Federal Court of Australia

Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2022] FCA 827

EVIDENTIARY RULINGS

JONATHON MALONE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE WESTERN KANGOULU PEOPLE Applicants | ||

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

O’BRYAN J:

Introduction

1 In this proceeding, the applicant seeks a determination of native title under s 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Native Title Act) in respect of an area of land surrounding the township of Emerald in the western part of the Central Highlands in Queensland. The claim is made on behalf of the Western Kangoulu people and is known as the Western Kangoulu native title claim.

2 On 6 December 2017, the Court made orders under r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that the following questions (the Separate Questions) be determined separately from any other questions in the proceeding:

1. But for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so, what land and waters of the claim area?

2. In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(a) Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

(b) What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

3 The trial of the Separate Questions is scheduled to commence on 30 August 2022. The applicant is the only party who will be adducing evidence at the trial. The applicant proposes to adduce evidence from a number of lay witnesses, genealogical evidence from Dr Hilda Maclean and anthropological evidence from Dr Richard Martin. Dr Martin originally prepared a joint report with Dr Dee Gorring dated 14 September 2018. However, Dr Gorring is no longer available to give evidence in the proceeding. Dr Martin has subsequently prepared a supplementary report dated 20 August 2021 (Dr Martin’s Supplementary Report) and a revised version of the report originally authored with Dr Gorring which is dated 18 March 2022 (Dr Martin’s Revised Report).

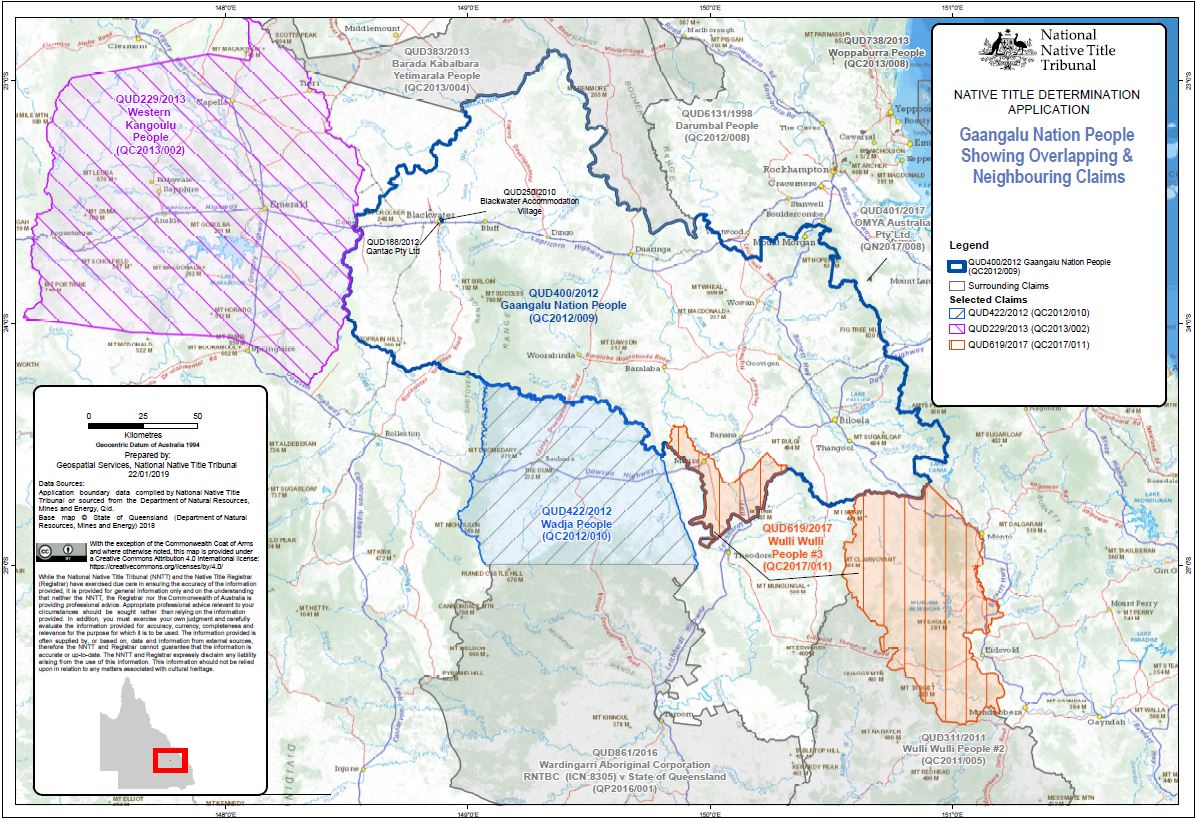

4 The applicant also proposes to tender a number of other reports that have been prepared by anthropologists in the course of this proceeding and three other proceedings which involve neighbouring native title claims: the Gaangalu Nation People native title claim (QUD 400 of 2012 but now QUD 33 of 2019, referred to herein as the GNP claim), the Wadja native title claim (originally QUD 422 of 2012 but now QUD 28 of 2019, referred to herein as the Wadja claim) and the Wulli Wulli People #3 (Part A) claim (QUD 619 of 2017, referred to herein as the Wulli Wulli 3A claim). A map showing the claim areas in respect of each of those proceedings is attached as an annexure to these reasons. As discussed below, there is a relationship between the four claims and, in the course of each of the proceedings, they have been collectively described with the alternative labels “Gaangalu cluster”, “Ganggalu cluster” or “GNP cluster”. The reports proposed to be tendered by the applicant are as follows:

(a) the Joint Statement in relation to society for the GNP, Western Kangoulu and Wadja claims dated 21 May 2018 and prepared by Dr Martin, Dr Gorring, Dr Kim de Rijke and Mr Kim McCaul (First Joint Statement);

(b) the Joint Statement in relation to common apical ancestors on the Western Kangoulu and GNP claims dated 31 May 2018 and prepared by Dr Martin, Dr Gorring and Dr de Rijke (Second Joint Statement);

(c) the Report of Dr Anna Kenny dated 9 November 2018 in respect of the GNP cluster (Dr Kenny’s Report);

(d) the Report of the conference of experts in respect of the Western Kangoulu claim held between Dr Martin and Dr Kenny on 21 February 2019 and signed by each on 21 February 2019 (First Conferral Report); and

(e) the Report of the conference of experts in respect of the GNP cluster held between Dr de Rijke, Dr Fiona Powell, Dr Martin, Mr McCaul and Dr Kenny on 22 February 2019, and signed by each on 5 March 2019 (Second Conferral Report),

collectively referred to herein as the Additional Materials. The applicant does not propose to call the authors of the reports as witnesses (other than Dr Martin).

5 In preparation for trial, and in accordance with orders made by the Court, the applicant and the State of Queensland have exchanged objections to evidence. Most objections have been resolved between the parties by agreement. However, there remains a significant area of disagreement between the parties in relation to certain aspects of the anthropological evidence proposed to be relied on by the applicant at trial.

6 By interlocutory application dated 18 March 2022, the applicant applied to have the remaining objections concerning the anthropological evidence determined before trial in accordance with s 192A of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act). The application was supported by two affidavits of David Knobel, a solicitor at the firm P&E Law representing the applicant, dated 18 March 2022 and 25 May 2022 respectively.

7 On 30 March 2022, I made orders listing the interlocutory application for hearing on 5 July 2022 and orders for the exchange of written submissions in respect of the remaining objections. Submissions in chief were filed by the State and the applicant on 10 and 13 June 2022 respectively, and responsive submissions were filed by the State and the applicant on 29 June 2022.

8 The State objects to certain paragraphs of Dr Martin’s Revised Report on the basis that Dr Martin’s opinion is not demonstrated to be based upon an application of his specialised knowledge to the relevant facts or assumptions, as required by s 79 of the Evidence Act. The majority of the objections concern Dr Martin’s reliance upon the First and Second Joint Statements. In summary, the State submitted that it is not permissible for Dr Martin to adopt the opinions expressed by others because that does not involve an application of his specialised knowledge to relevant facts or assumptions.

9 The State also objects to the tender of the Additional Materials. In summary, the State submitted that:

(a) the Additional Materials are hearsay and inadmissible under s 59 of the Evidence Act; and

(b) the Additional Materials are not acceptable basis material for Dr Martin’s Supplementary Report or Revised Report and, accordingly, are not admissible under s 60 of the Evidence Act.

10 The State also contests the applicant’s submission that the Additional Materials are admissible to show that Dr Martin’s opinion is in harmony with the opinions of Dr Kenny, Dr de Rijke, Dr Gorring and Mr McCaul.

Background

The Western Kangoulu claim

11 The Western Kangoulu native title claim was originally filed on 9 May 2013. The most recent form of the application was filed on 10 January 2019. The native title claim group is defined in Schedule A to the application as follows:

The group of persons claiming to hold the common or group rights comprising the native title is the Western Kangoulu People.

A person is a Western Kangoulu person if and only if the other Western Kangoulu People recognise that he or she is biologically descended from a person who they recognise as a Western Kangoulu ancestor, including the following deceased persons:

• Polly aka Polly Brown aka Polly McAvoy;

• John ‘Jack’ Bradley;

• Hanny of Emerald;

• Naimie, mother of Nelly Roberts; and

• Annie/Naimy Duggan and Ned Duggan.

12 The application describes the Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the claim area at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty as being part of a broader regional society. The application states:

5. At the time the crown acquired legal sovereignty over the Application Area, there was a body of Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the Application Area.

6. The Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the Application Area were part of a broader regional society, but were a localised constituent part of this society confining their primary territorial interests to the lands and waters of the Application Area. The contemporary members of the claim group have adopted the name “Western Kangoulu” to explicitly distinguish their localised interests from those of their regional neighbours to whom they have close social and cultural ties dating from the pre-sovereignty period.

7. The areas surrounding Western Kangoulu country belonged to groups who have or were identified as: the Jagalingu, Wangan, Karingbal, Kanolu, Wadja and Gangalu amongst others. Together these groups and the Western Kangoulu formed an interconnected cluster of distinct groups who interacted for cultural and social purposes, and shared common spiritual beliefs, religious institutions, social organisation and classificatory kinship systems, and common laws and customs. Together, these groups form what may be termed a regional society situated within the cultural bloc often referred to as the Maric cultural bloc by linguists and anthropologists so named for the common word for human (“Mari”) shared throughout much of this bloc.

The Ganggalu cluster

13 The Western Kangoulu claim area identified in the application is not overlapped by any other native title claim and there are no Indigenous respondent parties to the application. However, the claim area adjoins the boundary of one other native title claim area which in turn adjoins and was previously overlapped by other claims areas, which comprise the Ganggalu cluster. Specifically:

(a) part of the eastern boundary of the Western Kangoulu claim area adjoins the western boundary of the GNP claim; and

(b) part of the southern boundary of the claim area of the GNP claim adjoins the northern boundary of the Wadja claim and the northern boundary of the Wulli Wulli 3A claim.

14 In his Revised Report, Dr Martin states (at para 15) that, over the years, Ganggalu people have appeared in the ethnographic and historical record as an Indigenous group referred to by a number of different labels with a variety of spellings as commentators sought to write down the names they heard spoken. As is apparent, the claimants in the GNP claim use the spelling “Gaangalu”. The claimants in this proceeding use the spelling “Kangoulu”. When referring to the broader society of Aboriginal people occupying the claim area and surrounding areas at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty, Dr Martin uses the spelling “Ganggalu”. In these reasons, I have adopted that spelling when referring to the evidence concerning the broader society at the time of acquisition of sovereignty and when referring to the group of native title claims identified (the Ganggalu cluster), without intending to convey any view on the appropriateness of one form of spelling over another.

15 The applicants in each of the Ganggalu cluster claims have retained different anthropologists as expert witnesses:

(a) Dr de Rijke has been retained by the applicant in the GNP claim and has prepared a number of expert reports in respect of that claim including an application report in 2012 and a connection report in 2014.

(b) Mr McCaul has been retained by the applicant in the Wadja claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim in 2013. Mr McCaul was also previously retained by the applicant in the Western Kangoulu claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim in 2015.

(c) Dr Martin and Dr Gorring were subsequently retained by the applicant in the Western Kangoulu claim in place of Mr McCaul and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim dated 13 September 2018.

(d) Dr Kenny was previously retained by the State of Queensland and prepared an “Anthropology Overview Report” dated 9 November 2018 which assessed the expert and lay evidence filed for the GNP cluster claims (referred to earlier as Dr Kenny’s Report). The State has informed the Court that it will not adduce evidence from Dr Kenny at the trial of the Western Kangoulu claim.

(e) Dr Powell has been retained by the applicant in the Wulli Wulli 3A claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim dated 13 September 2018.

The First and Second Joint Statements

16 The First Joint Statement was commissioned in 2018 by the applicants in the Western Kangoulu, GNP and Wadja claims. The experts, Dr Martin, Dr Gorring, Dr de Rijke and Mr McCaul, were asked to produce a joint statement of their respective opinions on the nature and extent of the relevant society or societies in relation to the GNP claim, the Wadja claim and the Western Kangoulu claim, and how the society or societies may be defined, considering:

(a) its constituent groups and geographical extent;

(b) the traditional laws and observed customs which underpinned the relevant society or societies, including with respect to land tenure;

(c) whether some or all of the native title claim groups described in the GNP claim, the Wadja claim and the Western Kangoulu claim were part of the same society, or separate societies with social and cultural links arising from their regional proximity; and

(d) the continuing functioning and status of the constituent groups as a society or societies since the acquisition of British sovereignty.

17 The Second Joint Statement was commissioned by the applicants in the Western Kangoulu and GNP claims. The experts, Dr de Rijke, Dr Martin and Dr Gorring, were asked to produce a joint statement concerning:

(a) the evidence/ethnography and historic record regarding the apical ancestors in common to the GNP claim and the Western Kangoulu claim and their descendants including any contemporary assertions of rights in the claim area of the GNP claim;

(b) whether this evidence provides support for the proposition that the descendants of those ancestors today hold traditional rights and interests in the GNP claim area;

(c) to the extent that the proposition above is supported, the strength of this support, and the nature and geographic extent of such rights; and

(d) whether any omission of the common apicals from the claim group description of the GNP claim would be contrary to the evidence, including consideration of the society for the GNP claim.

Dr Kenny’s Report

18 Dr Kenny was retained by the State in October 2017 to provide expert reports in respect of the GNP cluster claims. Dr Kenny’s Report was titled “Anthropology Overview Report”. Dr Kenny described the content of the Report in the following terms:

To assist the Court and the parties in narrowing the issues that remain in dispute, this Anthropology Overview Report only addresses the main issues that emerge from the expert reports and lay evidence relating to the GNP cluster applications and is not intended as a comprehensive anthropological report on the GNP cluster. In summary, I discuss in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 of this report the land tenure system at Effective Sovereignty and the regional society; and in the remaining chapters I address the main issues that emerge from the expert reports and lay evidence and in turn deal with them.

The First and Second Conferral Reports

19 On 19 September 2018, the Court’s Senior Native Title Case Manager emailed the Ganggalu cluster parties, advising that the Registrar proposed to hold a series of expert conferences which included the experts of more than one of the claims comprising the Ganggalu cluster.

20 On 16 October 2018, Crown Law (on behalf of the State in each proceeding) emailed a common letter to each of the Ganggalu cluster applicants’ legal representatives requesting permission for Dr Kenny to have access to documents filed in each proceeding, to source documents referred to in them, and, where necessary, to refer to and comment upon that material in the other matters. The Ganggalu cluster applicants opposed the request made by Crown Law. However, on 29 October 2018, the Court made orders that the expert reports, their basis material and the lay evidence filed in the Ganggalu cluster proceedings be available to each of the parties’ experts engaged in each proceeding: Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland [2018] FCA 1621.

21 On 5 November 2018, the Court made orders deferring the date by which the conferences of experts were to be held to 1 March 2019. The orders also required the experts to set out in their joint report the matters and issues about which they were in agreement, the matters and issues about which their opinions differed and, where their opinions differed, the reasons for their difference.

22 Prior to the experts’ conference, the parties in the Ganggalu cluster proceedings consulted about the issues to be addressed by the experts at the conference. Relevantly, in this proceeding, a document titled “List of issues for consideration by the expert witnesses” was prepared (List of Issues).

23 The conference of the experts occurred on 21 and 22 February 2019, convened by two Registrars of the Court.

24 The first conferral (on 21 February 2019) related to each individual proceeding within the Ganggalu cluster. Relevantly, in respect of the Western Kangoulu claim, Dr Martin and Dr Kenny conferred and produced the First Conferral Report. The report addresses each of the questions set out in the List of Issues. However, as is common with joint expert reports prepared following a conferral of experts, the opinions expressed in the Report are briefly stated and conclusory in nature. Relevantly for present purposes, and by way of illustration, Dr Martin and Dr Kenny expressed their agreement with the following propositions:

(a) Sovereignty was asserted by the British Crown over the Western Kangoulu claim area in 1788. It is reasonable to infer that “effective sovereignty”, referring to the period of European settlement, in relation to the claim area was the period between 1845 and the early 1860s.

(b) At the time of effective sovereignty, the Aboriginal people of the claim area were part of a broader society that included local landholding groups and extended beyond the area covered by the GNP cluster. In the opinion of Dr Martin and Dr Kenny, other members of this regional society included the Garingbal, Wadja and Gangalu as well as others. From the limited ethnographic record, it appears that there were social networks that faded out in different areas depending on the location of the respective group.

(c) The apical ancestors listed in the Western Kangoulu application held rights and interests in the Western Kangoulu claim area under the traditional laws and customs of the regional society. The research undertaken had not revealed any other persons who held rights and interests in the Western Kangoulu claim area, or discrete parts of it, at the same time as the apical ancestors identified in the application.

(d) Land holding units at effective sovereignty were clans whose members held rights and interests as a clan group at a local level. Clan members were recruited by a system with a patrilineal bias.

(e) Today, the Western Kangoulu people are part of a broader or regional society.

(f) Today, the members of the claim group continue to possess rights and interests in land and water through their adapted system of traditional law and custom. All members of the claim group hold rights and interests in all of the claim area.

25 Attached to the First Conferral Report is a list of materials considered by the experts for the purposes of the conference (referred to as the “basis material”) which includes all of the material that had been filed in the Western Kangoulu proceeding. Each of Dr Martin and Dr Kenny signed a declaration stating that “in expressing the opinions attributed to me in this report [I] have had regard to the basis material and the statements made at the conference of experts and have made all the inquiries which I believe are desirable and appropriate and that no matters of significance which I regard as relevant have, to my knowledge, been withheld”.

26 The second conferral (on 22 February 2019) involved the experts for all of the Ganggalu cluster. Dr Martin, Dr Kenny, Dr De Rijke, Dr Powell and Mr McCaul conferred and produced the Second Conferral Report. The report is expressed in two sections. The first section is a collation of the joint reports in respect of each separate proceeding. Accordingly, the opinions expressed by Dr Martin and Dr Kenny in the First Conferral Report (that relate to the Western Kangoulu claim) are reproduced in the first section of the Second Conferral Report. The second section of the report is headed “Society propositions posed by Registrars”. It contains 16 propositions in respect of which the experts were invited to express their agreement or disagreement. Again, as is common with joint reports prepared following a conferral of experts, the opinions expressed in the second section of the Report are briefly stated and conclusory in nature. By way of illustration, the experts expressed their agreement with the following propositions:

(a) the entirety of the area covered by the GNP, Western Kangoulu, Wadja and Wulli Wulli 3A claims is part of a common regional society;

(b) at effective sovereignty (defined as being in the date range of 1844 to 1860), land holding rights under the traditional laws and customs of the regional society were held by members of local clan groups;

(c) at effective sovereignty, landholding rights of a particular clan may have overlapped the boundaries between the Ganggalu cluster claims and outside the boundaries of those claims; and

(d) since sovereignty, an adaptation of the existing land holding system through amalgamation of clan estates and broadening of territorial association is evident and this adaptation is rooted in traditional laws and customs pertaining to rights and interests in land and waters.

Dr Martin’s Supplementary and Revised Reports

27 Following the conferral of experts, discussions were held between the applicant and the State about the prospect of the application being resolved by way of consent determination. Ultimately, the State advised the applicant that it did not believe that the evidence that had been filed, including the First and Second Conferral Reports, provided a credible basis to demonstrate that the requirements of ss 223 and 225 of the Native Title Act were met in respect of the Western Kangoulu claim. In correspondence, the State stated that it had reviewed the totality of the material that had been filed and considered that:

(a) there was not a sufficient factual foundation for the expert opinions;

(b) the relevant society was not yet clearly articulated or understood, including the claimed society in the context of the regional society;

(c) the composition of the claim group was not settled; and

(d) the lay witness material was not of sufficient depth or detail to demonstrate continuing acknowledgement of traditional law and custom and connection to the claim area.

28 Disputation between the parties ensued, which is the subject of a separate judgment in Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 1188. Since that time, the parties have continued to prepare the proceeding for a trial of the Separate Questions.

29 Relevantly, the applicant has sought to address the State’s criticisms of the expert evidence in the proceeding by filing Dr Martin’s Supplementary Report. The applicant has also learned that Dr Gorring will be unavailable to give evidence in the proceeding. Dr Martin prepared the Revised Report which is an amended version of the report prepared jointly by Dr Martin and Dr Gorring in March 2018 but now authored solely by Dr Martin.

Relevant principles governing the admissibility of expert opinion evidence

General principles

30 For the most part, the principles governing the admissibility of expert opinion evidence and material relied on by an expert as the basis or foundation for the expert’s opinions (often referred to as “basis material”) were not in dispute between the parties. Those principles are stated in this section. As discussed below, the parties disagreed on one matter which is central to the State’s objections: whether and to what extent an expert’s opinion may be based on the opinion of others who are not being called as witnesses.

31 When first enacted, s 82(3) of the Native Title Act provided that the Court was not bound by the rules of evidence in conducting proceedings under the Act. However, s 82 was amended in 1998 and s 82(1) now provides that the Court is bound by the rules of evidence, except to the extent that the Court otherwise orders.

32 The admissibility of expert opinion evidence is governed by Pt 3.3 of the Evidence Act. The general rule, stated in s 76(1), is that evidence of an opinion is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed. There are a number of statutory exceptions to the general rule. Relevantly, s 79(1) provides as follows:

If a person has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience, the opinion rule does not apply to evidence of an opinion of that person that is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge.

33 The requirements of s 79 were considered by the High Court in Dasreef Pty Ltd v Hawchar (2011) 243 CLR 588. The following four principles emerge from the reasons of the plurality (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ):

(a) First, to be admissible under s 79(1), the evidence that is tendered must satisfy two criteria. The first is that the witness who gives the evidence “has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience”; the second is that the opinion expressed in evidence by the witness “is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge”.

(b) Second, expert evidence must be presented in a form which makes it possible to determine whether the requirements of s 79 have been satisfied (ie, that the opinion is wholly or substantially based on specialised knowledge based on training, study or experience).

(c) Third, it is ordinarily the case that the expert’s evidence must explain how the field of specialised knowledge in which the witness is expert, and on which the opinion is wholly or substantially based, applies to the facts assumed or observed so as to produce the opinion propounded. However, fulfilment of that requirement can often be met quickly and easily, such as in the case of a specialist medical practitioner expressing a diagnostic opinion in his or her relevant field of specialisation.

(d) Fourth, a failure to demonstrate that an opinion expressed by a witness is based on the witness’s specialised knowledge is a matter that goes to the admissibility of the evidence, not its weight.

34 Anthropological evidence is routinely adduced in native title cases. That an anthropologist has specialised knowledge based on his or her training, study or experience is rarely in contest. As discussed by R D Nicholson J in Daniels v Western Australia [2000] FCA 858; 178 ALR 542 (Daniels) at [24]:

The specialised knowledge of an anthropologist derives from the function to be performed by the anthropologist and for which he or she is trained and in relation to which study has been undertaken and experience gained. "Anthropology" is the science of humankind, in the widest sense: The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary p 87. Cultural or social anthropology is the science of human social and cultural behaviour and its development. Socio-cultural anthropology is traditionally divided into ethnography and ethnology. The former is the primary, data-gathering part of socio-cultural anthropology, that is, field work in a given society. This involves the study of everyday behaviour, normal social life, economic activities, relationships with relatives and in-laws, relationship to any wider nation-state, rituals and ceremonial behaviour and notions of appropriate social behaviour.

35 So too, in Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakay Native Title Claim Group v Northern Territory [2004] FCA 472; 207 ALR 539, Mansfield J observed (at [89]):

… Not only may anthropological evidence observe and record matters relevant to informing the court as to the social organisation of an applicant claim group, and as to the nature and content of their traditional laws and traditional customs, but by reference to other material including historical literature and anthropological material, the anthropologists may compare that social organisation with the nature and content of the traditional laws and traditional customs of their ancestors and to interpret the similarities or differences. And there may also be circumstances in which an anthropological expert may give evidence about the meaning and significance of what Aboriginal witnesses say and do, so as to explain or render coherent matters which, on their face, may be incomplete or unclear.

36 Anthropological evidence will inevitably contain a mixture of opinions and basis material. The admissibility of the opinions is governed by s 79 and it will be necessary for the anthropological evidence to explain how anthropology, as a field of specialised knowledge, applies to the basis material so as to produce the opinions propounded. When applying the requirements of s 79 to expert opinion evidence, however, it is necessary to have regard to the nature and characteristics of the field of specialised knowledge that is being applied. In Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 (Risk), Mansfield J expressed his agreement with the view of Lindgren J in Harrington-Smith & Ors on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 2) (2003) 130 FCR 424 (Harrington-Smith) at [26] that there are “great practical differences” between expert reports from different disciplines, going on to observe (at [468]-[469]):

468 Underlying [Lindgren J’s] statement is the notion that science and mathematics are exact disciplines, whereas the disciplines of anthropology, humanity, much of economics, and history are not. There is a longer list which could be created. In most if not all disciplines, opinion is formed by reasoning drawn from a group of ‘facts’. The facts may be drawn from a scientific experiment, historical documents or a series of conversations held with members of a native title claimant group. However, ‘facts’ themselves have varying degrees of primacy or subjectiveness. Some facts are now, in reality (and despite the deconstructionists) incontrovertible. Our communication systems make them so: the use of numbers in measurement is a clear example. Some are obviously more subjectively perceived: estimates, descriptions of persons or events, and the like ... Some are complex and themselves involve judgment. In the realm of expert evidence, the primary data upon which an opinion is based may comprise a mixture of primary and more complex facts. The opinion may then be further based upon an interpretation (sometimes requiring expertise) of those facts and that stage may require an exercise of judgment, sometimes fine judgment, by the person concerned.

469 This is not the occasion to dilate at length upon such matters. That is better left to others. The important thing in any expert’s report, in my view, is that the intellectual processes of the expert can be readily exposed. That involves identifying in a transparent way what are the primary facts assumed or understood. It also involves making the process of reasoning transparent, and where there are premises upon which the reasoning depends, identifying them. An understanding of the nature of the judicial process in addressing expert evidence would readily recognise the need for the expert’s report to communicate those matters to the court.

37 The basis material within anthropological evidence may take a number of forms but will often include observations made by the anthropologist in the course of field work undertaken by the anthropologist, information obtained directly or indirectly by the anthropologist from informants in the course of field work or in the preparation of the anthropological report and information sourced from other historical or anthropological writings. As observed by Selway J in Gumana v Northern Territory (2005) 141 FCR 457 at [156], evidence given by an anthropologist of his or her observations (in the course of field work undertaken by the anthropologist) will be direct evidence of primary fact admissible in the ordinary course. Information obtained directly or indirectly by the anthropologist from informants may be proved in court by testimony given by the informant, but would otherwise constitute hearsay. Information sourced from other historical or anthropological writings would also constitute hearsay (unless the other historian or anthropologist was called to give evidence). A number of exceptions to the hearsay rule may apply to both categories of evidence, including the exception in s 63 of the Evidence Act in respect of representations made by a person who has died and the exception in s 72 in respect of representations about the existence or non-existence, or the content, of the traditional laws and customs of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander group.

38 It is well established that s 79 does not include any common law “basis rule” to the effect that an expert opinion will be inadmissible if the factual basis for the opinion is not proved by admissible evidence: see Neowarra v Western Australia (2003) 134 FCR 208 (Neowarra) at [16]-[27] per Sundberg J, approved by the Full Federal Court in Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84 (Bodney) at [90]. Rather, the failure to prove the factual basis for an expert opinion will affect the weight to be attributed to the opinion rather than its admissibility.

39 As observed by the Full Court in Bodney, under the common law rules of evidence, experts were entitled to rely upon reputable publications as a basis for their opinions and could give evidence about the matters stated in such publications, notwithstanding that the publications constituted hearsay. The Full Court explained (at [92]):

Before the Evidence Act it was well established that experts are entitled to rely upon reputable articles, publications and material produced by others in the area in which they have expertise, as a basis for their opinions. In Borowski v Quayle [1966] VR 382 at 386 (Borowski) Gowans J, quoting Wigmore on Evidence (3rd ed) Vol 2 pp 784-785, said that to reject expert opinion because some facts to which the witness testifies are known only upon the authority of others, “would be to ignore the accepted methods of professional work and to insist on finical and impossible standards”. Experts may not only base their opinions on such sources, but may give evidence of fact which is based on them. They may do this although the data on which they base their opinion or evidence of fact will usually be hearsay information, in the sense they rely for such data not on their own knowledge but on the knowledge of someone else. The weight to be accorded to such evidence is a matter for the court. …

40 As further observed by the Full Court in Bodney (at [93]), there is nothing in the Evidence Act that displaces this body of law. Indeed, it is accommodated by s 60(1) of the Evidence Act which provides that the hearsay rule does not apply to evidence of a previous representation that is admitted because it is relevant for a purpose other than proof of an asserted fact. Under that provision, hearsay basis material referred to in an expert report is rendered admissible for the purpose of showing the basis or foundation for the opinions expressed in the report: Quick v Stoland Pty Ltd (1998) 87 FCR 371 at 377 per Branson J and 382 per Finkelstein J; Neowarra at [38] per Sundberg J. Unlike the position at common law, hearsay evidence admitted under s 60 is admitted for all purposes (including proof of a fact asserted in such evidence): Lee v The Queen (1998) 195 CLR 594 at [39]-[40]. The Court may, however, exclude such hearsay evidence under s 135 of the Evidence Act if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might be unfairly prejudicial to a party, might be misleading or confusing or might cause or result in undue waste of time. The Court may also limit the use to be made of such hearsay evidence under s 136 if there is a danger that a particular use of the evidence might be unfairly prejudicial to a party or might be misleading or confusing.

41 The above principles have been considered and applied in the context of anthropological evidence adduced in native title proceedings on many occasions: see for example Daniels; Lardil, Kaiadilt, Yangkaal, Gangalidda Peoples v Queensland [2000] FCA 1548 (Lardil); Harrington-Smith; Neowarra; Jango v Northern Territory (No 2) [2004] FCA 1004 (Jango No 2); Risk; Bodney; TJ (on behalf of the Yindjibarndi People) v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2015] FCA 1359 (Yindjibarndi); and Miller v State of South Australia (Far West Coast Sea Claim) (No 3) [2022] FCA 466 (Miller).

42 In a number of cases, respondents have sought orders under s 136 of the Evidence Act that certain hearsay material relied upon by an expert anthropologist be admitted for the limited purpose of showing the foundation for the anthropologist’s report (and not admitted for the purposes of proving the facts asserted in the hearsay material). In Lardil, the hearsay material comprised statements made by members of the native title claim group who were living at the time of the trial and who were either not called to give evidence or who were called to give evidence and did not give evidence in terms of the statements contained in the reports. Cooper J declined to make the order, but observed (at [26]):

… s 60 does not give to the hearsay evidence a weight or cogency which the circumstances do not warrant. The absence of an order under s 136 of the Act does not prevent the respondents from contending that in the circumstances of this case, the hearsay statements should be given little or no weight and should not be relied upon. Relevantly, those circumstances include the fact that no attempt has been made to tender original evidence of the contents of the hearsay statements when the witnesses gave evidence, the failure to call some witnesses at all, and that fact that certain oral evidence in inconsistent with the previous hearsay statement.

43 The approach taken by Cooper J in Lardil was followed by Lindgren J in Harrington-Smith at [39] and by Rares J in Yindjibarndi at [10]. Justice Charlesworth applied similar reasoning in Miller at [52]-[69].

Reliance upon other opinions as a basis for expert opinion

44 A central issue underlying the State’s objections to Dr Martin’s Revised Report concerns Dr Martin’s reference to the Additional Materials. The State submitted that the Additional Materials, containing the opinions of other anthropologists who are not being called as witnesses in the proceeding, are not admissible evidence and cannot be relied upon by Dr Martin as a basis for the opinions expressed in his report. While it is necessary to consider the specific objections made by the State below, it is convenient to address certain disputed matters of principle at the outset. On this topic, the State advanced three primary contentions.

45 First, the State contended that it is not permissible for an expert to base his or her opinion on the opinion of another person, in the sense of adopting and restating the opinion of another person. The State argued that an opinion formed in that manner is not an opinion within the meaning of the Evidence Act, being an inference drawn from facts (referring to Harrington-Smith at [40] per Lindgren J and Allstate Life Insurance Co v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (No 5) (1996) 64 FCR 73 at 75 per Lindgren J); nor does it involve the application by the expert of his or her specialised knowledge to the relevant facts or assumptions underpinning the opinion of others, as required by s 79(1). I accept the contention as far as it goes. In general, the mere adoption and restatement of an opinion does not involve the application by the expert of his or her specialised knowledge and therefore cannot satisfy s 79.

46 A different question arises, though, when an expert relies on an opinion of another (qualified) person about a particular issue in forming an opinion about a dependent or related issue. The State acknowledged that it is permissible for an expert to rely upon reputable articles, publications and material produced by others in the area in which those others have expertise. In that regard, the State referred to the decision of Borowski v Quayle [1966] VR 382 (Borowski) in which Gowans J cited (at 386-387) the following passages from Wigmore on Evidence (3rd ed) Vol 2 at 784-785, para 665(b):

The data of every science are enormous in scope and variety. No one professional man can know from personal observation more than a minute fraction of the data which he must every day treat as working truths. Hence a reliance on the reported data of fellow scientists, learned by perusing their reports in books and journals. The law must and does accept this kind of knowledge from scientific men. On the one hand, a mere layman, who comes to Court and alleges a fact which he has learned only by reading a medical or a mathematical book, cannot be heard. But, on the other hand, to reject a professional physician or mathematician because the fact or some facts to which he testifies are known to him only upon the authority of others would be to ignore the accepted methods of professional work and to insist on finical and impossible standards. Yet it is not easy to express in usable form that element of professional competency which distinguishes the latter case from the former. In general, the considerations which define the latter are (a) a professional experience, giving the witness a knowledge of the trustworthy authorities and the proper source of information, (b) an extent of personal observation in the general subject, enabling him to estimate the general plausibility, or probability of soundness, of the views expressed, and (c) the impossibility of obtaining information on the particular technical detail except through reported data in part or entirely. The true solution must be to trust the discretion of the trial judge, exercised in the light of the nature of the subject and the witness’ equipments. The decisions show in general a liberal attitude in receiving technical testimony based on professional reading.

47 The State acknowledged that Borowski has been considered in the context of anthropological evidence in a native title context in each of Jango No 2, Bodney and Yindjibarndi to permit reliance, by an anthropological witness, on writings of other anthropologists. The State submitted, however, that in each of those cases the expert witness relied on the writings of other anthropologists to provide the facts or assumptions on which the expert then based his or her opinion. The State contended that an opinion or conclusion of another cannot be an acceptable basis for an expert opinion. I will refer to that as the State’s second contention.

48 In so far as the State’s second contention sought to define a rule or principle governing the admissibility of expert opinion evidence, I reject it. There are numerous difficulties with any such rule or principle, not least of which it is not supported by authority. The distinction sought to be drawn by the State between facts and opinion, as a permissible basis for another opinion, is unsound. As is made clear by s 76 of the Evidence Act, an opinion concerns the existence of a fact. As recognised in the passage from Wigmore cited in Borowski, the state of knowledge in specialist fields at any point in time is often built upon a vast quantity of information that has been the subject of research or experimentation over long periods of time. A specialist in a field is not expected to know such information from personal observation. A specialist is entitled to use his or her judgment and rely upon opinions expressed by other qualified persons within the field, without interrogating the information relied upon by such other persons. In the context of anthropological evidence, submissions of the kind advanced by the State were rejected in each of Jango No 2, Bodney and Yindjibarndi. It is relevant to refer to each of those cases.

49 In Jango No 2, Sackville J considered an objection to anthropological evidence that relied upon opinions expressed in an unpublished anthropological report prepared by Dr Munn in 1965 from field work undertaken in 1964 to 1965. Justice Sackville observed (at [73]):

If an expert can express an opinion only if it is based on knowledge or information which is itself independently proved, serious practical difficulties are likely to arise. Thus in English Exporters (London) Ltd v Eldonwall Ltd [1973] Ch 415, Megarry J (at 420) made the following observations about an expert valuer’s opinion:

As an expert witness, the valuer is entitled to express his opinion about matters within his field of competence. In building up his opinions about values, he will no doubt have learned much from transactions in which he has himself been engaged, and of which he could give first-hand evidence. But he will also have learned much from many other sources, including much of which he could give no first-hand evidence. Textbooks, journals, reports of auctions and other dealings, and information obtained from his professional brethren and others, some related to particular transactions and some more general and indefinite, will all have contributed their share. Doubtless much, or most, of this will be accurate, though some will not; and even what is accurate so far as it goes may be incomplete, in that nothing may have been said of some special element which affects values. Nevertheless, the opinion that the expert expresses is none the worse because it is in part derived from the matters of which he could give no direct evidence. Even if some of the extraneous information which he acquires in this way is inaccurate or incomplete, the errors and omissions will often tend to cancel each other out; and the valuer, after all, is an expert in this field, so that the less reliable the knowledge that he has about the details of some reported transaction, the more his experience will tell them that he should be ready to make some discount from the weight that he gives it in contributing to his overall sense of values.

50 Justice Sackville concluded (at [75]) that the research work of Dr Munn, in so far as it provided the basis, or one of the bases, for the opinions expressed in the anthropological evidence, was relevant and, subject to the operation of ss 135 and 136 of the Evidence Act, admissible in evidence. However, his Honour was not satisfied that Dr Munn’s work did in fact form the foundation for any opinion in the anthropological evidence, and therefore the foundation for admissibility was absent (at [76]).

51 In Bodney, the Full Court concluded that the trial judge erred in disregarding anthropological evidence because it relied upon opinions expressed by another anthropologist, Prof Berndt, written in the 1970s with respect to the question whether the Noongar people had lost their traditions (at [84]-[95]). In a passage cited earlier, the Full Court confirmed that it is well established that experts are entitled to rely upon material produced by others in the area in which they have expertise as a basis for their opinions (at [92]).

52 Similarly, in Yindjibarndi, Rares J considered an objection to anthropological evidence which made reference to an earlier report prepared by other anthropologists for the purposes of satisfying the State (among others) about the applicant’s assertions as to connection to the land and waters the subject of the proceedings. His Honour refused the objection and said that the earlier report, on which the expert witness had relied, was admissible as material produced by others in the area in which those other experts and the expert witness had expertise (at [6]).

53 As stated earlier, the rule for admissibility of opinion evidence is stated in s 79: the witness who gives the evidence must have specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study or experience and the opinion expressed in the evidence by the witness must be wholly or substantially based on that knowledge. While I do not accept the rule or principle propounded by the State with respect to reliance on the opinions of others, an expert witness must nevertheless demonstrate that his or her opinions are wholly or substantially based on the witness’ training, study or experience. There may be circumstances in which the “mere” adoption of an opinion of another person does not satisfy the requirements of s 79, where the expert witness fails to demonstrate how the opinion of the witness is based on his or her training, study or experience.

54 The third contention advanced by the State is that qualifications to the hearsay rule, such as s 60, relax the restrictions on the admissibility of hearsay evidence, but do not relax other exclusionary rules such as the rules concerning opinion evidence in ss 76 to 79. The State argued that it is not permissible for an expert witness to rely on (hearsay) opinions expressed by others where those other opinions would not be admissible under s 79 of the Evidence Act. In support of that argument, the State relied on the High Court’s decision in Lithgow City Council v Jackson (2011) 244 CLR 352 where it was held that ss 76 to 79 of the Evidence Act apply not only to evidence of opinions given by witnesses in court, but also to hearsay evidence (which may be admissible by way of exception to the hearsay rule, such as in the case of business records) (at [18] to [22] per French CJ, Heydon and Bell JJ, with whom Gummow and Crennan JJ agreed at [77] and [83] respectively).

55 The State did not refer to any decided case in which its third contention had been considered. The contention sits uncomfortably with the common law approach to expert opinion evidence, described in cases such as Borowski and English Exporters (London) Ltd v Eldonwall Ltd [1973] Ch 415, which allowed expert opinion to be based on reputable articles, publications and material produced by others in the relevant area of expertise. The contention also sits uncomfortably with the cases decided under the Evidence Act. I reject the contention for the following reasons.

56 As discussed by Lindgren J in Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008] FCA 559; 76 IPR 618 at [765]-[766], the extrinsic materials (the Australian Law Reform Commission’s Interim Report on Evidence (ALRC No 26, 1985, Vol 1) at [685]) show that s 60 was introduced to enable hearsay evidence that is admissible for a non-hearsay purpose to be used by the court as evidence of the facts asserted by the evidence. This was expressly intended to apply to evidence forming the basis of an opinion. In that case, Lindgren J addressed objections to an expert report of a psychiatrist, Prof Montgomery. In his report, Prof Montgomery expressed opinions with respect to the therapeutic effects of a particular compound, and did so in reliance upon numerous published studies of the compound conducted by others. In considering an objection to Prof Montgomery’s evidence by reason of his reliance on studies conducted by others (who were not to be called as witnesses in the proceeding), Lindgren J observed (at [770]):

Sections 59 and 60 are perhaps an odd way of grappling with the present issue. It seems clear, however, that it was intended that in a case like the present one, statements of the bases for expert opinions like those made by Professor Montgomery were to be characterised as being relevant for a purpose other than proof of the facts intended to be asserted by the representations by the authors of the articles. Prior to the enactment of s 60, the summaries given by Professor Montgomery of the effect of the journal articles would have been ruled admissible as falling within the exceptions dictated by necessity referred to at [761]–[765] above.

57 While s 60 provides an exception to the hearsay exclusionary rule, s 77 provides the same exception to the opinion exclusionary rule. Relevantly, ss 76 and 77 provide as follows:

76 The opinion rule

(1) Evidence of an opinion is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed.

(2) …

77 Exception: evidence relevant otherwise than as opinion evidence

The opinion rule does not apply to evidence of an opinion that is admitted because it is relevant for a purpose other than proof of the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed.

58 In my view, the cases referred to above show that, if the opinion of an expert witness in a proceeding is based upon opinions expressed in publications and material produced by others, those other opinions are admissible to prove the foundation of the expert witness’ opinion. As such, the other opinions are admissible under s 77 “for a purpose other than proof of the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed” in the same manner as they are admissible under s 60. Once admitted, they may be relied on for all purposes.

Admissibility of hearsay opinions to show that they are in harmony with an expert witness’ opinion

59 Relying upon the decision of the UK Court of Appeal in R v Deputy Industrial Injuries Commissioner, ex parte Moore [1965] 1 QB 456 (ex parte Moore), the applicant contended that the Additional Material is admissible as evidence which shows that Dr Martin’s opinions, expressed in his Supplementary Report and Revised Report, are in harmony with the opinions of other anthropologists in respect of a number of relevant facts in issue including, for example:

(a) whether the forebears of the Ganggalu cluster claimants were part of the same society at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty;

(b) the laws and customs of that society;

(c) the extent of the rights and interests of the apical ancestors of the Western Kangoulu claim group; and

(d) the boundary between the Western Kangoulu claim and the GNP claim.

60 In so far as the applicant’s contention is to be understood as providing a separate basis for the admissibility of hearsay opinion evidence, I do not accept the contention. As discussed in the preceding section, in forming an opinion, an expert witness may rely on the opinions of other qualified persons in the field. Those other opinions will be admissible under s 60 for the purpose of establishing the foundation for the witness’ opinion. In one sense, it can be said that such evidence shows that the witness’ opinion is in harmony with the opinions of others qualified in the field. But the correct basis on which the hearsay opinions are admissible is evidence of the foundation of the witness’ opinion.

61 In contrast, hearsay opinions of other persons qualified in the field, which are not relied upon by an expert witness, are not admissible in order to prove that the witness’ opinions are in harmony with the opinions of others. It may be accepted that the hearsay opinions would constitute relevant evidence: the fact that the witness’ opinions are in harmony with the opinions of other qualified persons enhances the credibility of the witness’ opinions. However, the relevance of the hearsay opinions depends upon proof of the truth of the asserted opinion: that is, that the opinions expressed are opinions held by the author. As such, the hearsay opinions would be inadmissible under s 59 and would not be rendered admissible by s 60.

62 In my view, ex parte Moore does not require a different conclusion. The case concerned an application for judicial review of a decision under the National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946 (UK) concerning a claimed workplace injury, and specifically whether the rules of natural justice had been breached. The rules of evidence were not applicable to decisions made under the Act. In the course of a hearing before the relevant decision-maker (having the title “deputy commissioner”), medical witnesses were asked about opinions expressed by other medical witnesses in other matters decided under the Act in respect of similar injuries. One of the witnesses agreed with the other opinions, and the other disagreed. A writ of certiorari was sought on the ground that the decision-maker had breached the rules of natural justice by treating the previous opinions in other matters as evidence in the case at hand when they were not. The Court of Appeal dismissed the application for review. Relevantly, Willmer LJ concluded that (at 473-474):

… the medical opinions expressed in the other cases had become part of the evidence in the present case because they had been put to both the doctors who had been called as witnesses, and had been adopted by Dr Hayes. Dr Hayes must thus be regarded as having fortified his evidence by reference to those opinions, as well as by reference to the opinion of the other senior medical officer in the present case, just as he might have done by reference to a textbook. … Accordingly, even if this were a formal proceeding in a court of law governed by strict rules of evidence, I do not think that the claimant would have sufficiently shown that there was an error of law on the face of the record by reason of inadmissible evidence.

63 Similarly, Pearson LJ said (at 482-483):

The claimant's criticism is that the deputy commissioner wrongly treated as evidence in the present case the advice and evidence quoted from the previous cases. This criticism seems to me to be too technical and not well founded, even if the rules of evidence applicable to court proceedings had to be applied, strictly and in their entirety, in the hearing before the deputy commissioner. The advice and evidence given in the previous cases had been fully put to the medical witnesses in the present case, so that each of them had the opportunity of saying that they were incorrect or irrelevant to the present case, if that was his view. Dr. Hayes, by agreeing with the advice and evidence given in the previous cases, adopted them as part of his own evidence in the present case.

So incorporated, they added to the weight of the rest of his evidence, both because they were cogently expressed, and because they showed that Dr. Hayes's opinion on the general medical question involved (which was as to the aetiology of a prolapsed intervertebral disc) was not an isolated opinion, but was shared by other members of the medical profession. An expert witness must be allowed, if his opinion is challenged, to say that it is not merely his own opinion but is in harmony with the opinions of other experts in the same field, and for this purpose to cite their opinions in support of his own. …

64 So too, Diplock LJ said (at 490-491):

… The medical opinions given in other cases to which he referred in his written determination were put to the expert medical witnesses who were in fact called by the claimant and the insurance officer respectively. They were invited to comment on them and were cross-examined about them. The medical witness called by the insurance officer in fact accepted these opinions as correct and as coinciding with his own. Even in a court of law applying technical rules of evidence these opinions would have been admissible as having been adopted as part of that medical witness's own evidence, but I emphasise that the deputy commissioner was not bound to apply the technical rules of evidence and was entitled to treat these opinions as “evidence” in their own right even if neither medical witness who was actually called had adopted them. If both these witnesses had disputed the medical opinions, this would have gone not to their admissibility but to their weight, and would, no doubt, have reduced their probative value in the eyes of the deputy commissioner to practically nothing.

65 In my view, the above reasons of the Lord Justices are consistent with the common law principles referred to earlier concerning the admissibility of hearsay publications and material produced by other persons qualified in the relevant field which is relied upon by an expert witness in the formation of the witness’ opinions. In expressing their conclusions, each of the Lord Justices emphasised that the opinions of the medical witnesses in previous cases had been put to the medical witnesses in the case at hand, and the previous opinions had either been adopted or rejected by the medical witnesses. An expert witness may “adopt” the opinion of other qualified persons in explaining the basis upon which, or the reasoning by which, the witness formed his or her own opinion. In that context, it can be said that the witness’ opinion has been “fortified” by the other opinions relied upon, or that the witness’ opinion is “in harmony” with the other opinions relied upon. In my view, each of those expressions is describing the same concept: that the witness’ opinion has been formed in reliance upon the opinion of other qualified persons.

66 Conversely, the decision in ex parte Moore does not support any principle that hearsay opinions of other persons qualified in the field, which are not relied upon by an expert witness, are admissible in order to prove that the witness’ opinions are in harmony with the opinions of others.

Objections to Dr Martin’s Revised Report

67 This section of the reasons considers the State’s specific objections to Dr Martin’s Revised Report. The State does not contest that Dr Martin has specialised knowledge in the field of anthropology based on his training, study and experience. The basis of each of the State’s objections is that the impugned opinion is not demonstrated to be based upon an application of his specialised knowledge to relevant facts or assumptions, as required by s 79 of the Evidence Act. As such, the objection is based on the form of Dr Martin’s Revised Report and whether the report, as written, enables the Court to be satisfied that the impugned opinions are wholly or substantially based on Dr Martin’s specialised knowledge. The impugned opinions must therefore be considered in light of the whole of Dr Martin’s report. For the purpose of determining the objections, the accuracy of statements made in the report is assumed. If at trial it is shown that statements made in the report are not accurate, the State would be entitled to renew its objections.

68 Dr Martin’s Revised Report discloses that he holds the position of Senior Lecturer (Anthropology) and Director, UQ Culture and Heritage Unit, in the School of Social Science at the University of Queensland. He has held this, and similar, anthropological research and teaching positions at the University of Queensland since January 2012. Dr Martin’s formal qualifications are:

(a) Bachelor of Arts/Education (Hons 1st Class) majoring in English and History from the University of New South Wales awarded in 2003; and

(b) PhD from the School of Social and Cultural Studies, University of Western Australia, awarded in 2012.

69 Dr Martin’s PhD was obtained in the two disciplines of anthropology and cultural studies. Research for the PhD focused on race relations around the southern Gulf as well as Indigenous and non-Indigenous senses of place. This involved fieldwork with Aboriginal people, particularly Garawa and Ganggalida people to the west of the Leichhardt River, but including other Aboriginal and some non-Aboriginal people resident around the Gulf country.

70 Following the completion of his PhD, Dr Martin conducted academic research on a number of projects, including an Australian Research Council funded project entitled “Land and Identity: Comparative Studies of Belonging in Australia’s Gulf Country” (2012-2015) which investigated cultural continuities as well as changes in different groups’ engagements with environments around the Gulf. Interspersed with fieldwork for his PhD and post-doctoral academic research, Dr Martin has also completed work as a consulting applied anthropologist. Dr Martin’s Revised Report lists 11 reports prepared by him, each of which involved conducting ethnographic enquiries including participant observation among Aboriginal groups in the context of native title claims.

71 Dr Martin’s Revised Report also described the methodology utilised by Dr Martin in preparing the report. It is relevant to note the following tasks undertaken by Dr Martin:

(a) Dr Martin has read through and considered the findings of earlier researchers, commentators, and ethnographers regarding Aboriginal groups in Central Queensland.

(b) Dr Martin has undertaken archival research into records relating to Aboriginal groups in the region, assisted by Dr Hilda MacLean, an archival researcher and genealogist employed as a Casual Research Officer in the UQ Culture and Heritage Unit School of Social Science at the University of Queensland. As noted earlier, Dr Maclean has prepared genealogical evidence on behalf of the applicant.

(c) Dr Martin has drawn on his own anthropological research with Western Ganggalu people beginning in April 2018, and continuing through July and August 2018, in which he was assisted by Dr Gorring. This research began with the preparation of genealogies for the Western Ganggalu people, in respect of which Dr Martin was assisted by Dr MacLean. In addition, Dr Martin conducted fieldwork with Western Ganggalu people, assisted by Dr Gorring. Interviews and fieldnotes from the time spent with Western Ganggalu people have been partially transcribed for Dr Martin’s report.

(d) In addition to his own fieldwork (and Dr Gorring’s research), Dr Martin has also examined the results of fieldwork conducted by other researchers who have worked with Western Ganggalu people in the past. This includes fieldnotes produced by the anthropologist Mr McCaul.

(e) Dr Martin also relied on the First and Second Joint Statements which he contributed to in conjunction with the other anthropologists referred to earlier.

(f) Dr Martin also relied on witness statements made by members of the claim group and filed in the proceeding.

72 The State pressed objections to a number of paragraphs of Dr Martin’s Revised Report. The objections fall into two principal categories.

First category of objections

73 The first category concerns opinions expressed by Dr Martin in respect of which the State contends the basis of the opinion is not made express; that is, the State contends that Dr Martin has failed to identify the facts on which his opinion is based and failed to expose the reasoning for his opinions. The State submits that the opinion should not be admitted because the Court cannot be satisfied that the opinion is wholly or substantially based on his specialised knowledge based on his training, study or experience. In this category, objection is taken to paras 225A and 338 of Dr Martin’s Revised Report.

74 Paragraph 225A appears in section 3 of Dr Martin’s Revised Report titled “The Traditional Laws and Customs Acknowledged and Observed by the Society at Sovereignty”, and in a subsection which considers male and female rituals including initiation ceremonies occurring in the claim area at the time of effective sovereignty. At para 222, Dr Martin acknowledges that there is no specific information concerning such rituals in respect of the claim area, but states that there is extensive discussion of these matters in the literature for neighbouring regions. At para 223, Dr Martin states that initiation ceremonies, or what are commonly called “bora” ceremonies in the literature for Queensland, are well documented for the broader region. In paras 223 to 225, Dr Martin then refers to such literature, specifically the writings of R H Matthews, Prof Elkin and A Howitt. At para 225A, Dr Martin expresses the following opinion which is objected to as lacking an expressed basis:

… While descriptions of what occurred during such ceremonies is not explicitly discussed in relation to the claim area in the ethno-historical and anthropological literatures, based on my training, study and experience, such ceremonies probably involved education and rites of passage, particularly for young men, as well as knowledge-sharing, trade and exchange.

75 I do not accept the State’s objection to that opinion. The facts on which the opinion is based are identified in paras 223 to 225. The cited literature provides support for the opinion: the passage from R H Matthews describes the role of initiation ceremonies as providing education and rites of passage, particularly for young men; the passages from Prof Elkin and A Howitt explain that initiation ceremonies were intertribal. It can be accepted that Dr Martin’s opinion is extrapolated from the evidence presented based on his training, study and experience, but I see nothing objectionable in that extrapolation. I am satisfied that the impugned opinion is substantially based on Dr Martin’s anthropological expertise (specialised knowledge). The weight to be attributed to the opinion is a matter for argument.

76 Paragraph 338 appears within section 4 of Dr Martin’s Revised Report titled “Continuity” which reviews the colonial history in the claim area and its impact on the continuity of the acknowledgment of traditional laws and the observance of traditional customs by the descendants of the apical ancestors of the claim group to the present day (see at para 258). Paragraph 338 is within a sub-topic titled “Indigenous Corporations, Native Title and Cultural Heritage Practice” which considers the period since the 1970s and the claimants’ involvement in the formation of Indigenous corporations and actions taken under cultural heritage, land rights and native title legislation. In paras 323 to 337, Dr Martin documents that involvement. At para 338, Dr Martin states the following:

In my opinion, claimants’ assertion of themselves within the context of cultural heritage practice as the right people for the application area, and what appears to be the acceptance of this assertion amongst Aboriginal people from the broader area, is also evidence of some continuity alongside much strategic traditionalism of the kind illustrated in the quotation from Lizabeth Johnson presented above. An example of what appears to be the acceptance of this assertion amongst Aboriginal people from the broader area, is an incident near Bongantungan when Queensland Railways engaged a neighbouring Aboriginal group to manage its Duty of Care under the Queensland Cultural Heritage Act some ten years ago, improperly in the view of the claimant group. Jonathon Malone explained to me how ‘we drove to the top of the ranges, did a smoking ceremony’ near Hannam’s Gap as a result of that engagement, with this ‘smoking ceremony’ described by Jonathon as a way to make peace between these rival groups over the practice of cultural heritage in the application area by a group not comprising members of the Applicant (RM Fieldnotes 11/7/2018; see also Jonathon Malone, Statement, 29/8/2018, [109]). Jonathon Malone also explained to me about his conflict with another claimant group over cultural heritage work at Emerald when a group he identified as Bidjera lodged an overlapping claim over part of the application area (which has since been dismissed) (Jonathon Malone, Statement, 29/8/2018, [29]). Note that I have not undertaken fieldwork with Aboriginal people beyond the claimant group and am not able to offer a strong opinion on this matter of other Aboriginal people’s acceptance of the claimant groups’ assertions of connection to the area.

77 The applicant submitted, and I accept, that the opinion expressed in the first sentence of the above passage is based on the material presented in paras 323 to 327. In that sense, I consider that the basis for the expressed opinion is made clear. The opinion itself is quite limited. It is only to the effect that the activities referred to in paras 323 to 327 are evidence of some continuity of the acknowledgment of traditional laws and the observance of traditional customs. In my view, as an anthropologist, Dr Martin is entitled to express that opinion based on the facts presented recognising that anthropology is the science of human social and cultural behaviour and its development (as stated by R D Nicholson J in Daniels, cited earlier). Again, the weight to be attributed to the opinion is a matter for argument.

Second category of objections

78 The second category of objections concerns paragraphs of Dr Martin’s Revised Report in which Dr Martin expresses an opinion in reliance upon the First or Second Joint Statements. The State did not press the objections in so far as the relevant opinion was based on other stated facts and assumptions. It only pressed the objection in so far as the relevant opinion was based on the Joint Statements. To that extent, the State objected to the admissibility of the paragraphs on three grounds:

(a) it is not demonstrated that Dr Martin’s opinion has been the result of the application of his specialised knowledge and that his opinion is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge in circumstances where Dr Martin simply restates the opinions of others from the Joint Statements;

(b) the opinions of others in the Joint Statements are not an acceptable basis for Dr Martin’s opinion as they do not fall within the category of reputable articles, publications and material produced by others in the area in which they have expertise; and

(c) the evidence by Dr Martin of the opinion in the Joint Statements is irrelevant in circumstances where the other authors of the Joint Statements, namely Dr de Rijke, Dr Gorring and Mr McCaul, are not being called by the applicant as expert witnesses and will not be the subject of cross-examination by the State.

79 The State submitted that the third ground followed from the first and second grounds.

80 As noted earlier, at para 36 of his report within the section that describes his methodology, Dr Martin stated that he had relied on the First and Second Joint Statement in arriving at his opinions. As discussed further below, that statement cannot be regarded as incorporating the First and Second Joint Statements as part of Dr Martin’s report. The statement merely describes one of the sources used by Dr Martin in forming his opinions. In the remainder of his report, Dr Martin makes clear where he has placed reliance on the First or Second Joint Statement by stating that expressly (see for example para 172, considered below). Where an opinion is expressed without any (express or implied) reference to the First or Second Joint Statements, I infer that Dr Martin has not relied on the Joint Statements in forming that opinion.

81 It is necessary to consider each objection in turn.

82 The first objection concerns paras 115 and 117 to 145. Those paragraphs appear in section 2 of Dr Martin’s Revised Report titled “Traditional Society at Sovereignty” which considers the historical and ethnographic evidence concerning the Aboriginal people who occupied the claim area and surrounding areas at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty. Paragraphs 115 and 117 to 145 appear toward the end of that section under a subsection headed “Summary Opinion”. The applicant advanced submissions in respect of the impugned paragraphs on the basis that Dr Martin relied on the Joint Statements in forming the opinions expressed. It is not apparent to me that that is the case. In that regard, I note that Dr Martin’s Revised Report deleted para 116 of the previous version of the report which expressly referred to the Joint Statements. In paras 115 and 117 to 145, and in paras 59 to 114 which precede it, Dr Martin refers to a considerable body of historical and ethnographic material in support of the opinions expressed. On two occasions (in paras 106, 114B and 139), Dr Martin cites historical evidence and gives a reference to the First Joint Statement. However, the reference to the First Joint Statement appears merely to be a convenient means of providing a reference to the historical evidence; it is not a reference to any opinion or reasoning expressed in the First Joint Statement. Accordingly, it is not apparent to me that Dr Martin has relied on the Joint Statements in expressing opinions in paras 115 and 117 to 145). In those circumstances, the objection falls away.

83 The second objection concerns paras 172, 173, 175 and 176. Those paragraphs appear at the commencement of section 3 of Dr Martin’s Revised Report titled “The Traditional Laws and Customs Acknowledged and Observed by the Society at Sovereignty” which considers the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the regional society which took in the claim area at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty. In those paragraphs, Dr Martin refers to and places express reliance upon opinions with respect to that topic expressed in the First Joint Statement. At paras 177 to 255, Dr Martin sets out the evidence supporting those opinions. In my view, it is permissible for Dr Martin to rely on the First Joint Statement in forming his opinions in addition to the other evidence referred to in this section of his report. The First Joint Statement is a considered publication authored by Dr Martin and three other anthropologists, Dr Gorring, Dr de Rijke and Mr McCaul, expressing their joint (concurrent) opinions in relation to, amongst other things, the nature and extent of the relevant society or societies in relation to the GNP claim, the Wadja claim and the Western Kangoulu claim and how the society or societies were defined in terms of traditional law and custom at the time of the acquisition of British sovereignty. It cannot be said that Dr Martin has merely adopted the opinions of others expressed in the First Joint Statement as Dr Martin was a co-author and the document expresses concurrent opinions. Further, the materials relied on by the co-authors are identified and considered in the report. In my view, the First Joint Statement is material that is capable of providing a foundation for Dr Martin’s opinion and, in so far as it does so, is admissible under s 60 for that purpose. I therefore reject the objection to those paragraphs.