Federal Court of Australia

Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 5) [2022] FCA 763

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory application filed on 17 June 2022 by Johanne Dorothy Omeenyo be dismissed.

2. The consent determination listed in this proceeding relating to the native title held by the Southern Kaantju group proceed as listed on Tuesday 5 July 2022 at the Tjabukai Aboriginal Cultural Park in Smithfield, Queensland.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

Background

1 This is the fifth judgment delivered in the Cape York United #1 native title proceeding. It comes as there are four proposed determinations of native title scheduled to be made next week, on 5 and 6 July 2022. The Umpila People were also proposed to have a native title determination at this time but the s 87A agreement in their favour was not authorised by that group. One of the four proposed determinations is in favour of the Southern Kaantju People. It is their boundary with the Umpila People which is the subject matter of the present interlocutory application. I note that in the materials supplied to the Court there are a number of different spellings used for the names of the relevant groups. For the purposes of these reasons, I have used the spelling ‘Southern Kaantju’.

Ms Omeenyo’s application

2 On 17 June 2022, an interlocutory application by Johanne Dorothy Omeenyo was filed in this proceeding. The application seeks an order that Ms Omeenyo be joined as a respondent to the proceeding. It also seeks an order to postpone the Southern Kaantju determination scheduled to be made on 5 July 2022. The Southern Kaantju People authorised an agreement pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) on 6 April 2022.

3 Ms Omeenyo deposes in an affidavit filed together with the application:

I believe that it would be an injustice for Umpila People if the Southern Kaanju Determination of Native Title proceeds as scheduled before its boundary dispute with Southern Kaanju is resolved in a court hearing.

4 In other words, Ms Omeenyo contends, purportedly on behalf of the Umpila native title group, that at some time in the future there should be a court determination of the boundary between Umpila country and Southern Kaantju country, based on what she and those who support her say is an Umpila boundary that goes much further inland into country currently proposed to be part of the Southern Kaantju determination next week.

5 Ms Omeenyo’s application, and her supporting affidavit, were filed pursuant to an order made on 9 June 2022, following a judicial case management hearing at which the prospect of Ms Omeenyo’s joinder to the proceeding was discussed. In support of her application, Ms Omeenyo relied on affidavits from herself, Dr David Thompson – an anthropologist engaged by the Cape York Land Council in relation to this proceeding – and several members of the native title group for the Cape York United #1 claim. These deponents included Leila Marlene Clarmont, who identifies as a descendant of the Umpila ancestor Tommy Clarmont and a daughter of Billy Clarmont. Leila Clarmont, with her sister Ada Clarmont, had a particular role in the mediation between Umpila and Southern Kaantju which was the focus of quite a lot of evidence. The following affidavits were read on Ms Omeenyo’s behalf:

(1) affidavit of Johanne Dorothy Omeenyo, dated 17 June 2022 (and filed on the same date), including at Annexure 1 a report of Dr David Thompson entitled ‘Umpila Boundary Evidence Demonstrating that a Boundary Dispute Exists between Umpila and Southern Kaanju Peoples’, dated 14 June 2022;

(2) affidavit of George Stewart Brown, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

(3) affidavit of Leila Marlene Clarmont, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

(4) affidavit of Malcolm Thomas Congoo, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

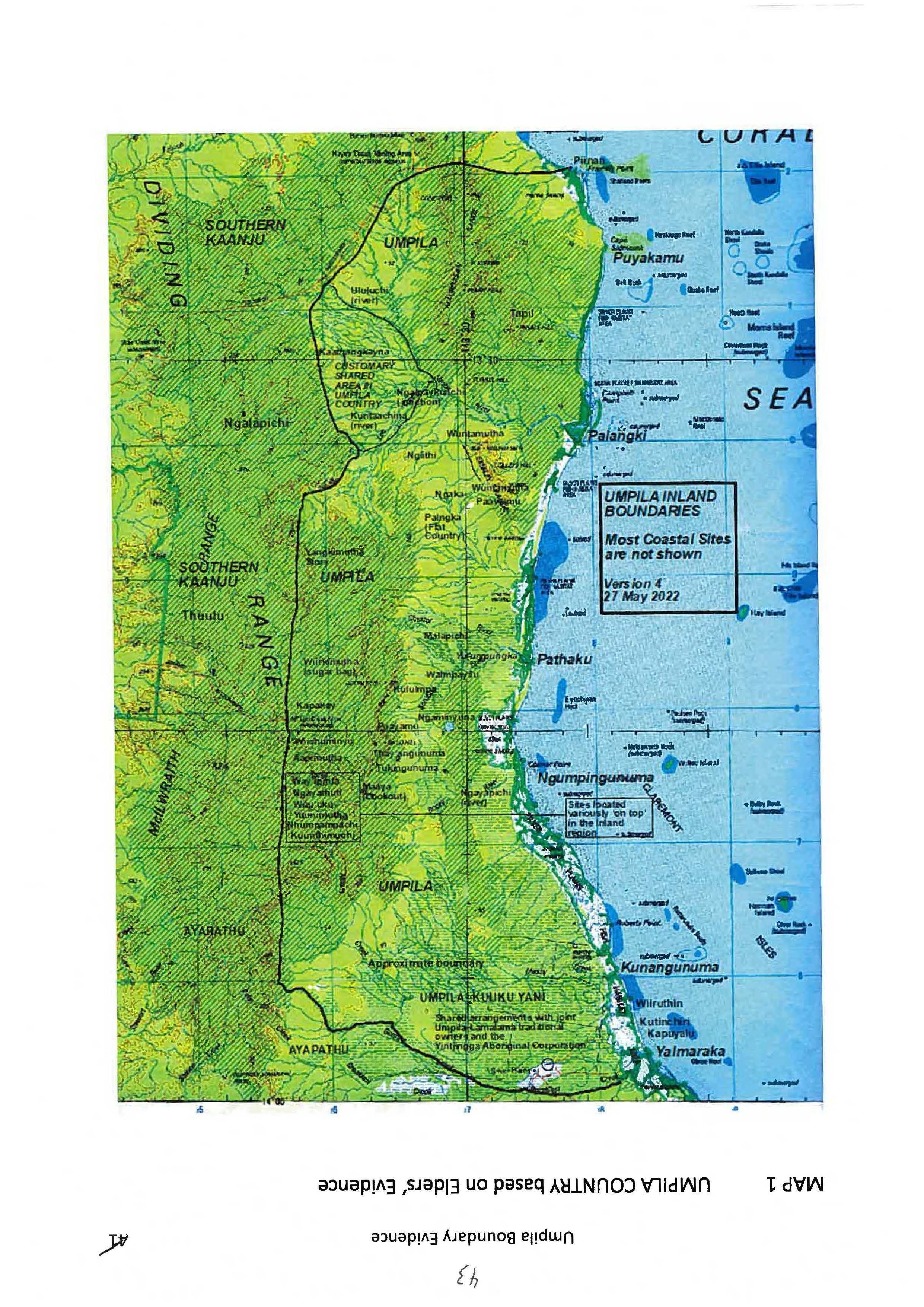

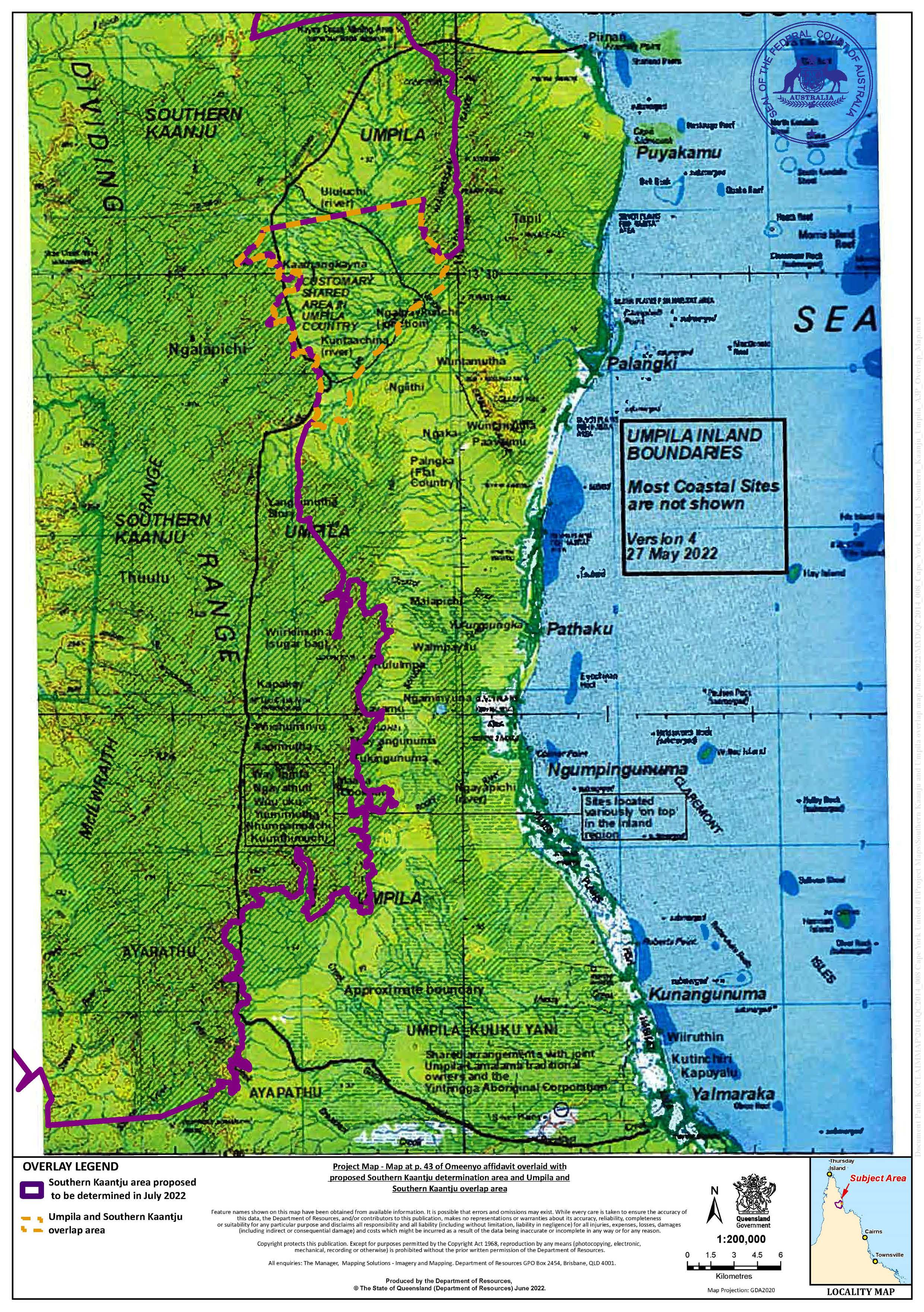

(5) affidavit of Dr David Alan Thompson, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

(6) affidavit of Lorraine Ann Rokeby, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

(7) affidavit of Samuel Henry Zaro, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022); and

(8) a further affidavit of Johanne Dorothy Omeenyo dated 24 June 2022 (and filed the same date).

6 A map of the areas relating to the interlocutory application, prepared at the Court’s request, was also relied on and read on Ms Omeenyo’s behalf.

7 The Cape York United #1 claim applicant opposed Ms Omeenyo’s application. In support of its position, it relied on affidavits from its legal representatives and several claim group members. These group members included Ada Clarmont, who, as mentioned, is also a daughter of Billy Clarmont, and who identifies as Umpila through her father, and Lama Lama through her mother. The following affidavits were read on the applicant’s behalf:

(1) affidavit of Michelle Amanda Cioffi, dated 22 June 2022 (and filed the same date);

(2) affidavit of Dion Reece Creek, dated 22 June 2022 (and filed the same date);

(3) affidavit of Dr Bernard Luke Singleton, dated 22 June 2022 (and filed the same date);

(4) affidavit of Parkinson Wirrick, dated 22 June 2022 (and filed the same date);

(5) affidavit of Ada Patricia Clarmont, dated 23 June 2022 (and filed on 24 June 2022)

(6) affidavit of Patricia Donna Clarmont, dated 23 June 2022 (filed on 24 June 2022);

(7) affidavit of Alan Francis Creek, dated 24 June 2022 (and filed the same date);

(8) affidavit of Amos James Hobson, dated 24 June 2022 (and filed the same date); and

(9) a further affidavit of Michelle Amanda Cioffi, dated 28 June 2022 (and filed the same date).

8 The State of Queensland opposed Ms Omeenyo’s application for joinder. It limited its submissions to the consequences of any factual findings that could be made by the Court in relation to Ms Omeenyo’s application, explaining which findings would lead to an order that the determination be postponed and which would not, in its opinion. The State relied on an affidavit affirmed by Kate Evelyn Marchesi – one of its legal representatives – on 27 June 2022, and filed on 28 June 2022.

9 The hearing of the interlocutory application was conducted by Microsoft Teams, over the course of a long hearing day. There was a timetable set for the day, to ensure for all those concerned that all cross-examination and submissions could be completed. Ms Omeenyo’s solicitor, who came on the record only the day before the hearing, cross-examined all of the applicant’s witnesses. Counsel for the applicant cross-examined Ms Omeenyo and Dr Thompson. The Court thanks all concerned for their cooperation.

10 I have considered all of the material relied on by the parties, as well as the evidence given orally at the hearing on Thursday 30 June 2022. These reasons have essentially been prepared overnight, so they are somewhat briefer than they might otherwise have been.

Facts not in dispute

11 In its written submissions, the State helpfully set out the following list of facts it considers uncontroversial. I agree with that submission and have added matters I consider in addition are not really in dispute:

(1) In late October 2020 there was a meeting of members of the Umpila native title group and the Southern Kaantju Native title group. Boundaries were discussed at this meeting. Dr Thompson attended this meeting.

(2) On 31 March 2021 and 1 April 2021 there was another meeting of members of the Umpila native title group and the Southern Kaantju native title group. Boundaries were discussed again. There was no resolution of the boundary issues between them. That meant the next step, according to the timetable provided in the Court’s orders, was a Court-organised mediation between the groups.

(3) On 9 June 2021 a mediation was conducted by Judicial Registrar Stride and National Native Title Tribunal Member Kelly between the Umpila native title group and the Southern Kaantju native title group (the 2021 mediation). It was held at a bowling club in Cairns. Cairns was seen as a neutral location. A limited number of representatives for each group were able to attend. CYLC attempted in good faith to secure attendance by those who could speak for the boundary areas in dispute and who otherwise were agreed to have authority to be at such a meeting. There were more Southern Kaantju people present than Umpila people. Southern Kaantju had nine, and Umpila had six.

(4) On 22 February 2022 there was a ‘pre-authorisation meeting’ of the Umpila native title group.

(5) On 3 March 2022 there was a ‘pre-authorisation meeting’ of the Southern Kaantju native title group.

(6) On 30 March 2022 there was an Umpila authorisation meeting. The proposed s 87A agreement was not authorised.

(7) On 6 April 2022 there was a meeting of the Southern Kaantju native title group, at which the group authorised entry into an agreement under s 87A in relation to the native title of the Southern Kaantju People.

Some issues

12 In an email to Ms Omeenyo and the active parties shortly after the interlocutory application was filed, the Court indicated to the parties what it saw, at that stage, as the main issues on the interlocutory application. The purpose of doing so was to try and focus the attention of the competing arguments, given there was very little time available for the hearing. The email stated the issues appeared to be:

(a) whether the right people for the area attended the mediation;

(b) whether there was any “duress” at the mediation;

(c) how much weight can be placed on the petition relied on by Ms Omeenyo;

(d) what is the relevance and weight of Dr David Thompson’s report; and

(e) what is the prejudice, if any, to the Southern Kaantju people if the consent determination is postponed.

13 Since evidence has been given, and submissions have been made, I now consider the issues might be structured a little differently, including because of what the State submitted about the issue of any connection between the failure to authorise the s 87A agreement and what happened at the mediation. Nevertheless, I still consider those five matters are important, and I address them below, albeit under different headings.

Has there been any unreasonable delay by Ms Omeenyo in making this application?

14 The applicant raised this issue. I reject the submission there has been delay that can be described as unreasonable. I accept Ms Omeenyo went back to discussions with Dr Thompson shortly after the 2021 mediation and that the evidence shows some dissatisfaction with the boundary agreed at the mediation since that time. Ms Omeenyo first wrote to Judicial Registrar Stride on 28 June 2021. It is unfortunate that some earlier communications to the Court by Ms Omeenyo appear not to have been sent promptly to the applicant and CYLC. They should have been. This matter might have been brought to a head much earlier. However, even if that had occurred, I do not presently consider I would have reached any different view to the one I have reached here.

15 I was made aware of Ms Omeenyo’s concerns in approximately early April 2022. Some time later a communication was sent to the parties about the need to discuss this matter at the forthcoming judicial case management hearing. That occurred. Orders were made giving Ms Omeenyo a chance to file an interlocutory application. The hearing of the interlocutory application had to be fitted in around a long trial that was part heard before me. These are the kinds of matters the Court needs to balance as between the interests of different litigants in the Court.

16 Ms Omeenyo complied with the orders of the Court, with (I find) the assistance of Dr Thompson. She has tried to do what has been required of her. While it is true that she could have filed an interlocutory application herself at an earlier point in time, I accept she felt to a large extent reliant on the assistance of others, such as Dr Thompson, to help her navigate the processes.

17 For whatever reason, no-one advised or suggested to Ms Omeenyo that she could file an interlocutory application herself, at an earlier time.

18 Contrary to the applicant’s submissions, the situation in cases such as Starkey v South Australia [2011] FCA 456; 193 FCR 450 can be distinguished. There, Mansfield J was satisfied that a claim group member who had been joined as a respondent was “interfering with” the progress towards consent determination. It can be inferred his Honour found there was no good reason for that obstruction. The situation here is different. Ms Omeenyo has a reason, and she is entitled to have that reason considered. Mr Perkins was correct to that extent in his submissions on Ms Omeenyo’s behalf.

19 Therefore, I make no adverse finding affecting my consideration of Ms Omeenyo’s application on the basis of any delay. I also do not consider it is correct to characterise Ms Omeenyo’s application as an abuse of process. Looking at the correspondence since the 2021 mediation, she expressed her change of position early on, and has held to that change of position. She has not sought to mislead other interested parties after the mediation. Ultimately I have not agreed with the position she has put to the Court, but in the circumstances I consider she was entitled to put it.

What country is disputed by Ms Omeenyo’s application?

20 This is one of the critical issues, and it has been the subject of some confusion.

21 However it is now clear that Ms Omeenyo’s present argument deals with the “inland” country said to be Umpila country, extending westwards into the Great Dividing Range. Much of this country is within the proposed Southern Kaantju native title determination. It is a very large area of country. Annexure A to these reasons shows a map annexed to Dr Thompson’s report of 14 June 2022 which, by the black line, is his revised estimate of Umpila country, being what is at the heart of Ms Omeenyo’s application. Dr Thompson described this map as being “more or less” the map he presented about at the 2021 mediation. I find he is responsible for the map. I discuss this in more detail below. Annexure B is a map showing that line, overlaid with a line showing the proposed Southern Kaantju determination boundary and also showing an oval area in the centre of the map which was agreed at the mediation to be “shared” country. I return to this below as well.

22 It is necessary to make some findings about how Dr Thompson came to these views, and the attack on his views on this application.

23 As stated above, annexed to Ms Omeenyo’s affidavit in support of her interlocutory application was a report dated 14 June 2022 by Dr Thompson. I accept Dr Thompson produced this report based on his knowledge and expertise. He is one of the anthropologists retained by the CYLC in respect of the Cape York United #1 claim. He is an experienced anthropologist and the CYLC has invited the State and other parties to rely on his work as part of the consent determination process in the Cape York United #1 claim. What I say in these reasons is not intended to impugn his expertise, but I do reach some adverse conclusions about the way he has applied it in the current circumstances.

24 Dr Thompson has worked in this region for a long time. For much of that time he worked with Professor Athol Chase, who passed away less than two years ago. Professor Chase was an acknowledged expert in this region. Between 2017 and 2019, that is, not long before Professor Chase passed away, Professor Chase and Dr Thompson digitised a series of recordings from Umpila elders, dating back to 1976, about Umpila country. The elders interviewed were Billy Clarmont, Charlie Omeenyo and George Rocky. According to Dr Thompson, these three men spent the early years of their lives on country, before the establishment of the Lockhart River Mission. Dr Thompson considers this fact significant in the weight to be given to their opinions and beliefs. Notably, Billy Clarmont was the father of Ada, Lorraine and Leila Clarmont, and the father-in-law of Patricia Clarmont. Charlie Omeenyo was Johanne Omeenyo’s grandfather. In this report, Dr Thompson states that the interviews with Billy Clarmont and Charlie Omeenyo – conducted in Lockhart River Creole – involved discussions of the Nesbit River and the Leo Creek, and the region in which they meet, which indicate that the Umpila People were traditionally connected to those areas. Dr Thompson also attests to what was said in the interviews with Billy Clarmont, Charlie Omeenyo and George Rocky about the Chester and Rocky Rivers. In Dr Thompson’s view, these interviews are important in demonstrating that the headwater regions west of the Macrossan Range and up into the Great Dividing Range traditionally belong to the Umpila People.

25 At [138] of his report, Dr Thompson says this about the map that is Annexure A:

In my opinion, the inland boundary line that I have drawn from the coast in the north to the Great Dividing Range and extending south along the upper slopes of the Mcilwraith Range is a reasonable representation of Umpila country on the east slopes of the Mcilwraith Range as evidenced by the recorded evidence of Billy Clarmont, Charlie Omeenyo and George Rocky.

(Emphasis added.)

26 I accept Dr Thompson’s oral evidence that he did not focus on the content of these recordings, and what they might mean for the extent of Umpila country, until the boundary negotiations between Umpila and Southern Kaantju began to take shape within the Cape York United #1 claim around 2020. It will be recalled that it was only in April 2020 that the Cape York United #1 claim was re-designed into a series of regional claims. I infer Dr Thompson then started to focus on the boundaries because of his relationships with, and support for, the Umpila group.

27 At [22] of his report, Dr Thompson states:

At the first boundary negotiation meeting between representative of Umpila and Southern Kaanju groups held in Cairns on 20 October 2020, I read key extracts of the 1976 recordings of Umpila elders Billy Clarmont and Charlie Omeenyo speaking of their connection to the Leo Creek-Nesbit River region. On large topographical maps their evidence was addressed in a draft boundary line drawn by myself and Dion Creek. This map was acceptable to the Umpila representatives but was not endorsed by the meeting. At later negotiation meetings on 31 March 2021 and 1 April 2021 (which I was unable to attend) no further progress was made.

(Original emphasis.)

28 Dr Thompson’s oral evidence was that the black lines on Annexure A were “put together” by him, based on what old people had said during the recordings. For the purposes of this application, I accept that evidence. He did describe himself as “searching through” those tapes for some evidence, which does tend to show how far away he has travelled from being an independent expert. But that does not mean his views are not honestly held. He gave oral evidence that the production of the 14 June 2022 report was partly of his own initiative and partly arose from discussions with Umpila people such as Ms Omeenyo (but not limited to her, I infer). Its date makes it clear it was designed to be used on an application such as the current one. I find Dr Thompson avowedly wishes to assist the Umpila People to agitate for a western boundary that reflects the views he has recently formed based on the 1976 recordings, and he has been active in providing them with such assistance.

29 Dr Thompson accepted in cross-examination that he has not had any contact with, or information from, Southern Kaantju people about the map at Annexure A and the asserted Umpila boundary. He appeared to accept it would be appropriate to do so, but insisted he was not able to, because of the way the anthropological reporting responsibilities in the Cape York United #1 claim had been divided up. That may be so. The important matter is that, even on his own evidence, I find his views as presented by this map must be preliminary or incomplete. Any reasonable anthropologist forming more than preliminary views on such matters would have to speak with, or at least consider sufficient source information from, the neighbouring group claiming rights in the same area. Dr Thompson has not been able to do that. His present views also involve disagreement with previously expressed expert opinions of Professor Chase, another matter which would need thorough examination and consideration.

30 I accept Dr Thompson is assisting Ms Omeenyo and those who agree with her position out of a genuine belief that he has found material suggesting there is a debate to be had about this extended Umpila country, and a genuine desire to assist Ms Omeenyo and those who support her. In doing so, he has departed from his independent position as an expert. He has become an advocate for some Umpila people in this situation, and really made that quite clear in his oral evidence. However, I accept his advocacy stems from his genuine beliefs, based on his experience and expertise, especially his more recently formed views based on the 1976 recordings.

31 However, taking into account the matters I have mentioned at [29], I find that for the purposes of this application, his opinions cannot be treated as more likely than not to be correct. They are opinions formed from one source, as the extract from his own report clarifies. The fact he has moved to a position of an advocate for some Umpila people means that it is likely his support is clouding his opinions, and making him less detached in the way he assesses all the available information. That is not a matter it was appropriate to explore, or test, during the present hearings. He has not spoken to Southern Kaantju about their traditional understanding of the boundary. Indeed, he has also not obtained any source information at all from present Umpila people, so there is no evidence at all of any continuity of connection by Umpila to this extended country. There is no evidence he has considered how current Umpila elders view his opinions. Dr Singleton’s evidence before me suggests some elders may not share his views. All this is, as I explain below, in contrast to the position for Southern Kaantju. Therefore, even as the evidence stands I do not find that Dr Thompson’s opinions, even if genuinely held, are more likely than not to point to an extended country belonging to Umpila people.

32 However, for reasons I explain below, Dr Thompson’s opinions do not control the outcome of this interlocutory application. But what I emphasise here is that I consider his opinions are properly described as incomplete, likely clouded by his newer position as an advocate for some Umpila people, and based on a limited range of sources. Therefore, they carry little weight in any event.

The mediation agreement

33 The “Agreement in principle” signed at the mediation is in evidence, exhibited to Mr Wirrick’s affidavit. I accept the submissions of the applicant that given the subject matter of this interlocutory application, evidence about what occurred at the mediation is admissible: see Papertalk on behalf of the Mullewa Wadjari People v State of Western Australia [2022] FCA 221 at [16], [131]-[133].

34 The mediated agreement provides:

1. The Umpila People and Southern Kaanju People agree to the boundaries between their native title areas as indicated by the attached map at Annexure A.

2. The Umpila People and Southern Kaanju People agree to recognise the hachured area indicated in the map attached to this agreement at Annexure A as an area in which both groups hold native title rights and interests (Shared Area).

3. The Umpila People and Southern Kaanju People agree that the native title model for the Shared Area is to be settled after each group has received legal advice about the best option to secure a native title determination.

4. The parties agree that Mediators can provide a copy of this agreement to the CYLC Principal Legal Officer.

5. The parties agree that the Mediators can advise the Court that Agreement in Principle has been reached in relation to their boundaries.

(Original emphasis.)

35 The map which is attached to the mediation agreement shows a boundary line which reflects the boundary line for the proposed Southern Kaantju determination next week, and shows the “shared area”, including the area around Nesbit and Leo Creek, to be outside that line, to the east.

36 It is signed by Ms Omeenyo, Ada Clarmont, Dr Singleton, Leila Clarmont, Jacqueline Rocky, Allan Creek, Jenny Creek, Dion Creek, Patricia Clarmont, Norman Bally, Margaret Rocky, James Creek, Gordon Bally and Sebastian Creek. Mr Zaro did not sign the agreement, and left the mediation early.

Has Ms Omeenyo established any duress or “pressure” at the mediation on the part of those who signed the in-principle agreement?

37 It seems clear on the evidence from both sides that Ms Omeenyo brought a map to the mediation which was of the same nature as the map contained in Annexure A to these reasons. I find this is what the witnesses supporting Ms Omeenyo called the “Umpila map” and I will adopt that description.

38 It is also clear that Southern Kaantju brought a map as well. Ada Clarmont’s evidence was:

The mediation went alright on that day. Johanne Omeenyo brought a map to the mediation. Southern Kaanju had their own map. Both groups talked about our own country and we agreed on boundary with a shared area around the Leo Creek area.

We all said yes to the boundary and the shared area with Southern Kaanju, except for Sam Zaro – he walked out. We then signed the agreement. …

39 There was some cross-examination of the applicant’s witnesses about why it was necessary to split off some people at the 2021 mediation into a separate room. Mr Hobson gave evidence that he felt the Clarmont sisters, who speak for the shared area, were being manipulated by Ms Omeenyo. He explained the “old girls were quite shy and I thought I could get them in a separate room and explain things to them”. Mr Hobson denied he was controlling anything and I accept his evidence. However, the cross-examination of the applicant witnesses about what happened in the “third room” is not relevant to the present application. What happened there was all about the so-called “shared area”, and that is not part of the proposed Southern Kaantju consent determination next week. Therefore, the evidence about what did or did not happen in that room, or did or did not happen about the way that shared area was agreed, has little probative weight in the issues the Court must decide.

40 The outcome of this current application turns very much in my opinion on what happened at the mediation about the area to the west of line on the map attached to the mediation agreement, which Ms Omeenyo presented at the mediation using the Umpila map, supported by Dr Thompson, as Umpila country.

41 I do not accept Ms Omeenyo did not understand what happened at the mediation, and I do not accept there was any duress or pressure applied to anyone during that mediation. I accept the officer from the NNTT showed everyone the maps on the screen, as agreed by those in the room, and that he asked if everyone was “happy with that” before they were printed and attached to the mediation agreement. That process could not have been clearer. The outcome of the mediation was clear enough for Mr Zaro to walk out, expressing, I infer, his disagreement with it.

42 I do not accept Ms Omeenyo’s evidence that the duress started when Mr Hobson took the Clarmont sisters into another room. Mr Zaro also went because he spoke for Nesbit but I accept Mr Hobson’s evidence that he did not say much. That was a proper event to occur during the mediation so that those who spoke for the shared area could discuss it amongst themselves. As I have said, that area is not for determination next week.

43 The Umpila people had Mr John Reeve from CYLC to advise them, as a lawyer for their side in this negotiation. He was there before the in-principle agreement was signed. I find Ms Omeenyo and the others who signed but are now protesting about the outcome well understood he was there to help them. I also find there is no particular difficulty for Ms Omeenyo operating in English. During her oral evidence her English was fluent, and she could read documents she was directed to. Her own evidence was that she wrote her affidavit with the “administrative support” of Dr Thompson, which suggests she felt comfortable drafting what are two clear and well-expressed documents in English. She was adamant the affidavits were her own work and that Dr Thompson provided “administrative support”. I accept that evidence, although as I explain elsewhere in these reasons, I find that Dr Thompson overall did much more than provide “administrative support” on this application. He has encouraged Ms Omeenyo and those who support her to continue to argue for extended Umpila country in accordance with his own views.

44 I reject any submissions that Mr Reeve and Mr Wirrick (who was there to advise Southern Kaantju) did anything other than act professionally and perform the advisory roles required of them. There is no basis in the evidence for any other finding. While individually Ms Omeenyo may not have been happy that the lawyers assigned to assist Umpila were from the CYLC, they were not the individual lawyers working on the Cape York United #1 claim. While other arrangements might have been possible, the choice by CYLC to use internal lawyers was not one which of itself tainted the mediation process.

45 Mr Zaro left the mediation and did not sign the agreement. I find Ms Omeenyo and the others who signed but now wish to recant had a direct example of what to do if they did not agree. That finding applies to Ms Omeenyo, as well as Leila Clarmont. They did not leave. They “picked up the pen”, as Dr Singleton put it in his affidavit.

46 At that point, I find they were prepared to agree, and intended to agree, even if it was a compromise. Many times, people who compromise in a mediation setting are not entirely happy with the outcome, even after they have agreed to it. A negotiated outcome generally involves compromise and that often means neither side is totally happy. That is the nature of negotiation. Some of the witnesses referred to choosing an option that would give them their native title. That is an entirely reasonable and rational choice to make – a compromise to get an outcome, even if not the one that in a perfect world they might wish for.

47 I find on the basis of Mr Dion Creek’s evidence that during the mediation, Umpila People could not themselves come up with sufficient “proof”, from their own knowledge, to persuade Southern Kaantju, or even to objectively demonstrate, that they knew the law and Story for the extended country Ms Omeenyo and those who support her present interlocutory application based on the Umpila map. And no such connection evidence has been adduced before me on this application. The most that has occurred is witnesses such as Ms Omeenyo saying that she agrees with Dr Thompson’s map and that it reflects what her elders told her. There is no evidence at all of continuing connection by Umpila people to that country to the west of the boundary agreed in the mediation map. That was the problem. Those Umpila people at the meeting who appeared to press for that western country could not do what Southern Kaantju in that mediation room could do in terms of telling the Story for that extended country, and establishing their connection to it. Southern Kaantju could demonstrate continuing connection to that country and they did so in front of Umpila people at the mediation: that is the evidence I have accepted. That in itself is a sufficient basis for the Court to act to ensure the mediation outcome is reflected in the determination of native title in favour of Southern Kaantju, together with the fact that Southern Kaantju as a whole group have authorised that outcome. Amongst other matters, they have authorised that boundary.

48 The evidence is clear that not all the Umpila people at the mediation agreed with the Umpila map or the position Ms Omeenyo was pressing. I entirely accept the evidence of Dr Singleton, whom I found to be a compelling witness. His affidavit stated (at [17]):

What I always believed is that Kaantju were on top and we Umpila were down bottom. I know that because I walked the country with Athol Chase and Thomas Creek in the early 1990s. Some people at that Authorisation Meeting were saying well hang on we've got land on top too, but I never had old people around telling me that.

49 Dr Singleton said this about the mediation itself, which I accept:

I was happy to sign the agreement that was reached between the Umpila and the Southern Kaantju at the mediation. There was a map attached to the document. I knew that I was signing an agreement with Southern Kaantju about the common boundary in accordance with that map.

I didn't feel any discomfort at that mediation. I felt no pressure to sign the agreement. No one stood over me to make decisions. I didn't stand over anyone to make them sign the agreement or anything like that. Nor did I see anyone else pressure anyone else to do anything that day at the mediation. There was a pen there, you either sign it or you don't. I don't know why Sam Zaro didn't sign it.

50 The same appears to be true for Ada Clarmont, who also gave evidence expressing her continued support for the mediation agreement.

51 It may well be that – quite separately – Dr Thompson has some early recordings which might provide some basis for a proposition about Umpila connection to that extended country in the past. I emphasise – that ‘might’ be possible. But the point was that at the mediation the very people selected to speak for the boundary of Umpila country with Southern Kaantju could not demonstrate to their neighbours the kind of connection they needed to demonstrate. I find it is more likely than not this is why all Umpila except Mr Zaro signed the in-principle agreement. I find they understood they could not tell the Stories necessary – they could not demonstrate their knowledge of that country to their neighbours. Aside from relying on Dr Thompson’s map and what Dr Thompson had told them about the recordings and his views of what those recordings meant, they could not themselves persuade their neighbours they had, as Umpila people, enough knowledge about that extended country to demonstrate a continuing connection to it.

52 Over the “shared area”, a compromise had been reached by those who spoke for that area – two Umpila ladies (Ada and Leila Clarmont) and Mr Hobson for Southern Kaantju. But in my opinion, on that day and by signing the in-principle agreement, the Umpila people other than Mr Zaro faced up to the fact that for that extended country, to the west and up into the higher country, they could not as Umpila people give their neighbours Southern Kaantju the ‘proof’ they wanted (and were entitled) to see.

53 I say ‘entitled’ because I am satisfied the evidence demonstrates a careful selection process had been undertaken to ensure the “right people” attended that mediation. Dr Thompson was involved in that selection and he helped make the selections about which Umpila people attended. He admitted to the CYLC that he also made the selections with some “negotiating on local politics”, but nevertheless he gave his views on who were the right people for that boundary negotiation.

54 Southern Kaantju people were entitled to see Umpila people signing as a good faith expression of a compromise. They were entitled to rely on that. And I find at the time the Umpila people who signed, including Ms Omeenyo, did so of their own free will. Mr Zaro in a sense did the right thing by walking out, and indicating definitely that he did not agree. It should be recalled that what everyone signed was a document authorising Judicial Registrar Stride to inform the Court that an agreement had been reached. The Court then has also relied on that outcome in its management of the proceeding since that time.

55 After the mediation, it might well be the case that Ms Omeenyo was unhappy, and at least some other Umpila people also were. That is why they spoke to Dr Thompson, who I find continued to emphasise to them that the recordings from the old people were important evidence that the extra country did belong to Umpila. In that sense, Dr Thompson was actively encouraging people like Ms Omeenyo to undermine the mediation agreement. That is how the petition came about, and I accept this issue may have contributed to the refusal to authorise the s 87A agreement, but it is not possible to make any more certain finding than that.

56 However, a change of mind after committing to an outcome is not evidence of any duress or pressure. I reject the suggestion of any duress or pressure being applied to any participant in the mediation.

What was being decided at the 2021 mediation?

57 It is critical to my conclusions to understand that the 2021 mediation was a mediation about one boundary. It was not a mediation about a whole claim area. It was about one boundary, out of several boundaries for both Southern Kaantju and Umpila.

58 As I have found, the right people had been selected to attend that mediation. There was no evidence given that important people who speak for that boundary were left out of the mediation. The selection process was careful, and resulted in the right people attending, as well as others who might be described as seeking to represent general authority in the groups, Ms Omeenyo being in that category. It was common ground she does not speak for any of the boundary area.

59 I accept the evidence of Dion Creek in his affidavit about what occurred at the 2021 mediation. Notably, Dion Creek was not cross-examined on this evidence at all. The following excerpt is from Dion Creek’s affidavit (at [10]-[19]):

At the start of the mediation, the mediator Katie Stride said that the mediation is an opportunity for the groups to resolve their boundaries. The mediator also said that if you can't resolve your boundary, the process will be taken out of your hands.

At that mediation, we decided to break into separate groups with maps. Both groups came back with a map where they believed their boundaries were. The Court had a person there that produced live images of the map. The maps drawn up by both groups were replicated by the specialist using his computer software. The maps were projected on a big screen that everyone in the room could see.

I presented the Southern Kaantju map to all those at the mediation, including the Umpila. I walked everyone through the map, saying "it goes from here to here to here" and I named all the story places. As I was doing that, the mapping guy plotted all the points based on what I was explaining. Based on the Southern Kaantju knowledge in the room, we were able to provide cultural connection to the areas we claimed. Our oral evidence, the information that was passed down to us, was supported by the anthropology provided by Dr Kwok and Dr Thompson.

During the mediation, the Umpila representatives had gone away to have discussions among themselves and put something together too but they couldn't support their position with evidence.

There was obviously a crossover with the boundaries. Because of the crossover, Southern Kaantju asked Umpila families if they could explain how they were connected to the area they were claiming. We said words to the effect, “if you can explain your knowledge and information, we will accept it and work through it”. Not a single person could identify a story place or a language name. They couldn't provide evidence of connection to that area. What I mean is oral evidence - what you've been told, what's been passed down. And what knowledge you have from being on Country. Allan [Creek] and James [Creek] have that knowledge from being on Country. They worked on that Country, they'd been through all that Country - and Umpila Country too.

During the mediation, Amos Hobson went into a room with Ada and Leila Clarmont and negotiated a shared area which all three were happy with. I know they were happy because they came back from that discussion with a map and the Southern Kaantju families in the room asked them, “are you happy with the shared area?” They all said yes.

I have always been told by my elders that where freshwater meets saltwater is where Kaantju meets Umpila - that is the Leo Creek area, the area we made a shared area with the descendants of Billy Clarmont. That is also Southern Kaantju area. My family speak for the Leo Creek area. We are the descendants of Thomas Creek.

I am of the opinion that the other Umpila people like Johanne Omeenyo have no connection to that Leo Creek area. I know Johanne is from Chester River area. Consequently, it wasn't for them to comment on. They are now pushing a boundary to an area they don't speak for.

When Umpila and Southern Kaantju reached agreement on the boundary, the mapping guy produced a final map and asked, “is everyone happy?” He printed it off, along with a paper for the signatories. I was absolutely clear what I was signing to on the day. An image of me signing the agreement with the map beside the execution page is annexed hereto and marked “DRC1”.

Sam Zaro who attended the meeting for Umpila didn't want to sign. No one forced him to sign, so he walked out. If other Umpila people didn't want to sign, they didn't have to. They could have just refused to sign - just like Sam Zaro had done. We didn't force anyone to do anything.

(Original emphasis.)

60 Mr Hobson is a man who speaks as both a Southern Kaantju and an Umpila person, through different lines. He was the only person in this category at the mediation. Mr Hobson stated as follows (see Mr Hobson’s affidavit at [8]-[12]):

At the mediation myself and my uncle James Creek said to Johanne Omeenyo if the area she said was Umpila country can she give us a language name for that area. She couldn't give us a language name - none of the Umpila people there could give us a name. I said I know the language names because I have been up there on that country and that is Kaanju country, Kaanju names. We asked if they had been up there and they couldn't respond because they hadn't been up there. I had been up there with my grandfather many times from when I was a little boy - my uchie took me up there.

I was not very happy because Johanne was not following protocol at the mediation, Johanne was trying to jump over me and make decisions for my area and for all of Umpila.

I said that I wanted to go into a separate room with Ada and Leila Clarmont, the people who could speak for the area of the Leo River. I saw that the old ladies were being pressured by Johanne Omeenyo which is why I asked the old ladies if they wanted to come into a separate room. They opened up when they came into the room. Bernie Singleton then came into the room. Johanne tried to come in but I said you can't speak for the Nesbit and Leo Rivers, you need to leave. Johanne said that Sam Zaro should be there and so Joanne left and Sam came into the room.

Sam is from Nesbit as well but he didn't say anything. I believe that he didn't say anything because he doesn't know anything about the country. In that room the old ladies, Leila and Ada Claremont said we don't want to keep going with this fighting, we want to get our native title back.

After the separate meeting, we went back out into the meeting with the other Umpila people. Sam left the room. We then all agreed to the boundary. Everyone was on the right page with the agreement, everyone was calm when they signed, even Johanne. I didn't see anyone being pressured into signing the agreement.

61 It is important to recall that Mr Hobson is here talking about negotiations for what has become known as the “shared area”, the oval shaped area in the middle of Annexure B to these reasons. That is not part of the proposed Southern Kaantju determination for next week.

62 Even if they had more probative value than I consider they do, Dr Thompson’s opinions about the extended Umpila boundary do not confront what I consider to be the central deciding factor in this interlocutory application – namely, what occurred at the 2021 mediation. I am satisfied the ‘right people’ for both Southern Kaantju and Umpila decided on a compromise. The Umpila people present, except for Mr Zaro, were prepared to sign a document that represented a compromise. I find that arose because, in a room with their Southern Kaantju neighbours, they had not been able to substantiate their position about the extended boundary Dr Thompson had been asserting, including his assertions at the start of the mediation during his online presentation.

What was the reason for the Umpila native title group’s decision not to authorise their s 87A agreement?

63 The State pointed, correctly in my opinion, it may be relevant for the Court to assess whether there was a direct connection between the failure of the s 87A agreement to be authorised by Umpila, and the debate about the outcome of the 2021 mediation, and the extent of Umpila country.

64 I find the evidence does not enable the Court to reach any finding on the balance of probabilities that there was a connection.

65 Again, I accept the evidence of Dr Singleton about what happened at the s 87A authorisation meeting, and the atmosphere at that meeting:

When Cape York Land Council brought mob down for the Authorisation meeting, they brought a lot of people. Some just came down to have a trip to Cairns. Cape York Land Council booked the hotels and gave them travel assistance money and they got drunk on that money. There were drunk people at the meeting, and still drunk from the night before. That’s why there was arguments.

A lot of them mob I’ve never seen them before. A lot of them have never been to meetings. If you go to Lockhart and have the meeting, they won’t come, even though they can just walk there.

The ones that were drunk or had been drinking the night before were the ones talking rubbish and causing arguments, but I didn’t really know them. I’ve never seen them at meetings. Some of them were swearing when they were talking, they were arguing. They didn’t know the Country, they've never been on the Country.

There were a lot of people there voting about Umpila Country. It seems those other people weren’t there for that. They were there to drink, not to make important decisions.

66 Mr Hobson and Ada Clarmont gave similar evidence, which they were not challenged on.

67 I accept that the petition organised by Ms Omeenyo might provide some evidence of group disagreement about the mediation outcome. Her evidence was that she spoke to about 30 or 40 Umpila people. From Dr Singleton’s evidence, it is clear Dr Thompson was involved in gathering signatures – another indication of how deeply he had fallen into the role of an advocate. How the other 70 or 60 people came to sign the petition is not the subject of any evidence. Nor is there is any evidence about what Ms Omeenyo and Dr Thompson told those people whose signatures they procured. The evidence on this application indicates that at least six Umpila people who signed the petition either did so without understanding its content, or now longer support the petition. These people are Gregory Omeenyo, Dr Singleton, Ada Clarmont, James Bally, Daphney Clarmont and Joseph ‘J Boy’ Clarmont. That is sufficient evidence for the Court to infer there were likely to be a reasonable number of other people who signed the document without really understanding what they were signing. Nevertheless, I have given some weight to the petition, as an indication that Ms Omeenyo has the support of a reasonable number of other Umpila people. How many, outside those who provided affidavits, it is not possible to say.

68 Considering the evidence as a whole, I find there is insufficient evidence for the Court to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the Umpila s 87A agreement was not authorised because of a belief that Umpila country in the west of their country extended well into the area identified as Southern Kaantju on the mediation map. I find the authorisation meeting was somewhat chaotic and dysfunctional, and it is not possible to make any findings about why the s 87A agreement was not authorised. This boundary issue may have been important for some Umpila people, such as Ms Omeenyo but no finding greater than that can be made.

The position of Southern Kaantju

69 This is an important consideration in my opinion. There is real prejudice to the Southern Kaantju in their determination being postponed. While as the State submitted there is still a portion of their area not contested by Umpila, the steps necessary to pull back any determination to this area would mean postponement until the end of 2022, at the very least. There may be older or infirm Southern Kaantju people for whom that will be too late. Further, if Southern Kaanjtu must face a trial over this boundary, that is a long, complex, resource intensive and stressful process. It is always the elders who face the most strain and anxiety in any connection hearing. The Southern Kaantju group have been entitled to consider that their agreement at the mediation avoided this risk. There would need to be very strong justifications to compel them to now endure a different process.

70 Southern Kaantju had a concluded boundary agreement with Umpila. They had all the right people for that boundary in a room, and an agreement was reached. They were entitled to conduct their own s 87A authorisation meeting on the basis of that agreement, which is what they did. The Southern Kaantju authorised that boundary, and I have accepted evidence that at the mediation they were able to demonstrate a continuing connection to that country, in a way which is more likely than not to have been responsible for the Umpila people making a compromise agreement, rather than walking out and making no agreement.

71 My findings about their demonstration of a continuing connection, by the right people, are an independent reason why I consider it is appropriate to ensure the Southern Kaantju determination goes ahead next week.

Conclusion

Should Ms Omeenyo be joined to the proceeding?

72 It is neither necessary or appropriate for Ms Omeenyo to be joined to the proceeding. The evidence demonstrates she has been consulted and involved in the decision-making about boundaries with Southern Kaantju, even if she now does not agree with all the outcomes of the boundary negotiation process. I find she was prepared to agree at the time of the mediation, when it was the correct time for her to express a view one way or the other.

73 A further reason why she should not be joined is that to do so would put her position as an Umpila person ahead of others – Dr Singleton being but one example. That is not appropriate, especially where the evidence is so unclear about how much support she has for her adoption of Dr Thompson’s views about Umpila country being greater than others consider it is.

Should the Southern Kaantju consent determination be postponed?

74 For the reasons I have given, the Southern Kaantju determination next week should go ahead as scheduled. There is ample basis for the Court to be satisfied that the proposed boundary in that determination accurately represents the country to which Southern Kaantju people have a continuing connection.

75 I end these reasons by emphasising, as I did in Papertalk, some important points about mediation in native title. Mediation by this Court under the Native Title Act is serious business. The Native Title Act gives mediation a special and important place in resolving native title claims. The Court puts a tremendous amount of effort in terms of experienced people, time and facilities and resources, to enable groups to reach agreements. So do the land councils and representative bodies. Mediation allows people who hold native title to reach compromises; they can agree to compromise what they see as their native title rights to get an outcome, just like any other litigants can agree to compromise their rights to get an outcome. Those who participate must take their roles seriously. They must understand that they are making commitments when they sign mediation agreements. They will be held to those commitments by the Court, unless there is a very strong justification not to do so, such as proof of fraud or duress. The central role of mediation in the legislative scheme of resolving native title claims would be undermined and frustrated if the Court were to allow participants, being the right people for the country under discussion, to walk away from agreements they have made, and which have been made in circumstances where very large amounts of public resources have been expended to enable those agreements to be made. If people do not wish to agree, they should not agree. But when they do agree, where it is in its power to do so the Court should, save for the exceptional kind of circumstances I have referred to, hold them to those agreements.

I certify that the preceding seventy-five (75) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Mortimer. |

ANNEXURE a – MAP ANNEXED TO dR tHOMPSON’S REPORT

aNNEXURE b – MAP FILED PURSUANT TO THE cOURT’S ORDERS

SCHEDULE OF PARTIES

QUD 673 of 2015

Federal Court of Australia

District Registry: Queensland

Division: General

Second Applicant | SILVA BLANCO |

Third Applicant | WAYNE BUTCHER |

Fourth Applicant | JAMES CREEK |

Fifth Applicant | CLARRY FLINDERS |

Sixth Applicant | JONATHAN KORKAKTAIN |

Seventh Applicant | PHILIP PORT |

Eighth Applicant | HS (DECEASED) |

Ninth Applicant | REGINALD WILLIAMS |

Interested Person | REGISTRAR STRIDE |

Second Respondent | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA |

Third Respondent | AURUKUN SHIRE COUNCIL |

Fourth Respondent | CARPENTARIA SHIRE COUNCIL |

Fifth Respondent | COOK SHIRE COUNCIL |

Sixth Respondent | DOUGLAS SHIRE COUNCIL |

Seventh Respondent | KOWANYAMA ABORIGINAL SHIRE COUNCIL |

Eighth Respondent | NAPRANUM ABORIGINAL SHIRE COUNCIL |

Ninth Respondent | PORMPURAAW ABORIGINAL SHIRE COUNCIL |

Tenth Respondent | WUJAL WUJAL ABORIGINAL SHIRE COUNCIL |

Eleventh Respondent | ERGON ENERGY CORPORATION LIMITED ACN 087 646 062 |

Twelfth Respondent | FAR NORTH QUEENSLAND PORTS CORPORATION LIMITED (TRADING AS PORTS NORTH) |

Thirteenth Respondent | TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED |

Fourteenth Respondent | ALCAN SOUTH PACIFIC |

Fifteenth Respondent | BRANDT METALS PTY LTD |

Sixteenth Respondent | LESLIE CARL COLEING |

Seventeenth Respondent | MATTHEW BYRON COLEING |

Eighteenth Respondent | STEPHEN LESLIE COLEING |

Nineteenth Respondent | LANCE JEFFRESS |

Twentieth Respondent | RTA WEIPA PTY LTD |

Twenty First Respondent | AUSTRALIAN WILDLIFE CONSERVANCY |

Twenty Second Respondent | MICHAEL MARIE LOUIS DENIS BREDILLET |

Twenty Third Respondent | CRAIG ANTHONY CALLAGHAN |

Twenty Fourth Respondent | BERTIE LYNDON CALLAGHAN |

Twenty Fifth Respondent | GRAHAM EDWARD ELMES |

Twenty Sixth Respondent | JAMES MAURICE GORDON |

Twenty Seventh Respondent | PATRICIA LOIS GORDON |

Twenty Eighth Respondent | MARGARET ANNE INNES |

Twenty Ninth Respondent | COLIN INNES |

Thirtieth Respondent | KIM KERWIN |

Thirty First Respondent | WENDY EVA KOZICKA |

Thirty Second Respondent | CAMERON STUART MACLEAN |

Thirty Third Respondent | MICHELLE MARGARET MACLEAN |

Thirty Fourth Respondent | BRETT JOHN MADDEN |

Thirty Fifth Respondent | RODNEY GLENN RAYMOND |

Thirty Sixth Respondent | EVAN FRANK RYAN |

Thirty Seventh Respondent | PAUL BRADLEY RYAN |

Thirty Eighth Respondent | SUSAN SHEPHARD |

Thirty Ninth Respondent | SCOTT EVAN RYAN |

Fortieth Respondent | BARBARA JOAN SHEPHARD |

Forty First Respondent | NEVILLE JAMES SHEPHARD |

Forty Second Respondent | THOMAS DONALD SHEPHARD |

Forty Third Respondent | SILVERBACK PROPERTIES PTY LTD ACN 067 400 088 |

Forty Fourth Respondent | THE TONY AND LISETTE LEWIS SETTLEMENT PTY LIMITED ACN 003 632 344 |

Forty Fifth Respondent | MATTHEW TREZISE |

Forty Sixth Respondent | BOWYER ARCHER RIVER QUARRIES PTY LTD ACN 603 263 369 |

Forty Seventh Respondent | RAYLEE FRANCES BYRNES |

Forty Eighth Respondent | VICTOR PATRICK BYRNES |

Forty Ninth Respondent | GAVIN DEAR |

Fiftieth Respondent | SCOTT ALEXANDER HARRIS |

Fifty First Respondent | DEBORAH LOUISE SYMONDS |

Fifty Second Respondent | MICHAEL JOHN MILLER |

Fifty Third Respondent | MICHAEL DOUGLAS O'SULLIVAN |

Fifty Fourth Respondent | PATRICK JOHN O'SULLIVAN |

Fifty Fifth Respondent | ESTHER RUTH FOOTE |

Fifty Sixth Respondent | AMPLITEL PTY LTD AS TRUSTEE OF THE TOWERS BUSINESS OPERATING TRUST (ABN 75 357 171 746) |

Prospective Respondent | JOHANNE DOROTHY OMEENYO |