Federal Court of Australia

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Squirrel Superannuation Services Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 702

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | SQUIRREL SUPERANNUATION SERVICES PTY LTD Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

PURSUANT TO S 21 OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA ACT 1976 (CTH), THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. By distributing to members of the public at a seminar on 28 April 2015 as well as by email on 9,420 occasions in the period March 2015 to January 2019, a brochure (in the form of the annexure to the judgment) conveying representations that:

(a) the “old rule of thumb is that residential property in metropolitan locations doubles in value every 7-10 years and generates a rental return of around 4-5% per annum”;

(b) if one were to purchase an investment property worth $800,000 using a 25% deposit from one’s superannuation fund, and taking out a mortgage for the balance ($600,000), one would obtain:

(i) an average annual return in the form of capital growth of 10%, and hence annual capital growth of $80,000;

(ii) an average annual rental income of 4%, thus $32,000; and

(iii) an average total return of $112,000 (or a total of 14%);

(c) if one took the “traditional approach” of investing $200,000 in a regular superannuation fund, one would obtain an average annual return of $14,000 (or 7%), as compared with the average annual return of $112,000 (or 14%) from taking the approach referred to in representation (b) above, and as such, the difference between the two strategies is “remarkable”; and

(d) the costs to manage an investment property through a self-managed superannuation fund are “surprisingly low” compared with using a financial planner to select a series of managed investment funds and, in particular, that the annual costs of the former (given an investment property valued at $800,000) are around $2,400, whereas the annual costs of the latter (given a managed investment of $800,000) are around $8,800,

the Defendant in trade or commerce:

(e) engaged in conduct in relation to financial services that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive, contrary to s12DA(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 1989 (Cth);

(f) in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion of the supply or use of financial services, made false or misleading representations that services had performance characteristics or benefits, in contravention of s12DB(1)(e) of the Act; and

(g) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of financial services, in contravention of s12DF(1) of the Act

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Pursuant to s 12GBA(1)(a) of the Act, the defendant pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $55,000.

3. The defendant pay the plaintiff’s costs in the sum of $20,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[5] | |

[12] | |

[13] | |

[18] | |

[23] | |

[30] | |

[38] | |

[46] | |

[57] | |

[58] | |

4.1 Relevant principles in relation to orders by agreement and assessment of penalty | [58] |

[65] |

BURLEY J:

1 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) commenced the current proceedings on 18 December 2020 alleging that Squirrel Superannuation Services Pty Ltd had, by the publication of a document entitled “How buying established residential property can super charge your superannuation” (brochure), engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 12DA(1), 12DB(1)(e) and 12DF(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 1989 (Cth).

2 Squirrel is a financial services licensee which, from at least March 2015, marketed and sold its services of assisting customers to establish and operate a self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF), including for the purpose of purchasing residential property. It published the brochure in the course of marketing those services and in so doing made the representations which brought about the proceedings.

3 Although the proceedings were initially contested, Squirrel now admits the alleged contraventions. The parties have cooperated in preparing a statement of agreed facts and admissions, which was filed on 7 February 2022. They join in submitting to the Court that the following orders are appropriate to resolve the proceeding:

(1) declarations pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that Squirrel engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 12DA(1), 12DB(1)(e) and 12DF(1) of the Act;

(2) an order pursuant to s 12GBA(1)(a) of the Act (as it applied prior to 13 March 2019) that Squirrel pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty of $55,000; and

(3) an order that Squirrel pay a contribution to ASIC’s costs in the sum of $20,000.

4 For the reasons set out below, I am satisfied that these orders are appropriate.

5 Section 12DA(1) of the Act provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

6 Section 12DB(1)(e) provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

…

(e) make a false or misleading representation that services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, uses or benefits;…

7 Section 12DF(1) provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any financial services.

8 A person provides a “financial service” if, inter alia, they provide financial product advice or deal in a financial product: s 12BAB(1) of the Act. The term “dealing” encompasses applying for or acquiring, issuing, varying, or disposing of a financial product: s 12BAB(7) of the Act. A “financial product” is, relevantly, a facility through which, or through the acquisition of which, a person makes a financial investment: s 12BAA(1)(a).

9 Section 12GBA(1)(a) of the Act in the form that applied prior to its amendment in March 2019 is relevant to the assessment of penalty, having regard to the date of the contravening acts, which were agreed between the parties to have occurred during the period March 2015 to January 2019: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Allianz Australia Insurance Limited [2021] FCA 1062 at [119]-[120] (Allsop CJ).

10 Section 12GBA(1)(a) provided:

If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened a provision of Subdivision C, D or GC (other than section 12DA);…

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

11 Section 21(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act provides:

The Court may, in civil proceedings in relation to a matter in which it has original jurisdiction, make binding declarations of right, whether or not any consequential relief is or could be claimed.

12 The following are the subject of the statement of agreed facts.

13 Squirrel is a small proprietary company. It currently has 5 employees and contractors, along with a number of third-party service providers. It provides services to approximately 800 customers, representing 0.13% of the total number of approximately 600,000 SMSFs in Australia (as at September 2021).

14 In or about March 2015, Squirrel first distributed the brochure, a copy of which is reproduced in the annexure to these reasons.

15 At the time, and until 12 June 2018, Damien Linn was the company secretary and sole director of Squirrel. He held himself out in company documents to be Squirrel’s managing director and chief executive officer. Until 9 April 2020, Mr Linn was ultimately responsible for Squirrel’s compliance with financial services laws and the conditions that applied to its Australian Financial Services Licence, which had been granted pursuant to s 913B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

16 Mr Linn liaised and collaborated with the designer of the brochure and approved it prior to distribution. Squirrel distributed the brochure to individual members of the public in order to promote Squirrel’s services and build its business. Recipients were persons who had voluntarily provided Squirrel with their contact details or were amongst the 59 consumers who attended a seminar on 28 April 2015, where the brochure was available for collection.

17 The brochure contained four false or misleading representations. By making them, Squirrel intended to persuade the recipient of the brochure that the choice of using Squirrel’s services to establish and operate an SMSF to purchase and invest in residential property would lead to remarkably superior results compared with investing the same funds in a retail or industry superannuation fund.

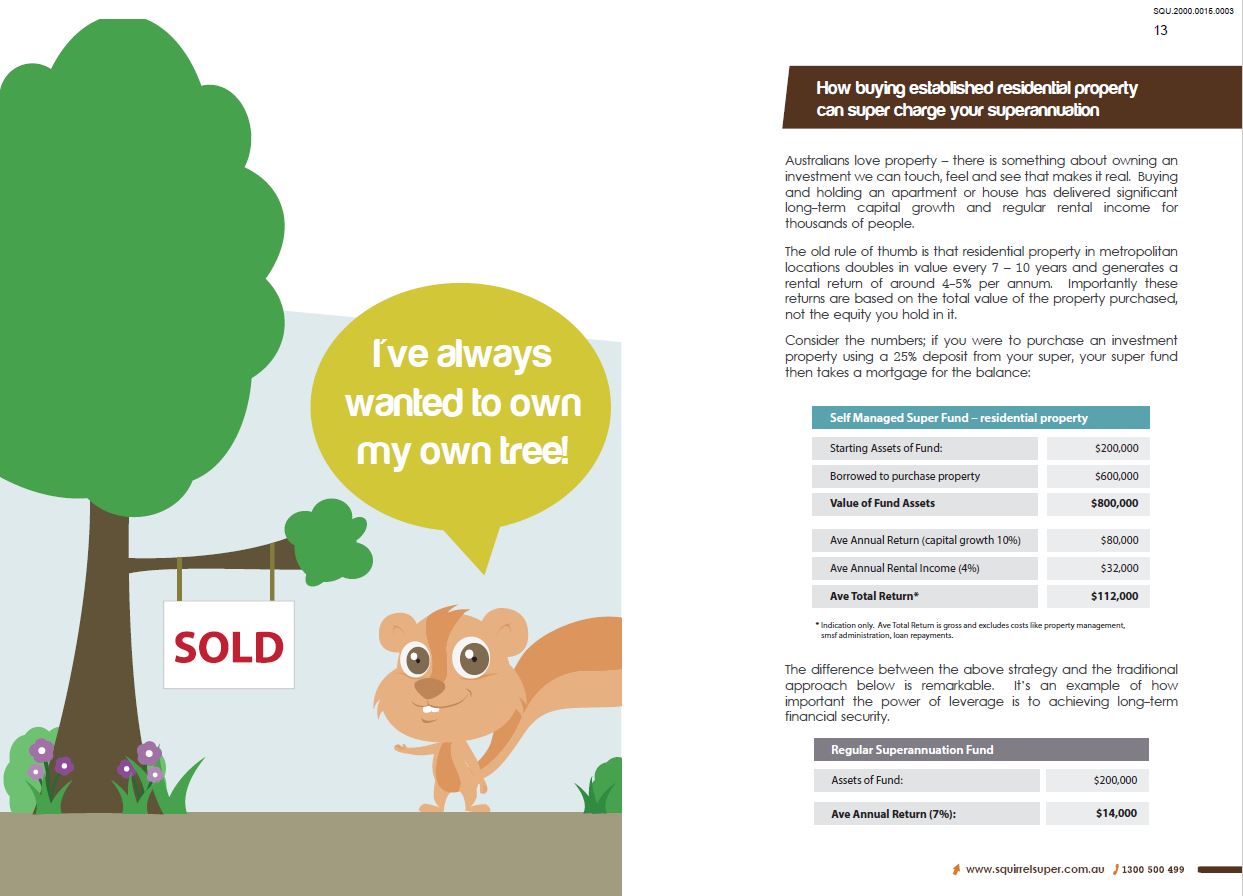

18 The first representation (page 2 of the brochure, second paragraph) was that the “old rule of thumb is that residential property in metropolitan locations doubles in value every 7-10 years and generates a rental return of around 4-5% per annum”.

19 The average annual growth in residential property prices in metropolitan locations in Australia in the:

(a) 10 years leading up to 30 December 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 respectively was approximately in the order of 5.42% (2014), 6.12% (2015), 6.04% (2016), and 5.22% (2017); and

(b) 7 years leading up to 30 December 2014 to 2017 respectively was approximately in the order of 4.11% (2014), 6.06% (2015), 5.39% (2016), and 5.5% (2017).

20 The consequence is that the average total growth in residential property prices in metropolitan locations in Australia in the:

(a) 10 years leading up to 30 December 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 respectively was approximately in the order of 69.57% (2014), 81.21% (2015), 79.75% (2016), and 66.45% (2017); and

(b) 7 years leading up to 30 December 2014 to 2017 respectively was approximately in the order of 32.57% (2014), 50.97% (2015), 44.38% (2016), and 45.54% (2017).

21 Accordingly, the first representation was false or misleading because it overstated the rate at which residential property in metropolitan locations had appreciated in the years preceding the receipt of the brochure. The first representation also conveyed that, from the time of the receipt of the brochure, residential property in metropolitan locations was likely to double in value every 7-10 years and generate a rental return of around 4-5% per annum.

22 In this respect the first representation was with respect to future matters and, at the time, Squirrel had no reasonable grounds for making it.

23 The second representation (page 2 of the brochure, from the paragraph beginning “Consider the numbers...” to the end of the table underneath that paragraph, including the asterisked words “Indication only. Ave Total Return is gross and excludes costs like property management, smsf administration, loan repayments.”), conveyed that, if one were to purchase a residential investment property worth $800,000 using a 25% deposit from one’s superannuation fund, and taking out a mortgage for the balance ($600,000), one would obtain:

(a) an average annual return in the form of capital growth of 10%, and hence annual capital growth of $80,000;

(b) an average annual rental income of 4%, thus $32,000; and

(c) an average total return of $112,000 (or a total of 14%).

24 The second representation was false or misleading because it was premised on the first representation (which was false or misleading for the reasons given above), and for the following further reasons.

25 First, the second representation was a representation with respect to future matters, namely the likely future capital growth, rental income and total return that an investor would generate by purchasing an investment property using a 25% deposit from their super and having their super fund take a mortgage for the balance.

26 Insofar as the second representation was a representation with respect to those future matters, at the time, Squirrel had:

(a) no reasonable grounds for representing that 10% average annual capital growth and 4% average annual rental income would be obtained in the future; and

(b) no reasonable grounds for projecting a future average annual return of $112,000.

27 Secondly, the asterisked qualification below the table (“Indication only. Ave Total Return is gross and excludes costs like property management, smsf administration, loan repayments”) is in small print and is insufficiently prominent to counter the dominant message comprising the second representation and does not properly or fully explain the fact that costs and charges would substantially reduce the (in any event overstated) returns, and indeed would be likely to more than offset them, resulting in a (pre-tax) negative cash flow, at least in the early years.

28 Thirdly, there is no disclosure of the significant upfront establishment costs, which, for setting up an SMSF and purchasing an $800,000 residential investment property, could reasonably be expected to be in the order of around $40,000 (including stamp duty, loan establishment costs, SMSF trustee and SMSF establishment costs, and conveyancing fees).

29 Fourthly, there is no or no adequate disclosure of the significant ongoing annual costs of this approach including:

(a) the annual repayment costs on a $600,000 loan, which is likely to be in the order of $35,000 to $50,000 (based on an assumed interest rate of 5.74% p.a., which was the average variable interest rate for SMSFs in 2015 based on 20 lenders assessed by CANSTAR); and

(b) other costs and expenses including property management fees, repairs and maintenance, rates, insurance, SMSF administration fees and levies, which is likely to be in the order of $8,000 per annum.

30 The third representation (at the bottom of page 2 of the brochure) conveyed that if one took the “traditional approach” of investing $200,000 in a retail or industry superannuation fund, one would obtain an average annual return of $14,000 (or 7%), as compared with the average annual return of $112,000 (or 14%) from taking the approach referred to in the second representation above, and, as such, the difference between the two strategies is “remarkable”.

31 The third representation was false or misleading for the following reasons.

32 First, the third representation was premised on the first and second representations which were both false or misleading for the reasons stated above.

33 Secondly:

(a) whilst the total average annual return in the table headed “Self Managed Super Fund - residential property” (which formed part of the second representation) was said to be gross;

(b) the total average annual return in the table headed “Regular Superannuation Fund” (which formed part of the third representation) was derived by Squirrel from a report published by the Grattan Institute in 2014 entitled, “Super sting: how to stop Australians paying too much for superannuation” which was net of fees and taxes and adjusted for inflation (which was then increased by Squirrel by 2% as a buffer),

hence the comparison was not like-for-like and was misleading.

34 Thirdly, the third representation failed to disclose any of the comparative disadvantages or risks in the approach of investing in residential property, compared with investing in a retail or industry superannuation fund, including that:

(a) there is a significant and unhedged concentration of risk from the absence of diversification of investments;

(b) real property as an investment is far less liquid (or readily sold) than assets such as cash or shares which are invested in a retail or industry superannuation fund;

(c) the maintenance of an SMSF is potentially time-consuming and complicated; and

(d) borrowing heavily ($600,000 out of $800,000) against the value of a property exposes the fund to interest rate fluctuations and other vicissitudes including the risk of a forced sale at less than full value.

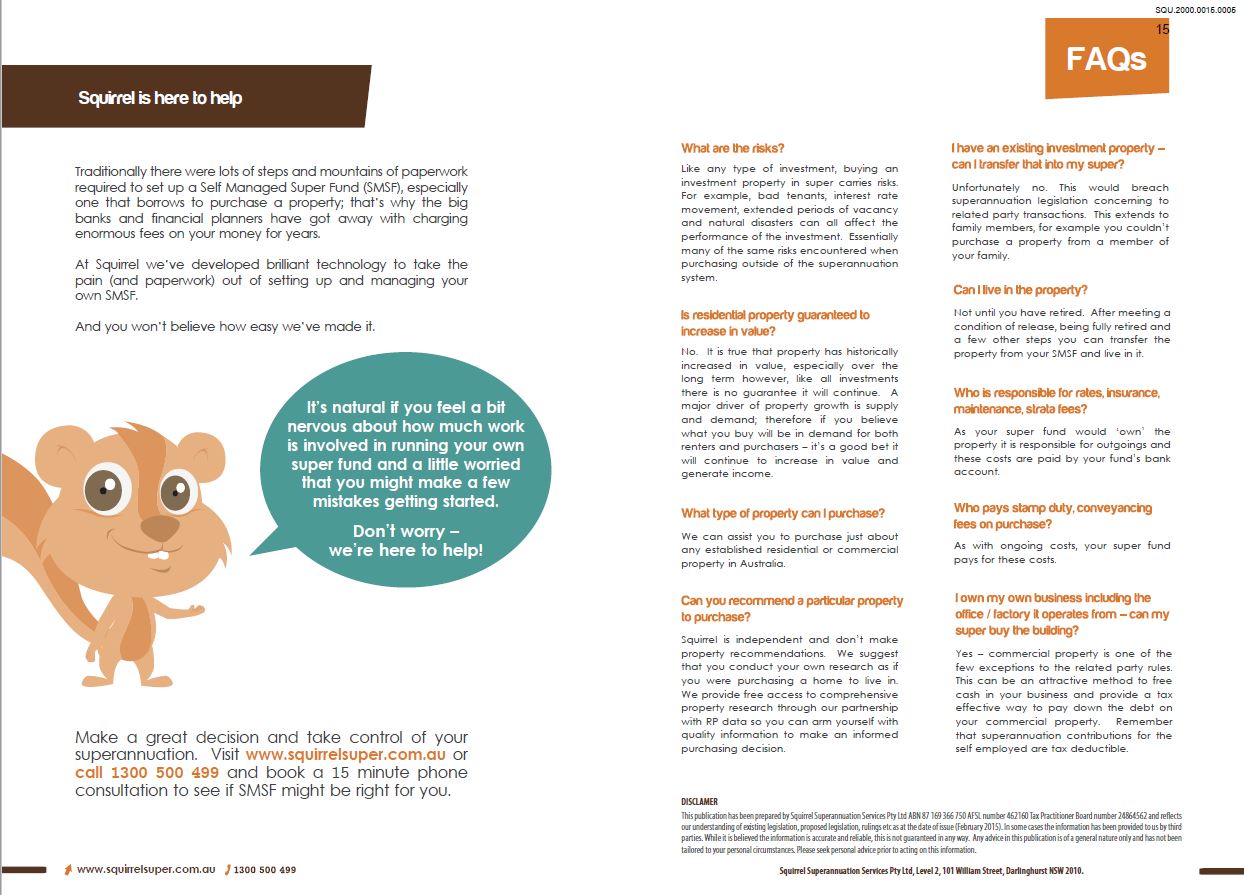

35 Fourthly, the misleading omissions (concerning costs, risks and disadvantages) were not remedied by the “FAQs” section on page 4 of the brochure which:

(a) did not detract from the dominant message contained in the third representation; and

(b) in any event did not disclose, or adequately address, the costs, risks and disadvantages described above.

36 Fifthly, the third representation was a representation with respect to future matters, namely the comparative future annual returns which one was likely to obtain using the two competing methodologies discussed at page 2 of the brochure.

37 At the time, Squirrel had no reasonable grounds for making the third representation insofar as it concerned these future matters, including because the third representation was premised on the first and second representations which also contained representations as to future matters which, at the time, Squirrel had no reasonable grounds for making.

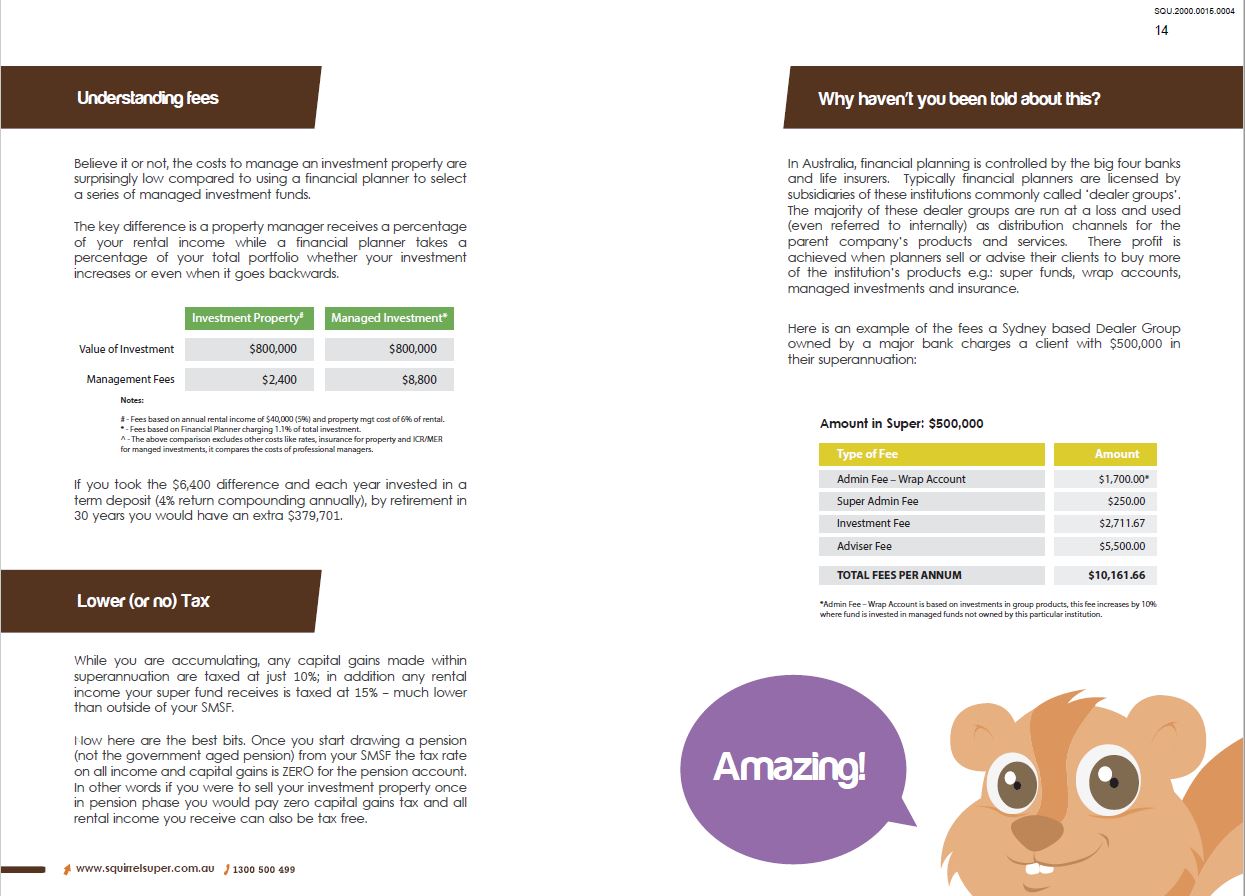

38 The fourth representation (at page 3 of the brochure under the heading “Understanding Fees”) conveyed that the costs to manage an investment property through an SMSF are “surprisingly low” compared with using a financial planner to select a series of managed investment funds and, in particular, that the annual costs of the former (given an investment property valued at $800,000) are around $2,400, whereas the annual costs of the latter (given managed investment of $800,000) are around $8,800.

39 The fourth representation was false or misleading in the following respects.

40 First, it implies (in the context of the preceding representations and the brochure as a whole) that it is necessary to use a financial planner on an ongoing basis to invest in a retail or industry superannuation fund. However, it is not necessary to use a financial planner to contribute to or invest in a retail or industry superannuation fund, and certainly not on an ongoing basis.

41 Secondly, the role of a property manager in managing an investment property does not correspond to the role of a financial planner in a retail or industry superannuation fund. The costs of using an SMSF to purchase an investment property will far exceed the yearly management fees of the property manager because they will extend to loan repayments, initial establishment fees, stamp duty, repairs and maintenance, taxes, rates, insurance, strata levies and fees (where applicable), and other costs and expenses.

42 Thirdly, the false or misleading nature of the fourth representation is compounded by the concluding words under the “Understanding fees” heading which assert that, if one took the $6,400 difference and invested it, one would have an extra $379,701 in 30 years.

43 For the reasons at [40] and [41] above, there is no proper comparison to be made between the expenses of a property manager and the fees which a financial planner might charge, even if they were used on an ongoing basis for ongoing advice.

44 Fourthly, the concluding paragraph of the fourth representation (beginning “If you took the $6,400 difference...”) was a representation with respect to a future matter, namely, that if one took the $6,400 “difference” each year and invested it in a term deposit returning 4% compounded annually over 30 years, one would generate an extra $379,701.

45 At the time, Squirrel had no reasonable grounds for making the fourth representation to the extent it was a representation as to future matters.

3.6 Events after first publication of the brochure

46 In the period from around 9 March 2015 to 14 January 2019, Squirrel staff (including Mr Linn) distributed the brochure as an email attachment to approximately 6,279 consumers. Additionally, from around 8 January 2018 to 31 July 2018, Squirrel staff sent emails containing a hyperlink to the brochure to around 2,150 individual consumers.

47 Squirrel received feedback from attendees following the April 2015 seminar and initially decommissioned the brochure. However, it subsequently continued to distribute the brochure.

48 On 10 July 2018, ASIC sent a letter to Squirrel noting its concern that the brochure contravened the Act causing Squirrel to again indicate that it would cease distributing the brochure. Squirrel, however, subsequently sent a further 112 emails either attaching or linking to the brochure. These additional instances of distribution were not disclosed to ASIC.

49 On 8 August 2018, Squirrel sent a letter to the recipients of the brochure it had identified including an apology and an offer of a complimentary consultation with one of Squirrel’s senior advisors. On this date, Squirrel stated to ASIC that the brochure had been distributed on 602 occasions. ASIC subsequently identified that there had been many more distributions of the brochure by this date.

50 On 18 October 2018, ASIC issued two infringement notices to Squirrel regarding the brochure for penalties of $12,600 per infringement notice. On 15 November 2018, Squirrel accepted in correspondence with ASIC that it was liable to pay the infringement notices and asked for an extension of time to pay the penalties. Squirrel did not pay the penalties.

51 On 20 August 2019, Squirrel was placed into voluntary administration. On 2 October 2019, Squirrel entered into a deed of company arrangement that came into effect on 31 January 2020.

52 It has not been brought to the attention of ASIC nor Squirrel’s current management that any recipient of the brochure suffered any loss or damage arising out of receiving the brochure, acting on any statements made in the brochure or obtaining from Squirrel the services described in the brochure.

53 Mr Linn is no longer involved in Squirrel’s management and has no financial interest in the business. The current sole director of Squirrel became involved in the management of Squirrel after the deed of company agreement was entered and has not received a salary or bonus from Squirrel.

54 Squirrel failed to lodge its audited financial reports on time for the 2019 and 2020 financial years, matters which have since been rectified. It has limited capacity to pay a penalty, including because its audited accounts for the year to 30 June 2021 show losses after tax of ($564,788) and net assets of $651,760.

55 Squirrel has not been the subject of previous adverse finding by a court.

56 ASIC and Squirrel resolved to settle these proceedings on 22 September 2021 following mediation.

57 In direct answer to the allegations of contravention, Squirrel makes the following admissions:

By distributing to members of the public at the Seminar as well as by email on 9,420 occasions in the period March 2015 to January 2019, a brochure conveying representations that:

a. the “old rule of thumb is that residential property in metropolitan locations doubles in value every 7-10 years and generates a rental return of around 4-5% per annum”;

b. if one were to purchase an investment property worth $800,000 using a 25% deposit from one’s superannuation fund, and taking out a mortgage for the balance ($600,000), one would obtain:

i. an average annual return in the form of capital growth of 10%, and hence annual capital growth of $80,000;

ii. an average annual rental income of 4%, thus $32,000; and

iii. an average total return of $112,000 (or a total of 14%);

c. if one took the "traditional approach" of investing $200,000 in a regular superannuation fund, one would obtain an average annual return of $14,000 (or 7%), as compared with the average annual return of $112,000 (or 14%) from taking the approach referred to in the second representation above, and as such, the difference between the two strategies is “remarkable”; and

d. the costs to manage an investment property through an SMSF are “surprisingly low” compared with using a financial planner to select a series of managed investment funds and, in particular, that the annual costs of the former (given an investment property valued at $800,000) are around $2,400, whereas the annual costs of the latter (given a managed investment of $800,000) are around $8,800,

the Defendant in trade or commerce:

e. engaged in conduct in relation to financial services that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive, contrary to s12DA(1) of the ASIC Act;

f. in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion of the supply or use of financial services, made false or misleading representations that services had performance characteristics or benefits, in contravention of s12DB(1)(e) of the ASIC Act; and

g. engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of financial services, in contravention of s12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

4.1 Relevant principles in relation to orders by agreement and assessment of penalty

58 The principles relevant to the making of orders and declarations by consent are well settled. First, there is a well-recognised public interest in the settlement of cases such as the present. Secondly, the orders proposed by agreement must not be contrary to the public interest and at least consistent with it. Thirdly, when deciding whether to make orders that are consented to, the Court must be satisfied that it has to power to make the orders proposed and that they are appropriate. Fourthly, once the Court is satisfied these requirements are met, the Court should exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising the proposed settlement terms, particularly where both parties are legally represented and able to understand and evaluate the desirability of the settlement. Finally, in deciding whether agreed orders conform with legal principle, the Court is entitled to treat the consent of the respondent as an admission of all facts necessary or appropriate to the granting of the relief sought against it: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [70]-[73] (Gordon J) and the authorities cited there.

59 Furthermore, where declarations are sought by consent, the Court will exercise its discretion under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act, but provided that; (a) the issue in respect of which the declaration is sought is not hypothetical or theoretical; (b) the applicant has a real interest in raising it; and (c) there is a proper contradictor; the Court will be slow to refuse to give effect to the terms of a settlement reached by consent; Coles Supermarkets at [75]-[76].

60 The principles regarding the imposition of pecuniary penalties in civil proceedings are well established, and were recently restated in Australian Building and Construction Commission v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 399 ALR 599 at [14]-[19]. Although that decision concerned s 546 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), the observations in that case concerning the assessment of penalty for the purpose of civil penalty provisions in the Act are apposite. In that regard, the main points to observe are that:

(a) The purpose of a civil penalty is primarily protective, in promoting the public interest in compliance by deterrence from further contravening conduct: Pattinson at [15];

(b) A penalty of appropriate deterrent effect “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Pattinson at [17] citing Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 at [62] (Keane CJ, Finn & Gilmour JJ);

(c) The assessment of penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors including: (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; (2) the amount of loss or damage caused; (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place; (4) the size of the contravening company; (5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market; (6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; (7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level; (8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, as evidenced by educational programs or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and (9) whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to contravention: Pattinson at [18].

(d) Ultimately the matters identified in (c) are not to be considered to be a rigid list of factors to be ticked off (Pattinson at [19]), but rather are to inform a multifactorial investigation that leads to a result arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” addressing the relevant considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [44] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ).

61 Pecuniary penalties for contraventions of ss 12DB and 12DF of the Act are dealt with in s 12GBA. Contravention of s 12DA is specifically excluded from the pecuniary penalty provisions: s 12GBA(1)(a).

62 As set out at [10] above, s 12GBA(1) relevantly provided that if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened one of these sections, it may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

63 Section 12GBA(2) provided at the relevant time:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Subdivision to have engaged in any similar conduct.

64 Section 12GBA(3) (as it was at the relevant time) provided in item 2 that the maximum penalty for each contravention by a body corporate was 10,000 penalty units.

65 As a result of the admissions made, I am satisfied that Squirrel, in trade and commerce, engaged in conduct in relation to financial services that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 12DA(1) of the Act. I am also satisfied that, in connection with the promotion of the supply or use of financial services, Squirrel made false or misleading representations in contravention of s 12DB(1)(e) of the Act that services had performance characteristics or benefits. I am also satisfied that Squirrel engaged in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of their services in contravention of s 12DF(1) of the Act.

66 I now turn to consider the assessment of penalty in relation to the contraventions under ss 12DB(1)(e) and 12DF(1).

67 I note that Squirrel distributed the brochure by email on about 9,420 occasions over the period from 9 March 2015 until 14 January 2019. The maximum penalty for a contravention of each of ss 12DB(1) and 12DF(1) would amount to several million dollars, in the event that this penalty were to be applied to each contravention. However, the appropriate range for penalty is best assessed by reference to other factors than the maximum potential penalty where the contraventions relied upon may be considered (as here) to amount to a single course of conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 at [231] and [234] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ). The totality principle requires the Court to consider the entirety of the underlying contravening conduct to determine whether the total or aggregate penalty is appropriate: Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; 166 CLR 59 at 63 [8]-[9].

68 Squirrel’s conduct in disseminating the brochure in its terms were such that it courted the risk that doing so amounted to contravening conduct, particularly in circumstances where the brochure included representations as to future conduct for which it had no reasonable basis for making. Squirrel’s misconduct was compounded when it continued to disseminate the brochure after receiving verbal feedback about it from attendees in April 2015 and, more particularly, after it had received notification from ASIC about its concerns in July 2018. The fact that Squirrel approved and distributed the brochure over an extended period may be taken to reflect a poor corporate culture of compliance and indicate that Squirrel had inadequate systems in place to ensure compliance with the Act. Further, although there is no evidence as to what profit Squirrel derived from its contraventions, it may readily be inferred that the representations were intended to persuade consumers that the choice of using its services would lead to superior results when compared with investing in a retail or industry superannuation fund and that Squirrel obtained a benefit from its contraventions.

69 Also relevant is the fact that Squirrel has a mixed record when it comes to cooperation with ASIC. Following notification of its concerns, Squirrel purported to cease using the brochure, but then continued its distribution. It also misled ASIC as to the number of occasions it had distributed the brochure. Furthermore, while it accepted liability to pay two infringement notices relating to the brochure, it failed to pay them. Such conduct should be discouraged.

70 As against these matters may be weighed the fact that Squirrel has agreed to pay the costs of the proceedings and has demonstrated contrition for its conduct by sending a letter containing an apology to recipients of the brochure. The person responsible for the misconduct was its then chief executive officer and sole director, Mr Linn, who designed and approved the brochure for dissemination. As set out above, Mr Linn is no longer involved in the management of Squirrel and has no financial interest in it. The company has since been placed in administration and is under new management. The current sole director became involved in the company after the contravening conduct had ceased and has received no salary or bonus from the company. There is no suggestion that since it came under its current management Squirrel has engaged in any further contravening conduct. Nor has any evidence been adduced to indicate that any recipient of the brochure suffered any loss or damage arising from receiving it.

71 In addition, Squirrel is a small company which has in the last financial year suffered relatively large losses after tax. It has limited means to pay any penalty and has agreed to pay such penalty and costs as are determined in instalments. In addition, it is noteworthy that Squirrel resolved with ASIC to settle these proceedings shortly after the second case management hearing.

72 Overall, whilst there have been many contraventions of the Act, in my view the relatively low penalty that the parties have agreed upon is appropriate in all of the circumstances of this particular case. I also consider that, having regard to the contravening conduct, it is appropriate to make the declarations sought, which are substantially in the form set out in section 3.7 above.

I certify that the preceding seventy-two (72) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Burley. |

Annexure

Annexure