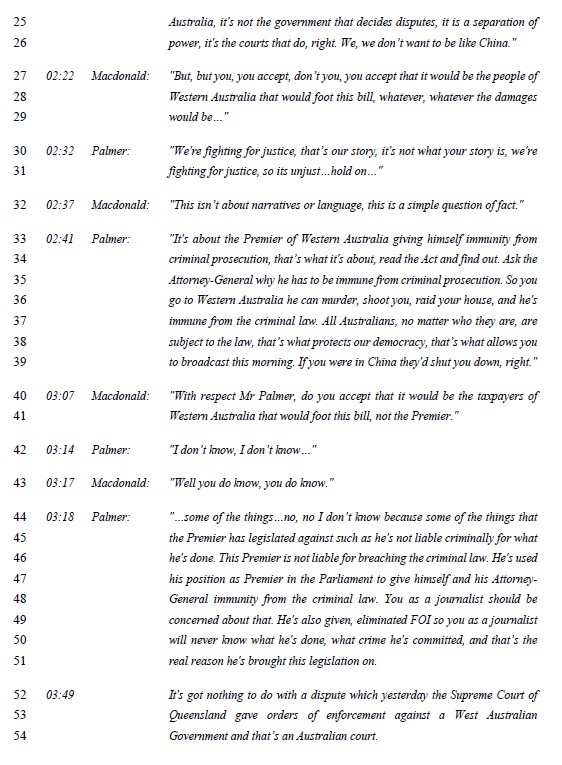

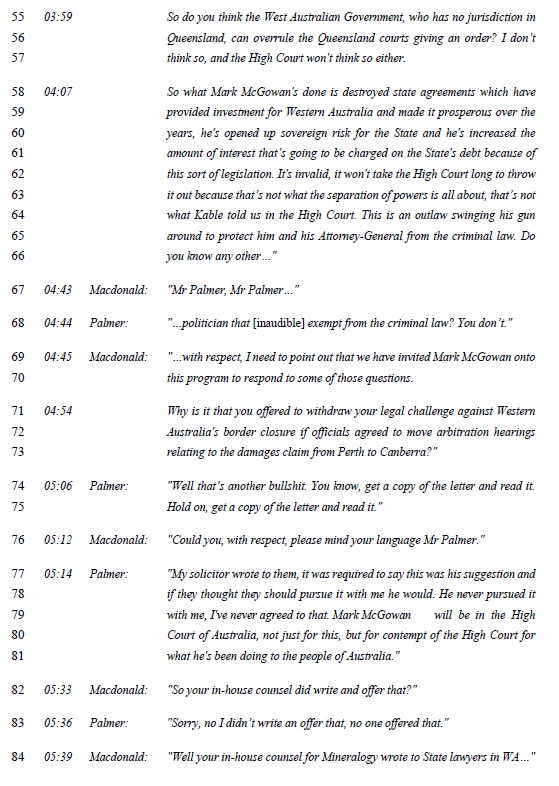

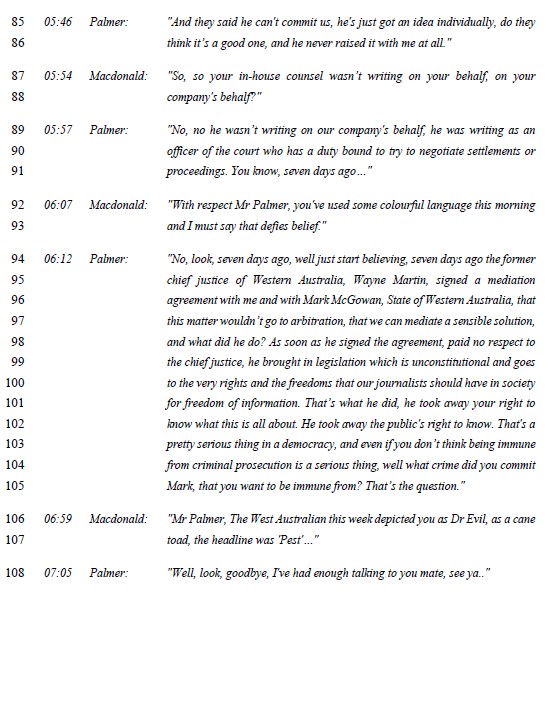

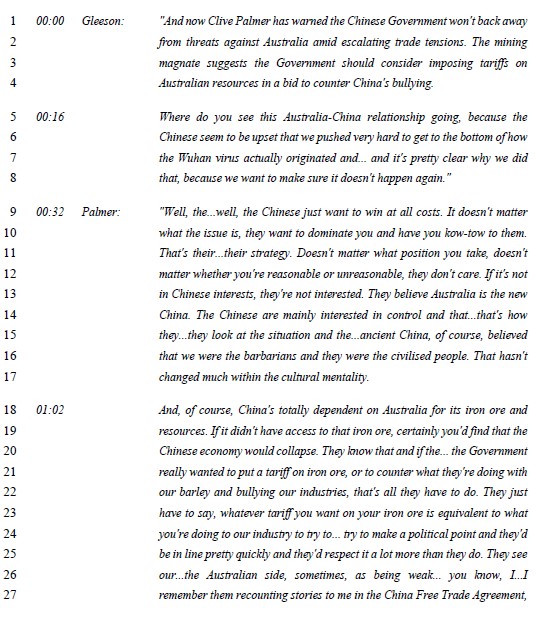

42 The Cross-Claim relies upon nine publications by Mr Palmer in the year 2020, being:

(1) statements by Mr Palmer on or about 1 August during the course of a press conference, republished in an AAP article and by other (unspecified) media (First Cross-Claim Matter);

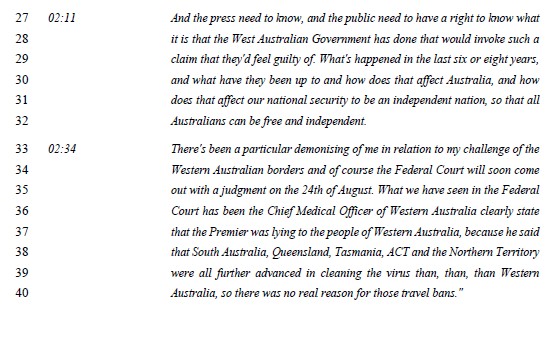

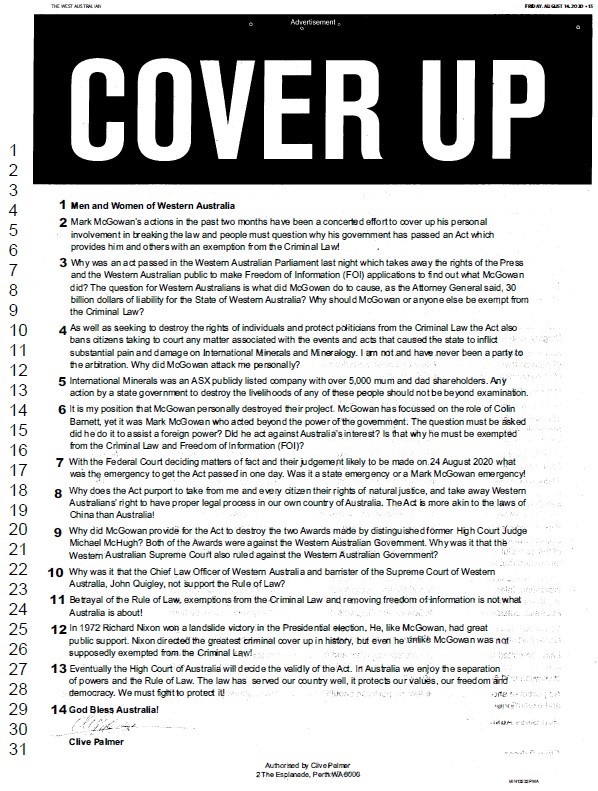

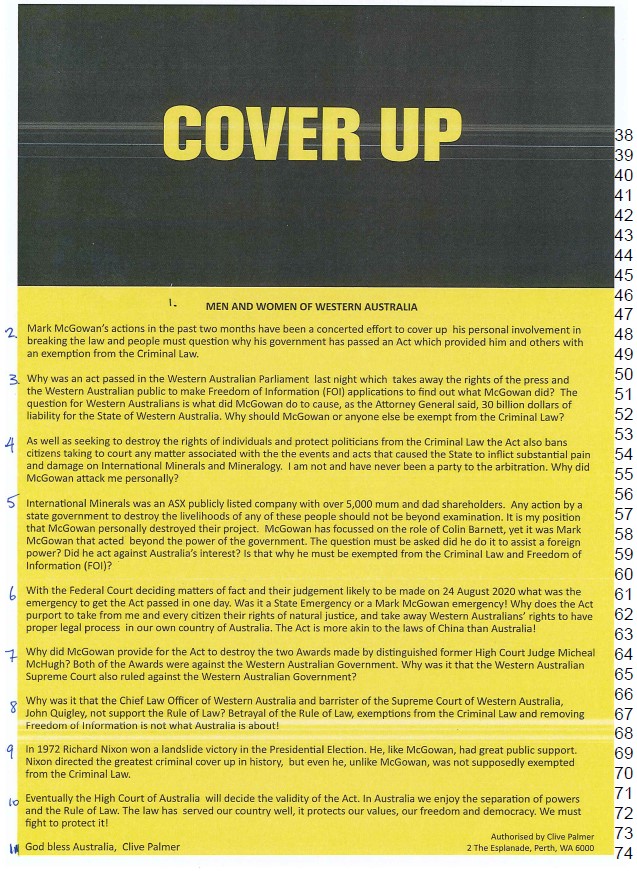

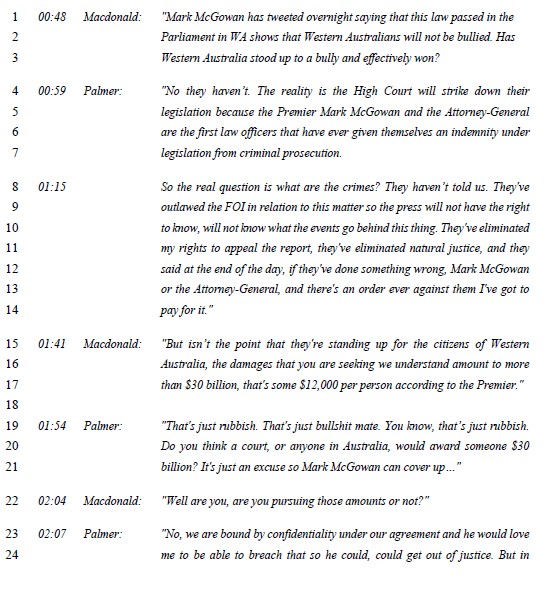

(2) statements by Mr Palmer on 12 August during the course of an interview on Sky News, alleged to have been republished by other (unspecified) media (Second Cross-Claim Matter);

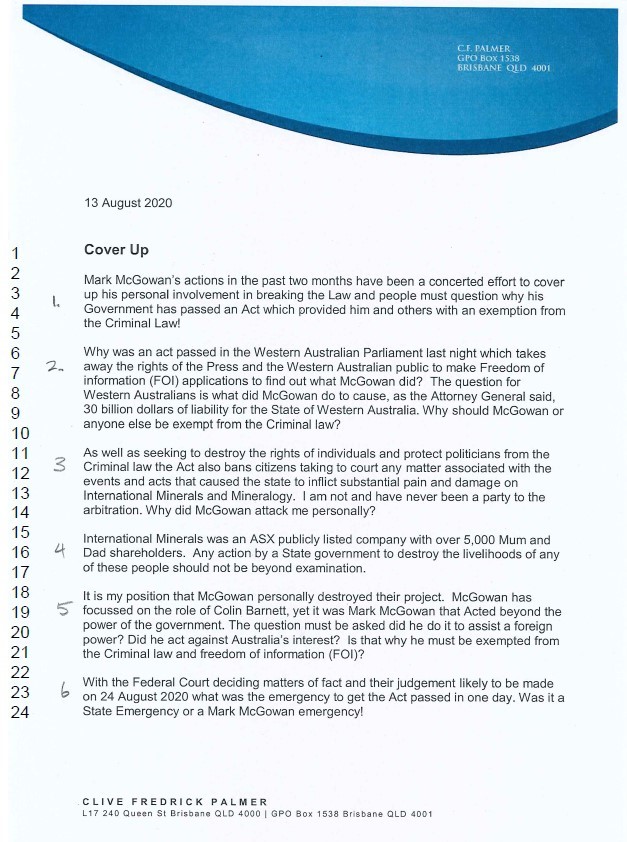

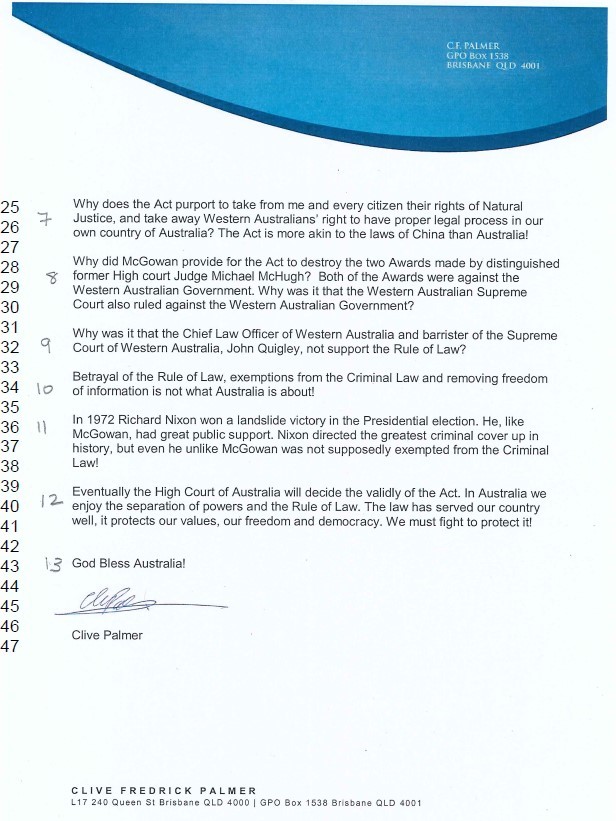

(3) a document published by Mr Palmer on and from 13 August, variously published on Google, the West Australian newspaper, Facebook, Twitter and by letterbox drop (Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Cross-Claim Matters); there are some differences between these five matters, but each of them is essentially in similar form; the document is also alleged to have been republished by other (unspecified) media;

(4) statements made by Mr Palmer on 14 August during the course of an ABC interview, alleged to have been republished by other (unspecified) media (Eighth Cross-Claim Matter); and

(5) statements made by Mr Palmer on 1 September during the course of an interview on the Sky News channel, alleged to have been republished by other (unspecified) media (Ninth Cross-Claim Matter).

43 A transcript of the First Cross-Claim Matter is Annexure D to these reasons; a transcript the Second Cross-Claim Matter is Annexure E to these reasons; the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Cross-Claim Matters appear at Annexure F to these reasons, and transcripts of the Eighth and Ninth Cross-Claim Matters are Annexure G and Annexure H, respectively.

44 Mr Palmer, in his further amended defence to cross-claim, pleads, in summary, as follows:

(1) in relation to the First Cross-Claim Matter, he admits that he spoke certain words at a press conference, and that it was a natural and probable consequence that those words would be republished;

(2) in relation to the Second Cross-Claim Matter, he admits he spoke the pleaded words at a press conference and that it was a natural and probable consequence that those words would be republished;

(3) in relation to the Third to Seventh Cross-Claim Matters, he admits that he authored and signed the document and is responsible for its publication in various media;

(4) in relation to the Eighth and Ninth Cross-Claim Matters, he admits that he spoke the words attributed to him;

(5) he denies the matters were capable of conveying the pleaded imputations or that they were in fact conveyed, and denies the matters were capable of carrying or in fact conveyed any meaning defamatory of Mr McGowan;

(6) he pleads substantial truth to three of Mr McGowan’s imputations (arising from the First and Second Cross-Claim Matters);

(7) he relies on the defence of contextual truth in relation to all matters; and

(8) he relies on the “reply to attack” species of common law qualified privilege for each of the First to Eighth Cross-Claim Matters.

45 Mr McGowan’s reply also alleges malice in defeasance of the qualified privilege defence.

46 It is common ground that the First to Fifth Matters were, to greater or lesser extent, republished in the mass media. Various particular republications are in evidence: see Annexure I.

47 In the Primary Proceeding, Mr Palmer’s pleaded defamatory imputations, and my findings as to whether those meanings were conveyed (which I explain in detail below at Section D.3), are as follows:

Matter | Imputation | Conveyed |

First Matter | Imputation 3(a): Mr Palmer is a traitor to Australia | No |

Imputation 3(b): Mr Palmer intends to harm the people of Western Australia | No | |

Imputation 3(c): Mr Palmer intends to harm the people of Australia | No | |

Imputation 3(d): Mr Palmer represents a threat to the people of Western Australia and is dangerous to them | Yes | |

Imputation 3(e): Mr Palmer represents a threat to the people of Australia and is dangerous to them | Yes | |

Second Matter | Imputation 5(a): Mr Palmer intends to inflict harm on the health and wellbeing of the people of Western Australia for his own selfish gain | No |

Imputation 5(b): Mr Palmer represents a threat to the people of Western Australia and is dangerous to them | Yes | |

Third Matter | Imputation 7(a): Mr Palmer promotes a drug which all the evidence establishes is dangerous | Yes |

Imputation 7(b): Mr Palmer is seeking to harm the people of Western Australia by providing them with a drug he knows is dangerous | No | |

Imputation 7(c): Mr Palmer is dishonestly promoting hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19 when he knows it is not a cure | No | |

Fourth Matter | Imputation 9(a): Mr Palmer deliberately intends to damage the health of Western Australians for his own personal gain | No |

Imputation 9(b): Mr Palmer selfishly uses money he has made in Western Australia to harm Western Australians | Yes | |

Fifth Matter | Imputation 11(a): Mr Palmer intends to harm Australians | No |

Imputation 11(b): Mr Palmer represents a threat to Australians and is dangerous to them | Yes | |

Sixth Matter | Imputation 13(a): Mr Palmer intends to steal $12,000 from every man, woman and child in Western Australia | No |

Imputation 13(b): Mr Palmer is prepared to bankrupt a state merely because he is unhappy with standard conditions set on a project by the State Government that apply to all mining projects | Yes | |

Imputation 13(c): Mr Palmer is so dangerous a person that legislation was required to stop him making a claim for damages against the State of Western Australia | Yes |

48 As to the Cross-Claim, Mr McGowan’s pleaded imputations, and my findings, are as follows:

Matter | Imputation | Conveyed |

First Cross-Claim Matter | Cross-Claim Imputation 3(a): As Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia when he said that he had acted upon the advice of the Chief Health Officer in closing the borders | Yes |

Cross-Claim Imputation 3(b): As Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia when he told them their health would be threatened if the borders did not remain closed | Yes | |

Second Cross-Claim Matter | Cross-Claim Imputation 5(a): As Premier, Mr McGowan was abusing the parliamentary system by overseeing the passing of laws designed to protect him against criminal acts he intended to commit | No |

Cross-Claim Imputation 5(b): As Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia about his justification for imposing travel bans | Yes | |

Third to Seventh Cross-Claim Matters | Cross-Claim Imputation 7(a): As Premier, Mr McGowan corruptly attempted to cover up the personal involvement of himself and others in criminal acts by overseeing the passing of laws designed to provide exemptions from the criminal law | Yes |

Eighth Cross-Claim Matter | Cross-Claim Imputation 9(a): As Premier, Mr McGowan behaved criminally, and was improperly seeking to confer upon himself immunity from the criminal law | No |

Cross-Claim Imputation 9(b): As Premier, Mr McGowan was acting corruptly by seeking to confer upon himself immunity against his criminal acts | No | |

Cross-Claim Imputation 9(c): As Premier, Mr McGowan was acting corruptly by seeking to confer upon himself criminal immunity | Yes | |

Ninth Cross-Claim Matter | Cross-Claim Imputation 11(a): As Premier, Mr McGowan was open to accepting multi-million dollar bribes from Chinese interests in return for permitting them access to valuable state natural resources | No |

49 As is evident from their terms, each of the imputations conveyed was defamatory.

50 At the conclusion of opening addresses, the parties agreed that it would be expedient for me to determine the issue of meaning before progressing further. This course was consistent with the overarching purpose of civil litigation in this Court reflected in Pt VB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), and meant that the defence case and any final submissions, could be directed only to the meanings actually conveyed. In accordance with this common position, I made an order pursuant to s 37P(2) of the FCA Act and r 30.02 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that the Court determine separately and before any other issue in these proceedings, and on a final basis, the following issues: (1) whether any of the imputations pleaded by Mr Palmer were conveyed; and (2) whether any of the imputations pleaded by Mr McGowan were conveyed.

51 It is worth noting that the task upon which the Court was engaged in deciding this separate question was the final determination of whether the publications did in fact convey the meanings pleaded (not the legal issue as to whether the matters were reasonably capable of bearing the defamatory meaning or meanings alleged). My reasons for my conclusions as to meaning are set out in Section D.3 below. But before coming to those reasons, it is necessary to deal with an issue that took up far more time than its importance merited: that is, identifying the metes and bounds of each matter pleaded by Mr Palmer.

52 As would already be evident, Mr Palmer sues on five oral publications, being the First to Fifth Matters, which were certain words spoken by Mr McGowan at a series of press conferences. Unlike the Sixth Matter (a post published on Mr McGowan’s Facebook page), there is a pleaded dispute as to whether Mr Palmer has established that the First to Fifth Matters were published in the form alleged.

53 Mr McGowan admits he spoke the words pleaded in each of the press conferences, but “says further he spoke other words on that occasion, a transcript of which will be relied upon at the trial of this proceeding”. Following a somewhat distracting debate in opening, the parties refined their positions as to the extent to which any of the First to Fifth Matters must be augmented by additional words spoken by Mr McGowan, whether as forming part of the matter, or as context. At my request, the parties prepared and provided to the Court a document entitled Agreed and Disputed Matters, which is Annexure B to these reasons.

54 I should note from the outset that Mr Palmer did not object to the whole of the extracts identified by Mr McGowan being received into evidence. He submits (subject to the qualifications canvassed below) that the extracts should not be substituted for the pleaded matters, but accepts that it may be appropriate to know the questions preceding particular words spoken by Mr McGowan and the whole of the extracts might be relevant to other issues such as reasonableness or malice.

55 It is trite to observe that every passage that materially alters or qualifies the complexion of the relevant imputations should be pleaded. Beyond this requirement, it is generally a matter of forensic choice for an applicant to select the manner of pleading. Accordingly, an applicant cannot be required to include additional material unless: (1) this additional material is part of what can reasonably be regarded as one publication that includes the material relied on by the applicant; and (2) the material relied upon may reasonably be regarded as part of a publication that includes the additional material: see Hayson v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 81 (at [9] per Bromwich J); Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Obeid [2006] NSWCA 231; (2006) 66 NSWLR 605 (at 611 [26(a)], 621 [69] per Tobias JA, with whom Hodgson JA and Ipp JA agreed at 606 [1] and 607 [10] respectively). The requirement to plead more than has been forensically chosen will only arise if the selection did not provide the “whole of the context” from which the tribunal of fact, considering the matter from the perspective of an ordinary reasonable reader, would be concerned to determine the meaning of what was published: Obeid (at 621 [69] per Tobias JA).

56 Here I am not concerned with the adequacy of the pleadings, but the distinct issue of determining, on a final basis at trial, the objective question of what constitutes the “matter”, as the first step of the enquiry into whether the pleaded meanings are conveyed. I accept that the approach taken to assessing the metes and bounds of a matter at the pleading stage has similarities to the relevant enquiry to be undertaken at trial. Although at the pleading stage it is open for the applicant to adopt their forensic course within the limits explained above, at trial the relevant task is identifying the matter.

57 But this whole dispute is a tempest in a teacup. None of the additional passages relied upon by Mr McGowan affected my views as to any question of meaning. Notwithstanding this, given the need to determine what constitutes the matter before identifying meaning, I will now record the conclusions I reached on this issue during the trial.

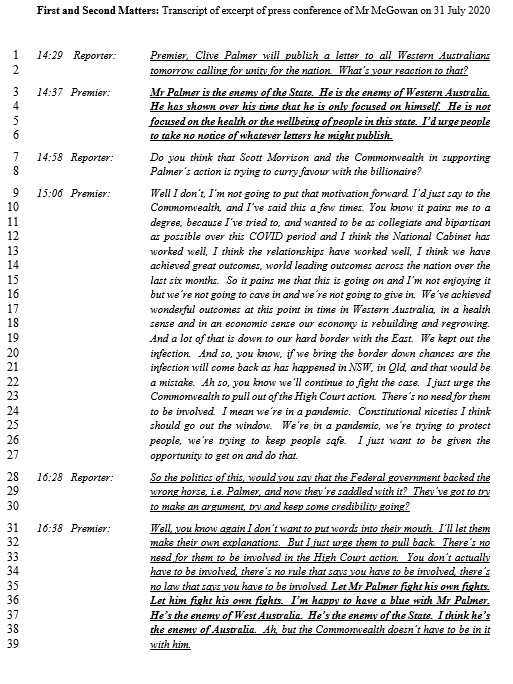

58 As to the First and Second Matters, from the outset it should be observed that these matters derive from the same radio interview (and the separate matters are pleaded in reverse order). As currently pleaded, the First Matter is located at lines 35–38 and the Second Matter at lines 3–6.

59 Putting to one side parts of the interview which are conceded or otherwise accepted as context, the dispute as to precise composition was as follows. Mr McGowan submitted the question of what might be motivating the then Prime Minister and the Commonwealth (lines 7–8), Mr McGowan’s answer to that question (lines 9–27), questions about the Commonwealth having joined the Federal Court Border Proceeding in support of Mr Palmer (lines 40–49) and discussion about the advice of Dr Robertson and the motivations for and desirability of a hard border rather than a travel bubble (lines 50–94), contextualise either the First or Second Matter. It was said that once it is accepted that the whole of lines 1–94 are relevant, the First and Second Matters should be combined as one.

60 Mr Palmer resisted the inclusion of lines 7–27 on the basis that while Mr Palmer is mentioned, the focus is generally on relations between the Commonwealth and the State, the hard border and the Commonwealth’s involvement in the High Court Border Proceeding. The same was said in respect of lines 40–49; that is, while Mr Palmer is mentioned, and Mr McGowan criticises Mr Palmer, these comments make no difference to the First and Second Matters as pleaded. Further, Mr Palmer resisted the inclusion of lines 50–94 on the basis that the introduction of Dr Robertson signals a shift in the subject matter to a discussion about the motivations for, and desirability of, a hard border rather than a travel bubble.

61 I was prepared to accept that lines 7–27 should be included as part of the First Matter. This is because the crux of what Mr McGowan is saying at lines 35–36 includes “[l]et Mr Palmer fight his own fights”, is a reference to the involvement of the Commonwealth in the High Court Border Proceeding. The preceding question as to what may be motivating the Prime Minister and the Commonwealth and Mr McGowan’s answer to that question (lines 7–27) are necessary to understand the question that follows. I was similarly prepared to accept that lines 40–49, which follow on this topic, fall within the same category. I was not satisfied, however, that these additional materials should form part of the Second Matter. While tangentially connected to the questions that follow, the Second Matter is a response to a general question as to Mr McGowan’s reaction to Mr Palmer’s call for unity of the nation, not the involvement of the Commonwealth in the High Court Border Proceeding.

62 Further, I rejected the contention that lines 50–94 should be included as part of the First or Second Matter. As Mr Palmer submitted, the introduction of Dr Robertson signals a shift in the subject matter, to a discussion about the motivations for and desirability of a hard border over a travel bubble. Finally, while I accepted that my findings therefore mean that the Second Matter finishes where the First Matter commences, there was no compelling reason to interfere with the pleader’s choice and combine the two. The First Matter is therefore constituted by lines 7–49 and the Second Matter by lines 1–6.

63 Mr McGowan pressed for lines 1–48 to be treated as part of the Third Matter. Mr Palmer has sued on the material in bold type in lines 31–37, and agrees on, or otherwise did not oppose, the inclusion of line 30, the balance of line 31 and lines 38–48. The real dispute was whether lines 1–29 should form part of the “matter”. Mr Palmer submits that lines 1–31 (up to “do it properly”) refer to the incorrect filling out of a form by Mr Palmer’s pilot, and cannot be said to be capable of affecting the three pleaded imputations, which are specifically linked to the topic of hydroxychloroquine.

64 I agreed. In lines 1–29, Mr McGowan was responding to questions concerning Mr Palmer’s attempted entry into Western Australia and mocking the inability of Mr Palmer to fill out an exemption form. Then, at line 31, there is a break to the different topic about hydroxychloroquine, prefaced by Mr McGowan stating “[j]ust to pre-empt your question Peter”. As such, the Third Matter comprises lines 30–48.

65 As to the Fourth Matter, Mr Palmer sues on the material at lines 29–33, which concern the topic of Mr Palmer allegedly using Western Australian money to try to damage the health of Western Australians. He did not resist the addition of lines 27–29. Mr McGowan submitted that the whole of lines 1–47 should constitute the Fourth Matter and that to construe the matter without these lines excludes relevant context, including the questions to which Mr McGowan was responding, such as the reporters’ reference to Mr Palmer’s tweets alleging that Mr McGowan was a dictator.

66 I disagreed. While it is true that the entirety of lines 1–26 are peripherally related to the High Court Border Proceeding, they are not necessary to understand what is pleaded as the Fourth Matter. Indeed, Mr McGowan specifically diverts the questioning to make note of Mr Palmer, stating: “Just on Mr Palmer, he’s not listening.” The extract then continues “I mean I was in Kalgoorlie yesterday, people there are very worried about the border coming down”, making it clear that the comments that follow are related to the High Court Border Proceeding. The dialogue in lines 34–47 is in the same boat as lines 1–26. As such, the Fourth Matter is constituted by lines 27–33.

67 As to the Fifth Matter, Mr Palmer accepted that some of the material for which Mr McGowan contended might reasonably be regarded as providing relevant context. Mr Palmer accepted that the whole of lines 1–43 may be treated as constituting this matter: see T120.1–11. I was content to find that the Fifth Matter is constituted by lines 1–43.

68 I cannot pass from this section without observing that the need to determine these granular issues at trial was a distraction in this case. While I accept that Mr McGowan had flagged this as a potential issue in his defence, this issue should have either been the subject of agreement or brought to a head before the first day of the trial. In any event, as I have outlined, it does not matter to resolving any dispute as to meaning (or any other real issue).

D.3 Were the Imputations Conveyed?

69 It is now convenient to record my reasons as to meaning.

70 There is no need to set out the relevant principles attending the resolution of this question of fact. They are well known, were not in dispute, and do not require, yet again, extensive summary. It suffices to note that I have previously summarised them in Oliver v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 583 (at [19]–[20]) and Stead v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 15; (2021) 387 ALR 123 (at 127–128 [14]–[15]). For a recent reminder of the important point that the ordinary reasonable viewer, listener or reader is prone to a degree of loose thinking and draws implications much more freely than a lawyer, especially derogatory implications, see Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 68; (2022) 400 ALR 56 (at 63–65 [28]–[31] per Rares J; 115 [242] per Wigney J; and 125 [305] per Lee J).

71 The only additional point I would make, which is relevant to meaning, relates to the reference made in the submissions and authorities as to the “single meaning rule”. In Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632, the Full Court, comprising Besanko, Bromwich and Wheelahan JJ, observed (at 646–647 [32]):

[a]though different people might in fact have understood the meanings conveyed by a matter in different ways, the Court must arrive at a single objective meaning … [t]he issue at trial is the single meaning that an objective audience composed of ordinary decent persons should have collectively understood the matter to bear.

72 Obviously enough, I am bound to follow this regularly applied (albeit differently stated) approach and will do so, although it is not without criticism as serving no useful purpose and is stigmatised as anomalous, frequently otiose and sometimes unjust: see, for example, in the context of malicious falsehood, Ajinomoto Sweeteners v Asda Stores [2011] QB 497 (CA) (at [31] per Sedley LJ; [43] per Rimer LJ; and [45] per Sir Scott Baker); and more generally, Rolph D, Defamation Law (Thomson Reuters, 2015) (at 103), where it is suggested that this “principle” only serves “to heighten the artificiality of an already highly artificial area of law”. But there is no need to dwell on this issue because in this case, even if I was to direct myself by simply asking the straightforward question as to whether the matters convey the substance of the pleaded imputation to an ordinary reasonable listener or reader, my answers as to meaning would be the same.

73 With respect to the First Matter, Mr Palmer submitted that Imputations 3(a)–(c) arise from the words “He’s the enemy of Western Australia. He is the enemy of the State. I think he’s the enemy of Australia”. An enemy, it was submitted, is equivalent to a traitor, and is a person who hates or intends to harm another. It was also submitted that the expressions are pregnant with historical significance, stemming from the notorious use of such language by authoritarian rulers. These submissions were reiterated in respect of Imputations 3(d) and 3(e).

74 Mr McGowan asserted that Imputations 3(a)–3(e) are not conveyed because the ordinary reasonable listener would understand a “traitor” to be a person who deliberately or intentionally betrays the interests of another. It was said that while the First and Second Matters refer to Mr Palmer as an “enemy of the state”, “enemy of West Australia” and “enemy of Australia”, in their context, those phrases would be understood as highly charged rhetoric. While the First and Second Matters are concerned specifically with the potential implications of the High Court Border Proceeding and the potential to undermine the State Government’s efforts to protect citizens from the effects of COVID-19, it was said that Imputations 3(a)–3(e) are pleaded generally. Indeed, Mr McGowan submitted that his view on this matter does not, without more, charge Mr Palmer with the general condition of being a “threat” or “dangerous”.

75 As with many disputes as to meaning, in the end it is about context. Mr McGowan was making a loaded political point against a political opponent. It is unrealistic to conclude that a hypothetical referee would take away from Mr McGowan’s comment the same message as say, a reader of the Pravda newspaper in 1952, upon seeing the same words being directed by Marshal Stalin against a member of the Central Committee (who would no doubt be an ex-member – and possibly an ex-person – by the time the words were read).

76 I am not satisfied the ordinary reasonable listener would draw Imputations 3(a)–(c). The matter is an exchange between reporters and Mr McGowan concerning the implementation of a hard border and the effectiveness of that measure in safeguarding the health of Western Australians. The listener is told that the High Court Border Proceeding (at that stage supported by the Commonwealth) posed a threat to that hard border and “if we bring the border down chances are the infection will come back as has happened in New South Wales, in Queensland, and that would be a mistake”. In such context, the use of terms such as “battle” and “fight” are plainly figurative and hyperbolic, and reflect those terms commonly used in the context of political (or indeed litigious) controversies involving adversaries contending for diametrically opposed positions.

77 Further, it would be silly to conclude that the term “enemy” in this context would be understood to be synonymous with “traitor”. The ordinary reasonable listener would understand a “traitor” to be a person who deliberately or intentionally betrays interests to which the person owes allegiance. While the First Matter refers to Mr Palmer as an “enemy of the state”, “enemy of West Australia” and “enemy of Australia”, in context, those phrases would be understood as highly charged rhetoric to convey that Mr Palmer’s actions are contrary to the interests of Western Australians and Australia. That is, they would not be understood to convey that Mr Palmer was deliberately or intentionally betraying the interests of Western Australia and Australia, or intends to harm people, which imputes wickedness. Rather, the listener is told that Mr Palmer “is not focussed on the health or the wellbeing of people in this state” – that is, his motives were elsewhere and skewed. Ultimately, the ordinary reasonable listener would understand Mr McGowan’s remarks as those of a Premier who was exasperated about Mr Palmer’s actions in challenging the border arrangements and considered them inimical to the interests of Western Australia and Australia more broadly, and was expressing that view forcefully.

78 Finally, with respect to Imputations 3(d) and 3(e), the term “enemy” does impute that Mr Palmer represents a threat and a danger. Indeed, Mr McGowan proclaimed his willingness to engage in “a blue” with “the enemy”, Mr Palmer, emphasising the perceived threat represented by him to the community.

79 Imputation 5(a), that Mr Palmer intends to inflict harm on the health and wellbeing of the people of Western Australia for his own selfish gain, is said to arise from the allegation that Mr Palmer is “the enemy”. The harm identified relates to the health and wellbeing of Western Australians, and the notion of selfish gain in relation to such harm arises from the reference to Mr Palmer being “only focused on himself” and, by contrast, not focused on the health or wellbeing of people in Western Australia. I am not satisfied that Imputation 5(a) is conveyed. The allegation that Mr Palmer is an “enemy” is not capable of imputing an intention on the part of Mr Palmer to inflict harm on citizens of Western Australia for his own gain.

80 Imputation 5(b), that Mr Palmer represents a threat to the people of Western Australia and is dangerous to them, is in a different category. Essentially, for the same reasons outlined above with respect to Imputations 3(d) and 3(e), the allegation that Mr Palmer is the “enemy” suggests that Mr Palmer represents a threat to the people of Western Australia and is dangerous to them. I am satisfied that Imputation 5(b) was conveyed by the Second Matter.

81 Mr Palmer submitted that Imputation 7(a), that Mr Palmer promotes a drug which all the evidence establishes is dangerous, is made out in terms by the Third Matter. Further, it was said Imputations 7(b) and 7(c) (that Mr Palmer is seeking to harm the people of Western Australia by providing them with a drug he knows is dangerous and is dishonestly promoting hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19 when he knows it is not a cure) are conveyed by the words “[a]ll the evidence is not only is it not a cure, it’s actually dangerous” and from the claim that the police “rejected” Mr Palmer. These statements imply, it was submitted, that it is obvious the hydroxychloroquine is dangerous, that Mr Palmer would know as much, and therefore he must be seeking to harm others deliberately by promoting it. Mr Palmer submitted that the imputation of dishonesty flows inexorably from the gap between what must be Mr Palmer’s actual state of mind, and his ignoble if not sinister objective.

82 I accept Mr Palmer’s submission that Imputation 7(a) is conveyed. Mr McGowan states explicitly that “[a]ll the evidence is not only is [hydroxychloroquine] not a cure, it’s actually dangerous. So, [Mr Palmer] coming to Western Australia to promote a dangerous drug I don’t think was a good thing for our State and I’m pleased the Police rejected him.” Counsel for Mr McGowan sought to contend that Imputation 7(a) cast the matter too broadly; that is, Mr McGowan was only denouncing the use of hydroxychloroquine specifically as a cure for COVID-19 as dangerous. This is unpersuasive. Mr McGowan is clearly stating that hydroxychloroquine is dangerous.

83 In contrast, I cannot accept Mr Palmer’s submissions with respect to Imputations 7(b) and 7(c). Mr McGowan’s words may indeed lead the ordinary and reasonable listener to conclude that Mr Palmer is gullible or foolish to accept what Mr McGowan described as “the Donald Trump view” of hydroxychloroquine, but this does not convey any knowledge of the danger of the drug on the part of Mr Palmer. Nor does it impute dishonesty or intent to harm to Mr Palmer. While I accept that Mr McGowan states, in definitive terms, that “[hydroxychloroquine] is not a cure”, it is too much of a stretch to say that vehement disagreement with Mr Palmer’s view conveys that Mr Palmer subjectively intended to cause harm or behaved dishonestly. I reach this conclusion notwithstanding I recognise that the ordinary reasonable is prone to a degree of loose thinking, and draws derogatory implications much more freely than a lawyer.

84 Imputation 9(a) is that Mr Palmer deliberately intends to damage the health of Western Australians for his own personal gain. The words relied upon to convey this imputation are as follows:

Mr Palmer is very selfish to pursue this High Court action. He uses money generated in Western Australia through West Australian mining projects to try and bring down our borders and damage the health of West Australians. It’s very, very selfish …

85 Once again, I am not satisfied that this imputes an intention on his part to try to damage or harm the Western Australian people. Rather, the intention of Mr Palmer, as conveyed, is to bring down the Western Australian border; a consequence of which is damaging the health of Western Australians. Selfishness is inward-looking and bespeaks of a lack of sufficient regard for others, whereas intentional or deliberate conduct is outward looking and imputes an element of deliberateness, which is not apparent from a contextual reading of the Fourth Matter.

86 By contrast, Imputation 9(b), that Mr Palmer selfishly uses money he has made in Western Australia to harm Western Australians, is conveyed in terms. In context, the proposition “to harm” does not, contrary to Mr McGowan’s submissions, inject an element of intention. Rather, it is the consequences of the selfish actions of Mr Palmer in “[using] money generated in Western Australia through West Australian mining projects to try and bring down our borders”. That is, the consequences of his actions in “try[ing] and bring down [the] borders” is to harm the health of Western Australians.

87 Mr Palmer contended that Imputation 11(a), that Mr Palmer intends to harm Australians, is conveyed in Mr McGowan’s claim of being at “war” with Mr Palmer. Mr Palmer submitted that the use of the inclusive pronouns “we’re” and “we” underscores that this is not merely a personal battle; rather, Mr McGowan is acting on behalf of the community against a common enemy, Mr Palmer. A state of war necessarily carries with it the contention that the enemy, against whom the “war” is to be prosecuted, intends to harm the people of the State.

88 Mr Palmer’s characterisation of Imputation 11(a) cannot be accepted. Imputation 11(a) contains an elevated subjective state of intention to harm not conveyed by the terms of the Fifth Matter. In context, the fact that the interview questions are concerned with the High Court Border Proceeding means that the ordinary reasonable listener would understand the language of “war” and “battles” to be rhetorical flourishes referring to the adversarial position taken by Mr Palmer in the litigation.

89 Imputation 11(b) is that Mr Palmer represents a threat to Australians and is dangerous to them. Mr McGowan submitted that given that the ordinary reasonable listener would understand Mr McGowan was deploying the language of war to describe the High Court Border Proceeding, the matter does not convey the general charge that Mr Palmer is either a threat or dangerous to Australians. I disagree. The imputation that Mr Palmer represents a threat and a danger does not require any malign intention, and is made clear by the two successive references to a “war” waged by Mr Palmer against “the people of Western Australia, indeed Australia”. I am fortified in this view by the fact that Mr McGowan urged Mr Palmer to “do the right thing” by Australians, implying he is currently taking actions inimical to their interests. Imputation 11(b) is conveyed.

90 Imputation 13(a) is that Mr Palmer intends to steal $12,000 from every man, woman and child in Western Australia. Mr Palmer submitted that the overall impression conveyed to the reader is that Mr Palmer was making a choice to “take” a huge sum of money, rather than to earn it legitimately. Mr Palmer submitted that the listener would understand he intends to take money to which he was not entitled. Indeed, it was said that Mr McGowan furthers this notion by reference to the fact that Mr Palmer pursuing this course “would destroy our State’s finances” (at [15]), necessitating Mr McGowan to “put a stop to” such deplorable conduct: at [16]. Mr Palmer also submitted that Mr McGowan alleges moral turpitude on Mr Palmer’s part: that is, Mr McGowan’s “conscience is clear” (as Mr Palmer’s cannot be), because (unlike Mr Palmer) Mr McGowan knows he has “done the right thing”: at [17].

91 I am not satisfied that Imputation 13(a) is conveyed. Mr McGowan notes that the Amendment Act is about “protecting WA from [Mr Palmer] claiming around $30 billion from us” (at [8]), that is, Western Australians, and that in doing so he is taking $12,000 from every many woman and child”: at [11]. While I accept the notion of “taking” can be more forceful than “claiming”, it is simply a graphic description bringing home the sheer scale of the claim. In context, “taking” is a quite different thing from Mr Palmer “stealing” (that is, dishonestly acquiring) $12,000 from every man, woman and child in Western Australia.

92 Imputation 13(b), that Mr Palmer is prepared to bankrupt a state merely because he is unhappy with standard conditions set on a project by the State Government that apply to all mining projects, is said to be conveyed in terms. This is true. Mr McGowan’s words suggest that Mr Palmer’s greedy choice, in refusing to comply with merely standard mining industry conditions, would bankrupt Western Australia, and that he was prepared to pursue this course.

93 Further, Imputation 13(c), that Mr Palmer is so dangerous a person that legislation was required to stop him making a claim for damages against the State, is said to be conveyed by the fact that the reader is being told that Mr Palmer represents an extraordinary threat. I am inclined to agree. The word “dangerous” is expressly used in relation to Mr Palmer’s claim at [14], but that concept also flows from the entire matter, particularly [8], [11]–[13] and [15]. The reader is told that Mr Palmer represents an extraordinary threat – a dangerous threat that had to be fought and defeated. Mr McGowan seeks to draw a distinction between Mr Palmer being a threat, and the threat of Mr Palmer’s claim, but they would be perceived as being the same.

94 Imputations 13(b) and 13(c) are conveyed.

95 Cross-Claim Imputations 3(a) and 3(b) are that (a) as Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia when he said that he had acted upon the advice of the Chief Health Officer in closing the borders; and (b) that as Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia when he told them their health would be threatened if the borders did not remain closed.

96 Mr Palmer did not oppose the finding that Imputation 3(a) is conveyed. As to Imputation 3(b), Mr Palmer submitted that the First Cross-Claim Matter does refer to the State Government having lied to its people about “threats that don’t exist”. However, even assuming that this lie in context relates to the justification for continuing the closure of the borders, it was said that the matter does not contain or convey any assertion that Mr McGowan had said that people’s health would be threatened if the borders did not remain closed. Rather, the lie of which Mr McGowan is accused is different: he is accused of saying that he was acting on the advice of the Chief Health Officer (in maintaining a hard closure of the border), when he was not.

97 I reject these submissions. Both Cross-Claim Imputations 3(a) and 3(b) are conveyed.

98 In respect of Cross-Claim Imputation 3(a), Mr McGowan’s alleged lie is that he relied on the advice of the Chief Health Officer in closing the borders. Mr Palmer purports to summarise what the Chief Health Officer’s advice on border closures really was, and describes it as “courageous”, creating the sense that Dr Robertson had broken ranks by speaking the truth. Indeed, Mr Palmer then squarely alleges: “Now, that’s a lot different to the lies that Mark McGowan has told the people of Western Australia, that he’s acting on the advice of the Chief Medical Officer.”

99 In Cross-Claim Imputation 3(b), Mr McGowan’s purported lie is that he has told the people of Western Australia that their health will be threatened if the borders do not remain closed. As Mr McGowan submitted, Imputation 3(b) is set up by the first line in which Mr Palmer first calls on the Government not to “lie to the Western Australian people about threats that don’t exist” in order to maintain border closures: lines 6–8. The “threat” alleged not to exist is the risk of transmission of COVID-19 across borders. Mr Palmer then goes on to “reveal” what he says was the Chief Health Officer’s advice (lines 10–18), exposing Mr McGowan as having told “lies … to the people of Western Australia” (lines 20–22) when he relied on that advice to keep the borders closed to protect the health of the people of the State.

100 Cross-Claim Imputation 5(a) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan was abusing the parliamentary system by overseeing the passing of laws designed to protect him against criminal acts he intended to commit. This is conveyed, it was said, by the entire Second Cross-Claim Matter but in particular by lines 17–32. The focus of the Second Cross-Claim Matter is on the conduct of Mr McGowan and, to a lesser extent, Mr Quigley.

101 It was submitted that starting at lines 1–5, Mr Palmer outlines the approach he claims to have taken to the dispute. By way of contrast, beginning at line 6, Mr Palmer expresses his disappointment that “the Premier, Mark McGowan, has acted the way he has last night”: lines 10–11. By this, it was said the listener is told that it is Mr McGowan who has instigated and is responsible for the conduct about which Mr Palmer complains. In that way, Mr McGowan and the Parliament are one and the same. Mr Palmer then describes that conduct. He complains of the apparent immunities from criminal liability: lines 14–16. Then, Mr Palmer asks rhetorically (at lines 17–18), “what are the criminal acts that the Government wants to do that they need an exemption from criminal liability”? Mr Palmer then contends that the right to “natural justice” and the “right to know” have been abolished by the Amendment Act (lines 19–21), the inference, it is said, being that this is a “wink and a nudge” that the public can never find out about the criminal acts and wrongdoings Mr McGowan is planning to commit.

102 This imputation is not so clear cut. Mr Palmer says that the Amendment Act “gave the Government an exemption [from] criminal liability”. He goes on to say: “So you may well ask, what are the criminal acts that the Government wants to do that they need an exemption from criminal liability”? While it could be argued that in context any reference to “Government” and “Mr McGowan” are synonymous, and that the reference to “criminal acts that the Government wants to do” implies Mr McGowan intends to commit criminal acts, I think, on balance, this would be a strained reading of the matter to an ordinary listener. There is no mention of Mr McGowan personally in this context. Further, the Second Cross-Claim Matter goes on to note (at 27–31) that:

… the press need to know, and the public need to have a right to know what it is that the West Australian Government has done that would invoke such a claim that they’d feel guilty of. What’s happened in the last six or eight years, and what have they been up to and how does that affect Australia, and how does that affect our national security to be an independent nation …

103 As Mr Palmer submitted, notwithstanding the use of the terms “wants to” in line 17, the thrust of what was said is all about the past. I have not reached the state of satisfaction to conclude Cross-Claim Imputation 5(a) is conveyed.

104 Cross-Claim Imputation 5(b) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan lied to the people of Western Australia about his justification for imposing travel bans. Mr McGowan submitted that this is conveyed by the following remarks of Mr Palmer (at lines 33–40):

There’s been a particular demonising of me in relation to my challenge of the Western Australian borders and of course the Federal Court will soon come out with a judgment on the 24th of August. What we have seen in the Federal Court has been the Chief Medical Officer of Western Australia clearly state that the Premier was lying to the people of Western Australia, because he said that South Australia, Queensland, Tasmania, ACT and the Northern Territory were all further advanced in cleaning the virus than, than, than Western Australia, so there was no real reason for those travel bans.

105 Mr Palmer’s only argument against this imputation being conveyed is that in August, Mr Palmer was not referring to Mr McGowan “imposing” travel bans (in early April) but to him maintaining those bans (months later) notwithstanding advice from the Chief Health Officer, and other States’ advances in dealing with the virus. The ordinary reasonable listener would not appreciate these subtleties. After all, what Mr Palmer says is that “there was no real reason for those travel bans”, that is, a blanket suggestion they were not necessary. Cross-Claim Imputation 5(b) is conveyed.

Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Cross-Claim Matters

106 Cross-Claim Imputation 7(a) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan had corruptly attempted to cover up the personal involvement of himself and others in criminal acts by overseeing the passing of laws designed to provide exemptions from the criminal law.

107 Mr Palmer submitted that this imputation is not conveyed because the matter does not refer to “corruption” or “criminal acts”. Rather, it refers to “breaking the law”: at [1]. “Corruption”, it was said, is not a conclusion which the ordinary reasonable reader (as opposed perhaps to the ordinary reasonable lawyer) would draw, particularly when the subject of the matters is the passing of legislation, and when it is made expressly clear the High Court is yet to rule on the validity of the legislation: see [12].

108 Cross-Claim Imputation 7(a) is clearly conveyed. An allegation is made that Mr McGowan used his position to obtain a personal benefit, namely, personal immunity from the criminal law. The ordinary reasonable reader would understand that if Mr McGowan, as Premier, has used his position and power to obtain a personal benefit, then he is corrupt. The headline, “Cover Up” is to the point. Mr Palmer submits that the ordinary reasonable listener would, given the political climate at the time (including the fact that it had come to light the Amendment Act had been drafted in secrecy and passed in haste), take any reference to a “cover up” as referring to the secret preparation of the Amendment Act, not that Mr McGowan had engaged in corruption or criminal conduct. I disagree. From the opening paragraph, Mr Palmer describes the legislation as designed to cover up “his personal involvement in breaking the law”.

109 The balance of the matters asks what criminal act Mr McGowan had committed such that he needed to enact legislation to cover it up. Mr Palmer posits various theories:

(1) “What did Mr McGowan do to cause, as the Attorney General said, 30 billion dollars of liability for the State of Western Australia.” (at [2]);

(2) Mr McGowan “destroy[ed] the livelihoods” of “5,000 Mum and Dad shareholders” in International Minerals (at [4]) and, “[t]he question must be asked did he do it to assist a foreign power? Is that why he must be exempted from the Criminal Law and freedom of information (FOI)?” (at [5]); and

(3) “Was it a State Emergency or a Mark McGowan Emergency!” (at [6]).

110 Mr Palmer leaves the reader in no doubt that he is accusing Mr McGowan of corruption when he compares him to President Richard M Nixon, whom he alleges (in an inapt Watergate reference) “directed the greatest criminal cover up in history, but even he unlike McGowan was not supposedly exempted from the Criminal Law!”: at [11]. Although it does not matter, as I noted during the hearing, this ahistorical reference seems to have overlooked the then controversial September 1974 pardon by President Gerald Ford of his predecessor (which incidentally, according to some, may have accounted for the 38th President losing a relatively close race to then Governor Jimmy Carter in 1976).

111 Cross-Claim Imputation 9(a) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan had behaved criminally, and was improperly seeking to confer upon himself immunity from the criminal law. Mr McGowan alleged that this imputation has two elements: first, that Mr McGowan has engaged in criminal conduct; and secondly, that he has used his position as Premier to give himself immunity. This, it was said, is conveyed by the entire matter and, in particular, the following passages:

(1) “… the High Court will strike down their legislation because the Premier Mark McGowan and the Attorney-General are the first law officers that have ever given themselves an indemnity under legislation from criminal prosecution” (lines 4–7);

(2) “So the real question is what are the crimes? They haven’t told us” (line 8);

(3) in answer to a question to the effect that Mr McGowan was in fact attempting to protect the state from a $30 billion damages claim, Mr Palmer scoffs, describes the suggestion as “rubbish”, and “bullshit”, saying that “[Do] you think a court, or anyone in Australia, would award someone $30 billion” and “[I]t’s just an excuse so Mark McGowan can cover up …” (lines 19–21);

(4) “It’s about the Premier of Western Australia giving himself immunity from criminal prosecution.” (lines 33–34);

(5) “Ask the Attorney General why he has to be immune from criminal prosecution. So you can go to Western Australia he can murder, shoot you, raid your house, and he’s immune from the criminal law” (lines 34–37);

(6) “… some of the things that the Premier has legislated against such as he’s not liable criminally for what he’s done. This Premier is not liable for breaching the criminal law. He’s used his position as Premier in the Parliament to give himself and his Attorney-General immunity from the criminal law” (lines 44–48);

(7) “This is an outlaw swinging his gun around to protect him and his Attorney-General from the criminal law” (lines 64–65); and

(8) “… well what crime did you commit Mark, that you want to be immune from? That’s the question” (lines 104–105).

112 Mr McGowan submitted that the ordinary reasonable reader is left with no doubt that Mr McGowan has committed crimes and while the nature of those crimes is unknown, whatever they are, they must be so serious as to warrant him using his position to confer immunity on himself (a course so extraordinary that Mr Palmer claims (at lines 4–7) it was unprecedented).

113 Cross-Claim Imputation 9(b) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan was acting corruptly by seeking to confer upon himself immunity against his criminal acts.

114 During the course of oral exchange on this topic, I formed the view that Imputations 9(a) and (b) did not differ in substance. This was because the reference to conferring “immunity against his criminal acts” limited Cross-Claim Imputation 9(b) to past acts (as did the effect of “had behaved criminally” in Cross-Claim Imputation 9(a)). This led Mr McGowan to seek leave to amend his statement of cross-claim to include a new Cross-Claim Imputation 9(c), that is, as Premier, Mr McGowan was acting corruptly by seeking to confer upon himself criminal immunity. This amendment was not opposed: T169.34.

115 Before turning to consider whether Cross-Claim Imputation 9(c) is conveyed, I should explain why, although not without some hesitation, I was satisfied Cross-Claim Imputations 9(a) and (b) were not. While I accept the high watermark is the statements of Mr Palmer, “Do you think a court, or anyone in Australia, would award someone $30 billion? It’s just an excuse so Mark McGowan can cover up …” (lines 20–21) and “well what crime did you commit Mark, that you want to be immune from? (lines 104–105), these matters must be viewed contextually. When the totality of the matter is appreciated, it does not convey a positive assertion that Mr McGowan had actually behaved criminally. Rather, it asks rhetorically, in the context of Mr McGowan having given himself an indemnity from criminal prosecution, what are the crimes? What could it be that gave rise to the need for such an extraordinary indemnity? No accusation of actual past criminality is made. To the contrary, the message to the listener is that Mr McGowan should disclose why he regards himself as requiring such an indemnity.

116 In contrast, I am satisfied Cross-Claim Imputation 9(c) is conveyed. The ordinary reasonable reader would understand that a politician who uses their position and power to obtain a personal benefit, namely, immunity from the criminal law, is corrupt.

117 Cross-Claim Imputation 11(a) is that as Premier, Mr McGowan was open to accepting multi-million dollar bribes from Chinese interests in return for granting them access to valuable state natural resources. Mr McGowan submitted that, in context, the ordinary reasonable listener would readily infer that what Mr Palmer is suggesting is that the Chinese Government will do anything to control resources and, given how close Mr McGowan is to the Chinese Government, he would be open to accepting vast sums of money from them in exchange for that control. This is said to be supported by the following aspects of the matter, and the reasonable ordinary listener “reading between the lines”:

(1) the reference to the Chinese wanting to “win at all costs” (line 9) and if it is not in their interests, “they’re not interested” (line 13), coupled with the statement that “of course, China’s totally dependent on Australia for its iron ore and resources” (lines 18–19) and that “So, the Chinese are about control because they want control of our resources in Western Australia” (lines 34–35);

(2) the reference to Mr McGowan having “a former member of the Communist Party as his Chief Whip in the Upper House” (lines 35–36) and that “McGowan’s very close to China and you see a lot of … I mean, I’ve heard stories of a lot of heads of state going up to China, being offered a passbook with the Bank of China with fifty or sixty million dollars in it and saying, ‘well, it’s available for you only through the Bank of China’” (lines 37–40); the reference to “heads of state”, it was said, implicitly being a (mistaken) reference to heads of government, including Mr McGowan; and

(3) the language “Well, I think Andrews and Mr McGowan are in the same mould [as China]. They … are in the Stalinist … communist mould … and this totalitarian government, I mean, there’s no reason why you’d extend the State of Emergency for 18 months, unless you wanted to establish that form of government” (lines 45–48), indicating that Mr McGowan is acting is consistently with how the People’s Republic of China acts, which is communist or totalitarian.

118 I am not satisfied this imputation is conveyed. Nowhere in the Ninth Cross-Claim Matter is it said or suggested that Mr McGowan “was open to accepting … bribes”, let alone with the further ingredient that the reason why Mr McGowan was “open” to such bribes was in return for permitting “Chinese interests” to have “access to valuable state resources”. The only passage referring to Mr McGowan vis-à-vis China is [6]. Mr Palmer’s words are that Mr McGowan is “very close to China”: line 37. Mr Palmer’s remarks in [1]–[9] (apart from the flourish that Mr McGowan is in the Stalinist or Communist mould) are primarily a critique of China’s conduct, not Mr McGowan’s. For example, Mr Palmer is asked a question about “this Australia-China relationship” (lines 5–8), in the light of the fact that “[Australia] pushed very hard to get to the bottom of how the Wuhan virus actually originated”: lines 6–7. In answering that question, Mr Palmer criticises the manner in which China attempts, generally, to cultivate and exert political and economic influence. He states among other things that “[t]he Chinese are mainly interested in control” (line 14), and employ a range of different strategies to achieve that end and to “protect their national interest”, including bribery: lines 41–42. While I accept that Mr Palmer makes reference to “stories” about offers of bribery having been made by China to “a lot of heads of state” (lines 37–40) immediately following him stating Mr McGowan being “very close to China” (line 37), this does not rise to the level that Mr McGowan was open to accepting multi-million dollar bribes from Chinese interests in return for permitting them access to valuable state natural resources. Further, any allegation that Mr McGowan has totalitarian inclinations is distinct from an allegation Mr McGowan accepts bribes.

119 Cross-Claim Imputation 11(a) is not conveyed.

E OBSERVATIONS AS TO THE WITNESSES