Federal Court of Australia

FKP Commercial Developments Pty Limited v Zurich Australian Insurance Limited [2022] FCA 862

ORDERS

FKP COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENTS PTY LIMITED ACN 010 750 964 First Applicant FKP CONSTRUCTIONS PTY LIMITED ACN 009 910 098 Second Applicant | ||

AND: | ZURICH AUSTRALIAN INSURANCE LIMITED ACN 000 296 640 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions for determination contained in the orders of 29 April 2022 be answered as follows:

(a) Question 1: no; and

(b) Question 2: no, in that the asserted facts are not sufficient to engage the insuring clause in the policy.

2. Within seven days of these orders, the parties confer and either file agreed orders for the future conduct of the matter or nominate a mutually convenient date for a case management hearing in the following seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

The separate questions

1 On 29 April 2022 I ordered that the following questions be heard prior to and separately from any other questions in the proceeding:

(1) Does the Policy on its proper construction provide that the insured’s sole right to payment of claims expenses prior to final adjudication of the claim is under the Advancement Provision (Claims Condition 1)?

(2) Is the whole of the claim made against the Applicants in the OC Proceeding a “claim for civil liability…based on the insured’s provision of the professional services” within the meaning of the Insuring Clause:

(a) where the First Applicant was a developer within the meaning of the Home Building Act to whom the OC was the immediate successor in title;

(b) where the Second Applicant entered into a design and construction contract with the First Applicant in the form of the head contract;

(c) if the Second Applicant sub-contracted the design and construction works it was obliged to perform under the head contract and itself performed only project management and construction management services, being services within the definition of ‘professional services’ in the Policy (Professional Services); and

(d) even if there is no causal connection between the provision of the Professional Services and the defects alleged in the OC Proceeding?

2 For the reasons that follow, question 1 is to be answered “no”. Question 2 is to be answered “no, in that the asserted facts are not sufficient to engage the insuring clause in the policy”. It will be apparent from the reasons below that while this is a case in which I disagree with virtually everything Zurich put to me in its written and oral submissions about the operation of the policy, I ultimately agree that the position which Zurich has taken accords with the policy.

Facts

3 The applicants, FKP Commercial Developments Pty Limited and FKP Constructions Pty Limited (together, the FKP parties), are insured under a Design and Construction Professional Indemnity policy issued by the respondent, Zurich Australian Insurance Limited (the policy).

4 In Supreme Court proceeding 2017/00233806, the owners of Strata Plan No 84298 as plaintiff claims damages from the FKP parties as defendants. The plaintiff is a body corporate constituted under s 8(1) of the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW) and is the registered proprietor of the common property in two residential and commercial apartment buildings at Rosebery, New South Wales.

5 In the Supreme Court proceeding, the plaintiff alleges that defects exist in the common property of the residential buildings and the FKP parties are liable for the resulting loss suffered by the plaintiff by reason of breach of the statutory warranties in the Home Building Act 1989 (NSW) (Home Building Act) and/or a common law or statutory duty of care owed to the plaintiff. The plaintiff alleges that:

(1) FKP Commercial was the registered proprietor of the land on which the residential development was constructed (prior to the registration of the Strata Plan);

(2) FKP Commercial entered into a contract with FKP Constructions to carry out the residential building work either itself or through third parties (the head contract);

(3) FKP Constructions entered into a contract or contracts to do all or part of the residential building work itself or through third parties (the third party contracts);

(4) by operation of the Home Building Act, the statutory warranties are implied into a notional contract between FKP Commercial and the plaintiff as if FKP Commercial was required to hold a contractor licence and had done the residential building work under that notional contract;

(5) by operation of Home Building Act, the statutory warranties are implied into the head contract and the plaintiff is entitled to the same rights as FKP Commercial against FKP Constructions in respect of the statutory warranties;

(6) by operation of the Home Building Act, the statutory warranties are also implied into the third party contracts and the plaintiff is entitled to the same rights as the third party has against FKP Constructions in respect of the statutory warranties;

(7) the residential building work contains defects and/or non-complying work in breach of the statutory warranties;

(8) as a result, the plaintiff has suffered and will suffer loss and/or damage;

(9) the FKP parties owed the plaintiff a duty of care both at common law and under s 37 of the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (NSW) (Design and Building Practitioners Act) (which provides that a person who carries out construction work has a duty to exercise reasonable care to avoid economic loss caused by defects) in carrying out the residential building work and breached that duty of care in causing or permitting the defects and/or non-complying work to be present in the common property; and

(10) as a result, the plaintiff has suffered and will suffer loss and/or damage.

6 The particulars of the breaches and non-complying construction work include defective installations of numerous items such as door and joints, defective items, insufficiencies, and errors.

7 The statutory warranties under s 18B(1) of the Home Building Act, are:

(a) a warranty that the work will be done with due care and skill and in accordance with the plans and specifications set out in the contract,

(b) a warranty that all materials supplied by the holder or person will be good and suitable for the purpose for which they are used and that, unless otherwise stated in the contract, those materials will be new,

(c) a warranty that the work will be done in accordance with, and will comply with, this or any other law,

(d) a warranty that the work will be done with due diligence and within the time stipulated in the contract, or if no time is stipulated, within a reasonable time,

(e) a warranty that, if the work consists of the construction of a dwelling, the making of alterations or additions to a dwelling or the repairing, renovation, decoration or protective treatment of a dwelling, the work will result, to the extent of the work conducted, in a dwelling that is reasonably fit for occupation as a dwelling,

(f) a warranty that the work and any materials used in doing the work will be reasonably fit for the specified purpose or result, if the person for whom the work is done expressly makes known to the holder of the contractor licence or person required to hold a contractor licence, or another person with express or apparent authority to enter into or vary contractual arrangements on behalf of the holder or person, the particular purpose for which the work is required or the result that the owner desires the work to achieve, so as to show that the owner relies on the holder’s or person’s skill and judgment.

8 The Supreme Court proceeding is continuing. It is not in dispute that the FKP parties are defending the Supreme Court proceeding and have and will continue to incur costs in that defence.

9 In the proceeding in this Court, there is evidence that:

(1) FKP Commercial was the principal/developer of the residential building project and, under a contract with FKP Constructions, FKP Constructions was the head contractor; and

(2) FKP Constructions performed its obligations as head contractor by using third party consultants and sub-contractors, and did not itself perform any design or construction works.

10 The FKP parties sought indemnity from Zurich under the policy in respect of any liability it might have to the plaintiff in the Supreme Court proceeding. Subject to certain reservations, Zurich confirmed indemnity to the extent that the FKP parties were liable to the plaintiff based on its provision of, or failure to provide, the professional services as defined in the policy. However, Zurich did not accept that all such potential liability was based on the provision of, or failure to provide, the professional services as defined in the policy. The FKP parties asserted that they were entitled to indemnity for all liability to the plaintiff and sought that Zurich pay their claim expenses of the Supreme Court proceeding under the insuring clause. Zurich responded that payment of claim expenses was dealt with exclusively by the advancement provision in claims condition 1 of the policy (defined below), rather than by the insuring clause.

11 The separate questions arise from these circumstances. As the FKP parties are continuing to incur and pay costs in respect of their defence of the Supreme Court proceeding, I accepted their submission that the hearing of the separate questions should be expedited on the basis that answers to these questions were likely to provide the most timely manner of resolving the issues in dispute.

The policy

12 The policy is styled “Design and Construction Professional Indemnity”.

13 The relevant sections of the policy include the insuring clause, definitions, limit of liability, extensions of cover, exclusions, claims conditions, and general conditions.

14 The insuring clause provides that:

We agree to indemnify the insured against loss incurred as a result of any claim for civil liability first made against the insured and notified to us during the period of insurance, based on the insured’s provision of the professional services.

15 The definitions include:

Civil liability

civil liability means liability of the insured on any civil cause of action for compensation, based on its provision of, or failure to provide, the professional services. It does not include any liability, of whatever nature and however arising, for aggravated, punitive or exemplary damages or for civil or criminal penalties, fines or sanctions.

Claim

claim shall mean any oral or written demand for compensation received by the insured during the period of insurance including but not limited to a civil proceeding commenced by the service of a statement of claim, writ, complaint or similar pleading, or an arbitration or other alternative dispute resolution proceeding…

Claim expenses

claim expenses shall mean all reasonable legal costs and expenses necessarily incurred with our prior written consent in the investigation, defence and settlement of any claim…

Compensation

compensation shall mean monetary compensation the insured is legally obligated to pay, whether by a judgment or award, or a settlement negotiated with our prior written consent, but does not include claim expenses.

Insured

insured means the following:

(a) the policyholder and any subsidiary at inception of the policy (or as otherwise agreed by us to be covered under Extension of Cover 18. ‘Newly created / acquired subsidiary’); or

(b) any current or former partner, principal or employee of the policyholder or any subsidiary in (a) above, but only whilst providing professional services on behalf of the policyholder or such subsidiary.

‘You’ and ‘Your’ is also used in this policy to mean one or more of the insured.

Loss

loss means the following for which the insured is legally liable:

(a) compensation and/or claimant’s costs pursuant to an award or judgment against the insured;

(b) settlements negotiated by us and consented to by the insured;

(c) settlements negotiated by the insured but only with our prior written consent;

(d) claim expenses;

(e) inquiry costs.

Policyholder

policyholder means the legal entity as specified in the schedule.

Professional services

professional services means one or more of the following services:

(a) design, including advice in relation to design, in accordance with all relevant building, construction or engineering codes and standards;

(b) drafting;

(c) technical calculation;

(d) specification;

(e) project management;

(f) construction management;

(g) feasibility studies;

(h) programming and time flow management;

(i) quantity surveying;

(j) surveying;

(k) training in respect of (a) to (j) above,

provided it is performed by or under the direct supervision of a properly registered engineer, architect, or surveyor, or quantity surveyor (who is a member of the Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors) or any other person (duly qualified by training or education) providing a professional service of a skilful nature, according to an established discipline appropriate for the professional services being performed or supervised.

Professional services shall not include:

(i) performance or supervision (where such supervision would normally be undertaken by a building contractor) of the construction, manufacture, assembly, installation, erection, maintenance or physical alteration of buildings, goods, products or property; or

(ii) environmental protection, workplace health and safety or industrial relations matters which would normally be overseen by a building contractor.

Sub-contractors

sub-contractors mean independent consultants or sub-contractors who provide services to the insured under a written or oral contract. This definition does not include any employee.

16 The extensions of cover provision states that:

Cover is automatically provided, and on the same terms and in the same manner as in the Insuring Clause (except as expressly stated), for the extensions of cover described below. Each extension of cover is subject to all the other provisions of this policy, including any additional terms stipulated in connection with it. No feature shall increase our limit of liability unless expressly stated otherwise.

17 Clause 3 in the extensions of cover section is as follows:

3. Consultants, Subcontractors and Agents

We agree to indemnify the insured for loss resulting from any claim arising from the conduct of any consultants, sub-contractors or agents of the insured for which the insured is legally liable in the provision of the professional services. No indemnity is available to the consultants, sub-contractors or agents.

18 Clause 19 in the extensions of cover section is in these terms:

19. Principal’s indemnity

To the extent that it is contractually required of the insured, we shall also indemnify any Principal in regards to professional services undertaken by or on behalf of the insured for the claim against a Principal, provided that:

(a) the claim is such that if made upon the insured, the insured would be entitled to indemnity under the policy;

(b) we shall have the conduct and control of all claims for which the Principal seeks indemnity hereunder or from the insured;

(c) this policy shall not extend to provide cover in respect of the Principal’s own breach of professional duty or other events not covered by this policy and the terms and conditions of this policy otherwise apply.

For the purpose of this clause, the Principal shall be deemed to be an insured. Nothing in this clause shall preclude the insured (not being the Principal) from the right to indemnity under this policy should the Principal instigate proceedings against such other insured for a claim which results from the provision of professional services, in the Principal’s own right.

19 The claims conditions provision states that “[t]he following Claims Conditions apply to your policy”.

20 The claims conditions section includes the following:

1. Advance payment of claim expenses

We will advance claim expenses incurred by an insured in the defence of a claim, as they are incurred and prior to the final adjudication of the claim, where:

(a) indemnity under this policy is confirmed in writing by us; or

(b) at our absolute discretion, without admitting indemnity, we agree to advance such claim expenses.

All such payments shall be repaid to us by the insured (or where more than one insured has received such payments, by such insureds severally and according to their respective interests) in the event and to the extent that the insured is not entitled to payment of such claim expenses under the terms and conditions of this policy.

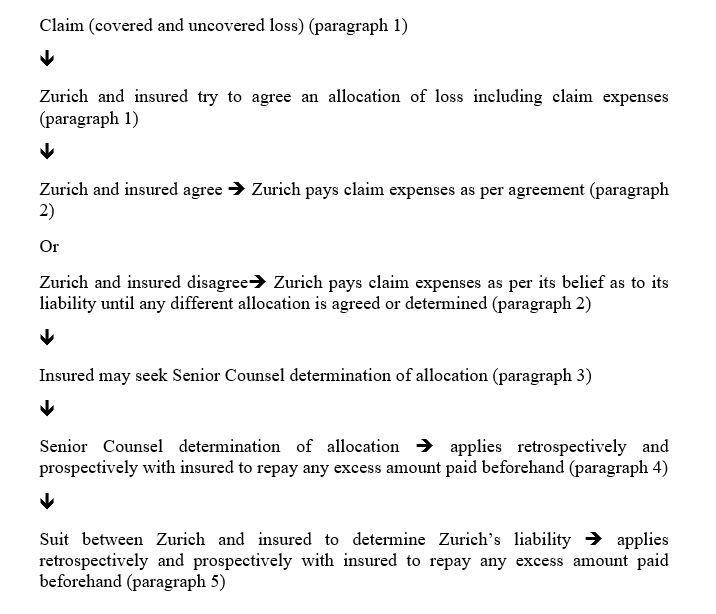

2. Allocation

If both loss covered by this policy and loss not covered by this policy are incurred, either because a claim includes both covered and uncovered matters or because a claim is made against both insured and others who are not insured under this policy (including those persons or entities referred to in the schedule as the insured), the insured and Zurich shall use their best efforts to agree upon a fair and proper allocation between covered loss and uncovered loss having regard to the relative legal and financial exposures attributable to the covered and uncovered parties and/or matters. We are only liable under this policy for amounts attributable to covered matters and parties, and our liability for loss, including claim expenses, otherwise payable by us shall be reduced to reflect such fair and proper allocation.

If we and the insured agree on an allocation of claim expenses, we shall, subject to Claims Condition 1. ‘Advance payment of claim expenses’, advance claim expenses in accordance with that Condition. If the parties cannot agree on such allocation, we shall, subject to Claims Condition 1. ‘Advance payment of claim expenses’, advance claim expenses which we believe to be covered under the policy until a different allocation is negotiated, arbitrated, judicially or otherwise determined.

If requested by the insured, we shall submit any dispute on allocation to a Senior Counsel to be mutually agreed or, in default of agreement to be appointed by the President of the Bar Association in the relevant State or Territory, on the basis that the Senior Counsel shall determine the allocation according to his or her view of the fair and proper allocation, but having regard to the relative legal and financial exposures attributable to covered and uncovered matters and parties, and the overriding intention referred to in this Claims Condition 2. The costs of Senior Counsel shall constitute claim expenses for the purposes of the policy and be part of and not in addition to the limit of liability.

Any such determined allocation of claim expenses on account of a claim shall be applied retroactively to all claim expenses on account of such claim, notwithstanding any prior advancement on a different basis. Any advancement of claim expenses shall be repaid to us by the insured severally according to their respective interests, if and to the extent that we determine that such amounts paid by us are not insured by this policy.

Any allocation or advancement of claim expenses in connection with a claim shall not pre-determine the allocation of other loss on account of such claim. In any arbitration, suit or other proceedings between us and the insured no presumption shall exist as to a fair and proper allocation, but will be governed by the intention set out in this clause.

21 I refer to claims condition 1 as the advancement provision and claims condition 2 as the allocation provision.

22 The exclusions in the policy include the following:

Exclusions

We will not pay anything in respect of:

…

8. Manufacturing/Efficacy/Faulty workmanship

any claim, loss or other amount comprising, directly or indirectly arising out of or in connection with any defect in or lack of suitability of any product or good unless it arises directly out of the provision of professional services.

Principles of construction

23 In Star Entertainment Group Limited v Chubb Insurance Australia Ltd [2022] FCAFC 16; (2022) 400 ALR 25 at [8], Moshinsky, Derrington and Colvin JJ stated that:

The principles to be applied in construing commercial instruments are well established. They require the language used by the parties to be interpreted objectively by considering what the language adopted by them would mean to a reasonable businessperson in the position of the parties. The language used by them is to be considered in the context of the surrounding circumstances known to them at the time of the transaction and the purpose or object of the transaction evident from those matters.

24 Their Honours noted further at [13] that:

A policy of insurance is a commercial contract and should be given a businesslike interpretation in accordance with the above principles: McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd [2000] HCA 65; (2000) 203 CLR 579 at [22] (Gleeson CJ); as approved in CGU Insurance Limited v Porthouse [2008] HCA 30; (2008) 235 CLR 103 at [43].

25 In LCA Marrickville Pty Limited v Swiss Re International SE [2022] FCAFC 17; (2022) 401 ALR 204 at [2], Moshinsky J stated that:

the task of contractual construction is to be approached objectively, in the sense that the meaning of the words used is to be ascertained by reference to what a reasonable person would have understood the language of the contract to convey; this normally requires consideration not only of the text, but also of the surrounding circumstances known to the parties, and the purpose and object of the transaction [citations omitted]. When undertaking this task, “preference is given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole”.

26 His Honour cited in support, amongst other cases, Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; (2005) 221 CLR 522 at [16].

27 The contract must be read as a whole to ascertain its meaning. As stated by Derrington and Colvin JJ in Swiss Re at [57]:

Necessarily, the identification of that construction can only be achieved by ascertaining how a contract or policy might operate as affected by each of the competing interpretations. This “iterative process”, involving “checking each of the rival meanings against the other provisions of the document and investigating its commercial consequences”, “enables a court to assess whether either party’s preferred legal meaning gives rise to a result that is more or less internally consistent and avoids commercial absurdity”: HP Mercantile Pty Ltd v Hartnett [2016] NSWCA 342 [134] quoting Re Sigma Finance Corp [2009] UKSC 2 [12].

Other principles

28 The parties identified other principles and cases, as suited their competing positions.

29 The FKP parties referred to Greentree v FAI General Insurance Co Ltd [1998] NSWSC 544; (1998) 44 NSWLR 706 at 718:

…the core of a “claims made” policy is a promise by the insurer to the insured that it will indemnify the insured for any claim that is made by a third party against the insured within the duration of the policy, no matter, subject to the provisions in relation to the time within which notice must be given, when the defined event affecting the third party occurred...It has been said that “the essence of a ‘claims made’ policy is that the insured’s right to an indemnity arises on the submission to him of a claim by a third party”.

30 To similar effect, the FKP parties referred to Sutton on Insurance Law (Thomson Reuters, 4th ed, 2015) at [23.450]:

A policy may include a reference to “claim” as one of the factors or elements which will give rise to the insured's right to an indemnity…The insured’s right to an indemnity runs from the event, namely, the making of the claim by the third party. There is a venerable and substantial line of authority and commentary which supports this position.

31 The FKP parties also referred to Dovuro Pty Ltd v Wilkins [2000] FCA 1902; (2000) 105 FCR 476 at [152] in which Finkelstein J said:

Speaking generally, it is not permissible to construe one part of a contract so as to render inoperative or as surplusage another part. In In re Strand Music Hall Co Ltd (1865) 35 Beav 153 at 159; 55 ER 853 at 856 Sir John Romilly MR said:

“The proper mode of construing any written instrument is to give effect to every part of it, if this be possible, and not to strike out or nullify one clause in a deed, unless it be impossible to reconcile it with another and more express clause in the same deed.”

See also SA Maritime et Commerciale of Geneva v Anglo Iranian Oil Co Ltd [1954] 1 WLR 492, although in Tea Trade Properties Ltd v CIN Properties Ltd [1990] 1 EGLR 155 Hoffmann J (as his Lordship then was) noted that draftsmen often “employ linguistic overkill” and use a number of phrases to cover more or less the same idea.

32 They referred also to XL Insurance Co SE v BNY Trust Company of Australia Limited [2019] NSWCA 215; (2019) 20 ANZ Ins Cas ¶62–211 at [72] in which Gleeson JA (with whom Bell P, as he then was, and Emmett AJA agreed) said:

The applicable principles with respect to redundancy of words in a contract were summarised by Ball J in AFC Holdings Pty Ltd v Shiprock Holdings Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 985; (2010) 15 BPR 28,199 at [13], as follows:

The general principle is that the words of a contract should be interpreted in a way which gives them an effect rather than a way in which makes them redundant: North v Marina [2003] NSWSC 64 at [45]; Davuro [sic] Pty Ltd v Wilkins [2000] FCA 1902, (2000) 105 FCR 476 at [152], [230]. That principle does not operate as an invariable rule. In some cases, it may be appropriate to interpret words in a way that makes them redundant. That may be appropriate where the alternative construction of the words is inconsistent with other provisions of the contract or where the alternative construction is inconsistent with the commercial purpose of the contract or where it appears that the words have been included out of abundant caution: see Re Strand Music Hall Co Ltd; Ex parte European and American Finance Co Ltd (1865) 35 Beav 153 at 159; 55 ER 853 at 856 per Sir John Romilly MR; Dryden Construction Co Ltd v New Zealand Insurance Co Ltd [1959] NZLR 1336; Beaufort Developments (NI) Ltd v GilbertAsh NI Ltd [1999] 1 AC 266 at 273–4 per Lord Hoffmann.

33 The FKP parties referred to Wilkie in support of the proposition that the insuring clause and the advancement provision in the policy provide alternative rights to the FKP parties as the insureds in respect of claim expenses.

34 In Wilkie:

(1) there was an insuring clause (“GIO will pay on behalf of the Insured, all Loss arising from any Claim first made against an Insured…”);

(2) “Loss” was defined to include “Defence Costs”;

(3) “Defence Costs” was defined to mean “costs or charges or expenses, incurred in defending or investigating or monitoring Claims”;

(4) a limitation provided that the Insured was not to incur Defence Costs without prior written consent from GIO and “GIO shall not be liable for any ... Defence Costs to which it has not so consented”;

(5) exclusion 7 excluded Loss arising out of any Claim based on dishonesty, fraud, or criminal or malicious act or omission “where such act, omission or breach has in fact occurred”, and for this purpose, “the words ‘in fact’ shall mean that the conduct referred to in those Exclusions is admitted by the Insured or is subsequently established to have occurred following the adjudication of any court, tribunal or arbitrator”;

(6) extension 9 provided that “If GIO elects not to take over and conduct the defence or settlement of any Claim, GIO will pay all reasonable Defence Costs associated with that Claim as and when they are incurred PROVIDED THAT: (i) GIO has not denied indemnity for the Claim; and (ii) the written consent of GIO is obtained prior to the Insured incurring such Defence Costs (such consent not to be unreasonably withheld)”; and

(7) extension 9 also said “GIO reserves the right to recover any Defence Costs paid under this extension from the Insured or the Organisation severally according to their respective interests, in the event and to the extent that it is subsequently established by judgement or other final adjudication, that they were not entitled to indemnity under this policy”.

35 GIO denied indemnity under exclusion 7. Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, and Kirby JJ said that:

(1) “[e]xtension 9 provides a distinct cover beside that under Insuring Clause A which obliges GIO to pay “all Loss arising from any Claim”. What is removed by Exclusion 7 is “Loss arising out of any Claim” which is based upon, attributable to or in consequence of any matter detailed in the text of that Exclusion. There thus is a correlated operation between Insuring Clause A and Exclusion 7”: [32];

(2) “[n]o such correlation is immediately apparent between the text of Extension 9 and of Exclusion 7”: [33];

(3) “[b]ut it is that very lack of congruence which reinforces the effect of the vital provision, stipulation (i) to Extension 9. The obligation the Extension imposes is to make advance payments of Defence Costs at times when, by hypothesis, the liability to indemnify in respect of the Claim may be uncertain because it awaits adjudication. The obligation so imposed is limited by the proviso in stipulation (i). This is expressed in broader terms than a denial of indemnity to pay Defence Costs in advance. Rather, it is concerned with a denial of “indemnity for the Claim”, that is to say, of indemnity in respect of the process alleging a Wrongful Act”: [34];

(4) GIO’s denial of indemnity for the claim did not disengage Extension 9: “…in such an action to enforce observance of Extension 9, it is no answer by GIO merely to point to a purported denial of indemnity for the Claim which, in turn, would be insufficient to meet an action for breach of the primary obligation of GIO under Insuring Clause A, were such an action to be brought. The efficacy in law of the purported denial based upon Exclusion 7 must be open to challenge in either case.”: [36];

(5) exclusion 7 “does not found a denial of indemnity for a Claim unless and until the phrase “in fact” operates in its defined sense”: [37];

(6) the ““gap” between present uncertainty and ultimate resolution is met in the second paragraph of Extension 9. This reserves to GIO a right of recovery if it be subsequently established that the appellant was “not entitled to indemnity under this policy” because, for example, GIO had made good its denial based on Exclusion 7”: [39];

(7) “[t]he contrary case put by GIO is that it is sufficient that GIO chooses, necessarily in good faith, to deny indemnity for the Claim on a ground stated in Exclusion 7, to then and there disengage Extension 9. This is said to be so even in circumstances in which the then present availability of that ground can only later be established “in fact”. However, this construction would permit GIO to rely upon a provision such as Exclusion 7 in anticipation of its operation. To that extent, the recovery right in Extension 9 would be deprived of work to do and there would be denied a consistent and harmonious operation in both Exclusion 7 and Extension 9 of the phrase “is subsequently established”” (which appears in the reservation at the end of Extension 9): [41]; and

(8) “[t]he evident purpose of the concluding words of Exclusion 7 … is to deprive the Insured of an entitlement to indemnity only where there has been a curial finding of misconduct of a kind specified. Where, by hypothesis, there has been no such finding, a necessary element of the exclusion is missing. In those circumstances, there is as yet no ground to which GIO can point as a legal basis for a denial of indemnity. The denial of indemnity of which Extension 9 speaks is a refusal of indemnity on a ground for refusal provided by the Policy, not a statement which foreshadows that indemnity will be refused if and when a ground for refusal becomes available”: [42]

36 The FKP parties also referred to the statement of Callinan J in Wilkie at [52] that:

There is a further reason to support their Honours’ conclusions. It is that the adoption of the construction for which the respondents contend would mean that in a real and practical sense they would become the final arbiters of the extent of their obligations because their insureds will frequently lack the means to defend themselves adequately against the charges levelled against them unless they are put in funds to do so. It would not have been a difficult matter for the respondents to have insisted upon a policy that put beyond doubt their right to postpone payment of defence costs until the outcome is known had they so wished.

37 Zurich responded that in Wilkie and other cases the advancement provision operated as an extension to the insuring clause, whereas in the present case the advancement provision is part of a claims condition.

Discussion

General

38 Wilkie (and other cases) establish that it is close attention to the provisions of the policy which is always required. For example, in Wilkie, if extension 9(i) had been read in isolation, the natural reading would have been to exclude liability for defence costs because GIO had denied indemnity for the claim. Extension 9(i) could not be read in isolation, however. It was critical that GIO had denied liability based only on exclusion 7. Exclusion 7 required, relevantly, dishonesty or fraud “in fact” where “in fact” meant “established to have occurred following the adjudication of any court, tribunal or arbitrator”. There had not been any such adjudication. As a result, GIO could not deny indemnity for defence costs unless and until there had been such an adjudication. The uncertainty of the position “in fact” at the time of the proceeding was dealt with by the reservation at the end of extension 9 which enabled GIO to recover defence costs if it was subsequently established by an adjudication that the insured was not entitled to indemnity.

39 It is this kind of detailed analysis of all provisions of the policy, including the iterative testing process described above, which is required.

Question 1

40 It is convenient to begin with the allocation provision as both parties said that it supported their construction of the policy.

41 Zurich contended that paragraph 1 of the allocation provision “speaks of a single task of allocation, not multiple allocations made throughout the life of the litigation”. As a single task of allocation of loss “is something that can only be done at the time that all elements of loss are known”, this can occur only at the final adjudication of the proceedings in which the underlying claim is pursued.

42 According to Zurich, paragraph 2 of the allocation provision deals with claim expenses and is subject to the advancement provision, not the insuring clause. For the allocation of claim expenses, the parties have agreed that they will attempt to agree an allocation, but if they do not, Zurich will advance what it believes is covered. Zurich’s decision is controlling until a “different allocation is negotiated, arbitrated, judicially or otherwise determined”. This reflects the fact that a claim may change over time: McCarthy v St Paul International Insurance Co Ltd [2007] FCAFC 28; (2007) 157 FCR 402 at [76]; Major Engineering Pty Limited v CGU Insurance Limited [2011] VSCA 226; (2011) 35 VR 458 at [29]–[36].

43 Zurich said that paragraph 3 of the advancement provision picks up the concepts in the first paragraph and provides for a mechanism to resolve disputes in relation to allocation. Paragraph 4 addresses how payments are to be adjusted over time should there be a change in allocation of claim expenses over time. Paragraph 5 records an express agreement that an allocation of claim expenses does not stand as a pre-determination of any other allocation of all loss.

44 Zurich submitted that:

From the above, it is plain that the parties have sought to deal with claim expenses in two distinct time frames – up to the point of final adjudication – which is addressed by the second and fourth paragraphs (providing for the potential for more than one allocation over time reacting to the status of the claim at that point) – and at the point of final adjudication – where claim expenses form part of loss and are dealt with by reference to the first, third and fifth paragraphs. During the period up to the point of final adjudication, the allocation of claim expenses is expressly described as subject to Claims Condition 1, i.e., the Advancement Clause.

The clause does not contemplate a route to the payment of claim expenses prior to final adjudication and their allocation by any route other than through the Advancement Clause. FKP’s contention that the Advancement Clause can be ignored and that they have an alternative route through the Insuring Clause is inconsistent with the careful structuring of this Claims Condition.

45 Key aspects of these submissions are not persuasive.

46 “Loss” is defined to include claim expenses for which the insured is legally liable. Claim expenses do not become a part of “loss” only once an allocation is determined. Claim expenses are always a part of “loss”. The insured “is legally liable” for loss if it is legally obliged to pay the sum. If there is any doubt about the insured’s legal liability to pay the sum, the legal liability exists once it is competently determined or agreed that the insured is legally obliged to pay the sum. The insured incurs the loss once the sum is in fact paid. The allocation provision is intended to operate where there is uncertainty about the extent to which the claim expenses form part of the “loss covered by this policy” or part of the “loss not covered by this policy”.

47 Consistently with this, paragraph 1 of the allocation provision recognises that a claim may involve covered and uncovered loss of the insured or of the insured and other(s) uninsured. Paragraph 1 says that if covered and uncovered loss is incurred, the insured and Zurich will try to agree an allocation between covered and uncovered loss. It also says that Zurich’s liability under the policy is limited to covered loss.

48 Nothing in paragraph 1 of the allocation provision says that the insured and Zurich will try to reach such an agreement about allocation once only and only after a final adjudication of the claim. Nor does any provision say that Zurich and the insured may not obtain a determination of Zurich’s liability under the policy before a final adjudication of the claim. There are also a number of positive indicators to the contrary of Zurich’s propositions.

49 Paragraph 1 of the allocation provision refers to “loss … incurred”. As loss is defined to include claim expenses, such loss will be incurred before a final adjudication of a claim. Paragraph 1 provides that Zurich is only liable for loss (thus including claim expenses) covered by the policy, and that it is “only liable under this policy for amounts attributable to covered matters and parties, and our liability for loss, including claim expenses, otherwise payable by us shall be reduced to reflect such fair and proper allocation”. Accordingly, it is apparent that paragraph 1 is performing multiple functions:

(1) it is reiterating that Zurich is ultimately liable only for loss covered by the policy;

(2) it is ensuring that the amount Zurich ultimately has to pay under the policy is no more than loss covered by the policy (up to the limit of liability for any one claim); and

(3) it is providing a mechanism for Zurich and the insured to agree upon an allocation of the amounts which it will pay including as claim expenses before the loss is ultimately determined which should reflect the distinction between covered and uncovered loss.

50 If an agreement is reached under paragraph 1, then paragraph 2 of the allocation provision provides that Zurich is to make advance payment of claim expenses in accordance with the advancement provision – these are payments made before any final adjudication (see the advancement provision which refers to claim expenses “as they are incurred and prior to the final adjudication of the claim”).

51 If an agreement is not reached under paragraph 1 of the allocation provision, then paragraph 2 provides that Zurich is to make advance payments in accordance with the advancement provision which Zurich believes to be covered under the policy until a different allocation is negotiated, arbitrated, judicially or otherwise determined. Again, there is no suggestion that there can be no such negotiation, arbitration or judicial or other determination until the claim is finally adjudicated.

52 If an agreement is not reached under paragraph 1 of the allocation provision, then under paragraph 3, the insured may request submission of the allocation dispute to a senior counsel who shall determine the allocation.

53 Under paragraph 4, the senior counsel’s determination of the allocation will be applied retroactively. Paragraph 4 also provides that “[a]ny advancement of claim expenses shall be repaid to us by the insured severally according to their respective interests, if and to the extent that we determine that such amounts paid by us are not insured by this policy”. I construe this to mean both that: (a) if, according to the senior counsel’s determination, Zurich should have paid a lesser proportion or amount of claim expenses to any insured, the relevant insured must repay the excess to Zurich, and (b) if, ultimately as contemplated by paragraph 5 (see below), it is determined that Zurich is not liable for some or the whole of the claim expenses, the relevant insured is to repay the amount for which Zurich is not liable. This is because there would be no reason for the determination of senior counsel to apply “retroactively” unless the object of that retroactive operation is to oblige the insured to repay any over-payment as calculated by reference to the determination of senior counsel.

54 Under paragraph 5 of the allocation provision, any allocation or advancement of claim expenses does not pre-determine the allocation of other loss on account of such claim. There is no presumption as to the fair and proper allocation, which is governed by the allocation clause. This means that Zurich’s agreement under paragraph 1 of the allocation clause and the determination of senior counsel about claim expenses are both immaterial when it comes to ultimate liability which may be determined, if necessary, in a suit between Zurich and the insured. Zurich’s ultimate liability for loss is to be governed by the intention of the allocation provision which is that Zurich is only liable for covered and not uncovered losses.

55 Under this scheme, paragraph 1 of the allocation provision does not permit only a once and for all allocation once the claim has been ultimately determined. It permits Zurich and the insured to agree on the advance payment of claim expenses under the advancement provision as they see fit from time to time. It permits the insured, if it ever disagrees with Zurich about the advance payment of claim expenses, to require the dispute to be submitted to senior counsel for a determination. That senior counsel determination, once made, applies both retrospectively and prospectively until any determination in a suit between Zurich and the insured as to a fair and proper allocation. On this basis, the allocation clause contemplates potential multiple allocations throughout the life of a claim and that the ultimate determination of Zurich’s liability will be in any suit as between Zurich and the insured. Again, there is no suggestion that there can be no such arbitration, suit or other proceedings until the claim is finally adjudicated. This proceeding is a suit between Zurich and the insured.

56 Under this scheme, Zurich is protected on both an intermittent and a final basis from any over-payment of claim expenses as paragraph 4 of the allocation provision provides that: (a) the senior counsel determination applies retroactively, and thereby it must apply before any final determination of an allocation in a suit between Zurich and the insured, with the consequence that the insured is to repay any earlier over-payments, and (b) the insured is to repay any amounts ultimately determined not to be covered loss under the policy.

57 Further, while paragraph 4 of the allocation provision refers to “if and to the extent that we determine that such amounts paid by us are not insured by this policy” (emphasis added), the context discloses that Zurich’s determination is intended to be a determination in accordance with the senior counsel determination or the determination which is an outcome of the arbitration, suit or other proceedings as referred to in paragraph 5. That is to say, Zurich is only free to pay the amount it believes is payable as an advance payment for claim expenses as provided for in paragraph 2 of the allocation provision if it and the insured disagree under paragraph 1 and until either a determination of an allocation by senior counsel under paragraph 3, or a determination in any arbitration, suit or other proceedings between Zurich and the insured provided for by paragraph 5.

58 Again, it is important to recognise that no provision says that: (a) the steps in the allocation provision must occur in any particular order, other than that a dispute about the allocation between Zurich and the insured is a pre-condition to an insured requesting a senior counsel determination, or (b) there cannot be any arbitration, suit or other proceedings between Zurich and the insured to determine the allocation before the final adjudication of the claim.

59 It follows from this that I do not agree with Zurich’s submissions about the way in which the allocation provision operates. The purported temporal bifurcation Zurich proposes (paragraphs 2 and 4 deal with claim expenses before final adjudication and paragraphs 1, 3 and 5 deal with claim expenses after final adjudication) is untenable. There is a simple and logical temporal sequence in the allocation provision which may be represented as follows, on the proviso that, as I have said, the provision does not make this sequence mandatory other than that there must be a dispute about the allocation before there can be a request for a senior counsel determination:

60 This sequence of events may occur before the claim is finally adjudicated. It may occur in part before the claim is finally adjudicated and in part after the claim is finally adjudicated. The sequence may also re-commence at some time during the life of the claim.

61 This rejection of part of Zurich’s submissions does not mean that Zurich must be wrong that the allocation provision does not contemplate a route to the payment of claim expenses prior to final adjudication and their allocation by any route other than through the advancement provision. However, it is relevant to that issue that:

(1) the allocation provision is engaged where both “loss covered by this policy and loss not covered by this policy are incurred”;

(2) the allocation provision operates before any final adjudication of the claim, and the provision is engaged where Zurich and/or the insured consider (but do not know) that the claim involves both “loss covered by this policy and loss not covered by this policy are incurred”;

(3) the dispute between Zurich and the insured contemplated by paragraph 2 of the allocation provision may relate to the details of the allocation or the question whether any allocation at all is required (that is, the insured may contend that the loss is all covered and/or Zurich may contend that none or some of the loss is covered);

(4) paragraph 2 of the allocation provision says that if Zurich and the insured agree on an allocation between covered and uncovered losses including claim expenses, Zurich shall pay claim expenses subject to and in accordance with the advancement provision;

(5) paragraph 2 of the allocation provision says that if Zurich and the insured disagree on an allocation between covered and uncovered losses including claim expenses, Zurich shall pay claim expenses as Zurich believes to be covered subject to and in accordance with the advancement provision pending a different determination of the allocation; and

(6) Zurich is protected at all times from any risk of over-payment of claim expenses by the repayment obligation on an insured under paragraph 4 of the allocations clause.

62 Zurich is also protected from any over-payment of claim expenses under the advancement provision which provides that:

All such payments shall be repaid to us by the insured (or where more than one insured has received such payments, by such insureds severally and according to their respective interests) in the event and to the extent that the insured is not entitled to payment of such claim expenses under the terms and conditions of this policy.

63 While the repayment obligations might involve some degree of redundancy, they ensure that the policy operates to require an insured to repay any overpaid claim expenses both where the allocation clause is engaged (paragraph 4 of that provision) and where it is not engaged (the last paragraph of the advancement provision). The key fact about the insured’s repayment obligation in respect of claim expenses is that it operates in the circumstance of uncertainty. There will be uncertainty about the extent of Zurich’s obligation to pay claim expenses until either: (a) the claim is determined and the covered and uncovered loss can be ascertained and agreed as between Zurich and the insured, or (b) the covered and uncovered loss can be ascertained and judicially determined.

64 On this basis it can be seen that a way of analysing the competing positions of the parties in this case in respect of question 1 is as follows:

(1) FKP’s position is that:

(a) the covered and uncovered loss can be ascertained and judicially determined in this proceeding;

(b) this can occur before the claim in the Supreme Court proceeding is finally adjudicated; and

(c) if this occurs and it is correct that the whole of the loss in the Supreme Court proceeding will be loss incurred within the meaning of the insuring clause, then it must follow that as each claim expense is incurred, it is also loss within the meaning of the insuring clause for which Zurich must indemnify FKP under the insuring clause; and

(2) Zurich’s position is that:

(a) the covered and uncovered loss cannot be ascertained and judicially determined in this proceeding, because the claim in the Supreme Court proceeding has not been finally adjudicated; and

(b) even if the covered and uncovered loss can be ascertained and judicially determined in this proceeding before the claim in the Supreme Court proceeding is finally adjudicated, any payment of claim expenses required can only be made under the advancement provision which operates to the exclusion of the insuring clause in respect of the payment of claim expenses “prior to the final adjudication of the claim”.

65 This way of analysing the competing positions both exposes the relationship between questions 1 and 2, and that an aspect of question 1 is whether the advancement provision necessarily and in all circumstances operates to the exclusion of the insuring clause in respect of the payment of claim expenses “prior to the final adjudication of the claim”.

66 Against this background, the required “iterative process” of ascertaining how the policy might operate as affected by each of the competing positions can be undertaken.

67 The insuring clause provides an indemnity for loss incurred as a result of a claim of the specified type. The insuring clause is different from that considered in Australasian Correctional Services Pty Limited v AIG Australia Limited [2018] FCA 2043 at [16]–[18] to which Zurich referred. In that case the insuring clause provided indemnity for “… all amounts which the Insured shall become legally liable to pay by way of compensation by reason of Personal Injury or Property Damage caused by an Occurrence in connection with the business”: [2]. At [15], Allsop CJ said that the clause was to be interpreted as covering:

“all amounts which the Insured shall become legally liable to pay” ascertained by judgment, award or settlement: Distillers Co Biochemicals (Aust) Pty Ltd v Ajax Insurance Co Ltd (1974) 130 CLR 1 at 25–26; Post Office v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd [1967] 2 QB 363 at 373–74 and 377–78; Vero Insurance Ltd v Baycorp Advantage Ltd [2004] NSWCA 390; 13 ANZ Insurance Cases 61-630 at [1], [48] and [89]; Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Bluescope Steel Ltd [2014] NSWCA 276; 87 NSWLR 332 at 349 [78], 381 [267]–[270].

68 His Honour continued:

[16] In policies of this character the nature of that primary liability can give rise to practical difficulties for insureds. Given that the legal liability of the insurer is not engaged until there is an event of liability by judgment, award or settlement, the insured may be left, in the meantime, to fund a defence or to settle the case, without the involvement of the insurer. Different policies deal with this difficulty, and related problems, differently. Some solutions are more favourable to insured, some more favourable to insurer. Such, no doubt, is reflected in the premium.

[17] The terms of a policy can be structured by the parties; benefits of terms are paid for. Thus, statements of commerciality or not of a construction of a policy in a debate about its terms and reach of cover must be carefully assessed. A lack of commerciality, so-called, may simply be the extent of the possible operation of the policy in respect of a claim that has in fact been paid for, by a higher or lower premium.

[18] One solution of the above difficulties has been to give the insurer the right, but not the duty, to take over the defence of a claim. Another has been to have a clause requiring the insurer to pay defence costs expended by the insured with its consent, which clause may be linked to the claims for which indemnity is provided, or it may be linked to the suit in which such claims are made. Another solution has been to require the insurer to undertake the defence of the suit in which the relevant claims are made.

69 This is not such a policy. This policy includes claim expenses in the definition of “loss” and the insuring clause provides indemnity for loss incurred as a result of the claim of the specified type, which includes loss in the form of payment of claim expenses. The problems to which a clause of this kind gives rise are different from those considered in Australasian Correctional Services.

70 If a claim is made against an insured under the policy in this case there are these possibilities at the time the claim is made:

(1) the claim is one that, before final determination of the claim, a court (or Zurich) can determine that the claim is for loss wholly within the insuring clause; or

(2) the claim is not one that, before final determination of the claim, a court (or Zurich) can determine that the claim is for loss wholly within the insuring clause.

71 If the circumstance in (2) applies, a further possibility arises – which is that the claim is one that, before final determination of the claim, a court (or Zurich) can or cannot determine that the claim is for loss partly but not wholly within the insuring clause.

72 Overlaid on these possibilities is that Zurich and the insured may agree or disagree about whether the claim is one that, before final determination of the claim, a court (or Zurich) can or cannot determine that the claim is for loss wholly or partly within the insuring clause.

73 For Zurich’s answer to question 1 to be correct, the advancement provision must operate to the exclusion of the insuring clause in respect of the payment of claim expenses in all circumstances, including where a court (or Zurich) can determine (or even has determined) that the claim is for loss wholly within the insuring clause before final determination of the claim. As with the insurer’s argument in Wilkie, the effect of Zurich’s position would be to prevent an insured from challenging Zurich’s denial of: (a) any indemnity and, as a result, a refusal to pay claim expenses at Zurich’s “absolute discretion” as referred to in (b) of the advancement provision, or (b) a complete indemnity and, as a result, a refusal to pay any or the whole of the insured’s claim expenses unless and until the claim is determined (as in the present case).

74 In argument I asked Zurich what the position would be on its construction of the advancement provision in this case if I determined that question 2 should be answered “yes” given that Zurich had not “confirmed in writing” indemnity under the policy as referred to in (a) of the advancement provision. Zurich responded that if I answered question 2 “yes” it would be bound by its obligation to act in good faith to provide its confirmation in writing of indemnity under (a) of the advancement provision, and if it did not, it would be unlawfully repudiating the contract.

75 Zurich’s answer fails to recognise that the purpose of the advancement provision and the allocation provision is to deal with uncertainty. This is why the provisions both provide for a repayment obligation in the event of over-payment of claim expenses. If there is no uncertainty about the extent of Zurich’s liability for loss under the policy, then there is no need for any repayment obligation because there cannot be an over-payment of claim expenses. Once this is accepted, it is apparent that recourse to the doctrines of good faith and repudiation as the source of a duty on Zurich to provide its consent in writing under (a) of the advancement provision is unnecessary. If a court can and does determine that all loss of an insured incurred as a result of a claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause, then the insuring clause applies in accordance with its terms so that: (a) as each claim expense is incurred, Zurich is obliged to indemnify the insured for that loss, and (b) once the loss as a result of the claim is determined Zurich is obliged to indemnify the insured for that loss, all up to the limit of the indemnity. The same conclusion applies if Zurich itself agrees with an insured that all loss of an insured incurred as a result of a claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause. Either way, there is no uncertainty on which the advancement provision or the allocation provision can attach.

76 Any concern on the part of Zurich that a court cannot and/or should not determine that all loss of an insured incurred as a result of a claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause is immaterial to the proper construction of the policy and to the answer to question 1. One reason that this concern cannot be relevant to the proper construction of the policy and therefore to the answer to question 1 is that it does not make sense to attribute to the parties to the policy a contemplation that a court may wrongly decide that it can and should determine that all loss of an insured incurred as a result of a claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause. This is because the parties would be attributed with the knowledge that judicial decisions are final and binding, subject only to rights of appeal. Putting it another way, the answer to Zurich’s apparent concern that a claim may develop and change over time is that it can be taken that a court will not determine that it can and should determine that all loss of an insured incurred as a result of a claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause if it is unable to do so or, if it does so, that such an error will be corrected on appeal.

77 The ultimate constructional choice is between the advancement provision: (a) operating in all cases prior to the final adjudication of a claim, including where a court has determined (or Zurich has agreed with an insured), for example, that the claim is for loss wholly within the insuring clause, in which event the duty of good faith operates to require Zurich to provide its confirmation in writing of indemnity under (a) of the advancement provision, or (b) operating in all cases where there is uncertainty about the fact or extent of the loss within the insuring clause, which does not exist if a court determines (or Zurich has agreed with an insured) that the claim is for loss wholly within the insuring clause, in which event the insuring clause operates in accordance with its terms prior to the final adjudication of a claim.

78 Given this constructional choice, nothing in the policy indicates that (a) should be chosen over (b). Rather (b) should be chosen over (a) as:

(1) the fact that the advancement provision is styled as a claim condition does not answer the question why the advancement provision would be construed as operating to the exclusion of the insuring clause in all cases prior to the final adjudication of the claim, rather than in a case where there is uncertainty about the fact or extent of the loss claimed being within the insuring clause;

(2) the advancement provision does not say that it operates to the exclusion of the insuring clause in all cases prior to the final adjudication of the claim. It says only that Zurich will pay claim expenses prior to the final adjudication of the claim in the circumstances identified;

(3) as discussed above, the circumstances identified do not cover the field of possibilities including the contention of an insured, as in this case, that all loss the subject of the claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause;

(4) the advancement provision does not purport to prevent an insured from seeking and obtaining a judicial determination that all loss the subject of the claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause;

(5) the express references to the advancement provision in paragraph 2 of the allocation provision are apt because they apply in circumstances where there is uncertainty about the allocation of claim expenses (that is, the extent to which Zurich must pay the claim expenses) which depends on the extent to which the loss is covered under the insuring clause. That uncertainty may exist because there has been no agreement about that issue between Zurich and the insured or, failing such agreement, no judicial determination of the extent to which the loss is covered under the insuring clause but uncertainty will cease to exist once there is such a judicial determination;

(6) the allocation provision does not purport to prevent an insured from seeking and obtaining a judicial determination that all loss the subject of the claim is and will be loss within the insuring clause;

(7) to the contrary, the allocation provision recognises that claim expenses are within the definition of loss and that claim expenses are able to be incurred before the final adjudication of a claim;

(8) further to the contrary, the allocation provision recognises that there may be a judicial determination between Zurich and the insured as to the allocation of claim expenses depending on the fact or extent to which the loss the subject of the claim is within the insuring clause;

(9) further again to the contrary, the allocation provision does not purport to say that such a judicial determination between Zurich and the insured can only be made after a final adjudication of a claim; and

(10) rather, and as is both necessary and appropriate, the allocation provision and the policy as a whole leave it to Zurich (if it agrees with the insured) or, failing agreement, the court to decide if a judicial determination between Zurich and the insured can and should be made as to whether the whole or part (and if so what part) of the claim expenses are within the definition of loss and accordingly the insuring clause prior to a final adjudication of a claim.

79 For these reasons, question 1 is answered “no”.

Question 2

80 It follows from my answer to question 1 that it is not the case, as submitted by Zurich, that the policy provides no “objective criteria for the determination of payments of claim expenses prior to final adjudication, but is tied to a decision of Zurich (a) as to coverage; and (b) in the exercise of its discretion”. This proposition is correct only insofar as there remains uncertainty about the fact and extent to which the loss the subject of the claim is loss within the insuring clause.

81 The contention of the FKP parties is that, in the presently known circumstances, the loss the subject of the claim is wholly within the insuring clause so that Zurich must indemnify them for all of its claim expenses as incurred up to the limit of its liability under the policy. The FKP parties may be right or wrong about this contention, but the immediately relevant point is that they have a current entitlement to seek (and, if they can, obtain) a judicial determination to this effect. Contrary to Zurich’s submissions, making such a judicial determination, if the Court determines it can and should be made, does not interfere with the commercial bargain of the parties, for the reason already given in answer to question 1 above. Zurich’s submission to this effect is based on its misconstruction of the policy.

82 Further, if it is the case that the Court cannot or should not make such a determination on the facts of this case, this conclusion says nothing about any other case in which it might be both possible and appropriate for a court to make such a determination before a final adjudication of the claim. Each case will depend on the nature of the particular claim and its facts.

83 In the present case, Zurich contended in its written and oral submissions that the criteria which engage the insuring clause (loss incurred as a result of any claim for civil liability against the insured based on the insured’s provision of professional services) mean that:

(1) the professional service must be personally performed by the insured. The insuring clause is not engaged if the insured merely has contractual responsibility for the performance of a professional service by another party;

(2) clause 3 of the extensions of cover provision is concerned with the legal liability of the insured for the conduct of others in providing professional services. In this regard, Zurich contended that:

(a) clause 3 depends on the insured being “legally liable” for the loss from any claim. This requires a judgment, arbitral award or settlement to operate. There is no such judgment, arbitral award or settlement in the present case and the FKP parties do not rely on clause 3 in their pleadings as the source of any present right to indemnity;

(b) given that the extensions operate “on the same terms and in the same manner as the Insuring Clause (except as expressly stated)”, clause 3 does not extend cover beyond the provision of professional services;

(c) clause 3 operates to extend cover to the provision of professional services where the insured is not the provider of those services which are, instead, provided by a consultant, sub-contractor or agent of the insured. Contrary to the submissions of the FKP parties, clause 3 does not operate in respect of the insured being legally liable in its own provision of professional services for any conduct of a consultant, sub-contractor or agent of the insured (whether or not the provision of professional services by the consultant, sub-contractor or agent of the insured) because this adds a qualification beyond the language of the extension; and

(d) accordingly, if the reason for a construction defect is defective work by a sub-contractor and “there is no established deficiency in [FKP’s provision of] project management services allowing the defect to exist”, then there is no liability under the insuring clause or clause 3;

(3) while “project management” and “construction management” are within the scope of the definition of “professional services”, to be professional services as defined, the “project management” and “construction management” must also satisfy the proviso in the definition (“performed by or under the direct supervision of a properly registered engineer, architect, or surveyor, or quantity surveyor (who is a member of the Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors) or any other person (duly qualified by training or education)…”) and not be within the exclusions (i) and (ii) in the definition;

(4) the fact that FKP Constructions may have personally performed some “professional services” within all requirements of the definition does not mean that all the work it performed is within the definition;

(5) the “based on” criterion means that the Supreme Court proceeding is to be treated as containing as many claims as there are different bases for relief (that is, there is a separate claim for each different basis of performed service) or, where a single claim (proceeding) consists of covered and uncovered matters the allocation provision applies;

(6) either way, only that part of the claim that is based on the insured’s personal provision of the professional services is covered;

(7) the “based on” criterion requires that the cause(s) of action against the insured in the claim depend(s) on the insured’s personal provision of the professional services. That is, the required causal relationship between the provision of the professional services and the claim must be one in which there is a causal connection between the insured personally providing the professional services and the residential building work in breach of the statutory warranties;

(8) accordingly, if FKP Commercial and FKP Constructions did not personally provide some professional service which caused (in some way) the residential building work in breach of the statutory warranty, then the insuring clause’s “based on” requirement will not be satisfied;

(9) the breach of statutory warranties claim in the Supreme Court proceeding does not depend on FKP Commercial or FKP Constructions having personally provided any professional services. Rather, it depends on the fact of the residential building work having been done under a contract in breach of the statutory warranties, which was “causally irrelevant” to the construction defects; and

(10) as it is common ground that the other claims in the Supreme Court proceeding are not supported by any expert evidence, it is unnecessary to have regard to those claims.

84 Although (regrettably) not the focus of its written or oral submissions, it is apparent that Zurich also contended in the course of its communications with the FKP parties that the definition of “civil liability” is relevant. Under the insuring clause, the loss must be incurred as a result of any claim “for civil liability” based on the insured’s provision of professional services. “Civil liability” is defined to mean liability of the insured on any civil cause of action for compensation based on its provision of, or failure to provide, the professional services. Zurich’s position (as recorded in a letter dated 24 September 2021) is that a “cause of action for compensation that has its basis in faulty workmanship, where the error arises from negligent construction or negligent supervision of construction, is not a cause of action that is based on the provision of or failure to provide professional services”. This letter continued as follows:

Under the HBA [Home Building Act] and DBPA [Design and Building Practitioners Act] , FKP Constructions’ liability arises from works that FKP Constructions, as head D+C [Design and Construction] contractor, delegated to others. It is the scope of those delegated works which is material, not the project management services that FKP Constructions performed.

There is no suggestion in the pleadings that FKP Commercial is sued for any professional services it provided. It is therefore not entitled to any indemnity under the insuring clause…

Similarly, FKP Constructions having delegated out the design and construction elements of the development, the only professional services provided by FKP Constructions, being the project management services, did not cause any loss. It follows that the claim against FKP Constructions is not based on its provision of, or failure to provide, the professional services.

85 Zurich referred to a number of decisions said to support these propositions, as follows.

86 GIO General Limited v Newcastle City Council (1996) 38 NSWLR 558 at 568–569 concerned an exclusion of liability which confined indemnity for a claim for “the rendering or failure to render professional advice or service” to a particular insuring clause. The observation of Kirby P (as his Honour then was) at 568 is that “relevant activities conducted by the respondent must be examined to see whether, in their nature, they are properly characterised as “professional”” (noting that “professional service” was not a defined term in the policy).

87 Government Insurance Office of New South Wales v Penrith City Council [1999] NSWCA 42; (1999) 102 LGERA 102 concerned the meaning of “conduct of any business dependent wholly or mainly on personal qualifications conducted by or on behalf of the Insured in a professional capacity” and its application to the facts of that case.

88 AIG Australia Limited v Kaboko Mining Limited [2019] FCAFC 96 concerned an exclusion from an insuring clause. The exclusion was “for any Loss in connection with any Claim arising out of, based upon or attributable to the actual or alleged insolvency of the Company…”. The term “Claim” was defined by reference to matters such as a written demand or proceeding for a specified act, error or omission, an investigation or an extradition proceeding (at [29]). The claim was by the company against former directors and officers for breach of their duties as directors in managing the company. The directors and officers claimed under the policy. The insurer denied indemnity on the basis that the claim was excluded by the insolvency exclusion. The insurer argued that the exclusion applied if (at [38]):

there was the requisite insolvency connection with either the bringing of the Claim or the nature of the Loss for which indemnity was sought (irrespective of whether the liability for the Loss was itself established by reference to a cause of action that depended upon demonstrating insolvency or a head of loss that was alleged to have been caused by insolvency).

89 The Full Court disagreed as:

(1) “[t]he insolvency exclusion could have been expressed as applying to any Loss arising out of, based upon or attributable to Kaboko’s insolvency or inability to pay debts. Had it done so then the specified insolvency link (arising out of, based upon or attributable to) would have to be evaluated by reference to an amount which AIG was otherwise liable to pay under the policy”: [45];

(2) “[t]he qualifying words that specify the insolvency link should not be read as applying to the Loss. Such an approach would give the words ‘in connection with any Claim’ no work to do. Rather, the insolvency link qualifies the types of Claims for which indemnity for Loss must be provided. If the Loss (liability to pay) is ‘in connection with’ any Claim with the specified insolvency link then it is excluded”; [47];

(3) “[t]he key question is whether it is the subject matter of the Claim that must have the specified insolvency link or whether the link is also established where, by reason of the circumstances that have led to the bringing of the claim, it can be said that the Claim arises out of, is based upon or is attributable to the actual or alleged insolvency of Kaboko or its inability to pay its debts when due”: [48];

(4) “…for the purposes of the insolvency exclusion, a Claim does not arise out of, is not based upon and is not attributable to the insolvency of Kaboko or its inability to pay its debts unless the subject matter of the Claim has that character (being a character derived in the case of civil proceedings from the acts, errors or omissions that are the subject of the proceedings and the associated loss that may become the Loss if the proceedings are successful). The exclusion is not to be read as applying where the insolvency of Kaboko or its inability to pay its debts might be said to have motivated or led to the Claim being brought (for reasons other than providing a material part of the basis of the Claim)”: [50];

(5) “[t]he clause does not refer to a Claim that is brought because of the insolvency of Kaboko. Rather, it refers to the Claim itself ‘arising out of, based upon or attributable to’ Kaboko’s insolvency or inability to pay debts. Given the nature of a Claim and the stated connection with Loss (resulting from a Claim) the language is more apt to direct attention to the subject matter of the Claim than the reasons why it was brought”: [53]; and

(6) “…the qualifying words which specify the insolvency link describe a Claim ‘arising out of, based upon or attributable to’ the insolvency of the company the subject of the policy or the company’s ability to pay its debts. The words used, especially ‘arising out of’ and ‘based upon’ indicate a focus upon the subject matter of the Claim”: [56].

90 Allianz Australia Limited v Wentworthville Real Estate Pty Ltd trading as Starr Partners (Wentworthville) [2004] NSWCA 100; (2004) ANZ Ins Cas ¶61–598 at [45] said that where an exclusion was for claims of a particular character it was necessary to consider the substance of the claim. In reaching this conclusion, it should be noted that Mason P (with whom Sheller JA and Pearlman AJA agreed) said at [23]–[24]:

It is submitted that the court must look at the substance of the claim, not the legal tag or tags which may be attached to it to signify the cause(s) of action, to determine whether the claim attracts indemnity under the policy. The manner in which a claim is framed against the insured will not be decisive as to whether liability falls within cover.