Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 875

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Between March 2016 and October 2018 the Respondent (Samsung Australia), in trade or commerce, in connection with the promotion of the supply of the Galaxy S7, S7 Edge, A5 (2017), A7 (2017), S8, S8 Plus and Note8 phones (Galaxy phones):

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth);

(b) made false or misleading representations that the Galaxy phones had performance characteristics, uses or benefits, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL; and

(c) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the characteristics and suitability for purpose of the Galaxy phones, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL,

by publishing or causing to be published advertisements and marketing materials set out in Annexure A to these orders, in Australia, which represented to consumers in Australia that the Galaxy phones would be suitable to be submerged in pool or sea water, when, in fact there was a material prospect that the charging port of the Galaxy phones might be damaged due to corrosion if:

(d) the Galaxy phones had been submerged in such water; and

(e) were charged or attempted to be charged while some such water remained in the charging port.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary penalties

2. Samsung Australia pay to the Commonwealth of Australia, within 30 days of the date of the order, pecuniary penalties of $14 million, pursuant to section 224 of the ACL, in respect of the contraventions of sections 29(1)(a) and (g) and 33 of the ACL identified in paragraph 1 above.

Other orders

3. Samsung Australia pay the Applicant, within 30 days of this order, a contribution to the Applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding fixed in the sum of $200,000.

4. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

ANNEXURE A

MURPHY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The respondent in this proceeding, Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd (Samsung Australia), is a company incorporated in Australia. Its parent company, Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. (SEC) designs and manufactures a wide range of consumer electronic products, including “Galaxy” branded smartphones. Samsung Australia markets and sells those phones to consumers in Australia via the internet and Samsung Australia stores, and also sells them to other retailers and distributors for resupply to consumers. SEC is one of the largest manufacturers of smartphones in the world, and Samsung Australia is one of the leading smartphone brands in Australia.

2 By its Originating Application dated 4 July 2019 and an amended Concise Statement dated 3 March 2021, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) alleged that Samsung Australia engaged in conduct which was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of ss 18(1), 29(1)(a) and (g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

3 The parties have submitted a joint statement of agreed facts (SOAF) and joint submissions dated 9 June 2022. By the SOAF, Samsung Australia has admitted that during the period March 2016 to October 2018 (relevant period) it published the 9 advertisements and marketing material (the advertisements) set out in Annexure A to the attached orders, and that:

(a) the advertisements represented to consumers in Australia that certain Galaxy smartphone models (S7, S7 Edge, A5 (2017), A7 (2017), S8, S8 Plus and Note 8) launched in Australia between March 2016 and August 2017 (Galaxy phones) would be suitable to be submerged in pool or sea water,

(b) when in fact there was a material prospect that the charging port of those Galaxy phones might be damaged due to corrosion if the Galaxy phones were submerged in such water and were then charged or attempted to be charged while some water remained in the charging port.

4 Samsung Australia has admitted that that by engaging in the conduct set out in the SOAF, it contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a) and (g) and 33 of the ACL. The parties jointly sought a declaration and the imposition of a pecuniary penalty totalling $14 million. For the reasons I explain I am satisfied that it is appropriate to make those orders. I now turn to explain my reasons for doing so.

RELEVANT LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS AND PRINCIPLES

5 Section 18 provides:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

6 Section 29(1)(a) and (g) provide:

False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

…

Note 1: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

7 Section 33 provides:

Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of goods

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this section.

8 The applicable principles concerning the statutory prohibition of misleading or deceptive conduct (and closely related prohibitions) in the ACL are well known. The central question is whether the impugned conduct (under ss 18 and 33) or the alleged representations (under s 29), viewed as a whole and in context, have a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 170; 42 ALR 177 at 200 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ); Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd [1982] HCA 44; 149 CLR 191 at 198 (Gibbs CJ); Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [98] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [25] (French CJ) and [102] (Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Keifel JJ (as her Honours then was)).

9 Where, as in the present case, the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally, the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class of persons to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]-[105]; Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Ltd [2020] FCAFC 65; 377 ALR 387 at [236] (Foster, Moshinsky, O’Bryan JJ). It is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; 249 CLR 435 at [6] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was)).

10 Although s 29 of the ACL uses the words “false or misleading”, there is no material difference between those words and the words “misleading or deceptive” in s 18: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] (Gordon J), cited with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; 278 FCR 450 at [21] (Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ).

AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONTRAVENING CONDUCT

11 I have drawn the following overview from the SOAF and the parties’ joint submissions.

Advertisements and representation

12 In the relevant period several models of ‘Galaxy’ branded smartphones were marketed and sold by Samsung Australia to consumers in Australia, and to other retailers and distributors for resupply to consumers. The Galaxy phones, as defined, are the S7, S7 Edge, A5 (2017), A7 (2017), S8, S8 Plus and Note 8 models. When first released, the recommended retail price (RRP) for each of the Galaxy phones ranged between $649 and $1,499, the average price being $1127.

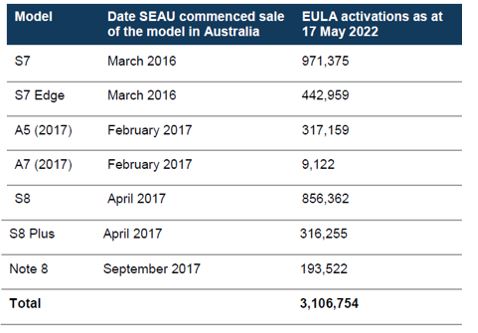

13 The estimated number of Galaxy phones sold in Australia, from their release to 17 May 2022, is set out in the table below. The table is based on the number of End User Licence Agreement (EULA) activations for each model of the Galaxy phones, from the date that the model commenced sale in Australia to 17 May 2022. All consumers who purchase a Galaxy phone and wish to use it are required to agree to SEC’s EULA as part of the initial device set-up process and thus the EULA activation figures are the most accurate way of determining how many Galaxy phones were sold to Australian consumers:

14 The media type and place of publication of each of the impugned advertisements and the period during which they were published is set out in Annexure A. By way of example:

(a) the 7th advertisement in Annexure A was contained in a booklet and included the relevant text, “Do everything you love this summer on the Galaxy A5. Whether it’s listening to your favourite song by the pool or capturing your Sunday surf session at the beach”. The text accompanied an image of a person on a surfboard diving under the water in the ocean. 10,100 copies of the booklet were printed and they were distributed to 28 Samsung Australia retail stores; and

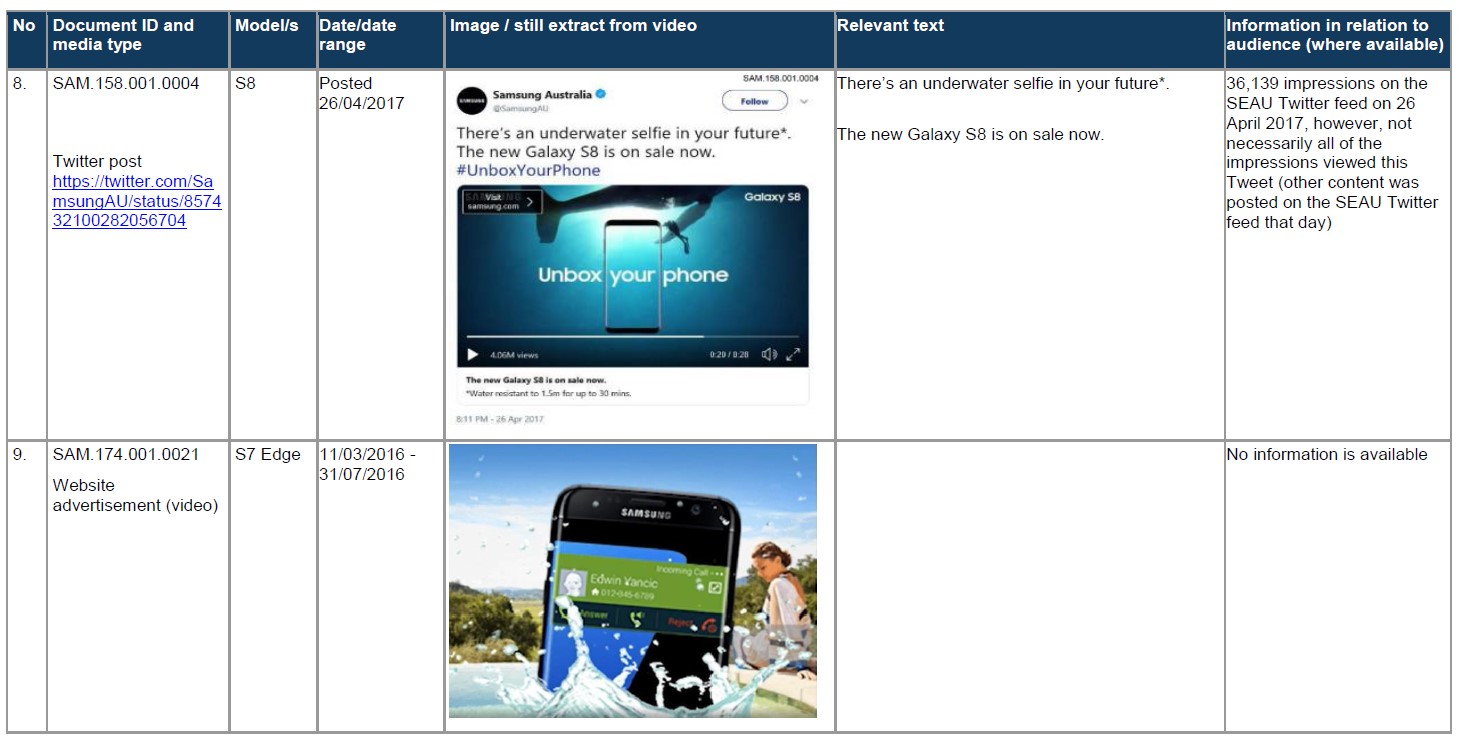

(b) the 8th advertisement in Annexure A was a video posted on Twitter which video contained footage taken from the perspective of someone who is in the ocean and looking up above them to the surface where there are two whales swimming. The relevant text accompanying the video was “There’s an underwater selfie in your future*. The new Galaxy S8 is on sale now.” 36,139 “impressions” were recorded on Samsung Australia’s Twitter feed on 26 April 2017; but all of the “impressions” do not necessarily relate to consumer viewings of the 8th advertisement because other content was also posted on Samsung Australia’s Twitter feed that day.

15 For the purpose of the proceeding the parties agree that the advertisements represented to consumers in Australia that the Galaxy phones would be suitable to be submerged in pool or sea water (the Representation).

Testing of phones

16 All of the Galaxy phones were tested prior to launch by a Korean government organisation, the Korea Electrical Safety Corporation, pursuant to the International Standard IEC 0529 – Degrees of Protection Provided by Enclosures (IP Code) published by the International Electrotechnical Commission, a non-profit international standards organisation which creates standards for electrical, electronic and related components. All of the Galaxy phones achieved a rating of ‘IP68’ following the testing. Compliance with IP68 meant that the Galaxy phone could be placed in up to 1.5m of still fresh water (not pool or sea water) for up to 30 minutes, without ingress of water.

17 In addition to the testing conducted in accordance with the IP Code, further water-related tests were conducted by SEC and another third party on the Galaxy phones. After each test, the sample Galaxy phone was assessed to ensure that it functioned properly and was inspected to ensure that there was no physical deformity (including corrosion or discolouration) or ingress of water detected at the conclusion of the test.

18 An overview of the testing performed or commissioned by SEC on samples of the Galaxy phones regarding water resistance included the following, drawn from a non-confidential version of Annexure C to the SOAF:

(a) IPX5 testing which reflects the degree of a device’s protection against water moving with force;

(b) IPX8 testing which is testing to reflect the degree of a device’s protection against total immersion in fresh water at a depth of 1.5 metres for 30 minutes;

(c) Submersion of the phones in each of salt water, chlorinated water and “body wash water”;

(d) Long, deep and repeated immersion testing, testing at different water temperatures, testing in appliances and in soapy water;

(e) Factory testing: every Galaxy phone was subject to a factory seal test following the conclusion of the manufacturing process and prior to the phone leaving the production factory. The factory seal test involves the use of equipment known within SEC as a Water Proof Checker (WPC), which tests and confirms the quality and integrity of each phone’s external water resistant seal;

(f) Pre-treatment water resistance testing which was followed by a WPC test, a “function test”, and the phone being submerged in 1.5 metres of fresh water for 30 minutes. This form of testing included each type of Galaxy phone:

(i) being dropped numerous times;

(ii) having the power turned on and repeatedly exposed to low and high temperatures;

(iii) having the power turned on and being exposed to a high temperature and high humidity for an extended period of time;

(iv) having the power turned on and the sim-tray mounted and removed repeatedly;

(v) having the power on, the charging port being connected to a charging cable and then having the charging cable shaken up and down repeatedly;

(vi) having the power on, a headphone cable connected to the headphone jack, and that cable then being shaken repeatedly; and

(vii) having the power turned on, and pressing the home key and the side key repeatedly;

(g) Water inflow testing which included:

(i) water being injected directly into the charging port of the Galaxy phones, which were then left to dry, and inspected for corrosion with a microscope; and

(ii) water being injected directly into the charging port of the Galaxy phones, which were then submerged in a container containing water for a period of time, left to dry, and inspected for corrosion with a microscope; and

(h) Randomised IPX8 testing: SEC’s factory seal testing is complemented with regular, randomised sample testing of the Galaxy phones. This involves SEC testing samples of units per model each week of production in accordance with IPX8. The randomised sample test is intended to confirm compliance with the IPX8 rating on an ongoing basis, and ensure the IP rating for each sample phone is not affected across the period of production, for example, by possible changes in the quality of parts, the manufacturing process or human operator error.

19 Tests of this kind were also performed by SEC on samples of individual components and/or materials used in the Galaxy phones prior to launch, which included testing on the charging port, speakers, and other phone parts.

Prospect of corrosion of the charging port

20 Prior to the launch of the Galaxy phones, SEC had been seeking to mitigate the effects of charging port corrosion arising from charging following exposure to water. The Galaxy phones were designed so that, in some circumstances, a message would automatically appear on the screen of the Galaxy phone to warn the consumer that moisture (including pool or sea water) had been detected in the charging port and for the consumer to ensure that the charging port is dry before charging the phone (warning message). The warning message would appear on the screen of the S7 and S7 Edge models if the phone was turned on and the charging port was connected to a power source; and the A5, A7, S8, S8 Plus and Note 8 models if the phone was turned on and moisture was detected in the charging port (whether the port was connected to a power source or not).

21 In addition, if the S8, S8 Plus and Note 8 model phones were turned off but the charging port was connected to a power source and moisture was detected in the charging port, then the following icons would be displayed on the screen of the phone:

22 Importantly, Samsung Australia admitted that if the Galaxy phones had been submerged in pool or sea water and the consumer then attempted to charge the phone while some pool or sea water remained in the charging port, there was a material prospect that the charging port might be damaged due to corrosion. The material prospect of damage due to corrosion was reduced if the phone would not charge when connected to a power source, as no electric current was created when the phone was connected. It also admitted that if the charging port corroded significantly then, among other things, there was a material prospect that the phone would be unable to be charged through the charging port and this port would no longer be functional, thereby damaging the phone and affecting its operability.

23 From the time of their launch, the Galaxy phones had in-built systems which, to varying extents, prevented the phones from charging if moisture (including pool or sea water) was detected in the charging port and the charging port was connected to a power source (charging interruption system). For the S7, S7 Edge, A5 and A7 models, the charging interruption system only functioned if the phone was switched on. The S8, S8 Plus and Note 8 models were launched with an upgraded charging interruption system such that if the device was submerged in either pool or sea water and the consumer attempted to charge the phone by connecting it to a power source while water was present in the charging port, whether the phone was switched on or off, the phone would not charge. This upgrade reduced but did not remove the prospect that the charging port of the Galaxy phones might be damaged due to corrosion in certain circumstances. Samsung Australia admitted that there remained a material prospect that the charging port might be damaged due to corrosion if any of the Galaxy phones were attempted to be charged (whether switched on or off) while pool or sea water was still present in the charging port.

24 In respect of subsequent models of Galaxy phones which were launched in Australia from March 2018 onwards, software and hardware upgrades were applied by SEC such that there was no longer a material prospect of corrosion in the circumstances described above.

The relevant class of consumers

25 Samsung Australia has admitted that the advertisements were published on websites, social media, in a press release and in stores across Australia. Samsung Australia is not aware of the advertisements being published by any other member of the SEC corporate group overseas and there is no evidence of that occurring.

26 The relevant class of consumers by reference to whom the likely effect of the advertisements is to be assessed are members of the Australian public who were or may have been interested in purchasing a smartphone during the relevant period.

The consequences of the contravening conduct

27 The parties agree that it is not possible to determine on the available evidence:

(a) how many consumers saw one or other of the 9 advertisements;

(b) how many of those consumers purchased one of the Galaxy phones;

(c) how many of those consumers would not have purchased the advertised Galaxy phone but for the Representation;

(d) how many of the consumers who purchased one of the Galaxy phones subsequently submerged the phone in pool or sea water and attempted to charge the phone whilst such water remained in the charging port; nor

(e) how many of the advertised Galaxy phones purchased by consumers were damaged due to corrosion as a result of a consumer submerging the phone in pool or sea water and attempting to charge the phone whilst such water remained in the charging port.

28 The parties accordingly agree that it is not possible to determine or estimate based on the available evidence the financial benefit likely to have been derived by Samsung Australia, nor the financial harm likely to have been suffered by consumers, as a result of the contravening conduct.

Samsung Australia’s financial position

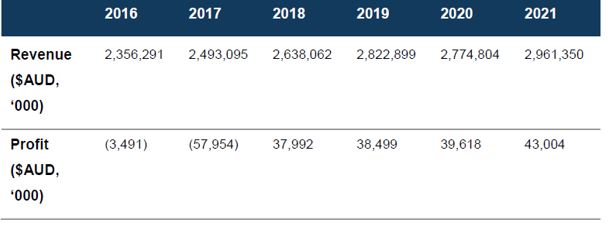

29 The gross revenue and profit of Samsung Australia for each full calendar year from the beginning of the relevant period to 2021 is set out in the following table:

DECLARATORY RELIEF

30 The parties seek an agreed declaration of contravention.

31 Pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) the Court has a broad discretionary power to grant declaratory relief. It is undesirable to fetter the exercise of the discretion by laying down rules as to the manner of its exercise, but ordinarily the following three requirements must be satisfied before a declaration is made:

(a) the question the subject of the declaration must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor, that is, someone who has a true interest to oppose the declaration sought:

see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 at 437-438 (Gibbs J); Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448 (Lord Dunedin).

32 Each of those requirements is satisfied. There is, or at least was, a real question as to whether Samsung Australia’s conduct contravened the ACL. The contraventions are established by the facts and admissions in the SOAF, and the terms of the declaration accurately reflect and are confined to Samsung Australia’s admitted contraventions. As the regulator under the ACL the ACCC has a real interest in seeking the declaration. The declaration will serve to support the ACCC’s regulatory functions and will enforce and promote compliance with the ACL in relation to false or misleading representations in advertising material. Samsung Australia, as the respondent, is a proper contradictor. Notwithstanding that Samsung Australia came to see that interest served by not opposing the relief claimed (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; 201 FCR 378 at [16] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ)), it has a genuine interest in opposing the declaration.

33 The declaration is appropriate because it will record the Court’s disapproval of the conduct; deter others from engaging in conduct which contravenes the ACL; vindicate the ACCC’s claims that Samsung Australia’s conduct contravened the ACL; assist the ACCC in carrying out the duties as conferred on it by the CCA; inform the public about Samsung Australia’s conduct, and serve the public interest in defining and publicising the type of conduct that contravenes the ACL; and make clear to other would-be contraveners that such conduct is unlawful: see generally Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v STA Travel Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 723 at [24] (O’Bryan J) and the cases there cited.

PECUNIARY PENALTY

34 At all material times s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL provided that if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of Part 3-1 of the ACL (which includes section 29 and 33), the Court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which it applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

35 The parties submitted that a pecuniary penalty of $14 million is appropriate in all of the circumstances for the contraventions of ss 29(1)(a) and (g) and 33 of the ACL. Section 18 of the ACL is not a civil penalty provision.

The considerations relevant to penalty

The mandatory considerations

36 At all material times, s 224(2) of the ACL provided:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Other relevant considerations

37 Other matters relevant to the exercise of the power to impose a penalty are commonly referred to as discretionary factors; but as noted by Edelman J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Ltd [2016] FCA 44 at [123], they are not truly discretionary. Once they become relevant they are considerations that the Court must have regard to. Those factors have been considered in numerous decisions and were usefully summarised by Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; 282 ALR 246 at [11] as including the following:

(a) the size of the contravening company;

(b) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(c) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravenor or at some lower level;

(d) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the relevant legislation as evidenced by educational programmes and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(e) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act;

(f) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(g) the financial position of the contravener; and

(h) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

38 Further considerations include:

(a) whether a contravener has shown remorse or contrition: Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Gibson (No 3) [2017] FCA 1148 at [50] (Mortimer J); and

(b) whether a contravener has paid or has been ordered to pay compensation so as to ameliorate the loss or damage suffered: Woolworths at [166].

39 I recently set out the applicable principles in relation to determining an appropriate penalty in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Colonial First State Investments Limited [2021] FCA 1268 at [39]-[47], as follows:

Deterrence

[39] The principal object of a pecuniary penalty is deterrence, directed both to discouraging repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and discouraging others who might be tempted to engage in similar conduct (general deterrence). The object of a pecuniary penalty is to attempt to put a price on the contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to engage in contraventions: Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762 at 44; [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152 per French J (as his Honour then was), cited with approval in Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [55] (French CJ, Keifel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

[40] The Court must fashion a penalty which makes it clear to the contravener and to the relevant market or industry, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of consumer protections cannot be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20 at [68]; 287 ALR 249 at 266 (Keane CJ (as his Honour then was), Finn and Gilmour JJ) cited with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54 at [64]; 250 CLR 640 at 659 (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). It must have sufficient sting or burden to achieve the specific and general deterrent effect that are the fundamental reason for imposition of the penalty: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union & Another [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157, 195 at [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

[41] Having said that, a penalty must not be so high as to be oppressive: Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chain Saws (Aust) Pty Ltd [1978] FCA 104; ATPR 40-091 at 17,896 (Smithers J) cited with approval in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was)).

…

The course of conduct principle

[43] In cases involving multiple contraventions, care must be taken to avoid the contravener being penalised more than once for what is in substance the same underlying misconduct.

[44] The course of conduct principle recognises that where there is a sufficient interrelationship in the legal and factual elements of the acts or omissions that constitute multiple contraventions, the Court may, in its discretion, penalise the acts or omissions as a single course of conduct. It involves treating multiple contraventions arising from the same underlying wrongdoing together, for the purpose of assessing the appropriate penalty for that conduct, so as to ensure that the sentence or penalty fairly reflects the substance of the offending conduct. The principle has been described as just a “tool of analysis” and the question as to whether contraventions should be treated as a single course of conduct requires consideration of all the circumstances of the case: see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1 at [41]-[47] (Middleton and Gordon JJ).

[45] Whether or not the course of conduct framework of analysis is used, the Court’s task remains the same: that is, to determine an appropriate penalty which is proportionate to the wrongdoing viewed as a whole and having due regard to the need to avoid double punishment: Transport Workers Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203; 267 FCR 40 at [83]-[91] (Allsop CJ, Collier and Rangiah JJ).

The parity principle

[46] Assessments of penalty in analogous cases may provide guidance to the Court in assessing an appropriate penalty, by assisting equal treatment in similar circumstances and thereby meeting the principle of equal justice. The circumstances in different cases are rarely precisely the same as the case then before the Court: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SMS Global Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 855; ATPR 42-364 at [80] and the cases there cited…

The totality principle

[47] The totality principle is the last step in the sentencing process, to be undertaken after the Court has determined what it considers to be an appropriate penalty for the contravening conduct. Where there are multiple contraventions the Court must apply this principle to ensure that, overall, the total penalty does not exceed what is appropriate for the totality of the contravening conduct involved. It operates as a “final check” to ensure that the aggregate penalty is just and appropriate having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct: Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; 166 CLR 59 at 63 (Wilson, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Wooldridge [2019] FCAFC 172 at [26] (Greenwood, Middleton and Foster JJ).

40 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 399 ALR 599 (Pattinson HCA) the High Court recently overturned the approach taken in Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 282 FCR 580 (Pattinson FCA) in relation to the significance of the maximum available penalty. The plurality (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ) cited Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [155]-[156] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ) with approval, and said that the maximum penalty, while important, is “but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied”, and it must be treated “as one of a number of relevant factors” (at [53]-[54]). Their Honours said that the Full Court in Pattinson FCA erred in treating the statutory maximum as implicitly requiring that contraventions be graded on a scale of increasing seriousness, with the maximum to be reserved exclusively for the worst category of contravening conduct (at [49]). They held that the maximum penalty does not constrain exercise of the discretion beyond requiring “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty” (at [53] and [55]); and the relationship of reasonableness may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravenor as well as those of the contravention, because either or both may have a bearing on the extent of the need for deterrence (at [57]).

Consideration regarding penalty

The maximum penalty

41 From the start of the relevant period in March 2016 up to 31 August 2018, the maximum penalty for a contravention by a company of a provision in Part 3-1 of the ACL, was $1.1 million: see item 2 of s 224(3) of the ACL. This maximum applies to each contravention of s 29.

42 From 1 September 2018 up to the end of the relevant period in October 2018, the maximum penalty for each contravention increased to the greater of either: (a) $10 million; (b) three times the value of the benefit to the contravener reasonably attributable to the contravening act or omission; or (c) if the benefit is not ascertainable, 10% of the annual turnover of the contravener during the 12 month period ending at the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur: see item 2 of s 224(3) and s 224(3A) of the ACL.

43 Careful attention to the maximum penalty will almost always be required because the legislature has legislated for it; and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, it provides a yardstick: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357 at [31] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) cited with approval in Pattinson HCA at [52]-[54].

44 Having noted that, where a representation is made in an advertisement, a separate representation is made and thus a separate contravention arises in respect of each person who reads the advertisement: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v La Trobe Financial Asset Management Ltd [2021] FCA 1417 at [91] (O’Bryan J) citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [16]-[17] (Beach J). I accept the parties’ submission that this is a case in which the number of contraventions is likely to be very large because of the manner in which the Galaxy phones were marketed, with the misleading representations made in various advertising and marketing material over a lengthy period. I also accept that the large number of contraventions in this case means that the total statutory maximum applicable to the wrongdoing is many orders of magnitude more than the amount required to ensure specific or general deterrence.

45 In other words, while the theoretical maximum remains relevant to the extent that it reveals that the legislature did not regard contraventions of the type that Samsung Australia has engaged in as trivial or inconsequential, the theoretical maximum penalty is so vast as to make precise calculation unnecessary and unhelpful, if it were even possible: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 (ABCC v CFMEU) at [143]-[145] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ) citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 at [82] (Allsop CJ); Reckitt at [139]-[145].

46 All except one of the advertisements ceased being published by 1 September 2018, and accordingly the contraventions arising from the vast bulk of the advertisements are not subject to the higher maximum penalty. The single exception is the press release (the 5th advertisement) which was initially published on 1 March 2016 but remained on the Samsung Australia webpage until 5 October 2018 (there were a total of 68 visits and 73 page views for that webpage from 1 March 2016 to 5 October 2018). While it is not possible or necessary to quantify exactly how many contraventions occurred in respect of that advertisement (in relation to which the higher statutory maximum applies), it is plain that the bulk of the contravening conduct is only liable to be penalised in accordance with the lower statutory maximum penalty.

Course of conduct

47 Whether or not the course of conduct framework of analysis is used, the Court’s task remains the same; that is, to determine an appropriate penalty which is proportionate to the wrongdoing viewed as a whole and having due regard to the need to avoid double punishment: Transport Workers Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203; 267 FCR 40 at [83]-[91] (Allsop CJ, Collier and Rangiah JJ).

48 In the present case there are interrelationships in the legal and factual elements of the acts or omissions that constitute the contraventions. All of the contraventions are based in advertisements published in various forms of media carrying the same broad representation that the Galaxy phones are suitable to be submerged in pool or sea water. The parties, however, submitted that a distinction may be drawn between Samsung Australia’s conduct prior to and after the implementation of the upgraded charging interruption system in relation to the S8, S8 Plus and Note 8 models. They contended that Samsung Australia’s contraventions could therefore be characterised as either one or two courses of conduct. The proposed single course of conduct comprises the advertisements with the same broad message, and the proposed dual courses of conduct comprise the conduct before and after the implementation of the charging interruption system.

49 I do not accept that the course or courses of conduct are as limited as the parties submit. In my view it is appropriate to group the contraventions according to the different media types and places of publication used for each advertisement. While the same broad representation was made in each of the impugned advertisements, the audience of each advertisement was likely to vary across the different media types and places of publication, and the text and imagery in the advertisements published on the social media platforms were different to those published in the website article. Dividing up the conduct according to this approach is consistent with authority: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra [2010] FCA 790; 188 FCR 238 at [231] to [235] (Middleton J); Trade Practices Commission v Bata Shoe Company of Australia Pty Ltd (1980) 44 FLR 149 at 176-177 (Lockhart J).

50 I therefore consider it appropriate to treat the contravening conduct as falling into three or four courses of conduct. Specifically, the advertisements giving rise to the contraventions might be divided into the following groups:

Course of conduct | Group | Advertisement # in Annexure A (and media type) |

1 | Text content on website/ distributed by email | 1 (website article); 4 (website article); 5 (press release on website and sent by email); |

2 | Video content | 2 (Facebook video); 6 (Facebook video); 9 (website video) |

3 | Posts on social media | 3 (Instagram post); 8 (Twitter post) |

4 | Print content | 7 (Booklet) |

51 Alternatively, the conduct could be divided into three courses of conduct by allocating the advertisements in the 2nd group in the above table to other groups: for example, the Facebook videos (the 2nd and 6th advertisements) could be allocated to the “Posts on social media” group, and the video posted on the website (9th advertisement) could be allocated to the first group (re-named as, “Content on the website/ distributed by email”).

52 I will approach the acts or omissions as four courses of conduct for penalty purposes, but should note that little turns on this in the particular circumstances of the present case.

Totality

53 When imposing penalties in respect of multiple contraventions or courses of conduct, the Court is not bound to impose the cumulative total of each of the penalties. The totality principle requires the Court to do a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole. It will not necessarily result in a reduction; however, in cases where the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too low or too high, the Court may alter the final penalties to ensure that they are “just and appropriate”: CEO of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v Westpac Banking Corporation [2020] FCA 1538 at [69] (Beach J). I accept the parties’ submission that a $14 million penalty is just and appropriate having regard to the conduct as a whole.

Parity

54 I accept the parties’ submission that while similar contraventions should incur similar penalties, the differing circumstances of individual cases mean that a penalty in one case cannot dictate the penalty in another. As a result, comparisons with previous penalties will rarely be useful. Insofar as any comparison with other wrongdoers in other cases may be undertaken, what is sought is not numerical consistency, but the consistent application of principle: McDonald v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2011] FCAFC 29; 202 IR 467 at [23]-[25] (North, McKerracher and Jagot JJ), applying the comparable principle laid out by the High Court in the sentencing context in Hili v The Queen [2010] HCA 45; 242 CLR 520 at [48]-[49] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell J) reiterated since in R v Pham [2015] HCA 39; 256 CLR 550 at [28]-[29] (French CJ, Keane and Nettle JJ).

The nature, extent and duration of the conduct

55 While it is not possible to ascertain exactly how many consumers viewed the advertisements, Samsung Australia has estimated how many consumers viewed 5 out of the 9 advertisements, set out in Annexure A as follows:

(a) advertisement #3: 468 likes and 46 comments;

(b) advertisement #5: 68 visits and 73 page views to the Samsung Australia website from 1 March 2016 to 5 October 2018;

(c) advertisement #6: 272,000 video views;

(d) advertisement #7: 10,100 booklets were printed and distributed to 28 retail stores; and

(e) advertisement #8: 36,139 impressions on Samsung Australia’s Twitter feed on 26 April 2017.

56 The estimated number of Galaxy phones sold to Australian consumers is approximately 3.1 million and the contravening conduct spanned a period of approximately two and a half years. The representations were made in the context of a highly competitive Australian mobile phone market in which there are numerous other competing phone manufacturers, including on the basis of the advertised features of their phones.

57 The Galaxy phones are mass consumer products which were the subject of a mass marketing campaign. The contraventions occurred over a lengthy period and in my view it is likely they affected a great many consumers and Samsung Australia’s competitors in a highly competitive market. They constitute serious contraventions of the ACL. All too often cases are brought before the Court in which products and services that have been ‘oversold’ to consumers in marketing campaigns, and in response to an application for a civil penalty the respondent argues that it is impossible to quantify or estimate the damage actually suffered by consumers and/or competitors.

58 I have no difficulty in accepting that the Galaxy phones provided a reasonable level of water resistance, but they were promoted by Samsung Australia as capable of being used in the surf, at the bottom of a swimming pool and in other similar circumstances, when they were not. Samsung Australia has now admitted that if the Galaxy phones were submerged in a swimming pool or sea water, there was a material prospect that the charging ports might be damaged by corrosion if the phones were charged or attempted to be charged while there was still some water remaining in the charging port.

59 The nature, duration and extent of the contravening conduct points to imposition of a substantial pecuniary penalty.

The circumstances of the conduct

60 As previously explained, the Galaxy phones were subject to various tests in relation to their water-resistance before they were put onto the market and during the relevant period. Plainly enough, the testing was insufficient as Samsung Australia has accepted that there was a material prospect that the charging port of the Galaxy phones was vulnerable to corrosion where the phone had been submerged in pool or sea water and the consumer attempted to charge the phone while some pool or sea water remained present in the charging port. Having said that, I accept the parties’ submission that the testing regime shows that Samsung Australia genuinely sought to design the Galaxy phones in a way that would mitigate the prospect of damage to the phones if they were exposed to water. In addition to the testing regime, the charging interruption system and the automatic ‘warning’ messages and icons that discouraged consumers from attempting to charge the device while moisture was detected in the charging port, are further indications of its genuine efforts to mitigate the prospect of corrosion of the charging port.

61 There is nothing in the evidence to indicate that Samsung Australia was aware of the risk, and took the chance of marketing the Galaxy phones with a known or suspected defect in order to increase its market share.

The loss or damage caused

62 The extent of the consumer and competitor loss and damage caused by Samsung Australia’s contravening conduct cannot be determined or even estimated. Approximately 3.1 million Galaxy phones were sold to Australian consumers in the relevant period, and there is evidence to show that some consumers had their charging ports replaced during that time. However, it is not possible to identify the number of consumers whose charging ports were replaced, why in each case the charging port was replaced, or whether the replacement of the charging port was due to water-related corrosion issues or some other issue (such as the intrusion of foreign objects into the charging port). In some cases, Samsung Australia’s authorised repairers replaced the charging ports at no cost to the consumer, while in other cases the authorised repairers charged the customer to replace the charging port (at a cost of approximately $180 to $245).

63 As the parties submitted, it is not possible to know:

(a) how many consumers saw each of the nine advertisements;

(b) how many of those consumers purchased one of the Galaxy phones;

(c) how many of those consumers would not have purchased the Galaxy phones but for the contravening conduct;

(d) how many of the consumers who purchased one of the Galaxy phones subsequently submerged the phone in pool or sea water and attempted to charge the phone while some water remained in the charging port; nor

(e) how many of, and to what extent, the advertised Galaxy phones purchased by consumers were damaged due to corrosion as a result of the consumer submerging the phone in pool or sea water and attempting to charge the phone while some water remained in the charging port.

64 But, in the circumstances of this case, it is appropriate to assess the penalty on the basis that a great many consumers are likely to have seen the offending advertisements; and a significant number of those who did so are likely to have purchased one of the Galaxy phones. It is likely that the misleading representations were material in many such purchases, as the capacity of the Galaxy phones to continue to properly operate after having been submerged in pool or sea water was the primary thrust of the advertisements; and that capacity was portrayed as a desirable and differentiating feature from many other phones available on the market. In my view many of those consumers who purchased a Galaxy phone are likely to have used it in a manner similar to that advertised. They were entitled to assume that a large company like Samsung Australia would not advertise that its Galaxy phones could safely be submerged in pool or sea water, if in fact they could not be.

Samsung Australia’s size and degree of power

65 The size of a contravening company is not only relevant to the power it can wield, but also to the size of the penalty necessary to have an appropriate deterrent effect, not only on the company itself but also on companies which will pay attention to the penalties imposed on businesses of a similar size: Reckitt at [158(2)]; Coles Supermarkets at [92]; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285, 293 at [D] (Burchett and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was)); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation (No 7) [2016] FCA 1553 at [7] and [53] (Edelman J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) [2005] FCA 254; 215 ALR 281 at [8]-[9] (Merkel J).

66 In relation to the relevance of the size of parent companies when determining the quantum of a pecuniary penalty, in Schneider Electric Proprietary Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 2; 127 FCR 170 at [49], Merkel J, with whom Black CJ and Sackville J agreed, said that “the size of a parent may be of relevance where, for example, the parent bore some responsibility for the subsidiary’s conduct or where it is relevant to the subsidiary’s capacity to meet a substantial pecuniary penalty”. Their Honours ultimately decided that the size of the parent company or of the group of which it formed part, was not a relevant factor in that case for three reasons: first, it was not suggested that the parent had any involvement in the contraventions; secondly, there was no question about the subsidiary company’s capacity to pay any penalty that may be imposed; and thirdly, it was clear that the subsidiary operated a substantial business in Australia in its own right. Those three factors are present in this case: there is no suggestion that SEC was involved in the contravening conduct and the advertisements were published only in Australia; Samsung Australia is one of the leading players in the Australian smartphone market, and during the years of the relevant period, Samsung Australia had very substantial annual revenue.

67 The assessment of the appropriate penalty in the present case must take into account Samsung Australia’s substantial resources as the penalty must carry a sufficient sting or burden to achieve the specific and general deterrent effect: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157, 195 at [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ). It must not be capable of being seen merely as a cost of doing business.

68 A penalty of $14 million exceeds Samsung Australia’s profit in the period in which the offending advertisements were published. The company was already in loss in that period, and if this penalty is retrospectively applied to those years, it would be even further in loss. Further, the penalty is approximately 14.5% of Samsung Australia’s total profit over the last six years.

Cooperation

69 Cooperation with the regulator in the course of an investigation and in a court proceeding can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise have been imposed. Such a reduction will increase the likelihood of cooperation in future cases; free up the regulator’s resources and thereby increase the likelihood that other contraveners will be detected and prosecuted; and furthers the object of the legislation: see Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [46] (French CJ, Kiefel J (as her Honour then was), Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ); NW Frozen Foods, 293 at [G], 294 at [A].

70 Through the early stages of this proceeding Samsung Australia denied that the advertisements conveyed the alleged representations and trenchantly denied that if the Galaxy phones were submerged in water there was a material prospect that they would be damaged and their operability affected. It strenuously opposed the appointment of an expert referee to determine the extent to which the operability of the phones might be reduced by being used after immersion in a swimming pool, sea water, or fresh water, as the advertisements represented.

71 The parties submitted that Samsung Australia’s cooperation has resulted in significant cost and time savings to the Court and the ACCC, having regard to the substantial time and costs that would have been required had the reference process and a contested hearing on liability and relief proceeded. They said that its cooperation should be treated as a significant matter because it indicates a lower need for specific deterrence than would be the case with a recalcitrant contravener which has continued to deny its wrongdoing; and that it should be taken into account to reduce the penalty that might otherwise be required, although not in such a way that undermines a penalty appropriate to securing general deterrence.

72 I do not consider Samsung Australia should be given much credit for its cooperation. It was quite late in making the admissions set out in the SOAF; and admitting the contraventions of the ACL. Its cooperation came after some years of trenchant opposition to the ACCC’s case. To my mind, it was obvious that the ACCC would be able to make out the allegation that the advertisements represented that the Galaxy phones were suitable for use after having been immersed in pool water and sea water; yet Samsung Australia did not admit the obvious.

73 I can accept that the lack of early cooperation by Samsung Australia may have reflected the breadth of the ACCC’s case until relatively recently, and it may be that the cooperation arose out of the ACCC’s agreement to narrow its case. And I accept that its cooperation has led to substantial cost and time savings for the Court and the parties.

The parties’ joint position

74 The fact that the ACCC, the specialist regulator, has agreed with Samsung Australia to propose a $14 million penalty to the Court must be given some weight. Where, as here, the Court is persuaded by the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the agreed penalty jointly proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, it is highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Director at [58]; Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; 284 FCR 24 at [124]-[129] (Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ).

CONCLUSION

75 No single factor is decisive in my determination as to the appropriate penalty. Instead, “[t]he fixing of a penalty involves the identification and balancing of all the factors relevant to the contravention[s] and the circumstances of the [respondent], and making a value judgment as to what is the appropriate penalty in light of the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty”: ABCC v CFMEU at [100]. Having made that judgment, and then standing back and having regard to the totality principle as a final check, I am satisfied that a penalty of $14 million is just and appropriate for all of the contravening conduct.

76 I am satisfied that a penalty of that magnitude will carry a sufficient sting or burden so as to deter Samsung Australia from a repetition of similar conduct, and it should serve as a salutary reminder to other large providers of smartphones to avoid such conduct. The significant quantum of the penalty will also send a positive signal to compliant businesses, which take care to thoroughly assess and validate claims about the stated benefits of their products before advertising those benefits to the public. There is always the concern that a large corporation like Samsung Australia in a highly competitive market might see a pecuniary penalty for misleading advertising as just a cost of doing business. However, having regard to its financial position over the period of the contravening conduct and its net profit over the last six years, in my view the penalty is sufficiently large to render any such risk/benefit analysis unpalatable.

77 I have made the attached orders.

I certify that the preceding seventy-seven (77) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Murphy. |

Associate: